Edmund A.Walsh School of Foreign Service

SFS shaped

Edmund A.Walsh School of Foreign Service

SFS is published regularly by Georgetown University's EDMUND A. WALSH SCHOOL OF FOREIGN SERVICE , in conjunction with Washingtonian Custom Media, a division of Washingtonian Media (washingtoniancustommedia.com). We welcome feedback and suggestions for future issues. Please contact Gail Griffith, Director of Outreach, Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service, Georgetown University, Intercultural Center 301, 37th and O Streets, NW, Washington, DC 20057; by phone at 202-687-8489; or by e-mail at gwg8@georgetown.edu. Website: sfs.georgetown.edu

Student

One MSFS student on his education, public service, and future plans.

“There are people from all over the world here...and they bring their experience and help put the theory into context.”

-WARREN RYAN, MSFS '14

A new Master's program in Global Human Development trains future development practitioners for a changing industry.

As humanitarian crises affect millions of people around the world, SFS research on refugees is both timely and relevant.

One new Georgetown institute works to prove that involving women in peacekeeping and security improves outcomes.

facebook.com/georgetownsfs

twitter.com/georgetownsfs

Search for our SFS Alumni & Student Network and Georgetown International Affairs Alliance groups vimeo.com/georgetownsfs

In the inaugural School of Foreign Service alumni magazine, we want to provide you a snapshot of who we are as an institution— and where we’re going.

Reflecting on our rich and illustrious history, we remember that the founder of SFS, Father Edmund A. Walsh, S.J., was driven by the post-World War I view that American interests were rooted in world commerce. The curriculum he created in the 1920s included courses on wharf management, exporting and importing, and international credit and collection. The first graduates of SFS filled the ranks of the American diplomatic and consular services, and many went into careers in international trade and shipping.

After World War II, with the launch of the German Marshall Plan, the era of 20th century development aid began. In part, development aid was a tool to counter the escalating influence of the Soviet Empire and, by the 1950s, the School’s curriculum reflected the burgeoning Cold War. While its Jesuit culture emphasized the moral dimension of international history, philosophy, politics, and law, the curriculum was re-structured to balance those with a more realistic understanding of foreign affairs. This balance influenced the School’s curriculum through the end of 20th century, and graduates found their way into increasingly diverse careers in public service, business, and finance.

At Georgetown, we recognize that there is no greater challenge or opportunity in the 21st century than eliminating global poverty. As you peruse the pages of this magazine, you will find that, when we talk about global human development, we refer to a comprehensive approach to economic, political, and social development in poor regions. We seek to help individuals advance their own capabilities, not just buoy struggling economies through investment.

Beginning on page 14, you'll fi nd an article on the school’s latest Master’s degree, an MA in Global Human Development. The program, which will graduate its first class this spring, offers a rigorous curriculum that teaches economics and politics along with concepts related to new technologies and innovations that impact development.

You will read about how SFS exposes students to real-world development settings through high-level summer internships with corporate, governmental, and nonprofit partners—preparing them to be successful professionals whether they choose to enter the public or private sector. These experiences, along with their classroom time, provide graduates of our program the preparation they need to be the change makers of the 21st century.

As part of our commitment to the next generation of global leaders, we also explore the issue of

MOVING SFS FORWARD Since becoming dean three years ago, Carol Lancaster has overseen the creation of two new Master's programs and a new research institute.

The Bachelor of Science in Foreign Service (BSFS) program offers a unique, interdisciplinary curriculum, focused on international affairs and customized to each student’s interests and background. To supplement core requirements, the program constantly adds new offerings that address emerging issues and utilizes ouside-the-classroom learning opportunities.

This year, BSFS began offering a course on the role of international art biennales, fairs, and museums in the world of cultural diplomacy and global exchange. The groundbreaking course is taught by professor Shiloh Krupar and museum and curatorial staff from the Phillips Collection.

16 Percent OF BSFS STUDENTS ARE FROM OUTSIDE OF THE US.

This year, 12 students from the Science, Technology, and International Affairs (STIA) major accompanied STIA director Tim Beach to Belize. The students conducted field research with Beach on how nature and humans have impacted forest and tropical-wetland soil formation over the last 10,000 years.

Myanmar

04

02

01

23

03

08

01

04

15

OF THE PHILLIPS COLLECTION PARTNERSHIP, STUDENT NAM HEE KIM SAID: “VISITING THE PHILLIPS COLLECTION AND SPEAKING WITH THE CURATORS IS THOUGHT PROVOKING BECAUSE WE LEARN THAT ART —A SEEMINGLY INNOCENT MATTER— CAN BE A USEFUL TOOL FOR DIPLOMACY AND POWER EXERTION.”

women and girls, whose contributions to preventing and resolving conflicts and to building peace in communities worldwide have long been neglected. In February 2013, we created the Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security, which conducts research, supports training and scholarship, convenes stakeholders, and inspires the next generation of female leaders.

This magazine also highlights the work of our Institute for the Study of International Migration, where researchers investigate critical issues related to refugees of war and other humanitarian crises. Conversations led by this institute address topics such as human trafficking, immigration reform, and the impact of refugees on the communities they join. All of these are tied to the wider development conversation that shapes SFS's work.

Within these pages, there are myriad stories we want to tell about our students, our faculty, our alumni, and the School's exciting collaborations with other important actors on the international scene. We hope that, as you learn more about our work, you'll find

that we remain true to the mission of our founding Fathers, while adapting to today's challenges and opportunities. Our Jesuit and Catholic identity affords us unique standing among schools of international affairs, as we investigate the theory and practice of international relations from a perspective of moral conscience and ethical behavior.

From my vantage point as Dean, I am enormously proud of our alumni and all that you have accomplished. You continue to be an extraordinary credit to this great institution. We look forward to hearing from you and encourage you to come back to the Hilltop from wherever your journeys have taken you to learn about how SFS has changed—and remained the same—since your graduation.

With all best wishes,

Carol Lancaster, F’64 Dean

1,424

TOTAL SFS STUDENTS

The Dean’s Leadership Fund is critical to SFS’s ability to:

EXPL O RE NEW EDUCATIONAL

FR O NTIER S

SUS TAIN A C ADEMI C

EX C ELLEN C E

S ERVE OUR

S T U DENT S AND

S TAY CO NNE C TED

W ITH O UR ALUMN I

SU PP O RT S T U DENT

RE S EAR C H AND

WO RK EXPERIEN CE

I write this letter as a person who wears many Georgetown hats—I'm a University alumnus, the parent of an SFS alumnus, a member of the SFS Board of Visitors, and the SFS representative to the University Executive Council overseeing “For Generations to Come: The Campaign for Georgetown.”

The council advises the University on campaign strategies, including engaging fundraising prospects and supporting the refinement of goals that are both University-wide and specific to SFS.

I am delighted to report that, as we enter our third year of the campaign's public phase, we have raised $1.19 billion toward the University’s goal of $1.5 billion.

Each year around this time, we have an opportunity to look back at the remarkable accomplishments of the School of Foreign Service, in order to create our annual Dean's Leadership Fund report. The report is designed to highlight a few of our successes and to acknowledge—with tremendous gratitude—your contributions to them. As you finish scrolling through the pages of this new magazine, we hope you'll feel better acquainted with our plans and priorities and the breadth of our reach as an institution.

The Campaign for Georgetown benefits the entire University community, but the Dean’s Leadership Fund is a distinct component in that it focuses specifically on SFS, aiming to provide the flexibility the School needs to pursue an ambitious agenda and support key initiatives such as faculty research, student internships, and career opportunities. These vital strengths are requisite to preserving the School's preeminence in these changing times.

Thanks to your support, our students have greater access to high quality educational experiences than ever before, our faculty are able to engage in more critical research projects, and our programs provide more extracurricular activities for students, which supplement their formal educational experiences.

Your contributions to the Dean’s Leadership Fund are crucial to our efforts to provide excellent education to every student at SFS, and your support helps us maintain our reputation as one of the world's topranked schools of international affairs year after year.

Contributing to the Dean’s Leadership Fund indicates that you understand the challenges and believe in the opportunities facing the School of Foreign Service now and in the future. And it underscores your commitment to ensuring that SFS plays a leading role in educating the next generation of global citizens.

In this magazine, you will read about the many extraordinary activities the School of Foreign Service has undertaken over this past year, none of which would have been possible without your contributions. Dean Lancaster, our faculty and staff, and the Board of Visitors all pledge that, with your help, 2014 will be no less impressive. We are sincerely grateful for your support.

With best wishes,

Steve Buffone, F '80, P '11, '14, '15 SFS Representative, Campaign Executive Council

This year, the Dean's Leadership Fund supported:

The Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security accepted its first student fellows in 2013.

GRADUATE EMPLOYMENT for students, who enter a range of industries—from consulting to government to nonprofits.

Programs in Global Human Development and Asian Studies will graduate their first classes in 2014.

Mr. Paul F. Pelosi, Chair F '62, P '88, '89, '91

Mr. Andrew J. Abbott F '74, P '10

Mr. Thaddeus T. Beczak F '72

Ms. Olga Maria Campano Beeck F '81, P '15, '17

Mr. Philip M. Bilden F '86

Dr. James Billington H '83, P '93

Mr. Kevin P. A. Broderick P '05

The Honorable Edward P. Brynn F '64

Mr. Steven P. Buffone F '80, P '11, '14, '15

Ms. Maria Teresa Alvarez Canida F '75, P '07, '11

Mr. Stephen D. Cashin F '79, P '10, '13

Mr. John C. Colligan F '76, P '07, '14

Mr. Anthony R. Coscia F '81, P '10, '12

Ms. Audrey A. Bracey Deegan L '80, G '80

The Honorable Paula Dobriansky F '77

Ms. Patricia M. Duff F '76

Ms. Denise M. Furey F '78

Mr. G. Robert Gage, Jr. F '77, L '80, P '16

Ms. Amy Rauenhorst Goldman F '86

Mr. Andrew Gundlach F '93, MSFS '94

The Honorable Maura Harty F '81

Mr. Edward J. Hoff F '77, P '15

Mr. Jong Han Kim F '86, L '89, P '16

Mr. George F. Landegger F '58, P '89, '02, '04

Mr. Matthew J. Lustig F '82

Mr. George M. Marcus P '91

Mrs. Virginia L. Mortara P '04, '09

Mr. Steven A. Raymund MSFS '81

Ms. Michele Metrinko Rollins F '65, L '68, '70

Mr. Mitchell Rutter P '12, '14

Ms. Nicole M. Bibbins Sedaca MSFS '97

Mr. Yunho Song F '86

Mr. George Tenet F '76, P '10

Mr. C.C. Tung P '93, '97

With GeorgetownX, the University enters today’s MOOC universe. “Globalization’s Winners and Losers” will be followed by “Genomic Medicine Gets Personal” and “Introduction to Bioethics” in the spring and a course on terrorism next fall.

“Georgetown adds a lot to our X consortium—the set of universities on our platform,” says Anant Agarwal, president of edX and a professor of electrical engineering and computer science at MIT. “Georgetown has a global presence and some world-leading areas such as the School of Foreign Service.”

MIT and Harvard jointly created edX in 2012, and nearly a million students from 192 countries have enrolled in MOOCs since. There are 29 global partners in the edX consortium, and courses range in topic from computer graphics to poetry to aerodynamics.

Designing Georgetown’s first MOOC was a complex exercise, says Moran—trickier than just setting up a camera in a classroom. The structure of “Globalization’s Winners and Losers” was devised by a group of Georgetown experts, including Moran, colleagues from SFS, and staff from the Center for New Design in Learning and Scholarship (CNDLS), the Gelardin New Media Center, and the Lauinger Library.

TSARAH KELLOGG

Thanks to a partnership with Massachusetts–based edX, SFS now offers “massive open online courses” (MOOCs) to thousands of students at a time. by

his October, more than 34,000 students from 150 countries took SFS’s new course, “Globalization’s Winners and Losers: Challenges for Developed and Developing Countries.” But none of them had to step onto Georgetown’s campus to do so. Instead, students used a Web-based platform to listen to lectures, contribute to discussion boards, participate in question-answer sessions, and attend office hours.

“It’s very exciting and interesting to be a part of this,” says Theodore H. Moran, the course’s lead teacher and the Marcus Wallenberg chair of international business and finance at SFS.

The eight-week course was the first offering from GeorgetownX, a partnership between Georgetown and edX, a platform for free “massive open online courses,” or MOOCs. Launched in October, the class explored global economic development and opportunities for public-private engagement.

A new form of distance learning, the MOOC blends broadcast and digital technology with well-designed educational content and expertise from professors. MOOCs provide rare opportunities for students from around the globe to engage with each other and with highly regarded teachers and researchers, generally for free.

“We help professors understand what it means to deliver their courses in a different medium,” says Edward Maloney, acting executive director of CNDLS, who says these courses require teachers to know what students generally care about, so they can spark dialogue in a virtual environment.

To help, four teaching assistants culled questions from discussion boards and dialogues for Moran to address. And Georgetown professors such as Anna Maria Mayda, Lindsay Oldenski (pictured below), and Scott D. Taylor contributed lectures to the course.

Moran says the experience has prompted him to work toward elevating teaching on the subject of globalization. “I think you get a second dimension of teaching using these kinds of programs,” he says. “It’s an intensive experience.”

Georgetown’s growing campus in Qatar educates cohorts that rank on par with their DC-based SFS peers. by

LORI SHARN

Less than a decade after taking root in the desert, Georgetown’s School of Foreign Service in Qatar (SFS-Q) is in full bloom. The campus began with seven professors and 25 students in August 2005, and by next fall, the striking building in an area of Doha known as Education City will house 300 undergraduates and 63 faculty.

The program “is expanding because it’s been so successful,” says Gerd Nonneman, who has led SFS-Q as dean since September 2011.

Its growth aligns with the goals of the Qatar Foundation for Education, Science, and Community Development— which funds SFS-Q and other university outposts in Education City while guaranteeing curricular, teaching, and research independence.

The small, gas-rich country in the Persian Gulf hopes to change the driving force behind its traditionally resource-based economy by 2030, and the location of top-tier universities on its soil helps in that effort.

That's why Qatar has been glad to welcome the 248 undergraduates currently enrolled full time at SFS-Q, who represent 44 countries. About a third are Qatari citizens. Another third are non-citizens who had lived in Qatar before enrolling, and the remainder have traveled specifically to attend SFS-Q.

“The diversity is really staggering,” says Nonneman. “You get students working and socializing together who are from completely different faiths, different nationalities, and different experiences.” This enhances the experience for everyone, he says.

EDUCATION CITY The sprawling Doha campus that houses SFS-Q is also home to outposts of other world-leading universities.

His graduates—158 so far—rank competitively with their SFS peers stateside and are well-regarded by employers such as governments and oil and gas companies, and by the top-ranked institutions where they pursue graduate studies.

The growing student body and expanding curriculum require more teachers, so SFS-Q is on a hiring spree. 15 faculty were hired this year, and ten more are being recruited for 2014-2015. A major in international history—the only one in the region—is new, as is a certificate in media and politics, offered jointly with Northwestern University in Qatar.

“The kinds of things that we can discover and enable here, in some respects, can feed back into the rest of Georgetown.”

The faculty will work to make SFS-Q as research intensive as its Washington counterpart, with a focus on issues affecting the region. Current research explores bioethics and Islam, migrant labor in the Gulf, and mass media and Muslims, for example. And SFS-Q has led development of an Arabic program aimed at heritage learners—who grew up speaking the language but need instruction targeted at its professional use—which will roll out to other schools in Education City soon and to schools around the world in the future.

With this sort of expansion in mind, SFS-Q is already reaching outside of Qatar. In July, students and staff traveled to Delhi, India, to host a model United Nations session for area high schoolers. “We’re here to be part and parcel to this society,” Nonneman says. “The kinds of things that we can discover and enable here, in some respects, can feed back into the rest of Georgetown."

Junior Elizabeth Holland spent last summer in Uganda, teaching lacrosse and building schools with Fields of Growth International, an American NGO started in 2009 by a lacrosse player just like her. by

NICHOLAS HUNT

Like anyone who has traveled the rutted roads of Uganda, Elizabeth Holland knows all about the ubiquitous mudcovered ovens that locals use to cure bricks. She knows the amount of work required to build their slowly smoking stacks and that getting the perfect ratio of water to dirt is tricky. She knows how much force is required to get a solid chunk of mud into its mold and how to cover new bricks with straw to help them dry without cracking.

For Holland, a junior studying international politics and a member of the school’s varsity women's lacrosse team, those bricks are a symbol of her time in Uganda. She visited the country last summer as a volunteer with Fields of Growth International—a nonprofit that connects lacrosse players with service opportunities and simultaneously works to grow the sport.

“I was shocked by the infrastructure of the country,” Holland says. “When we were making bricks, I just kept thinking: ‘Why do we have to make the bricks here? Why can’t we just have them sent from a factory somewhere?’”

It hadn’t occurred to her immediately, she explains, that without an effective way to transport the bricks within the country— like a system of highways or railroads— curing them on-site made the most sense.

The bricks were for the Hopeful School, a primary school for 250 children in the central Ugandan village of Kkindu. The school is the work of HOPEFUL Uganda, a community-based organization in the village with which Fields of Growth has partnered. Hopeful School is almost entirely built, but there is still a lot of work to be done— there aren’t yet dorms for the students or a health center, for example. Holland and her peers helped move the construction project closer to completion..

“It was great that we could actually be part of building the foundation.”

“It was great that we could actually be part of building the foundation,” Holland says.

She also helped lay the foundation for the country’s men’s national lacrosse team. During Holland’s stay in Kampala, Uganda’s capital, Fields of Growth held a three-day tryout for the national team. The Cranes, as the team is known, have a lot left to learn, Holland says, but they're talented and passionate about the sport.

“They just work really hard and are great teammates to each other,” she says, but they're fighting an uphill battle. “In the United States everyone goes to the gym, and everyone is excited about the next fitness fad. It is really not like that in Uganda. They have to motivate themselves because there is not that fitness culture already built into the society.”

Back stateside, Holland has continued working with Fields of Growth as an intern and is helping to raise money to send the Cranes to the Lacrosse World Cup in Denver this summer. She says her time in Africa has brought to life what she’s been studying in her classes at Georgetown.

“It definitely puts everything in perspective, and I understand it so much better now.”

For Arab Studies student Hannah Beswick (MA '14), a past Peace Corps posting in Morocco has enhanced her graduate study at SFS. by

NICHOLAS HUNT

In the small Moroccan community where Hannah Beswick was stationed as a Peace Corps volunteer, there were no truant officers to knock on doors or guidance counselors calling home. Girls often dropped out of school with no repercussions, and those who did remain in the educational system long enough to graduate from high school got married immediately afterward and started having children.

Beswick, now an Arab Studies Master's student, saw the community's women as ripe with potential. “I am all about women's leadership and empowerment,” she says. “In a small town, you can change one person’s life in a big way.”

As a youth-development volunteer, Beswick was asked to figure out what she could provide the kids who lived in the community and then develop programs for them. She started by teaching English and organizing camps and soccer games, but she says the capstone of her time in the town—Sebt el-Guerdane— was organizing and leading a

“Language is the key to effecting change.”

six-month health and exercise program.

“This was something that the community really wanted,” she says. “It was initially not considered appropriate for women to exercise, but after the program was over, several said that I had really helped change the perspective of the community.”

Beswick already knew that she was interested in graduate studies at SFS, but she says her time in Morocco increased her interest in the particular issues addressed in the Arab Studies program. She was familiar with the region—she’d studied abroad at the American University in Cairo as an undergraduate. But there, she was an elite studying with other elites; in el-Guerdane, she saw how average people in the region really lived without wealth, infrastructure, or support.

And she says that now, her background helps in her studies at Georgetown and in understanding the subtleties of development work. In her experience, she says, language is the key to effecting change.

“Not knowing the local dialect or the local language just builds these barriers that don’t need to be there in the first place,” she explains.

Beswick also pursues her interest in women's empowerment at home. In addition to studying at Georgetown and interning at Freedom House— which analyzes and speaks out against global threats to freedom—she serves as the co-president of Georgetown Women in International Affairs, which aims to increase the leadership skills of women on campus. Though her post-graduation plans aren't yet certain, she hopes to continue empowering women and facilitating cross-cultural understanding through development work.

Senior Peter Prindiville won a seat on the Georgetown neighborhood's governing board last year, and he’s learned that his coursework at SFS prepared him for the job.

by NICHOLAS HUNT

Students often dream of running for office and entering government during the distant unknown that follows graduation, but Peter Prindiville, a senior majoring in international history, has decided not to wait.

Raised in Woodstock, Illinois, Prindiville came to Georgetown and SFS for an international education based in liberal arts. He fell so in love with the neighborhood that, last year, he ran for a position on Georgetown’s Advisory Neighborhood Commission—an elected group of eight that advises the city government on nearly everything that happens in Georgetown. He won a seat in the November 2012 election and began serving the following January.

“I wanted to give back to this community that I’ve been happy to call my home.”

“I wanted to give back to this community that I’ve been happy to call my home and make sure that all of its residents were being represented in local government,” he says.

Those residents include the many Georgetown University students whose voices had not been heard in the past. But Prindiville recognizes that he’s not just a representative of the University and its student population. “I also represent families with kids in DC public schools, and I represent people who have lived in the District since before we got home rule,” he says.

At times in the past, tension between the University and local residents has run high. “Our homes, not GU’s Dorms,” was once regularly said by neighborhood residents, when they argued that the University should lower its enrollment cap and try to keep students on campus. But that’s changed in the last couple of years, Prindiville says, as school and neighborhood leaders have started working together much more.

As a commissioner, Prindiville has gained a unique perspective on issues he cares about—historic preservation and development, for example—that’s not available to most people, and certainly not most students. And he says that his time at SFS has equipped him to jump right into the issues facing his neighborhood.

As it turns out, he explains, the range of knowledge he’s gained in school helps him tackle a variety of esoteric matters dealt with by local government, from parking regulations to the intricacies of zoning. “The ability to see the big picture and small details as well as how systems engage with each other is vital to the international system and foreign affairs, but

it is also alive right here at home in our Georgetown community.”

Surprisingly, Prindiville says he doesn’t plan to go into politics once he graduates in the spring. But that doesn’t mean that he doesn’t plan to continue giving back.

As someone who’s always been interested in education, Prindiville sees teaching as one of the best ways recent graduates can help better their communities. He already teaches Sunday school, and once he graduates, he hopes to enter a Master's program in secondary education that places recent graduates in Catholic schools in low-income areas to teach for two years.

“We talk a lot about social justice at Georgetown,” he says, “and one way we can work to engage in social justice and alleviate some of these concerns is through education.”

Bachelor of Science in Foreign Service

Master of Science in Foreign Service

Center for Contemporary Arab Studies

Center for Eurasian, Russian and East European Studies

Center for German and European Studies

Center for Latin American Studies

Asian Studies Program

Global Human Development Program

Security Studies Program

CERES

DALLAS, TEXAS

Benjamin Priddy interned in ExxonMobil's public and government affairs division.

WASHINGTON, DC

BSFS

Naman Trivedi interned at GridPotential.

ASIAN STUDIES

Cecilia Zhou interned with the US House of Representatives subcommittee on the Asia-Pacific Region.

CLAS

BOGOTÁ, COLOMBIA

Jamie Lorena Salazar and nine classmates interned at the Colombian Agency for Reintegration, which uses socioeconomic initiatives to help demobilized combatants join civil society.

MSFS

RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL

Michaela Corr interned at the Brazilian Institute for Innovations in Social Healthcare.

GERMANY

Joshua Dill interned at the German Parliament.

MUNICH, GERMANY

Amy Soderquist interned at BMW AG.

GHD

LIBERIA

Three students studied in Liberia: Ted Hooley with the Clinton Health Access Initiative; Letitia Isasi with LRRRC; and Jake Wheeler with the Ministry of Finance.

MSFS MONROVIA, LIBERIA

Michael Podberezin interned with the Liberia Extractive Industries Transparency.

CCAS

CAIRO, EGYPT

Sarah Mousa interned at the New York Times Cairo bureau.

SSP

EGYPT AND SAUDI ARABIA

Andrew Engel studied in a languageimmersion program.

SSP

GHANA AND ZAMBIA

Roslyn Warren researched the security implications of female economic empowerment.

CERES WARSAW, POLAND

William Carden interned at the US Embassy.

CGES

KIEV, UKRAINE

Svitlana Orekhova interned with Citi Ukraine.

CERES

BISHKEK, KYRGYZSTAN

Eirene Busa interned with the Times of Central Asia.

SSP

RUSSIA

Lisa Bergstrom studied through a State Department internship.

ASIAN STUDIES

ULAANBATAAR, MONGOLIA

Lisa Dyson interned at the US Embassy.

BEIJING, CHINA

Yue Sheng studied at the Carnegie Tsinghua Center for Global Policy.

BSFS

NEPAL

Irene Cavros interned at WomenLEAD.

Whether taking classes or working as interns, SFS students spread out each summer to learn from leaders all over the world.

GHD INDONESIA

Anna Bonfert studied with the Ministry of Health.

ASIAN STUDIES

SEOUL, SOUTH

KOREA

Sam Mun studied at the ASAN Institute for Policy Studies.

For World War II veteran and Georgetown alum Thomas Wolfe (F '48), an SFS degree led to a seat at the Cold War negotiating table and a career in international business. by GAIL GRIFFITH

Thomas Wolfe was exposed at a young age to the world outside his family's New York home. Born in Greenwich Village in 1923 and raised on Long Island, Wolfe's childhood household was filled with family members speaking French. His grandfather and older brother worked as engineers for French shipping lines—large stakeholders in trans-Atlantic commerce at the time—and he set out on an international path like theirs early on.

When Wolfe enrolled at Fordham as a physics major, World War II was on the horizon. He dropped out in 1942 to enlist in the Army: “I wanted to go overseas; I wanted to see the world,” he says.

“Jesuits are the best teachers in the world,” Wolfe says of his experience at Georgetown. “They rigorously force you to examine your false notions.”

He remembers school on the Hilltop as tough, with little time for extracurricular activity. And he remembers the professor who most distinctly shaped his future: SFS institution Carroll Quigley.

Quigley’s dictum, “I have been trying to train executives rather than clerks,” tapped into Wolfe’s drive toward leadership, and he credits Quigley with encouraging his pursuits abroad.

After graduating in 1948, Wolfe returned to Europe. He studied at the Sorbonne and then, sights set on the Foreign Service, returned home to wait for a posting. He did research on Wall Street until receiving his first State Department deployment—to the French zone of Allied-occupied Germany in 1952.

When talks between the US, France, the UK, and the Soviet Union began two years later to determine the status of post-war Germany, Wolfe played a key role. By now fluent in English, French, Spanish, Italian, and German, he was tasked with translating the proceedings for Secretary of State John Foster Dulles.

Of the talks, Wolfe mostly remembers Soviet foreign minister Molotov. “Molotov was sure of himself,” Wolfe says, “able to take command and make instant decisions.” Meanwhile, he recalls Dulles as the least impressive man in the group, seeming to depend on consultations with others in the US delegation.

ON LEARNING

"Jesuits are the best teachers in the world. They don't pull their punches, and they rigorously force you to examine your false notions."

He would do just that, becoming a communications officer in Italy—where he picked up Italian—then spending the rest of the war in France and Belgium. When he returned to college, he'd lost his interest in physics and developed one in international relations. He began classes at SFS on April 1, 1946.

In Europe, Wolfe fell in love with a German ballerina. He planned to marry her, but the Foreign Service had strict rules governing the social lives of its officers, and Wolfe was forced to resign instead.

He returned to the States in 1956 and took a job in Manhattan with Chase Bank. “I felt lucky to get that job,” he recalls, noting that moves from public service into the private sector were uncommon and that he was likely afforded the opportunity only because he had previous Wall Street experience.

Before long, anxious to get back overseas, Wolfe was working for General Tire and Rubber Company, where he would stay for three decades heading operations in Morocco, Iran, and Tanzania.

After spending the early 70s in Tehran—he left shortly before the revolution—and elsewhere, Wolfe retired in 1985 and settled with his wife Ursula on the southern coast of Spain. The pair only returned to the US in 2012, in order to be closer to family.

Even now, Wolfe credits his success in business to the values—particularly honesty and decency— he learned at Georgetown. As he reflects on the vast sweep of 20th century history to which he was privy, he says he’s glad to have had such varied experience.

“Spend at least one year in another country,” he advises students. “Speak the local language and get involved in the local culture; if you don’t speak the language of a country, you don’t know the country.”

Eniola Mafe (MA '10) is using her SFS degree to empower women in the region where her family’s success took root three generations ago.

by SARAH KELLOGG

Looking back now, Eniola Mafe says she was destined to do development work in Africa’s Niger Delta. After all, her great grandmother, Madame Tinubu Alake Aina, put her children, nieces, and nephews through school with money she earned selling kola nuts in a village there.

“They called her Mama Olobi, the mother of kola nuts,” Mafe recalls. “The kola nuts were used for weddings, anniversaries, and naming ceremonies. She built the business from the ground up.”

As a result, she continues: “My life has been interwoven with the concepts of economic development, empowerment of women, serving vulnerable populations, peace building, and conflict resolution. And Nigeria, of course.”

Today, Mafe works as a program manager in Washington

ON DEVELOPMENT "Women can be the solution, and they certainly should be equal partners in any development story."

for the Niger Delta Partnership Initiative (NDPI), which creates innovative alliances for economic development and peace in the Nigerian region.

Before she was born, Eniola Mafe's parents, Babatunde and Oloruntoyin, moved from Nigeria to the UK in search of economic security and freedom from conflict. Mafe and her sister, Sarah, were born there. And though her parents now live in the States, Mafe says that little about their daily lives has change: “They have a way of creating a mini Nigeria wherever they go."

As Mafe tells it, her emigration to the US, studies at SFS, and brief stint as a Wall Street analyst have all shaped her world view. But “I am Nigerian above all,” she says.

At SFS, Mafe was part of the Master of Arts in German and European Studies (MAGES) program. “Eniola was right in the thick of things, fully engaged and always making a contribution,” says Jeffrey Anderson, Graf Goltz professor of government and director of the BMW Center for German and European Studies. “She is following exactly the kind of template we chart for our students—she’s helping solve the world’s problems.”

Mafe says her SFS experience gave her the perspective that shapes her interactions today: “You’ve got to understand the language of business and what motivates people,” she explains. “What's the monkey on their back? What are their constraints? Only then can you find a solution.”

At NDPI, she helps form partnerships to deliver aid

and build local capacity. By matching business values and objectives with social values and objectives, NDPI hopes to build economic stability and peace in the region. The organization’s work is funded by a $50-million commitment from global oil giant Chevron, which was matched by other foundations and non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

“The Niger Delta has seen a lot of violence and economic instability,” Mafe explains, saying that the nine states in the delta are home to 32 million of Nigeria’s 200 million people. “It’s a graveyard of lost economicdevelopment projects. It’s not ‘development lite.’ It’s not a region you go to and expect to have immediate success.”

But Mafe’s work has garnered attention. Pan-African business magazine Ventures Africa named her one of the “13 Young African Business/ Economic Leaders to Watch” in 2013, and the Diplomatic Courier, a global-affairs magazine, listed her as one of the “Top 99 under 33” in foreign affairs the previous year.

That recognition reflects her work at NDPI and before, when she worked as the program manager for Africa at Vital Voices Global Partnership, a Washington-based NGO that trains and aids emerging women leaders and entrepreneurs. There, she focused much of her energy on economically empowering women, mostly in sub-Saharan Africa.

“Sometimes people push programs to empower women aside and say they’re just for women’s issues,” says Mafe, noting how often she’s asked to substantiate their value. “All of my work has been to essentially say that women can be the solution, and they certainly should be equal partners in any development story.”

A new Master’s program in global human development— created by dean Carol Lancaster and director Ann Van Dusen— prepares students to become development practitioners in a rapidly changing world.

by MIRIAM BERG

“Today, more than at any other time, we have an opportunity to transform our world,” Liberian President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf told the UN General Assembly in September 2013. She would know.

After decades of violence, Liberia has been at peace for ten years; Sirleaf has been President for seven of those. With her country seeing exponential economic growth and renewed protection of human rights, it’s no wonder Sirleaf— who delivered the commencement address to SFS in 2010—was named co-chair of the UN’s panel on the post-2015 development agenda last year.

In that role, Sirleaf has utilized knowledge she gained working at the World Bank, Citibank, the UN itself—and, of course, running Liberia—to help formulate recommendations for a development agenda that was released in May 2013.

According to Steve Radelet, SFS development professor and economic advisor to Sirleaf, the UN’s Millennium Development Goals—the predecessors to the recommendations of Sirleaf's committee—were developed by UN staff and distributed to developing nations. Seeing that top-down approach as ineffective, Sirleaf's group formulated its recommendations differently. “She was a strong voice in recommending that the specifi c

goals be set by individual developing countries,” Radelet says, “rather than by the UN.”

Radelet stresses that Sirleaf’s expertise makes her uniquely qualified to lead development goal-setting. “President Sirleaf has more development experience than any other head of state,” he says. “Period.”

Radelet advises both Sirleaf and the President of Malawi, Joyce Banda, on their countries' economic policies. He served Sirleaf in a similar role previously—from 2005 to 2009—until he became a development advisor to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and, later, the chief economist for the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Radelet’s work as a practicing economist, and his research on economic growth, poverty reduction, and foreign aid in sub-Saharan Africa and East Asia inform both his work with the Presidents and his instruction at SFS.

Among the first experts that director Ann Van Dusen recruited to teach when SFS launched its Master of Global Human Development (MGHD) program in fall 2012, Radelet now works with 16 other professors to cultivate savvy human-development practitioners, the first class of whom will graduate in May 2014.

What seemed straightforward 50 years ago—that economic growth was key to improving quality of life for all citizens—has proven anything but. The past half century has taught researchers and practitioners that effective development requires social and political change as well as economic investment.

“We know that poverty is not destiny,” Van Dusen says. “And we’ve learned that both the challenges and opportunities of promoting global human development are complex, diverse, and themselves subject to rapid change.”

As a result, development theory and practice have become increasingly nuanced. Practitioners must know, for example, that what spurred a Green Revolution in Asia might not work in Africa, while conditional-cash-transfer programs can be as effective in wealthy countries as they are in Mexico. Regional and subjectmatter expertise are more and more necessary.

The logistics of development are also more challenging: governments and international organizations used to be the primary players in delivering health care to rural villages, for example, or improving the delivery of education and social services. Now, the web of actors is far larger—non-governmental organizations (NGOs), foundations, private companies, and entrepreneurs play major roles. As does technology, which requires that practitioners not only use the tools they have effectively but also stay at the forefront of new innovation.

As the field of global human development has become more complex, SFS's approach to research, education, and outreach has changed as well. Today, all undergraduate and graduate students—particularly the onethird of each Master of Science in Foreign Service cohort that pursues an internationaldevelopment concentration and those Bachelor of Science in Foreign Service students earning certificates in international development—learn the basics.

BSFS students, for example, learn tools for evaluating development impacts and get exposed to examples of both poverty and prosperity. Graduate classes, meanwhile, cover development theory and the foundations of international-development practice within the context of international affairs.

“The University in general, and SFS in particular, have made a commitment to expanding Georgetown's engagement with issues of global human development," says Michael Morfit, who has taught international affairs at SFS since 2007 and chairs the MSFS program in international development. "We are deliberately shifting away from a focus on the traditional great powers and the conventional framework of state actors…our real interest is in producing graduates who are informed, sophisticated, and effective actors," he says.

ASK THE EXPERTS

The Liberian President on the challenges facing today’s global human development practitioners.

What does global human development today require?

Global human development requires economic, social, and political empowerment. Economic empowerment gives every individual the opportunity to be productive and reap the benefits thereof; social empowerment allows each person to feel included in the society; political empowerment gives everyone the right to fully participate in the political process.

You served as co-chair of the UN’s High-Level Panel for the Post-2015 Development Agenda. What did your panel recommend in its May report? Evidence suggests that we could be the first generation to eradicate global poverty, but that is just the start. We need to ensure the fulfillment of human rights and dignity and put in place the building blocks of prosperity. We need to transform development efforts to: Leave no one behind E Ensuring access to basic economic opportunities and human rights for all persons, regardless of ethnicity, gender, geography, disability, race, or other status. Put sustainable development at the core E Making a rapid shift to sustainable production and consumption patterns and slowing the alarming climate change and environmental degradation that pose unprecedented threats to humanity. Transform economies for jobs and inclusive growth E Ending extreme poverty, improving livelihoods by harnessing innovation, technology, and

economic diversity, with equal opportunities for all. This commitment to economic transformation must remain an essential element of the African common position. Build peace and effective, open, accountable public institutions E In which peace and good governance are recognized as core elements of well-being, not optional extras. Forge a new global partnership E Anchored in our shared humanity and based on mutual respect and benefit.

In 2006, you became Africa’s first elected woman president. What role do women play in development in Africa? In addressing many of the key challenges to development, the full participation of women is paramount; we must harness the potential of one-half of the continent’s population—its women. Women are the bedrock of the African economy, but despite significant gains, much remains to be done about the place of women in African society. Africa’s future as an engine of global economic growth will be directly linked to the status of women on the continent, which will rise as they take steps to empower themselves—to actively seek out educational opportunities and take on leadership roles at all levels of society. There is no doubt that women are the future of Africa, and its leaders must invest in women’s development if they want their countries, and our continent, to advance in the 21st century and beyond.

“Africa's future as an engine of economic growth will be directly linked to the status of women on the continent, which will rise as they take steps to empower themselves.”

As international development continues to change, aspiring practitioners must know what the industry needs from them today and also how to remain effective as needs continue to evolve. That’s why SFS launched the MGHD program in 2012—to train students aspiring to work in development to make a lasting impact.

“There is a large pool of young professionals—some returning Peace Corps volunteers, others who have worked abroad in other capacities—who want knowledge, skills, and experiences that will make them more effective development practitioners," says Van Dusen, who spent almost 30 years with USAID and Save the Children before coming to SFS. "Given Georgetown’s strong commitment to—and expertise in—global human development across campus, launching the new Master’s program was a no brainer.”

Radelet says that SFS's MGHD program—one of the few of its kind in the country—is particularly innovative. “This sort of integrated Master’s program wouldn’t have existed 25 years ago,” he explains. “People would have been so focused on the economic side and the macro side that they wouldn’t have paid as much attention to the different dimensions of development."

But working in the industry today requires knowledge of public health, schooling, culture, and religion, in addition to economics and politics, so classes within the program address all these areas. And because the field is so dynamic, MGHD students develop practical skills through internships, workshops, and overseas summer work assignments.

The program utilizes the Jesuit principle cura personalis, which means to develop the whole person. It trains students to think innovatively and act as leaders. And it helps them develop an understanding of the hands-on “dirty work” of development, says MGHD's director for teaching, Gillette Hall. In fact, she adds, talks with potential employers about the types of skills they look for in new hires helped to shape the program.

“We are equipping students not to go out, pontificate, and impart wisdom from their development training—but rather, to be true partners in the development process,” Hall says.

Several times before they graduate, students apply their knowledge. First, they spend a summer working on development projects in the field: In summer 2013, students worked in more than 15 countries, with organizations such as Save the Children and Coca-Cola’s Last Mile initiative.

One student interned in Liberia’s Ministry of Finance, helping the oil, diamond, gold, and timber-rich country—which struggled for decades with conflicts over its natural resources—design policies to manage revenues from them. Another worked with International Medical Corps, evaluating mental-health programs for female Iraqi and Syrian refugees living in Turkey.

When students return to campus in the fall after their internships, their coursework focuses on a specialization—including topics such as social enterprise and global health. And during their final year, students intern with aid organizations, many of which are headquartered in Washington, and complete a final client-oriented capstone project.

The culminating project—directed by Radelet and Holly Wise, a professor of enterprise development and social entrepreneurship—is completed in place of a traditional Master’s thesis. Over the course of six months, students provide pro bono consulting to partner organizations such as Vital Voices and ABT Associates. They analyze problems brought to the University by these partners and propose solutions through full-length action reports, a type of document they'll likely need to prepare regularly once they graduate.

“We are equipping students not to go out, pontificate, and impart wisdom from their development training—but rather, to be true partners in the development process.”

Faculty and incoming MGHD students begin the year by discussing their experiences and the role of ethics in development. Students call this foundation important. "It is impossible to divorce the professional practice of international development from the ethical foundations that motivate our decisions," Peter Cook (MGHD '14) said after the inaugural retreat. "Each one of us is motivated in one way or another to pursue [this] career by fundamental ethical beliefs and considerations."

The program's foundational courses cover topics such as development-focused strategic planning, evaluation, and financing, and the role of education, health, and agriculture in development. MGHD partners with the McDonough School of Business to offer a fellowship in global social enterprise and an “innovation lab” for students to try out new technologies. During their two years of study, MGHD students practice both dreaming programs up and evaluating their impact.

Radelet says that the capstone project provides an opportunity for students to use the economics, political science, ethics, statistics, and management skills they've acquired throughout the program on something concrete before they graduate. “Most programs assume that, once students leave, they can put together all of these pieces,” he explains. But that's not always true, so MGHD asks them to do so as part of its curriculum. “That experience will make them even more skilled as they go out, after their degree, into real world,” Radelet says.

And while students polish their skills in the classroom and through practical application, faculty across the Hilltop lead a range of global human development activities. At an October 2 gathering to discuss the UN’s post-2015 development agenda, for example, former White House chief of staff, John Podesta—who is one of 27 members of the UN panel that Sirleaf co-chairs— spoke about ending extreme poverty by 2030.

Podesta and Sirleaf agree: Though one billion people around the world currently live in extreme poverty, this generation is the first with the capacity to eradicate it completely. That would mean creating a world in which nobody lives on less than $1.25 per day—an annual income of $456.25—and where nobody goes hungry. This is one of the great challenges of the 21st century and one that development practitioners graduating from SFS stand ready to take on.

At

students and researchers focus on the impacts of humanitarian crises all over the world.

by SARAH KELLOGG

Humanitarian disasters—earthquakes, droughts, long-running civil wars, famine—dominate global news and politics. They can define the terms of international relationships, undermine even the most stable economies, and displace millions of people at once.

The Institute for the Study of International Migration (ISIM) at SFS believes that the most critical factor in resolving these crises is accomplished leadership, which it trains students to provide—even in the most complex, sensitive, and urgent situations.

“We don’t want to just train people to deal with symptoms,” says Susan Martin, ISIM’s director and the Donald G. Herzberg chair in international migration. “We want them to understand the causes and how complex those causes can be. We want them to understand what the responses are and where there are possibilities for solutions.”

Founded in 1998, ISIM is a leader among programs of its kind in part because so many members of its faculty have been recruited from strategically important institutions in the field. Professors have worked and continue to work with the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), for example, and the Barbara Jordan Commission on Immigration Reform.

“Having worked for these different governmental and international organizations, we have developed vast networks of colleagues all over the world,” says Elzbieta M. Gozdziak, ISIM’s director of research. “We can call on them when our students want to gain experiences outside the Hilltop…or get a real job after they graduate.”

To address changing humanitarian needs, ISIM has launched a series of certificate programs and research projects in recent years. These are foundational and farsighted—they ask future policymakers and humanitarian workers to devise practicable solutions to entrenched migration problems.

One such initiative, the Refugee and Humanitarian Emergencies Certificate, requires six courses on topics such as the life cycle of crisis and reducing the risk of disasters.

“Some of our students want to work with refugees or displaced persons," Martin says, "and a lot of others plan to work more broadly in development or conflict resolution. Either way, they’re going into situations where it is highly likely there will be a humanitarian crisis, and this certificate gives them the tools to deal with it.”

ISIM is also pilot-testing an online certificate program, again aimed at training operatives in the field. The Certificate in International Migration Studies is designed for mid-career profes-

SYRIAN REFUGEES

Ask ISIM researchers Rochelle Davis and Abbie Taylor, and they'll tell you that one oftenignored factor in the conflict in Syria is the generosity of Jordan and Lebanon. By keeping their borders open to Syrian refugees, the experts say, the two countries have prevented even wider humanitarian disaster.

While surveying in Jordan and Lebanon last summer, the pair spoke with refugees about their experiences and with locals about refugee impacts. “In refugee studies, it becomes very important to not just look at refugees but also at the communities hosting them,” says Davis, an associate professor in SFS’s Center for Contemporary Arab Studies. “The host communities face some of the same problems as the refugees.”

Today, almost two-million refugees have fled Syria. They live in almost every village and city in Lebanon, and in Jordan, they’re concentrated in the north—woven into communities or living in camps.

The results of Davis and Taylor’s survey, which was funded by Georgetown’s Global Human Development Initiative, were reported in Syrian Refugees in Jordan and Lebanon: A Snapshot from Summer 2013.

“The people, in general, were grateful to us,” recalls Taylor, an ISIM research associate. “Refugees were grateful that Georgetown was trying to get their voices heard. NGOs were grateful for the attention. The people of Jordan and Lebanon were grateful that we cared about the struggles and challenges they’re facing.”

Davis has uncovered Syrian protest art such as this untitled work by graphic artist Imranovi.

The report finds that:

01 Refugees and host communities would benefit from increased local aid.

02 Education and health-care support for local communities should be a top priority.

03 Humanitarian aid should be distributed outside of city centers more innovatively.

04 More aid should be earmarked for young males.

Of this last point, Davis says, “We were surprised that the international community and the aid community are doing absolutely nothing for these vulnerable young men.” Noting that many of them had refused Syrian government conscription at great personal risk, she continues: “They have chosen to take themselves out of the fight in Syria, and yet we don’t do anything to help them make a living.” As a result, she says, they face hardship that can lead them back home.

Davis and Taylor spent four weeks surveying, with help from Syrian and Jordanian volunteers. “We felt that refugees interviewing one another might pick up on things that we would miss,” says Taylor, noting that even though she and Davis speak Arabic fluently, conversations between native speakers with shared experiences are inevitably more productive. “The results are richer because of them."

sionals who are looking to shift into the migration field or polish their already considerable skills. Previously taught exclusively on campus, the institute decided to look into a virtual option for the program after realizing that it wasn’t reaching everyone who needed access.

“There are a lot of good people working out there without the kinds of skills that would help improve their work,” says Lindsay Lowell, ISIM’s director of policy studies. “Online training opens our courses up to a broader audience of people who have a hard time coming here. The demand is out there, but the bottleneck has been their inability to leave their jobs and come to Georgetown.”

ISIM's researchers have also recently examined the way that women are affected by crisis, looking for ways to better tailor solutions to the needs of women and children. Gender, the institute's researchers have found, is a crucial issue in a host of areas during humanitarian disasters, including food distribution, health care, and economic development.

ISIM’s efforts in this area dovetail with those of the newly created Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security, so the two institutes will collaborate on gender, conflict, and peace issues.

“The fate of women and children is an absolutely essential part of what it means to understand humanitarian and refugee crises,”

Martin says. “If you look at any situation, about 70 or 75 percent of the affected population is women and their dependent children.”

This emphasis on gender has been influenced over the past decade by a growing focus on human trafficking. While sex trafficking receives the bulk of public attention, studies show that trafficking for forced labor is equally robust and pernicious. Not surprisingly, women and children worldwide are seized for labor in homes, sweatshops, and agriculture in far greater numbers than adult men.

That's why, in January 2013, ISIM and Deloitte sponsored a symposium entitled Anti-Human Trafficking: Transforming the Coalition. There, Academy Award-winning actress Mira Sorvino, the UN’s goodwill ambassador on human trafficking, urged experts to focus on sexual and forced-labor trafficking equally.

“We must make sure to give equal weight to sex trafficking and labor trafficking,” she said. “I have spoken to survivors who agree, among themselves, they do not wish one to be labeled more heinous, more worthy of fighting.”

Conferences like this contribute to the national and international dialogue on migration policy and showcase ISIM’s thought leadership on the subject. Of the impact of the institute, Lowell says: “Our students end up going to a lot of different places, and they are making a mark on the field.”

by MIRIAM BERG

Women are essential to peace and security worldwide. Oftentimes, their leadership in national-level politics and smaller communities draws attention to issues that can get ignored by all-male groups.

Women's increased involvement after conflict and regime change—in places like Afghanistan and South Sudan—has proven that societies seeking lasting peace must solicit help from all of their citizens, not just the men.

The Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security (GIWPS) leads research aimed at demonstrating that empowered women are critical to lasting peace and security. Launched in February 2013, GIWPS spearheads research and outreach that its founders hope will encourage developing nations to embrace women’s voices as they pursue peaceful progress.

Melanne Verveer, who became the first US Ambassador for global women’s issues in 2009, leads this effort as the institute’s executive director. A Georgetown alum (I '66; G '69), Verveer says: “The institute addresses an urgent global imperative, and Georgetown, with its commitment to social justice, academic excellence, and international leadership, is the perfect home for it.”

So what prompted its creation? In 2000, the United Nations adopted Security Council Resolution 1325, which called

for women’s full and equal participation in all peace and security efforts. But more than a decade later, the vision of the resolution remained unfulfilled. This sparked an interagency effort—involving several parts of the federal government and led by Verveer, then at the State Department—to create the US National Action Plan on Women, Peace, and Security. The NAP, as it's called, was launched by then–Secretary of State Hillary Clinton on Georgetown's campus in December 2011.

Verveer argued at the time that thinking about women's roles had fundamentally changed. "Women comprise half the world's population," she said, "their voices, economic productivity, and aspirations are essential to the well-being of their communities." And the NAP, along with the executive order that accompanied it, made that opinion the official position of the United States, by necessitating gender mainstreaming in all American diplomatic, development, and military engagements.

But that was just the beginning, explains GIWPS assistant director Mayesha Alam. Fully implementing the NAP requires policyoriented, practical research on women’s experiences in peace and security. That's why, at the same event at Gaston Hall, Clinton announced the creation of GIWPS.

GIWPS focuses on the roles and experiences of women during times of conflict, political upheaval, and rebuilding, emphasizing conflict prevention, peace keeping, and economic recovery. The institute’s research aims to gauge impact and track best practices with regard to women’s inclusion in these five arenas.

How women actively help to avert violence and use of armed force to shape paths of peace.

How gender-sensitive training in peace-support operations and the introduction of all-female peacekeeping and police units help to address issues like sexual violence in armed conflict.

How responders to humanitarian emergencies can acknowledge gender in the delivery of relief since, during crises, the burden of providing for families often falls on women.

How women’s contributions during transitional phases are vital to stabilization, and how involving women in post-conflict decisions can prevent future conflict.

How women’s contributions to postconflict economies affect local populations, since women often assume roles during conflict that had not been accessible to them beforehand and become inaccessible again afterward.

SFS dean Carol Lancaster and University president John J. DeGioia co-created GIWPS, and Verveer became executive director upon completing her tenure at the State Department, bringing decades of experience working on women'sempowerment issues there, at the White House, and with Vital Voices Global Partnership, among other places.

Research run by the institute is truly collaborative, involving a number of people and institutions across the University. It draws on the work of the Law Center, the Berkeley Center for Religion, Peace & World Affairs, the government department’s conflictresolution program, and several SFS programs. Even within SFS, contributing parties have widely varying areas of expertise. Members of the internal advisory board, for example, include Robert Egnell, the director of teaching at the Center for Security Studies, and Susan Martin, who heads the Institute for the Study of International Migration (ISIM).

Like other Georgetown institutes, GIWPS offers research-assistantships and annual summer research fellowships, named for Secretary Clinton. The fellowship program, which is open to graduate students across the University, accepted its first four fellows in 2013 to conduct self-designed research.

“The institute addresses an urgent global imperative, and Georgetown, with its commitment to social justice, academic excellence, and international leadership, is the perfect home for it.”

One fellow performed field research in Zambia, examining women’s access to land-titling rights and property ownership. Another studied gender mainstreaming in Syrian refugee camps in Turkey. A third worked with an NGO in Burundi to measure women’s participation in community-level conflict resolution. And the fourth compared models for survivor empowerment among victims of sexual- and gender-based violence in Somalia and the Democratic Republic of Congo. All of their findings will be shared in peerreviewed reports during the 2013-2014 school year.

Meanwhile, the institute organizes high-level conversations about the role of women in developing and maintaining security. Through conferences, symposiums, roundtables, and other events, GIWPS provides opportunities for students to engage with leaders in diplomacy, development, and the armed forces.

In just its first year, the institute hosted several landmark events. At its launch, a panel moderated by Tina Brown featured women on the front lines of change—including Burmese activist Zin Mar Aung, Guatemalan attorney general Claudia Paz y Paz, and Afghan advocate Nargis Nehan—who spoke of how their countries are developing and discussed the threats they still face.

Paz y Paz—the first female attorney general in her country’s history—said on the panel: “Five years ago [in Guatemala], violence against women in the home was not considered a crime." Changes have been implemented, she continued, but there is still much to be done. Nehan, the founder of Equality for Peace and Democracy in Afghanistan, pointed out later that even when progress is made, changing circumstances can cause regression. By way of example, she described her fear

that once American troops leave Afghanistan, the violenceprevention council and jobs for women that have sprung up in their presence will disappear, too.

In order to continue fostering high-level conversations of this sort, the institute has also established a 'Ministerial Series' through which world leaders are invited to address students on critical issues. Already, the series has attracted President Mary Robinson of Ireland, the UN special envoy for the Great Lakes region, and former Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard.

The institute also hosted its first symposium, Bridging Theory and Practice in the Field of Women, Peace and Security, in 2013. The event, which will be repeated annually, brought together 40 academic experts and practitioners from around the world to identify challenges and formulate recommendations for the role of women in security measures.

And this fall, panels on women and terrorism and progress in Afghanistan kicked off a series of lectures sponsored by GIWPS.

Asked to sum up the institute’s value, Alam says: “We are providing new and exciting opportunities for Georgetown students and faculty—and for societies worldwide that will be impacted by more active female citizens.”

One current GIWPS project involves collecting oral histories from a range of world leaders who are shaping the role of women in their societies. Their accounts are available to anyone with an internet connection at giwps.georgetown.edu. Profiles in Peace features stories of life and work experience from participants at all levels of development, from grassroots activist to President. Interview subjects include both men and women, all of whom are committed to empowering women to shape the their communities as they move forward.

Muhammad Yunus—whose Grameen Bank pioneered microfinance for women in Bangladesh and earned him a Nobel Peace Prize—speaks in his interview about how, with $27, he helped 42 women in his native country develop independent businesses. Previously, they had worked for a loan shark, who’d given them 25 cents for supplies to make stools and then taken all of the profits from their craftsmanship. With Yunus’s small investment, the women paid back their former boss and began to work for themselves. Yunus talks in his interview about how he's watched these first women and countless others like them flourish since he started the bank 30 years ago.

Another video features Razan Shalab Al-Sham of the Syrian Emergency Task Force, which provides humanitarian aid to Syrians while helping the country transition into an inclusive democracy. In describing her work, Al-Sham says: “We empower the women who participate in local councils. They have the capacity... but we need to encourage them to participate more and more.”

Interviewees thus far include:

ELLEN JOHNSON

SIRLEAF, President of Liberia and Nobel Peace Prize Laureate.

NANG LAO LIANG WON (TAY TAY), Cofounder of the Burmese Migrant Assistance Programme.

MONICA MCWILLIAMS, Northern Irish peace activist, scholar, and negotiator of the Good Friday Agreements.

HAWA ABDI, Somali human-rights activist, physician, and founder of the Dr. Hawa Abdi Foundation.

MUHAMMAD

YUNUS, founder of Grameen Bank and Nobel Peace Prize Laureate.

ATIFETE JAHJAGA, President of the Republic of Kosovo.

ELA BHATT, founder of the Self Employed Women’s Association of India.

PAULA GAVIRIA, director of the Victims Reparations Bureau of Colombia.

RAZAN SHALAB AL-SHAM of the Syrian Emergency Task Force.

MARIA ALEKSEJENKO, director of the Women’s Consortium of Ukraine.

SELIMA AHMAD, founder of the Bangladesh Women Chamber of Commerce.

SALLY DURA of the Women's Assembly within the Movement for Democratic Change party in Zimbabwe.

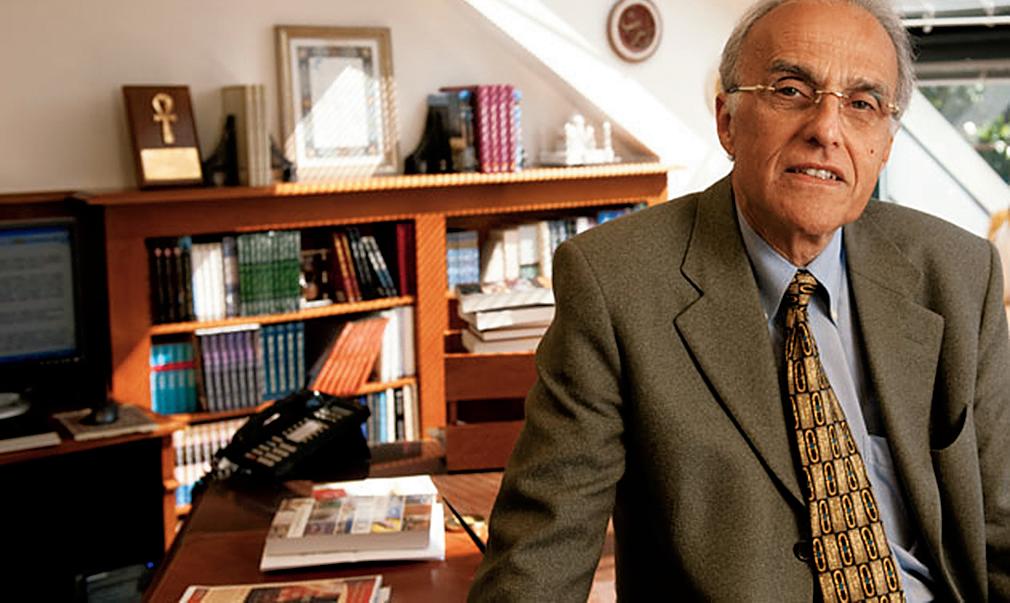

Professor Mark Giordano brings expertise in the connections between water, agriculture, and international relations to his teaching and research on the Hilltop. by NICHOLAS

HUNT

When professor Mark Giordano was in college, he worked as a farm hand during the summer. Until recently, it hadn’t occurred to him that the work he did in that temporary job has everything to do with the material he covers as a professor of environment and energy at SFS.

“I’d turn on these pumps to run the irrigation system," Giordano explains, "but at the time, I had no idea that the water I was pumping was actually groundwater. To me it was just water.”

Fast forward: The overuse of groundwater is one issue Giordano has spent the

last several years trying to solve.

Now an associate professor at SFS, he specializes in water and agriculture. His course, “Water,” grew out of research he did as a managing director at the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) and in other jobs.

“I try to bring into the class how things actually work on the ground,” he says. “So it’s partially theory and partially what I know works and what I know the issues are.”

He says that nearly all of his lectures include lessons—often counterintuitive ones—that he learned in the field.

Take leaky irrigation canals, for example. The obvious solution is to line the canals with concrete, to prevent water loss from leaks. But in Pakistan, Giordano and his colleagues found that water lost through leaks goes into the groundwater system, where it’s stored naturally and

“I try to bring into the class how things actually work on the ground.”

can be pumped and reused by farmers.

“You could put a lot of money into the construction of the irrigation system,” Giordano says, “and, in some cases, actually make the farmers worse off, all the while not reducing water use.”

At the beginning of his course, Giordano says that most of his students are unaware of the role water plays in the world, as he was at their age.

He finds that students prefer classes taught by people who have worked on the issues they cover for a long time, so they appreciate that he developed the course “Water” based largely on his knowledge and experience.

As an undergraduate economics student at Whitman College, Giordano spent a year in Eastern Europe studying Soviet satellite countries. After that, he knew he wanted to stay involved in international issues. And with a Master’s in economics, a PhD in geosciences, and experience researching relationships between agriculture, water, and politics all over the world, he’s equipped himself to do just that.

“Agriculture is the number-one user of water in the world,” he says, explaining that it accounts for nearly 80 percent of worldwide water use. “When you talk about solving global water problems, you really have to look at agriculture first and how water can be better used there.”

Most people, Giordano believes, don’t realize how connected water and agriculture are to international relations. But food security—which relies on access to water—and political stability are very closely linked, he says. When countries have problems with their food supply, their governments can fall.

This is one of the topics Giordano covers in his class on the Green Revolution—a program from the 1960s and ‘70s designed to stop the spread of communism to developing countries by increasing their crop yields. In classes like this one, he says, students are learning more than basic politics.

“The world is in a different place now than it was 30 or 40 years ago,” Giordano says. “What of those lessons can be used now to solve our current agricultural problems, and in what cases do we need to do something different?“

ON THE GROUND Mark Giordano's research on natural resources has taken him from Botswana to Cambodia, Taiwan to Zimbabwe.

Professor Oriana Skylar Mastro is a member of the SFS faculty, an Air Force reservist, and a strategy advisor to the Pentagon. She says each of her jobs helps her excel in the others. by NICHOLAS HUNT

Balancing the responsibilities of a professor and a military officer may seem all but impossible, but new SFS assistant professor Oriana Skylar Mastro —who’s also a lieutenant in the Air Force Reserve— makes it work with military precision.

“When people see the planning that occurs in my life,” she says, “it seems a little insane.” There are the systems that track her daily responsibilities as a professor of security studies and a strategist at the Pentagon. Then there are the big-picture plans for her year.

“Being a good defense planner involves listing out strategies, lines of effort, and priorities to help me decide, for example, which projects should come first. When I get opportunities to speak or travel, under what conditions do I say ‘yes’ and under what conditions do I say ‘no?’”

Mastro has been learning to prioritize since graduate school. She joined the Air Force Reserve halfway through her PhD at Princeton and was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant about a year later.

But what has become a defining part of her life almost didn’t happen. Growing up in Chicago, she had no real exposure to the military. She attended Stanford— which has no ROTC program—to pursue piano and drama, not foreign policy. But after taking a year off to live in China, she

became fascinated by the country. When she returned, she joined an honors program called the Center for International Security and Cooperation (CISAC).

Even then, she didn’t plan to join the military. In fact, when an Air Force General approached her during a conference her first year of graduate school, she thought his suggestion that she join up was crazy. “I thought that people joined when they were 18 or they didn’t join at all,” she says.