EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Becky HEMUS

EDITORS

Connie BROWN

Evangeline

RIDDIFORD GRAHAM

ART DIRECTOR

Alessandra BANAL

LOGO DESIGN

Felix HENNING-TAPLEY

ENQUIRIES

@the_art_paper_

Fair Ground Art © 2025

Reproduction is prohibited without permission

A narrative kink, a remix, legend, archetype, illusion, fairy tale, distortion. Things that are passed down and things that are falsely believed. Glitches. Welcome to MYTH.

COVER 01: Ashleigh TAUPAKI photographed by Luke WILLIS THOMPSON, styled by Dan AHWA. Taupaki wears DRESS Uma Wang (The Shelter) ▪ EARRINGS Anna Balasoglou (The Poi Room) ▪ PENDANT Alex Sands (The Poi Room)

COVER 02: Claudia KOGACHI photographed by Matt HURLEY, styled by Crystal LIM. Kogachi wears TOP Taur ▪ BELT Issey Miyake ▪ BOOTS stylist's own

Page Work 1 - 5

Lolani Dalosa, OVA TELE LOU PAIĒ , digital artwork. Courtesy of the artist and The Physics Room

28

Brittany Walker-Smith and Freya Burnett: Creature Comforts by Ailsa Coulson

30

Abigail Aroha Jensen: cab-sous vide by Ardit Hoxha

32

Li Ming Hu: Deliciously Authentic by Amy Wilson

34

From Flesh to Ether

Sarah Drinan in conversation with Zara Sigglekow

62

The Stench of Innocence George Watson by Hugo Robinson

72

Once upon a time: On Ayesha Green’s The Radical Utopia of the Great Pacifice by Francis McWhannell

84

Te matauranga o te Pākehā by Peter Simpson

92

These Vessels mothermother's Unifying Threads by Faith Wilson

108

Shore Boy, Shore Thing Lily McRae by Romily Marbrook

114

Atarangi Anderson’s expansive practice by Thies Vaihū

123

An errant navigator Loren Marks by Maya Love

128

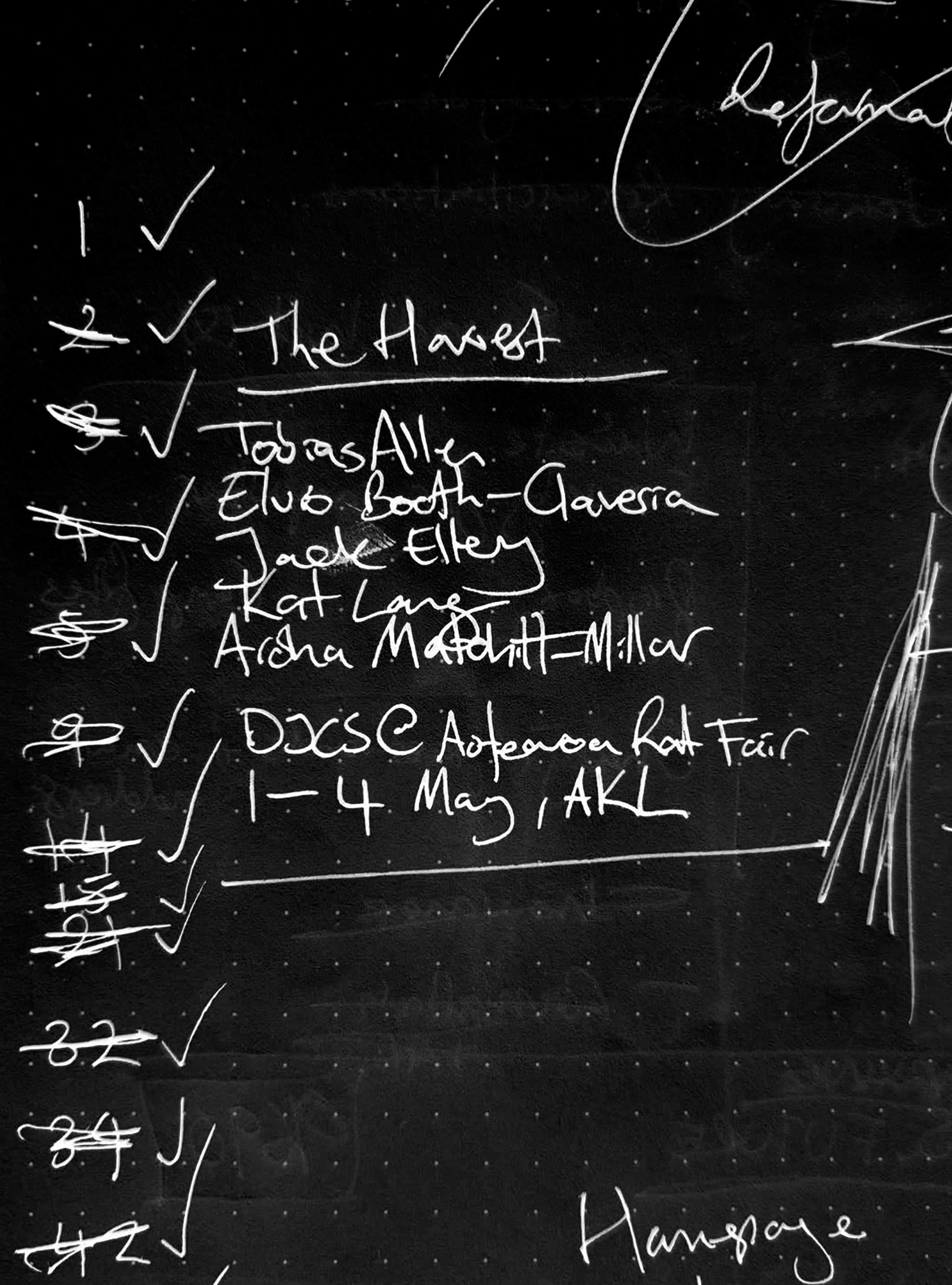

The Harvest by Samuel Te Kani

42

Myth, Māori and Multidimensionality by Ashleigh Taupaki

Photographed by Luke Willis Thompson

48

Claudia Kogachi’s Divine Self-Regard by Evangeline

Riddiford Graham

Photographed by Matt Hurley

100

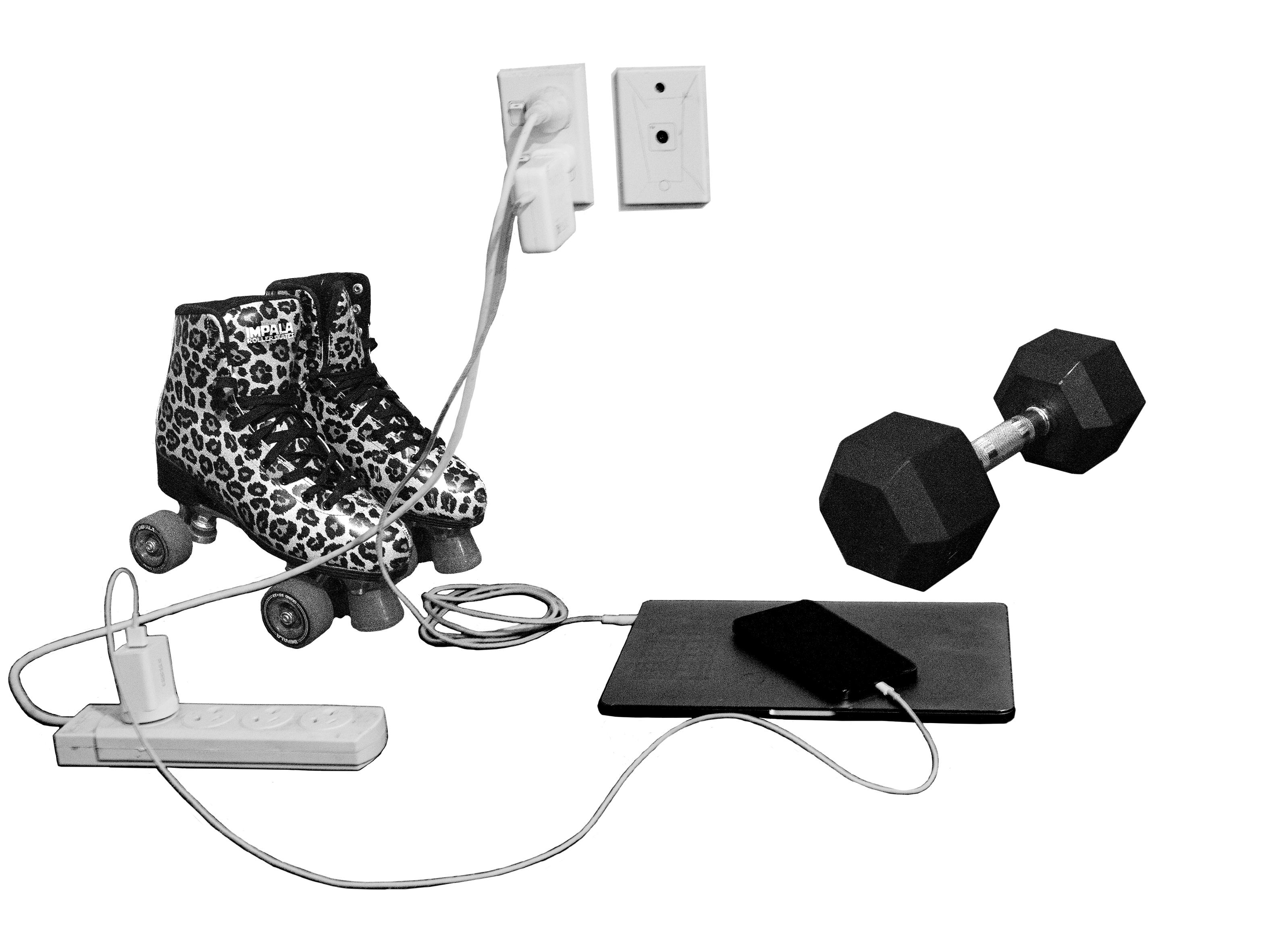

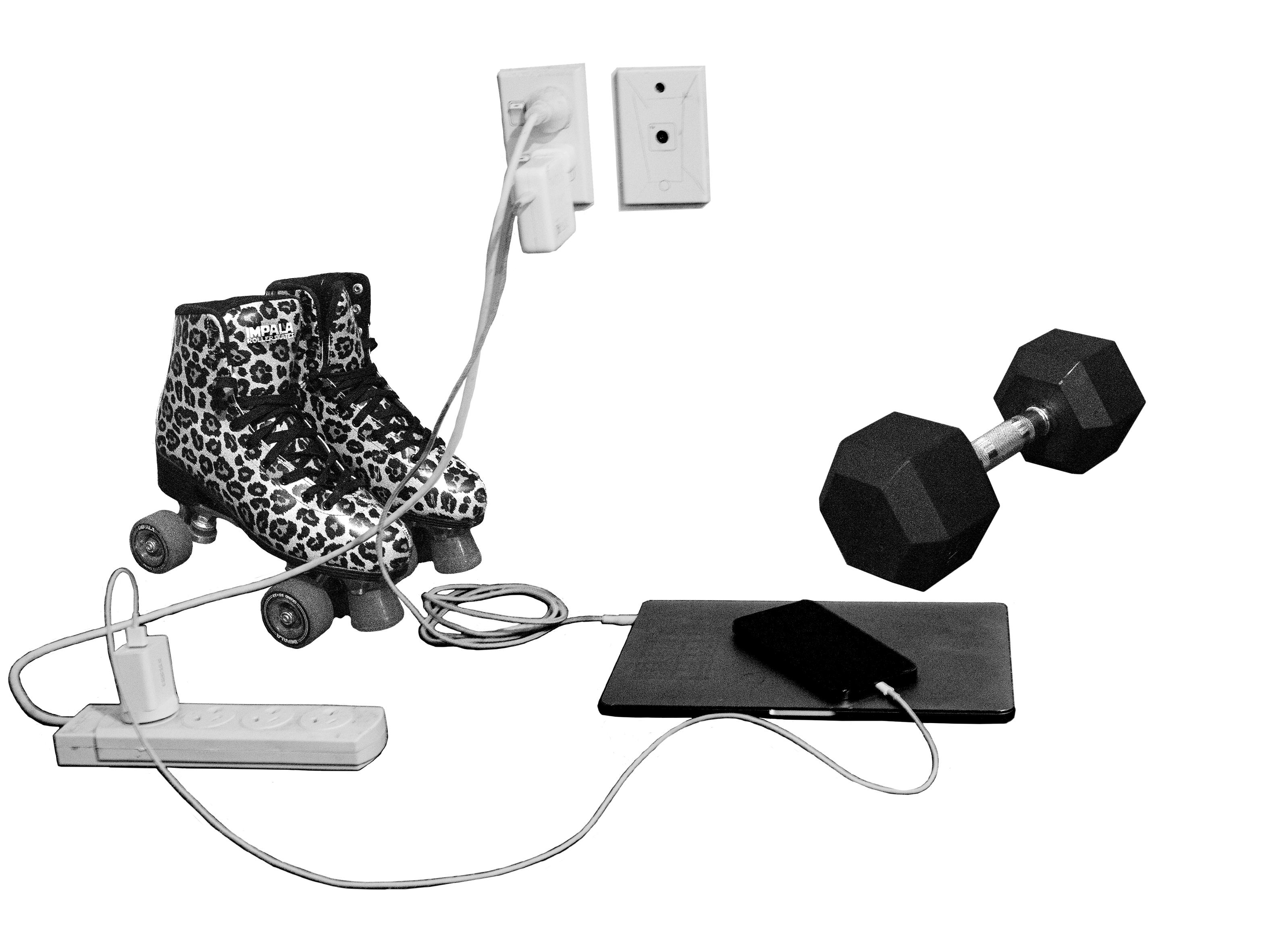

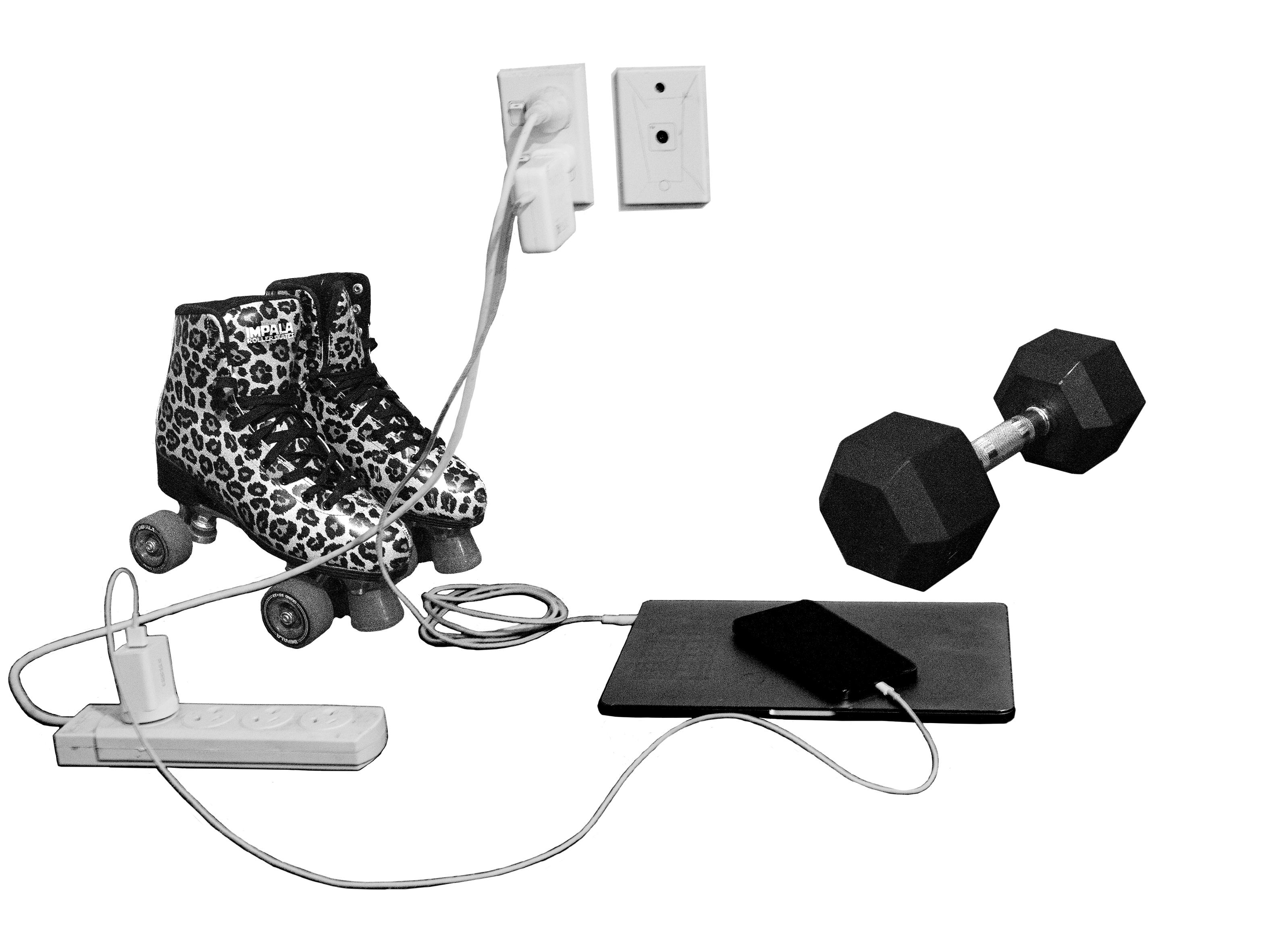

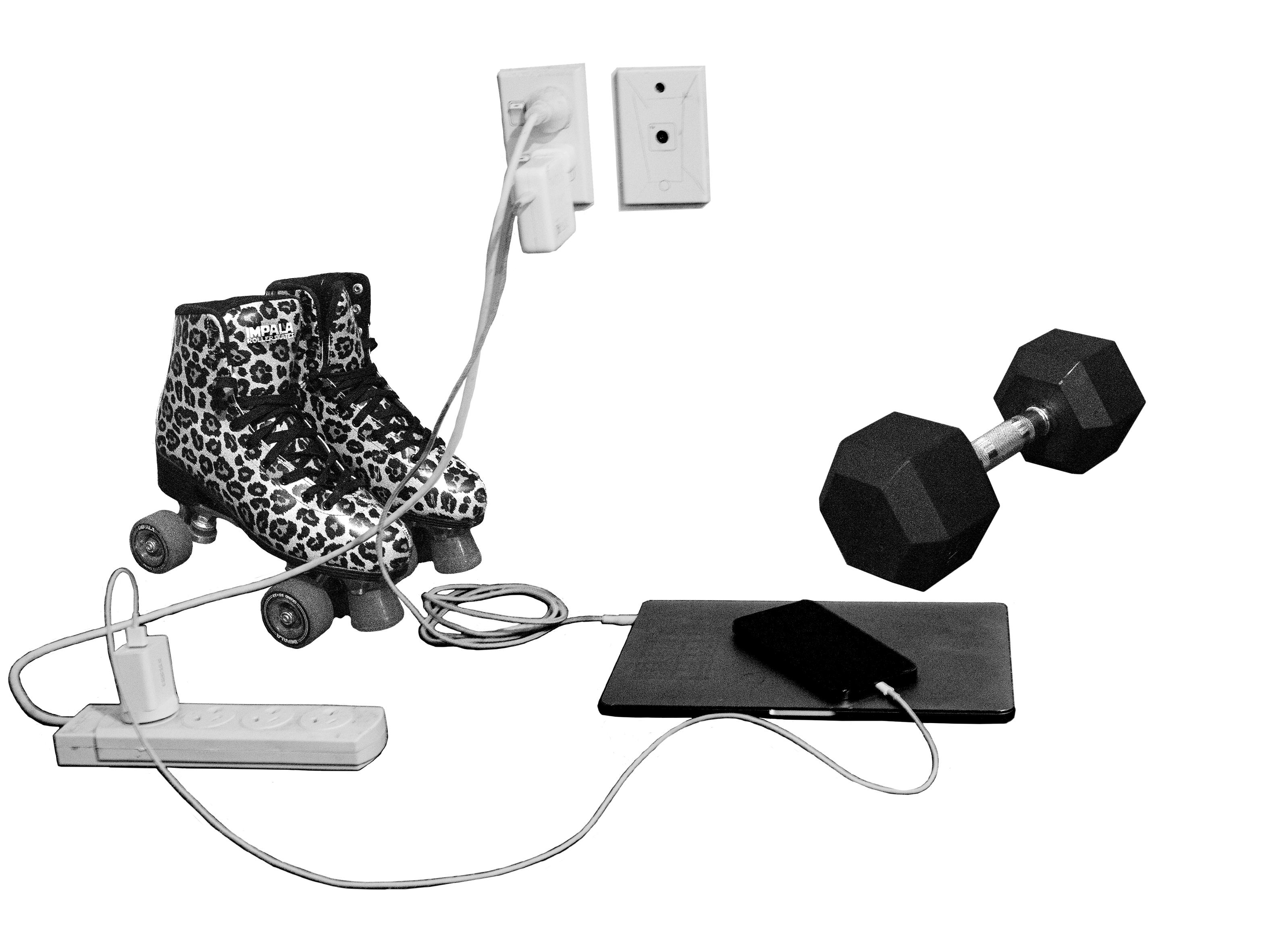

Anahera-Jade’s Studio Huaki guide

Photographed by Felix Jackson

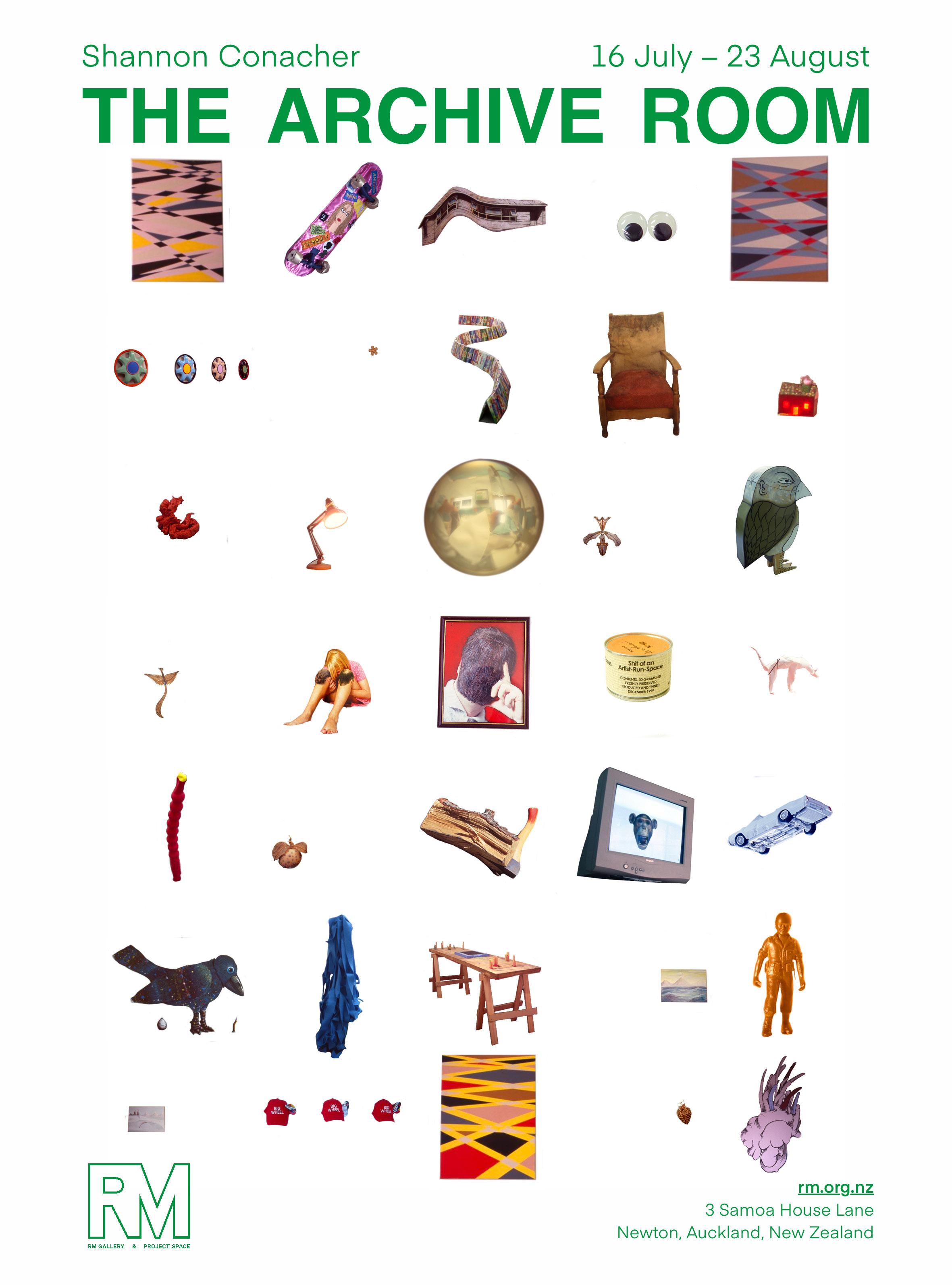

bergmangallery

3/582 Karangahape Rd (Entrance via 2 Newton Rd)

Tues-Fri 11am-5pm, Sat 11am-4pm Opening Fri 5 September. 5pm-7pm, all welcome bergmangallery.com

Onehunga, 4–25 October 2025

DICK FRIZZELL

Auckland City, 27 August–20 September 2025

3/582 Karangahape Rd (Entrance via 2 Newton Rd) Tues-Fri 11am-5pm, Sat 11am-4pm Opening Sat 2 August, 2-4pm, all welcome bergmangallery.com

A O T E A R O A N E W Z E A L A N D S U M E R . N Z

p. 26 Brittany Walker-Smith, I Don’t Understand Why They Have Pools on Cruise Ships?, 2025, acrylic, glitter, velvet, faux leather, 107 × 159 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Plomacy

p. 27 Freya Burnett, More Romanceee (detail), 2025, framed fine art print on photographic paper, 32 x 41 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Plomacy

The terrible print of the threadbare chattel couches in my draughty villa flat. During the pandemic we made it a home, throwing grandma’s hand-knitted blankets over the couches, putting up cheap satin over faded piss-yellow 70s flower print wallpaper; and filled the house with knickknacks, scrounged and saved, handmade vases, dried flowers, and an animal print rocking chair we found on Facebook Marketplace.

My first introduction to the art world. The same kids, the same people. A new world of style created by poor girls who want shoes, and bags, and fun prints to make the draughty flat feel more like home, more like a party. A pulse of life in the flats of girls across Auckland. Curious, beautiful objects lovingly brought home from semi-rural op-shops; altar pieces.

— 3D fridge magnets, black leather couches, velour tracksuits — Enjoyable, Stimulating, Like a Vibrator on Its Lowest Setting —

Girlypop is a feeling, a thrown-off phrase ripped from the internet and queer slang, used for besties, flatmates, sparkly font, frogs and rats, tiny bags. It combines elements of drag, performing femininity ironically but with codes and symbols of an ‘in’ club. Girlypop relies on persona, participation in a curated lifestyle as a form of expression.

— Jello cake, plastic table cloth, water bed — Have You Ever Been in an Empty Mall? —

I talked about the pandemic and the rise of cottage-core with WalkerSmith, about how these aesthetics take

rise in times of hardship. I remembered the Camp: Notes on Fashion Met Gala of the pandemic era. The ‘slay bestie’ memes shared around, the Juicy velvet, the brown 70s glass. Treasures only to be found on the fringes, on the edges of the consumerist centre. Burnett, in her collages and videos, takes a wondrous view of these sacred objects, placing herself among the young aesthetes seeking something original, crafted and one-off—a connoisseur of the object, on a quest to curate uniqueness. Her digital collages lovingly transform images, presenting knick-knackification, haphazard and curated from nostalgia: Y2k and 70s blowouts that are at once ironic … and then not.

Burnett speaks of the stress of space and things, finding a stuff-less solace in the camera. But quiet luxury is bullshit, and these girlypops don’t aspire to bullshit wealth, they aspire to girlhood, and witchcraft. To the creature comforts of things.

Walker-Smith cleans it up, pushes it through, lives it, and works it out. Working with plush velvet, animal print and leather, her works are a pastiche of the aesthetics she lives, finely painted over with text in a meme/RIP font. Her direct use of authorless online phrases sparks memories of those times; inside with the girls, inside with our crafts and our trinkets and our rinsed references.

Cloistered in that house, girlypop became the language of manifestation and sweet treats.

— An arcade, a low bar stool — More Romanceee —

Both artists use elements of found objects, found text, found fabric. The hand of the modern girl, the textures of the girlypop. For the internet era, materials and references combined to make not just an art object, but an atmosphere, a -core. I was transported to a young life reflected in prints. I can get overwhelmed by all the things I have, yet I love those things, I live with those things and call them sacred, and the worship of these found things can make them something new. WalkerSmith and Burnett have coalesced a life lived with the girls, curated, pulling from the many trends of texture, object and manifestation”irony. Of having beautiful thingsq

By Ardit HOXHA

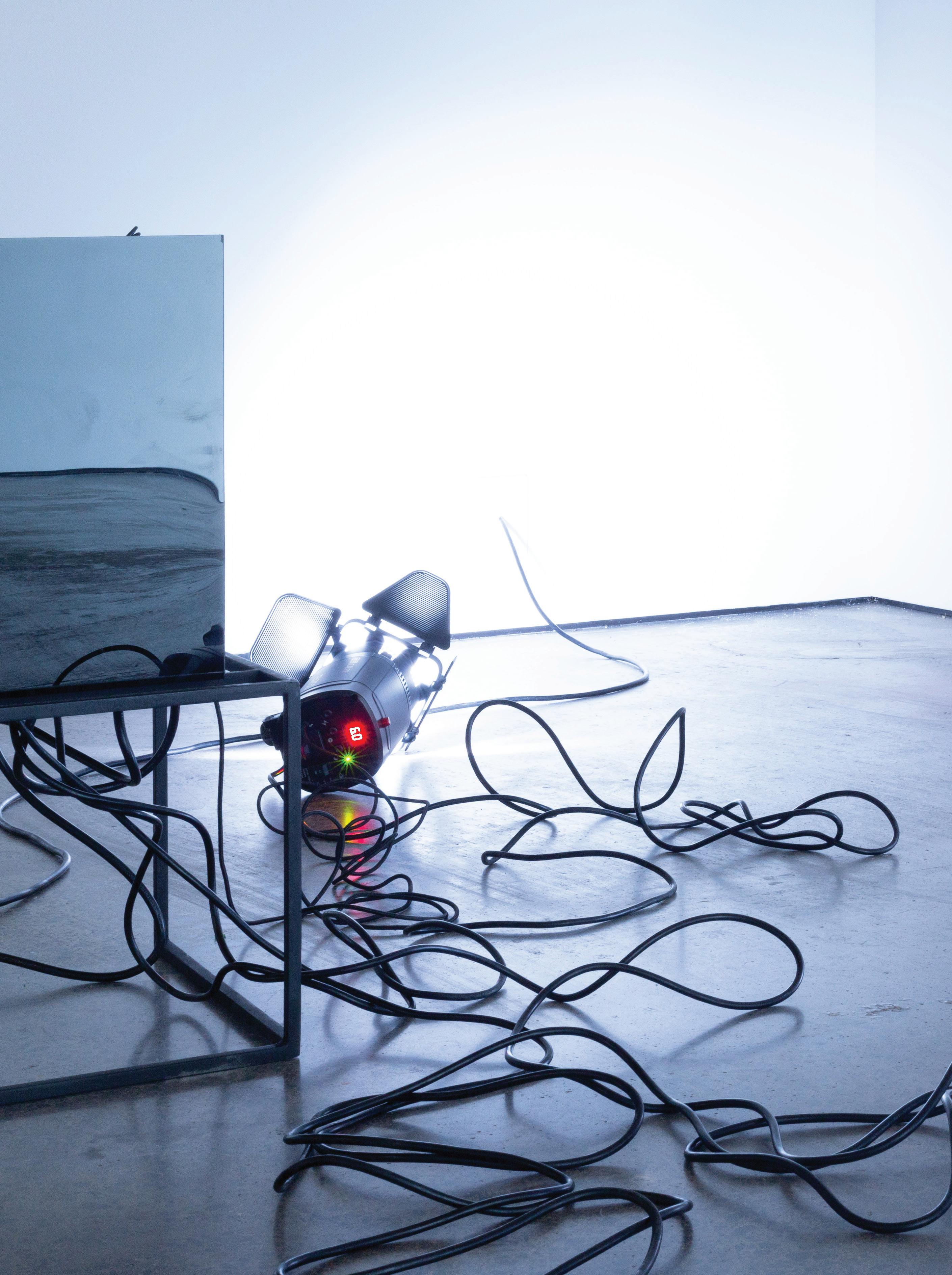

p. 30 Abigail Aroha Jensen, cab–sous vide. Installation view, The Dowse Art Museum, Pōneke, November 2024

p. 31 Abigail Aroha Jensen, cab–sous vide, 2024, mixed media installation, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist

Tucked away in an elevator, cab-sous vide is viewed in transit between much larger exhibitions, in a kind of space that artists typically fear being assigned. In this confined nook, Abigail Aroha Jensen presents the keepsakes she carries in the folds of her purse. Vacuum-sealed and hung across the three walls of the elevator, the lift is transformed into her own secret grotto of prized possessions. Jensen gleans the dredges of mass-produced junk here to cobble together an ode to love, its transformative powers in the face of capitalist consumption, where there is no object that is ever enough.

Upon entry, the viewer finds themselves quickly thrust into Jensen’s purse among a flurry of objects. Thrust up against worn packets of ketchup, salt, and pepper, the eye sifts and rummages through scribbled reminders, scrunched post-its, torn receipts, wrinkled coupons, and takeaway menus. My favourite: sentimental rubbish. In this self-declared papahou–treasure box, plastic tikis, bootleg crocs, and stubbed cigarettes find themselves on equal footing as peers. There are traces too of Jensen’s previous work, fragments of harakeke weaved and knotted into rope—her objet petit a, as she likes to call them—a titular nod to Lacan and the object cause of desire he enshrined.

But Jensen’s wilting junk seems far from the object that Lacan had in mind, an object that promises to heal the wounds of the subject’s desires. One which, to remain operable, must stay missing—because if

it were obtained, it would come up short against our fantasies. Jensen’s prized possessions demonstrate exactly this, the rot that creeps in when we come face to face with objects long pined for. And yet, Jensen swears allegiance to them all the more. Lovingly elevating these sweet nothings to the dignity of the Thing, so that they take pride of place in her box of treasures.

Yes, these objects are sealed, drained of oxygen, so they might be preserved in vain. But this barrier has been thoroughly breached, bubbles of air, liquid, crumbs, and kernels of corn having seeped through. In this way, Jensen’s mudded treasures both ascend and descend like the lift they are housed in. A dialectical move that sees us shift from the domain of desire, where perfect objects live, to the realm of love, where the wairua of the object is restored.

With this gesture, Jensen gives us much more than a series of objects to be puzzled and amused by. She offers the viewer a praxis, an approach to the object that might see it break out of the circuit of capitalist desire and its polyamorous appetite. Where consumers are encouraged to move quickly from one new object to the next, without ever settling on one. Jensen, in contrast to this frenzied movement, remains committed to her objects even when they no longer serve her.

Out of this fidelity, she creates new meaning out of objects that have otherwise been mass-manufactured. Objects that were once sold in sealed packaging now rub up against the reality of their use, so that new meanings emerge out of what once signaled the Others’ desire (money). More intimate–singular meanings that the Other could not possibly know or quantify. Jensen, in her stubborn commitments, transforms even the receipt, which, now treasured in the crevices of her bag, functions no longer as the simple index of a financial transaction, but becomes instead the index of a beloved memory, perhaps of a humble meal shared between friends?

It is not for us to know what particular meanings these objects might take on for Jensen. Irrespective of this ‘knowledge’, the objects are transformed. Turned into singular signifiers of Jensen’s own creativityq

By Amy WILSON

p. 32 Li-Ming Hu, I went to X’ian and all I got was…, 2024, glazed and unglazed porcelain, stoneware, 21 x 21 x 27 cm. Courtesy of the artist and RM Gallery

p. 33 Li-Ming Hu, Sweet Thai Chilli, 2024, glazed porcelain, 20 x 21 x 8 cm. Courtesy of the artist and RM Gallery

(01) Kyla Wazana Tompkins, Racial Indigestion: Eating Bodies in the 19th Century (NYU Press, 2012).

In Deliciously Authentic,, Li-Ming Hu adopts the syntax of advertising to dissect the performative burden of racial identity under the logic of commodity culture. Borrowing its title from the tagline of Trident, a supermarket-tier brand of ‘Asian’ condiments that litters the aisles of New Zealand grocery stores, the single-channel video work recounts the artist’s audition for one of the company’s advertising campaigns. The narrative—delivered in a tone poised between bemusement and resignation—reveals the latent violence beneath corporate desires for ‘natural’ representation. Here, authenticity is less a marker of cultural legitimacy than a stage direction. By the video’s climax, Hu smears red and white sauces across her mouth in an obscene pantomime, her body reduced to what she later terms an “optimal vehicle”—not for expression, but for consumption.

Hu’s deadpan delivery masks a corrosive undertow. Rather than dwelling in outrage, the work probes the uneasy threshold between complicity and critique. If the harm of exoticization is dulled by repetition—made banal by its persistence—then what responses are still available to the racialised subject asked to perform herself into legibility?

The question reverberates through Hu’s broader body of work. In an adjacent video that mimics the cadence of a YouTube makeup tutorial, Hu transforms into Jeremy Irons as René Gallimard in David Cronenberg’s M. Butterfly (1993)—a filmic adaptation of David Henry Hwang’s 1988 play, itself a counter to Puccini’s Madama Butterfly. Layering latex and foundation, Hu inhabits the strange

feedback loop of yellowface, where Asianness is fetishised and disavowed. She recounts instances of theatrical yellowface in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland and on Broadway (Miss Saigon, predictably), before finally restaging M. Butterfly’s infamous closing scene—Gallimard’s tragic apotheosis in ‘Oriental’ drag. What Hu calls “double drag” is a hall of mirrors in which power and performance blur: white men pretending to be Asian men pretending to be Asian women.

Such layered citation risks collapsing into moral equivalence—the trap of multicultural “balance” that grants symmetrical offense to asymmetrical histories. But Hu interrupts this reading. Addressing the camera in the work’s final moment, she breaks character with an acerbic aside: “We can’t end like that, can we? Not after all we’ve been through.” It’s a rupture that refuses closure, exposing the scaffolding behind the scene.

Elsewhere in the exhibition, porcelain fountains shaped like the famed Terracotta Warriors, their faces eerily cast from Hu’s own, spew thin jets of water from their mouths. The grotesque loop of ingestion and expulsion stages a final refusal: not just of food, but of the consumability of the Asian body. The work echoes writer Kyla Wazana Tompkins’s framing of racialised eating practices under empire, where appetite becomes a mode of domination— and indigestion, perhaps, a form of resistance.01

Hu’s practice unfolds within the paradoxes of identity-based art, where representation can be both a strategy of survival and a site of exhaustion. In mining her own image, her own marginalisation, Hu asks a disquieting question: what becomes of identity when it is the raw material of both violence and value? Amid increasing calls for authenticity as a remedy to systemic racism, Hu exposes the hollowness of this prescription. Authenticity, after all, has long served as a marketing category, not a route to freedom.

By refusing easy catharsis, Hu does more than perform critique—she implicates us in the conditions of her performance. Her work is not a plea for recognition, but a challenge: to imagine what kind of embodiment might exist beyond the roles we’ve been given—and whether we’re ready to confront thisq

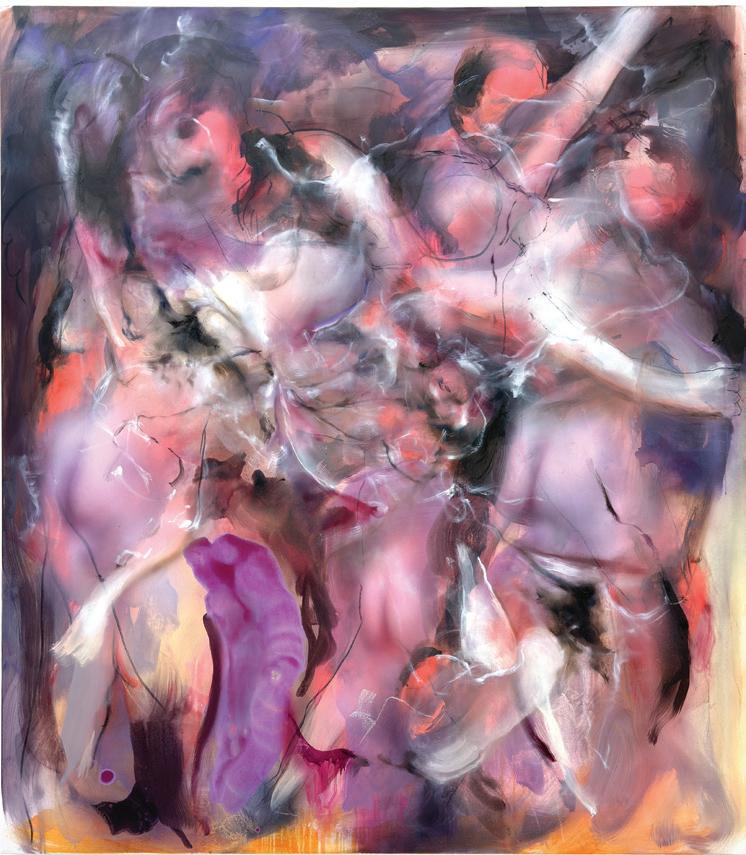

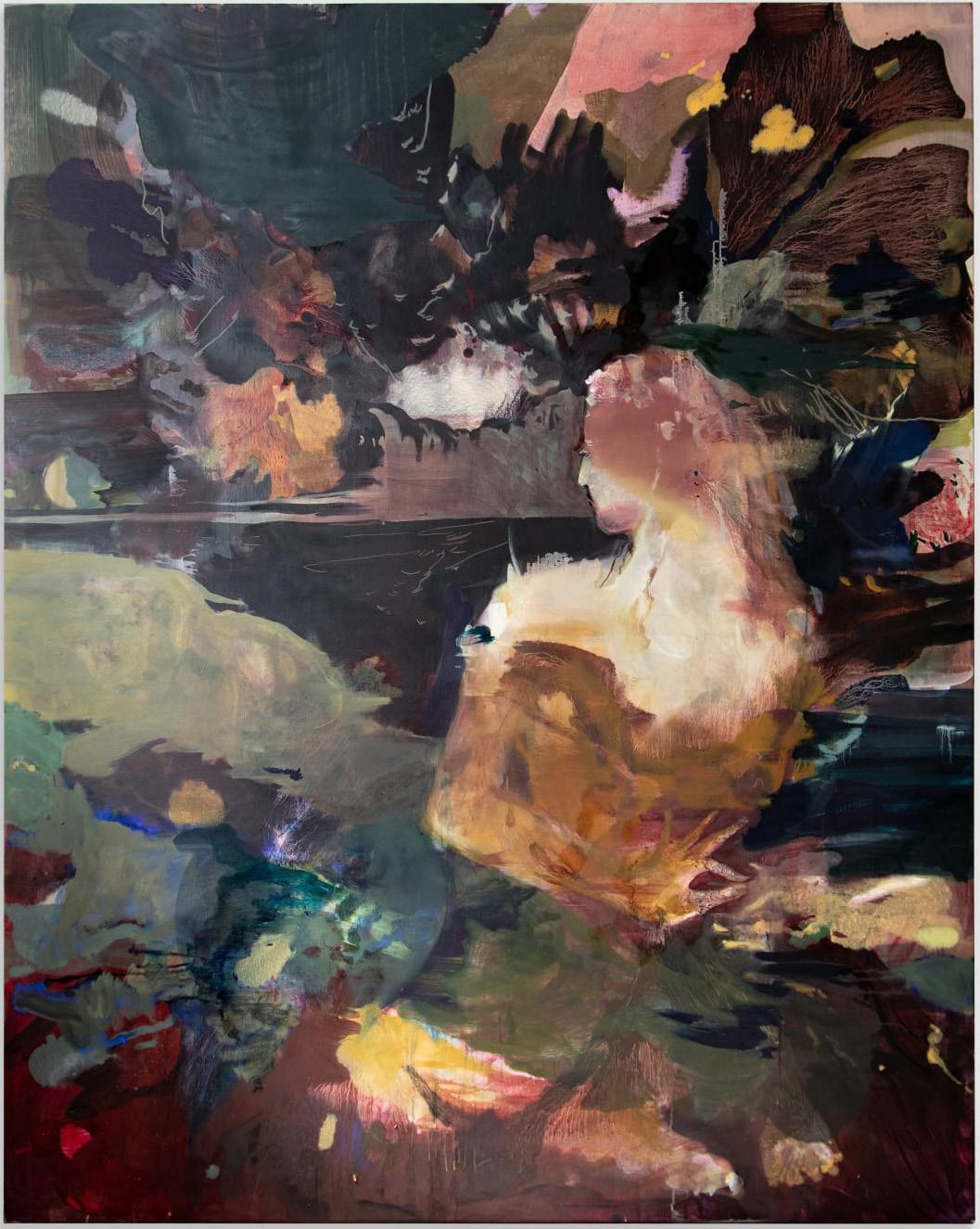

Zara Sigglekow: We're sitting in your studio in Collingwood, Naarm, surrounded by your new paintings. How are you feeling about your practice at the moment?

Sarah Drinan: I’m leaning into my paintings being a bit more playful. It’s almost like I’m letting myself dance my way through them and letting them evolve, rather than just executing finished images.

And you recently scaled the works up. They’re quite physical in their making.

Totally. Scaling the work up was something I’ve wanted to do for a while, but I felt a bit daunted by it, like, Where do I even start? But by painting bigger, you end up having to let go and allow the works to develop in different ways. Even just using bigger brushes and moving my body in a way that feels expansive and less restricted, there’s a physicality that comes through in the work.

The Turning Wheel has had five different versions underneath it. The canvas is big, body-sized, so there’s enough space to reform, remake, and respond to the previous layers every time I’m in the studio.

The way that my work has evolved to perhaps be more impressionistic is a by-product of me loosening up in my own body—feeling more free and open to play, suggestion, and accidental mark-making; working with whatever happens and finding a balance between creating something familiar or bodily.

There’s a kind of luminous fleshiness in your work that evokes Old Master paintings.

Absolutely. I’ve always been drawn to baroque-style works—those biblical or ascension scenes where bodies are rendered as fluid, morphing, almost angelic forms. It’s not something I consciously set out to replicate, but the body, and its mutability, has always been a central anchor in my practice. I grew up immersed in that kind of imagery, so it feels deeply embedded in how I paint.

Where did you first encounter them?

My dad was a painter and used to make replicas of Old Masters: muscles, shoulder blades, skin contours, thighs, glutes. He painted both masculine and feminine bodies. So when I think about painting, that’s the foundation—those kinds of forms and techniques. But sometimes, I feel too tied to that tradition and want to step away from it. There’s always this push and pull between trying to create harmony and balance with the body, and then trying to disrupt it—to get comfortable with mistakes and then lean into them.

I’m also quite a fast, intuitive painter—very responsive and immediate in my approach. Lately, I’ve been trying to step back more, to let marks evolve rather than controlling them too tightly. I’ve started using more acrylic, which initially made me feel like I wasn’t ‘doing it properly’. But the immediacy of acrylic suits my pace—it allows for layering, reworking, starting over. I think you can see it in the paintings—a visible evolution. That unpredictability, that sense of something unfinished or shifting, is what excites me, because it’s dependent on what area I focus on in the moment and what I leave behind.

There are lots of figures in your work. Seldom alone, often together, doing mysterious things. Quite anthropomorphic sometimes.

I’m interested in depicting the body in an ambiguous way that feels familiar yet distant, like it’s behind a veil. I’m interested in the unknown, the otherworldly, in an ephemeral quality that is slightly out of reach. As humans, we experience sensations we can’t fully grasp. I want to capture what it’s like to reach for something just outside our realm.

I’m also interested in our nature as humans to want more, to seek more, and the idea that we don’t fully know everything—that we’re restricted by our mortality. I like the idea that there’s a space around and within us that we can’t grasp but we know exists.

I’ve always read your work as being about inhabiting a physical body while also trying to transcend it.

Definitely. That tension is always present—the conflict between being bound by physicality and fragility, and reaching toward something more spiritual or intangible. There’s an absurdity in that push-and-pull, but also a kind of sweetness. Maybe painting is a way to move the body beyond itself, or to gesture toward another state of being.

p. 38 Sarah Drinan, The Reclamation. Installation view, Seventh gallery, Melbourne, April 2024. Photo: Imogen Jade. Courtesy of the artist and FUTURES

p. 40 Sarah Drinan, A spasm between god and a three-assed cog , 2025, oil, acrylic, pastel and charcoal on canvas, 178 × 157.5 cm. Courtesy of the artist and FUTURES

p. 41 Sarah Drinan, The Turning Wheel (detail), 2024, acrylic, pastel and charcoal on canvas, 198 x 168 cm. Courtesy of the artist and FUTURES. Photo: Damien Griffiths

Your intaglio etchings respond to this idea, too—depicting forgotten stories that feel familiar yet distant, maybe stories that we hold within us…

When I made these works, I was reading a lot of mythology, which definitely influenced my practice. For example, I created a series of prints based on Irish and Scottish folklore. One story that stayed with me was about the Selkie—a shapeshifting creature that transforms from seal to human. In the tale, a man steals the Selkie’s skin, trapping her in human form, where she lives a life of longing. Eventually, she finds her skin and reclaims her true self, abandoning the human world. That narrative resonated deeply with me—it speaks to the human and particularly the female experience, that tension between the authentic self and societal expectations. It’s a story and a space that feels very familiar.

My paintings aren’t literal illustrations of those myths, but there are parallels— between forgotten narratives and these ambiguous, bodily images. They feel like visual retellings of something lost or half-remembered.

Is there any contemporary visual imagery that influences your work? It’s always hard to pin down exactly, but sometimes I reference pornography— not literally, but I’m interested in the fleshiness, the tension in the skin, the shadows, the tonal range. Older porn videos have this particular blurriness I find compelling. I also use 3D modelling apps on my iPad to contort forms. That brings a slightly techie aesthetic into the work, which I embrace.

The fleshy glow in your paintings evokes both screen-based imagery and historical painting traditions.

Studying the old masters taught me how to paint from dark to light—a technical approach I still use. But I also enjoy disrupting that tradition. I’ve been experimenting with glazing, airbrush, and pastel to build depth and shadow. The iPad helps speed up my process—I can test shapes and colour palettes digitally before committing to them on canvas. It’s a tool that lets me work more quickly and intuitively. If I weren’t a painter, I think I might have gone into graphic design. I’ve always been drawn to image-making, colour, and composition—it just feels like a natural language to meq

By Ashleigh Taupaki

Shelter)

The NARRATOR speaks over the thrum of a river. Winter closes. Cloud—waning in anticipation of the arrival of springtime—drifts over pūriri and tawa hills, stagnant in the air like fading static. Wetting the inside of one’s nose with each inhale. The NARRATOR pauses to breathe in deeply with an intention visible in the chest. The river increases in volume and tempo.

The river, roaring, coldly wanders each crook with haste; over rock and incline with a gliding quickness only known by water.

River sounds soften to a thrum again. The wind joins in like steadied, rhythmic breath.

Te Waitangi o Hinemuri [NARRATOR gestures downwards and across as if tracing a river] —these are the tears of a girl left behind. She lives there [NARRATOR points towards Turner’s Hill in the background] , with UREIA, the famed taniwha of Hauraki. It had come across her one day, unkempt, walking mistily through bush and shadow. She barely started when it emerged from the water, resigned to hopelessness and memory. “Ko wai koe?” it asked of her, a curious empathy in its creatural voice. And [HINEMURI enters, following the river path as defined by the NARRATOR’S gesture] she told it her story.

Exit NARRATOR

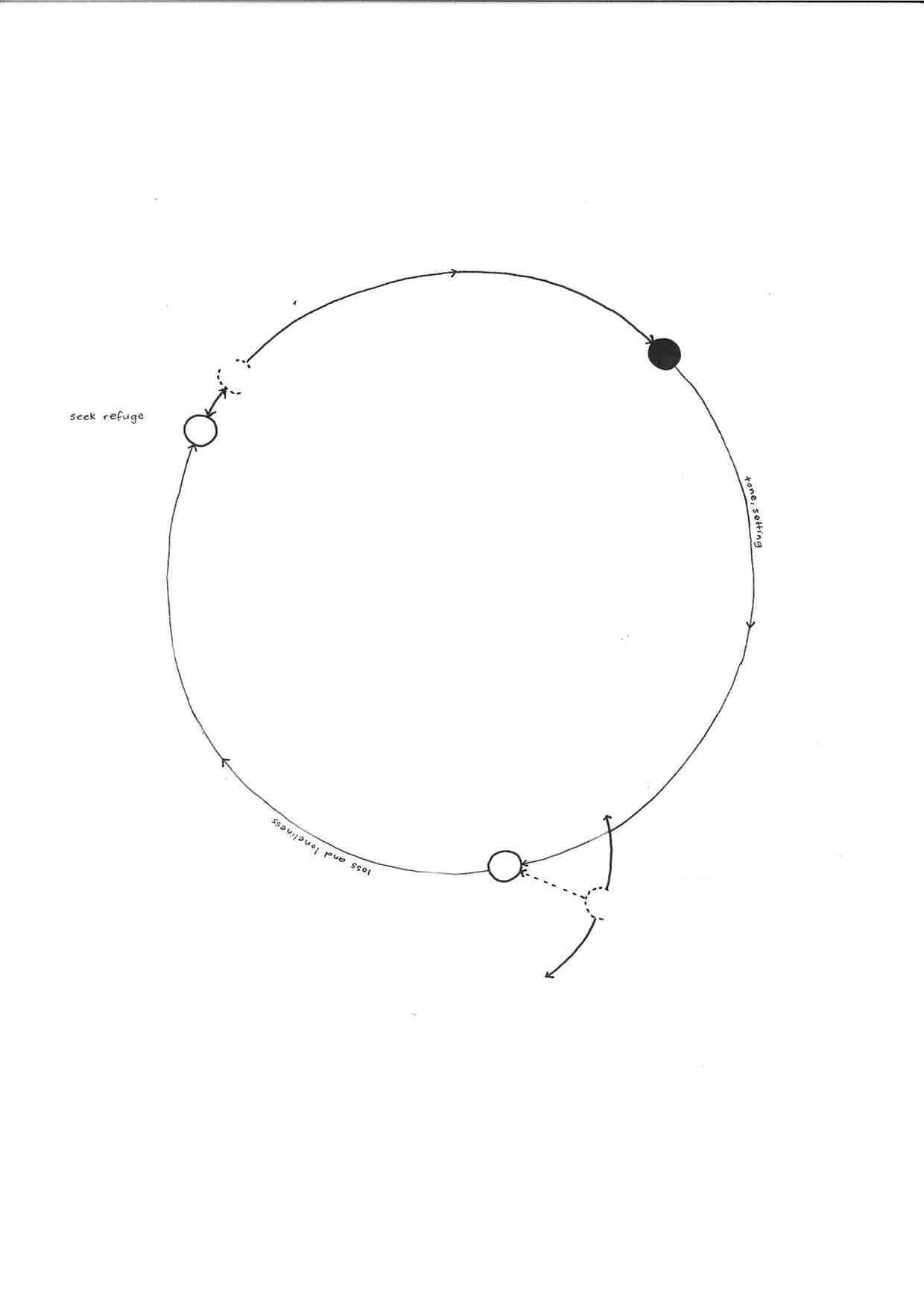

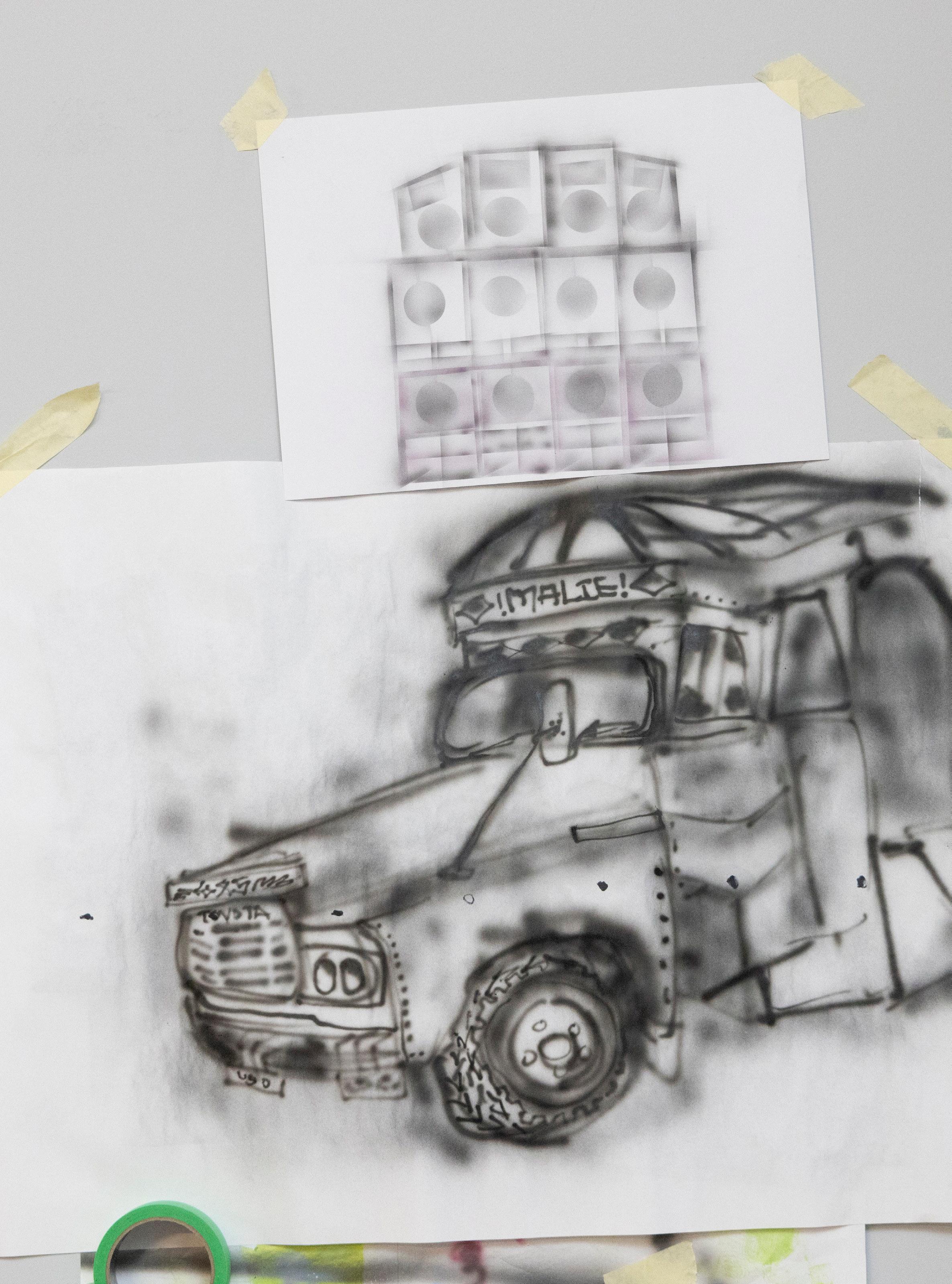

All images: Ashleigh Taupaki, mataika [preparatory sketches], 2024, pen on tracing paper

French literary theorist and philosopher Roland Barthes describes myth as a political mechanism, its purpose to maintain the separation of the West from everyone else, the oppressor from the oppressed: The function of myth is to empty reality. Myth is a value: it is enough to modify its circumstances, the general system in which it occurs. The oppressed makes the world, he has only an active, transitive (political) language; the oppressor conserves it, his language is plenary, intransitive, gestural, theatrical: it is Myth.01

Barthes’ definition of a Western myth—as the emptying of reality to affirm positions of superiority— aligns with Māori lawyer and

educator Ani Mikaere’s commentary on ‘mythmaking’ as the “coloniser’s justification of otherwise unjustifiable behaviour,” showing that the production of myth serves the purpose of maintaining systems of violence and oppression. Here, the term ‘myth’ connotes a falsity. These interpretations are antithetical to those within te ao Māori, because pūrākau are a representation of cosmologies, observations, genealogies, theory and tradition—subjective and long-lived realities, rather than the controversion of reality. Assigning the word ‘myth’ to that which is practised within Māori tradition is misleading and invalidating. These cultures relied on the longevity of relationality to ensure the preservation of narrative via oral tradition, utilising myth to interpret and reflect a daily reality.

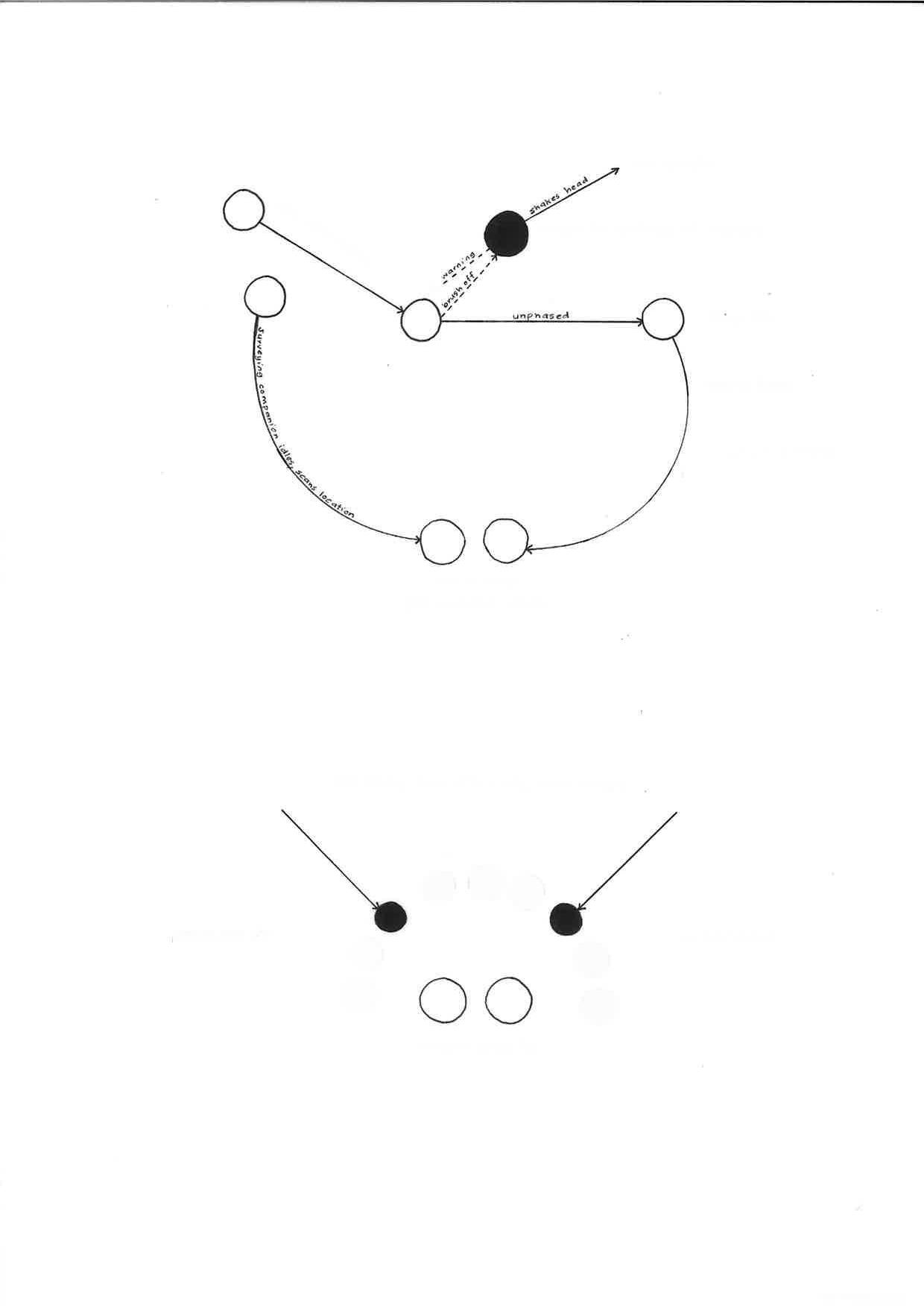

The work mataika for the 2024 Artspace Aotearoa group show, titled This is the house that Jack built, pertains to the shooting of Pākehā man Daldy McWilliams in 1879 at the hands of Ngāti Hako, who collectively opposed the illegal surveying of the Pukehange Block in the Hauraki region, resorting to this act of violence. There are locational determinants leading up to the incident that illustrate the cultural convergence of narrative and place. For example, the mythological personification of the Ohinemuri River—the larger setting in which mataika takes place—as a weeping young woman captures its moods and patterns. The hills bounding the river are steeped in pūrākau. The river’s name tells a story, Te Waitangi o Hinemuri, or the weeping tears of Hinemuri, referring to a girl who was left behind when a raiding party forced her people to flee their settlement. Distraught and alone, Hinemuri wandered the land until she met a taniwha, who, sympathising with her situation, took her to his cave, offering shelter and companionship. They lived there until her people returned to reclaim her, and the taniwha, heartbroken, tunnelled deeper into the cave until he emerged at Tīkapa Moana. This pūrākau explains the formation of the cave and river systems through the tears of Hinemuri and the burrowing of the taniwha. By personifying these processes, Māori can envision themselves as a figure in the narrative, relating to, within, and as the landscape.

There is a sense of reality, or credibility, in this story. The raiding of Hinemuri’s village is likely to have occurred as competing iwi fought over resources

and land. The presence of taniwha, although implausible in a Western sense, has often been understood by Māori as a natural phenomenon; an event that is out of the ordinary, a slight change in one’s environment, the uncanny, which is then imbued with meaning, allegory, tohu. Selected acts and scenes in mataika restore reality to the myths and forms of history that omit a Māori perspective, and aid in understanding the political and social framework within which Ngāti Hako are formed collectively, and in relation to the contested block in 1879. Act One brings us to the Ohinemuri River as the narrator performs breathwork, emphasising the wet, misty quality of the setting. Bodily diction invites the audience to participate as the narrator counts seconds in te reo Māori, prompting the rhythm with which one would inhale, pause and exhale. The narrator then establishes key landmarks before cueing Hinemuri to enter the stage. The scene is set. Although her speech is not included in the score, her emotion through stage direction is implicative. Addressing the taniwha during this retelling, her desolation at being left behind is insinuated through instructive language such as “look down, scan stage”, “timid, look at feet”, “eyes downcast”, “choke up” and “weep.”

Despite the proven truths that arise from multigenerational storytelling, its legitimacy only comes into question through the existence of materials that seem more tangible, stable and enduring, such as the written word, paper, film—languages and technologies incomprehensible to a people who relied on oral transmission to preserve

(02) Ibid., 120.

knowledge. This incompatibility was a characteristic that was taken advantage of by the oppressor. Despite the prevalence of Western materiality, which innately excludes Indigenous modalities, Barthes provides a potential solution to these fundamental differences in language, struggle and relationality. In his 1993 book titled Mythologies, Barthes offers a counter approach that lies in nonlinearity and compromise:

In the case of oral myth, this extension is linear; in that of visual myth, it is multidimensional. The elements of the form therefore are related as to place and proximity: the mode of presence of the form is spatial. Its elements are linked by associative relations: it is supported not by an extension but by a depth: its mode of presence is memorial.02

Although linearity often denotes a homogeneity or a boundedness, Barthes is attributing linearity to orality according to its literal transferral from one person to another. Whether transmitted consistently across generations, or in a short-lived interaction, orality is fundamentally a form of one-way, direct communication. Multidimensionality is presented as the antidote to the issues of oral linearity; the inclusion of the intricacies of place, history, people, memory and knowledge to understand the interrelations that contribute to a narrative. A compromise between these elements needs to exist to attain a holistic and more truthful telling of events—a fluid form of storytelling that allows us to apply a whakapapa framework to these colonial histories, perhaps, through diagrammatic, instructional meansq

Stylist Crystal Lim

Hair and make-up

Binh Minh Ha

For arty children in the early two-thousands with access to a computer, Microsoft Paint was a tool for wish fulfillment. Instead of wearing out your pinky finger and pencil lead colouring in a sky, you could flood it bright blue at the click of a mouse. Anyone could draw a straight line; plus there was that instant and powerful ‘undo’ button. Digital paint was a playpen for little gods, who said, Let the triangular flag of my castle be red—no, green, and it was so.

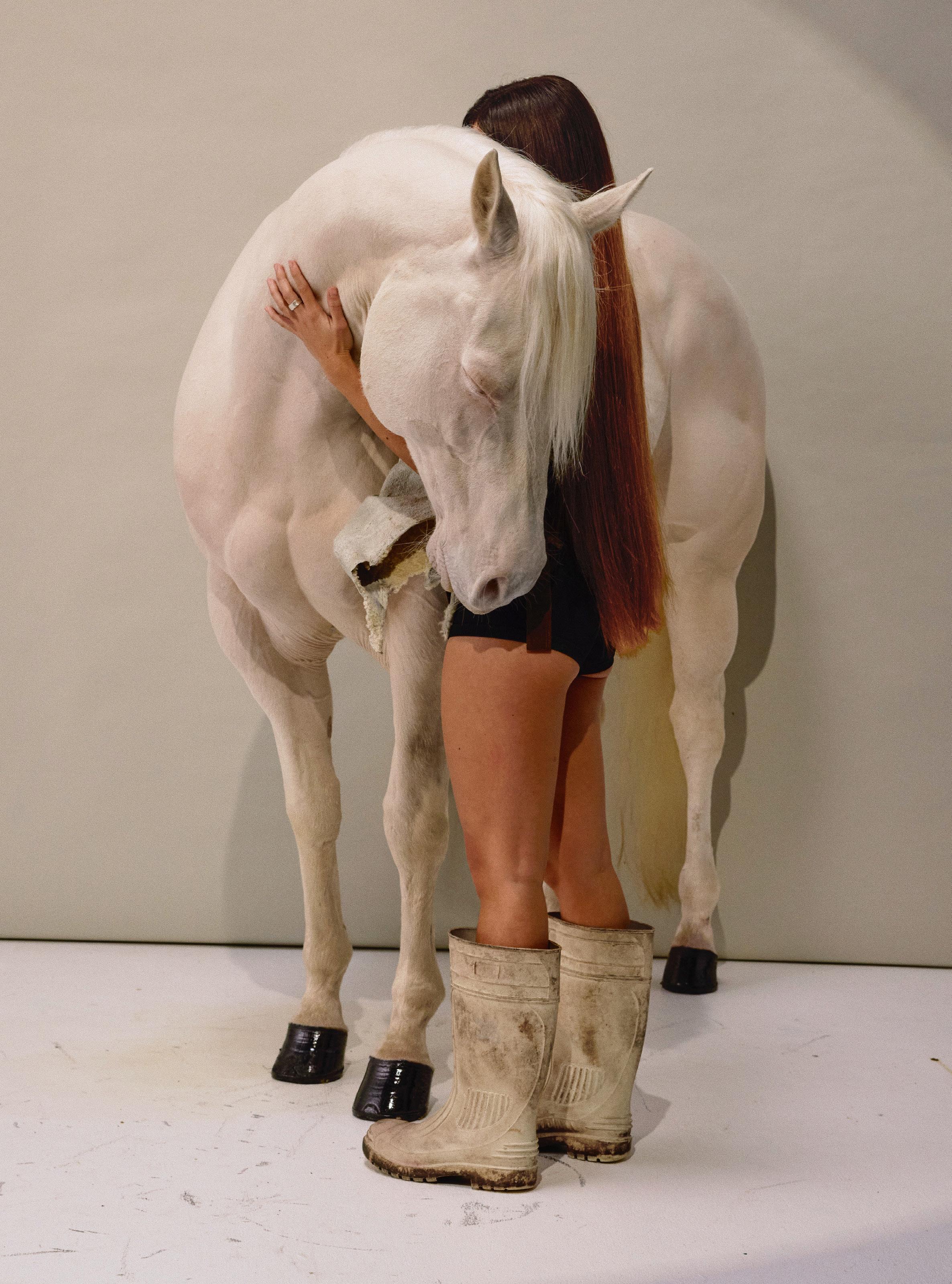

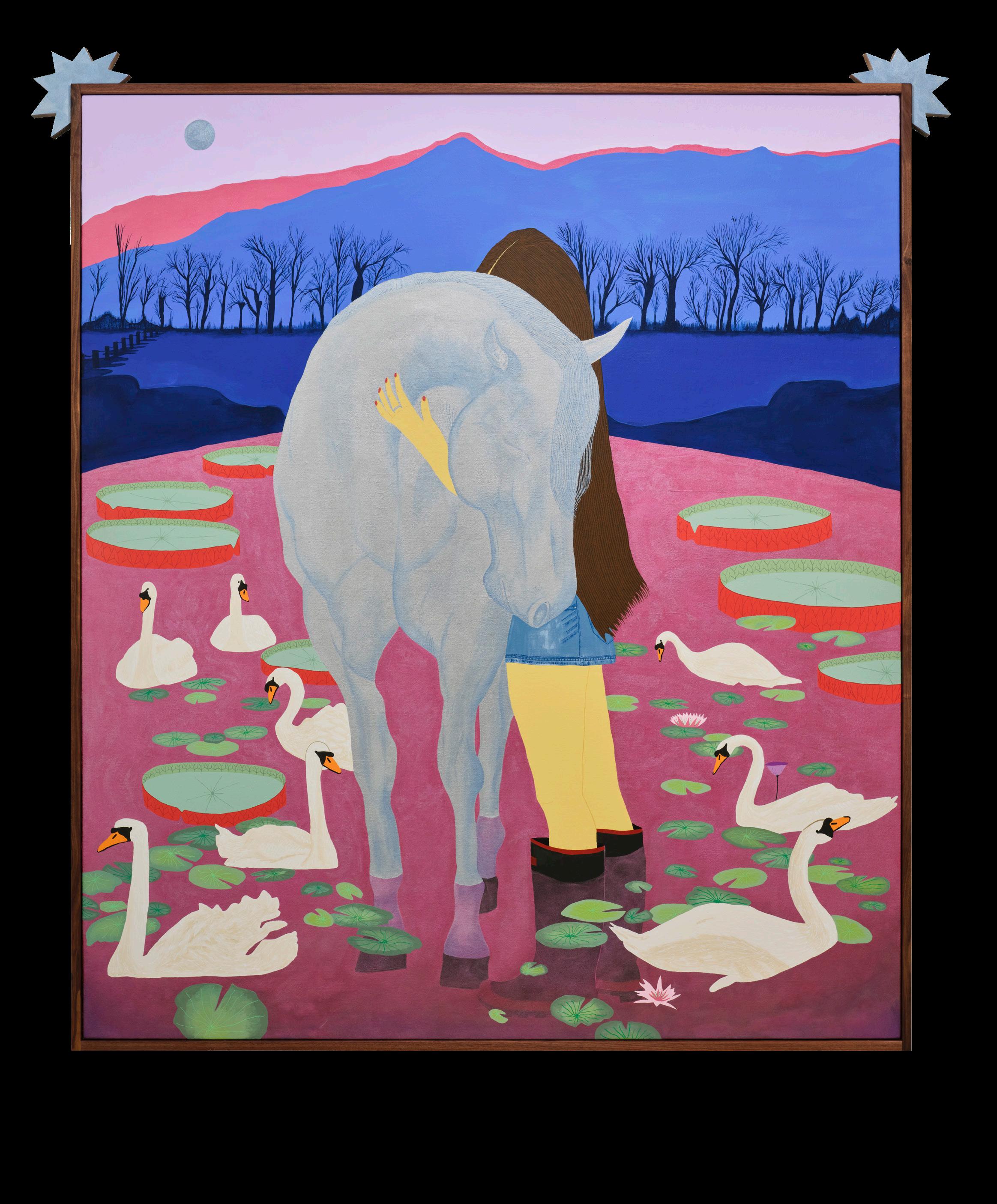

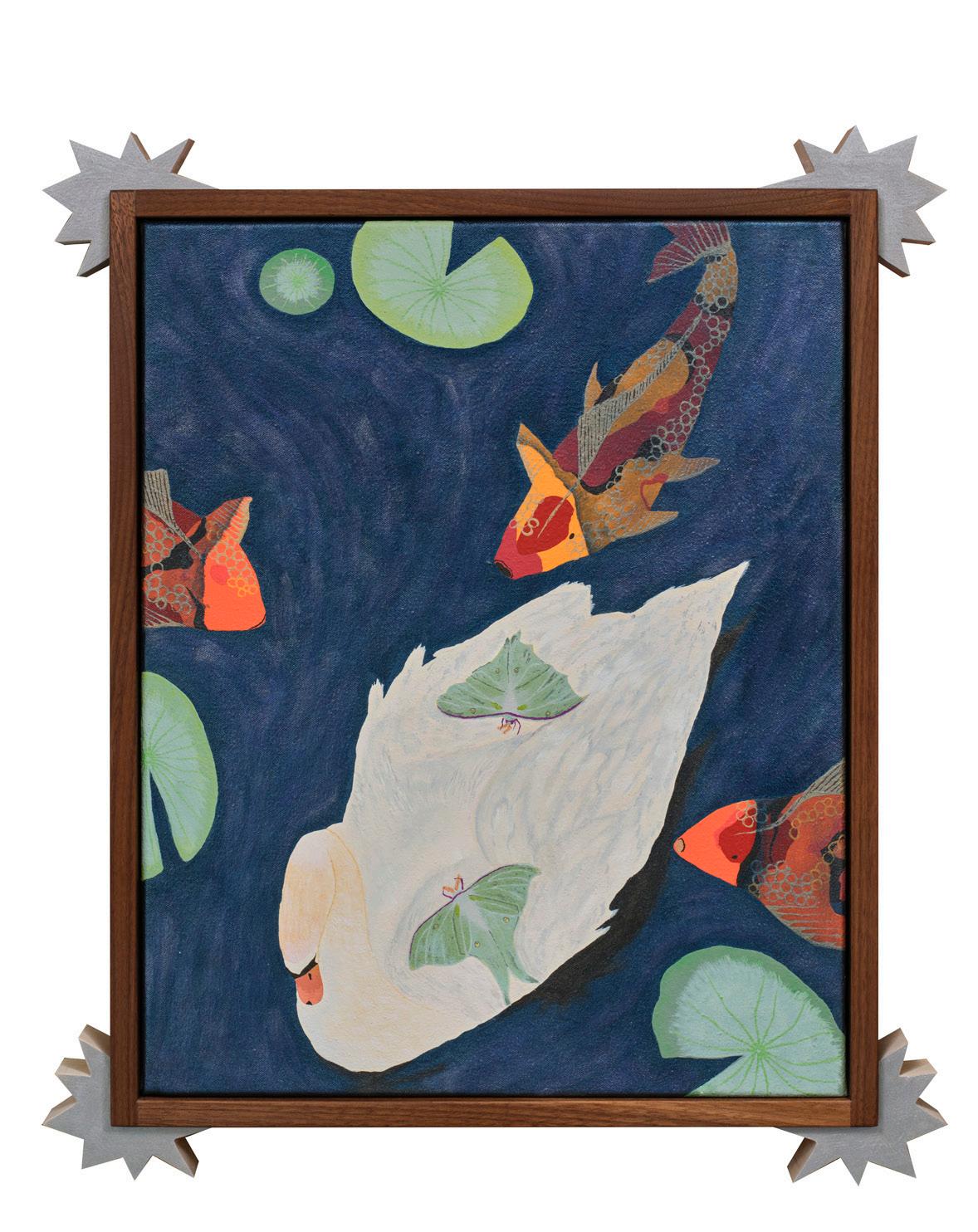

p. 51 Claudia Kogachi, Self-portrait with horse, 2024, acrylic on canvas with custom frame, 177 x 155 x 5.8 cm

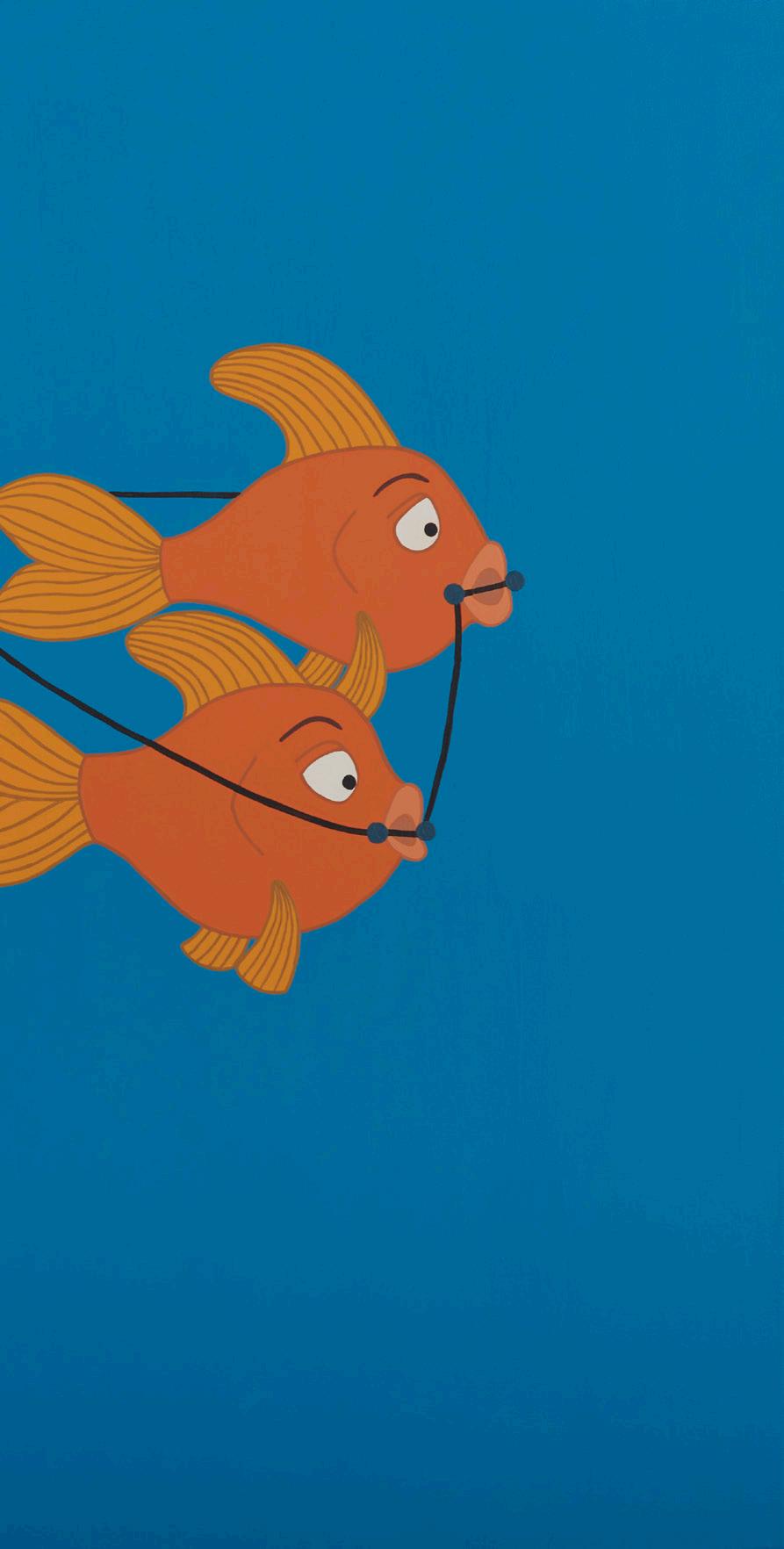

p. 55 Claudia Kogachi, Self-portrait with Koi, 2024, acrylic on canvas with custom frame, 177 x 155 x 5.8 cm

p. 56 Claudia Kogachi, Sitting with Koi, 2025, acrylic on canvas, handcarved frame, 177 x 155 x 5.8 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Phillida Reid

p. 57 Claudia Kogachi, Koi Pond, 2025, tufted wool on cotton backing, hand-carved walnut and painted maple frame, 100 x 70 x 12 cm

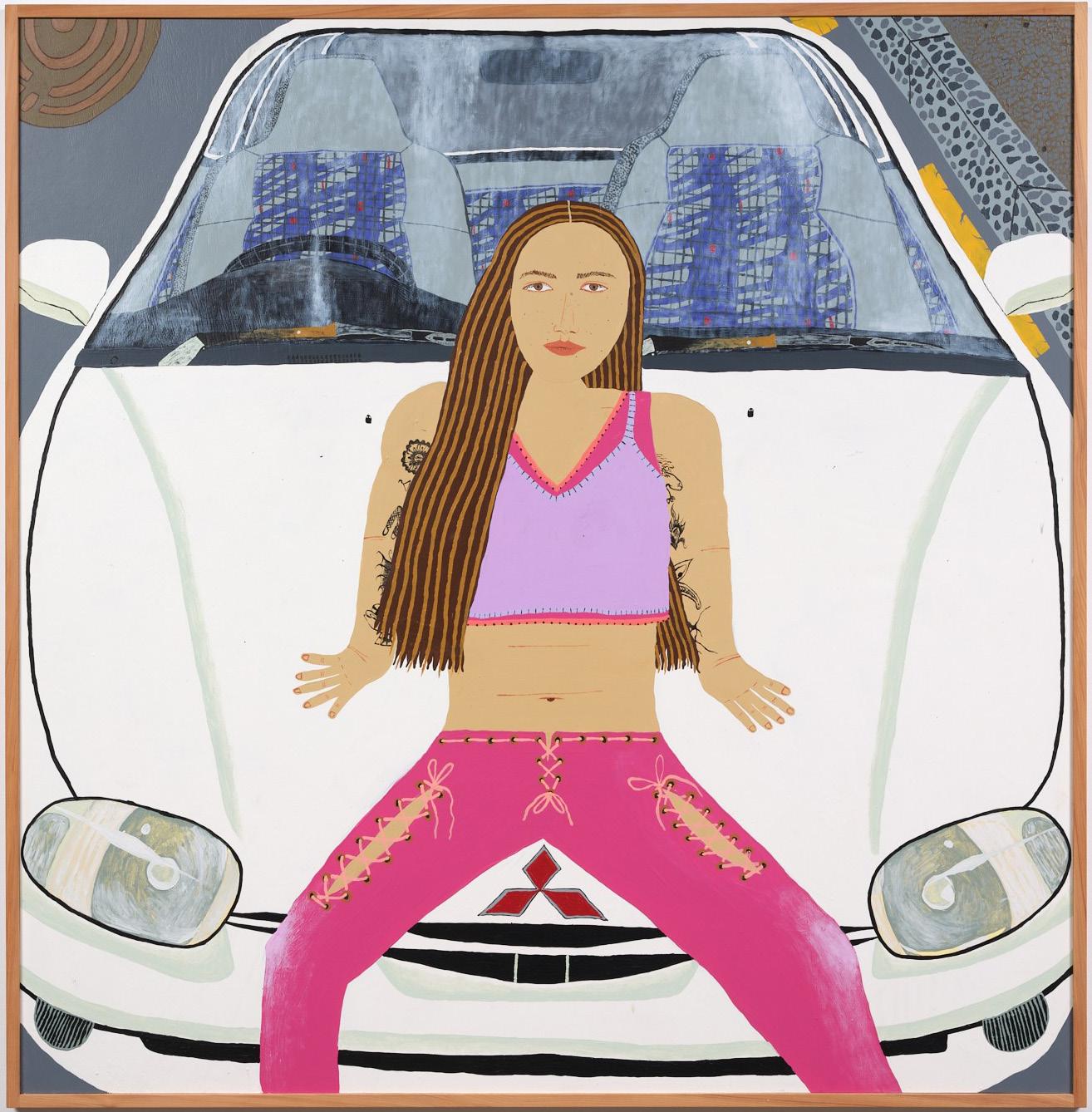

Block colors, emphatic outlines, and slightly unruly scenarios are also the essential materials of Claudia Kogachi’s painting practice. In 2019, the artist (born in 1995, Awaji-shima, Japan) won the New Zealand Painting and Print Award, beating out 40 finalists for a purse of $20,000. Her painting, Mom Wait Up, depicts someone else winning a race: Kogachi’s mother, muscular and calm. Like the daughter trailing behind, she has matchsticks for fingers, Squiggles® instead of hair, pedantically laced running shoes, and cobalt skin—a trademark of Kogachi’s paintings at the time. Mom Wait Up is painted in acrylic. But it shares that willfully naïve optimism that can still be found on Reddit’s Microsoft Paint message board, where a painstaking depiction of peeled grapefruit gets about the same number of upvotes as a hasty cartoon dialogue between a dog and a flea.

In the years since, Kogachi has rapidly built a reputation for figurative painting that eschews modeling and linear perspective, putting her in a tradition of contemporary painters that includes Ayesha Green and Kushana Bush. But where Green’s compositions probe the politics of any figuration in a postcolonial context, and Bush’s gouache fantasias pile on simplicities into a parasocial clamor, Kogachi is interested in the singular myth of the self. Whether a Kogachi painting features a lover, a grandparent, a horse, or a mosquito, the subject is always the artist.

In her 2019 painting Those are my fucking shoes, Kogachi depicted herself in competition with her mother in bouts of baseball, table tennis, and boxing (also in ‘dog surfing,’ ‘laundry soccer,’ and pyjamaclad kickboxing in the bathroom). The diptychs are, cleverly, almost symmetrical, and the blue women squaring off in them could be one another’s mirror. Almost. But one figure has frown lines, the other body hair; more importantly, when one figure is winning, the other is losing. If a daughter is no longer happy to act as a mirror—or runner up— to her mother, what does that make them? Friends? The paintings are wittily solipsistic: Everything that exists, in the blue double portraits, exists because the Kogachis are fighting over it.

There is one artwork attributed to Kogachi on Reddit: the textile work Nanny, which appears on Reddit’s r/Tufting board. During the pandemic, the

artist found a new medium, creating her images in reverse by using a handheld tufting gun to punch colored yarn through mesh. The images that came out the other side have a wan, pixelated charm, attributable partly to rug pile’s gridded backing, and partly to its innate disinclination to lie flat. They also introduce a perspectival shift: Nanny is part of a series of vertical works, exhibited in Rugged Heart at Visions, that depict Kogachi, large and alone in the frame, taking on different jobs: electrician, landscaper, realtor. Where the double portraits conveyed selfhood as source of anxiety and danger—the threat that Saturn might, at any minute, devour her young—the post-pandemic textiles and paintings convey an increasingly affirmative vision of the artist as a distinct, specific individual—a god with her own name, her own beauty spot and tattoos. The new god Claudia is the protagonist of her own pantheon.

Over the last couple of years, Kogachi has expanded her players to characters outside her immediate family, mostly setting aside stiff blue bodies for colors and lines that have become (somewhat) more naturalistic. Lovers and friends develop their own iconography: Josephine, the romantic partner who has crafted distinctive narrow wooden frames for Kogachi’s artworks for several years, makes a memorable entrance wearing a crown of boldly delineated yellow ringlets, later updated as a brunette halo.01 The artist’s Obaachan is often snacking or manning the grill. Other returning cast members are recognizable by their tattoos.

As is the prerogative of divines, the new god Claudia herself sometimes wears disguises—the long silver date-night tie of Brad Pitt in Mr. & Mrs. Smith, Cameron Diaz’s amoeba-shaped earrings in The Mask. But she remains recognisable, and recognisably in charge of her own destiny. As K. Emma Ng observes: Sometimes it feels like the painter is on a bit of a power trip. She gets to imagine how a situation might play out, manipulate each figure like a marionette, and set their features to her will. Having the last word is the artist’s privilege.02

But hey, this divine self-regard spills forth unto the viewer. Hangouts—dancing round a DJ set, dominoes and cappuccinos, basketball—inspire mutual pleasure. Smooches in the woodshop look pretty good. And Kogachi’s work has always had a sense of humor about its creator’s ego; even as this emboldened deity takes

p. 58 Claudia Kogachi, Self Portrait as Suki, 2021, acrylic on plywood, rimu frame, 127.5 x 125 cm. Courtesy of the artist, Visions and Artspace Aotearoa

p. 58 Claudia Kogachi, And Just Like That, 2023–24, acrylic on canvas, hand-carved frame made of kauri and recycled glass, 158 x 128 x 6 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Season

p. 54 & 59 Claudia Kogachi, Moth Visit with Future/ Old Self, 2025, acrylic on canvas, handcarved frame, 177 x 155 x 5.8 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Phillida Reid

p. 53 & 60 Claudia Kogachi, Ghost Horse, 2025, acrylic on canvas, hand-carved frame, 177 x 155 x 5.8 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Phillida Reid

p. 61 Claudia Kogachi, Swan, Moth, Koi, 2025, acrylic on canvas, hand-carved frame, 60 x 55 x 5 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Phillida Reid

(01) The real Josephine Jelicich has also made custom frames for Kogachi’s nearcontemporary Owen Connors, part of an eddy of new attention to other crafts—quilting, woodworking, pottery—that has rippled through the recent output of young New Zealand painters.

(01) K. Emma Ng, "Kogachiworld," The Art Paper digital, 29 January 2022, https://www. the-art-paper.com/journal/claudia-kogachiheaven-must-be-missing-an-angel

control of her own myth, she and her familiars are assaulted by the mundane irritations of cockroaches, jellyfish, and sandhoppers, and diarrhea (see Hot Girls with IBS at Hot Lunch, 2021).

Part of the point of these crowd scenes, funnily enough, is to convey a single, unified state of mind. Everyone here is drinking the same juice, and it’s the same stuff that oozes out of a tufted rug mosquito and propels beluga whales through the air: Kogachi’s mood. The principle is made explicit in Blue Moon, in which blue-skinned mirror-image Kogachi mermaids hold hands; blue-skinned, mirror-image Kogachi centaurs gaze into each other’s eyes, gamboling in water in which every ripple converges on a heart. What looks like a tableau of multiple contented figures is really just one.

Most recently, the artist has encountered her future self, silver-haired and tattoos faded, amidst traditional signifiers of Japanese and Okinawan (Ryukyuan) cultural identity—red-crowned cranes, Mount Fuji, a round red sun (Of Strands and Stars at Jhana Millers)— swimming through a clear pool, young hair entangling with old (The Waders at Phillida Reid).

In this latest show, The Waders, light and dark— long absent from Kogachi’s work, as other critics have noted—are starting to creep in. The god Claudia embraces a ghostly horse, as shadows pool around the swans and waterlilies at her feet. In another painting, she rises out of maple leaf–littered water and, encountering a friendly looking koi, seems about to speak. This is, quite literally, a more reflective mood: light bounces off the water, and bodies, submerged, darken and drift.

A deity, having laid out her legend in the bold lines of childhood and colored it in, calls the shots. But does she have immortality? In The Waders, we see a god inspecting her own iconography, enlarging it to include more of her past and more of her future. In water, that place of reckoning, where time collapses and our bodies remember themselves, Kogachi pauses. These deep pools might contain the root of eternal life. But like the demigod Gilgamesh, she might find it and forsake it. She might go back to the party. She might swim upstream and reemerge in a thousand yearsq

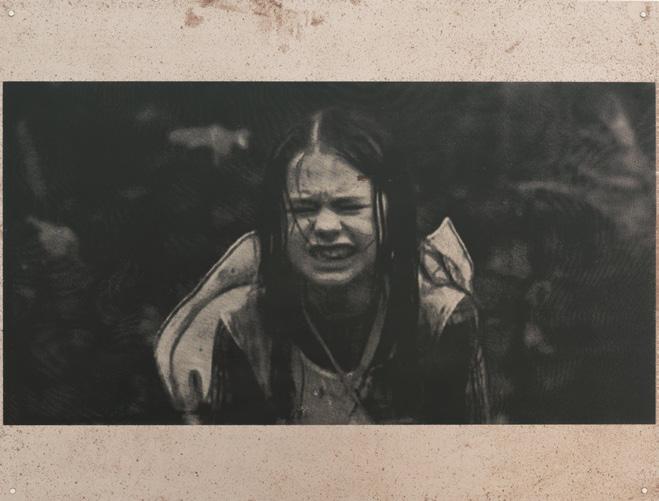

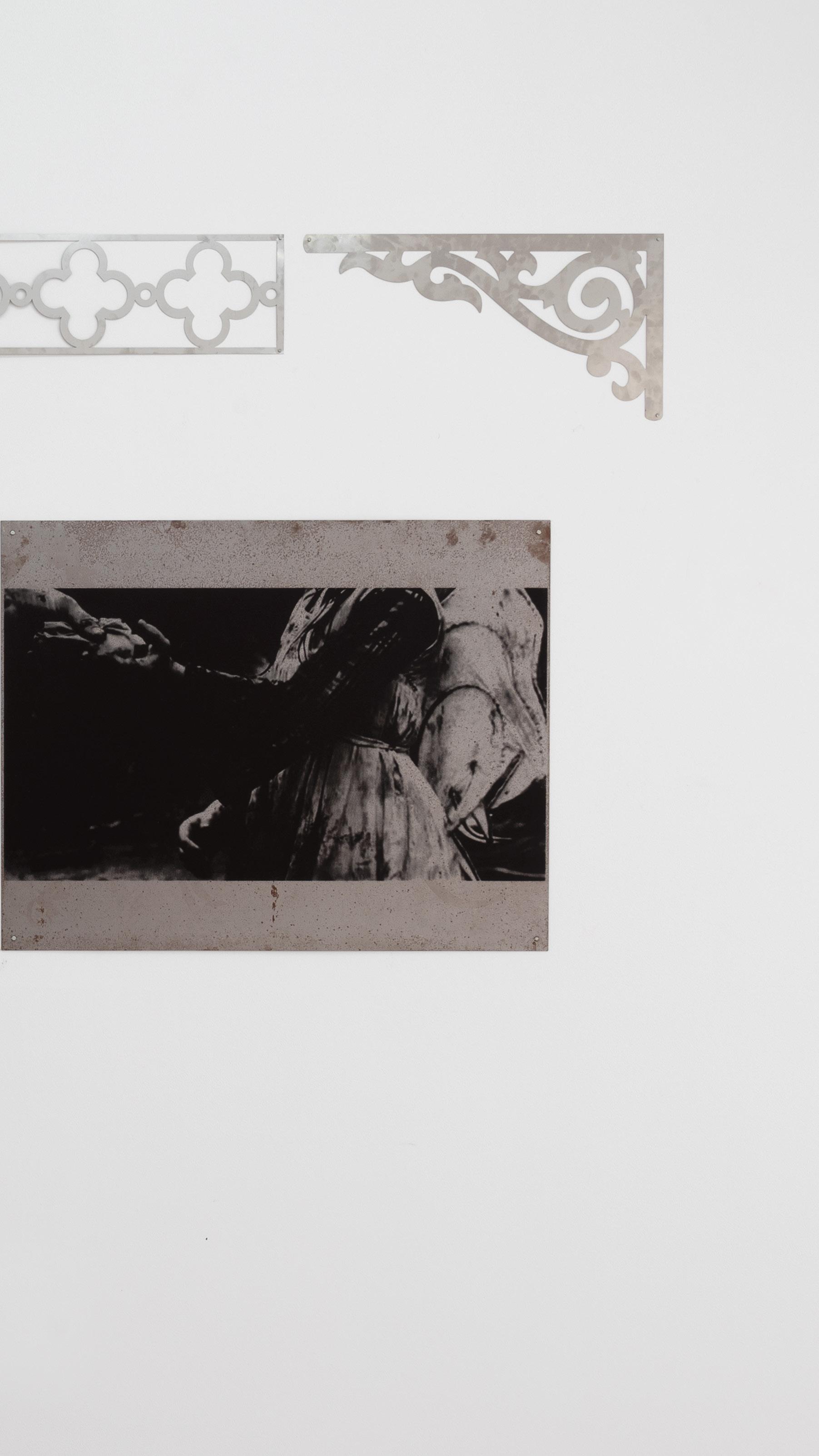

By Hugo Robinson

We stepped off the boat Light as a feather, White from the weather, Ready to seize our parcel among the wild.

p. 63

The premise of the colonial fantasy is to shed its own history, to claim innocence, and ultimately, to become Indigenous. George Watson’s work probes at this process. Most recently, her practice has centred on the aesthetic dimensions of the farm, and the farming family, as the proto-gentrifying nucleus of colonial New Zealand. A nucleus containing a particular mixture of working-class frontierism and devotion to the imaginary of Victorian gentry: rough metal and wood meet fine lace and ribbon. The encounter of these materials, and their inherent codes of class, gender and nationhood, are foundational to Watson’s recent work.

This exploration of the encounter is read alongside the popular tellings and retellings of early settler life, particularly through Katherine Mansfield’s work. Her stories tell of an emerging bourgeois settler culture, which in its newness may proclaim innocence. Indeed, in her poem To Stanislaw Wyspianski (1938), Mansfield expresses her disappointment at being born in “a little island and with no history” among “people [who] have had nought to contend with.” This naivety wilfully omits the brutality of her era. Yet, through the particular alienation of Mansfield’s work, we always sense the unease of home for “the little colonial”.

Watson’s work sits in this unease, pulling out the harshness of symbols and stories of homemaking— the sheepskin rug, the girl’s ribbon, the fretwork. Things that, in their own context, may feel like comfort, both of physical place and social location, fit awkwardly into the true reality of settler life. They are objects of abject refinement that cover the gaping question of their own provenance. This is the weaponisation of innocence that we see in Mansfield’s work and in the little colonial artefacts of the farmstead. They are props for Pākehā to play at being both New Zealander and British without ever being settler. There is no pure lineage when the thread goes halfway round the globe.

By examining the materiality of the works as a whole, their grotesque vocabulary, we see the internal logic of a particular tendency of Pākehā alienation brought to light—that is, the tendency to carry forth selected artefacts of the past while disavowing one’s place in that history. This erupts in a question that sits at the forefront of The Farm, and in other of Watson’s recent shows, such as Beauty Incarnate: whether to go on in innocence, or whether to recognise the material history that produces your own being in the world. Put another way, a central thesis of the work is how innocence is weaponised to enable a superficial engagement with history while staying invested in the world as it is.

p. 64 & 65 George Watson, Fields 2, 2024, hand-dyed silk, fence batons, staples, 174 x 39 cm overall. Courtesy of the artist and Coastal Signs

The farmhouse is due to be repainted, The walls are flaking, It makes the children cough, We are so lucky to have a home.

On a thousand-acre farm stands the villa. The farm is the medium through which the settler comes to know the land; not by relation but by domination. It is also one of the original outposts of gentrification, in which ornamentation is a significant feature. The farm is home to a mutation of working-class pioneering and a link back to the Victorian gentry.

The frock, the spire, the lace, the pearl, the cornice, the fretwork, the rose, the ribbon, the flag.

Rural gentrification, as we see from Watson’s work, is, as much as anything, an aesthetic stamp on the land. This mirrors the speculative aesthetic of the

New Zealand Company, which manufactured a romanticised image of the “little England across the seas” to entice settlers to buy land they had never seen before—thereby producing a market for land the company was often yet to have legal title to.

The Farm is imagined as a museum of these ideas: of how the ‘land of milk and honey’ was achieved through settlers taming the wild, claiming ‘unproductive land’, and displacing Indigenous ways of life. Moreover, to think of it as gentrification, as a mode of colonisation, draws attention to the internal class relations of settlers. In particular, it highlights the solidification of a discrete class identity in New Zealand based on those colonising ambitions of prosperity and social mobility.

Ornamentation is one way we see that identity play out. Ornamentation means something even when the original meaning has been lost or buried. The comparisons of Māori and Pākehā ornamentation that we see in works such as w tell us much about the value systems underpinning these worldviews. On the one hand is kōwhaiwhai, which contains multitudes of reference and connection to whakapapa and whenua. On the other, Victorian architectural vernacular largely serves as a marker of wealth in its ornate maximalism. It also cements a connection to and nostalgia for the monarchy, as a style popularised during Queen Victoria’s reign. Watson’s artwork illuminates the perverse reality of native timber being used to carve out these references. Now these buildings are protected heritage sites, while wāhi tapu face the constant threat of degradation and desecration; many stories of power are told through these inscriptions of wood. These aesthetic comparisons can be considered alongside the development of the colonial process from assimilation to a politics of recognition: the attempted nullification of Indigenous power by containing it within a framework of law, of politics, or indeed of aesthetics. It asks, what does this nation look like? At a fundamental level, what does a culture’s embellishment of its physical world tell us about its people? Does it signal status, or a mode of relating? Is it used for connection or for dislocation? What matters enough to be preserved?

Our girls were born out of shade, The memory of a grey summer, Hard work and little profit, Making something out of nothing.

Settler life is a garden party. Every Mansfield is aware of injustice in the corner of their eye: they know that the misery of the bourgeoisie is to give up its own humanity by wilfully ignoring the suffering that their wealth depends upon. Take Lapita Lolita, from the recent exhibition at Coastal Signs, for instance. It is a series of tiles, some whole, and others just shards, that have the look of being recently unearthed. The work is based on Victorian roofing tiles that were created using child labour. It is likely that the children’s delicate hands were best suited to removing the tiles from their moulds, and the process often left small handprints on the backs that remained visible after firing. Children were often used for finer work, on looms or in the mines.

Lapita Lolita is an archaeology of the backwardness of Empire. Even Victoria’s own children are sacrificed to appease its voracious industry. The presumed superiority of Empire is starkly revealed for its barbarism; something that drove so many settlers to seek a better life in New Zealand. Not only does it show the backwardness of imperialism, but it recalls the colonial idea that by enduring suffering, settlers could earn belonging.

We see Watson make this connection in her work based on stills from The Piano. Similar to Mansfield’s themes, Jane Campion’s film narrates the abjection of settler life and is a touchstone of imaginary remembrance. The crying girl is our child ancestor on the shore who made a life for us here.

Here, we come back to the innocence of the origin story and must ask: how is it so overwhelmingly forgotten? For so many Pākehā, the reality of moving to New Zealand as both settler and economic migrant is complex. It was a suffering, but an escape from an even greater suffering under the weight of Empire. This move meant a break from those class relations; however, it meant being freed from wretchedness to then live off the suffering of others. p. 68 & 69 George

The soil cannot take any more water, Our lamb has drowned, The children are getting restless, Flying like moths in the flour.

There can be no erasure of history, no claim to innocence. The question of innocence is shown to be irrelevant. Rather, we are urged to pay attention to the flourishes of a system of ideas.

Watson makes us think about the spatial arrangements and ornamentations of a social world where power and aesthetics are indivisible. She shows how the farm incubated a particular class with its own discrete understandings of taste, but also with its own material reality that it desires to reproduce; so deeply ingrained in capitalist politics in New Zealand.

On a scale both broader and finer, the work brings me back to the inevitable humanisation of politics through aesthetics; that somehow intimate, almost anthropological, view of a life—whether in its harshness or in small deceptions. And while Watson does not seek neat resolution, the critical thrust of the work is clear. It does not allow the settler to fade into abstraction. It names the stories and symbols that provide cover for a stolen life; the objects of beauty and memory that tie the knots in our historiesq

I have walked all around the boundary, And still do not see a way out, Except through the very dense bush, Or the road leading back to the shore.

(01) Katherine Mansfield, To Stanislaw Wyspianski (Privately printed for Bertram Rota, by the Favil Press Ltd, London, 1938), 2.

(02) Katherine Mansfield, The Katherine Mansfield Notebooks (Lincoln University Press and Daphne Brasell Associates, 1997), 166.

(03) Catherine Comyn, The Financial Colonisation of Aotearoa (Counterfutures, 2022), 47.

p. 70 George Watson, Fashion Bunny, 2025, sheepskin, chicken wire, hand-dyed silk, crayon, spray paint, pressed tin tile, gate hardware, 100 x 70 cm overall. Courtesy of the artist and Coastal Signs

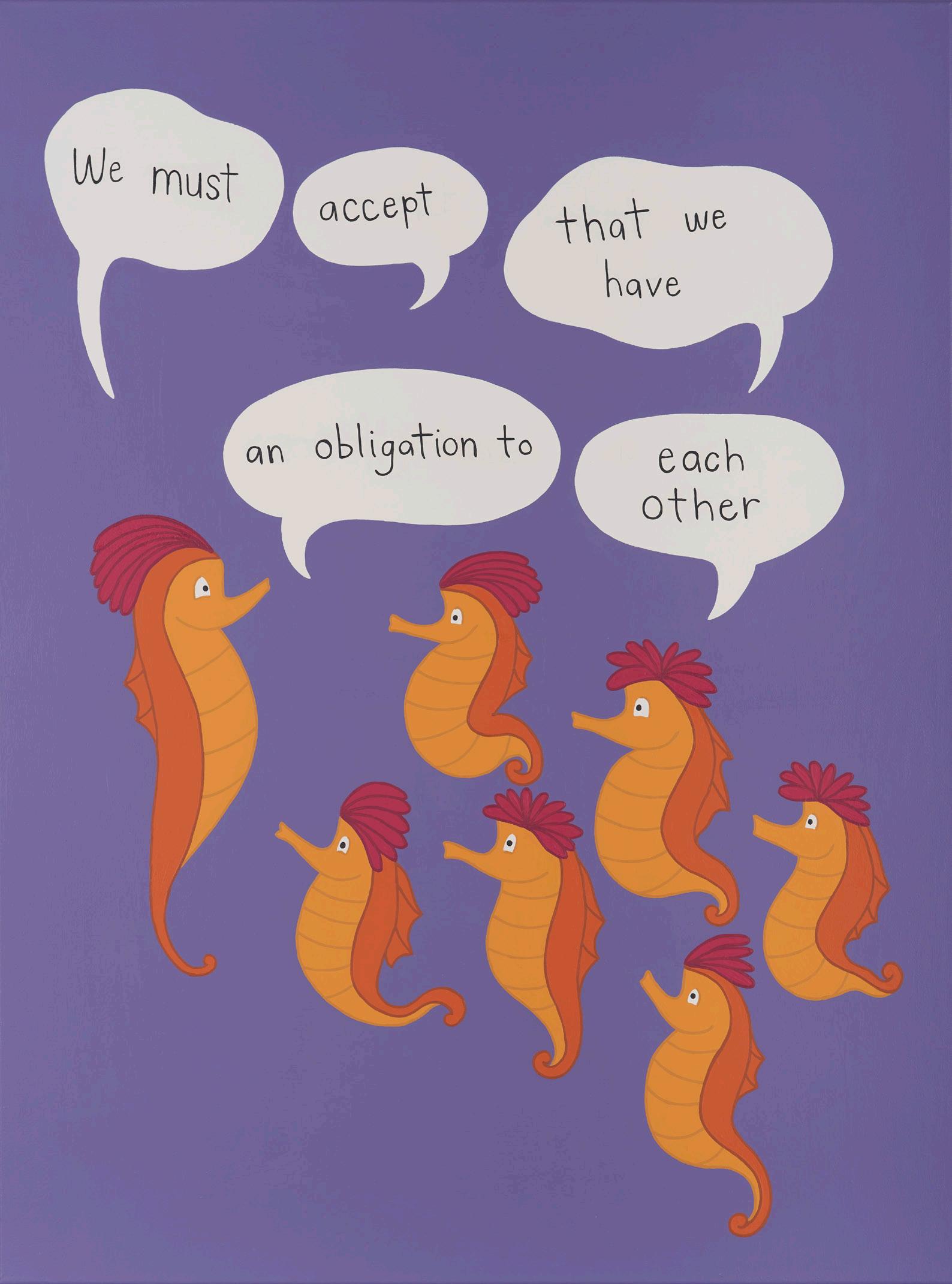

By Francis McWhannell

Once upon a time, Pānia, descendant of the People of the Sea, fell in love with Karetoki, the son of a great chief. She chose to be with Karetoki on land and it was there she gave birth to their son, Moremore. Although her life above ground was happy, each day Pānia could hear her people crying her name, calling her home to the water. One day Pānia could no longer resist the will of her people and swam home to visit them one last time. When she began her journey back to her family above the sea, Pānia’s people, unable to bear the thought of grieving for her again, cast her into a reef so she would lie forever at their side. Pānia never returned to land. Karetoki’s heart was broken.01

Once upon a time, there was an artist called Ayesha Green. She lived in a mighty archipelago in a vast ocean called Te Moana-nui-aKiwa by Māori, the people of the islands, and the Pacific Ocean by Pākehā, the people who came later, and who tended to disrupt any peace they came across. Ayesha, who was of Ngāti Kahungunu ki Heretaunga and Kāi Tahu, was fascinated by images. She made her own, as artists do, and she thought deeply about how they functioned. They told tales—real ones and fake ones, truths and lies. They taught people and deceived them. They were traded a great deal for great sums of money. Images, Ayesha observed, often served those in control. Likenesses of monarchs and political leaders, for instance, travelled the world like boats on the sea, on canvases and currency, in photographs and engravings, as monuments and souvenirs. They proclaimed the importance of their powerful subjects to the subjects of the powerful. Governments, corporations and other massive organisations created images too, often with the aim of staking claims to lands, resources and cultures to which they had no right, and for which they harboured little genuine respect.

Ayesha began to make copies of the images she saw—or notquite-copies. She would change things here and there to make her works say different things, or to give them distinct attitudes. Sometimes, she would insert herself into a picture, asserting her

right, and the right of Māori people more broadly, to be centred rather than marginalised. She often simplified the original images, purging extraneous detail and making her works look a bit like comics or picturebook illustrations, to emphasise the dimension of storytelling and education, or re-education, in the original images and in her versions. She was particularly interested in portraiture and had a knack for revealing things in her sources that might not be obvious to everyone: the curious way in which Queen Elizabeth I’s privilege is both signalled and concealed by luxurious costume; the possessiveness and dominance implied when Joseph Banks wears a kaitaka; the canniness of making Prince Charles, Princess Diana and baby Prince William into an ordinary family by picturing them on a picnic. She did with her subjects what good portrait-makers do, teasing out the essence of each image portrayed, even when the essence was not obvious, even when the image was doing its darndest to hide it.

In 2015, early on in her career, Ayesha created a painting based on Pānia of the Reef, a statue made of long-lasting bronze that stands on Marine Parade in Ahuriri Napier. Pānia of the Reef echoes another statue, Den lille Havfrue, or The Little Mermaid, by Danish artist Edvard Eriksen. The work derives from the fairy tale of the same title by Danish writer Hans Christian Andersen. It has become an icon of Copenhagen, where it was installed by the waterside at Langelinie in 1913. The mermaid sits naked on a large rock, her tail transforming into human legs.

Pānia of the Reef embodies a different woman of the sea, Pānia, who lived off the shore of Ahuriri, and whose story has long been told by Ayesha’s Ngāti Kahungunu tīpuna. Pānia sits on a rock in a similar pose to that of The Little Mermaid, dressed in a piupiu and with a huia feather in her hair. The model was Mei Robin, Ayesha’s nana’s cousin. Mei’s family owned, or cared for, the hei tiki Pānia is shown wearing. The statue was commissioned by the Napier Thirty Thousand Society, a group that advocated the swelling of the population of the city to that number and worked “to promote civic pride and to further the development of agriculture, industry, secondary education, transport and tourism in Hawke’s Bay and Napier.”02

Ayesha recognised the complex role played by Pānia of the Reef Unveiled in 1954, it quickly attained its own iconic status. The work has long served Pākehā interests, attracting Pākehā tourists who have stayed in Pākehā accommodation, eaten in Pākehā tea rooms, and bought things from Pākehā shops. It has helped Pākehā in Napier cultivate a sense of belonging. It has been an ambassador for the city, travelling around and beyond Aotearoa, cloned as statuettes, postcards, and keyrings. At the same time, it has been a source of pride for Māori. Mei herself has attested to this. She once commented that it was “proudly ours, as Māori”.03 In honour of her relation, Ayesha called her painting Mei

Over the years, Ayesha’s works have attracted quite a lot of attention.

Public galleries and museums have collected them, bringing them into direct communication with the same sorts of things she recreates. At present, several are on display at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Many of her pictures have entered ‘private’ collections. At times, Ayesha has questioned why people choose them, wondering whether her art is telling the right stories or whether the stories are being read correctly. She thinks about how some of her works make her culture, and even her identity, collectable. She hopes that they are circulating in good ways and good networks, to good ends. But she can’t be sure.

Once upon a time, there lived in Denmark a writer named Hans Christian Andersen. He wrote many things, but his most famous writings were children’s stories, so-called fairy tales. Among these is ‘Den lille Havfrue’, or ‘The Little Mermaid’, first published in Danish in 1837 and in English in 1845. It tells of a young mermaid, one of six daughters of the Sea King, who is curious about the world above the water. One day, she falls in love with a human prince, who is celebrating his birthday on a ship. She saves him from drowning when the vessel is wrecked in a storm.

74

75

Wishing to join the prince on land, the little mermaid visits a sea witch and agrees to exchange her voice—which is exceptionally beautiful—for a potion that will give her human legs. She is told that she will be able to walk and

dance as gracefully as she swims, but she will be in constant pain. The transformation will be permanent. She may never return to the sea. If she wins the love of the prince, she will gain an immortal soul, such as humans have. If she fails and the prince marries another, she will turn to sea foam, as mermaids do when they die, and will be gone forever.

The prince does not fall in love with the little mermaid. Instead, he chooses to marry a woman whom he erroneously believes to be the one who saved his life during the storm. The little mermaid’s sisters procure from the sea witch a knife that will allow her to become a mermaid once again if she uses it to kill the prince, but she cannot bring herself to do the deed. She dies. Rather than disappear, however, she becomes a ‘daughter of the air’, a being who can gain a soul by performing good deeds or by encountering good children. Here, the tale ends.

The moral and Christian themes within ‘The Little Mermaid’ are obvious enough, but it also explores notions of mutability—or the possibility of radical transformation—and curiosity about the unknown. It is thought by some that the text held a personal significance for Andersen, whose private writings suggest that he was bisexual, or perhaps biromantic. Rictor Norton has suggested that ‘The Little Mermaid’ is an expression of his unrequited love for his friend Edvard Collin, whose decision to marry a woman coincided with the writing of the text.04

‘The Little Mermaid’ has been adapted many times and in many different art forms. Among the most famous adaptations is the 1989 animated musical film The Little Mermaid from the Walt Disney Company. For children of the 1990s, The Little Mermaid was a staple of the rainy-day diet, watched again and again until the videocassette began to fail. For many, it is the version of the fairy tale, or at least it was until 2023, when a live-action adaptation was released. But that is another story.

Unsurprisingly, the animated film takes considerable liberties with Andersen’s text. Perhaps most interesting is what happens with the sea witch, called Ursula by Disney. She becomes a wholesale villain, requiring the little mermaid, now called Ariel, to sign a contract prior to her transformation.05 In

p. 76 Ayesha Green, Loves Me, Loves Me Not, 2024, acrylic on canvas, 140 x 170 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Jhana Millers

p. 78 Ayesha Green, I Dedicate This Song, 2024, acrylic on canvas, 140 x 170 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Jhana Millers

p. 79 Ayesha Green, Never, 2024, acrylic on canvas, 60 x 60 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Jhana Millers

exchange for her voice, Ariel will be given legs for three days. If during that time she secures the ‘kiss of true love’ from the prince, now called Eric, she will remain human. If she fails, she will turn back into a mermaid and will— rather alarmingly—‘belong’ to Ursula.

identity capitalism.

Some elements of Andersen’s tale are exaggerated in the film. For instance, Ariel displays a heightened enthusiasm for the human world, collecting trinkets from sunken ships. (In the original text, her sisters do this.) Other elements are discarded. Gone are the allusions to souls. So is any mention of pain associated with the transformation from mermaid into human. The ending of the story is inevitably altered. Ariel cannot die. She and her prince must live happily ever after.

Once upon a time, a Disney executive from America attended a Disney on Ice performance.06 Standing in line in the skating arena, Andy Mooney watched as young girls dressed as their favourite princesses milled about. Their costumes, he noted, had been cobbled together using an array of non-Disney products and materials. Some folks might find that situation charming, but not Andy. Andy saw a problem. No! Andy saw an opportunity to turn the tendency of children to identify with the princesses they saw on ice and screen into Disney profit. Indeed, to do so was essential, for the good of the company, and to honour its longstanding commitment to

So Andy developed Disney Princess, a media franchise centring on a series of female protagonists of Disney films. Today, the list of canonical princesses comprises Snow White, Cinderella, Aurora (that is, Sleeping Beauty), Ariel, Belle, Jasmine, Pocahontas, Mulan, Tiana, Rapunzel, Merida, Moana and Raya. The franchise licenses these characters to companies or brands, such as Fisher-Price, Hasbro, Lego and Mattel. The licensees generate an ocean of merchandise: toys, games, clothing, accessories, homeware, stationery, party supplies, and so on.

The princesses are occasionally shown together in imagery, in acknowledgment of their status as part of the same franchise family. Historically, in order to preserve “the sanctity of what Mooney called their individual ‘mythologies’”, they did not make eye contact.07 Instead, they looked outward or in slightly different directions, as if unaware of one another, or as if there was at play some unspoken enmity, which forced them to be photographed apart and only later edited into community.

In terms of the dates of their film premieres, the princesses span a great period. The earliest, Snow White, was introduced to the world in 1937, the most recent, Raya, in 2021. The childhoods of many people living today have coincided with the debut of a Disney Princess. Countless numbers have grown up under

their influence. Such ubiquity is powerful, forging deep nostalgia and shaping intergenerational consumption. Disney’s gradual move from blizzard whiteness to globe-spanning ‘diversity’ is no doubt a reflection of a changing moral landscape, but it also demonstrates the company’s awareness that the more little girls—or little kids—who see themselves in a Disney Princess, the larger the customer base grows.08

Once upon a time, an Englishman named Edward Gibbon Wakefield developed an interest in colonisation while he was interned in London’s Newgate Prison for his part in the abduction of a young heiress named Ellen Turner.09 After arriving at the prison in 1827, he set about reading up on the subject. He dreamt of a system underpinned “by private speculation”.10 Land in a given colony would be acquired from the ‘natives’ then sold to monied individuals at a significant price. Some of the proceeds of sale would be used to send ‘paupers’ to the colony, creating a ready supply of ‘labourers’ to work the land owned by the ‘capitalists’ at no cost to the British government.

Edward wrote about his ideas and cast around for support, exercising his charisma and powers of persuasion. In the early 1830s, he spoke of recreating “a perfect English society in South Australia”.11 Some of his plans were duly put into practice in that place, but Edward felt that land was being sold too cheaply.12

He set his sights on New Zealand. In 1837 (the same year that ‘The Little Mermaid’ was first published), the New Zealand Association was formed, with Edward at its core. He dismissed concerns about the effects of colonisation on Māori, citing “the inestimable benefit of civilisation” to them.13 Promotional materials were printed and artists were called upon to provide visual evidence of the desirability of the archipelago.

The New Zealand Association, supported by a good number of men of influence, sought parliamentary sanction to establish a colony. Opinion was divided. The Spectator and The Colonial Gazette “fell into line”, but The Times remained sceptical, referring sarcastically to the “moral and political paradise” and the “radical Utopia in the Great Pacific” touted by the association.14 Naysaying did nothing to curb the enthusiasm of Edward and his chums. In 1838 supporters of the association and an earlier body, the New Zealand Company (which had been established in 1825), formed the New Zealand Colonisation Company. This later became the New Zealand Land Company, also known as the New Zealand Company.

At an informal meeting of stakeholders on 20 March 1839, it was revealed that the British government intended to take control of the sale of land in New Zealand, thus impeding the company’s ability to acquire it cheaply from Māori.15 The company would need to reach New Zealand and make land purchases before any government expedition arrived. Edward memorably remarked, “Possess yourselves of the soil and you are secure.”16 Edward’s brother, William, was duly dispatched to do the possessing.

Hastening towards its goal of ‘systematic colonisation’, the company sold a large amount of land before it had been acquired, and emigrants were scheduled for travel before the ‘settlement’ they expected to arrive in had been established.17 But William would make things right. On 20 September 1839, he and an advance party entered Te Whanganui-a-Tara, now Wellington Harbour, on board the Tory. 18 Although Edward had complained indignantly of land obtained “for a few trinkets and a little gunpowder” in 1836, his brother soon ‘bought’ an enormous quantity for the company by precisely that method.19 Immigrants began to arrive in January 1840 on the Aurora and other vessels.

Following a failed attempt at the development of a primary base at Petone (Pito-one), Wellington became the “first and principal settlement of the New Zealand Company”.20 Surveyors proceeded to map out various pā and kāinga as though the land were unoccupied. Further settlements were established: Petre (Whanganui) in 1840, followed by Nelson (Whakatū) and New Plymouth (Ngāmotu) in 1841. 21 The company firmly opposed the Treaty of Waitangi, which guaranteed Māori their lands, and which “appeared to the company very simply as an iron door closing off their right to acquire the greatest

possible amount of New Zealand land at the cheapest price”. 22

There were difficulties. Colonists clashed with Māori, who frequently disputed supposed ‘purchases’ of land, as in the ‘Wairau Incident’ of 1843. The careful balance required to make the system of capitalists and labourers function—in both financial and practical terms—was not achieved. Despite these issues, the company supported the establishment of Dunedin (Ōtepoti) by the Lay Association of the Free Church of Scotland in 1848. That same year, John Robert Godley and Edward founded the Canterbury Association, which was affiliated with the Church of England and oversaw the establishment of Christchurch (Ōtautahi) in 1850.

Before long, the New Zealand Company failed altogether. It ceased operating in 1850 and was dissolved in 1858. Yet the settlements it had helped bring into being remained. More immigrants came and, although many found that things were not as they had imagined they would be, many stayed. They built places to live and pray, of course, but also farms, factories, shops, hotels, banks and warehouses. The New Zealand empire of commerce swelled, merrily selling to the rich man, poor man, white man and native all the good things a warehouse could contain.

Once upon a time, paintings were popular entertainment. In the eighteenth century, for instance, crowds would flood to the Summer Exhibition at the Royal Academy in London, and to the Salon of the Académie de peinture et sculpture in Paris. On the walls of galleries, or palaces turned into galleries, works hung in great profusion, jostling for space. Hierarchies mattered, with scale, quality and genre dictating placement. Until the mid-nineteenth century, ‘history paintings’—paintings depicting real, or purportedly real, histories, and scenes from mythology and the Bible—were deemed highest and accorded the best wall positions, because they traded in moral and spiritual themes.

Great exhibitions were sites of political discourse. Often, artists toed the party line or offered timid messaging. J. M. W. Turner did both with his Snow Storm: Hannibal and his Army Crossing

the Alps, presented at the Royal Academy in 1812. By depicting the Carthaginian military leader stymied in his campaign against the Roman Empire by nature or an act of God, Turner suggested that Britain’s foe of the day, Napoleon Bonaparte, was overconfident and under-blessed, sure to fail. There were more radical moments. Édouard Manet scandalised the Salon of 1865 with his Olympia (1863), which, it has been suggested, shows a sex worker receiving a client. Modelled on Titian’s Venus of Urbino (1538), which might itself depict a courtesan, the work was provocative due to its ‘indecorous’ subject matter as well as its modern style. Moreover, it was bold. Olympia is in command. She sizes up the hypocritical gentleman visitor to the Salon, wordlessly asking, “If I am good enough for you elsewhere, why do I trouble you here?”

Today, we think of art as political but not very popular— or not normally. There are exceptions. In 1985 attendance for a Claude Monet exhibition at Auckland City Art Gallery, now Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, surpassed 175,000. The Robertson Gift, a collection of mostly modern art that recently went on show at the same institution, is drawing large crowds. Aotearoa art seldom receives such attention, but that is surely down to executive decisions as much as audience tastes. At Toi o Tāmaki, the Mackelvie Gallery is permanently set aside for the display of European art. Many of

the works are low quality. In other parts of the world, they might be ‘skied’, hung so high as to obscure them. More likely they would not be shown at all.

At Te Papa, a crowdfavourite exhibition draws on European art history in a different way. Ngā Tai Whakarongorua | Encounters comprises a salonstyle presentation of portraits of Māori and tauiwi, many dating to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The pictures form a great wall of ancestors. Inevitably, the subjects of different works engage little with one another. They remain in their painted realms, held in place by heavy and luxurious frames. Yet a community is implied. It is a comforting gesture—not radical, but perhaps a little utopian. Wherever you find a salon hang, you will learn something about the institution that has done the hanging. You will gain insight into its methods of story- and history-telling, and into its priorities.

Once upon a time, a very ordinary man named Christopher Luxon led his political party to victory in the New Zealand national election. No one really knew how. He did not seem to have charmed the people with his charisma, nor impressed them with his knowledge. Unlike some politicians, he did not shine with intelligence or empathy. His grasp of important events, current and past, seemed flimsy at best. But maybe that is what people liked about him. Being unremarkable, he did not make them feel small.

Or maybe they just wanted a change. New wallpaper for the lounge, to go with the new settee. National, Christopher’s party, did not win enough votes to govern alone, and so they had to find coalition partners and make some deals. The prospective partners had some pretty clear, pretty bad ideas. For instance, New Zealand First, headed by a man called Winston Peters, really wanted to get rid of Māori names from government departments. The ACT Party, headed by a man called David Seymour, effectively wanted to do away with te Tiriti o Waitangi, the reo Māori version of the Treaty of Waitangi, which enshrines Māori sovereignty and takes precedence over the English version—a beast all its own. The situation was a bit odd because Winston and David have whakapapa Māori. But all kinds of people can be misguided or jerks. Christopher did not seem to have cared particularly about Winston’s and David’s ideas— which were aimed at appealing to folks who have a disdain for Māori and the poor but who deeply resent being called racist or classist. Perhaps he did not care because National does not much care for Māori and the poor, as evidenced by some of its own policies, like halting extra pay for government employees fluent in te reo Māori.23 Perhaps it was because National knew that it might one day pick up supporters from the coalition partners, if it played its hand right. Perhaps it was because National was more concerned about cabinet

(01) Adapted from Ayesha Green, For Karetoki, Window Gallery, University of Auckland, 2015, https://windowgallery.co.nz/ exhibitions/for-karetoki

(02) ‘Napier’s Development,’ Napier City Council Te Kaunihera o Ahuriri, 2024, https://www. napier.govt.nz/napier/about/ history/napier-development/

(03) Green, For Karetoki

(04) Rictor Norton, ‘A Fairy Tale: The Gay Love Letters of Hans Christian Andersen,’ Gay History and Literature, originally published 1998, https://rictornorton.co.uk/ andersen.htm

(05) Ursula’s appearance is based on the drag queen Divine, and— like so many Disney villains— she has become something of a queer icon. Tom Smyth, ‘The Little Known Drag Origins of The Little Mermaid’s Ursula,’ Vogue, 24 May 2023, https:// www.vogue.com/article/ursulalittle-mermaid-drag

(06) Peggy Orenstein, ‘What’s Wrong With Cinderella?,’ The New York Times, 24 December 2006, https://www. nytimes.com/2006/12/24/ magazine/24princess.t.html

(07) Ibid. The situation appears to have relaxed somewhat over time.

(08) It no doubt goes without saying that Disney seems pretty committed to the gender binary at present.

(09) Patricia Burns, Fatal Success: A History of the New Zealand Company (Heinemann Reed, 1989), 23.

(10) Ibid. 29.

(11) Ibid., 39.

(12) Ibid., 39–41.

(13) Ibid., 43.

(14) Ibid., 61.

(15) Ibid., 11–13.

(16) Ibid., 14.

(17) Ibid.,102

(18) Ibid., 114.

(19) Ibid., 111.

(20) Ibid., 131–36, 140.

(21) New Plymouth was established via the Plymouth Company.

(22) Burns, Fatal Success, 154.

(23) Phil Pennington, ‘Te Reo Māori: Govt Seeks to Halt Extra Pay for Public Servants Fluent in the Language,’ RNZ, 6 December 2023, https://www.rnz.co.nz/ news/political/504003/te-reomaori-govt-seeks-to-halt-extrapay-for-public-servants-fluentin-the-language

(24) ‘Iwi Files for Urgent Tribunal Hearing on Government’s te Reo Māori, Treaty of Waitangi Policies,’ RNZ, 12 December 2023, https:// www.rnz.co.nz/news/ political/504489/iwi-filesfor-urgent-tribunal-hearingon-government-s-te-reo-maoritreaty-of-waitangi-policies

(25) Disney’s Dumbo (1941) features crows that obviously mock Black Americans; their leader is even called Jim Crow.

positions than divisive messaging. Anyway, the deals were made. The coalition was formed.

Many people were worried about Christopher, Winston, David and their various plots. Māori especially jumped into action. In December 2023, Ngāi Te Rangi Settlement Trust filed for an urgent Waitangi Tribunal hearing, maintaining that the coalition was breaching Article 2 of the Treaty by failing to protect te reo Māori.24 That same month, advocates of Te Tiriti painted over the English version on display at Te Papa, protesting the museum’s approach to sharing the document’s histories. Kīngi Tūheitia Pōtatau Te Wherowhero VII called a Huiā-Motu, a nationwide meeting, at Tūrangawaewae Marae in January 2024. Countless people travelled to Waitangi the following month to demonstrate and to share ideas.

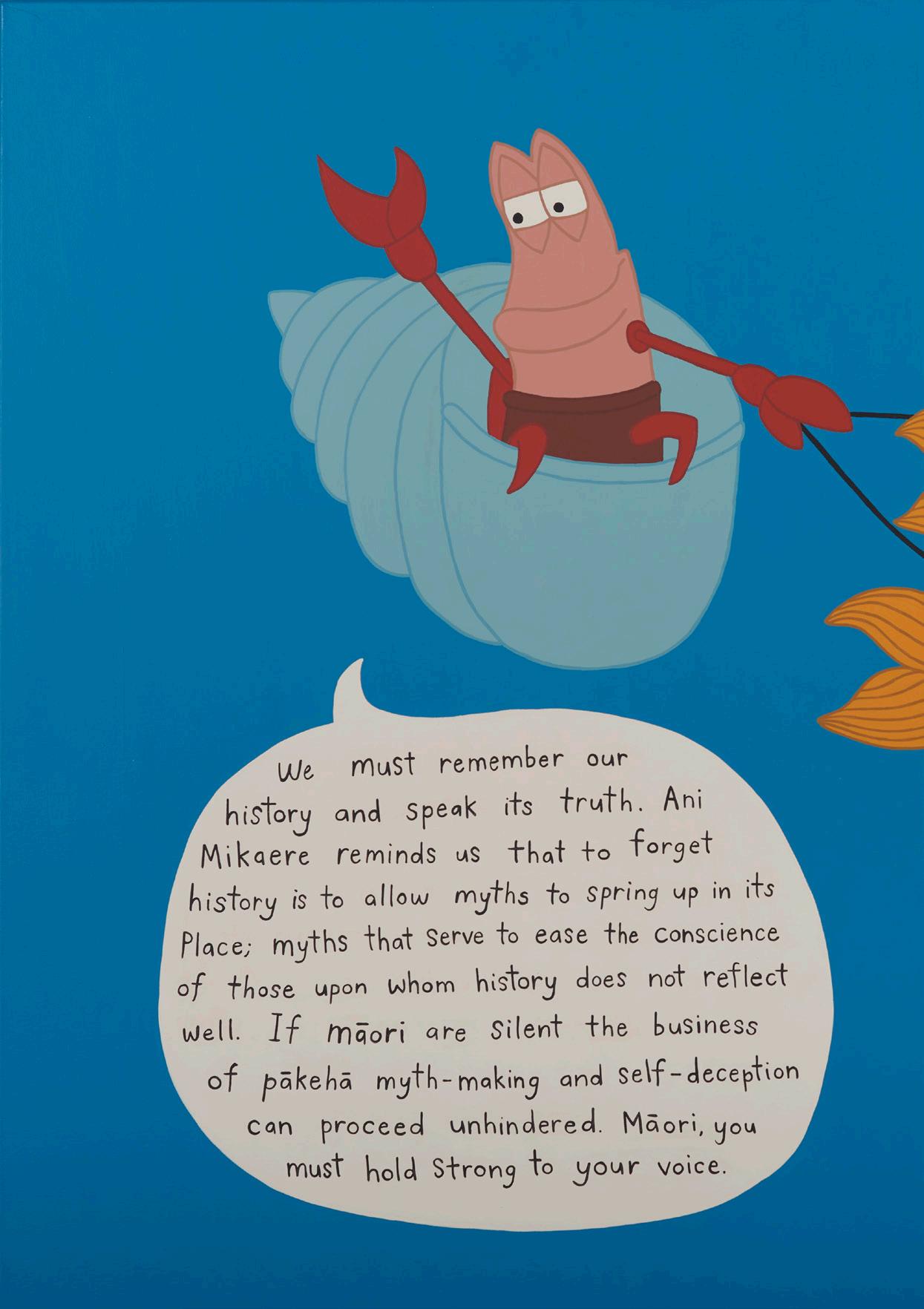

In her studio in Wellington, Ayesha Green began to think about how she could respond, and promote change. She thought about Māori scholars such as Ani Mikaere and the late Moana Jackson, whose kōrero shapes her ideas and positions, and is always lucid, generous and accessible. She thought about the people with whom she herself needed to communicate, people who might not seek out Mikaere’s or Jackson’s work but would seek out hers. She thought of visual analogues for their approach to communication, and landed on the animated fairy tale, a form that conveys well-defined morals and trades in empathy, practically demanding viewers to project themselves into the story.

We should not be surprised that she chose to focus in particular on The Little Mermaid. Ariel is for several reasons an apt vehicle for discussions of Māori experiences. She is someone for whom a vast ocean is home. She encounters a foreign, seafaring people with lifeshaking effects. Her engagement with their world involves the signing of a dubious document that entails the destruction of her voice—the core of her identity—and threatens her sovereignty. Of course, the film is not a perfect fit for Ayesha’s purposes, and so she has altered things, as Disney altered Hans Christian Andersen’s text, and as she has always altered her source materials. She pours herself into the characters. They express her attitudes, speak her words.

Ayesha harbours a degree of wariness about using a mermaid and attendant sea creatures to explore Māori ideas and values, being cognisant of the long history of associating Indigenous people and people of colour with something other or less than human. 25 At the same time, by turning to cartoon characters as avatars, she is able to remove Māori bodies from commercial circulation. It is not wholly clear how meaningful it is to infiltrate an empire of commerce. We might never know. But there is considerable power in turning a Disney Princess into an advocate of Indigenous sovereignty, especially in the present moment, given the Walt Disney Company’s deafening silence in response to the thousands of children killed in Gaza.

The Endq

By Peter Simpson

p. 84 and 88 Drawings by Peter Simpson. Courtesy of the artist

p. 85

Peter Simpson, I am free because of an open-plan kitchen, 2023, spray paint on kauri, 330 x 86 x 2.1 cm. Installation view, Three Approaches, Three Rooms, Gus Fisher Gallery, Tāmaki Makaurau, October 2024. Courtesy of the artist and Coastal Signs

p. 87

Peter Simpson, The knowledge of European knows how to destroy the world. They do not know how to put the world back together. We must take their tools away. (detail), 2023, building wrap, spray paint, 255 x 99 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Coastal Signs

Last year, artist Shannon Te Ao introduced me to BabaKiueria (1986), a twenty-nine-minute satirical film directed by Don Featherstone presenting a reverse of race relations in Australia. The film begins with Aboriginal people arriving to colonise a white Australia. First contact is made at a place of white importance, a barbecue area; thus, the title is a place name made through mistranslation. Over the next twenty-nine minutes the inversion continues, with a survey of white people’s lives in Australia after colonisation. The film asks why white people are so work-shy. Why can’t they get themselves out of poverty? Why is their culture so interesting? Are they actually good people when you get to know them? As the film continues, however, it turns from light comedy into unsettling reflection, using meticulous repetition to expose the brutal realities of racialised life for Aboriginal people.

What Te Ao wanted to discuss via BabaKiueria was a form of humour that operates within my work and the film. It’s quite amusing to refer to white people as ‘Te tangata o Kāpu tī’, or ‘People of the cup of tea’. As my supervisor, Hemi MacGregor, commented, it’s an interesting statement because it voices the way Māori look at Pākehā in our own terms, tangata whenua, tangata tī. Therefore, the work becomes confrontational by implication, as it seeds the idea of whiteness as a structural mechanism that contributed to how tea, as a colonial object, is known to us.