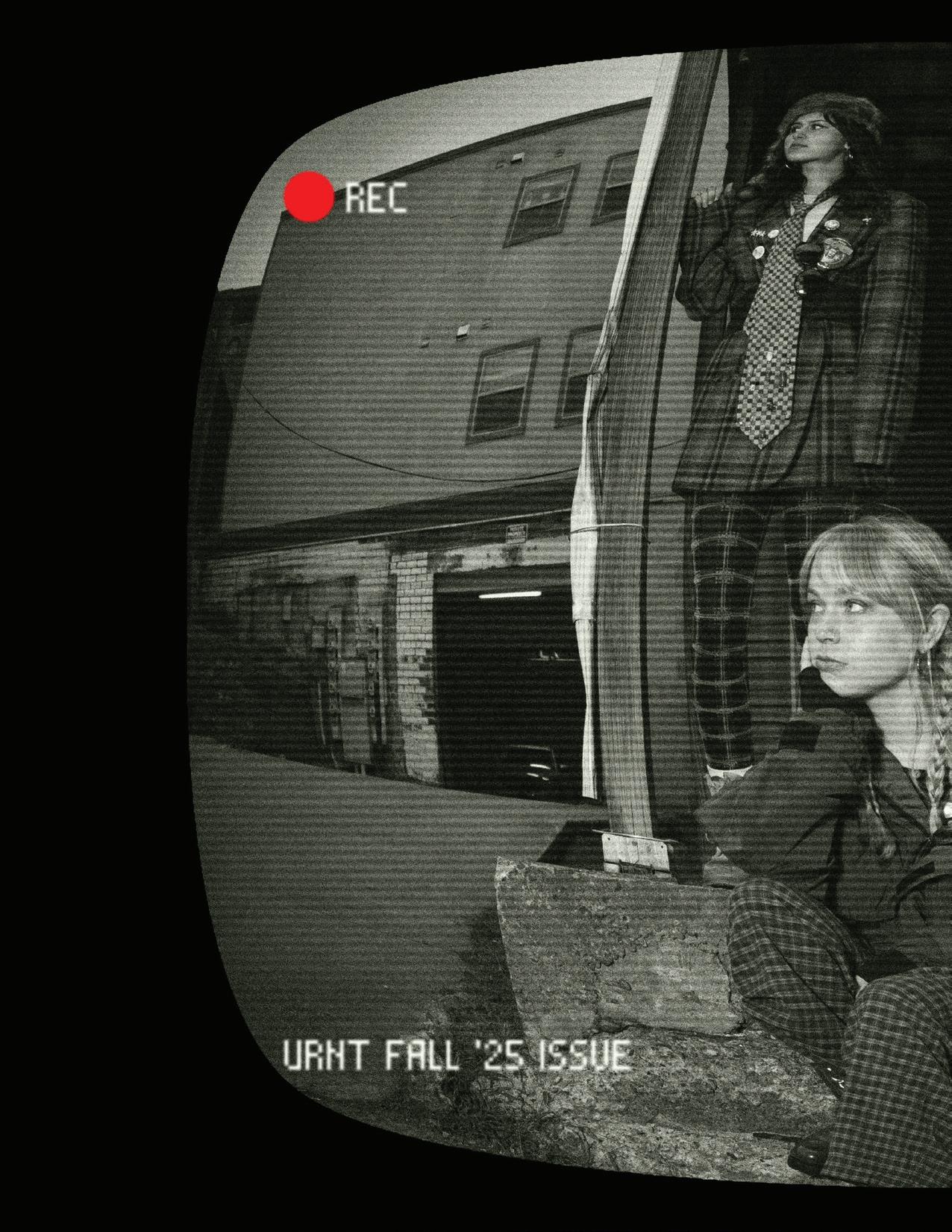

By Norah LeFlore Editor-in-Chief Variant Magazine

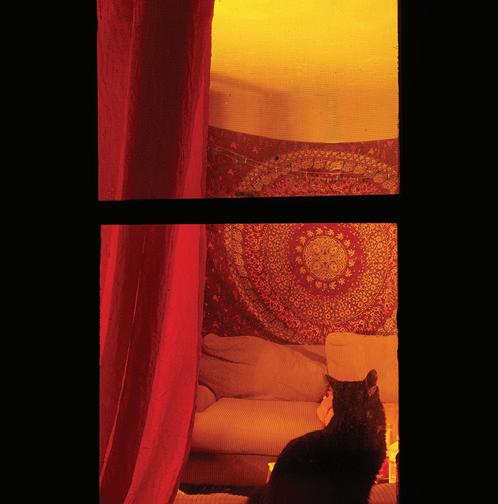

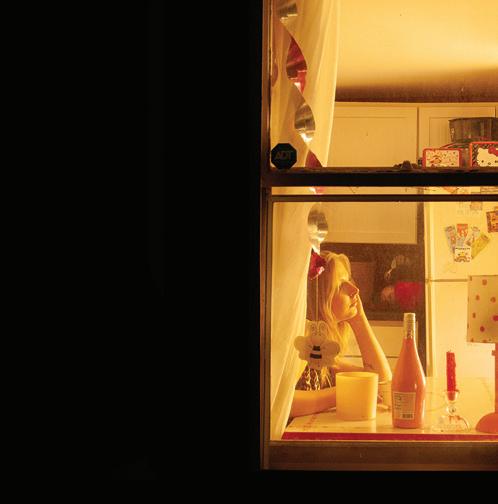

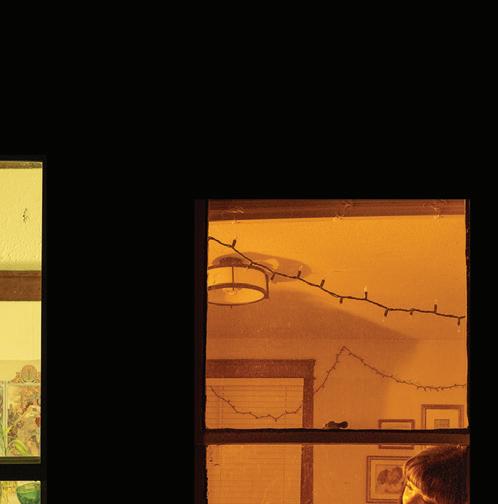

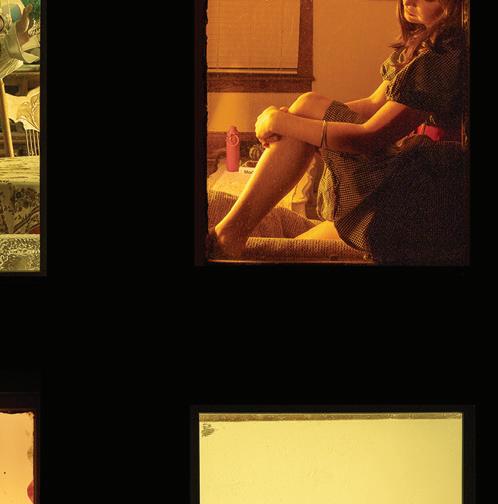

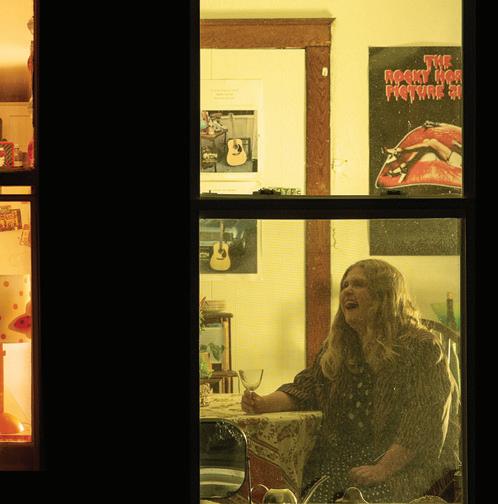

Welcome to Voyeur.

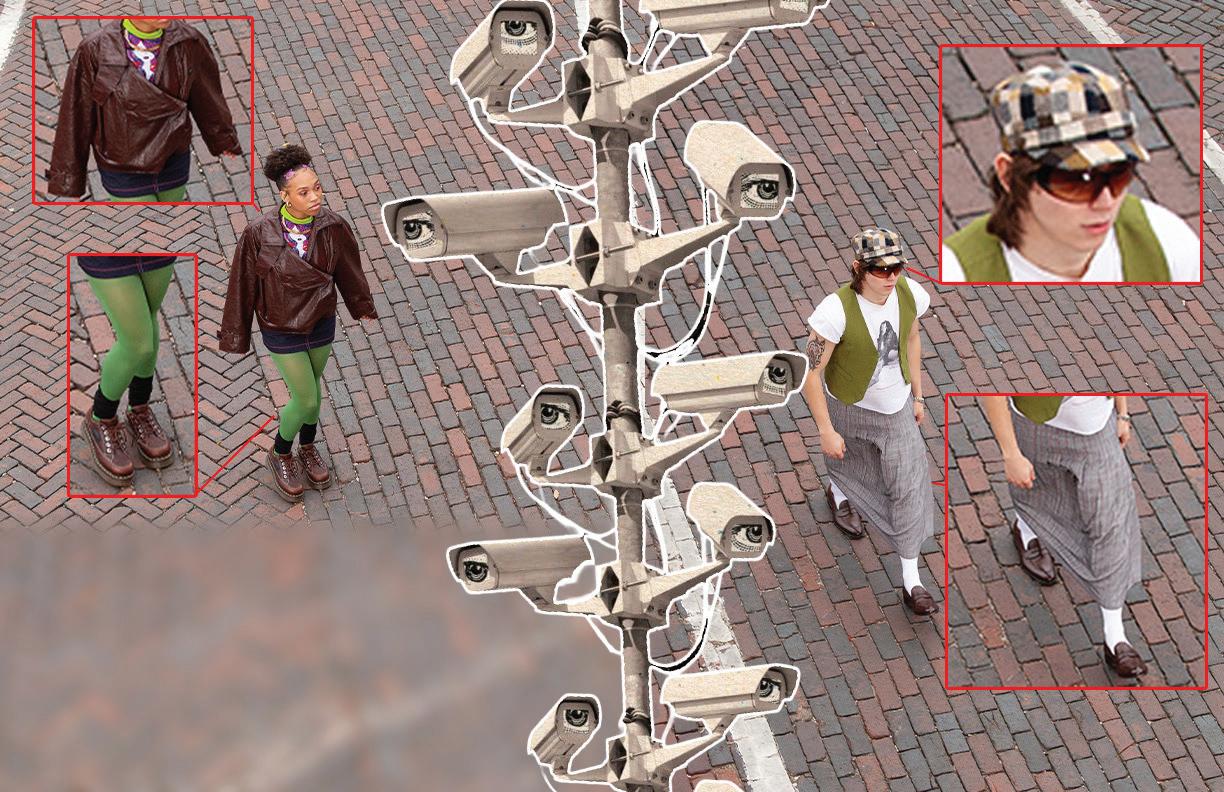

Variant’s fall 2025 issue examines what it means to look and be looked at in a world where visibility is constant, and intimacy feels both closer and further away. Today, our lives unfold in windows: screens, feeds, glances, and moments, captured and replayed. We peer into others’ lives for inspiration, validation, curiosity, desire, and sometimes simply to feel less alone.

But voyeurism isn’t just the act of watching; it’s the awareness of being watched. It’s the tension between vulnerability and performance; the askew balance of who we are privately and how we choose to show ourselves publicly. It’s the truth that our identities— sexual, creative, emotional—are shaped not only by how we see ourselves, but by how the world sees us.

To me, we are all voyeurs. We feel it in the way we move through spaces, build personas, share pieces of our lives, and guard others. It can be uncomfortable, liberating, empowering, or unsettling, but it’s undeniably human.

And as our Associate Editor Libby Evans puts it best: Where is the line between authenticity and loss of autonomy? We share our lives on social media. We share our art, our trauma, our beliefs, and we market our minds. Viewers want authenticity. They want to see your bedroom, your mundane tasks, visceral proof that you’re real. But are we being watched? Are we being supervised? Do we really have an individual government file, a digital footprint that can’t be washed away? We perform for hidden cameras and follow scripts tattooed across our eyes. Are we bystanders? Who is our Peeping Tom?

In these pages, we explore that complexity. We question the gaze, reclaim it, bend it, and let it reveal something honest.

Thank you for stepping inside.

Norah LeFlore Editor-in-Chief, Variant Magazine

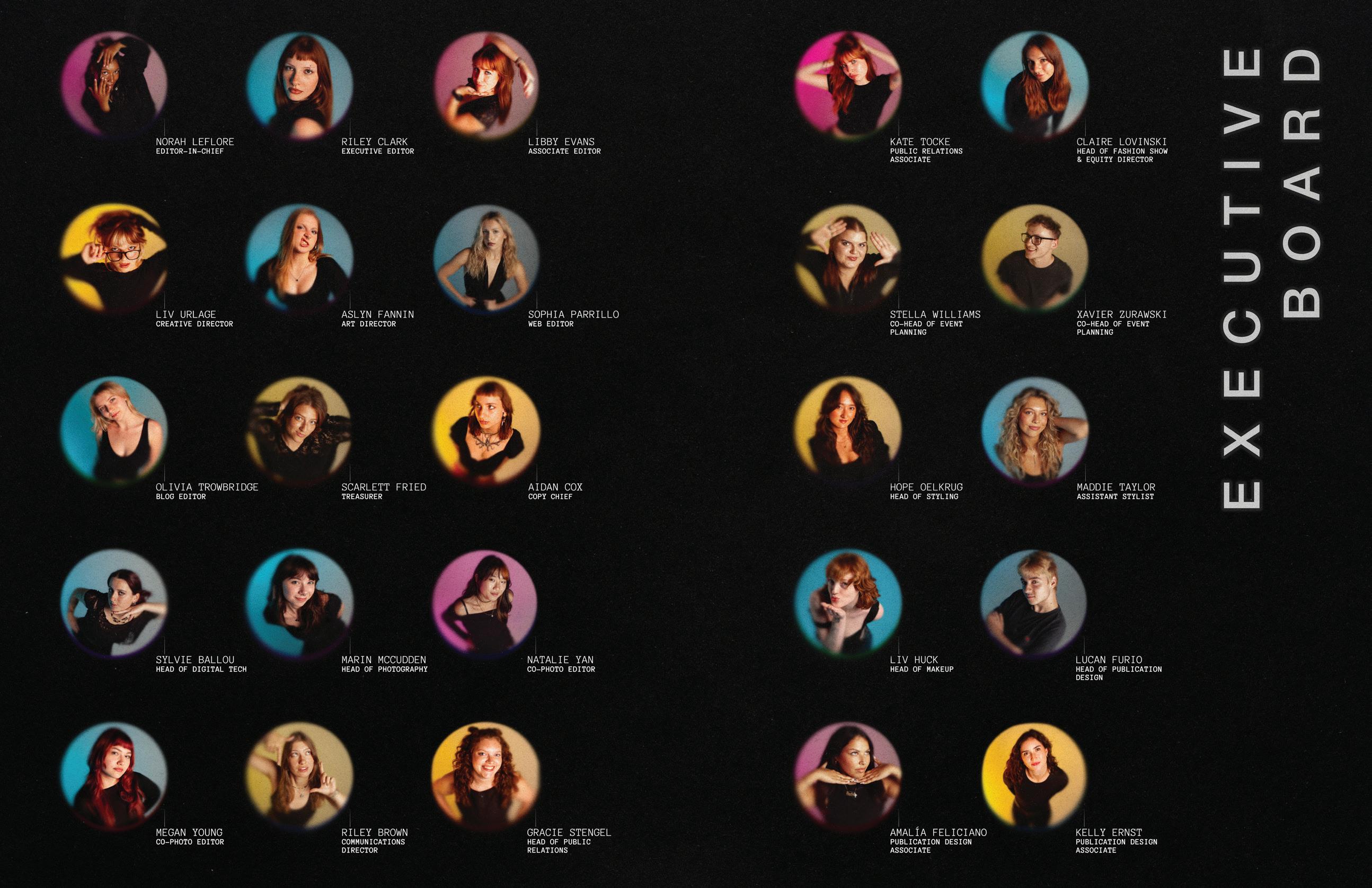

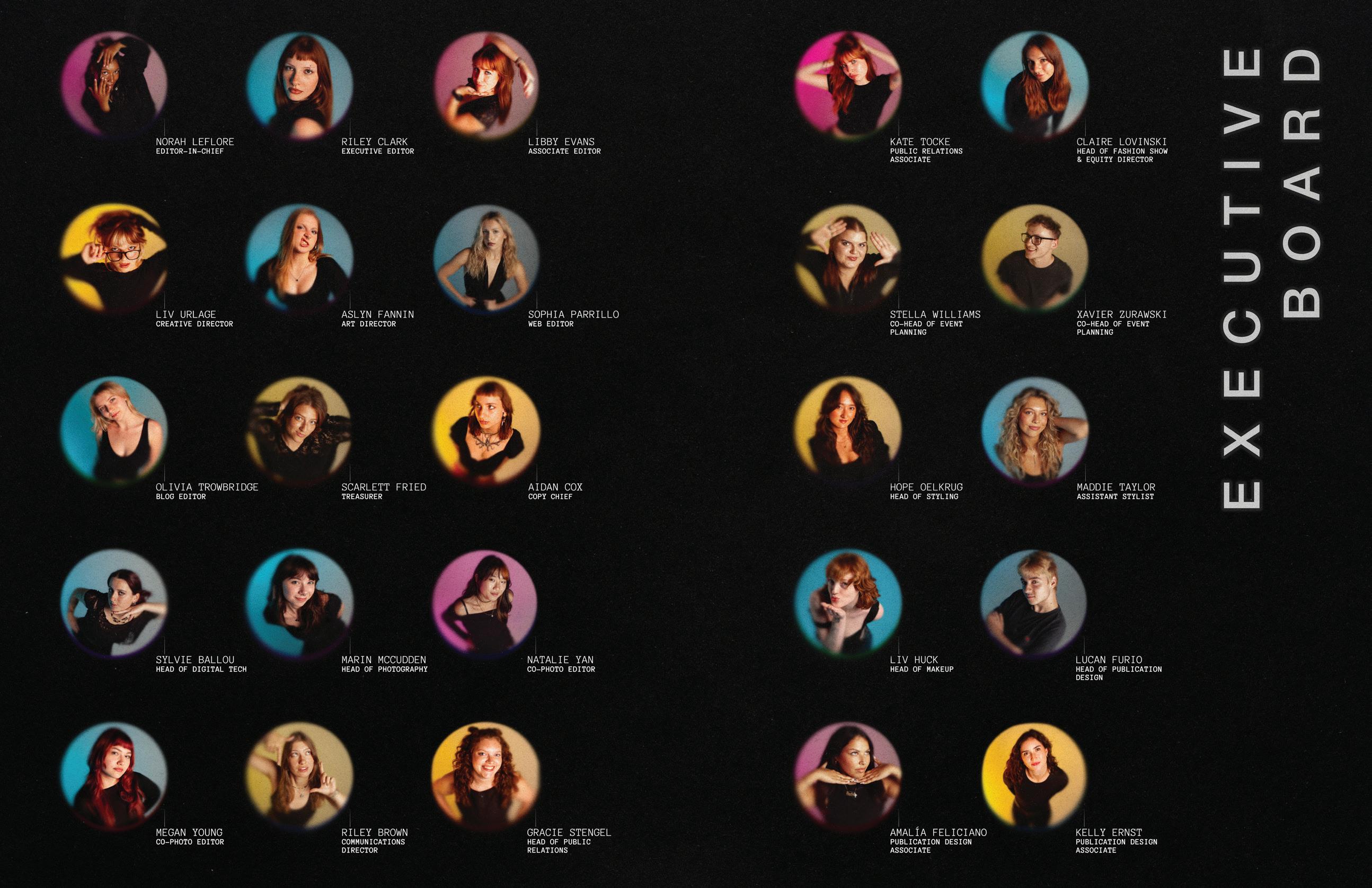

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

EXECUTIVE EDITOR

ASSOCIATE EDITOR

CREATIVE DIRECTOR NORAH LEFLORE

ART DIRECTOR ASLYN FANNIN

HEAD OF PHOTOGRAPHY MARIN MCCUDDEN

PHOTOGRAPHERS MADISON RIDGE, SARAH GORMLEY, ALLIE JONES, RYAN SCHEWIGER, MADELINE LYNCH, LUKE ALLEN, MEGAN YOUNG

PHOTO EDITORS NATALIE YAN, MEGAN YOUNG

WEB EDITOR SOPHIA PARRILLO

HEAD OF DIGITAL TECH SYLVIE BALLOU

PUBLICATION DESIGN DIRECTOR LUCAN FURIO

PUBLICATION DESIGN ASSOCIATES KELLY ERNST, AMALÍA FELICIANO

DESIGNERS EMILY ROESTI, EMMA HENRY, SYDNEY SAILING, HARLEE SHAE, MICAH KEIL, NADALIE PERDEW, OLIVIA SEIFERT LIV URLAGE

HEAD OF MAKEUP LIV HUCK

MAKEUP ARTISTS AND HAIR CLAIRE LOVINSKI, ADELINE PATCHEN, SA’NYA SUTTON, ANIYAH SPAULDING, AQUARIA ALBANO, COURTNEY MIERS, BROOKLYN BECKFORD, JENNA SKOK, EMMA SEYFANG

EQUITY DIRECTOR CLAIRE LOVINSKI

COMMUNICATIONS DIRECTOR RILEY BROWN

RILEY CLARK

LIBBY EVANS

LIV URLAGE

TREASURER SCARLETT FRIED

COPY CHIEF AIDAN COX

BLOG EDITOR OLIVIA TROWBRIDGE

WRITERS AIDAN COX, RILEY BROWN, RILEY CLARK, LIV URLAGE, NATALIE SCHNEIDER, ZION BUSH, JEN FOSNAUGHT, LIBBY EVANS

VIDEOGRAPHERS SOPHIE HINER, MEGAN YOUNG, ZION BUSH, PEARL HARRIS, RILEY CLARK

HEAD OF STYLING HOPE OELKRUG

ASSISTANT STYLIST MADDIE TAYLOR

STYLISTS CHLOE GATOO, HANNAH MOONEY, ANALYSSA TORRES, MARIKO COOPER, PAIGE FICKE, CRYSTAL FILLMAN, SARAH ZODY, RANIJINI SHANK, AQUARIA ALBANO, BRECKIN MILLER, JENNA SKOK, EMMA COOPER, BINDI JAAD STALEY, PAIGE CURRIER, IMALY FETTY, ANIYAH SPAULDING, CLAIRE LOVINSKI

CO-HEADS OF EVENT PLANNING STELLA WILLIAMS, XAVIER ZURAWSKI

HEAD OF PUBLIC RELATIONS GRACIE STENGEL

PUBLIC RELATIONS ASSOCIATE KATE TOCKE

PUBLIC RELATIONS BINDI JAAD STALEY, SALMA ZERHOUANE, RANJINI SHANK, EMMA SEYFANG, ANNA PARASSON, KALILA LIGHTLE

HEAD OF FASHION SHOW CLAIRE LOVINSKI

Emma Schroer, Jenna Skok, Riley Brown, Maybella Myers, Adaline Patchen, Gigi Twatchman, Emma Seyfang, Natalie Schneider, Jolana Hurtos, Blake Ament, Anna Parasson, Anaiyah Spaulding, Emma Henry, Sarah Zody, Claire Lovinski, Olivia Brinks, Adrienne Roselli, Tyah Williams, Linda Lacour, Hunter Gillespe, Sarah Goeke, Olivia Deacon, Molly Griffiths, Olivia Seifert, Crystal Fillman, Ada Sesay, Miya Moore, Jasmine Johnson, Imaly Fetty, Sophia Ives, Max Cartwright, Diego Buhay, Breckin Miller, Chloe Gatoo, Kyra Shy, Xavier Zurawski, Emma Prazer, Mckenna Rogers, Jacob Meshner, Camille Anders, Autumn Parham, Autumn Parham, Paige Ficke, Andre Hallenburg, Vincent Caplin, Luke Allen, Blue Williams, Victoria Robinson, Kendal Akers, Aidan Cox, Daniel Gorbett, Anna Scheider, Gretchen Sahr

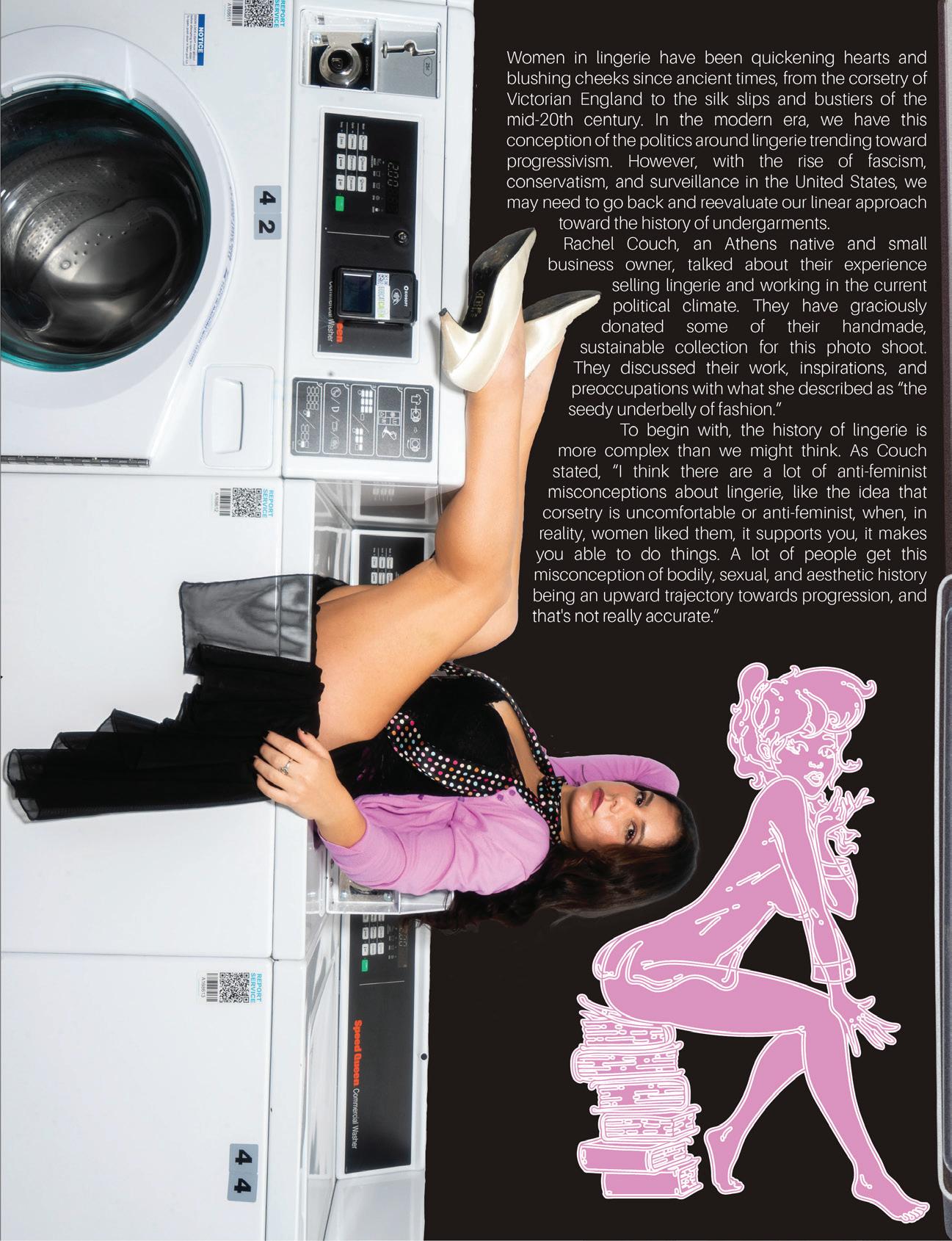

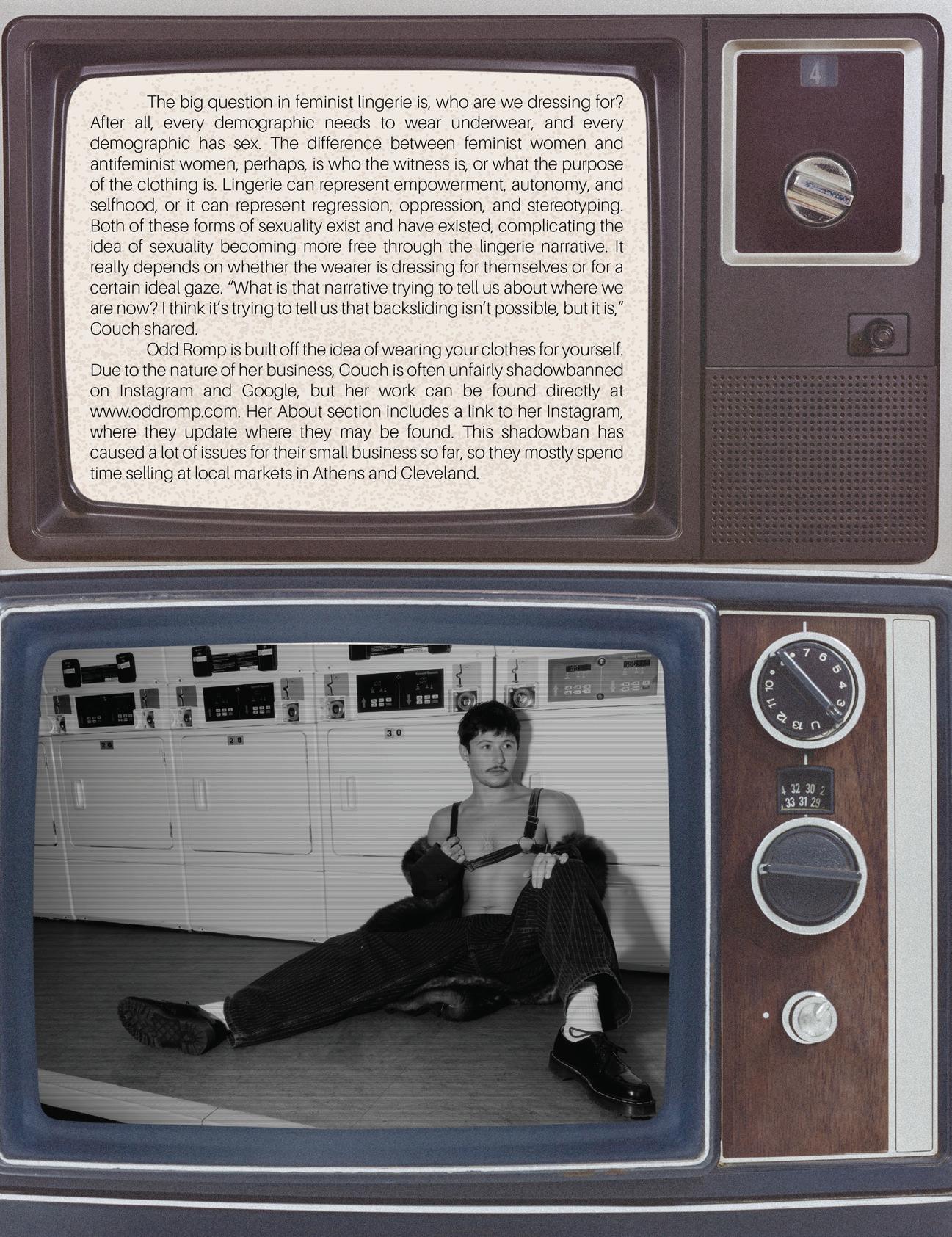

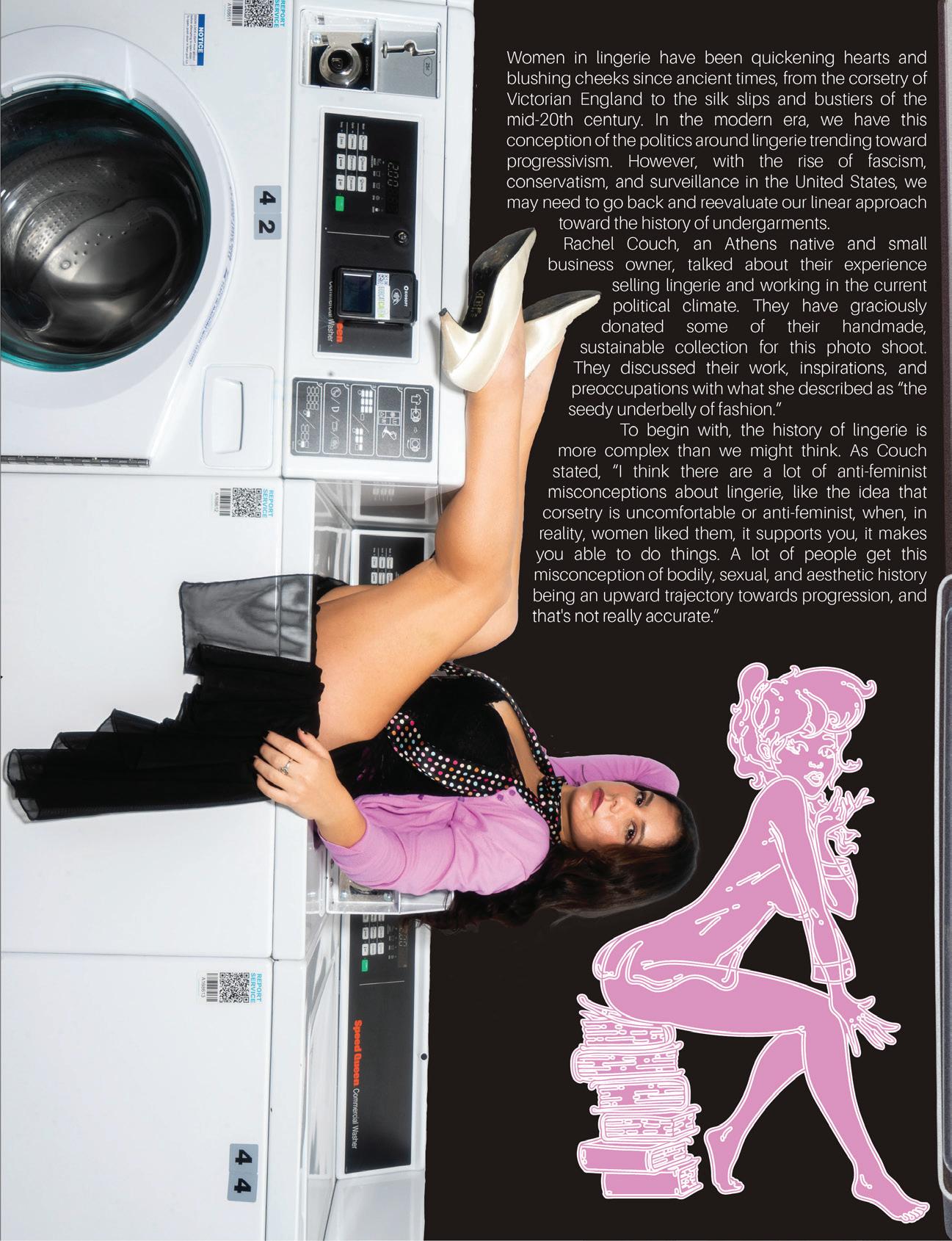

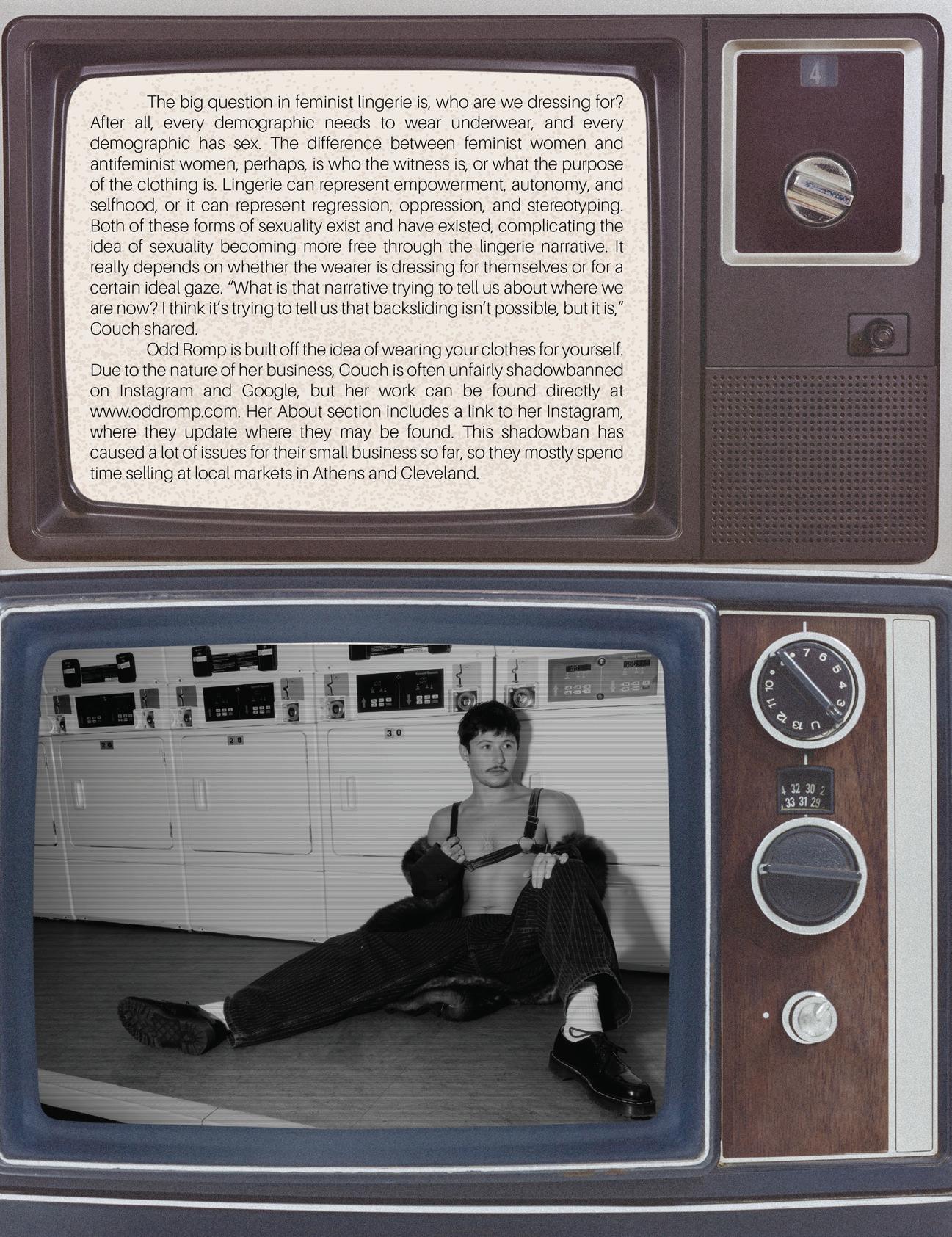

Couch explained her personal experience on how we now treat our bodies culturally: “I talked to my mom a lot about this, actually, because she was a teenager in the 70s,” Couch shared. “I like comparing her experience to when I was in high school, and she would often say that things were way more progressive for her aesthetically and sexually. I would honestly argue, even just in the time that I’ve been growing up, that lingerie and sexuality have become less progressive with the increase of surveillance and social media.” According to Gallup polls, in Generation Z, teens are twice as likely to identify as conservative compared to their parents 20 years ago. The majority of teenagers spend four hours or more on their phones as of 2023, inundated with images of perfect bodies, impossible lives, and echo-chambers that the algorithm sends them down. We are slowly shifting from living our lives to watching ourselves living our lives. This disembodied experience may be why 73% of Gen-Z report feeling loneliness consistently according to CNBC, and why our relationships are struggling as a result, with 86% of adults 18-24

remaining unpartnered despite constant access to dating apps, according to the Pew Research Center. Even when people are more willing to wear lingerie out in public settings or to certain events, they are still scared of being filmed, watched, or examined under the lens of anyone’s personal camera.

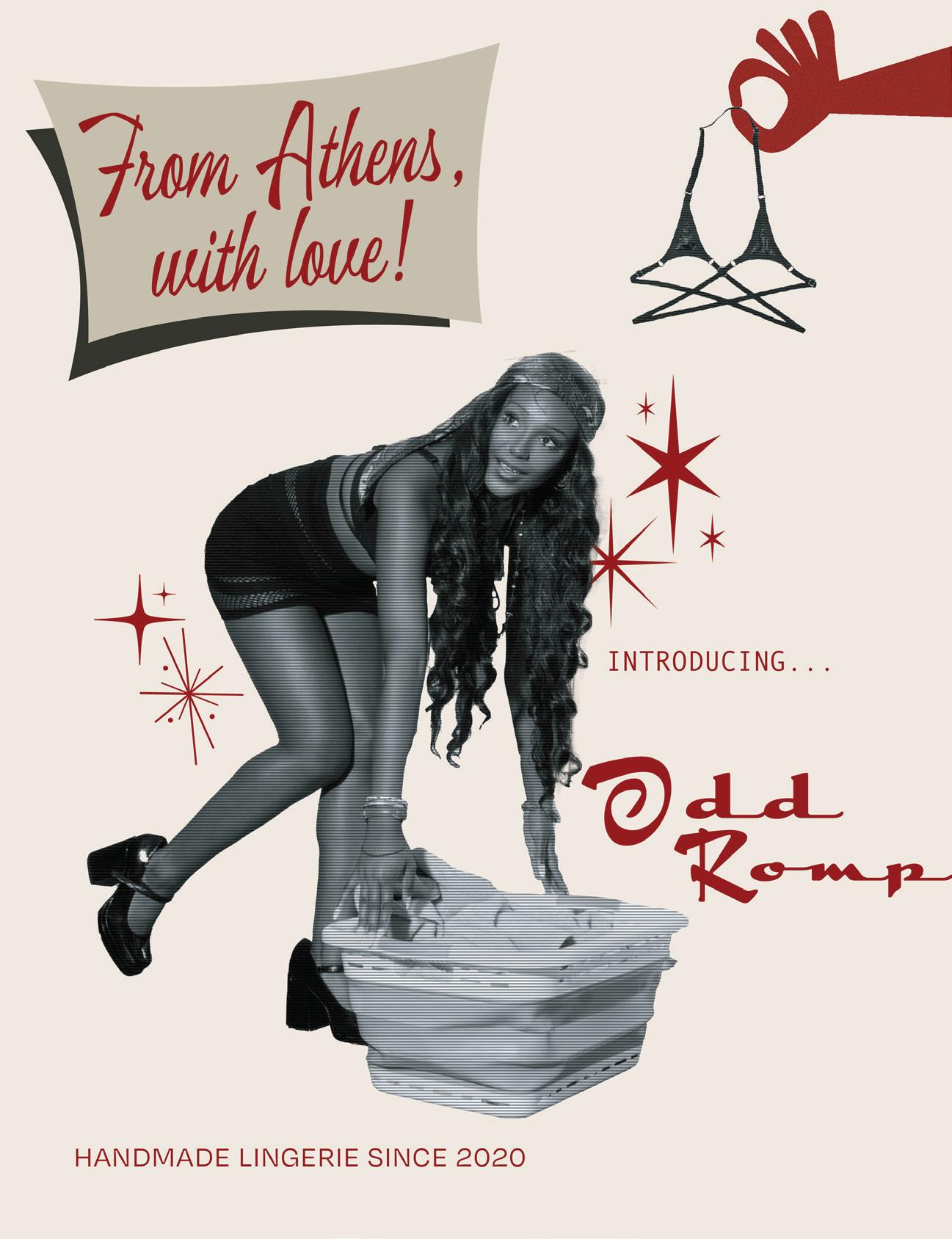

These statistics can paint a dire picture, but they do not speak to individual experience. That is where Odd Romp comes in. For Couch, her business ethos is rooted in comfortability. From her fabric sourcing to her personal history, she is very focused on the embodied sensations of wearing lingerie. She wants to embrace sensuality in a world that has lost its confidence, privacy, and freedom. Her history as a dancer and her mother’s professional life as an artist inform her interests as well. She is currently studying physical therapy at Ohio University. As you can tell, all of her passions evolve around the body. As she put it, “I’m studying physical therapy, partly because I’m very interested in rehab stuff, but I also feel pretty uniquely comfortable talking to people about their body experiences, right?” Couch asked. “Like, imagine if you were to go to pelvic floor physical therapy, for instance, after giving birth, or, you know, having a traumatic accident. A lot of your bodily sensations end up having to deal with how ashamed you feel talking about them. I really believe that if people can feel comfortable, they can heal. So with lingerie, if you can feel comfortable in your body, you can have fun with your body, and what Odd Romp is all about having fun with your body, right?”

This, in her opinion, is the way to meet the current intimacy crisis. We grow up perceiving and being perceived, taking in huge amounts of information about other people’s opinions, thoughts, and reactions to the world. This turns into an internal narrative, thinking about your body instead of feeling your body. The way to combat this? Couch says, “let yourself perform for yourself for once. Sit in your own audience. Be your own biggest fan.”

New York Fashion Week has always presented new themes that are meant to startle and catch the eyes of the audience members. Whether that’s celebrities walking in different brand shows, AI on the runway, or designers reflecting prevalent societal aspects through their work, there’s always buzz around the new season’s creative concepts. Last year’s Spring-Summer 2026 show “Shade” exemplified this trait. Hillary Taymour directed this show on an NYC helicopter pad. Pairs of models walked down this unconventional runway, one covered in white and the other in black. Collina Strada, the mastermind designer behind the show, usually focuses on lines that follow a whimsical and playful tone with brighter colors integrated in the various pieces. The concept was an invitation to the audience to explore the darker side to themselves instead of ignoring it— an intentional move toward shadow. Suddenly, the collection becomes more than fashion; it mirrors our cultural tendency to suppress discomfort, negativity, or crisis in favor of performative optimism— calling us instead to acknowledge and embrace the shadow.

The collection’s visual language emphasizes silhouettes with a moody color palette. The show

featured sharp contrasts, such as one model walking down the runway in a pink floral dress followed by their shadow counterpart in black. This emphasizes how we carry the darker parts of ourselves with us even if we don’t make those parts visible or public to those around us. The staging of the runway on the helicopter pad added another layer of tension to the show. It complimented the fashion line’s coloring with a contrast to the height of the runway’s scenery and themes of escapism in lieu of the weight of darkness. Off the runway at Fashion Week, Taymour even referred to the line in her show notes saying, “Our shadows walk among us,” showcasing that this fashion show was more than just displaying Collina Strada’s work, confronting what we repress internally.

Especially departing from Collina Strada’s “playful sustainability” narrative, as described by British Vogue, toward something more politically

and emotionally charged, emphasizing the duality of humanity and sense of self. The show captures a generational mood—one that’s tired of pretending everything’s fine. Online, we curate joy; offline, we wrestle with burnout, anxiety, and grief. Shade feels like a mirror held up to that tension, asking what authenticity really looks like when every emotion is filtered.

Additionally, the element of the shadow in the show is meant to showcase the repressed and disowned part of the human psyche. Ignoring these internal aspects of ourselves can be dangerous. It leads to the feelings or behaviors we’re so desperate to hide resurfacing, creating more harm than good. Whether suppression is on an individual level or collective as a society, the fear of being “negative” has contributed to a false portrayal of emotions by a mass majority. In contemporary culture, social media has an incessant demand for constant positivity. Whether that’s through “aesthetic” curation or performance of wellness, it becomes a performance of competitive comparison. Moreover, this behavior leads to shallow engagement with global crises such as wars, climate change, and systemic inequality, leading to many becoming desensitized. As a result, there’s a less informed public and less media literacy and understanding pertaining to world issues. Collina Strada’s SS26 line makes visible what we hide, exemplifying humanity’s unease with the grotesque and uncomfortable. It frames what we as a society need to grow within our own personal and public lives.

The way we operate in the 21st century is shaped by massive exposure. Lives are shaped by constant information and surveillance either through our own selfcuration or the presence of external observation. As a result, humanity exhibits front stage behaviors for the sake of public perception of our images, not our most authentic selves. For example, doomscrolling leads to toxic positivity, distorting how we process reality, very much affecting our brains. Ignoring darkness— whether internal or external— doesn’t erase it; it merely conceals it behind the latest cultural filter, a notion embodied in Strada’s SS26 line. In refusing to edit out the shadow, there’s a demand for its presence on the “runway” of life. What happens if societies collectively repress the bad news for the sake of optimism? The threat of apathy, disconnection, and fragility threaten to weaken the backbone and cloud our own perceptions of reality. Suspended between light and dark, optimism and shadow, Collina Strada flips the script. Once known for its playful, ecoconscious whimsy, the brand

6 7 takes a bold turn— joy now comes with critique. The shift mirrors a cultural mood where pure optimism no longer feels honest or even responsible. With shadow stitched into the seams, Strada moves beyond fashion into confrontation. Because fashion, like culture, isn’t just about escape— it’s about reflection.

SS26 Shade dares us to see discomfort not as chaos, but as growth. The shadow isn’t surface; it’s resistance. It’s the start of a new chapter— and we’re watching it unfold in real time.

PHOTOS BY ALLIE

DESIGN BY SYDNEY SALING

In fashion, seeing is everything— and these days, everyone is watching. Trend surveilling has become the industry’s ultimate weapon, wielded by brands, influencers, and digital tastemakers, shaping what is worn before garments even hit the shelves. Leading fashion houses like Dior, Gucci, and Louis Vuitton spearhead what is trending in a given European fashion season, with the United States following close behind.

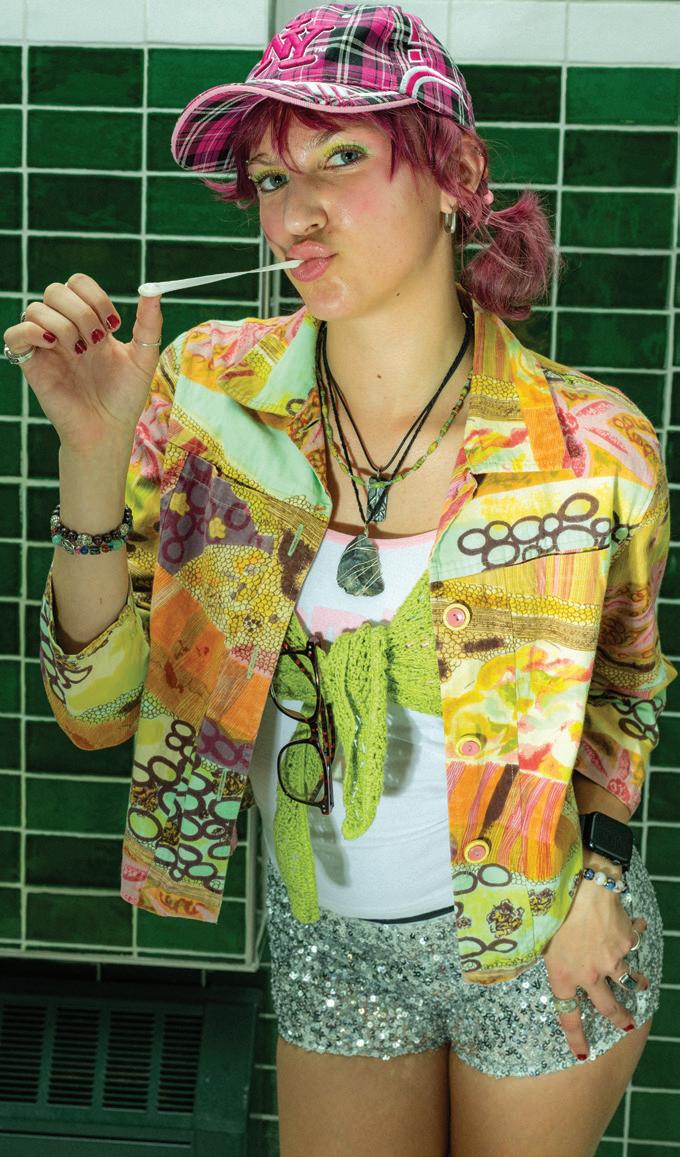

Fashion, the visual language of culture, has evolved as a reflection of broader social moods. The most visible styles of 2025 and beyond reveal an interplay between expression and social themes, blending nostalgia, resourcefulness, and rebellion against homogeneity.

The high tide of spring 2025 runway continues riding a maritime revival. W Magazine peeps sailor collars, Breton stripes, and naval caps popping up in Prada, Dior, and Chanel collections, proving the siren call of nautical style is louder than ever. But this is not just a throwback to classic sailor chic pioneered by Queen Victoria. Designers are fusing tradition with modern precision: envision crisp lines, doublebreasted tailoring, and that unmistakable navy-andwhite palette. What once kept uniformity amongst sailors now projects poise and control for the wearer.

Ohio University Professor and Program Coordinator for Retail and Fashion Merchandising, Lisa Williams, notes that style moves cyclically.

“Things come back into fashion with a twist for that particular reason,” she said. We cannot escape what is functional and familiar.

The 2025 twist includes blending seafaring and military influence. Khaki hues, cargo pockets, and structured belts transform uniforms from mere symbols of discipline into statements of adaptability, with the bonus of deep pockets and thick fabric functionality.

The era of “clean girl” minimalism is giving way to exuberance. The Byrdie feature “Prize Ribbons Are Replacing Rosettes” identifies handcrafted embellishments— pins, brooches, and reworked jewelry —as dominant accessories. ”Sex and the City” fashion protagonist Carrie Bradshaw, keeper of all things in style, is often seen sporting an oversized flower in the form of a choker or brooch. Though, what is within Carrie’s budget may be unattainable for the common person, ornamentation can be as simple as upcycling trinkets into wearable accessories.

This Do-It-Yourself movement celebrates imperfection and individuality, standing in opposition to algorithmic sameness and fast fashion repetition seen seeping out of

Shein sweat shops into retail chains. Williams connects this shift to environmental awareness. “Fast fashion and overconsumption have made this one of the most polluting industries… even with limited income, you can thrift and find quality pieces.”

Within her program, students participate in upcycling projects that challenge disposable consumption. The trend is less about excess for its own sake and more about authenticity, reclaiming crafting as a form of selfexpression. Ornamentation layered across outfits ignites tactile creativity: jingling, glistening, and clinking with any movement, shying away from the bounds of minimalism.

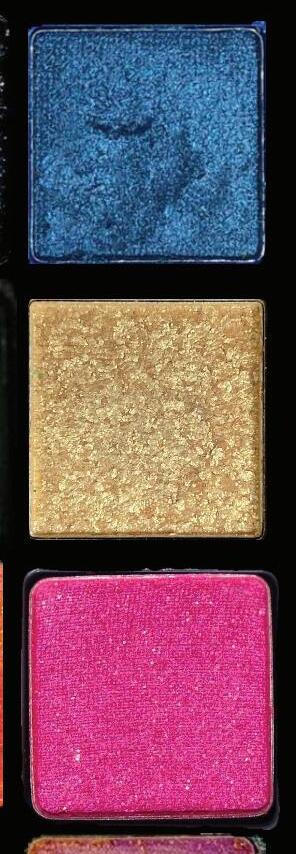

Fall/Winter 2025 is about walking the line between comfort and energy, and the season’s colorway speaks to it. Vogue spotlights powder pink, mocha brown, icy blue, slime green, and electric aubergine as key shades appealing to the fashionable eye. They are worn, muted, yet unmistakably optimistic; soft but full of life.

Williams observes a softening of color across younger consumers: “Last year I saw more metallic, but it didn’t last long. I don’t see a lot of pops of color, it seems to be more muted.” This palette reflects that moderation. Powder

pinks and mocha browns wrap wearers in warmth; icy blue and aubergine (an eggplant color) sophisticate. Slime green injects its own edge that keeps a look unpredictable. Married together, this palette isn’t just pretty, it paints an understated yet expressive picture. The versatility is perfectly suited for layered, mixand-match dressing that signals individuality without seeking attention.

Trend forecasting at Pantone signals Mocha Mousse as their 2025 Color of the Year with predictions of a green 2026.

According to Harper’s Bazaar, the Fall/Winter 2025 silhouette introduces translucent fabrics, visible underlayers, multi-belt styling, and oversized leather bags. This direction of trend merges sensuality and practicality. Sheer garments and exposed lingerie reinterpret early2000s transparency through a more curated lens: visibility is design, not exposure.

Williams considers this the rhythm of style. “If it’s a classic style, it’s still going to be there, it just may have a twist… it just depends on how fad it is,” she said. “If they add a color that’s really trendy, it’s going to go out faster even if the style is something classic.”

Trend forecasting serves less as prediction and more as cultural reflection. As WIlliams explains: “[Trend forecasting] is a tool that businesses use because they want to compete with those who are faster to market than them.”

The direction of fashion emphasizes recontextualization rather than reinvention. It is old ideas worn differently, materials reused creatively, and aesthetics merging high fashion with grassroots expression. It is more than capitalistic coercion. As active members of an intelligent society we participate, or withhold from trend cycles as a reflection of how we want to be perceived. We dress to be seen in whatever fashion may fit.

The twist is applied everywhere. A practical staple like the belt is now being seen multiplied across coats, dresses, even knitwear, looping and cinching into silhouettes that reinvent the article. Prominent in the 90s, the oversized bag can also be cycled back to Coco Chanel in 1955 when she released a revolutionary bag for the pocketless female fashion of the time, followed by the Birkin bag in the 80s. Taking “what’s in my bag” to limitless, Mary Poppins level heights, the repetitive resurgence of this oversized genre of bag is nothing short of pragmatic.

What’s the first thing you reach for each morning? Your phone, maybe? And when class ends or you’re settling in each night, do you find yourself scrolling through social media to see what you’ve missed? Now, how would you feel if this step was removed from your daily routine?

Scrolling, snapping, and sharing have become second nature, making it hard to imagine life without constant connection.

Technology allows us to be everconstantly involved in each other’s lives.

With Instagram, Snapchat, Facebook, and text messaging, learning the goings-on in others’ lives has never been easier.

It is only with a few clicks that you can instantly chat with a close friend, learn about the latest in Hollywood, or internet stalk a romantic fling.

However, this information overload has seemed to wedge its way into the emotional well-being of many. Social media has woven itself into many aspects of our social lives, blurring the line between connection and dependence. In response to this, some have found themselves taking breaks from social media and technology, or doing what many refer to as a ‘digital detox’.

Dr. Melissa Hunt, a clinical psychologist and the Associate Director of Clinical Training at the University of Pennsylvania, was interviewed regarding her research on social media and emotional well-being. Dr. Hunt was the principal investigator and lead author of the study “No More FOMO: Limiting Social Media Decreases Loneliness and Depression.” She, alongside her team, worked to examine the effects of social media on relationships. The study found that limiting social media use decreased both loneliness and depression;

therefore, indicating a strong connection between time spent on social media and a positive or negative emotional wellbeing.

The research process for this study lasted one academic year, and involved 143 undergraduate students at the University of Pennsylvania.

Within the study, each participant was restricted to 10 minutes of social media use per platform. Throughout, participants were regularly evaluated by “wellbeing surveys” to measure changes in their emotional state. Dr. Hunt explained the indicators

used to measure emotional well-being.The study’s criteria for “subjective well-being” originated from the ideas of influential psychologist Martin Seligman. “Human beings need a number of things to flourish, including positive emotions, engagement in work and play, relationships, meaning, and achievement,” Hunt said. The study used indicators drawn from this framework, including social support, fear of missing out, loneliness, autonomy, anxiety, depression, and self-esteem.

Dr. Hunt’s research, along with the experiences of students like Wain and Mater, revealed that social media can both bridge and widen the gap of connection to oneself and others. These platforms offer an illusion of closeness, yet have amplified comparison, anxiety, and a fear of missing out. Yet, the study showed that reducing social media use increased self-awareness and balance. With access to ever-growing amounts of information, it became necessary to reevaluate what genuine connection meant. Disconnecting from media played an important role in reconnecting with oneself and supporting overall well-being. The next time you reach for your phone without thinking, pause. Consider what you might gain from putting it down. Would you gain more time, clarity, or even more genuine connections? Or would you rather claim the factions of anxiety, make-believe pressure, and self-doubt. Remember that even small changes in your digital habits have the ability to shift your well-being in positive, meaningful ways. In a world where technology and social media has affected our ability to operate independently, choosing individuality and self care is impertinent to best facilitate individuality and true social kinship. messaging, music, and podcasts. After making this change, Mater shared experiencing “less brain fog and more free time.” Despite the positive repercussions, he noted often finding “workarounds” that allowed him access to social media. “I could access social media on my laptop pretty easily, so I ended up putting blocks on all my devices to keep me off those sites,” he said. Both Wain and Mater experienced withdrawal from the social world upon removing social media apps. As soon as you delete your social media apps, you become an outsider of sorts. You aren’t as tapped into digital culture as you once were,” Mater said. He believed this sense of disconnection contributed to the reluctance many people feel toward deleting social media.

A central conclusion of the study was the significant increase in “FOMO,” or fear of missing out, among participants. Without constant interaction with peers, many participants experienced heightened anxiety. When asked about the study’s measurement scales, Dr. Hunt emphasized the controlling nature of FOMO and the withdrawal-like feelings many people experience when distancing themselves from social media. “Fear of missing out is particularly relevant to social media, since seeing other people’s posts about things you weren’t invited to, don’t have, or can’t participate in often mediates the negative effects of social media use,” Hunt said. Several students from Ohio University have reported also taking steps to “detox” from social media. Alex Wain, a senior at Ohio University, deleted Snapchat last summer. “It was difficult at first; it was my main line of communication to friends both new and old,” Wain said. He later explained that sending pictures felt like a routine, something done “mindlessly.” This experience was not unique to Wain. A.J. Mater, a graduate student at Ohio University, says he has switched from a smartphone to a “dumb phone,” a touchscreen device that allowed only phone calling, text

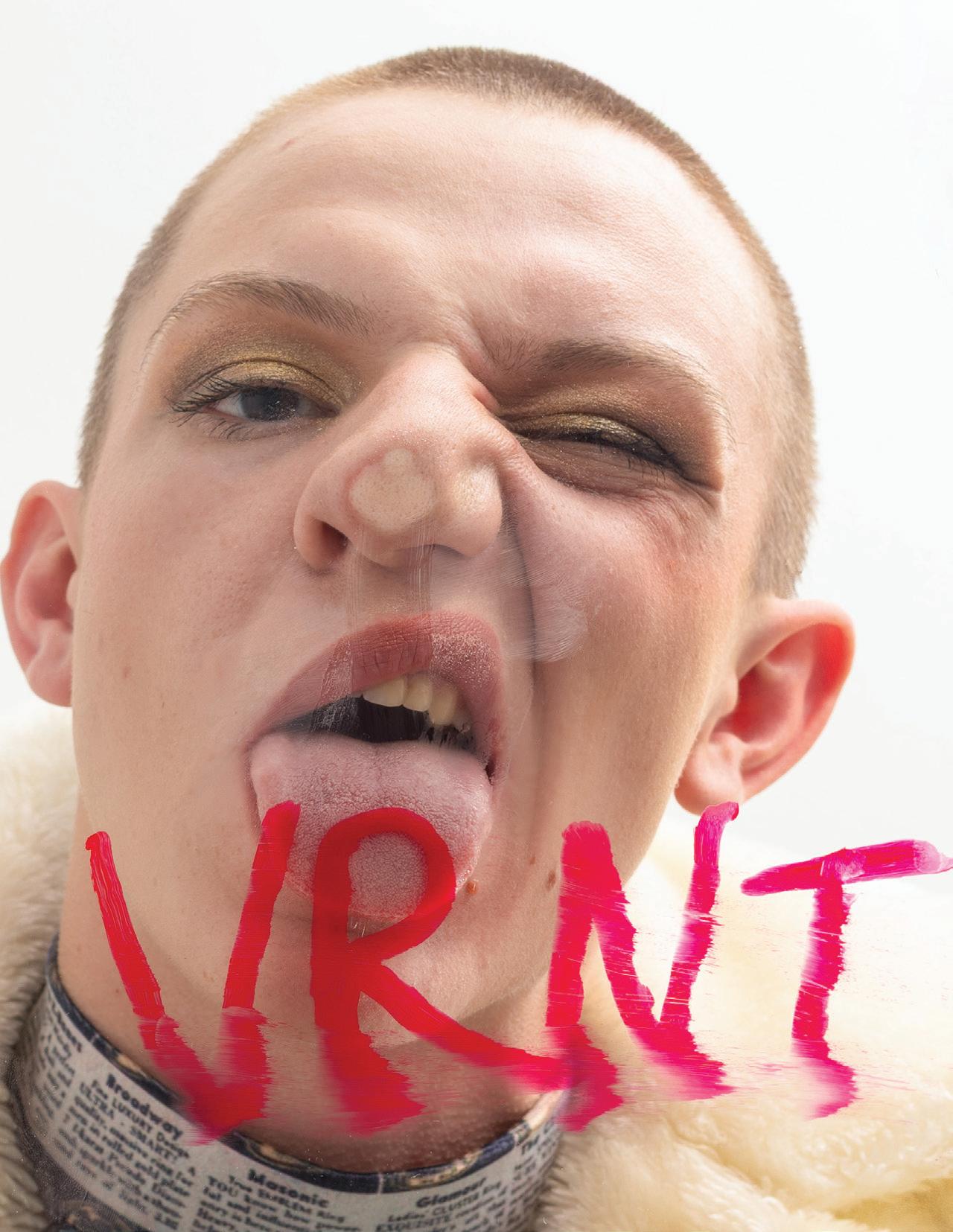

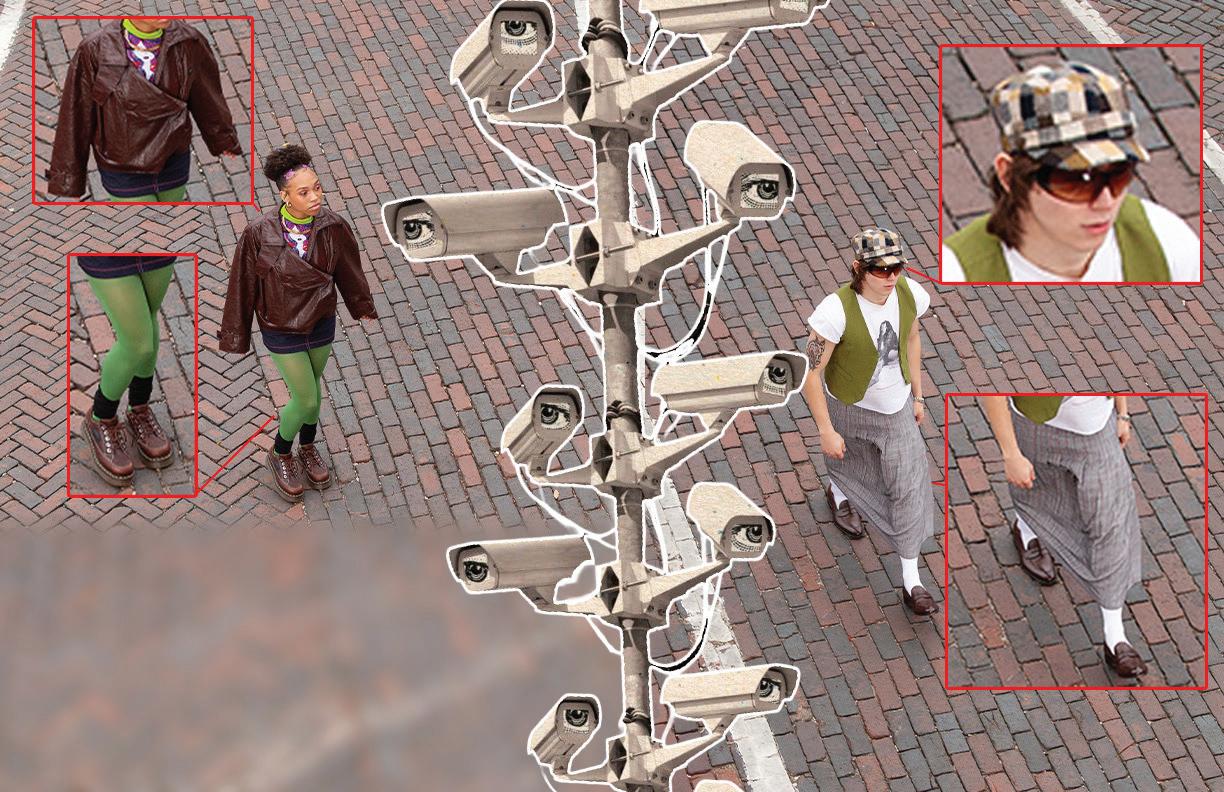

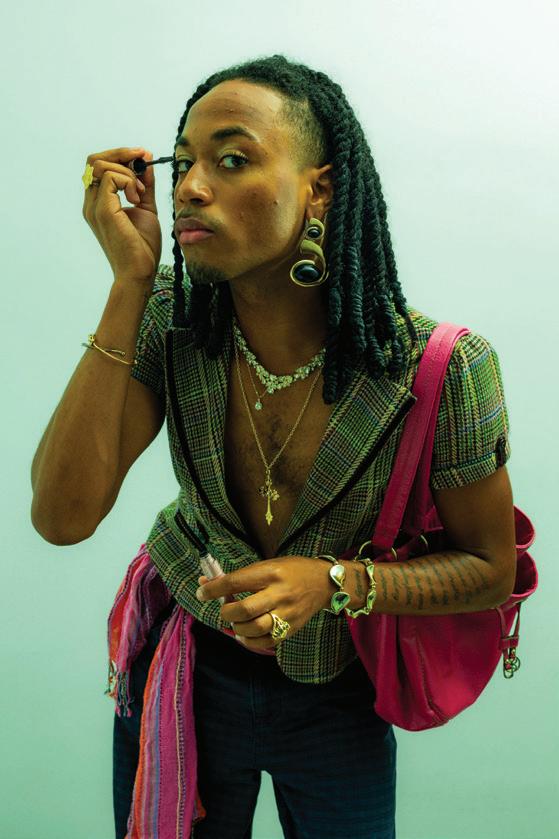

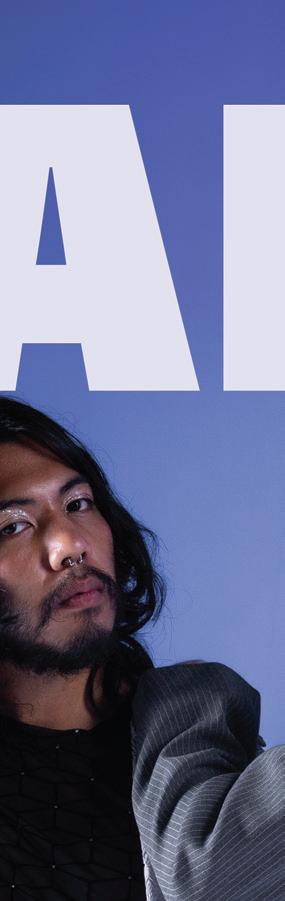

Androgyny pushes back against society’s ideas about gender by existing between being seen and misunderstood. This article shows how androgynous individuals navigate a world eager to define them. Between visibility and misunderstanding, they challenge society’s labels and show new ways of seeing identity beyond fixed categories.

Androgynous and gender neutral people are misread and misunderstood. Reflecting back on their own identity shows how although society may pressure to define them, they are confident in who they are. The world demands clarity: male or female, soft or strong, defined or erased. Androgyny disturbs that demand. It is both visibility and refusal, presence and protest. In society, every outfit, idea, and choice is analyzed and debated. Society is obsessed with defining “womanhood” and “manhood,” but androgyny and expression rebel that idea. Androgynous people exist in a space between fascination and misunderstanding, constantly seen but rarely understood. Their visibility challenges how society defines beauty and power through gender norms. Existing between visibility and understanding, androgynous people show how the heteronormative society defines, deceives, and fears what it can’t categorize.

being watched, online and in person. Every outfit, post and look is up for judgement. There’s this pressure to always be “put together” or to fit into some version of femininity or masculinity that feels performative. According to this article from Medium, the concept of the binary gaze describes how people are viewed through the eyes of heteronormative society and expected to look and act in ways that please or make sense to them. Androgynous people challenge that Their styles and presence blur the lines between what’s considered masculine

and feminine, forcing people, to pause and question.

Eve Ng, an Ohio University media and women’s gender studies professor, wrote the article “Networked transphobia in popular culture spaces.” “Feminist scholarship has argued against treating sex identity as a fixed binary, yet the emergence of trans-exclusionary feminisms in academic circles demonstrates that theories of gender remain under contestation,” they said. “A key way this plays out is policing the boundaries of gender categories, which gender non-conformity challenges.”

To put it simply, androgyny flips the script. It makes people question how they’ve been taught to see gender. Instead of performing for the gaze, androgynous identities exist outside of it. That’s what makes androgyny so powerful. But these ideas don’t just exist in theory, they show up in real people’s lives every day. It’s one thing to talk about the male gaze and visibility, but it’s another to experience what it feels like to move through the world while being read, misread, or not read at all.

HG, a grad student at OU studying photo journalism, notices people trying to “figure them out” just from how she looks. “When I start a new internship or

or class, people ask for my pronouns even if they don’t ask anyone else’s,” she said. “It’s not offensive, it’s just noticeable. They’re reading me.”

This kind of attention isn’t always negative, but it’s clear that people become curious when someone doesn’t fit neatly into what they expect. According to HG, she is constantly seen, sometimes even stared at, but rarely fully known. Her appearance makes people pause because it doesn’t immediately tell a clear story. It reflects back to society’s need for labels and boxes. When people can’t label what they see, they feel uncomfortable. Androgyny acts like a mirror in this

the person themselves, but the person looking. For HG, being androgynous, or gender neutral in her words, isn’t about trying to make a statement. It’s about being at peace with who they are.

“If someone calls me ‘sir’ or uses the wrong pronouns, I just laugh,” she said. “It’s not a big deal.” When asked to finish the sentence, “Being androgynous in this world feels…” she answered simply, “Grounding.” That word stands out. Even when others struggle to define HG, she remains sure of who she is. And maybe that’s the most powerful reflection of all. Not confusion, but confidence in existing beyond what society can easily define.

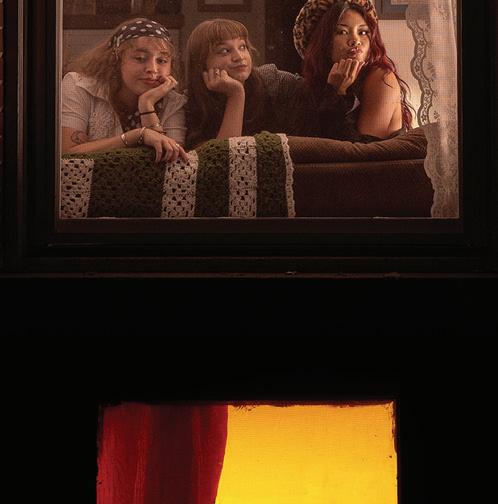

While HG’s experience shows how androgyny challenges society, on a personal level, the models in the photoshoot reveal these themes in a more public space. Their work in front of the camera brings visibility and perception to a whole new level.

per-

Blue Williams, a communications and digital marketing freshman, shared what it felt like to embody androgyny in front of the camera. When asked if posing felt like per forming or just being himself, Blue explained, “This is the first time where I get to be my authentic self… It’s really just a reflection of who I am.”

There’s this balance between authenticity and being watched, and through this shoot, it’s clear from Blue that the androgynous look and mirrors aren’t about fitting into a stereotype but rather about reflecting onto one’s true self. He described the theme of mirrors and reflection as something beyond just the visual but also as something more social and emotional. “Reflection is like journaling. It’s about asking yourself how you feel and learning who you are,” he explained.

Blue’s experience circles back to the themes of visibility and identity.

Androgyny’s visibility can be both power and pressure. Empowering and vulnerable. Through this photoshoot, androgyny is not something defined but more or so something lived and expressed. The camera mirrors how society looks at those who don’t fit into specific categories, and yet, there’s power. In front of the camera, being seen can become its own kind of reflection. And to be seen is to take control of perception and turn society’s gaze itself into a form of resistance. Through art and self expression, people like Blue, who exist beyond traditional gender roles, challenge society’s desire to define and show the world what it means to exist authentically.

JEN FOSNAUGHT

hen someone opens TikTok, they’re likely to eventually see a video from an influencer titled something like “What I eat in a day.” The video is likely uneventful, maybe just a woman showcasing the Cobb salad she had for lunch and the salmon bowl she had for dinner, filled with shots of her thin body facing the camera. These videos invite comparison. How could they not? When someone sees a person’s entire diet laid out in a fifteen-second video, it’s easy to notice what this influencer does that someone watching at home does not do. Perhaps the viewer has issues with snacking throughout the day, and this influencer doesn’t. Perhaps the influencer’s meals have significantly fewer calories than the viewer’s. A similar pattern can be seen with “A Day in My Life” videos, where celebrities or influencers take the viewer into their glamorous, typically affluent daily routine while showcasing

This content often inspires two emotions: connectedness and inadequacy. On the one hand, the videos feel personal. Celebrities and influencers are so far removed from the general public that they often feel aloof, mysterious, and perfect. The mundane parts of a celebrity’s life feel forbidden or unimaginable, and therefore seem private and important to see as an outsider. At the same time, it’s easy to feel worse after consuming this content. The influencer’s life seems shiny and successful, and their body or diet looks absolutely perfect. It’s easy to feel jealous or self-conscious as a result. But how is it possible to feel both connected and inadequate? Surprisingly, these two emotions work together to encourage further consumption

Personal content is on the rise, and users’ appetite for it is increasing as well. The number of users on the TikTok app increases by tens to hundreds of millions each year, similar the ways they are successful. of content.

currently standing at 955 million users in 2025, according to Statista. The hashtags #skincareroutine, #morningroutine, #WIEIAD (what I eat in a day), #dailyroutine, #dayinmylife, #adayinmylife, and #vlog all have over one million views on

The frequency of personal content isn’t only

possibly checks out their page, gives them a like, or follows them, the social media platform will recommend more from

When these videos continue to pop up over and over, the viewer starts to feel a connection with the creator. Chances are, someone who watches a creator from time to time knows this creator’s relationship status, hobbies,

fashion taste, and more, despite having never met them in

The Cambridge Dictionary defines the “connection that someone feels between themself and a famous person they do not know” as a “Parasocial Relationship.” This term was originally coined by Horton and Wohl in 1956 in a journal on mass media. In this journal, Horton and Wohl described that the new popularity of TVs, and therefore TV show hosts and performers, brought about a new type of

While this seems harmless initially, parasocial relationships bring a significant amount of harm to both the influencer and the viewer, forming a cycle that’s hard to break. Parasocial relationships give the illusion of intimacy, as celebrities speak to the viewers in a familiar, friendly tone, while showcasing things usually only a friend would have access to see. When viewers watch this content, it becomes a way of peeping into the life of another who doesn’t even know the viewer exists in real life. In some cases, this can be taken too far and breach into stalking. Many influencers and celebrities have detailed the horrific experiences that come from parasocial fans who take things a step too far.

The National Library of Medicine states, “People with poor self-esteem regularly turn to social media for affirmation, which may heighten feelings of inferiority.” Daily content and vlogs promote comparison culture, which in turn highlights faults the viewer dislikes about themselves.

Benjamin Gallati, a sociology professor at Ohio University, explains this in terms of the self-discrepancy theory, which argues that everyone has a “true” version of themselves (how they really are), an “ideal self,” which is who people ideally want to be (the best version of themselves), and the “ought self,” which is how people believe others want them to be.

“When there’s a discrepancy between the ideal self and the actual self, we feel depressed that we are not living up to who we want ourselves to be. When there’s a discrepancy between our ought self and our actual self, we tend to feel anxious that we’re not living up to other people’s standards,” Gallati said.

As a result, onlookers into celebrities’ lives, and those obsessed with influencers, experience worsened depression or anxiety. The stalking that social media encourages and the one-sided relationships it promotes are more harmful than beneficial, despite the allure.

“The point of those videos is, you’re getting an authentic behind-the-scenes look at [their] life, and there’s a real appeal to that,” Gallati said. “But what we’re not thinking about necessarily is that that’s also a performance that they’re doing. They’re still giving us an idealized version of themselves.”

Viktoria Maranova, an international student completing her PhD in mass communication, believes the best way to handle technology is to limit excess interaction and try to use it positively.

“You have to set boundaries with the technologies that are in your life,” Maranova said. “What determines the effects is how we choose to use that technology.”

WORDS BY LIBBY EVANS

We are watching. About 6,000 miles away is a country sick with war and death, and we are watching. A genocide practically live-streamed to our phones. Though it started decades prior, the first intifada, or Palestinian uprising against Israel, happened in 1987. The United States tuned in by watching television, reading newspapers, or listening to the radio, seeking out information and digging for answers. Almost 40 years later, this war persists, and we scroll mindlessly past short-form social media content of children dying, starving families begging for a like or comment, and protestors arrested for peacefully showing support. As of early November, over 69,000 Palestinians have been killed in the Israel-Hamas war that is hopefully coming to an end.

The word “voyeur” is defined by the Merriam-Webster dictionary as someone who takes pleasure in “observing something private, sordid, or scandalous.” It also defines Voyeurism as “the criminal act of surreptitiously viewing a person without their consent in a place where the person has a reasonable expectation of privacy.” To say we, as a society, are voyeurs, is not to say we take pleasure in witnessing the suffering of others. To use this word as a metaphor, we are watching, constantly scrolling, constantly being fed horrifying news, and we can’t look away. A study from the National Library of Medicine explained how instant gratification of short form videos encourages users to seek more stimulating content to achieve the same level of satisfaction, ultimately leading to desensitization. We do

take pleasure, often subconsciously.

We are not chained to our phones, but sit freely in a state of hypnosis, watching suffering around the world with seemingly no way to make it stop. Many take action and many do not, but it seems to be altogether out of our control. Watching the war in Gaza, it does not matter if these victims are from our country, our schools, or our neighborhoods; they are our people: mothers, fathers, children, priests, doctors, teachers, students, and friends. Technology offering surveillance-like access makes foreign conflicts feel personally close by and erases drastic measures of proximity. Over the past century, there have been endless tragedies in our country and in others. It seems as though, for every positive, happy person and every success for humanity, there is loss and suffering. Unfortunately, media is a business, and suffering sells. ells.

“If it bleeds, it leads,” is an infamous phrase in newsrooms helping editors pick the most “newsworthy” headlines. Bad news is a catalyst for the strategy of hopelessness, and we are regrettably drawn to conflict. It’s the feelings of shock, adrenaline, and empathy that raise a throbbing ache from the pit of the stomach. Victims are strangers, but also someone’s mom, someone’s son. Media is a business selling clicks, and the rising sadness after just 15 minutes of dark news is preyed upon. We are meant to feel small and insignificant. We are meant to feel alone in a dark world with no realistic way to help besides reading more content and losing friends for the sake of steadfast beliefs. When this war finally ends and peace is recovered, another war will reveal itself. There will always be suffering. There will always be an equal and opposite darkness to global light. It’s not fair or reasonable to only focus on good news because it won’t erase its bad counterpart nor will it fulfill our earthly desire to know what’s going on. But even if one is a constant stateof informative scrolling, it’s impossible to know everything. There is an endless stream of positive news: babies being born, miraculous surgeries, and soldiers returning from war; and there are endless miseries that all seem equally important and devastating. We must stay informed and do what

“As unwilling voyeurs, we must remember that our anger and anxieties are exploited to divide and distract us from the deeper, shared problems we face.”

we can, whether that means standing up for legislature that supports natural rights, or just taking care of those around you. Take care of yourself. It’s okay to take breaks from “staying informed” if it means resting your mind and your eyes. Practice compassion for yourself and for those with less fortune. With “doom scrolling” isolating and polarizing every audience member, all we can do is practice unity: listening to the unique perspectives of those around you, asking questions, and reacting with patience and curiosity instead of anger or violence. As unwilling voyeurs, we must remember that our

anger and anxieties are exploited to divide and distract us from the deeper, shared problems we face. It is important to stay genuine to our desire to stay informed and to stand for something greater than ourselves. When you see moving content you can, instead of sitting in hopelessness, move. Live well for those who can’t.