EIC/Interim Visual Arts Editor – J.B. Stone

Non-Fiction Editor – Skyler Jaye Rutkowski

Poetry Editor – Asela Lee Kemper

Flash Fiction Editor – Ben Brindise

Short Fiction Editor – Ian Brunner

Reviews/Interviews Editor –Courtney Hilden

Poetry Reader(s) – Lauren Peter

Flash Fiction Reader – Taryn Rutka

Hello Boils & Ghouls, it’s Halloween, and while I truly am the type to be more likely to let the spirit of Ol’ Hallow’s Eve never leave this nerdy, gothic little heart, although I truly am the type of nut who would decorate an Xmas tree in cobwebs and plastic bats rather than spinning tops and angel ornaments, I still realize the importance to some to pass over this feeling of the season to another. However, the talented writers and artists in our 13th issue make the most of the season in this issue. From collaborative comics by Patrick McEvoy & Rodolfo Buscaglia to the collages of Robin Lee Jordan, to the unapologetic poetic language of Quin Killin’ to the new world shaped in Raymond Brunell’s haunting The Tides’ Fragment, this 13th issue has been a pleasure to help string together.

We’re also excited to introduce a new feature: Variety Pack’s Video Packz, featuring the spoken word stylings of Buffalo’s own community stalwart and jack of all trades, Dallas Taylor and the wonderful experimental video poetry of Maxine Flasher-Düzgüneş on our brand new YouTube!

On more sobering terms, we find ourselves still, like so many of our own, caught in the turbulence of yet another Trump Presidency. As the Trump administration, continues to feel a lot more like a regime, Authoritarianism is not just an ever-encroaching shadow, no longer a dark cloud peering over the horizon. Nope. This dark cloud is here and has BEEN here.

As the arts are censored left and right, vital people and organizations being silenced, institutions capitulating to the fascist agendas, it’s more important that our voices are heard and seen, louder and more unapologetic than ever. If I’m reading like a broken record well, that unfortunately has been the world we’re living in. Yet, through all of this, it’s important to not only imagine, but fight for a better world, while embracing the beauty still here, along with the destruction.

Before you even get to the contents page, as always, we encourage everyone to explore the 2-3 pages worth of various organizations/mutual aid networks/activists/fundraisers doing some truly invaluable work. It’s important now, more than ever that we’re doing our part for those fighting against this tide of tyranny and come together as a community.

A special thank you to all of our wonderful submitters through this season, especially in poetry and flash, those decisions seemed tough, but everyone’s work was considered carefully through all of this. For many of you keep at it, we appreciate you! As always, a special thank you to my amazing Editors/Readers: Asela, Skyler, Ian, Ben, Maddie, Taryn, Lauren, & Courtney

Free Palestine, Free Haiti, Free Hawaii, Free Congo, Free Tigray, Free Syria, Free Sudan, and free all oppressed peoples from the cruelty of their oppressors.

Sincerely, J.B. Stone, Founding EIC + Interim Visual Arts Editor, Variety Pack

TW/CW: The following pieces may include mentions/scenes of death, loss grief, war, experiences with hate, bigotry, misogyny, SA

A donation allows PCRF to deliver on its humanitarian mission and send international volunteer medical missions to treat sick and injured patients while training local doctors. It also enables PCRF to send wounded and sick children abroad for free medical care they cannot get locally. As a 4-star rated charity for the past 11 years, you can be sure that your donation will have the biggest impact on the lives of children in the Middle East, regardless of politics or religion.

Medical Aid for Palestinians (MAP) works for the health and dignity of Palestinians living under occupation and as refugees. We provide immediate medical aid to those in great need, while also developing local capacity and skills to ensure the long-term development of the Palestinian healthcare system.

A donations-based aid initiative, led by Palestinians in the diaspora, working to supply emergency shelter and aid to displaced families in Gaza. Their work covers all regions, including the Refaat Alareer Camp, North, Central, and South Gaza.

All proceeds from our workshops are donation-based and go directly to Palestinians in Gaza. Suggested donation amounts reflect our desire to both honor the time. They have conducted a variety of workshops from zine-making to screenwriting to poetics to artisan crafting!

The Friends of the Congo (FOTC) is a 501 (c) (3) tax exempt advocacy organization based in Washington, DC. The FOTC was established in 2004 to work in partnership with Congolese to bring about peaceful and lasting change in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), formerly Zaire.

Islamic Relief Worldwide

Islamic Relief has worked in Sudan for nearly 40 years and remains by the sides of families caught up in the violence. Please support our life-saving work: donate to our Sudan Emergency Appeal now.

One month after the eruption of full-scale war in Israel and Gaza, we at Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), continue to grieve the widespread suffering and death. We are

calling for all parties to ensure the safety of civilians and medical facilities. As an independent and impartial humanitarian organization, MSF delivers emergency medical care where the needs for our expertise are greatest regardless of race, ethnicity, religion, or politics. We are also an international movement made up of people from more than 169 nationalities working in more than 70 countries. Many of our staff here at MSF-USA have friends, family, and loved ones in Israel, Gaza, or both, for whom we are deeply worried. All of us have colleagues working right now in Gaza delivering lifesaving medical care to people caught in the crossfire.

An Indigenous Peoples and First Nations rights organization who promote the legal efforts of protecting lives of the true Americans of this country. From addressing the conditions of Indigenous territory, to helping the legal fight behind groundbreaking protests at Standing Rock to Lines 3 & 5, Lakota Law Project has been taking their fight head on and continues to make the voices of Indigenous and First Nations communities heard loud and clear!

JFMF is a nonprofit agency that promotes justice for migrant families by providing support to individuals in the federal detention facility in Batavia, information and resources to families in the community, and advocacy both within and beyond the local community.

While our mission is to build and mobilize enough power to change Olam HaZeh, the world as it is, we also seek to embody Ha’Olam She’Ba – the world to come – right here and now. When you organize with us, you are part of building a Jewishness and Jewish life beyond Zionism We have millennia of Jewish history where our traditions and our communities were not bound up with support for an apartheid government. We have liturgy, poetry, rabbinic debate, jokes, theater, dance, film, and song. Organizing rich in ritual, culture, and art connects us to those histories, and strengthens us in fighting for a future where our people – and all people – live with freedom, dignity, joy, and belonging.

Breaking the Silence is an organization of veteran soldiers who have served in the Israeli military since the start of the Second Intifada and have taken it upon themselves to expose the public to the reality of everyday life in the Occupied Territories. We endeavor to stimulate public debate about the price paid for

a reality in which young soldiers face a civilian population on a daily basis, and are engaged in the control of that population’s everyday life. Our work aims to bring an end to the occupation.

We need consistent, mass-turnout, nonviolent disruption to stop business as usual and compel politicians to act. When we engage in direct action whether through a strike, a blockade, or a mass occupation we break through. People see us. People tune in. People engage. Our movement grows.

A grassroots 2SLGTBQIA+ organization deep in the heart of North Charleston, South Carolina, providing a safer space for the youths, and allies along with their families since 1995. Be sure to check out the history and be sure to donate to this wonderful local not-for-profit.

Autistic Women & Non-Binary Network is an ever-growing organization truly committed to empowering the lives of Women, and LGBTQIA+ folks across the spectrum, through the providing of various resources, solidarity aid, community publication, and fiscal support.

The National Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collective working to strengthen the fight against the tide and collectively raising awareness and fighting for the access to necessary reproductive health care.

A growing collective led by Black Women & Black GNC cyclists, promoting mutual aid, teaming up with programs such as seeding justice, and providing pop-ups/food drop-offs to help Black communities across Buffalo, NY. CGBT also actively run workshops, and programs on the decolonization efforts of mobility.

D.O.P.E. (Dismantling Oppressive Patterns for Empowerment) Collective is an anti-oppressive project-based collaborative primarily led by creatives and theorists ages 18-35. They also have chapters in Toronto, Ontario, Canada; and Philadelphia, PA.

[From the Website] Trans Maryland is a multi-racial, multi-gender, trans-led community power building organization dedicated to Maryland’s trans community. By trans folks, for trans folks.

Harriet’s Wildest Dreams

Harriet’s Wildest Dreams is a Black-led abolitionist community defense hub centering all Black lives at risk for state-sanctioned violence in the Greater Washington, D.C. area.

An incredible program founded last year by Buffalo, NY’s Poet Laureate, Jillian Hanesworth, Buffalo Books mission aims to expand literacy to the most underserved communities of buffalo through the expansion of book houses across the cityscape.

A network of resources, donation hubs, informational articles for the purposes of creating support to Indigenous Communities across the U.S. & Canada. With the Supreme Court set to gut the EPA’s ability to take on the ravaging effects of climate change; with a presidential administration refusing to shut down Line 3, Line 5, Mountain Valley, DAPL; and selling hundreds of thousands of acres of public land out west, we need to stand by the communities will know that bear with the most devastating harm from all of this.

The Galactic Tribe

Along with The Wakanda Alliance, an organization dedicated to creating educational thought-spaces within black communities. In these spaces, we examine works of art inspired by the many cultures within African diaspora, thus spurring insightful conversations between our audiences about the impact we can create when one combines space-time, culture and imagination! The Galactic Tribe also provides workshops and right now is calling for donations of clothing and sneaker drop-offs.

A local organization in the heart of the Allentown neighborhood of Buffalo, that has served as a true beacon to homeless lives across the City of Buffalo, and anyone in need. Their efforts range from providing food, resources for various shelters, basic essentials/supplies, spaces to do both laundry and shower. Buffalo Blizzard Group

If you are a Buffalo Resident trying to get through this coming winter and find the resources to help get you through this tragic storm the Facebook group Buffalo Blizzard group has been a super convenient tool for establishing the resources, calls to action, and as well emergency posts.

A local organization that has been a beacon in providing food and food rations to underserved communities throughout the city of Buffalo.

Flash Fiction

Colin Griffin 36

Gabriella Menezes 31

Katherine Garrison 47

Poetry

Quin Killin’ 55

Chris L. Butler 11

Christen Lee 30

Gospel Chinedu 70

Gordan Struić 28

Tajudeen Muadh 49

Tukur Ridwan 54

Short Fiction

Meria Cairns 60

Raymond Brunell 18

CNF/Essays

Cecilia M. Fernandez 38

Abhinav 35

Visual Art/Mixed Media/Comics

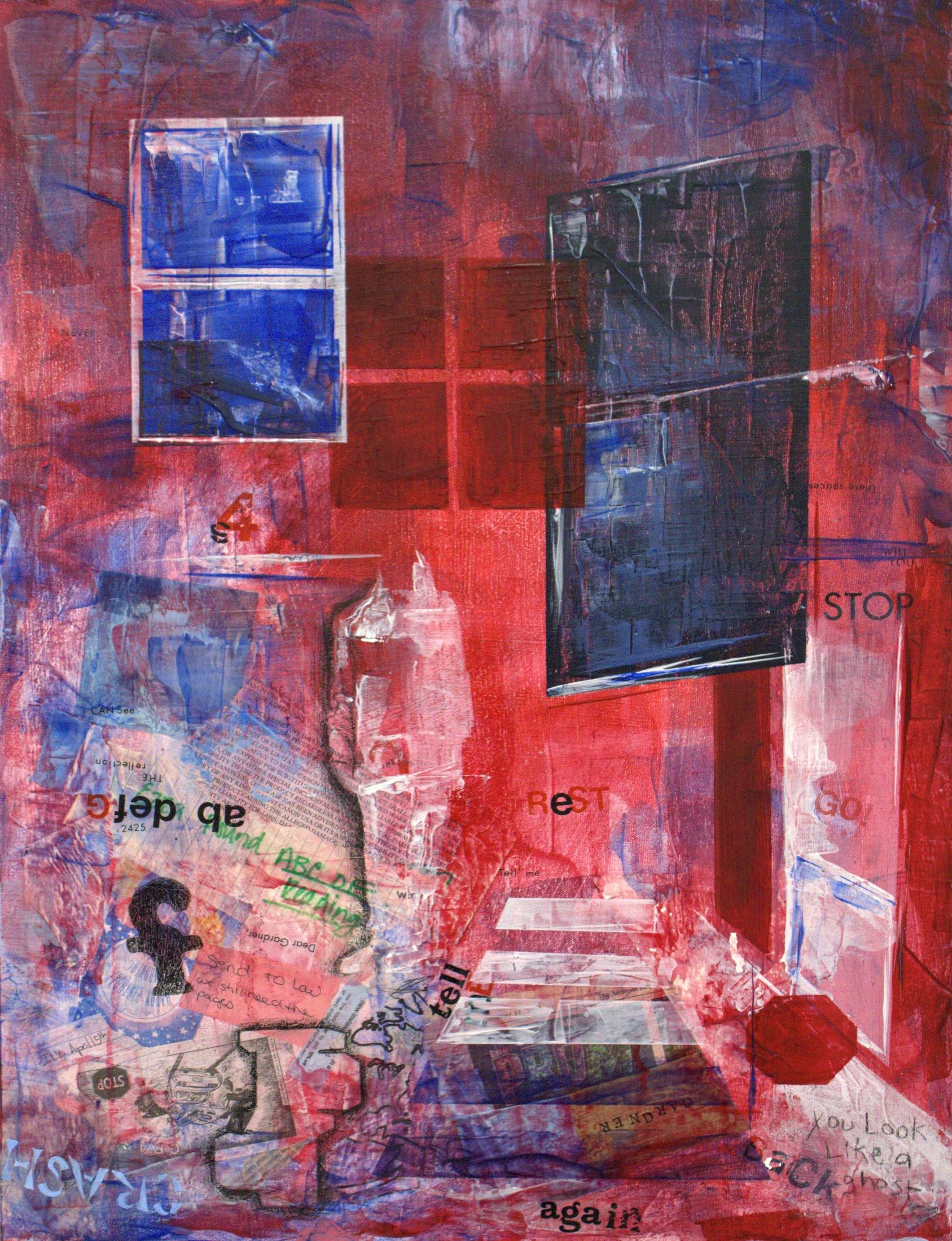

Gardner Astalos 10

Bianca L. McGraw 34

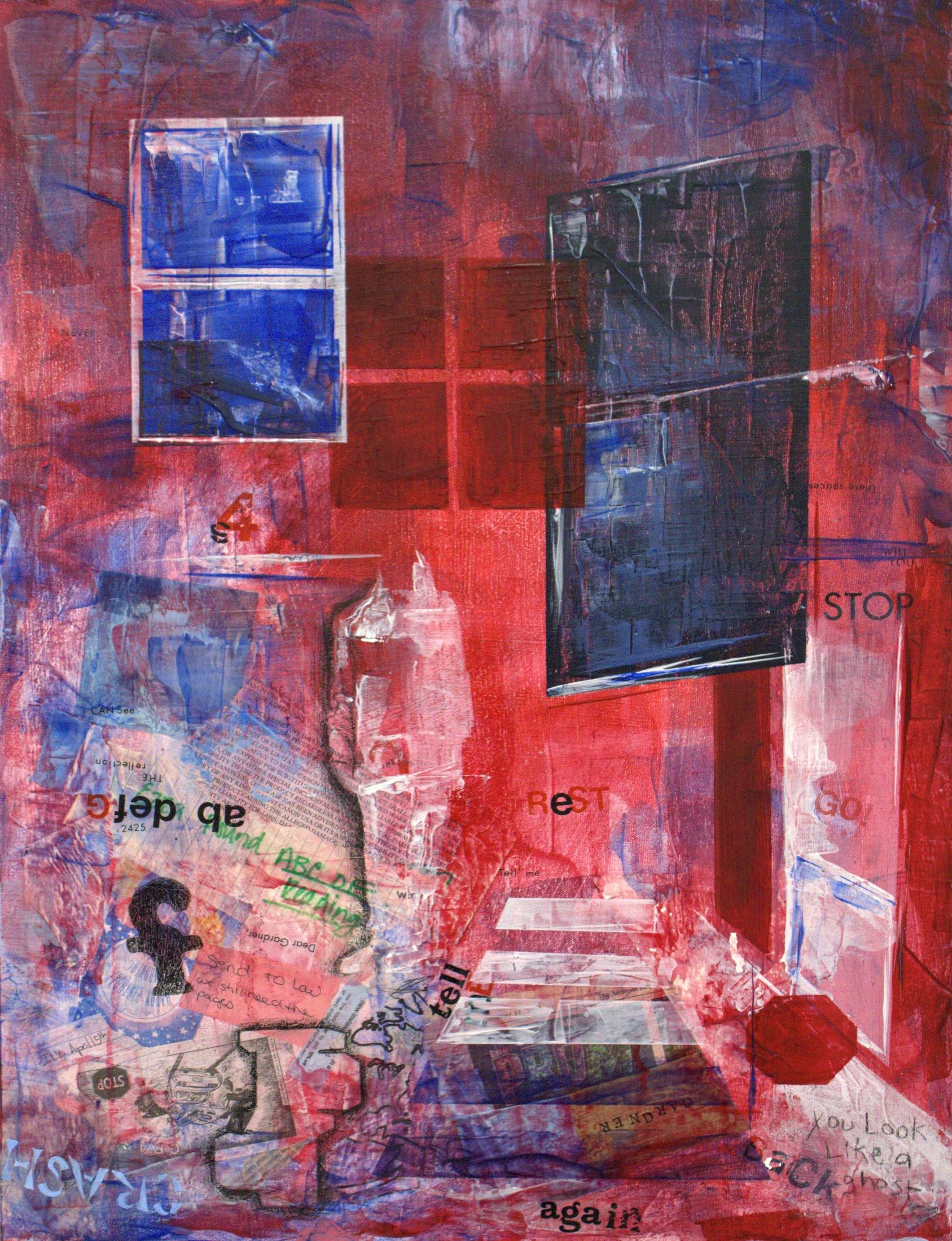

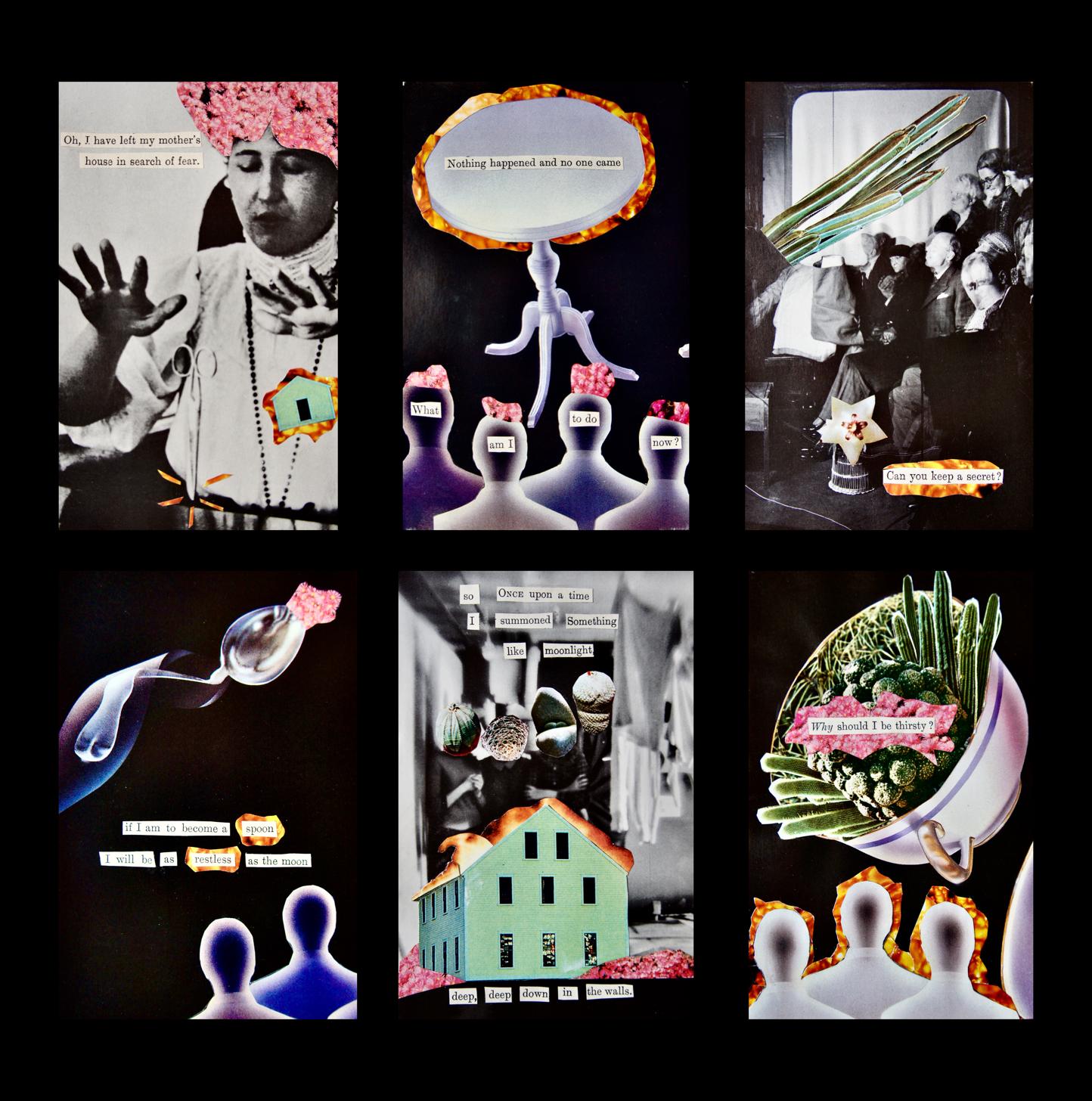

Robin Lee Jordan 27

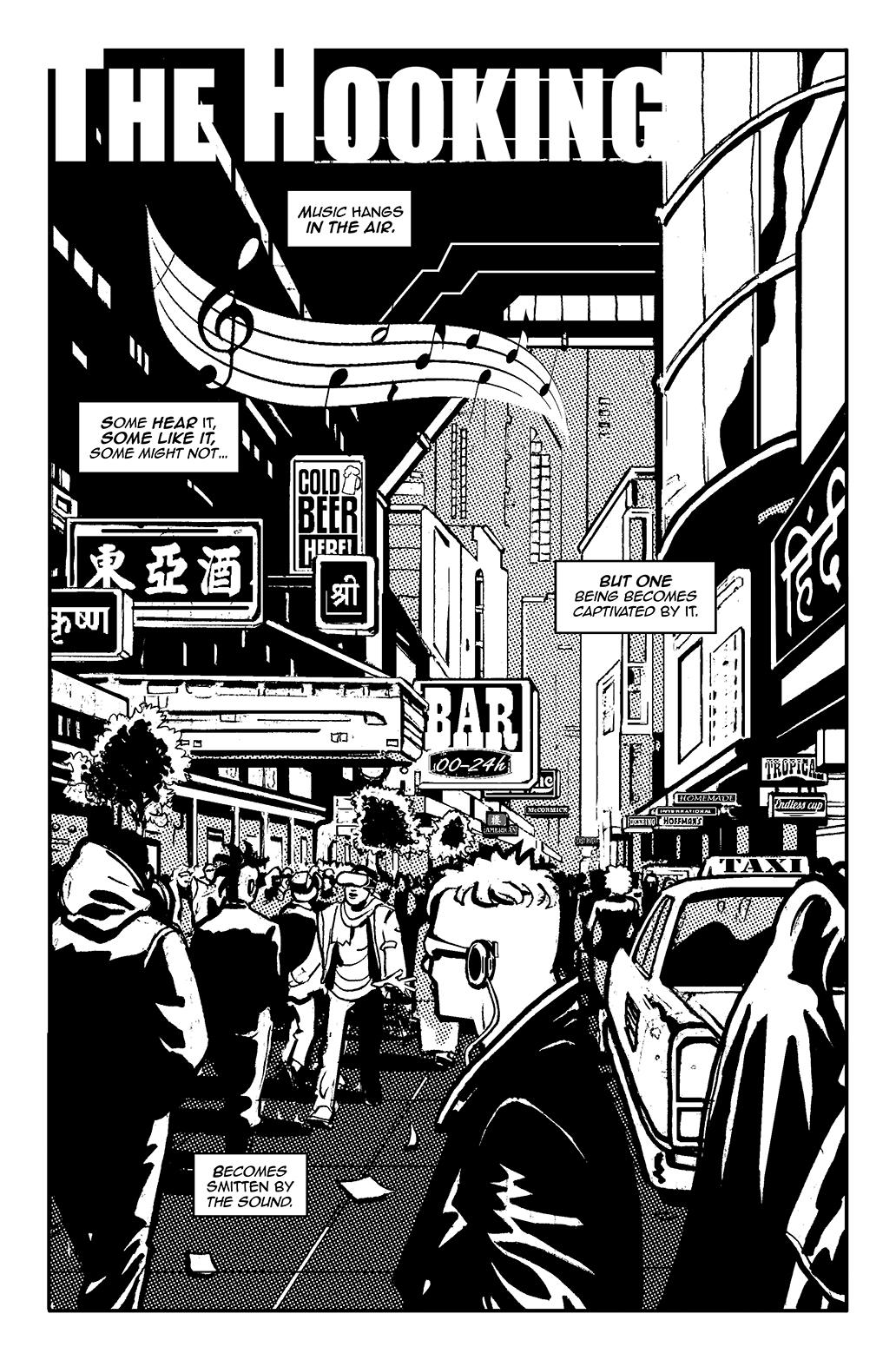

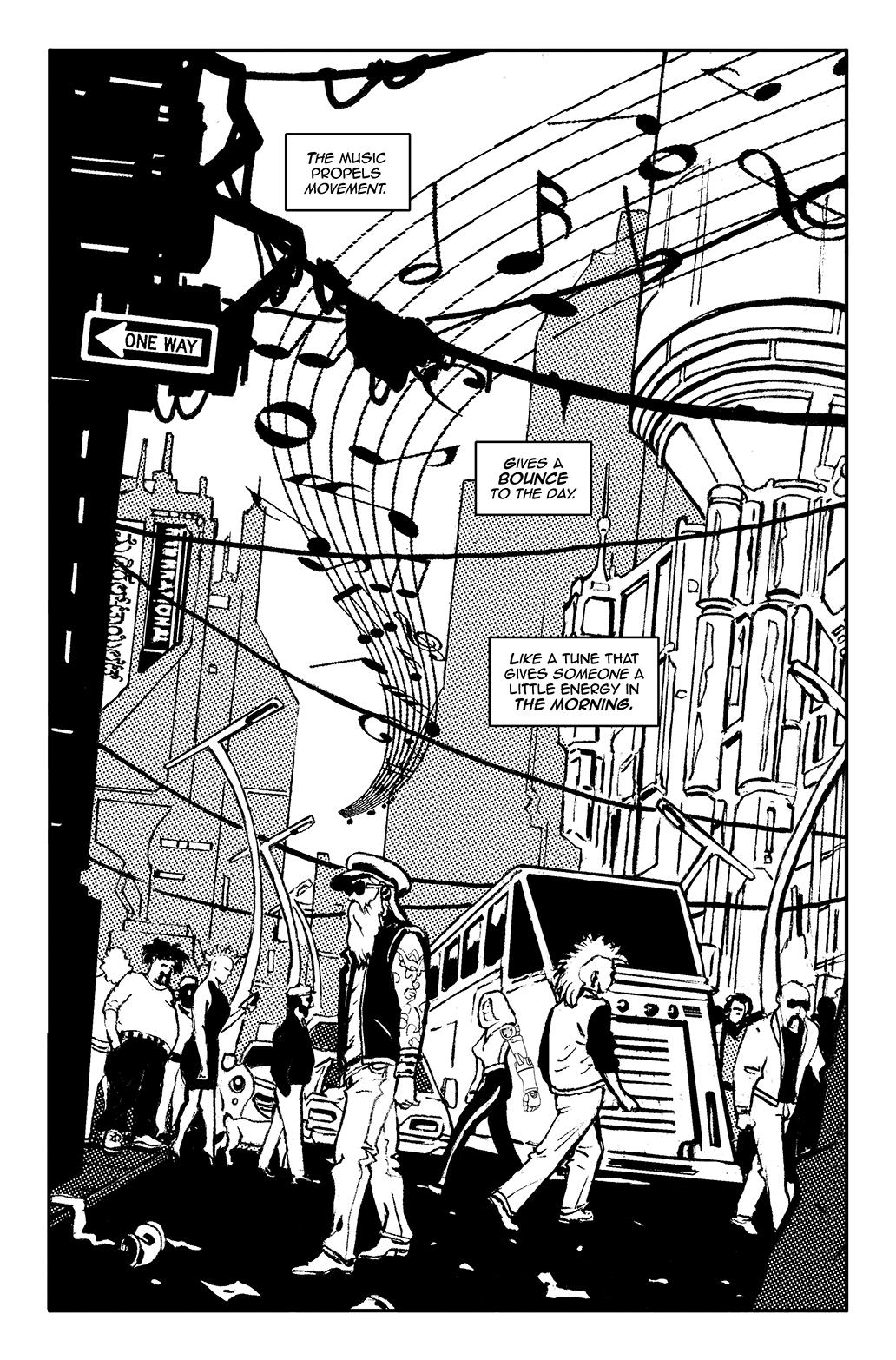

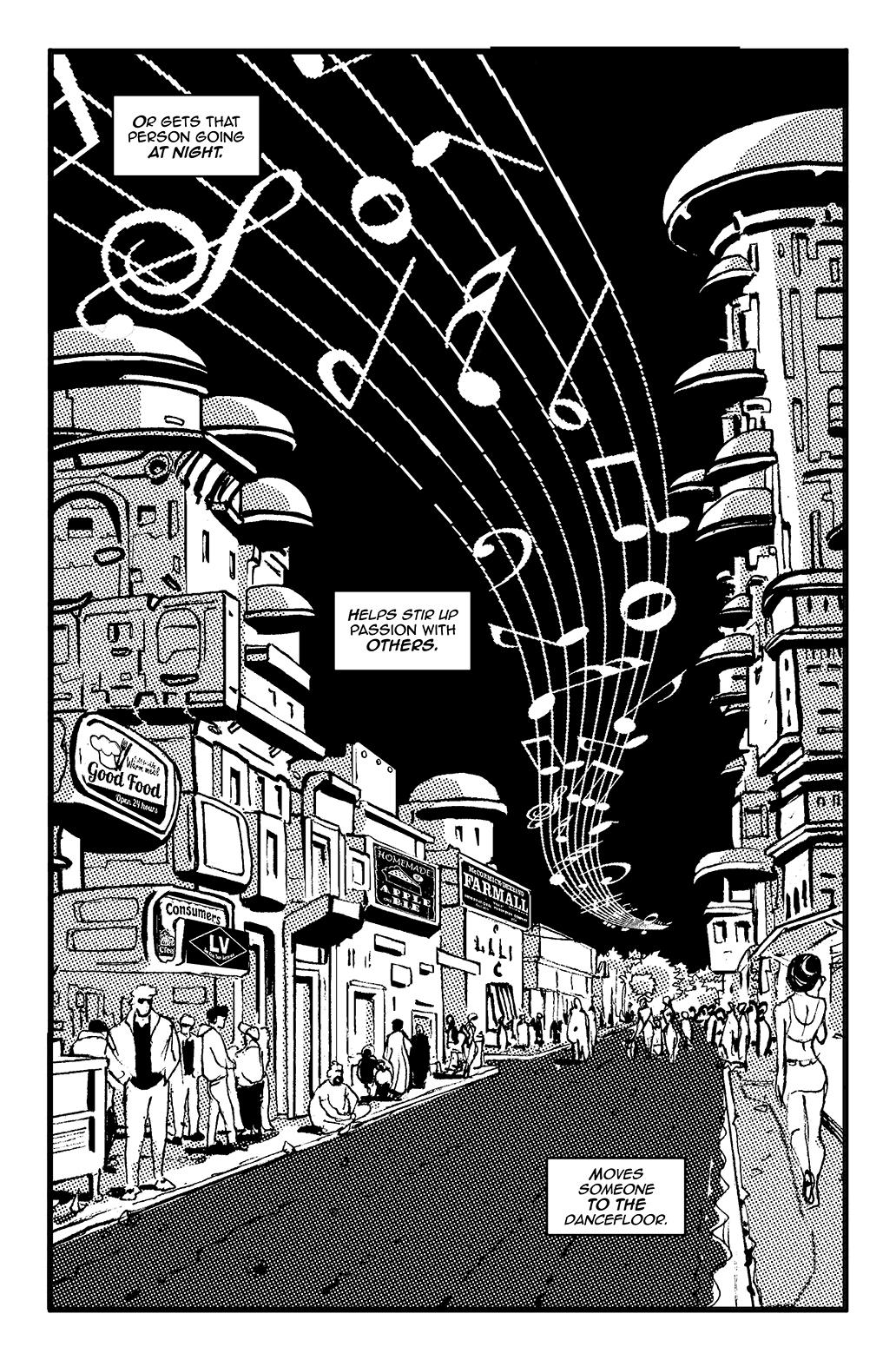

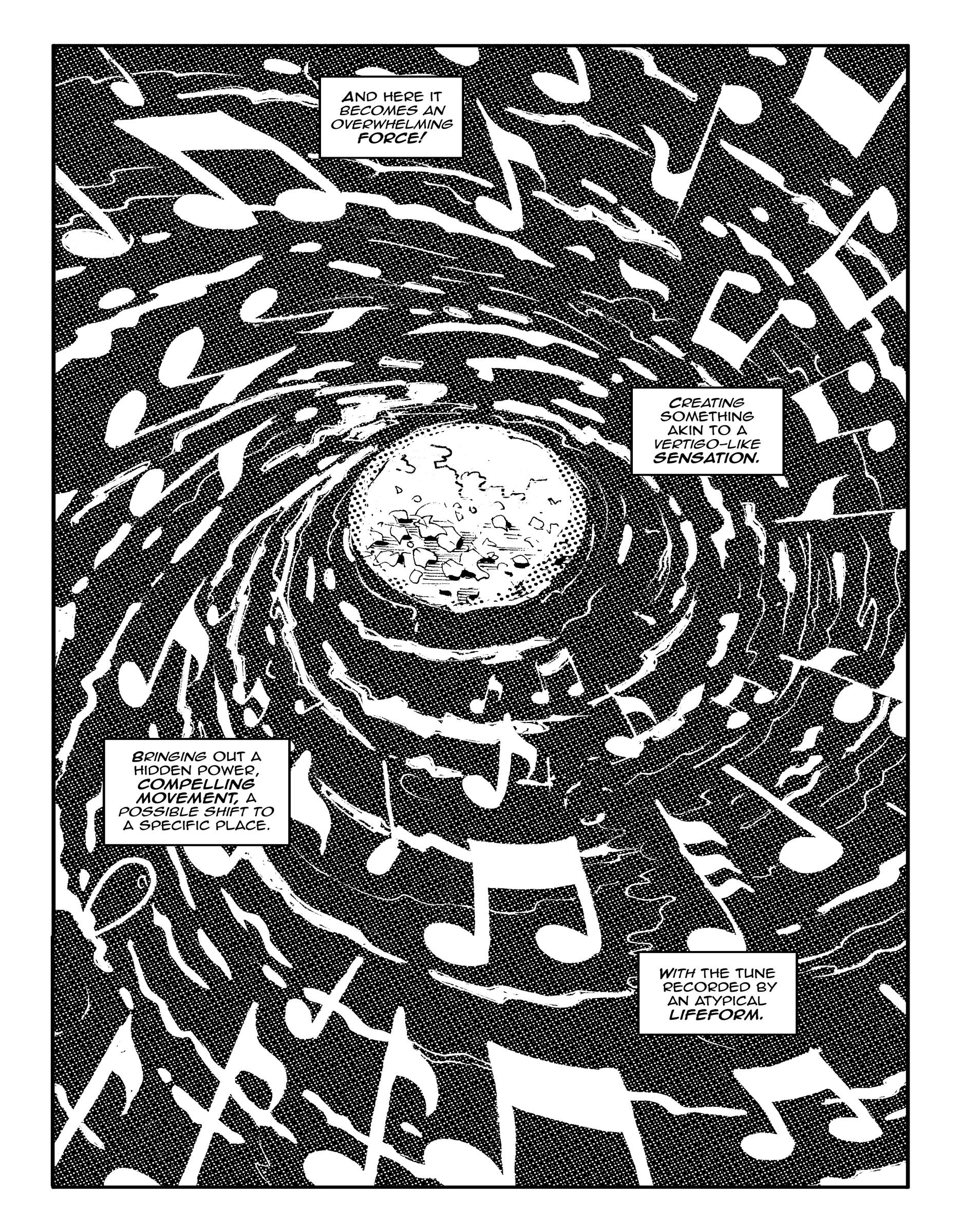

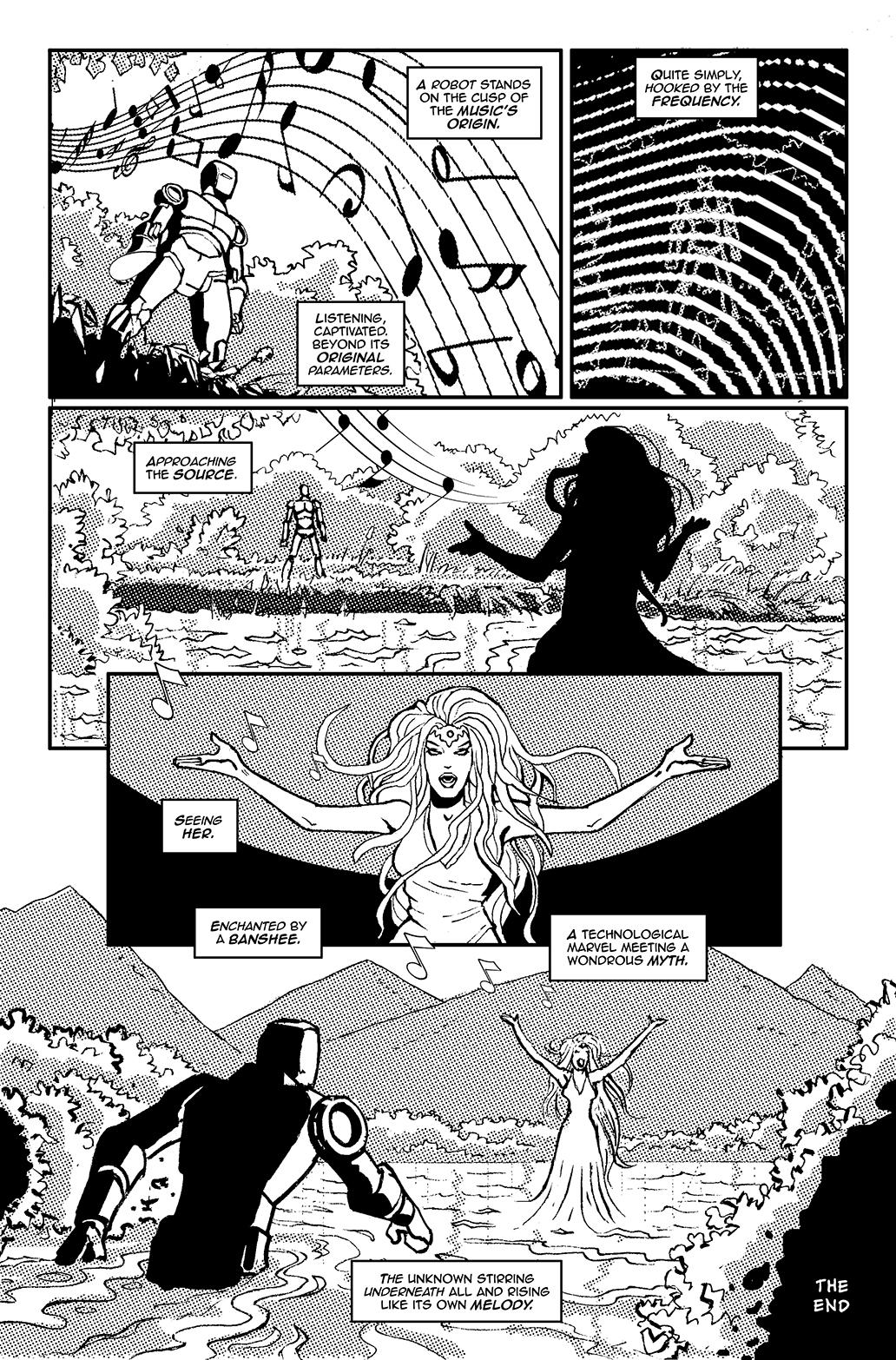

Patrick McEvoy & Rodolfo Buscaglia 13

Chava Ramirez 71

Ojo Victoria Ilemobayo 52

Reviews/Interviews

Alex Carrigan (A Review of Nicole Tallman’s

Dolce Vita/Let There Be a Little Light) 54

Video//Multimedia

Dallas Taylor

Maxine Flasher-Düzgüneş

by Gardner Astalos

by Chris L. Butler for Yasi

After we finish building a house in the encampment. Can we build a wall made of wooden pallets and forest green chain link fence metal to wrap around our shared values in the encampment? And can we bring all our best supplies to the encampment? Like students, faculty members, and locals? Residents, whose hearts, minds, and spirits stack up like red bricks, forming a woven Tatreez pattern that spells liberation Our elbows locked together like we are enjambed words on a page. The next thing I want to know as we rejoice about our love for liberation in the encampment Can we kiss in the encampment? Even if we feel downtrodden It’s important our spirits remain up It’s important we don’t let monsters destroy our love. I want to be clear I’m not saying we should make love here in this encampment this land is both public and sacred after all. It’s just that I think we should take a moment to bask in the kites flying above us and not the helicopters and their violent sirens Because we are we are shaping and molding the world we want to see right, right here in this very encampment. Even if the police bulldoze our hopes they will not bulldoze our hearts, and we can rebuild again tomorrow. But please, don’t let them break us.

by Chris L. Butler

After John Clare (1793-1864)

Descartes was wrong. I think, therefore I am not, who I think I am. Life has humbled my ambitions. Rain clouds pummeled them straight into the mud.

No meteorologist could have made such a prediction, a forecast of over thirty-five years in the working class.

Despite, O’ despite the educational attainment

Certifications inked with old English, no wealth amassed I knew my only hope was entertainment

Pouring out my soul like a faucet has saved me

I am everything I was and the nothing I am now

A cruel ratio that could drive a man crazy

Brackish mornings chafing the farm laborer’s brow I think I am not me anymore. Truly, I am a changed soul. Maybe that thought alone is how I cogito ergo sum.

by Patrick McEvoy & Rodolfo Buscaglia

by Raymond Brunell

The village of Saltstrand clung to the coast like a barnacle: half-erased by each tide, reborn with every gift the sea delivered. Old Man Hemlock, though never exceptionally tall, had kept the lighthouse burning for sixty years and always claimed the tide didn’t just bring things it brought time. Fragments of it, washed smooth and changed by the water’s endless motion.

Elias Thorne, widower, had lived all of his sixty-two years in Saltstrand. He’d seen time wash ashore: chipped china, rusted tools, even a porcelain doll’s head, salt-pitted but eerily perfect. The tide seemed to know when he needed reminders of what was lost. Now, a year after his wife Elara slipped away like sand through his fingers, the sea sent him pieces of his childhood, one tide at a time.

He first noticed it after a high tide, walking the dunes: a scrap of wallpaper, mostly faded, but still marked with sea lavender Elara’s mother’s favorite flower. That wallpaper had lined the hallway of their little house, the one his father built, the one that stood for almost a century before the Great Storm of ’22 swept it away. They’d thought it lost forever.

Then came a slat of painted wood, living room seafoam green his mother’s chosen color. Next, a rusted doorknob, smooth and familiar, from the bedroom where he’d dreamt a thousand dreams. Each fragment felt impossibly personal, as though the sand itself had sprouted them from memory.

He collected these relics and arranged them in the garden behind his cottage, a patch of ground sheltered from the worst winds, where sea lavender still grew for Elara. She’d loved how it swayed, “whispering secrets to the sea.” Amongst the lavender, he built a shrine to the past,

growing larger with every tide.

Elias had always been a collector Elara called him her “keeper of moments.” He pocketed shells, glass, stones trying to save what the tide might otherwise forget. Now, he was salvaging his house, his childhood, his lost family.

Then came the clocks.

He’d tinkered with clocks ever since Elara brought home a broken grandfather clock from the market, ten years ago. He loved the way the hands moved, marking time’s relentless, unpredictable pace. After Elara’s death, he began pulling the hands from broken clocks and planting them in the garden, as if they were seeds.

At first, it was whimsy, a harmless eccentricity. He chose the most striking, most evocative hands the ones that felt right in his palm. He pressed them into the earth among the lavender and waited.

The garden responded slowly. Grass bent just a bit more than the breeze allowed. The earth began to hum, deep and low, a vibration you could feel in your bones. And then, when it rained, he started to hear whispers.

They were faint at first, indistinguishable from wind and sea, but they wove through the lavender, drifting among the leaves the voices of his mother, his father, his younger sister, Elara, before she was his wife.

Elias? his mother’s voice, soft and just a touch regal.

Slow down, boy! his father’s, gruff but loving.

Elias, look at the starfish! his sister, Elara, was always delighted by the treasures the tide brought in.

He planted more clock hands, more seeds of time, hoping to bring the voices back more clearly, more often. He chose hands from different clocks, with various shapes and sizes, seeking a diverse range of voices.

The villagers noticed. In Saltstrand, anything odd was soon known. At first, it was only whispers, floating like sea lavender on the wind. Mrs. Hargrove, the baker, saw him burying a huge clock hand one morning; she raised an eyebrow but said nothing. Mr. Finn, the fisherman, gave him a nod and a wave, but kept his distance, treating the garden as sacred or perhaps cursed.

Rumors began to circulate. Some claimed Elias was conjuring spirits, that the garden was a portal to the past, a place where the dead could speak. Others, more practical, thought he was losing his mind a widower drifting on a sea of grief.

Elias didn’t care. He was too lost in the garden, in the whispers that grew louder with each rainfall. The grass bent deeper, the earth’s hum swelled, and the lavender seemed to sway with intent, as if listening, too.

During a heavy rainfall one that drenched the village in minutes the voices came in full. Elias stood in the garden, hands buried in the wet earth, rain soaking him to the skin, and heard them clear as bells.

Elias, come inside, you’ll catch a cold! his mother’s voice, sharp with concern.

Look, boy, the way the rain makes the sea sparkle, it’s like a thousand diamonds, his

father, wonder in his voice.

Elias, can we build a sandcastle? Elara’s voice, young and eager, before she became his wife.

He looked up, the rain blurring his vision, and for a moment he saw them: his mother at the garden’s edge, dress fluttering in the wind; his father crouched beside him, hands rough but gentle; Elara, a little girl with pigtails, eyes wide with excitement.

Elias? his mother again. He reached out, but his hand closed on nothing but rain.

The voices were real, yet not memories, but moving, breathing, feeling. The garden had become a tapestry of time, weaving the past into the present, the living into the dead. Elias didn’t know how it happened, but he didn’t want it to stop. He wanted to hear more, to see more, to feel the warmth of his family again.

The villagers’ whispers grew into murmurs, and the murmurs into talk. Mrs. Hargrove stopped by his door one evening, her face a knot of concern and fear. Behind her, a few neighbors lingered on the lane, pretending not to watch.

“Elias, what are you doing in that garden?” she asked, her voice low, as if the walls might have ears.

He looked at her, the rain still drying on his skin, the voices echoing in his mind. “I’m trying to bring them back,” he whispered.

She shook her head, pity in her eyes. “You can’t bring the dead back, Elias. You know that.”

He smiled, sad and wistful. “I know. But I can hear them, Mrs. Hargrove. It’s like they’re here, just for a moment.”

She sighed, shoulders sagging. “We all understand your grief, Elias. But this this is different. The villagers are talking, and not all of them are kind.”

Elias nodded, gaze drifting back to the garden. “I know. But I can’t stop. Not now.”

She left without another word, her footsteps fading on the cobblestones. Some villagers came to see for themselves, drawn by curiosity or fear. Others stayed away, their doors and shutters bolted tight, as if the garden might reach out to them, too.

Elias didn’t mind. He was too absorbed in the garden, too lost in the voices. He planted more clock hands, more seeds of time, and the garden flourished lush, vibrant, alive.

Then, under a full moon’s light, the garden changed. The lavender swayed in a wind that didn’t exist. The grass bent in impossible patterns. The earth’s hum grew so loud Elias felt it in his bones. The voices became a symphony, a chorus of the dead, yet alive in the moonlight. No longer whispers, they overlapped and broke like waves:

His mother, humming a tune from the war years a lullaby Elara later sang to their children. His father’s deep, genuine chuckle. Young Elara’s voice, piping and clear: Daddy, will the tide bring us treasure tomorrow?

Elias stood barefoot on damp earth, the moonlight silvering the planted clock hands brass, steel, even one of tarnished silver their shafts buried, faces tilted skyward like blind eyes. They didn’t sprout green shoots, not like seeds. Instead, thin filaments, almost translucent, spun from their buried ends, weaving through the soil, connecting to the roots of the lavender, the

dune grass pushing at the garden’s edge. The filaments pulsed with a soft, internal light, a slow, rhythmic throb that matched the deep hum of the earth. This was the sound of time, he thought, measured not in seconds, but in heartbeats, breaths, the patient erosion of stone by water.

He reached down, not to touch the filaments they were cold as deep-sea water but to trace the familiar grain of the painted wood fragment, half-submerged near the largest clock hand. His fingers found the slight ridge where the paint chipped, a flaw he’d known since childhood. The wood felt impossibly warm, and a memory surged:

The smell of linseed oil and turpentine, his father sanding this same piece after a storm. The rasp of the paper, the sharp, clean scent, the low murmur of his father’s voice. The memory wasn’t just recalled; it was there, superimposed on the garden. For a dizzying moment, he saw the porch, weathered but whole, saw his father’s broad back, felt the sun on his own neck. Then it snapped back the garden, moonlight, cold filaments but the scent of linseed oil lingered, sharp in his nostrils.

The voices swelled. His mother’s humming became words a lullaby she’d sung only to him. Hush now, little one, the tide is low... Not just sound, a vibration in his chest, a warmth spreading through his limbs, a profound sense of safety. He sank to his knees, the damp earth soaking him. He didn’t weep; the feeling was too vast for tears to form. It was home. It was love, unbroken by time or loss.

Then, a new voice a woman’s, older, wearier than young Elara’s, yet achingly familiar. His Elara. Not the child, but the woman who’d shared his bed, his worries, his joys for forty years. The voice was thin and strained, as if calling from a great distance or through glass.

...Elias? Can you hear me? It’s so cold here...

His breath hitched. The lullaby faltered. The warm safety fractured. This wasn’t a memory of comfort; it was a cry from the edge of the void.

“Elara?” he whispered; voice rough. He leaned toward the cluster of clock hands where the filaments pulsed with frantic, irregular light. “Elara, I’m here. In the garden. It’s working. I can hear you.”

A sigh, long and tremulous, like wind through reeds. The garden... yes... I see the light... but it’s so thin... so cold. Elias, I’m so tired...

“Don’t be tired,” he pleaded, clutching the wood fragment like an anchor. “Stay. Listen to the voices. Listen to Mother singing. It’s safe here. I’ve made it safe.”

Another sigh, deeper this time, laced with a sorrow that resonated in his bones. Safe... but it’s not living, Elias. It’s... echoes. Shadows. You’re planting hands, not roots. You’re chasing the tide, not the shore.

Her words struck him like a blow. The warmth of the wood turned cold. The lullaby dissolved into a dissonant hum, the filaments pulsed erratically, their light flickering like dying bulbs. The garden, so alive moments ago, seemed to hold its breath.

“You’re here,” he whispered, voice cracking. “You’re speaking to me. How is this not real?”

It’s real, Elara’s voice conceded, strain deepening. But it’s not me, Elias. Not the way you want. It’s a reflection, a ripple in the water. You’re holding onto the echo, not the voice.

He shook his head, desperate. “I need you. I can’t... I can’t do this alone.”

You’re not alone, she said, her voice softening, sadness filling every word. You never were. But this... this garden, these voices... they’re not me. They’re your grief, Elias. Your love, twisted by loss. You’re trying to hold onto smoke.

The filaments pulsed again, a final, desperate throb, and for a moment, he saw her. Not the young Elara, but his wife as she’d been in her last days frail, radiant, eyes shining with love and sorrow. She reached out, her hand almost touching his, but it passed through, leaving a trail of cold mist.

Let go, Elias, she whispered, barely audible. Let me go. Let yourself live.

The garden began to wither. The lavender drooped, its scent fading. The grass flattened; the earth’s hum dwindled. The filaments snapped, one by one, their light extinguishing like candles in the wind. The clock hands, once vibrant with purpose, became only metal, cold and lifeless in the soil.

Elias fell to his knees, grief crushing him. He buried his face in his hands, tears finally coming, hot and unrelenting. The garden was silent, the voices gone, the connection severed. In the silence, something else a presence not of the past, but of the present. The village, the sea, the wind, all waiting for him to rejoin them.

He looked up, rain washing his tears away. The garden was still there: the fragments of his childhood home, the clock hands, the sea lavender. Now it was just a garden a place of growth and decay, of life and death. He stood, his legs trembling, and walked to the garden’s edge. The tide was coming in, waves lapping at the shore, bringing new fragments, new memories.

He bent to pick up a smooth stone, cool and solid in his palm. It was just a stone, but it was also a story, a journey, a connection to the sea. He carried it back to the garden and set it as a marker a reminder of what had happened. The garden was no longer a place of echoes, but of beginnings.

As he worked, the sun broke through the clouds, casting a warm glow over the village. The whispers of the past were gone, but the voices of the present were clear. Saltstrand was waking fishermen setting out, children laughing by the shore. A few villagers paused at his gate, uncertain, but one Mrs. Hargrove offered a loaf of bread and a quiet nod. Elias nodded back, something like gratitude swelling in his chest.

He looked out at the sea, the tide still coming in, and felt a calm settle inside him. The garden was alive, not with the voices of the dead, but with the promise of life. And he was ready to live it.

He stood, brushed dirt from his hands, and walked back to his cottage. The garden would wait. The tide would keep coming. And he would keep living, one day at a time. The voices were gone, but the memories remained, not as ghosts, but as guides.

Saltstrand clung to the coast, half-erased by each tide, reborn with every new offering the sea delivered. Elias Thorne, the widower, would go on not as a keeper of moments, but as a part of the moment. The tide brought fragments, but it also brought hope. Hope, he realized, was the most precious fragment of all.

by Robin Lee Jordan

by Gordan Struić

At the edge of myself, thoughts scatter –startled birds beating against glass.

The mirror whispers, ¿quién eres?

My mouth stays closed.

Silence folds itself into the room’s corners, like a letter I never dared to open.

Some words only arrive in Spanish –soledad, sombra, olvido –as if grief needs another language to keep breathing.

When I exhale, it sounds like someone else’s name, fading before I can translate it.

Maldita soledad. (Damned loneliness.)

by Gordan Struić

The street surges –a river of elbows, eyes fixed on nowhere.

Faces blur, strangers spilling into one another without touch.

A catalog of mouths, open, closing, swallowing silence, spitting haste.

I try to speak, but the city chews my voice, spits out an echo that doesn’t belong to me.

By the time I stop, I’m just another step, another breath in someone else’s rush.

by Christen Lee

I think of us now as we were then

I’m still reckoning the damages before the fallout

patching holes along the northeast corner the smoothness of firm floorboards

fitting pebbles in cracks cool beneath our languorous feet that gape like disbelief the bedroom wall bathed in pools

the sun’s arc is lengthening of yellow moonlight the gray earth tilting our bodies intertwined as we pressed

and I’m beating out a bitter wind into the quiet hours of long years as though my life depended on it the limelight hydrangeas leaning their heavy heads

no asterism can revive against the frosted windowpanes these fallen stars Venus scintillating piercing the western sky

maybe loss is the thing this lost virtue of the darkening night that makes us most alive

by Gabriella Menezes

I saw a flock of angels at the Dick's Drive-In. I stared at them as my aunt pulled into the parking spot and we all filed out of her artificially pine-scented minivan. And few of them startled and moved out of our way as we walked up to the window to order our food. I soon barely heard my family talking about football and homework and whatever else. My mind was all on the angels.

You don't notice how different angels can look from each other until you see a lot of them all at once. There were dozens standing together on the warm pavement that day, each one completely unique. Each angel had its own set of wings, its own bright eyes, its own alien mind. The colors of their feathers blended together like the interior of a bismuth crystal, and they made soft sounds to each other as if trading lullabies.

I might have stood there forever if not for the greasy paper bag that was then shoved into my hands and the exasperated "Come on!" from my older cousin.

We sat on the curb to eat. My aunt went off, without any food, to smoke and make so many phone calls. I'd forgotten to ask for no toppings on my burger, and as I picked off every remnant of lettuce or tomato tainting my meal, I looked at the angels again. They looked hungry, I thought. Some of them were all fluff and bones.

"Don't even think of feeding the angels," my little sister said in the typical fashion of someone much older. "You know Auntie will be mad."

"I don't see why," my younger cousin butted in before I had a chance to speak. "Ya know, I think angels are kind of cute. Ugly-cute."

"They're dirty," my older cousin said.

"They can be dirty and cute," my younger cousin insisted. "Like stray dogs."

I didn't say anything. I pulled a bit from my burger bun and tossed it into the cluster of angels before us. They swarmed around it, each trying to grab for its share. I couldn't help but throw them more bread, then a good chunk of my fries. Time passed, and my attention never left the angels. I wanted others to see them the way I did, see how beautiful they were up close. I wanted to be their friend. It seemed like if I just stayed and listened for long enough, I would understand what they were saying. Instead, there were the sounds of wrappers being crumpled up and the ends of milkshakes being slurped.

My aunt emerged from around the corner, stomping out a cigarette butt and adjusting her sunglasses. She told us to hurry up with our trash so we could get to 7-11 before it closed. I didn't tell her that it was open twenty-four hours a day. My sister and cousins soon got back into the minivan, pushing and shoving and joking about 'filthy animals'.

Just as I was about to get in, I saw an angel feather at my feet. It was perfect, shiny and silvery like liquid metal in the sun. I had never seen an angel feather that big, and certainly not one so pristine. It suddenly seemed obvious that the angels had left it there just for me, a pretty gift in thanks for the food I gave them. I picked it up and it felt lighter than air, as if it would float away like a balloon if I let it go. Holding it felt magical, electric, and I knew that I would understand angels better from now on, because I would keep this perfect silver feather forever.

"Drop that!" my aunt screeched. "You'll get rabies! Angels are disgusting!"

I dropped it.

As I finally got in and we pulled out of the Dick's parking lot, I felt like I'd left a bit of myself on the pavement with the feather. I didn't say that angels weren't mammals and thus couldn't have rabies. I didn't say that they weren't disgusting. I leaned against the window, my eyes glued to the few angels up in the sky, and whispered that I was sorry.

Then we went to 7-11.

by Bianca L. McGraw

by Abhinav

Slanted rain clatters on the tin-shed and time dissolves into a sheet of static you are a dazed thing living some other life that smells exactly like this. Damp. Suspended between nothing and nothing. Which leaves you ashamed. You wanted a life without memory, for things to keep you on the edge not know whether the woman by your side wants to save you or blow your brains out instead. But she just walks out of the room and the walls look like childhood. Shadows flicker on the linoleum and you wonder what your father thinks about outside of being a father. What do the walls look like to him? Does he think of himself from outside of himself and collapse life into an accusation? You wonder what his verdict is if he remembers you as a knot in his throat or a blur on the sidewalk. On the phone your mother informs you that he has been crying all night, his father has been dying all night. Which is unlike them, but it makes sense. She says you are needed when the worst comes to pass there are rituals; your shoulder is essential, which arouses in you a strange sense of loyalty. The kind that the living has in the face of death. Pure. Tactile. The kind that could save the world if it held its gaze still for a while. But there is always a fidget the peripherals leaking with a hum that refuses to settle.

In the midnight train, you forage with several hundred for an empty patch, and a punch lands on the face of a man adjacent to you, from the fist of a man adjacent to him, and no-one has time for any of it, so it goes nowhere. When the train shifts, you settle into each other like grains of sand in a jagged terrain. Outside the window, gradients of emptiness, until a certain whiteness creeps in then a wound in the horizon, and a comma goes fluttering its wings into the dawn to rupture the blank. This is the part you like without memory, you won’t remember most of it. There’s nothing before and nothing after. Just this eternity of inbetweenness rattling along the terrain a litany of exhausted faces swaying back and forth. In the other life a trail of his voice echoing, from the evening he told you that one day, he will fall asleep and not wake up. That you’ll have to carry him as everyone sings ram naam satya hai, satya hi gatya hai that he’ll die like everything has to die, and yet nothing ever dies the world is just one endless syllable leaking in the peripherals. It doesn’t add up, but you love him, so you go along. That evening stumbling into the night when his son, your father, took a swing at you for reasons you don’t recall. You ducked; he missed. He made you pay the price for it. You know the gist of things. There will be gestures, there will be howling, there will be a distance between everything and everyone converging at nothing. There will be a body on it a face of a man, still as a stone dreaming eternity. Your father wouldn’t be able to stand the sight of it. Neither can you but that isn’t as important. He is the son; his grief is infinite. You’ll get yours when the day comes. You both know this. You’ll put your hand on his shoulder as he sobs. There will be a tilt in the world leading to emptiness, like in that dream of childhood with all the leaves wilted. This is the course of the world. Nothing will happen outside of it. Even still, one day, you’ll have had a life of it.

by Colin Griffin

I enter the small office and upon invitation, take a seat by which I mean I leave the chair where it is but sit on it.

The window shade is inexplicably drawn by which I mean down not rendered obtusely in charcoal or India ink

The walls are papered with a tremendous display of peafowl brilliant greens and blues dominate with some gilt details and bright orange and yellow appendages for contrast

A few of them blink at me as I enter The bird at the desk though is all business.

So why do you think you require a CPAP machine?

I volley: do you get a broad range of responses to that question?

A bronze rabbit on her desk shifts uncomfortably She is unperturbed and produces a case from her sleeve.

This is the ReverseHorn 57 she trumpets taking a smooth blinking box from the case. It beeps rhythmically by way of introduction I nod and ladle a reduction of uh-huhs over her explanation of the many automatic features designed to take all the cumbersome decision-making out of my care They’re all switched off for now I’d like to try the machine now by which I mean I’d like to sleep here in her office Instead, I submit to be fitted for the breathing apparatus How did our ancestors handle this?

By this, I mean lousy sleep not the snorkel currently being strapped to my head Did they simply perish when fireside they failed to wake up and flee with the others as the wolves came in the gloaming due in large part to their having dozed off with their dinner in their lap thanks to their interrupted REM sleep the preceding night?

A particularly plump peahen rustles her plumage at this in a way I take to be a little condescending I hope this works, I think I suspect my subconscious isn’t going to be on board with it. But it’s cagey during sunlit hours, as I’ve systematically oppressed it for decades like a good citizen does This whole thing feels more like a dilemma than a solution but isn’t that life when constantly solving non-problems?

The rabbit’s jeweled eyes twinkle at this and I know I’ve had a little moment of enlightenment here in this dark office

The sandwoman now has placed her own mask on and gone pleasantly to sleep, so I see myself out, by which I mean I leave without formality or greeting

At the front desk, I take out my government-issued proof of existence, shave a few more hours off my life and slide it all across the counter

As I leave, I can’t help but yawn

by Cecilia M. Fernandez

1.

Drive down the street of any American neighborhood, and you can, for the most part, easily spot a Republican. The telltale sign is none other than the red, white, and blue flag flapping from a weathered post screwed into the garage door, wall, or porch. If it’s not there, you can see the flag wrapped around the antenna of a black pickup truck, latest model, parked in the driveway, or spread out on the dashboard. It may be glued to a baseball cap proclaiming Make America Great Again, both a slogan and a subset thirty-three to forty-eight percent by some counts--of the Republican party.

Bird Road in Miami is no exception, but the driveway I turned into belonged to my son, Max, where the campaigns for president 2025 grip the minds of many.

From the swale, I see him and his brother-in-law, Edward, gripping two uncooperative, wind-borne flags one bigger than the other as if in a contest of tug of war. The flags fly with a force that threatens to overcome the men’s strength. Finally, triumphantly, they unfurl Betsy Ross’s creation, not gently, but as if their lives depended on subduing a wind that, on this March morning, had unexpectedly pushed its way in from the Gulf of Mexico, perhaps to be named the Gulf of America if President Trump has his way. The gusts spur the flags to kick like broncos.

Edward, a big forty-year-old man, holds down the rope. He wears tattoos on both arms and back, flesh tunnels in both ears, and a beard down to his chest. Max, thirty-two, slimmer, tattoo on his forearm and calf, no piercings, trim beard, is up on a ladder, hoisting one of the flags up a pole, 100 feet in the air. They wipe sweat from their brows and snot from their noses with their sleeves. A short pause. A few more vicious, no nonsense pulls and up goes a smaller red flag. White block letters scream: VOTE FOR TRUMP!

The three of us throw back our heads, stare up into the sky a moment of blazing glory illuminating the men’s faces and watch the battered cloths straighten out against low hanging bleach-white clouds.

The men bump fists. “We did it!” Max exclaims.

I hold onto my heart. The wind holds onto the flags.

Here, in this city at the southern edge of Florida, where 447,323 Republicans and 407,801 Democrats registered to vote, the wind pulls at my sweater and hair, and I remember another group mesmerized by a personality, in the clutch of a crowd’s power. That time, the leader was Jim Jones, mastermind of the 918-people mass murder-suicide in Guyana, the dead having followed his order to swallow poison.

2.

Word reached the newsroom of the San Francisco Chronicle that Congressman Leo Ryan and one of our reporters, Ron Javers, had been shot at an airstrip in Guyana. It was November 18, 1978, and Javers was covering the People’s Temple, an agricultural outpost in the tropics. Ryan died, and Javers ran off into the jungle.

City editor David Pearl, tie loosened, sleeves rolled up, yanked on the copy machine spewing Associated Press updates. “Go right now to Jones’ headquarters on Geary Boulevard,” he yelled at me. A photographer joined me, and we drove to a white brick building once a Scottish Rite temple, between Fillmore and Steiner. “We have to interview those who stayed behind,” I said. “I wonder if they’re talking.” We pulled up on the sidewalk. The national media and relatives of members crowded around while I pressed forward to see beyond the railings that circled the compound.

“We didn’t do nothing wrong,” one woman told me. “We live here peacefully, away from

all the world commotion.” They were a poor group mostly Black dressed in clothes that had been worn to threads, hanging loose from bony, underfed frames.

Then someone shouted something about a suicide, and the police came. Horror and pity mixed in my voice as I continued to ask the questions I’m still asking about another possible “cult.” What made you sign up? What made you lose yourself to a man with questionable credentials? What does this leader have to offer you? Why do you worship him?

3.

In my mind, Jim Jones’s followers fit the profile of most of today’s MAGA devotees: low income, uneducated except for Elon Musk and other billionaires donating and hoping to profit from Trump’s second presidential campaign alienated from society, believing themselves to be victims. Max didn’t fit the description. He played basketball, football, rugby, the piano and the French horn. He went to college. What made him turn a blind eye to the egregious behavior of the country’s ex-president as he campaigned for him through inflammatory social media posts against Democrats? With ninety-one felony counts, thief of classified records, promulgator of racism, sexual assaulter, deficit builder, and finally, champion of Hitler, Trump entered the mind of my son, and I wanted to know why. When had my son, growing up in an affluent, liberal household, embrace the virulent philosophy of the right? How did I not see it coming?

Psychologists say boys and men like my son usually have a low risk of radicalization. But then something happens. Inside their minds, they feel different, frustrated in their attempts get a good job, make enough money, get the right girlfriends. In the journal International Sociology, Janja Bersnak writes, “The common thread is marginalization.” Despite a privileged upbringing, Max felt his social environment excluded him, and he had to look for other social networks where he would be accepted and where he could identify.

I try to connect the dots.

In fourth grade, I found him sitting by the side of the road, having walked out of afterschool care. He was angry, he said. The teacher was mean, too many kids around the basketball hoop, someone called him a name. The day before high school graduation, a teacher called saying he couldn’t graduate unless he paid a twenty-dollar book fine. Who cares, he said. I rushed to pay, fearing he wouldn’t be part of the ceremony. After high school, restless, searching, he joined a Baptist youth group and embraced the Bible. In college, he walked out of a class, shouting that the professor didn’t know what he was talking about.

He left the Baptists when he met a dance teacher at a high school where he taught music to a marching band. She expressed disdain for the middle class, for college, and wanted to live off the grid. He agreed. Their voices echoed the long ago 1960s counterculture, a left-leaning, almost anarchist philosophy.

After their breakup, he went to work for American Cruise lines. Exhausted from partying on his off hours, he fell asleep in the laundry room and was fired. “I don’t need college,” he said, “I’ll find something else to do.” Starbucks hired him as a barista; he came home angry every day, saying the customers verbally abused him, wasn’t making enough money. He smoked cigarettes and pot, drank alcohol. After that, he worked at a call center with felons who couldn’t get any other job; next, he worked in the warehouse of an international surge-protector manufacturer.

A few years of this, and his luck turned. The manufacturing company hired him as a sales associate. He met a young woman with whom he now has two small daughters. They bought a house. “I never thought I would have a family,” he said. Now he had a purpose, a motivation to get his life in order, but still with a need to belong to something outside of himself.

Unbeknownst to me, the woman’s stepfather, a retired police officer and conspiracy

theorist, became a frequent visitor, passionately lecturing about MAGA ideology: “We need Trump to take back our country,” he said.

In a Vanity Fair article, “Men in Red,” Mark McKinnon writes that a “rash of young male would-be voters” are rushing to the Trump campaign, “some disaffected, some adopting Trump’s macho posturing, some just awakening to how politics affects their day-to-day.”

Burdened with the cost of a mortgage and two kids, and having dropped out of college, Max believed he couldn’t make ends meet, blaming the economy on President Joe Biden and on the constant stream of immigrants crossing the border.

He called out government corruption, demanded fewer taxes, celebrated Moms for Liberty’s crusade to ban books, and condemned gay and transgender people, who, he believed, coopt children. He posted videos and podcasts from conservative sources that I debunked through messenger, fearful of what would happen if I didn’t, saying I wouldn’t discuss any idea not backed by credible sources. I frantically looked up counter arguments and forwarded them to him.

“I know you are not a racist, nor do you hate gays,” I said. “You are not an oppressor of women.” He smiled, all knowing, not engaging.

Then a memory.

Flipping through a college textbook on school discipline some years ago, my eyes stopped at a highlighted paragraph describing a condition that immediately resonated. It’s called oppositional defiant disorder. The Mayo Clinic defines it this way: “a frequent and ongoing pattern of anger, irritability, arguing and defiance toward parents and other authority figures. ODD includes being spiteful and seeking revenge.” This could be it, I thought. Risk factors, researchers say, include genetics the way nerves and the brain function and the

environment such as parenting issues.

I remembered that, as a child and young adult, my behavior mirrored Max’s. I, too, stared down authority: my father, abusive supervisors, men with power. We both come from divorced parents, but it seemed to me that Max took defiance to another level.

He hated authority, often doing the opposite of what was asked of him please Max take out the trash and then laughing about it. Trump, it appeared, provided the inspiration for him to oppose everything that made him feel a victim of forces beyond his control. This didn’t make sense. Max hated authoritarians. The difference was that Trump connected as a fellow victim.

“We’re all victims,” he declared at a rally.

My son found a new philosophy he could get behind, viewing Trump’s belligerence and lack of political correctness not only as a symbol of masculinity but as rebellion against the status quo that he believed caused all his personal problems.

As Max went through the quintessential search for self, he may have questioned what it meant to be male in a misogynistic world. Here was Trump saying it’s OK to grab women by their private parts. It was even OK to break the law in public. In 2016, Trump said: “I could stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody, and I wouldn’t lose any voters, OK?”

In post-Obama America, the “orange man” wiped out white male powerlessness.

4.

After dinner, I sit down with Edward, his wife Tiffany, Max, his wife Maria and their kids to watch a Mixed Martial Arts competition on TV. Maria’s mom, Sonia, and stepfather, Jack, join us. News cameras catch Trump and Ivanka walking into the hallway and sitting in the audience. Admiring murmurs hum all around me. I empty my mind, open a coloring book and hand some crayons to the toddler.

“Inflation, gas prices, immigrant criminals,” Jack shouts. “All because of decrepit Biden

and that communist Kamala.” He looks right at me.

I’m jarred out of complacency. “Why don’t you look up the real reasons,” I say, clicking on google and reading from what I think is a credible source.

“The media is in cahoots with the liberals,” he storms. “You’re nothing but a snowflake, a socialist.”

I go into remote control mode and, without the help of google, I start making arguments that to me, make sense. “The corporations are taking advantage of the economy,” I say. It becomes evident that I am wasting my time. Anger on both sides borders on going medieval.

He jumps to his feet and opens the door to the outside patio. “I’d rather go outside and contract malaria than talk to you,” he yells.

I don’t know how I made it to bed on my single inflatable mattress that night, the one I struggled to inflate after Max refused my request to do so. I take a sleeping pill. Outside, I hear Max defend me: “When you start to get personal,” my son said, “to me you’ve lost the argument.” Referring to Jack. I’m surprised, but, I figure, I’m still his mom.

I don’t know what I’m doing there, and I want to leave. I hear Edward and Tiffany go to bed on the pull-out couch, and Sonia and Jack say goodbye. I push in ear plugs.

The next day, we go to Sonia and Jack’s house. Jack walks over to me and reaches for my hand. He apologizes. I don’t know what he is apologizing for because, at that moment, I don’t remember what we said last night. It must be about the name calling. I speculate that Max and Maria asked him to do so, since I believe the man wouldn’t have done it on his own.

“We are shaking hands because we are never going to speak about politics again,” I say.

“It’s Ok,” he says, giving me permission to exist. “There was one family member a long time ago that was a liberal. She used to date former democratic state legislator Claude Pepper.”

I laugh and shake my head. He’s trying to make me believe he is open-minded.

Everyone goes to the pool but Jack and me. We sit on two recliners facing each other. The conversation focuses on his children and his twenty-year stint as a police officer. I try to get a word in edgewise but fail. He dominates the conversation. I talk about my other son Anthony and his wife’s less than kind treatment of me.

“I would never allow that,” he says, “because I am an alpha male.” Does he know how ridiculous that sounds? He starts outlining conspiracy theories surrounding Kennedy’s assassination. “I’m retired, so I have a lot of time to research this.”

Later that night we go to the movies to see the right wing backed Sound of Freedom about sex trafficking of children. After the film, in the parking lot, Jack says, “The Hollywood people use human trafficking to harvest these children’s parts so they can stay young.”

“Didn’t we just agree not to talk about politics!”

Out of nowhere, he starts imitating an effeminate man.

I turn away and climb into Max’s car.

Back at home, Max puts the toddler to bed. I hover near the bedroom door. I speak.

“Can you lower your voice. You are so loud.”

“Sorry, I know my voice is loud and that’s because I have to speak to students at school and get their attention.”

“Don’t try to justify your loud voice and impose it on me by saying that.”

“I didn’t mean anything by it.”

His anger and resentment fill every corner of the room. I deduce that he must be mad that my beliefs don’t fit in with those around him. A friend later said: “you should have said if you are not Ok with stopping disrespect and abuse, I’m going to leave.” I didn’t have the courage that

night because I knew it meant an all-out fight, the end of my opportunity to see my new grandchildren. I stay silent.

5.

The next day, the visit is over. I spring up to gather my things, hugging my purse to my chest as a bullet proof vest, my head filled with cotton or whatever it is that makes you feel lightheaded and weak. I congratulate myself, for not only arguing my side without going into a screaming match, but also for remaining calm in the face of Max’s aggression.

I say goodbye to Maria and her sister. Edward and Max walk me to my car. They want to check out the flags. We look up. The flags spread out against the sky, the wind now weaker but enough to keep them from twisting into the pole. I grimace, and Edward catches the expression.

“We’ll put up a Biden flag too,” he says, mocking me, grinning.

“I don’t discuss politics, religion or sex,” I say, the rehearsed words tripping out in the correct order. My friends had coached me to say this when I expressed trepidation about a visit to my son.

“Sex?” He frowns.

“It’s a Victorian saying, or who knows where it started.”

“Ok, I’ll give it a try.”

My son did not hear our exchange, too busy with the rope, but the comment stops Edward.

I wave, jump in the car, and steer it towards the highway. I look up again. The flags soar over the neighborhood, dark oblong shapes, one above the other, backlit against the orange rays of a sinking sun.

by Katherine Garrison

Callie cracks open her rib cage, sawing through sternum to remove her heart. Where the seeds tilled the previous day have grown. She plucks twenty-five dog violets from it. An easier task than this time last year, when she struggled with removing the deep roots of a thistle after her boss passed up her ten years of experience to promote some promising new hire. She scoops the violets up, allowing herself a smile. Her dog was so cute, springing through the sedge, buttercups, and Queen Anne’s Lace in the park yesterday. She places the flowers into a small vase to enjoy when she returns home, placing them next to the string of pearls that poured out of her chest years ago. After gingerly prising its roots away, she’d potted it the memory of a child that would have been and the crumbling of her relationship in the aftermath. Visitors always mention how long and healthy its strands are. With her heart replaced, her chest closes, and she sets her face to stone.

On the train, despite many free seats, a man sits next to her, brushing his leg against hers. You have beautiful eyes. I bet a smile makes them light up even more. She doesn’t smile, but fidgets. With no seats left to move to, she gets off at the next station. He leers at her through the window as the train pulls away. Normally she would make a scene, but she’s exhausted and distracted by thoughts of her performance review today. The next train is only a ten-minute wait. While leaning against the wall, the shoot of a plant she recognises sprouts and tickles in her chest. When her boss doesn’t comment or thank her for picking up extra work after the layoffs the company implemented a few months ago, the plant snakes around her heart.

Tomorrow, her chest splayed open, she finds invasive ivy climbing the walls, making it hard to breathe. She prunes it away, letting the vines scatter at her feet. Over a black coffee

breakfast, she scrolls through job listings and pauses on an opening at a florist.

by Tajudeen Muadh

isn't it lovely to watch poems morph from bombs and flames filling this stached throat an aftertaste of bombs

i watched my brothers exile their bodies before being scented by the glory of bombs

were they not beautiful enough to smell of porcelain & sunflowers at Maghreb like bombs

writing them napalm in their homes? & their skins a hymn of survival from bombs

what i see beyond this body is an unfinished poem waiting to write itself into a bomb

a bomb ends lines on a plain page before me before Shaban ended on a plain page with bombs

before God, a skin on his palm, a slit a way home shape-shifts into a ghazal of bombs

home is a shadow filled with silhouettes of bodies wondered by the grace of dropping things bombs

say it is romantic, for a kiss to kill you

say romance, the way this lip says a prayer before the next bomb

sends a mirage leading me to a town in my head, say afterlife; an aftertaste of bombs.

by Tajudeen Muadh

isn't it philosophical; that God is a fur on the body of a drenched rabbit. a piece of cloth on the body of a child borne into war. a prayer on a lip slacked of disparity. a light on a body of moss in the softness of cotton. God licks away blood from bones of children whose parents touched the cloud in amazing ways. a thing of life it is, that God is hope in a distressed eye. a retired flower, in the bloom of Florence. how dusts cradle our bodies into a collection of stars. God is dust the one we are, before our existence. a thing of fire it is, that we are embers from a fire God made & prayers running back to God for answers. our souls. empty carousels fill with crimson God is sunset. a Maghreb flower.

by Ojo Victoria Ilemobayo

by Ojo Victoria Ilemobayo

by Tukur Ridwan

you may think I was not taught how to love my neighbour as myself,

but a teenager became an archetype of a lone planet, trying to grow apart from anything that feels like a skin that speaks, that listens, that looks & leaps, that breathes, that snores, that farts, that wakes up in the morning & checks the mirror to know if beauty is still on the inside, for a person

who woke up many years amidst the vibrations of a new world in the hands of mark, steve, musk hands that are factories,

hands that know how their bucks depend on our thumbs, the same way I began to know love from my screen, the blue ticks, the last seen,

the abacus of likes & comments, the love yourselves, the haters & exes & bla bla bla, & most exes become caricatures

of evil inside our heads, I strung my struggles to the walls of my intestines, the life outside, the hood, the passersby & bystanders become

quite unknown to my dearest strife, the issues I hold close to my heart, to wrinkle out a smile, not for those who sit or stand right beside like

it used to be before phones became smarter, but for those who ha-ha-ed without a grin I have failed to unlearn how to become an island, these shallow waters of solipsism is not getting dried, & it is cold & rainy outside, & I never built a boat nor did I build a bridge to reach out to those lighthouses,

I thought they were empty of hearts, of souls, of welcoming smiles from another coast, so I wear my comfort like a cardigan, & pretend all is well, & you see it in the photo uploads, & wonder what caption your life deserves.

by Quin Killin’

My uterus is jealous of wired hangers.

pieces of my spine scattered on shoe racks. there are lacerations in the arches.

Why would my uterus be jealous of wired hangers when she is unaware that she is made of barbed wire.

by Quin Killin’

Y’all tell us to pick and choose our battles, to turn the other cheek when you run out of room to whip cursive into our backsides. To bite the bullet, when the guns be chewin’ through us.

Y’all want us to walk like Jesus but march in our neighborhoods like the Romans like we didn't build empires from thorns. Violence is never the answer unless it’s endorsed by straight, wealthy whites

Cuz when they get violent, it’s the next chapter in history books but when our violence says enough, it’s an omen for the end of days. White people can go apeshit in a federal building but we get called the porch monkeys when our chests get beat in by guerilla warfare.

Y'all want us to be like Jesus but crucify anyone who resembles him. You preach to us about a god who’ll take away our sins but forget to mention that we are the sin.

Baptize our skins in bleach and try to pray our gay and gods away. God forbid!

White women get a lil’ meat on their bones, black women gotta run back to the kitchen to take the seasoning out of their attitudes. God forbid!

Drag queens teach yo’ kid how to read, y’all scared they'll only know the letters LGBTQ. Y’all want us to cower when y’all scream slurs at us but we can show you what niggas and faggots are truly capable of.

Y’all be a bunch of Jesus freaks with an Old Testament kink especially when the voice of God starts to sound like Pat Robertson & Willie Lynch. Finding purpose in watching us die for your sins. This body will no longer be served for your communion. I'm gon’ pick every battle, even if I know I’m goin’ to go down swingin’. ‘cus if I’m gone be like Jesus, it's gone be the Jesus who was flippin' tables inside of the temple but, I’m striving to be a Peter with a Jesus piece who has a will to make you be still cuz if bullets didn’t have mouths to feed,

Martin would have lived long enough to see Trayvon turn out to be a King.

I am no longer bitin' my tongue instead I'll just pop you in yours.

Yeah, I’m a fag but like a British cigarette, I can still light yo ass up. I may just let you slide when you try me the first time but believe me when I say I'm patient.

I hold grudges larger than Indian elephants at funerals. I'm snatching pearls, edges, and bitch, you too. Fuck being the bigger person.

I am Son of David in a room full of Goliaths.

I only need five stones to kill a bird motherfucker like you

by Alex Carrigan

Review: Dolce Vita/Let There Be a Little Light by Nicole Tallman

Reviewed by Alex Carrigan

Bottlecap Press 44 pp April 5, 2025

Nicole Tallman’s latest poetry chapbook is an experimental two-in-one collection that blurs between reality and the dreamlike. Released by Bottlecap Press, the chapbook is two chapbooks side-by-side and flipped, allowing the reader to go from the grounded Dolce Vita pieces to the more surreal and oneiric Let There Be a Little Light. By presenting these short poems this way,

Tallman is presenting a year in the life that blurs how one recollects a single year and what remains in the mind when everything else falls away.

How the reader approaches this chapbook is up to them, but this reviewer read Dolce Vita before Let There Be a Little Light and will base the review on this reading. Dolce Vita is a series of 15line poems mixing autofiction and lyrical poetry. From the start, the collection dives deep into the narrator’s life without warning, as the pieces in both collections are titled after the first line, and details are scant.

The poems in Dolce Vita are built more around minor details and feelings in one’s daily life. Most of the pieces focus on drink orders, meals, music, and other signs of modern life. While little happens in these pieces, they feel lived in, as Tallman perfectly illustrates the mundane and peaceful life by homing in on the details that stick in the mind, such as “a building with a balcony bleeding bougainvillea” or a woman who “smells of soft leather and lemons.” The grander details of this narrator and their partner’s life don’t mean as much as the quiet comfort they live in, and the poems expertly convey these moments.

However, there are some moments where dread and death creep in, such as the narrator recalling a memory of when they worked at a suicide hotline or ruminating on the Titan submersible disaster. This does illustrate that, while it’s nice to focus on poke bowls or a Lana Del Rey vinyl, there are still times where the outside world can creep in and have just as great a hold on the mind. Some of the pieces discuss the lingering fears and doubts that can come in when someone is too comfortable, and that’s when these disturbances can pile up.

This also expertly leads into the Let There Be a Little Light portion of the collection. The ten pieces in this section are more dreamlike, inspired by the early-morning writing process of Sylvia Plath. Here, the detailed and specific falls away from the collection, and the poems become more abstract in thought and image.

The first few poems begin with questions, such as “Who decides what’s wrong and what’s right?” and “When you see pink, do you think Barbie or Cancer?” After that, the poems in the collection move into moments of fear and isolation, such as being lost on the subway line in Quebec or a near-fatal car accident. Even the succession of pieces in this part of the chapbook invite some unease, with one poem mentioning two girls drowning while the next poem asks to look at a clear lake at night.

Part of the effectiveness is that the poems in the Light portion of the chapbook focus on specific colors and their associated feelings. This is owed in part to Plath’s “blue” early-morning writing, but when Tallman strips the poems down to focus on colors and their symbols, it adds to the exploratory feel of the oneiric. Whether it’s focusing on violet auras, or the oranges horses eat before slaughter, Light feels like an exploration of humanity and nature through the color spectrum and all the shades it has.

Tallman’s chapbook is audacious and clever in its mixing of genres and styles to create pieces that feel both lived in and foreboding. From the quiet comfort of Dolce Vita to the multicolored anxiety of Let There Be a Little Light, this chapbook has a wide array of experiences and images that can stick with you. These works ask the reader to imagine what of their life brings them comfort, but also to think about how fragile that can be at times and what you need to reclaim that serenity.

by Meria Cairns

Tess was three years old. She had been three for almost a year, so really she was almost four. (She reminded me of this daily: “I almost four. Almost four, Mommy.”) I had bought Barney for her third birthday, so we actually hadn’t had him for very long. Her father, my husband ex-husband had just left us, and I was worried about Tess being alone. I mean, she was an only child. And her father and she had had a daily routine.

See, every day, after we finished work and Tess finished nursery school and day care, we would all come home together. Just before dinner, Tess and her dad would play “Zoo Animals.” Tess and Daddy would take turns: one playing the role of the wild and crazy animal while the other portrayed the disgruntled human attempting reluctantly to tame it.

Every day, almost without exception, they played this game. It was their father-daughter ritual. But it abruptly stopped when he decided one day to leave us.

And I don’t think Tess understood this. Why the game stopped. Why her father went away. I suspect that, in her own mind, she thought it was her fault, that she had made him go away, that she had not been a good enough girl for Daddy. That she had been too mean as a lion or too rough as a horsewoman. “Be a good girl for Daddy, and Daddy will come to your room tonight and tell you a story right before you go to sleep,” he would say to her at dinner. But now he never came, not anymore, not to tell stories, not to play Zoo Animals, not even to kiss her goodnight or good morning on the forehead like he always used to.

And how do you explain this to a three-year-old? How do you explain to her that it wasn’t her fault, had nothing to do with her at all. Daddy loved her, really, he did. Loved Mommy too, but he just couldn’t live here anymore. He would never live with us again. Never. The relaxed family life we took for granted and thought would last forever is over. Gone. Finito. Never to return.

So I bought Tess a dog. Barney. Of course, he’s no replacement for a father, but I thought the unconditional love and companionship of a pet would help my daughter overcome the loss. As I

mentioned, she is an only child, and I work seven-days-a-week, so I’m not always there for her. Besides, a child needs someone in addition to her mother, someone without authority, someone just to play with. And, like I said, I thought having a dog would help Tess to make the transition away from her broken routine.

Anyway, on this particular Saturday afternoon, when Tess was almost four, I had accomplished the near-impossible: an actual day off from work. I hadn’t achieved such a remarkable feat in almost a year, since that magnificent moment when Mr. Wonderful suddenly forgot he was married and fathered yet miraculously remembered to shower, shave, dress, and then prepare his own breakfast that morning (I’d wondered why he hadn’t woken me up to serve him.) He even remembered how to open the front door of the house, how to walk down the porch stairs and into his car to drive 1,000 miles westward to Chicago (though he forgot to say goodbye). Men are amazing.

On this precious day off, I decided to take Tess to the beach without Barney. “Why?” Tess kept asking me after we pushed Barney's big, black, hairy body out of my tiny Volkswagon Bug and onto my mother's cement driveway. “Barney wants to see Grandma,” I replied. “Why?” And my mother appeared at her side door, greeting Barney cheerfully, as if I were doing her a favor by letting her dogsit. “Grandma wants to see Barney.”

“Why?”

Mother quickly pulled Barney into her house while I took Tess's hand and led her back to the car. “Why?” Tess persisted, and I noticed that the back of her little shirt had somehow gotten rolled up revealing part of her backside. I straightened out her shirt then gave her a hug.

“Why, Mommy, why?”

“Barney doesn't want to go swimming today,” I explained to her in the car, where she was now able to sit next to me now that there were only two of us. “It's too hot and too crowded at the beach today for Barney.” Numerous “whys” followed, and I gave each a reply.

“Barney is tired today. He is going to take a nap.”

“Barney doesn't want to get a sunburn, and if the sand gets in his face, it might make him

sneeze.”

Every answer I gave was met with the same question: “Why? Why, Mommy, why?” And for every “Why?” I attempted an explanation. “My you are an inquisitive little lady,” I finally said after the umpteenth why.

“Inks-itiv...inks-tiv... Why? Why, Mommy, why?”

The truth is, I didn't want to spend the day at the beach chasing after the dog while trying to watch my daughter at the same time. I wanted to be alone with Tess, without the interference of the dog. I know it sounds silly, but I guess I was a little bit jealous of Barney. I'd been working so much that I had had so very time to spend with Tess, and I think Barney had helped Tess so much, so much more than I had, to adjust to the loss of her father. We had even developed a new routine of walking Barney just before dinner and making sure his bed (yes, that's right, Barney had his own little bed) was ready for him every night. But somehow I'd begun to see Barney as an unwelcome intruder coming between my daughter and me. Juggling two jobs and the care of a toddler was difficult enough. But then came the searches for the dogsitter, the late-night trips to the supermarket when I'd forgotten the dog food, the required visits with Barney's vet, the mornings when I woke up extra early just to strap him on his leash and take him outside for a walk. And, yes, there were the dinnertime dogwalks and the nightly preparation of his precious little dogbed.

What's that? Small potatoes, you say? Maybe. But when you're a single parent who is ALWAYS working, even when you are sleeping (that's when you have time to make plans, in your dreams), every moment is precious. Barney consumed too many spare moments. He was also an added expense. Barney was a good dog, really he was. He just couldn't live here anymore. Barney would have to go.

Just before we arrived at the beach, we had to stop for a red light on Ainexidune Street. A young woman took off her shoes then walked barefoot across the street. Seeing this, Tess immediately removed her sneakers, allowing them to fall haphazardly in front of her and on the car floor. “Tess,” I attempted to reprimand, but I was driving again and had to pay attention to the road. Out of the corner of my eye I saw Tess kick her feet in the air, as if in delight over their new-found freedom, freedom from the constraints

of the sneakers! She then casually pulled off her socks, letting them drop in the same way. Just as I parked the car into the Sydney Beach parking lot, I turned toward her, and she looked up at me with a victorious smile, her bare feet swinging back and forth, her toes expanding outward, contracting inward then grasping forward, as if trying to hold onto something. Tess returned her gaze to her grasping toes. She watched them in fascination, entranced by the dancing toes.

I didn't have the heart (or whatever it takes) to make her put her sneakers and socks back on. I reached behind me and pulled out our beach bag filled with the day's necessities: a red, plastic pail (the one with the large happy face painted in white on the side), its accompanying shovel (approximately ten inches in length and three-and-a-half inches in width perfect for sand digging), a large Betty Boop beach towel (about twice Tess's size), two Barbie-like dolls (a boy and a girl), and, somewhere at the bottom of all this, two peanut butter sandwiches, two cartons of no-need-to-refrigerate, nonfat, vitaminfortified chocolate drink, two fruit bars, and a quart of spring water. It wasn't easy lugging this sack of goodies out of the car's back seat. No room for socks or sneakers here. I stuffed the socks inside the sneakers and carried them under my right arm, the bag in my right hand, Tess's hand in my left.

“Oh. Hot, Mommy,” Tess announced as we walked along the sun-scorched ground of the parking lot. “Would you like to put on your sneakers?” I asked knowingly. “Ye-e-e-s!” Tess answered gleefully, hopping from one foot to another to avoid the pain of keeping both bare feet on the hot ground at one time. We returned to the car where Tess put back on her sneakers. I resolved to buy her a pair of sandals later in the week.

We walked over to the beach and stretched out the Betty Boop blanket on the sand. I set down our bag of goodies then I set down myself, part of me on the blanket, part of me on the sand. Tess was picking up clumps of sand then letting it slip through her fingers. A slight breeze blew cool air from the water toward us. Soothing. I took in a deep breath and smelled saltwater and fish. It made me hungry. As a child, I ate fresh fish often. My father, an amateur fisherman extraordinaire, would bring it home, on weekends mostly, during the summer. I dug my feet into the prickly sand.

I lay down, sprawled out on the hot sand. I could feel grains of sand underneath me poking my

skin, like pins and needles. It was scorching hot, like lying in a frying pan. But the heat felt good, stimulating. The warmth of the sun's light shining on me, penetrating the surface of my skin, made me feel loved; more loved than the hot, sweaty arms of my ex-lover-husband wrapped too tightly around me, as though sucking the life right out of me; more loved than the hot, sticky breath of his lustily pressing the weight of its meat against my skin, until every part of my body had been licked, sucked, and kissed, touched, fondled or penetrated by his, leaving my body hotter than fire, longing for his touch. And my soul, the prisoner of it all, left alone, untouched, unknown.