JACKSON CIVIL RIGHTS GUIDE

As someone who’s been inspired my whole life by the places you’re about to see and experience, it’s an honor to welcome you to the Civil Rights Guide for Jackson, Mississippi.

This guide is an abridged version of the original Jackson Civil Rights Driving Tour, developed in 1999 by historian Alferdteen Harrison, PhD, Denoral Davis, PhD, and other scholars and activists under the leadership of Mayor Harvey Johnson Jr. The latest version is available on the Visit Jackson website.

This guide is focused on civil rightsrelated sites that are both extant and accessible to lead people to the spaces that exhibit the enduring legacy of the Jackson movement.

Jackson is an inspiring city to visit because there are so many places that speak to the notion of resilience. Of overcoming adversity. Of keeping the faith. This is a city where the waves of an incredibly powerful movement—The Freedom Movement—continue to shape, remake, and transform us today.

You’ll find that every place on these pages has a civil rights story, and these stories are important—not only in terms of understanding the history of Jackson but that of our country and far beyond.

Use this as a map to take you to the very places where that history happened to deepen your understanding.

I think you’ll see that this remarkable collection of music venues and chapels, historic homes and landmark eateries, cultural centers and museums offers not just a window to the past but to all possibilities of a bright, shining future.

Michael Morris Director of the Two Mississippi Museums

400 HIGH STREET

The Mississippi State Capitol was completed in 1903. Through much of the twentieth century, legislators passed many laws to segregate, disenfranchise, and subjugate Black Mississippians. In 1955, the legislators created the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission to “protect the sovereignty of the state of Mississippi … from encroachment thereon by the Federal Government,” spy on civil rights workers, and funnel money to the Citizens’ Councils—the largest private white supremacist organization in the nation.

On June 26, 1966, more than 20,000 people gathered in protest on the north side of the Mississippi State Capitol, a culminating moment of James Meredith’s March Against Fear. During the rally, James Meredith, Charles Evers, Martin Luther King Jr., and Aaron Henry spoke. Learn more about the march and rally at the Mississippi Freedom Trail marker on the north side of the capitol. In 1968, Robert Clark became the first African American legislator to serve in the state capitol in the twentieth century.

222 NORTH STREET

The Mississippi Civil Rights Museum opened alongside the Museum of Mississippi History in 2017. The museum explores the movement that changed the nation, featuring eight galleries that chronicle the centuries-long struggle for Black Mississippians to become full citizens. The heart of the museum is the third gallery—a central space lit by a dramatic light sculpture that plays the museum’s theme song, “This Little Light of Mine”—which celebrates heroes of the Mississippi movement and remembers those who laid down their lives for civil and human rights.

On May 28, 1961, police arrested nine Freedom Riders who arrived at this station on a Greyhound bus. Throughout the summer, 329 people were arrested and sent to Parchman Prison for attempting to integrate public transportation facilities in Jackson. Hezekiah Watkins, a Jackson resident, was the youngest arrested, at 13 years old. Learn more on the Mississippi Freedom Trail marker, erected here in 2011 to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the Freedom Rides.

528 BLOOM STREET

The Smith Robertson School, named for the city’s first Black alderman, was the first public school created to educate Black children in Jackson, Mississippi. The school operated from 1894 to 1971. Richard Wright, acclaimed author of Black Boy and Native Son, attended Smith Robertson, graduating as its valedictorian in 1925. The Citizens Committee for the Preservation of the Smith Robertson School led a community effort to save the building, establishing it as a museum in 1984. The city of Jackson has operated the museum since then, interpreting African American history and culture in Mississippi and the Deep South.

100 SOUTH STATE STREET

Constructed with enslaved labor in 1839, the Old Capitol is the oldest building in Jackson—and one of the most historic buildings in Mississippi. In 1861, the state seceded from the Union in the Old Capitol. After the Civil War, at least sixteen Black men served as delegates during the 1868 Mississippi Constitutional Convention, which embraced the 13th and 14th Amendments and established a system of free public schools.

Before the direct election of U.S. senators, the state legislature named Hiram Revels the first Black U.S. senator in this building. And in 1890, a new constitution was adopted at the Old Capitol to disenfranchise Black voters and establish the legal apparatus of Jim Crow power. The 1890 constitution became the model for segregationists in every Southern state.

509 NORTH FARISH STREET

The Big Apple Inn, which opened in 1939, was known as a safe space for civil rights activists to dine, socialize, and gather. In 1955, after being named the NAACP’s first field secretary in the state, Medgar Evers opened an office for the organization on the second floor of this building. After a few months, he and his wife, Myrlie, who initially served as his secretary, moved the office to the Masonic Temple on John R. Lynch Street. Many legal groups were eventually located here, including the National Lawyers Guild, the Lawyer’s Constitutional Defense Committee, and the American Civil Liberties Union.

(FORMER MISSISSIPPI NAACP-LDF OFFICE)

538 NORTH FARISH STREET

Marian Wright Edelman established the NAACP Legal Defense Fund (LDF) office here in 1964. Edelman, the first African American woman admitted to the Mississippi Bar, assisted other Black attorneys, including Jack Young Sr., R. Jess Brown, and Carsie Hall. Other LDF lawyers included Reuben Anderson, Fred Banks, and Melvyn Leventhal.

301 NORTH STATE STREET

On March 27, 1961, nine Tougaloo College students held a read-in at the whites-only Jackson Municipal Library. The “Tougaloo Nine” included Meredith Anding Jr., James Bradford, Alfred Cook, Geraldine Edwards, Janice Jackson, Joseph Jackson Jr., Albert Lassiter, Evelyn Pierce, and Ethel Sawyer—all members of the Tougaloo College NAACP Youth Council. Fellow student Jerry W. Keahey Sr. took the iconic photograph of the students. Learn more on the Mississippi Freedom Trail marker.

715 SOUTH JEFFERSON STREET

On May 20, 1963, Medgar Evers made history by delivering a seventeen-minute civil rights address that aired on NBC affiliate WLBT in Jackson and received intense racist backlash. In 1964, a group of Jackson citizens and the United Church of Christ challenged Lamar Life Insurance Company’s application for renewal of the WLBT license, charging racial discrimination. In 1971, Communications Improvement Inc., a biracial community board, began operating the station, and William Dilday Jr. became the first African American television station manager in the South. Learn more on the Mississippi Freedom Trail marker.

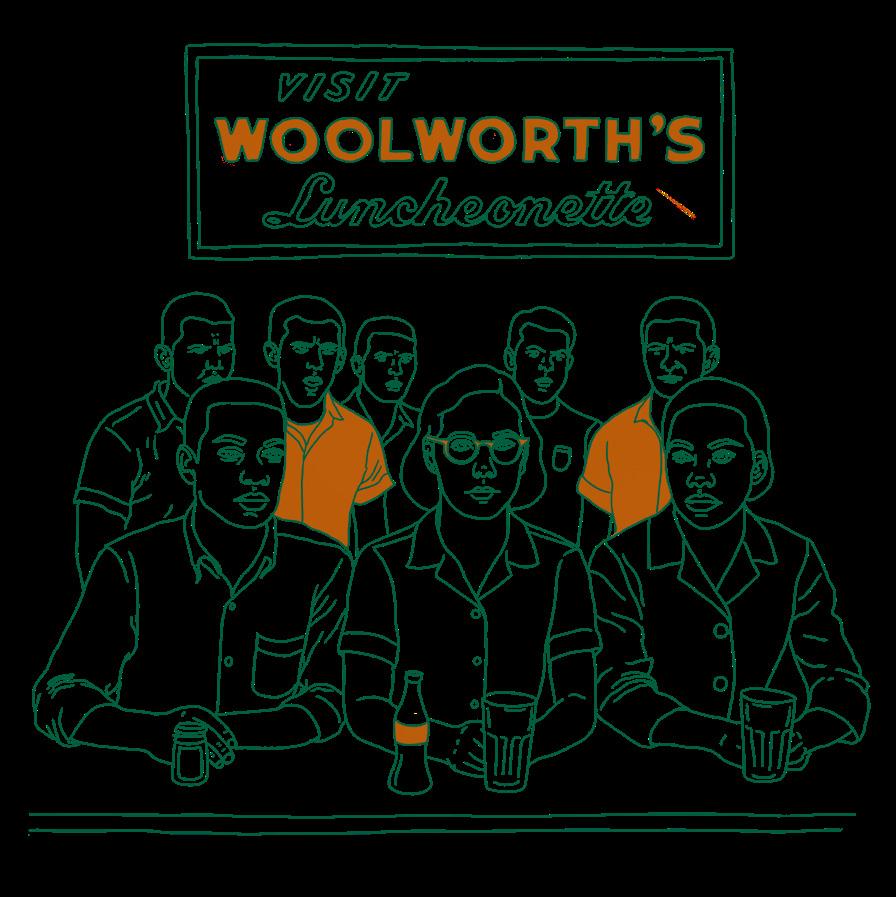

EAST CAPITOL STREET

On May 28, 1963, with Medgar Evers’ help, students and faculty from Tougaloo College and Jackson State College staged a sit-in at the Woolworth’s lunch counter in Jackson, Mississippi. John Salter Jr., Joan Trumpauer, Anne Moody, Walter Williams, and others were assaulted here by a mob comprised mostly of white students from nearby Central High School. Learn more on the Mississippi Freedom Trail marker.

2332 MARGARET WALKER ALEXANDER DRIVE

Medgar and Myrlie Evers were partners in the civil rights struggle. On June 12, 1963, a white gunman shot and killed Medgar Evers, field secretary of the Mississippi NAACP, in the carport of the Evers’ home. Myrlie Evers, who later served as chair of the NAACP’s board of directors, continued to advocate for racial equality and social justice. Today, their home is a national monument administered by the National Park Service. Learn more on the Mississippi Freedom Trail marker.

833 MAPLE STREET

First organized in 1925, Lanier High School was the first four-year high school for Black students in Jackson. During lunch on May 30, 1963, in response to the Woolworth’s sit-in, Lanier High School students staged a historic walkout. When students gathered on the school lawn and sang freedom songs, local police arrived with dogs. Students and parents were clubbed. The walkout inspired other area high schools to stage similar walkouts.

4215 MEDGAR EVERS BOULEVARD

The library and the street on which it sits were renamed after Medgar Evers. On June 28, 1992, a life-sized bronze statue of Evers was erected at the library site by the Medgar Evers Statue Fund Committee. The committee, led by Mirtes Gregory, Andrew Lee, and E.J. Ivory, raised $60,000 to commission the tribute to Evers.

1400

In 1903, Ayer Hall became the first building opened on the Jackson State campus. The Margaret Walker Center, located in Ayer Hall, is an archive and museum dedicated to the preservation, interpretation, and dissemination of African American history and culture. Margaret Walker was one of the most influential Black writers of the twentieth century, and she founded the Institute for the Study of the History, Life, and Culture of Black People at Jackson State in 1968. Now bearing her name, the center seeks to honor her academic, artistic, and activist legacy through its archival collections, exhibits, and public programs.

(FORMER COUNCIL OF FEDERATED ORGANIZATIONS HEADQUARTERS)

1017 J.R. LYNCH STREET

This building was the statewide headquarters for the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO), the epicenter of the modern civil rights movement in Mississippi and the organizational home for Freedom Summer in 1964. In 2011, the building reopened as a museum and civil rights education center at Jackson State University. Learn more on the Mississippi Freedom Trail marker.

1072 J.R. LYNCH STREET

Since Thurgood Marshall gave the dedication remarks in 1955, the Masonic Temple has served as the headquarters for the state’s Prince Hall Affiliated Masons. The lodge served as an important meeting place for civil rights activities, including the 1964 state convention for the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. Since opening, the Masonic Temple has also served as the headquarters of the Mississippi State Conference NAACP. The funeral of NAACP field secretary Medgar Evers was held here in 1963. Learn more on the Mississippi Freedom Trail marker.

(AT JACKSON STATE UNIVERSITY)

On the night of May 14, 1970, Jackson city police and Mississippi Highway Patrolmen responded to campus protests in full riot gear. The police and highway patrol turned on Alexander Hall, a women’s dormitory, and opened fire, spraying more than 400 rounds of bullets and buckshot in 28 seconds. Fourteen students were shot, and two of those young people were killed—Phillip Gibbs and James Earl Green. Dozens more were injured by shattering glass and bricks. No one was charged for the murders of Gibbs and Green. Learn more on the Mississippi Freedom Trail marker.

Tougaloo College, a private historically Black college founded in 1869, was known as a haven for civil rights movement activists. Inspired by Medgar Evers, students spurred much civil rights activity. Legendary activists such as Martin Luther King Jr. and Fannie Lou Hamer spoke at the historic Woodworth Chapel. Learn more on the Mississippi Freedom Trail marker.

Unbeknownst to members of the Beth Israel congregation, Rabbi Perry Nussbaum began ministering to Freedom Riders imprisoned at Parchman Penitentiary in Mississippi in 1961. After his experience with the Freedom Riders, Nussbaum became more outspoken about civil rights issues and more active in forging an interfaith response to racial injustice. His activism provoked outrage, and Klan members bombed the synagogue and Nussbaum’s home in 1967. Learn more on the Mississippi Freedom Trail marker.