Headwaters Magazine is 10 years old! We want to extend a massive thank you to all the marvelous writers, artists, editors, leaders, and visionaries that have contributed to the magazine over the years—Headwaters has flourished because of your efforts and continues to nurture inquisitive and compassionate publishing in your legacy. Thank you to our devoted readers for your enduring enthusiasm and love for this magazine. Headwaters would not be possible without continued support from UVM Student Government Association, the Rubenstein School of Environment and Natural Resources, and the Headwaters Leadership Team. Lastly, we would like to offer a warm welcome to our new faculty advisor, Dr. Peter Brewitt.

Over the years, Headwaters has been a container of stories on all scales, from exploring UVM’s own “Birding to Change the World” class, to local conservation efforts in California, Vermont, or Costa Rica, or grassroots organizing around the world combating climate change. Whether it be through poetry, illustration, journalism, collage, or short story, Headwaters’ urges us to be captivated with the beauties and complexities of the natural world and our place in it.

10 years ago, Headwaters Magazine was born as an electronic publication. One year later, the first print issue was released into the world; it was, and remains, UVM’s first student-run environmental publication. In our very first Letter from the Editor, President of the magazine, Dan Kopin ‘17, writes: “We are a small organization of students dedicated to a simple idea: by participating in public discourse, our voices just might make a difference. Headwaters are the small sources from which rivers originate. With hopes that our ideas may flow into greater bodies of knowledge, we have chosen to put our pens to paper.”

These are the hopes that still propel our magazine today, and they have proved their power again and again. Your voice matters. In the face of environmental and humanitarian devastation, it is our duty as creatives to not go gentle, nor believe the lie that we are grieving alone. Rather, we must put our pens to paper, and believe that though the headwaters may be small, or one among many, their combined impacts will be vast.

With love,

Megan Sutor ‘25

Editor-in-Chief

Megan Sutor

Managing Editor

Loden Croll

Managing Designers

Cali Wisnosky

Avery Redfern

Creative Director Via Hedley

Treasurer

Anna Hoppe

Social Media Manager

Emma Polhemus

Planning and Outreach

Addie Hayward

Contributing Editors

Talia Weizman

Sarah Johnsen

Avery Redfern

Thomas Chamberlain

Megan Sutor

Ruthie Bell

Ben Mowery

Kylie DelMaestro

Alma Smith

Anna Hoppe

Greta Albrecht

Contributing Artists

James Marino

Ella Rentz McCoy

Soraya Hammer

Katherine McGee

Cali Wisnosky

Liza Teleguine

Megan Sutor

Alma Smith

Pheobe Swartz

Brielle Howlett

Emma Polhemus

Avery Redfern

Sadie Holmes

Isabella DeGroot

Via Hedley

Ruthie Bell

Somemornings, I wake with a heavy head, full of ideas that tangle like twine. The task of untying the threads keeps me rising in the dark hours, walking the foggy line where night seeps into dawn. On a cold September day as the sun begins to rise, its light slowly traces my spine, filtering through the orange leaves outside the window. As always, I wait until my body is full of warmth before I rise from bed. It is time to start searching.

By the time my mind has come alive, I am passing the first bench on Spear Street. Look beneath the maple grove, through the wiry chain link fence, and over the crushed cans on the side of I-89 to see the intersection of my mind and body. I come alive here most mornings, 1.37 miles into my run. As the knot in my left calf begins to untangle, so does the path, opening to the golf course on one side and federally funded farmland on the other. I breathe in the sweet air of the morning until the scent of manure floods my nose.

A flock of wild geese fly over my head, crossing the street in the sky and then meeting the cold, misty dew as they touch down in a way that must feel like coming home. The once vibrant wetland running through hole sixteen has been covered in concrete pipes, turned into a stormwater filtration system. There’s something about the fall that always makes me wish for what I no longer have, and today I feel the longing before I know what I am lacking. Scattered wildflowers still inch up the sides of the pipes, and I see in their stubborn stems a strain for something less domesticated. My feet keep pushing forward, but a piece of my mind remains in the land behind me.

As my lungs adjust to the gusts of early autumn air, songs of robins and red-bellied woodpeckers begin to fill the sky. It is one of those days where the birds sound thrilled to be alive, their song tinted with adrenaline. The leaves are slowly turning yellow, like apple slices left in the open air, but unfortunately, there’s no lemon juice that

helps ease the change of seasons. The minutes always seem to move faster in the mornings. The gap between past and future shortens with every step and breath from my beating lungs and bounding legs. The impermanence of summer is evident as the trees shake off their green coats to reveal their true nature, stripped down and honest, baring themselves to the world. I run past the second and third bench onto a sturdy metal bridge that rests above an unnamed creek parallel to the highway.

Every time I approach the bridge, I have to stop myself from going underneath it and letting the creek’s rushing water run over my hands. I want to know what it is that makes me so loyal to the manicured path, never straying from the asphalt. Today, I pause as always, staring at the streaming current beneath me and listening to the groaning tires of hundreds of cars heading west on I-89. I wonder if the water used to flow right through the 2-car lane, sparkling against the rocks that have since been removed by construction crews.

I realize that if I am going to find answers, I am going to have to stop running away from the questions. Class starts in forty-three minutes, so I turn around and go home.

I wrestle with what it means to find solitude in an environment like this, a path that is expertly engineered for me to do so in a way that serves the market productively. The majority of the people I see on my mornings are commuting to work, and in those moments the path feels more like an economical equation than a place to sink into awe. Is it still truly reaching for something if the reward has been placed directly into my palms?

Whether my solitude is true or not is irrelevant to the schedule Spear Street seems to run on. Later in the afternoon, I return. Everybody I pass is going home. The

geese from earlier have gone away, carrying their calls for each other down towards the lake as stray feathers float towards the grass. I wonder if the geese know about the creek, or if there used to be another one before the houses were built in their field.

I continue onwards until I reach the bridge once more. This time, I do not make contact with the rusting iron, stepping immediately off to the left—it’s been getting colder, and in the coming weeks I know the flowing creek will freeze—I have to see the water. I can see a path outlined by crushed beer cans and an abandoned shopping cart. I begin to make my way to the creek. As I inhale, the unseen manure stuns my senses and reminds me where I am. This land, once wild, was converted into a shared-use path with a $300,000 federal grant. How do we know what’s worth destroying to build something “better”? How is anything alive worth destroying? This is why I don’t slow down often—the questions never stop. Submerging helps, always. Oceans, rivers, creeks, and lakes are where I find peace, if not answers.

I pull up my sleeve to check the depth of the water, and when my palm touches the moss at the creek’s floor, the water has crept up to my right tricep. The creek is only 3 feet wide, but the water flow is enough to push my fingers forward. I sit and cup the cold water in my palms. My gaze rises to the trees that crawl over the fence lining the highway. I see a small squirrel climbing into the canopy and a magenta tent shredded against the fence that separates me from the hot pavement of the highway. I stay here, breathing, devoting myself to detail and the duty of being deeply intertwined with a place.

My time at the creek is, at the very least, a partially successful attempt at replicating the conditions in which I learned to love this world. When I was too young to be in the water, I sat on rocky beaches while my siblings surfed. I thought about the water, the way it rendered us powerless without a single reservation. I saw the smooth rocks that had been reshaped over thousands of years, shifting to accommodate the waves. And I thought about what it meant to move the world, for the first time seeing the power of quiet persistence reflected in front of me. As I kneel by the creek, noting the shapes before me and the water’s closeness to the man-made highway, I remember the power of the rivers. The creek, even, was here years before the highway popped up, and before the recreational path was created. All the nature that surrounds me found its place gradually, unlike the jutting fence, clearly unwelcome.

The sound of a bike and a barking dog above me snap my head up, and I realize that I am a girl barefoot beneath a bridge. I’m thinking about shadows dancing like puppets with strings being pulled by the sun, and it’s all a bit ridiculous.

Eventually, the sun becomes overbearing, and it permeates my place among the rocks and leaves. I feel my scalp burning and see a mosquito on my ring finger and one on my ankle. When they find me, I know it is time to go. The brush lining the way back to the bridge pierces the bottoms of my feet, but it dries them off just the same.

At the top of the hill, there’s a squirrel struggling with a Hannaford bag. Once I’ve reached it, I take the grocery bag, untangling it at arm’s length from his paws as he writhes until he is freed from the plastic prison. Placing the trash next to the fresh lavender and goldenrod in the pocket of my jeans, I begin my walk back, heading north on Spear Street for the final time today. I turn the corner, and as the sky breaks open wide, I see the wild geese returning home with me.

I keep returning to the path, daily, never getting tired of the way the sky opens as I run past the golf course. The golden colors of autumn deepen, darken, and then fade. Slowly, the air takes on a sharper edge, the trees shedding the last of their leaves in a final exhale before winter settles in. Frost begins to linger past dawn, clinging to brittle grass, and the morning birdsong is replaced by the sound of wind moving through bare branches. The path is the same, but the world around it is retreating into itself, folding inward, waiting.

One morning, after winter has fully arrived, the tree shadows stretch across the frozen ground. The geese have long since left, and the air is thin and silent, muffled by fresh snow. Each footstep crunches against the ice-packed trail, the rhythm slower now, more deliberate. No bikes fly by me. I reach the bridge and pause, my breath curling upward, merging with the cold. The creek below is frozen beneath a thin sheet of ice. I wonder if the water still pushes forward below the surface, quietly persisting.

The questions return, as they always do. What does it mean to be still? To appear frozen but be full of movement? The path beneath me, the trees, the water—all suspended in winter’s quiet grip. I step off the bridge, tracing the same way down toward the creek. The world

here feels untouched, but I know better. A crushed soda can, half-buried in the snow, glints in the dim light. Even in the stillness, there are reminders of movement and the human presence infringing on nature.

I crouch beside the frozen creek, gloved fingers brushing the ice. I press my palm against its surface, feeling the cold radiate through the layers of wool. Beneath me, the creek waits, holding its course despite the freeze. I close my eyes and listen, not for birds or rushing water, but for the quiet itself, the way it wraps around me like a breath at the top of an inhale.

After a while, I stand, brushing snow from my knees. The world feels heavier in the winter, but also more open, stretched wide in its silence. Everywhere I look, in every season, there are simultaneous reminders of the wild and of our intrusion, my intrusion. I see the footprints marking my path and feel my impermanence when I remember they will only last until the next snowfall comes to erase them, making space for new steps. When I return to the bridge, I hesitate, glancing once more at the frozen water below. The questions stay, suspended like ice, waiting for the thaw. Some days, I want to run until my lungs burn, until my feet forget how it feels to stop. Other days, I want only to listen until the sounds settle in my bones. The world hums around me, even when it appears still. The creek moves, the geese move, the trees reach tall. I exhale and feel the weight of my own presence among them. The wind shifts, brushing past me like an answer I am not yet ready to understand. I used to think the answers would come if I asked the right questions or if I listened closely enough to the way the world was moving beneath my feet. But maybe the questions themselves are enough. I believe the act of wondering and noticing, of kneeling beside the water and pressing my hands into the dirt, is the closest I will get to understanding. I turn my back to the bridge, knowing I will return tomorrow, and the day after that. Then, with a final breath, I turn and head north on Spear Street, where the sky is soft with the promise of morning. H

What does it mean to be still?

by Sadie Neidecker

January 7, 2025, saw the emergence of a series of powerful fires that plagued Los Angeles County, particularly in Palisades, Eaton, and Hurst. The following days included mass destruction of homes, businesses, schools, and lives. One couple, Moogega Cooper and Alex Shekarchian, told ABC News that this was the second natural disaster that they survived in a three-month span. They were in Florida in October when Hurricane Milton hit as well. As the Eaton fire spread to the town of Altadena, the couple watched the flames shift towards the hills close to their home.

As climate change continues to increase the number of extreme weather events worldwide, it is imperative that special care is taken in cleaning up the damage. These complex processes must be conducted in the safest way possible for residents like Cooper and Shekarchian, and for the planet.

While sustainability within wildfire cleanup methods is important, prevention methods are key to ensuring a safer future. Sustainable land-use practices, accurate tree spacing, and forest management that promotes healthy ecosystems are three impactful ways that large-scale fires can be prevented. Implementing controlled burns at periods of low risk also helps to decrease the amount of fuel buildup that contributes to the disastrous extent to which wildfires gain momentum.

There are various sustainable methods of wildfire cleanup and prevention that avoid excessive impacts on the climate. The primary method is the Sustainable Resilient Remediation (SRR) framework. This method prioritizes health while also promoting social and economic resilience.

More precisely, SRR includes soil and water remediation, managing waste and erosion, vegetation restoration, and using monitoring tools to track progress. Soil and water remediation often includes adding organic material to the soil to benefit its health. Plants can also be used to absorb harmful substances through a process called phytoremediation: utilizing the ability of plants to detoxify compounds while not contributing to pollution. Phytoremediation is helpful for organic pollutants, which can be degraded, but it can’t be used to clean up toxic metals. However, this process reduces the presence of contaminants in soil as well as fighting erosion resulting from wildfires exposing soil. Phytoremediation uses plants to brace the soil and prevent more degradation.

Bioremediation is another method often used for sustainable wildfire cleanup that uses bacteria to dissolve the contaminants. The bacteria transform the pollutants into less toxic materials, resulting in faster ecosystem recovery. This process, paired with clearing debris and ensuring that hazardous materials are disposed of properly, crucially helps with waste management. Additionally, hydroseeding and the implementation of silt fences that redirect water flow aid in dealing with erosion, another common byproduct of wildfires. SRR restores vegetation loss by planting species that are strong and resistant to fire and drought. Doing so also prevents the spread of root rot, which kills trees and increases the number of fire outbreaks. Monitoring tools are used to ensure that these cleanup efforts are actively helping to sustainably rebuild after fire damage. Without them, there would be little knowledge of the status of cleanup methods and their success rates. Professionals in SRR who are dedicated to managing at-risk areas are crucial to ensuring the protection of ecosystems and human resident areas. Without these methods of cleanup, thousands upon thousands of homes, businesses, and natural areas would be lost.

Dealing with complex issues such as wildfires is daunting and has powerful impacts on climate health and many people’s lives. You might be wondering how you can help prevent the start and spread of these disasters, especially because we cannot rely on professionals alone. Use caution when building or extinguishing a campfire and making sure you are following the proper procedures for fire restrictions. Avoid driving on dry grass and ensure that your vehicle’s equipment is properly functioning; this is important and often overlooked. Damaged exhaust systems can cause sparks, or malfunctioning engines often

result in overheated vehicles, all leading to fire ignition. Furthermore, removing dry vegetation around your home keeps both your family and the environment safe. Spreading information about methods of wildfire clean up and prevention that stop further climatic damage is crucial. Communities such as those impacted by the Los Angeles fires and residents like Cooper and Shekarchian should not have to worry about future weather events that cause complete uproot and devastation in their lives. Paying careful attention to our actions when in high risk areas is a great way to help prevent such powerful disasters. H

1. Use caution when building or extinguishing campfires.

2. Avoid driving on dry grass and ensure proper vehicle function.

3. Remove dry vegetation from around the home.

4. Spread information about clean-up and prevention.

Loden Croll

MAYA

BOTSWICK 18’ - 21’ (she/her)

Contributing Editor and Managing Editor

Major(s) at UVM and/or what you’re up to now! I was an Environmental Studies major at UVM with minors in Spanish and Studio Art. I currently do freelance graphic design and am an administrative assistant at Edmunds Middle School here in Burlington.

What do you love most about Headwaters?

I truly love Headwaters’ commitment to quality. During my time at the magazine I was constantly impressed by the passion and work ethic of everyone who contributed to the magazine.

What is the most valuable thing that Headwaters taught you?

The writing and editing skills I developed at Headwaters are still skills that I use to this day. Being able to communicate your ideas with clarity and intention is an extremely valuable skill!

What do you think makes Headwaters so special?

The people, of course! From my experience, people get involved with Headwaters because they truly care about bringing a voice to environmental issues.

If you were a kitchen appliance, what would you be? A garlic press

BEN GREENBERG 17’ - 18’ (he/him)

Online

Writer and Fundraiser

Major(s) at UVM and/or what you’re up to now! Environmental Sciences

What is the most valuable thing that Headwaters taught you?

How to take writing criticism from strangers and how to word my own.

What do you think makes Headwaters so special?

It was the first and when I was there the only science publication at UVM that was completely student run.

What’s a Headwaters piece that you really loved?

Not an article but the first cover with the bee on the flower sticks out in my mind when I think of the magazine. I still have my copy of it. I was really happy we got enough money to get the magazine published to that level of quality.

JESSICA NEJAME 15’ - 19’ (she/her)

Author, Managing Editor, President, and Treasurer

Major(s) at UVM and/or what you’re up to now! Environmental Studies (BS) and Political Science (BA); now I’m the Land Trust Stewardship Coordinator at the H. L. Ferguson Museum in Fishers Island, NY.

What is the most valuable thing that Headwaters taught you?

The most valuable thing that Headwaters taught me is that we all have something to contribute. You don’t have to be the feature author to be an important part of the magazine: everything is essential, from writing to layout to fundraising to organizing. Bring what you can.

What’s a Headwaters piece that you really loved?

I still think about Hannah Chodosh’s “In Defense of (Climate) Necessity” from the Spring 2018 issue. It’s a striking write-up of climate activists turning the valves off on pipelines in an attempt to not only halt the flow of crude oil, but also to establish legal precedent protecting nonviolent civil disobedience as urgent and unavoidable to prevent greater harm. “Imagine you’re in the car. It’s going way too fast. The brakes aren’t working, and there’s a cliff up ahead. Everyone you love is also in the car.” Chills!

continued on page 13

(he/him) Editor-in-Chief, Managing Editor, and Contributing Writer

Major(s) at UVM and/or what you’re up to now! B.A. in Environmental Studies, Class of 2020. I am the environmental reporter for The Maine Monitor, an investigative non-profit news organization in Maine.

What do you love most about Headwaters?

The experience of toiling over phrases laden with metaphors and imagery with your editor(s), trying your hardest to stay vivid yet succinct (I often failed at the latter). Same goes for collaborating with Headwaters designers to capture your story’s message in the artist’s unique style.

What is the most valuable thing that Headwaters taught you?

How to communicate complex environmental concepts with accessible and creative language.

What do you think makes Headwaters so special?

The collaborative spirit that imprints the masthead’s fingerprints on each Headwaters story, poem, artwork and event.

continued on page 13

TERESA HELMS 20’ - 24’ (she/they)

Contributing Writer and Editor, and Editor-in-Chief

Major(s) at UVM and/or what you’re up to now! Forestry and Environmental Studies–these days I am working as a teacher at the Vermont Farm & Forest School in Roxbury, plus various seasonal work in the woods.

What do you love most about Headwaters?

What I love most about Headwaters is its collaborative nature. Seeing the work of so many, often multidisciplinary, writers, artists, and designers grow into a cohesive finished product creates such a rich and gratifying experience for both contributors and readers alike!

What do you think makes Headwaters so special?

Within an institution and broader community that generates so much conversation on the environment, Headwaters holds a special place as a purely student-led perspective. Headwaters creates a space for students to realize, perhaps for the first time, the value and power of their voice in these larger conversations.

JAMIE CULL-HOST 21’ - 23’ (he/they)

Social

Media Manager

Major(s) at UVM and/or what you’re up to now! Environmental Science major with a political science minor; now a Post-Bacc intern at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico.

What is the most valuable thing that Headwaters taught you?

Headwaters helped me realize that my love for art doesn’t have to be separate from my environmental activism and I will always cherish my time with the magazine for that reason.

What do you think makes Headwaters so special? Headwaters manages to combine journalistic activism with nature inspired art, and in doing so elevates both which is incredibly special.

What’s a Headwaters piece that you really loved?

My favorite piece is the last one I wrote for the spring 2023 edition titled What Once Was. I explored my feelings of anxiety and grief around both the environment and my own mortality. It was an extremely cathartic experience and I am so happy with how it turned out.

If you were a kitchen appliance, what would you be? I would be an air fryer because there is nothing more versatile.

continued on page 13

(Jessica Nejame cont.)

In what ways have you incorporated the skills and passions fostered by Headwaters into your current position or professional goals?

I’m very proud of the writing and copy editing abilities that I developed during my time with Headwaters. They’ve served me well through writing a master’s thesis and in pretty much every professional role I’ve had since undergrad. For example, in my current role as a Land Trust Stewardship Coordinator, we’re working on updating our trail guide, and you’d better believe that every single Oxford comma is exactly where it should be. Also, being a part of building Headwaters Magazine from the ground up instilled me with the audacity. We made a magazine, knowing nothing about what it takes to run a magazine. Now, whenever I feel daunted by some task before me, I remind myself that if I can spend 48 straight hours in Howe Library staring at the same dozen articles, I can do anything.

If you were a kitchen appliance, what would you be?

I may be the originator of this one! I definitely used it back in the day. I’ve always said that I’d be a blender because I get really loud and excited and go-go-go, and then I just stop.

(Emmett Gartner cont.)

What’s a Headwaters piece that you really loved?

I think it’s a tie between A Sinking City and its Push for Resilience (Fall 2019) and Smoke and Mirrors: Reframing Wildfire Coverage in a New Climate Era (Fall 2018). The first because I collaborated with the talented artist Alexis Martinez and it centers my hometown of Annapolis, MD, the second because it taught me humility, especially when editors Jess Savage and Julia Bailey-Wells

explained why they were cutting my phrase “Bermuda Triangle of my own manifestation” (it makes no sense).

In what ways have you incorporated the skills and passions fostered by Headwaters into your current position or professional goals?

Headwaters not only inspired me to become a professional environmental journalist, it showed me that it was possible. Every Headwaters story I worked on made me more confident with interviews, refined my writing/ grammar and made me a better teammate.

If you were a kitchen appliance, what would you be? A saucepan

(Teresa Helms cont.)

What’s a Headwaters piece that you really loved?

So many come to mind! “Hey stranger, bless this shiny little ant” by Hayley Kolding is a beautiful example of the intersection of science and prose, a hallmark of the magazine. Working on Val Kostelnik’s “The California Wildfire Season” was some of the most fun I’ve ever had while editing. As a writer, “How to be an Invasive Species” from the Spring ‘22 edition is a piece I hold dear. I’m so grateful to Eleanor Duva for her expertise and inimitable way with words that helped bring my ideas to the page.

If you were a kitchen appliance, what would you be? I would be an antique toaster (pictured below). Perfectly in control of the level of crunch in my bread, rejecting automation in favor of careful attention.

by Lucy Colby

Apostcard arrived in our mailbox the other day. Rain made the sender’s pleasant trip blurred and streaky, but corals waved from the frontside in unaffected pinks and yellows, and striped fishes went about their business. I thought about what my friend had said, about how we are most motivated to conserve the ecosystems we perceive as beautiful. I’ve seen plenty of postcards with striped fishes and taken pictures of the sun rising between mountains and put my arms around the tallest Sitka spruce. But I have never seen a bog on the cover of a magazine at the dentist’s office, and usually only hear about fens because they’ve been drained, and someone is just realizing that was a bad idea. When it comes to conservation ecology, wetlands tend to be neglected. Modern conservation practices are heavily influenced by the charismatic megafauna and megaflora. These are animals that are large and powerful—the most popular exhibits at a zoo, plants like the redwoods or giant sequoias, and ecosystems like coral reefs or areas managed by the US National Park Service. Their reputation has been manipulated by environmental non-profits and conservation organizations for decades in order to change public opinion on conservation and drive protective legislation for these animals. In many ways, the charm of these animals has greatly bolstered the environmental movement—my environmental career launched with a single-minded desire to dashingly rescue the polar bear from the ills of global warming. However, this phenomena means that animals and environments that people do not widely have an emotional connection to as a society, regardless of their conservation status, have less civilian support and therefore a more limited access to conservation and restoration efforts. Wetlands are not typically lauded as the pinnacle of charisma. They aren’t usually conducive to hiking or recreational swimming, they are home to creatures we are taught to fear, like crocodiles or snakes, and frankly, they can be quite stinky. Nevertheless, wetlands are some of the most ecologically diverse, resilient, and even charming, in their own way, places on the planet.

As of 2010, nearly nine million acres of wetlands have been inventoried by the US Fish and Wildlife Service in the Northeast, according to that year’s Results of the National Wetlands Inventory report. The inventory encompasses boreal forested wetlands, bogs, fens, marshes, wet meadows, floodplains, and coastal plain flatwoods across 13 states. Across those states and the world, wetlands are as undeniably beautiful as they are ecologically beneficial. Regardless of their marketability as vacation destinations or viable energy sources, we would do well to protect them.

The bog is an elusive thing. I’ve heard enough about the Rattlin’ Bog to know there are trees and birds, and also of cranberry bogs to be petrified of bog spiders. Nevertheless, I’m not so sure I could confidently pick a bog out of a wetland line up. A National Geographic article, appropriately titled “Bog,” explains that a bog is a living historic landscape largely consisting of partially decaying matter called peat. Peat is a fossil fuel in its first stage of development. For thousands of years, it has been harvested as an energy source, though only more recently have entire bogs been drained for peat excavation. Bogs can be found in northern climes, typically formed by the stagnation of water in lake basins left by glaciers in the most recent ice age. There are many varieties of bog, but all are dependent on the incredibly slow decay of plant matter, as terrestrial and aquatic plants live their green lives and then gradually rest forever on the bottom of the bog. Sphagnum moss is abundant, thirsting for water that might otherwise flood an unlucky home, and cranes nest between the reeds. Spotted salamanders waddle through the heather dodging carnivorous pitcher plants, and wolf spiders, though deterrent to my future as a cranberry farmer, munch on pests like fruitworms. If you’re looking closely, you might be able to spot a family of raccoons in the hollow of an oak tree.

Living in Vermont, it’s hard to imagine a life unconcerned with floodplains. Bodies of water naturally ebb and flow in their volume and natural borders, but every couple of years (or every year), water extends beyond these borders into the floodplain, where stormwater is slowed by vegetation and sediment is deposited. As Burlington Geographic describes, Burlington’s own Intervale is a historic floodplain of the Winooski River, where subsistence of Abenaki life revolved for thousands of years. Under European colonial influence, the area was cleared and became a high yield agricultural site. Consistent with the dynamism of other wetlands, a floodplain is not a prescribed singularity. Mature floodplain forests are shaded by silver maples that turn the canopy a translucent green, while ostrich ferns burrow tightly into the soil with their bulbous roots to withstand the force of a flood. Shaded areas of the river are cooler and perfect for species like brook trout or Atlantic salmon; from a high branch a barred owl hoots a buzzing call.

Art (below) by Emma Polhemus. Gouache. 2025. “Spotted Salamander.”

Last summer, while visiting Maine, I held a crab for the first time. We drove out to the winding and rocky coast, crossing single lane wooden bridges over the estuaries below. I stood on the rocks, surveying a wide, sloping expanse of beach at the foot of the dunes. At the heel, cordgrass blew smooth as green glass in the northern winds. A pair of twins chased one another and the terns over the sand, delighting in the small craters the soft rain made as it fell in the saltmarsh. When I waded in, the water sat just above my knees, brackish and cold; I strained to investigate the silty bottom, where an empty shell of a little green crab waits to be picked from the sediment, examined by Midwesterners, and placed gently on the shore among the grass. When the storm crawling toward us from the horizon breaks, the marsh grass will shelter the muddy soils in their places and prevent salt from infiltrating the inland water table. The endurance of this place will provide a home for three species of nesting sparrows, the protection of communities large and small from flooding, and the wonder and appreciation of native wetlands. H

I stand still,

Not to brag or bluster,

by Samantha Faber

But because my silhouette is a sacred silence, Cradled amongst chaos of traffic honks below, Sharp cawing of crows above. They circle their prey almost reaching the clouds— I would be one to know.

I stand tall, Even after you trample all over me, Carving paths across me, My surface scarred by your footprints. But my vegetation endures— My roots cling tightly to the soil

As if no other pine could again be felled— No two trees have the same rings.

You scraped away my greenery, Once admiring my trails of ivy— Their vines wrapped around your foot

Before you cut them off

To keep logging

In search of greener leaves, deeper woods

As if another fern could stop you in your tracks— No set of vines has the same veins.

Your concrete jungles boast their steel peaks, Believing their towers rise higher than I ever could. But no skyscraper feels the touch of the clouds

Or the thinning of the air

Quite as I do— I am the first to watch the sun rise, The first one to feel its rays warm my peak.

You took my bark, Walking away from the allure

That once held your breath. You grew accustomed to passing by my same old lush, And carved fresh paths across a new set of hills. My snow-dusted peaks that once filled your eyes

Became distant howls—whispers of the wind

That blew away your adoration

As snowy winters became monotonous to you.

Some still stop to wonder in awe, Others compare my slopes

Measuring where my hills reach higher— No longer high enough for your architecture, No longer as beautiful as your museum, And further beneath you than your subway.

You jump from hill to hill, From mountain to mountain.

But I stand still.

I stand tall— I make not a sound.

No skyscraper feels the clouds as closely as I do. H

Water sparks and glows, Even at night— It told me so.

Even by dawn It shines and laughs, It drinks its rain, It sprays a glance.

Water told me It’s moved far from home, It told me its mother was but skin and bone. It told me it swerved and swayed like snakes, Carving away: hard scales— slipping into lakes.

Water told me it’s tired, but happy. Tired of dripping into soil under plastic canopy. It told me it’s lost most of itself along the way It told me it’s thinking of escaping— through the bay.

Water is orange in autumn and seafoam green in spring. Water holds the stars that night will bring. Water told me it will keep planting its reeds, It told me space to dance is all it needs.

Anyonewho has experienced a suburban or urban area has most likely noticed the lack of stars in the night sky. Or, inversely, they’ve seen the clear constellations present in a remote location, amazed at the view that is visible when lights don’t mask it. When I first truly saw the stars, I was staying in a cabin deep in the Adirondack forest with my family. The first clear night, I stepped outside in awe. The clarity of the constellations was as jolting as the first breath of cold winter air entering my lungs. There was a stark contrast between the blackness of the sky and the glowing dots among it, different from the murky urban mix I was used to. Until that moment, tucked deep in the woods, I hadn’t considered how much light impacts the environment around us.

Light pollution is more complex than hidden stars. Space is very disconnected from down here on Earth. Yes, we are losing out on the beauty of constellations, but this doesn’t necessarily cause humans any direct harm. To understand the true im

which have always been a hotspot for human development. Most major cities are located next to the ocean or other large bodies of water. With nighttime light increasing by 2.2% each year, effects on ecosystems are more harmful than ever before. Coastal ecosystems are very fragile and rely on natural cycles of light to regulate ecosystem processes. Increased artificial light means a greater threat to the behavior, reproduction, and communities of coastal organisms.

I travel to the beaches of Rhode Island every summer. Each year, there are more houses, businesses, and restaurants along the coast. These have all brought in more people, and in response, more lights. When my family has our annual campfire on the shore, the lights from town give the sky an intense glow along the water’s horizon. I often wonder how the sea animals are able to sleep when their night is being converted into day.

Moonlight and starlight are both natural sources of light diminished by artificial light at night. Organisms depend on cues from these sources and are thrown off when the glow from the city overpowers them. Sea turtles are a perfect example of this. When sea turtles hatch, they use the light of the moon to guide them towards the

ocean. But when the shine of nearby cities is brighter, the hatchlings travel away from the water instead. Several studies of species in Australia have shown that directional mishaps increase turtle mortality due to entering vehicle traffic, encountering predators, or getting tangled up in plants. Similar issues are occurring for young seabirds. In the Hawaiian Islands, researchers concluded that thousands of birds are impaired by artificial lights lining their migratory paths towards the sea. It is estimated that between 32,000-60,000 seabirds are injured or killed per year due to the effects of artificial lighting.

Light pollution also impacts species below the waves. Coral reefs, one of the most biodiverse ecosystems on the planet, are already threatened by climate change and ocean acidification. Light pollution further endangers coral species by disrupting their reproductive patterns, which follow the lunar cycle. When moonlight is masked by artificial light along the shore, the timing of fertilization is skewed. In a study conducted at the University of Plymouth, it was found that 10 out of 12 types of coral experienced a shift in reproduction due to artificial light. This issue is detrimental to the future survival and recovery of coral ecosystems.

The consequences of light pollution don’t just harm animals. Humans rely on marine species for sources of food and economic stability. Brightness around water attracts more fish, causing them to be caught in higher numbers, which leads to overfishing. The entire marine food chain is being skewed by light pollution through the shifting of predator-prey relationships. Several studies of fish behavior have shown that predator success goes up as light sources increase. If this pattern continues, eventually there will be no fish left to catch. Many coastal economies and communities will be wounded if this issue continues to be ignored.

After learning about all the different problems light pollution causes, I found the situation quite hopeless. As the

population continues to increase, it doesn’t appear that our need for light at night will go away. But there are solutions, such as changing what type or color of light we use, and designing more efficient lighting. The type of light used in our communities determines its impact on the surrounding ecosystems. A study about deep sea oysters demonstrated that the color of light entering the water is directly related to how much the oyster is impacted. For example, blue and white light is proven to disrupt the natural behavior of oysters the most, while green light has the least harmful impacts.

There are also ways to design lighting structures that limit the amount of wasted light. For example, along the beaches of North Carolina, more efficient lighting is being implemented to help protect wildlife and reduce the eye strain of visitors. Over 200 shielded amber light fixtures have been constructed on Jennette’s Pier in the Outer Banks. Not only is amber light less disruptive to animals, but the shielded design of the light fixtures limits unnecessary shine towards the sea. By implementing similar shielded designs along the coast, or anywhere across the globe, we can give our communities a gentler glow that doesn’t heavily contribute towards light pollution.

Coastal ecosystems are a great place to begin making changes, as they represent the locations of many major cities. As more research is conducted, and citizens become more informed of the impacts of light pollution, we can start to lessen the issue. Overall, it is important to recognize the reality of light pollution and further study its consequences.

Experiencing a true night sky provides a serene feeling. Deep in the Adirondacks, under a sky full of stars, I was reminded of the importance of darkness to humans, animals, and the rest of the Earth. When lighting your residence at night, keep in mind: the plants and animals of the world need to sleep, just like us, and the stars are meant to glow bright. H

by Hattie McBride

Flying through oceans I find Depths which seek to swallow whatever fish, Impersonally, indifferently. I’m no longer digging gravel along the shores

Of that shallow channel I stem from. Slipping in and out, Weaving through the grasses and muddy sunlight.

Had I understood the gravity of my youthful wish Of leaving, of exploring, of danger, Of razor teeth and nets and fear, Raw, primal fear weighing me down.

I may have cherished it all a bit more, The fresh water flowing over my back

Wrapping around these scales. It calls to me each year.

My life’s current leads home, There’s a pull in my core

Seeking some nest Buried in that bank.

What great splendor!

To leap, fins unfurled beneath Such unfiltered sun, To slip between Ursa’s mighty mitts Preying on my capture.

I cannot be contained, Even while growing older, more tired

My body cannot be imposed upon And I surprise myself even now As I jump and twirl, Dance up this river.

And though the water is warmer than I remember,

There’s no doubt in my mind

That the stories of my mother

And hers before Are woven into these rapids. And my children will look to the eddy For a glance at their mother, Will return to me one day When they are older, more tired.

Our histories carved, our bodies sustained By this place.

Generations upon generations have been birthed here, have returned here

It runs within us. How else might we find it again?

This water makes up our existence

Makes up–

Roughly dropped on the bank

I curl over and under myself

Slipping between fingers and Knocking against shins

Snapping at every loosened grip, In my instinctive fight for the water.

Yet this body reaches an exhaustion

As entirely consuming as the ocean once seemed.

More so.

And these creatures bellies are as empty

As that vast hollow drop off, With too much space for indifference.

They raise a rock too heavy for ceremony, An act of mercy.

In that stillness I find myself believing In pouring out my blood, Giving of my body

To feed this strange kin

Our subsistence caught beneath Such unfiltered sun, Painting the sky a deep red

Just for me. H

“A bear prances through the bear woods.” by Brielle Howlett

Amurder of crows, Gliding over pines, Cheeky grins, And mischief-filled flaps of feathers, As the moon makes her ascent.

Corvus brachyrhynchos, They sing as we hang from trees, And skip through the fresh powdering, Boots soaked with the melted sign of earth’s hale pulse,

It’s a different world in Vermont, With similar chilly winters to my garden state, But here they last the way they did when I was younger. The snow shrieks and dances through several months, Ice crystals paint my windows, Mountains of white line the streets and sidewalks.

I gaze through sleet at the stark blue spruce. While wind rushes my ears, My fingers and jaw go blissfully numb. But the spruce stands still, Hearty and feather dusted, As if she had absorbed the sky’s color, Picea pungens.

Crisp days in late January, Brown bears rest in their sanctuaries As I do in my bed with a mug of mint tea. Their soil spackled mound of mud Mimics mine of cotton

We watch the brisk season dawdle, Through walls of dirt and brick, Waiting to awaken into the rich green warmth. Ursus arctos, Wild friends. H

by Pete Patrick

The cool winds of spring graze my face and the last glimmer of sunlight shines through the ash, maple, and beech on the hillside. The crunch of my footsteps on the dirt road reveals my presence to the chattering chickadees, robins, and bluebirds. Their songs weave into the valley’s soundscape.

Down the road, I spot a lonesome red-tailed hawk. I see it surveying the field with focus—eyes darting back and forth, keen on any movement.

My thoughts wander.

The hawk’s presence is unknown to the mice below, yet I have the privilege of observing these interactions from a broader perspective. Life as small as a mouse is vital for the ecosystem: dispersing blooming seeds whose buds feed chickadees, aerating soil that nourishes grass for grazing deer; the mouse is food for the hawk, and its energy will eventually return to the ecosystem through worms and fungi.

Sounds of geese returning recenters my thoughts, and I realize my longing for a perfect balanced ecosystem as illustrated above cannot exist so long as it is contradicted by human influence. The individual’s differing worldviews impact our thinking and our perception of our place in ecological systems. Understanding these worldviews and how they shape ecology is essential to combating today’s ecological and social issues.

Art (below) by Katherine McGee. Watercolor on paper. 2025. “Human Connection to Nature”

Ecology means the study of your home: to tap into the ecosystems that we live within, that surround us, and that we rely on. It is an ethic as much as it is a science that explores the abiotic and biotic, and the human and morethan-human. The scope of ecology radiates far beyond the field in front of my house or a local park, but that is where change begins. With studying your home—getting dirt stuck under your fingernails, neck pain from hours of birding, and stepping into creeks that are deeper than expected.

Aldo Leopold, a leading ecologist in the 20th century, was a firm believer in getting to know your home and the complex interactions that unfold right outside your door. In his words, people think we are dependent on industrialization when, really, we are dependent on nature.

Leopold emphasized the importance of three main points that are integral to maintaining ecological balance: First, there must be a combined effort of all individuals. Second, humans must begin to view themselves as a part of a community rather than as the autocrat of the Earth. Lastly, the Earth and all its inhabitants, specifically nonhumans, have inalienable rights to exist separate from economic value. A culmination of his entire ethic, in perhaps his most important doctrine, states, “A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community.”

Western science is driven by an anthropocentric viewpoint, and reduces the value of the ecological systems we depend on to the idea of “ecosystem services.” Defined by the EPA as the “life-sustaining benefits we receive from nature,” these services have varying practical applications depending on how the relationship between the human and nonhuman world is viewed.

From an anthropocentric perspective, nature provides services, such as commercial fishing for salmon or health benefits gained through time spent outdoors. Thus, natural communities are a commodity. Leopold criticized models of conservation that were driven by economic principles. For decades, conservationists and ecologists were forced to focus on the economic value of certain species in order to save them, while ignoring many of their ecological benefits. Ecosystem services are systems that exist in the natural world but tend to be protected more than other systems because they benefit humans. In contrast, kincentric ecology examines the human-nature relationship from an Indigenous perspective. Indigenous ethnobotanist, Dr. Enrique Salmón, describes this dynamic as “humans [viewing] life surrounding them as kin.” From this perspective, the human-nature relationship is reciprocal—humans influence their kin, and their kin influence them—unlike modern industrial systems where resource extraction is prioritized, yet nothing is given in return.

The earliest roots of the environmental movement focused on protecting human life rather than the full ecosystem. Environmental philosopher Arne Naess criticized this and the belief of humans’ dominion over nature, calling it “shallow ecology,” focused solely on the sustenance of human affluence, and advocated for a ‘hands-off’ approach to nature.

In the 1970s, a new movement emerged in Northern Europe influenced by Gandhi, Spinoza, the civil rights and environmental movements, and writers like Thoreau, Muir, and Carson. Combining their ideas with his own, Arne Naess coined the term “Deep Ecology,” a philosophy that reframes ecological science to emphasize nature’s intrinsic value beyond human interests. This perspective inspired leaders of radical environmental thought, like Dave Foreman, founder of Earth First!, to adopt extreme tactics such as tree-spiking and fishnet-cutting. Foreman’s controversial rhetoric on population control, including his statement, “The best thing would be to just let nature seek its own balance, to let the people there just starve,” further fueled criticism. While Naess’ intentions were far from eco-fascist, the movement’s interpretations have led to extremism, affecting its credibility. Nonetheless, it remains a form of ecological thought that must be considered.

Melissa Nelson, an author and ecologist, belongs to both Indigenous and European ancestry. She learned of deep ecology and was immediately drawn to how it “emphasized the intrinsic value of nonhuman nature and the peace found in ‘wilderness.’” She was troubled by the lack of Indigenous worldviews in deep ecology, as well as its ties to racism, with some claiming “Indians [to be] anti-environmental because they want to ‘use’ the ‘untouched’ wildlands.” Such ideas are akin to the early environmental movement.

Nelson adds that deep ecology is rooted in the “reinvention of very ancient principles” of Indigenous thought. Dennis Martinez, a restoration practitioner and colleague of Nelson, argued for a kincentric approach that recognizes “the reality of our extended family—the rock, the plant people, the bird people, the water people— and the human beings’ humble place in this web of kin.” Abundant wisdom lies within traditional ecological knowledge, and variation exists within the perspectives of the thousands of Indigenous tribes around the world.

Ecologists everywhere are urging world leaders to abandon the idea that humans and nature are separate, to stop valuing natural resources as a purely economic proposition, and to understand that wildlife are not simply here for viewing enjoyment, but are a part of ecosystems and play both integral and functional roles.

In Bristol Bay, Alaska, half the world’s sockeye salmon return every summer to complete one of the greatest ecosystem cycles on the planet. In 2001, a mine was proposed to be constructed in Bristol Bay, threatening this cycle. After twenty years of contention, the mine was officially vetoed, bringing a remarkable win for both Bristol Bay and modern conservation efforts. However, underlying the official veto is the continued justification of protecting natural areas only for their economic benefit, continuing an alignment with anthropocentric worldviews. The Anchorage Daily News reported the 2021 economic value of the salmon fishery to be around $248 million; the high economic value calls into question whether protection of Bristol Bay would have occurred had this commercial fishery not existed.

This anthropocentric worldview is also evident in staterun trout hatcheries. Advertised as a means to promote outdoor recreation, these hatcheries serve primarily as economic drivers, commodifying fish. In the 1800s, rainbow trout reared in California were shipped across the country and stocked in New York waters. Because of their high adaptability and high catch rates, these trout are now stocked worldwide. By prioritizing their commodity value over their ecological role, we not only lose aesthetic value, but also disrupt native ecosystems.

Modern ecology recognizes humans as integral components of ecosystems and advocates for integrating current practices with traditional ecological knowledge. This approach promotes stewardship while allowing for the limited commodification of ecosystem services. But is this enough?

As I reflect on my walk that spring, I realize the hawk is not separate from me, nor are the mouse, the trees, or the birdsong. We all exist within systems, engaging in relationships where our actions ripple outward, like the soundwaves of birdsong, influencing the world around us, just as we are shaped in return. Recognizing this interconnectedness dissolves the illusion that humans have dominion over nature. To embrace this truth is to let go of this illusion—to see ourselves not as rules of nature, but as participants in endless reciprocity. H

Lowry

Salt in my eyes, in my nose, crusted over my eyelashes, Turned into tiny icicles dripping down my face.

Skin covered in tiny brown freckles and layered in red, Transformed to a pale, white, smooth oasis for change. Hair; wavy, tangled, bleached with streaks of light, Darkened by the hours lost with the fall equinox.

Beams and rays dripping into my soul, Eventually become snowflakes gently landing across my body.

Breathless and seamless is our transformation, and that of the ground we walk upon. How delightful it is that the earth doesn’t mourn such a change, but revels in it, How courageous are our bodies for adapting to each direction the wind blows. H

Art (below) by Ella Rentz-McCoy. Watercolor and Ink. 2025. “Spring Equinox”

Alma Smith

Our barest understanding of Earth’s ecosystems is that nutrients cycle and energy flows. Our planet depends on this continuous spreading of resources between the layers and actors within our ecosystems. Minerals come in different forms in our environment; as rock, gas, liquids—even leaf litter—to be used by different plants and animals. When all of these species’ lives end, their bodies will decompose to release minerals, nutrients, and gasses back into the ecosystem. In some ways, energy appears to cycle through our ecosystems as well, but its path is more akin to a flow. The sun’s energy is taken up the food chain, and when an organism dies, the energy it had stored decomposes with it. While we have less control over how much energy is put into our environment, we have more of a say in the nutrients that we are feeding into the cycles of our ecosystem.

A certain level of carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and other nutrients are natural in our environments, but as with many things, human interference has influenced the balance that was struck millions of years ago. One of the biggest disruptions of the nutrient cycle to date are farming innovations. Phosphorus fertilizers were first introduced to farming in the first half of the 1800s, and nitrogen fertilizers were added in the Roaring Twenties. Both of these products, when applied liberally, increase farming crop yields, which is theoretically great for human health and industries, but fundamentally dangerous for our ecosystems. All nutrients, including phosphorus and nitrogen, have different forms that exist in our air, water, and soils. Each phase serves a different purpose in the environment, as various organisms require specific forms for uptake. For example, plants require carbon in its gaseous form, CO2, but mostly require nitrogen in its mineralized (inorganic) form, nitrate (NO3). An excess of these might benefit plants in the short term, but will wreak havoc on the ecosystem in the long term. Alternatively, if these nutrients aren’t present in our soils for plant use, it means fewer nutrients available to support the rest of the food chain and a less diverse, less resilient ecosystem. The typical balance is one where a diverse set of plants, microbes, and fungi work with the soil to

create an exchange of resources. But when a highly developed area like Burlington has too many grass lawns and paved roads, rainwater runs across these impermeable surfaces, unable to soak back into the ground, gaining speed and increasing erosion. You might be familiar with the cyanobacteria blooms that prevent safe swimming conditions on Lake Champlain in the summer heat. These are caused by phosphorus that is washed out of agricultural soils and other fertilized areas and finds its way to the lake. Bacteria and algae in the lake feed off this unnatural surplus of nutrients and spread their way across the water, blocking sunlight, taking oxygen, and releasing large amounts of CO2 and methane when they die off.

It’s not just lakes that feel the consequences of excess nutrients. Excess nutrients can pollute any waterway, and their effects can harm local species, making it easier for non-natives that don’t support our environment in the same ways to come in and capitalize on the lack of inter-species competition. This leads us to the question, how can we prevent not just water running off and eroding our landscapes, but also much-dreaded nutrient runoff?

Green stormwater infrastructure (GSI) is the newest first line of defense against the discharging of nutrients into our watersheds. GSI refers to any development created to mitigate severe stormwater runoff. GSI has become an increasingly relevant field of study, with recent increases of global warming “tells,” like severe storms and the floods that follow. GSI includes things like rain gardens and rocky margins on the sides of roads, but it also encompasses bioswales and bioretention cells. Bioswales are margins of vegetation, usually between roads and sidewalks, while bioretention cells are typically more engineered than bioswales. They often have various layers of different soils meant to draw up free nutrient ions to stop them from flowing further into the watershed.

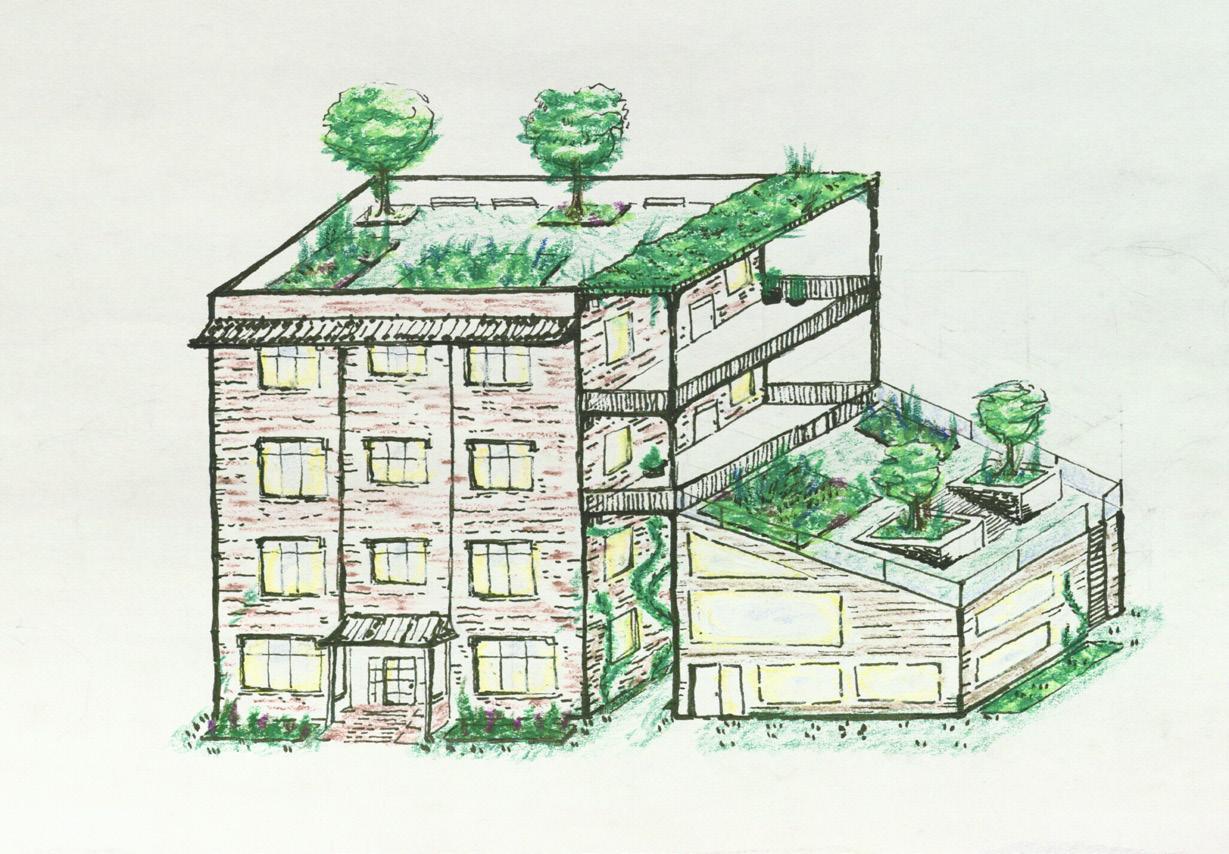

UVM began introducing green stormwater infrastructure to its campus as early as the 1980s with the slow and steady building of five water-holding facilities and has

continued to implement sustainable infrastructure where possible. Since then, our campus has seen the construction and reconstruction of entire buildings to give us state-of-the-art centers for study, but also to implement ecologically-friendly (or at least neutral) infrastructure. The behemoth that is the Davis Center and gem that is Aiken, completed in 2007 and 2012, respectively, were both designed with sustainability in mind. The Davis Center green roof is quite the unassuming garden. It has a great view, and some lovely plants, but most wouldn’t guess that it was built to hold as much water as possible, lessening the load of rain that would otherwise flow downhill into Lake Champlain. Aiken’s roof garden is infamously inaccessible to the public, or even students, these days. It was built with research in mind, as opposed to passive recreation like the Davis Center garden. The garden plots were built to both collect rainfall, and also filter it downwards into a viewing spot within the building, where buckets could show visually how much water each plot might be letting slip through. Though this system hadn’t been reliably active and open for research or passive recreation over a decade after its construction, students in the Fall 2023 “Greening of Aiken” course had the opportunity to maintain and study its green roof systems. It’s unclear how comprehensive this maintenance was, or if the roof will become a less elusive space for study in the near future.

Art (below) by Alma Smith. Mixed Media. 2025. “Green Roofs.”

but also providing food and shelter to birds, insects, and pollinators that keep our local ecosystem healthy and diverse.

The gardens in front of Jeffords Hall appeared just a couple years before UVM’s Bioretention Lab came to fruition behind the same hall. The Bioretention Lab includes eight garden beds, or bioretention cells, that are more engineered than meets the eye. Layers of soil, sand, and gravel filter and retain water to the benefit of our local environment. UVM’s Dr. Stephanie Hurley felt that the empty space behind Jeffords Hall, bounded by the impermeable surfaces of sidewalks, streets, and a huge parking lot, was a clear opportunity to bring in more green stormwater infrastructure to UVM. Thus, in 2012, the Bioretention Lab, stewarded by Dr. Hurley, began researching the cells dug into the margins between the sidewalk and street. Some beds are overflowing with buzzing purple aster, some with spiky switchgrass, but all of them were built to study how these engineered garden beds interact with the environment.

It’s important to remember that green stormwater infrastructure isn’t all overhauling buildings and green roofs. Many implementations to mitigate rainwater erosion, damage, and runoff blend into our surroundings. The majority of gardens you see on campus serve ecological purposes in addition to aesthetics. The gardens outside and behind Aiken Center and Jeffords Hall are prime examples of this. Believe it or not, having roots in the ground is a huge step-up from bare soil. Not only is this vegetation slowing water and stabilizing soil tenfold,

Across subsequent studies by PhD students including Paliza Shrestha, Michael Ament, and Amanda Cording, all guided by UVM professors, the cells were found to be great supporting tools for climate resiliency. These studies have manipulated soil content, plant diversity, precipitation rates, and other factors to understand just how efficient bioretention cells could be. In the very first experiment, by Cording et al., the team studied how the cells reacted to high inflows of water, and found them to not only lower the volume of water runoff but increase water quality. In the presence of deep rooted plants, as well as an engineered soil called SorbtiveMedia™, the cells were able to filter rainwater by holding nutrients in place. Shrestha’s studies in particular also determined that the bioretention cells were indeed absorbing more greenhouse gasses than they were emitting, making them “net sinks” as opposed to “net sources.” Though it might sound unimportant, this conclusion allows everyone in future

experiments to remain confident that bioretention cells have a net positive relationship to our environment, and that we aren’t substituting one evil for another.

As with all things, bioretention cells have a lifespan. There’s an upper limit to how much runoff they can hold before a heavy rain will wash away the excess, especially if there are too few cells and too much rain and nutrients. This can be solved by replacing materials, but it begs the question of what comes in the long term. The widespread application of bioretention cells would definitely be a promising way to mitigate flooding events that have increased in the past decade, as well as absorb carbon and other greenhouse gasses. The more we mitigate, even at a small scale, the better. The slowing of water and interruption of its path downhill is arguably our easiest way to help the environment, but is often underutilized. Our campus has been retrofitted with this in mind more than you might realize. Next time you’re out and about on campus, keep your eyes peeled for clusters of vegetation that might be sucking up and slowing water, or river rocks lining sidewalks, to keep water from carving miniature gulleys next to the concrete. These features are brought to us by UVM’s Grounds Maintenance, who have been steadily revamping our campus. For example, Grounds Manager Matt Walker says that his team had started lining our sidewalks with river rocks in just the past decade. Starting in the most needy areas, likely near erosion-prone sidewalks and green spaces, as well as any new walkways being built. This simultaneous top-down and bottom-up approach to renovation has helped our campus pivot into green infrastructure relatively quickly compared to the pace of city-wide projects that can take years to approve.

All of these implementations work together pretty well considering UVM is a high-traffic area with an abundance of impermeable surfaces, and a (usually) killer snow season. It’s easy to look at a college campus like UVM as a model for rapidly adapting city infrastructure, but it offers more guidance than just ecological band-aids. Vermont’s history with agriculture is a deeply relevant aspect of UVM’s pursuit of green stormwater infrastructure. Thanks to the striking decisiveness of Vermont communities, legislation and social programs have grown to encourage and reward caring for the environment. State programs like the Clean Water Initiative, and the “Three Acre Rule” encourage and even fund ecological infrastructure development. The three acre rule in

Art (right) by Via Hedley. Digital Collage. 2025. “Wetland Creatures.”

particular requires properties with more than three acres of impermeable surfaces to be up to date with state standards for stormwater treatment. So, how might these socioeconomic pressures influence agricultural areas that have historically contributed more to nutrient runoff issues? Shelburne Farms, for example, takes precautions to keep water from flowing directly off fields and into the lake by using snaking buffers of trees, bushes, and other plants to line their farms. Similarly, rain gardens pepper the waterfront downtown to absorb water and slow erosion. These ideas culminate at Hoehl park, a humble garden neighboring Lake Champlain and the ECHO Center in downtown Burlington. In fact, Dr. Stephanie Hurley worked in collaboration with ECHO to design this vegetative buffer. Using bioretention principles, she helped create a barrier between sediments and nutrients and their flow into the lake. This project involved investment from a handful of parties and community organizations and the final product is reflective of Burlington’s dedication to the natural world. The oversaturation of fertilizers and other nutrients might have been once rampant in this area, but these measures aim to rectify one facet of human activity that has negatively impacted our environment. Burlington’s current massive overhaul of Main Street is another example of efforts to adapt to our new climate and heal our local ecosystems along the way. GSI is being installed in a sizable portion of Main Street with hopes of slowing the streams of running water that appear during heavy rain. This change will make Burlington more resilient to extreme weather events and serve as an example for other communities. The more common we make these strategies, big or small, the easier it might become to get green infrastructure through bureaucratic “Chutes and Ladders.”

Making GSI the norm instead of the anomaly not only has the capacity to protect the environment, it can also save human lives and livelihoods. Our world is rapidly changing, and our adaptations and interventions are the key to survival and protection of fellow humans. Saying goodbye to summer algal blooms might seem trivial, but rising sea levels and decreasing air quality are not. For every warning sign Lake Champlain gives us, a very real consequence of human pollution looms. It’s our job to see the signs, listen to the Earth, and help it keep on cycling resources as it has for years before us. H

by Victoria Solodkova

Adive into a pool, a run into a lake, or maybe a tentative tread into an ocean are all prefaced by a big gulp of air to save for the journey. Breath-holding contests, long swims, and seashell searching all prep our lungs for the lack of oxygen under the surface. Our bodies are not adapted to life underwater, but the ocean does contain small amounts of dissolved oxygen that sustain aquatic life. The amount of dissolved oxygen decreases as depth increases, as reduced sunlight penetration prevents photosynthetic organisms from producing oxygen.

A recent discovery, however, could upend much of what we know about life in the deep sea. A team of researchers has uncovered ferromanganese mineral formations on the sea floor that could be splitting seawater and producing oxygen. Last summer, Andrew Sweetman and his team of researchers discovered this ‘dark oxygen’ in the Clarion Clipperton zone of the Pacific Ocean. This zone, spanning about 4.5 million square kilometers between Hawaii and Mexico, is known for its high concentration of valuable minerals. The team was investigating how much oxygen seafloor organisms in this zone consume. Yet, the oxygen levels they measured were rising instead of steady or falling, and Sweetman, so perturbed by these results, thought the sensors on his instruments were broken. He sent what he thought was his faulty equipment back to the manufacturer multiple times, even telling his students, “Throw the sensors in the bin. They just do not work.”

Then, in 2021, Sweetman and his team returned to the Clarion Clipperton Zone, this time using a different technique to measure oxygen, sending down three enclosed chambers to be partially covered by ocean-floor sediments. Over multiple exploratory cruises, whenever the trapped sediments in the chambers contained the ‘dark oxygen’ nodules, they saw elevated oxygen readings lasting a couple of days. At first, the researchers thought these readings were produced by deep-sea microbes, bacteria that recently have been shown to generate oxygen in light-deprived areas from freshwater aquifer samples beneath Alberta, Canada. Yet, laboratory tests where they poisoned the seawater with mercury chloride to kill

off the microbes disproved this theory. Finally, Sweetman concluded it was the metallic nodules among the sediments. The charge emitted from the nodules produces about the same amount of voltage as an AA battery. Scientists hypothesize that the gradual accumulation of different minerals throughout millions of years caused a gradient charge to develop between each layer, leading to oxygen production.

It has long been held that Earth’s first oxygen supply came from photosynthetic cyanobacteria in “The Great Oxidation Event.” Around 3 billion years ago, these microscopic water-dwelling organisms would’ve used sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide to produce oxygen as a byproduct. But this recent finding could mean that Earth has a brand new source of oxygen, a source in which photosynthesis is not necessary, a source that could mean new life. It leads us to ask: What if life first began in a completely different way than we ever thought?

Does this mean that Earth’s landscape is not the only one conducive to aerobic life? Europa and Enceladus, moons of Jupiter and Saturn respectively, have subsurface oceans under icy shells, making them particularly interesting for scientists in light of this new finding. Is it possible that they are teeming with life, harboring ecosystems built on these voltage-producing rocks? The implications of a new source of oxygen have the potential to bring light to discoveries on other planets like never before; an expanse of the universe previously untouched, potentially closer than ever.

Still, not everyone is convinced. One notable review came from the Metals Company, a deep sea mining company, who, in a formal assessment, wrote that Sweetman did not give a full picture of the evidence and that the elevated oxygen readings could be trapped air bubbles or leaking electricity from the deep-sea instruments the research team used. The chambers could have picked up oxygen from the water column as they were lowered to the sea floor, or when turned on, the fans in the chambers leaked electricity and accidentally induced electrolysis, another process that can create oxygen. Sweetman counters these claims of incompetent testing, citing data that show certain occasions where oxygen levels were not raised at all, something that would be impossible if the proposed counterclaims of oxygen production were true.

Though researchers other than deep-sea mining companies have been critical of Sweetman, the deepsea mining industry has a big reason to be worried. The naturally forming rocks that produce dark oxygen contain cobalt, nickel, copper, lithium, and other metals— materials that make them valuable in the deep-sea mining industry. These materials are mined for batteries, electric vehicles, and steel. If protections were suddenly put in place to protect these dark oxygen-producing rocks, the industry could lose a big source of its production materials. However, the repercussions of mining these nodules without figuring out their true potential could also have huge consequences. Removing

them in large quantities could harm carbon storage in the ocean, effectively destroying the balance of certain deep-sea ecosystems. Sweetman himself says it would be risky to harvest seabed minerals without knowing a lot more about their systems. Dark oxygen represents a shift in our understanding of the deep sea and so, removing this resource without understanding its full function would represent a huge loss.

This unveiling of dark oxygen will have funding to be explored further after recently being endorsed by the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission as a United Nations Ocean Decade activity. The UN Ocean Decade activity aims to stimulate ocean science to reverse the declining health of ocean systems and create new opportunities for sustainable development in marine environments.

Sweetman and his team are now diving into studying the deep seafloor in the hadal zone, an area up to 11,000 meters deep that makes up around 45% of the entire ocean. This habitat, full of deep ocean trenches, is still poorly understood. Sweetman hopes to uncover some of these mysteries with his continued studies into dark oxygen. They will explore what exactly is released from the nodules, what their ecosystem functions are, and how climate change is impacting biological activity. Though more and more questions will likely arise, it will be exciting to see what Sweetman and his team find lurking among the mineral formations in the dark depths of the ocean. H

by Cali Wisnosky

His negligence drips like rain through our fingers We let it through, and it becomes greater Than the sea

He sings to his garden Voice thick with water Stomata open They suck up every last drop

One breath from his mouth could level an entire forest He is the butterfly needle that flaps its wings to the beat of a drilling rig Black blood travels through vascular pipelines

The deep curve of her river snake So hungry it eats its own tail Compacted bodies of bacteria

Coughs the carcasses into the Chesapeake Bay Bears ears Mojave Trails Red Rock Canyon He squeezes them in his hand And we watch them bleed He puts a band aid over each borehole Refuses to cauterize

To stop the bleeding Malpractice phlebotomist

Art by Izzy Degroot. Digital. 2025. “For A Limited Time Only”

by Noah Anderson

July 27, 3:00 A.M. The wind is howling, practically yelling. It’s asking me what the hell I’m doing here. I’m on the summit of Mt. Pierce for the twenty-something-th time this summer. It’s cloudy, so I can’t see the stars. It’s cold, I’m exhausted, and I can’t even recognize how special it is to be here. It’s my third time hiking this stretch of trail in the last twelve hours. My two friends, who woke up 21 hours ago, have long since fallen deeply into hysteria and decided we were done speaking. We need to start working again in three hours. I take another step, my headlamp on its brightest setting, struggling to penetrate the clouds that whip around me. I barely notice I’m here; I barely notice anything at all.

* * *