BIG BEAST THEORY

Fox frame-up

Snapshot Wisconsin trail cameras are always capturing fun images, and this photo sequence of a red fox in Vernon County is no exception.

The first two images are taken a short time apart, with the third photo captured a bit later, after some melting of the snow. It’s almost as if the fox first finds the camera and stops to pose, then returns later to check on things again.

The red fox (Vulpes vulpes) is widespread and has adapted to a variety of habitats, including urban and suburban areas. They are active year-round, spending much of their time searching for food, and they breed in mid-winter.

We’re looking for your clever fox captions for this photo series. Please send short suggestions via email to dnrmagazine@wisconsin.gov. Or jot them down and mail by Feb. 1 to:

We’ll pick some of the best suggested captions to share in the next issue. For replies from the fall issue goose image, see the inside back cover.

Cedarburg

Jeff Hastings, Westby

Patty Schachtner, Somerset

Robin Schmidt, La Crosse

Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources

Karen Hyun, Secretary

Steven Little, Deputy Secretary

Mark Aquino, Assistant Deputy Secretary

FROM THE SECRETARY

Season’s greetings!

The migratory birds have left, the leaves have dropped, temperatures are falling and the sun is going down before many of us make it home from work. Yes, ready or not, another Wisconsin winter is upon us.

That doesn’t mean the outdoor fun has to stop, though. In fact, some of the very best outdoor activities of the year are just kicking into gear. From ice fishing Wisconsin’s thousands of lakes to snowmobiling or cross-country skiing our miles of trails, some of our state’s most cherished traditions don’t just persist through the freezing temperatures and falling snow, they literally need them in order to happen.

The winter, December in particular, is also a time for reflection and gratitude. I, for one, have an awful lot to be grateful for — my family, my friends and the opportunity to serve the people of Wisconsin as DNR secretary.

It is the honor of a lifetime to serve in this capacity, and I am equally honored to do so alongside the incredible staff working throughout the DNR to preserve and enhance the natural resources of Wisconsin and provide opportunities to enjoy them.

No matter where in this agency you look, you will find outstanding professionals, knowledgeable in their fields and committed to serving their state and its visitors to the very best of their ability. The work they do and the results they achieve no matter the challenges — from a changing climate to budgetary limitations — amaze me every day, and I am beyond grateful for each and every one of them.

I am similarly grateful for each of you reading this issue in print or online. Your continued support through your purchases of hunting or fishing licenses, various stamps, vehicle admission passes and subscriptions to this magazine makes everything we do possible. We do what we do for and because of you.

In this issue, you’ll find an in-depth breakdown of the ways climate change is altering plant hardiness zones and what that means for backyard gardens, with tips on how to handle unpredictable winters. There’s also a guide to Wisconsin’s conifers and instructions for making your own holiday wreath out of Wisconsin materials.

Readers will also find a story covering some of the state’s breathtaking ice formations, including frozen caves and icy waterfalls. Further, enjoy a scientific

Karen Hyun

explanation for what exactly drives the impressive size we see in many of our most famous mammals.

Finally, I hope you can find time over the coming weeks for some rest and relaxation alongside loved ones. However that looks for you and yours, whether that’s large family gatherings, quiet moments by a fire, gorgeous winter hikes through our parks, hitting the woods for the Holiday Hunt (Dec. 24-Jan. 1 in participating counties) or reading this issue in your favorite cozy place, I hope you find this season restorative.

Wishing you a happy holiday season and wonderful new year ahead.

DANIEL ROBINSON

Mill Creek Trail at Governor Dodge State Park

NEWS YOU CAN USE

REMEMBER ENDANGERED RESOURCES AT TAX TIME

The DNR’s Endangered Resources Fund has been instrumental in funding conservation success stories around the state, from bald eagles to trumpeter swans, and donating is as easy as checking a box when you fill out your state income tax form. Simply select the Endangered Resources Fund option in the “donations” area of the Wisconsin income tax form, including e-file.

All gifts are tax-deductible and are matched dollar for dollar, doubling the impact of every donation. Funds support the DNR’s Natural Heritage Conservation program, which works on behalf of the state’s most vulnerable wildlife and plant species and vital state natural areas.

Learn more about donating on your tax form at dnr.wi.gov/tiny/971.

GIVE A GIFT SUBSCRIPTION

Looking for a gift idea this holiday season? Give a subscription to Wisconsin Natural Resources magazine! The quarterly DNR publication brings you news of the state’s beautiful outdoors in every season — and it’s just $8.97 a year. To order a gift or subscribe for yourself, go to wnrmag.com or call 1-800-678-9472.

BONUS: Use the code IEXPLORE to save $2 off any regular or gift subscription!

FREE FISHING WEEKEND

Mark your calendars for another Free Fishing Weekend, Jan. 17-18, when no license is required on most Wisconsin waters and special events are planned statewide. Waterways might be frozen, but the fish still bite! Get all the details about fishing in Wisconsin at dnr.wi.gov/topic/fishing.

PROPER DISPOSAL OF USED BATTERIES

When replacing batteries around the house or disposing of battery-containing devices, it’s important to remember: Batteries should never go in household recycling bins.

Many batteries contain heavy metals and other materials that can be harmful to the environment and human health if not handled properly. In addition, certain types of rechargeable batteries create a significant fire risk when placed in the trash or recycling bins. And automotive-type lead-acid batteries, such as those found in vehicles and boats, are banned from landfills and incinerators by Wisconsin state law.

Here are tips for handling unwanted batteries:

y Single-use alkaline batteries can be thrown away in the trash; do not place in recycling bins. Some battery drop-off locations may accept them, often for a fee.

y Rechargeable batteries, like those found in cell phones, laptops, radios and cordless power tools, should be recycled at a drop-off location. Tape battery terminals or put each battery in its own plastic bag to reduce fire risk.

y Lead-acid vehicle batteries must be recycled. A retailer recycling program allows consumers to bring such batteries to any Wisconsin retailer that sells them. This service is free to customers who purchase a new battery when they bring in a used one; otherwise, customers may be charged a fee of up to $3.

For more on proper handling of used batteries and a link to find collection sites near you, go to dnr.wi.gov/tiny/1296.

Wisconsin-endangered American marten

LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

AMID THE MUSHROOMS

Thank you for the time and effort put into the magazine. We enjoy every issue. A September hike at Governor Thompson State Park (Marinette County) included beautiful mushrooms of all shapes and colors. It appears that the state of Wisconsin is in the middle of one of them.

Rachel and Dave Casillas Cudahy

SPIDER AT HOME

I just read your article about spiders in the fall 2025 magazine and wanted to share some pictures I got already this fall of an orb weaver living by my house!

Natasha Bethe Waupun

LUNA LANDING

My wife planted a zinnia patch in our garden this year. It turned out to be quite the butterfly magnet. I was lucky enough to find this luna moth.

Jeff Baker North Prairie

Write in by emailing dnrmagazine@wisconsin.gov or send letters to: DNR magazine, PO Box 7921, Madison, WI 53707

WILD TURKEY DETAILS

Page 55 of the fall issue said turkey stamps started in 1996. Mine is 1987, and I know that was not the first year.

Mark Fischer Oconomowoc

Thanks for writing, Mark. Here are some details to clarify the 1996 date referenced in the story: Reintroduction of wild turkeys started in Wisconsin in 1976, and hunting resumed here in 1983. A turkey stamp has been a requirement for harvesting since 1986, when it cost $11.25. The fee was reduced to $5.25 in 1991. Money from the Wild Turkey Stamp program was not specifically earmarked for turkey management until state statute began requiring it in 1996.

GREETINGS FROM MERRICK

My family and I had the pleasure of visiting Merrick State Park (Buffalo County) recently and would like to share a photo from our trip. We had a wonderful time visiting a unique and beautiful public land there on the Mississippi River.

Calan Kinnally

Sheboygan Falls

LOOK WHO’S WATCHING

On May 12, I was checking my Snapshot Wisconsin camera in Shawano County, and this little guy was watching me. I also came across a nest of turkey eggs while I was out there.

Daniel Morzewski

Wisconsin Rapids

CHERRY-PICKING MEMORIES

The story on cherries (summer 2025) stirred some memories. As a young kid, I spent a couple of weeks in 1951 and ’52 picking cherries. My dad drove me to Stevens Point, where I got on a bus with some other kids and landed on a farm outside of Egg Harbor. There was a big farmhouse made into a dorm where we ate and slept.

We got 9 cents a pail for the cherries we picked. A woman would dump your pail into a wagon and punch your card. Every night after supper, they would announce the top three pickers of that day. There was a tall, skinny kid from Stevens Point who was No. 1 almost every day. I came in third one day.

One evening, (a visitor) came to greet us. It was Don Hutson (Packers receiving great who lived in Green Bay after retiring in 1945). I stood with my mouth open, too shy to ask for an autograph.

Allen Knop

Madison

MORE TO AVOID

After reading the article “What is it and will it hurt me?” in the summer edition of Wisconsin Natural Resources, I wondered why water hemlock was not mentioned in the “Pesky Plants” section. Perhaps there isn't a lot of it in southern Wisconsin, but I see it frequently in roadside ditches all over the northern half of the state where we travel.

My father pointed out the plant to me when I was quite young. He instructed me to never pick water hemlock or even touch the plant because of the highly poisonous substance it contains.

Margie Novak Kennan

Thanks, Margie, you are right to note there are more things in Wisconsin we might want to avoid in the outdoors; our summer story highlighted just a few. Water hemlock, a native plant, and its nonnative relative poison hemlock are among other troublesome plants — highly poisonous if ingested by people or animals, according to the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service. For more on hemlock, check dnr.wi.gov/tiny/3936.

Water hemlock

JON JAROSH/DESTINATION DOOR COUNTY

Frozen features

Wisconsin’s breathtaking ice formations

AS WINTER SETTLES IN across Wisconsin, the landscape transforms. For some, snow and cold mean fewer opportunities for outdoor fun. But for those willing to brave the elements, Wisconsin’s winter can provide the most amazing marvels.

Add these frozen features to your winter to-do list and enjoy some of the season’s most fleeting and fragile natural phenomena.

Garrett Dietz is a public information officer in the DNR’s Office of Communications.

GARRETT DIETZ

Ice caves of Lake Superior at the Apostle Islands.

FROZEN FALLS

The roaring flows of summer and fall turn into cascades that can appear stopped in time during the winter. These frozen waterfalls suspended over rocky cliffs or lofty drop-offs create spectacular photo opportunities.

Nearly every corner of the state boasts these ice-encrusted enchantments. Here are a few notable locations.

Willow Falls

Those on the northwest side of the state might be familiar with Willow River State Park and the scenic falls and gorge that run through the property. In winter, the scene seems like it’s cut right out of a photo book.

Cavernous, snow-covered rock walls frame the 45-foot falls as they cascade along icy rock shelves. A short hike from the parking lot leads to the base of the falls, where visitors can hear the muffled roar of the water echoing through the gorge and see the icy shelves glistening in the winter sun.

Willow River State Park’s flowing gorge appears frozen in time — encrusted in ice during winter.

Stephens’ Falls

One of the largest state parks, Governor Dodge, offers all kinds of winter recreation in the rolling hills, valleys and steep gorges of southwest Wisconsin’s Driftless Region. Hidden back on a short, picturesque trail, hikers can find Stephens’ Falls.

The stream gently cascades over an outcropping before misting the rocky walls with ice. Sustained freezing can turn the falls into a dramatic ice formation.

Note: Even when precautions are taken, no ice is completely safe.

Falls,

There is a scenic overlook along a paved trail above the falls and steps leading to the bottom. Visitors should be mindful of conditions when hiking to the base of the falls. Uneven terrain and icy stone steps can make the trek difficult.

Stephens’

Governor Dodge State Park.

BRIAN THOMPSON

Wequiock Falls and Fonferek Falls

Wequiock Falls County Park, just east of Green Bay, offers views of the Niagara Escarpment — the glacial formation created millions of years ago that spans from Lake Winnebago to Niagara Falls. During the summer, Wequiock Falls can slow to a trickle, but in winter it transforms into the perfect photo spot.

Also in Brown County, Fonferek’s Glen Conservancy Area boasts a 30-foot waterfall with a scenic overlook platform. Plan to visit both sights in one day, or head to Door County for more icy exploration.

Below: Wequiock Falls County Park near Green Bay is part of the Niagara Escarpment, a rocky geologic formation running all the way to Niagara Falls.

LAKE MICHIGAN’S FRIGID SHORELINE

The Great Lakes provide outdoor adventure all year long, and winter brings its own unique opportunities. Two popular destinations for stunning winter ice formations along Lake Michigan are Door County’s Cave Point County Park and Whitefish Dunes State Park.

These connected properties offer views of Lake Michigan’s coastal dunes, rugged cliffs and caverns. Freezing winds and crashing waves break against the rocky shoreline and crystallize, creating ever-changing winter scenes.

Here, delicate frozen webs form between tree branches while nearby cliffs become completely encased in white, resembling cloud-like creations of ice and snow. These fairy-tale-like scenes can change daily, shaped by shifting winds, waves and temperature fluctuations.

These winter wonders are accessible from various trails originating at Whitefish Dunes State Park, including the Brachiopod Trail and the Cave Point Trail. The trails are ungroomed and may be icy, so hikers are encouraged to use caution. Snowshoes might help visitors access prime locations during the winter.

Left: Winter wonders await at Cave Point County Park and the adjacent Whitefish Dunes State Park.

LAKE SUPERIOR’S ICE CAVES

The red and brown sandstone cliffs along the Apostle Islands National Lakeshore are stunning attractions year-round. During the summer, many visitors take boat tours or sea kayaks along the shoreline to witness the wide arches and hidden nooks created by millennia of erosion. However, the depths of winter is when they really shine.

When the freezing winter winds blow across Lake Superior, they leave in their wake some of the most mesmerizing of Wisconsin’s winter scenery — ice caves.

Pillars of ice frozen to cliff tops create cascades of frozen water that glisten in the sunlight. Inside the ice caves, the frigid spray of the lake creates layers of frozen water that take on a life of their own, forming finger-like and tooth-like shapes reaching down from above.

Unpredictable conditions mean the ice formations are never the same, changing from day to day and cave to cave. And ice caves are as rare as they are unpredictable.

Ice caves only form under specific conditions and are not always reachable. Access depends on sustained sub-zero temperatures, light winds, an ice shelf anchored to the land at multiple points and ice thick enough to support emergency vehicles. The last access was allowed in 2015.

Access to Lake Superior’s ice caves requires just the right winter conditions, but when it happens, it can be spectacular.

KATHLEEN WOLLEAT

RICK KOHLMEYER

The National Park Service, which manages the Apostle Islands National Lakeshore, closely monitors ice conditions during the winter to determine if ice caves are accessible. To learn if conditions are right this winter, check nps.gov/apis/ mainland-caves-winter.htm

If conditions don’t allow on-ice adventures, outdoor enthusiasts can still hike the Apostle Islands Lakeshore Trail from Meyers Beach. This route takes visitors over miles of sandstone cliffs and the mainland sea caves, where they can overlook the frozen spectacle.

Remember to dress for the weather, and keep in mind that the trails are ungroomed and may be covered in ice or snow.

Winter transforms sea caves into magnificent icy marvels.

Below left: Freezing spray from Lake Superior creates fantastic formations at the Apostle Islands National Lakeshore.

Below right: Meyers Beach near Bayfield.

SUE CARROLL

KELLY NECHUTA

TIPS TO HELP YOUR GARDEN HANDLE UNPREDICTABLE WINTERS

WISCONSIN'S WINTERS ARE SHIFTING.

Experts are predicting we’ll have less white, fluffy snow and frigid days, and more rain and sleet in the coming years. And for now, we’re seeing lots of variability.

“Winter temperatures have been changing more than any other season in the long term, and there are some indications that winter may be the season in the future that changes the most,” said Steve Vavrus, state climatologist at UW-Madison.

Winters with little to no snow can be tough on plants. Snow cover provides insulation for plants, protecting roots and other important features from weather fluctuations, freeze-and-thaw cycles and strong winds.

Here are a few tips to help your plants “weather” the changes and keep your garden beautiful in a changing climate.

EMMA MACEK

PROTECT YOUR PLANTS

Without blankets of snow, plants can need extra protection from the winter elements. Applying a thick layer of mulch around perennials, shrubs and trees to insulate the roots can help. You can also leave leaves and plant material in your garden beds rather than cleaning them up to protect plants from sudden freezing.

“Not only will it allow the garden beds to be protected by mulch, but it will save a whole lot of insects that are on leaf material,” said Lisa Johnson, UW-Extension horticulture educator.

You can also place evergreen branches and straw after the ground freezes to help keep it frozen and prevent thaws during the winter months.

DON’T PLANT TOO EARLY

It can be exciting to see warm temperatures start popping up in the spring, but don’t be fooled. Temperatures can be unpredictable, and a late-spring frost is possible. Wait to start planting until no more frosts are expected for the year.

“Usually in the Madison area, I tell people to use May 20 as the last frost date,” Johnson said. That timing will vary slightly in other areas of the state.

If you plant earlier, make sure you have tools to protect your garden from late frosts. To help reduce frost damage, you can insulate beds with sheets, blankets, towels or straw.

You should also start your vegetable plants inside, if possible, especially those with a longer growing season such as peppers, basil and tomatoes.

CHOOSE CLIMATE-RESILIENT PLANTS

In addition to following the “right plant, right place” rule — where you select the best plantings for any given spot depending on sunlight and other conditions — it’s important to choose hardy plants that can withstand overall tough conditions.

Native plants are your best bet because they have a wider range of tolerance than nonnatives, Johnson said. “They're going to be much more resilient to weather.”

Native plants also require less maintenance, which is important when the weather isn’t ideal for yard work, and they support pollinators and other insects. There also are some great native cultivars, known as “nativars,” available in various sizes and colors.

To learn more about native plants, scan the QR code or visit dnr.wi.gov/tiny/1391

Emma Macek is a public information officer in the DNR’s Office of Communications.

RESILIENT PLANTS

Consider planting some of these durable species that can handle Wisconsin’s changing winters.

Woody plants

• Oaks

• Native willows

• Black cherry

• Native crabapples (prairie or American)

• Serviceberry

• Pines

• Maples

Perennials

• Asters

• Sunflowers

• Joe pye weed

• Rudebeckias

Shrubs

• Red osier dogwood

• Steeplebush spirea

• Prairie willow

• Bebb willow

• American plum

Frigid flyers Frigid flyers

Find can’t-miss cold-weatHEr eagle watching along the Wisconsin River

IS THERE A MORE SPECTACULAR SIGHT in nature than that of a bald eagle soaring through the sky? DNR Natural Heritage Conservation zoologist Rich Staffen doesn't think so.

“They are just such an amazing, iconic bird,” he said. “Seeing them in action, whether they're soaring above the treetops, perched atop their enormous nests or swooping towards the water before flying off with a fish, never gets old.”

Bald eagles are a common summer sight among the towering pines and beautiful lakes of Wisconsin's Northwoods, but that’s far from the only time and place to see them.

In fact, for anyone hoping to see our country’s national bird up close, the best bet might just be a lot closer to home — and in the depths of winter.

That's because, as many lakes ice over for the winter, bald eagles will congregate around open water in search of food. This includes areas below dams along the Wisconsin, Mississippi and Fox rivers, creating some of the best eagle watching opportunities of the year.

ZACH WOOD

The resurgence of the bald eagle is one of the country’s greatest conservation success stories.

ROBERT HILBERT

y The bald eagle has been the symbol of the United States since 1782.

y Bald eagles live about 20-25 years in the wild and sometimes even longer.

y If possible, eagles may return to the same nest every year, adding to its size each time; nests average 4-5 feet in diameter.

y Having an “eagle eye” is a real thing: Eagles can see wildlife the size of a rabbit running from 3 miles away.

y Bald eagles don’t develop the characteristic white feathers on their heads and tails until about 3-4 years of age.

y Average bald eagle wingspan is about 7 feet.

y When diving for prey, eagles can reach up to 100 mph.

Source: National Eagle Center, Wabasha, Minnesota; nationaleaglecenter.org

An eagle’s nest averages about 5 feet in diameter, with the same birds often returning to build on the nest each year.

One of nature’s most inspiring sights: a bald eagle soaring on high.

CAUSE FOR CELEBRATION

In Prairie Du Sac and Sauk City, winter eagle watching is so popular it has spawned an annual celebration. For more than three decades, Bald Eagle Watching Days has been drawing visitors to view eagles roosting in and around Sauk County’s Ferry Bluff State Natural Area.

Here, according to Staffen, the open water created by the Prairie Du Sac Dam can attract large numbers of eagles at one time. Parts of the state natural area are closed from December through March to protect the roosting eagles, but the birds can easily be seen from viewing locations nearby.

“If folks spend the full day, they might see a few dozen bald eagles come through the area,” Staffen said. “It's one of the best places to see these magnificent birds in the whole country.”

The local communities have embraced their winter visitors, including constructing a viewing platform with informational panels and a spotting scope for better viewing.

“The community has really leaned into it,” Staffen said. “The viewing platform is great, there are several parks along the river with great views of the birds, and the Ferry Bluff Eagle Council provides volunteers to help visitors spot eagles and (offer) activities for kids. It's really well done.”

NOT ALWAYS LIKE THIS

For Wisconsinites, bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) have become a relatively common sight, but that was not always the case.

“In 1974, there were only 107 breeding pairs in a handful of northern counties in Wisconsin,” Staffen said.

Throughout the country, the bald eagle population had been decimated by habitat destruction, lead poisoning (from eating contaminated prey), illegal shooting and especially DDT. The insecticide had come into widespread use by the late 1940s and caused bald eagles to lay eggs with shells that were much too thin for successful hatching, leading to huge population declines.

A federal ban on DDT in 1972 sparked the beginning of a rebound for this once-endangered species.

“Fifty-one years later, we have around 1,700 nesting pairs (in Wisconsin), with bald eagles nesting in every county in Wisconsin (all 72!),” Staffen said.

“The resurgence of the bald eagle is one of the greatest conservation success stories ever. It wouldn't have been possible without smart regulations on things like DDT, national protections for these birds and their habitats, and the efforts of scientists and volunteers.”

LEARN MORE

Bald Eagle Watching Days in Sauk County is co-sponsored by the Ferry Bluff Eagle Council, Sauk Prairie Area Chamber of Commerce, the DNR and the Tripp Museum in Prairie du Sac. Look for January 2026 dates and details at ferrybluffeaglecouncil.org

To find more events and places for viewing eagles this winter and learn how you can help protect them, scan the QR code or go to dnr.wi.gov/tiny/3941.

Pro tips

y When viewing eagles this winter, biologists advise onlookers not to venture too close, as it will cause the eagles to fly off.

y At Bald Eagle Watching Days, guests are encouraged to stay in a vehicle unless they are at a staffed viewing site.

y The best time to see foraging eagles is early morning as they depart their nighttime communal roosts to feed along open water and then again in the hours before dusk as they return to their roosts.

Bald eagle nesting pairs in Wisconsin have increased from 107 in 1974 to about 1,700 today.

Zach Wood is a public information officer in the DNR’s Office of Communications.

BUILT FOR THIS

Two rules of ecology help explain some whys of Wisconsin wildlife

WISCONSIN’S CLIMATE, PARTICULARLY OUR COLD WINTERS, shapes so much of who we are and how we live. All sorts of things from our clothing and pastimes to our economy, food and traditions have been molded by the winter weather.

The same rings true for many of Wisconsin’s wildlife species, which have seen historically harsh winters influence their diets and mold their behaviors while shaping, well, their shapes — and their sizes.

You read that right. The shape and size and of wildlife, particularly mammals, are often closely correlated with their respective climates.

This phenomenon is best explained through two established ecological principles: Bergmann’s Rule and Allen’s Rule.

ZACH WOOD

BERGMANN’S RULE

Bergmann’s Rule, named after 19th-century German biologist Carl Bergmann, involves taxonomy, the way scientists classify animal species. It suggests that within a broadly distributed taxonomic group, size correlates with latitude, or distance from the equator, where climates are warmest.

In these taxonomic families, animals living further from the equator are, in general, simply bigger.

“Animals within the same family tend to be larger in colder climates,” said Randy Johnson, DNR large carnivore specialist. And there is a good explanation for this.

“Animals with greater body masses are better able to maintain their body heat,” Johnson said. “So it follows that many species get bigger as you go north — they need to in order to survive.”

Mammals with more mass relative to body surface area — like elk of the Clam Lake herd in northern Wisconsin — are generally better at maintaining body heat.

ALLEN’S RULE

Like Bergmann’s Rule, another principle known as Allen’s Rule is all about regulating body heat.

Named for Joel Asaph Allen, an American zoologist active in the later 1800s and early 1900s, Allen’s Rule broadly states that animals adapted to colder climates tend to have shorter appendages than comparable species in warmer climates.

“Physical attributes like shorter legs, snouts and ears help an animal conserve body heat,” said Dani Deming, DNR assistant wolf specialist. “Warm-blooded animals, including humans, radiate heat away from our cores through the surface of our skin. It’s why we tend to sprawl out when we are hot and curl up when we’re cold.

“Smaller appendages generally mean less surface area, and the smaller an animal’s surface area, the less body heat is lost, and the warmer the animal stays.”

GET BIG, STAY WARM

To summarize these two rules, as climates get colder at increasing latitudes away from the equator, maintaining body temperature becomes paramount. The animals best adapted to survive further from the equator are typically those with larger body masses combined with shorter appendages.

This combination yields lower ratios of body surface area to volume, which helps to conserve heat. In short, it’s survival of the thickest.

And there are examples all around us.

Black bears found in Wisconsin’s Northwoods can be big, more than 500 pounds, but they’re lightweights next to the Arctic’s massive polar bears, which top out at over three times that.

Polar bear (Ursus maritimus)

Brown bear (Ursus arctos)

American black bear (Ursus americanus)

Asian black bear (Ursus thibetanus)

Andean bear (Tremarctos ornatus)

BEARS

Across the animal kingdom, there may not be a better demonstration of Bergmann’s Rule than among the world’s bears — the taxonomic family Ursidae.

“Bears are often used to demonstrate Bergmann’s Rule,” Johnson said. “With only eight species across the globe, it becomes really easy to map each species’ respective ranges and then compare that to their size.

“As the rule would predict, the species that lives closest to the equator, the sun bear, is the smallest of the eight species. As you move further from the equator, the bears get progressively larger.”

After sun bears, there are sloth bears, then pandas a little further north of that, then Andean (or spectacled) bears, which are south of the equator but further from it than pandas. Each of these bear species is larger than the previous, Johnson noted.

“This trend continues through the Asiatic and American black bears,” Johnson said, “on to the brown bears of the northwestern United States, Canada, Russia and Scandinavia, and finally arriving at the largest of all living bears, the polar bear, native to the Arctic and adjacent areas.”

Patterns regarding bear appendages appear, too, Johnson added.

“A great example of Allen’s Rule within the bears of North America is the differences in their ears,” he noted. “American black bears have relatively large, pointed ears. Brown bear ears are slightly shorter and more rounded.

“Then there’s the polar bear’s ears, which are much smaller and very rounded.”

Anybody who’s been outside without a hat in the winter knows how much heat you can lose through your ears. The polar bear’s compact ears are adapted to minimize that.

The same goes for head shape and size. For the greatest contrast, Johnson compares the head of a sun bear, the smallest of the bears, to that of a polar bear, the largest bear species.

In actual size, a polar bear’s head is bigger than that of a sun bear, of course, but what matters is the head size relative to the rest of the body.

“The sun bear has this big, blocky head that’s almost as wide as its shoulders,” Johnson said. “On the other hand, the polar bear’s head is noticeably narrower, leaving less surface area through which it can lose body heat.”

A smaller head relative to body size helps polar bears conserve heat — one example of Allen’s Rule.

Sloth bear (Melursus ursinus)

Giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca)

Sun bear (Helarctos malayanus)

CERVIDS

For another striking example of how size increases with latitude, consider various subspecies of whitetailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) across the United States.

The Key deer, the smallest subspecies of whitetailed deer, is found only in the Florida Keys, famously the southernmost point in the country and, therefore, generally quite warm. The largest of these unique deer grow to less than 3 feet high at the shoulders and top out around 80 pounds.

On the other end of the spectrum, the Great Lakes states and Canada have produced many of the largest white-tailed bucks on record, noted Brooke VanHandel, DNR assistant deer and elk specialist.

“No state has produced more Boone and Crocket record bucks than Wisconsin,” she said, “and several of the heaviest bucks on record have come from north of the U.S. border.”

This pattern is further reflected overall among cervids — members of the biological family Cervidae — and their comparative size on the landscape. This includes deer, elk and moose.

“Not only do the deer tend to get bigger as you move north across the U.S., but you will also start to see other, larger cervids,” VanHandel said. “Elk, including those in the Clam Lake and Black River herds, are much larger than whitetailed deer.

“Bigger still is the moose, the largest cervid on the planet, and still regularly spotted in Wisconsin’s Northwoods despite the species no longer maintaining a permanent presence in Wisconsin.”

The ranges of these cervids extend much further north than Wisconsin. And, as Bergmann’s Rule would suggest, the heaviest specimens of each are typically found towards the northern ends of their respective reaches.

Living in the warmth of Florida keeps the Key deer subspecies (above) on the small side compared to other white-tailed deer, such as some of the bigger bucks found in Wisconsin (below).

Elk in North Carolina areas of the Smoky Mountains (above) don’t grow quite as sizeable as their Clam Lake cousins (below).

COYOTES

For millennia, coyotes were restricted to their native range in the prairies and desert areas of Mexico and central North America, but things began to change in the early 1900s. As the United States expanded and became more developed, wolves and other top predators began disappearing from the landscape.

With wolves largely out of the picture, coyotes (Canis latrans) were able to move into the eastern and far northern parts of the country, even making it to Alaska. Although it’s only been about a century, the coyotes that now inhabit the colder parts of North America are already noticeably larger than their southern counterparts.

“A Wisconsin coyote might have 20 pounds on a coyote from the Mojave Desert or Texas,” Deming said.

As coyotes moved north and east, they interbred with wolves (Canis lupus) and domestic dogs, becoming bigger, more robust and better suited to the harsher winters. Being bigger also gave them the ability to go after the larger prey found in those areas (prey that was bigger to better handle those winters themselves).

“The recent history of the coyote really is a perfect example of Bergmann’s Rule,” Deming added. “What makes it unique, though, is that we can see it happening in real time as they continue to expand throughout North America.”

Per Bergmann’s Rule, the further north you go (Minnesota in this photo), the bigger the coyote.

LINDA FRESHWATERS ARNDT

Northern coyote

Southern coyote

NOTES AND EXCEPTIONS

Latitude and temperature aren’t the only factors that influence wildlife size. Habitat and the variety and quality of food available play major roles, too.

For example, the famously enormous Kodiak brown bears of Kodiak Island in Alaska have ample access to high-protein and calorie-rich seafood like salmon, which fuels their growth more effectively than the more varied and plant-heavy diets of the smaller inland grizzlies at the same latitude, Johnson said.

Also, as already noted, Bergmann’s Rule and Allen’s Rule primarily apply to mammals, along with some birds. But they do not hold true for cold-blooded animals and other wildlife that rely on external factors for temperature regulation.

Furthermore, some mammals don’t follow these rules; several species of rodents have adapted to thrive in cold climates through behavioral changes, such as burrowing and nesting, and thus do not require the thermoregulatory benefits that come with a larger body or shorter limbs.

Although certainly not absolute or without exceptions, Bergmann’s Rule and Allen’s Rule remain essential pieces of our understanding of the world’s ecology. They provide a strong set of guidelines in helping us answer the eternal question, “Why is that thing the way it is?”

For the capybara, the world’s largest rodent and a native of warmer climates in Central and South America, size can be attributed to factors such as habitat and historic lack of predators rather than the principles of Bergmann’s Rule.

Easy access to plenty of high-calorie salmon gives Alaska’s noted Kodiak bears a “bulk up” advantage over other brown bear species at similar latitudes, which must rely on more plant-based diets.

Zach Wood is a public information officer in the DNR’s Office of Communications.

Legacy and future

OF THE WISCONSIN CONSERVATION CONGRESS

JONNA MAYBERRY

Hunting plays a big role in WCC outreach. Here, delegates Bill Will, left, and Theresa Klawitter, center, scout locations for a waterfowl hunt at Sandhill Wildlife Area with a YCC delegate.

THE WISCONSIN CONSERVATION

CONGRESS has been protecting Wisconsin’s natural resources for decades, a role its members recognize and respect.

Unique to Wisconsin, the WCC is the only statutory body in the state where residents elect delegates to advise the Natural Resources Board and the DNR on how to responsibly manage Wisconsin’s natural resources for present and future generations.

The WCC consists of five elected delegates from each of Wisconsin’s 72 counties, chosen during the DNR’s annual fish and wildlife Spring Hearings. Each group of county delegates then selects a chair and vice-chair.

In addition, the WCC divides the state into 11 districts and fields a 22-person District Leadership Council. An overall Executive Committee is elected from among the leaders at the district level.

Finally, WCC delegates are assigned to serve on 20-plus advisory committees, working on a variety of fish and wildlife issues in an effort to listen, inform and advise.

“It's up to the WCC to connect the citizens and make sure that we, the delegates of the WCC, are capturing the voice of all the citizens of the state,” said Kevin Schanning, a 12-year WCC delegate and chair for Bayfield County.

ROOTS OF THE WCC

Early industries, including lead mining, forestry and farming, depended on Wisconsin’s natural resources. The dawn of the Industrial Revolution in the late 1800s brought unprecedented levels of environmental degradation, necessitating the development of clear standards and rules to conserve our state’s land and natural resources.

“The whole notion of conservation sponsored by the government was new,” said Ed Harvey, who has served on the WCC for 47 years and is the chair for Sheboygan County. “And things were not working out very well.”

People began to realize that conservation policy is a three-part concept, Harvey said.

“First, you have the political side of it — that is where all of the money comes from. Then you have the science side of it,” he noted. “But none of those can be effective unless they are to the agreement and satisfaction of the public side of it.

“And the public side was missing at that point.”

To fill the void, the WCC began as an idea from Aldo Leopold and other conservationists, and in 1934, the State Conservation Commission, a predecessor to the Natural Resources Board, established it.

“(It was) the vision of Aldo Leopold to have the public have an impact; Aldo Leopold's vision was to

protect,” said Mike Britton, a WCC delegate of 13 years and chair for Barron County. Britton’s father, Roger Britton, served as a past chair of the WCC.

Today, the WCC has institutionalized resident input and involvement in natural resources policy and management.

BIG WINS

Since its inception, the WCC has supported advancements for natural resources across the state, including some we might not initially think of, like the reintroduction of turkeys in Wisconsin.

“That has been an incredible recovery program that has had the support of the WCC over the years,” Britton said.

The annual Spring Hearings (with input now collected in person and online) represent another win, inviting residents to submit and vote on resolutions each year to guide conservation policy. As the world evolves, broad environmental issues also have become an increasing part of the WCC’s vision.

“There are huge threats to the environment … and it's so important for the voice of Wisconsin's citizens to be heard,” Schanning said.

Mary Ellen O’Brien, a retired environmental scientist, has served on the WCC for eight years in Dane County and is the chair of the group’s Environmental Committee.

“The WCC had the wisdom and the foresight to recognize that environmental factors were pretty important, so they established an Environmental Committee,” she said.

The WCC must continue to “foster the broader conservation vision,” she added, understanding that “conservation involves more than just hunting, fishing and trapping quotas. Environmental factors are also critical in keeping our waters and ecosystems healthy and viable.”

As for the future of Wisconsin’s natural resources and related policy, the WCC will continue to play a critical role.

“The whole concept of the congress is lofty and high and something we need to work on and make sure we do not lose,” Harvey said. “We do this every year and have since 1934, and we will continue to do this, I hope, for a long, long time.”

Jonna Mayberry is a public information officer in the DNR’s Office of Communications.

LEARN MORE

For details on the Wisconsin Conservation Congress, including how to connect with delegates in your county and become involved in the advisory process, scan the QR code or go to dnr.wi.gov/about/wcc.

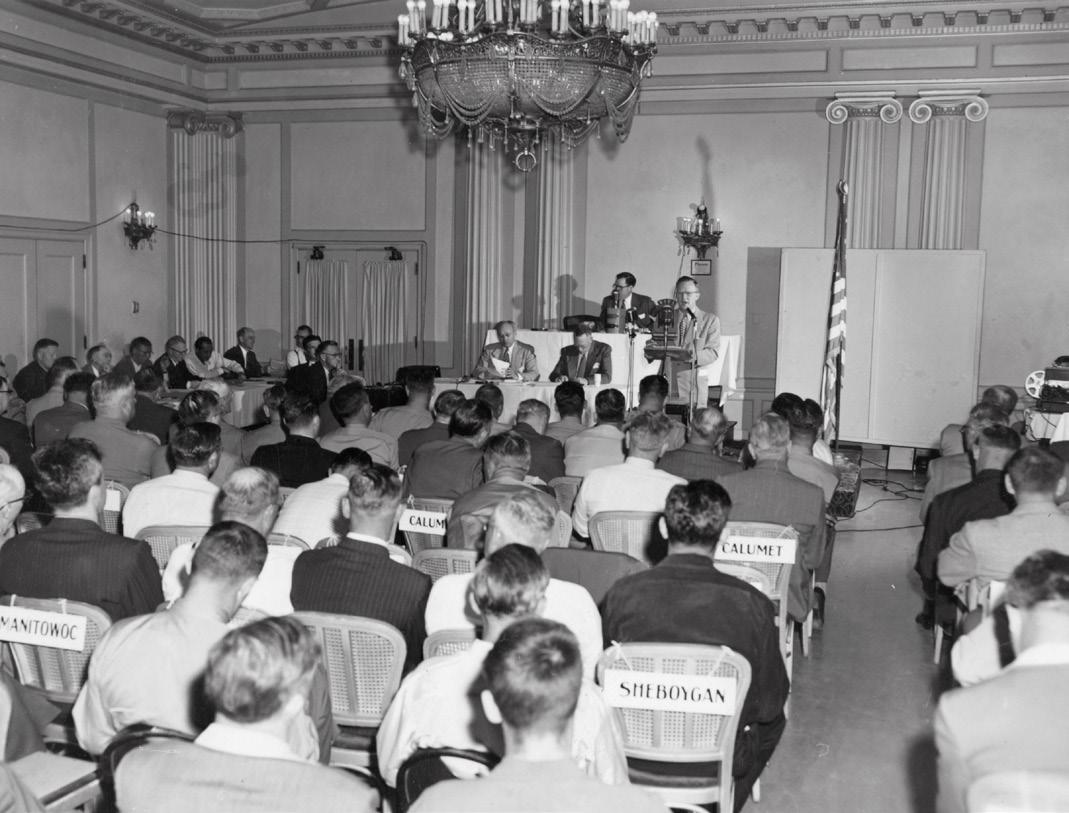

The Wisconsin Conservation Congress has been gathering public input to help guide state policy since 1934. This June 1952 photo shows Ernest F. Swift, then WCC director, addressing the group’s meeting in Madison.

For a look at the Youth Conservation Congress program, see Page 30

WCC delegates Keith Propson, left, and Nicole Gates, right, join YCC delegates to participate in duck banding activities at Collins Marsh Wildlife Area.

YCC HELPS SHAPE the next generation of conservation

JONNA MAYBERRY

WHAT IF SOMETHING like the Wisconsin Conservation Congress existed, but for youth?

Well, it does: It’s the Wisconsin Youth Conservation Congress!

The YCC, currently about 60 members strong, is a statewide program designed to foster the growth and development of future conservation leaders across Wisconsin.

As an extension of the Wisconsin Conservation Congress, the YCC provides young people with opportunities to engage in conservation activities, mentored hunting and fishing, service work, career development and educational experiences related to natural resources policy.

“The YCC was created to help develop conservation leaders,” said Kyle Zenz, the DNR’s Youth Conservation Congress coordinator. “We hope that YCC youth might eventually join the WCC as adults, but the program also just gives youth a better understanding of conservation and advocacy in general.”

The YCC focuses on county-level initiatives, mirroring the WCC. WCC delegates serve as mentors and

as a local contact point for the YCC delegates.

The WCC’s 21-member YCC Oversight Committee is responsible for setting the YCC’s curricula and guiding all aspects of the organization, including incoming donations. They give generously of their time to plan and participate in the many YCC activities, and often give monetarily as well.

“The Youth Conservation Congress is an important way to keep young people engaged in our conservation efforts,” said Mary Ellen O’Brien, WCC’s Dane County vice-chair. “It has been an absolute bright spot in the WCC's endeavors."

POLICY PERSPECTIVE

YCC activities cover every facet of conservation.

“When I was younger, I decided I would love to be a wildlife biologist. But I never considered the fact that there’s policy involved, that many moving pieces create a framework for natural resource management,” Zenz said.

“And so, I’m helping to try to give these youth a broad perspective of everything involved with natural

DNR fisheries biologist Evan Sniadajewski teaches YCC delegates about Mississippi River fish populations.

resource management, conservation and the sporting community as well, like hunting, fishing and trapping.”

YCC participants also strengthen valuable skills, such as problem-solving, effective communication, teamwork and leadership by working with other YCC delegates, WCC members and DNR staff. YCC members are encouraged to learn more about the WCC and participate in county meetings, local initiatives, mentored hunting and other activities.

MAKING CONNECTIONS

Along with the WCC connection, YCC delegates also volunteer with local conservation groups and natural resources professionals to learn more about careers. YCC delegates can assist with research tasks such as duck and goose banding, pheasant stocking, fish stocking, and fish and wildlife surveys.

Delegates often promote the YCC through civic organizations, local clubs, school classes and youth groups. YCC members may be eligible for academic credits (such as for a high school independent study project) by participating in YCC initiatives.

The YCC program offers opportunities for students of all backgrounds, from seasoned outdoor enthusiasts to those who might be newcomers to conservation.

The program is primarily meant for high school students, with some DNR volunteer activities only available for ages 16 and up. But there are no specific age requirements to join the YCC, and younger individuals are welcome to apply.

Youth can participate in the YCC through the end of the summer after their senior year of high school.

YCC EVENTS

The Wisconsin Youth Conservation Congress offers year-round opportunities for young people to grow as future conservation leaders. Here are some highlights.

January: Ice fishing weekend. All YCC delegates learn new fishing techniques from mentors and peers, review ice safety tips, learn about local aquatic ecosystems and enjoy fishing with friends.

March: Explore UW-Stevens Point. The YCC Oversight Committee meets yearly at UWSP, and YCC delegates get a behind-the-scenes tour of the school’s College of Natural Resources.

May: Annual Conservation Congress Convention. YCC delegates learn about the business of the WCC, participate in field trips, listen to presentations on local conservation initiatives, meet new YCC delegates and much more.

June: YCC career day. Delegates explore natural resource-related professions, discover jobs within the DNR and get information about educational institutions with natural resources degrees.

August: YCC summer program. At this four-day program, YCC delegates can investigate conservation careers, help with service work, develop leadership skills and spend time recreating outdoors. The YCC also partners with county, state and federal natural resources managers to find out more about local conservation efforts.

August: Youth Zone at the Waterfowl Expo in Oshkosh. YCC delegates lead learning stations and help with hands-on activities for families and youth.

October: Fall YCC hunt for upland birds or waterfowl. Novice and experienced hunters are welcome; equipment and instruction are provided.

For a look at the Wisconsin Conservation Congress, see Page 28.

LEARN MORE

Wisconsin students interested in the outdoors are invited to join the Youth Conservation Congress, a statewide program to support future conservation leaders. The YCC helps members learn about related careers and understand the processes that determine Wisconsin’s natural resources policies. For details, scan the QR code or go to dnr.wi.gov/about/wcc/ycc.

Jonna Mayberry is a public information officer in the DNR’s Office of Communications.

YCC delegates learn the art of fly-tying from WCC delegate Tashina Peplinski, right.

HEARTFELT DESIRE TO HELP

UNDERWATER DRONE TEAM ANSWERS THE CALL ON SENSITIVE SEARCH MISSIONS

THE DNR CONSERVATION WARDENS who search to find a loved one lost in water call it a mission of the highest order — a priceless act from a service heart to ease a broken one.

There are 10 wardens who train and dedicate their time, in addition to their regular duties, to pilot sophisticated underwater search drones, known as remotely operated vehicles. Together, they are the DNR’s Mission Ready ROV Team.

These wardens can find sunken evidence, storm debris, stolen property, submerged homeland security threats, infrastructure issues, invasive species and more, working in conditions from ice-covered winter waters to the shimmering waters of summer.

“Any task is a challenge, and it is a mission,” said

Lt. Drew Starch, who joined the team in 2019 and is among the most experienced of the ROV team. “You are driven to have an end result. It is rewarding when you are successful.”

STRESSFUL AND SOMBER

While all calls for ROV help from the DNR are important, the most critical call at any hour is to find someone who didn’t make it home, was seen breaking through the ice or struggling before going under.

The DNR team, often working with external partners, utilizes physics, water science, 911 calls and more to make searches as efficient and effective as possible. Such information, team expertise and ROV technology combine to help narrow search locations and speed what sadly may become a recovery process.

JOANNE M. HAAS

A remotely operated vehicle, or ROV, can be vital equipment for DNR wardens conducting underwater search operations.

Lt. Jon Hagen, Spooner Warden Team supervisor, studies the viewing screen while operating an underwater search drone.

Overall, the knowledge and experience of the ROV team can reduce or even eliminate long, exhausting search dives that stretch for hours in dark, cold and unknown water situations.

The heartfelt drive to help is real when trying to find a missing person fast, said Lt. Jon Hagen, the DNR’s Spooner Warden Team supervisor. Hagen joined the ROV team after accompanying others on ROV calls.

“You want to find this person as quickly as you can,” he said. “For all of us on the team, if I can drop (the ROV) one time and find the missing person, that’s what we hope for every time.”

OTHER USES

Recreation warden Jason Roberts, who has been on the DNR team for about a decade, is among the most deployed ROV pilots. He serves the state’s southeast region, which is loaded with popular waterbodies that can bring water-borne crashes.

When a crash occurs, the ROV call often is to find a missing passenger, but Roberts’ role doesn’t stop there.

“With the ROV, I can recover pieces and parts that get lost in the crash. I can find parts of the boats,” he said. “Then, we can determine impact and figure out how boats came together.

“Making sure we can get things back that we feel are important to making the crash make sense both to a judge and to the families — that’s a key part.”

Roberts and Starch also were on hand for the 2024 Republican National Convention in Milwaukee to keep watch for possible homeland security threats using ROV tools. And Starch has been deployed to search waters for weapons used in homicide cases, cement chunks left on a waterbody’s floor after a bridge was rebuilt, and a plane that crashed during Oshkosh’s 2023 Experimental Aircraft Association event.

WINTER ICE DIVES

Winter offers clearer water under the ice than the turgidity of summer water. The pilots will sit in a pop-up on the ice or on nearby land and fly the ROV unit with sonar under the ice, tracking the vehicle using monitors. Yearly ice dive trainings keep their skills fresh.

Search screen view of a sunken vehicle, including details such as water depth and temperature recorded by the ROV.

Gone are the days of sending a diver down to search in extremely cold and dangerously exhausting conditions.

“In the old days, we’d have to send a diver to clear and see,” Roberts said. Instead, the ROV can be sent and use its sonar, camera and lights to locate a missing person or item of evidence. “The only time a diver has to go down is if they see something (using the ROV).”

In water considered too dangerous for divers, the ROV can even be used to elevate a discovery to the water’s surface for recovery.

“Going under ice means whole different conditions,” Starch said. “It is frozen water and with that, we’ll have to cut holes to start the search.”

Hagen noted the ice often will reform after there has been a break by a snowmobiler, UTV or someone walking. This is when the team uses its expertise to determine drift, if any, of the missing person, along with other water conditions.

The DNR’s Mission Ready ROV Team is known for its skill, professionalism and remarkable speed. This is why partner agencies often call for help.

Joanne M. Haas is the public information officer for the DNR’s Division of Public Safety and Resource Protection.

ICE SAFETY

For all those heading onto Wisconsin’s many frozen waterbodies this winter to fish, hike, ski, use a snowmobile/ATV/UTV or just enjoy a winter day, please remember no ice is ever 100% safe. Proper planning and taking basic precautions can help ensure you return home safely. To learn more about ice safety, scan the QR code or go to dnr.wi.gov/tiny/901.

MAKE WAY — AND HOME

— FOR DUCKLINGS

You can fly! Well, not quite at this point, but it isn’t too early for this wood duckling to try.

STORY AND PHOTOS BY JEFF BAHLS

Come spring, wood ducks will appreciate a well-placed nest box

THE WOOD DUCK (Aix sponsa) is the most colorful duck and one of the most spectacular birds in Wisconsin. A favorite of waterfowl hunters and bird enthusiasts alike, it is now abundant throughout the state.

That was not always the case. A century ago, market hunting, along with logging of the trees that wood ducks depend on for nesting habitat, nearly wiped them out.

When the Migratory Bird Treaty Act became federal law in 1918, it made it illegal to kill, capture, sell, trade or transport any migratory bird — such as wood ducks — or harm their nest or eggs without a permit. In addition, the wood duck hunting season was closed and remained closed until 1941.

Fortunately, conservation-minded individuals also began to think “outside the box” to aid this species. Recognizing that wood ducks were losing their nesting habitat, they developed an interesting idea: What if we were to make artificial nest cavities and place them in the right habitat?

Dedicated waterfowl research pioneers like Art Hawkins and Frank Belrose climbed into known wood duck nesting trees. They measured hole size, cavity depth and diameter. They made 100 boxes and placed them in floodplain forests.

Wood ducks quickly used the boxes, and the wood duck nest box was born. After a few improvements along the way, we have a very successful tool that can help boost wood duck numbers.

PLACEMENT DETAILS

Wood ducks, which make their homes in cavities, can nest up to 2 miles from water. Luckily in Wisconsin we have an abundance of creeks, streams, rivers and ditches that can be habitat for wood ducks. So what are these birds looking for when it comes to nesting?

As far as location, they need a spot that’s easy to access and safe from predators, preferably with a woodland component. Floodplain forests, stream corridors, lakes, ponds and even suburban yards can work, if conditions are right.

A box mounted on a pole with a predator guard is key to successful nesting. This was one lesson learned from early trials. Yes, birds will use boxes placed on trees, but so will everything else, including raccoons, squirrels and various other nest competitors or predators. A pole with a guard is a must!

The box must have a clear flight path to and from the box, with no branches or leaves covering the hole. Hen wood ducks want to come and go from the box as quietly as possible.

Locate boxes 5–10 yards from a tree, as squirrels can jump quite a distance. This distance includes overhanging branches — keep the nest box away.

MONITOR THE BOX

If placing nest boxes in your yard, locate them where you can see them from your house. It’s always a bonus if you can see results, but don’t be discouraged if you don’t see action right away. Birds can come and go very early in the day and want to keep the nest location a secret from competitors and predators.

Wood ducks start looking for nest sites when they return from winter areas as open water becomes available. Make sure your wood box nests are in place just about the start of spring.

The first wood duck eggs can be laid around April 1 in southern Wisconsin. (Hooded mergansers, also cavity nesters, lay their eggs about 7–10 days earlier than wood ducks.) Hens lay one egg a day until their egg-laying is complete.

For about the first six eggs, hens will bury the eggs. Adding material such as wood shavings or pet bedding to the bottom of your nest box accommodates this practice in the beginning. After that, hens will start adding down from their breast to cover eggs once they start to incubate.

An annual clutch in a wood duck nest box will be about 12–16 eggs, sometimes more. New research has shown that nearly every box has eggs from multiple hens.

Also, hens will lay in multiple boxes, possibly as a way to provide genetic diversity and ensure at least some of a hen’s genes get passed along. It’s like the old saying, “Don’t put all your eggs in one basket.”

Nest boxes can be monitored with a cell phone camera — just put the camera up to the hole and take a picture. If a duck is present, back off and leave them be; if not, it’s safe to open the nest box and look for or count any eggs.

Pro tip: Do your monitoring in the afternoon, as most egg-laying takes place in the early mornings. This means less disturbance to the hens.

LEARN MORE

Horicon Marsh Bird Club will hold its annual Nest Box Seminar from 8 a.m. to noon on March 7 at the Horicon Marsh Education and Visitor Center, N7725 Highway 28 in Horicon. Talks and displays will include information on wood ducks, bluebirds and other cavity nesting creatures. Learn from the experts to make your boxes “pro-duck-tive!” For more about the Horicon Marsh Bird Club, check horiconmarshbirdclub.com.

Wood ducks nest near waterways, preferably in areas with a woodland component.

Mounting the nest box about 6-8 feet high allows for monitoring.

TIME TO HATCH

Wood duck eggs incubate for approximately 30 days. Cold weather, the amount of time a hen is off the nest (they take two breaks a day, morning and evening) and large clutches can affect hatching time.

Once pipping — the process of the baby bird breaking out of its egg — has started, hens will “talk” to the eggs. Hatching takes about 24 hours.

The ducklings then spend about another 24 hours in the nest box before it’s time to leave the nest.

Above: Location, location, location. It’s key for wood ducks looking for a nest box.

Above right: A wood duck incubates her eggs for about 30 days, adding down from her breast to cover them.

Pipping indicates the baby bird is beginning to break free of its egg.

A “ladder” inside the box (bottom of photo) helps ducklings climb to the opening when they’re ready to leave the nest.

Should I stay or should I go? Eventually, it’s time to make the leap.

THE JUMP

It’s a big day when the ducklings leave the nest, as they must jump from the nest box to the ground below. Calculating incubation, pipping and post-hatching times can help estimate when this will happen.

As far as the jump itself, the timing is typically mid-morning, though it really can vary from first thing in the day to early afternoon. Each hen is different in their approach. Some leave the box early in the morning — like they would on any other nesting day — presumably to scout the route; some stay in the box with their brood.

All hens will look out the box opening to spot potential predators. Some peek out and return inside the box multiple times, while others keep steady watch and wait, slowly moving their head to scan the area. Still other hens might look out for a minute or two and proceed.

Once the hen is satisfied it’s safe for the ducklings to exit, she will fly down and start calling to them. Ducklings begin peeping back and soon emerge, leaping from the nest box and running immediately to the calling hen.

The hen listens carefully until all the ducklings have jumped, then leads them to water. It only takes a couple of minutes for all the ducklings to make the leap and begin their new life.

Once all the ducklings have landed safely outside the nest box, they’re rounded up and led to water by their mother.

Jeff Bahls is a wildlife technician at Horicon Marsh State Wildlife Area and president of the Horicon Marsh Bird Club.

Before her ducklings jump, mother duck makes sure the coast is clear.

Here’s hoping for a soft landing.

BUILDING A WOOD DUCK NEST BOX

If you have the right habitat location, installing a wood duck box can help these beautiful birds with their nesting needs. Here’s what to know.

SIZE: This need not be exact, but a good size to aim for is 10 inches wide by 8 inches for the sides, with a height of 22–24 inches (using 1-inch cedar boards is recommended). The hole size on the front is more specific and should be 3 inches high and 4 inches wide, the minimum needed for a wood duck hen to enter, or slightly larger.

MUST-HAVES: All boxes require a few specific elements.

y Side or top that opens for cleaning the box.

y “Ladder” for ducklings to climb out of the nest and up to the box opening when they’re ready to leave the nest. Pieces of hardware cloth or plastic gutter guard stapled to the front inside of the box just below the hole work well, or use a saw to make kerf cuts in the wood as toeholds.

y Nest material for the box. Wood ducks do not bring in any nesting material (a natural tree cavity will have decaying wood inside for this purpose). Add wood shavings or use pet bedding, sold for rabbits, chickens and guinea pigs. Keep it about 3-4 inches deep, or enough to bury an egg.

INSTALLATION: The nest box should be mounted on a metal pole or wooden post about 6-8 feet high, which will allow access for maintenance and monitoring. For the post, use a 10-foot section of pipe or pole, buried about 2 feet deep for stability.

PREDATOR GUARD: This is a must when placing the nest box. Several types of predator guard can be made and attached to your mounting pole, including a metal or PVC pipe guard, a sheet metal cone or a steel sheet “sandwich.” If using a wooden post, it must be wrapped with aluminum trim coil to prevent raccoons and squirrels from climbing the post and making it past the predator guard.

POST-JUMP: Give some thought to where the wood ducks will go after the ducklings leave the nest. If you have a new pond or a spot that is bare around the shore, having a couple of logs, large branches or rocks that stick out of the water will give the ducks a resting area. Brush piles at the water’s edge also can enhance the pond by providing cover to ducklings and the macroinvertebrates on which they feed. Turtles, frogs and other birds will benefit, too.

BUILDING PLANS: Ducks Unlimited has additional information about wood duck nest boxes, including detailed plans for building, installing and maintaining a box and adding the all-important predator guard. Scan the QR code or check dnr.wi.gov/tiny/3966.

There’s plenty of green to see, even in winter, from Parnell Tower at the Kettle Moraine State Forest-Northern Unit.

Cool conifers Cool conifers

ANDI SEDLACEK

CONIFERS, EVERGREENS, PINE TREES … what’s the difference?

Conifers are trees that bear their seeds in cones. Evergreens are trees that keep their needles and are never totally without leaves. “Pine” is an overall term for trees in the Pinus genus.

Here’s how they all fit together: All pines and evergreens are conifers, but not all conifers are pines or evergreens.

This time of year, with the exception of one species (the tamarack), conifers are the trees that offer up a little green in Wisconsin winters, breaking up a crisp and white snowy landscape or freshening up a dreary gray one.

Here’s a look at some of the cool conifers you’ll find in Wisconsin.

TALENTED TAMARACK

As noted, not all conifers are evergreens — like the tamarack! It is the only conifer in Wisconsin that sheds its needles each fall, making it a deciduous conifer. In September and October, tamarack needles turn golden yellow just before falling, making them easy to spot in the fall and winter.

Another interesting thing about the tamarack is its fruit, which are small, round and hang on the tree for several years. In the spring, these small cones are a striking deep reddish-purple color.

PINING FOR FIRE

Jack pine protects its seeds from fire. While some of the cones on a jack pine tree open naturally, others stay tightly closed, sometimes for years. Then following a forest fire, these closed or serotinous cones will open from the heat and drop seeds on the freshly burned land, making it often one of the first tree species to occupy a site after a fire.

The tamarack tree bears small cones that turn deep reddish-purple in spring.

Jack pine cone

WHITE PINE? THINK 5

White pine needles occur in bundles of five, which distinguishes the trees from other native pines in Wisconsin. An easy way to remember and identify these conifers? The word “white” has five letters and white pine needles are in groups of five!

RARE REPRODUCTION

Trees, both deciduous and coniferous, can reproduce by sprouting or by seed. Wisconsin also has a conifer that can reproduce vegetatively (a new plant grows from the parent plant) in a more unusual way — by a method known as layering.

It’s common for lower limbs of the black spruce to touch the ground and then develop roots where moss grows over the limb. When that happens, the tip of the branch can become a new tree.

LEARN MORE

For details about trees in Wisconsin, scan the QR code or visit dnr.wi.gov/topic/forestry.

FOOD FOR ANIMAL FRIENDS

Conifers are important to wildlife, offering habitat and protection, but they’re also a key food source for many critters.

Northern white cedar (also called arbor vitae) is important for deer browse in the winter, as it’s one of their preferred meals. Other mammals like it, too: Porcupines snack on the thin cedar stems, and red squirrels nibble on the buds. Pileated woodpeckers will excavate large, oval holes in the sides of the white cedar in search of carpenter ants. Red cedar (or juniper) is a favorable winter food for some birds, like cedar waxwings, who love red cedar berries.

STATE

CONIFER SPECIES

Wisconsin has 10 species of conifers native to the state.

1. Northern white cedar/arbor vitae (Thuja occidentalis)

2. Red cedar/juniper (Juniperus virginiana)

3. Balsam fir (Abies balsamea)

4. Hemlock (Tsuga canadensis)

5. Jack pine (Pinus banksiana)

6. Red pine/Norway pine (Pinus resinosa)

7. White pine (Pinus strobus)

8. Black spruce (Picea mariana)

9. White spruce (Picea glauca)

10. Tamarack/American larch (Larix laricina)

Andi Sedlacek is communications director for the DNR.

White pine

Black spruce

Juniper berries provide food for the cedar waxwing and other birds.

Wisconsin Made

CREATE A WINTER WREATH USING FORAGED MATERIALS

AHOLIDAY WREATH is more than decoration, it’s a way to bring the beauty of Wisconsin’s outdoors into your home. The best part? You can make one with materials collected from your own yard or a nearby woods.

With just a little effort, you’ll have a winter wreath that celebrates Wisconsin’s natural beauty, supports local ecosystems and reduces waste.

Jada Thur is a communications specialist in the DNR’s Office of Communications.

JADA THUR

LEARN MORE

Be aware that gathering in state parks, forests and other public-owned lands may be subject to specific rules. Find out more at dnr.wi.gov/tiny/3976

GATHER MATERIALS

Native evergreen branches

Spruce

• Stiff needles that have a strong scent but dry out fast.

• Good but short-lived.

Fir

• Soft, flat needles that stay green the longest.

• Best for long-lasting wreaths.

Pine

• Long needles that give a fluffy appearance but shed easily.

• Good but short-lived.

Cedar

• Soft, dropping branches and very fragrant.

• Best for long-lasting wreaths.

Native accents

Red osier dogwood

• Red bark, adds a burst of color and woody texture.

American bittersweet

• Vibrant orange color.

Pine cones

• Add texture and shape.

Cranberries

• Bright pops of red and can be strung or glued in clusters.

Birch twigs

• Rustic and sturdy.

Dried grasses, milkweed pods or wildflowers

• Add variety and uniqueness.

Antler sheds

PREP THE GREENS

Harvest responsibly. Clip only small amounts from each tree. Never strip a branch bare, and never harvest illegally (i.e. with birch).

Tend to the stems. Lightly smash the cut ends with a hammer to help them drink water.

Soak the branches. Allow your cut greens to sit in water overnight to hydrate.

Store in a cool place. Keep your materials outside or in a garage until you build the wreath.

ASSEMBLE YOUR WREATH

1. Make a base

Use a wire or grapevine wreath form. You also can twist sturdy branches (willow or dogwood) or wild grapevine into a circle.

2. Layer the greens

Place small bundles of branches around the form, overlapping them like shingles.

Secure each bundle with floral wire or twine. Use natural twine instead of plastic ties or floral wire for a low-waste wreath.

3. Add texture

Tuck in pine cones, berries and twigs.

4. Finish strong

Tie on a fabric ribbon (upcycle old scarves or cloth scraps).

For indoor wreaths, mist with water every few days to keep the wreath fresh, aiming at the back where the cut stems are.

SUSTAINABILITY TIPS

Avoid invasive plants. This includes species such as multiflora rose, nonnative bittersweet, nonnative phragmites and grasses, and cut-leaved and common teasel.

Skip plastic decorations. Natural accents can be composted at the end of the season.

Avoid glitter and spray paint. These make your wreath noncompostable.

Reuse your base. Keep the wire or grapevine frame for next year.

Compost or mulch. When the season ends, return the branches to your yard or compost pile.

Northern white cedar

Eastern white pine

Red osier dogwood

Species on the rebound

WHY THERE’S CAUTIOUS OPTIMISM FOR THE SHARP-TAILED GROUSE

DANIEL POWELL

THIS FALL, FOR THE FIRST TIME SINCE 2018, Wisconsin allowed a limited hunt for sharp-tailed grouse. While this was great news for hunters, it also should be viewed as a win for habitat conservationists and bird lovers everywhere.

Once widespread across much of Wisconsin, sharptailed grouse are now only found in the Northwest Sands region of the state along the border with Minnesota. As most of their habitat was converted to agriculture and urban uses or lost due to fire suppression, this region’s relatively open landscape became the last stronghold of the bird.

Known as “pine and oak barrens,” the ecosystem of the Northwest Sands region once comprised around 7% percent of Wisconsin’s landscape. Historically, the sandy soil, left by outwash of melting glaciers, provided a habitat that hosted growth of prairie grasses and forbs, low-growing shrubs, sedge meadows and trees like pin oak and jack pine.

This scrubby landscape also burned regularly, keeping trees from reaching maturity. The wide swath of young “early successional” forest created by frequent fires was the perfect habitat for sharp-tailed grouse, upland plovers and other fire-dependent species.

HABITAT HISTORY

Around the turn of the 20th century, much of this landscape was converted for agricultural use. But adverse growing conditions led many farmers to abandon this region in the 1920s and ’30s, and many of these lands ended up in the hands of surrounding counties.

Much of the area was often left to mature into mixed, unmanaged forests or planted with red and white pine and designated for timber sales. As early as the 1940s, hunters and conservationists acknowledged a steep drop in sharp-tailed grouse populations, and piecemeal conservation work was started in the region.

In 1946, the state of Wisconsin purchased 12,000 acres of tax-delinquent land and started the Crex Meadows Wildlife Area. In 1956, the state acquired 5,700 acres from Burnett County and established the Namekagon Barrens Wildlife Area.

The properties were removed from timber rotation, cleared and returned to a more regular prescribed fire regime. Over time, the state continued to acquire more land parcels in the region. Surrounding counties also began converting timber holdings to more barrens-like cover.

This cooperative work created a mosaic of favorable sharp-tailed grouse habitat.

POPULATION PLUMMETS

Conservation work went far beyond foresters and biologists at the state and county levels. A host of concerned parties, including the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, regional tribes, wildlife organizations, Friends Groups, timber companies and private landowners continued to reshape the landscape.

Still, the historical fragmentation of habitat and lack of the large-scale fire disturbances needed to manage the landscape continued to hamper the rebound of the sharp-tailed grouse.

Considered area-sensitive, sharp-tailed grouse require large open blocks of contiguous habitat. Even with significant work being done in multiple locations on the ground, the birds were unable to move between properties. Population numbers continued to fall.

By the late 1990s, it appeared the sharp-tailed grouse population had entered what biologists feared was an extinction vortex. This perfect storm of catastrophic events on a small, fragmented population seemed dire.

By the mid-2000s, the state was approaching the sharp-tailed grouse hunting season with caution. Following the 2018 season, hunting of the species was paused in Wisconsin.

In early 2019, the Wisconsin Natural Resources Board approved the Northwest Sands Regional Master Plan, a comprehensive plan focused, in part, on restoring and connecting pine and oak barrens via “stepping stones” to address the lack of contiguous habitat facing sharp-tailed grouse.

Despite the many conservation measures on behalf of the sharp-tailed grouse, population numbers from a core group of managed public properties and private lands hit an all-time low in 2021.

NUMBERS SLOWLY REBOUND

The state’s Sharp-tailed Grouse Advisory Committee continued to assess lek surveys (data from the bird’s mating grounds) to determine population numbers. Habitat work at the landscape level — such as focused rotational prescribed burns at Crex and Namekagon wildlife areas — also continued, and the hunting season remained closed.

Slowly, something interesting has happened. In 2025, for the fourth consecutive year, population numbers of the sharp-tailed grouse have increased.

In fact, 2025 numbers represent a 7% increase over the previous year, the largest year-over-year uptick since 2010. Earlier this year, the Sharp-tailed Grouse Advisory Committee agreed that numbers had risen enough to support a limited hunt.

Mating rituals take place each spring at sharp-tailed grouse breeding grounds, known as leks.

“The committee used several criteria to evaluate whether the population could support a hunt,” said DNR wildlife biologist Bob Hanson, who has worked on sharp-tailed grouse projects for years.

“We looked at lek numbers, winter survivability, nesting and brood-rearing success, weather forecasts and habitat metrics. Based on the population response we’ve been seeing, the metrics considered were all satisfied.”

The data suggested the sharp-tailed grouse population “was large enough again” to allow limited fall hunting, Hanson added.

AWARENESS AND OPTIMISM