44 minute read

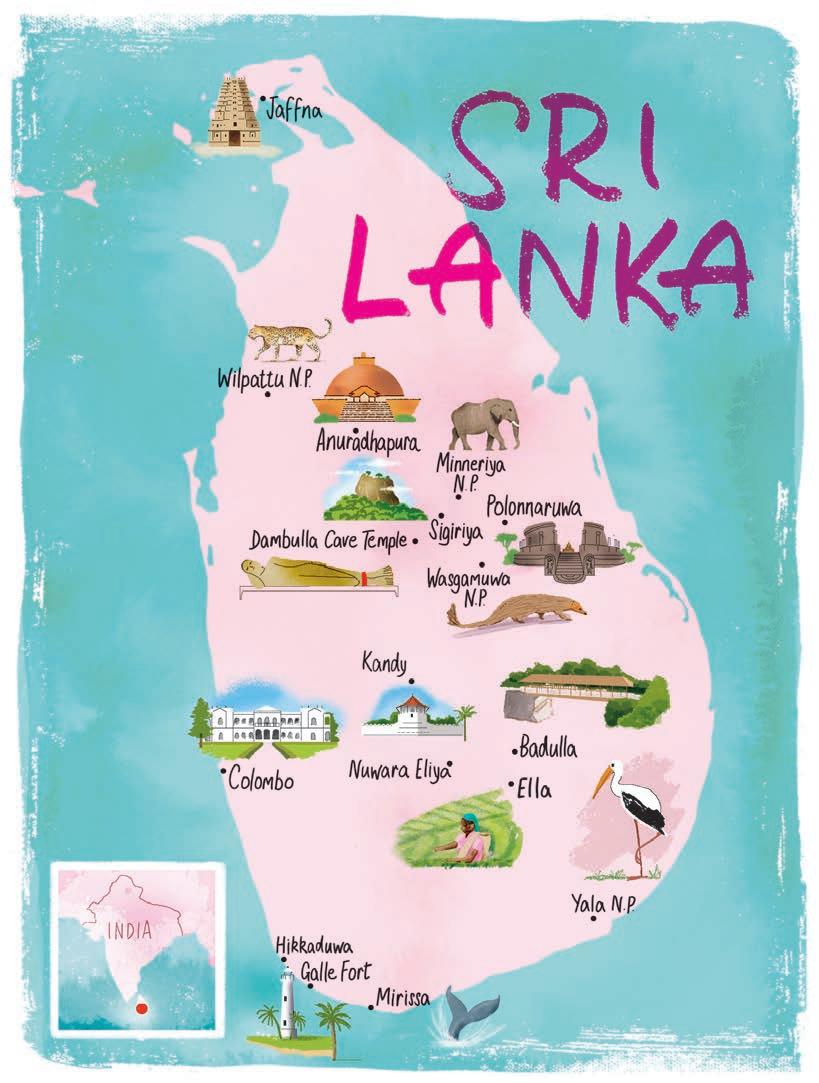

Sri Lanka

Beyond The Sea

With over 2,500 years of recorded history, those in search of archaeological and cultural treasures in Sri Lanka soon learn the Pearl of the Indian Ocean more than lives up to its name

Advertisement

Words & Photographs George Kipouros

et ready to experience Sri Lanka’s version of a full “Gmoon party,” warned Viraj, my story-loving guide, as we headed deep into the ancient citadel of the island’s first capital, Anuradhapura. Founded in the 4th century BC, the city continued for 1,300 years as Sri

Lanka’s foremost urban centre, and my gaze was pulled in every direction as we drove the remains of one of the largest monastic citadels the world has ever seen on a busy holy day.

This was just the start for me. I was on a journey that would take me to some of Sri Lanka’s finest treasures, on a route navigating the

Cultural Triangle linking the ancient “The Jetavanaramaya capitals of Anuradhapura, Polonnaruwa was the third and Kandy, ending at the island’s historic commercial gateway, Galle. tallest building in the

“You’re ver y lucky to be visiting ancient world”

Anuradhapura, one of the holiest places for Buddhists on the island, on a Duruthu full moon Poya,” said Viraj as we drove past dagobas and palaces. Every full moon in January, Buddhists commemorate the first visit of the Buddha to Sri Lanka (around 528

BC), and I’d arrived in time to see the festivities.

We headed first to Mahavihara, the oldest of the city’s monasteries. It was thronged by thousands of worshippers drawn to the holy Sri Maha Bodhi tree, said to be grown from a cutting of the original tree under which the Buddha attained enlightenment. Dressed in all-white, pilgrims carried colourful exotic flowers as offerings while loudspeakers blasted pirith chanting, to help with their quest for spiritual contentment. “It’s a little louder than usual with the use of speakers, but it really does help with meditation,” Viraj affirmed, acknowledging my surprise at the scene. “It wouldn’t be a par ty without loudspeakers, after all,” I smiled back at him. While the scale of Anuradhapura’s ancient citadel is extraordinary, nothing prepares you for that first view of the colossal dagoba of Jetavanaramaya, taking over a gargantuan square platform of over 233,000 square metres. Erected in the 3rd century AD, it is still the largest brick-built monument in the world and a highly revered site by Buddhists everywhere. A dagoba, also known as a stupa, is a dome-shaped shrine containing relics of the Buddha or a Buddhist saint. Anuradhapura boasts several fine examples, including the first built in Sri Lanka, the Thuparama dagoba. “After the Giza Pyramids in Egypt, the Jetavanaramaya was the third tallest building in the ancient world, originally reaching a height of 122m,” announced Viraj, “yet our own pyramids, our dagobas, are nowhere near as famous!” Today, the monument stands at just 71m high and has perhaps lost some of the pristine glory that its former glowing-white stucco-painted exterior once afforded. Regardless, for the pilgrims celebrating this full moon Poya, the Jetavanaramaya remains an essential stop, and I left them circling the circumference of this great remnant of Anuradhapura’s heyday. THE SECOND APOGEE In the 11th century AD, Anuradhapura succumbed to invaders from Southern India, forcing the city’s royalty to flee to Polonnaruwa, which later became the new royal capital. ⊲

Its peak would arrive during the 12th century when, under the reign of kings Vijayabahu I and Parakramabahu, striking monuments, both religious and secular, and exceptionally advanced irrigation schemes were built.

This ancient city, as well as the surrounding plains, were watered by a unique irrigation network known as the Parakrama Samudra (Sea of Parakrama). This allowed for significant agricultural development, enabling Polonnaruwa to export rice to many countries across Southern Asia.

“Thanks to this ancient system, this region of Sri Lanka still produces plenty of rice and other farming products, too,” said Viraj, pointing towards the lake-like Parakrama Samudra that survives to this day.

During the Anuradhapura era, stone became the primary building material, whereas brick was mostly used in the constr uction of Polonnaruwa, enabling the erection of many large-scale edifices in a comparatively short period of time. Among the city’s palatial and well-preser ved medieval buildings, an architectural tour de force stands out: the Vatadage. It is a type of building that is unique to ancient Sri Lanka, with only ten examples remaining in existence today – and the best-preserved is found right here in Polonnaruwa.

Vatadages were built to encircle small stupas for their protection, and had multiple levels. The example I saw in Polonnaruwa was built of both brick and stone, with the latter more visible in the ornate columns supporting what was once a wooden roof. I found the exquisite stone carvings stole the show, specifically the sandakada pahana (moonstones) on the doorways and the two muragalas (guard stones) which were located on the eastern façade. These were some of the most intricate, life-like examples of stone craftsmanship I’d encountered anywhere in Asia.

“Does it remind you a bit of Stonehenge?” asked Viraj, adding that a British couple who recently visited had found it quite similar. The circular shape was the only similarity

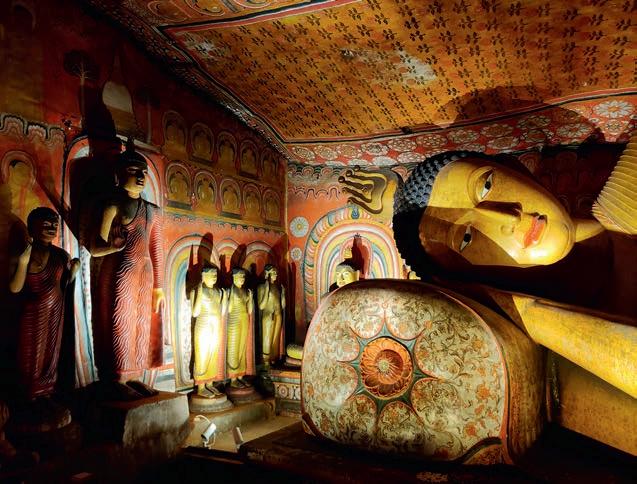

I could identify, and I promised Viraj a visit to Stonehenge when he was next in the UK, so he could see for himself. THE LARGEST PICTURE GALLERY IN THE ANCIENT WORLD As the most iconic of all Sri Lanka’s heritage sites, Sigiriya doesn’t fail to impress. Surrounded by a lush expanse of jungle, a sheer rock rises almost 200 metres upwards. Atop the summit lie the remains of a royal palace and citadel, while beautiful pleasure gardens nestle at its foot. “It’s a bit like Sri Lanka’s own Acropolis, isn’t it?” Viraj teased me with a smile. Well, the myth behind its short-lived rise and fall is certainly worthy of a Greek tragedy: Kasyapa, the son of a king, murders his father, whereupon a power struggle between him and his brother “The exquisite leads to him building an impregnable stone carvings fort, Sigiriya. Spoiler alert: it does not end well for Kasyapa, who only had a of the Vatadage few years to enjoy his new capital. Along stole the show” with a gift for megalomania, he did have an eye for beauty and artistic excellence, though. Sigiriya was as much an artistic masterpiece as it was a forbidding fortress. Indeed, Viraj was eager for me to see the true highlight of Sigiriya. “It’s not the rock itself nor the views from the top that make this a genuine cultural treasure,” he explained, “but the incredible 5th-century paintings we visit on the descent.” We stopped in front of a smallish gallery, seemingly full of uniformed minders yelling, “No photo!”. “John Still, a British archaeologist who did major research here in Sigiriya in the early 1900s, called this the largest picture gallery in the ancient world,” exclaimed Viraj as he pointed to what remained. “This is but a small fragment of an ancient band of paintings that once extended to the whole corner of this rock.” Indeed, Sri Lankan archaeologists have found the original painted area was about 150m long and up to 40m high. The Sigiriya frescoes are widely regarded as some of the most captivating examples of South-Asian apsara painting. Affectionally nicknamed the Sigiriya ladies, these sensational creations most likely represent celestial nymphs, divine beings and goddesses. Some archaeologists built on the uniqueness of each painting’s facial and bodily features to ascertain that they formed part of a “royal gallery” of queens and princesses dominating Kasyapa’s court. Aesthetically pleasing, highly sensual – some would even say erotically charged – the unique painting style of the Sigiriya ladies is a crowning achievement of ancient Sri Lankan artists. “We are very lucky that these paintings survive to show the level of artistic excellence in Sigiriya,” said Viraj. “And that Lord Elgin never visited your Acropolis,” I added with a wry smile. Heading south from Sigiriya, I couldn’t leave without a visit to the spectacular cave temples of Dambulla, hewn into a 160m-high granite outcrop. The transformation of the five caves into masterpieces of Buddhist art started when they allegedly provided shelter to a Sri Lankan king fleeing invasion back in the 1st century BC. King Valagamba of Anuradhapura later had temples built in the caves, initiating a tradition of fresco painting that would continue for many ⊲

centuries, creating the island’s – and one of the world’s – finest Buddhist viharas (temples/monasteries). Yet, it was Kandyan artists who were primarily responsible for the look and feel of this splendid vihara today. The five main temples were mostly repainted in the post-classical style of the Kandyan School of the late 18th century. Fittingly, my next stop would bring me to the capital of Sri Lanka’s last surviving kingdom, Kandy.

THE LAST ROYAL BASTION

locals, the city is a symbol of foreign invasion, hegemony and the occupation of their land; first by the Portuguese, then the Dutch, and finally the British Empire. As I entered, I couldn’t help but be taken by its size. Galle Fort is the largest and best-preserved sea fort not only in Sri Lanka but all of South Asia. UNESCO recognised its world heritage value as early as 1988, and its urban fabric is a testament to the productivity and craftsmanship of Sri Lankan society throughout the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, as well as the I was expecting to be mesmerised by this final stronghold of many artisans and expert builders involved in its construction. Sri Lanka’s indigenous royalty, a place that many locals I met I was staying at the city’s historic Amangalla Hotel, which spoke of with respect and admiration. “European visitors love once served as a residence for the Dutch Governor. Mithuru, Kandy,” confirmed Viraj as we waited in traffic to enter the city. who worked in guest relations, suggested a walk over to Galle’s Instead, I experienced a crowded, traffic-laden urban chaos bastions, originally built in 1620 by the Portuguese. that gravitated around an artificial lake, with the imposing “It was these stone defenses that protected the old town from Dalada Maligawa (Temple of the Tooth of Buddha) attracting many perils, all the way up to the 2004 tsunami that devastated a hive of pilgrim activity at one end. the region,” Mithuru explained, pointing to the city’s restored

The hypnotic murmur of Buddhist invocations provided rooftops from the hotel’s veranda. “Look at how different and the soundtrack as we entered the temple complex, following varied the buildings are – their colours, their frames.” airport-style security checks. The pilgrim numbers were so As we walked around the pedestrian-friendly fort, I came significant that we decided to skip the relic chamber that held across a unique amalgam of Dutch, Portuguese, British colothe revered tooth of the Buddha – Viraj added that this is possi- nial and South Asian forms. Nonetheless, the most remarkable bly the single most important pilgrimage site on the island. surviving buildings were predominantly remnants of activity I would instead shift my focus to the artisanship of the temple by the Dutch East India Company. and surrounding royal edifices, with The architectural diversity here is most surviving structures here dating matched only by that of the population, back to the 18th and 19th centuries. “Kandyan artists were Mithuru explained: “We have churches In tr uth, Kandyan architecture cannot be compared with the magnif- trailblazers, and there of multiple denominations, a mosque and a Buddhist temple in this tiny speck icent achievements of Anuradhapura are some excellent of land, and people of many ethnicities or Polonnaruwa. Its primarily wooden surviving examples of still call this home today.” buildings – of a simpler appearance and more measured scale – reflected the frescoes, lacquerware I met the fort’s artist-in-residence, Janaka De Silva, curator of The Galle different needs of the smaller, mostly and wooden carvings” Fort Art Gallery and a 100% Sri Lankan, agricultural community that made up as he proudly pointed out, despite his the Kingdom of Kandy. Kandyan artists, Portuguese-sounding surname. however, were far more trailblazing, and there are some excel- “Galle Fort has always been Sri Lanka’s gateway to the lent surviving examples of exquisite frescoes, fine lacquerware world,” he told me, “with people coming and trading goods and wooden carvings with ornate decorative patterns. and artworks – a tradition that in many ways continues today.”

“Kandy is the mecca of Sri Lankan craftsmen,” explained I agreed that it was certainly popular, though mostly filled Viraj as we walked past the many craft stores in town, “and it with day-trippers from the beach resorts that skirt the country’s is here that you will find some of the best-quality mementos southern coast. I was curious how locals viewed this. to bring back home from our island.” “It’s a good thing many people are coming here,” Janaka

The impact of royal artistic traditions on the area is particu- assured me. “They are helping to fund further restoration work larly evident in modern examples of weaving, brass and silver- and support a growing arts scene in town.” smithing, as well as painting. I was starting to see its influence His own unique painting style was a fusion of Asian and everywhere. That night, as I returned to Vil Uyana, the eco-re- European primitivism, with Galle Fort and its rich history sort that served as my base for exploring the Cultural Triangle, prominent among his subjects. “This pearl of a town is an my eye was suddenly drawn to the impressive mural adorning endless source of inspiration,” Janaka elaborated before invitits restaurant wall. Even here, the peculiar style of Kandyan ing me back for a longer stay, so we could visit the underwater painting worked its seductive charm. gallery that he’s developing off the coast of the fort. I assured him I’d return, for I too had fallen for the island’s SOUTH-ASIA’S BEST-PRESERVED magic, which has captivated visitors and conqueror-wannabes SEA FORT for centuries. I told him that the Ancient Greeks, at the time of The historic southern port city of Galle was the final stop on Alexander the Great, called this island Palaesimoundu, meanmy cultural treasure hunt. The island’s most cosmopolitan ing “beyond the sea”, and wrote of its mythical riches. outpost, with its naturally sheltered harbour, had been the “Ah, there is so much more to Sri Lanka than most visiprime channel for Sri Lanka’s contact with the world for the tors see, and it’s true that many more treasures lie inland,” he better part of the last four centuries, serving as a major hub of smiled as he handed over one of his Galle landscape paintings, Indian Ocean sea lanes. But its past is complicated. For many which would soon hang back at Wanderlust HQ in London. ⊲

Return of the WILD

Since Sri Lanka’s Jetwing Vil Uyana resort opened, its rewilded lands have lured native birds and animals back to the area, offering guests front-row seats, writes Mike Unwin

Photographs Mike Unwin

King of the old world

(left–right) A toque macaque admires the rock fortress of Sigiriya, a UNESCO World Heritage Site that was the seat of Sri Lanka’s capital more than 1,500 years ago – today, monkeys are among a host of wildlife to be seen among the island’s ruins; the nocturnal grey slender loris is difficult to spot, even in the forests around Vil Uyana As early evening arrives in central Sri Lanka, I find myself searching a dark forest for a small animal. The idea is to sweep the beam of my headtorch across the foliage to catch its reflected eyeshine. In truth, my focus is as much on avoiding the snaking roots along the trail. “There!” I hiss, spotting a twinkle in the dark tangle. “Fireflies,” says my more experienced companion. We move on.

Naturalist Chaminda Jayasekara has trodden this trail hundreds of times, so it’s hardly surprising that he’s seeing wildlife at every turn. First up: an Asian palm civet scuttling through the canopy; then a roosting Indian pitta on its perch, puffed up into an exquisite ball. Next, he spies a green vine snake suspended like a noose from – gratifyingly – a vine, its head mimicking a flower bud.

Chaminda soon spots what we’re looking for. I peer down his torch beam, its glare softened by a red filter, and see two saucer eyes staring back. Binoculars reveal a small, furry, squirrel-sized animal peering at us suspiciously from a tree fork. I make out skinny limbs, a tailless rear and dexterous little fingers, in which it clutches a struggling cicada. Bingo! A grey slender loris.

This appealing nocturnal primate is endemic to southern India and Sri Lanka, with its sister species, the red slender loris, found only on this island. Related to Africa’s bush babies, both are threatened by habitat loss. A close encounter is thus a serious privilege, and my eyes are glued to the animal as it takes one more bite from the unfortunate insect then clambers quickly away through the branches.

As we emerge from the trail onto a gravel path, I’m taken aback by the lights shimmering on the ⊲

lake. Back in the forest, it was easy to imagine that Beyond the fence, the buzz and beep of passing we were exploring some remote wilderness rather scooters and tuk-tuks is a reminder that we’re not than strolling the grounds of an upmarket hotel. in some national park; that a busy community

But Jetwing Vil Uyana is not any hotel. Located surrounds Vil Uyana, with farmers and fisherin the centre of Sri Lanka, just 15 minutes from men working the paddy fields and lakes. But the the celebrated World Heritage Site of Sigiriya, this resort’s wildlife is impressive proof of how biodieco-resort has undertaken an ambitious rewild- versity can flourish alongside people when farming project, converting abandoned paddy fields ing is kept small-scale, waterways are unpolluted into a wetland mosaic fed by irrigation channels and pockets of natural habitat are left to flourish. from the surrounding farmland, and planting A case in point is the resident two-metre-long thousands of indigenous trees. This suite of natu- female marsh (or mugger) crocodile that found its rally regenerating habitats has produced prolific way here via an irrigation canal. Last July, she laid biodiversity across its modest 24 acres. A 2005 a clutch of eggs just 50 metres from reception. baseline survey revealed 12 species of mammal, In November, Chaminda managed to film the three of reptile and amphibian, and 29 of bird. babies hatching, even capturing the formidable Since rewilding, these figures have now risen to reptile ferrying the brood to water in her massive an amazing 27, 44 and 157 respectively. yet tender jaws. At breakfast, from the restaurant,

“All these animals have chosen to make Vil I spy her cruising the lake. Uyana their home,” says Chaminda, vindicat- Amid such a profusion of nature, it is tempting ing the resor t’s ‘build it and they will come’ to stay put. Such is the dilemma for the wildlife approach. He has been integral to this success traveller: hang out in paradise and enjoy what story, monitoring the wildlife, advising on ecology comes along or chase around to tick off the “must and liaising with the local community. It was he sees” fur ther afield. Sri Lanka cer tainly has who, in 2010, first spotted a plenty of the latter. A typislender loris here, immedi- cal wildlife tour might take ately persuading the owners “Over my week at in the rainforests of Sinhato shelve fur ther building Vil Uyana, I notch raja, with its endemic birds; plans. Since then, he has become an authority on the up 60-plus bird the highlands of Hor ton Plains, with its herds of species, recording 23 births species from my sambar deer; or the coast, over 11 years and advising chalet alone” with its blue whales and the BBC when they arrived spinner dolphins. Even for t o f i l m l o r i s e s f o r t h e i r the casual tourist, the counblockbuster Pr imates series. try’s big game is high on the agenda. Leopards

Lorises are not the only stars of this show. As and sloth bears have put the south-eastern reserve we return to our chalet, Chaminda plays his beam of Yala firmly on the wildlife map, while Minnerialong the water’s edge, looking for one of Vil ya’s famous dry-season “Gathering” sees punters Uyana’s resident fishing cats. Camera-trap ID has arrive just in time for Asia’s largest congregahelped him identify seven of these elusive, semi- tion of elephants. aquatic felines that roam the property. There’s It is with these larger mammals in mind that no luck tonight, but his vigilance rewards us with we set out north-west to Wilpattu National Park. a brown fish owl hunting for frogs in a ditch. The This is Sri Lanka’s biggest reserve, and was the hefty bird puffs out its white throat, utters a deep jewel in the nation’s wildlife crown before three hoot, then takes flight into the darkness. decades of civil conflict placed it off-limits until

Over my week at Vil Uyana the wildlife keeps 2009. Today, visitors are returning to find the coming. I notch up 60-plus bird species from place has lost none of its appeal. The star attracmy chalet alone: exquisite sunbirds zip over the tion here is the leopard, Sri Lanka’s largest predabalcony, dazzling kingfishers (three species) hunt tor. To my amazement, we encounter three in one the paddy field below; barbets and bee-eaters day, something you’d be lucky to achieve in any perch atop a thicket opposite. Each morning, African park. Two sightings, admittedly, are brief, the dawn chorus awakens me with whistling with the big cats padding quickly away into the magpie-robins and the rather less melodic yowl- forest, and the third is just a spotted tail hanging ing of peacocks. And ever y stroll around the from a tree. But hey: they’re leopards! resort brings something new: a water monitor News travels fast at Wilpattu. So when a scrum swaggering along a path or a giant squirrel on an of vehicles materialises, bristling with cameras, overhead branch. In the midst of all this, leggy we move away to quieter corners, finding crested grey langur monkeys crash through the canopy, serpent eagles hunting the forest tracks and while bejewelled dragonflies dodge pond herons crimson rose butterflies dancing in sunlit glades. stalking the lily pads. It’s like leafing through Emerging at one lake, we watch a testostera children’s wildlife colouring book. one-charged wild boar causing mayhem as ⊲

he chases after females, who snort and squeal like steam trains.

Closer to Vil Uyana, we also visit the lesser-known Wasgamuwa National Park. Large mammals are more elusive here, but so are tourists, and we have the wildlife all to ourselves – including a beady-eyed ruddy mongoose chaperoning its youngster along the roadside. As the afternoon shadows lengthen, we also meet the largest mammal of all: elephants. A small breeding herd emerges from the forest, trailing a retinue of egrets, and we watch an old bull nearby, who shakes the soil from bunches of grass before stuffing them down his pink gullet.

With Vil Uyana sitting at the heart of Sri Lanka’s “Cultural Tr iangle” – an area connecting a tr io of ancient capitals, including Anuradhapura, Kandy and Polonnaruwa – it’s no surprise these are high on most visitor agendas. But in Sri Lanka, I discover, nature follows you around. Thus, explor ing the stupas of Anuradhapura, the ancient capital, I find Malabar pied hornbills gorging on the fruit of sacred ficus trees and toque macaques cavorting among the ruins. And climbing the breathtaking rock citadel of Sigiriya, I watch Indian paradise flycatchers trailing their tail ribbons and spy a troop of endemic purple-faced leaf monkeys in the forest canopy below. Even en route, we keep our eyes peeled. Driving to Sigiriya at dawn brings golden

jackals trotting along the verge, and coming the other way at dusk, a wild bull elephant sauntering down the middle of the road. The beauty of this prolifically biodiverse island, I’m discovering, is that wildlife is everywhere, and at every scale. It’s not just about the big hitters in the national parks. Bird, butterfly or lizard, there’s always something to hold your attention. And as a visitor, you needn’t make tricky choices between nature and culture: any village tour or historical excursion warrants bringing b i n o c u l a r s a l o n g . E ve n a luxury resort, sustainably “Two sightings are of managed, can house a mini cats padding quickly wild menagerie. On my final night at Vil away; the third is a Uyana, we set out by Jeep spotted tail hanging in search of more neighfrom a tree. But hey: bourhood noctur nals. We d o n ’t g o f a r , t r u n d l i n g they’re leopards!” slowly around the sleeping local community, past lakes, temples and paddy fields. But Chaminda’s spotlight keeps striking gold: a diminutive mouse-deer; a foraging ringtailed civet; a retreating pair of Indian porcupines, quills raised like the sails of a galleon. With fishing cats on my mind, my pulse quickens when I spot a telltale feline form crouched in a paddy field. But it’s a different species entirely: a jungle cat. The elegant animal blinks in our light, revealing a white muzzle and slightly tufted ears, then stretches its long limbs and stalks away along the bank. Another furr y gift from the Sri Lankan night.

SIX OF THE BEST: SRI LANKA WILDLIFE SUPERSTARS

LEOPARD

Sri Lanka’s leopard belongs to an endemic subspecies. They occur in all regions and habitats here, but Yala and Wilpattu national parks offer excellent sightings.

ASIAN ELEPHANT

Some 7,500 Sri Lankan elephants roam the wider countryside and reserves of the island. Hundreds can be seen gathering during the dry season at Minneriya NP.

SLOTH BEAR

This small, black, shaggy bear inhabits the island’s northern and eastern lowlands. It is unique among bears for feeding largely upon ants and termites.

BLUE WHALE

Found off Sri Lanka’s eastern and southern coasts, this huge cetacean is commonly spied in the waters off Mirissa in February and March, when krill is at its most abundant.

FISHING CAT

This shy, nocturnal feline is patterned with spots and stripes. It frequents wetland habitats where it feeds on fish, wading in to capture its prey. Found across southern Asia, it is nowhere more easily seen than in Sri Lanka.

SLENDER LORIS

Slender lorises are prosimians: small primates that predate the evolution of monkeys. Two species occur in the forests around Sri Lanka: the more common grey slender loris and the endemic red slender loris. ⊲

he bright skin-browning mid-afternoon coconut, rubber and tea from the plantations around sun drove me and a gaggle of locals Kandy to Colombo on the coast for export. For more than

Ttoward the cool shaded entrance of a century its locomotives rarely carried a single passenger. Galle Railway Station. In the open hall When Sri Lanka gained independence in 1948, however, there was no chattering split-flap desti- train use rose dramatically for a short period until the econnation displays, just a large chestnut omy flipped from agriculture to industry, and rails were board with the stations hand-painted suddenly eclipsed by roads. For sixty years, the railways fell neatly in yellow. A quaint hand-wound into decline. Diesel didn’t replace the old steam trains until analogue clock hung beside each one to the 1970s. But in 2010, a major reinvigoration project was denote the departure time. White-sneakered schoolgirls launched and the Sri Lankan rail network enjoyed a rebirth. with book-heavy backpacks shuffled Lovers of locomotives will be agog at forward in the ticket line like turtles. the shabby-chic crowded carriages. I booked a third-class ticket to Balapi- “Diesel didn’t replace Back on the platform, our the train tiya. The vendor handed me a purple the old steam trains was 25 minutes late. We waited on chit – like an old movie stub – printed benches, beside a salt-and-pepperwith calligraphic Sinhalese. It cost 70 here until the 1970s. haired lady, bags corralled around r upees, roughly 25 pence. “Hurr y, But in 2010, a major her sandalled feet. Sari-robed mothhur r y,” ushered our guide, Richard. “We only have four minutes reinvigoration project ers paraded up and down the platform hand-in-hand with their young until the train arrives!” saw the Sri Lankan daughters to keep them entertained.

If rail travel conjures images of rail network reborn” I noticed grass growing between the airless cabins crammed with glum tracks, a reminder that life often moves commuters buried in their phones or more slowly here and that there’s trapped in their own sphere of stress, let Sri Lanka redefine an enduring beauty in that truth. the experience. Home to some of the most scenic rail routes The voice of the announcer crackled over the speaker – first in the world, the “Teardrop of India” offers views of tower- in Sinhalese, then in English – and soon after, a burnt-oring tiers of neon-green tea fields wrapped around curva- ange locomotive chugged into view. The driver nodded at ceous hillsides, cascading waterfalls, cloud-shrouded pine me as I joined the queue, grabbed the handle and levered forests and cerulean seas curling onto white-sand beaches. myself up into the carriage. Inside, the corners of the brownForget stuffy rules. Here you can swap seats to natter with leather benches were dog-eared and the floor had worn thin your neighbour, hang freely out of windows and open doors in places. Small fans positioned above the aisles spun relentto catch the cooling breeze (though be careful). lessly in their cages, and the toilet was spotless. I noticed the

The idea of building railways here was first explored by seats at the end of each cabin were reserved not for women the British in 1842, with the aim of transporting coffee, and children, or indeed for the elderly, but “For Clergy”. ⊲

Golden age of travel

(clockwise from far left) Colombo Fort Railway Station was opened to the public in 1917 and is itself an attraction, such is its bustle and the heady scents from the vendors’ carts; a train pulls into Galle Railway Station – it was designed to be the terminus of the Coastal Line but this was later extended, meaning trains have to perform elaborate manoeuvres to continue onwards; forget digital displays, Galle’s wooden timetables conjure train travel from yesteryear

As we started to pull out of the station, I took a contem- palm tree-shaded homes that occasionally parted to offer plative walk through the train. Teenagers, sprightly now that tantalising glimpses of the azure Laccadive Sea and its surfschool had ended for the day, hooked their elbows out of the er-studded waves. And then, as we passed through Hikkaglassless window frames. Schoolgirls with long oiled braids duwa, a 30m-high cream-coloured Buddha loomed into and red headbands sat with their legs crossed demurely, view, a replica of one of the Buddhas of Bamiyan, destroyed watching the antics of the blue-shorted boys, mismatched by the Taliban in Afghanistan 21 years ago. The statue was socks sprouting from their scuffed black-leather shoes, as erected in memory of the 1,700 lives lost when the 2004 they giddily tickled each other across the aisle. tsunami struck the Queen of the Sea train at this point as it

A young g irl sat on her moth - travelled south from Colombo. It was er’s lap, her head resting gently on a moment of peaceful remembrance the window ledge as she watched “A 30m-high cream- before we rumbled on. the world spool by. I took a seat and noticed it had been too long a day for coloured Buddha Soon after, an older boy in a white Adidas T-shirt and red Nike baseball some: a young boy lay horizontal on loomed into view, a cap tapped me boldly on the shoulder. the bench, his school bag ser ving as replica of one that had “iPhone 13 Pro,” he announced, pointa pillow. He didn’t move an inch when ing to my hand that was filming out a pair of lads chased each other down been destroyed by the the door. I nodded. “Selfie?” he asked, the aisle, their white uniforms spat- Taliban in Afghanistan” slinging his arm around my shoulder tered with purple ink. “What’s going and effecting a model’s pout. on?” I asked with a grin. “It’s a dare!” We snapped a picture, and at the they laughed. “We have to see if we can escape getting hit.” next stop he and his friends jumped eagerly from the I pictured the look on their mothers’ faces when they sheep- train and waved at me animatedly until the slow-movishly returned home with tie-dye shirts and trousers. ing carriages inched away from the platform. It was the

The bodies only ser ved to amplify the humid air, so perfect reminder that train jour neys offer an immerI moved towards the door at the end of the carriage. Kids sion in local life that can’t be bettered, and that riding parted to let me lean out of the train, the wind whipping Sri Lanka’s railways, in particular, have a hazy, bygonemy hair and drying the sweat on my skin. We rattled past era romance that is rare to track down nowadays. ⊲

PLANNING A TRIP

Sri Lankan trains have three carriage classes: first, second and third. Third class – or “sardine class” as it could be nicknamed – is a buy-a-ticket-on-the-day crowded affair that offers unforgettable immersion in local life. Second class has both unreserved and reserved seating and fans. And lastly, a first-class ticket buys quieter cabins, softer seats and air conditioning, but windows and doors tend to be shut, so you’ll miss out on the whole joy and freedom of dangling out of the train as it goes, which often characterises Sri Lankan rail travel. Tickets for first- and reserved second-class seats can be purchased up to a month in advance from stations and local booking agencies, and it’s worth doing so during the high season (Dec–Apr). Outside of these months, you can often just turn up. Note that vendors at stations proffer parcels of curry and rice, but if you don’t like spicy food, pack your own snacks. It’s also never a bad idea to have a few spare sheets of toilet paper/tissues handy.

Alamy; Emma Thomson

SRI LANKA’S BEST RAIL ROUTES

KANDY TO BADULLA

Distance: 165km All aboard for one of the most scenic rail rides in the world. Once used for the transportation of tea, this British-built line curls for seven-toeight hours around hillsides tiered with neon-green tea bushes, their rows punctuated by the bright saris of the tea pickers, who wear baskets slung from their foreheads. Be sure to hold your nose to the air to catch occasional wafts of lemongrass, and hold your breath as the train traverses steep ravines and valleys. Look out too for the iconic Nine Arch Bridge, a colonial viaduct on the outskirts of Demodara nicknamed the “Bridge in the Sky” because it hovers above the jungle below. At Ella, be sure to hike back to the bridge later for unforgettable photos – it’s at its best (and quietest) at sunrise.

NUWARA ELIYA TO ELLA

Distance: 55km If the above seems like too long to spend on a train, you can abbreviate it by just doing part of the route. The three-to-four-hour section that snakes its way out of Nanu Oya Station, on the outskirts of Nuwara Eliya (Central Province), to the backpacker town of Ella (Uva Province) is magical. By road it would only take 90 minutes, but this route crosses steep mountain ranges, hence the extended travel time. It is home to the epic Ella Gap panorama, so snag a seat on the left-hand side for the best views and watch tiers of tea terraces – Nuwara Eliya sits at the heart of Sri Lanka’s tea production region – and ethereal cloud forests spool past.

COLOMBO TO KANDY

Distance: 125km Ride the rails of history. This classic journey traces a section of the country’s first major route, from Colombo to Ambepussa, which opened in December 1864. Trundle away from the tuk-tuk-crowded streets and high rises of the Sri Lankan capital and travel inland, past the serene greens of paddy fields and palm trees, to the leafy sacred city of Kandy that centres around a bird-rich lake and is home to the Temple of the Tooth, said to protect the Buddha’s left canine. You’ll be swapping dusty dry coastal air for the cool breezes of the highlands; the journey takes approximately 2.5 hours, with daily departures every three hours.

COLOMBO TO GALLE

Distance: 120km This two-to-2.5-hour coastal locomotive snakes down the western edge of the island from the capital to the southern Portuguese-founded city of Galle, which is also rich in Dutch colonial architecture. As you ride the line, tall buildings shrink to corrugated iron-roof shacks festooned with laundry, parting to reveal glimpses of the sandy beaches and clear-blue sea. In places, the tracks almost run parallel with the shore, so sit on the right-hand side for the best views of these unending seascapes, beachside towns and gaggles of wave-chasing surfers. As each minute passes, you’ll feel the stress of city life melting away.

ANURADHAPURA TO JAFFNA

Distance: 195km UNESCO-listed Anuradhapura is Sri Lanka’s ancient capital, characterised by giant stupas and temples, and is one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world. The route from there to Jaffna, in the lesservisited Hindu north of the island, was severed during Sri Lanka’s 26-year-long civil war. Rail travel came to a standstill, with this route only reopening in 2014. Travellers embarking on the 3.5-hour-long journey today will see flatter landscapes, salt pans and rattle through the Elephant Pass that controls entry to the Jaffna peninsula. The north boasts far fewer visitors and some of Sri Lanka’s best unspoilt beaches, making it a worthy escape. ⊲

Above the arches (right–left) The train from Demodara to Ella passes over Nine Arch Bridge, which rises 24m out of the jungle scrub and tiered tea terraces below – it has become a popular tourist attraction in recent years, with travellers hiking the 45 minutes from Ella (or taking a tuk-tuk) just to get a shot of it as a train goes by; a Sri Lankan train ticket

THE TRIP

Vital statistics

Capital: Colombo Population: 21.9 million Language: Sinhala, Tamil Time: GMT+3.5 International dialling code: +94 Visas: An Electronic Travel Authorisation (ETA) e-visa is required by all visitors and should be applied for online (eta.gov.lk/slvisa) prior to departure; it costs $35 (£26.50) for a double-entry visa for 30 days. Money: Sri Lankan rupee (LKR), currently around LKR370 to the UK£. Sri Lanka has a closed currency, meaning you are only able to purchase it within the country. Multiple ATMs and currency exchanges are found at Bandaranaike International Airport.

When to go

Two monsoon seasons affect the island’s climate: the north-east monsoon (Oct–Jan), which can affect the whole island but brings strong wind and rain to the northern and eastern coasts, and the south-west monsoon (May–Sept), which is more regional and far milder. December to April: This is peak season, especially in the south. In January, Duruthu Poya festival marks the first of the Buddha’s three legendary visits to Sri Lanka. It also sees the start of pilgrimage season at Adam’s Peak, as the chilly hill country warms up. Meanwhile, temperatures in the south-west can reach 30ºC. It’s a good time for whalewatching, with blue whales best sighted in February and March off the coast of Mirissa. May to September: The monsoon season has subsided up in the eastern and northern regions, where the beaches of Trincomalee and the lesser-visited far northern city of Jaffna offer a quiet escape. It’s a particularly good time to visit the Cultural Triangle, as humidity is at its lowest, though this area stays dry throughout much of the year. October to mid-November: Low season. The inter-monsoonal period is unpredictable and often sees heavy rains across the island.

George Kipouros was a guest of Sri Lanka Tailor-Made (+94 11 462 7739; www.srilankatailormade.com), which curated a bespoke journey focusing on Sri Lankan culture, history and archaeology. They offer tailor-made authentic travel experiences created by a team of specialists and guides. For guests looking for cultural inspiration, their private tours utilise renowned Sri Lankan artists, chefs, historians, archaeologists and architects. Mike Unwin was a guest of Jetwing Vil Uyana eco-resort (www.jetwinghotels. com/jetwingviluyana), which offers 10 days (9 nights) full-board from £2,790 per person sharing, including all accommodation, meals, airport transfers, day excursions and on-site activities.

Emma Thomson was a guest of Cox & Kings (coxandkings.co.uk), which has a 12-night tour of Sri Lanka from £1,895pp (B&B), including flights, transfers and guiding.

Health & safety

At the time of writing, all visitors must fill in an online health declaration form prior to travel and upload any relevant documentation; visit airport.lk/ health_declaration/index for information. Fully vaccinated travellers require neither quarantine nor a PCR test on arrival and can stay at any type of accommodation. This can change quickly, so do check before travel.

A yellow fever certificate may be required if you’re arriving from, or have transited ⊲

through, a county with risk of transmission. Recommended jabs include hepatitis A, hepatitis B, rabies, typhoid and tetanus.

Getting there

SriLankan Airlines (srilankan.com) offer direct flights from London Heathrow to Colombo’s Bandaranaike International Airport from around £660 return. From there, the Colombo Express Bus (LKR110/30p) connects the airport in Negombo to the capital’s Central Bus Station and Colombo Fort Station (railway).

Getting around

Rail is not only the best way to travel around Sri Lanka, but to experience it as well. Tickets are cheap (a few pence for a third class ticket bought on the day), but for more comfort, or to bag a spot in an observation car, you’ll need to book in advance (railway.gov.lk). Colombo is the heart of the rail network. Trains from the capital’s Fort Railway Station can take you deep into the hill country (Colombo–Badulla line), down to the historic fort at Galle (Colombo–Matara line), or out to the island’s eastern (Trincomalee) and northern (Jaffna) tips via Polonnaruwa and Anuradhapura respectively. Bus services are more comprehensive, though aren’t nearly as fun. You can buy a ticket on board, with most fares less than £1; they also mostly connect via Colombo.

Cost of travel

Massive inflation over the past few years means Sri Lanka isn’t as cheap as it used to be, though public transport is still a bargain. A meal can range from a few pounds in a cheap local cafe to Western prices in hotels and at the more upmarket fort area of Colombo. The cost of a half-day safari can range upwards of £70 for two people, including pick-up and entry fee, but this depends on your starting point.

Accommodation

Accommodation in Sri Lanka ranges from small B&B stays to plush beachside and jungle resorts. The authors stayed at:

Amangalla (amangalla.com), Galle, is a beautiful heritage stay inside the fort, dating from the 17th century; rooms from £340pn.

Jetwing Kandy Gallery (jetwinghotels.com) offers an eco-focused retreat in the lush hill country of Kandy; rooms from £220pn.

Jetwing Lighthouse (jetwinghotels.com) is a coastal slice of “Tropical Modernism” set on the shores near Galle; rooms from £150pn.

Jetwing Colombo Seven (jetwinghotels. com) offers a slick stay in the capital and an indulgent rooftop pool; rooms from £68pn.

Jetwing Vil Uyana (jetwinghotels.com) sits deep in the Cultural Triangle, not far from Sigiriya. Its rewilded land makes it a hotspot for wildlife watchers; rooms from £350pn.

Food & drink

One of the delights of Sri Lanka is its cuisine. Breakfasts typically include a hopper, a lacy, crepe-like Sri Lankan take on the pancake that is cooked in a small wok, meaning it takes on a bowl shape. An egg is cracked into its centre and this is served with a side of sambol, a ubiquitous coconut relish (grated coconut, chillies, onion and ground Maldive fish) that is highly addictive. Dhal curries and kottu roti (sliced pieces of roti bread fried up with egg, meat or prawns) are common, while the country’s Dutch influence is seen in its lamprais, popular among the Burgher community, which typically includes sides of eggplant, meatballs, egg and sambol all wrapped up with rice in a banana leaf. Be warned that the spice factor is high in Sri Lankan cooking, and that anything “devilled” is no mere boast; it will blow the roof off your mouth.

Further reading & information

Sri Lanka (Lonely Planet, 2021) co-written by Joe Bindloss, Stuart Butler and Bradley Mayhew – a comprehensive guide Elephant Complex (Quercus Publishing) by John Gimlette – a superb unravelling of the historical and cultural quirks of the island www.srilanka.travel – for official tourist information on Sri Lanka

SRI LANKA HIGHLIGHTS

1Sigiriya The palace of an unstable king who murdered his father and built a fortress around him atop a 200m-high rock (pictured) is every bit as dramatic as it sounds – and the artwork found here is exquisite.

2Anuradhapura Sri Lanka’s original royal capital is easily explored by tuk-tuk or bicycle, as you flit between 1,500-year-old ruins and grand dagobas that still attract Buddhist pilgrims by the thousands.

3Galle Fort Galle’s Dutch fort may have a chequered history, but there’s no shaking how joyful it is to wander its streets, gazing on 17th-century buildings and exploring the local artisanal shops and galleries.

4Wilpattu NP Along with Yala NP, this is your best chance to see a leopard in the wild here. There’s no guarantee, and safaris start at the crack of dawn, but it’s worth it. Plus, the consolation of spying any of the park’s water buffalo, elephants and sloth bears is just as tempting.

5Ride the rails to Ella This hill-country rail route is arguably the most beautiful in Sri Lanka, as you wind up into tea country from Nuwara Eliya, crossing the Nine Arch Bridge – which you can walk to afterwards.

6Spot a blue whale Between February and March, the chances of seeing a blue whale off the shores of Mirissa are at their highest. Boats depart around 7am, though it’s worth getting a private charter to escape the crowded decks.

WANDERLUST

RECOMMENDS

Sri Lanka: Wanderlust Travel Guide – https://www.wanderlust.co.uk/ destinations/sri-lanka Sri Lanka trip planner – https://www. wanderlust.co.uk/content/sri-lankabest-trip-planner/

Walk on the wild side

(clockwise from this) Asturias boasts 400km of protected coastline; a deer in the Cantabrian mountains; almost 400 species of birds can be seen in Asturias; the 606km Nature Trail of the Cantabrian Mountains crosses Asturias from east to west and beyond; the most well-known mountain in Picos de Europa National Park is the 2,519m Naranjo de Bulnes, also called the Picu Urriellu; an estimated 30 packs of Iberian wolves live in this part of Spain; Asturias is home to some 300 Cantabrian brown bears

ASTURIAS: INTO THE WILD

5 wildlife sightings in the Spanish natural paradise

reen Spain is a place

Gthat has earned its name. With its huge swathes of lush emerald forests and its undulating verdant mountains, this is a pocket of true natural wilderness. And the region has its own natural paradise, Asturias. This is the country’s beating green heart, home to its first national park, Picos de Europa, and a mosaic of limestone mountains, oak forests and 400km of protected coastline, the best preserved seaside in all of Spain. These all knit together to form seven UNESCO biosphere reserves, home to a huge diversity of wildlife. Here are just five animals to look out for...

1BROWN BEARS

Among Asturias’ forests and mountains prowl some 300 Cantabrian brown bears, the region’s wildlife icon. However, at one point in the 1990s, only 80 to 90 bears remained and it was feared that they’d become extinct. Conservationists duly stepped in and their numbers have been growing ever since. Somiedo Natural Park was created in the process and it, along with neighbouring Fuentes del Narcea, Degaña e Ibias, remains the best place to spot them. Hiring a guide will boost your odds of a sighting, as will visiting from April to late May when mother bears emerge from dens with their cubs. Late August and September are also good for sightings, with bilberry season luring hungry bears out to feast on fruit before winter’s hibernation.

2IBERIAN WOLVES

Wolves can be found across northwestern Spain, and you can spy them stalking the forests and rugged wilds of the Asturian

mountains. It is estimated that there are around 2,000 Iberian wolves in north-western Spain, with a large number of this population found in Asturias.

These creatures are elusive but your best bet for sightings is to look for them when they are at their most active, between August and September, or during the mating season which runs from December to February. Those who are eager to learn more should visit La Casa Del Lobo (House of the Wolf ) in Belmonte, a museum dedicated to the Iberian wolf and the landscapes it patrols.

3DEER AND IBEX

While bears and wolves often receive top billing in these parts, deer and ibex provide Asturias with one of its finest wildlife sightings – and both are much easier to spot. Often found roaming the upper slopes of mountains, such as Ponga and Aller, and Redes Nature Park, the guttural bellows of red deer reverberate around these rocky wildernesses during rutting season (between mid-September and mid-October). It’s a spinetingling, cathedral-like noise. This autumnal groaning is matched only by the fallow deer in the Sueve Mountains – the only place in Asturias you can spot them – while diminutive roe deer are seen pacing the thick forests and craggy plains of the Cantabrian Mountains. Asturias is also home to the Cantabrian ibexes, the majority of which love to stride the rocky highlands of Picos de Europa National Park’s western massif and the verdant limestone peaks of Redes Natural Park.

4WHALES

Life-affirming wildlife encounters don’t only exist on land in Asturias; there’s a bounty of them offshore, too. The Bay of Biscay boasts some of the most diverse sightings of cetaceans in the world, and Asturias is at the heart of it all. To give you a flavour of its busy waters, seven of the world’s 20 species of beaked whale are found here, including the Cuvier’s beaked, northern bottlenose and Sowerby’s beaked whale.

They are tricky to spot because they can spend over an hour submerged underwater, but guided whalewatching tours from Gijón/ Xixón and Llastres heighten your chances of encounters (as does visiting in spring or summer). They’re also not the only whales you can spy here: minke, fin and pilot whales are among the others, and you might also be lucky enough to see dolphins, porpoises, seals and turtles, too.

5BIRDS

Asturias’ tapestry of landscapes makes it a welcoming place for birds, and nearly 400 species roost here, around 70% of Spain’s total number of species. On the coast, the Villaviciosa and Eo estuaries serve up sightings of ospreys, cormorants and grebes, while shearwaters, Atlantic puffins and oystercatchers can be seen on a winter stroll among the plains and craggy cliffs around Gijón’s shores.

Inland, wooded areas such as Somiedo Natural Park and Las Ubiñas-La Mesa Natural Park hide woodpeckers, goshawks, peregrine falcons and the threatened Cantabrian capercaillie. Asturias reserves some of its finest birdlife for the mountains, though; nowhere more so than the La Reina lookout in Picos de Europa National Park. You and your binoculars can track three different types of vulture (griffon, bearded and Egyptian), golden eagles and red kites, all while enjoying the panorama of the mountains – a memorable end to a truly wild adventure in this natural paradise.