25th Anniversary of UN Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace, and Security

The content presented in this publication is intended solely for educational purposes and should not be interpreted as professional advice or a political position endorsed by Women of Color Advancing Peace, Security, and Conflict Transformation organization. We encourage readers to conduct their own research and consult relevant experts or professionals to address their specific needs and circumstances

Women of Color Advancing Peace, Security, and Conflict Transformation (WCAPS) remains steadfast in its mission to amplify the voices, leadership, and lived experiences of women of color within the complex and evolving landscapes of global peace and security. At a time when the United States and the international community face mounting challenges - from protracted conflict and forced displacement to the rise of authoritarianism, climate-driven insecurity, and shifting multilateral frameworks - our commitment to uplifting the voices and perspectives of, and about, women of color remains strong.

As a force multiplier for our growing membership, WCAPS serves as both an incubator and a launchpad We create spaces where women of color and our allies can dialogue, build coalitions, develop policy solutions, and lead the way in transforming systems that have long excluded them. Our programming - whether through working groups, mentorship initiatives, or fellowship experiences - centers not just the professional trajectory of our members, but also their intellectual power, cultural fluency, and commitment to justice.

This commitment to justice is a resounding theme in the United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325. The Women, Peace, and Security Agenda is what has allowed a platform for women to speak up about our involvement in peace processes. However, we know when they say women that doesn’t always include women of color Our knowledge, perspectives, lived experiences, and contributions are sidelined in many of these post-colonial spaces. Thus, WCAPS, in addition to our commitment to leadership development and community building, places an unrelenting emphasis on platforming the publication from, about, and for women of color In community with our allies, we are building the databases, addressing the gaps, and curating the materials we need to thrive in academic and policy spaces.

This edition of WCAPS Paper Trail Publication Program focused on the blind spots evident in the implementation and foundation of 1325. From the erasure of black and brown women from the development to the colonial legacies rooted in the very language of the UNSCR, the themes explored here speak to the ways in which women in developing countries, rural communities, impacted by climate change, and continued mobilization of grassroots efforts, the authors included here represent a fraction of the neglected stories, policy, and studies that exist within our membership and wider community

WCAPS is proud to host these topics, proud of the women and men who wrote them, proud to contribute to the discourse about us and our needs in an ever changing global arena We couldn’t do this without our wonderful members who stepped up to review and edit. Our volunteer, Taylour Holloway, who assisted with laying the groundwork for gathering and parsing through submissions, and of course, the authors who took the time to put fingers to keys and gift us with their thoughts

Thank you all. Your contributions breathe life into the vision of a more inclusive, just, and peaceful world

In

collaboration,

Andreanna F Mond

WCAPS Paper Trail: Special Journal Issue on the 25th Anniversary of UN Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace, and Security (WPS) Publication Collator

Twenty-five years ago, the adoption of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 marked a historic milestone in recognizing that peace is more sustainable when women are fully involved in its creation and preservation Today, as we honor that legacy through this Special Publication, we also reflect on how women of color around the world have carried the spirit of 1325 into new arenas, shaping peace processes, advancing global health, leading on climate action, and transforming security at every level

This issue is both a celebration and a call to action It amplifies the voices, research, and lived experiences of women whose leadership continues to redefine what peace and security mean in practice. Their work reminds us that the principles of inclusion, justice, and equity are not abstract ideals; they are essential tools for building a more peaceful and secure world

We remain committed to creating pathways for women of color to lead, influence, and innovate This publication embodies that mission A space to document, imagine, and inspire what comes next.

Reimagining 1325 for the next generation is not only about reflection but renewal, ensuring that the next wave of peacebuilders inherits a framework that recognizes their realities, voices, and visions Likewise, women of color who lead peace and security are not just contributors to this evolution; they are the architects of its future

Yet to truly honor this legacy, we must resist complacency. The world we face today demands new approaches Ones that embrace intersectionality, invest in emerging leadership, and challenge the systems that continue to silence or sideline women’s voices Keeping the momentum requires courage to do things differently; to rethink power, to innovate across disciplines, and to sustain solidarity across generations and geographies

May these pages spark dialogue, collaboration, and renewed commitment to the transformative power of women’s leadership in peace and security Together, we honor the past, shape the present, and build the future envisioned by 1325

With gratitude and purpose, Dr. Maleeka Glover Executive Director, WCAPS 2022-2025

Hello WCAPS Members and Community,

It is great to be back as Executive Director of WCAPS. While I did not anticipate doing publications when I founded the organization, I realized that another area where women of color are not being heard is through publications that reflect their expertise. I think back to that first publication, and now, five years later, the WCAPS publications are still going strong. The first publication was “Policy Papers by Women of Color: Top Issues in Peace, Security, Conflict Transformation, and Foreign Policy,” in March 2020.

I am so pleased to share with you this 2025 WCAPS publication, “WCAPS Paper Trail: Special Journal Issue on the 25th Anniversary of UN Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace, and Security (WPS).” At this 25th Anniversary, it is a time to both celebrate and critically examine the progress made since UNSCR 1325 was adopted This publication contains 24 submissions from our members, consisting of academic articles, policy papers, and practitioners essays I want to thank all the members who wrote the papers, as well as all those who volunteered to edit them also, a special thanks to Andreanna F Mond and Lourdes Sanchez for their dedication to completing this publication

Please enjoy the publication!

Ambassador Bonnie Jenkins Executive Director and Founder

Arab Feminism and the Women, Peace, and Security

Agenda: From History to Policy

A Shared Vision: How the Youth, Peace and Security Agenda Complements and Advances the Women, Peace and Security Agenda

Cinema as Soft Power: Advancing Women Peace and Security through Cultural Diplomacy in Benin

From 1325 to 2250: Why the Future of Peace and Security Must Be Intergenerationa

From Peace to Security: The Militarization of the WPS Agenda

Locating a Glitch in the Women, Peace and Security Agenda: A Cyberfeminist Reflection for the Future of Gendered Peace and Security Frameworks

Perspectives féministes critiques sur le militarisme, la sécurisation et la consolidation de la paix

Proximity Without Power: Race, Gender, and Gatekeeping in Global Health Policymaking

10

23

33

39

50

84

104

117

Reaffirming Health as a Human Right through the Women, Peace, and Security Agenda: Addressing the Needs of Women in Conflict and Post-Conflict During Outbreaks

When ‘Peace’ Is Gender-Blind: Liberal Peacebuilding vs. Indigenous Feminist Peace in the CHT

Author:

Gihan El Hadidy

Saji Prelis has over 25 years of experience working with youth movements, governments, and partners to build intergenerational trust and collaboration in over 35 countries As the Co-Chair of the Global Coalition on Youth, Peace, and Security, he co-led successful advocacy for the UN Security Council Resolutions 2250, 2419, and 2535 He also leads the Global Community of Practice on YPS National Action Plans Saji is the Director of Children & Youth Programs at Search for Common Ground Before that, he was the founding director of the Peacebuilding & Development Institute at American University in Washington, DC Over 11 years at the university resulted in him co-developing over 150 training curricula exploring the nexus of peacebuilding with development from a humancentered perspective Saji received the distinguished Luxembourg Peace Prize for his Outstanding Achievements in Peace Support He obtained his Master’s Degree in International Peace & Conflict Resolution from American University

Abstract

AAs resolution 1325 (UN, 2000), which established the women, peace, and security agenda, celebrates its 25th anniversary this year, Arab women continue to face heightened levels of violence, economic hardship, and marginalization Despite numerous programs attempting to implement the Women, Peace, and Security (WPS) agenda in the Arab world, progress has been minimal as dominant discourses remain detached from the complex lived realities experienced by women in Arab countries. For global WPS practice to resonate in the region, it must connect with both the intellectual foundations and the current political trajectory of Arab feminism. This policy brief seeks to redefine the Women, Peace, and Security framework for Arab communities by grounding it in the intellectual heritage of Arab feminism By drawing on the region’s own feminist thought and activism, the brief highlights how connecting with the past can inform a more authentic WPS agenda It also calls for elevating local women’s voices as producers of knowledge and agents of policy, rather than passive beneficiaries of externally designed frameworks. The recommendations will move beyond programmatic rhetoric to specify practical reforms.

This policy brief adopts a desk-research approach designed to translate historical insights into actionable policy within the Women, Peace, and Security (WPS) agenda. It begins with a guiding question: How can lessons from Arab feminism’s history inform more effective WPS policy in the Arab region today?

The first part will involve a historical analysis of the early feminist movement in Arab countries, drawing on both primary sources and secondary scholarship From this, I will extract core principles that have defined Arab feminist thought and practice, such as the interplay between nationalism and feminism, the use of literature and public debate as tools of resistance, the role of male allies, and the movement’s distinctly pan-Arab character This part will also shed light on the current challenges faced by Arab women

The second part will apply these principles as an analytical lens to selected WPS texts Three National Action Plans (NAPs) from Jordan, Tunisia, and Iraq will be analyzed. This comparative review will assess where WPS frameworks align with or diverge from the historical lessons of Arab feminism

The third part will translate these findings into concrete and actionable policy guidance For example, transforming the principle of male allyship into proposals for inclusive legal reforms, or drawing from pan-Arab feminist solidarity to recommend cross-border WPS networks. These “history-to-policy” pairings will be synthesized into clear recommendations specifying what should change and how different stakeholders should act

The early seeds of Arab feminism can be traced back to the late 19th century Egypt was the epicenter of a nascent Arab feminist movement (Al-Afifi, 2021) due to its role as the cultural and intellectual heart of the Arab world, where modern state-building and a vibrant press created fertile ground for women’s voices to emerge. Earlier in the 19th century Mohamed Ali Pasha, the Ottoman governor of Egypt, adopted a vision1 for a modern nation, which produced a paradoxical impact on women With the introduction of a capitalist order, upper- and middle-class women were secluded and prevented from pursuing public education; however, their family wealth granted them access to private learning (Exeter, 2019). This duality of seclusion and private

1 Mohammed Ali’s reign in Egypt extended from 1805 to 1848 He is widely considered the founder of modern Egypt

led those women to be the first to articulate a new vision for female identity in Egypt, and by extension, the larger Arab world (Exeter, 2019) In other parts of the region, a decaying Ottoman empire forced thinkers and intellectuals to embark on a soul-searching journey to rediscover their national roots (Chamlou, 2017). Arab feminism at its core emerged as a reflection of this historical, cultural and socio-economic context, not because of Western influence

In fact, colonial leaders in Egypt often depicted Arab and Muslim women as backward (Exeter, 2019) Selective feminism was applied in many cases to advance the colonial agenda (Choudhary, 2023). Lord Cromer, the British Controller General in Egypt, claimed that Egyptian women needed the British to free them from the oppression of Islam; however, he charged fees for schools that prevented young girls from enrolling, adding an additional layer of financial obstacles to women’s education He justified this by insisting that subsidizing education lay outside the proper “province” of government (Haq, 2022) In his homeland, Cromer founded the Men’s League for Opposing Women’s Suffrage in England His actions stand as a stark illustration of colonial hypocrisy: while proclaiming a civilizing mission abroad, he actively hindered women’s access to education in Egypt and led campaigns against women’s equality at home. Cromer’s approach towards the local population was part of a broader orientalist school that presented people of the Middle East as inferior and in need of rescue, creating a worldview that justified imperialism and western colonialism (Hibri, 2023) The orientalist perception of Arab women revolved around two narratives, one focused on objectification and sexualization, while the other depicted them as an oppressed victim of their religion, culture and men in their countries (Gerloff-Blood, 2024 p.2-3). Arab feminism evolved as a response to these colonial distortions, challenging both the orientalist portrayal of Arab women as passive victims and the colonial structures that sought to deny them agency, education, and equality

In the early days of Arab feminism, writing was a major domain of female expression Arab journalism, which started in the late 19th century, was especially vibrant in Egypt and the Levant (University of Chicago Library). Women were part of this growing industry. The Lebanese Warda Al-Yajizi published her poetry anthology “The Rose Garden” in 1867 and was one of the leading figures who opened the writing field to women Hind Nawfal launched Al-Fatah, the first women’s magazine in the Arab world, in 1892, and Zaynab Fawwaz published “The Happy Ending” in 1899, which is largely believed to be the first novel written by a woman in Arabic This period also witnessed the rise of salons in cities such as Cairo, Aleppo, and Jerusalem (Azam, 2019 p.232), which emerged as spaces where women could meet and engage in discussions around literary, social and political issues, sometimes in mixed settings of men and women

The feminist movement witnessed a significant leap with the establishment of the Arab Feminist Union (AFU) in 1945, chaired by the most prominent face of Arab feminism to this day, the Egyptian Huda Sha’arawi. The union comprised Egypt, Trans-Jordan, Iraq, Syria, Palestine and Lebanon in its membership (Britannica). It focused on women’s rights in Islam and the gendered

nature of the Arabic language, among other priorities Sha’arawi’s autobiography stands as a foundational text in understanding the principles of Arab feminism in the 20th century She emphasized that the struggle of “eastern women” is distinct from that of their Western counterparts. In her words, while Western women often confronted legal barriers perceived as encroachments on men’s rights, women in the East sought to reclaim rights already guaranteed to them under Islam, primarily through access to culture, education, and public life (Hindawiorg)

Sha’arawi’s framing of the Arab feminist movement comes in strong contradiction to the orientalist notions that portrayed Arab women as victims of their own culture In later years, more contemporary figures in Arab feminism adopted views that represent a wider ideological and intellectual spectrum, from the Moroccan Fatema Mernissi, who became a leading voice in Islamic feminism through her revolutionary book “Beyond the Veil: Male-Female Dynamics in Modern Muslim Society”, to more liberal figures such as the Egyptian Nawal El Saadawi known for her radical feminist and often controversial views

From this brief historical overview, several defining features of the Arab feminist movement can be discerned First, literature served as an early and powerful vehicle for women’s expression This comes as a continuation of longstanding historic traditions in the region that placed a high value on language and eloquence Arabic cultural heritage includes various examples of figures such as Al-Khansa and early Islamic mystics like Rābiʿa al-ʿAdawiyya, who used poetry as a means of articulating thought and identity. Rābiʿa al-ʿAdawiyya was considered as one of the key figures in Sufi Islam Many of her sayings were recorded, and her teachings on loving God for his blessings and graces regardless of fear or reward are held in high esteem in Arab and Islamic memory to this day (Sufimasterorg) This confirms the strong connection between feminist expression and cultural heritage Second, unlike some Western iterations of feminism, Arab feminism was marked from its inception by the active support of men who championed women’s education and empowerment. Intellectuals such as the Lebanese Butrus al-Bustani and the Egyptian Qasim Amin played a key role in advocating for women’s rights Al Bustani, one of the early leaders of the Arab renaissance, was not only a scholar and an educator, but he was also considered an avant-garde feminist (Nasser, 2019) His famous lecture “A Lecture on the Education of Women” in 1849 emphasized the role of women in society’s advancement (Nasser, 2019). In his own words, Al Bustani said: “If ignorance prevails among women in any place or time, we see it spread and take full hold over all its people. What makes a society either barbaric or civilized is, in fact, the woman” (Al Binaa Magazine) Qasim Amin’s seminal work Tahrir al-Mar’a (The Liberation of Women) in 1899 drew a powerful link between Egypt’s underdevelopment and the denial of education to women He supported emerging women’s associations and called for women’s rights as a nationalist necessity (Chamlou, 2017) He argued that it was social traditions, not Islam, that restricted women, and he used Qur’anic texts to demonstrate that the religion

in fact guaranteed women important rights (Chamlou, 2017) Huda Sha’arawi asserted in her autobiography that male support was a defining trait of women’s renaissance in the region She recounted in her memoirs the opening ceremony of the Women’s Union headquarters in Cairo, which was attended by many high-profile men. Prominent journalist Ahmed El Sawy Mohamed even described the event as a “glorious day” and “a day of pride for Egypt” (Hindawiorg) This is not to claim that males’ support for women’s rights back then was universal The notable Egyptian nationalist leader, Mustafa Kamil, strongly opposed Qassim Amin’s call for women’s liberation from the hijab He sharply criticized the idea of raising Egyptian girls on European principles, insisting that Egypt’s daughters should be nurtured within a framework rooted in religion and national identity (Mohamed Ismail El Mokadem, p.56). However, the support of male leaders remains an important feature of the early Arab feminist movement that undoubtedly lent visibility and credibility to the feminist cause Third, the Arab feminist movement possessed a distinctly pan-Arab character, culminating in its institutionalization through bodies such as the Arab Feminist Union, which sought to unify and coordinate women’s struggles across the region The specificity and uniqueness of national contexts did not cancel the need for cross-regional solidarity. Most recently, the Arab Spring uprisings emphasized the interconnectedness among Arab countries, not only in terms of economic realities and security environments but also in the aspirations of Arab women and the setbacks they grappled with

Today, the Arab region is experiencing a moment of crisis and backsliding with the second widest gender gap in the world after South Asia, according to the Gender Development Index (GDI) (UNDP Arab States) Participation in the labor force is a key weakness, with only one out of five women participating in the workforce, giving the region the lowest global ranking Arab countries have progressed slowly in closing the gender gap, which is expected to take another 153 years to close (UNDP Arab States).

Gender based violence is a growing challenge in much of the Arab world In parts of the Arab region, nearly two-thirds of women and girls report having been exposed to violence (UNFPA in the Arab States, 2024) One study found that 60% of women who use the internet in the region have been exposed to online violence (UN Women Arab States, 2023) Moreover, weaknesses in legislative frameworks create a culture of impunity, as penal codes are largely void of laws that punish gender based violence and marital rape (Imran, 2025). In fact, many countries allow clemency to be granted to men during trial if the crime was committed as an “act of rage” (Imran, 2025) Unlike the conventional understanding that such laws are grounded in Islamic sharia’a, the penal codes of Arab countries are still based on British and French laws introduced by the colonial authorities in the 19th century, especially the laws governing rape, murder, adultery and even

homosexuality For example, the laws allowing clemency are based on Article 324 of France’s 1810 Penal Code (Imran, 2025) A deeper symptom of the current crisis facing the Arab feminist movement is the stigmatization of terms like feminism and gender. Feminists are accused of destroying the nuclear family and other traditional values that have kept the social system intact for centuries (Allam, 2022)

Today, women peacebuilders in Arab countries carry forward the legacy of the pioneer feminists On the ground, their activism connects gender justice to resisting foreign intervention, authoritarianism, and war; however, the WPS agenda to date is reduced to donor-driven programs or cosmetic reforms that ignore historical context Looking across three National Action Plans (NAPs) from Iraq (2021-2024), Jordan (2022-2025), and Tunisia (2018-2022), some overlapping elements can be traced First, all three are written in a heavily programmatic language that aligns with the priorities of donor and international institutions rather than in terms that resonate with the living conditions of Arab women. For instance, there are numerous references to international frameworks, conventions, indicators, and outputs, which make these plans resemble bureaucratic project documents rather than social manifestos that outline a human-centered approach to peacebuilding This style contrasts sharply with the language of early Arab feminists, who crafted culturally resonant arguments around religious authority, nationalist aspirations, and literary traditions to advance women’s emancipation as central to societal progress

Second, women are largely portrayed as targets of protection and aid rather than as shapers of national and regional transformation Whether in relation to conflict, extremism, or displacement, the NAPs overwhelmingly frame women as victims who must be shielded from harm This framing undermines the agency of women who are not simply passive but have been and continue to be educators, writers, activists, and leaders of social and political movements

Third, the weak cultural or intellectual anchoring in these documents. The Jordan NAP makes some gestures to male allyship and the role of religious leaders, but these references are provided in a thin and instrumental fashion, not part of a sustained engagement with cultural debates On the other hand, Iraq focuses on conflict-related vulnerabilities, while Tunisia situates its plan within a geopolitical context, emphasizing instability in neighboring countries and the threat of extremism. A key weakness of these plans is the absence of a strong connection to the histories of women in their countries and how they have been agents of change, which can be leveraged on a larger scale

Fourth, the regional dimension is also missing Tunisia briefly acknowledges the NAPs of Iraq, Palestine, and Jordan, but none of the three plans use these references as an entry point for

serious cross-regional feminist solidarity Instead, each plan remains siloed within a national framework tailored to donor expectations, thereby neglecting the historical lesson that Arab women have long seen their struggles as interconnected.

Fifth, the NAPs treat education and awareness as technical outputs, not as engines of social transformation While the plans include references to training, capacity building, and awareness campaigns, these are offered in narrow programmatic terms and lack a broader cultural ambition

Finally, all three documents reflect a top-down model of state feminism. Ministries, security agencies, and donors are the primary actors in drafting and implementing the plans, while civil society organizations are presented as “partners” without real authority By consolidating decision-making at the state level and failing to devolve meaningful power to grassroots women’s movements, the NAPs risk reproducing the very patriarchal systems they claim to challenge Taken together, the examined Iraq, Jordan, and Tunisia NAPs reduce the Women, Peace, and Security agenda to a technocratic exercise. They can be improved by drawing on the region’s feminist history, and by engaging more deeply with sociopolitical realities They also neglect the importance of cross-regional solidarity and do not explore enough the potential for sub-regional cooperation networks As a result, they lack transformative energy that could make WPS a truly resonant and empowering framework A fresh and authentic WPS perspective for the Arab world must capture what peace means for Arab women. The connective tissue between Arab countries must be seen as an opportunity for knowledge sharing, amplification of common messages, and a tool for cross-border solidarity

III. Recommendations:

Policy Recommendations to the WPS Community:

Localization of the donor agenda is critical for the success of any WPS plan of action in the region. The international community should refrain from dictating programs that do not reflect the spirit of local communities Listening sessions with local representatives are essential for scoping and assessment Donor rules for funding, as well as monitoring and evaluation requirements, must be simplified and tailored to the needs of the local context Shift from top-down state feminism to grassroots power-sharing, by requiring that civil society organizations hold co-decision-making authority in drafting and monitoring NAPs, not just advisory roles, and allocating at least 30% of WPS budgets directly to grassroots women-led organizations, bypassing state bottlenecks

Replace programmatic jargon with culturally resonant framing, possibly through a WPS language taskforce composed of women leaders, writers, historians, and faith scholars to develop a glossary of terms that resonate locally.

Require that national action plans (NAPs) in the region integrate Qur’anic, historical, and literary references alongside international conventions to ground women’s rights in local intellectual and cultural traditions This helps win allies and strengthens the case for inter-faith dialogue and the revival of indigenous mediation practices (Kakar, 2029) that involve women Reframe women as agents, not only victims, by introducing mandatory women’s leadership quotas in peace negotiations, ceasefire monitoring, and reconstruction committees.

Document and highlight local case studies of women as mediators, educators, and community leaders to be included in each country’s NAP as models of agency.

Build a regional WPS network through a Pan-Arab WPS Platform2 that convenes peacebuilders from across Arab countries every year, producing joint regional recommendations and advocacy campaigns This network can support the creation of subregional solidarity clusters (i.e., Maghreb, Levant, Gulf, Sudan/Horn of Africa) to coordinate strategies, exchange lessons, and respond to cross-border crises.

Establish regional rapid-response funds to directly support women’s networks mobilizing during crises in Gaza, Sudan, Syria, Yemen, and beyond

Treat education as a vehicle for cultural transformation by funding literary and artistic initiatives (novels, plays, poetry, films) that center women’s contributions to peace and resilience. Partner with media outlets to run multi-country storytelling campaigns that showcase women’s leadership in conflict and post-conflict recovery.

Institutionalize survivor-centered accountability by integrating testimonies of conflict survivors into WPS reports and UN briefings to ensure policies reflect lived realities

Arab women must deeply reconnect with and rediscover the historic roots of the Arab feminist movement, which emerged as part of the national liberation and anti-colonial struggle This is key for countries navigating conflict or in post-conflict settings where ultraconservative forces portray the feminist agenda as a Western import that aims to disrupt societies’ religious and cultural infrastructure Incorporating the writings of leading Arab feminists into educational curricula is a good starting point, along with public lectures that invite religious and tribal leaders to reflect on the histories and inspirational stories of these women. These public forums could be ideal venues to debate around women’s rights in Islam that were buried under centuries of colonial neglect and were reclaimed by the early Arab feminists

2 This paper draws on insights from the Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security’s MENA Women Peacebuilders Initiative, which the author leads

Arab men must recognize that women’s rights do not come at the expense of their own They should work alongside Arab women to reform outdated personal status codes, governing marriage, divorce, child support, and inheritance, ensuring a fair distribution of rights and responsibilities for more just, and harmonious families and societies. These reforms are not only essential for advancing gender equality but also directly support the WPS agenda, which recognizes that sustainable peace depends on inclusive and equitable social foundations By embedding women’s rights within family and community structures, societies strengthen resilience against conflict and create the conditions for long-term stability

Liberal and moderate forces must support and embrace the feminist movement as a crucial partner and ally in the fight for social justice and mitigating the negative consequences of aggressive capitalism. The calls for decent work hours and childcare services for working women are of utmost importance Ensuring decent work hours, fair labor practices, and accessible childcare services reinforce sustainable peace that is rooted in equitable social structures and resilient communities By championing policies that enable women’s full participation in economic life, these forces help create the inclusive foundations necessary for lasting peace and societal stability.

As the Women, Peace, and Security agenda marks its 25th anniversary, its promise in the Arab world will remain unrealized unless it is reimagined through the lens of the region’s own feminist history and lived realities The early Arab feminist movement was not an imitation of Western ideas, but a deeply rooted struggle intertwined with anti-colonial resistance, cultural revival, and the quest for justice Reclaiming this legacy today offers a powerful framework for transforming WPS from a donor-driven, technocratic exercise into a locally grounded, politically resonant, and socially transformative agenda. By embedding feminist principles within cultural, religious, and historical contexts, amplifying women’s agency and leadership, building regional solidarity, and ensuring that grassroots voices shape policy design and implementation, Arab societies can unlock the full potential of WPS as a tool for peace, resilience, and equitable development

Bibiography

1. UN, Landmark Resolution on Women, Peace and Security, https://wwwunorg/womenwatch/osagi/wps/

2 Al-Afifi, Raneem, Feminism in Egypt: a Brief Overview, Medfeminiswiya, April 8, 2021, Feminism in Egypt: a brief overview - Medfeminiswiya

3 Muhammad Ali, Pasha and Viceroy of Egypt, Britannic https://wwwbritannicacom/biography/Muhammad-Ali-pasha-and-viceroy-of-Egypt

4. Exeter, CIGH, Tracing the Origins of Early Feminism in the Arab World, Imperial and Global Forum, July 8, 2019, https://imperialglobalexetercom/2019/07/08/tracing-the-origins-of-earlyfeminism-in-the-arab-world/

5 Chamlou, Nadereh, Women’s Rights in the Middle East and North Africa, Global Policy, October 3, 2017, https://www.globalpolicyjournal.com/blog/03/10/2017/women%E2%80%99srights-middle-east-and-north-africa

6 Choudhary, Zara, Silence Is Consent: White Feminism’s Selective Solidarity With Iran but Not Palestine, Amaliah, December 14, 2023, https://wwwamaliahcom/post/67504/white-feminismselective-solidarity-silence-iran-palestine

7. Evelyn Baring, 1st Earl of Cromer, https://enwikipediaorg/wiki/Evelyn Baring, 1st Earl of Cromer

8 Haq, Maheen, The War on Muslim Women’s Bodies: A Critique of Western Feminism, Georgetown Immigration Law Journal, January 17, 2022, https://www.law.georgetown.edu/immigration-law-journal/blog/the-war-on-muslim-womensbodies-a-critique-of-westernfeminism/#:~:text=However%2C%20during%20the%20British%20occupation,was%20also%20 founding%20the%20%E2%80%9CMen's

9. Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage, Spartacus Educational, https://spartacuseducational.com/Wmen.htm

10 Hibri, Cyma, Orientalism: Edward Said’s Groundbreaking Book Explained, The Conversation, Feb 12, 2023, https://theconversationcom/orientalism-edward-saidsgroundbreaking-book-explained-197429

11. Gerloff-Blood, Lily, Challenging Orientalist Cultural Narratives of Arab Women: an Analysis of a Short Film, The New Scholar, Leiden Student Journal of Humanities, 2024, https://wwwthenewscholarnl/indexphp/tns/article/view/31/arabwomen

12 Popular Press Holdings in the Middle East Department, Library of the University of Chicago, https://www.lib.uchicago.edu/e/collections/mideast/poppress/

13 Warda Al Yaziji, https://enwikipediaorg/wiki/Warda alYaziji#:~:text=Warda%20al%2DYaziji%20%281838%E2%80%93,Lubnaniyat%20%22%20by%20Emily% 20Fares%20Ibrahim.

14 Hind Nawfal, https://enwikipediaorg/wiki/Hind Nawfal

15 Zaynab Fawwaz, https://enwikipediaorg/wiki/Zaynab Fawwaz

16. Azam, Mohamed, Women’s Literary Salons and Societies in the Arab World, RESEARCH REVIEW International Journal of Multidisciplinary, Volume-04, Issue-08, August-2019 https://oldrrjournalscom/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/231-232 RRIJM190408049pdf

17 Arab Feminist Union, Britannica, https://wwwbritannicacom/topic/Arab-Feminist-Union

18. Huda Sha’arawi, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Huda Sha%27arawi

19

https://wwwhindawiorg/books/90647493/42/

20 Thomas, Maria, Five Incredible Arab Feminists You Need to Know, Natakallam Blog, https://natakallam.com/blog/5-incredible-arab-feminists-you-need-to-know/

21 Mernissi, Fatema, Beyond the Veil: Male-Female Dynamics in Modern Muslim Society, first published in 1975, Indiana University Press, https://wwwgoodreadscom/book/show/537182 Beyond the Veil

22. Nawal El Saadawi, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nawal El Saadawi

23 Rabia Basri, https://enwikipediaorg/wiki/Rabia Basri

24 Al-Khansa’, https://enwikipediaorg/wiki/Al-Khansa%27

25. The Knower of Allah, Rabia al-Adawiyya, Sidi Muhammad Press, https://sufimaster.org/teachings/rabia-al-adawiyya/

26 Butrus al-Bustani, https://enwikipediaorg/wiki/Butrus al-Bustani

27 Qasim Amin, https://enwikipediaorg/wiki/Qasim Amin

28 Nasser, Hanan, Remembering Boutros Al-Boustani: A Visionary, Lebanese American University, September 24, 2019, https://newslauedulb/2019/remembering-boutros-al-boustani-avisionary.php#:~:text=Al%2DBoustani%20embraced%20modernity%20in,of%20society%20as%20a %20whole.

208568article/archives/combinaaalwww://https/

30. Mustafa Kamil Pasha, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mustafa Kamil Pasha /9133/53book/wsshamela://https 56، 31 ص 2007

32 UNDP Arab States, Gender Justice and the Law in the Arab Region, https://wwwundporg/arab-states/gender-justice-law-arab-region

33. UNFPA in the Arab States, Gender-Based Violence, https://arabstatesunfpaorg/en/topics/gender-based-violence-8

34 UN Women Arab States, Facts and Figures: Ending Violence Against Women and Girls, https://arabstatesunwomenorg/en/what-we-do/ending-violence-against-women/facts-andfigures-0

35 Samir Imran, Yousra, For Gender Justice in Arab Countries, Abolish Colonial Laws!, New Arab, August 21, 2022, https://wwwnewarabcom/opinion/gender-justice-arab-countries-abolishcolonial-laws

36. Saif Allam, Rabha, Arab Feminism: Controversy in the Face of Social Reform, Future for Advanced Research and Studies, November 28, 2022,https://futureuaecom/beencephp/Mainpage/Item/7823/arab-feminism-controversy-in-theface-of-social-reform

37 Iraq Second National Action Plan to Activate Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace, and Security, 2021-2024, https://www.wpsnaps.org/app/uploads/2022/12/Iraq-NAP-22020-2024 arabic ENG-translation-Google-Translate.pdf

38 The Second Jordanian Action Plan for the Implementation of the UNSCR 1325 on Women, Peace and Security 2022-2025, https://women jo/sites/default/files/202403/JONAP%20II Revided%20version English%20001pdf

39 Tunisia National Action Plan 2018- 2022 1325

" Women, Security and Peace", https://wpsfocalpointsnetworkorg/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Tunisia-2018-2022 pdf

40. Kakar, Palwasha L., To Help End a War, Call Libya’s Women Negotiators, USIP, October 17, 2019, https://wwwusiporg/publications/2019/10/help-end-war-call-libyas-women-negotiators

41 MENA Women-Peace Builders Initiative, GIWPS, https://giwpsgeorgetownedu/menainitiative/

Author:

Saji Prelis

Saji Prelis has over 25 years of experience working with youth movements, governments, and partners to build intergenerational trust and collaboration in over 35 countries As the Co-Chair of the Global Coalition on Youth, Peace, and Security, he co-led successful advocacy for the UN Security Council Resolutions 2250, 2419, and 2535 He also leads the Global Community of Practice on YPS National Action Plans Saji is the Director of Children & Youth Programs at Search for Common Ground Before that, he was the founding director of the Peacebuilding & Development Institute at American University in Washington, DC Over 11 years at the university resulted in him co-developing over 150 training curricula exploring the nexus of peacebuilding with development from a humancentered perspective Saji received the distinguished Luxembourg Peace Prize for his Outstanding Achievements in Peace Support He obtained his Master’s Degree in International Peace & Conflict Resolution from American University

The Women, Peace and Security (WPS) agenda, codified by UN Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 1325, has spent a quarter-century laying the essential foundation for inclusive peacebuilding. It further established the definitive evidence that peace agreements are 35% more likely to last 15 years with women’s inclusion confirming the enduring impact women’s leadership brings to sustaining peace As the WPS agenda seeks to overcome persistent implementation challenges including the enduring presence of political tokenism, rigid identity siloing, and the chronic use of weak performance metrics that fail to measure true social change the younger Youth, Peace and Security (YPS) agenda offers a vital and complementary pathway for its advancement. This practitioner essay argues that the synergy between these two frameworks can significantly strengthen the future implementation of WPS by providing a robust measurement framework and prioritizing intersectional, localized action

Far from competing for resources, YPS is built on a non-adversarial, intergenerational model that directly addresses the systemic exclusion both movements share, particularly the "doublediscrimination" faced by young women. This refers to the structural and psychological exclusion experienced by young women who are often overlooked by WPS initiatives (which tend to prioritize older women) while simultaneously being overshadowed by the elevation of young men

in the nascent YPS space This inherent intersectional focus on age and gender allows YPS to advance gender equity a core WPS goal alongside young men

This article demonstrates how YPS offers three critical, practical tools for advancing WPS:

1 Correcting Exclusion: The YPS focus on grassroots, networked power provides a vital template for deeper, community-level penetration and combats tokenism

2 Quantifying Success: YPS introduces the Peace Impact Framework (PIF), an innovation that shifts measurement from simple activity reports to tracking five universal "Vital Signs" of social health including Agency and Institutional Legitimacy. The PIF provides a robust architecture for WPS to finally quantify the quality and sustainability of its inclusion efforts

3 Building the Investment Case: In a world where development assistance is shrinking, the YPS agenda’s proven Social Return on Investment (SROI) model demonstrates that every dollar invested yields a five-to-ten dollar economic return

By integrating the PIF and embracing this collaborative model, WPS can move beyond symbolic participation, transform social spending into an essential economic driver, and ensure the future of 1325 is one of collective, measurable, and enduring success

The Women, Peace and Security (WPS) agenda, with its foundational UN Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 1325, adopted in 2000, and its over two decades of work fundamentally reshaped global peacebuilding Its unwavering commitment to recognizing women as essential agents of peace not only challenged patriarchal power structures but also established the world's first formal link between gender and international security The WPS legacy is undeniable: it established 115 National Action Plans (NAPs) globally, as of October 2025 ((WPS Focal Points Network, n.d.) (Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security, 2025)., and its 2015 Global Study provided definitive evidence that peace agreements are 35% more likely to last at least 15 years when women are included (UN Women, 2015) This evidence base of success was the intellectual bedrock upon which the YPS agenda was constructed

The YPS agenda’s genesis was directly inspired by, and highly indebted to, the political architecture of WPS. The initial idea, conceived by a handful of leaders in civil society, the international youth networks, and UN was to replicate the success of 1325 for a youth demographic (ages 18 to 29) (United Nations Security Council, 2015), that lacked dedicated policy frameworks or institutional support (Prelis, 2022)

This effort was rooted in a foundational lesson from the WPS experience: systemic exclusion is violence. However, the YPS founders learned that achieving durable impact required a non-

adversarial, intergenerational approach Instead of framing the effort as a competition for resources, they focused on partnerships and trust This core group realized they couldn't do it alone and formed an interagency working group that, over several years, crafted the Guiding Principles on Young People’s Participation in Peacebuilding to establish a common language across the UN, governments, and youth-led groups (Prelis, 2022) The success of this collaborative horizontal leadership model culminated in the unanimous adoption of UNSCR 2250 in 2015, which was later reinforced by UNSCR 2419 (2018) and UNSCR 2535 (2020)

This process solidified a three-stream framework that governs the YPS agenda's work:

1 Setting Normative Standards: Establishing the political norms enshrined in the three UNSCRs (2250, 2419, and 2535) that recognize young people’s political agency for peace

2 Institutional Adoption: Helping institutions globally and regionally understand, adopt, and integrate these norms into their operations

3.National Collaboration and Trust: Improving trust and collaboration at the national level through national strategies (adopting WPS National Action Plan models), innovative financing models, and programs that strengthen intergenerational peacebuilding efforts

These processes were co-led by the Global Coalition on Youth, Peace and Security which was coled by civil society, youth-led network and the UN in partnership with key intergovernmental agencies (Global Coalition on Youth, Peace and Security (GCYPS) (2012).

Despite their differing timelines and primary focus groups, the WPS and YPS agendas share fundamental challenges rooted in structural exclusion, while their architectural differences define their complementary power

The most immediate common challenge facing both agendas today is the threat of resource depletion and political tokenism In an era of increasing global chaos, rising costs of living, rapid erosion of gender norms and gains, and inevitable decreases in foreign and domestic investment, both agendas risk becoming hollowed-out policy relics Furthermore, both WPS and YPS struggle with overcoming the “symbolic versus structural" divide: too often, states invite representatives for ceremonial "participation" without yielding any real decision-making power, a failure noted in the implementation of both WPS and the nascent YPS NAPs (Our Generation for Inclusive Peace (OGIP) (2019) (Leclerc, 2024)

Looking ahead, both agendas will inherit the future challenges of deepening intergenerational distrust and the impact of the median age gap Globally, approximately 1 8 billion young people (aged 15–29) represent a massive demographic reality, one that is often cited as a key factor in political instability and conflict when excluded from economic and political systems (UNFPA, 2015) This exclusion creates a growing vacuum of institutional legitimacy worldwide The urgency of this global reality is starkly reflected in the fact that, while the entire Continent Africa alone has a median age of 193 (Worldometer, 2025) and accounts for nine of the ten lowest-ranked countries in the 2023 Global Youth Development Index (YDI), the global Peace and Security domain has recorded the smallest overall improvement over the past decade (Commonwealth Secretariat, 2023). This demographic pressure is colliding with global insecurity: the 2025 Global Peace Index (GPI) found that global peacefulness has deteriorated for 13 of the last 17 years, with the key drivers of this decline being the Ongoing Conflict and Militarisation domains (GPI, 2025) Unless WPS and YPS collaborate, this demographic reality threatens to widen the chasm between formal institutions and the populations they serve, undermining the sustainability of any peace and security process.

It is against these alarming trends of rising violence and institutional fragility that the YPS agenda framed its trajectory around a fundamental, disruptive question: it deliberately shifted the focus away from asking simply why some young people pose a threat or why they join armed groups to investigate why the vast majority of young people are peaceful This foundational query reframed youth not as a risk to be contained, but as a critical and often-overlooked asset for sustainable peace (Prelis, 2022).

While sharing these obstacles, the YPS agenda is distinctively characterized by how it builds on and attempts to correct for the WPS legacy:

Framing and Tone: The WPS movement, in its early stages, necessarily had an adversarial component to challenge centuries of patriarchal power The YPS movement, building on the political space WPS created, adopted a non-adversarial, intergenerational partnership model from its inception, prioritizing the building of trust between youth, institutions, and traditional leaders (Prelis, 2022).

Decentralized Power: While WPS has primarily centered on vertical policy spaces (Security Council, national parliaments), YPS prioritizes horizontal/networked power the grassroots youth coalitions that operate outside formal corridors This focus on localization and youth-led ownership (eg, in Burundi, Cameroon, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Gambia, Jordan, Kenya, and Nigeria NAPs) provides a vital template for WPS to achieve deeper, community-level penetration (Leclerc, 2024).

The Double-Discrimination of Young Women: The fragmentation of the two agendas results in the systemic "double-discrimination" of young women who fall between the cracks of WPS (which tends to prioritize women generally above the age of 30 or 35 for high-level inclusion) and YPS (which often elevates young men) (OGIP, 2019) (Leclerc et al, 2023) In trying to overcorrect, sometimes the YPS agenda leaves young men more marginalized when they too are key for peace and security solutions Moreover, a narrow focus on women’s participation risks reinforcing existing gender norms that exclude young men from constructive, nonviolent roles, treating them solely as perpetrators or spoilers of peace. As a result, the YPS agenda is inherently intersectional, focusing on dismantling this specific age and gender barrier to advance gender equity a core WPS goal alongside young men The integration of both agendas is crucial because simply grouping young people without a gender lens, or grouping women without an age lens, both discriminates against young women and disregards their unique set of abilities as agents of change and their political agency (UN Women, 2018).

The most critical opportunity for the WPS agenda to revitalize its implementation comes through adopting the Peace Impact Framework (PIF), an innovation developed in the YPS space to overcome the persistent challenge of measuring actual, long-term social change (Lemon et al., 2023). This model shifts the focus from simple outputs (e.g., number of meetings held, policies written) to measuring the health and resilience of a society itself This allows WPS to tell a stronger, data-driven story of its impact, both alone and collectively with YPS

The PIF is built on the simple analogy of a human body: a doctor measures universal vital signs (temperature, pulse, respiration rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation) to assess health, regardless of a specific ailment (headache or knee pain) or other differentiating factors including gender or socioeconomic status Similarly, a healthy and peaceful society has five universal Vital Signs that must be tracked:

1 Agency: Do people, especially women and youth, believe they have the power to influence decisions and change their lives?

2.Institutional Legitimacy: Do people trust their formal and traditional institutions (police, government, community leaders) to be fair and responsive?

3 People’s Trust in Each Other or Polarization: How much do people trust each other across dividing lines (ethnic, political, generational)?

4 People’s Sense of Safety or Violence: Do people feel safe in their homes and communities, free from both physical and structural violence?

5.Investments: Are resources flowing into supporting peace and development rather than fueling conflict? And understanding the impact of existing resources including volunteer hours dedicated to addressing grievances

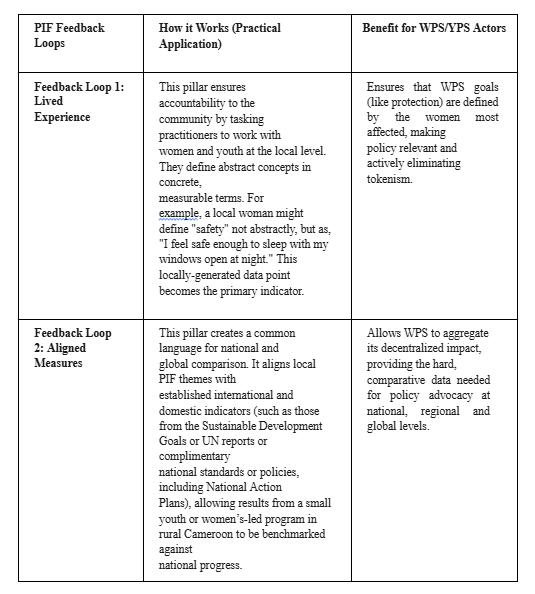

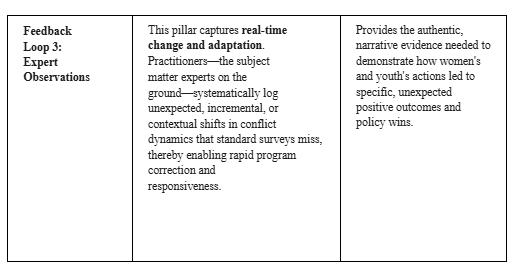

The true utility of the PIF lies in its three simple, practical pillars referred to as Feedback Loops which establish a shared methodology for measuring the five Vital Signs. This common language facilitates seamless collaboration on data between practitioners on the ground and policymakers in capital cities

The YPS agenda is actively testing this framework in National Action Plan contexts like the Cameroon, DRC, Gambia, Kenya, and Nigeria, yielding promising results that demonstrate a clear pathway for WPS adoption. This critical testing phase is designed to develop a scalable proof of concept, leveraging coordinated national coalitions and accessible data tools to ensure widespread, cost-effective youth participation without placing undue capacity burdens on underresourced grassroots organizations By integrating the PIF, the WPS agenda gains a robust, universal architecture that can quantify the quality and sustainability of inclusion, thus fulfilling the spirit of 1325's vision for transformative peace

The profound impact of this collaborative approach is visible in the work of young peacebuilders Their stories are not mere anecdotes; they are the evidence base for the new investment paradigm

For young women like Fatoumata from Mali (visually impaired) and Nyakang from South Sudan (resisting forced marriage), the YPS framework enabled them to overcome structural violence and increase their Sense of Agency (Vital Sign 1) (Search for Common Ground, 2025a, 2024b) Similarly, young men like Hussein, a journalist in Kenya from the informal settlements of Mombasa, and Lomong in South Sudan, who utilized conflict transformation skills to address gender-based violence and support vulnerable children, demonstrate the critical role of young men in advancing WPS objectives (Search for Common Ground, 2025b, 2024a).

This practitioner impact directly feeds the Investment Case The YPS agenda is using the Social Return on Investment (SROI) methodology to make the compelling economic argument that the impact generated by young people benefits all stakeholders. Research demonstrates that every one dollar invested in youth peacebuilding programs yields a five to ten dollar social and economic return on investment, benefiting the private sector, local authorities, and civil society groups, not just the youth participants (Kumar et al, 2023)

This quantifiable SROI, derived from strengthening the social vital signs of a community, underscores the importance of collaboration and partnership. It reframes investment in WPS and YPS not as social spending, but as an essential economic driver for resilient and stable societies. The YPS agenda, by providing a framework that is politically rigorous, economically justifiable, and practically measurable through the PIF, offers a roadmap for the WPS agenda to achieve its next phase of impact, ensuring the future of 1325 is one of collective success

References

Commonwealth Secretariat. (2023). Global youth development index update report 2023. Retrieved October 25, 2025, from https://thecommonwealth.org/publications/global-youthdevelopment-index-update-report-2023/global-picture

Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security (2025) From Resolution to Revolution: Lessons Learned from 25 Years of the Women, Peace & Security Framework Retrieved October 20, 2025, from https://giwps.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/From-Resolution-toRevolution.pdf

Global Coalition on Youth, Peace and Security (2012) Global Coalition on Youth, Peace and Security (GCYPS) Retrieved October 25, 2025, from https://cnxusorg/resource/gcypsglobalcoalitiononyps/ Institute for Economics & Peace (2025) Global Peace Index 2025: Identifying and measuring the factors that drive peace. Retrieved October 25, 2025, from https://www.economicsandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/GPI-2025-web.pdf

Kumar, S , Olsen, S , Mallett, A , & Prelis, S (2023) Building Evidence for Peacebuilding Investments: A Snapshot of Youth-Led and Youth-Supporting Peacebuilding Programs in Kenya Yields Five to Ten-Fold Social Returns on Investment (SROI) USAID Retrieved on October 20, 2025 from https://cnxus.org/resource/building-evidence-for-peacebuilding-investments-a-snapshot-ofyouth-led-youth-supporting-peacebuilding-programs-in-kenya-yields-five-to-ten-fold-socialreturns-on-investment-sroi/

Leclerc, K (2024) Claiming the Agenda: What Seven YPS National Action Plans Tell Us About Youth Ownership and Localization Retrived October 20, 2025 from https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/claiming-agenda-what-seven-yps-national-action-plans-tellleclerc-7vpuc/

Leclerc, K, Stoumen, N, Despain, A , & Zabihi, S (2023) Slipping Through the Cracks: Young Women's Exclusion from Peace and Security Processes Al-Raida, 47(1), 3-30 Retreaved October 20, 2025 from https://alraidajournal.lau.edu.lb/images/d912da7ca8270f720f5bc8e5b7cd0e4162a2d23c.pdf

Lemon, A , et al (2023) The Peace Impact Framework Retrieved on October 20, 2025 from https://cnxusorg/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/PIF Packet Final-Version May-2023pdf

Our Generation for Inclusive Peace (OGIP) (2019) Inclusive Peace, Inclusive Futures: Exploring the Urgent Need to Further the Women, Peace and Security and the Youth, Peace and Security Agendas. Our Generation for Inclusive Peace Policy Paper. Retrieved on October 20, 2025 from https://ourgenpeacecom/policy-papers/

Prelis, L S (2022) The Critical Movement for Youth Inclusion In C Koppell (Ed), Untapped Power: Leveraging Diversity and Inclusion for Conflict and Development (pp 95-120) Oxford University Press.

Search for Common Ground (2024a) Lomong’s Journey of Transformation and Hope Youth Talk: Success Story Retrieved October 20, 2025, from https://wwwsfcgorg/wpcontent/uploads/2025/03/Youth-Talk-Success-Storiespdf

Search for Common Ground. (2024b). Rising Above: Nyakang’s Courageous Path to Inspire Change. Youth Talk: Success Story. Retrieved October 20, 2025, from https://wwwsfcgorg/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Youth-Talk-Success-Storiespdf

Search for Common Ground (2025a) From Challenges to Change: Fatoumata’s Vision for Inclusion and Peace in Mali Youth Talk: Success Story Retrieved October 20, 2025, from https://www.sfcg.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Youth-Talk-Success-Stories.pdf

Search for Common Ground (2025b) Hussein - Becoming a Peace Ambassador Youth Talk: Success Story Retrieved October 20, 2025, from https://wwwsfcgorg/wpcontent/uploads/2025/03/Youth-Talk-Success-Storiespdf

United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). (n.d.). Youth participation and leadership. Retrieved October 25, 2025, from https://www.unfpa.org/youth-participation-and-leadership

United Nations Security Council (2015) Resolution 2250 (2015) S/RES/2250 Retrieved on October 20, 2025 from https://digitallibraryunorg/record/814032?v=pdf

UN Women. (2018). Young Women in Peace and Security: At the Intersection of the YPS and WPS Agendas UN Women Retrieved on October 20, 2025 from https://wwwunwomenorg/en/digitallibrary/publications/2018/4/young-women-in-peace-and-security

UN Women (2015) Preventing Conflict, Transforming Justice, Securing the Peace: A Global Study on the Implementation of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325. UN Women. Retrieved on October 20, 2025 from https://wps.unwomen.org/pdf/en/GlobalStudy EN Web.pdf

Worldometer (2025) Africa population Retrieved October 20, 2025, from https://wwwworldometersinfo/world-population/africa-population/

WPS Focal Points Network. (n.d.). Resources. Retrieved October 25, 2025, from https://wpsfocalpointsnetwork.org/resources/

Author:

Katherine Ntiamoah is a public affairs strategist, writer, and former US diplomat As Public Affairs Officer at the US Embassy in Benin, she initiated and led the Woman King cultural diplomacy program, advancing Women Peace and Security objectives by engaging government, security actors, youth, and cultural stakeholders Her portfolio has spanned gender equity, countering disinformation, and civic engagement across West Africa, Southeast Asia, Latin America, and Europe Katherine serves on the Dean’s Advisory Council of Indiana University’s Hamilton Lugar School of Global and International Studies and authors Still I Notice Everything, a Substack focused on policy, culture, and motherhood A first-generation Ghanaian American, she believes diplomacy must be more inclusive, more creative, and grounded in local agency She is especially interested in bridging cultural and policy tools to drive transformation within peacebuilding ecosystems and foreign affairs institutions

Abstract

This practitioner essay examines how The Woman King, a Hollywood-produced historical drama about the Agojie women warriors, became a strategic tool to advance the Women, Peace, and Security principles in Benin In May 2023, as Public Affairs Officer at the US Embassy in Benin, I initiated and led a cultural diplomacy program featuring director Gina Prince Bythewood and filmmaker Reggie Rock Bythewood. The mission used cinema as the entry point to convene government leaders, women in uniform, youth, creatives, civil society, and private sector stakeholders around shared values, including gender equity, national identity, and economic empowerment

This essay analyzes three dimensions of WPS advancement through this initiative. First, convening Beninese women leaders in the military, police, and judiciary elevated their voices and spotlighted gender challenges in national security These engagements aligned with UNSCR 1325's pillar on participation, reinforcing women’s visibility and influence in peacebuilding structures Second, diplomatic meetings with the ministers of Tourism and Microfinance catalyzed conversations on the development of national film infrastructure Commitments emerged to establish a national film commission, allocate land for studios, and promote tourism corridors grounded in historical memory. These institutional investments illustrated how culture can contribute to both economic recovery and gender-responsive development

Third, public programming at youth centers, universities, and innovation hubs mobilized more than 200 students and emerging creatives Young people were exposed to the mechanics of filmmaking, the career trajectories of the visiting artists, and the broader symbolic power of cultural production. The film’s resonance with local audiences inspired calls for a homegrown film sector that could rival Nollywood This demand signals a societal appetite to use art and storytelling to reconstruct national narratives through a gender lens

This case study highlights how cultural diplomacy can activate UNSCR 1325 in unconventional arenas. The national monument to the Agojie, artisan markets, and museum initiatives in Cotonou and Abomey already reflect a broader investment in cultural heritage and identity (The Art Newspaper, 2024; Akoroko, 2024) The Woman King itself had a budget of 50 million US dollars and grossed nearly 98 million globally (Wikipedia, 2024) It was filmed in South Africa due to Benin’s lack of production infrastructure, yet its spiritual and historical roots remain in the country

Drawing from my experience leading this program, the essay reflects on the role of creative diplomacy in operationalizing WPS It outlines how public engagement, strategic infrastructure investment, and narrative power together create new pathways toward inclusive peace, prosperity, and youth empowerment These lessons offer a model for future efforts that seek to align cultural initiatives with global peace and security goals

The adoption of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 (UNSCR 1325) in 2000 marked a landmark moment in recognizing women as essential actors in peacebuilding, conflict resolution, and post-conflict recovery. Over the past twenty-five years, the Women, Peace, and Security (WPS) agenda has expanded through both international and national mechanisms, yet its implementation continues to face structural barriers (United Nations Security Council, 2000) While much of the discourse surrounding UNSCR 1325 emphasizes traditional security frameworks and institutional reforms, this essay explores a less conventional avenue: cultural diplomacy.

In May 2023, as Public Affairs Officer at the United States Embassy in Benin, I initiated and led a cultural diplomacy program centered on The Woman King, a US -produced film that dramatizes the story of the Agojie, the all-female warrior unit that defended the Kingdom of Dahomey (present-day Benin) This program mobilized the film as a vehicle to convene women in security institutions, government ministers, students, creatives, and civil society leaders around themes central to UNSCR 1325, including participation, protection, and prevention.

By using cinema as soft power, the initiative highlighted how cultural narratives can activate WPS objectives in ways that extend beyond formal peace tables The program underscored three dimensions of WPS advancement: elevating the voices of women in uniform, catalyzing policy commitments toward cultural and economic infrastructure, and inspiring youth and creatives to imagine their role in shaping inclusive societies

The Agojie warriors occupy a prominent place in Beninese cultural memory. Represented in oral traditions, artifacts, and more recently in a national monument inaugurated in Cotonou in 2022, the Agojie symbolize resilience, national identity, and women’s leadership (The Art Newspaper, 2024) Their legacy has become a touchstone for both historical reflection and contemporary nation-building, particularly as Benin seeks to expand its cultural tourism and creative industries

The Woman King, directed by Gina Prince-Bythewood and starring Viola Davis, brought this history to a global audience. With a production budget of 50 million U.S. dollars and global box office earnings nearing 98 million, the film demonstrated both the commercial viability and cultural resonance of African stories In Benin, the film was met with widespread enthusiasm, selling out showings in Cotonou from September 2022 through March 2023 Its impact extended beyond entertainment, sparking debates about identity, representation, and the potential of the cultural sector to contribute to national development.

By situating this film within a diplomatic framework, the US Embassy in Cotonou was able to connect the WPS agenda to local contexts in ways that felt authentic and aspirational

One of UNSCR 1325’s most important contributions has been its call for the increased participation of women in security and decision-making structures Despite this, women in many African security sectors continue to face barriers to promotion, a lack of mentorship, and limited visibility (Hudson, 2022). As part of the Woman King cultural diplomacy program, the embassy convened Beninese women leaders in the armed forces, police, and judiciary to meet with the visiting filmmakers

These engagements provided a platform for women officers to share their experiences of both progress and persistent challenges. They also allowed U.S. diplomats and civil society partners to listen directly to the aspirations of these leaders. Such dialogues not only amplified their

voices within national security conversations but also reinforced the importance of peer exchange and international solidarity In this sense, the program directly aligned with UNSCR 1325’s emphasis on women’s meaningful participation in peace and security.

The second dimension of the initiative involved policy dialogue with the Beninese government. Meetings with the Minister of Tourism, Arts and Culture Jean-Michel Abimbola and Minister of Microfinance and Social Affairs Véronique Tognifodé revealed a shared interest in expanding the cultural and creative sectors Minister Abimbola announced plans for a national film commission and the allocation of 25 hectares of land for studio development He emphasized that cultural industries, particularly film, could serve as engines of both economic growth and youth employment.

These policy commitments resonate with UNSCR 1325’s focus on prevention and protection, not in the narrow sense of avoiding conflict, but in the broader sense of building resilient societies through inclusive development By investing in film and cultural tourism, Benin is creating opportunities that can reduce vulnerability to instability, while also affirming the importance of women and youth in driving national narratives.

The US Embassy’s role as convener and catalyst demonstrates the potential of cultural diplomacy to contribute to policy reform By connecting government stakeholders with international filmmakers and highlighting local enthusiasm for cinema, the program helped position the creative economy as a strategic priority.

The third and perhaps most dynamic aspect of the Woman King initiative was youth engagement More than 200 students participated in workshops, screenings, and discussions with Gina Prince Bythewood and Reggie Rock Bythewood These events took place at the American Center in Cotonou, the Eya Center, and Sèmè City, a regional innovation hub for education and entrepreneurship

Students were eager to learn about the process of filmmaking, the challenges of breaking into the industry, and the role of storytelling in shaping identity Many expressed aspirations to develop a Beninese film industry that could rival Nollywood, Nigeria’s globally recognized cinema powerhouse (PwC, 2020) For these young people, the presence of internationally acclaimed filmmakers was both inspiring and validating

Engaging youth through the arts aligns with UNSCR 1325 and the complementary Youth, Peace, and Security agenda It underscores the role of the next generation not only as consumers of culture but also as producers of narratives that can influence peace, governance, and social cohesion.

The Woman King cultural diplomacy initiative illustrates how non-traditional tools can operationalize UNSCR 1325 Unlike conventional approaches that focus on formal negotiations or institutional reform, cultural diplomacy works through narratives, symbols, and public imagination. This initiative demonstrates three important lessons for the future of the WPS agenda.

First, cultural heritage and storytelling can provide authentic entry points for engagement By grounding programming in the history of the Agojie, the initiative resonated deeply with local audiences and connected global WPS principles to national pride

Second, cultural diplomacy can catalyze cross-sectoral commitments. Policy discussions sparked by the program linked WPS objectives with economic development, tourism, and creative industries, expanding the scope of what peace and security can mean in practice

Third, cultural programs can empower youth as both creators and leaders By engaging students directly, the initiative helped cultivate a generation that sees itself as capable of shaping national and international narratives.

As UNSCR 1325 marks its twenty-fifth anniversary, the need to expand the tools of WPS implementation has never been greater. The Woman King initiative in Benin demonstrates that cultural diplomacy can serve as a powerful complement to traditional security approaches. By elevating women in uniform, influencing policy on cultural infrastructure, and inspiring youth through storytelling, the program advanced the principles of UNSCR 1325 in tangible and lasting ways

Cinema is more than entertainment. It is a site of memory, a platform for dialogue, and a catalyst for social change. When integrated into diplomatic strategies, it can help translate the ideals of the WPS agenda into lived realities The Benin case study suggests that the future of UNSCR 1325 depends not only on peace tables and policy documents but also on the cultural narratives that shape how societies imagine themselves

Akoroko. (2024, February 5). Why Benin is investing in a homegrown cinema sector. https://akorokocom

Hudson, N F (2022) The Women, Peace and Security agenda: An evolving framework for peace and conflict International Affairs, 98(4), 1197–1215

PricewaterhouseCoopers. (2020). Perspectives from the Global Entertainment and Media Outlook 2020–2024 PwC https://wwwpwc com/ng/en/assets/pdf/entertainment-and-media-outlook-2020-2024 pdf

The Art Newspaper (2024, April 17) Benin turns to culture to spur economic growth https://theartnewspaper.com

United Nations Security Council (2000) Resolution 1325 on Women and Peace and Security https://undocsorg/S/RES/1325(2000)

US Embassy Cotonou, Benin (2023, June 6) The Woman King Social media reporting https://x.com/USEmbassyBenin/status/1666083348673101830

Author:

Naseem Qader

Naseem Qader is a strategist and writer whose work explores the intersections of peace, diplomacy, and cultural intelligence in global affairs. She focuses on how overlooked narratives whether about migration, gender, or emerging technologies reshape power and perception. Through her Substack platform, The Global Rewrite, she amplifies marginalized voices and advances new ways of thinking about peace and security. She is a board member of the World Affairs Councils of America and has written extensively on peace, displacement, cultural intelligence, and AI governance. With a background spanning branding, philanthropy, and international engagement, she brings a crosssector lens to urgent global challenges and seeks to expand the space for inclusive, intergenerational approaches to diplomacy and security.

In October 2025, the international community will mark the 25th anniversary of United Nations Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 1325 on Women, Peace, and Security (WPS) This milestone coincides with the 10-year anniversary of UNSCR 2250 on Youth, Peace, and Security (YPS), the first Security Council resolution to formally recognize young people as essential partners in conflict prevention and peacebuilding. While both frameworks share a common DNA centering inclusion, prevention, and agency they remain siloed in practice, constraining their collective impact

This essay argues that WPS@25 offers a rare opportunity to move beyond parallel tracks and toward a unified intergenerational peace and security framework. Sustainable peace depends on bridging generations: drawing on the institutional experience of women’s peace networks alongside the dynamism, digital fluency, and forward-looking perspective of youth movements These constituencies are not competitors but complementary forces in building durable peace infrastructures

The essay takes a comparative, case-based approach, highlighting best practices from across regions In Sudan, intergenerational coalitions were central to the protest movement for democratic transition. In Colombia, young women have driven participation in transitional justice and reconciliation processes. In Liberia, the legacy of women’s mass action for peace continues to shape and mentor youth-led civic organizing

In Asia, women and youth jointly shaped the Mindanao peace process in the Philippines, where intergenerational councils now support mediation and reconciliation In the Middle East, women’s advisory boards and youth coalitions in the Syrian peace process have offered lessons on inclusive participation, even amid protracted conflict. These examples show how inclusive approaches can be institutionalized in peace agreements and post-conflict governance

Europe and North America also offer valuable lessons In Ukraine, women and youth are leading humanitarian relief, digital diplomacy, and war crimes documentation In Canada, Indigenous women elders and youth advance reconciliation and sovereignty, while in the United States, movements against gun violence pair mothers’ leadership with youth activism. Together, these diverse cases illustrate how women and youth especially those from marginalized and underrepresented communities are already forging shared leadership across contexts, even as international policy frameworks lag behind

Positioned within the political moment of 2025 when governments, UN agencies, and civil society will convene commemorative summits and pledges the essay calls for structural shifts: integrated national action plans, joint funding streams for women and youth, and consideration of a future Security Council resolution explicitly recognizing intergenerational peace Ultimately, the essay positions WPS@25 not simply as a milestone but as a launching point: transforming commemoration into commitment and laying the foundation for an intergenerational peace architecture capable of meeting the challenges of tomorrow.

“You can never leave footprints that last if you are always walking on tiptoe.” — Leymah Gbowee1

“As youth, we are not only demanding peace; we are creating it in our communities every day. We are tired of being seen only as victims or threats. We are partners.” Nisreen Elsaim2

In October 2025, the international community will mark two milestones: the 25th anniversary of United Nations Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 1325 on Women, Peace, and Security (WPS)3 and the 10th anniversary of UNSCR 2250 on Youth, Peace, and Security (YPS).4

Together, these resolutions represent two of the most significant normative shifts in the UN’s history of peace and security policy UNSCR 1325 reframed women as essential peacebuilders rather than passive victims of war, spurring more than 100 National Action Plans (NAPs)5 and reshaping how peacekeeping and diplomacy address gender UNSCR 2250 recognized that over 1 2 billion people under the age of 30 are central to preventing conflict and sustaining peace.6