Copyright © 2018 Paul Gartside.

All rights reserved. Except for use in review, no part of this book may be reproduced or used in any form, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, without written permission from the publisher. Permission requests should be addressed to the publisher at the address below: Paul Gartside

29 Malone Street, East Hampton NY 11937 USA www.gartsideboats.com

Book design and layout by Rami Schandall / Visual Creative.

Edited by Stuart Ross.

Printed in Canada by Friesens Corporation.

Cataloguing in Publication Gartside, Paul.

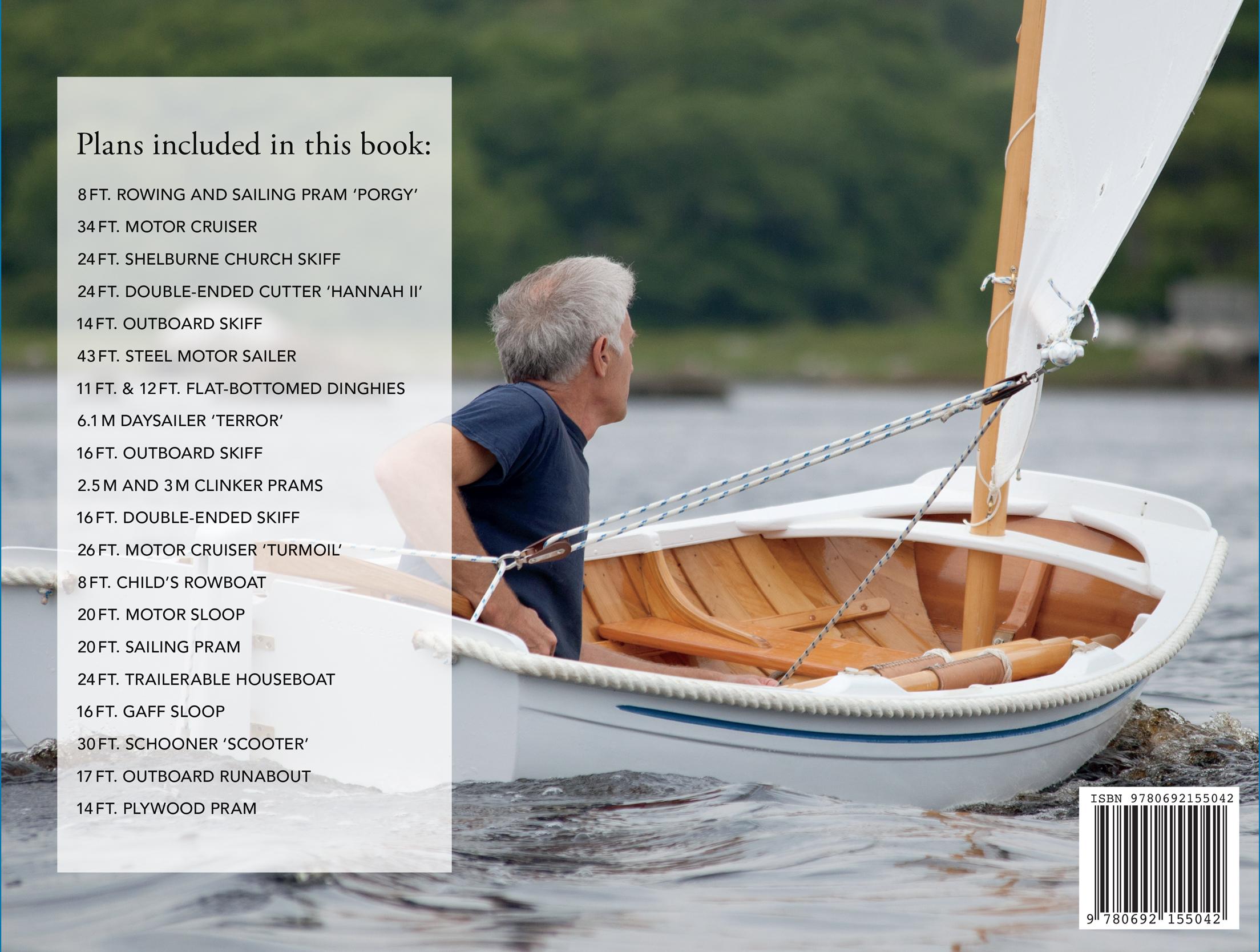

Plans & dreams. Vol. 2, 20 ready-to-build boat designs / by Paul Gartside ; with essays and advice from Water Craft. -- 1st edition.

200 pages 9 in. x 11.875 in. Includes index.

ISBN 978-0-692-15504-2

1. Boats and boating--Design and construction. 2. Boatbuilding-Amateurs’ manuals. I. Title. II. Title: Plans and dreams. Vol. 2, 20 ready-to-build boat designs. III. Title: 20 ready-to-build boat designs. IV. Title: Twenty ready-to-build boat designs. V. Title: Water craft.

All chapters have appeared in Water Craft Magazine. First edition: October 2018.

Table of Contents

Plans & Dreams, Volume II, continues the series of small-boat plans and essays begun in Volume I. These pieces were written for and first published in the magazine Water Craft in the UK from 2013 to 2016. During those years I was living in the town of Shelburne on the South Shore of Nova Scotia in Canada’s Atlantic provinces, an area with a deep maritime history and a tradition of wooden shipbuilding. The influence of that lovely place, its characters, and the materials available to us there will be felt throughout the book.

While the prime objective of the essays remains the conveyance of the technique and know-how of boatbuilding, beyond those intricacies lies the broader magic of our obsession with boats, which is explored in the musings accompanying each set of drawings and in a couple of essays written for Water Craft during the same period. On occasion these pieces wander far and wide, I admit, but their themes remain the same as those explored in Volume I.

First, they celebrate the simple pleasure of working with hand tools and natural materials, and the connection this gives us to the places we live. Every piece of wood we pick up grew somewhere, and its inclusion in our project connects us to that place, whether or not we choose to think about it. The use of local species allows those connections to be felt most strongly, and links us directly to builders of the past. In a world of diminishing forest resources, it is also the most ethical approach—that’s a constant refrain throughout these chapters.

Then there is the enjoyment that comes from building with our own hands, watching something come into being that has never existed before. Why we are in such a rush to deprive ourselves of these simple pleasures with our CNC machines and our 3-D printers, I am at a loss to understand. Outside of the commercial world, it seems a terrible impoverishment. John Ruskin’s statement, in response to the first Industrial Revolution, that the worth of an object or building is derived from the pleasure taken in making it, seems ever more apt.

But of course boats are about much more than the pleasure of building. They offer a door of escape from the world like no other open to us today. To cast off the mooring and watch the buoy fall away is to sense freedom and adventure in its purest form—even if it’s just for the weekend. Out there beyond the harbour mouth lies the real world, the one we have spent 50,000 years insulating ourselves from. To immerse ourselves in its unpredictability, even for short periods, is to return richer in memories than from time spent in almost any other endeavour.

I have always been struck by the contrast between these two aspects of the boat world: the quiet, fragrant atmosphere of the boat shop and the wild disorder of the sea, its discomfort and indifference.

I have a vivid memory from my boyhood of returning to the warmth of the boat-shop stove with sodden feet, the salt water stinging in the bramble scratches on my legs, thinking that maybe building boats is more fun than using them, after all. Hopefully I am a little more skilled at managing crew comfort these days, but I have known many good builders who find little to interest them beyond the tide line, and I do have some empathy for that point of view.

But equally I understand those for whom thoughts of the next boat and the next voyage are the very elixir of life, for there is a profound magic in building one’s own boat, then setting out in it on a voyage of discovery. For my part, while I know the vagrant gypsy life will never do for me, creative work having always been the deeper need, some of my most treasured memories are of small-boat wanderings of one kind or another, and I fully intend to bank more of them before I am done. I believe there is little in human experience to rival it.

Wherever the reader lands on the spectrum of delights that boats afford us, wherever that balance is struck, I hope this collection will prove both enjoyable and useful.

Paul Gartside May 2018

2.5 m and 3 m Clinker Prams

# 206

Length Overall 2.45 m (8 ft. 0 in.)

Beam 1.18 m (3 ft. 10 in.)

Depth Amidships 0.38 m (1 ft. 3 in.)

Weight 45 kg (100 lb.)

Pram dinghies of the round-bottom type are fun to draw and even more fun to build—perfect projects for the home builder with limited space, but with time and interest to settle into an absorbing construction project. We’ve looked at a couple of sailing models in this series already, but we’ve somehow skipped over the simple rowing model— the traditional clinker pram—and that’s an omission we’ll correct now.

Time was, every boatbuilder had one of these in his repertoire and they could be found in all manner of size and proportion. When I was growing up on the Fal estuary, our next-door neighbour had a pretty eight-footer of the low freeboard variety, a little like a scaled-down Norwegian pram, built for him by Benny of St Just in Roseland and used as tender to his much-loved sloop Dulcie. I can still see him rowing out to the mooring, with his little dog standing in the bow, sniffing the breeze. He used that pram for several decades, and when he retired from his job as a bank inspector, his colleagues had a new one made for him by the same builder—off the same moulds. It is one of my regrets that I never took the time to measure that boat; it was a good one, and had clearly stood the test of time.

I do have a battered photo of the first pram I ever built. I was taking classes in colour photography at the time and apparently hadn’t yet

# 206A

Length Overall 3.05 m (10 ft. 0 in.)

Beam 1.32 m (4 ft. 4 in.)

Depth Amidships 0.44 m (1 ft. 5 in.)

Weight 54 kg (120 lb.)

mastered the fixing process, but it’s a nice shot and the patina is a reminder of the time that’s slipped by since the afternoon it was taken somewhere on the upper reaches of the Tresillian River. I like the composition too; it places the pram in its proper context—a tidy grace note towing along in the wake of our daydreams.

For use as tenders, prams work best with some body to them—a minimum of 380 mm (11") depth in the smaller sizes and a flat section for stability. The bow transom should be kept as small as possible, commensurate with finding room for the hood ends of 18 strakes. I like the proportion that gives and the cockle-shell texture of narrow planking with a trace of tumblehome in the aft sections—very appealing. Even when they’re upside down in winter storage, I’ve felt an agreeable buzz just walking by these miniature vessels. Surely a sign there’s something here worth contemplating.

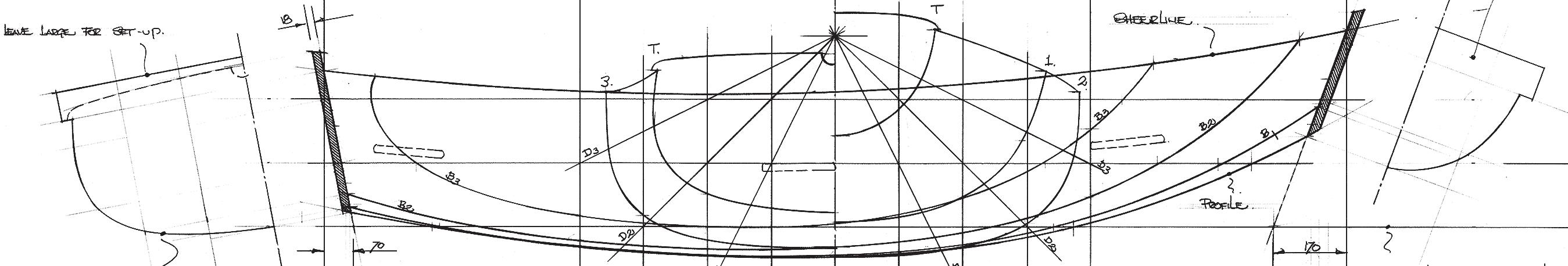

The attached drawings contain lines and offsets for two prams—one 2.4 m overall, the other 3.0 m. I’m using metric units here in response to requests from readers, but note the fastening list is based on British nail sizes. Metric equivalents may exist, but I am not aware of them. The construction drawings are based on the lines of the smaller boat, but scantlings and detail are interchangeable.

With the jig completed, the first job is to flat off the moulds and transoms for the keel plank. This can be a little thicker than the rest of the planking (say 9 mm) and should be glued and nailed to the transom at either end for a solid foundation. Note that the bow transom is thicker than the stern transom to handle the trickier nailing angles. Approximate widths for the keel plank are given on the plans. Next, line out for the nine remaining planks as shown on sheet 3. Be sure to make the sheer strake a little deeper than the one below it to allow for the masking effect of the rub rail.

Planking starts by knocking off the bevel on both edges of the keel plank to the width of the plank land, in this case 18 mm, and then planing down the rebates at either end to a feather edge. From here on, the shape of each plank is lifted by spiling, using the edge of the last plank and mould marks obtained by lining out as reference

points. When spiling for clinker planks, the key thing is to avoid any edge set. We’ve mentioned this before, but it can’t be overstated. While carvel planking can be driven up into place—with wedges if necessary—any edge set of clinker planking leads to distortion of the hull. If the plank ends are lifted, the plank is pinched onto the moulds; if they are pulled down, the planking grows away from the moulds. Either is undesirable and leads to problems later on.

The trick to getting a good spiling is to tack the batten together from two or three pieces to mimic as closely as possible the plank shape to be lifted—and have it bear on the lap of the last plank so it wraps at the proper angle. Then, when the marks are transferred to the board, add wiggle room by cutting a little oversize. Wood being the living material it is, a plank will often spring as it’s cut, so even with a good spiling, discrepancies can appear when it’s clamped into place. A little room for adjustment is helpful.

There are no frames to fasten to at this stage, so the planking is secured with the lap nails only, and if we are building upside down, as shown, they will be driven but not clenched. Frame locations are marked on the keel plank and transferred to each plank as they are fastened on. This gets a little tricky forward, where the frames are canted and don’t lie in a vertical plane. I would tack some thin battens to the inside of the keel in this area and bring them down to a batten tacked around the sheer to simulate the line of these frames. Adjust them until they look right and use that as a guide for nail placement—one per frame bay.

Fastenings into the transoms will be copper nails driven into pilot holes of just the right size. A drill made from a short length of bicycle spoke, flattened to a spear point, is the best tool for the job—it can be adjusted easily to suit the density of the wood and the length of the nail. Bed the plank ends in a little paint or varnish, but otherwise leave the laps dry.

When the planking is complete, the shell can come off the jig. With the tumblehome aft, this might take some gentle jiggling. Emphasis on gentle. But without frames, and with none of the nails riveted up, it’s a pretty loose bundle and should release without a struggle.

30 ft. Schooner Scooter

Length on Deck

30 ft. 0 in. (9.14 m)

Length Waterline 24 ft. 7 in. (7.50 m)

Beam 8 ft. 2 in. (8.17 m)

Draft 4 ft. 3 in. (1.30 m)

In any ranking of the most beautiful sailboat rigs, it is a good bet the schooner will come out on top. Quite why that is I can’t say, but the fact that it is as evocative on paper as in real life suggests it has something to do with the impact of proportion. A similar effect perhaps to that of the golden rule or the Fibonacci series, a firing of neurons in the aesthetic realm of the unconscious. One thing is for sure—it is not an appeal to the logical side of our brains, for in terms of performance, the schooner rig is not always the best choice, especially in smaller sizes. I hesitate to say that in a part of the world where the image of the working schooner is iconic and deeply embedded in the culture. One of the many charming things that happens when you move to Nova Scotia is they give you a licence plate with a picture of the Bluenose on it—it’s the nearest thing to a tribal insignia round here.

My interest in schooners goes back a long way, and I am the first to admit to the irrational nature of the attraction. When I was 16 I fell hard for a small schooner, John Atkin’s Florence Oakland design. It was a true infatuation, one I credit with helping me through some difficult school years. The margins of my class notes from those days were filled with doodles of her bowling along, running wing and wing

Displacement 8,600 lb. (3,900 kg)

Outside Ballast

Working Sail Area

lb. (1,273 kg)

or hove to in a blow—it was the perfect escape hatch. In those years I lived for 4:00 p.m. and the chance to get home and pick up the tools again. Between the building hours, the money-raising schemes, and school prep, weekends flew by in the blink of an eye. But somehow I managed to have her sailing by my first year in college and lived aboard in Scotland one memorable summer.

I loved that little boat and to this day carry images of events that occurred in our wanderings as vivid as if they happened last week. It was hard to let her go, but I came away with an understanding of the cost of a divided rig in small boats, the loss of performance to windward, increased rig weight and complexity compared to the single stickers. Her charm was undeniable, though, and judging by the response she provoked wherever we went, I was not entirely misguided in my choice. In the end, it comes down to a matter of balance. It is a mistake to think that boat design is a search for performance alone; that’s always important, of course, however we might choose to define it, but it is rarely the most valuable and never the most elusive quality. Clyde Davis of Anacortes, Washington, has been a regular correspondent for many years now, mostly on the subject of small schooners and their allure. As a result of his patient urging, the plans in this issue

The 22 ft. schooner Marie Sophie built to John Atkin’s Florence Oakland design by the author in 1969. Photo credit: Robert Gartside.

finally see light of day—and I find myself pondering the mysteries of our obsessions this sunny afternoon. It’s reassuring to know I am not alone in this one.

Our new design is 30 ft. (9.14 m) on deck, but overhangs fore and aft make it a small 30 ft. Displacement is a moderate 8,500 lb. (3,900 kg).

The hull lines show a slippery double-ender with nice symmetry fore and aft and the ballast slung low where it will do us the most good. Along with firm bilges, there should be lots for her to lean on.

When considering the rig for a small schooner, the two most important things are to keep weight aloft to a minimum and to get the balance just right. I’ve gone with a Bermudan main to save top weight here, which will also simplify handling. Both spars are round and should be hollow all the way. A wall thickness of about 20% of the outside diameter knocks a third off the spar weight for very little reduction in stiffness and is well worth the extra labour. For balance, I have placed the rig centroid a distance equal to 11% of the waterline length ahead of the centroid of the underwater profile. (See chapter 17 for an explanation of balance by the empirical method.) My little Atkin schooner was as well-balanced as any boat I’ve ever owned, and I went back to her for reference in choosing that number. Fingers crossed we get an easy helm and a smart tacker.

I was tempted to put the jib on a boom to make the whole rig selftacking, but went with the furling gear as the simpler arrangement. When coming up to a mooring or preparing to drop anchor, it clears the foredeck of obstruction quickly and can be hauled out again just as easily if we miss and need to go round again. We’ll require a pair of small cotton reel winches to nip it in smartly aft. If we use the favourite Wykeham Martin gear, we have furling only, no reefing, so we need some means of setting a small headsail for a serious wind.

That’s shown dotted on the plan set-up from the stem head and will be used with the foresail or reefed main.

Clyde requested a glued construction, so that’s drawn. In a small, shapely hull like this, we can get away without transverse framing for a nice clean interior, provided we start with a good thick laminate, then bond in all the joinery as part of the structure. Large laminated floor timbers with tapered arms extending well up into the bottom panel port and starboard are responsible for distributing the ballast