Spring 2023

A plant research powerhouse P. 14

Supporting historic Sumner High School P. 28

Two icons of anthropology retire P. 32

Spring 2023

A plant research powerhouse P. 14

Supporting historic Sumner High School P. 28

Two icons of anthropology retire P. 32

The Ampersand magazine shares stories of incredible people, research, and ideas in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis. It is published semiannually and distributed to alumni, faculty, students, staff, and friends of Arts & Sciences.

EMAIL ampersand@wustl.edu

WEBSITE ampersand.wustl.edu

DEAN

Feng Sheng Hu

PUBLISHER

Ebba Segerberg

EDITOR

Crystal Gammon

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR

Sarah Hutchins

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Sudon Choe

PUBLICATION COORDINATOR

Sarah Lu England

MARKETING MANAGER

LaRanda Parnacher Turner

DIGITAL EDITOR

Nathan Ralph

LEAD PHOTOGRAPHER

Sean Garcia

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS

Eric Burke, Sid Hastings

DESIGNERS & ILLUSTRATORS

Cydney Bibbs, Keren Guo, Kristen Wang, Carmen Xia

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Shawn Ballard, Simone Becque, Jenny Bird, Gerry Everding, Jeremy Goldmeier, Talia

Ogliore, Liam Otten, Sara Savat, Rachel

Sender, Elizabeth Swords, Diane Toroian

Keaggy, Josh Valeri, Chris Woolston

EDITORIAL ADVISORS

Deanna Barch, Andrew Brown, Sophia Hayes, Erin McGlothlin, Thomas Eschen, Adia Harvey Wingfield

Spring 2023

'No boundaries'

Dancers and choreographers Kendra Key (left) and Erin Morris, both master of fine arts candidates in the MFA Program in Dance, debuted a pair of new works as part of “No Boundaries,” the 2023 MFA Student Dance Concert.

2

(Photo: Eric Burke)

SEEDING DISTINCTION

This academic year, Arts & Sciences awarded scores of grants, fellowships, and endowed honors to support the research, scholarship, and creative practice of faculty members and graduate students. Here are a few highlights:

Our spring issue explores the work of four intrepid plant scientists: Joseph Jez, Kenneth Olsen, Rachel Penczykowski, and Xuehua Zhong. From verdant laboratories and weedy field sites, they and their colleagues seek to understand some of the fundamental mechanisms that allow plants to grow, develop, adapt, and thrive (p. 14).

Arts & Sciences has a lengthy and lauded track record in plant research, with thousands of publications, dozens of awards, and a deep pool of expertise within our faculty. But we also have no intention of resting on these laurels. Our scientists are pioneering cutting-edge research that employs genome editing, epigenetics, and other advanced approaches. We are also forging powerful collaborations with nationally renowned partners – including the Missouri Botanical Garden, Danforth Plant Science Center, and WashU’s Living Earth Collaborative – to make St. Louis a global hub for innovation in this field. With implications for climate change, medical breakthroughs, and food security, the outgrowths of this work are tantalizing and farreaching. One key to our success, Zhong notes, is having roots in a community that is rich with expertise and resources. “That’s why I came here,” she says.

INTERNAL RESEARCH GRANTS

Incubator for Transdisciplinary Futures (ITF)

– 14 collaborative projects supported

Transdisciplinary Institute in Applied Data Sciences (TRIADS)

–

10 collaborative projects supported

Seeding Projects for Enabling Excellence & Distinction (SPEED) Program

– 17 research grants awarded

FACULTY FELLOWSHIPS

Center for the Literary Arts (CLA)

Creative Practice Workshop Fellows:

– Flora Cassen: “Major Transitions in the History of Antisemitism”

– Ji-Eun Lee: Translations of travelogues by female Korean writers

– Edward McPherson: “The Long View”

GRADUATE STUDENT FELLOWSHIPS

7 Dean’s Distinguished Graduate Fellowships awarded to incoming PhD and MFA students who show exceptional promise

ENDOWED PROFESSORSHIPS

– 9 named chairs installed

– 5 inaugural installations, signifying new support for Arts & Sciences

An exploration of plant research is fitting, of course, for a spring magazine issue. But it’s also an apt metaphor for this incredibly exciting time for our school. Indeed, Arts & Sciences is in its own season of incredible growth and development. We are nurturing our strategic vision and watching it come to life. We are asking critical questions, collecting data, and using it to guide our growth. We are cultivating the next generation of leaders (p. 18) and preparing them for fulfilling lives and careers. And, like our plant research, the impact of this work will extend far beyond our campus.

We’ve launched exciting new initiatives that push the boundaries of traditional academic fields to explore new synergies, like the Immersive Technology Collective (p. 22). We’re expanding into new areas of research and education by bolstering expertise in quantum physics and data science (p. 11). We’ve seeded novel collaborations and avenues of exploration with internal funding opportunities to help launch research endeavors. And, with the support of our alumni and friends, we are recruiting, developing, and investing in absolutely stellar faculty members, further distinguishing Arts & Sciences as a world-class home for the liberal arts.

Like our plant scientists – whose work benefits from resources and collaborations across the region – Arts & Sciences thrives because of the ecosystem that surrounds us. Our vibrant community of alumni, friends, students, faculty, and staff ensures that we have the resources to support our ambitious ideas and the power to bring our vision to life.

I am honored to count you among this community of supporters. Thank you for all you do for Arts & Sciences and Washington University.

Warmly,

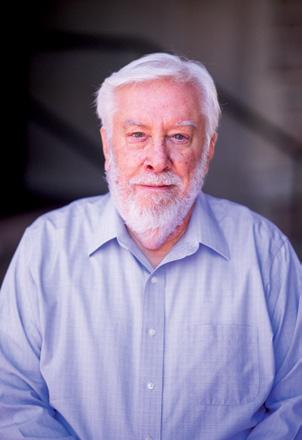

Feng Sheng Hu Dean of Arts & Sciences

Feng Sheng Hu Dean of Arts & Sciences

Lucille P. Markey Distinguished Professor Washington University in St. Louis

Lucille P. Markey Distinguished Professor Washington University in St. Louis

We are celebrating a season of incredible growth.

preserve

Arts

Sciences

28

behind the bench with four scientists whose evergreen passion for plants could fuel lifechanging discoveries that extend far beyond the greenhouse. 14 28 Masters of perception

part of the Incubator for Transdisciplinary Futures, faculty members across Arts & Sciences are working to decode the relationship between technology and the mind. 20 Features 20 4

Table of Contents Protect and

The Divided City Initiative brings together

&

and the Sam Fox School to support community-led efforts to save north St. Louis’ historic Sumner High School.

A plant research powerhouse Step

As

Volcano hunting on Venus

Two scientists created a map of volcanoes on Venus — all 85,000 of them.

The parent trap

New research by Joshua Jackson explains how a parent’s personality can have a significant impact on their child’s life.

Ephraim Oyetunji

The standout student researcher discusses his path to WashU and why he’s passionate about tackling medical mysteries.

Digging into the American dream

Icons of anthropology

Fiona Marshall and Richard Smith are retiring this year after decades of mentorship, research, and leadership.

From Student Union to City Hall

Tyrin Truong, AB '21, is using lessons from his time at WashU to push for big changes in his Louisiana hometown.

Recent faculty titles explore presidential power, Fred Astaire by the numbers, the art and science of slow birding, and more.

The Ampersand | Spring 2023 5

The Ampersand program “Examining America” helped

the nuanced history of St. Louis.

gift of mentorship Celebrating distinguished alumni

Conrad Lewis understand

The

36 40 32 18 12 26 42 38 39 Snapshot Undergraduate research expands Arts & Sciences 6 A Guggenheim tradition continues Department of English 11 Inherited gender bias Department of Political Science 8 Doing the math on solar power Department of Physics 10 Around the Quad Perspective Notes of Gratitude Faculty Bookshelf Conversation Memories and Milestones Student Spotlight Alumni Spotlight ampersand.wustl.edu

Around the Quad

Arts & Sciences

Expanding undergraduate research

The Office of Undergraduate Research relaunched in late 2022 with a new team and the goal of expanding and enhancing research opportunities for undergraduates across academic disciplines. Whereas the natural and social sciences more readily offer a direct pipeline to research and mentoring through faculty-run labs and fieldwork, the humanities present a different model. “We are looking for new ways to mentor those students earlier in their trajectory at Washington University,” said Erin McGlothlin, vice dean of undergraduate affairs. The goal is to find innovative ways to reach students from all backgrounds and support them in discovering their path to a rewarding research experience.

Feng Sheng Hu Dean of Arts & Sciences

Lucille P. Markey Distinguished Professor

A A L M K F D E B J G H I C

News, milestones, and spotlights from across Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis

Find expanded versions of all Around the Quad stories. artsci.wustl.edu/ATQ

Around the Quad 6

We want as many of our undergraduate students as possible to experience the transformative power of research.

Environmental Studies Program Climate conversations

Since 2011, WashU students in Professor Beth Martin’s “International Climate Negotiations” course have attended the annual United Nations Conference of the Parties (COP) to learn more about the international climate negotiations. In November, they returned from Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt, with fresh insight into the global and interdisciplinary complexity of the crisis. “The more time I've spent in the COP space, the more I realize the impact of its everyday realities on the people participating,” said Bea Addis, a graduate student in sociocultural anthropology and teaching assistant for Martin’s course.

Arts & Sciences

Senior scholars

Seniors Sabrina Hu and Sam Norwitz were among the 23 U.S. students selected for the prestigious Gates Cambridge Scholarship, which fully funds postgraduate study and research at the University of Cambridge. Hu majored in chemistry and history and minored in mathematics. She plans to earn a PhD in chemistry at Cambridge. Norwitz, who also received an NIH Oxford-Cambridge Scholarship, majored in neuroscience and minored in children’s studies. He plans to earn a PhD in medical science.

Department of Anthropology

Milk markers

E.A. Quinn, associate professor of biological anthropology, received a grant from the Leakey Foundation to study how certain hormones in breast milk contribute to brain growth in humans and primates. By comparing human and primate milk samples, she hopes to better understand the unique and essential function of breast milk. “I want to understand why and how human infants have evolved these large brains, these high levels of body fat, and how human milk is a part of that story,” Quinn said.

The Ampersand | Spring 2023 7

B

C A

Department of Anthropology

Park protectors

Biodiversity research led by Crickette Sanz, professor of anthropology and co-director of the Living Earth Collaborative 2.0, and at least 20 graduate and undergraduate students helped inform a decision by the Republic of Congo to protect a 36-square-mile area called the Djéké Triangle, making it part of the adjacent Nouabalé-Ndoki National Park — the only habitat in the world home to habituated groups of both gorillas and chimpanzees. Collaborators from WashU, the Saint Louis Zoo, and other groups screened thousands of video clips recorded at camera traps to document biodiversity in the Djéké Triangle, information used to elevate the area’s protected status.

Department of Political Science

Inherited gender bias

DNA may not be the only thing we inherit from our ancestors. New research by Margit Tavits, the Dr. William Taussig Professor, provides evidence that modern gender norms and biases in Europe have deep historical roots dating back to the Middle Ages and beyond. The findings highlight why gender norms have remained stubbornly persistent in many parts of the world despite significant strides made by the international women’s rights movement over the last 100-150 years.

Around the Quad C

D

(Illustration: Monica Duwel/Washington University)

8

(Photo: Wildlife Conservation Society)

Book to big screen

Doctoral student Sayed Kashua’s 2004 novel “Let it Be Morning” recently made its way to the big screen. The film follows a journalist who returns to his Palestinian village after working in Jerusalem for many years. One morning, he tries to commute to his job, only to discover that the Israeli military has blockaded all exits from the village. As a screenwriter, novelist, and journalist, Kashua considers storytelling to be his best tool for addressing political inequalities. “It has always been injustice that motivates me to write,” he said. “All of my work is about minorities struggling to express their frustrations.”

Department of Music

Classical music in Haiti

What inspires Haitians to devote extraordinary resources to practicing, learning, and performing classical music? Lauren Eldridge Stewart, assistant professor of ethnomusicology, is trying to find out. She recently received a six-month Career Enhancement Fellowship from the Institute for Citizens & Scholars to support her research. This new award, along with one she received last year from the Center for the Humanities, has provided Eldridge Stewart with two semesters of research leave to work on her book-length manuscript, “Recital: Classical Music and Narrative Power in Haiti.”

Departments of Sociology and African and African-American Studies

Tracing racial terror

David Cunningham, chair and professor of sociology, and Geoff K. Ward, professor of African and African American studies, received a $500,000, three-year grant from the Mellon Foundation for their project, “The Virality of Racial Terror in US Newspapers, 1863-1921.” Along with collaborators at other universities, the two will use digital humanities text-mining methods to trace the circulation of reports about anti-Black violence in United States newspapers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The Ampersand | Spring 2023 9

Program in Comparative Literature

G E

F

© Cohen Media Group

Departments of African and African-American Studies and Anthropology

We'd like to thank the Academy

Jean Allman, the J.H. Hexter Professor in the Humanities, and Tristram R. Kidder, the Edward S. and Tedi Macias Professor, are among nearly 270 newly elected members of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences, one of the nation’s most prestigious honorary societies. Founded in 1780, the American Academy of Arts & Sciences honors exceptional scholars, leaders, artists, and innovators and engages them in sharing knowledge and addressing challenges facing the world.

Departments of African and African-American Studies and East Asian Languages and Cultures

Honors for humanists

Karma Frierson and Hyeok Hweon Kang received fellowships from the American Council of Learned Societies. Frierson, assistant professor of African and African American studies, will be working on an ethnography of how locals in the city of Veracruz, Mexico, reckon with expectations of Blackness in the wake of late 20th century multiculturalism. Kang, assistant professor of East Asian languages and cultures, will examine the rise of early modern engineering as a global phenomenon, emphasizing how Korean artisans and practitioners developed a multimedia system of material design and production.

Department of Sociology

An inspiring advocate

Zakiya Luna, a Dean’s Distinguished Professorial Scholar and associate professor of sociology, was named the 2023 Distinguished Feminist Lecturer Award winner by Sociologists for Women in Society. Luna’s research and teaching focuses on social movements, reproduction, and human rights, with an emphasis on the effects of intersecting inequalities within and across these sites. Her nomination by current and former colleagues described her as “one of the most visible advocates of Black feminist sociology and praxis with an inspiring record of service, community activism, and public scholarship.”

Department of Physics

Doing the math on a solar-powered future

Anders Carlsson, professor of physics, and a collaborator used 40 years of data from the St. Louis region to figure out the ideal mix of solar generation and storage for a reliable power grid. Their calculations show that small improvements in energy generation and storage could have huge impacts on the overall reliability of a solar-powered grid. The math also points to an important lesson: “Extremely highly renewable systems are very expensive,” Carlsson said. “If we can get to 99% renewable in 10 years, versus 100% renewable in 30 years, we’d better figure out how to get to that 99%.”

Around the Quad

J

I

H

K 10

Arts & Sciences

The future of statistics and data science

Xuming He, a renowned leader in statistics and a proponent of interdisciplinary research in data science, will join Arts & Sciences this summer as the inaugural chair of the new Department of Statistics and Data Science. Leaders and faculty across WashU celebrated He’s appointment, noting the potential for cross-campus collaboration and innovative digital transformation. “Professor He is a truly exceptional scholar, educator, and leader,” said Feng Sheng Hu, dean of Arts & Sciences.

Department of Economics

New economics leader

George-Levi Gayle, the John H. Biggs Distinguished Professor in Economics, will take the helm of the economics department starting July 1. Gayle’s own work centers around inequality, human capital accumulation, and labor markets, but he’s also excited about the larger direction of the department. Arts & Sciences has world-renowned leaders in macroeconomic policy as well as a dynamic cohort of early-career scholars who are researching economic theory centered on the allocation of scarce resources — everything from kidney transplants to education to broadband. “There’s excitement and momentum in the WashU economics department,” Gayle said.

Department of English A Guggenheim tradition continues

Edward McPherson, associate professor of English, recently became the ninth Arts & Sciences faculty member since 2010 to receive a prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship. The award will provide McPherson with support for his new nonfiction book, a project that mixes history, reportage, and personal experience to examine the “delights and dangers” of taking the long view. “We are thrilled that the Guggenheim Foundation has recognized Edward’s work,” said Feng Sheng Hu, dean of Arts & Sciences. “He is carrying on a great tradition of Guggenheim Fellows in Arts & Sciences — one I believe we are poised to build on in the future.”

11

M H

L

The parent trap

BY CHRIS WOOLSTON

Ever feel like you’re turning into your parents? New research by Joshua Jackson sheds light on how a parent’s personality affects their child’s life.

Personality differences make life interesting, but the stakes are especially high for parents. A new study by Joshua Jackson, the Saul and Louise Rosenzweig Associate Professor of Personality Science, found that parents’ personalities — boisterous or reserved, agreeable or cranky, concerned or carefree — can shape the lives of their children, for better or worse.

The study, co-authored with graduate student Amanda Wright, involved nearly 9,400 German children aged 11-17 and their parents. Researchers considered the so-called “big five” traits psychologists use to describe personality in broad strokes: extraversion, agreeableness, openness, conscientiousness, and neuroticism.

The survey also included measures of the kids’ lives, including their overall health, grades in school, use of alcohol or cigarettes, the amount of time spent on leisure activities — beyond watching TV or surfing the internet — and the frequency of family arguments.

What were the major findings of the study?

We found that parent personalities have a significant impact on a child’s life, even after taking the child’s personality into account. For example, kids with extraverted parents tended to have lower grades. Kids with neurotic parents scored relatively low on several measures, including grades, overall health, body mass index (BMI), and time spent on leisure activities.

On the other hand, kids were likely to be healthier if their parents scored high on measures of agreeableness or conscientiousness, and they were more likely to stay active with hobbies if their parents scored high in openness.

Conversation

12

Amanda Wright and Joshua Jackson co-authored a study published in Infant and Child Development. (Photo: Sean Garcia)

Do you know why certain personality traits are associated with certain outcomes?

We can only speculate. We suspect that maybe extraverted parents are less likely to emphasize studying and homework. Maybe they are encouraging their kids to socialize instead of study, or maybe the parents are too busy with their own lives to help with homework. But there’s no way to know for sure from this dataset.

Can you say what type of parent personality is most closely associated with successful kids?

In general, kids do particularly well if their parents are extraverted, agreeable, conscientious, and open without being neurotic. That’s probably something close to the best-case scenario, but even that combination can have some downsides. As noted, kids with extraverted parents tend to have lower grades.

Putting parents aside for a moment, how did the personality traits of kids affect their lives?

A child’s own personality definitely makes a big difference. For example, we found that kids tended to have better grades if they were extraverted, agreeable, open, and conscientious, but they had worse grades if they were neurotic. Extraverted kids were more likely to smoke or drink, but being open, conscientious, or agreeable had the opposite effect.

Were there any parent-child personality combinations that seemed to be especially beneficial?

Sometimes the personalities of children and parents seemed to work in synergy. It’s clearest with family arguments. Arguments are less common when either parents or children score high for agreeability. But when both parents and children are agreeable, arguments dwindle dramatically. Also, we found that the highest grades were achieved by nonneurotic kids who had non-neurotic parents.

There was also some negative synergy. For example, neurotic kids with neurotic parents tended to have the highest BMIs.

Do kids generally end up with similar personalities as their parents?

Lots of people eventually have the feeling that they’re growing into their parents. But at least in terms of personality traits, the connection is not strong. For example, it’s not at all uncommon for extraverted parents to have introverted children and vice versa.

Can parents use this information to change their styles and potentially help their kids, or is personality so baked in that the die is already cast?

That question really gets to the heart of a lot of my work. So much of our personality is really beyond our control. If you’re introverted, you can’t suddenly become extraverted. But it is possible to change certain daily behaviors, especially if we’re aware of the consequences. We found that kids are likely to be healthier if their parents are conscientious. That’s very likely because conscientious parents encourage exercise and healthy eating.

It’s a good lesson for everyone: Personalities are largely set, but behaviors can change.

Extraversion: outgoing, energetic

Agreeableness: cooperative, gets along with others

Openness: creative, imaginative

Conscientious: organized, deliberate, careful

Neurotic: anxious, worried, nervous

The Ampersand | Spring 2023 13

The ‘big five’ personality traits, explained

Psychologists use these traits to describe personality in broad strokes.

A plant research powerhouse

BY CHRIS WOOLSTON

Step behind the bench with four scientists whose evergreen passion for plants could fuel life-changing discoveries that extend far beyond the greenhouse.

Some science labs gleam with sterilized countertops and freshly washed beakers. But walk into the laboratory of Xuehua Zhong, professor of biology, and you’re immediately immersed in green.

Zhong and her group raise a perpetual bumper crop of Arabidopsis thaliana, a delicate weedy plant commonly called thale cress. The ten thousand or more individual plants in her collection — including many in the Jeanette Goldfarb Plant Growth Facility — grow in precisely controlled conditions that replicate real-world challenges including drought and excess heat.

Zhong may have the greenest lab on campus, but she’s far from the only researcher working to understand the inner secrets of plants. “That’s why I came here,” she said. “The university has amazing resources, and there’s a community of plant scientists doing exciting things.” While dozens of standout Arts & Sciences researchers, from professors to graduate students, focus on plants, four took a short break from the lab to talk about their work, insights, and favorite leafy subjects.

A plant-powered approach to climate change

Joe Jez, the Spencer T. Olin Professor in Biology, embodies the department’s preoccupation with plants. He started his career as a biochemist with a plan to eventually get into pharmaceuticals, but over the years his work has become overrun with members of the plant kingdom.

Features 14

“Plants are nature’s original do-it-yourselfers,” he said. “Think about when a seed lands somewhere. It has to figure out how to grow roots; it has to figure out how to get sunlight. There’s just incredible chemistry within a plant.”

Jez’s lab uses X-ray crystallography and other methods to study the fundamental structures of plants.

His research has led to some surprising and potentially significant findings. In 2022, Jez co-authored a Science Advances paper describing a mutation in thale cress — the same species growing in Zhong’s laboratory — that increased the plant’s uptake of carbon dioxide (CO2) by 30%. While other researchers mapped out the genetic differences between plants, Jez used his expertise to identify the physical changes that turned the plants into carbon-gobbling machines.

If the same mutation that cranked up the carbon in cress could be introduced in other, more substantial crops like corn or soybeans, the impact could ripple across the planet, Jez said. “You could pull more CO2 out of the environment and maybe get bigger, more nutrient-enriched plants. That could have implications for our ability to remove carbon from the environment and ultimately slow climate change.”

In another study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2022, Jez and co-authors described

how thale cress controls the balance of auxin, a plant hormone that regulates growth. They found that plants use a complicated series of inhibitors to keep hormone levels in balance. Auxin was discovered decades ago, but the nuances of its ebb and flow in a plant had been largely unknown. “We already have roadmaps for the biochemistry of plants, but there’s a lot about metabolism that we still don’t understand,” Jez said. The finding, he said, is another example of an insight that could potentially be used to ramp up plant growth, which in turn could remove more CO2 from the atmosphere.

Jez’s ability to visualize the smallest components of cells has led to some surprising projects beyond the plant world. In a 2022 paper co-authored with, among others, Nupam Mahajan, professor of surgery at WashU’s School of Medicine, Jez and colleagues shared findings that could one day help researchers find new treatments for prostate cancer. Other scientists on the team had noted a genetic quirk in prostate cancer cells, but they needed help understanding the structures of the proteins involved. Before long, the cancer researchers had enlisted a plant specialist to join the team. “Collaboration is like a pick-up basketball game,” Jez said. “It keeps things interesting.”

Xuehua Zhong (right) studies the evolutionary strategies that plants use to thrive and survive. She frequently studies Arabidopsis thaliana, or thale cress. (Photos: Sean Garcia)

The evolution of rice

Kenneth Olsen, the George William and Irene Koechig Freiberg Professor of Biology, frequently works with international colleagues to study the evolution and genetics of plants. Much of his focus is on rice, a crop that has been grown under human control for 10,000 years. Olsen explained that domesticated crops are like prolonged experiments in natural selection. Twenty years ago, rice became the first plant to have its entire genome decoded. “That opened up a world of possibilities for studying the connection between genes and traits,” Olsen said.

In a 2023 study published in BMC Biology, Olsen and a team of researchers from China and the Philippines examined the genomes of 13 varieties of wild and domesticated rice to identify genes that were lost during domestication. In many cases, they were able to connect the genetic change to a specific trait. For example, in japonica rice, the most common variety grown in East Asia, the deletion of the gene Os03g27510 improved grain length.

has visited rice fields in Arkansas to inspect them and talk with farmers about this aggressive weed. “Farmers can lose up to 80% of their harvest to weedy rice,” Olsen explained. The farmers, he said, are eager to share their observations and get help. “It can be so incredibly valuable to interact with farmers and get the insights of people who really understand the biology of a given species in its natural environment,” he said.

In 2022, Olsen, Wedger, and Nilda Roma-Burgos, a professor of weed physiology and molecular biology at the University of Arkansas, published a study that explored the genomes of weedy rice samples collected from five Arkansas rice fields. They found that most plants are actually hybrids of domestic crops and weedy ancestors, a radical shift from just 20 years ago, when hybrids were rare. The researchers speculated that the widespread use of herbicides over the last two decades has created a new generation of hybrid weeds that are relatively resistant to chemicals. “It’s incredibly easy for these weeds to adapt and evolve,” Olsen said. The findings, he added, underscored the dangers of using just one method — in this case, a single type of herbicide — to control weeds.

Understanding the genetic basis of specific traits could help boost crop production through selective breeding or genetic engineering, Olsen said. Rice is a crucial component of global food supply, so any insight into its growth and cultivation could have significant repercussions. “I’m a basic research scientist, but I definitely recognize and value the potential impacts that our research could have on crop improvement,” he said.

Olsen and his team are also working to understand “weedy” rice, a feral form of the crop that has become a scourge to rice farmers in the United States and other parts of the globe. Marshall Wedger, a postdoctoral researcher in Olsen’s lab,

Science in the parks

Weeds are also on the mind of Rachel Penczykowski, assistant professor of biology. Penczykowski studies the interplay between plants and their pathogens, including a fungus known as powdery mildew. The fungus is a major headache for farmers growing melons, lettuce, tomatoes, beans, and many other crops. “Lots of different fungal pathogens affect plants that we care about,” she said. Powdery mildews also infest common weeds in the St. Louis area, which makes it easy to study the fungal pest close to home.

In January, Penczykowski received a prestigious CAREER award from the National Science Foundation to support her

We’re answering burning questions that are relevant to human health as well as plants.

The Jeanette Goldfarb Plant Growth Facility is a focal point for the WashU plant science community.

Features 16

(Image: Washington University Facilities Planning & Management)

investigations of powdery mildew on broadleaf weeds in and around the city. The award is reserved for junior faculty who excel at mentoring while successfully integrating research and education. Penczykowski involves undergraduates and even local high school students in her studies of weeds and mildews in various environments, from downtown St. Louis parks to the Shaw Nature Reserve in Gray Summit.

Penczykowski wants to know how variations in shade, heat, and other factors affect infestations. Previous work has shown that the fungus seems to do especially well in more urban environments. She speculates that the large amount of foot traffic through parks might help disperse fungus spores. But it’s also possible that the fungus thrives in the warmth generated by city living. “We know that there’s a lot of heat produced by industry and vehicles,” she said. As the climate warms, there’s a risk that mildews and other fungi will thrive even more.

Epigenetic control

Back in Zhong’s lab, graduate students adjust heat lamps and add precise amounts of water to trays of thale cress. The work is part of her larger mission to study the evolutionary strategies that plants use to thrive and survive. “We are looking at how plants respond to an ever-changing environment,” she said. The cress have an eight-week lifecycle, making it possible for Zhong and her team to track multiple generations.

The team focuses on epigenetics, a molecular process that controls the expression of genes without altering DNA. In 2022, Zhong co-authored a paper with colleagues at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the University of California, Riverside, that explained how enzymes attached to DNA in thale cress switch specific genes off and on. “That study addressed a long-standing unanswered question in the field,” she said. “We knew that epigenetic control is very stable and is transmitted from one generation to the next, but we didn’t know why it always happened in the same parts of the genome.”

Epigenetics is also a crucial process for human health, including the normal division of cells, so the findings in Zhong’s lab have implications far beyond the greenhouse. “We’re answering burning questions that are relevant to human health as well as plants,” she said. Zhong’s findings in cress have informed ongoing research into leukemia, a disease that can begin when normal epigenetic processes break down. In 2022, she received a five-year, $2.1 million Maximizing Investigators’ Research Award from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), a grant that continued the institute’s long-standing support of her research.

The NIH award is another reminder that plant science is ultimately about far more than the individual grasses, trees, or shrubs. “Climate change, crop improvement, sustainable agriculture, human health…we have the tools, the people, and the resources to go in all of those directions,” Zhong said.

“This is very unique to WashU.”

A rich environment for plant research

Plant researchers at WashU are part of a powerful research ecosystem that stretches across St. Louis. On the Danforth Campus, the three-story Jeanette Goldfarb Plant Growth Facility provides just about any type of growing environment a scientist needs, from desert to tropical.

WashU also maintains close research ties with the Missouri Botanical Garden, a 79-acre expanse of trees, flowers, and shrubs in St. Louis. “The botanical garden gives us access to a huge collection of plants and a number of people with specific expertise,” said Barbara Schaal, the MaryDell Chilton Distinguished Professor.

That partnership grew deeper in 2018 with the launch of the Living Earth Collaborative, a joint project of the botanical garden, WashU, and the Saint Louis Zoo that aims to promote conservation and biodiversity of plants and animals.

WashU also enjoys a symbiotic relationship with the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center, a St. Louisbased research institute that supports more than 400 scientists from around the world.

That combination — WashU, the Missouri Botanical Garden, and the Danforth Center — adds up to a plant research consortium that stands out on the global stage, said Schaal, a renowned expert in plant evolution.

Learn more about Arts & Sciences' plant researchers.

artsci.wustl.edu/PlantPowerhouse

The Ampersand | Spring 2023 17

When you bring those institutions together, their strengths are amplified.

Barbara Schaal, Mary-Dell Chilton Distinguished Professor

The evolution of Ephraim Oyetunji

Interview by

ELIZABETH SWORDS

Ephraim Oyetunji likes a good challenge. “Everything is a mystery to be solved,” he said. A senior biology major on the neuroscience track, Oyetunji quickly established himself as a standout researcher. He’s been named a WUSTL ENDURE scholar, a Hope Center Scholar, and a recipient of the prestigious Barry Goldwater Scholarship. Oyetunji discussed his path to WashU, his experiences in the lab, and why he’s passionate about tackling some of medicine’s biggest mysteries.

Where did your interest in biology come from?

I guess I always had an inkling for it. I’m from Nigeria, but I left when I was 2 years old. My mom came to the United States to study nursing, and, growing up, there would always be nursing textbooks on the counter. Biology was always something I’ve been interested in, especially when I got to do research in high school. It’s not just about knowing the information but applying it to create new knowledge.

What did you research in high school?

Going into my sophomore year, I worked with C. elegans to look at a gene called WDR-23 to learn how changing histone levels could impact cell division and potentially cancer progression. The next year I worked with fruit flies to see if caffeine could help reduce symptoms of Parkinsonian neurodegeneration. And then my senior year I did work at Florida State University with human stem cells, trying to increase the rate of biological production.

What made you choose WashU?

Knowing that WashU was a pre-med powerhouse was helpful. But I think the biggest pull was financial. I’m part of the John B. Ervin Scholars Program, and that’s a very big reason why I’m here. I feel everything I’ve gotten is partially, if not entirely, due to my participation in that program because the community is just so great.

When I was still in high school deciding where I wanted to go, a WashU junior who was also a Black pre-med student would call me, answer my questions, and make sure I understood everything. And that was just a great invitation to the awesomeness that is WashU.

Student Spotlight 18

Can you give me a rundown on your research here at WashU?

I attended a two-year summer internship program called BP ENDURE, which is a neuroscience program working to increase the number of minority scientists. My mentor Kathleen Schoch, assistant professor of neurology, introduced me to her project on Alzheimer’s research in Dr. Tim Miller’s lab. She had been focusing on one of the proteins called amyloid beta, but I was able to expand this research to also look at the tau protein. Having to think for myself and make my own decisions rather than following someone else’s procedure was a challenge at first, but ultimately really helpful. I like that there’s a very driven community of people here who are really excited about science. It’s a very egalitarian space. I have a lot of great mentors — MDs, PhDs, grad students — but they still value my opinion as equivalent to their own when we’re tossing up ideas for what to do next, things to consider for future research, or critiques on experiments.

What other activities do you participate in at WashU?

I’ve been a part of MAPS, the Minority Association of PreMedical Students, since my first year. We work to increase diversity in medicine. This spring we’re raising funds for the St. Louis Area Diaper Bank and working with them to help supply diaper and period products to the community. I’ve also done some volunteering with the St. Louis Children’s Hospital, particularly in the patient playroom, and worked with Interfaith Fellows, which is a group of people of different faith backgrounds coming together to talk about life’s big questions.

What’s next for you?

Next is medical school. I may take some time off before then to travel, particularly with the goal of learning Yoruba, which is a Nigerian language that my parents speak but I don’t. I think this would be a very unique time to learn it.

What is your ultimate career goal?

I think my long-term goal is to be a physician who is present in the community doing public health work, but also juggling research and innovations to help move the field forward. I’ve studied neuroscience, and a lot of the stuff that I work on, like Alzheimer’s, are things that don’t have cures or survivors. I would love to be in a space where I’m not just telling people, “There’s not much we can do for you.”

People are important and their stories are important. And I like that with medicine, you are able to change a person’s story for the better in ways that perhaps other professions are unable to.

Ephraim Oyetunji

Hometown:

Miramar, Florida

Major:

Biology, specializing in neuroscience

Minor:

African and African American studies

Activities:

• Interfaith Fellows

• John B. Ervin Scholars Program

• Minority Association of Pre-Medical Students (MAPS)

• Pre-Health and Science Peer Mentoring Program (PSPMP)

The Ampersand | Spring 2023 19

Everything is a mystery to be solved, and the only way to figure it out is to test. And, of course, you fail like a million times. But it’s very exciting to do something that no one else has done before.

Masters of perception

BY JOSH VALERI

BY JOSH VALERI

As part of the Incubator for Transdisciplinary Futures, faculty members across Arts & Sciences are working together to decode the relationship between technology and the mind.

Features

20

(Illustration: Keren Guo)

Can artificial intelligence help us better understand the mechanics of the human brain?

How can educators deploy virtual and augmented reality in the classroom?

What does modern mindfulness look like in a screen-driven society?

Faculty members across Arts & Sciences are collaborating to answer these questions and more as part of the Incubator for Transdisciplinary Futures (ITF), a signature initiative of the Arts & Sciences Strategic Plan.

“The Incubator for Transdisciplinary Futures is about supercharging novel and wild collaborations to pursue transformative research, design new learning experiences, and show us pathways for the university of the future,” said William Acree, co-director of the initiative with Betsy Sinclair. “It provides an incredible institutional framework for such innovation across Arts & Sciences, as well as across the university.”

Among the 14 research teams currently funded by ITF, three multiyear clusters are addressing an increasingly critical issue: the relationship between technology and the mind. Drawing on the expertise of several disciplines, researchers are exploring the nature of human understanding, the exciting (and frightening) future of immersive technology, and the renewed relevance of an ancient technology of perception.

“The faculty members working on these projects epitomize our values of convergence, creativity, and community,” said Feng Sheng Hu, dean of Arts & Sciences. “ITF positions Arts & Sciences to be a leader in transdisciplinary research and paves the way for groundbreaking educational opportunities.”

Toward a Synergy Between Artificial Intelligence and Neuroscience

Pull up a list of academic departments, and you’re likely to see the natural sciences split into subdisciplines. But that hasn’t always been the case, said Ralf Wessel, professor of physics.

“What we now call physics, chemistry, and biology were once called ‘philosophy of nature’ — a united human effort to understand nature,” he said.

As the rapid development of artificial intelligence challenges the very concept of human understanding, Wessel believes that reuniting the sciences is a crucial step in defining biological intelligence.

“In science, we often think that we understand something when we can create statistical relations between data. But that type of understanding is identical to what AI is doing today — often more effectively than humans,” Wessel said. “As a community, scientists must address the growing question: What exactly is biological intelligence?”

To help answer this question, Wessel is spearheading the cluster “Toward a Synergy Between Artificial Intelligence and Neuroscience” with Keith Hengen, assistant professor of biology, and Likai Chen, assistant professor of math and statistics. Through transdisciplinary research comparing artificial and biological intelligence, they aim to develop a better understanding of both.

“Over the last few decades, the models underlying AI were inspired by what we know about neurons in the brain,” Wessel said. Recently, however, AI models have become so successful that scientists are wondering if the relationship between neuroscience and computer science can be reversed: Can AI models help us understand how computations are done in the brain?

“Like the brain, AI models that perform human tasks are incredibly complex,” Wessel said. “But unlike the brain, where only a tiny fraction of the underlying mechanics are accessible, we have access to all of the information involved in making AI models work. So, we’re looking to use these models as steppingstones to understanding the brain.”

Wessel’s own research produced a compelling example of this approach. Using nature documentaries, Wessel and physics graduate student Zeyuan Ye trained an AI model to predict the next frame of a video. They then exposed this model to a static image, observing what concepts the model used to predict how the image would change. The team also tracked brain activity from mice exposed to the same image, allowing them to compare artificial and biological approaches to a similar problem.

“At a high level, we see conceptual similarities in how the AI model and the mice performed this task of ‘seeing the world,’” Wessel said. Working from similar statistical links between images, the artificial and biological “minds” looked alike.

Wessel hopes that learning more about the conceptual mechanics of AI models could have applications in other

The Ampersand | Spring 2023 21

areas, like treating brain disease. More immediately, he thinks an improved understanding could help chart a more responsible trajectory for AI.

“One of the bottlenecks to making AI better is a lack of understanding about how these models actually work,” he said. “If we can contribute to a deeper understanding of those mechanics through this cluster, that will be a great practical improvement.”

Immersive Technology Collective

“Someday — maybe soon — machines will be reading books and turning them into virtual reality,” said Seth Graebner, associate professor of French and global studies.

To some literature enthusiasts, that prediction might sound disturbing. To Graebner, however, it is a call to action. “I believe that humanists should be involved in virtual and augmented reality from the beginning,” he said. “That way, we can develop enough understanding and expertise around this technology to have some say in how it is deployed.”

Through the “Immersive Technology Collective” (ITC), Graebner is working with Elizabeth Hunter, assistant professor of drama, and Uluğ Kuzuoğlu, assistant professor of history, to promote creative applications of virtual and augmented reality across campus. “We want WashU to become a leader in this emerging space,” Hunter said.

Broadly speaking, the collective focuses on digital experiences that have broken out of a screen and into the physical environment, Hunter said. Having used such technology in her own research and pedagogy, she knows how exciting its applications can be.

“I’m interested in the way augmented reality (AR) emphasizes the user’s embodied presence while layering elements of the past onto their physical surroundings,” she said. Her latest project will use mobile AR to bring family memories into the present for patients with Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. Kuzuoğlu, meanwhile, is developing a completely immersive virtual reality (VR) project that will allow his students to experience what it would have been like to walk along the cosmopolitan waterfront in Canton, China, in the 19th century.

Top: In collaboration with the Fossett Laboratory for Virtual Planetary Exploration, the Immersive Technology Collective has given students and faculty the opportunity to use immersive technology for research and coursework. Bottom: First-year students in Todd Braver’s course "Mindfulness Science & Practice" participate in a mindfulness practice session. (Photos: Sean Garcia)

Features

22

“We are excited to see what faculty do with these tools once they become more familiar,” Hunter said. “Immersive technology will open up new ways of thinking across disciplines.”

The collective, which evolved organically from ongoing collaborations within the Fossett Lab for Virtual Planetary Explorations, has already helped faculty in departments ranging from chemistry to art history explore ways to integrate AR and VR into their teaching and research, and they’re only just beginning.

“In our experience, most fields have at least one person who wants to use immersive technology, but that person may not have the necessary resources,” Graebner explains. “We’re working to change that.”

Starting in the fall of 2023, the cluster will invite industry experts to host training sessions for faculty interested in using immersive devices like Microsoft HoloLens.

In the future, the ITC hopes to create a campus center for immersive technology that would host AR and VR technology and specialists, and where faculty could meet and discuss their work. As ITC members have already experienced, the opportunity to have such conversations can spur new developments.

“Speaking across disciplines to faculty who already understand how the technology works can provide a lot of insight into your own projects and even initiate transdisciplinary collaborations,” Hunter said.

The cluster also hopes to develop certification programs for students interested in working in immersive technology. These programs would emphasize ethical considerations in the burgeoning industry while also preparing students for job opportunities.

“We don’t want our liberal arts students to just point out when the technology is being misused,” Hunter explained. “We want them to play an instrumental role in creating and using this transformative technology.”

Mindfulness Science and Practice

In his Olin Business School course “Mindfulness and Performance in the Workplace,” Erik Dane and his students explore the benefits of putting down their smartphones and paying attention to the world around them through a range of experiential learning activities. “That’s been quite rewarding in a day and age where we’re bombarded by more distractions than ever,” said Dane, associate professor of organizational behavior.

To Dane and the other leaders of the “Mindfulness Science and Practice” cluster, the ancient practice is a promising solution to the growing mental health crisis among students and young people. “Mindfulness is a technology which may help address mental health problems without requiring money or medication,” said Ron Mallon, chair and professor of philosophy-neurosciencepsychology. “It has the potential to do a lot of good in the world.”

But even mindfulness, a 2,500-year-old practice of meditative perception, can be turned into a watered-down commodity. “I saw an ad for mindful hamburgers recently. I’m not sure what that meant, but mindfulness is everywhere now,” said Todd Braver, professor of psychological and brain sciences. “In that context, we want to promote a more substantive understanding of the practice.”

To do this, the cluster is planning a seminar on how mindfulness has been adapted in modern Western culture, and it has already initiated a lecture series highlighting the role of mindfulness in anti-racism efforts. The group is also planning an international scientific conference, a “Mindfulness Day” on campus, and an undergraduate minor in mindfulness science and practice.

The ability to work and share ideas across disciplines has been invaluable. “As a group, we can generate dialogues and engage in collaborative research that none of us would have come up with on our own. We can inspire each other,” Braver said.

The Ampersand | Spring 2023 23

MINDFULNESS IS ONE OF OUR BEST TOOLS FOR UNDERSTANDING OURSELVES, OTHERS.

Braver and Diana Parra, research assistant professor in the Brown School, worked together to convene the cluster after recognizing that there were people in various corners of the university who shared their passion for incorporating mindfulness into teaching, research, and personal practice.

“My interest in mindfulness came from using it as a way to cope with stress from work,” Parra said. “Over time, it started merging with my teaching. I now begin all of my classes with a short meditation practice.”

Braver also found and published quantitative evidence that his seminar, which teaches mindfulness to first-year students, helped improve their performance and stress levels.

Parra believes that the “technology” of mindfulness is more relevant than ever in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. “During COVID, everybody was forced to pause,” she said. “In that moment where you stop and take a break from everything — which is what you do in meditation — a lot of things rise to your conscious awareness that you might not be equipped to deal with. Mindfulness offers a tool for you to develop more compassion for yourself in those moments.”

According to the leaders of the cluster, mindfulness is a unique topic where ancient cultural traditions are in agreement with cutting-edge science. “There is a rapidly growing body of evidence indicating that mindfulness is one of the best tools we have for understanding ourselves and the people around us,” Braver said. “Hopefully, we can use that understanding to reduce biases and make the world a better place.”

Features

24

"Mindfulness Science & Practice" has helped first-year students improve their academic performance and stress. This spring, postdoc Jeff Yanli Lin (center) led the course while Braver was on sabbatical leave. (Photo: Sean Garcia)

Cross-Campus Collaborations

Nine multiyear clusters received funding for research and learning collaborations that bring together faculty from at least three distinct units, undergraduate and graduate students, and potential external partners.

Immersive Technology Collective

Faculty leads: Elizabeth Hunter, Performing Arts; Ulug Kuzuoglu, History; Seth Graebner, Romance Languages & Literatures/Global Studies

Mindfulness Science and Practice

Faculty leads: Todd Braver, Psychological & Brain Sciences; Ron Mallon, Philosophy; Diana Parra Perez, Brown School; Erik Dane, Olin Business School

The St. Louis Policy Initiative: Segregation, Public Health, and Environmental Policy

Faculty leads: Andrew Reeves, Political Science; Scott Krummenacher, Environmental Studies; Matthew Gabel, Political Science; Elizabeth KorverGlenn, Sociology

The Storytelling Lab: Bridging Science, Technology, and Creativity

Faculty leads: Jeff Zacks, Psychological & Brain Sciences; Ian Bogost, Film & Media Studies/ McKelvey School of Engineering; Colin Burnett, Film & Media Studies

Toward a Synergy Between Artificial Intelligence and Neuroscience

Faculty leads: Ralf Wessel, Physics; Keith Hengen, Biology; Likai Chen, Mathematics & Statistics

Trust and Public Health

Faculty leads: David Carter, Political Science; Matt Gabel, Political Science; Jimin Ding, Mathematics & Statistics; Mark Huffman, School of MedicineInternal Medicine/Global Health Center

Next Frontiers in Radiochemistry: Personalized Medicine for Infectious Diseases

Faculty leads: Timothy Wencewicz, Chemistry; Petra Levin, Biology; Manel Errando, Physics; Dan Thorek, School of Medicine - Radiology; Deborah Veis, School of Medicine - Pathology & Immunology

Police Body Camera Metadata

Faculty leads: Andrew Jordan, Economics; Christopher Lucas, Political Science; Soumendra Lahiri, Mathematics & Statistics

The Human-Wildlife Interface: Disease Dynamics and Pandemic Prevention

Faculty leads: Krista Milich, Anthropology; Michael Landis, Biology; David Wang, School of MedicinePathology & Immunology

The Ampersand | Spring 2023 25

Learn about the additional faculty collaborators working on the Incubator for Transdisciplinary Futures and the five groups that received programmatic grants.

artsci.wustl.edu/ITF

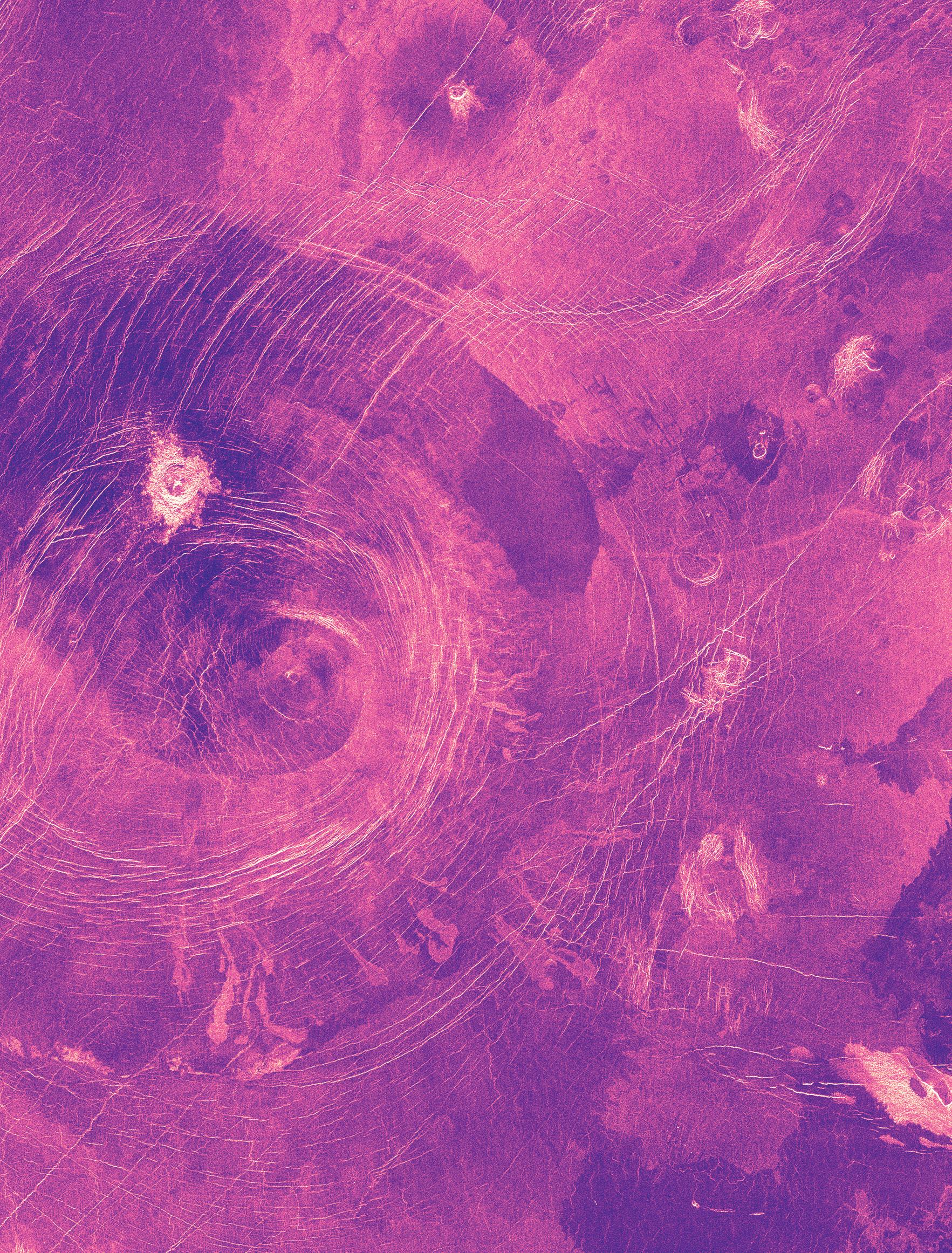

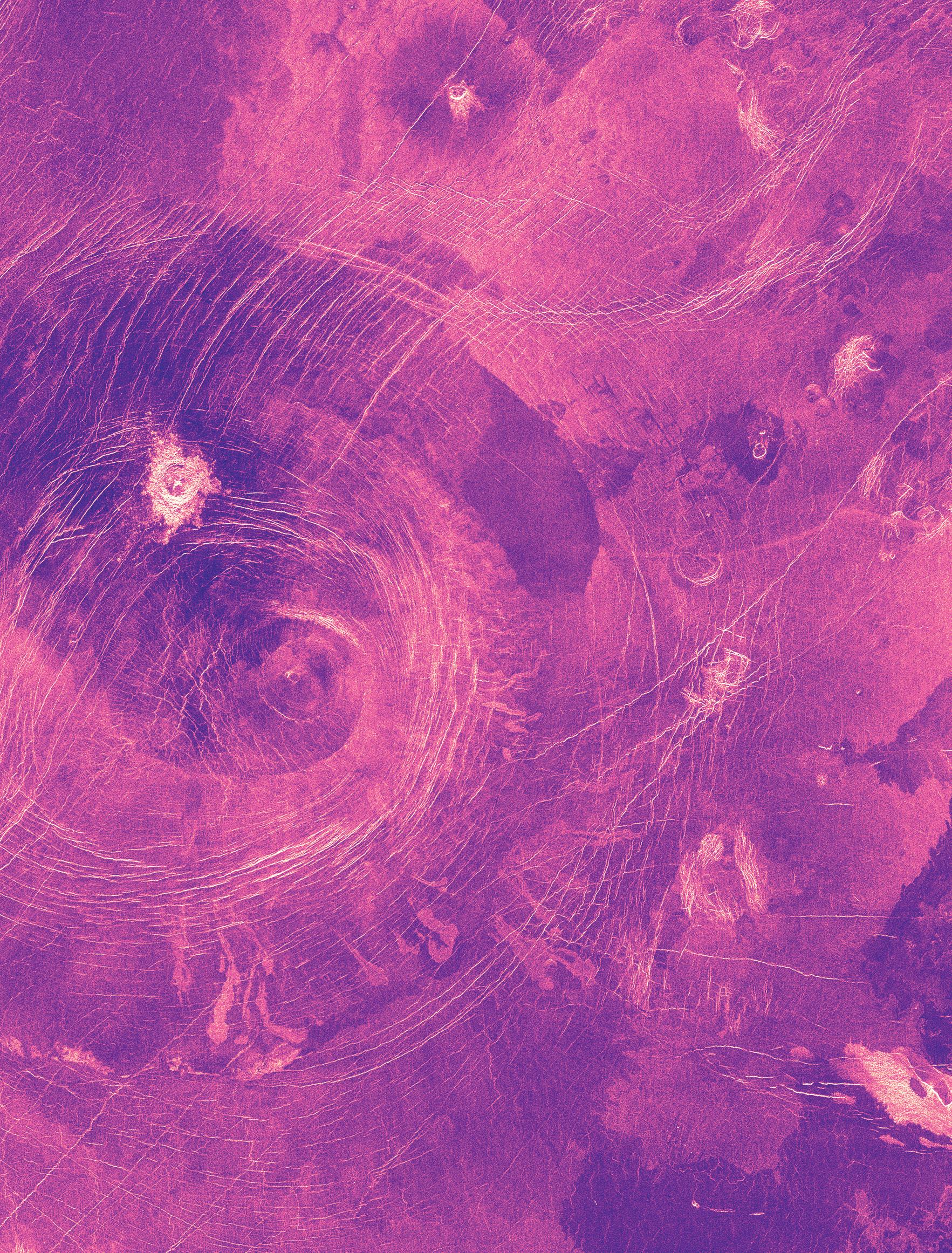

Volcano hunting on Venus

Planetary scientists Paul Byrne and Rebecca Hahn have created the most comprehensive map of Venus volcanoes — more than 85,000 of them. Byrne, associate professor of Earth and planetary sciences, and Hahn, a graduate student, used radar imagery from NASA’s Magellan mission to catalog volcanoes across the planet, including the circular corona volcano shown here. Corona volcanoes are especially intriguing to researchers because they could be active. Hahn and Byrne also paid particular attention to smaller volcanoes (less than 3 miles across), the most common volcanic feature on the planet. Their new dataset, hosted at WashU, is publicly available for use by other scientists.

(Image: Paul Byrne)

(Image: Paul Byrne)

26

Snapshot

30 Miles

Learn more about Byrne and Hahn's research.

artsci.wustl.edu/Venus

Protect and preserve

BY JENNY BIRD

BY JENNY BIRD

Features 28

The Divided City Initiative brings together Arts & Sciences and the Sam Fox School to support community-led efforts to save north St. Louis’ historic Sumner High School.

What does a building mean to a community?

Ask Michael Allen, lecturer in American culture studies, and he’ll tell you a building is more than a physical structure. Preserving the built environment can act as a “storehouse” against the forces that sweep in and change communities, he said. We save a space “not to prevent change, but to give neighborhoods the resources to push back and uphold collective values.”

So, when The Divided City — an urban humanities initiative funded by the Mellon Foundation that brings together the Arts & Sciences Center for the Humanities and the Sam Fox School — was invited to pitch in on a plan to save historic Sumner High School, the idea for the Sumner StudioLab was born.

Sumner is the oldest Black high school west of the Mississippi. It’s located in the Ville, a neighborhood just five miles northeast of WashU’s Danforth Campus with a rich legacy of Black excellence in culture, business, sports, art, music, and education. In its prime, Sumner High School’s striking Georgian-revival brick building was bursting with 3,000 students. But since the 1960s the neighborhood has experienced the effects of disinvestment and depopulation. Today, the high school is down to roughly 300 students. In 2021, St. Louis Public Schools slated it for potential closure. Sumner’s closure would devastate the Ville, according to Aaron Williams, board president of the community group 4theVille. Williams, AB ’08, formed the task force that crafted the Sumner Recovery Plan, an ambitious arts integration curriculum that seeks to save the school. The Sumner StudioLab aims to support those existing community-driven efforts.

Housed in an annex of the high school, the StudioLab is a community hub that brings together Sumner High School students, WashU students, and Ville residents to discuss and design the school’s future and celebrate its past.

We visited the space this spring to learn how Arts & Sciences students, faculty, and staff are working to deepen

understanding of Sumner High School and the Ville through internships, classes, and community engagement.

The Internships

Sumner High School student Kayleigh Lang has gone to the StudioLab every week for most of her junior year. The afterschool internship program has helped her learn more about her community and broaden her skills. “It’s not just another program at school,” she said. “I could be myself here. They see the real me.”

Laura Perry, assistant director for research and public engagement in the Arts & Sciences Center for the Humanities, and Matt Bernstine, associate director of the Office for Socially Engaged Practice at the Sam Fox School, run the internship program for Sumner students. They seek to support the growth of the Sumner community by empowering future leaders of the Ville. The internship program is funded by WashU’s Office of the Provost and was developed by Bernstine and Perry in response to critical feedback from community leaders about the importance of StudioLab programs that could offer direct, tangible benefits to Sumner students.

The interns have spent two semesters learning communitybuilding and design skills. Every program, listening session, or workshop the interns organize is an opportunity to enrich the neighborhood or learn how to document and preserve their community.

Last fall they interviewed elders in the Ville, hearing firsthand about the neighborhood’s storied past. This spring, the interns hosted a fashion arts workshop with St. Louis blogger and entrepreneur AK Brown that was open to the neighborhood. The internship also requires the students to serve on a Community Advisory Board alongside Ville residents and representatives from local organizations. That experience has been eye-opening for students like Lang. “I’m still a teenager, and I’m in a room full of adults, and it’s like, ‘Oh, we are making real decisions,’” she said.

Bernstine said the StudioLab’s internship program exists to support the ongoing work of community organizations in the

The Ampersand | Spring 2023 29

Sumner High School once enrolled 3,000 students. Now it's down to roughly 300. St. Louis Public Schools slated the building for potential closure. (Photo: Missouri History Museum)

Ville. “In some ways we are testing a model for thinking about Sumner High School’s future — a new model for public high schools as civic anchors.”

Sumner has served as “a beacon of Black excellence during a time of terrible urban segregation,” Perry said. For her, that’s reason enough to invest in the next generation of scholars. “Sumner is unique. There are not many places like it,” she said. “If the StudioLab can in any way contribute to supporting Sumner, that’s exactly what we hope it accomplishes.”

The Courses

For eight semesters, Michael Allen has taught a course on power, politics, and urban design called “The Unruly City.” But for the first time, this spring, Allen, who is also a senior lecturer in the Sam Fox School, offered the course from a new location: the Sumner StudioLab. Teaching the class in the high school annex offered his students a rare opportunity to directly address the issues they study.

This is the second course Allen has held in the StudioLab since it opened. Last fall he taught “Historic Preservation, Community, and Memory.” Both courses are cross-listed in Arts & Sciences and the Sam Fox School, and they have attracted students from a variety of majors including architecture, social work, African and African American studies, English, and musicology.

Allen tries to get students to engage with community problems in all his courses, but it’s rare that they are able to do so in the field. This semester, “The Unruly City” is split between discussion of readings and consideration of real-life issues in the Ville. “It used to be we’d have three hours to sit and have debates about policy,” he said. “Now we have to compress that and move on to thinking about how that relates to a problem in the neighborhood.”

During a class in early March, Kai Radford, a senior majoring in African and African American studies, presented a deeper look at the word “public” inspired by recent readings. Radford asked classmates: Do you consider yourselves the public? How do we define public? And does that change how we engage the public?

Sylvie Raymond, a junior majoring in English, said the course helped her speak in clear and direct terms about systems of power. “This class has given me lots of language to talk about how almost every issue of physical space is a social issue,” she said.

For their final assignments, Allen pairs each student with a community organization to work on projects like mapping, urban trail and sidewalk design, and documentation of public spaces.

For her project in “Historic Preservation, Community, and Memory,” Nkemjika Emenike, a senior majoring in history, mapped a community art project using the software ArcGIS. As she drove to class each week, Emenike noticed a series of portraits of important residents and other significant Black figures by artist Chris Green painted on homes throughout the Ville. One day she noticed that one of the paintings was on a vacant building that was being demolished. The potential loss of the painting inspired her digital project, documenting and mapping the portraits so that others could view them online and find them in person.

“The idea was to preserve and archive the art for future generations and highlight the importance of the figures on these homes,” Emenike said. “Preservation is crucial for maintaining the historical, cultural, and societal importance of the Black community in St. Louis.”

Having students make their way to Sumner and be present in the neighborhood every week has had an impact on the students, Bernstine said. “Even if they don’t explicitly say it, it resonates and shows in their final work.”

Features

Kai Radford (left) led a class discussion about the word “public” as part of Michael Allen's spring course "The Unruly City." (Photo: Sean Garcia)

30

Preservation is crucial for maintaining the historical, cultural, and societal importance of the Black community in St. Louis.

Community Engagement

The StudioLab hub also serves as a gathering place for listening sessions and workshops for Ville residents. Bernstine says the team has been intentional about supporting the fabric and organizational structure they are building in the neighborhood. “We are mindful of our position and want to play our part,” he said.

That means each event must go through a careful selection process. The StudioLab Community Advisory Board — comprised of the Sumner High interns, Ville residents, and community partners — must approve each idea to ensure workshops truly serve the neighborhood.

In early spring, the Urban Land Institute presented a handson workshop for Ville residents to learn about the issues and economics involved in urban design.

A creative button-making workshop with CJ Mitchell of the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis was also in the works. That event would be open to the neighborhood and include a discussion of community building and the use of buttons in activist movements.

Other workshops will focus on topics like urban gardening, holistic wellness, and civic engagement.

What comes next?

The Sumner StudioLab will continue to run through June, when the project’s funding from the Divided City Initiative comes to an end. But organizers Perry and Bernstine hope the work will find other ways to live on. “Moving slowly to build trust means that a year seems like the blink of an eye,” Perry said. “It feels like we are just getting started.”

Crystal Payne, a doctoral candidate in the English department who worked with the StudioLab, hopes to keep going even after her graduate assistantship ends. She’s loved working with the interns and getting to know the Ville, and she sees a significant connection to her work as a Caribbean scholar who studies borders, migration, and colonialism in literature.

“I think it’s important, putting a face to a theory,” Payne said. “We can talk about the tragedies of discrimination. We can talk about imperialism and colonization. But meeting the people it affects, I think that deepens our understanding of our field.”

The future of Sumner High School is still in flux. In the meantime, Michael Allen focuses on the small ways he and his students can contribute to the neighborhood. He wants students to understand their responsibility. “You’re going to be a neighbor, a fellow inhabitant of spaces, for the rest of your lives and careers. Any commitment that you launch in a class can be a lifelong practice wherever you go.”

Meet the Sumner High interns

Shahanah Hill junior

On what the StudioLab means to her: “This place helps you express yourself. It’s a place of peace.”

On serving on the Sumner StudioLab Community Advisory Board: “I’m still a teenager, and I’m in a room full of adults, and it’s like, ‘Oh, we are making real decisions.’”

On how he’s been challenged in the program: “They ask us if we’re willing to put our ideas out there and not be scared to be in front of people.”

The Ampersand | Spring 2023 31

Kayleigh Lang junior

Christian Windsor junior

Icons of anthropology

BY RACHEL SENDER

BY RACHEL SENDER

Memories & Milestones

Fiona Marshall and Richard Smith retire from Arts & Sciences this year after decades of mentorship, research, and leadership.

32

Fiona Marshall, the James W. and Jean L. Davis Professor

Fiona Marshall can still remember her first visit to the Washington University campus. It was 1986, and she had just completed her PhD in anthropology at the University of California, Berkeley. Through the windows of the anthropology department, she could see the campus alive with cardinals and redbuds.

“I remember feeling absolutely thrilled to be here,” she said. “It was such an exciting research environment.”

Marshall was introduced to archaeology at a young age growing up in Nairobi, Kenya, a hub for paleontological and archaeological research. She remembers spending time outdoors with her family, finding stone tools, and going to the Nairobi National Museum to hear talks by legendary archaeologists.

It’s the community of scholars in the anthropology department, however, that Marshall has enjoyed the most. When she joined the department in the late 1980s, she felt instantly welcomed and included by her fellow faculty, especially Patty Jo Watson, a leader who paved the way for women in science.

Friday Archaeology, a weekly forum where students and faculty give talks and discuss new research, was started by Watson to welcome Marshall to the university, build community, and incubate scholarship in the growing department. The meeting is as vibrant today as it was then, Marshall said.

“One of the things I have valued more than anything are my corridor conversations in McMillan Hall,” Marshall said.

As an undergraduate at the University of Reading, Marshall knew she wanted to study African archaeology and seized every opportunity to pursue it. She found a mentor in a talented, self-taught Kenyan expert on ancient animal bones. It turned out she had a talent for the work, too.

While looking for a topic for her undergraduate honors thesis, Marshall happened to be present when a graduate student asked for help identifying some Holocene fossils from Koobi Fora, Kenya. Marshall volunteered and went on to identify many of the bones as belonging to domesticated goats, much to the surprise of the graduate student. To this day, her honors thesis contains the oldest known evidence for domesticated animals in Kenya.

Marshall went on to a career filled with research related to animal domestication, the spread of food production, and hunter-gatherer ethnoarchaeology. That diversity prevented boredom and sparked new ideas, she said. “I found going back and forth between experimental, ethnoarchaeology, and excavation really stimulating.”

Today, Marshall is regarded as a global expert on human influences on African savannas and on animal domestication. Her research on cats and donkeys has shed light on domestication and emphasized the significance of donkeys for early trade routes, household mobility, and women’s work.

Marshall has loved her time teaching at WashU. “I have learned so much from teaching such wonderful students,” she said. This spring marks her 36th year teaching “Zooarchaeology,” a course featuring an incredible collection of skeletal materials that Marshall built into a necessity for any aspiring archaeologist or PreHealth student.

The Ampersand | Spring 2023 33

Marshall is a global expert on human influences on African savannas and on animal domestication. (Photo courtesy of Fiona Marshall)

One of the things I have valued more than anything are my corridor conversations in McMillan Hall.

“I have learned so much from my colleagues about diverse topics such as climate change, lost crops, or the latest discoveries. I have also forged meaningful relationships and exchanged cutting-edge information.”

In retirement, Marshall is looking forward to birdwatching, painting, and spending time with her grandchildren. She also plans to continue her research and professional activity.

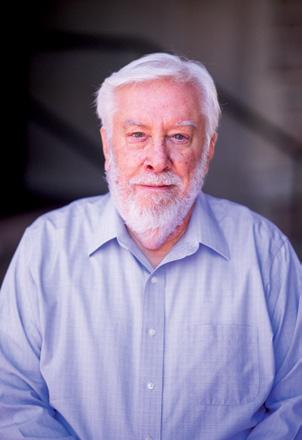

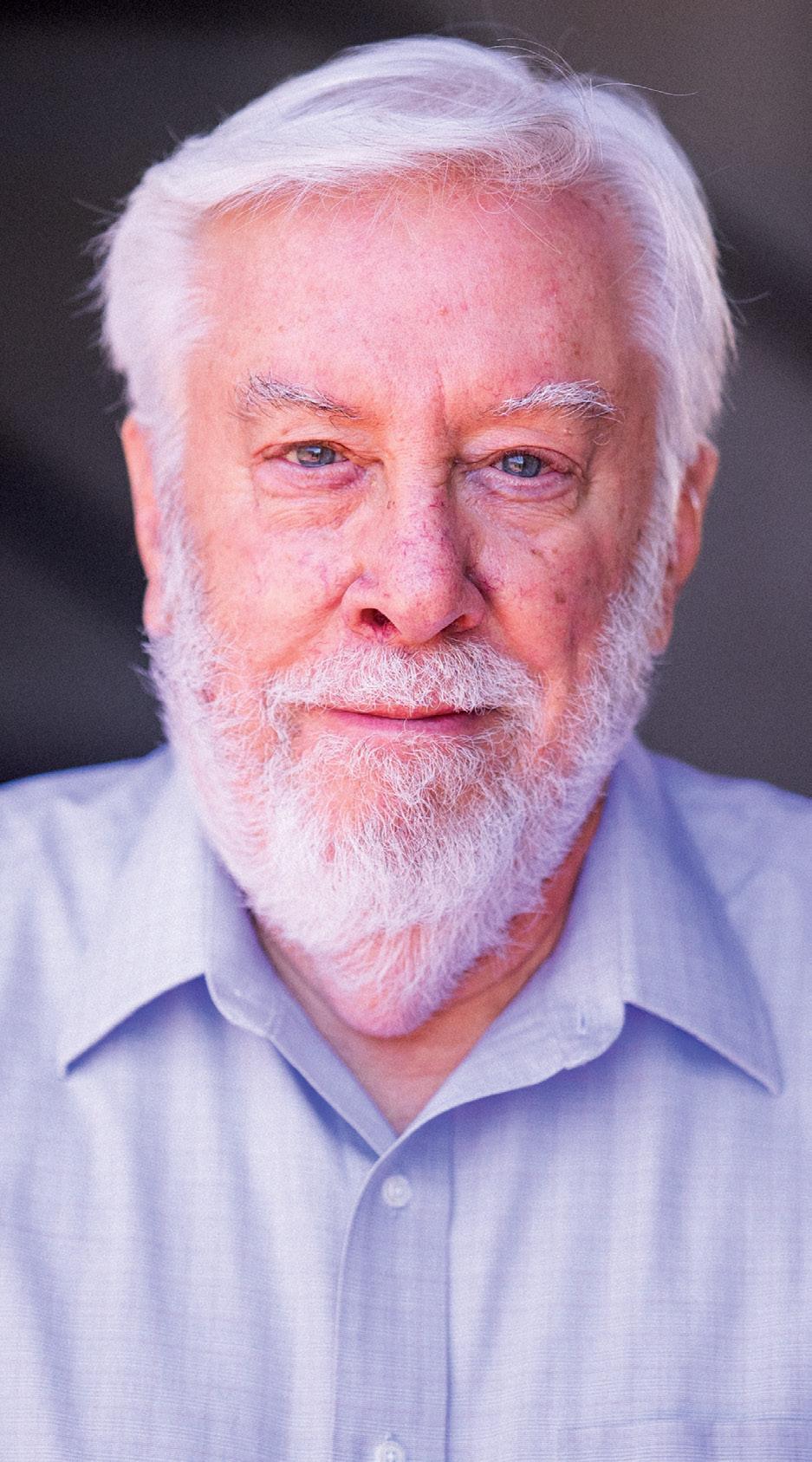

Richard Smith, the Ralph E. Morrow Distinguished University Professor

Richard Smith found the perfect job at WashU. “Other people talk about having the best job in the world because they don't know about this one,” he said with a smile. Smith’s retirement this year marks the end of a long and winding career in academia, including nearly four decades at WashU. He began his career as an orthodontist, a choice — made by a new college graduate, against the backdrop of the Vietnam War — born from necessity.

Smith began his time at WashU as a professor and chair of orthodontics in the now-closed School of Dental Medicine. Shortly after he joined the school’s faculty, he was asked to take on the role of dean and informed that he would need to help close the school. When it shut its doors in 1991, Smith transferred to the Department of Anthropology, where he’d had a joint appointment.

In 1993, Smith became the chair of the anthropology department. He also began teaching “Introduction to Human Evolution,” a seminal course that Smith transformed into a musttake for undergraduates. Smith’s goal was to teach a great course, one “where in the dorms

Memories & Milestones

Marshall (left) and team members excavate an ancient dung layer at the pastoral site of Indapi Dapo in southwestern Kenya. (Photo courtesy of Fiona Marshall)

34

students would say, ‘Oh, it doesn't matter if you're majoring in anthropology — take this.’”

And he succeeded. The number of anthropology majors at WashU increased during Smith's tenure, becoming the largest major for undergraduates.

Smith also won the deep respect of many students. After several years of teaching, students asked Smith to give “The Last Lecture,” a tradition started at Brown University that asks a notable professor to deliver their hypothetical final

and teaching. The change allowed him to “be the faculty member I always wanted to be.”

Smith has spent the last nine years publishing papers that challenge the status quo on statistical methods commonly used by biological anthropologists. He has also developed and taught two graduate-level courses that all anthropology doctoral students are encouraged to take.

Smith describes his time with anthropology as a “deeply meaningful, personal fit.” But after 39 years of service to the

lecture. Smith was the first WashU professor asked to give this lecture, and the experience is one of his fondest memories.

In 2008, after 15 years as department chair, Smith became dean of what was then the Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. The new role was more challenging than expected, however, due to the 2009 recession.

“It was stressful, coming up with solutions to problems that we never had before,” Smith said. “There wasn’t a roadmap for how you decide what funding to cut.”

Smith served as dean for six years before returning to the anthropology department. After nearly 30 years of administrative obligations, he was excited to focus on research

university, he is looking forward to spending retirement with his grandchildren, traveling, improving his chess game, and reading, while he and his wife Linda remain in St. Louis. When asked what books he plans to pick up, Smith said he plans to return to a childhood favorite: mystery novels.

The Ampersand | Spring 2023 35

Other people talk about having the best job in the world because they don't know about this one.

Richard Smith developed and taught two graduate-level courses that all anthropology doctoral students are encouraged to take. (Photo: Washington University Archives)

artsci.wustl.edu/Smith

Watch Smith deliver his popular "last" lecture.

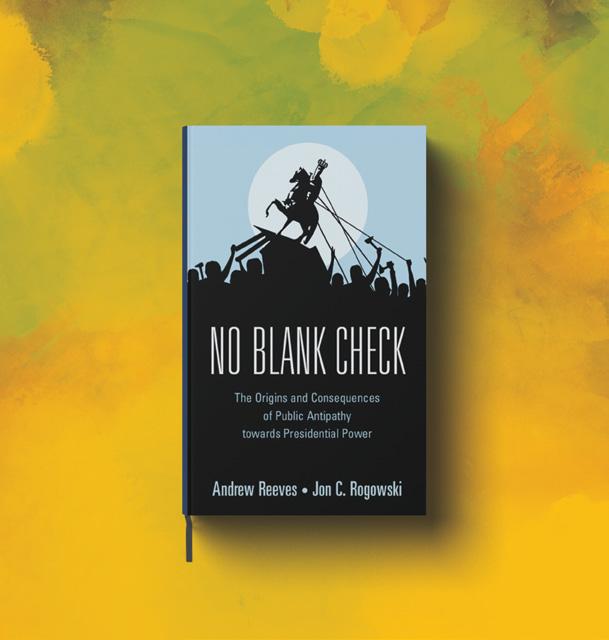

When presidential power meets public opinion

BY SHAWN BALLARD