weathering change the

The Washington State Climate Office has a hefty job. Like all state climatologists, the scientists who work in Washington analyze trends and provide information about the past, present, and future of the state’s climate. But in Washington, each region has such a large variation in weather, temperatures, and rainfall that statewide generalizations are nearly impossible.

“One size does not fit all from a climate perspective,” says Nick Bond, who worked as the Washington state climatologist from 2010 until last year, when Guillaume Mauger moved into the role. “The state has 10 different climate zones, and because of the diversity of the climate in the state, when we talk about what might be going on in the vicinity of the Olympic Mountains, that applies very little to, say, the TriCities area.”

For example, the availability of water varies greatly among the microclimates: areas of the Olympic Mountains can get up to 150 inches of precipitation a year, while parts of Eastern Washington get only 7-9 inches. Climatologists like Bond look at large-scale, widespread data for a region and refine it to a local scale, factoring in each zone’s specific climate. This provides people like farmers or utility workers with specific information about droughts, flooding, and temperature expectations so they can plan ahead.

Bond has always loved the weather. Growing up in the 1970s, he lived through both a major drought and subsequent flooding in California, which piqued his interest in weather and climate systems. After studying physics as an undergrad, he decided to pursue a Ph.D. in his passion from the University of Washington, where he went on to teach in the Department of Atmospheric Sciences before becoming the state climatologist.

In his time at the climate office, Bond says he could see the effects of climate change within the state, especially when it comes to increased temperatures and water availability. For example, in the mountains, there tends to

be more precipitation in the form of rain, with less snow. The mountain snow is important, because it accumulates in winter and melts in the spring, feeding into rivers and reservoirs in lower elevations and providing water for things like hydropower, irrigation, and drinking. Less snow runoff can be attributed to higher winter temperatures and, in some years, earlier snowmelt in spring, which leaves less water to sustain the region through the dry summer season.

“Certainly in the Yakima Valley — which has very high-value crops, such as vineyards and hops and orchards and so forth — the irrigation districts rely upon the snowpack,” says Bond, adding that the region’s reservoirs were also lower this winter than in the past, in part a “hangover” from last year’s water shortages. Because this water is needed for so many things, groups need to work together to allocate the water supply.

“There are a lot of folks that have overlapping but not identical interests and needs,” says Bond, adding that he’s been encouraged by how those groups that once had a more adversarial relationship have been able to work together in recent years. “This collective working together is going to be necessary to be able to deal best with the issues we face.”

And the climate office’s role in this, Bond says, is to give better information on what’s coming in the next month, the next season, and even further ahead, which will help people make decisions during times when water isn’t as plentiful.

“If irrigation districts know there’s going to be less water, they can inform their agricultural interests, and maybe this is the year they leave some of their land fallow,” he says. “Or if you have water rights, maybe it’s a year in which you can sell some of that water to other users who really need it.”

Bond said rising temperatures will also impact the region, causing some crops to be unable to grow and even allowing new pests or molds to thrive that currently cannot survive the Washington winters. Strangely, however, while there are clear drawbacks to warmer temperatures, he said there could also be some short-term benefits for Washington farmers, including longer growing seasons.

“If you grow alfalfa and you get an extra cutting, what’s not to like about that?” he says. “And for certain other crops, maybe the harvest can be accomplished before early frost in the fall damages the crops.”

In addition, the country might need to rely more on Washington produce as other regions become too warm to grow their current staples. For example, he says wine grapes need cool nighttime temperatures to develop the acids that give them flavor, and if temperatures in California continue to rise, there could be declines in quality, and Washington farmers would need to fill the gap. Peaches are another good example.

“They need a winter dormancy — cold enough temperatures — for the tree to go through its cycle and flower properly and have fruit,” he says. “And as temperatures rise, there is evidence that some growing areas aren’t going to be as suitable anymore, and perhaps Washington state is going to be more valuable and able to pick up the slack.”

In general, Bond says we should recognize that there will be continued shifts as climate change progresses, but it’s also important to remember that people are working to counter this on a global, national, and statewide level.

“The climate is changing and will continue to change, but we’re not sticking our heads in the sand,” he says. “Through being mindful about it and continuing the work that’s in progress right now, we’ll be able to better adapt to those changes that are occurring. We’re not giving up, and we shouldn’t.”

As for Bond, his career might be slowing down, but his love for climate science hasn’t dwindled. While he doesn’t miss the administrative aspects of his job at the climate office, he loves the research and services he provided in the role, and he said he’s still involved with climate research in the state.

“It’s been really rewarding to see the interest in what the state climate office is providing,” he says. “I just feel fortunate that I found a niche for something that obviously has a lot of interest and importance across the spectrum.”

Find more great stories at wagrown.com

"Their family came to Red Mountain on a coin flip. But their success here has nothing to do with chance."

Read more at wagrown.com

Watch the show online or on your local station

KSPS (Spokane)

"Her parents were farmworkers. Now she owns the farm."

Read more at wagrown.com

"We've got a responsibility to take care of it for future generations."

Read more at wagrown.com

Mondays at 7:00 pm and Saturdays at 4:30 pm ksps.org/schedule/

KWSU (Pullman) Fridays at 6:00 pm nwpb.org/tv–schedules/

KTNW (Richland) Saturdays at 1:00 pm nwpb.org/tv–schedules

KBTC (Seattle/Tacoma) Saturdays at 6:30 am and 3:00 pm kbtc.org/tv–schedule/

KIMA (Yakima)/KEPR (Pasco)/KLEW (Lewiston)

Saturdays at 5:00 pm kimatv.com/station/schedule / keprtv.com/station/schedule klewtv.com/station/schedule

KIRO (Seattle)

Saturdays at 7:30 am and Mondays at 2:30 pm or livestream Saturdays at 2:30 pm on kiro7.com kiro7.com/video

NCW Life Channel (Wenatchee)

Check local listings ncwlife.com

RFD–TV

Thursdays at 12:30 pm and Fridays at 9:00 pm (Pacific) rfdtv.com/

*Times/schedules subject to change based upon network schedule. Check station programming to confirm air times.

Some of the most versatile ingredients in the produce aisle are also some of the most interesting to cultivate.

There’s nothing quite like foraging through one of Washington’s many forests and stumbling across a treasure trove of wild mushrooms. Like a video game come to life, you can simply clamber over stumps and mossy patches to gather morels, chanterelles, and cauliflower mushrooms. It’s a favorite pastime for many Washingtonians for good reason — it’s great entertainment, and you get to head home with a bag of free food!

Washington residents have been finding mushrooms in the woods since time immemorial, but it’s only within the last century that farmers have begun farming them commercially. Though Washington is a hotspot for growing all sorts of plants, mushrooms have been slower to take root commercially — because technically, they’re not a plant at all.

Mushrooms are fascinating organisms that stand apart from plants and animals. They belong to the kingdom of fungi and have a unique way of thriving that sets them apart from other life forms. Unlike plants, which depend on sunlight to perform

photosynthesis, mushrooms absorb nutrients by decomposing organic matter. This process allows them to flourish in environments where sunlight is scarce, often thriving in dark, damp conditions. Their cell walls, composed of chitin — a material also found in the exoskeletons of insects — give mushrooms a distinctive texture and resilience.

Many people don’t realize that a mushroom is only one piece of the larger fungal life cycle. The main body of the organism is known as mycelium, which starts as a spore (which is comparable to a seed, but each mushroom produces tens of thousands of them) and grows in multiple directions as it seeks food to digest. Mycelium is to a mushroom what a vine is to a grape. Just as any good tomato grower knows that they need to grow healthy plants to produce beautiful tomatoes, likewise, a mushroom farmer must cultivate a healthy mycelium first and then create a favorable environment for mushrooms to fruit. When the environmental conditions are right, mycelium will form mushrooms.

Washington state is an ideal setting for the

cultivation of mushrooms, thanks to its climate and abundant resources. The Pacific Northwest is renowned for its mild temperatures and consistent rainfall, conditions that naturally create a humid environment perfect for mushroom growth. This natural moisture reduces the need for artificial humidification in commercial cultivation, making the production process more energy-efficient and sustainable. This mushroom-friendly climate is why the little things pop up all over, even where they’re not cultivated.

But what if they were cultivated? If mushrooms grow so easily here unattended, wouldn’t they grow even better under the watchful eye of a farmer? Well, yes — but the reality is complicated.

On one hand, Washington is a great place to grow mushrooms for a variety of reasons. In addition to the climate, the state's thriving forestry and agricultural sectors generate ample organic by-products, such as wood chips and straw, which serve as excellent substrates for mushroom cultivation. This synergy between agriculture and mushroom production not only makes economic sense but also promotes a circular, environmentally friendly approach to farming. Unlike many food crops, little or no land is needed to grow mushrooms. They could be grown in a closet or (as in the case of MarrowStone Mushrooms, featured on page 14) in the basement of a Seattle apartment.

But like any other farming, commercial mushroom cultivation is complex. The process begins with the preparation of a nutrient-rich substrate, which is often a small rectangular block of straw, sawdust, soybean hulls, or wheat bran. The block is sterilized to eliminate competing organisms, providing a safe haven for the mushroom mycelium. Once the substrate is inoculated with spores or mycelium, the controlled environment is maintained at optimal conditions until the mycelium fully colonizes the block. Later, subtle changes in temperature and humidity encourage the mycelium to form the mushrooms that are eventually harvested and brought to market. In Washington, producers carefully regulate temperature, humidity, and ventilation in indoor facilities to create an ideal environment for yearround growth.

The Evergreen State is a fertile ground for mushroom production of all types. The combination of innovative agricultural practices and a commitment to sustainability supports a growing industry that is projected to grow by 10% in the next five years. New mushroom products are coming to the market all the time, and the future seems bright for commercial mushroom production. Whether you’re foraging for mushrooms in the wild or piling up blocks of substrate in your spare closet, there’s nothing quite like the earthy magic of mushrooms.

Most commercially cultivated mushrooms start with a "block" of substrate, often housed in a plastic bag, which turns white as it is colonized by mycelium. When the conditions are right, the growers cut holes in the bag and mushrooms emerge.

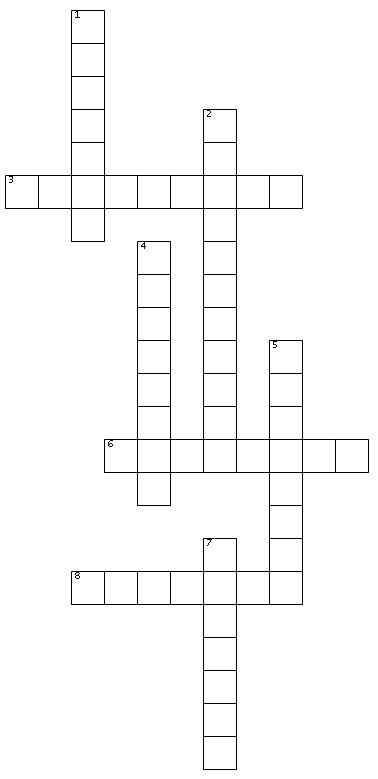

DOWN

1.The body part that Chef Ben Herreid says perfect dough should feel like

2.Bavarian-themed town in northern Washington

4.The root-like structure of a fungus

5.Mycelium establishing itself in an area

7.A small pasta envelope stuffed with meat or cheese

ACROSS

3.Nutrient-rich material in which mushrooms grow

6.The fruit that is created by mycelium and sold by growers like MarrowStone and Chesed Farms

8.The prevailing weather conditions in an area

ENTER TO WIN!

Sign up to be entered into a drawing for a $25 gift certificate to Larch in Leavenworth!

*Limit one entry per household

DID YOU KNOW?

Mushrooms are, in fact, the largest living thing on earth. There’s a type of honey fungus (the Armillaria solidipes) that spans 3.8km across the Blue Mountains in Oregon. Mostly underground, this tree-killing mushroom is a pretty humongous fungus.

or sign up at www.wagrown.com/wa–grown–magazine

Ben Herreid, the head chef of Larch in Leavenworth, says there’s a simple trick he learned years ago to make the perfect homemade pasta.

“Feel your dough,” he tells Washington Grown host Kristi Gorenson in Season 12, “and if it feels like your earlobe, then it’s the right texture.”

Gorenson laughs. “That’s a great rule of thumb, or maybe...”

“Rule of ear?” Herreid finishes, laughing.

In the adorable Bavarian-style town of Leavenworth, whose food options are mostly associated with bratwurst, schnitzel, and beer, Larch’s pasta-heavy menu is reminiscent of a country a little south of the Alps — but the Italian-inspired menu attracts a crowd.

“Look at all the little restaurants on the outside, but go to Larch,” said one customer who was dining at the restaurant when Washington Grown visited. “That’s where you’re going to get the best food.”

Larch is the second restaurant opened by Herreid and Spencer Meline, and its farm-to-table menu specializes in homemade pasta, fresh seasonal produce, and local fish and meat.

“We really try to use the bounty of what’s seasonal and what’s local,” said Herreid. “All the Washington produce, all the Washington fish, and all of those things.”

Herreid describes his pasta dishes as Pacific Northwest infused, and he said that he’s always discovering new styles of pasta that he hasn’t made before.

“I'm sure the Italian grandmothers might be a little upset if they saw the ways we take pasta sometimes," he says with a laugh. "There are so many shapes and sizes, it feels pretty inexhaustible.”

In the restaurant, the customers can’t say enough good things about Herreid’s food — and the restaurant in general.

“Every time we come here, they deliver,” says one diner. “It not only looks amazing, it tastes amazing.”

She continues, “The customer service, the food, the ambience, it’s just top notch.”

In the kitchen, Herreid and Gorenson are making Herreid’s signature mushroom ravioli and roasted mushrooms, dishes he says have been “a through line in my entire career.

“I’ve had that in all the restaurants I’ve created — we’ve always featured mushrooms and the mushroom ravioli,” he says, then adds with a laugh, “There might be people marching out front if we didn’t have those on the menu when they came.”

Herreid teaches Gorenson how to pipe the mushroom filling into the dough, which is carefully laid out on a metal ravioli frame.

“You don’t want to overfill it, or they will pop,” he tells her. “Just pretend like you’re doing toothpaste on your toothbrush.”

They add a rolled-out sheet of dough on top and press the stack into little ravioli shapes, then get to work on the sauce, which includes cream, lots of fresh thyme, chicken broth, salt, pepper, and nutmeg.

When the dish is finished, they both take a taste.

“It’s a nice subtle thyme flavor in the background,” Herreid says, “and it pairs really well with mushrooms.”

As he begins prepping the second mushroom dish, which is cooked with butter, salt, and pepper, then drizzled with honey before roasting, Herreid tells Gorenson that the mushrooms grown in Washington are some of the best you’ll find anywhere.

“We’re definitely all about the mushrooms,” he says. “We’re a bunch of real fungis.”