SURREAL METROPOLIS: LOOKING FOR AMERICA

DRAWINGS AND MASTER PAINTINGS

17-29 June 2025

Exhibited at Kate Oh Gallery 31 E 72nd Street New York, NY 10021

For extended catalogue essays, visit: www.winsorbirch.com

The Fine Art & Sculpture Company

1 The Parade, Marlborough, SN8 1NE, UK www.winsorbirch.com | enquiries@winsorbirch.com | +44 (0)1672 511058

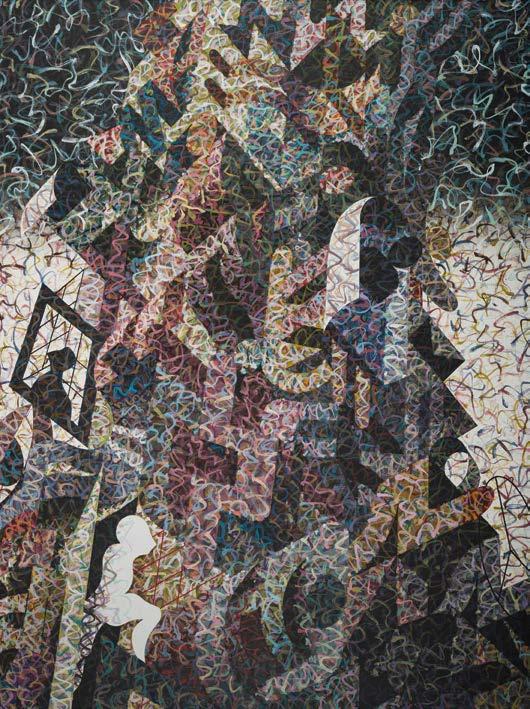

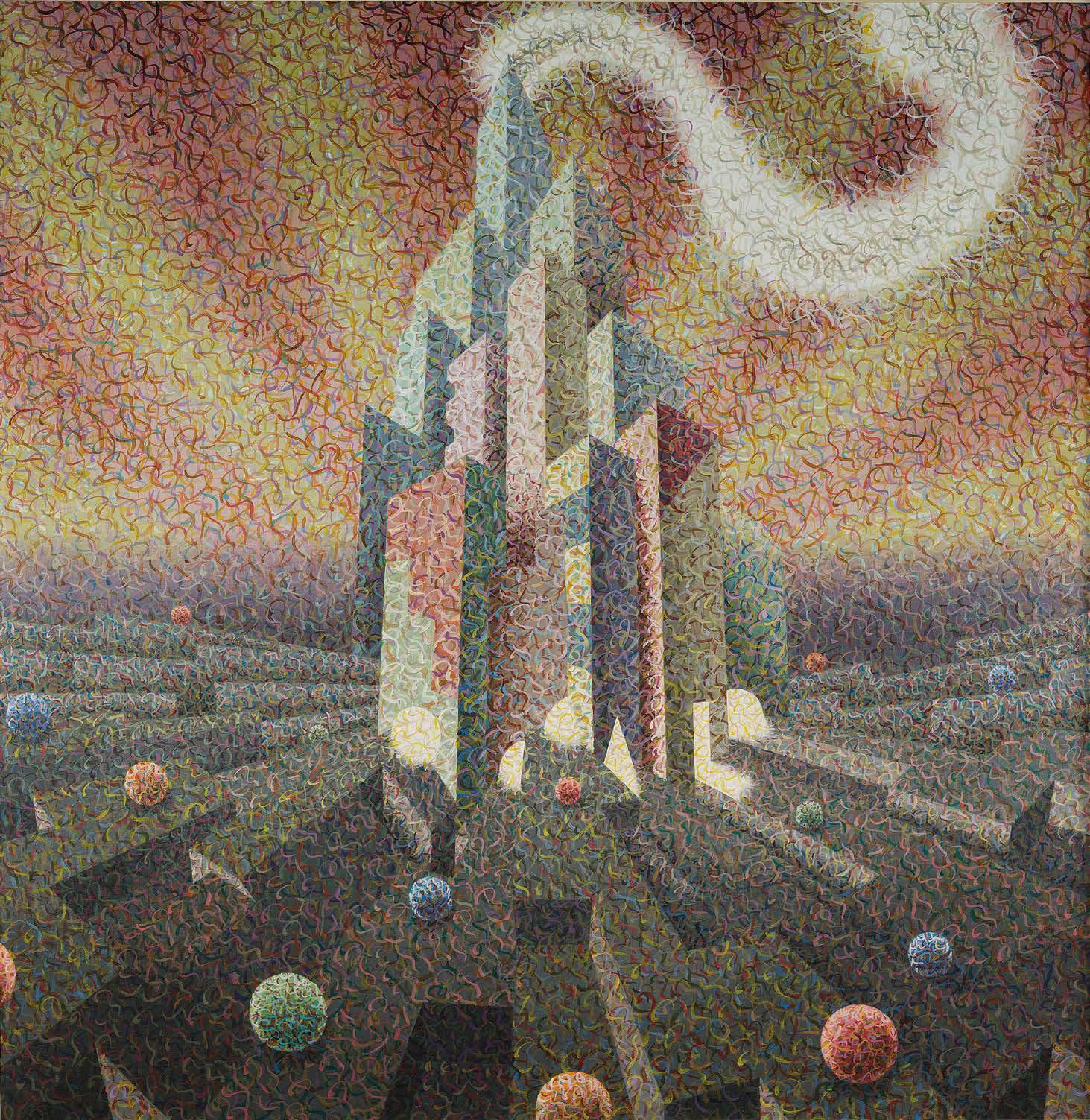

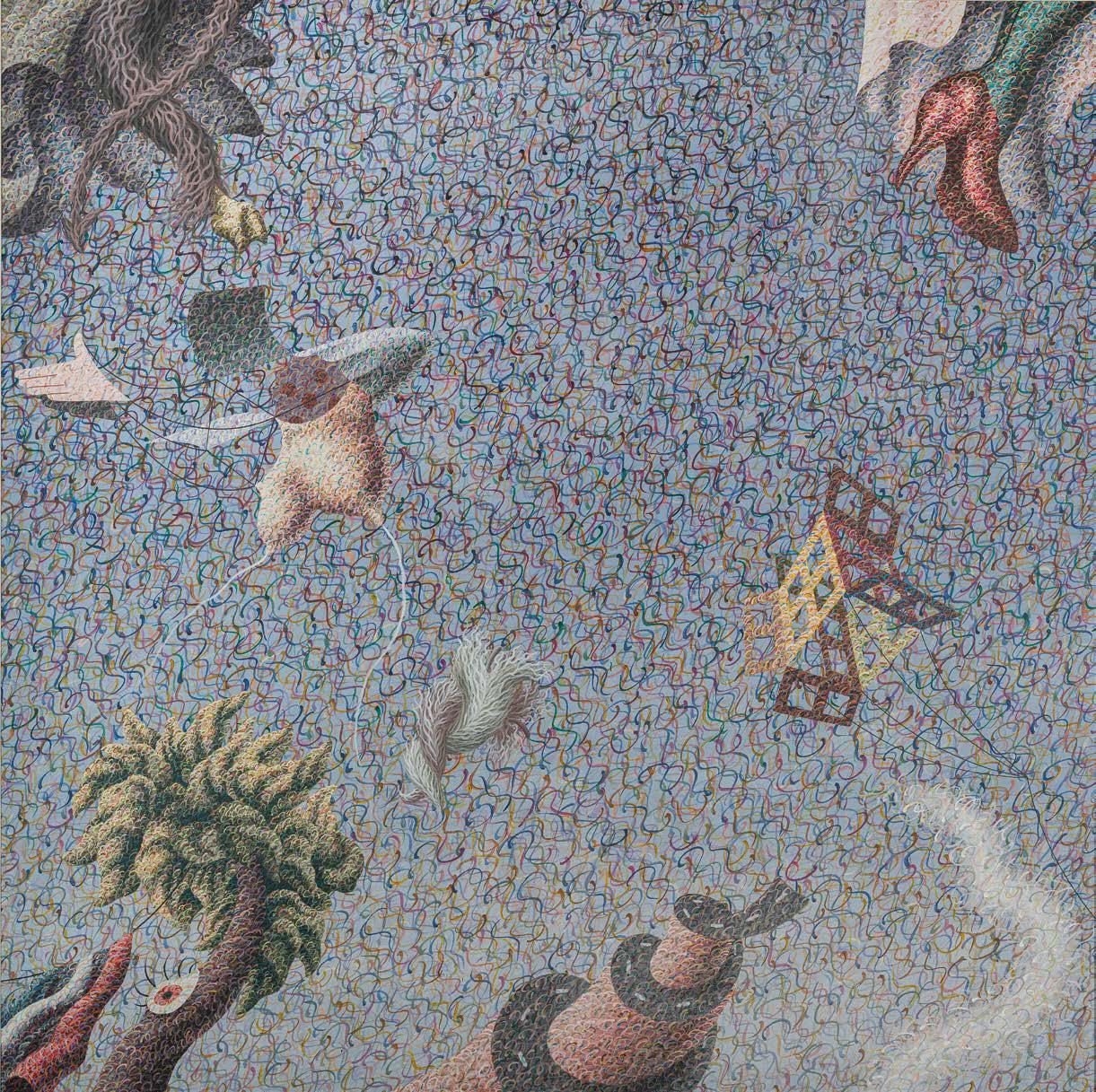

Cover image: Workers Rolling into New York, acrylic on canvas, 123.5 x 121cm; 48½ x 47½in.

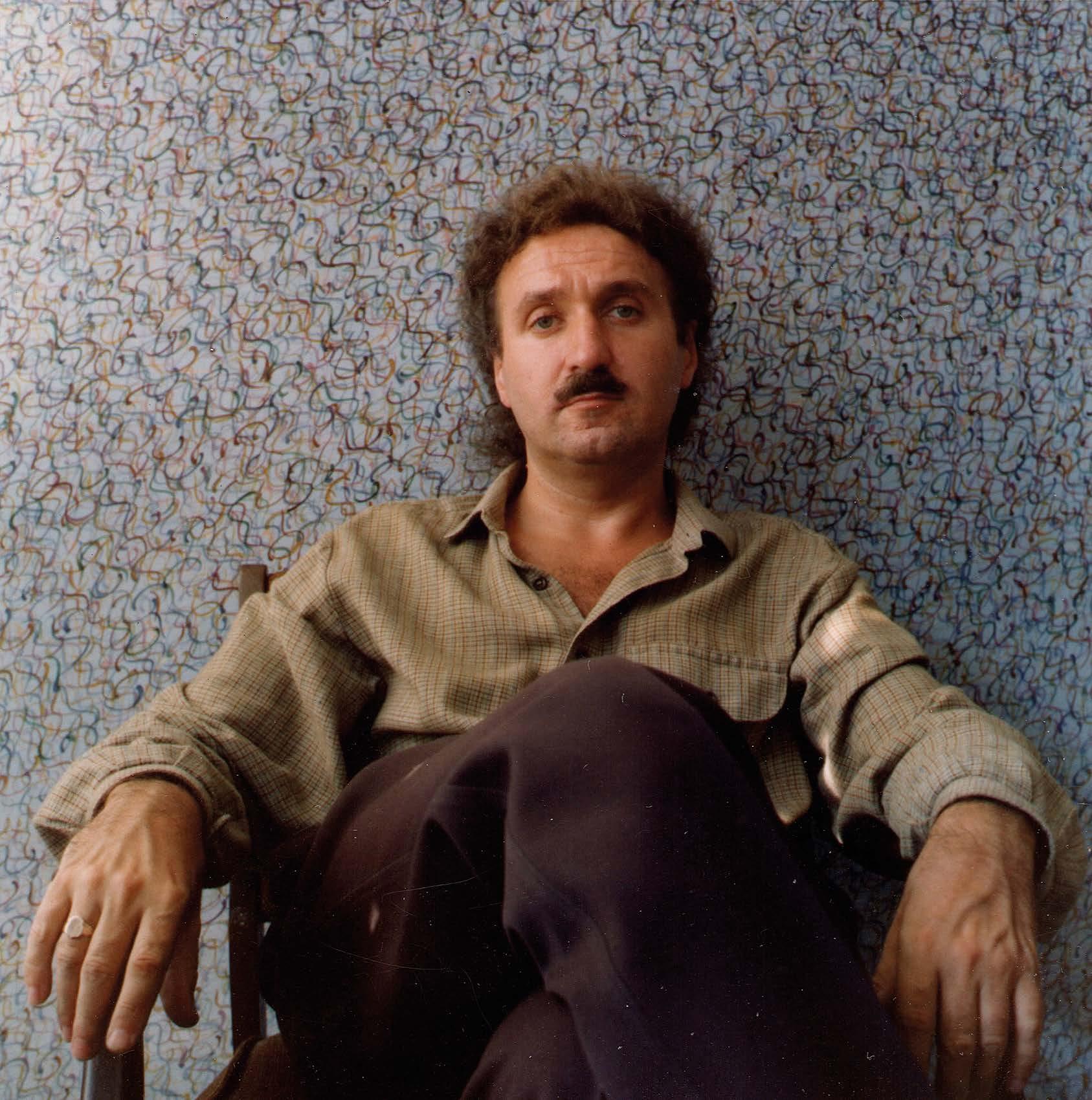

After decades in obscurity, Henry Orlik emerges as one of the most compelling chroniclers of American, urban life. The paintings, executed between 1980 and 1985, capture something essential about the American city, not just its physical reality, but its psychological landscape, the dreams and anxieties that pulse beneath the surface of metropolitan experience.

Orlik developed what he called “excitations”, a layered painting technique that builds tension through gestural intervention. The results are canvases that seem to vibrate with energy, where familiar city scenes become charged with unexpected meaning. A street corner transforms into a stage for unconscious desire; a skyscraper becomes a monument to collective memory. These are not simply paintings of cities, but excavations of what cities do to us, and what we project onto them.

This body of work represents a crucial missing chapter in the story of American Surrealism. While European Surrealists explored the unconscious through dreams and automatic drawing, Orlik found his inspiration in the American street. His paintings function like archaeological digs, revealing layers of cultural meaning embedded in everyday urban encounters. The familiar becomes strange, the mundane becomes mythic.

The timing of this exhibition adds particular resonance to Orlik’s vision. We are witnessing an extraordinary renaissance of interest in Surrealism, sparked by the centenary of André Breton’s founding manifesto in 1924. Major institutions worldwide have responded with landmark exhibitions: the Centre Pompidou’s ‘Imagine! 100 Years of International Surrealism’ and Tate’s comprehensive ‘Ithell Colquhoun: Between Worlds’. The art market has followed suit, with René Magritte’s L’Empire des Lumières achieving $121.2 million at Christie’s and Leonora Carrington’s Les Distractions de Dagobert setting a record of $28.5 million at Sotheby’s.

This surge of attention reflects the continuing relevance of Surrealism to our contemporary moment. In an age of urban displacement, digital alienation, and shifting national identities, Orlik’s paintings speak directly to our current condition. His return to New York, the very city that serves as both his subject and inspiration, creates a robust dialogue between past and present, between the America he painted and the America of today.

Orlik’s achievement extends beyond technical innovation. His canvases make visible the invisible forces that shape urban experience: the interplay of power and desire, the tension between individual identity and collective mythology, the way cities both shelter and alienate us. These works demand recognition not as historical curiosities, but as essential documents of the American experience, a nation still coming to terms with its own reflection.

This exhibition presents the most comprehensive examination of Orlik’s practice to date, positioning his work within the broader narrative of American modernism while asserting his unique voice as an interpreter of metropolitan life. These visionary New York paintings capture the soul of the city through a master’s eyes, offering a rare opportunity to encounter an artist whose time has finally come.

Grant Ford Curator

‘The psychological rule says that when an inner situation is not made conscious, it happens outside, as fate.’

– Carl Jung, Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self, 1951

By Sara Clemence

‘ To “have imagination” is to enjoy a richness of interior life, an uninterrupted and spontaneous flow of images.’

– Mircea Eliade, Images and Symbols, London, 1961, p. 20

‘Like a priest’1, Henry Orlik’s devotion to his painting is a calling, a vocation. Through his artworks, he develops his philosophy, exploring fate, evolution, eschatology, alienation, conflict, and memory.

As a surrealist, Orlik views the world differently and he brings his imagination and the surreal into our everyday world. ‘A Surrealist picture is an unshackled imagination (and the Surrealists have often claimed that every human being is endowed with imagination, be he aware of it or not) … The marvellous is within everyone’s reach.’2

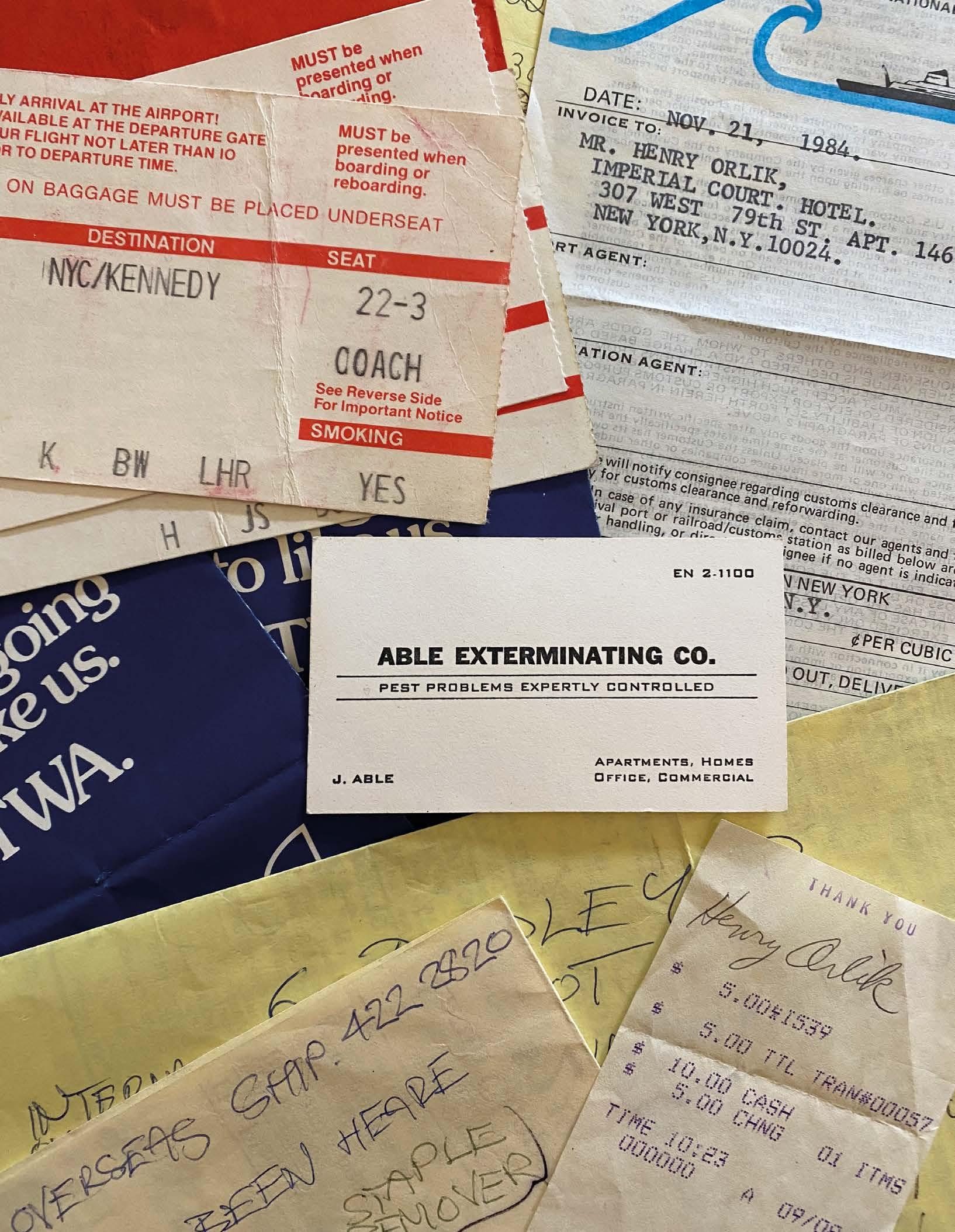

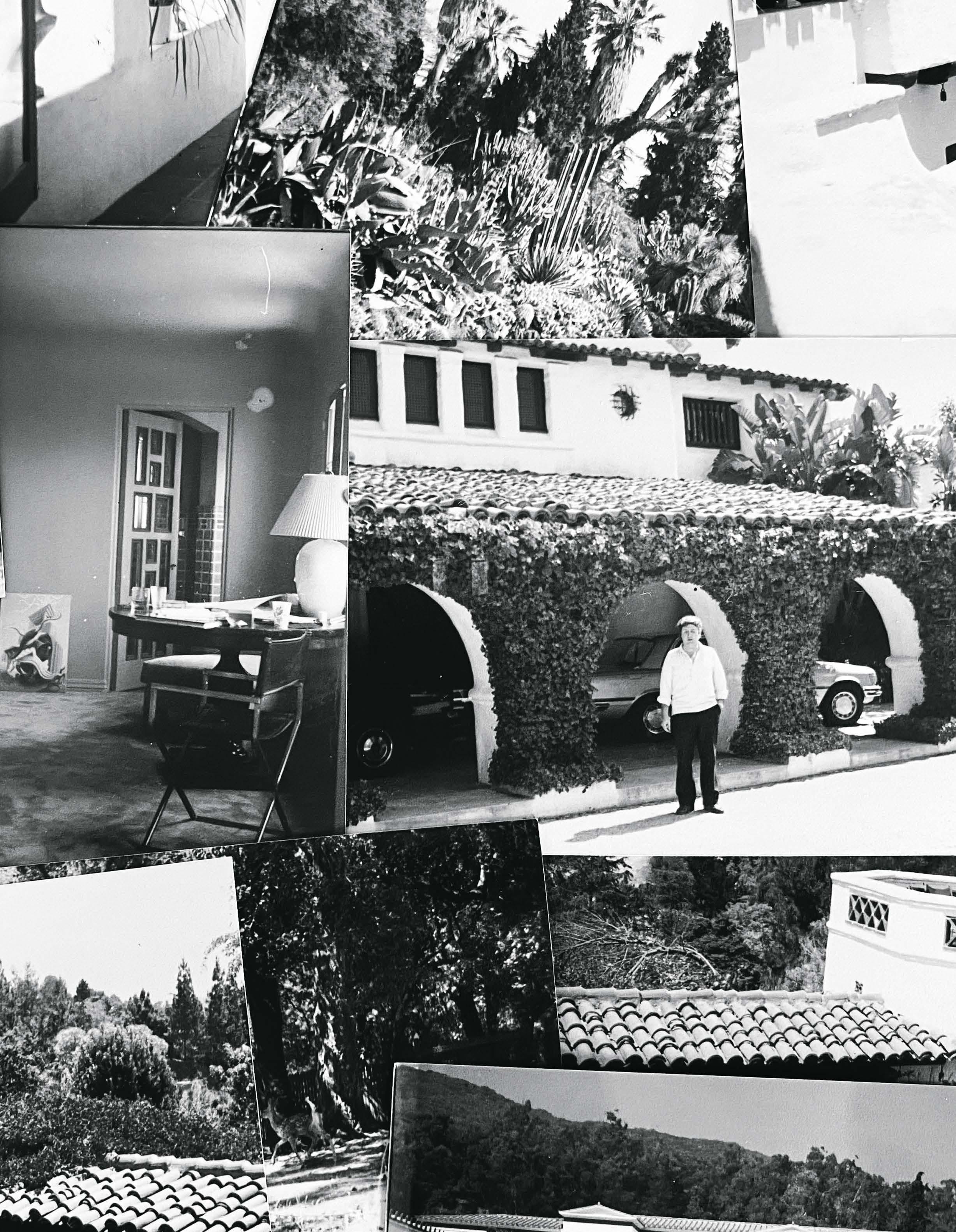

In 1980, following a run of successful exhibitions in London, Henry Orlik set his sights on America. He first travelled to California at the invitation of Beverly Coburn, ex-wife of American actor James Coburn, whom he had met in London. He then briefly made his home amongst a hippie commune in St Raphael near Sausalito, California, once famed as a stronghold for the hippie way of life in the 1960s and 1970s, but which by 1980 had started to fade.

The New York skyline eventually drew Orlik across the country in late 1980 and for the next five years the city would inspire some of his most monumental and dynamic works. From wide rolling landscapes, to soaring buildings screaming modernity into the sky alongside portrayals of the humble individuals who inhabited the streets around them, these works encapsulate America and New York as he experienced it.

As a trained draughtsman, Orlik was drawn to the geometry of the city, and the anonymous figures that haunt and charge them with energy and life. For him, the buildings come alive; they become the people who populate them with lives and characteristics of their own and, “they watch us”3. This is clearly demonstrated in the use of a wide-open eye in The Eye on New York (No. 8). Orlik did not feel oppressed or resent the buildings, “they are just there. I can fight them on canvas”4. With a deliberate use of perspective, he creates the impression of looming buildings that tower above the viewer. In 79th West Street, NYC Skyscraper (No. 24), the top of the building reaches beyond the canvas, giving the impression it extends forever into the skies.

The city Orlik portrays directly reflects his life in New York; his work Wall Street, NYC (No. 4) is his impression of the view from his bedroom window. The shapes, the figures and the colours provide fleeting snapshots of the ever-changing view. “I put everything into it”5 – his whole imagination roams across the scene.

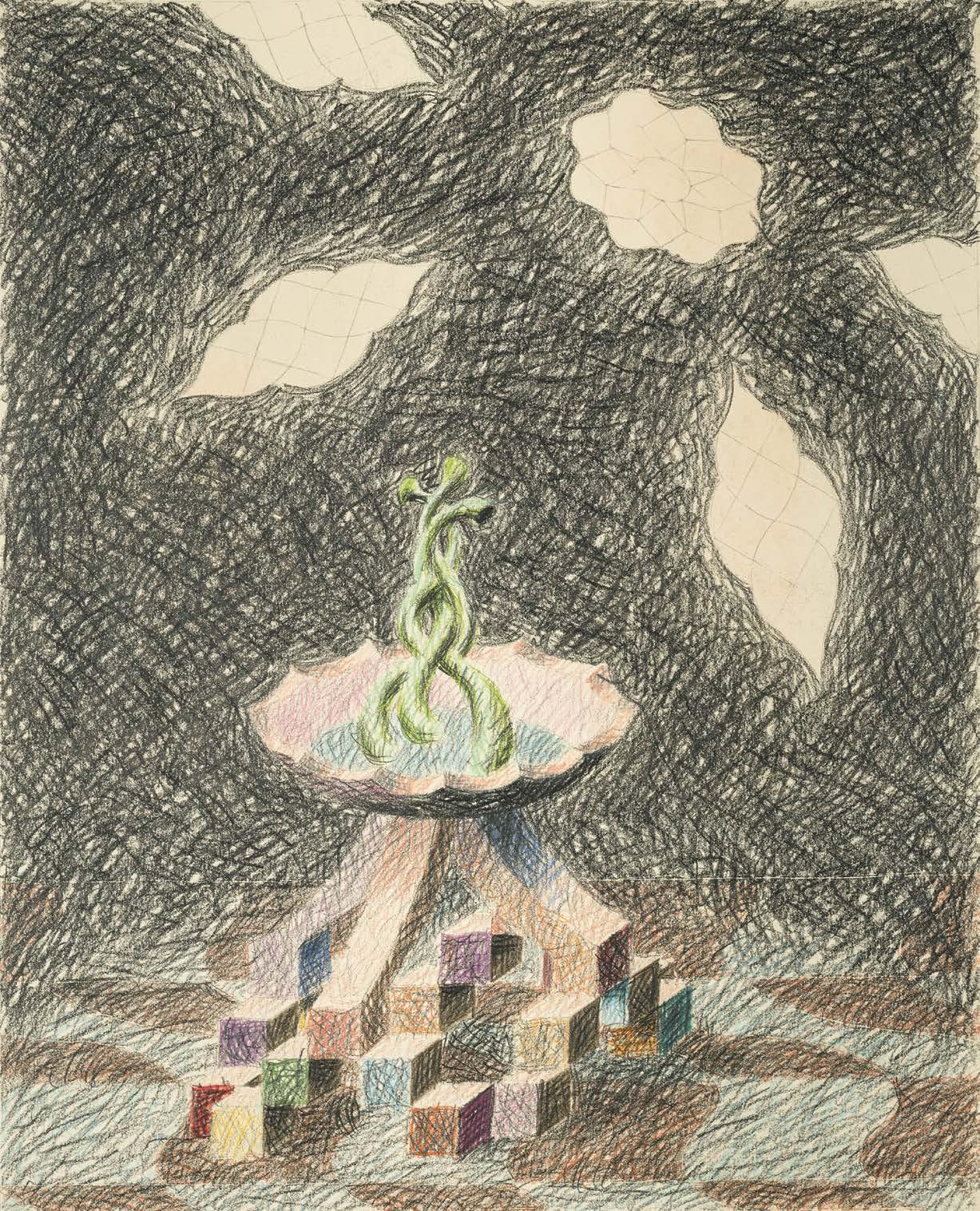

Elsewhere, New York references appear in such works as Green Fountain, NYC (No. 29), which portrays Orlik’s interpretation of the Bethesda Fountain in Central Park. Though Orlik has synthesised, refined and distorted the sculpture and situated it in an isolated location, it remains instantly recognisable. Central Park was also important – he ‘needed the green. It was a relief from the buildings’6. Orlik uses it as a backdrop for an imaginative exploration of Mermaid in Central Park, NYC (No. 18) and Winos in Central Park, NYC (No. 19 and No. 20), which portray both a lyrical romanticism and the underbelly of New York.

Orlik’s works are far from being realistic reproductions of a view. Instead, he seeks to capture the ever-changing nature of a landscape and the way it is experienced. Like the memory of a dream, a view constantly changes like a kaleidoscope and is impossible to pin down. For Orlik, memory is timeless and as current and real as the physical world around. His work is infused with images, ideas and stories that he has consumed. In works such as Workers Rolling into Work (No. 1), we can read references to The Wizard of Oz; in Mermaid in Central Park, NYC (No. 18) he evokes the stories of Hans Christian Andersen, and his watchful buildings intimate George Orwell’s 1984

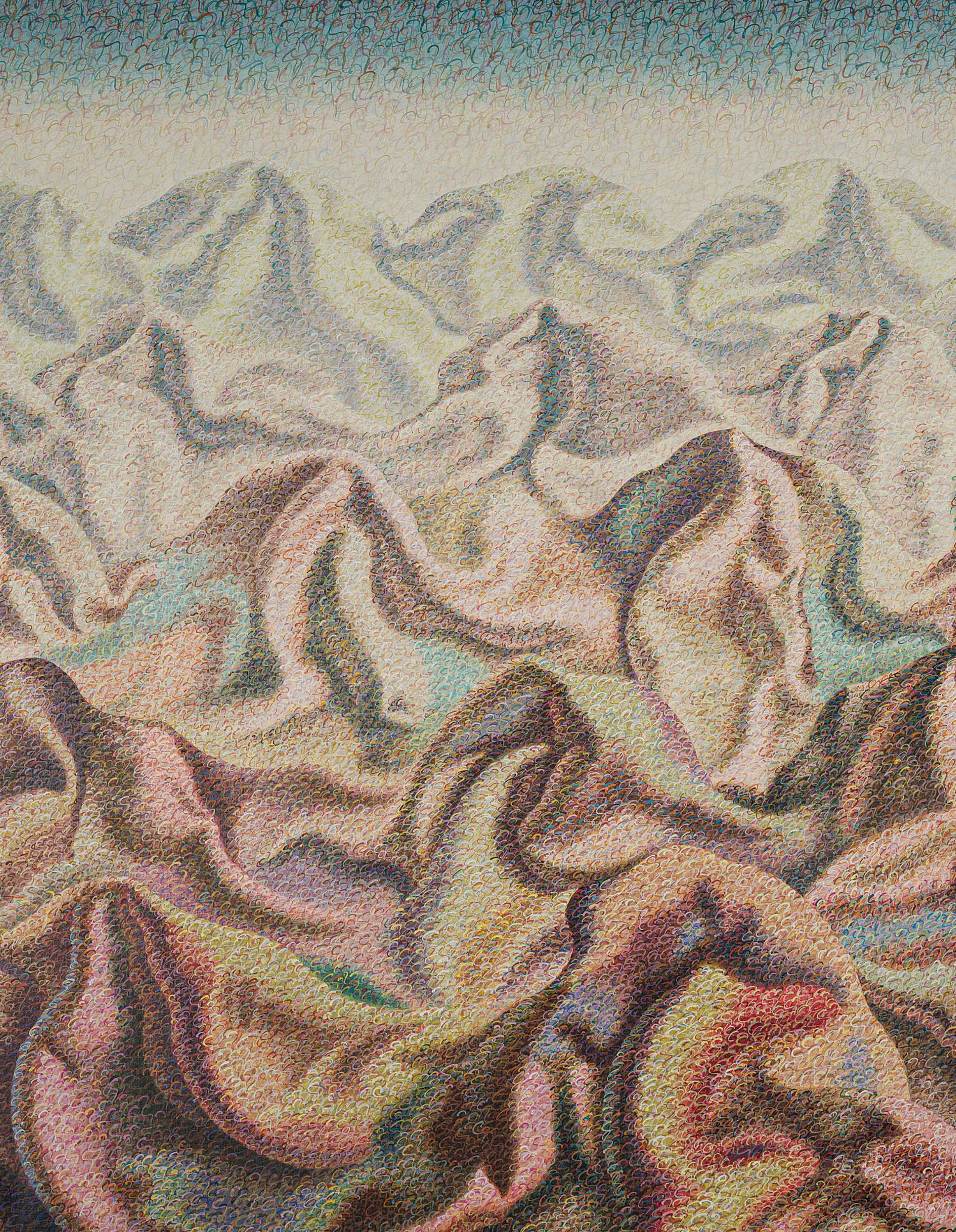

As well as views of New York City, works in Orlik’s American oeuvre examine the ancient expanses and mountainous regions of the rural American landscape. This landscape is most clearly seen in his works Totem (No. 6) and American Landscape (No. 17), in which he depicts the harmonious, undulating dunes and mountains of the American West. He allows for the sadness of the dark shapes in American Landscape, but by ‘treating each shape as if it were a world in itself’ he affirms ‘its existence even to the invisible depth of its microscopic agitations of atoms.’7 Orlik believes, ‘There is no separateness in reality, everything flows into one another, everything is related, as is

everything in my painting.’8 And so, Orlik commemorates not ‘transience but the strength of existence’9, which is remembered and embedded in the American landscape.

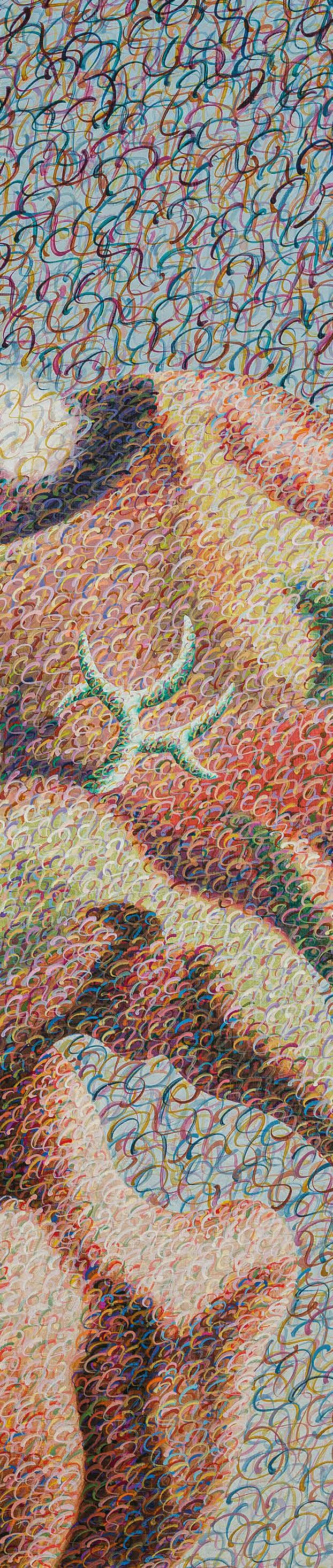

Each part of every painting is animated by Orlik’s ‘excitation’ brushstrokes, which are symbolic of the quantum field which makes up every living thing. This is Orlik’s ‘Quantum Painting’, and it represents the unseen element of the universe. Orlik describes these brushstrokes as the ‘living line’, a ‘technique of movement or animation’ which he likens to qi (‘vital energy’) as ‘life’s motion … a cosmic spirit that vitalises all things, that gives life and growth to nature, movement to water and energy to man. The artist is the expression of this energy – through his inspiration, he is the ‘vehicle for the expression’. It infuses all things animate and inanimate.’10 Just as every blade of grass is unique, so is each brushstroke. The brushstrokes represent the quantum dance between energy and matter, which invigorates and vitalises everything. It is ‘pregnant with unrealised meanings begging evocation and interpretation.’11

Orlik’s brushstrokes are both material (paint) and thought (Orlik’s energy, his qi). The paintings fizz with this energy – the sensation of being. His brushstrokes reflect his mood, his feeling for the painting: ‘If tired one cannot imitate energy … or if angry one cannot make the lines tranquil. It has the sensitivity of a lie-detector.’ Each space on the canvas teems with excitations, with potential. There is no empty space, the space without objects is animated with excitations, and alive with our thoughts because there is ‘no such thing as empty space. … We made it up’.12

Orlik intertwines suggestive images with older, timeless symbols. They are rich in references and associations. They are what Dante called ‘polysemous’ (of many senses), of multiple meaning, so that we must look beyond the merely visible; we must be led by our imagination.

In this catalogue, we offer interpretations of some of the paintings in the exhibition. These stem from what we know about Orlik from his writing, in conversation and the artists and books that influenced him. They are a guide to understand some of his intentions, his themes and belief system.

But they are not definitive because Orlik believes, ‘there is life to a painting’13 because ‘a painting is like the love between two people, it is something larger than oneself. And it becomes something distinct after the fusion of the two.’14

Orlik enchants the world using his own lexicon of symbols, prompting memories and our imaginations to make us question how we understand the world and why things are so. His paintings are transformative, alchemical; from a web of interconnections, our minds search for meaning and by searching Orlik’s subconscious for meaning, we search our own.

1. Henry Orlik, In conversation, 24th April 2025

2. David Gascoyne, A Short Survey of Surrealism, 1935, Enitharmon Press, 2003, p. 80

3. Henry Orlik, In conversation, 25th April 2025

4. Henry Orlik, In conversation, 5th May 2025

5. Henry Orlik, In conversation, 25th April 2025

6. Henry Orlik, In conversation, 5th May 2025

7. Henry Orlik, An Explanation of My Method, 1985

8. Henry Orlik, Let the Spirit be Moved, 1994

9. Henry Orlik, An Explanation of My Method, 1985

10. Ibid

11. Henry Orlik, Let the Spirit be Moved, 1994

12. Gary Zukav, The Dancing Wu Li Masters, first published 1979, 2009, Harper One, p. 267

13. Henry Orlik, In conversation, 24th April 2025

14. Henry Orlik, Let the Spirit be Moved, 1994

By Charlie Minter

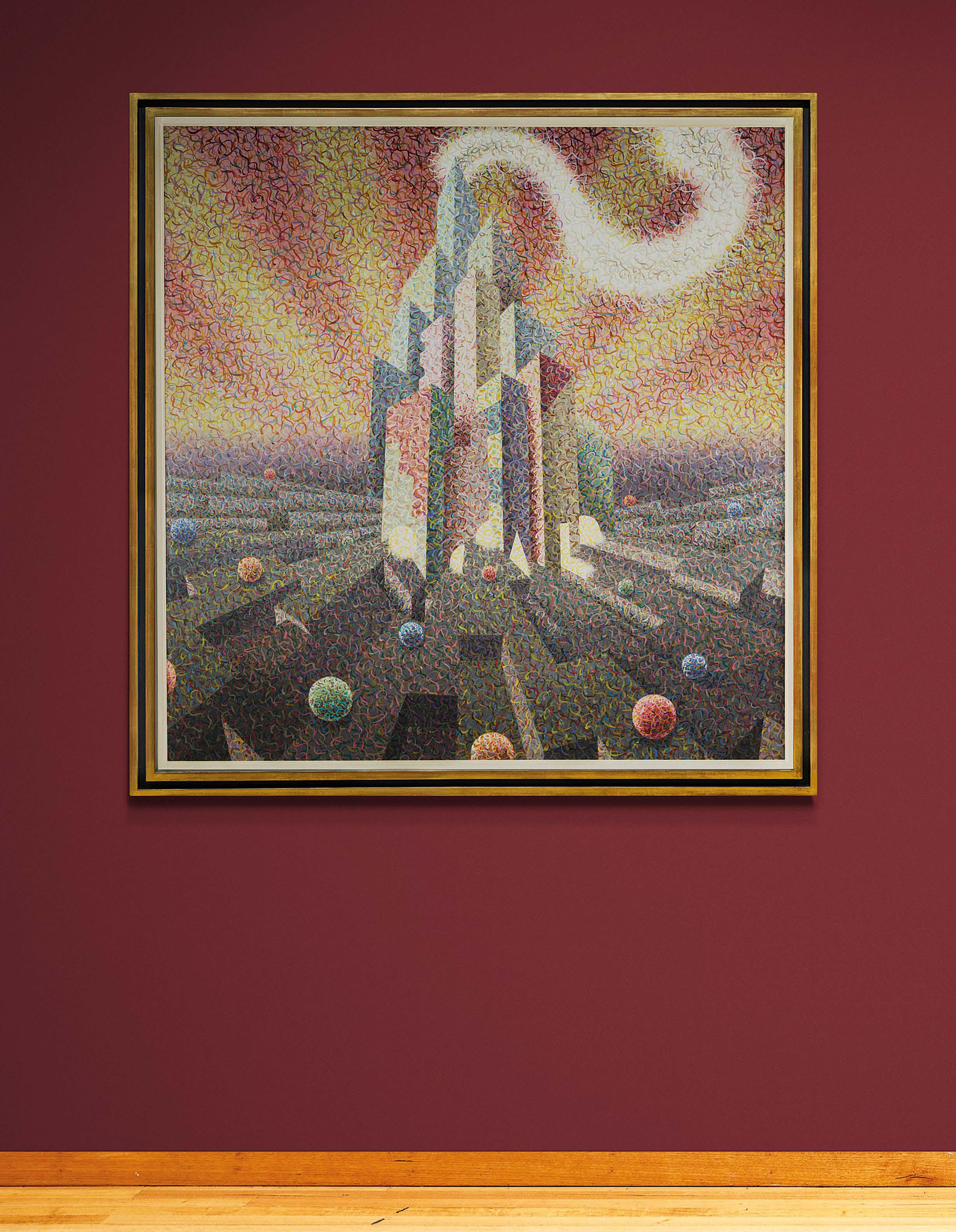

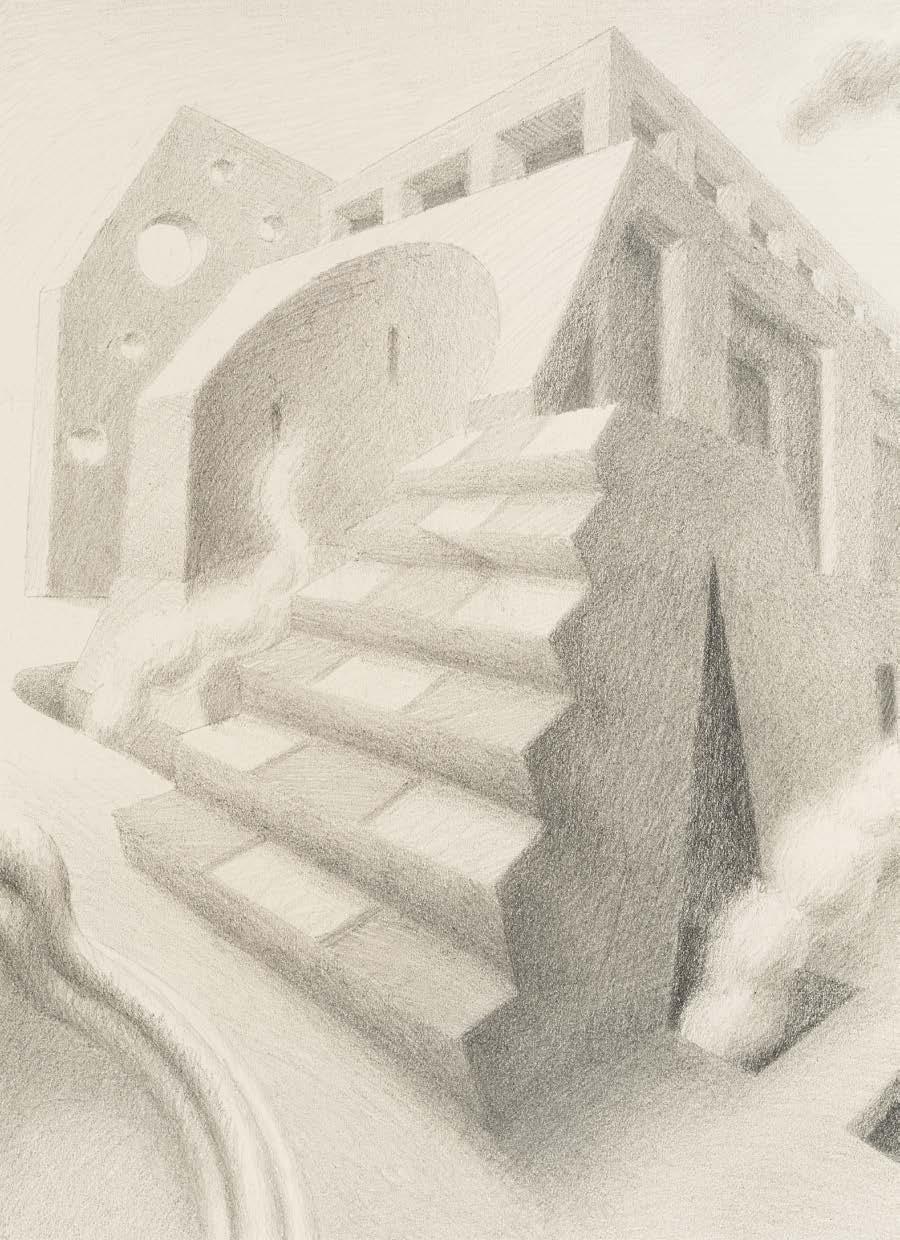

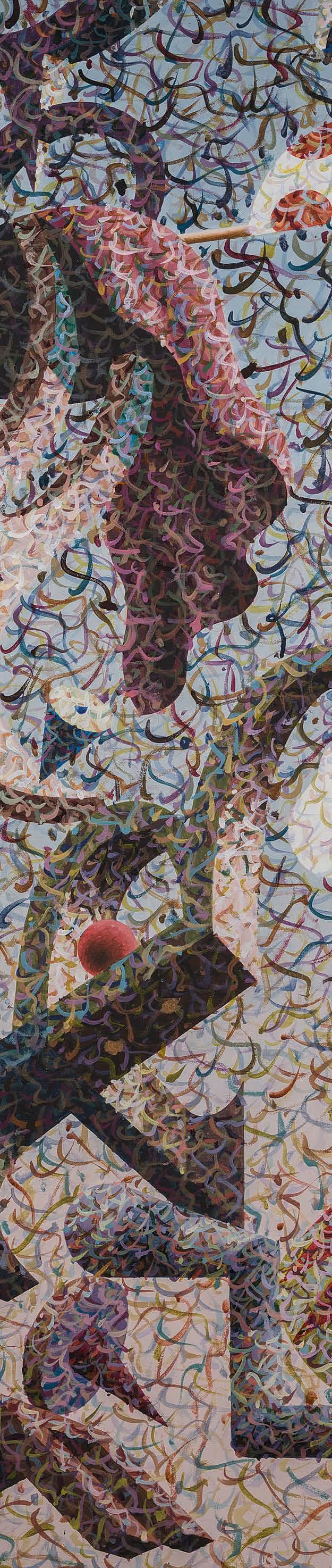

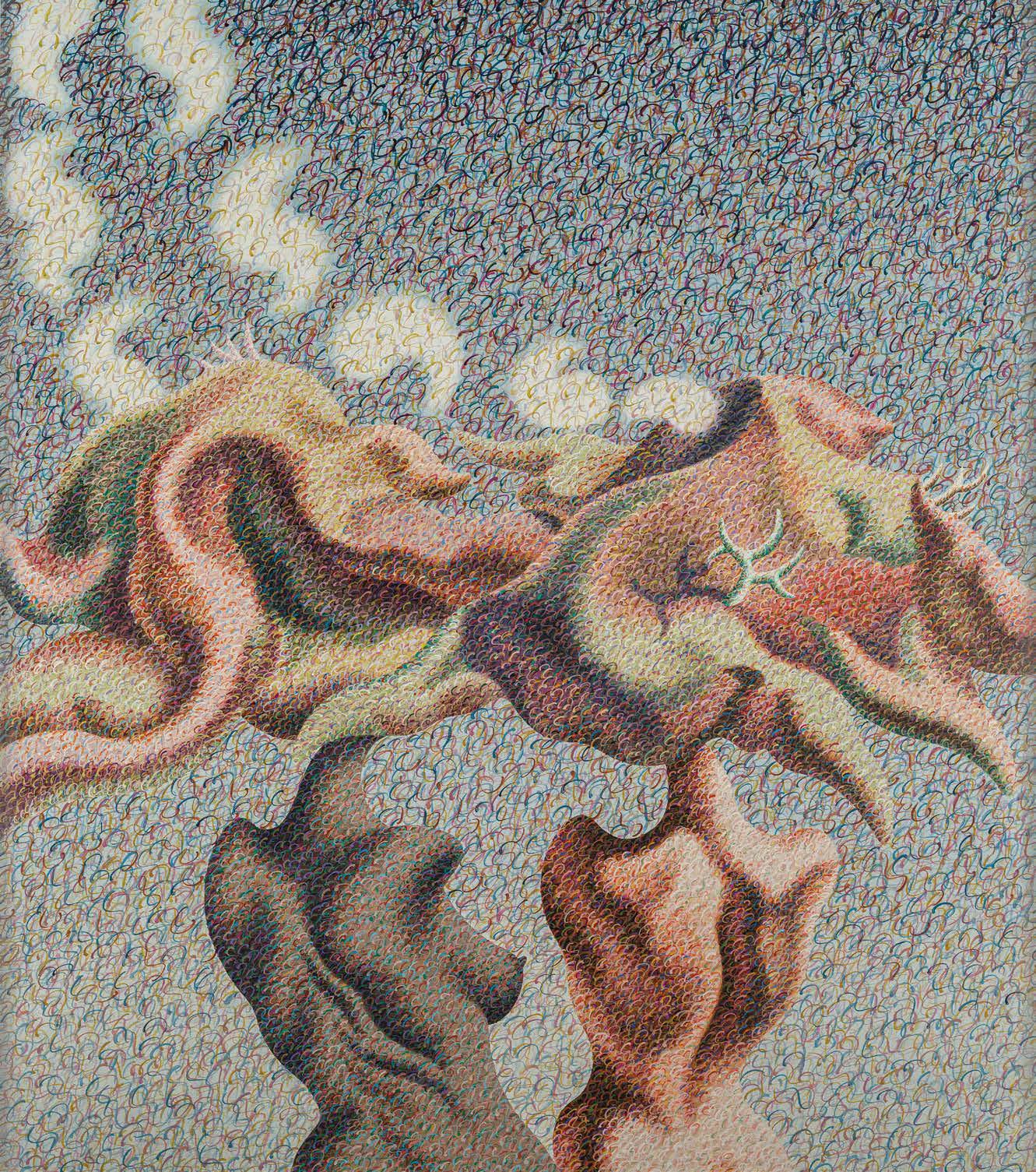

Within the extraordinary body of work Henry Orlik produced in New York, Fighting Skyscrapers stands as one of the most dramatic and thoughtprovoking. Revealed for the first time in forty years, for the modern viewer, it is impossible to view the image without referencing the tragic events of 9/11 in 2001. The painting, made twenty years before the world-changing day, could be seen in some way to bestow Orlik with ‘the terrible gift of foresight’.1

When Orlik arrived in New York in 1980 as an ‘outsider’, he was pursuing a wellworn path of individuals looking to the city for new freedoms or fortunes. New York was the commercial capital of the world; possibilities and ambitions awaited – to be fulfilled, or perhaps as often, dashed. The Twin Towers, which dominated the city’s skyline – the world’s tallest twin buildings at the time, and not yet a decade old –stood as symbols of the United States’ global trade and power. As an artist, Orlik responded keenly to the architecture of the city, not purely for its formal opportunities but most critically, to portray something of the life of its inhabitants and what the city represented – evidenced throughout the works in this catalogue. Cities are a melting pot of humanity, places of competing ideologies, and in Fighting Skyscrapers we have this strikingly presented in the anthropomorphising of the symbolic heart of the city.

Executed on an imposing scale, the two towers stretch skyward through the clouds; atop of each are strange creatures confronting one another in some kind of stand-off, unbeknownst to the inhabitants situated below the cloud line. Uniting and animating the painting overall is Orlik’s trademark painting technique: energetic swirls of brushwork of differing intensities – his ‘excitations’ – which are intricately linked to his understanding of the world through the lens of quantum physics. In tune with Surrealism’s ideology –blending reality with dreams, visions and unlocking the unconscious mind –Orlik questions the structures of the physical world. In doing so, the painting is elevated far beyond a traditional representation and provides a powerful image rich in interpretation.

As an image, Fighting Skyscrapers deserves a place in the canon of iconic 20th century paintings of New York. Across generations, artists from outside and within have responded to the city, whether lamenting the loss of neighbourhoods under the march of development as in George Bellows’ The Lone Tenement (1909), or celebrating its excitement and energy as seen in the American Impressionist Childe Hassam’s flag-bedecked depictions of Fifth Avenue (1917), both in the National Gallery of Art, Washington. Diego Riviera’s Frozen Assets (1931-32, Museum of Modern Art, New York) depicts dispossessed workers, critiquing the city’s inequalities especially resonant during the Great Depression. Piet Mondrian, in one of his last works, Broadway Boogie Woogie (1942-43, Museum of Modern Art, New York), brought his interpretation of the city through his unique process of grids and limited colours – its rhythmic pulses evoking the jazz scene he encountered there. At the same time, Edward Hopper’s iconic Nighthawks (1942, Art Institute of Chicago), captures the isolation of the city. In 1964, Andy Warhol, collaborating with John Palmer, made an eight-hour film, Empire (Museum of Modern Art, New York), focusing starkly and solely on the Empire State Building, evoking a sense of constancy, passing time and detachment. From the 1980s, Robert Moskowitz depicted the Twin Towers in a series of works exploring their formal potential (Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1996). With Fighting Skyscrapers, Orlik makes his own distinct and important contribution.

The title of the work denotes conflict – what exactly is being played out, Orlik does not make specific. The two buildings are actors on a stage and a vehicle for Orlik to explore and evoke ideas. He depicts each tower differently: the one on the left has horizontal stripes of alternate light and dark reds, while the one on the right is coloured grey and interspersed with darker vertical stripes. At their peaks sit a bird-like creature, or perhaps something from a watery underworld, and a beast with protruding tusks and black hair draped in a grey cloth. Not unknowingly, they are from different taxonomic classes.

The buildings stand as opposing forces rather than as a unit of two similar buildings. They thus come to represent two opposing ideologies. To some extent, the hard-fought elections between Ronald Reagan and Jimmy Carter in 1980 and 1984, may have suggested the painting to Orlik – with the red tower referencing the Republicans and the blue/grey the Democrats.

It seems likely, however, that the towers, more broadly invoke a representation of all opposing ideologies, such as the Soviets and the Nazis whose totalitarianism had a severe impact on the lives of Orlik’s maternal and paternal families. The towers represent the antagonism between two ways of being and they ignore the drive for coherence which at the quantum level – Orlik’s pervading philosophy – unites us all. It is a view perhaps best surmised in Danah Zohar’s book, The Quantum Self (1990), which declares the basis of us, as quantum selves, to have a ‘commitment to the whole world of nature and material reality’ in the recognition that we are ‘all, basically, stuff of the same substance. And the same can be said of spiritual values such as love, truth and beauty.’2

Orlik’s conflict is manifested in the world of commerce (as referenced by the skyscrapers). By doing so, it acknowledges the facelessness and lack of individuality often associated with such a world; how mankind, in its highrises, has become detached from the natural world. Like writers, artists and thinkers before him and today, Orlik questions at what cost comes the relentless pursuit of wealth and ‘progress’.

Such themes and explorations presented in the manner of Fighting Skyscrapers, which so emphatically displays Orlik’s technical ability, united with a genuine Surrealist vision, makes for a profound and compelling work on its own terms. The events that transpired twenty years later, frame it in an even more poignant and prophetic context. Post-9/11, it is a highly emotive and suggestive work and an image for our time.

As Fighting Skyscrapers and the paintings in this catalogue reveal, Orlik’s oeuvre makes a major contribution to the artistic landscape of the 20th century that we are only now coming to witness, and which is all the more remarkable for it.

Workers Rolling into NYC

In Orlik’s cityscape, colourful skyscrapers rise like a fairytale castle while workers—depicted as vibrant balls—roll along geometric pathways like a giant pinball game. A white plume crowns the tallest tower, resembling both a medieval cap feather and industrial smoke. The scene evokes both the Emerald City from The Wizard of Oz and Fritz Lang’s Metropolis.

Initially, the city appears harmonious, with everything following predetermined paths. Yet closer inspection reveals pitfalls and dark holes where these ‘billiard-like particles’ might fall or collide. The seemingly smooth paths show unpredictable indentations, transforming the city’s rhythm into a deceptive façade.

Orlik suggests that like Lang’s Metropolis where ‘the mediator between head and hands is the heart’, true art requires more than mere technique—it demands looking beyond materialism toward an invisible inner life united with the sensible world. He compares this integration to music, where reducing a symphony to individual notes loses its essence.

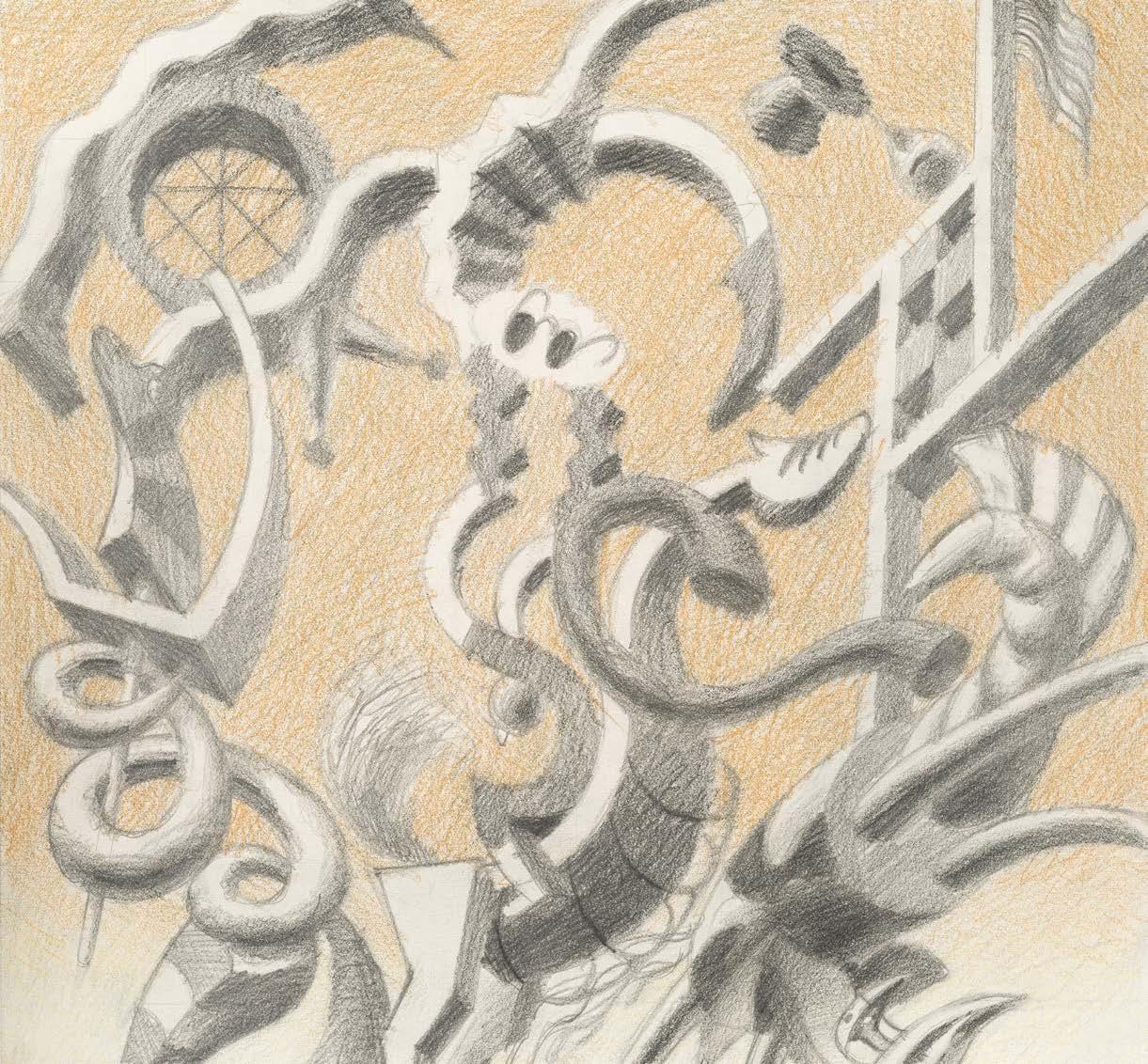

4.

Wall Street, NYC

In Wall Street, New York City, the financial district transforms into a living entity—a cityscape of diverse buildings with anthropomorphic features both menacing and humorous. A snake slithers from a wall, symbolizing both deception and renewal. A plait of hair descends from a high window like Rapunzel’s escape attempt and a pink tongue protrudes rudely from a double-arched window. Below, a building resembles a dragon with windows as teeth and a porthole eye. In the background, a squat building features windows forming a triangular nose, a grinning mouth, and menacing red eyes.

Walking Wall Street, one can see how these buildings sparked Orlik’s imagination—a glance at 23 Wall Street’s windows can readily suggest a face. Orlik’s unique vision brings these elements to life, challenging viewers to question their environment. A black eagle banner, symbolizing imperial power, hangs prominently. Opposite stands a hieroglyphic glimpse of domestic life—an apartment with two chairs around a table: a reminder of the city’s workers – beneficiaries of, or slaves to, commerce?

Below hangs a swinging lightbulb – a symbol of both torture and enlightenment – and nearby lies a naked sleeping woman, a recurring symbol in Orlik’s work representing escape through dreams.

The suggestive imagery implies that Wall Street represents all imperial cities throughout time, reflecting Orlik’s fascination with temporal cycles of rise and fall.

With artist’s stamp verso Acrylic on canvas 124 x 104cm; 48¾ x 41in.

‘Men cannot live without mystery. He has a great need of it.’

– John Fire Lame-Deer (1903-1976)

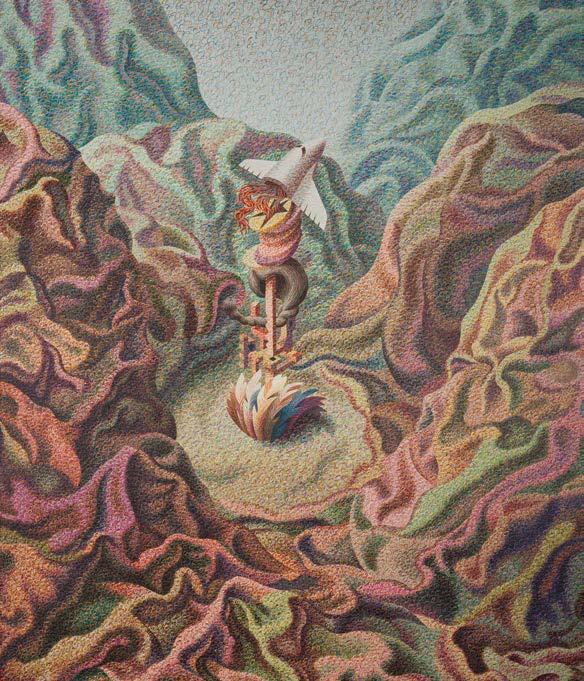

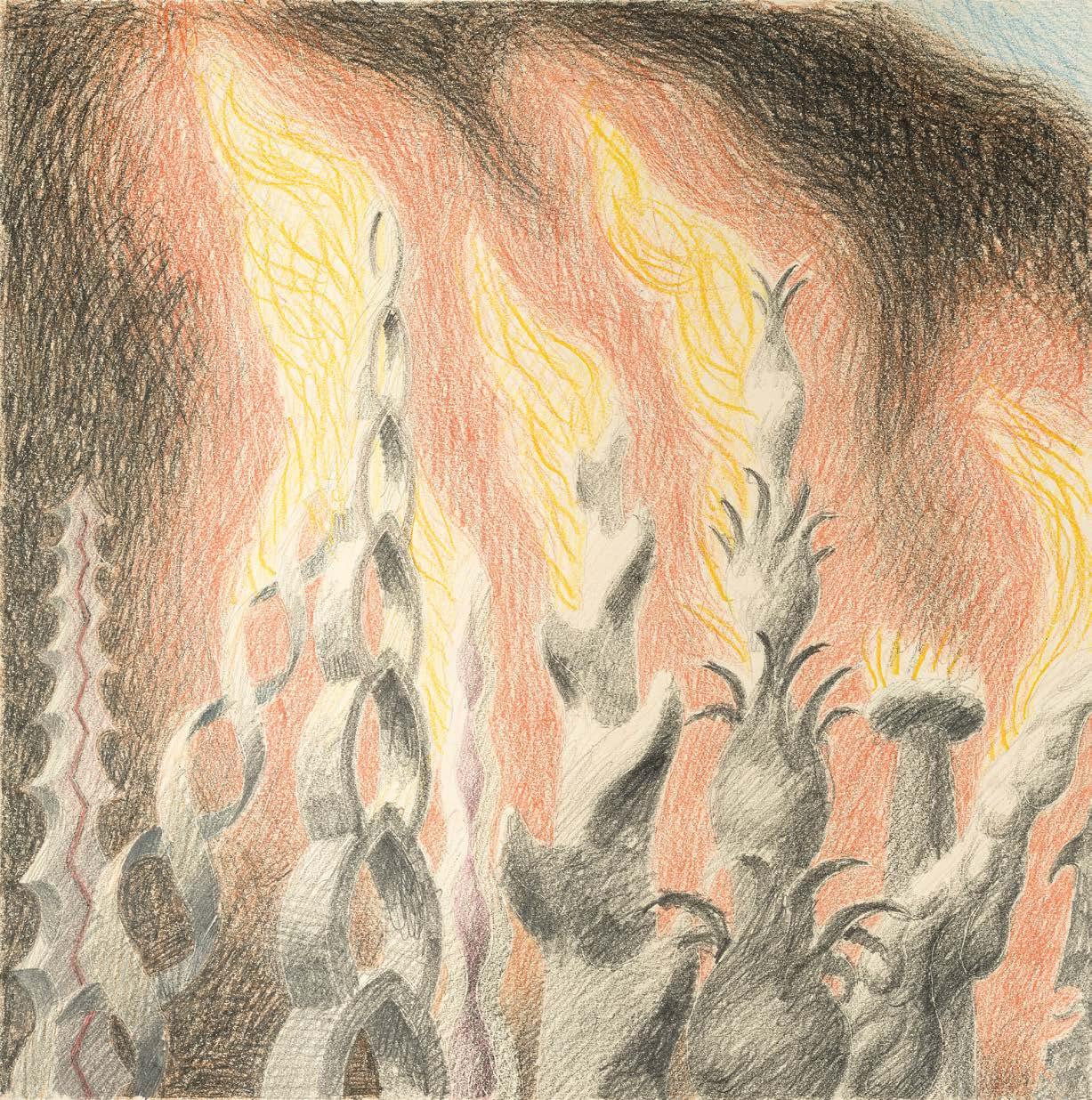

In this extraordinary painting, a space shuttle has crashed, causing a crater to form and the land to displace in colourful, rippling waves creating a clearing. It is both totem pole, space shuttle and jack-in-the box. There is something circus-like about the scene. The clearing has become a circus ring, in which the totem is a clown (a heyoka, or sacred clown) performing a rickety balancing act, and the surrounding scenery – the earth – has become the rippling audience, agape to see what will happen next. Paradoxically, at the same time as crashing, the space shuttle is about to blast off. It has strands of flaxen-red hair which stream out of it, like fire, and it rises from a bed of feathers which are both funeral pyre and the fire from take-off.

The totem pole is a symbol used by First Nation people with which they memorialise their ancestry and document their histories. It is both a memorial to a significant moment in their history and sometimes mortuary pole to commemorate the deceased. Here, poignantly, there is a black-haired scalp with plait that makes up part of the rocky fabric of the totem. It is pierced by a straight, rigid spike – like a stake – which is the only straight and upright object in the painting and which, both pierces, and holds the structure together. Interestingly, the space shuttle nose of the totem is the same colour as the sky and the other parts (some of them like casino chips, and one hazy crescent moon) are earth coloured: they are of the landscape.

The space race is as pertinent now as it was in the 1980s with man’s desire to reach space at the forefront of the news. Here, the wonky space shuttle is fragmented, and it seems it is only time before it is overwhelmed and subsumed by the writhing land; or perhaps it does make its rickety way to be lost in the misty sky. It has become an emblem itself – a totem memorial – of its own history and mankind’s reverence for science which has superseded a reverence for nature and the earth. It is a memorial to the inexorable, incessant creep of progress.

Orlik painted Totem in his apartment in New York and shipped it to England in 1985. On its tenth flight on 28th January 1986, the Space Shuttle Challenger catastrophically broke up seventy-three seconds after liftoff, killing its seven crew. The Space Shuttle Columbia completed twenty-seven missions before its disastrous flight on 1st February 2003 when it disintegrated on re-entry into the Earth’s atmosphere; all seven crew members died.

‘

The awareness of speed in our age has given us a new conception of space and time. There does not have to be a distinction between pictorial form and sculptural form any more. I build my pictures by applying layers of animated lines as if I was using bricks.’

– Henry Orlik, An Explanation of My Method, 1985

8.

‘ The city of New York is like an enormous citadel, a modern Carcassonne. Walking between the magnificent skyscrapers one feels the presence on the fringe of a howling, raging mob, a mob with empty bellies, a mob unshaven and in rags.’

– Henry Miller, The Cosmological Eye, 1939

11. Fighting Skyscrapers, NYC

With artist’s stamp verso Acrylic on canvas

126.5 x 105.5cm; 50 x 41½in.

‘ There is nothing more poetic and terrible than the skyscrapers’ battle with the heavens that cover them.’

– Federico García Lorca (1898-1936)

14.

Subway, NYC

With artist’s stamp verso Acrylic on canvas 169 x 129cm; 66½ x 50¾in.

‘

The words of the prophets are written on the subway walls …’

Subway, NYC exuberantly captures the physical sensation of subway travel, with a train’s approach conveyed through swirling energy. The tunnel’s spiral creates a disorienting vortex, while noise is suggested by colourful swirls and megaphone-like purple bands. Bright colours and excitation brushstrokes evoke the blur of clothing and advertisements seen from a moving train, suggesting lives momentarily intersecting. Silhouettes appear in tunnel ‘windows’—passengers glimpsed fleetingly. Similar to Futurist dynamism, which Orlik knew well, the painting captures urban energy and excitement.

Inspiration came from Simon & Garfunkel’s ‘The Sound of Silence’ and ‘A Poem on the Underground’, responding to the character with a ‘coloured crayon’ waiting in the shadows.

Beyond immediate representation, the black ‘holes’ suggest deeper meanings related to Orlik’s interest in quantum science. These reference Einstein’s concept of time’s illusory nature and Taoist philosophy’s ‘mystical Void’ with its ‘infinite creative potential.’1 Two tunnels appear—one dark, one light—with pure energy lines emerging from a white ‘hole’, perhaps representing light at the tunnel’s end, referencing Plato’s cave allegory and recalling Hieronymus Bosch’s Ascent of the Blessed (c. 1505-1515, Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice).

By transforming an everyday subject, Orlik captures sensory experience while encouraging viewers to transcend ordinary reality.

17.

American Landscape

With artist’s stamp verso Acrylic on canvas

103 x 178cm; 40½ x 70in.

‘I am responsible for the world because I am the world.’4

In American Landscape, six tipis form an abandoned Native American village among writhing dunes. Only skeletal tent poles remain, and black, phantom-like shapes—once buffalo hide coverings—envelop them like disembodied cloaks or amorphous creatures. These dark forms evoke the smoke of extinguished campfires, sending mournful messages across time. The wooden poles suggest both deer antlers and shamanic spirits, rising like flames from ashes in a ghostly circular dance.

Natural pigments from the vanished community have bled into the landscape, warming the dunes with earth tones—soft pinks, lilacs, subtle greens, and jewel-like aqua suggesting distant oases. These colours, once used in rock art, clothing, and basketry, originated from the land and have returned to it. Though the ancestral population is gone, their spirit merges with the living landscape—land and people become one.

Orlik creates a poignant scene, treating ‘each shape as if it were a world in itself’ while affirming its existence ‘to the invisible depth of its microscopic agitations of atoms.’1 His philosophy—‘There is no separateness in reality, everything flows into one another’2—commemorates not ‘transience but the strength of existence’3 which is here embedded in this remembered landscape.

18.

Situated within Central Park is a bronze statue of Hans Christian Andersen, author of The Little Mermaid, The Emperor’s New Clothes and The Ugly Duckling, amongst other classics. Placed there in 1956, children have since gathered around the sculpture on Saturdays to hear stories, fairytales and folktales. From this starting point, Orlik then references Edvard Eriksen’s famous bronze sculpture of The Little Mermaid (1913), which sits on a rock in Copenhagen harbour.

In Orlik’s re-imagining, the mermaid appears by a small pool in Central Park. Unlike her static statue counterpart, she is animated—one knee raised as if preparing to dive, her hair rising like an antenna receiving cosmic signals. The landscape transforms from Central Park into a vast desert with undulating dunes that resemble ocean waves. Above, a mysterious red and white celestial object emits signals, perhaps offering escape from her confined pool bordered by crazy paving.

Orlik’s signature ‘excitation brushstrokes’ invigorate the mermaid, landscape and sky, representing unseen quantum energy. This aligns with the Mermaid or Melusine’s historical significance as an alchemical symbol bridging visible and invisible realms.

The painting resonates with André Breton’s Arcanum 17, in which he uses the Melusine to symbolize hope and renewal. The object in the sky closely parallels Breton’s description of Sirius, ‘the Dog Star,’ which shines brightest in the sky just before dawn, ‘its points are of red and yellow fire… and below the luminous blaze…a young woman is revealed, nude, kneeling by the side of a pond…’1

The mermaid also connects to Orlik’s Polish heritage, as it appears on Warsaw’s coat of arms and in legend is thought of as a protector of the city.

Orlik captures the joie de vivre of two ‘winos’ with humour and camaraderie. They appear to float in their drunkenness, clothes rising as wine bottle and glass tip over. Fireworks burst overhead, echoing their ebullience. The woman kicks up her legs in dance, revealing a butterfly tattoo, her spiky blonde hair resembling the Statue of Liberty’s crown. A snake-like table leg symbolizes temptation fully embraced.

Their unrestrained behaviour mirrors Orlik’s fluid, vigorous brushstrokes animating the canvas. Only the wine glass, bottle, and metal railing escape this treatment—representing boundaries normally constraining the subjects, though ineffective in this moment of eternal joy.

Orlik viewed painting as ritualistic dance, describing his ‘brush lines, like dancers responding to a musical score, the score being the picture’s subject.’1 The figures become musical notes merging with cosmic dance, while the railing represents the musical staff normally imposing order. Here, however, these notes break free into spirited improvisational jazz, achieving liberation through joyful abandon.

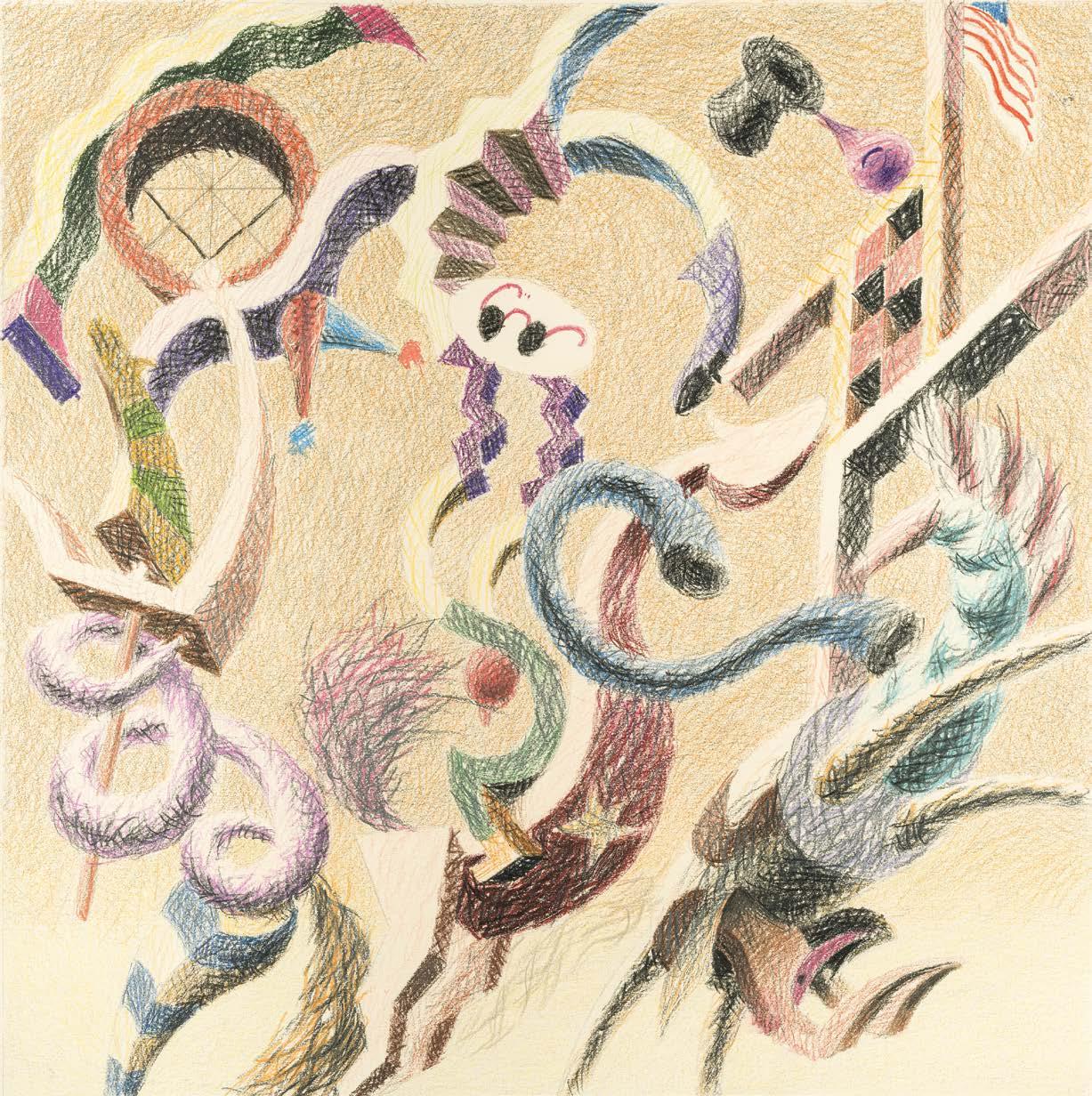

21.

7 th Avenue, NYC

With artist’s stamp verso

Acrylic on canvas

123 x 123cm; 48½ x 48½in.

7th Avenue, NYC is a wonderful representation of Orlik’s vivid imagination in which everything is entangled. It is a dreamlike composition where objects spill beyond canvas edges like fleeting thoughts, evoking the whirlwind from The Wizard of Oz.

On the left of the composition, a medieval manus dei (hand of God) appears in the sky, connected to a transparent frame resembling both airplane and angel’s wings. Below hangs the Madonna lactans, nurturing the world from between heaven and earth. In the corner, a medieval devil playfully reaches toward the plane/angel in a game of cosmic chase between good and evil.

Opposite, a woman’s leg in green stocking and Dorothy’s sparkling ruby slipper- now stiletto- extends from a white dress, merging the Good Witch, Wicked Witch, and Dorothy into one complex entity.

Unlike traditional fixed-perspective painting, Orlik invites viewers to ‘wander through the painting discovering new things at every step’1. Among commonplace elements like a washing line hanging from a watchful tree, Orlik raises cosmic questions by blurring the otherworldly and human. A winding road rises like unrolled film before ending abruptly—perhaps symbolizing life’s journey, while a trail of white cloud remains as the last vestige of creative whirlwind.

‘I

would give the greatest sunset in the world for one sight of New York’s skyline. Particularly when one can’t see the details. Just the shapes. The shapes and the thought that made them. The sky over New York and the will of man made visible. What other religion do we need?’

– Ayn Rand, The Fountainhead, 1943

Orlik’s painting reinterprets Hieronymus Bosch’s painting, The Ship of Fools (1500-1510), but here Orlik has transplanted a leg of ham for a man’s reaching arm, a large circular flower for a bowl of cherries and a sail, which is also a crescent moon, for the curved shape of the jester’s rounded back. Historically, the jester, or fool, was often the only person who could poke at authority by speaking truth to their powerful overlord and is, for Orlik, an important figure. Bosch’s watching owl in the tree has become an egg. Additionally, Orlik has placed two fighting eagles, with agitated wings, on the top of the tree.

The theme of The Ship of Fools comes from Sebastian Brant’s (1458-1521) novel, Das Narrenschiff (The Ship of Fools, 1494). This had become a medieval motif which could be loosely traced to a story in Plato’s Republic (Book VI) which tells of a ship with a dysfunctional crew, with no capable leader at the helm. It allegorically represents a political system without a wise leader to govern it. Katherine Anne Porter’s bestselling novel The Ship of Fools (1962) re-frames the allegory in a twentieth century setting. It was adapted for film in 1965 with a starstudded cast and was Vivien Leigh’s last film.

Orlik used the eagle as a symbol of imperial power as it has been used by imperial powers from Ancient Rome onwards. In The Ship of Fools, the eagles are fighting. Orlik explained them as opposing forces: “we are always fighting our neighbours.”1 One wonders, in Orlik’s painting, what the eagles will hatch from their egg.

28.

In Cyclops: Self-Portrait, Orlik turns his all-searching eye onto himself rather than the world outside of him. Indeed, in prescribing the title ‘Cyclops’, Orlik playfully suggests his singular-vision and his single-mindedness. Misunderstood and alienated, Orlik has lived only for his art and his vision of the world, which finds such extraordinary expression in his paintings.

Despite the title ‘Cyclops’, the painting includes two eyes – Orlik never settles for a singular reading. One eye, most reminiscent of Cyclops, is a round white object with a central black dot, unseeing and superficial; the other is an arched window, an eye to the soul.

The self-portrait is a rite of passage for artists and has resulted in some of the most powerful works across the ages, as gifted painters grapple with their identity and their perception, both of themselves and the world. For the Surrealists, from Dali to Magritte, it has led to some of the most visually arresting. In the present work, Orlik makes his own distinct and vital contribution.

31. Fairground

With artist’s stamp verso Acrylic on canvas 138 x 138cm; 54 x 54in.

‘Each object has an individual shape and character of energy, by applying my method to it, I want to express its essence and life-force.’

– Henry Orlik, An Explanation of My Method, 1985

‘ The brushstroke is action art, but it is also a controlled force, regurgitated, capable of expressing a state of mind with a multitude of variations.’

– Henry Orlik, An Explanation of My Method, 1985

‘Ask yourself whether the dream of heaven and greatness should be left waiting for us in our graves-or whether it should be ours here and now and on this earth.’

– Ayn Rand, Atlas Shrugged, 1957

In Tombstones, the colourful ‘hanging’ above the dull, heavy tombstones represents the mystery of God and of goodness1 The shapes rising above the tombstones could also be interpreted as musical notes or a church organ and so the aura becomes the ’music of the spheres’, the musica universalis – the harmony of the cosmos, of which the harmony or disharmony of the earth plays a part. In the macrocosmic universe, if the earth – we (the microcosm) – are out-of-balance, we unbalance the whole cosmos. Orlik warns us that we are the tombstones – drab, colourless and earthbound and how we live our lives has a bigger consequence than our immediate surroundings (or even ourselves).

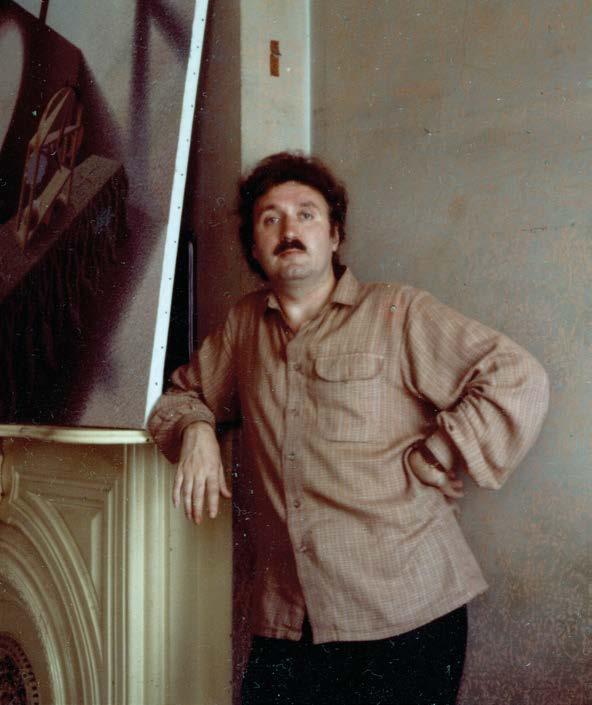

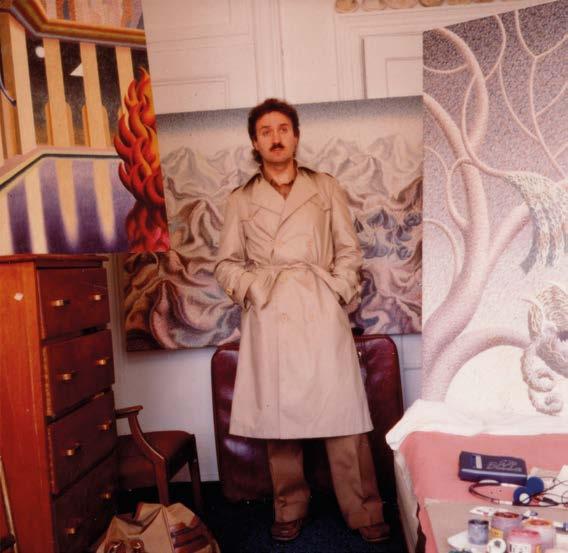

Born in Ankum, Germany in 1947, Henry Orlik first arrived in England in 1948. His Polish father, Josef Orlik, had served in the Polish Parachute Brigade, alongside the Allied forces in World War Two and, unable to return to Poland, resettled in England with his Belarussian wife Lucyna and young son. The early part of Orlik’s life was spent in various Polish resettlement camps in Gloucestershire and the Cotswolds. The Orliks, like many Polish families, eventually settled in Swindon, Wiltshire which was rapidly expanding post-war.

In 1964 Orlik enrolled at Swindon Art College where he studied for three years, continuing his studies at Gloucestershire College of Art, Cheltenham between 1966 and 1969.

Orlik was already making a name for himself by 1971 when he exhibited a painting at the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition. In 1972 he had a highly successful one man show at the world-renowned Surrealist Art Centre, Acoris, in Brook Street, London W1. Orlik participated in Acoris’ mixed Surrealist Masters exhibitions in 1972 and 1974. In these exhibitions his work was exhibited alongside many of the most celebrated Surrealist artists, including René Magritte, Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst and Georgio de Chirico.

From 1972 Orlik lived and worked in London.

In 1980, at the invitation of Beverly Coburn, whom he had met through Stooshnoff Fine Art, Orlik travelled to Los Angeles. He moved to New York in 1981 and remained there until 1985 when he returned to London.

After his return to England, Orlik increasingly retreated from public life and the art world, choosing instead to focus his attention solely on his work.

Orlik now lives in Wiltshire.

Biography

1947: Born in Ankum, Germany

1948: Arrives in United Kingdom

Education

1955-57: St Francis Xavier School, Hereford: Polish boarding school run by priests

1958-1960: Cirencester County Secondary School

1961-1963: Polish School, Swindon: studied Polish history, language and geography; took part in Lodz performances (Polish dancing)

1960-1963: St Joseph’s Secondary School, Swindon

1962: London Art College, correspondence course

1964-66: Swindon Art College

1966-69: Gloucestershire College of Art, Cheltenham, diploma in Art and Design

1970: Art teacher’s Certificate, Brighton College of Art

Solo Exhibitions

1972: Acoris Surrealist Art Centre, Brook Street, London W1

1974: Stooshnoff Fine Art, Brook Street, London W1

1978: Drian Galleries, 7 Porchester Place, London W2

1978: Obelisk Galleries, 15 Crawford Street, London, W1H 1PF

1994: ‘Retrospective’, Exhibition Hall, Swiss Cottage Central Library, London, NW3

2024: Winsor Birch, ‘Cosmos of Dreams’, held at The Maas Gallery, 6 Duke Street, St James’s, London, SW1Y 6BN

2024: Winsor Birch, ‘Cosmos of Dreams II’, 1 The Parade, Marlborough, SN8 1NE

Group Exhibitions

1971: The Royal Academy Summer Exhibition

1973: ‘Surrealist Masters’, Acoris, Brook Street, London W1

1974: ‘Surrealist Masters’, Acoris, Brook Street, London W1

1977: ‘4 Artists’, Aberbach Fine Art, Savile Row, London W1

1977: ‘Annual Exhibition’, POSK (Polish Social and Cultural Association), King Street, Hammersmith, London W6

1978: Chelsea Artists’ Annual Show

1979: Chelsea Artists’ Annual Show

1979: ‘Portraits’, POSK (Polish Social and Cultural Association), King Street, Hammersmith, London W6, exhibited portrait of Lucyna Orlik

1983: 80 Washington Square East Galleries, New York University

Published in 2025 by Winsor Birch.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise, without first seeking the permission of the copyright owners and the publishers.

All images in this catalogue are protected by copyright and should not be reproduced without permission of the copyright holder. Details of the copyright holder to be obtained from Winsor Birch.

© 2025 Winsor Birch.

Designed and produced in the UK by Footprint Innovations – www.fpiltd.com Images by Greenlys Photography – www.greenlysphoto.com – 01488 685256

Back cover image:

NYC,