THE WHITGIFT REVIEW

identity / community / change

Welcome to another edition of the ‘W’

When choosing the themes for this year’s ‘W’, I was guided not only by the themes we have explored in our Academic Enrichment programme, but also by the current zeitgeist of the school. As a Form Tutor for the first time this year, I have been more attuned to the social minds of the students. As in any group, questions of identity and belonging to a community are natural, and these are at the forefront of their minds. Indeed, as we creep further and further out of the hinterland of the pandemic years, we are all striving to figure out how we fit into the wider world once again. What makes this even more complex is the ever-changing nature of our society; just in the last couple of years we have experienced globally significant conflicts, higher threats to our environmental stability and the exhilarating yet mildly disconcerting development of Artificial Intelligence. When you add to this the societal dependence on social media, from which you can glean every piece of news (whether significant or not!) at the tap of a screen, our students must face these changes every day.

Exploring AI in the Ignite course (a new topic this year), I was struck by the sheer magnitude of knowledge the students possessed on the subject, and by the mature way in which they debated about it. In this age of AI and information obsession, students of all ages are acutely aware of the world around them; perhaps sometimes so absorbed in affairs happening to others to fully reflect on who they are as people. As one of my students asked the class in an Ignite lesson: “If AI can speak for you, and produce ideas for you, how can you keep hold of your own identity?”, leading to a lengthy and passionate group discussion. These brilliant questions from students reflect not only their willingness to ask the ‘bigger’ questions, but also show how they encourage each other to think in new ways. How they are willing to change their conceptions about identity and indeed how they use their community to ponder what binds them together and what distinguishes them from each other; I hope this curiosity is reflected in the ‘W’.

Working on this year’s edition of the ‘W’ has been an absolute pleasure. From essays on the universality of love to the exploration of worlds beyond our own, the student work this year has, as ever, been immensely impressive. I have chosen work from a myriad of sources; articles from the Academic Enrichment programme, the Junior Library Chronicle and the history magazine Pravda , outstanding thought pieces and essays from Ignite , and excellent pieces from classwork that I hope will inspire reflection and showcase that in their daily endeavours, our students produce brilliant work.

Finally, I would like to thank all who have contributed to this edition, from students to staff, you have all created wonderful pieces of work that were a joy to read. In this issue of the ‘W’ we also say farewell to our Headmaster, Chris Ramsey, and our Senior Deputy, David Cresswell, both leaving for pastures new, and they have brilliantly written tributes to each other in the valediction section of the magazine. As ever, I am also hugely grateful to the brilliant Graham Maudsley for his outstanding graphic design work on the ‘W’; this edition would not be possible without his hard work and aesthetic genius, for which we are lucky indeed.

Words / Julia Morris

Assistant Director of Learning and Innovation

Teacher of French, Spanish and Italian

No cloud nor sun but one equal light, no noise nor silence but one equal music, no foes or friends but one equal communion and identity (Donne) 1

One man in his time plays many parts (Shakespeare) 2

When, seven years ago, we decided to make the annual ‘Whitgiftian’ more of a collection of writings, the then editor, Ben Miller, devised a series of themes. His successors, Chris Jackson and now Julia Morris (all of them excellent by the way) have continued the idea: this year’s ‘Identity’ is the hardest of all to tackle. Serves me right, I suppose. John Donne, a devout Christian, sees perfection (paradise) as all our differing identities disappearing into one: God’s, I suppose. Shakespeare, more practical, points out that we all have plenty of ‘identities’.

I agree. If you ask me ‘who are you?’, I might reply: I am a husband, a father, a friend, a teacher, a Headmaster, a lover of film and theatre, an Arsenal fan (who knew?) and many other things. In other words, I don’t have ‘one’ identity. Some fathers are also Arsenal fans, some theatre lovers are teachers, but the unique combination of my identities makes me, well, unique. There literally is no other Chris Ramsey. As an aside (and since I’ll never write for ‘W’ again, why not have a few sidetracks?) there are in fact several others, which has amused and confused many a bored student: there’s an edgy stand-up comic Chris Ramsey, and there’s an ex-Brighton footballer and QPR manager too. I’d have been delighted to be either, but I’m not.

other words, I don’t represent ‘Headmasters’, though I am one. Perhaps this is partly because I have always been a reluctant joiner or ‘club member’. I never wear ‘membership’ ties, you may have noticed. But identity as part of a group is, ironically, important to me. So, whilst I am not (I think) ‘defined’ by my Headship, when I am in that situation, I believe there are certain ‘Headmaster behaviours’. And whilst every Whitgiftian is of course unique, while they are at Whitgift, it’s reasonable to expect conformity to ‘how Whitgiftians behave’. And I mean both staff and pupils here, by the way.

To me, the uniqueness of each person supersedes their characteristics

identity is more important than the school’s, and if that were true of everyone, the school would have no identity. We think it’s important that it does.

The notion of ‘role playing’ also explains why I have never liked identity politics. To me, the uniqueness of each person supersedes their characteristics. In

In the context of our community, in short, individuality takes a back seat. We have rules and conventions, which may be arbitrary, but have been considered and decided, and which like it or not, we adhere to. To take an unimportant, but often contentious example, we don’t remotely believe that it is somehow morally better to wear your hair short and undyed, or wear black not brown shoes; we are not on an evangelical mission to ban white socks from the world. But while you are at Whitgift, wearing the correct uniform is what you have to do, because to do otherwise would be to say that your own unique

And we stand for some things: hard work, fairness, respect, including respect for authority – schools are not democracies – and also dealing with failure.

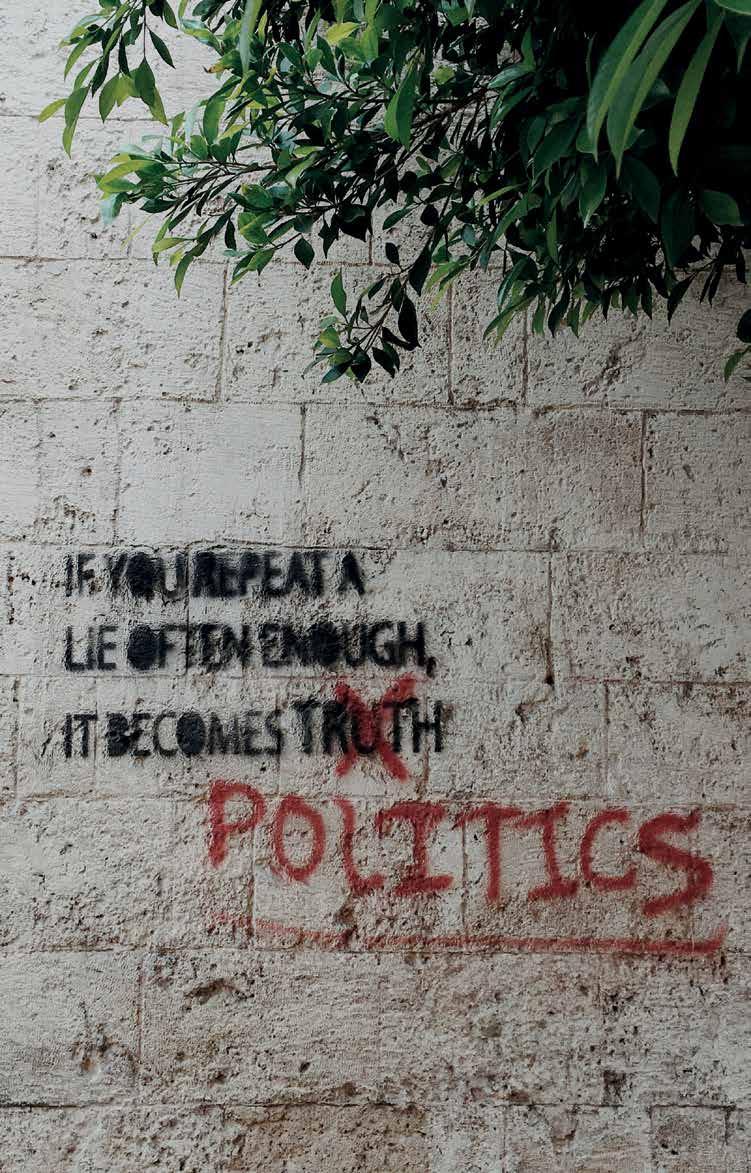

And we stand against some things: prejudice (not all Arsenal fans are delusional and not all fervent religious believers are intolerant), victimhood (being of a certain background does not always make you a victim: it might, but it might not); ignorance (why not consider evidence and history before you jump to or believe conclusions?); arrogance (we are seldom if ever ‘better’ than others).

And I would finally argue that we at Whitgift – like all good places of education – stand up in favour of the real, rather than the virtual world. The value and power

of presence, of speaking face to face, experiencing debate, discussion, activity and relationships in person. So the answer to the question ‘what is your identity?’ is a confused one. I wish, a wise colleague said to me recently, ‘that people, especially passionate, angry, intolerant people, could recognise that we are all a work in progress’. I certainly am, and I suggest you readers are too. Which leads us back to Donne: maybe, just maybe, one day we will be perfect. But we aren’t now: live with it.

Words / The Headmaster Illustration / Nick Fewings

2 As You Like It (lines spoken by Jaques)

The ship carried 492 Caribbean migrants, many of them veterans of the Second World War

My name is Dylan Carter, I am of Caribbean Descent, second generation British and this article is about the Windrush Generation from which I descend.

This year is a landmark year for Windrush, and it was earmarked as Windrush 75 – a year of national celebrations to mark the historic arrival of HMT Empire Windrush on 22nd June 1948. Throughout the year there has been various celebrations; 45 Community Projects around the UK have been funded by the Government Windrush Day Grant Scheme including cricket matches held at the Sheffield Caribbean Sports Club and a procession celebrating the Windrush generation from Clapham Common to Brixton’s Windrush Square. My own mum organised a Community Family Day to celebrate June 22, where lots of families attended, and heard a speech about Windrush, as well as taste the amazing foods of the Caribbean.

The Windrush era is an important time in the British History timeline, it was from 1948 until 1971. Many people from the Caribbean – Jamaica, Trinidad, St Lucia, and other British Colonies – were invited after World War 2 to help with rebuilding the British economy, as there was a desperate labour and housing shortage.

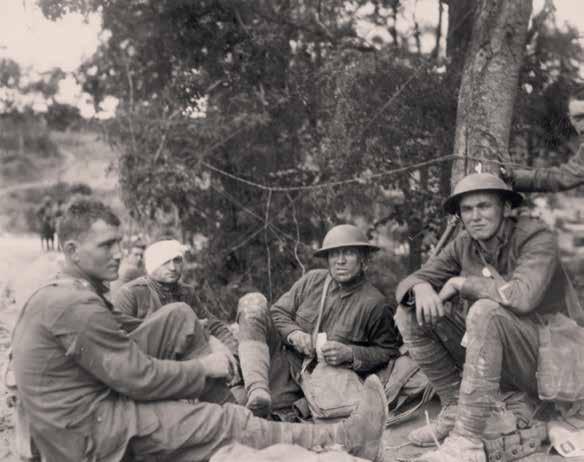

One of the first ships to arrive in Great Britain was the HMT Empire Windrush which arrived at the Port of Tilbury on 21 June 1948; Its passengers disembarked a day later.

The ship carried 492 Caribbean migrants, many of them veterans of the Second World War. The picture above is an iconic image to this day – it shows the joy of the passengers upon their arrival onto British soil – the ship and its passengers have symbolic status as the start of the Windrush Generation.

I am fortunate, that my GreatGrandmother (Nanny) is still alive, so that I can speak with her about her experience of being part of the Windrush era.

My Nanny told me that her family could not afford the passage (fare) to come to Britain, and that her best friend who had come to England two years before her sent her the money so

that she could come over. My Nanny’s family was extremely poor, and she left behind her two children aged 2 and 4, her 7 brothers and sisters, who all lived together in a two-bedroom home in the countryside. In fact, many people from Jamaica, came from similar backgrounds, and thought that England would allow them greater opportunities to send money back to their loved ones and provide a better life for them.

The journey to England on the boat was a great experience, my Nanny recalled; She met loads of people from different islands, all of them excited to be going to Britain. Unfortunately, the experiences of people who came over in the Windrush eras were not as they had expected. There was a saying in Jamaica that England was the country of ‘milk and honey’, but instead of being welcomed, they were met with many hostilities, discrimination and unfair practices from the people that were indigenous to England. It was difficult to find homes to rent, and to be hired for certain jobs. Many Caribbean people opted to live together in one room, and would rotate the sharing of beds, cooking and washing facilities to save money.

The National Archives holds so much data around the Windrush Era and is a great place to start the journey of understanding this time in Britain.

There is a tainted legacy left behind: the Great Windrush Scandal, in which many Caribbeans were wrongly targeted by immigration officials due to the UK’s ‘hostile environment’ practices. Immigrants were refused access to government services, jobs and had their ‘right to remain’ removed. A compensation fund was set up back in 2018 to help rebalance the wrongs of the government policies.

This year of Windrush 75 is important, the events allow for people to understand the history of Windrush, and the positive contributions the people who came over made to Britain.

Words / Dylan Carter, 2TPW Photography / IWM (FL 9448)

If Artificial Intelligence has ‘intelligence’ does it have an identity?

With the current rise in Artificial Intelligence (AI), more people are worrying about whether AI could develop an identity and take their jobs. They are supposed to be capable, sentient beings that are fully capable of independent thought. The focus of my article is to ascertain whether AI’s characteristics match identity and if it doesn’t, whether it is possible for the future. The point of my research is to figure out if we actually need to worry about AI fighting back. This is important as if it turns out it is possible, then there will be problems with using AI in the future. I believe this is possible, but I also believe that there is nothing to worry about if we make sure we keep it under control.

In order to have an identity, it must be able to say what culture it is from, where it comes from, form its own opinions, and also have thoughts and feelings. However, at the moment, AI is just a machine with higher processing power than most other computers and acts like a search engine that does something with the information, it finds information on what you ask, and then puts it together to form a picture or to write something like an essay or speak like a human. This shows that AI doesn’t have an identity just yet, but I will explore whether it can in the future in my next paragraphs. There are some reasons that AI could possibly become fully sentient, such as the fact that if given enough time and the right network, could form its own brain that mimics that of a human. We know that this is possible due to the fact that the brain is just an organic collection of wires that disconnect and reconnect in different ways and patterns to form thoughts and memories. If we can replicate this with artificial networks, then we might be able to form intelligence. Furthermore, if you took a scan of someone’s brain, you could replace each neuron until all the organic matter has been replaced. This should end up with a being that is an exact copy of the brain

and so should behave exactly the same and should have all the same memories as the brain it was copied from. This shows that it should be possible to create a fully sentient AI that has an identity.

On the other hand, this is only the brain and in order for something to become fully sentient, most people say that it not only has to have a neural network, it also needs a body, as, according to Stuart Russell, three components must be present in order to become sentient:

1. A perfect unity of an external body and internal mind

2. A defining original language for the AI to access

3. A defining culture to wire with other sentient beings.

This shows that even if you have a complete neural network, it is impossible to become a fully sentient being until you have a body that can experience things like humans. This shows that even if you have a completely artificial neural network, you can’t be sentient as you don’t have the same feelings as an organic organism, and it also needs its own language and its own culture as well. This shows that AI can’t have an identity as it needs to be sentient to do this. However, this can be overcome by creating an artificial body covered in sensors that are almost exactly the same as a human body and then inserting the neural network so that you have almost an exact copy of a human body.

In conclusion, I believe that it is possible to create AIs that are fully sentient and that have an identity. However, I don’t believe that AI could ever become a threat as, due to the way they are trained, they won’t do anything that isn’t in our interests as they are programmed that what we give them is true, so as long as we program them on the fact that we are their masters and in charge, then they will do as we say.

Words / William Ewels, 2LAC

Photography / Amanda Darljborn

I am the dead, That you forgot. Sleeping soundly in the lonesome dark. An innocent who fought for desperate glory, Only a child I was.

All lame, All blind, All of us fighting, For that same desperate glory. The misplaced hope that might, bring us home, Home to outstretched arms.

Nobody speaks of us anymore, Forgotten youth we shall remain, In a bed of bright red flowers, Covered by piles of dirt.

When you look at me

What do you see?

Do you see a boy who has ASD?

That is only one small part of me; I’m about to tell you something that’s key; This doesn’t define my identity.

The real person in me; You just don’t know; And many-a-time, I’ll put on a show; To cover anxiety and try to fit in; Conversations don’t come easy or know where to begin; There are things about me I want you to see; So here it goes, I’ll show you the real me.

I am a Son, a Grandson, a brother, a friend; I am trustworthy and loyal right to the end; Adventure and nature is what I adore; Competitive in sports – determined to beat my best score. But sometimes I can get a little frustrated; But it’s not a bad thing, it’s what God has created.

With an exceptional palate, and love to eat out; I can get a little excited and let out a shout; You see I’m an enthusiastic and passionate guy; And one of my flaws is I’m unable to lie; When I am happy, excited, nervous or scared; I act a bit different to others, I can’t be compared;

Adventurous and brave and a little artistic; ‘A’ student in maths, Chinese and science (because I’m autistic); An adrenalin junkie and love to have fun; Spending time at the beach, outside in the sun; Inquisitive, quirky, funny and genuinely kind; I strive to be the best version of me I can find.

Next time you see me

What boy will you see?

Will you see the boy who has ASD?

Or the young man who lives his life to the max; And now that you know me, can start to relax. My ASD is only one small part of me – it doesn’t define my identity.

Words / Dylan Ball, 4JPH

Photography / Luis Vilasmil

History has been kind to George Washington, the man who liberated the colonies from the imperial yoke of the British empire and set in motion the most dominant superpower the world has ever seen. History has not been so favourable to Simón Bolívar, a name many in the Western world would be unfamiliar with. Bolívar, however, achieved a similar, if not more impressive feat, in the liberation of much of northern South America from the Spanish. In Marie Anna’s book Bolivar: The Epic Life of the Man Who Liberated South America comparisons are drawn between Washington and Bolívar and their liberations of their homelands. These comparisons do not do justice to the monumental task Bolívar achieved through his struggle against the Spanish Crown. Bolívar would go on to liberate the territories of New Granada (now a mixture of Columbia, Venezuela, and Ecuador) and the crown jewel of Spanish holdings in South America, Peru. Simón Bolívar was not merely South America’s George Washington. He was El Libertador, a freer of men and conqueror of empires.

Simón Bolívar had a somewhat turbulent upbringing in the town of Caracas. Born in 1783, both of his parents died at an early age leading to him being shipped off to be educated in Spain. It would be in Spain where Bolívar would find his one true love and only wife María Teresa, however upon bringing her back to Caracas in 1803, she died shortly after due to yellow fever. Bolívar initially adrift without purpose, returned to Europe to go on a Grand Tour of European countries which resulted in him declaring that he would rid the Spaniards from South America atop the Mons Sacer. Returning to South America in 1807, Bolivar had a new sense of purpose and conviction which would lead him to his ultimate destiny of becoming El Libertador.

Bolívar’s struggle against the Spanish crown is one of immense fortitude and persistence, from liberating what is now Venezuela, to controlling an army of divided generals and characters all with their political machinations in mind. He would take this ragtag army across the freezing Andes, losing a third of his men to the frost and all his horses to the extreme conditions. Nevertheless, Bolívar, always the opportunist and gambler, surprised the Spanish at the Battle of Boyacá in 1819, inflicting a crushing defeat whilst only losing 13 men to the Spanish 1,800. This was the turning point in the liberation of South America

as Bolivar then marched into Bogota as a champion of the people and liberator of South America. Yet he was not finished in his conquest as he raced down to Peru to free the remaining subjugated people. This accomplishment, much like Hannibal’s forced march over the Alps, should have earned him worldwide fame and recognition as one of the greatest military generals in modern times, but the tales and exploits of Simón José Antonio de la Santísima Trinidad Bolívar Palacios Ponte y Blanco go unnoticed in the western world. Perhaps Bolívar’s most lasting legacy is that of the nation of Bolivia, formerly known as Upper Peru, which bears the liberator's name in honour and gratitude for his liberation of the territory from the Spaniards. Bolívar, however, was not a hero without serious flaws. Despite his heroics across South America as a liberator and military mind, Bolívar has been criticised as a corrupt and powerhungry tyrant who manipulated the Congresses of the nations he freed to attain absolute power for himself. In fact, his harshest critic in his lifetime was his own Vice President of New Granada, Francisco de Paula Santander. Santander would ultimately betray Bolívar, forcing him from office and into exile to Santa Marta in 1830. Bolívar would die a painful death from tuberculosis, betrayed by his once-great friend Santander and by many people whom he helped liberate from Spanish control. His legacy should not be determined, however, by the jealous whims of Santander, as it is clear now that Simón Bolívar’s true legacy will forever be one of a tireless liberator, who dedicated his adult life to creating the idea of a unified South America, an idea that future revolutionaries such as Che Guevara would try to take forth into the 20th century. Bolívar, forever enshrined as the greatest hero of South America, should be taught and remembered throughout the Western world as a prime example of dedication to the idea of liberty and self-governance. Although compared to historical greats such as Washington, Simón Bolívar’s true impact on the nations that he left behind far outstrips any of Washington’s achievements. Perhaps it is time to consider Washington as North America's Simón Bolívar, rather than the reverse.

Words / Dougie McWilliam, U6LCG

Photography / Jonathan Monck Mason

Simón Bolívar’s true impact on the nations that he left behind far outstrips any of Washington’s achievements

Four letters. That is all it takes to form one of the most controversial words in history and one that still holds many controversies up to this day. But why? Why is a word so vague able to tear civilisations, even humanity itself, apart. I have chosen to write about this topic because I myself have two parents of very different ethnicities and have always wondered how other people like me were treated centuries ago. Not only this, but I am also intrigued as to what they would have been seen as. As a result, I have decided to focus on the topic of mixed-race people.

T he s Tar T of mixed - race people

As expected, the origin of mixed-race people of both black and white origin historically stems from the colonial history of Africa. Since slave masters had come over from European countries such as Spain and France and the slaves were African (black as a result), this meant that certain interactions between the slaves and their masters may have resulted in mixed-race kids being born. Nevertheless, the nature of the slave societies at that time gives us reason to believe that more often than not these were not pleasant interactions: mixed-race children during the transatlantic slave-trade era were often a result of black slaves being raped by their white-slave owners.

a m i W hi T e or am i B lack ?

The complexity of mixed-race identity was simply trimmed down into the invention of the ‘one-drop rule’. As the straightforward name implies, this rule (which was used widely across the United States) the ‘one-drop rule’ ensured that mixed-race people would always be on one side of the division between black and white people. The rule stated that anyone with a single drop of black blood resulted in them being legally as well as socially treated as a black person, no matter how light-skinned they may look.

Something I found very interesting about this is why white people chose to class mixed-race people

as black based on them having at least one drop of black rather than the other way around. This can be viewed as another act of power from white people at the time to make sure that black people knew they could never be equal in society. However, I see it as a sign of weakness and that they felt threatened almost by mixed-race people because they were the bridge between black and white people.

Furthermore, if they were classed as white then some would argue that people who are not purely white can achieve that social level as well. I find this interesting because I would interpret that the white community would have classed mixed-race people as white to ensure that the black community understood that the only way that they would be accepted in society was if they were white which was an unachievable task for them. Contrary to this, it can be argued if someone were a black father, and they had a mixed-race son, their legacy has been accepted into society which could philosophically mean that the man has somewhat been accepted into society. This would, as a result, give off signs of weakness from the white community which is evidently the exact opposite of what they would have wanted if they had classed the mixed-race community as white.

h alf B reed ?

During the early 20th century, a relationship (romantic) between a black person and a white person seemed to be so disturbing to the English community that it was able to warrant academic research. Rachel Flemming had carried out a study in the 1920s which

somehow, although unsurprisingly, resulted in mixedrace kids being classed as ‘wretched children’. Of course, this was all based on academic research, so it was “surely reliable”. This brief and false sense of reliability from Rachel Flemming’s study influenced the political spheres of power, as well as the way people spoke. An example of this would be Rachel Flemming’s results sparked the new term ‘half-caste’ to describe mixed-race people which is now seen as an offensive term to describe people whose parents are of different ethnicities.

d on ’ T W orry , i ’ ve go T your B ack

In 1958, on Latimer Road in London, an argument between a black husband and a white wife led to a group of white men interfering in an attempt to protect the white woman and similarly a group of black men came in aid of the black husband. The incident led to three days of rioting and swastikas were being painted on the doors of black families. Another example of this kind of situation is a mixed-race couple being attacked in Liverpool by a mob of white people with the motive being they were a mixed-race couple in England; they were clear

victims of prejudice. This was not unusual in the 1970s and had happened before. The police detectives on the case claimed that the attack was not racially motivated, and no culprits were ever found. In the 20th century, it was made clear that relationships between people from different ethnicities in England had to be abolished, including mixed-race people.

T he end.

Although mixed-race people have generally been seen as black and continue to suffer from prejudicial ideas, we can also be seen as a sign that the end of racism is here. This is because we are the products of white and black people who have come together despite all the hatred they would have received and added another possibility in terms of race.

Words / Ayo Sholebo, 2HIM

Photography / Clay Banks

1.

2.

It’s been said that the turn to identity politics occurs when mainstream politics fails to assimilate minorities, although the obverse is also true: it occurs when minorities reject assimilation. To start with an example less familiar in the UK: the official census figures for First Peoples in the US declined from the end of the 1700s to 1900 when it became more advantageous to identify as “Native American” because of the (slight) privileges apportioned to Reservation-dwellers, rather than trying to Europeanize for the sake of finding work away from ancestral lands. The two-century decline was due to a series of wars of extermination alongside germ warfare and deliberate campaigns to weaken indigenous communities with alcohol and narcotics (as the British did in early-19th century China, or the CIA did to African-Americans in the 1960s). Nonetheless, there was a period of self-erasure or succumbing to “passive genocide” whereby the unique characteristics of a group or society are eradicated, without overt violence. When the indigenous population became small enough, US laws shifted to the erasure of cultural identities rather than the active destruction of bodies, hence the late-19th century saw the advent of laws prohibiting culturally specific dress among minorities

The late-19th century saw the advent of laws prohibiting culturally specific dress among minorities

which remained on the books so long that queer people of the Stonewall generation, whether cis gay men or trans women, might be arrested for wearing make-up on charges that originally referred to warpaint rather than, say, lipstick or rouge, while cis gay women and trans men might be charged with wearing an insufficient number of items appropriate to their gender that originated in laws designed to differentiate the genders of Chinese immigrant labourers, such was the Euro-American anxiety about being able to tell whom to seduce… or whom to under-pay. It’s due to countless examples like these from former European colonies around the globe that 21st century discourse on gender identity describes trans and queer people as having “colonized bodies” since we’re still constrained by colonialist ideology serving to dominate and control. (I say “we,” here, because, as a trans woman, my body did not feel like my own for most of my life prior to hormonal and social transition in my 40s but I also believe the simplistic gender binary that was consolidated in the colonial era harms us all.) In surveying the evolution of identity politics from Colonialism to the Culture Wars in this essay I want to “think through” the historic construction of various oppressed or colonized peoples to the current, increasingly contested construction of trans identity, considering what it says that people are still determined to cross literal and symbolic borders that are patrolled with an increasing amount of violence in the 2020s after what only seemed like two decades of upward progress.

Commoditizing Identities and Pathologizing Identities

I’ve started with socio-economic factors but cultural constructions of identity at any point in history are the products of multiple discourses. Some are unforgivably vile, such as the Greco-Roman notion that slaves are “human-footed animals,” while others that now seem abhorrent can also be seen (with more awareness of historic context) as the least-badavailable framework to reconceptualize those who were formerly vilified, e.g. mentally ill women who were formerly deemed to be possessed began to be diagnosed as “hysterics” by proto-psychiatrists in 19th century France, removing the religious stigma. Arthur Koestler’s The Sleepwalkers (1959) demonstrates that the arc of progress isn’t ever upwards but more of a barbed wire coil going periodically backwards to go forwards, hence falseconsciousness about who or what different peoples are, ontologically, can be revived centuries after we should have learned better, for instance when the US in the 18th century began to model itself on the Greek & Roman empires built on slave labour. When it wasn’t building cities full of obelisks, pyramids, and mock-Parthenons, to project the image of imperial power, the US rationalized its practices by citing Aristotle and Cato (responsible for notions about the non- or sub-human status of slaves), so as to legitimize the source of its wealth; to this day, one

relic of this is the popularity of African-American names borrowed from the Classics, echoing those conferred on “beloved” slaves by plantation owners patting themselves on the back for having built a new empire, albeit without any moral evolution in the intervening millennia.

The artificiality of identities imposed on peoples can be most clearly revealed when we note the inconsistency of how, when, and where this happens. Consider the historic anomaly that Haitians gained the legal status of humans a full 50 years before the “Wild Irish.” The former had achieved one of the most successful slave rebellions in human history, before a response from the French army under Rochambeau that harked back to the treatment of Christians in the Coliseum in its savagery. The Irish, on the other hand, were close enough to England that a large force could be sent to subdue them, quickly, and there was no need for sops like beingregarded-as-human. In the two centuries since the rebellion, Euro-American literature has constructed Haitian Vodou as the epitome of evil, often muddling its religious rites and ethnomedicine with some of the most disturbing European mediaeval folk practices. Two centuries after the Rebellion, one can still feel the ripples of that original shock in popular representations of Black Magic (which didn’t originally refer to Vodou, either), whereas the cultural arm of British imperialism continues to operate by ignoring the history of Anglo-Irish relations, to the extent of largely omitting it from the National Curriculum.

As a species, we started to improve slightly as medical constructions of identity gradually shed their moral subtexts. Foucault’s History of Madness (1961) excavates the socio-economic conditions enabling the construction of prisons and hospitals, which in turn determined categories of criminal and patient. As European societies grew wealthier (largely by plundering the Americas), the mentally ill could be accommodated in asylums (with some semblance of professional care) rather than being left at the mercy of relatives or hanged as witches on flimsy pretexts. This trend continued in parallel with the rise of carceral institutions which became more affordable hence societies could praise themselves for becoming enlightened for focusing more on rehabilitation than punishment (even as they held onto the death penalty, rather arbitrarily applied).

As mentioned above, people once said to be “possessed” were reconceptualized as “hysterics” in the 19th century, but this meant preserving the mediaeval idea that neuroses were caused by the “wandering womb” since more were women and girls, and their doctors were more likely to overlook male manifestations of neurosis. “Hysteria” was split into a range of conditions in the 20th century as the misogynist connotations of the term became more obviously offensive. Nonetheless, the “shellshock” identified during the Great War, now known as PTSD, was for decades known as hysteria with the

distinct implication that the men so-afflicted were “unmanned” by their failure to hold their nerve under fire. Medical diagnoses, in short, are informed by cultural constructions of gender, and vice versa For all their perceived rationality, objectivity, and empiricism, Medicine and Psychiatry have frequently served as Ideological State Apparatuses to validate constructions of race and sex that are only pseudo-rational and serve a political agenda more than some dispassionate ideal of Science purity. Consider the fact that “race” is almost meaningless in biological terms: all “types” of humans that might be distinguished by pigmentation can nonetheless interbreed successfully, producing fertile offspring – that is what it means to be a species – and there is a likely benefit from “hybrid vigour” when people of different ethnicities have children. What does not happen is the “pollution of the blood” that obsessed “scientific racists” in early 20th century America, who were brought over to Nazi Germany to inform their own programmes of sterilization (initially targeting the patients of Hans Asperger’s clinic and the transsexual patients of Magnus Hirschfeld’s) before moving on to larger groups and ultimately exterminating them. Even now, pseudo-science is deployed in the UK & US (among other supposedly Developed Nations) to explain away the deaths of Afro-Caribbean people in police custody (rather than institutional racism), and to justify sentencing that punishes possession of drugs more commonly used by some Black people than White people (thereby keeping more African-Americans out of the electorate, in quasislavery).

Cultural & Medical Constructions of Trans Identities since 1979

In this third section, I examine the changing construction of Trans identity in my own lifetime as a case-study whose trajectory provides some insight into the trajectories of other groups toward general societal acceptance – or demonization when our values move backward. As a trans child, out to herself from the mid-80s, my own process of identity formation involved a bit of Medicine here, a bit of popular culture there, but no coherence to any of it, and certainly no critical framework I was taught in an age-appropriate manner at school because of Section 28: the ban on teaching anything about LGB identities from 1988–2003, which encompassed my entire secondary education, BA, and MA. Even after Section 28, none of the psychiatrists, counsellors, or GPs I spoke to between 2003 and 2021 seemed to know a fraction of what many trans people know, in 2024, thanks to the vast array of peer-reviewed journal articles freely available online. There were plenty of clues that some had a deep suspicion if not distaste for anyone trans, and yet I accepted this because of the culture I’d grown up in (as had they for 10, 20, or 30 years longer), which caused me to internalize so much transmisogyny.

Imagine being mostly culturally invisible but defined by psychiatry as disordered

Turning to constructions of sex and gender, the long history of feminism shows us how pseudoscientific constructions of sex in any given age have been attacked by feminists as facile arguments to deny women their rights. It is feminists who have most often pointed out that sex is not binary, while it is feminists who most enthusiastically embraced the idea of gender as a category only loosely articulated to ones perceived sex, if not unmoored, as discussed in Judith Butler’s Who’s Afraid of Gender? (2024). In the 2020s, almost unthinkably, women’s rights to bodily autonomy have again come under attack, after women’s (especially mothers’) lives have become objectively harder since the last major financial crisis in 2008 with 29% of the average UK salary being spent on childcare (the highest in Europe), the worst adolescent mental health in Western Europe, SureStart centres introduced by New Labour mostly closed, as well as rape crisis centres and shelters. Who is to blame? No need to spell it out. Whom to scapegoat, though, and demonize as a distraction from numerous failure of government? That is a question for the next section...

Imagine being mostly culturally invisible but defined by psychiatry as disordered, as I was for the first ¾ of my life, until 2013, with almost a decade to go before transition. Having your core identity pathologized makes you see yourself as diseased when you’re at a low ebb, and you’re still hoping for a “cure” when you’re optimistic, having been acculturated to believe that Gender Dysphoria is integral to being trans, as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Psychiatric Disorders (or DSM ) implied until 2018. It’s a short step from thinking yourself “disordered” to thinking yourself “degenerate” as we were considered to be by the Nazis within years of “transsexual” being coined in 1923, becoming one of their first targets for harassment and, later, deportation to the camps. Homosexuality may always be regarded as a disorder by bigots and religious fundamentalists but it ceased being regarded as one in 1973 1, and there were several active organisations to fight for gay rights, whereas transsexuality would continue to be regarded as a disorder for a further 40 years, making it one of the factors in our lack of support from Stonewall (the charity) until 2015 2, despite our historic role in… Stonewall (the riot) back in 1968. But theoretical frameworks do change. In 2013, the DSM-5 replaced Gender Identity Disorder with Gender Dysphoria (i.e. to be trans is to experience acute distress at having to live as ones Assigned Gender at Birth but not actually to be disordered) and, at this juncture, the American Psychiatric

Association affirmed their support of transgender rights. A decade later, Gender Dysphoria is widely felt to be a problematic term. “Acute distress” suggests a strong urge to self-harm, to hide away from people, to seek relief through drugs and alcohol, to succumb to depression; speaking to dozens of trans people over the past few years, we all know someone who does or has done much of the above, and we all seem to know someone who’s not here now – even the 20-somethings I’ve met. Nonetheless, a more useful term, which every trans person (and their allies) should keep in mind to describe how we feel a lot of the time is Gender Incongruence (coined in time for the WHO’s International Classification of Diseases guidance in 2018), which entails certainty about ones identity over a long period of time but doesn’t require distress to be at the centre.

True, the misconception that to be transgender is to have a mental illness persists among many people – even those who are trans; it’s our collective task to disabuse people (cis & trans alike) of this notion. One way to be an ally to others – and to yourself – is to dig into the evidence until you know how to convince others – and yourself – that it’s not a disorder. If you’re lucky enough to experience Incongruence with little or no Dysphoria (partly because there are fewer cultural and social and familial pressures to conform to a highly polarized gender binary among Millennials and Generation Z) rest assured that you’re “Trans Enough” We don’t have to suffer anymore – whether for being trans, or so as to be considered “authentically trans” – and we never did.

Words / Kay Naomi Mellor, Teacher of English, Head of EPQ Photography / Lena Balk

1 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4695779/

2 https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2015/feb/16/stonewall-start-campaigningtrans-equality

3 The Transgender Tipping Point | TIME

4 Free copy available from: The Transgender Issue: An Argument for Justice Trans Reads

5 New data: Rise in hate crime against LGBTQ+ people continues, Stonewall slams UK Gov ‘inaction’ Stonewall

6 'Not fit for purpose' Stonewall's response to draft trans guidance for schools in England Stonewall

7 Lawyers told ministers schools trans guidance was 'high risk' - BBC News

My hope for everyone pre-hormonal- or even social transition is they’ll discover that you can be afraid of having wasted years of your life by never transitioning… and then the weight of those years drops away and they become an abstraction as soon as you start socially transitioning in the simplest of ways (disclosing to partners, friends, relatives… colleagues) and then that fear and shame becomes almost immaterial when the hormones kick in. Most of us use the term HRT, but I prefer its official name in trans healthcare – Gender Affirming Hormone Therapy –because of the way that subtle personification makes it sound as if the molecules themselves are high-fiving your brain cells and all those body parts that should have had a different morphology to match the brain. Even here, Identity Politics is apparent. One of the things that helped me most in the months leading up to hormonal transition (in June 2022) was the good fortune that my newfound awareness that this was an option – without having to satisfy a panel of medical gatekeepers after two years of “living in role” as was the protocol for most of my lifetime – converged with a second “Transgender Tipping Point” in Popular Culture. This time, the icons were far more personally appealing than Caitlyn Jenner (disowned by most trans people, now, for her Republicanism) and the frustrating stereotype played by Laverne Cox back in 2014, when she appeared on the cover of Time magazine for their “Tipping Point” issue 3 , having been cast as an African-American hairdresser in a women’s prison (although she’s done great work as an activist and documentary-maker, since). 2021 saw Torrey Peters being longlisted for the Woman’s Prize for fiction, Shon Faye’s The Transgender Issue 4 , and the very public transition of Abigail Thorn (of Philosophy Tube). There was cutting-edge electronica by Arca, Elysia Crampton, and SOPHIE; there were two instant-classic albums, from Ezra Furman and Ethel Cain, of dark indie rock with lyrics that stand up as poetry and articulate a spiritual dimension to the experience of transition. True, Summer 2023 was the moment when public opinion in the UK on a range of trans issues swung to net negative after a sustained campaign of transphobia from the Right-wing Press and the government – the Home Office’s own statistics saying transphobic violence had increased by 186% in five years 5 . Nonetheless, the very existence of so many siblings in the public eye made me believe I’d found my tribe and, like the First Peoples circa 1900, that it was time to stop trying to assimilate because, even if I had to be the first out trans teacher in this school’s 400 year history, at least there were other trans people I could relate to, who haven’t been homogenized to a bland, retrograde version of womanhood for ease of consumption on American talk-shows. Having spent years on the margins of work by cis people where we appeared as rather dispiriting caricatures (at best), at last we have a rich, varied culture of our own. This will only continue to grow and outlast individuals, in spite of the restrictions on healthcare (already fatally inadequate for many) and government efforts to deter the transition of minors (via the NonStatutory Guidance released in December 2023) that will only cause unnecessary suffering 6 , after the government’s own lawyers told them they couldn’t ban transition outright 7 , as they’d wanted to do for purely political reasons and no regard for the evidence of the benefits of transition 8 . These are genuinely frightening, dangerous times for trans people, and the efforts to take away our safety, dignity, healthcare and rights should be regarded as a dire warning for democracy, but after decades of having a primarily psychiatric identity we have that most distinctive feature of humanity – a cultural identity, which will be harder to take from us.

8 What We Know What does the scholarly research say about the effect of gender transition on transgender well-being? What We Know (cornell.edu)

PAST

I look back on my past, It seems to have happened so fast, My history is long, And I did many things wrong, But I have done good at last.

Max Kan, L1JGP

Whoever you are, Your identity can change, Come out of your shell.

Calum Davidson, 1AMS and Arshia Saffarizadeh, 1JRS

Trapped in a body, Ventriloquising power, Searching for true fate.

Arvin Pappala, L1FMO and Aaron Patel, 1JEJ

All of us are one, But all of us are different, We are all equal?

Sami Carroll, L1TJD

Identity is The reflection of ourselves We should value it.

Sheil Nursing, 1JRS and Alfie Roberts, 1AMS

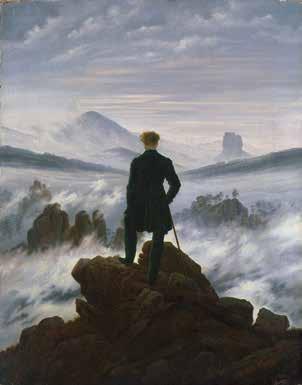

My favourite books are about outsider individuals: coming of age, dying of old age, defining an age. Think of Tolstoy’s arch odd-ball Pierre Bezukhov in War and Peace or Leopold Bloom – often labelled an “Everyman” by people who’ve only read the blurb. Through Joyce’s linguistic pyrotechnics, we see Dublin afresh, all through the quirky lens of the outsider. Joyce teaches us that we are all potential outsiders: and a jolly good thing too. However, these literary heroes are against the zeitgeist which is a cocktail of roundedness, extroversion, and affability. I wonder whether the authentic, the curious, the risktaking are qualities we see admire more in the mimetic mirror of literature than real life. What would happen if Pierre ran the post-office? If Bloom were director of the NHS? Howard Jacobson once quipped that no one has ever been robbed by a person with Middlemarch in their back pocket. Worth pondering.

I’ve been trying to better my French this year by slogging through books in the original. The slogging has just started to resemble reading. Every book that I pick up seems prove that France possesses the echt outsider literature. Leaving the obvious (dare I say, overpraised?) book by Camus aside, Michel Tournier takes the outsider topos to a sinister extreme in his Goncourt winning novel Le Roi des Aulnes – “the Erl-King” – by mapping out how weirdoes or “ogres” can flourish in fascistic societies that reward their inverted logic. In a Gogolian turn, the contemporary novelist Emmanuel Carrère has his protagonist shave

off his moustache one day. However, everyone he knows then refuses to admit that he ever had one. This is satire at its finest: the triviality of the bourgeoisie skewered through a mix of neurosis and slapstick. France has always elevated the outsider, ever since the controversial execution of Robert Brasillach, for collaboration in 1945. The fact he’s the go-to example indicates how few received his fate. France has gone further than any country to give amnesty to its thinkers and artists, no matter how mad, bad, or dangerous to know! Few questions were asked about Sartre’s quietude during the occupation, De Gaulle closing the matter with his usual hauteur: “you do not silence Voltaire.” LouisFerdinand Céline, literary genius turned antisemite of the most vitriolic order, was haunted with the fear of being forgotten in his forced exile after the war. He eagerly returned after the 1952 amnesty for collaborators to rekindle his reputation. I have, so far, only been able to glimpse Celine’s greatness as a stylist in his own language– his lyrical powers (weaving formal French with the coarse and the demotic) are hard for a novice to grasp quickly. But to the overwhelming question: how could his inventive imagination have succumbed to the ideology of National Socialism? It’s enough to test Jacobson’s faith in outsider culture as a shield against barbarism. Outsiders, it seems, come in as many shapes and sizes as insiders.

Words / Mr Adam Alcock, Director of Higher Education and Oxbridge, Teacher of English Photography / arvndvisual

“We do not desire at all that the great masses become well off and independent… how else will we rule over them?” Friedrich von Gentz

The Storming of the Bastille on 14 July 1789 not only represented the revolutionary insurgency in France but also the awakening of a new form of governance across Europe – one which laid the bedrock for modern democratic values and liberal economic beliefs.

Prior to the French Revolution, England was one of the few states where some form of liberalism existed.

The Glorious Revolution established a parliamentary monarchy in England, yet this system of government stayed relatively isolated for the next century. When similar demands for a reduction in monarchical power ensued in France at the end of the 18th century, the entire continent of Europe was influenced. Why was there such a significant difference of scope in the outcomes of these seemingly similar events, and does it offer an explanation for the structure of modern societies?

On 4 August 1789, the National Constituent Assembly passed a new constitution, abolishing feudalism within France. Additionally, special privileges for nobles were revoked, including their titles. Two years later, France officially became a constitutional monarchy: where there was equality of rights for all men, and the role of the monarch was considerably reduced. These reforms highlight two key changes in French society. Firstly, they theoretically reduce, if not entirely remove, absolutism. Secondly, they create a much more centralised state for more effective decision-making. These two concepts are key to creating ‘inclusive’ institutions (both political and economic), a term widely used in institutional economics. The shift from extractive institutions, where society is organized to extract wealth to the hands of a few individuals, to inclusive institutions, where everyone in society benefits, was (and still is) the formula for thriving states.

Despite its short-lived nature, the Constitution was the beginning of political reform across Europe. This

was almost certainly because of Napoleon’s conquest of Europe. During his time as Emperor of France, he conquered much of Europe including Austria and Prussia, and whilst doing this, spread French ideals across the continent. Napoleon also believed in many of the liberal values established following the French Revolution and was one of the reasons behind the creation of the Napoleonic Code which consolidated many of the principles established in 1789, such as civil equality, and the abolition of feudalism. It also strengthened property rights and created a more centralised state through the prefectorial system – a patchwork of administrative authorities which were centrally controlled. Underlying much of the code was the notion of equality of opportunity, which would facilitate social mobility. During and after the Napoleonic wars, the Code became the basis of European law.

This is particularly true in modern-day Germany.

Following the collapse of the Confederation of the Rhine in 1813, the German Confederation was formed, an organization of 39 states. This decision at the Congress of Vienna was a key prelude to the unification of Germany. Napoleon’s legacy continued to influence these German states, in which the sentiments of nationalism and liberalism were growing. This is evidenced by the Hambach Festival of 1832, where over 25,000 nationalists met to discuss a nationalist revolution. The tricolour flag – which at the time represented nationalism and revolution – was hoisted. Many states began to adopt more liberal constitutions, such as Saxony and Hesse-Cassel in the 1830s. Alongside this, a form of economic liberalism was emerging. Friedrich List, a German-American economist published ‘The National System of Political Economy’ – his belief that any economic behaviour should be in the interests of the state and its citizens, a divergence from prior economic thought of individualism in the economy. He strongly advocated for increased trade within the Confederation and eliminated all trade barriers and tariffs inside Germany. He supported the Zollverein – the Prussian Customs

Union – which bolstered trade across states in Prussia and the Confederation. Furthermore, List argued that railway networks should be improved to create a centralised economy. This again highlights the shift towards inclusive institutions, where centralisation is important to achieving growth. Although he pushed for free trade within the German states, he wanted external barriers to remain, particularly with the English, to protect German industry from English competition. These ideas were key to forming a state, not only with political liberty but also economic liberty, where merchants could sell their goods across a centralised German state to improve their living conditions, not just the wealth of a monarch. However, the move towards inclusive political and economic institutions was not without resistance. European aristocracies were adamant about suppressing any national or liberal movements, particularly after witnessing the execution of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. The bloody scenes from the revolution were to be avoided, and the loss of power from the elite was restricted. Francis I, alongside Metternich, led Austria on a reactionary path, in an attempt to suppress liberalist movements –effectively under a police state. Robert Owen, a British social reformer, wrote to Metternich to advocate for liberalism. The response from Metternich’s assistant, Friedrich von Gentz stated, “We do not desire at all that the great masses become well off

and independent…how else will we rule over them”. This epitomises the reactionary belief of withholding inclusive economic and political institutions from the people to retain their personal power and luxury. Despite this resistance, liberal forces across Europe became more organised and allowed for permanent liberal democracies to be established.

Napoleon’s original influence in creating panEuropean liberalism cannot be understated. Whilst the Glorious Revolution had little to no impact on the rest of Europe, the French Revolution was monumental in creating inclusive institutions across the continent. Today, this means we have access to democratic pluralism, freedom of speech and voting rights, alongside other liberties. Moreover, we live with economies in which secure property rights, equitable distribution and social mobility are fundamental aspects. Over the last 230 years, starting from the French Revolution, and being aided by economic thought from those such as List, Europe has progressed into a continent thriving due to its inclusive, liberal values.

Words / Vatsa Dubey, L6KAG Photography / WikiImages

My question aims to discover how much of an impact the new rules about family heritage do have on team selection and ability. However, in order to tackle this question, it is important to establish a clear definition of family heritage, especially in rugby. From research, it signifies the history of a family where a family came from and all the traditions, customs and more that have been passed down from generation to generation. I have undergone this by researching 3 different individual articles by separate news producers about the new rules in rugby, and I am not writing about the rules in all sports. This is an interesting topic because the rules have a big say in the ability of teams which can massively affect who wins tournaments and who is the best rugby country in the world, the main goal of rugby. I will answer this question by evaluating the three sources: one by the BBC, another by the Racing Post, and the final source from Guardian, comparing their similarities as well as their differences before finally discussing all three of them together.

The first article, How birthright rule is giving teams the X-factor for Rugby World Cup , (The Guardian, 2023) states many facts as well as quotes from players current and past as well as coaches and reporters. It was written by Gerard Meagher in August 2023. Summarising the article, it mainly describes how the new change can positively affect the new teams, making previously strong teams even stronger if big players decide to make the move. It mainly talks about the Pacific Islands (Tonga, Fiji & Samoa) and how they will be massively affected for the better, as proficient

players that play for New Zealand for example could now move to these smaller islands. The purpose of the article is mainly to inform people about the new rule where players can now switch nations, and it uses many quotes from well-informed people within rugby. It also is quite opiniated because of how it states a lot of quotes from people like Eddie Jones, Charles Piutau and Steve Hansen. This article is quite reliable because it comes from a fairly well-known news producer (The Guardian) and it states a lot of facts so the producer of the article is clearly educated on this topic. But in spite of that, it was written over 5 months ago, back in August 2023, so it will not be very outdated, but the topic might have moved on from now, especially with another major tournament passing (The Six Nations) so they will want the rules to be as up to date as can possibly be.

My second article, World Rugby to vote on easy rules on player Test team switches , (BBC, 2021) mainly just explains the possible new rules as well as the current rules as well. For example, it explains the new rules: “a player is 'captured' once they have won a senior cap”, as well as, “players will be able to represent the country of their ancestors' birth after a 3-year standdown period.” The purpose of this article is also to inform people about the current and potential rules as well as many other facts based on these rules as well as giving a couple of examples of players that have or have not played for their home country such as Nathan Hughes and Malakai Fekitoa. On the one hand this article is very reliable because it comes from a variation of a very well-known news outlet - BBC Sport being a variation of the British Broadcasting Company, a very famous news producer. However, on the other

Players can now switch nations

hand, the article was published all the way back on the 2nd of November in 2021, talking about how the new rules might come into place, whereas we now know that these rules have been put into place, so it is very outdated, especially on some of the facts that are in place. Then again, the author of this article is a rugby union correspondent, proving once again that they will have a lot of knowledge on the topic of rugby as their job is specifically based on it.

My third and final article I explored was New rules open the door for Pacific Island nations to realise their potential (Racing Post, 2023). In general, it explains how teams like Fiji, Tonga and Samoa will be massively impacted because of how better players that choose to represent Australia or New Zealand instead of their actual country for a better chance of victory could now switch back. This is shown when it says, “Tonga and Samoa have both taken advantage by selecting members of New Zealand's 2015 World Cup-winning squad for this year's edition. Malakai Fekitoa is set to play for Tonga alongside fellow former-All Blacks Charles Piutau and George Moala, while 38-cap Wallaby Adam Coleman should start in the second row.” It also states a couple of past fixture scores for these countries such as, “Samoa, who famously beat Wales in both 1991 and 1999,” and, “Fiji lost to Uruguay in Japan in 2019 but they are a far more professional outfit now with quality running throughout their squad and, after impressing in last week's 34-17 defeat to France.” This article is fairly reliable because although it comes from a news source that is not very famous, it is still fairly recent, having been published on the 25th of August 2023. Also, the fact that it states quite a few facts does improve the reliability.

The second and third articles are similar because they both mainly state facts in their articles whereas the second article by The Guardian consists of a lot more quotes rather than facts. Also, the article by the BBC is different to the other articles because they talk a lot about the Pacific Island teams and how they will benefit the most. My second article by the BBC and my third article by Racing Post are similar in the sense that they are fairly unreliable, however, they are unreliable for different reasons. The article by the BBC is unreliable because it was written 3 years ago so it is out of date whereas the article published by the Racing Post is unreliable due to how it comes from a not well-known news producer. The first and final articles are similar because they were both written six days apart, meaning they would both have similar facts. After all, the laws would have been the same during that short time difference between each one being published. Another evident difference is that they are all from different news producers, which can be quite important as they will probably have gleaned their information from different sources.

The sources analysed have shown me that the changing laws stated in each article are helping certain teams for performance as well as becoming a disadvantage for some countries. People didn't know that the new rules were also a disadvantage for teams but due to my research I now know that it negatively affects Uruguay and Georgi; Uruguay have said countries such as theirs are in effect being penalised for focusing their efforts on producing homegrown players. Georgia has asked why Tonga and Samoa have been granted permission to pick All Blacks while Georgia, who continue to make strides based on domestic development, cannot enter the Six Nations. I was also able to find out about a lot of the rules in more depth compared to what I already knew before, where I had a rough idea of what the rules could change to be. In line with what I hypothesised, the research I have undergone supports the initial view I had that the new laws do substantially impact the ability of these teams. My initial hypothesis before I read the article was that the new rules being put into place by the World Rugby would massively impact a few certain countries (such as the Pacific Nation countries such as Tonga, Samoa and Fiji) based on family heritage and even just the home country that the player is from, even though players do switch to play for or not play for the countries they were born in. An example of this is Stephen Lorenzo Varney, who chose to play for Italy even though he was born in Wales, specifically Pembrokeshire and can speak fluent Welsh (British Broadcasting Corporation - BBC, 2020). These results contribute to a clearer view that the changing laws do affect the talent as well as the players in the squads, especially for smaller countries such as Tonga, Samoa and Fiji that have lost a lot of good players to bigger teams such as New Zealand and Australia for a better opportunity. The new rules that I have now understood in better detail have also helped me become conscious of why these players would

switch countries as well, showing me that they would do it for the opportunity of winning competitions, even if that means not playing for their home nation but now switching back because they can, due to the new rules. This is shown by big players such as World Cup-winning centre Malakai Fekitoa; New Zealand fullback Charles Piutau; Steve Luatua; New Zealand fly-half Lima Sopoaga; Christian Leali'ifano who was another newcomer after representing Australia; Charlie Faumuina, who also played in the World Cup final and New Zealand centre George Moala all making the change to the Pacific Nation countries. There are many limitations to my question, with one being that it is quite a specific topic, even in the world of rugby, meaning there are not actually that many articles based on this topic, meaning my data isn't very broad but rather very specific, only based of 3 articles. Another limitation to this question is the fact that the articles are quite out of date, with one being made in November of 2021 and the other two being made in August of 2023, meaning the topic could have moved on from now, damaging the reliability quite a lot, especially with rugby laws changing quite a bit. Further research is needed to establish really how much of a difference the rugby laws about family heritage do affect team selection and ability. I would recommend many people go on and do more research on this topic; with around 500 million people being interested in this sport (World Rugby, 2024) in the world, it is surely an important potential phenomenon.

To conclude, the new laws do hugely impact teams and their squad selection and ability because of better players leaving or joining, or even re-joining back to their team. I was not able to directly discover why players have switched from their home country to play for a bigger, and thus more victorious country, however, I was able to hypothesise why this may be the case. Teams are likely to want the opportunity to win more trophies and play better-quality rugby, which they would prefer rather than playing for the home country, which would surely like more than their new country. Based on how captivated I have become from my question and research with which I have engaged, I would like to follow this up with a different analysis of the bunker system and how much of an impact the new rules about that make, either for better or worse. This is also a big question because it can improve the decisions made by referees, which has been a complaint for all sports.

Words / Thomas Bland, 2ECW

Photography / James Coleman

Jones, C. (2021) World Rugby to vote on easing rules on player Test team switches, BBC Sport. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/rugby-union/59139431

(Accessed: February 28, 2024).

Meagher, G. (2023) How birthright rule is giving teams the X-factor for Rugby World Cup, The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2023/aug/31/how-birth-right-rule-is-givingteams-the-x-factor-for-world-cup-rugby (Accessed: February 28, 2024).

Ogalbe, J. (2023) New rules open the door for Pacific Island nations to realise their potential, The Racing Post. Available at: https://www.racingpost.com/sport/opinion/ new-rules-open-the-door-for-pacific-island-nations-a9TdM2w4e1Wb/ (Accessed: February 28, 2024).

guardian of liberty or restriction on freedom?

to a restaurant; the law is there. If you eat without paying, you violated the law. When you go to school, there are regulations. When you go to work, there’s a code of conduct; even when you go back home, there’s a set of rules as well. Your job, your home, your relationships, your everyday life, and your death all are controlled by law. The society needs to have a form of law to regulate the people’s behaviours. Many people thinks that law is limiting their liberty, but I think law provides a model of how people should behave. In this essay, I would like to discuss about the history of law and discuss if it has conflicts with our liberties. The earliest writings of law were destroyed during the Dark Ages, so the concept of crime and punishment and where it all began starts in the year 500 AD. It was governed mostly by superstition and local

laws and stayed pretty much the same up through the year 1000 AD. And then we have ten commandments, one of the most important rules released in human’s history. After the Norman conquest of England in 1066, common law started to develop and helped standardize law and justice. Until then the legal system among the early English or Anglo-Saxons and everywhere else in Europe during that time, was decentralized. In Qin Dynasty from China, because he wanted to maintain the social discipline, Qin Shi Huang proposed a lot of laws that seemed to be irrational to modern day people, for instance each county was divided to different groups, each formed by 10 families. People inside each group must monitor each other and immediately report any crimes to the government, if one of the families committed a crime and other families didn’t report, other families would receive the punishment as well, the law in Qin dynasty was very strict that if you stole 1 cent, you would be sentenced to death. The evolution of law throughout history reflects the changing needs and values of societies. Granted that laws sometimes limit personal freedom, they play a significant role in establishing order, protecting rights, and promoting justice.

One of the earliest known sets of laws can be traced back to the Babylonian king Hammurabi, who reigned in the 18th century BCE. It aimed at maintaining social order but mirrored the authoritarian nature of early legal systems. It consisted of 282 laws that covered various aspects of life, including commerce, property, and family matters. The aim was to maintain social order and ensure fair treatment of individuals

within the community. In ancient Greece, the concept of law was further developed by philosophers such as Plato and Aristotle. They believed that laws should be based on reason and justice, and that they should serve as a guide for individuals to live harmoniously in society. This idea of laws to uphold justice and promote the common good has remained influential throughout history, it shows that the purpose of law is actually to keep the social system working.

The Roman Empire also made significant contributions to legal systems. The Roman legal system, known as civil law, emphasized the importance of written laws and legal codes. This approach provided a foundation for the development of legal systems in many countries today, including those based on the Napoleonic Code and the modern civil law systems.

The Magna Carta, signed in 1215 in England, is considered a pivotal moment in legal history. It established the principle that even the ruler was subject to the law and provided protection for individual liberties. This document laid the foundation for the development of common law, which is based on legal precedents and the decisions of judges.

But the law doesn’t stand still (you won’t see the policy of Qin dynasty nowadays at least). Globalization, the change of the society, rapid advances in modern technology and the change of the form

Law is an essential component of a functioning society

of the government all resulted in the change of law. For instance, in 2013, the marriage act has been extended to same-sex marriage. This law was enforced on 13th March 2014 and since then many couples have finally been able to get married. This is one of the biggest laws passed this decade as it has led to a wider acceptance of same-sex couples across the UK. This shows that the law changes from time to time, and it is not the same in different countries as Saudi Arabia doesn’t accept LGBTQ. Another example is The Industrial Revolution, which led to the need for new labour laws to protect workers' rights. Similarly, the rise of the internet and digital technology has necessitated the creation of laws to address issues such as cybercrime and data privacy.

Yet, a crucial question persists: Can law encroach upon liberty, or do they synergize to forge a harmonious society? Law serves as a ‘fact of pure reason’; it constitutes what is human about human beings. Law presumes and implies freedom. Together with the law, freedom is the fundamental theme that gives the modern world its ethical and basic anthropological shape.1 Some people might argue that while laws provide essential governance, a perpetual tension exists between regulating behaviour for the common good and ensuring the protection of personal liberties. For me, they are not incompatible. The answer lies in the delicate equilibrium between the need for societal order and the preservation of individual freedoms. Think about it, when everyone dumps their rubbish on the floor without being regulated by the authorities, yes, they claimed it as freedom, but it affects our rights to use the road

because no one would walk on a road full of stinky rubbish. Law maintains social order while protecting our personal rights as well. Without law, everyone does what they want without consequences, the society will not be secure and prospect. The Article 10 of Humans Right Act 1998 has protected our freedoms. According to the United Nations, the backbone of the freedom to live in dignity is the international human rights framework, together with international humanitarian law, international criminal law, and international refugee law. Those foundational parts of the normative framework are complementary bodies of law that share a common goal: the protection of the lives, health, and dignity of persons. The rule of law is the vehicle for the promotion and protection of the common normative framework. It provides a structure through which the exercise of power is subjected to agreed rules, guaranteeing the protection of all human rights.

Law is an essential component of a functioning society. It provides a framework for governing people's behaviour, resolving disputes, and protecting individual rights. Indeed, it sometimes seems restrictive, but it serves as a crucial purpose in maintaining order, promoting justice, and adapting to societal changes. All parts of society have a part to play in upholding the rule of law. Those working in the UK’s democratic and independent institutions have a responsibility to promote public trust in the rule of law, while the public’s commitment to this fundamental principle is essential for it to be maintained in the long term. We should appreciate the presence of law safeguarding the country and acknowledge that it is not 100% against our freedoms.

Words / Ryan Cheng, 3SCR Photography / Rashid Khreiss / Mark Duffel / Kyle Glen

One of the things that first appealed to me about the German language was its apparently limitless ability to create new words. Combine this with its indefatigable sense of logic, and you can create words whose meanings leave language learners more often than not frustrated by the lack of a neat, identifiable equivalent in their own language. However, I find myself in awe at the simplicity with which these compound words can express feeling and emotion, or indeed sum up something so contritely that I am left to despair that my native English language cannot offer anything as worthy.

One such compound German noun is the word “Gemeinschaftsgefühl”. One English equivalent is “sense of community”, but it could also be translated as “sense of connectedness” or even “feeling of belonging”. At its core, this word is able to encompass the very essence of togetherness and community in perfect simplicity.

“Gemeinschaftsgefühl” was first coined in the early 20th century by the Austrian psychologist Alfred Adler. He placed enormous emphasis on the importance of feelings of belonging and on what he called “social interest”, which refers to an individual’s sense of worth and belonging and which plays a key role in both metal and physical health. For Adler, human happiness and fulfilment can only be achieved when we have a sense of belonging to a community, be that with family, friends, or colleagues.

Abraham Maslow, an American psychologist working a generation or so after Adler, picked up on this theme with his work on the human hierarchy of needs. Towards the top end of this hierarchy is Maslow’s idea of self-actualisation, a higher order human need that can most effectively be met though social interest, a community feeling or a sense of oneness with all humanity.