Washington Trails

National public lands need hikers to speak up more than ever

Quick stretches for your next day on trail

How one hiker used trip reports to find more joy outside

National public lands need hikers to speak up more than ever

Quick stretches for your next day on trail

How one hiker used trip reports to find more joy outside

President | Ken Myer

Secretary | Bhavna Chauhan

Treasurer | Anson Fatland

VP Development | Halley Knigge

VP Governance | Todd Dunfield

Directors at Large

Bryce Bolen • Jared Jonson • Paul Kundtz

Chris Liu • Matt Martinez • Sully Moreno

Arun Sambataro • Ashleigh Shoecraft

Kelsey Vaughn

WTA Leadership

Chief executive officer Jaime Loucky

Washington Trails Staff

Magazine editor | Jessi Loerch

Communications director | Doreese Norman

Hiking content | Tiffany Chou

Graphic designer | Jenica Nordstrom

Copy editor | Cassandra Overby

Contributors

Writers | Melani Baker, Tiffany Chou, Loren Drummond, Chloe Ferrone, Joseph Gonzalez, Linnea Johnson, Anne Kang, Jaime Loucky, Erin McMillin, Sarah Nordstrom, Sandra Saathoff, Catherine Vine

Proofreader | Rebecca Kettwig

Designers | Lisa Holmes, Victoria Obermeyer

Trail team | Tiffany Chou, PJ Heusted, Rod Hooker, Shannon Leader, Craig Romano, Catherine Vine, Holly Weiler

The early summer months are always a busy time for WTA, and for everyone who loves trails and the outdoors. This is the time of year when our volunteer trail maintenance work expands in scope across the state, backcountry trips kick off, and partners and communities look for more ways to get outside and enjoy the benefits of time in nature.

These benefits are positively seismic. Some 90% of Washingtonians participate in walking, hiking or other forms of non-motorized recreational trail use each year. This represents a huge contribution to our state’s mental and physical health, as well as our economy. In addition to the benefits to one’s mood and mental health, trail activities unlock some $390 million dollars in health savings by lowering risk of chronic diseases like cardiovascular disease, diabetes and obesity.

Similarly, trail activities and outdoor recreation contribute roughly $8.2 billion dollars and over 81,000 jobs to Washington’s economy each year. Put in perspective, that is 11 times larger than commercial logging and seven times what our state’s many beloved breweries contribute.

Despite all these benefits to individuals, communities and our state’s economy, public lands in Washington and across the country are increasingly at risk. Nearly two-thirds of public lands in Washington are owned and managed by the federal government, which continues to cut funding and staffing to the agencies responsible for managing and maintaining these lands (page 16).

At WTA, we believe that people will choose to protect the places they love to recreate. This is why we work so hard to help people and communities get outside safely, and to connect them with opportunities to give back to trails and public lands.

And we have seen the power of that collective action. Over the past 30-plus years WTA has helped more than 50,000 volunteers complete more than 2.7 million hours of critical trail work. Together we can make a difference.

So as you plan your summer outdoor activities and get outside, please keep speaking up in support of trails and public lands. Because just as we rely on trails for physical and mental health, trails rely on us, and they need us now more than ever.

Washington Trails Association

705 Second Avenue, Suite 300, Seattle, WA 98104

206-625-1367 • wta.org

General information | wta@wta.org

Membership & donations | membership@wta.org

Editorial submissions | editor@wta.org

Meet all our staff at wta.org/staff

Jaime Loucky | Chief executive officer

The U.S. Forest Service, and other national public land mangers, are being set up to fail with major funding and staffing cuts.

Forest roads are a vital link to trails. But years of declining funding have left them in bad shape. WTA highlights 10 roads in need of urgent work.

20 A new perspective

One WTA staffer’s goal to write more trip reports changed her relationship with hiking and the outdoors.

24 From fear to comfort

How a researcher is trying to understand and combat bias in the outdoors.

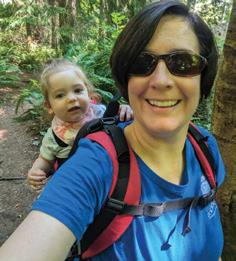

31 Hiking after a big change

After becoming a parent, one trip reporter found a new way to hike. (And hike a lot!)

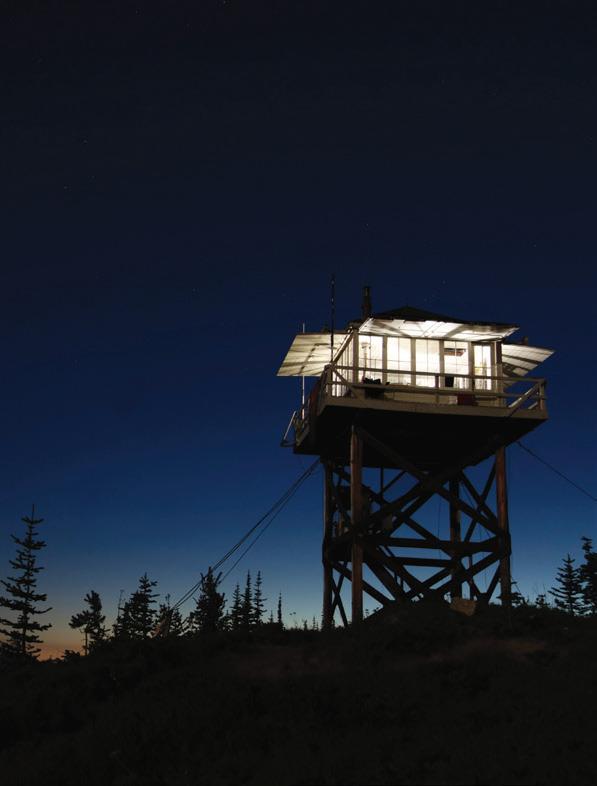

On the cover

saw two out-of-towners having coffee and enjoying the view. Daniel managed to capture the special moment.

The Pass to Pass program helps folks with Parkinson’s disease continue to backpack, with the help of pack-carrying llamas.

Greetings from our chief executive officer and magazine editor.

Three hikers explain why they join WTA’s Hike-a-Thon every August — and why you should join them, too!

Why one assistant crew leader considers WTA work parties her “third place.”

When you backpack, it’s important to know how to store your food safely. That way you — not the bears or raccoons — get to enjoy it.

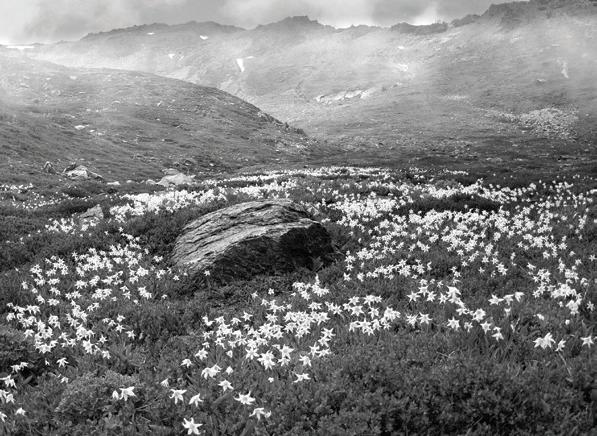

Find inspiration for your next hike.

Washington Trails Association is a nonprofit supported by a community of hikers like you. By mobilizing hikers to be explorers, stewards and champions for trails and public lands, together, we will ensure that there are trails for everyone, forever.

Recently, I went to a book reading with my mom and my aunt. It was a glorious day, and afterwards I joined them for an impromptu walk in an area I hadn’t visited before. Walks with my family are full of regular stops to watch or listen to birds. I’ve been taking walks like this my whole life. I like the way it’s made me think about hiking. The small details are just as important as the miles or the destination. Spending time outdoors like that, slowly and with a lot of time to observe, is good for me. Especially when I feel like I have the least time, it always helps me reset.

I think a lot of hikers know that time outside is good for their mental and physical health. In this issue, we’re focusing on some of those stories. My coworker Tiffany Chou writes about how setting an ambitious goal for trip reports (page 20) helped her connect to hiking in a whole new way — and was good for her mental and physical health. Erin McMillin, who works on our trails team, collected some of the team’s favorite stretches (page 28) for trail work, hiking or, honestly, just before you spend a day at your desk. I’ve been trying them out when I need a break from the keyboard and it’s been lovely. We’re also telling the story of a researcher who’s trying to better understand how people feel safe on trail — with a specific goal of helping people of color feel more comfortable when they head outside (page 24).

I hope you enjoy these stories and the rest of this issue, and that it encourages you to head outside this summer and all year.

WTA was founded by Louise B. Marshall (1915–2005). Ira Spring (1918–2003) was its primary supporter. Greg Ball (1944–2004) founded the volunteer trail maintenance program. Their spirit continues today through contributions from thousands of WTA members and volunteers.

Summer 2025 | Volume 60, Issue 2

Washington Trails (ISSN 1534-6366) is published three times per year by Washington Trails Association, 705 2nd Avenue, Suite 300, Seattle, WA 98104. An annual subscription for a physical copy of Washington Trails magazine is $20. Single copy price is $4.50. Periodicals postage paid at Seattle, WA, and at additional mailing locations.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Washington Trails Association, 705 2nd Ave., Suite 300, Seattle, WA 98104.

I also wanted to let you know about some changes that are coming to our schedule for Washington Trails. Since WTA’s beginnings as Signpost magazine, a vital part of our work has been telling stories of hikers and everyone who loves the outdoors. The way we’ve done that has changed a lot over the years to fit the needs of hikers and WTA. This year, we’re adjusting again. Going forward, as a member, you’ll receive three issues of the magazine each year, in spring, summer and fall, and a calendar with gorgeous photos from our Northwest Exposure photo contest in the winter. And, starting in 2026, you’ll see a refreshed magazine design with a more modern and engaging look and feel as you explore the pages. This change will help us bring you the most important stories and work, while ensuring WTA can maintain a sustainable budget.

What won’t change is our dedication to telling stories important to hikers and to giving you the tools you need to get outside safely, have fun and care for the places you love. As a member, your support is what makes this magazine — and all of the work that WTA does — possible.

Thank you for being here and for supporting trails. And I always love to hear from you. If you have ideas for what you would like to see in upcoming magazines, drop me an email.

Happy hiking!

Jessi Loerch | Washington Trails editor | jessi@wta.org

I’ve hitchhiked scores of times across hundreds of miles. Here’s how you can do the same (legally and responsibly). By Joseph Gonzalez

itch·hike (verb): to travel by securing free rides from passing vehicles. It’s a universal strategy employed by travelers worldwide. And for hikers in rural areas of the United States, it’s one of the cheapest, most convenient ways to travel. The rules are simple: Travelers just need to be near a road and stick their thumb out.

Whether you’ve completed a point-to-point trail and need a ride back to your car or you’re in a pinch and need to travel quickly, hitchhiking is an efficient, cost-effective way to get from A to B. It’s is a rich cultural experience based on the currency of conversation — no cash required. Hitchhiking is practical and also a great way to learn about the locals of the area you’re visiting.

The decision to hitchhike or pick up a hitchhiker is a personal one. There’s never an expectation to pick up a hitchhiker and offer them a free ride. It’s not always safe or legal to hitchhike. Here’s what you need to know.

Washington: Know the hitchhiking laws in Washington, go.wta.org/hitchhiking_rules, before you try to pick up a ride. The short version is:

• It’s illegal to solicit a ride from a public roadway at any place where a vehicle can’t safely stop.

• It’s illegal to solicit a ride where pedestrians aren't allowed, such as on- and off-ramps to freeways.

• It’s illegal to solicit a ride in emergency exits.

• A county, city or land manager might have different hitchhiking rules based on their specific needs.

Mount Rainier National Park: Hitchhiking is legal except:

• Within 0.2 mile of an entrance station.

• Within 200 feet of a concession business, park service office building or visitor center.

• While holding a sign larger than 1 foot by 2 feet.

• At night, on unsafe surfaces or under the influence of drugs or alcohol.

• There is a specific exception for Wonderland Trail hikers to hitchhike between Box Canyon and Reflection Lakes to avoid a hazardous stretch of trail. Check the park’s website for information on current conditions.

Olympic National Park: Hitchhiking is illegal except at visitor centers and trailhead parking lots, and only when vehicles can safely pull off. The Sunrise and Maggie’s pullouts on Hurricane Ridge Road are also legal.

North Cascades National Park: Hitchhiking is illegal in the North Cascades National Park Service Complex. U.S. Forest Service: Hitchhiking is legal.

Washington State Parks: Hitchhiking is legal.

How to hitch a ride

Now that you know where you can hitchhike, next is to learn how. Here are some best practices:

• Plan ahead! You can avoid hitchhiking by creating a foolproof transportation plan in advance.

• Know which direction you’re going before you stick your thumb out.

• Budget your time. The hitchhiking rule of thumb is that it will take you twice as long to hitchhike from A to B than it would to drive yourself.

• Stand in a safe but visible section of a highly trafficked area with plenty of space for a vehicle to safely pull out. Intersections, trailhead parking lots, viewpoints and other areas where cars slow down are your best bet. When possible, stand where there’s space for the driver to get a full look at you before stopping.

• Put your best foot forward! Take off your hat and sunglasses so drivers can see your face. Keep your backpack off and make eye contact, smile (not too much — be friendly, not creepy) and gently wave.

• Keep your group small (three hikers or less) and have the most approachable person in your group stand in front. A sign with the name of where you’re going also helps.

• Do a quick hygiene check. Your ride will appreciate it.

• Secure all loose items in your backpack. Keep your keys, phone and wallet on you, in case your backpack sits separately from you. If you’re tracking with a GPS device, keep it tracking until you are at your destination. Consider keeping your trekking poles or a pocket knife on you for protection.

• When a car stops, walk to the driver’s window with a gentle sense of urgency and confirm the direction they’re headed.

• Express gratitude for your ride! Drivers generally

won’t ask you to pay, but you should expect to entertain them. Folks aren’t just picking you up out of the kindness of their hearts. They’re looking to hear about your journeys.

• Trust your gut: If you don’t feel comfortable, kindly decline the offer for a ride. It never hurts to take a peek at to confirm there are no weapons or open containers of alcohol in the car.

Hitchhiking isn’t just reserved for travelers needing a ride. There are benefits for drivers as well! It can be a way to connect with people you might not have met otherwise.

• Before picking up a rider, familiarize yourself with the rules above, ensure your vehicle has space and that you feel comfortable. You might notice hikers around national scenic trails or famous parks. They’re often easily spottable by their backpacking gear.

• Remember, the people most likely to pick up a hitchhiker are those who have hitchhiked themselves. Keep these elements of selflessness and gratitude in mind for the next time you need a ride or if you want to pick up a hitchhiker. You never know when you might need the favor returned!

by

Share a story

I grew up hiking and backpacking, mostly with my dad, and it’s definitely in my blood. So when I became an adult and rediscovered my love for boots in the dirt, I found the resources WTA provides and became a member soon after. In 2015, I signed up for Hike-a-Thon (H-a-T) as a way to give back to the trails and set goals for my summer hiking. I always kick it off with an overnight trip on Aug. 1. This will be my 10th year, my daughter Jaiden’s fifth and my son Cash’s first. H-a-T is a staple of our summer. Spending time on the trails is so important for me, my body and spirit, continually proving to myself that

Join us online!

I am capable of more than I think. I am grateful for the opportunity to share something I love with my family and friends and to help create respect for the outdoors in my kids.

My Instagram page is a direct reflection of who I am, all of the joy, pain, struggle, goofiness and crazy (just like Washington weather). My goal is to motivate everyone to lace up their boots and explore. We are all different, but a love for the outdoors connects us.

In 2020, I set a H-a-T goal to hike every day. A week in, our daughter (5 at the time) decided it was time for her first

backpacking trip. Two days later, we were off to Watson Lakes before she could change her mind.

Fast-forward to 2024: Our son told me he wanted to go hiking and sleep in the woods. It only seemed right to visit Watson Lakes again, and we all enjoyed swimming, eating wild blueberries and exploring every side trail. On the hike out, one of the best parts for me was the way my daughter used the same motivational speeches I do to help keep her brother hiking and happy!

— Cori Lauerman-Little, @ninjaracerchick

by

A quick look at what WTA is accomplishing on trails around the state

In April, Washington Trails Association, King County Parks, Earth Corps and members of the public celebrated a new trail system at the Glendale Forest in the North Highline area. King County acquired this 5-acre parcel of land in 2020 to help increase accessibility to trails for neighborhoods that have had limited access to green spaces. WTA hosted more than 80 work parties at the space, helping to create a more welcoming and accessible trail system. Micki Kedzierski (in blue hat), who led and participated in 26 work parties at Glendale, was excited to celebrate with some of the youth volunteers who worked there, too.

In Mount Rainier National Park and Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument, access is limited by road closures and construction work this summer. If you’re planning to visit either of these areas, be sure to check trip reports and conditions before you go. And check out our information for the areas at wta.org/ rainier2025 and wta.org/sthelens2025.

This spring, Washington Trails Association volunteers have been working with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife to provide trailhead outreach and education at a trailhead at Ancient Lakes, which is an hugely popular day hiking and backpacking destination. We recruited 17 volunteers for this program, most of whom are new to WTA, to do trailhead outreach at the Lower Ancient Lakes Trailhead on weekend mornings in April through the end of May. The volunteers talked to hundreds of recreationists, including day hikers, backpackers, mountain bikers, equestrians, boy and girl scout troops and college outdoor groups. The main goal of this outreach is to teach folks about how to recreate responsibly and Leave No Trace principles, in particular reminding people to pack out their trash, stay on trail and respect the wildlife that live in the area.

The Washington Department of Health is using WTA trip reports to help track the distribution of ticks, wta.org/ticksdata This information can help determine the risk for tick-borne disease across the state. If you encounter ticks on trail, please mention it in a trip report!

HIKE-A-THON

By Catherine Vine

Every August, hikers come together to support Washington Trails Association during Hike-aThon, our annual community fundraiser. Throughout the month, participants hike, share stories of their outdoor adventures and raise funds that directly support trails in Washington. They also have the opportunity to earn fun prizes while enjoying time outdoors. We held our first Hike-a-Thon in 2003. Since then, more than 3,600 people have hit the trail during the event to help power our work.

Hike-a-Thon is more than just a fundraiser; it’s an opportunity for participants to join a community, spend time outdoors and make a difference for the trails they love. We talked to a few Hike-a-Thoners to learn why they participate and what they enjoy about this event.

Yoshiko has participated in Hike-aThon for the last 3 years and is also an avid trail work volunteer. In fact, she wrapped up last year’s event with a multiday log-out trip to Dorothy Lake in the Snoqualmie area. Yoshiko was pleasantly surprised to discover how her friends and family rallied around her during the fundraiser.

“I was very grateful to learn of their kindness and support,” she said.

Yoshiko chooses to raise funds for WTA during Hike-a-Thon because “WTA supports our local community in a positive way. They promote outdoor activity, educate people on how to protect our lands and provide important information.”

She also enjoys participating in the bingo challenge during Hike-a-Thon. Last year, she was able to check off three bingo squares in one trip to Glendale Forest — talk about efficiency!

Hike-a-Thon

Want to join the Hike-a-Thon community this year?

• Register starting on June 16.

• Hike from Aug. 1 to 31.

• Share your trail stories and connect with other hiking enthusiasts in the Hike-a-Thon Facebook group.

• Win prizes and celebrate your achievements.

• To register, or for more information, go to wta.org/hikeathon

Owen loves that Hike-a-Thon supports things like WTA’s trail work.

Owen is an assistant crew leader and dedicated trail work volunteer. He first joined Hike-a-Thon in 2021 after hearing about it while on a trail work party.

“I figured if I was going to be hiking anyway, I might as well raise some money for WTA while doing it,” Owen said. “Selfishly, from a volunteer crew leader perspective, I wanted to help pay for more trail crews!”

Both Hike-a-Thon and trail work provide Owen with opportunities to be outside.

“Being outside helps me reduce the stress of everyday life, get exercise and see the incredible beauty around Washington state,” he said.

“Working as a volunteer crew leader provides the opportunity to introduce new people to trail work and how rewarding and fun it can be.”

One of Owen’s favorite memories of Hike-a-Thon is from his first year. He and his wife tried to only hike in places they hadn’t been to before, so they visited lots of new trails and enjoyed post-hike lunches at new restaurants. Owen typically hikes around Kitsap County, but he also enjoys the trails in the Olympics and the Issaquah area. He noted that he should probably start counting all his miles hiking to and from trail work sites with tools, and we agree!

Owen is excited to continue participating in Hike-a-Thon.

“I love helping the mission of WTA through this fundraiser, and I have fun with Team Olympic Rowdies to try and beat our (mileage and fundraising) totals from previous years,” he said.

“Miles the Marmot T-shirts don’t hurt, either.”

When Kris signed up for her first Hike-a-Thon in 2021, she did so with some trepidation. It turned out that she loved spending a whole month focusing on all the activities associated with hiking.

“Participating in Hike-aThon helped me balance my priorities and goals,” she said. “It reminded me of the amazing natural beauty that is unique to Washington and the trails that make that beauty accessible.

I am always amazed at the range of individuals and groups on the trails, from school groups, to families carrying kids in their backpacks, to older folks like myself taking advantage of every flat part of the trail. The trails truly are for anyone.”

Kris participates in Hike-a-Thon as part of the family team Changes in Latitudes, Changes in Attitudes, which spans three generations.

“Just the act of coming up with a name and planning some hikes together (united us) around the shared love of our family and the spectacular and diverse beauty of Washington state,” Kris said. “And participating as a team introduced the smallest bit of competition that pushed us — or at least me — to hike on those days when I could have just sat at home. Hike-a-Thon is now part of our family history. Passing on the legacy of loving and caring for our trails and the natural environment they traverse is as good as it gets!”

Kris loves introducing people who are new to hiking or to Washington to our amazing trails. When she worked at the University of Washington, she realized that many students never got out of the city, so she started organizing day hikes. Kris still hikes with some of those students, including Andrea Michelbach, who is now WTA’s director of development.

The future of roads that connect us to trails and the outdoors

By Melani Baker

orest roads are an essential connection between hikers and our national forests. These roads connect us to a variety of outdoor experiences — from barrier-free trails and family-friendly hikes to multiday remote backpacking trips.

But the U.S. Forest Service has approximately 15 percent of the budget it needs to maintain the 90,000 miles of forest roads in Washington and Oregon.

However, key parts of the Forest Service road system are eroding, restricting our ability to get to hiking trails across the state. Through WTA’s public survey in August 2024, we heard from 1,271 hikers about your experiences on forest roads. We also heard about cases where road conditions kept you, and your family members, from reaching some of your favorite outdoor destinations in Washington state.

Your feedback, along with information from WTA’s trail maintenance staff and partners at the Forest Service, helped us create a report of the top 10 forest roads in our state that need funding to preserve, or regain, public access to the outdoors. This report will help WTA advocate for investments needed in our national forests and make the case for funding and staffing for our federal public lands. Thanks to your input, this report will serve hikers for years to come.

1. Road to Slab Camp Creek

2. Deadhorse Creek Road

3. Hart’s Pass Road

4. Road to Iron Gate

5. Road to Sullivan Mountain

6. Sloan Creek Road

7. Chiwawa River Road

8. Middle Fork Snoqualmie Road to Dingford

9. Cayada Creek Road 10. Silver Star Road

of maintenance can leave roads undrivable, cutting off access to national forests. Roads to Silver Star (top) and Dingford (right).

What hikers said about roads

92.6% of hikers surveyed reported that road conditions were a factor, or a main factor, in determining where they hike.

66.6% of hikers surveyed reported that, in the past year, road conditions caused them to change their hiking plans.

By Anne Kang

or many people, there are three important social places in our lives: home, work and a third place. The third place is somewhere an individual can relax and meet new people: church, book club, the gym. Third places are safe environments where you can learn, grow and find community. Some people — like me — consider WTA work parties their third place.

I have been volunteering with WTA for almost 2 years and have participated in close to 200 work parties. The community of people at work parties keeps me coming back. Every work party starts off with three WTA rules centered around safety, fun and work. Organized intentionally to place work last, these three rules have led to a third place where people can gather and find community as a crew with a common goal. Once connected, they focus on completing the

project, but there is never pressure; the work parties are always fun, and the volunteers are friendly.

I love seeing familiar faces on trail. It brings me joy to see faces light up when volunteers see me at the start of a work party. During the day, I like to joke around with the crew leader and other volunteers, especially if I haven’t gotten to catch up with them in a while. I feel safe being around the people at WTA. It’s a place where I can relax and enjoy the beauty around me.

But what I love most about coming out to a work party is the work we accomplish. Over the many work parties I have participated in, I’ve learned that sometimes the beauty of working together isn’t apparent after only one work party. I like to remind new volunteers that the quality of work is more important than the quantity.

For instance, the majority of the work at the Tiger Mountain summit is tree root removals. After spending many work parties there, I’ve started to consider each root ball I work on as an opportunity to meditate. Each one is a never-ending puzzle, so I stay focused and calm as I clear dirt away. It can take a while, but at the end of a work party, the sense of protecting our public lands and working with other people gives me a warm, fuzzy feeling.

As an assistant crew leader, I also get the opportunity to work with volunteers of all ages, including kids as young as 10 years old and with WTA’s amazing youth crew leader, Kaci Darsow.

Recently, the youth program spent several months working on different sections of West Seattle’s Longfellow Creek Trail. Crews did brush work, removed organic material from the trail, and re-graveled the tread, using a form to keep the trail edges clean and compacting the gravel. It was rewarding to see the older kids work with the younger kids on using the forms.

The quality work our youth volunteers can do never ceases to amaze me, and it’s something other users notice too. During the project, people living in the nearby community said they were grateful for the work we had done on the trail to make it more accessible for everyone.

Day work parties give me the opportunity to meet a wide variety of volunteers. However, backcountry response team trips bring together people from all parts of the state, and after volunteering for a while, I decided I wanted to try one.

Working in different landscapes helps me expand my knowledge of trail maintenance while learning new things about the plants and trees in the area. So in 2024, I registered my husband and myself for a trip to Columbia Mountain. It was in February, and I was excited to try out snow camping.

It was going to be a challenge; we were tasked with working all the way to the summit. However, due to weather and time constraints, we weren’t able to reach the top of the mountain. We were disappointed not to summit but had a great time anyway. This year, we tried again. We came back to Columbia Mountain, and it was a dream come true. We bagged the peak and got

I feel safe being around the people at WTA. It’s a place where I can relax and enjoy the beauty around me.

— Anne Kang

a lot of work done. It was rewarding to see that the work we had done last year had held up, and as we got higher up the mountain, the view was more rewarding. I felt determination running through me. A moment of pure bliss hit me when I saw that the climbing was done and I had made it to the top. Physically I knew I could do it; mentally the willpower was there. One volunteer from previous year’s crew was there to share the success with me. Moments like this are why I love being part of the community at WTA.

WTA’s focus on safety, fun, work and a shared love for trails creates a community in which I’ve had fulfilling friendships and countless memorable experiences. Creating and maintaining trails brings me pleasure, but the memories created make WTA a fantastic organization to be part of. WTA created a third place for me, and I encourage you to come and find a place for yourself!

The administration’s actions are making it nearly impossible for the U.S. Forest Service and other land managers to do their jobs, leaving hikers less safe and reducing access to public lands.

By Jaime Loucky

Access to public lands, including for recreation, is rooted in the understanding that public lands belong to — and benefit — everyone. Right now, though, national public lands — and all of the benefits they provide to people’s health, the economy and the environment — are at risk. The agencies that manage national public lands, including the U.S. Forest Service, are facing a crisis of funding and staffing.

Across the nation, the Forest Service has lost some 5,200 people since February, leaving the agency severely understaffed. National forests in Washington have lost about 25 percent of their staff, and that lack of adequate staffing is going to be obvious as you get outside this summer.

The Forest Service is being set up to fail — it cannot effectively do its job under these conditions.

In Washington, the Forest Service manages more public land than any other agency. More than 9,000 miles of trail cross those lands, including in some of our state’s most iconic places. But those places need the trusted, expert staff of the Forest Service to help steward them, so they will still be iconic and healthy in the years to come.

Without Forest Service employees, we won’t have maintained forest roads, trails, bridges or signage. They help ensure human waste is dealt with appropriately. They fight fires and respond to emergencies. They patrol popular recreation areas and remind visitors how to visit responsibly. They staff visitor centers and give out expert information. These are talented, knowledgeable people who have devoted their careers to serving the public and maintaining the landscape we know and love.

In many places this summer, those staff simply won’t be there. In the Enchantments, a beautiful and delicate alpine area where managing trails, the flow of visitors and backcountry toilets is an enormous job, the number of rangers has been cut from 13 to one. These unprecedented cuts make hikers

and other recreationists less safe in the outdoors and put our landscapes at greater risk of damage. With fewer Forest Service employees, visitors to forests are going to be at increased risk from wildfires and other emergencies. They will also have less access for recreation. Hikers can expect trails blocked by logs and overgrown with brush, locked or less-frequently cleaned toilets and overflowing trash cans. Maintenance work, like repairing broken bridges, will remain undone.

While WTA and our dedicated volunteers can help close the gap on some trail work, we can’t do that work without our partners at the Forest Service. They identify high-need areas, coordinate across organizations, provide pack-animal support and materials and have a long-term understanding of issues that need to be addressed.

WTA is committed to stepping up, but we and other nonprofits are struggling with the lack of clarity, reduction in staff and frozen funding. The administration’s many changes mean we don’t know if or when federal funding will be available to support our work — or which of our long-time federal partners will still be with the agency. Even now, we often have a hard time getting someone on the phone.

We are doing what we can to plan through the chaos, and to prioritize work that addresses the biggest needs in national forests. But so much of the work that the Forest Service does can’t be replaced by volunteers. Employees have scientific knowledge and expertise that goes far beyond what any nonprofit could do. And the public trusts their expertise. In addition to providing information to hikers, managing waste and doing trail work, they combat invasive species, conduct research to determine if wildlife populations are healthy and protect public lands from wildfires. Forest Service staff balance conservation and resource use needs, providing longterm benefits for everyone.

The Enchantments are one of many areas being put at risk by massive reductions in Forest Service staffing and funding.

Public lands are a public good

National public lands are one of America’s best ideas — selling them off is one of the worst.

In May, the U.S. House Committee on Natural Resources introduced legislation to sell off thousands of acres of public land in Utah and Nevada. Ultimately, that provision was removed from the House bill, but it’s alarming the idea made it that far. Selling public lands is deeply unpopular. A majority of people in the Western U.S support protecting public lands, regardless of political affiliation.

Maintaining public lands is an investment in the long-term health of our natural landscapes and in the communities that use them. Public lands support clean air, clean drinking water, wildlife habitat and climate resilience. Selling them off, on the other hand, prioritizes quick profits and makes it harder for the public to access land.

Access to public lands is a vital part of living in Washington, and it generates enormous economic and health benefits to Washingtonians. Many people live here because they enjoy the quality of life provided by access to a diversity of beautiful outdoor places. And that time

in nature has measurable benefits to our physical and mental wellbeing. Trail use results in over $390 million in health savings each year in Washington state.

Additionally, outdoor recreation contributes $1.2 trillion to the national economy, including $22.5 billion to Washington’s economy. It also supports over 120,000 jobs in our state, and is an important part of the livelihoods of people in rural communities.

Even if you never visit public lands, you are benefiting from them. The administration’s efforts are putting all of these benefits at risk.

This summer, you’re likely to see the impacts of these federal agency cuts on national public lands. If you see trash, closed visitor centers, downed trees or other issues on public lands and trails, it won’t be because those spaces are badly managed. It will be because the people who maintain those lands are being forced to do their jobs with a tiny, everdecreasing fraction of the staffing and funding that they need. When you see these folks working, please show them patience and respect.

Be an advocate

Join WTA’s Trail Action Network, wta.org/tan, to know when you can speak up for national public lands.

Support WTA’s work Members provide critical funding to help WTA fill on-the-ground gaps and advocate for long-term solutions. If you recently joined, gave early or increased your giving, thank you.

Amid all of these challenges and uncertainty, we can guarantee you that WTA will keep speaking up for better funding for the Forest Service and other federal land managers. And we’ll keep working to fill the gap where we can.

National public lands play a crucial role in preserving our natural and cultural heritage, fostering public health, supporting local and rural economies and contributing to the fight against climate change. And, if we want them to remain a space of healing and inspiration, clean air and clean water, we all have to speak up.

You can help by making your voice heard. Write to the administration or the editorial board of your local newspaper, talk to your friends, make a case for the value of these lands wherever you can.

Join WTA’s Trail Action Network, wta.org/tan, and we will let you know when there’s a specific moment where you can lend your voice.

We need to work together to defend the public lands we love, and the agencies that maintain them. Now is the time. These landscapes need our support now more than ever.

By Loren Drummond

With national public lands stretched thinner than ever on staff and funding, hikers and trail users can help by taking extra care of the lands we all love. Here are a few ways you can help our shared lands and the people and organizations who work hard to protect them.

Flex your planning and packing skills. It might be harder to know what conditions you’re getting into this year, especially if no one has posted a recent trip report. Choose a trip you feel confident everyone in your group can do safely, and go with a backup plan. Pack more than you think you need and plan for anything. You always intend to bring the Ten Essentials — this is the year to actually do it.

Adjust your expectations. Once you arrive, expect fewer trailhead services. Bathrooms may not be serviced as frequently. If parking is full, it’s more important than ever to head someplace else rather than snarl up roads for

emergency responders. On trail, anticipate more challenges — like trees down or bridges out — on familiar trails. If you get into trouble and need to call for help, there are fewer people to support search and rescue operations this year, so do everything you can to prevent accidents.

Be kind. The land managers left working on national public lands are doing their best to maintain trails and facilities while dealing with the challenges of reduced resources. Hikers and other public land users are navigating these changes, too. Show respect and patience for each other — especially for the folks working so hard to protect the water, habitat and trail experiences on our public lands.

Set the example of respect. See if you can go beyond the Leave No Trace ethos and leave the landscape better than you found it. Pack a trash bag and pick a few things up on your hike. When it’s no one’s job, it’s all of ours. (Plus, when

there is less visible trash, people are less likely to litter.) Don’t feed wildlife, secure your food and keep pets on leash. Your example will set the tone for everyone.

Volunteer. You’re already someone who cares deeply about public lands and supports the work of Washington Trails Association. If you want to help out on trails, volunteer with an established trail maintenance or restoration organization. (Ad hoc trail maintenance by individuals can actually make things worse and use up limited resources.)

Advocate. Sound a steady drumbeat for trails with your federal representatives about the value of public lands.

File a trip report. This is a year when trip reports are going to matter more than ever, even on popular trails. So, if you’ve been meaning to post one, there’s no better summer to take a few minutes after every hike and share the good, bad and ugly you’re spotting. Hikers — and land managers — are counting on you.

I made a goal to write 100 trip reports in a year. I didn’t expect it to change the way I thought about hiking.

By Tiffany Chou

Photos from some of my more than 300 WTA trip reports.

’ve always been a numbers person. I like keeping track of stuff.

When I first discovered hiking, I was drawn to the stats; I even made a spreadsheet tracking mileage and elevation gain of my hikes. Physical activity always kind of scared me (I hated P.E. in school; that carried into adulthood), but I fell in love with hiking. In a way, those stats showed me “what I could do.” My attachment to the stats meant “hiking” had a specific definition to me, bound to a trail’s distance and climb and its proximity to the mountains.

I found WTA’s trip reports and used them extensively as a newbie hiker to know where to go and to get up-to-date information to stay safe. Because of that — and my love of tracking things — I wrote my first trip report about my first-ever solo hike, and I never stopped writing.

A trip report goal … and then a second one

By the start of 2024, I’d written 167 trip reports.

I’d been inconsistent with both hiking and writing trip reports for a while due to some health issues, but I had been gradually getting better, so I made a trip report goal to get outside more.

The goal: get my 200-trip-report badge by the end of the year. I needed to write 33 reports.

I started going on a hike about once a weekend. It felt nice to wear down my trail runner tread and click that trip report “submit” button. I could tell getting outside was doing me good, so I started planning hikes with friends when we’d normally get coffee or dinner. My friends varied greatly in the hikes they enjoyed, and our hikes ranged from lowkey park rambles to intense huffing-andpuffing excursions.

I hadn’t written many trip reports for my local outings in the past. For some reason, it hadn’t felt “worth it,” like maybe folks wouldn’t find it useful for me to share conditions on my urban hikes.

But as the year continued, I’d visit local green spaces — many new to me — and

they felt too delightful to pass up writing trip reports for.

A vivid waterfront sunset. A bounty of springtime blossoms. A tiny turtle on a log. It seemed almost a waste not to post trip reports on these hikes, if only because I wanted to share the pictures I’d taken.

So, I did. I wrote about my hike — after all, shouldn’t everyone know it’s time for flowers or mini turtles? — and proudly shared my favorite pictures. Over time, I discovered that folks did get useful information from my urban trip reports. Someone liked my pictures of colorful blooms at the Washington Park Arboretum. Another hiker asked which lake separated Mount Rainier from Seward Park. Someone else recently thanked me for sharing a map of the West Duwamish

Greenbelt, which can be confusing without one. If the “helpful” votes have been any indication, other hikers were getting something out of these reports (if only some nice pictures).

Once I started writing trip reports for my local hikes, it didn’t take long to hit my trip report goal, so I made a bigger goal — posting 100 trip reports in 2024.

As the year continued, I kept finding special moments on my local trails I wanted to remember. A heron enjoying the beach. A perfect reflection of fall colors in a clear lake. A night hike (and I generally don’t love hiking in the dark).

And something interesting happened — a subtle, but significant, mental shift.

Before, when I’d plan my weekends, my goals would revolve around my original

Learn how to file your own trip report at wta.org/postreport.

definition of “hiking,” ruled by the high country, long distances and steep slopes.

But that trip report goal — combined with my newfound appreciation for urban hiking — focused me on just getting outside as much as possible. Concentrating less on big hike stats also slowed me down; I took more breaks and paid more attention to everything around me. All of that, in turn, opened up my definition of a “hike.”

With each trip report I wrote, I became more eager to add new parks and urban forests to the growing list of places I’d been. Instead of consisting only of hikes with trailheads hours away on dusty forest roads, my trip report bank became peppered with hikes a 15-minute drive or bus ride away, parks I’d lived near for years but never visited and city trails I’d seen signs for but never stopped to hike on. For those who regularly enjoy our local green spaces, I know I’m late to the game. But, as they say, better late than never. Sometimes I’ll log into my WTA account and scroll through my reports, just to remember the cool places I’ve visited, the beautiful things I’ve seen. It’s all cataloged and organized for me and makes flipping through my old adventures so easy. Oh, and about that trip report goal — on my birthday in early December, I wrote my 100th trip report of 2024. I ended the year with 107.

Nowadays, I consider myself a more “well-rounded” adventurer — I’m grateful for how trip reports have slowed me down and changed the way I think about the time I spend outside. I still love the type 2 fun of a steep climb in the mountains, but I also love visiting an unfamiliar park and exploring a pocket of urban greenery. I often pull up WTA’s Hike Finder Map to find new hikes close to home and revisit local parks when feeling tired or down. I’m more mindful and take more breaths and breaks, and “hiking” these days includes more cityscapes and shorter drives.

And I’m always excited to post a new trip report because it’s another memory I can file away to look back on. I recently wrote my 300th trip report. I look forward to writing my 500th trip report. And my 1,000th. I just know I won’t tire of writing trip reports — whether for a multiday backpacking trip or a post-work neighborhood walk — anytime soon.

Tiffany Chou’s love of hiking has taken her across thousands of miles and hundreds of journal entries, over countless Washington trails and a thru-hike of the Pacific Crest Trail. She works on WTA’s communications team, telling the stories of hikers and trails.

PRESENTING PARTNER | $100,000+

Find out if your company matches charitable gifts. Your donation could go twice as far! To learn more about supporting WTA’s work, email amichelbach@wta.org.

$50,000+

$25,000+

$10,000+

$5,000+

$2,500+

Hiking isn’t fun or beneficial when you face discrimination on trail. Here’s how one researcher is shaping a more welcoming outdoors for BIPOC recreators.

By Linnea Johnson

rowing up, Dr. Ian Munanura loved spending time outdoors. In the forest, he found peace, fun and revitalization.

“The forest has always been a place for me to rejuvenate, to renew myself,” he said.

As a researcher, Ian spent 15 years working and recreating in tropical forests throughout subSaharan Africa. When he arrived in the U.S. he was eager to explore forests in his new home, but his carefree experiences outside were short-lived.

“I realized shortly after (I arrived) that (the outdoors here are) not safe for me because of how I may be perceived. I started learning about how people like me may be perceived as a risk or threat,” Ian said.

The more Ian learned about the pervasiveness of racism in American culture, the less safe he felt recreating alone. He hiked less and only felt comfortable camping if he was with a White friend.

“I do research in these spaces, but I can’t enjoy them the way others enjoy them,” Ian said.

Now, as an associate professor at Oregon State University in the department of forest ecosystems and society at the College of Forestry, Ian is studying this very phenomenon. He’s working to document how fear of threats in forests creates barriers to recreation — and therefore barriers to the myriad health benefits of time outdoors.

I do research in these spaces, but I can’t enjoy them the way others enjoy them.

The recreation gap

According to Ian, people of color make up more than 39 percent of the U.S. population — yet Black, Indigenous, Latino and Asian people combined account for only 5% of people who recreate in public forests.

This means that there is also a gap in access to the health benefits of

— Dr. Ian Munanura

outdoor recreation, benefits which are broadly supported by scientific evidence. According to a study by the Washington Recreation and Conservation Office, physical activity outdoors is associated with a reduced risk of chronic illnesses like heart disease, hypertension and diabetes. Broad evidence indicates

that time in nature helps ease anxiety and improve mental health.

Due to structural racism embedded in the American health system and other systems, Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) populations are disproportionately affected by chronic illnesses and mental health challenges. Thus it is especially important that these groups have access to the many benefits of nature.

“This is a problem that is affecting a huge number of the U.S. population,” Ian said. Over the past three decades, researchers

have worked to establish the root causes of the underrepresentation of BIPOC individuals in outdoor recreation. Most research has explored individual barriers, like fear of animals, and structural barriers, like the cost of passes, but hasn’t addressed racism headon. Ian’s research, on the other hand, seeks to document how stress and fear related to racial discrimination prevent BIPOC individuals from recreating at a disproportionate rate. He’s surveying folks from diverse racial backgrounds in Oregon and Washington to understand what factors (if any) prevent them from

It’s on all of us to ensure that trails are welcoming places.

Many BIPOC folks choose not to engage in outdoor recreation based on the potential for threat.

going outside. He’s also exploring which factors increase respondents’ ability to withstand or overcome those stressors and recreate anyway.

Bias on trail tests hikers’ resilience

Whether or not someone has previously experienced a racist interaction on public lands, Ian says that racism is so prevalent in American culture, media and policy that many BIPOC folks choose not to engage in outdoor recreation based on the potential for threat. Infamous evidence of discrimination — such as the 2020 video of White dog walker Amy Cooper calling the police with false accusations about Black birder Christian Cooper in Central Park — erodes the perception of safety outside.

Additionally, to reach many public lands, visitors must drive through predominantly White suburban or rural areas that may not feel safe — especially with the knowledge of hate crimes like the 2020 murder of Ahmaud Arbery, a Black man who was pursued and murdered by three White men while jogging.

Unfortunately, Washington is not immune to racism in the outdoors. At WTA, we hear from our community and read in trip reports about interactions that leave hikers feeling threatened or unwelcome.

In a 2021 article for WTA, South King County-based hiker and facilitator KJ Williams shares candidly about her own sense of safety on trail.

“As a Black, queer woman who hikes, I am always concerned about who I might run into on trail … What is my number one fear? Not animals or insects but WHITE PEOPLE! I am constantly on guard. I don’t allow our 10-year-old to scamper ahead for fear of what might be done or said to her before I catch up. It is nerve-wracking, yet the sense of serenity from being outdoors and my need for physical health propels me to continue,” KJ said.

Unfortunately, KJ’s concerns were affirmed by an interaction on her first camping trip, where a White woman nearly hit KJ and her group with her car and would not apologize or engage with them after they called attention to her dangerous behavior.

In another example, a hiker of color (who preferred to remain anonymous) wrote in a WTA trip report about a discriminatory encounter on a popular trail. The trip reporter asked a White hiker to leash her dog, but she refused. The hiker with the dog asked, “Where are you from that makes you think you can ask me to leash my dog?” This language was harmful because it implied that the trip reporter did not belong — which is unacceptable anywhere, let alone on public lands we all share.

KJ Williams and her daughter enjoy the sunshine on the Oyster Dome trail.

The sense of serenity from being outdoors and my need for physical health propels me to continue.

— KJ Williams

If you need to interrupt discrimination on trail, KJ recommends taking one or more of these steps, from Right to Be’s “Five Ds of Bystander Intervention:”

Distract: Draw attention away from the victim.

Delegate: Include a third party.

Document: Use your phone to record the incident.

Delay/Debrief: Wait for the situation to end, then check in with the victim.

Direct: Directly and intentionally engage the perpetrator of the bias.

Read more at wta.org/ interrupt_bias.

Where do we go from here?

No single government agency, organization or hiker can address racism in the outdoors alone. But there are things all three can do to make public lands safer.

By identifying factors that contribute to — or detract from — BIPOC hikers’ sense of safety, Ian intends to provide land managers with evidence-based recommendations to create more inclusive spaces.

“I hope my work helps to point recreation managers to potential solutions that get as many forest-fearful people into forests (as possible),” Ian said.

Here are a few of Ian’s recommendations:

• On trailhead signs, include imagery of diverse hikers and provide information in multiple languages.

• Post signage with tips to help hikers recognize, overcome and interrupt bias.

• Adjust shared spaces to serve people with various cultural norms. For example, to make a park more welcoming to people from communal cultures, provide tables and shelters to facilitate celebrations.

Ian

For those individuals who claim allyship with people of color, we are calling on you to be disrupters.

— KJ Williams

Of course, land managers can only make strides toward inclusion when they have the funding, staff and support to do so, Ian says. Due to recent cuts and the prohibition of diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives, federal land managers are severely limited in their ability to do this work.

That means it’s especially important for individuals and nonprofits to do everything in our power to build a more inclusive outdoors. One way hikers can help other hikers feel safer in the outdoors is by intentionally being welcoming.

“If you meet, you smile! That’s welcoming for me. If you meet, you converse. For example, ‘Did you pass by this trail?’ ‘I just saw a beautiful bird.’ Such conversations reduce bias and help me feel

WTA works to help make the outdoors more welcoming for everyone. Learn more about our work, from training crew leaders on how to interrupt bias on trail to loaning out gear through our gear lending libraries, at wta.org/ trailsforeveryone.

included … like someone recognizes my presence in this space,” Ian said.

Beyond contributing to a welcoming atmosphere, hikers can prepare in advance to take action when we observe bias, discriminatory language or unsafe behavior on trail, KJ says.

“Access to outdoor space and the freedom and safety to navigate those spaces without fear of harm is the responsibility of all of us — but we are not all treated equally … For those individuals who claim allyship with people of color, we are calling on you to be disrupters focused on changing whatever space you occupy,” KJ said.

At WTA, we believe that outdoor recreation and its health benefits are rights that all people should have access to. We hope you’ll join us in building a reality in which trails are safe and welcoming for everyone.

Start the day off right, on trail or at home, with these short warmups.

By Erin McMillin

Whether you’re going for a hike or joining a WTA trail work party, taking time to warm up your body is one of the best ways to prevent injuries.

Here are some stretches developed by professional trail workers that you can try on your next trail day. They’re also a nice way to start your work day or take a break to move.

This sequence of movements is designed to encourage smooth movements of your nerves, which can alleviate pain caused by tightness or inflammation. This sequence was developed by professional trail crews at the Montana Conservation Corps.

We recommend you flow through three circuits of these six movements. Go at your own pace, using your breath as a guide. Try to keep a neutral spine through all movements, meaning don’t arch or stretch your back.

Prayer hands (exhale)

Push your palms together in the center of your chest. Keep elbows parallel with the ground. Bow your head to your hands.

Shoulder stretch above head (inhale)

Interlace your fingers and bring them above your head with palms facing up. Keep your chin parallel to the ground and keep your shoulders relaxed.

1 5 7 6 4 2 3

Slowly lower your hands outward with arms extended until they are parallel to the ground. Keep your hands flexed with fingers to the sky. Keep your shoulders relaxed.

Radial nerve glide (inhale)

With arms outstretched and parallel to the ground, tuck your thumbs into your palms then roll each finger into your hand one by one to make a fist. Try to focus on moving one finger at a time.

Chest stretch behind back (exhale)

Stretch your arms behind your back and interlace your fingers or grab one hand with the other. It’s OK if your hands touch the back of your body. Move your shoulders back to open your chest. If you feel pain in your lower back, relax and re-establish a neutral spine.

Forward fold (3 breaths)

Release your hands and hinge at your hips to bend forward. Relax your head and neck. Keep your knees slightly bent, and let your arms hang or place your hands behind your legs for stability.

See these stretches online at wta.org/ stretches.

Slowly rise to standing and begin the sequence again. Repeat 2–3 times.

WTA staff favorites sequence

Neck circles

Slowly rotate your head clockwise and counterclockwise. As you rotate, remember to breathe and keep your shoulders relaxed.

We asked our staff crew leaders how they warm up for a day of trail work. Here’s a collection of their favorite stretches that you can use to wake up your whole body, especially the muscles used most for trail maintenance.

Shoulder crosses

Cross one straight arm across your chest and use the other hand to pull it closer to your chest. You should feel this stretch in your shoulder and your back. Repeat with the other arm.

Hand and wrist stretch

Extend one arm straight in front of you with your palm forward and fingers to the sky. Use the other hand to gently pull your fingers back toward you to

stretch your hand and wrist. Then gently pull your thumb backward. Repeat with the other arm.

4 2 3

Keep your legs shoulderwidth apart with feet facing forward. Keeping your hips forward, rotate your upper body 90 degrees to each side. For an extra stretch, grab on to a tree trunk behind you to rotate more than 90 degrees.

Raise one foot and slowly turn your foot clockwise and counterclockwise. 1 5 7 8

Standing on one leg, elevate your other leg and rest your ankle on the standing thigh to create the shape of the number four. Bend your standing knee to lean into the stretch. Repeat with your other leg.

6

Extend one leg in front of you, resting your heel on the ground and elevating your toes. Bend your other knee and hinge forward at your waist until you feel the stretch in the back of your leg. Repeat with your other leg.

Step forward with one leg while keeping the other leg extended backward. Keep your front knee above your ankle, and do not bend your knee more than 90 degrees.

I discovered hiking as an adult and fell in love. But I lost track of that passion after parenthood. Here’s how I found it again — and how I’m getting out more than ever.

By Sarah Nordstrom

I moved to Washington fresh out of college, and was enamored by the beauty. In 2014, a friend invited me to go hiking. She was the type of person to jump into something new headfirst and I was ready for an adventure. She took me to Dosewallips State Park and we explored in our jeans and sweatshirts. We loved it so much that next we went to Green Mountain (Gold Creek Trail) and Fremont Lookout. I was hooked.

As the years passed, I pored over WTA trip reports and Facebook groups, finding so many beautiful places. As someone who was usually a homebody, hiking got me fresh air and the mountains gave me peace from day-to-day stresses. I worked up to completing hikes like Mailbox Peak, summiting Mount St. Helens and scoring an Eightmile Enchantments permit. And then I got pregnant and my focus shifted. I hiked a little while I was pregnant, but then my son was born, COVID struck and I returned to homebody status. I occasionally scrounged up the energy to hike with a friend, dragging my kid along in my notso-comfortable hiking pack. Yet I missed the hobby I had treasured.

About a year and a half ago, now a mom of two, my work schedule changed, giving me more free time with my daughter while my husband was at work and my son was in preschool. I started taking her on walks through the neighborhood in the backpack, and then trails near home. I enjoyed it so much that I started taking both kids to smaller local trails, like Theler Wetlands and Guillemot Cove, that I never visited as a childless adult with only big alpine views on my mind.

While I was enjoying my return to hiking and sharing that love with my kids, I was regretting that I never fully dove into backpacking. I remember standing in the shower, mourning the lost opportunity and feeling sorry for myself, when it dawned on me that I could just go backpacking with my kids. We had already been car camping as a family,

and the kids had the stamina for short hikes. I just needed to decide I wanted to do it — and then figure out how to make it happen. And I did. I purchased the gear I needed for my 4-year-old son, and took him on his first, second and then third backpacking trips. Soon, we were both hooked!

By the end of that year, I realized we had done 40-something hikes. I was so surprised and proud of that number.

“That’s not that far off from 52,” I thought to myself, remembering the hikers I knew who had completed the 52-hike challenge. “I bet we could do that.”

Now, my kids, David and Holly, are 5 and 3. And here we are, on week 20, and I’m 22 hikes in, David is at 21 and Holly is at 18. And my daughter will get her first backpacking trip this summer.

Along the way, I’ve been documenting

our hikes with trip reports. I like to write trip reports so I can share our experience from the perspective of hiking with kids, since so many trip reports are from the perspective of adults. I try to note things that my kids enjoyed (wildlife, berries, views) or struggled with (terrain, obstacles, stinging nettle) that other parents might find valuable. I also write trip reports because some of the small trails we hike don’t get as much attention, and I hope that writing reports will help put them on the map for other families.

Now, as I think about how we got here, I realize the biggest hurdle was myself — it took me a while to convince myself that hiking with my kids wasn’t as daunting as I made it out to be. It helped starting small and then exploring farther out. Happily, my kids have really taken to hiking with enthusiasm. As the weekend approaches, my son always asks, “Is it going to be a hike day?” and my “Yes” is always followed with cheers. My daughter runs to her boots when she hears we are going hiking. The hardest part of hiking with my kids has been facing my own impatience. I’m not a fast hiker, but going from being a slower adult to toddler speed was challenging. But the more

we get out, the more I enjoy things from their perspective. Kids appreciate so many things about being outside that I never paid attention to. My son has taught me about so many plants (which he learned from my in-laws). I’m looking forward to berry season, which is something I didn’t think much about before having kids.

Committing to this goal has definitely helped me get out regularly. Even with a short, easy hike I still feel a great sense of peace and calm from being outdoors, and the connection it brings with my kids is wonderful.

The best thing about taking regular hikes with my kids is being able to share something with them that I love, and them loving it just as much. That’s such a special bond and I hope we continue to share that passion as they get older. They motivate me to follow my passion and I am so lucky that we can share it.

Sarah Nordstrom is a hiker and mom in Port Orchard. This year, she’s trying to hike at least 52 times and go backpacking both with her kids and on solo trips. She hopes her adventures inspire other families to get out as well.

Start small: My advice for parents who want to start hiking with kids is to start with a local park with a short, easy trail and take your kids on a walk beyond your neighborhood. Pack a bag of snacks (way more than you think you need, and clip them outside your backpack so you’re not taking your pack off every 5 minutes), water and bandaids.

Make a plan: It helps to make a plan in advance. I find I am more likely to get out when I have a plan (even if I just make the plan just the day before). If the weather looks bad, don’t be afraid of it, just plan for it. And, if you’re planning a long car ride, try to time it around nap time.

Find what’s fun: Find activities your kids enjoy on trail — for us that’s role-playing and storytelling. We also like to use the Seek app to identify plants.

Slow is OK: With frequent outings, you’ll get an idea of your kids pace and how far/long they can go, which will help you plan more outings. Prepare for slow — like, an hour for 1 flat mile.

Bring a friend: Invite friends, if that helps you get out (it does with me).

these outdoor gatherings

This signature event is a camping experience geared toward Black, Indigenous and people of color — and allies — to build community through outdoor recreation, art and conversation.

Aug. 10 | Pre-Fest Party | REI Flagship, Seattle

Aug. 22-24 | Tolt MacDonald Park & Campground | Carnation

Sundaes Outside: A Celebration of Black Folks

A family-friendly event series highlighting the rich contributions of Black folks in the outdoors.

June 22 | Bridle Trail State Park | Kirkland

July 25–27 | Campout: Cornet Bay Retreat Center at Deception Pass State Park | Oak Harbor

Sept. 18–21 | Campout: Ramblewood Retreat Center at Sequim Bay State Park | Sequim

A shorter version of the signature full festival, featuring seasonal outdoor recreation activities and the building of a healing space.

Nov. 28 | Seahurst Park | Burien

When a lifelong hiker was diagnosed with Parkinson’s, he found a way to keep getting outside, with a little four-legged help.

Bill Meyer (in red raincoat) founded Pass to Pass to make it easier for hikers with Parkinson’s to get out on trail, with the help pack llamas.

Pass to Pass hikers ford Bumping River (left) during a hike on the Pacific Crest Trail.

By Chloe Ferrone

On summer days, you might be lucky enough to run into a group of backpackers with a string of llamas in tow. Although thousands of outdoor enthusiasts flock to Washington’s rugged wilderness areas each summer, this group is hiking with one particular thing in common: Parkinson’s disease.

For Bill Meyer, being outdoors has always been a big part of his identity. As a lifelong hiker, backpacker and rafter, he’s spent a lot of time exploring the wilderness. But when he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, he realized he needed to approach backpacking much differently than he’d been doing his entire life.

When he was in his mid-50s, Bill began seeing symptoms of Parkinson’s.

“I started seeing rigidity of the body; everything was stiff,” Bill said.

That was the beginning of a long journey learning how to manage symptoms as they progressed. In late 2009, his tremors started and he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s soon after.

In 2009, Bill started on medication to manage his symptoms. In 2015, he decided to try deep brain stimulation (DBS) surgery,

Parkinson’s is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the destruction of nerve cells in the brain. The disease impacts the body’s ability to produce and transmit dopamine, which is necessary for controlling the body’s movements. This results in tremors and other motor symptoms, loss of sense of smell, mood and sleep disorders, and cognitive and psychiatric symptoms, as well as the compounding of normal aging symptoms.

to Pass trips (clockwise from

a procedure that implants electrodes in the brain and uses electric impulses to stimulate brain activity. For Bill, the DBS was incredibly helpful.

“It turned me around,” he said. “DBS was like it brought new life into me. I felt so good all of a sudden. I decided to try backpacking again because I loved the outdoors and getting into the mountains.”

Bill said the progress he made with DBS was great motivation to find a way to get back on the trail. That same year, Bill did a test hike to see what he was capable of.

“It was too much to carry a full backpack and deal with the elevation and implants, so I decided to get some friends together and that’s really the idea that started Pass to Pass,” Bill said. “We decided to make it an annual trip, and it grew from there.”

Although there is no cure for Parkinson’s disease, exercise often helps people manage their symptoms. And for many people, scaling back their backpacking ability because of mobility issues is a difficult thing to grapple with. Bill and his wife,

Nadean, decided to start Pass to Pass, a nonprofit to help other outdoor enthusiasts with Parkinson’s who otherwise would not be able to continue backpacking.

Four-legged helpers

In 2016, Pass to Pass launched its first trip.

Right away, Bill and Nadean knew that it had been the right idea. The feedback they got from participants was overwhelmingly positive. But there was also some fine-tuning required. Initially, they used horses for pack support, but they created some challenges.

“The first year, I didn’t know if this whole thing would be sustainable, because horses were expensive and couldn’t go where we wanted to go,” Bill said. But then they decided to switch to llamas and things started falling into place.

Nowadays, the majority of Pass to Pass’s multiday trips utilize llamas, allowing hikers with Parkinson’s — “Parkies,” as Bill refers to them — to hike with only a small day pack.

The group size is generally four Parkies, four support hikers and four llamas. Trips vary in length and difficulty, but generally trips are 6 days long, and the group averages about 5 miles a day.

Trip leaders and board members take on the bulk of the trip planning, while individuals are tasked with fundraising and asking for donations to cover their personal travel expenses, food and gear needs. Bill has found that sleeping outdoors with Parkinson’s can be challenging at best, so Pass to Pass provides extra-thick sleeping pads for Parkies, plus chairs and first-aid kits.

This year marks Pass to Pass’s 10th anniversary. Over the last decade, Pass to Pass has welcomed hikers from 25 states and provinces, and they’ve expanded their multiday trip options to include hikes in Washington, Oregon, California and, new this year, Montana and Virginia.

“I never imagined it would get as big as it did,” Bill said. “We just added another trip in Oregon; we had about 170 hikers in 2024 and it’ll be even more this year.”

Hikers covered over 3,000 miles in 2024, and there are about 3,500–4,000 miles of treks on the books for 2025. Bill said participants have covered over 13,000 miles of trails since the group began in 2016.

As the organization has grown, it has also evolved to include day hiking options and multiday trips that involve lodges or carcamping. There are 15 multi-day trips listed on the website for the 2025 season, ranging from lodge-based day hikes at Rainier to a Hart’s Pass to Rainy Pass backpacking excursion on the Pacific Crest Trail. Some trips are llama-supported; others rely more heavily on support hikers.

This season, Bill will have a chance to step away from trip leader recruiting and hand that task over to one of the other volunteers, which is something he’s very excited about.

“A lot of that excitement comes from bringing new people on and having better capacity. We’ve also got a new llama team and the challenges that brings, plus a new area as we branch out into Montana trips,” Bill said.

Looking back at the last 10 years, Nadean said that the biggest surprise has been the community.

“Bill has made so many friends. Most of us don’t want to talk about Parkinson’s, but we talk about it here. We offer advice, share stories and different tricks to help,” she said. “It’s healing to find that community.”

There are a number of ways to support Pass to Pass. Most of the trip leaders and support hikers are those who have Parkinson’s, or are family or friends of those hiking. But volunteers are frequently needed in other ways, such as assisting with transportation to and from trailheads for hikers arriving from out of state, delivering trailhead lunches, or attending conferences and tabling for the organization.

In the midst of all their undertakings, Bill and Nadean also still find time to give back to their community in other ways. When he was younger, Bill was an avid trail user and volunteered with Washington Trails Association as a way to give back to the trail community. He also has helped support land acquisitions for the Pacific Crest Trail Association to link the north and middle sections of the Pacific Crest Trail. Bill has also been a long-time donor to WTA and is helping fund one of the Lost Trails Found crew trips and work at Mica Peak in Spokane this summer.

To learn more about Bill and Nadean Meyer, Pass to Pass or ways you can get involved, visit passtopass.org.

June 21 is Washington Trails Day

We are calling on everyone who loves the outdoors to take action with WTA on Washington Trails Day. By bringing our voices together and showing what public lands meant to us, we can protect these special places. Take action at wta.org/watrailsday

Here’s how to keep your food (and critters!) safe when backpacking.

By Sandra Saathoff

Bear cans are required if you’re backpacking on the beaches in Olympic National Park. (See the bear on the beach for one of the reasons why.)

Backpacking food can be an amazing experience — everything tastes so much better on trail! A hot meal at the end of a long day helps refuel our weary bodies. Some of us can’t live without our warm mug of caffeine in the morning. Hiking is an opportunity to savor favorite snacks. But what happens if your cheerfully packed food bag is lost, damaged or destroyed? Suddenly you’re hungry and miles — sometimes many miles — from civilization. Oh, the horror! Don’t let it happen. Let’s look at the potential threats to our food stores and options for keeping them safe.

Bears: When most people think of backcountry food storage, the first thing that pops into their minds is bears coming to steal their food. And it does happen. Bears have an incredible sense of smell and can detect food from miles away. Once they associate humans with food rewards, they become habituated, which can lead to dangerous encounters and result in the bear having to be euthanized. Both black and grizzly bears are a risk, though in Washington it would most often be black bears, as we have few grizzly bears here.

Rodents: The more common actual threat is mice and their relatives. Washington is full of those! While bears might be more intimidating, mice, squirrels and other small mammals can be equally destructive to our food supply. They are adept at

Human food is bad for wildlife — and bears that get into human food are at risk if they become a problem. Proper storage keeps wildlife safe.

chewing through tents and food bags — even into backpacks. And they can be very bold, depending on whether they’ve come to associate people with food.

Raccoons: For some areas in Washington, raccoons getting into food storage is not an issue. In some areas, however, particularly along the coast, it’s a different story. The little “trash pandas” are brazen, intelligent and dexterous. If they’ve learned to associate humans with food, they’ll go to nearly any lengths to get into food storage. How long will it be until they can even open bear canisters?

Weather: A fourth common threat to food stores is the weather, though of course that depends on how long one is out for. Rain, humidity and extreme temperatures can make food inedible. Moisture can lead to mold growth; heat can cause spoilage.