HEADWATERS

The University of Vermont’s Environmental Publication

1st: A Hairy Woodpecker sits on a branch in the Saint Michael’s College Natural Area. 2nd: The view from the top of Mount Philo on a sunny fall day. 3rd: A sailboat on Lake Champlain at sunset. 4th:

Northern Leopard frog hiding in the grass at Derway Cove.

CONTENTS AND FEATURES

Contributors

Editor-in-Chief

Megan Sutor

Managing Editor

Loden Croll

Editors

Alma Smith

Anna Hoppe

Anna Eldridge

Caroline Deir

Cole Barry

Greta Albrecht

Kylie DelMaestro

Myla van Lynde

Ruthie Bell

Sarah Johnsen

Thomas Chamberlain

Talia Weizman

Managing Designers

Cali Wisnosky

Avery Redfern

Artists and Designers

Allison McBrill

Alma Smith

Benjamin Erik Peterson

Cali Wisnosky

Casey Benderoth

East Underwood

Ella Rentz McCoy

Es Sweeney

Isabella Shinkar

James Warren Marino

Katherine McGee

Megan Sutor Via Hedley

Creative Director Via Hedley

Treasurer

Anna Hoppe

Social Media Manager

Cali Wisnosky

Planning and Outreach

Addie Hayward

Want to see your writing or art in the Spring 2025 edition? Submit a 100 word pitch outlining your intended topic and approach to uvmheadwaters@gmail.com or stay up to date with our Instagram for prompts @uvmheadwaters

We’re starting a podcast! DM us on Instagram with interest.

Look through our archives at uvmheadwaters.org

This magazine was written, produced, and printed on the land of the Abenaki Tribe. For more information, visit https://abenakination.com.

Cover art by Addie Hayward. Copyright © 2024 Headwaters Magazine.

Dear Reader,

Welcome to the 17th edition of Headwaters Magazine—the Vermont edition. The magazine you hold in your hands was composed by a stellar team of student designers, illustrators, writers, and editors who once again have gone above and beyond in bringing to life insightful and thought-provoking narratives about the natural world. We extend the utmost gratitude to the UVM Student Government Association, the Rubenstein School of Environment and Natural Resources, and the Headwaters Leadership Team.

If you’re reading this magazine, it’s likely that the Green Mountain State has, in some way, been threaded into the story of your life. However near or far you may be from our small corner of New England, the essence of Vermont can always be found in the sweetness of maple syrup, brilliance of autumn foliage, cheerful calls of black-capped chickadees, red barns nestled in rolling pastures, glowing sunsets over Lake Champlain, or white ski runs carved into sturdy mountains. This land, sculpted by glaciers, sand, and seas, has been tended for generations by Indigenous peoples, in particular the Western Abenaki.

In recent years, the pace and scale of changes in our landscape have become impossible to ignore. From devastating floods to shifting traditions in farming and recreation, these transformations remind us that change is one of life’s few certainties. Yet, this edition of Headwaters serves as a testament to the resilience and determination of those who refuse to passively watch these changes unfold. Students are mobilizing for sustainable solutions, scientists are strengthening our understanding of ecosystems, and politicians are championing transformative legislation, showing that Vermont’s future is not just something that happens to us, but something we actively shape.

In these pages, you will also find lessons on how to embrace failure and discomfort, weather disappointment and devastation, and survive in a world of compounding inequities. The way is often murky, and the stakes are very high, but these pieces illuminate the abundance of beauty, courage, and energy around us. We hope that you will be reminded of the majesty of Vermont, and perhaps take a moment or two to listen to the wind or birdsong to deepen your connection with the land that sustains you.

Sincerely,

Megan Sutor

Loden Croll Editor-in-ChiefManaging Editor

Hard Things

By Naomi Cocker

“911, what’s your emergency?”

“Hi,” I choked into the receiver through gasping sobs, “I think I need Stowe Mountain Rescue.”

When my body sat itself down just before summiting Bolton Mountain, I was somehow, despite the sheer pain I was in, truly surprised. I didn’t even realize I was giving up until the words were out of my mouth. The summit wasn’t even the end of the hike that I was on, but with fewer than ten miles to go, I was so physically drained I couldn’t go on. I ground to a halt, looked up at the next incline I would have to go up, and burst into tears. There was no way I could continue.

The original plan, and why I was even in this situation, was simple. Myself and three other people were going to walk from Camel’s Hump to Mt. Mansfield in one 35 mile go, hopefully in under 24 hours—a hike known as Man-Hump. A casual 8,000 feet of elevation change, summiting Camels Hump, Bolton Mountain, Mt. Mayo, and Mt. Mansfield. Easy! Until it wasn’t. My trio of hiking partners gathered around me as I sat, exhausted in the middle of the trail, and we evaluated what our next steps were. I needed to get off this mountain. So I called 911. I never expected to have to call them, much less for myself. But, nearly 16 hours and 25 miles into the hardest day of my life, I was left with little to no choice. I didn’t know exactly where we were in relation to our goal of Mt. Mansfield. All I knew was that I could not physically take a step further. I had already pushed myself to my limits, and past them. The last half mile up Bolton Mountain I had spent telling myself, “you still have more gas in the tank,” emphasizing every word with a single

incline actually was. I was slowing my group down to a crawl, turning an expected 30 minutes of walking into over an hour. My feet felt like lead, my legs were on fire, I felt shaky in every limb, and the pain from the blisters on my heels had risen to an unignorable scream.

“I’m on the Long Trail, and I need to get off,” I tearfully explained to the man on the phone. “I just don’t know where to go.”

“Alright, Naomi. Let’s get you off the mountain.” By pure stroke of luck (or maybe divine intervention), my body had given out mere meters from the beginning of a trail in the Bolton Valley Ski Resort. I was given directions to the trail and told to follow it until I reached the parking lot.

How did I even get here? I was ready for the challenge of this hike, or at least I felt like I was. I was a Boy Scout, comfortable with multi-day backpacking trips with long mileage. I had done long day hikes before, though never more than 12 miles over the course of an entire day. I had first aid certs, wilderness skills, and followed the ten Leave No Trace principles religiously. I trained for the hike, too! I hiked as much as I could beforehand, though the hikes were often cut short by this summer’s incredibly rainy season or prior commitments. I was ready for this.

In reality, I was underprepared—I recognize that now. I didn’t bring enough water or food. The food I did have was not food I wanted to eat, which made it difficult to get enough calories. I had no emergency shelter, and my ten essentials kit was admittedly a little light. But worse than all that: I wore the wrong shoes. The boots I was

caused serious blisters unless I wore the right socks. And wouldn’t you know it, I didn’t have the right socks! The blisters started at mile two and steadily got worse. That would be my downfall.

I found myself trying to explain my self to the man from Stowe Mountain Rescue—telling him I was an expe rienced hiker who tries to do every thing as safely as she could, it was just this hike that has gotten the best of me, I swear! He cut me off, gently and kindly.

“You’re doing the right thing, Nao mi,” my rescuer told me. “You don’t sound prepared.”

On our final descent down the mountain, I fell more than I walked. I had no control over my legs, and it was all I could do but try to keep my balance as I tumbled down the Bolton mountain-bike trail. I didn’t care about finesse, placing my foot just-so, or finding the safest and easiest way down the trail. I just wanted to be off the mountain. I was so numb that often I didn’t even feel that I had fallen, I just found myself looking at the canopy. Every time I slipped, I sprang right back up to my feet to walk another 50 feet before tumbling down yet again. My body was in survival mode; it knew it had to get me off the mountain, so there was no choice but to walk, and walk fast. If I fell, I needed to get back up and keep walking.

cling back to my coworkers this summer, who had spent weeks asking me about this hike, expressing desire to see me succeed and wishing me luck every step of the way. I couldn’t bear the thought of telling them I failed. But why? Why was I so impacted by this bail-out?

I’ve failed at things before! I’ve had my fair share of failing grades, embarrassing sports moments, horrible ski experiences, and more. But this was the only failure that had me crying this hard as I tripped down the mountain on numb feet.

Every 15 minutes I was supposed to call my rescuer from Stowe Mountain Rescue to provide coordinates and updates on my condition. The first time I called Brian and gave him our coordinates he said with surprise, “Oh, you’re a lot further down the mountain than I thought you would be!” I had just enough energy in me to laugh at the irony; the only part of our journey that we were ahead of schedule on was the unplanned bail-out down Bolton Mountain.

I spent the hike down apologizing to my hiking partners both for bailing on our attempt and for our grueling tumble down the mountain. I felt so guilty. I knew it was the right decision for me to bail, but I could feel the disappointment settle heavy on the shoulders of my friends. I was disappointed in myself. Despite every warning

During the quiet moments of this last section of the hike, I kept thinking about my role in Vermont sports culture as a whole. I had heard of an acquaintance, who, during the fall semester had a break in between classes and decided to use that time to run up and down Camel’s Hump in the scant few hours between lectures. Or even my friends on the hike, two of whom were training for a marathon. I wasn’t doing any of that. I was just good at walking! Or so I thought.

There’s a different definition of ‘walking’ in Vermont, I figured, one based in extremity and pushing limits. The whole hike I just bailed on was a symptom of this ‘new’ definition: I couldn’t just walk ten miles, or even just five, and call it good, I had to walk 30 instead. I had to prove to the unseen pressure of Vermont sport culture that I belonged there. I had to be able to post on Instagram and Strava and AllTrails and all the other platforms a successful, ‘easy,’ and fulfilling hike. I had taken

photos and videos the entire time for the sole purpose of being able to post them later and feel a part of the club. We walked on. I made a joke about writing a Headwaters article. My friends discussed, half-kidding, that after I left the woods, they would turn around and return to the trail to finish it that day.

When we spotted the gravel road that signaled the way to the hallowed Bolton Valley Ski Resort parking lot, the discussion on whether or not to go back up the mountain was getting more serious.

I told them they shouldn’t continue.

“I don’t think that’s a good idea,” I argued, both worried about their ability to finish ten more miles before predicted rain at 2:00 a.m., and because I was searingly, blindingly jealous. Why do they get to finish this hike and not me? The rain must have listened to me, because not soon after, a flash of lightning filled the sky, and the decision was taken out of our hands.

When we reached our unplanned pickup (in the form of my roommate, who had driven so fast up the access road her car smelled like burnt rubber), the backs of my heels were ripped to shreds. I was bleeding from where my blisters had been rubbed away. I was running on fumes. After 16 hours and 25 miles, I had called it quits.

I called a lot of things quits that summer. I found myself breaking a 75-day long swimming streak, partly because my legs were so tight and painful I couldn’t really walk far, and partly because I felt like such a loser that why not break another streak? I didn’t return to the lake until several weeks later, guilty and solemn and feeling weird about it all.

It was not until I had the gift of hindsight and amazing friends with a different perspective that I started to analyze my reaction to the hike and come to the conclusion that it was definitely informed by negative conceptions and was maybe a little overblown.

“Naomi,” My roommate told me incredulously. “You still walked 25 miles. That’s a huge achievement.”

“You definitely weren’t the only person struggling on that hike, you were just the first one to show it,” one of the people who hiked with me told me later.

“Why are you beating yourself up about this? Be proud

of what you did do and not upset at what you didn’t do!” Hearing the support from my friends made me feel better about the whole thing, but I still hadn’t squared it away with myself, yet. I still hadn’t shaken off the sense of failure.

I was chatting with a friend on a trip to Maine a few weeks later when she asked me something that knocked the wind out of my chest, and smacked some sense into me.

“Do you feel like because you failed this hike, you also failed at being an outdoorsy person?” She asked, turning to me with a knowing look. “Because that’s stupid. Naomi, you are studying the outdoors. You do other things outdoors. You succeeded at doing other things outdoors! You’re the captain of the Timbersports team, for crying out loud!”

Oh. Oh yeah. I guess that was true, huh? To hear it from someone else recontextualized the hike for me. I hadn’t ‘failed’ the hike, I simply hadn’t completed it, because it was out of my reach for my body at the time. And that is okay. I can do other things with my body that feel just as good to complete, are just as challenging, and aren’t excessively dangerous or difficult like Man-Hump ended up being for me. It didn’t mean that I was not an outdoorsy person, or that I wasn’t living an active lifestyle, or whatever self-doubt I was continually reinforcing and believing. It just meant that 35 miles of 8,000 feet of elevation gain is super hard, and I was not up for the challenge, and nothing more than that.

Just before my 21st birthday, I made a promise to myself: to never forget that I can do hard things, and to go out and do those hard things.

“Wait—you want to do it again? Naomi, you just told me how much it sucked and how you couldn’t do it!”

“No, no, no! I want to finish the last 10 miles I didn’t get to do. Want to come with me?”

Okay, do hard things, within reason, thank you very much. A ten-mile revenge hike felt like the perfect challenge, and the best way to honor the promise I had made myself. I just needed a few friends to go with me and to share in my joy at finishing the hike. “So, what do you say?”

“When do we start?” H

Life On Mars

By Casey Benderoth

Mars,

October 21, 2374 – Once a distant dream, life in outer space is now a reality for millions of families who have fled Earth after it became unsustainable for human life. Escaping Earth was not a quest for paradise, rather a stark choice between adapting to a hostile new world or facing extinction. Witnessing Earth’s collapse—its landscapes turned to wastelands, species vanishing one by one—left the survivors with no illusions. Mars became humanity’s next hope for survival.

“We had no choice but to flee,” explains Elizabeth Buckley, an elder of the R29 community on the southern hemisphere of Mars, as she vividly recalls her life on Earth. “It was either adapt or die.” Mrs. Buckley pauses, glancing at a holographic art piece of Earth in the entryway of her home. The image is familiar but unrecognizable; a blue-green haven now cloaked in ash-gray hues, its atmosphere shrouded with pollution. “People thought of Earth as a forever home, but this—” she motions to the red plains and highlands beyond,“—this is our home now.”

Survival here demands ingenuity and determination. The Martian colonies, established over the last several decades, have become vibrant, self-sustaining communities. Life on Mars has been designed for long-term habitation with the innovation of artificial gravity and vast hydroponic, aeroponic, and subterranean agricultural systems. Resources are distributed equitably, prioritizing the well-being of the community and the environment over profit or personal gain.

One of the most critical aspects of sustaining life on Mars has been the adoption of revolutionary agricultural techniques. At first, cultivating Mars’ barren soil seemed an insurmountable challenge. With Mars’ surface conditions—intense radiation, extreme temperatures, and thin atmosphere—making traditional farming impossible and an environment for wildlife nonviable, inhabitants have turned underground, transforming the Martian soil beneath them into fertile ground for crops to sustain communities.

To gain a better perspective on Martian agriculture, I visited the home of Duran and Georgia Allohak to discuss their infusion of traditional Lenape knowledge with the novel Martian environment. Their gardens are a microcosm of resilience. In their underground plot, polycropping rows of Martian-adapted crops like beans, corn, and squash grow tightly together, each plant serving a role. Corn provides structure, beans fix nitrogen, and squash retains moisture, a nod to traditional Lenape agricultural practices. Water is scarce here, but the couple has devised a slow-drip system, capturing every drop from their home’s condensation unit to preserve natural water.

“We’ve had to learn new ways to steward the land,” Georgia explains, gently pressing the soil to check moisture levels. “The environment here is nothing like Earth’s, but we’ve found ways to make it work. Back on Earth, some people would plow the land until the soil was practically dead, then rely on chemicals to force it to grow crops. Here on Mars, we had to learn quickly that those same mistakes could cost us everything.”

Watching them, it’s clear this is more than agriculture— it’s survival, passed down and reimagined. Their practic-

es honor their heritage while adapting to Mars’ demands, with each technique a careful balance between conserving resources and coaxing life from the barren soil.

Community members like Duran and Georgia are bringing in a new generation of knowledge and devotion to land across the entire planet. Most people have recognized and learned from the mistakes made on Earth and have begun to practice more multicultural and respectful ways of living. Incorporating Indigenous knowledge from Earth with experimental ideas from Mars is just one way these new inhabitants are coexisting with their environment.

As humanity settles into its new home on Mars and reflects on its past, the consequences of neglecting Earth’s resources are becoming increasingly apparent. The loss of biodiversity, exploitation of natural areas, and extinction of wildlife forced the human race to flee its cradle of origin. Mars offers humanity a second chance.

Some settlers advocate for reshaping Mars’ atmosphere and landscape to make it even more terrestrial. They propose large-scale projects like creating artificial lakes, engineering a thicker atmosphere, and physically remodeling the geology of the surface for grasses and trees. For these settlers, the idea of terraforming is tied to a sense of conquest; the Red Planet is another frontier to bend to humanity’s will. In their eyes, reshaping Mars to resemble Earth is not just a necessity for survival but an extension of human progress, a new chapter in the ageold narrative of expansion and control over nature.

However, others question whether humanity should impose its will on yet another planet. “We already know what happens when you try to force a planet to be something it’s not. Mars isn’t here for our taking. If we don’t adapt to Mars, this second chance might be our last,” argues local scientist and community member Dr. Swanne

Hernandez. “What’s the harm in appreciating what we have? I have little patience for terraforming advocates.”

The debate over Mars’ future is far from settled, and only time will tell whether humanity can learn to coexist with this new world—or if it will fall back into the same habits that led to Earth’s downfall.

Despite these concerns, some people feel a lingering connection to Earth. Depictions of Earth displayed in homes and public spaces serve as a reminder of what was lost, and some hold out hope for their home planet’s restoration. Yet, for most, Earth is a distant memory, fading with each passing generation. As Mars-born children grow up with no real understanding of the blue-green world their ancestors once called home, their connection to Earth weakens, leaving Mars as their only reality.

“People are already talking about looking for extraterrestrial life on other planets,” says Mrs. Buckley, shaking her head. “But maybe, if we’d focused on the Earth back then—on the importance of biodiversity and community, on protecting what we had—none of this would have happened. We laughed at how wild it was to think we’d run out of resources, but then…well, look at where we are now. It’s a hard lesson learned too late.” H

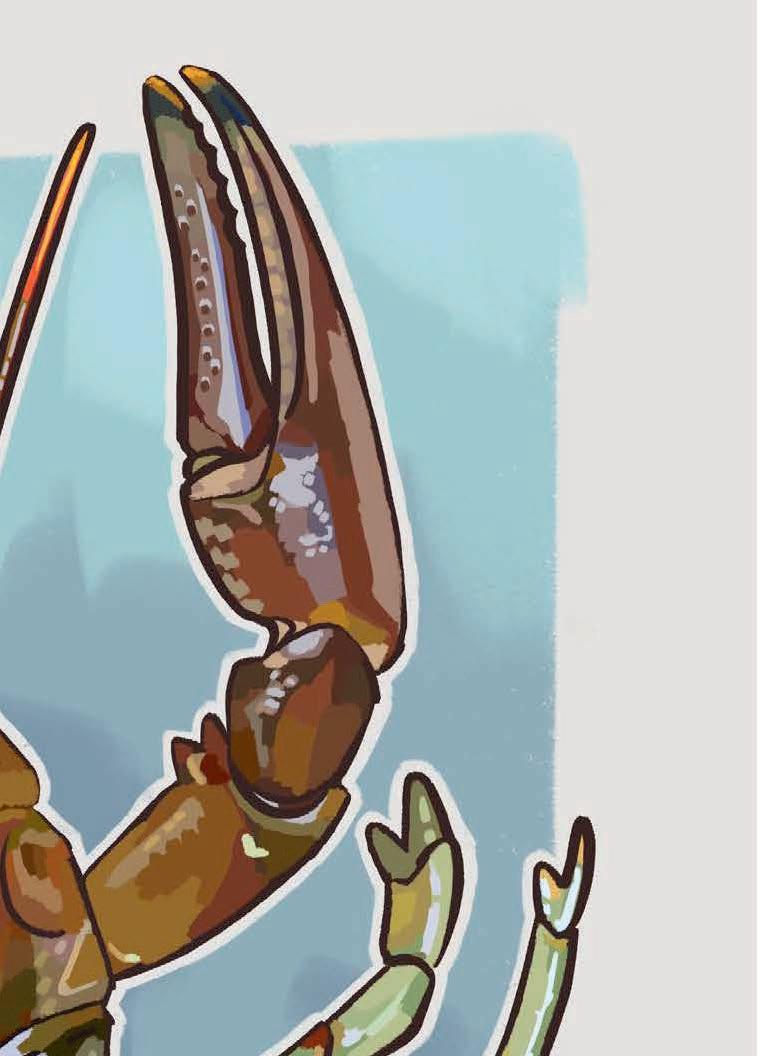

Art by Benjamin Erik Peterson

Answering the Bat Signal For Local Conservation

By Casey Benderoth and Cody Weintraub

Inthe quiet of Aeolus Cave outside East Dorset, Vermont, a colony of hibernating bats stir—some more fragile than others. Little brown bat populations have plummeted, and the northern long-eared bat has seen a nearly 99% decline. White-nose syndrome (WNS) is a deadly fungal disease that has swept through bat populations across North America after accidental introduction, likely from Europe or Asia, wiping out entire colonies and leaving only a shadow of what used to be. In Vermont, six of the nine native bat species have been affected by WNS. Despite these odds, signs of recovery are emerging.

According to researchers Isidoro-Ayza et al. (2024) who describe the pathogenesis of WNS, Pseudogymnoascus destructans affects hibernating bats because of their state of metabolic dormancy, meaning bodily processes are stopped or slowed down to conserve energy during hibernation. Because of these weakened immune responses, WNS rapidly attacks the thin epidermal layers of wing and tail membranes, causing necrosis in glands and tissues. Significant lesions appear on the skin of susceptible bats, and their immune systems begin to attack themselves. Without the evolution of immunity, bats can quickly spread this fungus throughout their body and meet an unfortunate end. However, many researchers are witnessing recovery and resistance in certain species. Increased winter fat storage through natural selection and heritable traits has led to a reduction in mortality of little

brown bats by 58-70%, according to researchers Cheng et al. (2024). By improving body condition in preparation of hibernation, bats can independently facilitate increased survival, reproduction, and the evolution of resistance or tolerance to WNS.

Researchers have also discovered various ways humans can facilitate resistance to WNS. Human intervention, such as implementation of a vaccine or complete eradication of the fungus, has been relatively unsuccessful, but bat rehabbers like Barry and Maureen Genzlinger support bats in their care to rid the fungus from their system. They combine baths and disinfectant application with a quiet environment, high humidity, high temperatures, and lots of food. These conditions show rapid healing in the individuals in less than two months.

Barry and Maureen dedicate much of their lives to bat rehabilitation through the non-profit Vermont Bat Center and in their own garage. When pups are dropped off in their care, they feed each baby every 1.5 to 2 hours around the clock, and when adult bats are ready for release, they travel more than 300 miles in one night around Vermont returning the bats to their homes. Along with their direct impact on bat conservation, Barry and Maureen prioritize educating others about the importance of bats in our ecosystems and how to protect a bat if it were to be found in your home. They say that “any hole you can fit your pinky into, a bat can fit into,” explaining how a bat can easily find their way into an attic or kitchen. However, bats are tiny creatures and are more afraid of you than you are of them. It is important to address misconceptions about bats and convey the importance of protecting injured or orphaned bats to reduce stress on their populations.

Barry and Maureen follow a direct conservation approach, while federal and state wildlife officials follow an indirect approach, like Alyssa Bennett of Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department. As Vermont’s Small Mammal Biologist, Alyssa conducts

surveillance of WNS and identifies important habitat conservation measures for bats. Different species need a variety of requirements like aquatic features, foraging habitat, habitat connectivity, trees for roosting, or caves for hibernation. Alyssa also educates stakeholders about the interplay between various land components like agricultural and forested areas, and human-made structures like roofs and attics, which can serve as essential habitats for bats. She amplifies outreach of her conservation message by “training the trainers” to think like a bat; by putting yourself in a bat’s shoes, so to speak, you can better envision different needs, such as where to find your food or preferred shelter. Alyssa’s work highlights an alternative and indirect conservation approach from a governmental perspective, including wildlife training, conservation incentives, and education to all stakeholders.

Bats are key elements to the ecosystems they inhabit and help humans in a variety of ways. All nine of the bat species found in Vermont are insectivorous, meaning that their diet consists almost exclusively of insects and other bugs. When mosquitos don’t seem to bite as frequently as they used to, you can thank your local bat. Many insects are classified as agricultural pests, and bats can play a critical role in reducing the threats that some of these pests may pose. Removal of these helpful bats can have unforeseen negative consequences. Frank et al. (2024) made an alarming connection between bat population loss due to WNS and increased infant mortality rates in humans. With a decreased presence of insectivorous bats in US counties, farmers were forced to use a greater quantity of toxic pesticides on their crops, which correlated to a 7.9% increase in internally caused infant mortality. When asked why the Genzlingers followed the path of bat rehabilitation, Maureen told us it was because “every little face meant something.” Regardless of what benefits bats may bring to humans, they are a key piece of Vermont’s rich biodiversity and deserve to live in a land they’ve inhabited far longer than we have.

WNS cannot be solved or eradicated, but we can support bat populations and their natural responses to survive the disease. By supporting conservation of their

other needs, like ensuring they have adequate foraging habitat or connectivity and shelter, bats can persist through a minimization of their stressors. Conserving aquatic environments near hibernacula is critical to ensure bats have enough food to survive throughout the winter and increase their fat storage to reduce susceptibility to WNS and other diseases, according to Cheng et al. (2018). Bat houses are strongly recommended for species that commonly roost in buildings; installing a bat house on your property may increase bat presence, decrease pests, and promote biodiversity in your local communities. At Shelburne Farms, a bat house shelters a thriving colony of over 400 bats, a group that has faced significant declines and has reached numbers as low as 75 due to WNS. Thankfully, the colony is now showing significant signs of recovery. This resurgence offers a hopeful glimpse into the future for local bat populations through facilitated support and conservation.

While there are many ways to indirectly support bat populations and their journey through rapid evolution, the most important actions to directly protect these critters are by educating your peers and supporting organizations like Vermont Bat Center and other non-profits through donations to provide the resources needed to rehabilitate bats. By teaching others about bats and how we can help them, we can modify public perception to be less dismissive of this species and more empathetic to their cause. Additionally, by supporting non-profits and other organizations doing on-the-ground research, conservation, and rehabilitation, we can contribute to the preservation of bat populations, protect critical ecosystems, and foster a deeper understanding of their vital role in maintaining biodiversity. Those hibernating bats of Aeolus Cave serve as a poignant reminder of the beauty and importance of these creatures; their tiny faces and gentle nature challenge us to see beyond the myths and embrace them not just as essential members of our ecosystem, but as undeniably cute creatures worth protecting. H

Photos

A Brave Little State

By Katie Ebre

The climate crisis is here—and it’s hitting Vermonters hard. From devastating annual state-wide flooding to late-spring freezes and record-breaking heat, Vermont has become all too familiar with the future that is promised by a changing climate. In May 2024, as families and communities faced the emotional and economic hardships of rebuilding homes, roads, and livelihoods, the Vermont state legislature passed first-in-the-nation legislation to hold the world’s most prolific polluters accountable for the damages they have caused. Act 122, the Climate Superfund Act, aims to hold the biggest oil companies importing into Vermont financially responsible for the costs associated with climate change. It has found unprecedented success. I spoke with Joshua Ferguson, the Climate and Energy Associate for the Vermont Public Interest Research Group, about this bill’s journey through the State House and the overwhelming support this idea received, as well as the future for legislation of this kind.

While many Headwaters readers will be well acquainted with the concept of a Superfund site, applying the concept to an entire global industry may be less familiar. The Superfund model rose to prominence more than four decades ago as a tool to make polluters pay for the cleanup of toxic chemical waste. Passed in the wake of a number of truly devastating disasters, the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act sparked the idea of charging polluters for cleaning up their messes. More than 40 years later, the Superfund program has been relatively uncontroversial and widely successful. Act 122 represents an expansion of the Superfund model to hold international oil companies accountable for the cost associated with climate change, from weatherizing homes to flood recovery. The fundamental basis of the case against the oil industry is the fact that ExxonMobil knew about climate change and the impact their product would have on the warming climate more than 40 years ago, and that they actively engaged in a misinformation campaign to protect profits. Like the tobacco industry, ExxonMobil and similarly prolific oil companies knew their product could not remain profitable if the general public understood the risks, so they remained publicly adamant that the science was inconclusive while funding the very research that proved how detrimental a continued reliance on oil would be.

Act 122 got its start on the national stage in 2021. The Polluters Pay Climate Fund Act (proposed by Senator Chris Van Hollen (D-MD.) and Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT.), among others) introduced the idea of holding oil companies fiscally responsible for the cost of addressing climate change and claimed that it would be possible to definitively attribute the rise in carbon and methane in the air to these oil giants. While the legislation stalled out at the federal level after it was excluded from President Biden’s Build Back Better framework in 2021, this Climate Superfund concept has not faded away. Two states, Vermont and New York, have now passed Climate Superfund bills through their respective state legislatures, while Maryland and Massachusetts have introduced similar legislation. Ferguson views this bill as “a leveling-up of past legislation.”

When asked about the motivating factors behind such a swift adoption of this legislation in Vermont, Ferguson mentioned that timing was paramount. The ‘Make Big Oil Pay’ campaign was launched in the heat of a summer plagued by severe flooding, on the coattails of a costly late-spring freeze after a winter of record-low snowfall. The FEMA assistance costs from the summer of 2023 dwarf those associated with Tropical Storm Irene, the last flood of this magnitude to hit the state. With more than $500 million in public and individual declared damages, Vermonters were brought face-to-face with the costly burden of a changing climate, and they were ready to pass the bill onto the companies deemed responsible.

“The timing in conjunction with the flooding that summer made the bill feel incredibly relevant,” Ferguson said. “The idea of building an emergency response fund so that Vermonters could help themselves in times of crisis felt really appealing.”

Beyond the environmental factors, the Vermont political landscape was poised to make significant progress in the climate and energy sector. Our State House had a ‘climate supermajority,’ a coalition of Democrats, Progressives, and Independents dedicated to voting in support of novel climate legislation and capable of overriding a governor’s veto. The majority flexed their might again and again throughout this legislative session; overriding six vetoes in one day and passing progressive legislation like Act 122, with supermajority margins.

Another factor driving the success of Act 122 here in Vermont is the prevalence of climate disasters in every corner of our state. Vermont has the 5th highest spending per capita on climate disasters in the country, while also having the lowest GDP and the highest percentage of rural residents in the country. Vermonters are already being faced with the costs of surviving the climate crisis. Every county in our state has been struck by four or more climate disasters in the last 10 years, with six of the 14 counties experiencing 10 or more. In the flooding of July 2023 alone, 4,000 homes and 800 businesses experienced significant damage, while over 100 roads closed across the state. These damages are a significant burden for Vermont’s many small, rural communities to shoulder alone, especially when we consider the toll climate change is taking on culturally significant and economically vital industries across the board. Winter sports, the timber industry, maple sugaring, and seasonal tourism are all industries threatened by changing weather patterns. Vermont now sees an average of 16 fewer days below freezing each winter than it did in 1990, and by 2050, Vermont will see an average of twice as many days above 90 degrees as it does right now.

So much of what defines Vermont’s character is now threatened by climate change. As the obligation to respond through policy becomes increasingly pressing, a divide has taken shape over how our state should respond. While Ferguson maintains that “this bill makes it simpler for Vermonters to help each other out in times of crisis,” his confidence is not universal.

Despite the widespread support this legislation received, uncertainty and opposition to the bill is undeniable. Perhaps unsurprisingly, legislation placing the blame and financial burden for climate change on oil companies has been met with significant resistance. Even before its passing, fears about the impact this importation fee would have on the cost of gas at the pump and heating oil made Vermonters reconsider the pragmatism of this policy. Ferguson argued that “Vermonters have seen a significant amount of misinformation surrounding this bill, which is riling them up against the possibility of a greener future.” Preliminary scientific analysis of the costs associated with this bill seems to agree that fears about rising costs are unfounded. A New York University School of Law policy brief found that New York’s Climate Superfund Act is unlikely to have an effect on the price of gas at the pump or crude oil more generally. Because the proposed structure entails a onetime fee based on the companies’ past contribution to the existing state of greenhouse gas emissions, present

and future revenue should not be impacted by the Act. Competition prevents oil companies from passing these costs onto consumers, and profit motivations encourage these companies to leave production levels and prices on retail gasoline steady. Outside of these market factors, national antitrust laws prevent oil companies from retaliating against New York and Vermont by raising prices together. This practice of price fixing, agreeing to raise, lower, or maintain prices, is heavily regulated. Though provisions like these have been built into the Act and are intended to protect consumers from rising prices, concerns about the cost effectiveness of this plan and the costs associated with the legal battle it may inspire caused Gov. Phil Scott to allow the bill to pass without his signature.

Beyond disagreements among constituents about the financial viability of this legislation, a larger question about if oil companies can be held legally responsible for climate damage is taking shape as the corporations fight back. While lawsuits challenging these Superfunds have not been filed yet (as of October 2024), Ferguson is confident that it is a matter of when, not if, for these challenges. Successfully upholding the bill may be a matter of convincing other (larger, more monied) states to join in the fight. Gov. Scott expressed concern that Vermont was choosing to “go-it-alone” in attempting to recover costs associated with climate change. This is an undeniably ambitious goal for the second-least populous state with the lowest GDP in the country, and having other states follow suit and pass similar legislation could become instrumental to the law withstanding a legal battle. As mentioned, New York passed a Climate Superfund bill the week after Vermont did, and the House of Representatives reintroduced the Polluters Pay Superfund Act in September. The re-introduction of this legislation at the national level is encouraging for supporters and, as Ferguson said, “we are building a tangible road forward for retributive climate solutions.”

The Climate Superfund Act was met with overwhelming support from lawmakers during the 2024 legislative session. Despite the questions still lingering for some Vermonters, a supermajority of legislators agree that taking on Big Oil is a worthwhile project, even for our little state. As we usher in a new era of environmental legislation, one where accountability for the most prolific polluters is prioritized and the experiences of communities devastated by climate disasters are centralized, it is heartening to see states like Vermont bring bold and innovative legislation to help their citizens survive and live well through the climate crisis. H

ThatWhen the Birds Sing

By Devan Kajah

morning, the rivers foamed at the mouth, snarling. I traversed the gnarled bank, watching chunks of earth slip away into the water. Closing my eyes, I attempted to drown out the sound of the river and tune into the birds, though it didn’t seem like there were any around to hear. The forest had gone silent in mourning.

Over the past few summers, I have witnessed the rivers I love churn into unrecognizable beings. My favorite swimming holes, once rippling with reflected stars, were now full of chunks of Styrofoam, creating their own galaxy. The dirt road leading to my home had washed away, giving the winter plow guy a new summer excavating job. A fruitful addition, considering that the days of endlessly plowing driveways might be behind us.

This summer, I worked with Audubon Vermont as a conservation intern. I spent early mornings weaving through dew-covered dogwoods and viburnums with my ears tuned in to the subtle buzzing of the golden and bluewinged warblers. These birds, which rely on shrubby edge habitats for mating and nest building, often interbreed. This interbreeding set Audubon Vermont on a quest to determine the golden-to-blue ratio in the Champlain Valley. Determining the ratio could increase funding for habitat work and hopefully halt the decreasing numbers of the winged warblers in Vermont.

Audubon Vermont received grant funding in years prior to carry out habitat restoration work to better support the warblers. I couldn’t wait to start this project. There are several spots across Northern Vermont where Audubon has done restoration work such as planting shrubland along nearby rivers to support the elusive warblers.

Throughout the early parts of summer, this was all my boss talked about.

“I collected more seeds from the center!”

“I planted the seeds, and they got pretty big, but then the squirrels got to them.”

“I found some more seeds to plant and now they are finally sprouting, but the rain in the forecast might drown them out.”

“Don’t worry, we will plant them eventually. We should probably wait until after the rain this weekend to do that, though.”

That was the last time he talked about the seed before rain came and flooded the state. Twice. For the second summer in a row, my Instagram feed was full of videos of water ripping through towns, lawn chairs and wiper fluid bottles floating away, and countless people looking for any support their community could offer.

Lives were put on pause to recover from an unnatural climate change-fueled flood. Again.

It felt wrong to return to work while people were still shoveling propane-infused muck out of their homes. But the next week I received a text from my boss: “Let’s meet at the center tomorrow morning, and we will check out the planting site.”

That morning, we trudged through grasses matted down by floodwater and debris. Ghosts of shrubs planted in years past now haunted the floodplain, obscured from sight by knotted grasses and green plastic fencing. The morning inventory had shifted into a rescue mission. The next few hours were spent feebly attempting to dig out the discouraged saplings. While the destruction from the flooding was nowhere near as severe in this small corner of Lewis Creek as it was in other parts of Vermont, it was painfully obvious that we would not be able to plant more this summer.

How can we work to slow climate change if climate change itself is preventing us from doing the work?

There are so many restoration projects and conservation tools out there working to heal the land and slow the chaos that is hurtling forward, but what do we do when it feels like we can’t do anything?

It is a question I and many others don’t yet have the answer to. Though with wicked problems like these, I’m not quite sure there will ever be an answer.

A week or so after we visited the planting site along Lewis Creek, we returned to the center in Huntington to conduct one more banding session before the summer was over. The walk to the first net was somber; the morning air was quiet and not even the usual crowd of

Gray Catbirds stopped by. The second net wasn’t there at all. Instead, it was somewhere downstream with the rest of the bank. Shocked avian bystanders were quiet in the wake of the flooding.

Aside from the few brave souls who visited the nets that morning, they were empty. Either the birds had been washed away, or they had sought higher ground. I chose to believe the latter.

I realized in the wake of everything, that if I listened closely enough, I could hear the robin’s morning chorus wake the world up, and could finally hear them over the water rushing around. If I took the time to stop and listen, maybe I could find the answer as to how to keep moving forward when it often seems like there is no way ahead.

I decided to listen to the birds, and in the final few weeks of the summer, my boss showed me some of the new seeds he had planted. He collected more seeds from the centers’ trails, and soon the pots were armored with chicken wire to keep the squirrels out. In that mo ment it all seemed to pay off.

We kept pushing forward even when the times seemed bleak, listened to what needed to be heard, and held hope close.

Despite the seemingly futile nature of our efforts, I would not have it any other way. I see no point in giving in to these wicked problems when we can still have a positive impact through our small actions. I cannot give in.

I will continue to listen to the morning chorus of birds, to do my part, and plant the saplings with care into the open arms of the earth. H

Art by Isabella Shinkar

Collecting Seashells

By Sophia Lemerise

Theocean is a community of artists. A big blue art museum, whose priceless works wash upon the shore in the form of shiny pebbles or uniquely colored seashells. Every summer, I return to the coast of Rhode Island, a perfect canvas for shells. Dotting the sand are colorful scallops, dove snails, cockles, mussels, wentletraps, and shiny rocks weathered from the persistent waves. The abundance of shells was hard to comprehend as a child; I found them from the rocky ends of the beach to the shallow water, with big piles by the dunes, where they tanned with the tourists under the sun. I would always go for the shells wet in the water, still controlled by the tide. As they tumbled around, I would rush to grab them before they were pulled back by the waves.

The night before our trip to Rhode Island, my siblings and I could barely sleep due to excitement. Our bags were all packed far in advance, bathing suits ready for use. I willed the morning to arrive faster while dreaming of the beach and the beautiful weather awaiting me. The sun would finally rise and, once my dad had shoved every last suitcase in the trunk, we would set off. This was our routine every July, at the peak of summer. The arrival of July meant the smell of salty air would weave its way into my braided hair once again. It meant another year had passed, the celebration of yet another birthday. Summer heat would leave my body warm even in the middle of the night, the slight sunburn on my face a happy reminder of a day spent on the coast. July meant scavenging for shells.

Buckets in hand, my siblings and I would race down the beach in search of the best shells. A myriad of colors, sizes, and shapes peppered the sand, catching the light of the sun and our fascinated gazes. The shells clunked into our buckets, our version of golden coins in a pirate’s treasure chest. It never took long to fill a bucket, and when it got too heavy, I’d have my dad carry it for me. Any special shells found after this point were held in my

cupped hands. A full bucket wouldn’t prevent me from stashing away a few more prizes. There appeared to be an endless supply to choose from, and a child like me wasn’t pausing to challenge this assumption. The shells were there, so I took them.

Once my search was complete, it was time to inspect and display my findings. Using my neon pink Boogie Board as a tabletop, the shells were arranged in neat rows and columns: smaller shells towards the top, bigger ones at the bottom. Dirty shells would be dunked in a small pail of seawater and then promptly returned to their spot. I closely studied my exhibit. Some shells were dull on the outside, but reveal a stunning array of colors on the inside, like faded watercolor. Some were delicate and smooth, others rough like the sand and bumpy with barnacles. There were scallops with bold pinks and oranges, and mussels with deep navy blue and shiny purple on the inside. Cute wentletrap and miniature cerith shells reminded me of ice cream cones. Smooth, marbled moon snails with a squishy animal still hiding inside. Sometimes I achieved a more rare, celebratory find: a big whelk, which I would put to my ear to listen to the waves. My favorite shell, the extremely thin and delicate mermaid’s toenail, remained hard to come by. A rich golden shade, nearly transparent, it felt like finding a jewel when I spotted one sparkling in the sand.

These shells were all so delicate, so full of detail, that I often wondered how such intricate, colorful, creations could emerge from the harsh waves. As I got older, I handled these shells with more care, speculating if such fragile creations were as abundant as I previously imagined. I had recently learned about deforestation in school. But, unlike shells, trees were large and cut down in great numbers across the globe. Certainly my little collection wasn’t harming the Earth to the same extent.

One week at the beach was never enough. Not enough

time to spend within the waves, feeling the strong force of the ocean and the thick salty water against my skin.

On our final day in Rhode Island before driving home, we would spend the remainder of our trip out on Block Island. You can faintly see the island from the main shore and, after a 45-minute ferry ride, the gorgeous bluffs of Block Island are in clear view. The island is always bustling with activity on Main Street. But time seems to slow down as you travel further from the ferry dock, with pedestrians and cars few and far between. There, the sound of the sea overpowers voices and engines. The island’s unique beauty seems to grow every summer as I appreciate the small features of this place more and more. At the bottom of the Mohican Bluffs, down by the water, there is no sand. Instead, rocks ranging from fist to penny-sized are dragged forward and back by the waves. All day, the pull of the tide creates a delicious crackling sound as the stones bump against each other, like the sizzling of water boiling on the stove or change jingling in your pocket.

The streets meander through the hills like a river, unpredictable and arbitrary. Once the road straightens towards the end of the island, dozens of shops line the streets and attract visitors with brightly colored signs and artwork. “Wanna stop in this place and get some inspiration for your art supplies?” My dad pointed towards a small local gallery.

He was referring to the paint, canvases, and brushes I had received for my 14th birthday only a few days ago. My family followed me into the store. The walls were covered in paintings, watercolors, and sketches of the island. I was immediately pulled to the back corner, towards a stack of illustrated poetry books created by a local sailor. I flipped through the vibrant pages, stopping at a particularly intriguing poem. The words completely enveloped me:

“There was an old fisherman, resting along the shore

I waved hello, he only crinkled his nose

‘What’s all that in your hand?’ he called in a voice as deep as the water

‘I’m collecting some rocks to take home.’

His eyebrows screwed tightly together; the man stood up with the help of a sturdy boulder

‘Why should you take them?’ his gaze was steady and unforgiving

‘I beg your pardon. I enjoy collecting rocks, sir.’

‘Do you need those rocks?’

‘I don’t think nature will miss a few,’ I chuckled

Not a bit of humor could be found in the fisherman’s expression

‘If every person who visited this spot took five or six rocks, that’s a lot of rocks gone missing.’

I considered this. I looked down at the pile in my hand. I suppose I didn’t need them after all.

‘Nature has more use for those rocks than you do’”

I thought of the buckets of seashells I took home every summer. My collection remained deep in my closet, tucked away in the constraints of a plastic storage bin, collecting dust. I felt a pang of guilt for hoarding all those beautiful pieces of art when I didn’t even need them. Other people wouldn’t be able to view those shells. Nature wouldn’t continue to wear them down; I was preventing them from being eroded into sand, the natural process of the waves. Dunes barricading the beach were missing out on extra additions to their piles. Smaller dunes meant less flooding protection, less wildlife habitats, and less carbon sequestration. All these invisible but immensely important ecosystem services of coastal dunes were being prevented by my actions.

I pictured my favorite Rhode Island beach, nestled within a rocky cutout of land. I love this place because of the tall dunes blocking out the noise and eyesores of vehicles traveling by. The sand piles are covered in beautiful golden grass plants, like long shining hair, swaying in the wind and creating an illusion of isolation from the world. Yet here I was, limiting the beauty of those towering dunes by stealing their building blocks. The consequences of my actions wouldn’t end there. Nutrients from shells, such as calcium or carbon, were being held

captive in my closet instead of naturally cycling back into the sea or becoming important sediments. The shoreline would erode at a faster rate due to large shell removal. Seabirds were missing out on building material for their nests, and other organisms like algae, small fish, and hermit crabs were losing shelters to withstand the crashing waves. My actions within a single week altered the environment of local residents and animals for a much longer span of time. This was my vacation spot; others called it their permanent home. I wouldn’t be feeling the impacts of my collection, and this naive outlook had prevented me from seeing past my own desires.

Everything on Earth is connected; not seeing or feeling the direct impacts of our day-to-day choices doesn’t give us an excuse to dismiss them. When the consequences don’t directly touch our lives, it’s easy to forget they exist. I saw my seashells as treasure, but digging for buried treasure doesn’t occur without pushing around the Earth. I hadn’t grasped the detrimental effects of my collection until it was too late, once I had already changed the course of the landscape. I had my riches, but at what cost?

The following summer, my altered perspective towards seashell hunting changed how I interacted with the environment. I now strive to leave the beach exactly how I found it. Instead of racing around with my bucket, I simply take my time observing the shells. Like catching fish and returning them to the water, I enjoy their beauty, then place them back in their sandy spot. Satisfied with observation, I leave the shells undisturbed and back in the hands of the Earth.

This new outlook has demonstrated how our possessions serve as a house for memories and emotions to live in. Stuff only becomes important when we associate it with something. My shells remind me of family, of my favorite beaches, and of those long relaxing days in the sun. But I can anchor these memories elsewhere, in a less materialistic way. I can paint them, photograph them, even journal them: all methods of preserving my sentiment while preserving the Earth.

It’s eye-opening to view our consumption habits in the same manner. I now consider the full consequences of all my purchases: Do I really need that cute skirt from Amazon I’ll only wear once? Is it necessary to order a new bag when my old one is still in good condition? Would I benefit more from eating at home than from buying Chipotle again, emitting carbon from my car while producing more plastic waste? Sure, luxuries like eating out or buying fun products are still okay, as long as they are done in moderation and with more apprehension. We owe our planet a second thought before devouring the beauty it has provided us with. Nature can only bestow us with so much treasure. If we continue to take and take and take, eventually there will be nothing left for the Earth to give.

I still find golden mermaid toenails glittering under the summer sun. I still run to pick up and observe a cool stone before it’s engulfed by a wave. However, I no longer view the coast as an endless supply of shells to take from, but as an art museum constructed by the creatures within the sea. I have what I need, and I leave the shells among their sandy canvas, for nature and time to take over. H

whatanimal are you?

Where do you spend the most time?

A. Redstone Pines

B. Pottery Co-op

C. Andrew Harris Green

D. Amphitheatre

E. Cat Bus

F. Billings Library

G. Patrick Gymnasium

Pick a major.

A. Engineering

B. Studio Art

C. Agriculture

D. Environmental Science

E. Communications

F. Political Science

G. Food Systems

Pick a UVM dorm.

A. Jeanne Mance

B. Trinity

C. Central

D. Harris/Millis

E. L and L

F. University Heights

G. Wing/Davis/Wilks

Pick a UVM club.

A. Timber sports

B. Kayak Club

C. Horticulture Club

D. Ski and Snowboard Club

E. Songwriters Circle

F. The Cynic

G. Beekeeping Club

What is your favorite place in Burlington?

A. Rock Point

B. Salmon Hole

C. Burlington Farmers Market

D. Outdoor Gear Exchange

E. Oak Ledge Park

F. Centennial Woods

G. Metrorock

By Cali Wisnosky

UVM

What is your bad habit?

A. Hoarding

B. Swearing

C. Gossiping

D.Pickingfights

E. Speeding

F. Staring

G. Sleeping through classes

What do you think is your best attribute?

A. Your smile

B. Your style

C. Your hair

D. Your height

E. Your athletic ability

F. Your eyes

G. Your strength

Pick a game.

A. Pick up Sticks

B. Go Fish

C. Hopscotch

D. Keep Away

E. Red Rover

F. Eye Spy

G. Kick the Can

Pick an item from the UVM starter pack.

A. Overalls

B. Nalgene water bottle

C. Skida hat

D. Blundstones

E. Yerba

F. Vintage Sweater

G. Hammock

What is your favorite UVM retail dining place?

A. Halal Shack

B. Redstone Market

C. Broccoli Bar

D. Skinny Pancake

E. The Marketplace

F. Campus Perk

G. Marche

answer key

Mostly A’s: Beaver

The trees are calling, and you must go! Like a beaver you are generally laid back, but you don’t mess around when it comes to your friends or family. You are a homebody through and through, but occasionally you can be spotted hammocking in the Redstone pines or birling with UVM Timbersports. You are most likely in Rubenstein and never leave home without your trusty ecoware. In true beaver nature you are a collector of things – stolen dining hall cups and silverware, stickers from ActivitiesFest, empty yerba cans you are using as plant pots. You love your trusty overalls and are obsessed with oral hygiene. However, you have a particular disgust for six-hour Dendrology labs, fake Christmas trees, and drippy faucets.

Mostly B’s: Rainbow Trout

Rainbow Trout are sensitive to water conditions and environmental changes. Because of this fact you may see yourself as an empath and are very attuned to your emotions and the emotions of others. You may also feel unrest when uncertainties and new challenges enter your life. However, just like ourfishyfriends,you have theability to overcome these situations and pride yourselfonbeingflexible. You have alwayshadanaffinity for waterandmost likely have spent many summers lifeguarding or raft guiding. In your free time you love rippin’ and dippin’ with UVM Kayak Club and watching roll compilations on YouTube. Your hobbies include channeling your colorful personality into art with the pottery co-op, making kombucha in your dorm, and excessively scrolling on Pinterest. Your most prized possessions are your Melanzana, your sticker covered Nalgene, and your polarized sunglasses. Some things you despise include turning on “the big light,” skinny jeans, and paper straws.

Mostly C’s: Cottontail

In true cottontail fashion you embody the cottagecore aesthetic. When you aren’t working a shift at Trader Joe’s, you enjoy picking lavender with the Horticulture Club, frolicking around the Burlington Farmers Market, and attending Contra classes in Mann Hall. You love building fairy houses, broccoli bar, escape rooms, mending clothing, making your own sourdough, and crocheting with the Yarn Club. You have a personal vendetta against cow milk and refusetodrinkanythinginyourcoffee that isn’t non-dairy. You love bringing people together for potluck dinners or game nights especially when there is a charcuterie board involved.

Mostly D’s: Moose

You love stomping around Outdoor Gear Exchange looking for some new equipment or picking up supplies at basecamp for your next big adventure. You probably live in a gear room and have ascratch-offNationalParkposter hanging alongside your collection offlatbrimhats.Whenyouinviteyour friendsoverthereismostdefinitely going to be a pile of Blundstones and Chacos near the doorway. The second Vermontgetsitsfirstbluebird day you are skiing the glades at Bolton or hitting some moguls at Smugglers Notch. You most likely have an extensive list of hobbies including rock climbing, mountain biking, backpacking and whitewater rafting. You love farm to table, hacky sacking, hanging keys on your belt loop, mountain silhouette tattoos, slacklining and seasonal work. However, you have a particular disgust for people who don’t follow leave-notrace practices, or use Dr. Bronner’s 18-in-1.

Mostly E’s: Hummingbird

center,

Like our colorful friend the hummingbird, you stand out due to your bold and authentic person ality. You channel that energetic attitude into your job as either an orientation leader, intra muralsportsofficial,orUVMtourguide.Your preferred mode of transportation is the Cat Bus so you can speed around to all your commit ments. You enjoy fast paced activities and are probably a part of one or more club sports. You lovetakingcyclingclassesatthefitnesscenter, running on the Burlington bike path, and forc ing people to follow your Strava. You most likely have acaffeineaddictionandcan’t get through the day without a yerba. Even though you have a busy social calendar you make time for your favoritehobbiessuchashand-pressingflowers, taking spikeball way too seriously, and running ultra marathons. However, you tend to be impa tient and have a low attention span, so you dis like things such as reading and waiting in the ice cream line at grundle.

Mostly F’s: Barred Owl

In true bear fashion you have a laid-back ap proach to life valuing rest and comfort. You can

proach to life valuing rest and comfort. You can befoundtyingflieswithUVM Fly FishingClub or leading hive tours with the Beekeeping Club. While some may be shredding black diamonds at Sugarbush, you prefer to beat the cold by hanginginthefireplacelounge,orperfecting your bouldering skills in Patrick Gym. You love foraging with the Herbalism Club, hanging in yourhammock,andsniffingoutasweettreat in the dining hall. During the day you and your friends like to sunbathe in the grass, climb the nearest tree, or make homemade granola bars. However,youhateloudnoises—specifically thosemadebythefirealarmsthatgooffatinconvenient hours—and people talking on the secondfloorof Howe library.

Your friends and family like to call you an old soul because you listen to The Smiths and love Dead Poets Society. It is likely that you were either obsessed with Greek Mythology or Harry Potter as a child. You split your time between Billings library studying for your political science class, the vintage market, and DJing for WRUV90.1FM. You putalotofeffortinto organizing your Spotify playlists and learning Latin on Duolingo. Like a Barred Owl you are an observer and enjoy documenting campus activitiesthroughfilmphotography for TheCynic. You love sweater vests, gothic architecture, the dark academia aesthetic, and the rain. However, you despise summer fashion and mainstream culture. -

Fostering Environmental

TheUniversity of Vermont campus is renowned for its beauty and abundance of green spaces. However, even while fallen leaves litter the sidewalks and birds sing overhead, many students do not feel as if they are in nature when on campus. This demonstrates the reality of modern-day environmental beliefs: one cannot feel a connection to nature in the presence of a manmade civilization. The idea of human-nature separation stems from centuries of conquering nature to build civilization. Over time, Western ideas about wilderness have created

an increasing feeling of alienation from both nature and the rest of the world. Now that the wilderness is in severe decline, some feel the need to repair the relationship between the two. Many people seek a connection to the environment in places that are considered “natural”—wilderness areas set aside by humans that are untouched by civilization. However, this thinking reinforces Western alienation and fails to recognize that nature is present even in man-made society and a strong connection to the environment can be formed in everyday life.

Environmental Connection at UVM

By Meredith Loney

Some Eastern philosophers believe that human-nature separation elicits a lack of wholeness and an inability to connect to something outside of one’s self. This sense of incompleteness often surfaces when people seek an environmental connection, but can only feel it outside the bounds of man-made society. One approach to combating this feeling is a practice known as egocide, where the ego, or the human belief in self-importance over nature, is acknowledged, killed, and replaced by new perspectives. Appreciating the existence of the environment in urban places can symbolically kill the ego by recognizing that the belief should be replaced. This new perspective about how human life and the environment are intertwined leads to feelings of connection to the rest of the world and the satisfaction of experiencing wholeness.

One of the easiest ways to “kill” the ego and form a connection to nature in a suburban or urban area, including on the UVM campus, is through sound. Birdsong is a prominent sound in suburban settings, but it takes effort to hear them. Birdsong is often mixed with the manmade noises of everyday life, like car tires screeching or construction equipment beeping. But, by acknowledging sounds like birdsong, even in noisy places, you can gain an understanding of the connection between natural and manmade sounds. Even if bird presence is sporadic, you can recognize the trees on campus that are habitats for many different bird species, each with a distinct song. On the UVM campus, some of the most common birds are American robins, whose song consists of cheerup and zeeee sounds with short pauses in between, and Dark-eyed juncos, which make various trills and warbles. Studies demonstrate that listening to bird sounds has many benefits, including reduced stress and fatigue.

Another method to connect to the environment is by identifying the sound of the wind. The practice of “sensing the wind,” or listening to individual sounds of the wind, like the movement of grass blades or the rustling of leaves, is inspired by the early Chinese philosophy of feng, the idea that all winds and airs create natural music. “Sensing the wind” transforms the listener into an ecological perceiver who navigates the environment using actions that enhance specific senses and finding the music of the sounds in the greater context of one’s environment. When you become an ecological perceiver,

you search for the direct value of natural music for personal enjoyment or a greater understanding of your surroundings. This not only creates a stronger relationship to nature, but allows you to understand the value of what nature has to offer. Recognizing Eastern practices like “sensing the wind” can help kill the ego, challenge Western beliefs about the environment, and create new perspectives on what can be gained through environmental connection.

In general, being attuned to natural aspects of your environment is proven to positively impact mental health, with improvements in memory, concentration, and overall mood. These benefits are still prevalent when the connection is formed in an urban or suburban area. Campus greenspace, classroom windows, and sidewalks are all opportunities to form a connection between you and your environment while on campus. When you have a relationship with the environment, you can build a sense of kinship and understanding similar to a relationship with another human. In some non-Western cultures, the act of listening to the land is a demonstration of care and the desire to maintain a healthy relationship with it. If more students have a stronger desire to care for the on-campus environment in addition to Vermont as a whole, protecting green space and on-campus species will be more important at UVM. Overall, rejecting Western beliefs of the separation of nature and human civilization can help create individual change by improving one’s mental and emotional health, as well as change how nature is perceived in today’s society. H

“Campus greenspace, classroom windows, and sidewalks are all opportunities to form a connection between you and your environment while on campus.”

EAST UNDERWOOD

By LODEN CROLL

ECOLOGY

Scarf

FROG

MITTENS

EQUINOX

HIBERNATION

PHENOLOGY

SNOWFLAKE

TORPOR

Washing Machine Heart

By Clara Marotta

Beforetossing your dirty shoes into the wash, take a look at the ways this action is contributing to water pollution.

Did you know that the average 13-pound load of laundry expels more than 700,000 microplastics in the form of fibers into wastewater? This is equivalent to throwing one plastic bag into the ocean for each load. That’s about all of your clothes for the week: six shirts, two pairs of jeans, shorts, underwear, and sheets from dorm beds. What’s more, over 60% of these textiles are made from synthetic fibers. These plastic fragments are shaped like threads or filaments and can leach out of almost anything with our clothes being at the top of the list. Washing machines are one of the largest contributors to this shedding, comprising almost 35% of global microplastic release. While systems like wastewater treatment plants can filter out most fibers, there is still an overwhelming flow of these plastics directly into the ocean and soil. Unlike the giant, floating garbage patches that are broadcasted on national news, microplastics pose a threat whose effects are largely unseen. The main risk is evident in a phenomenon called bioaccumulation, where microplastics move up through food webs. When we eat fish that have ingested microplastics, the fibers in their muscle tissue are transferred to our own bodies. These plastics cause physical damage such as clogging organs, stopping digestion, and ingestion of toxic chemicals. Plastics can also carry pathogens and parasites, which have the potential to reach human bodies or disrupt the health of entire marine ecosystems. These issues cannot be addressed without looking at the bigger picture. Our clothing materials, for example, are a main component of overall pollution. Finding both sustainable and equitable materials has morphed into a wicked problem that speaks to the complexity of textile improvement.

So, how does this cycle actually work? Surely there are efficient systems in place due to these appalling figures. Even after being processed at local wastewater treatment facilities, the sheer number of fibers cannot be fully accounted for. The average family does about 300 loads of laundry every year, meaning more plastics than can be filtered by treatment plants are produced. As of 2022, there are almost 20,000 households in the city of Burlington alone. The number of plastics from

just our city is equivalent to dumping 1.2 million buckets of sand into wastewater systems. This overloads the filtration process, allowing almost half of the fibers to travel into local rivers, lakes, and oceans. Septic systems are also inefficient at catching particles. Many exist in sizes too small to be caught through septic tank screening and are allowed to pass through as effluent. Farmers use effluent, or sludge, as fertilizer. Over time, this can clog soil pores due to their inability to biodegrade.

Through the Lake Champlain Sea Grant, students at SUNY Plattsburgh conducted research on the basins feeding into Lake Champlain. The results found that Burlington alone releases 16,843 plastic particles per day. More importantly, these synthetics do not biodegrade, staying in landfills or water bodies forever. While this is a point-source of the overall microplastic issue, it relies heavily on the textile industry itself.

It is not as if sustainable clothing materials do not exist yet. There are a range of replacements for synthetics spanning from plantbased fibers such as recycled cotton and organic hemp to animal-sourced materials like recycled wool. The issue lies in the feasibility and equity of making these sources available to everyone. These materials are made by hand, making them more expensive to produce. Let’s say that instead of buying new clothes, we turn to thrifting to invest in second-

hand clothing and upend aspects of fast fashion. The risk then becomes a form of gentrification, as middle- and upper-class overuse of thrift stores has increased price points to higher than costs of fast fashion chains. Unfortunately, fast fashion still trumps global supply at the cost of exploiting workers in demanding astronomical quotas and decrepit working conditions with 2% of workers earning life-sustaining wages. The textile industry embodies not only inherent issues in equity, but also the fact that “solutions are needed across the full lifecycle of synthetic textiles to eliminate microfiber pollution,” as stated by Dr. Anja Brandon, the Associate Director of the U.S. Plastics Policy at the Ocean Conservancy. There is not a single, identifiable stage at which the issue starts, there must be a rethinking and reworking of how clothing is distributed.

We’ve broken apart the simple act of washing clothes into issues of sustainability in ecosystems, equitable resources, and overall consumption patterns. Regarding washing machines, each data point and trend certainly sends a foreboding and demoralizing message. Fortunately, private organizations and even legislation have started to give more attention to combatting this issue. On an individual scale, several brands such as

tics from aquatic bodies but not fully disposing of

PlanetCare have developed external filters to attach to machines, removing filaments from rinse water. Byproducts from these filters go into solid waste rather than wa ter streams, keeping plas tics from aquatic bodies but not fully disposing of them. Organizations hop ing to contribute to this include CARE Internation al, who mainly focus on so cial inequities associated with textile production and Conscious Fashion and Lifestyle Network who hosts online platforms for industries to show contributions to Sustainable Development Goals. National policy in France and Australia created quotas for new washing machines to be equipped with microfiber filters by 2030, with the U.S. lagging behind. Sen ator Jeff Merkley D-OR proposed the Fight ing Fibers Act, which would require both prop er filtration equipment on washing machines and future impact assessment research. He recognizes that lack of public awareness is a large component to the issue stating, “We know microplastics negatively affect human health and our environment. However, many people do not know that clothes are a major contributor to our global plastic pollution crisis.” While finances are the main barrier to this legislation, filters would not increase machine prices by more than $20.

This is not to say that there aren’t practices that can be implemented to “do your part,” mainly by focusing attention and intentions towards sustainability. In reducing the number of partial loads, using cold water, and choosing front-loading washing machines, the cycling and rubbing of clothing becomes smoother and decreases filaments released. The steps that have been taken on the national and international scales seem promising but the lack of public awareness on the issue is what is most alarming. Through raising awareness and employing sustainable practices in our daily routines, we can take those essential steps towards protecting our environment and reducing pollution on various scales. H

Environmentalactivism at UVM is currently at a critical juncture; students and activists are increasingly frustrated by the widening gap between the University’s sustainability commitments and its material actions. The University has presented ambitious goals such as achieving net-zero emissions and reducing waste. However, many perceive these initiatives as falling victim to greenwashing—appearing to promote sustainability efforts without making substantial changes. For instance, the “Net-Zero by 2030” campaign lacks transparent steps on how this target will be achieved, raising concerns that it might be more of a marketing tactic than a genuine effort. Buzzwords like “carbon neutrality” and “sustainable growth” are often used in campus communications, but tangible progress is not always evident.

ENVIRONME BY LINDSEY MASCHLER

Attend and Speak at Burlington City Council Meetings!