SY ST EMS: RESI I ENCE SCI ENCE UPLDAT ES Open up any newspaper, switch on your TV, or log into social media, and you’ll likely be overwhelmed within seconds with news on COVID-19. It seems that these months, all our attention goes out to this global crisis. However, while COVID-19 keeps us busy, it is by far not the only disaster we are facing. For instance, the southern hemisphere just ended the worst fire season ever recorded (with events like the Australian Black Summer Fires), though all the world’s attention has bottlenecked to COVID-19. Concerningly, these kinds of fire seasons may become more frequent as the climate emergency worsens. And while the northern hemisphere is prioritizing fire containment and crew safety above all else in the face of COVID-19, it leaves many open-ended questions for many communities facing high levels of manufactured poverty and social injustice that make them more vulnerable to COVID-19 and fires, all taking place within the long-term disaster of climate change. If we only keep our eyes glued on COVID-19, and do not consider all these factors combined, we can be caught by surprise, unprepared and vulnerable to these disasters again and again. In other words, the more we focus only on one risk, the riskier other risks become. For example, since the start of the global pandemic, there have been tornados in the US, earthquakes in Croatia and Iran, floods in Indonesia and Kenya, all of which have been exacerbated due to COVID-19. As we enter drought and fire season in some areas, hurricane season in other areas, and monsoon season in still others – all of which will occur under and will be influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic – it is imperative that we consider how these disasters intersect with each other and with our social, cultural, and political frameworks.

Looking at disasters as social-ecological entanglements There are no “natural” disasters First of all, let’s pause and rethink the term “natural disasters.’’ The term puts us on the wrong foot: disasters are rarely, in fact, purely natural. Rather, we can speak of disasters as processes emerging through technological and social processes (including cultures, policies and economies) that interact with the natural world (#NoNaturalDisasters, n.d.). In the context of wildfires, this means embracing the fact that fire’s context is rooted not just in ecology or the arrangement of fuels, but also in our cultural conditions, politics, socio-economics, and even the language we use to describe fire itself (Wuerthner, 2006). Once we understand that most disasters aren’t so natural at all, we can reflect upon humanity’s relationship with nature: we are deeply entangled. However, in an attempt

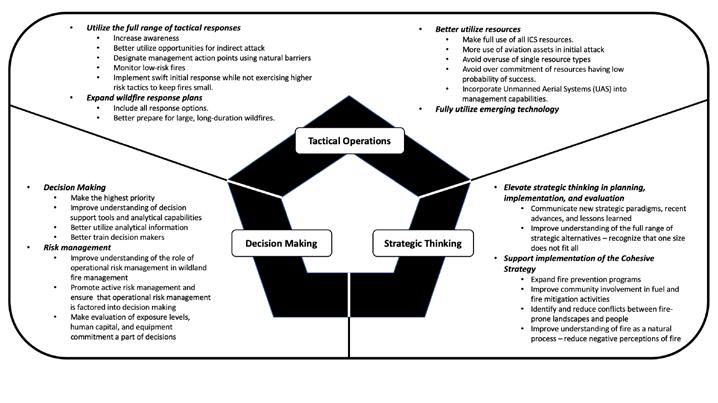

to distinguish ourselves from it, as well as to manage and control it, our westernized cultures tend to create all sorts of human – nonhuman distinctions (Herrero, 2015). This creates the notion of an “other,” opposing force that “we” need to rally “against.” In the case of wildland fire, even though fire remains an essential component of land management, and certainly is a necessary part of the natural world, wildland fire is often portrayed and understood to be our adversary (i.e., when we are fighting a fire, we are fighting a foe) (Ingalsbee, 2006).

This is not a war (language matters) Within the field of disasters, one way of creating distinctions between humans and nature is by using war metaphors. Often, when something is difficult to describe, people reach for metaphors and various other figures of speech, using comparison to illustrate context and put abstract concepts into something concrete or relatable. For example, the comparison of wildland firefighting with fighting a war (e.g., battling the flames, punching in the fireline, suppressing the fire) is prevalent throughout fire literature and media coverage (Pyne 2004). Likewise, with COVID-19 we talk about “controlling, attacking, fighting, war….” For instance, Costanza Musu explains why using these metaphors are so compelling: “It identifies an enemy (the virus), a strategy (“flatten the curve,” but also “save the economy”), the front-line warriors (health-care personnel), the home-front (people isolating at home), the traitors and deserters (people breaking the social-distancing rules).” (Musu, 2020) This framing, both in the context of wildfires and the pandemic, creates a paradigm that pits us against an adversary and creates a sense of fear, as well as a sense of duty (Hauser, 2015). And yet, several studies and literary works discuss the need to stop using the war metaphor in many fields, because it limits how we examine problems; it creates unrealistic and simplistic pictures of complex, dynamic interactions and in some cases can hurt certain prevention behaviors (Sontag, 1979). By drawing these strong lines between “we” (humans) versus “others” (nature), we tend to re-naturalize disasters: media outlets have largely treated COVID-19 as if it’s a natural phenomenon because it’s a virus, without linking it both to the context that allowed its creation and global proliferation. It is in fact our extractive industrial economies and globalized food system that cause biodiversity loss and deep societal inequality, and which further provoke the unfolding social and economic disaster (e.g. widespread contagion in care homes, economic upheaval which affects the most socially vulnerable first...). Again, we can draw a parallel here with wildfire: it is widely known that climate change aggravates the global wildfiremagazine.org

|

wildfire

27