14 minute read

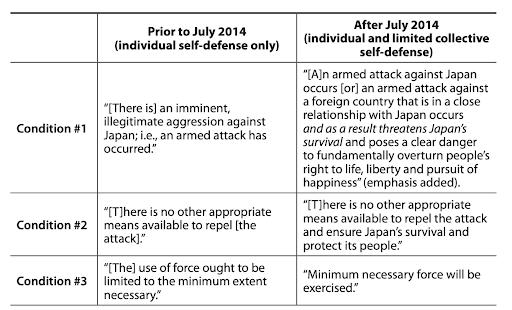

TABLE 1: CONDITIONS FOR THE USE OF FORCE IN EXERCISING THE RIGHT OF SELF-DEFENSE

The most recent, and perhaps most consequential and “historic” example of this line of constitutional reinterpretation legislation is in Abe’s passing of the ‘collective self-defense’ provisions. The table below is helpful in differentiating what specifically changed in the 2014 legislation from previous politics, outlining the specific provisions that allow Japan the “use of force to aid an ally under attack” (Liff 2017, 139-72).

This change, however, can be described as more “evolutionary than revolutionary” with the conditions to use force remaining strict, necessitating an “armed attack posing existential threat to Japan’s security” for Japan to take action (Liff 2017, 160). Thus, despite the varying reinterpretations of the constitution, substantial change has been limited and minimal in effect since the inception of Article 9, with Japan’s “persistent, albeit stretched” security policy maintaining a self-defense focused approach (Liff 2017, 162).

Advertisement

Abe and his Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) administration have spearheaded the shift from proposals to reinterpret the constitution to proposing revision in order to more “fundamentally transform” Article 9, especially in more recent years. These attempts have not only been made through political avenues in the Diet, but also in domestic politics through efforts at altering historical perceptions and memories to a more nationalist rhetoric. The most significant of these revision attempts was the “official party-wide proposal in 2012,” which called for “revision to Article 9’s existing two clauses” (Liff 2021, 479-510) Though there wasn’t much dramatic change proposed, the most significant alterations were turning the wording more nationalistic and explicitly stating the right to collective self-defense. These proposed revisions, among others, have been met with resounding disapproval and failure (Liff 2021). Despite these efforts from the dominant, rightwing, and conservative LDP to amend the Article to allow more liberty and flexibility in military and security policy, the moderate and left-wing parties are firmly in opposition. They instead support constitutional reinterpretation and passing legislation within the narrow bounds of Article 9 (Nippon 2020). In the next section, these factors of political disagreement—along with a variety of other reasons behind the continued failure of politicians, specifically Abe, to enact constitutional revision—will be examined.

Why Have Attempts at Revision Failed?

There is not a single explicit reason behind why various attempts at constitutional revision, most specifically and pertinently from Abe, have been resoundingly unsuccessful. Various explanations that help account for the sustained life of the original Article 9 include the influence of the US-Japan security alliance, domestic inter-Diet political conflict and division, foreign politics, and nationalistic, occasionally inflammatory rhetoric.

Whatiskeytorecognizeinalloftheseconstitutional reinterpretations is their core emphasis of Japan’s right to and ability of self-defense while establishingamethodbywhichJapancaninteract with its allies as a fellow economically-powerful global leader in times of security crises without reclaimingarighttoastandingmilitary.

Political Division: How Reinterpretations Succeeds Where Revisions Fail

A. Ratifying Revisions Versus Reinterpretations

A specific question many have is why constitutional reinterpretations have found marginal success, but revisions have never successfully been passed. Indeed, oftentimes the only major difference between a proposed constitutional revision and reinterpretation is the word itself, with a piece of legislation failing to pass under the name revision but being approved of as a reinterpretation. A possible explanation for this lies in the significant political and institutional difficulty in passing a constitutional revision as opposed to a far simpler constitutional reinterpretation process (CFR n.d.). Article 96 of the Japanese Constitution outlines the process for revision as requiring a “two-thirds” majority in both the Upper and Lower Houses, after which the proposed revision will be “submitted to the people for ratification” where a majority vote would pass the legislation (Constitution of Japan n.d.).

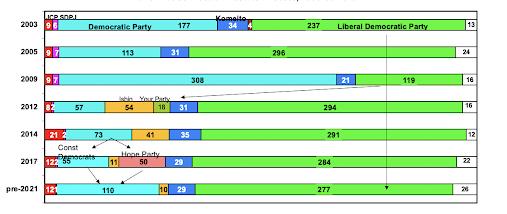

Looking at the distribution amongst parties of Diet seats during the past twenty years, the LDP alone has never been able to gain a two-thirds majority. By combining with its longtime coalition partner, the Komeito, it can often meet the majority, but this alliance then presents the issue of the Komeito’s pacifistic principles and strong opposition to revision (Liff and Maeda 2019, 53-73). In 2021, election results left the LDP with 261 out of 456 seats in the lower house, which is roughly 57% of the house (Reynolds 2021). Given these numbers, it is unlikely that proposed revision would even pass the first requirement of garnering a two-thirds majority vote in both houses of the Diet.

However, even assuming that both houses ratified the proposed revision, it would most certainly fail to pass in a public referendum. Public support for actual revisions to the constitution is a minority opinion held by roughly a third of the population, and revisions only continue to grow less popular despite Abe’s efforts (Liff 2021, 486). As opposed to the extensive and difficult process of constitutional revision, reinterpretation and passing legislation within the bounds of Article 9 is a relatively simple process that only requires a simple majority in the Diet, which the LDP often holds.

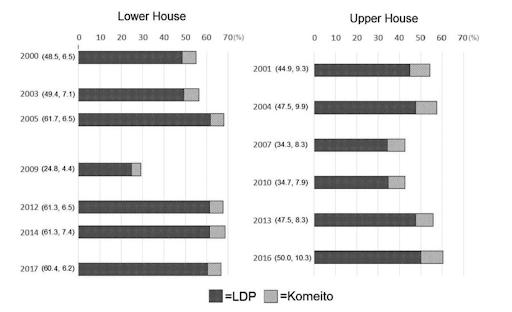

B. Role of the Komeito

To expand on the previously discussed role of the Komeito, they are a smaller political party and have been a longtime coalition partner of the LDP. They are similarly conservative, but they hold pacifist views and are thus opposed to proposed amendments of Article 9. Despite this key difference in policy and other “ideological differences on fundamental policy,” the LDP-Komeito cooperation has persisted for over two decades (Liff and Maeda 2019, 67). The origins of this coalition lie in the LDP’s “pursuit of a controlling majority” in the upper house, which the Komeito helped and continues to help to provide, with the Komeito receiving the backing of the dominant party in both electoral races and within the Diet (Liff and Maeda 2019, 70).

Figure 3

The LDP cannot pick and choose which policy issues they collaborate with the Komeito on in the Diet, as the coalition requires consistent negotiation and agreement. As there is a mutual dependence between the two parties and the Komeito are opposed to revisions of Article 9, the LDP has time and time again had to revise their proposals surrounding revisions both in scope and nature by turning them into reinterpretations in order to appease the Komeito. This has been one of the most consequential reasons behind Diet failures to pass constitutional revisions: maintaining the crucial support of the Komeito, who, despite being a “small party,” provide the invaluable “numerical support to achieve a powerful two-thirds majority” (Walton 2020).

C. Continued Hesitancy

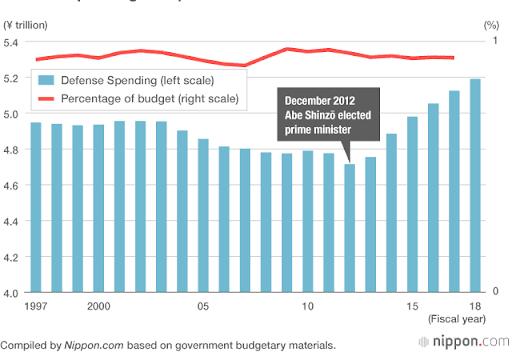

Outside of constitutional revisions, the LDP, despite having the power to pass reinterpretations and enact new security policies that can either stay within or push the bounds of Article 9, rarely do so. One example of this relative inactivity of the LDP is in defense spending. Though a ban on spending more than 1% of GDP on defense was lifted in 1987, there is still a de facto ceiling in effect since Japan has yet to push this boundary (Nippon 2018).

This example reflects the overall continued hesitancy of the LDP and Japanese politicians in general to extend beyond established boundaries of their security policies, even in factors as seemingly non-threatening as spending more than 1% on defense, especially when compared to other countries. The US, for example, easily spends triple this amount. whether or not the member states provide the UN with money, personnel, or the legal right to inspect weapons’ sights, coordinate peacekeeping operations, regulate commerce, measure pollution, or any other litany of actions the UN might want to take to address the aforementioned issues (Sengupta, 2017).

Abe’s Rhetoric: Its Effects on Domestic and Foreign Opinions

The second key reason behind the failures of revision proposals is the rhetoric and symbolism behind changing the actual wording and firm meaning of Article 9, which negatively affects significant political and domestic support. In examining why there is such a marked difference in response to proposals of revision versus reinterpretation, the way that politicians present and discuss the significance of revisions to the public is key. Abe often depicts revisionism as Japan “breaking out of the postwar regime” and “tak[ing] back Japan,” an idea that may work as a campaign slogan but is otherwise wholly ineffective in pushing constitution reform (Hanssen 2021, 177). Despite LDP officials’ insistence that revision proposals would not be substantially different from reinterpretations, opposition lawmakers often argue that revisions have more significant effects and have the potential to “drastically expand the legal scope” of Japanese security policy and the SelfDefense Forces (Yoshida 2017). What presents the biggest fear to Japanese lawmakers and citizens alike is the substantial and dramatic symbolism of revising a constitution which—for three-quarters of a century—has gone untouched and the message it would send to allies and the international community (Auer 1990, 171–87). Thus, the combination of institutional and political challenges in passing constitutional revision, along with the significant symbolism in passing actual revision over reinterpretation, has made revision unlikely to occur. Abe, in employing this hawkish approach and rhetoric of “promoting [excessive] nationalism,” was forced to “settle for relatively marginal gains” in defense policy and national discourse on defense (Berger 2014).

Additionally, one of Abe’s major policy efforts was to reverse the Yoshida Doctrine’s policy of navigating through the international system as “a defeated and low-profile power” and instead return Japan to its “rightful… place amongst the great powers” by promoting nationalism (Hughes 2015, 9). While this may not initially present itself as a contentious and controversial decision, Abe’s approach to accomplish this was historical revision—specifically in terms of Japanese war crimes and actions taken during its imperial era and World War II—and in nationalistic education. Through these policy and rhetoric shifts, Abe hoped to “overturn taboos on constitutional revision and garner support from the populace but achieved much of the opposite—only further alienating both politicians and the public who still seek to distance themselves from the memories and mistakes of the war period, and thus constitutional revision (Hughes 2015, 9).

Domestic Politics: A Longstanding and Prominent Post-War Memory

Beyond the Diet and the failure of politicians to agree upon and pass constitutional revisions, the largest barrier in this effort is the lack of domestic desire and support for revision. Japan’s postwar identity focused on being “anti-militarist” and “peaceful,” a significant divergence from the militaristic prewar Japan (Kolmaš 2018, 4). Thus, the “idea of a pacifist, Yoshida-doctrine reactive state has been rooted into institutions and public emotions,” making Abe’s overt revisionist and nationalistic rhetoric surrounding constitutional revision unpopular, unconvincing, and unsuccessful (Kolmaš 2018, 65). Abe’s revisionist narrative has centered on downplaying, and even erasing, certain dark and unsettling aspects of Japanese history, such as Japan’s cruelty in the colonization of Korea and actions like the Nanking Massacre during World War II.

His rhetoric in the past decade and its effect on domestic politics and perception of the constitution are intimately intertwined, to the detriment of revision advocacy. In associating constitutional revision with a reclaiming of pre-war national pride and in historical revisionism that has raised the ire of many Asian countries, many in the public see these reforms as dangerously nationalistic and militaristic and thus undesirable.

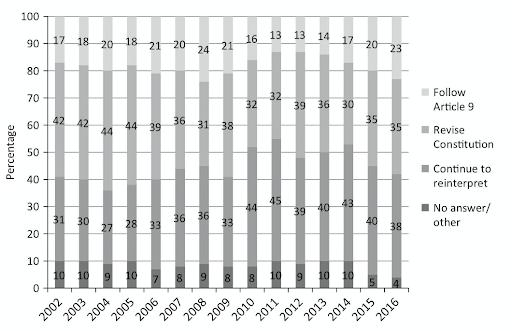

FIGURE 5: PUBLIC OPINION POLL ABOUT ARTICLE 9 REVISION

This is a constant reflected in public opinion polls over the years, with desire to revise the constitution never reaching the 50% majority level that would potentially ratify such changes in a referendum. In fact, the numbers have been decreasing over the years, and they continue to do so. These numbers were even falling at a slightly accelerated pace during Abe’s Prime Ministership—further evidence of the ineffectiveness of his nationalist posturing of constitutional revision. The two major constraints that hindered Abe’s revisionist attempts, therefore, were the institutional and political factors combined with public and emotional factors (Kolmaš 2018). Thus, “without major domestic political realignments” in Japan, it is “unlikely” that any “ambitious effort to fundamentally transform” Article 9 will ever be formally ratified; domestic barriers are perhaps the greatest obstacle in constitutional revision efforts (Liff 2017, 160).

Foreign Politics: A Highly Visible yet Largely Unimportant Influence

A. US-Japan Security Alliance

Without the capability to maintain a standing army, Japan still very much relies upon the United States for its security and military protections in the region. Japan consistently refers to the US-Japan Alliance as the “cornerstone” of not only their defense but also of “regional peace and stability” (Liff 2021, 486). Since 2012, the movement to “strengthen the Japan-US alliance” has “significantly accelerated,” with Japan’s 2017 Defense White Paper devoting an entire chapter to the relationship (Japan Ministry n.d.).

However, it is important to note that the United States has never been opposed to proposed Japanese revisions to Article 9 and expansions of Japanese security policies but rather has encouraged it. Even the original 1951 Security Treaty stated that the US expected Japan to “increasingly assume responsibility for its own defense against direct and indirect aggression,” something that has not been upheld by Japan (Bilateral Treaty n.d.). This was evidenced as recently as the ‘Iraq Shock’ during the Gulf Conflict, in which the US encouraged Japan to send military forces. When Japan staunchly denied the request and instead sent billions of dollars in support, they were criticized for being nothing more than a “cash machine” (Purrington 1992, 161-81). Even the recent passage of the collective self-defense provision was seen as a “major step” in creating more of an “equal alliance” and a “step in the right direction” for the U.S.-Japan alliance (Blair 2020).

The continuation of a security policy centered on the U.S.-Japan alliance echoes the desire of the vast majority of the Japanese public, despite statements and efforts of the previous Prime Minister Abe and the LDP to reinstate Japan’s military and increase defense capabilities (Liff 2021, 502). In fact, the majority of senior members of his own party, the opposing parties, and the vast majority of the public are deeply in favor of continuing the U.S. military alliance and maintaining bases in Japan without significant revision (Yoshida 2017). Thus, while the U.S. itself is not a significant barrier preventing constitutional reinterpretation or revision but rather encourages security and defense developments, Japan itself often employs American military presence as a reason to not revise or pass reform.

B. Korea and China Response

Since Japan’s emergence as an economic powerhouse on the world stage in the 1970s, there have been concerns from China and Korea that Japan becoming a “military great power is not too distant,” which would place Asia back on “high alert” (Dong-a Ilbo 1970, 3). Though Japan has yet to become, and is unlikely to become, this great military power that was feared so many decades ago, whenever discussions surrounding Japanese security policy and constitutional revision arise, tensions between these nations also rise.

Returning to the discussion of the role of Abe’s rhetoric, during Abe’s Prime Ministership, the majority of these tensions were not a result of proposed legislation but rather his inflammatory and controversial rhetoric surrounding revision efforts. Most specifically, rhetoric surrounding his visits to the Yasukuni Shrine, which had become a “focal point of ire” for a perceived “lack of remorse for wartime deeds,” as well as his historical revisionism, which has only “served to continue to alienate” South Korea and China (Fackler 2007; Hughes 2015, 9).

Though these conflicts have had drastic effects–such as the South Korea-Japan trade war in 2019 that was largely based on disputes about “colonialism and historical grievances,” –negative responses from South Korea and China likely have not had a significant impact in decisions surrounding changes to Article 9 (Kim 2019). This is evidenced by the lack of significant response to the actual policy questions, reinterpretations, and proposed revision of the constitution; rather, focus has mainly centered on Japanese rhetoric surrounding these proposed shifts.

Conclusion: Current Status and Modern Complications

In a rapidly changing geopolitical environment which is becoming increasingly corrosive and dangerous to Japan, with North Korean missile threats and Chinese incursions in the South China Sea and disputed island chains, the US—rather than reaffirming its military and defense commitment to Japan—has become a more flippant and less reliable ally. This was particularly true during the Trump administration, during which Japan was told to almost quadruple its contribution from $2.5 billion to $8 billion for the cost of the US military in Japan under the threat of “withdraw[ing] all US forces” from the island (Johnson 2020). Policymakers in both the US and Japan have additionally questioned the continued US presence in the country as the “common threat presented by the Cold War diminishes” while “skepticism of the military presence” increases (Hosokawa 1998, 2-5). Despite all these possible points of contention, however, the U.S.-Japan military alliance remains a ‘cornerstone’ of Japanese security policy. This is all incredibly relevant to the question of sustaining Article 9, as a significant constitutional revision will remain unlikely while the alliance thrives, or at least survives, as it negates the necessity of significant change to its provisions. Besides the significant role of the U.S.-Japan security treaty, the domestic and inter-Diet political barriers and disagreements have yet to—and, in the near future, are unlikely—to support revision. Though foreign affairs, Japan’s security policy, and the politics of constitutional revision are sensitive areas of policy that are highly subject to change, in examining the trends and reasons behind the continued failed attempts at changing Article 9, it seems likely that this 75-year provision will last through the century and beyond.

Auer, James E. 1990. “Article Nine of Japan’s Constitution: From Renunciation of Armed Force ‘Forever’ to the Third Largest Defense Budget in the World.” Law and Contemporary Problems 53, no. 2. Durham: Duke University School of Law. https://doi. org/10.2307/1191849.

BBC News. 2021. “Japan Country Profile.” BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/ world-asia-pacific-14918801.

Berger, Thomas U. 2014. “Abe's Perilous Patriotism: Why Japan's New Nationalism Still Creates Problems for the Region and the U.S.-Japanese Alliance.” Center for Strategic and International Studies, https://www.csis.org/analysis/abe%E2%80%99s-perilouspatriotism-why-japan%E2%80%99s-new-nationalism-still-createsproblems-region-and-us.

"Bilateral Treaty - Asia for Educators | Columbia University." New York: Columbia University Press. http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/ps/japan/ bilateral_treaty.pdf.

Blair, Dennis. 2020. “An Expanding Role for Japan: An Interview with Admiral Dennis Blair.” Nippon.com, https://www.nippon.com/en/ in-depth/a05304/.

Cha, Victor D. 2009. “Powerplay: Origins of the U.S. Alliance System in Asia.” International Security 34, no. 3, The MIT Press. “The Constitution of Japan.” The Constitution of Japan, https://japan.kantei. go.jp/constitution_and_government_of_japan/constitution_e.html.

Dong-a Ilbo. 1970. Hyo˘nhaet’an no˘mu˘n ‘anbo’ pulti, chuhanmikunkamch’ukkwa il panhyang [The ‘Ampo’ flashpoint reaches across the Genkai Sea, the reduction of the US Army in Korea and its repercussions for Japan].

Fackler, Martin. 2007. “Abe's Gift to the Yasukuni War Shrine in Japan Is Scrutinized.” The New York Times, https://www.nytimes. com/2007/05/08/world/asia/08iht-japan.2.5617692.html.

Hanssen, Ulv. 2019. Temporal Identities and Security Policy in Postwar Japan. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429447143.

Hanssen, Ulv. 2021. Temporal Identities and Security Policy in Postwar Japan London: Routledge 2021.

Hosokawa, Morihiro. 1998. “Are U.S. Troops in Japan Needed? Reforming the Alliance.” Foreign Affairs 77, no. 4: 2-5. https://doi. org/10.2307/20048959.

Hughes, Christopher W. 2015. Japan's Foreign and Security Policy under the 'Abe Doctrine': New Dynamism or New Dead End? London: Palgrave Macmillan.

ISDP, et al. 2018. “Amending Japan's Pacifist Constitution - Article 9 and Prime Minister Abe.” Institute for Security and Development Policy. https:// isdp.eu/publication/amending-japans-pacifist-constitution/.

Johnson, Jesse. 2020. “Trump Demanded Japan Cough up $8 Billion for U.S. Troops - or Risk Pullout, Bolton Says.” The Japan Times, June 23, 2020. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2020/06/22/national/usdonald-trump-japan-troops-john-bolton/.

Johnston, Eric. 2020. “75 Years on, Legacy of the U.S.-Led Occupation of Japan Still Resonates.” The Japan Times. https://www.japantimes. co.jp/news/2020/08/30/national/us-occupation-japan-wwiianniversary/.

Kim, Catherine. 2019. “The Escalating Trade War between South Korea and Japan, Explained.” Vox. August 9, 2019. https://www.vox.com/ world/2019/8/9/20758025/trade-war-south-korea-japan.

Kolmaš Michal. 2018. National Identity and Japanese Revisionism Abe Shinzō's Vision of a Beautiful Japan and Its Limits. London: Routledge.

Liff, Adam. 2021. “Japan’s Defense Reforms Under Abe.” In The Political Economy of the Abe Government and Abenomics Reforms, edited by Takeo Hoshi and Phillip Lipscy, 479-510. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Liff, Adam P. 2017. “Policy by Other Means: Collective Self-Defense and the Politics of Japan’s Postwar Constitutional Reinterpretations.” Asia Policy, no. 24: 139-72. National Bureau of Asian Research. https:// www.jstor.org/stable/26403212.

Liff, Adam P., and Ko Maeda. 2019. "Electoral Incentives, Policy Compromise, and Coalition Durability: Japan's LDP–Komeito Government in a Mixed Electoral System." Japanese Journal of Political Science 20, no.1: 53-73.

Nippon. 2020. “The Article 9 Debate at a Glance.” Nippon.com, May 30, 2020, https://www.nippon.com/en/features/h00146/.

Nippon. 2018. “Japan’s Defense Budget and the 1% Limit,” Nippon.com, May 18, 2018. https://www.nippon.com/en/features/h00196/

“The Politics of Revising Japan's Constitution.” Council on Foreign Relations, https://www.cfr.org/japan-constitution/politics-of-revision.

Purrington, Courtney. 1992. “Tokyo’s Policy Responses During the Gulf War and the Impact of the ‘Iraqi Shock’ on Japan.” Pacific Affairs, vol. 65, no. 2: 161-81. Vancouver: University of British Columbia. https:// doi.org/10.2307/2760167.

Liff, Adam P. 2017. “Policy by Other Means: Collective Self-Defense and the Politics of Japan’s Postwar Constitutional Reinterpretations.” Asia Policy, no. 24: 139-72. National Bureau of Asian Research. https:// www.jstor.org/stable/26403212.

Reynolds, Isabel. 2021. “Japan’s Kishida Defies Forecasts, Keeps Majority in Election.” Bloomberg, October 31, 2021. https://www.bloomberg. com/news/articles/2021-10-31/japan-s-ruling-party-may-not-keepparliament-majority-nhk-says.

Schoppa, Len. 2021. Class Lecture: Administrative Reform: Did it produce stronger PM leadership?

Shinoda, Tomohito. 2003. "Koizumi's Top-Down Leadership in the Anti-Terrorism Legislation: The Impact of Political Institutional Changes." SAIS Review 23, no. 1: 19-34.

Takahashi, Kosuke. 2021. “Shinzo Abe's Nationalist Strategy.” The Diplomat, December 10, 2021. https://thediplomat.com/2014/02/shinzo-abesnationalist-strategy/.

Walton, David. 2020. “Japan: Article 9 Conundrum Rears Its Head Again.” The Interpreter, February 24, 2020. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/ the-interpreter/japan-article-9-conundrum-rears-its-head-again.

Yoshida, Reiji. 2017. “Abe's refusal to clarify Article 9 proposal worries opposition,” The Japan Times, May 15, 2017. https://www.japantimes. co.jp/news/2017/05/15/national/politics-diplomacy/abes-refusalclarify-article-9-proposal-worries-opposition/.