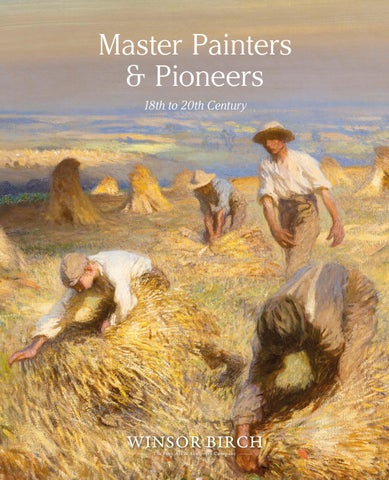

Master Painters & Pioneers

18th to 20th Century

The Fine Art & Sculpture Company

CONSIGNED FROM PRIVATE COLLECTIONS 18th to 20th Century

A SELLING EXHIBITION

Monday 28 July – Saturday 16 August 2025 Exhibition at GALLERY 8 8 Duke Street, St James’s London SW1Y 6BN 10 am – 6pm daily

Enquiries

Grant Ford grant@winsorbirch.com +44 (0)7770 787160

Charlie Minter charlie@winsorbirch.com +44 (0)7872 621632

The Fine Art & Sculpture Company

1 The Parade, Marlborough, SN8 1NE, UK www.winsorbirch.com enquiries@winsorbirch.com | +44 (0)1672 511058

Foreword

Master Painters & Pioneers chronicles an extraordinary journey of artistic achievement, from the founding principles of the Royal Academy to the pivotal moment when that same institution finally welcomed female members. This exhibition, drawn from distinguished private collections built over decades of passionate collecting, narrates the story of British and European art through its most influential figures.

The exhibition begins with Sir Joshua Reynolds, the founding President of the Royal Academy, whose classical vision established the institutional framework that would both support and limit artistic growth for generations. From Reynolds’ 18th-century authority, we see the gradual rise of new sensibilities: the atmospheric poetry that would challenge academic orthodoxy and the social awareness that would redefine the purpose of art.

We witness the revolutionary achievements of the 19th century’s greatest innovators. Edward Burne-Jones’s mystical St Barbara, St Dorothy and St Agnes transforms Pre-Raphaelite idealism into profound spiritual symbolism; James Tissot’s sophisticated modernism captures the cosmopolitan elegance of contemporary life while Frederic Leighton’s subtle portraits are exemplars of Aestheticism. These works mark the moment when British art began its dialogue with Continental innovation, a conversation that reaches sublime expression we see reflected in Camille Pissarro’s Impressionist mastery and Henri Martin’s Post-Impressionist synthesis of colour theory with humanistic vision.

Sir George Clausen’s agricultural scenes showcase how sophisticated pictorial techniques can express deeply empathetic themes, transforming everyday labour into a universal reflection on human dignity. His work bridges the gap between Victorian social awareness and modernist aesthetic independence, laying the groundwork for the bold new voices of the 20th century.

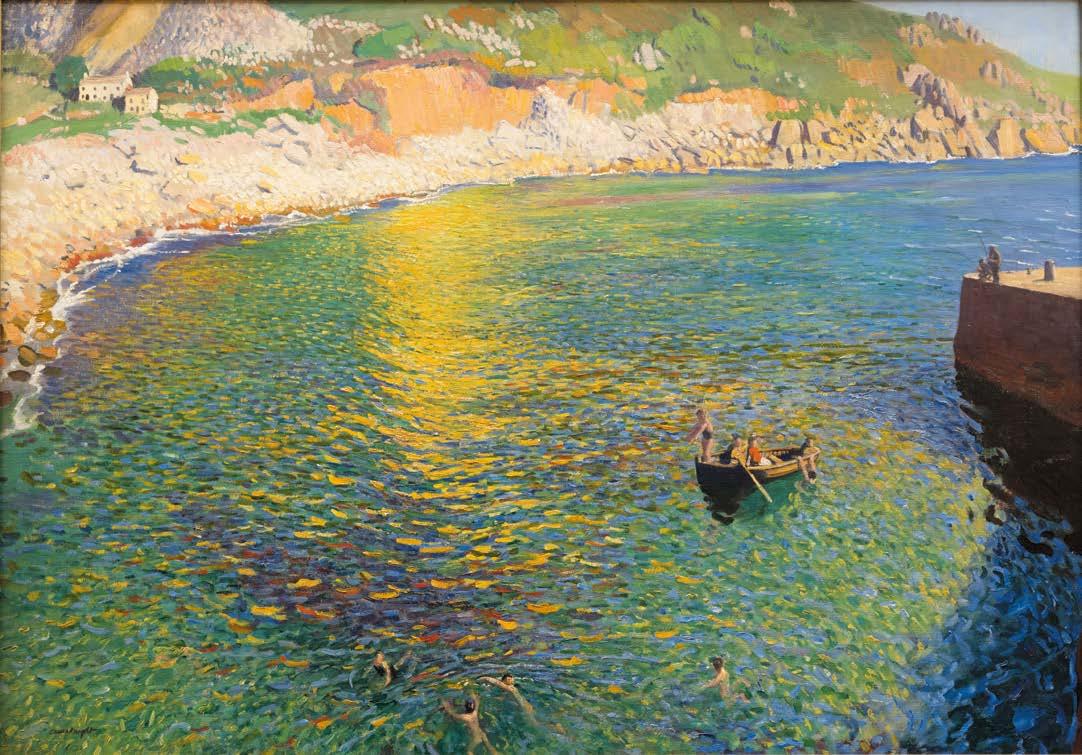

Dame Laura Knight’s Lamorna Cove is a dazzling panoramic of Cornish waters, painted by an artist who, in 1936, became the first woman elected as a full Royal Academician, 168 years after its founding. Knight’s achievement resonates strongly with current interest in female artists whose contributions were historically overlooked. Her inclusion alongside Elizabeth Stanhope Forbes and the women depicted in Burne-Jones’s and Tissot’s paintings highlights art history’s ongoing reassessment of gender and artistic authority.

These masterpieces embody not just individual achievement but also the remarkable collectors who have preserved them, often across generations. As these works pass to new custodians, they carry forward both their creators’ revolutionary vision and their guardians’ dedication to cultural stewardship.

Grant Ford Curator

Image:

Sir Joshua Reynolds, R.A.

(1723-1792)

The Yellow Boy – Lord George Seymour-Conway, 1770

Oil on canvas

Unframed: 62.2 x 46.2 cm.; 24½ x 18 in.

Framed: 82 x 69 cm.; 32¼ x 27 in.

PROVENANCE

Painted for the sitter’s father, afterwards 1st Marquess of Hertford

By descent to the 7th Marquess of Hertford

Sold 1938, by Spink’s to H.M. King Carol of Romania

Bequeathed to his mistress Madame Lupescu

Sold by her to a lady resident in Mexico City

Bequeathed by her to her niece resident in Portugal

Christie’s, London, 27 March 1981, lot 150 Agnew’s, London (purchased from the above)

Private Collection (purchased from the above)

EXHIBITIONS

Worcestershire Exhibition, 1882

London, Grosvenor Gallery, 1883, no. 202

Guildhall, 1890, no. 191

London, 45 Park Lane 1937, no. 50

London, Royal Academy, 1986, no. 76

LITERATURE

Graves, A., and Cronin, W.V., History of the Works of Sir Joshua Reynolds, vol. 1, London, 1899-1901, pp. 191-2

Waterhouse, E.K., Reynolds, London, 1941, p.61

Cormack, M., The Ledgers of Sir Joshua Reynolds, Walpole Society, XLII, 1970, p. 116

Penny, N. et al., Reynolds, London, 1985, p. 120 (illustrated), pp. 244-245

Davis, L. and Hallet, M. et al., Joshua Reynolds: Experiments in Paint, London, 2015, p. 20 (illustrated) Mannings, D., Sir Joshua Reynolds: A Complete Catalogue of his Paintings, New Haven, 2000, p.143

Reynolds stands as a giant of eighteenth-century British art, the visionary genius who transformed a provincial painting tradition into an international force rivalling the continental masters. As founding President of the Royal Academy and Britain’s first knighted artist, he helped establish the intellectual framework that placed British portraiture among Europe’s finest achievements.

Painted in 1770 during Reynolds’s prime decade, the present portrait of Lord George Seymour-Conway (1763-1848) exemplifies his innovative blending of Van Dyck’s aristocratic grandeur with intimate childhood observation, a fusion that fundamentally changed British portraiture. He presents the young nobleman in a three-quarter view against moody brown tones, his golden curls catching light through Reynolds’ signature loose brushwork. Each strand looks lively, shifting between amber and bronze as light moves across the surface. This technique turns still hair into lively texture through purely painterly means.

The Van Dyck costume functions as a sophisticated piece of historical commentary. The vivid yellow silk doublet, slashed to reveal white undergarments, directly references seventeenth-century court portraiture, notably echoing Van Dyck’s The Three Eldest Children of Charles I (Royal Collection Trust) and creating a deliberate dialogue between historical and modern nobility. The Seymour-Conway family were descendants of Charles I’s courtiers. The intricate bobbin lace collar flows across small shoulders, while the asymmetrically draped olivegreen cloak showcases Reynolds’s mastery of fabric weight and texture through subtle tonal variations.

The child’s gaze, directed at an angle away from the viewer, has an introspective quality rarely seen in contemporary childhood portraiture. Reynolds captures natural contemplation instead of artificial poses, revealing personality beneath ceremonial dress. The slightly parted lips hint at imminent speech; the eyes reflect inherited dignity tempered by childhood curiosity.

Commissioned by Francis Seymour-Conway, 1st Marquess of Hertford, as part of an extensive family programme, the portrait remained in their collection for nearly two centuries. Many of the works were subsequently inherited by Sir Richard Wallace and now form part of the Wallace Collection.

Joseph Wright of Derby, A.R.A. (1734-1797)

Portrait of Anne Parker, 1785

Oil on canvas

122 x 99 cm.; 48 x 39 in.

PROVENANCE

Sir John Thursby (born 1921), Ormerod House, Burnley, Lancashire

Thence by descent to Ruth Aspinall, his granddaughter;

Sotheby’s, London, 6 July 1983

Private Collection (purchased from the above)

EXHIBITIONS

London, Tate Gallery, Wright of Derby, February-April 1990

LITERATURE

Judy Egerton, Wright of Derby, exh. cat., Tate Gallery, London, 1990

Within eighteenth-century British portraiture, few works possess the immediacy of Joseph Wright of Derby’s Portrait of Anne Parker, painted in 1785 when she was 17. This traditional Georgian society portrait showcases an artist at the height of his talents and a young woman caught as childhood innocence transitions into mature understanding. Previously tentatively identified as ‘Miss Parker’ from Wright’s Account Book entries, recent genealogical research by the current owner has transformed our understanding of both sitter and context, elevating what was once an enigmatic figure into a fully realised historical individual whose brief life sheds light on the network of Lancashire’s landed gentry.

Anne Parker was born in 1786 to Robert Parker of Cuerden Hall, Lancashire. Her powdered hair, elegantly dressed and adorned with pearls, catches the ambient light with subtle brilliance, whilst her complexion radiates that peculiar luminosity Wright achieved through his understanding of flesh tones.

The artist’s technical mastery peaks in his portrayal of the shimmering, amber silk gown. This was almost certainly selected from Wright’s studio wardrobe rather than being personally owned by the sitter. The fabric drapes into sculptural folds, while the sleeves, gathered at the elbow, flow in graceful curves.

Anne’s hands are poised with studied naturalness. A bracelet appears on her wrist, possibly containing a lock of her father Robert Parker’s hair, who died in 1779 when Anne was eleven, according to family tradition preserved through the painting’s provenance. At her feet, a brown and white spaniel gazes up at Anne, a symbol of fidelity and devotion.

Anne’s expression blends alertness with introspection. There is a sense of watchful reserve in her face, as if she were both present in the moment and contemplating something beyond the artist’s studio. Within eighteenth-century portraiture, Wright offers a distinct stance among his peers. While Sir Joshua Reynolds might have glorified his subject through classical allusions, and Thomas Gainsborough might have showcased fashionable elegance with virtuosic brushwork, Wright produces something more straightforward yet equally refined.

John MacVicar Anderson (1835-1915)

The Thames from Hungerford Bridge, 1871

Signed and dated on the barge lower left ‘JOHN ANDERSON 71’

Oil on canvas

76 x 152.5 cm.; 30 x 60 in.

PROVENANCE

Christie’s, London, 26 November 1999, lot 93 Private Collection

John MacVicar Anderson’s The Thames from Hungerford Bridge offers a profound reflection on Victorian London’s architectural transformation, moving beyond simple topographical recording to become a refined urban portrayal. This 1871 work captures the city at a crucial moment when industrial modernity clashed with ecclesiastical tradition, portraying the Thames as both a literal route and a symbolic channel of change.

Anderson’s vantage point from Hungerford Bridge places the viewer in the very heart of London’s transportation revolution. The railway bridge, completed just seven years before this work was conceived, marked Sir John Hawkshaw’s triumph of engineering pragmatism over Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s earlier suspension footbridge. This strategic viewpoint enabled Anderson to craft a symphonic scene where Wren’s church spires punctuate the skyline with baroque precision, culminating in St Paul’s Cathedral’s commanding dome. The foreground buzzes with commercial activity: hay barges pass beneath Waterloo Bridge, their lowered masts demonstrating the artist’s careful attention to maritime detail.

The composition’s horizontal format highlights the Thames’s role as London’s main artery, while the pearl-grey atmosphere captures the city’s unique luminosity created by coal smoke and river mist. Somerset House’s neoclassical grandeur dominates the left quadrant, its Portland stone façade contrasting sharply with the South Bank’s industrial warehouses and factory chimneys – a far cry from the cultural quarter it is today. Anderson’s architectural training under William Burn shows in the work’s structural precision, elevating veduta into sophisticated urban form.

Spanning the Thames is Waterloo Bridge. Built between 1811 and 1817 to commemorate Wellington’s victory, the bridge was a masterpiece of Regency engineering, with its nine elliptical arches and paired Doric columns creating what Canova famously declared ‘the noblest bridge in the world, worth a visit from the remotest corners of the earth.’ Anderson’s depiction preserves this architectural marvel for posterity with archaeological accuracy, a prescient act given that the bridge was demolished in 1936 and replaced by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott’s modernist interpretation.

Richard

Brydges Beechey, H.R.H.A. (1808-1895)

The Admiral’s Hard, Stonehouse, Plymouth

Signed and dated lower left ‘RBeechey/ 1865’; titled lower right Oil on canvas

Unframed: 78 x 112 cm.; 30¾ x 441/8 in.

Framed: 93.5 x 126 cm.; 37 x 49½ in.

PROVENANCE

Christie’s, London, 17 November 1989, lot 4 Private Collection (purchased from the above)

Richard Brydges Beechey holds a unique position as both a naval professional and a skilled artist, bringing an authentic sense of experience to his canvases that sets his work apart from many of his contemporaries. Created in 1865, the year after Richard Brydges Beechey retired as Admiral, this substantial canvas marks the peak of an extraordinary career that included Pacific exploration, Irish coastal surveying, and extensive knowledge of Royal Navy protocol. Very few artists in British maritime tradition held such genuine credentials: son of Royal Academician Sir William Beechey, veteran of the 1825-1828 Pacific voyage aboard HMS Blossom, and notably the first to sketch John Adams, the last surviving mutineer from HMS Bounty, on Pitcairn Island.

Viewed from the western shore of Stonehouse Creek, the artist depicts a bustling scene with an eye for detail that extends throughout the composition. Gathered on the jetty are uniformed naval officers greeted by women and children; behind more boats can be seen arriving on the jetty that recedes into the distance, where a steam-assisted warship symbolises the evolution of naval power. The accuracy of architectural detail, careful observation of costume, and feel for atmosphere exemplify Beechey’s naval paintings. Its scale and ambition places it within the celebrated tradition of 17th-century Dutch marine painting.

In 1835, Beechey was appointed to the Admiralty Survey of Ireland and in 1844 he married Frideswide Maria Moore Smyth of Portlick Castle. Over three decades he made valuable surveys of the Irish coast and in 1868 was elected an Honorary Royal Hibernian Academician for his dual contribution to Irish art and cartography.

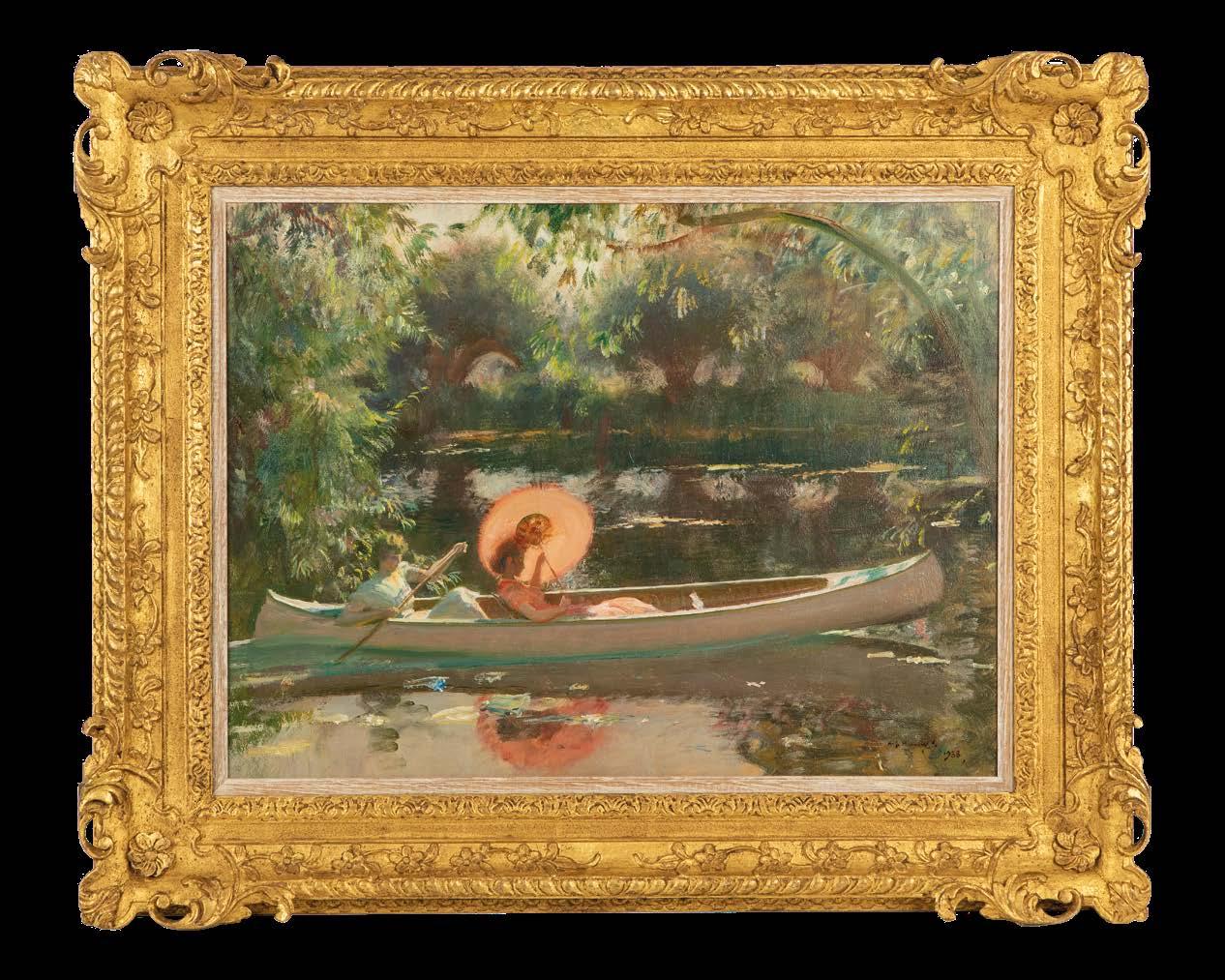

James Jacques Joseph Tissot (1836-1902)

The Lover’s Tiff, 1876

Oil on canvas

Unframed: 72.5 x 48 cm.; 28½ x 18¾ in.

Framed: 80 x 64 cm.; 31½ x 25 in.

PROVENANCE

Sold by Tissot in 1876 for £525 to Alexander Kay as Quarrelling

Alexander Jafferson Buist (1818-1901); John Charles Buist by 1912

Hammer Galleries, New York, March 1955

Charpentier Auctions, Paris, June 1956

Christie’s, London, 26 July 1957, lot 96 With Miss Wellesley by 1967

Agnew’s, London, 1983

Private Collection

EXHIBITIONS

Glasgow International Exhibition, 1901

Victoria Art Galleries in Dundee, 1912

American Federation of Arts: James Tissot: Victorian Life/Modern Love, 22 September 1999 – 2 July 2000, touring exhibition, no. 43; Oxford, Ashmolean Museum, 2017

LITERATURE

James Tissot’s sales notebook or Carnet de ventes (whereabouts unknown; photocopy in Mantion Collection), second entry under 1876;

James Tissot’s photograph album, London. From 1871 to 1878 (private collection), unnumbered, 38th of 64 images, Connoisseur, March 1955

Etching by Tissot dated 1876 (Wentworth 18) published by Tissot in Ten Etchings by J. J. Tissot Tissot 1876; James Jacques Joseph Tissot: A Retrospective Exhibition, Exh. Cat., Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence and Art Gallery of Ontario Toronto, 1968, no, 63;

Willard E. Misfeldt, ‘James Jacques Joseph Tissot: A Bio-Critical Study’ PhD dissertation, Washington University, 1971, p. 159;

Michael Wentworth, James Tissot: Catalogue Raisonné of His Prints Minneapolis Institute of Art, 1978, p. 90, fig. 18b; Michael Wentworth, James Tissot, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1984, p. 111, p. 121, pl. 97; James Tissot, Exh. Cat., Barbican Art Gallery, London and Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, 1984-1985, p. 116;

James Tissot, Exh. Cat., Petit Palais, Musée de BeauxArts, Paris, 1984, p. 186;

Christopher Wood, Tissot : The Life and Work of Jacques Joseph Tissot, 1836-1902, London, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1986, pp. 76-77, fig. 74;

Willard E. Misfeldt, J. J. Prints from the Gotlieb Collection, Alexandria, VA, 1991, p. 52;

Nancy Rose Marshall and Malcolm Warner, James Tissot: Victorian Life/Modern Love Exh. Cat., Yale Center for British Art, New Haven; Musée du Québec, Québec City, and Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, 1999-2000, pp. 105-107, illustrated back frontispiece; Katharine Lochnan (Ed.), Ann Saddlemyer, ‘Spirits in Space: Theatricality and the Occult in Tissot’s Life and Art’, p. 147 and p. 151, fig. 54 and Carole G. Silver, ‘Tissot’s Victorian Narratives: Allusion and Invention’, p. 132; in Seductive Surfaces: The Art of Tissot, New Haven, Yale University Press, 1999; Melissa E. Buron with Krystyna Matyjaszkiewic, James Tissot, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Delmonico Books, 2019, p. 291, illustration pl. 51;

An etching of Querelle d’amorureux was exhibited at the Royal Academy, the Paris Salon and Durand Ruel’s gallery in 1876 under the title The Garden at St John’s Wood

Within the private enclosure of his St John’s Wood garden, Tissot captures a psychologically complex and visually striking moment in Victorian narrative painting. The Lover’s Tiff presents itself not merely as a snapshot of romantic discord but as a refined meditation on desire, social conventions, and the intricate choreography of human relationships.

The work demonstrates Tissot’s unique ability to transform the everyday gestures of fashionable society into profound studies of emotional ambiguity. The painting shows two figures suspended in a moment of tension beside the artist’s renowned colonnade, which is itself a replica of the romantic folly from Baron Haussmann’s Parc Monceau in Paris.

The woman, turning with deliberate coyness, steps carefully onto the ornamental pool’s stone parapet, an action that suggests both retreat and allure. The exquisitely rendered brown silk dress, with intricate pleating and luxurious fur trim, serves as social armour, a facade of respectability that masks her true emotional state. The raffia hat’s red cherries echo goldfish below and scattered rose hips, creating a visual symphony while conveying Victorian symbolic meaning: innocence intertwined with sensuality.

The gentleman leans against the column with deliberate nonchalance, hands clasped behind his back. His pristine white ‘sack’ suit exemplifies casual elegance, while his John Lobb spectator shoes, originally designed for cricket enthusiasts in 1868, identify him as a gentleman of leisurely sporting tastes.

“A painting by Mr. Tissot will be enough for the archaeologists of the future to reconstruct our era.”

Élie Roy, 1869

Tissot’s compositional brilliance shines through in how he transforms everyday gestures into compelling psychological theatre. The column acts as both a physical barrier and a symbolic divide, representing societal constraints that influence the lovers’ interactions. The leaning willow mirrors the gentleman’s inclined posture, suggesting that nature itself participates in this romantic drama. Light plays a vital role, flowing through the hanging branches to catch the nape of the woman’s neck, highlighting her escaped curls and creating an almost golden glow that elevates her into an object of aesthetic admiration even as she withdraws.

The apparent privacy of Tissot’s lovers, their escape from observation, would have held significant transgressive implications for contemporary viewers constrained by social courtship customs. The painting exemplifies Tissot’s skill in achieving pictorial ambiguity, setting him apart from his British contemporaries, who focused on moral clarity. Unlike traditional academic paintings that are symbolically transparent, Tissot intentionally complicates straightforward interpretation; viewers cannot easily tell if this depicts a real quarrel, an elaborate flirtation, or a ritualised romantic performance that both participants understand and enjoy.

The placement of The Lover’s Tiff within Tissot’s career is quite significant. Created during his most successful period in London, when he was earning the equivalent of a Cabinet minister’s salary, the work reflects both the confidence of professional success and the start of his personal change. Soon after completing this painting, Tissot met Kathleen Newton, the divorced Irish beauty who would become his muse, model, and companion until her tragic death from tuberculosis in 1882. Looking back, The Lover’s Tiff can be seen as Tissot’s last major commentary on romantic relationships as a social performance, before his own experience of deep passion altered his artistic perspective. The deliberate ambiguity of the garden encounter stands in stark contrast to the tender intimacy that would later define his portraits of Newton. Through its skilful blend of technical mastery, social insight, and narrative complexity, The Lover’s Tiff attains what Charles Baudelaire regarded as the highest artistic aim: turning contemporary life into a lasting aesthetic experience.

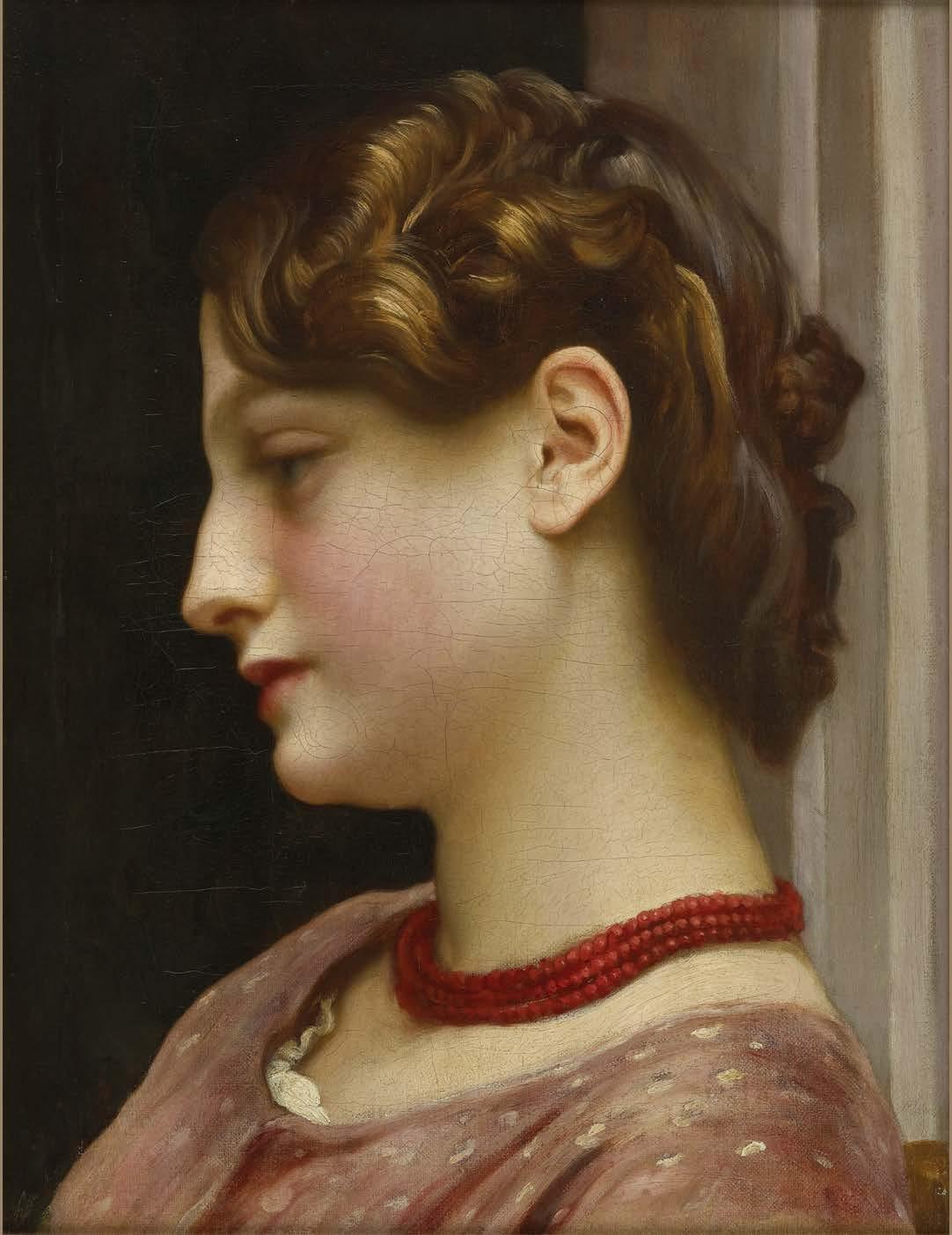

Frederic, Lord Leighton, P.R.A. (1830-1896)

6. The Coral Necklace Oil on canvas

Unframed: 43 x 33 cm.; 17 x 13 in.

Framed: 63.5 x 51 cm.; 25 x 20 in.

PROVENANCE

Christie’s, London, 25 November 1988, lot 97 Private Collection

Leighton stands as arguably the most distinguished artist of the late nineteenth century, a figure whose influence extended well beyond his Holland Park studio to shape British artistic culture. Elected President of the Royal Academy in 1878, a position he held with unprecedented authority until his death, Leighton wielded influence akin to that of a minister of state in the realm of the arts. His elevation to the peerage in 1896 marked him as the first and only British artist ever to receive such an honour. However, he enjoyed this distinction for merely one day before his death, creating the shortest-lived title in British history.

Leighton’s residence at 12 Holland Park Road, designed by his close friend George Aitchison, served not merely as a home but as a temple of aesthetic refinement, embodying the Victorian ideal of how a great artist should live. This extraordinary house, with its famed Arab Hall adorned with tiles from Damascus and its purpose-built studio, where masterpieces including Flaming June (1895, Museo de Arte de Ponce, Puerto Rico) were created, functioned as both an artistic laboratory and a cultural salon, welcoming prominent personalities of the age, from Robert Browning to Queen Victoria herself. The domestic environment from which The Coral Necklace emerged was thus one of unparalleled sophistication, where every surface and object was carefully chosen to create what contemporaries called a ‘private palace of art.’

Within the intimate confines of a modest canvas, Leighton’s portrait transcends mere representation to become a meditation on feminine virtue, aesthetic philosophy, and the enduring dialogue between antiquity and modernity that defined nineteenthcentury British art.

Depicted in profile, the model’s downcast eyes indicate introspective reverie. Leighton’s sublime technical proficiency is seen in her porcelain skin which contrasts sharply with the dark background; in the golden hues of her hair and in the delicate embroidered drapery. It is a masterful arrangement of textural harmonies, embellished still with the eponymous coral necklace, serving as the focal point around which the painting is built. Its deep crimson beads, meticulously detailed to highlight their natural irregularities, provide the only splash of saturated colour in an otherwise muted palette. Coral, prized since antiquity for its protective qualities and association with feminine virtue, symbolises the delicate balance between natural beauty and cultivated refinement that characterised Victorian ideals of femininity.

Leighton’s synthesis of classical idealism with contemporary naturalism positioned him at the forefront of the Aesthetic Movement, where narrative content gave way to compositions that relied entirely on mood and formal harmony. We witness this perfectly distilled in The Coral Necklace.

Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, BT., A.R.A., R.W.S. (1833-1898)

St Barbara, St Dorothy and St Agnes, 1869

Oil on canvas, in original frame

Unframed: 83.5 by 83.5 cm.; 33 by 33 in.

Framed: 95 x 96 cm.; 37½ x 37¾ in.

PROVENANCE

Purchased from the artist by William Graham in 1869 (listed as no.15 in his 1882 inventory)

Sold by the beneficiaries of William Graham, Christie’s, London, 3 April 1886, lot 156 to Sir John Gray Hill of Mere Hall, Birkenhead with whom it remained until 1911

His sale, Christie’s, London, 11 February 1911, lot 119 to Gooden & Fox, London

Sotheby’s, London, 18 March 1964, lot 138 Maas Gallery, London Agnew’s, London

Lord Lambton by 1971

Private Collection, London

Christie’s, London, 22 November 2006, lot 230

Sotheby’s, London, 10 December 2019, lot 15

Private Collection (purchased from the above)

EXHIBITIONS

London, New Gallery, Exhibition of the Works of Sir Edward Burne-Jones, Bart., 1898-9, no.107 Sheffield, Mappin Art Gallery, Burne-Jones, 1971, no.24

LITERATURE

Fortunee de Lisle, Burne-Jones, 1904, p.182 Arsene Alexandre, Sir Edward Burne-Jones, 1907, illustrated plate 8 from a photograph by Frederick Hollyer

Oliver Garnett, ‘The Letters and Collection of William Graham – Pre-Raphaelite Patron and Pre-Raphael Collector’, Walpole Society, Vol.62, 2000, pp.249, 290

Within the reflective silence of Burne-Jones’ St. Barbara, St. Dorothy, and St. Agnes, three martyred saints rise from the artist’s most turbulent personal crisis to become powerful symbols of virtue victorious. Painted in 1869 during his passionate affair with model Maria Zambaco, this remarkable canvas paradoxically serves as an intimate tribute to his wife Georgiana, whose steadfast devotion endured her husband’s emotional infidelities.

The work moves beyond religious iconography to become a psychological depiction of feminine strength, created with the otherworldly intensity that characterises Burne-Jones’ most notable achievements.

Three female martyrs stand on gleaming marble before a pastoral landscape. The pure white balustrade creates a symbolic boundary between earthly and celestial realms, while the polished floor reflects azure draperies in pools of light that heighten the painting’s ethereal atmosphere. Each figure occupies a distinct space yet participates in unified visual harmony, showcasing Burne-Jones’ mastery of Renaissance compositional principles. St Barbara, positioned on the left, gazes outward with deep introspection. Draped in flowing blue beneath a green mantle, she embodies scholarly devotion, clutching a volume that signifies religious learning, while beside her rises the cylindrical tower that has become both sanctuary and prison. The structure’s barely visible three windows symbolise her devotion to the Trinity, the revelation that led to her martyrdom. Her peacock feather, enigmatic yet possibly alluding to resurrection, completes her iconographic identity whilst suggesting the transcendence of earthly vanity through faith.

The central figure, St Dorothy, was a 2nd Century maiden of Caesarea in Cappodocia, put to death by sword by the Emperor Diocletian for refusing to marry on the grounds that she was mystically espoused to Christ. An angel stands before her carrying a basket of roses, the miraculous flowers Dorothy promised to send from heaven’s garden to the mocking Roman notary, Theophilus, leading to his own conversion. Dorothy’s red undergown, visible beneath her blue mantle, provides the painting’s most striking colour contrast, while symbolically referencing both royal lineage and the blood of martyrdom.

“In the palace of art there are many chambers, and that of which Mr. Burne-Jones holds the key is a wondrous museum. His imagination, his fertility of invention, his exquisiteness of work, his remarkable gifts as a colourist—all these things constitute a brilliant distinction.”

Henry James, 1877

St Agnes adorns the right side – another victim of Diocletian’s suppression martyred in Rome in 304AD. Her cascade of hair references the miracle of her execution, when her tresses grew to preserve her modesty. She gently holds a lamb, both a symbol of her identity and a nod to her name’s Latin origin, with protective tenderness. Yet, her expression displays unwavering faith upheld through persecution. She is a symbol of sacrificial innocence, linking Agnes to Christianity’s broader story of redemption.

The biographical subtext of the painting is unavoidable. In 1869, Burne-Jones’s involvement with Maria Zambaco reached a crisis when she attempted suicide with laudanum, forcing him to confront the destructive potential of his romantic obsessions. The three saints, with their shared dedication to virginal purity and rejection of earthly marriage, serve as stark contrasts to the sensual Venus archetype that Maria embodied. More importantly, all three martyrs clearly resemble Georgiana BurneJones, whose quiet strength and moral authority supported both her husband’s career and their troubled marriage. Her Methodist upbringing, emphasising moral integrity and spiritual discipline, is perfectly reflected in these figures who chose divine love over earthly passion.

Technically, the work reveals Burne-Jones’ progression from early Pre-Raphaelite linearity to a refined Italian Renaissance synthesis. The drapery modelling reflects Giotto’s Scrovegni frescoes, while the elongated figures echo Botticelli’s elegant style. The background landscape, with its atmospheric perspective and rolling hills, evokes Giovanni Bellini’s sacra conversazione, creating infinite depth beyond architectural boundaries.

The work’s origins lie in designs for All Saints Church, Cambridge, linking it to Victorian church decoration and the Gothic Revival movement.

William Morris was commissioned to create the East Window in 1866 and turned to Burne-Jones to produce 15 cartoons, which included individual portrayals of St. Barbara, St. Dorothy and St. Agnes

Uniting these figures into the present painting, it was purchased shortly after by Burne-Jones’ greatest patron, William Graham (1817-1885). Graham, whose collection included the artist’s finest works, recognised a union of technical skill and emotional depth that ranked it among Pre-Raphaelitism’s most notable achievements. The painting connects the movement’s early medievalism with the aesthetic sophistication that would influence later Symbolist artists. Its blend of narrative clarity, technical skill, and psychological depth makes it a major achievement in Victorian religious art.

Sir Edward John Poynter, P.R.A. (1836-1919)

Proserpine, 1871

Signed with initials and dated lower right ‘EJP 1871’ Oil on canvas

Unframed: 24 x 18.5 cm.; 9½ x 7¾ in.

Framed: 35.5 x 32.5 cm.; 14 x 12¾ in.

PROVENANCE

Maas Gallery, London Private Collection Ireland, Private Collection, circa 1960s, thence by family descent

Proserpine (Proserpina or Persephone in Greek) –Goddess of the Underworld whose myth represents the story of the seasons – was a popular subject in Victorian times as questions about the after-life, religious faith and the ideas of theosophy loomed large, all amid a Classical Revival which influenced paintings, sculpture, novels and the theatre. Subjects from classical mythology had become increasingly important stimuli for artists from the 1860s onwards. Notable interpretations of Proserpine include Walter Crane’s The Fate of Persephone (1878, sold Christie’s London, 12 June 2002); Lord Frederic Leighton’s The Return of Persephone (1891, Leeds Art Gallery) and Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Proserpine, (1874, Tate Britain).

Rather than concentrating on the more dramatic moments of Proserpine’s myth – her abduction by Pluto (Hades), her eating the pomegranate seeds which ensure that she must return to the Underworld or her reunion with her mother Ceres (Demeter) who has been desperately searching for her – in this small, exquisite oil, Poynter offers an alternative vision. He depicts an instant of tranquil flowergathering, where the figure seems to float weightlessly through an idealised Arcadian landscape. It relates to larger painting of Proserpine Poynter exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1869, depicting a young girl in classical robes picking flowers in a landscape. Agnes Poynter (the artist’s wife) wrote that it caused ‘quite a sensation, one hears of it on every side. We have just had another offer for it … the Queen insists upon a copy.’ (Christopher Wood, Olympian Dreamers, 1983, p. 138).

Poynter’s Proserpine is draped in a diaphanous white robe, which billows with sculptural grace while revealing the goddess’s silhouette through the translucent fabric. Golden, flowing ribbons crown her auburn hair, while delicate crimson sandals anchor her to the lush earth. She carries a wicker basket filled with vivid scarlet poppies and azure blooms, their symbolic meaning resonating with both life and death, consciousness and eternal slumber.

Dappled sunlight filters through ancient trees, creating an atmosphere of a mystical sacred grove. Behind the figure is a hint of flowing water, whilst distant hills add compositional depth. Every element contributes to an overwhelming sense of lyrical beauty, transforming the mythological narrative into an aesthetic experience.

This intimate work marks a departure for Poynter, shifting away from his usual archaeological reconstructions towards a more emotionally immediate approach. The work’s contemporary relevance to Aesthetic Movement principles becomes clear through its focus on beauty rather than moral lessons, and classical form over modern social critique.

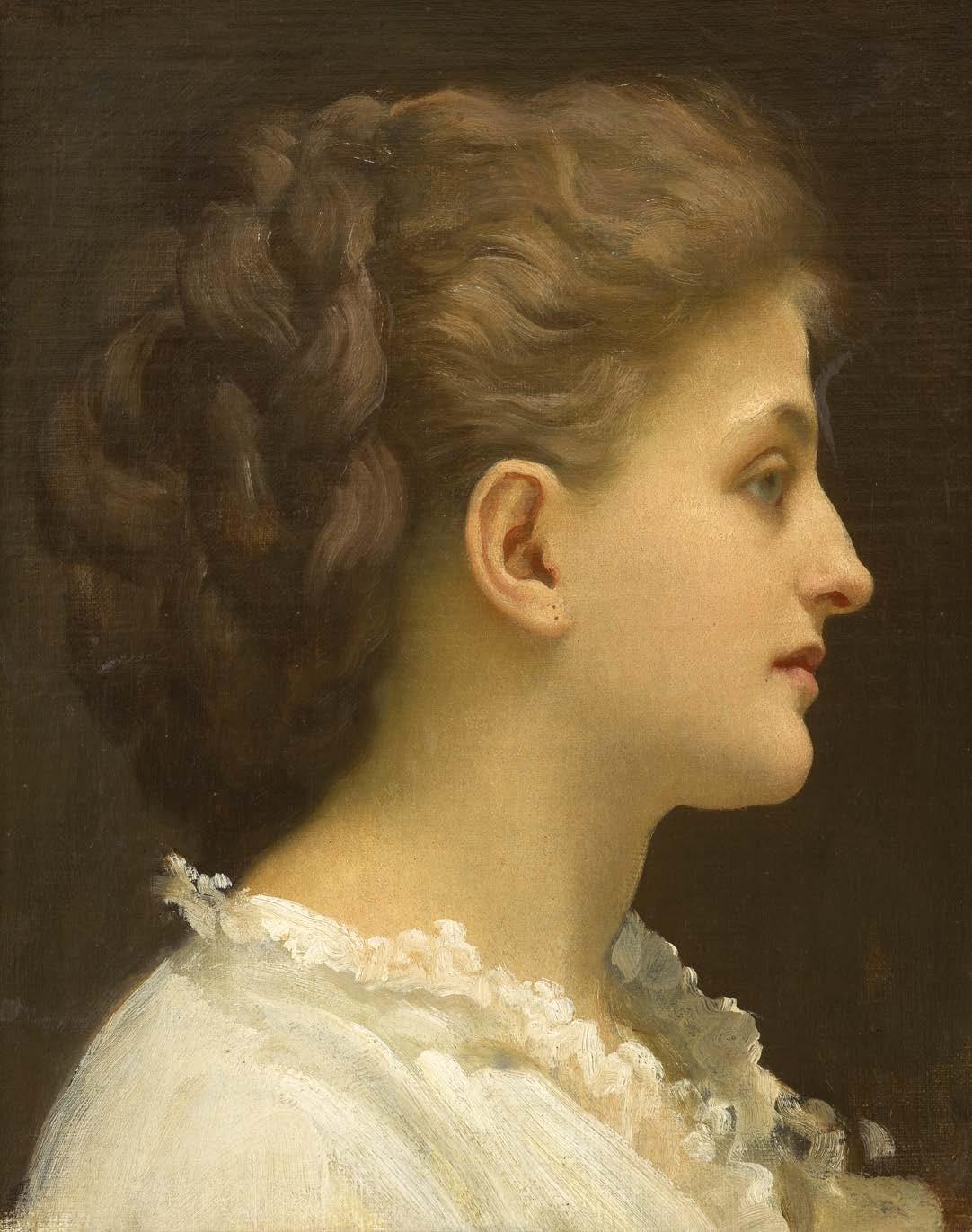

Frederic, Lord Leighton, P.R.A. (1830-1896)

Lady in Profile

Oil on canvas

Edgcumbe Staley, 1906 9.

Unframed: 24 x 20 cm.; 9½ x 7¾ in.

Framed: 39.5 x 35cm.; 15½ x 13¾ in.

PROVENANCE

Sotheby’s, London,26 November 1986, lot 39 Thomas Agnew & Sons, London Private Collection (purchased from the above)

Stripped of superfluous detail, Lady in Profile is an exercise in formal arrangement and feminine beauty on their own terms – an aesthetic approach that defined Leighton’s celebrated career. The profile of the sitter, one of quiet reverie, also recalls Roman imperial coinage; yet Leighton reinterprets ancient conventions through a distinctly modern lens. With remarkable subtlety and technical proficiency, the model’s luminous flesh tones emerge from the enveloping darkness through delicate gradations, creating a sculptural presence that showcases Leighton’s Continental training from Frankfurt to Paris. The background’s velvety opacity functions not as negative space but as an active part of the composition, generating dramatic tension between illumination and shadow, reminiscent of Ingres’ psychological depth while maintaining distinctly British restraint.

The sitter’s elaborately styled coiffure is masterfully rendered, with golden strands carefully defined yet smoothly blending into a larger architectural form. The delicate, white garment, crafted with surprisingly liberal brushwork, offers a textural contrast to the hair’s structured complexity and the skin’s porcelain smoothness.

Through this modest yet profound portrait, Leighton realises the Aesthetic Movement’s ultimate aspiration: art liberated from narrative obligation towards pure formal beauty. It is a timeless work that represents Victorian portraiture’s most sophisticated engagement with tradition whilst pioneering modernist aesthetic independence.

‘[His head studies are an] epoch in themselves in Leighton’s story of eclectic beauty. Each one is marked by loveliness and distinction, each head is ideal.’

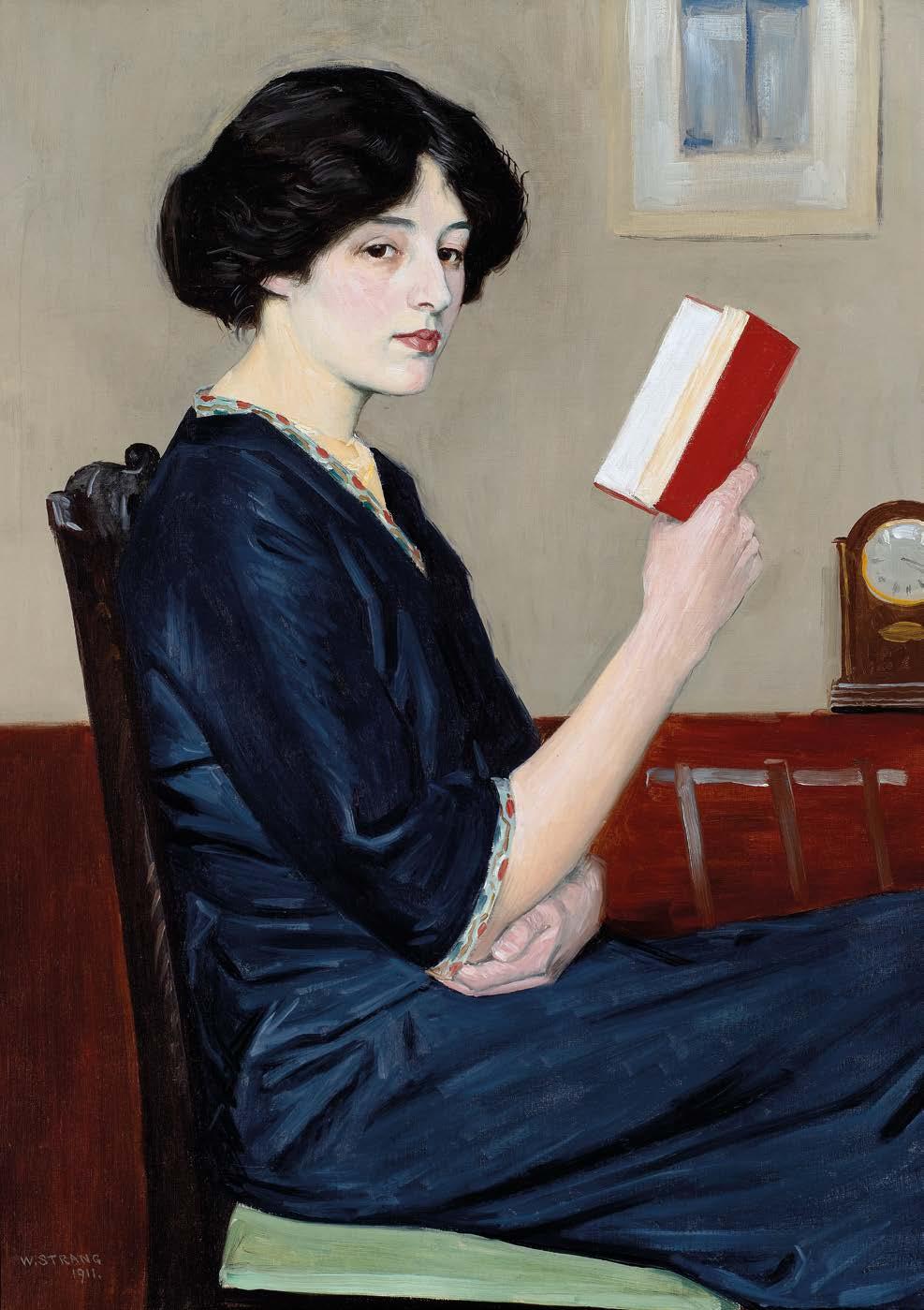

Philip Wilson Steer, O.M. (1860-1942)

A Turn of Cards, 1903

Signed and dated lower centre ‘P. Steer 1903’ Oil on canvas

Unframed: 81 x 66 cm.; 32 x 26 in.

Framed: 100 x 87.5 cm.; 39¼ x 34½ in.

PROVENANCE

Edgar Hesselein, acquired from the New English Art Club, 1903

Sotheby’s, 20 June 1962, lot 36 (sale of the collection of the late Mrs. Emily Hesselein of New York City)

The Fine Art Society, London

R.F. Glazebrook, Brynbella

Sotheby’s, London, 2 June 1994, lot 361

Sotheby’s, London, 27 November 1996, lot 18 Private Collection (purchased from the above)

EXHIBITIONS

New English Art Club, 1903

Bradford, Cartwright Hall, 1904

Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, Loan Exhibition, 1922

LITERATURE

D.S. MacColl, The Life, Work and Setting of Philip Wilson Steer, Faber & Faber, London, 1946, p. 205.

Bruce Laughton, Philip Wilson Steer, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1971, pp. 75-76, 142, no. 315, (illustrated pl. 135)

In the forge of British Impressionism’s development, Philip Wilson Steer’s A Turn of the Cards is an exquisite example that goes beyond simple portraiture. Painted in 1903, the artist’s progression from radical experimentalist to a skilled interpreter of domestic psychology demonstrates how Continental techniques could be adapted through British sensibilities.

The composition centres on a young woman, likely Theodora or Helen Bennett, a frequent subject during this period, absorbed in deep thought as she shuffles playing cards delicately held in her hands. This depiction of the sitter’s introspection adds a layer of psychological depth that is both captivating and thought-provoking. The cards themselves serve as narrative focal points, drawing attention to hesitant hands that suggest both chance and deliberation, a metaphor for life’s uncertainties that elevates this domestic scene beyond mere documentation.

Steer positions his restrained subject within a floral-upholstered armchair, its pale pink and white chintz creating luminous contrast against her seagreen dress, demonstrative of Steer’s refined colourist sensibilities. The garment’s lustrous surface, created through distinctive broken brushstrokes, shows the artist’s ongoing adherence to Impressionist techniques while revealing greater sophistication in capturing the interaction of light with fabric.

Compositionally, Steer employs geometric precision that is concealed by an apparent spontaneity. The echoing colour of the sitter’s hair, the table and chair, and the sitter’s triangular silhouette anchors the pictorial space, whilst the dark wooden table introduces horizontal stability.

The work occupies a unique position between Victorian academic tradition and modernist innovation. Unlike contemporaries who embraced either conservative approaches or radical Continental developments, Steer forged a distinctive synthesis that honoured both influences while maintaining an individual voice. His ability to capture psychological interiority through material observation aligns him with Vermeer’s legacy, whilst his Impressionist technique places him within contemporary discourse. Tradition and innovation singularly blend in Steer’s work. Through deft technique combined with deep psychological insight, he crafted not just a portrait but a reflection on solitude, contemplation, and the quiet moments that shape the human experience.

Camille Pissarro (1830-1903)

Bouquet de Fleurs; Iris, Coquelicots et Fleurs de Choux, 1898

11. In the autumn of 1898, as the nineteenth century approached its conclusion, Camille Pissarro sought refuge in the tranquillity of his studio to capture something profoundly personal yet universally resonant. His Bouquet de Fleurs, Iris, Coquelicots, et Fleurs de Choux emerges not merely as a still life, but as a meditation on transience, domesticity, and the revolutionary potential inherent in the seemingly mundane. The subject represents a masterful synthesis of Impressionist technique and PostImpressionist sensibility, revealing Pissarro at his most contemplative and technically accomplished. The composition showcases an asymmetrical arrangement that defies classical conventions while maintaining perfect visual balance. A forest-green vessel anchors the arrangement against an ambiguous, mottled grey-blue ground. Golden mimosa cascade in delicate sprays, juxtaposed with deep purple iris petals. Scarlet poppies punctuate the arrangement, while ornamental cabbage leaves introduce an element of domesticity.

Signed and dated lower right ‘C. Pissarro 98’ Oil on canvas

Unframed: 60.5 x 73.5 cm.; 23¾ x 287/8 in.

Framed: 83 x 96 cm.; 32½ x 37¾ in.

PROVENANCE

Mme. Julie Pissarro (the artist’s widow), Paris

M. Knoedler & Co., New York

Henry Ittelson, Jr., New York

Edward Speelman, London, 1959

Mrs. Neville Blond, O.B.E.

Christie’s, London, 23 June 1986, lot 5

Private Collection (purchased from the above)

EXHIBITIONS

Paris, Galerie Nunes et Fiquet, Collection de Madame Yve. Pissarro, May-June 1921, no. 35

Paris, Galerie Charpentier, Les Fleurs et les Fruits depuis le Romanticism, 1942-43, no. 123

Paris, Galerie Charpentier, Tableaux de la Vie silencieuse, 1946, no. 52

New York, Wildenstein & Co., Magic of Flower Painting, April-May 1954, no. 51

London, Marlborough Fine Art, Pissarro in England (a loan exhibition in aid of The Save the Children Fund), June-July 1968, no. 20 (illustrated p. 50)

LITERATURE

L.R. Pissarro and L. Venturi, Camille Pissarro, son art, son oeuvre, Paris, 1938, p. 229, no. 1063 (illustrated)

Joachim Pissarro, Camille Pissarro, London, Pavillion Books Ltd., 1993, p. 271, no. 319 (illustrated)

Pissarro’s broken colour technique, a significant aspect of his artistic evolution, is evident throughout the vibrational grey-blue tonalities of the background. This technique, which involves applying small strokes of pure colour to a canvas, creates atmospheric unity while preserving the visibility of individual brushstrokes. It demonstrates his transition from a pure plein-air methodology to a synthetic vision that incorporates Neo-Impressionist colour theory.

The still life occupies territory between Cézanne’s geometric investigations and Van Gogh’s psychological intensity. Unlike contemporaries who infused similar subjects with symbolic meaning, Pissarro pursues pure optical sensation, asserting presence through visual truth rather than metaphorical content. The work’s sophisticated colour relationships and spatial complexities anticipate Fauvist developments while remaining anchored in Impressionist observational honesty.

The enduring presence of this painting lies in its ability to transform the most ordinary of subjects –cut flowers in a domestic setting – into a profound statement about the nature of seeing and the possibilities of paint. It offers a vision of art’s capacity to find significance in the seemingly insignificant, beauty in the commonplace, and permanence in the transient.

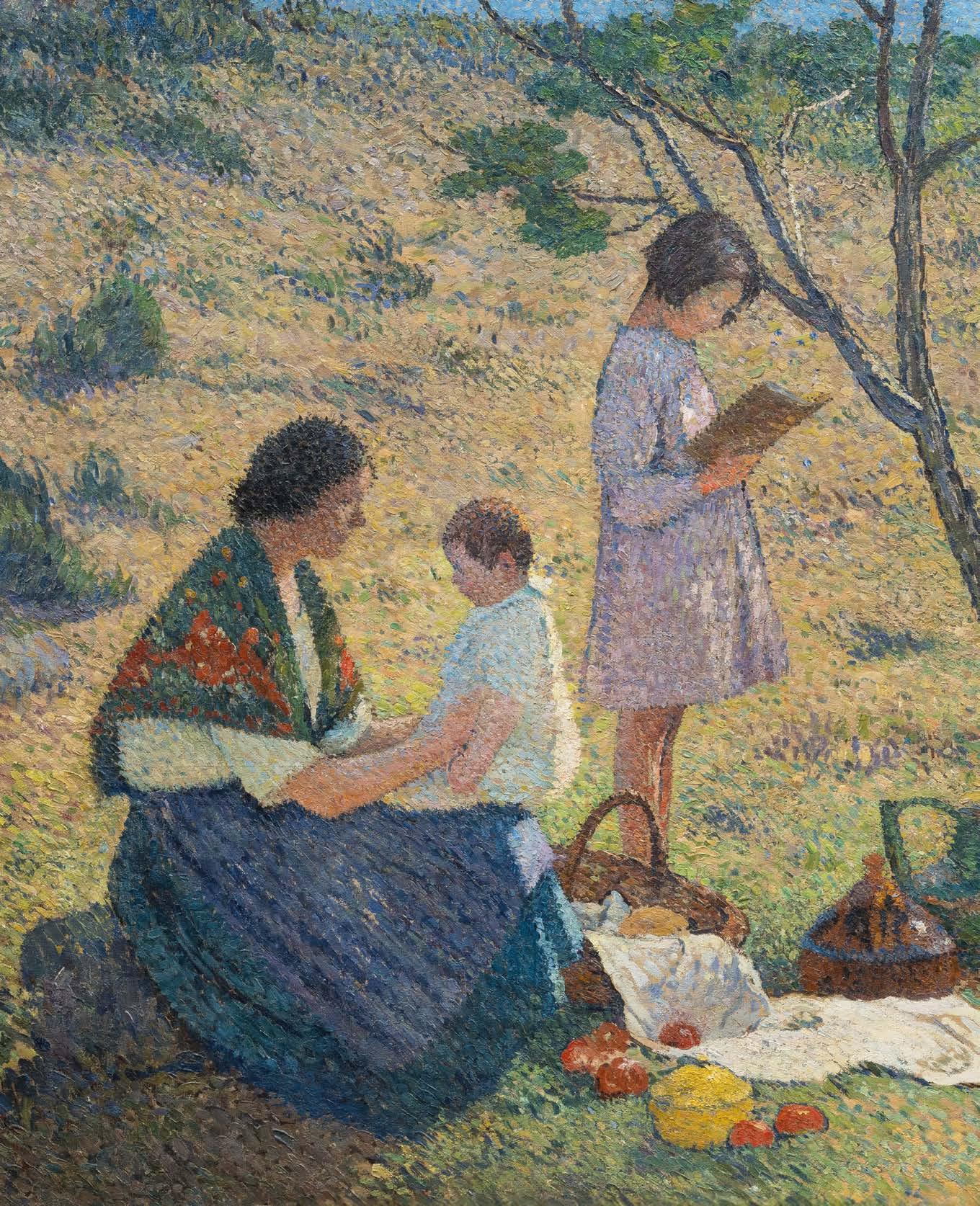

Henri Martin (1860-1943)

Bucolique, c. 1932

Signed lower right ‘Henri Martin’ Oil on canvas

Unframed: 199 x 323 cm.; 78¼ x 127 in.

Framed: 218 x 340 cm.; 85¾ x 134 in.

PROVENANCE

Commissioned by the Chambre de Commerce et d’Industrie, Béziers, in 1932

Christie’s, London, 25 June 2008, lot 497 Private Collection (purchased from the above)

A native of Toulouse, Henri Martin’s roots in the South of France gave him an innate love of sundrenched landscapes and a profound sense of man’s need to coexist harmoniously with nature. His paintings evoke the southern sun and have an other-worldly, dream-like atmosphere, often celebrating mankind embroiled in and at one with his surroundings.

“My preoccupation with rendering atmospheric effects increased...after three months in the country, face to face with nature. Trying to capture its diverse effects, I was compelled to paint it differently. The natural light, now brilliant, then diffuse, which softened the contours of figures and landscape, powerfully obliged me to translate it any way I could, but other than using a loaded brush—through pointillé and the breaking up of tone.”

Martin studied at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts and received a grant enabling him to go to Paris to continue his studies. In 1885 he travelled to Italy where he observed the Italian Renaissance masters which had an intense effect on his work. The work of Giotto, in particular, with his tranquil, light-filled landscapes, helped Martin to distance himself from his academic training and develop his own style, with affinities to Symbolism. By the 1890s, he had moved towards a new way of painting clearly influenced by the Impressionists and the Neo-Impressionist pointillist technique. His fame during his lifetime came from the numerous murals he painted, which suggest classical components clearly impacted by the work of Puvis de Chavannes. His murals are visible all over France and in Paris, in the Hôtel de Ville, the Sorbonne, the Palais Royal and the Conseil d’Etat Bucolique is a masterpiece of tranquillity, harmony and balance in atmosphere, colour and structure. Martin felt at his most comfortable in a rural setting, producing his best works while he lived at his country estate, Marquayrol, which he purchased in 1900, overlooking La Bastide du Vert near Cahors. The Musée d’Orsay, which houses several of Martin’s most important canvases including his introspective self-portrait from around 1912 and the monumental Sérénité (1899), acknowledges the artist’s refined method of applying ‘the division of colours’ to ‘capture the vibrating light of the south of France.’ The painting’s title, Bucolique, places the work within an artistic tradition extending back to classical antiquity. Virgil’s pastoral poems, the ‘Eclogues’, established the bucolic mode as a means of examining humanity’s relationship with nature through idealised rural imagery. Martin’s canvas thus engages in a dialogue spanning centuries of artistic expression, from Poussin’s classical landscapes to Millet’s peasant scenes, from Corot’s silvery pastoral scenes to the sunlit canvases of the Impressionists. Yet, where many pastoral works retreat into nostalgic fantasy, Martin’s vision remains grounded in the authentic rhythms of Mediterranean agricultural life.

Henri Martin quoted in Petra ten-Doesschate Chu, Eden Close at Hand: The Paintings of Henri Martin, Beverly Hills, 2005, p. 26

Bucolique is one of six landscapes that Martin was commissioned to paint for the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Béziers, in Hérault, the premier wine-growing department of the Languedoc region in the South of France. The landscapes celebrate the pastoral way of life and wine-growing industry which existed in Hérault since the 7th century BCE. The founding of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Béziers in 1902 was necessitated by the burgeoning importance of the local wine industry. Its relocation into the beautiful Renaissancefacaded Hôtel du Lac led to Martin’s commission for the Salle des Délibérations

In four vertical canvases, he depicted the key seasonal occupations of wine growing: ‘déchaussage des souches’ by labourers under the mild early spring sun in Le cultivateur ; the sulphating of the vines traditionally carried out between Easter and Pentecost in Le sulfatage ; September grape-picking in La cueillette ; and Autumn harvesting in Les vendanges Idylle and Bucolique, two horizontal paintings, accompanied the four canvases. In the series, Martin ennobles the workers, celebrates the timelessness of their labour and lends poetry to the ancient symbiosis of man and agriculture through harmonious compositions and a brilliant palette. The warmth of the Mediterranean sun radiates from the canvases, which are suffused with the golden light of the late summer, and the vegetation and soil of the Midi are evoked in vivid green and orange tones on a lusciously textured, impasto surface.

In Bucolique, Martin used small brushstrokes of colour interspersed with a lighter tone to convey the idea of a sun-filled scene. The outline of the tree and figures indicate a strong sunlight as do the colourfilled shadows. The painting is strangely reminiscent of Pre-Raphaelite landscapes in its bright colours and every stroke of paint seems to represent a blade of grass, a leaf or light dappling on the water. The group of mother and two children connects with the group of goats to the right. As the nanny goat feeds her kid, so the mother and children are provided with the produce of the land laid at their feet. Three men work in the middle distance –mimicked in number by the trio of conifers and the three sailing boats behind them. Man works in harmony with nature and reaps the rewards. All is harmony, all is bucolic in this pastoral idyll.

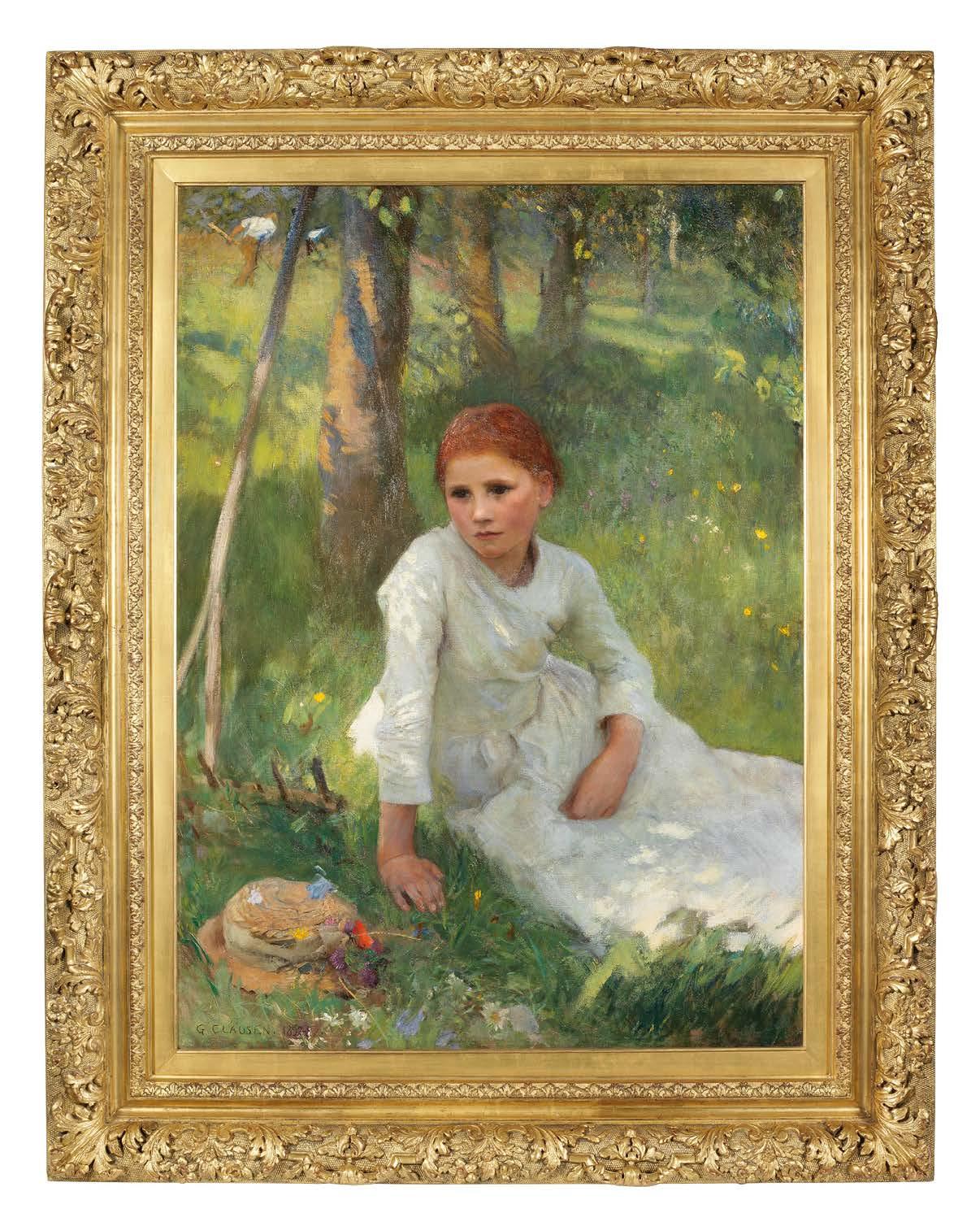

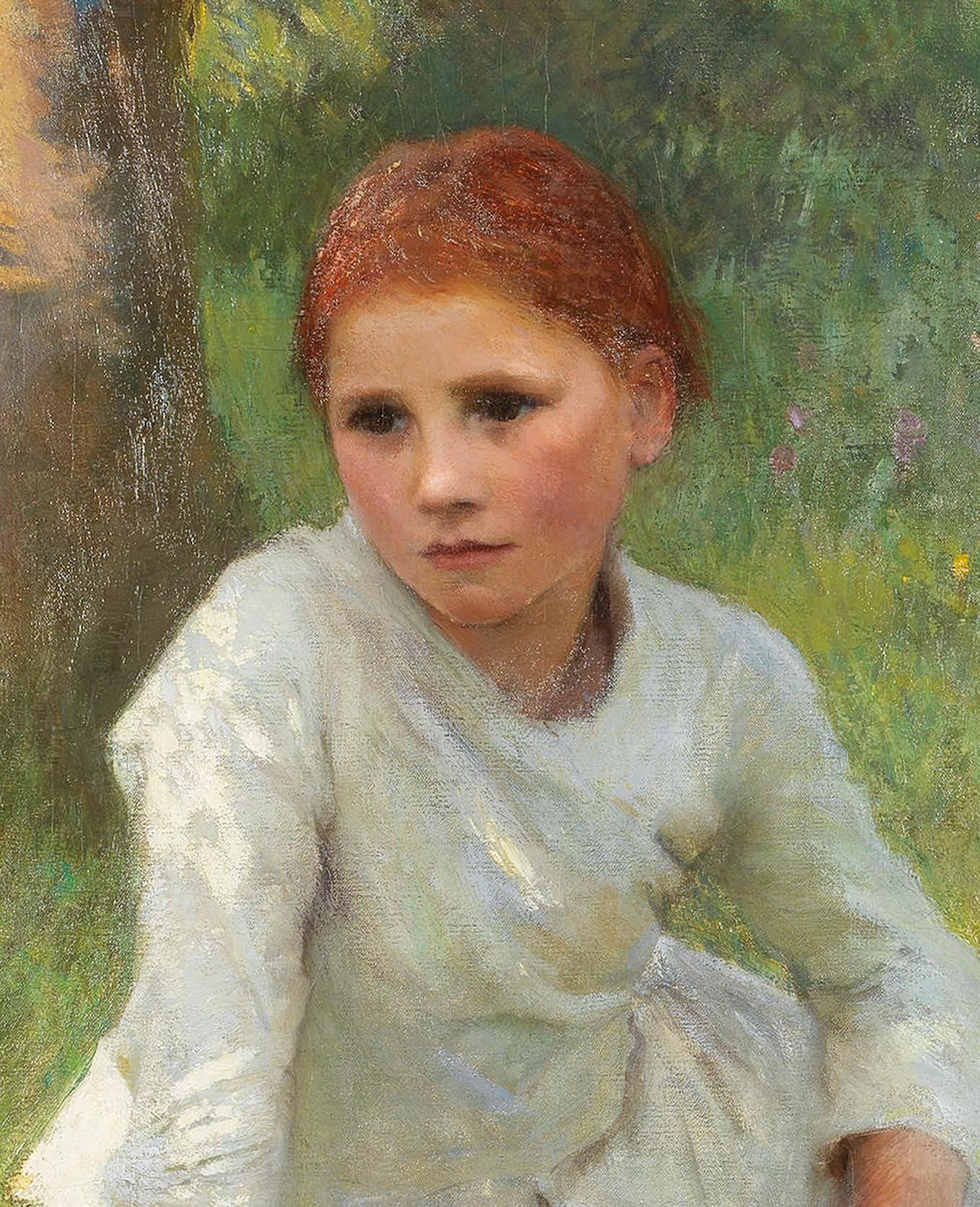

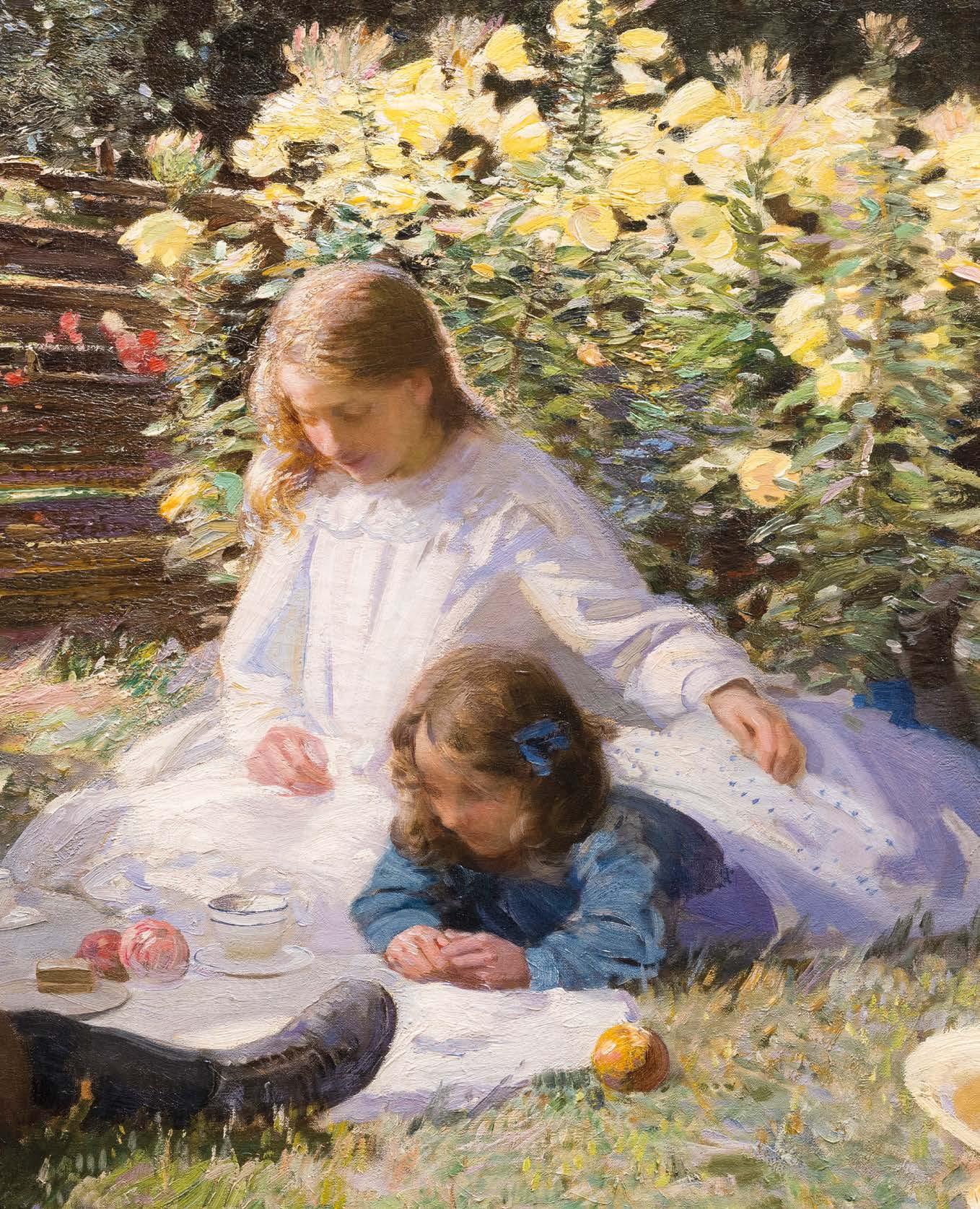

Sir George Clausen, R.A., R.W.S. (1852-1944)

Noon in the Hayfield, 1897-98

Signed and dated lower left ‘George Clausen. 1897-8’; signed and titled on the reverse Oil on canvas

Unframed: 116.5 x 84 cm.; 46 x 33 in.

Framed: 150 x 118 cm.; 59 x 46½ in.

PROVENANCE

The Artist, to Isaac Smith Esq, JP, Field House, Dausy Hill, Bradford

His sale, Christie’s, London 15 May 1911, lot 43 (90 gns)

Private Collection, by descent

Sotheby’s, New York, 28 February 1990, lot 122

Private Collection, Germany

Sotheby’s, London, 23 May 2013, lot 27 Richard Green Gallery, London

Private Collection

Bonhams, London, 27 September, 2017, lot 114

Private Collection

LITERATURE

Kenneth McConkey, George Clausen and the Picture of English Rural Life, Edinburgh, 2012, pp. 122-3 (illustrated in colour)

In 1897 Clausen gave a small oil sketch to his friend, the sculptor, William Goscombe John, Girl in a Field, (National Museum of Wales, Cardiff). Painted around seven years earlier, the sketch was part of the elaborate planning procedure for a major work abandoned at the time, but now being revisited. The circumstances surrounding this act of generosity remain obscure, but the little picture itself is not insignificant. It shows a girl with red hair, sitting under a tree. The full sunlight strikes her white dress. Swift, slashing strokes of paint indicate that this figure study was blocked in very quickly – but then, the artist knew exactly what he was doing as he worked towards the realization of Noon in the Hayfield , the major canvas he had temporarily put aside back in 1891.

Some of Clausen’s earliest preoccupations are reflected in the work. These stretch back to 1880 when, in his late twenties, he stood in front of BastienLepage’s Les Foins, (Musée d’Orsay, Paris), the great picture of resting haymakers, then on show at the Grosvenor Gallery. It, as much as anything, prompted his move to the country the following year, and by 1883 his own version of the subject, Day Dreams, (private collection) was exhibited at the Institute for Painters in Oil Colours in London. Here, two women, young and old, are resting in the shade, while nearby, a young mower pauses and realizes that it is time to lay down his rake. By 1886, when he painted A Midsummer Day (private collection), Clausen had witnessed such moments of reverie on many occasions.

By 1890, sketchbook studies in pencil, at least one pastel and the Goscombe John oil, indicate that he was reworking the same pose using a younger model, Rose Grimsdale. But what did this mean? Was the content – a haymaker’s rest – a given, and technical advance the true priority? Was this innocent idleness, a moment’s respite from relentless toil, or an experiment in new techniques? As Clausen returned to apply the finishing touches to Noon in the Hayfield, in 1897, the work that had been in gestation for over a decade, would all become clear?

Clausen left London in 1881 at a time of great unrest in the countryside when labouring families, like that of his model, had been drifting to the burgeoning industrial centres for several generations. A crisis was fast approaching. The country was no longer selfsustaining in food production. For many landowners, the situation was exacerbated by tighter regulation that affected the employment of children at key points

in the farmer’s year. While the Education Act of 1880 demanded compulsory school attendance for all children up to the age of ten, it was not unusual for classrooms to be empty during the month of June when ‘haysel’ – the hay harvest – occurred. This required boys and girls to follow the mowers, their job simply to rake the fallen grass into ‘haywakes’ to aid the drying process This was labour-intensive. On small holdings, where fruit trees were often planted at the edge of a meadow, the use of new-fangled machinery was impossible.

Around 1890 Clausen’s sketchbooks record men scything, rick-building and tending livestock. Implied narratives of youth and age or secret trysts are excluded as his young fieldworker is placed at the edge of the meadow. Sketchbook studies of Rose are drawn and redrawn in reverse. And while we can vouch for the accuracy of Clausen’s observation, by the late nineties it had become clear that he and his French and British contemporaries were not so much recording an occupation as bolstering a threatened way of life. It was this powerful sense of a stable society under threat that kept the image of the country girl in focus as plein air painting moved ever closer to Impressionism. The planning for what would become Noon in the Hayfield had started in earnest and the resting fieldworker was redrawn in outline on a larger scale with trees and haywakes in the background, almost as a cartoon (Study for ‘Noon in the Hayfield’, c. 1890, Royal Academy of Arts, London).

‘...he [Clausen] has seldom painted anything more finely than these unsophisticated young country girls with their healthy pink faces glowing through their own shade. In this sort of natural study the best energies of some of our strongest young painters are now engaged.’

‘The

By 1891 an exhibition-piece watercolour was nearing completion, when Clausen’s circumstances changed. Early in the year it became apparent that his lease on Grove House, Cookham Dean was coming to an end and he would have to move. With a growing reputation, he also required a larger studio, and the stimulus of a new working environment. The early summer of 1891 was spent

house-hunting in the northern reaches of Essex until he hit upon ‘Bishops’ at the village of Widdington, where he moved just before harvest time. At the last minute, the watercolour, Idleness, (private collection) was submitted, ex-catalogue, to the Royal Society of Painters in Watercolours as he set to work exploring the fields and farms of a new landscape. The large painting, later to be known as Noon in the Hayfield, was put on hold.

New subjects – harvesting, ploughing and barn interiors followed – but the contact with his Cookham Dean models, Rose Grimsdale and the Baldwin sisters, was severed. It was only when he started to look again at head studies of Rose in 1896 and had found new girls and boys in Widdington who were willing to pose for him, that the thought of finally finishing the picture returned. He looked again at all the planning he had done and made some changes. The hat, which in Idleness lies behind the girl, was brought into the foreground. The windfalls that lie on the grass in the watercolour, suggesting an orchard in autumn, are removed, and the rake, essential in midsummer mowing is added, as in the outline drawing. Having begun to modify the mechanical ‘square’ brushwork of his early naturalist pictures, Clausen was thinking more about colour. Sundry references in letters indicate that he had been looking critically at the work of Manet, Monet and Degas. The high colour key derived from pastel, reveals the degree to which new attitudes were informing Clausen’s technique in all media. Questions of métier, of how to represent, overtake those connected with what to represent. His previous reference to Rose at this point was the halflength, Brown Eyes, (Tate Britain), held over from Cookham days to be shown in 1892 and when Noon in the Hayfield was finally resumed five years later, Clausen had been elected Associate of the Royal Academy by a popular vote.

Clausen’s long gestation of the resting haymaker had, for all its suave naturalism, resulted in one of his most rigorously taut and deeply pondered compositions. Rest, reverie and the sunlit glow of field and wild flowers combine to produce one of the most satisfying visions of the English countryside at the end of the nineteenth century.

Kenneth McConkey

Cosmo Monkhouse,

Institute of Painters in Oil Colours’, The Academy, 12 December 1885, p.399

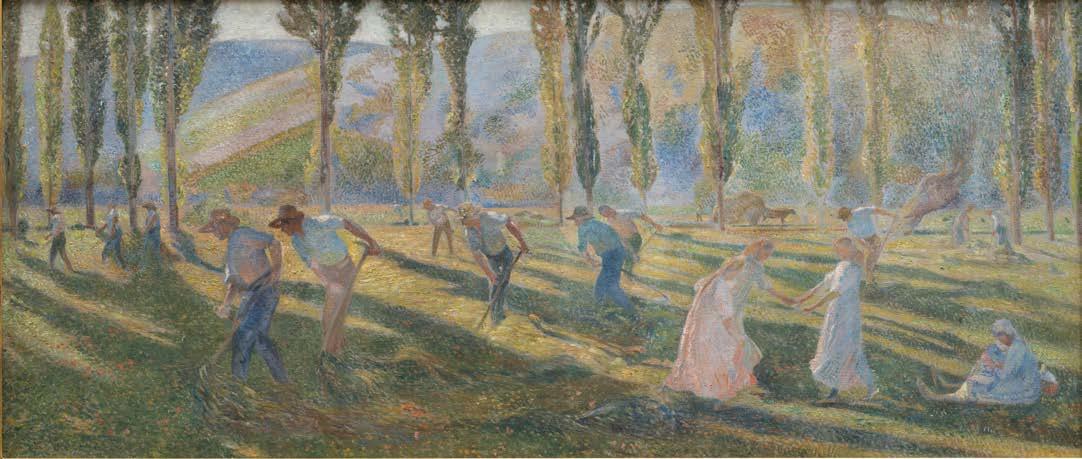

Henri Martin (1860-1943)

14.

Les Faucheurs, c. 1903

Oil on canvas

Unframed: 66 x 150.5 cm.; 26 x 59¼ in.

Framed: 91 x 175 cm.; 35¾ x 69 in.

PROVENANCE

Armand Alexis Larroque Collection, Toulouse L. Mascart Collection, Paris, by 1910

Christie’s, London, 24 June 1997, lot 146 Private Collection

EXHIBITIONS

Paris, Salon, 1906

Paris, Galerie Georges Petit, June-July 1910, no. 171

Paris, Petit Palais, Retrospective de Henri Martin, 1935, no. 16

“Henri Martin was without contest an Impressionist and one who had the deepest sensitivity, certainly equal to that of Monet, whom he most admired. Their interpretation of nature is certainly owing to their utmost sensitivity and not through research of a technical process, a poetical evocation hued by a thousand colours which can undoubtedly be called a work of art.”

Jac Martin-Ferrières, Henri Martin, Paris, 1967, p. 35

Photo: Interior of the Capitole de Toulouse showing the full-scale L’été (or Les Faucheurs) in context.

Painted circa 1903, Les Faucheurs is an idyllic vision of rural harmony bathed in the light of southern France. Themes of harvest labour – portrayed as both documentary record and poetic meditation –comprise some of Martin’s most celebrated works, many the result of commissions housed in public buildings throughout France.

The present example is one such, being a smaller version of Martin’s expansive mural cycle housed in the Capitole de Toulouse, comprising three monumental canvases entitled ‘Le printemps’, ‘L’été and ‘L’Automne.’ L’été – also known at Les faucheurs (mowers)– is the central panel. The figures are arranged with expert skill, Martin positioning the haymakers in a rhythmic sequence that draws the viewer’s eye from the shadowed foreground through the sunlit middle ground and the distinctive poplar trees, to the distant purple hills beyond. This thoughtful choreography turns manual labour into a pastoral ballet, where each movement adds to a larger visual symphony. This is directly expressed in the three girls performing a dance to the right of the composition, and in contrast to the otherwise masculine activity.

Martin’s characteristic use of divisionist brushwork, applied with intuitive fluidity, allows colour variations to breathe across the canvas and evoke an atmosphere of shimmering light. His palette combines warm ochres and golden yellows with cool violets and blues, which energises the whole composition and evocatively suggests the late afternoon sunshine of southern France.

Martin, who studied under Jean-Paul Laurens at the École des Beaux-Arts, belongs to a generation of artists who aimed to bridge the gap between academic tradition and avant-garde experimentation. His interest in the harvesting theme was prevalent throughout his career. Indeed, sketches from 1901 reveal his early ideas for the present composition.

Exhibited at the prestigious Paris Salon in 1906, it was also included in Martin’s retrospective at the Petit Palais in 1935, where it was positioned as a key example of the artist’s mature style and his influence on the development of Post-Impressionist painting.

Sir George Clausen, R.A., R.W.S. (1852-1944)

Harvest, Tying the Sheaves, 1902

Signed and dated lower right ‘G.CLAUSEN 1902’ Oil on canvas

Unframed: 89 x 63.5 cm.; 35 x 25 in.

Framed: 103.5 x 94.5 cm.; 40¾ x 37 in.

PROVENANCE

Agnew’s, London, December 1902

C. J. Galloway, 1905

Sharpley Bainbridge, Hatfield House, Lincoln, by 1910

His sale, Christie’s, London, 10 February 1922, lot 110 (310 gns. to Thomson)

David Croal Thomson, Barbizon House, London; Private Collection, 1927, by descent

Christie’s, London, 30 November 2000, lot 26 Private Collection (purchased from the above)

EXHIBITIONS

Manchester, City Art Gallery, Exhibition of Modern Paintings, Drawings and Prints, 1910, no. 88 Pennsylvania, Pittsburgh, Carnegie Institute, no. 97 (not traced)

Ottawa, National Gallery of Canada, Exhibition of Contemporary British Paintings, 1915, no. 23

LITERATURE

The Barbizon House Collection, The Studio, February 1923, p. 106 (illustrated as the frontispiece)

The Barbizon House Record, 1927, no. 30 (illustrated) Christopher Wood, Paradise Lost, Portraits of English Country Life and Landscape 1850-1914, London, 1988, p. 89, pl. 77

Kenneth McConkey, George Clausen and the Picture of English Rural Life, 2012, Atelier Books, Edinburgh, pp.129-130 (illustrated)

15. During the final quarter of the nineteenth century, conditions in the English countryside preoccupied writers and artists. With imperial expansion, the rapid growth of cities and the ready availability of cheap foodstuffs from North America, agricultural production was in decline. Britain, which led the world in industrial mechanization, was slow to modernize its farming processes. Alongside the continued reliance upon labour intensive methods, an impressive rearguard action was mounted by Edwardian intellectuals who sought to justify healthy outdoor work, in contrast to that of the factory. The countryside embodied healthiness and the city, degeneracy. George Clausen was central to this cultural movement, and within his work, the groups of pictures of field work, rick-building and grain-sifting, painted around 1900, are its pictorial archetypes. The field gang pictures, principally, Sons of the Soil, (private collection, R.A. 1901, no. 378), the present work of 1902, and Harvest: In the Bean Field (1904, Durban Art Gallery), show different stages of crop production, from seed-time through to harvest. The cool spring palette used for the painting of a group of men hoeing in Sons of the Soil gives way to the rich golden glow of the present work. The fact that the laboureres are few in number reminds us that the period of large itinerant gangs had passed, and that by 1900, harvesting depended upon smaller groups based upon old tithed families. Boys, men and old men would work together. Here Clausen accentuates the rhythmic, co-ordinated activity of the group by emphasising the movement of hands and forearms. There are no tools for this task. Two foreground labourers, one dramatically foreshortened, are bent over their work, gathering the final sheaves at the edge of the field, here indicated by a patch of rough soil and some wild meadow flowers at the bottom edge of the canvas. Once collected and tied, the sheaves are stacked upright in groups of five or six, in a stook. Dots of colour in the middle distance, indicate that this same activity is going on in a far off field, while the striding harvester on the right, with his swinging arms and massive hands, provides an almost symbolic presence in what must be considered one of the most expressive of Clausen’s works.

Clausen had tackled this subject before, around 1890, in his sub-Bastien-Lepage manner. However, the two most important precedents for the present work were the much criticised Harvest (untraced; R.A. 1895,

no. 91) and Setting up Sheaves (untraced, formerly Lady Plender; R.A. 1900, no. 4). The second of these won considerable favour, being praised by The Magazine of Art for its ‘brilliancy of illumination and daintiness of aerial colour’. Taking a close-up view of two labourers, gathering and setting up sheaves, Clausen delights in the fanning strokes of pigment used for the corn stooks, which imitate pastel, a preferred medium of the period. This canvas formed the basis of Harvest, Tying the Sheaves a work, so successful in itself, that the painter produced a later, simpler variant of the composition, Binding Sheaves (private collection). Drawings related to this sequence of compositions are retained in the Royal Academy (particularly Sketchbook 21, 1902). As is clear from the contemporary canvases of Léon Lhermitte, Julien Dupré and others, these simple practices were also consistent with French agriculture of the period, although in France, men and women worked together in tying the sheaves. Where Lhermitte habitually deployed a landscape format for such a scene, showing a line of workers cutting into the corn, Clausen accentuates the visual drama by allowing more air around his figures, in an upright presentation. The landscape itself is more than simply a backdrop against which his figures perform: they progress through it, defining their spatial relationships as they move. The painter was preoccupied with movement, as his sketchbooks of the period indicate. He had first experimented with this format in Summer in the Fields (sold Christie’s, New York, 22 October 1997, lot 142), a picture of two girls resting on an open hillside, overlooking an expanse of fields near the painter’s home at Widdington in Essex. As with the Impressionists, Clausen was preoccupied with the concept of an ‘envelope’ of coherent atmosphere in which figures, foreground, middle distance and background are all seen together and partake of the same palette. This is especially clear in the present work where, in a palette reminiscent of Van Gogh’s gleaners and harvesters, after Millet, the brilliant blues, mauves, ochres and whites reverberate throughout the canvas.

The picture was dispatched to Thomas Agnew in December 1902, and presumably passed immediately to his client, Charles Galloway, a Cheshire industrialist who owned a number of fine rustic pictures, including Henry La Thangue’s An Autumn Morning (1897, private collection). By 1910, when the picture was shown in Manchester, it had passed to Clausen’s most important early patron, the Lincoln retailer, Sharpley Bainbridge, who owned early works like Labourers after Dinner (1884, private collection) and The Mowers (1891, Usher Gallery, Lincoln). In 1927, Barbizon House Record, referring to Harvest, Tying the Sheaves noted that,

‘the less scientific, less logical, more wayward, more charming English impressionists, Wilson Steer and Clausen, made Impressionism affectionate, with a sort of English wildflower poetry.’

James Bones, Barbizon House Record

Kenneth McConkey

Henri Martin (1860-1943)

La Moisson, c. 1918-22

Signed lower left ‘Henri Martin’ Oil on paper laid down on canvas

Unframed: 60 x 117 cm.; 24½ x 47 in.

Framed: 89 x 143 cm.; 35 x 56½ in.

PROVENANCE

Hammer Galleries, New York

Private Collection, acquired from the above circa 1970s

Sotheby’s, New York, 23 May 2008, lot 192 Private Collection

Henri Martin’s La Moisson offers a panoramic vision across a sunlit wheat field where peasant workers bend to their ancient task of harvesting grain. Martin’s bold, broken brushwork, recalling that of Van Gogh, sweeps across the canvas like currents of light and shadow. These energetic marks do more than just describe the surface; they embody the very essence of movement, growth, and seasonal change that characterises agricultural life.

Martin constructs his scene with expert attention to the relationship between figure and environment. The harvesters, depicted with deliberate simplification, appear as essential parts of the landscape rather than just its inhabitants. Their bent postures mirror the

curved lines of the wheat sheaves, creating a visual harmony of repeated forms that suggest the seamless integration of human activity with natural cycles. Two horses, at first almost indistinguishable in the centre, wait patiently while the hay is collected. Unlike the more radical departures of Paul Cézanne or Paul Gauguin, Martin’s evolution remained rooted in observational painting, albeit transformed by the lessons of colour theory and expressive brushwork learned from his avant-garde contemporaries.

The work is a preparatory study for Martin’s grand decorative cycle housed at the Conseil d’État in the Palais Royal completed in 1920 (see Le Port de Marseille, no. 20, for another related example). The commission called for four monumental canvases illustrating the labours of France: Agriculture, Commerce, Industry, and Intellectual work. Martin’s fame during his lifetime came from these successful public commissions, which also included the Hôtel de Ville in Paris, the Sorbonne and the Palais Royal .

On this smaller although by no means inconsequential scale, the painting’s expressive qualities are more immediately felt, particularly through the sweeping brushwork. It is an absorbing pastoral idyll which demonstrates why Martin was regularly sought to carry out some of the nation’s most significant public commissions.

Photo: Interior of the Conseil d’Etat, Paris showing the full-scale La Moisson in context.

Henri Martin (1860-1943)

La Conversation, 1912

Signed and dated lower right ‘1912/ Henri Martin’ Oil on canvas

Unframed: 54 x 96 cm.; 21¼ x 37¾ in.

Framed: 78 x 119 cm.; 30¾ x 46¾ in.

PROVENANCE

Phillips, London, 23 June 1986, lot 27 Private Collection (purchased from the above)

Seated on a terrace in the golden glow of late evening, two women pause in intimate discourse, their forms almost dissolving amongst the flowers and landscape unfolding behind them. The left figure, dressed in luminous whites with violet shadows, sits facing her companion clad in rich blue-violet garments, engaged in what seems to be needlework. The curved yellow-green space between them creates a kind of aureole, imbuing the work with a spiritual dynamic.

The location for the work is Martin’s countryside home Marquayrol in Labastide-du-Vert in the south of France. He purchased the estate in 1900, and his time there marked a decisive shift from his Symbolist roots to a personal form of Neo-Impressionism. Like Monet’s Giverny or Le Sidaner’s Gerberoy, it was a cultivated paradise: lush, ordered, and endlessly inspiring. He painted the grounds from countless angles over four decades, compare for example Le Terrasse de Marquayrol, 1920 (sold Sotheby’s, 25 June 2025, lot 141).

“By discovering Marquayrol, Henri Martin had found his equilibrium, his personal and artistic fulfilment.”

Claude Juskiewenski, Henri Martin 1860–1943, Paris, 1993, p. 103

The compositional structure evokes the tradition of enclosed gardens – ‘hortus conclusus’ – prevalent in Christian art from the Middle Ages onwards, often used to suggest purity and symbolic of a sanctuary for feminine contemplation. In this regard, the painting relates to the work of the Symbolists with whom Martin had associated, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes once declaring Martin his successor. Their work is infused with mystery and allegorical

undertones which go beyond simple observation. La Conversation functions simultaneously as a glimpse of observed life and as a reflection on the themes of communication, creativity, and the passage of time. The cyclical nature of seasonal change, implied by the flowering garden, mirrors the rhythmic continuity of human discourse and domestic labour.

Martin’s consistent and sophisticated use of colour and light is a defining feature of his career and emphatic in La Conversation . The warm Mediterranean sun permeates every element of the composition through a bold palette of complementary pigments, which he applies in a variety of gestural brushstrokes that suggest rather than describe form, and which animate the entire surface.

The painting holds a fascinating position between tradition and innovation. While Picasso and Braque were fragmenting reality through Cubist analysis, and the Fauves were exploring pure colour as emotional expression, Martin pursued a more contemplative path that honoured both classical composition and modern chromatic theory.

Sir George Clausen, R.A., R.W.S. (1852-1944)

Summer in the Fields, late 1890s

Oil on canvas

Unframed: 108 x 81.5 cm.; 42½ x 32 in.

Framed: 128 x 102 cm.; 50½ x 40 in.

PROVENANCE

The Artist’s Studio sale

Christie’s, London, 19 October, 1945, lot 136 Mitchell Galleries

Christie’s, London, 10 November 1950, lot 100 (10gns. to Salz)

Private Collection

Christie’s, London, 19 November 2004, lot 76 Private Collection (purchased from the above)

EXHIBITED

Munich, Secession (catalogue untraced)

Clausen’s Summer in the Fields captures a perfect moment: two girls resting from haymaking in golden English sunlight. One sits alert, gazing across distant fields; her companion sleeps peacefully beside her. This seemingly simple scene represents one of the outstanding achievements of British Impressionism.

Created in the late 1890s, the painting reveals Clausen transforming French influences into something unmistakably English. He drew the elevated perspective and figure arrangement from Jules Bastien-Lepage’s Les Foins (1878, Musée d’Orsay, Paris), which he had studied with great intensity. However, while the French masterpiece harboured undertones of rural poverty, Clausen’s vision feels uplifting, even romantic.

The composition draws us in through masterful spatial orchestration. Positioned high above the scene, we observe both intimate human drama and the expansive Essex countryside around Tilty and Clavering, near Clausen’s home. Our eyes naturally traverse from foreground figures across patchwork fields to the horizon, creating a seamless visual flow.

“Those who take a superficial view, such as is unfortunately inevitable in hurrying through these galleries, so rich as they are in fine works and masterpieces, may fancy that in Mr Clausen they see a pupil of the French masters, Millet and Jules Breton. But I would beg them to give a little longer study to this painter; they will find that they are in the presence of a really original artist –a rare bird even on the English side of the Channel.”

Clausen’s technical brilliance is evident throughout the canvas. The girl’s face is delicately modelled, capturing luminous flesh tones, while bold palette knife work in the sky creates clouds that appear to move. Small dabs of pure colour in the grass generate an optical shimmer, perfectly reflecting the essence of summer heat. Warm ochres and siennas contrast with cool violets and greens, while the seated girl’s face glows with an almost halo-like effect created by surrounding touches of mauve and emerald.

Summer in the Fields marks Clausen’s transition from literal naturalism to atmospheric experimentation. By painting specific English landscapes rather than generalised rural scenes, he helped to establish a tradition that celebrates native places and instils a sense of national pride. This was not just artistic innovation; it was cultural assertion. By the 1890s, British artists were tired of being seen as mere followers of French fashion. Clausen and his contemporaries were developing a distinctly British variant of modern painting that honoured international developments while celebrating native traditions and landscapes. Summer in the Fields is an exemplar and its exhibition at the Munich Secession is testament to the international recognition that British Impressionism had received by this period.

French critic, Philippe Gille in Le Figaro, 1889

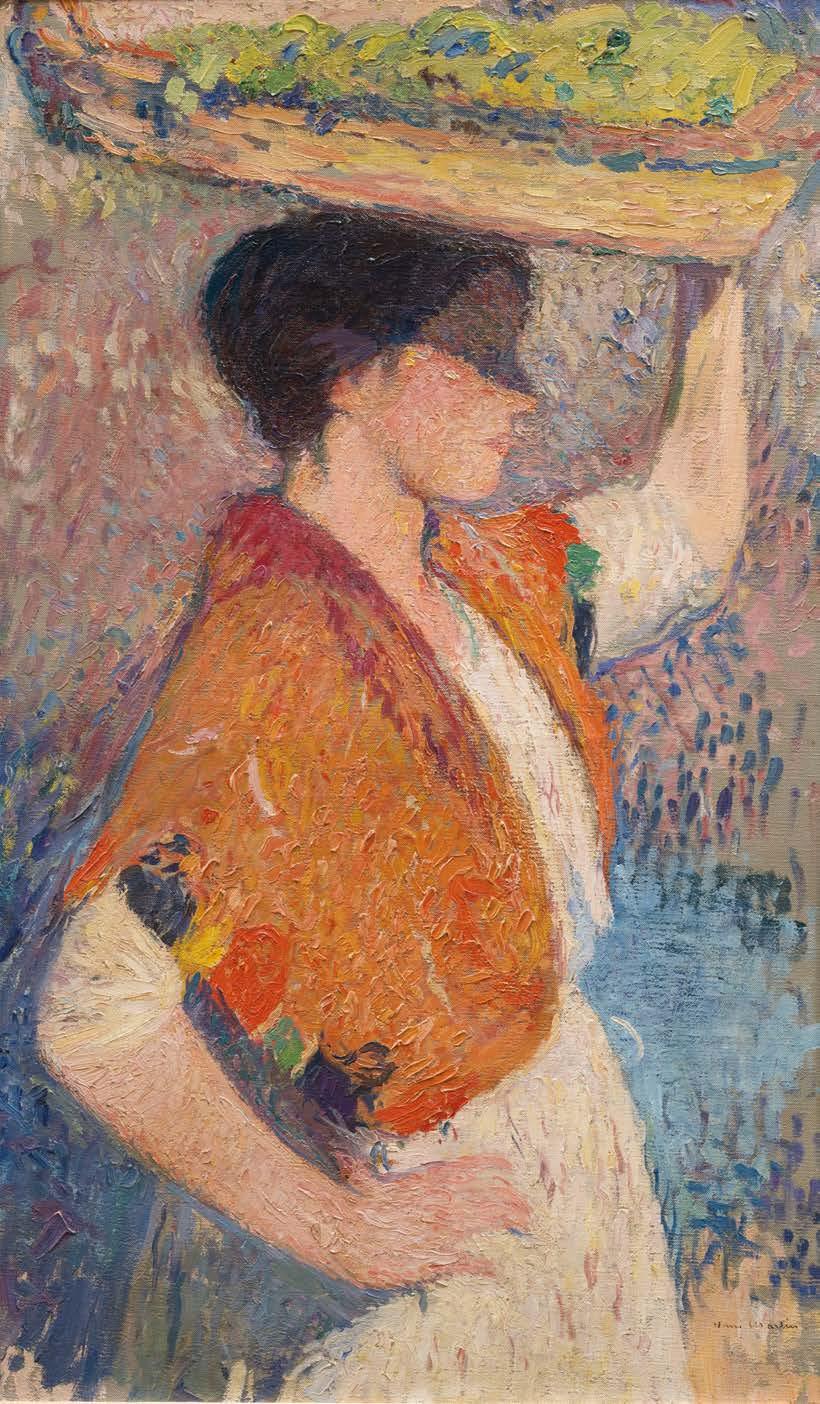

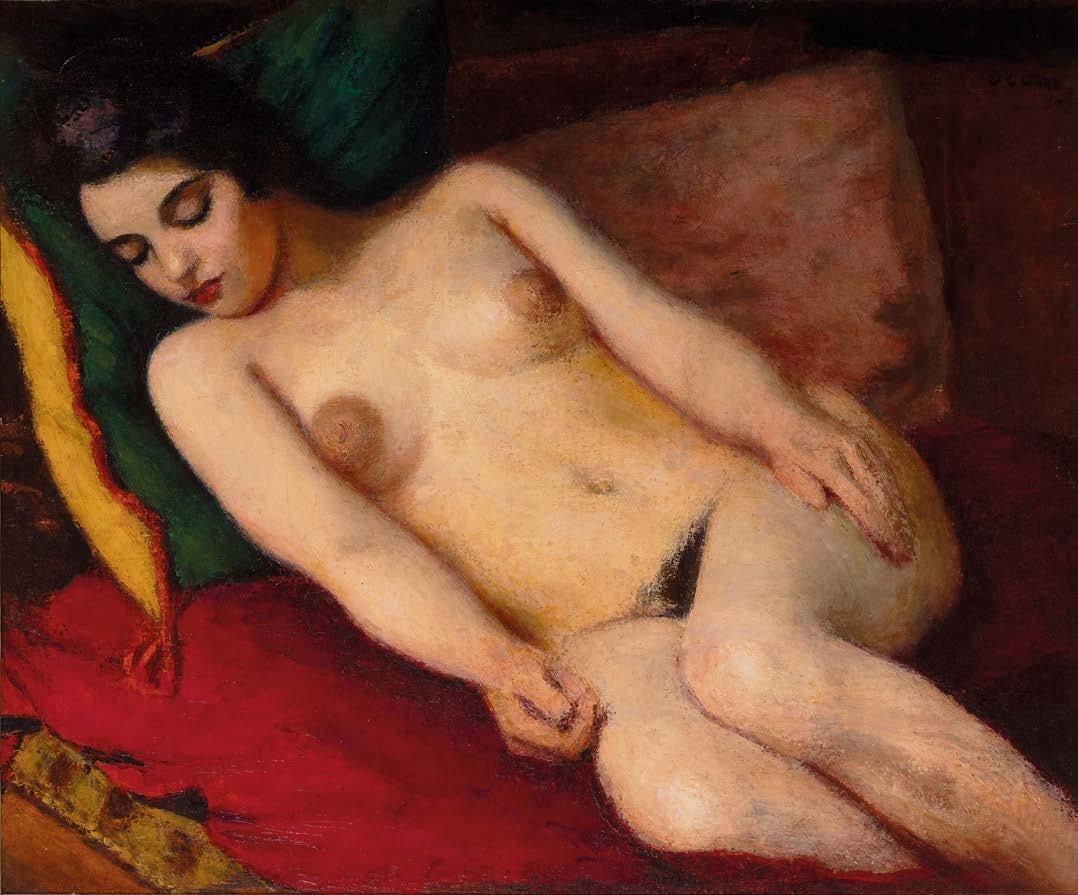

Femme à la Corbeille, c. 1918-22

Signed lower right ‘Henri Martin’ Oil on canvas

Unframed: 97 x 57 cm.; 38¼ x 22½ in.

Framed: 121 x 81 cm.; 47½ x 32 in.

PROVENANCE

International Galleries, Chicago (acquired by 1965)

Christie’s, New York, 2 October 1990, lot 49 Private Collection, Japan (acquired 1994) Private Collection

Femme à la Corbeille is a character study for the central figure in Henri Martin’s Le Port de Marseille –a monumental painting he was commissioned to paint for the Conseil d’État in the Palais-Royal, commissioned in 1914 and finished in 1922. It formed part of a larger decorative scene on four grand allegories of Agriculture, Industry/Public Works, Commerce – represented by the activity of the port of Marseille – and Intellectual Labour. Another preparatory painting for that work is included in the current exhibition, no. 20, in which the present figure can be seen. There, she forms part of broader panoramic of activity along the quay; extracted in the present work, she stands as a striking figure in her own right.

The wicker basket held aloft on her head and filled with harvest produce, also serves to shield her eyes from the Mediterranean sunlight. The sensation of heat is evocatively conveyed through the bold colour palette. The figure’s garment pulses with vermilion and orange, applied through distinctive colour separation, achieving what Albert Dubois-Pillet described as ‘vibrating light’ through contrasting complementary hues. The ambiguous background is also a masterful example of Martin’s highly developed painting technique. Unlike traditional Pointillism, Martin uses broader, gestural brushstrokes worked in various directions that animate the composition. The overall effect is a captivating moment suspended in time that leaves an enduring impression.

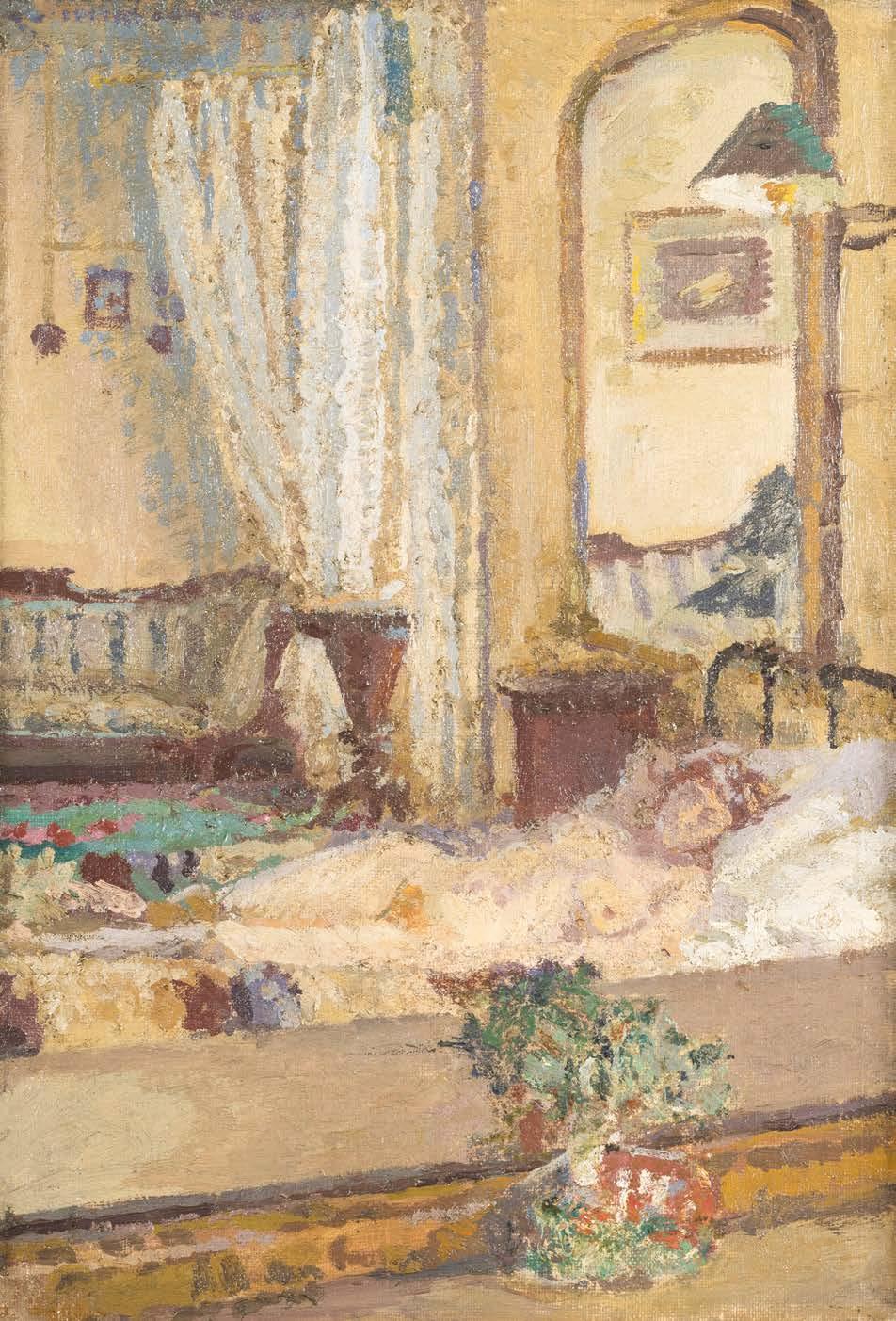

Henri Martin (1860-1943)

Henri Martin (1860-1943)

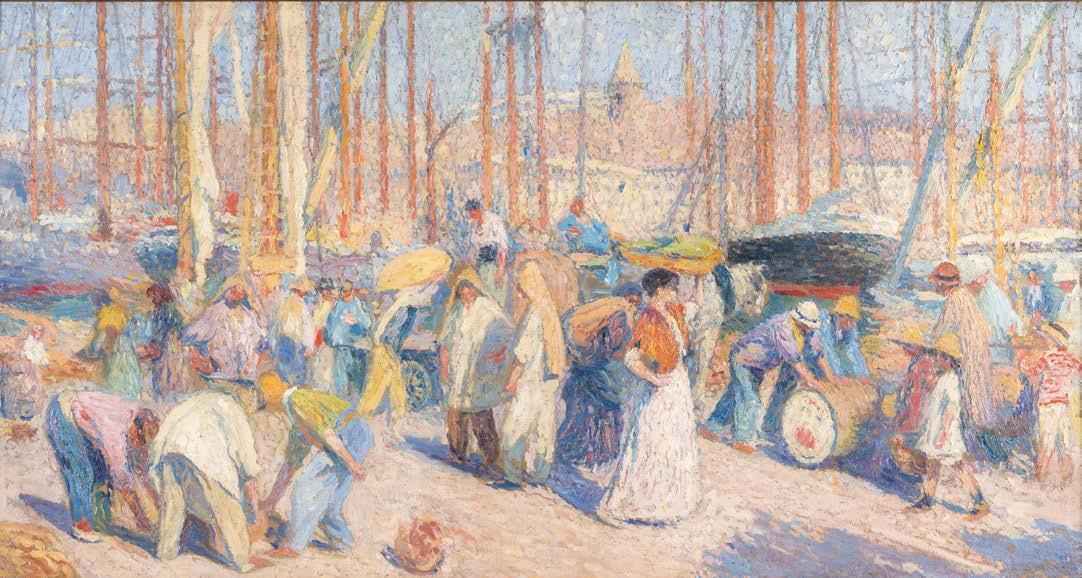

Le Port de Marseille, c. 1918-22

Signed lower right ‘Henri Martin’ Oil on canvas

Unframed: 61 x 117 cm.; 24 x 46 in.

Framed: 86 x 139 cm.; 34 x 54¾ in.

PROVENANCE

Sotheby’s, New York, 6 October 1989, lot 16 Private Collection (purchased from the above)