MANOOMIN MANOOMIN

WILD GOOSE CHASE

Come fall, many Canada geese in Wisconsin hightail it south for the winter, leaving the state before lakes, marshes and other habitat areas freeze over.

Geese are among the numerous migrating birds that congregate on Wisconsin’s waterways each autumn and are commonly seen taking to the skies in their classic V-shaped flight formations. They’re also a popular species for waterfowl hunting enthusiasts (all state goose zones open Sept. 16).

We’re looking for your silly goose entries for this issue’s Caption This.

Send your captions via email to dnrmagazine@wisconsin.gov Or jot them down and mail by Nov. 1 to:

DNR magazine PO Box 7921 Madison, WI 53707

We’ll pick some of the best suggested captions to share in the next issue.

Communications Director Andi Sedlacek

Publications Supervisor Molly Meister

Managing Editor Andrea Zani

Art Direction Douglas Griffin and Sunny Frantz

Printing Schumann Printers

Governor Tony Evers

Natural Resources Board

Bill Smith, Shell Lake, Chair

Rachel Bouressa, New London

Douglas Cox, Keshena

Deb Dassow, Cedarburg

Jeff Hastings, Westby Patty Schachtner, Somerset Robin Schmidt, La Crosse

Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources

Karen Hyun, Secretary Steven Little, Deputy Secretary Mark Aquino, Assistant Deputy Secretary

FROM THE SECRETARY

Growing up in the northeast U.S., I’m no stranger to the spectacles of fall — but there’s something about fall in Wisconsin that just feels extra special.

Farmers are busy harvesting crops, kids are excited about the new school year, Badgers and Packers football games highlight our weekends, apple picking abounds and the long-awaited (for some, at least) return of sweater weather is right around the corner.

Here at the DNR, our work lives at the intersection of the natural environment and the many ways people — the heart of our economy and culture — interact with and enjoy it.

Whether it be outstanding fall musky fishing and our iconic deer hunting season or breathtaking hikes at state parks, fall is prime time for popular outdoor activities and time-honored traditions that Wisconsin residents await all year and visitors come from all over to experience.

With that in mind, this is the time to shine for the incredible DNR staff who work throughout the year to manage, study, protect, promote and improve the natural resources that make these activities possible. It is an honor and privilege to work with and learn from so many outstanding professionals. In my time as secretary, I’ve been so impressed with our talented and passionate staff working statewide on everything from habitat conservation and water quality to waterfowl management and outdoor skills trainings for the public.

Our expert staff are also the primary sources behind many of the articles you’ll read in this and other issues of Wisconsin Natural Resources magazine, sharing their experience and expertise to help provide the highest quality and most informative stories possible.

Karen Hyun

Within the following pages, you’ll find details about the early results of the DNR’s Southwest Wisconsin CWD, Deer and Predator Study and what it means for deer management in the future. There’s also a breakdown of how trout and waterfowl stamps help to improve habitat and tips to help you protect pollinators during your fall yardwork.

This issue also includes a look at fall movement patterns and fishing tips for some of Wisconsin’s most popular gamefish, the science behind the DNR’s waterfowl migration monitoring efforts and a look at Wisconsin’s forest products industry and the everyday items it produces.

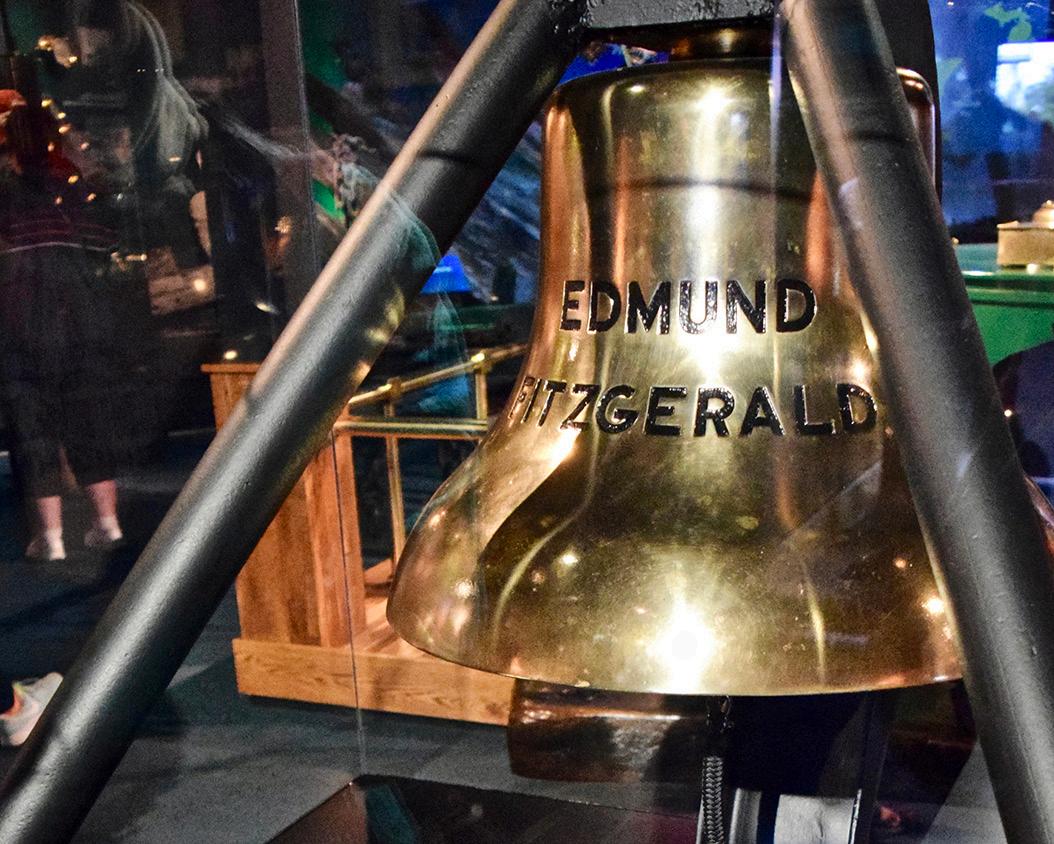

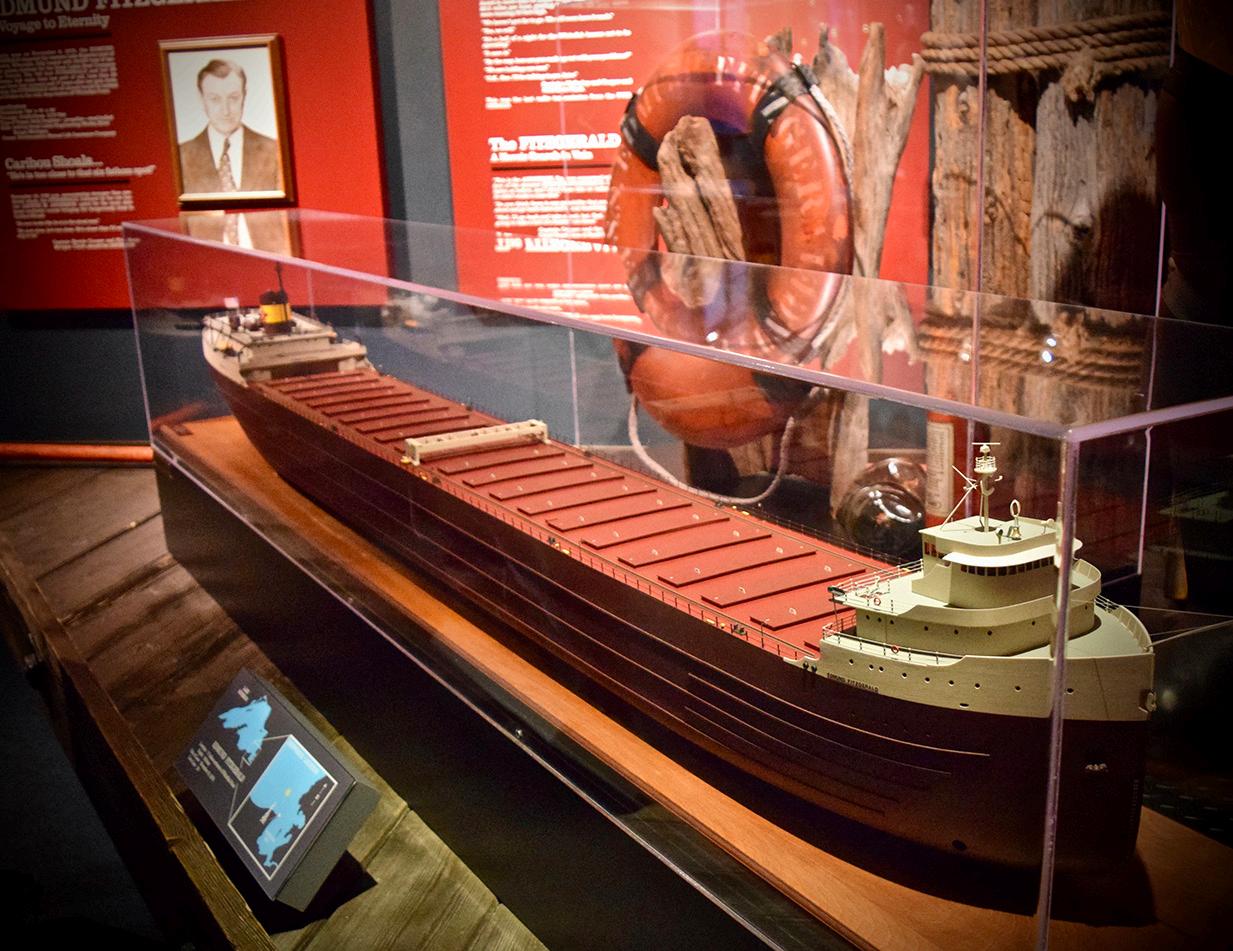

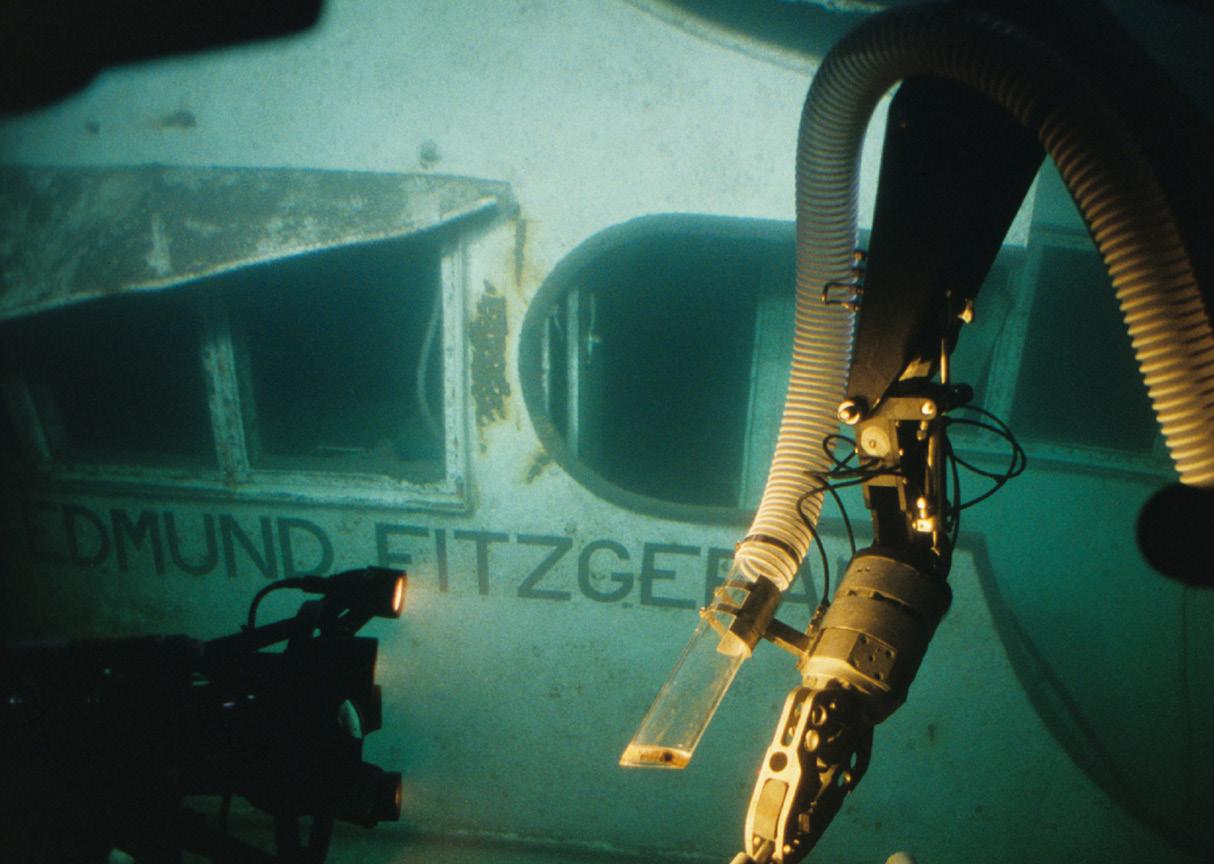

Readers will also find a special look back at the Lake Superior sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald — the history, mystery and legacy 50 years later.

Lastly, I would be remiss if I didn’t again pause to celebrate the 125th anniversary of our Wisconsin State Park System and our state’s amazing public lands.

The DNR has the privilege and responsibility to acknowledge the Indigenous people who have called this land home for generations. This acknowledgement demonstrates our strong commitment to collaborate and partner with the sovereign tribal nations in Wisconsin.

No matter where you are in the state, you are on the ancestral land of a tribal nation. I encourage you to take the opportunity to learn about and appreciate the history of these lands and the great historical, present and future contributions of Indigenous people.

However you choose to enjoy the outdoors this fall, I hope you and your family have a fantastic, safe and successful season and find time to savor this special time of year.

DANIEL ROBINSON

Hartman Creek State Park

DANIEL ROBINSON

NEWS YOU CAN USE

DNR HAS YOU COVERED FOR HUNTING

It’s nearly fall, which for many in Wisconsin means one thing: hunting. Here’s some information to help you have a safe and successful season.

Species forecasts

Each year, the DNR releases detailed hunting and trapping outlooks for a variety of popular game species, based on data such as surveys, DNR research and local expertise. For links to fall forecasts, including deer, waterfowl, furbearers and more, check dnr.wi.gov/tiny/3886

Focus on firearm safety for an incident-free hunt.

Firearm safety

T — Treat every firearm as if it is loaded.

A — Always point the muzzle in a safe direction.

B — Be certain of your target, what’s before and beyond it.

K — Keep your finger outside the trigger guard until ready to shoot.

General resources

The DNR’s hunting webpage offers everything you need to know to enjoy the hunt. Scan the QR code or check dnr.wi.gov/topic/hunt.

FIND FALL FUN AT STATE PARKS

Autumn is an amazing time to enjoy our beautiful state properties, and fun fall events are planned all season in the Wisconsin State Park System — celebrating its 125th anniversary this year! For the latest in parks programming, check the DNR Events Calendar at dnr.wi.gov/events.

HAPPY 10TH TO HORICON MARSH EXPLORIUM

It’s been a decade since the Horicon Marsh Explorium first opened its doors in 2015, offering activities for all ages to teach about the vast freshwater cattail marsh in Dodge County. This fall, the Explorium is celebrating its 10th anniversary with a special event, “From Mammoths to Marsh,” free and open to the public.

Join the fun on Oct. 11 from 10 a.m.-3 p.m. at the Explorium, part of the Horicon Marsh Education and Visitor Center, N7725 Highway 28 in Horicon. Learn about the history of Horicon Marsh from the Ice Age to the present and dive into the wildlife that makes it special.

If you can’t make the anniversary event, don’t worry! You can visit the Explorium during regular hours at the visitor center, 9 a.m.-4 p.m. on weekdays and 10 a.m.-4 p.m. on weekends; closed on Sundays from November to mid-March. Call 262-269-9275 to verify hours.

Visitor center entry is free, but fees apply for the Explorium (except for the anniversary celebration). For details, check dnr.wi.gov/tiny/1591 or vist the Explorium page of the Friends of Horicon Marsh, horiconmarsh.org/visit/explorium. You also can contact Horicon Marsh natural resources educator Liz Herzmann at elizabeth.herzmann@wisconsin.gov or 920-210-9054.

COLOR UPDATES

Get the latest leaf news around the state with the Fall Color Report from Travel Wisconsin: travelwisconsin.com/fall-color-report.

The Horicon Marsh Explorium is celebrating a decade of learning and fun this fall.

LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

A WILDERNESS TRIBUTE

Howdy, I'm a 76-year-old Army vet. These past 40 years I have created a man-made wilderness alongside the sandstone cliffs of the South Fork of the Hay River. Turned poor grade corn land with the planting of 230,000 trees, changing it into pine plantations, 14 grass clover meadows and 12 ponds. There are 15 miles of trails I have to groom four times a year.

This is a labor of love to honor my son I lost in 1992. He was killed along with 11 others in a training accident at Utah’s Great Salt Lake. He was an Army Ranger. Over the past years, I have seen many types of wildlife on the preserve — bear, bobwhite quail, wolf, swans everywhere and a 180-inch buck I hunted last fall. Last summer, I saw two whooping cranes.

The picture is of a bear I have been following these past 15 years. Every other year, she will have cubs and often a cinnamon cub.

Reading the Wisconsin Natural Resources magazine (summer 2025), I came across two items about the eastern massasauga rattlesnake. This year, I saw my first massasauga, around 12 inches long. It was underneath my son’s marker stone next to a huge rock alongside a 100-year-old red cedar tree. It was the prettiest snake I have ever seen.

Byron Bird Jr. Amery

BACKYARD BUCK

Hello, just wanted to share this photo of a beautiful majestic white buck in our backyard. He was with another white deer at the time and let me get pretty close to him to get this great photo. There have been quite a few white deer in our area over the last 5-10 years.

Bonnie Kauth

Wisconsin Rapids

Write in by emailing dnrmagazine@wisconsin.gov or send letters to: DNR magazine, PO Box 7921, Madison, WI 53707

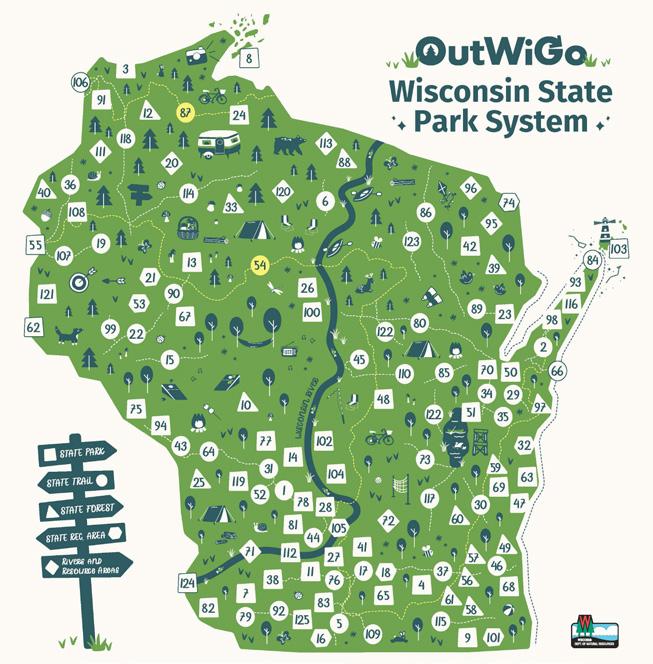

PARKS POSTER IS GREAT RESOURCE

First off, I want to let you know that I am a huge advocate of the Wisconsin DNR and all the wonderful work the organization does to support beautiful Wisconsin. Being a master naturalist has taught me so much more about our wonderful state and all it has to offer.

I was so excited to receive the summer Wisconsin Natural Resources magazine with the park poster — a great source for me to use to explore our park system and more of Wisconsin. Thank you.

Margie Schroeder Wales

OUR SPRING BREAK STAYCATION

EDITOR’S NOTE: This account of a day of exploring was sent to us in the heart of spring, early April. We can only imagine what outdoor fun they’re up to as fall arrives.

A dozen miles west of our front door, but still in Sheboygan County, streams an adventure through the Southeast Glacial Plains. It's our best-kept secret in Sheboygan County. We layer up, put on waders and of course our warm socks, heading out for a day of adventure.

Climbing through brush and bristle, we find our treasure, LaBudde Creek. Last week, it was a bustling stream, but this week there is ice clear as glass. Next week, who knows, maybe we’ll spot a trout?

Our adventures adapt to the ever-changing, ever-unexpected weather of Wisconsin — our home sweet home.

La Tasha Jackett Sheboygan

S’MORE SUBMISSION

EDITOR’S NOTE: Our call from the summer issue for your special s’mores recipes yielded a few results, though perhaps people are more likely to savor their s’mores than write in about them. But here’s a good one — thanks for sharing, Virg!

What’s my s’more? Caribbean s’more: molasses cookies, a slice of mango, cooked marshmallow and caramel sauce. Delicious.

Virg Gamroth Independence

FALLS IN SUMMER

Hi, I visited Big Manitou Falls recently (at Pattison State Park) and wanted to share this photo I took.

Clari Walbridge Minneapolis

GENERATIONS OF CONSERVATION

I saw your article on the Civilian Conservation Corps camps (spring 2025). My dad was at one near Dunbar. I myself was at the first Youth Conservation Corps camp in Manitowish Waters. I was a junior in high school. Years later, my son went there. It sure brings back good memories — thanks for the article!

Bob Lotto Green Bay

LIFE-SAVING STORY

Wow! I am so glad I found your magazine! It’s so diverse, and you present the topics in eye-catching ways with script well-written. I eagerly look forward to each issue.

The summer issue with the article “Ready to serve” thrilled me. I am a sudden cardiac arrest survivor. I have had 10 years of extra life because of an AED (automated external defibrillator). I was down for over 10 minutes and was shocked three times by an AED when I experienced my SCA.

Thank you for bringing awareness to people about what an AED is and how it truly saves lives. But AEDs can only save lives if they are available. Time is of the essence when an SCA occurs — a sudden cardiac arrest can be fatal in minutes. Having AEDs with Wisconsin DNR wardens will save lives!

Nancy Compton Braschler Hudson

DANIEL ROBINSON

‘foodgrowsthaton water’

DNR PARTNERS WITH TRIBES TO SUPPORT WILD RICE

WISCONSIN

HAS

INCREDIBLE NATURAL

RESOURCES to enjoy, and for some of those resources, the cultural significance is undeniable. Wild rice, or “manoomin” in the Anishinaabe language, is one of them.

Found only in the upper Midwest and parts of Canada, wild rice was once abundant in northern Wisconsin and still serves a vital role in Indigenous culture and spirituality. But its presence in state waters has declined significantly over the past several decades.

“It's really kind of hard to picture what life would be like without wild rice because that's the very core of who we are,” said Kathleen Smith, a member of the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community. Smith is the Ganawandang manoomin, or “she who takes care of the rice,” for the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission.

GLIFWC’s most recent Climate Change Vulnerability

Assessment listed manoomin as the most vulnerable species, ranging from “highly vulnerable” to “extremely vulnerable.” Highly vulnerable indicates abundance and/or range is likely to decrease significantly by 2050, while extremely vulnerable means abundance and/or range is extremely likely to substantially decrease by 2050 — or disappear altogether.

“It is tough knowing, especially hearing from elders, the struggles that wild rice has gone through, especial-

ly in the last few decades,” said Nathan Podany, tribal hydrologist with the Sokaogon Chippewa Community Mole Lake Band of Lake Superior Chippewa. “It was such a prevalent plant across the region.”

Learning why wild rice is declining and finding ways to stop that downturn is paramount to saving it. The DNR is collaborating with the Sokaogon Chippewa community, GLIFWC, UW-Madison Trout Lake Station and other tribes and partners to learn why wild rice is declining and help it grow better in a changing climate.

“If we don’t figure out how to counter this decline, we’ll lose an important Wisconsin resource, as well as the historical and cultural ties to it,” said Jason Fleener, DNR wetland habitat specialist.

CLIMATE THREATS

Wild rice is a resilient plant, but it’s also very sensitive and requires specific conditions to grow.

“All of the systems, plants and animals evolved under consistent weather, and as the weather gets more consistently abnormal, it's going to have an effect on wild rice,” Podany said. “And it’s not just rice; it's all habitat and all plants and animals.

“As we lose them, they’re harder to bring back and restore the wild rice water.”

With climate change, stronger and more frequent storms are affecting wild rice at every life stage,

About 18 inches of water is the sweet spot for wild rice, which relies on fallen grains that must overwinter to produce each year’s crop.

EMMA MACEK

especially during the floating leaf stage when the plant is most vulnerable. Intense storms and flooding can drown, damage or uproot the plant, and tribal members say precipitation makes it difficult to dry out the wild rice during processing.

Temperatures are increasing, too, negatively affecting wild rice pollination and seed production. The plant needs cold stratification — an overwintering hardening period of near-freezing temperatures — to promote seed germination in spring.

Increased temperatures also reduce ice cover in winter. This cover is needed to set back aquatic plants that compete against wild rice for space, such as water lilies and cattails.

Brown spot disease is also on the rise in wild rice due to temperature and humidity. Caused by a fungus, the disease can reduce seed production by up to 90%. It’s likely to become more prevalent with larger rain events and increased summer temperatures.

Other challenges include herbivory, which has become more problematic as increasing breeding

populations of geese and swans are putting additional grazing pressure on wild rice beds during vulnerable stages of growth. Plus, human land use changes such as dams, culverts and new roadways can alter hydrology and negatively affect wild rice.

FINDING SOLUTIONS

Researchers are teaming up to learn what they can about wild rice to save it and help the cultural traditions live on.

“The more we learn about it, the better we are equipped to come up with strategies to manage and be the stewards of the resource,” Fleener said.

Much of the DNR’s research efforts involving wild rice are funded by a grant through the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation’s America the Beautiful Challenge. The DNR recently hired Cheyanne Koran, a member of the Menominee Nation, to oversee the grant and facilitate wild rice research projects.

Here’s a look at some of the ongoing work seeking to address specific issues facing wild rice.

Successful wild rice battles difficult conditions and competing plants, eventually producing flowers by mid-summer.

LEARN MORE

You can be a good steward of wild rice by checking your waterway for the plant, taking steps to protect it and learning how to harvest it sustainably. Scan the QR code, visit dnr.wi.gov/tiny/1076 or reach out to your local tribe.

Herbivory

DNR researchers are working with tribes, GLIFWC and other groups to study wild rice herbivory from waterfowl. Amy Shipley, DNR waterfowl and wetland research scientist, is leading a multi-year research project studying the impacts of herbivory on rice growth and seed production.

The study includes using 10-by-10-foot floating fences, called exclosures, on 26 waterbodies across northern Wisconsin, including at Spur Lake State Natural Area in Oneida County. The exclosures, constructed of plastic fencing on a PVC frame and supported with pool noodles, are placed in the water to keep waterfowl out of study plots.

The team measures rice characteristics inside and outside the plots to compare how the rice is doing in protected vs. unprotected areas.

Researchers are also collecting waterfowl fecal samples for diet analysis, conducting in-person bird surveys and monitoring trail cameras to determine what waterfowl species are present. Similar research is happening on the St. Louis River Estuary.

Vegetation

Different vegetation can affect wild rice growth, and scientists are learning how through a variety of research projects.

The DNR recently partnered with researchers at UW-Madison’s Trout Lake Station in northern Wisconsin to study rice growth. The team compared rice growth in three groups: successful populations; unsuccessful populations with declining harvestable rice; and populations that interacted with nonlocal, or invasive, species such as Eurasian watermilfoil and curly-leaf pondweed.

“We found some evidence that rice grains right at the surface without any protection are at a higher risk of being uprooted during the early growth season,” said Gretchen Gerrish, UW-Madison Trout Lake Station director. “If the grains were even an inch down or a couple of inches down into the muck, they had a better hold for their roots.”

In addition, the UW-Madison team is starting a new project studying how the roots of local vegetation, such as lily pads, affect wild rice growth.

Vilas County’s Island Lake, a key location for wild rice and related research, is seen during a drone survey to collect herbivory study data.

These plants have large rhizomes, and as they naturally decay in the water, they release gases like methane and carbon dioxide. Those gases can then uplift the waterbody sediment where wild rice grows.

Researchers are trying to learn more about those chemical reactions to create a better habitat for the rice, especially in restoration areas.

At Spur Lake State Natural Area, a historically important wild rice water, researchers are creating a long-term record of the aquatic plant species found. Traveling by canoe, they follow a grid system, stopping at predetermined points. They then plunge a rake into the water, spin it around and pull it up to identify each species found on the rake.

They are trying to understand how removing competing vegetation, including lily pads and watershield, influences wild rice growth.

A couple of years ago, with support from the Natural Resources Foundation of Wisconsin and the Brico Fund, Podany and Carly Lapin, DNR

conservation biologist for Spur Lake, brought in a mechanical harvester to remove perennial floating aquatic plants in study plots.

The study includes a combination of cut vs. uncut and seeded vs. unseeded plots. Results show that seeding works well in both cut and uncut areas, with a little more success in cut areas.

Water

Research over the years has shown that wild rice grows best in water that is 12-24 inches deep, with 18 inches being the sweet spot. Teams are working to reduce water levels in lakes where the water is too high for rice to grow successfully.

This includes hydrology studies to determine what is creating the high water levels — such as culverts, roads or even beaver dams — and working to find solutions. Along with that, researchers are monitoring water temperature, chemistry and quality, including contaminants.

Other research focuses on the influence of groundwater on wild rice growth.

For harvesters of manoomin, spending time in the plant’s unique environment can be a remarkable experience.

1. The rice is starting to grow

2. The root sprouts

3. Floating on top of the water

4. The rice is flowered

5. Rice stalk (plus the rice)

6. The rice falls

UW-Madison researchers Eliana Cook, left, and Marin Danz collect plant data as part of wild rice studies at Trout Lake Station.

TRADITIONAL KNOWLEDGE

Even as scientific studies progress, researchers understand the importance of including the knowledge of wild rice that has been passed down through generations in the Ojibwe community.

Sagen Lily Quale, a member of the Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Ojibwe, is a UW-Madison graduate student working with Gerrish at the Trout Lake Station. Quale is interviewing wild rice experts from the Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa and nontribal groups to learn how wild rice populations have changed over time.

“That tradition of passing down knowledge through voice and story is really important,” Quale said.

Fleener hopes continued research, collaborations and restoration efforts will feed into each other and sustain Wisconsin’s wild rice legacy for years to come.

“If our restoration efforts spark more people to care about wild rice, then we will continue to gain support to protect it,” he said.

Emma Macek is a public information officer in the DNR’s Office of Communications.

Sagen Lily Quale, left, and Gretchen Gerrish carry bags of wild rice harvested for research at UWMadison’s Trout Lake Station Manoomin Camp in northern Wisconsin.

AUDREY

Manoomin in Wisconsin has long been harvested for food and has served a vital role in the state’s Indigenous cultures.

In awe of the wild rice ecosystem In awe of the wild rice ecosystem

THERE ARE TWO KINDS OF MANOOMIN in Wisconsin. “Northern rice” (Zizania palustris) is harvested by people for food and found in lakes, rivers and flowages in northern Wisconsin. “Southern rice” (Zizania aquatica) is typically found in rivers in the southern part of the state. Since the seeds are smaller, it’s not usually harvested.

Wild rice creates its own “very unique ecosystem,” according to Scott Van Egeren, DNR water resources management specialist. He still remembers being amazed the first time he saw wild rice while canoeing on a lake in northern Wisconsin.

“It was like you were in a field, just surrounded by it, and it was the coolest ecosystem,” Van Egeren said. “It’s awe-inspiring to be in it when it’s that dense because it’s different than anything you’ve ever experienced as a biologist.”

Wild rice, one of the only aquatic plants that is an annual, provides a rich food source and habitat for wildlife, including waterfowl, blackbirds and muskrats. The plant is also known to be an indicator of good water quality and a healthy ecosystem.

‘OUR BIGGEST TEACHER’

This unique and productive ecosystem is part of why the Ojibwe people set up villages in areas where wild rice was found. Tribal ancestors were guided by “the prophecy” to migrate to the region to find manoomin, or the “food that grows on water.”

Another of Wisconsin’s tribes, the Menominee, also are closely tied to manoomin. Their name in Algonquin, “Omaeqnominniwuk,” means “wild rice people.” It was said that wild rice followed Menominee and would disappear when they left an area.

For tribes, the plant has been a key part of ceremonies, feasts and food security.

The traditions surrounding the wild rice harvest carry on all year and include researching areas beforehand and gathering needed materials, such as birch bark for the baskets and venison for the associated feast. Then, depending on the lake, rice is harvested around September.

“You’re out there connecting to the landscape and all the relatives that are around us,” said Kathleen Smith of the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission.

Smith, from the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community, then chuckled, calling to mind the “manidoons” — “little spirits” or bugs — encountered while harvesting rice. Or the rice worms that bite.

“They’re always out there reminding us that we are still human.”

Tribes believe wild rice teaches many such lessons, Smith added.

“It’s not just a plant, but it’s also our biggest teacher, as manoomin is really important to our culture,” Smith said. “We believe that these lessons from manoomin teach us resilience, adaptation and relational accountability for us as humans.”

— EMMA MACEK

FALL YARD CLEANUP: Less means more for pollinators

Keeping flower stems intact helps birds (like this American goldfinch), bees and other species.

Common eastern bumble bee on aster flowers.

JAY WATSON

MOLLY MEISTER

JUDY CARDIN

AS THE LEAVES BEGIN TO TURN and eventually fall and your flowerbeds start to fade and wither, you might be starting to think about fall yard cleanup.

Before you ready your rakes and sharpen your pruners, the DNR and our partners at the Wisconsin Bumble Bee Brigade and Xerces Society ask you to keep those tools in the shed and “let things go” a bit over the fall and winter months.

Allowing all the plants in your yard to go through their natural cycles without human intervention means less work for you while providing critical overwintering habitat for bugs and other native critters. Any patch of yard, no matter the size, can be a self-sustaining and extremely biodiverse ecosystem unto itself if left to its own devices.

Here are four simple things you can do to protect pollinators and countless other species who rely on them:

❶ SAVE THE STEMS. Many insects, including native solitary bees, bundle up in the tiny cavities of flower stems and lay their broods of eggs. Hold off on cutting down stems until March, if at all, and try to leave at least 12 inches of the stem intact when pruning to maximize insect survival and reproduction rates. The unsightly stems will be covered up with fresh growth in no time!

❷ LEAVE THE LEAVES. Epic leaf piles are satisfying, we know, but letting the leaves settle where they drop is the best thing you can do for both insects and soil health. A thin layer of leaves provides essential cover, food and insulation for insects trying to make it through the colder weather.

❸ START A BRUSH PILE. Create the ultimate bug paradise by collecting felled sticks and other woody material in a single spot anywhere in your yard — and once in place, do not disturb! This pile of organic material is a treasure trove of resources for motivated insects and nest-building birds, and it can serve as home sweet home for many backyard species, including chipmunks and rabbits, not to mention thousands of bugs.

❹ AVOID USING PESTICIDES, including fungicides, herbicides, insecticides and other chemical treatments. Letting your yard go au natural as much as possible keeps all creatures great and small happy and healthy.

Asters and other fall-blooming plants can extend garden color and provide late-season nourishment for butterflies like the common buckeye.

Bonus: Consider planting late-blooming native plants.

Want to continue enjoying your garden later in the season? Plant asters, goldenrod and other lateflowering native plants to keep the color going. Fall is the perfect time to plant native flowers. To help insects and wildlife, select native plants that combine to provide blooms from April through October.

Taking these actions can make a big impact for our tiny friends. By turning even one corner of your yard into an insect oasis, you’re contributing to a more biodiverse community of which we are all a part.

Create a brush pile in your yard to provide a wealth of resources for insects, birds and wildlife.

LEARN MORE

For more tips on making your yard the ultimate pollinator resort, check out the Xerces Society’s handy guide at dnr.wi.gov/tiny/3806 or additional resources from the Wisconsin Bumble Bee Brigade at dnr.wi.gov/tiny/3811.

Molly Meister is a publications supervisor in the DNR’s Office of Communications.

JAY WATSON

THIS YEAR MARKS THE 125TH ANNIVER -

SARY of the Wisconsin State Park System, and we’ve been celebrating with fun events and exciting outdoor adventures. Join the fun this fall by exploring new places.

LEARN MORE

Interstate Park was established in 1900, officially founding the Wisconsin State Park System. In addition to that anniversary, other state properties are marking milestones in 2025. Here are a few highlights.

For more on the Wisconsin State Park System, including a link to the DNR’s Find a Park tool, scan the QR code or go to dnr.wi.gov/topic/parks.

EMMA MACEK

DANIEL ROBINSON

Lizard Mound State Park

PENINSULA STATE PARK

Must do: Take your pick of unique seasonal offerings at this popular Door County park, including Eagle Tower, with an 850foot accessible canopy walk to the top; 18-hole and six-hole golf courses, open spring, summer and fall; and Northern Sky Theater, an outdoor venue with shows through Oct. 25.

PATTISON STATE PARK

Fun fact: Big Manitou Falls cascades over a 165-foot drop, making it Wisconsin’s highest waterfall, while just a few miles up the Black River, Little Manitou Falls drops 31 feet.

Must do: Both falls offer accessible overlooks.

LIZARD MOUND STATE PARK

Must do: Hike the limestone and grass trails that loop past 28 well-preserved burial mounds. But stay on designated trails, as walking on the mounds is prohibited. An interpretive center chronicles the park’s Native American history.

GOVERNOR KNOWLES STATE FOREST

Fun fact: At 55 years old, that’s one year for every mile this state forest extends along the St. Croix National Scenic Riverway. Must do: Equestrian lovers will feel at home here, with more than 40 miles of marked trails and an equestrian campground.

GOVERNOR NELSON STATE PARK

Must do: Explore restored prairies on the 2.4-mile Morningside Trail, which also passes Lake Mendota and Six Mile Creek. In winter, the trail is open for skiing and snowshoeing.

HOFFMAN HILLS STATE RECREATION AREA

Must do: Check out the 60-foot observation tower. It sits atop one of Dunn County’s highest points and provides picturesque views — all the more beautiful in autumn.

Note: A vehicle admission pass is not required to enter Hoffman Hills; pets are not permitted.

FRIENDSHIP STATE TRAIL

Must do: Invite a friend to join you on the trail! The 4-mile Friendship State Trail connects to Calumet County’s Mike Ariens Run for Life Trail, which provides access to prairie, woodland and marsh habitat for wildlife viewing. Visit the nearby Brillion Wildlife Area for more hiking and birdwatching.

Note: Calumet County maintains and operates the Friendship State Trail, and a state trail pass is not required.

GOVERNOR THOMPSON STATE PARK

Must do: Try the Otter Trail for a 1-mile hike that winds through the Woods Lake area. You can also check out the Woods Lake Day-Use Area, which has a beach, a reservable shelter and a huge picnic area.

Emma Macek is a public information officer in the DNR’s Office of Communications.

MAJOR MILESTONES

Here are places in the Wisconsin State Park System with anniversaries in five-year increments in 2025.

125 Interstate Park

Moraine State

Abe State Trail

DANIEL ROBINSON

Nelson Dewey State Park on the Mississippi River

Across the ages

Today’s park moments make tomorrow’s memories

ANDREA ZANI

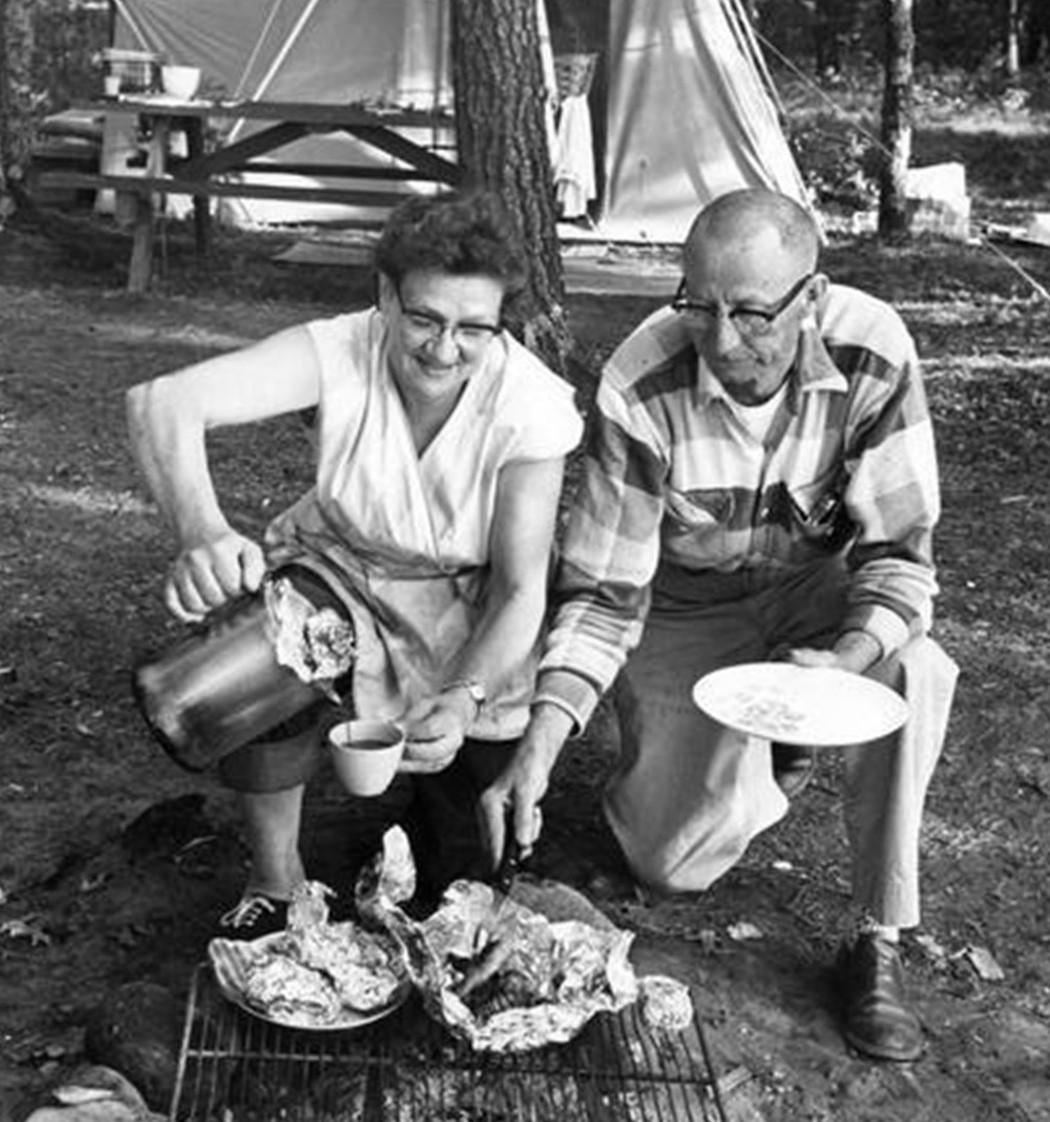

AFLEETING MOMENT IN TIME. That’s all it takes to create a special memory.

It’s safe to say millions of indelible moments have occurred at state parks, forests, trails and recreation areas in the 125 years of the Wisconsin State Park System. For the people experiencing them, these happy times might be recalled for years to come.

Sometimes, the moment is captured by a camera. Historic images show people embracing our beautiful state properties dating as far back as the early 1900s, when the Wisconsin State Park System was in its infancy.

Perhaps not surprisingly, modern images often mirror what we see in the hazy black-and-whites of yesteryear. Viewed side by side, these images illustrate common threads of outdoor enjoyment that weave through the ages.

As we welcome another century of the Wisconsin State Park System, it’s hard not to think about all the wonderful times past and get excited for many more to come.

You can be part of the long-running community of people who have made special memories at state parks and more. Try camping, fishing, paddling, hiking, biking and other activities to be part of the park experience — then and now.

Andrea

Zani is managing editor of Wisconsin Natural Resources magazine.

Potawatomi State Park, 1938

Willow River State Park

Merrick State Park, 1939

Family portrait by tent, early 1900s

Peninsula State Park

KATHLEEN HARRIS

Wyalusing State Park

CHRISTOPHER TALL

Campfire cookout, 1963

Lake Kegonsa State Park

RACHEL HERSHBERGER/TRAVEL WISCONSIN

Ready for fishing, circa 1940

Governor Dodge State Park

Devil’s Lake State Park, 1919

Wyalusing State Park

NICK

COLLURA/TRAVEL WISCONSIN

Northern Highland-American Legion State Forest, Crystal Lake campground

LEARN MORE

Use the DNR’s Find a Park tool to search for recreational opportunities throughout the Wisconsin State Park System. Scan the QR code or go to dnr.wi.gov/tiny/801

Elroy-Sparta State Trail, circa 1967

Peninsula State Park

Brule River State Forest, 1943

Military Ridge State Trail

TAKE THE LONG WAY

WISCONSIN’S STATE TRAILS ARE PERFECT

FOR PUTTING IN SOME MAJOR BIKING MILES

ANDREA ZANI

SCENIC WISCONSIN STATE TRAILS make for beautiful biking opportunities as summer blends into autumn. Tree-lined routes turn so many shades of burgundy, yellow, red and orange it can be like pedaling through a Bob Ross painting.

Short rides are fun for sure, but longer rides offer an added element of two-wheeled workout and extended adventure to go with the picturesque scenery.

Our friends from the Wisconsin Bike Fed know a thing or two about lengthier cycling trips. They bring us the annual Ride Across Wisconsin and programs such as Cycling Without Age and Wisconsin Bike Week.

We asked the Bike Fed folks to help with some longer-haul ride planning for fall, and they had plenty of tips for routes and preparation. Plus, we tapped into the DNR’s own Wisconsin State Park System resources to put together a few suggestions for taking the long way, bike-wise, this fall.

CAPITAL CITIES CONNECT

Dave Schlabowske, former executive director for Bike Fed, loves to continue sharing his passion for cycling through blog posts, social media and other means. A few years ago, he wrote about biking from the Mississippi River to Lake Michigan (Potosi to Milwaukee).

We’ve modified that route here, taking about half of it and using Schlabowske’s insights to create a ride from Wisconsin’s first capital city, Belmont, to the current capital of Madison.

START: At Belmont, in Lafayette County, you can hit the Pecatonica State Trail at Bond Park (South Park Street).

PEDAL: Bike 10 miles through the picturesque Bonner Branch Valley along the old Milwaukee Road railroad corridor and link to the Cheese Country Trail in Calamine for a ride of 35 miles or so through Darlington and the villages of Gratiot, South Wayne and Browntown to Monroe. From there, connect to the Badger State Trail (West 21st Street) for the trip up to Madison.

TRAVEL TIP: Schlabowske noted that because both the Pecatonica State Trail and Cheese Country Trail allow year-round ATV use, they might present a bit rougher surface than trails that don’t permit motorized traffic. Bikes with wide tires and lower air pressure for better stability are the equipment of choice, he suggested.

END: At Madison, you’ll find a host of other trail options, including the Capital City State Trail and the Southwest Bike Path. Or if you really want to keep rolling, hit the Military Ridge State Trail (parking at old PB and East Verona Avenue in Verona), which goes west about 40 miles to Dodgeville.

ADDED SPIN: Start in Platteville on the Mound View State Trail (near East Mineral Street and Valley Road at Rountree Branch Trail) and head the 7 miles to Belmont, then start the above journey. Or join the Badger State Trail at Monticello after biking over on the Sugar River State Trail from either New Glarus (parking at 418 Railroad Street) or downtown Brodhead.

Sugar River State Trail

READY TO RIDE

PLANNING A LONG BIKE TRIP involves more than just choosing the right route.

EXTEND your mileage gradually to build up to a longer ride.

PICK the right bike. A road bike is fine for paved surfaces and smoother trails, while mountain or gravel bikes are best for more rugged rides.

DECIDE if you will need to stay overnight along the way and plan accordingly. You can reserve hotels and similar accommodations or try bikepacking — cycling’s version of hiking and camping. The Wisconsin State Park System offers plenty of terrific camping options close to bike trails.

GEAR UP as needed for whatever way you choose to go. A tent, sleeping bags and sleeping pads can be carried with panniers (bags attached to a rear rack on a bike), while handlebar bags, frame bags and seat packs can carry smaller items such as bike tools, water bottles, first-aid kits and cell phones.

HYDRATE and pack snacks to keep up your energy levels.

WEAR a helmet for safety and plan for weather conditions you might encounter along the way by packing appropriate clothing.

ALERT others to your plans and arrange rides or “sag wagon” support for supplies and other help if needed.

— ANDREA ZANI

LEARN MORE

Here are several resources to help you plan a long-haul biking trip.

y The Wisconsin Bike Fed is a great source for all things cycling in Wisconsin, wisconsinbikefed.org.

y Local bike shops are excellent places for everyone from beginners to expert riders to find information and equipment, wisconsinbikefed.org/ explore/bike-shops.

y To locate a state trail or other state property for your next ride or bikepacking adventure, use the DNR’s Find a Park tool, dnr.wi.gov/tiny/801

y A state trail pass is required for riders age 16 and up on most state trails, dnr.wi.gov/tiny/1556.

y Regarding electric bikes, they are allowed on many bicycle trails in Wisconsin but must observe a 15-mph speed limit when the motor is engaged. See the DNR’s bicycle trails webpage for more, dnr.wi.gov/tiny/3776

y Wisconsin has hundreds of miles of state trails, including 39 rail-trails. For details, check dnr.wi.gov/tiny/1596.

Take plenty of water on a longer biking trip and consider carrying small tools for possible maintenance needs.

Kendall Depot on the Elroy-Sparta State Trail includes a railroad history museum.

URBAN LAUNCH

The Bike Fed’s annual Ride Guide is a great resource for all things Wisconsin cycling, and the 2024 issue included a nice tale from Jeremy Ault, an educator at Escuela Verde charter school in Milwaukee and a Bike Fed supporter.

Ault recounted a trip he took with Anthony Casagrande, education instructor and lead mechanic for Bike Fed, and 10 students from Ault’s high school.

“We took advantage of Escuela Verde’s location right along the Hank Aaron State Trail and pieced together a course to Delafield that went through Waukesha, hooking up with the Glacial Drumlin State Trail,” Ault wrote.

Here’s similar riding that uses both of those trails.

START: Join the Hank Aaron State Trail at Milwaukee’s Lakeshore State Park on Lake Michigan.

PEDAL: Take the Hank Aaron about 12 miles west to Dearbourn Park in Wauwatosa and connect with the Oak Leaf Trail. Go south to Greenfield Park, where you’ll find the New Berlin Recreation Trail to take you west to Waukesha. Use local trails and roads to reach the trailhead for the Glacial Drumlin State Trail at Waukesha’s Fox River Sanctuary (North Prairie and West College avenues), and head west.

TRAVEL TIP: When heading out with riders of different experience levels as Ault was, he noted the importance of “being mindful of the various riding abilities.” He and his group took a “slow and deliberate pace on the trail,” stopping frequently for rest and hydration breaks.

END: From Waukesha, the Glacial Drumlin State Trail goes all the way to its western terminus at Cottage Grove, a 52-mile stretch.

ADDED SPIN: The Oak Leaf Trail is a great way to get around the Milwaukee metro area. It features more than 135 miles of paved pathways for biking, running, hiking and roller-blading, with many access points and connections to other area trails.

Hank Aaron State Trail

Tunnels on the Elroy-Sparta State Trail make the ride fun, but watch out for slippery surfaces when passing through.

Glacial Drumlin State Trail bridge

CLASSIC EXCURSION

No discussion of biking on Wisconsin’s beautiful state trails would be complete without mentioning the grandaddy of them all, the Elroy-Sparta State Trail, established in the 1960s and considered the nation’s first rail-trail.

START: In Elroy, in Juneau County, hop on the Elroy-Sparta State Trail (Main Street and State Highway 80).

PEDAL: Ride 32 miles northwest through scenic prairies, wetlands and farmlands, passing through the villages of Kendall, Wilton and Norwalk. A restored railroad depot in Kendall serves as trail headquarters and includes a railroad history museum.

TRAVEL TIP: While three rock tunnels along the route make this ride even more fun, it can be a bit tricky to navigate them because of the dark and possibly wet, slippery conditions. Walking bikes through the tunnels is recommended, and bring a flashlight or headlamp.

END: Sparta, the county seat of Monroe County, is the western terminus of the Elroy-Sparta State Trail — or the start of the trail, if you head west to east.

ADDED SPIN: For a longer ride, catch the 400 State Trail at its headquarters in Reedsburg (Railroad and South Walnut streets) and bike 22 miles northwest to Elroy for the start of the Elroy-Sparta ride.

Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest, where the Nicolet State Trail follows an 1800s rail corridor through three counties.

THE LONG OF IT

SOME STATE TRAILS take you a long way in and of themselves. Here are four of the state’s longest trails to try.

Mountain-Bay State Trail: This rail-trail runs 83 miles between Rib Mountain near Wausau and Green Bay — the geologic features that give the trail its name — traveling through Marathon, Shawano and Brown counties.

Nicolet State Trail: Northeastern Wisconsin is home to this county-operated trail (Oconto, Forest and Florence counties), which meanders more than 89 miles through the Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest from Gillett to the Michigan border. It follows the original 1800s rail corridor that served the timber industry in the state’s pine and hardwood forests.

Tuscobia State Trail: This 74-mile trail travels from Park Falls to just north of Rice Lake, passing through part of the Flambeau River State Forest along the way. It connects seven small communities in Price, Sawyer, Washburn and Barron counties and meets up with the next trail on the list for even more riding.

Wild Rivers State Trail: Connecting to the Tuscobia near Rice Lake, this especially scenic northwest Wisconsin trail stretches 104 miles in Barron, Washburn and Douglas counties. It runs through areas of rich wildlife habitat, lush forests and striking waterways that include the Namekagon River, part of the St. Croix National Scenic Riverway, before ending near Superior.

— ANDREA ZANI

Andrea Zani is managing editor of Wisconsin Natural Resources magazine.

DANIEL ROBINSON

• HUNTING-FREE STATE PARKS •

Find them here

EMMA MACEK

IT’S FALL IN WISCONSIN, and for some, it’s the long-awaited hunting season. For others, it’s the perfect time to hit the trails with prime temperatures and beautiful fall scenery.

Most Wisconsin state parks have areas open to hunting and trapping during the state’s hunting sea-

LEARN MORE

sons, but a few properties don’t allow hunting due to their size, proximity to urban or residential areas, environmental sensitivity and other factors.

If you prefer your fall adventure to be hunting-free, plan a visit to one of these state parks.

Looking for other areas to explore? Many state properties only allow hunting during specific seasons or in certain areas. There are plenty of no-hunting zones throughout the Wisconsin State Park System. Scan the QR code or go to dnr.wi.gov/topic/parks/hunt to learn more and find hunting and trapping maps for state parks, including areas closed to those activities.

DANIEL ROBINSON

Lakeshore State Park on Lake Michigan

COPPER CULTURE STATE PARK

Oconto

Dive into history to learn about the ancestors of the Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin who lived and traveled around the upper Great Lakes region and made various tools, projectile points and innovative fishing gear using copper from the area.

In addition to a museum with artifacts and exhibits, you’ll find a historical monument and a meadow. For hiking, there are four family-friendly, year-round trails on the property with views of the Oconto River.

A vehicle admission pass is not required to use the park. Copper Culture Museum, operated by the Oconto County Historical Society, is free and open daily from Memorial Day weekend through Labor Day and most weekends in September. Check the city of Oconto and the Oconto County Historical Society Facebook pages for specific fall weekend opening dates and times.

GOVERNOR NELSON STATE PARK Waunakee

Located on Lake Mendota, Governor Nelson State Park mixes nature with proximity to Madison. This day-use park offers a beach, boat launch, picnic areas and over 8 miles of trails through diverse habitats. Check out the fall colors, do some birdwatching and hike to see restored prairie and Native American effigy mounds. Fun fact: You can see the State Capitol across the lake.

HERITAGE HILL STATE PARK Green Bay

Learn about Wisconsin’s past at Heritage Hill State Park. This outdoor museum features a paved path connecting 24 structures highlighting Wisconsin’s history. The Fox River State Trail runs through the property and can be accessed near the river at the park.

The park and museum are operated by the Heritage Hill Corp. There is a per-person admission fee; a Wisconsin state park vehicle admission pass is not required at the property.

LAKESHORE STATE PARK Milwaukee

This urban park is adjacent to the Henry Maier Festival Park (Summerfest grounds) and Discovery World on Lake Michigan in downtown Milwaukee. Accessible paved trails travel along the lake and through short grass prairies, with views of Milwaukee’s skyline. Those trails also connect to other lakefront parks and the Hank Aaron State Trail.

In the fall, tree foliage, native grasses and flowers change color. You might see purple aster flowers in the park’s prairie areas and, once the temperature drops, trout or salmon species jumping out of the water while they’re moving to spawn in shallower areas of the basin. Lakeshore is also on a migratory path for many birds, so the park is a great birdwatching spot for species like black-bellied plovers or American coots.

LOST DAUPHIN STATE PARK De Pere

Emma Macek is a public information officer in the DNR’s Office of Communications.

Lost Dauphin State Park is a small hidden gem along the Fox River. The park has rolling hills, towering trees, river views, a play area for kids and picnic tables under a pavilion. The park is operated locally by the town of Lawrence.

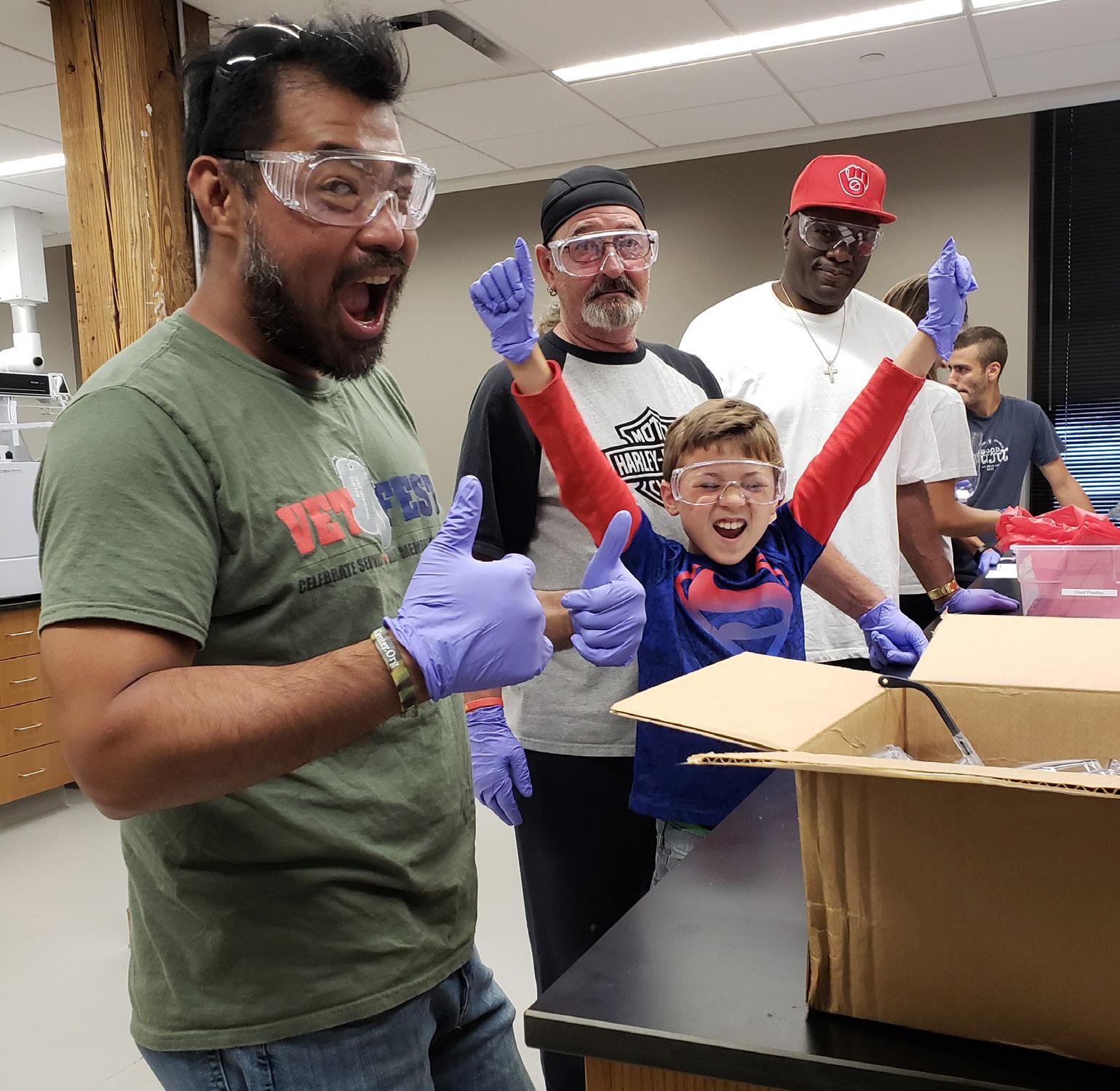

SUPERB SUPPORT for SAFETY INSTRUCTORS

DNR outdoor skills trainers make backing our volunteers job No. 1

Safety education activities require the help of many volunteers, who in turn are supported by DNR staff.

BEHIND EVERY WISCONSIN VOLUNTEER

safety instructor is someone like Kayla Sasse.

Sasse, a native of Lincoln County in north-central Wisconsin, is one of five outdoor skills trainers with the DNR. It’s a job title that’s had more than a few people wrinkling their brow and asking for a definition.

“Yes,” she said with a laugh. “I get asked a lot what that title means and what is it that I do.”

At the most basic level, an outdoor skills trainer, or OST, is a safety specialist who coordinates the recreational safety and education programs taught to youth and adults throughout the state. Courses are taught by hundreds of volunteer safety instructors and focus on four areas: ATV/UTV, snowmobile, boating and hunting.

But what specifically does an OST do?

“The OST’s primary job is to work with the volunteer safety instructors,” said Sasse, a UW-Stevens Point graduate with degrees in forestry recreation and adventure education. “We provide the curriculum — it’s standardized.”

That makes teaching the safety classes easier for the instructors, Sasse added.

“Imagine if every instructor had to make up their own curriculum for the different safety courses. It would be difficult to know where to start,” she said. “We provide all the training, certifications and equipment they need.”

Volunteer safety instructors teach in each region of the state. Some specialize in one area of expertise while others teach in two, three or even all four areas.

The OST team supports each instructor so they can be most effective and also enjoy providing a valuable service in the name of safe outdoor recreation.

SEASONAL CHANGES

Just as most Wisconsinites are familiar with adjusting their layers as the seasons change, the OST team also sees its year-round duties dictated by weather.

“There is a seasonality to being an outdoor skills trainer,” Sasse said. “Spring is event season. That’s when you’ll see us at sports shows and community events.”

JOANNE M. HAAS

The usually slower months of summer offer the OST team valuable time to train instructors. “The focus is basic safety,” Sasse said.

Fall is always busy, with numerous hunting seasons opening from September through November.

“In the winter, we switch to ATV and snowmobile safety classes and helping those volunteer instructors,” Sasse said, adding it’s also a time to check on the equipment used in safety classes.

MORE, PLEASE

While there are thousands of safety instructors who volunteer their time to ensure outdoor enthusiasts can access basic safety training, Sasse said, “We always need more!”

A major part of the OST job is recruiting instructors to continue the volunteer work that’s so integral to the DNR’s Public Safety and Resource Protection division, which includes the OST team. The division’s top mission is to protect the state’s precious natural resources and ensure the safety of all who enjoy them.

The OST team uses a basket of strategies involving traditional and social media outreach and event appearances to recruit volunteers. Schools also have been a resource, as teachers are already trained in teaching skills and often are well-versed in educating various ages.

“We have recruited safety instructors from several schools across the state,” Sasse said. “We certify teachers through professional development courses.”

Still, she said, the most effective messengers often are the volunteer safety instructors themselves. “A lot of it is word of mouth — the instructors do a lot of the recruitment.”

Sasse, an OST since 2022, is based in Green Bay and handles the state’s northeast region, where she has about 1,000 volunteer safety instructors. There are four other state regions, each with a dedicated OST: Linda Xiong, Eau Claire, west-central; Kimberly Chroninger, Fitchburg, south-central; Spencer Jost, Waukesha, southeast; and Katie Renschen, Rhinelander, northern.

ONLINE AND IN-PERSON

There are fewer instructors today than about a decade ago due to the creation of online-only certification options, but not everyone prefers that method.

“There will always be a demand for in-person instructors,” Sasse said. “Those in-person classes are easy to fill.”

The classes can continue to be offered, thanks to the dedication of volunteer safety instructors.

“It is a lot for volunteers,” Sasse said. “But many are committed to running one or more (classes) in their communities, and it helps those communities.”

Joanne M. Haas is the public information officer for the DNR’s Division of Public Safety and Resource Protection.

LEARN MORE

Volunteer safety instructors can get certified by attending a DNR training session or connecting with a local instructor group. The minimum age for full certification is 18, but a junior instructor program welcomes ages 12-17. A background check is required for all new instructors. Scan the QR code or check dnr.wi.gov/tiny/3841 to learn more and find contact information for the outdoor skills trainer in your region.

Kayla Sasse and other DNR outdoor skills trainers often find outreach opportunities at events such as the National Archery in the Schools Program.

JOANNE M. HAAS

DAVID NEVALA

Proper handling of firearms is a key component of hunting safety instruction.

STUDY TELLS THE

STUDY TELLS THE

Large-scale research project illustrates impacts in Wisconsin

CAITLYN NALLEY

FOR MANY WISCONSINITES, fall is synonymous with deer hunting. This not only means time spent in the field pursuing Wisconsin’s most iconic wild animal, but also brings chronic wasting disease front and center for avid deer hunters and conservationists alike.

For those unfamiliar with CWD, it is a disease that can affect animals in the cervid family such as deer, elk, moose and reindeer. It is caused by infectious, misfolded proteins known as prions that progressively accumulate throughout the body, including in the brain, eventually leading to cognitive decline and death.

Because CWD is always fatal, a big concern is its potential impact on deer populations. This is what prompted the DNR to launch the Southwest Wisconsin CWD, Deer and Predator Study in 2017.

Led by DNR deer research scientist Daniel Storm, Ph.D., the Southwest Study sought to provide the most comprehensive understanding yet of how CWD is impacting Wisconsin’s deer population.

The sheer scale of the project was massive, with over 1,100 captured and collared deer and more than 100 collared deer predators (bobcats and coyotes).

“We worked in the part of Wisconsin where CWD has been around the longest and where CWD prevalence is highest,” Storm said. “This ensured that we’d collar a good sample size of CWD-infected deer.”

KEY TAKEAWAYS

For years, scientists closely monitored the lives of these collared animals, performed necropsies (animal autopsies) when they died and thoroughly analyzed the data. Their hard work and the robust study design resulted in two main takeaways.

First, for both females and males, the probability of a CWD-infected deer surviving to the next year was substantially lower than that of an uninfected deer surviving. For infected females, the survival rate was 41%, compared to 83% for uninfected females, and for infected males it was 17%, compared to 69%.

Scientists used this finding, in conjunction with data on deer recruitment (deer that survive to around 6 months of age are considered “recruited” into the population), to model how population growth might change depending on the prevalence of CWD.

The model predicted that when about 29% of adult female deer are CWD-infected, the local deer population can be expected to decline.

CWD STORY

CWD STORY

DATA DETAILS

So, CWD spells trouble for white-tailed deer in Wisconsin, but how do we know that CWD specifically is what’s causing these deer to die? To answer that, let’s look at the life of deer #7202, one of the 1,133 deer included in the Southwest Study.

On Feb. 27, 2017, the research team captured #7202, a 4-year-old doe in Grant County, and fit her with a

The Southwest Wisconsin CWD, Deer and Predator Study has provided the best look yet at how chronic wasting disease is affecting the state’s deer population.

GPS tracking collar. During this initial collaring, the team also performed a quick biopsy by taking a small amount of rectal tissue and later testing it for CWD.

The test revealed that #7202 was CWD-positive. Despite this, she did not appear sick at capture. In fact, she appeared to be in great physical condition and weighed a whopping 170 pounds, considerably heavier than the weight of an average adult doe (about 145 pounds).

JERRY

DAVIS

Just three months after her initial capture, on May 29, 2017, scientists received an alert from #7202’s collar indicating she had died. The team rushed out and, after locating her at the base of a hill she had fallen down, brought her body to UW-Madison for a necropsy.

#7202 now weighed an alarming 106 pounds, but there was minor predator scavenging, so she probably weighed around 110 pounds at death. In the time since her initial capture, she had lost roughly 35% of her body weight, including all body fat and some muscle mass.

The necropsy also revealed that #7202 had contracted pneumonia and developed holes in her brain, known as spongiform encephalopathy, typical of endstage CWD.

“CWD-infected deer produce more saliva and have trouble swallowing, so saliva or food can go down the wrong pipe, which can introduce bacteria to the lungs and cause infection,” Storm explained.

“It’s also important to note that this deer starved during a time of plentiful food, so we’re confident that the starvation was driven by CWD, not food availability.”

Sadly, #7202 was also found to be carrying a mummified fetus, meaning she had been healthy enough to get pregnant about seven months before her death.

END RESULTS

Along with the extreme and rapid weight loss, the case of deer #7202 illustrates just how brief and severe the end stage of CWD can be compared to the disease’s entire infection period, which is believed to be between 18 and 24 months. However, it’s important to note that infected deer are still spreading the disease well before they might appear sick.

Every deer in the Southwest Study received a unique number for tracking.

#7202 is one of many deer from the Southwest Study that demonstrates the end result of CWD infection. Although each deer has its own unique circumstances, they all consistently tell the same story: CWD is directly reducing deer survival.

So what does this mean for Wisconsin’s white-tailed deer?

The bottom line is that where CWD prevalence is high, Wisconsinites can expect a smaller, sicker deer herd. Fortunately, however, Wisconsin does have an otherwise highly productive deer population, with uninfected deer boasting relatively high survival rates.

This means we’ll always have deer — they won’t go extinct. And while it can understandably feel a bit doom and gloom to talk about CWD, it’s important to acknowledge the threat it poses, recognize opportunities and focus on what we can do.

HOW YOU CAN HELP

Aside from prevention, thorough sampling to detect new introductions as early as possible and active steps to reduce disease transmission are our best tools to combat CWD, especially in areas of the state where the disease is not yet highly prevalent.

If you’re a hunter, the best thing you can do to help is to keep hunting. It’s a powerful population management tool because, when the hunter harvest is high enough, it can help keep local deer populations at reasonable levels and thus help reduce CWD transmission rates.

If you have opportunities to harvest more deer than you normally do, consider it! Just be sure to follow all listed baiting and feeding bans, dispose of any carcasses properly and, if you harvest a deer, get it tested for CWD.

More than 1,100 deer were collared as part of the Southwest Study.

ROBERT ROLLEY

JERRY

Searching for fawns to tag as part of the Southwest Wisconsin CWD, Deer and Predator Study.

Testing is a valuable source of information that allows scientists and decision makers to better understand how CWD is spreading throughout the state, especially in the identified priority sampling areas. For the most recent sampling map, see dnr.wi.gov/tiny/3791.

If you do harvest a deer, keep in mind that although there have not yet been any reported cases of CWD transferring to humans, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advises against consuming meat from deer testing positive for the disease.

If you don’t hunt, review the deer feeding regulations in your county, dnr.wi.gov/topic/hunt/bait. Even if feeding is allowed where you live, consider avoiding feeding deer in your backyard. While well-intentioned, feeding sites can cause deer that might not otherwise interact to come together and potentially transmit CWD and other diseases.

Finally, anyone can help by learning more about CWD, asking questions and attending future public forums on the subject.

The primary results of the Southwest Study have been an important step in gaining a better understanding of CWD in Wisconsin. The unprecedented dataset the project has provided will continue to inform additional analyses well into the future.

As we look toward that future, we hope that by sharing the science of the Southwest Study today, we motivate more hunters, landowners and wildlife lovers to help combat the spread of CWD in our state.

Caitlyn Nalley is a communications specialist in the DNR’s Office of Applied Science.

LEARN MORE

To see additional case examples of deer from the Southwest Wisconsin CWD, Deer and Predator Study, check out the study’s Field Notes newsletter, dnr.wi.gov/tiny/3796. (Please note that in an effort to best explain the science behind the Southwest Study results, this newsletter contains images of dead deer that may be upsetting to some readers.) More information on CWD as well as guidelines and best practices can be found on the DNR website, dnr.wi.gov/tiny/3786

Wood you know Wisconsin forest products are all around us

Money doesn’t grow on trees, but toilet paper, mulch and maple syrup do — kind of. Those three things and many more have something in common: They’re all Wisconsin forest products.

Wisconsin’s forest products industry is a powerhouse, contributing $42 billion in total economic value to the state, ranking second nationally for production value. The industry also ranks sixth nationally in generating forestry employment, with more than 123,000 related jobs in the state.

Forest products are not only important to Wisconsin’s economy, but they positively impact our lives. From paper products such as food packaging and toilet paper to lumber used to build homes, flooring and furniture, we depend on forest products daily.

Forest products also play a vital role in mitigating the changing climate. Trees store carbon, offsetting greenhouse gas emissions while they are growing, and they retain the stored carbon throughout the useful life of forest products.

From the backyard to the doctor’s office, Wisconsin forest products are everywhere.

LEARN MORE

Harvesting trees in the name of forest management has benefits beyond producing products we use every day. Forest management is important to encourage tree growth, manage habitat for wildlife and improve water quality. Find out more about Wisconsin’s forest products industry and DNR forest management efforts. Scan the QR code or check dnr.wi.gov/tiny/3866.

Andi Sedlacek is communications director for the DNR.

ANDI SEDLACEK

IN THE KITCHEN

› Locally produced maple syrup

› Liquid smoke

› Coffee filters

› Wood cutting boards

› Wooden rolling pins

› Wooden spoons

IN THE MAIL

› Cardboard and paper packaging

› Shipping envelopes

› Excelsior for packaging (thin, curly wood shavings used for packing or stuffing)

IN THE BACKYARD

‹ Mulch ‹ Wood chips

‹ Skateboards ‹ Baseball bats

› Cedar fence posts and furniture

‹ Wood pellets for heating and smoking meat/barbecuing

‹ Mushroom logs for growing mushrooms

AROUND THE HOUSE

› Toilet paper › Toilet seats

› Paper › Paper grocery bags

AT SCHOOL OR IN THE OFFICE

› Wooden alphabet blocks

› Desks › Copier paper

› Construction paper

› Holiday trees and décor › Wooden toys

› Softwood and hardwood lumber to build homes, furniture and flooring

FOR FOOD PACKAGING

› Cardboard strawberry containers

› Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup wrappers

› Cupcake wrappers

› Popcorn bags

WOOD ITEMS FROM URBAN TREES*

› Furniture › Wall panels › Flooring

*The highest value of an urban tree is when it’s living; however, if a tree in an urban area is killed or damaged and needs to be removed for safety reasons, there are many ways to give it a new purpose as a forest product.

AT THE DOCTOR

› Medical paper products

› Dental bibs

› Moist towelettes

› Surgical towels

› Disposable exam gowns

by Jada Thur

Illustrated

Lessons from Water

Milwaukee-area groups learn stewardship, leadership, appreciation

ANDREA ZANI

WHAT DID YOU DO THIS SUMMER? It’s a common question heading into fall as people catch up with news among friends.

For a cohort of community groups working with Milwaukee Water Commons, the answer might feel especially satisfying: They helped to “make a splash at summer Water School.”

For the past 10 years, teams from Milwaukee-area neighborhood-based groups have joined together at Water School, developed by Milwaukee Water Commons to foster local leadership through water education, develop stewardship projects and build cross-community relationships.

Each Water School summer session consists of five teams of five people of all ages. With four meetings held at different Milwaukee-area waterways, participants learn about important water issues from local experts while also enjoying activities such as fishing, kayaking and art-making to grow their knowledge and build teamwork.

“The name might make it feel like you’re going to be in a classroom, but you’re really going to be out, in and on water,” said Janet Veum, director of communications for Milwaukee Water Commons.

Once Water School wraps up, participants receive a small grant from Milwaukee Water Commons to develop a project in their own neighborhoods.

Water School supports the organization’s vision of Milwaukee as a model Water City, encouraging stewardship at grassroots levels, said Rhonda Nordstrom. As community education manager for Milwaukee Water Commons, Nordstrom coordinates programming for the nonprofit.

“We say we’re fostering a city network of leadership on water,” she said. “Water School is one of the ways we do that.”

PASSION AND INSPIRATION

Water School participants are people passionate about water and committed to supporting the watersheds of Lake Michigan and the Milwaukee River Basin. Many come to it after hearing from someone else who has completed the program.

The Menomonee River, including this segment in Wauwatosa, is part of the Milwaukee Estuary.

WILLIAM KAISER

Water School

ABOUT THE MILWAUKEE ESTUARY AREA OF CONCERN

Milwaukee is a city built on water, but the waterways we see today look significantly different than they did in the 1800s. As the city grew on the ancestral homelands of the Potawatomi, Ho-Chunk and Menominee, Milwaukee was drastically modified.

Rivers were straightened, dredged and widened to accommodate large commercial shipping vessels and industry. Manufacturing companies and factories took advantage of the area’s accessibility to Lake Michigan for shipping and commerce.

Milwaukee’s industries (it was the largest leather producer in the world by the 1900s) allowed the economy to prosper and society to advance. But that came at a cost to the environment and to water quality during a time before regulatory safeguards were in place.

The Milwaukee Estuary was designated an Area of Concern as part of the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement in 1987. Now, the DNR and many partners, including Milwaukee Water Commons, work together to engage everyone in finding ways to address water quality issues.

For details about the Milwaukee Estuary and Wisconsin’s other Great Lakes Areas of Concern, check dnr.wi.gov/tiny/3846

Fishing at Mauthe Lake, Kettle Moraine State Forest-Northern Unit, was one of the hands-on outings for recent Water Schoolers.

Water School participants have fun learning at the Global Water Center in the Walker’s Point neighborhood of Milwaukee.

Angelique Sharpe fishing at Mauthe Lake.

And Water School graduates often create lasting relationships that enhance the work they do on behalf of clean water, Veum noted.

“It’s not just the projects, it’s also the lasting connections people make,” she said. “People meet at Water School and realize they have this common passion for water, then end up working together for years.”

Nordstrom added that the sense of common purpose can make Water School “inspirational and motivational.”

“They’re learning about neighborhood-based initiatives that are happening throughout the city,” she said. “So there’s lots of inspiration that comes from finding themselves in a roomful of folks who are doing things and dealing with the same issues they care about, too.”

Cohorts have included groups like the Center for Veterans Issues, CORE El Centro, Discovery World, Friends of Lakeshore State Park, Kinnickinnic River Neighbors in Action, Milwaukee Public Museum and Urban Underground. Schools, faith-based groups and others also have learned from Water School and put projects into action.

“There are so many different approaches people take,” Nordstrom said. “They’re putting on their own

workshops and trainings, investing in local infrastructure like rain capture systems, putting on a camp for young people. It really is such a range.

“People feel so much flexibility and opportunity to build what they want to see.”

Water School has become such a success, it has even expanded to a winter session. The program helps “build a broad network” of people who care about water and related issues, Nordstrom said, “and it connects people with resources throughout the city.”

CREATING CONNECTIONS

One of the most unique things about Water School is how it incorporates arts and culture to teach about and celebrate water.

“There’s this idea that people have been disconnected from water and in order to steward it well and address water issues, people need to reconnect,” Nordstrom said. “Bringing creativity into the process helps to do that.

“Water School is very arts and culture focused to make space for people.”

Enjoying water and interacting with it also are key components of Water School, she added, with sessions “really centered on the recreation experience surrounding water.” State properties play a big role there.

Areas explored during summer Water School sessions have included Lincoln Creek in Havenwoods State Forest, Mauthe Lake in the Kettle Moraine State Forest-Northern Unit and Lakeshore State Park. The first winter Water School featured a cross-country skiing outing in Kettle Moraine’s Lapham Peak unit.

“We really appreciate our relationships with our nearby state parks,” Nordstrom said.

Even hiking at places like the Ice Age Trail, which passes near Milwaukee, can help teach about connections to water through its history and geology.

“Let’s remember how the Great Lakes even formed,” Nordstrom said.

“Because water is so central to Milwaukee’s location and formation and history, I think people walk away not having just learned about water and water in the city, but they’ve learned about the city itself.

“Folks who have lived in Milwaukee their whole lives have learned the history of a neighborhood they never knew before. And it was through the gaze of water that they got that.”

Andrea Zani is managing editor of Wisconsin Natural Resources magazine.

For a look at one participant’s experience with Water School, see Page 44.

Leading the way on water

MILWAUKEE WATER COMMONS was founded about a decade ago — shaped by feedback from throughout the greater Milwaukee area, said Rhonda Nordstrom, the nonprofit group’s community education manager.

“That really became an anchor for the work,” she said of public input.

With the Milwaukee Estuary designated an Area of Concern, the organization sought to engage everyone in finding ways to address water issues. A “Water City agenda” was created, focusing on six pieces: drinking water, arts and culture, water quality, education and recreation, blue green jobs and green infrastructure.

“Water School was one of the first programs of the organization,” Nordstrom said, developed to advance those six initiatives through education and funding of neighborhood projects.

“When teams go to Water School, there are very few parameters on the grant funding except that they speak to at least one of those initiatives,” she said. Groups can lead the way and take action “hyperlocally,” she added.

Water School isn’t Milwaukee Water Commons’ only successful water-focused program. Other work includes:

y We Are Water, an annual event celebrating shared waters and community.

y Branch Out Milwaukee, supporting the city’s urban tree canopy, which can help mitigate issues with urban flooding, storm damage and air quality.

y Beach Ambassador Project, partnering with the Milwaukee Community Sailing Center, Milwaukee Riverkeeper, Wisconsin Sea Grant and local water safety leaders to hire ambassadors who help communicate beach conditions along Lake Michigan and increase water safety awareness city-wide.

y Artists in Residence, tapping local artists who use their work to highlight themes of common waters and community engagement.

For details about the work of Milwaukee Water Commons, including its Water School program and how you can get involved, see milwaukeewatercommons.org.

— ANDREA ZANI

Cohort from the first winter Water School, Havenwoods State Forest.

WHEN ALEJANDRA JIMENEZ WAS GROWING UP in Cuernavaca, Mexico, her area didn’t have consistent access to clean drinking water.

The landlocked community south of Mexico City wasn’t near a large freshwater reservoir source and lacked some of the needed infrastructure to deliver water from its underground aquifer to individual homes. She remembers her family regularly bringing in water as needed for drinking and cooking.

The experience helped teach her the vital importance of water. “I really know how important it is to conserve water,” she said.

She also developed a deep appreciation for this indispensable resource.

“My whole life, I’ve spent time outdoors exploring. I feel connected to water,” said Jimenez, who now lives in Milwaukee — with its welcome access to inland lakes, rivers and Lake Michigan.

“It’s so calming, I love to swim. I feel so comfortable being around water and know how important it is.”

That’s a big reason why Jimenez was so excited when she learned about Milwaukee Water Commons’ Water School.

ANDREA ZANI

When her father visited from Mexico, Alejandra Jimenez was able to take him along to a Water School session that featured canoeing at Mauthe Lake in the Kettle Moraine State Forest-Northern Unit.

Alejandra Jimenez often uses her experience as an educator and her knowledge of traditional Mexican dance to highlight the importance of water.

“I found out about it on social media,” recalled Jimenez, a 2024 Water School participant. “It said it was a school about water, and that caught my eye.”

She wasn’t disappointed in the experience. Beyond providing many new and fun lessons about water, it also allowed her to connect with others of all ages and backgrounds who feel the same way she does about the value of water.

“The first thing I saw was the welcoming environment,” she said of Water School. “It was intergenerational, with youth and adults. It was really neat to see all the different ages meeting about water, seeing the point of view of different backgrounds.”