September – October 2025

Alice Rekab, Bunchlann, Buncharraig, 2025, installation at Liverpool ONE; photograph by Rob Battersby, courtesy of the artist and Liverpool Biennial 2025.

First Pages

6. Roundup. Exhibitions and events from the past two months.

9. Drift Days. Cornelius Browne chronicles his use of driftwood as supports for his plein air paintings. The Ban, The Voice, And Nothing More. Roisin Agnew outlines the research underpinning her bafta-longlisted film.

From The Archives

10. Attention as Fulcrum. Jason Oakley’s interview with Michael Warren was first published in the SSI Newsletter in 1996.

Moving Image

12. Grenfell. Grace O’Boyle gauges the impact of Steve McQueen’s film, currently showing at the MAC in Belfast.

Career Development

14. Maelstrom. Aengus Woods interviews Maud Cotter about the evolution of her sculpture practice.

Residency

16. Leaking Light. John Gayer interviews Clíodhna Timoney during her residency at Helsinki International Artist Programme.

17. How the Heart Sees. Eslam Abd El Salam reflects on his recent residency at Kunstverein Aughrim.

Critique

19. Noel Hensey, Rejection Rejection, 2021

20. ‘Soft Surge’ at Luan Gallery

22. Rachel Doolin at glór

23. ‘Together in Commune’ at Rua Red

24. ‘Foreword’ at The International Centre for the Image

26. ‘Encounters with Failure’ at South Tipperary Arts Centre

Exhibition Profile

28. Beirt le Chéile. Catherine Marshall interviews Bernadette Cotter and Áine Ryan about their show at Grilse Gallery.

29. The Home that Held Us. Clara McSweeney outlines a recent exhibition at Fire Station Artists’ Studios.

30. Out of the Strong. Aisling Clark reflects on a recent group exhibition commemorating 30 years of Gay Health Network.

Festival / Biennial

34. Bedrock. Miguel Amado reviews the Liverpool Biennial.

36. It Takes a Village. El Reid-Buckley interviews the curatorial team for the 41st EVA International.

38. Shelter: Below and Beyond. Maeve Mulrennan reviews the third edition of the Helsinki Biennial.

40. Ireland Invites. Joanne Laws reports on an initiative conceived to enhance the international exposure of Ireland-based artists.

Member Profile

42. Between Real and Shadow. Áine Phillips interviews Breda Burns about her show at Custom House Studios and Gallery.

44. Uisce Salach Agus Dríodar. Anna Maria Savage outlines the research underpinning her recent paintings. First-person. Isabel English discusses her forthcoming Exhibitions at LHQ Gallery and GOMA Waterford.

45. Diagonal Acts. Marie Farrington chronicles several exhibitions emerging from her unfolding cross-site project.

Last Pages

46. VAI Lifelong Learning. Upcoming VAI helpdesks, cafés and webinars.

The Visual Artists’ News Sheet:

Editor: Joanne Laws

Production/Design: Thomas Pool

News/Opportunities: Thomas Pool, Mary McGrath, Lewis Olivier

Proofreading: Paul Dunne

Visual Artists Ireland:

CEO/Director: Noel Kelly

Office Manager: Grazyna Rzanek

Member & Artists Advice, Advocacy & Development: Mary McGrath

Advocacy & Advice NI: Brian Kielt

Services Design & Delivery: Emer Ferran

News Provision: Thomas Pool

Publications: Joanne Laws

Accounts: Grazyna Rzanek

Special Projects: Robert O‘Neill

Impact Measurement: Rob Hilken

Shared Island Advocacy: Brian Kielt

Board of Directors:

Deborah Crowley, Michael Fitzpatrick (Chair), Lorelei Harris, Maeve Jennings, Gina O’Kelly, Deirdre O’Mahony (Secretary), Samir Mahmood, Paul Moore, Ben Readman.

Republic of Ireland Office

Visual Artists Ireland

First Floor

2 Curved Street

Temple Bar, Dublin 2

T: +353 (0)1 672 9488

E: info@visualartists.ie W: visualartists.ie

Northern Ireland Office

Visual Artists Ireland

109 Royal Avenue

Belfast

BT1 1FF

T: +44 (0)28 958 70361

E: info@visualartists-ni.org

W: visualartists-ni.org

Fingal County Council Arts Office in partnership with MART Gallery & Studios, are offering a funded studio space to support the professional development of recent graduates. The award offers space to develop creative projects and practice, connect with artists and take part in MART’S Annual Exhibition Award show in 2026.

To be eligible to apply, applicants must: have been born, have studied, or currently reside in the Fingal administrative area.

Closing date for applications is Monday 29th September 2025 at 4.00pm

To apply and find out more, visit: www.mart.ie

For further information email: ciara@mart.ie

Professional artists working in all artforms are welcome to apply.

Deadline:

26th September 2025 at 5pm. Applications will be accepted online. www.mayo.ie/arts/public-art/current-projects

Contact:

Aoife O’Toole, Public Art Coordinator, E: aotoole@mayococo.ie T: 094 9064 376

Kerlin Gallery

‘Pictures of You’, curated by Miles Thurlow, brought together 16 international and multigenerational artists, whose images, objects and actions evoke specific, often fleeting, moments. Artists included Eve Ackroyd, Simeon Barclay, James Cabaniuk, Samuel Laurence Cunnane, Hollis Frampton, Ryan Gander, Nan Goldin, Merlin James, Sooim Jeong, Laura Lancaster, Rachel Lancaster, William McKeown, Robin Megannity, Wang Pei, Hannah Perry, and Ki Yoong. On display from 4 July to 23 August.

kerlingallery.com

The Summer Group Exhibition ran from 24 July to 23 August, presented a mix of works by artists including John Behan RHA, Margo Banks, Leah Beggs, Comhghall Casey, Tom Climent, Clifford Collie, Eamon Colman, Julie Cusack, Orla de Brí, Ana Duncan, Margaret Egan, Bridget Flinn, Carol Hodder, Stephanie Hess, Bernadette Madden, Maggie Morrisson, Eilis O’Connell RHA, Helen O’Connell, Helen O’Sullivan-Tyrrell, Michael Quane RHA, Bob Quinn, John Short, Corban Walker, Michael Wann, and more. solomonfineart.ie

Temple Bar Gallery + Studios

‘Faigh Amach’ is an initiative by Temple Bar Gallery + Studios in partnership with Culture Ireland and Southwark Park Galleries, London, to support an artist in presenting their first solo exhibition outside Ireland. Roughly translating as ‘discover’, ‘Faigh Amach’ takes place as a group exhibition at TBG+S in late summer, bringing together three artists selected through an open-call process: Ella Bertilsson, Kathy Tynan, and Emily Waszak. The exhibition continues until 21 September.

templebargallery.com

LexIcon

‘Returning / Heritage’, was an exhibition of new artworks by Maeve McCarthy. The exhibition opened at the Municipal Gallery, dlr LexIcon in Dún Laoghaire on 6 July and ran until 3 September. The exhibition featured new paintings, charcoal drawings, objects and a film. Through her work, McCarthy explores her mother’s family story, from their roots in County Down to her grandparents’ move from Kilmainham to Sandycove in the 1930s. ‘Returning / Heritage’ is the result of McCarthy being awarded a dlr Visual Art Commission.

dlrcoco.ie

Taylor Galleries

Garrett Cormican’s latest exhibition, ‘Trading Places’, explored cities, cultures, time, and identity. His paintings of Istanbul, a city where past and present collide, capture the pulse of its architecture, markets, and bustling trade routes. Vibrant still-life works, echoing both modernist and classical styles, celebrate the vitality of food, movement, and cultural exchange. Cormican, a self-taught painter, curator, and author, has exhibited widely across Ireland and Northern Ireland. ‘Trading Places’ was on display from 1 to 23 August.

taylorgalleries.ie

TØN Gallery

‘Radical Acts’ presented the work of five Brooklyn-based painters, exhibiting together in Dublin for the first time: Jared Deery, Judi Keeshan, Paz Mallea, Rachel Ostrow and Til Will. Each artist creates their work in moments of stillness amidst the intensity of New York, transforming quiet reflection into bold expression on canvas. Their practices signal a radical gesture of presence and creativity, emerging from the city’s industrial corners yet resonating far beyond, offering viewers powerful glimpses into contemporary painting. On display from 7 to 31 August.

tondublin.com

ArtisAnn Gallery

‘Representing Nature’ by Colin Watson RUA was on display from 2 July to 30 August. Alongside studies towards fully realised paintings, this exhibition also presented standalone, spontaneous, intuitive works that directly respond to observed natural phenomena. This selection of artworks represented a cross section of the artist’s working methods beyond the finished paintings. Watson lives and works in Belfast, and has held seven solo exhibitions in London, as well as in Dublin, Northern Ireland, and Morocco.

artisann.org

Belfast Exposed

‘Frits de Ridder: Staring at the Sun’ marks the first exhibition by the Dutch photographer in over 30 years. ‘Staring at the Sun’ presents an unflinching portrait of life, illness, and resistance during the height of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. This landmark exhibition, realised with the full support of de Ridder’s family and unprecedented access to his archive, marks the first public presentation of his photographic estate since his passing in 1994. The exhibition continues at Belfast Exposed until 20 September.

belfastexposed.org

Golden Thread Gallery

‘Beyond the Gaze – Shared Perspectives’, by Sophie Calle, was presented from 21 June to 27 August at Golden Thread Gallery. The exhibition brought the work of Calle, one of the most celebrated and influential conceptual artists in the world, to audiences in Northern Ireland for the first time. ‘Beyond the Gaze – Shared Perspectives’ presented video works (Voir la Mer, 2011) and photographic pieces (L’Hôtel, 1981–1983). The work presented in the exhibition was loaned from the Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris, and supported by Galerie Perrotin. goldenthreadgallery.co.uk

Atypical Gallery

University of Atypical partnered with Dublin-based Connections Arts Centre (CAC) to bring their group exhibition to Northern Ireland. Connections Arts Centre is a not-for-profit social enterprise that supports neurodivergent adults, including adults with learning disabilities, in Ireland. CAC exists to enhance inclusivity and empowerment by tackling inequalities faced by disabled people, by providing accessible and innovative training, arts, and community education programmes. On display from 7 to 27 August.

universityofatypical.org

Rónán Ó Raghallaigh is an artist from Kildare working with painting, writing and performance. His practice engages with pre-Christian Ireland as a means for contemporary postcolonial action. Folklore, history and archaeology rooted in the Irish landscape form a foundation for research. His exhibition ‘Turais Taibhsí’ is the result of a personal pilgrimage to a sacred place in the Irish landscape. He researched the folklore imbued in these places, their logainmneacha (Irish place names) and archaeology. On display from 7 August to 11 September. culturlann.ie

Shankill Road Library

‘All in Colour’ was an exhibition of new paintings by Louise French at Shankill Road Library. It was the eleventh of Flax Art Studios’ annual exhibitions in partnership with the library – an opportunity for an artist to present their work in a community setting. ‘All in Colour’ presented a new series of paintings made on surfaces with pre-existing imagery. Through experimentation with materials and processes, the paintings explore colour and form. On display from 14 July to 31 August.

flaxartstudios.org

Alley Theatre

‘Strange Enlightenments – Responses to the work of Brian O’Nolan’ is a group exhibition at the Alley Theatre in Strabane.

Curated by Dr Marianne O’Kane Boal, the show features painting, drawing, sculpture and photography, selected in response to a quote from The Third Policeman. It points to each artists’ journey in interpreting the writings of Brian O’Nolan/Flann O’Brien, the experience of creating their responses, and the aesthetic outputs that provide strange enlightenments for the viewer. On display from 23 June to 30 September. alley-theatre.com

‘Fissure’ features the work of eight Master of Arts in Creative Practice students from the School of Design and Creative Arts (SDCA), Atlantic Technological University (ATU), Galway. Curated by Soňa Šmédková, the featured artists are: Dina AbuSehmoud, Mohamed Alkurdi, Carine Berger, Rocío Romero Grau, Kate Hodmon, Laurence Hynes, Cheryl Kelly Murphy & Evan Murray. The title of this exhibition draws on notions of gaps, marks, pauses, boundaries, and margins. The exhibition is on display from 8 to 23 September. galwayartscentre.ie

Sculpture Centre

‘Matters of Process’ is a new series of exhibitions that explores the work of artists who completed a Technical Development Research Residency (TDR) last year at Leitrim Sculpture Centre. During their research phase, the artists (Niamh Fahy, Lucy Mulholland, Blaine O’Donnell, Kate Oram, and Sonya Swarte) conducted experiments with diverse materials and objects. ‘Matters of Process’ highlights these processes and showcases how they influenced the generation of new work and ideas. On display from 8 August to 6 September. leitrimsculpturecentre.ie

Backwater Artists Group

‘A Deeper Well’ by Róisín O’Sullivan was on display from 3 July to 1 August. The exhibition consisted of new and existing work spanning painting and wood carving, exploring the emotional and spiritual dimensions of the natural world and our place within it. Inspired by her surroundings, Róisín uses abstraction to communicate the indescribable qualities of being in the natural environment, referring to experience and memory, and an innate elemental connection.

backwaterartists.ie

GOMA Waterford

‘To be spat back out’, by Bassam Issa Al-Sabah, Jennifer Mehigan and Caoimhín Gaffney, ran from 26 July to 23 August at GOMA Waterford. The exhibition revelled in waste and excess, examining the expressions of excessive emotions as a queer strategy of resistance. Through storytelling, images and texts, reality bends to a breaking point; mirroring how trauma distorts, remakes and retells lived experience in its own image. The exhibition employed non-linear storytelling, poetry, surreality, virtual reality, and daydreaming. gomawaterford.ie

Sirius Arts Centre

‘Symplegmatic Portals’ by Samir Mahmood featured newly created works, including a series of large-scale scrolls, alongside an extensive selection of works made between 2017 and 2024. These works explore what the artist calls ‘queerscapes’ – transcendental spaces of liberation where bodies, on their own or in dialogue with nature, are interacting, mutating, coalescing. The term ‘symplegma’ carries multiple meanings related to sexuality and connectedness. The exhibition continues at Sirius Arts Centre in Cobh until 13 September. siriusartscentre.ie

Custom House Studios + Gallery

‘Caught in Blue’, a solo exhibition by Sarah Wren Wilson, was on display from 24 July to 17 August. This exhibition invited the viewer into a liminal space – a deep blue space within another space. Blue, with its associations of depth, vastness, and the unknown, creates an atmosphere of openness and quiet immersion. By entering, the viewer becomes more than a passive observer; they become part of the artwork. This immersive encounter opens a dialogue between the inner and outer worlds; between what is seen and what is felt. customhousestudios.ie

Hamilton Gallery

‘Seeing is Believing’ by Charles Harper RHA ran from 2 to 23 August at the Hamilton Gallery in Sligo. For Harper, the act of painting is what matters, as he sees the actual process as one of exploration and discovery, stating that: “The process, the making excites me more than any end product.” He uses recognisable images to convey his ideas, and his work always illustrates a structure and organisation. Harper works in series, and his preoccupations have focused on the human figure, with a brief expansion into landscape paintings. hamiltongallery.ie

The Model

Curated by Michael Hill, ‘Extra Alphabets’ is the largest exhibition of Mairead O’hEocha’s work to date. New large-scale paintings depict tabletop arrangements, birds invading a garden lunch, an octopus in a trophy room, and a blizzard observed from indoors. Also included are paintings of animals behind glass in museums, thereby illuminating art-historical ideas of containment, timelessness, and display. In addition, painted interventions charge the gallery walls. The exhibition continues until 20 September.

themodel.ie

Esker Arts

‘As One Leans Into Another’, by Naomi Draper, was presented at Esker Arts in Tullamore from 5 July to 30 August. Draper’s work references a diverse range of research sources centring around botany and botanical activity throughout history. Her practice investigates processes of collecting, preserving, and archiving natural particles, fragments and found objects, harvested from our landscape. The artist is interested in the role of production processes and making in the negotiation of relationships between humans and other matter.

eskerarts.ie

Highlanes Gallery

‘Dysphoric Euphoria’, by Peter Bradley and Stephen Doyle, was on display from 28 June to 10 August at the Highlanes Gallery in Drogheda. The exhibition presented the polarising extremes of queer existence, with Bradley and Doyle explored the joys and the hardships of queer experiences through painting. The exhibition also tackled themes of societal exclusion, religious power, and identity in a contemporary Irish society. Accompanying the paintings within the show were texts by El Reid-Buckley, FELISPEAKS, and William Keohane. highlanes.ie

Uillinn

‘Grá’ is an exhibition drawn from Crawford Art Gallery Collection, selected by the Salt & Pepper group (West Cork’s elder LGBTQI+ arts collective) with artist Toma McCullim. Accompanying this curated selection are responses to individual artworks in the exhibition made by artists from the Collective. Featured works from the collection include Victoria Russell’s Portrait of Fiona Shaw (2002), The Red Rose (1923) by John Lavery, and Patrick Hennessy’s Self Portrait and Cat (1978). The exhibition continues until 20 September. westcorkartscentre.com

CORNELIUS BROWNE CHRONICLES HIS USE OF DRIFTWOOD AS SUPPORTS FOR HIS PLEIN AIR PAINTINGS.

AFTER STORM ÉOWYN, our local beach lay strewn with sea-worn treasure. Before those tempestuous hours, we had fallen into the habit of beachcombing. In the wake of her brain haemorrhage, collecting littoral odds and ends became part of my wife’s rehabilitation. Slow walks along the sands in the shadow of mortality, one hand gripping her walking stick, the other hand clutching mine, gradually improved Paula’s balance. In winter light, unable to turn her head sideways, she developed an eye for mermaid’s tears – tiny pieces of sea glass, winking at the low sun.

Trodden underfoot, to healthy walkers, these scatterings of colour seem invisible. I’d bend and raise each find towards Paula’s gaze. Perhaps a century in the Atlantic for bottles or ink wells or whatnot to metamorphose into frosted jewels of turquoise, green, white, brown, or array of blues. Unbeknown to Paula, my heart panged every time a teardrop resembled the shade of her eyes.

Rougher gifts were torn from the waves by Éowyn. Little did we know, as we devoted short gloomy days to gathering driftwood, that my painting was about to undergo a transformation. Our lives have played out far from the world of art galleries and museums, and batches of years without seeing a single exhibition are common. The beauty of the wood we found, half wedged into sand or partly hidden among rocks, had us all but bowing to the sea. Astonishing show! Breathtaking artist! Saltwater, time and violent forces had sculpted segments of old ships or broken piers into pieces of startling expressive power. Paula floated the idea of an artistic collaboration, between me and the ocean. As electricity was painstakingly restored across the country, the prospect grew from a glimmer on the horizon.

This light had climbed to the zenith by the time our first mini heatwave arrived. Having checked that the driftwood was uninhabited (shipworms live in networks of burrows), drying out the wood on hillslopes familiarised my hands with each piece, performing turns as the hot sun crawled

overhead. At the priming stage, Paula and I decided not to coat to the edges, leaving a rough border of surface exposed. Rusty nails were left protruding; holes and gashes remained unfilled. The past bestirred, much as Éowyn had stirred up the sea to drag hidden objects from the ocean floor.

All year, I’ve been reliving pages of a diary kept during 1985, when I painted outdoors almost every day. Materials scarce, my younger self often resorted to using found wood. I’ve been painting in the same places on the same days, recreating lost pictures. These are drift days, pulled ashore by paint from the sea of time. I’m painting on bygone days. The ineptly sawn boards I habitually use are by conventional standards, rough and ready. Yet sometimes the paint yearns for wilder.

Painting on driftwood, the fragile craft of my brushwork launches onto waves of sensuous richness. Calm mornings call for pieces smoothed by the sea and blanched to pale greys. Should the afternoon wind rise, my easel berths gnawed chunks. Into crevices and gouges, I push paint, liberated from the flatness of manners. Enveloped in silvery rain and painting through the thickness of weather, an odd courage reaches me from rough-hewn sections of driftwood. Without decorous framing edges, they chant robustly, having already withstood storms and battering white horses. Peeling layers of ancient boat paint greet my fresh oils. Charred driftwood I leave unprimed, the raw dark meeting my brush on the same beach it was found, as I paint marine nocturnes. To aged scraps that have lived and suffered, I bestow lustrous moons.

Heading out on drift days to paint, I leave behind a house protected by hag stones. They perch on our windowsills to attract good fortune. Old magic. A contemporary enchantment one can light upon by slowing down to make these discoveries. Through each holed stone lies another world.

ROISIN AGNEW OUTLINES THE RESEARCH UNDERPINNING HER BAFTA-LONGLISTED FILM, STREAMING FROM NEXT MONTH.

IN HIS TREATISE on the voice, Slovenian theorist Mladen Dolar equates the voice with conscience before casting doubt: “A long tradition of reflections on ethics has taken as its guideline the voice of conscience… And why the voice? Its metaphoricity has uncertain edges. Is the external voice literal and the internal one metaphorical?”1 In 2006, this might have read as more Lacanian pulp, but in hindsight, it seems prescient in anticipating the intensifying assaults on the voice and its external form – speech – we are now witnessing.

In the summer of 2022, I unexpectedly won a pitching competition with a proposal for what ultimately became an unproducible film. The project aimed to examine the Derry Film and Video Workshop (DFVW), a Republican feminist collective, active within the 1980s Workshop Movement. I proposed to explore the transnational solidarities that emerged from Channel 4’s ‘Workshop Declaration’, a radical broadcasting initiative that provided equipment, training, producers, and airtime to communities historically excluded from television. The proposed film would trace how anti-colonial movements of the era found expression on screen and beyond, linking collectives like Sankofa, the Black Audio Film Collective, the DFVW, and figures such as Isaac Julien, John Akomfrah, and Pat Murphy, while situating these within political flashpoints like the Brixton Riots and the hunger strikes of 1981. The result would have been a cinematic hagiography of a politically charged period in British and Irish cultural history.

Archival access complications brought the project to a halt. But research led me to materials involving Mairéad Farrell, an IRA volunteer and one of the Gibraltar Three, killed by the British SAS in 1988. Her death prompted Channel 4 to withdraw what would become DFVW’s most recognised work, Mother Ireland (1988), a film directed by Anne Crilly that examined the intersections of nationalism and emerging feminist identities in Ireland. It featured several interviews with Farrell. The withdrawal was due to the Broadcast Ban.

A relatively obscure historical measure, with serious consequences far beyond its remit in Northern Ireland, the Broadcast Ban was so farcical in design that it became an ideal film subject. Introduced by Margaret Thatcher in October 1988 to deprive “terrorists” of “the oxygen of publicity,” the ban used the Prevention of Terrorism Act and the Licensing Bill to prevent the voices of members of proscribed groups “and their supporters” from being broadcast. It was widely understood as targeting Sinn Féin and its then leader Gerry Adams, who had been gaining electoral momentum.

I had been accessing undigitised footage through Northern Ireland Screen’s Digital Film Archive and approached them

about commissioning a new film, offering both financial support and a treatment. They agreed, and together with producer Sam Howard, I began what became an 18-month process of reviewing 108 hours of archival material to construct The Ban (2024). Some of the more visually compelling sequences came from a film shot in Belfast in the early 1990s by Alison Millar, who was then a student at the National Film & Television School in Beaconsfield, England. We also secured key clips, including a sketch from The Day Today in which Steve Coogan plays a helium-inhaling fictional IRA leader. Northern Ireland Screen generously covered the licensing fees. What emerged most clearly in the research was the British government’s fixation with the voice itself. Politicians referred to “voices in our sitting rooms,” as if the mere sound of republican Irish voices constituted a threat. After initial journalistic opposition was ignored, broadcasters – particularly the BBC – sought creative ways to comply while subtly resisting. Actors were hired to dub censored speakers, but both government officials and BBC executives insisted the dubbing be deliberately poor –out of sync and using mismatched accents – to further diminish credibility. The voice was not simply silenced but twisted for political ends.

The Ban was released in 2024, marking 30 years since the lifting of the Broadcast Ban in September 1994. A year after release, The Ban has had a modest but resonant afterlife, largely due to its relevance in a moment of resurgent censorship. At the time of writing, Palestine Action has been designated a terrorist organisation in the UK, and supporters risk prosecution. Dolar took the title of his book from Plutarch, A Voice and Nothing More, evoking the Greek chorus as a communal and moral force. The Ban reflects on how detaching voice from body was a tactic to discredit a message that nevertheless endured, conveyed through a strange chorus of actors who, in voicing it, became complicit. Today, resistance often requires assuming that same position, bearing the risks of speech as a final act of solidarity.

Roisin Agnew is an Italian-Irish filmmaker and writer based in London, where she is a PhD student at Goldsmiths’ Centre for Research Architecture and an associate lecturer at London Film School. @roisin_agnew_

The Ban will be available for streaming on The New Yorker website from October.

1 Mladen Dolar, A Voice and Nothing More (MIT Press, 2006).

IN THE FIRST of a series of interviews with distinguished Irish sculptors, Michael Warren, a maker of dignified and spartan forms, talks about his working disciplines and the self-imposed limits of his practice.

JASON OAKLEY’S INTERVIEW WITH MICHAEL WARREN WAS FIRST PUBLISHED IN THE SSI NEWSLETTER IN 1996.

Jason Oakley: I’d like you to talk, first of all, about your work in the outdoors, where I think some of your key concerns of rootedness in place and natural forces like gravity, are very apparent. Michael Warren: Yes, I have a great interest in making outdoor works. A characteristic I like is that it’s work for someone – work with an audience in mind. Chances are, someone is inviting the work, be it the mayor, local authority, an architect or a developer. With public money involved there is an obligation on the part of the artist not to be too obscure – to provide entrance points. In addition, there are strict limitations and curtailments which I find very challenging: a given location may dictate horizontal treatment or verticality – the range of appropriate materials will be limited –history of place and function are likely to be considerations. Then there are matters, that depending on one’s temperament, one can find a challenge or hindrance, such as the teamwork, site control and general diplomacy which are part and parcel of any big project. Of course, all of this isn’t worth two hoots if the artist doesn’t instil his or her own creative integrity and personal preoccupations – it’s a multi-levelled process, a dialogue. Too much twentieth-century work is a case of the artists working in a bubble. When so much explanation has to be joined onto artwork, there is something very wrong going on.

J.O: Your piece at the civic offices at Wood Quay is a good example of working to such constraints.

M.W: In that particular instance, I worked in close collaboration with the architect Ronnie Tallon. The verticality and scale of the work was determined by the building. A big consideration was of course the juxtaposition of the sculpture to the strict undercut form of harvested cedar, which was a nice foil to this, while the work’s base, 17 metres of white limestone, was a horizontal that had to be established.

J.O: And there are a number of obvious entry points to the work, such as the shape of the river at that point, a Viking longship...

M.W: If you go to the top floor of the building, where the planning offices are, you can see clearly the echo in the shape of the river, the bridge and the dome of the Four Courts. Much controversy surrounded the site with the Viking excavations: the work had to be a reconciliation of place past and present. As a new and important centre of civic administration, it needed a certain seriousness of intent and dignity. But to mark the full sense of place, it could not be forgotten that historically the Viking longships came right up the Liffey to this point. I took measurements from Scandinavian excavated longboats, the dimensions across the bow are replicated in the width of my sculpture. If you look at the sides of the sculpture, each laminate is uniquely tapered, feathered and fitted like the prow of a longship – tedious work!

J.O: To what degree do you find curtailments stimulating? Is an idea of limit important in your studio practice?

M.W: As I say, I find such public situations a tremendous challenge; I really look upon each new project as an adventure. In fact, I do not find any conflict between my more intimate scaled pieces and the public works. There is a clear common denominator – a common thread throughout. In both cases limit takes the form of a gravitational force. My indoor work could be taken as one continuous meditation on space and gravity. Activity takes place solely towards the bases of the work, with the descending vertical forms suddenly undercut at the last minute: the work has to be read downwards.

J.O: In this respect, I would regard your work as making a fairly significant step in terms of the history of sculpture. Most accounts centre on ideas of the sculpture freeing itself from the plinth, and perhaps gravity, to expand into a wider spatial realm.

M.W: From an art historical angle, I, like many students during the late 60s and early 70s, looked very closely at the discoveries of the Russian Constructivists. I later named my home and studio “Letatlin” after Tatlin’s famous aeroplane, the title combining his name with the Russian verb ‘to fly’. (In retrospect, I would have been better advised to call it Witsend or Taj Micheal!) The whole raison d’etre of Constructivists like Rodchenko and El Lissitzky was to elevate the mass. But we are talking about such brave talents here, such revolutionary understanding and usage of material, that a certain soil aesthetic unintentionally clung on to their spiralling shapes. I consciously combined my enthusiasm for Constructivism with my reading of philosophers such as Simone Weil and systematically set about inverting this thrust, replacing elevation of mass for its contrary. I needed to give anchorage and ‘here – and nowness’ to the work. That sense of ‘nowness’, presence and immediacy are vital issues in my work.

J.O: A lot of sculptors are dealing with this in the very broad sense of uncovering the social and cultural meanings of space; how does your work relate to this?

M.W: There is, I believe, a kind of innocence of perception that has vanished. In Medieval times, ceremonial costumes of heraldry registered like a trumpet call. We on the other hand are saturated with colour, form and sound. These, our very capacity for attention, our sense of place, have all been diminished and trivialised by technology.

J.O: Returning to the question of outdoor work, are natural settings of particular interest?

M.W: Yes, I particularly enjoy natural settings. There is a certain reverence of place which I am very conscious of. I take care not to interfere with trees, rocks or other environmental features. In the 60s space was venerated, whether enclosed or perforated, the attempt was made to make visible the invisible. In the same way, a section of natural landscape can be taken and worked to make that place a little bit more precious, mysterious, if not mystical. Something very good then has been achieved. In our Celtic druidic past, from what little we know, there seems to have been a strong sense and reverence of place. Historically, however, Ireland has suffered from having its chance of putting down roots and ‘rootedness in place’ undercut.

J.O: So, to some extent your work is addressing the post-colonial legacy?

M.W: Well, I don’t know about that – certainly, like it or not, we are all living and working within that framework – we are a young nation still very much trying to define our identity. Until recently there has been a psyche in Ireland of life being elsewhere, be it in Canada, America, England, or indeed in heaven! In Ireland we have become familiar with the anguish of living without putting down roots. I think that until we can really appropriate matter, its presence, and weight, it is idle to talk of spiritual renewal or cultural advance. There simply has been no long tradition of sculpture in Ireland. When I started out, I was part of what was only the second generation of Irish sculpture. There’s little point talking about High Crosses, which after all is the goldsmith’s art transferred to stone. Sculptors like Oisín Kelly and Gerda Frömel really were like ice breakers, and their achievement within the Irish context of sculpture wasn’t a lot short of heroic. I initially apprenticed under Frank Morris who tragically died very young. He had a great influence on me. We had a challenge, in fact, we had a whole psyche that had as yet not been explored in terms of visual art. At a time when a lot of European art was starting to look a little tired, there appeared to be advantage in our historical disadvantage.

I did a work in 1994, Trade Winds and Turtles, the first non-figurative sculpture on Guadeloupe, part of the French West Indies. It’s an island that has experienced horrendous colonialisation and has suffered cultural dislocation and rupture. Also, there is meant to be racial integration, which clearly there isn’t. 6% of the population is white – the others are largely tourists. Anyway, what I did there, working with traditional boat builders – wonderful people – was to take a 5-metre diameter circle shape – a pure form, a complete wholeness – and cut and dislocate it, just as their culture had been broken, but then reassemble the pieces to articulate a new story. The re–arrangement had clear references to things maritime, which made sense to a fishing boat orientated community. The circular base, 10 metres in diameter, partly cantilevers over the quay of a small fisherman’s bay. Then, because it was made from wooden laminates, I secured the structure with pegs of tropical hardwood, which I left protruding from the form. Very interestingly, even the children responded to these pegs (this was totally unplanned on my part) as having something to do with the epoch of slavery. When you get to know these people, they talk about slavery as do say people in County Clare talk about the Famine – as if it just happened yesterday. These pegs seemingly were associated with the locking system of the human yokes slaves were made to wear.

J.O: Could you talk about the significance of your move from constructed work, with obvious bolting and bracing, to your recent Stele works, carved from single pieces of wood?

M.W: Talking of my previous timber constructions, one of the devices evident in say the IMMA work Beneath the bow (1991), that I frequently used, is an elbowing out of plane of the predominant vertical. I have always been interested in parallelism in the arts.

It’s a nice thing, for example, to look at this interruption of the one-line fixation which I have explored in sculpture, in different disciplines.

J.O: Turning to your recent work, the Stele pieces and so on, shown at the Douglas Hyde Gallery last October [‘Simple Measures’, 1995], it might be described as condensing your concerns. The sculptures are rather minimal and free of specific references.

M.W: The reading of references will be governed by the social and cultural background of the people making the perceptions. My current work is not so far removed from – what should I say? – an almost primitive gestural aspect. My earlier sculpture beside these new works looks somewhat fussy. But yes, all in all, accessing these pieces is not easy and that is deliberate. The real subject matter lies between viewer and object – they are contemplative works with contemplation itself being the main issue. Timber as a material: material as matter – these too are important. Side references are severely minimalised if not eliminated, which is not to say this is Minimalist work.

Some critics like to label this work Minimalism. But whilst I have looked long and hard at Minimalism, American Minimalism can be said, to paraphrase Gertrude Stein, to assert that “A box is a box is a box is a box.” But for me as a European, a box can never be just that. Paul Klee wrote that forms, however abstract they are, never lose their power of association, a box is a throne, is a chair, is a table...is a tomb...

J.O: So, these pared down forms are open to many symbolic readings and forms of contemplation; is there any particular one you have in mind, when you have been making these works?

M.W: I could describe my Stelae as mandatas of a sort; they are private attention props if you like. Sculpture here is a function of attention. Their making as well as their viewing, to use unfashionable terminology, is a form of prayer. Their contemplation is not dissimilar to the goal of Buddhist ‘one-hand clapping’.

J.O: The Stelae then, are a very precise statement of your concerns that have put boundaries on your practice and defined the significance of its limits?

M.W: Yes, I think so. In an interview with Milan Kundera I once read, he notes, talking about the modern novel, that we live in a society saturated with answers. Art too is looked to for answers, whereas he, Kundera, sees its function lies properly in the domain of questions – not answers – the right questions... I have staked my life’s work on a single belief, namely that when an attention is directed at matter here-and-now, in all its density and intractability and precisely when an attempt is made to express what is always silent, the object is transcended and a reality beyond the immediate is touched.

The fulcrum is attention: gravity has become an upward movement.

This is a streamlined version of an interview between SSI Editor Jason Oakley (1968–2015) and sculptor Michael Warren (1950–2025), first published in the SSI Newsletter, September –October 1996, pp. 17–19. The original full text is now available on The VAN website. visualartistsireland.com

GRACE O’BOYLE GAUGES THE IMPACT OF STEVE MCQUEEN’S FILM, CURRENTLY SHOWING AT THE MAC IN BELFAST.

A SERIES OF self-portraits by Gambian-British photographer, Khadija Saye, was recently presented at the Irish Museum of Modern Art as part of the exhibition, ‘Take a Breath’. The title of the series, Dwelling: In This Space We Breathe, takes on a prophetic poignancy when viewers learn that the works were first shown at the Venice Biennale’s Diaspora Pavilion in May 2017 – just weeks before Saye and her mother, Mary Ajaoi Augustus Mendy, died in the Grenfell Tower fire. The exhibition opened at IMMA on 14 June 2024 in quiet acknowledgment of the seventh anniversary. Saye’s portraits, rendered now as spectral objects, leave the viewer with a deep sense of loss – not only for Grenfell’s 72 victims, but for the art Saye will never make.

In December 2017, six months after the fire, Oscar-winning British filmmaker and artist Steve McQueen filmed Grenfell, a 24-minute film, captured from a helicopter. The film was first presented at the Serpentine in Kensington Gardens in April 2023, following private viewings held for survivors and the families of those who died. Without construction hoarding or visual obstruction, Grenfell serves as a record of the building in the direct aftermath of the tragedy. Now showing at the MAC in Belfast, as part of a UK tour coordinated by Tate, Grenfell offers a space for viewers to encounter McQueen’s critical exercise in remembrance.1

A quiet unease hung in the theatre when I attended the MAC in late July. Fellow viewers were subdued, almost solemn, as if gathered at a site of mourning. We shared a space bound by collective silence – one that, in moments, gave way to private introspection and anguish. In these moments, the space became a fertile threshold for intimacy and humanity; although alone, we grappled with the weight of failure and social injustice together.

A glaring blank screen induced a feeling akin to white noise

frequency – it purified our sight and the room. The film begins with aerial views of London’s sprawling conurbation. The camera placement produces a simulation-like effect as we hover over the landscape. A moment of birdsong is heard, but there is no narration or soundtrack in this film. As viewers, we occupy the space between land and sky, observing green fields, residential suburbs, and an expanding horizon line. Suddenly, the path re-routes, and London’s skyline appears, enveloped by smog. Buildings are veiled in a gossamer golden light. However, the futuristic cityscape is a deceptive aesthetic; futurism tends to intersect with themes of hope and is often used when reimagining cities towards social progression.

The camera sweeps over London as life is burgeoning below. The urban vernacular is visible: Wembley Stadium, Kensal Green, Willesden, and the Westway motorway. It is a slow passage towards Grenfell Tower in North Kensington, which has been distant and undecipherable up until this point. The camera begins to drop as a loud mechanical noise disorients the senses. The charred remains of the tower become pronounced, visually woven into the everyday fabric of a busy city.

The skeleton of the tower is intact; white panels of hoarding cover the lower floors. Eventually, the entire 24-storey building will be wrapped in panelling that shields it from public view. The gaze is resolute – there are no pauses; this is a single, unedited shot. The cam-

era circles the tower creating a bird’s-eye view. Moving closer, the shot focuses on debris. Failed materials, such as insulation and cladding, have mutated – they appear to have coagulated and foamed. This visual is grotesque and affecting. According to the Grenfell Tower Public Inquiry, the building products firm, Kingspan, based in County Cavan, was found to have demonstrated a “complete disregard for fire safety” in its marketing of the insulation product Kooltherm K15.

The camera continues its orbit around the tower block, scrutinising each angle in methodical detail. Plastic film is tightly wound around the remainder of the shattered windows. Bags pile on the floor, and forensic investigators in white hazmat suits sift through the wreckage. The scale of disaster is demonstrated by McQueen through his quiet, exhaustive exploration of the site – up, down, around and through. He enlists the viewer to investigate the scene. One thought pervades: “How could this happen?”

As a filmmaker, McQueen approaches his subjects with integrity and assertiveness. He rejects the indulgent allure of spectacle and instead makes space for us to quietly witness. His objective is clear in Grenfell – he lays bare institutional failure and corruption by making visible the material and emotional devastation caused by negligence and systemic dysfunction. The film is a call to action and a defiant act, in not allowing this preventable tragedy to fade from the foreground of public

memory.

In his accompanying essay, ‘Never Again Grenfell’, Paul Gilroy, author and professor at University College London, suggests that “there is much to gain in confronting the meanings of the damaged structure and making the shock of our painful contact with it instructive”.2 The Public Inquiry, led by Sir Martin Moore-Bick, found in 2024 that the fire was the result of decades of failure across government, the construction industry, architects, and regulators. The inquiry concluded that all 72 deaths were preventable.

Outside the screening, there is a table of small booklets featuring Gilroy’s essay. Flicking through the publication, Khadija Saye’s name appears in a memorial list for those who lost their lives – she is second last from the bottom. The encounter induces a similar feeling of loss to that of witnessing her portraits at IMMA. It engulfs the moment – a thread of grief and remembrance, spanning from then until now. Grenfell screens at the MAC in Belfast until 21 September (themaclive. com).

Grace O’Boyle is a curator, writer, and Collection Officer at the Arts Council of Ireland.

1 Charlie Brinkhurst-Cuff, ‘Steve McQueen’s ‘Grenfell’ Is a Critical Exercise in Remembrance’, Frieze, 20 April 2023.

2 Paul Gilroy, ‘Never Again Grenfell’, 24 April 2023.

Aengus Woods: Tell me about your formative years as an artist. Maud Cotter: I went to the Crawford College of Art. John O’Leary taught drawing and was foundational in setting me on the right track. He told me never to take any notice about what anybody thinks of my work. He also said that a drawing itself isn’t of value – it’s what it does in your mind. So, I realised that art was about perceptual capacity and inquiry. I began very quickly to move towards things that were of value to me, and I managed to persuade John Burke to let me into his sculpture department. Around then, I went to America, and I was confronted by Rothko and Roberto Matta. I was very drawn to line, but line having a quality in space.

AW: So, a transition from drawing to sculpture but still a relationship between the two?

MC: Absolutely. I remember I was invited by the staff to be part of an exhibition with them, which was hugely affirming for me. But not long after that, John Burke came into the studio and we had an extreme conversation. He said you can either work with me in the way I am – which was very Caro-esque with plates of steel and an industrial feel – or you can resist me. I realised then that I was interested in this state of resistance. In fact, he was acknowledging that I would be in resistance, which I think was very generous of him.

AW: You also encountered Joseph Beuys around then?

MC: In 1974, I came back from the States and Beuys visited the college. And I had been doing these particular line drawings with a whole system of weights, growth lines and symbols – geologically layered drawings with man as a kind of vertical thing. But I wasn’t sure how one activated the other or how anything worked; it was

an evolving system of thinking.

Then Beuys came to the Crawford and gave this most incredibly dynamic lecture. He did a drawing of a head and put a line right through the top of the skull. That was it for me; it symbolically created that social space, but also a kind of a level of connection. I continually revisited that drawing by Beuys over a period of a week. As he was so influential, I had to avoid what I used to call the ‘Beuysian Pit’! Beuys’s exhibition, ‘The Secret Block for a Secret Person in Ireland’ at the Municipal Gallery of Modern Art in Dublin (25 September – 27 October 1974), was so integral to his conceptual development. So, you could imagine, I was in heaven… it was amazing!

After college, I felt I had to mature, so I stayed in Ireland. I became involved in glass because of its power to mediate energy beyond itself, which keyed in with my desire for materials to do the same. But I eventually went to London in 1991. Location was a big problem; how to locate oneself culturally within the context of the UK was a heavy influence. I had to find that subjective distance between America, the UK, Ireland, and Europe, and just find my way.

AW: So not just between two competing monolingual frameworks, but within multiple scenarios and the concerns that come with that?

MC: The 70s were such an incredibly intense feminist environment, within which every woman worth her place in the world had to become an activist. I couldn’t do it, because my work addressed humanity and not particularly feminist issues. But exposed to the urbanity and complexity of London, I began to make works like Outer Veil, Inner Shroud (1996) for the Economist Plaza in London. which was a kind of mourning for the self that was dying and the emergence of a new self, and In Absence (1998), my molecular wall I made for Rubicon Gallery, facing the consequence of the body in the city.

Then I began to work with cardboard and so forth. I felt like I was finding my subject in terms of taking on larger scale abstractions and bringing more psychological moments into focus; more intangible moments around being and matter, which, if you think back, were really the context of my early drawings. I then did a lot of work that was somehow in thematic series, akin to [T.S. Eliot’s] Four Quartets. I began to work with this feeling of somehow meaning being drained. Things of No Fixed Meaning (2000) was a piece I made when in residence at IMMA. It explored the idea that meaning is a volatile thing within objects and can bleed away.

AW: A lot of public art is based on a sense of apparent timelessness. You get a commission to make something that is supposed to last a long period of time; however, you use materials that change and deteriorate and have a different temporality to that kind of permanence. MC: Yes, but they also have porousness. I understand objects as having almost an exhalation and inhalation, an oscillation of energy. They project the range of associations in our mind and then they pull back in. I began working with found materials, spending a long time with them until the material almost becomes undressed, shifts, and finds commonality in other things. In a way, this kind of anticipated the New Materialism. I was very interested in the way Agnes Martin made her pieces – she didn’t use a long ruler to get an absolute line, because within the over-described absolute is death. She found her line by hand. So, while they were still within a geometry, they had all these minute inflections and when you stood back, that’s what became the piece. It’s the tissue of thinking. It’s also a lack of possession, allowing things to grieve and be, creating territory into which other people can enter. I don’t bring my pieces to their finish. I did with one piece but it died in front of me, so I brought it back to an earlier stage. Now I never bring things to an ultimate end.

AW: You must have strategies to move against that sense of completion if you see it approaching?

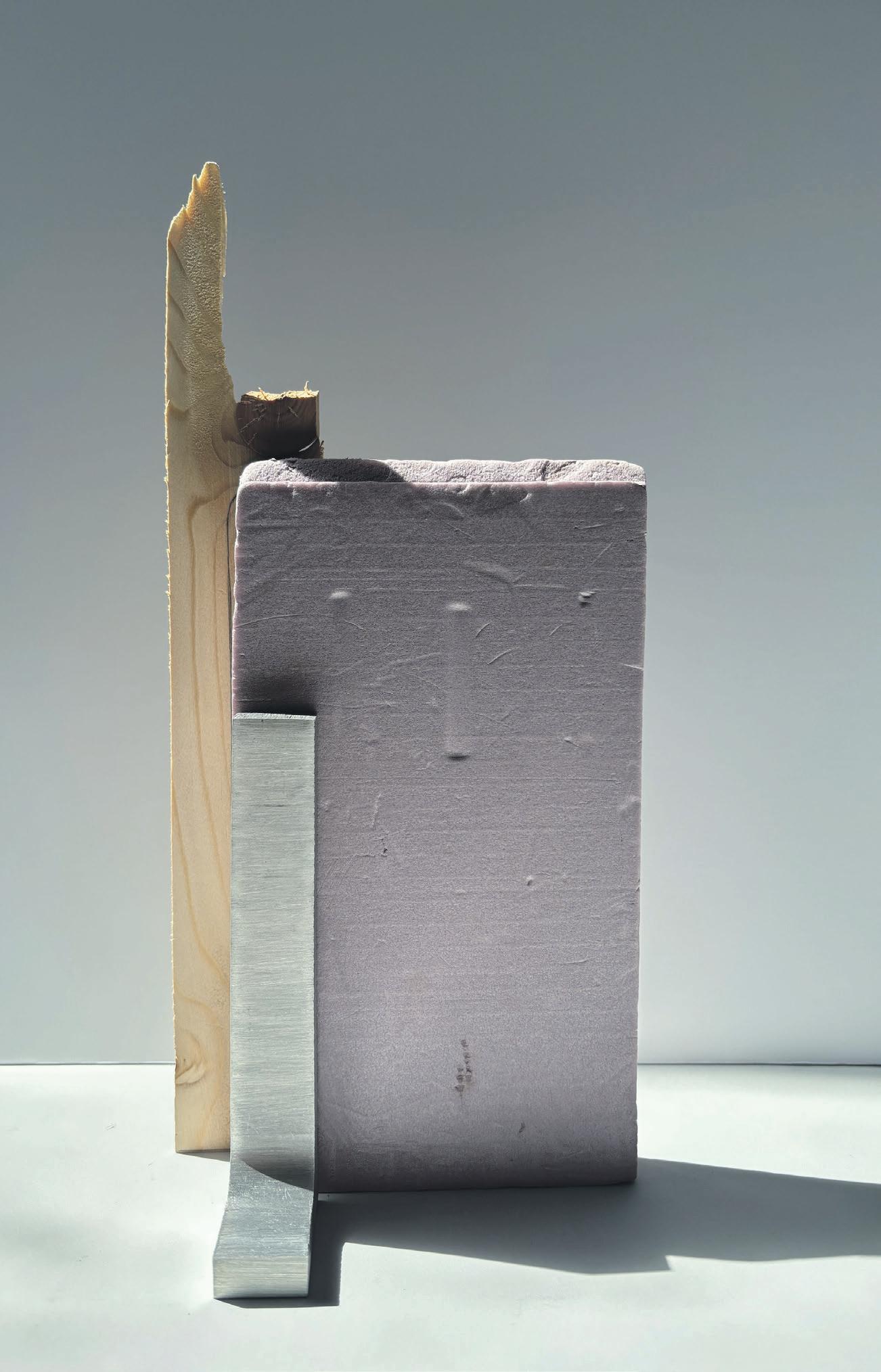

MC: I do. I avoid it. My aluminium piece, all things seem to touch so they are (2025) is a case in point. I was

very fortunate to have Amanda Hunt working with me. We both learned aluminium welding together. For me, that piece is just a bare skin of oxidization; the inside of it is like liquid, so it becomes a kind of neural pathway. It is very much about consciousness, in a way. If you sand and polish aluminium it instantly begins to turn away from the world, since it acquires oxidization almost immediately. It’s a beautiful and very mysterious metal.

AW: Can you discuss your forthcoming show at Highlanes Gallery?

MC: I was very grateful to get the invitation from Highlanes because I knew I could put the spiral piece, maelstrom (2024), in the downstairs space. And the aluminium piece was ready to be made. Sometimes things are just ready to be made. You could intellectualise forever about something, but until it’s ready to be made, you can forget it. Everything just kind of fell into place. There’s also the piece, what was never ours to keep (2022), commissioned by MOCA in Jacksonville, Florida, on the occasion of my first museum show in America. It focuses on ideas of possession and the degree to which corporate interests now possess information.

AW: Tell me about the marbled papers.

MC: Yes, the Suminagashi pieces. The thing about the Suminagashi technique is that it involves compressed soot, floating on water! So, it has that elemental, ancient quality. You dip one brush in the ink and then dip another brush in with a little soap in the water and one repels the other and it creates this kind of duality. It is fascinating in its proprietary power. Jennifer O’Sullivan, print technician at Crawford for years, taught me this and I worked with it over several weeks, just slowly pulling the papers off and drying them. You could never, ever get one to be like the other.

AW: Language is a big part of your work. Not only concerns with meaning but the texture of words themselves and pieces you have done with Coracle Press. MC: The thing is that words are resonances for me, and they take possession of sound and space. I came across the phrase recently, “the breath turned between words,” which is actually very core to the tenacity or the gelling system in all my work.

AW: It’s almost as if you’re most interested in the ‘airy’ aspects of language – the actual speaking of it, the

mutation of it, and by extension in your sculptures, that sense of the visible aspect of the air, the animation of it.

MC: But that’s the embodiment! That’s the part that we’re all going to lose, you know, through this AI idea we are somehow meeting. We’re already meeting it in our mobile phones, where we find out things we don’t know – but then where’s the embodiment to come from? I am wary of AI because it doesn’t carry the complexity, the incredible nuances and differences, and the sheer intelligence and understanding that we are capable of bringing to everything.

AW: It's almost like AI is designed to hide the complexity; that is its very function and virtue.

MC: Well, because it’s an instrument of commodification. I feel everything I come upon has its rootedness in my psyche. AI lacks one major thing for me, and that is this idea of embodiment.

AW: I remember a few years ago, we were getting a little anxious about social media and the preferred ways of engaging with art. I presume that you still want people to come and physically experience your work?

MC: Duchamp did a series of afternoon conversations, and he said an interesting thing: that the Mona Lisa would fade, would dry out, by virtue of being seen too much. It’s a controversial thing to say but an interesting idea because of course, the shifting consciousness and understanding of an artwork will leave it dry or activate it – it’s not a stable thing. So, yes, I like people to see my work. But I quite like the challenge of coming up with an image accompanied by piece of text, that there’s somehow an interactive thing going on. It resonates at a certain frequency, and by virtue of that, has its own little oscillation, that somehow it can enter that world combatively and still generate its own associative connections.

Aengus Woods is a writer and critic based in County Louth.

@aengus_woods

Maud Cotter is an artist based in Cork City. maudcotter.com

Cotter’s solo exhibition, ‘Maelstrom,’ continues at Highlanes Gallery until 1 November. highlanes.ie

John Gayer: Examining artists’ paths fascinates me, since it can divulge previously unknown links between early and recent works. Your HIAP studio on the island of Suomenlinna includes things that are pictorial, textural, segregated into groups and/ or layered. What’s the background?

Clíodhna Timoney: While doing this work, I recalled the portfolio course I did when I was 17. And though our work develops over time, the crux of things endures.

JG: We can’t escape ourselves, can we?

CT: No, we can’t. But to answer your question, whilst studying for my MFA in London, I was reflecting on the rhythms that places have. The rhythm of County Donegal, for instance, has a certain specificity. When I asked people about this, they said it relates to the sea or the hills, which got me thinking about the human and nonhuman, and our relationships with the site. Going back further, my works have always furnished insights into rhythm, movement and resonance. But when the pandemic happened, I returned to Donegal, realising my works would engage with these ideas in relation to that space’s materiality. So, for my MFA graduate show, I created works out of the metal, car parts, lights and other things left in the garage and sheds at home. One work that stood in a field like a spectre or figure, I photographed at dusk. The timing was important, as I view dusk as a point of transition which can ignite behavioural changes. I titled it Keep ‘er Lit (2021).

JG: Did you say “Keep her lit”?

CT: Yes, it’s a local term in relation to car culture. Another work, also comprised of remnants, intimated it could be drawing energy out of the ground. But after laying

it in a hollow in the ground when it was dark, it became more of a burial and alluded to death and life. Its title is Clean Wired (2020), which is just another…

JG: …Car related term?

CT: Yes, or a colloquialism that describes a sensation of visceral intoxication. Then, in another work, titled P.E.T.R.O.L (2020), I staged the contents of a shed. Its theatrical lighting references dramaturgy and is a meditation on how we perform in spaces, continuing my approach of making proplike sculptures.

JG: Would Pebbledash (2019) be an example?

CT: Yes, the sculptural work, Pebbledash, refers to a wall that fascinated me as a child. The added sound piece addresses the material’s strangeness.

JG: Hearing it impressed me. It accentuates the surface’s pointiness.

CT: I used the TB-303 synthesiser – a seminal sound in acid house music and rave culture – to create it. The sound of this synthesiser interested me as an undergraduate student, and its relation to the idea of ‘becoming’. For my degree show, titled ‘TB303’, I made other prop-like works. Each work in this series was an awkward, in-between thing – like Pebbledash. While I work predominantly in sculpture, for my three-month residency in Helsinki, I’ve focused more on photographic processes and the use of light. And though I’ve used these mediums for years, they still seem new and unfamiliar to me.

JG: The dynamic play of light and darkness in Clean Wired (2020) surprised me. Has

anyone noted that it’s Caravaggesque?

CT: No one has, but I did think that myself. It has this legacy of drama. There is artifice in what I do, and staging interests me greatly. The sites that attract me – such as backroads and crossroads – can be viewed as stages. The performances occurring on that stage can be intimate or violent as well. I reflect on this in the video work, When Crossroads are Empty Give Her Plenty (2020). Crossroads were once places where people would gather to dance, before being outlawed by the Public Dance Halls Act of 1935. Growing up on a farm on the edge of a town, edgelands have always intrigued me. While many differentiate urban and rural, to me they are enmeshed. The title for The Stranger (2021) – which refers to these enmeshments and the stage – derives from ecologist Timothy Morton, who talks about the ‘strange stranger’ and the existence of ‘hyperobjects’. Though the sculpture is wearable, the image of me wearing it became the artwork.

JG: Was it used in a performance?

CT: No. Though performance makes sense, I haven’t reached that threshold yet. The Stranger led to Flashes of Light (2022), a body of work that, by referencing both the farm and rave culture, aims to highlight the edges and permeability of enclosures, and bodies, both human and nonhuman. Then, for EVA International in 2023, I researched the Showband Era, which reaches back to the Rainbow Ballroom of Romance, built in County Leitrim in 1934. The installation, In the Wee Hours (2023), isn’t meant to be nostalgic, but a commentary on people’s desire to connect. It focuses more on the journey to the dancehall, as well as a specific type of light. Where the hand dyed textile

pieces, Lines of Flight, represent gradients of light, Spit on me, a series of glistening ceramics, refers to Dickie Rock, a popular singer in the 1960s. Despite the oppressiveness of the times, women would make a particular gesture by shouting: “Spit on me Dickie.”

While in London in 2024, I visited a friend in Greenwich – the home of Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) – which became the catalyst for what I’m doing on this residency in Helsinki, and prospective future works. I am considering how to reflect the absurdity of this hyperobject of time. I visited Finland to experience the light, the seasonal/cyclical temporalities, and their relationship to industrialised time, all of which differ from Ireland. I’ve been researching, visiting archives, going for walks, and taking photographs. My favourite images are those affected by the leaking light.

John Gayer is an artist and writer based in Helsinki.

johngayer.weebly.com

Clíodhna Timoney (she/her) is a visual artist working across imagery, sculpture and sound.

cliodhnatimoney.com

The TBG+S/HIAP International Residency Exchange supports Ireland-based visual artists to spend three months at Helsinki International Artist Programme. The exchange also supports Finnish artists to live in Dublin and work from a studio at Temple Bar Gallery + Studios. templebargallery.com

DIRECTOR OF KUNSTVEREIN Aughrim, Kate Strain, got in touch with me last year, through the loveliest email, asking if I was interested in a studio visit, so that she could get to know my practice more. I was filled with excitement, as I find it rare these days that curators would genuinely reach out to artists to have a conversation. It was refreshing to say the least.

Kate mentioned that she was thinking of developing an artist residency programme in Aughrim and asked whether I’d be interested in participating in the pilot programme in summer 2025. In my head, I was already there – in Aughrim and all around County Wicklow. I have only been to the Wicklow Mountains once, back in 2019, and was warned by my friend, Michael, that there was going to be an abundance of light and beauty.

Can you see with your heart? This question sums up my time in Aughrim and is the title of a new body of photographic research, which combines with another ongoing photographic project of mine, called ‘Little Did I Know’. It felt natural and easy to imagine these two projects in communication, almost like a phone call, informing each other about the past and the present.

In ‘Can You See With Your Heart?’ you will find me listening to past conversations that never left me, about the different ways

I’m trying to stay in touch with my heart when it comes to seeing. A verse from the Quran became an anchor: “Have they not journeyed through the land, so their hearts may understand, and their ears may listen? Indeed, it is not the eyes that are blind, but it is the hearts within the chests that grow blind.” (22:46)

Personally, that verse has always stuck in my mind, for many reasons, and the more I age, the more it all makes sense. Eyes can be cloudy, judgemental at times, and confused. That doesn’t necessarily mean that the heart won’t fall for the same tropes, but when understood, guarded and gently protected, seeing can become moral and spiritual sustenance for the soul and body. Would you agree that this is our most precious gift? How the heart sees will lead us to moving as a spiritual process. I have been on the move since last December, not by choice. Five homes, four months; the minute your body settles or tries to recognise the way from your bedroom to the kitchen and other surroundings, it’s time for you to leave. The discomfort, both physical and emotional; the quiet uncertainty that clouds over your days. Those movements – steps in all their metaphorical and literal sense –are a blessing. I saw light I wouldn’t have otherwise had the chance to encounter. The geographical distance at play with each house was so much fun; the way my body

ached from carrying bags and holding, releasing breath. The ways in which I felt held by friends. Moving is required, and the flexibility that comes with it is invaluable, mostly to your heart. It’s a long braid and a dialogue that never ends.

At the start of the residency, Kate mentioned that one of the things she connects with most in my photographs is the depiction of the human element as a body of nature. Sitting with her comment was like an opening for me to ask questions about the ‘nature’ that we develop and acquire with time as living, breathing, mobilised bodies.

In one of these photographs, we see an adult called Marc holding a toy horse. Horses, to me, are graceful, sensitive, and utterly divine creatures; every time I encounter one up close or from a distance, my heart just skips a beat. Marc embodies their nature of immense honesty and purity, strength and fragility that you want to hold and shield. When I saw the toy horse in his cottage, and he told me it was a gift from his mother at the age of nine, I smiled at how it all made sense.

To mark the end of my residency, my exhibition, ‘Can You See With Your Heart?’ launched at Kunstverein Aughrim on 27 June, presenting a series of photographs and objects (found, gifted and collected) in a state of mirroring one another. Small

echoes of an inner shift; gentle reminders of things felt but rarely seen. Through the years, certain themes have never left me. They grow with me, and they reform and change as I get older. Home, foreign and familiar to us all, never ceases to reveal dimensions not previously perceived. Family dynamics. The variety of questions asked and raised about synchronicity, time, and fate. Grief and the colours and stages of it. The main pillar of my practice is walking – more specifically and recently, walking as an act of remembrance and how that relates to grief.

Eslam Abd El Salam is an Egyptian visual artist based in Belfast. Through the mediums of analogue photography, polaroid, text, and mixed media, Eslam considers notions of synchronicity, specifically in relation to friendship and serendipitous encounters with others.

@eslamabdelsalam_

Eslam undertook a month-long residency at Kunstverein Aughrim in June as part of Aughrim’s Craic in the Granite Music & Arts Festival 2025, supported by Wicklow County Council Arts Office festival awards, funded through the Arts Council. kunstverein.ie

Edition 81: September – October 2025

‘Soft Surge’

Luan Gallery

27 June – 7 September 2025

WHEN IS AN experience of an exhibition so resonant that its viewing becomes an act of participation? With ‘Soft Surge’ at Luan Gallery in Athlone, Aoife Banks has curated an evocative and affecting group show featuring works by women artists. Interrogating personal and cultural memory through a distinctly feminist lens, this exhibition is not amenable to passive viewing.

Shirani Bolle’s colourful textile sculptures – Thank You Very Much, Treaty, and Baby Blanket – (all 2025) and photographic installation, The Birthday Party (2024), offer explorations of intergenerational grief and inherited memory, infused with a legacy of traumatic experiences. The daughter of a Holocaust survivor, Bolle has created a deeply personal set of artworks that pay tribute to her mother, and to all women who experience loss and displacement.

The memorialisation of grief and loss is further explored in Emily Waszak’s newly commissioned work, Obaachan I (2025) – a large-scale, handwoven, textile sculpture, made from waste yarn, and suspended from the ceiling. With references to her Japanese heritage, the artist draws on ancestral weaving practices to reclaim the importance of ritual for processing of grief. Like all of the presented works, there is much to engage with, both aesthetically and conceptually.

As one moves through the exhibition, the ideological depth of the artworks becomes increasingly absorbing. It is impossible not to be moved by the personal experiences revealed, and by the reminders of female oppression and exclusion, rendered creatively in a multiplicity of approaches. Textile materials and traditional processes (such as knitting, embroidery, crochet and weaving) are repurposed here as radical forms of expression, which serve to reclaim the ancestral feminine principles of creativity, resilience, and interconnection.

Mythological and classical references infuse the exhibition, nowhere more clearly than in Ursula Burke’s intricate and beautiful textile works, Embroidery Frieze – The Politicians (2015–24), The Politicians (2017–18), and Truncheon (2019). The artist mines classical and art-historical sources to shine a light on contemporary politics, including post-conflict scenarios, while drawing on the cultural memory of violence and war.

With Mother Medals 1–5 (2018) and The Assumption (2018), Rachel Fallon engages in critical correspondence between women’s historical, religious, and contemporary experiences. Using soft materials – including household sponge, embroidery threads, and wool – Fallon has created works that provide powerful commentary on patriarchal oppression, especially as it relates to the denial of women’s bodily autonomy, reproductive rights, and freedom.

Poised on a clothes rail and protruding from a wall, Lucy Peters’ series of snaking sculptures, Making it Laaaast (2022), also applies the subversive potential of textiles to reveal circular, exploitative connections –namely, between women working in clothing factories in the Global South, the pollution caused by the textile industry, and the naivety of young consumers. Painstakingly assembled by weaving and knotting strips of discarded garments, these large, soft,

tactile forms appear as conduits, even harbingers, of the catastrophic impacts of fast fashion under late capitalism.

If the exhibition title, ‘Soft Surge’, refers to an inexorable force of feminine energy and resilience, this swell reaches a high point with Dee Mulrooney’s film installation, The State of Her (2025). In this newly commissioned work, the artist takes on the persona of vulva-clad Growler, becoming the embodiment and expression of generations of suppressed female rage. Through music, ritual, spoken word, and incantation, women’s power is celebrated and reclaimed.

The State of Her is a dynamic, totemic monument to the women and children who were incarcerated in mother and baby homes in Ireland. A handcrafted quilt from the Irish NAMES Project (1990) – the inclusion of which adds a powerful, commemorative thread to the exhibition – can also be seen as an enduring memorial, honouring lives lost to the AIDS epidemic, as well as the public act of collective mourning.

In highlighting that memory does not exist in isolation, but is shaped by performativity, as philosopher Judith Butler theorises, the exhibition prompts reflections on what might constitute a monument. With feminist and intersectional frames of reference, Banks’ curatorial approach proposes an alternative paradigm, rooted in active remembering. Thus, ‘Soft Surge’ extends the meaning and experience of a monument, from a static object to a dynamic, subjective, and participatory set of events. For its beautiful evocations of women’s lived experiences and shared rituals, this voluminous exhibition will remain in the mind and the heart for some time to come.

Rachel Doolin, ‘Heirloom’ Glór, Ennis

14 June – 6 September 2025

MULTISPECIES ETHNOGRAPHERS HAVE used the term ‘contact zones’ to describe spaces where encounters between humans and other species occur.1 Doomsday seed vaults and art exhibitions can both be seen as mediated contact zones, where life or work is removed from its original setting and reframed. This concept is central to ‘Heirloom’, an exhibition by Cork-based artist, Rachel Doolin, currently showing at glór in Ennis. Through sculptural installation, visual media, and digital experimentation, ‘Heirloom’ highlights the artist’s response to the “profundity of seeds.” The collection and preservation of heirloom seeds is a profound form of resistance to extractive capitalism and industrial agriculture, functioning as an act of multi-species solidarity that supports biodiversity and ecosystem regeneration. For this series, Doolin worked with local collaborators such as Irish Seed Savers in County Clare, who preserve over 800 varieties of heritage, open-pollinated vegetables from Ireland, using seeds and crops to protect biodiversity and celebrate cultural heritage. The obligation to preserve species locally and globally is important in the Anthropocene, and in the Digitocene.2 This duty extends beyond the physical preservation of life to safeguarding stories, codes, and cultural lineages, often using digital technologies and accompanied by detailed genetic, ecological, and geographic data. Svalbard Global Seed Vault (SGSV) is one safety system designed to preserve and protect against loss of biodiversity. Opened in 2008 within the Arctic Circle, the vault stores backup copies of seeds from 1,700 gene banks worldwide. The vault currently houses 1.3 million seeds in ‘black box conditions’. If any species housed in the seed bank are lost due to disaster, war, or human error, the original gene banks can request replacements

from Svalbard to restart their collections. The SGSV represents a vision of ecological reversibility, offering the possibility of undoing catastrophic damage.3

‘Heirloom’ takes as its conceptual and material departure the cryogenically preserved seed specimens held in Svalbard, drawing attention to the precariousness of genetic biodiversity in the face of climate catastrophe and global conflict. A photographic image of the vault’s exterior, taken during a 2017 Arctic residency, is displayed at the centre of glór’s atrium. The work captures the tension between the vault’s role as a contact zone for ecological preservation and the reality that human access to the vault is minimal. Doolin’s works are often community focused and the solitary image of SGSV is startling in its bleakness.

In contrast, installed at the entrance of the glór atrium, the large-scale sculptural installation, SeedARIUM (2022), originates from a community engagement project inspired by the Sanctuary of Hope in Calasparra, Spain, and is conceptually linked to the Svalbard Global Seed Vault. The flawlessly fabricated sculpture houses a collection of seeds donated by individuals across Ireland and abroad, including adults and children, gardeners, growers, and conservationists. Here, there is no scientific classification; the seeds are embedded in bio resin and illuminated by the gallery lighting. SeedARIUM functions as a community archive, shaped by the collective acts of gifting, gathering, and preserving seeds in solidarity.

At the opposite end of the atrium, SeedCLOUD (2022) is an interactive audio-visual sculpture featuring eight seed varieties in individual bowls, each linked to a recorded story, accessed via NFC-enabled devices or a gallery-provided tablet. Global biodiversity

projects increasingly use bioinformatics, transforming seeds into digital objects with accompanying genetic, ecological, and geographic data. SeedCLOUD links physical seeds to the digital and offers the stories that contextualise human connections to them. Developed over two years, partly in response to Covid-19 lockdowns, the work invites visitors to experience seeds as vessels of knowledge, connection, and conversation. Recordings are also available on the artist’s website. By placing seeds within an artistic and community context, ‘Heirloom’ invites reflection on the gap between storing seeds as insurance against global catastrophe, and sustaining the local conditions in which life and art can flourish.

Gianna Tomasso is a writer, artist and researcher. Gianna lectures in Limerick School of Art and Design.

1 S. Eben Kirksey and Stefan Helmreich, ‘The Emergence of Multispecies Ethnography,’ Cultural Anthropology, Vol. 25, No. 4, November 2010, pp. 545–576.

2 The neologism ‘Digitocene’ appears to have been first publicly used in 2016 to 2017 as the title and thematic frame of an MA in Digital Art at the Far Eastern Federal University, Vladivostok, Russia, where it was defined as a conceptual epoch shaped by the pervasive influence of digital technologies on culture, perception, and the environment. The term has since been adopted in art criticism, media theory, and ecological discourse.

3 Leon Wolff, ‘The Past Shall Not Begin: Frozen Seeds, Extended Presents and the Politics of Reversibility,’ Security Dialogue, Vol. 52, No. 1, 11 June 2020, pp. 79–95.

‘Together in Commune’ Rua Red 27 June – 13 September 2025