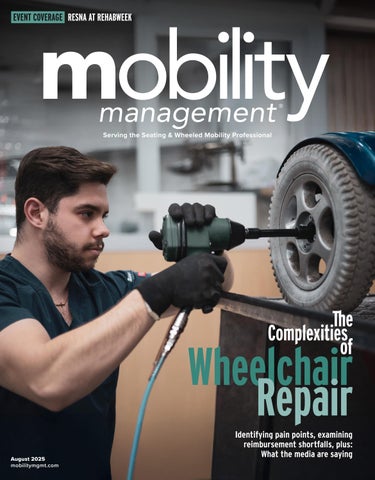

Identifying pain points, examining reimbursement shortfalls, plus: What the media are saying

Identifying pain points, examining reimbursement shortfalls, plus: What the media are saying

This spring, my washing machine began leaking, with rinse water eventually exiting downstairs into my neighbor’s garage. A week later, my manager, Executive Editor Bob Holly, reported his family’s washer had broken as well. (Bob and I very frequently align on editorial matters, and eerily, also on life’s misadventures.)

I called a repair person, who charged me $75 to drive a few miles to my home, haul the washer from its closet, and confirm the diagnosis initially made by the plumber summoned to deal with the leak. I needed a new drain hose, which the tech ordered, but didn’t arrive on time.

We rescheduled the repair for after I returned from the RESNA conference (event coverage on page 4).

Even with the back-ordered part and my trip to Chicago, my washer was back to properly sudsing and rinsing within two weeks.

In the meantime, I used my parents’ washing machine during a weekend visit. Bob used a laundry service. We both made do until our washing machines were back in business — a hassle, but completely feasible.

Compare that model — with plenty of repair service companies nearby, service call fees, quick turnarounds, workarounds that functioned just fine — to the repair model for complex seating and wheelchairs. The repair process for complex wheelchairs is bloated with superfluous prior authorization requirements, but without adequate compensation for service technicians’ commuting time to wheelchair riders’ homes or the time needed to diagnose what needs to be fixed. Wheelchair riders justifiably complain that repairs to their custom-configured chairs can take months, during which time they have no functionally equivalent equipment.

The efficient washing machine repair model “was set up by consumers and the washing machine [service] people,” said Wayne Grau, executive director of the National Coalition for Assistive and Rehab Technology (NCART) in our interview. “This repair process for wheelchairs was not created by the consumers; they never would have agreed to this. This was not created by us, either. This was created by regulators and by insurance companies, who put together this process and now require both the consumers and us to participate in that process.”

The current wheelchair repair process is inefficient and insufficient for everyone, including payers. But, like the wheelchairs it seeks to service, the process is also complex. In this issue, we start our deep dive into wheelchair repair, beginning with what the problems are and how we got here. m

Laurie Watanabe, Editor in Chief lwatanabe@wtwhmedia.com @CRTeditor

August 2025

mobilitymgmt.com

CO-FOUNDER & CHAIRMAN, WTWH MEDIA Scott McCafferty

CEO Matt Logan

EDITORIAL VP, EDITORIAL DIRECTOR Tim Mullaney

EXECUTIVE EDITOR Bob Holly

EDITOR IN CHIEF Laurie Watanabe lwatanabe@wtwhmedia.com

ART VP, CREATIVE DIRECTOR Matt Claney mclaney@wtwhmedia.com

SALES

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT & HEAD OF CONTENT STUDIO Patrick Lynch VP OF SALES Sean Donohue

INTEGRATED MEDIA CONSULTANT Randy Easton

Mobility Management (ISSN 1558-6731) is published 5 times a year, March/April, May/June, July/August, September/October, and November/December, by WTWH Media, LLC., 1111 Superior Avenue, Suite 1120, Cleveland, OH 44114.

© Copyright 2025 by WTWH Media, LLC. All rights reserved. Reproductions in whole or part prohibited except by written permission. Mail requests to “Permissions Editor,” c/o Mobility Management, 1111 Superior Avenue, Suite 1120, Cleveland, OH 44114.

The information in this magazine has not undergone any formal testing by WTWH Media, LLC, and is distributed without any warranty expressed or implied. Implementation or use of any information contained herein is the reader’s sole responsibility. While the information has been reviewed for accuracy, there is no guarantee that the same or similar results may be achieved in all environments. Technical inaccuracies may result from printing errors and/or new developments in the industry.

Corporate Headquarters: WTWH Media, LLC 1111 Superior Avenue, Suite 1120 Cleveland, OH 44114 https://marketing.wtwhmedia.com/

Media Kits: Direct requests to George Yedinak, 312-248-1716 (phone), gyedinak@wtwhmedia.com.

Reprints: For more information, please contact Laurie Watanabe, lwatanabe@wtwhmedia.com.

CHICAGO — For the Rehabilitation Engineering and Assistive Technology Society of North America’s (RESNA) 2025 conference, it would be hard to imagine a more beautiful location than the city’s Riverwalk, where the Chicago River meets Lake Michigan.

For the May 12-16 conference, RESNA members had company. The meeting was part of RehabWeek 2025, which brought seven additional societies to Chicago. The International Consortium on Rehabilitation Robotics, the International Functional Electrical Stimulation Society, the International Industry Society in Advanced Rehabilitation Technology, the International Society for Virtual Rehabilitation, the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine, MotusAcademy, and Masterclass in Neurotechnology were co-located with the RESNA conference this year. Attendees came together for keynote sessions, exhibit hall hours, and lunch and coffee breaks, but they were also free to attend any RehabWeek educational sessions.

With thanks to RESNA, and Executive Director Andrea Van Hook in particular, here are my notes from an intriguing and inspiring few days in Chicago.

This was an engineering-centric event. Quantum Rehab was the only wheelchair manufacturer in the expo hall, though Matia Mobility (TEK RMD stander) and Partners in Medicine (Kinova JACO robotic arm) were among the other exhibitors.

There were plenty of seating-themed posters and educational presentations, but in Chicago, those presentations had an engineering flavor.

For example, Jonathan Duvall, Ph.D., and Jorge Candiotti, Ph.D., both from the Human Engineering Research Laboratories, University of Pittsburgh/U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, presented “How to Build a Simple Robot,” which explained robotic basics, from microcontrollers (acting as robots’ brains) to motors, motor controllers, power supplies, and user interfaces.

Duvall demonstrated a snow plow he built using the power base from one of his old power chairs. The chair’s elevating legrest was repurposed as a snow plow; the robot cost Duvall about $500 to build, excluding that recycled power base.

David Savage, ATP/ SMS, RET, Children’s Specialized Hospital, Mountainside, N.J., demonstrated an Early Intervention Power Wheelchair (eiPWC) in the 2025 RehabWeek Developers’ Showcase. “Volitional movement in early development promotes cognitive perceptual development,” the entry said. “Children with profound mental and physical disabilities are missing milestones due to their inability to move themselves through space. These same children often require supportive seating to maintain any position against gravity and have limited fine motor ability.”

The pediatric power mobility system on display combined a child’s existing seating — Sunrise Medical’s Kid-Kart seating, as one example — with a power base also adapted to carry a ventilator and oxygen equipment. The sample system was equipped with both switch and proportional controls to demonstrate that it could meet young children where they are. The system is also transportable, thanks to a compact power base and seating that is easily and quickly removable.

The Early Intervention Power Wheelchair won the Developers’ Showcase Audience Favorite Award, as voted on by attendees.

The conference was international in scope

RESNA’s keynote session took place the morning of Wednesday, May 14. RESNA President-Elect Rita Stanley introduced Sujatha Srinivasan, Ph.D., professor in the department of mechanical engineering and head of the TTK Center for Rehabilitation

Complex Seating. Simplified.

www.symmetric-designs.com

Fit a custom molded back in one appointment

Single tool adjustment

Completely ventilated custom seating

HCPCS Coded E2617 and E2609

Demos available

Beat the heat with for fully ventilated custom seating! StimuLITE ®

Back Kits available with a full range of sizes, shapes, padding/covers and mounting options.

Research and Device Development (R2D2) and the National Center for Assistive Health Technologies (NCAHT-IITM) at the Indian Institute of Technology, Madras, India.

Srinivasan spoke on “Engineering for Equity: Transformative Innovations in Assistive and Rehab Technology.”

In explaining that there are 30 million people in India with mobility-related disabilities, and that only one in 10 people worldwide have access to the assistive technology they need, according to the World Health Organization, Srinivasan noted the challenges in matching people to technology that would optimally support them.

“Too-simple” technology — donated standard manual wheelchairs, as one example — is often abandoned because it’s not functional enough for the recipients or is incompatible with users’ environments. Technology that’s too high end is often too expensive to be attainable and therefore remains confined to the academic arena.

The middle ground between those two planes is where technology needs to be developed, Srinivasan said. Technology that’s not too simple or too high end needs instead to be affordable, functional, and of high quality.

Among the assistive technology that Srinivasan has been involved in creating are the manual Superstand mechanical stander, and the Arise standing wheelchair, both of which require only human power to operate. The Arise wheelchair costs approximately $500 to manufacture, Srinivasan added.

Srinivasan also discussed the Neofly self-propelled wheelchair; the Neobolt power-assist system that attaches to the front of wheelchairs; and the NeoStand powered standing wheelchair, all from startup company Neomotion.

Srinivasan’s presentation discussed seating and wheeled mobility challenges on a global scale and provided a funding perspective outside of North America, as well.

The expo was dominated by exoskeletons, robotics, and other high-tech products.

One example: MouthPad, a hands-free touchpad custom built for every user. The device is 3D printed using dental resin following a dental scan of the user’s mouth. Worn on

the roof of the mouth, MouthPad translates head, mouth and tongue movements into “seamless cursor control and clicks” that can control phones, computers and tablets — but not power chairs, yet, due to wheelchair regulations in the United States. The device connects to electronic devices via Bluetooth and needs no software. Once inside the mouth, MouthPad is so unobtrusive that the user can carry on conversations without those around them being aware of the device.

But there were low-tech examples in the expo, as well. One attendee favorite in the Developers’ Showcase was a cylindrical dispenser that can be attached to a wheelchair and releases dogs treats at the single push of a lever. Because it doesn’t require hand dexterity, the device can be easily operated by wheelchair riders with limited hand function, thus making it possible for more people to bond with their pups.

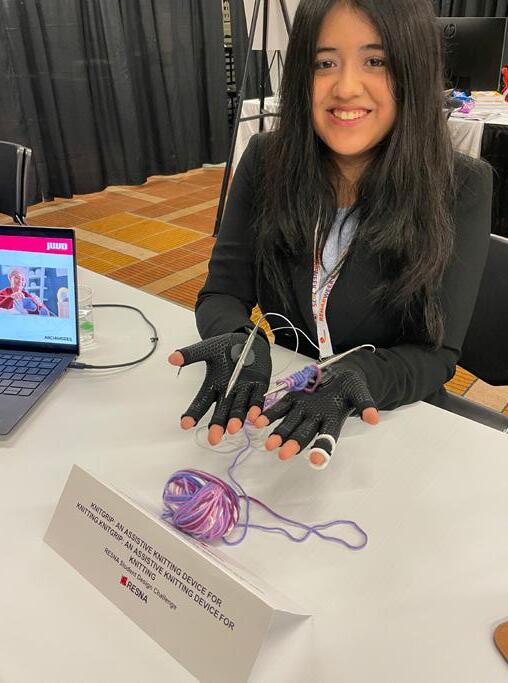

And a group of college freshmen entered their adaptive knitting device in the Developers’ Showcase. Designed for knitting fans experiencing limited finger dexterity due to conditions such as arthritis, these gloves enable their wearers to knit via palm movements.

My kind of town (and show), Chicago was I’m thankful to RESNA and RehabWeek for showing me assistive technology in a broader context.

My focus on Complex Rehab Technology is sometimes myopic, focused on function and medical necessity. Undeniably, those are important. But at RehabWeek, I also saw that assistive technology can make us more fully human, better able to participate. Happier. More fulfilled.

At its best, assistive technology integrates so seamlessly and works so well that we largely forget about it. As Dr. Srinivasan asked, how many of us wear custom-made prescription glasses without thinking of ourselves as “disabled” for using them?

That’s assistive technology at its best. That’s what I’ll remember from Chicago. m

— Story & photos by Laurie Watanabe

Our all-new Signature power positioning system has been completely re-imagined, delivering a new modern aesthetic, enhanced adjustability and all the durability and reliability Amylior is known for. Available on every Alltrack model, Signature boasts industry leading modularity and the capability to provide Tailored Solutions for even the most complex positioning needs.

• Tailored for the user

• Durability meets design

• Efficiency and reliability

• Adjustable and adaptable

• Custom Solutions

Wheelchair service is broken. The way forward is complicated

By Laurie Watanabe

Regarding repairs for complex seating and wheelchairs, stakeholders seemingly agree on one thing: The process takes too long, leaving wheelchair riders without the technology they depend on to optimize their function and independence.

From consumers and caregivers to clinicians, providers, manufacturers, researchers, legislators and policy experts, stakeholders agree that repair reform is desperately needed. But the problem itself has many causes.

Wayne Grau is the executive director of the National Coalition for Assistive and Rehab Technology (NCART).

“The process has been broken for a long time,” he said. “It’s just gotten worse. As more managed care companies have come in, there’s been a lot more emphasis on prior authorization and a lot more on regulations and so forth.

“The gist of it is consumers want their equipment fixed quickly. That’s incredibly reasonable. However, it’s not a cash market. It’s not

like a washing machine market or appliance market. It is controlled by insurance companies, and they have very specific things we’ve got to do to take care of that consumer. And that is what, in a lot of cases, is slowing everything down.”

Julie Piriano, PT, ATP/SMS, is NCART’s senior director of payer relations & regulatory affairs.

“It’s a consumer-initiated process without a consumer-driven solution,” she said of the current system. “Consumers identify the need, but can’t just make a phone call and get their equipment fixed, because the financial transaction isn’t between the consumer and their provider. There’s a middleman in there.”

One of the common requirements from middlemen — i.e., many funding sources, but excluding Medicare — is prior authorization for repairs to equipment that’s already been approved and provided as medically necessary.

“We understand that third-party payers have a fiscal responsibility to ensure that the money going out the door is appropriate, especially state Medicaid programs,” Piriano said. “As a taxpayer, there’s a part

of me that says, ‘I’m glad they’re making sure the expenditures are accurate and appropriate.’ That makes sense, and in conversations with third-party payers, we’re not saying, ‘Eliminate prior auth for the initial investment of the equipment.’ But once it has been determined that the equipment is necessary for the person as a lifetime medical need — because they have a permanent disability — then it’s understood that that equipment will require periodic maintenance and repair to keep it safe and operable for its five-year reasonable, useful lifetime.’”

Piriano added that because consumers typically are the ones who report that their chairs need service and are wary of being without them for any length of time — removing prior authorization requirements would not open the door for provider fraud or abuse.

“[Service] isn’t a cash cow,” she said. “People don’t call up and say, ‘I need my chair repaired’ unless they really do. Suppliers aren’t calling their customers saying, ‘Hey, do you need your chair fixed? I’ve got some parts here that I’d like to sell you.’ None of that occurs. So concern for the financial resources expressed by the insurance company, state Medicaid programs, and the MCOs [managed care organizations] is really unfounded. Yet they’re hesitant to consider alternatives, like the elimination of prior authorization for repairs to Complex Rehab, because they’re afraid that they’re either going to lose control over the expenditures, or they won’t have the necessary accountability for those expenditures.”

As a clinician, Piriano knows the consequences of a repair system that can deprive wheelchair riders of their equipment for months.

“Obviously, when the initial chair is spec’d out, it is designed to fit and function for that one person, based on their diagnosis, presentation, body shape, size and configuration,” she said. “When you think about the provision of Complex Rehab, it’s not just identification of need, prescription and delivery. There’s a lot that happens in between. Then once the chair is delivered, it’s fit, adjusted and individually configured the rest of the way for that person.”

She gave an everyday example of how personal configurability impacts function: “I wear a size-six shoe. Not a lot of people can fit into my shoe. Could you make it work? Could you put part of your

specific needs could fall out of the chair; develop a pressure injury; have cardiac, respiratory or circulatory issues, or problems with chewing, swallowing and digestion; or experience bowel and bladder complications in a short amount of time, Piriano noted. If drive controls aren’t precisely mounted where they need to be or aren’t programmed as needed, the consumer could have difficulty using them, thus impacting independence and the ability to engage in their activities of daily living.

“It’s duplicative,” Grau said of prior authorization requirements. “They’ve already approved the medical necessity for the chair; this is a repair. The insurance companies know that repairs are going to be needed, so why make people jump through hoops and wait for paperwork to be collected and requests to be approved to get it done?”

Without prior authorization requirements, he added, “In some cases, we could get things fixed pretty quickly. Like a set of batteries: Most [service] drivers have extra batteries in their vehicles. They could go out [to the client’s home] and say, ‘Yep, you’ve got bad batteries. Here are new ones. Thank you. Bye.’”

In explaining why repairs frequently take so long, Grau said, “A lot of [consumers] don’t have access to transportation. Those wheelchair-accessible vans are not cheap. There’s very limited funding and coverage for people to take public transportation. With non-medical transportation, they can take it to go to the doctor or the dentist, but they’re not allowed to take it to come in for a [wheelchair] repair.

“So that means we have to go to the person’s home — which we’ll do when necessary. There are going to be some people who cannot get into our facilities. But if we can get additional people to come into our facilities, where we have more parts and we have all the tools, we can get it done quickly. I’ve worked on a power chair before. When it’s on the ground, it’s not easy. It’s a lot easier and quicker to bring it into a shop, lift it up and do all the work.”

Doctors no longer make house calls because they can treat more patients by seeing them in the office. But Grau said currently, 82% of repairs, on a national basis, are done in consumers’ homes.

We have to protect those consumers who need service in their homes, we absolutely do

— Wayne Grau

foot in and use it temporarily? You could, but bad things are going to happen to your foot if you have to use it for days or weeks, waiting for shoes that fit your feet to be fixed and returned to you.”

Piriano added that an identically configured wheelchair to use on a loaner basis “isn’t readily available. It’s not standard DME [durable medical equipment], used for a minimal number of hours a day so a standard size would work. With CRT, the intimate fit of the device is what’s critical. And when you try to make do, preventable secondary complications and adverse occurrences can happen pretty quickly. ”

Consumers borrowing a power chair not configured to their

“We have to protect those consumers who need service in their homes, absolutely we do,” he said.

“But if there was funding for medical transportation to our facilities, as part of the continuum of care, I think a lot more consumers would prefer to come in and have their chairs repaired quicker and in a setting where we can check out a lot of different things to make sure everything is operating properly.”

But doing more repairs at provider locations only improves the process if prior authorization doesn’t stand in the way.

“Even if the consumer can bring their wheelchair in, and the diagnostics can occur right there, and all the things that are needed to fix it are right there — the repair cannot be done because the provider has to get a prescription and documentation that the person still has the disability, still needs the wheelchair, and is still using it,” Piriano said. “Then everything needs to be submitted for

prior authorization, and we have to wait for the payer to determine if they will cover and pay for the repair, when you could literally fix it and send [the consumer] out the door in an hour. Unfortunately, they have to either leave their chair and go home with one that does not have the same intimate fit, or go back home with a chair that’s in need of repair. So yes, coming in is advantageous, except that you can’t do anything once they come in, and that’s a problem too.”

Provider perspectives: Inventory challenges, funding gaps

Even in the much more straightforward worlds of washing machine or automotive repair, dealers don’t stock every replacement part in existence. The same goes for complex wheelchair providers.

“We’ve got five major manufacturers of [power wheelchairs] out there, and they all have a lot of different parts,” Grau said. “There are some similar parts — batteries, for instance, and casters. But there are 75,000 different SKUs. There’s no way [a provider] can carry 75,000 parts.”

Most providers, he added, “will carry the top 25 to 40 parts across the board. They’ll have them in stock: battery chargers, batteries, casters, arm pads. But for anything like a motor, they’re going to have to order it. And motors change over time, too, as they get better. That’s why providers carry a lot of parts, but they can’t carry everything.”

From the provider perspective, another problem is lack of funding for critical portions of the repair process, such as commuting to the consumer’s home and, once they arrive, diagnosing the wheelchair’s problem. Unlike appliance technicians who charge service call fees to drive out and examine a homeowner’s dishwasher, wheelchair techs aren’t reimbursed for that time or expertise, even if the commute is long and needs to be repeated once the prior authorization comes through.

“Reimbursement is not there for us to be going to consumers’ homes, and it’s not there for the repair assessment time,” Grau said.

Mixed messages for manufacturers?

Complaints about the repair process regularly point fingers at manufacturers,

especially power chair manufacturers, who are called upon to produce more durable products with longer warranties (see sidebar) ... though without, of course, higher reimbursement rates for providers.

Piriano said manufacturers are, in fact, producing devices to high standards as required by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

“For the chairs — at least in the power mobility space, which is where this typically comes up — to be code verified, there are dedicated, independent testing requirements in place,” she said. “They validate that chairs will last a five-year, reasonable, useful life.

“For the testing protocol — and especially when it comes to the drop and drum test, the strength and fatigue testing — the chairs literally get dropped 6,667 cycles. They’re run through the ringer. So the concept [that manufacturers should be making] better chairs — I can’t wrap my head around that, because they are required to be made to a standard that is pretty high.”

Piriano acknowledged that even rigorous testing can’t always duplicate real-life usage — the fact that some wheelchair riders stay mostly indoors, while others are in their chairs 12 to 18 hours a day and riding over rocks, gravel, concrete and other rougher terrains. That doesn’t mean chairs that need repairs weren’t built durably; it simply means they are being used

“When you go through the doorway and

you shear off your joystick because you cut it too close, that has nothing to do with ‘The manufacturer didn’t make it strong enough,’” she said. “They’re not tanks. You could add a whole bunch of different structural materials and welds and make it a really heavy beast of a chair that now won’t fit on the lift, right?”

Grau agreed: “We can make you a tank with a seating system, but you’re not going to be able to take it anywhere.”

The mainstream media has been quick to blame manufacturers and providers for repair problems — at least in part leading to rightto-repair movements in multiple states. But Grau and Piriano are hopeful that stakeholders can come together to effect change.

“The system was not set up by us or the consumer,” Grau said. “We’ve tried to reach out to payers and explain this to them. You’re seeing a spotlight being put on prior authorization overall in D.C. — not just for us. It’s time that insurers make common-sense changes. If a person has ALS [amyotrophic lateral sclerosis], they know [service must] be expedited. But for CRT in general, it has to be expedited because consumers could be stuck at home otherwise.”

Educating stakeholders is key.

“Trust users of the chair to know when something’s not operating properly,” Piriano said, advocating for “training them how to be good, first-class noticers. For wheelchair

users, when it’s not sounding right, operating properly or not going the distance, they need to able to articulate that, instead of waiting until it dies to say, ‘My chair needs to be fixed.’

“But they’re very hesitant. They know they can’t be without their chairs. We’ve got to work to fix the problem and start regaining their trust, so that if something’s amiss, they’re not afraid to make the call.”

Grau added that the more that legislators and their staffs learn the complexity of the issue, the better they’ll see the entire challenge.

“If there’s anything we need to learn, it’s that all stakeholders need to work together,” he said. “It’s not just the providers or the consumers or the manufacturers or the clinicians or the academics. It’s everybody.”

Grau pointed to a hard-won 2023 funding victory. “We got one great thing done by working together, and that was seat elevation,”

he said of Medicare’s coverage decision. “That took a long time, but we got it done because everybody was rowing in the same direction. Everybody wanted the same thing.

“This is that same issue. We want the same thing: quick repairs for wheelchairs. We’ve got to stop looking at each other and saying, ‘What’s your fault?’ Let’s work together to get this thing done. Because if we can do this, this is going to be fantastic for the consumers. It would be win, win, win for everybody.”

Piriano said the key is educating all stakeholders. “When we think about legislators and regulators who aren’t really part of the process — this has to be well defined and communicated. Then our group gets bigger, because legislators and regulators are, in fact, part of the process. They then influence the laws and the regulations that govern how this moves forward. It’s kind of exciting.” m

the remote assessment.” Prior authorizations would be eliminated for repairs costing less than $1,000.

A Massachusetts House bill, H. 1278, introduced by Rep. James O’Day (D-Worcester), would also set deadlines for wheelchair repair, along with eliminating prior authorizations for repairs on wheelchairs with prescriptions that are less than five years old.

In June, the New York State Senate passed the Consumer Wheelchair Repair Act, S. 4500, authored by State Sen. Patricia Fahy (D-Albany). The bill — which has a companion version in the State Assembly — “aimed at addressing long repair wait times and limited consumer choice for powered wheelchair users,” the New York State Senate reported on June 16. “The bill would require manufacturers to provide independent repair providers and wheelchair owners with the necessary parts, tools and documentation to conduct repairs, ensuring a more competitive and accessible repair market.”

“I’m thrilled that the State Senate has passed my legislation that will provide wheelchair users in New York a real right to repair,” said Fahy. “For too long, wheelchair users and New Yorkers living with disabilities have faced outrageous delays and exorbitant costs just to repair their own essential mobility equipment. This bill gives consumers the right to access the resources they need to repair their own wheelchairs or work with independent repair providers, cutting down on unnecessary wait times and improving mobility for thousands of New Yorkers.”

In January, Massachusetts State Sen. John J. Cronin (D-Worcester and Middlesex) introduced S. 210, legislation that would expand wheelchair warranty protections. Among the changes: Wheelchair manufacturers would be required to provide warranties of at least two years, and could be required to replace the wheelchair or refund its purchase price if repair efforts fail. The bill would also require the manufacturer or authorized dealer to perform remote repair assessments within three business days of being notified by consumers “and if necessary, perform an in-person assessment not more than four business days following

The stories — a tiny sampling of wheelchair repair reporting in the mainstream media in recent years — demonstrate the challenges the seating and wheeled mobility industry faces in trying to bring about repair reform … and how reporting often slants against the industry.

For example, GBH, a media company reporting on the Massachusetts bills, quoted a wheelchair user who said the bills are “about restoring dignity, independence and basic rights.”

The story noted that Wayne Grau, executive director of the National Coalition for Assistive and Rehab Technology (NCART), “voiced some of the only opposition” to the Massachusetts bills, even as Grau noted that NCART had “engaged with various stakeholders, including consumers, legislators and MassHealth,” the commonwealth’s Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program.

Grau also tried to explain the challenges of manufacturer warranties being extended to two years, but the story gave that minimal mention.

These bills are just a few examples of the challenges that NCART and other professional and consumer organizations face as they work to reform the layers upon layers of mobility repair policies. As consumers understandably demand quicker repair turnaround timelines — seemingly with the mainstream media in agreement, judging from the amount of coverage the topic receives — seating and wheeled mobility manufacturers and providers contend with prior authorization policies they didn’t create but must follow, and rules that change from state to state (and territories) and payer to payer.

As Grau told Mobility Management, “The system is not set up by us or the consumer. There are a lot of different issues here. And there’s not one silver bullet. But we have ideas for what we think will fix it. We want to focus on taking care of the consumer and getting this fixed as fast as possible, period.” — L. Watanabe m