1 THIRD QUARTER 2022 CONVERSATIONS WITH THOUGHT LEADERS: Philip D’Anieri | Author, “The Appalachian Trail: A Biography” René Rodgers | Head Curator, Birthplace of Country Music Museum

Many of Virginia’s recreational trails are designed to accommodate multiple different types of users. Horseback riders get the ultimate right of way at New River Trail State Park, built on a discontinued right-of-way donated by Norfolk Southern Railway.

Chart a Trail Through Virginia History

Virginia’s Path of Presidents

Eight presidents were born in Virginia, more than in any other state. Here’s where to learn

about the leaders who shaped America

The Heart of the Appalachian Trail

inside look at the mountains, towns, and

that Appalachian Trail thru-hikers

find in Virginia’s portion of the trail

A Trail for Everyone

a great variety of scenic

trails open to various types of vehicles

Heritage Music Shapes the Future of Southwest Virginia on The Crooked Road

Virginia’s contributions to country music history

alive at the venues that make up

Crooked Road: Virginia’s Heritage Music Trail

Monumental Footprints

Northern Virginia is home to several monuments honoring the contributions of Americans who served the country

The Story Behind

American Hike:

Following The Crooked Road: A Conversation With René

Virginia

code

songs

Trail Mix of

Virginia artists

soundtrack

Distilled Spirits, Prince William County

Terry Co., Northampton County

hike.

Mountain Brewery, Nelson County

1 Contents Heather Lusk H.M.

Taylor Smack Blue

Kevin Szady MurLarkey

10 26 32 38 54 20 48 46 Subscribe today. Visit www.vedp.org/Virginia-Economic-Review Facts & Figures04 58 68 74 Selling Virginia Delicacies Along the Commonwealth’s Tourist Trails George Hodson Veritas Vineyards, Nelson County Regional Spotlight Economic Development Partners in Virginia 06 Selected Virginia Wins

Virginia’s historical sites and trails offer opportunities to reflect on an eventful past and contextualize major historical events

an Iconic

A Conversation With Philip D’Anieri

An

quirks

can

Virginia offers

recreational

more

Rodgers Headed out on a

trail? Scan the QR

for a

great

from

on Spotify to

your

come

The

Commissioned by President Thomas Jefferson in 1804, the New Point Comfort Lighthouse is the 10th-oldest lighthouse in the United States. The lighthouse’s location at the convergence of the Chesapeake and Mobjack Bays makes it a popular destination for kayakers.

A Long Walk Down Virginia’s Top-Notch Trails

ONE OF MY FAVORITE things to do in my spare time is to get outside and experience nature with my family. Upon relocating to Virginia, I was struck by the vast array of wonderful trails the Commonwealth has to offer. From the mountains to the ocean, one could spend a lifetime traveling Virginia’s trails and barely scratch the surface of its natural beauty.

Those recreational trails are featured in this issue of Virginia Economic Review, from urban bike trails to multi-use nature trails through the Commonwealth’s mountains, waterways, and forests to the iconic Appalachian Trail, nearly a quarter of which runs through Virginia. But those trails are just one venue in which Virginia shows off its amazing assets. The Commonwealth’s rich history is on display in our historical timeline, which highlights the role Virginia played in events that shaped American history, from the American Revolution to the Civil War to the civil rights movement, and our articles on Virginia’s presidential sites and monuments. We also highlight Virginia’s cultural trails, including The Crooked Road: Virginia’s Heritage

Music Trail, which celebrates Virginia’s role in the growth of country music, and the food and beverage trails that highlight the most delicious treats the Commonwealth has to offer.

Also included in the issue are discussions with two thought leaders with intimate knowledge of Virginia’s top-notch trails: Philip D’Anieri, author of “The Appalachian Trail: A Biography,” and Dr. René Rodgers, head curator at the Birthplace of Country Music Museum in Bristol.

We hope you enjoy this look at the recreational, historical, and cultural trails that help make Virginia such a wonderful place to live.

Happy trails,

Jason El Koubi President and CEO, Virginia Economic Development Partnership

Jason El Koubi President and CEO, Virginia Economic Development Partnership

3

Facts Figures ROANOKE RIVER Best Urban Kayaking Spot 2022#1 ABINGDON Best Small-Town Food Scene 2022#1 JAMES RIVER Best Urban Kayaking Spot 2022#3 VIRGINIA CREEPER TRAIL Best Recreational Trail 2022# 4 BIRTHPLACE OF COUNTRY MUSIC MUSEUM Best Pop Culture Museum 2022# 3

RIDGE

DRIVE

ABINGDON Top Small Adventure Town 2021#1 DAMASCUS Top Tiny Adventure Town 2021#1 RICHMOND One of 19 of the Best Cities in America for Street Art 2018 WILLIAMSBURG Top 20 Small Towns 2022#2BLUE

PARKWAY Top 10 Scenic Drives 2022#1 SKYLINE

Top 10 Scenic Drives 2022#4

Selected Virginia Wins

The LEGO Group, manufacturer of the beloved plastic construction toys enjoyed by children around the world, will invest more than $1 billion to construct a manufacturing facility in Chesterfield County in the Greater Richmond region. The project will create more than 1,760 new jobs.

The facility in Meadowville Technology Park will be designed to be carbon-neutral, with 100% of day-to-day energy needs matched by renewable energy generated by an on-site solar park. The site will also be designed to minimize energy consumption and the use of non-renewable resources. A temporary packaging site will open in an existing building nearby in 2024 and create up to 500 jobs, while production is slated to begin in 2025.

Founded in Denmark in 1932, the LEGO Group remains a family-owned company headquartered in its original location. The company’s products are sold in more than 130 countries, and Time included the company on its list of the Top 100 Influential Companies in 2021. The Chesterfield facility will be the company’s seventh factory worldwide and the only one in the United States.

Support for the LEGO Group’s job creation will be provided by the Virginia Talent Accelerator Program, a workforce initiative created by VEDP in collaboration with higher education partners that accelerates new facility startups through the direct delivery of recruitment and training services that are fully customized to a company’s unique products, processes, equipment, standards, and culture. All program services are provided at no cost to qualified new and expanding companies.

We were impressed with all Virginia has to offer, from access to a skilled workforce to support for high-quality manufacturers and great transport links. We appreciate support for our ambition to build a carbon-neutral-run facility and construct a solar park and are looking forward to building a great team with support from the Virginia Talent Accelerator Program.

7

NIELS B. CHRISTIANSEN CEO, The LEGO Group

Selected Virginia Wins

Greater Richmond

EAB

Jobs: 206 New Jobs

CapEx: $6M

Locality: Henrico County

The LEGO Group Jobs: 1,760 New Jobs CapEx: $1B Locality: Chesterfield County

Unilock Jobs: 50 New Jobs CapEx: $55.6M Locality: Hanover County

Hampton Roads

Massimo Zanetti Beverage USA Jobs: 79 New Jobs CapEx: $29.1M Locality: City of Suffolk

Northern Virginia

Hanley Energy Jobs: 343 New Jobs CapEx: $8M Locality: Loudoun County

Hilton Jobs: 350 New Jobs Locality: Fairfax County

Nodal Exchange Jobs: 37 New Jobs CapEx: $300K Locality: Fairfax County

Southwest Virginia

Coronado Global Resources Inc.

Jobs: 181 New Jobs

CapEx: $169.1M

Localities: Buchanan County, Tazewell County

Multiple Locations

DroneUp Jobs: 655 New Jobs CapEx: $27.2M

Localities: Dinwiddie County, City of Virginia Beach

8 I81-I77 Crossroads New River Valley Roanoke Region Southwe st Vir ginia

9 Central Virginia Easte rn Shor e Greater Richmond Hampton Roads Virginia’s Gateway Region Lynchburg Region Middle Peninsula Northern Neck Northern Virginia Shenandoah Valley Southern Virginia South Centr al Virg inia Northern Shenandoah Valley Greater Fredericksburg Washington, D.C.

10

Arlington

National Cemetery

Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello

Robert Russa Moton Museum, Farmville

Chart a Trail

Through Virginia History

Virginia’s place in American history dates back to the establishment of Jamestown, the first permanent English settlement in North America, in 1607. Since then, the Commonwealth has played an integral role in the wars that shaped the United States — Virginians wrote the Declaration of Independence and led the Continental Army in the American Revolution. The last significant battles of that war and the Civil War took place on Virginia soil. In the 20th century, Virginia hosted numerous key events in the civil rights movement, including a student walkout at Robert Russa Moton High School in Prince Edward County that led to one of the cases that was combined into Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark Supreme Court decision that overturned racial segregation in U.S. public schools.

Like the rest of the country, Virginia continues to reckon with the aftereffects of its past, including its role in the slave trade and the injustices that followed. The Commonwealth’s rich network of major historical sites strives to tell those stories honestly and effectively. Visitors can stand at the sites where these momentous events took place, gaining real-world context on events many only read about in textbooks. As the philosopher George Santayana said, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it,” and few American places offer as much of an opportunity to immerse oneself in the past as Virginia.

Virginia’s history is still being written. As the Commonwealth continues to develop as a hub of the global economy, Virginia’s historical sites and trails offer an opportunity to reflect on the eventful past and contextualize major historical events. Read on for an overview of Virginia’s role in the growth of the United States and learn how you can chart your own trail through history in the Commonwealth.

11

Historic Jamestowne

Cumberland Gap National Historical Park

1607

Wahunsenacawh (also known as Powhatan) unites 30 Native American tribes into the Powhatan Confederacy

Powhatan’s Chimney historical marker, Gloucester County; Werowocomoco archaeological site, Gloucester County (in development as historical park)

1607

Virginia Company settlers led by Christopher Newport land at Jamestown and establish the first successful English colony in North America

Historic Jamestowne, James City County

1619

First enslaved Africans are brought to Point Comfort in Hampton (now Fort Monroe)

Fort Monroe Visitor and Education Center, Hampton; Hampton History Museum

12

CHART A TRAIL THROUGH VIRGINIA HISTORY

Historic Jamestowne

1619

First official English Thanksgiving in America held at Berkeley Plantation

Berkeley Plantation, Charles City County

1676

Nathaniel Bacon’s men occupy the building now known as Bacon’s Castle in Bacon’s Rebellion, the first full-scale armed insurrection in Colonial America Bacon’s Castle, Surry County

1693

The College of William & Mary, the second-oldest institution of higher learning in the United States, is founded in Williamsburg

The College of William & Mary, Williamsburg

13

CHART A TRAIL THROUGH VIRGINIA HISTORY

Bacon’s Castle

1732

George Washington, the first president of the United States, born in Westmoreland County

George Washington Birthplace

National Monument, Westmoreland County

1743

Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States and the author of the Declaration of Independence, born in Albemarle County

Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello, Albemarle County

1751

James Madison, the fourth president of the United States, born in King George County

Belle Grove Plantation, King George County

1776

The fifth Virginia Convention adopts the Virginia Declaration of Rights, declaring Virginia a free and independent state

Capitol, Williamsburg

1781

Jack Jouett, the “Paul Revere of the South,” rides to Monticello to warn Thomas Jefferson and other members of the state government about the approaching British Army

Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello, Albemarle County

1781

The Continental Army, led by Gen. George Washington, defeats British troops at Yorktown in the last major land battle of the American Revolution

Colonial National Historical Park, James City and York counties

14

CHART A TRAIL THROUGH VIRGINIA HISTORY

George Washington Birthplace National Monument

St. John’s Church

1775

Patrick Henry gives his famous “Give me liberty, or give me death!” speech at St. John’s Church

St. John’s Church, Richmond

1775

Virginia militias muster in response to Lord Dunmore’s removal of gunpowder from the magazine in Williamsburg; the event, now known as the Gunpowder Incident, was one of the earliest conflicts of the American Revolution

Colonial Williamsburg Powder Magazine, Williamsburg (currently closed)

1775

Daniel Boone opens a trail through the Cumberland Gap, a key passageway through the Appalachian Mountains and part of the Wilderness Road into Kentucky

Cumberland Gap National Historical Park, Lee County

1786

The Virginia General Assembly passes the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, a key precursor to the First Amendment to the Constitution that guaranteed freedom of religion to people of all faiths

Valentine First Freedom Center, Richmond

1804

Virginia-born explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark set out on the Corps of Discovery Expedition to explore the Louisiana Purchase

Lewis & Clark Exploratory Center, Albemarle County

1831

Nat Turner leads the only effective, sustained rebellion by enslaved people in the United States

Nat Turner historical marker, Southampton County

15

CHART A TRAIL THROUGH VIRGINIA HISTORY

The Capitol at Williamsburg

1844

Robert Lumpkin buys property in Richmond’s Shockoe Bottom that would become the largest slave-holding facility in the city, by then the biggest supplier of the interstate slave trade Lumpkin’s Slave Jail Site, Richmond

1856

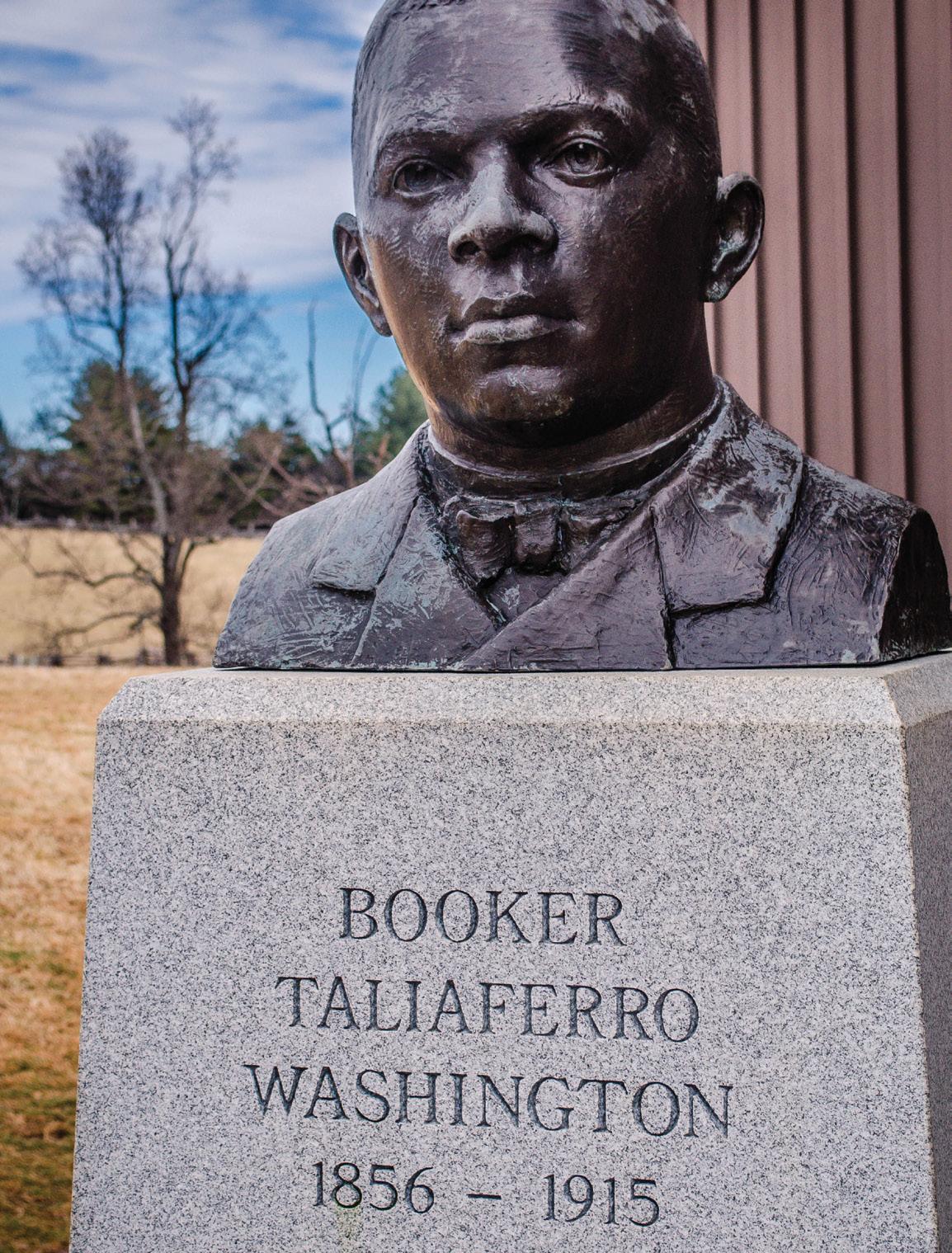

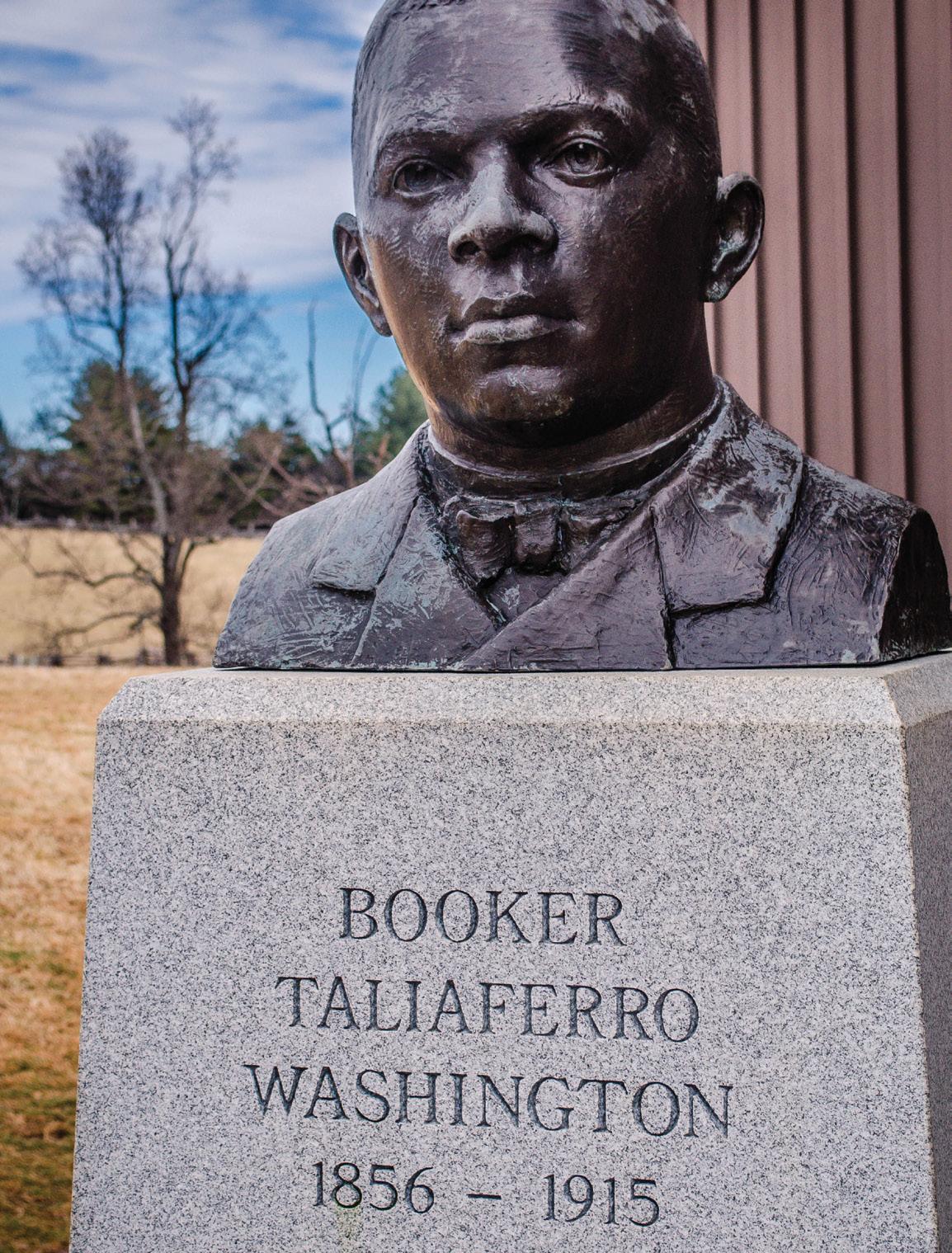

Booker T. Washington, a key Black leader during the Reconstruction era, born in Franklin County

Booker T. Washington National Monument, Franklin County

1861

Union and Confederate forces clash in the first major battle of the Civil War, known as both the First Battle of Bull Run and the Battle of First Manassas Manassas National Battlefield Park, Prince William County

1862

Union and Confederate forces fight the Battle of Fredericksburg, one of the most lopsided Confederate victories in the war

Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park, Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania counties

1863

Confederate forces defeat Union forces in the Battle of Chancellorsville; however, Confederate Lt. Gen. Stonewall Jackson is hit by friendly fire and dies from his injuries eight days later

Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park, Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania counties

1863

The Emancipation Proclamation is read for the first time in the South at what is now known as the Emancipation Oak at Hampton University

Emancipation Oak, Hampton

16

CHART A TRAIL THROUGH VIRGINIA HISTORY

Booker T. Washington National Monument

Manassas National Battlefield Park

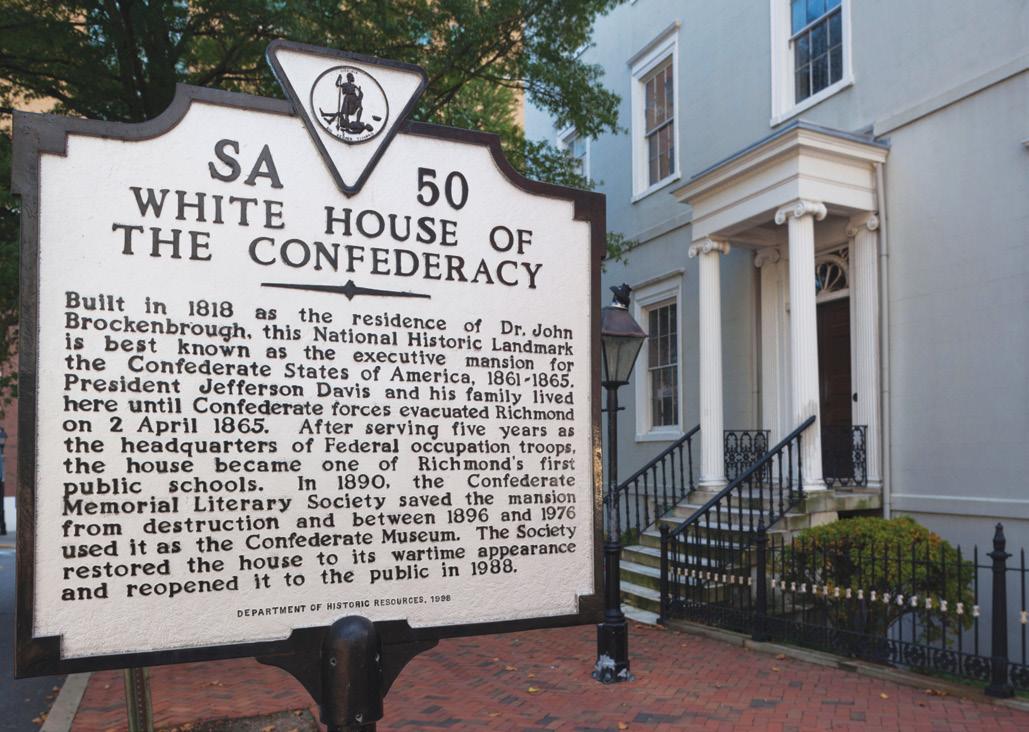

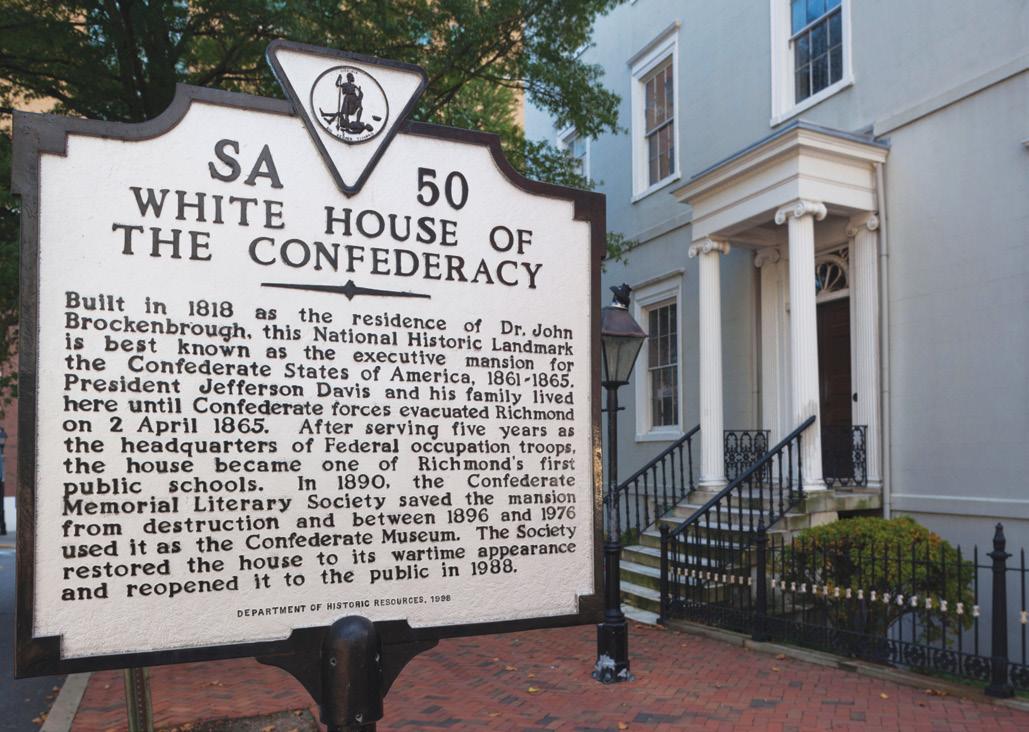

White House of the Confederacy

1861

The Confederate States of America moves capital to Richmond from Montgomery, Ala.

White House of the Confederacy, Richmond

1861

The Civil War begins with the Battle of Fort Sumter in South Carolina; the Battle of Big Bethel in Hampton is one of the first land battles of the war

1861

At Fort Monroe, Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler of the Union Army classifies escaped slaves as “contraband of war,” which meant the army had no obligation to return them to their owners

1864

William Henry Christman becomes the first soldier to be buried at Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington County

Battle of Big Bethel

historical marker, Hampton

1864

Union Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant begins his Overland Campaign against Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee at the Battle of the Wilderness Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park, Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania counties

Fort Monroe Visitor and Education Center, Hampton

1865

The Siege of Petersburg leads Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee to begin his retreat, leading to his eventual surrender

Petersburg National Battlefield, Petersburg and Dinwiddie and Prince George counties

17

CHART A TRAIL THROUGH VIRGINIA HISTORY

Arlington National Cemetery

1865

Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee surrenders to Union Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox, bringing an end to the Civil War

Appomattox Court House National Historical Park, Appomattox County

1882

Virginia Normal and Collegiate Institute (now Virginia State University), the first fully state-supported institution of higher learning for Black people, is established in Chesterfield County

Virginia State University, Chesterfield County

1903

Maggie L. Walker becomes the first Black woman to serve as a bank president

Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site, Richmond

1951

Students walk out at Robert Russa Moton High School, a segregated high school for Black students, leading to a lawsuit that became part of Brown v. Board of Education

Robert Russa Moton Museum, Farmville

1958

NASA launches Project Mercury, the country’s first manned spaceflight program; the program’s astronauts trained at NASA’s Langley Research Center

NASA Langley Visitor Center, Hampton

1959

Prince Edward County closes public schools instead of admitting Black students, part of Virginia’s “massive resistance” to integration

Robert Russa Moton Museum, Farmville

18

CHART A TRAIL THROUGH VIRGINIA HISTORY

Virginia State University

Appomattox Court House National Historical Park

NASA Langley Research Center

1917

The U.S. Navy establishes Naval Station Norfolk, home to its Fleet Forces Command and the largest naval station in the world

USS Wisconsin, Norfolk

1943

The Pentagon, the headquarters of the U.S. Department of Defense and the world’s largest office building, opens in Arlington County

Pentagon, Arlington County (visitors must register two weeks in advance)

1950

Prince Edward State Park for Negroes, a segregated state park, opens in Prince Edward County; it was renamed Twin Lakes State Park in 1986

Twin Lakes State Park, Prince Edward County

1960

Nine Black high school students stage a sit-in at Danville Public Library (now Danville Museum of Fine Arts and History), demanding the right to use the facility

Danville Museum of Fine Arts and History, Danville

1967

The U.S. Supreme Court rules laws banning interracial marriage unconstitutional in Loving v. Virginia, brought by Caroline County couple Mildred and Richard Loving Mildred and Richard Loving historical marker, Caroline County

1976

NASA Viking probes land on Mars; part of program run from NASA Langley

NASA Langley Research Center, Hampton

19

CHART A TRAIL THROUGH VIRGINIA HISTORY

USS Wisconsin

VIRGINIA’S PATH OF PRESIDENTS

A visitor could spend years in Virginia without seeing all of the Commonwealth’s historic sites. Even just a tour of sites connected to U.S. presidents could be a vacation on its own — eight presidents were born in Virginia, more than any other state, while others chose Virginia locations convenient to Washington, D.C., for their retreats. (Only seven of the Virginia-born presidents have historic homes in Virginia — the eighth, Zachary Taylor, moved to Kentucky at a young age.) Here’s where to learn more about the leaders who shaped America.

George Washington’s Mount Vernon

Born in Westmoreland County on the Northern Neck, the first president took over Mount Vernon, his family’s Potomac River estate, in 1759. Today, Mount Vernon accommodates one million visitors each year, drawn by the grounds and exhibits that tell the story of Washington’s life.

20

21

Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello

The iconic design of Jefferson’s plantation estate in the Albemarle County mountains appears on the back of the U.S. nickel. Like other destinations highlighted here, Monticello offers both an illuminating look at its most famous resident and an honest depiction of the way such homes relied on the labor of enslaved workers.

James Madison’s Montpelier

Madison’s Orange County estate showcases exhibits on the fourth president and his work to promote American self-governance. Today, Montpelier hosts several popular annual events, including the Fall Fiber Festival in October and the Montpelier Hunt Races in November.

James Monroe’s Highland

Adjacent to Monticello in Albemarle County, Highland (formerly known as Ash Lawn-Highland) was the home of James Monroe, the fifth U.S. president, for 25 years. In 2016, archaeologists discovered the foundation of a much larger home than anything previously found on the property, indicating that the house originally believed to be Monroe’s quarters was actually a guest house.

Berkeley Plantation

Located in Charles City County on the banks of the James River, Berkeley Plantation was the birthplace and home of William Henry Harrison, the ninth U.S. president and the shortest-tenured, having died just 31 days after his inauguration. In addition to its political history, the property hosted the first official Thanksgiving in America in 1619 (see page 10).

John Tyler’s Sherwood Forest

Sherwood Forest in Charles City County is the only private residence in the United States to be owned by two U.S. presidents. Tyler, the 10th president, purchased it from his predecessor, William Henry Harrison, who never lived in the house. Today, guests can schedule an appointment to tour the house or take a self-guided tour of the grounds.

Pine Knot

President Theodore Roosevelt used Pine Knot, near the town of Scottsville in Albemarle County, as a country retreat. At the time, the trip took eight hours from Washington — four hours by train to Charlottesville and four hours on horseback to reach the cottage. Today, the property is open to the public by appointment.

Rapidan Camp

President Herbert Hoover built the “Brown House” in Shenandoah National Park to use as a retreat during his presidency. He often brought visitors to the camp to fish and discuss key issues — notable guests included Winston Churchill, Thomas Edison, and Charles Lindbergh. Today, the camp features exhibits on Hoover and his wife, Lou Henry, and is accessible via a four-mile round-trip hike.

24

VIRGINIA’S PATH OF PRESIDENTS

Thomas Jefferson’s Poplar Forest

One of two Jefferson estates in Virginia, Poplar Forest in Bedford County was Jefferson’s private retreat — notably, he and his family retreated there to evade capture by British forces in 1781 after being warned by Jack Jouett (see page 10). Like at Monticello, the work of enslaved people at Poplar Forest generated significant income for Jefferson. The main house is one of the earliest octagonal houses built in the United States.

Woodrow Wilson Presidential Library & Museum

This property in the city of Staunton includes the 28th president’s birthplace, along with a museum with exhibits on his life and an extensive research library. The museum showcases materials and exhibits about World War I, as well as a 1919 Pierce-Arrow limousine, part of the White House fleet that Wilson used as his personal car after leaving office.

25

The Story Behind an Iconic American Hike

A Conversation With Philip D’Anieri

Philip D’Anieri is a lecturer in urban and regional planning at the University of Michigan’s Taubman College of Architecture & Urban Planning, where he teaches courses on the built environment. He is also the author of “The Appalachian Trail: A Biography,” published in 2021 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. VEDP President and CEO Jason El Koubi spoke with D’Anieri about the history of the Appalachian Trail inside and outside Virginia, why he chose to cover the trail’s history through a human lens, and the inseparability of urban planning from the natural environment.

26

Jason El Koubi: You’ve described yourself as a day hiker only. How much of the Appalachian Trail (A.T.) would you say you’ve hiked in the course of researching your book, and how did you combine the research project with the experience of the trail itself?

Philip D’Anieri: I’ve hiked on the trail in short sections in each of the 14 states it passes through. I’ve seen a lot of the trail in its various guises, the different locations that it’s in, the different forms that the trail itself takes. Sometimes it’s a sidewalk down a main street. Sometimes it’s a gorgeous mountain vista. A lot of the time, it’s just a trail through the woods that seems like any other trail. I’ve hiked on the trail enough to sample a lot of its different characters, but I’m not — and I never pretended to be — an avid long-distance hiker.

I’ve seen a lot of the trail and gotten a feel for it, but there are just thousands and thousands of people who have thru-hiked the entire 2,100 miles, sometimes in one trip, sometimes in several trips over the course of a lifetime. Sometimes they’ve dedicated themselves to just one portion of it. And one of the things I try to make clear in the book is that as awesome as that is — and as much as I might have hoped to do that, once when my knees were in better shape — that’s not the perspective of the book, where I’m really looking at the history and ideas behind the trail.

El Koubi: What makes the Appalachian Trail special and what inspired you to make this a major focus?

D’Anieri: It’s always been this iconic place. It’s not uncommon to be driving down an interstate highway and there’s a pedestrian bridge going over the freeway that says “Appalachian Trail.” In my urban planning studies, I came across the fact that the trail was actually conceived of by somebody who was thinking about cities and nature all at the same time and thought of the trail in part as providing a natural counterpoint to the cities.

A shorter answer is I was interested enough in the trail that I wanted to read this book and it really wasn’t out there. I thought, “Maybe I could take a crack at it,” and I did. There wasn’t a history of the trail for a general audience, and I thought there ought to be one.

El Koubi: How do you go about writing a biography of a trail? You made a decision to focus on some of the major figures in the trail’s history. Can you talk about your particular approach and how it affected the final product?

D’Anieri: There was no A.T. before Benton MacKaye came up with the idea, and before a whole bunch of people organized around that idea and built the thing. So, it’s a human construction. I thought a good way to tell the story of the trail, as something that people created for themselves, was to tell it from the perspective of who those folks were at different points in time. What were they after? What did they see in a big long-distance trail over the mountains? What hopes and dreams and aspirations was it satisfying? How did those hopes and dreams and aspirations change over the years from even before the trail itself was proposed, all the way up to the present day?

I’m not going to write a guidebook to the trail. There are plenty of good ones out there. I’m not going to write about my experience. There are plenty of good books out there in that vein, as well. But what I was trying to get at was why, and how is this place the way it is, and how has that changed over the years?

In the same way that you would write a biography of a person — what were the influences? What were the times that person grew up in?

This idea of “The Appalachian Trail: A Biography” was twofold. Number one, I wanted to get at the character of the place. And number two, I wanted to do it with a bunch of individual biographies — here’s who Benton MacKaye was and how he came to it. Here’s who Myron Avery was,

To commit to the trail and its environment for months to walk the whole thing in one go, that’s a particularly American kind of escapism. It’s got this quality of ‘I’m going to prove something to myself and to others. I’m going to connect with the natural world in this really intense way.’

PHILIP D’ANIERI

Author, “The Appalachian Trail: A Biography”

27

the field general who really got the thing built in the 1930s, ‘40s, and ‘50s. Here’s who Bill Bryson was, this author who popularized the trail when he wrote a book about it in the ‘90s. So, that was the thinking behind the term “biography,” even though it’s a biography of a physical thing rather than any one person.

El Koubi: Were there any big surprises or things you learned about the trail while doing your research?

D’Anieri: A few things. The first is how much of the Appalachian Trail is just a trail. If it didn’t have this narrow painted white blaze on a tree every 10 or 20 yards, you wouldn’t know that you were on the world-famous Appalachian Trail, versus a trail through a park in your community or in some state park. Although it does have incredible places with incredible vistas, for a lot of its length, it’s just a trail. I found that mundane quality really interesting.

I don’t think that takes anything away from the experience. I think it adds to it. A trail can be about a routine different perspective on the world without having to be atop some gorgeous mountain with an incredible view of everything.

The other thing that was really interesting was how many different types of people come to the trail, and come with their own version of what it is and why they’re doing it. In one chapter of the book, I talk about Earl Shaffer, widely recognized as the first thru-hiker, and Emma “Grandma” Gatewood, the first solo woman thru-hiker. They accomplished those tasks roughly 10 years apart, but were entirely different people.

Shaffer was a young person just out of the Army, trying to find himself. Gatewood was a grandmother from Appalachia who just wanted to go for a walk. I think a lot of folks, including myself, carry in our head with respect to the A.T. the idea, “Oh, it’s this thru-hiking venue. It’s for the hardcore outdoors person who’s going to hike the whole thing in one summer.” In fact, that’s a tiny, tiny percentage of

28

We’ve always had a real physical connection between our urban life and the natural world around us. One thing trails do is provide the gateway from one to the other.

PHILIP D’ANIERI

Author, “The Appalachian Trail: A Biography”

A CONVERSATION WITH PHILIP D’ANIERI

the people who use the A.T. That’s not at all what it was built for. It serves a lot of different people’s needs in different ways.

El Koubi: So, where did that thru-hiker goal come from in our country’s cultural imagination?

D’Anieri: One of the places it comes from is the one thing that makes the A.T. unique — the fact that it’s nearly 2,100 miles. I was saying how being on it can feel everyday and mundane. It can. But then you get these notions of “Wow, it doesn’t end at this one mountain peak,” or “It doesn’t loop back to the parking lot I started from.” It goes and goes and goes for an almost infinite distance in terms of your day-to-day experience of it. Not surprisingly, people started to wonder, “What if I just committed myself to doing the whole thing?” It offers this opportunity for separation from our day-to-day lives.

While you can get that from a three-hour or three-day hike, to commit to the trail and its environment for months to walk the whole thing in one go, that’s a particularly American kind of escapism. It’s got this quality of “I’m going to prove something to myself and to others. I’m going to check out from the day-to-day of my job and my neighbors, and I’m going to go off and be in the woods. I’m going

to connect with the natural world in this really intense way.”

I think that taps into a lot of cultural trends that are out there. And it didn’t take long after Earl Shaffer did this hike in the ‘40s for that idea to catch on with a lot of people. Nowadays, in the era of social media, it’s an incredibly popular source of online personality.

El Koubi: I’m interested in how this book connects with your other work as a university lecturer focused on the built environment. How does planning outdoor attractions like hiking trails intersect with the needs of other parts of the built environment, such as cities and towns?

D’Anieri: The idea of Benton MacKaye, who thought up the A.T., was we’ve got cities defined by and dependent on the natural world around them. They need fuel sources. They need raw materials for their factories. This is in the 1920s. It’s 1921 when he publishes his article. That’s where the water power is coming from to power mills. He saw this intimate connection between the physical landscape at a regional scale with the urban lives lived within that.

Think about how Virginia runs from the Appalachians in the western part of the state through gradually flattening terrain

all the way out to the coastline. That physical geological reality has defined where the cities are, what they do, what industries popped up within them.

We’ve always had a real physical connection between our urban life and the natural world around us. One thing trails do is provide the gateway from one to the other. As urban planners, we’re always thinking about the natural environment. Obviously, we think about trails from the perspective of recreational planning.

I love to point out to folks that the U.S. National Park Service has its own standalone urban planning office. Everyone asks, “How can that be? The parks are the opposite of the cities. Why would the national parks do urban planning?”

What happens when you go to a national park? You’ve got to park your car. You’ve got to stay somewhere. Facilities have to be provided. Different uses are allowed in different parts of the park, just like we use zoning to carve out different land uses in different parts of the city. So, this divide we like to have between, “Oh, well, here’s the urban and the built. And then over there’s the natural and the environment” — it’s not so clear. They actually blend into and overlap with one another a fair bit.

When we can be on a trail, we appreciate nature, the trees, the animals. Just the fact that we’re moving under our own power with dirt under our feet, up and down the terrain — we can see and appreciate that, as well as the working farmers’ fields and small towns, or the valleys we can see from these vantage points. Sometimes that gives the walk a different character, when we realize it’s got this human history made at the same time as this natural timelessness.

29

A CONVERSATION WITH PHILIP D’ANIERI

PHILIP D’ANIERI Author, “The Appalachian Trail: A Biography”

To me, it made perfect sense as somebody who’s interested in urban planning and the built environment to go all the way to one extreme of that, the Appalachian Trail, and look at how it itself is built and what people were trying to do when they built it. Maybe that gives us a more accurate perspective on how the natural and the built connect to one another.

El Koubi: What can an attraction like the Appalachian Trail do for nearby cities and towns? Are there any towns or communities along or near the trail, whether in Virginia or other states, that really seem to be doing a good job of connecting to the trail, embracing it, capitalizing on its value as a cultural and recreational asset?

D’Anieri: Probably the best example along the whole A.T. is in Damascus, Virginia, which describes itself as Trail Town USA — not only because the A.T. comes through there, but also the Virginia Creeper Trail and others. Damascus is one of those places where, as a practicality of building the trail, it comes down out of the mountain, runs through town, uses a road bridge to get over the river, and then goes back up into the hills on the other side. And Damascus, over the years, has developed a whole culture and identity

with shops serving hikers and hostels or campgrounds where hikers can camp or spend the night.

It’s an entire economic identity for a town that otherwise, like a lot of places built up as forest towns and the forest products industry, doesn’t have that livelihood anymore. Now they have this new identity around recreation in general, and the trail in particular. That phenomenon of smaller rural mountain towns and communities seeing an economic resource in the trail has happened up and down the trail — to the point where now the Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC) has a formal Trail Towns program cities can qualify for and announce themselves as Trail Towns. That features in their own economic development efforts and makes for valuable partnerships between the trail and its community of hikers and the towns it runs through.

El Koubi: We want all our readers to read “The Appalachian Trail: A Biography.” But I’m also interested in other things you ran across in your research for folks who want to learn more. Are there other books, articles, or films about the Appalachian Trail that you would recommend, or about trails in general?

D’Anieri: On the history of the trail itself, last year the ATC published “From Dream to Reality” by Tom Johnson, who unfortunately died just before its publication. It is the full, thick, authoritative history of the trail and the folks who built it. My book is a slimmer look at how and why we would have a trail, but this is a denser deep dive on everything you could want to know about the trail and its development over the years.

I think a lot of folks carry in our head with respect to the A.T. the idea, ‘It’s for the hardcore outdoors person who’s going to hike the whole thing in one summer.’ In fact, that’s a tiny, tiny percentage of the people who use the A.T. It serves a lot of different people’s needs in different ways.

PHILIP D’ANIERI

Author, “The Appalachian Trail: A Biography”

At the other end of the spectrum, a book that’s not exactly about the A.T., but written by an A.T. thru-hiker, is “On Trails” by Robert Moor. It’s a fascinating explanation of why we care so much about trails. Why do we keep creating these paths and using them? He goes to a bunch of places and examines different kinds of trails. It’s a very interesting philosophical reflection on why this idea of a trail keeps attracting us.

30

A CONVERSATION WITH PHILIP D’ANIERI

El Koubi: One of the personal projects I’ve been working on is trying to hike every mile of trail in Shenandoah National Park here in Virginia. It’s about 100 miles long, and there are actually about 500 miles of trail throughout Shenandoah National Park. Are there any insights you’ve learned that might be helpful to me, or that would help enrich the experience of a person who just likes to get out and hike in and around the A.T.?

D’Anieri: What I found interesting as I hiked was trying to understand the human history of the place. When we can be on a trail, we appreciate nature, the trees, the animals. Just the fact that we’re moving under our own power with dirt under our feet, up and down the terrain — we can see and appreciate that, as well as the working farmers’ fields and small towns, or the valleys we can

see from these vantage points. Sometimes that gives the walk a different character, when we realize it’s got this human history made at the same time as this natural timelessness. That might be something to ponder as you shuffle down the path.

El Koubi: One thing that makes Virginia’s relationship with the Appalachian Trail special is that we have a larger portion of the trail than any other state. Any thoughts on the Virginia section?

D’Anieri: Across that length, it takes in a lot of different landscapes — all of them mountainous and a lot with great viewpoints. But the mountainous terrain at the southern end of the A.T. in Virginia is different than up by West Virginia and Maryland.

A big part of the A.T.’s history was the

Grayson Highlands State Park is one of the first major sites northbound Appalachian Trail thru-hikers will encounter after crossing into Virginia. The park is convenient to Virginia’s two highest mountains, Mount Rogers and Whitetop Mountain.

fight between it and the builders of parkways, especially Skyline Drive in Shenandoah and the Blue Ridge Parkway, all the way down to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. They fought over the ridge line. So, a large chunk of the A.T. in Virginia was moved as much as 50 miles from its original location to get it away from the Blue Ridge Parkway. That’s definitely a key part of the trail’s history, which is especially visible in Virginia.

El Koubi: That’s really interesting. Thank you so much for joining us today. This has been terrific.

D’Anieri: It’s been a joy to talk about it. Thanks for having me.

For the full interview, visit www.vedp.org/Podcasts

31

THE HEART OF THE APPALACHIAN TRAIL

Virginia Offers Challenge and Respite as Midpoint for Thru-Hikers

IT

happens every spring and fall in Virginia. In the south, on the Tennessee border, they come just as the dogwoods bloom. In the north, they stumble in from West Virginia, walking south as the leaves in the Shenandoah Valley change from green to orange. From either direction, they look the same — bedraggled, unshaven, caked with endless layers of sweat, dirt, and insect repellent.

They are burdened, always by a pack, but also in other ways — by the hardships of an existence lived entirely outdoors, or by the half-remembered remnants of the life they’ve temporarily left behind. They are the thru-hikers of the Appalachian Trail (A.T.). By the time they reach Virginia, they have traveled nearly a thousand miles by foot. And Virginia — roughly the halfway point of the trail — welcomes them as it always has.

McAfee Knob in Roanoke County is billed as the most photographed spot on the Appalachian Trail. The summit is one of the three “Triple Crown” hikes north of Roanoke, along with Dragon’s Tooth and Tinker Cliffs.

WALKING ANCIENT PATHWAYS

Almost every casual hiker living in the eastern half of the country has heard of the Appalachian Trail. Many could tell you that the trail is about 2,000 miles long and about 2 feet wide. Most know that it runs along the spine of the Appalachian Mountains from northern Georgia to central Maine.

Fewer Americans can speak to the unique character of the A.T., one of two trails named National Scenic Trails when that designation was created in 1968. (The Pacific Crest Trail, which runs through California, Oregon, and Washington, is the other.) To hike the A.T. is to travel to an age when 20 miles in one direction wasn’t a quick errand by car, but a serious undertaking requiring equipment and a certain amount of mental and physical fortitude.

The A.T. is as close to a time machine as man is ever likely to invent. It transports perspective just as surely as it transports the body. To walk long on the Appalachian Trail is to send one’s soul traveling. The trail is built upon ancient paths — the footways trod by the mountains’ original inhabitants. It provides moments of sublime isolation near some of the densest population centers in America. It winds through glacier-carved mountains that were already ancient before humans invented writing. The hills are lush, verdant, and deceptively soft, and they often surprise travelers more familiar with trails in western mountains.

Where a western trail would switchback gently up an incline, the A.T. often goes straight up at a lung-collapsing grade, then straight back down again at a similar angle. Western hikers can expect sweeping, inspiring views of snow-capped peaks and sparkling lakes on the Pacific Crest and Continental Divide trails. Hikers on the Appalachian Trail are lucky to get a glimpse of blue sky between the dense forests and thick clouds that wreathe the Appalachian peaks. Thru-hikers can generally expect to get rained on every few days, and much of their ample downtime is spent fantasizing about dry socks.

Such are the travails of the A.T. Thru-hikers who make it to Virginia have survived several winnowing factors. People who cannot adapt to physical discomfort — hunger, cold, heat, dampness, insects, and all manner of aches and pains — generally quit within the first two weeks. Those who cannot hack the mental game — repetition, separation from family, and the machinations of their own undistracted minds — are gone within a month.

Thru-hikers who are prone to injury or don’t pay close attention to minor wounds or hygiene weed themselves out by month two. Financial pressures catch up to others at some time in month three. The ones who are left — the ones who reach Virginia — are rangy, smelly, and determined to see the endeavor through. Trail wisdom holds that if you can make it

34

THE HEART OF THE APPALACHIAN TRAIL

Virginia’s portion of the Appalachian Trail includes numerous spur trails accessed from the main trail. Many of these hikes are located in Shenandoah National Park, including the hikes to various scenic points on Stony Man, the second-highest mountain in the park.

Big Meadows in Shenandoah National Park is known for its stargazing opportunities.

The park holds Night Skies events on select Fridays with presentations on light pollution and the stars above.

through Virginia, you can make it all the way. True to form, the “Roller Coaster,” a 13-mile stretch billed as one of the toughest portions of the trail because of its many rapid elevation changes, dumps northbound hikers just a few miles south of the West Virginia border in the Northern Shenandoah Valley, where the A.T. leaves the Commonwealth for good.

Virginia, then, is more than a halfway point. It represents hope in the wilderness.

CHALLENGES AND COMFORTS

Virginia holds more than 500 miles of the A.T. — nearly a quarter of the trail’s total length. Sometimes thru-hikers feel like they’ve been in Virginia for years. Trail time is not normal time, and sometimes it can trickle rather than flow, particularly if hikers aren’t treated to psychological rewards like crossing state lines.

So it’s fortunate that the Virginia section of the A.T. has so much to offer thruhikers. The striking overlook at McAfee Knob, north of Roanoke, is one of the most photographed spots on the entire trail. The Grayson Highlands — which include Mount Rogers, Virginia’s highest peak — resemble a landscape out of Tolkien, including the feral horses that call the peaks home. The trail follows the rim of Burke’s Garden, a remote, high-elevation valley in Tazewell County known as “God’s Thumbprint.”

Despite its location just an hour west of the hustle and bustle of Washington, D.C., Big Meadows is known for its clear skies, relatively free of light pollution, and hosts regular stargazing events. The Shenandoah River offers a chance to leave the trail behind for a time in favor of travel by canoe — a precious respite that footsore thru-hikers refer to as aqua-blazing.

Shenandoah National Park is an opportunity to beg spare candy bars off of well-fed park visitors, while the famously welcoming trail town of Damascus, just north of the Tennessee

border, plays host to hundreds of past and present hikers each May with its annual Trail Days celebration.

Damascus isn’t the only Virginia town that offers comfort and unique amenities appealing to thru-hikers. Trent’s Grocery in Bland County, an otherwise unassuming convenience store, boasts a shower facility for weary hikers. Unique accommodations have also sprung up near the trail — the Woods Hole Hostel in Giles County offers massages and yoga. (Other in-town highlights are more obliquely related to the hiking community, including Waynesboro’s New Ming Garden, billed as one of the best Chinese buffets on the trail.)

Many residents of these towns offer housing and shuttle services to hikers completely free of charge. Thru-hikers call them Trail Angels, and they make the trail a better place in a thousand small ways.

THE CRUCIBLE OF THE TRAIL

“Don’t worry. Virginia is flat.” That’s a phrase you can hear on a hundred steep mountainsides up and down the Appalachian Trail. As any Virginian knows, such a thing is manifestly untrue. Call it rumor, call it the nature of hope, call it a little bit of both. Thru-hikers are inclined to believe any sort of good news about the terrain and the weather, even in opposition to their own lived experience and common sense.

But what is true is that the Appalachian Trail in Virginia is largely a ridgeline trail. And if that doesn’t make it flat, it does, at the very least, make it more gentle.

In Virginia, thru-hikers come face to face with their last shreds of reservation and self-doubt. It is not the final physical crucible, but it might be the final mental one. And if one must endure a crucible — must face oneself in such an uncompromising and unforgiving fashion — it certainly helps to do it in such a lovely spot.

37

THE HEART OF THE APPALACHIAN TRAIL

38

Virginia’s 544 miles of the Appalachian Trail offer stunning vistas, great exercise, and hiking camaraderie — but only on foot. Fortunately, the Commonwealth offers a great variety of scenic recreational trails, many of which are open to various types of vehicles. From urban bike trails to multi-use rail trails to the world-class ATV, bike, and equestrian Spearhead Trails in Southwest Virginia, the Commonwealth has a trail to accommodate anyone’s interests and preferred mode of recreation.

The Virginia Creeper Trail, open to pedestrians, cyclists, and horseback riders, runs for 35 miles from the town of Abingdon to the Mount Rogers National Recreation Area. The trail’s elevation change isn’t massive, but the westbound route has users going mostly downhill.

The Spearhead Trails in Southwest Virginia were built to accommodate numerous different types of users, with more than 600 miles of trails dedicated to ATVs, bikes, horses, and cars.

The Virginia Capital Trail comprises more than 50 miles of paved, dedicated trail running between Jamestown and Richmond — from the Commonwealth’s original capital to its current capital. Attractions along the trail include the homes of former presidents William Henry Harrison and John Tyler (see page 20) and Upper Shirley Vineyards.

The TransVirginia Bike Route runs along mostly unpaved country and forest roads from Washington, D.C., to the town of Damascus near the Tennessee border. Most riders who bike the entire length take between nine and 15 days to complete the route, although the fastest known ride took slightly over three and a half days.

Open to pedestrians and cyclists, the 18-mile Mount Vernon Trail runs along the Potomac River from Mount Vernon to Theodore Roosevelt Island in Washington, D.C. The trail largely consists of a dedicated path, but part of the middle section follows Alexandria city streets.

In the Great Channels in the Channels National Area Preserve in Russell and Washington counties, hikers can explore 20 acres of slot canyons created during the last ice age that are reminiscent of the canyons of the American Southwest.

The Virginia Bird & Wildlife Trail is a system of more than 50 individual loops across the Commonwealth that showcase Virginia’s natural diversity. The Tidewater Loop includes the Big Woods Wildlife Management Area in Sussex County, the only place in the Commonwealth where the public can view the federally endangered red-cockaded woodpecker.

Heritage Music Shapes the Future of Southwest Virginia

Crooked on The Road

AS U.S. ROUTE 58 WINDS west along the southern border of Virginia into the Blue Ridge Mountains, the road takes on another name — drawing on the distinctive music for which southwestern Virginia is known.

Country music can trace its roots to the 1927 Bristol Sessions recordings by legends like the Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers, now known as the “Big Bang of Country Music.” Yet the old-time string bands and a cappella gospel, blues, ballad, bluegrass, and other performers playing here today have a broader listening audience than ever.

The Crooked Road: Virginia’s Heritage Music Trail is a 330-mile driving route through Southwest Virginia, governed by a nonprofit organization that helps drive tourism to the region. In 2004, the Virginia General Assembly approved the economic designation that officially united a region linked by nine major venues for traditional music. Since that time, The Crooked Road branding has expanded to cover 19 counties, four independent cities, more than 50 towns, and 60-plus affiliated venues and festivals.

According to data gathered from the nonprofit’s 2019 economic impact survey, in combination with reporting from partner organization Friends of Southwest Virginia and the Virginia Tourism Corporation, the draw of traditional music contributes to $6.4 million in annual spending in southwest Virginia. Add to this the impact of related business and employee spending, and The Crooked Road generates an annual impact of closer to $9.2 million in a largely rural region.

Major venues on the trail include the Floyd Country Store and its Friday Night Jamboree concerts and County Sales, a record store known for its large selection of bluegrass and old-time titles. The Galax Old Fiddlers’ Convention has drawn 30,000 attendees a year to the city since 1935, and the Rex Theatre hosts heritage music as part of its Blue Ridge Backroads radio show. Just outside Bristol is the Carter Family Fold, owned by descendants of the legendary Carter Family, one of the first groups to record commercially produced country music.

The Country Cabin II in the city of Norton is the longest continuously

The Carter Family Fold in Scott County hosts performances from musical groups like the appropriately named Crooked Road Ramblers.

running venue along The Crooked Road, having operated since 1938. Half an hour up U.S. Route 23 in Clintwood is the Ralph Stanley Museum, which showcases memorabilia from the legendary singer and banjo player’s 60-year career.

The affinity for traditional Virginia music defies state borders. The nonprofit has traced approximately 42% of Crooked Road venue attendees to outside the region. Visitors hail from nearby North Carolina and Tennessee, but also as far away as the United Kingdom, Brazil, Australia, and Japan.

The traditional “high lonesome sound” may be what attracts listeners, but The Crooked Road organization keeps looking

46

forward. The nonprofit is taking steps to create a strong future for musicians interested in carrying on these traditions.

“We’re trying to make sure that the musicians are supported and know that they can be paid for their craft,” said Carrie Beck, executive director of The Crooked Road.

This includes helping musicians book concerts and supporting performance series at local venues. The Crooked Road has established a heritage music fund that offers grants to musicians of up to $500 for use toward professional projects such as recording work, website development, and headshots. The organization also launched an Artist-in-Residence program in 2021,

which provides a stipend and support to a local musician.

North Carolina transplant Andrew Small is the first to take advantage of that program. A versatile musician, Small is accomplished as a singer and performer on the fiddle, mandolin, banjo, guitar, and double bass.

It was with outreach in mind that The Crooked Road invited Small to serve as a consultant for events such as the Southwest Virginia Music and Culture Institute, hosted by the Virginia Department of Education, which provided an opportunity for music teachers to explore traditional music, folk instruments, and improvisation. According to Small, “That includes things like learning music by ear and playing

together without sheet music in small ensembles and learning things on the fly. It’s a different way of learning, by sharing music in a communal way.”

That’s just one way traditional music is shaping the region’s future. But for the artists jamming on any given weekend along The Crooked Road, this blending of yesterday and tomorrow is part of the beauty of the music they play.

“There’s this amazing culture of dance music in Virginia, and locals come out and dance to this old-time music. It’s a beautiful thing to see how it brings the generations together,” Small said. “The Crooked Road keeps these music traditions alive.”

47

Crooked Road FollowingThe Crooked Road

48

Headed out on a Virginia trail? Scan the QR code for a Crooked Road Trail Mix highlighting Virginia’s place in the growth of country music.

A Conversation With René Rodgers

Dr. René Rodgers is head curator at the Birthplace of Country Music Museum in Bristol, where she leads the museum’s collections, permanent and special exhibits, and other educational programming. VEDP President and CEO Jason El Koubi spoke with Rodgers about Virginia’s role in the popularization of what’s now known as country music, the complexities of promoting tourist attractions across state lines, and how the museum has benefited from the presence of The Crooked Road: Virginia’s Heritage Music Trail.

49

Jason El Koubi: Can you tell us about Bristol’s place in country music history? How did the city of Bristol contribute to the growth of this incredible musical tradition?

René Rodgers: In the 1920s and 1930s, record labels were searching out what they called “hillbilly music,” and what we think of as early country music — old-time traditional tunes.

Before 1927, a lot of that recording was done in the major studios for those record labels — in places like New York City, Atlanta, Richmond, Indiana — but because there was a change in technology around 1925 or 1926, recording technology became more portable and record labels started to look at places where they could go out for location recording sessions. One of those sessions was here in Bristol in 1927.

These weren’t the first hillbilly recordings. A lot of people assume that because we’re called the Birthplace of Country Music Museum it’s about the first recordings, but it’s more about the significance of the recordings here in 1927 and how they influenced early commercial country music. What made Bristol significant is, first off, that change in technology meant records were more sellable because they sounded better. The sound was more balanced, more nuanced, and that electric amplification and electric technology meant better-quality records were produced.

The other thing was that the record producer who came here from the Victor Talking Machine Company, Ralph Peer, was a real visionary. He knew the kind of music he was looking for. He knew what would sell well.

Jimmie Rodgers, who’s now known as the Father of Country Music, and the Carter Family, who are now known as the First Family of Country Music — the first time they ever recorded was here in Bristol. That perfect storm of technology, visionary record producer, artists, and songs that came together in Bristol set the foundation for the early commercial country music industry.

Bristol itself is contributing to that legacy today. We’re sharing that history and music widely via the museum and our radio station, Radio Bristol. We have the annual Bristol Rhythm & Roots Reunion music festival every year, in our 21st year this year. We partner with the Heritage Music Trails, The Crooked Road in Virginia, and also the Music Trail in Tennessee. Most recently, we have had the Mississippi Music Trails put a marker in Bristol about Jimmie Rodgers.

El Koubi: How did things evolve after that in Bristol? What’s the country music culture of Bristol today?

Rodgers: After the 1927 Bristol Sessions recordings, which were so important, Ralph Peer came back in 1928, trying

The Birthplace of Country Music Museum houses a sculpture honoring the musicians who recorded at the 1927 Bristol Sessions. Shown above are the Carter Family, Alfred Karnes, and Uncle Eck Dunford, all Virginia natives.

to remake that magic. Ernest Stoneman recorded again here, and the Stoneman Family is hugely foundational to country music, up to and through the 1960s and ‘70s, and even today. Ralph Peer and Ernest Stoneman continuing to work together is significant. Stoneman also recorded some songs that have become Appalachian standards and harken back to old-time music. Despite the fact that those recordings were made here, Bristol didn’t become a center for country music recording at that time.

But that history was very influential

50

A CONVERSATION WITH RENÉ RODGERS

on Bristol staying a hub for live performances. You definitely see that today, not just in country music, but in a wide variety. On the country side, the Bristol Rhythm & Roots Reunion has grown from 4,000–5,000 people attending to a festival of 40,000.

At that festival, you’re going to hear country music, old-time, bluegrass, ballads, but you’re also going to hear other roots music like blues and gospel and Americana. You’re going to hear where it started, how it’s evolving, and what it might become.

We also have some amazing venues downtown, like The Paramount Center or Paramount Bristol, which is actually on the Tennessee side of State Street. And then The Cameo on the Virginia side of State Street, both of which are big live music performance venues. There are also multiple places downtown and within Bristol sharing this type of music.

The other thing that’s really cool to me is how some of the businesses downtown are embracing the music. For instance, we have a music school that teaches music performance, from singing to guitar to

ukulele. We also have places like The Earnest Tube, which is a live direct-tolacquer recording studio. On their website they talk about being inspired by the 1927 Bristol Sessions and doing the same type of recording that harkens back to those days.

El Koubi: Can you tell us more about what The Crooked Road is and how it has increased interest in the Birthplace of Country Music Museum? What are some other things the museum has explored to capitalize on the wider region and pull together the threads that exist along this music trail?

51

RENÉ RODGERS

Head Curator, Birthplace of Country Music Museum

Rodgers: The Crooked Road is an amazing organization that works so hard to emphasize and celebrate the music, especially in Southwest Virginia. It’s a heritage music trail with both large venues and smaller sites along it that tell the story of music in this region. The Birthplace of Country Music Museum is one of the major venues, and the trail is instrumental as a tourism driver for music heritage. We have so many people coming to the museum who tell us they are following The Crooked Road for their vacation. We collaborate with The Crooked Road, and they definitely drive tourism to our region through their marketing and promotional efforts.

We’ve partnered with them on concerts and events. For instance, recently we had some Crooked Road musicians at one of our Farm and Fun Time® shows. We’ve also worked with them to bring musicians in for professional development or educational programming at the museum.

El Koubi: Any other organizations that come to mind? Just partnerships with the museum and ways that you’re collaborating to draw tourists to Southwest Virginia?

Rodgers: I’ve been working with the

Southwest Virginia Experience Museum Steering Committee. It’s a newish organization working to create a museum trail of this area for all sorts of museums, collaborating and promoting each other.

We also work with organizations like Arts Alliance Mountain Empire to promote events and their speaker series. We’ve partnered with King University in Bristol to help host some of their speaker series. We’ve worked with Virginia Folklife on numerous events.

We’re also a Smithsonian Institution Affiliate. That’s a great draw for tourism because we’ve been able to tap into Smithsonian resources and bring their special exhibits to the museum.

Another cool thing is our Main Street organization, Believe in Bristol. They represent both Virginia and Tennessee, and we work with them a lot. We’re so fortunate to have them on our side. They do tremendous work to promote Historic Downtown Bristol on both sides of State Street and to promote the museum. We also work with our local tourism agencies and our Chamber of Commerce.

We have a great relationship with Bristol Motor Speedway and with the hotels

downtown. For instance, at the Bristol Hotel, we offer museum admission to their guests. We’re getting those people who might not have known about the museum to come visit. We’re also looking for ways to work with the Hard Rock Casino once it’s established in Bristol.

El Koubi: On the cultural economy and leveraging cultural assets, how does a musical trail like the one you’ve described come together? How can cultural organizations contribute to the development of trails like this one?

Rodgers: Obviously, there’s job creation, not only for the people working for the organization, but for the musicians we or any other sites along the trail might hire for concerts or programs. They’re independent musicians, nine times out of 10, and that’s how they make their living.

We’ve been talking about the tourism dollars that can bring into a region. Who’s coming and spending money that wouldn’t be here normally? A Chamber of Commerce or tourism agency calls them heads on beds. The more cultural sites you have, and the more things you have for tourists to do, the more likely you are to get those people staying multiple nights and spending their money at those

52

That perfect storm of technology, visionary record producer, artists, and songs that came together in Bristol set the foundation for the early commercial country music industry.

sites, in hotels, in restaurants, at the service stations, and all those places that are part of your local economy.

Having cultural sites and things like The Crooked Road and other heritage trails is about quality of life. If a business wants to start a manufacturing site or start a bigger business in your area, quality of life is one way that you attract them. Those businesses then attract employees, and these sites and these cultural experiences mean that those people are more likely to want to move here because it’s a nice place to live.

A lot of the way that cultural organizations contribute to that is advocacy. That means talking to legislators about the impact that cultural heritage sites, music trails, and other types of things have on the region. Talk to the tourism sites, businesses, main street organizations, and build close relationships and partner with them to be advocates for you, and you advocate for them, because they’re also a big part of that discussion. They help to bring money into the region.

El Koubi: You’re a Bristol native and you lived overseas for many years and then came back. What drew you back to Virginia?

Rodgers: We are so lucky to live in a state that’s filled with natural beauty, cultural assets, and so much history. All of those are things I’m interested in. But when I left Bristol to go to college, and then after college moved to England, I

didn’t think I wanted to be back here. But my little patch of Virginia has developed so much since I left.

My main reason for coming back was first and foremost about family. I’m an only child. My parents were getting older and it was getting harder and harder to be so far away. I thought, “I’m going to come back to Bristol — just for a few months — then I’ll find somewhere else on the East Coast to live, but I’ll be nearer to my family.” But once I moved back, I hit it at just the right time. And I got recruited very quickly. I worked for Believe in Bristol, the Main Street organization, for two years, which gave me a really great connection to my community.

I think that’s key to why I’ve stayed and what kept me here. I made that connection — a conscious effort to connect with my community.

I love being near the outdoors and the natural beauty. It is so easy to get out into that from where I live. So much has changed — it’s a vibrant, wonderful place, but there’s so much potential for Bristol to change and evolve even more. And not just Bristol, but this region. I just see the potential there, and it’s exciting.

El Koubi: What are the best places to listen to music in Virginia?

Rodgers: The Crooked Road is a great starting point. If you go onto The Crooked Road website, you see

all the sites. Then you go onto their individual websites and see what music they have. But the places that come to mind immediately — the Carter Family Fold is huge. Every Saturday night they have performances. You’re going to always hear great music there. The Floyd Country Store is another great place. The Blue Ridge Music Center. The Old Fiddlers’ Convention in Galax. Blue Ridge Institute & Museum, Ralph Stanley Museum, the Southwest Virginia Cultural Center. And then there are lots of smaller festivals.

You have ample opportunity to find music in Virginia. I’ve mostly concentrated here on Southwest Virginia, because that’s what I’m most familiar with. But another great way to find out about music and musical traditions in your area is to go onto the Virginia Folklife website because they’re talking about all of the music, crafts, art, and traditions across the state. If country music or old-time music isn’t your thing, you’ll find everything from calypso to Iranian music to Mexican folk music. There are so many opportunities to find music and culture in Virginia.

I encourage people to dig deep into those websites and support them, because that’s how we survive and grow. It really matters a lot to have that support and visitors coming through our doors every day.

For the full interview,

53

visit www.vedp.org/Podcasts

MONUMENTAL

FOOTPRINTS

Washington, D.C., just a quick trip over the Potomac River from Virginia, is famous for its monuments — but Northern Virginia has plenty to offer in that regard. Most of the monuments honor groups of people instead of specific individuals, largely groups connected with the military. Visitors can take a break from visiting presidential memorials to appreciate the work of the less famous Americans who served their country.

Arlington National Cemetery

American servicemen and women killed in wars have been buried at Arlington National Cemetery since the Civil War. One of the cemetery’s most famous memorials is the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, guarded continuously by Army soldiers since 1937.

U.S. Marine Corps War Memorial

The U.S. Marine Corps War Memorial in Arlington County depicts Joe Rosenthal’s iconic photo of six Marines raising the U.S. flag during the Battle of Iwo Jima in World War II. Despite the flag only having 48 stars when that picture was taken, the flag that flies over the monument is required to be up to date to represent the memorial’s dedication to all Marines who died in combat, regardless of when their deaths took place.

55

U.S. Air Force Memorial

The U.S. Air Force Memorial in Arlington County depicts the contrails of three Air Force Thunderbirds, with that number chosen to represent the “missing man” formation often used at Air Force funerals.

George Washington Masonic National Memorial

This building is modeled after the ancient lighthouse in the Egyptian city of Alexandria and sits atop a hill in the Virginia city of the same name. The memorial, which honors Washington’s involvement with the Freemasons, shares a Metro stop with Alexandria’s Old Town neighborhood.

56

Pentagon Memorial

The Pentagon Memorial in Arlington County consists of 184 illuminated benches — one for each victim who died at the Pentagon during the September 11 attacks — interspersed with crape myrtle trees.

Women in Military Service for America Memorial

Located next to Arlington National Cemetery, the Women in Military Service for America Memorial features quotations about military women etched into skylights to reflect on the memorial’s walls, as well as an interactive database featuring military records and memorabilia for nearly 300,000 servicewomen.

57

MOVERS MAKERS&

From fourth-generation oyster farms to award-winning distilleries, Virginia’s food and beverage trails offer a bounty for hungry travelers. Here’s how some of those businesses have benefited from being on these trails.

Food

Fields of Gold: Shenandoah Valley’s Farm Trail Virginia BBQ Trail Virginia Oyster Trail

Wine

Artisanal Wineries of Rappahannock Bedford Wine Trail

Blue Ridge Whisky Wine Loop Chesapeake Bay Wine Trail Fauquier County Wine Trail Foothills Scenic Wine Trail

Grapes & Grains Trail

Heart of Virginia Wine Trail

Loudoun: DC’s Wine Country Monticello Wine Trail Mountain Road Wine Experience Shenandoah County Wine Trail Shenandoah Valley Wine Trail

Beer/Spirits

Beltway Beer Trail

Blue Ridge Cheers Trail

Brew Ridge Trail Coastal VA Beer Trail Helltown Beer Trail Nelson 151 Trail Richmond Beer Trail Shenandoah Beerwerks Trail Shenandoah Spirits Trail Southwest Virginia Mountain Brew Trail Spirits of the Clinch Virginia 58 Beer Trail Virginia Spirits Trail

58 77 64 81 ROANOKE DANVILLE

59 85 66 95 64 95 64 81 81 RICHMOND NORFOLK CHARLOTTESVILLE ARLINGTON WASHINGTON, D.C. HARRISONBURG LYNCHBURG DANVILLE

Kevin Szady Head Distiller,

MurLarkey Distilled Spirits

Prince William County

What inspired you to begin making spirits?

I’ve always been a whiskey guy. Back in the day, a lot of people were making beer in their garage or basement. I went another route. I tried my hand at whiskey and the rest is history.

How has being part of the Virginia Spirits Trail affected MurLarkey’s business?

MurLarkey has grown to be a local attraction. We were blessed to be named twice in Travel + Leisure’s “25 Best Distilleries in the U.S.” — No. 16 in 2018 and No. 4 in 2020. I think this popularity combined with the Virginia Spirits Trail is helping to put MurLarkey and Virginia spirits on the map.

What are the benefits of operating in close proximity to other distilleries? Certainly, this offers convenience to the tourist or even locals looking to hit a few places on a day trip or weekend getaway. Kentucky and Tennessee have done a wonderful job in fostering their respective bourbon and whiskey trails. MurLarkey sees the opportunity to foster a similar scene here in Virginia.

How important is local/regional authenticity in marketing touristoriented businesses like distilleries?

Authenticity is very important. Consumers can tell if something is fake. This, of course, goes hand in hand with superior product. As with any artisan craft product, tourists (and consumers) are seeking what they can’t get in their local market. They want the experience, not just spirits. That combination is the magic of MurLarkey.

61

VIRGINIA MAKERS

VIRGINIA MAKERS

Heather Lusk

Vice President, H.M. Terry Co., Inc. Northampton County

What are the geographical benefits of operating an oyster farm on the Eastern Shore?

The Eastern Shore is a great place to grow shellfish. We have good water quality on both sides of the peninsula, but on the seaside in particular, which is where most of the hatcheries are located, we have pristine ocean water. We are also located in a relatively rural area with a smaller overall population than other waterfront areas in the state, which helps reduce use conflicts on the water.

How does Virginia’s merroir come through in your oysters?

Oysters are a true reflection of their place and time of harvest. Oysters are grown in Virginia in so many parts of the state — the seaside of the Eastern Shore, and the many creeks and waterways on both sides of the Chesapeake Bay — and each growing area produces a unique flavor profile. Our oysters are traditionally grown on the seaside, which gives them a punch of brine, followed by a sweet finish.

How has being part of the Virginia Oyster Trail affected H.M. Terry’s business? Has it increased coordination or collaboration with other aquaculture businesses?

Being part of the Virginia Oyster Trail has allowed us to tell our story and share the unique family history of H.M. Terry. Through the Oyster Trail, we have had the opportunity to collaborate with other growers and also pair with complementary businesses like Virginia wineries and restaurants.

62

MAKERS

George Hodson

CEO, Veritas Vineyards Nelson County

What makes the Charlottesville area such a hotspot for wineries?

The Monticello American Viticultural Area (AVA), which encompasses Charlottesville, truly is a great place to grow grapes and make wine. It holds some of the best vineyards and winemakers in the entire state. Combined with the natural beauty and great food scene, it has become a destination for those who want to experience great Virginia wine adventures.

How has being part of the Monticello Wine Trail affected Veritas’s business? Has it increased coordination or collaboration with other area wineries?