122 minute read

II. 1914–1917 “Present and future needs”

1914–1917 “Present and future needs”

GeorGes majoux, Le TraiT, 15 oCTober 192220

20 Speech given by Georges Majoux on the occasion of a visit to Le Trait by Paul Strauss, Minister for Hygiene, and a delegation from the Social Hygiene Alliance on 15 October 1922 – quoted in the journal, Alliance de l’hygiène sociale, congrès de Rouen, 13 au 16 octobre 1922, pp. 227–231. Source: www.gallica.bnf.fr, and www.wormsetcie.com – archives 1922.

The Ateliers et Chantiers de la Seine-Maritime, circa 1921

Unless otherwise specified, all documents produced or received by the Le Trait shipyard or Worms & Cie, and quoted in this chapter, may be found on the website www.wormsetcie.com; the documents are listed according to the date on which they were issued (yyyy/mm/dd).

Henri Nitot, who headed ACSM from 1921 to 1960, mentioned in his memoirs21 “the powerful Maison Worms,” when as a youth, he walked by the company’s headquarters at 45, Boulevard Haussmann in Paris, and dreamed of pursuing a career there. From dream to reality!

Hypolite Worms (1801–1877), founder of Maison Worms

21 Henri Nitot, memoirs, non dated printed text, private archives.

Worms & Cie, 16 january 191422

Reviewing its history in early 1914, Maison Worms described itself23 in terms that warrant repeating: the company “was founded in 1848 by Hypolite Worms,24 […] and was one of the first, if not the first, to export English coal to France” and abroad. It remained a simple trading house until 1874, when Hypolite Worms, in partnership with Henri Josse,25 registered his company as a general partnership “Hte Worms & Cie.” This change enabled the company to outlive its founder, who died on 8 July 1877. In 1881, the company became a limited partnership under the new name of “Worms Josse & Cie.” Following the death of Henri Josse on 23 July 1893, Henri Goudchaux headed the company, which was renamed “Worms & Cie” on 1 January 1896 “and has remained

22 Historical note on Maison Worms dated 16 January 1914. 23 Ibid. 24 Maison Worms was actually established in 1841–1842 at 46, Rue Laffitte in Paris. Up until 1848, Hypolite Worms, a merchant banker, was a jack of all trades, dabbling in mercantile transactions (cotton, cast iron, grain and oats, indigo fabric, tin, coffee, etc.) for his personal account or for third parties to whom he granted cash advances; purchases of shares in railways; equity holdings in for example the Compagnie des Charbonnages de Sauwarten in January 1843, an investment that led him to trade in Belgian coal between 1844 and 1846; the sale in France of gypsum from the Buttes-Chaumont quarry in Paris from 1846 to 1865 (at least), etc. Consequently, 1848 marked a commitment to his longest-lasting business activity: international trade in English coal. 25 A Frenchman exiled in Great Britain in 1851, Henri Josse (1828–1893) was recommended to Hypolite Worms by the Committee for the Relief of Deportees of the Coup d’État of 2 December 1851 (opponents of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) led by Michel Goudchaux, himself the uncle of Séphora Goudchaux, the founder’s wife. Henri Josse created the subsidiary Worms Great-Grimsby in 1856. A naturalised British citizen, toward the end of his life (1892) he became a Liberal member of the English Parliament, a duty from which he resigned shortly afterward, once his partners convinced him that the relationships with public administrations and the Minister for the Navy in France risked being affected by the presence of a member of the English Parliament in Maison Worms.

so ever since.” “In the fuel merchanting, the Maison is considered as one of the world’s leading companies; […] it enjoys a place and authority truly unrivalled by any other.” Maison Worms set up shop in the main British coal ports: Cardiff, Newcastle-on-Tyne, Grimsby, Goole and Hull, as well as Swansea, Sunderland, Liverpool, London and Glasgow.26 The company sold its coal through its branches in Le Havre, Dieppe, Rochefort, Tonnay-Charente, Angoulême, Bordeaux, Bayonne, Marseilles and Algiers, as well as Port Said and Suez in Egypt. Its clients, whether for exports of English coal or for supplying coal bunkers where ships from all over the world came to refuel, included: “the French Navy, several foreign navies, the Suez Canal Company, the Messageries Maritimes, the Compagnie Générale Transatlantique (French Line), the Chargeurs Réunis, the main French shipping companies” and many of the largest shipping companies in England (including Peninsular & Oriental Steam Navigation Company – P&O), Belgium, Holland and occasionally Germany. When the Suez Canal opened in 1869, Maison Worms established a presence in Port Said, supplying the coal needed for the steam dredgers owned by Borel Lavalley & Cie, the contractor responsible for completing construction of the canal after the abolition in 1864 of the forced labor imposed on the fellah workforce; “since 1869, Worms & Cie has maintained its leading position as a provider of shipping services” in Egypt. “Despite the large number of coaling stations established there, the company was responsible for 32% of the 1,555,000 tons of coal” traded in Port Said in 1913. The company regularly won, there as in Algiers, “almost without exception, contracts from the French Navy”; “besides, the company was well known to the Ministry of the Navy, a regular customer since the Crimean War [1854–1856], and whose opinion was often consulted for purchase and charter transactions,” even though “the company no longer handled those transactions, following modifications” made in 1912 to the terms of naval supplies.27 “Maison Worms also supplied railway companies and gasworks in France and abroad, and its various branches and agencies engaged in operations for the industrial needs of the regions they served.” As an extension of its British coal trade, Maison Worms entered the shipping industry in 1856. The owner and operator of its ships registered in Bordeaux, the company was initially the co-owner28 of the largest share of steamers belonging to the Le Havre company Hantier Mallet & Cie (later to became F. Mallet & Cie), a company created in 1851 at the instigation and with the financial support of Hypolite Worms by one of his representatives, Frédéric Mallet.29 In 1881, Maison

Floating Worms coal warehouse in Port Said (Egypt) in 1872

26 The company held such a prominent place in Great Britain that it was mistaken with an English company by the public at large. For example, in 1892, when Worms Algiers won a three-year contract to supply coal to the French Navy in Algiers, Bone (now Annaba), and Philippeville (now Skikda), the Algerian newspaper, La Bataille, published an article on 24 February entitled: “Amirauté d’Alger – les fournitures de charbon pour la flotte française confiées aux Anglais.” 27 See, for example, the provisions relating to Cardiff coals destined for military ports and naval forces, which, because of their “great extension,” were transported by coal freighters chartered by the Navy (most often on time charter), while their purchase was made in Cardiff by the French consul or a special delegation of the Central Markets Committee, see Bulletin officiel de la Marine (t. 129, vol. 2, No. 14) on www. gallica.bnf.fr. 28 The French word designating the co-owner of a ship is a “quirataire”; “quirat” being the ownership share of a ship. 29 Frédéric Mallet was Chairman of the Chamber of Commerce of Le Havre from 1875 to 1890.

Henri Goudchaux (1846–1916), Worms & Cie General Partner from 1881 to 1916, engraving by Walter

Worms took over the company, directly operating its lines.30 The company made a similar move in 1905, taking over the service between Dieppe and Grimsby “which in the past had been in the hands of Maison A. Grandchamp of Rouen,” with whom Hypolite Worms had teamed up in 1851. Specialised “in reserved cabotage31 and international cabotage, Worms lines served the majority of French ports between Bayonne and Dunkirk, with operations extending from Pasajes (Spain) to Great Grimsby (England), Antwerp (Belgium), Bremen and Hamburg (Germany).” In addition to its Fuel Merchanting branches and its branches in Bordeaux, Le Havre, Dieppe and Rouen (which combined trade in fuel and shipping services), Worms & Cie operated branches in Dunkirk, Boulogne, Brest and Nantes, as well as in Belgian, Dutch and German ports, to service its needs as a shipping company as well as those of the companies to which it provided

30 See the Bordeaux–Le Havre–Hamburg line inaugurated in February 1859, and the Bordeaux–Antwerp line opened in 1869–1870. 31 Unlike free cabotage, reserved cabotage (under a national flag) means transporting goods and people from one point to another within the territory of a State which limits the trading rights to its own subjects. services. Its fleet included eighteen steam-powered vessels, complemented by four further freighters ordered in June 1913 from the Ateliers et Chantiers de la Loire in Nantes. Merchandise transported under the Worms flag “totalled 534,602 tons in 1912, and 578,151 tons in 1913. Despite its status as a shipping company engaged solely in cabotage,” the company was “an uncontested authority in the world of the Merchant Navy.” In 1903, the company was instrumental in founding the Central Committee of French Shipowners, with Henri Goudchaux serving as its treasurer from the very start.

Hypolite Worms and Georges Majoux: a taste for entrepreneurialism

When the First World War broke out in the summer 1914, the General Partners of Worms & Cie were Henri Goudchaux and his son, Michel, as well as Paul Rouyer and Hypolite Worms. Rising up to become head of the Port Said branch in 1887, Paul Rouyer entered the management board in 1896. After retiring in 1916, he was replaced by Georges Majoux, head of Shipping Services since 1907. The grandson of the company’s founder, Hypolite Worms started at Maison Worms in 1908 at the age of 19.32 For three years, he followed a training programme that led him from the branch in Cardiff, “where he worked at the most mundane tasks in exchange for ten pounds per month,”33 to Port Said, then to Le Havre, close to Georges Majoux. Appointed a General Partner in December 1910, he proved to be so adept that Henri Goudchaux put him in charge in September 1914 when he himself joined the government in Bordeaux. When Henri Goudchaux succumbed to a serious illness on 25 April 1916, it was his wish that his closest colleague, Hypolite Worms, succeed him. He was not yet 27!34 Twenty-two years his senior,

32 Hypolite Worms was born on 26 May 1889. 33 Interview with Hypolite Worms on 24 July 1948. 34 Appointing young people to positions of responsibility had been a constant feature of Maison Worms’ management ever since its establishment: F. Mallet (1825–1899) was 24 years old when he took charge of the commercial office in Le Havre in 1849; J.R. Smith was 26 years old when, in 1851, he founded the Cardiff branch; Georges Schacher (1835–1883) was 22 years old when he opened the Bordeaux branch in 1857.

Georges Majoux35 had “great experience in matters of shipping.”36 Between 1903 and 1906, he headed the Denain and Anzin branch in Dunkirk.37 At the time, “the Société des Hauts Fourneaux, Forges et Aciéries de Denain et Anzin had its own fleet of cargo ships, transporting iron ore from Spain (and Bone in Algeria) to Dunkirk, as needed for its operations.”38 The company placed an order with ACSM for the ship “Ostrevent” which was launched in September 1925. Previously, in November 1899, Georges Majoux had founded the maritime trading company Georges Majoux & Cie in Calais, Dunkirk and Paris. In 1901, he helped create the General Committee for the Defence of the Interests of the Port of Dunkirk.39 That same year, he was listed in the Annuaire de la société des ingénieurs civils de France. 40 A savvy industrialist, Georges Majoux also made his mark with various scholarly societies: in August 1905, he served as secretary to the 26th National Congress of French Geographical Societies, while in 1927 he became a member of the Normandy History Society. His appointment as head of the Worms Maritime Services in 1907 coincided with the opening of a Worms branch in Dunkirk, which was probably set up specially for the purpose of recruiting this valuable man. His new duties led him to settle in Le Havre, where the management of Worms Shipping Services had been based since 1881. In the 20 July 1911 issue of Navigazette, Georges Majoux

35 G. Majoux was born on 7 February 1867 in Villeron (Vaucluse department). 36 Worms & Cie administrative circular of 1 January 1907, announcing the appointment of Georges Majoux as head of Shipping Services. 37 Georges Majoux married Antoinette Brabant in Dunkirk on 28 June 1902. 38 Notice regarding the ship “Capitaine Arsène Guillevic,” formerly the “Ostrevent,” on the website of the Union Industrielle et Maritime. 39 Cf. “Revue des questions ouvrières et de prévoyance,” in Revue politique et parlementaire, April 1905, p. 161, regarding the organisation created in Dunkirk on 14 January 1901, by Mr de Wulf and Mr Majoux, known as the General Committee for the Defence of the Interests of the Port of Dunkirk. Source: www.gallica.bnf.fr. 40 Cf. Annuaire 1901 de la Société des ingénieurs civils de France: “Majoux, Georges-Édouard, Consul of Bolivia; Maison Georges Majoux et Cie, a maritime trading company; Deputy Head of the maritime division for the Société de Denain et d’Anzin, Rue de Metz, in Calais and Quai de la Visite, 12, in Dunkirk.” Source: https://archive.org.

Hypolite Worms (1889–1962), Worms & Cie General Partner from 1910 to 1962, portrait dated 1913

was listed among the members of the Association of Labour Employers in the Ports of France. Managing a fleet in normal times, and pursuing a career as a shipping agent, required many fields of expertise: - Technical (knowledge about each ship’s characteristics and transport potential, based on the shipping routes and ports served); - Commercial (type of merchandise exchanged between regions and countries; prices and prospecting for goods in France and abroad); - Legal and fiscal (maritime law; port legislation; customs systems, taxes, etc.); - Personnel management (seafaring personnel, shore personnel; traders, agents, dockers, etc.). Day-to-day problems had little in common with the chaos brought on by a state of war. As obvious as it seems, this finding surely weighed upon the decision made by Maison Worms in 1916 to launch its shipbuilding business. One of the questions needing to be answered was the following: How should it rejuvenate its fleet and repair its cargo ships given that nearly all French and foreign shipyards were no longer able to accept orders? The question was even more pressing, as major contracts had been concluded with the Ministry of the Navy.

juLes avriL, Journal du Havre, 29 november 1921

The “initial project”

GeorGes majoux, 4 auGusT 1921

The official version

Maurice Quemin introduced his book, Le Trait berceau de 200 navires […], with a foreword by Charles Duguet, the last ACSM Secretary General: “Upon its establishment in 1848,” he wrote, “Maison Worms had the opportunity to serve the government, in particular by ensuring the transport of supplies during the Crimean War.41 During the First World War, the company again responded affirmatively to the request of the public authorities which sought investors for shipbuilding yards, both to counter the significant losses of ships torpedoed by German submarines and to ensure that the Merchant Navy would flourish once peace was restored. These were the reasons behind the construction of the Ateliers et Chantiers de la Seine-Maritime between 1917 and 1921.” These words took their inspiration from the speech delivered by Georges Majoux on 15 October 1922 to the members of the Social Hygiene Alliance:42 “The government,” he said, “is urgently calling for private initiatives and capital to construct, without delay, major shipyards in France, capable of providing all the vessels that the country needs. The public authorities sought out our company in particular, as it had no doubt caught their attention through continuing, despite all difficulties, to ensure regular shipping services, and perhaps as well, to make up for the heavy losses that the torpedoes inflicted upon its fleet.”

41 In 1991, Gabrielle Cadier-Rey, history professor at ParisSorbonne University, analysed the Maison Worms archives for 1854 and 1855, and established that in each of these two years, Hypolite Worms provided the Baltic squadron with 100,000 to 120,000 tons of coal, a sizeable quantity which made him the main supplier to the French Navy. 42 Alliance de l’hygiène sociale, congrès de Rouen, 13 au 16 octobre 1922, op. cit.

Georges Majoux (1867–1941), General Partner of Worms & Cie from 1916 to 1925

Unquestionably, during the months in which Worms & Cie resolved to build a shipyard, the issue of rebuilding the French merchant fleet was raised, with the government asking for help from the private sector to meet demand. Nonetheless, several indications lead us to believe that Maison Worms reached its decision prior to the government’s appeal. In a long article on ACSM published in the Journal du Havre of 29 November 1921, Jules Avril wrote: “Worms & Cie, like all shipping companies, suffered from losses of its vessels and a lack of repairs. It contacted the existing shipyards, but either their orderbooks were full or they were focused on military production. To many, the

problem seemed insolvable, but not to Maison Worms. What it was unable to procure from others, it resolved to build on its own, by creating a shipyard, its very own shipyard.” The Journal de la marine marchande of 8 December 1921 corroborated these words: “In 1916, Worms & Cie, faced with the losses that submarine warfare had inflicted upon its fleet, thought about creating a new branch of industrial activity, for the purpose of reconstituting its fleet, in the face of overburdened shipyards.” Georges Majoux himself made a similar statement to the members of the French Association for the Advancement of Science on the occasion of their visit to Le Trait on 4 August 1921:43 “Worms & Cie,” he told them, “decided to create the Ateliers et Chantiers de la Seine-Maritime for the purpose of constructing ships needed to replace those destroyed by the enemy. […] Moreover, the initial project has been completely reworked and enlarged to meet the government’s urgent entreaties to reconstruct the national fleet.” Thus, between his speeches in August 1921 and October 1922, Georges Majoux removed any reference to the more modest original design, undoubtedly for the purpose of highlighting the intentions of the public authorities and the higher purpose for which the work was being accomplished. This highlighting of the government’s role was most likely not devoid of ulterior motives: his words served to tell Maison Worms representatives that they were to remind the administration, in their negotiations with it for new vessels, of its responsibility to provide work to ACSM at a time when it was cruelly lacking (we will look at this aspect later on in this text). Pushed to its extreme, this version allowed some to affirm: “In November 1917, the government selected Le Trait,”44 without any reference to Worms & Cie and its activity. The only person referring to “this initial project” would seem to be the essayist, Roger Mennevée, in the 1940s, who went so far as to give it a name. In one of the articles devoted somewhat obsessively to Banque Worms in his newsletter, Les Documents de l’agence indépendante d’informations internationales,45 he asserted (with some chronological approximations): “After the Armistice [sic], the naval shipyard of Le Trait […] which had previously operated under the name ‘Société Auxilliaire de Constructions Navales’ and under the direction of Mr Majoux, had been established as a special ‘division’ within Maison Worms, assuming the name ‘Ateliers et Chantiers de la Seine-Maritime – Worms & Cie.’” There is no trace of this original name in the archives. A company called Société Auxiliaire de Constructions Navales did exist, but it had nothing to do with Worms and ACSM.

Two Worms ships destroyed in 31 months of war (August 1914 to March 1917)

One of the reasons generally given by newspaper articles and company brochures to explain why Maison Worms established ACSM was that “like all shipping companies, [it] had suffered [heavy] losses”46 that “[German] torpedoes had inflicted on its fleet.”47 The oldest document preserved in the Worms archives regarding Le Trait is dated 9 November 1916; it is a letter addressed to the Le Havre branch by James Little & Co., a company located in Glasgow: “We have observed with pleasurable interest,” the letter reads, “a report that you have purchased a large piece of ground on the river Seine for the erection of shipbuilding yards, to be known as the Ateliers et Chantiers de la SeineMaritime.” Research undertaken by the historian, Paul Bonmartel,48 established that Georges Majoux visited Le Trait in September 1916 to study the site there. The first (known) land purchase contracts date back to December 1916. These witness accounts infer that Maison Worms launched its shipbuilding project in early autumn 1916 (at the latest). Establishing this point of reference raises the question about the extent of losses suffered by the Worms fleet during this period. Just how many vessels had the company lost? On 1 August 1914, eighteen cargo ships flew the Worms flag: “Hypolite-Worms,” “Suzanne-et-Marie,” “Séphora-Worms,” “Emma” (the third bearing this name), “Thérèse-et-Marie,” “Michel,” “Sauternes,” “Haut-Brion,” “Bidassoa,” “Barsac,” “Cantenac,”

43 Compte-rendu de la 45e session de l’Association française pour l’avancement des sciences, Rouen, 1921, published in 1922, pp. 197–199. Source: www.gallica.bnf.fr. 44 See Serge Laloyer, “Le Trait et son chantier naval, 7 années de lutte,” published in No. 6 of the journal Le fil rouge, 1999. 45 February 1949 issue. 46 Jules Avril, Journal du Havre, 29 November 1921. 47 Speech by Georges Majoux, Le Trait, 15 October 1922, see Alliance de l’hygiène sociale, congrès de Rouen, 13 au 16 octobre 1922, op. cit. 48 Paul Bonmartel, Les pionniers traitons. La cité-jardin 1916-1936, auto-edition, 2006, p. 29.

“Fronsac,” “Listrac,” “Pessac,” “Léoville,” “PontetCanet,” “Pomerol” and “Margaux.” Four vessels came into service at a later date: “Château-Palmer” in October 1914; “Château-Yquem” in November 1914; “Château-Lafite” in April 1915; and “Château-Latour” in March 1916. “Saint-Émilion” was purchased in 1917, and “Ar-Stereden” in 1918. The company thus operated a total of twenty-four vessels during the four years of war. Maison Worms suffered eleven losses. The first was the cargo ship “Emma,” torpedoed on 31 March 1915.49 This was followed by the sinking of “Léoville” which hit a mine on 19 January 1916. After an interlude of more than one year without losses, German submarines – U-boats – and floating mines carpets wreaked havoc on the fleet: “Michel” was the third ship to sink, hitting a mine on 19 March 1917. The fourth was “ChâteauYquem” which also hit a mine on 30 June 1917. One month later, on 27 July 1917, a fifth cargo ship, the recently purchased “Saint-Émilion,” was torpedoed. Six other vessels suffered the same tragic fate: two went down in August 1917: “Sauternes” on the 5th and “Thérèse-et-Marie” on the 19th; two others sank just hours apart in January 1918: “Barsac” on the 11th and “Château-Lafite” on the 12th; “Pontet-Canet” disappeared on 25 August 1918, and “Ar-Stereden” on 21 October 1918. This last ship had such a brief career that it is generally not included in the inventory of Worms vessels. While this list shows that Maison Worms was “seriously hit by the losses inflicted upon its fleet by submarine warfare,”50 most losses occurred after the company had purchased the first parcels in Le Trait. Therefore, its decision to create ACSM could not have stemmed from the decimation (that had yet to occur) of its fleet,51 a fact confirmed by the evolution in tonnage. Considering the launch of the “Château-Palmer,” “Château-Yquem,” “Château-Lafite” and “Château-Latour,” and despite the loss of “Emma” and “Léoville,” the company still had twenty ships in March 1916, two more than on 1 August 1914. Similarly, its total deadweight had increased: 33,755 tons in September 1916 versus 27,830 tons when France entered the war. It fell to 24,430 tons on 1 November 1917 and to 19,380 tons on 1 February 1918.

The shrinking and redeployment of Shipping Services

While tonnage had not yet gone down in 1916, shipping operations were certainly in a state of considerable upheaval. Since its creation, the Worms cabotage network had been focused on Northern Europe: the flagship Bordeaux-Le Havre-Hamburg line, as well as that between Bordeaux and Bremen, “held a monopoly in shipping between France and northern Germany.”52 Opened in 1869–1870, the line between Bordeaux and Antwerp was also very popular. Other services, albeit less regular, connected French ports along the Atlantic Coast with Baltic ports: Malmö, Gdynia, Danzig, Kronstadt (St. Petersburg), and depending on opportunities, with Arkhangelsk, in the White Sea. Germany’s declaration of war on France and the invasion of Belgium, in application of the Schlieffen Plan (3 August 1914), put a stop to these Shipping Services, as illustrated by the case of “Listrac.”53 On 31 July 1914, the Hamburg port authorities forced the cargo ship, about to leave for Le Havre, to remain anchored. On 6 August, Worms Le Havre, still without news of the vessel, was convinced that it would not hear “anything more before the end of the war.” On 8 August, the eventuality that the ship would be seized – “a true attack

49 Marc Saibène, in La Marine marchande française, 19141918, l’approvisionnement de la métropole et des armées en guerre (Marines-Éditions, 2011), devoted an article to the sinking of the “Emma” (p. 63), highlighting that the loss of life (there were only two survivors) could have been reduced had life vests been more readily available. The Under-Secretary of State for the Navy therefore demanded that life vests be stored on the bridge of the ships and close to rescue boats. 50 Journal de la marine marchande, 8 December 1921. 51 Worms management could certainly not wait to witness its ships to sink one after the other before reacting. However, since 1856, the year during which the company commissioned its first two steamships, “Séphora” and “Emma” (the first vessel with this name), Maison Worms had to contend with several shipwrecks. In 1897, it lost “Blanche” on 3 March and “Marie” on 25 December. Yet these losses did not cause the company to consider becoming a shipbuilder. 52 Historical note on Worms & Cie dated 16 January 1914. 53 See the correspondence between the Le Havre and Bordeaux branches on www.wormsetcie.com – archives 1914.

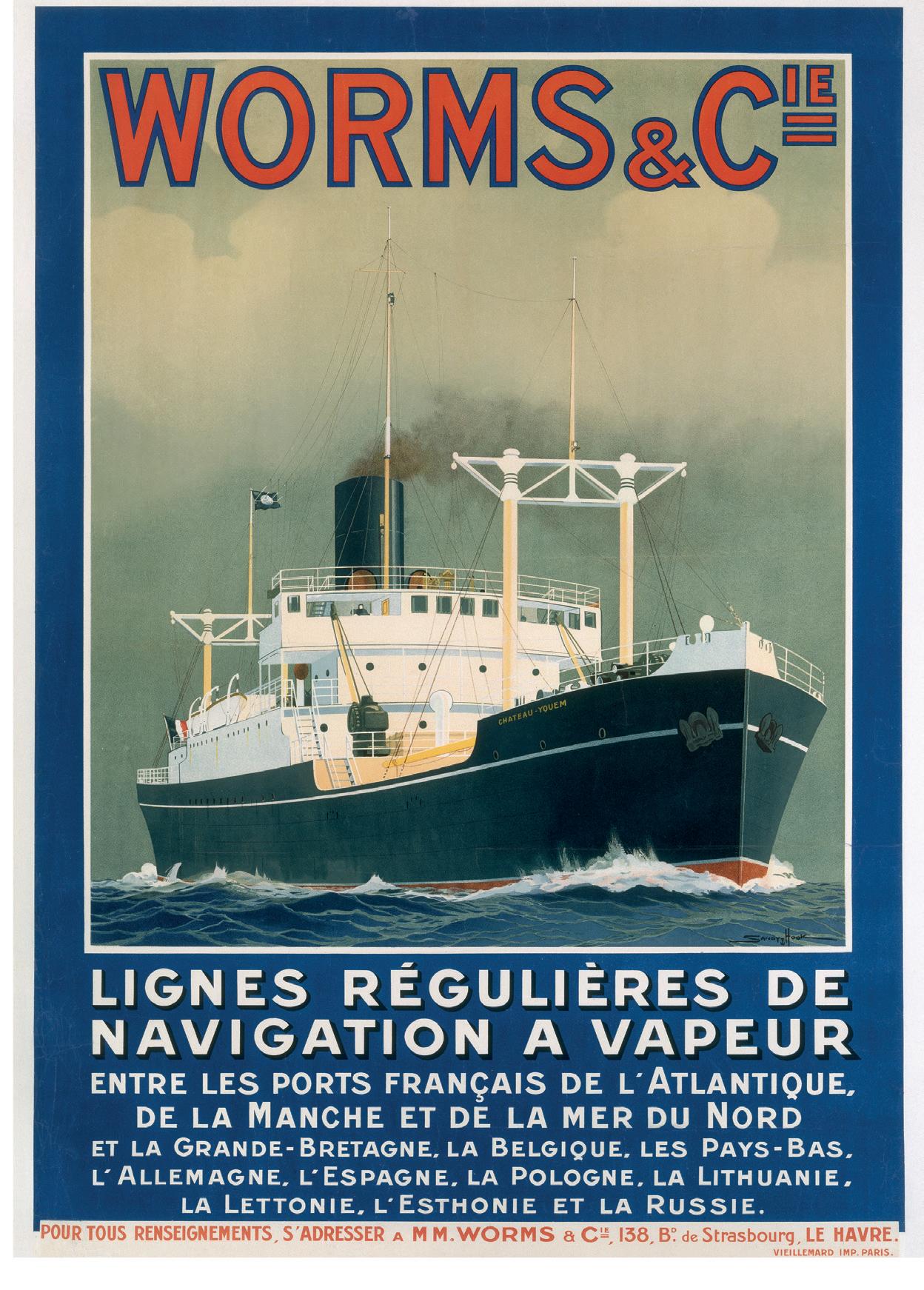

Sandy Hook poster in the 1920s – portrait of the cargo ship, “Château-Yquem”

on people’s rights” – seemed more and more likely. The publication of a decree giving German steamships moored in France “a period of seven days starting from the date of the decree (4 August) to leave the ports where they were docked” still left room for hope, although they were somewhat dashed by the declarations of the harbourmaster in Bordeaux who “in no way intended to honour the decree and would continue to hold two seized German steamships and one Austrian steamship.” Such was the fate of “Listrac,” which remained impounded in Hamburg throughout the conflict. The interruption of the lines also stemmed from the mobilisation of the crews. For example, in Bordeaux at the beginning of August 1914, ships belonging to Moss, Hutchison, Chevillotte Frères and Vapeurs du Nord had all been stopped, whereas those belonging to Chargeurs Réunis were awaiting their requisition orders, and ships owned by “La Transat” (French Line) would soon be used to transport troops. Ten cargo ships from Worms & Cie were immobilised in French ports, while others were rerouted: instead of being sent to Germany, “Michel” was sent from Le Havre to Bordeaux; “Haut-Brion” from Dunkirk was sent to Rouen instead of Hamburg. Only three vessels based in Bordeaux had a sailing plan: “Bidassoa” destined for Bayonne, “Fronsac” en route to Nantes, and “Margaux” to Le Havre via La Pallice. Convinced that maintaining seagoing routes between the coastal ports, Rouen and Paris offered a transport alternative “at a time when the railways were fully occupied with the mobilisation,”54 Maison Worms viewed “with regret that public authorities had lost interest in this marvellous tool” and feared “that once they want us to deal with it, it will be too late, because people and equipment will be scattered or not in any useful condition.” From the outset, the company affirmed its intention “to maintain regular services between Dunkirk and Bayonne, ensuring supplies for the points served.”55 With this in mind, the company called upon the government, since “it was from Paris, where everything was centralised, that the instructions [had] to come […] to order all ports to organise themselves, using all their available resources, so as to immediately establish regular services. Departures to a set schedule will ensure that the various centres receive supplies, and by using the Seine, it will be possible to bring the variety of goods found along its banks all the way to Paris.”56 That was the idea! However, putting it into practice meant the French Navy would have to stop removing “part of the crews belonging to the latest mobilisation categories and assigning them into the Army.”57 In addition to reinforcing its national cabotage lines, Worms committed its fleet to developing shipping lines with Great Britain for the dual purpose of bringing in France supplies and merchandise to the population and the

54 Letter from Georges Majoux dated 7 August 1914. 55 Letter sent on 6 August 1914 by Georges Majoux to General Capiomont, Governor of Le Havre. 56 Letter from Georges Majoux dated 7 August 1914. 57 Letter from Georges Majoux dated 6 August 1914, op. cit.

army, and of ensuring that the French Navy and public services were supplied with fuel and raw materials. In July 1915, a weekly Le Havre–Bristol–Swansea service58 was launched, complementing the existing line between Dieppe and Grimsby, in operation since 1856. The midOctober 1914 occupation of two-thirds of the Nord Pasde-Calais coalfield and the cessation of imports from Belgium and Germany swelled demand for English coal. Thanks to Maison Worms having a presence in Great Britain where its branches were specialised in the purchase and transport of fuel, the company was able to increase imports of coal, indispensable to the functioning of the French economy and to civil and military logistics.59 Demand as well as the volume imported shot up. Orders for Welsh coal from Cardiff, the quality of which was in high demand for propelling battleships, exploded. In mid-December 1914, the Ministry of War turned to Worms to supply this variety of coal. The plan was to supplement the four ships already designated to transport merchandise for the troops between Bordeaux and Dunkirk with two further cargo ships to transport coal from Cardiff to Bordeaux. The government placed its orders with the branches in Dunkirk, Brest, Le Havre and Bordeaux. By early 1915, the shipping network had been organised, and all ships were deployed. In mid-January 1916, the Navy planned to maintain a monthly stock of 8,000 tons of coal in Port Said, to be supplied by the Worms branch.60

58 See letter of 23 November 1915 which details the freight loaded on board the “Haut-Brion” for the French Navy, the British Marine Engineering Corps, the Belgian Army and industry. It is specified that “the Under-Secretariat of Artillery and Munitions, which closely monitored the functioning [of] the three lines [...] (Grimsby–Dieppe, Bristol–Swansea–Le Havre and Newport–Le Havre) had to make representations to the Minister for the Navy to ensure that, as far as possible, no disturbance was caused to their operation by requisitioning the steamers assigned to them.” 59 Correspondence exchanged on 15 and 24 January 1916 among Worms Port Said, the consul of France, and Worms Paris. 60 A Decree of 3 July 1917 linked the Services of coal import, production, and distribution to the Ministry of Armaments and War Production, proving (if necessary) the strategic importance of this raw material.

What was required by State contracts

In the same vein, a contract was signed on 26 September 191661 with the Ministry of War for the monthly delivery to Brest of 8,000 tons of coal from Wales. This amount was reduced to 6,000 tons on 25 October 1917.62 On 30 January 1917, an agreement was reached with the government63 under which Maison Worms promised to assign thirteen of its ships for services between Bordeaux and Dunkirk and between other French ports; the administration took responsibility for the war risks, based on the individual values set for each ship. The first of these contracts was signed in September 1916, i.e. at a time when Worms was in the process of seeking a location for a shipyard, an aspect which could not be coincidental. Given Maison Worms contractual commitments vis-à-vis the public authorities, the company had an imperative need to ensure regular deliveries, and consequently, to maintain its transport capability. Under such conditions, being unable to replace a lost ship or, in the event of an accident, having to wait indefinitely for repairs, posed a serious risk. Consequently, ACSM was intended first and foremost to safeguard against the potential catastrophe resulting from the destruction of the ships under State contract (irrespective of the amount of damages set forth in the charter) rather than against losses of its vessels that had already occurred.

“Lack of repair”

juLes avriL, Journal du Havre, 29 november 1921 Both the operation of a ship and the renewal of its classification by the Bureau Veritas64 depend on the reliability of its equipment and its structures. If the equipment wears out, structures can deteriorate (during a collision, in particular). As a result, the ship has to undergo regular maintenance and inspections to ensure its seaworthiness. For larger work (the servicing of boilers, for

61 Cf. letter sent on 19 February 1918 by Worms Le Havre to the Central Department for Maritime Stewardship. 62 For the date, see the collection of information from January to December 1917 on www.wormsetcie.com. 63 Information taken from a memorandum filed in May 1918. 64 “The mission of the company was to provide insurers with all information needed regarding the condition of the ships and their equipment, and to keep them apprised of the premiums and specific terms in practice in large commercial areas,” cf. www.bureauveritas.fr.

Damage to the prow of the cargo ship, “Suzanne-et-Marie” (1891–1933)

example), Maison Worms called upon specialised companies, such as Établissements Caillard in Le Havre. Moreover, since 1901, Maison Worms had operated its own repair yard on the Quai de Saone in Le Havre.65 This facility, suitable for repairing peacetime damage, was, unfortunately, not designed for repairing wartime damage or that incurred in the congested basins or locks, particularly in Le Havre where an English military base had been established in August 1914.66 Up to 1919, no less than 1,900,000 British soldiers entered France via Le Havre.67 Various quayside sheds and out-

65 See historical note of 11 June 1948. The repair shop was an old three-masted ship, the “Hélène-et-Georgina,” which had been refitted. 66 Three of the nine British bases in France were located in Seine-Maritime: in Le Havre, Rouen and Dieppe. See “Les bases anglaises de Seine-Inférieure dans la Grande-Guerre” on https://rouen1914-1918.fr/armee-britannique. 67 Cf. the presentation of Yves Buffetaut’s book, Rouen-Le Havre 1914-1918, dans la Grande Guerre, on http://www. ysec.fr: “The Seine-Inférieure operates to English time, and the two British bases receive men from throughout the Empire: the local Normandy population thus crosses paths with Englishmen, Scots, Australians, Canadians, South Africans, New Zealanders, Indians and Chinese, not to mention German prisoners of war. Entire towns have sprung up to lodge tens of thousands of men.” side storage areas were made available to this expeditionary corps to stock provisions and materials, which a fleet of barges transported daily up the Seine to a second base in Rouen. Supplementing this already dense traffic were the ships supplying merchandise and raw materials to people and factories between the coast and Paris. Congestion was further fuelled by the thousands of people belonging to the Belgian Governmentin-exile based in Sainte-Adresse (a municipality adjacent to Le Havre). So great was the congestion that it was extremely difficult for shipping companies to operate there: ships were forced to anchor for unusually long periods outside the harbour, prey to German U-boats,68 before weaving their way to the wharf to unload their cargo. Any delay led to the payment of heavy demurrage. To avoid incurring any such charges, captains and crews took risks that resulted in a much higher than usual number of collisions, broken equipment and injuries.

68 In 1915, a floating barrier was set up at the entrance to the port, then a 25 km anti-submarine wire mesh was installed across the Bay of the Seine, see the digital exhibition Les Havrais dans la Grande Guerre on htps://archives. lehavre.fr.

“Shipyards […] were overladen with orders or had oriented their operations towards war production”

juLes avriL, Journal du Havre, 29 november 1921 In 1916, four generations of cargo ships sailed under the Worms flag. The oldest, the steamship “Hypolite Worms” had entered into service in October 1882. The most recent, “Château-Latour,” had been delivered in March 1916. Between these two dates, twenty-four units joined the fleet, while fifteen were sold or scrapped. This process, which alternated between orders placed with shipyards or purchases from other shipping companies, and sales or scrappings, stemmed from the need to align the fleet with changes in traffic and technological progress. The competitiveness of the shipping companies was at stake. The war put a stop to this mechanism. One reason was the conviction, largely shared by military strategists and politicians (at the beginning of the conflict, at any event), that victory would be achieved on the ground. This certitude meant that most of the 31,000 shipyard workers in 191469 were sent to the front line. Deprived of a large slice of their workforces, businesses were forced to cancel or suspend unfilled orders for new ships, and to complete the ships already on the slipways with the remaining personnel as best they could and with long delays. As a result, “Château-Palmer” and “Château-Yquem” were delivered respectively two and three months late, “Château-Lafite” seven months late and “ChâteauLatour” nineteen months late. Even production for the French Navy – a domain in which France, with its 793,729 tons70 of old and mismatched battleships, had fallen behind its Allies and belligerents71 – suffered (at

69 Figure provided in the report by the French Shipbuilding Consortium of July 1934, p. 11. 70 This tonnage is indicated by the Naval Encyclopedia. André Tardieu, in L’Homme libre dated 14 February 1930, estimated the French naval forces in 1914 at 964,000 British tons (1,016 kg) in service and under construction, plus 174,000 tons to come. The maximum weight a ship can carry is expressed in deadweight tonnes (dwt) and its total volume (including all closed superstructures) in gross registered tons (grt). 71 Under the impetus of international tensions and the impact of The Influence of Sea Power upon History, published in 1887 by Alfred Thayer Mahan, which presented naval supremacy as key to the modern world, England, Germany, Norway, Japan, and the United States […] launched a race to produce warships. Within ten years, the German Navy was ranked second in Europe, behind the Royal Navy, and ahead of France. least during the years 1914–1915) from this belief in the superiority of its land forces, which caused shipyards to turn into land military weapons factories.72 “Let us not forget,” said Louis de Chappedelaine, Minister for the Merchant Navy, before the French Shipbuilding Consortium on 21 March 1936,73 “that the operations of our shipyards during the great ordeal from 1914 to 1918 contributed to saving our country’s independence. Must I remind you that […] these shipyards turned out more than three million shells, repaired hundreds of locomotives, built carriages for all calibres of cannons, tirelessly forged on behalf of the war effort, and manufactured tanks.” Thus, arms manufacture replaced the replenishment of ship stocks. Having entered the conflict with 2,192 ships (representing 2,498,000 gross registred tons), all the French Merchant Navy could do was to count its losses. Maison Worms decided to take action.

First steps

Choosing the site

In September 1916 (at the latest), a small group set out to find the best location for the new Worms division.74 Heading up the group was Georges Majoux, assisted by Colonel Le Magnen.75 Two people in Maison Worms bore the name Le Magnen: Edmond and Paul. Edmond had run the Dieppe branch76 from its inception in 1905 until 1913, when he (unofficially) became a management advisor. An engineer, Paul Le Magnen was taken on as head of the Technical and Shipping Personnel Department on 1 January 1902. His training as a naval architect leads us to believe that it was him who worked in association with George Majoux.

72 Cf. Marc Saibène, op. cit. p. 15. 73 See the article in Le Matin, which in its 22 March 1936 issue reproduced the conclusions from the speech by Louis de Chappedelaine before this Consortium. Source: www. gallica.bnf.fr. 74 See Paul Bonmartel, op. cit., p. 29. 75 Le Magnen was known in Le Trait for embellishing the first municipal garden with a bandstand, where “La Lyre,” the ACSM musical group, performed. 76 The Dieppe branch opened following the resumption by Worms, in 1905, of the Grimsby line created in 1856 by A. Grandchamp with Hypolite Worms; Edmond Le Magnen managed this line for many years before he entered Worms & Cie in 1905.

Worms Le Havre, Coal and Patent Fuel Services

The team also included Commander Louis Mongin and Louis Achard. The former chaired the Société Immobilière du Trait from January 1919. The latter was – as we shall soon see – the man who led the building and start-up of ACSM. Like Georges Majoux, Louis Achard, a marine engineer, pursued his career in Dunkirk, where he worked for Bureau Veritas, before joining Worms. Four experts were also poached from the Dunkirk or Saint-Nazaire (Penhoët) sites: the engineer Scheerens, the workshop manager Rialland, the industrial designer Boldron and the carpenter Loiseau.77 Thus, no fewer than eight people, including one General Partner, combed the countryside. Criteria guiding their choice reflected both the needs of the shipping industry and those inherent to running Maison Worms. Their

77 P. Bonmartel, Le Trait, cité nouvelle (1917-1944), and Histoire du chantier naval du Trait 1917-1972, Luneray: Bertout, 1995 for the former, 1997 for the latter. Albert Rialland, Alphonse Boldron and André Loiseau were included on the list of employees “having more than thirty years of presence” established at the end of the book Un centenaire - 1848-1948 - Worms & Cie. They were inscribed with the mention “1916. Le Trait,” which suggests that the ACSM staff department was formed in that year. search zone: Normandy. This region, long known for its shipbuilding sites78 – similar to all regions bordering the French coast – was also the company’s traditional stamping ground. Hypolite Worms (the company’s founder) had begun his career there: between 1829 and 1837, in Rouen, operating under the name Worms Heuzé & Cie, he ran a wholesale business in draperies, local cotton fabric and “toiles peintes,” amongst others.

78 Jules Avril, op. cit., wrote: “La Mailleraye, located on the left bank, slightly downstream [from Le Trait], had been an important shipbuilding centre.... Remember that the first ship fitted out by Le Havre shipowners for fishing expeditions in Newfoundland was a sailing ship constructed in La Mailleraye. […] It must be said as well that La Mailleraye held such a place in the shipping world that any ship passing by this community tilted its flag and fired three cannon shots, to which the castle responded. A mandatory gesture up until the Revolution, the custom continued until 1830, although as a courtesy.” Other shipyards worth mentioning were the Honfleur shipyards established in the 16th century; those in Cherbourg, or the Établissements Augustin Normand, which relocated to Le Havre in 1816.

Although his business activities subsequently summoned him to Paris, Hypolite Worms continued to maintain relationships with Normandy merchants and industrialists until his return, occasioned first by his trade in plaster, then coal. His first two shiploads of coal imported from England were delivered to Le Havre in November 1848 and sold to two clients in Rouen. Without doubt, his thorough knowledge of the Normandy economy gave his coal trade the impetus guaranteeing its success.

“Roughly halfway between Rouen and Le Havre”

As noted in the preceding chapter, most of the press articles and internal memos devoted to ACSM in the years 1920–1930 start by stating the location of Le Trait as “roughly halfway between Rouen and Le Havre.”79 Several journalists were more precise: on 24 September 1921, J. Blondin highlighted in the Revue générale de l’électricité80 that the “small municipality is located slightly less than 30 km from Rouen.” La Vigie de Dieppe, in its 2 December 1921 issue, stated that this village was located “between Duclair and Caudebec, on the right bank of the Seine.” This topographic data resonated with Worms & Cie in a particular way. Le Havre served as its fleet’s base, the centre of its Shipping Services.81 It was the home port of all its ships. Since the company was going to build a shipyard, it might as well be located in the vicinity of

79 For example, see the account of the visit to Le Trait by the Association Normande on 28 July 1927, in Annuaire des cinq départements de la Normandie, or the article by Georges Benoît-Lévy published on 25 April 1931 in the journal, L’Hygiène sociale. Source: www.gallica.bnf.fr. 80 Source: www.gallica.bnf.fr. 81 Reminder: The opening of the Worms branch in Le Havre in April 1849: management was entrusted in January 1850 to the young Frédéric Mallet, who, on 1 April 1851, founded, together with one of his principal competitors, the company Hantier, Mallet & Cie, of which Hypolite Worms was the limited partner. This subsidiary was absorbed in 1881 by Maison Worms and replaced by a branch office in which the general management of the Shipping Services was established. The evolution of the Worms facility in Rouen followed the same pattern: at the beginning of 1849, Hypolite Worms entrusted his business to a local representative; in 1851, he participated with one of his competitors, Achille Grandchamp, in the establishment of the company A. Grandchamp & Fils, of which he was the limited partner – and in April 1905, the company was bought out under the name Leblanc, Guian & Cie, by Worms & Cie (Dieppe–Grimsby line + three ships). this port. If damaged, ships would not have to travel far for repairs, and ships could be commissioned as soon as they were launched! Furthermore, and most importantly, Le Havre was located relatively close to the English coast: a hundred or so miles from Portsmouth, and approximately 90 from Brighton or Newhaven. At a time when the occupation of Nord Pas-de-Calais deprived France of its steelmaking operations, the close proximity to England – where Maison Worms had been established for decades, where the company had bank accounts, where its name was known – guaranteed a steady supply of materials and equipment not found in France, yet essential for the construction of shipyard. The plan was simple: buy the necessary equipment in England, ship it to Le Havre, and then send it on by train or barge to Le Trait. Having been used by Maison A. Grandchamp, of which Worms had been a limited partner since 1851, the Seine proved to be a vital supply route during the war, making Rouen a leading French port.

Saint-Martin-de-Boscherville or Le Trait?82

In his book, Les pionniers traitons. La cité-jardin 19161936, Paul Bonmartel quotes from the private journal of Abbot Quilan, priest of Le Trait, in which he paid a posthumous homage to Louis Achard, who died in October 1921. “Arrived in September 1916,” wrote the priest, “already parcels of lands on the banks of the Seine were being studied in many places. Le Trait was his preferred site. […] In his mind, he was already constructing everything that we see today.”83 Among these “many places,” two retained the attention of Maison Worms: Le Trait, obviously, and Saint-Martinde-Boscherville. These rural communities, located 17.5 km from each other by road and 37 km via the Seine, shared many characteristics. Neither was close to the front. Neither was densely populated84 – meaning there would only be a small number of property owners with whom to negotiate the purchase of the land. Neither was heavily industrialised. And because they were

82 See the websites: https://anciennephotodutrait.jimdo. com and http://www.boscherville.fr/fr/information/70678/ notre-histoire. 83 Paul Bonmartel, op. cit., p. 29. 84 Gilbert Fromager, Le Canton de Duclair - 1900-1925, Fontaine-le-Bourg: Le Pucheux, 2014 (1st ed., 1985), p. 111. There were 644 inhabitants in Saint-Martin-de-Boscherville in 1900, and 629 according to the 1911 census.

surrounded by forests, both guaranteed a steady supply of wood for the shipyard (part of ACSM would be constructed on wooden piles). In both locations, the Seine was wide enough and deep enough to launch ships measuring 170 metres in length and with a tonnage of up to 18,000 tons.85 At first glance, neither seemed to offer an advantage over the other. At first glance! Saint-Martin-de-Boscherville was situated approximately 90 km by road from Le Havre and 13 km west of Rouen. Le Trait was 60 km from Le Havre and 30 km from Rouen. Le Trait, with its closer proximity to the Channel port – and thus to England – had the added advantage that the Seine ran in a relatively straight line up to the mouth of the river, whereas between Le Havre and Saint-Martin-de-Boscherville, the river included two meanders, explaining why the distance by river between the two neighbouring villages was twice as long. One additional advantage was that Le Trait had a sand quarry:86 sand was an essential ingredient for producing the mortar and concrete needed to construct the shipyard and housing. Last but not least, this village had been connected to the main Paris-Le Havre railway line since 1882 via the branch line between Caudebecen-Caux and Barentin.

Assembling the land parcels for ACSM —

Once Le Trait had been selected as the location, land purchases started in late 1916 and were completed with great speed. In the (previously quoted) letter of 9 November 1916, James Little & Co. affirmed: “You have purchased a large piece of ground on the river Seine for the erection of shipbuilding yards,” leading us to believe that purchases had begun even earlier. Nonetheless, there are no witness accounts to support this probability. The oldest land purchase agreements preserved in the Worms archives are dated 13 December 1916, and were included on a list drawn up in 197787 in the context of researching a book published by Worms & Cie the following year: Cent ans boulevard Haussmann. Here is the list:

85 See Normandie illustrée, No. 10, January 1918. 86 See the article by Jules Avril, op. cit. 87 Letter of 14 November 1977 from Mr Jean Chalain to Francis Ley, Banque Worms.

Parcels listed by purchase dates

Lot numbers Location Purchase date Sellers

B 43 44 45 and 55 La Barrière des Prés 13 December 1916

B 1 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 La Barrière des Clos 13 December 1916

76 77 83 83ter 84 85 86p 87p 88 Le Renel 13 December 1916

296 311 313 Le Clos des Voies 13 December 1916

A 554p 556p Le Clos des Voies

B 22-23, 24-25, 26-27 59 60 61 La Barrière des Prés 15 December 1916 15 December 1916

B 115p 115b 116 116b B 117 b Les Palfondenos 15 December 1916 Les Palfondenos 26 December 1916

B 115 p Les Palfondenos 26 December 1916

B 309 310 312 Le Clos des Voies

26 December 1916 B 113p 114 p Le Renel 26 December 1916

B 288p 289p Le Bout des Voies 26 December 1916

B 302 B 303 Le Clos des Voies 26 December 1916

B 93p 96 97p 100p 101p 104p 294

B 314

A 553 Le Renel 28 December 1916

Le Clos des Voies 28 December 1916

Le Clos des Voies 30 December 1916

Le Clos des Voies 9 January 1917

B 292 293 Le Bout des Voies 9 January 1917

B 298 299 300 Le Clos des Voies 9 January 1917

B 49 50 51 52 53 54 La Barrière des Prés

30 January 1917 B 46 47 48 Barre des Prés 30 January 1917

A 554 554p 555 556p

Le Clos des Voies B 40 41 42 56 57 La Barrière des Prés 30 January 1917 30 January 1917 Mrs Piceni

Mr and Mrs Léopold Baillif

Mr and Mrs Léopold Baillif Mr and Mrs Léopold Baillif Mr and Mrs Gobin

Mr and Mrs Gobin

Mr and Mrs Gobin

Mr and Mrs Fournier

Mr and Mrs Aubert

Mr and Mrs Gabriel Baillif Mrs Boquet and Mr and Mrs Charles Boquet Mrs Boquet and Mr and Mrs Charles Boquet Mrs Boquet and Mr and Mrs Charles Boquet Mr and Mrs Auguste Leroy Mr and Mrs Auguste Leroy Mr and Mrs Montier

Mr and Mrs Derivery

Mr and Mrs Derivery

Mr and Mrs Derivery

Mr and Mrs Quillet

Mrs Bien

Mr and Mrs Alphonse Leroy Mr and Mrs Alphonse Leroy

B 290 291p Le Bout des Voies B 112p-291p Le Renel et le Clos des Voies 3 February 1917 15 February 1917

B 295-295 bis Le Clos des Voies 15 February 1917

B 5 6 7

B 315p vicinal road No. 2, No. 9, No. 10 La Barrière des Prés

20 February 1917 Le Marais 19 March 1917 Mrs Crevel

Mr and Mrs Michel and Mr Pierre Baudouin Mrs (widow) Crevel and Mr and Mrs Treboutte Mr and Mrs Adophe Dehais City of Le Trait

B 73 74 75 Le Renel 5 April 1917 Mrs Sausay - Mr and Mrs Hebert, Ms Vandu

B 109 p Le Renel 2 May 1917 Mr, Mrs, Ms Landrin

B 117 p Les Palfondenos 2 May 1917 Mrs Lamant

B 29p 30 31p 32p 35p 36 37 B 2 3 4 La Barrière des Prés La Barrière des Prés 1 June 1917 Cauvin partners

24 November 1917 Mr Pierre Baudouin

B 58 71 72 Le Renel 24 November 1917 Mr Pierre Baudouin

78 79 80 81 Le Renel 24 November 1917 83 83b 86p 91 Le Renel 24 November 1917 Mr Pierre Baudouin

Mr Pierre Baudouin

92 94 95 98 99p 102 B 304 305 306 307 308 Le Renel 24 November 1917

Le Clos des Voies 24 November 1917

B 283p 287p Le Bout des Voies 24 November 1917

38p 105p 106 La Barrière des Prés

24 November 1917 107p 108 110 Le Renel 24 November 1917 Mr Pierre Baudouin

Mr Pierre Baudouin

Mr Pierre Baudouin

Mr and Mrs Michel

Mr and Mrs Michel

63p 64 65 66p 69p 70

La Barrière des Prés A 542 546 Le Clos des Voies

A 547 Le Clos des Voies 24 November 1917 24 November 1917 6 February 1918

B 90 Le Renel 13 February 1918 Mr and Mrs Michel

Société Isidore Bernard Mr and Mrs Baillif

Mr and Mrs Duquesne

B 301 - 301b Le Clos des Voies 13 February 1918 Mr and Mrs Duquesne

B 315p Le Marais 13 April 1918 City of Le Trait

B 89p 112p Le Renel 18 June 1918 Mr Pierre Cauvin These parcels of land were listed in Article 2 of a lease agreement concluded on 16 October 194588 between ACSM and Maison Worms, in reference to the “land on which the various workshops and shipbuilding facilities operating under the name ‘Ateliers et Chantiers de la Seine-Maritime’ are located.” This land was distinct from that on which the workers’ housing estate was built, which was covered by a separate agreement.89 Today, it is difficult to pinpoint the exact location of the parcels in “Barrière des Prés,” “Barrière des Clos,” “Palfondenos,” “Renel,” “Clos des Voies,” and “Bout des Voies.” With the exception of “Le Marais,” these names have all disappeared from the land registry. They are now grouped together under the name “Les Chantiers.” Research using the land registry map of 1827 nevertheless allows us to locate them in the area between the banks of the Seine and the N182 road (see map, page 11). The total surface area covered by both the shipyard and the workers’ housing estate varied according to sources: in the presentation given on 4 August 1921 to the members of the French Association for the Advancement of Science,90 Georges Majoux estimated it to be 300 hectares; the area was reported as 275 hectares in the minutes of the excursion to Le Trait on 28 July 1927 by the Association Normande,91 and as just 175 hectares in the article devoted to ACSM by Georges Benoît-Lévy in the 25 April 1931 issue of L’Hygiène sociale. 92 However, most testimonies in the interwar period agree that 25 hectares were dedicated to the shipyard.93 According to the list of documents drawn up in 1977, the initial purchase transaction involved (if not in total, at least its largest slice) the participation of about fifty

88 To finance the rebuilding of the Le Trait shipyard after the Second World War, that Worms & Cie decided in 1945 to incorporate as a public limited company. 89 This contract is also dated 16 October 1945. 90 Cf. Compte-rendu de la 45e session de l’Association française pour l’avancement des sciences, op. cit., p. 197. 91 Cf. Annuaire des cinq départements de la Normandie, op. cit., p. 143. 92 Source: www.gallica.bnf.fr. 93 In the agreement of 30 November 1959, in which Worms & Cie assigned various assets to ACSM, the surface area of the shipyard was estimated at 12 hectares 48 ares 6 centiares. In the merger document for ACSM-La Ciotat of 5 April 1966, the surface area was “23 hectares 15 ares 33 centiares, connected to SNCF and listed in the updated land registry for Le Trait under Section AC, No. 9, known as ‘Les Chantiers.’”

landowners and required the signature of fifty or so documents. Most of these were signed in the presence of Mr Rousée, a notary in Jumièges, either directly or standing in for Mr Garrigue, a notary in Duclair – and also in the presence of Mr Dubost, a notary in Savignysur-Orge, who stood in for Mr Leclair, a notary in Caudebec-en-Caux; in the presence of Mr Clé, a notary in Longjumeau, or in the presence of Mr Weber-Modar, also a notary in Jumièges. Two-thirds of the land purchase deeds (33) were signed between 13 December 1916 and 1 June 1917 (twenty-eight had been signed before the end of February 1917). After a six-month pause, forty lots were sold on 24 November 1917,94 including twenty-seven by Pierre Baudouin, the largest landowner. Another two-month hiatus ensued until February 1918. These pauses may have stemmed from the fact that some residents of Le Trait took longer than others to decide to sell. But they may also have been due to the expansion of the project scope: to create a shipyard to meet not solely the needs of Maison Worms, but to assist in the effort to reconstruct the French Merchant Navy. It is interesting to note that, in February 1918, Mr and Mrs Baillif sold a parcel located in “Clos des Voies,” the same location as the two lots they had sold fourteen months earlier, in December 1917. Proof of ACSM’s need to enlarge, or a consequence of procrastination? Given the lack of land references for the time period in question, it is impossible to know why Maison Worms bought a particular parcel before another. The final deed (to which reference is made in 1977) was signed on 18 June 1918. It took eighteen months to finalise negotiations. In a society traditionally attached to the land,95 it is surprising that all landowners agreed to sell. It seems that no expropriation proceedings were undertaken,96 most likely because Worms & Cie offered a fair price.

— and for the garden city

As with the shipyard, the information available makes it impossible to reconstruct how the land needed for the workers’ housing estate was purchased. One source provides an inventory of the parcels involved: the lease agreement of 1945.97 The plots were listed by number according to their corresponding locations. Some place names are still in use: “Candeux,” “VieuxChâteau,” “Hazaie,” “Neuville” (and its extensions: “Plaine Neuville” and the “Village de La Neuville”); others, such as “Haut Camp,” “Clos Mouton,” “Plaine Saint-Martin,” have disappeared from the land registry. Several documents have been preserved by the Norman Seine River Meanders Regional Nature Park (PNR). Among them, two contracts stipulated that on 25 and 26 December 1916 a piece of land was sold “as fine sandy land for ploughing, in what is known as the Plaine Saint-Martin, traversed by the major road from Rouen to Saint-Martin de Colbosc [sic] [with a surface area of] 3680 square metres, but according to land surveys, consisting of 2570 square metres.” Parcels were

94 The sales granted by Mr and Mrs Michel were announced in the Journal de Rouen, on 24 August 1918: “Law office of Mr Lebreton, a solicitor in Rouen, rue Jeanne-d’Arc, No. 31. Legal redemption [of mortgage]. In accordance with recorded contract received by Mr Rousée, notary, in Jumièges on 24 November 1917, Worms & Cie, whose headquarters is in Paris, boulevard Haussmann, purchased from Mr JosephVictor Michel and Mrs Gabrielle-Eugénie Baudouin, his spouse, who reside together in Notre-Dame-de-Bondeville, rue du Chemin-de-Fer, No. 14. 1o: One piece of meadowland known as ‘Barrière des Prés,’ crossed by ‘Chemin des Voies,’ comprising approximately 3000 square metres, according to the titles, and listed in the land registry under numbers 29, 30, 31, 35, 36, 37, 38p, of Section B, for a total area of 3579 square metres and according to a recent measurement, containing 3338 square metres. 2o: A meadow in what is known as ‘Renel,’ a plot traversed by the ‘Chemin des Voies,’ listed in the land registry under Nos. 105p, 106, 107, 108, and 110 of Section B, for a total surface area of 3964 square metres, and according to a recent survey, comprising 4266 square metres. 3o: A piece of meadowland known as ‘Barrière des Prés,’ crossed by the ‘Chemin des Voies’ at the ‘Chemin du Malacquis,’ listed in the land registry under numbers 63, 64, 65, 66p, 69, and 70 of Section B, for a total surface area of 4624 square metres, and according to the recent survey, comprising 4513 square metres. A collated copy of the aforementioned sales contract was filed with the court clerk of the Civil Tribunal of Rouen on 7 June 1918, as certified in a filing certificate drawn up on the same day, by the head court clerk of said Tribunal. Notification of said filing was given to the public prosecutor for the Civil Tribunal of Rouen, in accordance with the writ from Mr Terrier, court usher in Duclair, dated 25 July 1918, recorded along with a declaration made by said magistrate. […] Signed: Lebreton.” Source: http://recherche.archivesdepartementales76.net. 95 R. Schor, Histoire de la société française au XXe siècle, Paris, Belin, 2005, and F. Démier, La France du XIXe siècle (1814-1914), Paris: Le Seuil, 2000. 96 Given the lack of land registry records, it is not possible to know whether the zone devoted to the future shipyard was connected to the public services or not. 97 Contract of 16 October 1945.

added for a total surface area of 16471 square metres, and were sold altogether for 10,212 francs (F), paid by “Mr Achard, on behalf of the assenting company […] in cash with legal tender and bills.”98 Another contract was signed by Mr and Mrs Aubert on 29 March 1917, involving “a piece of pasture land, in what is known as the ‘Plaine de La Neuville,’ listed in the land registry under numbers 496 and 497, 498P and 499P Section B, with a size of 3805 square metres, but which, according to a recent survey, corresponded to 4532 square metres.” This document also authorised the sale of a “piece of land for ploughing, in what is known as the ‘Haut Camp,’ listed in the land registry under number 425 Section B, with a size of 1560 square metres.” The transaction was concluded in exchange for 3,170 F. One final example: the sale granted on 18 June 1918 by Mr and Mrs Delafosse of a “piece of land for ploughing located in the location known as ‘La Carrière’ consisting of 10352 square metres” for a price of 1,800 F. According to the Napoleonic land registry, the lot numbers corresponded to parcels spread over the village territory, located on either side of the road traversing Le Trait, as well as on both sides of the swamp between the hamlets adjacent to the Seine, and the land at the end of the forest.99 The possible draining of this swamp100 offered the possibility for future extension. This sizeable land purchase transaction had the impact of uniting the city and incorporating the hamlets scattered over its territory.

The builders: Louis Achard, the Director; Joseph Lanave, the Chief Engineer; Gustave Majou, the “architect of public housing”

In a speech delivered on 4 August 1921 to members of the French Association for the Advancement of Science,101 Georges Majoux stated that “the work [building the shipyard] began in April [1917] and continued until after the Armistice.” The oldest contract in the Worms archives relating to the structural

98 Norman Seine River Meanders Regional Nature Park Archives: 6J/D113. Sales documents. 99 Departmental Archives of Seine-Maritime. Land registry maps. Section B, Sheet 1 – March 1826. Entry 3P3_3413 Le Trait. 100 Wooden piles were used to make this swamp suitable for construction. 101 Compte-rendu de la 45e session de l’Association française pour l’avancement des sciences, op. cit. work is dated 13 March 1917; concluded with Veuve Hottat et Fils, the contract was referenced in a memo sent on 27 November 1920 from Maison Worms to A. Lebreton, a solicitor in Rouen. A new agreement signed with Veuve Hottat et Fils on 12 June 1917 also referred to the original contract: “Worms & Cie,” stipulates the second agreement, “seeking to construct a dry dock at the Ateliers et Chantiers de la Seine-Maritime […] has drawn up, under the direction of Mr Achard, Engineer and Director, through his architect, Mr Majou, who lives at 41, Rue Laffitte in Paris, the specifications and specific terms and conditions governing the performance of this work. The general specifications and specific terms of the contract of 13 March 1917 will apply to this project.” Thus, exactly three months after the first land had been purchased (in the period 13 December 1916 to 13 March 1917), Maison Worms enlisted the services of a construction company to undertake the construction of the shipyard, placing said company under the dual authority of Louis Achard and Gustave Majou, the architect. Trained at the French National School of Fine Arts (1881–1886), Gustave Auguste Majou (1862–1941) was known for the development, together with his colleague, Henri Provensal, of a group of 321 lodgings and 31 workshops in 1909, located at 8, Rue de Prague in Paris (12th arrondissement), in the context of a competition launched by the Rothschild Foundation to “improve the conditions of workers’ material existence.”102 His recruitment by Maison Worms (unfortunately, at an unknown date) – underscores the priority accorded to social affairs by Maison Worms, albeit perhaps not an immediate priority. A document drawn up on 2 September 1918 by Charles-Arthur Terrier, court usher with the Civil Tribunal of Rouen, at the request of Veuve Hottat et Fils, introduced Gustave Majou as the successor to Louis Lanave at ACSM.103 This replacement might have been related to the previously mentioned change in the scope of the “original project.” Louis Lanave may have been recruited at a time when Maison Worms was seeking to build a shipyard solely

102 Cf. notices on https://agorha.inha.fr and https://structurae.net/fr. 103 In correspondence of 2 September 1918, Charles-Arthur Terrier wrote: “I […] tendered my resignation to Mr Gustave Majou, the successor to Mr Louis Lanave, who resides in Le Trait, in his capacity as Director and Representative of Worms & Cie.”

for its own needs, and that it changed its architect on committing to a larger-scale industrial programme, including a garden city to house its workers. In a letter dated 29 December 1918, a subcontractor by the name of Marcel Duchereau “hastened to point out that, prior to undertaking minor fitting work, [he had] provided Mr Lanave, at the time serving as Project Director, with the design drawings which he [had] approved, and [had] agreed with him on all points.” Moreover, Lanave and Majou had completely different profiles. Born in 1856, Joseph Louis Lanave was a State Public Works Engineer (he retired on 1 January 1926).104 Among his credits was the construction of the FrancoEthiopian rail line between Djibouti and Addis-Ababa (1897–1917), for which he served as Interim Director. He was the author of Agenda-aide-mémoire des travaux publics, published in 1902; and of Procédés généraux de construction, terrassements, routes, navigation fluviale and maritime, chemins de fer et tramways, constructions civiles. As for Gustave Majou105 he was described as “a proponent of public housing architecture” in early 20th century Paris,106 a topic to be discussed later in this book. When exactly did Majou replace Lanave? A summons filed on 30 November 1918 by Mr Émile Asselin, attorney and court usher with the Civil Tribunal of the Seine, at the request of Marcel Duchereau, emphasised that Mr Duchereau “during a visit he made to Le Trait in March 1918 to the sites where the proposed construction was to be undertaken,” stated to Mr Lanave, Project Director, and Mr Achard of Worms & Cie that he would agree to undertake said construction only if a secondary workforce […] were provided to him.” Clearly, Lanave was working on the site in March 1918. On the other hand, in a document filed on 2 September 1918 by the Court Usher Charles-Arthur Terrier, Majou was said to have replaced Lanave: “Through a writ from Mr Dessaix, court usher in Paris, dated 26 August, Worms & Cie, acting at the request and in the best

104 See National Archives, entry F/14/19561. 105 He was a member of the Society of Friends of Parisian Monuments and of the Central Society of French Architects. He was listed as the architect for the Cité Saint-Éloi in Le Trait. See the note that Marie-Jeanne Dumont dedicated to him in Le logement social à Paris, 1850-1930 : les habitations à bon marché, Éditions Mardaga, 1991. 106 See the website of the Committee for Historical and Scientific Works, http://cths.fr. interests of Mr Lanave.” The two men have worked together for some period of time; Lanave may originally have been represented the Project Owner, a position which was later added to the duties of Majou, thereby making the latter responsible for the entire project. Just as chronological details are missing, so too are the terms of the mission assigned to Gustave Majou. Activities attributed to him are deduced from the contracts, memos and correspondence in which he is cited. The contract of 12 June 1917 indicates that Majou acted under the direction of Louis Achard. This subordinate link is also mentioned in a contract concluded with Guyon Frères on 6 November 1917. In addition to drawing up the plans, it was incumbent upon Majou to “draw up […] the specifications and specific terms and conditions related to the execution of the work.” On several occasions, he was presented as “Director and Representative of Worms & Cie” – a peculiar title inferring that he was linked to the company not through an architect’s contract but through an employment contract, i.e. he counted as a Worms employee, thus receiving a salary, not fees. In fact, some of his correspondence was signed on letterhead stating “head of construction at the Ateliers et Chantiers de la Seine-Maritime,” work for which he had both technical and administrative control. The bulk of his correspondence refers to him grappling with subcontractors. He was responsible for gaining information on “both [their] morality and [their] financial resources as well as [their] technical capabilities”107 and their references. He selected them (alone or together with Achard) on the basis of their ability to perform a task for which he had designed the plans and defined the specifications; and he followed the project step by step. In the (numerous) cases in which legal proceedings were initiated by or against service providers, Gustave Majou, as a representative of Worms & Cie, dealt with the attorneys and court ushers when defending the interests of his employer-client. For instance, on 3 June 1919, he described conversations he had just had with various parties in the dispute with Marcel Duchereau, along with possible solutions. According to a letter dated 1 March 1920, Gustave Majou performed functions similar to those described

above for the Société Immobilière du Trait, a subsidiary created by Worms & Cie in 1919 for the purpose of building, managing and maintaining the garden city, as will be discussed later. Between autumn 1916 and the first quarter of 1917, Maison Worms project took on form. It found the site on which to build, purchased the land needed for the construction of its shipyard and the future housing for its employees, assembled the team responsible for supervising the contractors selected, and began the work. Its commitment to shipbuilding responded to internal concerns raised by the execution of State contracts and the ensuing commitments. Since the conditions that had determined its new orientation […] continued to deteriorate, the company would go beyond the scope of its initial project and embrace national interests. Conditions worsened primarily as a result of the havoc wreaked on merchant fleets by German submarines from 31 January 1917 onwards108 and on French Navy vessels. Subjected in November 1914 to a blockade by the Royal Navy in the North Sea and by France in the Adriatic, Germany sought to loosen their grip by attacking the merchant vessels of its adversaries and neutral countries without warning, a previously unknown circumstance. In an article of 20 July 1917, Le Figaro109 illustrated the substantial number of vessels sunk or severely damaged by the U-boats: “In the past week, there were fifty-two submarine attacks against ships belonging to the three Merchant Navies [England, Italy, France], and sixty-nine the week before. Twenty-three steamships sank last week, twenty-four this week.”

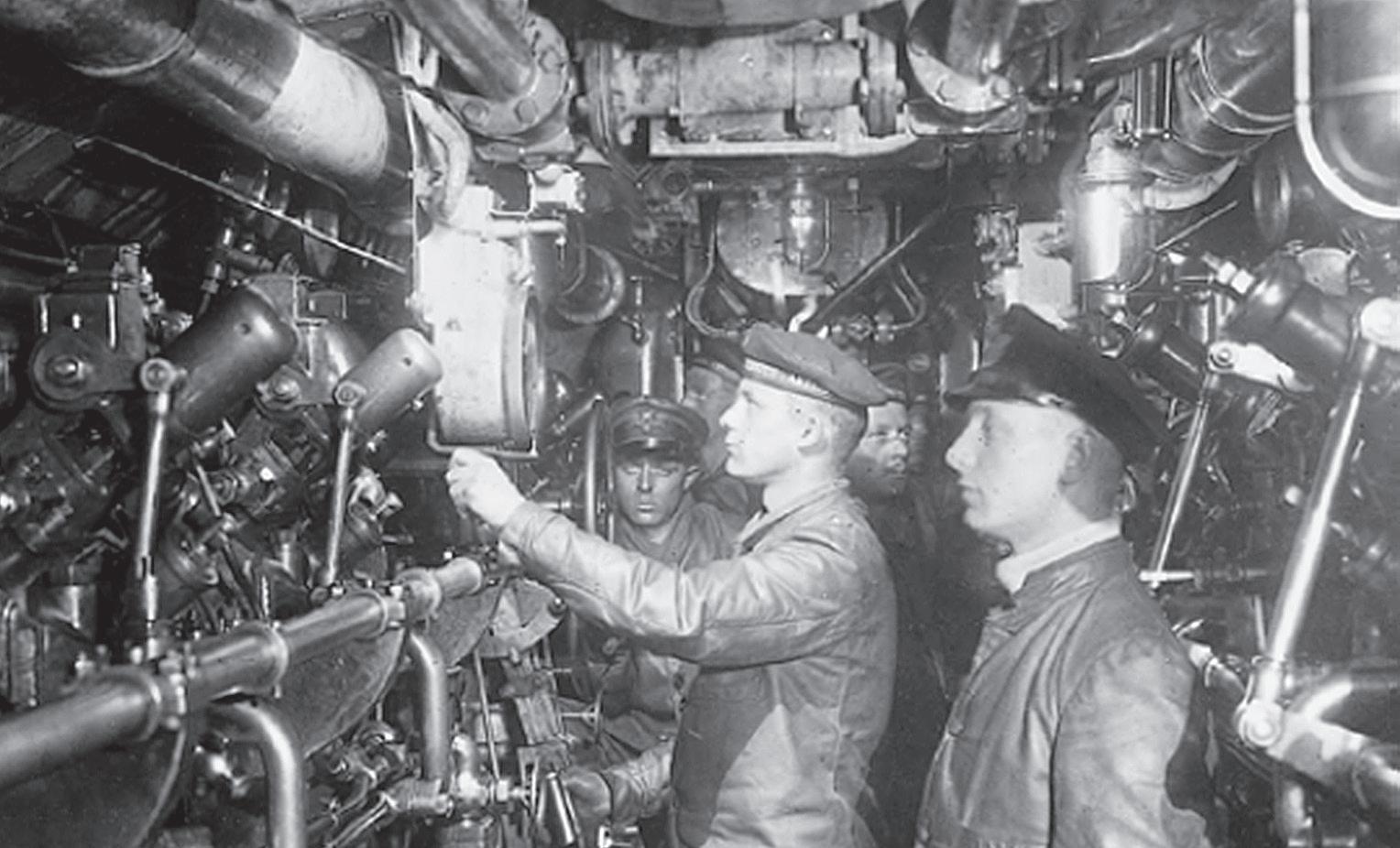

The interior of an U-boat – Larousse collection 108 The destruction of three American civilian vessels in March 1917 prompted the USA to declare war on Germany (6 April 1917). See R. Girault and R. Frank, Turbulente Europe et nouveaux mondes (1914-1941), Paris: Payot, 1998, pp. 78–91. 109 Source: www.gallica.bnf.fr.

GeorGes majoux, 4 auGusT 1921

Anatole de Monzie in 1925

As mentioned earlier, Georges Majoux, in his speech on 15 October 1922,110 underscored how “the government’s urgent entreaties” in 1917 shaped the future of the Ateliers et Chantiers de la Seine-Maritime. Stemming from Anatole de Monzie, Under-Secretary of State for the Merchant Navy at the time, these entreaties were heard by Georges Majoux111 and Hypolite Worms, when Majoux, assisted by the latter, sat on the Merchant Shipping Advisory Committee; this committee, known as the “Comité des Cinq” because it was composed of five directors of the most important French shipping companies, was established on 12 July 1917, that is to say about ten months after the creation of ACSM was initiated.

Anatole de Monzie

The man “for whom the position of Under-Secretary of State for the Merchant Navy has been created”

le Figaro, 22 marCh 1913 The MP for Cahors since 1909, former Cabinet Chief for Joseph Chaumié, Minister for the Public Instruction in 1902, then Minister for Justice in 1905, Anatole de Monzie112 at 37 years of age, entered the government formed by Louis Barthou (22 March 1913 to 2 December 1913) on 22 March 1913, under the presidency of Raymond Poincaré (18 February 1913 to 18 February 1920). Le Figaro113 spread word of his appointment in an article on the new government team, which ended with the following words: “Last but not least, winding up the list of those called to serve, one name that had never been uttered appeared on the horizon, that of Mr de Monzie, for whom the position of Under-Secretary of State for the Merchant Navy has been created. Mr de Monzie […] is a talented speaker, having given several striking speeches in the Chamber.” The purpose of the portfolio assigned to him was to centralise civilian shipping services, up to now scattered among various ministries: the status of seafarers, shipping safety, the policing of fishing, and the administration of maritime affairs all depended on the Navy; shipping premiums came under the Ministry of Commerce; health and safety under the Interior Ministry; subsidies were granted by the postal services to shipping companies engaged in postal operations; the construction, maintenance and policing of ports, lighthouses and buoys were the responsibility of the Ministry of Public Works; while the tax regime governing maritime trade came under the aegis of the Ministry of Finance. Shipbuilding was controlled by the Navy. “This

110 Alliance de l’hygiène sociale, congrès de Rouen, 13 au 16 octobre 1922, op. cit. 111 On the functions of Maison Worms in various public bodies, see the Decree of 18 April 1914, in which Georges Majoux was named a member of the Commission tasked with studying the modifications that needed to be made to the Law of 11 April 1906 on towing. 112 Anatole de Monzie (22 November 1876 to 11 January 1947) performed the duties of Minister for Finance (3 to 17 April 1925 and 19 to 23 July 1926); Minister for Public Instruction and Fine Arts (17 April to 11 October 1925); Minister for Justice (11 to 29 October 1925); Minister for National Education (3 June 1932 to 30 January 1934) and for Public Works (23 August 1938 to 5 June 1940). 113 Source: www.gallica.bnf.fr.