This semester, I’ve had the privilege of teaching an undergraduate psychology course on how organizations make decisions about sustainability. Funded in part by a generous grant from Ballmer Group (p. 8), this course gives upper-division USC students from all majors the opportunity to learn how sustainability decisions are made in the real world.

The course has included meetings and tours with parallel organizations in California and Switzerland, so that students can see firsthand how policy, culture, and economics can affect sustainable decision-making. For instance, in L.A., the students learned from our local commuter rail provider Metrolink, and in Zürich, they learned from national commuter rail provider SBB.

It’s no secret that this is a challenging time to be conducting research, educating students, and engaging the public on the environment and sustainability. But this psychology course has been a bright spot of hope for me this spring, and I hope it will encourage you, too. It has been a timely reminder that the Wrigley Institute is far from alone in our work. People and organizations around the globe are striving, in all kinds of ways, to build a thriving future. And many of our young people are eager to learn about and carry forward those efforts.

Most importantly, we - both the Wrigley Institute and you, our friends and supporters - are not alone because we can look to each other for hope and inspiration. This year, Soundings is as much about providing that hope and inspiration as it is about keeping you informed of our activities or motivating you to support our programs. My desire, and the desire of the institute’s dedicated team, is for you to find encouragement in these pages. I hope they’ll be a reminder, both now and going forward, that many good things are happening for our planet and all who live on it.

Thank you for all you do to support our work, and for all the ways you join us in creating a more sustainable future.

Cover: USC student Alex Luce freedives while shadowing a marine biology course on Catalina Island. Luce participated in the 2024 Wrigley Institute environmental communications internship as the Wrigley Marine Science Center photography intern. He spent the summer on Catalina Island, focused on storytelling for the Wrigley Institute’s summer research and educational programs. (Photo: Nick Neumann/USC Wrigley Institute)

CUTTING ACROSS BARRIERS

NEW GIFTS SEED MAJOR INITIATIVES

STEWARDING HOPE

WMSC JOINS THE HOPE SPOT CONSERVATION NETWORK BRIGHT MINDS GROW IN VIBRANT GARDENS

At the Wrigley Institute, faculty research casts a wide net.

Our core faculty, in the Dornsife Environmental Studies Program, conduct research with undergraduate students. Cross-cutting initiatives in carbon and plastics solve big, multi-faceted environmental issues by bringing together affiliated faculty from accross the university. And our research launchpads support faculty projects centered around themes that address our planet’s systems, scientific solutions to climate change, and human behavior toward sustainability.

In addition, we support faculty research mentorship, by helping to fund Ph.D. students or undergraduate research interns who work in affiliated faculty labs. The Wrigley Marine Science Center, our campus on Catalina Island, is also open to faculty researchers and their graduate students seeking to conduct fieldwork in the island’s unique environment.

Learn more about Wrigley Institute research programs: bit.ly/wies-research.

In the Arctic, permafrost traps naturally occurring mercury, which is highly toxic when released.

However, as the Arctic warms due to climate change, that mercury is leaching into the watersheds and soil of a region that houses 5 million people.

Josh West, a professor of Earth sciences and environmental studies, has developed a new method for tracking the mercury in Arctic ecosystems. This approach is more accurate than previous methods, providing a way for scientists to better evaluate the health of the region.

Original reporting by Darrin Joy (photo: Michael P. Lamb). Learn more about West’s research: bit.ly/westmercury-research.

As part of the Wrigley Institute’s comprehensive, cross-disciplinary approach to solving environmental and sustainability challenges, we’ve made the arts an integral part of our work.

The arts have a unique ability to capture people’s attention, seed change, and spur action. By commissioning original works of art and incorporating the arts into our programming, we’re adding a new dimension to the climate conversation and galvanizing people to create a more sustainable future.

Recent art activations have included “El Respiro,” a partnership with USC Visions & Voices to sponsor an original project by world-renowned artist and USC alumna Carolina Caycedo. The Wrigley Institute has also supported and exhibited immersive installations, sculpture, photography, and poetry by USC students and faculty.

Learn more about Arts @ Wrigley: bit.ly/wies-art.

In spring 2024, Wrigley Institute Curator Allison Agsten saw a need for hope. “Doom-and-gloom climate news coverage is not successful. People shut down when they encounter too much of it,” she says.

One solution: a collaboration with the USC School of Cinematic Arts, using AI to help envision a future, sustainability-centered Los Angeles.

Called “City Ascendant: Imaginging the Future of L.A. through A.I.,” the exhibit debuted at our annual Climate Forward conference and was praised in the Los Angeles Times climate column “Boiling Point.”

Learn more about “City Ascendant”: bit.ly/cityascendant. Photo: Nick Neumann/USC Wrigley Institute.

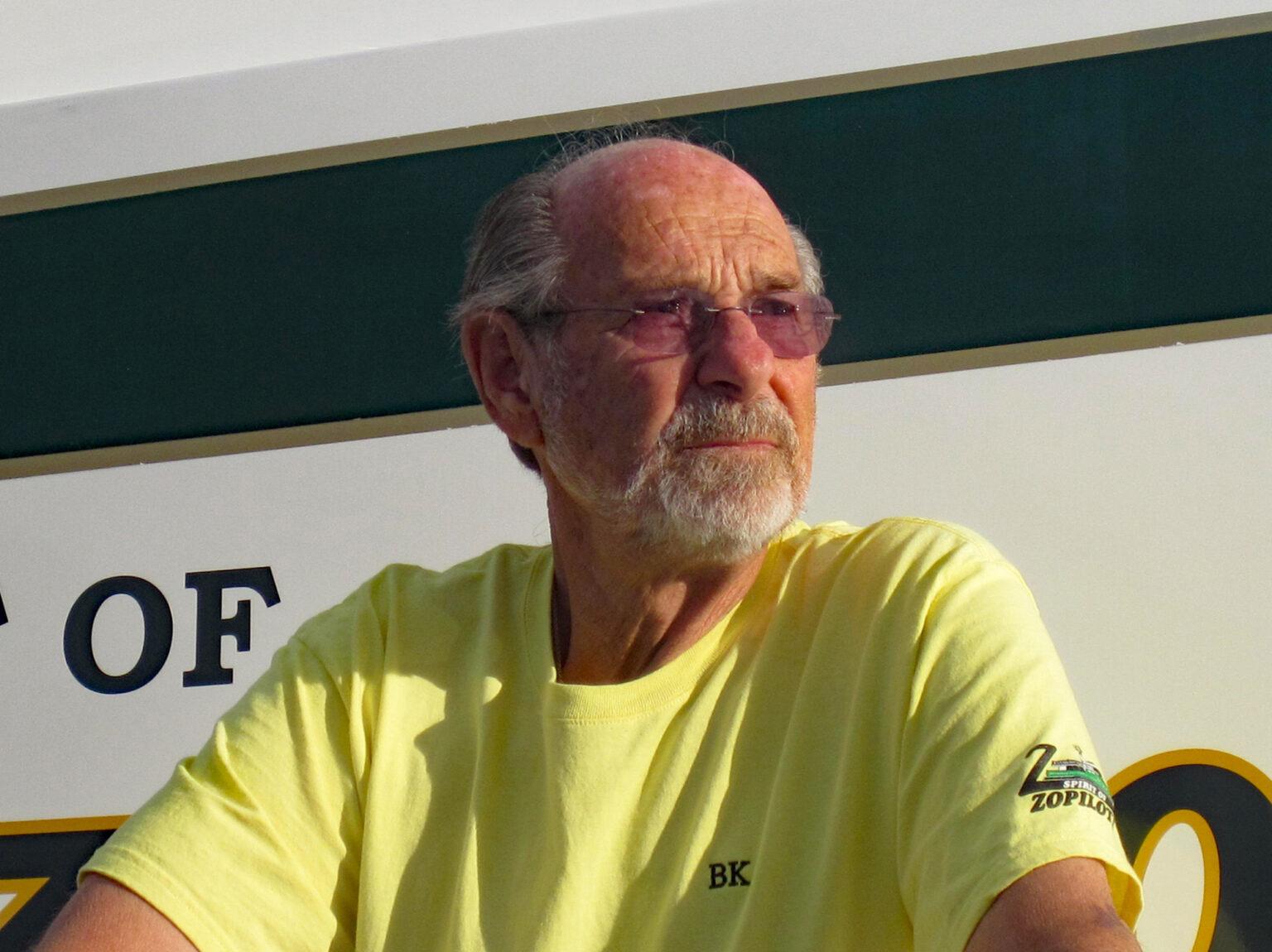

Bruce Kessler, a benefactor and former board member of the Wrigley Institute, died April 4, 2024, at his home in Marina del Ray, California. He was 88 years old.

Born in Seattle, Kessler moved to Los Angeles when he was 10 years old. After successful careers as a race car driver and TV producer (his hits included The Rockford Files and CHiPs), he became a renowned sailor and boat designer.

This third career exposed Kessler to the need for environmental action. Sailing to communities around the world, he and his wife Joan noticed the difference between ecosystems that had been carefully tended and those that had not. “We started to ask each other, ‘What can we do to help solve this problem?’,” Joan says.

The experience brought Bruce to the Wrigley Institute’s board and, later, led him to leave a bequest to the institute. His legacy will now support our mission for years to come.

“Thanks to support from the Ballmer Group, the Wrigley Institute’s talented scientists and innovators have a chance to play an ever larger role in creating a sustainable future for many generations to come,” Árvai says.

Hailed as a wonder material when it was first created, plastic has since proven to be a more complicated solution. It provides unparalleled benefits in certain situations, such as hospitals, where plastic packaging ensures the sterility and safety of bandages, IV tubing, and other life-saving supplies. However, its wide-ranging use has also created numerous environmental problems.

Because plastic is made from petroleum products, its manufacture increases the use of fossil fuels. The chemicals in it can leach from packaging and storage containers into food and beauty products, exposing us to potential toxins. And as recent research has uncovered, microplastics (tiny, sometimes microscopic plastic pieces that fall off plastic items) are literally everywhere: in our ocean, our soil, the animals around us, and even our bloodstream.

The Future of Plastics Initiative explores multi-pronged solutions to the plastics problem. These include developing alternatives to single-use plastics, removing plastics from our environment, and developing ways to safely recycle or upcycle existing plastics.

NOAA funding, awarded to the Wrigley Institute and USC Sea Grant, focuses on the last two approaches. The grant supports a three-phase project that (1) removes plastic trash from the local environment, (2) converts the trash into sustainable consumer products, and (3) studies consumer attitudes about trash-derived products.

Project participants include faculty from multiple USC schools and departments. Chemistry professor Travis Williams, pharmacy professor Clay Wang, and engineering professor Richard Roberts will manage the first two steps in the process. Williams and Wang previously developed a method that uses chemical catalysts and hungry fungi to turn ocean plastics into life-saving medications. With Roberts’s help, they’ll adapt this method to create sustainable laundry detergents and fabric dyes.

Wrigley Institute Director Joe Árvai and USC Sea Grant Director Karla Heidelberg, working in collaboration with community agencies and organizations such as Heal the Bay, will manage the third part of the project. By investigating what consumers think about trash-derived products, and how to encourage adoption of these products, Árvai and Heidelberg will provide the final puzzle piece for long-term removal of plastics from the environment.

“We’re excited to be part of an interdisciplinary project that has such immediate and beneficial applications of research,” Heidelberg says. “In addition, we are excited to partner with municipalities and local nonprofits on public education and acceptance.”

Catalina Residential College, where students participate in immersive summer courses that investigate the intersection of people and the planet. Classes take advantage of the unique coastal setting to study Catalina Island’s natural systems and their complex relationships with humans. The WMSC campus also hosts prominent speakers every year. In fact, Dr. Earle herself visited the campus in May 2022 to meet students and faculty and give a plenary talk on her career.

“My fondest memories and most impactful learning experiences at USC were made possible by the Catalina Residential College,” says Nancy Summerfield ‘24, who participated (twice) in the program’s four-week residential Maymester. “It was an experience like no other, and I would have come back every year if I could. The experience...deeply ingrained in me the beauty and importance of preserving our natural world.”

The Wrigley Institute’s collaborators in stewarding the Hope Spot include the Catalina Island Conservancy and the Catalina Island MPA Collaborative.

“Catalina Island’s iconic coastal and marine ecosystems are unique in the greater California marine protected area network and worldwide. This designation celebrates the collaborative conservation achievements made here and serves as a model for balanced island stewardship everywhere,” says Conservancy Conservation Operations Director Chris Young.

Lauren Oudin, co-chair of the MPA Collaborative, agrees. “Inclusion of Blue Cavern as a Hope Spot provides visibility about these sites to a broader audience and highlights both the multi-decadal protection here and the more extensive network of marine protected areas across California,” she says.

Blue Cavern State Marine Conservation Area is part of a statewide MPA network that currently covers roughly 16% of California’s coastal waters. In 2020, California Governor Gavin Newsom issued Executive Order N 8220, which committed to conserving 30% of California’s lands and coastal waters by 2030 as part of a broader effort to fight climate change, protect biodiversity, and expand access to nature for all Californians. This Hope Spot aims to support that commitment.

“We aspire to offer the Blue Cavern Marine Conservation Area Hope Spot as a model for other marine protected areas,” says Wrigley Institute Director Joe Árvai. “We aim to build new partnerships and collaborations in both research and education, and to encourage awareness to benefit management and public stewardship.”

A Garibaldi fish in Big Fisherman cove. Garibaldi are plentiful in the cove and nest in the rocky reefs around its edges. Highly territorial and unafraid of interference in the protected cove, they often approach divers for a closer look. They’ve been nicknamed “Catalina goldfish” and are California’s state marine fish.

Scan the QR code with your phone’s camera to watch a video about the Blue Cavern MPA Hope Spot.

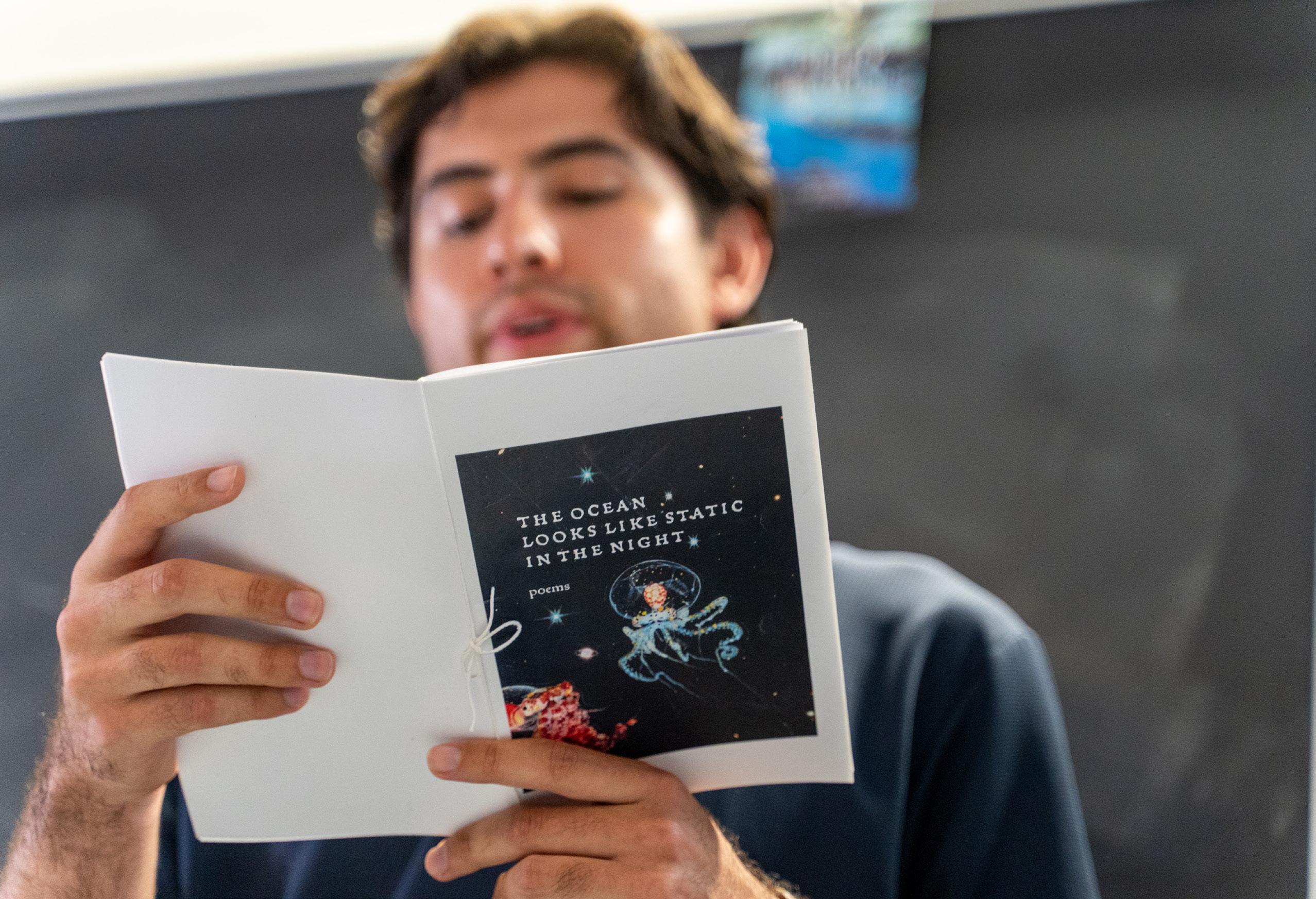

English major Mario Castellanos reads from a poetry chapbook created for the 2024 Wrigley Institute Julymester English course Writ in Water: A Creative Writing Lab on Catalina Island. The course immersed students in the island’s ecology, which served as inspiration for writing about the marine environment.

Part of the institute’s Catalina Residential College, Julymester is a one-month living-learning program at the Wrigley Marine Science Center on Catalina Island. Students earn full-semester credit for a four-week course and participate in cohort activities to help them build cross-disciplinary connections with their peers. (Photo: Vanessa Codilla/USC Wrigley Institute)

Obiefule says these lessons encourage students to step outside of their comfort zone and try nutritious foods. For example, many who didn’t like salad from grocery stores recently learned how to make a tasty soy sauce dressing and changed their perspective on the healthy dish.

In addition to the garden’s educational focus, Chen highlights another key benefit: a calming space to recharge. “If you look at the surrounding neighborhood, there’s really not a whole lot of green spaces. With the garden here, [students] get to spend time outside and in nature, which is a really important break from the classroom,” she says. “I noticed that whenever they come here,

they’re always really excited and have smiles on their faces as they help us with planting or interact with compost. It’s a great way to supplement their education.”

When they’re not interacting with students, Obiefule and Chen complete caretaking tasks to ensure that the garden can support its various educational programs. They water plants, weed the beds, and help compost food waste for the garden’s Cafeteria to Compost program.

For Obiefule and Chen, the chance to work with the Garden School Foundation came from their enrollment in ENST 492: Directed Environmental Policy and Science

Environmental studies major Muna Obiefule holds produce she has just harvested from the garden at 24th Street Elementary School. As a student in ENST 492: Directed Environmental Policy and Science Internship, Obiefule was matched with the Garden School Foundation. The organization operates school gardens where students can learn about environmental stewardship, sustainable agriculture, and related topics.

By Nina Raffio

Despite covering just 2 percent of the ocean, coastal wetlands are responsible for storing nearly half of all carbon found in ocean sediment. These “blue carbon” ecosystems naturally absorb vast amounts of carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere and bury it deep within their soil.

But rising sea levels threaten to disrupt the delicate balance of microorganisms essential for carbon storage. Rising tides could also transform salt marshes into mudflats, releasing stored carbon back into the atmosphere and worsening climate change.

With support from a Wrigley Institute Faculty Innovation Award funded through the Climate and Carbon Management Initiative, researchers are studying this threat in the salt marshes of Upper Newport Bay Ecological Reserve. The reserve spans more than 600 acres along Southern California’s Orange County coastline and supports populations of shorebirds, waterfowl, native plants, and several rare and endangered species.

The research team is examining how sea level rise may affect the marsh’s microbial communities, which ultimately influence carbon capture and storage.

“Salt marshes can actually store as much carbon as the Amazon rainforest, making them powerful allies in the fight against climate change,” says postdoctoral scholar David Bañuelas, the project’s lead researcher. “Our goal is to . . . quantify the amount of carbon at risk and identify restoration techniques to ensure continued carbon capture and storage well into the next century.”

Microbes play a critical role in the carbon cycle of coastal wetlands. These small but mighty organisms absorb CO2, convert it into organic matter, and

(depending on the species) either store the carbon or release it back into the atmosphere.

“Microorganisms control all the carbon cycling on planet Earth,” says Cameron Thrash, associate professor of biological sciences and co-investigator on the project.

“As much as humans are putting CO2 into the atmosphere, microbes control what the ultimate fate of that CO2 is.”

Coastal wetlands often store carbon through the breakdown of dead organic matter by microorganisms. Bacteria and fungi convert the matter into a form that can be used by other organisms, such as plankton. These organisms are then consumed by larger animals higher up the food chain.

However, as sea levels rise, saltwater intrusion can change which microbes are present in a system, potentially altering the way organic matter is processed and moved through the food chain. These disruptions can have cascading effects on the entire ecosystem, affecting the nutrients available to carbon-storing salt marsh vegetation.

Over time, this carbon accumulates in layers of peat, soil, and sediments, forming longterm carbon reservoirs. These carbon-rich deposits can remain intact for millennia.

“We know that in 50 to 100 years, much of the salt marsh will turn into mudflats, which are actually sources of carbon emissions. Without vegetation, a lot of the carbon that would otherwise be stored is going to be

photographs of

and by time she

spent there. “I always paint the places I visit, but Upper Newport Bay is different; it’s a place I’ve loved, explored, and called home,” she says. “As one of the few remaining estuaries in Southern California, it’s a reminder of the beauty and importance of preserving our natural world.”

released back into the atmosphere,” Bañuelas says.

In aquatic ecosystems, microorganisms are incredibly diverse. They are also highly sensitive to environmental changes, such as rising sea levels and saltwater intrusion. Understanding how these changes affect microbial communities is crucial for predicting the future of carbon capture and storage in coastal wetlands, Thrash says.

Partnering with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, the Newport Bay Conservancy, and the Irvine Ranch Water District, the researchers are closely tracking the most common microbial groups in the marshes of Upper Newport Bay, including one key group of bacteria (called SAR11) that play a major role in the carbon cycle.

Traveling out to the marsh by kayak or boat, the team regularly collects water samples to identify and quantify the different microbes present on the marsh. The researchers then process the samples by extracting DNA to study the microbes’ genetic code and the water’s chemistry. The team then decodes this data from the microbes to gain insights into their carbon-processing abilities.

“Our goal is to accurately predict where different microbes will be found based on salinity forecasts,” Bañuelas said. “This will help us anticipate and respond to climate change impacts, allowing us to better protect our vulnerable watersheds.”

To protect and restore Upper Newport Bay’s salt marshes, the researchers are also

exploring solutions that would increase carbon storage in the marsh.

To do this, they’ve teamed up with USC’s Felipe de Barros, an associate professor of civil and environmental engineering. Together, they are developing advanced computer models to predict how microbes and their carbon-processing potential will respond to climate-induced changes in the marsh.

The findings will extend beyond Upper Newport Bay and could be relevant for coastal marine and estuarine systems worldwide.

“By studying the interconnectedness of salinity, microbial communities, and carbon cycling in Upper Newport Bay, we’re developing a blueprint for understanding and predicting the impacts of environmental changes on coastal ecosystems worldwide,” Thrash says. His research group is conducting similar studies in major estuaries, including around the Mississippi River and Atchafalaya River deltas, to better understand microbial dynamics that could inform conservation efforts and ecosystem management.

“The future of our planet depends on the health of our oceans and coastal ecosystems,” Bañuelas says. “By preserving blue carbon habitats, we’re taking an important step toward a more sustainable future.”

Scan the QR code with your phone’s camera to watch a video on this research.

Above: Environmental studies students look through archives in the USC Libraries Special Collections Room. Their research was for a fall 2024 course on the community impacts of urban development projects in Los Angeles. (Photo: Nick Neumann/USC Wrigley Institute)

Below: Wrigley Institute staff member Juan Aguilar (left), a champion freediver, trains a scientific diving student. Freediving lessons help students improve their strength, breathing, and confidence in the water. (Photo: Alex Luce/ USC Wrigley Institute)

Her preference for getting out into the field runs deep. Growing up on the rural North Carolina coast, Lloyd spent many hours exploring the environment around her home. She was particularly fond of the ocean–so fond of it, in fact, that at age 13, she literally knocked on the door of the Duke University Marine Lab and asked if she could assist the researchers.

“I went to college with the aim of majoring in biology and just got sucked up by chemistry,” Lloyd says. “It was like solving puzzles. But I couldn’t imagine spending the rest of my life only in a lab, so I decided to study oceanography as well.”

Now that Lloyd has arrived in Los Angeles, the destination seems almost inevitable. She first encountered the Wrigley Institute and USC as a Ph.D. student, when she attended a summer course taught by faculty affiliate Will Berelson at the Wrigley Marine Science Center. That experience touched off a long-term connection with USC, even as she went on to a postdoctoral fellowship in Denmark and joined the faculty at the University of Tennessee Knoxville.

Over the years, she collaborated numerous times with the late Jan Amend, who was a microbiologist and USC Dornsife divisional dean of life sciences. Many of her other coresearchers have been USC graduate students or alumns.

Lloyd says that USC’s unique strengths in marine microbiology, geobiology, Earth sciences, and engineering were a strong draw for her. Add the wealth of local opportunities for collaboration–with JPL, Caltech, UCLA, Cal State, and the Natural History Museum of L.A., to name a few–and it was an easy “yes” to make the cross-country move from Knoxville to L.A.

Lloyd is excited to be in a coastal city once again, and to have the world’s largest ocean (or, from her perspective, living lab) right on her doorstep. One of her first projects in her new role: studying methane-eating microbes in the San Pedro Channel between L.A. and Catalina Island.

Methane is a planet-warming gas that is up to 20 times more potent than carbon dioxide. It occurs naturally as plants and animals decay, but it’s also created by human activity, especially the use of agricultural fertilizers. Methane in the San Pedro Channel comes from human and natural sources and is both produced in the ocean and carried to it by runoff.

The gas is not naturally very soluble in water, so it tends to escape quickly into the atmosphere–unless methane-eating microbes get to it first. Through their natural movements, or when they die, these microbes sequester the methane by taking it to deeper waters. Deep ocean water cycles to the surface slowly, so methane stored this way may stay out of the atmosphere for tens, hundreds, or even thousands of years.

“A huge biosphere lies under our feet all over the world, and we’re just beginning to figure out what they’re doing and how they can help us.”

--Karen Lloyd

We don’t currently know how much methane is in the San Pedro Channel, how much of it is escaping to the surface, or whether the local microbes are keeping up with the supply. Those are the questions Lloyd hopes to answer, aided by two Wrigley Institute postdoctoral researchers and the institute’s San Pedro Ocean Time-series.

The results can help us understand the effects of runoff from large urban areas like Los Angeles, how quickly climate change may intensify as methane enters the atmosphere, and what we can do to protect ourselves and our planet. She also hopes her work will help people appreciate just how important these hidden, mysterious microbes are to our lives.

“This kind of activity is happening not just in the channel but in groundwater, in the Arctic, in hot springs, and other places,” Lloyd says. “A huge biosphere lies under our feet all over the world, and we’re just beginning to figure out what they’re doing and how they can help us”

Karen Lloyd on a December 2024 research cruise to sample deep-ocean microbes.

(Photo: Karen Lloyd)

Lloyd’s research on methane in the San Pedro Channel is supported in part by the Wrigley Institute’s Ballmer Group-funded Climate and Carbon Management Initiative.

fires if ignited. This creates a typical fire season that overlaps with the dry season.

Monalisa Chatterjee (Associate Professor (Teaching) of Environmental Studies): We have a chaparral ecosystem that requires fire to regenerate. Many of our native plants have evolved to depend on periodic fires for germinating seeds and regenerating, making fire key to maintaining the health of our ecosystem.

William Deverell (Professor of History, Spatial Sciences and Environmental Studies): If we go back deeply enough into the historic record, we find evidence of Indigenous burning, for both environmental management and spiritual reasons. As a tool for wildfire prevention, however, controlled burning was shelved by successive Spanish, Mexican, and American regimes.

[Pre-20th century], we also did not see dense development climbing into canyons and the high spots of arroyos.

Why are wildfires becoming more extreme?

Sohm: Climate change makes normal weather conditions more extreme. So California has been experiencing more droughts and higher temperatures. This causes plants to dry out more completely, which causes fires to burn hotter and be more destructive when we have high wind conditions.

Deverell: Historically, L.A. county could expect more wintertime precipitation than we are now seeing. Our low humidity, the absence of rainfall, and ferocious winds make a recipe for catastrophe.

Chatterjee: Part of the problem is that, for several decades, we have been trying to prevent fires from occurring naturally. As a result, we have accumulated a lot of fuel. Then, we added a lot of non-native plants that dry out and burn quickly in our environment.

like these?

Sohm: The ecosystems in Southern California are adapted to wildfire and will be able to recover, although we can help them along with restoration and planting efforts.

The most immediate concerns are the health impacts of the air pollution created by the fires. Burned material included not just vegetation, but also homes filled with materials that are unsafe to inhale.

Another concern is the potential for mudslides in areas that burned. The vegetation that normally helps prevent erosion and mudslides will not be there to hold the soil together.

Sam Silva (Assistant Professor of Earth Sciences, Civil and Environmental Engineering and Population and Public Health Sciences): Wildfire impacts on air quality are most strong when the fire is burning and we are breathing smoke. Once the wildfire is put out, the overall threat decreases significantly.

However, there is a secondary impact to worry about in locations that [were] really inundated with smoke. The smoke can settle on surfaces and be reintroduced into the atmosphere when it’s disturbed, causing lots of health problems.

What are the challenges we face when trying to live more sustainably with wildfire, and how can we solve them?

Chatterjee: Generally speaking, we don’t prepare for wildfires, we react to wildfires. Wildfires are rarely considered in the decisions we make about where we live, what kind of built environment we create, or how we build community.

Successful adaptation requires adjustment in the way we live with the environment. It requires economic mechanisms that encourage residents to change the way they’re altering the physical environment. We also need to establish communication and consensus-building patterns, so that government agencies and residents can make quick decisions during emergencies without losing trust with each other.

Joe Árvai (Director, USC Wrigley Institute; Dana and David Dornsife Chair and Professor of Psychology, Biological Sciences, and Environmental Studies): How we think about risk depends a lot on when we might be exposed to it, as well as the probability of exposure. A fire that might happen sometime in the future is heavily discounted [as a risk] in our minds. Of course, when a fire is raging near where you live, the risk is very close in time and more certain in terms of probability. But by then, it’s too late to do much about it.

Another thing my collaborators and I have observed in our research is that when a fire has occurred, people tend to believe they just suffered their once-in-a-century or one-in500-years event, so there’s no need to worry about the future. But in a place like Southern California, the annual fire probability is so high that we can’t use the old estimates of frequency. What might have been a once-

in-a-century event a decade ago might now be something that happens roughly every 5 years.

Victoria Campbell-Árvai (Associate Professor (Teaching) of Environmental Studies): The more difficult, expensive or complicated a behavior, the less likely people are to adopt it. Governments at all levels can reduce or eliminate these barriers through default options that are good for wildfire resilience, messages that highlight the popularity of a behavior, or by appealing to a broad diversity of values.

Additionally, a decision to protect the environment is often seen as a sacrifice: we are giving something up, but not getting anything tangible in return. This is all the more challenging if we perceive that few of our neighbors are making these “sacrifices.”

Governments and community organizations can do important work in how they frame environmental action by switching from the language of sacrifice, hardship, and zero-sum games, to that of innovation and community. They can emphasize a life where we derive pleasure, self-worth, and identity not from endless consumption, but from relationships of trust and reciprocity with others and with the natural world.

In terms of policy or governance, what can we do to reduce the likelihood of disasters like this?

Árvai: We need to think about the risks we face in areas where people are planning to rebuild. Let’s make sure that anything we build there is resilient and supported by the necessary disaster-management infrastructure. If we can’t guarantee either of these conditions, we should think twice about what and where we rebuild.

decisions, and adopt environmentally significant behaviors. She focuses especially on these actions in the context of energy and climate, urban ecosystems and ecosystem services, and human-nature interactions.

Monalisa Chatterjee

Associate Professor (Teaching) of Environmental Studies

Chatterjee studies climate change risk, impacts, and vulnerability; constraints and barriers to climate adaptation; and how economic and environmental policies affect sustainable development. She focuses especially on urban environments and translating science for policymakers.

William Deverell

Professor of History, Spatial Sciences and Environmental Studies

Deverell is an American historian who studies the 19th- and 20th-century American West, including its environmental and wildfire history. He is also the founding director of the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West.

Sam Silva

Assistant Professor of Earth Sciences, Civil and Environmental Engineering and Population and Public Health Sciences

Silva studies atmospheric chemistry and composition, including air quality and climate change. He focuses especially on using modern data science and machine learning to help build computer models of the atmosphere and cloud patterns.

Jill Sohm Director, USC Dornsife Environmental Studies Program; Associate Professor (Teaching) of Environmental Studies

Sohm’s research background is in biological oceanography and microbial ecology. She currently focuses on Southern California ecosystems, with recent projects studying water pollution, invasive seaweed in marine environments, aquaponics food systems, and native plant restorations along shorelines.

As wildfire recovery progresses, Wrigley Institute researchers continue to assist with context, decision-making, and rebuilding. USC has also launched a program offering free soil testing to property owners in Pacific Palisades and Altadena.

For a full Wildfire Guide with regularly updated stories and resources from Wrigley Institute researchers, visit bit.ly/wieswildfire-guide.

These communicators believe the switch will help raise public concern about climate change, increase people’s sense of urgency on the issue, and motivate more people to act.

From a commonsense standpoint, this assumption makes sense. After all, the words “crisis” and “emergency” carry more urgency than the word “change.” But what does the research say?

According to the study, “climate change” is actually the most effective of the three phrases at generating concern, urgency, and a desire to act. Explaining their findings in The Conversation, Bruine de Bruin and Sinatra wrote, “It turns out that Americans are more familiar with - and more concerned about - climate change . . . than they are about climate crisis [or] climate emergency.”

While research provides data-backed insights for current communicators, the institute is also prepping a new generation of professionals to spread the environmental message.

Created in 2021, the Wrigley Institute environmental communications internship is a full-time, paid summer program for USC students from across the university. Students with majors in environmental studies, business, film, journalism, marine biology, and more apply for the internship each year.

The institute embeds students in faculty labs and university departments to learn how to translate environmental and sustainability research for the general public. Mentors for the internship come from the natural and social sciences, USC Sea Grant, and the institute’s own communications team. To aid in career development, interns also attend

weekly discussions with journalists, scientific illustrators, podcasters, and other environmental communications professionals.

In 2024, interns worked on a variety of projects:

• Shima Konishi-Gray, a PR and advertising major, created graphics about plastics recycling for chemistry professor Megan Fieser;

• Valerie Kuo, an environmental studies major, and Luisa Tripoli-Krasnow, a journalism major, created educational materials on water pollution and sustainable seafood for USC Sea Grant;

• Alex Luce, a film and TV production major, produced photos and video about the Wrigley Institute’s summer courses and research on Catalina Island;

• Abhay Manchala, an environmental studies M.A. student, wrote blog posts on international environmental policy and activism for environmental studies professor Shannon Gibson;

• And Arian Tomar, a film and TV production major, created a YouTube series featuring conversations between Wrigley Institute Director Joe Árvai and several of the institute’s graduate fellows.

Like many of the interns who’ve participated in the program, Konishi-Gray came away with a new understanding of how to make complex environmental topics understandable for a broad audience.

“I’m excited to apply what I’ve learned in the future to different spaces. Moving forward, I hope to bridge the gap between complex ideas and accessible content by breaking down information for anyone to understand. My goal is to inspire everyone to contribute to environmental and community efforts, no matter how small,” she says.

USC’s Carly Kenkel (left), facilitator Liz Neeley (center), and University of Texas Rio Grande Valley’s Alexis Racelis (right) provide feedback on a project concept during the 2024 Wrigley Institute Storymakers program. Held at the Wrigley Marine Science Center on Catalina Island, Storymakers is a week-long program that trains established environmental researchers in the art of narrative storytelling, so they can reach the public in creative and compelling ways.

Fellows come from the natural sciences, social sciences, and humanities, with home institutions across North America and in Europe. They learn from award-winning instructors in a variety of media, including writing for general audiences, podcasting and other audio production, and immersive media and experiences, such as museum exhibits. The Storymakers program is supported in part by the Lott Foundation. (Photo: Vanessa Codilla/USC Wrigley Institute)

Each year, the Wrigley Institute funds a cohort of USC Dornsife Ph.D. students researching the environment and sustainability. In recognition of the way that environmental and sustainability issues touch every aspect of our lives and of academic endeavor, the fellowship encompasses the natural sciences, social sciences, and humanities.

In 2024, the institute selected 16 graduate fellows to join the cohort. Each fellow participated in professional development activities during the spring semester, then received a stipend to support summer research. Their varied projects were based at USC’s University Park Campus in Los Angeles, at the Wrigley Marine Science Center on Catalina Island, in 5 other U.S. states and territories, and in the UK and Columbia. Keep reading to learn about some of their research.

(Photos: Nick Neumann/USC Wrigley Institute)

In the western United States, water is at a premium, with climate change making droughts both more frequent and more intense.

But it hasn’t always been like this. During the last ice age, for instance, Utah’s Great Salt Lake was a 300-meter-deep body of water called Lake Bonneville.

Rachel So studies this wetter period of the West’s climate history. Using sediment samples, she can piece together the climate history of the lake over the last several ice ages. Her findings provide a key point of reference for understanding both the current and possible future effects of human-caused climate change.

Learn more at bit.ly/rachel-so.

Despite being part of the United States, Puerto Rico struggles with energy costs that are far more expensive, and a grid that is far less reliable, than those on the mainland. This situation stems in part from the island’s fraught history with petroleum companies.

Jaden Morales studies that history and how today’s Puerto Ricans live with and respond to it. His work uncovers important lessons about how social issues are tightly intertwined with energy policy and communities’ resilience in the face of climate change.

Learn more at bit.ly/jaden-morales.

L.A.’s freeways define its urban terrain and shape the daily lives of millions of people. But their construction involved decades’ worth of deliberate decisions, many of which displaced vulnerable residents and blighted oncevibrant neighborhoods.

Through her research, Amber Santoro uncovers the backstory of L.A.’s freeways, as well as how and why other cities in the state charted a different path. Her goal: to develop insights that can help us plan a future L.A. that serves all residents, visitors, and the health of our planet.

Amber was supported by the Sonosky Graduate Fellowship for Environmental Sustainability Research. Learn more at bit.ly/amber-santoro.

Chemistry Ph.D. student and 2024 Graduate Fellow Yeshvi Tomar in the lab. Tomar studies the use of iron electrodes in large-capacity batteries, which currently rely primarily on lithium and lead. Those two metals, however, have significant efficiency issues. In addition, lithium is both rare and prone to explosions and fires. Iron is more efficient than the other metals, and stabler and far more plentiful than lithium.

Through her research, Tomar hopes to improve techology for batteries that would be used in vehicles and for grid storage, applications that are crucial for an effective transition away from fossil fuel-based energy. Learn more about Tomar’s research at bit.ly/yeshvi-tomar. (Photo: Nick Neumann/USC Wrigley Institute)

The Wrigley Institute for Environment and Sustainability is housed within USC’s Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences and encompasses several divisions.

• The Wrigley Marine Science Center, located on Santa Catalina Island, is our satellite campus that uniquely bridges the island’s pristine ecosystem and the conurbation of Los Angeles.

• The USC Dornsife Environmental Studies Program is our primary education arm and houses undergraduate and master’s degree programs.

• USC Sea Grant provides peer-reviewed science to policymakers and collaborates with nonprofits, K-12 schools, and other stakeholders to solve the problems of the urban ocean.

• Our research enterprise, consisting of our Cross-Cutting Initiatives and our Research Launchpads, supports USC faculty, postdocs, and students as they conduct solutions-focused investigations into pressing environmental and sustainability challenges.

• Our Engagement Center encompasses events, key outreach programs, and our marketing and communications efforts.

SENIOR LEADERSHIP TEAM

Dr. Joe Árvai, Director

Dr. Jessica Dutton, Executive Director

Dr. John Heidelberg, Director, Wrigley

Marine Science Center

Dr. Karla Heidelberg, Director, USC Sea Grant

Dr. Jill Sohm, Director, Environmental Studies Program

Sean Conner, Associate Director of Operations, WMSC

Holly Nielson, Associate Director for Business Strategy & Finance

Kathryn Royster, Associate Director for Public Communications

ADMINISTRATION

Katie Chvostal

Shai Coronado

Lauren Geving

Alex Montances

FACILITIES

Art Mireles

Carl Oberg

Randy Phelps

Tom Russo

Mark Serratt

COMMUNICATIONS

Vanessa Codilla

Nick Neumann

CATALINA HYPERBARIC CHAMBER

Karl Huggins, Executive Director

Eun-Jung “Julie” Aguilar

Larry Harris

ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES

Dr. Scott Applebaum

Dr. Victoria Campbell-Árvai

Dr. Monalisa Chatterjee

Dr. Sean Fraga

Dr. Shannon Gibson

Dr. David W. Ginsburg

@uscwrigley