On Call

‘A pivotal moment’

Honing surgery skills in key third-year class

‘A pivotal moment’

Honing surgery skills in key third-year class

This fall, the UW School of Veterinary Medicine welcomed its newest cohort of students to campus. The class of 2029, which numbers 100 students , is the school’s largest-ever first-year class and is the first group of students to engage with our innovative new ‘ OnWard ’ curriculum (scan to learn more).

One of a kind: UWVC clinicians treat goldendoodle

While Timmy always had an unusual gait when walking, it didn’t slow him down. That is, until he slipped trying to get into the car one afternoon. The fall left him unable to stand up or walk. He was rushed to UW Veterinary Care, where the hospital’s neurology service discovered he was born without a key vertebra.

Page 10

‘A pivotal moment’:

Each year, third-year students at the UW School of Veterinary Medicine enroll in the school’s junior surgery course — a major milestone in their veterinary medical education. Working in teams of four, the students care for a feline patient through the entire spay surgery process, under the guidance of faculty and teaching staff. Page 12

section for alumni of the Veterinary Science and Comparative Biomedical Sciences graduate programs

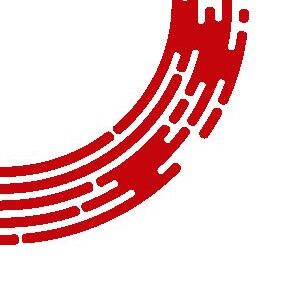

Student Emily Springer (DVMx’27) assesses a teaching cat during an early lab session of the UW School of Veterinary Medicine’s junior surgery course. A major milestone in veterinary medical education, the class helps students hone their surgery skills, working in teams of four to care for a feline patient and perform a spay surgery.

Having completed my first full year as dean of the UW School of Veterinary Medicine (SVM), I’m more energized than ever by our work creating the future of veterinary medicine. Our students, faculty, and staff bring incredible talent and enthusiasm, and each day on our campus I observe countless examples of the strength of our community.

The 2025–26 academic year marks a milestone: we welcomed our largest-ever DVM class of 100 students, the first to experience our new OnWard curriculum. We’ve also unveiled our new five-year strategic plan, a plan that builds on our tradition of collaboration and innovative, bold thinking.

It will guide us in educating veterinarians and scientists ready for tomorrow’s challenges, advancing groundbreaking discoveries in animal and human health, delivering exceptional and accessible veterinary care, and improving wellbeing across Wisconsin and the world. Already, we’re making meaningful progress toward expanding our DVM/PhD program (thanks to a new endowment) and efforts to modernize and expand our facilities to continue growing our class size.

UW Veterinary Care (UWVC) continues to meet the challenges of some of our most pressing health concerns and diseases, including cancer. Home to a comprehensive cancer center, UWVC brings together world-class specialists in medical, radiation, and surgical oncology to provide individualized, comprehensive care for every patient. Our leading experts in medical and radiation oncology were bolstered over the summer by the arrival of Megan Mickelson (’09 DVM’13), one of just 68 fellows in surgical oncology recognized by the American College of Veterinary Surgeons (see page 8).

Through the RISE initiative — a university-wide effort designed to address significant, complex challenges facing Wisconsin and the world — we’re recruiting foundational and clinical science faculty focused on healthy aging as well as faculty members studying artificial intelligence. These new positions will strengthen our academic community and expand our impact across research, education, and clinical service.

As always, we continue to closely monitor federal funding developments, working with campus partners to advocate for necessary investment in the school’s mission.

Until next time ... On, Wisconsin!

Visit our strategic planning website

WINTER 2025-26

Administrative Advisory Committee

Jonathan Levine , Dean

Kristen Bernard , Chair, Department of Pathobiological Sciences

Nigel Cook, Chair, Department of Medical Sciences

Fariba Kiani , Chief Financial Officer

Gillian McLellan , Chair, Department of Surgical Sciences

Lynn Maki , Associate Dean for Student Academic Affairs

Peggy Schmidt, Associate Dean for Professional Programs

Chris Snyder , Associate Dean for Clinical Affairs and Director, UW Veterinary Care

M. Suresh , Associate Dean for Research and Graduate Training

Kristi V. Thorson , Associate Dean for Advancement and Administration and Chief of Staff

Chad Vezina , Chair, Department of Comparative Biosciences

Editorial

Editor : Maggie Baum

Lead Writer : Jack Kelly

Contributing Writers: Simran Khanuja, Grace Bathery

Photography : Seth Moffitt

Design : Lexi Swain

Jonathan

Levine, Dean @uwvetmeddean @uwvetmeddean.bsky.social

Please send your feedback and comments to oncall@vetmed.wisc.edu, 608-263-6914, or On Call Editor, 2015 Linden Drive, Madison, WI 53706. www.vetmed.wisc.edu www.uwveterinarycare.wisc.edu facebook.com/uwvetmed facebook.com/uwveterinarycare x.com/uwvetmed x.com/uwvetmeddean youtube.com/uwvetmed instagram.com/uwvetmed linkedin.com/school/uwvetmed bsky.app/profile/uwvetmed.bsky.social bsky.app/profile/uwvetmeddean.bsky.social

On Call is also available online at: www.vetmed.wisc.edu/on-call

The printing and distribution of this magazine were funded by donations to the school. To make a gift, contact Heidi Kramer at 608-327-9136 or heidi.kramer@supportuw.org.

Just like it is for humans, dental care is an important component in the health and happiness of pets. One of the UW School of Veterinary Medicine’s boardcertified dentistry experts, Christopher Snyder (associate dean for clinical affairs and director of UW Veterinary Care), shared tips on dental care for pets during a recent interview with Wisconsin Public Radio.

Here’s a summary of Snyder’s recent conversation on ‘The Larry Meiller Show.’

Scan to listen to the interview

What can be done at home for pet dental care? Before home dental care takes place, a cleaning at the vet should be done to clean beneath the gumline where harmful bacteria live and to ensure there is no baseline discomfort. Brushing a pet’s teeth at home before identifying discomfort can cause a pet to dislike toothbrushing and make them more prone to resist brushing long term. After a preliminary cleaning at the veterinarian, effective dental care can be managed at home with toothbrushing, dental diets, and toys and treats designed to reduce tartar.

What can I do about my pet’s bad breath? If bad breath is irregular and happens when a pet is burping up air, it is likely diet related.

Chronic bad breath is typically caused by an underlying problem in the mouth. The only way to know with certainty is the pet going under anesthesia for a complete exam and cleaning. Prior to anesthesia, it’s important to get bloodwork done to make sure your pet is safe for anesthesia and that all organs are working properly.

What kinds of treats and toys are safe for pets? The muscles in the jaw that help pets chew bones or hard toys can generate more pounds per square inch than teeth can withstand, leading to teeth breakage and the need for root canals. A rule of thumb to follow is if you can whack yourself in the knee with a toy or treat and it hurts, it’s probably too hard for your pet to safely enjoy. When deciding what diet, treats, and toys to give your pet, a good resource to turn to is the Veterinary Oral Health Council’s website. The site features products backed up by quality research showing they clinically and statistically reduce plaque and tartar buildup.

Our dedicated experts are always available to consult with you and/or your primary veterinarian if you have questions or concerns. Do you have a question you’d like to see answered in an upcoming issue?

Send it to oncall@vetmed.wisc.edu For health issues needing immediate attention, please contact your veterinarian directly.

To see more inspiring animals, student experiences, and behind-the-scenes SVM content, follow @uwvetmed on your favorite platforms and stay in touch!

Meet Matti Renikow, one of the Dawn Stewart Memorial Scholarship Recipients.… Alpacas have shaped her education, her career goals, and her passion for camelid medicine. Inspired by Dawn’s dedication to the alpaca community, Matti hopes to carry that legacy forward by becoming a mixed animal veterinarian who provides specialized care for camelids.

With this scholarship supporting her studies at the University of Wisconsin School of Veterinary Medicine, Matti looks forward to easing the burden of student debt and giving back to the animals that have given her so much.

– National Alpaca Foundation via Facebook

We are fortunate and grateful for UW Veterinary Care to provide Ezmae with her veterinary care. They are amazing and Ezmae gives them 4 paws up! ����

–UW-Milwaukee Police Department K9 Ezmae via Facebook

The SVM’s Dairyland Initiative (DI), which delivers research-driven strategies to enhance dairy cow health and productivity, continues to be a resource to dairy farmers around the world.

DI Outreach Specialist Courtney Halbach recently traveled to South Africa to present at an annual dairy farming conference hosted by Dairy Management Consulting. The event, held just outside of Cape Town, brought together veterinarians, nutritionists, and farm managers and owners who raise Holstein cows in the county’s Western Cape. Halbach delivered a presentation about barn ventilation techniques, including optimal metrics to hit when designing ventilation systems and how to create fast moving air in a cow’s resting space.

Halbach also visited 13 dairy farms, ranging from 500 to 5,600 cows, where she tested air speeds and gave recommendations for fan placement to reduce summer heat in barns and milking center holding areas.

“It was a fantastic experience being able to see dairying in a different part of the world and to share resources with dairy farmers, veterinarians, and nutritionists who are progressive and welcoming,” Halbach says. “I learned just as much from the South African dairy industry as I hope they did from my presentation.”

Created by author Ted Kerasote to honor the life and legacy of his cherished Labrador retriever, Pukka’s Laryngeal Paralysis Fund supports innovative research to uncover the causes of late-onset laryngeal paralysis and other canine nerve diseases and discover possible treatments. Pukka succumbed to the disease when he was 16 years old. By giving to the fund, you become part of a compassionate community committed to advancing animal health and honoring the deep bond we share with our animal companions.

Visit go.wisc.edu/pukka to donate today.

‘Parasitology’ publishes SVM paper on stowaway insect

The SVM’s Tony Goldberg (Department of Pathobiological Sciences) is at it again. He recently published a paper detailing an obscure parasite that he discovered in his armpit after working in the field.

The paper is about furuncular myiasis, a skin disease caused by parasitic flies. Goldberg, who in 2013 found a new tick species in his nose, described the condition as “a pimple with a surprise inside.” The surprise is the fly’s larva, which burrows under the skin and grows. “The condition is not lifethreatening,” Goldberg says, “but it’s also not fun.”

Goldberg identified his parasite as Lund’s fly, a poorly known species that occasionally afflicts travelers returning from Africa. Published in Parasitology, the paper is based on a decade of research the scientist conducted in Uganda’s Kibale National Park. Goldberg collected 21 larvae from people, including himself, and wild nonhuman primates. Surprisingly, all were Lund’s flies. The research suggests that the park could be a “hotspot” for this parasite, and that primates play a major role in the fly’s lifecycle. This discovery may finally have solved the 120-year-old mystery of where Lund’s fly resides in nature.

At the SVM’s annual alumni tailgate in September, the School of Veterinary Medicine Alumni Association recognized two outstanding graduates with the 2025 Alumni Distinguished Service Awards for their exceptional contributions to veterinary medicine, biomedical science, and the broader community.

Kathryn Meurs, a 1990 graduate, is internationally recognized for her pioneering work in veterinary cardiology and genetics. She currently serves as dean of the North Carolina State College of Veterinary Medicine and is this year’s DVM recipient of the award.

Scan to read the full paper

Mary Haak-Frendscho earned her PhD in Veterinary Science from UW in 1991 and has built a remarkable career spanning academia, biotechnology, and pharmaceutical innovation. She currently serves as president and CEO of Spotlight Therapeutics and is this year’s graduate program award recipient.

Building on a tradition of excellence, UW Veterinary Care’s (UWVC) comprehensive, integrated oncology service continues to transform how cancer care is delivered. The newest addition to the renowned team is Megan Mickelson (’09 DVM’13), an alumna and one of just 68 fellows in surgical oncology recognized by the American College of Veterinary Surgeons.

“With at least one specialist in medical, radiation, and surgical oncology seeing each patient that visits the hospital, UWVC provides compassionate, comprehensive cancer care that is unmatched in Wisconsin and the upper Midwest,” says SVM Dean Jonathan Levine

With the recent completion of the SVM and UWVC’s building and renovation project, the oncology service and related departments are leveraging expanded, state-of-the-art spaces to continue to build on their strong foundation. Advanced diagnostic and treatment tools, including PET-CT and Radixact (current generation Tomotherapy), help UWVC’s worldclass clinicians push the boundaries of what’s possible through leading-edge clinical research and treatment protocols aimed at improving cancer treatments for both pets and people.

UWVC’s integrated oncology team also includes medical oncologists Ruthanne Chun (’87 DVM’91), Xuan Pan, MacKenzie Pellin (’06 DVM’11), and David Vail, who work closely with

radiation oncologists Neil Christensen, Michelle Turek, and Nathaniel Van Asselt.

“I’ve known about our leadership in this area since I was a veterinary medical student at Cornell,” says Levine. “UW was always a place that was on the tip of everybody’s tongues when talking about oncology, and it’s a thrill to see this service continually advance life-saving clinical trials and treatments to improve our odds against cancer.”

Watch for in-depth coverage of our comprehensive veterinary cancer center in the next issue of On Call.

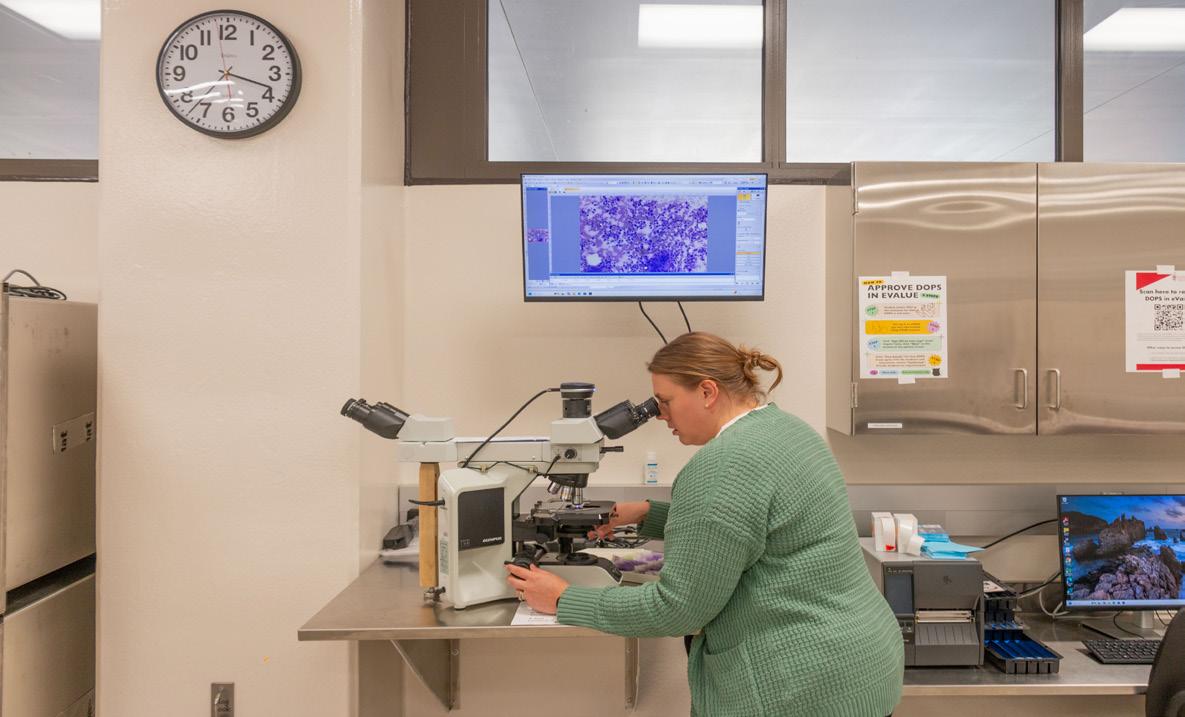

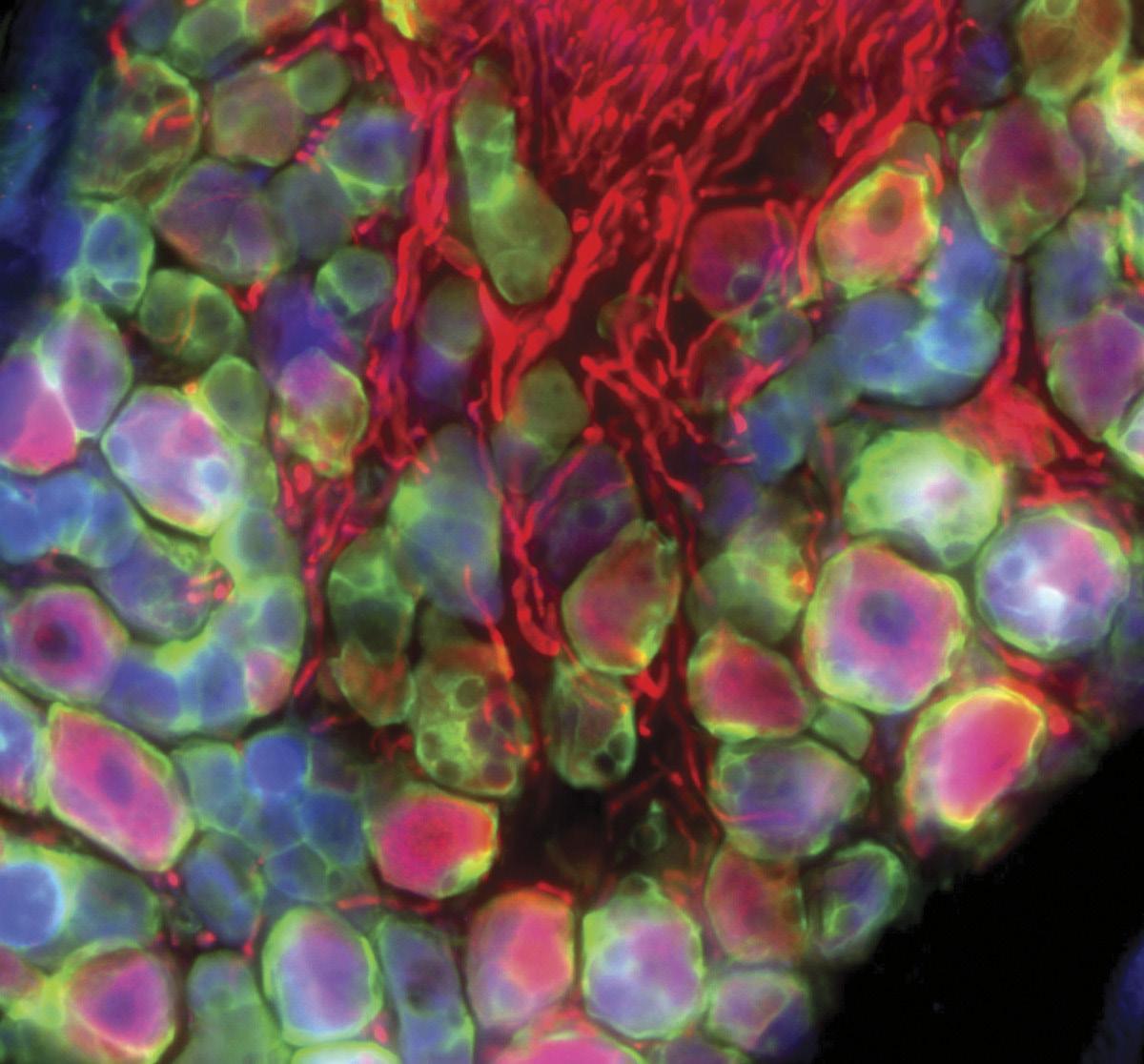

With support from LaTasha Crawford (Department of Pathobiological Sciences), Emily Tran, a Comparative Biomedical Sciences graduate program student, produced two of the 13 winning images in the 2025 Cool Science Image Contest. The campus-wide contest showcases the research, innovation, scholarship, and curiosity of the UW–Madison community. Tran’s images, alongside other winners, are featured in an exhibit on the ninth floor of the Wisconsin Institutes for Medical Research that runs through January 2026.

The SVM was featured in a recent TV news segment focused on the school’s role in performing a necropsy following the death of Ruth, a 43-year-old elephant at the Milwaukee County Zoo. Ruth was euthanized on Sept. 20, 2025, after falling for the second time in a month and being unable to get up.

The SVM is a key partner in the care of animals at the Milwaukee County Zoo, as well as at the Henry Vilas Zoo in Madison, the Dane County Humane Society, and numerous other wildlife and conservation groups.

In addition to helping determine an individual animal’s health history, necropsies can also advance research and play a vital role in species conservation.

The story includes interviews with David Gasper (PhD’15; Department of Pathobiological Sciences), the anatomic pathologist who led the necropsy, and second-year anatomic pathology resident Dalia Badamo

“The opportunity to work with these animals is rare, and I would like to keep it rare, “ Gasper says. “So, we work to identify what diseases are present that act as obstacles to maintaining healthy captive populations and help with conservation efforts.”

The SVM extends its condolences and shares the grief of the Milwaukee County Zoo community.

Scan to view the full story

Left: Each unique color marks a thready cell in tissue from a mouse bladder as a different type of sensory neuron, reporting different conditions to the animal’s nervous system. By sorting out the types of neurons at play, researchers hope to improve treatment of bladder pain in humans.

Right: A bundle of mouse nerve cells (distinguished by different colors) is wrapped in signal-regulating cells, which are shown in green and called satellite glia. These bundled neurons carry signals from the body to the brain via their long, red extensions known as axons.

by Jack Kelly

While Timmy always had an unusual gait when walking, it didn’t slow him down. The two-year-old goldendoodle’s steps were different than how most dogs walk around — bouncier, and at times a little wobbly — but he lived his early years like any other dog.

Until he slipped trying to get into the car one afternoon.

The fall, which occurred in June 2025, left him unable to stand up or walk and with minimal ability to move his legs. A family member caring for Timmy while his owner was out of town rushed him to UW Veterinary Care’s (UWVC) emergency department, where he arrived in significant pain. He was admitted and transferred to UWVC’s neurology service.

Clinicians started with a neurological exam and determined there was a problem with Timmy’s neck, says Starr Cameron (MS’21; Department of Medical Sciences), head of UWVC’s neurology service and assistant dean for clinical and translational research at the UW School of Veterinary Medicine (SVM). From there, advanced imaging was ordered to determine the cause of Timmy’s immobility.

Timmy’s care team was looking for a fractured vertebrae or herniated disc, Cameron says. But it’s what an MRI and subsequent CT scan didn’t show that caught the clinicians’ attention: the young goldendoodle was missing a key piece of his spine. He was born without his C1 vertebra, which connects the skull to the backbone.

“This sort of malformation has never been described before from an anatomic standpoint,” Cameron tells On Call “Nobody’s ever seen anything quite like this.”

In the weeks immediately following his initial visit to UWVC, Timmy regained most of his pre-accident mobility. However, Cameron and Karina Pinal, a third-year neurology resident, determined that Timmy required surgery. They feared that another fall, even a minor one, could be fatal for him.

The clinicians spent several days preparing for an advanced, first-of-its-kind procedure. Cameron conducted a thorough literature review to understand how procedures in similar cases were conducted and reflected on prior surgeries she had performed to develop a strategy.

Cameron used the CT scan of Timmy’s spine to produce a 3D-printed model of his backbone. The model proved to be “critical,” Cameron says, because it allowed the clinicians to prepare using an exact replica of Timmy’s unusual anatomy.

On the day of Timmy’s procedure, Cameron and Pinal were joined in the operating room by neurologist Natalia Zidan (Department of Medical Sciences), radiologist Samantha Loeber (Department of Surgical Sciences), and second-year diagnostic imaging resident Mattisen DiRubio. Timmy was positioned on his back for the surgery, and Cameron conducted the procedure through a six-inch incision over the dog’s neck.

To begin, she cleaned away large amounts of scar tissue that had formed around Timmy’s spine. Then, Cameron inserted two pins to connect the pup’s skull to his fully formed C2 vertebra. Finally, they embedded four screws to help anchor the pins. The surgeons did it all while navigating around key pieces of Timmy’s anatomy, including his trachea, esophagus, and jugular veins.

The clinicians’ work was aided by UWVC’s state-of-the-art 3D C-arm, an advanced type of diagnostic imaging that combines regular X-ray with a CT scanner to provide detailed, three-dimensional views of the body during surgery. The technology gave the team real-time assessments of implant placements and allowed them to make any necessary adjustments. In total, the procedure took about four hours.

“Traditional imaging technology requires post-operation scans and additional operating room time to make adjustments, which can be challenging for some patients,” says Loeber. “The 3D C-arm’s accuracy and real-time imaging is hugely beneficial to making efficient and effective surgical adjustments while in the OR, reducing burdens for both our patients and our clinicians.”

Today, Timmy is doing great and is expected to live life just like any other dog born with a fully formed spine. He’s visited UWVC for physical therapy and two follow-up appointments, and has returned to being the playful, two-year-old pup he was before the accident.

Top right: From left to right: Natalia Zidan, Starr Cameron, Karina Pinal, Mattisen DiRubio, and Samantha Loeber in an imaging room.

Bottom right: Left, a model of a typical canine spine. Right, the 3D print of Timmy’s backbone.

by Jack Kelly

The excitement was palpable amid the intermittent beeping of medical equipment and hushed conversations of two dozen students, clinicians, and instructional specialists. So were the nerves. It was junior surgery day — a major milestone for third-year students at the UW School of Veterinary Medicine (SVM).

Working in teams of four — two as anesthetists, two as surgeons — the students care for a feline patient through the entire surgery process, under the guidance of faculty and teaching staff. Upon arrival, they perform physical exams and monitor for any existing ailments. On surgery day, they give the cat premeds, induce anesthesia, transport them to the operating room, prepare for surgery, and perform a spay procedure. Finally, they closely monitor the patient through recovery and discharge, producing detailed medical records throughout the whole process.

“For a lot of students, this is a big milestone — something they’ve been working towards for years,” says Maria Verbrugge (MS’97 DVM’03; Department of Medical Sciences), clinical instructor of primary care at the SVM. “Sometimes there are some growing pains for students in taking on the responsibilities of the course, but in general, it’s an exciting time of a lot of firsts.”

The students enrolled in the course feel the same way.

“Junior surgery is one of the big things that you work toward,” says Kamber Cofta (’23 DVMx’27). “It’s also one of the most high-pressure things we do,” her classmate, Emily Napiwocki (’22 DVMx’27), is quick to add.

That makes the surgery course an inflection point in their veterinary medical education, the students say.

In keeping with tradition, some students decorate their lockers following their first spay procedure.

Left page: From left to right, third-year students Michael Reidenbaugh, Greer McKinley, Liz Erb, and Carly Strauss prepare their patient for surgery.

Right page, Top: Grace Linscott, Kamber Cofta, Emily Napiwocki, and Spencer Krug work with clinician Maria Verbrugge on surgery day. Middle: Napiwocki and Krug. Bottom: McKinley makes an incision during surgery.

“This is where you see all that you’ve learned come together,” says Grace Linscott (DVMx’27), who worked on the surgery team with Cofta and Napiwocki. “Up until now, for the most part, it’s been individual classes. And now, it’s anesthesia, surgery fundamentals, pharmacology, physical anatomy — everything’s coming together for this procedure.”

It’s also the first chance for students to fully have a sense of ownership of a patient’s case, says Spencer Krug (DVMx’27). “This is the logical next step,” he says. “We’re ready for it.”

“Surgery day is a long day,” Verbrugge says. “It’s a lot to remember and a lot of things that the students haven’t done before. We do quite a few prep labs, skills check-ins, and orientations to get them prepared, but that also can contribute to a bit of emotional wind up in anticipation.”

The school’s faculty members and instructional specialists work hard to ensure the students feel prepared for surgery day, Verbrugge adds. “The level of dedication of the teaching team, both the doctors and the instructional specialists, is incredible.”

“We try to strike a balance between making sure they understand the importance of being prepared to do a big, difficult thing, while also trying to make sure they feel as calm and well-supported as possible,” she says.

The course also underscores the SVM’s commitment to serving the community: The feline patients come from partner animal shelters.

The SVM’s partnership with the Iowa County Humane Society has bolstered the shelter’s ability to care for animals, says Hannah Guenther, the organization’s kennel manager. Through the junior surgery program, the shelter is able to provide free spays and vaccinations for both adoptable housecats and trap, neuter, release cats.

It’s been particularly important for the shelter’s trap, neuter, release program, Guenther says. “Cats get through surgery faster, which means they can be adopted or released sooner, which opens up space for more animals to get the care they need.”

“All around,” she adds, “it’s been a win-win: our animals get the care they deserve, and students get real-world experience that sticks with them.”

“We’re so grateful to the rescue groups that entrust us with patients,” Verbrugge says. “We couldn’t provide this learning experience without them.”

Wrapping up surgery week, the students said goodbye to their patients, each of whom had undergone a successful spay procedure and were recovering well.

“It was nice to have the responsibility and feel confident in my abilities,” Krug says. “There is so much to learn and to do, but taking a moment to realize that I have the knowledge to successfully complete a surgery feels meaningful.”

For Linscott, the high stakes and stress were worth it. “This is a pivotal moment,” she says. “This experience helped me realize that I am capable of managing real clinical situations, and that shift in mindset has made me feel more prepared for the responsibilities that lie ahead.”

Supporting the Companion

Fund creates better health

pets…and the people who love them by Maggie Baum

What if there was a meaningful way to honor and celebrate the human-animal bond while at the same time working toward improved health and wellbeing for our pets? The Companion Animal Fund (CAF) at the UW School of Veterinary Medicine (SVM) does just that.

Gifts to this fund — which come from individuals as well as many of our valued veterinary friends and partners (see sidebar) — support a range of critical health care studies. The common thread of these studies is that they are designed to improve the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of the diseases that afflict companion animals. What we learn in these studies is sometimes directly translated to human health, as

exemplified by the projects in this article that focus on laryngeal paralysis. On the flip side, sometimes improved practices and treatments in human medicine — such as the dried blood spot tests — offer ways we can test and treat our companion animals more safely and efficiently.

As we work to create the future of veterinary medicine, we’re grateful for the generous CAF donors who help advance incredible SVM research initiatives that work toward longer and healthier lives for pets.

The following are a selection of projects that CAF funds have supported this year.

Principal investigator: Katie Anderson (Department of Medical Sciences)

When a dog or cat is suffering from chronic vomiting or diarrhea, veterinarians often recommend a blood test called a GI panel to determine the cause. The GI panel assesses digestive health by measuring cobalamin (B12), folate (B9), trypsin-like immunoreactivity (TLI), and pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity (PLI). These test results often guide treatment decisions, such as dietary changes, vitamin supplements, or enzyme therapy, which can improve a pet’s health and quality of life. Currently, laboratories recommend fasting a pet before performing the GI panel, but this advice has not been proven through scientific research. This study aims to determine whether fasting — which can be stressful for pets and owners and often requires an extra trip to the vet — is truly necessary before the test.

Principal investigator: Robb Hardie (Department of Surgical Sciences)

Laryngeal paralysis is a relatively common problem in older, large breed dogs that results in laryngeal obstruction and respiratory distress. The current standard of care for dogs with laryngeal paralysis is a surgical procedure that opens the larynx. The procedure is relatively successful in relieving an obstruction but can lead to coughing and aspiration of food and water. Similar to cardiac pacemakers, laryngeal pacemakers provide an electrical stimulus to the muscles that open the larynx resulting in a more physiological function compared to current surgical techniques. This study is testing whether a commercially available pacemaker can stimulate the muscles of the larynx and adequately open the airway in dogs with laryngeal paralysis.

Principal investigator: Jordan Kirkpatrick (Department of Surgical Sciences)

The goal of the research is to evaluate the effects of trazodone, a calming medication that can be given to animals prior to a potential stressful event – such as, for horses, gait assessment and lameness evaluation. If there are minimal to no effects of trazodone on gait and lameness, this medication may benefit horses that become stressed by veterinary evaluations if given prior to their assessment. This would help make the assessments less stressful and safer for the horse, owner, and veterinarian without compromising the veterinarian’s ability to accurately assess gait abnormalities and lameness.

UNDERSTANDING HOW LATE-ONSET PERIPHERAL NEUROPATHY AFFECTS NERVE AND MUSCLE

Principal investigator: Susie Sample

(MS’07 DVM’09 PhD’11; Department of Surgical Sciences)

Late onset peripheral neuropathy (LPN), commonly termed laryngeal paralysis, is a devastating and life-limiting disease. Labrador retrievers represent about 75% of cases, and there is currently no disease modifying therapy for LPN. The objective of this project is to understand how LPN affects the interface between the nerve and muscle, and to determine whether dogs with LPN have altered sensation through sensory nerve fibers. This work will build foundational evidence into potential sensory involvement for the disease and inform how LPN results in weakness. Ultimately, this work will provide necessary data that will inform management, clinical decisions, and discovery of treatments.

Principal investigator: Alyssa Scagnelli (Department of Surgical Sciences)

Measuring vitamin D in reptiles is crucial for their health and in making sound recommendations on their care. Unfortunately, our knowledge of what constitutes normal vitamin D concentrations is lacking and we cannot make appropriate dietary recommendations for these species. Currently, vitamin D testing requires large blood volumes, serum separation, and overnight shipping, posing challenges for small patients. For human blood samples, dried blood spots (DBS) offer a practical alternative by allowing small blood samples to dry on filter paper with proven long-term stability and minimal storage and transport needs. This study aims to determine whether DBS can assess vitamin D concentrations in reptile blood to offer a simpler diagnostic tool, enabling broader studies on reptile vitamin D metabolism and improving clinical care for these popular pets.

To learn more about studies supported by the CAF, visit go.wisc.edu/svm-caf

There are many ways to commemorate and honor a pet or a person with a gift to the Companion Animal Fund: Scan to learn more about making a gift

• Express sympathy for the loss of a cherished companion

• Thank a veterinarian for exceptional care

• Honor a friend or family member who loves and values animals

Years of clinic participation effective December 31, 2024

30-39 Years

Country View Animal Hospital

Dodgeville Veterinary Service

Family Pet Clinic

Kaukauna Veterinary Clinic

Layton Animal Hospital

Loyal Veterinary Service

New Berlin Animal Hospital

Northside Veterinary Clinic

Omro Animal Hospital

Oregon Veterinary Clinic

Park Pet Hospital

Shorewood Animal Hospital

Thiensville-Mequon Small Animal Clinic

West Salem Veterinary Clinic

Wright Veterinary Service

20-29 Years

Bark River Animal Hospital

Jefferson Veterinary Clinic

Muller Veterinary Hospital

Tecumseh Veterinary Hospital

Wittenberg Veterinary Clinic

10-19 Years

Delafield Small Animal Hospital

Lake Country Veterinary Care

Metro Animal Hospital

Northwoods Animal Hospital, Eagle River

Northwoods Animal Hospital, Minocqua

1-9 Years

Birch Bark Veterinary Care

High Cliff Veterinary Service

Southwest Animal Hospital

Each year, SVM donors help us make life-improving and life-saving medical advances for both animals and humans, deliver an innovative educational experience, and provide best-in-class care in our teaching hospital.

Scan to view a list of all donors who made gifts or pledges of $100 or more between July 1, 2024 and June 30, 2025

by Simran Khanuja

Dogs and cats. Horses and cows. Birds and rabbits. Each year, UW Veterinary Care (UWVC) provides care for almost 30,000 patients who vary widely in shape, size, and species. But in addition to the two- and four-legged friends you might expect to find in someone’s home or on a farm, the hospital’s team of world-class clinicians also provides top-notch care to less common and exotic species. This story features a collection of profiles underscoring the incredible breadth of patients that visit UWVC in a year — from racing pigeons and lions to ostriches and kangaroos.

When Nelson, a young male lion belonging to an Oklahoma circus, fractured his left tibia while jumping from a platform in his enclosure, his journey for care stretched far beyond his home state. After undergoing orthopedic surgery in Oklahoma City, Nelson traveled to Wisconsin during his two-week recheck exam, where UWVC

clinicians coordinated a multidisciplinary effort to assess his healing.

Lions must be heavily sedated for any examination. Accordingly, the UWVC team used a pole syringe to deliver anesthesia before safely moving him to the hospital’s large animal radiology suite. Once intubated, Nelson underwent radiographs and a full physical exam. The images showed a small area of delayed bone healing, but the clinicians chose not to place a cast, knowing he would likely chew it off. Instead, Nelson’s recovery plan emphasized containment, limited activity, and careful monitoring.

Kurt Sladky (’81 MS’88 DVM’93; Department of Surgical Sciences), clinical professor of zoological medicine and a leading clinician on this case, says the case was especially meaningful because of the unique challenges involved in treating animals traditionally considered dangerous.

“Unlike dogs and cats where an exam and bloodwork can typically be performed prior to sedation to help minimize risk, many zoo and wildlife patients must be sedated or anesthetized before any handling is possible,” says Sladky. “Careful planning, clear communication and the presence of experienced clinicians are essential to reduce the risk of injury to both the people and the animal involved.”

A noticeable bulge on the jaw of Vinny, an adult female grey kangaroo, set off alarm bells for her owners.

Concerned that the swelling, caused by a suspected tooth root abscess and mandibular osteomyelitis, commonly called “lumpy jaw,” could rapidly progress to sepsis, they brought her to UWVC for specialized evaluation. The

owners, who care for several kangaroos and wallabies, wanted expert guidance to ensure the condition was managed safely and effectively.

Once Vinny was sedated, UWVC clinicians performed a CT scan to evaluate the extent of the abscess. They also collected material from the site for bacterial and fungal

A sudden collision sent feathers flying when Birdbeak, a female ostrich at Safari Lake Geneva, ran headfirst into a wooden fence while being chased by another bird, leaving a deep wound on her left upper thigh. UWVC has a long history of treating Safari Lake Geneva animals, and the facility’s staff quickly brought Birdbeak in as an emergency case. A multidisciplinary team from several of the hospital’s services worked together to treat her.

Female ostriches are relatively easy to manage, Sladky says, as the team was able to hand-inject her to induce anesthesia, carry her from the trailer, and intubate her in the large animal hospital. Once under anesthesia, the surgical team cleaned the deep wound and closed it with multiple layers of sutures. Birdbeak also received protective medications, including a tetanus vaccine and an antiinflammatory injection.

when a hawk swooped down and attacked him. The neighbor intervened, scaring off the predator and rushing the badly injured bird to UWVC.

When Sky Biscuit, a racing pigeon, veered off course after a flight, he accidentally landed in a neighbor’s backyard. What seemed like a minor detour quickly turned life-threatening

Upon arrival, Sky Biscuit was in shock and severe pain. The team immediately stabilized him before cleaning a large wound under his wing. But bandaging presented a special challenge: pigeon skin is thin and delicate, and the team had to ensure the dressing supported healing without hindering movement.

“This was a good teaching moment for our students to show them that their

cultures to guide the most effective antibiotic treatment. The sedation, procedure, and recovery went smoothly, Sladky notes, and the UWVC team provided detailed instructions for ongoing management with the referring veterinarian.

Marsupials have unique characteristics and their own common diseases, Sladky

fundamental knowledge and skills can take them far, even with a species they don’t have much experience with,” says Fred Torpy, a resident with UWVC’s special species service.

Even with his injuries, Sky Biscuit’s strength quickly became apparent.

“Despite being attacked and severely wounded, he perked up quickly, started eating, and got on with his life,” Torpy says. “His resilience is what stands out most to me about this case.” Today, Sky Biscuit has fully healed and transitioned into

says, making species-specific knowledge critical for diagnosis and treatment. He also says that kangaroos can defend themselves with powerful kicks and sharp claws, which requires careful handling.

“The part of this case that I found especially meaningful is the importance in understanding the natural history,

The surgical repair went smoothly, and Birdbeak safely recovered. Follow-up reports indicate she has resumed her normal, healthy life.

“This case highlighted the benefits of being at a multispecialty institution,” Sladky says. “Being able to pull together a team with multiple backgrounds and specialties allowed us to give Birdbeak the well-rounded care she needed.”

retirement. Kennymac Durante, an intern with the special species service who helped oversee the bird’s care, said that Sky Biscuit now lives with a close friend of his original owner, living his best life as a companion pigeon.

“It was moving to see the neighbor show so much compassion for Sky Biscuit,” says Torpy. “I always hope that these situations, where we focus on an animal in need, can lead to everyone involved growing in their compassion, even just slightly.”

behavior, and diet of a species,” he says. “This knowledge of different species is critical for focusing on diagnostic and therapeutic plans.”

by Jack Kelly

Scientists at the UW School of Veterinary Medicine (SVM) are on the front lines of understanding H5N1 avian flu and developing tools to fight the virus.

Their work comes at a critical juncture, with the virus continuing to fuel outbreaks in poultry and cattle on farms in the U.S., according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Several human cases affecting poultry and dairy workers have also been reported.

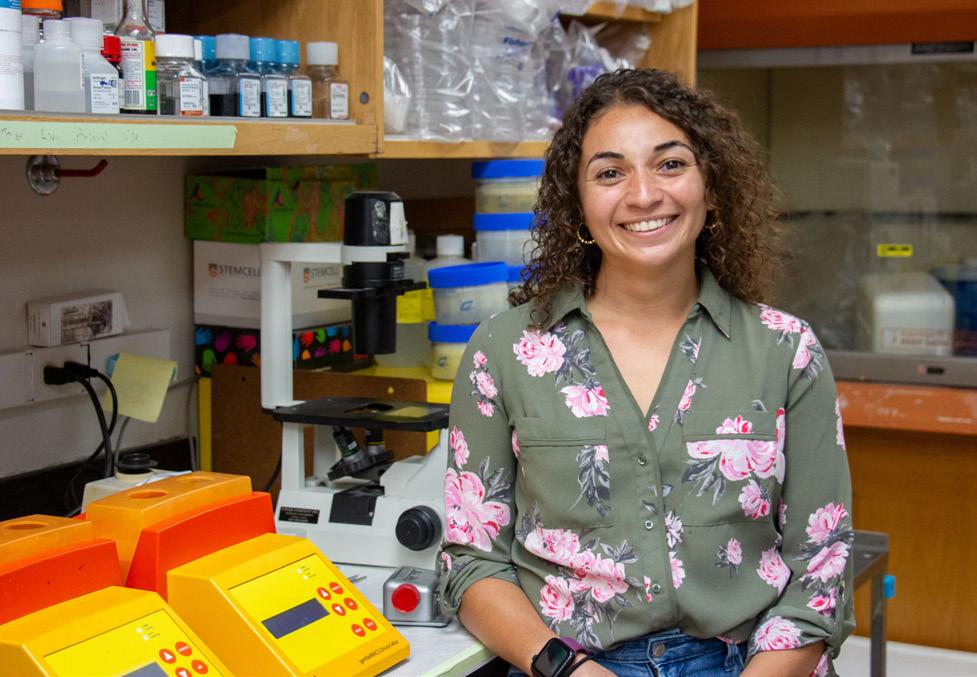

Clara Cole (BS’17 DVM’21), a second-year PhD student in the Comparative Biomedical Sciences Graduate Program, is investigating the impacts of H5N1 on mammals, with a particular focus on how the virus affects the mammary glands. Her DVM coursework at the SVM, including a class taught by Marulasiddappa Suresh (Department of Pathobiological Sciences), inspired her to pursue a PhD in immunology. Suresh, John E. Butler Professor in Comparative and Mucosal Immunology, also serves as the SVM’s associate dean for research and graduate education. Cole now works in his lab.

“I like solving puzzles, solving mysteries,” Cole says. “I like getting my hands dirty. And my current work brings all of those things together.”

The puzzle she’s trying to crack now has serious implications for both the economy and public health. The spread of H5N1 has contributed to increased prices at grocery stores for things like eggs, Cole says, because infected flocks have been culled to limit the spread of the virus.

H5N1 threatens the dairy industry, too, because the virus can cause mastitis (inflammation of the mammary glands) in dairy cattle which results in reduced milk production and lower quality milk. And there are public health concerns: If the virus continues to spread among different species — it has been detected in sheep, pigs, seals, and even polar bears — it is more likely to undergo gene segment reassortment or mutate, Cole says. While the virus in its current form struggles to infect

humans, a future reassortment or mutation could be the source of the next pandemic.

H5N1 appears to spread among dairy cows not primarily through the upper respiratory tract, the usual route for flu viruses, but through the udders after cows encounter contaminated milking equipment.

That presents two challenges to Cole, who, in collaboration with Suresh and Yoshihiro Kawaoka (Department of Pathobiological Sciences), is working to develop an effective vaccine to protect cattle against H5N1 and similar viruses.

Not only do the animals need to be protected against respiratory transmission, but they also need safeguards against infection via their mammary glands — something that’s never been done before, Suresh says. This is especially important because the animals have considerably worse symptoms when they are infected via their udders.

The scientists are conducting immunogenicity studies, which test to see whether a vaccine candidate stimulates an immune response. Early results have been remarkably promising, says Suresh, who also serves as the school’s associate dean for research and graduate training.

The researchers have been able to elicit antibodies in both the blood and milk of cows that have received the vaccine. Antibodies help neutralize the virus before it can infect cells. They have also detected a T-cell response in the cows’ blood. T-cells target and kill infected cells.

Cole, whose work is supported by a National Institutes of Health T32 training grant, is now studying whether the new vaccines can stand up to the virus in mice. Using a carefully regimented hormone series, she is able to make the mice lactate without being pregnant — simulating a dairy cow at a much smaller scale. The milk produced by the mice is collected each day and certain tissues are tested after the mice have encountered the virus.

Her colleagues are still examining the effectiveness of vaccine candidates against the virus and hope to have a clearer picture of their efficacy in the coming months. Science takes time, Cole notes, and she remains committed to doing work that helps improve the health of both animals and humans.

“On the off chance the virus does mutate and humans become more susceptible to it, I want to help prevent another pandemic,” she says. “I want to do whatever I can to help save both animal and human lives.”

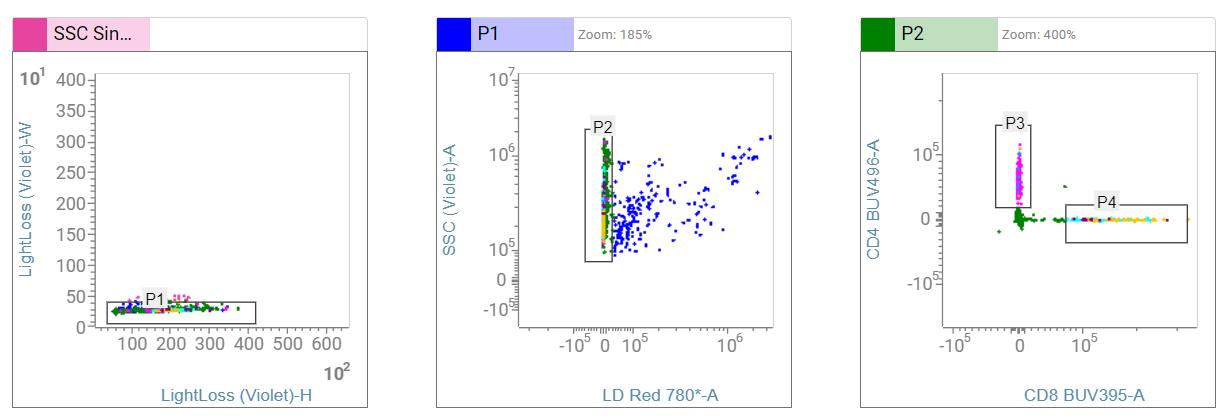

This image shows the step-by-step process of “gating” (or selecting) specific groups of cells from a larger sample using a flow cytometer machine. Think of it like using a series of digital filters to isolate certain cells, one filter at a time. The goal of Cole’s work is to isolate and study certain T cells — white blood cells essential for immune response — related to vaccine-induced immunity.

This fall has been an exciting time for us in the Comparative Biomedical Sciences Graduate Program (CBMS) as we’ve welcomed the following students who recently started their graduate school journeys with us. Students are listed here by name (left) with their mentor(s) (right) whose lab they are joining:

• Jenn Adams – Sam Weaver (’14 PhD’18)

• Xueling Ding (’23) – Yongnu Xing

• Jessica Lipschultz – Lyric Bartholomay (PhD’04) & Jordan Richard

• Shreya Nair – Chad Vezina

• Riley Parks (’23) – Nick Burgraff

• Memi Pearsall – Freya Mowat

• Adam Shumate (’24) – Lyric Bartholomay (PhD’04) & Susan Paskewitz

• Austin Stram (’20) – Sean Ronnekleiv-Kelly

• Zach Tower – Hao Chang

We’re thrilled to have this talented incoming class settle in and get to work. The excellence of the CBMS program and its faculty helps us attract students with immense skills and incredible ideas. Also, it’s a plus for many considering programs that we are a “direct admit”

program. Where other graduate programs admit students for rotation experiences, the CMBS program accepts students when they are successfully connected to a major professor. That faculty member commits to supporting their students throughout their training with a research assistantship and support for the research project they’ll be conducting.

This is a sizeable class — and of course they have a full workload! Yet, students are already establishing strong ties to their cohort and the CBMS and SVM communities thanks to the efforts of the program’s social committee. Committee members have planned and hosted a boat outing on Lake Mendota, a campfire at Picnic Point, and a Halloween-themed pumpkin carving event. While we are all here to do important work, it is our intention that events like these help build community, inspire positive connections, and create great memories for our students.

Lyric Bartholomay (PhD’04)

Professor, Department of Pathobiological Sciences Director, Comparative Biomedical Sciences Graduate Program Dr. Bernard C. Easterday Professor in Infectious Disease

by Maggie Baum

“I may be biased but, having worked with students from nearly every veterinary medical school, I continue to see the exceptional education that the UW School of Veterinary Medicine (SVM) provides,” says Kari Musgrave (DVM’15), an alumna who currently serves as director of animal health at the Saint Louis Zoo.

A native of Bloomington, Indiana, her grandparents owned and operated a large apple orchard and farm. Musgrave also was an avid Animal Planet viewer, which fostered her early fascination with wildlife, particularly reptiles. She participated in 4-H for more than 10 years, raising rabbits to show at the county fair and across the Midwest. A 4-H volunteer project in high school led her to a local low-cost spay/neuter clinic, where she cleaned kennels and surgical instruments and had the opportunity to observe a few of the procedures.

And so, her lifelong interest developed into a career path in veterinary medicine. Musgrave did multiple zookeeper internships while pursuing her undergraduate degree in biology and chemistry at Franklin College in Indiana and recalls an opportunity at the Indianapolis Zoo as especially impactful.

“I saw the interaction between the veterinarians and their clients — the keepers — and how different this was from a typical small animal veterinarian,” she says. “The

Above: In 2022, Musgrave traveled to Madagascar with the Saint Louis Zoo Institute for Conservation Medicine and the Turtle Survival Alliance to assist with the pre-release health evaluations on nearly 2,000 radiated tortoises that had been previously rescued from smugglers.

keepers are the experts in the natural history of that species that we rely on, and we all have the wellbeing of the animal in mind, working together to figure out the best path forward.”

The well-rounded education she received at the SVM — she was exposed to large, small, and exotic animals during her time at UW-Madison — was a crucial foundation for her current day-to-day work, Musgrave says. Choosing the “other” track during the fourth year of the DVM program allowed her to build a solid foundation in a variety of hospital rotations and gave her the opportunity to rotate at four different facilities that had post-graduate training programs: Omaha’s Henry Doorly Zoo, the Oklahoma City Zoo, San Diego Zoo Safari Park, and the Indianapolis Zoo.

“These experiences set the stage early on for me pursuing a zoo internship and residency by getting exposure to and letters of recommendation from diplomates in the American College of Zoological Medicine,” she says.

All of these experiences ensure she can tackle the immense variety of tasks each day brings in her current role (see “typical” day sidebar). While she never knows exactly what a new day might bring, she’s ready for any challenge and has had her share of highlights. A few that stand out, she says, include discovering the beneficial impact of adding artificial UV lights on the health and welfare of Speke’s gazelles, and the first artificial insemination and subsequent birth of the Saint Louis Zoo’s Asian elephant calf, Jet, who turns one in November.

Musgrave cites Jan Ramer (DVM’95) and Michelle Bowman, who were mentors during her undergrad experience at the Indianapolis Zoo, as the reason she applied to the SVM as an out-of-state student. Knowing how important their guidance, as well as exposure to a wide variety of experts and organizations, was for her career trajectory, she has two pieces of advice for current veterinary students.

“First, the beauty of veterinary medicine is that there isn’t one way to do anything, whether that is a specific medical procedure or your career pathway, they are all unique,” she says. “Also, never be afraid to ask questions. I ask for help from people in other areas of veterinary medicine and even other industries all the time and I always learn something new and helpful.”

While her days are dominated by zoo animals and leading her team, Musgrave treasures family time with her husband, Tyler Majerus (DVM’15), and their two young sons, Vernon and Clive. Her boys, of course, are big fans of the Saint Louis Zoo and especially love its “waddle waddles” (her two-year-old’s name for penguins).

On a beautiful September morning, we were thrilled to unveil Forward Together in the school’s new courtyard – an event seven years in the making, held in a beautiful space that connects our north and south buildings. This incredible bronze sculpture celebrates the four-year DVM educational journey and highlights experiences unique to the University of Wisconsin. Created by John Hallett (DVM’90), Forward Together showcases reflections and stories from numerous students, alumni, and faculty and staff.

The piece includes numerous delightful details – specific nods to our school’s physical and social community – and students served as models. Importantly, Forward Together shows both the challenges and rewards of being a DVM student; celebrates the importance of the relationship between pets and people; and reflects the school’s rich tradition in research and discovery that advances both animal and human health. The sculpture serves as an inspiration and a comfort to all who visit the school.

I oversee a department of 15 animal health professionals: four staff veterinarians, a zoological medicine veterinary resident, a staff pathologist, a zoological manager of animal health, six veterinary technicians, an animal health keeper, and an administrative assistant. In short, I’m responsible for providing the overall vision of how to ensure the Saint Louis Zoo’s Animal Health Department is innovative and providing the best care to our animals.

My day-to-day varies tremendously. There are many days where I’m in meetings helping plan for our new Saint Louis Zoo WildCare Park and walking through the new hospital under construction, plus figuring out preventative health and vaccine protocols for a new species that is arriving.

On any given day, I might be doing a neonate exam on a Speke’s gazelle, looking at a cataract in a penguin, or examining a wound on a hellbender that could later be released back into the wild.

I get to make an impact on both the individual animal, and — in some cases — an entire species. The combination of population health and individual medicine, which is so unique to zoo medicine, is what excites me most, and that every day is different.

My most sincere thanks to Dr. Hallett, who recently completed his MFA at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design, for donating his time and talent. A generous matching gift from Jack and Margo Edl inspired alumni and other friends to cover production and installation costs. For all who contributed gifts and stories, thank you.

Forward Together is a crown jewel of our building expansion and renovation project that celebrates the school’s students and alumni, our commitment to compassionate care, and our impact on Wisconsin and the world. The sculpture is best experienced in person: I promise you will discover something new each time you see it! If you can’t visit us soon, learn more about this incredible work of art at go.wisc.edu/forwardtogether

Thank you.

Kristi V. Thorson (‘94 MA’97) Chief of Staff

Associate Dean for Advancement and Administration

on Molly Racette’s path to becoming a veterinarian by

Jack Kelly

Clinician. Professor. Mentor. Counselor. Coach. Project manager. Molly Racette (MS’14; Department of Medical Sciences) plays all these roles and more during an average day in UW Veterinary Care’s (UWVC) emergency and critical care unit (CCU).

By 7 a.m., Racette, who serves as section head of the hospital’s emergency and critical care service, is deep in discussion with the service’s overnight clinicians. Patient by patient, they recap the night: Who was comfortable? Who struggled? What went well? How can she help? Around them, machines whir, dogs bark, staff chatter, and shifts change.

Then she’s off to the emergency department. A 10-week-old puppy greets her with kisses en route to the debrief. It was a slow — which does not mean easy — night. One case ended in heartbreak: a pet discharged against medical advice didn’t survive. “It ruined my night,” the overnight clinician tells Racette. “It would have ruined my night, too,” she responds. They sit in somber, companionable silence for a moment before Racette assures him he did everything he could.

Another case went well. “I got lucky,” he tells her. Racette corrects him. “Don’t say luck — say skill!”

Once the debrief is over, she swaps coffee for gummy bears and is back with patients. She performs an ultrasound on a little black kitten, followed by a German shepherd, and then a pit bull mix. She checks on the 10-week-old puppy, who’s desperate for attention from his specialized kennel. “I’d climb in there with you if I could,” she jokes. “But I have work to do.”

As cases come in, she teaches. Residents, interns, and veterinary students gather around the department’s whiteboard and markers race across its surface. What do we know? What does that tell us? What should we do next?

Afternoon brings a potential cancer patient and a dog with bite wounds. Through it all, Racette doesn’t slow down.

While she always wanted to be a veterinarian, Racette’s path to emergency medicine wasn’t linear. She spent her first three years of veterinary medical school studying to be a large animal surgeon, until a summer job changed everything.

She worked the overnight shift as an intensive care unit nurse and “absolutely fell in love with it,” she says. “It’s just you and the patient. They’re often really sick and you get to dedicate all your time to them.”

Molly Racette with her cats, one of which was a patient at UWVC.

Racette hasn’t looked back, and she remains especially appreciative of the unpredictable nature of emergency medicine. While some might find it daunting, Racette treats every day, regardless of what patients come through the door, as an opportunity to learn.

“I’m not a cardiologist, but we see cardiology cases and I get to learn what’s new in the field,” she says. That’s true across all the hospital’s services, Racette adds, because a teaching hospital fosters collaboration across departments.

The desire to never stop learning is something she tries to pass on to early career veterinarians and students. “When I’m on the clinic floor, although I am a clinician, I’m trying to be a teacher to the residents, interns, and students,” she says. “I love giving them tools to connect what they’re learning in class and seeing in clinics to future cases they might see.”

Racette also focuses on the process. “There are some things that are inherent to emergency and critical care, including the unstable nature of our patients,” she says. “We are always focused on the process of triage: Is the patient stable and, if not, how can we stabilize them so that we can then figure out what’s going on?”

Through it all — the heartbreak, the happy outcomes, the sour gummy worms — Racette keeps moving. And managing. And teaching.

“Dr. Racette has been an invaluable mentor to me,” says student Isabella Susi (DVMx’26). “She has consistently modeled how to translate knowledge into practice, supported my growth in the ER, and invested in opportunities to help students succeed outside of coursework.”

2015 Linden Drive Madison, WI 53706-1102

The holiday season is near and the UW School of Veterinary Medicine (SVM) has a unique gift for the animal lovers on your list — one that truly helps those special animal companions in our lives.

The SVM is pleased to present original artwork for its holiday card fundraiser each year. “Dashing through the Snow,” right, features the work of Wisconsin artist Mallory Stowe. For a $10 donation per card, the SVM will send a holiday card to the recipient of your choice — a thoughtful gift for family, friends, neighbors, veterinarians, or even pets. These heart-warming, full-color cards include a greeting stating that a donation was made to the school in the recipient’s name and that proceeds will support projects that advance animal health.

There are also opportunities to purchase packs of 10 cards for $40 with “Happy Holidays” on the inside. Sets will be mailed to you to share with your family and friends.

Scan to purchase cards online or download an order form

Questions? Contact Sarah Ryan at 608-262-5534 or scryan2@wisc.edu.

Mallory Stowe is a contemporary oil painter and educator interested in the natural world. She received her MFA from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 2025, and her BFA from Ohio University in 2022. Stowe teaches drawing and painting courses at UW-Madison and Wheelhouse Studios.