Sagebrush, Wildfire, and Homeowners Associations: Climate Adaptation Opportunities in Summit County, Utah

Rebecca Ivans1, Kendall Becker1,2, Wesley Crump3, J. Bradley Washa4, Lewis Kogan5, Scott Hotaling1,2

1 Utah State University (USU) Climate Adaptation Intern Program

2 USU Department of Watershed Sciences

3 USU Extension Agriculture and Natural Resources

4 USU Department of Wildland Resources

5 Swaner Preserve & EcoCenter, Utah State University

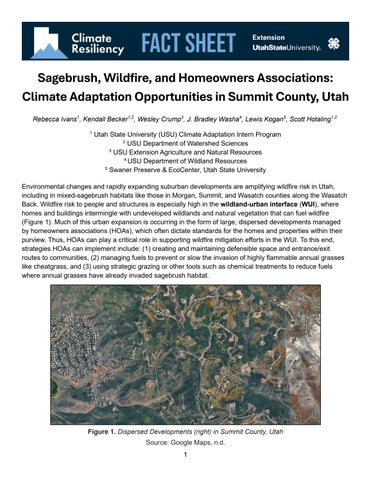

Environmental changes and rapidly expanding suburban developments are amplifying wildfire risk in Utah, including in mixed-sagebrush habitats like those in Morgan, Summit, and Wasatch counties along the Wasatch Back. Wildfire risk to people and structures is especially high in the wildland-urban interface (WUI), where homes and buildings intermingle with undeveloped wildlands and natural vegetation that can fuel wildfire (Figure 1). Much of this urban expansion is occurring in the form of large, dispersed developments managed by homeowners associations (HOAs), which often dictate standards for the homes and properties within their purview. Thus, HOAs can play a critical role in supporting wildfire mitigation efforts in the WUI. To this end, strategies HOAs can implement include: (1) creating and maintaining defensible space and entrance/exit routes to communities, (2) managing fuels to prevent or slow the invasion of highly flammable annual grasses like cheatgrass, and (3) using strategic grazing or other tools such as chemical treatments to reduce fuels where annual grasses have already invaded sagebrush habitat

Figure 1. Dispersed Developments (right) in Summit County, Utah

Source: Google Maps, n.d.

Sagebrush in Summit County

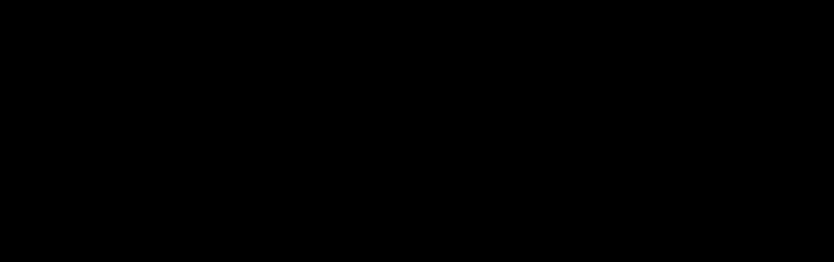

About 20% of Utah, including parts of Summit County, is sagebrush shrub–steppe (Birch & Lutz, 2023). This ecosystem type is common in the Great Basin and Colorado Plateau. In these regions, sagebrush plays an important ecological role by supporting wildlife and slowing the melt of winter snowpack, making it a conservation priority (Kormos et al., 2017; Remington et al., 2024). While sagebrush habitats historically (i.e., pre-1850) burned every 35–450 years, contemporary climate change, loss of native bunchgrasses, and invasion of annual grasses are increasing the frequency and severity of wildfire, which is particularly problematic due to new human developments in the area (Figure 2; Baker, 2006; Miller et al., 2011).

Cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum) is an invasive annual grass of particular concern because it is widespread and reproduces rapidly, especially where clumps of native bunchgrasses have been depleted by grazing (Miller et al., 2011). While sagebrush shrubs and native bunchgrasses typically maintain space between plants, cheatgrass forms a continuous fuel bed that facilitates fire spread. Moreover, cheatgrass, a cool-season grass, matures early in the growing season and then dries out, so the continuous fuel bed is flammable for a longer period. Typically, cheatgrass recovers within 2 years after fire, but sagebrush shrubs can take 3–12 decades to reestablish (Baker, 2006; Grant-Hoffman & Plank, 2021). In some areas where cheatgrass now dominates, fire frequency has increased dramatically. For example, as of 1990, heavily invaded pockets of sagebrush in the Snake River Plain of Wyoming were burning every 5 years (Miller et al., 2011).

Source: Strickland, 2017 CC-BY-2.0

In Utah, over 1.9 million acres of sagebrush habitat burned from 1984–2022, with 25% of that area burning at high severity (Birch & Lutz, 2023). Of the 1,477 wildfires larger than 100 acres that burned in Utah during this period, sagebrush was present in 96% of them (Birch & Lutz, 2023). The higher severity and large size of recent wildfires in sagebrush habitat could be due to existing invasions of annual grasses, which have been considered problematic in the western U.S. since at least 1941 (Remington et al., 2024).

Within sagebrush habitat, a cheatgrass-wildfire cycle exists where wildfire facilitates the spread of cheatgrass, which in turn increases wildfire risk. As of 2024, many areas in western Utah that burned in the past four decades are designated “containment” zones, where invasive annual grasses are so well-established that restoration to native bunchgrasses is no longer realistic (Birch & Lutz, 2023; Boyd et al., 2024). However, the northern region of Summit County near Castle Rock still contains intact sagebrush habitat. Here, early detection and removal of invasive grasses remains the recommended conservation strategy (Boyd et al., 2024). In addition, several other areas near Castle Rock and Echo have only moderate invasions, and suppressing invasives and restoring perennial bunchgrasses are recommended (Boyd et al., 2024). Cheatgrass has likely been slower to invade Summit County because of the cooler temperatures and longer period of snow cover at higher elevations. However, as native vegetation even at higher elevations is increasingly stressed by earlier snowmelt, prolonged drought, and wildfire due to climate change, spread of cheatgrass may accelerate in Summit County (Becker & Hotaling, 2024). Indeed, cheatgrass has already been observed in Summit County in the footprint of the 2018 Tollgate Canyon Fire and along the roads and highways in the Park City area (elevation 6,980 feet), where vehicles, mountain bikes, and hiking shoes can transport seeds

Figure 2. Sagebrush Shrubs (green) Invaded by Highly Flammable Cheatgrass (tan)

Sagebrush, Wildfire Risk, and Management Strategies

Maintain the Natural Sagebrush Ecosystem

While sagebrush habitat can pose a wildfire risk that escalates with annual grass invasion, maintaining sagebrush has multiple benefits:

• Sagebrush provides habitat for native animal species, including bees, sage-grouse, small mammals, and big game (Cane & Love, 2016; Remington et al., 2024). It also provides valuable rangeland for cattle grazing (Davies et al., 2024).

• Sagebrush helps sustain water supply for animals and people. Compared with juniper-dominated rangelands, snowpack in intact sagebrush melts out 9 days later on average and supports higher streamflow (Kormos et al., 2017).

• Sagebrush maintains ecosystem integrity. Its degradation or removal invites the rapid establishment of invasive grasses such as cheatgrass, which increases the risk of wildfire Thus, removing sagebrush puts communities at risk because it could be replaced by more flammable, invasive vegetation (Harrison, 2024; Remington et al., 2024).

Steps can be taken, however, at the community and household levels to prevent the spread of wildfire while preserving Summit County’s natural sagebrush ecosystem.

Establish Defensible Space

Creating “defensible space” around neighborhoods and individual homes is one recommended strategy. Defensible space refers to a series of buffer zones, referred to as the Home Ignition Zone, between a property and the surrounding wildland area (Figure 4; Cal FIRE, 2024a). The premise is to start at the home and manage vegetation outward, reaching to 100 feet and potentially beyond. Vegetation closer to the home should be more heavily managed (Cal FIRE, 2025a). Part of this management should include fuel reduction, or the removal of combustible vegetation, including dead weeds, grass, and debris. This is vital to slowing the spread of wildfire and protecting homes from stray embers, flames, and heat. Fuel reduction also helps firefighters When firefighters have a safe area from which to defend a property, they can be more effective (Cal FIRE, 2025b). Defensible space is broken into three zones, explained in Table 1, and illustrated in Figure 4

Immediate

Closest to the home, 0–5 feet from the outer walls, porches, or decks.

Intermediate 5–30 feet from the home

Extended 30–100 feet from the home and beyond.

Keep this area devoid of anything combustible to protect against stray embers igniting the home. Some refer to this as the lean, clean, and green zone.

Prune flammable plants and cut overgrown vegetation.

Trim grass to no more than 4 inches in height, and maintain space between trees, shrubs, and flammable items like patio furniture and wood piles.

For HOAs and their members, applying these guidelines to common areas and Home Ignition Zones reduces the community’s vulnerability to wildfire.

Table 1. Three Defensible Space Zones

Create Dispensable Buffer Zones

In addition, HOAs can create larger, dispensable “buffer zones” between neighborhoods and adjacent wildlands (Cal Fire, 2024a). Dispensable refers to property that is beneficial to the community but not necessary for its residents’ immediate survival for example, playgrounds and parks. These structures and spaces, while certainly valuable to neighborhoods, can serve as important barriers between wildlands and homes. In the worst scenario of a wildfire encroaching on a neighborhood, the value of a lost playground is substantially smaller than a lost home.

Monitor and Reduce Annual Grass Invasions

HOAs can also coordinate with local land management agencies to monitor and reduce annual grass invasions. Early detection and removal of invasive grasses can help maintain intact sagebrush habitat (Boyd et al., 2024). Where annual grasses have already invaded, targeted early-season grazing can tamp down annual grasses, reduce fuel, and give native, less flammable bunchgrasses an advantage later in the growing season (Davies et al., 2024). Chemical treatments and hand-pulling of annual grasses are also options if the invasion is still relatively small.

Resources

Preparing for wildfire makes Utah’s neighborhoods and homes safer. Utah’s Division of Forestry, Fire & State Lands as well as local fire departments and fire protection districts provide resources to help HOAs and homeowners create and manage “firewise” landscapes Utah Fire Info hosts a real-time map of wildfires burning in Utah, with detailed information regarding location, duration, and containment status. Utah State University Extension’s Post-Wildfire Resources include useful guides to help communities and individuals recover after wildfires.

Acknowledgments

This publication is the product of a partnership between the Climate Adaptation Intern Program (CAIP) and Swaner Preserve & EcoCenter in Summit County, Utah. CAIP was supported by the “Secure Water Future” project, funded by an Agriculture and Food Research Initiative Competitive Grant (#2021-69012-35916) from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, as well as funding from USU Extension and a USU Extension Water Initiative Grant. We improved this fact sheet based on feedback from Kelly Kopp, Ph.D., Sara Jo Dickens, Ph.D., Martin Holdrege, Ph.D., and CAIP participants. For correspondence, contact Scott Hotaling: scott.hotaling@usu.edu

References

Baker, W. L. (2006). Fire and restoration of sagebrush ecosystems. Wildlife Society Bulletin (1973-2006), 34(1), 177–85. https://doi.org/10.2193/0091-7648(2006)34[177:FAROSE]2.0.CO;2 Birch, J. D., & Lutz, J. A. (2023). Fire regimes of Utah: The past as prologue. Fire, 6(11), 423. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire6110423

Boyd, C. S., Creutzburg, M. K., Kumar, A. V., Smith, J. T., Doherty, K. E., Mealor, B. A., Bradford, J. B., Cahill, M., Copeland, S. M., Duquette, C. A., Garner, L., Holdrege, M. C., Sparklin, B., & Cross, T. B. (2024). A strategic and science-based framework for management of invasive annual grasses in the sagebrush biome. Rangeland Ecology & Management, 97, 61–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rama.2024.08.019 Bowen, B. D. (2021, June 7). Lessons from anticipatory intelligence: Resilient pedagogy in the face of future disruptions. Resilient Pedagogy. https://uen.pressbooks.pub/resilientpedagogy/chapter/lessons-fromanticipatory-intelligence-resilient-pedagogy-in-the-face-of-future-disruptions/ Cal FIRE. (2025a). Defensible space. https://www.fire.ca.gov/dspace Cal FIRE. (2025b). Defensible space. https://readyforwildfire.org/prepare-for-wildfire/defensible-space/

Cane, J. H., & Love, B. (2016). Floral guilds of bees in sagebrush steppe: Comparing bee usage of wildflowers available for postfire restoration. Natural Areas Journal, 36(4), 377–391. https://www.fs.usda.gov/rm/pubs_journals/2016/rmrs_2016_cane_j001.pdf

Chen, J. (2024, July 27). What is a homeowners association (HOA), and how does it work? Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/h/hoa.asp#:~:text=HOAs%20are%20composed%20of%20and,the%20 HOA’s%20rules%20and%20regulations.

Davies, K. W., Boyd, C. S., Bates, J. D., Svejcar, L. N., & Porensky, L. M. (2024). Ecological benefits of strategically applied livestock grazing in sagebrush communities. Ecosphere, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.4859

FEMA Geospatial Resource Center. (2023). WUI awareness. https://gis-fema.hub.arcgis.com/pages/wuiawareness

Flavelle, C., & Rojanasakul, M. (2024, May 13). As insurers around the U.S. bleed cash from climate shocks, homeowners lose. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2024/05/13/climate/insurance-homes-climate-change-weather.html Google Maps. (n.d.). https://www.google.com/maps/@40.7610727,111.5467418,2456m/data=!3m1!1e3?entry=ttu&g_ep=EgoyMDI1MDYxMS4wIKXMDSoASAFQAw%3D%3 D

Grant-Hoffman, M. N., & Plank. H. L. (2021). Practical postfire sagebrush shrub restoration techniques. Rangeland Ecology & Management, 74. 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rama.2020.10.007

Harrison, G. R., Jones, L. C., Ellsworth, L. M., Strand, E. K., & Prather, T. S. (2024). Cheatgrass alters flammability of native perennial grasses in laboratory combustion experiments. Fire Ecology, 20(103). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42408-024-00338-z

iPropertyManagement. (2025). HOA statistics https://ipropertymanagement.com/research/hoastatistics?u=%2Fresearch%2Fhoa-statistics#hoas-by-state

Keys, B. J., & Mulder, P. (2024). Property insurance and disaster risk: New evidence from mortgage escrow data. National Bureau of Economic Research. http://www.nber.org/papers/w32579

Kormos, P. R., Marks, D., Pierson, F. B., Williams, C. J., Hardegree, S. P., Havens, S., Hedrick, A., Bates, J. D., & Svejcar, T. J. (2017). Ecosystem water availability in juniper versus sagebrush snow-dominated rangelands. Rangeland Ecology & Management, 70, 116–128. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rama.2016.05.003

Lambert, L. (2024, November 15). The housing market’s home insurance shock, as told by an interactive map Fast Company. https://www.fastcompany.com/91229352/housing-market-home-insurance-shockinteractive-map?utm_source=flipboard&utm_content=topic%2Fbusiness

Li, Z., & Yu, W. (2025). Economic impact of the Los Angeles wildfires. UCLA Anderson Forecast https://www.anderson.ucla.edu/about/centers/ucla-anderson-forecast/economic-impact-los-angeleswildfires#12

Loftsgordon, A. (2024, October 22). What are covenants, conditions & restrictions (CC&Rs) in HOAs? https://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/what-are-convenants-conditions-restrictions-ccrs-hoas.html McGinty, E. I. L., & McGinty, C. (2009). Rangeland resources of Utah: Fire in Utah. https://extension.usu.edu/rangelands/files/RRU_Final.pdf

Miller, R. F., Knick, S.T., Pyke, D.A., Meinke, C.W., Hanser, S.E., Wisdom, M.J., & Hild, A.L. (2011). Characteristics of sagebrush habitats and limitations to long-term conservation. In S.T. Knick, & J.W. Connelly (Eds.), Characteristics of sagebrush habitats and limitations to long-term conservation (pp. 145–184), Greater sage-grouse: ecology and conservation of a landscape species and its habitats. Studies in Avian Biology. https://agsci.oregonstate.edu/sites/agscid7/files/eoarc/attachments/712.pdf

National Centers for Environmental Information. (2025). U.S. billion-dollar weather and climate disasters. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/billions/statesummary/UT

Remington, T. E., Mayer, K. E., & Stiver, S. J. (2024). Where do we go from here with sagebrush conservation: A long-term perspective. Rangeland Ecology & Management, 97, 200–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rama.2024.08.009

Strickland, J. (2017, June 21). File:Sagebrush surrounded by cheatgrass (36940014932).jpg [Photograph]. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sagebrush_surrounded_by_cheatgrass_(36940014932).jpg

United States Census Bureau. (2024). U.S. Census Bureau quickfacts: Summit County, Utah https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/summitcountyutah/PST045216 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (n.d.). CPI inflation calculator https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm Washa, J. B. (2025, January 17). Ask an expert: Is Utah at risk for wildfires similar to those in Los Angeles? https://extension.usu.edu/news/ask-an-expert-is-utah-at-risk-for-wildfires-similar-to-those-in-los-angeles Wasserman, T. N., & Mueller, S. E. (2023). Climate influences on future fire severity: A synthesis of climate-fire interactions and impacts on fire regimes, high-severity fire, and forests in the western United States. Fire Ecology, 19(43), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42408-023-00200-8

In its programs and activities, including in admissions and employment, Utah State University does not discriminate or tolerate discrimination, including harassment, based on race, color, religion, sex, national origin, age, genetic information, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, disability, status as a protected veteran, or any other status protected by University policy, Title IX, or any other federal, state, or local law. Utah State University is an equal opportunity employer and does not discriminate or tolerate discrimination including harassment in employment including in hiring, promotion, transfer, or termination based on race, color, religion, sex, national origin, age, genetic information, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, disability, status as a protected veteran, or any other status protected by University policy or any other federal, state, or local law. Utah State University does not discriminate in its housing offerings and will treat all persons fairly and equally without regard to race, color, religion, sex, familial status, disability, national origin, source of income, sexual orientation, or gender identity Additionally, the University endeavors to provide reasonable accommodations when necessary and to ensure equal access to qualified persons with disabilities. The following office has been designated to handle inquiries regarding the application of Title IX and its implementing regulations and/or USU’s non-discrimination policies: The Office of Equity in Distance Education, Room 400, Logan, Utah, titleix@usu.edu, 435-797-1266. For further information regarding non-discrimination, please visit equity.usu.edu, or contact: U.S. Department of Education, Office of Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights, 800-421-3481, ocr@ed.gov or U.S. Department of Education, Denver Regional Office, 303-844-5695 ocr.denver@ed.gov. Issued in furtherance of Cooperative Extension work, acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914, in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Kenneth L. White, Senior Vice President for Statewide Enterprise and Utah State University Extension.

August 2025

Utah State University Extension Peer-reviewed fact sheet