INDIAN ARCH STHANIYA

Greetings from NASA India!

It brings me great joy to pen down the Foreword for the 2023-24 edition of Indian Arch. Being a part of this incredible organisation, NASA India, has been an exhilarating journey for me over the past five years. This period has been transformative not just for me but for many individuals associated with NASA India. It serves as a testament to the vast potential this organisation holds, and it continues to evolve dynamically.

The structure of NASA India is both dynamic and diverse, leaving everyone who has been part of it awestruck after a five-year tenure. The transition from a student to a licensed architect is undoubtedly challenging, marked by countless sleepless nights, broken coffee mugs, and a cupboard filled with archived drawings waiting for a nostalgic revisit someday. This journey is a shared experience among architecture students across the country.

While NASA India may not make this path easier, it stands as a steadfast companion and a reliable guide for those choosing the road less travelled. The Indian Arch 23-24 is a compilation of the unconventional thoughts and creations that may not find a place in traditional studio settings. It serves as a platform, giving voice to the rebel within you who aspires to enhance the environment not just for personal gain but for the silent peers struggling to articulate their opinions.

Over the years, our organisation, NASA India, has gained tremendous momentum, particularly in our engagement with students. We take great pride in our efforts to orient and guide students toward their individual goals through various initiatives. Our extensive network of collaborators, both in India and globally, has played a significant role in shaping this journey. It’s particularly noteworthy that all our members are students under 23 years of age, and I am immensely proud of the versatile work that NASA India accomplishes. Our organisation provides a unique platform where students not only delve into

the realm of architecture but also gain exposure to a diverse set of skills. From marketing and graphic design to event management, academia, negotiation, and team leadership, every student associated with NASA India acquires a multitude of competencies. The architecture journey, in essence, opens pathways to various facets and professional careers. Many of our graduates pursue careers beyond traditional architecture, showcasing the breadth of knowledge acquired.

As a nation, we often look beyond our borders and tend to perceive architecture in other countries as superior to ours. However, we must recognize and appreciate the skills our ancestors demonstrated in building this nation, evident in our temples, forts, and monuments. It’s time to embrace a holistic approach that interplays the richness of our past with the needs of the future, forging a truly Indian identity.

India boasts a rich indigenous style of architecture that not only varies geographically but is also deeply rooted in our cultural and social fabric. This edition of Indian Arch explores and celebrates this vibrant amalgamation of styles. At NASA India, we firmly believe that this ‘modus operandi’ should be integrated into our individual characterizations, creating a diverse tapestry that contributes to a new ‘Indian Architecture movement’. This edition serves as a reverb for Indian Architecture, echoing the essence of our unique architectural identity.

Happy reading!

If you are reading this, I assume you are already familiar with NASA India or may hold a preconception that it is merely a student organization focused on extracurricular activities. However, in reality, it represents a pervasive culture found in almost all architectural colleges in India. This culture entails students dedicating their nights to competitions after studio sessions and lectures, fostering an environment of learning and knowledge exchange between seniors and juniors. It involves student representatives from over 300 colleges nationwide delving into multiple arguments with their faculties for few permission or wandering around the management offices for some signature or convincing their college students to take part in some or the other NASA India activities. Moreover, it’s been a culture of few eccentric students taking up the council posts, striving to balance their academic commitments with their responsibilities to the association. Its genuine intuition that it’s insane that these students take up more responsibility and pressure on them, barring the fact that architecture in itself is a very engaging course, but this tradition has persisted for 66 years, with students endeavoring to establish a platform beyond institutional boundaries for exploration and networking.

With the experience of working closely with past 5 year councils of NASA India, it was such a privilege to see dedicated individuals spending sleepless hours discussing, arguing, manifesting yet devising reforms and initiatives in general body meetings aimed at benefiting more architecture students, coming up better solutions that brings student, professionals and society on one platform. I’d like to quote Jed Bartlet from West Wing which truly stays with me.

“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful and committed individuals cannot change the world. Because that is the only thing that ever has.”

However, traversing the corridors of memory, revisiting old documents at the Headquarters and hearing stories from ex council members it is pretty evident that there was an agitation amongst students of architecture that led to formation of the association, agitation to unite the architecture students and raise the voices for the imparity towards the architecture field but it’s hard to see it dwindling year by year, the strength of the student community

is losing its potential. Despite the association’s efforts to address issues such as low pay for architecture interns or legislative matters concerning architects, its voice has often lacked the necessary resonance to provoke action from bureaucrats.

One of the primary concerns our field currently facing, is the declining enrollment of architecture students nationwide. Various stakeholders could be implicated in this trend, whether it’s the students themselves not embracing the profession positively, professionals failing to serve as effective mentors, government officials unable to facilitate adequate opportunities, or the demanding nature of the course itself, which requires high levels of patience, consistency, and creativity. However, when viewed from a different perspective, that’s what strives to be a successful individual, and NASA India emerges as an invaluable resource in the collegiate experience of every Indian architect, offering a platform for networking, engagement, and growth.

Therefore, it is imperative to envision future prospects of this ever evolving field by leveraging emerging technologies and value systems, promoting the importance of architecture and design community by utilizing opportunities to justify the association’s importance, and making choices that contribute to the improvement of the architectural fraternity and societal welfare. This is an opportune moment to demonstrate the potential of the student community by spreading the network with like minded individuals, excelling academically while fulfilling responsibilities, utilizing NASA India as a platform for professional development before entering the field.

While this article was initially intended to summarize my understanding and experiences within the association over the past four years, despite the challenges and exertions endured in the pursuit of progress, if queried, my response remains steadfast: It was all worthwhile, down to the last moment.

Happy reading ahead!

Grateful,

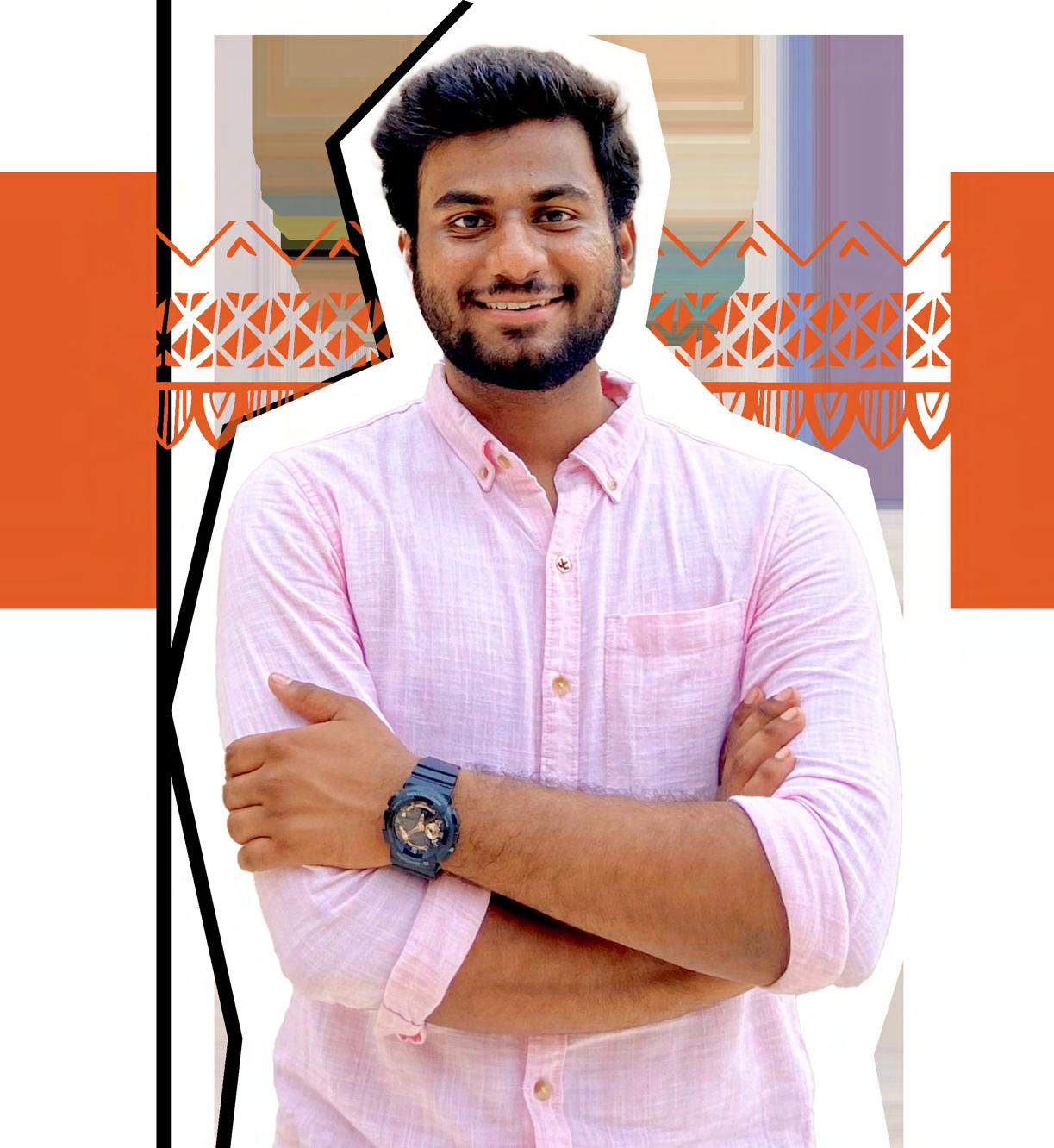

Syed Abdus Samad NASA India

Hello Indian Arch Readers! STHĀNĪYA, our theme for this edition, invites you to explore the rich heritage of indigenous architectural marvels and celebrate the wisdom of local craftsmanship and sustainable design principles. Join us as we unveil the stories behind these timeless creations and gain insights into the profound connection between people, place, and built environment. We genuinely hope you find as much delight in reading it as we did in putting it together!

Arushi Ponnala, Editor in Chief Rachit Jain, Designer in ChiefForeword by Tarun Krishna, 65th Year National President

Note by Syed Abdus Samad, 66th Year National Secretary

65th Year Council Note

66th Year Council Note

Meet the Team

• Vernacular Architecture Conservation

• The role of Courtyards in Vernacular Architecture

58-87

• Cultural Symbolism as an important aspect of the Vernacular Style

• Vernacular Urbanism, the last puzzle piece of Transnational Urbanism

• Vernacular Stalwarts: Architects of a timeless future

• Citation 1

• Citation 2

90-117

• Special

• Special

• Special

1

2

3

18-49

• A journey with Ar. Rafiq Azam through art, nature and the built environment

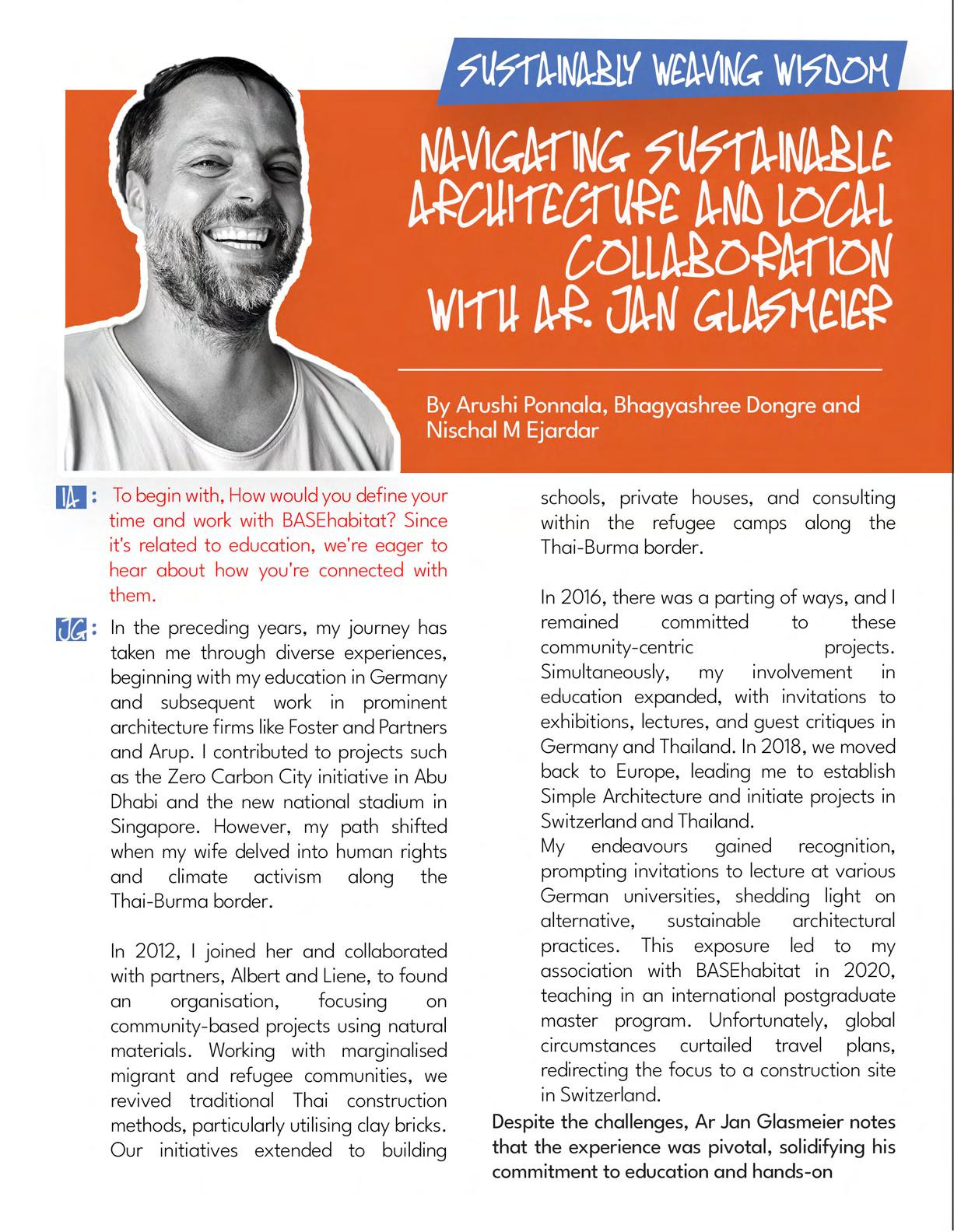

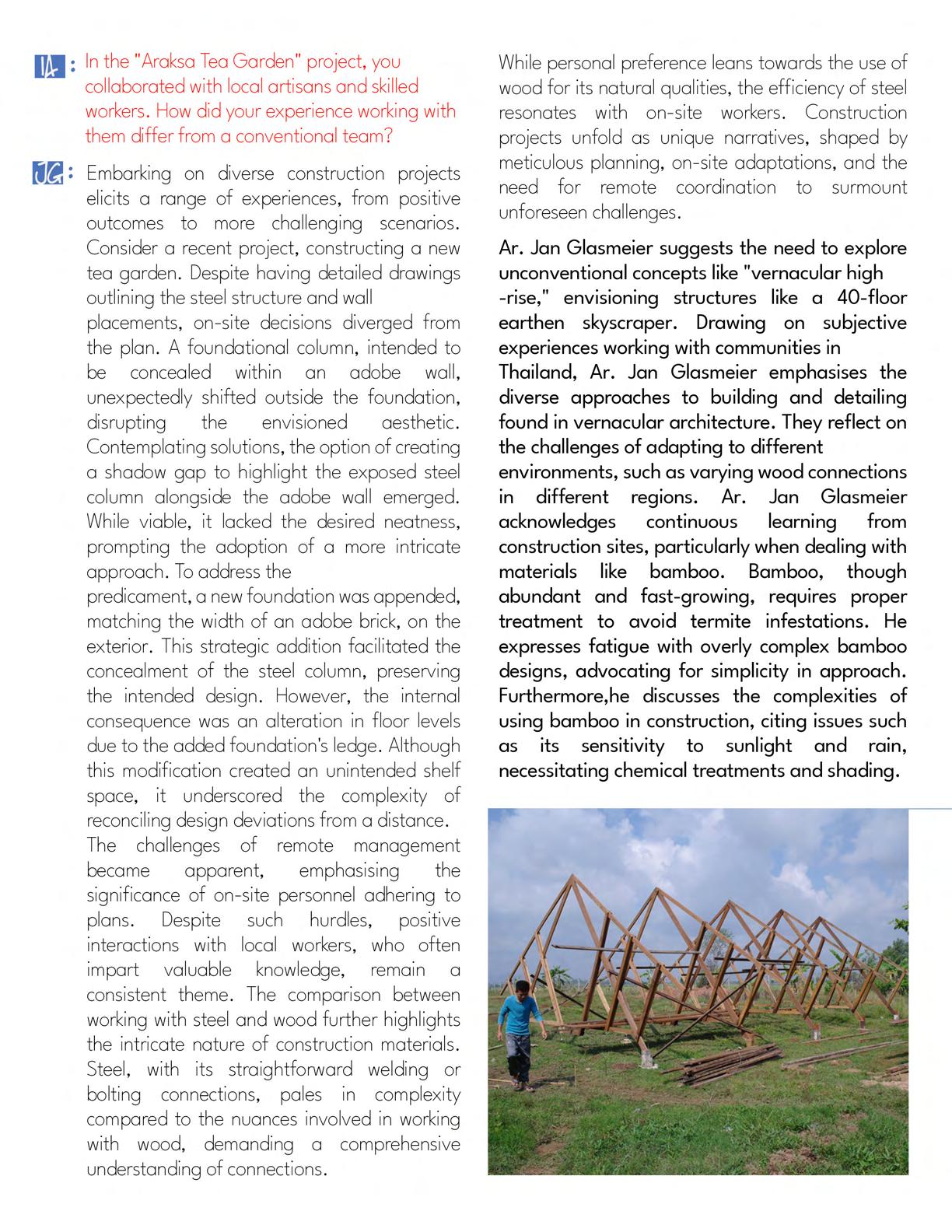

• Navigating sustainable architecture and local collaboration with Ar. Jan Glasmeier

• Ar. Eugene Pandala’s Odyssey in Sustainable Architecture

• Nurturing Architectural Integrity in a Collaborative Journey with VANAMU

Feature: Are we ready for 75th year? by Ar. Chaitanya Gajbhiye

50-55

120-135

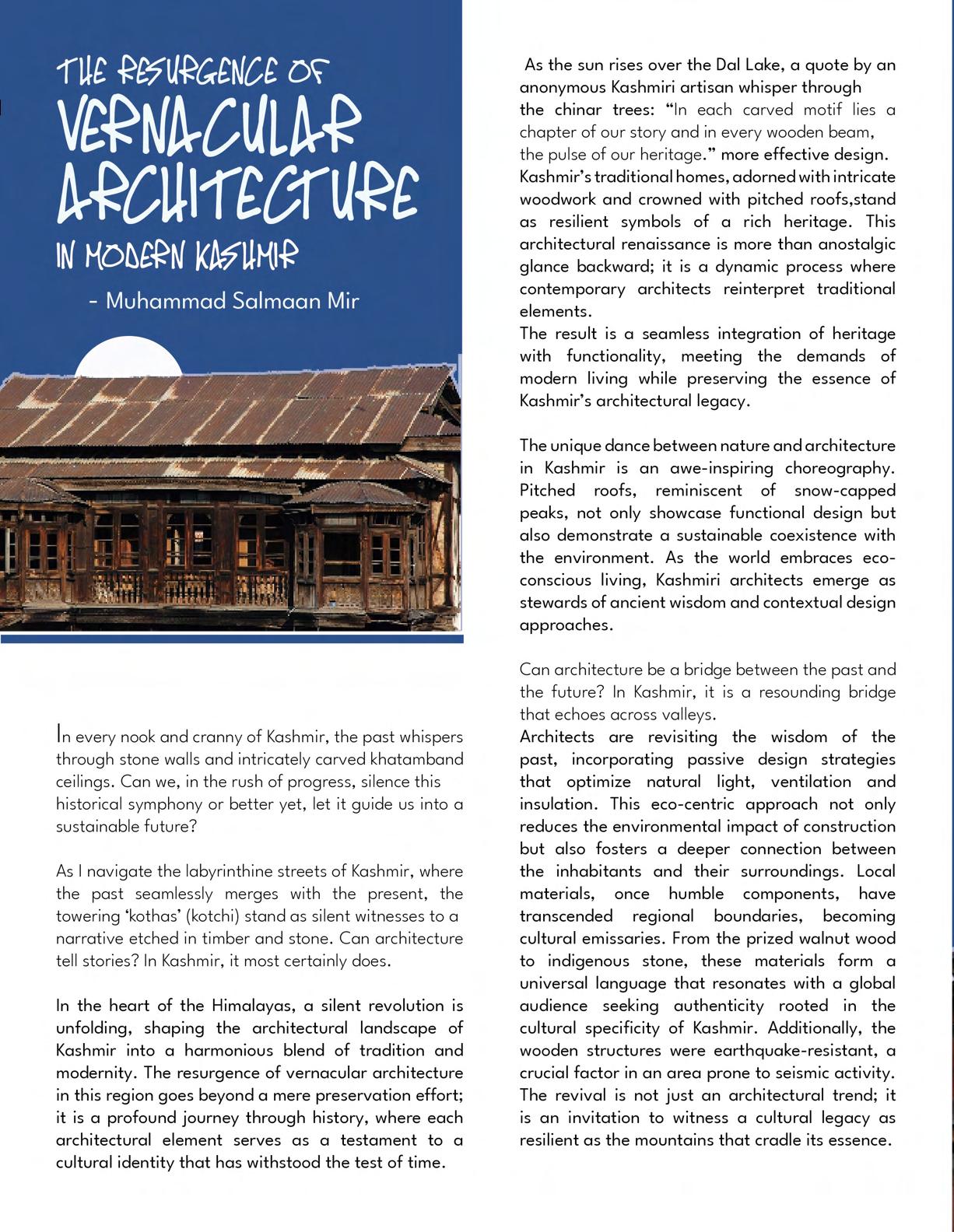

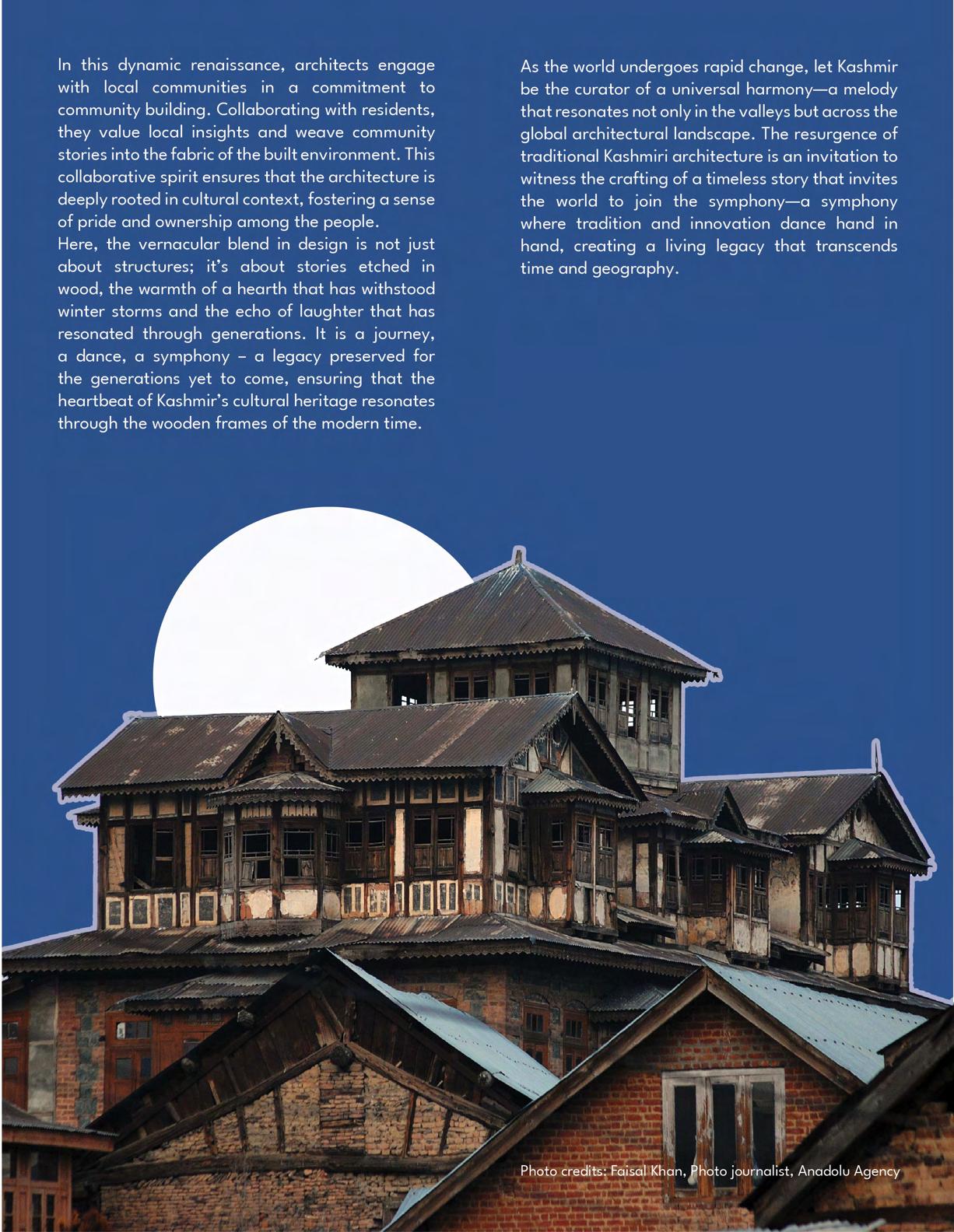

• The resurgence of Vernacular Architecture in Modern Kashmir

• Architectural Resilience: A journey through mud houses of Vattavada

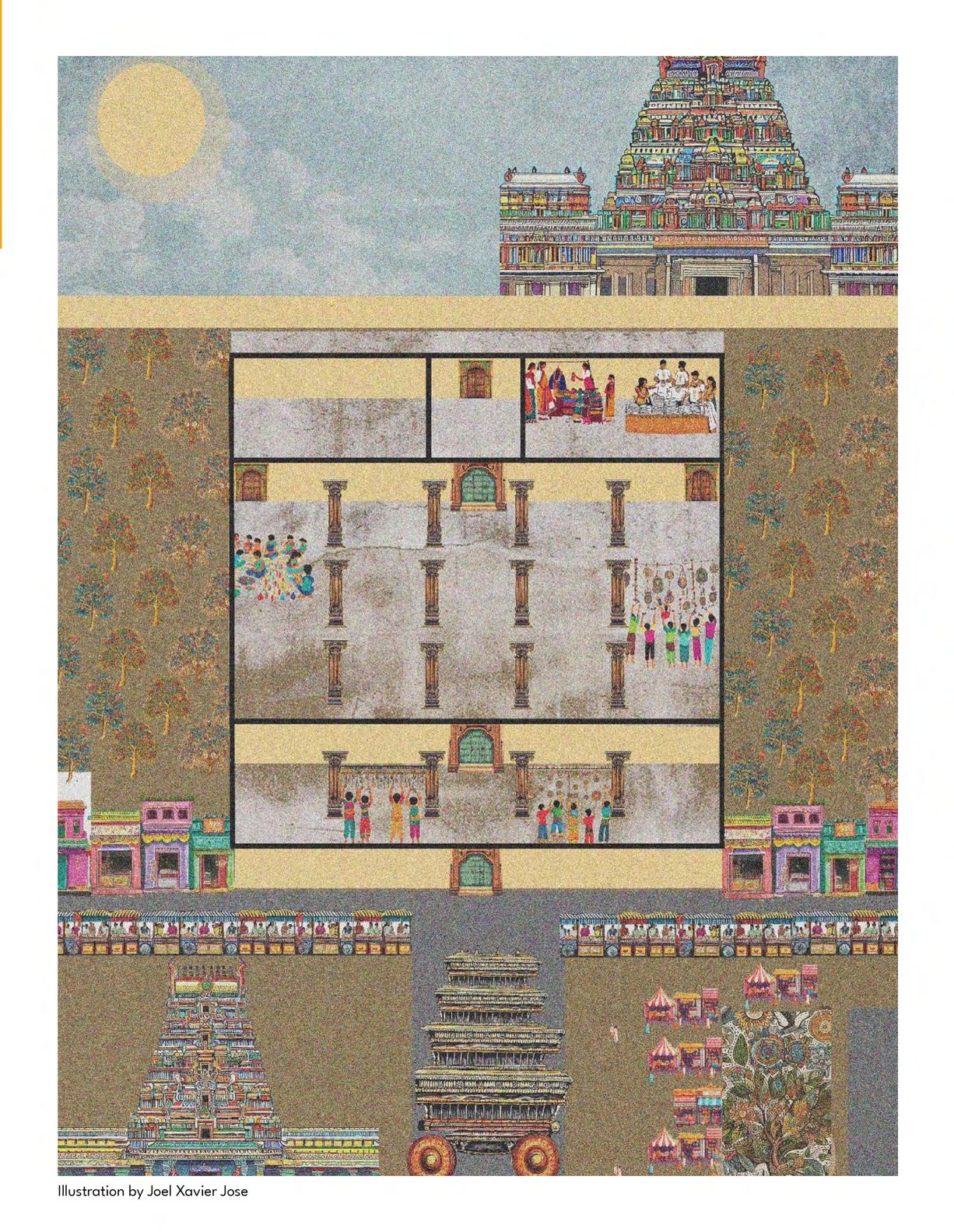

• Southern Realms of India: An Architectural Symphony

• Vernacular Architecture

• Photographs

Unveiling the Mosaic of Vernacular Architecture from Coast to Desert

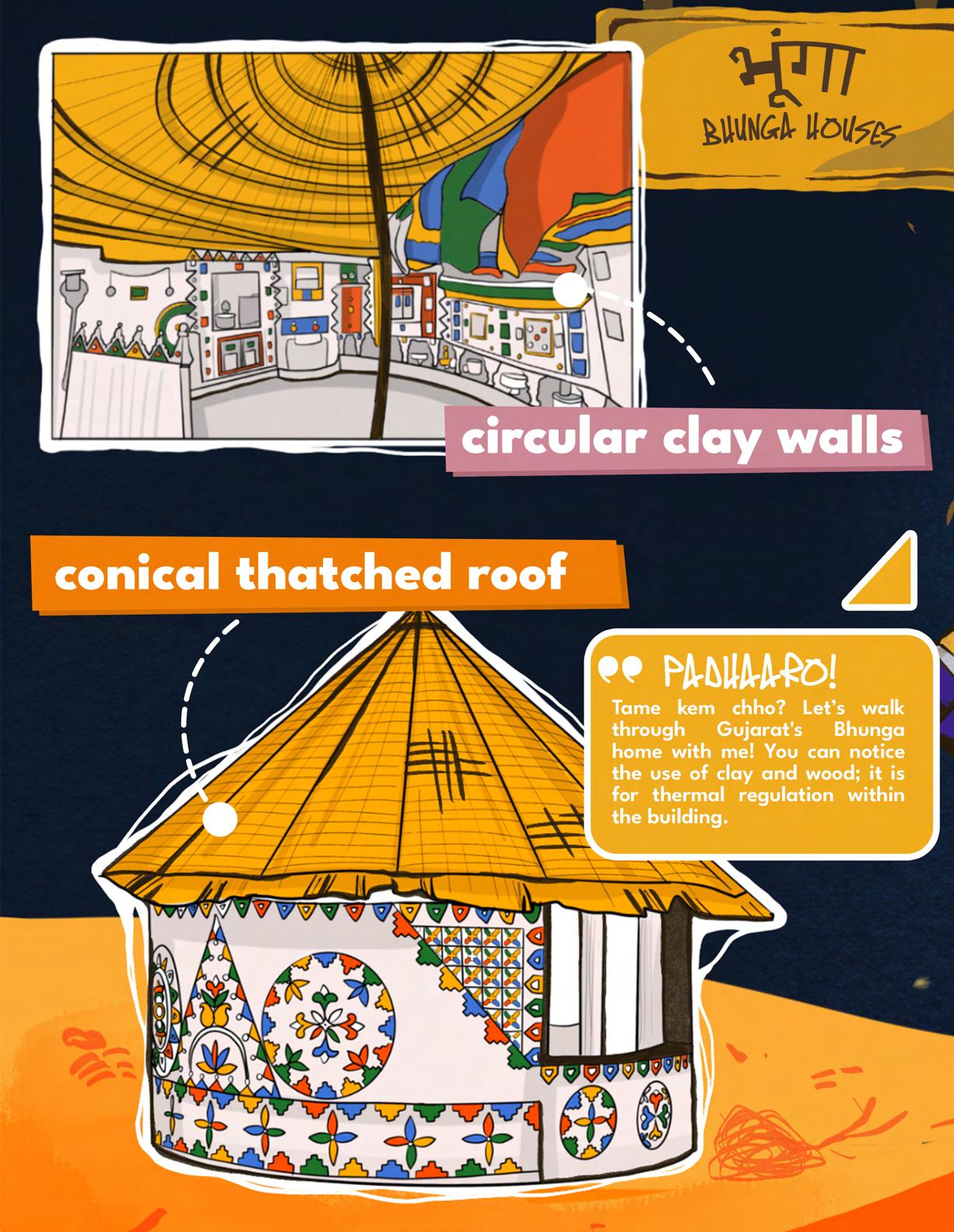

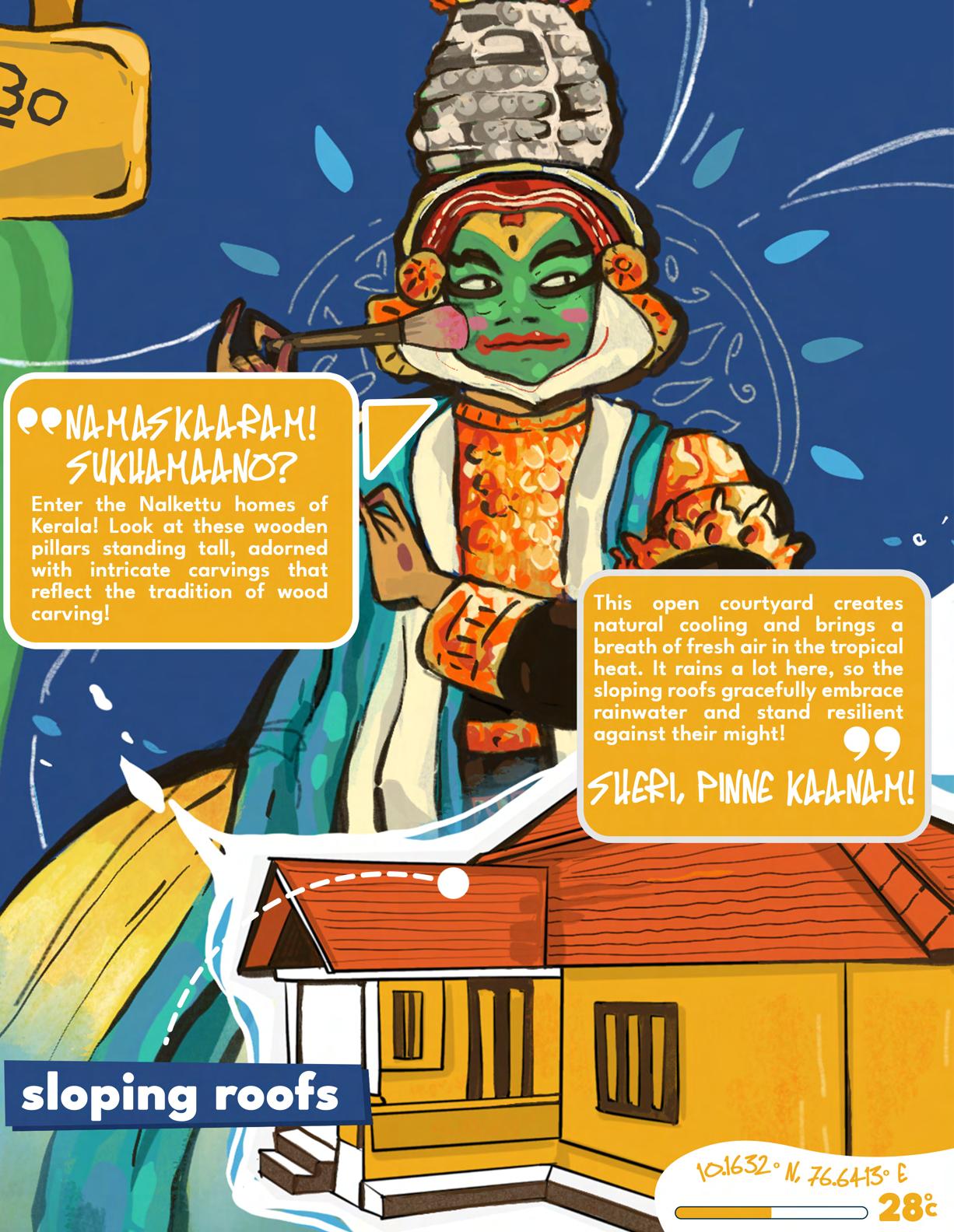

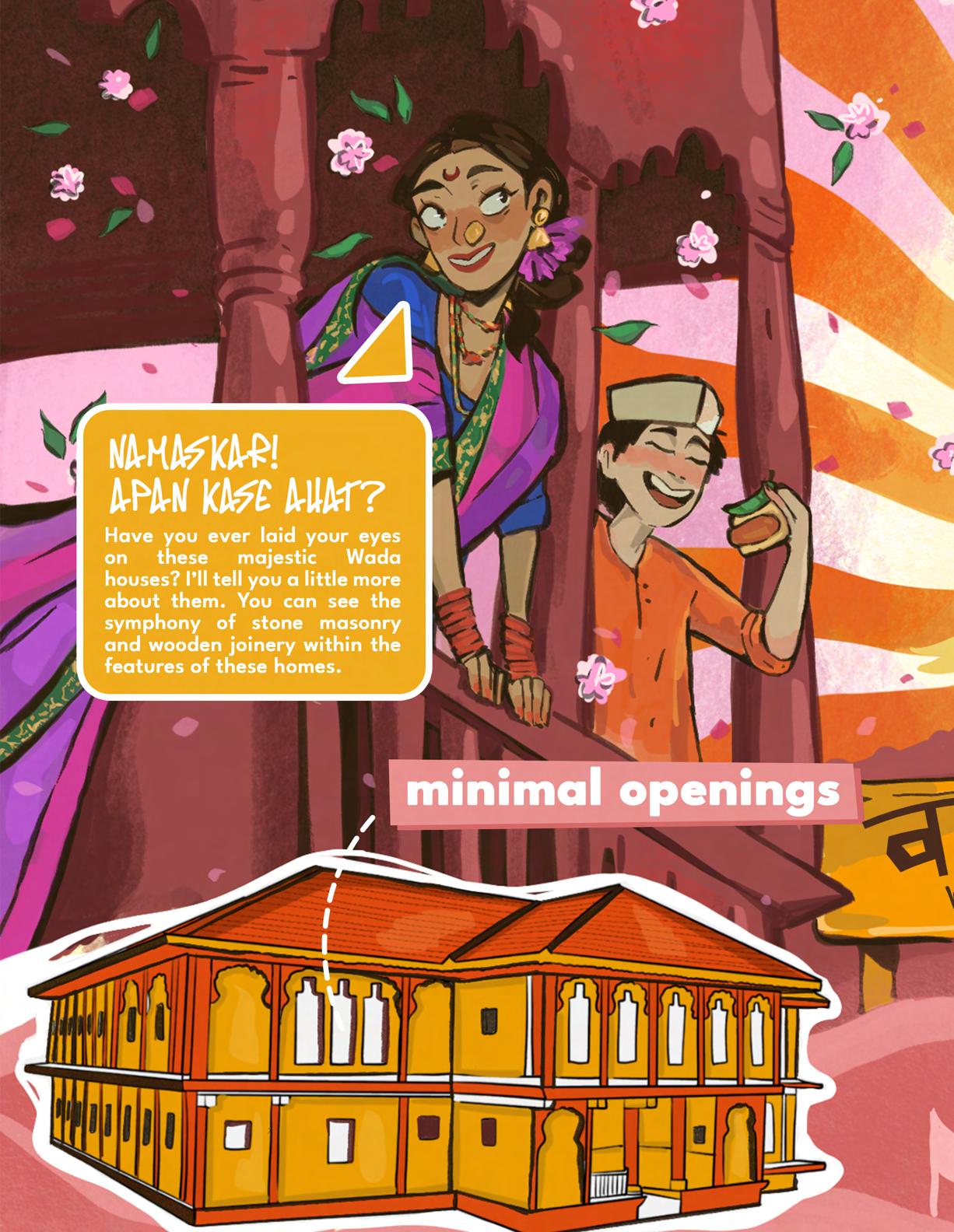

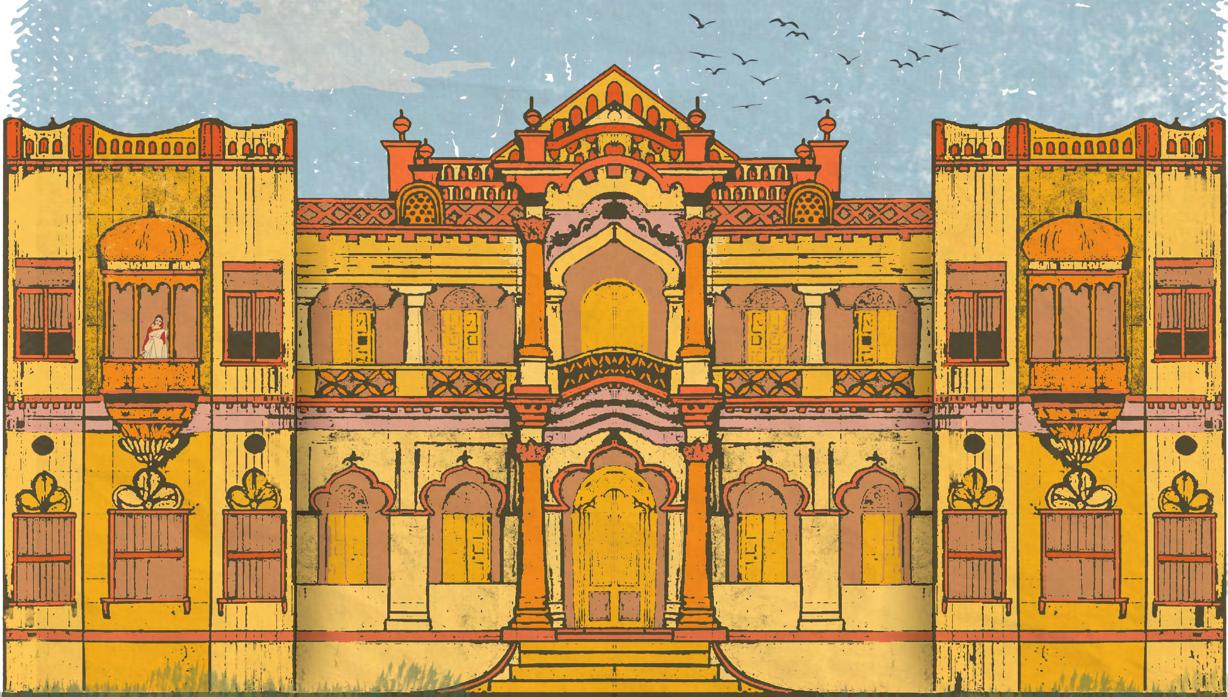

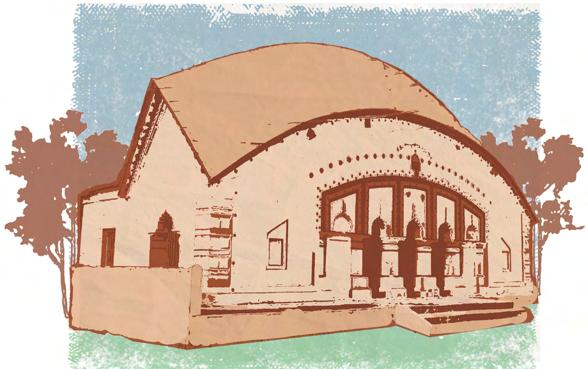

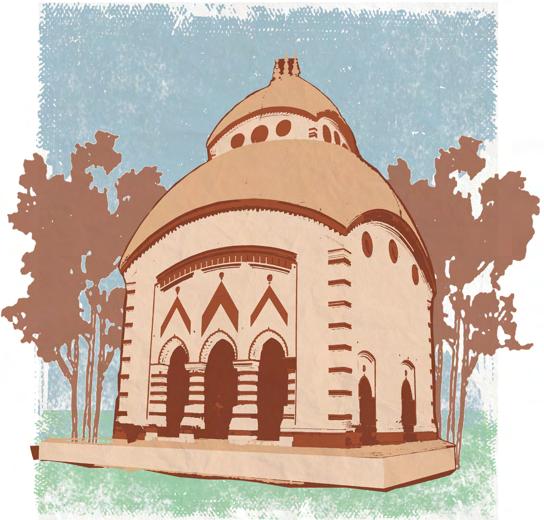

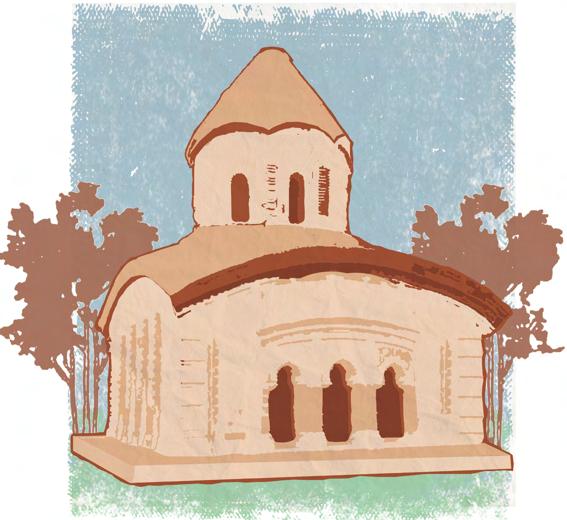

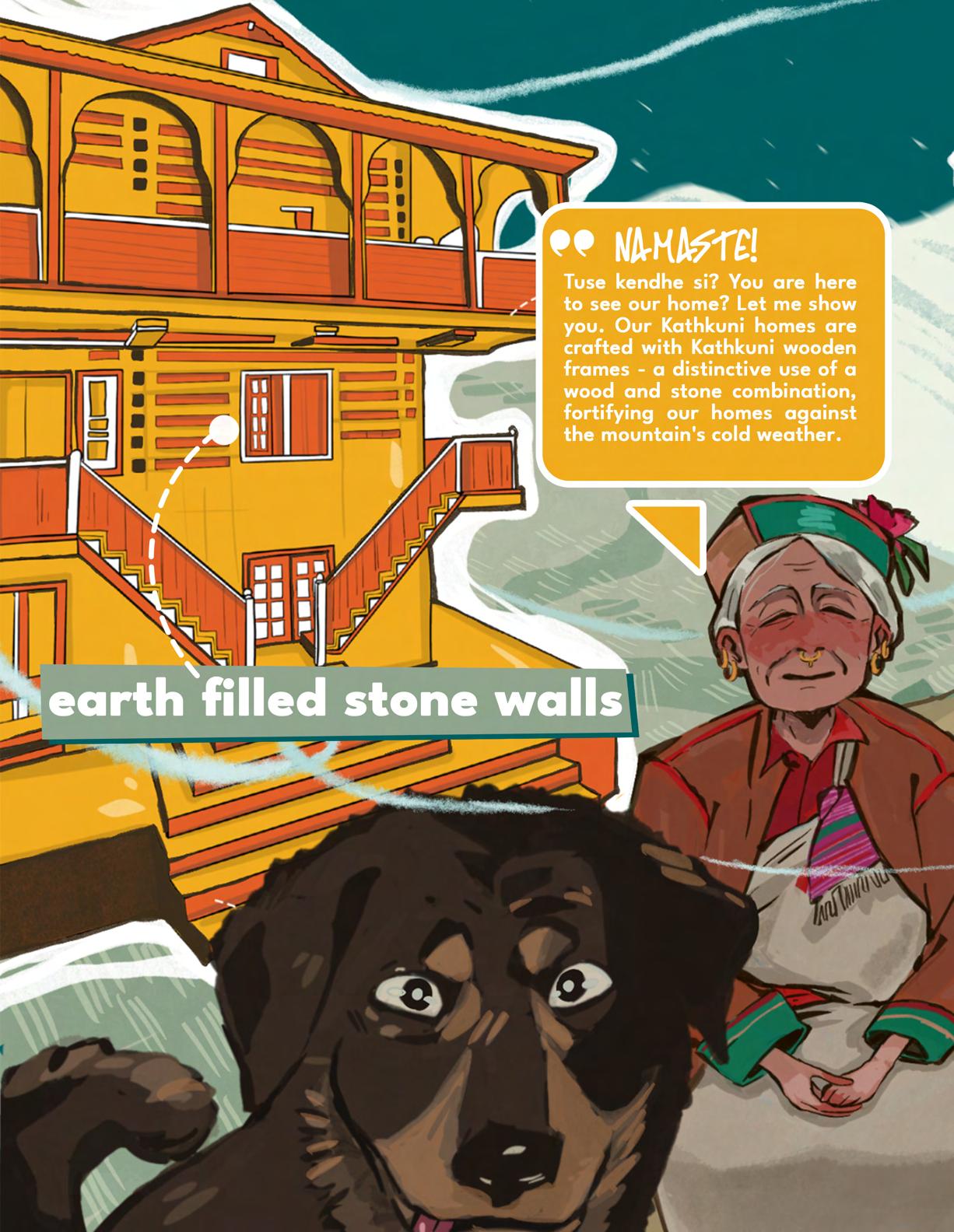

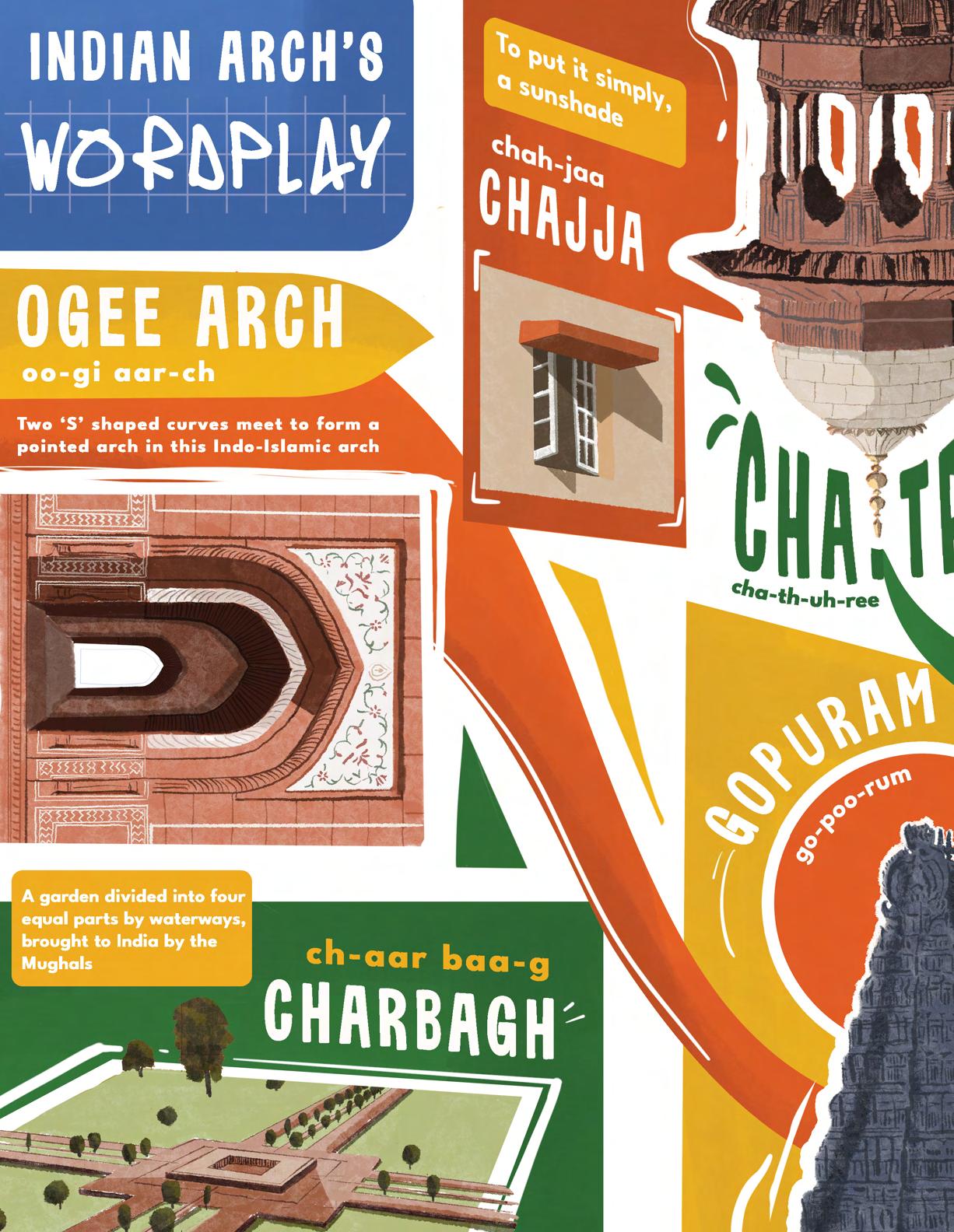

Explore our thoughtfully curated buffer pages showcasing few Vernacular Architecture styles across our diverse nation. From enchanting havelis to historic wadas, these playful illustrations guide us on a captivating journey through the distinctive elements of each architectural typology. Join us in celebrating the rich tapestry of India's architectural heritage!

26-27

34-35

42-43

56-57

66-67

72-73

78-79

84-85

4. Havelis 5. Nalukettu 6. Wadas 7. Kathkuni 8. Koti Banal

Ponnala, Bhagyashree Dongre and Nischal M Ejardar

04

In 1976, at 13, Ar. Rafiq Azam embarked on a journey into watercolour painting, aspiring to become an artist. This passion led to the receipt of the prestigious Jawahar Nehru Memorial gold medal in an international competition. Despite initially envisioning a future solely as an artist, the speaker eventually found themselves immersed in the field of architecture, feeling an undeniable connection between the two forms of expression. The lush and watery landscapes of Bangladesh, Ar. Rafiq Azam’s home country, served as a significant inspiration throughout their artistic and architectural endeavours.

Beginning with your early exploration and interest in watercolour painting, we understand that it has had a deep impact in your practice. How important do you see art and creativity as a part of architecture?

Creativity is crucial in life, whether it’s expressed through computers, painting, or any passion. Despite being a poor student, my journey unfolded uniquely. In my second year, a teacher couldn’t grade my designs, deeming them below passing. Graduation brought uncertainty, leading me to explore Eastern Music Appreciation and a world course for a year. Filmmaking in Australia taught me parallels with architecture. Photography training in Germany and Japanese management studies broadened my perspective.

Critics questioned my diverse pursuits, but I aimed to understand human and artistic creation. Early struggles emerged as I eschewed quick riches in interior design. Friends prospered, but I focused on comprehending human behaviour and mechanisms. I persevered, learning and evolving. Presently, my expertise makes it challenging for others to replace me. Architecture mirrors sports, and I may retire as a coach in my sixties, ensuring a graceful transition. At 45 or 50, architects begin their prime, but a mindful note emerges. Care for your body now; it’ll be your ally later. Wisdom develops when body and mind align. By 70 or 75, one may create masterpieces. In advising the youth, I emphasise holistic well-being, envisioning a future where both body and mind harmonise, enabling the creation of unparalleled architecture in later years.

You mention that your architecture is like watercolour. What is your typical design process when you are approaching any project?

Watercolour is your mind state, everything is so poetic, what I like is oil painting. It is something laborious. You must do it for one year and go on thick water, thick brushes, and thick paint. But watercolour is very fragile. In one and a half hours, you complete the watercolour. Not half a year. So it is like Japanese poetry, haiku. So, that is my power. But that is not all, it needs other things, architecture requires a lot of other things that I learned.

Rafiq Azam serves as the principal architect at Shatotto, an architectural firm in Dhaka dedicated to “architecture for green living.” Established in 1995, Shatotto aims to rediscover the lost history and heritage of Bengal, reconstructing the connections between urban and rural cultures. The firm endeavours to bridge the gap between architectural values and the current need for responsible architecture, sparking conversations among people, communities, and nature to foster a healthier society.

Rafiq Azam’s extensive body of work, as reflected in Shatotto Architects’ collective portfolio, showcases a remarkable alignment with and deep understanding of their contexts. The architect has crafted an outstanding body of work characterised by environmental sensitivity, socio-cultural awareness, artistic ingenuity, technical expertise, and a penchant for experimentation.

Initially I thought to myself that I want to be an architect, I am a painter, but later I learned that a lot of calculation and a lot of investigation is important. Regularly visiting sites, I spent hours observing the surroundings, noting the sun’s movement, the time of day, the month, wind direction, and the historical context of the site. This comprehensive approach became integral to my architectural process. Whether it’s a graveyard or an archaeological site, I undertake thorough investigations to unravel its mysteries. Understanding the context involves delving into the country, place, genealogy, culture, archaeology, anthropology, and even climatology. Unlike complete structures like Humayun’s Tomb in Delhi or the Agra Fort, many archaeological sites require a nuanced approach. My investigative process doesn’t always involve formal scientific research, but rather a comprehensive exploration to inform my decisions and creative direction.

Ar. Rafiq Azam passionately describes Bangladesh as a country intimately linked to water and boats, a land characterised by its fragility, vulnerability, and poetic beauty. The unique climate, featuring six seasons, extraordinary monsoons, and the intricate network of rivers, makes Bangladesh a poetic and sensitive nation. Ar. Rafiq Azam emphasises the need for architects to scientifically organise spaces, considering the movements of the sun, wind, and fragrance to create harmonious environments. Reflecting on their early architectural practice, Ar. Rafiq Azam shares the experience of exhibiting ‘ARTchitecture,’ expressing a strong identification with being an artist rather than just an architect. The connection between watercolour painting and the layers of built structures on land is highlighted, with transparency in watercolours paralleled to the necessity of transparency in architecture to reflect the essence of a community

IA :

RA :

You frequently discussed the climate, noting that Bangladesh experiences six distinct seasons, which differs from the more typical seasonal patterns we are accustomed to. How do we begin to ensure that we are sensitive to nature, and climate and also maintain sustainability? Firstly there’s the terminology Anthropocene. The term Anthropocene marks an era where there’s a prevalent belief that humans are in control, asserting themselves as the rulers of design.

However, when you consider your position within the ecological context, you’ll realise the limited extent of our influence. If you go through your position, in ecology, you will see you are nowhere almost.

In the grand scheme, everything—Earth, trees, birds, and animals—will endure without us. We are but a small part of the intricate tapestry.

Recognizing this fosters sensitivity, humility towards nature, and a responsibility to care for every living being, from birds and butterflies to trees and our own kin. Survival hinges on cooperation, not on a survival-of-the-fittest mentality. It’s about thriving together, not one against another.

We all will sustain ourselves together as friends. Adopting an ecological, rather than egoistic, perspective should be integral to your education. Embrace an ecological, not egoistic, approach in your education. Recognize your connection to nature, humanity, and other races. With this mindset, life becomes more manageable.

IA :

You’ve described nature as being the best teacher when it comes to design, what are some things you’ve learnt when designing with nature?

RA :

Nature encompasses all. Look at the towering trees in polar regions, resembling eucalyptus giants in Canada and Australia. In the Middle East, it shifts to tiny cacti and small trees,

adapting to the arid environment. Tropical areas boast multi-story trees with persistent dark leaves, essential for survival under direct sunlight. Trees, always active, adapt to sustain themselves. Their leaves, thin and translucent, allow sunlight penetration. In winter, they shed their leaves, awaiting the return of sun in summer. Nature, a profound teacher, conveys stories. Drawing parallels to the human body’s selective flexibility, particularly in the neck and joints, inspires architectural principles. Every junction, beautifully crafted by a higher power, becomes a design inspiration for buildings.

Austrian philosophers echo this sentiment, correlating it with homeostasis—the body’s delicate balance maintaining a 98-degree Celsius temperature. The body’s substantial energy investment underscores the importance of architectural equilibrium. Buildings, like the human body, should maintain an ecologically acceptable homeostasis. Inspired by these philosophies, the focus shifts from European ideals. The interconnectedness of the built environment with nature becomes paramount. This transformative perspective guides architectural endeavours towards sustainability and balance.

Ar. Rafiq Azam has had a global journey through his architectural projects in Bhutan, Pakistan, and Malaysia. Each project is intricately connected

to the cultural and environmental context of its location, demonstrating the architect’s commitment to sustainability, energy efficiency, and diplomatic engagement. The designs not only integrate with local architectural languages but also address environmental challenges unique to each region.

You’ve said that your designs are influenced by the philosophies of Rabindranath Tagore.Could you delve deeper into how and why he shaped your architectural vision?

Indeed, Rabindranath Tagore embraced the notion that everything is interconnected—a perspective derived from his background as a physicist, not a botanist. This unconventional stance led to challenges in his later life, as others questioned his foray into botany, urging him to stick to physics. Tagore’s mission was to demonstrate to the world that every object possesses life, transcending disciplinary boundaries.

Every entity, whether animate or inanimate, shares a fundamental similarity. Despite our human tendency to categorise things as living or non-living for convenience, Tagore contended that this artificial distinction is not sustainable in the long run. Just like human beings, everything has an inherent life within it. Tagore’s literature served as a vehicle for expressing this profound insight, revealing the life that exists within every object.

Ar. Rafiq Azam draws parallels between the philosophies of iconic figures like Lalon and the practice of architecture. Exploring the concept of the human being as a composition of thoughts and the body, akin to the negotiation between architecture, nature, and the elements, Ar. Rafiq Azam emphasises the poetic and artistic nature of architectural design. Nature’s elements, such as rain, fragrance, and air, are seen as integral components in the negotiation between the built environment and the surrounding landscape.

We have seen a spike in high rise construction. So in this trend, how do we try to maintain a harmonious balance between trying to live up to the modern world and modernism, but also keeping and ensuring that vernacular architecture stays for a very long time? Modernity doesn’t entail abandoning everything. It’s akin to crafting a beautiful courtyard while upholding respect for our ancestors who originally designed such spaces thousands of years ago. When we create a courtyard today, it’s not a mere replication of the past, but an homage, a connection to our history. Embracing modernity doesn’t mean discarding tradition; instead, it allows us to be versatile—modern, traditional, vernacular, contemporary, and global all at once.

Returning to their roots in Old Dhaka, Ar Rafiq Azam tackles social issues through revitalising public spaces. The examples of the Mayor Mohammed Mosque and the Shishu Park highlight the architect’s efforts to foster communal harmony, accessibility, and the transformation of neglected areas into vibrant, inclusive spaces. The challenges faced in negotiations with local communities and political entities are highlighted.

Do you think curriculums in architecture schools in today’s day need to evolve and incorporate their understanding?

I am deeply concerned about the state of our educational system and curriculum. Recently, I explored the situation with the Indian curriculum in our country and authored a paper on it. Bangladesh, currently a financially growing nation, holds the 40th position out of 200 countries in terms of financial strength. As the country undertakes significant projects, many renowned architects are joining, contrasting with the outdated and egoistic approach of local architects’ training.

Local architects often isolate themselves, perceiving their role as servants to the rich. Mega projects, valued in trillions, are taken up by setup architects, leaving others relegated to drafting roles due to inadequate education. To address this, we must prepare architects as leaders with a comprehensive understanding of psychology, sociology, finance, globalisation, capitalism, socialism, and politics. Leadership requires the ability to collaborate, manage egos and work effectively with a diverse community.

I have experienced navigating this intricate landscape while dealing with politicians, local administrators, professional engineers, and chief engineers of city corporations and PWBU. Working with egoistic chief engineers demands skillful diplomacy to avoid jeopardising projects. Architects need training that includes collaboration with sociologists, engineers, electromechanical professionals, philosophers, poets, and more. Unfortunately, the current training does not adequately equip architects to handle the societal and industry pressures they face, especially students and fresh graduates.

Finally, I’m curious if you could share any advice for fresh graduates and students on how to sustain fulfilment as they navigate their careers.

Who is an architect? This question prompts introspection about the role and abilities of architects. Unlike dancers, actors, or writers who have distinct roles, the essence of an architect is enigmatic. The Ramayana scripture defines an architect as the most knowledgeable person in society, emphasising the power of knowledge. An architect, akin to a social activist, may wear different hats—sometimes acting as a poet or an engineer. The fluidity of roles is downplayed, as the speaker does not take it too seriously.

The analogy of an architect as a juggler or magician is introduced, highlighting the skill to seamlessly handle multiple responsibilities. Successfully juggling various tasks, like a magician, represents the architect’s ability to transform situations. The speaker acknowledges that being an architect is not a static role; rather, it involves continuous learning and adaptation. The comparison with magicians, whose tricks may be entertaining but lack substance, underscores the architect’s responsibility in shaping lives rather than deceiving.

The metaphorical magician hidden within each architect requires practice, time, and learning. The process involves creating diverse elements, such as making a movie or combining different skills into a coherent narrative. The message is clear: an architect’s magic lies in the transformative power to shape lives over time.

Ar. Rafiq Azam concludes by emphasising the transformative power of architecture in resolving social problems and creating positive change. The focus on the community, job creation, and sustainability highlights Ar. Rafiq Azam ‘s vision for a harmonious future where architecture plays a pivotal role in enriching lives, fostering a sense of pride, and belonging. The journey from watercolour painting to global architectural projects and local community revitalization represents a profound evolution, encapsulating a lifetime dedicated to artistic expression and societal betterment.

Architecture for me, is about connecting and creating spaces between man and the earth.

- Brinda Somaya

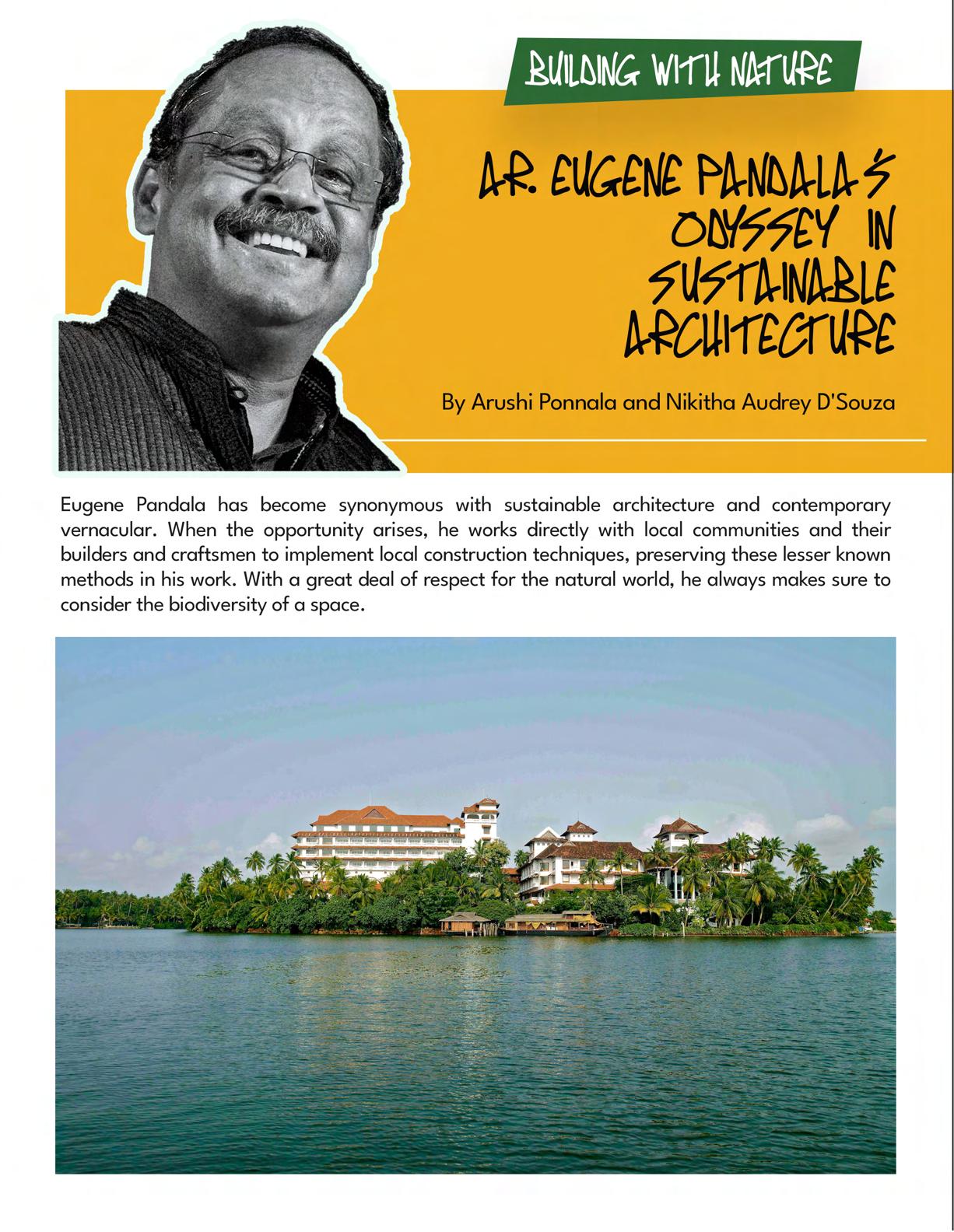

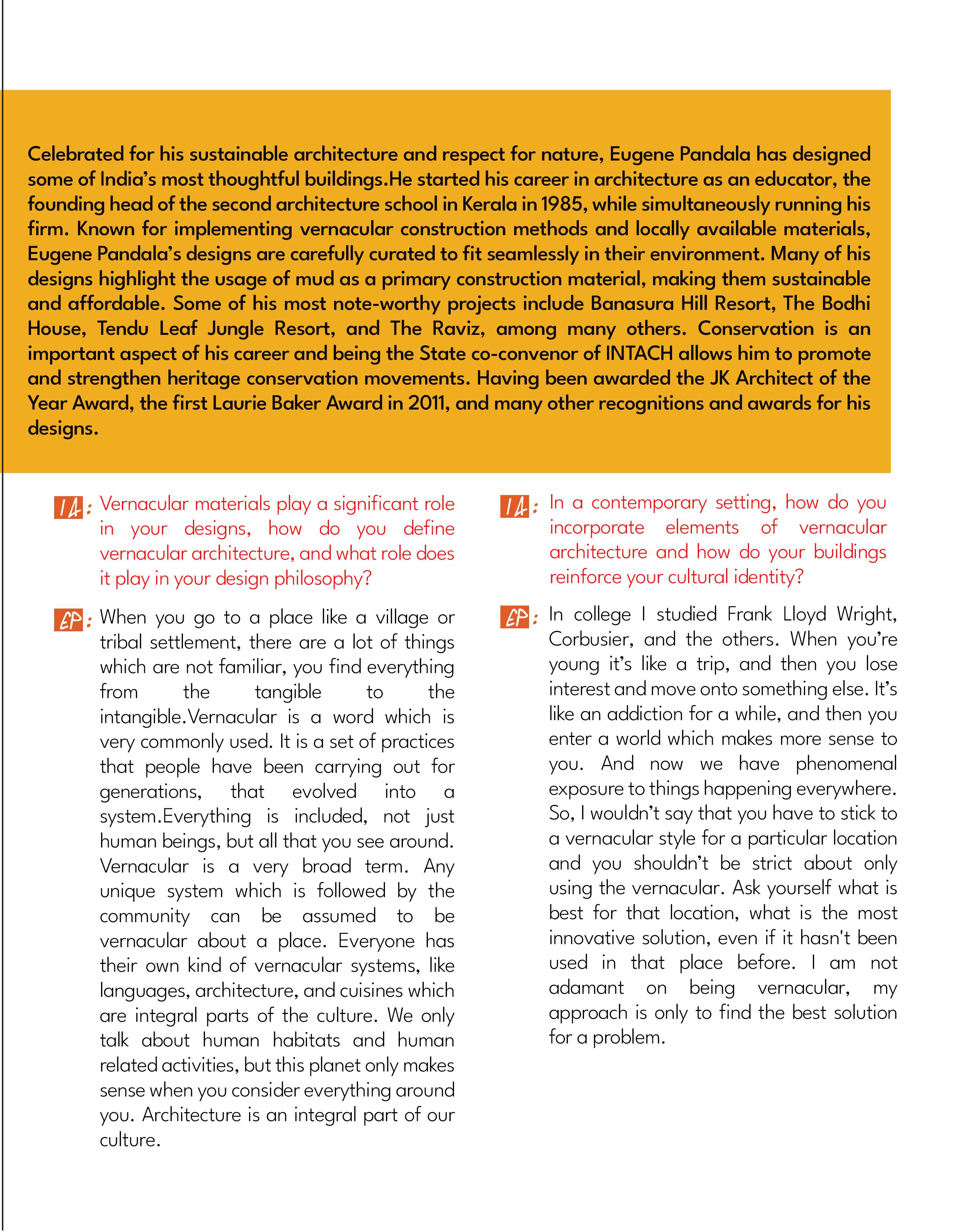

Celebrated for his sustainable architecture and respect for nature, Eugene Pandala has designed some of India’s most thoughtful buildings.He started his career in architecture as an educator, the founding head of the second architecture school in Kerala in 1985, while simultaneously running his firm. Known for implementing vernacular construction methods and locally available materials, Eugene Pandala’s designs are carefully curated to fit seamlessly in their environment. Many of his designs highlight the usage of mud as a primary construction material, making them sustainable and affordable. Some of his most noteworthy projects include Banasura Hill Resort, The Bodhi House, Tendu Leaf Jungle Resort, and The Raviz, among many others. Conservation is an important aspect of his career and being the State co-convenor of INTACH allows him to promote and strengthen heritage conservation movements. Having been awarded the JK Architect of the Year Award, the first Laurie Baker Award in 2011, and many other recognitions and awards for his designs.

shaped his current

living

material

you

and coco and coconut client.

was

them. If

that considered. ideas.

Tell us about your firm ‘Vanamu’, and how is it different from other firms?

We are, specifically, a research-based firm and not a practice-based firm, which means most of the projects that we undertake are specifically for the advancement of knowledge rather than advancement of profit.

Being very early career individuals, we practice so that we learn, because we intend to keep Vanamu that way for a few more years to gain the sufficient amount of knowledge now, rather than later. The reason why we’re doing this as a practice is two-fold, with the first being to safeguard the diminishing generational wisdom of traditional crafts held by our artisans. Since their continuity relies on intergenerational transfer, we’re ensuring that we do so in a responsible manner by laying an equal emphasis on our research and practice wings.

Your studio’s philosophy revolves around collating information about processes from diverse parts of the country. Can you share an insight gained from this cross-cultural approach that significantly influenced your design or construction methodology?

In our quest to blend traditional practices with contemporary projects, we view each undertaking as an opportunity for artisans to apply their skills, making the project a privileged recipient of their time and expertise. With this mindset, choosing clients who appreciate the

artisans’ knowledge and skill base becomes an essential factor.

One example could be our collaboration with a Rajasthani craftsman called Dauji Ibrahim, whose ancestry in plastering Rajasthani Havelis dates back to the sixteenth century.

In a 2019 project, our client sought a costeffective approach, and recognizing how artisans like Dauji were now scarce and could do only premium projects due to time-constraints, we proposed the client to save on other aspects of the house by allocating a higher budget for Dauji’s natural lime plasters. What this also meant, was to save the plastering costs of the exteriors of the building. So now we have a strong structure crafted in mud and mudmortar, showcasing Dauji’s traditional interior plasters while giving the client a certain flexibility to plaster the exterior’s rammed-earth aesthetic at his own timeline.

To share the insight we could’ve possibly gained on this project is perhaps a reassurance to our commitment of prioritising our artisans and not going the conventional way, because while the exteriors are unconventional, the client is happy to have a haveli-like finish in a normal house, which satisfies our intentions of contributing to the revival of natural building techniques.

The team at Vanamu acknowledge that the essence of vernacular architecture lies in the artisans.

Vanamu, an innovative architectural firm, sets itself apart through a research-driven ethos, emphasizing the preservation and transfer of generational wisdom above commercial interests. Their projects, deeply rooted in vernacular knowledge, highlight the significance of materials and artisan skills.

For Vanamu, knowledge transfer is a reciprocal process, extending beyond learning to instilling the right intent in those receiving this wisdom. Their unwavering commitment to meticulous experimentation, fair pricing, and the preservation of vernacular techniques which shapes their forward-looking vision. As they navigate this continuous learning period, Ar. Varun Thautam and Ar. Namrata Toraskar remain steadfast in assimilating knowledge, sharing experiences, and actively contributing to the safeguarding of vernacular wisdom.

They actively work to connect these skilled craftsmen with projects that honour and recognize their invaluable expertise. The studio, cautious about proposing projects commercially, emphasizes the importance of informed experimentation and underscores the delicate balance between curiosity and overconfidence when engaging in vernacular techniques.

Did your exploration of traditional practices help you re-discover Architecture in a newer light?

Would you describe it as a journey full of growth, or simply a fulfilment of the curiosities you’d fostered while completing your education?

Going back, I’d mention a key moment which happened during my first internship in Seattle while I was still in my last semester at IIT Roorkee. They were working on luxury homes for some of the richest people, athletes, and musicians worldwide. While impressed with their design calibre, I remember being taken aback by the immense energy and environmental impact these designs demanded. The entire industry, in this context, seemed reduced to an aspirational pursuit catering solely to the desires of the world’s wealthiest.

This realization prompted a shift in my perspective, because then, I sought the opposite extreme and discovered at Auroville, where a focus on mud and natural materials stood in stark contrast. That experience was transformative, and I found it to be fostering artisanry and

joy, satisfaction, and profound learning in the ways I was receptive to.

The environment of collaboration and an escape from the rut of commercial architecture was something which opened up the spectrum for me, and yes, though it still poses extreme challenges, they’re often outweighed by the sense of satisfaction that our kind of practice gives us at the end of the day.

IA :

How do you navigate the balance between creating unique, comfortable, and cost-effective environments while incorporating traditional techniques in contemporary architectural designs? Would you describe this

Maintaining this balance is a tricky task. To begin with, the ideal client appreciates the values of vernacular architecture or at least the use of natural materials, which in-turn helps in aligning our values to get the best possible result out of the project.

For example, it’s good to have a client who doesn’t urge us to be cost-effective just for the sake of it, as people have often misconstrued the term.

Cost-effectiveness varies with personal choices and societal strata, and fundamentally, it is every architect’s duty to approach all projects cost-effectively.

Going low-cost, on the other hand, is what we strive to do by building and using our expertise in building with natural materials and vernacular techniques.

So, while this differentiation is clear for us as creators, it is still difficult to communicate it to clients who may have adopted incorrect notions on the matter, and tend to confuse among the two concepts, which, at times, also challenges our intent to promote the skills of our craftsmen at the right remuneration.

Secondly, our research endeavours intend to disseminate this assimilated knowledge to diverse audiences responsibly. When we say that it is essential to preserve the essence of vernacular skills, we emphasize that the true ‘vernacular’ lies not in materials but in the artisanry and knowledge passed down through generations, so that it shifts the focus to our heritage and the knowledge embedded in it.

Ar. Thautam’s architectural journey, triggered by an eye-opening internship in Seattle, unfolded as a quest from designing opulent residences for the elite to embracing the earthy simplicity of Auroville. This exploration of extremes early in his career served as a transformative experience, urging him to challenge conventional paths.

Addressing the delicate balance between uniqueness, comfort, and cost-effectiveness, Ar. Thautam dismantles the misconception that “cost-effective” implies “low-cost” and stresses the duty of architects to achieve cost-effectiveness in every project they undertake.

He urges architects to make intelligent choices, navigating an evolving landscape while preserving the authentic foundations of the profession. This narrative serves as a beacon for the rising generation, encouraging thoughtful exploration and a commitment to core architectural values.

Was your design approach different from what you mentioned earlier while working on the award-winning project “Cabin for Casa Naomin”?

Certainly, community-led projects like this one differ significantly from commercial endeavors. In community projects, the economic exchange is intertwined with learning and fostering a collaborative atmosphere where individuals contribute based on their skills and receive compensation in various forms. While commercial projects remain driven by transactions, community projects prioritize goodwill which creates a unique family bond among stakeholders.

So, the absence of a rigid transactional framework here, allowed for genuine connections and shared experiences, fostering a deeper understanding among participants. This contrasts sharply with the competitive nature of commercial transactions, where each party seeks to maximize gains. The communityled approach emphasizes collaboration, humility, and continuous learning, reflecting in design and contracting fees that, despite delivering superior results, remain modest. Prioritizing collaboration over transactions, Vanamu’s approach to community projects seeks sustained relationships and future collaborations. This ethos aligns with the values of shared growth, humility, and a commitment to creating meaningful spaces that resonate beyond mere financial transactions.

IA :

You’ve also said, “I find no distinction between art and work and meditation and education while working with the Earth.” Would you elaborate on this experience?

You see, Earth isn’t just a material; it’s a canvas for art, a source of grounding, a stress-reliever for both humans and animals. It’s a teacher, and as you learn, you also begin to teach.

Picture it like a pot – you’ve got to empty it to fill it again.

To be architects, we must not limit ourselves to be just that. It is important to accept that we’re students, teachers, doctors, astronomers, farmers, artists, and even chefs. Remember your grandparents? They were masters of various trades, creating magic in their practices. Becoming an architect is like becoming your grandma, offering experiences rather than just structures. It involves meditation, intuition, and a deep connection with nature and oneself –lessons you don’t find in schools. We want to create a space that serves wisdom and a humble, loving meal. It’s about passing on a taste of the accumulated knowledge of humanity, much like a grain of rice.

In 2024-25, we’re getting closer to building that space. Our daughter, Mira, will grow up surrounded by this wisdom. It’s our little secret in one corner, where we hope to share this heritage with friends, just like Grandma’s recipes.

Ar. Thautam reflects on the distinctive dynamics of community-based projects, emphasizing the profound sense of goodwill and collaboration they foster. In contrast to transactional relationships in commercial projects, community endeavors prioritize shared learning and growth, fostering lasting connections beyond the project’s completion.

Regarding the intertwining of art, work, and meditation in his approach to earth-based architecture, Ar. Thautam views working with the earth as a grounding and soothing experience. Quoting his mentor, he likens architects to straws, emphasizing the constant flow of information in and out, discouraging the storage of information in one’s mind to prevent friction.

In their truest form, he says, architects embody diverse roles like students, teachers, doctors, astronomers, farmers, and artists, finally contributing to a holistic approach to life.

Considering the demanding nature of our present curricula at architecture schools across the country, what could be some ways in which Architecture Students can remain involved with the collaborative model (as one fostered at Vanamu) in an attempt to be more connected with our vernacular heritage?

Absolutely. Considering the prevailing intensity of architectural education, sustaining a collaborative model akin to that of Vanamu’s (in view of today’s curricula) is challenging.

Firstly, let’s not blame colleges because they’re responding to market needs. However, yes, they excel at disillusioning students into the market by simultaneously faltering in anticipating the future. This isn’t a critique, but an observation from someone who emerged from the same system.

You see, the real change lies in the mix of philosophy, skills, thought, and process in architecture. Each school finds its balance based on its faculty. The curriculum isn’t fundamentally flawed because it does provide the student with basic skills. The real wisdom, and the common sense, however, stems from faculty interactions. It’s like paying for a concert experience rather than just the artist’s album.

Architecture education is not just about skills; it’s about instilling values that endure. Yes, skills may fade, but values persist with practice. So essentially, the essence of architectural education is not just in what you learn but also ‘who’ you learn from – your faculty members - who can change the trajectory of your life. Values outlive skills, and that’s the core purpose of architectural education. It’s not just about studying; it’s about practicing, embodying, and preserving values that define the architect’s journey. So, while you can acquire knowledge online, the true magic happens in personal interactions, exchange of notes, and the cultivation of values that last a lifetime.

Ar. Thautam shares invaluable advice for aspiring architects, stressing the profound significance of early projects undertaken for family and friends. He likens these opportunities to debut performances, where success leaves an indelible mark on one’s career.

Drawing from personal reflections, Ar. Thautam emphasizes the enduring impact of these initial doors, cautioning one against compromise and external influences. He emphasizes on the importance of approaching these opportunities with utmost dedication, authenticity and command, recognizing that success in such endeavors lays the foundation for a meaningful and respected professional legacy.

Through his own journey, he underscores the irreplaceable value of aligning one’s work with personal values and the enduring satisfaction of having positively impacted the lives of loved ones through architectural endeavors

Lastly, what piece of professional advice would you like to share with architecture students and young architects?

One crucial aspect we haven’t discussed is family. As young professionals, you’ll embark on diverse journeys, perhaps even beyond architecture. However, when your family or closest friends entrust you with a project, that opportunity would turn into a pivotal moment in your career. These are rare opportunities which define you as a creator – both, to the world, and in your own mind.

Approach these chances with careful consideration; they are the initial doors to your professional room. Opening them opens the path to countless future opportunities, but missing your mark might shut doors that are hard to reopen.

In architecture, your early projects carry lasting significance, and because the profession is brutal in some aspects, it will keep reminding you of both - your successes and missteps.

So, this would be my advice to young architects: strive for excellence in those first projects; they shape your professional narrative for the world and more so, to your own self.

Throughout my tenure, certain individuals have been my guiding lights, shaping, welding, molding, and occasionally challenging my vision for the association. It’s an intriguing aspect to reflect upon now. I hold the old-school belief that written/ published matter retains relevance, capable of inspiring readers even years later. One notable note was by the ‘88s president titled ‘Ask the President,’ marking the 30th year of NASA, if my memory serves me right (2nd IA). A bookmark in the timeline of the updates/issues/situations faced by council in those times…

Let’s begin with the basics— the goals and objectives of the association. For some, it’s just those six lines on our sluggish website (hope it loads fast now), while for others, it’s the legal binder facilitating operations and financial aid. For some - aspirations, for some constraints. These goals intertwine the aspirations of stakeholders, key players of the collective journey of 66 years and beyond.

We strongly assert that NASA India is for the students, by and what not…, but does it genuinely reflect that sentiment? Consider who the true stakeholders

are? Those 7 founding colleges? Or those ambitious few led by Dana Balaji or Peres da costa? Or Prof Reubens & Prof Merchant who guided them (21st & 25th IA)?. Stakeholders are those invested in this system’s outcome. Students - often lack clarity on their needs, and the Council - often forgetting they are students too. The college administrator’s, HoDs role, practitioners, the fraternity? Well, it’s a bit ambiguous. So, who are the most significant stakeholders? You? If you’re reading this, you likely are one. How do you perceive NASA India? What has it done for you?

If you screen it in an Etic perspective, it appears to be a convivial gathering of 60,000 students enjoying themselves at the conventions, perhaps diverting from the original purpose. The same echoed in the speeches of the Chief Guests from the last two ANC events, the presidents of their resp. governing bodies. Ah, Conventions - the debate, Darshan Raval or Benny Dayal, the next should definitely be Diljit! Whose concert shall grace our event, overshadowing who’s for the keynote? Generational Gap? Not to lay blame but to trace the roots, for this dilemma isn’t a new tune.

Six months have elapsed since my 4+ year tenure in the Executive Council and Volunteer service officially terminated, passing the torch to capable successors. I’ve polished off my stint, lost some touch and more importantly I am not a ‘student’ of architecture and I am a licensed Architect, as I pen this down.

It’s worth reading about the start of Indian Arch, where those ambitious few in the MB hostel of SPA-D raised funds and gathered student’s work by snail mail and STD calls, a herculean task imagined now with evolved society and evolved purpose (Interview of Ar. K. Gangadhar, 25th IA). Reflecting on this evolved purpose, this article may serve as a ‘guide.’ Some rules before proceeding - the distinction between the bold and subsequent lighter text reflects my formal note juxtaposed with your subconscious musings! more relevant for those in Councils (EC-ZC-UC). With a few tangential and parallels, the following article is to be perceived as a means to instigate, open discussions and act upon those needful or be ‘ignored’ as an old boy’s sayings. And yes, the brutal draft didn’t quite make it to the final print. But hey, I’m just a call away if you want to dive into it.

Here’s few lines from the note of Sanjay Kumar, G Sec of the 29th Year Council: “The ambitious few would never have imagined, even in their most dreaded nightmares, that NASA would become what it is today - a cultural round-up, or a ‘get-together for fun’ - a Melagreater importance being given to cultural events, rather than academic, which ultimately shakes NASA at its roots - ‘Just-a-Minute’, ‘Dumb Charades’, etc. in a convention on architecture!”

(Kumar, 1987) (1st IA)

From an Emic perspective, students predominantly engage with NASA India for the competitiveness (or at times, the perceived toxicity) of the Trophies. For many, NASA is synonymous with the charm of Trophies and the grandeur of Conventions. Can’t blame the influencers within colleges, since it was only the Trophies being a recurring initiative in NASA’s history. The perception extends beyond students & seniors; even faculty members often view NASA primarily through the lens of trophies and conventions, reflecting their own experiences during their student years.

So professionals understood the assignment? You may find this article to be full of criticism, but you can also connect to max tho in this way. Amid the ubiquitous posters on Instagram, adorned with glam-

BnW photos celebrating architects (you know what i am talking about), a vital question arises. Amidst architect-centered festivities, does the general public, unaware of architects’ significance, remain engaged? (something the governing entity is always worried about; lessened admissions to College of Architecture in the nation too) Architectural fest! Expo! Biennale! It’s like an unstoppable wave—from London to Milan, Shenzhen to Sharjah, Beijing to Bucharest—there’s this immense surge of triennials, biennales, architecture weeks. [1] 50 grand events in India alone (Yes, I am talking about those… and those too). But amidst all this, a critical question lingers: What’s their true purpose? It seems they’ve grown so rapidly that we’ve rarely pondered whom or what they’re genuinely meant to benefit—perhaps, calculated tools for business and promotions.

If you’re a student reading this—although it’s still rare given the large membership numbers (and the funds we receive validate this)—you might not know we allocate 10-15% of our budget to publications. (Annual Budget: simple math - 60k+ students paying 100 & 150 bucks). You contribute, so it’s worth pondering what happens with that ₹100 or ₹150. Your Unit Secretaries should definitely answer.

Highlighted in the President’s note of an Indian Arch of 55th Year: Did we ever try to imbibe what we learn and trace the GOLDEN FOOTPRINT? (Chaphale, 2013) (25th IA) brought me to this thinking - A constructive approach to self-analysis - which involves scrutinizing our journey through the lens of the ‘Annual Themes,’ meant to guide our path - ‘Prior to ENVISIONing and pooling ideas into an ASSEMBLAGE, it’s prudent to delve into the GRASSROOTS of past actions. Have we delved into the RUDIMENTS of the association, or have we recently EMBARKed on a new trajectory? Alternatively, are we UNTRAVERSing back to a [RE]VOLUTIONary approach, contemplating REFLECTIONs on past initiatives, and formulating PARALLEL PROJECTIONS in the present? Assessing this TRANSFORMATION against the backdrop of CONTEXTUALITY—considering Time, Space, and People—begs the question: What do our FOOTPRINTS signify?’ (*breathes heavy*, thanks chat gpt) It’s essential to evaluate whether the current councils, including yours, have successfully aligned with the expectations or visions outlined in the theme notes.

Shall we usher in ‘Change’, or ‘Adhere’ to the progression outlined by our advisors? The beauty of this dynamic structure lies in our ability to ‘Choose!’ The previous structure has been tailored to meet the association’s basic needs, but any deviation could lead to collapse of Dominoes. Without a constant God’s eye perspective, how do we ensure the association’s progress graph is exponential?

Speaking about bringing a change, in the process, only the amendment-year council truly has the luxury to contemplate beyond defined goals and objectives but lacks the time to implement them in their tenures (Amendment of NASAs constitution takes place every 5 years, I happen to be a part of

to these changed clauses, which isn’t necessarily bad. Yet, a necessary ‘constant’ is vital amidst dynamic structures. During my tenure, I observed shortcomings in post replacements – Experimenting the Programs, Events, and now the Trophies head. This exemplifies the dynamism and freedom each council has to decide and modify the structure. But the challenges of running this business – the fate of the post depends on the newly elected - duties exist in the minds of Thinkers (whose tenures are terminated) & Doers are still unaware. With fewer days in tenures, all we wait for is a hiccup to replace the post.

Can one option be - distinguish between the Needed and the Desired, Functional and Operational –Office bearers & Vision runners - akin to Recurring and Discretionary Expenses (Art 22 of Constitution). Could there be a post or a council of Heads to work towards the ‘Operational aspirations’ of the association? You are open to ponder upon these possibilities, & share suggestions with the new council.

The dynamic structure of NASA is indeed its greatest strength, isn’t it? Just as compound investment leads to exponential growth, NASA’s structure allows for steady progress and adaptation over time (Compound Math! Yes, I was National Treasurer too!). While trophy participation may seem like a primary focus for most units and even ZPs, we must not lose sight of the larger goals of the association’s existence. How do we ensure its growth is in ‘good state’ and in ‘good hands?’

As for Good Hands - Elections, uncertain, but why? All we say - we need capable candidates and representatives but USecs don’t talk in GBM nor attend Roundups, blah blah… We often doubt the caliber of USecs before elections, but, have we made efforts to mentor or develop them into effective leaders? If you find yourself reading these lines, you may be thinking about submissions to site visits, alongside personal commitments required for both yourself and those in the council. Yes, everyone deserves to enjoy their student lives, right? So from an ideal perspective, the question arises: How much time should one allocate to understanding/exploring

“In the corporate realm, the ratio of management to leadership is more than 80:20, meaning leaders aren’t given the time they need to lead. Instead, they act more like subject matter experts, overseeing day-to-day operations and providing input as part of a leadership process.” [2] Council members may similarly be consumed by day-to-day tasks, overlooking opportunities for strategic leadership. In the dynamic landscape of NASA India, where time is a valuable resource, the challenge is to find balance - streamline processes, incorporate automation to make our lives easier and continue to function effectively and efficiently.

How do we lead - We do so with 14 other individuals if elections successfully fill up the positions. For new readers, we have a ‘Constitution’ and a set of ‘Operation guidelines’ - a guide to steer us through the process, preventing hiccups and maximizing efficient use of time - Another ‘constant’ to this dynamic structure. Three councils I have been part of tried making this 200-page doc — hopeful to be out soon. Similarly, there are tens of unfinished, properly brewed ideas within the council, developed through experiences and directed towards the wellbeing of the association or to ease the burdens for their successors, forgotten in time.

How do we maintain Continuity - establishing and upholding certain constants - Intangible ones. Not in favor of an Advisory Committee or involving the Exes in the working structure, although the decision is no longer mine to make. I vouch for an idea by my colleague Abinaya from 64th Council - An Incubation Cell - a collection of these forgotten agendas and effective mentorship program for incoming leaders.

In this dynamic structure, committees, often overlooked, play a pivotal role. While the Constitution defines individual responsibilities, the small ventures we embark upon are swiftly forgotten every two years (New pair of UC & EC). Committees are the constants, like intangible beings, carry on their roles in these dynamic settings. But the problem lies in continuity… to some extent the HQ fills up this slot but it again all pressure melts down on the same. If at all there lies any unforeseen hiccup for the HQ in the near future, what happens to the association? Like tax demands of a crore inr, I pray it doesn’t happen again. We had a hiccup around the 1970s

when colleges began joining the association but didn’t contribute enough to organize an ANC for several years. It wasn’t until Z301 hosted in 1976 that the culture and spirits were revived once again. (Mukherjee, 1987 President) (25th IA).

Wait a second, why are we reading about Councils and Committees? Because, should the stars align one day, you might lead one. I believe colleges should do more than just receive; they should actively contribute.

Are colleges pulling their weight? What hurdles do students face? “Admin won’t allow,” they say, facing administrative restrictions and faculty hesitations. Why this lack of trust in students for NASA work? ZCMs fall short; they don’t groom future leaders. Why did elite colleges bail at the start of this decade? (One of them racked up 29 LeCorbusier Trophies— yes, 29! And still left… Winning trophies isn’t the real NASA deal; it’s about leading, speaking out, and driving change!)[5]

A random question. How do we save NASA from getting exploited by the ___ ? (Who, How, Why! If that’s what raising student’s voice means)

You’ve likely participated in surveys probing your aspirations, needs, and desires. Wait what? No! Have we communicated directly with students enough? Major decisions used to require approval from the General Council in GBMs, but now it seems programs are initiated without broader input. (Did I not tell you we operate democratically?) Thinktank members (EC) often prioritize NASA over academics, jeopardizing their own studies, often on the verge of flunking their theses (especially secretaries). Despite this, they’re entrusted with decisions on student development. This isn’t to demean anyone, but to emphasize the need for direct stakeholder communication. How many surveys have we conducted to tailor programs to student interests? It’s typically been the other way around.

66 years and still few operational defaults, how do we cope up and think ahead? How should one ideate a vision? Firstly, for EC-ZC-UC, it shouldn’t be about seeking validation from your nominators. As someone who has been on the election committee, I can attest that most of the agendas submitted barely merit consideration these days. Library project, internship forum, renewed names but recurring ideas in election forms. [29th IA - annual report] So, what should it truly entail? It’s unlikely that no one in the past has considered the agenda you’re contemplating. So is it a matter of inventing; rather rediscovering what has already been thought of?

When do we find time for serious contemplation? Usually when we’re financially or emotionally broke, or perhaps when we’re simply stuck at home with ample time on our hands. The seeds for the Vision Committee may have unconsciously sowed during the 63rd year’s Council, or the pandemic council as some might call it. Originally slated as an amendment year, it prompted a reconsideration of the Constitution clauses (which shifted to the 64th).

“They cannot make history who forget their past.”BR Ambedkar. Inspired by this sentiment, the Vision Committee emerged after the Archive Committee’s establishment, emphasizing the importance of learning from history to shape the future. This was also a derivative of a Workshop we did within the 64th Council in 2nd ECZC under Advisor Simarjeet. I firmly believe that many viable solutions from the past remain untapped, waiting to be revisited. Like transforming NSC, launched 8-9 years back, into a comprehensive training program for incoming USecs - ‘Usec Bootcamp!’ Yes, you must train them to be a NASA representative before asking their votes on college degradations or vandalism cases.

I’ve always hoped to provide more leadership opportunities within our defined hierarchy and operational structure. With Nexus now in play, my question for the future council is simple: Are we willing to give some autonomy within the Nexus structure and empower students to decide what to do and what not? After all, you are students

yourselves, and sometimes the best ideas come from those directly affected by them. I envision at least 30-40 coordinators (students serving as USecs or similar roles) and perhaps an equal number of Nexuleads. More leadership opportunities mean greater involvement and outcomes. The goal is to distribute responsibilities widely. Because why should the chosen 14 (or cursed, depending on the perspective) have all the “fun” (or endure all the death-wish experiences)?

As a nation poised for progress, we Indians are at the forefront of a better tomorrow for our citizens, added on to it is the demographic dividend of a vibrant youth population. Having recently hosted the G20 summit, the world turns its gaze towards us, laden with expectations… is there a room for an international summit of architectural students? Why not ? Let’s not just engage in international dialogues but create a forum of our own, where we lead the world. Well if it’s too ambitious for your term, Aligned with our architectural pursuits, there’s room to foster interallied relations, exchanges, and broaden our collaborative horizons by making an All India Designers forum?

I can list 20 ideas developed during and after my tenure, along with 100s from my seniors and peers, but merely listing them won’t suffice. It’s not aligned with the dynamic nature of our structure, nor do I want the election candidates to copy their forms. However, I’m open to discussions, and I hope the future councils are too. Let’s engage in meaningful dialogue to drive progress and innovation.

That’s the Vision Committee for you. I hope some of it resonated with you or stirred a desire to do something positive if you’re still with me until the last paragraph of this article. Still more to speak but cutting it down for now. This could be a great excuse for you to share your thoughts. Let your council know about your needs, dreams, and aspirations for the largest architectural student body in the world by dropping emails. It’s your association too and your voice matters!

01

02

03

Steering through Challenges and Embracing Opportunities

by Shree Varsha ElangoThe role of Courtyards in Vernacular Architecture

by Nischal M EjardarCultural Symbolism as an important aspect of the Vernacular Style

Traversing Vernacular Wonders and Timeless Innovations: Case of Bengal

by Shourjo Dutta04

Vernacular Urbanism, the last puzzle piece of Transnational Urbanism

by Chandana Chandra05

Vernacular Stalwarts: Architects of a timeless future

by Priyanka SinhaSlowly losing the battle of time and urbanization but holding tightly to its cultural identity – vernacular architecture is a concept that adds meaning to a building and its context. It is tangled deeply in the roots of culture, and remains as a reflection of a locality’s heritage, climatic conditions and traditions that are passed down through generations. It embodies the different design factors of architecture – responding to its geographic context, with addition of built features that coalesce to form an optimal living environment and conserving ecosystems, inviting biodiversity.

A concept that appreciates the land that a building stands on - which takes and gives back to the environment, is an important idea to document, protect and take inspiration from. So, what led to the slow and consistent decline in this style of architecture and ‘way of life’?

Changing times and technology led to a demand that vernacular architecture could not address – a sudden growth in population and an adaptation to western culture. Newfound materials that could answer all their problems – steel and concrete, changed the art of buildings in rapidly developing cities. Globalization and expansion of urban environments led to neglect of the vernacular style - its footprint eroding in people’s minds when they began to recall places in their memory.

Presenting unique challenges, conservation of vernacular architecture requires comprehension of various factors that may pose threats to an existing structure’s deterioration – both physically and cognitively.

Illustration by Isha Londhekar

Illustration by Isha Londhekar

• Understanding historical context and usage of the structures over time

Gaining a deeper understanding of the structure or site that is to be conserved is challenging – especially due to the mixture of buildings that have infiltrated a historic site or due to the slow deterioration of structures. It is difficult to understand the reason behind many of the developed features and requires extensive field work and background research – like reference to archives, historic maps, consulting local people or professionals, and literature studies, to draw a clear understanding of the site context over a historic time frame.

• Material decay and destruction of historic structures

Time weathers the structures that once stood tall, stripping them of their original appearance. It is often discussed that the passionate craftsmanship and building techniques that once existed cannot be replaced even by the greatest technology. Migration to cities and declining population in rural areas have led to loss of knowledge about construction techniques and material utilization. Maintenance of structures as they age helps to preserve their existing features, however most buildings today remain unrecognized by people and deteriorate as the materials lose their original characteristics, or sometimes even demolished to build new structures.

• Important buildings lost in the shadows of new construction

A noticeable hierarchy was followed during the planning of towns and cities of olden times, allowing the central structure to remain as a landmark even when viewed at a distance. This can be observed by studying the mapping of thoughtfully planned ancient towns and cities – a central node where the town development radiates from, dominates the surrounding area.

Filling the gaps within these towns are concrete skeletons that hinder the imageability of these historically important regions and congest these areas. They interfere with the setting that once existed and block the views of the important hierarchical landmarks. Lack of building development rules for these unrecognized areas allows unsupervised development that breaks the scenery that once existed.

Within these challenges lie opportunities that lend a hand to the preservation of cultural treasures and a legacy of architectural styles whose voices echo the stories of the past. They create the pathways to join hands of the past and the present, creating unique doors to ingenuity.

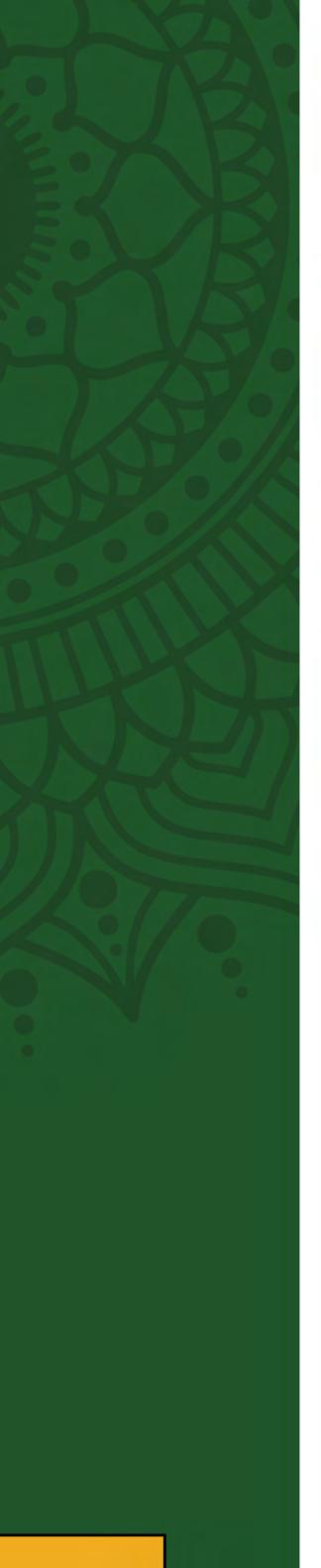

• Digital documentation methods –Photogrammetry

Digital documentation of ancient buildings is one of the most effective preservation methods for historical archives, since they do not deteriorate with time like paper documentation.

Falling under this label, photogrammetry is a procedure that transforms a physically existing structure into a virtual replica for historical records. The methodology includes the capturing of highresolution photographs to create three dimensional models with maximal accuracy. These models can be used to develop models in part or as a whole –ultimately aiding the study of construction techniques, material treatment and design strategies. This is an important step towards conservation since it allows to apply the right methods to preserve existing structures.

For an illustrative demonstration of Photogrammetry, one can explore the Pallimeda of St. George Orthodox Church in Kadamattom, Ernakulam, as documented digitally. Revered as an enduring and unmistakable symbol within the chronicles of Christian spirituality in Indian history, St. George Orthodox Church stands out prominently. The meticulous documentation of this architectural marvel was undertaken by Ar. Prasanth Mohan from Running Studios, employing advanced drone technology.

• Adaptive Reuse of buildings

Breathing life into deteriorating historic structures ensures that the original building fabric serves a new purpose and is also maintained well due to their newly introduced functions. A sustainable approach to designing, it fosters the vernacular buildings and builds a bridge between tradition and modernization.

Adaptive reuse contributes to the urban development of a region – historic structures add to the variety in an urban environment and stands as a testament to the resilience of the vernacular architectural style in a modern backdrop.

With modern demands, adaptive reuse of structures ensures that the buildings tell their stories along their corridors and contribute to the cultural tapestry while also engaging a modern audience and reducing material use.

• Application of vernacular architecture strategies on modern buildings

Integration of design strategies once used in vernacular buildings adds to the sustainability aspect, climate responsiveness and cultural authenticity of modern buildings. Vernacular practices initially originated around the site context and environmental conditions of a region - incorporating these ideas into modern age buildings can address future challenges including social responsibility towards the surroundings.

Preservation of cultural wisdom that is passed down through generations resonate through the designs of vernacular architecture and tie buildings down to their cultural roots. A circle of traditional knowledge is created and establishes awareness to the local community on building according to the site and climatic context.

• Engagement of local communities to foster ownership

Creating understanding of the local building context and the role that they played in the society during historical times by imparting knowledge of the cultural and historical significance of buildings brings people together by creating a sense of ownership towards these structures. Involving the local community in decision-making processes during the reconstruction and conservation ensures that they play an important role in protecting their architectural legacies for the future generations to come. Hands-on building experiences also creates understanding of local material use and their application in the historical context.

• Case study of architecture in Kanchipuram and its conservation

Kanchipuram, or as we know it “the City of Temples,” is a falling victim to the threat of urbanization – with its historic structures being shaded by the upcoming modern concrete infrastructure. Recognizing the need to protect this authentic city, Kanchipuram falls under the City HRIDAY Plan proposed by the government – for which an evaluation of all infrastructure projects will be conducted, followed by the proposal of a city level plan.

The process of conservation involves processes of detailed surveys to understand the socio-economic conditions and the existing settlement of weaver’s colonies and their current state, connected to the temple complexes.

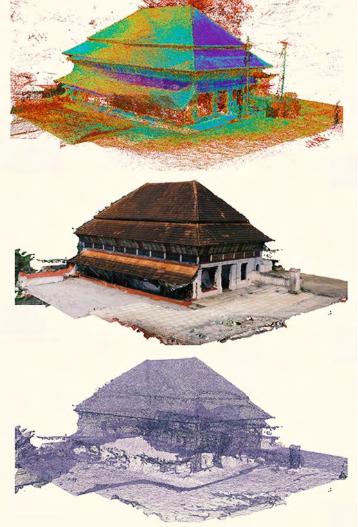

Following the traditional Agraharam style, the vernacular row houses are lined from east to west with common walls – the focal point being the temples. Some typical features of these homes include sloped roofs covered by baked-clay tiles, supported by wooden rafters. The walls that form a courtyard are covered by lime plaster, floors layered with red oxide, and a thinnai extends towards the street – acting as an informal seating and interaction space.

Workspaces called koodams - are integrated as a part of the dwelling spaces, they accommodate the loom, positioned in a pit - which reflects the socio-economic setting of the local community. It indicates that profession was an important factor that contributes to the lifestyle of the people in this region.

However, the open spaces that once acted as the backyard for these houses are now exposed to urban development and a dense built environment has emerged. The low-rise structures of the Agraharam houses are now overshadowed by taller concrete structures. This change can majorly be observed due to the younger generation moving towards modern culture and expectations of the current society – making them move away from the traditional weaving profession.

This calls for the protection of the existing weaver’s settlement, and laying regulations for further development by the government, in order to maintain the viewscapes that were once created with hierarchy and towards the temples of Kanchipuram. The local community must be well aware of and notified about upcoming developments to ensure that their collaborative ideas are implemented – with growth towards their urban fabric and their traditional craft. Conservation of the vernacular architectural style is of prime importance since it allows us to travel back in time and understand the historic setting and the society that once prevailed in a region. It involves the appreciation of skilled craftsmanship, the identity of a community, sustainable building practices, and many other crucial factors that must be considered during building design, even today.

“Step into the heart of homes, where the courtyard isn’t just an architectural marvel but a living testament to the intricate dance between tradition and innovation—a space that breathes life into the very essence of human connection and adaptability.”

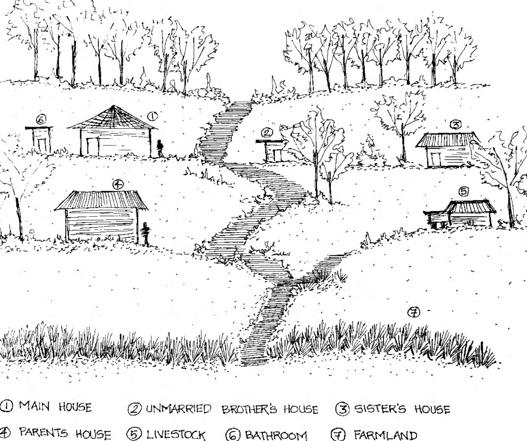

A courtyard is a designated open area within a residence, devoid of enclosed walls, allowing the ingress of natural sunlight. Particularly noteworthy in rural locales, such as Indian villages, courtyards function as the central hub of the home. These spaces serve both social and utilitarian purposes, acting as a gathering spot for leisurely conversations and shared moments. Besides its social function, the courtyard assumes practical significance, acting as a source of rainwater collection, then repurposed for culinary activities, effectively serving as an outdoor kitchen. Furthermore, the courtyard provides a serene setting for relaxation. Nevertheless, this architectural concept transcends antiquity, finding resonance in contemporary dwellings, with modern houses increasingly incorporating courtyards due to their adaptation and multifunctionality. So, whether you live in an old-fashioned village or a modern home, the courtyards remain important and useful in daily life.

Courtyard houses, dating back to 6500-6000 BC, extends far beyond architectural structures, embodying profound cultural and climatic responses witnessed globally, notably in India. The central courtyard concept, seamlessly blending indoor and outdoor spaces, gained popularity for its adaptability.

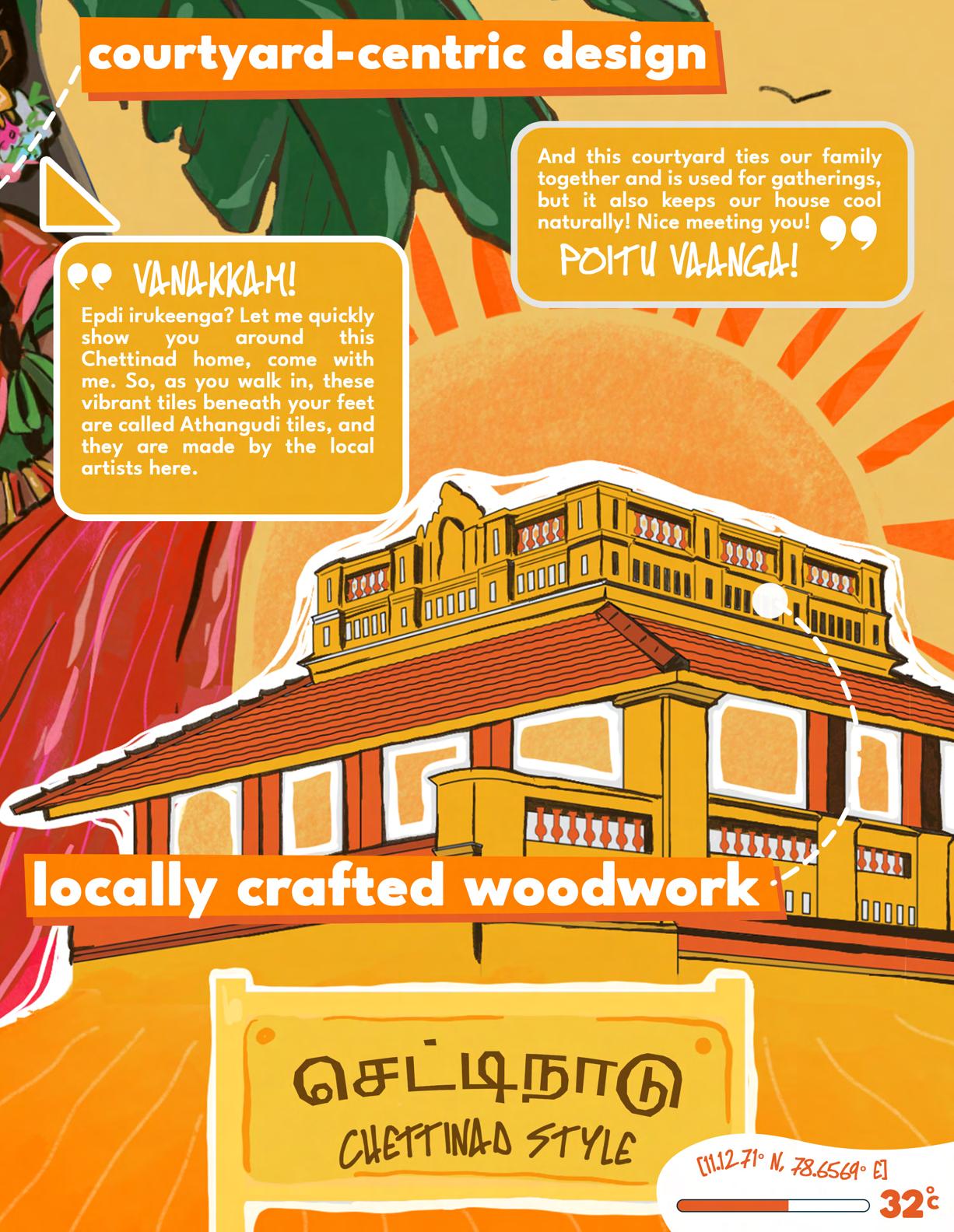

In India, unique variations emerged in Chettinad and Haveli, reflecting regional nuances. These courtyards transformed living spaces into a central hub for family activities, which was crucial in joint family living. Spatial arrangements accommodated large families and played a crucial role in ceremonies, contributing to the vibrant social fabric. Beyond utilitarian roles, courtyard houses were cultural symbols, known as Wada houses in Maharashtra, Chettinad in Tamil Nadu, and Thottimane in Karnataka, encapsulating India’s rich heritage.

These architectural marvels are living narratives, illustrating the profound interconnectedness of individuals with nature and traditions, epitomizing the dynamic relationship between architecture and India’s diverse historical and cultural landscape—a profound expression of communal living through the ages.

Traditional courtyards become more distinct than historical artifacts; they become living narratives of adaptability and cultural resonance. These courtyards emphasize natural elements such as light and air, incorporating cultural elements and water features for both aesthetic and practical purposes.

Constructed from local materials such as mud, stone, or bamboo, courtyards seamlessly blend with their surroundings, illustrating a commitment to sustainable practices. Beyond architectural elements, these spaces embody the essence of communities, preserving traditions with simplicity and depth, connecting the past seamlessly with the present.

Courtyards in traditional architecture serve as unique gathering spaces meticulously crafted to harmonize with the distinctive lifestyle and natural surroundings of the region. These spaces prioritize using natural light and air, often incorporating privacy screens and cultural touches that make them unique. Some even have a refreshing water feature, such as fountains, adding both beauty and practical coolness.

Courtyards are cleverly designed to adapt to the weather, serve various purposes, and highlight intricate details like carvings. Besides being architectural elements, these courtyards depict a story about the people, highlighting their history, culture, and lifestyle. These spaces are not just physical space in a building; they are living representations of the community, preserving, and preserving traditions in a straightforward yet profound manner. They are testaments to the community’s identity, offering a glimpse into its cultural richness and wisdom embedded in its sustainable architectural practices.

Courtyards are crucial in community buildings because they are like open spaces that bring people together. These areas in the middle of houses help create a sense of togetherness by hosting events and celebrations. Think about traditional African village compounds, for example. In these places, the central courtyard is like the heart of the community, where people come together for rituals, stories, and teamwork. It is not just about the buildings; it is about how these open spaces help everyone feel connected and part of something bigger. So, courtyards are not just parts of buildings; they are like friendly spots that make communities stronger, livelier, and united.

In India, courtyards within community buildings serve as vibrant hubs, embodying a sense of unity and liveliness. Whether in rural “Angans” or urban chawls, these central spaces promote daily interactions, celebrations, and cultural events, creating a dynamic atmosphere that unites residents.

https://www.architecturaldigest.in/story/step-into-a-keralahome-built-around-a-beautiful-traditional-courtyard/ Photographer:Justin Sabastian

Temples also incorporate courtyards as communal areas for festivals and spiritual gatherings, which are exemplified by the Jagannath Temple in Puri. Besides their architectural function, these courtyards are a crucial factor in shaping the social fabric of communities, acting as catalysts for togetherness and contributing to the overall vibrancy and unity within these shared dwelling spaces.

Courtyards outside India, such as the Mediterranean terraces, Moroccan riads, and Japanese tsuboniwa, exhibit diverse architectural styles and design elements. Mediterranean courtyards often feature stone floors, low walls, and central fountains, creating tranquil and accessible spaces. Moroccan riads prioritize privacy with high walls surrounding intricately tiled central spaces. Japanese tsuboniwa, in contrast, embrace simplicity with carefully arranged rocks and plants for a contemplative atmosphere.

On the other hand, courtyards in India reflect the rich tapestry of regional architecture. Rajasthani haveli courtyards have intricate carvings, vibrant frescoes, and central water features, while Tamil Nadu’s Chettinad courtyards feature open-to-sky spaces with thulasithara and verandas. Mughal gardens in India, seen in iconic structures like the Taj Mahal, are characterized by symmetrical layouts, water channels, and lush greenery.

The cultural significance of Indian courtyards often intertwines with religious practices, as seen in the placement of holy basil plants or traditional frescoes, adding depth, and meaning to these architectural spaces.