theHarvestFollowing

The past, present, and future of harvest labor

Meet the apple farmer who made it big on TikTok

The James Beard nominee focusing on Filipino cuisine

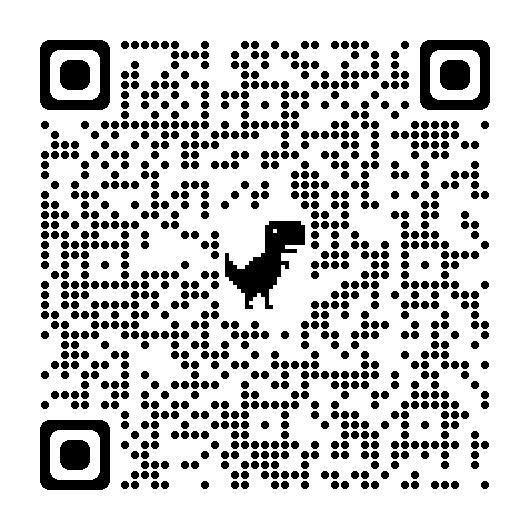

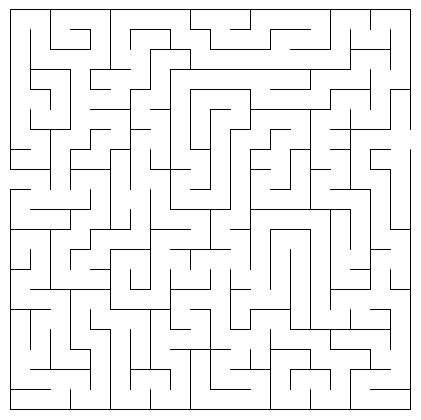

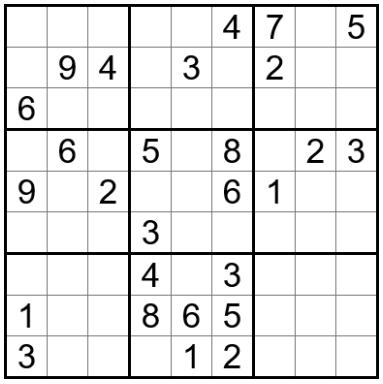

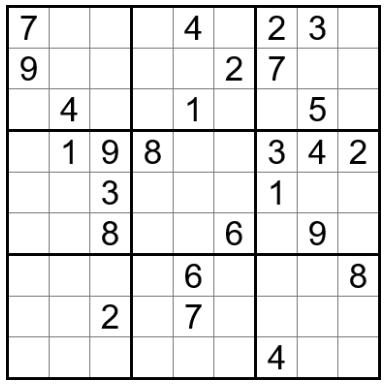

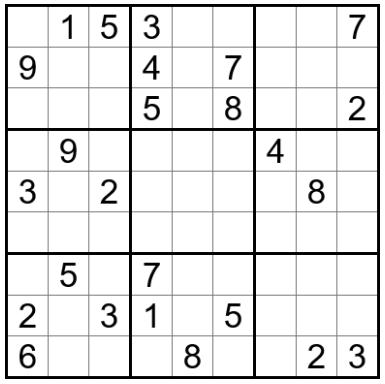

Games and puzzles related to this issue

The past, present, and future of harvest labor

Meet the apple farmer who made it big on TikTok

The James Beard nominee focusing on Filipino cuisine

Games and puzzles related to this issue

"Temporary harvest laborers" are an irreplaceable part of the agricultural world – but some experts worry about the future.

For all of recorded history, growing crops has followed the same basic pattern: planting the seed takes a lot of work, and harvesting the crop takes even more work. The time in between, the duration of which is different for each crop, often requires less hands-on work (though every farmer would tell you there is still lots of work to do). That hurry-up-then-slow-down-then-hurry-up nature of farming has been consistent all around the world since the Neolithic Revolution.

For nearly as long, farmers have relied on temporary labor for those busy seasons. Farms often operate with their “full-time” team for most of the year – made up of a mix of family farmworkers and hired hands – but in many cases, farms need three to five times more laborers during harvest than they do the rest of the year, so many choose to hire temporary “harvest laborers.” In areas of the country that are rich in agriculture, like Washington state, temporary harvest laborers are an irreplaceable part of the local economy – and some experts warn the hiring pool is getting smaller each year.

In the years after the Great Depression, farmworkers began the practice of “following the harvest," migrating north and taking temporary jobs as different crops came ready to harvest, often starting in Texas and following the harvest through Califor-

nia and eventually to Washington state. It was such a phenomenon that John Steinbeck wrote a series of feature articles about it, published as a pamphlet called “Their Blood is Strong.” Since World War 2, in large part due to the Bracero Program, a predominantly Mexican workforce has taken over those harvest labor jobs and inherited that route from Texas or California up to Washington.

Even in our modern age of technological advancement, many of Washington’s most prized fruits and vegetables are still meticulously harvested and packed by hand. So in the present day, when those temporary harvest laborers arrive in Washington, they’re greeted with joy and relief – because if there aren’t enough workers, the harvest could die on the vine. In the last few years, that steady stream of harvest laborers from Texas and California has quietly dried up. Now, many farm owners say their top concern is finding enough workers to get their crops picked before it's too late.

“We know we’re nothing without our employees,” said Mikala Staples-Hughes, interim director of human resources at Sakuma Brothers Farms. “When there’s a labor shortage, it hurts, and we can’t be successful. We want the best for our employees, and we work hard to promote from within and treat people as best we can.”

When temporary laborers arrive, farmers quickly put them to work, often using a piece-rate pay system that incentivizes workers to work quickly and efficiently. The “full-time” team is critical during these early days, providing training and supervision and passing along the culture of the farm to large crowds of newcomers.

“Newcomers” may not be the most accurate word here. For established farms, many of the temporary harvest laborers who come to work each season are not new at all, but rather familiar faces that have been returning year after year. Laborers find it easier to return to the same farms each year than to locate new employment, so they return every year at the same time. These longtime harvesters often bring reinforcements, recruiting cousins, uncles and aunts, and adult children to come along for the promise of steady work. Family members arrive together, work together for the season, and then move on to the next harvest together.

Farm managers have noted that in recent years, many families who previously migrated between California and Washington have chosen to instead remain in Washington full time. Because there is such a great diversity of crops grown in agricultural hubs like Skagit County and the Columbia Basin, and because there are so many processing plants in Washington, temporary farm laborers have been able to stay busy year-round without having to migrate.

In Skagit County, for instance, many workers historically would arrive in June – just in time to pick strawberries

– after spending the winter in the Central Valley of California. After the strawberries were picked, the workers would move to blueberry fields. After blueberries, they may move to blackberries, or potatoes, before packing up to head to California again for the winter. Now, however, those laborers often stay in the Skagit Valley, moving on to Brussels sprouts or tulip bulbs or into one of the many processing plants to work throughout the winter.

“I believe that the more diverse a person can be, the better employee they are,” said Kristi Gundersen, CFO of Knutzen Farms in Burlington, Wash. “It is a real strength for us – they bring different skillsets in from the other farms they work on. And this community fosters each other really well. When there is a new person on the floor of our packing facility, the other co-workers on the line are helpful and nurturing, training and supporting each other.”

Despite the abundance of temporary farm work in Washington, many farmers are reporting a decline in how many domestic laborers they are able to recruit each year. The H-2A Program allows farmers to bring foreign nationals to the United States to fill those temporary jobs, but the cost is high, and some farmers are skeptical. Many are worried about what a prolonged labor shortage would do to their farms. Right now, they’re able to strike a delicate balance – able to hire the labor they need, when they need it – but the future is uncertain. For now, farmers just keep doing what they've always done: feeding the world, one harvest at a time.

Find more great stories at wagrown.com

"Their family came to Red Mountain on a coin flip. But their success here has nothing to do with chance."

Read more at wagrown.com

"Her parents were farmworkers. Now she owns the farm."

Read more at wagrown.com

KSPS (Spokane)

Mondays at 7:00 pm and Saturdays at 4:30 pm ksps.org/schedule/

"We've got a responsibility to take care of it for future generations."

Read more at wagrown.com

KWSU (Pullman) Fridays at 6:00 pm nwpb.org/tv-schedules/

KTNW (Richland) Saturdays at 1:00 pm nwpb.org/tv-schedules

KBTC (Seattle/Tacoma) Saturdays at 6:30 am and 3:00 pm kbtc.org/tv-schedule/

KIMA (Yakima)/KEPR (Pasco)/KLEW (Lewiston) Saturdays at 5:00 pm kimatv.com/station/schedule / keprtv.com/station/schedule klewtv.com/station/schedule

KIRO (Seattle)

Saturdays at 7:30 am and Mondays at 2:30 pm or livestream Saturdays at 2:30 pm on kiro7.com kiro7.com

NCW Life Channel (Wenatchee)

Check local listings ncwlife.com

RFD-TV

Thursdays at 12:30 pm and Fridays at 9:00 pm (Pacific) rfdtv.com/

*Times/schedules subject to change based upon network schedule. Check station programming to confirm air times.

Kait Thornton is a favorite on social media, sharing apple facts, family stories, and little glimpses into life on the farm.

Depending on your algorithm, scrolling through TikTok or Instagram Reels will probably deliver lots of food recipe videos, travel highlight videos, funny memes, or makeup tutorials. But some users, adrift in that vast sea of content, will be lucky enough to get to see 30-second snippets of life on an apple orchard in Tonasket, Wash.

Meet Kait Thornton, who, in addition to being a fourth-generation farmer, is what you would call a big deal online. She has hundreds of thousands of followers on TikTok (@apple. girl.kait) and Instagram (@applegirlkait), where she shares videos documenting her life. In some videos, she explains how apples get irrigated, or why some have blemishes on the skin, or how pollinators make their orchards come to life. In other videos, she gives updates on her classic pickup truck named Blueberry or uses trending audio for a “day in the life” post. There are no TikTok dances or thirst traps — just educational, entertaining glimpses into life on the farm –

and her audience loves it.

“You want people to feel like they’re really coming along with you,” Kait told Washington Grown host Tomás Guzmán when the show visited Tonasket in Season 11. “You kinda just carry them along as you go about your day.”

As much as Thornton may be known for her internet presence, her first love is the farm. She grew up surrounded by the hustle and bustle of the 400-acre orchard and has been involved in the operation of the farm since she was young. But her career as an “agriculture influencer” kicked off in earnest when she had just reached high school, and her dad made a bet with her.

“I wanted to make some side money, and we had some apricot trees,” she said. “My dad said, ‘If you sell 20 boxes of apricots, I’ll be impressed.’ I sold 44 boxes that year. Within a few years, my senior year, I sold over 1,200 boxes of fruit.”

Sign up to be entered into a drawing for a $25 gift certificate to Musang in Beacon Hill!

*Limit one entry per household

Her secret weapon in selling fruit came down to three specific strengths — her passion for farming, her knowledge of the product, and her bubbly personality. In her work on social media, Kait has struck a winning combination using a similar formula: her viewers get entertainment, education, and a chance to feel like part of the Thornton family.

“The new apple called SugarBee is one of our top varieties,” she told Guzmán in one such example. “One thing I’ve made videos about is how to check for what we call ‘fruit finish’ on a SugarBee apple. Once it’s polished, rub the apple along your lip and feel how smooth it is.”

She paused as Guzmán brought the apple to his lips, then chuckled. “I’ve done the same thing with my pickup after I wax it.”

Before the show wrapped up shooting at Thornton Farms, Guzmán asked Thornton to teach him the secret to posting on TikTok. She held out her phone and pressed record as the two leaned together and started bantering about the SugarBee apples.

NOVEMBER 12 & 13, 2024

WHERE?

CenterPlace Regional Event Center Spokane Valley, WA

This annual event drives regenerative agriculture in the Pacific Northwest. Over two days, attendees will join a community focused on increasing access to healthy, locally grown food, empowering farmers, and reducing reliance on synthetic inputs. Led by the Spokane Conservation District's BioFarming Program, the symposium emphasizes the vital link between soil and human health, advocating for transparency and integrity in the food system.

“Let’s show them a little crunch action,” Thornton said as they both bit into the apples in their hands. She put away her phone and then turned to Guzmán, laughing. “You just got a free TikTok promo! Don’t worry, I’ll bill you!” or sign up at www.wagrown.com/ wa-grown-magazine

Washington ranks first in the nation in the production of six crops:

Apples

Blueberries

Hops

Pears

Spearmint

Sweet cherries

In addition, Washington ranks second in the production of six other commodities:

• Potatoes

• Grapes

• Apricots

• Asparagus

• Raspberries

• Wine

That's not all! Washington also ranks third in the production of four other crops:

• Dried peas

• Lentils

• Onions

Peppermint oil

In a converted Craftsman home in Seattle's Beacon Hill, Melissa Miranda cooks dishes that are reminiscent of her home and family. Even the name of her Filipino restaurant — Musang — is a homage to her father.

“‘Musang’ means wild cat,” says Miranda. “My dad had a black Mustang, and the T fell off, so he became ‘Musang,’ and his friends just called him that.”

Miranda said she spent a lot of time cooking with her dad while she was growing up, and he helped instill the love for Filipino food and culture that continues to this day, and which she now passes on to her diners.

“We want the guests to experience what it’s like to be in a Filipino home,” Miranda said.

“The food actually reminds me of how my parents cook,” said a woman eating in the restaurant. “In fact, my parents love the food at Musang — and that says a lot, because my parents are very picky about their Filipino food.”

Miranda, who was nominated this year for a James Beard Best Chef award, opened Musang in 2020, and she wants her restaurant to reflect the strong Filipino community that has always lived in Beacon Hill.

“This area has a lot of history, especially with the Filipino American community,” said another customer dining in the restaurant. “It’s a really great opportunity to share our culture with the rest of the community.”

He also said the powerful flavors at Musang remind him of his mother’s cooking.

“If you’re not familiar with Filipino food, I think

Musang is the perfect place to start,” he said. “It just feels like home.”

Musang is open for brunch and dinner, and its menu includes traditional Filipino dishes that are often inspired by Miranda’s parents’ and grandparents’ cooking, with her own twist. For example, because she cooks with Washingtongrown produce when it’s in season, the ingredients are often different from what you’d find in the Philippines.

“A lot of the things that my parents had access to, we don’t have access to here,” she said. “I take the flavor and the idea of what the Filipino dish is, but then maybe add a different veggie or whatever’s in season.”

In Musang’s bright, airy kitchen, Miranda taught Washington Grown host Kristi Gorenson how to make pinakbet, a traditional Filipino soup with veggies, pork belly, fermented shrimp paste, and garlic.

“It wouldn’t be a Filipino dish if there wasn’t garlic,” Miranda said, laughing.

Musang has a version of this dish on the menu, but it’s very different from the traditional version Miranda taught Gorenson to make while still retaining the flavors and essence of the original. When her aunts visited from Los Angeles recently, they remarked that they’d never seen pinakbet like this — but that it still tasted like pinakbet.

“I won’t be able to mimic my mom or my grandma, but what I can do is at least try to trigger a memory of nostalgia for them,” she said. “Whenever my parents or grandparents come, it’s always like, I hope they like it!”

When the soup is ready, she takes a bite and smiles. “I think my grandma would be proud.”

James Beard-nominated chef Melissa Miranda is giving Beacon Hill a taste of elevated Filipino home cooking.

1 tablespoon canola oil

• 1 onion, peeled and chopped

• 2 cloves garlic, peeled and minced

• 1 tablespoon shrimp paste

• 2 Roma tomatoes, chopped

• 2 cups water

• 3 cups calabaza squash, peeled and cut into 1-inch cubes

8 okra, ends trimmed

• ½ bunch chinese long beans, ends trimmed and cut into 3-inch lengths

• 1 large eggplant, ends trimmed and cut into 1-inch cubes

• salt and pepper to taste

Pinakbet is a Filipino stew that usually showcases hearty vegetables, and like most stews, you can usually throw in just about whatever you have on hand. In this version, from Musang in Beacon Hill, the eggplant and okra balance each other nicely, and the shrimp paste, which can be found at most Asian grocery stores, packs a powerful punch of flavor. If you can't find calabaza, butternut squash or pumpkin make a nice substitute. Add the vegetables in the pot according to how long they cook: sturdier ones such as calabaza go in first, followed by eggplant and okra, which take less time to soften. This stew is best served with a bowl of steaming white rice.

In a soup pot or dutch oven, heat oil over medium heat. Add onions and garlic and cook, stirring regularly, until softened. Add tomatoes and cook, mashing with the back of a spoon, until they have softened and released juice.

Add shrimp paste and continue to cook, stirring occasionally, until it begins to brown.

Add water and squash and simmer for about 2 minutes or until almost tender.

Add long beans and continue to cook until tender-crisp. Add eggplant and okra. Continue to cook for about 4 to 5 minutes or until vegetables are tender yet crisp.

Season with salt and pepper to taste. Serve hot.

The salty, earthy flavors of the pinakbet pair really well with a bright Washington chardonnay like Canoe Ridge's Expedition Chardonnay Horse Heaven Hills.

At an open-air wet market in Vietnam’s Ho Chi Minh City, vendors line the streets, selling a rainbow of flowers and produce, fresh meat, and fish. As fast-moving mopeds weave in and out of traffic, Washington Grown hosts Kristi Gorenson and Tomás Guzmán stroll through the colorful stalls, stopping to admire rows of Asian-grown fruits like jackfruit, lychee, dragon fruit, and durian.

“It’s so fresh, so colorful,” says Gorenson. “So many, many items that I’ve never seen before!”

A few minutes later, Gorenson and Guzmán are delighted to come across a familiar sight amid the array of enticing yet unfamiliar produce: a bright, colorful display of Honeycrisp, Gala, and Golden Delicious apples.

In Vietnam, wet markets are the traditional way to shop for fresh food, and in Ho Chi Minh City, 11 fresh markets feature thousands of vendors that draw locals and tourists to sample the delicious, fresh food grown in Asia and imported from all over the world, including Washington.

In Vietnam, the most popular Washington-grown food is by far the apple, according to the Washington State Department of Agriculture, followed by dairy, wheat, seafood and fish, fresh sweet cherries, and frozen french fries. In 2023, the country spent $157 million on Washington-grown foods, and Vietnam was one of Washington’s top 10 countries for exports.

Washington apples are especially beloved by the locals for their sweetness, color, and crispness. One vendor that Washington Grown spoke with at the wet market said she eats a Washington apple every day, and another woman said apples and pears are especially popular to give as gifts for the Vietnamese new year, and also to decorate for the holiday.

But how does a Washington-grown apple even end up at a colorful, bustling, open-market stall in Ho Chi Minh City?

First, the apple is harvested at a Washington farm over 7,000 miles away, where it is sorted and packaged for shipping, then loaded onto a shipping container on a cargo ship headed to Vietnam. After the ship docks at a Vietnamese port like Cat Lai Port in Ho Chi Minh City, the containers of produce are unloaded and sent to distributors and wholesalers in Vietnam and across Asia, who sell to the market vendors. At these markets, customers can load their shopping bags with a crunchy, delicious taste of the Pacific Northwest.

In the heart of Ho Chi Minh City, as Guzmán takes in the display of apples from his home state, he begins to laugh.

“Here we are, so far from home across the globe, but look, there’s Washington state represented right there,” he says. “Home is always with us, no matter where we go.”

Whether they know it or not, Mexican beer lovers have a lot to thank Washington for. In 2023, according to the Washington State Department of Agriculture, Mexico imported $16 million worth of hops from Washington state, a 40% increase from the previous year. When Washington Grown visited Mexico City, we spoke with Luis Enrique de la Reguera, the owner of the brewery, Casa Cervecera Cru Cru, about his love for beer, brewing, and U.S. hops.

How did you get into brewing?

I used to be a product designer, and one day, I got a “How to Make Beer” kit, and I brewed my first kit just two months after I got married. And I said to my wife, “Okay, I’m going to quit” — and then we started the brewery.

What is special about your brewery?

For us, it’s really important to develop the Mexican

Marketing Director

Brandy Tucker

Editor-in-Chief

Kara Rowe

flavors. And if we are going to be involved in beer, we want to represent our country the best way we can.

What have you learned along the way?

At the beginning, we were excited about making beer. And now we’re excited about making good beer. And you can’t make good beer if you don’t have good ingredients. Not only hops, but barley and good water, good grist. But hops are really important in beer, especially in the styles that are growing here in Mexico.

Why are U.S. and Washington hops so important for Mexican beer?

The hops from the U.S., they're a really big part of the Mexican beer industry. We’re going behind the freshness of the aromas and the citrus, and you can only get that with hops from the States. I truly believe that the hop is the future of beer here in Mexico.

The Washington Grown project is made possible by the Washington State Department of Agriculture and the USDA Specialty Crop Block Grant program, through a partnership with the state's farmers.

Assistant Editors

Trista Crossley

Elissa Sweet

Writers Jon Schuler

Editor and Art Designer

Jon Schuler

Elissa Sweet

Images

Tomás Guzmán

Jon Schuler

Kait Thornton

Musang

Shutterstock

Washington Grown

Executive Producers

Kara Rowe

David Tanner

Chris Voigt

Producer

Ian Loe

Hosts

Kristi Gorenson

Tomás Guzmán

Val Thomas-Matson