Vol. 1 Spring Summer 2025

Published by The Bridge

Head of Research

Dr Karen L Taylor

ktaylor@wellingtoncollege.org.uk

The Bridge

Wellington College

Dukes Ride

Crowthorne

RG45 7PU

Email: thebridge@wellingtoncollege.org.uk

Web: thebridge.wellingtoncollege.org.uk

Follow us on: LinkedIn

Phone: +44 (0) 1344 444 238

Karen L. Taylor

Welcome to the first volume of The Bridge: Journal of Educational Research and Theory!

This journal seeks to build a vibrant community of inquiry that explores the interconnectedness of educational theory, research, practice, and purpose. We aim to foster meaningful collaboration between classroom practitioners and university researchers in a dialogic space of mutual exchange—one that challenges hierarchical notions of knowledge and promotes a shared, transformative understanding of learning and teaching.

Together, we contribute to a growing body of knowledge that addresses the complexities of contemporary education. The articles in this volume offer a wide range of provocative insights into teaching and learning across diverse contexts. Collectively, they invite us to reexamine our principles, values, and practices as educators. We hope these articles stimulate reflection, dialogue, and continued inquiry into the pressing challenges and possibilities in education today.

as agents of positive transformation

A focus on leadership, defined in varying ways, is frequent in both the discourse on education and in society. Evan Dutmer explores a virtue ethics-based approach to leadership education at Culver Academies. He emphasizes the dynamic, co-constructed relationship between leaders and followers, aiming to cultivate virtues that support the flourishing of both individuals and societies.

Assessing the true effectiveness of online learning tools

Giancarlo Dentico presents school-based action research into the effectiveness of Tassomai, a leading UK EdTech platform. While students enjoy using the tool, the study found no statistically significant impact on KS3 progress—raising important questions about engagement, efficacy, and the need for independent evaluation of EdTech claims.

Cyrus Golding and Katy Millis offer a practical methodology for helping schools measure their carbon emissions. Their approach empowers students and teachers to foster sustainable school cultures through methodological transparency and collaborative inquiry.

Interdisciplinary collaboration for effective innovation

Inspired by a presentation on agile, decentralized decision-making in a military context, Ryan Clinesmith Montalvo examines how interdisciplinary collaboration in high-performing teams can inform educational innovation—particularly in preparing students for an uncertain future.

Supporting cultural and linguistic identity in refugee education

Lipsey Ojok challenges us to reflect on what inclusive education means beyond our own contexts. His study of Uganda’s Education Plan for Refugee and Host Communities highlights how the policy aims to build trust and address inequality. The findings underscore the need to critically reframe notions of ‘quality education’ in support of social cohesion, peacebuilding, and the rights of refugee learners.

Evan Dutmer

Abstract

Since 1894, Culver Academies has aimed to develop leaders of character. Rooted in the military academy and boarding school traditions, Culver has centered leadership development around central virtues and values. In 1986, recognizing the need to provide integrated, successive leadership learning experiences for students across 4 years, Culver instituted a standalone academic Department of Leadership Education. The Department of Leadership Education, housed in the Schrage Leadership Center, is unique among secondary boarding schools in offering four successive academic leadership education classroom experiences alongside Student Life curricula. Each year’s curriculum is centered in a transformational leadership framework, utilizing evidence-based tools to guide students’ leadership and character growth at each level. Ultimately, students’ growth is assessed by faculty (and students themselves) according to core leadership and character competencies developed by the Academies. Continual improvement of the department is ensured through a comprehensive triennial review process. The aim of this article is to illustrate a successful, iterative character and leadership education experience in a 4-year secondary school context. ¹

Keywords: leadership, character education, virtues, values, transformational leadership, competencies

Introduction

The mission of the Culver Academies is to educate “students for leadership and responsible citizenship in society by developing and nurturing the whole individual— mind, spirit, and body—through integrated programs that emphasize the cultivation of character” (About Culver Academies, 2023). Culver lives out this mission across two constituent academies— Culver Military Academy and Culver Girls Academy. Following in the military academy tradition, each academy is organized around the school’s foundational virtues and values (Zanetti, 2020; Metcalf & Heller, 2022). The Culver Virtues align with the High Six Virtues of the VIA Classification of Character Strengths and Virtues: wisdom, courage, justice, moderation, humanity, and transcendence (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). The values, again evidencing the influence of the US military, are honor, truth, duty, service.

In 1986, Culver Academies inaugurated the Department of Leadership Education, marking a significant step toward fostering an integrated, consistent leadership education experience for every student. The driving force behind this initiative was the conviction that while the Honor Code, Code of Conduct, and Student Life curricula left students well-prepared for their personal and career futures, a unified, integrated leadership education experience would further guarantee virtues- and values-based leadership development for every student. Led by the Committee on the Culver Experience, this department was designed to harness the institution’s diverse program offerings in pursuit of a unified goal: producing exemplary leaders of character who aimed to selflessly serve their communities.

¹ CONTACT evan.dutmer@culver.org © 2024 The author(s) This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Citation: Journal of Character & Leadership Development 2024, 11: 277 - http://dx.doi.org/10.58315/jcld.v11.277

In other words, at Culver, leadership and character were already caught (through the Student Life curriculum) and sought (through the inculcation of the Culver Code of Conduct and other aspirational creeds); but it remained for the Academies to make sure that leadership and character were consistently and comprehensively taught in academic, classroom settings (Arthur et al., 2022).

Over the past three and a half decades, the Department of Leadership Education, housed in the Schrage Leadership Center, has evolved while maintaining the unwavering focus on the overarching aim of cultivating leaders and citizens of character. The department remains committed to educating whole individuals who embody the virtues and values necessary for responsible citizenship and developing the capacity to inspire others within a democratic society (Bass & Bass, 2008). Rooted in Culver’s virtues and values, the curriculum merges ancient and contemporary virtue ethics, leadership studies, psychology, and positive organizational scholarship (POS) to deliver a comprehensive and iterative educational experience for each student.

Building on the seminal work of James MacGregor Burns, the department views leadership as a collaborative process shared between leaders and followers, transcending traditional hierarchical roles, and in service to elevating ends. Accordingly, the department agrees with Burns when he writes that “[transformational leadership] occurs when [leaders and their followers] … raise one another to higher levels of morality and motivation” (Burns, 1978, p. 20). Burns critical of understandings of leadership that exaggerated the role of designated leaders, argued that leadership is a process in which power is derived from a relationship between leaders and followers. Burns underscored the significance of the relationships between leaders and followers and highlighted the ways in which leaders and followers can mobilize one another bi-directionally. This has been called understanding leadership “as a coconstructed process” (Northouse, 2022, p. 364; see also Kotter, 1990).

The result is energizing leadership that can bond teams, transform organizations, and elevate individuals’ character (Bass & Riggio, 2006; Sosik & Jung, 2018). This understanding of leadership draws inspiration from historical figures such as Mahatma Gandhi, Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Nelson Mandela, Desmond Tutu, contemporary voices like Malala Yousafzai, Pope Francis I, and Indra Nooyi, and extensive social science research on organizational effectiveness demonstrating how transformational leadership can catalyze positive change on personal and societal levels (Bass & Riggio, 2006).

The department’s approach to leadership education is underpinned by Culver’s Virtues and Values. Far from advancing a “naked power-wielding” analysis of leadership, the department aims to draw on renewed interest in ethical, values-driven leadership in the last 50 years (Ciulla, 2012, 2014; Jones, 2023; Lamb et al., 2022). The department emphasizes the concept of leadership as a catalyst for personal and collective growth—especially with respect to human potential. Leaders are envisioned as agents of positive transformation who not only uplift themselves but also elevate their followers and team members, all in pursuit of better societies and human flourishing (Cameron & Winn, 2012).

The department educates, then, for what has been called “authentic transformational leadership” (Bass & Steidlmeier, 1999; Sosik, 2015). Authentic transformational leadership is understood as transformational leadership that is rooted in leaders’ and followers’ mutual

pursuit of the good and character development and growth, namely, virtues and flourishing or individuals and societies (Sosik, 2015).

This ideal of authentic transformational leadership connects to the department’s broader commitments to educate students in the foundations of POS. Students learn how virtuousness in organizations has been connected to greater effectiveness on traditional measures of workplace performance while noting the power of strengths to improve individuals’ subjective well-being and engagement in organizational contexts (Cameron, 2021; Miglianico et al., 2020). Consequently, a strengths-based approach using the VIA Classification of Character Strengths and Virtues (including students taking the VIA Inventory of Strengths (VIA-IS) Assessment each calendar year) is employed at each grade level. John Yeager led the integration of VIA Strengths across Leadership Education curricula beginning with his arrival in 2007 (Yeager et al., 2011). Further, the department serves a leadership role within Culver as a resource for enacting positive leadership practices among faculty and staff to enhance virtuousness across the entire organization.

Curriculum Design: An Integrated Path to Transformational Leadership for Each Student

The academic journey through the Department of Leadership Education is carefully structured to instill transformational leadership at each stage of a student’s education and run alongside and in complement to the athletic, extracurricular, and Student Life residential curricula at each grade level. The current core iteration of courses in the department were co-created by a core teaching team and has been in place since 2014. These courses are (in order from grades 9 to 12): Learning Living Leading (LLL), Teaming and Thinking (TNT), Ethics and the Cultivation of Character (ECC), and Senior Leadership Reflection (SLR). Throughout each course, instructors take care to order their experiential learning designs around core learning strategies that have been recently identified as the “Seven Strategies for Leadership and Character Development” (Lamb et al., 2022). These strategies (virtue practice, virtuous exemplars, virtue literacy, moral reminders, reflection, systems awareness, and friendships of mutual accountability) serve as helpful guides to in-class instruction and help to further ground the experiential emphasis of the course design across the department (Kolb, 1984).

A student’s leadership education journey begins with a required 9th grade leadership, learning, well-being, and belonging course. This course builds on an understanding that leadership begins as “self-management” (Drucker, 2005). Self-awareness, character development, well-being, power awareness, implicit and explicit biases, and bias mitigation are emphasized. Students take the VIA Strengths Inventory as a first step of strengths spotting, connecting institutional virtues and values to those present in evidence-based positive psychology. Students engage in a wellness module in support of institutional aims in health and well-being and continue this learning through an integrated wellness check-in running throughout the course. Further, students engage in basic routines of Social Emotional Character Development, especially through emotional self-awareness and self-regulation using the Mood Meter, developed at the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence (Brackett, 2019).

Committed to a vision of leadership education that honors the structures of individual human brains and learning, students also learn how to learn best through a basic understanding of the science of learning and relevant brain science (Barrett, 2020; Willingham, 2022). Key to this portion of the course is students’ engagement with growth mindset research and examination of their own academic mindsets (Dweck, 2007).

Students use these resources in engaging in early study of transformational leadership. Students familiarize themselves with the five practices model of exemplary leadership and reflect on exemplary leadership they witness around campus and how they could leverage their VIA Strengths to effect those practices themselves in varied team contexts (Kouzes & Posner, 2018).

In the 10th grade course, TNT, students embark on an in-depth study of teams, team dynamics, and effective teaming. Using a transformational framework which emphasizes the bidirectional processes of leadership, students analyze their existing teams for varied leadership actions and reflect on both effective and ineffective teams they have participated in. The department utilizes the Five Behaviors model of effective teaming for this reflection (Lencioni, 2011).

Students conclude their experience with a presentation describing an exemplar effective team and setting goals for future teams and team leadership positions they will occupy in their 11th grade year. This course nurtures experiential learning in complex human groups, empathy, problem-solving, and an appreciation for diverse perspectives in team environments.

The 11th grade course, ECC, is a graduation requirement for every student. It consists of an enacted, practiced virtue ethics course and a deeper introduction to an ethical leadership model via authentic transformational leadership. Students study ancient origins of contemporary virtue ethics and positive psychology through Aristotle, Confucius, and other character-based ethics around the world (Dutmer, 2022). Further, students apply their learning through several applied reflective exercises — for instance, constructing a goal hierarchy that leverages their VIA Signature Strengths in service of drafting possible “ultimate concerns” (Duckworth, 2016). The Seven Strategies complement the curriculum for the course and, in particular, assist in guiding the structure of the applied experiences.

The application backbone for the course is an ongoing Character Lab that runs throughout the entire course. It is a weeklong intention-setting and evidence-gathering exercise that allows students to chart their growth toward mastery of particular virtues and character strengths. Growth in the virtues over the 9-week experience is ordered around a spiral curriculum model, as has previously been developed at the Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues (Arthur et al., 2017). Contemporary topics in leadership studies introduced include emotional intelligence, empathy, and leadership applications of the dual process theory (fast and slow thinking). The course provides opportunities for competency performance via an interview for an imagined student leadership position of character integrator (modeled on some of the recent curricular work at the United States Military Academy), an ethical film analysis podcast (ethical films viewed and studied include SELMA,12 Angry Men, and He Named Me Malala), and a final written performance reflection that draws on each weekly Character Lab and is assessed around evidence of growth in the five leadership education competencies.

Each senior engages in a comprehensive reflective experience on competencies across 4 years of leadership experience, drawing on extensive research in educational psychology emphasizing the importance of developing students’ reflective capacity for deeper learning (Lamb et al., 2022). Students craft an essay that reflects on summative performances relating to each of the core leadership competencies. These reflections offer an opportunity for

both celebration of accomplishment for students while also providing excellent evidential opportunities for competency assessment by the SLR faculty facilitator. The department collects a repository of qualitative evidence of students’ leadership experience that could be used for future internal and external research.

Building on its deep curricular connections with contemporary psychology, the Department of Leadership Education also offers an introductory and advanced course in psychology. Both focus on positive psychology and the psychology of leadership. Psychology of Leadership is an upper-division course taught as an introduction to POS, focusing on virtues and strengths development in complex human organizations. The concluding performance for the course consists of an academic literature review on an area of POS of students’ choosing.

An Honors Seminar in the Theory and Practice of Leadership offers advanced students an opportunity for continued study of leadership through a college-level seminar in Transformational Leadership, culminating in creation of research papers in conversation with contemporary leadership studies, presented before the Department of Leadership Education. Students simultaneously engage in a college course in Leadership Studies while practicing essential academic skills for upper-level collegiate research. The research paper is understood as an academic service to the Academies community.

As part of its most recent triennial review process, the department engaged in a thorough renovation of its curricular documents using the Understanding by Design (UBD) framework in 2022–2023 (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005). Key to this work is the crafting of shared core understandings and essential questions for our students’ leadership education careers. These core understandings and essential questions can be integrated horizontally and vertically across courses according to the spiral curriculum previously discussed. In this way, students are able to engage with core knowledge and understandings at greater levels of complexity over successive years.

The department has arrived at some of the following core leadership understandings and essential questions to guide its work:

• Virtues are alive, and to be lived, and practiced. As virtues are applied and practiced, human beings can improve and continue to strive for a eudaimonistic life.

• Ethical leadership in teams requires continual character improvement among leaders and followers toward ends that contribute to overall human flourishing.

• Transformational leadership requires transformation (higher levels of character and higher levels of productivity/engagement/motivation) from both leaders and followers.

• Leadership requires an understanding of human behavior and attitudes.

• Leadership can be understood as a co-constructed process (between leaders and

followers) in human organizations.

• Leadership is a phenomenon in human organizations that can be studied using the tools of psychology.

• Organizational culture impacts employee performance and well-being.

• Leadership practices can be taught and are improvable.

• Certain team member behaviors can enhance teamwork; others can hinder it. Service is promoting the welfare of others in the community.

• What is leadership?

• Who is a leader? Who is a follower?

• What does good leadership look like?

• How do I improve and grow as a leader?

• How can I connect my philosophy of leadership with my practice of leadership?

• How do I live out my philosophy of leadership in my community?

• How do I help develop and nurture others for leadership?

• What observable evidence is there for effective leadership?

Each level of the curriculum offers successive opportunities to engage with these understandings and questions at great sophistication and depth. Further, cross-course agreement on foundational key understandings enhances student learning across course experiences (Bruner, 1960; Mehta & Fine, 2019).

Evaluation of Culver’s leadership and character education has evidenced the need for continued development of the department’s evaluation methods. Further, Culver has enacted an institution-wide adoption of competency-based learning. As part of this curricular evolution, Culver has developed a draft of competencies around five core distinguishing characteristics of a Culver graduate: leadership, scholarship, communication, well-being, and citizenship. These competencies were developed by cross-campus, interdisciplinary drafting teams aiming for maximum interdepartmental feedback and ownership of the competencies. Each of these core distinguishing characteristics is accompanied by 4–6 competencies. Accordingly, the department has begun and continues to make important changes in its assessment of student growth through adoption of five core leadership performance competencies and four process competencies.

The Department of Leadership Education, following a growing number of educational institutions, has begun to assess student growth according to two sets of competencies: performance competencies and process competencies (Paulson Gjerde et al., 2017). The performance competencies under “Leadership” are:

Positively Influencing: A Culver graduate practices effective leadership approaches by positively influencing others.

Achieving Goals: A Culver graduate achieves goals for personal growth aimed at improving their contribution to their team or group.

Modeling and Empowering: A Culver graduate serves as a model for peers and empowers

leaders and followers in order to support community values and the group’s purpose.

Serving Communities: A Culver graduate fulfills their responsibilities and engages in meaningful acts of service in order to improve their communities.

Power Awareness: A Culver graduate recognizes the power dynamics inherent in systems, events, and circumstances and that change is made by working within or challenging existing systems.

The process competencies are collaboration, iteration, perseverance, and behaving honorably. These are shared across the campus rather than being the possession of any single department. This is indicative of broad agreement across departments and disciplines that these competencies are important habits for students to develop as learners and leaders in the campus community. They are as follows:

Iteration: A Culver graduate engages in cycles of practice, feedback, reflection, and revision to improve.

Collaboration: A Culver graduate shares responsibility for group goals, exchanging ideas and questions with respect and humility.

Perseverance: A Culver graduate perseveres in the face of setbacks through their own agency or by seeking appropriate assistance.

Behaving Honorably: A Culver graduate speaks up for and acts on behalf of what is right and holds themselves and others accountable for what they do and say.

The proficiency indicators—established by a school wide calibration—are distinguished, proficient/distinguished, proficient, developing/proficient, developing corresponding to traditional grade point averages of 4.0, 3.7, 3.4, 3.0, and 2.7. Faculty regularly meet to calibrate standards within levels and across the department and offer students chances to assess their own proficiency according to rubrics for each of the above competencies.

Following its most recent triennial review process, the department has identified key areas for growth and improvement in the coming years. First, Culver is uniquely positioned to engage in leadership and character research on its campus. The department has committed to engage in measurement of student progress in its curricula using standard tools. For example, the department plans to provide for each student assessment of leadership behaviors in a transformational framework through the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ; Bass & Riggio, 2006). Further, following the example of the Jubilee Centre of Character and Virtues, the department will build on its work assessing student character strengths and development through a process of triangulation (Kristjánsson, 2015). VIA-IS Assessments, on this method, can be combined with other measures of character development, especially those that aim to activate virtue-relevant schemas in students (Walker et al., 2017). Along with teachers’ assessment of students’ progress toward the leadership and character competencies outlined earlier, this process of triangulation will help to produce a fuller snapshot of students’ character and character development over a Culver academic career.

Next, the department recognizes the need to continue deepening integration of its leadership and character development aims across campus and between its two constituent academies, Culver Girls Academy and Culver Military Academy. Student Life, extracurricular, and athletic areas offer excellent opportunities for continued collaboration and development of the

leadership performance and process competencies outlined earlier. The shared leadership competencies—identical across campus and both academies—will greatly accelerate this collaboration. With a central repository of student competencies, faculty and staff across the Academies will be able to offer feedback regarding students’ progress. Further, given the connections between positive psychology and the science of well-being (PERMA Theory of Well-Being - Positive Emotion, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, Accomplishment), there exist opportunities for continued and deeper collaboration with the Department of Wellness. As the department leverages its programming in support of these complementary departments, it will assist in achieving the overarching mission of the Academies.

Culver Academies has striven to educate and mold leaders of character since its inception in 1894. The Department of Leadership Education, founded in 1986, is a key part of that mission. The Department of Leadership Education has ensured each student receives a reflective, charted course of leadership and character growth as a graduation requirement. Through a 4-year sequence of course offerings, Culver offers a unique level of ethical and leadership training for high schoolers in a US context. Given the recognized need and continued desire for character and leadership development programs that engage students to learn more deeply beyond standalone course experiences, Culver Academies Department of Leadership Education stands as an important example among secondary schools that aim to cultivate the whole person.

The author acknowledges and thanks current and former colleagues in the Department of Leadership Education and senior administration at Culver Academies for their energy, collegiality, leadership, support, and vision in aiding in the continued success of this department. The author would like to thank Don Fox, Susan Freymiller deVillier, Joshua Pretzer, Jacqueline Carrillo, Emily Uebler, Deirdre Dolan, Kevin MacNeil, John Yeager, Stephanie Scopelitis, and Chris Kline, in particular.

References

About Culver Academies. (2023). Culver Academies. https://www.culver.org/about Arthur, J., Fullard, M., & O’Leary, C. (2022). Teaching Character Education: What Works. Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues, University of Birmingham. https://www.jubileecentre. ac.uk/project/character-education-pedagogies/ Arthur, J., Kristjánsson, K., Harrison, T., Sanderse, W., & Wright, D. (2017). Teaching character and virtue in schools. Routledge. Barrett, L. (2020). Seven and a half lessons about the brain. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Bass, B., & Riggio, R. (2006). Transformational leadership. Psychology Press. Bass, B., & Bass, R. (2008) The Bass Handbook of Leadership: Theory, Research, & Managerial Applications. Simon and Schuster.

Bass, B., & Steidlmeier, P. (1999). Ethics, character, and authentic transformational leadership behavior. The Leadership Quarterly, 10(2), 181–217. https://doi. org/10.1016/S1048-9843(99)000168.

Brackett, M. (2019). Permission to feel. Celadon Books.

Bruner, J. (1960). The process of education. Harvard University Press.

Burns, J. (1978) Leadership. Harper & Row.

Cameron, K. (2021). Positively energizing leadership. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Cameron, K., & Winn, B. (2012). Virtuousness in organizations. In G. Spreitzer & K. Cameron (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of positive organizational scholarship (p. 231–244). Oxford University Press.

Ciulla, J. (2012). Ethics and effectiveness: The nature of good leadership. In J. Antonakis & D. Day (Eds.), The nature of leadership (p. 508–540). SAGE.

Ciulla, J. (2014). Ethics, the heart of leadership. Praeger.

Duckworth, A. (2016). Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance. Scribner.

Drucker, P. (2005). Managing oneself. Harvard Business Review Press.

Drucker, P. (2008). Managing Oneself. Harvard Business Review Press.

Dutmer, E. (2022). A model for a practiced, global, liberatory virtue ethics curriculum. Teaching Ethics, 22(1), 39–67. https://doi.org/10.5840/tej2022824115.

Dweck, C. (2007). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House. Jones, G. (2023). Deeply responsible business: A global history of values-driven leadership. Harvard University Press.

Kristjánsson, K. (2015). Aristotelian character education. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. Kolb, D. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Prentice-Hall.

Kotter, J. (1990). A force for change: How leadership differs from management. Free Press.

Kouzes, J., & Posner, B. (2018). The student leadership challenge: Five practices for becoming an exemplary leader. Wiley.

Lamb, M., Brant, J., & Brooks, E. (2022). Seven strategies for cultivating virtue in the university. In J. Brant, E. Brooks, & M. Lamb (Eds.),Cultivating virtue in the university (p. 115–156). Oxford University Press.

Lencioni, P. (2018). The Five Dysfunctions of the Team. Jossey-Bass.

Miglianico, M., Dubreuil, P., Miquelon, P., Bakker, A., & Martin-Krumm, C. (2020). Strength use in the workplace: A literature review. Journal of Happiness Studies, 21(2), 737–764. https://doi. org/10.1007/s10902- 019-00095-w.

Metcalf, E., & Heller, J. (2022). Building a Deliberate and Repeatable Program for Developing Leaders of Character. Journal of Character and Leadership Development, 10(1), 58–64.

Mehta, J., & Fine, S. (2019). In search of deeper learning: The quest to remake the American high school. Harvard University Press.

Northouse, P. (2022). Leadership: Theory and practice. SAGE.

Paulson Gjerde, K., Padgett, M., & Skinner, D. (2017). The Impact of Process vs. Outcome Feedback on Student Performance and Perceptions. Journal of Learning in Higher Education, 13(1), 73–82.

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Oxford University Press, American Psychological Association.

Sosik, J. (2015). Leading with character: Stories of valor and virtue and the principles they teach. Information Age Publishing.

Sosik, J., & Jung, D. (2018). Full range leadership development: Pathways for people, profit, and

planet. Routledge.

Walker, D., Thoma, S., Jones, C., & Kristjánsson, K. (2017). Adolescent moral judgement: A study of UK secondary school pupils. British Educational Research Journal, 43(3), 588–607. https:// doi.org/10.1002/berj.3274

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design. ASCD.

Willingham, D. (2022). Outsmart your brain: Why learning is hard and how you can make it easy. Simon& Schuster.

Yeager, J., Fisher, S., & Shearon, D. N. (2011). SMART strengths: Building character, resilience and relationships in youth. Kravis Publishing. Zanetti, N. (2020). Values and virtues in the military. Peter Lang.

Gianpaolo Dentico

Abstract

Tassomai, an online learning platform widely used in the UK, employs a combination of videos, quizzes, and feedback to enhance pupil’s understanding of subjects such as science, maths, and English. Despite its popularity, peer-reviewed assessments of its core spaced repetition platform are limited, with much of the existing research conducted by Tassomai themselves. This study investigates the effectiveness of Tassomai in aiding Key Stage 3 (KS3) science pupils in Tianjin. Two randomly selected classes from Years 7, 8, and 9 were assigned either to use Tassomai as a supplement to homework or follow traditional homework methods from October 2023 to June 2024. Pupil progress was assessed using the computer-based PTS test. The study found no evidence that Tassomai accelerated pupil progress in KS3 science. Survey responses indicated positive pupil perceptions of Tassomai, despite the lack of measurable academic benefits. This study suggests that while Tassomai is popular and perceived as helpful by pupils, its efficacy in enhancing broader science learning at KS3 is questionable. Future research should continue to evaluate the impact of educational technologies with rigorous, independent methodologies to address the current research gap.

Keywords: Online learning, science learning, Tassomai

Introduction

Tassomai is an online learning platform designed to provide personalised and adaptive learning in subjects such as science, maths, and English. It combines videos, quizzes, and feedback aiming to help pupils learn and retain information more effectively. The platform is widely used in schools across the UK, with over 500 schools and 300,000 pupils enrolled (Our Impact! Tassomai makes a difference — Tassomai, 2024).

Tassomai’s design is rooted in retrieval practice, a well-established cognitive science strategy that enhances long-term retention by requiring learners to actively recall information over time. Research has shown that retrieval practice strengthens neural connections, improves memory consolidation, and deepens understanding (Agarwal & Bain, 2019; Roediger & Butler, 2011). Tassomai leverages this effect through algorithm-driven quizzes that space out questions and adapt to pupil responses and claims to reinforce learning in a structured manner. Given the strong theoretical support for retrieval practice, Tassomai has the potential to improve pupil learning and retention—though the extent to which this translates into measurable academic progress remains an open question.

This study aims to evaluate the impact of Tassomai on KS3 pupil learning (Years 7, 8, and 9) in Tianjin, assessing whether the platform enhances progress beyond traditional methods.

Despite the widespread use of Tassomai in the UK, the evidence base for the platform is limited. A search on Google Scholar found only one peer-reviewed journal article that mentioned Tassomai (Morrison et al., 2021). However, this study did not test Tassomai’s core spaced repetition platform but evaluated the effect of video feedback on learners’ ability to answer science questions correctly. On the other hand, the author of this study could not find a single peer reviewed article evaluating Tassomai’s core spaced repetition platform, highlighting a

significant research gap in the field.

An MSC thesis that assesses the impact of a four-week Tassomai course on pupil premium pupils’ GCSE results in a UK state school is available online (Lean, 2015). This study found a positive impact of Tassomai. However, it is worth noting that the authors did not mention how they selected their control and intervention groups, so we cannot confidently conclude that Tassomai was causal in improving GCSE performance in their intervention group.

Despite the extensive use of Tassomai and its self-conducted research on the platform’s impact on UK-based GCSE pupils, there is a clear need for third-party research. This is particularly true for the platform’s impact on pupils internationally or on KS3 pupils. This study aims to provide an independent evaluation of Tassomai’s effectiveness in helping KS3 pupils progress in science, filling this crucial research gap.

Tassomai’s website presents several claims about the platform’s effectiveness, with figures that may appear highly impressive at first glance. However, it is essential to interpret such results with caution and consider potential sources of bias or confounding factors that could influence the findings. As Tassomai is a commercial product, there is an inherent motivation to present its impact in a favourable light to encourage subscriptions and continued adoption by schools. Therefore, independent evaluation is necessary to assess the platform’s true effectiveness in improving pupil outcomes.

Claim 1:

“When students use Tassomai regularly (i.e. they complete 80% of the course material by working through the online quizzes), their GCSE science grades have been significantly higher than the national average.” (Tassomai: Helping Our Pupils Succeed with GCSE Science, 2018).

Claim 2:

“From the 68,010 module results we’ve received from schools, we’ve seen that of those “regular users” (the students completing 80% of the course), 50% had achieved an A or A* grade in their GCSE science exams and 90% achieved a grade C or above” (Tassomai: Helping Our Pupils Succeed with GCSE Science, 2018).

Claim 3:

“Some schools had uniformly low Tassomai usage (with the majority of their students spending less than 5 hours on the site all year); others had uniformly high achievement on the software (where all their students covered at least 75% of the course content). In the high-coverage schools, the A* to C pass rate was 26% greater, overall.” (Tassomai: Helping Our Pupils Succeed with GCSE Science, 2018).

It is worth noting that the claims 1 & 2 compare pupils who meet Tassomai’s rather strict criteria (80% course completion) with a control group based on the performance of pupils nationally. Tassomai provides no information on the number or proportion of pupils in the experimental group who completed 80% of the course over the study period. This means that that the study may not have controlled for a major factor in pupil performance – trait conscientiousness as measured by tests of the big five personality traits (Poropat, 2009; Richardson, Abraham, & Bond, 2012). The pupils who have completed 80% of the course could reasonably be more conscientious on average than both those pupils in the experimental group who didn’t complete the course and the control group, who did not use Tassomai at all. This means that the observed performance difference could be due to increased levels of conscientiousness as opposed to the use of Tassomai.

In addition, no information is given about the schools involved in the comparison, which took place in 2017. Schools trailing this platform in 2017 may have had pupils from different socioeconomic backgrounds and demographic makeups than the control group. This is alluded to in the MSC thesis (Lean, 2015), which states that at the time of the trial, “a high percentage were private school students, and the programme had not been deployed in state schools due to the costs involved.” This cannot be confirmed as no additional information about the original trial can be found online. However, any differences in socioeconomic background between the control and treatment groups would be major flaws in a study aiming to judge the impact of an educational intervention (Sirin, 2005; Bradley & Corwyn, 2002).

Pupils in Years 7, 8, and 9 were assigned to either the Tassomai group or the non-Tassomai group. Each group followed the same curriculum throughout the school year to ensure comparability. In Year 7, different teachers taught the two groups; however, they followed an identical scheme of work, teaching materials, and instructional activities to maintain consistency in content delivery. In Years 8 and 9, both groups were taught by the same teacher, reducing potential variability in instructional approach.

Pupils in the Tassomai group used the platform as a supplement to traditional homework. They were required to complete retrieval practice on Tassomai at least four times per week. Pupils engaged with the platform by answering quizzes designed to reinforce topics covered in class, earning points towards a daily goal as part of its gamified learning system. The non-Tassomai group completed traditional homework assignments without access to Tassomai.

Unlike previous studies conducted by Tassomai, which often excluded pupils who did not fully adhere to the treatment, this study included all pupils originally assigned to the groups. This decision was made to reflect the real-world implementation of educational technology, where pupil compliance is often variable (Slavin, 2002). By retaining all participants, the study aimed to provide a more representative and valid assessment of Tassomai’s effectiveness in typical classroom conditions.

The Progress Through Science (PTS) assessment by GL Assessment was chosen as the instrument to assess pupil progress in this study. PTS provides a Standard Age Score (SAS), which allows for the comparison of individual pupil performance against a representative national sample of pupils educated in the UK. This means each pupil’s progress is compared not just within our school, but against the broader performance of pupils in the UK at the same age. By using these scores, we can objectively determine if our pupils are making more, less, or the expected level of progress relative to their British peers. Rather than merely assessing final or raw scores, this method evaluates pupils’ improvement from their initial baseline score (taken at the start of the academic year) to their score at the end of the academic year, offering a clearer measure of the progress each pupil has actually made. This approach reduces potential distortions in results due to pre-existing differences in pupil attainment. Additionally, choosing the computer-marked PTS assessment, instead of internally marked end-of-year assessments, reduces the risk of unconscious or conscious bias affecting outcomes, making the evaluation more objective and reliable, especially important in a study aiming to independently assess the effectiveness of Tassomai.

Unlike the studies published by Tassomai, which excluded pupils from the experimental group who did not strictly follow the intended protocol, we have not excluded any pupils who started the trial. We hope that this decision gives a more relevant analysis of the feasibility

and impact of using Tassomai in a real-world school as non-compliance is a factor that affects the success of any educational intervention (Slavin, 2002). Furthermore, whilst including some pupils who have not strictly followed the protocol in the analysis may cause some issues with the validity of the comparison, it will also reduce the potential for bias.

An independent samples t-test was conducted to compare pupil progress between the Tassomai and non-Tassomai groups in Years 7, 8, and 9. The t-test is appropriate for comparing the means of two independent groups to determine whether there is a statistically significant difference in their progress (Field, 2018). P-values were reported with a threshold of p < 0.05, following conventional statistical significance standards.

Cohen’s d was also calculated to assess the magnitude of any observed differences between groups (Cohen, 1988). Effect size provides a measure of practical significance, indicating whether any differences, even if not statistically significant, might be meaningful in an educational context. A Cohen’s d value of 0.2 is considered small, 0.5 moderate, and 0.8 large (Cohen, 1988). Reporting effect sizes alongside p-values is considered good statistical practice, as it provides additional context to significance testing and helps interpret the meaningfulness of findings (Wasserstein & Lazar, 2016). This addition strengthens the interpretation of the results.

The table below shows the average number of daily goals per week, the fractional daily goals per week (including goals that weren’t 100% completed and extra work) and the standard deviations of these numbers during the trial period. It also shows the percentage of pupils who complied with the four daily goals/week average over the trial period.

No year groups strictly complied with the four daily goals/week protocol as suggested by Tassomai. However, when accounting for partial goals and additional work, year seven and year nine pupils met an average of four weekly goals. Furthermore, year eight pupils were only 0.04 fDG away from meeting expectations on average. Compliance with the protocol was highest in Y7, with 93% of the treatment group completing an average of over four fDG/week.

The tables below show the PTS SAS conducted in May 2024 (New) against the SAS of the PTS assessment conducted at the start of the academic year (Old). Progress is the difference between the two scores. A progress score of 0 indicates expected progress. Pupils with positive scores are making greater levels of progress than they would be expected to make in other schools.

Overall, PTS scores indicate high levels of progress across KS3, regardless of Tassomai usage. Out of 110 pupils, only four were not making expected progress, and Year 9 showed the highest levels of progress, with 65% of pupils achieving higher or much higher than expected progress. The mean progress scores for the whole cohort were 10.9 in Year 7 (Much Higher than Expected), 5.1 in Year 8 (Higher than Expected), and 17.73 in Year 9 (Much Higher than Expected), according to PTS criteria.

The Tassomai group had a mean progress score of 8.94 (SD = 10.31), while the non-Tassomai group had a mean score of 12.94 (SD = 15.85). The non-Tassomai group improved by nearly four points more on average than the Tassomai group. A statistical comparison showed no significant difference between the two groups (t = -0.819, p = 0.210). The effect size (Cohen’s d = –0.30, Hedges’ g = –0.29) suggests a small negative effect, meaning that if any difference exists, it slightly favours the non-Tassomai group, though the difference is too small to be meaningful.

The Tassomai group had a mean progress score of 4.56 (SD = 11.84), while the non-Tassomai group had a mean score of 5.80 (SD = 12.17). The non-Tassomai group improved by about one point more on average, but the difference was not statistically significant (t = -0.278, p = 0.392). The effect size (Cohen’s d = –0.10, Hedges’ g = –0.10) was very small, suggesting little to no real difference in progress between pupils who used Tassomai and those who did not.

The Tassomai group had a mean progress score of 19.69 (SD = 12.40), compared to 15.77 (SD = 12.24) for the non-Tassomai group. While the Tassomai group’s mean score was slightly higher, this difference was not statistically significant (t = 0.780, p = 0.221). The effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.32, Hedges’ g = 0.31) suggests a small-to-moderate effect in favour of Tassomai, but since the p-value was above 0.05, this result could easily be due to natural variation rather than a real impact of the intervention.

This study found no statistically significant evidence supporting the claim that Tassomai enhances pupil progress at KS3. Pupils in the non-Tassomai groups in Years 7 and 8 demonstrated slightly higher progress, according to the PTS assessments. Although pupils in the Tassomai group in Year 9 showed modestly greater progress, this difference was not statistically significant, indicating it could easily have arisen by chance rather than as a genuine effect of the intervention.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting these findings. First, there may be alignment issues between the content assessed by the PTS tests and the topics delivered in class and practiced using Tassomai. While PTS predominantly measures recall and factual knowledge rather than conceptual understanding, this critique is somewhat mitigated by the fact that Tassomai itself targets knowledge recall through retrieval practice. Nonetheless, differences in the sequencing or emphasis of topics could affect the sensitivity of the tests in detecting Tassomai’s true impact.

Another important consideration is pupil engagement with the platform. Compliance data revealed no year group fully achieved Tassomai’s recommended usage target of four daily goals per week, although Year 7 pupils came closest with 93% regularly achieving this in fractional terms. Year 8 had notably lower compliance, which aligns with the negligible difference observed between groups in this year. This suggests that consistent usage may be a necessary condition for any potential benefits of Tassomai to become measurable, but further research is needed to confirm this.

Ensuring the experimental group complies with the treatment is a common challenge in educational studies (Slavin, 2002). Our study is limited by the level of compliance with Tassomai’s suggested protocol, which may limit the validity of our conclusion. Nevertheless, we chose not to skew our analysis by solely comparing pupils who strictly adhered to the daily goal allocation against the control group, as had been done in Tassomai’s studies, as this may result in a biased data set consisting of the most diligent pupils who have higher levels of motivation for revision than the average pupil in the control group. It also provides a clearer picture of what can be expected if the Tassomai platform is introduced in real-world schools.

Despite the lack of third-party evidence regarding Tassomai’s efficacy, it remains a popular platform amongst schools and pupils. The popularity of the platform is reflected in our pupil survey responses. Our cohort tends to think using Tassomai is helping them, with over 75% of pupils agreeing that the platform is very helpful or somewhat helpful, and 60% saying they would recommend it to a friend. Pupil perceptions of the platform may be influenced by the system’s design, which is gamified and visually appealing, and progress can easily be tracked by watching a tree grow (Hamari, Koivisto, & Sarsa, 2014). It is possibly a more rewarding system than traditional revision methods, which may be much more cognitively challenging and uncomfortable than using Tassomai.

It seems that whilst pupils can quickly remember the answer to a specific multiple-choice question in the Tassomai platform, it may not help them to make generalisations and apply this knowledge in other contexts, such as in the PTS test, which is another multiple-choice platform, relatively similar to Tassomai. Assuming that Tassomai cannot help bridge the gap between these two computer-based multiple-choice platforms, we can reasonably doubt that it impacts pupils’ wider performance in science.

Whilst we did not gauge teachers’ views on Tassomai via a survey in our school, Tassomai’s research claims that 98.6% of teachers using Tassomai would also recommend the platform to a colleague. This aligns with research showing that teachers are often influenced by EdTech marketing claims that emphasize workload reduction and the latest educational trends (Selwyn, 2016). After reading the marketing materials, it is easy to understand some potential reasons for these high levels of teacher approval. The website is awash with all the latest educational buzzwords and links to hot topics in educational research – retrieval practice, AI, Edtech, individual needs. In addition, claims of a solid evidence base and paragraphs about why any tool used in schools must have a strong foundation in research are likely to appeal to science teachers especially. Finally, teachers are not required to set any work or give feedback on Tassomai, reducing teacher workload. In fact, the platform itself recommends that teachers not interfere with the algorithms. It even sets reminders if you attempt to do so, reinforcing trust in its spaced repetition software. Members of staff in our school were initially impressed by these marketing materials. However, the unexpected results of this study prompted a more critical evaluation of some of Tassomai’s claims. It is important to remember that this is a single, flawed study that should be contextualised within other research on the platform. Decisions on whether to continue with the platform should, therefore, consider research from elsewhere. In addition, Tassomai is bringing out new innovations on a regular basis, and some of them have a reasonable basis in evidence. For example, they have added video-based interventions to the platform (Tassomai Receives Evidence Applied Award from UCL, 2019). However, the results of this study cast doubt on

some of Tassomai’s own research.

Ultimately, this study underscores the necessity of independent, rigorous evaluations of educational technology platforms like Tassomai. The results and limitations discussed here will inform future departmental decisions regarding the continued use of Tassomai, alongside other potential strategies for improving pupil learning outcomes.

References

Bradley, R. H., & Corwyn, R. F. (2002). Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(1), 371–399. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Field, A. P. (2018). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS Statistics (5th ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd.

Hamari, J., Koivisto, J., & Sarsa, H. (2014). Does gamification work? A literature review of empirical studies on gamification. Proceedings of the 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 3025–3034. https://doi.org/10.1109/HICSS.2014.377

Lean, J. (2015). Supporting Pupil Premium Attainment in Science Exams (pp. 1–87) [MSc Thesis]. https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:afdf75ed-b43f-4052-b7ef-47d024be5725/files/ma22e214c54bce7686e5eb81f3ba4d83f

Morrison, M., Blake, C., Embleton-Smith, F., Gosiewski, J., & Zvesper, J. (2021). Pre-emptive intervention and its effect on student attainment and retention. Research for All, 5(1). https://doi. org/10.14324/rfa.05.1.05

Our Impact! Tassomai makes a difference — Tassomai. (2024, June 3). Tassomai. https://www. tassomai.com/our-impact#:~:text=The%20program%20is%20used%20by

Poropat, A. E. (2009). A meta-analysis of the five-factor model of personality and academic performance. Psychological Bulletin, 135(2), 322–338. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014996

Richardson, M., Abraham, C., & Bond, R. (2012). Psychological correlates of university students’ academic performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 138(2), 353–387. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026838

Selwyn, N. (2016). Minding our language: Why education and technology is full of bullshit… and what might be done about it. Learning, Media and Technology, 41(3), 437–443. https://doi.org /10.1080/17439884.2015.1012523

Sirin, S. R. (2005). Socioeconomic status and academic achievement: A meta-analytic review. Review of Educational Research, 75(3), 417–453. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543075003417

Slavin, R. E. (2002). Evidence-based education policies: Transforming educational practice and research. Educational Researcher, 31(7), 15–21. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X031007015

Tassomai receives evidence applied award from UCL. (2019, March 7). Tassomai. https://www. tassomai.com/blog-content/2019/3/07/tassomai-evidence-applied-award-from-ucl-educate-programme

Tassomai: Helping our Pupils Succeed with GCSE Science. (2018, March 27). Tassomai. https:// www.tassomai.com/blog-content/2018/3/27/2017-results-how-tassomai-is-helpingstudents-succeed-at-gcse-science

Wasserstein, R. L., & Lazar, N. A. (2016). The ASA’s statement on p-values: Context, process, and purpose. The American Statistician, 70(2), 129–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/00031305.20 16.1154108

Cyrus Golding and Katy Millis

Abstract

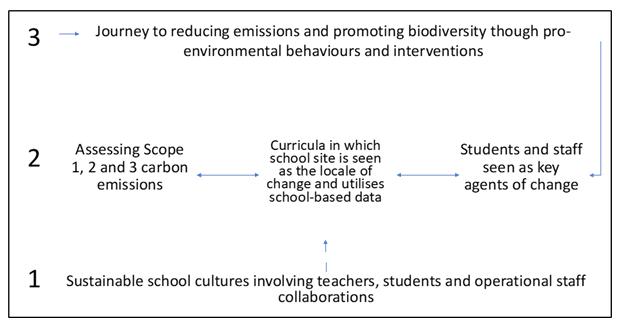

There is a pressing need for scholarly work which explores the specific ways in which schools can reduce their carbon emissions on a path to achieving net-zero by 2050 in line with UK government guidelines. This article makes several key contributions to literatures on net-zero, education for environmental sustainability (ESD) and school-based professional cultures. 1) It provides what we understand to be the first complete practical methodology that enables schools to account for their carbon emissions; 2) it argues that this data is key for galvanising pro-environmental student actions in which students can become agents of change supporting schools on their net-zero journey; 3) we develop the concept of ‘sustainable school cultures’ to argue that carbon accounting is more than a technical process and must begin by and be enabled through creating a distinctive ethos of methodological transparency and collaboration.

Keywords: Education for Sustainable Development, Sustainable Development Goals, School culture, Climate change

Introduction

The importance of schools in managing and mitigating the effects of the climate emergency is becoming increasingly apparent. The Department for Education (DfE) (2022: np) strategy on sustainability and climate change provides explicit policy direction for English schools to ‘reduce direct and indirect emissions from education and care buildings… to meet legislative targets and provide opportunities for children and young people to engage practically in the transition to net-zero’. These legislative targets relate to the UK’s legal responsibilities to reach net-zero by 2050 (Deben et al., 2020).

Net-zero is a concept which emerged from physical climate science (Fankhauser et al., 2022). This is a shift away from stabilising levels of atmospheric CO2 towards keeping within the 1.5 degrees of warming above pre-industrial levels as called for by the 2015 Paris Agreement. The key idea is that there is a balance between the release of greenhouse gas and its removal from the atmosphere (Allen et al., 2022). However, net-zero is not without its challenges as often the largest amount of emissions are beyond direct control of schools themselves. These emissions are classed as Scope 3 emissions meaning they are generated up and down an organisation’s supply chain (Jones, 2023).

In short, Scope 1 emissions relate to emissions produced within a school and under its direct control. Scope 2 emissions are those from externally supplied energy. Despite increasing pressures from internal and external stakeholders for schools to account for and reduce their carbon footprint, including from children themselves in the form of climate activism and school sustainability committees, there remains a lack of an agreed methodology for school carbon accounting and, more broadly, a paucity of academic literature on reaching net-zero that pertains specifically to schools. This makes it difficult for all but the most well-resourced schools to begin accounting for their emissions. The few schools that have begun to do this have done so by devising their own methodologies often in conjunction with external consultants (see A Planet Mark x ICS, 2023). This methodological opaqueness masks the political decisions behind carbon calculations (Blakey, 2021), and potentially underreports emissions and limits opportunities for student/ teacher participation

by framing the calculation of carbon footprints as a purely technical endeavour.

At the same time as attempts to account for and reduce the carbon emissions on school sites, there has also been a parallel effort to increase Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) in school curricula. ESD can take many forms from educating children about the causes and consequences of climate change to taking actions in their own lives that can make a difference (Greer et al., 2023). Whilst some authors have begun to acknowledge that ESD is most effective when students are exposed to real-world data and problems (Rap et al., 2022), we wish to take these arguments a step further to argue that effective ESD should see students directly involved in debating and critiquing carbon accounting methodologies and using this information to inform pro-environmental action in and around the school site. This ethos of methodological transparency, data sharing and involvement of students is core to the concept of sustainable school cultures which we develop here and acts as the ethical foundation to how schools approach their work around net-zero targets.

This article therefore makes two original contributions. The first is technical in that it provides what we understand to be the first complete methodology for school-based carbon accounting (assessing Scope 1, 2 and 3). We do so as a starting point for discussion across different schools in the UK and internationally not to advocate for a one-size-fits all methodology. The second is we argue we argue that students themselves are a crucial component in helping schools get to net-zero both through their actions being informed by school carbon emissions data and when they are empowered to interrogate the methodology behind school carbon data.

There are difficulties in reconciling planetary-scale environmental changes with the types of actions that should be taken at the school-scale. The Independent Schools Council (2023) highlights case studies of sustainable actions undertaken by UK schools which involve actions such as switching school energy supplies away from gas in favour of renewable supplies, offsetting emissions through tree planting and introducing charging points for electric vehicles. Yet, there are a paucity of examples of where students are intimately involved in the decision-making or monitoring process for these projects in a way which empowers them to make change and validates the practical application of their environmental knowledge. Moreover, without calculating a school’s carbon emissions first, it makes monitoring the carbon reduction of any student interventions difficult and inhibits the ability of students to understand the most important areas in which emissions can be reduced.

Students’ own ideas are valuable in shaping the priorities related to the teaching of environmental change in the school curriculum (e.g. Dunlop et al., 2022; Rushton, 2021; Dunlop and Rushton, 2021). However, there is a lack of work that explores how students can be seen as collaborators in the journey to net-zero on school sites, particularly in regards to the technical aspects of emissions calculations. We suggest, this is not only important as a form of democratising environmental knowledge, but it also transfigures the spaces and locales in which climate change actions can be undertaken to the more local scales of the school site.

There is therefore an inherent politics to the scales at which climate change is and should be tackled as local scales may hide the structural factors such as economies based on consumption, which continue to contribute to climate change, species loss and land degradation (e.g. Wright and Nyberg, 2015; Baer, 2012). Yet, it might well be at the local scale of the school site that students can exercise their ideas across a whole range of sustainabilityrelated issues from purchasing decisions to the temperature of classrooms that not only create learning opportunities for the application of ESD, but potentially more ethical decisions rooted in everyday, collaborative decision-making (Gibson-Graham et al., 2013).

It is this interconnection between the school site, operational expertise, curricula and students that has been neglected in literature on enabling sustainable transitions. Some recent work has foregrounded the importance of dialogue between teachers and students and the importance of short and longer-term goals in enabling climate action (Tappel et al., 2023; Almeida and Vasconcelos, 2013). Whilst others have argued that sustainable transitions in any institution occur when there are ‘openings’ or disruptions to the policy landscape which allow for new innovations and ideas to take hold (Lawhon and Murphy, 2011). It could be argued that as the realities of climate change are being felt in concert with increasing pressure from students (including climate anxieties), organisational pressure from groups such as ‘Let’s Go Zero’ (letsgozero.org) and recent government policies mean there is a window in which meaningful action between students and school emission reduction can start to take place. A concern about the contribution of UK schools to climate change is not new. A 2008 report explored the carbon emissions from English schools and estimated that across the whole school estate 45% of emissions are from procurement, 37% from buildings, 16% from travel and transport and 2% from waste making up an estimated 9.4 million tonnes of carbon dioxide (Sustainable Development Commission, 2008). The report showcases early examples of strategies schools were taking to reduce their emissions including advocating for the idea of creating targets for emissions reductions and the idea that we might one day create opportunities to compare carbon emissions data between schools. Whilst it is far from universal, some councils have developed their own policies to reach net-zero by 2030 and provided guidance to schools. For example Hertfordshire Council has provided guidance to maintained schools to cut electricity and reduce carbon emissions (Herefordshine Council, 2017). Yet, there is a tendency to focus mainly on electricity as this has immediate cost reduction implications for schools but calculating the emissions from the whole school operation, including procurement (Scope 3), which is where most emissions are likely to lie, is more complex.

In the following section we provide what we regard to be the first methodology of accounting for a school’s carbon footprint. There is a risk however that the methodology behind such calculations is not open to proper democratic scrutiny from students, school staff and the broader school community, thus obscuring the political choices through which carbon is calculated potentially creating crude trade-offs between consulting students and arriving a quantified carbon footprint. In outlining our methodology we invited students and other stakeholders to question the assumptions behind it and advocate for the ‘making public’ of carbon data else we mask the political deliberations which go into such methodologies and close down opportunities for meaningful discussion and debate (see also Latour, 2005; Braun and Whatmore, 2010).

Methodological reflections

Methodological philosophy

We write this article as a joint exercise between an academic Head of Department with a background in geography and the other a Head of Sustainability and Procurement. It is through our own work, reflections and collaborations that this paper and the methodology for carbon calculation comes about. The empirical detail we discuss is derived from own school: a large inner-London UK independent school with the objective of providing a framework which schools in the UK looking to reduce their emissions and involve students and teaching staff in the process can adapt as their starting point and can guide other schools’ journeys.

In publishing this methodology, we are doing so alongside an increasing trend towards methodologies for carbon calculation across a range of sectors. For example, recent pioneering

work has provided methodologies for calculating the CO2 emissions from digital data (Jackson and Hodgkinson, 2023) and, for example, recent work which calls for methodologies for carbon reporting across higher education (EAUC, 2023).

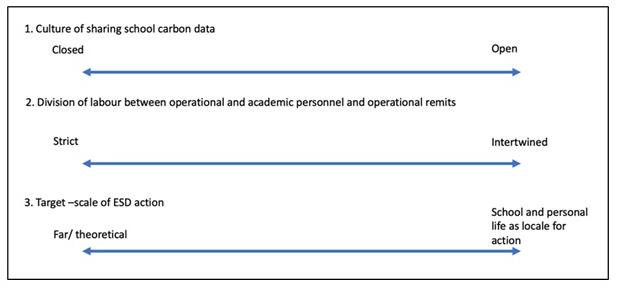

Our own philosophical position is one which resists calls for standardisation and instead advocates for methodological transparency and visibility. Standardisation risks closing debate and conversations between students and stakeholders. Whilst there are indeed commonalities between all schools such as electricity use and waste, there may be differences to account for such as the commuting of boarding students, meaning that we intend that the methodology below should be taken as a starting point for discussion and data collection across different school types and geographies.

The methodology we present below is derived by using the Greenhouse Gas Protocol (GHGP) as its starting point [https://ghgprotocol.org]. This is a multi-stakeholder partnership of businesses, non-government organisations and governments convened by the World Resources Institute (a US based NGO) and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (a Geneva-based coalition of 170 International companies). Launched in 1998 they developed an internationally accepted greenhouse gas accounting and reporting standards for businesses and promote their broad adoption across different organisations. The GHGP initiative will be used throughout this paper as a reference document to assist in calculating carbon emissions within educational organisations.

Within the GHGP there are technical guidance documents which we have drawn on and adapted to create a methodology for Scope 2 (Sotos, 2014) and Scope 3 guidance (WBCSD and WRI, 2008) bespoke to schools. This methodology has been adapted for schools and, therefore, includes guidance for all categories that relate specifically to the secondary education sector. We developed and used this methodology at Dulwich College to create a baseline carbon footprint in 2022. However, it can be adapted to start a carbon accounting journey for all schools.

One key difference between school types (maintained/ trusts/ academies) is where information is captured and stored within each school environment; for example, a trust may operate all energy procurement centrally and information may be held within a head office. Requesting data from a central office will enable schools to understand, action and therefore make changes to their own individual campus carbon footprint. We suggest that calculating carbon footprint at the school-level rather than trust level may provide more opportunities for student involvement given children’s familiarity of their own specific educational setting.

Within the methodology for calculating emissions, schools are required to look-up the emissions values of the different aspects of their operation including energy, waste disposal, transport and recycling.

• DESNZ & BEIS conversion factors are used for any data that is measured in weight, distance, volume, energy (see Department for Business Energy & Industrial Strategy, 2022). These are most likely to be useful in the calculation of Scope 1 and 2 emissions.

• DEFRA conversion factors are used for any data that is measured in currency (specifically, GBP) (see DEFRA, 2023). These are most likely to be useful in Scope 3 emissions calculations.

It is also possible to convert between the different conversion factors. For example, the cost of a given fuel could be used to estimate the number of litres – the carbon emissions of which could then be looked-up using the DESNZ & BEIS conversion factors. The conversion factors listed ‘for most uses’ should be sufficient for these calculations.

A well designed and maintained inventory of greenhouse gases (GHG), specifically carbon dioxide in the case of this methodology, can serve several organisational goals including:

• managing GHG risks and identifying reduction opportunities,

• public reporting and transparency,

• participating in mandatory reporting programs,

• recognition for early responsible action.

i) Define the recording period

When starting to review carbon emissions consider where information might already exist. Choose the period for an annual carbon review across all scopes; this may fall within a financial year or an academic year. All data collected for Scopes 1, 2 and 3 must align with the agreed reporting period.

ii) Calculating Scope 1 emissions

Gas

Create a spreadsheet for Scope 1 emissions which include Meter Point Reference Number(s) [MPRN]s from gas billing. Record the total used kilowatt hours [kWh] for each month per meter reference point. The carbon emissions can then be calculated annually for gas use in all areas. Utility brokers can also help provide this information.

Vehicles and equipment

Scope 1 also includes fuels used for actions relating to day-to-day activities and services, these may include petrol, diesel and oil. To track all fuel consumption, use invoices from suppliers. List fuels and track litres purchased on a monthly basis. It is then possible to use the conversion factors to look up emissions.

It can help to list all vehicles which the organisation owns or leases which can then be used to calculate the emissions from fuel use. In an educational establishment this may include:

• minibuses,

• service vans,

• grounds vehicles,

• sports vehicles.

Note their engine type and fuel used. This can be cross-referenced with the conversion factor for that particular fuel to calculate the carbon emission. Other uses of fuels may include oilbased heating or diesel or petrol fuelled power tools or grounds equipment, including leaf blowers or grass cutting equipment.

F-gas emissions are included under Scope 1: these are emissions from air conditioning leakage. F-gases are greenhouse gases which act as a coolant in air conditioning units. If any gas leaks occur from air conditioning units over the reporting year, it must be captured in the inventory by assuming the amount of gas needed to re-gas equals the amount of gas lost to leakage.

Using data already collected is the first action to start the school’s carbon balance sheet. As more data is collected a clearer picture can be established; however, this method will serve as a starting point.

iii) Calculating Scope 2 emissions

For Scope 2 emissions, list the Meter Point Administration Number [MPAN]s from electricity statements or billing.

Electricity emissions are calculated on a location and market-basis. Location-based calculations use country-specific grid emission factors whilst market-based calculations use contract-specific emissions factors based on the proportion of renewable energy in the contract.

List the MPANs on a spreadsheet with meter numbers and a location description. If a utility broker is used, ask for assistance in putting this information together. Compile kilowatt hours [kWh] data consumed for each month for each meter point.

Once there is a full 12-month history which falls into the chosen reporting period, emissions can begin to be calculated.

Most of the information for Scope 3 will be found in a school’s purchase ledger reporting. To do this, download the annual spend of a school or college for the reporting period: include invoices paid, direct debits and any other method of payment, including corporate card spend. Once this data has been compiled, it can then be manipulated to identify key suppliers and service providers. To assign the correct spend conversion factors, identify the products/ services provided by each supplier (see Table 1). To make this exercise more manageable focus on top suppliers first before becoming increasingly granular in matching specific spend to the respective conversion factor.

Note the total spend of the whole portfolio of suppliers, take any providers with an annual spend over £20,000 to analyse in year 1 to create a baseline of analysed data. Do not delete the remaining supplier spend. This will be needed to extrapolate emissions data to cover the full spend over the reporting period.

Once a list of top suppliers has been compiled, these will be the fundamental analysis that needs to be reviewed and subsequently relationships established to work on reducing emissions together, through positive engagement and communication (Tidy et al., 2016).

Some items not relevant to Scope 3 include:

• utilities which are removed as they are accounted for in Scope 1 and 2;

• fuel including fuel card bills which is accounted for in Scope 1.

Table 1 provides a non-exhaustive list for subcategorising spending:

Subcategory

IT services

Food

Scope 3 Category

Category 1

Category 1

Water Category 1 & 5

Waste Category 5

Consumables Category 1

Legal services

Category 1

Insurance services Category 1

Professional services

Pupil clothing and sports kit

Sports equipment

Routine maintenance

Capital goods and site improvements

Staff clothing and PPE

Print services

Category 1 and 2

Category 1 and 12

Category 1

Category 1

Category 1

Category 1

Category 1

Subcategory Scope 3 Category

Copiers services or lease

Exam board services

Health services

Council tax and business rates

HR Services

Grounds services

Books

Fixtures and fittings