AMALA EKPUNOBI

LAB HARASSMENT

(Scene, pg 3)

(Forum, pg 6)

(Scene, pg 3)

(Forum, pg 6)

(Sports, pg 8)

VIA POOLOS MANAGING SCENE EDITOR

VIA POOLOS MANAGING SCENE EDITOR

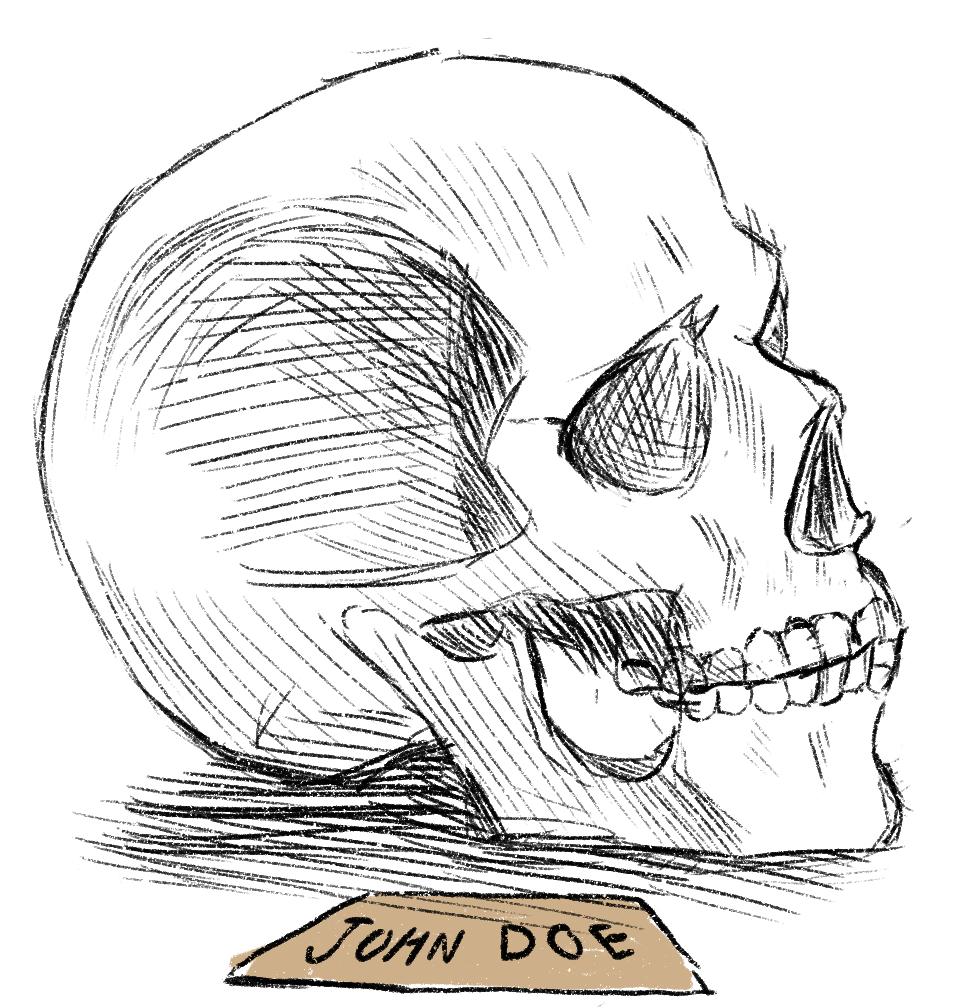

Junior Ben Norin was holding a fragment of a human skull in his anatomy lab on Nov 9 when Dr. David Strait, professor of biological anthropology, walked in and told the class that the lab was canceled. “I walked out with a friend, and we just looked at each other like ‘what just happened?’” Norin said. “Like okay, we’ll leave, but this is really strange.”

The following Monday, Strait told all 600 of his Anatomy and Human Evolution students that they would not be learning the pre scribed material. Instead, he had something very serious to share with them. Norin said that during class, Strait was overcome by emo tion and teared up while talking to them.

When he recounted the tale to me a few days later, he spoke softly, as if he was reading a bedtime story. But instead of sheep jumping over fences, the story was about the ethi cal quandary presented by human remains.

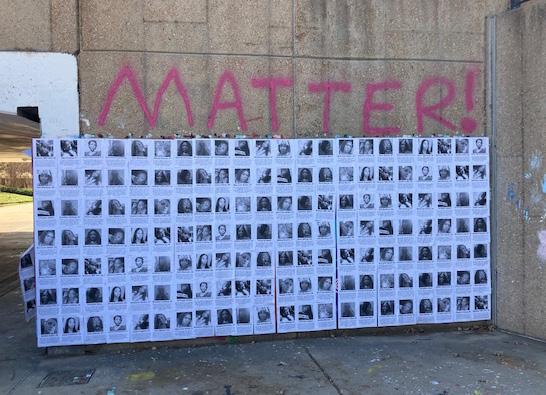

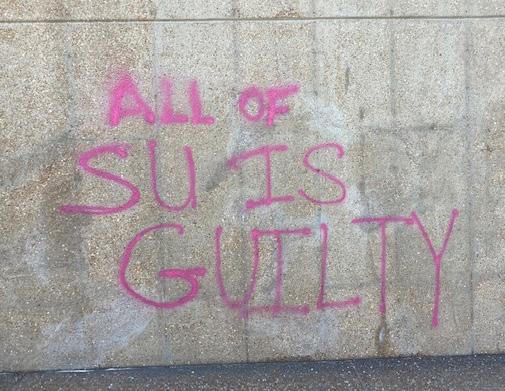

JAMES ELLINGHAUS AND ANNIE POWELL SENIOR NEWS EDITOR AND CONTRIBUTING WRITERSpray-painted graffiti near the South 40 criticized Student Union (SU) for SU Treasury’s vote to bring in a conservative speaker, who many view as anti-trans, to speak on campus, Dec. 5. Additional trans-affirming graffiti and a wall of flyers recognizing deceased trans people of color were put up around the South 40 underpass.

The graffiti included the com ments: “All of SU is guilty,” “Speak up against SU,” and “Protect Black trans lives.” The University removed the graffiti by Tuesday afternoon.

This demonstration followed Treasury’s approval of over 11 thou sand dollars in funds for PragerU influencer Amala Ekpunobi to speak on campus at an event hosted by the WU College Republicans.

“I am not aware that anyone has been identified as the individual or individuals responsible for this,” Rob Wild, Associate Vice Chan cellor for Student Affairs, wrote in statement to Student Life, Dec. 6. “If we were to determine that a

student or students were respon sible for not following University policy in painting the underpass, there would likely be consequences for those students for not following our underpass guidelines.”

Many students were angered by SUs decision to fund Ekpunobi’s visit. In an Instagram post from the WU College Democrats, Ekpunobi was labeled as “transphobic, racist, and misogynistic.”

Freshman Oliver Tramel, who identifies as trans, was in sup port of the anti-SU rhetoric of the demonstration, but had difficulty supporting the way the dissent was carried out.

He said that viewing posters of people who were killed or hurt for being trans was difficult for him to see. “That’s a scary thought because that’s me.”

However, Tramel added that the spray paint did allow him to feel seen. He said that a better idea would have been to reserve a space on the underpass so that the mes sage would not be taken down by the University.

Tramel also stated his support for the graffiti comments that called out the entirety of SU in a negative light.

“The best thing to do to [bring attention to the Ekpunobi contro versy] is to say that everyone in Student Union is guilty,” he said.

SU members did not respond to questions from Student Life regard ing the graffiti and the protests against Ekpunobi.

The Solidarity Showcase, an event protesting Ekpunobi’s visit, was held on Saturday, Dec. 3, in Hillman Hall, featuring student speakers and performers from over 20 campus organizations.

However, Ekpunobi’s visit was postponed that day, because she told the College Republicans she was sick.

“The idea behind the showcase was to essentially gain the support of a wide variety of student groups on campus to show our support for marginalized communities, espe cially the trans community in light of the transphobic speaker that SU funded,” Sophomore and SU Trea surer Saish Satyal, who performed at the event as a part of the Stand Up Comedy Club and voted against funding the speaker, said.

Sophomore Leah Karush, who attended the showcase, was “morti fied” that the SU Treasury voted to use student funds to give Ekpunobi

a platform.

“I like to think of WashU as an accepting, progressive student body, and seeing that belief be directly contradicted was disap pointing,” she said.

A sophomore, who chose to remain anonymous, performed slam poetry about their personal experiences with the University guidelines in regards to sexual assault.

“I spoke directly from my expe rience with [the Title IX process] and talked a lot about the dehu manization, and the way that the university, in this case, treats its stu dents more as a part of a business than they do as people,” they said.

The slam-poet also expressed how the event created a community in which people of marginalized identities could freely share their experiences.

“The intent of the event was to be a separate space for people to go and protest and show how they’re really not okay with [Ekpunobi],” they said.

Ekpunobi’s talk has been rescheduled to Friday, Dec. 9 at 7:00 p.m.

In the week prior, Strait had made two discoveries. First, was that WashU’s osteology collection, which the anthropology depart ment used to teach with, contained specimens from the Terry collec tion, a group which consisted of nearly 1800 individuals from Mis souri. Second, and much more dire, was that the Terry collection came from people who probably never consented to be collected.

Strait said that originally, he was under the impression that the bones the anthropology and anatomy departments used to teach classes with were from WashU Medical School donations, where a patient explicitly asks that their body be donated to research after death. Yet some skeletons — Strait says a max imum of 20 — were part of the Terry collection. “[Even] if I had known, actually I don’t know if it even would have registered as an issue of concern,” Strait said. The alarm bell began to ring when he read an article in Science published on November 2, titled “Medical, scien tific racism revealed in century-old plaque in Black man’s teeth.”

The article reported that Robert J. Terry, former head of WashU’s anatomy department, amassed his collection by “taking advantage of the lack of legal protections for marginalized people in the 19th and early 20th century.” It went on to explain that in the early 20th century, people whose family mem bers died in state institutions were

This past week, two commem orations took place on campus to memorialize those who lost their lives due to China’s Zero -COVID policy, and to demand greater civil liberties and an end to one party rule in the country. The events were attended by both domestic and inter national students on, Nov. 29 and Dec. 1.

The two demonstrations took place as part of a global protest move ment sparked by a fire in the city of Ürümqi, China that killed ten peo ple because of a heavily enforced quarantine policy. Many protesters said that the deaths could have been

CONTACT BY POST

prevented if it were not for the Zero–COVID policy.

The first event was a vigil that took place under the overpass to the South 40 on Nov. 29. More than 50 students came together in silence to pay respect for those who passed away in the fire. Almost all wore masks to protect their identities, out of fear that the Chinese government might retaliate against dissent.

Organizers of the event lit can dles, and participants left bundles of flowers in honor of those who passed away. Some put up posters with polit ical demands and slogans similar to the ones being made by protestors in China — an end to unrelenting quar antine, political persecution, and

ONE BROOKINGS DRIVE #1039 #320 DANFORTH UNIVERSITY CENTER ST. LOUIS, MO 63130-4899

suppression of freedom of speech.

An international student from Beijing described what he has wit nessed back home since the start of COVID. This student, and oth ers quoted in the piece, will remain anonymous to protect against poten tial retaliation from the Chinese government.

“These [Zero -COVID] policies have been in place for three years,” the student said. “They have caused so many businesses and people to die, and more people [have com mitted] suicides because of [these policies] rather than dying from the virus.”

He said he was proud to see the protest movement take off following

CONTACT BY EMAIL EDITOR@STUDLIFE.COM NEWS@STUDLIFE.COM CALENDAR@STUDLIFE.COM

prolonged periods of hesitation and acquiescence to the status quo in China.

A Taiwanese Ph.D. candidate similarly said that she was touched seeing Chinese citizens finally take action, and she expressed hope that China would eventually become democratic.

“Even though the politics across the Taiwan Strait has been very antagonistic, it is my wish that China can give up its [Zero COVID] policy and give some normality back to the people,” she said.

Other non-Chinese, international students felt a sense of camaraderie at the event. A student from Turkey

CONTACT BY PHONE NEWSROOM 314.935.5995 ADVERTISING 314.935.4240 FAX 314.935.5938

Opposing views on whether a divisive conservative speaker should come to campus.

WU graduate student drops PhD program after harassment by mentor.CHARLIE JACOB 5th year Charlie Jacob comes back for one more season, leading the Bears in scoring. PHOTO BY STUDENT LIFE Students hold candle-lit vigil in honor of those who died in the Ürümqi fire.

said that “because we are more connected to home, we are more aware of what is going on overseas.”

“As a Turkish person, I do relate to the experiences of Uyghurs in China,” the stu dent added. “It’s very easy to disregard this because this is not near me, but just giving them my emotional support here as a fellow WashU stu dent is essential.”

The second event took place on the Bear’s Den Patio, decorated with flowers and candles. Student attendees held the same symbols found in China throughout the protest.

The most powerful

symbol for the movement so far has been a simple sheet of A4 paper. Xiao Qiang, a researcher from U.C. Berke ley, was interviewed by The New York Times and explained that people have a common message to express that the authorities know all too well: “If you hold a blank sheet, then everyone knows what you mean.”

Online censorship inside the country usually deletes any controversial comments and leaves a blank webpage that has since become synon ymous with the blank sheet of paper.

Another key symbol is a picture of the signage for

“Ürümqi Road” in blue and white, printed in Chinese and English. People in Shang hai have protested on this street to connect with the city where the fire took place. In response, Chinese authori ties took the signage away, an action that was viewed as a national farce by protesters.

After moments of tranquil ity reserved for the deceased, students began to muster the courage to chant songs and voice their demands. Protes tors sung “L’Internationale” and “Do You Hear the People Sing?” to show support for the movement.

One student commenced by saying the popular “Four

Demands” that Chinese nationals worldwide are advancing: to allow public vigil for those deceased, to end brutal lockdowns and Zero COVID policy, to release protestors defending funda mental civil liberties, and to protect human rights at large.

The “Four Demands” drew inspiration from the “Five Demands” of Hong Kong protestors in the AntiExtradition Movement in 2019. “Glory to Hong Kong,” the Cantonese theme song for the movement, was also played publicly as a tribute, further emphasizing how this movement is impacting all of China.

Others at the venue recited verbatim rights reserved to the people and protected by the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China: the free dom of speech, of publication, of assembly, of protest, and of demonstration.

Impassioned chants from the participants intensified afterward, calling the incum bent and the Party to step down for their failures and crimes against humanity.

A Ph.D. candidate study ing law at the University expressed her support for the actions of international students.

“This is something we all need to show up for,” she said.

Another Ph.D. candidate from Beijing quoted a popu lar saying back home.

“To be and stay present for each other, even from afar,” he said.

Cities in the Sinosphere have the custom of nam ing their streets after other cities, which the Ph.D. candi date said resonated with this moment.

“Just like these cities stay ing conscious of the presence of each other, even from afar, we have to stay together and unite, so that our voice, in aggregate, can be spread across the world and let the world know what is happen ing inside China,” he said.

Researchers at Wash ington University received an 11.7 million dollar grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to study and treat pain, along with reduc ing opioid use.

The grant was given to the school for research in human genes and nerve cells. The goal of the research is to better understand how cells transmit pain.

Dr. Robert Gereau, director of the Washing ton University Pain Center, explained the general goal of the initiative, which is called the Helping to End Addic tion Long-Term (HEAL) initiative.

“The NIH initiative was launched to address the kind of parallel crises of opioidrelated overdose deaths and

chronic pain,” Gereau said. “Part of how the opioid cri sis started was [a] diversion of opioids that were being ostensibly distributed for the treatment of chronic pain. So, the goal of the HEAL initia tive is to have a whole bunch of different programs that address these problems, create new treatments for addiction, and prevent overdose deaths.”

Gereau leads the Inte grated Research Center for Human Pain Tissues (INTERCEPT), which is focusing on how different cell types and genes transmit pain signals, especially in relation to chronic pain. The research center is made up of three groups, all focusing on pain treatment.

Gereau also said there were many students who are helping with the initiative, including fifth-year Neurosci ence PhD student, Jiwon Yi.

Yi said she pursued a bach elor’s at Pomona College and a master’s at the University of Cambridge. While at Cam bridge, she said someone recommended that she looked into Washington University for graduate school.

“I ended up choosing WashU for grad school,” Yi said. “There’s a great pain center and a strong collection of research labs that focus on pain. I thought that was unique about WashU.”

Yi said one of the strengths of the grant is that the research ers get to utilize human tissue rather than exclusively using rodents.

“We use human tissue to validate what we find in rodents, and then we bring that to clinics if we think it is going to be useful,” Yi said. “We can go directly from rodent trials to human trials, which is useful for not failing

in clinical trials.”

Yi described her work as creating an “atlas” for pain treatment.

“I would call it an atlas. It could be publicly avail able and look at things like gene expression or electro physiological properties,” Yi said. “Other groups around the world that are looking at doing pain research and look ing at the peripheral nervous system can then access that atlas, and also use it as a tool to inform their research.”

David Perlmutter, exec utive vice chancellor for medical affairs and dean of the School of Medicine at Wash ington University, described the relationship between NIH grants and the University as something similar to other top research universities.

“Washington University’s medical school, like most top research-intensive medical

schools, has relied on NIH grants for its research activ ities since that became the standard way to get funding after World War II,” Perlmut ter said. “It’s always been a part of the medical research culture at top universities.”

Perlmutter explained that the NIH is a good metric of how competitive a university’s research and science is. Along with funding the actual grant and administration, NIH grants also typically fund research infrastructure.

Yi said she has had a good experience working on the project.

“For a lot of people that are doing pain research, an end goal is to find new targets and new therapies that can be used to treat pain without being addictive or having adverse consequences,” Yi said. “And direct human tissue is a great platform that speeds up the

process — it bridges the gap of preclinical research to rodent research to clinical research.”

In terms of broader research, Perlmutter stressed that grants are not the main reason why the school strives to be so competitive in terms of medical advancement._

“The NIH grants are not the reason that we do research; the reason we do research is to advance knowledge and improve healthcare,” Perlmut ter said. “The NIH funding makes that possible and lets us do more of it. It’s a metric of having great science.”

Read the rest online:

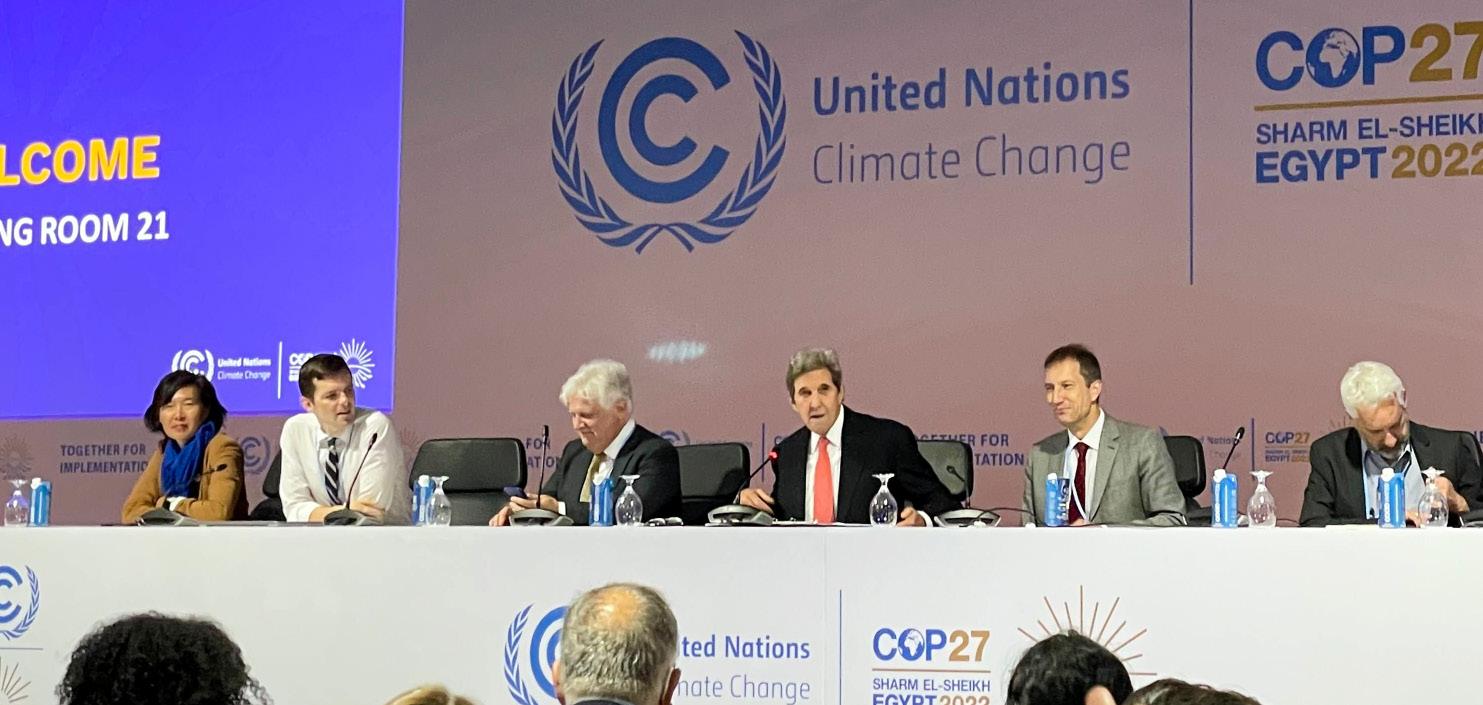

12 Washington Univer sity students attended the 2022 Conference of the Par ties summit (COP27) of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, Nov. 6-18.

The International Climate Negotiation Seminar, a class held every Fall semester since 2016, prepared enrolled stu dents to attend and observe the UNFCCC as a delegate of the University.

There are nine groups of NGOs or constituencies that have been granted observer status to the UNFCCC. Uni versity students attended COP as a part of the Research and Independent Non-Gov ernmental Organizations (RINGOs) constituency, the only non-advocacy group and the second largest

constituency recognized by the UNFCCC.

RINGOs serves to use “research and analysis to develop strategies addressing both the causes and conse quences of global climate change,” hosting daily meet ings while COP is occurring to discuss negotiation devel opments and any relevant information.

Senior Shira Lyss-Loren, a member of the University delegation to COP, described the opportunity to travel to COP as “one of WashU’s best kept secrets,” as she and other student delegates heard about the International Cli mate Negotiation Seminar by word-of-mouth.

“[COP] just felt like a very cool opportunity to get an international perspective on climate and also see how these solutions that I learn about in class are being implemented on a global scale,” Senior Dylan Fernholz-Hartman,

who also attended COP as a delegate, said.

The International Cli mate Negotiation Seminar is a 3-credit course led by Teaching Professor in Envi ronmental Studies and Interim Director of Wash ington University Climate Change Program Beth Mar tin, who also serves as a RINGO co-focal point.

Senior Ranen Miao, University COP delegate, described Martin as a “fantas tic professor” and “incredible resource” given her extensive experience as a leader of the RINGO delegation.

“Because she’s gone to COP so many years in a row now she knows all these dif ferent people. She will be talking to us and an ambas sador or a negotiator from another country will walk by and be like, ‘Hello Beth, good to see you,’” Miao said. “It’s so rare to have that incredible opportunity.”

While universities from all over the world attend COP, the seminar provides a unique experience for University stu dents to learn UN climate history, politics, and jargon to better prepare to observe the development of international climate diplomacy through interdisciplinary discussions.

“You end up being a lot more informed than a lot of the other people there by

knowing things like the acro nyms, knowing the different agreements that are being referenced, knowing the dif ferent conferences that led up to the current point and the ongoing global tensions that may be contributing to differ ent types of negotiating and diplomatic outcomes,” said Miao.

Lyss-Loren felt she was as prepared for the conference as

possible.

“I think some of the things that I didn’t feel prepared for

BONES from page 1

allotted just 36 hours to claim the body before the deceased became “unclaimed,” and able to be donated to researchers.This is the part of the story that Strait could not get over. “We live today in a world where we have these devices” — Strait shook his cell phone at me — “where we can communicate with everybody,” he said. “And even today, you know, you might not know someone is missing for more than 36 hours. Right? So you can imagine 100 years ago…” He gestured helplessly. “I had this visceral reaction.”

The WashU anthro pology department is no stranger to murky questions regarding human remains. This, strangely, is a sign of progress. Decades ago, archeologists had few con versations about right and wrong when it came to dig ging up, and keeping, human remains. Today’s experts in the field have been left to deal with the consequences.

Grant Stauffer, an archaeolo gist with the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma and a former WashU archeology gradu ate student, is very familiar with archeological ethics. He said colonists and settlers, starting with Julius Caesar, were amateur archeologists. “Oftentimes when they [found] stuff, the resources that are that [were] unearthed end up becoming their pos sessions,” Stauffer said.

These days, many former colonial powers have begun the work of repatriating bones to their rightful homes. In 2020, France returned 24 skulls that purport edly belonged to Algerian resistance fighters back to Algeria. It was meant as a gesture of reconciliation to the formerly-colonized country, which only won its independence after a bloody war. However, the process isn’t always perfect.

Just this year, The New York Times discovered doc uments that revealed only six of the skulls were actu ally freedom fighters, with the rest made up of a few Algerian French army men, or imprisoned thieves. Some European countries, like Germany, Norway, and the UK (though not France) have rules enforcing repatriation of colonized bones to their home countries.

The United States also passed a law in 1990: the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. NAGPRA required federal agencies, museums, universities, state agencies, local governments, or any institution that receives fed eral funds to give human remains and funerary objects back to the appropriate tribes. Afterwards, NAG PRA institutions rushed to hire anthropologists to go through their collections and repatriate remains, Stauffer said.

Many are still trying 32 years later.

“What NAGPRA rep resents is basically to take a step in the right direction ethically, but…many uni versities and museums are, for lack of a better term, doomed to determine where these human beings should go back to,” Stauffer said. Failure becomes a mark of shame. “It is basically evi dence of misconduct in the past,” he said.

A week before the dis covery of the The Science article, Strait told me that while WashU complied with NAGPRA to the best of its ability over three decades ago, well before most of the current anthropology faculty came to WashU, the process wasn’t perfect. “There are,” he said, “a small number of human skeletal remains that for various reasons — a lack of revenue or lack of context — could not be returned in that sense.”

Stauffer, during his time as a graduate student, was aware of the remains’ exis tence. He explained that modern archeologists are taught to be respectful of the dead, referring to human bones as “individuals’’ and “people.” To allow students to handle people who did not explicitly donate their bodies to research would be incred ibly disrespectful, he said.

“Those tribal groups, like their ancestors in the past, have very specific beliefs about how human beings who have passed away should be treated,” Stauffer said.

Under NAGPRA, the bones — if Native American — would be legally barred from use. But oddly enough, if the bones were from any one else, the federal rules don’t apply. Still, given the apparent lack of knowledge about the individuals’ his tory, Strait said that no one touches them. They’re kept separate from the “teaching lab,” which relies on cadaver donations used in anatomy classes.

I asked Strait a series

of hypothetical questions, which he batted at, one after another. What if we knew the bones were not Native American? Well, even if the department knew that, it’s not obvious there would be someone to return them to. What if we never figure out who they belong to? Strait threw the question back at me, holding his hands up as if in surrender. “What would you do? I mean, we’re not going to go to Forest Park and dig a hole.”

WashU is not the only university faced with the conundrum of unmarked bones in the basement. The San Francisco Chronicle published an article in 2018 titled “UC Berkeley Struggles with how to return Native American Remains.” Profes sors and experts quoted refer to the “ethical dilemma” and talk about “cultural repa triation.” Another piece, published by The Con versation, details how the University of Cape Town uncovered 11 skeletons, collected decades ago that “research suggested should not be at the University.”

Yet underneath the buzz words and best intentions, the bones often remain untouched and unclaimed. WashU’s particular individuals are kept in a tem perature-controlled storage room, on the ground level of the anthropology building.

For now, WashU’s mark of shame isn’t being erased any time soon. Strait said that for the foreseeable future, the unmarked bones are here to stay. “We want to do what’s right with the stuff. And that might entail hanging on to it,” he said.

It was the impulse to do the right thing that led to Strait’s startling discovery about the Terry Collection. The Science article reported that most of the individuals were “poor and institution alized,” and over 50% Black. These facts, along with the 36-hour rule, raised doubts on whether the deceased or their families ever consented to donation.

Dr. Geoff Ward, pro fessor of African and African-American stud ies, helped the researchers contextualize the life of the person studied in the collec tion. He was first approached for the project in 2020. “It was clear that we needed to spend more time on this dis cussion of structural racism in St. Louis, particularly in relation to the medical pro fession,” Ward said in the piece.

Ward wasn’t surprised to learn that the Terry Col lection took advantage of Black and populations with low socioeconomic status. The societal and legal rules at the time allowed for white supremacy, which laid the groundwork for Terry to col lect bodies in the way he did.

“If living African Amer icans had no rights, in this context of white suprema cism, surely this applied to the deceased,” Ward said. He was surprised, how ever, to learn that part of the Terry Collection was held at WashU, despite having researched the history of the individuals. “I was under the impression that the entire collection had been donated to the Smithsonian,” he said.

The article threw the anthropology department into chaos. Though the Terry Collection individuals haven’t been used this semes ter, they had been handled by classes in previous years. Strait struggled to articulate the reason for his visceral reaction to the discovery that students and faculty have been handling the bones of the dispossessed. “I guess it would be the families,” he said finally. “What happens after death is mostly for the living. Not for the dead.”

In the meantime, the individuals in the Terry Col lection have been retired from classroom use. They still remain in the teaching lab, separated into drawers by code that detail collection and type. Norin, like Strait, also struggled to articulate what he thought would be the most moral decision for

the individuals. “It’s not right for students to use them. It’s also not right just to put them in a box and forget about it,” he said. “But it feels impossi ble to rectify anything.”

The Smithsonian has restricted access to the col lection, specifically putting a ban on any research that would use Black individuals.

Both the archeology and anatomy departments are combing through the records and calling former faculty, hoping someone knows more about who these people were and how they came to be in the University’s basement.

But how can an institu tion right a wrong done to someone who has been dead for a century? Strait said he won’t be the one deciding what happens next. The final solution will be decided on by the entire anthropology department, any administra tors or professors that want to be involved, and members of the community who could share expertise. “We want to make sure that we’re on the right side of history going for ward,” Strait said.

Ward believes that the best thing to do is to publi cize what has been found. “I don’t know what to do with the bones. That’s not my field. But I think we should certainly find ways to pay respects that are long over due,” he said. “I think we have a responsibility to do that. We didn’t make those decisions in the past, but here we are faced with the ques tion of what to do with [the remains].”

Even though he’s far from the final say, Strait outlined a few possibilities. Ideally, liv ing kin members would be notified so they could decide on the fate of their ances tor. If that’s not possible, the bones could be cremated or re-buried. There may be a commemorative ceremony to lay the dead to rest.

Otherwise, they may remain in the universi ty’s basement indefinitely: unnamed, untouched and unclaimed.

Alleged sexual misconduct ends in unfinished PhDattempt, and an unfinished degree.

In the end, however, her path through a high-caliber neuroscience lab culmi nated in a quiet HR report, a failed Title IX investigation

VOLUME

Lila came to WashU from the Salk Institute at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where she worked to gain more research experience before applying to a graduate program. Lila found WashU School of Med icine professor of pathology and immunology Dr. Johna than Kipnis’s lab because she was interested in understand ing how the immune system interacted with the brain.

“For a very long time, I had been interested in the Kipnis Lab because they kind

of combined my future inter est in immunology with my current interest in neurosci ence,” she said.

When she was accepted to WashU, she reached out to Dr. Kipnis to do a rotation — a typical part of the Ph.D. program.

Upon acceptance into the lab, Lila was thrilled. She was assigned a mentor, a post-doc in the lab, and he offered to pick her up from the airport and get lunch the day she flew to St. Louis.

“I’ve been very close with my lab mates [prior]. So I was like, ‘Okay, this is just

like a nice research mentor kind of thing,” Lila said. “I didn’t know anyone in St. Louis. I guess I was pretty vulnerable.”

As Lila began to settle into her new position at the lab, she was eager to make friends. There was a weekly journal club on Friday eve nings that always ended up as a social function. Lila said people would drink beers during the meeting and then go out to a bar or someone’s house to continue drinking afterwards.

“I felt like [drinking] was pretty central to the lab,” she

said. “And I was new and try ing to make the impression that I could fit in.”

After Lila’s second time at journal club, her postdoc mentor offered her a ride to his apartment, where he said the post-meeting festivi ties were to take place. When he came to pick her up, he told her that everyone else had canceled, and it was just going to be the two of them. The postdoc kept offering Lila drinks. At the end of the night, he made advances, try ing to kiss her.

“I got really freaked out, because I did not see that

coming. And it’s my mentor, which is very messed up,” Lila said.

She rebuffed him and said she needed to leave. The postdoc offered to drive her, though Lila said that at the time, he was clearly intoxi cated. Lila Ubered home.

SEE PHD, PAGE 4

144, NO.

Levin Coleman General Manager a.coleman@studlife. com

Madireddi Jared Adelman Senior Multimedia Editors multimedia@studlife.com

and the local community.”

For Washington Univer sity students, the overture of Roe v Wade on June 24 meant suddenly residing in a state where abortions are completely banned, unless there is evidence of a medi cal emergency. If students want to get an abortion, they must travel to the nearest state where abortions are still legal: Illinois.

While many remain discouraged by the clear obstruction to women’s health equity, WashU’s chap ter of Planned Parenthood Generation Action (PPGA) has made it their mission to serve as the resource hub for all students looking to gain access to contraceptives and navigate the barriers of Mis souri’s abortion laws.

Junior Olivia Danner, who serves as the president of PPGA, believes that PPGA’s work is critical in protecting women’s autonomy across college campuses and is set ting an example for the rest of the nation. “Reproductive health is something I have always cared about, even in high school,” she said. “But once I came to Missouri and realized how restrictive the laws were, particularly around abortion, I became really interested in trying to make a difference at WashU

Danner noted that the organization was introduc ing a plethora of initiatives related to reproductive health resources. These include working on a comprehensive reproductive health guide that gives students infor mation about reproductive health resources around cam pus, creating a free Plan B program for students (oper ated by Habif Health), and running a clinic escorting program with Planned Par enthood in Fairview Heights.

In addition to their current programs, PPGA’s monthly General Body Meetings (GBMs) include panels on reproductive freedom with locals from Missouri’s Abor tion Fund, sexual education trivia, and opportunities for students to meet professors, doctors, and activists engaged in the field of reproductive health.

PPGA’s most recent pro gram, which opened in early November, has already had major success in its goal to expand access to contracep tives. Partnering with Habif Health, the Sumers Recre ation Center now houses PPGA’s free Plan B program in the Zenker Suite, which is open 9am-5pm Monday to Friday. While sexual health coordinators remain on call to ensure all individuals take just one contraceptive, the

program has a “no-strings attached” policy, meaning students are not required to undergo any consultation from Habif.

Another major initiative is clinic escorting through Planned Parenthood, which has greatly expanded in response to the recent over turn of Roe v Wade.

“We weren’t surprised when Roe was overturned,” said Briony Rutzinski, Brand Partnerships Lead at Planned Parenthood of the St. Louis Region and Southwest Mis souri. “With the makeup of the Supreme Court, we saw the writing on the wall and have been preparing for this for years. But for other folks, it came as a huge surprise, and they're now emboldened and energized to fight back to regain abortion access in banned states like Missouri.”

Through Planned Par enthood’s partner clinic in Fairview Heights, Illinois, clinic escorts can volunteer to work on site to ensure patients are safely ushered into the clinic without harrassment from pro-life protestors.

“Protestors try to distract patients from entering the Planned Parenthood, try to get them to turn around, and try to give them pamphlets to deceive them into thinking they’re Planned Parenthood employees,” says junior Rekhta Sashti, Treasurer of

the PPGA. “[Protestors] also have a van next door where they advertise free ultra sounds and convince patients to go there instead of the clinic.”

Sashti explained that they travel to the abortion clinic in Fairvew Heights in response to these large amount of pro testors that surround the clinic. Protestors remain out side the Planned Parenthood for as long as it is open, stand ing outside the gate on public property and holding signs to discourage patients.

Sashti recently had an opportunity to attend one of these trips and serve as a clinic escorter herself. “Our job is to make sure we are directing [patients] safely into Planned Parenthood and assuring them the protes tors are not associated with Planned Parenthood. We carry signs that say ‘those are protestors, please move for ward’ in order to make that clear to patients.”

“When the protesters stop patients, they risk being late to or missing their appoint ment and possibly causing an accident by blocking the driveway,” Rutzinksi said. “The protesters give out faith-based propaganda and misinformation. They do not provide medically accurate information or compassion ate care. Some protesters scream obscenities at patients

or try to shame them for com ing to Planned Parenthood.”

When PPGA members volunteer, they work as greet ers and combat the protesters. “Greeters help folks get into the building safely, from clear ing a path in the driveway to walking someone from their car into the health center and then back to their car after the appointment. Our goal is to make sure everyone who walks through our doors feels safe and supported.”

The program began at the start of the school year, and clinic escorting is open to anyone who wants to sign up through Planned Parent hood. PPGA’s main goal is

to create a community where student volunteers can travel together, ensuring all students feel comfortable. For those who don’t have a car, PPGA provides reimbursement for car shares and Ubers, for the 30 minute drive to Fairview Heights.

Sashti said the impor tance of their work is pivotal now more than ever. “This year in particular, repro ductive healthcare access is under attack, and I think it represents a general decline in appreciating women’s auton omy in making their own decisions about their body,” Shashti said.

away for a little while.

“I realized how happy I was to not be anywhere near there,” she said.

A few months before, in February, Lila met her cur rent partner, Jackson. In July, he supported her in going to the Health Equity Justice pro fessors in the medical school and reaching out to WashU’s Title IX to ask about the steps involved in filing a report. Lila, who said she was still nervous about the repercus sions of an investigation, told Title IX over email that she was going to tell her PI.

be redundant. Lila, however, says she never told Dr. Kip nis about her communication with the Title IX office.

On August 31, in screen shotted text messages, Kipnis tells Lila “You don’t need an investigation now, even though you will probably win the case.” He then goes on to say that it would be “men tally unhealthy for you, and I think we need to avoid it.”

the individual about whom you made your sexual assault report is no longer affiliated with the University. There fore, that portion of your complaint must be dismissed as a Title IX matter.”

Lila came into the lab a couple days after, she said her mentor was really quiet and wasn’t communicating quickly about important lab updates like he had before.

“I wasn’t sure if that was because he felt weird about it. Or because he was mad at me, but it was just very strange,” she said. “And that really stressed me out because I was like, this is the person that’s the main way I’m gonna get evaluated for my rotation.”

At the time, Lila didn’t tell a higher-up — Dr. Kipnis or any professor or adminis trator at the medical school — about what had happened after the journal club.

“I didn’t even think about it. Honestly. I think I was just shocked,” she said.

At the next journal club, Lila hung out with everyone afterwards and got drinks. Her mentor offered to drop people at home, but he saved Lila’s apartment for last. Once they got there, he said they should go back to his place. There, she said he gave her more drinks and pres sured Lila to have sex with him. This time, extremely intoxicated, Lila said she complied.

“The next three days he gave me the silent treatment again. It was impossible to do work again,” she said.

The postdoc told Lila that she could never tell their boss.

“I didn’t know what to do because I was so freaked out that I would get kicked out of lab. Because at that point, my goal was still to be in the Kip nis Lab and become a grad student,” Lila said. “And I was scared that this would get back [to Dr. Kipnis] and

I would be the one kicked out or fired.”

It became a vicious cycle, Lila said. Her mentor would text her to come over. Often, she would. Then in the lab, he would either act normal, give her the silent treatment or become angry.

“I was just walking on eggshells every day to make sure no one found out and to keep him from being angry.”

Lila says the postdoc had authored papers and was well-respected in the lab. She didn’t report either the first advance or the continu ing relationship, out of fear of backlash.

“I’d always heard in STEM ‘if you’re a whistle blower, if you tell, that the woman always gets the short end of the stick.’ The one that gets labeled,” Lila said.

“I didn’t want the label of my career to be a #MeToo thing. So I just kept quiet.”

Dr. Robyn Klein, Director of the Center for Neuroimmunology & Neu roinfectious Diseases at the WashU Medical School, said that “academic medicine and science is rife with racism and sexism.” She said she had heard stories from women in academia that highlighted some of the worries Lila had about reporting abuse.

“[The women] were blamed for things that were not their fault that were going wrong when they had a lead ership position,” Klein said. “And they were fired. So I’ve seen stuff like that happen to women and not to men.”

In October, a few weeks after her mentor first made advances, Lila began talking to the principal investigator of the Systems Neurobiology

Laboratory at the Salk Insti tute, Dr. Kay Tye. Lila had a close relationship with Dr. Tye.

“From pretty early on she was like ‘you should report.’ And by Christmas, she was like “I’ll talk to [Dr .Kipnis], this is unacceptable,” Lila said.

Dr. Tye said that by Thanksgiving, it was clear that Lila was suffering. As the semester wore on, Dr. Tye continued to give advice, pressing Lila more and more.

“It was obvious that it was super toxic, and she needed help,” Tye said. “And I said ‘report to [Dr. Kipnis], he is obligated to solve this problem.”

But Lila, still terrified she would be kicked out of the lab, told Dr. Tye that she needed a little more time. Lila said that she still felt she was learning a lot from her time in the lab, and that the postdoc was a good teacher when he wasn’t ignoring her.

“I was just terrified to lose that, because I felt like it was helping me in a science way even though it was really hurting me in an emotional and physical way,” she said.

Lila’s friend, who was a second-year medical stu dent at WashU at the time, confirmed that Lila seemed uncomfortable with her men tor by this point. She said Lila would tell her stories about him asking for sexual acts in-lab, and ‘becoming rough’ during their relationship.

In May 2021, Lila, who was supposed to rotate in multiple labs, moved to a col laborator lab. Though she was still in contact with her mentor from Dr. Kipnis’s lab, she said it was a relief to be

In August of 2021, Lila held a Zoom meeting with Dr. Kipnis and Dr. Tye. She detailed what occurred between her and her mentor.

In the script Lila had writ ten out, which Dr. Tye said she read ‘word for word’ in the meeting, Lila wrote:

‘Each time I was given the silent treatment, I couldn’t focus on school. Being in lab was so stressful. I couldn’t be productive anywhere in my life.’

She added that, ‘My lack of action continued because I didn’t want the silent treat ment in-lab, or to have my hard work wasted, my authorship compromised, or risk him telling someone.’

During this meeting, Dr. Tye said that Dr. Kipnis said he would fire the mentor immediately. In a text to Lila later, said he would: ‘Squash him like an ant.’

According to the WashU’s Title IX and Gender Equity guidelines, Dr. Kipnis, as a faculty member at the Uni versity, is classified as a mandatory reporter. A man datory reporter is required to “report all incidents of sexual harassment, sexual violence, sexual assault, rela tionship violence, stalking or other forms of misconduct” to a higher-up or the Title IX office.

Cynthia Copeland, Assis tant Director Gender Equity and Title IX Compliance Office, confirmed the above statement in an email to Stu dent Life.

Joni Westerhouse, who works in Medical Pub lic Affairs at Washington University School of Medi cine, said that since Lila had already reached out to Title IX, Dr. Kipnis’s report would

Dr. Kipnis then asks her if she was fine with him ‘fil ing a complaint’ about her mentor, which Lila agrees to, though to her knowledge, no action was taken. Kipnis did not respond to multiple requests for comment about his handling of the situa tion and the alleged report, though eventually delegated to Westerhouse.

In an email to Lila on August 24, Dr. Kipnis assured her that the postdoc, “will leave the lab as of imme diately,” and that “I told him that I would not be providing a letter of recommendation [for future hiring purposes].”

In her email back, Lila thanked Dr. Kipnis pro fusely, commending him “taking action so quickly and for handling it in a way that kept it as confidential as possible.”

In text messages between Lila and Dr. Kipnis later that summer, he tells Lila that the postdoc would stay on until December 31 in order to fin ish his experiment, coming in after-hours, but that his resignation letter would be in within the week.

In an email sent in Janu ary 2022, Dr. Kipnis told Lila that though the post-doc was not employed by his lab but planned to stay in St. Louis with his girlfriend, who was employed by a different WashU lab.

In January, Lila finally went to launch a Title IX investigation herself. Upon attempting, however, Lila was told that the postdoc had left the lab and was no longer a WashU employee, meaning that no investigation through WashU could take place.

A letter from WashU’s Title IX office to Lila, dated January 31, 2022 reads:

“After reviewing the information in the complaint you submitted on January 8, 2022, I have determined that

The letter goes on to say that inappropriate “culture and conditions” brought up — mostly the presence of alcohol, Lila says — are not a Title IX matter, and that those issues were being referred to HR.

An HR investigation into lab culture was con cluded in June 2022. The HR representative said in an email statement that “a thorough investigation and subsequent appropriate rec ommendations can take time to complete,” but that they “have shared recommenda tions with department and School of Medicine leader ship to act on.”

The recommendations themselves were not shared since they related to “per sonal information of other employees,” the HR email said.

These days, Lila has put her Ph.D. on hold to focus on her medical degree. She doesn’t want to work in a WashU lab right now, since her memories are colored by her interactions with the postdoc.

“I still love asking ques tions in science. I’m always driven by that. I’m just hav ing a hard time imagining being back in a lab space at WashU right now. In another place, I could easily do a Ph.D.,” she said.

Lila says she still respects Dr. Kipnis as a scientist. But she wishes he had bet ter handled the situation that she brought to him. Lila also wishes she was better prepared herself for how to handle the situation.

“[The postdoc’s actions were] clearly against Title IX and HR, [and] rules and regu lations at WashU has, but no one made that clear to me,” she said.

Most of all, Lila is upset that no action against the postdoc was taken, and that he’s able to move freely to other labs. “I know he’s gonna hurt someone else,” she said.

There are currently 18 people living under death sentences in the state of Missouri. Until a few days ago, there were 19. But at 7:40 p.m. on Nov. 29, the state murdered Kevin “KJ” Johnson with a lethal injection of pentobarbital. While it is a well-known fact that the death penalty in this country is rife with error and racial bias, Kevin’s case is a tragic example of how it targets the most marginalized, stigmatized, and traumatized people in our society.

In 2007, at 19 years old, Kevin Johnson was sentenced to death for the killing of William McEntee, a white Kirkwood police officer. His case involved erroneous and unfair court rulings, grossly ineffective counsel, and racist prosecutorial policies. These blatant injustices led St. Louis County Prosecuting Attorney Wesley Bell to appoint a special prosecutor to review Kevin’s case to determine if he was wrongfully convicted.

And wrongful conviction is exactly what the special prosecutor, Edward Keenan, found.

In a motion to vacate Kevin’s death sentence, Keenan argued that at every stage of the capital prosecution overseen by former Saint Louis County Prosecuting Attorney Robert McCulloch, race played a decisive factor. Keenan detailed numerous incidents of racial bias, including McCulloch using his peremptory strikes to eliminate Black jurors and ensure a predominately white jury, a clear violation of Batson v. Kentucky, a Supreme Court case that prohibits prosecutors from using peremptory challenges to remove prospective jurors based on race.

Keenan also found disparate treatment between Kevin and white defendants who had committed similar crimes. For example, Trenton Forster, a white 18-year-old, killed a police officer after posting about his desire to kill cops on social media, indicating premeditation which was not present in Kevin’s case. However, McCulloch chose not to seek death for Forster, and he was instead sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

Based on his findings, Keenan concluded that the State violated the Equal Protection provisions of the Missouri and United

States constitutions in prosecuting Kevin.

On Monday, Nov. 28, just one day before the execution, the Missouri Supreme Court heard oral arguments on Keenan’s and Kevin’s attorney’s motions for a stay of execution in order to hold a full hearing on the finding of racial bias. Even though the law unambiguously requires such a hearing, which Justice Breckenridge noted in her dissent, the court denied the motions, stating that claims of racial bias had already been raised by Kevin’s attorneys and dismissed in previous appeals.

It is in light of this unjust background that we must view Kevin’s story.

On the evening of July 5, 2005, believing police played a role in the death of his 12-year-old brother earlier in the day, Kevin shot and killed Officer McEntee.

McCulloch personally tried the case, an unusual move, perhaps motivated by the fact that his own father was a police officer killed in the line of duty. McCulloch sought the death penalty for Kevin but was unable to even secure a conviction; the jury hung, 10-2 favoring a lesser, non-capital, charge.

Kevin was finally

Make for yourself a teacher, and acquire for yourself a friend; judge all people with the scale weighted in their favor. — Pirkei Avot (Ethics of our Ancestors)

I have known the above quote from Jew ish writings since I was a teenager, but its meaning has become more clear to me only in recent years. As this semester draws to a close, most students will return in the spring, but some will graduate; still more will leave our cam pus after spring semester. So, I write about getting and keeping in touch, from the perspective of a student and then a teacher.

I recently attended my high school reunion, which gave me occasion to travel to Dallas, Texas, my hometown. I have made it a practice on most visits to reconnect with teachers I had at Hillcrest High School, the ones who had such an impact on the trajectory of my life. I graduated from Hill crest High School in 1976, with a love of math that was mostly attributable to Maxyne Cammack, who was my math teacher in 10th and 11th grade. She hailed from the small

SPONSORED BY:

town of Longview, some 100 miles east of Dallas,

college

try and with no plans of becoming a teacher. She was not happy with lab work, so when she heard of an opening at a school, she began her long career of teaching math, first at lower-grade levels and eventually at my high school, where she taught for 28 years.

My classmates and I remember her for her fierce command of the classroom, for know ing her 23 times tables, and for being able to tar get the trash can with objects from anywhere in the room. She would be solving a problem on the

board, which might cul minate in 23x107, and she’d turn to us for the answer. When nobody had the product ready, she’d lament that we didn’t know our 23 times tables, and she would then write the answer immediately on the board. Many years later, when I asked her how she did that, she told me the problems were the same every year, so after a while she remembered the answers. Let’s return to the opening quote: “Make for yourself a teacher.” It turns out that sitting in a classroom with a person lecturing up front does not make that person your

Following the announcement that the WashU College Republicans (WUCR) were planning on hosting conservative speaker Amala Ekpunobi, significant controversy was raised surrounding the event and the source of its funding. Despite current WUCR President Nathaniel Hope and WUCR Treasurer Abby McGowan following proper procedure to request the appropriate funding from the Student Union Treasury, there arose a considerable amount of

criticism for the event following its approval.

With some arguing that the use of SU activities funds effectively “endorsed” the views of the speaker, it is important to acknowledge the role of events of this nature in fostering civil dialogue among university students.

As Social Chair of WUCR, I believe that one should certainly be able to disagree with Ekpunobi’s point of view. However, attempting to suppress a commentator for peacefully expressing their views only serves to exacerbate partisan divisions within our student community. Moreover, I firmly believe that those who find

themselves politically at odds with Ekpunobi should especially attend the event to improve their understanding of views they may not personally agree with. With social media and news networks often pushing us to stay within the confines of our preferred political echo chambers, having the chance to listen to an individual with beliefs different from our own is truly an invaluable opportunity. Whether you would be inclined to agree or disagree with Ekpunobi on policies or other issues, attending the event allows us to engage in a form of civic and social dialogue fundamental to being a politically well-versed

American.

Coming from a racial minority background myself as a Mexican American, I find Ekpunobi’s perspective as a Black conservative woman to be especially interesting for all students to hear. Constant partisan polarization in the recent decade has driven society to unfairly assume a person’s political allegiances or views simply based on their appearance or ethnicity. Although some may oppose her approach to breaking this mold of associating identity with ideology, Ekpunobi can provide valuable insight into a journey of personal political growth that has stemmed

from her many lived experiences. Since stories of individuals shifting their personal views in response to arbitrary societal assumptions often go unheard, Ekpunobi’s speech will let us hear how one woman changed her political attitudes as a result of current social trends and expectations.

As many members of the College Republicans and SU Treasury have stated, the Ekpunobi event is important for creating debate among the student body and fostering healthy discourse across political boundaries. From my perspective, giving Ekupunobi the opportunity to speak on campus is fundamental

to supporting minority voices from diverse social and political backgrounds.

Regardless of a student’s opinion on Ekupunobi’s rhetoric, I would strongly encourage them to attend in order to hear different ideological perspectives and experience a unique story of personal development. If you are interested, Amala Ekpunobi will be speaking this Friday, Dec. 9 at 7 p.m. To get your free ticket in advance, please use the registration link on the @washugop Instagram page’s bio.

Universities, particularly those that cost almost $80,000 per year to attend, often pride themselves on their commitment to the noble quest for knowledge.

Washington University’s motto Per Veritatem Vis, meaning “Strength Through Truth,” is one of the best examples of this pride. As young people grow up, we realize that the world is complicated and that there is no one truth to guide us.

Eventually, we realize that any semblance of truth can only be attained through immersing oneself in a range of diverse viewpoints and modes of thought. So, we attend college and surround ourselves with people from different backgrounds and identities. Each person that we befriend brings their own viewpoints, shaped by their own experiences, that are understandable. We end up learning just as much from our peers as we do in our classes. This experience is one of the best facets of living on a college campus.

However, this diversity of knowledge that we obtain through our communities is only obtainable if everyone in our community feels safe and respected. Our friends will only feel comfortable expressing themselves, their identities, their experiences, and their viewpoints if they understand that we respect them, and that we are willing to listen to them. People are open when they feel welcome and respected. That is a basic tenet of social interaction.

It is due to this idea that I cannot understand the choice to bring Amala Ekpunobi, a transphobic content creator for PragerU, to Washington University’s campus (nor can I understand paying almost $11,000 for her). As a member of the SU Treasury, I spent hours combing through Ekpunobi’s videos, and they seem to show a clear contempt for the identities that many people hold on this campus. Discussion and dialogue require respect and a recognition of the other person’s humanity. Ekpunobi does not hold that respect towards transgender people.

In a video of her reacting to a Good Morning America

interview with Lia Thomas, a trans swimmer on the University of Pennsylvania women’s swimming team, Ekpunobi repeatedly refers to Ms. Thomas as a man, uses the wrong pronouns for her, and states that Ms. Thomas probably transitioned in an effort to win more medals while swimming. The video was disgusting to watch. Ekpunobi showed a blatant disregard for Ms. Thomas’ lived experience and identity, refusing to acknowledge her identity and afford her the basic dignity of calling her by the right pronouns.

In other videos, Ekpunobi has made comments claiming that “women are not natural leaders’’ and that “men think more logically than women, and they’re more logic-minded than women, typically.” There are also other videos in which Ekpunobi is entirely dismissive of LGBTQ+ experiences; in one, she claims that there was no need for Pride Month because gay people are widely accepted.

In the same video, she implies that more children are expressing that they may not be straight because it is a

trend that could gain them attention. She ignores the fact that hate crimes based on gender identity have been slowly climbing, and she ignores a 2015 survey from the National Center for Transgender Equality in which 46% of the 27,715 trans adults surveyed reported that they had been verbally harassed in the previous year.

During their presentation to the Student Union Treasury, the College Republicans made the point that Ekpunobi would facilitate discussion on our campus. Her viewpoint, they argued, was interesting and important, especially since she is a young, Black, conservative woman who grew up in a far-left household. Not only is her unique experience valuable, but she would also force us to examine our own viewpoints and reconsider our stances! For all of these reasons, they said, Amala Ekpunobi was the perfect choice for our campus.

On the surface, it is difficult to disagree with these points. Especially for those who do not know the type of content that Ekpunobi

AMELIA RADEN CONTRIBUTING WRITER

AMELIA RADEN CONTRIBUTING WRITER

Today, during my Management (MGT) 100 lecture, I was greeted by a mostly blank screen, only containing the question, “Why are you here?” The professor repeated what was on the board. Only one hand shot up. My class mate promptly answered, “I want money.” “Good,” responded my professor, as he made eye contact with the rest of my peers’ broad smiles.

When I was applying to colleges, I applied every where as an English major, except for the select num ber of schools, like WashU, with Entrepreneurship

programs. Entrepreneur ship, in my mind, was the creative side of business: all of the basics, but with an emphasis on idea gener ation and innovation.

Once I arrived at WashU, I was thrilled, enthusiastic about even the dreaded business requirements, MGT 100 and 150. It didn’t take long for me to realize that the vast majority of my peers in Olin were studying finance, hoping to gradu ate with guaranteed jobs as investment bankers and financial consultants. It was these students that I felt my lectures were catered towards, justifi ably enough. According to the Weston Career Center,

Staff editorials reflect the opinion of a majority of editorial board members. The editorial board operates independently of our newsroom and includes members of the junior and senior staff.

Managing Forum Editors: Reilly Brady, Jamila Dawkins

Managing Sports Editor: Clara Richards

Managing Chief of Copy: Ved Patel

of the Class of 2021, 25% of Olin graduates went into finance or manage ment and 31% went into consulting. Many of these students were likely signed to these positions as early as their junior years. The creative side of business that had drawn me to WashU felt lost and even suppressed. I had not even learned about the school’s Skandalaris Center for Entrepreneurship until I began work on this article.

Money became cen tral to our learning; the starting salaries of for mer Olin students found their way into my lec tures more times than one, greeted by cheers from the other students. I found

myself so wrapped up in talk of potential earnings and management that I had forgotten what I had wanted out of my BSBA experience.

The conversation of how to make money seemed to reign above all else in my lectures, which left me searching for something in addition to creativity: discourse about ethical business. I wanted to learn how to preserve important values while operating in the business world. Ethical business is the way to mitigate sys temic issues in society and injustices against alreadymarginalized groups. In my experience, this con versation never once

produces, this may even be a convincing argument. After all, aren’t college campuses committed to learning and diversity of thought? Why shouldn’t we host her on our campus, then?

It’s because Ekpunobi’s rhetoric is harmful to our peers whom we respect and value. She claims to have no problem with a person’s sexual orientation or gender identity, but disparages them when they express that orientation and identity in any way. She claims that, on the basis of the sex one is assigned at birth, one is made intellectually inferior to another. Claims such as these are harmful to those with marginalized identities. These claims do not inspire conversation or discussion. In fact, they diminish and dismiss the real, lived experiences of hundreds of students at this university, implying that our peers are faking their identities for attention. That is an indignity that we should not be encouraging at this school. Those students should not have to converse about their rights or about whether someone should

respect their name and what they prefer to be called. They deserve the basic decency of not being forced to prove their humanity.

When we — those who oppose the platforming of Ekpunobi’s rhetoric — speak out in protest of her arrival, Amala Ekpunobi is going to see it as some kind of stifling of free speech. She’s going to claim that we have shut ourselves off to new viewpoints and want to live in our comfortable little bubbles. I think that the opposite is true. In order to hear new viewpoints, we want to make sure that individuals feel comfortable enough to take their seat at our table and speak. In order to do so, we have simply decided that we do not want to hear from those who do not abide by the rules of basic human decency, or those that build their careers off of disparaging marginalized identities and stoking the flames of hate. It’s not that we’re stifling anyone’s free speech. We just think that some people are a–holes, and we don’t want to pay them to be on our campus.

Photography Editor: Holden Hindes

Senior Multimedia Editor: Jared Adelman

Poulsen

ILLUSTRATION BY TUESDAY HADDENappeared in any class-led discussion, which is highly concerning as this is taking place in enclaves of brand new business students trying to build a founda tion for later life. In fact,

writer’s name and email or phone number for verification. We reserve the right to print any submission as a letter or opinion submission. Any submission chosen

only 3 of the 120 required credits to graduate with a BSBA include the ethics of business, and that course, titled “Ethics,” is for

for publication does not necessarily reflect the opinions of Student Life, nor does publication mean Student Life supports said submission.

IAN HEFT STAFF WRITER

IAN HEFT STAFF WRITER

With less than 30 sec onds left in regulation and the score knotted at 58, sophomore Hayden Doyle knew to get the ball to Charlie Jacob. The fifth-year guard Jacob had been the fulcrum of the Bear’s success all season, and Saturday night was no exception. “We wanted to get him a post touch,” said Doyle postgame. “Give him space, and he’s going to get a good look off.”

And indeed he did — Jacob dribbled twice and made his move towards the lane, creating more than enough separation to get off a smooth 16 footer. The shot barely moved the net as it fell through to give the Bears a 2-point lead in the finals of the 38th Annual Lopata Classic.

The game headed to overtime after PomonaPitzer was able to tie the game at the buzzer with a putback secured from a missed box out. In over time, it was first-year Will Grudzinski’s time to shine, as he hit two big 3-point ers, one to even the game with one minute and fiftyone seconds left, and the second to cut the deficit to one with six seconds on the clock.

After two

Pomona-Pitzer free throws put the Bears at a late deficit, Doyle was fouled with 1.8 seconds on the shot clock. After hitting the first, Doyle intention ally missed the second free throw wide right and the Bears were able to secure the rebound. Despite the brief momentum, they could not get off a shot to send the game to double overtime in a 71-69 loss. The Bears fell to 5-2 on the season.

Grudzinski, who put up 23 points in the tourna ment semifinals, led the way for the Bears with 17 points, tying a Lopata Classic record with 12 three-pointers in the two games. Jacob and sopho more Drake Kindsvater notched 16 points apiece while Doyle added in 13 points and a team seasonhigh of 6 assists.

In a game with 12 lead changes, nine ties, and neither team able to go ahead by more than seven points, whoever got hot at the right time would come away with the win. In the end, it was Pomona-Pitzer, led by tournament MVP Joe Cookson, who got the best of the Bears. Thus far, four of the WashU squad’s seven games have been decided by just three points or less.

The weekend’s games were part of the 38th

Annual Lopata Classic, a tournament funded by a gift from the late Stanley Lopata, a Washington University in St. Louis alumnus and emeritus trustee, and his late wife Lucy. WashU had won the classic 26 times but was unable to get the job done on Saturday.

Despite the loss to an unranked opponent, there is much to be excited about for the rest of the Bears’ season. The team secured a decisive 87-70 win against Eureka College to advance to the tournament finals, and prior to the overtime loss, they had been on a four game winning streak. The squad is young and

hungry; after Jacob’s team high of 16.1 points per game, the team is led by five underclassmen: soph omore forward Kindsvater (14.3 ppg, 5.9 rebounds), freshman Grudzinski (11 ppg), sophomore Doyle (9.1 ppg, 4.0 assists), soph omore big Jake Wolf (6.4 ppg, 6.6 rebounds), and freshman guard Yogi Oliff (6.0 ppg, 2.3 steals), who sat Saturday with a heel injury.

Replacing former stars Jack Nolan and the late Justin Hardy as the team’s leading shooters, Jacob and Grudzinski have formed WashU’s own “Splash Brothers” tan dem. Jacob is shooting .433 from outside the arc,

and Grudzkini a scorching .465 clip on close to six attempts per game; both received all tournament honors. When asked about his hot start, Grudzinski attributed it to the rest of the team and head coach Pat Juckem’s game plan: “Honestly, reading our teammates and what they do best. Most of my shots I haven’t created, they’ve been created through the system, so it’s all cred ited to my teammates.” Outside shooting should continue to be key to the Bears’ success: after Saturday’s game, the team is second in the UAA in 3-point percentage.

Grudzinski was also clear about Jacob’s impact

on both himself and the team early in the season. “He’s been a big mentor towards me…it’s not just on the court, it’s every thing: in life, the way he carries himself, and how good of a teammate he is.” His teammates were in agreement: “He’s a great player but an even better guy,” said Doyle.

“He’s always picking me up, picking everyone [else] up.”

Jacob himself, who started every game last season and has played for Juckem since his first year at WashU, was equally complementary to the underclassmen. “It’s just a different level of joy that brings me to watch them come along and spread their wings,” Jacob said.

“All the young kids, I think so highly of — they’re gonna be such good play ers. I told them yesterday, I can’t wait to come back in like four years and just watch you dominate. Like when you’re my age? It’s gonna be great. Must-see TV.”

The Bears will continue their season at Fontbonne on December 7th. Their next home game is December 11th versus Principia. UAA play won’t begin for another month, when WashU will take on UChicago on January 7th.

convicted and sentenced to death at his second trial, despite the numerous injustices against him detailed in the special prosecutor’s motion. Notably, Kevin’s courtappointed lawyers failed to submit mitigating evidence — abundant in Kevin’s case — to the jury. Mitigating evidence can reduce the punishment for the convicted offense and typically addresses the defendant’s background, including a history of mental illness and previous trauma.

Kevin’s childhood was filled with abuse, neglect, and trauma. He entered the foster system as a toddler, and throughout

his childhood spent time in several group homes. A social worker at one of these facilities recently wrote an op-ed about the many ways the foster care system failed Kevin and let him fall through the cracks. Kevin aged out of the child welfare system at the age of 18, despite pleas from his greatgrandmother to keep his case open and provide him the help that he desperately needed. But CPS closed his case, a final example of how the very system that is supposed to protect abused and vulnerable children failed Kevin Johnson.

Kevin is survived by his 19-year-old daughter, Khorry, who fought to

be with her father at the execution, but was unable to be present due to a Missouri law that requires execution witnesses to be at least 21 years of age. Khorry, who has a newborn son of her own, was a zealous advocate for her father. In Kevin’s clemency video, Khorry talked about how her dad was a loving, supportive father, even from behind bars. Through tears, she tried to articulate what it would be like to lose him, but there are no words to properly describe the pain of losing a father.

The death penalty is a cruel and barbaric practice. Its racist application only adds to the horror

of state-sanctioned murder. According to the ACLU, “people of color have accounted for a disproportionate 43% of total executions since 1976 and 55% of those currently awaiting execution.”

Despite the fact that white people make up one-half of all murder victims, “80% of all capital cases involve white victims.” When the defendant is Black and the victim is white, this is further exacerbated — according to the Death Penalty Information Center, 301 Black defendants have been executed in cases where the victim was white; whereas only 21 white defendants have been executed in

cases where the victim was Black.

The special prosecutor’s conclusion that race played a role in Kevin Johnson’s conviction only confirms what we already knew: the death penalty is racist. Allowing his execution to proceed with this knowledge was a disgrace to this state and this country.

17 years ago, Officer McEntee’s family endured an unspeakable tragedy. Killing Kevin Johnson did not erase their pain. It only inflicted that same pain on Kevin and his innocent family. Kevin, by the mere fact of his humanity, deserved to live. Death is not justice.

Missouri has two more executions scheduled in the coming months — Amber McLaughlin on January 3rd and Leonard “Raheem” Taylor on February 7th. Governor Parson has the power to grant clemency to both and commute their sentences to life without the possibility of parole. Call (573) 751-3222 to ask Governor Parson to spare Amber and Raheem’s lives. Murray, Myles, and Shahin are members of Missourians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty, an advocacy group that leads clemency campaigns and fights to abolish the death penalty in Missouri.

teacher. Only you can bring such a relationship into existence. You make that person your teacher when you are open to learning, willing to strug gle with new material and new ways of thinking. The quote continues to say that you level-up the relationship by acquir ing that teacher as your friend. I see from my vis its to Maxyne Cammack the joy that such visits can bring to a teacher. She has indeed become my friend. At the end of our last visit, I said that her love of math was so great that it inspired me and many oth ers to share in that love.

As a teacher, I appreci ate that the highest honor my students have given me is staying in touch. Some visit me when they are in town, and I often see them when in their towns. It would be exhausting and impractical to do this for all teachers and stu dents, but for the ones

who become friends, it is a perpetual reminder of the learning we once shared, and I truly enjoy seeing the paths their lives take after graduation.

The final part of the quote has been the most puzzling for me, but here is what I think it means. As a teacher or a student, we should judge each with the scale weighted in the other one’s favor. I assume my students are here to learn and to grow in knowledge, confidence, and achievement. My stu dents have been likewise gracious in assuming that I do what I can to teach them well.

As you think about how you might spend your holiday break, may I suggest that you get in touch with a teacher who made a difference in your life? I predict that such a visit will be unexpectedly rewarding for both you and your teacher.

upperclassmen who have already established a foun dation in business without ethics. Morality and Mar kets, a course offered this spring which explores just that, is an ArtSci course, not an Olin one.

Clearly, the way Olin operates is working for the school. According to the Weston Career Cen ter, 97% of Class of 2021 BSBA graduates seek ing employment accepted a job, compared to 74% for Class of 2019 WashU graduates overall. But just because this frame work works for them does not mean it works for me. Although I am still enrolled in my Olin classes from this semes ter, I have transferred out of the business school.

An Olin major proved too confining for what I wanted, which was cre ativity in business. Now, I am working to carve out a place for myself in Olin. I am pursuing a minor

in Business of the Arts, and I have registered for two courses that explore the ethics of business: Morality and Markets and Endgame of Entrepre neurship. I am hoping that these factors will supple ment my time here well, allowing me freedom to study what I originally came here for and to use Olin’s many resources to my advantage.

However, I should not have had to leave Olin to find creativity in business, especially when innova tion and entrepreneurship are meant to be some of its pillars. From what I have learned through my experience in the busi ness school, Olin and its students would benefit greatly from opening up a discussion about ethi cal business, creativity, and ensuring that there is a place for everyone.

Charlie Jacob stands out on the court, and it’s not just from the three-pointers that he sends from behind the arc or the defense that he’s constantly polishing. He also stands out because he has the best — and only — man bun on the team, his hair usually extra-secured with a head band. He’s probably grinning ear-to-ear, the same smile that helped him land a mod eling contract. He’s definitely locked in to the game.