Tis time, like all times, is a very good one if we but know what to do with it.

RALPH WALDO EMERSON

WE ARE :

Sugarmaker & Editor

DAVE MANCE III

Christmas Tree Grower & Editor

PATRICK WHITE

Business Manager

AMY PEBERDY

Designer

LISA CADIEUX / LIQUID STUDIO

FOR THE LAND PUBLISHING BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Marjorie Ryerson, President

Trevor Mance, Vice President

Chuck Wooster, Secretary

Kate Whelley McCabe

Lora Marchand

Jack Michael

Very special thanks to Virginia Barlow and Brett Ann Stanciu, whose fngerprints are all over this book.

BEHIND THE SCENES

John Douglas, Chris Doyle, Marian Cawley, Giom, John K. Tiholiz, Tamara White

Volume iv: Copyright 2023 For the Land Publishing, Inc., PO Box 514, Corinth, Vermont 05039 For purchase inquiries, or to sponsor our work, please contact amy@vermontalmanac.org. Direct all editorial correspondence to dave@vermontalmanac.org.

For the Land Publishing, Inc., is a 501 (c) (3) public beneft educational organization. Printed in Milton, Vermont.

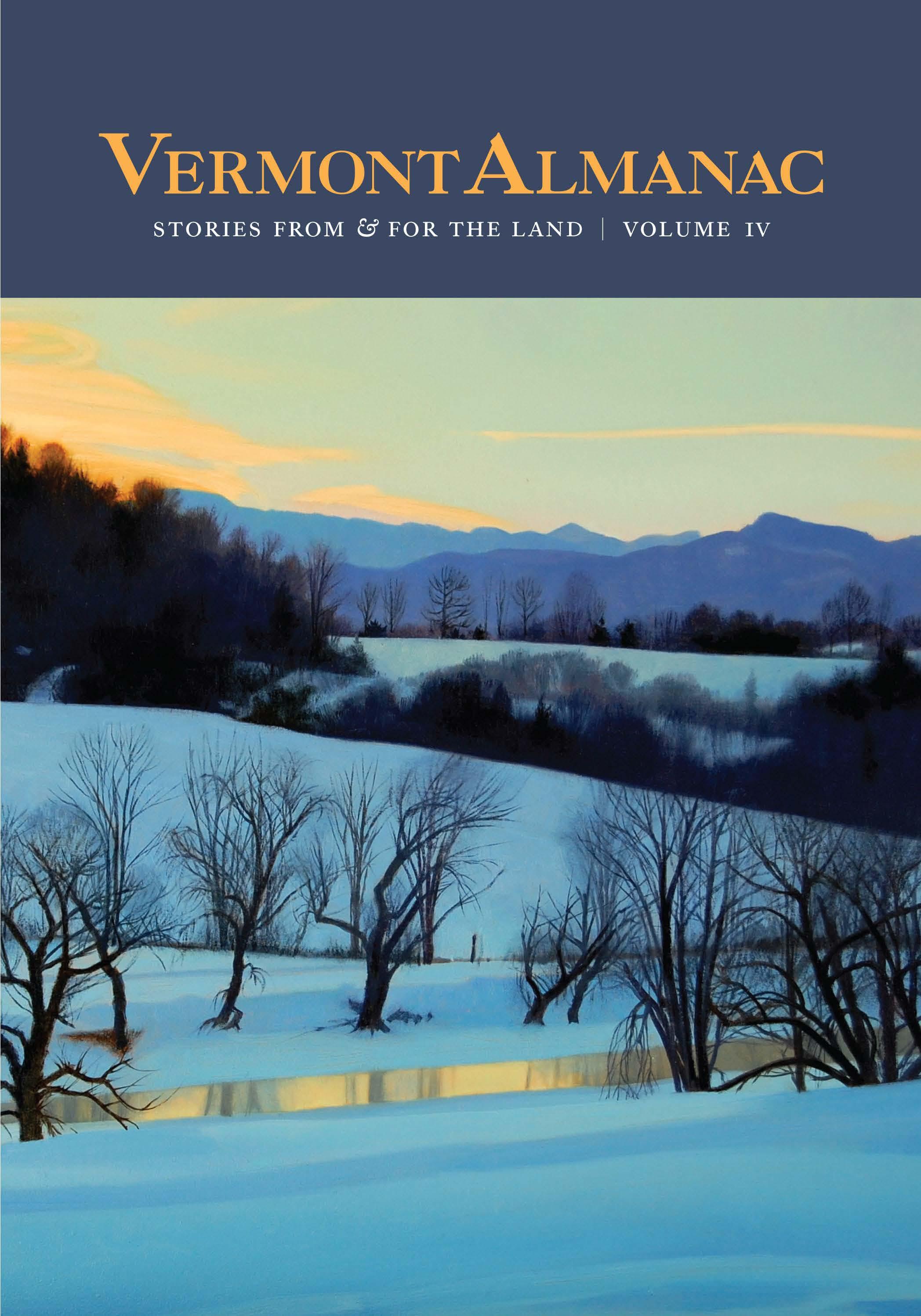

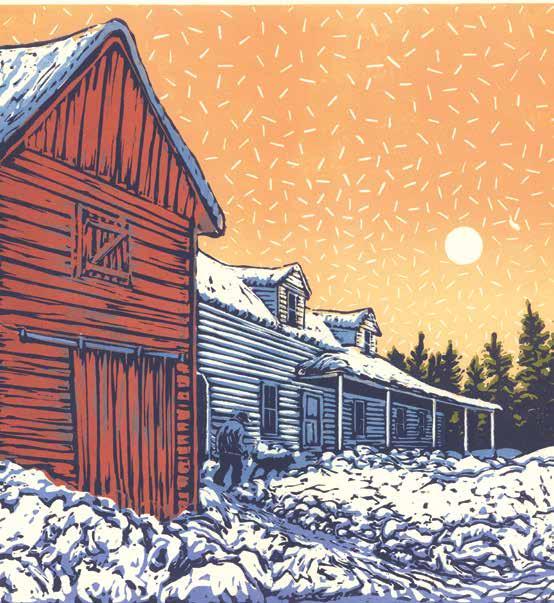

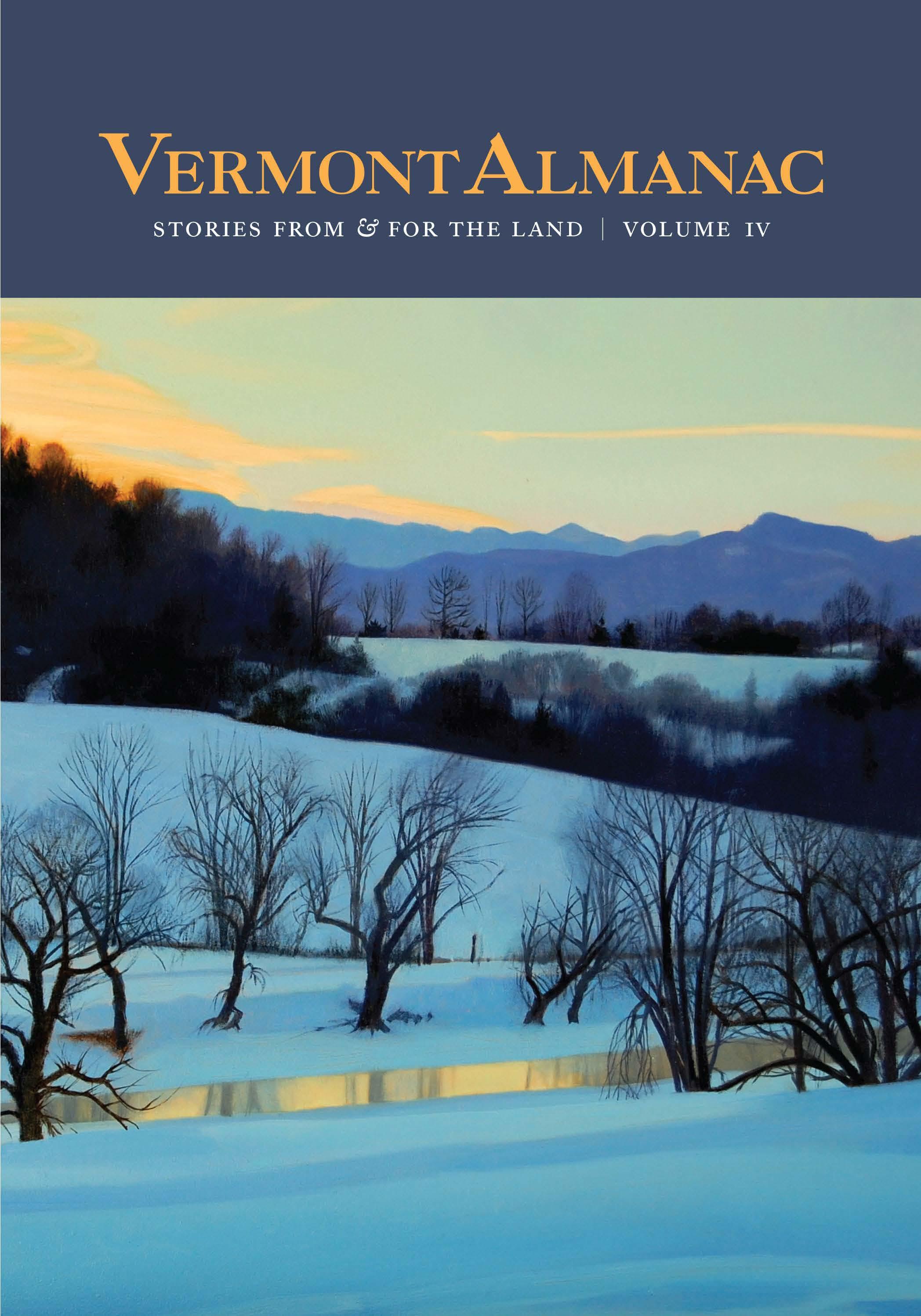

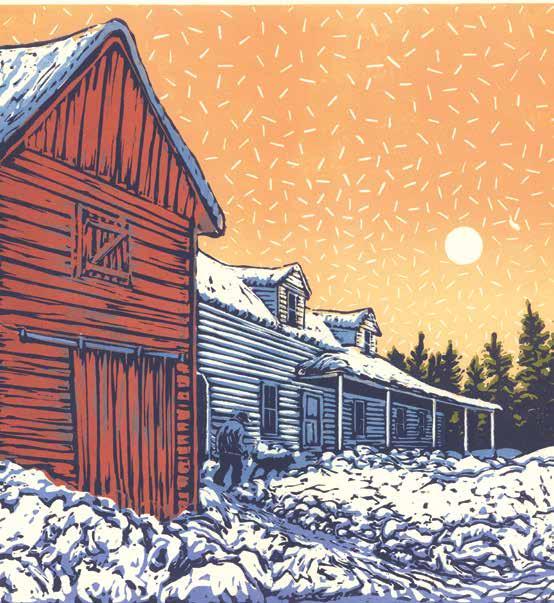

COVER PAINTING

Kathleen Kolb

Te beauty of snow, what it does to how we see the landscape, is really moving to me. Snow simplifes what we see by hiding so many smaller things, reducing them to soft bumps of blue or white. In this way it gets us closer to the essential, the transcendent, which is my goal in making all my work. Painting snow involves working with a lot of blue, perhaps my favorite color, but I also love the challenge of looking deeply into snow to see what colors are there in addition to white and blue. Tere is so much there to see and appreciate!

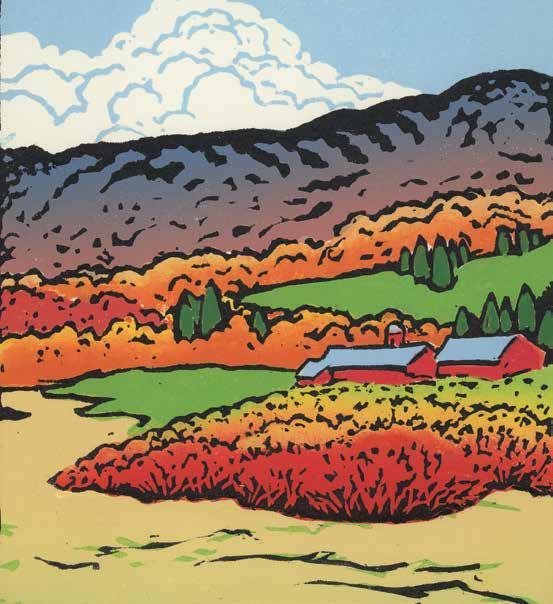

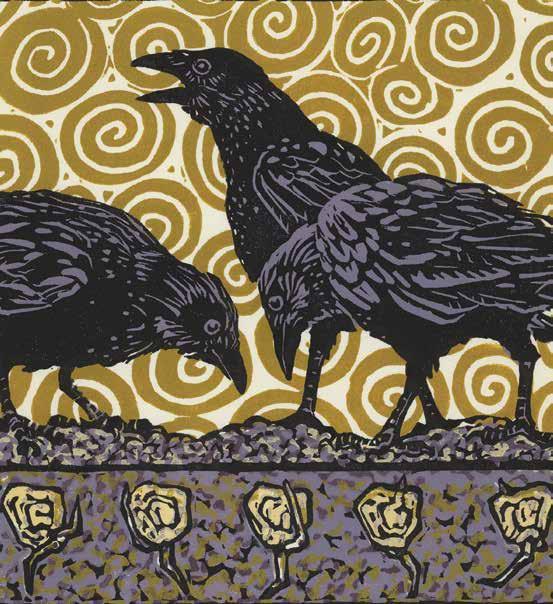

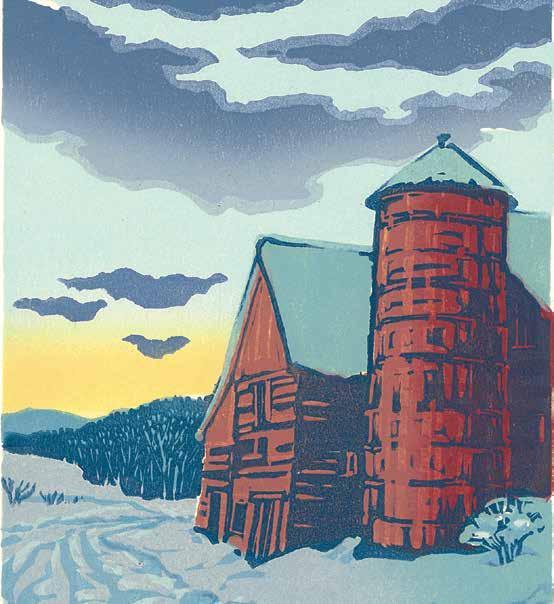

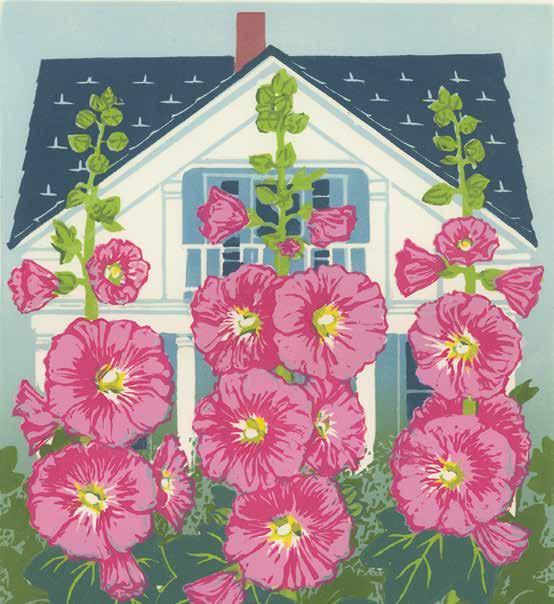

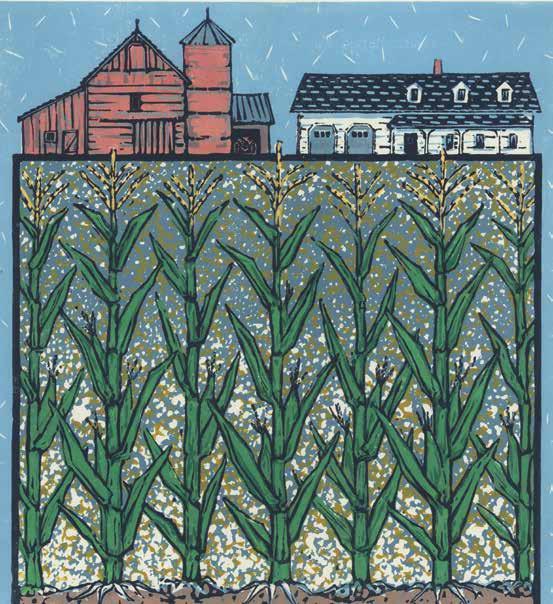

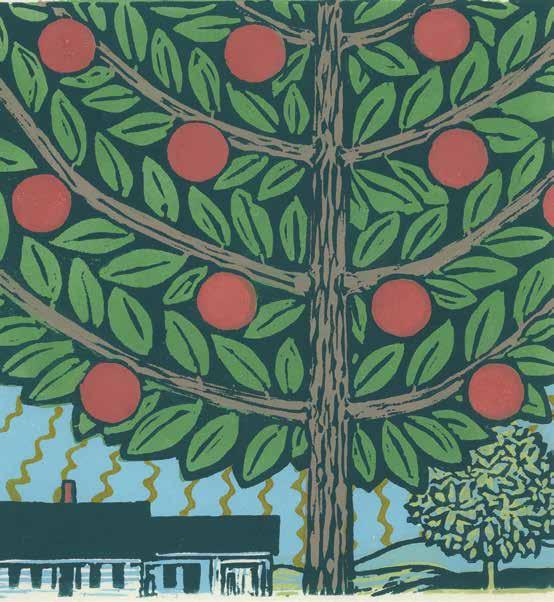

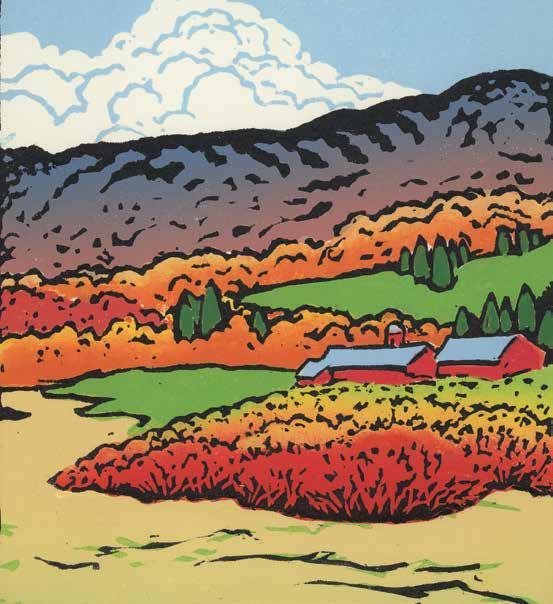

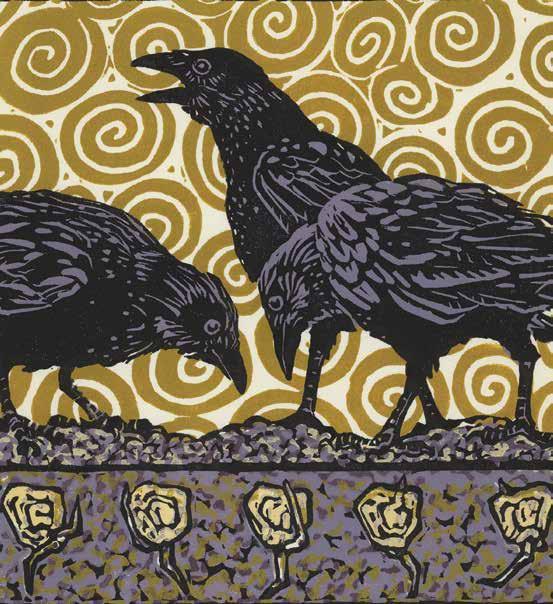

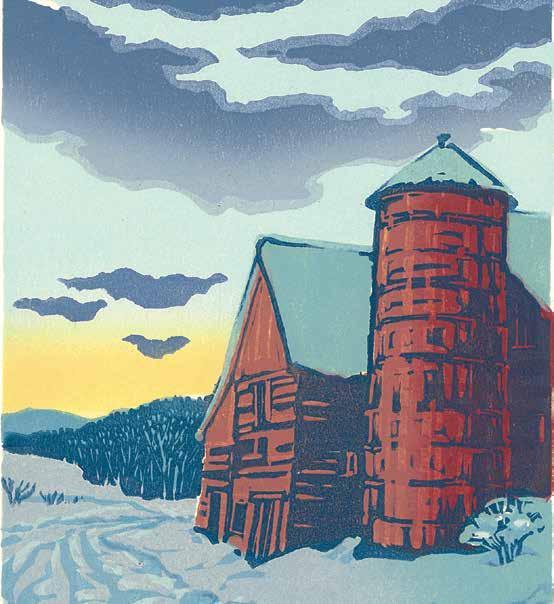

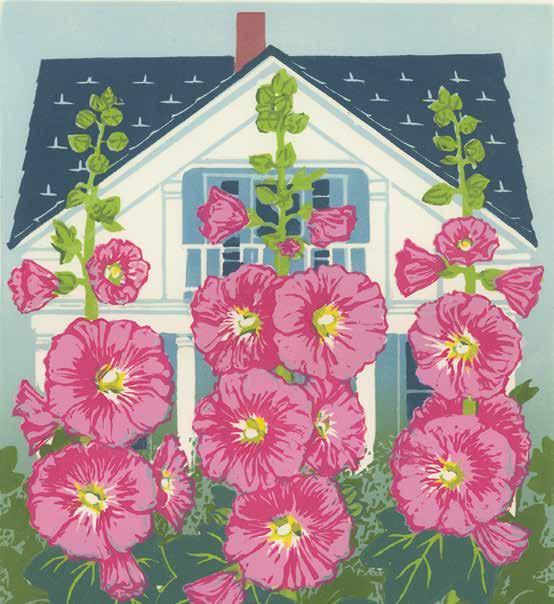

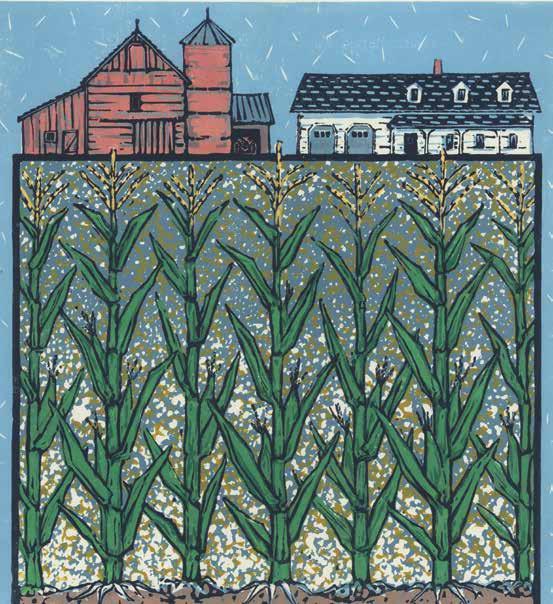

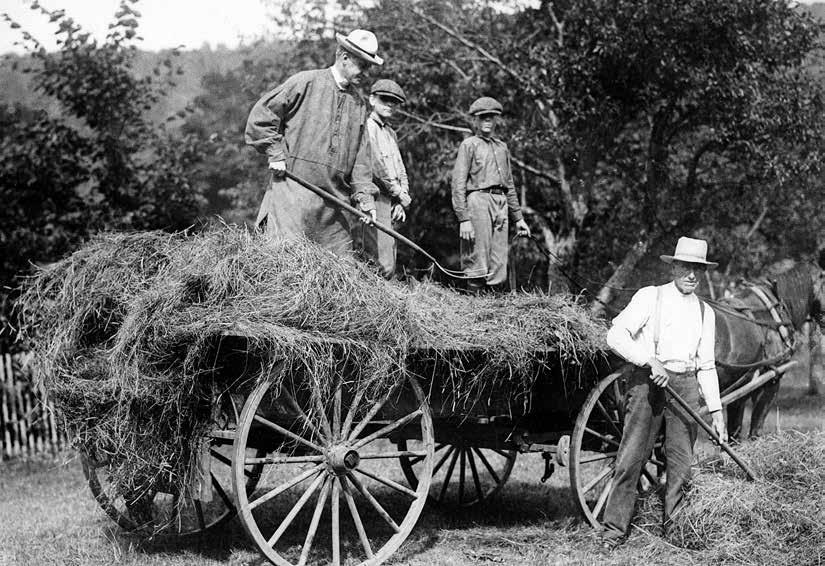

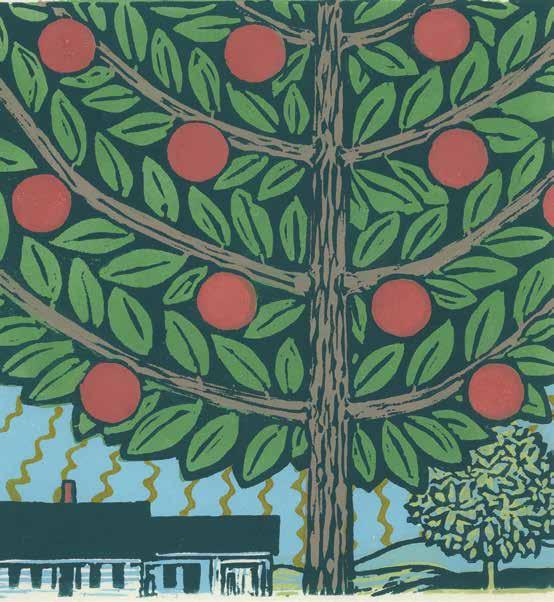

MONTHLY PAINTINGS

Mary Simpson

I make relief prints using blocks of vinyl and linoleum that are carved, inked, then pressed onto paper. Tis manual method of creating pictures suits me. I grew up on a family dairy farm with plenty of people and animals and enough work to go around. It was a hands-on life, and I am still doing it by creating these rural tributes, block by block.

WWW

. VERMONTALMANAC . ORG

CHAD ABRAMOVICH is a native

MICHELLE ACCIAVATTI , MS, is a nationally recognized natural deathcare worker and educator who operates Vermont Forest Cemetery and Green Mountain Funeral Alternatives with her husband and partner, Paul. She lives in Montpelier and her spare time is spent outdoors.

HEIDI ALBRIGHT grew up in southern Vermont as a free-range kid. After earning a master’s degree in Biology from UVM, she became a farmer-artist in the mountains of central Vermont with her family. She can be found outside in all types of weather.

JOYCE AMSDEN is a homesteader, therapeutic horticulturist, and UVM Extension Master Gardener. While working the Central Vermont subsistence farm where she was raised, she teaches homesteading skills and presents nurturing and restorative nature-based activities.

SEAN BECKETT is the Program Director at North Branch Nature Center where he arranges and leads nature-based outings and classes ranging from birding to geology to naturalist adventures abroad. For more about NBNC’s programs, visit northbranchnaturecenter.org.

TANIA AEBI lives in Corinth and is excited about having had one bee hive survive two winters and going into its third. She is very attached to the bees and their honey and hopes they’ll stick around for many more winters. And summers, falls, and springs.

BETZY BANCROFT has been learning, teaching, and practicing herbal medicine for decades, notably cofounding and serving as a faculty member of the Vermont Center for Integrative Herbalism. Besides the forest, her favorite place to be is her kitchen.

JANE BROWN grew up on a farm in Cabot and has co-authored an oral history titled Cabot, Vermont, Memories of the Century Past, and West Danville, Vermont, Ten and Now, 1721-2021. She publishes a popular blog, Joe’s Pond Refections.

stories from & for the land 3

Vermonter, local weird worker, photographer, raconteur, and explorer.

VIRGINIA BARLOW has worked as a forester, writer, and editor in Corinth, Vermont.

contributors

LISA CADIEUX was born and raised in Swanton and spent her childhood in the woods creating imaginary wildlife habitats. As an adult, her creative work includes book design, interior design, metalsmithing, and cooking.

DR . HEATHER DARBY is a Professor of Agronomy at the University of Vermont. She has been conducting outreach and research on industrial hemp since 2016. More information about Dr. Darby’s research can be found at www.uvm.edu/extension/nwcrops.

H .

a

LUCY CLARK is a full-time stay-athome-mom and a part-time freelance writer. A former editor at EatingWell magazine, she has a passion for writing about food and farming.

JANE DORNEY is a geographer and writer who does project-based work on Vermont’s cultural landscape patterns and their connections to the natural landscape. She also writes a newspaper column called Connect the Dots for the Vermont Community Newspaper Group.

and science communicator. She teaches at Williams College and lives in Bennington.

BILL DRISLANE is a board member of Sundog Poetry, lives in Jericho, earns a livelihood in his solo law practice, and enjoys and works with people, and the mix of words, song, and the natural world.

MEGAN DURLING is the head of school and a liberal arts and sciences teacher at East Burke School. When not exploring great books and the great outdoors with her students, she enjoys spending time with her family at home in Newark.

4 vermont almanac | volume 1 v contributors

KERRY DEWOLFE is an almost retired attorney who lives in Corinth with her partner Fritz, Border Terrier Elsie, horses, chickens and accordions.

STEPHEN

DEVOTO is

Dutch American, he was a scientist, and is now a farmer. He and his wife Joyce are restoring a diversifed farm in Corinth.

PHOEBE A . COHEN is a paleontologist

MELANIE FINN is the author of four novels including Te Hare, winner of the Vermont Book Award. She lives in Kirby, with her family, various animals, and mismatched socks.

SHIRLY HOOK grew up on West Hill in Chelsea. She’s a citizen of the Koasek Traditional Band of the Koas Abenaki Nation and serves on the Council of Chiefs. Her frst book, called My Bring Up, was published in 2020

ROWAN JACOBSEN is the author of nine books on nature, agriculture, and ecology, including Fruitless Fall and Apples of Uncommon Character. He lives in Calais.

LAURA HARDIE is a marketing and communications professional and owns a business called Te Red Barn Writer. Specializing in food and agriculture, she provides copywriting and content strategy to her clients and has a lavender farm in Waterbury.

JIM HORST grew up on a dairy farm in Bennington and has been planting Christmas trees for more than 50 years. For the past 23 years, he has also served as executive director of the NH-VT Christmas Tree Association.

Born in Bennington and raised in Manchester, PHILIP R . JORDAN is the retired editor of Vermont Magazine and lives with his wife Edie in a quirky old schoolhouse in Sunderland. His crime novel, As Crooked as Tey Come, was published in 2021.

MARY HOLLAND is a naturalist/ environmental educator/writer/ nature photographer. She spends much of her time with her lab Greta looking for interesting fnds to photograph and put on her Naturally Curious blog.

MARK ISSELHARDT leads the UVM Extension Maple Program and is based out of the Proctor Maple Research Center. He draws on degrees in forest management, plant biology, and 26 years of experience in maple to provide research-based education.

STEVE JOSLIN is a Waitsfeld native and a UVM graduate (class of 1965). He’s been a Sergeant in the US Army, based in Germany, and a claims manager for Vermont Mutual.

stories from & for the land 5 contributors

NATALIE KINSEY is the author of 21 children’s books, and is currently working on 2 books about Amanda, one a historical novel, and the other a non-fction account of her life. Natalie lives in Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom.

Te author of the best-seller, In the Fall, and fve other novels, JEFFREY LENT was raised in Vermont and New York State on small dairy and sheep farms, powered by draft horses. He lives in central Vermont with his wife Marion.

DAVE MANCE III learned to love the natural world through hunting, fshing, trapping, logging, sugaring, gardening – through the pursuits and the associated mentors. Now he’s trying to pay it forward.

PHILIP LAMY , Ph.D., is a professor of sociology and anthropology and the Director of the Cannabis Studies Certifcate Program at Vermont State University, Castleton.

DEBORAH LEE LUSKIN hunts and writes in southern Vermont and blogs about Living in Place. Learn more at www.deborahleeluskin.com

KERRIN MCCADDEN received the 2022 Herb Lockwood Prize in the Arts and is the author of the poetry collection American Wake (Black Sparrow Press, 2021), a fnalist for the New England Book Award. She teaches at Te Center for Technology and lives in South Burlington.

SYDNEY LEA , author of 23 books, is the 2021 recipient of Vermont’s Governor’s Award for Excellence in the Arts. A Pulitzer fnalist and winner of the Poet’s Prize, he was the founding editor of New England Review and Vermont’s Poet Laureate from 2011 to 2015

CHARLOTTE LYONS (House Wren Studio) is a textile artist and teacher inspired by the humble simplicity of traditional art and craft and the inventive use of repurposed materials.

A co-founder of the Vermont Center for Ecostudies, KENT MCFARLAND is a conservation biologist, photographer, writer, and naturalist.

6 vermont almanac | volume 1 v contributors

SARAH MERRIMAN is the elected Town Clerk of Middlesex, as well as an author (under the name Sarah Strohmeyer) of mysteries published by HarperCollins.

BRYAN PFEIFFER is a writer, educator, and consulting feld naturalist specializing in birds and insects. He lives with his partner Ruth and their English shepherd Odin on a hillside in Montpelier. www.bryanpfeifer.com.

SEAN PRENTISS is a poet and memoirist who lives with his wife and daughter on a lake in northern Vermont. His books include Finding Abbey and Crosscut: Poems www.seanprentiss.com

MARGOT PAGE is the author of several non-fction books and a former contributor to Te New York Times and other national publications. For nearly 40 years,

OLIVIA PIEPMEIER used to be a librarian but now she’s an artist (and she uses those other skills quite often). She is delighted to live somewhere that values and celebrates art, food, land, and community.

MARIA BUTEUX READE spent 27 years as a boarding school teacher and then became a writer, farmer, and cook. She serves as managing editor of Edible Vermont magazine. Maria lives along the Battenkill River with her artist husband, Ned.

CAROLYN W . PARTRIDGE served in the Vermont Legislature for 24 years. She is a self-employed farmer, seamstress, and a Windham County Assistant Judge. She is a Windham Regional Commissioner and a member of the Windham Community Organization.

VERANDAH PORCHE is a cultural worker: poet, songwriter, mentor, scribe, and selectboard member, based in Guilford. Hear songs and poems on www.patreon. com/pattyandverandah and verandahporche.com. A new album is in the works.

CHELSEA CLARKE SAWYER is an artist and naturalist, and the Communications Coordinator at North Branch Nature Center. She holds a master’s degree from the University of Vermont’s Field Naturalist Program and a bachelor’s degree from Maine College of Art.

stories from & for the land 7 contributors

JODY SCHADE is a devoted gardener and canner with more than 25 years practice. She works as a landscaper in the Northeast Kingdom and lives in Barton.

BRETT ANN STANCIU is the author of Unstitched: My Journey to Understand Opioid Addiction and How People and Communities Can Heal and Hidden View. Her writing has appeared in many publications. She lives in Hardwick.

ALLAN THOMPSON is the President of Vermont Woodlands Association, a Vermont licensed consulting forester, and certifed wildlife biologist.

SARAH SHAW is the co-owner and co-president of Hillside Botanicals, a certifed organic medicinal herb farm and apothecary in West Brookfeld. She is a clinical herbalist and educator and works as a consultant in the natural products industry.

DON STEVENS is Chief of the Nulhegan Band of the CoosukAbenaki Nation. He helped obtain legal recognition, acquire land, and federal settlement agreements for the Abenaki People. Don served in the US Army and holds several Honorary Doctorate Degrees.

LIZ THOMPSON is an ecologist with an abiding passion for wild places, plants, and patterns in nature. With Eric Sorenson and Bob Zaino, she wrote Wetland, Woodland, Wildland: A Guide to the Natural Communities of Vermont

After more than three decades as part-timers, JON STABLEFORD and his wife moved into their South Straford home in 2010 as permanent residents. He is a retired teacher.

LAURA SULLIVAN is a fber artist and farmer living and working in Vermont. She will be pursuing hemp fber research further this winter as she embarks on her MFA degree at Vermont College of Fine Art.

IAN VAIR sells mushrooms and tinctures at farmer’s markets and through his website (greenmountainfungi.com), leads mushroom foraging workshops, and gives lectures. Tose in the Rutland area probably know him from his local cable-television cooking show.

8 vermont almanac | volume 1 v contributors

THOMAS DURANT VISSER has worked with historic barns since he was a teenager. A professor at the University of Vermont History Department and Historic Preservation Program, he is the author of Field Guide to New England Barns and Farm Buildings

MIKE WHITE lives in Bennington County, is a licensed forester, and helps manage a cross country ski area.

JOAN WALTERMIRE was in her frst of many years as Curator of Exhibits at the Montshire Museum of Science when she wrote her most important poem – about opossum reproduction. Tis attracted her longtime mate. Tey live in Vershire.

WHITE is currently teaching himself how to weld. He is proving to be a poor teacher.

JESS WEITZ is a multidisciplinary artist and writer living on a mountain, in a feld, in Marlboro, Vermont. She facilitates art and meditation classes and can be contacted through www.jessweitz.com

stories from & for the land 9 contributors

PATRICK

October 2022 - September 2023

In some traditional cultures, the year begins with the harvest. Larders are full; things are at their peak in the natural world. Next comes seven months of decline, and then fve months of renewal. Vermont Almanac marks a year’s time in the same manner.

contrib utors 3

preamble 11

october 13

november 39

december 61

january 85

february 107

march 133

april 155

may 177

june 199

july 221

august 245

september 267

A content index of the many people, places, and topics covered in Volume I, Volume II , and Volume III is avilable online at vermontalmanac.org. A similar index for Volume IV is in the works.

10 vermont almanac | volume 1 v

Among other things, this book is a celebration of rural culture. Tat word, culture, is often employed in an empty way, its power diminished by overuse in a million non-proft fundraising letters. Other times, culture is wielded sharply, as in the “culture wars.” Tere can be a jingoistic tint to it all: Are you in or out? Whose side are you on?

Tis baggage trailing an otherwise deeply meaningful word suggests a need for us to clarify: What, specifcally, are some of the elements of rural culture worth celebrating?

A culture of doing, for one. Of self sufciency. Each fall we celebrate turning wood into fuel, and plants and animals into nourishment for the winter months ahead. Tese natural rhythms carry over into the next season and then the next – around and around. Te repetition is key, as the high calling of culture comes from long-nurtured habits. Lots of cultures celebrate doing. Tech culture is racing madly to put a new iPhone in your pocket and develop a machine that makes thinking obsolete. Urban culture builds and then tears down and then builds again, monuments to and of a human-centered existence. Te doing in rural culture, on the other hand, is closely linked to the natural world. And those of us who appreciate this are endlessly grateful for the connection.

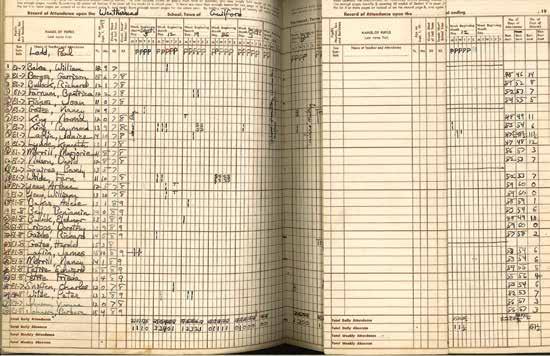

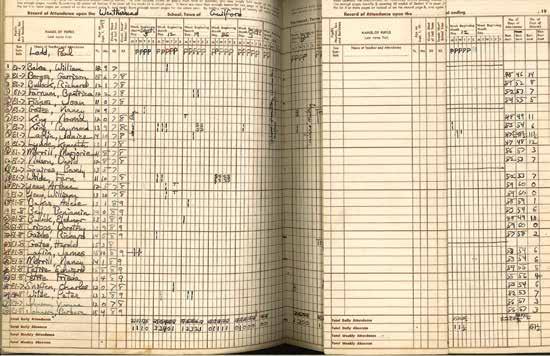

Te rural culture worth celebrating is a free-thinking one. Tere’s a story about a Vermont teacher from the 1950s on page 166, told through the words of his students 70 years later. Te teacher was a young idealist from away, a man “who pursued what pleased him;” the students were rural Vermonters in the tiny town of Guilford who, as their reminiscences bare out, pursued what pleased them. Who were the free thinkers in the story – the teacher who followed his dreams and ideals to Vermont, or the provincial kids who would go on to spend their entire lives in a tiny town, ignoring the “Oh the Places You’ll Go” commencement speeches and the push to uproot, earn, and consume? Tey all were. And this free-thinking spirit goes hand in hand with Vermont’s spirit of live and let live, which people here are rightly proud of.

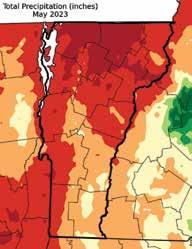

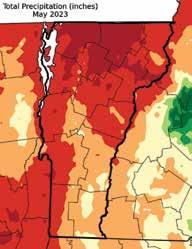

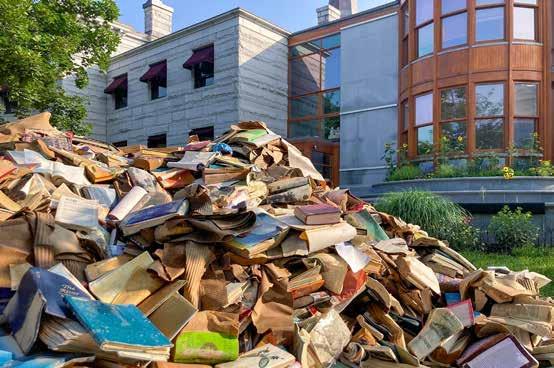

Te rural culture that’s worth celebrating is generous, which was clearly seen this summer when parts of the state were decimated by food waters and neighbors dropped everything to pitch in. We see it in the way people are proud to support local businesses. We see it in a million little transfers of knowledge about our Vermont ecosystems – both human and natural – from person to person, from generation to generation. Te self-sufciency described above does not come at the expense of community.

Tis book exists because its contributors are driven to dig in – sometimes fguratively and sometimes with a tool in hand. It exists because our free-thinking readers are drawn to our subject matter and are willing to pay for home-grown content. It exists because of the generosity of these contributors, as well as our readers, and sponsors, and donors. Tank you all.

stories from & for the land 11

PREAMBLE

OCTOBER

stories from & for the land 13

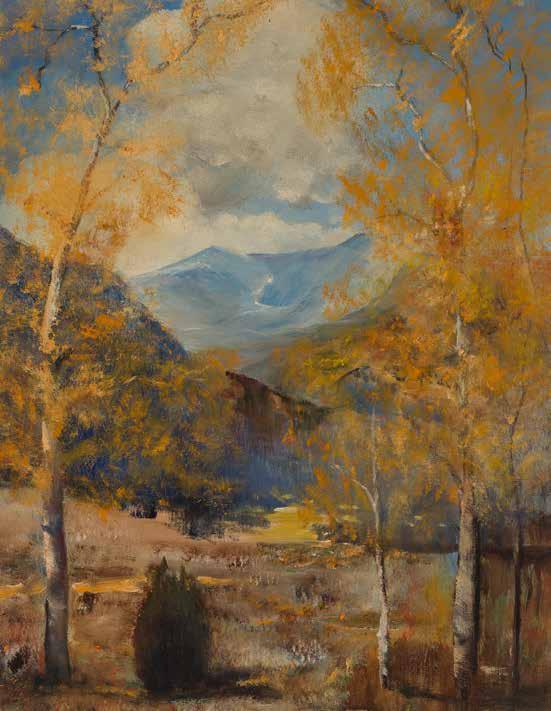

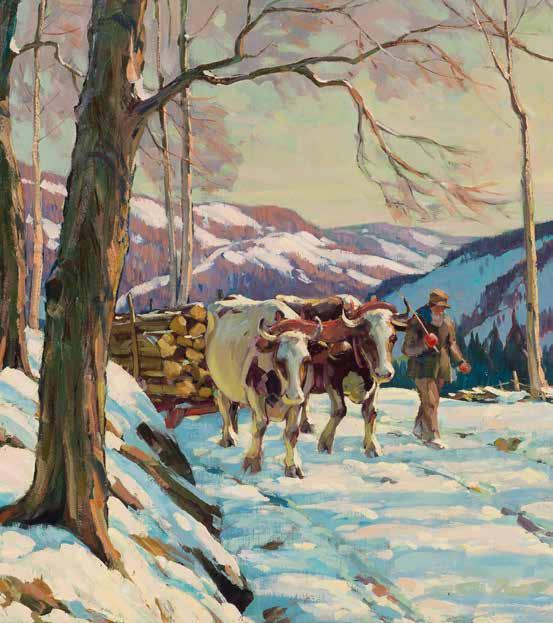

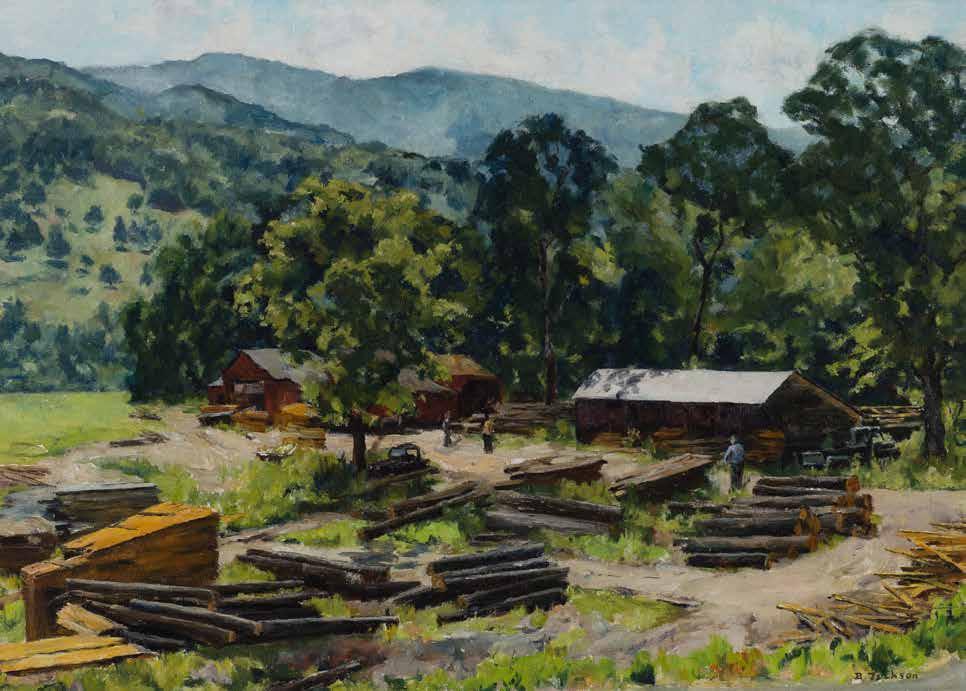

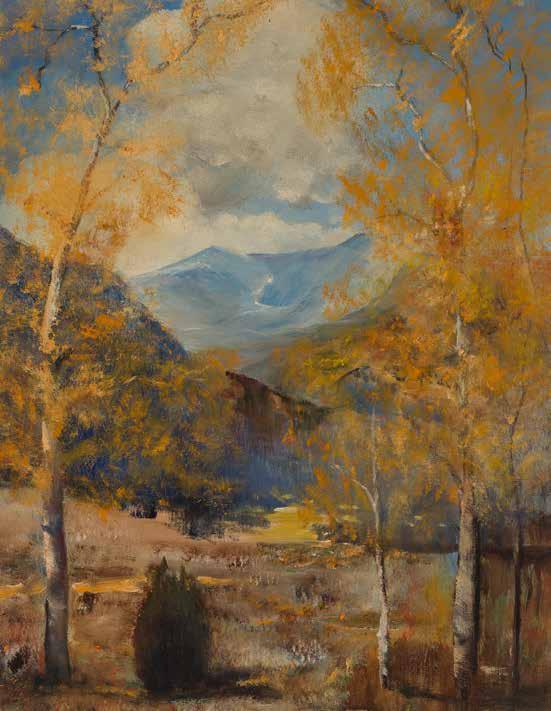

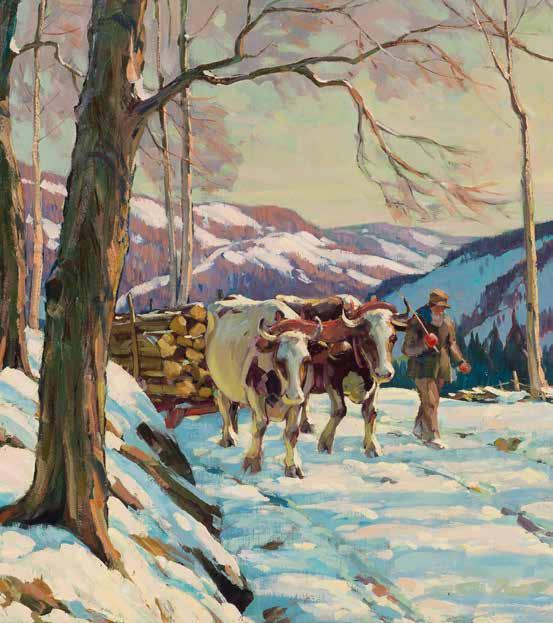

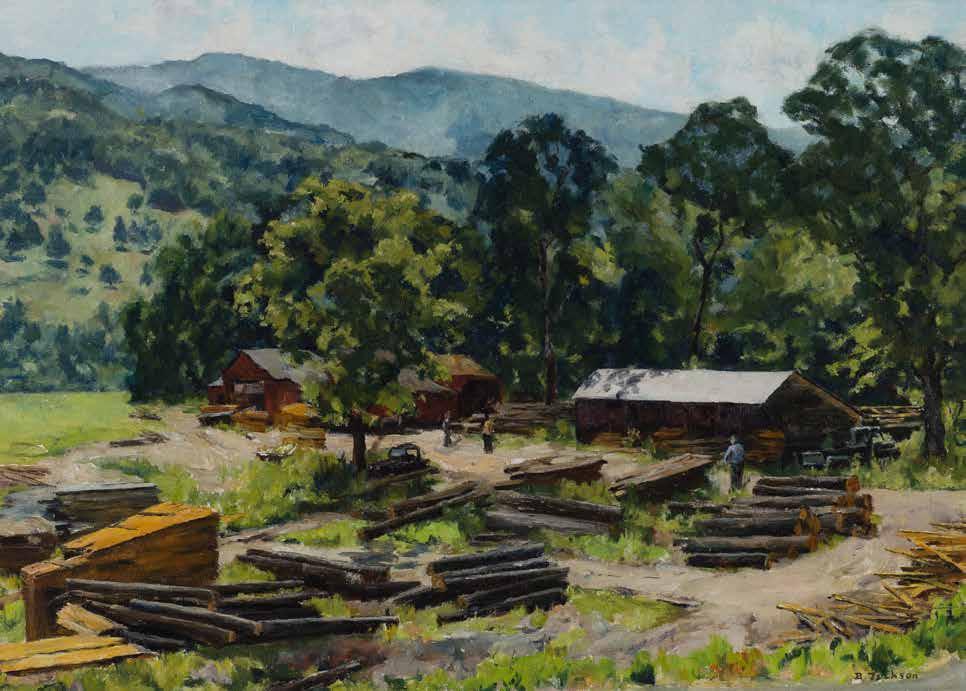

For the past 45 years, years, Lyman Orton, best known as the proprietor of the Vermont Country Store, has been collecting Vermont artwork. Tis year, the Bennington Museum and Southern Vermont Arts Center staged a joint art exhibition and displayed over 200 pieces from his collection, including this oil painting by John Lillie (1867-1942), a mason, builder, farmer, and self-taught painter from Dorset. You’ll fnd other pieces from the collection scattered throughout the book.

14 vermont almanac | volume 1 v october

BLUE AND GOLD ( 1915 )

OF THE LYMAN ORTON COLLECTION OF THE ART OF VERMONT

COURTESY

THE YELLOW LEAF

Tis morning races in, low clouds fying, leaves scattering to the wings where just yesterday in quiet light the gold and burnt oranges, the burnished greens, were all in company draped in a broad October stillness like a curtain behind a stage.

Te players had come out, a mechanic in his yard, a young man and woman staring at their pickup’s broken gate, a neighbor hauling out her horse’s bale of hay, a man walking the narrow shoulder of the road, a pair of cyclists abreast, talking, all intent in their myriad of purpose below a sun flled sky and a quiet proscenium of colors.

But, look now – one from among them returns today, kneeling in this wildness of wind, holding back her hair as she would like it, to reach for a yellow leaf October just blew into the brindled grasses.

—Bill Drislane

stories from & for the land 15

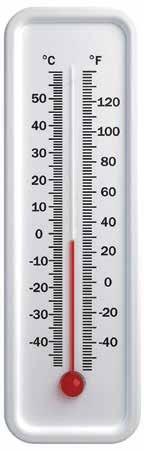

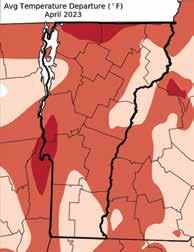

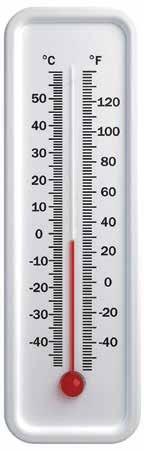

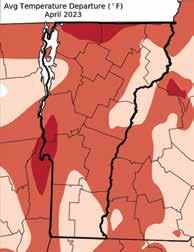

RLargely Lovely

According to the National Weather Service, the average frst frost date for Montpelier between 1991 and 2020 was October 3. In 2022, the frst frost in Montpelier occurred on October 3. After a year that featured an ice storm and notable drought, a year where a third of the months featured heat that ranked among the top ten warmest ever, there was something reassuring in that mundane glimpse of “normal.”

Te by-the-book weather continued through the frst part of the month – it was October in Vermont as you might see it in a movie. A beautiful stretch of seasonal weather culminated in parts of the Green Mountains on Columbus Day weekend in a snowliage event – that rare occurrence when the valleys are at peak foliage and the mountains covered in fresh snow.

Te state monitors fall color on Mount Mansfeld at three elevations, and peak color at 2,600 feet

16 vermont almanac | volume 1 v october

WEATHER

MATT

SUTKOSKI

Matt Sutkoski captured this beautiful shot of “snowliage” on October 8, 2022.

was slightly earlier than the long-term average, but similar to the long-term average at other elevations (1,400 feet and 2,200 feet). Maples at every elevation dropped their leaves slightly earlier than usual. Tings started to trend warmer than normal towards the end of the month. Te last week of the month featured record highs – on the 25th it was 78 degrees in Burlington and 70 in Saint Johnsbury. Te nighttime low temperature in Montpelier – 62 – was 9 degrees warmer than the previous record. Dew points during the warm spell were in the 60s, which is August-like. Trappers who wandered afeld on the fourth Saturday of the month – the traditional season opener – were in t-shirts by mid-morning. And gardeners hoped their garlic bulbs wouldn’t be tricked into sprouting as they tucked them into

garden beds for the winter. Te warmth extended through Halloween and into early November. When all was said and done, the monthly average was 2.8 degrees warmer than the 20th century average and 1 2 degrees above the 21st century average. We’re relying on data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Information Center for our temperature averages this year. One of the cool things about their data set (nClimDiv, which is based on the Global Historical Climatological Network Daily database) is that it provides us a glimpse of both recent temperature averages and a 128-year average covering the entire 20th century. Most of the averages you hear reported by meteorologists are 30year averages, which underreports how dramatically things have changed since our grandparents’ day.

October 15, 2022: Te weather for the Southern Vermont Flannel Festival at Rockingham Hill Farm in Bellows Falls was more crispy than crisp. Will we need fannel t-shirts in the future?

We looked back at our weather summaries from the past three volumes of Vermont Almanac and saw that October 2021 was the fourth-warmest October on record and was signifcantly wetter than normal. October 2020 was a relatively average month for both temperature and precipitation. October 201 9 was exceedingly wet, with 8 5 inches of rain recorded in Burlington. Statewide, it was the sixth-wettest month on record.

stories from & for the land 17 ROCKINGHAM HILL FARM

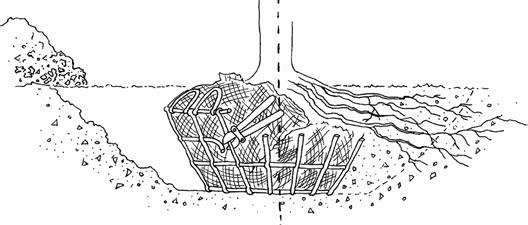

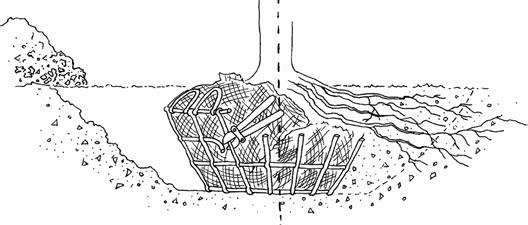

EVER WONDERED WHAT AN UNDERGROUND YELLOW JACKETS NEST LOOKS LIKE ? Here’s one we dug out of the backyard once a killing frost had killed the wasps. Female wasps create the paper by chewing up dead wood and plant stems and mixing it with their saliva to make pulp.

WHILE VERMONT IS NOT KNOWN for its charismatic fossils, they do exist. Fly-fshing guide Emily Murphy found this one along a creek in Bennington County in October 2022 – it’s an olenellid trilobite, which is probably more than 500 million years old.

eAsters Change Colors

For a diferent fall color show, take a close look at the fowers of New England aster when the plant is in bloom in late fall. Te fowers have violet-purple to pink “petals” (really sterile fowers), and contrasting central disks made up of fertile fowers. Tis is where the real business happens – where pollination results in the production of fruits and seeds. Some fowers in the disk are yellow, but in others the disk may be purple or a mix of both colors… Has something gone awry here?

Not at all.

Each disk fower changes color from yellow to reddish when it is pollinated, a change that leads to greater success for both the fower and for its visitors. Pollinators, especially visual animals like insects and birds, have learned to read the color change as a signal that a fower has already been visited and given up its nectar or pollen. Tey avoid these fowers, saving time and energy by concentrating on fowers with a greater reward. Tis also benefts the plants through more efcient pollinator visits.

—Joan Waltermire

18 vermont almanac | volume 1 v october NATURE NOTES

HOWARD WEISS-TISMAN

Crowd-sourcing

On Oct. 12, 2022, photographer Craig Hunt took a series of photographs of a peregrine falcon in Brattleboro, which he later posted on Vermont iNaturalist. Hunt noted that the bird was banded, but couldn’t make out the number. Sharpeyed viewers helped inspect the bands and narrowed down a possible number; they also shared that the placement of color bands on the left leg indicated that this bird was a female, and the combination of black over green color bands indicated that this was a bird banded in eastern North America. Craig sent this info, along with the photos, to the USGS Bird Banding Lab and learned that this peregrine falcon was banded as a hatchling alongside three siblings in Lewiston, Maine – roughly 200 miles away – in May of 2021. Te lab even sent a picture from the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife of the same peregrine falcon on the day she was banded.

stories from & for the land 19 MAINE DIFW CRAIG HUNT CRAIG HUNT

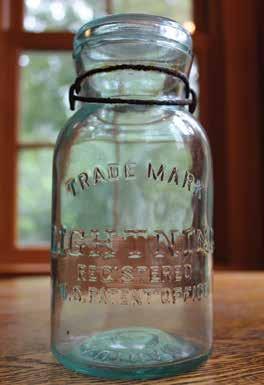

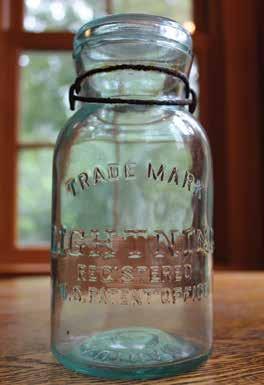

BETZY ’ S RECIPE FOR FIRE CIDER Fill a wide-mouth quart canning jar about halfway with chopped onion, garlic, ginger, horseradish root, and chili peppers, in whatever proportion you like and have on hand. If you’d prefer it not to be so spicy, leave out the chilies. You can also include other favorful medicinal herbs like turmeric, black pepper, rosemary, thyme, or sage leaves; mustard seeds; lemon or other citrus fruits, with peels; pine, spruce, or balsam fr needles – anything you like. Add enough apple cider vinegar to cover the herbs. Ideally there should be one to two inches of vinegar over the chopped herbs. Add a couple tablespoons of honey, and give it all a good shake or stir to mix the honey and other ingredients well. Cover the jar with a plastic or a non-metal lid (vinegar corrodes metal lids), and leave it in a warm place for a few weeks to a month, shaking occasionally. Strain out the solids using a kitchen strainer or cheesecloth, and bottle it. Enjoy!

FFire Cider

ire Cider is an oxymel, a mixture of honey and apple cider vinegar, infused with the favors and goodness of spicy herbs. Te recipe was developed from older traditional tonic recipes in the 1980s by Rosemary Gladstar, a beloved herbal elder and resident of Vermont. It’s a delicious way to get the benefts of stimulating herbs in our diet. I love to splash it on cooked greens, add it to dressings and sauces, and incorporate it into beverages like an after-ski or -snowshoe toddy. Use it like hot sauce.

If you take it by itself, the “dose” of fre cider is just a light shot –about half or a full ounce. It can be taken without diluting it, but fre cider is often mixed with water. Just be careful – fre cider can be very spicy if you include chilies, and it can be quite stimulating, making a fery person feel fushed and sweaty. Herbalists call this a diaphoretic efect – it chases of chills, colds, and some fevers by opening the pores and moving energy outward. Fire cider also improves circulation, which has many benefts, from warming chilly hands and feet to promoting better cognitive function. It also stimulates digestion and helps clear the sinuses. Te benefts will vary somewhat depending on the herbs you include in your recipe. —Betzy Bancroft

20 vermont almanac | volume 1 v october

AT HOME •

PHOTOS BY BETZY BANCROFT

Wild Cider

Well over a century ago, cider making came to be dominated by industrial production. Sameness meant greater ease in mechanized harvesting and predictability in outcome. But anyone who has made their own apple cider knows that the best apples for fresh-eating are often not the best for pressing. Simply put, perfection and homogeneity are boring. Te best cider has a complex favor, not a uniform and bland one.

Te best cider I ever had was made from wild apples by students at the brave little school where I have the pleasure of teaching. Cidering is one of East Burke School’s most beloved traditions, and the hours we spend each fall harvesting, grinding, pressing, and pasteurizing hold many lessons beyond the practical.

Our secret ingredient is variety: we get added, interesting favors by sourcing from crabapples and wild apple trees growing along Vermont’s roadways. Some of these apples are perfectly good for fresh-eating, but others are varieties that you wouldn’t necessarily choose on their own: they may be excessively tart, perhaps even bitter. But throw these into a grinder with the sweet, and you end up with a much more memorable glass of cider than you’d have if you’d stuck with a single, eminently marketable apple variety.

Making cider with wild apples serves as a reminder that we grow when we look beyond the narrow realms of our favorite things. Tat’s a lesson that can be applied to friendships, to politics, to learning in general. We need crabapples in life, just as we need them in our cider. —Megan Durling

stories from & for the land 21

PHOTOS BY MEGAN

DURLING

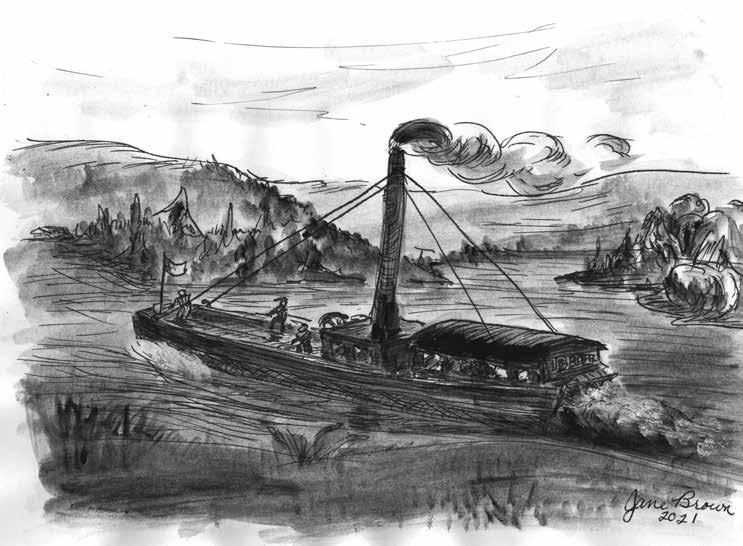

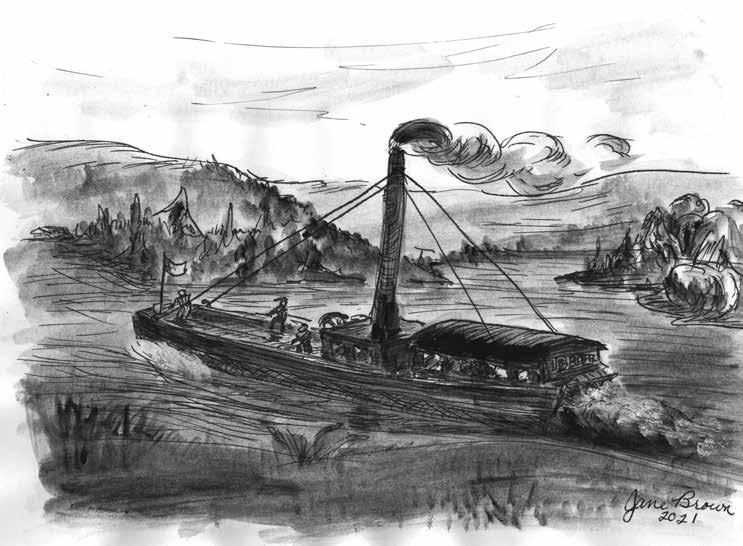

Te Steamboat “Barnet”

In the early settlement days, towns throughout the Connecticut River Valley depended heavily on their namesake river. Te Connecticut begins as a narrow stream out of high-elevation lakes, then after some meandering fows south along the 238mile border of Vermont and New Hampshire. It is reinforced by tributaries and becomes a broad, swift river by the time it empties into Long Island Sound, some 400 miles south.

Only a few hundred residents lived along the river north of the Massachusetts border in the 1760s, and river trafc was mostly Native Americans or trappers with canoes or dugouts loaded with animal hides and furs. However, by 1791, about 44,000 people lived in the Vermont counties of Windham, Windsor, and Orange on the west side of the river, and at least twice that many east of the river in New Hampshire. All of them needed better transportation methods than dugouts and canoes.

To meet this need, fatboats were built, typically 70-75 feet long and 12-14 feet wide. Fully loaded, they could carry some 30 tons and drew only about 12-18 inches of water, making them perfectly adapted for travel into the shallow reaches of the upper Connecticut River. According to Lyman Hayes, who wrote a detailed history of the Connecticut River in the early 20th century, the river was navigable as far north as Wells River in the early 1800s.

Flatboats depended on either wind or manpower. Most had a tall mast in the middle of the deck with one large sail and six men (three men working on either side) with poles that were about 20 feet long with a spike on one end. Te men planted the spiked end of the poles on the river bottom, placed the other end against their shoulder, and walked towards the stern of the boat, moving the boat ahead. Each man would then return forward in a constant rotation, often for long hours at a stretch and in all kinds of

22 vermont almanac | volume 1 v october

A

•

LOOK BACK

weather. A pilot who knew the river well guided the boat with a rudder that was operated from the roof of a cabin at the rear of the boat.

At falls and rapids along the Vermont/New Hampshire route, cargo had to be unloaded and transported overland by teams of oxen or horses to boats on the other side of trouble spots. Between 1800 and 1829, canals or locks were built around these hindrances. Te improvements made of-loading cargo unnecessary, which substantially reduced the cost and efciency of transporting goods.

Even with the canals, navigation was still difcult. Te riverbed changed with every rainstorm, and after spring runof, previously unseen boulders and new sandbars appeared. Dry years and foods added to the ever-changing conditions that challenged even the most experienced riverboat pilots.

In the early 1800s, there were opposing views about how best to transport goods to the northern region’s growing towns. One proposed solution was to build canals and locks to connect major lakes and streams throughout Vermont. Tese people were called Canalites. Tey explored possibilities for a series of canals to connect Lake Champlain on Vermont’s western border with the Connecticut River on the eastern border. Another group, called Riverites, felt it was better to spend money to improve the existing waterways by dredging and building locks at trouble spots.

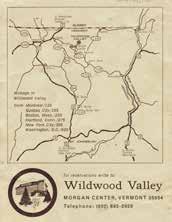

After a bad food in 1824 took out dams and bridges, a representative group of Riverites met to discuss how to make the river more navigable. Tey raised money for dredging and canals, envisioning boats reaching as far north as the town of Barnet, north of McIndoe Falls. To prove their point, they engaged the Connecticut River Company of New York City to build a small steamboat, specially designed to navigate the rugged upper Connecticut River.

Te little steamer was 75 feet long, 14 5 feet wide, and drew 22 inches of water. It had a fat bottom and walled sides, with a cabin and a paddle wheel at the stern. Finished in 1826, the craft was named the Barnet to honor the town it was expected to reach.

On November 24, 1826, the Barnet left Hartford, Connecticut, and proceeded north. A river boat captain named Palmer took her as far as Northampton, Massachusetts, about 40 miles south of the Vermont border. From there, Captain Strong, a noted river man who knew the upper Connecticut River well, took command. When the Barnet reached “Warehouse

Point” in Brattleboro, it was greeted by bonfres and bell ringing as well-wishers followed along the riverbank in celebration. However, at the rapids called “ Te Tunnel,” the little steamer came to a standstill. Hayes described how Captain Strong pushed the boat hard until, “with fre blazing from the smoke-stack” he grabbed a spiked pole and “punch[ed] against the bed of the river,” trying to move the vessel forward himself. Strong lost his balance and tumbled into the rapids but was quickly rescued. At that point, he admitted defeat. A few days later the Barnet tried again, and that time, with the assistance of a winch, made it through.

Festivities welcomed the steamer at Bellows Falls, and Captain Strong proudly showed of her speed and power by taking a few turns around the eddy. Several dignitaries were present that day and ofcers of the Association for Improving the Connecticut River boarded the boat, along with ofcials of the steamboat company that built the Barnet. Te celebration lasted for two days, with plenty of food and many barrels of whiskey consumed. Te general merriment continued as the boat departed north, and a joyful toast was ofered: “To the town of Barnet – may she be speedily gratifed by the sight of her frst-born.”

However, it turned out that the Barnet was too large to go through the locks north of the Bellows Falls. Disappointed at the obvious error in calculations by the steamer’s designers, and some 80 miles short of its intended destination, there was nothing to do but give up the quest and return downstream. As the little steamer left, a cannon discharged 124 rounds (possibly representing the distance back to Hartford) to bid her farewell. Some 200 people followed along the banks of the river as far south as Westminster where they watched her retreat down the river. She pulled into Hartford a few days later and never sailed that far north again.

Almost exactly a year later, the Barnet came to an unfortunate end near Milford, Connecticut, when her boiler blew up and a river pilot was killed.

Te need for better transportation of freight remained, and other steamers such as the Vermont and the John Ledyard successfully plied the lower Connecticut River until the mid-1800s when locomotives were introduced and proved to be a far more efcient and cost-efective method of moving goods and passengers. But the little steamer Barnet deserves to be remembered for her valiant efort to go where none like her had gone before. —Jane Brown

stories from & for the land 23

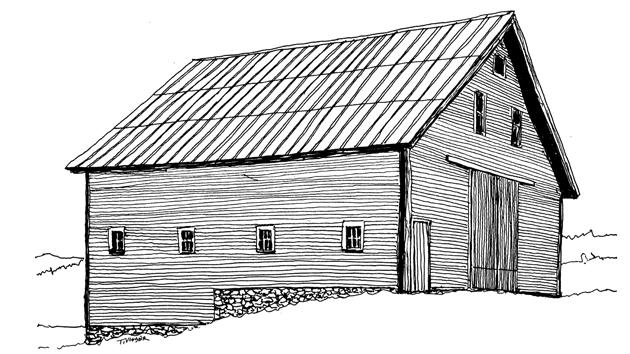

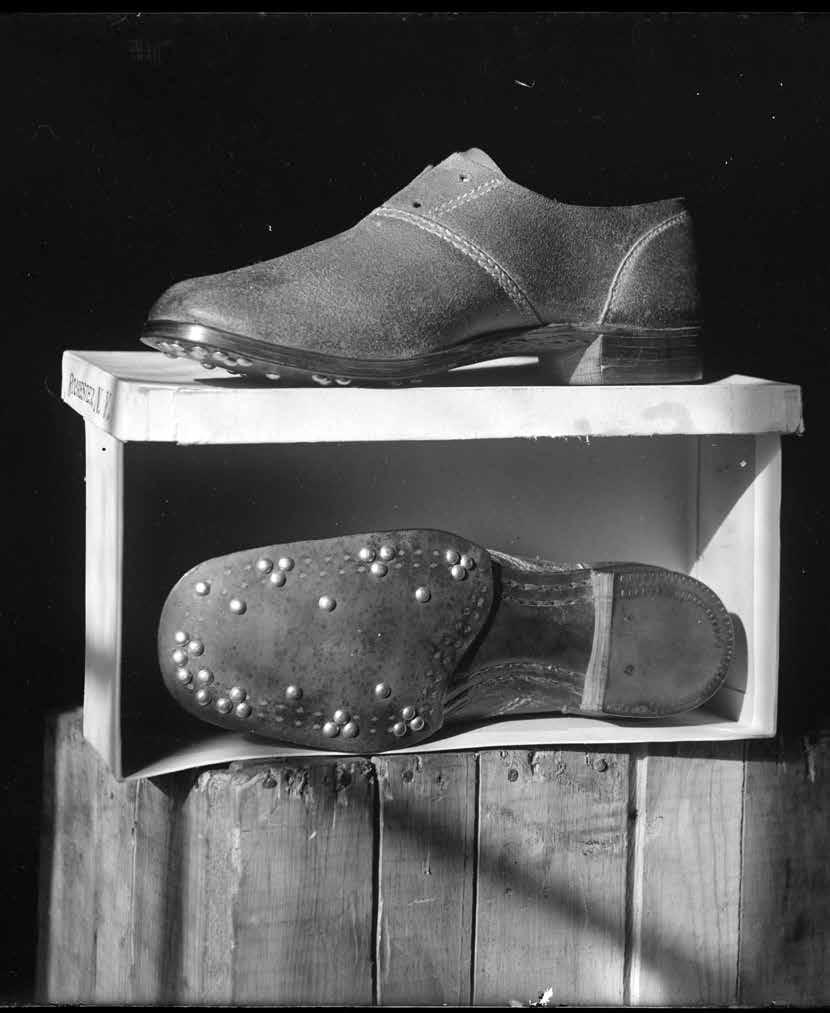

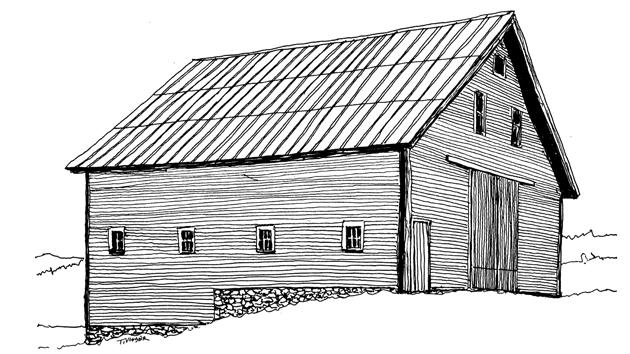

History of Vermont Barns

24 vermont almanac | volume 1 v october INDUSTRY f

English barn, Worcester

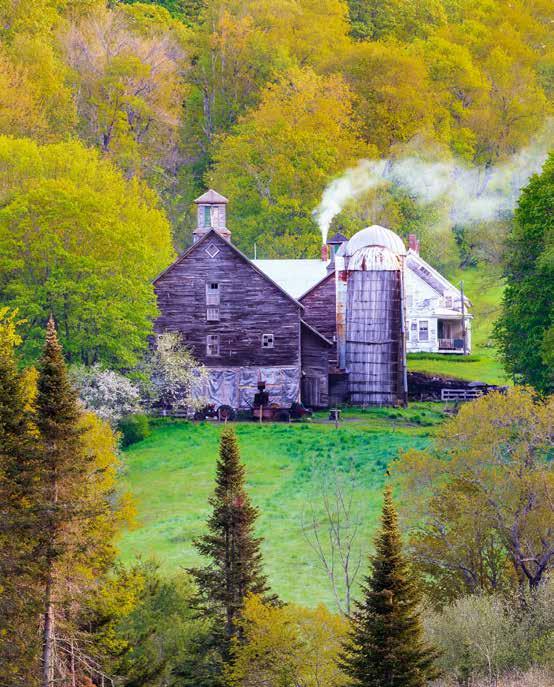

Barns are ubiquitous across the rural Vermont landscape. Teir presence tells us where farms are, where they were, and – more hopefully – where they might be again. Teir architecture can also tell us a lot about when the barn was built and what it was likely used for. Learning to recognize these seven distinct types of historic barns can help you trace our state’s agricultural heritage.

ENGLISH BARNS ( CIRCA 1770 s TO CIRCA 1840 s ) were commonly built by Vermont settlers who migrated into former Native American lands after the Revolutionary War. Identifying features include a wide doorway on the eaves side, unpainted vertical sheathing boards, and hand-hewn timber frames. Typically measuring about 30x40 feet with sills set close to the ground, many of these gable-roofed barns served Vermont families who were sustaining themselves through subsistence farming. English barns feature a central drive foor fanked by a large hay mow extending to the roof on one side; on the other side there’s an enclosed space for sheltering animals with additional hay storage above. As soil fertility waned and the importance

of returning animal manure to nourish croplands became recognized, some farmers had their barns built on sloped sites with basements beneath for collecting manure.

GABLE FRONT BARNS ( CIRCA 1840 s TO CIRCA 1880 s ) By the 1840s, people were leaving rural Vermont for opportunities out West. Tis also coincided with a shift to dairy farming in Vermont, as the prior “sheep boom” waned due to global competition. As farm labor shortages were compounded by the American Civil War, various “model barn” design innovations were encouraged in agricultural periodicals. Rotating the plan of the barn by shifting the main entrance to the gable end provided important advantages. With a center drive foor running lengthwise beneath a ridge line, these barns could be made larger by adding bays, thus supporting larger dairy herds. Typically constructed on sloping sites, gable front “bank barns” also typically featured manure basements. Sheathing barn walls with shingles or painted clapboards were other innovations prompted by the theory that if stabled cows could be kept warmer in “tight barns” during the winter, they would need less feed, thus dairy herds could be increased without more acreage.

stories from & for the land 25

English barn

DRAWINGS BY THOMAS DURANT VISSER

Gable front barn

CUPOLA BARNS ( CIRCA 1860 TO CIRCA 1890 s ) Many dairy farmers soon discovered that the shift to “tight barns” brought an undesirable problem – poor air quality. Indeed, with eye-watering fumes rising from manure basements, and moldy dampness rotting wooden walls and roofs, it became clear that better ventilation was needed. At frst, simple boxy wooden ventilators were added to barn roofs to vent moist air. Tese evolved into Victorianera cupolas featuring large louvers and brightly painted decorative trim and brackets associated with the Italianate and Queen Anne styles of architecture.

Often capped by gold-leafed weathervanes, fancy cupola barns soon became symbols of farming success during the railroad era. At summer estate farms, these barns were trophies of the wealthy.

HIGH DRIVE BARNS ( CIRCA 1880 s TO CIRCA 1900 s ) are a distinctive type of Vermont barn that feature open ramps or covered bridges that lead to the hay lofts. Tese multi-story “gravity fow” bank barns were designed to reduce labor as hay could be easily dropped down chutes to feed cows in stalls on the foor below.

ROUND BARNS ( CIRCA 1890 s TO CIRCA 1910 s ) that combine a circular or multi-sided plan with features of the previous model “gravity fow” barn designs are another rare, but noteworthy late-Victorian era design variation found in Vermont. Some were constructed with 8, 12, or 16 sides.

26 vermont almanac | volume 1 v october

Cupola barn

High drive barn

Round barn

GROUND - LEVEL STABLE BARNS ( CIRCA 1901 s TO CIRCA 1940 s ) A harsh reality destroyed the optimism and fortunes of many dairy farmers in Vermont in the early 1900s as it became understood that devastating diseases like tuberculosis were spread by milk contaminated by airborne bacteria from the dusty manure in gravity fow barns. Entire herds were culled, and soon milk markets refused to accept milk from barns with wood-foored dairy stables. To address the problem, new dairy barn designs were developed with concretefoored dairy stables located on the ground level that could be regularly cleaned by washing manure into gutters. Also, to reduce the spread of diseases, cow stables were lined with windows to increase the level of ultraviolet sunlight; ceilings and walls were whitewashed with lime; separate milking parlors were added; and sophisticated ventilation systems were installed with air ducts leading up to manufactured steel ventilators on the roofs. Designs for these

ground-level stable barns become standardized through much of the dairy farming areas of the United States and Canada. Many featured engineered trusses with double-pitched gambrel or Gothic-arched roofs that sheltered the upper story haylofts. Large wooden stave, tile, or cement silos for storing fermented chopped corn stalk fodder also became common features of Vermont dairy barns during the frst half of the 20th century.

SURFACE BARNS ( 1950 s TO PRESENT )

As advances in medical research led to the development of pharmaceuticals able to control such infectious diseases as bovine tuberculosis, single story dairy barns became common by the early 1950s. Some operated as free stall barns with the cattle moving in and out freely. Many current large Vermont dairy farms now keep their dairy herds stabled inside large single-story, concrete-foored surface barns throughout the year and rely on outdoor bunker silos to store fermented corn silage. Tomas Durant Visser

PRESERVING HISTORY

If you have a historic barn in need of restoration, there are two grant programs that might be able to provide fnancial assistance. Te Preservation Trust of Vermont (ptvermont.org) has a grant program to ofset the cost of a professional assessment of the barn’s needs, and the Vermont Division for Historic Preservation (https://accd. vermont.gov/historic-preservation/funding) ofers matching grants for the preservation of historic agricultural buildings.

stories from & for the land 27

Ground-level stable barn

Surface barn

New Life for Old Barns

For Luke Larson, restoring a barn is a journey into history – the wood used and the axe and chisel marks tell a story.

f 28 vermont almanac | volume 1 v october

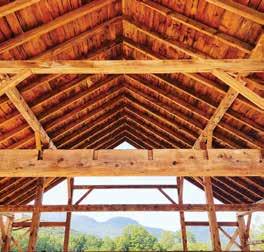

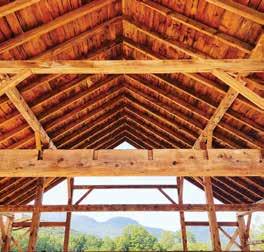

We step out of the sunlight and into the cavernous main barn at Green Mountain Timber Frames’ headquarters in Middletown Springs. Its roof soars stories above us. Te warmth of centuries-old beams and boards surrounds us as sun pours in through the wavy glass of restored windows. It’s the kind of space that just feels welcoming. “We believe it was built around 1780 – certainly pre-1800. It’s a pretty classic Englishstyle threshing barn,” explains owner Luke Larson, pointing to the three-bay layout with large doors accessing the center bay from each side.

Larson has made restoring old barns his life’s calling. He’s interested not just in the bones but also the history of these structures – what the barns were used for, when they were built, and who built them. “We try to learn as much history on the barns as we can, so we go back to old land deeds and often meet with the local historical society,” he says. Tis barn came from just over the New York border in Saratoga County, and the builder was a farmer named Reuben Wait, who would have been born before the United States.

Larson grew up on a dairy farm in Wells and as a high schooler he started working for Dan McKeen, a master timber-framer who started Green Mountain Timber Frames in 1983. At that time, the focus was exclusively on building homes with milled timbers. But after one client asked for a timber frame addition made from old barn timbers, a new passion was ignited. After college, Larson decided this was the career path for him and he purchased the company in 2015 when McKeen retired. Since that time, Larson and his team – including his wife Sara Young and three to fve employees – have restored (“saved, really,” he says) more than 50 historic barns.

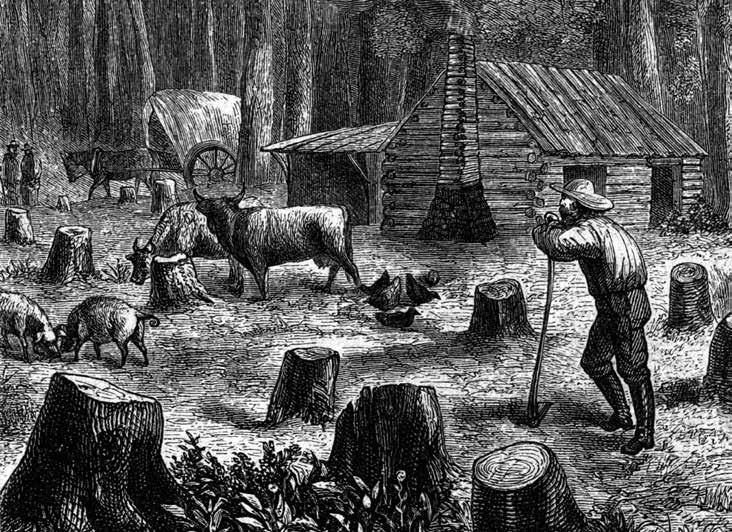

“I am passionate about timber framing as a practice. I love chiseling. I really geek out on joinery,” says Larson. “But I’m equally passionate about keeping the stories alive – the history that these barns embody. Standing inside a barn like this one, built around 1780, you think some of these larger trees were at least 200, if not 300 years old when they were cut down, so we’re standing inside a structure built with trees that predate Columbus. I spend quite a bit of time thinking about that, starting with the trees, and then through the individuals who built the barn, hardy souls. I just can’t imagine walking out into the woods with an axe and just starting to clear a space for a 32-foot barn.”

Larson has a special appreciation for the wood

In June 2023, Jack Snyder guides a beam while Issac Yackel moves it with a tractor (top) and Jamie Austin chisels out a mortise. By late July they had re-erected the restored structure in Dorset.

stories from & for the land 29

– dense, straight – used to build early barns. “We’re standing inside ash trees in this barn,” he says. “Beech is another common species that was used in this area. Some red oak; we have a little bit more red oak here than white. Not as much chestnut right here. So hardwoods, and then the upper system of the barns is usually pine, because that’s what they could get the longest, straightest piece out of. Tis barn that we’re in right now has fve beams that are 42 feet long.”

In the late 1700s and early 1800s, when many of the barns that Larson works with were frst built, there were few traveling carpenters. Te majority of

these barns were put up by the family, with help from neighbors, using layouts and construction techniques common in their European homelands. “I’ve been fortunate enough to take down and restore some barns, 10 or 20 miles apart, that I’m quite confdent were built by the same person, or at least the same advisor,” he explains. “Sometimes the measurements are exactly the same. Or they used the same system of marriage marks to label each piece of the frame.”

Larson points to a barn he restored some years back in North Hero, where he found the remains of a rudimentary living structure beside the barn, as

Clockwise from top: Te restored pre-1800 Reuben Wait barn that now serves as home to Green Mountain Timber Frames, as well as a place for educational events and community gatherings. Nearly all work is done with hand tools, using techniques that are centuries old. Te original builder’s “marriage marks” on the frame of a barn.

30 vermont almanac | volume 1 v october

PHOTOS

COURTESY OF GREEN

MOUNTAIN TIMBER FRAMES

typical of how things were done. Often the settlers would arrive, erect a rough log cabin to live in, and then get to work on building a barn – which was often constructed with much more precision than the living structure. “ Te builders put such care into those barns because they were relying on them to house the animals and store the food they’d need to survive the coming winter,” says Larson.

He also fnds huge appeal in the communal nature of building a timber frame, even today. “A timber frame is really designed to be crafted and assembled as a community,” he explains. “For the farmers who had to start by clearing the land, I imagine it would often take months if not a couple of years to hew out all the timber. And then they would probably do a lot of the joinery in the winter. And then on the barnraising day, the whole town would come together. It was a work day, and then at the end of the day there was often a celebration.” Tat’s still the case when his team erects a barn frame for a client.

Larson focuses exclusively on pre-1900 barns. In some cases, like a 2022 project in Pittsford, the barns are restored to be returned to agricultural use. In others, they are relocated and used as outbuildings or homes. Te restored Reuben Wait barn showcases the versatility of these old structures. From the inside, it appears much as it might have originally. Te interior holds some secrets that have been uncovered: grooves in the posts on each side of the door, for instance, into which a board could be inserted during threshing to prevent the loss of grain. “ Tat’s where the term threshold comes from,” Larson explains. But the outside holds some modern secrets of its own: Larson has added an exterior shell around the barn, which along with invisible insulation panels in the roof, allow the old structure to meet modern energyefciency standards.

For budget-driven projects, or where the barn is critical to an ongoing farming operation, Larson and his team will show up to prioritize and make repairs onsite. He credits barn grant programs in Vermont for playing an important role in helping owners to preserve historic barns and keep them structurally sound. Tat challenge is never-ending as the ravages of time continue to wear on old barns. “Wood is a living thing – even 300 years after it was cut. Te strength of wood is its fexibility,” says Larson, who marvels at how barns hold together even as they sink into the ground, slide downhill, or partially collapse.

While in-place repairs are important, Green Mountain Timber Frames’ niche is really complete restorations. “What my team and I specialize in is barns that are kind of beyond shoring up. We take the barns down completely. We label every board. We pop out the old wooden pegs, separate the joinery. Label every piece. Bring it back here to our facility. Wash it, pull a gazillion nails, which we save if they’re old.”

Larson uses the word label a lot. When you’re disassembling and reassembling a 250-year-old structure board by board, beam by beam (the process actually happens twice, as a dry run reassembly is done at the shop before fnal reassembly on site), organization is critical. In some cases the structure has been altered over the centuries, so they need to fgure out how the original timber frame was assembled and what parts might be missing. All of the wooden pegs are replaced when reassembling a frame, the new ones custom-made to ft holes that are rarely standardized.

Te goal is always to use as many of the original posts, beams, and boards as possible. Te company has built up a boneyard of old timbers to pick from when rot or other defects have damaged a particular piece beyond repair. Te work of ftting any new pieces is all done by hand, the only nod to modern efciency is a small chainsaw mortiser used to speed the rough-cutting of new mortise pockets before they are hand-fnished with a chisel.

Because of the size of the frames, the team works mostly outside, year-round. Many of the barns they work on are purchased from owners who don’t have either the desire or the fnances to restore them, but don’t want this important part of Vermont’s history to be lost. Tis day they’re working to reassemble a barn that will be re-erected at a new home in Dorset.

Te Green Mountain Timber Frames property is home to a few permanent structures. Te most notable is the main barn building, which moonlights as a space for community music nights, author talks, and more. An old blacksmith shop was just moved, piece by piece, from Benson and now sits just behind the main barn. Tere’s also a 1860s sheep barn at the site – it’s much longer than the early English barns, with an open lower level for the sheep and a large enclosed upper level for storing hay.

Larson says people are drawn to these old barn structures because they can sense their history. “I think it’s really important that we look back and learn from it and appreciate it,” he says. —Patrick White

stories from & for the land 31

A Vermonter in Paris

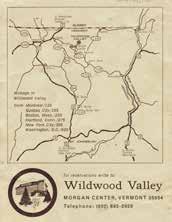

Will Wallace-Gusakov, who owns and operates Goosewing Timberworks in Lincoln, spent the frst six months of 2023 in France. Instead of crafting custom timber frame homes and outbuildings as he does in Vermont, Gusakov was working as part of the team charged with rebuilding the wooden roof frame of the grand Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, which burned in 2019 as the world watched. We asked the mostly self-taught timber frame carpenter about the once-in-alifetime experience…

WAS REBUILDING NOTRE DAME , AMONG THE MOST FAMOUS BUILDINGS IN THE WORLD , SOMETHING YOU HAD EVER ENVISIONED ?

No, no way. I never, ever would have been so presumptuous as to think that could happen. When Notre Dame burned, folks around here who knew I do historic timber framing work and knew that I’d lived and worked in Paris about 10 years ago, asked, “Are you going to work on the rebuilding?” And I said, “ Tere’s no way. Tat job will go to some huge company.”

SO HOW DID YOU END UP INVOLVED ?

After the fre, a narrative was being promulgated by those who wanted to modernize Notre Dame that it wasn’t possible to rebuild the timber frame as it had been, because supposedly there weren’t enough big oak trees in French forests, and supposedly there were no longer carpenters with the skills to do it. Both of these ideas were patently false. So a group that I belong to called Charpentiers sans Frontières, (Carpenters Without Borders), which does hand-tool restoration work on historic buildings around the world, started a public campaign

to help educate the public and the decision-makers that, in fact, both the material and the knowhow were available. In 2020 they even created a full-scale replica of one of the large timber trusses of the nave roof, using only hand tools, in just nine days. Tey

helped to make it impossible to deny that Notre Dame could be rebuilt as it had been, and it was decided to recreate the original medieval framing. A small French company run by a friend of mine was awarded the job of rebuilding the nave roof (the

Will Wallace-Gusakov at work hewing a nave timber for the reconstruction of Notre Dame Cathedral.

32 vermont almanac | volume 1 v october

f

COURTESY OF WILL WALLACE-GUSAKOV

PHOTOS

central large open space of the cathedral where worship services took place). I met him in France through Carpenters Without Borders about six years ago, and we’ve worked together on several projects since then, in France, Italy, Maine.… he’s also come to stay with us and see our shop in Vermont. He reached out and asked if I would be interested in being a part of his team.

IT SOUNDS LIKE THE DECISION WAS MADE TO RESTORE THE STRUCTURE NOT ONLY IN A HISTORIC WAY , BUT IN A HYPERHISTORIC WAY . Yes, that’s true, particularly with the nave and choir. Te transept and spire were largely redone about 1850 by a famous architect, Eugène Viollet-leDuc, and it was decided to rebuild that whole section to that 19th-century state since Viollet-le-Duc’s creations have become iconic and beloved. Tose sections are being painstakingly rebuilt exactly as they were in about 1850, following Violletle-Duc’s original drawings. For the nave and choir roofs, it was decided to recreate the original medieval design. Te Notre Dame cathedral was built in phases between 1180 and 1260, and the original medieval roof framing of the nave and choir had survived 850 years, until the fre in 2019. Te architects had to do a huge amount of work to analyze not only what had been there at the time of the fre, but which of those parts had been added or repaired over the centuries. Te goal was to go back to the original framework.

HOW HARD WAS IT TO TRY TO UNDERSTAND AND REBUILD A STRUCTURE THIS LARGE THAT WAS BUILT MORE THAN 800 YEARS AGO ?

After the fre, very little remained of the timbers, basically just a pile of charred rubble. Fortunately, the structure of Notre Dame had been very well documented, just 10 years earlier, by some architecture grad students as their thesis. Tey documented the nave and choir roof system very well, and those detailed measured drawings are what enabled it to be rebuilt faithfully.

AND THAT WAS THE PORTION OF THE PROJECT THAT YOU WORKED ON ? Exactly. Te nave and choir roofs are the two big medieval sections.

Te site of Notre Dame in Paris – a massive construction project. Te wood nave roof structure will eventually sit atop the stone walls of the cathedral.

Our partner company did the choir and our little company of 20 people (Ateliers Desmonts) did the nave. We worked mostly in Normandy, about two hours outside Paris, but had a chance to visit the site of the Notre Dame rebuilding and it was incredible. It’s a huge project.

HOW COMPLEX WAS THE WORK COMPARED TO A NORMAL PROJECT YOU COMPLETE ?

It was much more complicated. First of all, the top of the masonry walls where the roof framing sits aren’t level, or straight, or parallel,

stories from & for the land 33

or regular. Te frame we were building was irregular in just about every possible dimension! Every roof truss was diferent from every other one (there are a total of 57 trusses in the nave). And then, we had loads of various documentation to study and compare: we had computer-drafted plans from an engineering frm to follow, but then we had those hand-drawn architectural studies. And we were told to compare the two. And then we also had historical photographs – whole huge reams of fles on tablets and computers. Plus, we were always getting more photos from various sources and adding them to the trove. And we also needed to consult images from a 3D point-cloud scan that had been done before the fre. Basically, we were creating a replica of something that wasn’t standardized when it was built. Even the same type of piece could vary quite a lot from one truss to the next. And some of the sculpting details, the swells around joinery, varied quite a bit from piece to piece. If there was historical evidence then we would recreate it, and if there wasn’t, then we – together with the architects who were very involved in this kind of stuf – came up with methods and standards and a logic so that the details we made were harmonious with the frame as a whole.

DID THAT TAKE AWAY SOME OF THE ARTISTRY OF THE HAND - WORK AND THE MORTISE AND TENON JOINERY ?

No, there was still plenty of room for artistry. In most cases the approach we decided on was to try to get into the mind of the Gothic

carpenter and do something that would have made sense with the tools they had. Te architects were really down to earth and very interested in what we carpenters had to say and in our take on why certain things look a certain way. Tat was something really cool for all of us, who are pretty passionate about this type of thing – getting to think about these things, discuss them with the architects, and then actually create them.

WHAT TOOLS DID YOU USE ?

Tere were certain tools that needed to be period appropriate. And most of those had to do with the look of the fnished product. Most important were the hewing axes – the broad axes. Carpenters Without Borders visited a diferent building in Paris that is also from the twelfth century and has some similarities with Notre Dame. Tey researched the joinery and the tool marks – especially the traces of axe marks. Tey saw, for example, that the axe blades from that time period were of a certain size range, and that they all had a curved “bit” (cutting edge). Together with the architects they came up with certain “spec” for the broad-axes that were approved for work on the cathedral. A friend of mine did some design work with a group of French blacksmiths, and designed a couple diferent types of joggling and hewing axes. And this group of really great blacksmiths got together and collectively made 60 axes on commission, specifcally for this project. Te fact that all of the timber is being hand-hewn is a really huge deal in France – it’s the frst time that a signifcant historic building has been restored

this way. Hand-hewing was pretty much a lost art in France 30 years ago, and a few groups (Carpenters Without Borders chief among them) has done a lot to help revive the technique. But it’s still quite a rare niche skill, and so it is very signifcant that the Notre Dame timber frame is being hewn. And there was a lot of hewing – it took our crew of 20 from November through April full-time to hew the nave timbers – it was a ludicrous amount of work.

WHAT ABOUT THE TIMBERS YOU WERE HEWING ?

All the timber is Quercus robur, aka European oak, and the logs were donated from both public and private forests all across France. A whole army of foresters was mobilized to select and supply the logs for all of the roof framing –in all, several thousand very high quality and large oaks. Often, carpenters would go out into the forest with the foresters and the two trades would share their knowledge about the intersection between forestry and carpentry –two trades that have always been very closely linked until modern industrial times. Te biggest timbers that we had in the nave were the tie beams, which were 14 meters long and as large as 22 x 33 cm (about 9 inches x 13 inches x 46 feet). Not as massive as people might think. (Te very biggest timbers are part of the base for the spire – those were massive.) But there was a lot of big timber in the frame. Te 57 nave trusses (11 of them principal trusses and 46 secondaries) all had two rafters each at 12 meters long. So we had hundreds of extremely straight and

34 vermont almanac | volume 1 v october

beautiful oak logs coming in, and there were really strict tolerances for knot size, sweep, slope of grain etc.

WHAT ABOUT THE LOGISTICS OF WORKING OVER IN FRANCE FOR SIX MONTHS ?

It took about eight months of preparation before the trip, fguring out what type of work permissions and visas might be required, getting through all the paperwork and immigration stuf, etc. A huge part of the experience for me was that my wife and our two toddler boys came over for fve out of the six months, which was wonderful. I could never have taken part in the project without the support of my wife, and I’m so grateful to her for making it happen for our family. It did add some extra planning on our end though, to fgure out accommodations, health care, vehicle, etc., for the family. I also put my business on hold while I was gone, although I was able to bring one of my employees over to work on the cathedral, and there were actually a few other Vermonters involved on the team, as well.

YOU HAD TO RETURN BEFORE THE NEW FRAME WAS ACTUALLY RAISED , STARTING IN AUGUST . WAS THAT BITTERSWEET ?

Yes, I had to get back to Vermont because of work commitments. It was hard to leave, because I’ve been so invested and had such a great time, and I would have loved to see it through to the end. But I’m very grateful to have been part of it for six months! And it’s been great to jump back to work in Vermont on projects that clients had been very graciously waiting for.

A six-month stay in France gave Wallace-Gusakov a chance to be inside Notre Dame (a UNESCO World Heritage Site) during reconstruction.

DID YOU SEE OR LEARN ANYTHING IN FRANCE THAT MIGHT BE APPLICABLE TO YOUR TIMBER FRAMING IN VERMONT ?

I’ve been thinking about that a lot, and I think the infuences I picked up will come out over time. Te styles and typology of French historic timber framing are quite diferent from the New England tradition, and I’m excited to incorporate more historic European infuences in my designs. It’s so cool to be able to design and create frames that can pull from various traditions – French, British, New England, medieval, contemporary…

NOW THAT YOU ’ VE CHECKED WORKING ON A WORLD - FAMOUS CATHEDRAL OFF YOUR LIST , ANY FUTURE SPECIAL PROJECTS YOU ’ D LIKE TO TAKE ON ?

I’d love to build what’s called a tithe barn, which is a type of large barn that was built across western Europe in the medieval period, often by abbeys or churches, to store taxes in the form of agricultural crops. It’s a really gorgeous iconic form of barn seen in France and in the UK. So if any Vermont Almanac readers want a tithe barn built, call me up!

stories from & for the land 35

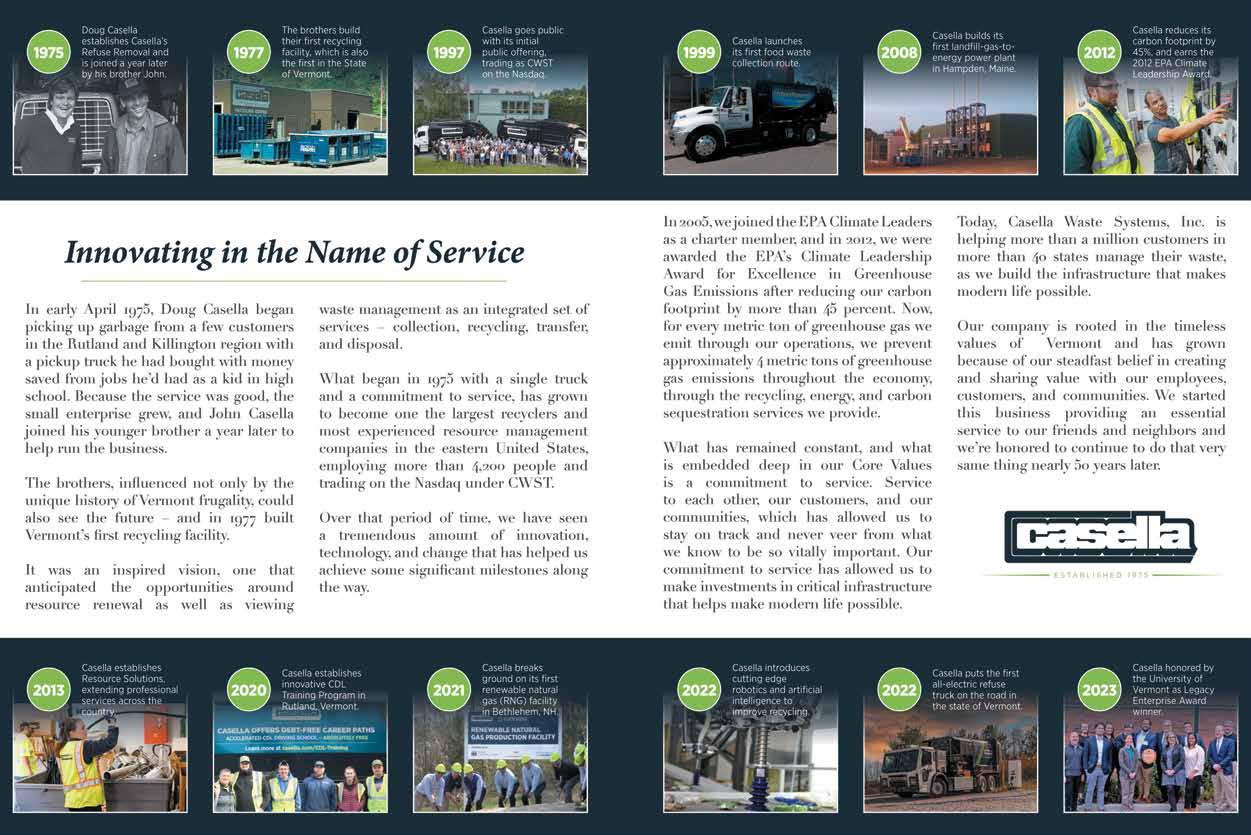

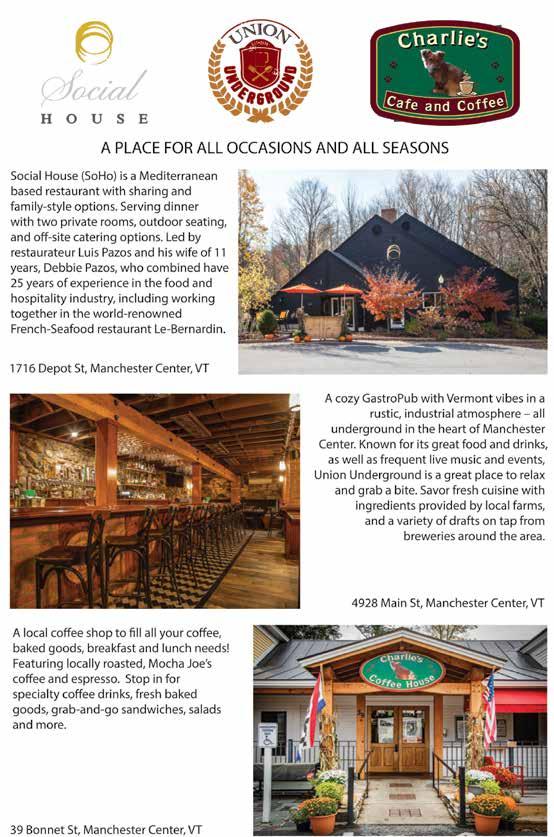

36 vermont almanac | volume 1 v sponsor

stories from & for the land 37 sponsor

NOVEMBER

stories from & for the land 39

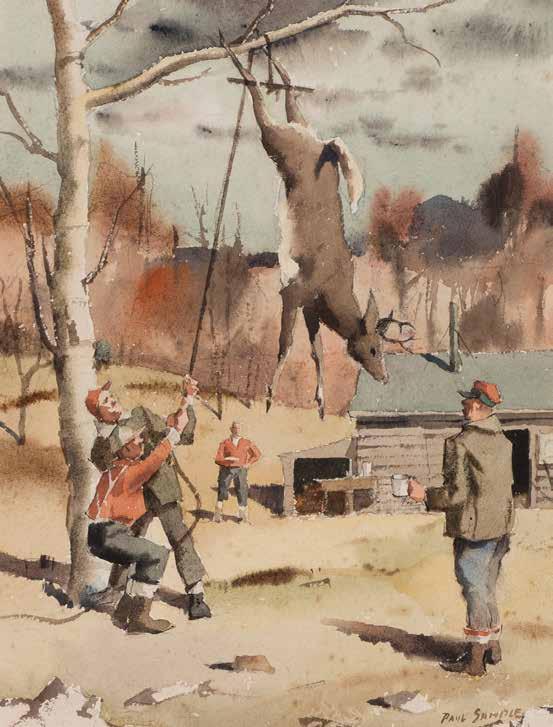

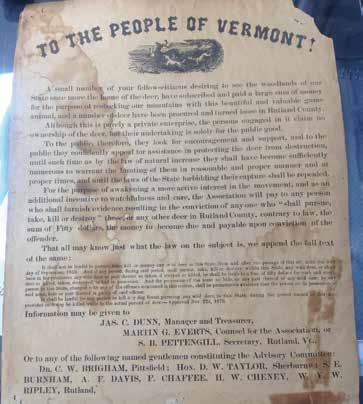

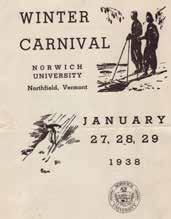

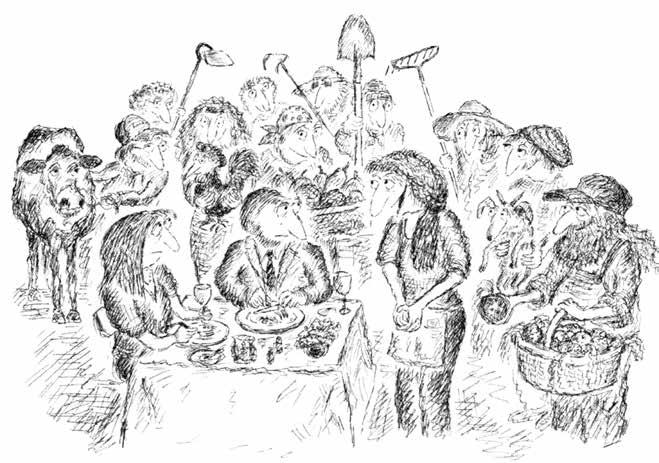

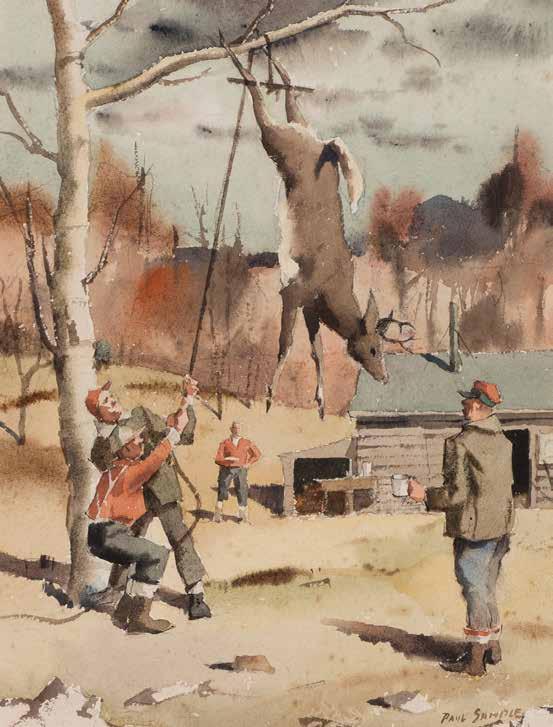

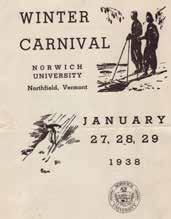

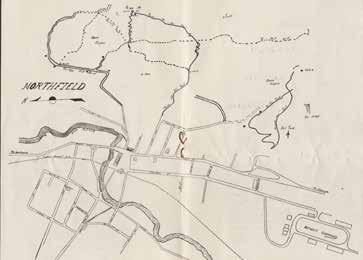

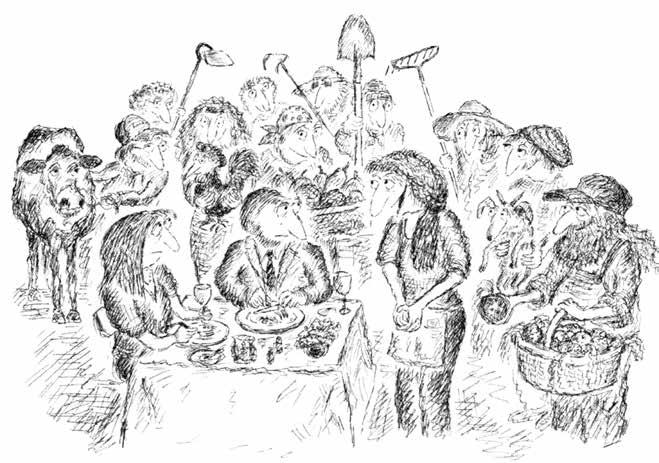

THE TROPHY

Tis watercolor by Paul Starett Sample (1896-1974), an artist from Norwich, is part of the Orton Collection. Te paintings, and the stories behind them, are collected in a lovely book, written by Anita Rafael, entitled For the Love of Vermont, available through the Vermont Country Store. In it we learn that Lyman Orton was able to buy this painting at a low price because “who else besides a Vermonter would want it hanging in their home?”

40 vermont almanac | volume 1 v november

COURTESY OF THE LYMAN ORTON COLLECTION OF THE ART OF VERMONT

Even for non-hunters, November means deer season – an explosion of orange clothing, pickups pulled over on roadsides and hayfelds, and spontaneous gatherings at the scale outside the general store when a hunter shows up to register a kill. Count me among the ambivalent – not a hunter but unable to resist creeping forward for a look. My rational side believes in hunting, both for food to feed families and for wildlife management; and who am I to question the traditional values of native Vermonters? Since we signed our deed in 1976, we have never posted our land; most of the hunters who enter our woods come from families who have been hunting here since long before we arrived. My emotional side veers in another direction because the death of an animal is dispiriting to witness. Once as a young boy visiting my grandmother’s farm, I unwisely insisted on watching the slaughter of a goose. I walked away in a daze, and the next day when the goose appeared on the dinner table, I felt for a second time the nausea of remorse. I have a small rife and will use it to defend my garden and my dog, but any relief I feel from the elimination of a groundhog or porcupine is soon eroded by the stark reality of its corpse.

For many years this battle between my rational and emotional sides has intensifed each November with the daily sightings of deer on our land, sometimes just a few feet from our door. Deer are elegant creatures, each with its own markings and foibles, and when one stares back at you with a wild apple in its mouth, it looks thoughtful. Does show up with fawns that will grow up before our eyes like household pets.

Six years ago my ambivalence began to evolve when my son and his family moved from Brooklyn to a house just a ten-minute walk from us on a trail through a woods flled with deer. My son knew these woods as a boy, and after two decades as a city-dweller and the arrival of his frst daughter, he decided he was ready to take up hunting. He began slowly and methodically, buying a deer rife and taking a course in hunter safety; and for the next few years he spent many hours in the woods each November without taking a shot. He saw plenty of deer but never the right one. I admired his patience. I also reminded him over and over not to ask for my help when the time came to dress and butcher a deer.

We want our children to be happy, to be successful at what they set out to do, but I never anticipated how far my feelings on this matter would move. Tis past November I wanted my son to get a deer, and as the days of the season slipped by, I felt something like urgency on his behalf. On the fnal day of rife season he killed a fve-point buck. I could hear the single shot from our house. After dressing his deer, he texted a photo, not the typical trophy shot of a head and antlers, but a picture of the heart and the hole his shot made passing through.

My wife’s feelings about hunting hadn’t migrated quite as far as mine. She’s a mother, and she worries about guns; when I showed her the picture, she winced. But she also loves a good story, and soon she was texting the news to her twin sister, whose children live in suburbs where no one hunts, and to our daughter, who eats no red meat but who is squeamish about nothing. One afternoon nearly a week later my wife saw the dressed deer. We were driving our granddaughter home after dark, and it hung from a post just inside the barn door, wreathed in a nimbus of soft light from a bare bulb. I held my breath while our granddaughter gathered her things.

“It looks nice,” my wife said as I turned the car around, “homey and rural.”

—Jonathan Stableford

stories from & for the land 41

The warmth continued in early November to an exceptional degree. On the sixth, the high temperature in Burlington was 76 and the low was 62. On the 10th, someone sent us a picture of a wreath display cooking on the asphalt in front of the Bennington Hannaford supermarket, the needles already falling. “ Tese will last until Christmas, right?” the note read. Ten out of the frst 12 days of the month were above 65 degrees in Brattleboro.

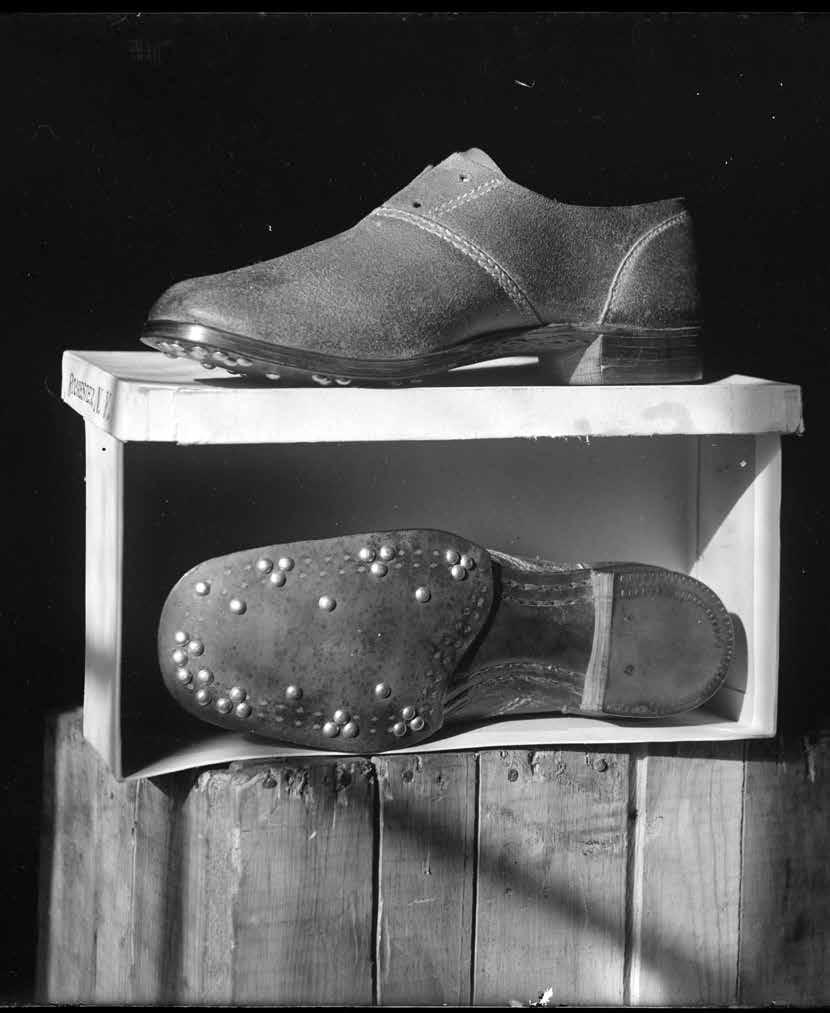

Te warmth ran right up until opening day of deer season, and then, as if the prayers of Vermont’s 79,664 hunters were answered, the weather turned on a dime.

Te two-week, three-weekend rife season, which ran from the 12th to the 27th, was about perfect temperature-wise. “Hanging weather,” as the old-timers say. When you shoot a deer, there’s a grace period as the animal’s heat leaves the body, but within roughly 24 hours you’ll want to get the carcass chilled. Forty degrees is something of a magic number –beneath that you’re golden. Above that, you’re playing with fre. With

R

Answered Prayers

daytime highs averaging in the 30s, the outside was as good as a walk-in cooler through much of rife season. It gave hunters time to relax, savor their success, chip away at processing their venison throughout the week in the hours after work. We don’t always have this luxury.

Tere was some snow – we’ll call it an average amount. No big storms, but the mountains had a trace to a few inches throughout much of the season. Fourteen of the pictures of giant bucks that were posted on the Vermont Biggest Buck Club Facebook page had snow in them, 10 did not. Tat seems like a pretty normal representation of a typical rife season. Snow helps hunters because it allows them to see deer better. Cold also prompts deer to move during daylight hours.

By the end of the month, temperatures moderated again. Tanksgiving weekend is the unofcial start of Christmas tree selling season, and opening weekend started by looking, if not feeling, a bit like Christmas, as many farms had at least

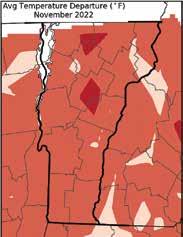

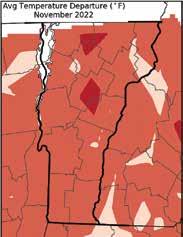

a ground-covering of snow. However, the sun came out and temperatures climbed into the 40s, dropping only into the upper 30s at night; the snow quickly melted, leaving behind muddy conditions. For the many tree farms that use their felds for customer parking, frozen ground is critical, and in this regard the 2022 season did not cooperate. When all was said and done, the average November temperatures were 5 4 degrees above the 20th century mean and 3 4 degrees above the 21st century mean.

We looked back at our weather summaries from the past three volumes of the Vermont Almanac and saw that November 2021 was a bit colder than average, with good tracking snow on the third weekend of deer season. November 2020 was a deer season dud, with record-breaking warmth; it was six degrees warmer than the 30-year mean. November 2019 featured record-breaking cold. At 6.6 degrees below the 30-year mean, it was the coldest November on record in much of the state.

42 vermont almanac | volume 1 v WEATHER

november

Early November warmth made for an enjoyable extended fall; a bit of snow in mid- to late-November helped hunters track deer; opening weekend of Christmas tree season came with warm temperatures that melted the snow, softened the ground and left many farms a muddy mess.

stories from & for the land 43

BY

BY

MID - NOVEMBER , most eastern chipmunks have gone or will shortly disappear into their tunnels where they have gathered and stored their winter food supply. Up to half a bushel of nuts and seeds can be stored here. Tey will visit this chamber every two or three weeks throughout the winter, grabbing a bite to eat between their long naps.

In order to minimize the number of trips taken to fll their storage chamber, chipmunks cram their cheek pouches as full as possible. A review of the chipmunk literature fnds that they can carry an astounding amount of food in their mouths at one time. Researchers have documented a chipmunk carrying 31 kernels of corn in its mouth; also, 13 prune pits, 70 sunfower seeds, 32 beechnuts, 6 acorns. — Mary Holland

eWinter Wrapping for Beehives

All winter, even on the coldest nights, the core of the cluster of bees inside a beehive is kept above 90 degrees. Fueled by stored honey, the bees generate heat by shivering their indirect wing muscles.

When winter weather sets in for keeps in November, most beekeepers in Vermont wrap their hives with insulating covers to slow the loss of heat. A recent study of 43 hives in Illinois has confrmed that this is a wise practice. Covered hives had a 22 5 percent higher winter survival rate than the uncovered ones, although all the hives were equal in weight and had the same level of mite infestation at the start. In addition, bees in the covered hives consumed less of their winter stores than the uncovered controls.

Before about 2000, nationwide winter colony loss was thought to have been around 20 percent. But more recently the combination of new pests, parasites, and pathogens – and exposure to pesticides – has resulted in winters being more deadly, averaging 39.6 percent over the past 12 years – despite the fact that winters have become warmer.

Te hive covering study was carried out in a warmer place than Vermont, so it may be that covers here are even more benefcial. Colony losses here for the whole year – from April 1, 2022 to April 1, 2023 – were 48 2 percent, almost as bad as in 2020-2021, our worst year, when 50 8 percent of bee hives perished. —Virginia Barlow

44 vermont almanac | volume 1 v november NATURE NOTES

MICHELLE PARSONS RAUCH

MARY HOLLAND

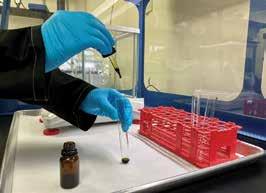

Covid Rates Low in our Wildlife

One of the many unsettling things about the Covid virus is that it’s constantly mutating and evolving. It does this as a matter of course, but the risk of mutation rises when the virus is passed from one species to another and then back again. And so it behooves us to understand where it’s present in wild animals.

For the past two years, Vermont Fish and Wildlife partnered with UVM to test wild mammals that were harvested by hunters and trappers in the state. In all they tested 487 deer, 19 foxes, 77 fshers, 43 otters, 32 coyotes, 79 bobcats, and 2 black bears. Somewhat surprisingly, none of them tested positive, though they were only collecting nasal swabs, which only detect active infections.

Additional samples from deer went to USDA Wildlife Services, where they tested blood in addition

to the nasal swabs. From these blood tests they could see if the deer had been infected with Covid in the past. Final results aren’t in at the time of this writing, but preliminary results found 27 samples, or 5 7 percent of the total samples, tested positive.

Te take home, said Nick Fortin, Vermont’s Deer Project Leader, “is that some of our deer have been infected with SARS-CoV-2, just like deer pretty much everywhere else in the country. Prevalence in our deer population is fairly low, and a lot lower than some of the early reports of Covid in deer that came from more densely human-populated areas. Tere are still many, many unknowns in all of this, including how exactly deer are (repeatedly) contracting the virus from humans. Fortunately, USDA funding came through in mid-summer, so Covid testing will be conducted on deer again this fall.”

PURPLE CROWBERRY , a diminutive alpine plant that grows low to the ground in rocky habitats above tree line, was documented on Mount Mansfeld in 1908. Vermont botanists have searched for the plant since then and never found it, even going so far as to list it as “no longer present in the state” on rare plant lists. Tat is until the fall of 2022, when Liam Ebner, a trained summit steward for the Adirondack Mountain Club, spotted a clump.

“ Tis is an extraordinary fnd,” said Bob Popp, a botanist with the Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department. “ Tis discovery emphasizes the beneft of having a community of keen botanical observers on the ground.”

stories from & for the land 45

GLEN MITTELHAUSER

Putting Your Lawn in Perspective

Lawns are getting a lot of negative press these days, and there’s good reason for this. As pollinators struggle, and as Lake Champlain and other water bodies bloom with algae that’s fed, in part, by fertilizer from lawns, and as we all try to cut down on fossil fuel emissions, the Scotts Lawn ideal is due for an update. Te problem is that many of the

Tsolutions being sold are just impractical. Te idea that you might – or you might hire someone to – tear up your sod and replace it with a pollinator garden that you’ll have to maintain or pay someone to maintain is just not going to work for most people.

A more passive and realistic approach is to diversify your lawn and then mow it less, and if this sounds appealing, now’s the time to get started. Mow the section of lawn that you’re looking to diversify low during the last mow of the season in October, after the soil has become too cold for seed germination. Ten broadcast dutch white clover, self heal, and creeping thyme seed over the area. Te freeze/thaw cycles in winter will passively work the seed down into the soil and it will germinate the following spring when it’s ready. It may take a few years, but eventually you’ll have a diversifed lawn with a heavy foral component – no sod removal necessary.