Simon Das, former editor of Touch magazıne, looks back at the scene that ımprinted ıts DNA on the sounds of today

The 1980s and ’90s may not seem a lifetime ago now, but four decades is a long time in culture, and like all historic periods, narratives become re-written as more time passes. Although the greatness of the Britpop era has been etched into the frmament of Britain’s cultural psyche, and hip hop has become recognised as the foundational domain changing force of black music and arguably R&B music, by comparison the acid jazz scene seemed a mere footnote until recently, acknowledged by this curated exhibition and magazine.

It was a collection of sounds, sights and events, as you will read about in these pages, by the very people who brought it to us, things that connected together an unlikely, but potent, mix of London’s existing 1980s jazz-funk fans, with the ‘90s breakbeats of hip hop, the artistry of R&B, the ‘illicit’ underground club culture of acid house - all packaged in a what now seems like a slightly kitsch retro mod style ethic, nostalgic of the mid-20th century before it actually called time.

Many people have, in the following pages, tried to defne ‘acid jazz’, but unifying these narratives is that we all agree - it was not one sound, one feel, an ethic, a club, a label or a locality. It was a scene – and one that really spread its influence. Three decades on, I still spend time close to youth culture, only now as a professor, where I see a new wave of creative people and what they bring forth. For all that promise, one thing aside of technology stands out as different to me; and it’s that in 2023 the feeling and ‘family’ that ‘scenes’ had in the 1980s and 1990s no longer exists. It’s

the intention that these pages, and in this exhibition, that it will revive exactly what one looked like, sounded and felt like – even if you weren’t there!

My own recollection of the acid jazz scene was, like many, frst as a student. It was where I went to the clubs, the pubs, jazz bops, and SU concerts that linked the dots in my growing record collection, one based then on fnding samples and jazz and blues music heritage in hip hop, rock and soul. I attended many clubs of some of the contributors to this project. I helped edit the mags and fanzines of the record owners, I booked the DJs as a young man, all just to hear an imported Brazilian jazz rarity or a new fusion beat feast of some sort. I remember, above all, the Blue Note Club, the trips to New York to Giant Step, the links I had with Italian friends, Catalan club ‘promotores’ and the independent magazines, such as Touch – one started by Kiss FM when it was a ‘pirate’. In a way, acid jazz epitomised what was to come next in culture in the 2000s: connections and connectivity.

From this viewpoint, we know what legacy was left from this scene. OK, so acid jazz may have fzzled out from the mix of genres one might regularly browse on Spotify, but if we give credit where credit is due, it’s a legacy that lives on in many musical genres, and artists’ work since its heyday. From the future jazz of today’s Ezra Collective, the bossa samples in the new wave grime of Knucks or the chart-friendly neo soul of Lizzo – acid jazz’s eclectic DNA lives on, if you’re listening and looking carefully enough.

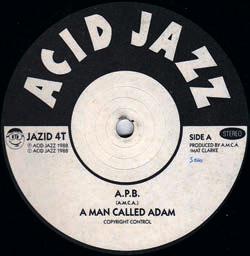

Let’s get this straight: There’s no such music as ‘acid jazz’. Acid jazz was an in-joke amongst 20 or so friends in London that became a movement. The frst single on Acid Jazz Records was Rob ‘Galliano’ Gallagher ranting Last Poets’style poetry over the top of Pucho’s version of ‘Freddie’s Dead’, the frst album was house music in style by Chris Bangs, the second album was Afro Cuban jazz by me.......... there you go. What do you make of that? Was this jazz at all?

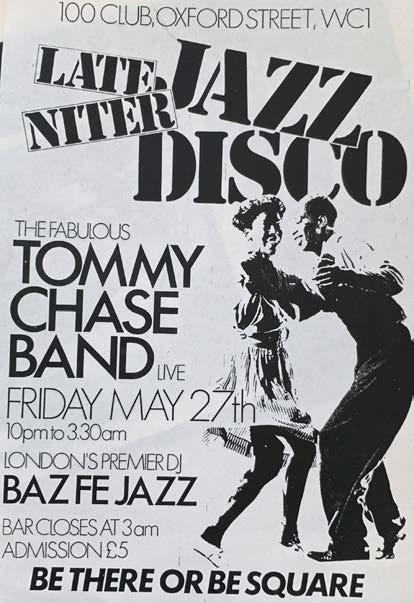

The touch paper was lit for acid jazz back in the mid-1970s with Chris Hill and Bob Jones leading the way playing jazz records to soul and jazz funk dancefloors. There was such a taste for it that club nights would appear in all its forms: samba fusion, Afro Cuban and hard jazz funk). Nights appeared at The Horsehoe in Tottenham Court Road with Paul Murphy or Colin Parnell and Boo in 1981, Sylvester, Baz Fe Jazz from the Midlands (who worked at Paul Murphy and Dean Hulme’s Fusions Record shop in Borough Market, London) and myself flying the flag for it in Essex!

That underground fever for fast Jazz on the dancefloor in London and the home counties reached its pinnacle in 1982 in the upstairs Jazz Room at the Electric Ballroom in Camden with Colin Parnell and Boo and then Paul Murphy. After a year Paul left to start his Jazz Room every Monday night at Chris Sullivan’s Wag Club in Soho. It meant Paul could play jazz of all kinds, particularly the Blue Note sound. Paul handed the reigns of the Jazz Room at the Electric Ballroom over to Gilles Peterson, who in turn, again, left for the exact same reasons as Paul; needing to play more diverse tempos

and other styles of music.

Gilles started to DJ with Chris Bangs at Nicky Holloway’s The Royal Oak in Tooley Street (known as ‘The Special Branch’) in Tooley Street, London, which was the incredible clash of London and home counties DJs – Nicky Holloway, Simon Dunmore, Danny Rampling, Pete Tong, Chris Brown, Sean French, Ed Stokes, Bob Jones, Jeff Young and Bob Cosby. It became the home for all of us; a huge community. A family. Over those magical two floors you could hear anything from Def Jam and other cutting-edge imports to Art Blakey to brand new independent soul 45s. You could argue this is where acid jazz started.

Of course, it’s well documented that it was Nicky’s Ibiza event started the whole Ibiza phenomenon in ‘86, and some of the DJs that created the acid house night at ‘Shoom’. It was this same collective of DJs that did Nicky’s events ‘Doo At The Zoo’ (yes, in a Zoo!) and the same collective of DJs that did that night at The Watermans Arms in Brentford, West London, where, following on from Danny Rampling’s set of acid house, with the word ‘Acid’ strobing on the wall behind the decks, Gilles turned to Chris Brown and said ‘What’s this all about?’ to which Chris said, ‘It’s acid jazz isn’t it?’, to which Chris followed the acid house with either Art Blakey or ‘Iron Leg’ by Micky and the Soul Generation. Anyway, the term ‘acid jazz’ was born, and we’ve all been confused ever since! Label owner Eddie Piller had become a part of the community since he and some of his other forward-thinking Mod friends saw Gilles and Chris at The Special Branch. Ed

by Snowboy…was already a veteran (at such a young age) of the record industry having already worked for various record labels, so he helped get Gilles Peterson’s Galliano record released. It sold an enormous amount. At that time Gilles lived at the house of Simon Booth in Brownswood Road in Finsbury Park, and after the Wag on a Monday it became very social and much was discussed. There was a buzz happening. A lot of the Funky Hammond B3-based soul jazz typical of the late-‘60s Prestige and Blue Note record labels were getting discovered. Eddie Piller was managing the James Taylor Quartet at the time. James was already an icon from being a member of the new wave of Mod bands, The Prisoners, and Ed and Gilles were trying to get James interested in these Prestige and Blue Note sounds that were big at the time. James told me that it wasn’t his world but he related to it, due to the heavy presence of the Hammond B3.

I started to play for the James Taylor Quartet in ‘89 and through him I really saw how ‘acid jazz’ had exploded. James played the 1,825 capacity Town And Country Club (later The Forum) in Kentish Town 12 times that year, and sold out 11 of them. Now that is big. We played colleges and universities to 600 to 1,000 each time. Without doubt James was the frst superstar of that scene, none surpassed him until Jamiroquai. Paul Bradshaw’s ‘Straight No Chaser’ magazine had taken off; a magazine in response to The Wire’s writingoff of this runaway-train of acid jazz. It was everywhere. The scene had crossed over.

By the early ‘90s it appeared that a new generation of

students had discovered ‘acid Jazz’ but without the actual jazz reference that we all grew up with. Band-wise Eddie Piller’s label Acid Jazz and Gilles Peterson’s new Talkin’ Loud records grew. Through Ed’s mod influence a certain ‘look’ was defnitely appearing and taking hold, so much so that The Face did a piece highlighting ‘Nouveau Mod’, a look which crossed with the Galliano look of vintage Gabicci, contrasting to my Rockabilly attire!

It is curious that as enormous as the scene had become, it was mainly London-centric. We had the Chapter And Verse project in Manchester, we had Russ Dewbury’s enormous Jazz Bops at The Top Rank and weekly night at the Jazz Rooms in Brighton, and something quite immense in Leeds every week, where they almost or virtually rivalled London, revolving around The Dig Family (Gip Damonne, Chico Malo, Lubi Jovanovic and Ez), but otherwise acid jazz was centred around universities. When it came to the US, the mighty New York club ‘Giant Step’ had to make their take on the scene more hip hop-based, because of that culture being so all-encompassing.

Reading the sleeve notes to my 1997 LP ‘Something’s Coming’, you can see that I was trying to get the buyer to understand what acid jazz was and wasn’t. Was it Soul II Soul style, funky rock, trip hop? Afro beat or house? During mid ‘90s everything blended and became removed from the disco and jazz dance scene that it had come from, leaving people asking ‘What is acid jazz?’ Look, I’ve told you ‘It was a scene not a style of music’.

Photo: Dean Chalkley

Photo: Dean Chalkley

Unravelling the working life of Gilles Peterson is bordering on impossible. The DJ / broadcaster / A&R man / Record label and Digital Radio station owner has been on the move since he launched his own pirate radio station from his back garden in the suburbs of south London. He was in his mid teens back then and rapidly got a slot on another pirate station, Invicta, before setting up his own K Jazz collective. Coinciding with his Talkin’ Loud DJ session at Dingwalls he hosted a wild show called Mad On Jazz for BBC Radio London. He was pivotal to the launch of Jazz FM but was later sacked for playing “peace jazz” in relation to the Gulf war. After being snapped up by Kiss FM he quickly moved on to the BBC… frst Radio One and now BBC 6 Music… Phew!!

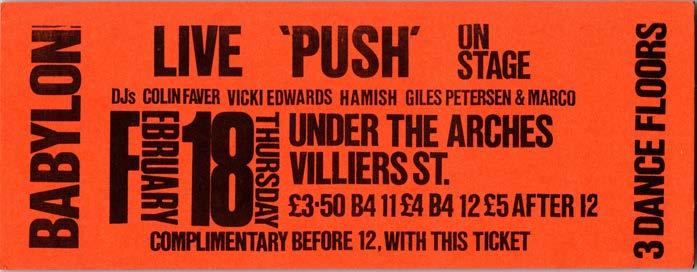

This journey was underpinned by numerous club nights … Talkin’ Loud / Dingwalls, Babylon, The Fez, Jazz90, That’s How It Is, Talkin Loud @The Fridge, That’s How It Is!… and endless tours to Japan, Europe and the US.

In ’88 Peterson executive produced and co-produced with Simon Booth (Emmerson) the two Acid Jazz & Illicit Grooves albums for Polygram. Reflecting on those albums he maintains that both of those LPs are actually more attuned to the acid jazz ethic than any other record that arrived in their immediate aftermath.

After briefly partnering with Eddie Piller to launch Acid Jazz Records, in 1990, Peterson moved over to Phonogram where he set up Talkin’ Loud Records to release a swathe of eclectic, often jazz rooted recordings. In the mix were artists like the Young Disciples, Galliano, Incognito, Omar, The Roots, Nu Yorican Soul, Terry Callier, MJ Cole, Steve Williamson, Carl Craig, 4 Hero, Nicolette and Reprazent.

In 2006 he launched his own Brownswood label which continues to present with a flood of homegrown and outernational talent – Kokoroko, Zara McFarlane, Daymé Arocena, Maisha, Ghostpoet, Swindle, Str4ta, Yussef Kamaal, Shabaka and the Ancestors, Kassa Overall – while producing projects in Brazil and Cuba with radics like Mala of Digital Mystikz. The Brownswood Bubblers project has released thirteen albums and toured the country stopping off in major cities to invest in and mentor dozens of up’n’coming artists from this current generation.

Post Covid, Peterson was recently compelled to put on hold his excellent digital radio station Worldwide FM but he continues to host his annual Worldwide festival in Sète in France. Building on the Brownswood ‘We Out Here’ compilation we now have the wonderfully eclectic We Out Here festival which in 2023 reps the underground nu-jazz scene more than ever.

Finally, Gilles Peterson has compiled more offcial mix albums/comps than anyone else on this planet. From jazz juice to the BBC sessions he has helped lay the foundation for many new labels to grow and flourish. The man’s record collection is out of this world … he’s as smart as a whip… he’s notched up nuff awards and and you can get a taste of his knowledge in the 600 page book Lockdown FM: Broadcasting In A Pandemic that he produced post Covid. Basically, the journey continues.

(Paul Bradshaw / Straight No Chaser) Photo: Dean Chalkley

Photo: Dean Chalkley

’87-97; What are your recollections of this time?

The making of my life! I started the label with Gilles Peterson; we were only together for 8 months but it was a fantastic launchpad and although from the start there was a rivalry between the two labels, Acid Jazz and Talkin’ Loud. Acid Jazz exploited the opportunity from the independent side and Talkin’ Loud from the major side, with great success for both - within a couple of years Mo Wax and Wall of Sound joined in - so 4 labels working essentially within the same genre. Good competition.

What does acid jazz mean to you?

To me acid jazz means the record label, but basically it was a term invented by Chris Bangs as a bit of a joke, a buzzword which only really took a life of its own in 1989/90 after Gilles had left. By then it was too late to change the name of the label (although it was considered) and we just went with it. It was enormous. You can’t imagine what it was like from 1990; for 3 or 4 years it was the biggest thing in the world. It was fucking massive, I don’t care what anyone says.

How would you defne your place in the acid jazz movement?

Bit of a chancer! Gilles and I both used the term freely to describe the label and what was going on around us at the time. When Gilles left I carried on using it to describe the term; so my role is facilitator and record producer and DJ. Which radio station or show would you listen to in your area?

Mad on Jazz on Radio London, a whole gang of us used to go down there, answer the phones, messed about, it was a social club with about 20 of us, people like Chris Phillips, Jez Nelson, Rob Gallagher & Alfe.

Which live concert or club session stands out from that era?

Too many to say, Dingwalls, The Wag and of course the Blue Note which later on managed to capture every aspect of that political and social scene around from Norman Jay to Coldcut to Andy Weatherall as every aspect of acid jazz had become broader and that was the flowering of the scene.

Top 10 songs ?

‘Sphinx’: The Brand New Heavies. ‘Don’t Wanna See Myself

Without You’: Terry Callier. ‘Theme from Starsky & Hutch’: James Taylor Quartet. ‘When U Gonna Learn’: Jamiroquai.

‘Take A Trip Down Brick Lane’: Mother Earth. ‘I’m The One’: D’Influence. ‘Just Reach’: Galliano. ‘Love Sick’: Night Trains. ‘Something In My Eye’: Corduroy. ‘Earthly Powers’: A Man Called Adam.

Which magazines did you read during this era?

Touch, Jazid and Herb Garden (which was hilarious actually). The most unlikely place you encountered acid jazz in 1987-97?

The top of Everest! We asked people to send in photos of themselves wearing an AJ t-shirt for AJ News and a bloke sent a pic of a photo of him wearing it on the top of Everest. In terms of the scene though, it was huge in Greece where they were still totally in to their vinyl, plus of course Italy, Japan and on a different level, Indonesia where they sold everything on bootleg cassettes, and while on holiday I found every possible thing on Acid Jazz on a bootleg…. Possibly the most important achievement though is that Acid Jazz records broke America; TBNH, Jamiroquai and so many other Acid Jazz artists succeeded where bands like Oasis etc failed.

What genres of music or artists have been your main inspiration?

Mother Earth, because Mother Earth started as me in a sample studio, and then Bunny joined to help. After the frst album came out I put a band together which then became the band, which grew into itself and made a brilliant album (People Tree). I’m really proud of that whole Mother Earth period, plus of course Jamiroquai, who couldn’t even get signed – the people at Sony UK turned him down twice so I had to go to Columbia in the US to get the deal done. What is the influence of acid jazz on today’s music?

Easiest to answer that in two words: Terry Callier. Acid jazz created things, and with Terry we found him and persuaded him to come out of retirement, or Gregory Isaacs who we sold 150,000 albums on Acid Jazz for, miles more than he had ever sold before. For me, acid jazz's legacy is the understanding and appreciation of older artists and their back catalogues.

I got my frst club gig at a place called Bogarts in West London playing soul, jazz funk and disco - Players Association, The Whispers, Deodata, a bit of Philly Soul. I worked there 5 nights a week for a couple of years and I went out clubbing a lot. Most clubs played chart disco and soul but there were a few decent clubs with DJs like Chris Hill, George Power, Chris Brown and Sean French playing much better tunes with a lot of jazz funk in the mix.

Some friends told me about this DJ Paul Murphy who was playing obscure jazz funk. I went along to his night; there were about 11 people in there but the music was amazingrare Roy Ayers tunes, Ingram's "Mi Sabrina Tequana", Barbara Carroll's "In The Beginning;" the whole night was jazz funk or jazz with one 'disco' tune in the whole set, Clyde Alexanders "Got To Get Your Love". That night changed me forever as a DJ as I fgured there was a world of jazz & jazz funk music that people weren't hearing and that's what I wanted to play. I did a few gigs with Paul, but meeting Gilles Peterson when he was 16 gave me the chance to develop as a jazz DJ. Gilles had been playing hard jazz fusion at Camden's Electric Ballroom and I came from a more suburban soulboy scene. I had a much less serious approach to playing jazz in clubs than some other jazz DJs and the mix of our two styles proved to be a winner. We started running our own gigs together and played jazz fusion, Latin jazz, Blue Note, rare funk 7"s and what we used to call 'dodgy bossa' which was pretty much anything with a cheesy Latin beat. Those Gigs were about keeping the whole night as a party without trying to ‘educate’ everyone and generally playing records that were brilliant to dance to rather than bleating on about

John Coltrane or hard bop. We had those records but who wants to hear them on a Saturday night out !

There was a big warehouse scene in the UK in the mid 80's playing what became called rare groove with all kinds of other stuff mixed in from Dinosaur L to Studio One Reggae plus a bit of Northern Soul. It was much more London-based and the crowd were much more fashion conscious and really into their music. Gilles and I were playing a lot of rare groove in our sets but we were playing slightly different stuff to most of the rare groove DJs. We used to track down funky stuff on labels like Blue Note, Groove Merchant and Prestige. We both already had hundreds ( probably thousands by then! ) of Jazz records that we used to spin Samba or Latin tunes from and it was just a matter of revisiting those same LP's and digging out the funk tunes from them , mixing it up with our own rare groove 'discoveries' and some of the better early hip hop stuff. That was the mix that became acid jazz, and for me it all started when Gilles got a Monday night residency at the Wag Club in London. They'd had a jazz night there for a few years with Paul Murphy, then later Baz Fe Jazz & Sylvester playing bop, Latin jazz & a bit of rare salsa with some of the best UK jazz bands playing live. When Gilles took over I came down every other week. We'd play our funky Jazz mix downstairs, and upstairs was more Jazz Fusion for the dancers. Upstairs was more of a musical playground and we started spinning some crazy stuff scratching ‘accapella’ Jazz stuff, mad sax intros and Beat poetry like Allen Ginsberg's "Howl" over hip hop drums next to crazy jazz fusion like Dewey Redman's ‘Unknown Tongue.’ (Steve Hoffman)

’87-97; What are your recollections of this time?

All a bit hazy to be fair. Gilles and I had been playing a much more diverse mix of music dropping rare grooves, funk tracks from old Blue Note and Prestige album we previously played bop dancers or sambas from mixed with a few bits of US rock, America, Hendrix and the like, we were pushing at the boundaries and coming up with the acid jazz scam we were able to give it all a name.

What does acid jazz mean to you?

That’s the thing about acid jazz; for me it was about breaking down musical barriers. The whole original idea was to avoid genres and stereotypes ( the Freedom Principle) and we ended up creating a new one instead.

How would you defne your place in the Acid Jazz movement?

Well, that’s a tough one, I came up with the name at a Special Branch as a bit of a laugh really, I designed the goofy smiley logo and we (Gilles Peterson and I) rustled up a load of press and spread the word about this crazy hot music. Which radio station or show would you listen to in your area?

Gilles “ Mad On Jazz “ show on Radio London was the essential listening in the 80s. It was a breeding ground for getting people into Jazz rather than the more soul, jazz funk pirate stations, a bit like Robbie Vincent’s Soul show had worked a few years before. All the people coming to our gigs were getting familiar with the tunes we were both playing out via his show. We had an agreement that as soon as one of us found a new tune we’d immediately try and get the other one a copy of the same track. I don’t think acid jazz would have spread without that show.

Which live concert or club session stands out from that era?

Cock Happy ! Defnitely where it all started really , the frst gig we advertised as an acid jazz gig. First was at The Cock Tavern in Smithfeld Market, London, but the best for me was at Waterlow House, a beautiful arts centre in parkland near Highgate. Who knows how they let us in there? We had bustlin’ jazz dance downstairs, a terrace overlooking the grounds, and beat poetry and noodling jazz upstairs where everyone sat on the floor smoking joss sticks. Lol

Top 10 songs?

This would change every time you ask but for now;

‘Step Right On / Get Yourself together’: Young Disciples, ‘When You Gonna Learn’: Jamiroquai, ‘Masterplan’: Barrie K Sharpe & Diana Brown, ‘Open Our Eyes’: Marshall Jefferson, ‘Fairplay / Back to life / Keep On Movin’: Soul II Soul, ‘Dream Come True’: Brand New Heavies, ‘Welcome to the Story’: Galliano.

Which magazines did you read during this era?

The Face / ID / New Sounds, New Styles / Blues and Soul

The most unlikely place that you encountered acid jazz?

Kew Steam Museum , a Cock Happy gig surrounded by giant victorian steam machines.

What genres of music or artists have been your inspiration?

Well, I was never a soulboy in my youth so I grew up listening to spacey rock, Gong, Hawkwind, Hendrix, Santana, Pink Fairies etc, thru that into Jazz Rock, Isotope, Soft Machine and fnally getting into soul Stevie Wonder, Marvin and Curtis Mayfeld who I’d have to say is Numero Uno across the whole lot.

What is the influence of acid jazz on today’s music?

Not a lot now really, not sure Stormzy is big on acid jazz, but it was fun while it lasted.

ROCHESTER CASTLE

THURSDAY 06 JULY 2023

DOORS: 5PM-11PM

TICKETS

EVENTIM.CO.UK

ROCHESTERCASTLECONCERTS.COM

What are the roots of this phenomenon we now call ‘acid jazz?’ The short answer is ‘clubland.’ The arrival of alternative West End clubbing arrived in the form of The Wag Club. It was the early Eighties and The Face magazine spread the vibe nationwide. By 1987 the thriving suburban soul ’n’ funk scene found a home on Monday nights at The Wag and it went beyond Brit-Funk to embrace ‘jazz’… Hammond powered soul jazz, percussion driven Latin jazz and tuff jazz Messenger style hard bop. The DJs were Baz Fe Jazz, Andy McConell, Russ Dewbury, Sylvester…the don – Paul Murphy and a little later Gilles Peterson.

While The Wag might have cornered the media attention the ‘jazz dance’ scene was gathering momentum all over the UK. For the deep roots of this scene you need to seek out Mark ‘Snowboy’ Cotgrove’s seminal ‘From Jazz Funk & Fusion To Acid Jazz: The History Of The UK Jazz Dance Scene’ which takes us on a journey the length and breadth of the UK. But for this exhibition I’ll just mention a select few and leave the flyers and posters to do the rest.

As is revealed elsewhere in this exhibition, the term acid jazz was frst coined at Chris Bangs’ and Gilles Peterson’s Cock Happy sessions. The Cock Happy parties at Lauderdale House were legendary and took place alongside Nick Holloway’s parties at the V&A Museum and London Zoo… yes, the ‘Do At Zoo’! Paul Murphy’s Jazz Room, upstairs at the Electric Ballroom is also the stuff of legend and is captured brilliantly on Dick Jewell’s grainy B&W flm.

In Manchester Colin Curtis, John Grant and Hewan Clarke reigned at Rafters and Berlin. There was The Cooker in Leeds, Tin Tin’s sessions at the Thekla in Bristol, Bongo Go in Birmingham, and the incredible Jazz Bops in Brighton. Lest we forget there were parties in Bari, Hamburg and The Black Forest, Tokyo with UFO and Kyoto with the Okino brothers.

Back in the metropolis there was the long standing, dark, sweat soaked, musically charged Sunday Afternoon sessions at Dingwalls – Talkin’ Loud & Saying Something – with Gilles Peterson and Patrick Forge. The club’s name says it all. There was Jazz90 and Babylon – which lasted around a year at Heaven and was regarded, by those who know, as the real root of acid jazz. We witnessed Gilles Peterson taking on The Fridge in Brixton on a Friday (bold move!) and caught him sparring with Mo’ Wax’s James Lavelle at That’s How It Is on a Monday night.

There was no internet, sessions were promoted by flyers (respect to Janine Neye and her flyer girls!), pirate radio and word of mouth. For the jazz oriented cognoscenti there were a lot of late nights flled with shape shifting, no half steppin’ musical selections. Good times!

(Paul Bradshaw / Straight No Chaser)

Photo: Janine Neye

Photo: Janine Neye

Mongo Santamaria at Dingwalls. Photo: Janine Neye

Mongo Santamaria at Dingwalls. Photo: Janine Neye

Photo: Dean Chalkley

Photo: Dean Chalkley

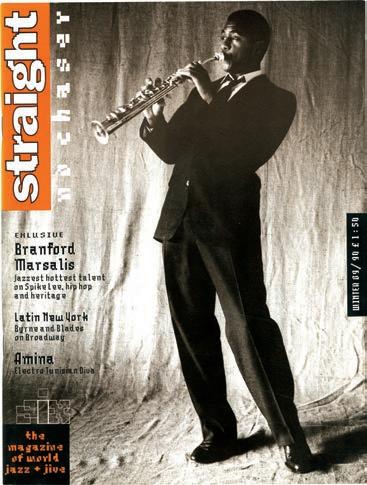

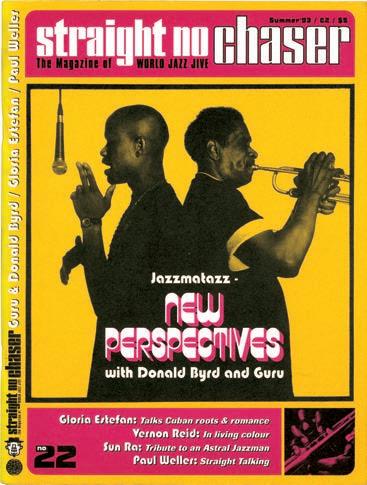

It was one Sunday afternoon at Talkin Loud & Saying Something at Dingwall’s in Camden Town. Someone handed me a white label 7” single. The writing on the label read: ‘Frederic Lies Still’ - Galliano. It was the frst record on Gilles Peterson and Eddie Piller’s Acid Jazz records and it delivered a groundbreaking sliver of ‘jazz-oetry’ over Pucho & The Latin Soul Brother’s version of ‘Freddie’s Dead’. It was enough for me to feature the man called Galliano in the very frst issue of our designer fanzine - Straight No Chaser.

Legend would have it that Peterson’s friend and mentor, Cock Happy DJ, Chris Bangs was the frst person to coin the term ‘acid jazz.’ It was 1987… or was it ’88? It was around that Tim a certain Nick Holloway was also doing his Do At The Zoo parties and some would say that Ecstasy arrived on the scene via his now legendary parties in Ibiza. The summer of love exploded in ’88, sunrise and acid house raves cause moral panics across the nation. The club scene was never to be the same and if the term ‘acid jazz’, complete with an alt-Smiley logo, kept the jazz dance scene from being totally eclipsed, then it was all good.

As it goes the Piller-Peterson partnership was short lived as Gilles went off to Phonogram to launch Talkin’ Loud records while Eddie pursued his own acid jazz mission. The number of clubs mushroomed… Leeds, Bristol, Brighton, Birmingham. We did pirate radio - K Jazz. ‘acid jazz’ compilations materialised via the BGP label and alongside them came ’Acid Jazz & Other Illicit Grooves Vols 1 & 2’, both of which were curated by Working Week’s Simon Booth (Emmerson). They helped pave the way for the emergence of a home grown, diverse movement of aspiring musicians and bands who began to spread the acid jazz vibe as far away as NYC and Tokyo.

‘Acid jazz’ is not a genre of music. It was a relatively shortlived movement grounded in clubland. The music it offered maintained a retro edge but the dots were boing joined. It felt natural to embrace the vibe of hip hop’s Native Tongues movement and to push the artistic, cultural and political boundaries to embrace artists like Yusef Lateef, Pharaoh Sanders, the Art Ensemble Of Chicago and Sun Ra. There was to be no standing still. History shows that the music consistently marches forward and the creative thread that has its roots in jazz has found its way into the drum ’n’ bass of 4 Hero and Roni Size, the Detroit techno of Carl Craig, the New Yorican Soul of Louie Vega and Kenny Dope, the spiritual house of Joaquin Clausell… and inevitably into the offerings from today’s nu-jazz music makers like Shabaka Hutchings, Joe Armon Jones, Ezra Collective and Kokoroko to name but a few. Let’s call it the Freedom Principle.

(Paul Bradshaw / Straight No Chaser) Photo: Michael McFadin

Photo: Michael McFadin

’87-97; What are your recollections of this time?

For those of us who were involved, these were rollercoaster years with little opportunity to take stock or appreciate what was happening. I recall the chemistry of Dingwalls brought together so many elements; rare groove refugees, hardcore jazz dancers, boogie boys, ravers and mods. The heads and the curious. A confluence of people mirrored by the coming together of many different musical styles.

What does acid jazz mean to you?

It’s diffcult to think of acid jazz as a genre, it’s more of a conundrum or even a contradiction. On one hand, there is a huge retro element which mirrors the gargantuan amount of vinyl archaeology (soul-jazz, jazz-funk, Latin jazz, bossa nova, soundtracks...) On the other, it was joining the dots essential to the foundation and forward motion of music.

Gilles Peterson and I always looked for new music that ft our sets; 808 State’s ‘Pacifc State’, S.O.H.O’s ‘Hot Music’ and Gang Starr’s ‘Jazz Thing’ were all huge tunes at Dingwalls. How would you defne your place in the acid jazz movement?

The birth and heyday of acid jazz was a phenomenon that I certainly played a part in, but I see myself as more someone who bore witness from the inside. As the nineties rolled on, I compiled the Rebirth Of Cool compilation series for Island records between ’91 and ’98 and although they were never described as acid jazz compilations, they defnitely occupied some of the same territory.

Which radio station or show would you listen to in your area?

It’s very diffcult to disentangle myself from the story of Kiss FM and its journey from pirate station to legal dance music broadcaster. I was with Kiss throughout this period. Of course, I checked Gilles’ radio shows on Jazz FM and BBC Radio London. Gilles was a huge inspiration to me, as were Norman Jay, Colin Faver, Colin Dale, and more on Kiss.

Which live concert or club session stands out from that era?

Poncho Sanchez, Roy Ayers, Mongo Santamaria, Dave

Valentin, The JBs, Incognito, Brand New Heavies - all at Talkin’ Loud And Sayin’ Something at Dingwalls. I also loved Omar, Galliano, Joyce at Talkin’ Loud at The Fridge in ’94 and Terry Callier, Pharoah Sanders at The Jazz Cafe

Top 10 songs?

‘Moon Child’: Pharoah Sanders, ’Road To Freedom’: Young Disciples, ‘Voodoo’: D’Angelo, ‘In The Fast Lane’: Jean Luc Ponty, ‘Nuyorican Soul’: Nuyorican Soul, ‘In Pursuit Of The

13th Note’: Galliano, ‘Low End Theory’: A Tribe Called Quest, ‘Galactica Rush’: Jhelisa, ‘Groove Now/ New Goya 10’: New Sector Movements, ‘Samba De Flora’: Airto Moreira

Which magazines did you read during this era?

Straight No Chaser reigned supreme, but honourable mentions to Vibe (a small fanzine out of Birmingham) and Soul Underground. Notably the frst issue Wax Poetics was published in 2001.

The most unlikely place you encountered acid jazz in 1987-97?

The most mental event of acid jazz history has to be The Jazz FM weekender in November 1990 that Gilles and Janine managed to get the station to sponsor. The line up was Pharaoh Sanders, A Tribe Called Quest, Roy Ayers, Galliano, Brand New Heavies, Snowboy’s Descarga, Incognito, Working Week…unreal.

What genres have been your main inspiration?

“Jazz is the teacher, funk is the preacher.” James Blood Ulmer

“There are only two kinds of music, good music and the other kind.” Duke Ellington... and I could write a list of artists several pages long.

What is the influence of acid jazz on today’s music?

The ripple effect of acid jazz has created nothing short of a revolution in taste. Beneath the froth of retro funk and hybrid forms that are often associated with it, there was a deeper reckoning. A recalibration of black music history that shone a light on much that been neglected or forgotten and a loosening of ideas about what jazz is and could be.

While the mixture of jazz and club culture mashed together by DJ’s such as Paul Murphy, Gilles Peterson, Baz fe Jazz, Chris Bangs, Colin Curtis and others were the route of the acid jazz scene, live musicians had already started to set the framework. Where Gilles Peterson’s seminal ‘Jazz Juice’ compilations was introducing a new generation to dance floor cuts primarily from the past, artists such as Working Week & the Jazz Defektors were pushing UK live jazz into a more contemporary direction.

The London-based Jazz Warriors were assembled in 1986 and introduced us to future stars such as Courtney Pine, Steve Williamson, Cleveland Watkiss, Phillip Bent, Orphy Robinson, and Gary Crosby. Their sole album ‘Out of Many, One People’ (1987) is regarded as a benchmark and the beginning of the new wave of British jazz which continues today with artists such as Nubya Garcia, Kamaal Williams, Binker Golding, Kokoroko, Ezra Collective and many more.

Snowboy (real name Mark Cotgrove) started as a DJ when he was 17 years old. Inspired by the legendary DJs Chris Hill and Bob Jones, he used to hire the country’s most legendary black music club, The Goldmine.

The Goldmine was Chris Hill’s residency and it was voted the UK’s No. 1 club for 12 years and was Snowboy’s grounding in jazz, funk and soul. He quickly found that his collection was getting more biased towards the Latin fusion that was prominent in the clubs in the late 70s/ early 80s and Snowboy got interested in making all the ‘exotic’ sounds on these records (particularly by Brazilian percussionist Airto). So after working a summer season as a prestigious ‘Redcoat’ at a Butlins holiday centre in 1982, with his bonus, the day he returned he went and bought his frst set of congas. After a year of trying to teach himself, Snowboy started having lessons studying Afro- Cuban and Brazilian percussion with the UK’s grandfather of Latin music, Robin Jones, who he met at a samba night at London’s Wag Club run by the legendary jazz dance DJ Paul Murphy.

In 1985 Snowboy’s debut 3 track single was released, called ‘Bring On The Beat’, but it was the b-side ‘Wild Spirit’ of his Latin jazz follow-up, ‘Mambo Teresa’, that broke out big with the jazz dance scene. The follow up single ‘Ritmo Snowbo’, was another Latin jazz track and, once again, cracked it on

the dance-floor, with a B-side version of the jazz classic ‘A Night In Tunisia’ sung by Jackson Sloan (whose debut album was also produced by Snowboy).

In 1987 the jazz dance scene had just been re-named acid jazz as an in-joke amongst a group of prominent DJ’s in that scene as acid house was breaking big. (Obviously, musically, these styles have nothing in common.) The home of this movement was at a club called Dingwalls in London which Snowboy was very much part of, playing there very often in different bands. A label was formed by the main DJs there, Gilles Peterson and Eddie Piller. The label was called Acid Jazz and Snowboy was approached to record an album for them. What is Latin jazz doing on Acid Jazz records? The biggest mistake the public made was not realising that acid jazz was a scene rather than a style of music. The music was jazz dance, i.e. any jazz-based music you can dance to. Snowboy was part of an acid jazz (scene) project on Polydor called The Freedom Principle which showed off the diversity of our scene. Snowboy contributed a Latin house track which got to No.21 in the national club charts.

Snowboy’s debut album in 1989 was one of the frst on Acid Jazz records. Label co-owner Gilles Peterson wanted to put something out that documented Snowboy’s career to date by licensing all the early singles, plus record a few new tracks

to make it current. The album was called Ritmo Snowbo’. As well as playing as a percussionist with Robin Jones King Salsa and Basia, Snowboy then also joined the James Taylor Quartet, enjoying 16 great years with them. Through playing with James, Snowboy met Noel McKoy (JTQ’s singer then) and featured Noel on two singles (Snowboy’s singles usually represent him as a producer, giving him a chance to reflect his varied music taste as a DJ).

The frst of the two, ‘Give Me The Sunshine’, actually went into the UK national charts at No. 51.

Snowboy never wanted to put a band out on the road because he was so busy playing and touring with other bands (and particularly with Lisa Stansfeld, who he is still working with to date), but because of so many requests for gigs in 1992 he started performing regularly (as time permitted). Another album was released called Descarga Mambito, but it was his album, Something’s Coming, in 1994 that gave him the most exposure. The label Acid Jazz was at its height (as was the scene) and Snowboy was in every other music publication (even on some covers), so this album surprised everybody by flying into the U.K. Indie Charts at No.9 (alongside Depeche Mode and The Smiths!) – an Afro Cuban jazz album! Snowboy did 88 European gigs that year and has since played all over the world from Australia, Hong

Kong, Japan and Singapore, Turkey to Scandinavia to Ireland. Snowboy is a also producer, a re-mixer (check his re- mixes of Lisa Stansfeld, Roy Hargrove, Coldcut etc.) and has played or recorded with artists such as Lisa Stansfeld, Imelda May, Mick Hucknall, Mark Ronson, Basia, Mica Paris, Gibonni, Airto Moreira, Jon Lucien, James Taylor Quartet, Incognito, Flaco Jimenez, Big Boy Bloater , Mother Earth, Corduroy, Speedometer and many more. Altogether, so far Snowboy has had 22 singles and 16 albums released on various labels ranging from Polydor, Big Life, Acid Jazz, Ubiquity/Cu-Bop (a label that specializes in Afro Cuban jazz), Chillifunk and Freestyle. His latest critically-acclaimed album, New York Afternoon, is on his own label, Snowboy Records. Also a writer, Snowboy had a music history book published on the UK Jazz Dance scene called From Jazz Funk And Fusion To Acid Jazz – The History Of The UK Jazz Dance Scene. It was published in 2009 by Chaser Publications. Snowboy’s proudest association is with his No.1 fan –Professor Robert Farris Thompson of Yale University. He is one of the world’s leading authorities on Afro-related Art, History and Music and was quoted as saying “In one man’s opinion, I think, for Afro Cuban music, Snowboy is doing, and can do at ever higher and widening levels, what the Beatles did for Rock”.

Straight No Chaser #1 arrived in 1988… the ‘summer of love.’ Tagged the magazine of World Jazz Jive, its manifesto declared:

Straight No Chaser: An attitude, a new magazine, a new time

Straight No Chaser: A 1956 tune by the ‘Hat & Beard’ –Thelonious Sphere Monk. A total original.

Straight No Chaser: Committed to the Freedom Principle. Dedicated to the music and all its champions. Musician and fan. Past, present and future. The focus will be the people and their ideas. The perspective will be global. Stay tuned!

Straight No Chaser was hailed as a ‘designer fanzine.’ It was initially based in Hoxton, a shady, run down, working class area in east London. Our offce was in a cobbled street, a stone’s throw away from the Bass Clef jazz club – a club that would morph, in the early 90s, into the radical Blue Note. We sold SNC outside clubs, in record shops and the odd newsagent. It cost £1.00. We were part of a thriving DIY club scene, and that was reflected in our long list of writers, photographers and illustrators; through SNC club guide –Destination Out – and the DJ charts which illuminated the evoalution of jazz related club sessions around the globe. As it evolved Straight No Chaser took on a new mantle of “Interplanetary Sounds : Ancient To Future”. It reflected a modern world view that embraced and illuminated the music of the African diaspora from the blocos of Bahia, to the mbalax of Senegal to the hip hop of the Bronx and Brooklyn to the house music of Detroit to the jazz visions of Tribe in LA and the AACM in Chicago. As for acid jazz, we

were up for the ride and there’s no doubt, for a moment in time, it helped take the music global and paved the way for the collision of hip hop and jazz.

Straight No Chaser was the hub around which a worldwide jazz-oriented community gathered. It provided a home for their music. We took the sparks and fanned the fre. As a publication we hopefully projected pride and intelligence, it was militant and always beautifully crafted and designed by our art director Ian Swift aka Swifty.

In 2007, fnancial pressures rooted in the rise of the Internet caused us to abandon ship and call it a day. #SNC97 was to be our fnal issue. However, a decade later, just as a fresh and thrilling brand new jazz generation was emerging, we launched #SNC once more. We picked up where we left off with #SNC98. It looked good, felt good, it was tangible: it sat on your desk or shelf, not on your desktop.

Old connections were revived, new connections were made. Once more #SNC went worldwide. There were two more issues before the pandemic hit. We celebrated the publication of #SNC100 with features on masters and visionaries – Pharaoh Sanders, McCoy Tyner, Yusef Lateef, Kahil El Zabar, Gary Bartz, Flora Purim, Terry Callier, Abbey Lincoln and Fontella Bass – alongside the nu-generation of jazz warriors – IG Culture, Steam Down’s Wayne Francis, Wonky Logic, Rosie Turton, Shirley Tetteh, Ishmael Ensemble. It felt good.

The pandemic delivered a seismic shift in all our lives and as its impact subsided we found ourselves back at square one. Where the future for #SNC lies we’re not 100% sure.

“A Luta Continua”... the struggle continues!

(Paul Bradshaw / Straight No Chaser)

The ‘Jazz Bop’ name began in London in the middle of the 1980s with BBC Radio London DJ Gilles Peterson and Chris Bangs presenting legends of the jazz-dance scene such as Richie Cole and Big John Patton at the Town and Country Club in North London along with UK jazz artists such as Tommy Chase and the Jazz Defektors. In the late ’80s DJs Russ Dewbury and Baz Fe Jazz brought the ‘Jazz Bop’ concept to Brighton, with a spectacular array of live acts and DJs that became essential for anyone involved in the acid jazz world at that time. Artists included Pucho and the Latin Brothers, Jamiroquai, Eddie Russ, The Brand New Heavies, Terry Callier, James Taylor Quartet, Melvin Sparks, Galliano, Charles Earland, Omar, Jon Lucien, Carleen Anderson, Snowboy and many more. DJ Graham B also took the Jazz Bop to Amsterdam for a series of successful nights with the same mixture of live artists and DJs.

Acid Jazz Records is a British record label that was founded in 1987. It continues to roll on along its idiosyncratic and fercely independent path 35 years after co- founders Eddie Piller & Gilles Peterson set up the label in an attempt to document the music that was emerging from their London scene. It became famous for its eclectic mix of jazz, funk, soul, and hip-hop music, and played a signifcant role in the development of the acid jazz movement in the UK. The label’s frst signing was jazz-poet Rob Gallagher’s band, Galliano, which released the label’s frst single Frederick Lies Still in 1987. The single featured a take on Freddie’s Dead by Curtis Mayfeld.

Gilles Peterson left to form Talkin’ Loud Records via major label Phonogram. Eddie Piller continued with the Acid Jazz Records music policy with a revamped team – including current label partner Dean Rudland. A sense of the wonder of the potential of great soul music made international stars of Jamiroquai, The Brand New Heavies and The James Taylor Quartet, whilst newer signings Mother Earth and Corduroy lay down exciting sounds and critically acclaimed recordings to further the label’s success.

Some of the Acid Jazz label’s associated projects included

the legendary and ground-breaking Blue Note nightclub in Hoxton Square, and the music of all-genres radio station Totally Wired Radio. Acid Jazz Records even sponsored Surrey Cricket Club for a season in the mid-90’s! While always holding true to its love of the classic soul, jazz, funk, mod, folk and psychedelic sounds, it has mixed a tendency to look back with an excitement at embracing the future. These are always in accordance with a continued dedication to releasing music old and new on the label and its subsidiaries.

Today, Acid Jazz Records remains a prominent force in the UK’s music industry, and its legacy continues to inspire new generations of musicians. The label is the home to Matt Berry’s exceptional records, The Lightning Orchestra’s psychedelic afro-beat adventures, the roots explorations of the Soul Revivers, and the highly successful On The Corner with Martin Freeman and Eddie Piller compilation series. A collaboration with Argentinian producer Kevin Fingier brings a melting pot of retro soul, Latin and African influenced 45s on his Fingier Records subsidary. New signing from Los Angeles Billy Valentine brings the label full circle with one of the label’s greatest releases to date.

The label that brought us The Young Dıscıples, 4 Hero and Ronı Sıze

In 1990, when Gilles Peterson was head-hunted to work for Phonogram records he left his Acid Jazz partnership with Eddie Piller behind. At Phonogram he had allies such as fellow DJ Norman Jay MBE along with Paul Martin –now a university lecturer, writer and some-time producer. Though ‘jazz’ was Peterson’s brief he was keen to develop an alternative stream of music and that became Talkin’ Loud records. The stream was British based, racially diverse and initilally rooted in live performance. GP’s vision was grounded his seminal Sunday afternoon club session Talkin Loud & Saying Something… a play on James Brown/Bobby Byrd’s rare groove anthem ‘Talkin’ Loud & Saying Nothing’. Down the line, it was the Bar Rumba session – That’s How It Is! - that was the testing ground. The music on Talkin’ Loud was aimed at the dance floor but also reflected Peterson’s deep passion for jazz, soul, funk, fusion and the sounds of Brazil. It was eclectic and attuned to the

times. In the early days, the label had the Young Disciples, Incognito, K Creative and the original vibe tribe – Galliano – but as time progressed a host of ground breaking artists appeared on the Talkin’ Loud roster including MJ Cole, Carl Craig’s Innerzone Orchestra, 4Hero, Steve Williamson’ That Fuss Was US, Courtney Pine, Nicolette, Krust and Roni Size’s Reprazent. The visuals were strong, as was the label’s attitude to pursuing artistic freedom. Talking’ Loud delivered the Roots debut album, produced the groundbreaking Nu Yorican box set with Louie Vega and Kenny Dope, championed Tokyo’s United Future Organisation and won a Mercury Prize with Reprazent’s ’New Forms’. In an interview with Galliano from ’80’s, Rob Gallagher declares, “Peterson… he just loves music, he’s got so much energy and enthusiasm… he sees links.. there and there and there!!… and if there’s no link he’ll make one… then he’ll just push it and go, ‘Look at this!’”

’87-1997; What are your recollections of this time?

Cool clothes, facial hair, old school trainers, long keyboard solos and students trying to grow sideburns with socks on their heads.

What does acid jazz mean to you?

A mismatch of varied musical styles, released by an independent record label, that bear little relation to the assumed genre of acid jazz.

How would you defne your place in the acid jazz movement? Super shy bass player in a cult band signed to the label. Which radio station or show would you listen to in your area?

Radio 1, Jo Wiley & Steve Lamacq.

Which live concert or club session stands out from that era?

Jazz Stage at The Pheonix Festival, Main Stage at Reading Festival, Quatro Tokyo, Shepherds Bush Empire, Alexandre Palace and giving away a Mini Cooper at The Town & Country.

Top 10 songs?

‘Girl from the Mountain’: Harvey Averne, ‘Car Chase’ - JTQ, ‘Never Did I Stop Loving You’: Alice Clarke, ‘Speed King’: These Animal Men, ‘Stories’: Izit, ‘Compare Yourself’: Mother Earth, ‘Spinning Wheel’: New Jersey Kings, ‘Lucky Fellow’: Snowboy & Noel McKoy, ‘Out of My Head’: Subjagger, ‘Whole Lotta Love’: Goldbug.

Which magazines did you read during this era?

N.M.E.

The most unlikely place you encountered Acid Jazz in 1987-97? A taxi cab in Hong Kong.

What genres of music or artists have been your inspiration?

Mod, psychedelia, funk, soul. The Who, Sly & The Family Stone, The Jam, Cream, The Stranglers, Love, The Damned, Sammy Davis Junior and Devo.

What is the influence of acid jzz on today’s music? Adidas Gazelles.

Richard Searle, Corduroy

’87-97; What are your recollections of this time?

I moved to New York in the summer of 1987. I had just graduated University in London and planned to go to New York for a few months to make some money working in restaurants and soaking in the NY club scene. At this point I was very much into rare groove, jazz funk and some house music. After a quick trip to Brazil at the start of 1998, by the spring I was back in NY and this time there to stay. After unsuccessfully trying to get a music industry job, I started trying to do my own club nights influenced by the parties at Dingwalls and The Wag Club. There was nothing close to what was going on in Europe and it wasn’t until I met a kindred spirit Jonathan Rudnick (who I founded Giant Step with). By late summer 1990 Giant Step the club started, but it wasn’t for another 8 months that the party really took off. The weekly club with DJs Smash and Jazzy Nice became the epicenter for Acid Jazz in US. First stop for bands like Brand New Heavies, Jamiroquai, Galliano and Gilles Peterson to name a few. The club grew from strength to strength with the weekly club, plus concerts and tours too including trips to Europe, Japan and South America. With that we set up a management company for local acts like Groove Collective and Dana Bryant. By the mid 1990s Giant Step was also a label and our highlight of 1997 was putting out Nuyorican Soul album in the US.

How would you defne your place in the acid jazz movement?

Giant Step was at the center of the scene in US

Which radio station or show would you listen to in your area?

There were no stations in NY that were close to the pirate stations in the UK or specialist stations in Europe. Instead we had to depend on college stations and public radio WBAI

Which live concert or club session stands out from that era?

Too many to name as there were so many magical nights. Some stand outs. Jamiroquai’s US debut, Guru’s Jazzmatazz frst show, a night at the club when the DJs, musicians and dancers were all vining together.

Top 10 songs?

‘Road To Freedom’: Young Disciples, ‘Blue Lines’: Massive Attack, ‘Nuyoican Soul’: Nuyorican Soul, ‘Hot Music’: Pal Joey, ‘I Want You’: Groove Collective, ‘Dominican Girdles’: Dana Bryant, ‘Low End Theory’: A Tribe Called Quest, ‘Cool Like Dat’: Digable Planets, ‘Park Bench People’ - Free Style Fellowship, ‘New Forms’: Roni Size.

Which magazines did you read during this era?

Straight No Chaser was the Bible

What genres of music or artists have been your inspiration?

Growing up in Manchester in the 70s and early 80s I was exposed to all types of music. However the band that opened my ears and mind to Latin, jazz, Brazilian and funk was Santana, I also loved Weather Report.

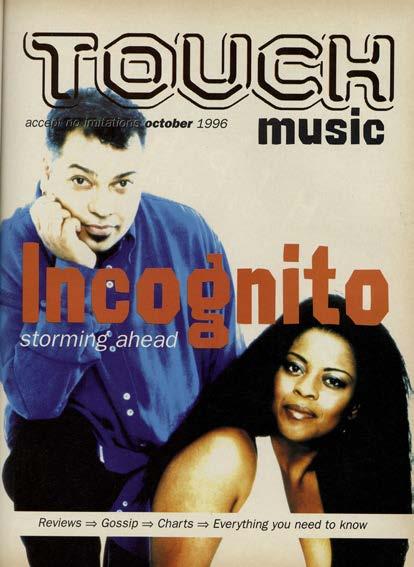

Touch magazine, quite simply, was way ahead of its time. In April 1991 when it frst launched, it had been preceded by Free magazine, produced largely by the same team at Kiss FM, then a pirate station that wanted Free to help promote the emerging music scenes that Kiss DJs talked about and the sounds they played. It was, of course, part of a journey to help one of the best-known radio brands in the UK to obtain a license. Once legal, Kiss cut Free and its team loose and Touch emerged within three months, a little grumpy about the circumstances with a ‘fuck you we’re doing it without you anyway’ attitude. With many Kiss DJs still contributing, the magazine became an engine room of young raw talent from the editorial through to the design and photography, and ironically Kiss FM got bought by EMAP – the magazine publishers of FHM….

Touch was not about money (it was free of charge until Issue 32!) and all the contributors earned their main incomes by DJing, producing, club-promoting and holding down very different nine to fve jobs. Mainly nocturnal though, what they did share, was a love and passion for the music and the underground scenes which made the articles, reviews and interviews fresh and helped unknown acts along their

journeys by giving them coverage way before they were noticed by the mainstream press. All of Touch’s contributors were totally immersed in youth culture and when Joe Pidgeon joined the team full-time in 1993 to make the magazine commercially viable, youth brands (via their more multicultural interest and markets) eventually became keen to try and get cooler by association, allowing the magazine to flourish by the mid ‘90s, even launching foreign language versions in Holland and Germany by the end of the decade. Over its 15 year reign, Touch gave debut UK interviews and front covers to a whole host of new musical talent including the Young Disciples, Vivienne McKone, D-Influence, Bryan Powell, Courtney Buchanan, Jhelisa Anderson and a very young Jay K from Jamiroquai.

Not just a media product, but an outlet for the creativity of diverse and minority backgrounds who had not been given a chance by any other publications, it put their content alongside already household names like Normski, Trevor Nelson and Norman Jay. Touch contributors from the ‘90s went on to become documentary makers, journalists, authors, academics, photographers and even Hollywood flm-makers.