Issue 6 – May 2024

Thringboard

A journal for teacher development and research

Contents Welcome to the sixth edition of Thringboard

Rewards and sanctions: some introductory thoughts by Becky

Kay, Assistant Head: PastoralThe impact of athletic development on sports injuries at Uppingham School: a case study review - Part 1 by Kris Borthwick, Head of Athletic Development

Ensemble approaches to teaching Shakespeare by Tom Toland, Teacher of English and Drama

The evolution of the ‘Leicestershire Plan’ by Rupert Fitzsimmons, Teacher of History

In this issue, we begin with an explanation of the rationale behind our recent shift in behaviour policy, grounded firmly in evidence and thoughtful consideration. Becky shines a spotlight on the intricate interplay of rewards and sanctions while illustrating how our innovative approach seamlessly aligns with our educational ethos.

The next two articles focus on approaches within the classroom and sports arena. Kris offers invaluable insights into injury prevention and management, advocating for a nuanced approach to reintegration in sports activities. Meanwhile, Tom invites us into the world of ensemble teaching methodologies, echoing our commitment to nurturing inquisitive and inventive learners.

In a groundbreaking moment for Thringboard, Rupert unveils a historical retrospective on the ‘Leicestershire Plan’ — a bold departure from conventional governmental policies and educational dogmas of its time.

Happy reading!

Hugh Barnes Assistant to the Assistant Head: Teaching and Learning

Rewards and sanctions: some introductory thoughts

By Becky KayThere is debate within education about the ‘right’ approach to discipline and reward, and trends seem to come and go over the decades. It is an obvious comparison to make, of the change from corporal punishment to its banning in state schools in 1986 and independent schools in 1998. However, in 2008, a TES survey suggested that 20.3% of teachers wanted to bring back corporal punishment.

Sanctions In the real world, our everyday behaviour is not usually driven by fear of a scale of smaller sanctions, yet schools seem to rely on them and trust completely in their effectiveness. However, Baker and Simpson (2020) suggest that the same people often appear again and again in detention – the behaviour we see does not change. This is something that this paper will seek to explore – how effective are sanctions in changing behaviour in the long term?

Baker and Simpson also point to the fact that if basic needs are not met, then behaviour can be affected. Lack of sleep, overstimulation, fear of being unsafe (no consistency, lack of boundaries), the want of communication with home, and an absence of belonging can all impact on a pupil’s behaviour and can be experienced commonly in the boarding house. To give out sanctions, rather than to use a more supportive measure, can be to ignore the cause of the behaviour and may not help to resolve issues.

There are numerous articles available which comment on the detrimental effect that boarding can have on people’s long-term mental health and much of this is linked to sanctions. Hierarchical systems where pupils mete out punishments on those younger than themselves in the boarding house seem to be particularly damaging, with one Times article of 2021 quoting a pupil called ‘Thomas’ who said, “they’d make you write pages of lines or shake bottles of milk until they turned to butter.” White, A (2023) wrote in the Daily Mail about how children were forced to suppress their emotions, including homesickness, in part because of the fear of response from other pupils. Fortunately, at Uppingham, most of the hierarchy of the 20th century has been eradicated. It does, however,

mean that we need to keep considering the impact of our systems on young people.

There is also a risk that pupils are treated differently across boarding houses when HsMs have the autonomy to manage behaviour. In some schools, it was found that behaviour in one house that may result in a verbal warning may be a more significant sanction in another. This can manifest in particular between girls’ houses and boys’ houses. Pinkett, M., and Roberts, M., (2019), in their study into boys’ behaviour and motivation, found comments in their research such as ‘girls get away with poor behaviour because teachers don’t expect them to be naughty’ and ‘boys are told off more and punished more for similar behaviour’. Because a boarding house is also a pupil’s home away from home, there have been reports in some schools of a reluctance to damage relationships with sanctions. There is also a sense of pride in the house, and some HsMs may not want the reputational damage of reporting sanctions. Therefore, at Uppingham, we want to ensure that we continue to apply sanctions, and indeed rewards, in a consistent way, but also carefully consider if a sanction is always the best and most effective course of action.

Rewards

There are few schools that would be so bold as to do away with a rewards system; indeed, Willingham, D.T., (2006) states that ‘praise is such a natural part of human interaction in our culture that it would be difficult to stop praise altogether’. Research seems to show that it ‘can motivate and guide children’ (Willingham, 2006), however, there is a lot of evidence that suggests that it is imperative to reward the right things and in the right way.

Praise does not work if it is used to control pupils. Willingham and Kohn agree that this is the case and Kohn, A., (1993) implores us to be ‘honest with ourselves as to why we are rewarding’ claiming that whilst they can succeed in getting pupils to change their behaviour, ‘we pay a substantial price for their success’. Children can become almost immune to reward and seek greater or more regular rewards for the same impact.

Kohn, A (1993) suggests that ‘what rewards and punishments do is induce compliance’. This is not the starting point that I wish to work from at Uppingham as we aspire to produce independent, self-motivated individuals. This is particularly important within a boarding house as we want to develop character rather than just enforce behaviour. Kohn also suggests that ‘rewards usually improve performance only at extremely simple – indeed, mindlesstasks, and even then they improve only quantitative performance’. If we want to improve quality, then rewards must be used carefully to recognize behaviours and not just as a way of encouraging compliance.

Overall, the research seems to suggest that at Uppingham we should aim for rewards to be unexpected, sincere and used to reward behaviours rather than outcomes. Rewards should also be selected carefully and should be immediate. Expanding the remit of commendations to include positive behaviours displayed across all areas of the school will also help demonstrate to pupils what it is that we value as an institution and further promote recognition and gratitude.

Restorative practice

According to a University of Cambridge, Faculty of Education news article, (2023), “Most schools in England follow a ‘behaviourist’ approach to student discipline, reinforcing positive behaviour and implementing escalating sanctions for repeated misconduct” and the Evidence into Practice blog (2016) suggests that this word ‘“behaviourist” is sometimes used in a pejorative way.’ It seems that this system, as explained above, can be detrimental to some pupils and Laura Oxley suggests in the Faculty of Education news article, “for significant numbers of children, the current approach isn’t working”.

Restorative practice is, according to Hendry et al., (2011), ‘an alternative way of thinking about addressing discipline and behavioural issues’ and the Restorative Justice Council (2021) claims that ‘Restorative practice in education has enormous potential to transform relationships…creating happy, healthy school and college communities.’ Education Scotland (2023) claim that ‘a restorative approach recognises that people are the experts of their own solutions’ which chimes with the Graydin approach to coaching which we have established within our school, and therefore it was seen that this would fit neatly within our culture.

Restorative practice is an approach that uses conversations and interventions to help build and maintain positive relationships and resolve difficulties. It allows pupils to reflect and be educated and thus hopefully make positive long-term changes to their behaviour.

Restorative practices take time and effort to embed into the culture of a school; however, the positive outcomes can be well worth this investment. At Uppingham, we are in a good place with our behaviour systems. This might beg the question – why make changes?! Well, we are now embarking on the next step to ensure that pupils can be responsible for their own behaviour and hopefully help their personal development. We should always be willing to try new approaches to continue to make progress as individuals and as an organization. Education is about creating an environment where pupils feel safe and valued so that they can thrive, and the intention is that a restorative approach to behaviour can help achieve this.

The impact of athletic development on sports injuries at Uppingham School: a case study review - Part 1

By Kris BorthwickWhile participation in youth sport offers a wealth of benefits, including fostering self-esteem, developing social skills and improving overall health and well-being, these rewards are not without the inherent risk of injuries. These injuries can range from mild sprains and strains to more severe fractures and ruptures, potentially leading to long periods out of school. Therefore, understanding the injury landscape is crucial for designing, implementing, and evaluating an effective school sport programme. It is important to acknowledge that while injuries in sports are not entirely preventable, we can significantly mitigate the risks. This article delves into the specific times when injuries occur at Uppingham School, explores the potential contributing factors, and shines a light on how Athletic Development plays a crucial role in reducing these risks.

Before we delve into the impact of Athletic Development on injuries at the school, some may be thinking ‘what actually is Athletic Development?’ So, let’s start here.

Athletic Development is the strategic application of sports science principles aimed at optimising athletic performance while minimising injury risk. It focuses on enhancing core physical qualities like speed, power, strength, and endurance, which ultimately expands the foundation for athletic development in various sports. The primary goal of the program is to improve pupil’s athleticism not simply increase bodyweight or muscle mass.

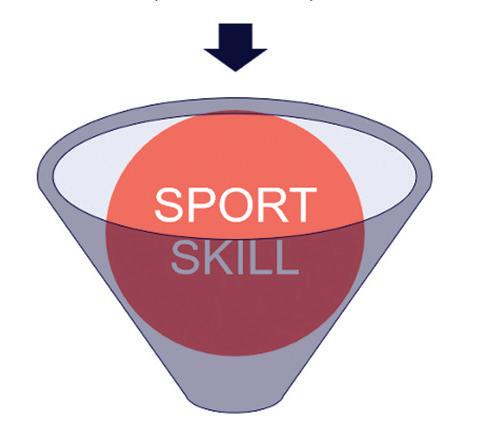

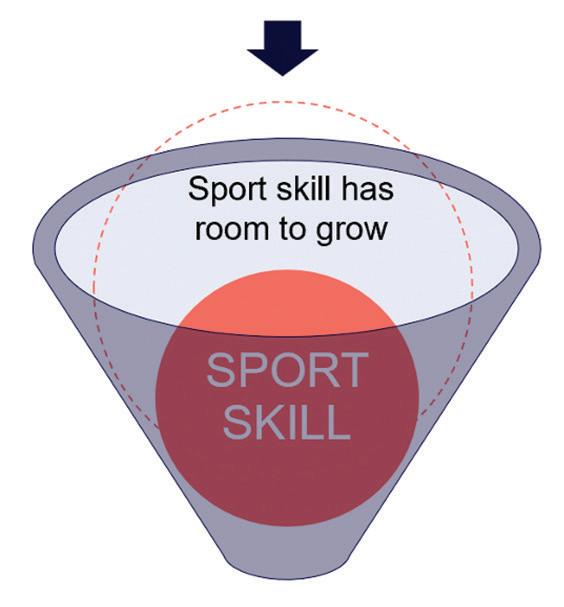

Imagine a bucket representing an athlete’s physical capabilities. The larger the bucket, the more space there is for skill development. Athletic

The lower the physical capacity, the lower the number of repetitions that can be completed in a session, limiting overall skill development.

Lessons, Practices, Matches

Development helps expand the bucket, allowing for greater growth potential in specific sports. Just like a fish grows to the size of its environment, athletes with a stronger physical foundation can reach their full potential in their chosen sport.

Showing injuries occur because of the demands of sport exceed the capacity of the tissue.

Capacity

Demands

No Injury

Demands of the sport are within the capacity of the tissue/body

Demands

Capacity

Injury

Demands of the sport exceed the capacity of the tissue/body

Beyond improving athleticism and sports performance, Athletic Development plays a crucial role in reducing the likelihood of injury by strengthening muscle tissue. Injuries occur as a result of the demands of the activity exceeding the capacity of the tissue (Figure 2). This occurs in two ways, either acutely, generally through a contact-related issue (think rugby collisions or a stick/ball to the head in hockey) or chronically, through increased repetitive loading over a 3-5 week period (Figure 3).

We know why injuries happen; let’s take a look under the hood to see how and when they occur here at Uppingham School, as well as what we are doing to help mitigate these risks.

Uppingham Injury Data

From September 2023 to Spring Half Term 2024, a total of 472 game sessions were missed due to injury. As illustrated in Figure 3, injury rates tend to increase progressively from the start of each half term. This aligns with research by Malone (2017) and Sole (2017), who found increased injury rates following periods of unmonitored or minimal training such as Summer, Christmas, or Easter holidays. Creating sudden spikes in training volume and intensity leads to demands exceeding capacity, resulting in injury (Windt, 2017; Blanch, 2016), which is what happens when pupils return to school and train as if they had never been away.

As a result, a pupil’s first three weeks back in school are, by far, the most dangerous in terms of injury risk. Excessive workloads during this period contribute to putting our pupils in harm’s way. Research by Windt (2017) suggests that even overdoing it for one week increases an athlete’s risk of injury 2-4 times in the next 7 days. This underscores the importance of managing pupils’ training loads on returning to school in order to minimize their risk of injury.

In essence, managing training load is like baking a cake. If you undercook a cake, you can check it and put it back into the oven to achieve the desired consistency. Conversely, if it is put into a piping hot oven for too long and burned, you can’t reverse the cake into a masterpiece. It remains burned. In the context of pupils returning from holiday periods, if you immediately place a high load on pupils, you “burn the cake,” which is difficult to recover from, or worse, they get injured. By slowly increasing volume over time,

you end up with the perfect “cake” – an injury-free, physically prepared pupil, hungry to excel in their chosen sports.

The role of Athletic Development in reducing injuries

Having explored the factors contributing to injury risk, let’s take a look at how Athletic Development helps reduce the risk of injury.

Strength training, a key element of a well-structured Athletic Development program, acts as a protective ‘vaccine’ against soft tissue and load-related injuries (Figure 5). By increasing an athlete’s capacity to withstand forces, strength training significantly reduces the likelihood of injury during a strenuous term. The robustness that strength training produces is just as important as its performanceenhancing effects.

The effectiveness of our Athletic Development programme in reducing injury risk is demonstrably evident.

3.

Shows the weekly distribution of injuries from academic year 2023-24 up to the latest half term (Spring 2024). Data is recorded from pupils when signing into rehab during their games period when signed off games.

Pupils who regularly take part in the Athletic Development programme were found to be injured much less than those pupils who did not:

• In academic year 2022-23, a staggering 82% of all injuries occurred among students who did not take part in Athletic Development.

• This year, the trend continues, with 78% of pupils off games/injured being those pupils who do not follow an Athletic Development programme.

These figures highlight the program’s significant impact in safeguarding students from injuries.

Key Takeaways

Similar to developing skills like reading and writing, Athletic Development is a learned behaviour that requires consistent practice. Therefore, education on proper training techniques is crucial to enhance learning, optimise outcomes and cultivate a lifelong interest in physical fitness. This, in turn, contributes to both improved performance and reduced injury risk.

Incorporating a gradual return to sport protocol is essential in reducing injury during the first three weeks of each term. Games staff should be particularly mindful of training loads during this vulnerable period. Additionally, integrating Athletic Development into each sports timetable significantly reduces injury risk. A combination of both strategies creates a blueprint for a healthy and high performing student body.

Reduction in number of injuries

Faigenbaum et al., 2016

Figure 5.

Shows the most effective methods that reduce injuries.

References

Malone S, et al. The acute:chronic workload ratio in relation to injury risk in professional soccer. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 2017; 20: 561-565.

Sole C, Kavanaugh A, Stone M. Injuries in collegiate women’s volleyball: a four-year retrospective analysis. Sports 2017; 5, 26

Faigenbaum, A. D., Lloyd, R. S., MacDonald, J., & Myer, G. D. (2016). Citius, Altius, Fortius: beneficial effects of resistance training for young athletes: narrative review. British journal of sports medicine, 50(1), 3-7.

Windt J, Gabbett TJ. How do training and competition workloads relate to injury? The workload-injury aetiology model. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2017;51:428–435

Blanch P, Gabbett TJ. Has the athlete trained enough to return to play safely? The acute:chronic workload ratio permits clinicians to quantify a player’s risk of subsequent injury. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2016;50:471–475

Ensemble approaches to teaching Shakespeare

By Tom TolandUK education policy has undoubtedly seen many challenges in recent years: economic crises, the pandemic, the rise of university tuition fees which puts students in the positions of consumers. Perhaps the question of the value of the arts is one of the most salient and least noted of these challenges; the public articulation and understanding of the value of the arts is at a distinctly low level, shaped by a culture that values ‘outputs’, quantitative evaluative measures, and functional transactional exchanges (e.g., if I pay this, I get that—not, if I see this play, I may think differently). This question of the public articulation of the value of the arts crops up in much of the literature around formative arts education. For instance, Michael Gove’s 2013 paper, ‘Cultural Education: A Summary of Programmes and Opportunities’, notes that ‘[t]he arts are the highest form of human achievement, and through art we not only make sense of ourselves in the world, but we also make our lives enchanted.’ It’s as if these assertions need to be made in order to persuade people—whether the public or others in government— that the arts justify being placed at the heart of education policy, and, further, justify public funding. Yet in the decade that has passed since Gove’s humanities-focused document, the arts have seen a decrease in funding, ever-falling numbers of students, and have become increasingly perceived as elitist and/or specialised. At the same time, initiatives by practitioners passionate about the arts are growing, both inside and outside of education. Outside of educational settings, for instance, organisations such as The

Reader makes it its mission to bring about a ‘reading revolution’, sharing reading with those who tend not to think of themselves as readers.

A vital step for teachers is ensuring that within the classroom they create a challenging and safe learning environment. Government initiatives and expectations for teachers perceive the relatively autonomous role that teachers play in the classroom; yet the Royal Shakespeare Company highlights the ‘ensemble approaches’ championed by former artistic director Michael Boyd, who noted that “trust, empathetic curiosity, and courage [are] conditions for achieving excellence in a rehearsal process.”1 There are direct parallels between teaching and learning in the classroom and the way that plays are developed in the theatre. The process of rehearsing a play is collaborative. As a group, the actors and director will make choices about the interpretation of plot, characters, themes and language of the play. They also explore the key themes and dilemmas that are present in the text.

At its heart, the purpose of these ‘active approaches’ directly responds to several of Michael Gove’s principles, including cultural opportunities for all pupils; nurturing talent; excellent teaching; and celebrating national culture and

1 Irish, Tracy. Would you risk it for Shakespeare? A case study of using active approaches in the English classroom. English in Education, Vol 45, Issue 1, February 2011

2 Neelands, Jonothan. ‘Acting together: ensemble as a democratic process in art and life’, Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance,14:2,173-189)

identity. The unique ethos of this process enables the pedagogical method of classroom space to be more like a rehearsal room. Pupils, like an ensemble, have shared learning that is supported by a teacher, who acts at times as a director. There is an inherent freedom and sense of fun here for pupils, enabling exploration of what Geoffrey Streatfield calls “improvising, and reworking on the floor with an astonishing freedom and confidence.”2

One technique that is frequently employed via ‘active approaches’ is an exploratory sense of questioning. In order for pupils to develop their ideas when looking at the works of Shakespeare, they must question

everything that occurs within a classroom, which may allow them to have a greater understanding of Shakespeare’s work overall. This exploratory approach deviates somewhat from policy-led attainment markers from the Department of Education, especially as the most common examples of ‘questions’ in the national curriculum are prescriptive. Teachers tend to be limited to simply exploring ‘essential questions’: questions that are necessitated by exam boards. Doug Lillydahl notes that teachers deliberately teach students during the research process that inquiry must grow and adapt by spawning subquestions in response to their learning. This progression of the

inquiry provides a sense of accomplishment in addition to their growing understanding of topics.3

Lillydahl’s perspective draws out the importance of student experience in exploring questions, something that is vital, not least as such questioning attitudes are not something many pupils have when they interact with Shakespeare. Classroom settings, as per the necessities of the national curriculum, are dominated by the pressure to achieve highly, making teachers reactionary and discussion of Shakespeare often monological. There is a trend for Shakespeare to be taught as having a certain flat line of interpretation: Othello is about jealousy and racism; Macbeth is about power and its distortions, and so on. But to present the plays not as readymade products, but as explorations of contemporary realities which do not offer answers, would, I suggest, enliven student engagement considerably, and also catalyse student interest in how the arts more broadly, well beyond Shakespeare, might interact with politics and our present-day lives.

The use of ‘ensemble approaches’ highlights several key words, including ‘ownership’, ‘empowerment’, ‘problem solving’ and ‘relevance’. The key point here is recognising the need for risk-taking, which occurs when we engage with the dialogical imagination of students through a text. This reiterates the point that theatre, at its best, is a risky business: it should make us think. Tracy Irish notes that Shakespeare “walked a tightrope with the censors of his time; the ambiguities in his plays allow him to question the politics and social norms around him.”4 Performances continue to try to perpetuate such questioning.

Often, the notion that pupils are studying a play is somewhat absent from a classroom setting. Deborah Britzman describes how natural it is to fall into the “cultural myth” of “teacher as expert, as self-made, as sole bearer of power and as a product of experience”. 5 Teachers want to be seen as risk-takers, but often are reactionary knowledge-givers. (Irish somewhat counters this, however, by suggesting that ‘effective risk’ is not about random, uncalculated risks, but planning clear boundary settings and allowing for reflective assessment.) This sense of the teacher’s role is key, as good teachers have an enormous effect on children at school. For instance, the CEDAR (Centre for Educational Development Appraisal and Research) at the University of Warwick showed a difference in attitude to Shakespeare that was four times higher between classes than between schools, thereby indicating the massive difference made by particular teachers. This raises the question of what a ‘good teacher’ actually is. Would you rather impart knowledge, or do you want to secure high attainment grades? There is something to be said about framing ‘good teaching’ in such a way: there is more than only these binary options. Does it mean that if you do not seek active approaches in Shakespeare, or if you look to impart knowledge instead of achieving exam grades, that you are a ‘bad’ (or ‘good’, depending on your perspective) teacher?

3 Lillydahl, Doug. “Questioning Questioning: Essential Questions in English Classrooms.” The English Journal, vol. 104, no. 6, 2015, pp. 36–39

4 Irish, Tracy. Would you risk it for Shakespeare? A case study of using active approaches in the English classroom. English in Education, Vol 45, Issue 1, February 2011

5 Britzman, Deborah P. “Who Has the Floor? Curriculum, Teaching, and the English Student Teacher’s Struggle for Voice.” Curriculum Inquiry, vol. 19, no. 2, 1989, pp. 143–62

The evolution of the ‘Leicestershire Plan’

By Rupert FitzsimmonsI am currently studying for a MA at King’s College London. I am enrolled on a course called Education, Policy, and Society. The modules vary enormously in their focus but the intention behind them is to give students, of whom around a fifth are teachers, an understanding of the politics, history, consequences, and philosophies of education. During the course I have had the opportunity to speak with government policymakers about school curriculum design and to work closely with other teachers and world-leading academics to explore key issues in education. Some of these issues have been to do with classroom practice. Other topics have been social issues like racism, class and gender.

The key message tying all these topics together is that everyone who works in education needs to be aware that the spaces and frameworks we inhabit are the product of many decades’ debate and compromise. We should therefore not take the claims of government or school leaders at face value. We should consider why they make the claims they do and whether there are better ways to serve our pupils that those who hold various positions of power might not be aware of or might be afraid of. We might even, through careful analysis of the history and language of their policies and claims, identify biases or consequences of their ideas that they were unaware of themselves. I would like to emphasise that this is not about being a cynic but about providing clear and knowledgeable insights and suggestions from an outsider perspective. At its most basic, the course is about encouraging education professionals to ask ‘why?’

Here is a short essay I wrote for the course. It is targeted at government policymakers and it explores an example of education professionals questioning received wisdoms and discarding them in clever ways so as to better serve their pupils. It analyses the development of the so-called ‘Leicestershire Plan’ for schooling which readers who were raised locally may well be the product of.

I hope you enjoy the essay. Should you like to know more about the Leicestershire Plan or the MA course please stop me for a chat.

The Leicestershire Plan

A contemplative awareness of the past is argued to be critical for education policymakers (Ball, 2021, p.65; History and Policy, date unknown). A case which illustrates this are the school reforms of a group of intrepid education leaders in mid-twentieth century rural Leicestershire. The ‘Leicestershire Plan’ was an attempt to provide access to the best education for all children through a repurposing of the existing regional school infrastructure. Unlike the separation of pupils into streams based on ability as ordained by the 1944 Butler Act, the Leicestershire Plan subverted government demands. It developed a comprehensive system which saw all pupils attend grammar schools for the last years of their education (Mason, 1964).

An appreciation of this episode is helpful in several ways. Firstly, a resurgence of the Leicestershire Plan in popular consciousness might promote more informed public discourses about education. Secondly, due to the parental and rural influences on the Plan it problematizes the centralisation of decision making and urban focus of today’s policies. Thirdly, given recurrent statements by political leaders regarding selective schooling, it provides worthwhile insights into themes which were at the forefront of education debates for much of last century and show no sign of receding in the twenty-first (Rimi, 2022; Turner, 2022).

The Leicestershire Plan can only be understood in the context of the 1944 Butler Act. The Act was partially inspired by a desire to rebuild post-war Britain quickly as well as to make the most of the potential gains to human capital following the onset of the so-called ‘baby boom’. It set in motion a raising of the school-leaving age to 15 by 1947 and the reorganisation of schooling provisions across England and Wales.

Today it is mandated that teachers employ practices like ‘adaptive teaching’ in predominately comprehensive classrooms to cater for the diversity of pupils’ needs (DfE, 2019, pp.17-18). Contrastingly, the politicians of the 1940s had been raised under a Victorian set of values articulated by figures like Matthew Arnold who believed ‘[T]he education of each class has, or ought to have, its ideal, determined by the wants of that class, and by its destination’ (Arnold, 1864, as cited in Ball, 2021, p69).

The 1944 Act reflected this view by establishing what was known as a ‘tripartite’ system of schools. The most academic, as determined by examinations at the age of 11, could attend grammar schools until the age of 18. The aspirational but academically ill-disposed would attend new technical schools until the legal leaving age. The

rest would attend secondary modern schools, another new development. Again, pupils would leave when legally entitled to but were unlikely to have access to nationally recognised qualifications like GCEs. Admission into these streams seemed to be dictated by wealth, due to access to exam coaching, more than any rigorous assessments for intelligence (Ball, 2021, p.74).

By 1957 Leicestershire’s Director of Education, Stewart Mason, and his colleagues opposed tripartism. For the aspirational rural communities of the county the 1944 Act was a failure. Foremostly, the separation of pupils by ability at the age of 11 was the subject of growing parental discontent. It was felt unfair to decide upon the future of a child’s education so young and through the blunt mechanisms of exams. Mandler has found that many of the arguments developing in Leicestershire reflected a growing national public opinion which had not yet debuted in Westminster. While politicians remained silent on growing inequalities caused by educational streaming, Local Education Authorities (LEAs) and parents discussed among themselves their dissatisfaction. They began seeking ways to improve their lot without the need for central government input (Mandler, 2020, pp. 50-52). Over the following years Leicestershire’s LEA established its new comprehensive approach. Meanwhile central government did nothing to address national concerns until 1965 when Anthony Crosland, Labour Secretary of State for Education and Science, issued Circular 10/65 marking the beginning of a slow change in direction. This deafness of Westminster to entrepreneurial LEAs and parental pressure should motivate today’s policymakers to listen to those affected by changes and work closely with regional experts. More care in this regard might have saved time in attempts to best serve the people. Moreover, should future plans to expand selective schooling be pursued then similar views and regional subversions would undoubtedly follow.

There were practical problems with tripartism too. Leicestershire’s LEA did not have the funds to establish new secondary modern schools, let alone technical schools. The disparate nature of Leicestershire’s population meant that an impractically large number of new schools would have been required. Furthermore, even if funds had been available to build new schools their cohorts would have been too small. It would have been inefficient to staff them with suitably expert teachers to match pupils’ interests. Tripartism had been planned for densely populated and rapidly changing cities. It was not appropriate for the countryside where funding was hard to come by and populations were sparsely distributed.

Policymakers and academics today continue to focus on cities. Working with cities can help policymakers affect significant and rapid changes because of their large and dense populations (Ball, 2021, p.122). This same feature helps researchers identify and theorise systemic issues with clarity. The diversity among groups living side-by-side emphasises the differences between experiences and permits research in which geographical context can cease to be an obscuring variable (Pratt-Adams et al., 2010, pp.20-22). The Leicestershire Plan highlights the dangers of following this approach without an appreciation of its limitations.

The Leicestershire Plan is not a commonly told story within narratives of English education history. Given that today its influence remains evident in Leicestershire and other rural counties such as Dorset and Wiltshire, its place in public memory should be firmly entrenched. Furthermore, policymakers would be wise to remember the importance of popular opinion, regional expertise, and rural needs if they are to be effective in delivering equity and excellence in education.

References

Ball, S. J. (2021). The Education Debate (4th ed.). Policy Press.

Department for Education. (2019). Early Career Framework Department for Education. Available at https://shorturl.at/ bFY15 [Accessed 28.10.2023).

Fairbain, A. N. (Ed.). (1980). The Leicestershire Plan Heinemann Educational Publishers.

History and Policy. (date unknown). What we do Webpage of History and Policy. Available at https://shorturl.at/ cmGNT [Accessed 29.10.2023).

Mandler, P. (2020). The crisis of the meritocracy: Britain’s transition to mass education since The Second World War Oxford University Press.

Mason, S. C. (1964). The Leicestershire Experiment (3rd edition). Councils and Education Press.

Pratt-Adams, S., Maguire, M., & Burn, E. (2010). Changing Urban Education. Continuum International Publishing Group.

Rimi, A. (29 July 2022). Sunak says he would bring back grammar schools as PM. Independent online. Available at https://shorturl.at/pGJSZ [Accessed 29.10.23].

Turner, C. (19 August 2022). Tory leadership latest: ‘More grammar schools in every area,’ Liz Truss says. Daily Telegraph online. Available at https://shorturl.at/aghtI [Accessed 29.10.23].

We hope that you have found something that has interested you in these pages, and welcome any feedback you have, particularly if there are any specific areas you would like to see in future issues.

Are you an inspiring Thringboard author?

Do you have something we could publish, now or in a future issue?

If you are/have been working on some small-scale research or have an area of expertise that the Common Room should know about, please do get in touch and let me know!