EXCEPT FOR THEIR PANEL.

BRING ADDED SAFETY AND RELIABILITY TO YOUR VINTAGE AIRCRAFT WITH THE GI 275 ELECTRONIC FLIGHT INSTRUMENTS AND THE GFC™ 500 DIGITAL AUTOPILOT.

EXCEPT FOR THEIR PANEL.

BRING ADDED SAFETY AND RELIABILITY TO YOUR VINTAGE AIRCRAFT WITH THE GI 275 ELECTRONIC FLIGHT INSTRUMENTS AND THE GFC™ 500 DIGITAL AUTOPILOT.

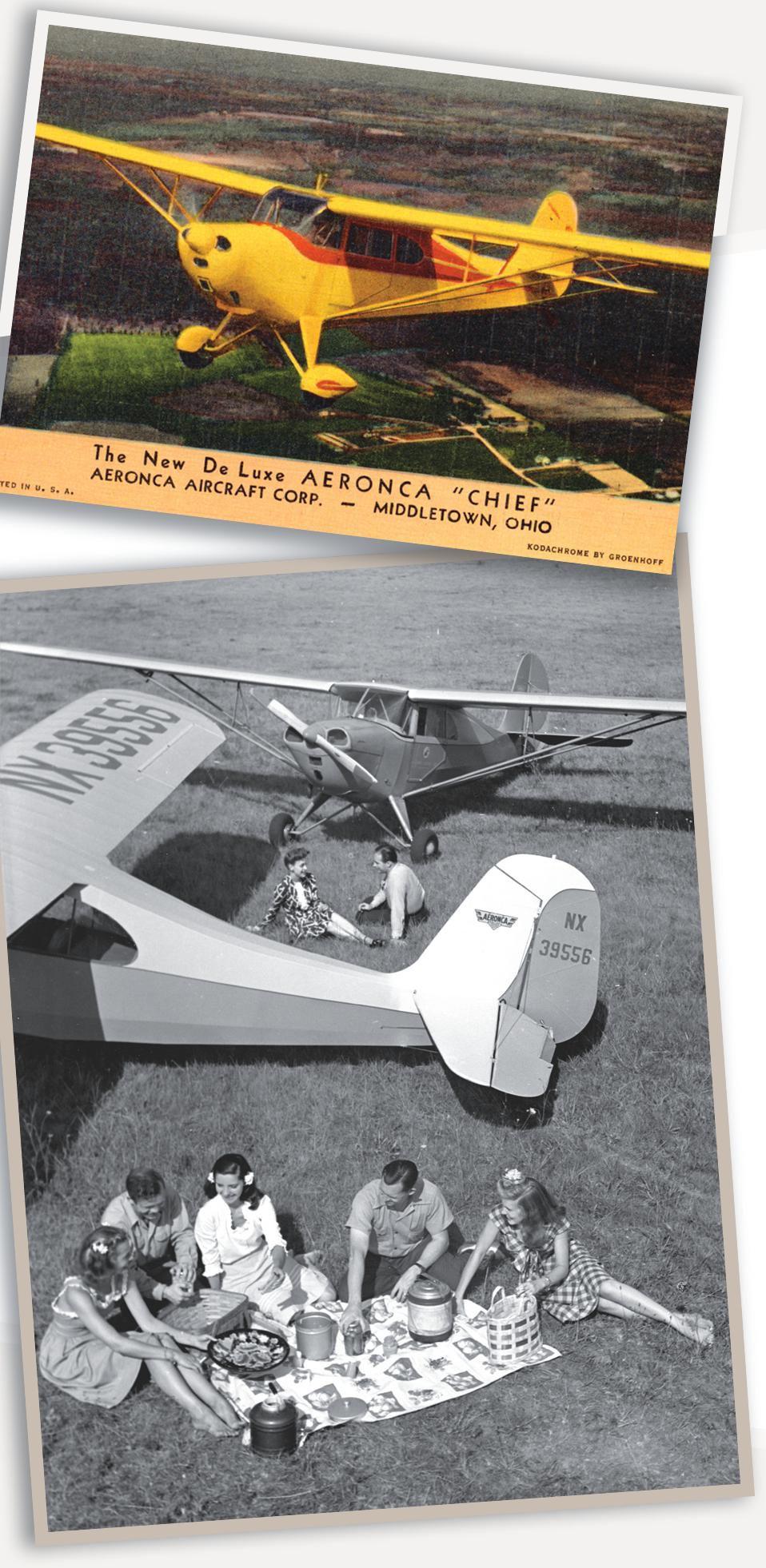

AERONCA NATION 2024! At the writing of this letter, we are well on our way to a spectacular event at EAA AirVenture Oshkosh this upcoming summer. The number of Aeronca airplanes and pilots who have registered for the event has overwhelmingly surpassed our original estimates, which is keeping those of us who are managing the event really busy making sure that everyone can be accommodated in a seamless fashion. All in all, an unexpectedly large gathering of Aeroncas is not a bad problem to have! It’s just keeping us busy!

I’m tracking the different models of the Aeroncas (and Champions!) that have registered. Included in the nearly 100 aircraft already registered are the usual Champs and Chiefs along with a smattering of the more unusual Aeroncas such as the LCs, K’s, C-2s, C-3s, 65CAs (one of which

The number of Aeronca airplanes and pilots who have registered for the event has

overwhelmingly surpassed our original estimates.

is a stick Chief!), an Aeronca-built PT-19A, and one of my all-time favorites — the Aeronca 15AC Sedan. At least 10 pilots with their Sedans have already registered to attend Aeronca Nation 2024. I might add that when I was in my mid-20s I bought, restored, and flew an Aeronca 7AC Champ. I remember it as one of the sweetest-flying airplanes that I have ever flown. I restored it in my garage, and my most memorable experience with that restoration was the day that I let a flat-bladed screwdriver slip, which then gouged a sliver of bone out of my thumb just above my fingernail on my right hand. The pain was excruciating. I immediately walked out of the garage and threw that screwdriver completely over the horse barn. (I had horses then!) I have never thrown anything so far before or since that painful altercation with the screwdriver. That screwdriver may still be behind the barn. I left it where it landed.

Anyway, I am certainly looking forward to seeing all of these magnificent airplanes and visiting with the owners and pilots.

Vintage in Review Chair Ray Johnson is again planning to wow us all with his array of Aeroncas that he has chosen for display in front of the Red Barn and Vintage Hangar. For those of you who may not know it, that display area is under Ray’s control, and every year

CONTINUED ON PAGE 64

March/April 2024

Publisher: Jack J. Pelton, EAA CEO and Chairman of the Board

Vice President of Publications, Marketing, Membership and Retail/Editor: Jim Busha / jbusha@eaa.org

Senior Copy Editor: Colleen Walsh

Copy Editors: Tom Breuer, Jennifer Knaack

Proofreader: Tara Bann

Print Production Team Lead: Marie Rayome-Gill

Advertising Manager: Sue Anderson / sanderson@eaa.org

Mailing Address: VAA, P.O. Box 3086, Oshkosh, WI 54903

Website: EAAVintage.org

Email: vintageaircraft@eaa.org

Phone: 800-564-6322

Visit EAAVintage.org for the latest information and news.

Current EAA members may join the Vintage Aircraft Association and receive Vintage Airplane magazine for an additional $45/year.

EAA membership, Vintage Airplane magazine, and one-year membership in the EAA Vintage Aircraft Association are available for $55 per year (Sport Aviation magazine not included). (Add $7 for International Postage.)

Please submit your remittance with a check or draft drawn on a United States bank payable in United States dollars. Add required foreign postage amount for each membership.

P.O. Box 3086, Oshkosh, WI 54903-3086

Monday–Friday, 8 AM—6 PM CST Join/Renew 800-564-6322 membership@eaa.org

EAA AirVenture Oshkosh www.EAA.org/AirVenture 888-322-4636

QUESTIONS OR COMMENTS?

Send your thoughts to the Vintage editor at jbusha@eaa.org.

For missing or replacement magazines, or any other membership-related questions, please call EAA Member Services at 800-JOIN-EAA (564-6322).

Nominate your favorite vintage aviator for the EAA Vintage Aircraft Association Hall of Fame A great honor could be bestowed upon that man or woman working next to you on your airplane, sitting next to you in the chapter meeting, or walking next to you at EAA AirVenture Oshkosh. Think about the people in your circle of aviation friends: the mechanic, historian, photographer, or pilot who has shared innumerable tips with you and with many others. They could be the next VAA Hall of Fame inductee — but only if they are nominated.

The person you nominate can be a citizen of any country and may be living or deceased; their involvement in vintage aviation must have occurred

To nominate someone is easy. It just takes a little time and a little reminiscing on your part.

• Think of a person; think of their contributions to vintage aviation.

• Write those contributions in the various categories of the nomination form.

between 1950 and the present day. Their contribution can be in the areas of flying, design, mechanical or aerodynamic developments, administration, writing, some other vital and relevant field, or any combination of fields that support aviation. The person you nominate must be or have been a member of the Vintage Aircraft Association or the Antique/Classic Division of EAA, and preference is given to those whose actions have contributed to the VAA in some way, perhaps as a volunteer, a restorer who shares his expertise with others, a writer, a photographer, or a pilot sharing stories, preserving aviation history, and encouraging new pilots and enthusiasts.

• Write a simple letter highlighting these attributes and contributions. Make copies of newspaper or magazine articles that may substantiate your view.

• If at all possible, have another individual (or more) complete a form or write a letter about this person, confirming why the person is a good candidate for induction.

We would like to take this opportunity to mention that if you have nominated someone for the VAA Hall of Fame, nominations for the honor are kept on file for three years, after which the nomination must be resubmitted.

Mail nominating materials to: VAA Hall of Fame, c/o Amy Lemke

VAA

P.O. Box 3086

Oshkosh, WI 54903

Email: alemke@eaa.org

Find the nomination form at EAAVintage.org, or call the VAA office for a copy (920-426-6110), or on your own sheet of paper, simply include the following information:

• Date submitted.

• Name of person nominated.

• Address and phone number of nominee.

• Email address of nominee.

• Date of birth of nominee. If deceased, date of death.

• Name and relationship of nominee’s closest living relative.

• Address and phone of nominee’s closest living relative.

• VAA and EAA number, if known. (Nominee must have been or is a VAA member.)

• Time span (dates) of the nominee’s contributions to vintage aviation. (Must be between 1950 to present day.)

• Area(s) of contributions to aviation.

• Describe the event(s) or nature of activities the nominee has undertaken in aviation to be worthy of induction into the VAA Hall of Fame.

• Describe achievements the nominee has made in other related fields in aviation.

• Has the nominee already been honored for their involvement in aviation and/or the contribution you are stating in this petition? If yes, please explain the nature of the honor and/or award the nominee has received.

• Any additional supporting information.

• Submitter’s address and phone number, plus email address.

• Include any supporting material with your petition.

For one week every year a temporary city of about 50,000 people is created in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, on the grounds of Wittman Regional Airport. We call the temporary city EAA AirVenture Oshkosh. During this one week, EAA and our communities, including the Vintage Aircraft Association, host more than 600,000 pilots and aviation enthusiasts along with their families and friends.

As a dedicated member of the Vintage Aircraft Association, you most certainly understand the impact of the programs supported by Vintage and hosted at Vintage Village and along the Vintage flightline during EAA AirVenture Oshkosh every year. The Vintage flightline is 1.3 miles long and is annually filled with more than 1,100 magnificent vintage airplanes. At the very heart of the Vintage experience at AirVenture is Vintage Village and our flagship building, the Red Barn.

Vintage Village, and in particular the Red Barn, is a charming place at Wittman Regional Airport during AirVenture. It is a destination where friends old and new meet for those great times we are so familiar with in our close world of vintage aviation. It’s energizing and relaxing at the same time. It’s our own field of dreams!

The Vintage area is the fun place to be. There is no place like it at AirVenture. Where else could someone get such a close look at some of the most magnificent and rare vintage airplanes on Earth? That is just astounding when you think about it. It is on the Vintage flightline where you can admire the one and only remaining low-wing Stinson Tri-Motor, the only two restored and flying Howard 500s, and one of the few airworthy Stinson SR-5s in existence. And then there is the “fun and affordable” aircraft display, not only in front of the Red Barn but along the entire Vintage flightline. Fun and

affordable says it all. That’s where you can get the greatest “bang for your buck” in our world of vintage airplanes!

For us to continue to support this wonderful place, we ask you to assist us with a financial contribution to the Friends of the Red Barn. For the Vintage Aircraft Association, this is the only major annual fundraiser and it is vital to keeping the Vintage field of dreams alive and vibrant. We cannot do it without your support.

Your personal contribution plays an indispensable and significant role in providing the best experience possible for every visitor to Vintage during AirVenture.

Contribute online at EAAVintage.org. Or, you may make your check payable to the Friends of the Red Barn and mail to Friends of the Red Barn, P.O. Box 3086, Oshkosh, WI 54903-3086.

Be a Friend of the Red Barn this year! The Vintage Aircraft Association is a nonprofit501(c)(3), so your contribution to this fund is tax deductible to the extent allowed by law.

Looking forward to a great AirVenture 2024!

ROBERT G. LOCK

ROBERT G. LOCK

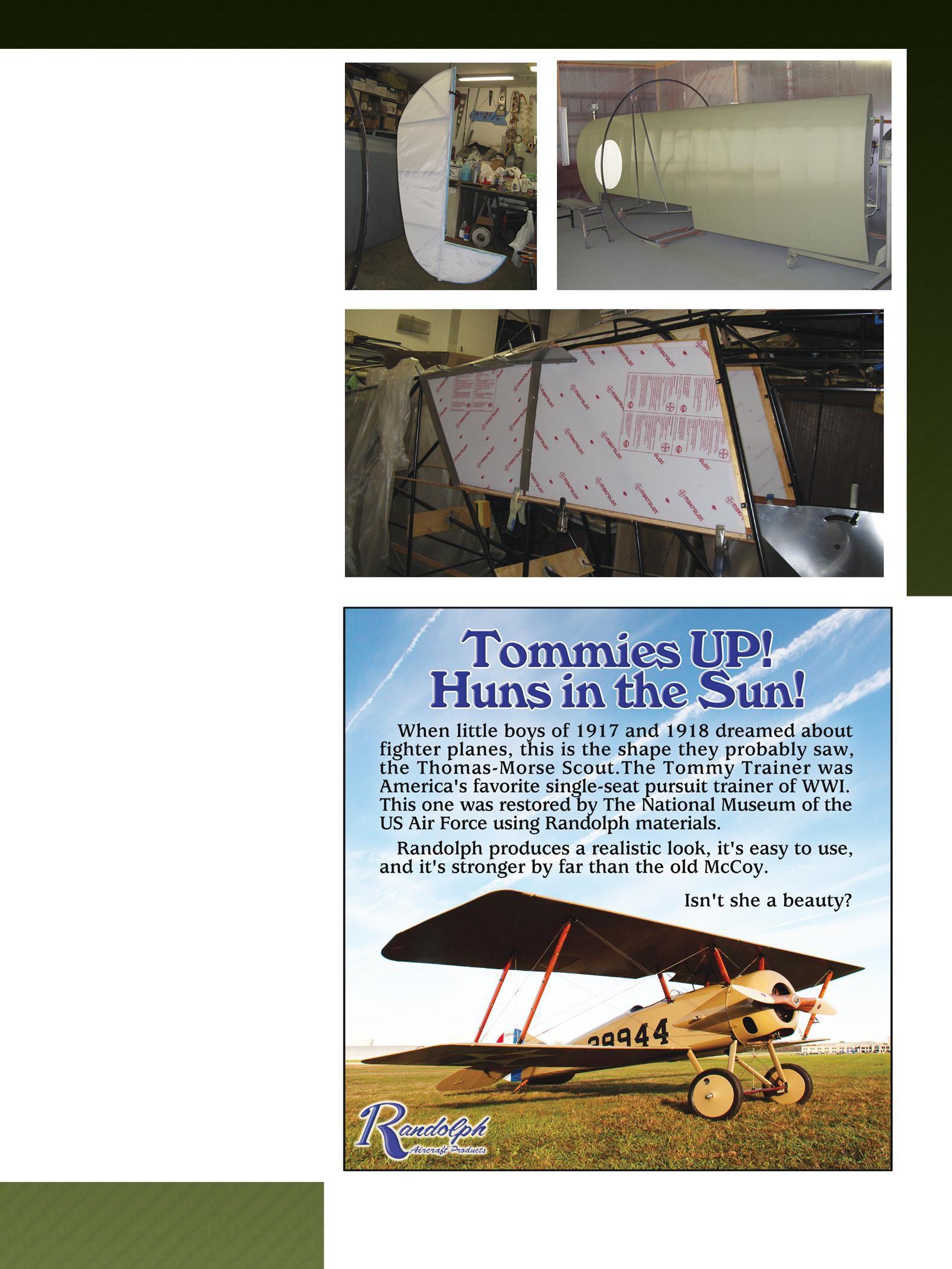

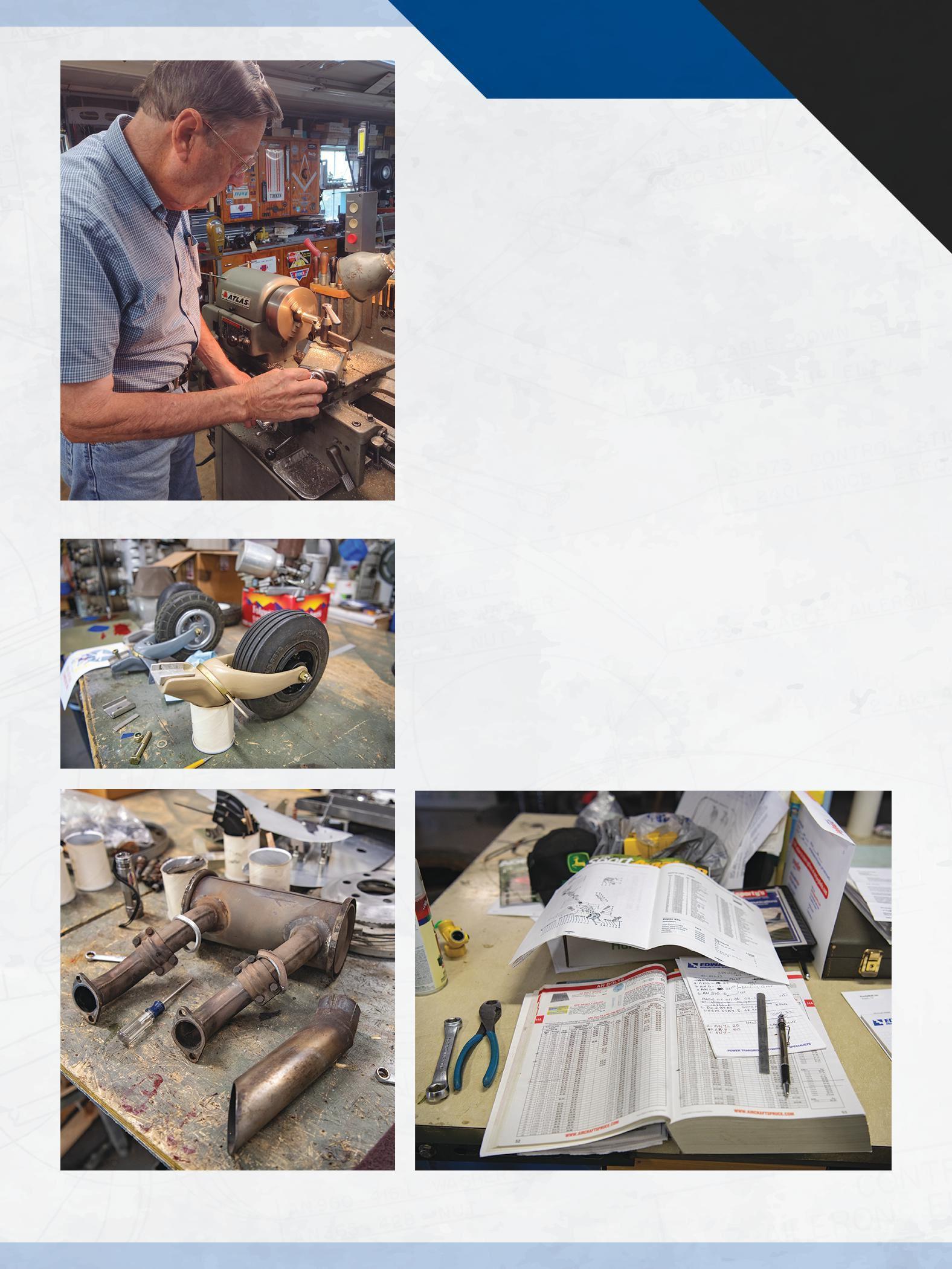

WITH THE ADVENT OF advanced composites, tap testing became the most widely used method to determine delaminations and disbonds near the surface of a part. Tapping and listening to the resulting sound gave the mechanic a sense of where a disbond or delamination was located. I have experimented using this technique (which I taught at the college) and adapted it to a steel tube structure. In my shop is an old Command-Aire fuselage frame, and the experimenting took place on it because I know where bad tubing is located. Chromoly tubing can rust from the inside, thus thinning the wall and making the tube unairworthy. The practice is to tap on a tube you know is good and then tap on a tube you know

is bad, listening intently to the resulting sound. Take a new piece of tubing and tap it with the tool, and the resulting sound will be a “metallic ring.” Tap on a tube that has internal corrosion and thinned walls, and it will have a “dead” sound. This process is just another way, but not the only way, to detect internal corrosion in structural tubing.

So what does the composite tap testing tool look like? Well, it’s a very simple tool, and one that can be made using a

short piece of welding rod and a swage ball end used on a cable assembly. Photo 1 shows a typical tap testing tool.

Tap testing should begin at the tail post of the lower longerons and proceed forward, tapping on the bottom of the longerons. Tap a diagonal or cross tube and listen to the sound it makes, then tap along those longerons and the lower tail post. If there ever was moisture from condensation, that is where it usually settles.

Photo 1 shows tap testing an 83-yearold longeron on a Command-Aire fuselage frame. The lower longerons are all rusted out on the inside to a point where holes have eaten through the tubing and are visible to the naked eye. This longeron was a good practice piece to work on my tap testing of steel tubing.

Start by taking a new section of 4130 tube and tap using this special tool. Listen to the sound it makes, then go to the fuselage frame and tap on top longerons, cross and diagonal tubes, and listen to the sound. If it sounds like the new tube, it is good. If it sounds dull or it does not have a good “ringy” sound, it’s probably bad on the inside. Locate the areas where the sound is dead and cut open with a hacksaw to observe the inside. This is good practice to learn how to use the tap tester. Once you’ve mastered using the tool it is amazing what you can accomplish in a short period of time.

Once dull or dead areas are mapped out, take a small center punch and a small ball-peen hammer and tap in those areas. If the wall is thin, the punch will go right through and you’ll know immediately. I always complete my testing by using the punch/ball-peen hammer routine.

Photo 2 shows the left lower aft longeron with my trusty punch stick through the tube, indicating that the inside has corroded and there is very little wall left.

This is how you do it.

From

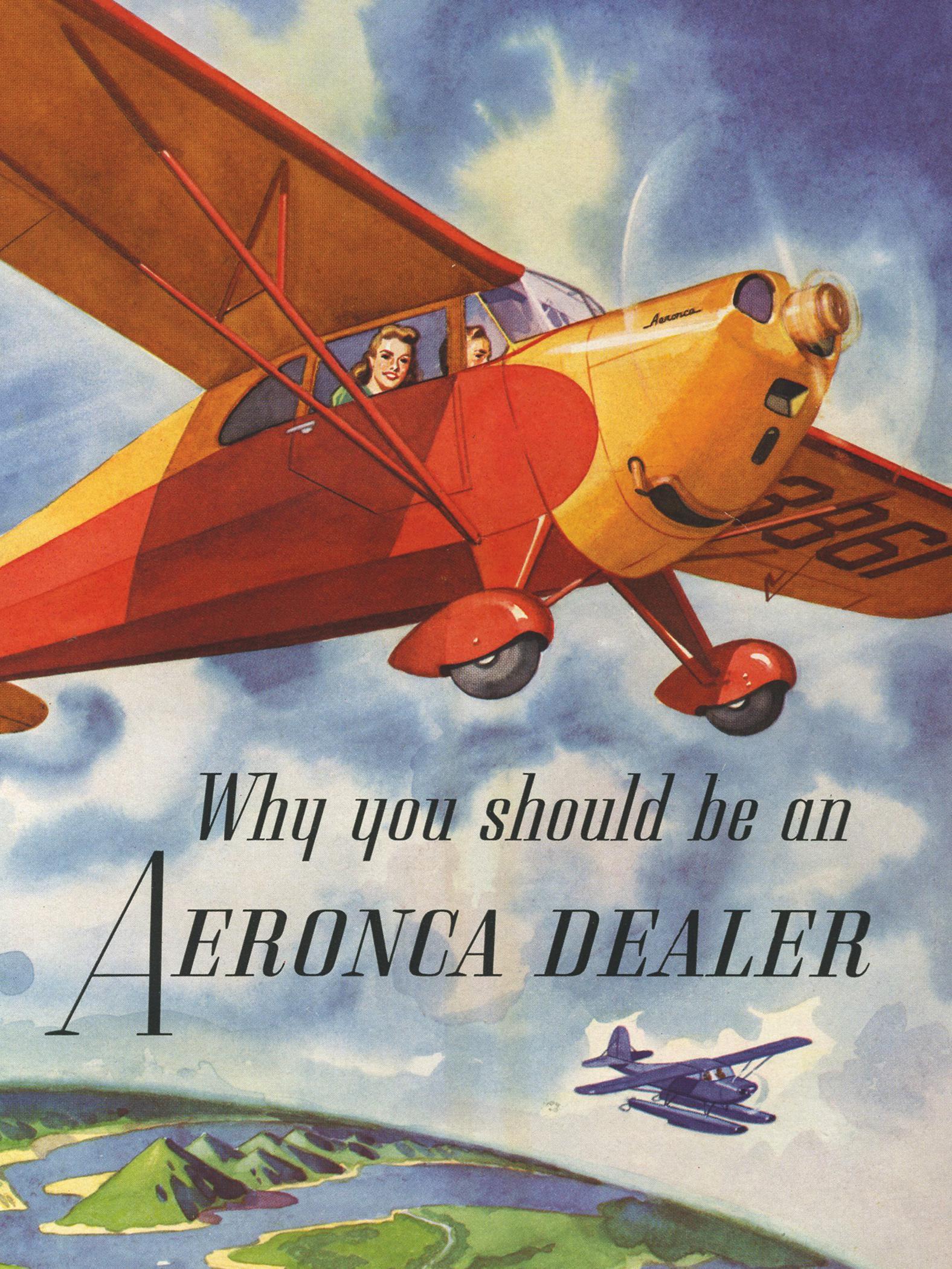

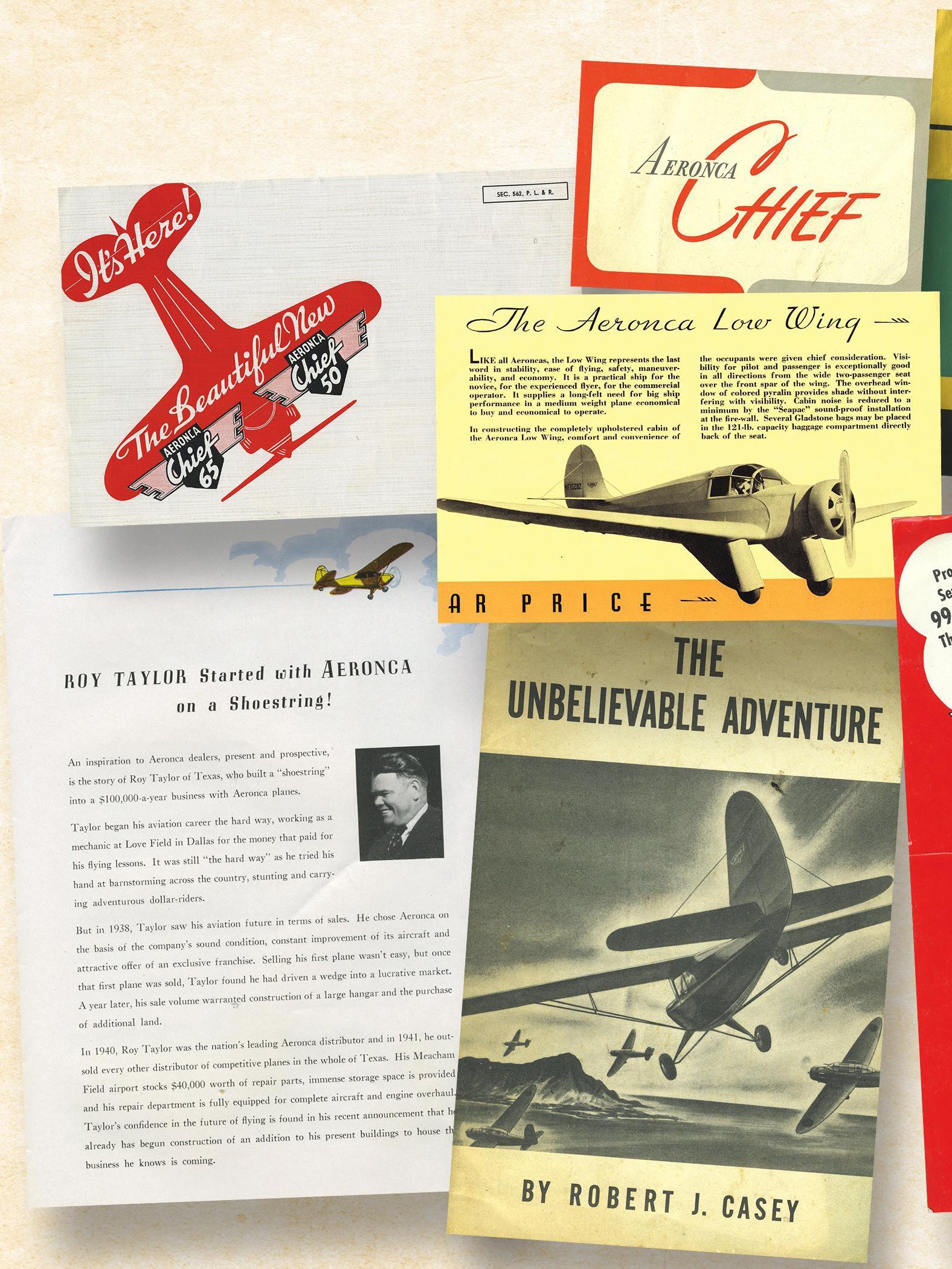

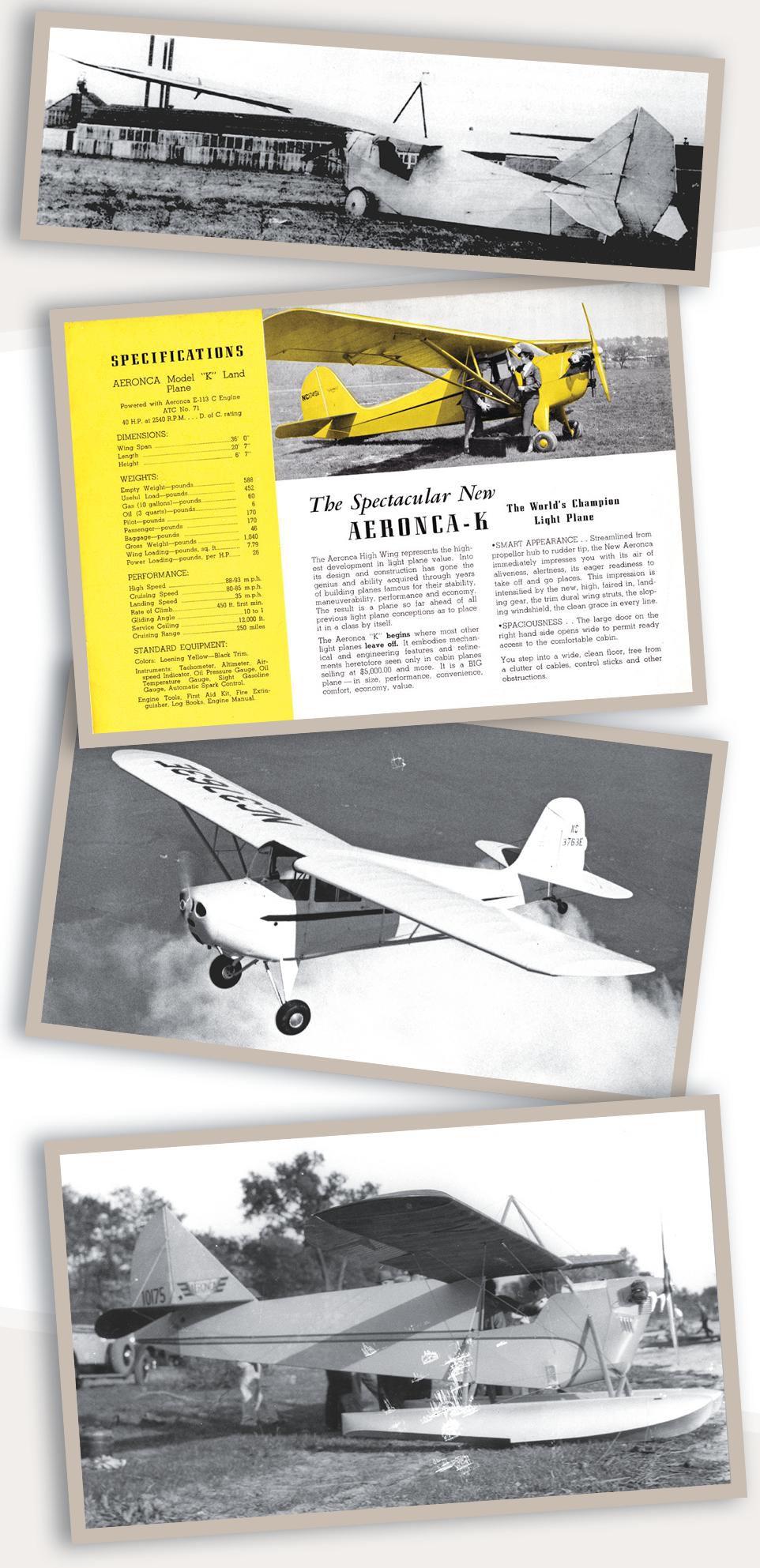

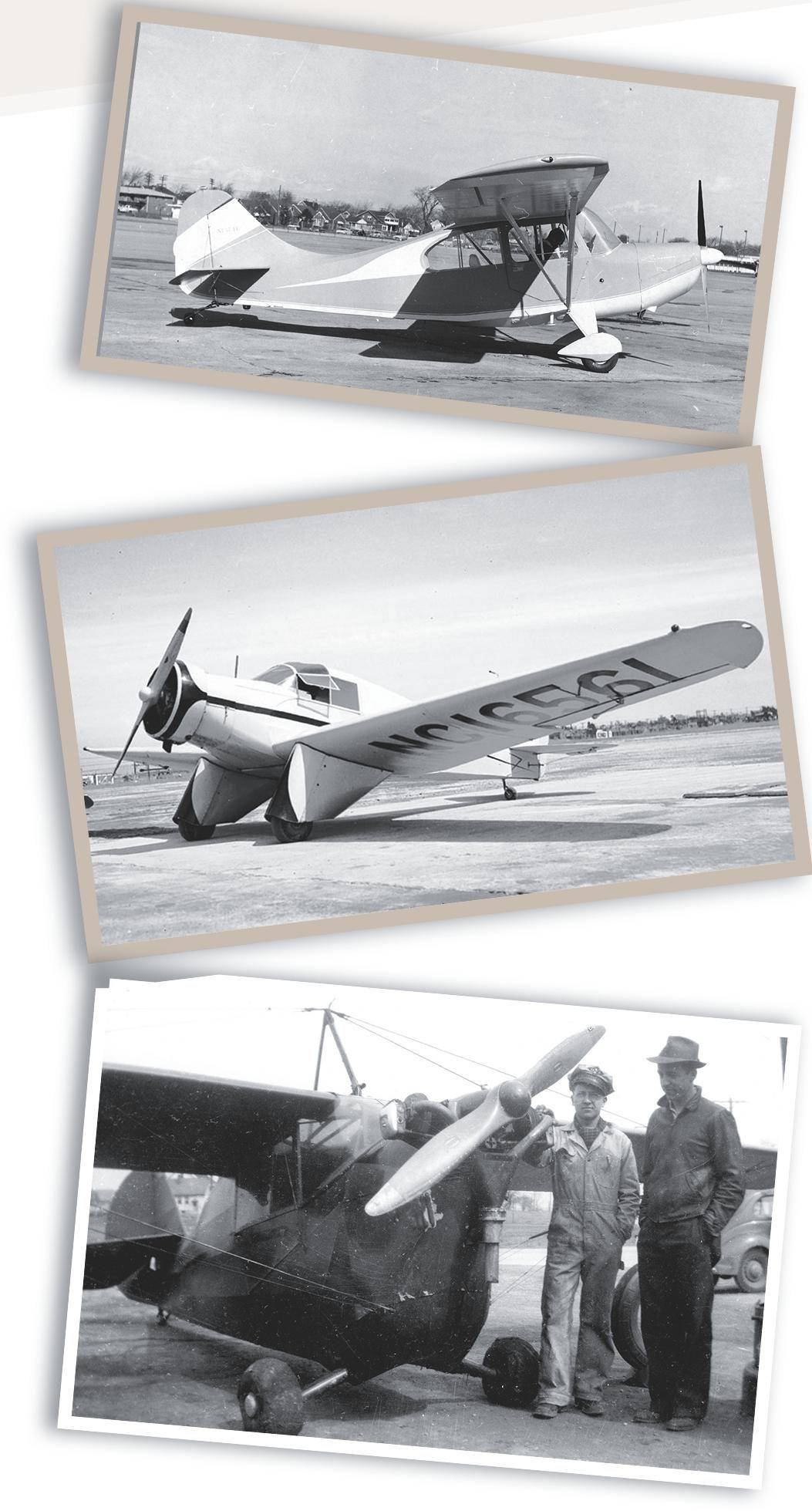

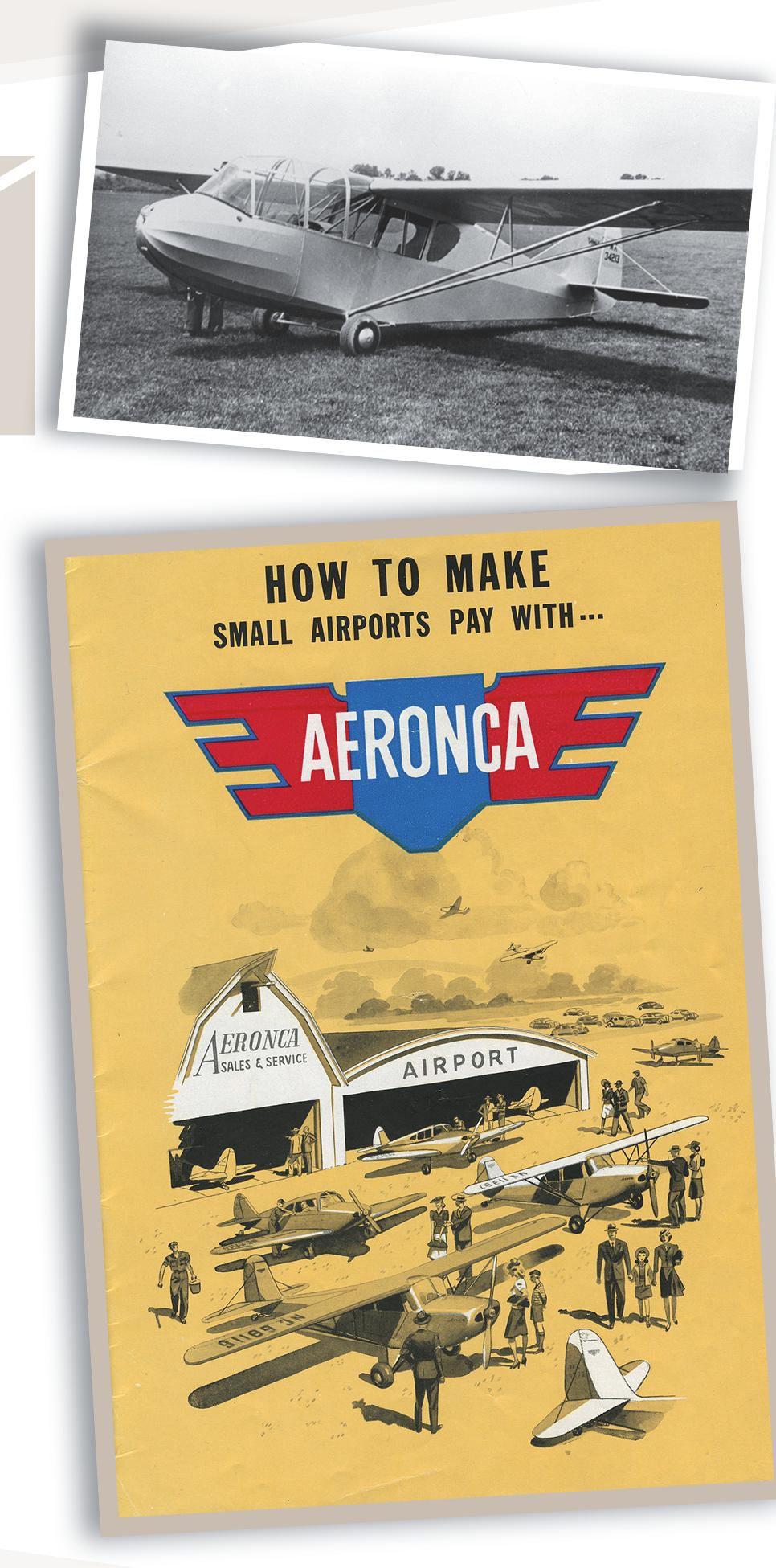

Take a quick look through history by enjoying images pulled from publications past.

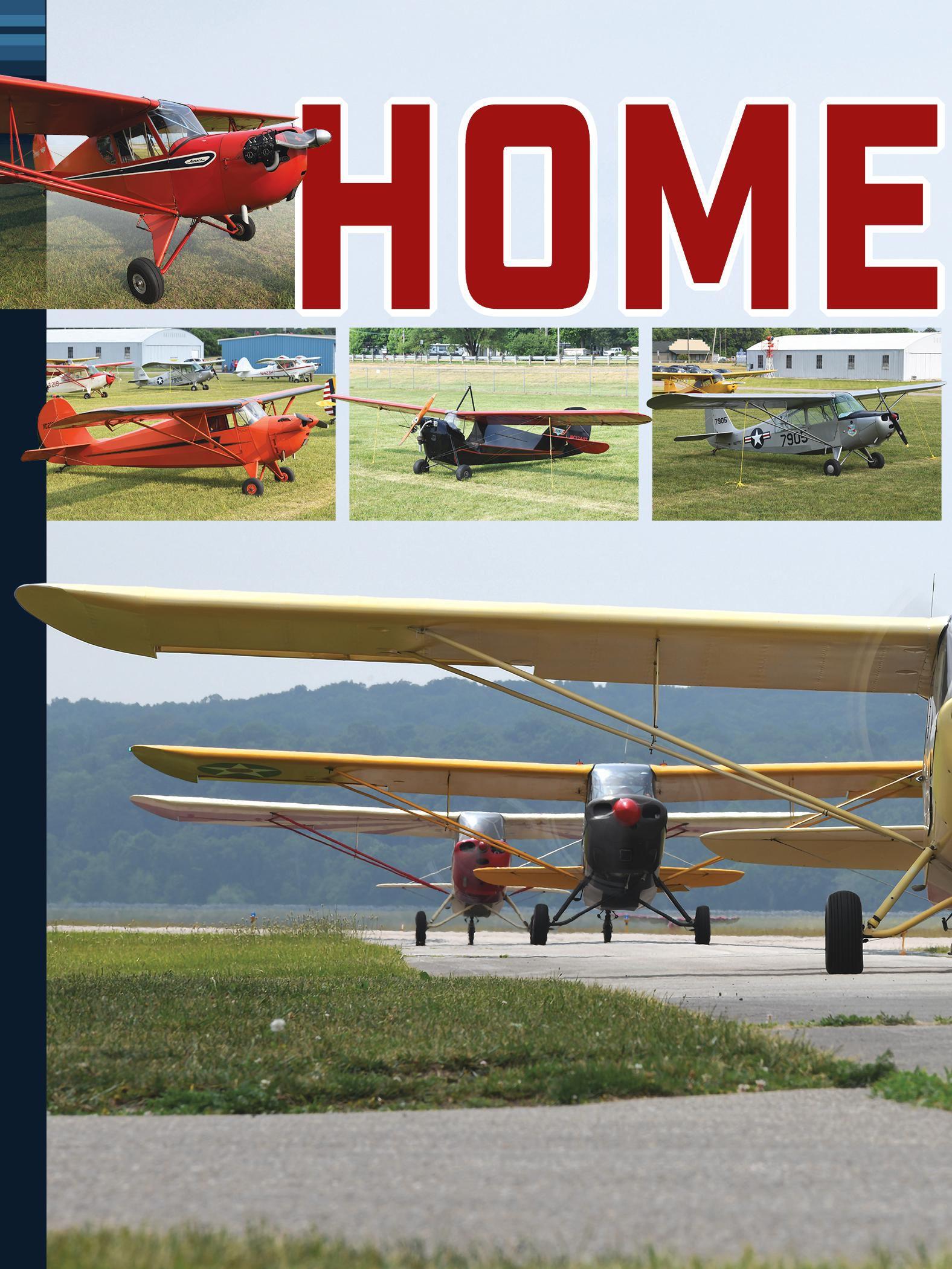

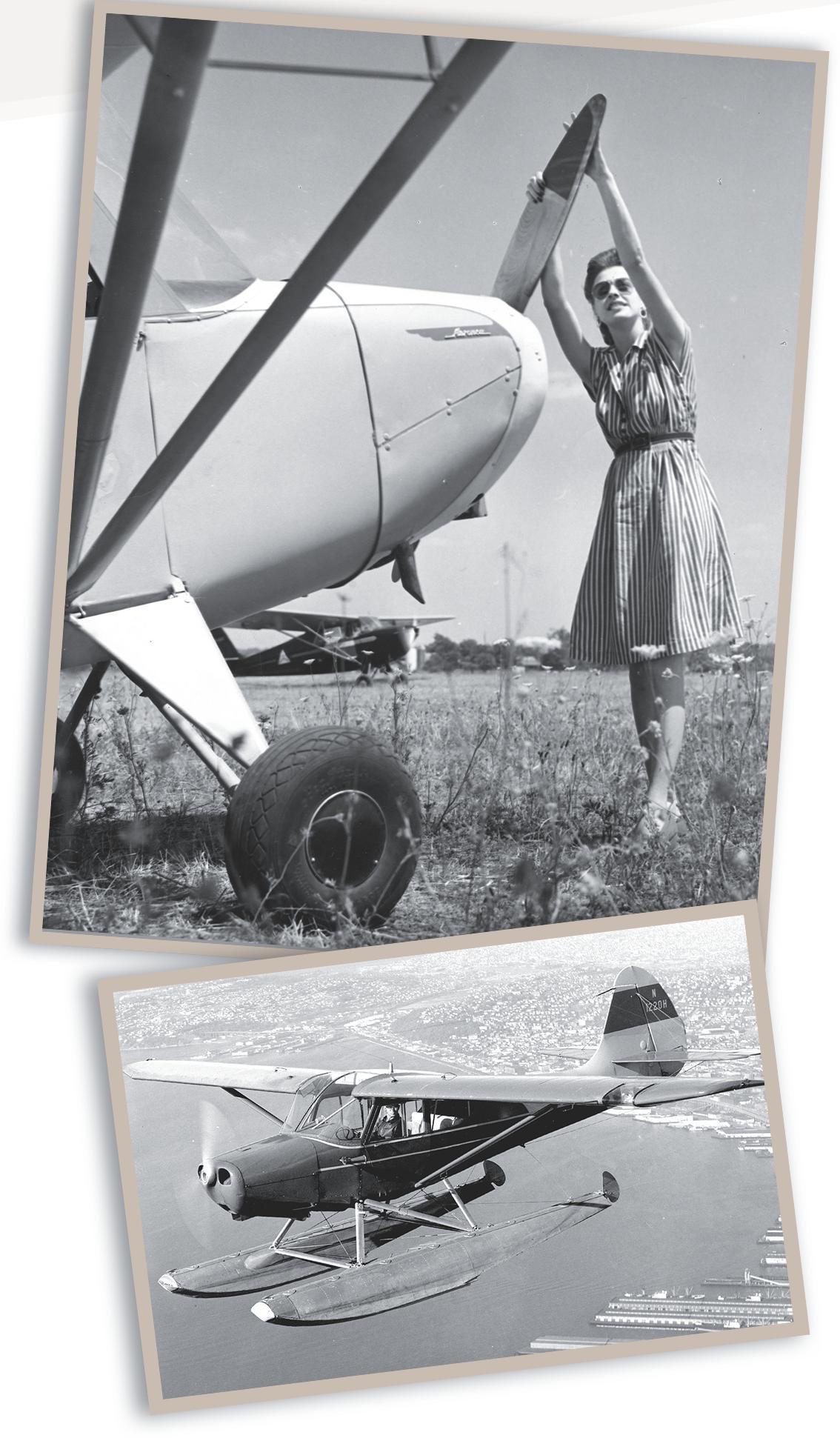

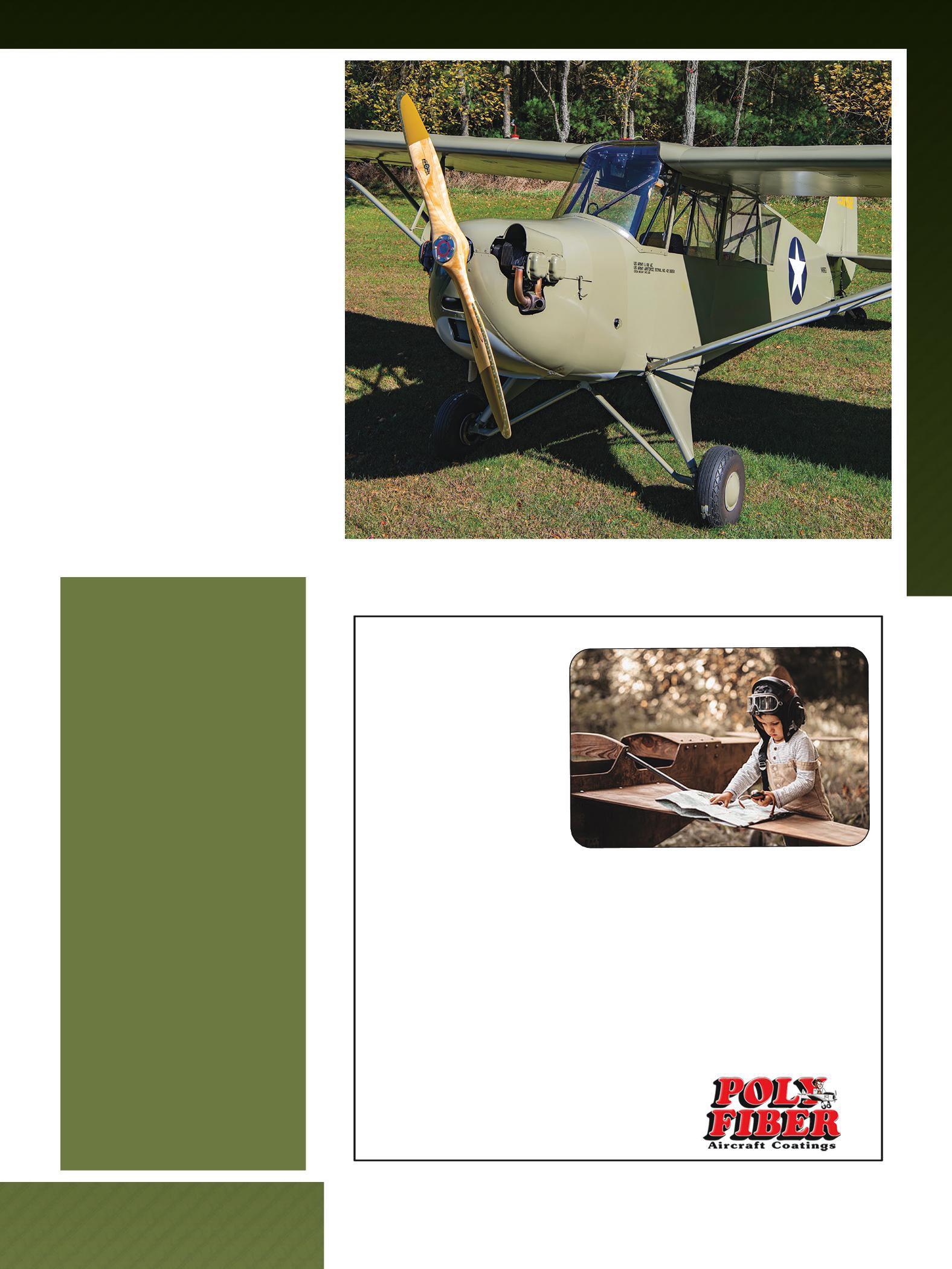

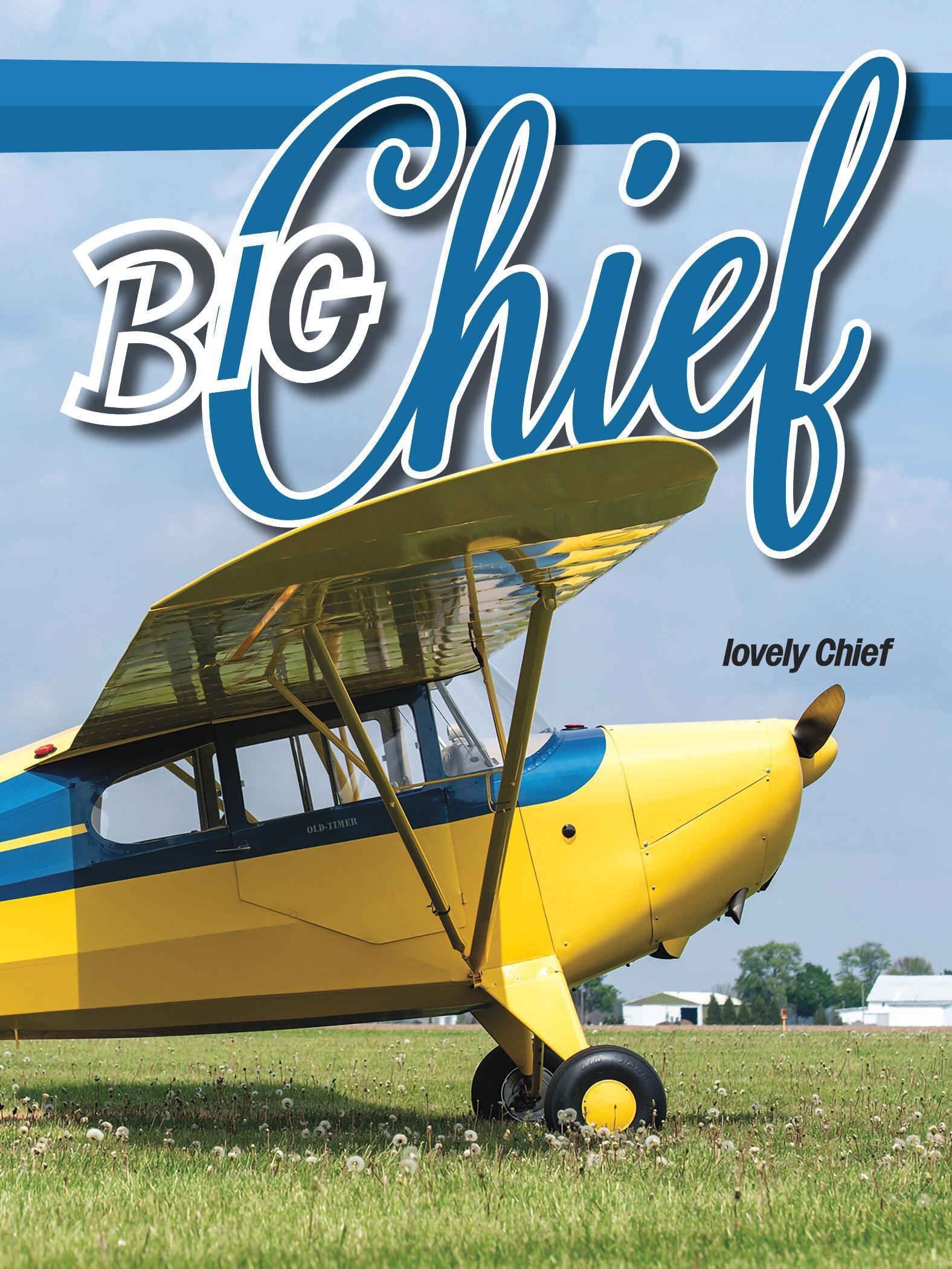

THE GUEST LIST FOR THE 21ST NATIONAL AERONCA ASSOCIATION CONVENTION was “eclectic” tosaytheleast.Thelineup included Bathtubs, Tandems, K’s and L’s, Defenders, Chiefs, Champs, and Sedans. Some were in original civilian or military paint schemes, while others sported cartoon characters, military crests, or personalized nose art.

They arrived back home on June 15, 2023, for a fourdaybiennialeventfromall parts of the country. Although shrouded by hazy Canadian wildfire smoke, none were deterred, navigating their way toward Ohio as their wheels kissed thegrassrunwaysatHook Field in Middletown.

Old airplanes and old friends once again rekindled memories of the past as theygatheredunderfabric wingsorstrolledoverlush green Ohio grass in the shadow of the old Aeronca plant, admiring some of this country’s greatest lightplane aviation achievements.

Sit back and take a stroll through memory lane as you enjoy the photos of Aeroncas and the people who are proud to own and fly them.

Coming to EAA® AirVenture® Oshkosh™ 2024: Aeronca Nation, hosted by the Vintage Aircraft Association. Parking spaces are being reserved for Aeroncas and Champions, but spots MUST be occupied prior to Sunday night, July 21. After that empty spaces will be filled with other aircraft on a first come, first served basis with ABSOLUTELY NO EXCEPTIONS.

To park in one of these spots, you MUST BE PRE-REGISTERED. Parking volunteers will be checking the list and only parking those aircraft that have registered prior to arriving.

To register, email AERONCA.NATION.2024@gmail.com with the following information for each aircraft you plan to bring:

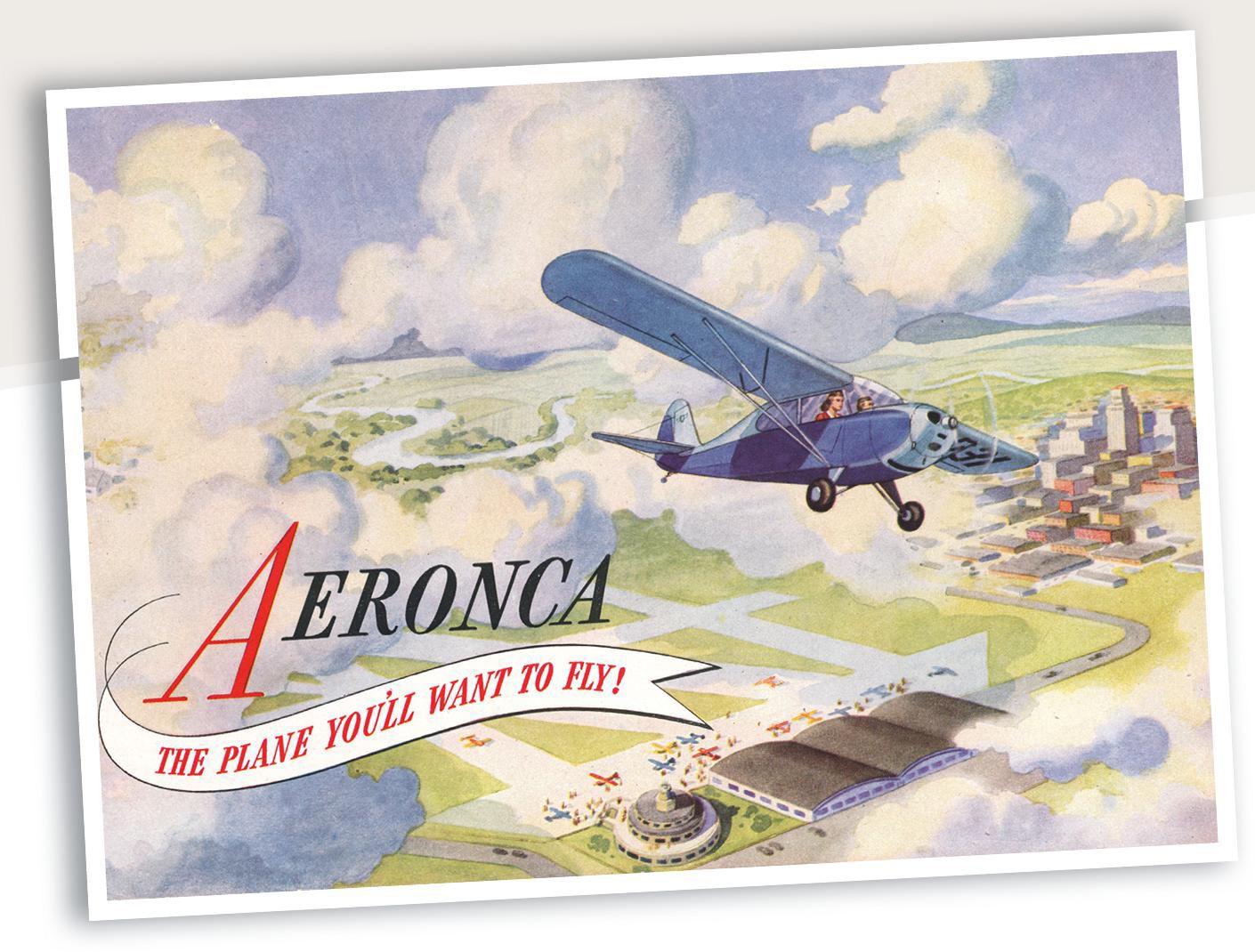

DURING THE HEIGHT OF the aviation craze that swept over the United States following Charles Lindbergh’s solo flight across the Atlantic in May 1927, many designers and manufacturers worked to create an “everyman’s airplane.”

Jean Roche, an engineer with the Army Air Corps in Dayton, Ohio, was fascinated by the concept of a lightweight sportsman’s airplane, a little plane that could be flown for fun and perhaps a bit of cross-country flying. By 1923-24, he had interested his assistant at McCook Field, John Dohse, in partnering to build the first Roche lightplane. Dohse was a lifelong aviation enthusiast, having two decades earlier witnessed the Wright brothers flying at Huffman Prairie, near his family’s farm.

Once the design was completed it looked like it was ready to go, but for one little problem that often stymied aviation visionaries.

An engine.

The powerplants of the day were either too expensive or just too big and heavy. Fortunately, just the right guy was working in the shop right next door at Wright Field. His name was Harold Morehouse, and he too worked for the Army Air Corps. To replace the 18-hp motorcycle engine they originally installed, Morehouse designed an 80-cubic-inch displacement engine that would produce 26-29 hp at 2500 rpm.

On September 1, 1925, at Wilbur Wright Field near Dayton, John Dohse was ready to test the Roche lightplane. He had intended to only taxi test the airplane, but with the added power of a new engine, it popped into the air quickly. He surprised not only himself but also his partners in the project. He continued flying instead of pulling back on the throttle and putting the untested airplane back on the ground. There was only one problem.

Even though he had some dual instruction, he’d never soloed!

He sure didn’t want to wreck the new airplane, so he gently climbed and circled the field. He got a feel for the airplane and gingerly worked his way down to a landing. Like a few of the pioneer pilots at the dawn of flight two decades earlier, both the pilot and the airplane had their first flights on the same day, at the same time.

The airplane proved to be popular with all who flew it. A couple of years later, what could have been a disaster turned out to be a mixed blessing. With his brother stuffed aboard the one-place airplane, John Dohse got a bit too slow in a turn while low to the ground and crashed the Roche lightplane. His brother was unhurt, but Dohse came out of the crash with a broken ankle.

All these years later the Aeronca name is still a much sought-after airplane, one of the brightest gems of the golden age of lightplanes.

The little lightplane was crunched, and the nose caved in, rendering the original Morehouse engine unusable. With Morehouse gone, Ray Poole and Robert Galloway redesigned the engine to be slightly larger with more horsepower. Their design, based on the Morehouse engine, would eventually be produced as the twin-cylinder Aeronca C-107, later the E-113.

In late 1928, a small group of prominent citizens of Cincinnati, including Sen. Robert A. Taft, the son of the former U.S. president, incorporated a company they named the Aeronautical Corporation of America. They saw a big future in aviation, but had one little problem.

While the company name sounded grand, it didn’t have anything to make or sell. It had no factory and no airplane to produce even if it had a building. By early 1929, Conrad Dietz, a local businessman who also had an interest in aviation, was hoping to interest the new company in a biplane he had the rights to produce. They didn’t want the biplane, but Dietz, recognizing that monoplanes were quickly gaining traction in the aviation marketplace, suggested the company take a look at a nice little lightplane created by some talented guys up in Dayton.

The principals of the fledgling firm had decided their new company’s location would be at Cincinnati’s Lunken Airport, on the bottom land alongside the Little Miami River, near its confluence with the Ohio River. Since saying the full company name was a bit of a mouthful, it quickly became known simply as “Aeronca.”

After a demonstration of the airplane in the late spring of ’29, within a few weeks a firm offer was placed to buy the production rights to the Roche lightplane. Roche, unwilling to give up his position at Wright Field, was hired in an advisory capacity.

Aeronca now had a product to sell. By the end of 1929, Aeronca bought the Metal Aircraft Co. factory at Lunken Airport.

Aeronca hired a well-known engineer, Roger Schlemmer, to work with Roche to bring the design up to production standards. He added a small windshield and a skylight. Soon, the lightweight airplane was in production, with the first C-2, serial No. 2 (the Roche lightplane was considered serial No. 1), NX626N, flying for the first time on October 20, 1929. A few days later, serial No. 3, NX627N, was pushed out the factory door.

Just a few weeks later, the two airplanes were introduced to the public at the Western Aircraft Show in Los Angeles. The public was smitten. With a list price of $1,495, reduced in 1931 to $1,245, and costing but a penny per mile for gas and oil, the price was hard to beat. Even at the height of the Great Depression, the C-2 held the top sales position over as many as 23 competing “flivver planes.”

By the start of 1931, it became clear Aeronca had some work to do to keep its lead. At that point, most lightplanes had two seats, while the C-2 was really a single-place airplane. The enlarged version of the Aeronca lightplane would be called the C-3 and would prove to be even more popular.

The C-3 would be powered by the updated 36-hp E-113 engine, versions of which would power Aeronca lightplanes for many years to come. Through the next few years, the C-3 would undergo many changes to increase its appeal. Doors would be added, as well as a more rounded aft fuselage to approximate a more comfortable, autolike cabin. They were flown from twin-float Edo pontoons, or with

their balloon Goodyear Airwheels soaking up the bumps of the turf.

For the first half of the 1930s, sales were good, but by 1935 it was clear the design had run its course. When production ended in 1936, 617 airplanes were built of the various versions of the C-series of lightplanes produced under the Aeronca name.

Aeronca engineers had already started work on two new projects: a sleek two-place, cantilevered low-wing monoplane and a new high-wing, strut-braced monoplane. The latter design was pushed by revisions to the Civil Air Regulations, which essentially outlawed the use of wing structures braced solely by bracing wires. A single wire failure could cause the entire wing structure to fail, inevitably resulting in a fatality. With a reasonably good safety record, Aeronca management wanted to be seen as a progressive company, and its chief engineer, Roger Schlemmer, got to work on both projects.

The Aeronca L was a remarkable-looking airplane for its day. The tapered, unbraced wing was a bit of a novelty as well. Schlemmer had done his homework and kept up with the latest NACA engineering reports, applying that new information to the innovative design.

The landing gear, with its large air wheels, was faired by voluminous fairings dubbed “spats,” after the popular shoe fashion of the day. While the first version was powered by the 36-hp E-113, it didn’t give the airplane the required oomph to get it off the ground and around the pattern with any reasonable margin of safety. For production, three versions were offered: the Model LA, with a 70/75-hp LeBlond engine; the LB, with an 85/90-hp LeBlond; and the LC, with the 90-hp Warner Scarab Junior. Even with its futuristic looks and nice performance, the L series didn’t sell all that well; only 66 were built by the time production ended in 1937.

At the same time the work on the L was being done, Schlemmer had been crunching the numbers and laying out a more conventional-looking high-wing monoplane. With a wing braced with a pair of V-struts, it looked much like its

competitors from other up-and-coming aircraft builders.

Pilots and their passengers were expecting a more comfortable experience, and manufacturers were quick to adapt, using automobiles as their cue for what the public wanted.

The engine for the Aeronca K was the Aeronca E-113, now pumping out 40 hp. The prototypes of the new airplanes were built simultaneously at the Lunken Airport plant. While the futuristic-looking low-wing’s engineering seemed to go right along on schedule, it took longer for the final engineering approval to be completed on the K. With the C-3 still selling, Aeronca had two new offerings to add to the C-3 for the aviating public. Aeronca was at the top of its game, and prospects were looking bright.

Cue the disaster.

Like many rivers, the Ohio and Little Miami rivers were prone to flooding. The winter of 1936-37 had been exceptional when it came to precipitation. It became clear by mid-January the flood was going to be of extraordinary proportions.

On January 21, 1937, the levee protecting the lowlands near the Ohio River, including Lunken Airport, gave way. The word went out to Aeronca staff that they had little time to remove as much data, drawings, and nearly finished airplanes as they could. Within days, the airport was under 30 feet of swirling, muddy water. When it crested, the water was lapping above the roof of the old airport administration building, with only the weather instruments sticking out of the murky waves.

As the water receded, a massive cleanup got underway, and amazingly Aeronca was back producing airplanes

Piper and Aeronca were both turning out airplanes at rates never dreamed of before. Pilots across the country were enjoying that “new airplane smell” like never before.

by late March and early April 1937. But the production lineup had been trimmed.

Before the flood, the decision had been made to phase out production of the C-3 in early 1937. The flood just put a more abrupt end to that plan. Also taken out of production was the L series. It just wasn’t selling at the rate that justified its place in the plant; even the C-3 was outselling it 2-to-1. The few that had been flown out of harm’s way just after the dike broke were completed and delivered. But the K, having just been issued its Civil Aeronautics Administration type certificate, was to be Aeronca’s future.

The K’s initial production was with the two-cylinder Aeronca engine, but it was becoming clear that more horsepower was needed for subsequent models. The engine was a technological dead end, and to add two more cylinders was going to be cost-prohibitive.

Continental Motors was building its new four-cylinder engine, and although it too only produced 40 hp, it showed potential to grow in the near future. Offerings from Franklin, Lycoming, and Menasco were all options in the second half of the 1930s, setting the stage for the use of air-cooled, flat opposed engines for decades to come.

The K series had done a great job of transitioning the company’s offerings from lightplanes of somewhat limited utility to something with more capability.

Aeronca’s next airplane for mass production was to be called the Chief. With the sunsetting of the Aeronca engines, the new side-by-side airplane would be powered by one of the four-cylinder engines now dominating the 40-60-hp range of powerplants. The new engines were reasonably reliable, available for moderate cost, and their weight was appropriate

for their output. They also showed great potential for power growth. In fact, in less than a decade, the basic Continental engine, once the design evolved to separate cylinders, would grow from 65 hp in 1939 to 90/100 hp.

The 50C series of airplanes, the first Chiefs, were nearly identical to the K series, except for a wider cabin, more fuel capacity, and a fully cowled engine. No longer were the cylinders sticking out in the breeze. A 50-hp Continental provided the power.

The years immediately prior to World War II were filled with defense preparations. The increase in federal spending on infrastructure, including airports, also meant a dramatic rise in flight training. By January 1939, the Civilian Pilot Training Program (CPTP), originally a program begun the year before to build up the number of civilian pilots, had transitioned to a more military-centric program designed to move them from primary training directly to the military.

Aeronca took comments from CPTP instructors and developed its first design intended primarily to create new pilots. The new T series design, dubbed the Tandem Trainer, was rolling off the line in early 1940. With a four-longeron fuselage and aluminum ribs in the wing, the company moved into new construction techniques when it introduced its first airplane with tandem seating. The rear seat was situated 5 inches above the front seat, giving the rearseated instructor a good view ahead while keeping an eye on the student’s activities. The T and its cousin, the TA Defender, would prove to be popular with CPTP schools.

The demand for increased production also meant it was time to move from “sunken Lunken.” A new factory was in the works. The company built a new factory adjacent to the airport in Middletown, Ohio. Over the coming months, demand from the CPTP schools for more airplanes kept the trainer line busy, and Chiefs were selling at a brisk pace as well.

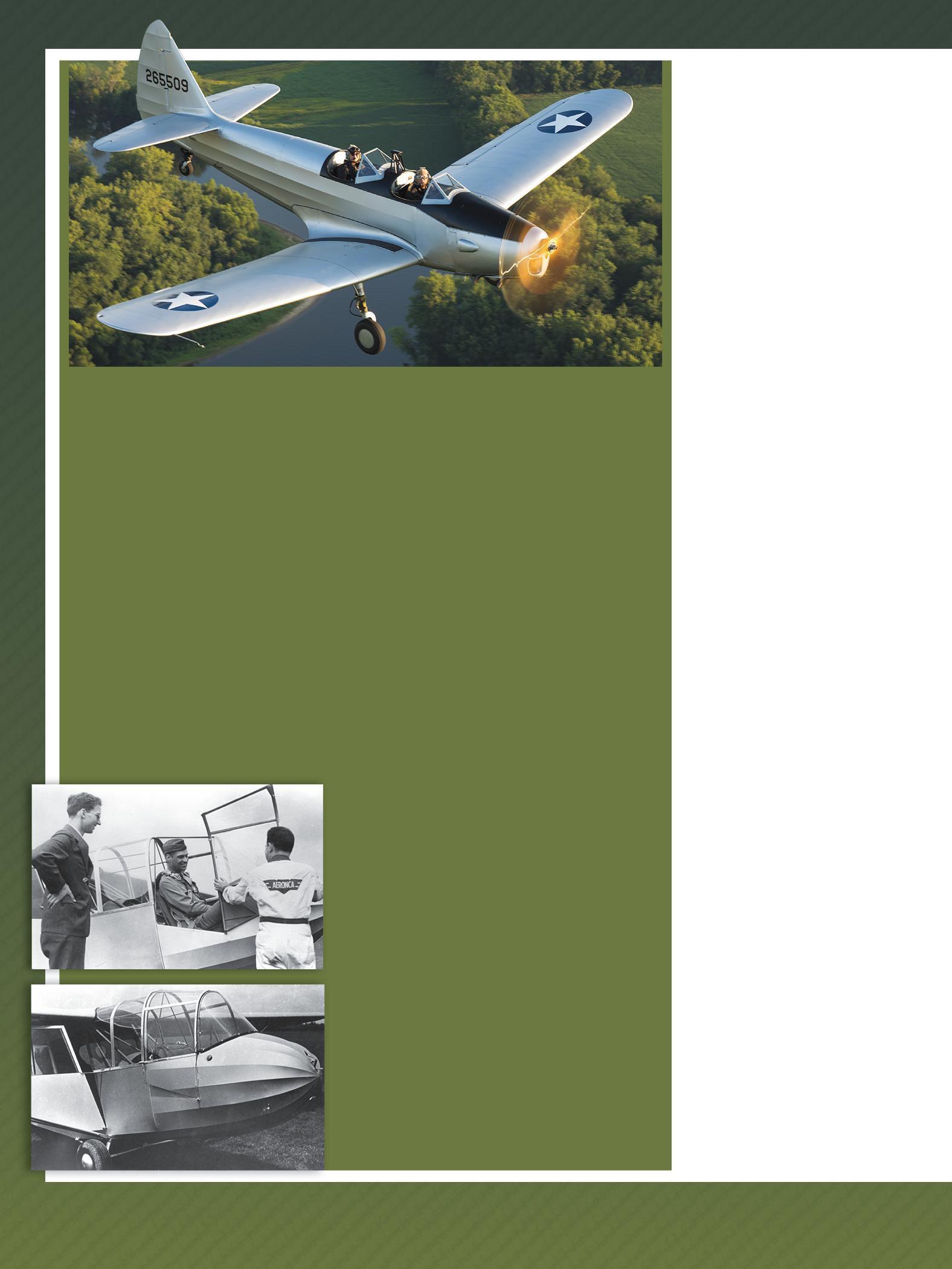

In the summer of 1941, a new avenue for supporting the military came along. The Army Air Forces saw a need for real-time eyes on the battlefield from above, and it was felt that the current crop of lightplanes would fit the bill. Along with aircraft supplied by Piper and Taylorcraft, the Aeronca Defender was shown to be a valuable asset to the commanders in the field. The two

airplanes that would dominate the liaison duties would wind up being the Piper L-4 and Stinson L-5, but the Defender, designated the YO-58 (later the L-3) after being ordered by the Army, would also be useful, with 1,224 of the various military versions delivered, plus the TG-5 glider.

The war years of 1941-1945 saw the production capabilities of the new factory put to use building the Fairchild PT-19 (powered by the in-line Ranger engine) and PT-23 (with a Continental R-670 on the nose) in 1942-43. During the later part of the war, engineering and production capacity began to open up at the plant, and Aeronca management began to think about a postwar future.

In early 1944, a new trainer design was sketched out. Ray Hermes, Aeronca’s chief engineer, took the many comments received about previous trainers, especially those built prior to the war, and designed an airplane that was to be more student and instructor friendly.

It would still feature a tail wheel, but the fuselage and cockpit were built so a pilot of average height could still see over the nose (mostly). The cabin would be entered by a big automobile-style door, making it easy to get in and out. The landing gear was designed with an oleo strut shock-absorbing unit in each gear strut, hoping to avoid the crow-hopping tendency of bungee-cord equipped airplanes (although many of us still have managed to put the new design’s landing gear to the test and bounded our way down the runway!).

In mid-April of 1944, the first of the 7 series, now known as the Champion,

was completed and flight testing began. With a 65-hp Continental engine, it could climb at 500 fpm and showed excellent handling characteristics. In engineering, the production line, and the sales department, the feeling was clear: They had a winner on their hands. Enthusiastically received during sales tours, with four preproduction airplanes, advance sales looked great.

Hermes also had been thinking about a sister ship to the trainer, one that would appeal to the sportsman pilot. The 11 series Chief would use a different fuselage with side-by-side seating, but most of the other parts would be identical. Wings, tail surfaces, landing gear struts were all interchangeable. This sharing of components kept engineering, production, and parts costs down. Even with Chief production moving to an auxiliary plant in Vandalia, Ohio, costs were well contained.

When the first Aeronca 7AC Champs were sold in early 1946, they were priced at a reasonable $2,295. The low price of the Champ kept it as a viable option for training school operators for the next few years.

The military took note of the Champ’s capability as well, and a military version, the L-16, was ordered, with 609 delivered for use primarily by the Civil Air Patrol. With a higher-horsepower Continental C-90 engine, it was built with a bit of area added to the vertical fin, and thanks to tests done by the Army, a longer stroke oleo landing gear was installed. The new landing gear soaked up the bumps of an unimproved airstrip or a less-than-elegant approach and touchdown.

Aeronca management was keen to expand its product line with a four-place airplane, and they were behind the power curve when it came time to produce one. Their Eagle project proved to be unworkable, and they had to scramble. Cessna had its 170, which was proving to be popular.

Management directed Ray Hermes to come up with a design as soon as possible, but he was to keep costs to a minimum by using parts and materials already on hand whenever possible. Sheet aluminum for the wings was chosen, and the Champ’s door and nose cowl were adapted to the new high-wing design. George Owl, later of Owl Racer fame, did the aerodynamics, and a young Harry Zeisloft, who would later serve as the technical director for the EAA Aviation Foundation’s Kermit Weeks Flight Research Center, designed the installation of the six-cylinder Continental C-145. Built with a steel-tube fuselage and tail surfaces, costs were kept in line and the airplane was offered for $4,395. When introduced in late 1947, the Aeronca 15AC Sedan was hailed as roomy, comfortable, and durable, if not a bit slow with its 107-mph cruising speed (the 170 cruised at 115 mph). The Sedan proved to be popular, but sales didn’t match the

d, e ed e he uri-

competition. When production ended, 561 15AC Sedans would be built.

The 11 series was also selling well when introduced, although never at the rate of the 7AC. Both models were regularly updated, with new models featuring nicer interiors and upgraded power from the Continental engines that dominated the postwar era. The last versions of the 7 and 11 series, the 7EC and 11CC, were downright luxurious compared to the company products of only a decade before.

In the months that followed the end of the war in August 1945, the reality was that the expectation of military pilots who would want their own airplane in civilian life just didn’t hold up. For the first year and a half after the war, there seemed to be no end in sight to the upward sales trend. Piper and Aeronca were both turning out airplanes at rates never dreamed of before. Pilots across the country were enjoying that “new airplane smell” like never before.

By 1950, it was clear that for the company to survive, it had to diversify beyond the production of airplanes. The last Champ rolled out the production hangar doors in January 1951, Chief production having ended in 1950. With the exception of one more 15AC completed in October 1951 out of remaining parts, Aeronca was done building airplanes. On that day, the company had built a total of 17,408 airplanes of Aeronca and Fairchild design; 8,199 of the 7 series were built, and 2,418 of the 11 series among them.

It was not to last. Sales figures for the month of December 1946 showed 103 Champ deliveries and 133 Chiefs. That was less than half of the previous month’s output.

Bob Hollenbaugh, a 42-year veteran at Aeronca, recalled that it was common for a number of ferry pilots to show up at the end of the week to fly all the new airplanes away. But one Saturday in March 1947, they just didn’t get off the train or bus. April came, and there were still few ferry pilots showing up. By early summer, sales had taken a steep decline, and the ferry pilots never returned in the numbers seen during the frenzied production of the previous 18 months during 1946-47. The great postwar slump in sales had begun. With the market saturated with new production and surplus military airplanes, most lightplane manufacturers would find themselves in a financial pickle. Piper and Taylorcraft both felt the pain, and Aeronca was no exception; reorganization was required.

By that point, Aeronca had already gone into the subcontracting business, and in fact, it is still in the aviation subcontracting business today. It became pioneering leaders in the production of braised honeycomb metal structures (the outer panels of the Apollo spacecraft were one of its products), and today it’s acknowledged as a leader in the building of jet aircraft cowling and thrust reverser systems.

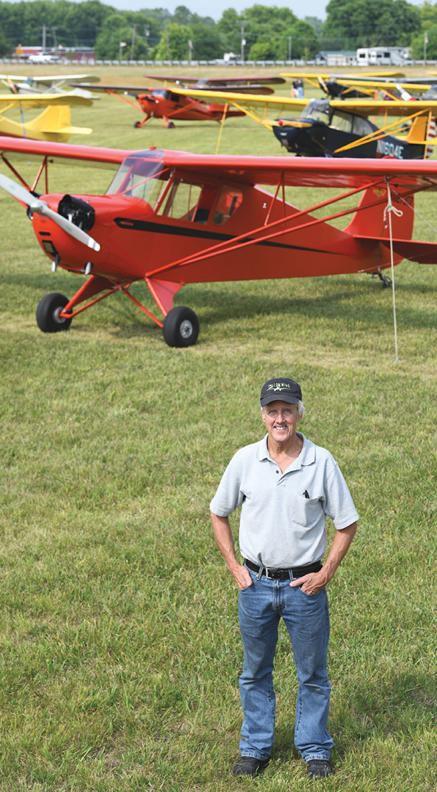

As enthusiastic attendees can attest to at the National Aeronca Association’s biennial fly-in at Hook Field in Middletown, Ohio, all these years later the Aeronca name is still a much sought-after airplane, one of the brightest gems of the golden age of lightplanes.

There is so much more to the history of this pioneering company that we couldn’t possibly fit in an article of this length. If you’d like to dig deeper into the history of Aeronca and the foresighted men and women who made it flourish, I’d suggest the following books:

Aeronca C-2: The Story of the Flying Bathtub, by Jay P. Spenser, published by the Smithsonian Institution Press, 1979, ISBM 0-87474-879-8

Aeronca: A Photo History, by Bob Hollenbaugh and John Houser, published by Aviation Heritage Books, 1993, ISBN 0-943691-10-9

Aeronca’s Golden Age, by Alan Abel, Diana Welch Abel, and Paul Matt, published by Wind Canyon Books, 2001, ISBN 1-891118-42-0

The Best of Paul Matt: Aeronca, published by Sun Shine House, 1988, ISBN 0-94369102-8

While none of these books is currently in print, they are often available from usedbook sellers.

WHEN WATCHING A 7AC CHAMP float off a grass runway for another sunset tour, it’s hard to remember that Aeronca contributed mightily to the amazing production numbers that came out of World War II.

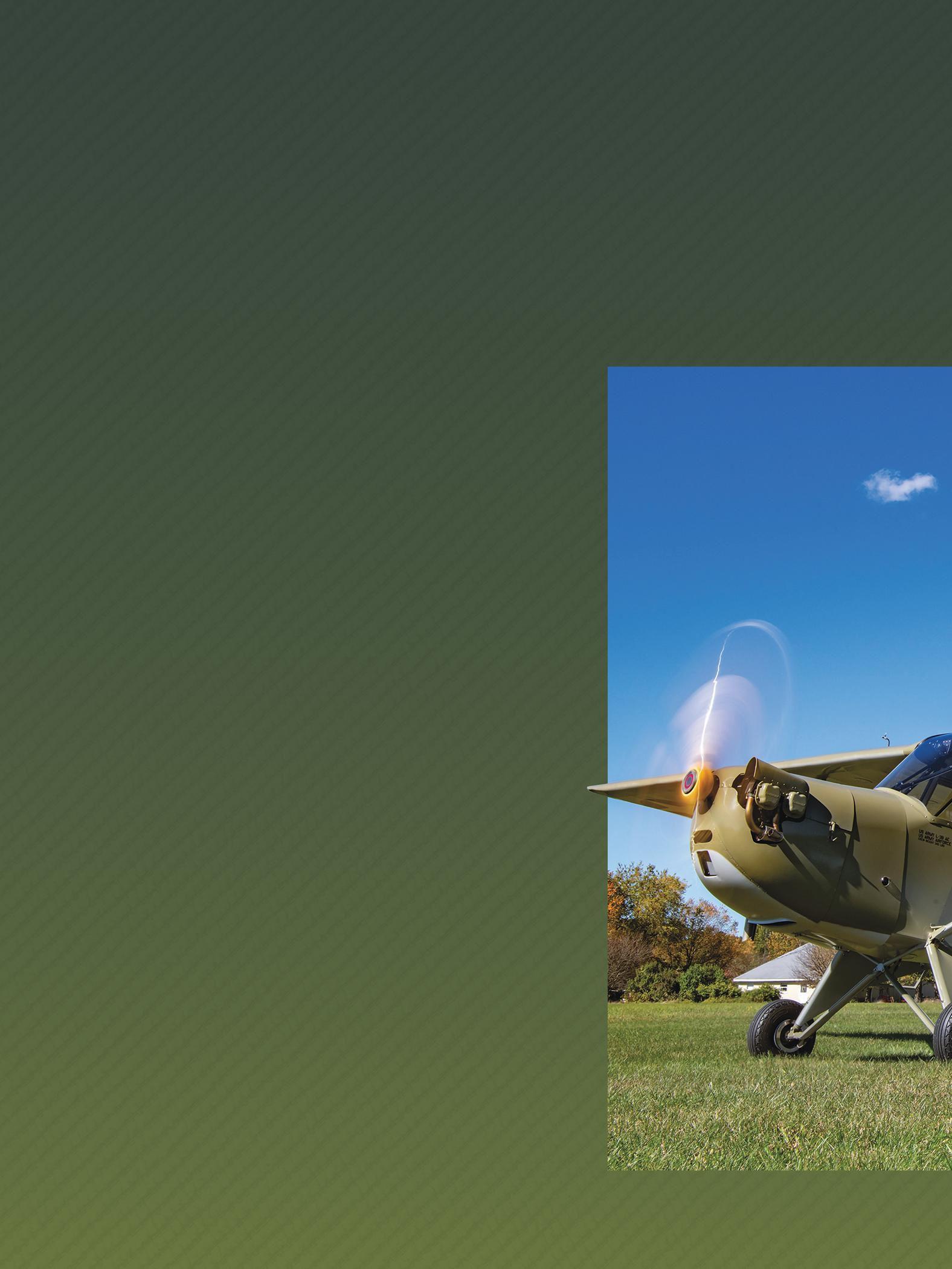

During the war, the United States produced approximately 300,000 airplanes of all sizes. If a little old-fashioned arithmetic is applied and it is assumed we were in wartime production for less than four years (it was actually three years, eight months, and change), those 300,000 airplanes are 223 per day, or 9.2 per hour, 24 hours of every day from late 1941 to September 1945. The labor force required to make that happen numbered in the millions. WWII aircraft production had so many stories hidden within stories and so many faces and facts, it is impossible to make a concrete statement about the period and know that it’s an absolute truth. However, here is one concrete, irrefutable statement: Not one of those millions of men and women who were machining steel, riveting aluminum, and shaping wood thought the airplanes they were building would still be flying 75 years in the future! They were tools designed and built for a single purpose: Win the war. But survive for three-quarters of a century? No way! Longevity wasn’t part of the equation. However, courtesy of folks like Mike Hoag, EAA 228838, of Three Rivers, Michigan, and his L-3 Aeronca, the fragile aerial artifacts of a long-ago time still soldier on.

Here’s a thought that puts the age of Mike’s L-3 in perspective: When his airplane rolled off the Aeronca production line in April 1942, 82 years ago, it had only been 40 years since the Wright brothers proved that man could fly. Furthermore, 81 years before his L-3 was built was April 1861, when the first shots of the Civil War were fired. So, in 2024, we’re about as far from WWII and the L-3’s birth as they were from the beginning of the Civil War.

Of the 300,000 aircraft American industry fielded, about 15,000 were L-birds with 2,000 Taylorcraft L-2s, 1,300 Aeronca L-3s, 5,000 Piper L-4s, and 3,900 Stinson L-5s. So, the only Grasshopper that is rarer than Mike’s L-3 is the seldom-seen (320 were produced) Interstate L-6. Of that batch, only the Stinson L-5 Sentinel was specifically designed to be a liaison bird. All the rest were two-place civilian flivvers that were already in production dressed in fatigues. In the case of the L-3, Aeronca was already producing its TC-65 Defender. In 1941, the Army Air Corps bought four tandem aircraft from each of the big four light aircraft companies, and during their 1941 war maneuvers tested them for various purposes, including being artillery spotters. During WWII, most of the battlefield liaison work was assigned to the L-4 and L-5, although a number of L-3s did find their way to the European theater with many serving with the Free French forces in North Africa throughout the war. The rest became the trainers that taught Grasshopper pilots their trade before going overseas.

The L-3 was originally designated an O-58, but in April 1942 a new designation system renamed it L-3 and changed all other designations from “O” for observation to “L” for liaison. The L-3 was relieved of duty before the war came to an end, and they were sold to the civilian market. Most of them were nearly brand new and were sold for around $600, which would be $11,325 today.

For the first decade or two after the war, civilian L-3s were plentiful. Then they became long-term residents of back tie-down lines on rural airports. First their tires went flat, and weeds grew up to their bellies. Then their fabric became brittle and began to crack and tear. While all this was happening, the tubing was rusting and their wood parts began to come apart. The first L-3s had aluminum ribs, but most of them had wooden truss ribs, and the glue began to fail; the wood spars began to discolor and rot. They were designed to be a low-dollar, expendable airplane to begin with, so few were saved. It wasn’t until sometime in the 1970s when anyone thought seriously about remanufacturing a nest-infested, rusted, and corroded L-3. Restorations were practically unknown. Little by little they began to disappear, most going to scrap heaps. A few, however, although existing only as partial skeletons, found refuge in barns or, as in the case of Mike Hoag’s airplane, wound up in a vocational school where it survived. More or less. His airplane is lucky he came along and saved it.

There’s a very distinct sequence that the parts must follow to be assembled. It was a jigsaw puzzle for which we had no picture to follow. It took a while, but we got it right.— Mike Hoag

Enter Mike Hoag

Mike has always been an Aeronca guy.

“I started flying in my late 30s,” he said. “I taught myself to fly an ultralight, but when I was thinking about a pilot’s license, a friend told me about a guy who was selling an Aeronca Chief and was an instructor. I bought his Chief and he taught me to fly in it, first flight to checkride.

“When out of college a few years, I joined the sheet metal workers union and began working for major manufacturing companies,” he continued. “I did that for 40 years until I retired in the spring of 2004. My wife and I had bought a small 27-acre farm, and I put two runways on it, configured in an ‘L’ shape. They are 1,700 and 1,320 feet long. Plus I have a 50-by-100-foot workshop that I’ve kept full of my various projects, most of which are Aeroncas of one kind or another. The first was a Champ, but I’ve bought six or seven Aeronca Sedans and still have five, one of which, a ’48 model, I’ve put over 400 hours on. I can’t help it. I just like Aeroncas.”

Mike said the L-3 came to live with him by accident.

“I was in school working on my A&P, and one of the other students told me of a friend who had an L-3 that was in need of rebuilding,” he said. “At the time, I’m not sure what I was expecting, but I went over to look at it and found a damaged fuselage and wings that were only useful as patterns. The wood was just about gone. By this time I was busy with our sheet metal business, so I put it in the attic and pretty much forgot about it for 25 years while I messed with other Aeroncas. In fact, a friend had a flying L-3, and he encouraged me to start working on mine, but it was missing a bunch of parts. Along the way, I somehow wound up with a K-model Aeronca that had the wrong wings. They were for the glider version of the L-3, the TG-5, so I traded them to a guy who needed them for his project for a bunch of L-3 parts I needed for mine.”

According to Mike, the event that got him started in rebuilding the L-3 was when his friend with the flying L-3 damaged his airplane.

“He came to me for help repairing it, and we decided to build both airplanes at the same time,” he said. “So, mine came down out of the attic into my new workshop, and we went to work on them in 2017. The whole process consumed three years.

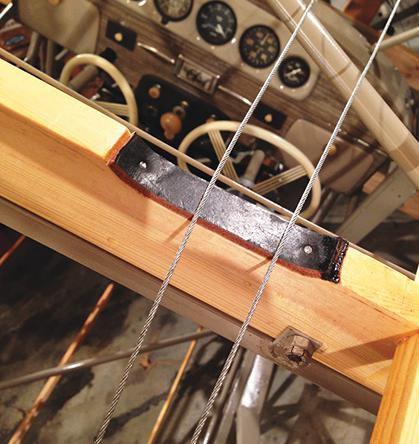

“When I first got my L-3, there wasn’t much information on them, but that changed greatly when the Aeronca Association put out a disc that included all of the blueprints for the L-3. As I understand it, in 1951 one of Aeronca’s engineers, John Hauser, rescued original Aeronca blueprints that were being thrown out by the factory. When the Aeronca Association was formed, he worked with them to digitize them, and the association makes them available to their members. Without them, my L-3 project would have been nearly impossible to do accurately. I still had to do a lot of research, but the blueprints gave me almost all of the structural information I’d need.”

Like all airplanes of its vintage, Mike’s airplane had seen some hard times. At one point, it was severely groundlooped, and the lower, forward part of the fuselage was heavily damaged. The only thing that kept it from the scrap heap was that the owner made no effort to save it and donated it to a vocational training school. There, the students attempted a little rib work, but primarily it stood in a corner, its fuselage standing vertically on its firewall and the shattered wings hanging somewhere out of the way.

“When the landing gear was torn off, everything up front was either destroyed or twisted out of shape,” Mike said. “If I hadn’t had the factory drawings with all of the original dimensions, repairing it would have involved either a lot of guesswork or measuring another supposedly undamaged fuselage. However, knowing the exact dimensions let me build a jig and establish all of the important intersections before I started cutting tubing out to replace it. Also, along the way I had collected some surplus parts, which saved some work. It must have gone into the vocational school shortly after the accident, because the steel doesn’t look as

if it spent much time outside. Besides the obvious damage, the rest of the tubing was pretty good, with just a little rust. The wings, however, were a different story.

“The woodwork was obviously never meant to last this long, so even if they hadn’t been damaged, the wings would have had to be built new,” he added. “The fittings were all there, so they were bead blasted and painted, but I was missing the drag and anti-drag tie rods. Plus, the wings were quite a bit different than Champions, so I couldn’t use many of those parts. The tie rods, for instance, are 1/4 inch where the Champs are 3/16. And the spars are 7/8 inch versus 3/4 inch. Everything about the L-3 was stout! Here again,

having the blueprints made a world of difference. I built the rib jigs using the blueprints, and they made the fabrication of the missing bellcranks easy.

“The wing struts were basically scrap because they were bent and twisted,” he said. “Streamlined tubing of that size is no longer available, so I was going to have to find a set of originals. One year at Oshkosh, I was haunting the swap mart, as I always do, and found some landing gear parts. I was in the process of buying those when I asked if the seller had any other L-3 parts, including struts, and he said he did back at home. I had a set, but they were too long and were for the glider conversion. His were the right size, so I strapped mine to the top of my car and drove up to Wisconsin and traded.”

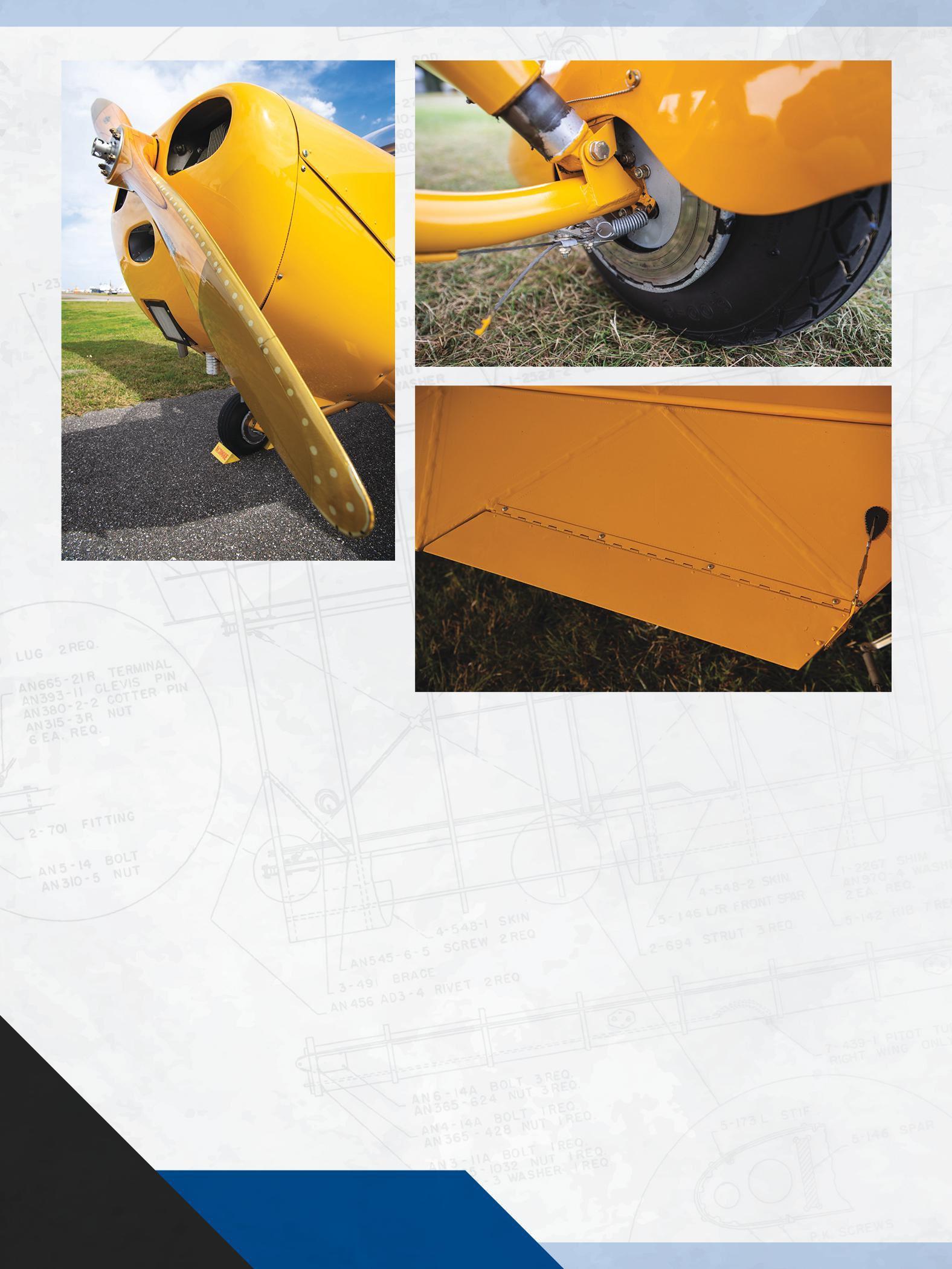

Except for the much bigger Stinson L-5 and its six-cylinder Lycoming, the entire liaison fleet was powered with the ever-present 65-hp Continental O-170/A65. The same engine powered the majority of two-place classic/ antique designs beginning in 1939 (or thereabouts). However, as reliable and plentiful as they were, Mike had flown plenty of them so he had other ideas for his L-3.

“The A65 wasn’t going to get it!” he said. “My Champ had 85 hp, and I had flown them with 65 hp and knew the C85 would make a much better performer of my L-3 and wouldn’t change the appearance a bit. So, using four different STCs for the installation, I went that route and am really glad I did.”

One of the unique aspects of the L-3 engine installation is that the cowling is mounted to the engine, not the firewall. So, Mike said the eyebrows and mount brackets have to be just right.

“I didn’t have a cowling that was even close to usable, and the nose bowl is compound curved, which I can’t do. So, I took it to D&D Classic in Covington, Ohio. They specialize in exotic car restorations, and, using my crumpled nose bowl, after hammering it out, they built a buck and formed two new noses for the two

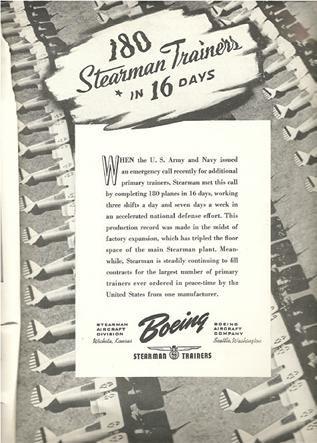

Two of the basic reasons the United States contributed so heavily to the outcome of WWII were, first, we didn’t have to worry about our factories and homes being bombed or shelled. Oceans are effective moats. Secondly, our industrial system adhered to the Henry Ford highly efficient system of manufacturing in which it was one man, one part. Not one man, one rifle/airplane/shell/etc., as many other countries did. America’s amazing wartime output was the result.

Further, as a German field marshal said during an interview after the war, “We never considered that America would double their available workforce by including women.” The net result was we out-produced the bad guys, which included developing an endless logistical combat support system.

During America’s time at war, manufacturing was everything. Virtually every manufacturing company of any kind devoted its capabilities to producing war goods. Underwood Typewriter, IBM, National Postal Meter, International Harvester, and many others built rifles. Ford built bombers. Heinz built glider wings in addition to food-goods. Every manufacturing company was contributing something.

Aeronca was tasked with helping Fairchild expand its primary trainer production because it was stretched to the limit building four-place utility aircraft (F-24) in addition to the trainers. The Fairchild PT-19 included producing much bigger airframes than anything Aeronca had attempted, but the materials and objectives were the same. The solidly built steel tube fuselages and all-wood wings (including wood skins) were familiar processes. However, the 200-hp, inverted six-cylinder Ranger in-line engines were greatly different than the Continental A65s that powered Aeroncas. Further, as the supply of Rangers became tight, the PT-19 was redesigned to take the 220-hp Continental W-670 radial, as used on Stearmans. In total, while fulfilling the Fairchild contract, Aeronca built 477 PT-19As and 143 PT-19Bs (both with 200-hp Rangers), as well as 375 PT-23s (Continental radials).

Aeronca also built TG-5 glider-trainers that were actually L-3s with the engine replaced by a pilot position. This required the canopy be extended to cover a three-position cockpit. The TG-5’s role in WWII was to train the glider pilots who would eventually be flying the huge Waco CG-4 troop gliders into combat.

With the war over, Aeronca was contracted by the U.S. Army to build a replacement for the WWII generation L-birds, the L-2, L-3, and L-4. The new aircraft, the L-16A, was basically a civilian 7BCM Champ powered by the 85-hp Continental C85. Five hundred nine were built, with 376 of them going to the Air National Guard. They earned their combat stripes by providing liaison service throughout the Korean War.

The L-16B received the 90-hp Continental C90 engine, and 100 were built. All L-16 variants featured Plexiglas windows extending past the rear cockpit and over the top of the fuselage, aft of the wings. Otherwise, they were simply Champs with elaborate radio systems.

L-3s we had going together. I built the eyebrows and brackets.”

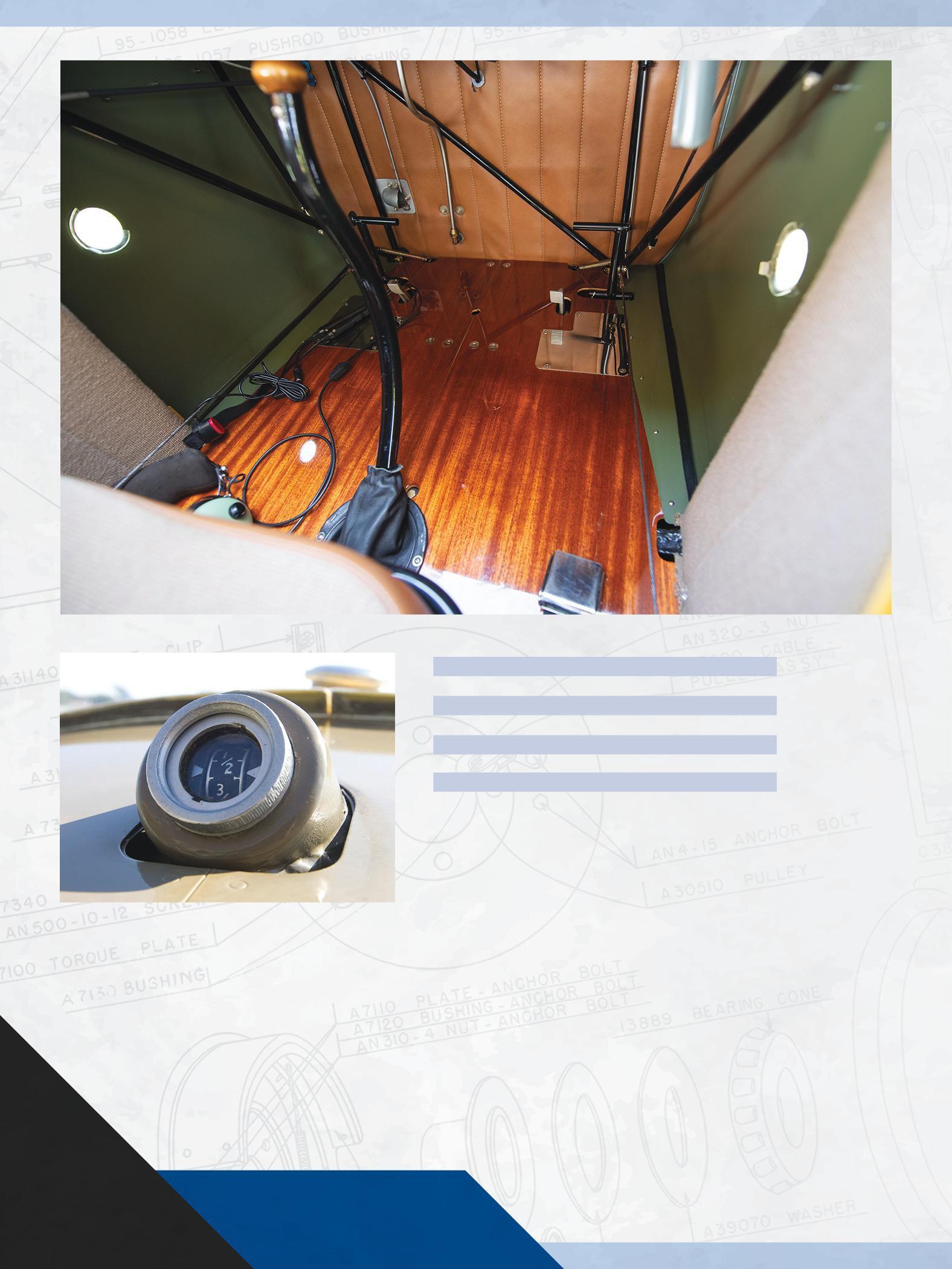

Shortly after liaison airplanes were surplused, almost all of them gave up their greenhouse flight deck enclosures in favor of civilian fabric covering. The original greenhouses were difficult to maintain and were ready-made for letting rainwater in. However, the acres of Plexiglas extending well behind the wing are what set the military birds apart from their civilian forerunners. They also present their own challenges when rebuilding them.

“The greenhouse was probably the most difficult part of the entire build,” Mike said. “First, there are a million pieces of aluminum framing and fairing strips involved. Also, the prints we had didn’t include all the proper information. In reality, we probably had prints from different phases of the production, and the design changed just enough that not everything would fit. The fairing where the trailing edge of the wing comes into the fuselage, for instance, took a while to figure out. Plus, there’s a very distinct sequence that the parts must follow to be assembled. It was a jigsaw puzzle for which we had no picture to follow. It took a while, but we got it right.”

With the greenhouse behind him, the fabric, finishing, and the rest of the airplane were relatively “normal.”

“I used the Stewart System for the finishing,” he said. “It’s water-based and, if you follow the directions exactly, works well. I did the scheme in the colors and markings of an L-3 unit that was based at Clovis, New Mexico. I had the sign shop cut the fuselage stencils,

as indicated in the blueprints, so I could paint them on rather than using press-on lettering.

“For the instrument panel, we had the drawings to follow, but we had nothing for the radio installation, and that was important to L-birds,” Mike said. “We did, however, have some decent photos of the cockpit, so we used those as guides. I built the radio itself, then used a sign shop for the decals and picked up old knobs at swap meets. Compared to the greenhouse, it was fun to do. Even better, it doubles as the battery box. No one knows it’s there.”

So now Mike has a veteran standing proudly in the middle of all his classics. Does he have another project in mind?

“Oh, yeah! I’m already well along with my 1947 Aeronca Super Chief,” he said. “And then there’s all those Sedans I’ve squirreled away.”

It looks as if Mike Hoag has found a way to keep himself busy while retired.

In its previous civilian life, the L-3 was an Aeronca TC-65 Defender, one of which played a role in what was probably the most fateful day in America’s history, December 7, 1941.

The location was Oahu, Hawaii, and the pilots were Roy Vitousek and his teenage son, Martin. An attorney and territorial legislator, Vitousek had just learned to fly and was taking his son for an early Sunday morning ride.

They were trundling along in one of the Hui Lele Flying Club TC-65 Aeroncas. Suddenly, they were engulfed by formations of military aircraft, all of which carried the Hinomaru “meat ball” insignia. Initially, Vitousek tried to hide from the attackers by staying low; however, they were attacked but were able to disappear and return to Rogers Field, which is now Honolulu International.

The Vitousek airplane now hangs in the Pearl Harbor Aviation Museum located on Ford Island in Pearl Harbor.

“Let’s see if I hit Dayton about noon, then steer say 310, I should make Chicago at about two-thirty Plenty of time to take my nap and still take in the Cubs game.”

Early on, Ohio was a big aviation state: the Wright Brothers, John Glenn, Eddie Rickenbacker, Dominic Gentile, and of course General Barnett Overbite, USAF, Retired, shown here planning a cross country early in his career.

Very late in his illustrious career he wandered into the unattended cockpit of a Boeing 737, sat in the right seat, pushed the gear lever up, and proclaimed most assertively “Bombs away!” By design, only the nose gear came up, causing panic, screaming, and a mad scramble for the doors General Overbite was then gently escorted to some nice new quarters

OVER THE YEARS OF REBUILDING, flying, and inspecting Aeronca airplanes, I have encountered many problems that seem to occur repeatedly. Some parts never get inspected or even looked at during annual inspections. One of these items is the trim cable pulleys behind the rear seat and at the tail post. Sometimes these are frozen due to a lack of oil. The cables have cut deep grooves in the pulleys, and the cables are ready to break. Also, the rudder cable pulleys behind the rear seat panel may not be turning, and cables may have cut through the pulleys and into the studs, requiring new studs to be welded on. Check and make sure the cable guards are not rubbing the cables. Some clevis bolts, which connect the front and rear rudder pedals (cables 1-2280), have been found worn half through. Also, some rudder pedal tab holes were elongated and had to be replaced. See Page 18 of the service manual, Control System Rudder and Trim.

Airworthiness Directive (AD) 48-39-01 on the control stick sockets requires the AN4-10 bolt and AN310-4 nut to be removed, the AN24-16 clevis bolt and AN320-4 shear nut to be finger-tight, and a cotter pin to be installed on the front and rear stick sockets. The socket casting end should be inspected for cracks per AD instructions. Most 7ACs have had this AD complied with at one time or another. The problem occurs when the owner rebuilds his Champ, and either he or his mechanic is not familiar with all the small details and goes by the service manual. Page 16 — Control System Aileron, Elevator, and Brake — shows an AN4-10 bolt and AN310-4 nut on the bottom and top of socket 2-705. On top of the rear control stick socket attaches the down elevator link 1-2356. This should also have a clevis bolt. This is what AD 48-39-01 is about. The service manual was written in 1945, and the AD was the first of the 39th week of 1948.

Another important item to check for wear is the ends of the throttle cable at the throttle lever and carburetor. I have found the seal most worn into. Check the carburetor heat cable where the cable comes out of the housing for wear. It may be necessary to unhook the cable at the heat box and pull it out of the housing to inspect it. Check the carb heat box butterfly shaft and end bearings for wear. This is a high-vibration area and wears quickly.

It seems like the tail wheel never gets any attention until it falls off or the main leaf spring

breaks. I have seen aileron cables routed under fuselage member No. 43 (see service manual). Open the zipper in the headliner and inspect the cables. This is the aileron balance cable that runs straight through the wings with the turnbuckle overhead. The cable should be over the top of the tubing members, No. 43. Usually if they are under the tube, there will be a grinding sound and the stick will be hard to move from side to side.

Check rudder cables for proper routing. I have found some coming out of the fabric behind fuselage member No. 35, and they have worn a groove halfway through the tube and frayed the cable very badly. They should come out of the fabric about 5-3/4 inches above tail wire fitting No. 8318. Another important area to check is the elevator and trim cables. I have also found these wrapped around each other back at the tail. This is sometimes a hard area to see. I had a gentleman call me about the trim cables being too short. He had just finished a rebuild job with all new cables. I told him to make sure they were not wrapped around the end of stringer 1-2366. He called back later to tell me that, sure enough, they were.

I have mentioned before in my writings, every Aeronca owner should have a copy of Aeronca Champs and Chiefs by Charles W. Lasher and the Aeronca Service Manual, 7AC or 11AC. They are good

Bill Pancake and Michael Boggs.

books and will help answer many of your questions. These are available through the association. The 1949 11CC Red Chief on the back cover of Charlie’s book is one I rebuilt in 1976, and these are the original colors.

I make no attempt in this writing to cover all areas of inspection. It is my intent to pass along to you some problems I have encountered while working on Aeronca airplanes. Remember, it is the responsibility of the owner/operator and pilot in command to maintain and ensure the airworthiness of the aircraft.

The second in this series of articles will discuss the Eisemann mags and converting the Continental A65-8 engine to the A75-8. One question I get asked about the Eisemann magnetos is the internal timing of the LA-4 and AM-4 magnetos. These magnetos are used on the A65-8 and C85-8 Continental engines. The mag used on the A65-8 and C85-8 is right-hand rotation. The C85-12 engines are left-hand rotation. When holding the mag with the left hand and facing the drive gear, turning the gear clockwise is righthand rotation. For right-hand rotation, the “Y” mark on the large distribution gear is aligned at assembly with the punch-marked tooth on the rotor shaft gear. The other mark is for left-hand rotation.

cap with magneto wax. This is just a suggestion, and all work must be done in accordance with the manufacturer’s maintenance manual, service bulletins, and your A&P mechanic.

I would like to discuss with you some thoughts on converting the A65-8 Continental engine to an A75-8 engine for use in the Aeronca 7AC. First, you must have a copy of Continental Service Bulletin M47-16 (revised September 25, 1958, or later). The best time to convert the engine is at major overhaul because several parts must be changed. Some Aeronca owners may want to upgrade to a Continental A75-8 engine by modifying the A65 in accordance with Continental Service Bulletin 47-16, which covers the upgrade. This is typically done at major overhaul and requires changing the piston, piston pin, connecting rod, exhaust valves, and mag timing. The pistons have a waffle-type design under the head, with connecting rods and an oil squirt hole cap end to squirt oil under the head for better cooling. This is covered under an October 6, 1939, patent by Carl Bachle as a means of cooling horizontally opposed pistons using oil sprayed from the opposite cylinder’s rod cap (US2230893). I have disassembled some small Continental engines, both the A and C series and a few O-200s, where the connecting rods had been improperly

installed. In these cases, the oil squirt pointed the wrong way. These engines had been field overhauled, and it is apparent to me that the mechanics doing the overhaul work did not read or understand the overhaul manual in its entirety. If your engine has been overhauled and is operating at a higher temperature than before, long after the overhaul has been completed, this is a common cause.

To install this modified A75-8 engine back into your 7AC or 11AC, you must have STC SA3-435. A common misconception on A75 conversion is that the carburetor requires modification, but that is not correct; no carburetor modification is required when converting the A65 to the A75. Note: The A65 and A75 carburetors are the same, so no conversion to the carburetor is necessary. You must have an STC or FAA field approval to install the engine in the Champ. The STC is the easiest way to go. Other requirements are a new prop, and some instrument markings are changed. The tachometer redline is 2600 rpm. Aeronca Service Helps and Hints No. 26 is required. The crankshaft may be a problem if it is one of the older ones having 1-3/16-inch crankpin lightening holes. It must be replaced if the conversion increased the engine power rating.

Note: Continental Service Bulletin M47-20 Supplement No. 1, dated April 1, 1948, and existing airworthiness directives prohibit grinding to 0.01 “O” undersize any “A” diameter lightening holes in the crankpins. These crankshafts were made until 1941. There are still some around, as I have one.

The CG range and gross weight remain the same. There is some difference in takeoff and climb performance with the extra 10 hp. The cruising speed is still the same. Be sure to follow the service bulletins closely, and get your paperwork to avoid inconvenience and unnecessary trouble.

Over the years, I have heard many discussions about how much an Aeronca 7AC weighs. The original factory weight was about 760

pounds. The factory service manual, however, lists the weight as 710 pounds. I have weighed many 7ACs with weights ranging from 796 pounds to over 1,000 pounds, depending on what additional equipment had been installed. The 796-pounder was Bob Armstrong’s Grand Champion winner of Oshkosh 1983. A few years ago, I rebuilt a Champ for Dick Love of Dillsburg, Pennsylvania. I weighed

this airplane complete but with no fabric or paint. It weighed 748 pounds. After covering and painting, it weighed 815 pounds (without gas and oil).

Looking over the list of CAA required equipment — wood propeller, safety belts, altimeter, airspeed indicator, tachometer, oil temperature and pressure gauges, compass, carburetor air heater and air scoop, wheels and brakes, and tail wheel — another 67 pounds are added to the weight. Another 4 pounds are added for factory-installed equipment: carburetor air filter, step, and cabin heater. Optional factory equipment could add another 57 pounds to the aircraft’s total empty weight. This alone has increased the empty weight from 760 to 888 pounds. This leads me to believe the factory listed the empty weight with no CAA requirements, or factory-installed equipment such as soundproofing, plush floor carpets and seats, vinyl headliner, padded side panels, and thick firewall covers. All of this will probably add another 50 to 60 pounds. Additionally, a metal prop will add 12 pounds over a wooden one.

Some of the heavier Ceconite fabrics with many coats of dope and paint could add as much as 45 additional pounds. You can put an extra 100 pounds of equipment on a Boeing 747, and it’s not noticeable. If you add 100 pounds to a light airplane, the difference is very noticeable.

One other thing about weight: The original side windows in the 7AC and 11AC were 0.08 inch thick. Most that you buy today are 0.125 inch thick. This also adds additional weight. LP Aero Plastics

in Jeannette, Pennsylvania, makes an original type 7AC windshield and side windows. They look nice and fit right and are worth the extra money. They are the only ones I will use.

I have been asked many times if it is legal to fly a 7AC solo from the rear seat. Page 3 in the service manual states 20 pounds of baggage when flying solo rear and 40 pounds when flying solo front. Let’s do a sample weight and balance for flying from the rear seat.

Page 5 in the 7AC service manual states the center of gravity range is +10.9 inches to +21.5 inches most rearward. Try working the center of gravity with minimum fuel and see what you get.

When giving flight instruction or doing annual inspections on 7AC or 11AC Aeroncas, I find that a lot of times the paperwork is not in order. I often find no weight and balance statement, or an incorrect one, no operating limitations, and no instrument markings, redlines, or placards. I also check the engine and aircraft data plate serial numbers for a proper match with the logbooks and other paperwork. I have even found old airworthiness certificates issued under the CAA. In my area (Baltimore FSDO), the FAA likes to get the old airworthiness certificates and reissue ones that have FAA on them. The aircraft owner and operator should ensure that maintenance personnel make proper entries in the aircraft logbooks when repairs or equipment changes have been made. There have been many books written about weight and balance. Pilot’s Weight and Balance Hand-book AC 91-23 is a very good book. Other books to

reference include AC 43.13-1A — Acceptable Methods, Techniques, and Practices, and AC 43.13-2A — Aircraft Alterations. These are good books and well worth the money.

Tip: Before you start a rebuild project, make sure you have a mechanic to work with who knows your type of aircraft. This will cause fewer hassles when getting the airplane approved for return to service.

I receive many calls and emails from new and older Aeronca owners and mechanics who are not aware there is a wealth of information available for these older aircraft. Examples include Aeronca service helps and hints, Aeronca service letters, and Aeronca factory drawings, as well as the Aeronca service manuals. With regard to the drawings, all drawing numbers and part numbers are the same. No. 1 drawings are 8-1/2 by 11 inches, No. 2 are 11 by 17 inches, No. 3 drawings are twice the No. 2, and so on and so forth. Over the next few paragraphs, I will provide small excerpts about common questions or problems that I am called about.

Regarding conversions, the 11AC series aircraft, the Aeronca Chief, may be converted to an 11BC model by removing the A65-8 or 8F engine and installing a C85-8 or 8F. In accordance with Service Letter 17, it will require installing a larger vertical fin, Hanlon & Wilson muffler system, and several other modifications that are listed in Service Letter 17. The 11AC is also approved for a C85-12 or 12F in accordance with STC SAO-4202AT. With this STC, no large fin is required, but it is an option. It’s important to note that the large vertical fin was never approved on the 11AC with the A65-8 or 8F. There are other STCs available for O-200 Continental engines and Lycoming O-235s. The Lycoming O-235 is much heavier than the C85 and the O-200 and may

reduce useful load to the point that the airplane effectively becomes a single-place aircraft with limited fuel.

Aeronca 7 series were built under Type Certificate A-759; 24 different models of aircraft were built from the October 18, 1945, to present. Each one has a different type design, so owners and mechanics need to be aware that what is approved for one model may not be approved for another.

A common unapproved installation I see on some 7AC and 11AC aircraft is a Brackett air filter in accordance with STC SA71GL. Again, it’s important to note that this is not approved, and will require a field approval, as well as a modified carburetor heat box 4-601.

Serial numbers come up frequently when discussing Aeronca aircraft. Aeronca never put serial numbers on any parts. The only item that is serialized is the data plate for the aircraft, e.g., 7AC-4951. The proper location for the data plate itself is on the right rear of the front floorboard.

On early Aeronca 7ACs (1945 models), some had rear wing struts of the same size strut tubing as the front strut. If you have an early model 7AC, be aware that this is correct; the smaller tube for the rear strut came about later in 1945.

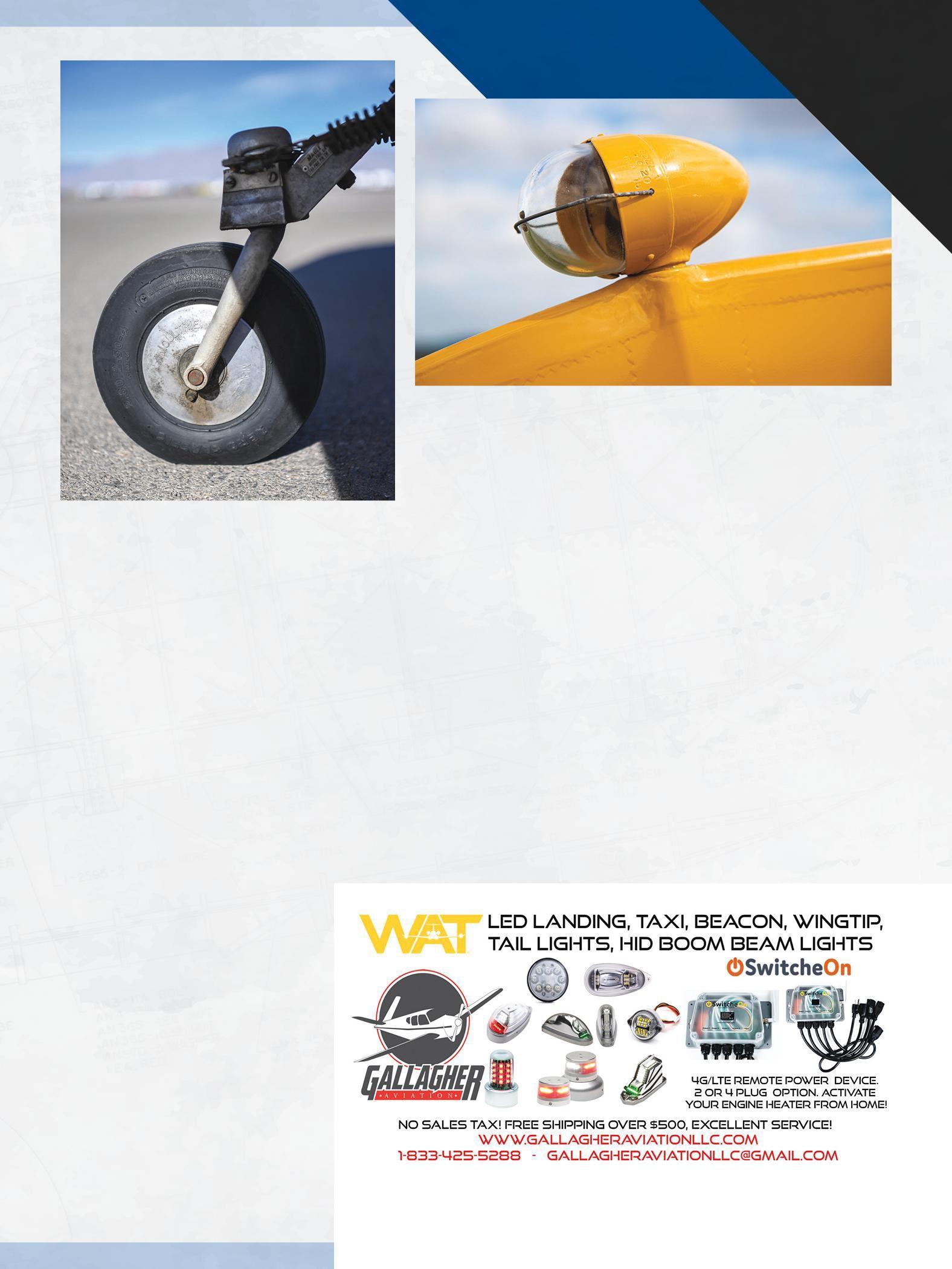

The early Aeronca 7AC and 11AC airplanes had a three-piece landing

gear axle strut. I have mechanics call me frequently, thinking that the three-piece strut was an unapproved repair. Aeronca made changes throughout production of its aircraft, and the drawings became obsolete and were later destroyed.

Aeronca itself never used VanSickle wheels on postwar aircraft. It used Cleveland DMB wheels, which were magnesium (AD-48-08-02), required at each 100 hours. They also used Goodyear wheels model 6.00-6 L6MBD assembly 511413M. See Type Certificate A-759, landing gear and floats, 201(a), (b), and (c), for your aircraft.

The landing gear is probably the most neglected part on most aircraft. Some common issues I see: dirty and mostly worn, low or no oil in the oleo strut, main spring (PN 1-2256) weak or broken, case frame bushing (PN 1-2565) worn, or the fuselage fitting worn or misaligned from repairs. See fuselage drawing 7-450 in the service manual. Per the landing gear yoke section (PN 1-2326): If these are misaligned during repair, it will cause toe-in or toe-out where none should exist. The landing gear axle strut has a 29-degree bend at the bottom end for the wheel assembly, and a small amount of twist because of fitting (PN 1-2326) will cause toe-in or toe-out.

One popular method of realigning is to bend the axle strut while it is still on the airframe to get the wheels to track properly. This I strongly

disagree with, as this procedure places a lot of stress on the landing gear fittings and bolts and may crack them or cause other damage to the fuselage fittings. Although the axle strut is not heat-treated, some have been heated to bend them.

The fittings I have found to cause the most alignment problems are the axle strut fittings (1-2326) in the center of the fuselage. The left and right cluster, 3-439-2 LUR and 3-439-21/2 UR, are easiest to align. Usually, the front fitting is the one that pulls out in a landing accident. One method I use for alignment is to place a 3-foot-long, 3/8-inch-diameter rod through the front and rear fitting, making sure it is parallel with lower longeron No. 12. Tack-weld the fitting in place and then remove the alignment rod. Do the same procedure for the center gear fitting using a 5/16-inch-diameter rod. If the center fitting is not properly aligned, this will change the toe-in or toe-out of the wheels. The wheels should have no toe-in. To check the toe–in, place a 4-foot straight edge on each wheel — not the tire — there should be no toe-in or toe-out. After welding, ream holes with the proper size reamer, reinstall the gear assembly, and recheck alignment. Remember, this is not an easy job without the proper tools, equipment, and experience. The fabric should be removed from around the area to be

welded. Don’t burn the airplane. After making repairs and you are satisfied with the alignment, the repair area should be thoroughly cleaned and recoated with zinc chromate or epoxy primer.

In 1953, when I was a kid working at the Keyser, West Virginia, airport, we had a CAP L16B with a C90-8FJ engine with high time and due for an overhaul. There were a couple of old Air Force mechanics who did a major overhaul and removed the fuel injector and installed a carburetor. The engine was installed back on the L16B and started up with zero oil pressure; the mechanics kicked the tire, cursed the airplane, but still no oil pressure. A few days later, an old guy named Herb shows up, and the mechanics tell them what they did. Herb told them they left the injector drive gear off the end of the camshaft, and the oil goes out the six screw holes that hold the gear on, and the only thing to do was disassemble the engine and put the gear back on the cam and safety-wire the screws. I get calls from time to time about this and discuss this problem with the owners/mechanics working on the Continental C85-8FJ, C90-8FJ, and the O-200, and they all use this same gear. The mechanics see no need for the gear to be reinstalled because they will not be using the injector system or the vacuum pump on the O-200. They have a big surprise when they start the engine for the first time.

All repairs should be made in accordance with FAA AC 43.13-1&2 and Aeronca service manual and drawings. This repair work should not be attempted by anyone other than a certified aircraft mechanic.

BY SPARKY BARNES

BY SPARKY BARNES

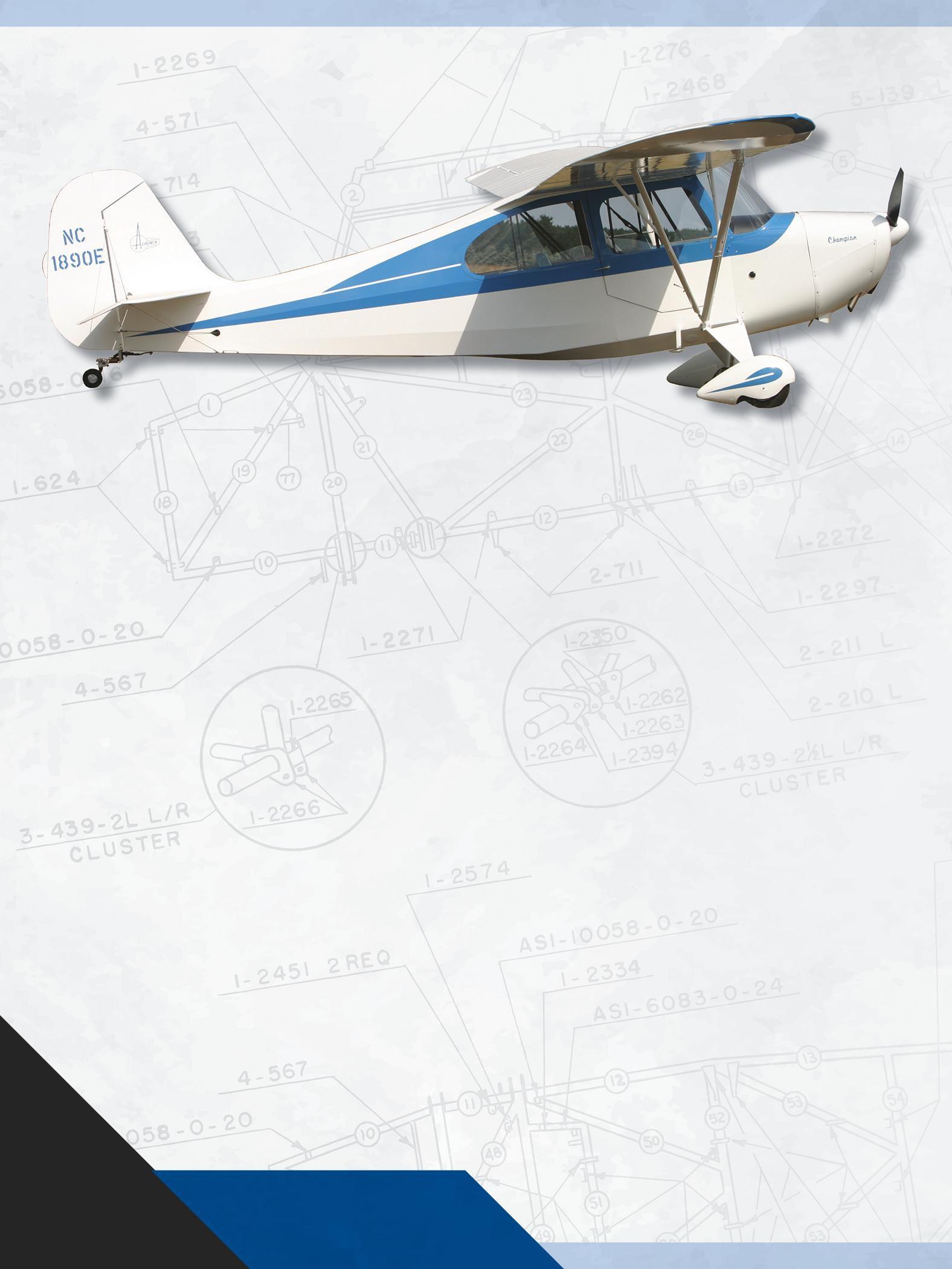

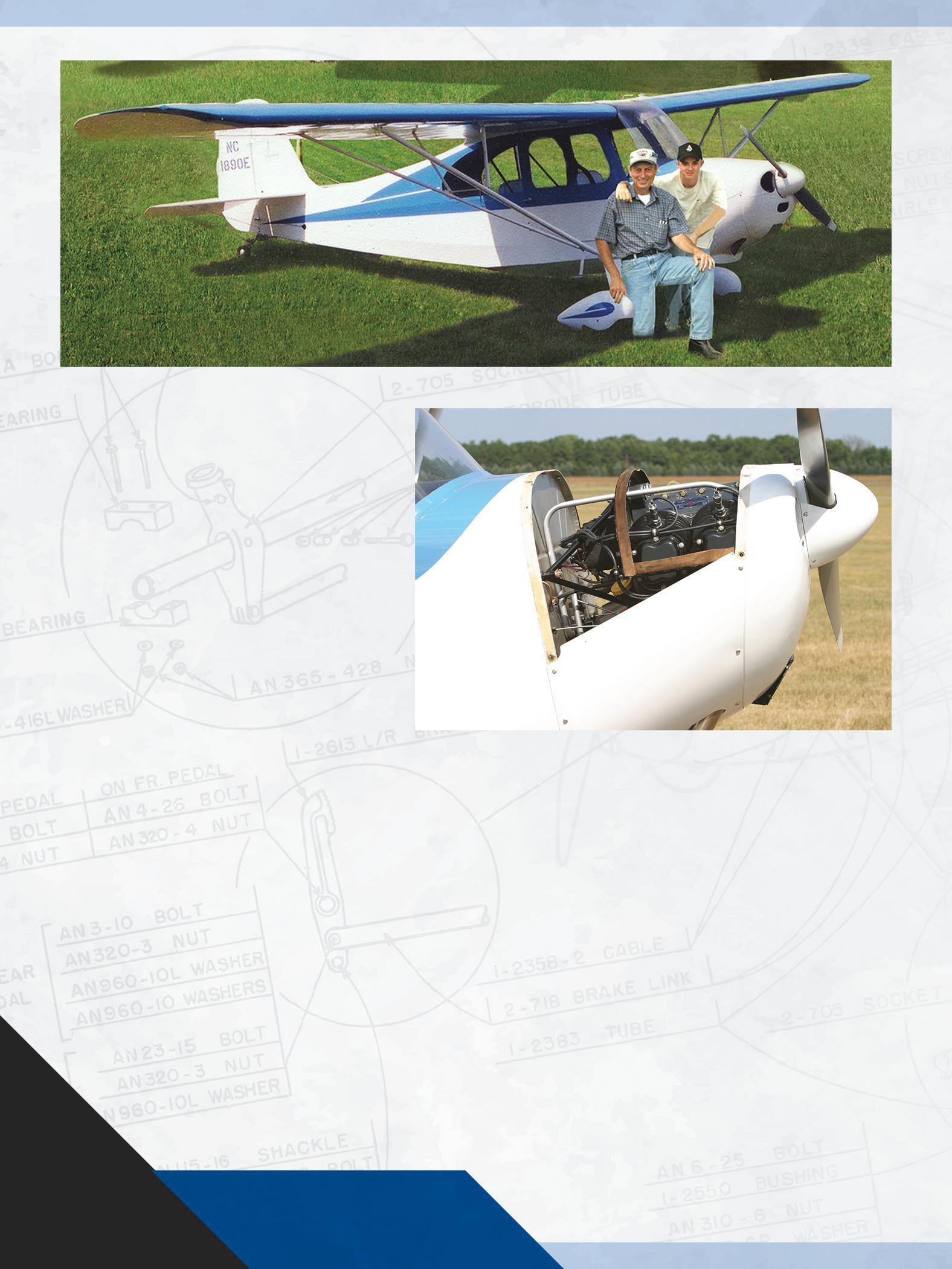

MERELY A SENTINEL OF THE PAST, a small T-hangar survived the passing of seasons on the Leasure family farm for decades. It didn’t really dawn on a young Mike Leasure that the building had at one time sheltered his grandfather Herold’s Aeronca Chief. Mike and his family simply referred to the weathered structure as “the hangar,” and nature slowly reclaimed the vestiges of the old “X” north/south and east/west airstrip.

Mike doesn’t remember his grandfather well because he died when Mike was 6, and the Chief had been sold before then. As Mike grew a little older, he learned about his grandfather’s love for flying … and then “the hangar” evolved into a tangible harbinger of things to come.

“My grandfather Herold purchased a 1946 Aeronca Chief (NC3361E) in the 1950s, and he built that hangar for it. He flew the Chief for about a 10-year period, then sold it,” Mike said. “The flying bug skipped a generation, and then I started flying model airplanes when I was a kid. I was flying all kinds of rubber band-powered Cox and engine-powered models.”

For his 15th birthday, Mike’s father paid for half of his flight training at their local airport, Arens Field in Winamac, Indiana. He ended up changing instructors right in the middle of his lessons, so although he had an early start, he didn’t solo until years later. Mike went to college at Purdue, acquired his A&P mechanic certification, and finished his bachelor’s degree. Then he moved to Arizona and three years later acquired his IA (inspection authorization).

He’s been involved in aviation, whether at work or at play, ever since. He taught at Vincennes University in its A&P program for six years.

“While I was in Arizona, I owned a weight-shift Microlights Eagle ultralight,” recalled Mike. “I soloed a Schweizer 2-32 tandem trainer glider, so my very first solo with a power plane was in a Cessna 152 when I was 25. Around 1987, I bought an Aeronca Scout, which was my first vintage tailwheel airplane.”

Mike moved back to Indiana in 1996 and started teaching at his alma mater. All told, he taught aircraft subjects for 30 years before retiring about four years ago. He’s also owned nine airplanes through the years. He wanted to personally get back into working on airplanes and flying them, so he bought a Cessna 120 that needed to have its wings re-covered. While he was working on that 120, he started musing about his grandfather’s Chief.

“I looked on the registry, and a new owner had registered it in a town north of here — Kouts, Indiana. So I wondered what had happened with it, because the last I had heard about the Chief was from the owner’s son, who was in one of my classes in A&P school. He came up to me one day and said, ‘We have an airplane that was owned by Herold Leasure — are you any relation to him?’ I said, ‘Yeah, he was my grandfather!’ He told me that the airplane was still stored in his dad’s barn on a private strip up in Medaryville, Indiana,” Mike recalled, “and that’s the last I heard of it. I actually tried to buy it at that time, but he wanted a ridiculous amount of money for it.”

Realizing that NC3361E had changed hands, Mike contacted the new registered owner, who replied that he’d be willing to sell the project. “So I went up there to look at it. It was all basically complete. The wings were off, the covering was off, the fuselage had been mostly disassembled, but it was still up on its landing gear. The engine was sitting on a crate, but it was all there and had the

Continental A65 came on a pallet with the project.

All new wood formers and stringers being installed.

New wood formers and stringers; the wool headliner is being installed.