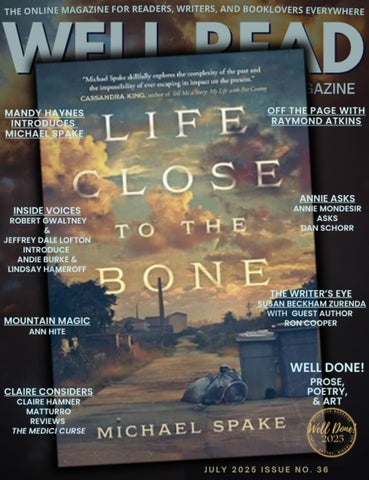

Life Close to the Bone Michael Spake

JohnGreenburnusedtobesomebody.Now,he'sjustamiddle-agedguy, sitting behind his computer screen, waiting for his life to come to a screeching halt. Cognitive-Pharma, a Florida-based pharmaceutical companywithdeeppocketsandasecrettohide,hascaughttheattention of the U.S. Department of Justice. The allegation? Medicare fraud. No one is more on the hook than John, who, as the Chief Ethics Officer at Cognitive-Pharma, has been the canary in the coal mine for the last 12 months. Not that his CEO cares much.

The CEO, a flashy, profit-driven type, certainly doesn't care that John's own mother, Francis, is in desperate need of CognitivePharma's top-selling drug to slow her memory loss. Haunted by what he knows of the fraud allegations - and the investigation's impact on the thousands of patients who depend on the medicationJohn draws closer to the memories he has of his own mother, Francis, and the ways she pushed him to be somebody.And, not just somebody, but the greatest youth tennis player upstate South Carolina had ever known. With Francis' memory deteriorating, John's time to understand both himself and his mother, a product of the rough mill town that shaped her, is slipping away.

Life Close to the Bone moves from present day Florida and back in time to John's successful tenure on the youth tennis circuit and the textile mill in upstate South Carolina that, through Francis, shaped John's adolescence. It depicts a matriarchal family's relentless striving to overcome their "linthead" heritage and explores what it means to live for yourself and, ultimately, to forgive parents shaped by their own generational hardship.

“In Life Close to the Bone, debut novelist Michael Spake skillfully explores the complexity of the past and the impossibility of ever escaping its impact on the present.As protagonist John Greenburn, a former tennis star turned pharmaceutical ethics attorney, struggles to uncover the potential danger of a new drug, he is drawn back into a past that threatens to undermine all he’s worked to achieve. Despite his reluctance to revisit old traumas, John’s only hope for redemption is to face headlong the longburied demons he has yet to acknowledge. Ultimately, John’s journey in connecting the past to the present belongs to all of us.” – Cassandra King, author of Tell Me a Story: My Life with Pat Conroy

“Michael Spake spins a profoundly textured story of corporate intrigue, boundless greed corruption, and personal ethics amid a hardscrabble mill village legacy, and a meticulous mother’s rapid cognitive decline as her lawyer son reconciles their past through revelatory truths. Life Close to the Bone triumphs with the lasting impact of what strong mothers pass on to you.” – Tim Conroy, author of Theologies of Terrain and No True Route

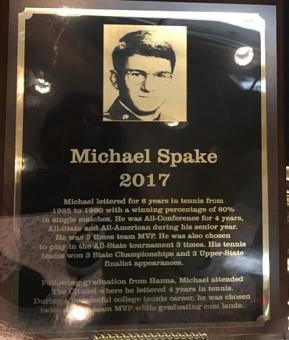

Michael Spake is a healthcare attorney and writer. His debut novel, Life Close to the Bone, a coming-of-age story about the shift in memory that comes with moving from adolescence to adulthood, as the story’s protagonist learns about love and loss in a textile mill town located in upstate, South Carolina.

Michael and his wife Mary Lucia celebrated their 27th wedding anniversary. They have four children (22, 18, 18, and 13). Michael is from Anderson, South Carolina and graduated with honors from The Citadel with a BA (English) in 1994.

Michael currently lives in Lakeland, Florida. At home, when not writing, he gardens and raises chickens.

Did you miss last month’s issue? No worries, click here to find it as well as all the past issues.

“My wife, Mary Lucia, always told me I had a story to tell…”

Mandy Haynes Introduces July’s Featured Author, Michael Spake

I’m very excited to introduce you to this month’s featured author. I had the pleasure of meeting Michael through his writing when he submitted a story to WELLREAD in 2023 and then again in 2024. When I heard he was working on a novel I knew it was going to be one I’d want to share with our readers. Let’s jump in! Your novel, Life Close to the Bone,is fiction but are there some “true” stories weaved within the pages?

Yes, many of the stories in the novel are drawn from my own experiences growing up. While some are exaggerated, all the tennis stories and tournament locations are true. I hoped they’d resonate with others from the USTA circuit, and I’m grateful several former tennis colleagues have reached out to say the book brought back fond memories.

The fictional town of Shoals is based on my hometown, Anderson, South Carolina. It’s a place full of fond memories, and I wanted to honor both the town and those experiences in the story.

What part of the book was the most fun to write?

The fun was including anecdotes about my family of six. Mary Lucia and I celebrate 30 years of marriage this year, and our kids— Henry (23), twins Katie and Mary Clare (20), and Vivian (15)— keep things lively. Our home is full of daily comedy, and it was a joy to share some of the moments we all laugh about.

I also enjoyed writing about nature. While writing, I took a year-

long course with Janisse Ray, Journey of Place, which deepened my appreciation for the outdoors. Exploring the connection between place, history, culture, and ecology gave me a stronger sense of belonging.

Finally, I loved including stories about my wonderful grandparents. At book signings, I often bring a projector to share photos of them and hometown landmarks featured in the novel.

What was your hardest scene to write, and why?

Pretty much everything about my mother. My biggest fear in writing Life Close to the Bone was that it might come off as just complaints about my adolescence. Yes, my mother and I had our battles—she mastered the guilt card, and I kept coming back for seconds—but that felt typical of growing up in the South in the ’70s and ’80s.

In addition, I think this dynamic blended well with my purpose of writing a story that included references to the old textile mills that once covered upstate South Carolina. In the prequel to Life Close to the Bone, which I am currently drafting, there is a part that reads:

Today, what is left of the crumbling mills and its culture, continue to haunt the generations of Lintheads, those once struggling farmers like my family, who had no choice but to answer the mill’s siren call. Like those same broken bloodlines, my family still bears the inescapable stain of being a Linthead and having it stitched into the fabric of our being. No matter how

fiercely we labor to sever this burdensome thread the old voices of disparagement still echo still, hollow and stubborn, in the marrow of our remembering.

My mother, although both sides of my family grew up and worked in local textile mills, appeared to hold a desire centered on forgetting/“erasing” her family’s participation with the mill, its history, and especially its memories. At the same time, towns appear to have done the same. They appear to have forgotten the mill’s history and its people as old mill buildings lie in crumbles covered in weeds. In my hometown alone there are at least three mills like this – one being the Appleton Mill where my paternal grandparents, Henry “Grinny” andVivian Spake, lived and worked their entire lives.

I think the stories of the mill and the people who worked and lived there should never be forgotten. I wanted my mother to serve as a vessel for this message about never forgetting and understanding.

Finally, I also thought this mother/son relationship emphasized another theme of redemption, understanding the past and how it will always be a part of you.

In summary, I truly wanted the dynamics of the protagonist’s relationship with his mother to be part of a larger theme about the past and how it is always a part of us.

What did you edit out of this book?

I cut about 40,000 words, which I’m now using to write a

prequel titled Lint and Forgotten Destitution. It begins with the mill’s arrival in Shoals and spans from 1895 to 1942, offering a historical perspective. The prequel ties into Life Close to the Bone through the story of my mother and her fictional adoption.

In summary, I edited this out because it created more timelines than I could mentally handle.

How long did it take you to write this book?

I started in 2019 when I read Tell Me a Story: My Life with Pat Conroy. Because I attended the Citadel (1990-94) at a time when the school and Pat were at odds, I had never read Pat Conroy’s novels other than the Water is Wide when I was in high school. My mother—who wasn’t an avid literary reader—had nevertheless devoured all of Conroy’s books. She loved Pat.

Reading Cassandra King’s memoir stirred something in me, especially Pat Conroy’s words: “Everyone has a story.” In 2021, I visited the Pat Conroy Literary Center in Beaufort, where I had the pleasure of meeting Cassandra and Pat’s sister, Kathy Harvey. A year later, Kathy emailed me with a message that felt like a jolt— an insistence that I begin calling myself a writer. She recommended The Great Yes, her brother Tim Conroy’s essay in Our Prince of Scribes. I had the pleasure of meeting Tim at his reading for his second book of poetry, No True Route.Around that same time, I met novelist Bren McClain, who offered simple but profound advice: “You’ve got to put yourself in the story.”

How did you come up with the title for your book?

The University of North Carolina has a wonderful project, Oral Histories of the South. Interviews of textile mill workers going back to those you worked in the early 1900s can be found online in the section titled, “The Industrialization of Noth Carolina’s Piedmont Region.” In one of those interviews someone made the comment that they survived by living life close to the bone. When I researched the phrase I found many idioms about living with something uncomfortable, something emotionally tense, something direct and maybe harsh, stripping away the superficial. I thought it fit many of the themes I was attempting to explain and provided some intrigue that may persuade people to pick up the book and explore it.

What was an early experience where you learned that language had power? What is the first book that made you cry?

The answer to both questions is high school, when I read Pat Conroy’s The Water Is Wide. The emotional range was powerful— one moment I was laughing, the next crying. For me, it offered an early glimpse of Pat’s resilience, which defined his life and work. At the same time, it has inspired me to question the status quo and be a little more daring in the face of community indifferences.

How long have you been writing or when did you start?

I started writing off and on as an English major at The Citadel,

aiming to write a novel and a nonfiction book on Christian mysticism after graduating. Graduate school, law school, raising a family, and starting a career came first, but I’ve since completed the novel and begun a short nonfiction work on the language of mysticism.I hope that as my career winds down I can spend my latter years writing. I have a rather long inventory of ideas.

What is your writing schedule-are you an early morning or late night writer?

I've always been a morning person. Even in college, I preferred early starts, struggled to study past 10:30 p.m., and got teased for going to bed so early. But I’ve always loved the quiet and the gradual crescendo and rhythms of the morning.

Who has been the biggest supporter of your writing?

My wife, Mary Lucia, always told me I had a story to tell. She’s been a constant source of inspiration and encouragement, offering valuable feedback and edits along the way.

Writing can be a solitary journey so it’s important to surround yourself with people who understand. You have lots of friends in the writing community. Would you like to give them a shout out here?

Bren McClain (One Good Mama Bone) and I met in 2021, although we are both fromAnderson, South Carolina. She has been

a great motivator for me and is always checking in to see how things are going.

Rebecca Bruff. Her novel Trouble The Water is such a great story about a South Carolina hero, Robert Smalls. I was blown away when I read her novel, because growing up in SC I had never heard of Robert Smalls.

Tim Conroy and Kathy Harvey gave me great encouragement, especially in the beginning when I was tentative about writing. I guess you can say they helped pull me out of my comfort zone.

Estelle Ford Williamson. I had the pleasure of meeting Estelle after she published Rising Fawn. Her passion about family stories is very inspiring.

Finally, Cassandra King. Had I not read her memoir Tell Me a Story I would have probably never met the people mentioned above. She essentially opened a lot of doors for me – both internal and external.

If you could tell your younger writing self anything, what would it be?

First, don’t wait. Start writing earlier in life.

Two, introduce yourself to Pat Conroy. When I attended the Citadel no English course, including freshman composition, included anything about Pat Conroy. In fact, many were hesitant even to mention his name. I recall a moment from sophomore year when my classmate and fellow English major, Chris, told an English professor—a Citadel graduate before Pat Conroy—that he

was enjoying Pat Conroy’s novels. The professor, unimpressed, advised Chris that if he hoped to earn a degree from the Citadel, his literary tastes would have to drastically improve.

I am super proud of the relationship the Citadel and Pat Conroy had later in his life. But during my time at the Citadel, he was taboo. As a result, I never gave meeting Pat a thought and did not even read his novels until after meeting Cassandra in 2021.

You are a great short story author! I know, because I’ve had the pleasure of publishing some of them here. I love writing short stories, but lots of authors say they are harder to write than a full length novel. Do you have any plans to write a short story collection? Do you have another novel in the works?

I appreciate the support of WELL READ Magazine. Pop’s Boat and Dog Days are about two very special people in my life, my wife’s grandfather, who took me flounder fishing each year in NC and my maternal grandmother, who really did kill a snake with a hammer while talking on the phone with her pastor.

I am finding a little time to craft some short stories. One challenge currently in front of me is I have these hilarious memories from the neighborhood where I grew up. I was about 8 and a group of teenagers (15-16) lived in the three houses opposite us. They were always playing practical jokes well through their high school days. For example, one year they stole a mannequin from the Belk Department store, which for almost a year made

lewd appearances in surprising places around the neighborhood. The challenge is getting enough substance and action to create them into a short story, but they are too hilarious to not give it a try. I will let you know what comes from my attempts.

To the left is a photo of Michael and his grandmother, Hazel, who shows up in his short story, Dog Days.

And Mrs.Arbuthnot Patricia Feinberg Stoner

Mrs Arbuthnot didn’t 'do' the Internet. Nor did she do Christmas, frivolous literature or summer fayres (she shuddered at the spelling). She baked her scones, she looked after her cat – the evil-tempered Chairman Miaow – and waged a permanent, though mild, war against her neighbour Professor Mainwaring.

But even in a sleepy West Sussex village, the outside world must sometimes come a-knocking…

In these twelve tales from Gorehampton on Sea you will read how MrsArbuthnot fought for the book club, rescued a kitten, braved a shopping mall, survived Covid and visited Iceland on a sleigh.

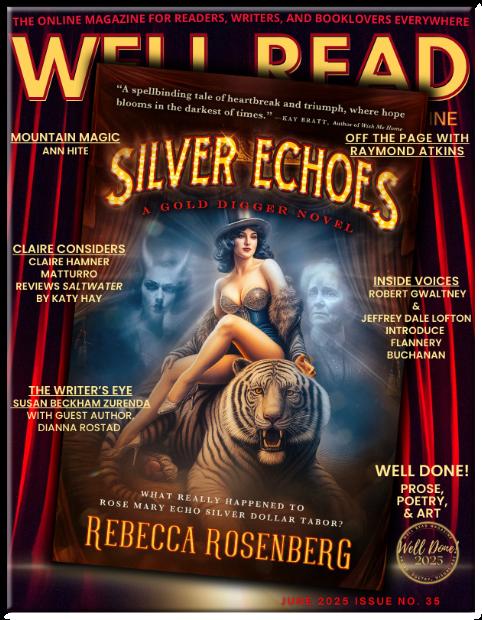

Silver Echoes:AHistorical Roaring Twenties Novel (Gold

Digger Biographical Fiction)

Rebecca Rosenberg

A Spellbinding Saga of Ambition, Identity, and Redemption. Based on a true story.

Chicago, 1920s: Movie starlet Silver Dollar Tabor's glittering life shatters after a brutal attack awakens a hidden self. Plunging into the city's dangerous underworld of burlesque speakeasies, she blurs the lines between ambition and destruction, testing her love for screenwriter Carl. This Jazz Age, Prohibitionera tale explores the dark side of fame and the fragility of identity.

Colorado, 1932: Haunted by Silver's disappearance, her mother, Baby Doe, fights to save their family's silver mine. A desperate search for her daughter unearths a shocking truth, rewriting their history. This dual timeline novel weaves a tale of resilience and the enduring bond between mother and daughter.

From the dazzling heights of the Flapper era to the rugged legacy of silver mining, Rebecca Rosenberg's "Silver Echoes" delivers a gripping historical fiction experience. Baby Doe Tabor's relentless quest for truth unearths the secrets of Silver Dollar Tabor. Perfect for fans of strong women in historical novels and stories based on real events.

What really happened to Silver Dollar Tabor?And can her mother uncover the truth before it’s too late?

In Nameless as the Minnows, poems move through an early consideration of one’s yet unrealized self being washed toward a faceless future, into an exploration of growth and resilience through family and loss, and farther into the miracles of forming a new family and finding one’s true name among the wonders of the natural world, culminating in the spirit yet reaching toward the stars, the universe, still questioning the unknowable and praising “the small rituals of becoming and being.”

After inheriting her late grandmother’s property in the deep forests of Georgia, twenty-two-year-old Clara Graham is forced to return to the beautiful, magical house where she lived briefly during childhood. But as she finds herself submerged in the dark secrets her grandmother left behind, she must face her own terrifying childhood memories that have come crawling back into the light, demanding a reckoning.

This essay collection spans a lifetime’s worth of characters, settings, themes, and ways of organizing. It is, after all, a collection of Gary Fincke’s best work. Yet, for the variety of content covered, from coming-of-age to family to nuclear weapons to space exploration to mass shootings to rock attacks on cars to the author’s mother’s obsession with potato chips, this collection has a durable thread that ties them all together: the need to observe and record everything. Struggle and resilience. Fear and pleasure. Faith and despair. Love and loathing. All of those tensions are closely examined within the shadow cast by death. As Gary Fincke writes, “Somewhere, early every day, I think the acolyte of terror dreams our bodies as it decides the exact address for delight.” This “thinking,” in essay after essay, is brilliantly articulated in an ever-evolving, contemporary style. The metaphors are beautiful, the prose is clipped and clean, and the reader is constantly surprised by the connections Fincke draws like the one between his daughter and Charles Manson.Apanorama of screams, another of hearts, another of headlights, all of them transformed into memoir. The subjects as varied as a four-part exploration of different kinds of hands, a meditation on terror and the fireworks American children know as Sparklers, and eulogies seeded by love of potato chips and crossword puzzles. Like the best essays, all of these “discover” in an intimate, personal way.

MADVILLE PUBLISHING seeks out and encourages literary writers with unique voices. We look for writers who express complex ideas in simple terms. We look for critical thinkers with a twang, a lilt, or a click in their voices. And patois! We love a good patois. We want to hear those regionalisms in our writers’ voices. We want to preserve the sound of our histories through our voices complete and honest, dialectal features and all. We want to highlight those features that make our cultures special in ways that do not focus on division, but rather shine an appreciative light on our diversity.

These straightforward and often beautifully interwoven essays by an outstanding storyteller and poet go straight to the heart of our common humanity. With candor, compassion, and an unobtrusive erudition, they probe the varieties of human vulnerability and remind us of the vigilance all real love requires.

—Robert Atwan, Series Editor, Best American Essays

Townsend Prize Finalist

In October of 1918, the world, still in the midst of a massive war in Europe, is experiencing a new challenge—a pandemic of what came to be known as the Spanish flu. But Cotella Barlow, living in an isolated county in Appalachian Virginia, has only heard rumors about it. Cotella, known as "Telly," makes her way in the world taking care of the families of new mothers who are "lying in" after their labors and deliveries. She travels home to home, eeking out a living, loved by many but always conscious of the stares and winces caused by her disfiguring condition.

Until she enters the home of her next "momma," who, days before delivery, is dying in a strange new way, her husband missing, and her four other children frightened, uncared for, and hungry. Telly must meet the challenge with no knowledge of the outside world that is shutting down while people suffer, die, and quarantine. Winter is coming, and there is no one to help, or so it seems.

This is a story of devotion, courage, strength, and love with iconic characters readers will come to cherish.

Released on May 20, 2023, this gripping novel has spent the past year drawing readers into the mind and moral dilemma of Kevin Elcott—a man who thinks he has life all figured out until one promise to his mother changes everything. With a prestigious job, a brilliant companion in Felicity, and a future mapped for success, Kevin never planned to trade ambition for obligation. But when family calls, will he answer—or escape? What does it mean to choose duty over desire?

Sudden Future invites us to reflect on sacrifice, relationships, and the uncertainty of what comes next.

AJourney of Family, Loss and the Power of Love

Born in the heart of the Great Depression, Jeanne Cahill's earliest days began in Dixie Union, a South Georgia hamlet on U.S. route 1, where she learned resilience, hard work, and the deep value of family. But her journey didn't stop there. From humble beginnings with an outhouse in the backyard to standing in the White House as a trusted advocate, Jeanne's remarkable life story is one of perseverance, service, and the unbreakable bonds of love.

With a spirit that refused to be confined by convention, Jeanne broke barriers long before it was common to do so. She became a trailblazer-an entrepreneur, an activist, and a confidant of Jimmy Carter-whose voice helped shape conversations on women's rights and social justice. Through personal loss, reinvention, and an unwavering commitment to those she loved, Jeanne's story is a testament to the strength found in self-determination and the enduring power of human connection.

At Colorful Crow Publishing, our mission is to amplify diverse voices and champion stories that resonate across communities. We believe every story matters, and we are dedicated to creating a welcoming, supportive platform for authors to share their unique perspectives. By fostering a collaborative environment, we aim to publish works that inspire, connect, and make a lasting impact on readers everywhere.

5.0 out of 5 stars Absolutely must read! A beautiful story quilted with fiction and well researched history. You'll fall in love with the characters and feel all the joy, love, heartbreak, and perseverance as they carry you through every page.

In Volume One, you’ll find thirty-eight submissions written by a fantastic mix of awardwinning authors and poets plus new ones to the scene. Three submissions in this volume were nominated for a Pushcart Prize: Miller’s Cafe by Mike Hilbig, Sleeping on Paul’s Mattress by Brenda Sutton Rose, and A Hard Dog by Will Maguire. The cover art is by artist, Lindsay Carraway, who had several pieces published in February’s issue.

Contributors: Jeffrey Dale Lofton, Phyllis Gobbell, Brenda Sutton Rose, T. K. Thorne, Claire Hamner Matturro, Penny Koepsel, Mike Hilbig, Jon Sokol, Rita Welty Bourke, Suzanne Kamata, Annie McDonnell, Will Maguire, Joy Ross Davis, Robb Grindstaff, Tom Shachtman, Micah Ward, Mike Turner, James D. Brewer, Eileen Coe, Susan Cornford, Ana Doina, J. B. Hogan, Carrie Welch, Ashley Holloway, Rebecca Klassen, Robin Prince Monroe, Ellen Notbohm, Scott Thomas Outlar, Fiorella Ruas, Jonathan Pett, DeLane Phillips, Larry F. Sommers, Macy Spevacek, and Richard Stimac

InVolumeTwo, you’ll find fortythree submissions written by a fantastic mix of award-winning authors and poets plus new ones to the scene. Three submissions in this volume were nominated for a Pushcart Prize: A Bleeding Heart by Ann Hite, A Few Hours in the Life of a Five-Year-Old Pool Player by Francine Rodriguez, and There Were Red Flags by Mike Turner. The cover art for Volume Two is by artist, DeWitt Lobrano, who had several pieces published in November’s issue. Enjoy!

Contributors: Ann Hite, Malcolm Glass, Dawn Major, John M. Williams, Mandy Haynes, Francine Rodriguez, Mike Turner, Mickey Dubrow, William Walsh, Robb Grindstaff, Deborah Zenha Adams, Mark Braught, B. A. Brittingham, Ramey Channell, Eileen Coe, Marion Cohen, Lorraine Cregar, John Grey, J. B. Hogan, Yana Kane, Philip Kobylarz, Diane Lefer, Will Maguire, David Malone, Ashley Tunnell, Tania Nyman, Jacob Parker, LaVern Spencer McCarthy, K. G. Munro, Angela Patera, Micheal Spake, George Pallas, Marisa Keller, Ken Gosse, and Orlando DeVito

TheyAll Rest in the Boneyard Now by Raymond L.Atkins

(Author), Evelyn Mayton (Illustrator)

“Raymond Atkins writes with intuitive wisdom, as he channels those from beyond the grave. His poetry gives voice to those who once mattered, those who time wants us to forget. In They All Rest in the Boneyard Now, Atkins wrestles death from the dusty clay and breathes life into dry bones while reminding us that every soul who once had breath is worthy of being remembered. These saints, sinners, socialites, and the socially inept are all victims of time, or circumstance, as we too shall one day be. Atkins offers salvation to all who are tormented, and solace to those who seek eternal rest.”

– Renea Winchester,Award-winning author of Outbound Train

The Cicada Tree by

Robert Gwaltney

The summer of 1956, a brood of cicadas descends upon Providence, Georgia, a natural event with supernatural repercussions, unhinging the life of Analeise Newell, an eleven-year-old piano prodigy. Amidst this emergence, dark obsessions are stirred, uncanny gifts provoked, and secrets unearthed.

During a visit to Mistletoe, a plantation owned by the wealthy Mayfield family, Analeise encounters Cordelia Mayfield and her daughter Marlissa, both of whom possess an otherworldly beauty, a lineal trait regarded as that Mayfield Shine. A whisper and an act of violence perpetrated during this visit by Mrs. Mayfield all converge to kindle Analeise’s fascination with the Mayfields.

Analeise’s burgeoning obsession with the Mayfield family overshadows her own seemingly, ordinary life, culminating in dangerous games and manipulation, setting off a chain of cataclysmic events with life-altering consequences—all of it unfolding to the maddening whir of a cicada song.

Haints

on Black

Mountain:AHaunted Short Story Collection by Ann Hite

Ann Hite takes her readers back to Black Mountain with this haunted short story collection.

An array of new characters on the mountain experience ghostly encounters. The collection took inspiration from her beloved readers, who provided writing prompts. Wrinkle in the Air features Black Mountain's Polly Murphy, a young Cherokee woman, who sees her future in the well's water. Readers encounter relatives of Polly Murphy as the stories move through time.The Root Cellar introduces Polly's great grandson, who tends to be a little too frugal with his money until a tornado and Polly's spirit pays the mountain a visit. In The Beginning, the Middle, and the End, readers meet Gifted Lark on an excessively frigid January day. This story moves back and forth between 1942 and 1986 telling Gifted and her grandmother Anna's story. This telling introduces spirits that intervene in the spookiest of ways.

Red Clay Suzie by

Jeffrey Dale Lofton

Anovel inspired by true events. The coming-of-age story of Philbet, gay and living with a disability, battles bullying, ignorance, and disdain as he makes his way in life as an outsider in the Deep South—before finding acceptance in unlikely places.

Fueled by tomato sandwiches and green milkshakes, and obsessed with cars, Philbet struggles with life and love as a gay boy in rural Georgia. He’s happiest when helping Grandaddy dig potatoes from the vegetable garden that connects their houses. But Philbet’s world is shattered and his resilience shaken by events that crush his innocence and sense of security; expose his misshapen chest skillfully hidden behind shirts Mama makes at home; and convince him that he’s not fit to be loved by Knox, the older boy he idolizes to distraction. Over time, Philbet finds refuge in unexpected places and inner strength in unexpected ways, leading to a resolution from beyond the grave.

The Smuggler's Daughter by

Claire Matturro

Ray Slaverson, a world-weary Florida police detective, has his hands full with the murders of two attorneys and a third suspicious death, all within twenty-four hours. Ray doesn’t believe in coincidences, but he can’t find a single link between the dead men, and he and his partner soon smash into an investigative stonewall.

Kate Garcia, Ray’s fiancée, knows more than she should. She helped one of the dead attorneys, just hours before he took a bullet to the head, study an old newspaper in the library where she works. Kate might be the only person still alive who knows what he was digging up— except for his killer.

When Kate starts trying to discover what’s behind the murders, she turns up disturbing links between the three dead men that track back to her family’s troubled past. But she has plenty of reasons to keep her mouth shut. Her discovery unleashes a cat-and-mouse game that threatens to sink her and those she loves in a high tide of danger.

The Bystanders by Dawn Major

The quaint town of Lawrenceton, Missouri isn’t sending out the welcoming committee for its newest neighbors from Los Angeles—the Samples’ family. Shannon Lamb’s “Like a Virgin” fashion choices, along with her fortune-telling mother, Wendy Samples, and her no-good, cheating, jobless, stepfather, Dale Samples, result in Shannon finding few fans in L-Town where proud family lines run deep. Only townie, Eddy Bauman, is smitten with Shannon and her Valley Girl ways. The Bystanders is a dark coming-of-age story set in the 1980s when big hair was big, and MTV ruled. In a quiet town of annual picnics and landscapes, the Samples’ rundown trailer and odd behaviors aren’t charming the locals. Shannon and Wendy could really use some friends but must learn to rely upon themselves to claw their way out of poverty and abuse if they want to escape Dale.

The Bystanders pays homage toAmericana, its small-town eccentricities, and the rural people of the Northern Mississippi Delta region of Southeast Missouri, a unique area of the country where people still speak Paw Paw French and honor Old World traditions.

The Girl from the Red Rose Motel:ANovel by Susan Beckham Zurenda

Impoverished high school junior Hazel Smalls and privileged senior Sterling Lovell would never ordinarily meet. But when both are punished with in-school suspension, Sterling finds himself drawn to the gorgeous, studious girl seated nearby, and an unlikely relationship begins. Set in 2012 South Carolina, the novel interlaces the stories of Hazel, living with her homeless family in the rundown Red Rose Motel; Sterling, yearning to break free from his wealthy parents' expectations; and recently widowed Angela Wilmore, their stern but compassionate English teacher. Hazel hides her homelessness from Sterling until he discovers her cleaning the motel's office when he goes with his slumlord father to unfreeze the motel's pipes one morning. With her secret revealed, their relationship deepens. Angela-who has her own struggles in a budding romance with the divorced principal-offers Hazel the support her family can't provide. Navigating between privilege and poverty, vulnerability and strength, all three must confront what they need from themselves and each other as Hazel gains the courage to oppose boundaries and make a bold, life-changing decision at novel's end.

The Best of the Shortest: ASouthern Writers Reading

Reunion by

Suzanne Hudson (Author, Editor), Mandy Haynes (Editor), Joe Formichella (Author, Editor)

“Some of the happiest moments of my writing life have been spent in the company of writers whose work is included in these pages. They all brought their A-game to this fabulous collection, and at our house it is going on a shelf next to its honored predecessors. The only thing that saddens me is that the large-hearted William Gay is not around to absorb some of the love that shines through every word.” ―Steve Yarbrough

“The Best of the Shortest takes the reader on a fast-paced adventure from familiar back roads to the jungles of Viet Nam; from muddy southern creek banks to the other side of the world, touching on themes as beautiful as love and as harsh as racism. However dark or uplifting, you are guaranteed to enjoy the ride.” --Bob Zellner

“I had some of the best times of my life meeting, drinking and chatting with the writers in this book, times matched only by the hours I spent reading their books. This collection showcases a slice of Southern literature in all its complicated, glorious genius. Anyone who likes good writing will love it.” --Clay Risen

Walking The Wrong Way Home by Mandy Haynes

Spanning nearly twenty decades, the struggles and victories these characters face are timeless as they all work towards the same goal.

A place to feel safe, a place to call home.

Sharp as a Serpent's Tooth: Eva and other stories by Mandy Haynes

Each story features a female protagonist, ranging from ten to ninety-five years of age. Set in the south, you’ll follow these young women and girls as they learn that they’re stronger than they ever thought possible.

Oliver by Mandy Haynes

“Dear God…and Jesus and Mary…” Even though eleven-year old Olivia is raised Southern Baptist, she likes to cover her bases when asking for a favor. Unlike her brother Oliver, she struggles with keeping her temper in check and staying out of trouble. But Oliver is different, and in the summer of ’72 he proves to Olivia there’s magic in everything - it’s up to us to see it.

Mandy Haynes spent hours on barstools and riding in vans listening to great stories from some of the best songwriters and storytellers in Nashville, Tennessee. After her son graduated college, she traded a stressful life as a pediatric cardiac sonographer for a happy one and moved to an island off the east coast. She is a contributing writer for Amelia Islander Magazine, Amelia Weddings, and editor of Encounters with Nature, an anthology created by Amelia Island writers and artists. She is also the author of two short story collections, Walking the Wrong Way Home, Sharp as a Serpent's Tooth Eva and Other Stories, and a novella, Oliver. She is a co-editor of the Southern Writers Reading reunion anthology, The Best of the Shortest. Mandy is the editor-in-chief of WELL READ Magazine and the editor of four WELL READ anthologies.

Like the characters in some of her stories, she never misses a chance to jump in a creek to catch crawdads, stand up for the underdog, or the opportunity to make someone laugh. At the end of 2024, Mandy moved back to middle Tennessee and now spends her time writing and enjoying life as much as she can.

If you’d like to feature your work in the reading recommendation section with live links to your website and purchase link, and personalized graphics of your ad shared to WELLREAD Magazine’s social sites, click here to see examples of the different options and moreinformation.

Click here for more information on purchasing a cover.

Don’t let the low prices fool you - WELL READ was created by an author who understands how much it costs to get your book in the best shape possible before it’s ready to be queried by agents, small presses, or self-published. Showing off your book and getting it in front of readers shouldn’t break the bank.

WELL READ Magazine receives approximately 8,000 views each month on Issuu’s site alone (the world’s largest digital publishing and discovery platform available). Your book will be included with the featured authors, great interviews, submissions, essays, and other fantastic books inside each issue. There is strength in numbers. Let’s get our books seen!

Ad rates for 2025:

$50 - One FULL PAGE AD

$75 - TWO-PAGE SPREAD

$100 - TWO HIGH IMPACT - FULL COLOR PAGES - (this is NOT a standard two page spread)

$100 - TWO-PAGE SPREAD to advertise up to THREE books with one live link to your website. For publishers only.

$75 BOOKSTORES, PUBLICISTS, AUTHORS - two-page spread to promote book events

$550 FRONT COVER - includes TWO full color interior pages for book description, author bio, and/or blurbs.

$350 INTERIOR COVER or BACK COVER - includes TWO additional full color interior pages for book description, author bio, and/or blurbs.

*All covers include a one page ad in the next three consecutive issues following the month your book is featured on a cover.

Prices include creating the graphics for the magazine pages and all social sites. Everything is taken care of for you.

INSIDE VOICES

Robert Gwaltney and Jeffrey Dale Lofton

introduce

Andie Burke & Lindsay Hameroff

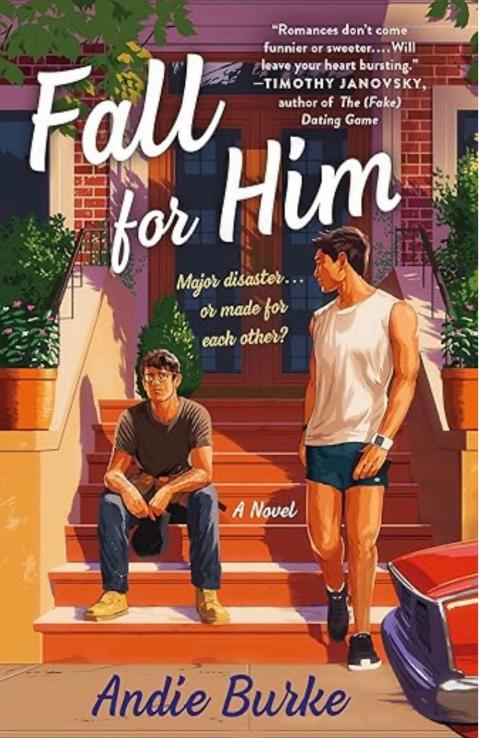

Andie Burke writes romantic comedies in between her pediatric RN shifts. She lives in Maryland with an alarming number of books, ultra-fine point pens, dehydrated houseplants, and two small humans. Her debut Fly with Me was listed as one of POPSUGAR’s Best Romance Books of 2023 and AUTOSTRADDLE’s Best Queer Books of the Year. Her latest book is Fall for Him and came out in Fall of last year. Andie has another book coming out this fall With Stars in Her Eyes.

Lindsay Hameroff is the author of Till There Was You, Never Planned on You, and other love stories that make you laugh and swoon in equal measure. Her books have been listed as most anticipated by The Nerd Daily, Zibby Magazine, and other outlets, and her debut novel was selected as one of New York Public Library's "Best New Romance Books." A native of Baltimore, Maryland, she now lives in Harrisburg, PA with her husband and two kids. If she's not writing, reading, or cleaning up cat hair, she's probably at the grocery store.

Inside Voices/Jeffrey: How did you find your way to writing?

Andie: Storytelling has been a compulsion since I learned how to hold a pencil. I traipsed around the woods on my own (it was the

Robert Gwaltney & Jeffrey Dale Lofton

Andie Burke & Lindsay Hameroff

90s) while creating fictional worlds in my head. I figured out who I was as a confused teenager through being a voracious reader and finding characters whose struggles mirrored my own. As I headed into adulthood, I wasn’t quite sure how writing would fit into my life. Although I was an English literature major in college, I pivoted into nursing for graduate school. I kept writing in a variety of ways, but about ten years ago I started seriously writing adult fiction in a variety of genres and trying to figure out how to pursue it as a career.

Lindsay: I’ve wanted to write books since childhood, but I had no idea how to break into it. I didn’t know anyone who was an author, and the dream of seeing my name in a bookstore seemed as far-fetched as becoming a movie star. But things changed during the pandemic. I had spent a decade teaching middle school English and was on maternity leave when the world shut down. Suddenly, I was home all day with two young kids and a lost sense of identity. I desperately needed something for myself and so, I revisited my first love: writing. I started drafting short humor for publications like McSweeneys, and those outlets wanted me to have a Twitter account. 2021 was an ideal time to be on Twitter because everyone was at home and hanging out online. It served as an unofficial mentorship program, where other writers coached me on how to query an agent and build my resume.When a literary agent reached out and asked if I had interest in writing a book (only the dream of my life!), I enrolled in an online novel writing workshop, where I

completed my first draft of my debut novel. I sent it out six months later and have been writing ever since.

Inside Voices/Robert: Why do you write what you write?

Andie: As a reader, I always gravitated toward stories with a compelling romantic subplot. I grew up reading a lot of fantasy and mysteries, and if my parents suggested a book series to me, I would always ask if there was romance in it first. I got into reading the romance genre as an adult. I love that romance is one of the only genres that makes its readers a promise. It’s a fun challenge to find new and creative ways to help my characters reach their happily ever after. I’ve written in many genres, and no matter what kind of book I’m working on, I hope my characters help readers feel seen.

Lindsay: I took a few classes with The Second City when I was predominantly writing humor, and an instructor imparted the writing advice I live by: write the thing you want to read. I love rom-coms and stories that are swoony, but I also want to laugh out loud. I want to fall head over heels for a fictional man, and I want a protagonist I’d befriend in real life. Most of all, I want to have fun and be smiling when I read. I also love pop culture and millennial humor, because one can never have too many jokes about these topics. So, I strive to write books that are all those

Robert Gwaltney & Jeffrey Dale Lofton introduce Andie Burke & Lindsay Hameroff

things.

InsideVoices/Jeffrey:Andie, how does your medical career and writing career intersect? How does it show up in your writing?

Andie: I’ve spent over a decade working in pediatric nursing. I’ve witnessed both ecstatic and tragic pivot points in people’s lives—the kind of moments where people will forever look back and divide their life into a before and an after. I’ve seen grief and excitement and joy and anger and fear. These experiences helped me develop emotional depth in my writing. Nurses learn a lot about humanity in the hours we spend in our scrubs. And I find that my time at work affects my life outside it as well. I process what I’ve seen and felt by making up my own stories and working through my own big feelings about it while helping my characters do the same.

Inside Voices/Robert: So, these are your second books. How was the experience of these different from your debut experience?

Andie: Hoo boy. I wish I could say I felt more confident and knowledgeable the second go-round. In reality, I feel like

publishing continues to be an enigmatic, many-headed monster. I have absolutely no idea what I’m doing at any given moment. I’m lucky to have an incredibly supportive publisher, editor, and agent who help guide me through the process when I feel like I’m on the verge of being gobbled up by anxiety.

Lindsay: So much of my debut experience consisted of learning about publishing. I had no idea what to expect or how the business worked. Every time my agent would email me, I’d say, “This sounds great! Also, what does this mean?” To my chagrin, there’s no onboarding package, so there was a huge learning curve. By the time I was drafting my second book, I knew the ropes a bit, but I was also juggling editing and promoting my first book. Everything seemed to move faster the second time around. It felt like an endless wait for my first book to get published, and then the second completely snuck up on me.

In terms of craft, the biggest difference in writing my second book was that I trusted myself more. With my first, I was constantly seeking feedback from anyone willing to read my pages and then second-guessing all my choices. With my sophomore novel, I was selective with beta readers and followed my own instincts.

Inside Voices/Jeffrey: Both of your second books have characters that appeared in your first books. How did you expand

upon their smaller role in your first books to flesh them out to have their own stories?

Andie: My second book was easier to write because Derek, one of the main characters in Fall for Him, has been a real person to me for a couple books now. So much of my writing process feels more like transcribing an extended hallucination rather than an intentional plot development process. I knew I wanted Derek to have a happily ever after, and then I just wrote down the story as I saw it play out in my imagination. I’m realizing this is probably a terribly unsatisfying answer. I have no idea where the story comes from. I knew Derek was a bit of a control freak, so obviously he needed to be bombarded with as much chaotic hilarity as I could fit between the covers. (Pun intended)

Lindsay: The main character in my second book was a side character in my first. When it came time to pitch book two, I had this kooky idea about a wedding planner who shared a matching tattoo with the groom. My editor said, I like this idea, but can the main character beAli, the best friend from your first book?Ali was a chef, not a wedding planner, so I had to do some brainstorming to figure out how to make that work. But once I did, the rest of the story flowed.

In some ways, it was easier to write a character I already knew. To expand on her, I asked myself questions about her origin.Ali is

Robert Gwaltney & Jeffrey Dale Lofton

really funny–in my first book, she provides comic relief in nearly every scene. But as the main character in her own story, she needed more depth. So, I found myself wondering, what self-doubts and fears is she masking with that trademark humor? What kind of relationship does she have with her family? What drives her decision-making? And most importantly, what was keeping her from finding love in the first book? In a way, it was like solving a mystery by working backwards and that was a lot of fun.

Inside Voices/Robert: How do you keep the experience of writing, especially with a deadline, a fun process?

Andie: I always try to find ways to lose myself in the story. If I slow down or get stuck, I follow the authorial dopamine to a chapter or scene that will energize me. I don’t always write perfectly chronologically. I don’t sit down at my laptop every day. I do a lot of “writing” in my head on the days I’m not putting words on a page. When I can, I give myself a few days in a row to bingewrite. During times like this, I end up getting proof-of-life check-in texts from family members. Nothing’s more fun for me than getting to completely immerse myself in the drafting process without tons of distractions. It propels my momentum forward in the best way.

Lindsay: Writing on a deadline is hard! I try to keep myself organized with a daily word count. Sometimes it’s helpful, but other times, it just makes the whole thing feel like a chore. I’ll find myself checking my word count constantly to see if I’m “finished” yet, the same way I check my watch during a workout class.

To stay energized, I’ll write off-topic. If there’s a scene I’m excited about but comes later in the book, I’ll spend 30 minutes writing it. I may have to rewrite it later or scrap it all together, but at least the muscle gets stretched in a fun way. I’ll also pull writing prompts off the internet and write from those, just for fun. I also find that my mood plays a huge role in whether the writing feels enjoyable. Sometimes I’ll go watch an episode of a sitcom that makes me laugh because I find the words come easier when I’m happy.

Inside Voices/Jeffrey: Why do women like men written by women?

Andie: I was raised Southern Baptist, and when I was a little girl, I was taught that I was responsible for the thoughts and behavior of the men around me. My greatest imperative was to find a good Christian man to marry. My greatest danger was for a bad man to take my purity before marriage. Ugh, I know.This might be an odd way to start this answer, but I think it speaks to the

Gwaltney & Jeffrey Dale Lofton

underlying tension in the way young girls are socialized with regards to men. Men are simultaneously saviors and threats.As we grow into womanhood, too many of us encounter Wickhams or Willoughbys masquerading as—or even perhaps believing themselves to be—our heroes. (Please forgive the Austen reference). We don’t need saviors. We certainly don’t need threats. Usually, we don’t even need heroes, exactly. A good man written by women often feels safest because in the end, they simply are who they seem to be.

Lindsay: Men written by women, especially in a novel that has dual POV, offers female readers something they’ve always wanted: the ability to know what men are thinking. It also grants readers access to the depth of a man’s feelings, his insecurities, and his vulnerabilities.Aman written by a woman is an open book and that makes him so much more endearing.

It’s grim to say this, but men written by women are also safe. The hard truth is that in real life, women need to be on constant alert around men. But a fictional man is not going to hurt you. I think morally gray men are popular in romance because women want a pathway to exploring fantasies without risking real danger. Plus, fictional men spend a lot less time on the toilet.

Inside Voices/Robert: Lindsay, I heard you say something about Romance not getting its due. Would you both comment on

Robert

Robert Gwaltney & Jeffrey Dale Lofton

Romance stories’place in the literary pantheon?

Lindsay: I don’t think it’s any secret that romance is viewed as an “unserious” genre. It’s not a widely respected form of literature, which is laughable because it is the most popular and highest selling genre in the industry. Rebecca Yarros’ books have sold 55 million copies worldwide, and yet a recent article described her writing as “dragon smut.” The lack of respect for successful romance writers is wild.

I also don’t think it’s a coincidence that the primary producer and consumer of romance is women. Unfortunately, it seems that anything that is primarily for and by women is not taken seriously.

Inside Voices/Robert: What’s next for you?

Andie: My third book With Stars in Her Eyes comes out September 16 of this year. It’s a sapphic romance set in a quirk indie bookstore wherein an incognito rockstar meets an astrophotographer. It’s set in the same world as my first two, but all three books can be read as standalones. I’ll be doing some fun events at bookstores for that book release. Can’t wait!

Lindsay: My third book, Rewrite the Stars, comes out July 7,

Robert Gwaltney & Jeffrey Dale Lofton introduce Andie Burke & Lindsay Hameroff

2026. It features all new characters and leans a bit more contemporary romance than rom-com. It’s also set in Pennsylvania! I’m really excited about it.

"With strong friendships, a full cast of delightful characters, and a story told from alternating points of view, this enemies-to-lovers and forced-proximity romance from Burke (Fly with Me) explores serious issues such as neurodivergence, alcohol-use disorder, toxic family expectations, forgiveness, and grief, while still being a steamy, humorous, and hopeful read."

- Library Journal (starred review)

Fall for Him Andie Burke

"A pure delight...It’s giving ’90s chick flick, in the best way." –

Glamour Never Planned on You: A Novel Lindsay Hameroff

Click above to go to the BETWEEN THE PAGES YouTube channel, or on one of the links below to listen to the podcast. Please take a second to like and subscribe if you enjoy the channel - we appreciate you!

Mountain Magic in Person

By the time, dear readers, you read this column, I will be hidden away in my beloved mountains, far from phones, where the only sounds I hear at night are owls calling back and forth, the stars so numerous in the sky I am speechless, the painting of the horizon so brilliant I won’t remove my stare to capture a photo that would never do it justice anyway; instead I relax into experiencing it in the moment. Writing the words in my head to describe if for a later use. Yet, will that fall short? Surely so.

ThisretreatisatimeofstillnesswhereIhearthevoicesdeepinmy thoughts, telling stories in a haunting stenciled kind of way. Think about the cave drawings found stenciled on the rocky walls. Paint blown over a human’s hand.The art created from what was removed. Stenciled like a tattoo for those thousands of years in the future. In this way we have proof of the ancient artists that felt moved to create longbeforetheyhadthewrittenword.Theseweretheirstories.Magic is in the voices lingering on these walls, inspiring those in the future to create, to spin straw into gold.

On this trip, I will meet mountain magic in person, hear the whispers calling me before the road rises into the softly rounded, cloud-shrouded mountains. The mist hugs the ground in the valley at dusk, the gray light, the time the stories of the past lives, overlaps like

agrainyblackandwhitefilm.IfIamquietandlisten,mountainmagic gives me a tale, a poem, sometimes even a book. The cool air swims in on the cries of the wild turkeys as they find their place to roost for the night. This is the time of haints, of haunting lives, important stories imprinted on the soul of the land.

As a child my heart was open to imagination, the magic, the belief that rivers were living beings, that fairies hid from adults in the form of fireflies. Mountain magic was my constant companion that I kept closest to my heart. As a writer I believe in mountain magic, still, to this very day. My art is the rushing water that overflows its banks, spillingintowordsthatpaintimages,thattellthestoriesweashumans depend on, feed on, nurture ourselves with.

As my annual meetup with mountain magic nears, my dreams are filled with new characters, a magic house with its own voice. If we wanttobloomasartists,wemustopenourmindstothehauntingtales that seem the most unlikely, our hearts to the books attempting to be written.Wehavetosuspendthepracticalbeliefineverydaylife.Cross over into the heart of telling. The place my granny loved the most when she sat with her sisters talking about the once upon a times.

Where does the mountain magic reside for you, dear readers? Are you still engaged enough to hear its whispers, to grow in the uncanny offer in front of you? Be open to magic. Seek it out. Create, dream, andjustbeinsideofit.Putpentopaper,painttocanvas,handstoclay. Mold what is deep within you. Be the cave people from so long ago. Stencil your hearts on the walls. Happy hunting!We will meet again when I return.

Special thanks to Jerry Hite for the two photos of the mist over the land

Never Give Up

Janet Clare

When my first novel was published seven years ago, the writer and literary critic, John Freeman, suggested I write an essay about publishing a book as an “older” writer. Beyond my desire not to be categorized—not by age, and/or gender, and/or anything at all other than a still-breathing writer—I wrote an essay and positioned myself, not as a debutante, but as someone nevertheless making my debut.

As we all know, the passage of time is relentless. Whether the years are filled with sublime happiness or utter sadness, or, like most of us, with a combination of both. It just goes, and sometimes, our dreams go with it. We turn around and ten or twenty years have whipped by and we are left to wonder what else we could have, should have, done.

As a lifelong reader, I admired writers above all and I’d always wanted to write. But it seemed there was never the time or the space or the confidence to begin. Plus, I’d been married to a writer, which works for some, but not for me; not enough air and patience

for two of us. Then everything changed. Divorce, business shuttered, remarriage. Though well past forty, I finally sat down to write nearly every day. At first, it was a kind of journal, which today might be called a blog, but after a year I decided it needed to have form, to tell a story, and I started a novel. I had no idea what a difficult goal I’d set for myself, didn’t know enough not to do it. So I kept writing until I found the heart of the story that later would become my first novel.

Ayear into it, I got sick. The kind of sick that alters your day-today existence and threatens your life. However, I was one of the lucky ones, (nearly twenty-eight years later, here I am), and more than anything, once I got through to the other side, I just wanted to finish my book. I kept writing for another year until I had what I thought of as a first draft. But the real turning point came when I happened into an extension class at UCLA with the best of all possible teachers—someone who became a mentor, a guide. It’s likely I wasn’t always the oldest person in his class, although sometimes, I might have been. But it didn’t matter, and I didn’t care. I rarely divulged personal information, wanting to be as anonymous as possible to avoid any preconceptions. I threw out everything I’d written and started over, changing the POV from third person to first. Writing, as every writer knows, is rewriting. Fortunately, I had fallen in love with the process. I was hooked, and years later, after my mentor’s sudden and devastating death, I kept at it. I thought I couldn’t write without him somewhere in my life, but I discovered I could. He was that good, his wisdom had

become a part of me. I couldn’t not write. After a few more years and multiple drafts, I had a finished manuscript to send out, and, amazingly, I found an agent in New York. I thought my troubles were over. I was wrong. The agent did nothing, and I was beyond discouraged. After holding on far too long, I realized the wrong agent might as well be no agent, so I fired her and worked on a new book, although in the back of my mind I kept returning to my Australian story.

Yes, Australia. As an American born in New York and raised in California, I’d always been intrigued by the most far-away places. Australia, Botswana, Patagonia, and I’d been fortunate to travel to some of them. A number of years ago, I was told the true story of a man from Australia who, having spent most of his life in the United States, returned home for his father’s funeral only to find that he had a whole other family living on the other side of the country. It is, of course, a big country. But it got me thinking about families and secrets, and all the spaces where we can hide ourselves in a vast and solitary land, the distance between us not always measured in miles. I realized, too, that whenever I’d traveled to remote places, especially outside of cities, it was usually the sky and the air that made the greatest impact on me. And so, I was drawn to the openness of the Australian outback, particularly to the old stock routes where cattle once ran. My interest grew as I learned how these routes were established—by explorers on camels, with wells dug a days’ drive apart—and decided to set my story along the famous Canning Stock Route that

runs from Halls Creek in the Kimberley of Western Australia to Wiluna in the midwest. Crossing both the Gibson and Great Sandy deserts, 1,900 kilometers through some of the most isolated wilderness on the planet, the Canning is still considered the roughest outback track in the country. In thinking about my story, I wondered what it would be like for an American woman, a New Yorker, to find herself out of her element in a place she never expected to be.

In the early days of my research for the book, I connected with the flying doctors, those magnificent aeromedical professionals who offer emergency and primary health care to remote areas, and I was in touch with them when they rescued the famous art critic, Robert Hughes, after a near-fatal accident while filming in the way outback. “Yup, that was me,” my guy said, after swooping in and picking up the crew. “Notice we didn’t get any credit.” And it was true, news reports rarely referred to the flying doctors, unsung, everyday heroes. I had conjured up a fictitious doctor in an early version of my novel, but he got lost in the dust of later drafts. It happens.

I read everything I could about Australia, visited museums, discovered the deadliest of snakes, the oddest of animals, a multitude of flora, and virtually stalked bikers from the Netherlands as they attempted the Canning Track. All the while, I listened to the beat of the great dead heart of the desert. What I discovered about research was to do it and forget it. Simply let everything you’ve learned become a part of you so that it seeps into

your story. It certainly did for me, and, frankly, has never really left.

After parting with my original agent, I made a number of attempts to connect with the right person, until I finally gave up. But I still believed in my story. Meanwhile, I worked on two other books. Finally, encouraged by the wonderful writing of an Australian friend, and still obsessed by the country itself, I pulled out my manuscript, looked it over, did a bit of sprucing up, and sent it off to a small Australian publisher. They loved it. I was thrilled. For an American writer to find a publisher in Australia, where my heart had traveled for so long, was perfect. My publisher didn’t change anything from the original story.

So hardly a debutante in life, I made my debut. It had been quite a while getting there, and like most books, it went through many changes, as did I. But I truly believe in the power of never giving up, and I like to think it took just as long as it was supposed to. I write to be read, and hopefully my story has found an audience. And now, miraculously, I’m making what I like to think of as another debut with my second novel. But the most important thing I’ve learned, beyond the extraordinary joy of writing, was to never stop, to always make time to do what you love most, and above all, power on.

Janet Clare’s first novel, Time Is the Longest Distance, was published in 2018 and she previously published fiction and essays in a variety of online journals and anthologies. True Home her second novel, will be published May 20, 2025. She lives in Los Angeles.

Burtrell’s Pieces

Jeff Clemmons

Burtrell's desire for Lorraine started long before he loved her. In fact, twenty years into their marriage and nineteen years after his desire had tempered, love remained little more than an inkling of an idea simmering on the back burner of his unconsciousness. It wasn't until their firstborn died in childbirth - Lorraine rising every morning against her grief to bottle feed their newly orphaned grandbaby - that Burtrell, whose heart had broken into a hundred tiny pieces, began to love his wife.

BURTRELL’S PIECES

Jeff Clemmons is a cofounder of M’ville, an Atlanta-based writing salon. In addition to writing two books – Rich’s: A Southern Institution and Atlanta’s Historic Westview Cemetery – and a screenplay, he, along with three others, was nominated for an Emmy Award for producing Georgia Public Television’s “Rich’s Remembered.” He is currently working on a biography of avant-garde novelist Frances Newman.

Lady Sings the Blues

Mike Ross

“Good evening, GOOD EVENING, LADIES AND GENTLEMEN!!” A woman’s voice rises above the crowd. “Welcome, welcome! I’m Lilly and I’m so glad to see you all! Sit back, relax with a whiskey and cigarette and let me entertain you.” The voice is practiced, professional, the delivery precise and measured. She has done this hundreds of times. The glare of the lights dances off glass and polished wood. Every head is turned toward her as she commands attention.

“I’d like to start with a request from the audience. Would someone like something special?” I hear nothing, as if the crowd is too mesmerized to speak. “Yes… yes… of course I know it, sweety!” she smiles at someone near the front. “Band… that’s it… that’s the number.” After a few seconds, a dark, rich-as-coffee voice floats over us, surrounding the crowd. A few of them have bottles of whiskey, others, cartons of cigarettes, serious partiers. Lilly looks up at the lights, one hand high, her eyes closed and she starts a Billie Holiday jazz favorite, Stormy Weather. The cabaret

song envelopes us and the crowd watches silently as she croons.

Don’t know why, there’s no sun up in the sky, Stormy Weather . . . .

The low, smoky voice resonates like mahogany. With her eyes closed, belting out this classic, Lilly is in a world of her own, cocooned, warm, a place she knows well.

No one stirs, no one raises a hand to order a drink. The voice dominates us, smoothly professional.Like musical magic, Lilly transports her audience, as she warbles her lament about her lost lover. We are lost in her, transfixed, in the moment. It’s easy to imagine we’re in a smoky cabaret in Berlin or New York and not here.

She sings the last baleful lines,

“Since my man and I ……ain’t together, keeps raining all of the time,” low and throaty, and finishes with head bowed.

“Thank you, thank you all. You’re a wonderful audience.” With both hands she throws the crowd a kiss. The place is silent. A few people set down packages and clap a bit, nervously, then a few more join in, until everyone is applauding in a crescending din. Someone yells for an encore.

Adisturbance just out of eyesight gets my attention.Thumps and crashes follow the men as they push their way through the throng toward the lady, suitcases and bags tumbling, they bustle toward the performer, the reality of security guys breaking the spell. Lilly hears them, too, and shields her eyes against the blazing lights to see them.

Her face contorts from sublime to confused, frowning first, then changing to fear as she looks around at the displays of stacked cartons of cigarettes, the rows of liquor bottles and the perfume counters in the Duty Free Shop in Frankfurt Airport. She begins tugging at her left ear lobe like a life rope as the men approach. No longer in the cabaret of her mind, she’s thrust out of her warm, comfortable world and back into the reality of the airport. The fear is frozen in her eyes.

Someone near her offers her a hand and she steps down off the Canadian Club crate she’s using as a stage. A store employee retrieves the candy cone that was her microphone but her other hand still holds an imaginary cigarette. She tugs at the earlobe, making it red raw.

“What is your name please, madame?” a young man asks her in clipped German. She looks at him stupidly. I step forward to translate. The throng that had surrounded her has gone back to shopping, pushing tiny grocery store carts filled with anything but groceries.

“Lilly, the men are asking for your name? Are you Lilly?” I ask her.

She turns to me. “Oh no dear! Tell them my stage name is Lilly. My real name…” But she trails off. On her bag is a name tag. Mildred Hawkins. I read her name in disbelief. She is one of the passengers I’m waiting for at FrankfurtAirport; she’s scheduled to be on my next tour.

I tell the security men her name and that she’s with me, that I am

theguideforhertour.Theyseemskeptical.Ishowthemmycredentials buttheylingeramoment.Throughoutthis,Lillyisfixatedonatenfoot high display of Ritter Chocolate, having forgotten about the men.

“I’ll take care of her,” I tell them, but I haven’t a clue what I can do. TheynodandmoveoffafterIassurethemshewillnotsingagain.Too bad, I think, this place could use a bit of livening up.

“Lilly… uh, Mildred, where is your husband, Lloyd?” I ask her. Lloyd had been the one to make their reservations with me. About three months ago we’d finalized the trip details and agreed to meet at the FrankfurtAirport. I’d not spoken to him since. Mildred looks like she hasn’t heard me so I repeat the question. She gazes around the arrivals hall.

“He must be in the men’s room. He must be,” she says. She notices theDutyFreeShopandthecrateofCanadianClubandblinks.“Where am I?” In careful words, I tell her where she is.

She turns to me and smiles, “Hello.And who might you be?” I say again who I am and suggest we look for Lloyd. “Lloyd?” she says, as if she has never heard the name.

“Your husband,” I say.

“Lloyd? Where is Lloyd?” she asks. “Is he here? Oh, my, I want some of that chocolate!” Mildred points at the Ritter Sport display in the shop and takes a step toward it.

“Mildred,”IsayasItakeherelbow.“PleasesitoverhereandI’lltry to find Lloyd.” She sits but cranes her neck to see the Ritter, no longer tugging on her ear. Keeping her within my sight, I call the emergency numberIhavefortheHawkinsandthedaughterinWaukegan,Illinois,

picks up. I explain who and where I am and that I have Mrs. Hawkins next to me.

“Oh, OH! Thank god!” comes the relieved voice. “You have my mother!” she sniffles. “We’ve been so worried!” she gasps. “Her memory care residence called me yesterday when she didn’t come to breakfast and we’ve been sick with worry ever since!” She excuses herself to get a tissue.

“M’am,I’mlookingforMr.Hawkinshereintheairportbut…”Iget no further when she interrupts.

“No, no,” she says. “My father, Lloyd, died about two months ago. When he got sick, he told me he’d have to cancel the trip. I guess he didn’t. My mother forgets everything. I don’t know how she remembered or how she got on the plane?” I tell her about Lilly’s rendition of Stormy Weather in the Duty Free Shop and the security guards.

“Oh dear,” she gasped. “Was she arrested?” No, I tell her, they left herinmycare.“MymomusedthenameLillyonstage,”sheexplains. “She was a headliner in jazz clubs in Chicago and cabarets in New Orleans. She loved that life, that world. She breaks into song all the time in her care home.”

I look over at Mildred. Now in her late 70s, she still had the voice that commanded an audience, if not a grasp of reality. “Can I speak to her please?” I hand the phone to Mildred who asks at least four times who“this”is.ThefirstthreetimesMildredtellshershedoesn’thavea daughter but something breaks through on the fourth try and I see her smile.

After some minutes of Mildred just listening she hands the phone back to me. The daughter tells me she will be on the next flight to Frankfurt. I explain how to find us in the city.

“I’m going to get some of that,” Mildred says as she points at the Ritter chocolate. On our way she stops and stares at the crate of Canadian Club. In one quick step, she’s on it again, hesitates, then raises her face into the brilliant track lights. She lifts her arms and breaks into another torch song. This time it’s Lady Sings the Blues. In one transformative instant, Mildred is Lilly again. She’s back in her own reality, where she’s young and happy, safe and warm.

To hell with security, I think, as a new crowd begins to form. Let her have this moment. Her voice soars across the hall, her face tilts into the rapture of the song. She’s in a New Orleans cabaret, belting out the lyrics, far, far away from here.

The author, Michael Ross, has flipped burgers at Burger Chef, been a County Jail administrator, a German teacher for 35 years, and a tour guide for 45 years. He lives in Michigan, with his wife, Dianna (an awesome editor), and has loads of kids and grandkids. He is a traveler, runner and skier but his first love is writing.

Cardinal Sins

Mike Nemeth

Oscillating blue and red lights shone through the dirty sheer curtains on the front window, interrupting our boisterous conversation and laughter.

“Oh, crap!” Eli said. Ready to flee, he sprang to his feet and pulled his wife up from the battered green leather couch.

“Police!” a man yelled while pounding on the front door.

“Too late to run,” Eddie said.

He moved to the door and looked through the small window. A tall, hollow-cheeked man in a checkered sport coat did the pounding. Beside him, a thick Black man with closely cropped hair wore shades although the sun had already set. The black cop wasn’t tall, but he was thick and muscular, like a football running back. He wrote on a clipboard while the white cop glared at Eddie through the cracked window.

“Open up!” the white cop said.

The duplex had no driveway so two squad cars, a small paddy wagon and one unmarked land yacht huddled on the weed-infested

lawn. The paddy wagon driver leaned against his rig nonchalantly, arms folded.

“The door is broken,” Eddie shouted. “Go around back and I’ll let you in.”

The cops exchanged looks. They hadn’t brought a battering ram.

“I’ll let you in the back,” Eddie assured them.

The white cop stationed two uniformed cops on the tiny front porch. He and the black cop hustled around the side of the duplex followed by two more uniforms.

Eddie turned away from the door and surveyed the room. Eli and his wife, Tiffany, had resumed their seats on the couch. Ricky and his underaged girlfriend—Eddie thought her name was Amber or Crystal, something pole dancers used on stage—stood next to Eddie’s roommate, Cole, near the kitchen. The teenager was holding a sixteen-ounce glass of crushed ice and Jack Daniels. Eddie grabbed the glass and gave it to Cole who scratched his head.

“Stay calm and we’ll be okay,” Eddie said to the room. He walked through the cramped kitchen to the back door that opened onto a porch. On the adjoining porch, behind the other half of the duplex, the little weasel-y guy, Damon, threw something into the backyard, gave Eddie a scared look, and disappeared inside like a chipmunk ducking into its tunnel to evade a predator.

The uniforms appeared from the side of the duplex, vaulted onto the porch and shoved Eddie inside. They herded Eddie all the way into the living room and took up guard positions blocking the

kitchen and the doorway to the bedrooms. The gaunt white cop ambled in and announced that he had a search warrant. He instructed everyone to remain in the living room while the two uniforms searched the bedrooms and the single bathroom. The black plainclothes cop then took the kitchen apart one drawer and one cupboard at a time while the white cop stood watch in the living room.

Tiffany stifled a chuckle as the toilet in the other half of the duplex flushed repeatedly. Cole gulped the teenaged girl’s drink and shuffled from one foot to the other.

The black plain clothes cop tired of dumping food containers and dishes into the sink. The two uniforms reentered the living room and shook their heads. The white cop said, “Search them and put them in the kitchen.”

One at a time, Eli, Tiffany, Cole, Ricky, the teenaged girl, and Eddie passed through hand searches by the uniforms on their way to the kitchen. When everyone was jammed into the tiny space, the uniforms searched the living room. There wasn’t much to search, a TV cabinet and the shabby green couch, but a few minutes later, one of the uniforms shouted, “Found it,” and ran into the kitchen to show the white plainclothes cop what he had found, like a bird dog bringing its master a dead pheasant. In his hand he cradled a ball of silver tinfoil.

“It was between the cushions of the couch,” the uniform said.

Carefully, the plainclothes cop unraveled the tinfoil to reveal stems and seeds, a few crumpled leaves. “Well, well.” He stuck his

nose close to the greenish brown vegetation and sniffed. “Mary Jane, for sure,” he said.

The plainclothes cop looked from one cowering person to another. “Whose is it?”

Eyes downcast, no one responded. Cole started to point a finger, then thought better of it.

“Okay,” the white plainclothes cop said, “who lives here?”

“Cole and I do,” Eddie said, pointing to the big man squeezed between the table and the refrigerator.

“Okay, everyone else out of here.”

Ricky, the teenager, Eli, and Tiffany scurried out the back door. The black cop took IDs from Eddie and Cole and recorded their names on a form on his clipboard.

“You’re under arrest for possession of a controlled substance, to wit: marijuana,” the white cop said.

“Why? It’s not ours,” Cole said.

“It’s on your premises, so it’s yours. Ipso facto,” the white cop said with a gleam in his eye.

“That’s ridiculous,” Eddie said. “We weren’t sitting on the couch.”

“It’s the law,” the white cop said.

The black cop shrugged.

“Let’s go.” The white cop took Eddie’s arm and led him out the back door. The black cop escorted Cole, the bigger man who could cause a problem. The cops ushered the two young men into the back of the paddy wagon and the driver slammed the door shut.

Through the back windows, Eddie saw Eli, Tiffany, and their weasel-y roommate standing on the porch of the other half of the duplex where they lived.

As the paddy wagon made its way to the Savannah city jail the driver said, “Y’all stationed at the base?”

“Yes, sir,” Cole said. “Just back from Nam.”

“You, too?” The driver meant Eddie.

“Yeah, me too.”

“Well, the country is proud of you for doing your duty but y’all shoulda kept your noses clean.You’da been back home in no time. Now ya gonna be a guest of Uncle Sam in a different way.” He shook his head like it was a sad shame. ***

At this hour, the jail was nearly empty. The cells were arranged back-to-back in one long row with a solid steel spine down the center and steel side walls. Bars on the fronts and ceilings of the cells reminded Eddie of the cages for the big cats at the circus. A jailer locked them into the second cell from the front on the inside row. To the left in the 8’x8’space were anchored bunk beds, to the right a shiny steel commode. One prisoner at a time could stand in the leftover space. Eddie stood.

Cole sat on the lower bed, his elbows on his knees, face in his hands. “It wasn’t even ours.”

“It won’t stand up in court.” Tired of standing, Eddie climbed

onto the top bed and stared through the bars at fluorescent lights.