Freed from the brain Patients with locked-in syndrome often have excellent cognitive abilities but are locked in their brain due to paralysis. Researchers at Brain Center Rudolf Magnus are developing brain-computer interfaces that allow these people to communicate again.

By Jolein de Rooij Image: Bram Belloni

T

he late, great scientist Stephen Hawking was also the world’s most famous ALS patient. At the end of his life, the discoverer of Hawking rays used his cheek muscles to select sentences, words, and letters and have them spoken by a speech synthesizer. However, Hawking ran a great risk of becoming ‘completely locked-in’. In anticipation of this fate, he began working with researchers at Intel, at the beginning of this century, to develop a system that translates the brain activity patterns behind facial expressions into actions. This system would never see the light of day. Hawking would, therefore, have been very interested in the achievements of a research team at Brain Center Rudolf Magnus. In 2016, this team, led by professor 14 | New Scientist | Brain Center Rudolf Magnus

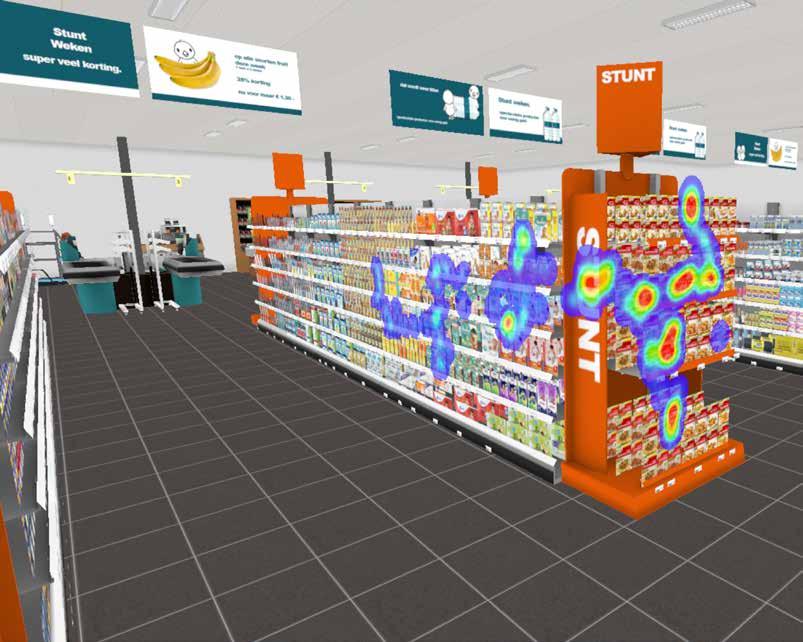

Nick Ramsey, made headlines worldwide with a system that patients with locked-in syndrome (LIS) can use autonomously, at home, day and night, to call a carer and to communicate. A 58-year-old ALS patient learned to use the system to make ‘brain clicks’ with which she can select letters on a screen attached to her electric wheelchair. She does this by trying to touch her ring finger with her thumb. Even though this doesn’t result in a real movement of the hand, the system catches the motor signal and generates a click on the screen. ‘The greatest thing is that I can go outside again and that I can communicate,’ the first user told New Scientist in 2016.

No bells and whistles Since then, the team has been hard at work on new and improved methods of translating brain activity into all types of useful actions for people who have lost control of their muscles. Patients with locked-in syn-