EIC/Interim Visual Arts Editor –J.B.Stone

Non-FictionEditor–SkylerJayeRutkowski

Poetry Editor – Asela Lee Kemper

Flash Fiction Editor – Ben Brindise

Short Fiction Editor – Ian Brunner

Social Media Editor – Courtney Hilden

Poetry Readers – LaurenPeter, Maddie Petaway

Last year for a sweet combo of looking out for my mental health, giving my awesome and amazing editors a damn break for a change, and giving our own lit mag a much-needed infrastructure overhaul we went on hiatus, laid dormant like grasshopper huddled in the warmth of dirt underneath a veil of winter frost, only to crack through the clay womb of the forest floor of a brand-new summer solstice. In other words… WE’RE SOOO BACK!

However, on more sobering terms, we find ourselves like most of our fellow Americans, and much of the world, caught in the turbulence of yet another Trump Presidency. As the world finds itself at the brink with another warmongering president, whose ambitions of violence and prejudice are even more intense than his predecessors, from continued support for Israel’s horrific genocide in Palestine to trading missile shots with Iran, to the expanse of ICE enforcement mainly against communities of color, the attempted erasure of Queer communities, the massive slashing of public funding for an unsurmountable list of programs, it’s more than understandable to feel beyond broken and dismayed right now

As to the solidarity with the continued struggles across the globe, still standing, still trying to stay strong in many situations where strength was bore out from the blight of state-sanctioned suffering, we wanted to highlight said voices, especially in this theme featuring Voices of the Modern Diaspora. Throughout this issue I’ve tried to grapple myself on what diaspora means, and many of our submitters and contributors reminded me of truths I already am fortunate to know, Diaspora is more than just a position of displacement. It’s about cultures carried, stories that traveled with the artists and writers gracing our issue here, whether that migration was through the means of escape from a localized warzone, fleeing the relentless assault of my own Imperialist nation, or maybe trying to move to a new nation just for the sake of a new life, a new opportunity; we wanted to hold a space for these voices of vulnerability, courage, and unapologetic imagery.

Before you even get to the contents page, as always we encourage everyone to explore the 2-3 pages worth of various organizations/mutual aid networks/activists/fundraisers doing some truly invaluable work. It’s important now, more than ever that we’re doing our part for those fighting against this tide of tyranny and come together as a community.

Sincerely,

J.B., EIC at Variety Pack

& As Always a Special Thank You to my Amazing Editors/Readers: Asela, Skyler, Ian, Ben, Maddie, Lauren, & Courtney

TW/CW: The following pieces may include mentions/scenes of death, loss grief, war, experiences with hate, bigotry

A donation allows PCRF to deliver on its humanitarian mission and send international volunteer medical missions to treat sick and injured patients while training local doctors. It also enables PCRF to send wounded and sick children abroad for free medical care they cannot get locally. As a 4-star rated charity for the past 11 years, you can be sure that your donation will have the biggest impact on the lives of children in the Middle East, regardless of politics or religion.

MedicalAidforPalestinians(MAP) worksforthehealthand dignityof Palestinianslivingunderoccupation and as refugees. We provide immediate medical aid to those in great need, while also developing local capacity and skills to ensure the long-term development of the Palestinian healthcare system.

A donations-based aid initiative, led by Palestinians in the diaspora, working to supply emergency shelter and aid to displaced families in Gaza. Their work covers all regions, including the Refaat Alareer Camp, North, Central, and South Gaza.

All proceeds from our workshops are donation-based and go directly to Palestinians in Gaza. Suggested donation amounts reflect our desire to both honor the time. They have conducted a variety of workshops from zine-making to screenwriting to poetics to artisan crafting!

The Friends of the Congo (FOTC) is a 501 (c) (3) tax exempt advocacy organization based in Washington, DC. The FOTC was established in2004to work inpartnership with Congoleseto bringabout peaceful and lasting change in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), formerly Zaire.

Islamic Relief has worked in Sudan for nearly 40 years, and remains by the sides of families caught up in the violence. Please support our life-saving work: donate to our Sudan Emergency Appeal now.

Doctors Without Borders

One month after the eruption of full-scale war in Israel and Gaza, we at Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), continue to grieve the widespread suffering and death. We are calling for all parties to ensure the safety of civilians and medical facilities. As an independent and impartial humanitarian organization, MSF delivers emergency medical care where the needs for our expertise are greatest regardless of race, ethnicity, religion, or politics. We are also an international movement made up of people from more than 169 nationalities working in more than 70 countries. Many of our staff here at MSF-USA have friends, family, and loved ones in Israel, Gaza, or both, for whom we are deeply worried. All of us have colleagues working right now in Gaza delivering lifesaving medical care to people caught in the crossfire.

An Indigenous Peoples and First Nations rights organization who promote the legal efforts of protecting lives of the true Americans of this country. From addressing the conditions of Indigenous territory, to helping the legal fight behind groundbreaking protests at Standing Rock to Lines 3 & 5, Lakota Law Project has been taking their fight head on and continues to make the voices of Indigenous and First Nations communities heard loud and clear!

[From the website] BLRR is a member-led, abolitionist organization of Black folk and POC that believe through leadership development, a shared politic, and community organizing–we will build safe and flourishing communities that resist the ills of white supremacist, cis-heteropatriarchal, capitalism; including policing.

While our mission is to build and mobilize enough power to change Olam HaZeh, the world as it is, we also seek to embody Ha’Olam She’Ba – the world to come – right here and now. When you organize with us, you are part of building a Jewishness and Jewish life beyond Zionism We have millennia of Jewish history where our traditions and our communities were not bound up with support for an apartheid government. We have liturgy, poetry, rabbinic debate, jokes, theater, dance, film, and song. Organizing rich in ritual, culture, and art connects us to those histories, and strengthens us in fighting for a future where our people – and all people – live with freedom, dignity, joy, and belonging.

Breaking the Silence is an organization of veteran soldiers who have served in the Israeli military since the start of the Second Intifada and have taken it upon themselves to expose the public to the reality of everyday life in the Occupied Territories. We endeavor to stimulate public debate about the price paid for

a reality in which young soldiers face a civilian population on a daily basis, and are engaged in the control of that population’s everyday life. Our work aims to bring an end to the occupation.

We need consistent, mass-turnout, nonviolent disruption to stop business as usual and compel politicians to act. When we engage in direct action whether through a strike, a blockade, or a mass occupation we break through. People see us. People tune in. People engage. Our movement grows.

Agrassroots2SLGTBQIA+ organization deep in the heart of North Charleston, South Carolina, providing a safer spacefor the youths, and alliesalong with their familiessince 1995. Be sure to check out the history ad be sure to donate to this wonderful local not-for-profit.

Autistic Women & Non-Binary Network is an ever-growing organization truly committed to empowering the lives of Women, and LGBTQIA+ folks across the spectrum, through the providing of various resources, solidarity aid, community publication, and fiscal support.

TheNationalWomenofColorReproductiveJusticeCollective working to strengthen the fight against the tide and collectively raising awareness and fighting for the access to necessary reproductive health care.

Colored Girls Bike Too

A growing collective led by Black Women & Black GNC cyclists, promoting mutual aid, teaming up with programs such as seeding justice, and providing pop-ups/food drop-offs to help Black communities across Buffalo, NY. CGBT also actively run workshops, and programs on the decolonization efforts of mobility.

D.O.P.E. (Dismantling Oppressive Patterns for Empowerment) Collective is an anti-oppressive project-based collaborative primarily led by creatives and theorists ages 18-35. They also have chapters in Toronto, Ontario, Canada; and Philadelphia, PA.

[From the Website] Trans Maryland is a multi-racial, multi-gender, trans-led community power building organization dedicated to Maryland’s trans community. By trans folks, for trans folks.

Harriet’s Wildest Dreams is a Black-led abolitionist community defense hub centering all Black lives at risk for state-sanctioned violence in the Greater Washington, D.C. area.

Buffalo Books & Literary Freedom LLC.

An incredible program founded last year by Buffalo, NY’s Poet Laureate, Jillian Hanesworth, Buffalo Books mission aims to expand literacy to the most underserved communities of buffalo through the expansion of book houses across the cityscape.

A network of resources, donation hubs, informational articles for the purposes of creating support to Indigenous Communities across the U.S. & Canada. With the Supreme Court set to gut the EPA’s ability to take on the ravaging effects of climate change; with a presidential administration refusing to shut down Line 3, Line 5, Mountain Valley, DAPL; and selling hundreds of thousands of acres of public land out west, we need to stand by the communities will know that bear with the most devastating harm from all of this.

Along with The Wakanda Alliance, an organization dedicated to creating educational thought-spaces within black communities. In these spaces, we examine works of art inspired by the many cultures within African diaspora, thus spurring insightful conversations between our audiences about the impact we can create when one combines space-time, culture and imagination! The Galactic Tribe also provides workshops and right now is calling for donations of clothing and sneaker drop-offs.

Friends of the Night People

A local organization in the heart of the Allentown neighborhood of Buffalo, that has served as a true beacon to homeless lives across the City of Buffalo, and anyone in need. Their efforts range from providing food, resources for various shelters, basic essentials/supplies, spaces to do both laundry and

Buffalo Blizzard Group

If you are a Buffalo Resident trying to get through this coming winter and find the resources to help get you through this tragic storm the Facebook group Buffalo Blizzard group has been a super convenient tool for establishing the resources, calls to action, and as well emergency posts.

Alocalorganizationthathasbeenabeaconinprovidingfoodandfoodrationstounderservedcommunities throughout the city of Buffalo.

Flash Fiction

Christine Arroyo 51

Elia Rathore 46

Benjamin Joe 52

Poetry

Jenny Stachura 50

K B Kalaw 57

Lethe Mei 41

Fendy S. Tulodo 58

Jordan Nishkian 56

Nnadi Samuel 33

Elena Lelia Radulescu 54

Diem Okoye 27

Short Fiction

Jason Low 42

Victoria Pudova 16

CNF/Essays

Rowan Tate 10

D G Rosales 35

Visual Art/Mixed Media/Comics

Nasta Martyn 48

Susan Kouguell 14

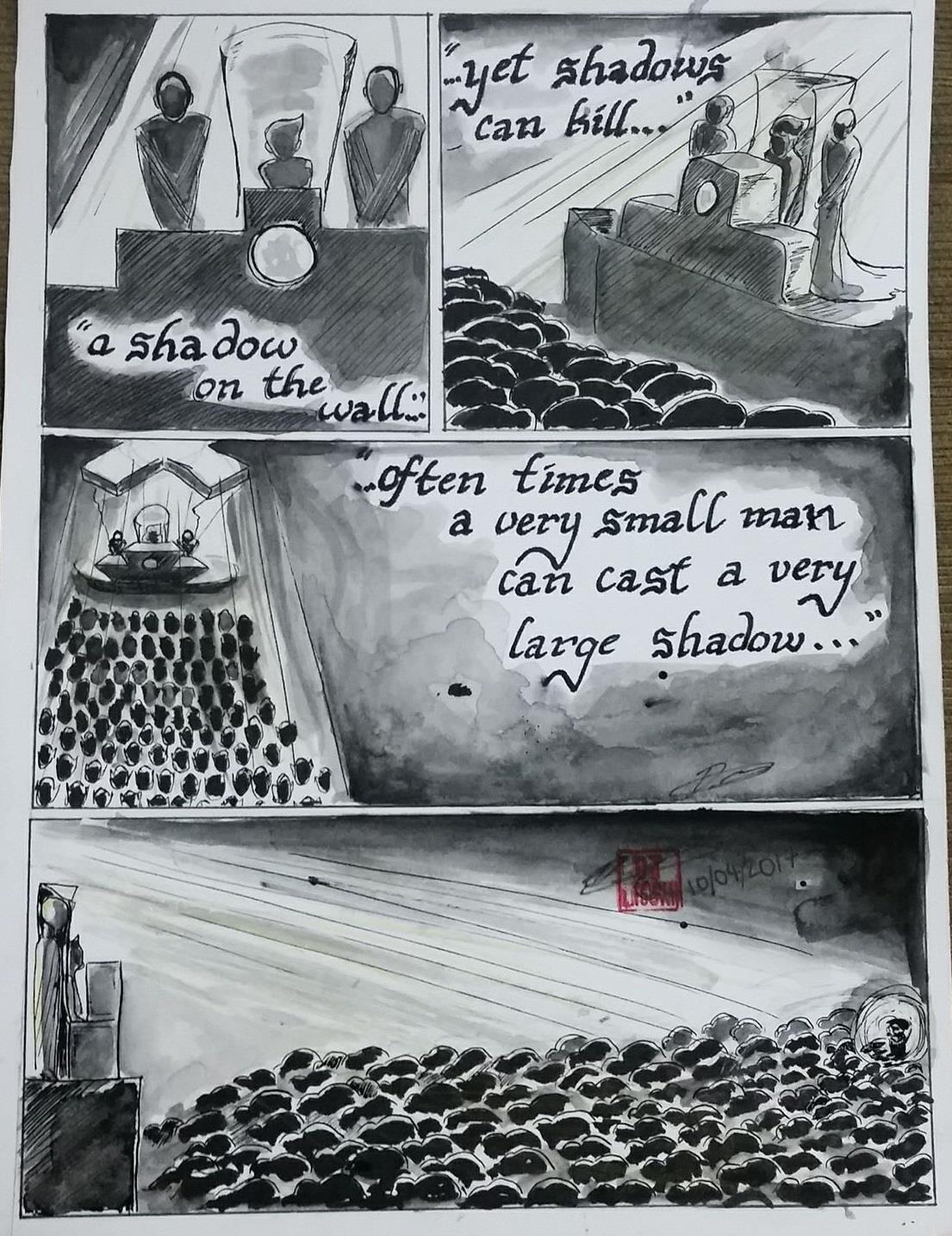

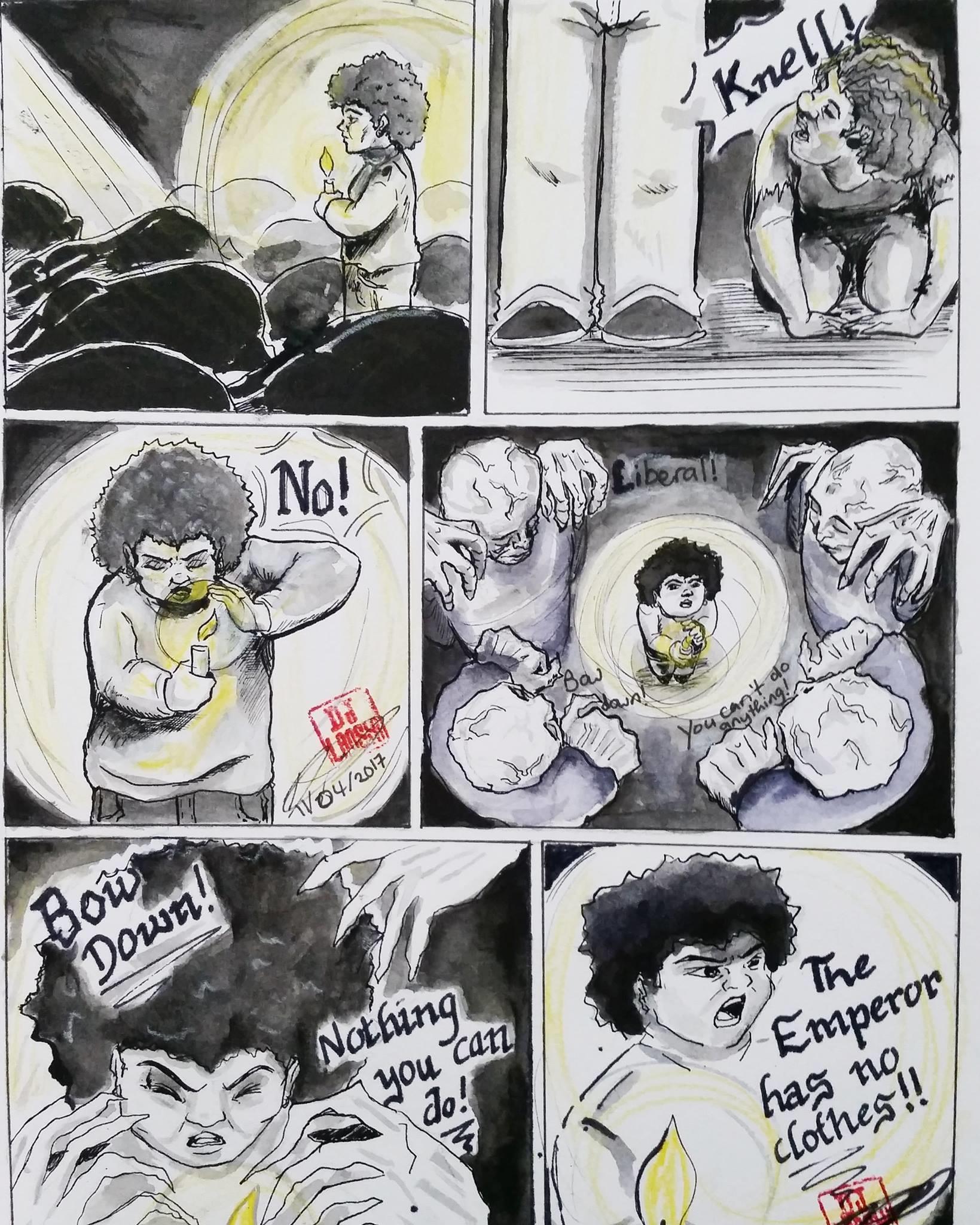

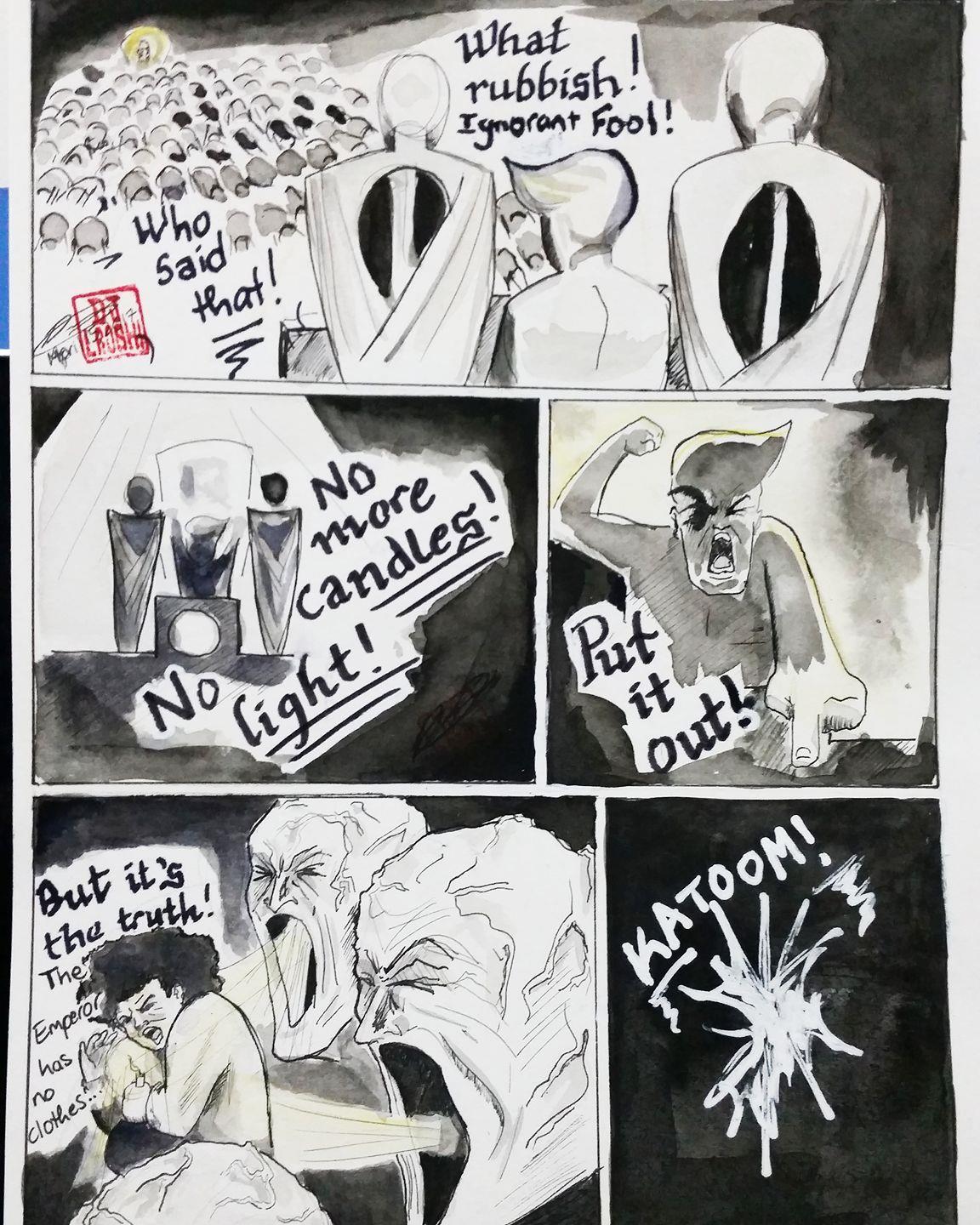

DJ Laoshi 28

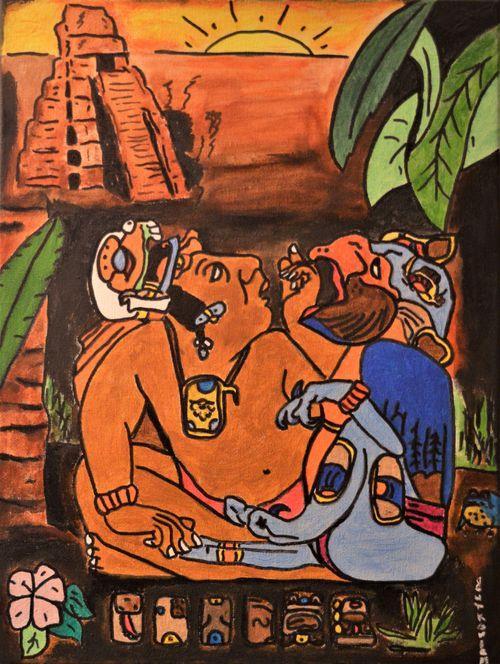

Michael Loren Butkovich 59

by Rowan Tate

I put onion juice in my hair. I cut it all off yesterday, my grandmother said I look like a boy. She doesn’t believe in that old folk remedy anymore. We have switched places: I live in the Romania my grandmother escaped from thirty years ago, when you stood in long lines for rations of butter and turned your neighbors in. My grandmother calls me from her queensize bed in America. I tell her to come visit, knowing what she’ll say. That isn’t my country anymore.

I go to the city that made my mother, Bacau. It is very ugly. I tell my mother this. It is the ugliest city I have seen in all of Romania. I know, she says. It made everywhere else beautiful. The Communist blocs rear over me in crude and crumbling concrete, like monolithic gravestones. I try to imagine a childhood here, my childhood here its water balloon fights and swing-jumping knee scrapes, the five-gallon buckets of plums and funeral services for birds. There isn’t room for it. Or maybe there is. I see my mother running in the streets, chasing her brothers, her stomach cramping with hiccup-laugh and hunger, all of them imagining another world around them in a defiant, nevertheless. This city is a Communist cemetery, I tell my mother. I know.

The first time I try to make sarmale I burn them. I spend two days preparing the cabbage, walk across town to the market to buy fresh pork, cook the rice and the meat and mix it with my hands, and work for two hours stuffing and rolling and unrolling the cabbage leaves, trying to remember how my mother arranged them in the oală. Sauerkraut and bacon and bay leaves. Was there tomato juice? How much water? Do I add salt? Bake for three and a half hours. My cuticles sting. In college, cooking for myself felt was a “waste of time,” all those dishes to wash for one plate. I am bent over the kitchen sink, calves tired from standing, rubbing onion juice into my scalp. Something is burning. I am 23 years old and I turn my Dutch oven black the first time I use it. My mother says to fill it with hot water and lemons. My grandmother says baking soda and vinegar. I hold the charred remains of my sarmale over the open-mouthed oven and cry.

My mother would tell me: The first time she saw a pineapple was in America. The first time she had blueberries was in America. The first time she had watermelon was in America. Her father brought home a banana once, in Romania, but they didn’t know how to eat it so they ate the peel. The fruit here is so cheap, I text her. It tastes so sweet. The tomatoes in America taste like water. I go to the piață and buy a purple plastic bag full of grapes. They have seeds. I don’t know if I should swallow them or spit them out. My mother has her groceries delivered in a box.

I sign the lease for my first apartment in Timișoara. The revolution began here. No one knew how many died some reports said 700, some 7,000, some 70,000. My dad says he’d like to visit. He has bad memories of Timişoara. He came by train in December 1989, a week after the first protest, to see for himself. They left the bodies in the streets, he says. They were black. The air was sweating with the stench. They slayed them like pigs. People were still in the square, chanting, we won’t leave, the dead won’t let us. I walk through that square every day now, to get a Starbucks. The building with the bullet holes of the shots the Communists fired is now a McDonald’s.

Some people speak of Ceauşescu with nostalgia. It was better then. Everyone could find work. He gave us houses, education. Now, who helps you? Some people think the revolution was ‘orchestrated.’ The world fed on gruesome stories of Timişoara’s massacres, martyrs, and mass graves. Foreign press published photos of naked corpses; a dead baby laid on the chest of a woman. Twenty years later, it was discovered those photos were fake. The bodies were exhumed from a local cemetery. The pictures were staged. One man tells me his wife died in his arms, shot during the uprising. Her body disappeared from the morgue. He says it was the securitate, it is what they did to erase the extent of the casualties.

The death of Nicolae Ceaușescu and his wife by firing squad was televised live on national television on Christmas day, 1989.

There is an Orthodox cathedral in the center of the city, I can see its green-and-gold spackled spires from my balcony. I think about the hundreds of protestors who tried to hide inside it from the barrage of bullets and who bled to death on its steps, the doors locked in their faces by priests. I think of the bodies of the injured smuggled by the secret police from the hospital to be incinerated, their ashes thrown into the sewers. The bells will ring, sometime, while I am Face-Timing my friends. It sounds so European, they will say. I will look at it, silhouette spearing the sunset, and feel generations of Romanians looking at it through me, drawing a collective breath. When it comes to God, the wounds go very deep.

by Rowan Tate

On the outskirts of my city in Romania, there is a care home for the elderly called Casa Harmonia, where most residents spend their day in wheelchairs and have lost their minds. I visit them every Tuesday, walking an hour along the Bega river along the nice parts and then the ugly parts, until the asphalt becomes a gravel road and stray dogs yap at my heels, which frightened me at first but they know me now. Most of the residents don’t know me still, even though they see me every week. There is one woman who thinks I am her daughter. Another thinks I am one of the nurses. There is a man who says, to everyone who passes by, impusca-ma, which means ‘shoot me.’ Another resident tells me he fought in the war (unspecified), as if to explain why, in the background, while I play piano, he is begging everyone to kill him. My least favorite is a woman who seems only able to say one word, gata, which depending on context can mean ready or done or shut up, which is why the first time I played piano at Casa Harmonia, I cut off Chopin’s Nocturne Op. 27 No. 2 after the Db major modulation into A major, only 26 bars into the piece, not long enough time to decide you don’t like Chopin.

I am six years old when my grandmother first shows me a catalogue of caskets and tells me she wants a lilac crepe interior, a tombstone that says “în sfârșit s-a terminat” (“finally, it is finished”), and a funeral service where everyone sings “Unde pot găsi eu pace?” (a Romanian hymn, “Where can I find peace?”).

I call my grandmother every day. We usually have the same conversation. She tells me how she couldn’t sleep because of her high blood pressure and how she has to wash the windows but there are so many of them. Her name is Elena, but our family calls her Mamici (muh-meech). Mamici lives in a house in America that is too big for her; she doesn’t own enough to fill three bedrooms. She seems to enjoy telling me how the dress she is wearing today is older than I am, although she says this gravely, as though it’s something I shouldn’t repeat. The ontological difference between my childhood and hers amazes me: she grew up in Tăcuta, a rural Moldovan village of whitewashed mud houses and wells. Her family were boieri (landowners). She remembers orchards of gutui and plums, walnuts and grapes, apple trees and three kinds of cherry trees. They grew nearly everything they ate. They had more than 100 chickens and it became her job to care for them when she was four years old. I forget sometimes that she knows how to make cheese. My grandmother still gathers dandelions and nettles to dry on her dining room table. When she sees lime trees, she hands me her purse so she can collect linden flowers for tea.

My grandmother was married when she was 16 years old. He was 17. As she often reminds me, by the time she was my age (24), she had seven children. My grandfather was a shepherd boy. He only went to school for three years. I don’t know very much about him because he doesn’t say very much and because they are unhappily married, but my grandmother did tell me once that he wore shoes for the first time when he was 13 years old.

Mamici remembers a lot of her life but that’s because it was very sad. The stories she tells best and most often are the ones that make her cry. She doesn’t as easily remember that she told me yesterday and also the day before that they cut down the big tree in her front yard and now she won’t have walnuts in August.

One of these sad stories is about her father, who refused to support the Communist takeover, and because of this, she was barred from attending school and never advanced beyond the fifth grade. Mamici says she still remembers the day the Communists came and took her father and all his land and crops except for one large sack of flour, which was slumped behind an open door. Mamici says that was the only reason they didn’t starve that winter.

I ask her where they took her father or what they did to him. She says she doesn’t know. He was gone for four years and they thought he was dead until one day he reappeared in time for dinner. He never mentioned the Communists, and no one ever asked.

At Casa Harmonia, people forget me from one visit to the next. A man tells me he fought in a war but can’t remember which one. A woman who thinks I’m her daughter holds my hand with both of hers and cries when I say I have to leave. It’s not just names and dates that disappear it’s the order of things, the sense that yesterday is connected to

today. What does it mean to care for memory when it is no longer able to care for itself? Memory doesn’t empty all at once. It takes its time. One man forgets his name but still hums cântece bătrânești (these are traditional epic ballads, literally "songs of the elders"). Another forgets where he is but folds his napkin after every meal, like he’s done his whole life. My grandmother, who sometimes loses track of her thoughts mid-sentence and forgets that we called yesterday, still knows which plants are good for cramps and reminds me to collect red clover in June.

The thing I am afraid of most is losing my mind. My grandmother seems to remember everything she wishes she could forget and to forget everything she wishes she could remember.

One Tuesday, it’s someone’s birthday and they serve albinuță (honey cake) on flimsy paper plates and play traditional Romanian music at an aggressive volume. The song, which is meant for dancing the hora, only exaggerates the lifelessness of the room. Have a slice of cake. Okay. Sit here. Okay. I take in the vacant stares and sagged bodies, the wheelchairs lined up like abandoned furniture, some elders complaining that the music is too soft and some complaining that the music is too loud. They were all once mothers and fathers, needed, the sources of life, now abandoned to decay as if time itself has declared them unnecessary. Maybe that’s why I keep going back to Casa Harmonia.

My grandmother is on Instagram and her algorithm feeds her the kind of health accounts I worry are spreading misinformation. Sometimes she sends me screenshots of posts saying things like “okra water prevents chronic diseases” or “ginger is 10,000x more effective at killing cancer than chemo.” I tell her maybe she should spend less time on her phone. She says doing what, she has been scared to use the car recently because everyone on the road drives like they could kill her. I ask her how her plants are doing. She takes me to the garden to see but she doesn’t know how to flip the camera on FaceTime so I don’t actually see anything. In the winter, Mamici tucks her potted plants in at night like children and hauls them back outside by morning with the devotion of a full-time caregiver. She talks to the herbs on her windowsill. She grieves the tree in her front yard as though it were a person.

by Susan Kouguell

Note:

by Susan Kouguell

by Victoria Pudova

In the bed you lay, your sheets are white and your blanket is burgundy. It’s not really a bed. The sleeper sofa was prepared for you. It’s been six years since you’ve visited your family, excluding your mom and your sister with whom you live in New York. They were so reluctant to let you go.

“Are you sure about this?” your mom asks you, gripping your arm just as you’re about to head through security. “It’s a long road from Warsaw. The train ride alone is some ten hours long. Everything there has changed. It won’t be just as you remem ”

“I know. And that’s why I have to go,” you say. “You keep saying we’ll go when the war is over but when is that going to be?” How long am I to wait? What if it’s too late by then? you think but don’t say. You’ve enough self-control, even in your emotional state, not to voice the question that she’s already internalized.

“Just don’t try to act smart when you’re there, okay? Listen to your godfather and don’t be stubborn. You haven’t lived like they have. There are ”

“And you have?” You love her but you stare her down. You’re tired of being lectured. “You haven’t been there for even longer than I have, let alone during the war. What do you know that I don’t?”

Your older sister, Vira, intervenes, “Guys, come on. Don’t argue. You’ll both regret saying goodbye this way.”

Your mom’s grip loosens as she pulls you into a hug. She smells like her lotion: tea tree oil, lavender, and shea butter. The skin at her neck is smooth against your cheek. Later, you’ll cry thinking about this. Thinking about how badly you wish to wrap your arms around her. But right now you do it half-heartedly, with love and impatience because you’re desperate.

You hug your sister before you leave and you don’t bother saying “I love you.”

You just turned eighteen. You’re an adult now but you don’t want to be. The last time you were in Ukraine, you were twelve. You don’t know what it means to be an adult, much less in a place where you were once a child, happy and free. But you’re determined to find out.

When you first enter your godfather’s apartment, you go straight to the windows to look at the view. The sun is setting. Your godfather’s face seems to reflect dread at the sight of the oncoming darkness following the radiant vomit of borscht that splatters across the sky. He’ll have to go to work soon.

A lot happens at night, but you do not fully understand this. Not yet. Your eyes catch on the windows of the apartment buildings that reflect the colorful wonder that’s like the disarming smile someone gives you just before they lean in and whisper, “I’m going to ruin you” in your ear. You laugh because how can any of this be serious? But then you pull away and their face tells you the truth that’s always been there.

“Are you hungry?” your godfather, Artem, asks.

“No, I ate on the plane,” you say. “And the train.”

“Are you sure? We have some beef cutlets in the fridge. They’re delicious.”

“I’ll try them tomorrow. I just want to sleep now.”

He lowers his head in one brisk motion. “Right. Uh, you’ll hear the sirens. Don’t worry. They’re false alarms a lot of the time. The city is quite protected. We’re usually able to strike down any missiles before they hit. So, don’t be scared. If anything, Ivanka will wake you.” He stares into your untainted eyes which don’t have the dark eye bags that surround his. You didn’t know that eyes could darken from exhaustion around the eyelids, too. But here’s the proof. “I’m glad you’re here,” he says. “I’ll give you a grand tour this weekend.”

Strike. “Can’t wait,” you say, smiling. Missiles. The words resound in your mind, finding no precedent.

Other than action movies and maybe the few documentaries you’ve seen in your history class in high school. You’ll want to think of the worst possible scenarios chunks of buildings scattered like volcanic rock, bloodstained sidewalks, uncontrollable tears and agonizing pain and maybe even you amidst it all, glass embedded in your skin and rubble crushing you as if you were being grinded down with a mortar and pestle because you’ve a vividly cruel imagination. But instead, you fog up the glass with the same nonchalant attitude that everyone around you has and pretend you can see clearly.

He leaves you to settle in and a few minutes later, his wife Ivanka comes in. She asks you if you need anything. You tell her everything is perfect. She’s also glad you’re here. “Your cousins are still with their grandparents in Zbarazh but they’ll be back in two days. They’re bored out of their minds! They keep asking

about you,” she says.

“They do?” you say, pleased.

“Yeah, they want to hear all about how their cool, American cousin is doing.”

You laugh. Of all the things to be, that wasn’t a bad thing.

You’re left alone. You wash up and change into pajamas. Your bare feet pad on the wooden floor, submerging into the silky bliss of the covers.

You were once told stories before bed, whether you asked for them or not. Artem freely gave them and you greedily took them. Maybe he’ll still humor you. You hold onto this wish in your sleep as you bury most of your face in your pillow. You don’t dream. If you do, you don’t remember. You sleep through everything.

“Did you get scared?” Ivanka asks you in the morning.

“Of what?” you ask.

“The sirens. You didn’t hear them?”

“I must be a heavy sleeper.”

“A real heavy sleeper at that.”

“Are you a light sleeper?’

“Not anymore, actually. I’ve kind of morphed into a heavy sleeper. I need to get some sleep or else how will I work? I’m just surprised they didn’t wake you.”

She takes the coffee off of the stove and pours you a cup each.

You shrug and clink mugs with her. She still does that, you think to yourself in amusement. If it’s any sort of container and holds liquid in it, Ivanka will demand you clink your drink against hers before you take a sip. Even if it’s soup. She’ll lift the bowl and bring it over to yours. “It tastes better this way,” is her claim.

You agree with her. It does.

It’s Friday. Ivanka took the day off to spend time with you. When your cousins are back, they’ll be the ones keeping you company while everyone is at work. For now, you sling some grocery bags over your shoulder

and head out with Ivanka to the supermarket.

She tells you anecdotes from her job as a nurse at a nearby hospital. “How do you send me to the wrong patient?” she tells me. “And he looks at me and says, ‘Elizaveta, is that you?’ He’s hallucinating! These are things you’re supposed to know beforehand.” She shakes her head and laughs. “It’s really not funny. Elizaveta was his daughter. She died in a blast just as she came home from school. He was supposed to pick her up but was running late, so she decided to get home on her own because it would be faster.”

You don’t know how to respond. You wanted to hear about what you and your cousins were like as kids. You wanted to hear the amusing, Ukrainian-like aspects of living here that you could contrast from the American way of life. Everything from how people curse and what idioms they use, to how they express camaraderie and connect to one another. The pranks coworkers play and the jokes made about shared experiences and history.

And that insight is what you’re getting. All the time, now. Except it’s not what you had in mind.

“Is that the park with that blue fountain I got soaked in?” you say, pointing to a path lined with trees across the street that leads somewhere shady and inviting.

“What? Oh.” She laughs. “Yes, it is. You remember that?”

“How could I forget Oleksiy pushing me in? I’m still mad.”

“Oh, he knows. You should push him in this time. He’ll never see it coming.”

“You really think so?”

You’re startled by the sirens you hear in broad daylight. The sun shines hot and bright and it seems to exist in symmetrical contradiction to the blaring sound that bounds down the steps and into the metro station. People gather in the tunnel with their backpacks and briefcases, in suits and skirts, with bouquets of flowers and tufts of dill and cilantro sticking out of their grocery bags. You feel the emptiness of your own grocery bags as you press them flat against the side of your body.

People’s faces startle you. They all have the same quality of boredom and irritation. A middle-aged man in a grimy wife-beater and a bright, orange hard-hat tucked under his arm says, “There go the moskali again.” He fake spits at the ground. It seems he’s talking to you. You notice how clean it is here. Underground. You

think of New York. Of the rats and shattered beer bottles and the smell of piss. When the danger is over, another sound blares, informing you of this fact. Everyone relaxes and goes on about their day. That a single sound dictates one’s life is jarring to you.

It takes a while but you finally end up at the supermarket and help Ivanka track down what’s needed.

It takes even longer to get back to the apartment.

“Don’t look,” Ivanka says.

You don’t listen.

“I said don’t look!” she shrieks.

If you can wish for anything, you would wish that you listened. Only later will you be glad that you didn’t.

“Was that…an apartment building?” you ask.

Ivanka took the grocery bags from you. When did she do that? “I told you not to look,” she says, lips pressed tightly together. She walks fast. Somehow, you don’t trip trying to keep up.

“Was it?”

“I told you not to look,” she repeats. “I told you.”

You’re not sure who she’s speaking to.

Artem calls you. “We’re dealing with them,” he tells you.

“I know you are,” you say.

You’re incredible, you’d like to say. Later, he’ll tell his military stories at the dinner table, fully animated and cackling while downing vodka. He’ll describe in detail being on a mission for Збройні Сили України, the Armed Forces of Ukraine, and how he shot a Russian in the stomach.

“That’s when I learned that you always have to fire two shots,” he’ll say. “I hadn’t killed him. He lifted his rifle, the bastard, and then I shot him again. In the chest. And it was done.”

The conversation will border the line between humor and despair and you’ll never be able to figure out in

which direction it leans. You’ll try to come to a conclusion by studying Artem’s facial expressions and the slightly crazed glint in his eyes.

Once he gets going, no one can stop him until he himself decides he’s done talking. It’s you he directs his stories to. His Ukrainian American godchild. There are things he wants to teach you. Wisdom he’d like to leave you with. You don’t have to be anxious about responding with something equally profound. He expects you to listen. To understand. To remember.

You’ll want to say it then, too. You’re incredible.

But he’ll have stopped talking. He’s dozing off.

Your sister’s face is grainy on the screen. She freezes mid-sentence when she says hi to you but you don’t say anything about it. You know the connection won’t get any better.

“Were you scared?” she finally asks. It’s what everyone’s been asking you all day.

“Pshhh. No. Why would I be scared?” you respond with an automatic smile.

She stares at you. Even pixelated, her eyes reveal her turmoil. You weren’t aware of how well you knew every lift of her eyebrow, every swivel of her eyes and quirk of her mouth. Not until now. “I wish I was there with you,” she says and you know she’s lying.

When she’s lying, it looks like she’s being pulled back by some unknown force. Like her body cannot commit to a falsehood. “No, you don’t,” you say.

“I do. If it wasn’t for my internship, I would’ve gone with you. I would’ve been with you.”

“I’m glad you weren’t. The internship is important. And you didn’t really want to go anyway.”

“That’s not true…I just, I wasn’t as compelled to go as you were.”

For the rest of the call, she tells you about her internship at a finance company you can’t remember the name of because she says it so quickly. You tell her about the nice restaurants and pretty squares in Kyiv without mentioning what she’d probably read on the news. She doesn’t bring that up again and you understand it’s because she wouldn’t know what to say to you if she did, and that would be the first time that’s happened. When you get off the phone, there’s one word that stays with you.

Compelled.

You sit on the rug of Zoryana’s bedroom. Oleksiy sprawls out his body, taking up most of the rug.

Zoryana rests her head in your lap and you’re jolted by the realization that you’re needed. She nudges you to massage her head. You obey. This is what Vira would do for you when you were twelve.

“Tell us everything,” your cousins demand.

The joke is that you saw what even they haven’t seen. And they’re the ones who live here.

“You’re a true Ukrainian now,” Oleksiy said. “Fully initiated.”

“A true Ukrainian,” you repeat.

Oleksiy has an electric guitar now. And a girlfriend. He says little about his girlfriend. But he chatters excitedly to you about the bands he likes and the songs he’s learning. “You know the Arctic Monkeys, right?

His excitement gives way to frustration as he strums the wrong chords. It’s worse because you’re his audience member. His cousin from far away, visiting him. He wants to show off. The air siren sounds again.

“Fuck,” he says. He thrusts his guitar into the stand and reclines on the sofa where you sleep. “Try learning a song with this going off every fucking hour.”

This one ends quickly but he’s no longer in the mood to play for you.

I like your playing, you’d like to say. You’ve only been at it for a little while and I think you’re quite good. Don’t stop practicing. The challenges make the reward more satisfying.

You pick at your words and frame them in your head as if they were the positive affirmation signs that are sold in one of those cheap stores with countless random and useless gadgets in between. These establishments irritate you.

You can’t stand yourself so you crash on the sofa next to Oleksiy and stare at the ceiling with him.

Zoryana takes you to a cafe a block from the apartment. You’re not allowed to stray too far. You drink

coffee and eat medivnyk. You try to remember what you were like when you were twelve.

“I want to go to Japan,” Zoryana tells you, licking her spoon clean and looking past you out the window.

“Why Japan?” you ask.

“Or America. Or anywhere.”

“So, anywhere but here?”

“Yeah…I guess.” She sounds guilty. “My dad and I fight about it. I tell him I want to study abroad and he says there are good schools here. I know there are but…”

“But what?”

“I’m tired. He wants me to be a patriot. Go into medicine like mom. Do something meaningful. Oleksiy is gonna be a pilot. He doesn’t want to live anywhere else. He loves it here.”

“Well, what do you want?” you ask.

She places her hand, nails painted red, on her black and white baguette bag. You take in her long black skirt and flowy blouse and the pearl pins in her hair, and you’re not at all surprised by her answer.

“I’d like to be a fashion designer.”

If that’s what you really want, you’d like to say, then fight for it. I believe in you. You’ll be unhappy if you just listen to what your parents want you to do. Taking risks is necessary if you want to succeed.

You can’t stand yourself, so you just tell her, “That’s cool,” and sip the cold coffee in the bottom of your mug. #

On a particularly bad day, you’re taken to the bunker. It’s dark and there’s no wifi connection. The only thing to do is talk. But Oleksiy and Zoryana are too annoyed to hold a conversation.

“Why do we have to be here?” Zoryana whines.

“We never go down,” Oleksiy says.

They band together to make their argument. That, at least, is heart-warming to see. Oleksiy gave Zoryana his sweater. She was shivering. Now, he is shivering and trying hard to hide it.

“Your dad said it was serious, so just stop complaining,” Ivanka says, exasperated. She leans against the

concrete slab of a wall with her bare shoulders. She shows no sign of being cold.

“Whatever,” Zoryana huffs. “It’s always serious.”

After a few minutes, she snuggles up to Ivanka and silently cries. Oleksiy sits on a crate with his arms crossed, looking over all of you protectively.

He acts like he could keep the outside world from touching you.

He’s fifteen.

“So, what’s your girlfriend like?” you dare to ask.

It’s the first time he smiles since being down here. “She sings when I play,” he says. “Sometimes…we write songs together. Come up with the melody and the lyrics. It’s nice. Really nice. She’s…” The silence finished the thought for him. Each of his words leave him like a drawn-out exhale and you irrationally think that he might not take another breath.

Whether he’s in love or not, you can’t be sure. You’ve never been in love. You’ve nothing to add. He drums his fingers on his thigh and by his sad gaze, you know he’s thinking about her.

Zoryana has stopped crying. She’s staring at the wall and fiddling with a hole in Ivanka’s blouse.

They don’t understand why they’re here, but you do. That’s because your mom was right and you didn’t know how things are and you’ll never actually know. You go home in three days and they don’t.

They’re already home.

The bed with the white sheets that you’ve rumpled after a week and the burgundy blanket that you bring up to your chin has never felt this confining. When your arm falls over the side and brushes the wooden floor, it brushes nothingness instead. The floor and the ceiling around you have been ripped out in the middle of the night. Your sleeper sofa is like your raft on an island that’s not yet an island. You’re still connected to the apartment but barely. You’re not yet lost. You don’t know if your eyes are open or closed. You don’t know if the other rooms are there or not.

Artem, Ivanka, Zoryana, and Oleksiy flit across your mind.

One after the other.

Then your mom and Vira.

That’s one, two, three, four, five, six.

Six people.

Six whole people.

Your family has never felt this big before.

Even when you return to Boston in three days, you keep touching the nothingness beyond the covers and feeling the hot wind from outside reminding you that you have six people to worry about.

That’s six I love you’s that you must never forget to say.

That’s six I love you’s you can’t afford to be lazy with.

I love you, Artem.

I love you, Ivanka.

I love you, Zoryana.

I love you, Oleksiy.

I love you, mom.

I love you, Vira.

You’ll spend everyday in bouts of anxiety, imagining the different combinations of that list and who could be missing from it at any moment.

You tell Artem at the dinner table and you make sure he’s sober enough to hear you.

You tell Ivanka while clinking your bowl of soup with hers.

You tell Zoryana as you thread your fingers through her hair.

You tell Oleksiy once he finishes playing a song for you.

You tell your mom at the airport when she picks you up.

You tell Vira on the ride home while holding her hand.

You cry at things you’ve never cried at before.

You’re easily moved. Easily touched.

You’re twenty.

You’re thirty.

The war is over, but nothing has changed.

You’re still almost rolling off the bed.

Six times, every night.

by Diem Okoye

Such a heavy word on my tongue: mother smelling like palm nut soup and kimchi stew, soft hands that smell of ginger and shea butter, wise eyes, oceans holding both joy and ache. I always wanted a sister more than that, I always wanted a guide. You were never just a protector, not simply a shield. You were the soil where my roots found strength, the rain that fell on my leaves, your lullabies still echo in the marrow of my bones. Mother, you are the hearth I return to, the home I carry wherever I go.

by DJ Laoshi

by Nnadi Samuel

It starts as a swallowing. a heartbeat tucked in the wrong place & fear self-breeds like a tumor I wear my tongue with a large spittle that rewashes its white in a foamy stain. each sentence, made wet as a threat. I do not self-ruin here. I have to cut the syllable into size, to meet the demand of the eyes that owls on me skin-searching for luster. I breathe a panting. asked God for a spare lung. this one is in dire need of repair. the microphone on stage is a triggering object. I blunder through the mouthpiece, to arrive at an unintelligence that raise brows: "was he born this way, a trembling black thing?

“will he ever be capable of making sense? I hum the answer to a swallow. a boy thinks himself a therapist & touch the glass of my body with a light pen, as if to write me into medication. I translate the moment into adlibs & perform a mouth-to-mouth phonation, where noise eats the air flow from my throat. the accent comes out hungry. you feed a language this morning & it turns stale by noon: a malnourished echo, a migrant’s way to name a loss he cannot pronounce. I've named too many things that do not survive the next day like my joy for black sonnet: a dead phrase, erased from my draft.

I am knocked out of living by the bare fist of sound. I glove a chorus of shouting. inside of me, a ring melting into a sigh. isn't it a tournament of some sort, how we make our speech bone-clean of error. the way we're fast paced with words: something of brilliance I lack the brightness to engage.

I crawl back, gentle as a stop crowned by the corner of a blank page, punctuate the wind with my heavy sobbing. the reptile of my tongue, carving out glyphs from its raised stand. I sip a cold spit, while the business of outspeaking each other is done in first person narrative: all the I's & Me's, a thing I wish to imitate at some point. all eyes on me to model after this gesture which I do bravely, careful not to break a pronoun. we're fragile things in the hands of change: an overwhelming potluck. as if, something larger than life, something not in the menu is reaching for our throat.

I bash my head on the rock surface of a pillow, shed my skin on the baobab stain of my bed to weed me off the parasite that drinks the egg of my speech

before its hatching. I do it dirty as an animal, as any cold-blooded specie. I do not excite the air with my hissing.

I excrete so close to strangers, to mark territory: my pheromone of poisonous exchange. when the words gush out, they come in spit.

by D.G. Rosales

Danny walked alone from homeroom. Not a part of the crowd of students around him, but rather carried by it, a pebble caught in a rushing current.

Television sold Danny this idea that high school in the U.S. had to be like a Disney Channel original movie bright colors, easy friendships, and a sense of belonging.

Then he stepped into the inviting corridor: cold, bare concrete. His version of High School Musical was devoid of color and in slow motion.

The corridor led to a similarly cheerful lunchroom, alive with the cacophony of student life: conversations of friends who hadn't seen each other during winter break, discussions about class schedules and teachers, laughter from animated stories and inside jokes years in the making.

Everyone slipped back into a rhythm Danny recognized. Except, it felt further away than from behind a TV screen.

Disney Channel got a lot wrong about high school, but not the cliques.

Groups of people huddled around each other, sitting at communal tables. Islands with a one-seat buffer between cliques, a DMZ with snipers at the ready.

Even those sitting on the floor had found a way to belong only to each other. All closed loops, leaving Danny no opening.

Back in Guatemala, English had been a superpower, a secret language he’d speak with his family, a code nobody could crack. He was proud, but most importantly, his family was proud of him.

“Mira que pilas, cómo habla de bien.”

“Qué inteligente le salió el patojo, doctor."

Now, he spoke too slowly, too clumsily. Always with the wrong inflection.

Not special at all. Not even competent.

At sixteen, and the son of a doctor (back home, things like that mattered), Danny had carried an air of easy confidence. Drop him into any room and he’d make conversation with anyone. With adults, talking about food or travel was easy and would bring easy smiles. With kids his age, fútbol and Dragon Ball Z were easier still.

Here, each person seemed a looming tower; unscalable, impenetrable. He was on the wrong side of Babel; the tower already built, language already scattered, and him left holding his broken words.

Nobody had been hostile. This was January of 2009. Racism had been done away with by the election of President Obama. Right?

No one had extended a hand either. Couldn’t anyone see him do a double-take after reading every word? Flinching every time he had to take a step?

Danny was new. New to this school and to this country. But he wasn't just a new kid, he was a second semester junior. In the best of cases, friendships had a whole semester to solidify. In the worst, years.

He was also new to this English.

The language he'd formed a bond with had betrayed him. He'd spent countless hours of formal classes and exams. Preparing, memorizing. Countless hours of fun, too: books, movies, and English-language music. Getting lost in the loud guitar of Jon Bon Jovi or the fantastical wardrobe of C.S. Lewis.

He'd done the thing:

Passed the TOEFL Test of English as a Foreign Language. The highest possible rung in the ladder of academia.

He'd gotten lost in Narnia and Earthsea, visited New York through Friends, and shot hoops in Bel Air with Will Smith. He was fluent. He had prepared.

Then why?

It could only be his fault. If he could just speak to someone, anyone, take the initiative, ask for help, he wouldn't be alone... but he had misplaced his confidence along with his words.

Danny followed the crowd. It crept along, coalescing into a lunch line toward the front of the room. A dam broke with the ring of the bell, and the river flowed toward the promise of food.

A hairnet-clad lunch lady loomed over Danny at the front of the line. "I have free lunch," he mumbled.

The words had to be said. Aloud. He had to eat. But voicing them was a betrayal too. He was outing his parents in front of his peers. Announcing, “Look at me, my parents can’t afford to buy me lunch.”

The lunch lady tapped a fingernail against the register. "Just tap your number in there, hun."

His number... His student ID! He'd known that this morning, it started with a 9... The binder!

He fumbled through his bag and found it. The binder that held the pieces of his new life: bus routes, locker combinations, class schedules...

"What subject do they teach in Homeroom?"

That morning's conversation fragment haunted him even now. More embarrassing with each loop. Stupid. Stupid. The line behind him swelled.

Danny’s heart thudded in his chest. Page flip. Not there. Another flip. Still not there. “I wrote it down, I know I did.” There! He had missed it once already in his frenzy to find it, pages shaking along with his hands.

Danny could feel the glares from his peers (real or not) as he had held the line a minute longer than he ought to have.

After punching his number into the terminal, he was rewarded. A veritable buffet of cold snacks and unappetizing single-serve packages waited for him.

He picked what he recognized: a fruit cup, an orange juice, and a cheese pizza that could fit in the palm of his hand.

A far cry from the hearty home-cooked meals Mom used to pack for him and his siblings.

He checked the time. He’d been out of class and in line for what surely was a small eternity, ten minutes tops.

Time he could have used to scan his surroundings. But the struggle to find his ID number had taken all of his concentration.

Danny reluctantly stepped out of the line. No one said anything. No one rushed him. But that was somehow worse.

He could still get through this day unscathed.

His eyes scanned the lunchroom once, twice, but he made no move. There was nowhere he would fit. Still no welcoming committee, no band of misfits proclaiming Danny as one of their own. Just the same closed loops. The same disposable lunch.

Disney Channel strikes again.

He needed somewhere to go. A place to hide and regroup. Somewhere he could just sit and be himself again.

His feet moved without thinking, like they knew that if he just kept walking, nobody would notice how alone he was. Danny found himself facing a small, enclosed room. It had a door, and it closed! A world away from the overwhelming weight of all the changes: a bathroom stall.

He closed the door, hoping, at least, no one would need this handicapped stall in the time he was there. Each bite of the cold, gluey pizza came with a crunch, a loudspeaker announcing his secret, his shame.

He wasn't supposed to be there, and if anyone found out, well, it’d be better if the ground opened up and swallowed him whole. For the moment, he didn’t have to worry about the lunchroom outside.

All he had to fight was himself. Because he was the one who knew he didn’t belong.

"If you were braver, you'd be out there."

"¿No que muy pilas?"

He wouldn’t let himself cry, because coming out of lunch with red, puffy eyes meant defeat. Being caught. And that might actually break him.

Danny remained in the stall until the warning bell told him it was time for his next class.

Time in which he pored over the binder. Relentlessly, purposefully. It was a crutch, sure, but also his only lifeline. A roadmap to this new life.

Maybe if he memorized every number, every schedule, every thing, he could belong.

So he forced himself to remember his student ID. No way he’d hold that line up again. He learned the way to English class, then Civics (the only junior in a freshman class).

He quietly exited the stall, splashed water on his face, and took a step forward.

Danny made his way to English class almost from memory; thank you binder

He paused at the threshold. A couple of students chatted animatedly at the door, most were already settling in for the lesson ahead.

This room wasn’t the lunchroom. It was bright and welcoming, large windows, light pouring in, posters on the walls, a teacher at the helm... Most importantly, there were assigned seats.

This room would always have a space for him.

This week, they’d be reading Huckleberry Finn, Mrs. Burns informed them, with the speed of a rushing waterfall, wrapped in a bless-your-heart, North Carolina accent. The perfect complement to Huck and Tom Sawyer's adventures, but not for Danny, who was struggling to keep pace.

From the desk next to him, another boy leaned in.

“What did she say?” he asked, conspiratorially.

Danny glanced over and shook his head ‘no,’ caught off guard, the question making him also lose his thread.

But it didn’t matter, because he had heard it.

There it was.

The faintest hint of a Spanish accent.

Danny wasn't alone.

by Lethe Mei

It feels like a conquest, not the blood of brutalized bodies burning through breeches buttoned up

but fine white sugar in my fine black tea. I love nothing so much as whalebone cross-stitching my ribs erect and

replicating respectability. It feels like war, somewhere else. When I wrestle my wayward lips into o’s

only to intone, The horror!

O how you gaze at me. With eyes like fingers you complete me, piece by piece,

knead my limbs into recalcitrant wings. My skin is tough: it stretches taut in teeth dreaming of ivory; it will not

break. Yes I adore grossly, obsequiously, you false idols. I confess. Wearing like a cross your words around my neck,

sometimes I undress, one petticoat after another, to remember the fever of foreign flesh. And it feels like violence

observing you, the mirror that is art that is life spent sweetly in the sin of some careless country that is not mine.

by Jason Low

Days after the Japanese invasion of Brunei in 1941, the Chinese camphor chest was relocated to an old farmhouse in Seria Town, where it has remained ever since. Rosie Lee’s hands trembled as she lifted the rusted clasp and opened the lid. She pulled out the batik sarong adorned with bird motifs and unfolded the delicately embroidered kebaya blouse that appeared to be alive with frangipani and chrysanthemums. She changed her clothes, peered at the mirror, and suddenly felt quite embarrassed. The sarong-kebaya seemed too loose, too ethereal, like it would float away from a body that was dreadfully thin and frail. But if she didn’t wear it today, when would she wear it? Then, for a moment, she wondered about where all of her old things, piling up here and pouring out there, would end up. Ari, her son, did not want any of them. Nostalgia is an ailment that was what Ari once said.

Rosie Lee pushed open the shutters of the window. The morning was dense, electric. The papery bracts of the bougainvillea plant overflowed with bright red ink; swatches of blue sky rippled on the puddles from yesterday’s rain; mist floated along the sprawling rice field. But one could not just go on looking at things forever. Rosie Lee wrapped her arms around herself and turned away from the window. She reached for a dusty bottle of cologne from inside the chest and sprayed the herbaceous scent onto her neck. She had bought the cologne from the duty-free shop in Brunei International Airport years ago, as a present for Ari, to thank him for flying her out to visit him in Perth whilst he was there on business from New Zealand. The bottle never reached him.

… “Passport!” the immigration officer snapped. Rosie Lee handed over her travel certificate. The man flipped through the booklet and stared at the computer terminal. His face clouded and discouraging words poured out from his barely moving mouth: “The certificate has you down as a resident of your country, but the system has you labelled as being stateless. You’re not able to transit without a nationality.” Rosie Lee tried to explain, but the officer said that the only course of action would be to re-board the aircraft on its turnaround journey home. Waiting in the corner of a sparsely furnished room with other immigration detainees, she realised how easy it was for people to become visibly invisible and alienated. Sensing fear and panic in the young man seated next to her, Rosie Lee held his hand and said, “People don’t see us.” By the end of the day, she was back in Brunei listening to Ari rant

and rail on the telephone about the unfairness of life. He painstakingly laid out the merits of living with him in New Zealand. She replied in a cool voice, “You sound like a salesperson. Seria is where home is, regardless of the legal situation. You can always come and see us here.” …

“Did you hear me?” Mr. Lee said. “I can smell something burning!” “What?” Rosie Lee replied. She looked at her husband. There was a fishing magazine on the floor by his chair, ash falling like microscopic white moths from the cigarette in his hand. “One day, you’ll burn the house down. Didn’t I tell you not to leave the pot on the stove for too long?” he said. “It’d be a shame if you ruined the food.” She nodded and looked at the clock. Was there time to get things sorted before Ari got here? What had he said on the land line? Something about him riding in a bus to Seria through Tutong District, and arriving at noon for lunch. Ari was just too much, really. To make a journey from New Zealand to celebrate his birthday in Seria with them, bringing grilled glutinous rice rolls from that famous stall in Tutong. Rosie Lee suddenly felt pressure building inside her soles; her feet looked wickedly swollen in those stupidly small slippers. She forced herself to push through the pain and walked to the kitchen with slow, uncoordinated movements. Mr. Lee looked at his wife curiously. “I wish you’d let me take you to see the doctor,” he said.

Rosie Lee lifted the pot simmering on the stove. She scraped the tofu stuffed with mushroom and bits of glass noodles out onto a plate, and went to the mesh-lined cupboard to get the coconut cake. “Remember to check the water around the cupboard’s legs, too! I don’t want Ari getting all uppity about the house being under siege from a barrage of animals. We didn’t hear the end of it the last time he visited,” Mr. Lee yelled out. She bent down to inspect the cupboard’s legs standing in bowls of water. This place is a health hazard. How can you both still want to live in this dump? Ari said things like that. Rosie Lee spooned out the ants surfing on the water. “And check for millipedes!” Mr. Lee shouted. She corralled the millipedes congregating by the decaying wood around the tap and placed them into the compost heap. She was about to slice the cake when she heard a loud explosion from outside the house.

… The family heard their neighbours screaming: “The war has arrived! The Japanese military police are here!” “Pack up a few keepsakes and gather the important necessities. There’s an abandoned farmhouse in the jungle a few miles away from here. We’ll hide there. And Rosie, hold on to Rufqa by her leash,” Mr. Chua said.

Rosie Chua watched her father scramble to gather documents, tinned food and clothes to pack into the portable Chinese chest. She watched her mother light up joss sticks to burn before the ancestral portraits hanging in ornate frames, bowing wildly and praying incoherently for protection.

Panic set in when the snapping twigs underfoot alerted the soldiers to the family’s movements. “Everyone keep still and be quiet!” Mr. Chua whispered. Rosie Chua turned her head slowly and saw the Japanese soldiers carrying indifferent metal arms swinging across khaki uniforms heading in their direction. It was then that Rufqa bolted from Rosie’s hand. The golden retriever ran a few hundred metres and then stopped to look at Rosie. She could hear her thoughts cry out to the animal: “Don’t do this! Please don’t leave me!” She could see her dog’s flaming tongue, its breath coiling in the humid air, its chest heaving in preparation for its next move. The dog suddenly twisted its head and raced off, and the soldiers chased after it. Rosie Chua tried to scream, to call out to Rufqa, but a protective hand had moved in anticipation to cover her gaping mouth. …

“It’s only the neighbour’s car’s tires exploding from the heat,” Mr. Lee said, poking his head a short way into the kitchen door. “Oh, I’ve gotten out your family’s Peranakan porcelain ware for you. Hopefully, Ari would appreciate us using them to celebrate his birthday.” Rosie nodded, washing up pots and pans in the sink. “Give us a shout when you’re ready to serve the dishes,” Mr Lee said, taking two steps back and disappearing.

Something going past the window caught Rosie Lee’s eyes. There! That ghostly slick of a blur padding around the mango trees Rufqa! Her face was a nebulous mass of darkness, featuring bloodshot eyes and a jaw that dangled; her feet were long and untidy, dragging on the ground. Was that Rufqa’s appearance when they buried her? Rosie Lee couldn’t shake the feeling that Rufqa was showing up more often than before. Yesterday, she spotted Rufqa intently watching her whip up six eggs to make a coconut cake. A week ago, she glimpsed Rufqa fumbling joyfully through the front garden. Rosie Lee wasn’t afraid, but she tried to push out of her mind something her mother said so many years ago.

… “Don’t talk about supernatural things! Don’t attract attention!” Mrs. Chua shouted. Rosie Chua was looking out of the living-room window, making barking and grunting sounds, and communicating with short sentences and a high-pitch register like the way people often did when speaking to infants and pets. She turned away and said: “Rufqa has found me! Rufqa will warn me about things. She will protect me.” “No! It’s bad luck to

talk like that!” Mrs. Chua cried hysterically. Mr. Chua burst into the room, his face pale and contorted at seeing his daughter gazing serenely at the emptiness behind the metal bars of the window. He pushed Rosie Chua aside and struck the window repeatedly with a broom. …

Suddenly, a cool breeze whined through the trees, disarraying the clothes hanging on the nearby washing line. There was another presence; a man, head obscured, standing immobilised behind the clothes that were flapping and shimmying in the sun’s hazy glare. Rosie Lee could tell who he was from the way he was holding up the small plastic bag with one pointed finger. There appeared to be food (is this your gift?) inside the bag, steam escaping in gentle puffs. The back of her kebaya blouse felt sweaty and clammy. She waved at him several times and wiped her wretchedly wet eyes on the sleeve of her blouse. “I see you,” she murmured. The Asian Koels sang their “ku-oo” notes while the crickets chirped in leathery rhythmic waves what was his message?

As Rosie Lee was about to move, a hand gripped her elbow and led her away from the sink overflowing with water. “Are you alright?” Mr. Lee asked. “Of course,” she replied. “It’s gone past 1 P.M. Ari needs to show some common sense and call us if he’s going to be late. Let’s eat before everything gets cold. The bus service to Seria through Tutong can be slow and unreliable,” Mr. Lee said. “Do you ever think about how remarkable it is that salmon can swim upstream travel miles and miles with the last of their energy to return to where they were born? They have an internal compass, a powerful sense of home and belonging,” Rosie Lee added vaguely. “What are you talking about? You’re always full of secrets and mysteries. I will make an appointment for you to see the doctor after Ari’s visit. Get your medication adjusted,” Mr. Lee replied. Rosie Lee listened as he carried on to do all the talking.

From the kitchen, Rosie Lee brought forth a succession of food: stuffed tofu, rice salad, stir-fried water spinach, grilled prawns, slices of coconut cake. As she spread the plates around the table on the veranda, a bicycle bell rang out. It was the delivery boy with the afternoon newspaper. “Ari might like a copy as a souvenir,” Mr. Lee said. Rosie Lee watched him walk down the steps in his red wooden clogs, hand the boy some money, and stare straight at the frontpage. She could see colour leeching away from Mr. Lee’s face and could guess the headlines on the printed page.

by Elia Rathore

They tell an old story in my family of nobodies. They say a group of American businessmen go to some quaint European city. They force and plop into a small rustic restaurant with a Michelin star. They cannot understand the menu, and don’t care to try. They pass dismissive glances to one another. They tell the waitress, a pretty girl whose youth is gorgeous, devourable, to bring out whatever the house specialty is. They have the money, they want her to know, and the Company will write off whatever they demand. They are told with great difficulty and gesticulation that it will be five courses, an elegant presentation, a gourmand’s dream to remember. They all holler and smoke and drink in wait, saying things like, well, I might remember the girl, but all these nowheresville shitholes look the same to me. They think the Europeans uppity, stagnant, and the Europeans think them obnoxious, coming apart with pomp, but appreciate their business in stagnant times. They are served their first course; a giant snail is placed in the middle of the table alongside crusty artisan bread of the rustic attitude. They notice that the snail is alive. They notice that the waitress smiles politely and do not notice her explaining something in broken English that they find so ugly. They are already on to the next moment and she seems to be lingering at the last. They notice when she tells them to enjoy their meal in her broken English that they then notice is somewhat charming now that they have been released from it. They all look at each other, knowing innately what to do with the live snail, the giant slug squirming gently in front of them. They don’t discuss it, they don’t need to, knowing each other’s glances so well by then. They take their knives and start stabbing the slug, the snail, the breathing creature dead. They are in the midst of the stabbing when the waitress comes back with more drinks. They jolt annoyed when she screams a scream so loud you’d think they’ve murdered somebody. They watch her cry, sob, the manager comes out, he screams at them in his unintelligible language, he starts crying too, it’s pandemonium in this ancient restaurant that’s

used to hushed tones and solemn gratitude. They are approached by another disgusted diner who scoffs in their direction before telling them they just killed the beloved pet of the restaurant, an icon in his own right. They look at each other once again, not wanting to look at the diner. They get a little huffy, start questioning why these bumpkins would put a pet on their table. They are told that they were supposed to take his slime, his secretions, and have it with the bread. They all sit in silence for a bit while the waitress whimpers in the corner and the manager calls the police. They have a moment where each of them feels human again because they feel shame. They then remember who they are and where they came from. They look at the man who speaks English and ask him how much it’ll cost to make it all go away. They know it will go away. They have seen greater things disappear. They know other things now as well. They try but they cannot reverse the knowing. They know and the knowing stays with each of them in the night. They see it sometimes when they return home and face their children. They see it in the shadowy corners of homelike rooms before their eyes adjust. They know again when they are close to dying. They then remember.

by Nasta Martyn

Martyn

by Jenny Stachura

Our birth mothers in Korea Have they forgotten our names? Did they cut a wispy lock of our hair as a keepsake?

Do they remember our piercing wails, our birth weights, our flailing arms? Or did they gnash their teeth in disappointment when they discovered some of us were girls? Did they cry like dust because their lives were too barren to soothe a clinging child? With marks stretching half a planet as far as a knotted umbilical cord, cut, we can count the distant years like a rosary since we left them, straining in vain, with eager ears, for an answer to our echoing mewls.

by ChristineArroyo

In her dreams she goes through a corridor lined with armor – walls hung with metal plates, chainmail, bulletproof vests – closing in on her, suffocating her, making her small, small, small until she is a worm slithering under the door into a blackish blue infinity of water swirling around her.

And now she’s floating in armor - a horseshoe crab shell buoying her forward past dark beds of kelp and stingrays and sharks. Spears plummet at her and fishing lines with hooks like a gauntlet she is too exhausted to traverse.Ahook catches the edge of her shell and she’s swung up past the water’s surface into the air, her body crashing against the sides of the shell.

Hands grasp her, shake her, laughter, beer cans opening up, someone starts beating her shell like a drum or are they tapping her outer shell with a knife? The blows feel piercing, unrelenting. Please stop! She wants to scream but she has no voice, has never had a voice, will never have a voice, and so she waits in silence for the crack to come when the shell will be pried open and the hands and mouths will reach in, ready to devour her.

And she will scream but no one will hear her and her silent scream will become everyone’s silent scream as it echoes across the sand and ocean, into an infinity….

Later, as she bites into a crab sandwich she will feel faint and slightly strange, as if she is devouring something inside of herself, something that wanted to have a voice but was silenced by the sheer violence of the world.

MEMORABLE TIMES RUNNINGAWAY:An Excerpt from “GOING”

by Benjamin Joe

“They want to escape their lives,” he said to me. Well, I could give them that, I thought, I had escaped mine for a good four years just living it. Maybe even sell it for some money to a publisher.

That would be something.

This is what I wrote:

“I drove through the night – smoking cigarettes mostly – and trying to find music on the radio. For some reason, all my Bob Dylan CD’s felt old to me now and through my search, somewhere near Houston, I got reception of ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’and that was kind of cool because they didn’t really play much Nirvana on Massachusetts radio stations.

It was completely dark and I was driving about 75 down the highway in a starless night.

My friend from high school, and fellow drop-out, was sleeping in the passenger seat. He’d just spent the better part of two days making sure I didn’t get mugged in the French Quarter of New Orleans and tirelessly kept an eye on my back. Now he was passed out, doubtlessly dreaming of people and places we’d left behind. He spent most of Texas this way.

At one point, somewhere in the beginning of the evening, near Houston again, I saw great flames poking up over the landscape. Turns out these were oil-refineries that kept huge candles glowing throughout the night – burning untold amounts of gas. I still do not know what these contraptions are used for, but I didn’t care then. It was new, it was different. It was something. I had never seen it before and though many are not very surprised of things like this, I was a newcomer, and very thankful.

I had seen something that many in New England hadn’t even conceive of and that was enough for me to say I had grown.

Then, early in the morning, the sun came up behind me and we’d gone past Houston and SanAntonio on the 10 and I saw these pink-purple bands on the horizon and on top of them a great red plume of what I thought was dust but were actually mountains.

On either side of us was the horizon, and out there in the distance these mountains sprang up from–I don’t know where–probably El Paso, and I knew as I drove ever closer that I’d soon be crossing these and there I’d be. Icy peaks so far away from the October chill of Leominster.

I would be the one who saw them, the one who lived it, and that would make all the difference.”

So, that’s what I wrote.

by Elena Lelia Radulescu

Calling a hunting mate, an owl breaks off my sleep.

Night is still black like tar freshly poured on the highway.

In the kitchen, ghosts make themselves at home.

On a cushioned chair, Aunt Lena rests one leg, swollen ankle, veins bulging like earthworms after rain. She doesn’t complain of her day at the store counter, but wants to know what am I’m doing in America.

Where a church is built inside the shopping mall, so, you sin buying more than you need, later, press a button, light a candle, ask for mercy, shop more. Doamne, Doamne. From her pocket she fishes an old prayer book, pages stained by indelible faith.

Cousin Livia-Mara wonders about my dreams postponed month after month like visits to rude relatives. You don’t even have enough sleep to host a dream, holding two jobs, sending money back home where poverty shines like an empty cauldron in the moonlight. But what about you?

She straightens a few strands of her foxy red hair, fixes her fiery lipstick.

Aunt Vera spreads the tarot cards on the kitchen table.

Let’s see what the future will say What we know, what we don’t know what we will know.

She chants in a soft voice, her hands hovering over the major arcana. I choose a card, the eight-pointed star. The water of life and the sign of desire. No destruction is final. It’s still hope.

Outside, with a song, the mourning dove parts the night to one side of the apple tree.

by Jordan Nishkian

The only thing Google could tell me about “Kah-Vitz” was that the Toyota Vitz (or Yaris) was manufactured from 1999 to 2019.

I glance over the ingredients set out on my counter, reading the distressed recipe card out like a scripture:

“From the kitchen of Araksi.

● ½ cup butter

● 1 cup flour

● 1 quart milk

● 1 cup sugar

Boil milk, cook melted butter and flour until butter comes out.

Add warm milk gradually, then add sugar.

Pour in a buttered pan, dot with butter.

Bake till light brown on top.”

(Araksi Roxie was my almost-namesake.)

I pour the milk into a saucepan, waiting for the gas range to bring it to a tepid simmer. (Would I be so different?) I mumble over “until the butter comes out.”

Perhaps a roux?

I parrot what I’ve seen chefs do on Food Network and YouTube. (I may have been a better baker.) I turn down the milk’s heat when small roars break its surface. (I may have been a better Armenian.) I fumble with preheating the oven 375°?

(My hands and tongue would know what to do with milk and sugar.) A slow pour of warm milk over tanned roux; stirring, stirring until the sugar snows in and dissolves. (My eyes would know if this looked right.) I smear the butter wrapper over a cake pan and begin to pour.

(My mind would know what it means to “dot” something with butter, how to read the aybuben, how to cross an ocean for the sake of legacy.)

Ribbons of batter fold into the pan. (There are so many things my family is okay with losing).

I place the pan in the oven, then crouch in front of the window, waiting for my great-grandmother’s kah-vitz to brown.

by K B Kalaw

My father speaks of villages burned, Of family scattered like leaves in wind, His voice cracks, a dam breaking, Releasing floods of pain I cannot touch.

I was born here, in this land of plenty, Where his scars are invisible, Where my questions are naive, “Tell me about home,” I ask, But home for him is a graveyard, Aplace of both love and loss.

I hold his hand, silent, Wishing I could mend what was broken, But some wounds are too deep, They must heal from within, Across generations, slowly, Like the earth reclaiming what was taken.

by Fendy S. Tulodo

They stitched their new flag from five different grocery bags, hung it inside the tent like a question.