WINONASTATE UNIVERSITY

A History of One Hundred Twenty-Five Years

R. A. DuFresne

A History of One Hundred Twenty-Five Years

R. A. DuFresne

A History of One Hundred Twenty-Five Years

To thosesteadfast souls whose vision and courage established here the foundations upon which succeeding generations would build.

Copyright 1985 by Winona State University Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 85-50717

Printed in the United States of America

All Rights Reserved

Everyone admires success. In relating the history of Winona State University, Dr. Robert DuFresne shares with his readers a great success story —the events and circumstances that have created this outstanding institution. Published on the occasion of the one hundred and twenty-fifth anniversary of the founding of Winona State, the book is timely, serving to remind us that if we are to plan our future, we must have an understanding of from whence we have come.

No one is better qualified to tell the story of Winona State than is Dr. DuFresne. Having served with distinction as President of Winona State for over a decade, from 1967 to 1977, he is currently a Distinguished Service Professor in political science. In addition to his professional duties Dr. DuFresne serves the University in special areas where his experience and expertise are unusually beneficial. While we know that writing a university history is usually a labor of love—and this work is no exception—it is also a task demanding long hours of painstaking detail. With clarity and great care Dr. DuFresne chroniclesthe transformation of a struggling normal school with thirty-one students into a regional comprehensive university with a student body of over five thousand. ‘Throughout the book the reader will be impressed with the strong resolve shown by faculty and staff in building and maintaininga fine institution of higher learning designed to serve the citizens of Minnesota. Through strong commitment and dedication the school became not only a place to prepare teachers (thousands of them) to teach children (millions of them), but it also became a symbol of civilization in a pioneer land.

I trust that the readers of this book will find, as I have, that the book describes a legacy and creates an appreciation for Winona State’s distinguished past. At the same time the book heightens an understanding of the present and sharpens a focus on the future for this fine old institution.

Thomas F. Stark President Winona State University

The history of WSU falls rather neatly into three eras. The first began in 1860 when the doors first opened, and continued up to the turn of the Century, a span of forty years during which the school struggled just to exist in this rugged pioneer land during the early years of Minnesota’s statehood.

By 1900 the institution had become firmly established, at least to the point where it was receiving regular if insufficient funding from the legislature, and was beginning to assume a few of the physical and scholarly characteristics of an academic enterprise. At that point it needed a strong president who would lead it out from its historic confines of “normal training” to where it could become a regular four-year teachers college with full accreditation and genuine degree offerings.

It found that leader in the person of Guy Maxwell who was to be its mentor for nearly forty years and under whom the Normal would mature and develop in spite of a major war and a major depression. This period extended from about 1900 to the time of Maxwell’s death in 1939 and the beginning of World War II.

The third period began at that point and continues on through the date of this publication, again a period of about forty years. During this era the institution changed even more dramatically than during the Maxwell years, going from the status of a well-established teachers college through that of a rapidly growing state college whose teacher education role was steadily being challenged by the growth of other professional and liberal arts programs, until in 1975 it assumed the title, Winona State University. By then it was a regional institution of 4,000 students offering a variety of programs and options not even dreamed of forty years earlier.

The development of Winona State from its beginnings in 1860 through its Centennial in 1960 has been recorded in three separate works. The first of these, entitled HISTORICAL SKETCHES AND NOTES: Winona State Normal School 1860-1910, was compiled by C. O. Ruggles, a member of the history faculty. It is a relatively com-

plete review of those early years and was the product of the combined efforts of many individuals with Mr. Ruggles serving as coordinator and editor.

The second work, entitled The Winona State Teachers College, was edited by Erwin S. Selle, who taught government and sociology. It encompassed the years 1910 through 1935. Mr. Selle, too, shared the authorship, describing his duties as “editing the contributions that came from different resources so that they will fit into the scheme as harmoniously as possible.”

The last version of the school’s history was prepared for the celebration of the Centennial Year, 1959-1960, and was entitled First State Normal School 1860, Winona State College 1960. It was published in the form of six quarterly bulletins, four of them serving as actual chapters, and the last two making up an extended appendix of alumni listings. Written byJean Talbot, Professor of Physical Education, it consisted of a brief overview of the first seventy-five years, but more importantly, summed up much of what happened during the twenty-five years between 1935 and 1960, a very large contribution to the record, much of which might be lost by this time but for her work.

In considering this undertaking, the question arose whether simply to record events from 1960, thus adding a fourth book to the collection, or somehow bring together that which had already been written, adding developments over the last twenty-five years. The decision was to consolidate it all into one volume for obvious reasons: 1) The previous history was recorded in three separate volumes, written by several different persons over different periods. This makes it difficult to read them without losing continuity and perspective, even if one should be so fortunate as to locate one of the few copies still in existence. 2) The history of the institution had not been recorded since 1960, a period of twenty-five years during which it experienced its greatest growth, its greatest physical expansion and its greatest change in purpose. 3) The necessary expansion or contraction of previous writings required to synthesize and bring it all together called for access to documentation immediately, before the old books and records became permanently lost or misplaced. Also there were still a number of persons living in Winona whose memory of the campus went back to the ’20s and before. But another ten or twenty years would see many of them having gone off to California or their eternal reward as the case may be, making them quite unavailable for documentary evidence in either event.

This is one of the oldest, ongoing institutions of any kind in the state, and an important one in the lives of many people. It was fascinating to consider in depth its beginnings, its continuing development, its contributions to the betterment of this great state. It has few rivals in these respects, for it goes back to the very beginning of statehood.

The history of a college or univefYsity is not as exciting as an account of the Great Train Robbery or Scenes from the French Revolution. The reader will probably never stand up and cheer as Good triumphs over Evil, nor be titillated by tales of intrigue, sex or violence. On the contrary, faculty and students alike appear to have been a’ decent lot overall. I thoroughly enjoyed writing it at any rate, and if a few people read it and become better acquainted with their alma mater, thereby enhancinga bit the loyalty, pride and appreciation which this old school deserves, my efforts will have been amply rewarded.

I am indebted to several people who have assisted me in various ways: Dr. Nels Minné, former president, who contributed materially as did Dr. John Fuller, professor emeritus and a former dean; Dr. George Bates whose study of the histery of WSU women in the work force is a part of the appendix; Ms. Barbara Atherton who extensively reviewed and advised over the complete text; Ms. Carol Rustad whose efforts were essential in getting the manuscript in final form for publication; Dick Davis who advised on design. Other individuals who at various times reviewed and typed the manuscript were Joan Valentine, Michelle Dupont, Betty Grangaard, Peggy Erickson, and Mary Pieper. Many others gave advice and information. My thanks goes to all of them.

R. A. DuFresne

Proper documentation is one of the outward manifestations of a scholarly presentation, and is presented at the ends of the chapters. However the trappings of scholarship can be overdone, so sources that seem obvious from the context or common sense have been omitted. Also much of the material in the first five chapters comes directly from the Ruggles book or the Selle book since that portion is essentially a rewrite of those works, and I have not presumed to make any essential changes in what they had to say. Annotations relevant to the text are shown at the bottom of the appropriate pages.

The normal school idea seems to have originated in France about 1681 with the establishment of the “Ecole Normale” at Rheims.

Founded by the Abbé de la Salle, it became the famous Christian Brothers School, forerunner of the system of schools still operating under the aegis of that same Catholic order today.

The theory was simple enough. It called for the training of selected individuals in the basic skills of reading, writing, arithmetic and related subjects, with the thought that those individuals would then pass that knowledge on to groups of children for their improvement and edification as well as for the overall betterment of the State, the Church, or whatever the sponsoring agency might happen to be.

If that appears elementary in this day and age when education is seen not only as an advantage but as a legal right, it was not so simple back then. Education was anything but universal. It was, in fact, just emerging as a concept, a product of the Renaissance. To most people of those far off times the thought of everyone being able to read and write was as remote as most of the other social advantages which the Western World now takes for granted.

The concept eventually caught on, however, and normal training along withit. Roughly one hundred years later the press for secularly trained teachers in France was such that the National Assembly established another Ecole Normale in Paris. In the meantime the idea had been introduced into Germany by Herman August Frank and his disciple, Johann Julius Hecker as early as 1738. By the end of the century Germany (Prussia) boasted six such institutions. It was from the German system that the idea was brought to the United States.

Although universal education was little discussed in the early history of this country, and not even mentioned in the Constitution, visits made to Europe for the inspection and personal examination of its

normal school system by such early educators as Professor Julius Bache ofGirard College, Professor Edmond Stowe of Lane Seminary, Ohio, and Horace Mann of Massachusetts caused a marked awakening among educational circles in the United States.!

It was urged in the Massachusetts Magazine as early as 1789 that steps be taken to improve education. Noah Webster believed that the want of good teachers was “the principal defect in the plan of education in America.” A Master’s thesis at Yale in 1816 on “The State of Education in Connecticut” elaborated a plan for an Academy for Schoolmasters.”

It would be impossible to adequately acknowledge, even by the mere mention of names, those prominent in the normal school movement in the United States from the beginning of the nineteenth century to the end of the third decade of the century when the first school was established, but a few stand out most prominently.

The Rev. James G. Carter is usually given credit for being the “father ofthe normal schools” in America. Carter graduated from Harvard in 1820 and immediately began writing on the subject of education. In 1824 he published “Essays on Popular Education” and in 1826 published a second volume containing an elaborate plan for the education of teachers. But it was as a member of the Massachusetts Legislature after 1835 that Carter did his greatest work for the normal school idea as a member of the educational committee and for some time its chairman. When surplus revenue was distributed to the states in 1837, for example, he sought to divert Massachusetts’ share to the cause of education. The passage by the Massachusetts Legislature of the Normal School Act of 1838 was said to be due solely to his efforts.%

In accordance with this act, the first normal school under state auspices in America was opened at Lexington, Massachusetts, July 3, 1839. It was to be open to women exclusively, and only three presented themselves as candidates for the entrance examination. From that modest enrollment, the number increased within a few weeks to twelve. By October a model school had been organized and placed under the charge of a Miss Mary Swift.

However, the new institution was soon to come under attack. Within a year after its opening the committee of education was directed by the Massachusetts Legislature to consider abolishing the institution. The committee did, in fact, submita bill to abolish the normal school system, but through the efforts of Horace Mann and others the bill

was defeated. Within five years the school outgrew its accommodations. In May, 1844, it was moved to West Newton, where one Hosiah Quincy, Jr., purchased a building previously used as a private academy, which he gave to the Secretary of the Board of Education who had searched in vain for a suitable structure within the means of the Board. The building was out of repair, but at the expense of the ever present Horace Mann, along with the contributions of the citizens of West Newton, it was soon put in proper order.

The school increased in numbers, and in 1850, the Board of Education took measures to bring before the Legislature its increasing needs and wants. In May, 1853, the sum of $6,000 was placed at the disposal of the Board to defray the expenses of providing a better site and building. The Board was directed to receive propositions from towns and individuals, and afterwards to make such selection as would, in their opinion, best serve the interests of the institution. After carefully considering the propositions presented, they determined to transfer the school to Framingham, where it was opened December 15, 1853. By 1867 the number of students who had entered this school was 1,541, ofwhich number 1,092 had graduated»The graduating class of 1867 numbered 158.

Massachusetts founded two other normal schools, one at Barr which was to be open to both sexes, later moved to Westfield, and one at Bridgewater, before any other state had established such an institution. By 1865 Massachusetts was appropriating $18,000 annually to the support of normal schools, $4,000 of which was to aid students attending the schools.

Twenty years after the establishment of the normal school system, Governor Boutwell, the Secretary of the Board of Education, determined to test the question of the influence of the normal schools upon the cause of education and accordingly issueda circular to school committees of every town in the state. Replies were received from 202 towns of the 332 in the state. Sixty-eight replying had never employed normal school graduates; eleven were opposed to the system, while 106 of the towns expressed themselves favorably with degrees of feeling “from calm moderation to ardent enthusiasm.”

New York was the next state to act. The Albany Normal, the fourth in the United States, was established in 1844 and was, along with the New Jersey Normal School at Trenton, destined to have great influence on normal training in general and upon the new normal school at Winona in particular.

The importance of education seems to have been recognized early on in Minnesota. In the act of March 3, 1849, which organized Minnesota into a territory, the school system of the future was duly considered.> According to section eighteen of this act, one eighteenth of all the land in the territory was to be set aside for school purposes. This liberal support of education was no small factor in bringing many eastern people into the new territory as can be surmised from a paragraph taken from the report of the First Normal Board:

The pioneers ofthe Territory (now State) from 1849 to 1857 came here many of them expecting mote than ordinary educational advantages when we becamea state on account of the very large appropriation of lands for that purpose. The present population has had an average of four or five years’ residence, and unless these anticipated advantages shall be enjoyed within the next five years, that class of persons between the ages of six and sixteen at the time of emigration will have passed beyond their reach; a more meritorious class will never occupy their places. Their deprivations cannot be computed in dollars and cents; even now with the most prompt action, but little can be done for them. But what they lost, it is our duty to secure to their children.®

The framers of Minnesota’s constitution also warmly endorsed the idea of popular education. It was their belief that it was the duty of the Legislature to establish and provide for public education, and they placed in the constitution (Art. VIII, Section 1) a positive declaration to that effect.

The Governor of Minnesota in his message to the Legislature in 1857 stated that the cause of education had “by no means been neglected in the midst of the strife for wealth and speculation,” and he called legislators’ special attention to the report of the superintendent of public instruction. This report maintained that “to make a state requires more than the axe, the saw and the water-wheel; mind, knowledge, and education are required as well to make as to govern; for the children of today may be the rulers a quarter of a century hence.” The superintendent further maintained that it was doubly important, in new countries whose institutions in a measure are yet to be formed, and formed by the people themselves, that school facilities should be as numerous and widely extended as possible. He noted

that small communities wereno sooner settled within a tew miles of each otherthan the voice of all demanded a school for their children.’

The bill which actually established the normal school system of Minnesota was introduced into the House of Representatives on July 17, 1858, byJoseph Peckham. It was read a second time July 23, 1858, and passed by the House bya vote of forty-five to four 6n July 27, 1858.

On July 28 the bill was reada first time in the Senate. On July 29 the Senate Committee to which the bill had been referred, recommended its passage without amendments. By a unanimous vote of twenty to zero the bill passed the Senate on July 30, 1858, and on August 2 was approved by Governor Sibley.® Because of its historical significance in establishing the normal school system the act is reproduced here in its entirety.

Sec. 1. There shall be established within five years after the passage of this act, an institution to educate and prepare teachers for teaching in the common schools of this State, to be called a State Normal School. There shall be established within ten years after the passage of this act, a second State Normal School, and within fifteen years a third: PROVIDED, there shall be no obligations to establish the first Normal School until the sum of $5,000 is donated to the State in money and lands, or in money alone, for the erection of the necessary buildings and for the support of the professors or teachers in such institution, but when such sum is donated for such purpose, a like sum of $5,000 shall be, and hereby is appropriated by the legislature on the order of the proper officers, and shall be paid out of any moneys in the Treasury not otherwise appropriated by law, for the use and benefit of such institution.

Sec. 2. Whenever a second sum of $5,000 shall have been donated to the State for the establishment of a second State Normal School, a like sum of $5,000 shall be and hereby is appropriated by the legislature, and shall be on order of the proper

officers, paid out of any moneys in the Treasury not otherwise appropriated by law, for the use and benefit of such institution.

Sec. 3. Whenever a third sum of $5,000 shall havebeen donated to the State for the establishment of a third State Normal School, a like sum of $5,000 shall be and hereby is appropriated by the legislature, and on the order of the proper officers shall be paid out of any moneys in the Treasury, not otherwise appropriated by law, for the use and benefit of such institution.

Sec. 4. The Governor, within thirty days after the passage of this act, shall appoint six electors, one from each judicial district, who shall constitute the State Normal School Board of Instruction. Those appointed from the even judicial districts shall hold their offices for the term of four years, and those appointed from the odd judicial districts shall hold their office for the term of two years. The Legislature shall, during its session in 1860, elect three Normal Directors to fill the vacancies created by the expiration of the term of office of the three directors appointed from odd districts, and biennially thereafter, the Legislature shall elect three directors to fill the vacancies created by this act. The Legislature shall also fill from time to time all vacancies that may arise by death, resignation, removal from the State, or otherwise; PROVIDED, that the Normal Board shall have power to fill any vacancy occurring during the recess of the Legislature till its next meeting.

Sec. 5. The Normal Board, at their first meeting, which shall be held at the capitol of the State, shall severally take and subscribe an oath or affirmation to support the constitution of the United States and of the State of Minnesota, and faithfully to execute the trust and discharge the duties of their office. ‘They shall elect one oftheir number president, who shall continue in office for two years and until his successor is chosen, and they shall appoint some suitable person as treasurer, who shall hold his office for one year, but may be removed at any time at the pleasure of the Board. The treasurer, before entering upon the duties of his office, shall give bonds in the penal sum of $5,000, faithfully to execute the trust and discharge the duties of his office. The State Superintendent of Public Instruction shall be exofficio a member of the Normal Board, and shall be secretary of the same.

Sec. 6. Immediately after the organization of the Board, they shall proceed to divide the State into three Normal Districts, uniting in the formation of the first, two contiguous Judicial districts, of the second, two, and of the third, two.

Sec. 7. The Normal Schools provided for in this act shall be located by the Normal Board, but only one shall be located in any one Normal District. In locating any one Normal School, the Board shall have due regard to healthfulness and beauty of situation, to accessibility and general convenience, to the wants of the common schools, and the wishes of donorswho may make munificent donations, conditioned upon a particular location.

Sec. 8. It shall not be within the province of the Legislature or of the Normal Board, to remove any State Normal School from its original location, during the period of ten years from its establishment, without the consent of the donor or donors, who made to the State the first donation of $5,000 for the foundation of such school.

Sec. 9. The Normal Boards are authorized and empowered to contract for the erection of all buildings connected with the State Normal Schools, to appoint all professors or teachers in such institution, to prescribe the course of study and the prerequisites for admission, and in general to adopt all needful rules for the government of said schools.

Sec. 10. The Normal Board are authorized annually to appoint for each Normal School a Prudential Committee, consisting of three persons, one of whom shall be a member of said Board. Said Prudential Committee shall have the general oversight and management of the prudential affairs of the several schools, subject to the order of the Board, to whom they shall each make a detailed report of their doings, and of the condition and wants of the particular institution committed to their care.

Sec. 11. There shall be no charge for tution to persons who may be admitted to the privileges of any State Normal School and who shall sacredly engage to become teachers of the public schools of the State for such times and on such conditions as shall be prescribed by the Normal Board.

Sec. 12. The Board, through the State Superintendent, shall make an annual and detailed report of their doings to the Gover-

nor, who shall transmit the same to the Legislature. They shall also report respecting the condition, success, and progress of the several Normal Schools.

Sec. 13. The Normal Directors in any Normal District, with the State Superintendent, shall be the special visitors of the Normal School in such district, and they, together, or by one or more of their appointment, shall visit and examine such school at least two days each session, for ascertaining the mode of instruction and the progress of the pupils, and for promoting the best welfare of such institution and of the common schools of the State.

Sec. 14. This act shall take effect and be in force from and after its passage.?

The man most responsible for the passage of this legislation was Dr. John D. Ford, a citizen of Winona who, with the help of the legislative delegation from Winona County led by State Senator Daniel S. Norton, kept the issue before the legislature and was its chief lobbyist. Ford, a physician, had come to Winona from Connecticut in 1856. He was apparently a man of broad culture and of more than ordinary intellectual endowments. Asa citizen of the little pioneer community, he tooka lively interest in all that tended toward the improvement and elevation of the people with whom he had cast his lot. Such a person could not overlook or underrate the importance of efficient schools as a prime factor in the growth of society, so it was only natural that he early manifested his interest in the schools of the city, was chosen as a member of the board of education and placed at its head. Under his leadership, Winona was the first town in the state to organize graded schools. Given his interest and the efforts he exerted in favor of the movement, it is not surprising to find his name among those who comprised the first Normal Board of Directors, along with Dr. A. E. Ames, Dr. E. Bray and Lt. Governor William Holcombe, who had lent strong support to the legislation and was appointed president of the Board of Directors. This group held its first meeting in the library of the Capitol at St. Paul, at twelve o’clock, on Tuesday, August 16, 1859, and resolved, in accordance with the new law, that Judicial districts numbered 3 and 5 should constitute the First Normal District, numbers

1 and 2, the Second Normal District, and numbers 4 and 6, the Third Normal District; that the Secretary should be required to correspond with the Secretaries of Normal Schools in other states and obtain, as soon as possible, the proceedings of said schools, their manner of teaching, rules and regulations, and building plans; that a committee of three including the President of the Board be appointed to attend the next session of the legislature to secure such legislative aid as might be necessary to establish the first State Normal School; and that the newspapers of the State, friendly to the cause of education, be requested to publish the proceedings of the State Normal Board.

Although Ford had endeavored to have the first normal school located in Winona by legislative fiat, his draft of the bill was amended to provide for its location in the town that pledged the largest amount toward the purchase of a site and erection of a building. A minimum of $5,000, “In money or lands or in money alone,” would be matched by the legislature, and the project would be under way. There appears to be no record of other communities bidding for the institution, but in any case Winona offered a subscription of $7,000 $2,000 in excess of the amount required by the Act! Accordingly, the following resolution was offered by Dr. Ford on August 16, 1859, and passed unanimously:

RESOLVED: That the First State Normal School be located at Winona, provided the subscription fromWinona of $7,000 be satisfactorily secured to the uses of said school, as directed by the board of directors.'°

From the Winona Republican for August 17, 1859, we learn that this subscription was made in a few hours, “and,” continued the Republican, “the amount will be materially increased at any time, if necessary, to secure the location at this point.”

Thus was located at Winona the first State Normal School in Minnesota and at that time the only state normal school west of the Mississippi. San Jose State in California, and Western Oregon State were established earlier than the Winona Normal, but did not actually become normal schools until many years later.

Sylvester J. Smith, Dr. J. D. Ford, Rev. D. Burt, and William S. Drew, all citizens of Winona, were appointed as the first prudential committee for overseeing the school’s proper development. That the citizens of Winona had an early interest in higher educa-

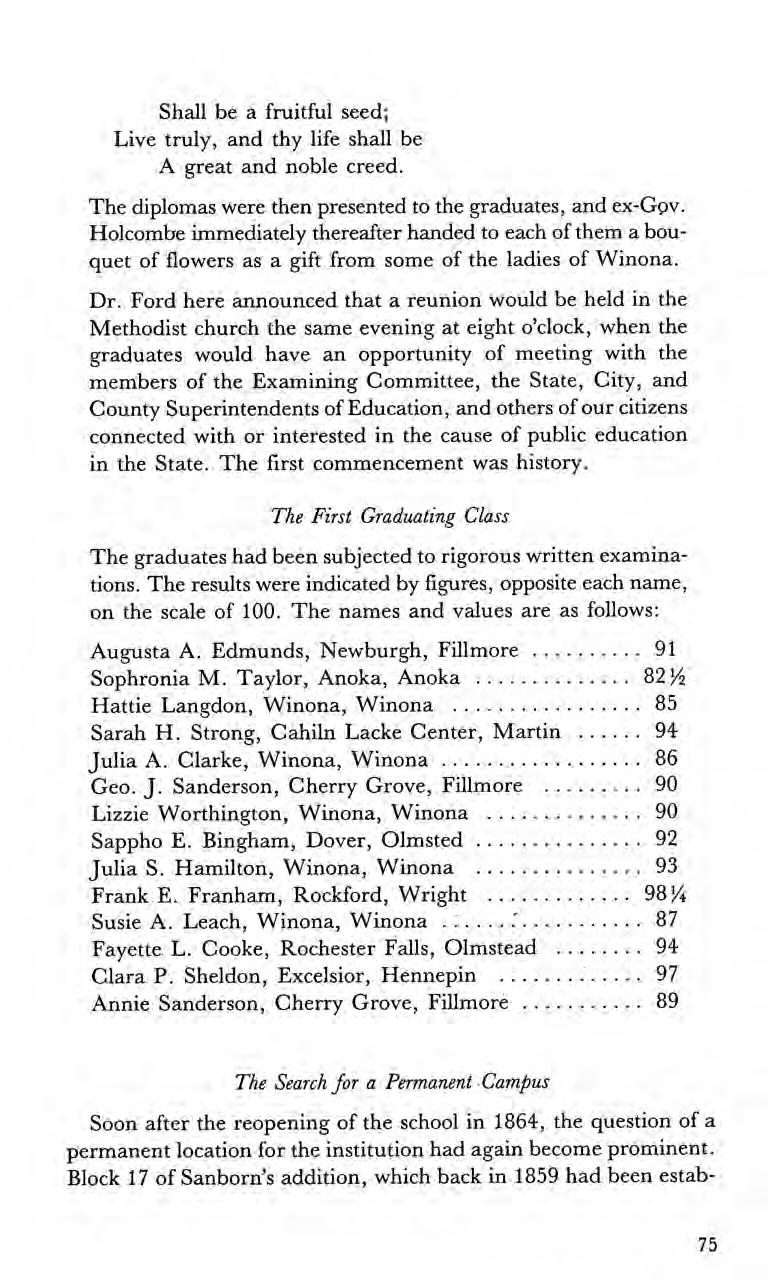

tion is seen in the fact that there was a movement as early as 1856 for the founding of a university in the city. The Winona Argus opposed the establishment of such an institution, because it claimed such a university threatened to be an Abolition Institution. The Argus did not think an institution should be established which would “teach that the national constitution originated in sin.”1%

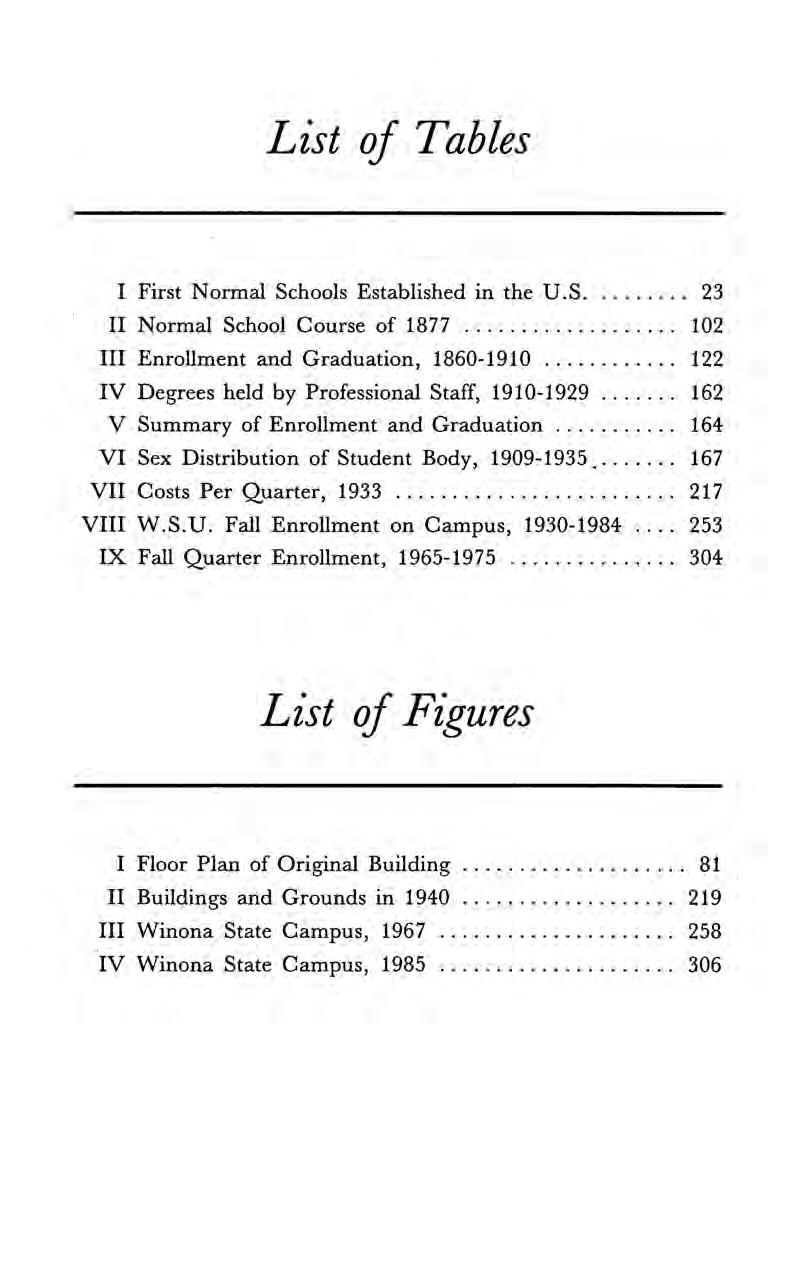

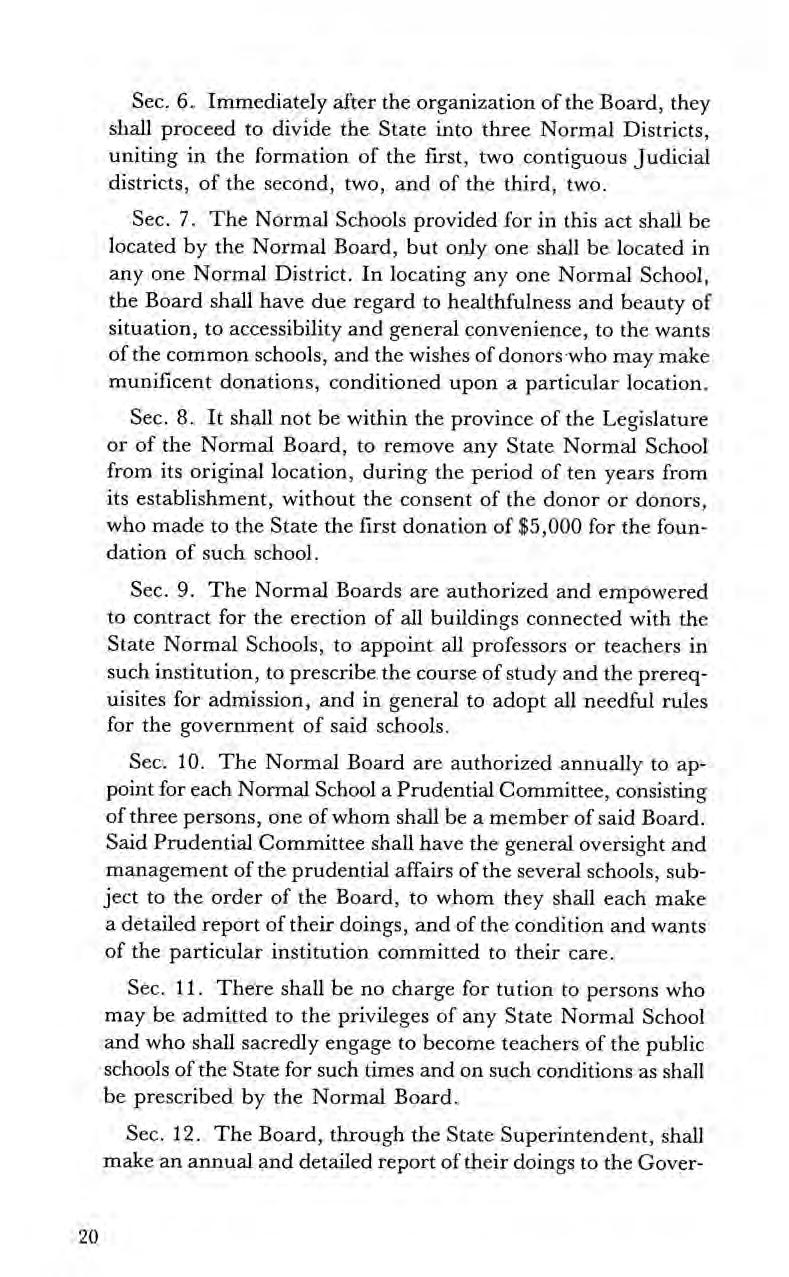

1. Framingham, Massachusetts 1839 1839

2. Westfield, Massachusetts 1839 1839

3. Bridgewater, Massachusetts 1839 1840

4. Albany, New York 1844 1844

5. Girls’ Normal School, Philadelphia. 1848 1848

6. New Britain, Connecticut 1849 1850

7. Ypsilanti, Michigan 1849 1853

8. Briston, Rhode Island 1852 1852

9. Salem, Massachusetts 1853 1854

10. Trenton, New Jersey 1855- 1855

11. Normal, [llinois 1857 1857

12. Charleston, South Carolina 1857 1859

13. New Orleans,-Louisiana 1858 1859

14. Winona, Minnesota 1858 1860

Although talk of a university doubtlessly seemed a bit ambitious to a few members of the community, the somewhat less elaborate idea of a normal school appears to have enjoyed wide acceptance. It was evidently seen as necessary to the future of the area and something more than simply a matter of local boosterism as evidenced by the following taken from an early Winona newspaper:

The Normal system of education, which has received but comparatively little aid or encouragement from the Government, lies at the foundation of all the others; and to be rendered useful to its greatest and most profitable degree, should be the first to be established and put into practice, and thus pave the way both

for a flourishing common school system and for the more advanced collegiate course.

The friends of education throughout the State entertain this view with regard to the system of Normal Schools; and many of them we are happy to learn, are active in their endeavors to aid in the establishing of the firstNormal School in Winona.'*

The second meeting of the Board was held at Winona, November 9, 1859, at which meeting block 17, Sanborn’s addition was, after considerable deliberation, selected as a suitable site for the proposed school, the Board preferring a central location in order that a “model department” might be maintained in connection with the normal school.* At this meeting the Board resolved “that the first State Normal School be opened for the reception of pupils at the earliest period practicable,” and the Secretary of the Board was directed to procure a principal for the school and plans and specifications for the normal school building. The first state tax for school purposes was authorized and levied upon the recommendation of this Board as part of the financial undergirding necessary to the carrying out of their plans. Apparently there was a great demand for places for the Board decided that candidates for admission should be apportioned throughout the state:

Two candidatesshall be admitted for each senator in the State Senate, as now districted. Where two counties compose a senatorial district each county shall have equal opportunity, if both claim the privilege. Where three or more counties compose a senatorial district the applicants from each county shallhave preference in the order of application. If any applicant shall be rejected upon subsequent examination, the next applicant in point of time trom the same district shall be in order for admission. All candidates shall have preference in the order of application. Candidates from districts entitled to admission must apply two weeks before the term commences: Other applicants not entitled to admission by appointment shall be next in order. All

*Model departments were composed of regular classes of children who would be taught by experienced teachers and by student teachers under supervision.

applications must be made to the principal, either by mail or in person.

Any candidate having signified his or her intention in writing to teach for a term of at least two years in the common schools of Minnesota, and having presented satisfactory testimonials of good moral character and natural adaptation for the office of teacher, shall, upon a satisfactory examination by the principal and prudential committee of said school, be admitted to all the privileges of the State Normal School, according to the rules of appointment in the previous resolution; provided, that such applicant be at least sixteen years of age, and of sound physical health; and provided further, that if fifty candidates do not apply who will pledge themselves to teach in the State the required term, then the number of fifty may be filled by students without such pledge, upon payment of tuition.’®

This pledge to teach in the schools of the state, adopted so early in the history of the normal schools, remained in effect until 1933. It also included free tuition for those who planned to become teachers. The discharge of this pledge rested upon the honor of the student, but failure to meet this obligation was said to be very infrequent; not more than two per cent of the entire number. Students who found it inconvenient to teach generally secured an honorable release from the obligation by payment of full tuition for the time of attendance at rates fixed for non-professional students. The following is the form of a pledge used:

I, being at least sixteen years of age, do solemnly declare that I will faithfully attend this Normal School for one term or more, for the purpose of fitting myself for the work of teaching, and that, thereupon, I will, to the best of my judgment and ability, teach in the Common, Graded, or Normal Schools of this State for a period of two years, immediately after ceasing to be a student of this school. And I further agree to make a report semiannually to the President of this school, until the above pledge shall have been fulfilled, stating in such report when, where, and how long I have taught. Sickness or unavoidable cause only may excuse me from the strict performance of this obligation.*®

The first Normal Board was composed of serious minded members, a fact which becomes obvious as one views the results of their labors.

It is especially interesting to review their thinking, their perspective on education, and their perceptions of the place of the normal school in the scheme of things. They were idealists, and unashamedly ready and willing to work toward thoseends which they viewed as necessary and important to the betterment of the new society ofwhich they were a part.

The following paragraph taken from theBoard’s first report lends perspective on the depth of its commitment:

In the correspondence held with the Normal Schools of our sister States, we find the conclusion to be irresistible, that the art of teaching ought to be reduced to a profession, this being theobject of the Normal School. It is to the common school what the military and naval academies are to the army and navy. The same necessity that demands of the government the establishment of such institutions, requires the State to maintain and support the Normal Schools; and that necessity is the principle of self-preservation, as the general government must have officers skilled in all the applications and arts of war, to command her armies in times of danger in order to maintain her rights against her foes, so the State must have skilled and experienced teachers to elevate and maintain the standard of the general intelligence, upon which alone rests the prosperity and perpetuity of our republican institutions. !”

Address of the Lieutenant Governor Holcombe

On the evening of the second meeting of the Board, Lieutenant Governor Holcombe, President of the Board, delivered in the Baptist church of Winona an address on the subject, “Education with reference to the establishment of the First Normal School of Minnesota”. This address was said to have made a deep impression upon the young community and to have done much to elevate that sentiment in favor of the support of educational interests which has marked the history of Winona.

Lt. Governor Holcombe had evidently expended much time and labor studying his subject and preparing his address. He entered into a history of the origin and design of normal schools and clearly showed the great good which they had accomplished in the cause of education in Europe and this country. He contended that the people of Minnesota owed it to themselves, to their children, and to the best

interests of the state to set up a high standard of education in the common schools so liberally provided for in the organization of the state government, and maintained that this could in no way be done as well as by the establishment and proper maintenance of normal schools in Minnesota. He highly commended the location of the school at Winona and he hoped that the energy and liberality which had secured that location would not be permitted to languish, but that the institution would soon be placed upon an enduring foundation. The address was lengthy and was replete with information and encouragement for the furtherance of the design which formed the topic of his discourse. In the closing paragraph of his address, Lt. Governor Holcombe referred to the subscriptions already given:

I have in my hand a paper which contains the origin, and source, and the earnest of the first Normal School of Minnesota. It has its origin here in this city, and the names written on that paper are as pictures of gold, and should be handed down to future generations as evidence of their wisdom and benevolence. This paper subscribes about $7,000 to the establishment of the Normal School here, the most ofwhich, over $5,000 has been secured promptly to the state for that object. The duty I have discharged is every way an agreeable one, no circumstances could have occurred with respect to the interests on the state to afford me higher gratification than to meet you here on such an occasion as this. The City ofWinona has distinguished herself in taking the lead in establishing for the benefit of the rising generation of this state for allwho shall yet call the state their home. I think the Normal Schools should precede the common schools of the country, for then we would have trained teachers to conduct them. When this school shall be in operation it may be regarded as an auspicious era, whence to date in the future the origin of many blessings, and the commencement of a perpetual course of improvement and prosperity to the people at large.'®

One of the first responsibilities ofthe newly appointed normal board was that of locating a principal for the school—a formidable task in a day when there were few enough university graduates, let alone one having normal school experience in addition.

JOHN OGDEN Principal, 1860-1861

However a candidate was located and at its next meeting the board resolved, among other things, “that Professor John Ogden be engaged as Principal of the State Normal School at Winona, the ensuing year, and that his salary be $1,400 per annum, to be paid quarterly in State Warrants out of or from the balance now placed to the credit of the State Normal School Board upon the books of the State Auditor.” !9 William Stearns, a graduate of Harvard University, was chosen tutor. John Ogden was born in Ohio in 1824. At nineteen, while working at blacksmithing, he was kicked by a horse and his arm was broken. He later stated that, not being able to work at his trade for some time, he decided to enter teaching, and found it so congenial that he made it hishfe work.

He studied and taught in the Ohio Wesleyan University at Delaware, Ohio; was principal of one of the schools in Columbus, and later was president of the Hopedale Normal School, Hopedale, Ohio. He had been engaged in institute work for a number of years before coming to Winona. He was clearly a well-qualified individual and, as the history of the next few years would show, a patriot as well as a man of courage and vision.

The board had decided that “the Principal should be requested to visit all important localities and present the necessity of normal schools to the permanent prosperity of the state, and the desirableness of citizens demanding competent teachers for their children.” This he did during the months ofJuly and August. He was back in Winona to take charge when the new schoo! was opened for admission on September 2, 1860.

A teachers’ Institute, the first ever held in the state, was conducted during the opening week. “A goodly number of teachers from various parts of the state were present, and a number of distinguished gentlemen including the Rev. F. D. Neill, Chancellor of the University, Ex-Lieutenant Governor Holcombe, J. W. Taylor, Esq., and many others. A large number of letters were received and read from the Principals of other normal schools and other noted educators throughout the country.”°

The order of exercises for the opening ofthe institution of September 3, 1860, was as follows:

Nine o’clock a.m.— Examination of candidates at the school-

house. “All are expected to be present at the hour. Examinations will be private.”

Monday Evening, half past seven Opening address at the Baptist Church by Rev. F. D. Neill, State Superintendent of Public Instruction, ex-officio.

Tuesday “Will be devoted to the exercises of a Teacher’s Institute. Teachers and friends of education from all parts of the State are earnestly requested to be present and participate in the exercises.”

Tuesday Evening Address by Chancellor Barnard of the Wisconsin State University.

Wednesday Forenoon—Lectures and addresses before the Institute.

Wednesday Afternoon Reading of letters and other communications from educational men.

Wednesday Evening—Inaugural Address by the Principal.

Thursday Forenoon, nine o’clock—A permanent organization of the Normal School.

“The governor and other state officers are expected to be present during the exercises of the week.”

“Arrangements will be made for the gratuitous entertainment of all who may attend during the first week.”

The “Opening Address” of the institute by Reverend Neill was delivered at the Baptist Church, before a large audience. His address set forth the benefits of educational institutions conducted under the patronage ofthe state, particularly as these benefits manifest themselves in the creation of a sense of national unity among widely diverse and incongruous elements of a society having its origin in all parts of the globe. It also appealed to the citizens of Winona to support the state normal school no matter what the expense in time, patience, and means, without which no educational institution could flourish.The closing paragraph of Chancellor Neill’s address also brings home the realization of how primitive and new this territory really was:

Twelve years ago the Winnebago nation, bya treaty stipulation abandoned their homes in Iowa and commenced their long weary march to their new home near Sauk Rapids, in the northern part of this state. In the charming month ofJune, by mutual agreement, parties by Jand and water to the number of 2,000 arrived on this prairie. As they viewed the vast amphitheatre of lofty bluffs, the narrow lake on one side, the great river in front, they felt that it was the spot above all others for an Indian’s Lodge, and purchasing the privilege ofWabasha, the chief of the Dakota band that then lived here, they drew themselves up in battle array, and signified to the United States troops that they would die before they would leave.

Twelve years hence, if the citizenswho have taken the place of the rude aborigines will be large-hearted and foster the normal school, the public schools, and thechurches of Christ, Winona will be lovelier than the “Sweet Auburn”of the poet; and educated men and cultivated women, as they gaze on your public edifices and other evidences of refinement, will be attracted, and feel that here is the spot for a home, and like the indians in 1848, they will desire to tarry until they die.?!

Principal Ogden occupied much of the attention of the Institute, touching in a general manner on the design of the normal school and the object of education. He declared that education is not merely the acquisition ofknowledge, “but the development ofthe whole character of the individual, physically, educationally, morally, and religiously.” He spoke of the relationship of such a school to the wants of the rising generation, of the need for insuring the sufficiency ofthe educational supply to meet those wants. He emphasized the importance of raising the teachers’ calling to the rank of a profession. Education had not yet receivedits proper attention, he said. While the learned professions had received the highest degree of systematic development, the vocation of the ceacher, the basis of all professions, had dropped into the rear rank of the professional movement of the age. He also conducted drills in grammar which, says the Winona Republican “were highly instructive and interesting, and elicited a good many hints in regard to teaching grammar.” “But these exercises,” continues the Republican, “should have been witnessed to be properly appreciated.”??

A-canvass of the institute members showed seventeen names from New England, eighteen from New York, two from Pennsylvania, two

from Ohio, one each from NewJersey and Wisconsin, and two from Illinois.

The inaugural address of Mr. Ogden was also delivered at the Baptist Church to a large audience of citizens and students. Dr. Ford had invited Lieutenant Governor Holcombe of Stillwater to preside, and in so doing, alluded to theactive efforts of that gentleman in behalf of the normal school enterprise and the warm interest which he hadmanifested in its success from the very beginning up to that auspicious moment.

Letters were then read from the Rev. Neill and Governor Ramsey, at the close of which Mr. Ogden delivered his inaugural address.

Actually, there were seven major speeches that week in addition to a variety of other activities. The audience must have been well informed on such topics as morality, patriotism and educationby the time Principal Ogden, the last of the speakers, took over the podium. If they were not, they certainly were after he finished, for his speech was the longest of the lot and seems to have covered the entire spectrum of educational thought of the middle eighteen hundreds.

All of the speeches that week were highly moralistic in tone and replete with references to God and country in keeping with the mood of the times. Mr. Ogden’s was no exception. Secularization as we know it today was clearly not large in the thinking of the founders of the Winona Normal School. Religion and education were inextricably bound and there was little agonizing over where to draw the line separating church and state.

It is understandable then, that many, if not most ofthe young people who enrolled at the “Normal” developed a kind of missionary zeal for what they were setting out to do, something, which for some of them at least, transcended the merely vocational aspect of their efforts. A short exerpt from Principal Ogden’s speech will suffice to show some of the flavor of that period:

It shall be the leading object ofthe Normal School, so to distribute its labors and other exercises, that all the faculties of the pupil physical, intellectual, moral, and spiritual, shall be addressed in due preparation, at the proper time, and in the proper manner; and so to develop, strengthen, elevate, and purify these powers in the student; and so to train him in the education pro-

cesses, that he may readily apply them to the education of the children and youth committed to his care.

And, again:

A fool cannot teach wisdom; neither can a bad man teach goodness, except in a negative way. Satan cannot correct sin; therefore, his emissaries should not be employed to cultivate the vineyards of the Almighty, where so much sin and moral obliquity are to be dealt with. Knowledge and goodness grow best together. Therefore, no attempt to separate them should be tolerated. Religion and science go hand-in-hand. Their mission is the redemption of the race. “That, therefore which God has joined together, let no man put asunder’.”?

The original building was owned by the city and was loaned to the Normal Board as part of the subsidy which the city was extending to the new institution. The structure was anything but prepossessing, and rather recalls a description by a visitor to Rutger’s during its early years: “The College, unadorned by cupola or dome, stood lonely and bare, upon its bleak little eminence, exposed to the scorching rays of sun in the summer, without a tree to shade us as we approached it, or to break for us in winter the chilling blasts ofthe whistling north wind.”2*

But for its time it was adequate and appreciated apparently by one and all. Furthermore, it was another evidence of the friendliness of the citizens of Winona to this struggling institution. The use of the building was continued for eight years without charge to the state. A sketch from the original minutes of the Normal Board is of interest in this connection:

The City of Winona, for the purpose of accommodating the school, erected a hall in a central and convenient part of the city, containing one large school room, one recitation room, a library room, and a suitable cloak room, and offered the same, without charge, to the Prudential Committee, until more permanent arrangements could be effected. This liberal offer has been accepted. Although the present number of pupils, and even more, may well be accommodated, from indications in all parts of the

state, these rooms will soon be too crowded, and the necessities of the school will demand a suitable and permanent normal building.?®

As it turned out, the $7,000 subscribed by the citizens of Winona was not used for operating expenses, but was reserved for the construction of the permanent building in 1867-68 by which time the original subscription with its appreciated values amounted to about $10,000.

At the first meeting of the State Normal Board held in St. Paul on August 6, 1859, the secretary had been directed “to correspond with the secretaries of other state normal schools and obtain at as early a day as possible the proceedings of said schools, their manner of teaching, rules and regulations, plan of building and furniture”. Presumably with this information before them, and after determining a plan of districting the entire state for equitable apportionment of students entering the school, the Board at its second meeting, November 10, 1859, determined “that any candidate having signified in writing his or her intention to teach for a term of at least two years in the common schools of Minnesota and natural adaptation for the office of teacher, shall upona satisfactory examination by the Principal and Prudential Committee of said school, be admitted to all the privileges of the State Normal School according to the rules of apportionment in the previous resolution, provided that said applicant be at least sixteen years of age and of sound physical health.”?6

With requirements for admission thus partially established, Dr. Ford and Mr. Taylor were appointed at the third meeting, June 6, 1860, “to confer with the Principal and prepare a course of study,” for submission to the Board for approval.” Five months later the following additional entrance requirement was recommended: “They must sustain a satisfactory examination in reading, writing, spelling, geography, and arithmetic to the end of rules for interest, and so much of English grammar as to be able to analyze and parse any ordinary prose sentence,” together with the following statement of the course of study:

The school will be classified into three classes: ,TheJunior, the Middle, and the Senior. The course of study will be as follows:

First Term— Reading and spelling; word exercises; parts of speech; arithmetic, oral, intellectual, and written; descriptive geography; map drawing and penmanship.

Second. Term—Reading and spelling; simple analysis of sentences; arithmetic, oral, intellectual, and written; political geography; map drawing and penmanship.

Third Term—Reading and spelling; phonetic analysis; arithmetic; intellectual and written; English grammar and composition.

First Term Reading and etymological analysis; mathematical and physical geography; meteorology; algebra; higher arithmetic and bookkeeping.

Second Term — Natural philosophy and astronomy; history of the United States; high analysis oflanguage; algebra continued; geometry commenced.

Third Term Natural history and botany; rhetoric; rules of construction and criticism; geometry and science of education.

First Term History and constitutional law; algebra completed; English language and literature; geometry and trigonometry; teaching in the model school.

Second Term — Intellectual philosophy; human and comparative physiology; practical chemistry; geology; school laws; practice in model school.

Third Term Intellectual philosophy and logic; moral philosophy and natural theology; study of school systems and practice in the model school.

It is interesting to note that this course emphasized mathematics, requiring at least ten terms thereof, and that besides geography there were eight terms of science. No language other than English was offered, but in the last term there appeared a formidable array of in-

tellectual philosophy, logic, moral philosophy, and natural theology. Practice teaching, carried throughout the senior year, with a study of school laws and school systems, and the science of education, made up the pedagogical work of the course.

Because of the closing of the school for the period from March, 1862, to November, 1864, no students completed the course as outlined, but several had completed a year, and it can be safely assumed, went out to teach in rural schools of the day, often barely one year ahead of their young charges.

In spite of its newness, the first year seems to have been most successful, and “commencement” time came and went without incident. Although there was not as yet a graduating class, end-of-term exercises were nevertheless held the last week in June, 1861, at the Baptist Church. They continued the entire week and closed with a strawberry festival for the benefit of the school. According to the Daily Republican the visitors present included a Mr. Hickok, Ex-Superintendent of Public Instruction to the State ofPennsylvania, a Mr. Allen, secretary of the Board of Normal Regents of Wisconsin, C. C. Andrews of St. Cloud, Lieutenant Governor Ignatius Donnelly and a Dr. Reid of St. Paul. Hickok, Donnelly and Andrews delivered addresses. The Board of Examiners consisted of a Mr. Markham of St. Paul, a Mr. Stone of Minneapolis and a Mr. Williams ofWasioja.”°

The Republican describes the scene: Over the wide platform of the Baptist Church, stretching from wall to wall, two American flags were hung, on one the word “God” on the other “Liberty”. Above these, in letters of living green was the motto, “The Education of the people, the strength of the Republic”. Beneath them hung the portrait of Washington. Over the doorway hung the portrait of Lincoln.

Concerning this picture the Republican observed:

“He looks a little lean and lank; butstill the Old Abe of antisecnotoriety; we thought he was pleased with what he saw before him, and that he occasionally nodded at Washington and nudged Webster, whose picture is nearby, as much as to say, ‘Good for Minnesota’.”

High on the gallery wall was a circle of green enclosing the words, “The true Emblem of Education”. Another important picture in the room was the representation of the first prayer in Congress. Other

details of the first commencement in the first Minnesota State Normal School recorded by the Winona Daily Republican are as follows:?9

The closing exercises of the Normal School, on Friday last, was the great day of the feast. A three days’ examination in the studies pursued during the year and was the fatiguing introduction to the brilliant display of Friday afternoon and evening. Classes had been examined in arithmetic, geography, grammar, algebra, geometry, natural philosophy, Latin and botany; indeed in almost the entire range of science and literature. The peculiar and most interesting feature, however, was the teachers’ class. As we looked and listened we could not but think, that, if the good people of the State could be present with us, and see and hear what we heard and saw, they wouldlearn how much better qualified young men and women are to teach the youth of the land after a course such as can be obtained here. The drill is perfect. We predict for those who have gone out to undertake that which is to be the work of their lives, a success which will be both acknowledged and felt.

The great object of the Normal School is the preparation of teachers. It was for this purpose that the institution was established, and the close of the first year of its existence proves that its mission has not been forgotten. Nor will it ever be. ‘That which was but lately an idea is nowa fixed fact. The State Normal School will live, and in the coming years thousands of brighteyed boys and rosy-cheeked girls, as they sit in comfortable school rooms, and drink in lessons of wisdom and truth, from the welltrained instructors, will callthe originators and supporters of this enterprise, blessed.

Friday, we said, was the feast day. Early in the afternoon, fathers, mothers, sisters, friends and people generally wended their way to the Baptist Church to witness the literary performance of the students, and to listen to the strains of sweet music which all knew were in store for them. It was a pleasing spectacle! We never saw a more attentive audience; all were interested and all pleased. Patriotism was abundant and of the genuine stamp. It was but the outburst of that which has been burning within their hearts, ever since the Stars and Stripes fell from the flag staff of Sumter. The young men of the Normal School are loyal and

full of fight; they will stand by the right and battle for their country through storm and sunshine.

They will teach our children not only knowledge, but patriotism. Long may they wave.

The ladies, too, acquitted themselves with honor and we feel proud to think that these were to go out as representatives of Minnesota culture and thought. Their essays were attractive, both in shape and matter; and while womanly, were noble. ‘Their articulation was distinct and full, yet having that subdued melody which tells of the gentle and quiet spirit.

We forebear any further comments. It is only allowed us to allude to the presentation of Professor Ogden, the Principal of the school, of a magnificently bound copy of the Holy Scriptures. The remarks, by one of the young ladies of the school, on the occasion, were peculiarly touching, and the reply of Professor Ogden brought tears to eyes unused to weep. In the evening, Honorable C.C. Andrews and Lieutenant Governor Donnelly delivered able lectures: after which a social reunion was had at the home of the Principal, and the first commencement of the Normal School was ended.

We print herewith the programme of exercises on Friday afternoon, to which allusion has been made above:

Music Prayer Music

Salutatory: R. C. Olin, Northfield

Diversion: A. A. Bates, Northfield

Popular Education: D. D. Kimball, Winona

Music: Our Country: Anna M. White, Plainview

A Scripture Proverb: Mary E. Hoffman, Minneapolis

Douglas: G. R. Tucker, Winona

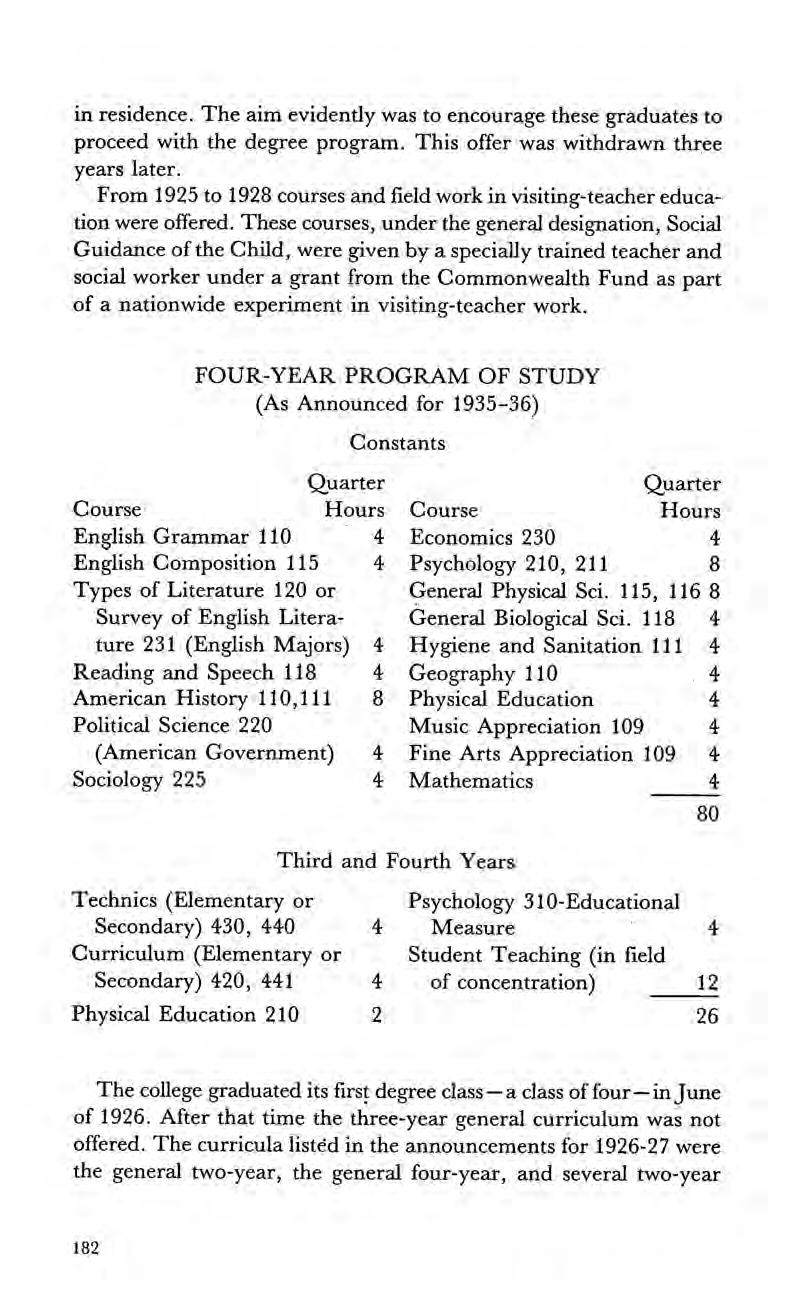

Events of the Century: G. G. Gray, Warren

Debate: “Is it right to use force to extend civilization?”

Affirmative: A. W. Williamson, Pajutazee

Negative: H. P. Hubbell, Winona

American Oratory: P. G. Hubbell, Winona

Colloquy: Etta R. Howe, Winona

Lottie I. Denman, Winona

Bessie M. Thorne, Winona

Music

Flowers, an Allegory: Nellie M. Temple, New Boston

Death before Life: Gussie A. Brewster, Stillwater

Necessities: S. T. Robinson, Winona

Ellsworth: G. W. Knox, Winona

Music: A Family in Heaven: Mary E. Winter, Winona

Memories of Western Life: M. Louise Worthington, Winona

Valedictory: Joseph D. Ford, Winona

Music

Benediction

The foregoing, which would today seem a bit overdone, was typical of that day and age. There are numerous such examples in the archives.

A conflict was impending however, which wassoon to disrupt these deliberate and traditional ways of doing things, and which would substitute for poetry and debate the death and destruction of war. The local Prudential Committee had announced that, “Encouraged by the decided success, so fully conceded by the Board of Examiners and others competent to judge, the State Normal Board has directed the committee to announce that the second school year will commence on Monday, September 2, 1861”.

But there was a feeling of tentativeness. Mr. J. D.McMynn, for example, who had been engaged as an assistant teacher, resigned in October to become a major in a Wisconsin regiment. Many of the students of the school had already entered the volunteer army in defense of the Union. Finally, Mr. Ogden, himself, resigned his principalship on December 14, 1861, at the close of the fall term. His letter of resignation clearly reflects the spirit of those stirring times:°°

Winona, Minnesota, December 14, 1861.

To the Prudential Committee of the First State Normal School of Minnesota.

Gentlemen:

I hereby tender you my resignation of the principalship of the

institution intrusted by my care, thanking you most sincerely for the generous support and counsel you have given me.

In taking this step, it is proper that you and the public should understand the reason that impels me to it.

My distracted and dishonored country calls louder for my poor service just now than the school does. I have, ever since our national flag was dishonored, cherished the desire and indulged in the determination that— whenever I could do so without violation of a sense of duty —I would lay aside the habiliments of the school room and assume those of the camp, and now I am resolved to heed that call and rush to the breach, and with my life, if necessary, stay, if possible, the impious hands that are now Clutching at the very existence of our free institutions. What are our schools worth? What is our country without these? Our sons and daughters must be slaves. Our beloved land must be a hissing and a byword among nations of the earth. Shall this fair and goodly land, this glorious Northwest become a stench in the nostrils of the Almighty, who made it so fair and so free? No, not while there is one living soul to thrust a sword attreason. I confess my blood boils when I think of the deep disgrace of our country.

My brethren and fellow-teachers are in the field. some of them the bravest and the best — have already fallen. Their blood will do more to cleanse this nation than their teaching would. So will mine. I feel ashamed to tarry longer. You may not urge me to stay.

With these feelings, I am, with very great respect,

Your most obedient servant, John Ogden

In the Winona Daily Republican appears the following commentary concerning Principal Ogden’s resignation:

Professor John Ogden, who as Principal of the Minnesota State Normal School, has successfully conducted that institution from the beginning, has resigned his situation, and will shortly leave our city for another and widely different field oflabor. The causes

which induced this resignation are fully set forth in a card to the Prudential Committee of the Normal School, printed in another column.

Mr. Ogden, as indicated in the card referred to, has determined to enter the service of his country in a military capacity, and will be connected with a regiment of cavalry being organized in Wisconsin.

While we much regret his departure from among us, we cannot but applaud the patriotic and self-sacrificing motives which have led him to this determination. During his residence of nearly two years in Winona, Mr. Ogden has conducted himself in such a manner as to win applause as a professional educator, and to acquire many warm friends as a man. He will leave our city attended by many sincere and ardent hopes for his future success.*!

TheFirst State Normal School at Winona was closed on March 2, 1862. The original minutes of the Normal Board show that Resident Director David Burt and V. J. Walker, principal of the Winona High School, were temporarily in charge of the school during the second term. Further sessions remained suspended until November 1, 1864.

The reasons for the suspension of the school for over two years are clear: the interest in the great struggle then pending overshadowed and overwhelmed everything else, and as a natural result competent teachers could not be found to take charge of the school. ‘The means for the support of the school was inadequate since the state had made no appropriations beyond the first $5,000. Minnesota was suddenly too busy with the war to worry about its educational interests.

1. C. O. Ruggles (Ed.), Historical Sketch and Notes Winona State Normal School, 1860-1910. (St. Paul, Minnesota State Normal School Board, 1910) p. 12. Most of this chapter is based on Ruggles, therefore citations will be limited to particularized statements of fact.

E. Tichman, Massachusetts Magazine, June, 1789. Massachusetts Statutes, 1883.

Ruggles, p. 12.

General Laws ofMinnesota, March 3, 1849.

Minnesota State Normal Board, Minutes, 1858.

Minnesota House, Journal, July 27, 1858.

Minnesota Senate, Journal, 1858, p. 605.

General Laws ofMinnesota, 1858, pp. 261-263.

Minnesota State Normal Board, Minutes, August 16, 1859.

Winona Daily Republican, August 17, 1859.

Winona Argus, 1856.

Winona Daily Review, November 23, 1859.

Minnesota State Normal Board, Minutes, November 9, 1859.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Address by Lt. Governor Holcombe, Winona, November 9, 1859.

Minnesota State Normal Board, Minutes, June 6, 1860.

Winona Daily Republican, September 3-7, 1860.

Ibid.

Tbid. Ibid.

12. “‘Barnard’s American Journal of Education,’? New York State Department of Education, (January 1905). 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19, 20. 21. 22. 23. 24.

Richard McCormic, Rutgers a Centennial History (New Brunswick, Rutgers University Press, 1966), p. 36. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31.

Minnesota State Normal Board, Minutes, June 6, 1860.

Ruggles, p. 121.

Minnesota State Normal Board, Minutes, June 6, 1860.

Winona Daily Republican, June 24-27, 1861.

Ibid.

Letter from John Ogden to the Normal Board, December 14, 1861. Winona Daily Republican, December 17, 1861.

By May 11, 1858, when Congress finally approved Minnesota’s constitution(s)* and awarded the territory full statehood, the fires of rebellion were already burning brightly in the South. Southern leaders had warned that if Lincoln were elected, secession would follow, and they were true to their word, with South Carolina leading the way on December 20, 1860. On April 13, 1861, Fort Sumter fell; on April 15, Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers; on April 19, he ordered the blockade of the seceding states. The Civil War was underway! Several months earlier Governor Ramsey had wired Lieutenant Governor Ignatious Donnelly to begin to organize volunteers from the new state to fight in the War. On April 14, 1861, one day before Lincoln’s general call for militia, Governor Ramsey offered the President 1,000 men, giving Minnesota the distinction of being the first state to offer troops to the Union cause. The First Minnesota Regiment left Fort Snelling on June 22, 1861."

Among those new troops were men who had been students at the normal school as well as faculty members like PrincipalJohn Ogden who had resigned to fight for the cause. As with every great war, and particularly this one, practically everything constructive came to a halt as energies and resources were concentrated on the war effort. There were no funds for the normal school nor for any other kind of school for that matter except for the occasional building of a one-

*Minnesota actually had two constitutions. During the territory’s Constitutional Convention ofJuly, 1857, there was sucha rift between Democrats and Republicans that two constitutions were adopted, one by each party since neither side would vote for the other. Because they were fundamentally the same, however, they were both adopted on October 3 of that year, and state officials then were appointed. On May 11 the following year Congress gave Minnesota statehood.

room school by the residents of some newlypopulated area ofthe state.

The resignation of Mr. Ogden had affected the normal school enterprise in two important ways; one, the obviousfact that his leadership as principal was no longer available during the organizational period when it was most needed; two, that his leaving was in effect a signal to all able bodied males to volunteer to fight to save the Union. Patriotism ran high in this brand new state. It might well be expected that pioneers would have enough to do just taming the wilderness and bringing the land under control in order to survive, without volunteering to leave their homes and families to fight in a war a thousand miles away.

But volunteer they did, for God'and Country. If the terrible charge at Gettysburg was Minnesota’s most famoussacrifice in helping win that war, it was not the only one, for Minnesota volunteers fought and died on many other battlefields also, and the state’s contributions in the form of food and raw materials were, if anything, even greater in volume than its contributions to the militia.

But four years and 700,000 lives later it was all over. Communities found themselves returning to pre-war interests and endeavors which had been set aside for the “duration”.

In Winona’s case, the normal school, perhaps the town’s most ambitious and forward-looking project, had been among the earliest of the war’s casualties. It had been shut down for almost three years by the time hostilities came to an end and even its loyal supporters were wondering whether it could possibly have survived that extended hiatus or ever again capture the imagination of the local populace. But the communityquickly regained its enthusiasm for the enterprise, spurred on as always by Dr. John Ford, and it was not long until the lawmakers of the state were again feeling pressure from the people of the Winona area.

During the session of the Legislature of the spring of 1864, an act was passed largely through the efforts of Ford and E. S. Youmans, a member of the State House of Representatives, renewing the appropriations and re-establishing the normal school on a permanent basis. This act provided that the sum of $3,000 be appropriated for the year 1864, $4,000 for the following year, and $5,000 annually thereafter.”

At the next meeting of the Normal Board it was resolved “that arrangements should be made for the opening of the institution at the earliest practical moment,” and the Prudential Committee was directed to secure a building for its accommodation. In case the requisite conveniences could not be obtained for the temporary use of the school, the Committee was instructed to erect a building at an expense not exceeding $2,500. Fortunately, this step was rendered unncessary by the liberal action of the Common Council and the Board of Education of the City of Winona. The first story of the building occupied by the normal school prior to the war was re-arranged,repaired, and refitted for the accommodation of a “model” department. By this means two rooms were made available, each one built to receive about forty children, thus forming the beginnings of that branch of the normal system designed to afford prospective teachers the means of observing and practicing “the best methods of teaching and governing a school”.*

While more will be said about the model school, it should be noted here that such an operation was still a novelty in the United States at that time. A school with model teachers, model equipment, and, with a bit of luck, even model students, would be the standard against which the fledgling teacher would measure himself or herself as well as the source of much of that teacher’s educational philosophy and technique. And many of those schools were, indeed, models. Others seem to have eventually taken on the characteristics of ordinary, average public schools or become financially undernourished and eventually phased out. Nonetheless, the idea persists down to the present day and on many campuses, as is true at Winona State, there will be found somewhere a building with the inscription, “Model School” over the door, confirming its placein history as part of the normal school era.

Another action of the Normal Board at its May meeting was the election ofJohn G. McMynn of Racine, Wisconsin, as principal at a salary of eighteen hundred dollars per annum. But Mr. McMynn resigned without even taking office, and the process of securing a principal had to be started all over again.

The Board was convinced that securing exactly the proper person as principal was all important to the future success of their venture, but the efforts and the negotiations which followed consumed more time than the Board had supposed would be necessary. Consequently, the reopening of the school was.delayed to a later period than was

originally contemplated. It could have been effected earlier ifthe Committee had felt justified in accepting, in their words, the services of “inferior and inexperienced men”, but in deciding a question so vital to the future welfare and success of the institution the Committee believed that it was justified in acting with deliberation even at the risk of disappointing public expectations for an early start. Apparently they were right, for as a result, they secured the services of a gentleman who probably had a more extended experience in the cause of normal school instruction than had any other person in the country, having been actively engaged in the work for nearly twenty years in the states of New York and New Jersey. As usual it was not mere luck that brought William Phelps to the position he came to hold for so many years as the head of the first normal school of this state but, again, hard work on the part of one man in particular.

Dr. Ford had been delegated to find the right person for the principalship. He had opened an extensive correspondence with eastern educators, which brought several applications for the position. About the same time E. S. Youmans, now a member of the board, wrote to his brother Edward L. Youmans of New York City setting forth the desires of the Board. In response his brother, who was himself an educator, wrote that he had been called to lecture before the State Normal School of New Jersey at Trenton a while back and that the principal of that school, a Mr. William Phelps, had impressed him as more advanced in his ideas of popular education than any other person he had met. He did not know, however, whether Phelps’ services could be secured, although in conversation concerning his work in that school, Phelps had expressed impatience at being hampered by an “old fogy” board of education. Mr. Youmans gave the letter to Dr. Ford who was planning to go East to have personal interviews with the applicants with whom he had been in correspondence. He added the name of William Phelps to his list.

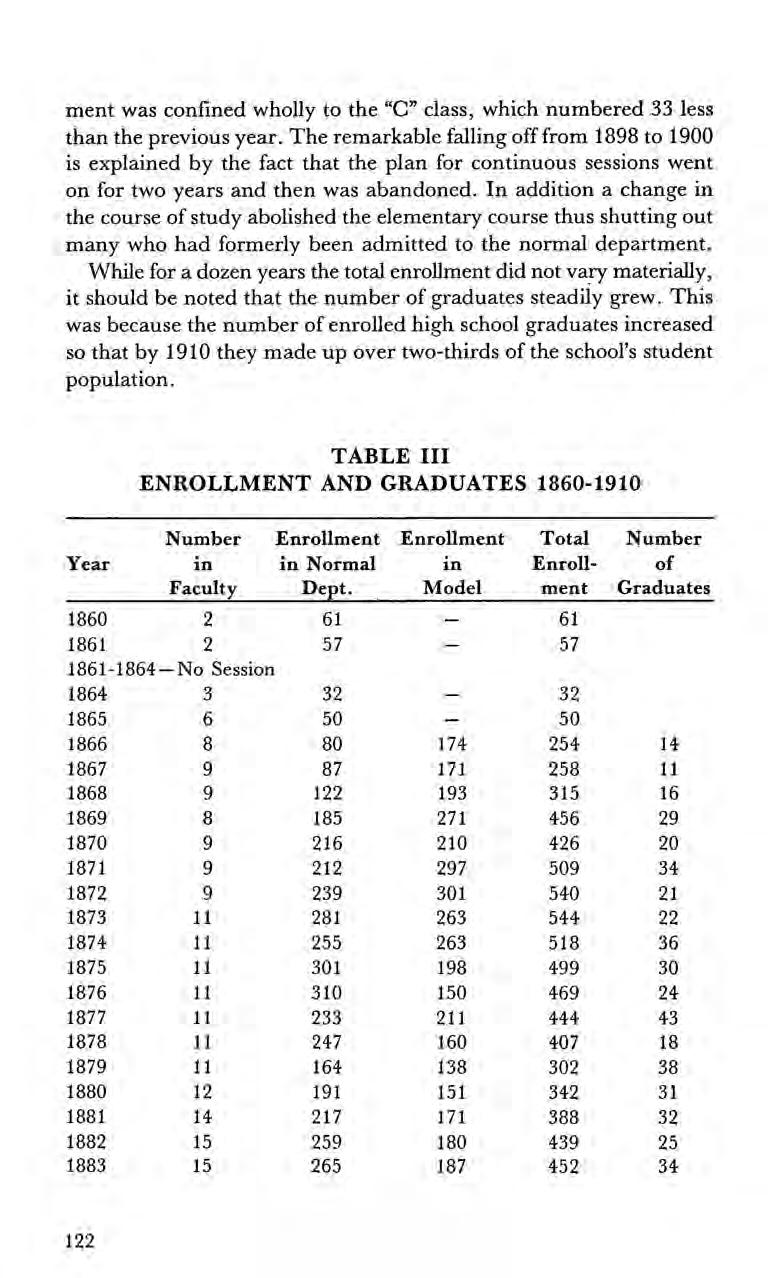

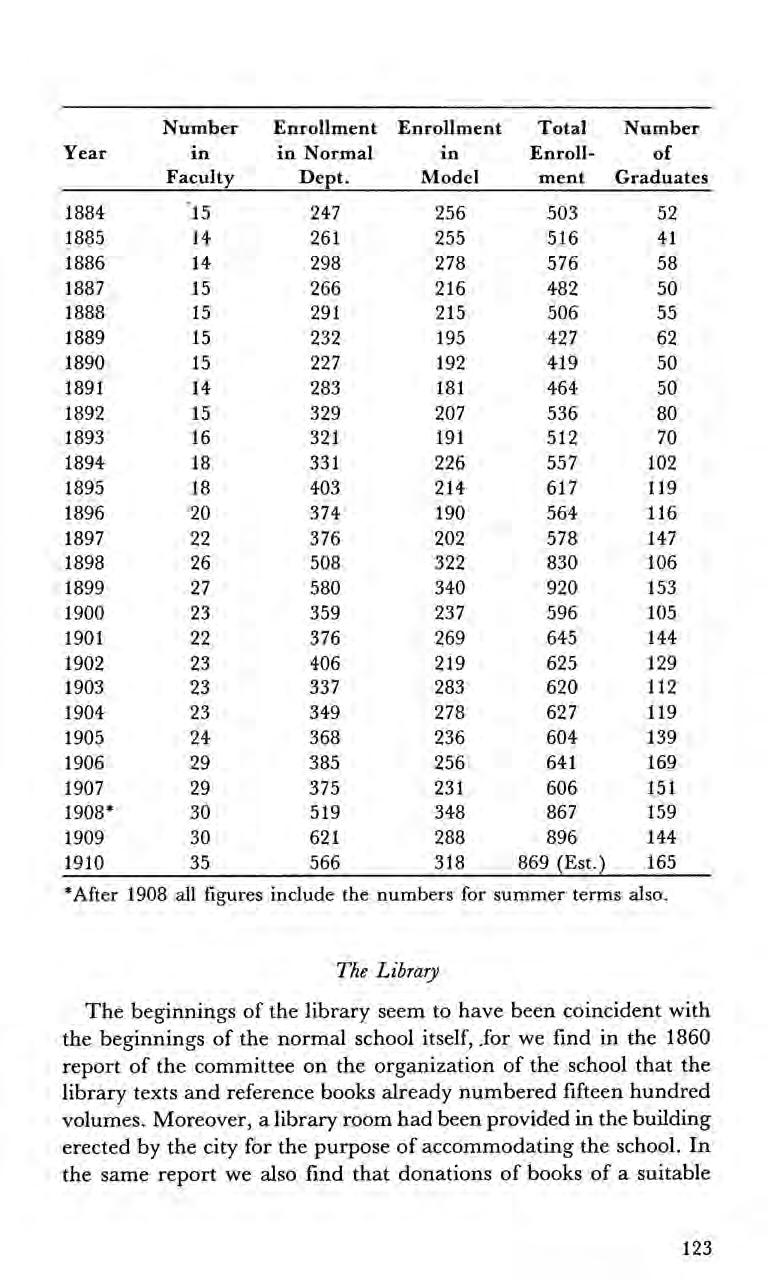

Ford soon found that none of the applicants came up to his standard and somewhat discouraged he went on to Trenton. He approached his first meeting with Mr. Phelps simply as one connected with a normal school in the West, who desired to visit Trenton and look over their methods that he might perhaps pick up a few pointers. That interview, however, made a deep impression on him for he found not only a principal, but a teacher full of enthusiasm who thorougly appreciated the importance of common school education and the relation of the normal school to the advancement of such an education.