20 minute read

I. “Industrial activity sprung up in an abandoned corner”

Ch. PinChon, Havre-Éclair, 30 november 1921

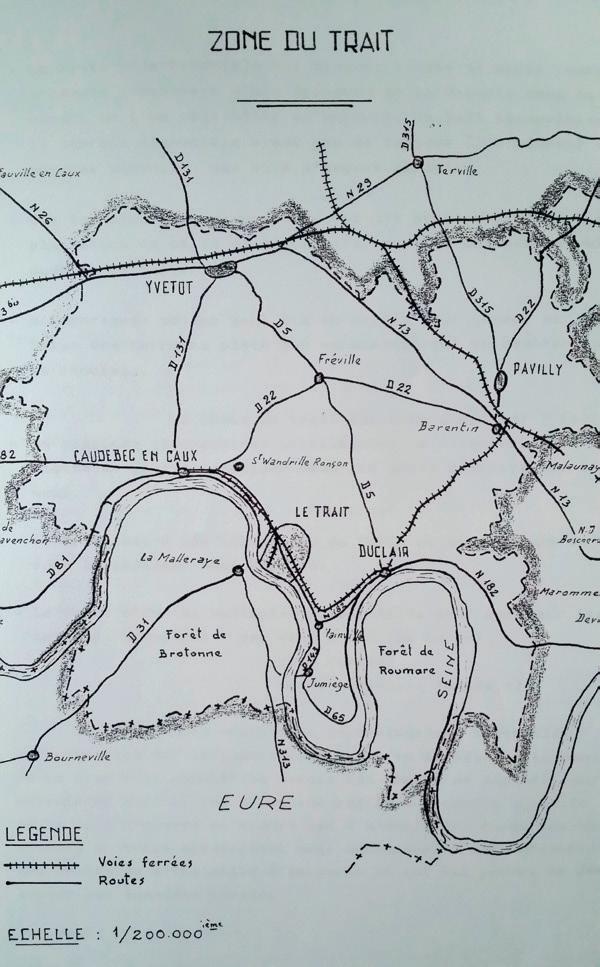

1 - Le Trait on the road to Rouen 2 - Map of the Le Trait zone, B. Maheut, Histoire des chantiers du Trait, p. 12

To grasp the magnitude of the upheaval that struck the village of Le Trait in 1917, we need to know its precise location and trace its history as far back as memory allows.1 The village is located exactly 60 km from Le Havre and 30 km west (downstream) of Rouen, on the right bank of the Seine, in the Seine-Maritime department (known as Seine-Inférieure until 1955) in Upper Normandy. At Le Trait, the meanders of the river narrow as it heads towards Rouen, the regional capital.

Le Trait: a river crossing or “narrow place”?

The site had been inhabited, so it seems, since Antiquity. Small bronze axes were discovered there, possibly dating back to 1500 BC. By then, metals were already coming from England. The Seine, wider than it is today, was a trade route connecting Le Trait to Northern Europe. The village was surrounded by thick forests which most likely grew down to the riverbanks and provided wood in large quantities. For centuries, harvesting wood was the main source of income for many of the inhabitants of the nearby town of Canteleu. Trajectum is the Latin name for Le Trait. Its meaning is similar to that of Maastricht: Trajectum ad Mosam or Mosae trajectum, meaning a river crossing on the Meuse. Le Trait had a ford allowing travellers to cross over to the left bank of the Seine. It was also a transit point to Rouen or Le Havre. To document its etymological relationship with Maastricht, we cite Treiectensis in 634, Triecto, Triectu in the 7th century, Triiect from 768–781, Traiecto in 945; so many patronymics for the Dutch city strongly resemble that of Le Trait. The village of Lettret in

1 J. Derouard, Simples notes sur l’histoire du Trait, Groupe Archéologique du Val de Seine, 1979. the Hautes-Alpes department provides another indication: like Lettret, Le Trait may mean “narrow place.” The oldest written documents on the ford refer to that of Yainville to designate a single parish: Saint-André, Saint-Martin and Saint-Nicolas; for many years, Le Trait and Yainville together formed one and the same subdivision. A river crossing, but also a land crossing: apparently, a Roman road traversed Le Trait, serving as a shortcut, a path through the forest to reach the hamlet of Vaurouy. The population of Vieux-Trait must have lived around the castle, the outline of which can still be discerned between the Calvary and the Seine; the “Vieux-Château footpath” keeps the memory of this initial settlement alive. In his Simples notes sur l’histoire du Trait, Jacques Derouard recalls discovering “pucks made from polished stone pierced with a hole,” which were used to keep fishing nets under water when fishing for sturgeon, salmon, sole or eels. Noted in documents dating back to the 11th century, a church in Clos Saint-Martin, the foundations of which were found during construction of the shipyard, leads us to believe that the first inhabitants of Le Trait settled near here.

Several characteristics result from the history of Le Trait during the Middle Ages. Certain local lords and abbots agreed to exploit the resources of the territory, the borders of which seemed fairly fluid. Where exactly did the village begin and end? Documents from the Abbey of Jumièges confirm that the monks operated a ferry there before the Norman invasions, prior to the 8th century. A charter by Guillaume Longue-Épée dated 930 cited the “Le Trait d’Avilette manor” as belonging to Jumièges. According to Jacques Derouard, the oldest reference to Le Trait as an organised community – a village, so to speak – dates back to 1027, in a charter issued by Richard II, Duke of Normandy. This charter confirms the possessions of the Abbey of Jumièges in the Seine valley, extending from Belinguetuyt (Bliquetuit) to

Josephsartum (Joseph-Essart) and on up to Vuitvillam (Yville), passing through Euuenvillam (Yainville) and Tractus (Le Trait) on the right bank of the river. Conversely, nearby Gothville (Gauville) belonged to the Abbey of Saint-Wandrille. The document by Richard II mentions the existence of farms in these villages. In 1027 (or 1024), the Count of Évreux apparently forced the Abbey of Jumièges to sell him “the ground and woods of Le Trait, from the Yainville valley all the way to the Croix du Comte.” Legal proceedings involving the monks of Saint-Wandrille similarly provide evidence that they were allowed to exploit the woods, especially for heating.

Wood: a coveted source of wealth

The village actually described itself as a border territory, a Middle Ages buffer between the abbeys of Jumièges and Saint-Wandrille.2 At stake: the forest. But the forest ultimately fell to the Counts of Évreux (Richard and his heirs) who served as arbiters between the rival abbeys. Between 1055 and 1066, a charter issued by William the Conqueror (or William the Bastard), Duke of Normandy, granted Richard, Count of Évreux, the tithe on all his revenues north of the Seine, notably the Le Trait forests and the Mesnil-sous-Jumièges mills. The wood was used to build manors and houses, agricultural equipment and warships. Before 1066 and the conquest of England, William of Évreux, son of Richard, reportedly had eighty ships built from logs originating in Le Trait and Maulévrier. Trunks and firewood were transported down the Seine to the naval shipyards in Villequier and Caudebec. There were apparently two chapels in Le Trait. A few archaeological details of the current Saint-Nicolas Church – such as the position of its buttresses – lead us to believe that the church was constructed on the site of a 12th-century chapel. Establishing a single village centre based around a single religious monument probably proved difficult. Conducted under the aegis of Jumièges and SaintWandrille, forest clearance extended cultivable land. At the beginning of the 13th century, some woods were cleared for Richard, Lord of Yvetot and Touffreville, isolating the Le Trait forest in the north from the rest of the

2 The presence of a fortified castle reinforced the idea of a border territory separating two powers.

The Seine, as seen from the Le Trait forest

forest. Cleared at that time, the hamlet of La Bucaille (meaning “little woods”) serves as a testament to deforestation in the 13th century.

The Seine, source of nourishment

In the 14th century, the Duke of Normandy asked the Viscount of Caudebec to pay Gautier Bourgeois, a ferryman, and his fellow sailors the sum of 24 gold deniers, as payment for transporting him by boat from Jumièges to Harfleur. As with the other towns and villages along the Seine, daily life in Le Trait was dictated by the river. A fort was built, the significance of which prompted a visit by the “bailli” of Rouen in March 1369. Throughout the Hundred Years’ War, the fort was in the hands of the lords of Tancarville, who took over from the County of Évreux which had entered the royal domain due to its dependency on King John of England. The important Counts of Harcourt and Melun served in succession among the lords of Le Trait. The last of the Melun line was killed at the famous battle of Agincourt in 1415. The fortifications fell into Burgundian hands in 1418, only to be captured one year later by the English. These fortifications were mentioned in the capitulation deed of 1449. In 1485, mention was made of a ferry on the Seine plying “from the mudflats of Le Traict all the way to Mesleraye.” A pier was apparently located at “Buquet de Lisle.” On the right bank, the ferry departed from

among the pastures within the area named Traict de Goville, among the marshes at La Hazaie. The area seems to have been generally marshy. At the end of the 15th century, the monks of Jumièges complained that the land to which they had rights was entirely fallow. In the 16th century, the residence of the feudal lord was transferred to the castle of Le Taillis near Duclair. During that same century, a post house was established in the village.3 From the 16th century to the Revolution, the Lords of Vaurouy and the “Sires” of Carouge owned the village. An edict of 1566, renewed in 1569 and 1571 and discovered by Jacques Derouard, put up “wastelands, fields, marshes, grounds planted with bushes and woods” for sale.

Forest clearance

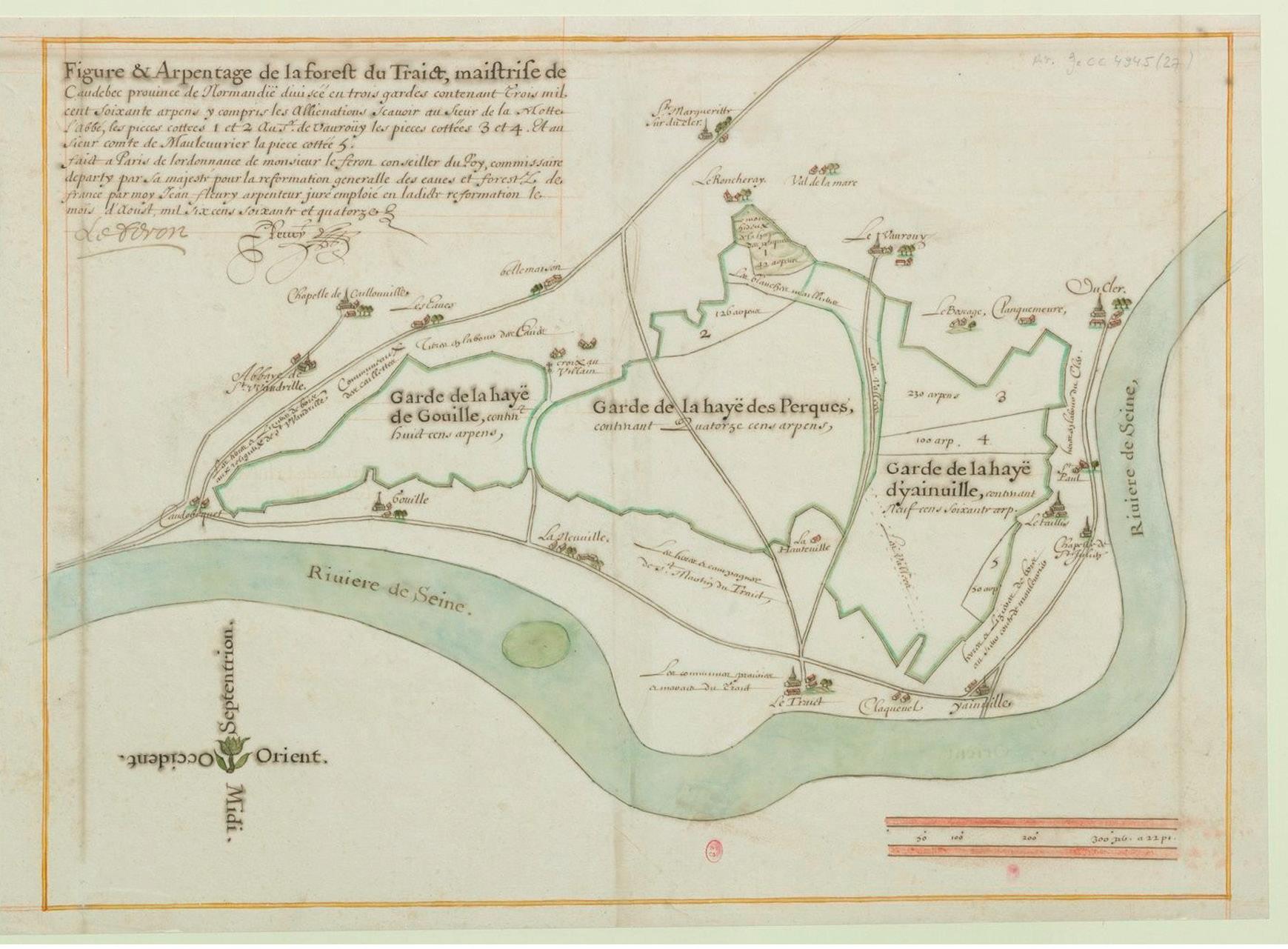

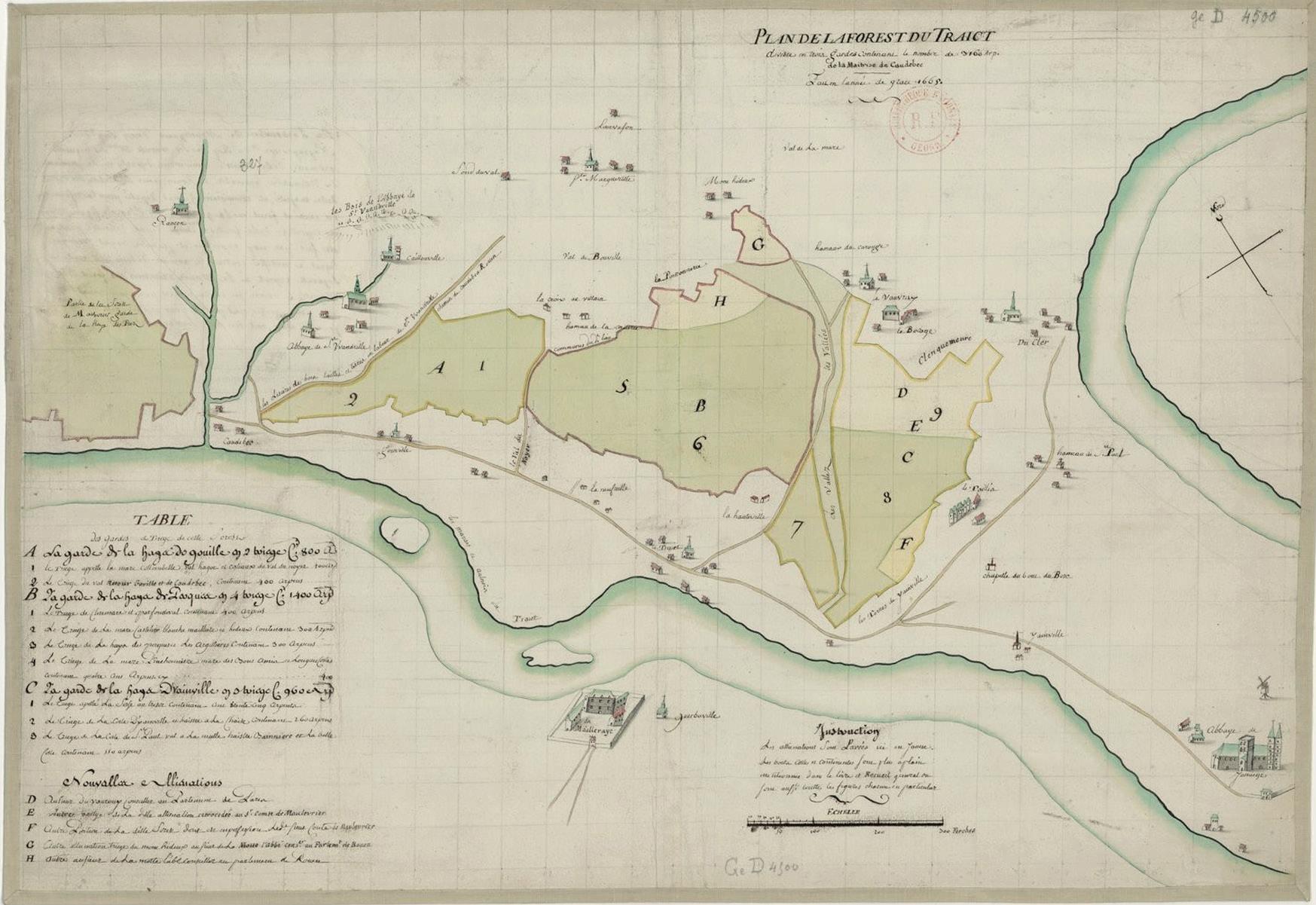

On a “map of the Le Traict forest”4 drawn up in Paris by Jean Fleury in August 1674 the domain, with a surface area of 3,160 arpents (1,080.32 hectares), was divided into three “gardes.”5 Fleury drew a sort of triangle, two sides of which bordered the Seine. Along it were marked the villages or hamlets of Caudebec, Gauville, Neuville (which faced an island), Le Trait and its marshes, Claquenel, Yainville, La Chapelle de SaintJulien, Saint-Paul, and Duclair. In a first map drawn up ten years earlier by Pierre Delavigne in 1665 on the orders of Jean-Baptiste Voysin de La Noiraye, a second island6 was shown alongside La Mailleraye, whose castle or manor was presented within a vast enclosure. A port was depicted around a site known as “La Plage” (the Beach).7 The total surface area, similarly split up into three parts, covered an identical 3,160 arpents.

3 https://anciennephotodutrait.jimdo.com. 4 Maps of the forest of Le Trait by J. Fleury entitled Figure et arpentage de la forest du Traict […] / faict à Paris de l’ordonnance de Monsr Le Feron, conseiller du roi […] par moy Jean Fleury, arpenteur, 1674, and by P. Delavigne, entitled Plan de la forest du Traict, en la maistrise de Caudebec, divisée en trois gardes ansy qu’il appert par la table suivante, contenant le nombre de 3160 arpens, faict l’an 1665 (see illustration). 5 Dictionary Littré: “Extent of the jurisdiction of an official in charge of preserving the woods.” 6 The island was known as “Candie,” or “Platon du Trait.” 7 J. Derouard, op. cit. However, sixty years later, a third map drawn by a surveyor named Lefebvre and dated 17 March 1735 showed that the forested area had shrunk by over three hundred arpents (total area: 2,844 arpents), probably due to forest clearance: for example, in 1699, Abraham Carrier purchased some lands for ploughing which were said to have been formerly wooded. Likewise, tree feller huts were constructed near the edge of the forest in Hauteville. According to a document dated 17 March 1628, a captain and an archer aboard a “flambart” (a small sailing boat) apparently had a longstanding mission to stop ships on the river to check whether their cargo contained salt, as its transport was subject to the payment of a royal tax.

Plan de la forest du Traict by Jean Fleury

Map of Le Trait by Pierre Delavigne

Le Trait, the Route du Passage (across the Seine)

The ferry

In the 18th century, the ferry was located in VieuxTrait. The road leading to the ferry, the “chemin de La Quesnaye,” was so steep it was difficult to use. The ferrymen had come from the Abbey of Jumièges since the 14th century, with the job being passed down from one generation to the next. They lived in the ferryman’s cottage and were able to maintain a small farm. Some had more than one job. For example, ferryman Michel Rollin was also a merchant. The ferrymen lived off the ferry proceeds, only having to pay the abbey the cost of the lease. They were required to carry out all repairs to the boat and received no money for transporting the monks. According to a public notice in July 1779, for each peddler or passenger, they could collect one “sou Tournois”; for each riding horse, two “sous”; for each horned animal, one “sou six deniers”; for each pig, nine “deniers.” Bushels of wheat, bales of hay and cider “pots” were the ordinary fare transported for the peasants. Navigation along the Seine was risky, if not downright dangerous, because there were no dikes along the river, and many sandbars formed vast bare islands which shifted at the whim of the currents. In 1827, someone named Jaustin mentioned the plains of Le Trait being snatched by the river after it washed away sections of a wall. In 1870, a syndicate was formed for the purpose of protecting riverside properties. Floods and tidal bores occurred as frequently as shipwrecks, such as the one in Villequier that swept away Victor Hugo’s daughter, Léopoldine, and his son-inlaw. The ex-voto ships adorning the church of Le Trait bear witness to the villagers’ concern for guarding against these perils. Drowned victims were frequently found in the marshes. Their remains were buried on the spot, in a seated position. In the mid-1950s, in an area previously covered by the Seine, a grave containing three seated corpses was exhumed in open ground along the Rue Denis Papin. When the deceased were Christian, they were taken to the cemetery via a route known as the Valley of the Drowned (“Val des Noyés” now spelled “Val des Noyers” – Valley of the Walnut Trees).8

A Normandy village still half-asleep (19th century)

Le Trait and its inhabitants

1835 marked the election of the first Mayor of the community; his name was Jean-Baptiste Doucet, and he held this position until 1869. When Worms & Cie started operations in Le Trait, the municipal council was headed by Paul Aubert, its sixth mayor. His term ended in 1919.

List of Mayors of Le Trait from 1835 to 1974

Period Name Party Occupation

1835 1869 Jean-Baptiste Doucet 1870 1873 Antoine Gustave Sécard 1873 1878 Amédée Léon Delametterie 1878 1900 Adrien Boquet 1900 1908 Alphonse Leroy 1908 1919 Paul Aubert 1919 1933 Octave Pestel Teacher

1933 1941 Achille Dupuich Director of the Société Immobilière du Trait

1941 1945 Eugène Hardy 1945 1974 Raymond Bretéché SFIO ACSM employee Source: Wikipedia (French version)

Demographic change

Between 1793 and 1851, the Le Trait population increased by barely one hundred from 476 to 570, though the trend started to reverse in 1856, going down to just 366 in 1911. As the statistics clearly show, the region’s population had been in decline since the end of the 19th century.9 Normally, a base of rural workers formed a labour reserve, providing a large portion of the skilled personnel for major enterprises. The population decline in Normandy posed an additional challenge for Worms & Cie during the construction phase of the naval shipyard and during the crises of the 20th century, such as in the reconstruction phase after the Second World War. On the other hand, this rural isolation encouraged the labour force to put down roots. Faraway from the major agglomerations (Rouen or Le Havre), the inhabitants of Le Trait organised their lives around services provided by the company.

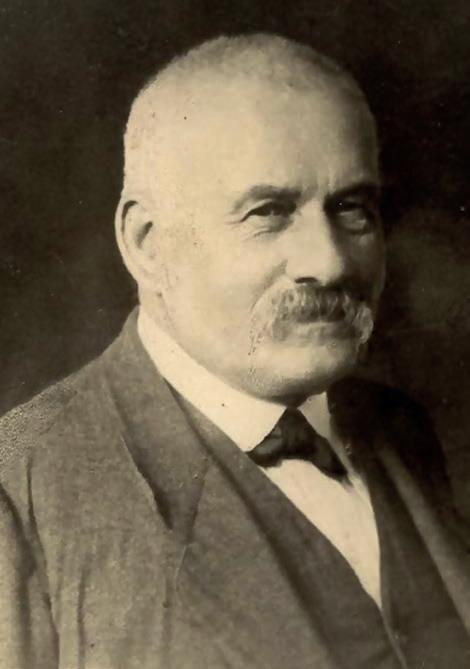

Octave Pestel, Mayor of Le Trait from 1919 to 1933

Evolution of the population10

1793 1800 1806 1821 1831 1836 1841 1846 1851 476 458 448 501 464 517 530 532 570 1856 1861 1866 1872 1876 1881 1886 1891 1896 543 536 522 465 504 445 466 498 460 1901 1906 1911 1921 1926 1931 1936 1946 1954 427 392 366 1 570 1 767 2 932 3 200 3 593 4 569 1962 1968 1975 1982 1990 1999 2006 2007 2012 6 407 6 408 6 321 5 917 5 485 5 397 5 217 5 186 5 239 The official records of births, marriages and deaths of 185811 listed twenty names, highlighting the common patronymics within the canton: Déhayes, Lefebvre, Levillain, Lebourgeois, Leboucher, Blondel, Caron, Leroy, Binard, Duhamel, Moret, etc. The listed occupations proved not so different from other Normandy villages: for example, Sire Lebourgeois was a farmer native to Le Trait, whose parents – themselves residents in the village – were both landowners and farmers. His wife, “née” Tanquerel, was also a farmer and from Le Trait. Eugène Anquetil, the witness at their wedding, was originally from Berville-surSeine, a nearby village located “on the other side of the water.” The civil-status record was filed with Mr Bicheray, a notary with offices in Jumièges. The community teacher, Alphonse Rivette, was one of the men in the public eye; he witnessed deaths and other deeds associated with the inhabitants’ daily lives. Accordingly, he was declared a “friend” of the inhabitants of Le Trait, at least among those mentioned in the civil registry. The majority of the population were farmers, with husband and wife working shoulder to shoulder. The rest included day labourers, several wood carriers, as well as a seaman, a weaver, a laundress, a seamstress, several people “without an occupation,” a carter and a servant. In 1900, the list included six customs officials, one carpenter, twenty-three farmers, five railway employees, two cartwrights, thirty-one day labourers, one road mender, one blacksmith, two fishermen, one crossing keeper, one cobbler, one boatman, nineteen servants, two seamstresses and two seafarers.12 The five railway employees were the one anomaly in the register, as their presence revealed that the industrial world had arrived in the heart of the Normandy countryside. The baker came from Caudebec-en-Caux, organising his rounds to supply the households. In 1906, the village consisted of one hundred and thirty-seven houses.13

9 On this subject, see the diagram on demographic change in Normandy, in Y. Marec, J. Quellien, J. Laspougeas, B. Garnier, and J.-P. Daviet, La Normandie au XIXe siècle. Entre tradition et modernité,Éditions Ouest-France, 2016. 10 See fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/LeTrait#Démographie until 1999, then INSEE (National Institute of Statistics) starting in 2006. 11 Departmental Archives of Seine-Maritime: civil registry of Le Trait for the year 1858. We have chosen this year and this particular registry because of the completeness and legibility of the information. The inventory counted 543 inhabitants in Le Trait in 1856. It included the population in all hamlets associated with Le Trait. 12 G. Fromager, Le Canton de Duclair (1900-1925), Fontaine-le-Bourg: Le Pucheux, 2014 (1st ed., 1986), pp. 138–149. 13 Ibid.

The village’s surface area totalled 1,752 hectares, dotted with woods and hamlets. The community owned a rowboat, a smaller version of the ferries typically found in the valley. That same year, in 1906, Saint-Martin-deBoscherville, just 17 km upstream and soon also to be a contender for the Worms naval shipyard, counted thirty or so craftspeople – laundresses, bakers, saddlers, a butcher, a pork butcher, cartwrights, innkeepers, café owners, a grocer, fruit merchants, a doctor, a carpenter, masons, a painter, a forest warden – and had its own ferry. In 1911, a gas lamp was installed to light the square in front of Saint-George’s Abbey.

Arrival of the railway

Railway development began in the 1830s. In 1843, under the reign of Louis-Philippe, the Paris–Orléans and Paris–Rouen lines were launched; four years later, in 1847, the Paris-Rouen line reached Le Havre, thus making the sea accessible from the capital in six hours. Positioned at the heart of the rail network, Paris was connected to all the major regions of the country, including Normandy. On 20 June 1881, the Barentin-Duclair line was inaugurated14 and, in 1882, extended all the way to Caudebec. Le Trait got its own railway station.15 However, the station that really influenced the choice of sites for the Worms shipyard was La Mailleraye-Guerbaville, on the right bank, on the line to Caudebec-en-Caux. Better suited for transporting freight, the station would ultimately be connected to the industrial complex by a dedicated branch line. The station at Le Trait (or Vieux-Trait), a simple halt alongside the Seine, would be used by shipyard workers coming from the surrounding areas, who then had to walk another two kilometres to reach their place of work.

The industrialisation of the Seine valley: from farmer-soldier to farmer-worker

Upon returning home from war, the men from the Seine valley – peasants for the most part – resumed their farming. Though factory work offered far more

14 F. Aubert, P. Sorel, G. Devaux, Duclair, un regard sur le passé, Fontaine-le-Bourg: Le Pucheux, 2011, p. 195. 15 J. Derouard, op. cit. See also M. Decarpentry and J.-P. Ferrer, Précis chronologique d’histoire. Les chemins de fer en terre de Caux, coll. “Les cahiers de terres de Caux,” 2015. opportunities and the promise of better salaries, people nevertheless generally continued to cultivate their own patch of land, provided they owned one. Everyday village life was dominated by the farming timetable: hay required a large labour force in June; straw at the end of July/beginning of August; the harvest in September; fruits in summer and autumn (cherries in July; greengage plums (la “Verte Bonne”) in August and the beginning of September; apples in October and November); cider-making at the very end of the season.16 Companies needed to prove their attractiveness in order to lure the labour force away from the fields.17 In the late 19th century and early 20th century, factories sprang up on the banks of the Seine, providing employment for hundreds of Normans. But it was the First World War that dramatically and very rapidly changed the face of the valley. The Latham airplane factory was built in 1916 in Caudebec-en-Caux. Forced to leave the combat zone, the Société des HautsFourneaux et Fonderies from Pont-à-Mousson opened a coal tar factory in Yainville in 1917. Standard Oil filed for authorisation to set up a refinery in Le Trait in 1917. Large-scale construction work on a new power plant took place in Yainville that same year. New wharves were built there for the purpose of unloading coal shipped in from Cardiff. The ships included colliers belonging to Maison Worms, which had set up shop in the large Welsh port in 1851. In 1921, a nut and bolt

16 According to the memoirs of Henri Nitot (private archives), the ACSM management referred to the inhabitants of the area as “apple gatherers.” 17 The problem of farm leases (over which a crisis erupted in the 1920s and 1930s) prompted several peasants to take on factory work, as incomes from farming were low due to lease payments. See D. Bellamy, Geoffroy de Montalembert (1898-1995). Un aristocrate en République, Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2006, p. 110; and C. Bouillon and M. Bidaux, André Marie (1897-1974). Sur les traces d’un homme d’État, Paris: Autrement, 2014, pp. 136–137. André Marie was continuously asked to plead for revisions to farm leases before the Chamber of Deputies. This brings to mind the agricultural crises mentioned by Noiriel, crises that contributed to cutting off peasant-workers from their rural environment. See G. Noiriel, Les ouvriers dans la société française XIXe XXe , Paris: Le Seuil, 2002 (1st ed., 1986), p. 90 and p. 143, on the isolation of factories within rural environments, which fostered the workers’ local roots.

Traditional Normandy thatched-roof cottage

factory started operations in Duclair. In the 1930s, a soap factory and an oil mill opened in Yainville.18 As often reported in the regional press,19 this industrialisation raised standards of living, and parents could now hope to see their children moving up the income and social ladder.

18 P. Bonmartel, Histoire du patrimoine industriel de Duclair-Yainville-Le Trait (1891-1992), Luneray: Bertout, 1998; and E. Real, Le paysage industriel de la basse Seine, coll. “Images du patrimoine,” Connaissance du patrimoine de Haute-Normandie, Région Haute Normandie, 2008. 19 Normandie : Revue régionale illustrée mensuelle de toutes les questions intéressant la Normandie : économiques, commerciales, industrielles, agricoles, artistiques et littéraires, Nos 9 and 10, Alençon: Imprimerie Herpin, 1918. In P. Bonmartel, Les pionniers traitons. La citéjardin 1916-1936, auto-edition, 2006, terms such as “far west” were used to depict the brutal transition from rural area to large industry. Similar terms were also used to describe the steel industry in Lorraine. See G. Noiriel, op. cit., p. 124. The arrival of the Ateliers et Chantiers de la SeineMaritime added to the overall enthusiasm. But it remains no less true that Le Trait, at the time Worms & Cie was interested in the location, had absolutely no industrial infrastructure (with the exception of its railway station). Any advantages to the site were to be sought elsewhere. To understand its attraction, we need to study the personality of Maison Worms and the problems it had been facing since the outbreak of the war.