THE

Vol. XXXVI. 1

Vol. XXXVI. 1

C. L. S. '11.

Only a lily, tenderly waving, Breathes the soft radiance Of spring;

Only a sun-kiss, calmly descending, Casts a warm rainbow hue Along

Infinite cloud-masks, shading life's aureole, Blackened with sorrowful Dismay;

Only a moonbeam, softly engraving On a bright flowerlet

A ring

Clear as the dew-b ells, born of the fairies, Brings to the mocking bird

A song;

Only a rosebud, hinting of angels, Draws from the fount of night New day.

BY PAULINE PEARCE, '11.

THE meadows were pied with daisies and the forests with flashing bird-wings. A streamlet danced over the pebbles·and babbled its song of glee. A little child laughed back at the ripples with childish gaiety. That stream was the barrier beyond which the child had never dared to go. On hands and knees beside it he shook his curls until they touched the ripples; and he laughed again as the stream gave bad<: their flash of gold and showed his eyes as blue as the reflected sky. He arose and put one wee bare foot into the glancing water, but drew it back quickly with a little catch in his breath. The blue eyes looked about him. There was no grown-up to see and forbid. Again one little foot went into the water, then the other. Baby cried out a little; the water was so cold. But the voice of the water was low and sweet, and it was whispering, "Baby, baby, fairies are in the wood beyond, fairies and elves and angel-winged people. Do not go back, baby. On, on, on." And baby went on.

In a moment the murmuring stream could see him no more, but it whispered to the bending willow and the willow told the oak and the oak prod.aimed it to the rest of the forest, "A little child has come to you. See to it that he suffers no harm. He is the child of the Great Spirit come once more to dwell among men. Mother Earth sent up a spring to me from her · throne at the center of the Universe bearing this message. Hold him dose in your embrace, for his soul will fly heavenward if touched too soon by the rude mind of man."

So the forest opened beautiful aisles before him and led him on to its center. Then the birds brought seed and the moles dragged underground the roots. All the animals helped to prepare the soil and a tiny cl.oud gave a miniature shower so that in a little while the center of the wood was encl.osed by a magic circl.e of tangled vines and sapplings. The inner side of the circle

RICHMOND COLLEGE MESSENGER. 357 was covered with delicate flowers and downy leaves, but without thistle and cactus presented thorns and impenetrable blackness to the wayfarer.

The child ate of the abundant berries and fruit, then peacefully and quietly lay down to sleep.

Here he lived happy and contented. Even the fairy people soon lost their timidity and came forth to minister to him. They came from flower and leaflet. They brewed him strange drinks while he was yet a child. They gave him all knowledge but the knowledge of evil and all power but the power to do wrong. There ~e lived and grew into manhood always content, because the Spirit of the Earth came to him with every rainbow and instructed him as to his mission in life.

Now many thousands of years before this time the Fates had one day become angry with the Earth and had decreed that the whole world should connive at a crime committed against the Sun God and that from that time on the Sun should not shine but as a red skeleton until the Earth should give her choicest son as a willing sacrifice. Upon him alone would the red skeleton~sun look until the beams from the empty .eye-sockets had devoured him. As the beams should go out from the eyesockets the sun would gradually resume its wonted appearance; and henceforth things should be as they were before.

One day as the child of the Great Spirit was resting upon his mossy couch within the magic circle, he heard a groan from the heart of the earth, and at the same moment the light of the sun changed from its glorious white to an awful red. Slowly the reclining youth said,

"This is my hour. Now must I save those multitudes whom I have never seen. Now must I redeem the Spirit of the Earth from eternal woe."

Even as he spoke the Spirit of the Earth stood beside him. She looked old and grief-stricken as she cried,

"Oh, thou, my beloved, thou whom I have trained to go forth and teach mankind the way of right, must thou go as an awful sacrifice to the mad Fates? Toowell have I loved thee. Alas, alas!"

The skeleton sun grinned as the Spirit of the Earth grew faint.

The youth, more beautiful than the child had ever been, stood there in the glorious strength of his young manhood.

"Lead me, thou who hast taught me the way of the right, lead me to the appointed place."

The drooping spirit mounted with him into her rainbow chariot. As they went on, he looked down upon cities possessed of demons and fields where only the slimy reptile and the brakish throne flourished. Grief and contrition filled his heart that he had not before sought to aid those in such dire distress.

The rainbow ended at the top of a lofty mountain. There he lay him down and looked with unfaltering eyes into the eyes of the skeleton. Those red eyes poured their awful radiance upon him until he became a mere shadow; then finally vanished.

At that moment the sun resumed its wonted appearance. A shout of joy rent the air. Flowers bloomed upon the desert; birds sang joyously; and the heart of man was glad. But th~ stream, which the Child of the Great Spirit had crossed when a baby, was sad; nor would it dance or laugh merrily until a blue-eyed child, like unto the first, again shook his golden curls over its waters.

BY R. C . DUVAL, ' 11.

TODAY there are more than 20,000 illiterate white children of school age ·in our State. How to educate these children is one of our most vital problems, and an immediate solution is necessary, for these children will soon be be;ond the reach of the public schools. The problem is not a new one, but has been successfully worked out by Germany, France, England, and other countries of Europe, as well as by our Northern and Western States. The solution they have hit upon is compulsory education; and in the light of their experience it seemed that we too might find a way out of the difficulty.

Let me say in the very beginning that by the term compulsory education, I do not refer to any indirect method, as the factory laws of Connecticut, or even local option, but the requiring of all children in the State of a specified age to attend school for a stated number of days each year.

Like all progressive movements this plan has its enemies, and their objections have been many and varied. One of these is that it infringes on the right of the individual. In a way this is true; but does not all temperance legislation curtail the individual right? And yet temperance laws are passed every year. The ignorant man is just as much the enemy of society as the intemperate man, and the law must reach both alike. Some men can only be reached by a show of force, and if this is wrong then we can easily overlook the method when we think of the benefit it will bring to the child and to the State. When a man has become so selfish .and depraved that he will willingly keep his child away from the education that will lift it from its hard and narrow existence then it is time for the State to take a hand and show that man his duty. Every child in the State should have an opportunity to develop its innate powers-it is his God-given right-and the State must secure it to him,

regardless of the wishes of the parent. We all concede the right of the State to care for the child that has no parents. Should it not also care for the one whose parents are unfit, unable, or unwilling to do this for him? We may talk about the sacred liberty of the parent, but in our zeal for this, we must not forget the liberty of the down-trodden child whose law is the lightest wish of a narrow-minded father.

Again it is urged that compulsory education works a hardship on the popr. As if it were not the poor above all others that need just such a law. It is a help to those that are utterly helpless. When we realize that the poorer classes are bound down by ignorance and superstition, and that they will never break these shackles until the State comes to their aid, then we see that this hardship is really a blessing in disguise.

Many of these boys and girls are ambitious and with the education and opportunity that is rightfully theirs would become an honor to the State and a potent factor in raising the standard of our citizenship . Let us give them this opportunity, for their need is great; and although satisfying this need may mean a time of hardship to the parent, it will be of short duration and the benefit will extend to generations yet unborn.

Another objection is the expense. Some say that our taxation is already heavy enough and that the people will not stand for any increase. This point, I think, is not well taken, for the present school levy is not excessive, and the people have always responded quickly and willingly to the call for school funds. For the year of 1907 the per capita wealth of Virginia was $674, while the per capita expenditure for school purposes was only about $1.40. This is much too low and could be increased without putting a heavy burden on the taxpayers . The latter does not object to the added levy when the returns are as sure, quick and tangible as in this case. He realizes that it is not a rash outlay but an investment that will bring an income of mind and character development that is invaluable. We cannot afford to put our love of money in the balance with moral and intellectual growth; our aim should be to expand the plastic minds of our future citizens and then material prosperity will necessarily follow.

The objection has been raised that we must have increased equipment before we can accommodate the larger attendance caused by such a law. I admit that we must increase the equipment, but this will not be done until the pupils are in school and the need pressing. It is absurd to say that our school authorities should put up new buildings and enlarge old ones in anticipation of the time when this law will be in operation. It will not be done. First the children must be enrolled and then the equipment will necessarily follow. By passing this law and bringing all the children in touch with the schools, a sentiment for education will be created that will not stop until illiteracy is practically stamped out and our State freed from the stigma of ignorance. Of course this cannot be done all at once, but we can take a step in the right direction and the rest is only a matter of time.

Still another objection is that this law will apply to the negro as well as the white man. This is very true. The negro is with us to stay, and must be educated. At the present time, illiteracy among the blacks is actually decreasing faster than among the whites, and if this continues the time is not far off when the educated negro will surpass the ignorant white in every point of contact. This will be unbearable to the white race and we must use every legitimate means to prevent it. I believe the best way to do this is to educate both races, for then the white will undoubtedly be superior-or where is our boasted white supremacy? The contention that education demoralizes and makes criminals of the blacks cannot be proved by statistics. In fact just the contrary is proved. Another reason for aiding the black man is a moral one. This is a day of altruism. His race, although nominally free, is still very dependent on the white and we must lend them a helping handmust direct their aims and their thought-if they shall reach their highest developments. We are in a way the guardians of this people, and our sense of justice, our love of right, our sympathy for an inferior race, and our common humanity, all demand that we be true to the trust.

There are several urgent reasons for introducing compulsory education, and I believe the most important one is the need. There are many who deny this and who say that we are already

making rapid progress along all lines of educational endeavor. I fully admit this progress and do not mean to depreciate the great work that is being done by Superintendent Eggleston and his assistants,-indeed our progress in the last few years has been marvelous,-but we have a long way to go before we reach the mark set by some of our sister States. We Southerners are too prone to boast complacently of our greatness, our resources, and our future prosperity, and yet be . blind to the fact that all these things depend directly on an educated citizenbody. The census of 1900 shows that there were at that time 23,108 native white illiterates between the ages of 10 and 19 in the State of Virginia. Add to this the number of negro and adult white illiterates and the total is astonishing: 312,120 persons, or about 22 out of every 100, ten years or more of age, unable to read or write. Few people know that in the counties of Pittsylvania, Smythe, Wythe, Washington, Gloucester, Carroll, Franklin, Lee, Stafford, Scott, Dickenson, Russell, Patrick, Greene, and Buchanan the proportion of white males of voting age who are illiterate, is 20 per cent. and upward. In fewness of illiterates, Nebraska (which has a compulsory law) ranks first among the States with a little over 3 children in every 1,000. Virginia ranks fortieth with 156, and yet some say the conditions here are satisfactory. It is true these statistics are not quite accurate today, as they are taken from the census of 1900, but they will help us to get a better conception of the need and of the importance of some immediate action toward bettering present conditions.

Compulsory education could be urged simply on the ground of the State's duty to the taxpayer. Every property owner must pay his proportion of the school tax regardless of whether he sends any children to school or not; this is as it should be, for the public school system is not kept up only for the benefit of the individual pupil but in a larger sense for the upbuilding and strengthening of the State. A man should not be taxed to educate the children of one neighbor while those of another are allowed to grow up in ignorance, and he has a just complaint against the State if such a con,dition exists. It is clearly the State's duty to use its school fund in such a way as to benefit

RICHMOND COLLEGE MESSENGER. 363 those who have subscribed to it and this can only be done by expending it in educating the whole mass of the people.

One of the strongest arguments for compulsory education is the economic value to the State. It is the wealth producing capacity of the educated man as compared to that of the ignorant one. Virginia today is in a transition period and she needs the intelligent co-operation of every one of her citizens. New industries are being developed, new resources tapped, and her factories, mines, and farms all need trained workers. The machine is rapidly displacing the ignorant laborer and the successful man of the next generation will be the one who has the ability to think. In view of all this the State cannot afford to let its future citizens grow up without the educating and character building influence of the school. Our children must be trained in the duties and privileges of citizenship-in the use of the ballot. Great problems confront us which can only be solved by the whole people. A few earnest men may lead the way but their efforts will be useless without the active following of an intelligent citizen body and this can only be secured by a well enforced compulsory education law.

Although the enrollment of illiterate children is the main purpose of the compulsory law, yet it is not the only one. Such a law would promote regular attendance among those already enrolled, and thus greatly simplify the work of the teacher and increase the efficiency of the school course. Every teacher knows that a pupil's progress and love for his work is measured by his attendance, and that as the one is promoted the other will likewise increase. In Virginia the average daily attendance is only about 37 per cent. of the school population. It should be noted too that this is largely a rural problem, for the children in cities attend much better than those in the country districts. For the enforcement of a rural attendance law there must be created an interest in the school work and this is being done by putting vocational courses in the curriculum and adapting the whole course to the need of the child. Why should we teach a country boy about the wonders of ancient Egypt and let him grow up in ignorance of the wonders of plant growth at his feet? It is absurd to make a farmer boy attend school and go through

a course that fits him for life in the city; and yet this is very often done. We must make the education of the country child more practical; must teach the girls sewing, cooking, and housekeeping, as well as compound interest and bank exchange, and the boys methods of increasing the farm yield, the value of legumes, and the proper rotation and cultivation of crops. Such a change will to a great extent obviate the difficulty of enforcing a compulsory law, and would materially advance the prosperity -of the State.

Compulsory education is not an untried experiment, one that will bring us into bankruptcy and all sorts of complications. It has been tried in three-fourths of our States and in almost every case has proved successful. Massachusetts has reduced her illiteracy to less than 6 per cent., Ohio to 4 per cent., Iowa and Nebraska to 2.3 per cent., and other States in proportion. In Germany, a country which has had compulsory school laws 'for many years, illiteracy is practically unknown, and her present day standing is ascribed largely to her thorough ele,. mentary education. We Virginians are naturally very optimistic as to our future and look forward to the day when our Statesmen will be leaders in the construction thought of the Union, and the voice of our State heard in the counsels qf the nation. To reach this ideal we must raise the average intelligence of the whole people and experience has shown that the only sure way to do this is the adoption of a wise compulsory education law.

BY FRANK GAINES, '12.

"If I were damned, body and soul, I know whose prayers would make me whole, Mother o' mine, 0 mother o' mine!"-Kipling.

Oh, it surgeth unjustly, this sea of mankind; The vast tide ebbing out seems to leave far behind A lost flotsam, that's helpless and stranded and blind, Star of my hope, decline; For 'tis naught but a wreck that my voyage doth see And I still list in vain for the title's sympathy And the only heart-tears that are e'er shed for me, Mother of Mine, are thine.

O'er the deep lengthy shadows now grimer, now dark. And the night's on the brow, and the night's on the heart And the glory of day and the sailing depart, Star of my love, decline; For I trusted too well in the warmth of the sea And its breath seemed cold as it ever will be And the only heart love, reaching far out for me, Mother of Mine, is thine.

Let the day pass away with its shriek that I fail, Let the darkness now muffle the heart's piteous wail, Let the peace of the night still the soul's bitter gale, Star of the day, decline; For I'm sick of a day that is black misery, Of a world in whos e breadth there is no certainty; But the faith which one heart, that doth err, has for me, Mother of Mine, 'tis thine.

I hear the low call of the sea's sounding song, Then submerge me, 0 billows, untrammeled and strongEven fade with the sunset this poor gift of song, Star of my life, decline. And when I have sunk d 'eep in the bot:tomless sea Where the tide roareth low, now and eternally, Oh, the only heart prayers that shall come after me, Mother of Mine, are thine.

BY VIRGINIUS C. FROST, '10.

IT wanted but an hour of midnight when we rode down the highway that led to the little village of Chantilly. The night was perfect. The moonlight fell in broad, white patches through the arching trees, and it was almost tangible in its brightness. Not a breath of wind was stirring, yet the air was clear and the atmosphere was invigorating. Along the side of the road our shadows played fantastically, but silently we rode, for a se'nse of serenity was over the night.

We at length came to the road which I knew led to the house of the man to whom General Lee had directed us, and there we. stabled and feed our horses. By a short path, which the old farmer pointed out to us, we arrived at the rear of the inn. Several lights shone through the shutters of the building, and from within the sound of clinking glasses was audible. Intermittently, there floated to us the fragment of a ribald song, but more frequently we heard shouts of coarse laughter. The structure was built low upon the ground, and it was an easy matter for us to peer beneath the shutters. The dirty curtain which had served as a partition between the lobby and the saloon had been torn down, and the rooms were now one. Gathered about tables of every size and shape sat groups of Federal soldiers dealing_ besmeared and grimy cards. A fog of tobacco smoke hovered about the players and rose in a dense cloud above them. The air was humid and foul with the reek of cheap ale and doubtful cigars. The men gathered together in the dirty saloon, smoked, drank and expectorated ceaselessly, exchanged rude and uncouth persiflage and made wagers in loud tones. Old Bordley rushed hither and thither looking to the wants of his guests, and presently he passed without the room to the passageway. I intercepted him at the rear of the house, and engaged a room.

Until dawn we three sat and discussed plans for the fulfillment of the mission with which we had been entrusted. As we gave our views on proje'cts, and discussed the adaptability of plans, our real characters were revealed to each other. Rank was forgotten and our common purpose brought us closer together in affection and cemented the bonds of friendship in a firmer union. There and then we pledged ourselves to stand by one another in our present hazardous undertaking, and to remain unchanged to each other through the varying vicissitudes of our worldly life. The pledge is still unbroken, though forty years have intervened since that night.

The plan adopted by us was the most advisable one under the circumstances. To have attempted to travel the patrolled roads by day would have been the height of folly, and then, too, this Captain Griffin seldom traveled otherwise than by night. We, therefore, decided that the safest course to pursue was the one wherein lay the less danger of discovery. Accordingly, we remained within our room during the day and at night we traveled up and down the various roads in the vicinity of the hotel. searching for the figure in the black cloak. We would return before dawn, stable and feed our horses at the old farm house, and then sneak up to our room where we would discuss the night's happenings in low tones.

The room we occupied was situated most favorably for us. It was the only one upon the. third floor, and in reality it was a cupola. A window on each side afforded excellent views of the surrounding country. We divided the day into three watches of four hours each, and in this manner each of us obtained sufficient rest, while there was always someone on the lookout.

It was during the long autumn hours of my watches that my thoughts would turn involuntarily to the girl whom I had met that eventful night in September. I went over in my mind the scenes when she and I had been so close together, and I had been her friend. I wondered over and over would I ever see her again, but the thought was too sweet for adventure. How often would I repeat to myself the words she spoke to me the morning after the fight at the old house. "I can never forget you," she had said, and I wondered, as a man will wonder, if she spoke the

truth, and if, indeed, I ever was the object of her thoughts. I thought of her sufferings and my heart longed to comfort her. What I had not dared to admit to myself for these two months was now a conviction. I loved this girl; loved her for her innocence, her gentleness, and her heroism. But even in these moments of reflection, when my heart longed for this girl, my thoughts would turn subconsciously to the man Griffin. There was no evading the issue that I was facing. He was her relative I was assured, and that circumstance and the mission which I had sworn to fulfill precluded any idea of ever being other than an enemy to this girl as a natural result of a most unusual state of conditions . And so as I reflected calmly upon the issue I was facing, I resolved that I would fulfill the mission with which Lee had entrusted me, at whatever cost, and that I would forever put this girl from my thoughts.

We had been at the inn for some ten days, and every night we had ridden up and down the roads in a vain search for the cloaked figure. Several times small groups of cavalry passed us on th€:! highways, but we were never challenged, and at no time was there danger of being discovered. I continued to wear the black cloak which I had taken from the dead Federal, and as a precaution Mulvaney and Larkin concealed their uniforms by long capes which the farmer furnished. ·

These nocturnal excursions were our only recreation and exercise, yet we had grown tired of their monotony and inactivity. We longed for the time to come when we might have the opportunity of executing the purpose which had brought us to the village.

We had completed our nightly ride along the Washington road where McClellan's camp lay, and the village clock was striking the eleventh hour when we cantered up the fork that led to Herndon. This had been our regular schedule during our search for the cloaked figure, since these roads were the only highways which led to Federal camps. We had determined to press close to the Union lines about Herrtdon, and with this end in view we traveled at a lively pace. We had covered nigh onto ten miles, and the scenery was becoming less familiar, for we had not ridden this distance before. It had been a dull gray day,

-

369 and the night was one of inky blackness. The landscape on each side of us looked like a black robe spread over the earth, and a white fence that bordered the road appeared ghostly gray as it zigzagged among the trees. My heart beat thickly as we moved along, for I could not forbear to think of the girl, and to wonder if she were staying at the old house.

Instinctly we pulled our horses •to a walk, and in another moment we had rounded the bend which obscured the building from view. The scene which met our astonished sight was wholly unexpected. The house was illuminated from cellar to attic, and from within there floated to us the wheezy strains of a fiddle. Now and then there flashed before our vision the bright costume of a girlish dancer, as she was led through the measures by her soldier partner. Tethered to trees in the grove were groups of horses who kept up a continued pawing and whinnying. Frequently groups of soldiers left the building, mounted their horses and rode away. It was evident that the entertainment was drawing to a close, and so we decided to conceal ourselves in the shadows of the house and watch for our "game."

We tied our mounts in a part of the wood not far from the structure, and Mulvaney and Larkin hid beneath the front steps, while I concealed myself behind a flower rack at the end of the veranda. The night was warm for November, and the front doors were open while we also had an excellent view of the drive.

Gradually the guests departed, and one by one the lights in the rooms above were extinguished. Down stairs, however, the chandeliers continued to burn, but only in the two front rooms and in the .rear of the house. There was not a sound to be heard but the mechanical rattle of the silver as the servants cleared the tables, and it appeared that no one was astir in the house but them. I heard the old butler close the front doors, and his footsteps die away as he returned to the rear of the house.

Slipping around the comer, I peered beneath the shutters of the room. It was a luxuriously furnished library, but no one was within. I went around to the other side of the house and looked inside. The shutters were opened, and the windows up. The room was a parlor, furnished with a studied elegance, but there was no occupant.

I signalled to my friends beneath the steps, and they had no sooner reached the shadow of the porch, when a group of horsemen galloped up the highway and turned into the drive. They were five in number, and in their lead by forty feet rode Griffin, for whom we had searched these ten days. They pulled up in the shadow of the grove, but he rode close to the house, an.a dismounting, sprang up the steps, and tapped lightly upon the doors. That rap spoke volumes. This man had evidently come to the house by appointment.

I had formed a plan before the sound of his knock had died away. By entering the parlor through the open window I might conceal myself before the butler responded to the summons. In case the man entered the room where I was hidden, his capture would be but the work of a moment. If he entered the other room, it would be but a matter of crossing the hallway. It could be done ere the butler reached the rear of the house, and Mulvaney and Larkin could take the unconscious form through the window. Our horses were not a hundred yards distant, and in case we were discovered we had planned that no trooper should escape. Should I fail in capturing him, I was to signal to my friends outside, and they were to fall upon the troopers waiting in the shadows, and then come to my assistance. We swore to capture this man at whatever cost.

Entering the room, I drew my revolver and looked about me for a place of concealment. The only shadow in the room was that afforded by a huge flat-topped old piano which was pulled diagonally into a corner. By hiding behind this I could see what occurred in the hallway and the two rooms. I took a step forward, but checked the movement half way. Portieres hung between the doors of the parlor and the room directly behind, and a person was untying the cords which held them together. Before I could stir, the curtains parted, and I looked into the startled eyes of Catherine Wellford. · "Oh!" she said, and her voice trembled pitifully, "why have you come to this house?"

"To fulfill an honorable duty, Catherine; that is all." I replied.

Then she came close to me and laid her hand upon my arm, and

- RICHMOND COLLEGE MESSENGER. 371 looked up at me with an expression in her eyes which I had never seen there before.

"You must go away," she said slowly and deliberately; "you are in great danger here. There are Federal soldiers outside now. They will enter presently, and your life won't be worth the asking if they catch you here. Please go," she pleaded, "please go before it is too late." But before I could make reply, there came to us the sound of a footfall in the hallway, and the girl pushed me behind the portieres through which she had entered.

Peering through the curtains, I saw the cloaked figure enter the room where the girl stood facing him. He was the first to speak.

"Kate, dear," he said abruptly in his deep voice, "I ha:ve come.''

"Yes," the girl replied calmly, "to receive the same answer."

"Then you have not reconsidered?" he asked slowly. "No."

"Kate," he said calmly, and with an effort, "I ask you not to say that; it means much to me. I move south tonight. God alone knows whether I shall ever return alive. Burnside has superceded McClellan, and we move in three days, to attack Richmond, but my work sends me ah~ad. I ask you to reconsider, Kate."

"I have given you my final answer, Curtis," she replied with emphasis. "It is useless for you to ever again ask me."

"Why?" he asked, after a moment's thought.

"Because," she said, and her voice became tense with emotion, "I hate you; I will always hate you."

"Then there is another?" he asked in a husky tone.

"Yes," the girl replied calm! y. ·

"That rebel spy, I suppose," he said with fine scorn.

"A rebel, as you please," she retorted, and her little chin went up in the air, "but a brave officer, and a noble gentleman."

"As for your rebel officer," he said, his voice trembling with passion, "he will soon see that this war is my war," and he turned on his heel, and took a step in the direction of the door.

I drew my sword, and stepped into the room.

"Stop!" I cried, and the man wheeled instantly.

"Hell!" he cried, his hand flying to his sword, "what can it mean?"

"Your surrender," I replied calmly.

"Never!" he almost yelled, and straightway he drew his long saber and swinging a chair out of his way, he made a long thrust at me, but it went wide of its mark.

I prepared to return it, but the girl grasped my arm, and stepped in front of me. I pushed her behind the piano, but she continued to clutch my cloak.

"Stand back, Miss Wellford," I said, "this affair is between God, that man, and me. It was to capture him that I came to this house tonight. Do you know who he is?" I.asked.

"He is my cousin," she replied doubtfully, "Curtis Zelwick."

"That he may be," I cried, "but he is the foulest spy in the Union army, and his name is Philip Griffin."

"You lie!" the man hissed, and throwing his long cloak over his shoulder, he charged straight at me.

I parried his lunge, and the man reeled from the force of his rush, but he was around and at me in a flash, and for the next few moments I had as much as I could do warding off his thrusts, which,had they reached home, would have been my last. The man had a superb strength of wrist and a length of arm that was extraordinary for his height, but the power of his long thrusts and deft parries was ill directed, for he beat my blade with a force that I knew full well could not last for long. All the while he was circling with a rapidity that was marvelous, and once or twice he attempted to "cut" in his circle, but I was too quick for him, and straightway he began to beat my blade with rapid strokes, attempting to break down my guard. When I perceived the "coup" he was playing, I realized that by playing the defensive I could tire him out, and then disarm him. He, too, saw the plan I was pursuing, and he circled the faster, casting his eyes hither and thither for a chance to trap me 1nto a stumble, or draw me from my position; for I had my back against the door as a precaution, should he attempt to escape. But I warded off every blow and parried his every thrust, and our blades were ringing loud and clear. Then he withdrew from my

373 reach and lowered his weapon, waiting for me to follow with a thrust and get within his guard, but I saw the cunning plan to grapple me, and I remained motionless, waiting for his next play.

Then the cowardly instincts in the man asserted themselves. He caught a light chair in one hand, and whirling it over his head, sent it flying through the air at my breast. With my unengaged hand I warded it off, and was in the nick of time to save myself from a thrust that came near being my last. He retreated to the end of the room with me following, and as he nearly knocked the sword from my hand in parrying my attack he placed his finger to his mouth and whistled loudly.

Instantly from outside came the sound of popping revolvers, yells and curses. The man half-way checked himself in a forward movement, and I could not forbear to smile at the expression on his countenance. In signaling for his own men, he had, unwittingly given the signal that my friends and I had agreed upon to open fire upon the troopers in the grove.

"Damn you," he cried, and rushed at me with all his force; "you'll pay for this."

His force rendered it impossible for him to thrust with any degree of accuracy, and I jumped clear of the ill aimed blade. His rush carried him into the piano, but he was around and at me with the swiftness of a cat, and I had to abandon my position to dodge his terrific blows. He followed doggedly my retreat around the room; I fighting backwards, and he pressing me as I was never pressed before. By a sharp thrust that ripped his great cloak from the shoulder to the waist, I checked his onslaughts, and gained my old position with my back against the door.

Then upon the instant, there came to us the sound of a rush upon the porch, and presently a man burst through the door at my back. I turned to gain a safe position, but I saw that I was too late. The federal held his weapon aloft with both hands, and I was powerless to ward off the terrific blow, and his sword literally cleaved my right side.

I lost my grip upon my saber, and I staggered and fell upon the piano. There came the sound of a sickening crash at my elbow, and turning, I saw the big Mulvaney's saber buried in the man's

head to the base of his neck. The sight sickened me, and I turned away, but out of the corner of my eye I saw a chair hurled through the air and strike the big Irishman, and in a half-conscious manner, I knew that the figure in the black cloak was rushing upon me; but I was powerless. I closed my eyes at the sight of his long saber.

Then there was a loud report, and looking up I saw the cloaked figure reel and fall, and the girl with my smoking revolver in her hand, was gazing before her, a blank expression upon her face.

"Quick, Wendell," I heard Larkin cry, . "there's a troop comin' over the ,hill."

"I'm done for, men," I gasped. "Carry him to the Colonel at Manassas."

I saw my friends lift the dead man through the window, and as they followed, I cried out to them with what breath remained in me:

,

"Mulvaney-Larkin, Burnside's in command-will move on Richmond-three days."

I felt my consciousness slipping from me, and I strove in vain to keep a hold upon the piano. I staggered, collapsed and fell senseless to the floor. The room reeled and danced before my eyes; I struck out blindly at the darkness which was enveloping me, and my ears rang with the sound of blade upon blade. Semi-consciously I knew that I was down, striving to · rise, but a cooling hand was laid upon my forehead, and fingers of velvety softness were placed within my own. My head was lifted from the floor, and my mind cleared for an instant. I was conscious of a beautiful face above me, of hot tears falling upon my forehead, and looking up, I smiled into dear Kate's eyes '. Then her waving hair blinded me, but a pitiable weakness was upon me; my eyes closed, and I knew no more.

Often at that time of evening when the shadows begin to lengthen, when the night and the day are so evenly balanced, and the constraint of hours of labor is forgotten, I seat myself on the old settee in front of the hearth and gaze into the glowing coals. The past rises up before me like the morning mist from a valley, and my mind travels back over the forty years to that rainy night in September, when Buck and I splashed up the

Chantilly road. One by one, the scenes and actions that followed the night in the old inn pass before my vision, and foremost in the pictures is the form of a girl. I must needs dwell upoq the sweet, s'ad faced little figure as she watched day in ,and day out beside my bed. And nursed me back to life through the long fever and delirium of my wound. ·I see again the same sweet face and the eyes of deep hazel lustre, as she leaned upon my arm in the little village church that bright February morning. I feel the pressure of her little hand as she answered the good man's questions, with her wonted courage and trustfulness. Half consciously, my hand reaches out to a figure beside me, and my clasp tightens upon the fingers of her hand. My arm slips aroun,d the delicate form, and her head of white hair rests upon my shoulder.

seven)

Ahasuerus, King of Media and Persia, and ruler over an hundred and seven and twenty provinces. Haman, Chief Minister of Ahasuerus.

Mordecai, a Jew.

Harbonah, } Chamberlains.

Hagai,

Esther, niece and adopted daughter of Mordecai, and queen to Ahasuerus.

Musici,a,ns, Servants, Attendants.

Scene, In the palace of Ahasuerus at Shusan.

Time, about 520 B. C.

THE PLAY.

Scene Six.

Ahasuerus' Chamber. The King is discovered lying on his couch. Night of the day on which Scene Five takes place. The fourth watch of the night. During the scene, dawn begins. Harbonah enters with a torch.

Harbonah.

What ails thy lordship? Didst thou call?

Ahasuerus.

I dreamed And I awoke-I know not what I dreamedAnd then I tossed upon my easeless bed, More troubled than a ship in midst of storm,

RICHMOND COLLEGE MESSENGER.

For I was thinking of the faithless Mordecai. I lay here with the darkness on my face

As lepers feel the hand of death creep on O'er inch by inch of their decaying flesh;

Each moment did I think some poisoned tongue Would leap out from the rayi;, of death-bearing dark, And suck the sap of life from all my limbs; Then in a robe of silvery brightness stood Above me, Mordecai; a chain of gold He held, and bending lower, thrust it round My neck. I felt my life leak out and strove

To call. Again, and then again I strove

And called. Now light the silver censers. M ,ake The howling tempest wreak less gloom within.

Harbonah.

My lord, my bosom burns with news for thee; I waited in the ante-chamber long

Above a watch, to learn if thou wouldst wake; But then the voices of the night so weighed Upon my deadened senses that I fell Into a sleepless slumbering. On eve Of yesterday a woman crept along The road that leads to Shusan's mighty gates From Araby. The winds tossed wildly o'er Her tangled hair, the rain stole, snake-like, through Her dress which hung in shreds about herself; And much fatigued, she fell beneath the weight. Our soldiers took her to the tent where she Doth lie in raving fever.

Ahasuerus.

Didst thou learn her name?

Harbonah.

Most righteous king, let not thy wrath rebound Upon thy lowly servant, if his news Doth give thee sorrows. But nought she said Could give us clew to con her name. A letter We found on her and brought to thee. Peruse The contents.

(Ahasuerus reads the letter.)

What wild woes entwine themselves

Upon thy lordship's countenance. What pain Thus writhes thy face in agony?

A hasuerus (excitedly.)

Go, goCanst thou find Haman at this time of night?

Harbonah.

Ay, my good lord, he lieth in the court, For news concerning Mordecai, he said Must in thy ears before the morrow's sun.

Ahasuerus.

Bid him come hither; then, fetch Mordecai. Servant goes out. Ahasuerus crosses the chamber, takes down the book of his chronicles and reads:

"'And it c'ame to pass in the third year of the reign of Ahasuerus, in the sixth month and the first d a y of the month ·

Hamar and Harbonah enter.

that Bigthan and Teresh, two •of the kings chamberlains, sought the life of Ahasuerus, king of Media and Persia. And Mordecai, the Jew, heard of this thing and Mordecai, the Jew,

RICHMOND COLLEGE MESSENGER. 379 told it unto Esther the queen. And Esther made it known unto Ahasuerus, the king. And Bigthan and Teresh were hanged on a tree."

Haman.

My lordAhasuerus.

Let me not trouble thee. Mayhap Thy duty calls thee to thy labors.

Haman.

Nay,

My lord, my duty is to wait upon Thy grace. What favor wouldst thou ask of me? Though I am worthy not to grant it thee, It shall be done, at thy most slight request.

Ahasuerus.

Here in my chronicles I read the deeds Done by the hated Mordecai-how he Did risk his life to save my very own.

Haman reads and Ahasuerus observes him closely.

Haman.

My lord, the hand that writ those shameful words Did stray, being guided by the Hebrew's God.

Ahasuerus.

Thou liest-thou hast deceived me. (aside) Methinks That Haman was that God. (To Haman with passion) Go, go, thou fool, If thou wouldst win thyself a smile from grace, Redeem the wrong done unto Mordecai.

Thou wicked fool, didst think thyself couldst move The righteous to believe thy lies? What faith I placed in thee shall be transferred to him.

Haman starts out and Ahasuerus pauses, as if another mode of procedure shows itself.

Nay, Haman, I am swept by passion's flood

Orito the rocks of doubt. Forgive the fire With which my words did burn themselves in thee .. What thinkest thou the King should do to honor Him whom he loves?

(Haman (aside).

Whom should the King more love

Than me? (To Ahasuerus) 0 let the royal robes be brought

And put upon the man thou deemed to love, Let him be ridden in State throughout the City, The herald's voice ringing in wondrous praise, "This is the man Ahasuerus loves." Let him be crowned in glorious dignity, That all in Shusan shall be forced to cry, "This is the man Ahasuerus loves." And thusAhasuerus.

It shall be done. Go Haman, thou Must do to Mordecai as thou hast urged; For he's the man . Ahasuerus loves.

Haman.

My lord-

Ahasuerus.

Nay, tarry not, but do as I command.

Haman staggers out. A scream is heard in the ante-chamber. The King starts, but is reassured when he sees Harbonah present.

Ahasuerus.

What means this scream?

Harbonah. My lord it is-

A woman, clothed in rags, rushes in, raving.

Ahashiterus (stupefied).

Vashti!

Scene Seven.

Queen Esther's Banquet Hall. Ahasuerus and Haman discovered at the table with Esther. Chamberlains, attendants and servants · stand eagerly watching. Flowers, music. They drink wine. Tenth hour of same day.

Ahasuerus.

Ah! Haman, hast thou done the King's command?" Haman. Ay, my good lord.

382 RICHMOND COLLEGE MESSENGER.

Ahasuerus.

Harbonah, send at once

For Mordecai. Sweet Queen, what sayest thou 'Gainst his partaking of these joys with us?

Esther (sadly).

It suits me well.

Ahasuerus.

Vain sorrows lies upon Thy brow like foam upon the clearest brook; Why art thou sad?

Esther.

I have been troubled late For Mordecai, thy servant and my kinsman.

Haman (aside).

No more than I.

Ahasuerus.

He hath been honored much To-day; ridden through the streets of Shusan, The royal crown upon his honored brow, Himself upon the King's best steed; and Haman Was ordered to proclaim the pealing words, ''This is the man Ahasuerus loves"~ · And, Haman, was this done?

Haman.

It was, my lord .

RICHMOND COLLEGE MESSENGER. 383

Ahasuerus.

Still troubled, sweet? Queen, ask me what thou wilt, And I will give it thee; even will I cut In twain my lands to grant thee thy request.

Esther rises, crosses to the King and kneels beside him; her head upon his knees. Mordecai and Harbonah enter.

Esther,

I pray thee, grant at my petition life; For me and for my people, 0, my lord, We all are sold to be destroyed and slain, Our heads to lie entombed in dust, our lands Ta'en from us, and our houses burned. If we Have e'er offended thee, my lord, then strike.

Ahasuerus.

Who is this dastard that hath done This thing?

Esther.

Yon sniveling Haman is the man.

Haman cowers. Ahasuerus.

I learned this morn that I had been deceived, That Haman, whom I trusted with my goods, My life and love and honor-proved false And sought to rob me of them all. Sweet Queen, But Mordecai unravelled the mystery And showed the full deceit of Haman's heart. Speak Mordecai-what knowest thou of this letter?

Ahasuerus reads aloud.:

To Ahasuerus, king of Media and Persia, from his faithful and humble servant, Mordecai.

Know, 0 King, that Haman hath a plot with Hadrael to murder thee and steal Queen Esther for himself. Let not Haman know that thou dost suspicion him, but have thy servants watch him. My duty bids me to remain hither. This news I send to thee b:s, Hadrael's mistress, whom we may trust.

Haman turns pale, rises, then staggers across the stage and attempts to go out.

Ahasuerus (aside to Harbonah).

See thou that Haman go not hence.

Mordecai.

My lord; Wouldst thou know how I came into the secret?

Ahasuerus.

Nay, nay, not now, but, Mordecai, I would Converse with thee alone. Come, Mordecai.

Ahasuerus and Mordecai leave through the door that leads into the garden. Esther falls upon her couch. Haman comes over to her, stands for a moment above her, and then falls beside her.

Esther (faintly).

Harbonah, is this woman gone?

Harbonah. She's dead.

Ahasuerus re-enters.

RICHMOND COLLEGE MESSENGER.

Ahasuerus.

Lay hands upon him! Bear him hence!

Harbonah and servants cover Haman's face and bind him.

Harbonah.

There is the gallows fifty culits high Which Haman built for Mordecai.

Ahasuerus.

My lord,

Take him,

And bear him thither. Let him hang until The ravens pick his rotted flesh.

Harbonah and servants drag Haman out. Ahasuerus goes to Esther and slips his arm under her.

Ahasuerus (to musicians and attendants).

Leave me-

Stay, Hagai-

M usicians and attendants go out.

(To Esther).

Thy people must be saved.

He reaches the roll of papyrus and writes.

Hagai,

Bid thou my scribes make copies of this news; Have all the swiftest horses mounted and With speed spread this throughout my kingdom.

Hagai goes out. Ahasuerus turns to Esther. She rises.

Sweet,

Weep not, for I have given orders that Thy people all shall gather force and arms And thus defend themselves. And Mordecai, Shall rise e'en higher than Haman ever stood.

Esther throws her arms around his neck. Shouts heard outside, as slowly descends the

W. A. SIMPSON, '12.

INDIVIDUALISM was a movement which took its rise in the early part of the eighteenth century, but which did not reach the zenith of its power and influence until more than a century later. If we should attempt to sum up the whole movement in a single sentence we should say: Individualism asserts the rights of personality against tradition, form, and established orders. But this is too meager a phrase to convey even in the slightest degree any definite idea of what the movement was or what it stood for in the life of the time. We must go deeper, and examine separately the five underlying principles which combined to make Individualism.

The first and most important of these is Romanticism. Romanticism was primarily a revolt against pseudo-classicism; a return from the monotonous commonplace of everyday life to the quaint world of old romance; a craving for the original and adventurous; an emphasizing of the picturesque, the romantic at the expense, if need be, of correctness and polished elegance, and the current laws of conformity. peep humour, strong pathos, profound pity, are amongst its clearest notes. We may understand this movement better if we compare it briefly with the influence which preceded and partially overlapped it; that is ' Classicism.

The main marks of Classicism are reverence for authority, reverence for correctness and form, repression of passion and imagination, and exaltation of reason. lndivualisim on the other hand is a break from conformity to authority, conformity to correctness and form, repression of passion and imagination, and lastly a break from exalted reason. In a classic work of art, there are no evidencies of a lack of harmony between the ideas and the medium, no suggestion of something remaining that cannot be expressed as a natural consequence, the person-

ality of the artist is not expressed, the artist is lost in his work, which stands impersonal and objective. He does not show his own attitude toward fhe subject with which he is dealing. The Romanticist on the other hand puts himself into his work; it is no unit of beauty that he seeks to express, but his own . peraonality, the longings, hopes, and ideals of a spirit that has a tendency toward the infinite and which, therefore, can never express itself in any objective medium.

Romanticism, in a sense, was a revolt against Classicism, but the change was without violent initiative. Passion did not suddenly return in its bolder forms, but a growing melancholy shook the passive breast ~ Hence we ee that although Romanticism was in a sense an 1mtgrowth of Classicism, it was directly and outwardly opposed to the foundations of Classicism.

James Thomson was the pioneer of the whole Romantic · movement; the publication of his "Seasons" in 1730 may well be taken ·as its beginning. Here he simply revels in the beauty of nature: he observes nature directly, and describes her with genuine poetic feeling. Nevertheless his ~liction is stilted and he is inclined to be moralistic now and then. His "Castle of Indolence" is a better example of the Romantic tendency since it is an excellent imitation of Spencer's "Faerie Queene." It contains so much that is original that it is a real contribution to English poetry and English Romanticism.

The next and prob.ably the most significant of these underlying movements was the "naturalistic movement" or the growing love for nature. Previous to this period, writers, if they looked at nature at all, found in her only a thing made to order. Now there was a genuine love for real nature, not nature made into · clipped hedges and gravelled walks, but as simple nature in her freest bounds. Pope might have brought a swan or a peacock into a poem, but he would hardly have thought it fitting to introduce beetles or swallows, save the swallows that "roost in Nilus's dusty urn." Nature, according to the school of Pope, was rude and perhaps a little vulgar until smoothed and trimmed and made into lawns and gardens. Later on in the century came the most natural of all the naturalists, Robert Burus, the man

who even when he happened to turn a daisy down by the ploughshare saw in it a fitting subject for a poem.

The third movement and the most unsusceptible to the men of the age was "Emotionalism." This was the sentimental or emotional tendency of the writers of the age to introduce bits or whole pieces of sentimentality. Lawrence Sterne's "Sentimental Journey" is an excellent example of this movement. Another man who inadvertently became emotional was Samuel Richardson. His pathos, which is forever present in his works, soon becomes rather usual and finally it developes into sentimentalism.

The fourth and most note-worthy influence was the important religious revival. The ideals of this movement are in perfect harmony with those of Individualism. In fact, in this religious revival the rights of the individual as typified by the death of Christ for the individual's benefit, was in perfect concordance with the ideas of Individualism. Its direct influence on literature is, nevertheless, generally small, but its influence on English life can not be overrated. The hymns of Wesley, the "Night Thoughts" of Young and the later works of Cowper are probably the most significant works of the movement.

The last and in my opinion, the foremost of the influences was the so-called democratic spirit. There was more interest in man simply because he was man, and not because he was rich or of noble birth. Pope had foreshadowed the new spirit sufficiently to say:

"An honest man's the noblest work of God."

But this tendency grew until at the end of the century theimmortal "Bobby Burns," burst forth with:

"A inan's a man for a' that."

And in conclusion as we summarize these five movements we see that Individualism was more than a mere movement in the literature of the eighteenth century; it was a factor in the lives. of the men of the age, an integral art of the social world. It was as truly a gradual development of Classicism as Classicism was a development of the Renaissance.

BY C. W. BLUME '12.

Down among the pine-clad hills in the Piedmont section of Virginia, a tiny river wends its way. Long ago the Indians called it the Occoquan, a name which has clung to it long since the last warrior glided over its glassy bosom. The Occoquan flows through wooded slopes and fields of waving corn, through meadows dotted with sleek cattle and through bramble thick'ets, the haunt of the mocking bird and black snake.

In some places the water flows sluggishly through the rank weeds and grasses growing from its bed, and curls and ripples around the half sunken log on which the watermoccasin suns his lazy length. Again it runs over the shiny sand or murmurs over the black pebbly bottom, or laps the base of some jutting spur of mossy rock. Farther on the water flows swifter, and a dull, hollow roaring indicates the nearness of the Falls of the Occoquan.

One sunny afternoon I wandered down through the fields and thicket skirting the stream, on my way to the falls in search of the black bass. When I reached the falls I sat down on a ledge of rock just below them and overhanging a deep pool hollowed out by the seething waters, an ideal place for bass. The fish were not biting that afternoon, and my pole hung listlessly over the water, while my gaze wandered over the green trees and grassy · banks, and my thoughts went back to the old days when these hills had rung with the Indian's war-whoop. A little way up the stream was a small sand-bar covered with waving grass and sloping down to the water. The stream was already flecked with the lengthening shadows of the afternoon, and a cool, dreamy border of shadows fringed the bank until a curve hid the river from view. Far up the stream a black log was slowly drifting down; somewhere in the distance a cow bell was tinkling; in an overhanging waterbirch a jar fly was rasping his monotonous

note. The ceaseless roar of the waters, the warm, drowsy day, the dull drone of the beetle-Suddenly a canoe shot around the bend, a girl in the prow steering and a man in the stern desperately paddling. They were settlers, doubtless, fleeing from some ravaging band of Indians. The white, drawn, but otherwise beautiful face of the girl, the tense straining movements of the man, the anxious glances they continually cast behind them indicated the approaching danger.

So intently were they watching that they failed to notice the falls until too late to reach either bank. Uttering a sharp cry, the girl swerved the canoe toward the sand-bar, while the man frantically paddled to change its course in the swift current. A last effort, and both sprang out as the canoe grated on the shelving edge. They looked around for a place of concealment, but there was none.

Presently the girl turned and uttered a low cry. A band of Indians was coming down the stream in a canoe, which under the impulse of four brawny pairs of arms, was fairly leaping over the water. They yelled in triumph as they caught sight of their victims, and leaped upon the bar as the canoe grounded.

The man and girl had retreated to the other end of the island, and as the savages landed they met in a swift embrace, a kiss, a sob, and he grasped his long rifle and waited . Only one shot, and then it must be hand to hand. How well that shot should count! He loosened his hunting knife in his belt and was ready. The girl had sunk in a heap beside him and was gazing fixedly at him. One swift look into her eyes--eyes that spoke volumes, and the savages, yelling like demons, were upon him. Singling out two in a line together, he fired and both fell. One lay still. Clubbing his rifle, he met the foremost as he came within reach, and the stock shattered as it crushed the warrior's head. As they seized him with upraised tom-a-hawks for the death-struggle his long hunting knife flashed and buried in the side of a third.* * * * * * *

When the struggle was over the warriors turned to the girl. Her eyes were dilated with terror and her trembling limbs could scarcely sustain her body, but as the Indian next in power to the fallen chief advanced toward his intended prize, she swiftly

392 RICHMOND COLLEGE MESSENGER.

fled to the upper end of the bar where the canoes were. As the braves dashed in pursuit, she leaped into a canoe and frantically pushed into the current just out of reach of the eager, red hands stretched to grasp it. Rising in the canoe she gave a terrified look at the disappointed savages on the shore, a lingering one at the spot where he was lying, and the next moment the canoe shot over the falls with a loud crash.

I started. The block log was swinging round in the eddies at the foot of the falls. Overhead the jar-fly was still rattling; the wind was toying with the tall grasses on the sand bar; and from somewhere in the distance drifted the musical tinkle of the cowbells.

BY FAIRY, '11.

Spring, spring!

Arise and sing

All ye that breathe! And ring Aloud, ye dainty hyacinth bells

The joyful tale the robin tells, While madly from his ruddy throat There gushes many a joyous note.

Blue, blue,

The sky for you Aloft spreads out its hue. And all the little breezes blow

To tell, with gentle whispers low, That glorious spring is near, is near With life and hope-or stay, 'tis here!

White, white

Yon cloudlet bright

Floats in the warm sunlight Green buds are bursting here and there; Mad joy is here, is everywhere. The earth no more is old, but now Declares its youth in every bough.

Mad, mad With gladness, glad! 0 nevermore be sad!

Awake, awake to joy divine, To glorious youthful hope ashine With light eternal! Joyful sing To everliving, wondrous spring!

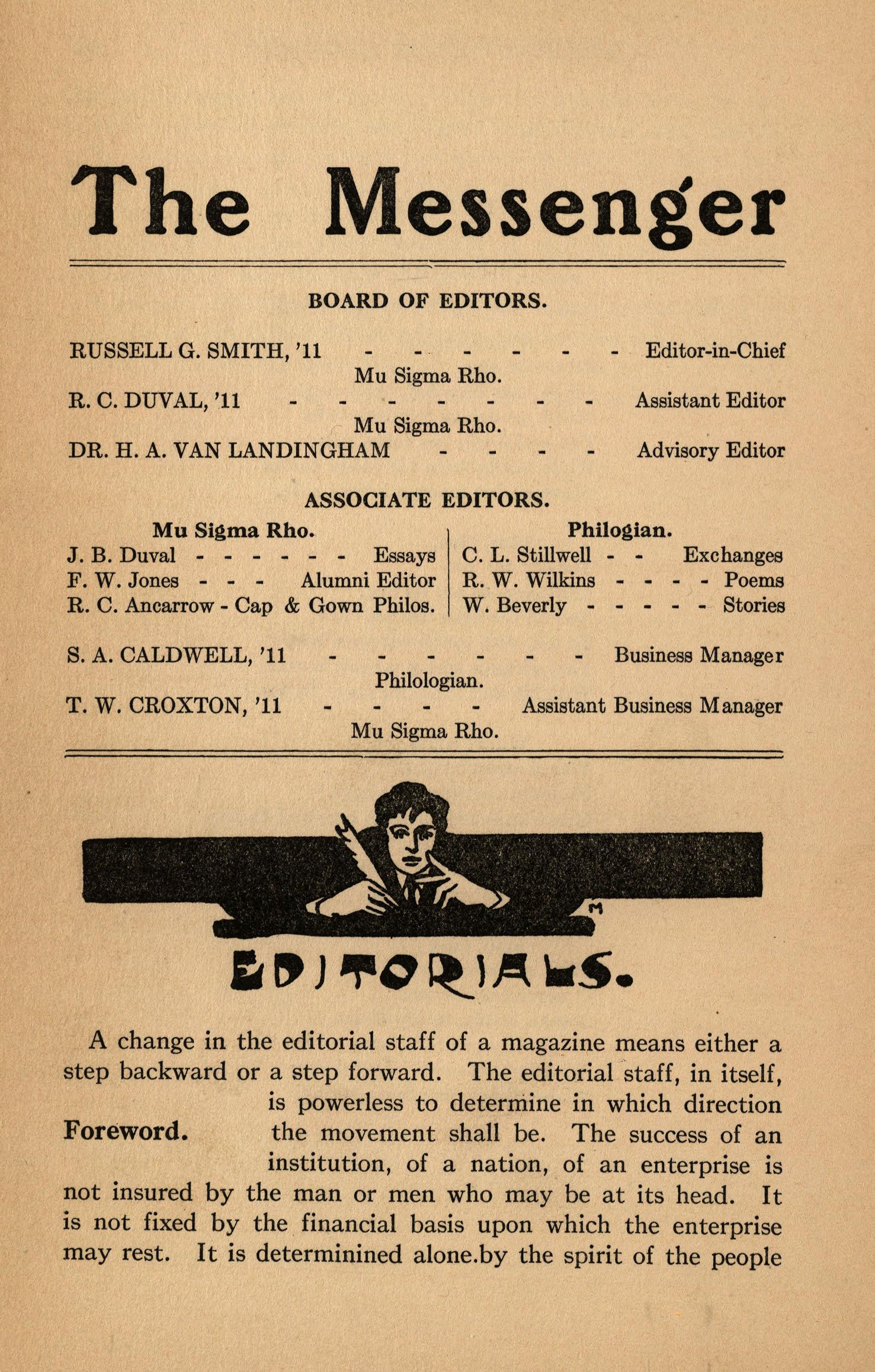

BOARD OF EDITORS.

RUSSELL G. SMITH, '11

R. C. DUVAL, '11

Mu Sigma Rho .

Mu Sigma Rho.

DR. H. A. VAN LANDINGHAM - Editor-in-Chief

ASSOCIATE EDITORS.

Mu Sigma Rho.

J. B. Duval

Essays

F. W. Jones Alumni Editor

R. C. Ancarrow - Cap & Gown Philos.

S. A. CALDWELL, '11

T. W. CROXTON, '11

Assistant Editor Advisory Editor

Philogian.

C. L. Stillwell Exchanges

R. W . Wilkins -- Poems

W. Beverly - -- Stories

Business Manager

Philologian.

Mu Sigma Rho.

Assistant Business Manager

A change in the editorial staff of a magazine means either a step backward or a step forward. The editorial staff, in itself, is powerless to determine in which direction Foreword. the movement shall be. The success of an institution, of a nation, of an enterprise is not insured by the man or men who may be at its head. It is not fixed by the financial basis upon which the enterprise may rest. It is determinined alone.by the spirit of the people

who are behind that enterprise . Now it can only be determined by the students of Richmond College whether or not the Messenger shall continue to improve. What are you going to do about it?

We have not yet reached the high water mark. Under the able management of the last editor, the Messenger has greatly improved, but perfection is still on the far horizon. We can not afford to stop where we are. Progress is the keynote of the twentieth century. The enterprise that is not progressing in this age has no excuse for . its existence. Every is sue of the Messenger should be just a . little better than the preceding issue. And this should be the ca se not only because it is in keeping with the spirit of the age, but also because every issue of the Messenger should profit by the issues that have gone before it.

Now there are two obstacles at present in the way of the Messenger's progress. The first is the fact that only about four per cent. of the entire student body of Richmond College are contributing to their own magazine. To be very frank, this is a disgraceful state of affairs. It is absolutely impossible for the Messenger to reach the highest standard without the support of the student body. It is a startling but true statement that but for the "loyal few" the Messenger would cease to exist. Now don't make excuses for yourself by saying that you haven't the ability, or that you are overworked. Call your faults by their ti:ue names, and in this case be frank with yourself and say that it is laziness and lack of college spirit.

The second obstacle that is impeding the Messenger's progress is the fact that many of those students who do nothing, criticise those who have spirit enough to back their college's magazine. If you are unable to help, don't hinder. A word of encouragement is better than destructive criticism, especially when you are no critic. Listen. When the interest of the whole college is concerned, let us put aside personal feelings and work together. The college is oftimes judged by its magazine. Let us make the judgment as favorable as possible. There are nine college periodicals in Virginia. Where do we stand in the list?

To anyone who has investigated the methods and manners of college periodicals, the most striking feature is, perhaps, the woe-

ful lack of good short stories. With the exception of one or two magazines, we have yet to find a college periodical that is not at fault in this particular line.

There are numerous causes that combine to cause this condition of affairs, the most important of which is, perhaps, the average undergraduate's idea of what a short story is. We do not claim to be authorities in this matter, but we do know one or two things that are not productive of good short stories. The first and most important of these is the idea that a short story consists of an expanded and decorated "I love you." We acknowledge that love, in one of its many phases, is always an appropriate theme for any kind of literature; but we also most emphatically deny that the love which consists merely in "Will you?" "Yes!" "Dearest!" "Darling!" is any longer in date.

The second cause which aids in the lowering of the standard of the "college" short story is the repetition of that time honored theme "How Frank Earnest Achieved Success" or some such title. The old, old, unrealistic, unnatural account of the trip to wealth and fame was, perhaps, enjoyed in the early twenties, but certainly it is no longer a source of pleasure.

The call for the short story, however, is being heard today stronger than ever before. There is a demand for it; and nowhere is there a greater demand than in the realm of college periodicals. There are some under graduates .who have talent in this line and don't know it. There are also some who haven't · talent and also don't know it. But you may belong to the former class. Perhaps you would succeed if you would try. The Messenger is calling for short stories. Why not try it?

R. C. ANCARROW, Editor

Cap and Gown Philosophy.

,On March 4th the seventy-sixth anniversary of the founding of Richmond College was celebrated in the Thomas Hall Museum with a brilliant rec.eption. Even the "GRINDS" crawled forth from their dingy dens and fed at the expense of the college. Down the awe-inspiring line went the "STOODS" and then they were seen making their way stealthily toward the refreshments. We have only one regret to note and that is that the dance to be led by Professor Dicky did not materialize.

The other bit of tragedy during the month was the utter annihilation of the Philologians by the Mu Sigma Rho's in the annual inter-society debate. This was an affair par excellence from the view-point of the Mu Sigma Rho's. The Philologians seem to be devoid of any views on the subject, though we are told that many bitter tears have flowed.. Note you that history repeats itself.

398 RICHMOND COLLEGE MESSENGER.

Turkey Buzzards were seen circling around Science Hall on Sunday the sixth. We are not sure as to whether they were in search of the Dogs in the dissecting room of Biology Lab. or were only seeking one of "Doc" Thomas's discarded theories.

We are told that "RAT" Rogers had a very remarkable experience with a pseudo tramp the_other evening. ··The sum and substance of th.e story is that "RAT'S" and Hundley's figures illustrated the campus beneath "RAT'S" window.

With the flowing of the sap and the twittering of the birds comes King Baseball. And he is very much in evidence each afternoon. The Varsity men have their "Diamond" while the rest of the campus swarms with inter:dormitory and scrub teams, which by the way should be very much encouraged.

But even Baseball had to give way to those dreaded Exams. Now is the time to seek your students, for the lights burn late, or rather early, even in Memorial Hall, that haven of discontent.

We wish to apologize and stand corrected. There was one Suffragette at the "Anti-Suffragette stunt" noted in the last issue.

But speaking of Suffragettes, we quote from Professor and Mrs. Gaines, as follows:

Professor and Mrs. Gaines were discussing with enthusiasm the lecture which Dr. Anna Shaw recently delivered in this city, when during a lull in the conversation, they over-heard young Miss Gaines, completely absorbed in her Latin, say the following: "Dux-ducis; masculirte. Yes, for in them days the leaders were men."

J. B HILL, Editor.

On the afternoon of March the nineteenth, some five hundred or more people witnessed the opening baseball game of this season. The game was played with the Medical College of Virginia, at Broad Street Park. It was a very good exhibition of baseball; and the prospects for good teams, and winning ones for 1910, at the Medical College of Virginia and at Richmond College are bright. It is, however, too early in the season to say what kind of team we may put out, but from the showing made in this first game it is safe to say that every man in college has sufficient reason to believe that the year 11)10 will produce a winning nine for the Red and Blue.

This in a measure was a try-out game. Only a few of the men remained in the game during the entire nine endings. Every man who had an opportunity to show his baseball ability presented a very crepitable appearance and made those looking on believe that after more practice they could "show them how."

Those playing were: first base, Beverly and Arnold; pitchers, Meredith and Gwathmey; catchers, MacFarland and Guy; second base, Underwood; shortstop, Jenkins, captain; third

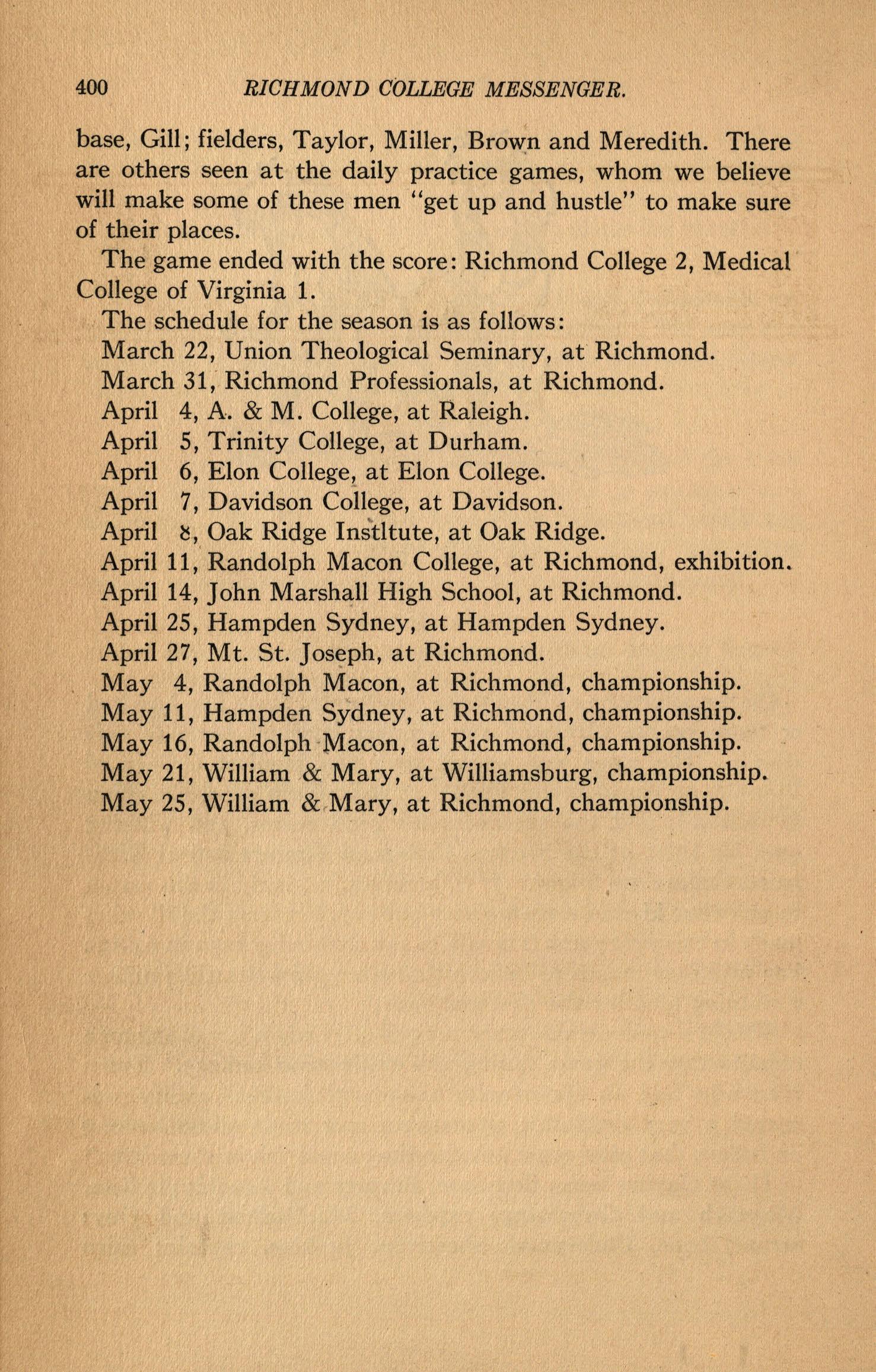

base, Gill; fielders, Taylor, Miller, Brow:n and Meredith. There are others seen at the daily practice games, whom we believe will make some of these men "get up and hustle" to make sure of their places.

The game ended with the score: Richmond College 2, Medical College of Virginia 1.

The schedule for the season is as follows:

March 22, Union Theological Seminary, at Richmond.

March 31,- Richmond Professionals, at Richmond.

April 4, A. & M. College, at Raleigh.

April 5, Trinity College, at Durham.

April 6, Elon College! at Elon College.

April 7, Davidson College, at Davidson.

April ~. Oak Ridge Ins'tltute, at Oak Ridge.

April 11,· Randolph Macon College, at Richmond, exhibition.

April 14, John Marshall High School, at Richmond.

April 25, Hampden Sydney, at Hampden Sydney.

April 27, Mt. St. Joseph, at Richmond.

May 4, Randolph Macon, at Richmond, championship.

May 11, Hampden Sydney, at Richmond, championship.

May 16, Randolph -Macon, at Richmond, championship.

May 21, William & Mary, at Williamsburg, championship.

May 25, William & .Mary, at Richmond, championship.

C. L. STILLWELL, EDITOR.

In the Exchange Department of "The Georgetonian," for February, we read the following:

"Why is it, that with few exceptions, our college magazines do not manifest much thought on the part of those who furnish the contents? Is it because the college men and women of today are not thinking, or is it that the magazines for which they are writing are not worthy of thought?"

Such a sentiment cannot fail to win our highest approval, but the words we have just quoted are a good case of tragic irony when they are found in such a magazine as the one in question. It comes to us with one story, one essay, one sketch, and one poem of twelve lines. We do not mean for a moment to condemn the magazine on account of its size, but if it has any hope of becoming a successful publication, the lack of quantity must be made up in quality and this is not true of "The Georgetonian." If nothing better than "Luck or Else" or "Sweethearts Always" could be obtained, we are indeed glad that the contents are small. The former labors through about three thousand words. There is an attempt to tell a story, but the author had nothing to tell. The movement is entirely too slow. In the closing paragraph are the words, "It is an old, old story-it has been told through all ages, yet it is ever fresh somewhere." And there's the rub. Do not try to tell an old, old story, unless it is told in a new, original manner. · The same may be said of the sketch, "Sweethearts Always." We cannot see that it has any purpose whatever,

unless it is to fill up space-and we agree with "The University of Virginia Magazine" that if material is published to fill up the magazine, we see no reason why the magazine should be filled.

It is not "The Georgetonian" alone, that is at fault in this respect, for the majority of college stories seem to be told with absolutely no regard for technique. The beginning would suit a novel; no thought is given to working up to a climax with one clearly outlined idea in mind; while the subject matter is only suitable for those who desire to sleep.

Again, some college magazines pay no heed to balance and arrangement. "The Mercerian" for February has twenty-three pages of literary matter, twenty-six pages of departments and twelve half-pages of clippings, the other half of each page being taken up with advertisements. "The Mercerian's " attention has been called to this defect before. We hope the staff will remove this cause of offence, for otherwise there is a very e en balance and very good arrangement.

We notice in some of our exchanges, no poems; in others, very few stories or essays. We delight in an all-round magazine. There are few people who are not interested in one or the other of these kinds of literature, but a magazine that lacks any one kind will be less widely read.

"The Randolph-Macon Monthly" gives close attention to the general appearance of their publications. The editors seem to know their business. "Billy Brint" is an interesting character through and through. The plan of having a central figure in a cycle of college stories is seldom used, and it should be used oftener. Let us hope that others will follow Mr. Tatem's method and catch some of his sense of originality as well.

We have been very much interested in the cycle of stories in "The University of Virginia Magazine"-"The Scarlet Fairy Book." T.here is in some of these stories a delicate strain of pathos, in others, a touch of satire, in others, delightful humour, while there is an occasional mingling of all three. Though some of them are love stories, they are not of the gushing, schoolboy love, but love of a more serious nature, wherein sickly sentimentality never enters. This magazine is decidedly the best

403 that comes to our exchange table-in appearance, arrangement and subject matter.

"The Chisel" hails from our sister institution in the city, and it is always a welcome visitor. While "The Chisel" is dull in some particulars, there is much good material. The poem, "Vicissitude" makes us regret that it is the only one. The magazine is lacking in that respect. The thought in the poem is good and well expressed. We quote:

" 'Tis flowers crushed yi eld perfume rare; 'Tis sorrow drives the soul to prayer; In effort power and will are born; He earns the rose who dares the thorn."

"An Unusual Romance," while the name does not appeal to us, is an interesting story; yet, the passage of time is awkwardly indicated. The plot is fairly good and the climax is well handled. The article "Woman Suffrage," which takes the negative standpoint, advances some good proof, but for the most part, proof gives way to sentiment. We rather condemn such articles for college publications. There is little about them publishable. The Woman Suffrage movement is one that is very much discussed at the present time, and it is difficult to give anything original on the subject. Such papers are more suited for debate.

"The Hollins Quarterly" for February is full, as usual. We are sorry, for we have too much bark to dig through to get to the wood. "Kismet" is laboursome verse, and has no poetic thought. "The Evening Star" is excellent. We like the

" * * * * glimmering shape the rosy clouds enfold, A jeweled islet in a sea of light ."

But this poem, as is the case of almost all of the others in the "Quarterly," is too short to hope for anything better than a few beautiful lines. "A Winter Night" has such lines. "The Land of the Evening Sky" is a delightful poem. "Love's Seasons" abounds in poetic figures. Why did the "Quarterly" not publish more poetry? That is decidedly the best department in the present issue.

"Man of Muse" has some interesting. well handled situations, a good plot, and a successful climax. "The Recluse" is altogether a failure if the author attempted to throw an air of mys-

tery around the main character. The story is too commonplace. "Larry Flaggherty" is well worked out, and has a good plot. A line or two of dialogue and a more interesting character would improve it. "The Story of the Mexican Waltz" is a scrap of a story; or rather, a mere incident which seems to have been written to no purpose. "The Curious Case of John Graves" is out of place. It should have been submitted to a Sunday School magazine. We do not mind a lesson, but it should not be the principal part of a story.

"An Old-Fashioned Artist" gives us an interesting account of Jane Austen, and is fair in its treatment of her as an author. The author of "The Glamor of the North" has an admirable flow of language, and she has given us an equally admirable essay. She chose ' a subject which almost assured her success.

"The Quarterly" is one of our best exchanges in general appearance. The staff has seen the advantage of departments rightly used. "Blue Pencil's" introductory remarks are especially pertinent and good. We should like to read more issues of the "Quarterly" equal to the standard set by the classes of preceding years. It has suffered a decline within the present session.

In addition to our regular exchanges, we acknowledge receipt of "The Roanoke Collegian."