High schoolers in Connell drive tractors to school

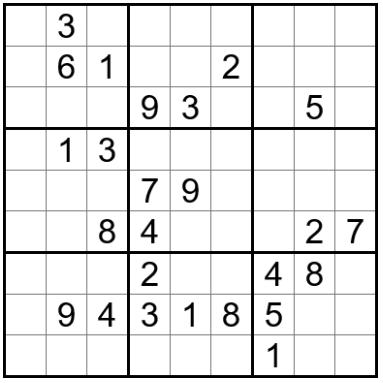

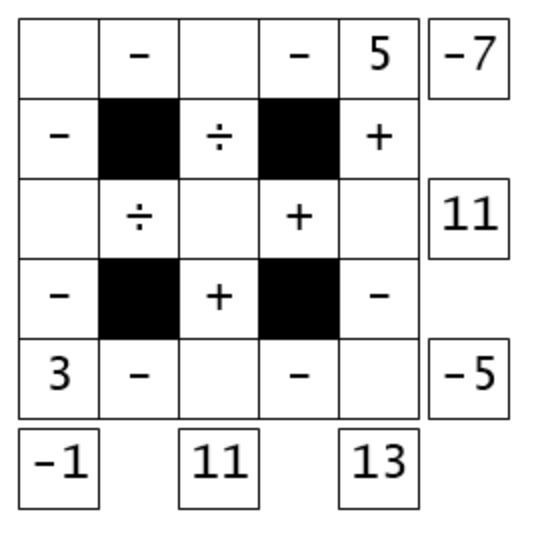

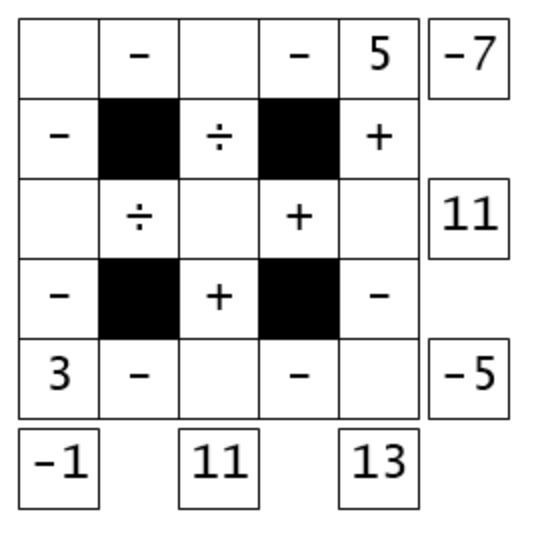

Mint Progressive Indian is delicious and beautiful Games and puzzles related to this issue

magazine

DELICIOUS BEEF SHORT RIB RECIPE INSIDE

WORLD-TRAVELING magazine

From the dirt to the dinner plate

Washington's Potatoes INCREDIBLE

2 WASHINGTON GROWN MAGAZINE MAY 2024

All heroes must go on a great journey.

EVERYONE LOVES A GOOD “HUMBLE BEGINNINGS” STORY. No matter what culture or part of the world you find yourself in, people are drawn to stories like Jeff Bezos starting Amazon out of a garage, or JK Rowling writing the outline of “Harry Potter” on a napkin in a London diner.

But what about the humble beginnings of Washington’s potatoes? Sure, we all see potatoes in their most glamorous forms, cut into salty french fries or crisp potato chips. But how do they reach our lunch trays or dinner tables after being grown underground?

The early life of a potato is quite dark and dirty — literally. The rich soils of the Columbia Basin and Skagit Valley in Washington make for a fertile and productive potato industry, but when those potatoes are harvested each summer, it is the first time they ever see the light of day. Potato harvesters lift the potatoes from the ground and move the crop (along with lots of extra soil) onto a series of webs where the loose soil is sieved out. The potatoes are then carried on a conveyor belt to a side elevator and into a trailer pulled behind a semitruck.

Their journey has just begun.

These trucks carry tons of potatoes in bulk to their next destination: the storage facility. Washington’s temperate climate offers ideal conditions for longterm storage, with facilities equipped with advanced temperature and humidity-control systems. Potatoes are stored in ventilated warehouses or specialized storage units, where conditions mimic the cool, dark environment of their underground origins. This careful storage ensures that Washington's potatoes remain crisp and flavorful, and it also allows for the potato harvest to last the whole year. Customer demand for potato products is consistent all year, so it’s critical to be able to store potatoes after the summer harvest until, say, January.

Around 90% of Washington potatoes are processed, mostly within the state. The potatoes are mainly processed into frozen french fries, with many going to overseas markets. Japan, South Korea, and Mexico purchase approximately 70% of the french fries made from exported Washington potatoes every year, generating around $969 million.

Processing plants in Washington use state-of-the-art technology to peel, slice, dice, and package potatoes according to customer specifications. Each processor is a bit different, but the broad strokes are the same: After potatoes have been cleaned and peeled, they are

then sliced and blanched in boiling water. After drying, they are then fried in oil, which partially cooks them and gives them their golden color. Finally, after cooling and drying, the fries are flash frozen and packed.

The processed potatoes are then packaged and prepared for export to destinations around the world. Washington's strategic location on the West Coast provides easy access to major ports, facilitating efficient export operations. Potatoes are loaded onto cargo ships or transported via rail to reach global markets in Asia, Europe, and beyond. Each shipment represents not only the culmination of months of meticulous cultivation and processing but also the embodiment of Washington's commitment to quality and excellence in agriculture.

The journey of a potato from harvest to global export is a testament to the ingenuity and dedication of Washington state's agricultural industry. From the fields to the ports, every step of this journey is meticulously planned and executed to ensure that Washington's potatoes reach consumers worldwide in optimal condition. As these humble tubers traverse continents and cross oceans, they carry with them the rich flavors and traditions of the Pacific Northwest, making Washington synonymous with quality potatoes on the global stage.

4 WASHINGTON GROWN MAGAZINE MAY 2024

Find more great stories at wagrown.com

"Their family came to Red Mountain on a coin flip. But their success here has nothing to do with chance."

Read more at wagrown.com

"Her parents were farmworkers. Now she owns the farm."

Read more at wagrown.com

Watch the show online or on your local station

KSPS (Spokane)

Mondays at 7:00 pm and Saturdays at 4:30 pm ksps.org/schedule/

"We've got a responsibility to take care of it for future generations."

Read more at wagrown.com

KWSU (Pullman) Fridays at 6:00 pm nwpb.org/tv-schedules/

KTNW (Richland) Saturdays at 1:00 pm nwpb.org/tv-schedules

KBTC (Seattle/Tacoma)

Saturdays at 6:30 am and 3:00 pm kbtc.org/tv-schedule/

KIMA (Yakima)/KEPR (Pasco)/KLEW (Lewiston)

Saturdays at 5:00 pm kimatv.com/station/schedule / keprtv.com/station/schedule klewtv.com/station/schedule

KIRO (Seattle)

Saturdays at 7:30 am and Mondays at 2:30 pm or livestream Saturdays at 2:30 pm on kiro7.com kiro7.com

NCW Life Channel (Wenatchee)

Check local listings ncwlife.com

RFD-TV

Thursdays at 12:30 pm and Fridays at 9:00 pm (Pacific) rfdtv.com/

*Times/schedules subject to change based upon network schedule. Check station programming to confirm air times.

WASHINGTON GROWN MAGAZINE MAY 2024 5 wagrown.com @wagrowntv

Brother's

For the Christensens, growing "Tatoes" is a family affair. Keeper

6 WASHINGTON GROWN MAGAZINE MAY 2024

DAMON CHRISTENSEN WALKED THROUGH a potato field at Del Christensen and Sons in the Columbia River Basin, bending down to inspect a tangle of brown, dried-up potato vines. Despite the sound of dead plants crunching underfoot and the sight of brown as far as the eye can see, Christensen said these fields are very much still alive and healthy under the soil.

“We do what we call top-kill desiccation — it just takes out what’s green on top and leaves it like this,” he said, adding that it makes harvesting the potatoes much easier. He unearthed a huge, beautiful Russet Norkotah potato from the soil, a variety he said is known for their nice, blocky shape.

DEL CHRISTENSEN AND SONS MATTAWA

“That’s something I would grab in a grocery store,” he said, brushing off the dirt and admiring the tuber.

Christensen and his brothers Dean, Alex, Dallon, and Dexter, along with their parents, Del and Daneen, own and operate Del Christensen and Sons in Mattawa, which is known for its Tatoes brand of potatoes and onions. The Christensen family has been farming in Washington since the 1950s, and although working with family can sometimes be hard, Christensen said it’s mostly a great experience.

“We have ups and downs, but I feel like between my brothers and I, we’re our own best friends,” he said.

Del Christensen and Sons grows, packs, and ships all their produce to ensure that the best products end up in stores. After the potatoes are harvested from the fields onto huge trucks, they are loaded onto a conveyor belt and into large storage bins inside a dark, cool warehouse facility. Darkness is crucial to keep the potatoes fresh, said Christensen, both at the warehouse and in the kitchen at home.

“As a potato receives light, it starts to green up,” he said. “In your home, keep them in a dark corner — cool dark is best.”

After the potatoes are washed and cleaned, they head to the mechanical sizer, where cameras snap photos of each tuber zooming through at 50 miles an hour to determine whether it meets the size criteria.

“It gives a green light on the size to hit these little bumpers down here,” Christensen said, pointing down at a complex system of cables and flaps that sorts potatoes into large bins.

Finally, the potatoes are packed into bags and boxes and taken to a cold room, where they will be staged to go out on trucks for delivery. And with that, the staff at

Del Christensen and Sons can finally say goodbye to the products of their hard work.

“This is the last thing I have to worry about,” Christensen said, smiling.

Overseeing every step from planting to shipping is a big job, but Christensen wouldn’t have it any other way.

“A good day is this — being out in the field,” he said. “I am not an office person, so the more I’m outside, the happier I am. … It’s very fulfilling to put something in the dirt and watch it grow, then turn around and pull it out of the dirt in the end.”

8 WASHINGTON GROWN MAGAZINE MAY 2024

While the harvesters work the fields, Damon Christensen (below left) and Washington Grown host Val Thomas-Matson inspect the harvested potatoes in the warehouse outside Mattawa.

Did you know that a passive-aggressive chef accidentally invented the potato chip? IN 1853, chef George Crum was head of the kitchen at Cary Moon’s Lake House in Saratoga, New York, a place where railroad mogul Cornelius Vanderbilt liked to dine. Vanderbilt wasn’t a fan of the thickcut potatoes on his plate, so one day he sent them back to the kitchen, a move that annoyed Crum.

ENTER TO WIN!

Sign up to be entered into a drawing for a $25 gift certificate to Mint Progressive Indian!

*Limit one entry per household

or sign up at www.wagrown.com/wa-grown-magazine

In retaliation, Crum sliced the spuds as thinly as he could, fried them in oil with some salt, and turned them into crispy potatoes, thinking he would make Vanderbilt angry. Instead, Vanderbilt loved them, and the chef’s revenge turned out to be the genesis of one of America’s most popular snack foods.

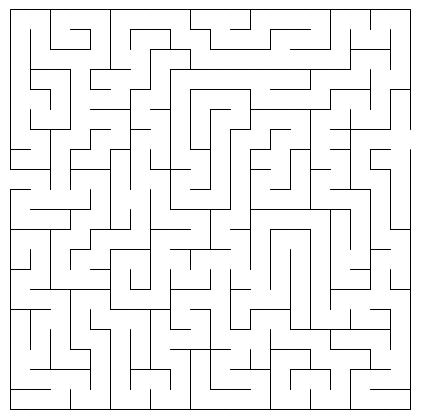

START FINISH

DID YOU KNOW?

FOOD IS ART AT MINT PROGRESSIVE INDIAN

10 WASHINGTON GROWN MAGAZINE MAY 2024

What happens when traditional Indian food meets local Northwest ingredients, in the hands of an artist? Magic.

At Mint Progressive Indian in downtown Seattle, executive chef Abhijit Sarkar puts the finishing touches on a plate of beef short rib mappas, arranging fresh micro-turnips atop artfully arranged carrots and purple potatoes seared in butter. He adds dots of local blueberry chutney on a steaming short rib and gently pours creamy coconut milk sauce over everything.

Sarkar said he’d gone to Pike Place Market earlier to purchase the produce, which was grown on farms here in Washington.

“In Washington especially, the berries are very famous,” he said.

The restaurant focuses on combining traditional Indian flavors with Pacific Northwest ingredients to create food and drinks that are original and yet familiar.

One customer summed it up well: “They take traditional dishes, and they kind of add their own twist to it.”

A recent menu’s offerings included tandoori lobster benedict, Dungeness crab kulcha flatbread, and paneer rosettes with blueberry chutney and microgreens. Many of the ingredients come directly from Washington.

“We use a lot of local ingredients like purple potatoes, apples, berries,” said Goldy Singh, Mint’s CEO. “It’s a very big aspect of our food here, where we try to incorporate all those local ingredients into our menu.”

Including local ingredients is a large focus of progressive Indian cooking in general, according to Sarkar. And Singh said the progressive Indian cooking style is about creating food that is

MINT PROGRESSIVE INDIAN SEATTLE

approachable and appealing to a wider audience, even those who are not familiar with Indian food.

“We try to showcase that in more modern and inclusive ways to bring new people to this sort of cuisine,” Singh said. “Food is art.”

One customer in the dining room said that while the food feels very Indian, it’s not the same as the food you’d eat in India.

“It has all the flavors you would have in India, just combined together,” she said.

The restaurant also features an innovative craft cocktail menu that incorporates Indian spices and ingredients in its recipes. A few of the drinks on a recent menu included a smoked old fashioned with black walnut bitters and chai; a cardamominfused gin cocktail; and a martini with white tea and jasmine.

“Our bar team works very closely with the kitchen team,” said Singh. “So all those cocktails pair really well with everything that’s on our menu.”

Before becoming the executive chef at Mint, Sarkar worked in New Delhi, where the movement of progressive Indian cooking began, said Singh, adding that Sarkar’s experience contributes to the art he makes in the kitchen.

“We’re excited to have him, and he’s great,” Singh said.

The customers cannot seem to get enough of Mint’s beautiful, innovative and delicious food.

“I would never have thought of this,” said one diner, pointing at his plate. “It’s not style over substance — it’s all here.”

WASHINGTON GROWN MAGAZINE MAY 2024 11

MINT

PROGRESSIVE INDIAN'S

Beef Short Rib Mappas

12 WASHINGTON GROWN MAGAZINE MAY 2024

• 4 beef short ribs

• 2 onions, chopped

• 3 tbsp chopped ginger

• 3 tbsp chopped garlic

INGREDIENTS

• 16 oz Coconut Milk

• 1 Tbsp red chili powder

• 2 Tbsp curry powder

• 2 Tbsp salt

• 4 medium purple potatoes, peeled and cubed

• 8-12 rainbow carrots, peeled

• 6 pieces micro turnips or baby turnips (optional)

• 8-10 curry leaves

• 1 tsp black pepper

• 8 oz neutral cooking oil

• 3 cups beef stock/broth

• 1 cup water

Complexity: Medium • Time: 4 hours • Serves: 4

This rich dish is a show-stopper at Mint Progressive Indian in Seattle! We’ve modified the recipe slightly to make it more accessible for home cooks - make sure to visit the restaurant to see what makes their version so special. When shopping for short ribs, look for a cut with lots of meat atop the bone. While you can serve the short rib on the bone, the chefs at Mint Progressive Indian separate the meat from the bone and serve it boneless.

Mix salt, curry powder, red chili powder (or Paprika) and 3 Tbsp oil to make marinade. Coat the short ribs well. Cover and refrigerate at least 6 hours (preferably overnight).

Preheat the oven to 325 F.

In a dutch oven, add 2 Tbsp of oil and bring the pan up to high heat. Add the ribs and sear aggressively all over (around 5 - 7 min in total).

Remove the ribs from the dutch oven and reduce to medium heat.

Add 2 tbsp oil. Add onion, garlic, ginger and curry leaves into the same pot and cook until onions soften (around 3-4 minutes). Stir occasionally with a wooden spoon, scraping the fond from the bottom of the pot.

Add the short ribs back to the pot in a single layer, meat side down. Add beef stock and water until meat is submerged.

Cover with lid and transfer to oven for 3 hours, or until the meat can easily be pried apart with forks.

Remove beef carefully, keeping the meat on the bone. Transfer the remaining liquid and vegetables to a blender and blend well. Then strain the liquid through a fine mesh sieve back into the pot and bring to medium heat.

Add coconut milk and reduce for 15 minutes to make the sauce.

In a separate pot, cover potatoes and carrots in water. Over high heat, bring to a boil and simmer for 8 minutes. Then drain water and lay out potatoes and carrots to dry.

Heat 1 tbsp oil in a pan over high heat, then sauté purple potatoes, carrots, and turnips for around 3 minutes, seasoning to taste with salt and black pepper.

Serve hot with rice (optional)

Driver's Ed

High school students in Connell are taking to the streets with an important message: pay attention to agriculture production.

Connell High School teacher Charlie Dansie poses with the school's FFA officers on "Drive Your Tractor to School Day".

It’s a gorgeous March morning in Connell, Washington. The sun still lays low on the horizon, sending long, orange-hued rays through the windows of the tractors lined up at Rob Davis’ house on the outskirts of town.

Cars drive by on State Route 260 just past the end of the driveway. Some pull into the school parking lot just down the road. Police cars sit at the intersection, casually watching morning traffic.

There are definitely cars in this town. So why are so many high school students driving tractors to school today?

At precisely 9:15, a few dozen high school students burst out of the shop behind the Davis’ house and began climbing into the assembled tractors, followed by one of their FFA advisors, Charlie Dansie.

“This is the best day of the year,” he says with a smile. “‘Drive Your Tractor to School Day’ is one of my favorite parts of living in Connell.”

The event began 7 years ago, about the same time Dansie arrived in Connell. He moved here, in part, to work with Heidi Shattuck; another ag teacher at Connell High School who is a legend in ag education. In 2019 she was inducted into the Mid-Columbia Agriculture Hall of Fame for her contributions in the classroom. When Dansie arrived in town, he thought that encouraging students to drive tractors to school, creating a parade of red and green machines, would serve as a helpful way to remind the community of just how important farming is - which would in turn result in more enrollment in the ag education programs at Connell High School.

“It’s just a fun event, a real celebration,” says Shattuck. “A lot of people think that since we’re a farming community that everyone knows about agriculture. But more and more families are further removed from the farms. It’s really important to bring awareness about where our food comes from.”

This year, as always, the festivities begin with a safety briefing. Though some of these students have been

since before they could walk, they are reminded about speed limits, when to yield, and how much space to leave between each tractor. They nod along dutifully, but they’re eager to be on with it.

Each year since it’s inception, the line of tractors has paraded down Clark Street, past the high school, led by the school’s FFA officers. This year officers Hardy Shattuck, Anna Geddes, Adrian Kniveton, Aram Bonba, and Brandy Ferguson climb onto a trailer at the front of the column and cheerfully call their fellow students to begin lining up.

“I mean, it’s such a huge thing for our community,” Kniveton says as the tractors roll by. “Especially the little kids, they’re so excited to see us driving past. I think it helps show that our community really loves our farmers.”

The giant machines pull out, one by one, onto the street and toward the school, where students have been let out of their first period classes to line the street and wave. Not only high school students, either -Connell Elementary teachers lead their classes of 7 and 8-year-olds out onto the lawn to cheer for the tractors driving by. Their little eyes go wide and huge smiles light up their faces. Inside the tractor cabs, 14 and 15-year-olds smile and wave back.

Of course everyone is smiling. It’s the best day of the year.

WASHINGTON GROWN MAGAZINE MAY 2024 15

Washington Grown ingredients... at a culinary school in Vietnam.

When culinary students in Vietnam use Washingtongrown ingredients to create original dishes, amazing things can happen. When the Washington Grown team visited the Huong Nghiep A Au culinary school in season 11, we were lucky enough to get to judge a student cooking competition focused on dishes made from Washington ingredients.

How did the contest work?

Before beginning the competition, chef and culinary instructor Cam Thien Long gave a cooking demonstration, creating a seafood dish using Washington ingredients including potatoes, apples, blueberries, flour, and pears. After the demonstration, the students formed teams and were given a short amount of time to create their own dishes using Washington ingredients, and the judges tasted each and voted on their favorite.

What were the judges’ reviews?

At the end of the competition, Long, along with hosts

Kristi Gorenson and Tomás Guzmán, tasted — and judged — 13 delicious dishes ranging from noodles and seafood to soups and desserts. “There’s some beautiful dishes here!” Guzmán remarked, gesturing to the counter covered with plates and bowls of food. Long agreed: “The plating is really nice.” After the judges had a chance to taste everything, the winners were announced and given prizes, but as Gorenson said, “The real winners were us judges. That was delicious!”

What will the culinary students do after graduation?

The school has nearly 30,000 students each year, who go on to work in hotels or restaurants in Vietnam or around the world, like the United States or Australia. One student said he came from a family with many generations of chefs, and he was excited to travel after he finished school. “I want to travel around the world, to explore many new ingredients,” he said. “And maybe I can mix it into Vietnamese cuisine and make some new dishes.”

The Washington Grown project is made possible by the Washington State Department of Agriculture and the USDA Specialty Crop Block Grant program, through a partnership with the state's farmers.

Marketing Director

Brandy Tucker

Editor-in-Chief

Kara Rowe

Editor and Art Designer

Jon Schuler

Assistant Editors

Trista Crossley

Elissa Sweet

Writers Jon Schuler

Elissa Sweet

Images

Jon Schuler

Mint Progressive Indian

Shutterstock

Washington Grown

Executive Producers

Kara Rowe

David Tanner

Chris Voigt

Producer

Ian Loe

Hosts

Kristi Gorenson

Tomás Guzmán

Val Thomas-Matson

Tomás

Guzmán