Walsh School of Foreign Service

THE NEW EU A confluence of challenges

MIGRATION’S EVOLUTION No longer just an economic force HANDS-ON TEACHING One professor’s real-world classroom

THE NEW EU A confluence of challenges

MIGRATION’S EVOLUTION No longer just an economic force HANDS-ON TEACHING One professor’s real-world classroom

International affairs’ need for science and technology

GEORGETOW N UNIVERSITY • 2016-2017

SFS is published regularly by Georgetown University's WALSH SCHOOL OF FOREIGN SERVICE , in conjunction with Washingtonian Custom Media, a division of Washingtonian Media (washingtoniancustommedia.com). We welcome feedback and suggestions for future issues. Please contact Jen Lennon, Director of Communications, Walsh School of Foreign Service, Georgetown University, Intercultural Center 228, 37th and O Streets, NW, Washington, DC 20057; by phone at 202-687-5736; or by email at jll87@georgetown.edu. Website: sfs.georgetown.edu 02 Dean Hellman Reflects

Origins of SFS SFS’ mysterious founder Constantine McGuire. 08 Student Profiles Meet three standout SFS students. 10 SFS-Q Research Center for International and Regional Studies’ latest work.

12 Showcasing Alumni

Two alums share how SFS shaped their careers.

26 Meet Our Faculty

Two professors discuss what they love: teaching.

32 Alumnus Spotlight

One SFS alumnus talks about representing America around the world.

“There’s a sense of change in many students who say that science is now a part of international affairs.”

—MARK GIORDANO, Cinco Hermanos Chair in Environment and International Affairs

SFS science, technology, and international affairs’ majors embrace an interdisciplinary curriculum.

20

The future of the European Union is uncertain after the Brexit vote, the current refugee crisis, and Russia’s looming threat.

24

Worldwide migration patterns are no longer for just economic gain, but forced by global environmental and political changes.

facebook.com/georgetownsfs

twitter.com/georgetownsfs vimeo.com/georgetownsfs

New dean, Joel Hellman, sets priorities for SFS’ international scope, collaboration, and the ICC.

Dr. Joel S. Hellman’s first year as dean of the Walsh School of Foreign Service coincided with a significant shift in the geopolitical climate. “We’ve seen a backlash against globalization, the rise of right and populist parties worldwide, and more national political dialogues turning inward,” Dean Hellman says. “Our mission— to prepare young leaders to solve complex problems in an increasingly interconnected global environment— has never been more important than it is today.”

He describes SFS as a place designed to engage with the world in an effort to preserve SFS’ foundation for global commitment, engagement, and service, as well as a place to prepare and educate future global leaders.

Training in international affairs is critical not just for future diplomats, Dean Hellman says, but for people entering business, technology, the arts, science, and of course, government.

“More than ever, all fields are ‘global’ today,” he says. “And SFS is the best place to train students in international affairs, period.”

Dean Hellman came to SFS after 15 years at the World Bank, where the Georgetown ethos of service was a powerful connection. He served as the Bank’s first chief institutional economist and also led its engagement with fragile and conflict-affected states as director of the Bank’s Center on Conflict, Security, and Development in Nairobi, Kenya. “I have lived the values of SFS for the bulk of my career,” Dean Hellman says.

ue to draw upon passion for the SFS mission, current students are “doing first-rate work in the classroom and in the real world” with equal optimism, and faculty and staff have expressed ways to invest in bold, new ideas for the school’s next 100 years.

Drawing from these conversations—as well as the work of a faculty committee charged with creating a Centennial Vision— Dean Hellman formulated priorities for the next era at SFS.

» Intensifying SFS’ international character. SFS pioneered international education in the U.S., but many other schools have caught up, Dean Hellman notes. He believes SFS is paramount to Georgetown’s transition into a “truly” global university, and that every SFS student should be required to study and/or work abroad, so that they can apply international context to their existing knowledge. Equally important, SFS will attract a larger group of the best international students from more nations and socio-economic backgrounds.

» Creating collaboration: Dean Hellman believes that collaboration between SFS and other Georgetown schools creates opportunities for superior problem-solving. For example, the link between private sector solutions and international development translates into collaboration between SFS and experts from the McDonough School of Business. Similarly, addressing climate change means SFS needs to offer more science courses and work with the College to place students into innovative laboratory environments.

The recent incorporation of the Laboratory for Global Performance and Politics into SFS addresses Dean Hellman’s recognition that “narrative is now central in shaping how people look at international affairs.”

“More than ever, all fields are ‘global’ today.”

» Reimagining SFS’ space: Calling the ICC a “maze” and “physically fragmented” with 23 institutes and centers across four buildings, Dean Hellman proposes re-thinking the layout of the school to encourage better collaboration. He recalls a poem written in chalk in Red Square last summer: “Your eyes are like the ICC / I could get lost in them all day.” He laughs, but calls SFS’ classrooms “handcuffs on the incredible methods that SFS faculty members are developing” which include simulations, design thinking, game theory, and lab-style learning. “We need to reimagine our space so that it draws us together into productive conversation and collaboration,” he says.

Since arriving in July 2015, Dean Hellman has been continually engaged in conversations with alumni, students, faculty, and staff about pushing the school in new, innovative directions. During his first year at SFS, he spoke to hundreds of alumni, many who called their Hilltop training “indispensable.” Everyone, he says, has visions for the school’s future: alumni contin-

The dean’s vision extends well beyond the upcoming centennial. “When I first interviewed for this job, I realized the importance of the word ‘service’ in the name of the school,” he says. “I feel that word daily as we work to imagine a second century molded for the better.”

» Jean Dimeo contributed to this story.

SFS UNDERGRADUATES IN D.C. >

250

SFS undergraduates in Doha, Qatar

860

1,400

GRADUATE STUDENTS

29,000

SFS ALUMNI LIVING IN 120 DIFFERENT COUNTRIES

Alumni frequently ask how they can help SFS. Here are a few ideas:

Do we have up-to-date contact information? Make sure your information is correct and re-introduce SFS to your classmates. Email: addup@georgetown.edu

Facilitate philanthropic support of SFS by providing introductions to foundations, corporations, and organizations. Email: Maryam Henson, Office of Corporate & Foundation Relations, ocfr@georgetown.edu

Set up a student internship, post job openings, arrange a site visit, volunteer for a career panel, or serve as a career resource for resume reviews and mock interviews.

Email: Anne Steen, sfscdc@georgetown.edu

Sponsor a dinner, reception, or lecture for alumni, parents, friends, students, and faculty to foster SFS community engagement. Email: Eleanor Jones, Eleanor.Jones@georgetown.edu

Join fellow alumni online for GUAA Alumni Career Services webinars, offered on a variety of professional development trends. Web: alumni.georgetown.edu/careers

Your support of Georgetown University directly benefits thousands of Hoyas every day, enabling them to make a difference in their communities and around the world. Web: giving.georgetown. edu/#howtogive

Email: Katherine Smyth Haskins, kes34@ georgetown.edu

Suggest additions to the “Prominent Alumni List” which is posted on the SFS website. Web: sfs.georgetown.edu/prominent-alumni/ Email: sfscontact@georgetown.edu

Apply to join the Georgetown Alumni Association Board of Governors.

Web: bog. georgetown.edu

Email: guaa@ georgetown.edu

FATHER

TSFS

founder Constantine

McGuire launched a mission that echoes 100 years later.

he Walsh School of Foreign Service is named for Edmund A. Walsh, S.J., the Jesuit priest who guided and defined the school from its founding in 1919 until his death in 1956. The original idea for the first U.S. school of international affairs, however, was framed by a different man with a carefully guarded history: Constantine McGuire.

McGuire was born in 1890 in Boston and educated at Harvard, earning his doctorate in history in 1915. While in Paris, he studied at the École des Langues Orientales Vivantes, and after graduation he worked in Washington, D.C., at the Inter-American High Commission, a group that facilitated economic relations between nations. Between 1916 and 1917, McGuire began to draw up plans for an American school that would provide a specialized education in

foreign policy and languages, recreating the unique education he had acquired in France.

Most of McGuire’s career and personal life is unknown. He was rumored to be the model for Elliot Templeton, the Catholic-American ex-pat living in Paris who acts as a contrast to Somerset Maugham’s spiritual hero in “The Razor’s Edge.” Like Templeton, McGuire was alleged to be such a financial expert that he wisely sold off his stock just before the 1929 market crash. He would leave the High Commission in 1922 to work as an economist at the Brookings Institution. He later served as a financial and economic advisor to Venezuela and authored articles on the economies of Germany and Italy. Friends believed him to be among the most influential Catholic laymen in the United States and a financial advisor to the papacy.

SFS professor Carroll Quigley’s article on McGuire called him a “Man of Mystery” and noted that “McGuire avoided all publicity and covered his activities with a cloak of secrecy which is almost impenetrable.” McGuire was known for turning down honorary degrees and refused to appear in “Who’s Who in America” and “American Catholic’s Who’s Who.” During his years in Washington, D.C., his only known address was “Box 1, the Cosmos Club,” the social club he used as an office.

Having conceived of an American school of foreign relations, McGuire tried to convince various Jesuits in the capital to take it on in 1918. After being turned down by both Georgetown University and Catholic University, McGuire got a second meeting with Georgetown President John B. Creeden, S.J., who asked Father Walsh, back from the Student Army Training Corps at the end of World War One, to run the new school.

In one surviving 1953 letter, McGuire himself noted how few people “have any knowledge what -

ever that I had something to do with the origin of the school” and remarked on his own “incurable allergy” to taking credit for things. However, McGuire was responsible for hiring the initial faculty of SFS in his role as the school’s unofficial executive secretary between 1919 and 1922. Memoranda addressed to Father Walsh show that McGuire advised on many details of the school and, perhaps most importantly, convinced James A. Farrell, the president of U.S. Steel, to make the initial contribution to the SFS endowment.

McGuire, ironically, grew disenchanted with the growth and direction of SFS over the next few decades. Although McGuire was professionally involved in trade

policy, a letter he wrote in 1953 expressed disappointment that SFS provided training in “accounting, commercial law, and commercial activities generally… I had not contemplated a school with dozens and dozens of instructors and many hundreds of students.”

Despite his misgivings, SFS started with one foot in commercial practice and another in the theory of international relations. “Going back to Constantine McGuire and Father Walsh and the origins of the school gets at something that is as true now as it was 100 years ago,” says SFS Dean Joel Hellman. “Economic relationships across the world are critical.”

“Maguire avoided all publicity and covered his activities with a cloak of secrecy.”

» Jean Dimeo contributed to this story.

For

Bethan Saunders (SFS ’17), academic and professional experiences at SFS solidified her passion for studying conflict in sub-Saharan Africa. by

MAXINE JOSELOW

When Bethan Saunders (SFS ’17) enrolled in the School of Foreign Service, she hoped to cross paths with influential policymakers over her four years on campus. But she never dreamed she would meet the German ambassador to the United States.

This fall, Saunders was one of a dozen students who spoke with the ambassador over coffee. Their discussion included Brexit, the Syrian refugee crisis, and European economic development.

“We got to hear from an ambassador himself about what it was like to be in foreign service,” Saunders says. “It was a very special opportunity.”

Saunders is originally from London; growing up, she split her time between London and Los Angeles. As a senior majoring

in international politics, Saunders counts this conversation among the high points of her academic career. But she is quick to list a handful of other highlights that helped further her professional ambitions.

For instance, Saunders talks about interning at the White House. She took a semester off to intern for the Council of Women and Girls, working on women’s issues in an international context.

“I was really challenged to apply what I’d learned in the classroom and dive headfirst into the Obama administration,” Saunders says. “It was great to be in D.C. and see what it’s like for people in my field.”

From the White House, Saunders headed to the State Department for a subsequent internship for the Secretary’s Office of Religion and Global Affairs. She was tasked with working on security issues in sub-Saharan Africa, which gave her another glimpse into the field of international relations.

The internship at the State Department also had an unforeseen effect: It helped Saunders narrow her academic focus. While she had entered SFS interested in the Middle East, she knew after the internship that she wanted to study gender and security in sub-Saharan Africa.

“I was able to see everything that I was learning in class play out

in real time.”

Graduate student Keishi Abe (MSFS ’18) is a trained medical doctor who wants to make a difference in global health security. by

ROSA CARTAGENA

When Ebola spread across West Africa and made global headlines in 2014, Keishi Abe (MSFS ’18) was responsible for Japan’s preparations despite its far proximity. “Japan is literally the opposite of Africa on the globe,” says the MSFS graduate student and physician. “But we have to prepare for all the possibilities.”

This change of focus paved the way for another standout experience: studying abroad in South Africa last year. Saunders went to Capetown at a time of political upheaval. As a result, her classes on conflict had a direct bearing on the protests occurring at nearby universities.

“I was able to see everything that I was learning in class play out in real time,” Saunders says. “It was one of the most challenging and enlightening experiences.”

As a recipient of the Mortara Undergraduate Research Fellowship, Saunders was even able to travel around Africa during a break. The fellowship funded her trip to Rwanda, where she studied conflict resolution after the genocide.

Saunders looks forward to graduating this spring. She envisions herself working in the private sector before ultimately pursuing a career in public service. With her combination of skills and experience, she’s already snagged a job offer working for Morgan Stanley on the international sales desk.

How do you prepare for a crisis? Risk communication is key, he says. Abe, who was dedicated to the infectious disease crisis management unit in Japan’s Ministry of Health, says one of the hardest parts of his job was gathering correct information from those on the ground. People are sometimes so busy managing the crisis at home that they don’t have time to share their updates.

The health crisis affected politics, too. “This kind of public health issue is really a political issue,” says Abe. “If the government cannot contain [it]

immediately, people’s opinion of the government will become very harsh.” Thankfully, there were no cases of Ebola that arrived in Japan. Abe was in charge of the effort to send Japan’s doctors to Sierra Leone and Liberia, two countries that were seriously affected. In February 2015, Abe traveled to Guinea with his colleagues to survey the Ebola epidemic firsthand to assess what was needed and what resources Japan could offer. It was difficult to see. The treatment centers were in a worse condition than he expected, but Abe sought to find out how his country could continue to help.

Abe realized his passion for health security at a young age when severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) broke out in neighboring China and Southeast Asia. Though the disease caused panic in the region, he admired the dedication of one doctor, Carlo Urbani, who was instrumental in its early detection and containment.

Inspired by Urbani’s commitment, Abe pursued medical school in his home country of Japan. Soon after his residency in neurosurgery, he turned to policy. With his appointment in the Ministry of Health, crisis preparedness was essential.

Abe says that there was always a possibility that infected patients could come to Japan. He had to make sure that if any did arrive, the country would be ready and he would be able to act quickly under pressure.

Abe is eager to expand his international security perspective while at SFS. When he visited Guinea, he was impressed with how the military assisted in emergency response operations. He wants to study the interaction between public health and security. “I’d like to contribute to my country and to the world,” Abe says.

A

stint in security studies reveals

a leader in SFS graduate student

Preston Marquis (SFS ’16, SSP ’17)

by HAYLEY GARRISON PHILLIPS

Preston Marquis (SFS ’16, SSP ’17) is very much a generalist when it comes to international affairs. “Given how interrelated tools of national power are, you can’t achieve ends in the world just using the military, or diplomacy, or economics,” he says. “It all fits together.”

As an undergraduate student at the Walsh School of Foreign Service, Marquis had a concentration in U.S. national security policy which, as he explains it, deals with resources, decision-making processes, and strategy, all great tools for an aspiring bureaucrat with an interest in policy development.

But after a few minutes spent speaking with Marquis, it’s clear that he is destined for more than a career as a behind-thescenes bureaucrat.

“You can’t achieve ends in the world just using the military, or diplomacy, or

economics.”

With an undergraduate degree from SFS, a two-year internship at the FBI, and an internship in the office of the Secretary of Defense for cyber policy under his belt, Marquis is now a graduate student in the accelerated security studies master’s program. By staying involved at Georgetown, he has also managed to

carve out time to mentor undergraduate students researching topics in security studies.

Given Marquis’ early life, it’s easy to understand how his passion for public service began. His father was an FBI special agent, and his mother was an assistant U.S. attorney, something Marquis says influenced him greatly. “That really shaped my world view on the potential for service to be a good factor for helping to improve our communities,” he explains. As a young boy he was actively involved in the Boy Scouts of America, which taught him about problem-solving, collaborating with others, and giving back to the community. In high school, he further honed those skills in Model U.N. and even participated in an FBI youth leadership program. By the time Marquis was scoping out colleges, his general interest in public service had transformed to a worldview, a deeply-rooted belief in the power of pursuing positive change by dedicating oneself to the greater community. Marquis’ sights were set on the largest community of all: the global one. He was drawn to Georgetown for its nearly century-old School of Foreign Service—he wanted a separate program, not one built into a larger liberal arts degree—and he was also thinking of the opportunities living in D.C. would afford someone in his particular field of study.

For Marquis, interning at the FBI seemed to bring things in his life full circle. “There has always been this inertial, sort of inevitable pull to the Bureau,” he explains. “I feel like it did a lot to shape my own career aspirations.”

Whether he ends up in national security, defense, or foreign policy, he isn’t sure, but he definitely wants to stay involved. “I’m less concerned about where I end up sitting because I know that, at the end of the day, it’s all feeding the same end goal.” For Marquis, that means a better world through public service.

Georgetown’s Center for International and Regional Studies contributes seminal research on the Gulf region and beyond. by SYDNEY MAHAN

Innovation and collaboration. These are the tenets that Dr. Mehran Kamrava, director of the Center for International and Regional Studies (CIRS) and professor at the Walsh School of Foreign Service in Qatar, says the CIRS will continue to bring to the world stage.

Established in 2005 as part of the founding of the SFS campus in Doha, Qatar, CIRS has grown to become one of the Gulf region’s leading research institutions, filling the gaps in existing literature while also raising new questions to be explored through pioneering books and publications on the Gulf region and Middle East.

“Our strength lies in our ability to look at the region from within, our local networks, local resources, and the vantage point we have,” Kamrava says. Generally, it has prioritized the study of the Persian Gulf region. “But we have also taken on other topics where we think we could make original and significant contributions related to the broader Middle East and topics that relate to it.”

examined topics ranging from the role of religious authorities in the Middle East to media and politics during the 2011 Arab Spring.

CIRS opened in 2005 in conjunction with the launch of SFS-Q, and Kamrava joined in 2007 as its first director. Kamrava has spearheaded the research facility, focusing on four main activities including research, publications, public affairs programming, and faculty engagement.

Under his leadership, CIRS has produced more than 30 multidisciplinary research initiatives. They range from world renowned scholars and policymakers in the fields of international relations, political economy, domestic politics, and more, as well as undergraduate students.

“We always make sure to have a balance in terms of geography and disciplines,” Kamrava says when discussing the process of CIRS’s research. “Geography, meaning we try not to bring scholars from only North America or only scholars from Europe or only scholars from the region. We make sure there’s a multiplicity of perspectives and backgrounds as well as disciplines.”

This variety is important to CIRS’s overall work, Kamrava says, as it brings everyone to the table.

“We literally have a round table that seats 26 people,” says Kamrava. “So the students are involved at every level…They sit around the table with these world-renowned scholars, talking about what is original in the area of their specialization and the students provide summary reports of [these] discussions.”

In addition to its focus on the Gulf region and the Middle East, over the past couple of years, the center has also begun to complement its research of the region by looking to the east. Projects focus on the South Caucasus in Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan, as well as a study on central Asia, Kamrava says.

“These are topics [that], to a non-specialist, may not seem as interesting or relevant,” Kamrava says.

The Gulf Working Group discuss sectarian politics in the Persian Gulf.

Focusing on inter-state and intra-state conflicts, as well as socioeconomic and political trends, CIRS has, through its multitude of original empirically-sound research projects, grant programs, and monthly academic discussions,

“We make sure there’s a

multiplicity of perspectives and backgrounds as well as disciplines.” INNOVATING

“But for us, these are pioneering topics that have enabled us to contribute original findings to the literature.”

To learn more about CIRS’ research projects, publications, and how to get involved, visit cirs. georgetown.edu.

(LEFT TO RIGHT) Aislinn McNiece: Barcelona, Spain, study abroad; Connor O’Brien: Tbilisi, Georgia, Russian language; Ryan Sudo: worldwide (pictured in Taiwan), Circumnavigator’s Grant; Sarah Mack: Seoul, South Korea, North Korea Strategy Center; (ROW 2) Soham Banerji: Jakarta, Indonesia, Coca-Cola 5by20 Initiative; Elizabeth Bujwid: Kunming, China, Chinese language; Anthony Bernard-Sasges: Beirut, Lebanon, UNHCR; (ROW 3) Caitlin Garrabrant: Copenhagen, Denmark, study at Copenhagen Business School; Brian Moore: Honolulu, Hawaii, Pacific Forum CSIS; Andrea Welsh: New Delhi, India,International Center for Research on Women; Eric Salgado: Brasilia, Brazil, U.S. Embassy.

Internships are an integral part of the SFS education and prepare undergraduate and graduate students for careers in the international arena. Internships provide students with the opportunity to enhance their academic coursework; gain professional experience and insight into career opportunities; develop contacts in their field of interest; and explore the public, private, and non-profit sectors. SFS students intern around the world for organizations that include the U.S. State and Defense departments, the United Nations, international NGOs, and Fortune-500 companies. Some attend intensive language courses to achieve mastery of their chosen foreign language, or conduct research for their theses.

and new programming.”

While there’s no “typical day,” Soleimani spends her time at work meeting with her team to decide which grants to give out, talking to reporters, pitching stories, and interacting across teams. All to make sure the world knows about Google.org’s accomplishments and that they are authentic to Google.

Soleimani has been at Google for over four years. She initially joined on the product PR side for Google search and then covered corporate initiatives around people operations and culture before moving into her most recent role. “The people that I work with and the causes that I get to support” are the most enjoyable part of her work, she says.

Roya Soleimani (MAAS ’11) harnesses Google’s global reach to fund nonprofits and causes around the world. by JENNIFER

TMESCHEWSKI

he power of Google is immense, but it’s also the work they do off-line that makes an incredible difference in the world. And for SFS alumna Roya Soleimani (MAAS ’11), to be a part of that humanitarian arm is a fulfilling moment of her career.

For the past year, Soleimani has been working at Google.org, the philanthropy branch of Google. Google.org is how Google is able to support nonprofits that are doing innovative work, she says. It is philanthropy, employee volunteering, crisis response, and much more. “You can come to the table with an idea and you can get people and dollars behind it,” she says. “It is a proud moment to see all of the various causes that we dedicate ourselves to.”

When asked to describe her typical day working at Google, Soleimani laughs. “There is no typical day at Google,” she says. “Each day can be its own adventure, depending on our news announcements, launches

Some of the initiatives she’s worked on include: raising $16 million to be used towards the Syrian refugee crisis; providing funding and 3D technology to the new National Museum of African American History and Culture in D.C.; and helping George and Amal Clooney’s mission to educate Syrian refugee children in Lebanon. “It is the level of scale and authenticity that makes me proud to be at Google,” she says.

Soleimani’s move to Google was not typical for a Georgetown SFS graduate. While pursuing her Master of Arts in Arab Studies at SFS, Soleimani was most interested in how Iran interacts with its Arab neighbors. Being able to study with people who know the area was very exciting, she said. She describes Georgetown as a “living classroom,” which meant taking classes with and interning for practitioners like Secretary Madeleine Albright. She also credits her Arabic professors for her ability to speak Arabic. Following graduation, she moved back home to California and started working at Google a few months later. Though it doesn’t seem like Arab studies relates to the Google search engine, Soleimani says that Google’s global reach was a natural connection for her SFS background, particularly now on the philanthropic side of the business. “I feel like it is feeding that Georgetown interest everyday,” she says.

Joanna Williams (SFS ’13) says SFS taught her how to use privilege to make a difference. by ANGIE HILSMAN

Joanna Williams (SFS ’13) first encountered the Kino Border Initiative (KBI) at a 2010 presentation while she was a student at Georgetown University. Williams decided to volunteer at the binational Jesuit ministry—aimed at protecting families and individuals as they migrate across the U.S.-Mexico border—after her experience volunteering in migrant communities in Northern Virginia. She took a leave of absence and spent a semester assisting with humanitarian aid, educational groups, and interviewing migrants for KBI in 2011.

“My experience at KBI in 2011 broke my heart open to love more,” she acknowledges.

“As I got to know individuals at the comedor and cared more and more about their journey, I was constantly challenged by my powerlessness. That motivated me to want to continue to learn and experience more so that I might be better able to respond to their situations.”

Williams continued her advocacy—researching with the Institute for the Study of International Migration, volunteering at a migrant shelter in Veracruz, and coordinating educational resources for workers’ rights advocates through the Kalmanovitz Initiative—before finishing her degree in international culture and politics in 2013. She then received a prestigious Fulbright grant to research the reintegration of deported and returned migrants in Jalisco and Puebla in Mexico.

In June 2015, Williams returned to KBI as the director of education and advocacy.

“The core of what we do is focus on the dignity of the people here at the border and respond to their needs,” Williams says. She explains that migration often includes Border Patrol abuse, lack of protec-

tion for individuals fleeing violence, and family separation during the detention process.

Williams’ week might include listening to migrant stories, conference calls with the Department of Homeland Security, and welcoming immersion groups. Groups visiting from her alma mater will serve migrants in soup kitchens, she says, while longer visits include walking in the desert and court dates in Tucson.

“We want them to not just understand migration in the abstract, but to get to know these people and walk in their shoes a little bit,” she says.

Williams recalls a youth from Central Mexico who was a victim of violence and was then forced to transport drugs across the desert. He sought asylum in the U.S., but is still being detained as part of the asylum process, she says.

“It’s shown me both the problems of the system and the strength of the individuals who we have the honor of working with,” Williams says.

While Williams leans on her 16-person team (staff from both Mexican and American outposts), and more than 100 volunteers, she also draws heavily from her education. Williams says that SFS challenged her to use her talents to make a difference, citing Professor Matthew Carnes’ question: “How do we use our privilege and gifts, and what is our call in that?”

“I

was constantly challenged by my powerlessness.”

“The work I did at Georgetown prepared me to do advocacy,” she says. “I understand the historical issues of asylum and the political reasons why it is the way it is, and I use that knowledge every day to understand what people might face in the system.”

The science, technology and international affairs program opens SFS students up to new ways of solving problems. by

HERE’S AN OLD JOKE AT THE SCHOOL OF FOREIGN SERvice that SFS really stood for “Safe From Science” as diplomats-in-training studied policymaking and international affairs, leaving science to the scientists.

Today, no one is safe, as technology creeps into everyday lives, professions, and global affairs. And it’s become even more evident as the school’s science, technology, and international affairs (STIA) major has grown in popularity in recent years.

“To be good in public policy or business, you should understand that science and technology issues are important, and have the confidence to understand them or know who to ask,” says Mark Giordano, director of the STIA program and the Cinco Hermanos Chair in Environment and International Affairs at SFS. “We want [students] to grapple [with] it for themselves.”

And grappling they are. From biology and organic chemistry to computer science and multivariable calculus, students are diving right into the thick of disciplines previously avoided. Today’s

RIN-RIN YU

students recognize the importance of having an interdisciplinary background when it comes to international affairs. They know that “if they can’t claim something on the science side, they are losing some credibility,” Giordano says.

It’s not that easy to just throw some social science students into the deep end of hard science, but STIA students aren’t afraid. “Maybe it’s a Georgetown trait,” Giordano muses. “If you raise the bar, they’ll take the challenge.”

Originally a concentration under the international politics major, STIA slowly began to build and grow through the 1980s. It was propelled by the Cold War while the anti-nuclear protest was mounting and when President Reagan put forward the idea of the Strategic Defense Initiative. The Three Mile Island partial

nuclear meltdown in Pennsylvania had already occurred in 1979; scientists were investigating what would happen to the environment if nuclear war ever broke out. Astronomer Carl Sagan coined the phrase “nuclear winter” to describe those environmental effects. People were becoming aware of the vanishing ozone layer by the 1970s, and two important documents were produced for its protection: the Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer in 1985 and the Montreal Protocol in 1987.

“How can you not have something like STIA in an environment like this?” asks Kathryn Olesko, associate professor and former director of the STIA program and founding co-director of the Center for the Environment. “It was really prescient of the deans to keep the SFS curriculum up to date by instituting something like STIA.”

Thanks in part to Olesko’s strong advocacy, STIA became a full-fledged major in the 1990s. As a concentration, it had only interested a few students each year, but as a major, there were approximately 40 students per class by 1997. Today there are about 75 students per graduating class, and it’s growing: STIA is the second-largest major in SFS, right behind international politics.

STIA was never intended to merge science and diplomacy, Olesko emphasizes. STIA places international affairs in the context of science, health, and technology, which is a far wider umbrella than having “foreign service officers help scientists conduct work abroad.” STIA, she says, involves the gamut of international affairs, including “treaty, convention, and protocol negotiations; science, technology, and development; international health issues; and so on.”

jor. Ambassador Robert Gallucci was named SFS dean, and he brought with him years of experience in nuclear diplomacy. He served as deputy executive chair of the U.N. special commission overseeing disarmament of weapons of mass destruction and long-range missiles in Iraq at the end of the Gulf War and as chief negotiator in the 1994 North Korean nuclear crisis. Gallucci brought comprehensive nuclear policy experience and a firsthand understanding of what students needed to learn.

“I had no science background, I had no background in math,” he says. “But my career was shaped by my enthusiasm for the science and the security policy, so I developed an expertise in nuclear energy for nuclear power purposes.”

Currently, he teaches a course on nuclear weapons and international security. The first part of his course focuses on the technical aspects of nuclear energy, so the students have a solid grasp of the fuel cycle. Then he spends time examining how nuclear energy is harnessed for use in weapons and how those weapons are acquired. Students look at countries, such as Japan, which uses nuclear energy as a power source but does not have any nuclear weapons, contrasted with those countries that do.

“It was really prescient of the deans to keep the SFS curriculum up to date by instituting something like STIA.”

Alumnus Michael Rogol (SFS ’94) was a product of the original STIA major. He recalls hot topics circulating around nuclear armaments and spent nuclear fuel in a post-Cold War world, climate change from carbon concentrations in the atmosphere, and the rise of information technology such as email, cell phones, and the potential of the internet. With an eye on working in the energy sector, Rogol says STIA was the ideal major. “Being in this sector requires a multidisciplinary approach drawing from science, technology, economics, finance, accounting, environmental studies, etc.,” he says. Today, Rogol runs Photon Consulting, a global business investing and consulting company in the solar power sector. His company has hired Georgetown STIA majors from nearly every graduating class.

Olesko considers 1996 a major turning point for the STIA ma -

“I want them to be more than the intelligent reader on these issues,” he explains. “More expert than people in government who haven’t spent the time to really look at what a chemical separation plant looks like, or what different enrichment technologies look like.”

While Gallucci was dean of SFS, the school went hunting for a professor who could fill a STIA role. It wasn’t easy. “One could not find many faculty in the field of science, technology, and international affairs,” he says. However, they managed to find Charles (Chuck) Weiss, a biochemist and the first scientific advisor at the World Bank. Weiss was named the next director of STIA.

Weiss grew the major to become what it is today, but Olesko says Weiss’s creation of the foundation course, STIA 305: Science and Technology in the Global Arena, was a major highlight. The course provides a comprehensive overview and coverage of the STIA major itself. It was redesigned two years ago to become a team-taught course, divided into sections along the professors’ lines of concentration. It introduces students to the STIA professors, and sometimes introduces “the same problems from different angles,” Giordano says. Each of the units ends with a three-day simulation of a contemporary international issue that requires students to apply their scientific and technical knowledge.

Top: A classroom simulation to develop a feasibility plan for solar powered irrigation pumps in Ethiopia. Bottom, left to right: A representation of India’s plate of grass to Pakistan, after Pakistan said it would eat grass for a thousand years but still build its own atomic bomb; Prof. Joanna Lewis with STIA students in Paris during COP21climate negotiations.

STIA was divided into four tracks in the 1990s and today those tracks are:

• ENERGY & THE ENVIRONMENT: addresses climate change, geosciences, energy economy, global food supply, and water crises.

• BUSINESS, GROWTH & DEVELOPMENT: examines transformative technologies and international competitiveness, innovation policy from Wall Street to nation-states, information technology, and entrepreneurship.

• BIOTECHNOLOGY & GLOBAL HEALTH: studies emerging infectious diseases, technology’s role in healthcare systems and health equity, and the biotech revolution.

• SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY, & SECURITY: discusses nuclear proliferation, low- and high-tech terrorism, cybersecurity and cyberwarfare, space, aerospace, and military technology strategy.

Today the tracks mirror the issues handled by the White House’s Office of Science and Technology Policy and other government agencies. The four tracks are distinct, but often cross over, which is intentional, and also natural.

STIA has always prepared students to understand current events, even staying well ahead of them as the events unfold. For example, by 2009, when the Stuxnet virus infected the computer system running Iran’s centrifuges and crippled the country’s capability to produce weapons-grade uranium, SFS students were already up to speed on the state of information warfare since 1998. The program has expanded its technical courses in geographic information system (GIS), remote sensing, and environmental geosciences. In 2017, Olesko says, a course on space and security taught by

an expert affiliated with NASA and the Department of Defense will be offered.

Current students welcome the ever-changing nature of the STIA major. “It gives you a capacity and skill set to take whatever is thrown at you, and focus on how science and technology is always in flux,” says Sophie Faaborg-Anderson (SFS ’18), who is passionate about environmental issues and is pursuing the business track.

Where do STIA majors go after graduation? The first STIA graduate (1983) went on to earn a Ph.D. in the history of science from the University of Pennsylvania and is chief historian at the NASA Ames History office. Two recent graduates work at the Department of Defense. Another, Christopher R.M. Henderson (SFS ’03), chose medicine as his profession, which he says is a direct result of his STIA training.

Another graduate, Sydney Young (SFS ’16), works for NASA DEVELOP, a part of the agency’s applied sciences program. With her STIA-security concentration, Young was able to compete and earn a spot in the program. “The STIA program prepared me for intensive research positions by providing many opportunities to learn how to read and write technical reports, how to conduct a thorough literature review, and how to plan a complete methodology,” she says.

“If they can’t claim something on the science side, they are losing some credibility.”

For the most part, STIA students are big fans of their studies, which contributes to STIA’s escalating popularity. Several point to a single course or project that solidified their decisions to pursue the major or concentration. “I had a chance to learn firsthand about funding gaps for important programs and help identify new sources of support,” says Samantha Lee (SFS ’17), about her environmental justice course that applied community-based learning.

Aaron Silberman (SFS ’18) says a course on environmental peace building inspired him to pursue the energy and the environment track. He’s active with the campus Environmental Futures Initiative, where he invited the former president of Kiribati, a vocal leader in climate displacement, to speak at a co-sponsored event. Silberman had met the Pacific island leader at a United Nations Environmental Assembly meeting in Nairobi, Kenya, the first time UNEA had invited a university delegation. Mostly, these scholars are aware that a strong technical education cannot be avoided anymore. “There’s a sense that you can’t just joke around. Technology is everywhere and related to international relations,” Giordano says. “You look ignorant if you say, ‘I don’t want to take that stuff.’ There’s a sense of change in many students who say that science is now a part of international affairs.”

What does planet Mars have to do with global affairs on Earth? Plenty, in fact. When SFS brought on Sarah Johnson, a planetary scientist who also works on the Science Team for the Mars Curiosity Rover, the school took a new angle on international collaboration with regards to space travel.

Johnson teaches an extremely popular environmental geoscience course and has taught a proseminar on Mars exploration. She also teamteaches the gateway course,

STIA 305, which includes a blend of scientific and political discussions during class.

“The expanding exploration of space, particularly in terms of non-state actors, raises complex questions,” Johnson explains. “What rules govern private companies like SpaceX? What if they’re launching from international waters instead of U.S. territory? What are the ethics of exploration and colonization?”

She also runs a research lab, primarily focused on using tools from molecular biology

and organic geochemistry to look for traces of life in environments on Earth that are analogous to other planet bodies. The group is involved with current space missions and works with international collaborators. “Big scientific endeavors, like exploring outer space, inherently have political and economic dimensions,” she says. “That’s one of the great strengths of STIA, helping to ensure that scientists and policymakers speak the same language.”

It’s been fascinating for

Johnson, who says that STIA majors are really not afraid to delve into the tougher parts of science. “STIA majors want to go deep with science, but they are often also looking for ways to connect their studies to the society, culture, and political system in which they live,” she says. She says it can be a challenge to provide students with the technical tools while providing the broad perspective as to why those tools matter, but “when we’re successful, it’s immensely fulfilling.”—R.Y.

Although the EU has been hit with a series of outside threats, SFS experts say the real challenges lie within. by GARY THILL

AS THE EUROPEAN UNION APPROACHES ITS 60TH anniversary, it’s no small irony that the very thing it was largely founded to prevent now threatens to tear it apart.

“There is nothing like [the EU] in the world, and there’s not been anything like it in history,” says Charles King, professor of international affairs and government. “It’s not an international entity, nor is it a nation state. It’s something in between those two things.”

In 1950, fresh from the atrocities of World War II, six European countries, determined to never let the scourge of war scar their nations again, entered into an agreement to put coal and steel— the very instruments of war—under a common management.

“The pooling of coal and steel production... will change the destinies of those regions which have long been devoted to the

manufacture of munitions of war, of which they have been the most constant victims,” declared French Foreign Minister Robert Schuman, who first proposed creation of the European Coal and Steel Community.

Seven years later, the six nations signed the Treaty of Rome, creating the European Economic Community. Over the years, that community would expand into the supranational entity now known as the European Union—the world’s mightiest industrial superpower with 28 countries, 508 million residents, and a GDP of $18.9 trillion. (As of 2015, U.S. GDP was $18.3 trillion.) Even almost 60 years later, the EU experiment remains unparalleled.

But today a new international atrocity—the Syrian conflict— and all its attendant issues threaten this fledgling entity like

never before. “It’s a series of sequential overlapping crises that have Europe in its most dire position since the European integration project was launched,” says Jeffrey Anderson, director of the BMW Center for German and European Studies at SFS.

Anderson and others say how Europe responds to these crises will affect not only the continent, but the world as a whole.

Those crises are manifesting in many different forms across Europe, but experts agree they come down to three major ones: immigration, Brexit, and an emboldened Russia.

While it’s tempting to view the current pressures separately, they are all interrelated, says associate professor Abraham Newman, director of the Mortara Center for International Studies. “In many cases these things feed off each other,” he says. “They’re not independent of each other. In some cases, they have direct relationships with each other, and in others, they resonate with each other in the background.”

Still, Newman and others agree that immigration is the largest issue facing the EU. Fueled by the Syrian war and other unrest in the Middle East, more than a million migrants streamed into Europe in 2015, largely by sea, according to Eurostat. This unprecedented population shift has sparked a number of is-

sues as countries struggled with the sheer numbers and who should take the burden of resettlement. Varying by country, 63 percent to 94 percent of Europeans are unhappy with how the EU is handling the influx of refugees, according to a 2016 Pew Research study.

Fear of terrorism and a worry that immigrants can move too easily within the EU—thanks in part to the Schengen Agreement, which allows EU citizens passport-free movement between countries—has made Europeans question the wisdom of union and fueled the rise of right-wing nationalism. But King says it’s countries with the least immigration experience such as Hungary and Poland that are seeing some of the biggest increases in right-wing populism. Indeed, the Pew study shows that citizens of those two countries are most likely to believe refugees will increase domestic terrorism with Poles at 71 percent and Hungarians at 76 percent.

As a result, many countries have temporarily suspended Schengen travel. But Anderson says that, at least initially, it was carried out “willy-nilly” without much, if any, coordination from Brussels. That is beginning to change, though. Meanwhile, the EU itself has tried to better control immigration through agreements with Turkey that have reduced overland refugee traffic, Newman says.

Perceived or real, those refugee fears also fueled one of the biggest shocks to the European Union this year—Brexit. Former British Prime Minister David Cameron originally placed the

exit referendum on the ballot as a way to silence conservative critics. While the vote to leave will have long-lasting repercussions, experts believe exiting will hurt the United Kingdom more than the EU. “Brexit is terrible for the U.K.,” Newman says. “But Europe in general will be fine.”

Already, the EU is signaling a hard exit—meaning all ties to the U.K. will be cut and all trade benefits will be revoked—that’s beginning to hurt Britain. But even if the U.K. feels most of the pain, untangling a nation from the EU will have lasting implications. “You’re talking about pulling a country out of all of those areas that have developed over half of a century,” King says.

Still, as that exit unspools, and the effects begin to take shape, Newman and others say it’s unlikely other countries will want to follow suit—if everything remains stable.

Once again, these issues are interdependent. So whether other countries will want to exit depends on how national politics play out. For example, immigration fears have fueled the rise of the hard-right National Front in France led by Marine Le Pen. If she makes a successful bid for president, an exit referendum will likely be put before the French, Anderson says. However, he and others say the chance is small of the EU breaking up because of countries leaving. “I don’t think further exit is a real danger,” he says.

Danger is more omnipresent—albeit more difficult to pin down—with the third variable in the interplay of issues facing Europe: Russia. The threat from Russia isn’t a full-out invasion, but rather a continuing fomenting of the issue facing Europe, Anderson says. For example, Russia’s Syrian policies exacerbated the immigration crisis. Putin is also funding right-wing groups in other countries, such as Hungary, Ireland, Greece, Italy, Germany, Montenegro, and France’s National Front Party; and fueling disturbances on the EU’s northern border. “Russia’s trying to undermine a lot of what Europe stands for right now and that makes the situation all the more challenging,” Anderson says.

But whether it’s Russia, Brexit, or immigration, all of these issues have one commonality: they strike at the weakest links in the European Union, King says. “The problem has been that these external shocks have hit precisely those areas where the European Union is least integrated,” he notes.

While the European Union has done a good job integrating itself economically, it hasn’t yet harmonized domestic laws. And in the face of crisis, most countries have hunkered down with their own laws rather than look for commonality or inte -

While experts agree Europe may be facing its most serious challenges ever, they also question whether the “crisis” is more existential than actual.

“When the United States faces similar challenges, very few people question its existential nature. That goes to the very root of the issue: People are uncomfortable with the European Union,” says Abraham Newman, associate professor in the School of Foreign Service. “The U.S. has not had much luck with these issues because they are all very complicated. But then people don’t say that the U.S. is a bankrupt foreign power. A lot of people’s anxiety about the meta question of the EU is because it’s just such a weird thing.”

Indeed, that weirdness makes it seem more susceptible to global upheavals. “Europe has lurched from crisis

to crisis. It’s just par for the course,” says Charles King, professor of international affairs and government. “This is the most important attempt in the modern world to create not just an international organization, but a state above the level of nation-states.”

As such, the European Union, relatively young by nation-state measures, can be seen as simply growing up, says Jeffrey Anderson, director of the BMW Center for German and European Studies at SFS. “It’s like leaving adolescence and entering maturity,” Anderson explains. “It’s not clear that a country could deal effectively with all these things happening at the same time. The EU is just having growing pains. It’s now dealing with the ‘it sucks to be an adult’ phase of its existence.”—G.T.

gration. “It’s a great identity crisis for all countries,” King says.

In some ways, the fact that Europe hasn’t yet integrated domestic laws shouldn’t come as a surprise, he adds. After all, the nations involved are some of the world’s oldest. “This is about really challenging traditional notions of sovereignty of nation states and surrendering the purview of a national government to a transnational entity,” he says. “We’re probably at a point where the speed of integration and the depth of integration are both going to diminish.”

That’s why if Europe is going to find its way out of this latest series of crises—as it has done since its inception—the solutions will be more about politics than policy, King says. The question is: Will national politics allow the EU to move forward and find solutions? In today’s globalized world, he points out that’s not just a question for Europe, but a question for democracy itself. Nearly 60 years later, the very specter it raises is the same one the European Union was formed to never allow again.

“These external shocks have hit precisely those areas where the European Union is least integrated.”

“There is a global uncertainty about the ability of democracies to solve human problems that to me is extremely dangerous, because that was the source that gave rise to what happened in the 1930s,” King says. “It wasn’t just fascism and the rise of right-wing parties. The initial problem was the loss of faith in democracy as a practical solver of domestic problems. Now we see exactly that same skepticism of democracy rearing its head.”

THE STATUE OF LIBERTY HAS LONG BEEN A SYMBOL of freedom and prosperity and served as a welcome to migrants in the 20th century who were relocating primarily in pursuit of economic gain. However, migrants today are instead being forced to leave their homelands because of war, terrorism, and environmental disaster. And that, says SFS migration expert Katharine M. Donato, is a trend that will define much of worldwide migration in the near future and perhaps for generations to come.

“The 21st century story of human mobility will be largely driven by threat avoidance rather than by economic opportunity,” says Donato, who recently joined SFS as the Donald G. Herzberg Professor of International Migration, and the director of the Institute for the Study of International Migration. “Economic factors will definitely continue to matter in migration,” Donato says, “but more migration will now be driven by threats, whether those threats are a humanitarian crisis related to war or an environmental humanitarian crisis related to climate change.”

Several events occurred around the world over only two weeks in October that illustrate Donato’s point.

At the start of the month, immigration centers in Tijuana, Mexico became overwhelmed by the sudden arrival of thousands of Haitian immigrants. Most of them had initially been dislocated by the 2010 earthquake that devastated their island nation. They settled in Brazil, but after the economy there faltered, they left

en masse believing the U.S. would grant them the special refugee status it had extended after the quake. When that didn’t happen, the Haitian migrants ended up stranded in Mexico.

By mid-month, as the crisis deepened in Tijuana, Turkish government officials in Ankara announced that they were preparing to accept tens of thousands of migrants from Iraq who were already steaming north, fleeing the early stages of intense fighting between Iraqi forces and the Islamic State in the city of Mosul.

Just days after that, Italian authorities rescued 2,400 North African migrants from makeshift boats that had been drifting for days off of their country’s coast. And only hours after that rescue, French authorities began dismantling a makeshift migrant camp that had been growing for months in Calais. Known as The Jungle, the camp was home to as many as 8,300 people from North Africa and the Middle East, nearly all of whom were trying to resettle in the United Kingdom, just across the English Channel.

This is all part of the new pattern of modern migration that Donato has identified: People are fleeing environmental disaster, economic stagnation, war, and terrorism, only to arrive in countries that may not be prepared or may simply be unwilling to welcome them.

“We may think of it as just being Syria,” Donato says. “But these are issues facing migrants from all over the world.”

Already, millions of displaced Syrians, Iraq-

is, and Afghans are seeking asylum in the European Union or have moved to refugee camps in Pakistan and Iran. According to the International Organization for Migration, 38 million people were internally displaced—forced to move within their own countries’ borders—by conflict and violence in 2014. Other affected nations included South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Nigeria.

Donato says climate change is forcing migration as well. The New York Times recently reported that China’s desert had grown by 21,000 square miles since 1975, rendering once-thriving areas inhabitable and forcing residents to move closer to the cities. At the same time, cities are expanding out into the desert.

Donato has closely studied the environmental drivers of migration from villages in southwestern Bangladesh, where high levels of out-migration occur partly in response to increasingly frequent cyclones and monsoons. In that part of the country, where levees are not maintained and flooding is frequent, she was told, “Everyone has one foot out the door at any given moment.”

“The 21st century story of human mobility will be largely driven by threat avoidance rather than by economic opportunity.”

For policymakers, this shift in the primary motivations behind most of the world’s migration presents serious challenges. “I think all nations who are receiving immigrants need to think about risk-related migration and how to accommodate the demand that we’re going to be looking at in the years to come,” Donato says. “That’s especially true in the U.S. We have to develop a policy regime that’s responsive to people who move suddenly because of risk versus a regime that’s designed for people who can plan their move.”

Donato notes that one key law governing much of U.S. immigration, the Immigration and Nationality Act, was adopted in 1965 and has had only a handful of modifications since. Another key law, the Refugee Act of 1980, allows for refugees to be treated differently than other migrants, because the president has the ability to set the number of refugees the country will accept in any given year without Congressional approval. “But our policies, whether for refugees or migrants, are not very dynamic. The numbers are set and they’re hard to change in response to world events.”

Considering that those events include hard-to-predict conflicts, terrorist attacks, or environmental disasters, world leaders are likely to continue to struggle with this new kind of migration. But Donato is confident that researchers can help by providing a better understanding of how and why people have fled such events in the recent past.

“Research will help us get out in front of these issues rather than responding on the back end,” she says. “As complicated as the issue of human mobility and migration is, and even as it has become more complicated now that there are more risk-related factors driving it, we can find ways to do things that make life better for many people who have to leave their homes because of threats.”

a partnership between the McDonough School of Business and SFS. The 12-month program brings graduate students to campus for four, week-long residencies to study international relations in tandem with contemporary issues in global business. Students also spend two weeks abroad and complete two online courses. The inaugural class will commence in January 2017.

Professor Marc Busch aims to break students out of the classroom bubble and into the real world of international trade. by

"Lab-style teaching is the future," says Marc Busch, the Karl F. Landegger Professor of International Business Diplomacy at SFS and professor of business administration at the McDonough School of Business. Busch has always advocated a hands-on approach to give students a realistic look at what they’re studying.

Labs, he says, create a classroom environment “almost like we’re discovering the world in real time.” And the format allows him to “constantly renew” the course and his approach to teaching it.

“We’re all discovering new ways of teaching now,” he says. “I'm always trying to find ways to make the learning experience more real.”

This year, undergraduate SFS students studying with Busch will advise the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) on the legal arguments informing a dispute with the European Union.

“It’s our first time doing a ground-up, real-world project” in the class, Busch says. Students in the past have conducted research and devised strategies for ongoing international trade cases—but their contribution was limited to the classroom.

The students are working in conjunction with TradeLab (www.tradelab.org), an international organization that pairs academics and lawyers with companies and governments in need of legal advice. The undergraduates will be presenting their legal analysis to USTR negotiators

SHARON O’MALLEY

and litigators.

Working with TradeLab, Busch says, is “a pedagogical tool to get these kids immersed in what’s going on in the global economy.”

The current TradeLab project is the first to involve undergraduates, whose student contributors typically are in law school. The SFS course, which he has taught for a decade, currently includes a total of five undergraduates and one Ph.D. student. “We’re really pushing the envelope, throwing them into the deep end,” Busch says.

Busch is also co-academic director of the university's new master of arts in international business and policy program,

“The novelty of the program is that it provides a political economy approach to studying international business,” Busch explains. “It combines the core strengths of an MBA with the political and institutional factors that increasingly shape competition in today’s global economy.”

Busch has received high recognition for his teaching everywhere he’s worked, including Harvard and Georgetown. Forbes named his course, “Business, Government, and the Global Economy” as one of the Top 10 Most Innovative MBA courses in the United States in 2010.

Busch earned his doctorate in political science from Columbia University. But Georgetown is now family to Busch: his daughter, Lelia, is a sophomore at SFS, and his son, Zach, graduated from SFS in May.

“I’m always trying to find ways to make the learning experience more real.”

Off-campus, Busch mentors military veterans as they transition from the battlefield to civilian jobs. He works with a former SFS student, Diana Tsai, who began a program called Veterati (www.vetarati. com) to help veterans navigate their way to corporate jobs. The service aspires to help as many of the 1.2 million veterans who are transitioning into civilian life as they can, says Busch, who has taught dozens of veterans in his Georgetown classes.

Busch, who is not a veteran, says he is “amazed by people who serve. I’m stunned that we don’t do more for them when they get home.”

The professor of Jewish Civilization devotes a new book to the importance of the classroom. by SHARON O’MALLEY

Every eight years or so, Dr. Jacques Berlinerblau likes to shake his career up a bit. His seventh book, “Teach or Perish,” to be published in June, could do it again.

The new book is an effort to “start a discussion in which professors themselves ask what our fundamental mission is as scholars,” the professor of Jewish Civilization says.

The tome’s message: Teaching responsibilities like lecturing, holding office hours, grading papers, and mentoring undergraduates are “heroic acts” requiring “a deep commitment to pedagogy.” And he calls good teaching “a proper mix of creativity and fun and specialized knowledge,” a blend that students who take his Fiction of Politics and International Relations class at the Walsh School of Foreign Service say he has mastered.

Working on a book about teaching, Berlinerblau says, “got me fascinated because that’s what we do here.”

Still, Berlinerblau, who holds doctorates both in sociology and Ancient Near

Eastern Languages and Literatures from The New School for Social Research and New York University, divides his time between the classroom and writing. Among his books are “How to Be Secular: A Call to Arms for Religious Freedom” (2012) and “Thumpin’ It: The Use and Abuse of the Bible in Today’s Presidential Politics” (2008). He has also penned dozens of scholarly and popular articles.

Berlinerblau has taught at Georgetown since 2005 and says he expects to

Good teaching [is] “a proper mix of creativity and fun and specialized knowledge.”

“stick with [teaching] fiction for the rest of the ride” after turns offering classes on the Bible, anti-Semitism, and secularism.

As director of the yearold Center for Jewish Civilization on campus, he oversees a certificate program and a minor focusing on American-Middle Eastern foreign policy; the Holocaust and genocide; Jewish-Catholic relations; and Jewish literature, culture, and religious expression. The Center focuses on Judaism as a religion and a civilization, and opens dialogue about the role of religion in international affairs. It had started in 2003 as the Program for Jewish Civilization; in 2016, the Center was launched.

The Center operates from a $21 million endowed fund and is part of the School of Foreign Service—the only one in the country with an internal center that focuses on Jewish studies, he says. Its classes have drawn hundreds of students, the professor says.

And those students flock to Berlinerblau’s fiction courses, in which they learn “how stories are told about war, conflict, genocide, terrorism, the play of power, discrimination—in short, the things that SFS students study,” says Berlinerblau, who assigns authors such as John Updike, Philip Roth, and even Shakespeare.

Berlinerblau’s eight-year itch, however, has compelled him to make “really radical suggestions for reformation” of higher education that he says could help professors restore “the balance” between research and students. He bemoans what he calls “the death of tenure,” noting that three-quarters of professors in the humanities will never be employed in tenure-track jobs.

The multidisciplinary Center for Jewish Civilization, he says, stresses pedagogy. “Undergraduate teaching is what we are about,” he says, “no matter what our area of specialization. Our students are well taught.”

01 Jeffrey Anderson received the highest civilian honor from the Federal Republic of Germany for his years of service promoting transatlantic relations. Throughout his career, Anderson has worked to enhance Germany’s standing abroad through his study of the European Union and postwar German politics and foreign policy. “It’s a great personal honor, but it would not have been possible without an amazing team effort,” Anderson says of the award.

02 Fr. Matthew Carnes, S.J. was named the new director of the Center for Latin American Studies (CLAS) in July 2016. Carnes hopes to help the Center take advantage of its resources and history to remain a leader in its field. “In the coming year, I’m looking forward to leading a serious rethinking of the Center’s efforts, drawing collaboratively on all CLAS constituents—from faculty to students to staff and friends and supporters of the university—in order to ensure that CLAS remains at the forefront of Latin American Studies,” Carnes says.

03 Dennis Deletant was awarded the National Order of the Star of Romania, Romania’s highest civilian decoration, by Romanian President Klaus Iohannis. The award recognizes Deletant’s contribution to Romanian studies and his efforts to promote Romanian history, language, and culture.

04 Katharine M. Donato joined SFS as the new director of the Institute for the Study of International Migration (ISIM) in August 2016. Taking the helm of ISIM, now in its 18th year, Donato looks to strengthen ISIM’s core programs and seek out new opportunities for collaboration across campus. For her, this includes innovative research projects for which she wants to partner with faculty in disciplines from computer science to international security studies. “I would like to strengthen all of what exists at ISIM,” Donato says. “Given what’s happening in the world, it’s a topic of great relevance.”

05

Charles King received a grant from the National Endowment for Humanities for a book project that analyzes the work of a group of early 20th-century social scientists and their fight against racism and other forms of prejudice. The project, “The Humanity Lab: A Story of Race, Culture, and the Promise of an American Idea,” is expected to be published in 2019, and will focus on the work of pioneering anthropologist Franz Boas, one of the first to argue against the idea of race as a biological reality, and his peers. The work will be King’s seventh book.

06

Erick Langer was honored by the Bolivian Academy of History for his contributions to the Bolivian Congress and the field as an eminent historian. He was awarded honorary membership in the academy, associated with the Universidad Mayor de San Andrés. Langer traveled to Bolivia to accept the recognition and spoke on the role of history as a tool for equitable development in Bolivia and throughout Latin America.

07 Oriana Mastro became a Stanton Nuclear Security Fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations this year. She was also awarded the Asia Foundation Faculty Research Grant on the Domestic Dimensions of IR, and published “The Vulnerability of Rising Powers: The Logic Behind China’s Low Military Transparency” in the journal Asian Security.

08

Abraham Newman was named the new director of the Mortara Center for International Studies in August 2016. Newman plans to focus on two parts of Mortara’s mission: supporting the research efforts of SFS faculty and students and helping that research be disseminated beyond the Hilltop. “Mortara will continue to serve as a vital convener for the SFS community and, at the same time, work to catalyze cutting-edge research that brings together teams of scholars and students working on these global challenges,” he says.

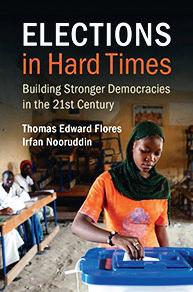

09

Irfan Nooruddin, newly-elected SFS faculty chair, is the Hamad bin Khalifa Professor of Indian Politics at SFS and is a member of the school’s Asian studies program. He directs the Georgetown India Initiative and advises the student-run Georgetown-India Dialogue. He is the author of “Coalition Politics and Economic Development: Credibility and the Strength of Weak Governments” (Cambridge, 2011). Nooruddin specializes in the study of comparative economic development and policymaking, democratization and democratic institutions, and international institutions.

10

Anna von der Goltz was awarded a Kluge Fellowship from the Kluge Center at the Library of Congress for her book project, “The Other Side of ‘1968’: Activism of the Center-Right in West Germany’s Age of Campus Protest,” which looks at student involvement of the Center-Right and unrest during the cultural and political upheaval of the 1960s.

Victor Cha published “Powerplay: The Origins of the American Alliance System in Asia,” explaining the formation of the alliances between the U.S. and Asia in the context of the Truman and Eisenhower administrations and tracing the significance of these relationships to the present day.

Robert Lieber authored “Retreat and Its ConsequencesAmerican Foreign Policy and the Problem of World Order,” evaluating the Obama administration’s foreign policy in the context of global commitment and credibility. He argues that the U.S. has harmed its ability to defend the international order and norms it has historically worked to protect.

Irfan Nooruddin published “Elections in Hard Times: Building Stronger Democracies in the 21st Century,” examining countries that struggle after “free and fair” elections. He and his co-author, Thomas Flores, explain the rapid expansion of democracy that occurred in the late 1980s-1990s and the challenges facing these new inexperienced democracies.

Joseph Sassoon authored “Anatomy of Authoritarianism in the Arab Republics,” a comparative analysis of eight authoritarian regimes in the Arab world. Sassoon draws upon historical narratives to illustrate differences and commonalities among these coercive governments.

Jeffrey Goldberg Awarded 2016 Edward Weintal Prize for Diplomatic Reporting

OCTOBER 20, 2016

Jeffrey Goldberg, editor-in-chief of The Atlantic, was the recipient of the 2016 Edward Weintal Prize for Diplomatic Reporting, presented by the Georgetown Institute for the Study of Diplomacy (ISD).

“The depth of Jeffrey Goldberg’s reporting represents the very core of what we celebrate as the continuing legacy of Teddy Weintal and the Weintal Prize for Diplomatic Reporting,” said Ambassador Barabara Bodine, ISD director.

The Weintal Prize is open to journalists in both print and broadcast media. Previous recipients since the first Weintal Prize was awarded in 1975 include Tom Brokaw, Christiane Amanpour, Stobe Talbott, Don Oberdorfer, Marvin and Bernard Kalb, and David Ignatius.

OCTOBER 19, 2016 Art can be used to help the public see the world in a different way, said Brazilian artist and sculptor Denise Milan at a Georgetown exhibit of her work. Milan discussed the importance of fusing art and science by dissecting the meaning behind each of her pieces. The pieces were grouped into “I. Paradise,” “II. Paradise Lost,” “III. Paradise Regained,” “IV. Cosmogenesis,” and were followed by a panel discussion.

The panel included Georgetown’s Thomas E. Caestecker Professor of Music Anna Celenza, who presided over the panel as moderator, MIT Institute professor emeritus and 1990 Nobel Laureate in physics Jerome Friedman, Georgetown associate professor of Portuguese emerita Naomi Moniz, and chairman and CEO of Conservation International Peter Seligmann. The event was part of the SFS Centennial Event Series on the environment.

John Kerry Visits Georgetown for Summit on Ocean Sustainability

SEPTEMBER 16, 2016

U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry addressed the Georgetown community in a discussion on ocean sustainability and climate change as the culmination of a two-day conference entitled “Our Ocean: One Future Leadership Summit.” The conference included 15 panels dealing with a variety of issues pertaining to the health of the oceans. A group of 150 students, including 39 Georgetown students, were competitively selected to attend these panels. The Summit was part of the SFS Centennial Event Series on the environment. As the School of Foreign Service approaches the 100th anniversary of its founding in 2019, it is curating a yearlong event series that convenes thinking and reflection on vital issues across the school, the university, and the community.

Actor and environmentalist Adrian Grenier also participated in the discussion with Secretary Kerry, moderated

by SFS Dean Joel Hellman.