172 minute read

VI. 1960–1972 From bad to worse – the final chapter for ACSM

1960–1972 From bad to worse – the final chapter for ACSM

ChrisTian bonneT, Journal oFFiciel, dÉbats parleMentaires, 19 november 1959

ACSM had gone through critical periods (the 1930s, the Second World War) since its establishment, but the extent of the looming crisis was unprecedented. Although the company was still making profits in 1959, the White Paper published in December of that year left it with little hope: Le Trait was evidently not going to be among the four or five shipyards (of the fourteen operating in France) “named by the Merveilleux du Vignaux Commission to form ‘the powerful and economically sound backbone of French shipbuilding.’”698

The unprecedented boom of the 1950s

Between 1950 and 1960, shipbuilding went through an unprecedented boom: worldwide production grew by 139%, with gross tonnage climbing from 3,489,000 to 8,359,000 tons and its annual growth rate reaching 12.3%. In France, 443,000 gross tons were launched in 1958 while 217,000 tons of new ships were produced in 1951. This boom can be traced back to a combination of several factors. ► More efficient production techniques Technological innovations – oxy-cutting of steel plates, prefabrication of a ship’s various sections in workshops, welding instead of riveting – shortened the occupancy time of slipways and helped rationalise

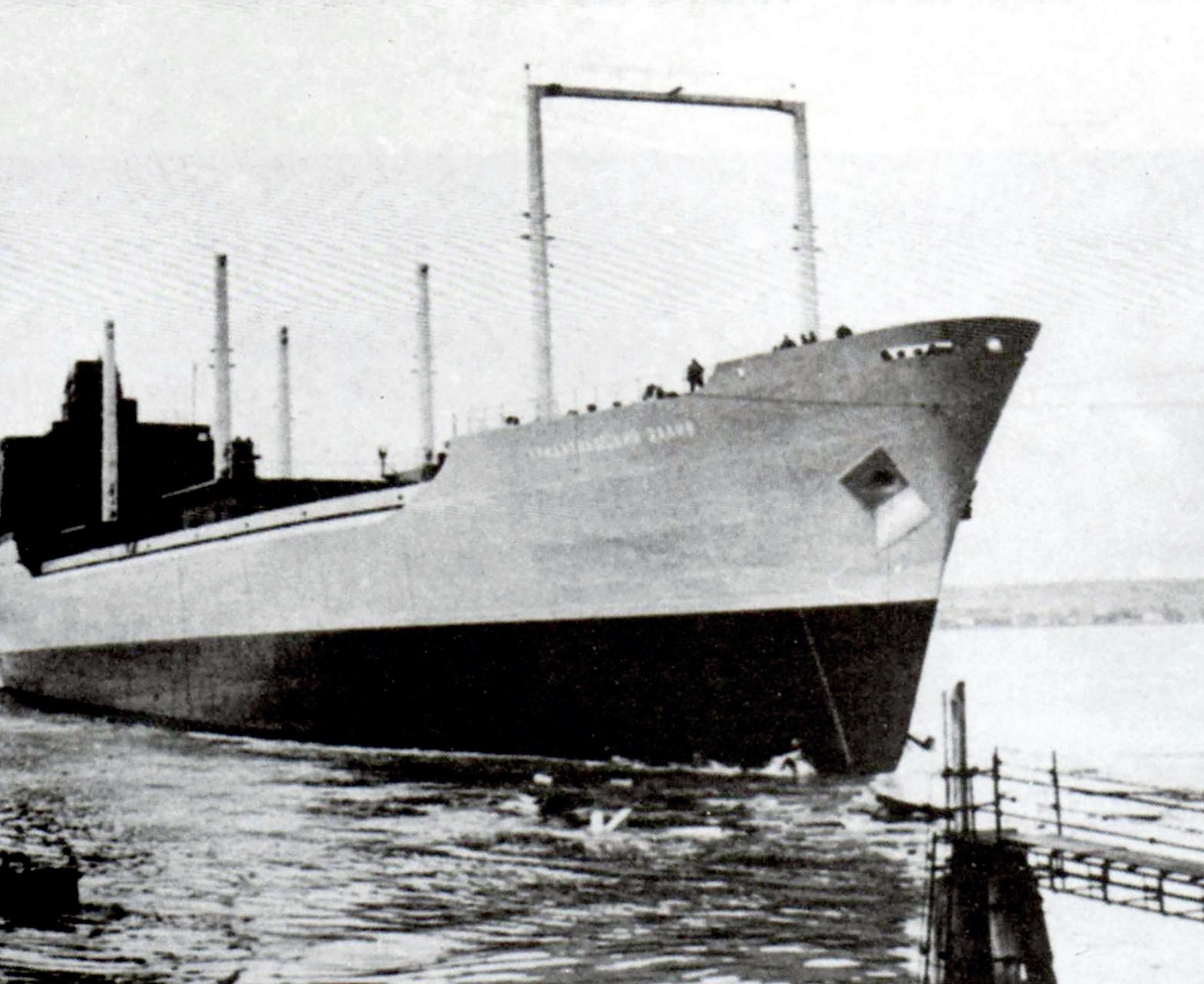

µ The Chantiers Navals de La Ciotat: launch of the oil tanker “Béarn” on 23 April 1960, for the Société Française de Transports Pétroliers (SFTP)

698 Report issued by the Merveilleux du Vignaux Commission, Chief Counsellor at the Court of Auditors, p. 5, quoted by Jean Domenichino, in “Construction navale, politique étatique, stratégies patronale et ouvrière; les Chantiers et Ateliers de Provence de Port-de-Bouc (1950–1965),” in Le mouvement social : bulletin trimestriel de l’Institut français d’histoire sociale, No. 156, July–September 1991, Éditions Ouvrières, p. 56. methods and construction processes;699 this rationalisation, particularly in the best-equipped yards, spurred the shift from custom-built vessels to standard ships produced in series.700 Another notable transformation was the construction of vessels capable of carrying increasingly heavy loads. The average unit tonnage for oil tankers doubled between 1945 (16,000 dwt)701 and 1960 (30,000 dwt). When the Suez Canal closed during the first Suez Crisis (October 1956 to March 1957), this trend intensified: freed from the constraints on the ship’s draught imposed by the Canal, builders increased the deadweight of oil tankers and other ore-bulk carriers to satisfy the demands of shipping companies keen to offset the additional costs caused by the obligation imposed to ships to sail round Africa via the Cape of Good Hope. Increased transport capacity led to savings in financing (the higher the ship’s tonnage, the lower the investment cost in relation to deadweight tonnage), in payroll (a 30,000-ton ship required fewer crew members than two 15,000-ton ships), fuel consumption, duties and taxes, etc.

699 See Pierre Léonard, “Y a-t-il une crise de structure de la construction navale ?,” in Revue économique, vol. 12, No. 4, 1961, p. 568: “By way of example, in just six years a French shipyard, through the use of prefabrication and a systematic policy of series production, has managed to reduce the time needed to construct the metal hull of an average-sized freighter from 110 to 60–65 hours per ton, or a saving of over 40% for a series-produced ship. Between the first ship and the fifth, the impact alone of series production makes it possible to save, for the entire freighter, 20% of shipyard hours, [item] corresponding to approximately one-third of the vessel’s production cost. At the end of the day, shipyards will be producing more and larger ships using fewer slipways, with less and less shipyard work per unit of gross tonnage.” 700 Ibid. Pierre Léonard emphasised that standardisation was suitable for certain classes of ships: oil tankers and bulk carriers. 701 Deadweight tonnage (dwt): the maximum load that a ship is able to transport.

In “Y a-t-il une crise de structure de la construction navale ?,” Pierre Léonard stated that “between 16,000 dwt and 30,000 dwt […] the cost to transport one ton of crude oil from the Middle East to the English Channel [is] reduced by one quarter.” This same search for productivity prompted an increase in the speed of passenger liners and line freighters (20 knots in 1960 versus 10 knots in 1945, with average tonnage transported increasing from 4,650 gt702 in 1950 to 7,400 gt in 1960). ► More and more shipyards and an increasingly competitive world market World supply was marked by the rise of Japan to become the world’s leading shipbuilding nation in 1956 (its 24 main shipyards produced 1,340,000 tons in 1960–1961); and by the market entry of a new generation of builders (Spain, Poland, Yugoslavia), followed by several emerging countries (Brazil, Argentina, Peru, Ireland, Israel).703 This surge in production capacity occurred at the expense of Great Britain (16% of world production in 1960, versus 38% in 1950, and 51% in 1930). It also affected the six other members of the European Free Trade Association704 as well as the six members of the European Economic Community,705 which, despite an increase in their respective production (production in EFTA countries more than doubled and that of the EEC quadrupled between 1950 and 1960) declined. In 1950, these thirteen countries accounted for 74.1% or 2,586,000 gross tonnage of worldwide production; in 1960, the 5,276,000 gross tonnage launched by their shipyards accounted for no more than 63% of the total. Other countries now produced 37% (3,800,000 tons out of a total of 8,356,000 tons in 1960).706 ► Exceptional growth in trade Backed by “the surge of industrial production worldwide and the exceptional growth of trade”707 (the amount of freight transported doubled in ten to eleven years), maritime transport posted a growth rate of around 7%, while the tonnage of the world fleet increased by 4 to 4.5% on average per year. “The share carried under the French flag also increased,” wrote Bernard Cassagnou in Les mutations de la marine marchande française de 1945 à nos jours. “French imports carried by French vessels surged from 40% in 1938 to 58% in 1955 and to 68% in 1960. […] As regarded French exports, the share moved from 55% in 1938, to 47% in 1953 and 58% in 1960. At the time, these percentages were higher than those of Great Britain, West Germany and Italy.” These growth phases alternated with sharp downturns on shipping markets (cyclical by nature). For example, 1952–1954 and 1957–1961 were marked by decreases, while the Korean War (June 1950 to July 1953) and the Suez Crisis threw international trade into a panic, causing demand for transport to explode: the former, to develop safety stocks of raw materials; and the latter, to compensate for the extended sailing times caused by the Canal’s closure. 15 million gross tons were on order at the end of 1951, against 7 million at the end of 1950 – and 30 million in 1956–1957, or one-third of the world fleet.708

702 Gross tonnage or gross registered tonnage (grt): total inner capacity of a ship. 703 See Pierre Léonard, op. cit., p. 572: “Typically, developing countries are benefiting from the depressed state of shipping markets not only to build up merchant fleets under relatively cheap conditions, but also to get the shipbuilders, with whom they have placed their orders, to set up shipbuilding companies in their countries. To fill their threatened order books, many large shipyards, by providing technical and financial support, have readily contributed to setting the conditions for a future increase in market competition.” 704 The EFTA was established by the Convention of 4 January 1960 between Austria, Denmark, Norway, Portugal, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. 705 The EEC covered France, the Federal Republic of Germany, Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Italy, signatories to the Treaty of Rome on 25 March 1957. 706 In 1950, these countries’ share was 26%, with 903,000 gt, out of a total of 3,489,000 gt; in 1930, their share was 16.5%, with 477,000 gt out of a total of 2,889,000 gt. 707 Bernard Cassagnou, “Les mutations de la marine marchande française (1945-1995)”,ˮ Recherches contemporaines, No. 6, 2000–2001, p. 38. 708 See Pierre Léonard, “Y a-t-il une crise de structure de la construction navale ?”ˮ, op. cit., and Bernard Cassagnou, Les grandes mutations de la marine marchande française (19451995), vol. 1, IGPDE – Comité pour l’Histoire Économique et Financière de la France, 2002.

► State incentives: the case of France More or less in line with the majority of producing countries,709 French shipbuilding had benefited from subsidies ever since the adoption of the Defferre Law710 of 24 May 1951. This post-war legislation sought to encourage shipping companies to place their orders in France, thereby neutralising French shipyards’ lack of competitiveness (due to the burdens of the French tax system, customs protection, the rationing of materials, etc.) on the international market and compensating for the (fluctuating) gaps between their production costs and the prices offered abroad (20–30% lower in England, for example). In return for this financial aid, builders undertook to enhance their productivity and participate to the fullest possible extent in the effort to reconstruct the Merchant Navy. The goals of this policy were to: - stabilise the balance of payments by avoiding a flight of capital spent on purchasing or (above all) chartering ships abroad;711 - stimulate foreign trade by encouraging the export of a portion of production; this export drive also benefited from the devaluations of the franc in August 1957 and December 1958;712 - safeguard the safety of the country’s supplies, and thus, its independence;

709 For example, in Italy, the Tambroni Law of 17 July 1954, offset “the inferiorities of the regulatory system (fiscal and customs) for the Italian shipbuilding” by keeping on “unemployed workers in the company, even if this meant receiving government funds to pay for this particular subjection (system of the disoccupati)” – Ref. Pierre Léonard, op. cit. 710 Gaston Defferre, Minister for the Merchant Navy (12 July 1950–11 August 1951). The Law of 24 May 1951 was revoked in 2001 on the order of the European Commission. 711 In fact, even subsidised, shipbuilding created value: a ship was used for 20 years on average, and even at a high price, it was always more cost-effective to purchase than to charter. Cf. B. Cassagnou, in Recherches contemporaines, op. cit.: “In 1952, the Merchant Navy is still using 1.5 million gross tons of ships chartered abroad. This is one reason why shipping is a main contributor (200 million dollars) to the balance of payments deficit totalling 1,060 million. The shipping industry – i.e. the sum total of all shipping companies – plays a key role in the French economy, with its turnover reaching 261 billion old francs [equivalent to 4.2 billion Euros in 2016] in 1959. The industry employs 60,000 seafaring and sedentary staff and accounts for 4% of world tonnage.” Total = 130 million grt in 1960. 712 The franc was devalued by 20% in 1957 and by 17.55% in 1958. The “heavy franc” came into effect on 1 January 1960. - protect employment in areas or regions where shipbuilding was the only – or almost the only – economic activity (as was the case with eleven of France’s fourteen main shipyards),713 and in the companies which, little integrated into diversified groups,714 were unable to offer their workforces redeployment opportunities.

“Beyond the needs of the national and international market”715 – market saturation and the collapse of demand

Although intimately bound to one another, shipping companies and shipbuilders nevertheless had differing interests (the one sought to buy at the lowest price what the other sought to sell at the highest price), especially as they were part of discordant economic cycles. In an increasingly uncertain economic climate, the lag between the circumstances (most often exacerbated by international tensions) under which orders were placed, the time required to build a ship and the context in which it was delivered (as shipping market circumstances have changed) was one reason for market saturation: for example, the surge in ships ordered during the Suez Crisis but delivered long after the turmoil had subsided flooded the market and led to a drop in demand, a decline in freight rates and massive decommissioning. Beyond this hiatus aggravated by the worldwide economic slowdown in 1958 and 1959, the dynamism of the shipbuilding industry itself was at issue. “The balance,” wrote Pierre Léonard in 1961, “between the rapidly growing supply of new ships [nearing 10% per year] and the equally growing – albeit to a lesser extent [it varied between 6.5% and 8.5% per year] – demand no longer existed.”716 Worldwide merchant tonnage hovered

713 Pierre Léonard, “Y a-t-il une crise de structure de la construction navale ?,” op. cit., pp. 585–586. “Of the fourteen main French shipyards, eleven were located in cities with no other dominant industrial activity or in weakly developed regions: Le Havre (two companies), Le Trait, Saint-Nazaire, Nantes (three companies), La Pallice, Bordeaux, La Ciotat, Toulon. The exceptions to this rule were the shipyards of Dunkerque, Rouen and Marseilles.” 714 Ibid., p. 592: The shipyard in Le Trait belonged to the Worms group (shipping), while the Bordeaux shipyard belonged to the Schneider group (metallurgical industry). 715 Jean Domenichino, “Construction navale, politique étatique, stratégies patronale et ouvrière,” op. cit., pp. 54–55. 716 Pierre Léonard, op. cit.

around 110 million tons,717 while maximum shipbuilding capacity was 11 million tons per year. This meant that the shipyards were capable of replacing every ton in service within ten years. Yet, ships were operated for twenty years on average, and the fleet doubled every seventeen years. This distortion reduced to nothing 15–35% of production, “or 1.7 to 3.9 million grt, a gap that could only increase over the medium term, in the absence of a political crisis generating exceptional and unforeseeable demand.”718 The collapse of demand also stemmed from technical innovations and the “race for high tonnage” unleashed by technical progress. While still far from the supertankers displacing several hundreds of thousands of tons (such as the 555,000-dwt “Prairial” capable of transporting 667,380-m3 of crude oil), the trend started in the 1950s was proving irreversible: the commissioning of the first 50,000-dwt oil tankers whetted the appetite of shipping companies, with mid-tonnage ships being gradually supplanted by these “giants of the seas.” In the same vein, large bulk carriers of 30,000 or more deadweight tonnage increasingly made inroads.719 Allowing a reduction in the number of vessels needed, the cost-effectiveness of these ships resulted in the growth rate of the merchant fleet (approximately 3.5% per year) falling behind that of seaborne trade, causing orders for new vessels to dwindle. “For this reason,” noted Pierre Léonard, “while world traffic in dry goods increased by 42% between 1951 and 1957, the corresponding fleet in service only grew by 22%.” Competition from rail (proven effective in the transport of goods) and civil aviation (emerging in the transport of passengers) also influenced shipbuilding insofar as it increasingly put pressure on maneuver margins (above all on freight rates) and growth potential of shipping companies. For example, the passenger liner “France,” “the jewel of French shipbuilding and shipping built with public money,” was already doomed on decommissioning in 1962 by the “entry of the Boeing 707–120 B into the transatlantic passenger market, and

717 Bernard Cassagnou, in Recherches contemporaines, op. cit., reported (p. 29) that on 1 January 1962, the French fleet totalled 4.8 million grt: passenger ships: 12%; freighters: 43.5% and oil tankers: 44.5%. 718 Pierre Léonard, op. cit., p. 581. 719 Their introduction went hand in hand with the construction of major international port complexes, linked by sea to the production centres of raw materials. the advent of mass air transit.”720 These problems were compounded in France by: ► The adverse effects of State aid “The subsidies received under the Law of 1951,” wrote Jean Domenichino, “did not all lead to the intended results. Designed to promote a certain conversion of shipyard activity in the long term, they achieved the opposite, causing an increase in shipbuilding capacity and reflecting the classic phenomenon whereby any product benefiting from State aid is favoured by the producers.”721 The paradox here was that “the more the shipyards produced, the dearer they became” for public finances. Unable to rival international prices, French shipyards failed to prevent shipping companies placing orders elsewhere in the world or to develop a foreign clientele. ► Decolonisation and its impact on the French flag Between 1956 and 1960, twenty-two African countries were granted independence; seventeen722 were former French colonies or protectorates (Madagascar). However shipping services with these territories were the monopoly of the French fleet. “Sheltered from foreign competition, French shipping companies, both large or small, defend[ed] valuable – even marginal – market shares in a private and protected area, which assure[d] the viability of their activities.”723

720 Bernard Jardin, Un demi-siècle de pavillon français (1960-2010), June 2011; on the website of the French Institute of the Sea. 721 Jean Domenichino, “Construction navale, politique étatique, stratégies patronale et ouvrière,” op. cit., p. 55. The following quote, by the same author, comes from La construction navale en Provence : essor et déclin d’une industrie, text posted on https://fresques.ina.fr. 722 Having joined Liberia (26 July 1847), South Africa (31 May 1910), Egypt (28 February 1922), and Libya (24 December 1951), were the following countries: in 1956, Sudan (1 January), Tunisia (20 March), Morocco (7 April); in 1957, Ghana (6 March); in 1958, Guinea (2 October); in 1960, Cameroon (1 January), Senegal (4 April), Togo (27 April), Madagascar (26 June), Democratic Republic of Congo (30 June), Somalia (1 July), Benin (1 August), Niger (3 August), Burkina Faso (5 August), Ivory Coast (7 August), Chad (11 August), Central African Republic (13 August), Congo (15 August), Gabon (17 August), Mali (22 September), Nigeria (1 October), Mauritania (28 November). 723 Antoine Frémont, “De la Compagnie générale transatlantique à la CMA-CGM,” in Revue d’histoire maritime - histoire maritime, outre-mer, relations internationales, La marine marchande française de 1850 à 2000, Pups, 2006.

“In the years 1945–1962,” wrote Bernard Dujardin, “marked by the colonial conflicts at the end of the French empire, the French flag experienced an ephemeral apogee, climbing to fourth place in the world. Booked cargoes and military freight between French ports and those of its overseas colonies filled French ships’ holds. Decolonisation signalled the end for this monopoly. […] When André Malraux stated: ‘Every colony is born with a sign of death on its forehead,’ he might as well have said: ‘Every colonial flag is born with a sign of death on its forehead.’”724 Bernard Cassagnou provides the

724 Bernard Dujardin, “Le pavillon français, une compétitivité à conquérir,” L’Ena hors les murs, No. 428, 2013, pp. 31–32. meaning of this expression: “Decolonisation forced French shipping companies to redeploy their fleets,”725 revealing their lack of competitiveness. “In 1961 […] the French Government became aware of the precarious means of the French fleet to fend off competition in the context created by the onset of the international shipping crisis in 1957 and the impact of French decolonisation on the use of ships. […] For shipping companies operating the lines to French overseas territories, this meant the collapse of de facto or de jure protections and consequently, under the new shipping relations established between these countries and France, the definition of new statutes, sometimes completely different. […] The new, independent governments could finally realise their ambitions to trade with countries other than France and to operate several ships under their national flags. […] In Algeria, French shipping experienced the scheduled end to its decadesold monopoly on seagoing traffic with France in 1961. ‘On top of this inevitable upheaval’726 came the prospect of increasing foreign competition when the Treaty of Rome came into effect in 1958. Its anti-protectionist clauses allowed the new Common Market countries not only to invest in African fleets, but also to divert shipments intended for France to Northern European ports.”727 ► The discovery of oil in Algeria The discovery of natural gas deposits in Algeria in 1954 (we shall return to this topic later) was followed by that of two oil fields in January and June 1956.728 The nationalisation of the Suez Canal, which threatened supplies of Middle Eastern oil to France, hastened the implementation of a proper infrastructure to exploit these resources. In 1960, Algerian crude oil accounted for more than 20% of liquid hydrocarbon imports into France and more than 32% in 1962.

725 Bernard Cassagnou, Les grandes mutations de la marine marchande française (1945-1995), vol. 1, op. cit. 726 Lucien Poirier, Économie maritime, course given at the ENSTA (French Graduate School of Engineering), 1977, p. 102, quoted by Bernard Cassagnou. 727 Bernard Cassagnou, op. cit. 728 Research and exploitation licences had been granted to four French companies: Société Nationale de Recherche et d’Exploitation des Pétroles en Algérie (SN Repal); Compagnie Française des Pétroles – Algérie (CFPA); Compagnie de Recherche et d’Exploitation Pétrolières au Sahara (Creps); and Compagnie des Pétroles d’Algérie (CPA).

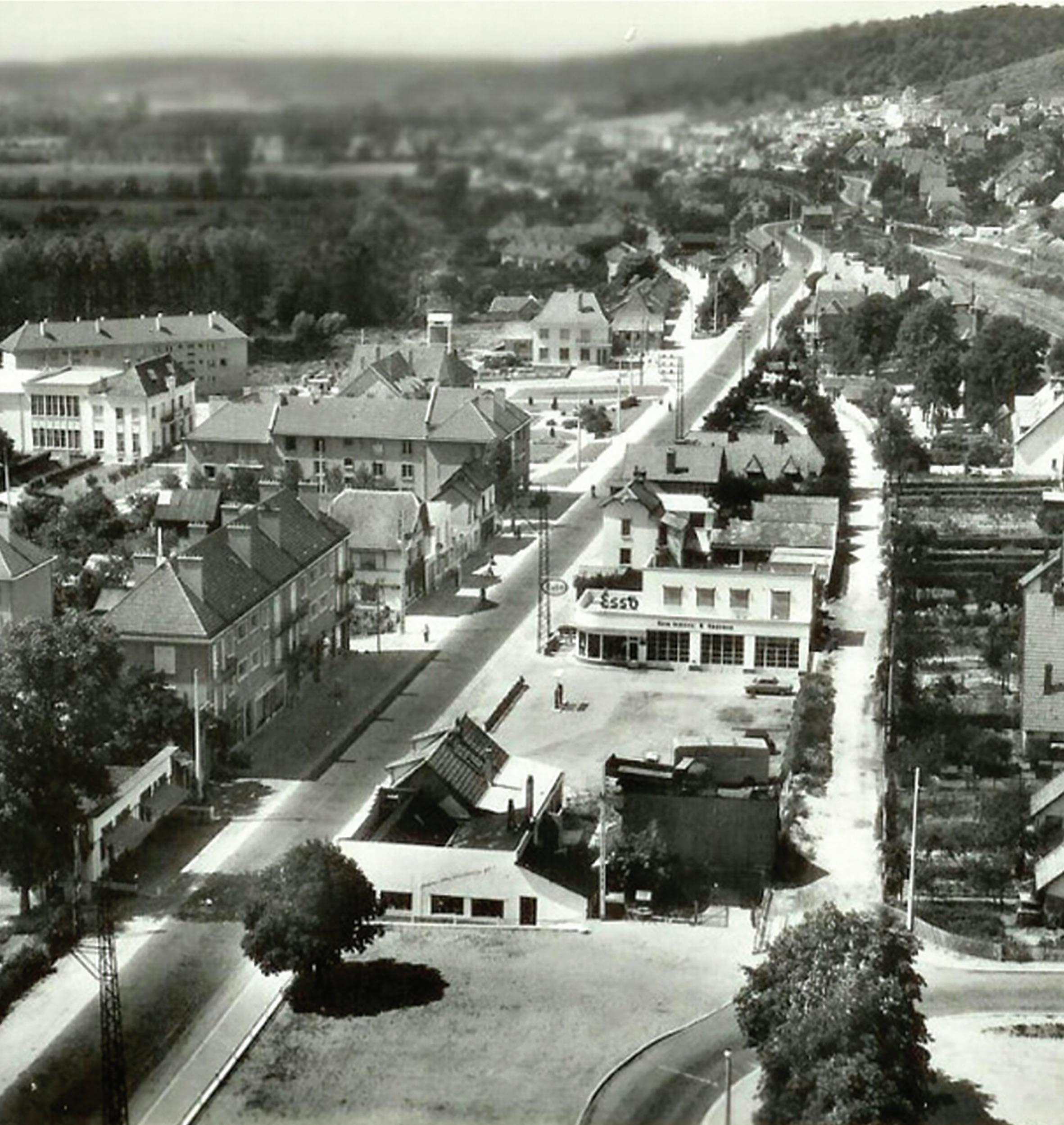

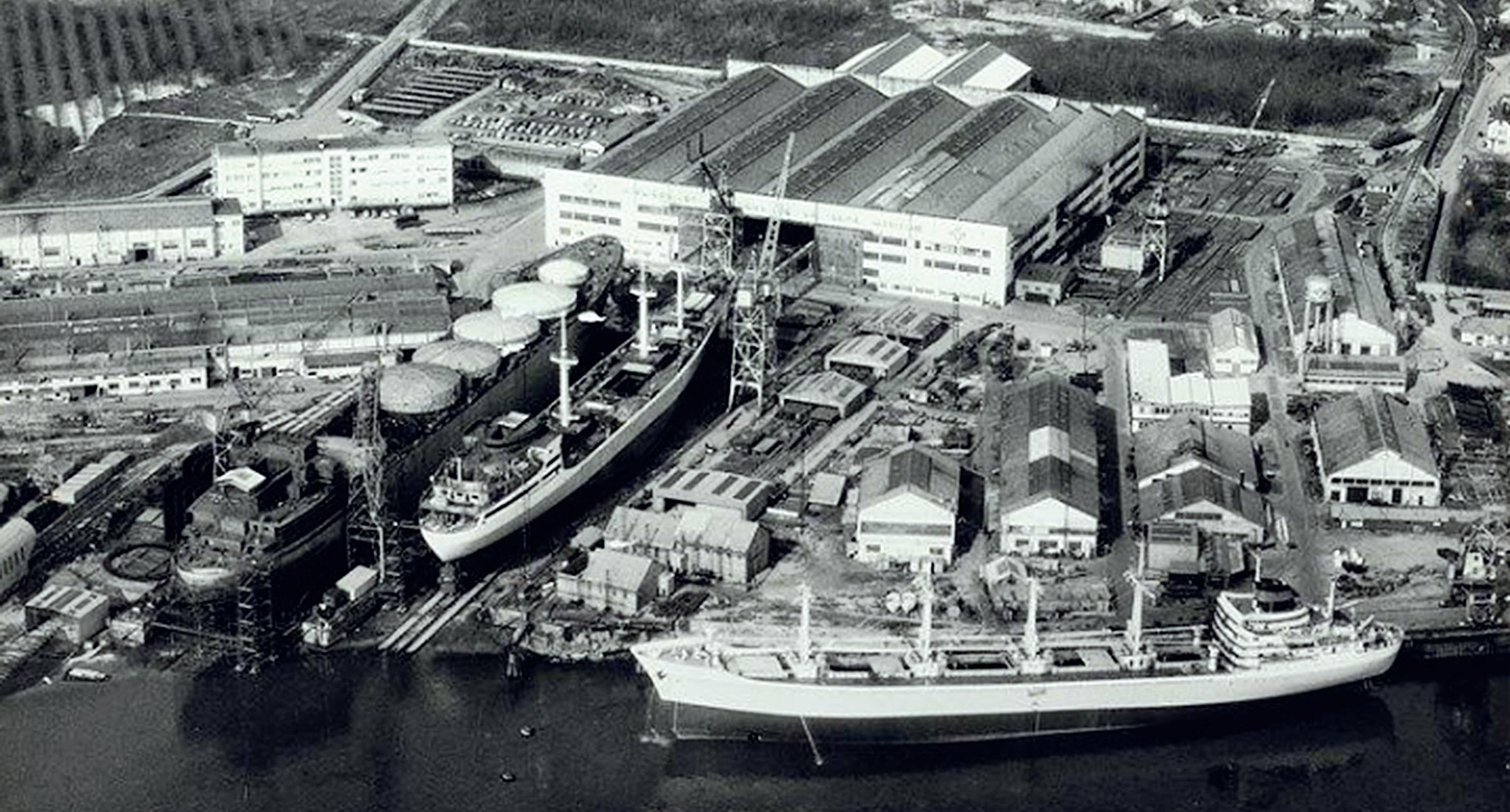

Aerial view – at the fitting-out quay, the tank-landing ship (LST) “Dives” launched on 28 June 1960; in slip No. 1 the self-unloading bulk carrier “Gypsum Countess” and in slip No. 2 the ore carrier “Penchâteau”

Saharan deposits, the strategic importance of which influenced the Algerian War of Independence (1954–1962) – at least in its duration, had an impact on shipbuilding: as they were closer to France than those in the Persian Gulf, fewer tankers were needed to transport the extracted oil. “The experts at the Organisation for European Economic Cooperation,” wrote Pierre Léonard, “calculated that Europe’s supply of crude oil from North Africa instead of from the Middle East, for each 5-million-ton tranche, resulted in a savings in ships equal to 21 T2 oil tankers729 (considered as a unit of measure).”730 ► French Navy programmes entrusted solely to Navy arsenals In 1962, the government decided to entrust all French Navy shipbuilding to the Navy arsenals. This made a big gap in shipyard order books, since “traditionally 30 to 50% of new warships were dedicated to

729 Ship with deadweight tonnage of 16,500 tons and a speed of 15 knots. 730 Pierre Léonard, “Y a-t-il une crise de structure de la construction navale ?,” op. cit., p. 574. private shipyards.”731 This change doomed some of them to disappear (notably Augustin Normand, in 1964). The late 1950s and the ensuing years were marked by considerable overcapacities in the world shipbuilding market, which Great Britain and Japan estimated at one-third of their capacities.732 As for seagoing oil transport, “endogenous fluctuations of the market, independent of any specific catastrophic situation, resulted in surplus (decommissioned) tonnage in 1959 equal to 10% of the fleet in service.”733 The consequence: “Prices of new ships [in 1961] for the most current types of ship hovered in the area of 60% of 1957 prices.”734

731 See Rapport au Sénat sur la loi de finances 1962 – session du 14 novembre 1961. “The decision to create the Directorate General of Armaments in 1963 leads to defence being turned in on itself and military shipbuilding being reduced to arsenals alone,” cf. Alain Merckelbagh, Et si le littoral allait jusqu’à la mer : la politique du littoral sous la Ve République, Éditions Quæ, 2009. 732 See Pierre Léonard, op. cit., p. 583. 733 Ibid., p. 574. 734 Ibid., p. 587.

And the report published by the Merveilleux du Vignaux Commission estimated “that the imbalance between supply and demand was not cyclical and indeed had a strong chance [or risk] of increasing in 1963.”735

Downsizing production

The crisis was thus structural in nature, forcing governments to make decisions. In France, a lot was at stake: 39,500 people were employed in the sector,736 or 60,000 if subcontractors were added. Unlike 1951, it was no longer a question of stimulating productivity, but rather of downsizing production, especially since the Treaty of Rome imposed a reduction in subsidies, which had reached 131 billion francs between 1954 and 1958. The 30 July 1959 meeting of the Council of Ministers set the ceiling for subsidies at 97.2 billion until 1963,737 an amount that dropped to 19 billion during the following period. The workforce was to drop to 27,000 persons between then and 1965, and to 17,000 in 1970. Ideally, the number of shipyards was to drop to three, or one per maritime facade. Rumours circulated that the three would be Dunkerque, Saint-Nazaire and La Ciotat. “It was an obvious break with the practices of 1951,” wrote Jean Domenichino. From that point onwards, State aid became one of the primary means used by the government to intervene in an industrial sector [financed by private capital] and to impose its assessment of future developments through “a policy oriented not towards maintaining an increasingly uneasy and unpredictable and artificial situation, but toward the realistic choice of true remedies.”738 Since the “realistic choice” meant adapting French shipbuilding to the needs of the market, estimated at 400,000 grt per year – in contrast to the total shipyards’ capacity of 700,000 grt – in plain language this involved eliminating sizeable production capacities. Subsidies were assigned a double task: to help those shipyards “the situation of which remains sufficiently healthy, allowing them to face international competition”739 and to contribute to the necessary reconversion of shipyards who needed to “work on creating new non-shipbuilding activities […]” in order “to reclassify the highly skilled workforces and assign them to other tasks.”740 In the context of this struggle among French shipyards and in the face of international competition, ACSM suffered from three major handicaps impeding its ability to overcome these threats: - its production capacity (estimated at three 20,000-grt oil tankers per year on the basis of a 48-hour working week) did not put it in the leading bunch of companies within the sector; - its location on the banks of the Seine made it impossible for the shipyard to build vessels in excess of 24,000; 26,000; 27,000; or 30,000 tons,741 at a time when the “race for high tonnage” was dominating the market; - its location in a region suffering from an “industrial monoculture” to use the expression of Pierre Léonard, while the specific nature of its industry did not allow it to redeploy all or part of its workforce in the other subsidiaries belonging to the Worms group. If solutions were to be found, it was up to ACSM to create them. To do so, they had to innovate in cuttingedge techniques, intensify their reconversion efforts, and create partnerships.

735 Cf. Jean Domenichino, “Construction navale, politique étatique, stratégies patronale et ouvrière,” op. cit., p. 55. 736 Ibid. The average workforce evolved as follows – 1953: 39,464 people – 1954: 39,208 people – 1955: 39,917 people – 1956: 39,674 people – 1957: 39,876 people – 1958: 39,447 people. 737 Ibid. In 1960: 28.2 billion; in 1961: 25.5 billion; in 1962: 24.3 billion; in 1963, 19.2 billion. 738 Footnote (p. 56) in the document by Jean Domenichino, “Construction navale, politique étatique, stratégies patronale et ouvrière,” op. cit.: “Livre blanc, p. 16 : excerpt from a letter from the Prime Minister, Michel Debré, to the Chairman of the Chamber of Shipbuilders, Abel Durand, dated 17 August 1959.” 739 Ibid.: “Livre blanc, p. 17.” 740 Ibid.: “Livre blanc, p. 13 and p. 18.” 741 The maximum production capacity was estimated in various ways, depending on the documents (advertisements, loan requests, annual reports, etc.).

The battle for survival

“With more than 2,000 blue- and white-collar workers, technicians and engineers, [and a] very large industrial complex spread over 26 hectares of land, of which 50,000 m2 were under cover,”742 the Le Trait shipyard was ready to fight. It enjoyed a sound financial structure and highly efficient production facilities.

Ready for the fight

A sound financial structure

Since being incorporated as a public limited company in July 1945, the Ateliers et Chantiers de la SeineMaritime’s share capital, initially 10 million old francs,743 had been increased on three occasions. On 3 August 1949, in an Extraordinary General Meeting, it was increased to 50 million old francs, by drawing on the special revaluation reserve (the par value of the shares went up from 1,000 to 5,000 francs). On 15 June 1951, in application of the provisions approved by the Ordinary and Extraordinary General Meeting, share capital was raised to 100 million old francs by incorporating 50 million francs, 25 million of which were taken from the special revaluation reserve and the other 25 million from the general reserve (par value of the shares: 10,000 francs). On 29 September 1952, the shareholders increased share capital to 350 million old francs by issuing 25 thousand shares with a par value of 10,000 francs each, created as payment for the contribution in kind by Worms & Cie of tangible and intangible assets valued at 821 million francs,744 encompassing the main part of its industrial site and production assets in Le Trait. At the end of 1959, a further capital increase was scheduled. “In 1952,” stipulated a memo of 19 November 1959, “Worms & Cie made a contribution in kind to the Ateliers et Chantiers de la Seine-Maritime SA, in the form of its fixed assets which had already been reconstructed. The contribution of the remaining fixed assets was postponed until these had been fully replenished. Now that said reconstruction has been completed, the contribution in kind of the remaining land, buildings and equipment shall be finalised, so that Worms & Cie, while retaining only its banking activity, will no longer own the shipyard, but only a share [100%] in said shipyard. Since the Ateliers et Chantiers de la SeineMaritime SA does not own the aforementioned fixed assets, it could not benefit from depreciations in their value. […] Going ahead with consolidating the ACSM balance sheet, it seems justifiable to incorporate into the company’s share capital, in parallel with the contribution of the remaining fixed assets, the sum of 210 million francs resulting from the accumulation of aforementioned depreciations not booked as such by the company, but which it would have been entitled to do, had the fixed assets been fully contributed sooner. In our opinion, this retroceding seems to be the only possible solution.” The contribution was to lead to the ACSM clearance of accounts from the Worms & Cie books, in particular settling the war damage accounts, the total amount of which was over 337 million francs.745 Above all, the aim of the transaction was to bolster the company’s financial stability vis-à-vis its competitors. A memo of 17 November 1959 assessed “the optimal level of ACSM capital” in comparison to six companies (see table on next page746) and concluded: “We can justifiably consider an amount of 600 million.”

742 Undated document on ACSM, filed in 1961. 743 On 1 January 1960, the new franc replaced the old franc: each new franc (NF) being worth one hundred old francs. 744 Cf. memo from Robert Malingre, head of financial and administrative services at Maison Worms, to Robert Labbé, dated 11 January 1960. 745 Cf. memo from Robert Malingre to Robert Labbé, dated 9 October 1959. 746 The memo specified that Forges et Chantiers de la Méditerranée was highly involved in activities other than shipbuilding.

- Chantiers de l’Atlantique

Share capital (in old francs) 2,000,000,000 - Ateliers et Chantiers de France 765,000,000 - Forges et Chantiers de la Gironde 540,000,000 - Chantiers navals de La Ciotat 720,000,000 - Forges et Chantiers de la Méditerranée 2,279,440,000 - Chantiers et Ateliers de Provence 525,000,000

The Extraordinary General Meeting of shareholders was convened747 on 12 December 1959, first, “for the purpose of deliberating the capital increase and the subsequent amendment of the articles of association,” and second, of appointing “auditors in charge of the report required by law.” The contribution agreement was signed on 30 November 1959 by Raymond Meynial on behalf of Worms & Cie, in his capacity as its General Partner, and Robert Labbé, on behalf of ACSM, in his capacity as Chief Executive Officer. The agreement covered: - total land of 12 hectares 48.6 ares,748 valued at 10 million francs; - the industrial complex (building for sharpening saws, acetylene plant, launch slips, infirmary, a wharf, administrative building housing the executive offices), valued in excess of 97 million francs (97,190,684 F); - housing (the Georges Leygues Pavilion, a villa located at 3, Rue du Maréchal Foch, a house on Rue Denis

Papin 6/8, four 2-apartment houses located on the

Rue de Dunkerque) with a total value of more than 24.5 million francs (24,563,632 F); - various utilities (fencing, pits, pipelines, drinking water facilities, and changing rooms) valued at more than 25 million francs (25,680,588 F); - equipment and tools (presses, forge and electric ovens, tools for fitting, woodworking, electrical maintenance, sheet metal and welding); all valued at 25 million F;

747 Convening notice signed by Henri Nitot, Board Secretary, and proxies of 26 November 1959. 748 A memo of 16 November 1959 listed the parcels that were not transferred to ACSM in September 1952, based on the land registry of Le Trait; stating that several lots had been “corroded by the Seine” or exchanged for plots of land within Le Trait. - various furniture and furnishings, for the most part located in the office building, all estimated at more than 8.4 million F (8,416,355 F). In addition to these assets, ownership of which was scheduled to be transferred on 31 December 1959 for a total price of 190,851,259 F, Worms & Cie undertook to transfer a receivable amounting of 209.209,148,741 F to ACSM.749 As a result, total contributions reached 400 million francs, to be paid for via a capital increase of 250 million francs.750 Said capital increase was ultimately approved by the Extraordinary General Meeting of 28 December 1959, which subsequently modified Article 6 of the articles of association: “share capital is now 600 million francs (6 million new francs); divided into 60,000 shares with a par value of 10,000 francs each, all of the same class and fully paid up, numbered from 1 to 60,000.” The size of ACSM’s share capital was now higher than that of the Chantiers et Ateliers de Provence and the Forges et Chantiers de la Gironde. In addition to its permanent capital (paid up share capital + earnings retained in reserves and depreciation), ACSM (particularly to pre-fund ship construction; i.e. to purchase materials and supplies while waiting for payment of the amounts owed by public and private clients) had the following financial means at its disposal:751 1) Loan from the Consortium of Shipbuilding Companies (4%, 1946), repayable at constant annual instalments until 8 October 1970, inclusive. On 30 September 1958, the outstanding balance was 118,365,000 F.

749 The contribution agreement of 30 November 1959 stipulated: “The sum of two hundred and nine million one hundred and forty-eight thousand seven hundred and forty-one francs, representing a portion of the open creditor account itemised in the accounts of ACSM SA as ‘Worms & Cie – Le Trait’ in the name of the limited partnership of Worms & Cie and amounting to two hundred and fifty-four million two hundred and eighty-two thousand three hundred and thirtyfour francs on 30 November 1959.” 750 See the memo from Robert Malingre to Robert Labbé dated 11 January 1960. All the deeds: contribution agreement and the minutes to the general meetings of 12 and 28 December 1959, along with their appendices, were received by Mr Chalain, notary, on 4 and 6 January 1960; they were registered on 8 January 1960 and filed with the Commercial Court Registry at the Seine Tribunal on 15 January 1960. 751 Cf. the ACSM memo of 19 May 1959. An annual cash position was presented by ACSM to the Banque de France starting in 1959.

2) Long-term loan from the credit institution, Crédit National of 50 million old francs, granted on 11 October 1950 and to be repaid in ten annual instalments of 5 million francs, payable on 15 October, 1956 through 1965, inclusive. On 30 September 1958, the outstanding balance was 40,000,000 F. 3) Medium-term credit of 100,000,000 F granted by the Crédit National on 19 June 1957, useable up to: - 100,000,000 F, until 21 June 1959; - 80,000,000 F, until 21 June 1960; - 60,000,000 F, until 21 June 1961; - 30,000,000 F, until 21 June 1962. On 30 September 1958, this credit was valued at 100,000,000 F. 4) Long-term loan from the Crédit National of 205 million francs, granted on 12 September 1957 and to be repaid: - in four instalments of 5,000,000 F, payable annually on 30 June, 1959 to 1962, inclusive; - in ten instalments of 18,500,000 F, payable annually on 30 June, 1963 to 1972, inclusive. As of 30 September 1958, the outstanding balance was 205,000,000 F. These last two credits were obtained to partially finance the construction and equipping of a fitting-out quay on the Seine. A second long-term loan for 3 million francs was taken out on 23 November 1960 with the Normandy Regional Development Company; along with a third for 5 million francs in December 1963, again with the Crédit National. The increase in equity resulting from the capital increase served as a guarantee of financial solvency, as did the backing of Maison Worms.

The backing of Worms & Cie: the men of Maison Worms

Meeting at the company headquarters at 45, Boulevard Haussmann in Paris, the ACSM Board of Directors was chaired by Robert Labbé, General Partner of Maison Worms since 1944 and Honorary Chairman of the Chamber of Shipbuilders. Board members were: - Hypolite Worms, General Partner of Worms & Cie since 1911; - Raymond Meynial, who becamed General Partner of

Worms & Cie in 1949; as well as three legal entities: - Worms & Cie, represented by Jacques Barnaud752

752 Jacques Barnaud was a General Partner of Worms & Cie from 1930 to 1944, and from 1949 to 1962.

(nominated on 23 December 1949, approved on 12 July 1950); - the Union Immobilière pour la France et l’Étranger (Unife), a company founded by Maison Worms in 1929, and fully owned by it; - and the Forges et Chantiers de la Méditerranée, represented by Pierre Chevalier; in 1956, FCM became a

Board member of ACSM (appointment ratified at the

General Assembly of 31 August 1956), as a result of a technical and commercial cooperation agreement between the two companies which gave ACSM access to FCM know-how in ship engine construction. Board Meetings, with Henri Nitot, Executive Director of the company, as Secretary, were held in the presence of two representatives of the Works Council, René Biville and Raymond Brétéché. On 26 January 1960, the Board welcomed two new members (subject to approval at the future General Meeting): - Henri Nitot; - and Pierre-Ernest Herrenschmidt753 (1906–1999), who had been named General Partner of Worms & Cie six days earlier. On that same day (26 January 1960), the Board members set forth in a circular: “As Henri Nitot, Executive Director of our company, has expressed his wish to retire, we have decided to appoint him as Honorary Executive Director, in acknowledgment of the eminent services rendered to our Ateliers et Chantiers de la Seine-Maritime for nearly forty years. We have appointed Joseph Brocard, previously Deputy Director General, to replace him as Executive Director of our company. He will assume his duties effective Tuesday, 26 January.”

753 See Roger Mennevée, Les Documents de l’Alll of March 1963 (changes to Worms & Cie deed of incorporation since 20 January 1960): “Born in Paris on 15 February 1906, and a graduate of the Free School of Political Science (section: public finance) in 1926, Pierre-Ernest Herrenschmidt, after performing his military service (November 1928 to October 1929), entered the Inspectorate of Finance on 15 May 1931. Named Inspector, 1st-class, on 1 January 1942, he became Director of the Central Administration of the Ministry of Finance on 4 January 1946, and was assigned as Director of the Crédit National, by Decree of 15 May 1946. He was promoted to Commander of the Legion of Honor, and Honorary Inspector General of Finance on leaving the public administration to become a General Partner of Worms & Cie on 20 January 1960.”

The appointment of Pierre Herrenschmidt was mentioned in a short article published in Carrefour on 18 October 1961, penned by Gilles Roches: “Pierre Herrenschmidt (55 years of age), Honorary Inspector of Finances left the management of the Crédit National in January 1960 to become General Partner of Worms & Cie. He serves as Director for the following companies: Antar Pétroles de l’Atlantique, Pechelbronn, Société Française de Transports Pétroliers, Société d’Investissements Vendôme, Société d’Assurances pour le Commerce Extérieur, Nouvelle Compagnie Havraise Péninsulaire,” all companies belonging to the Worms group.

The impact of the Worms group on the ACSM’s reputation

As at the time as when the shipyard had formed one of its four divisions, Maison Worms made every effort to promote ACSM in the documents presenting the group’s activities, or in inserts published in newspapers and specialist magazines. The Worms group’s maritime subsidiaries did the same in their presentation brochures: Worms Compagnie Maritime et Charbonnière (Worms CMC),754 Nouvelle Compagnie Havraise Péninsulaire, Société Française de Transports Pétroliers, all three of which were clients of the shipyard and promoted the vessels built for them by ACSM. ACSM thus benefited from this support from Maison Worms which, as often as it could, directed orders to its shipyard from companies within its maritime group.

Impact on the order book

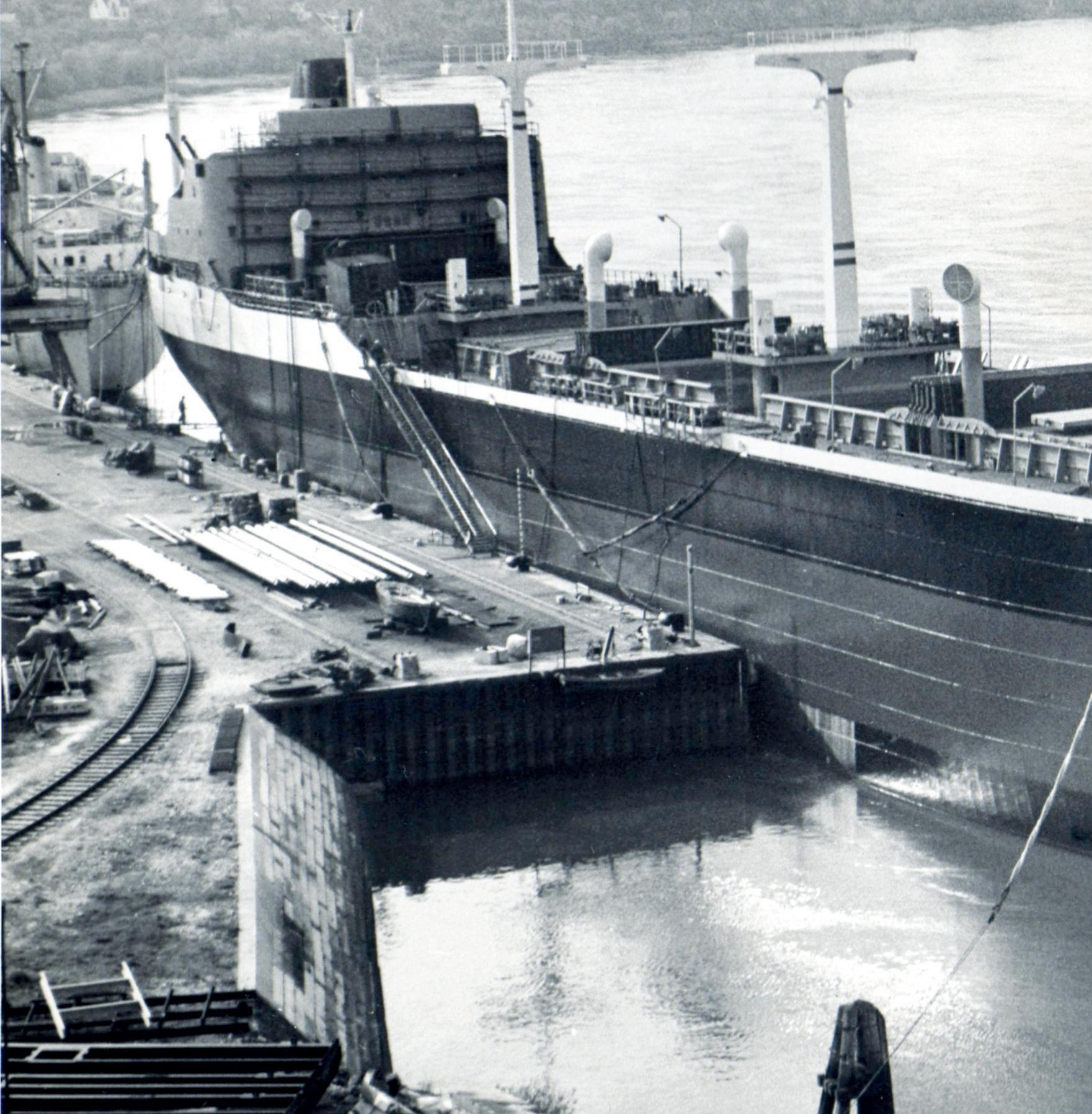

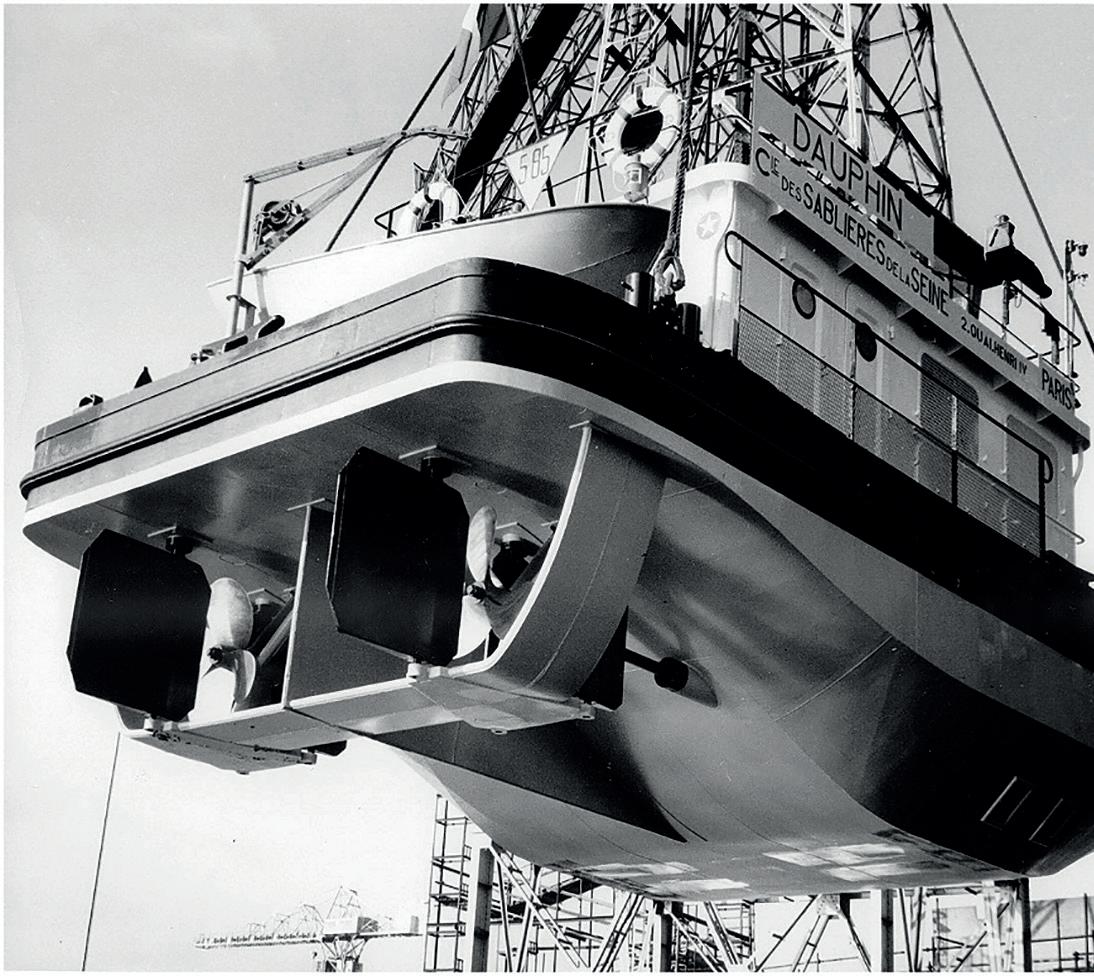

For example, in December 1959, Worms Compagnie Maritime et Charbonnière (Worms CMC) signed a contract for the construction of the 3,600-dwt collier-bulk carrier “Yainville,” to be delivered in 1961. The keel was laid on 14 April 1960 in slipway No. 6. In addition to this vessel, ACSM started construction on: - in slip No. 1 – the 18,410-dwt ore carrier “Pentellina” for the Compagnie Nantaise des Chargeurs de l’Ouest, a Worms & Cie affiliate (absorbed by Worms in 1968); the order was co-signed by the Union Navale, and the vessel was on the ways in July–August 1960; - and in slip No. 2 – the 12,302-dwt cargo ship “Ville du Havre” for the Nouvelle Compagnie Havraise Péninsulaire. This vessel, the keel of which was laid on 16 November 1960, was the first in a series of four vessels ordered from Le Trait;755 - the “Mostaganem” and “Bidassoa” completed the order book. The former was a 5,500-dwt cargo liner for the SA Les Cargos Algériens – its keel was laid in slipway No. 8 on 10 August 1960 – while the latter was a 2,235-dwt landing ship tank (LST) for the Navy: it occupied slip No. 7 between 30 January 1960, the date on which its keel was laid, and 29 December 1960, its launch date. Its specifications were identical in every detail to the LST “Dives” (keel laid on 7 August 1959) launched from slipway No. 8 on 28 June 1960. More than 40,000 tons were thus under construction. 1960 was also marked by the end of construction and launch of: - the 3,700-dwt bulk carrier “Eldonia” on 31 March 1960 – shipping company: Union Navale - the 2,235-dwt LST “Dives” (see above) - the 10,720-dwt self-unloading bulk carrier “Gypsum Countess” on 5 August 1960 – shipping company: Panama Gypsum Co., Inc. - the 8,432-dwt ore carrier “Penchâteau” on 5 November 1960; shipping company: Compagnie Nantaise des Chargeurs de l’Ouest. On top of these were two barges built between 28 October 1959 and 18 January 1960 for the Compagnie Togolaise des Mines du Bénin, for a price of approximately 300 million francs, according to a contract signed on 27 July 1959. All these contracts ensured that slipways Nos. 1, 2, 6, 7, and 8 were occupied throughout 1960.

754 In an undated document summarising the activities of Worms CMC, filed in 1961, it is noted: “Worms & Cie, formerly shipbuilders, entrusted this branch of its business activity to its subsidiary, the Société Anonyme des Ateliers et Chantiers de la Seine-Maritime, in Le Trait (headquartered in Paris, at 47, Boulevard Haussmann) in 1945.” In a brochure published on 20 February 1961, Worms CMC wrote: “This yard is completely equipped to build vessels of any specification up to 24,000 tons dead-weight.” 755 The book, Les 100 ans de la Havraise péninsulaire (Charles Limonier, 1992), states that these were “freighters with two decks, ‘full scantling’ vessels with poop deck and long – forecastle, fully welded.” They were baptised “Ville du Havre,” “Ville de Brest,” “Ville de Bordeaux” and “Ville de Lyon” (see next paragraph).

28 June and 29 December 1960: launch of the landing ship tanks (LST) “Dives” and “Bidassoa”

Specifications

Length

Width

Height

Gross Tonnage

Deadweight

Full load

Propulsion

Speed 102.1 metres overall (96.6 pp) 15.5 metres 3.2 metres 1,750 tons 1 400 tonnes 4,225 tonnes 2 Pielstick diesel engines 2,000-HP 11.5 knots

1961: the last year of normal activity

On 13 February 1961, the collier-bulk carrier “Yainville” was launched in the presence of Robert Labbé, Hypolite Worms, ACSM Director Marcel Lamoureux, André Marie,756 Mr Brétéché, General Councillor and Mayor of Le Trait, and Mr Passerel, Mayor of Yainville, as well as numerous guests, including several reporters who covered the launch in the local press.757 Worms CMC took charge of the ship on 7 April 1961. At that time, the newspaper Paris-Normandie published an article entitled, “Navire au port, le cargo neuf ‘Yainville.’” According to the article, this vessel, “intended to transport bulk goods and timber, can also be used to transport cars, as a removable intermediate deck can be installed in each of its four holds.” The same newspaper again referred to the “Yainville” on 5 November 1963, citing its specifications: “This ship, a regular sight in Normandy ports, has a gross tonnage of 2,662 tons and net tonnage of 1,537 tons. Length: 97 m; width: 13.50 m; speed of 13.5 knots.” This was the last vessel bearing the Worms colours (blue flag adorned with a white disk) built in Le Trait. The ore carrier “Pentellina” left slipway No. 1 on 6 April 1961. The cargo ship “Ville du Havre” left slipway No. 2 on 10 August 1961 and was delivered to NCHP on 25 January 1962. “Mostaganem” was launched on 14 September 1961. Only two of the vacated slipways of the five operated were immediately reoccupied. Slip No. 1 was used as of 12 April 1961 for the construction of the “Ville de Brest,” the second 12,264dwt freighter ordered by the Nouvelle Compagnie Havraise Péninsulaire; while on 10 August 1961, slip

The collier-bulk carrier “Yainville” in slip No. 6

756 MP for the Seine-Maritime department, André Marie was Minister for Justice (1947–1948 and 1948–1949), President of the Council (26 July to 5 September 1948), and Minister for National Education (1951–1954). In addition, he served as Chairman of the Fédération Française des Universités Populaires. 757 See the article of 14 February 1961 entitled “Le ‘Yainville’ a été lancé au Trait pour la Cie Worms” in Le Havre libre. Moreover, in an interview granted to Francis Ley in 1977 for the purposes of the book Cent ans boulevard Haussmann, Pierre Darredeau, Director of the Shipping branches first in Le Havre, then in Algiers, as well as coordinator of Shipping Services in North Africa in 1950–1960, said the following about the freighter: “As for our bulk carriers in 1961, we had the ‘Yainville,’ which we operated in conjunction with the Union Navale, and the ‘Château-Margaux.’” On 3 April 1964, the loan department of Crédit National wrote: “In a letter of 24 March 1964, Crédit Naval has requested on behalf of its client [Worms & Cie, or Worms CMC?] that we release the mortgage registration taken out on ‘Château-Yquem,’ with the balance of the loan being guaranteed by the 3,000,000 F mortgage taken out on the ‘Yainville.’”

No. 2 welcomed the “Stylehurst,” a 21,700-dwt ore carrier intended for the English shipping company, Grenehurst Shipping Co. Ltd. While slip No. 8 was vacant for just four months (until construction started on 15 January 1962 on the cargo ship “Saint François”), slip No. 7 remained empty from 29 December 1960 to 25 November 1962, i.e. for 24 months. Slip No. 6 remained vacant from 13 February 1961 to 1 December 1964, or for more than 45 months. This vacancy was a sign of a recession that was going to worsen. The worrisome situation was aggravated by the deaths, a few weeks apart, of Hypolite Worms and Jacques Barnaud.

10 August 1961: launch of the cargo ship “Ville du Havre,” the first in a series of four vessels ordered by NCHP

6 April 1961: launch of the ore carrier “Pentellina” for the Compagnie Nantaise des Chargeurs de l’Ouest and the Union Navale

1962: the grief-stricken Maison Worms

Hypolite Worms died suddenly on 28 January 1962 at the age of 72. Considering his lifetime activities from 1914 to 1962, it is striking that, over the course of the years and with the assistance of expert partners, he transformed the Maison Worms he had inherited into a powerful group open to shipbuilding, shipping, trade, banking and financial services, and industrial activities. In a speech given in Port Said in January 1950, he himself described the development of the bank and the group to their present proportions: “In 1928, we created the Banking Services of Maison Worms. […] Thanks to the men at its helm, this division has since become one of the most active private banks in France, perhaps one of the largest business or commercial banks in France. […] This is why Maison Worms, originally a Fuel Merchanting and Shipping company, has now become a multi-faceted company, because being a business bank implies its interest in the commercial and industrial affairs under its umbrella, and which, thanks to its involvement and its resources, it has helped develop, and is now involved in a whole new range of activities.” Twelve years later, upon the death of the leader of Maison Worms, these words assumed even greater truth and depth. At the time of Hypolite Worms’ death, Jacques Barnaud himself was seriously ill. The fellowship and trust between these two men had been as indestructible as they were fruitful. For over thirty years, the Banking Services had benefited from the skills and financial talent of Jacques Barnaud. During his last few months at the helm of Maison Worms, before passing away on 15 April 1962, he provided one last service by redefining the tasks of the partners. Despite these deaths, Worms & Cie had to move forward, while its company name had to live on. Thus, in March 1962, Hypolite Worms’ widow was named a General Partner, but without managerial duties, while two new Board members were appointed: Guy Brocard758 and the son of Jacques Barnaud, Jean Barnaud (a former Navy officer who joined NCHP in 1948 and was serving as its Executive Director at the time). Upon his father’s death, a new partnership deed

Hypolite Worms (1950s)

was signed (July 1962), under which Jean Barnaud was appointed a General Partner, joining Raymond Meynial, Robert Labbé and Pierre Herrenschmidt. The positions formerly occupied by Hypolite Worms were distributed among the latter two: Robert Labbé assumed the chairmanship of the Nouvelle Compagnie Havraise Péninsulaire de Navigation, while at the same time, since he was already serving as Chairman of Worms CMC, resigning as ACSM Chairman. Pierre Herrenschmidt became Chairman of ACSM, at the same time replacing Hypolite Worms as head of the Société Française de Transports Pétroliers and as a Board member of the Compagnie Nantaise des Chargeurs de l’Ouest. At the beginning of March 1963, Robert Labbé assumed the chairmanship of the Central Committee of French Shipowners.

758 Joining Worms & Cie Banking Services in 1937, Guy Brocard became a member of its management team in 1944, before becoming its Director General in 1951.

In his memoirs, Henri Nitot established a causal link between the deaths of Hypolite Worms and Jacques Barnaud and the demise of ACSM four years later: “I believe,” he wrote, “that even in the face of difficult industrial circumstances, neither would ever have abandoned the shipyard which they considered their life’s work; they felt responsible for its survival, for a place where, through their efforts, two successive generations of workers had been employed in full job security, where many families had gone through great pains to build their small houses, sheltered in their minds from any incident; and as great patrons, they certainly would have considered that their honour required them to spare so many honest workers and employees the concerns, indeed the deficiencies, of any resettlement.”

Ω The ore carrier “Stylehurst” at the fitting-out quay, after its launch on 4 May 1962 for Grenehurst Shipping Co. Ltd

The cargo liner “Mostaganem” launched on 14 September 1961 for the Cargos Algériens

Innovating for survival

In the face of the crisis, the main priority of ACSM was to stay at the forefront of progress and attempt to make up for its infrastructural handicap (slipways unsuitable for constructing giant ships) by building ‘high-tech’ vessels. Along with its partner, the Forges et Chantiers de la Méditerranée, ACSM launched into cryogenic techniques, building liquefied petroleum gas (methane) carriers. The two companies were not however the sole builders in contention, facing competition from the Chantiers de l’Atlantique and the Chantiers de France et de Dunkerque.

The epic story of transporting liquefied natural gas – LNG

Ever since the discovery of gas deposits in Hassi R’mel in the Algerian Sahara (reserve estimated in 1965 at 1,000 billion cubic meters) in 1956, the logistics of importing this fuel to France had been under study. “In the face of the events in Algeria, the idea of building a gas pipeline linking Northern Africa and Europe has been abandoned, with thoughts instead turning to LNG tankers to deliver the fuel by sea. Naval architects are stepping up their research into transporting liquified gas, as the distinctive feature of methane is that it reduces its volume 600 times at cryogenic temperatures.”759

“In June 1959,” reported Niko Wijnolst and Tor

Wergeland, in Shipping Innovation,760 “the Chairman [sic] of Worms & Cie, Mr Labbé, visited the United

States to attend the 5th World Petroleum Congress

Conference in New York.” He was accompanied by “a brilliant engineer-consultant in Marine Engineering,”761

Audy Gilles, who at the time was Managing Director of the Société de Mécanographie Japy (an important subsidiary of Worms & Cie) and who “through his highly valued technical knowledge, [had already] been providing invaluable services to Le Trait for years.” He was set to play a leading role there. “By that time,” continued the authors of Shipping Innovation, “it was clear to him [Robert Labbé] that although considerable progress has been made in France, economies could well be achieved by taking a licence from the

US group, which by now had successfully shipped several cargoes of LNG [liquefied natural gas] across the

Atlantic in the prototype ship ‘Methane Pioneer.’ The

Americans, however, felt so sure about themselves that they refused to grant him a licence. Therefore, the French decided to continue with their own studies.” To do so, Robert Labbé brought together engineers, naval architects, shipping companies and financial partners in a structure set up in (April?) 1960762 under the name of Méthane Transport and sponsored by Gaz de France (future Engie). The number and names of the partners making up this research company, with capital of 2,600,000 NF, varied according to the sources: a pool of banks including Worms & Cie, the Banque de Paris et des Pays-Bas, the Banque Industrielle de l’Afrique du Nord, Vernes & Cie;763 five shipping companies and even “a group of the main shipyards,”764 to

759 Cf. www.gtt.fr/fr/qui-sommes-nous/histoire. 760 IOS Press BV, The Netherlands, 2009. 761 This and subsequent quotations are taken from the memoirs of Henri Nitot. 762 La Correspondance économique devoted an article to the creation of Méthane Transport in its issue of 16 April 1960. 763 See Roger Mennevée, Les Documents de l’agence indépendante d’informations internationales, published in March 1963, and “Les transformations de la banque Worms & Cie - Les affaires de Worms & Cie en 1964,” published in Les Documents de l’Alll, in April 1965. 764 See the article published in Paris Normandie on 18 October 1963, penned by André Renaudin.

which Bernard Cassagnou765 added Gaz de France (on its own), Air Liquide, and the Société d’Exploitation du Gaz d’Afrique du Nord. The goal of Méthane Transport was to finance the testing of transporting liquefied gas by sea; Robert Labbé served as its Chief Executive Officer.766

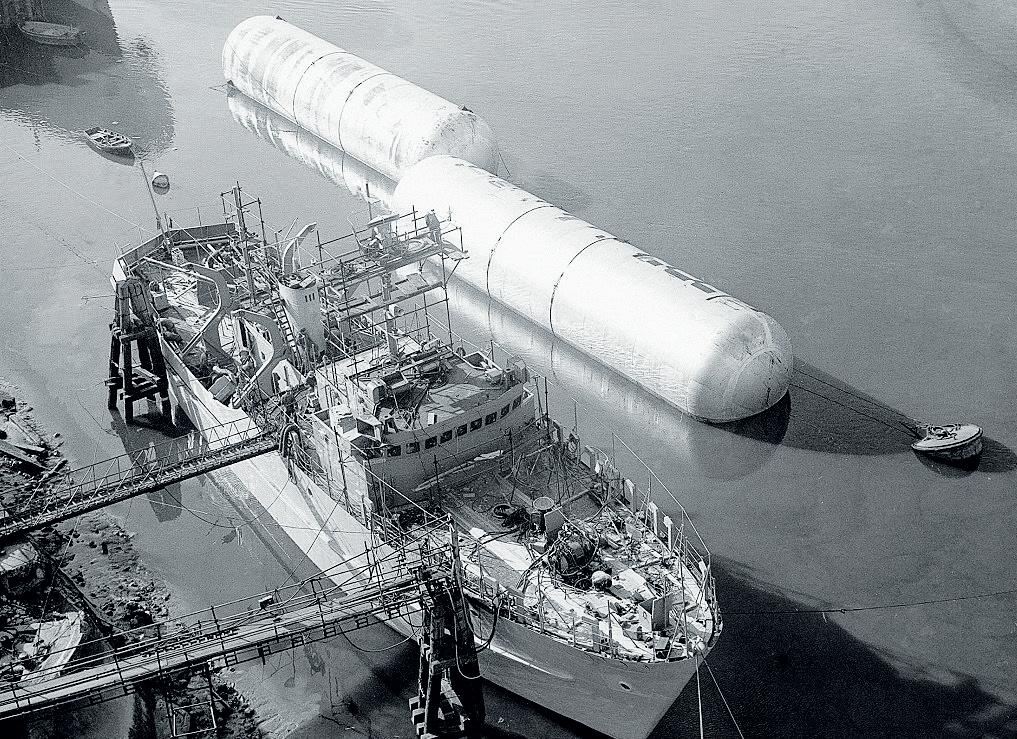

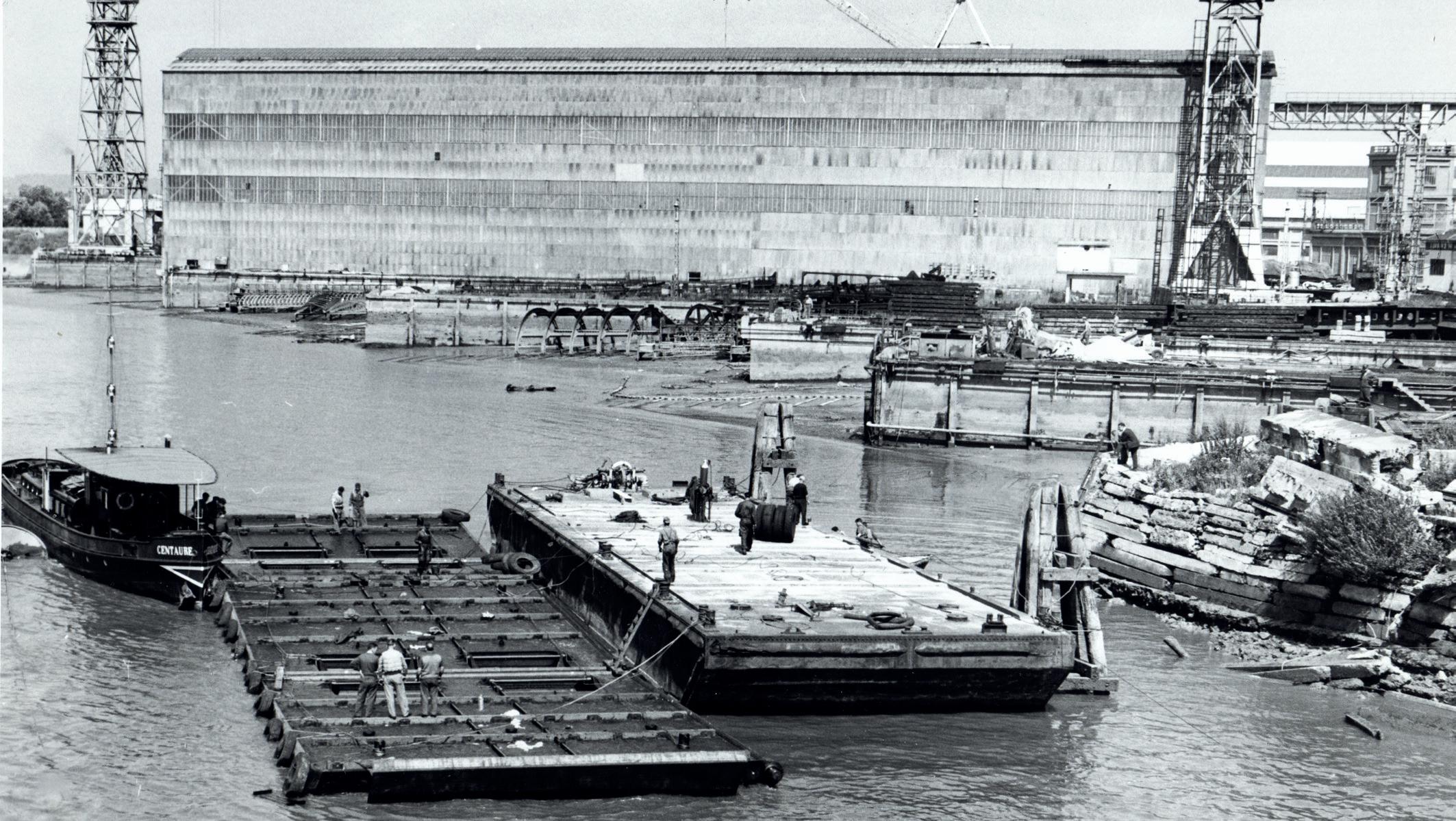

Trials on the Liberty ship “Beauvais”

The available information on the origin and development of this activity is very fragmented and often contradictory. However, we can piece together that: - in the very early 1960s, the Ministry of the Merchant Navy, “under the guidance of Jean Morin, at that time its Secretary General,” was interested in the “behaviour at sea of tank prototypes in a variety of shapes and materials, separated from the ship’s hull by a ‘secondary barrier,’ itself protected from the cold by balsa wood or perlite,”767 together forming a system capable of transporting LNG. The Ministry called upon Méthane Transport to test its effectiveness. “Objective: to test the lab theories in practice and to compare the solutions implemented onboard. The tanks, their insulation, their anchoring, as well as all accessories (pumps, piping, valves and safety devices) [must be] observed in minute detail.”768 Méthane Transport worked with four (or rather, three) shipyards:769 the shipyard in Le Trait in partnership with the Forges et Chantiers de la Méditerranée, the Chantiers de l’Atlantique in Saint-Nazaire, the Chantiers de France770 et de Dunkerque, - to conduct the trials, Méthane Transport made available the Liberty ship “Beauvais” (formerly, “JohnLowson”), a Second World War supply ship which the State (according to some) or Méthane Transport (according to others) acquired in July 1959; according to Ludovic Dupin, the shipping group included Gaz de France, Air Liquide, Technip and CMP,771 - the ship was decommissioned in Dunkerque, and its management entrusted to the Compagnie Nantaise des Chargeurs de l’Ouest772 “on behalf of Méthane Transport,”773 - in February 1961, the “Beauvais” was in Nantes and in March the transformation of the ship into an experimental gas carrier began at the Chantiers de l’Atlantique774 (in Saint-Nazaire?). The companies participating in the trials installed on board three self-supporting tanks of their own invention (Ludovic Dupin mentioned only a single “small 500-m3 tank”), whereby the main difficulty had been to achieve welds of sufficient quality to satisfy the demands of the classification companies: • one of the three tanks, “prismatically shaped (and) constructed of aluminium alloy,” was built by the Chantiers de l’Atlantique, • the second, this time “a multi-lobed tank,” was “constructed of 9% nickel steel and built by the Chantiers de Dunkerque-Bordeaux,” • the third was “cylindrical, and constructed of 9% nickel steel, built by the Chantiers de la Seine-Maritime and the Forges et Chantiers de la Méditerranée.”775 In addition, “a large variety of handling equipment, control systems, valves and pumps, insulation materials will be tested and evaluated during the trials.”776

765 See Bernard Cassagnou, Les grandes mutations de la marine marchande française (1945-1995), op. cit. 766 See Roger Mennevée, op. cit. 767 In Le magazine des ingénieurs de l’armement, Caia No. 97, March 2012, see Alain Grill’s account: “Profession ? Ingénieur du génie maritime.” 768 Cf. “GDF Suez, 50 ans d’innovation dans le GNL” on http://pelhammedia.fr. 769 Bernard Cassagnou, op. cit. 770 This company name was only used from 1967 (after the Bordeaux shipyard had closed) to designate the company created in 1960 through the merger of the Bordeaux and Dunkerque shipyards; between 1960 and 1967, the company was known as the Ateliers et Chantiers de Dunkerque et Bordeaux (France-Gironde); which may explain why some authors erred on the number of (four) companies involved in the research: the Chantiers de France et de Dunkerque were in fact one and the same company. 771 Cf. Ludovic Dupin, “Il y a 50 ans, quand les Français étaient les rois du gaz,” in L’Usine nouvelle, June 2015. 772 Some sources refer to this company as Société Nantaise des Chargeurs de l’Ouest, although it had not been established before 1968. 773 “GDF Suez, 50 ans d’innovation dans le GNL,” op. cit. 774 The fact that the latter firm resulted from the merger in 1955 of the Ateliers et Chantiers de la Loire, based in Nantes and Saint-Nazaire, and the Chantiers de Penhoët, based in Saint-Nazaire, undoubtedly explains why some mistakenly reported that the conversion took place in Saint-Nazaire. 775 Cf. Commandant Boudjerra, “Rétrospective du transport de gaz naturel liquéfié (1910-2010),” for master’s degree, 2008–2009. 776 Ibid.

The website of the International Group of Liquefied Natural Gas Importers (GIIGNL) states that “James Coolidge Carter of Costa Mesa, California, provided a submerged electric-motor pump (SEMP) for use on one of the three tanks on the ship.”777 The reconversion was completed in February–March 1962 and trials began in March; they were to last six months.778 According to an anonymous account found on the Internet, “the manoeuvres with gas on board were performed by the shipyards that designed each tank. Inside the Roche Maurice gas plant in Nantes, Gaz de France had installed a pilot station for the liquefaction and storage of liquid methane. The nearby wharf was equipped with marine loading articulated arms connecting the storage tanks to the ship. Gaz de France personnel oversaw the loading and unloading operations at the Roche Maurice wharf, thus enabling the staff and crew of the ship, and the shipyard personnel performing the onboard manoeuvres, to be trained in handling LNG. Their training specifically included lessons on how to fight methane fires. As a result, no incidents of note ever occurred during the loading and

777 Cf. “LNG Shipping at 50” on https://giignl.org. 778 Ibid. “In July 1962 members of the Methane Transport research group, along with several others, were invited to a tank test in Oslo. The invitation was from shipowner Øivind Lorentzen and Texas-based investor Carol Bennett who wanted to demonstrate the viability of a membrane tank system based on an idea developed by Det Norske Veritas (DNV) engineer Bo Bengtsson. Attending, and impressed with the tests carried out using liquid nitrogen, were Pierre Verret from Gaz de France, Audy Gilles from the Worms group and Jean Alleaume and Gilbert Massac from Gazocéan. Following these observations, Gazocéan acquired the Norwegian patents and set about making substantial changes to the original design and registering new patents. In time, and through cooperation with Conch Océan, the Gazocéan membrane concept was to become the basis for the Technigaz Mark I containment system. Conch Océan was established as a 60/40 Conch/Gazocéan joint venture in 1967.” unloading operations.”779 Simultaneously, in May 1962, the economic viability of the project took a decisive step forward with the creation of Gaz Marine, a company devoted to transporting liquefied methane.780 Its share capital of 5 million NF, divided into 50,000 shares of 100 NF, was subscribed by Gaz de France (50%); Gazocéan (17.50%) – a shipping company founded in 1957 by Gaz de France and NYK Line, and specialised in the transport of LNG; the American company, Bennett (10%)781 in the name of a Texas investor; the remaining 22.50% were distributed in equal parts between Worms & Cie, the Banque de Paris et des Pays-Bas, and the Union Européenne Industrielle et Financière.

ACSM wins the contract

On 26 June 1962,782 thanks to qualities of the experienced process, ACSM won the call for tenders recently pitting them against their colleagues:783 Gaz Marine

779 Cf. “1950-1961, Beauvais entre à Shimazu 2” on https:// www.flickr.com – the author of this account described the six phases of the trials: 1. At the Saint-Nazaire quay: key [sic] chilling of liquid nitrogen 2. At the Roche Maurice quay: alongside the Gaz de France methane liquefaction station: filling the LNG into each tank and empting; checking the related equipment 3. At sea: series of voyages with tanks 2 and 3 full, and tank 4. in travel position on ballast At sea: series of trials with tank 1 full, and tanks 2 and 3 in travel position on ballast 5. At sea: succession of transfers between tanks, with intermittent reheating of tanks to check resistance to repeated thermal shocks 6. At sea: emptying the gas tanks and reheating. The “Beauvais” returned to Roche Maurice between each phase to adapt its cargo to the requirements of the subsequent phase. The results for all tanks proved satisfactory, as did the pumps; only the electric submersible pump experienced a blockage, but this was easily fixed.The results for all tanks proved satisfactory, as did the pumps; only the electric submersible pump experienced a blockage, but this was easily fixed. 780 The sources refer to an article on Gaz Marine, published by La Correspondance économique on 12 May 1962, which could not be found. 781 See footnote 778. 782 See protocol of 20 July 1962. The order is dated 27 June 1962 according to “GDF Suez, 50 ans d’innovation dans le GNL,” op. cit. 783 See “Vingt mille lieues sur les mers” on http://www. paris-normandie.fr.

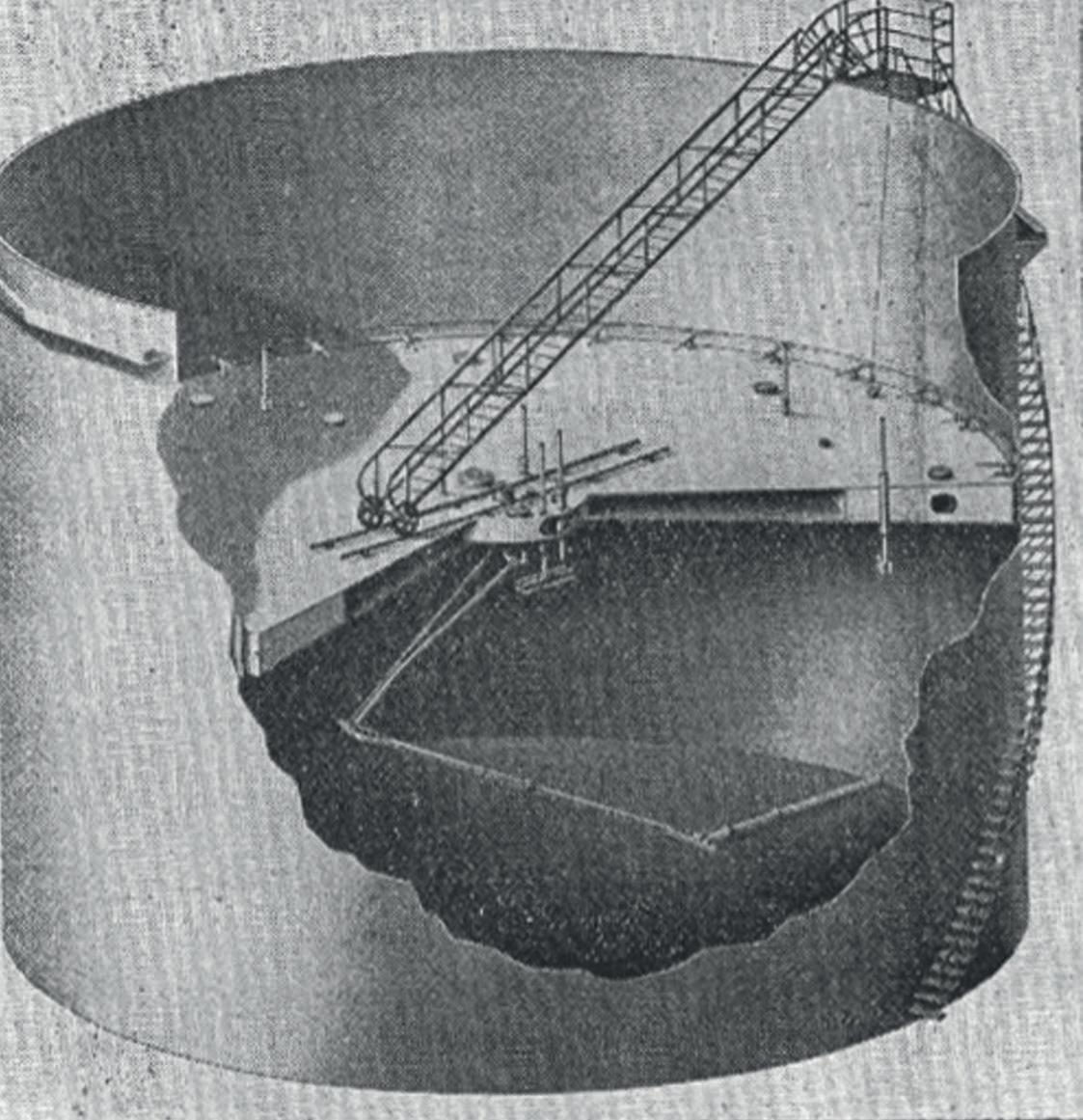

placed an order with ACSM for one 25,000-cubic metre methane carrier.784 The tested and approved technique was “self-supporting,” involving the use of cylindrical tanks made of a material recently developed by the Aciéries Françaises: steel with a 9% nickel and very low carbon content. The cylindrical shape of the tanks made it possible to obtain the highest possible reduction in their weight and in the cost of the components keeping them in place. Insulation – of primary concern, since methane is transported at a temperature of minus 161 degrees below zero centigrade and under pressure of one bar – was guaranteed either by modern materials such as Klegecell, applied using special arrangements devised by ACSM, or by perlite, a powdery insulant. “The trials on the ‘Beauvais,’” wrote Audy Gilles in 1963 in Nouveautés techniques maritimes, “confirmed what several technicians had already been thinking; namely, that it was likely that several different processes could be used successfully to construct tanks for methane carriers, along with the tank insulation. In sum, one could say, a bit schematically, that the construction of a methane carrier requires more technological ‘knowhow’ than patented ideas. Performing the experiments on ‘Beauvais’ has been costly, but it has put the group of shipyards involved in the tests in a position to accept orders for methane carriers.”785 Alain Grill wrote in Le magazine des ingénieurs de l’armement: “Never again in my career was I to find such synergy meticulously orchestrated by the Secretary General himself, Jean Morin. […] Nor will I ever forget this maritime venture, when, as General Manager of Chargeurs Réunis, we took a stake in Gazocéan; nor when, in Malaysia, having become the Chief Executive Officer of the Chantiers de l’Atlantique, I signed the largest contract of my career: five 130,000-m3 methane carriers.”786 Gaz Marine and ACSM signed a protocol, under which Gaz Marine demanded from ACSM that FCM “be involved in the execution of the construction contract so as to ensure that under all circumstances, the construction and completion of this ship will be brought to a successful conclusion.” Although both shipyards had participated in the technical tests and although ACSM was committed to building the hull of the future methane carrier while its engines were to be constructed by FCM, this latter firm had not agreed to be named in the contract as a builder with “joint and several” liability. On the other hand, FCM agreed to sign an agreement on 20 July 1962 as the primary sub-contractor, and to perform the obligations set forth in Article 1 of the contract under the following terms: “In addition to the contractual obligations as principal sub-contractor; and in the event that the shipbuilder fails to perform its obligations, FCM agrees to assume full responsibility for the commitments agreed to by the shipbuilder. […] Formal notice shall be served by the shipowner on the shipbuilder demanding the execution of said obligations by a specified deadline. In the event that the shipbuilder fails to react to said notice, and one month after expiry of said deadline, the shipping company may, at its own risk, proceed to substitute the principal subcontractor for the shipbuilder, notwithstanding any possible recourse by either party to arbitrage, subject to all rights and means of the parties. In the event that the substitution is enacted, Gaz Marine will make any payments owed following said substitution in execution of the present contract, directly to FCM. […] Worms & Cie, on behalf of ACSM, will provide surety to FCM for any commitment hereinabove entered into by ACSM.” It seems that the contract signed between Gaz Marine and the Le Trait shipyard had no impact on the trials that continued throughout July: “On 2 July,” reported an article from GDF-Suez, “the ‘Beauvais’ sailed up the Loire to unload its cargo at the Roche-Maurice facility, using the marine loading arms [MLA].”787 And OuestFrance reported that, that same month “in the vicinity of Belle-Île, the sea trials of the ‘Beauvais’ are being conducted with twenty-six sailors and about fifteen engineers and technicians from several shipyards on board […] all of them volunteers, given the dangerous nature of its cargo of 100 tons of methane. […] Each evening, the inhabitants of Belle-Île, mingling curiosity with concern, observe this black and red hull moored

784 See the article in La Correspondance économique of 29 June 1962. 785 Words quoted in “1950-1961, Beauvais […],” article published on https://www.flickr.com. 786 Cf. “Profession ? Ingénieur du génie maritime,” op. cit.

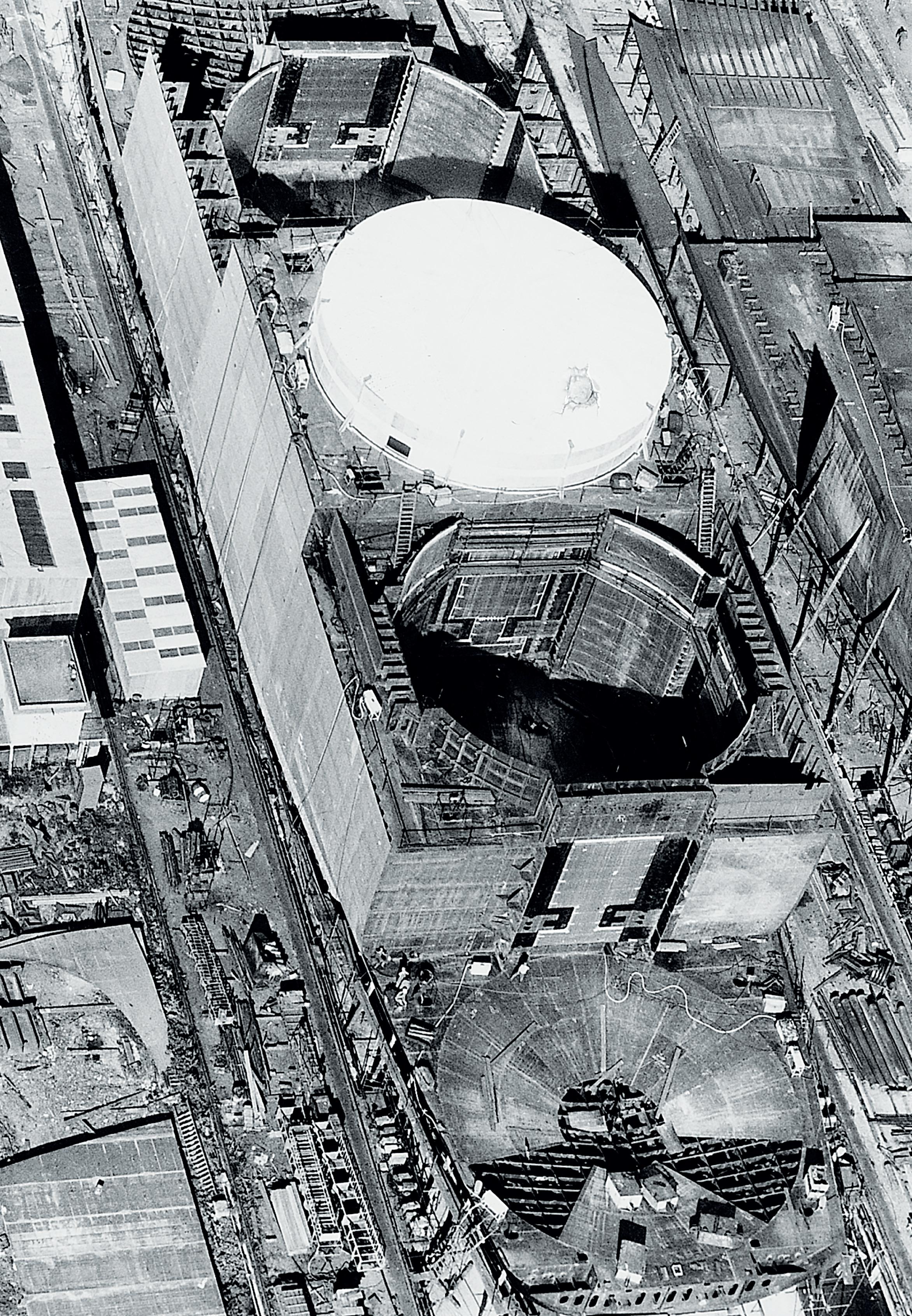

The methane carrier “Jules Verne” under construction Ω

one nautical mile from Le Palais. Converted into a laboratory ship in Penhoët, this former Liberty ship, with one of its masts serving as a gas exhaust pipe, has something worrying about it.”788

The Hassi R’Mel and Arzew gas complex

Once the Evian Accords (18 March 1962) had ended the Algerian War, Gaz de France intensified its relations with the former colony. In May 1962, GDF and SEHR789 signed “the first major gas contract between France and Algeria.” The agreement provided for the construction of a plant (operated by the Compagnie Algérienne de Méthane Liquide) in Arzew, a port located 40 km from Oran, for the purpose of liquefying the natural gas transported from the Hassi R’mel gas field via a 510km pipeline with an annual capacity of 3 billion-m3. In addition to GDF, British Methane / British Gas Council participated in the venture. The foundation stone was laid on 15 September 1962,790 in the presence of the newly elected President of Algeria, Ahmed Ben Bella, the French Ambassador and other officials. At the same time, work began on a methane terminal in Le Havre. This future Gaz de France plant, with a total storage capacity of 36,000-m3, received around half a billion-m3 of natural gas every year and covered 40% of the Paris region’s annual gas consumption via gas pipelines laid specifically for this purpose.791

The “Jules Verne,” the first French methane carrier, is built in Le Trait

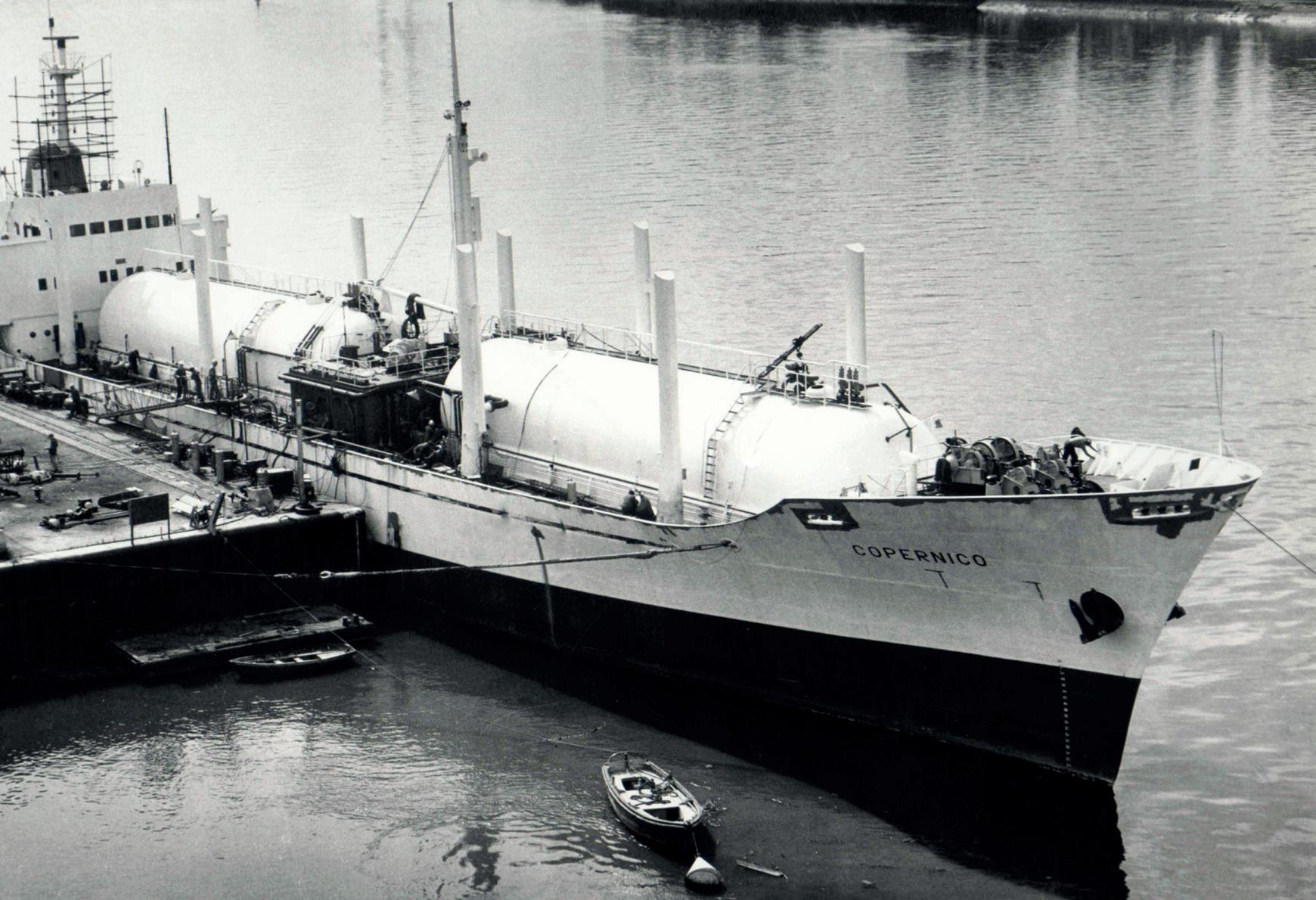

In Le Trait, the keel of the methane carrier, soon to be known as the “Jules Verne,” was laid on 17 April 1963 in slipway No. 2 under construction No. 171. Six days earlier (11 April), ACSM had launched two ships: the butane carrier “Copernico” (freeing up slipway No. 2) for the Chilean shipping company, Naviera Interoceangas SA; and the hydrographic survey vessel

788 Cf. “1962 : Un inquiétant prototype méthanier,” on https://www.ouest-france.fr. 789 SEHR: Société d’Exploitation des Hydrocarbures d’Hassi R’Mel. See “50 ans d’innovation dans le GNL,” at http://www.engie.com. 790 See L’Algérie indépendante (1962-1963) : L’ambassade de Jean-Marcel Jeanneney, by Anne Liskenne, Jean-Noël Jeanneney, Maurice Vaïsse, Armand Colin, 2015. 791 Cf. “50 ans du GNL - 1962-1965 : construction du premier terminal”; this article on http://Ing.gdfsuez.com is no longer available. “Astrolabe”792 for the French Navy. This dual launch provided an occasion for Pierre Herrenschmidt to deliver a speech, during which he announced “the conclusion of a technical cooperation agreement between ACSM and FCM. The latter company,” he stated, “owns shipyards in La Seyne (Var department) and in Le Havre-Graville which employ a total of 3,500 people. The Ateliers et Chantiers de la Seine-Maritime in Le Trait, downstream from Rouen, has a workforce of 2,000. The two shipyards have already established a research company for the seagoing transport of liquefied gas. In this respect, the Ateliers et Chantiers de la Seine-Maritime will soon be starting construction on the first French methane carrier.” Published in Le Monde on 13 April, this information was reproduced in Agence économique et financière on 16 April 1963, under the heading: “Forges et Chantiers de la Méditerranée. An agreement has been reached with the Ateliers et Chantiers de la SeineMaritime which seeks to strengthen the ties that the two companies have forged within the technical and commercial field over the past years. We should recall, first, that the two companies share boards members, and second, that they have adopted a joint policy to construct ships designed to transport liquefied gas.” The attention accorded by the Worms shipping group to the innovations led Robert Labbé, in May 1963, to establish Techni-Marine, a limited liability company,

792 Along with the “Boussole” this ship was listed as a hydrographic auxiliary vessel in the ACSM’s General Meeting report of 29 June 1965.

The “Jules Verne” in slip No. 2; the “Ville de Bordeaux” in slip No. 1 and the “Ville d’Anvers” at the fitting-out quay

for the purpose of “undertaking technical studies and research on seagoing transport; these studies shall focus primarily on the design and operation of specialised ships, as well as on ways of reducing their production costs and operating expenses; to provide advice [… and…] to undertake, on behalf of third parties, any study or project related thereto. The share capital of 100,000 F is fully paid up by the various partners: Worms CMC,793 Compagnie Nantaise des Chargeurs de l’Ouest, Nouvelle Compagnie Havraise Péninsulaire de Navigation, Société Française de Transports Pétroliers, Société Maritime des Transports Pétroliers, all companies affiliated directly or indirectly with Worms & Cie; Audy Gilles served as one of the managers of TechniMarine, together with Mr Neufville, Technical Director of NCHP.”794 In October 1963, an article written by André Renaudin appeared in Paris Normandie:795 “Le Havre, methane port – The model for the first methane ship under construction at ACSM in Le Trait was presented in Paris yesterday evening. […] Numerous VIPs from the world of shipping, LNG and banking, were welcomed by the representatives of Gaz de France and

Inside the tanks of the “Jules Verne” 793 The minutes of the Worms CMC Board Meeting on 24 May 1963 show that the level of the company’s participation in SARL Technimarine was 20%. 794 Cf. Roger Mennevée, Les Documents de l’agence indépendante d’informations internationales, published in March 1965. This article refers to a press conference given on 15 May 1963, by Robert Labbé, in his capacity as Chairman of the Central Committee of French Shipowners, regarding the programme to redeploy the French merchant fleet. Mennevée summarised Labbé’s words as follows: “The government must provide subsidies to shipping companies to help them demolish their old ships; additional subsidies to help them order new ships; and further subsidies to make them easier to operate.” 795 Paris Normandie on 18 October 1963.

its affiliated companies, Méthane Transport and Gaz Marine. The ACSM management team – its Chairman, Mr Herrenschmidt; Managing Director, Mr Lamoureux (he was to retire shortly thereafter), and the current Deputy Director, Mr Grillat – were present. Mr Grillat has been given the special assignment of overseeing ACSM activities next year. […] The first French methane carrier will thus succeed the ‘Beauvais’ in 1964. On each trip between Arzew and Le Havre, [the ship] will transport the equivalent of 13.8 million-m3 of gas, the annual gas consumption of a conurbation like Rouen or Rennes. It is scheduled to be commissioned in the fourth quarter of 1964. We know that an agreement was concluded in 1962 with the Société d’Exploitation des Hydrocarbures in Hassi R’Mel (Sahara). As a result of this contract, Gaz de France will receive 420 million-m3 of gas, which will then be sent to the Paris region.”

The “Jules Verne” is launched on 8 September 1964