Out & Proud

Celebrating 50 years of LGBTQ Pride in D.C.

Out & Proud

Celebrating 50 years of LGBTQ Pride in D.C.

Washington Blade’s unique archives chronicle highs, lows of our movement

The magazine you’re holding represents more than 50 years of hard work by countless reporters, editors, advertising sales reps, photographers, and other media professionals who have brought you the Washington Blade since 1969.

In these pages, we are revisiting in photographs the Blade’s oneof-a-kind archives chronicling the rise of Pride celebrations in the Nation’s Capital since that frst block party in 1975. ach of the fve chapters here looks back at a decade in the growth of Pride and includes an essay reminding us of what was happening both nationally and locally in the LGBTQ movement.

As the nation’s oldest and most acclaimed LGBTQ news outlet, the Blade is uniquely positioned to bring you this comprehensive look at how the local LGBTQ community came out, fought back, celebrated, and grieved over the years. From the unimaginable tragedy of AIDS to the thrills of winning marriage equality, the Blade has documented all of our ups and downs and in many cases, was the only news outlet covering the issues important to our community.

Thank you to our talented team that put this together. njoy this complimentary look back at 50 years of Pride in D.C. Support the Blade’s vital mission by becoming a Blade member today. At a time when reliable, accurate LGBTQ news is more essential than ever, your contribution helps make it possible. ith a monthly gift starting at just 7, you’ll ensure that the Blade remains a trusted, free resource for the community — now and for years to come. Visit washingtonblade. com and click “Fund LGBTQ Journalism” in the upper right-hand box. Lynne Brown, Kevin Naff, & Brian Pitts Owners, Washington Blade

ADDRESS PO Box 60664

ashington DC 00 9

PHONE 0 -747- 077

E-MAIL news washblade.com

INTERNET washingtonblade.com

PUBLISHED BY Brown Naff Pitts Omnimedia, Inc.

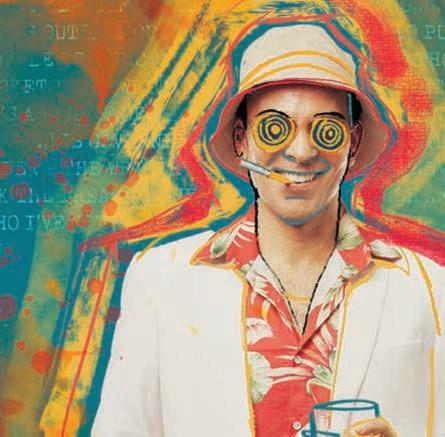

ith orldPride coming to D.C. during its 50th anniversary year, I’ve found myself re ecting on my own journey nearly 0 years since I came out. Growing up Mormon in a small, conservative town in California, I knew from a young age that I was attracted to men. I learned to hide it, often masking parts of myself with humor or sports so friends and family wouldn’t suspect. My truth came out just as I was preparing to move to D.C. for college (thank you, MySpace , and the years that followed brought both challenges and growth. But through it all, one thing anchored me Pride. It’s what helped turn D.C. into my forever

hat’s beautiful about our community is that each of us has our own unique path to becoming who we truly are. e all remember our coming out stories our frst time at a queer bar, our frst kiss with someone who felt like love. Pride gives us the space to honor those moments in whatever way feels right. hether it’s a day, a week, or a whole month, it’s a time to be surrounded by people who understand the highs and lows. Our backgrounds may differ, but what unites us is a shared truth It’s OK to be yourself even if no one else understands. It’s OK to love who you love, to dress and express yourself however you choose, even if others wouldn’t do the same. The Washington Blade holds one of the richest and most enduring legacies in LGBTQ history. hat began as a single sheet of paper in 1969 then called The Gay Blade has withstood the test of time to become the oldest LGBTQ newspaper in the country. Like me, the Blade has faced its share of challenges. But through it all, it has remained the Newspaper of ecord for our community.

I’ve been proud to call the Blade my family for the past 1 years. It’s more than a job it’s a vital part of our community that truly makes a difference. Our team doesn’t shy away from telling the full story the good, the bad, and the uncomfortable truths. As I’ve explored our more than 55 years of archives, I’ve come to fully understand the importance of preserving our history especially now, in a time when so many would rather see us erased.

hen we began planning how to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Pride in D.C., we went straight to the Blade’s archives. e are the only publication to have documented all 50 years of Pride in the nation’s capital. This magazine is a re ection of that work a testament to our past, a celebration of our present, and a commitment to the

And in a moment when our community is under attack from threats to marriage equality, to the rollback of trans rights, to the rise in hate crimes there was nothing more important to me than ensuring this magazine made it into the hands of anyone willing to read it. If these photos and stories help just one person feel seen, or help someone better understand who we are, then it has done its job.

As you look through the pages and re ect on the rich history of our community, I hope you’re inspired to make your own mark on your own terms. Be you. Be loud. Be proud. And never forget the icons who paved the way rank Kameny, Lilli incenz, Marsha P. Johnson, and so many others. This magazine is a reminder that we will never be erased and we will always have pride. Stephen Rutgers Director of Sales & Marketing

PUBLISHER

L NN J. B O N lbrown washblade.com ext. 8075

EDITOR K IN NA knaff washblade.com ext. 8088

PHOTO EDITOR

MIC A L K mkey washblade.com ext 8084

Contributing writers Lou Chibbaro Jr., Michael K. Lavers, Christopher Kane, Joe eberkenny, Joey DiGuglielmo. DESIGN/PRODUCTION

M AG AN JUBA production azercreative.com DIRECTOR OF SALES & MARKETING

ST P N UTG S srutgers washblade.com ext. 8077

SR. ACCT. EXECUTIVE B IAN PITTS bpitts washblade.com ext. 8089

ADMINISTRATION

P ILLIP G. OCKST O prockstroh washblade.com ext. 809

or distribution, contact Lynne Brown at 0 -747- 077, ext. 8075. Distributed by Southwest Distribution Inc. All material in the ashington Blade is protected by federal copyright law and may not be reproduced without the written consent of the ashington Blade. The sexual orientation of advertisers, photographers, writers, and cartoonists published herein is neither inferred nor implied. The appearance of names or pictorial representations does not necessarily indicate the sexual orientation of that person or persons. Although the ashington Blade is supported by many fne advertisers, we cannot accept responsibility for claims made by advertisers.

0 5 B O N NA PITTS OMNIM DIA, INC.

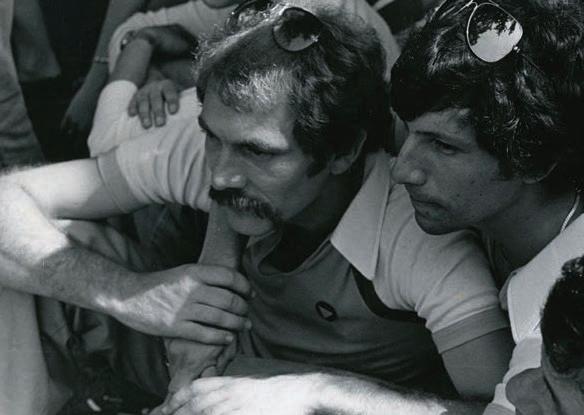

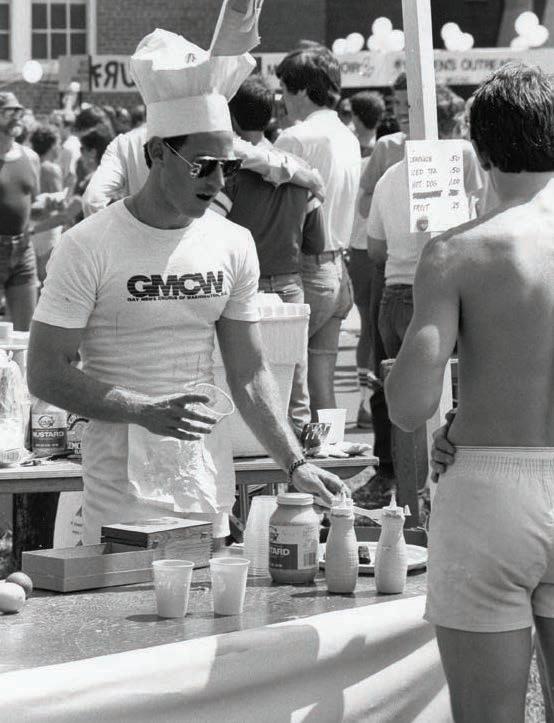

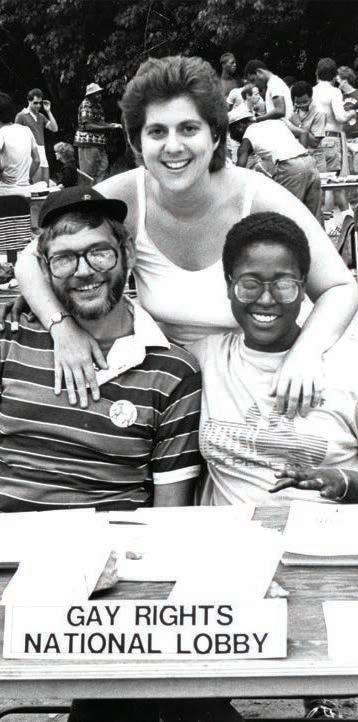

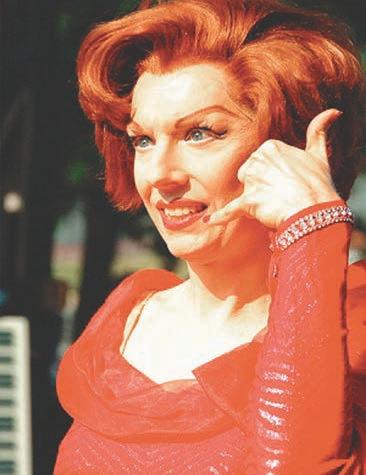

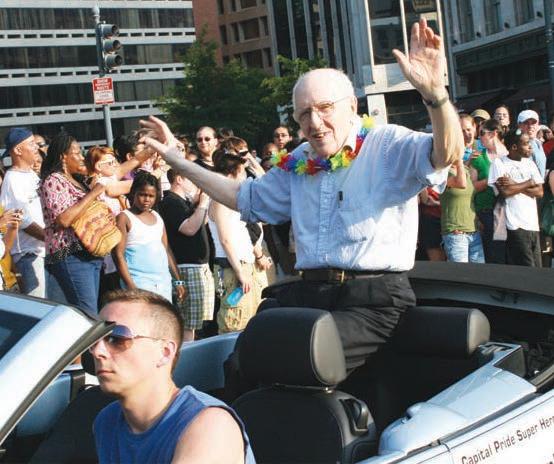

Below: is director of the

If our movement has taught me anything, it’s that Pride was — and still is — a promise that none of us would have to walk alone. Beyond the celebrations, Pride is the visible result of generations of work — work to love ourselves, to fght for our rights, and to open the door wider for those who come after us.

In supporting our LGBTQIA+ community ahead of World Pride 0 5, one thing I am most proud of is that we are not defned by one story, one identity, or one path. We are trans and nonbinary elders who paved the way when few listened. We are queer youth carving out joy in uncertain times. We are parents, drag artists, service workers, policy nerds, neighbors, and families. Our community is not defned by one identity, one moment, or one Pride celebration. e are many. And it’s in that plurality — across Black Pride, Trans Pride, Latinx Pride, Youth Pride, AANHPI Pride, Silver Pride, and more — that we fnd our collective power and beauty.

This year, as we invite the world to experience the vibrancy of our communities and neighborhoods, I look forward to celebrating our elders as they receive the owers and recognition they deserve, supporting our queer youth as they take the lead and create space for each other, and dancing with old friends while making new ones. I’m also deeply committed to the advocacy and visibility moments that remind us of the work that continues to shape our future. Because Pride is not just a celebration of who we are — it’s a call to action for the kind of community we want to create. The true power of Pride isn’t just in the crowds we gather, but in the communities we strengthen, the voices we lift, and the future we dare to imagine together.

I’m proud — deeply proud — to be part of this moment in our city’s story. And I know the spirit of Pride lives far beyond a single month, because it lives in each of us: in how we show up, how we lead with love, and how we keep building a world that makes room for all of us.

Japer Bowles Director

Our Community Grants program has awarded or approved over $5 million to grassroots LGBTQ+ organizations since 2020

Our TransPLUS Resource Center seeks to center, support, and uplift the most vulnerable members of our community

Our SilverConnect program celebrates our community as we enter our golden years through meaningful connection and intergenerational learning

Our LGBTQ+ Pride Coalition allows organizers in the NY tri-state area to connect, network, and learn more about celebrating Pride in their local communities, not just in June, but every day

Our LGBTQ+ Advocacy Fund supports large-scale projects rooted in pivotal progress in the LGBTQ+ equality movement

And Coming Soon: Let's Get Back Together: A resource to support LGBTQ+ Student Centers on college campuses

LGBTQ+ Executives and Directors: Developing the next generation of LGBTQ+ community leaders leonardlitz.org

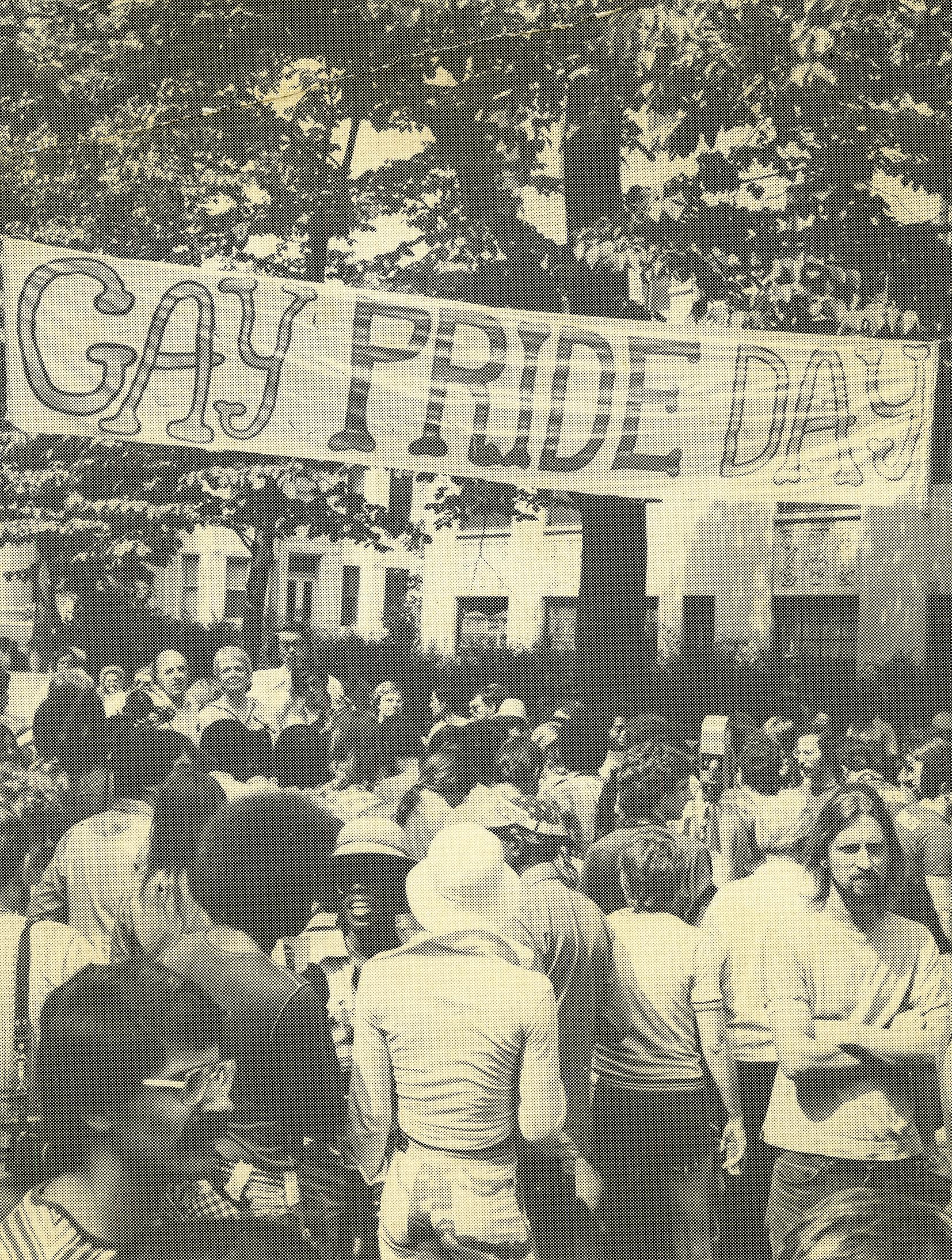

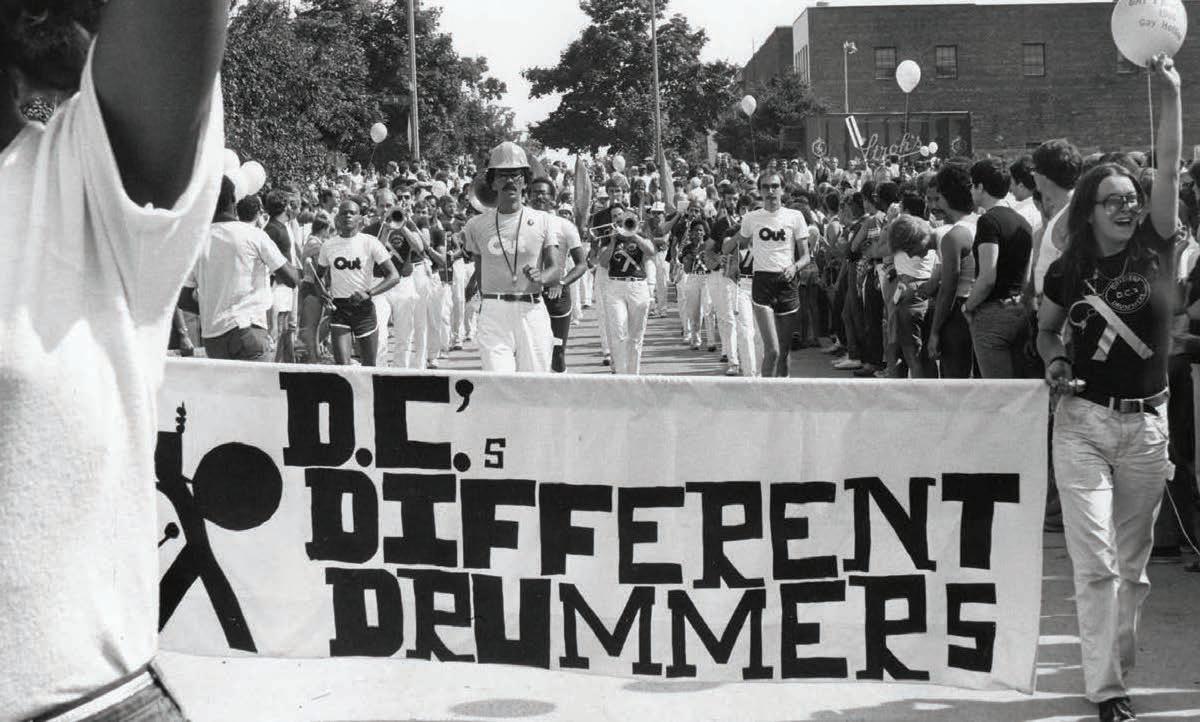

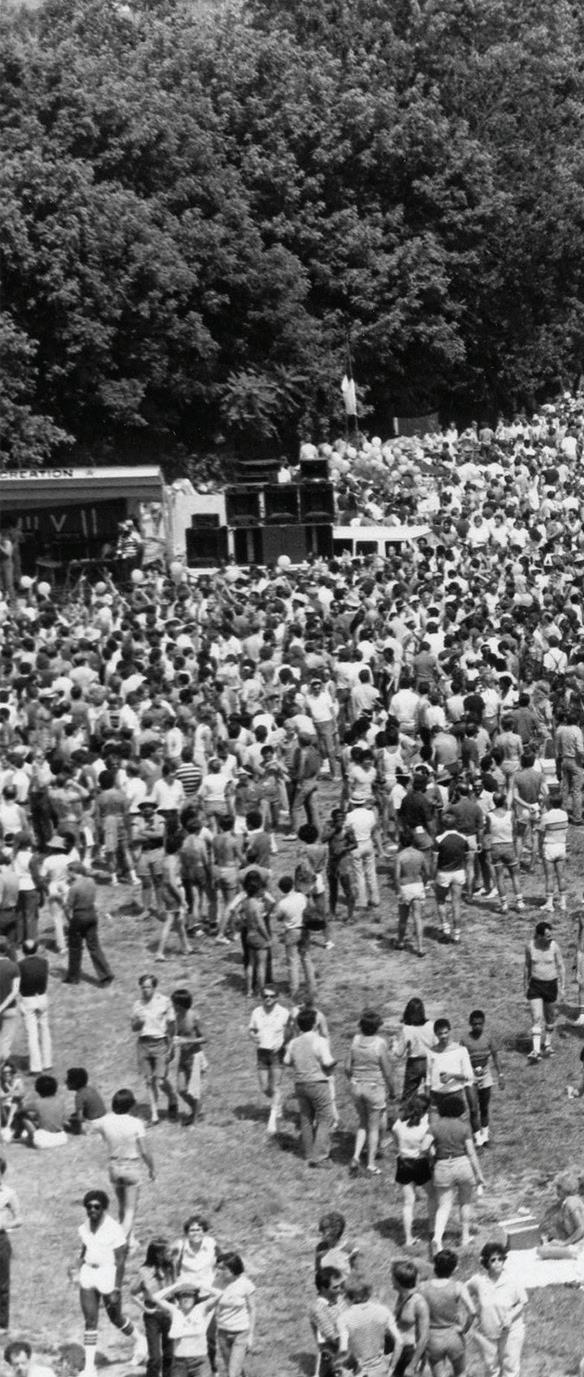

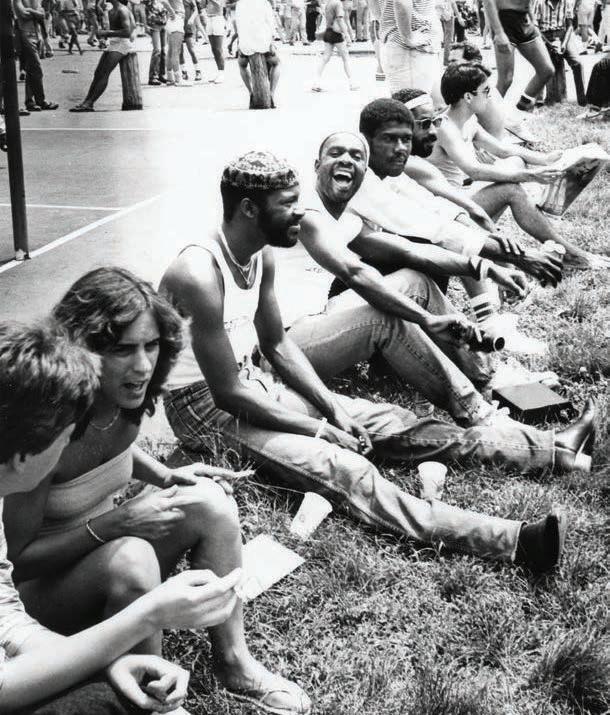

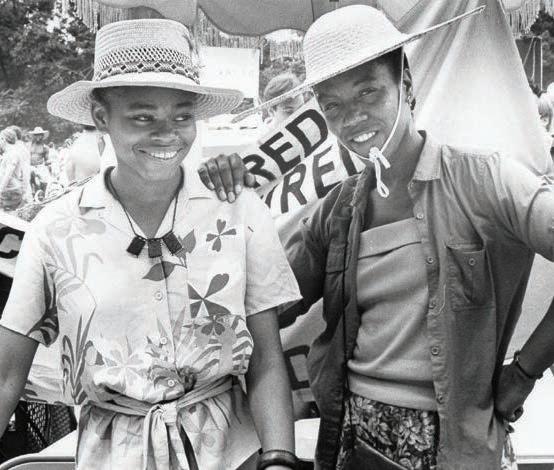

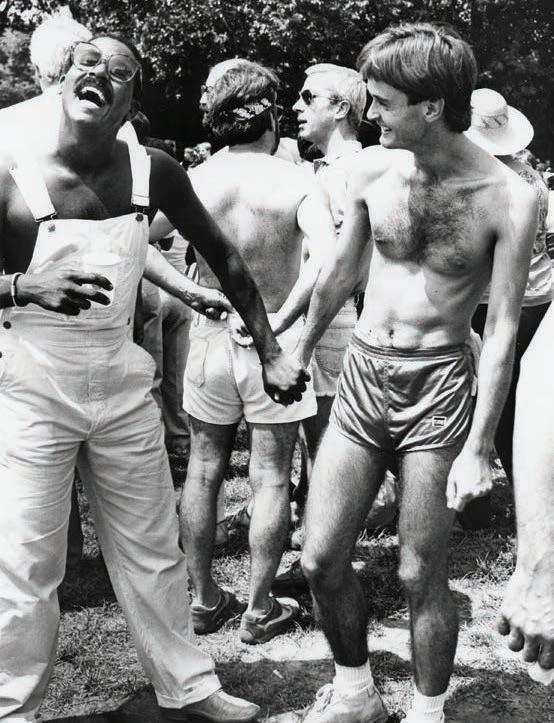

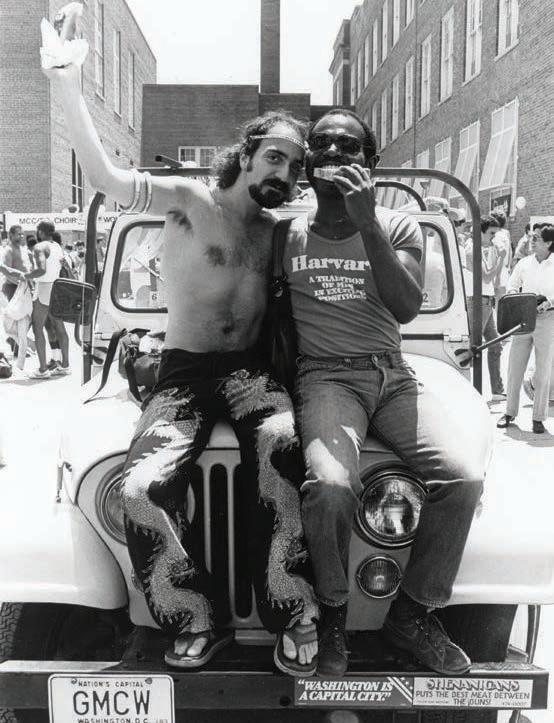

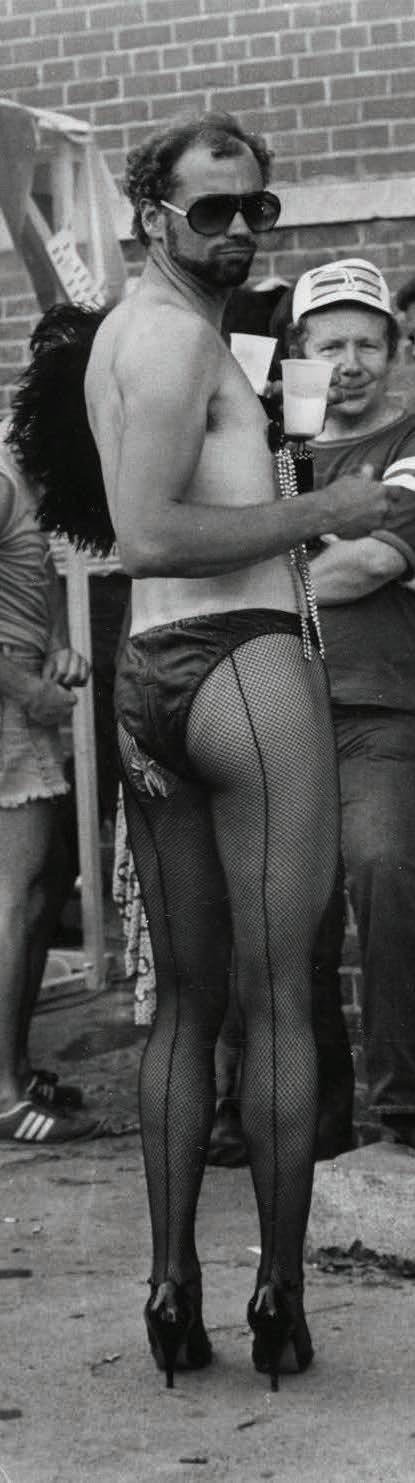

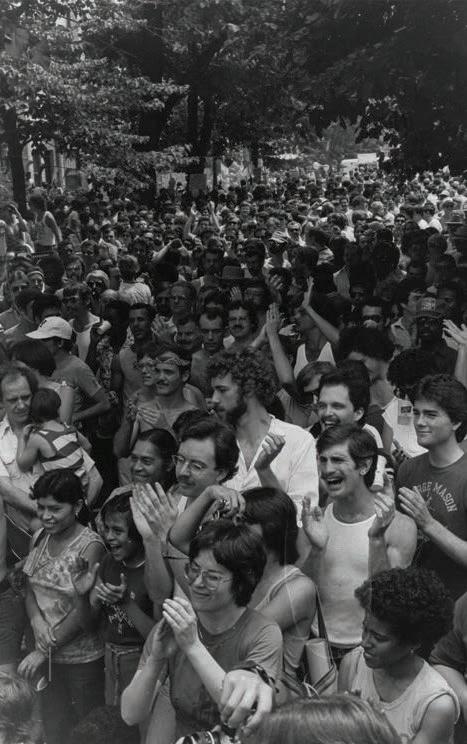

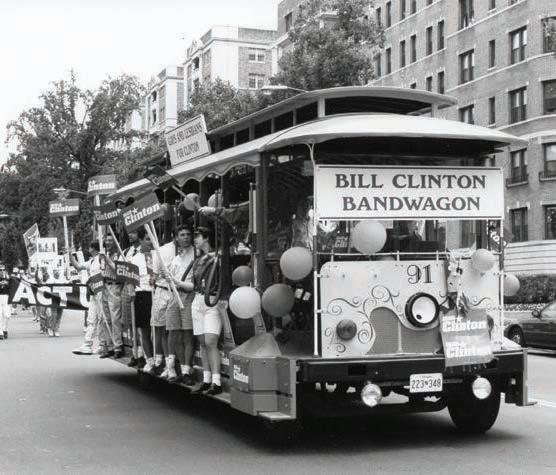

50 years of celebrations began with 1975 ‘Gay Pride Day’

Initial turnout of 2,000 grew exponentially, coinciding with arrival of AIDS plague

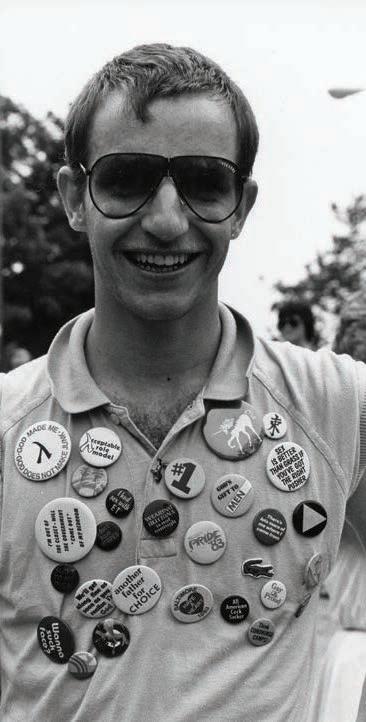

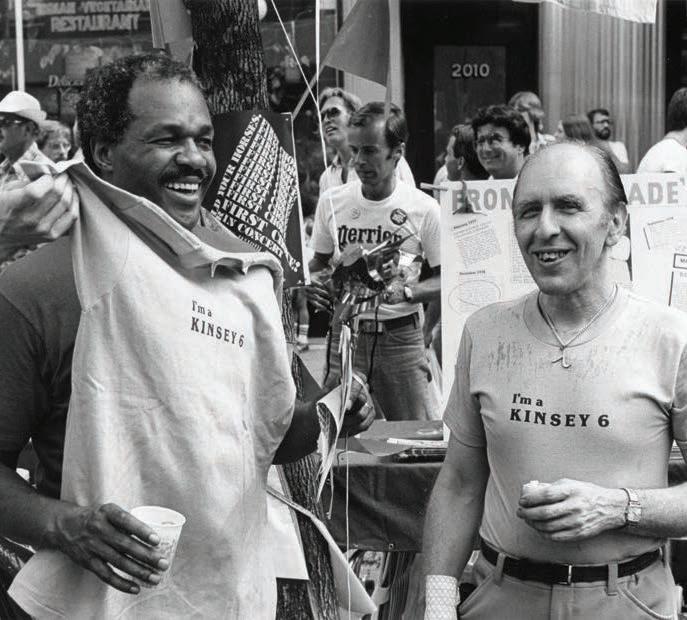

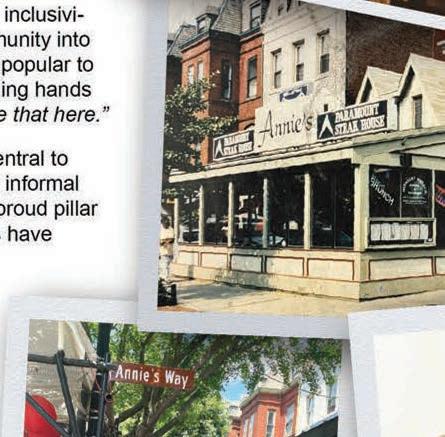

Deacon Maccubbin, owner of the D.C. gay bookstore Lambda Rising, which opened in 1974 (and closed in 2010) is credited with organizing the frst LGBTQ Pride celebration in the nation’s capital in 1975.

Maccubbin had been attending the New York City Gay Pride celebrations since they began one year after the historic 1969 Stonewall Rebellion that triggered the modern LGBTQ rights movement. e said he and several of his gay activist friends decided it was time for D.C. to have its own Pride event.

The 1975 D.C. Gay Pride Day event took place on the third Sunday of June as a block party on the 1700 block of 20th Street, N.W., near Dupont Circle, where Maccubbin’s Lambda ising bookstore was located.

Maccubbin has said that although he and his volunteer helpers promoted the event by distributing yers at all the city’s gay bars and arranged for an announcement in the then-Gay Blade newspaper, only a few people arrived on the block at the event’s offcial starting time.

While his supporters were alarmed that the event might turn out to be a op, Maccubbin recalls saying, Don’t worry, I think people will arrive on gay time.

And sure enough, a short time later, at least ,000 people descended on 0th Street. They were greeted by about a dozen booths set up by local LGBTQ groups, including the then Gay Switchboard and Gay outh group, along with a few vendors selling beer and soft drinks.

Among those attending the 1975 D.C. Gay Pride Day event was D.C. City Council member John Wilson (D), whose Ward 2 district included the Dupont Circle area. ilson presented a Gay Pride Day proclamation that he arranged for his fellow Council members to approve.

It was a gesture of support for the then gay community that took place during the second year of D.C.’s newly created home rule government that continued each year thereafter.

Maccubbin said the turnout for D.C. Gay Pride increased each year through 1979, when more than

By LOU CHIBBARO JR.

10,000 attended the event, which had expanded to three blocks of 0th Street. Then-Mayor Marion Barry became the frst D.C. mayor to attend the Gay Pride event in 1979.

During those frst fve years, while the D.C. government was supportive of the LGBTQ community, Maccubbin recalls that many Gay Pride attendees worked for the federal government and worried about possible adverse action if their government and in some cases private employers learned they were gay or lesbian.

Maccubbin and his fellow organizers attempted to address this issue during the frst few years by putting out the word that those who did not want to be identifed or outed as gay or lesbian should stay on one side of the street. Maccubbin said he and fellow organizers then asked news media photographers and T camera crews that covered the event to limit their photo or flm coverage to the other side of the street, where attendees did not mind being photographed or flmed.

The one objection raised during D.C.’s Gay Pride Day in the frst two years by a few candidates running for D.C. Council and some community activists was that it took place on ather’s Day. Maccubbin said he chose the third Sunday of June to hold Gay Pride Day to enable him and others to attend the New ork City Pride event, which had been and continues to take place on the fourth Sunday in June. Maccubbin said he did not intentionally select the third Sunday because it was ather’s Day.

To address this issue, Maccubbin decided in 1977 to move D.C. Gay Pride Day ahead one week to the second Sunday of June, where it has remained since then.

At the end of the 1979 event, it was decided the 20th Street location could no longer accommodate Gay Pride.

It was too many people to be held in that threeblock space, Maccubbin told the ashington Blade in a ebruary 0 5, interview. So, we turned it over to the nonproft P Street estival group so they could continue it at the new location.

e was referring to the 1980 D.C. Gay Pride event, which took place at the outdoor athletic

feld grounds and parking lot of D.C.’s rancis Junior igh School at 4th and N streets, N. . The rancis School grounds are located next to a section of ock Creek Park known as P Street Beach, a longtime gathering place for members of the LGBTQ community.

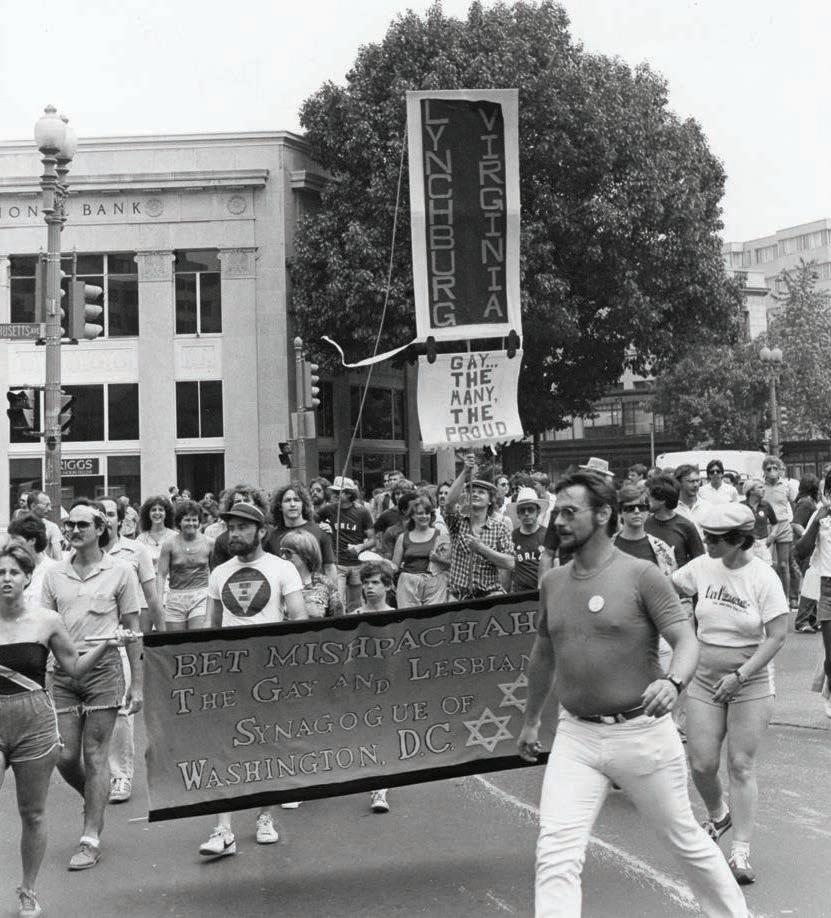

Attendance continued to grow at the new location, and in 1981 P Street estival organizers renamed the event Gay and Lesbian Pride Day and organized D.C.’s frst Pride parade that year. The parade began at 16th Street, N.W. at Meridian Hill Park and ended at Dupont Circle, which is located a few blocks from the Francis Junior High School grounds, where parade participants went for what was then called the Gay and Lesbian Pride festival.

According to P Street estival organizers, the attendance grew from about 11,000 in 1981 to about 0,000 by 198 . By 1984, the one-day festival had expanded to become a weeklong series of events, including meetings, dances, art exhibits, and parties.

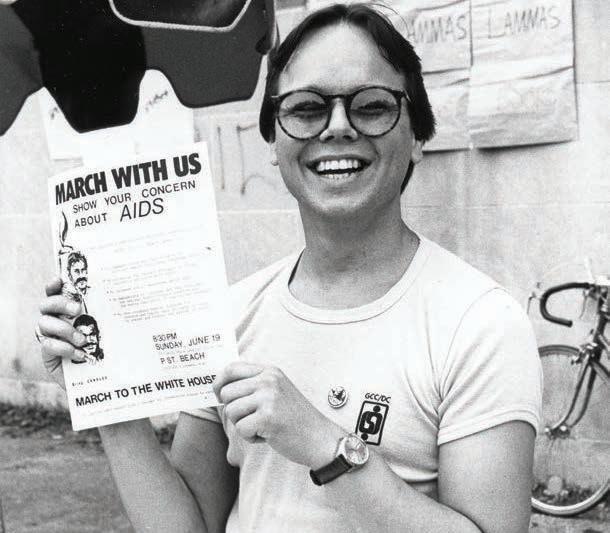

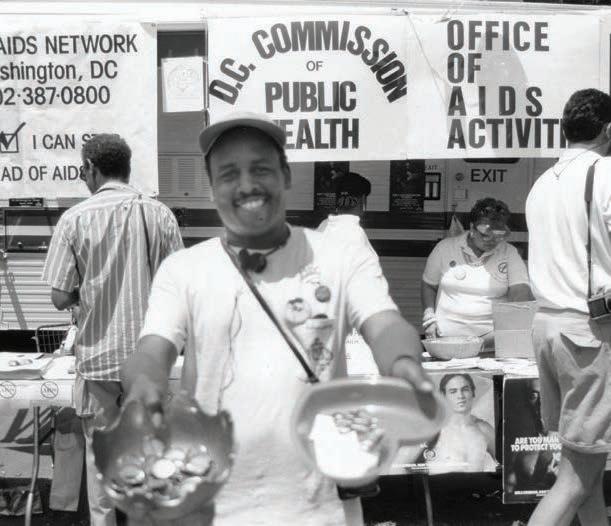

But around that time the AIDS epidemic, which frst surfaced in 1981, became a topic of interest among Pride organizers and attendees. ith then-President onald eagan in offce, some of the AIDS activists who staged protests outside the White House on grounds that the Reagan administration was failing to adequately address the epidemic, joined D.C.s Pride Parade.

Maccubbin, who along with his partner and husband, Jim Bennett, moved Lambda ising to two other locations in the Dupont Circle area before closing it in 010 to retire, said he and Bennett continued to attend D.C.’s annual Pride celebrations since the events moved off 0th Street. e said the two are looking forward to attending this year’s orldPride events.

In observing the D.C. Pride events since the frst year he organized them in 1975, Maccubbin said he continues to be moved by how the events impact people attending them for the frst time. very year that it’s held there have been people who were experiencing it for the frst time, he said. It will happen again this year, I’m sure. It’s a real eye opener.

50 concerts. 25 venues. 30 choruses. 16 days.

Experience the power of music as voices from LGBTQ+ choruses and groups from around the world come together in harmony with the Gay Men’s Chorus of Washington, DC to celebrate love, diversity, strength, and pride. The festival will include John Bucchino’s A Peacock Among Pigeons and the world premiere of Our Wildest Imaginings, a new work by acclaimed composer Dominick DiOrio, at select performances.

Free performances every day. Premium passes available for sale.

MAY 24 TO JUNE 8, 2025 FOR FULL LINEUP AND MORE

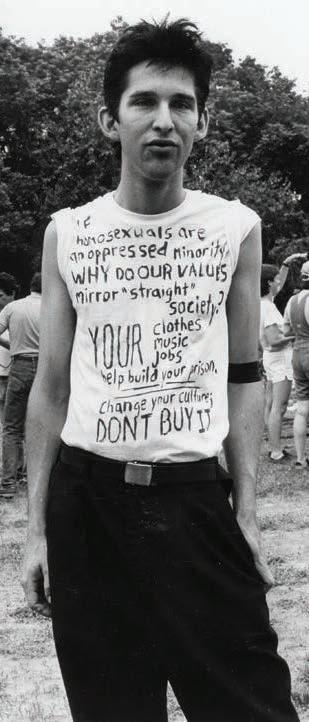

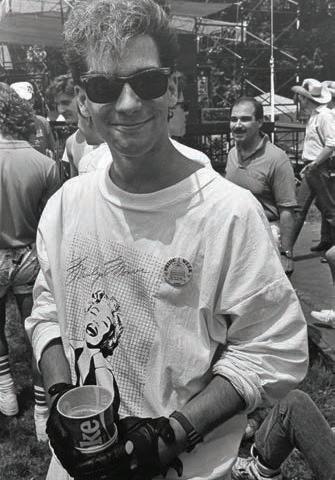

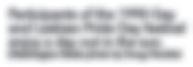

What is now called the LGBTQ rights movement in many ways came of age from the mid-’80s to the mid-’90s with multiple game-changing developments.

LGBTQ Boomers and historians tend to agree that I AIDS is the defning issue of the cause from at least 1985-1994. Things would change in 1995 when the frst protease inhibitors were approved, but the years prior brought a house-on-fre urgency the movement had not previously known.

As the number of deaths soared, wrote gay historian ric Marcus in his 00 book Making Gay istory the alf-Century ight for Lesbian and Gay qual ights, gay and lesbian people and gay rights organizations (in the 1980s) redirected their energies. Many thousands of gay people who had never participated in gay rights efforts were motivated to join the fght against AIDS. New organizations joined existing ones to provide care for the sick and dying, conduct AIDS-education programs, lobby local and federal governments for increased funding for AIDS research, pressure medical researchers and drug companies to become more aggressive in their search for treatments and a cure and fght discrimination against people with AIDS and those infected with I .

Hollywood leading man Rock Hudson died of AIDS in 1985 and pianist Liberace succumbed to the disease in 1987, putting well-known faces (both

By JOEY DiGUGLIELMO

closeted) to the devastation for millions of Americans.

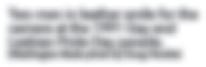

ACT UP, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, was founded in New ork in 1987 by playwright Larry Kramer and others. ACT UP is credited with accelerating the FDA’s drug approval process, lowering AIDS-related drug costs, and forcing the U.S. government to address the crisis.

ACT UP activists halted rush-hour traffc in New ork’s fnancial district on March 4, 1987 and on San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge on Jan. 31, 1989 among hundreds of other protests. Other activist groups also emerged during this time. Queer Nation’s frst major action happened on April 8, 1990, when 500 activists marched in Greenwich Village to protest a pipe bomb attack on a gay bar. Local ACT UP and Queer Nation branches sprouted in 60 cities, according to Rodger Streitmatter’s book Unspeakable the ise of the Gay and Lesbian Press in America.

D.C. was certainly not immune to the deaths or the protests. Rev. Candace Shultis, former senior pastor of Metropolitan Community Church of Washington, the D.C. parish of a mostly LGBTQ Christian denomination (The Universal Fellowship of Metropolitan Community Churches), recalled in a 2011 Blade interview that the church’s ministry throughout the 1980s and into the 1990s was “defned by I and AIDS. ou just can’t say anything

but that. It was just real clear this had a huge impact on the community and we lost a lot of people. … e became kind of known as the place where you could come and we would do your funeral.

Dignity Washington, the regional chapter of DignityUSA, continued its ministries to LGBTQ Catholics in those years, having been founded in 197 . In 1985, a former chapter president, John Willig, became the church’s frst member to die of AIDS.

Other D.C. chapters of national groups, such as the Gay Men’s Chorus of Washington (founded in 1981 also saw their memberships ravaged by AIDS.

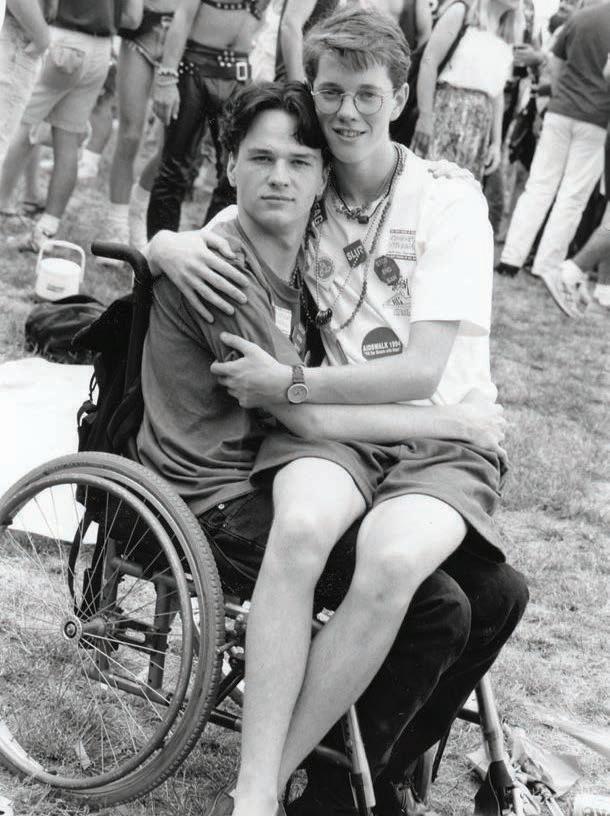

In 1986, Washington’s Gay Activists Alliance, under the leadership of then-president Lorri Jean, changed its name to Gay and Lesbian Activists Alliance (GLAA). Among its achievements in this era were a 1986 D.C. Council bill that prohibits insurance companies from denying coverage to HIV-positive residents, anti-hate crimes legislation in 1990 and a 199 domestic partnership bill. Whitman-Walker Health, which had opened as the Gay Men’s D Clinic in 197 but rebranded in ’78, launched the AIDS Education Fund and the AIDS valuation Unit in 1984, becoming the frst gay, community-based medical unit in the U.S. focused on AIDS.

Amid all of this, national progress on LGBTQ rights was not easily secured. The Reagan and (George H.W.) Bush administrations were hostile to

LGBTQ causes and in 1986, a Supreme Court ruling upheld a Georgia law ruling that consenting adults do not have a constitutional right to have gay sex in private.In 1987, the U.S. banned HIV-positive people from traveling or immigrating to the U.S. That law stood until 2009.

More than 50 openly gay and lesbian offcials were elected to public offce in the 1980s, including Massachusetts congressmen Barney Frank and Gerry Studds. The frst openly gay and lesbian judges were appointed and openly gay and lesbian clergy were ordained in a handful of progressive Christian denominations. Some religious leaders in those years expressed support for, if not marriage, blessings for same-sex couples, Marcus notes in “Making Gay History.”

By the early ’90s, more than 100 cities and counties in the U.S. and four states had passed laws protecting the rights of gay people and a handful of municipalities, Marcus writes, passed domestic partnership laws that extended limited rights to same-sex couples that were sometimes viewed as symbolically signifcant.

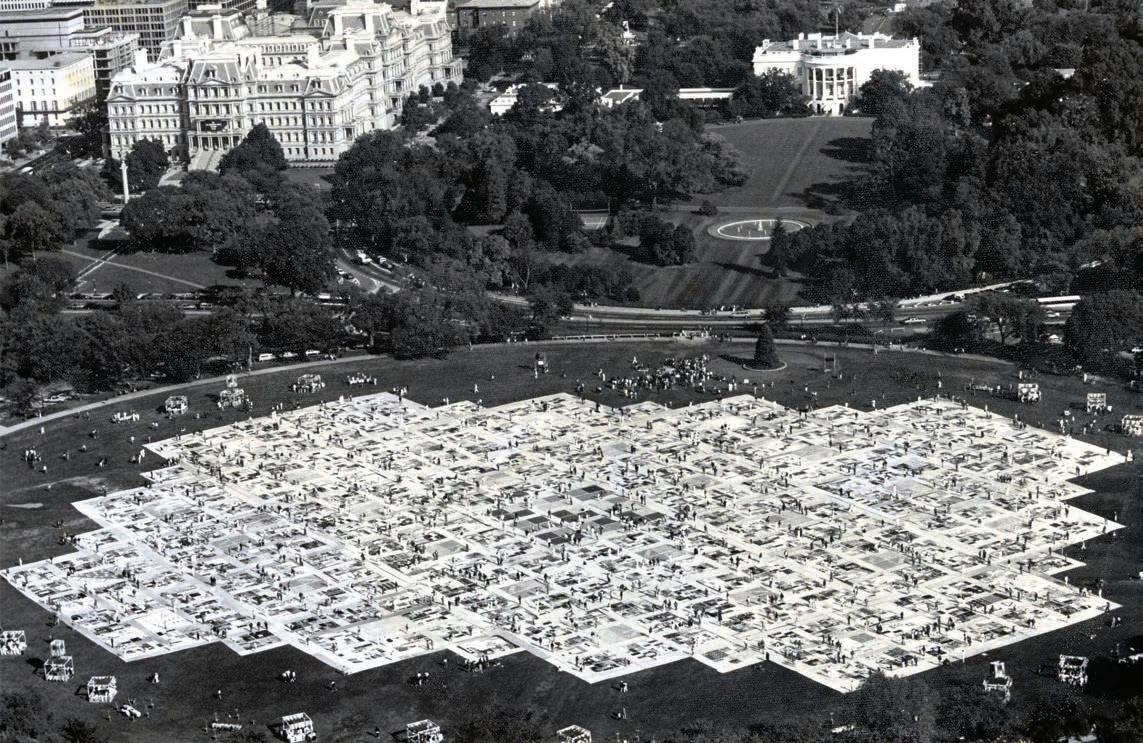

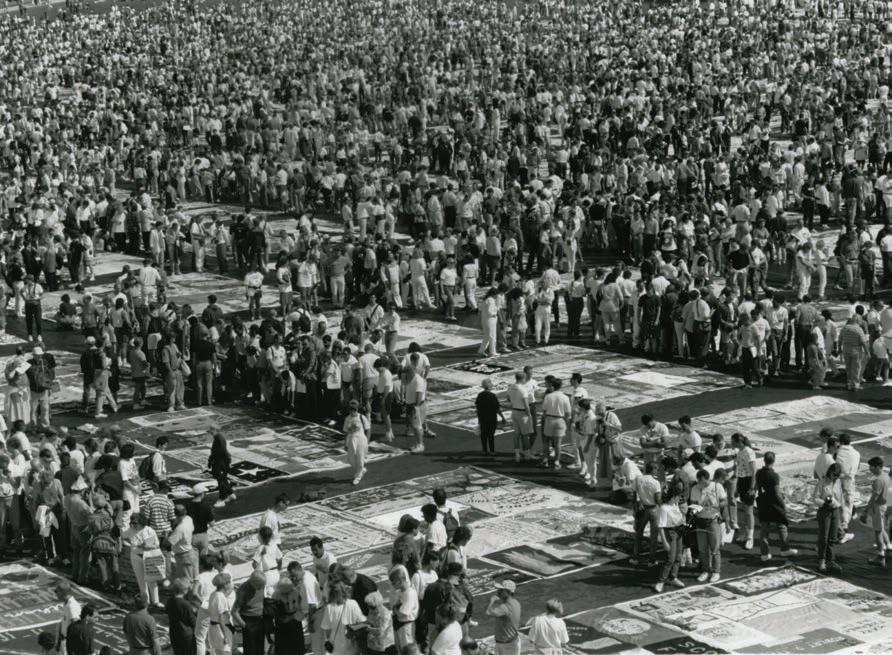

• The National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights was held on Oct. 11, 1987, drawing 200,000-650,000 people. A previous march was held on Oct. 14, 1979. Another was held on April 25, 1993, drawing nearly 1 million.

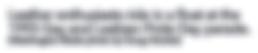

• The AIDS Memorial Quilt, unveiled at the 1987 March, featured 48,000 panels and was billed as the largest piece of folk art in the world covering 50 miles and weighing 54 tons.

• The frst National Coming Out Day was held on Oct. 11, 1988, the one-year anniversary of the second National March.

• The book “And the Band Played On: Politics, People and the AIDS Epidemic” by Randy Shilts was published in 1987. An

HBO adaptation aired in 1993.

• On April 23, 1990, President George Bush signed into law landmark legislation that required a fve-year study on crimes motivated by prejudice based on race, ethnicity, or sexual orientation. It’s the frst time gay rights advocates are invited to a White House ceremony.

• President Bill Clinton won the November 1992 presidential election with an overwhelming majority of the gay vote, but his efforts to end military discrimination against gays sours many. The number of gays discharged rose under “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” and late in his second term, Clinton dubbed the policy a failure.

• Servicemembers Legal Defense Network was founded in 1993 to lobby for those negatively affected by “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.”

•In 1985, the National LGBTQ Task Force (then the National Gay Task Force) moved its headquarters from New York to Washington and under the direction of Jeff Levi, secured federal funding for community-based AIDS organizations, a frst.

• In 1991, Lambda Legal stood up for an outspoken gay Russian activist (Alla Pitcherskaia) and helped a lesbian whose partner’s parents barred her from visiting after the partner was paralyzed in a car accident.

• The Gay & Lesbian Victory Fund was founded on May 1, 1991 as a nonpartisan political action committee aiming to boost the numbers of out LGBTQ elected offcials holding public offce.

• Immigration Equality was founded in 1994 to advocate for LGBTQ and HIV-positive immigrants.

• Lesbian Avengers was founded in New York

in 1992 to promote lesbian visibility.

• GLAAD — initially known as Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation — formed in 1985 to protest defamatory gay/lesbian media portrayals.

• Keith St. John became the frst openly gay Black man elected to public offce (city council) in the U.S. in Albany, N.Y. in 1989.

• Deborah A. Batts became the nation’s frst openly LGBTQ federal judge. She was confrmed to the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York and confrmed by the Senate in 1994.

• The Bisexual Resource Center was founded in Boston in 1985.

• Berkeley, Calif., became the frst jurisdiction in the country to pass a domestic partnership ordinance for municipal employees in 1984.

• Hawaii’s state Supreme Court ruled (with one dissenting vote) that barring same-sex couples from marrying violates the state constitution’s ban on gender discrimination in 1993.

• “The Crying Game” (1992), “Philadelphia” (1993) and “Interview With a Vampire” (1994) became the highest-grossing LGBTQ-themed movies of these years.

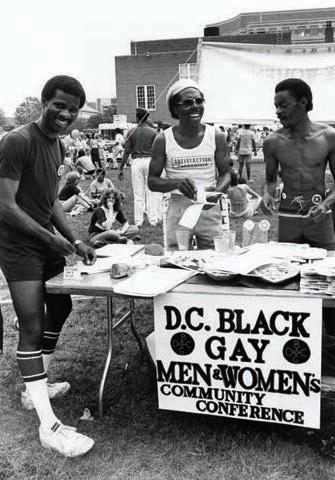

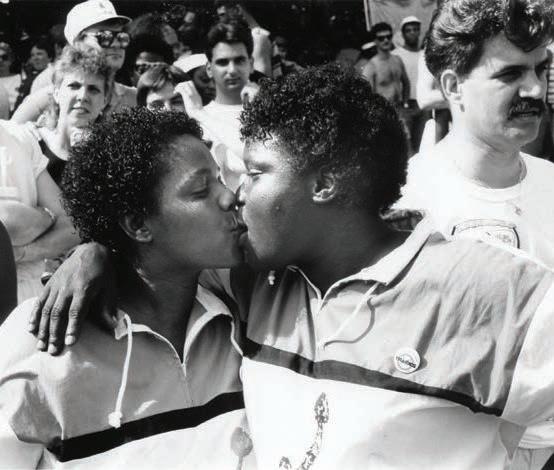

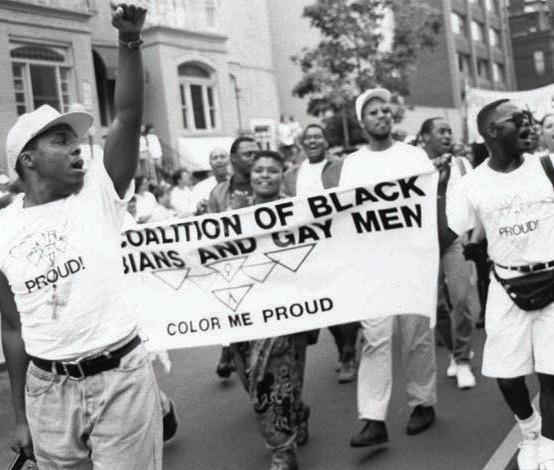

Closer to home, on May 5, 1991, the frst Black Lesbian and Gay Pride Day was held in Washington, D.C.

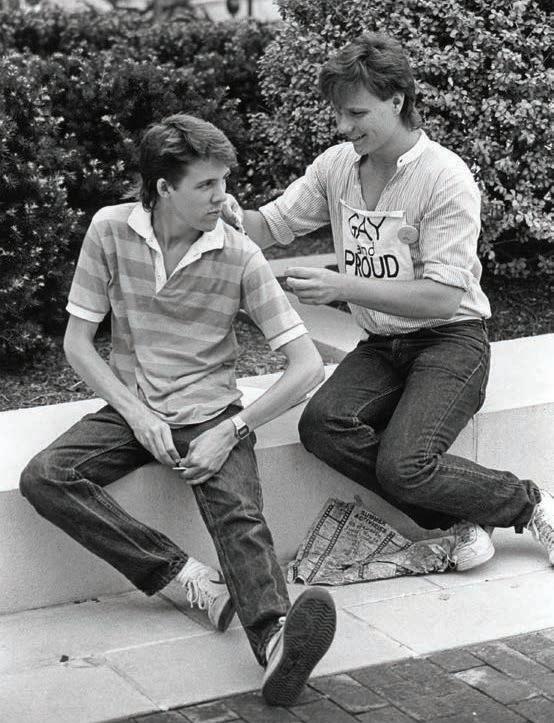

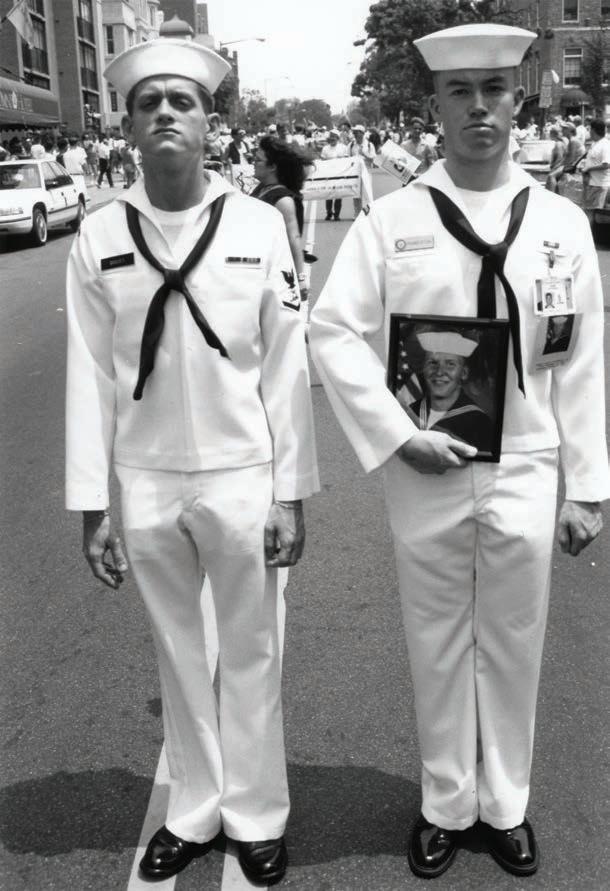

D.C. Pride, frst held in 1975, grew exponentially in the early ’80s, but attendance, likely affected by AIDS death tolls, was down signifcantly by 1986 and ’87 (around 10,000 compared to 20,000 in ’83). Pride of Washington, a new group, formed in 1991 and soon saw growth return. By 1991, the street festival expanded to about 200 booths and for the frst time, active duty and retired American military personnel marched openly in the parade.

Ma y & Kennedy Cent e r Conce r t Ha ll

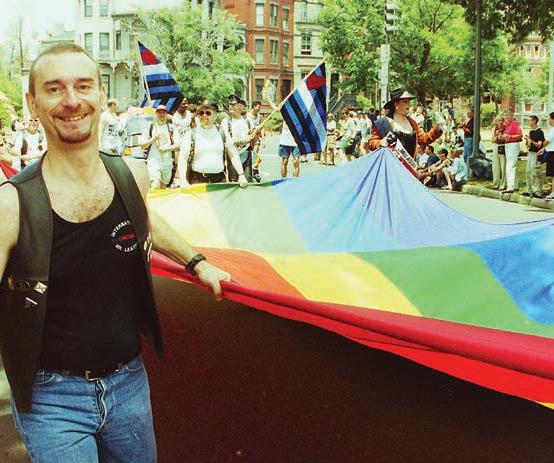

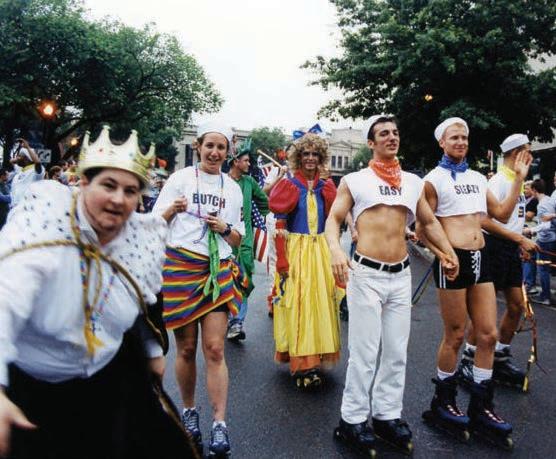

The 1993 Gay and Lesbian Pride Day parade moved along P Street, N.W. in the Dupont Circle neighborhood.

What if my cancer comes back? It ends my love of climbing?

What if it doesn’t?

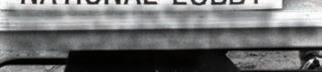

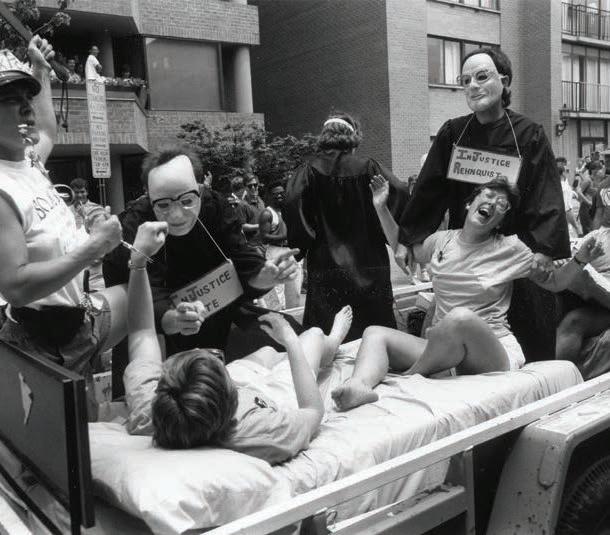

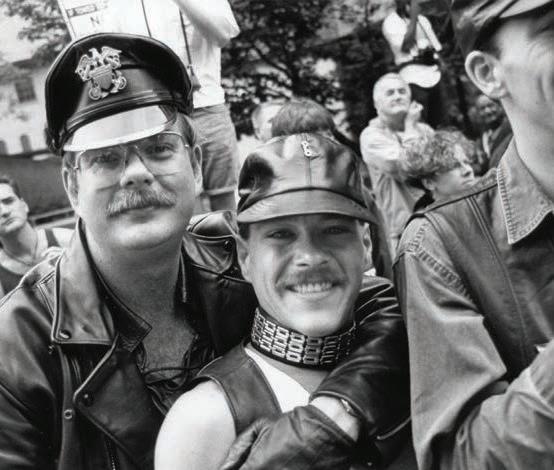

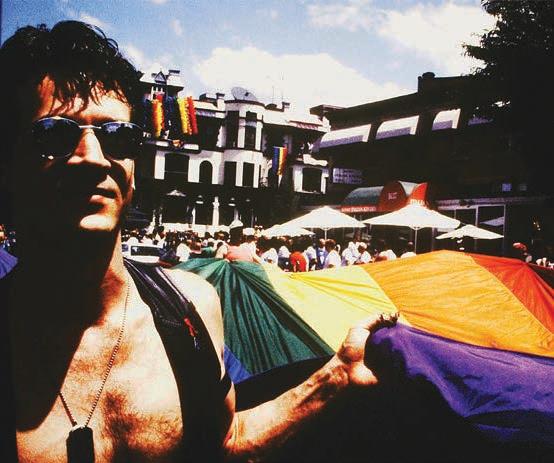

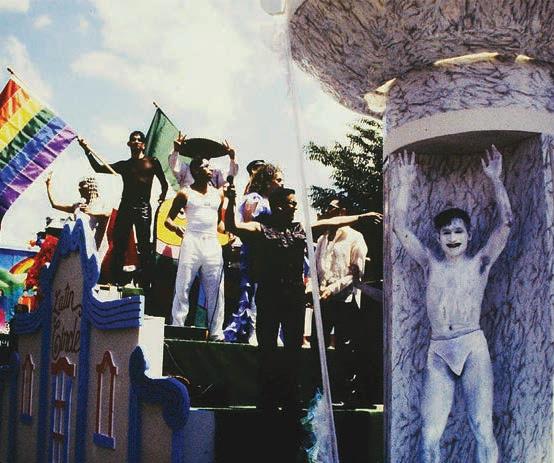

in the 1988 Gay and Lesbian Pride Day parade stage a tableau depicting the “InJustices” of the United

Saturday, June 14, 7 p.m.

Three-time Tony Award-winning composer and living legend of musical theater, Jason Robert Brown, performs an intimate evening filled with musical brilliance. JRB & Friends o ers a close-up look at the career of the composer, director, orchestrator and lyricist.

The LGBTQ community by the mid-1990s had begun to assert its power through the courts and in Congress. The fght to protect its rights, however, was far less certain.

The D.C. Council in April 1993 repealed the District of Columbia’s sodomy law. All references to it were removed from the criminal code in May 1995.

Tyra unter on Aug. 7, 1995, died from injuries she sustained in a car accident after D.C. emergency personnel who responded to the scene declined to treat her once they discovered she was transgender. unter’s death and accounts by witnesses that a ire Department rescue worker laughed and jeered at [Hunter] and temporarily stopped treating him [Hunter] triggered a series of protests by Gay activists and members of groups representing transgendered people, the ashington Blade reported on Nov. 7, 1995. ent, Jonathan Larson’s musical that features a group of young artists who lived in Manhattan’s ast illage during the height of the I AIDS epidemic in the late 1980s and early 1990s, premiered at the New ork Theatre orkshop on eb. 1 , 1996. The Blade’s coverage of the pandemic continued.

The Blade’s May 17, 1996, issue, for example, contained an AIDS page with headlines that included

• “Take-at-home antibody test wins FDA approval

• Inoculations cause spurt of I replication

• “Company acquires rights to three antiretrovirals

• Some vaccine volunteers become infected

The U.S. Supreme Court three days later, on May 0, 1996, in omer v. vans ruled a Colorado constitutional amendment that banned discrimination based on sexual orientation under the 14th Amendment’s qual Protection Clause is unconstitutional. Then-President Bill Clinton on Sept. 1, 1996, signed the so-called Defense of Marriage Act, which banned the federal government from recognizing same-sex marriage and defned marriage as between a man and a woman.

llen DeGeneres offcially came out on the cover of Time magazine’s April 15, 1997, issue. The actress two weeks later once again declared her sexual orientation on her eponymous sitcom.

The ABC network has given the April 0 coming out episode of llen’ a T -14 rating more restrictive than the T -PG rating the show usually receives, reported the ashington Blade on April 5, 1997. A spokesperson for ABC told the Blade that the change was due to the episode’s sophisticated themes.’ awaii in 1997 also became the frst state to legally recognize same-sex couples.

Matthew Shepard, a gay 1-year-old college student, died on Oct. 1 , 1998, after Aaron McKinney and ussell enderson brutally beat him and left him tied to a fence in Laramie, yo. McKinney and enderson received life sentences for the murder.

By MICHAEL K. LAVERS

Then- isconsin state ep. Tammy Baldwin on Nov. , 1998, became the frst openly LGBTQ person elected to the U.S. ouse of epresentatives. oters in Alaska on the same day approved a constitutional amendment that banned the state from recognizing same-sex marriages. awaii voters on Nov. , 1998, approved a state constitutional amendment that allowed lawmakers to defne marriage as only between a man and a woman. ita ester, a Black transgender woman, was found stabbed to death in her Boston apartment on Nov. 8, 1998. er murder sparked the Transgender Day of emembrance, which takes place each year on Nov. 0.

A ermont law that allowed same-sex couples to enter into civil unions took effect on July 1, 000.

Mark Bingham, a gay rugby player, is among the United light 9 passengers who took control of the aircraft on Sept. 11, 001, before it could reach D.C. David Charlebois, the frst offcer on American light 77 that crashed into the Pentagon, was also gay and lived on Swann Street, N. ., in Dupont Circle with his partner, Tom ay.

Gay and bisexual men wanting to help out in the form of blood donation in the wake of Tuesday’s lethal attacks in New ork City and ashington, D.C., will be unable to do so under a U.S. ood and Drug Administration restriction banning such donation, reported the Blade on Sept. 14, 001.

Then-Secretary of State Colin Powell on Sept. 18, 001, swore in Michael Guest as the U.S. ambassador to omania. Guest, a longtime oreign Service offcer, is the frst openly gay man confrmed for an ambassadorship. Powell during the swearing in ceremony recognized Guest’s partner. (James ormel was the frst openly gay person to serve as a U.S. ambassador. When Republican opposition emerged to his nomination, President Clinton used a recess appointment to name him ambassador to Luxembourg in 1999 without Senate approval.

The U.S. Supreme Court on June 6, 00 , struck down Texas’s sodomy law in the landmark Lawrence v. Texas ruling. Massachusetts’s Supreme Judicial Court on Nov. 18, 00 , in Goodridge v. Department of Public ealth ruled the state must allow same-sex couples to legally marry.

Massachusetts on May 17, 004, became the frst state in the country to extend full marriage rights to same-sex couples. ormer President onald eagan, who faced scathing criticism over his administration’s response to AIDS, died on June 5, 004.

oters in Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, and Oregon on Nov. , 004, approved constitutional amendments that defned marriage as between a man and a woman. Then-President George . Bush, who championed the ederal Marriage Amendment that would have defned marriage as between a man and a woman in the U.S. Constitution, on the same day won re-election.

Pride in D.C. evolved and grew during this period.

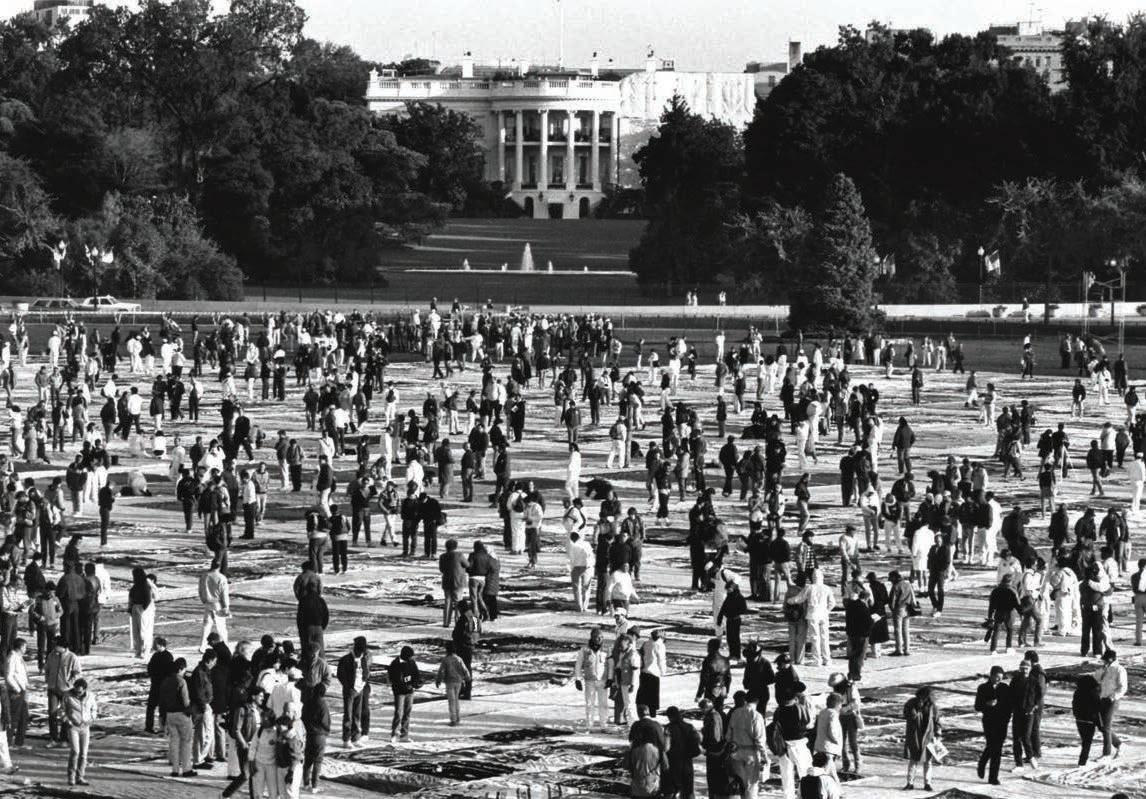

One in Ten, a D.C. organization that hosted an annual flm festival, took over Pride and moved the festival to reedom Plaza. The parade route began at rancis Junior igh School, and ended at reedom Plaza. Attendance grew from around 5,000 people in 1994 to more than 100,000 in 1996.

The dual rainstorms that afternoon didn’t drown the spirits of the roughly 100,000 Gays who turned out for the annual Lesbian and Gay reedom estival on Sunday, June 9, reported the Blade in its June 14,

1996, issue.

The Blade article observed that for most, Gay Pride Day is a communal birthday that marks the beginning of the modern Gay civil rights movement, and it is symbolic to many of their own coming out. or all, it seems a day of rejuvenation.

Lindsay Cobb of Columbia, Md., and his boyfriend, Don Kirk, of Baltimore, were among those who enjoyed the revelries.

e have the rest of our lives to deal with the rest of the world, Cobb told the Blade. Today is ours.

Pride in the nation’s capital in 1997 evolved further when hitman- alker Clinic, as it was then known, joined One in Ten as a co-sponsor. They also renamed the event Capital Pride. Corporate sponsorships increased from 80,000 in 1997 to nearly 50,000 the following year.

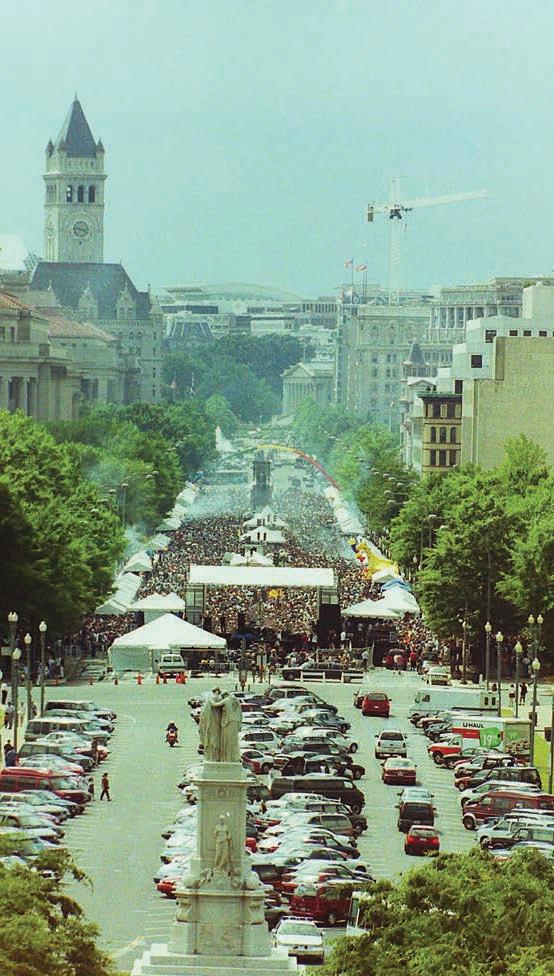

hitman- alker Clinic in 000 became Capital Pride’s sole sponsor, and the festival moved once again, to Pennsylvania Avenue, N. ., between 4th and 7th streets. Its main stage was repositioned to ensure the U.S. Capitol was prominently visible in the background. The Latino GLBT istory Project, as it was then known, formed in 000.

L P was founded by leaders who had been at the front lines of multiple civil rights movements across race, ethnicity and sexual orientation, says the organization on its website. At a time when Latinx LGBTQ communities were being left out of mainstream Latino and LGBTQ organizations, these leaders built their own space.

DC Black Pride celebrated its 10th anniversary in 001. More than 100 contingents participated in the 00 Capital Pride parade.

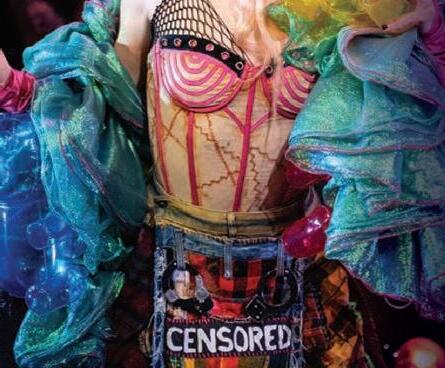

Dykes on Bikes, with leather-clad motorcycle mamas and rainbow ags ying from handlebars, led the parade, the frst of more than 100 contingents, the Blade reported in its June 14, 00 , issue. or the next hour and a half, drag queens adorned in tiaras and titles, scantily clad leathermen, colorful oats with muscle-bound men, politicians perched in convertibles and various gay groups vied for the crowd’s appreciation and the judges’ high marks.

The Blade reported more people of color were present at this year’s festival, as well as a greater representation from the transgender community. A few drifters from the neighborhood Philippines festival even wandered about the gay festival, adding to the mix of ethnicities and faces.

Upwards of 100,000 people attended various Capital Pride events in 004, which took place days after eagan’s funeral. The Blade’s June 11, 004, issue notes Bush fails to issue Gay Pride proclamation and federal employees are pressured to hold low-key Pride events.

Similar to past years, the parade drew large contingents of gays and their supporters from a wide range of religious denominations as well as gay sporting groups, reported the Blade on June 18, 004.

But it wasn’t all fun and games, the article notes. ith the backdrop of a potential constitutional amendment banning gay marriage looming in Congress while, at the same time, the nation’s frst state-sanctioned gay marriages began taking place last month in Massachusetts, the evening also presented an important opportunity for participants to bring their political messages to the masses.

Pride in D.C. then, like today, was political.

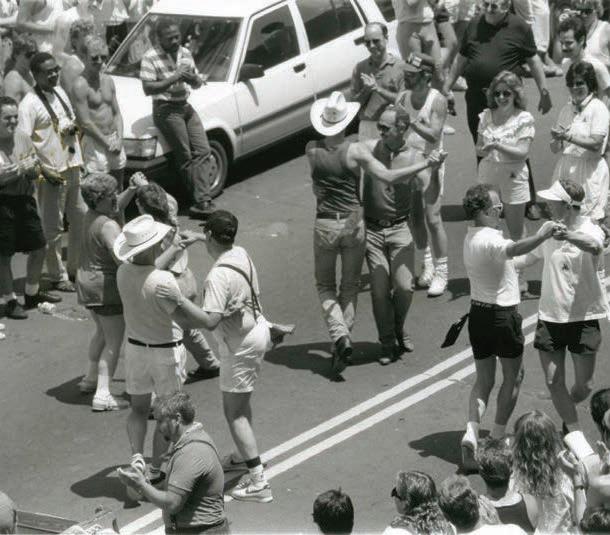

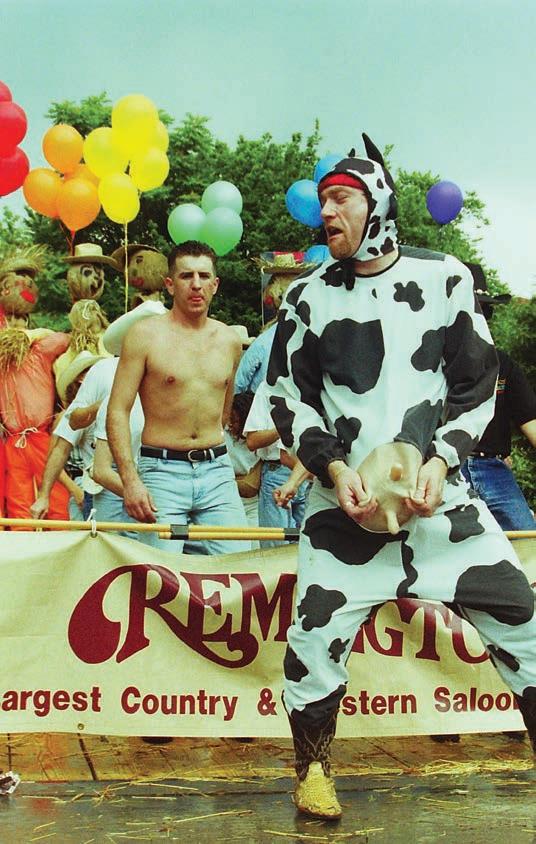

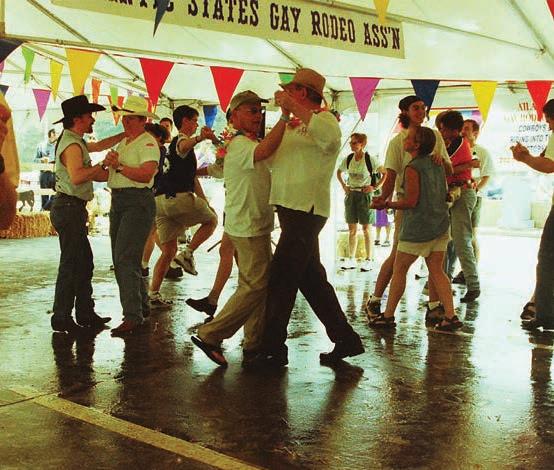

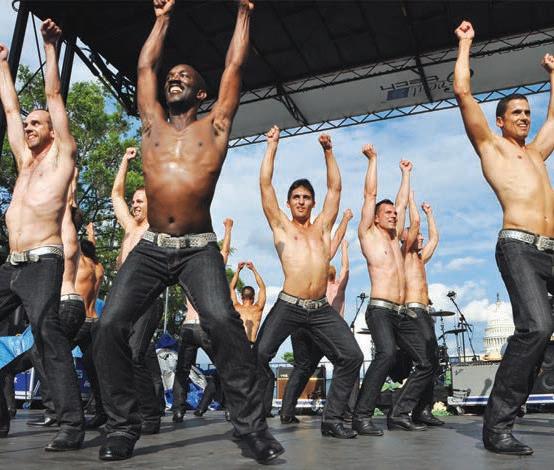

Members of the DC Cowboys perform a routine in the 2004 Capital Pride Parade.

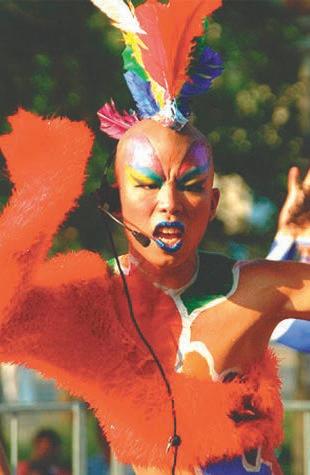

Left: eight-member color guard representing each of the eight branches of the U.S. Armed Forces joined the 2014 Capital Pride parade. (Washington

In the weeks since Donald Trump won his gambit for a second term in the White House, the minority party has been licking its wounds while looking back a couple of decades for lessons on how best to recover (Build Back Better, anyone?).

Not without reason: The 2024 presidential election was similar to the 2004 presidential election — at least, for Democrats, who lost the popular vote along with their Senate majority, and for queer people, who saw their rights on the ballot and in the headlines as same-sex marriage and gender diversity each came to the fore at a pivotal moment in American politics.

What comes next? Some clues can be found if we narrow the aperture to focus on the LGBTQ movement in the years leading into the end of the Obama era, and in our seat of government, the Nation’s Capital.

“If you saw the reports last fall in the Washington Blade about a proposed anti-gay D.C. ballot initiative, you know that we are not immune from the Radical Right’s nationwide assault on our equality,” the late activist A. Cornelius Baker wrote on behalf of the group he chaired, Foundation for All D.C. Families.

The year was 2004. After a Massachusetts court gave the nod and then gay and lesbian couples began to wed in San Francisco (some in ceremonies that were offciated by the city’s newly elected district attorney, Kamala Harris), Republican U.S. Rep. Jo Ann Davis of Virginia introduced a bill to outlaw same-sex marriage in the District.

As momentum for gay marriage grew, President George W. Bush urged Congress to ban the practice by constitutional amendment, which would have required two-thirds majorities in both chambers before the states were allowed to vote for or against ratifcation.

It was a heavy lift, and so anti-equality actors set to work fnding other ways to effectuate a ban. And in response, while the group acknowledged the importance of political organizing, the Foundation for All D.C. amilies was interested, frst, in developing a strong ground game.

“No one has previously done a comprehensive poll of D.C. voters on gay issues. Especially given the Right’s aggressive courtship of the African-American faith community, and the success of anti-gay initiatives around the country, we need more than our instincts and anecdotal information to assess voter’s views,” they wrote — also acknowl-

By CHRISTOPHER KANE

edging that, yes, “all of this is costly.”

The Human Rights Campaign stepped in with an early pledge of $15,000. The following year, HRC kicked in an emergency $30,000 donation to Capital Pride, which at the time was supported solely by hitman- alker as the clinic was experiencing fnancial duress. (The city of Washington also pitched in, agreeing to waive thousands in street closing and police overtime fees.)

Also in 2005, HRC debuted its Religion and Faith Program, targeting clergy to mobilize support for LGBTQ rights, and helped to formDC Clergy United for Marriage Equality, which was instrumental in the passage of same-sex marriage in Washington in 2009 — with Mayor Adrian M. Fenty signing the bill in a ceremony at All Souls Unitarian Church.More than 100 clergy members had signed a declaration in support of same-sex marriage.

By 2006, Capital Pride boasted 200,000 attendees and had become the nation’s fourth largest Pride event, perhaps in large part because the event welcomed and focused on not just faith communities but rather all communities.Several events such as dance parties, a youth prom, a transgender event, leather pride, and more by now were under the overall umbrella.

The following year, several other local non-profits joined Whitman-Walker to form the Capital Pride Planning Committee. In March 2008, Whitman-Walker awarded the production rights to the newly formed Capital Pride Alliance, a group of volunteers and organizations formed by members of the Capital Pride Planning Committee. By 2009, the Alliance was the sole producer of the event.

The event reached its 35th anniversary in 2010 and continued to expand its offerings with about 60 events held over a 10-day period and a record high of 250,000 attending the street festival. About 100,000 watched the 2013 parade.

“Our goal is to foster the conversations that should already be happening among the diverse communities of our city, to renew its traditions of tolerance and equality for all,” Foundation for All D.C. Families wrote in a 2004 letter. “If we rise to this occasion, Washington will be the stronger for it — regardless of what mischief others make.”

The Rainbow History Project notes that, “Along with growing rights for LGBTQ+ individuals, which were later challenged by conservative Christian leaders again in the late 2010s and early 2020s,” the early 2000s “witnessed growing interfaith conversa-

tions and commitments to LGBTQ+ inclusion.”

In Washington, in 2007,Cleveland Park CongregationalUnited Church of Christ “amended its constitution to declare itself to be Open and Affrming and three years later celebrated one of the frst legally sanctioned same-sex marriages in D.C.”

In 2011, Cleveland Park Congregational joined the First Congregational United Church of Christ and the Westmoreland Congregational United Church of Christ in sponsoring a booth at the Capital Pride Festival, which has continued each year “until the pandemic halted Pride festivities.”

The Rainbow History Project further notes that, “To this day, there are a number of religious organizations in the DMV area that purposefully include LGBTQ+ individuals. Because of lack of documentation, they were not added to this timeline, but should be acknowledged for their important historical work. These include the Muslims for Progressives alues DC Chapter, Affrmation LGBTQ Mormons Families & Friends D.C. Chapter, The Great River Tendai Sangha, Temple Sinai DC, Friends Meeting of Washington, DC.”

Over the years, the evolution of Capital Pride to include representation from not just faith groups but also other traditionally conservative institutions like the U.S. military and the FBI signaled the extent to which the movement for LGBTQ rights had grown from the time when volunteers struggled to come up with the money to put on the event.

By 2014, same-sex marriage had become legal in states that contained more than 70 percent of the U.S. population, whether through decisions by state or federal courts or through legislation. And the U.S. Supreme Court had struck down the law barring federal recognition of same-sex marriage, the so-called Defense of Marriage Act, in 2013 (U.S. v. Windsor).

The other major front in the battle for LGBTQ rights, repealing the military’s discriminatory “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy, was won in 2012.

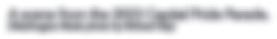

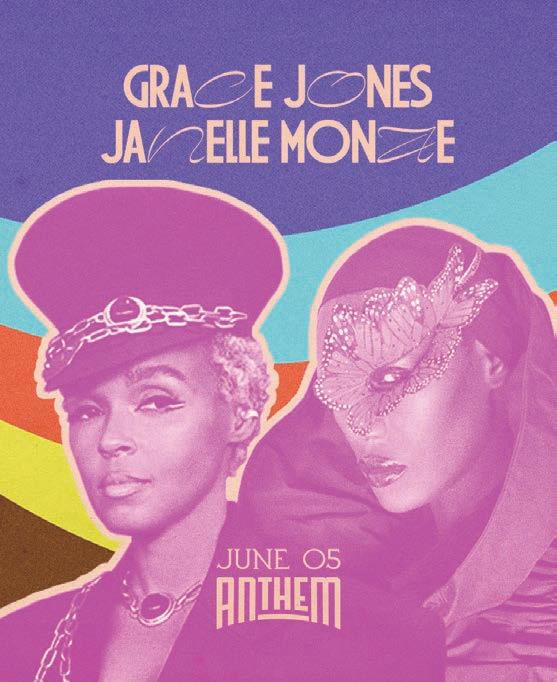

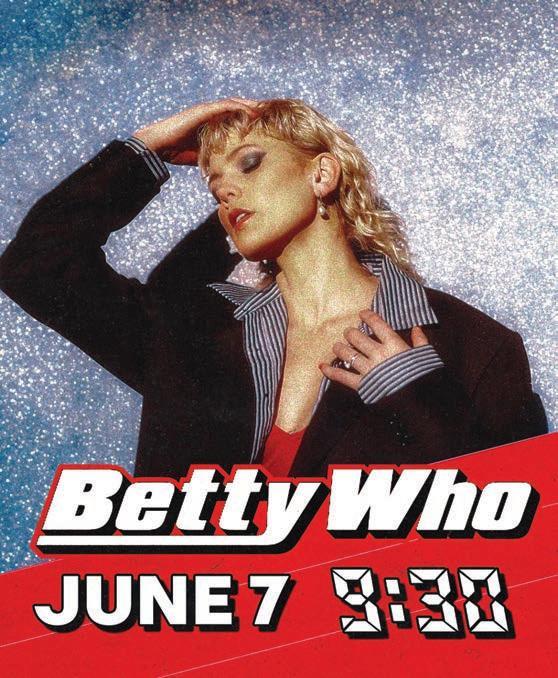

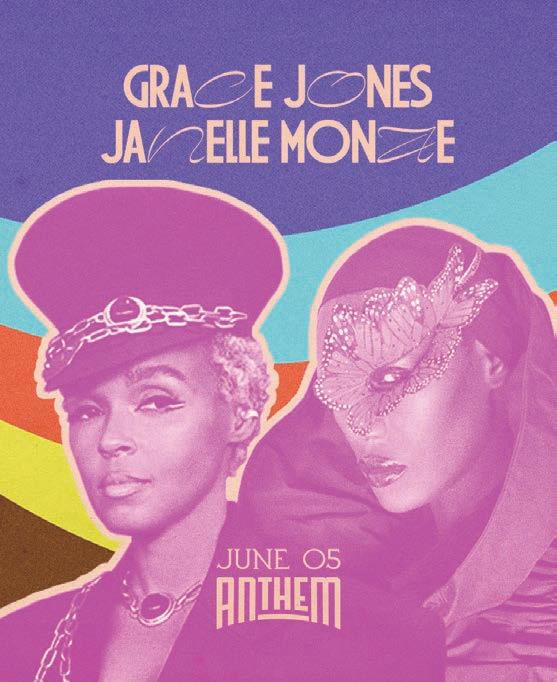

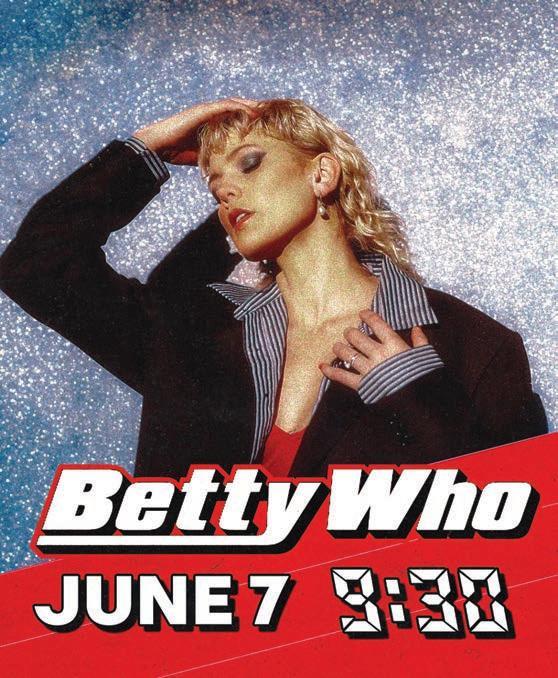

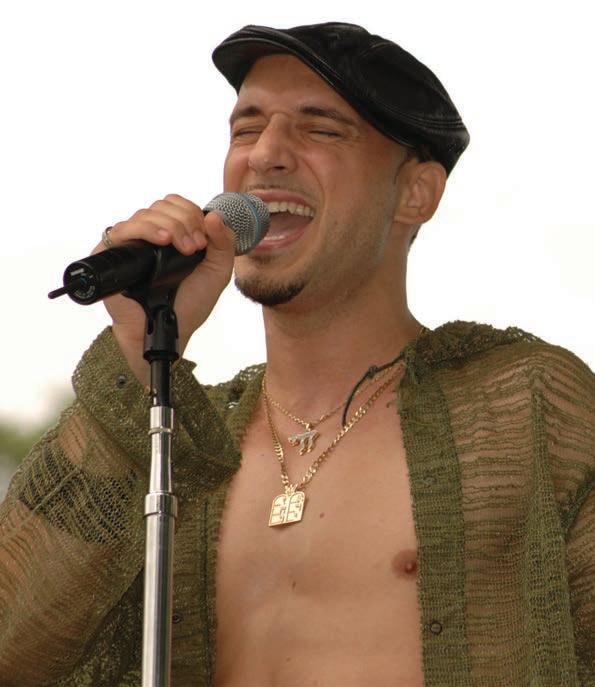

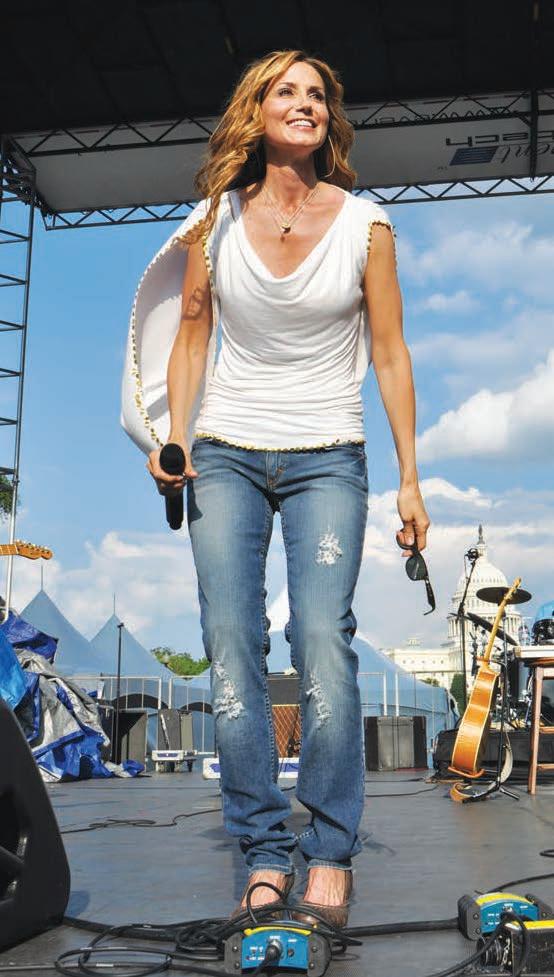

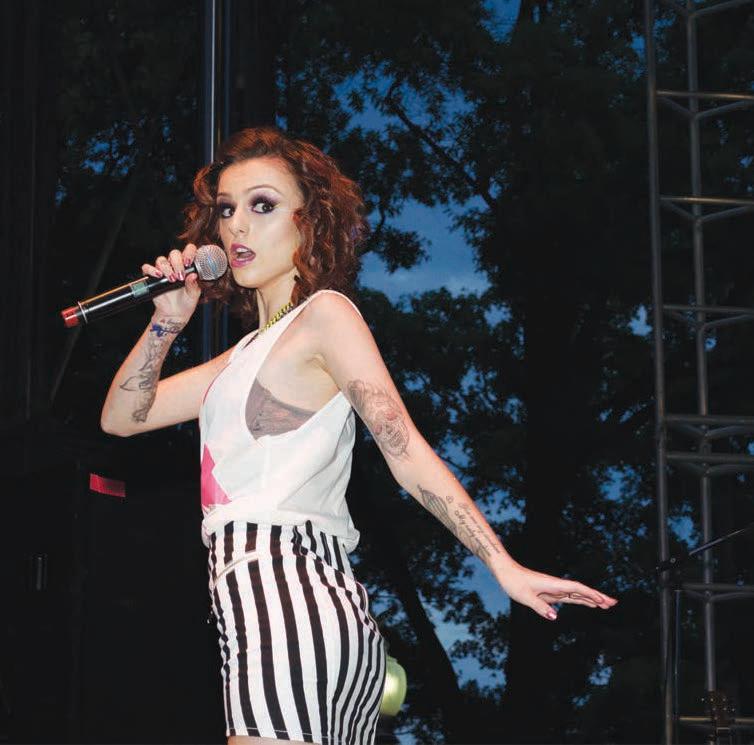

An offcially sanctioned eight-member color guard representing each of the eight branches of the U.S. Armed Forces joined the 2014 Capital Pride parade, an unprecedented event with 100,000 attendees at the parade and an estimated 250,000 at the various week-long events. Rita Ora, Karmin, Bonnie McKee, Betty Who and DJ Cassidy performed. The theme was “#BuildOurBrightFuture.” Former Minnesota Vikings player Chris Kluwe, an ally, served as grand marshal.

The past decade has been a roller coaster for LGBTQ people celebrating Pride in the nation’s capital. It began with the Supreme Court legalizing same-sex marriage in Pride month of 2015 and ended with those rights under threat once again as Donald Trump returns to power.

The year 2015 marked a milestone for LGBTQ rights and Pride in D.C. More than 150,000 attended the 40th annual parade, featuring a shirtless grand marshal ilson Cruz and for the frst time the Boy Scouts marched in the parade. The festival drew 250,000 to Pennsylvania Avenue with Carly Rae Jepsen, Wilson Phillips, Amber, En Vogue and Katy Tiz all performing under stormy skies. With the theme “Flashback,” Capital Pride continued to grow.

Weeks later, the Supreme Court’s Obergefell v. Hodges ruling legalized same-sex marriage nationwide, making that year’s Pride especially historic. Meanwhile, Olympic gold medalist Caitlyn Jenner came out as transgender, sparking conversations on trans visibility. On the big screen, “Carol” brought a lesbian love story to mainstream audiences.

The year 2016 was a time of both celebration and tragedy for the LGBTQ community. D.C.’s Pride theme, Make Magic appen re ected the continued growth of the festival, with headliners Melanie Martinez, Alex Newell, Meghan Trainor, and Charlie Puth taking the stage. Gay actor and icon Leslie Jordan served as grand marshal, bringing his signature humor and twang to the streets of Washington.

Beyond D.C., major strides were made in LGBTQ rights. The United Nations appointed its frst independent investigator to combat violence and discrimination against sexual and gender minorities worldwide. Meanwhile, Ellen DeGeneres received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Obama for her advocacy, philanthropy, and role in increasing LGBTQ visibility in entertainment.

However, the year was also marked by a devastating tragedy. On June 1 , a gunman opened fre at Pulse, a gay nightclub in Orlando, killing 49 people in what was then the deadliest mass shooting in U.S. history. The attack sent shockwaves through the LGBTQ community, turning Pride events across the country—including in D.C.—into both celebrations of resilience and acts of mourning.

Many queer voters were shocked and devastated in November when Donald Trump defeated Hillary Clinton in the presidential election.

The following year was a time of activism for the LGBTQ community in D.C. as Trump took offce. Capital Pride embraced the theme “Unapologetically Proud,” with headliners The Pointer Sisters, Tinashe, and Miley Cyrus. Marriage equality icon Edith Windsor served as grand marshal, highlighting the progress made since her landmark Supreme Court case. However, the parade faced disruption when protesters from a group called No Justice No Pride blocked the route, demanding greater inclusion of trans women of color in leadership roles, stricter vetting of corporate sponsors, and the removal of uniformed police offcers from Pride events.

By JOE REBERKENNY

Beyond D.C., LGBTQ rights took center stage in politics and culture.

“Moonlight” made history at the Academy Awards, becoming the frst LGBTQ-themed flm to win Best Picture. Meanwhile, thousands gathered in Washington for the National Equality March, protesting Donald Trump’s anti-LGBTQ rhetoric. Democrat Doug Jones defeated notorious homophobe Roy Moore for Alabama’s Senate seat, and Danica Roem of Virginia unseated another anti-LGBTQ fgure to become the nation’s frst out transgender person to be elected and seated in a state legislature.

In 2018, Capital Pride embraced the theme “Elements of Us,” with headliners Alessia Cara, Troye Sivan, and MAX. Activist Judy Shepard, mother of Matthew Shepard, whose murder caused a national outcry for federal protections against hate crimes, served as grand marshal. That year, Capital Pride implemented a major policy shift following concerns from marginalized LGBTQ people of color, banning uniformed D.C. police offcers from marching in the parade.

On the national stage, the Supreme Court ruled in Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission that private businesses could refuse service to LGBTQ people based on religious beliefs, a decision that raised concerns about broader discrimination. Meanwhile, after months of Democratic opposition, the Senate confrmed Richard Grenell as U.S. ambassador to Germany, making him the highest-profle openly gay offcial in the Trump administration.

D.C. saw major shifts in its LGBTQ nightlife scene, with the beloved Town Nightclub closing due to redevelopment in Shaw. However, one of the city’s gayest events gained offcial recognition — D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser designated the 17th Street High Heel Race as a city-sponsored event, ensuring its place in the city’s traditions and history.

In 2019, Capital Pride honored the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Rebellion with the theme “shhhOUT: Past, Present & Proud.” Headliners included Shea Diamond, Todrick Hall, Zara Larsson, Marshmello, Calum Scott, and “RuPaul’s Drag Race” alum Nina West, while grand marshals featured activists Earline Budd, Brandon Wolf, Matt Easton, and the cast of “Pose.” owever, the parade was brie y thrown into chaos when reports of gunshots in Dupont Circle caused a panic. Though it was a false alarm, the disruption led to dozens of participants missing their chance to march.

The Washington Blade celebrated its 50th anniversary in 019, marking fve decades as the nation’s LGBTQ “newspaper of record.” Meanwhile, New York City hosted World Pride, bringing millions together to commemorate the legacy of Stonewall.

In a major symbolic victory, the U.S. House passed the Equality Act, a long-awaited bill aiming to prohibit anti-LGBTQ discrimination in federal law. Despite the bill failing to make its way through the Senate, it showed how some Republicans were able to acknowledge and support LGBTQ people even if it meant going against party lines.

Of course, 2020 will forever be remembered as a time of upheaval, resilience, and coming together for the LGBTQ community. As the COVID-19 pandemic gripped Washington and the world, Capital Pride organizers made the unprecedented decision to cancel the parade and festival. Instead, Pride moved online, with virtual events such as community conversations, a web series spotlighting local talent, and a summit focused on minority groups within the LGBTQ community.

Despite the challenges, LGBTQ political representation reached new heights as a record number of LGBTQ candidates were elected to offce in the 2020 election. Meanwhile, the Supreme Court delivered a major victory in June, ruling that workplace discrimination against LGBTQ employees violates federal law.

The year was also defned by the fght for racial justice. The murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police sparked nationwide protests, fueling the Black Lives Matter movement and demands to reform or defund the police to end systemic racism in all its forms, including within the LGBTQ community.

As the year came to a close, Joe Biden and Kamala Harris won the White House, ushering in what would become the most pro-LGBTQ administration in history.

The year 0 1 marked ashington’s frst in-person Pride celebration since the pandemic shut down the world, leading to several adjustments to ensure the event remained safe and pandemic-conscious. One of the most notable changes was the shift from celebrating in June to October to provide a safer environment for attendees. The theme for the celebration was “Colorful,” encouraging city residents to decorate homes, businesses, and even themselves in the vibrant hues of the Pride ag. Instead of the traditional festival and concert lineup, Capital Pride hosted a Block Party and Fair.

Finally, 2022 brought the highly anticipated return to the traditional parade, festival, and concert Pride celebration after two years of unique, pandemic-conscious methods. The theme of the event was “reUNITED,” celebrating the in-person festivities that had been absent since the pandemic began. DNCE, the pop-rock band fronted by Joe Jonas, headlined the Pride festival. In a signifcant moment of the celebration, Vice President Kamala Harris and second gentleman Douglas Emhoff made a surprise appearance, where Harris encouraged the crowd of 450,000 LGBTQ individuals and allies to Build unity Build coalitions and fght with pride.”

owever, 0 also saw several signifcant challenges for the LGBTQ community. In Texas, the Department of Family and Protective Services began investigating parents who provided gender-affrming care to their transgender children, prompting many families to ee the state to seek safety and support. Meanwhile, in Florida, Gov. Ron DeSantis signed the “Don’t Say Gay” bill into law, which restricted discussions of sexual orientation and gender identity in certain grade levels, further limiting LGBTQ representation in schools.

Additionally, the Mpox virus, previously known

as monkeypox, began spreading in Washington, D.C. in June. The virus primarily affected men who have sex with men, prompting the D.C. Department of Health to begin administering vaccinations to curb its spread.

The theme of the 2023 Pride celebration was, “Peace, Love, Revolution,” and attempted to highlight the joys and celebration of fghting for LGBTQ rights, while also acknowledging there is still more work to be done. Hayley Kiyoko, Monet X Change, Debbie Gibson, and Shanice performed in front of the Capitol, with Idina Menzel headlining the festival. Dr. Rachel Levine, the U.S. Assistant Secretary of Health and admiral in the U.S. Public Health Service Commissioned Corps, with Earline Budd, a transgender activist, served as grand marshals of the parade.

State legislatures across the country introduced more than 500 bills targeting the LGBTQ community in 2023, passing 75 in 23 states. Most of the bills targeted gender-affrming care for transgender youth putting both trans people and their medical caregivers in jeopardy.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration eased restrictions on queer men donating blood. The FDA created a new, gender-inclusive screening process for all donors regardless of sexual orientation that focuses on actions each person does rather than their sexual or gender identity.

The 2024 Pride theme was “Totally Radical” in-

tending to highlight various developments of the LGBTQ community in the 1960s and 1970s, including the AIDS epidemic, ACT UP, the response from the federal government to the crisis, as well as other social and political hurdles. Grand marshals Billy Porter and Keke Palmer led the parade down a new route from 14th Street to Pennsylvania Avenue before performing the next day at the Pride festival. Other performers included Ava Max and the female vocalist group Exposé.

President Joe Biden issued historic pardons for approximately 2,000 LGBTQ service members who had been discharged from the military and were court-martialed over their sexual orientation or gender identity under discriminatory policies of the past, like “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.” Delaware State Sen. Sarah McBride became the frst transgender candidate to be elected to Congress. The D.C. Council approved $5 million for the city to host WorldPride in 2025, which the city secured after Taiwan withdrew from hosting the event.

President Trump was reelected to a second term in the White House, defeating Vice President Harris in a heartbreaking outcome for most LGBTQ Americans. The twice-impeached president’s return to offce has already brought major setbacks, especially for the trans community targeted by his hostile executive orders. LGBTQ advocates are busy challenging the attacks in court and in regular street protests.

More than 80,000 people joined the 2017 Equality March for Unity & Pride following Donald Trump’s

At ViiV Healthcare, we’ve been here since the beginning of the epidemic and we’ll be here until the end.