In our polarized world, jumping to conclusions about societal issues has become common, while balanced perspectives grow scarce

This year’s theme, Balance, highlights sociology’s role in fostering evidence-based, reasoned insights. With recent developments in technology, politics, and culture fueling division, it is crucial to approach humanity’s challenges with informed observations

Dear Readers,

It is with great excitement that I present to you this year’s issue of the Undergraduate Sociology Journal. As always, our mission is to spotlight the diverse and thoughtprovoking work of undergraduate scholars who are engaging deeply with the social world. This year, however, our issue takes on a particularly timely theme: Balance

In our increasingly polarized world, jumping to conclusions about complex societal issues has become common, while balanced, evidence-based perspectives are growing ever more scarce. This year’s contributors rise to the challenge, demonstrating how sociology at its best grounds us in reasoned, rigorous inquiry, even amid uncertainty and division.

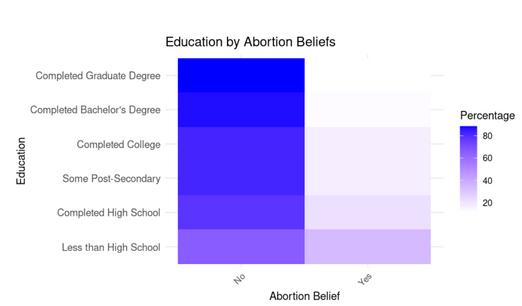

The articles in this volume reflect a range of approaches, but all share a commitment to understanding social life through a lens of nuance, critique, and care. Whether analyzing how social norms shape what we eat, who we love, and how we navigate family life; investigating how socio-economic conditions impact issues such as elder abuse in nursing homes, student achievement, housing precarity, and attitudes toward abortion; or exploring the personal and political legacies of coloniality, our authors resist easy answers choosing instead to pursue clarity, context, and connection.

I would like to thank all those who made Volume VII of the USJ possible Thank you to our copy and design editors for their tireless work in reviewing and preparing this issue, and to our contributors for their insight, creativity, and courage. This journal would not be possible without the generous support of UofT’s Department of Sociology whose continued encouragement of undergraduate scholarship makes this work possible. I’d also like to extend a heartfelt thank-you to Emily Mastracci and Jenkin Yuen, Co-Presidents of the Undergraduate Sociology Student Union, for their dedication to uplifting student voices. Above all, I thank you our readers for engaging with these ideas. I hope this journal inspires you to ask new questions, rethink old assumptions, and seek balance in how you understand and interpret the social world

Warmly, Libby Li Editor-in-Chief

Undergraduate Sociology Journal Volume VII 2025

Libby Li

Greta Billingsley

Hasti Dehdashtian

Michael Ladd

Liam Marshall

Jenna Mihalchan

Michael Saleki

Lily Sharma

Amanda Singh

Madelyn Stanley

Mio Sugiugra

Shania Winter

Albert Xie

Gabriel Yi

Esther Yoon

Callie Zhang

Aliyah Rahim

Rochelle Wu

Nicole Zeng

Michael Ladd is a third-year Sociology Specialist and Political Science Minor at the University of Toronto – St George. His current research interests are urban sociology, the sociology of education, and the sociology of religion

Anastasia Markandonis is a second-year student studying Criminology and Sociology with aspirations to pursue a career in health law Across her various roles, she remains a tenacious advocate, using her writing to drive meaningful discourse She looks forward to engaging with readers and sharing her work

Tamara Altarac is a recent BSc graduate with a double major in Criminology & Sociolegal Studies and Psychology She plans to pursue graduate studies in law, driven by her passion for sustainability, policy, and equity.

Sophia Bannon is a fourth-year Sociology and Urban Studies student She pursues diverse research interests, including data analysis, urban issues in Toronto, settlement experiences in immigration and failures in the shelter system. She appreciates the opportunity to have her work shown in the USJ and the sociology courses that sparked her interest in quantitative research.

Amitav

is an undergraduate student at the University of Toronto, specializing in Financial Economics with minors in Mathematics and Statistics His research interests include macroeconomic modelling and data-driven policy analysis.

Xie is a third year student at the University of Toronto, specializing in Sociology with a minor in Education Her academic interests include intergenerational familial trends, social change, and educational equity She is particularly interested in how family dynamics evolve across generations and how these patterns shape broader social outcomes.

Simona Agostino is a third-year undergraduate student at the University of Toronto St. George, double-majoring in Sociology and Criminology and minoring in Art History In her spare time, she enjoys illustrating and working on her family tree

Polina Gorn

is in her third year of Urban Studies and Human Geography double major She is passionate about equity planning and community resilience as ways of challenging the modern-day capitalist city

Jenkin Yuen is a fourth- and final-year undergraduate student at the University of Toronto, pursuing a double major in Sociology and Women & Gender Studies, and a minor in Anthropology (as of March 2025) His recent research includes an ethnographic study on young heterosexual male friendships in gym settings, a collaborative project on sports and disability, and an independent study on the unspoken behaviours and interactions in public washrooms. His research in early 2024, published in the Undergraduate Sociology Journal (USJ), touches on the issues of elder abuse and social isolation in Hong Kong.

Hannah Bharmal is a creative 3rd year undergraduate student double majoring in Sociology and Environmental geography at the University of Toronto. Passionate about social justice and decolonial frameworks.

Sydney Baxter is a fourth year Sociology major

Anastasia Markandonis

Abstract

Balance is a principle that has been incompatible with society throughout history. Our society glamorizes pursuing activities in their maximal form, and prizes obsession. This relentless drive can carry dangerous unintended consequences The case of ‘eating orders’ is explored below This piece will highlight the utmost importance of finding a balance in all aspects of life.

According to 20th-century sociologist Max Weber (2003:1), the ascetic ethos that arose from the rise of Protestantism provided a unique rationale for the capitalist system Weber asserts that humans did not engage in a capitalist mode of production for purely materialistic reasons, and delves into the theological value systems that underpin it (Weber 2003:1) Being disciplined, diligent, and self-restraining was a symbol of religious righteousness, which unintentionally brought economic and social rewards. Although Weber considers the expression of Protestant values extending to limits on consumption and encouragement of frugal spending, he omits the manifestation of the Protestant Ethic in the realm of the restriction of food consumption This omission is a significant oversight, particularly considering the experiences of women during his time.

My paper argues that the elective affinity –the complementary reinforcement of Protestantism and capitalism (Weber 2003:1) – is also found within the ‘spirit of thinness’ that pervaded Weber’s time. Firstly, I will discuss the unique social context, namely, the rise of Protestantism, which established thinness as a virtuous and holy pursuit Secondly, I will explore the interaction of the rationalization of the world – an increase in universal efficiency and calculative ability – with the pursuit of thinness Thirdly, I will apply Weber’s ‘iron cage’ metaphor to the confinement of individuals to the pursuit of thinness, and the consequent loss of spirituality, freedom, and joy. Similar to Weber’s analysis of the contemporary work ethic, I do not ignore materialistic factors or events that may have contributed to the rise of the thin ideal, but rather note an elective affinity that amplified the desire for thinness. The virtuosity of thinness is largely owed to the rise of Protestantism. Resisting the ‘temptations’ of the body, such as hunger, indicated moral purity and superiority (Owen 2007). The human body represented a vehicle to express this superiority by suppressing biological instinct. Hence, thinness was equated with righteousness,

and fatness with immorality Gluttony was regarded as a carnal sin in Protestantism (Schwartz 1986), as fatness was associated with being greedy, lazy, and ingesting ‘excess’ food. Lay citizens often looked down upon such qualities as they conflicted with the idea of righteous and frugal Protestant values. As individuals believed that adherence to the Protestant Ethic was a sign of their worthiness of a place in heaven, this belief led people to reduce their food intake and indulgence to act as a sign that they were spiritually among the righteous Although these expectations were universal, they had an exaggerated impact on women, in part due to the social and bodily ideals portrayed. Protestant churches began to monitor the amount of communion wafers given to women (Schwartz 1986) It later became common practice for women to ingest worms in order to “eat up the impurity they had consumed” (Galán-Puchades and Fuentes 2022). These connotations reflect Weber’s postulations on the Protestant Ethic of frugality and restriction, in the case of food consumption.

The thin ideal became increasingly attainable due to the “rationalization of the world” in the 17th century (Weber 2003:4) Progress in scientific rationalization made the knowledge of food items’ nutritional contents known New information became available about caloric content, and new methods for weight loss became accessible (Owen 2007). This awareness contributed to the labeling of certain foods as ‘good’ or ‘bad,’ and creating ‘eating orders’ of rules or regimens that dictated what to consume. Weber’s (2003:4) description of the magnitude of the capitalist system’s role in prescribing individuals an “unalterable order” as a way of life can be applied to the pursuit of thinness as well. Individuals of Weber’s time who pursued thinness had a distinct way of eating, exercising, and going about their day (Schwartz 1986) In 1903, psychiatrist Dr Piaget observed techniques used for weight loss among females, such as purging, restriction, and compulsive exercise (Jr, Hudson, and Mialet 1985). As further evidence of this magnification, the pursuit of thinness at its most extreme form can present

eating disorders, which were on the rise in the early 20th century (Owen 2007).

Weber’s (2003) assertion that functioning in a capitalist system invades everyday life and entraps individuals in a cycle applies in the context of thinness as well. His metaphor of the ‘iron cage’, in the context of the capitalist system, demonstrates how individuals lose their freedom by hyper-focusing on the acquisition of money, depleting their pursuits of religious virtues such as humility and modesty (Weber 2003:3) In this endless cycle, individual freedom is suffocated as humans are presented with an all-encompassing “immense cosmos” of how to act around food (Weber 2003:4). The iron cage in the case of thinness resembles capitalism’s relentless cycle of restriction, compulsion, and rigid routines such as long workdays, but with our relationships with food. Similarly to how Weber (2003:3) notes an attack on spontaneity at a time of capitalism, the pursuit of thinness restricted the ability of individuals to engage in social activities. The lack of freedom and abundance of rigidity around food simultaneously contaminated individuals’ aptitude for being flexible and spontaneous at social gatherings. Likewise, similar to how possessing a strong work ethic “communicat[ed] to the world” that one was a hard worker, being devoted to restrictive eating signaled discipline to the Protestant Ethic (Weber 2003:4). Akin to Weber’s analysis of the spirit of capitalism, thinness too was transferred from a means of religious reward to one of societal validation. The avoidance of ostentation was a Protestant virtue, yet the societal ‘prize of thinness’ took precedence

In conclusion, the elective affinity between the Protestant Ethic and capitalism can be extended to the pursuit of thinness. The ability to pursue thinness was amplified in a time of increasing rationalization and created an iron cage, akin to the one that evolved from capitalism. Hence, it is not surprising that frugality in terms of food manifested as a form of symbolic righteousness. Weber’s omission of the relationship between the pursuit of thinness and his Protestant Ethic thesis is a crucial oversight; it may be responsible for frugality at its most extreme form, take in the case of eating disorders (APA 2024) If this connection is valid, then a broader sociological implication is that achieving a thin physique in the modern day must be considered in an idealist sense. Current epidemics of eating disorders and ‘spirits of thinness’ that pervade society should be viewed with attention to their sociological context. The extension of Weber’s Protestant Ethic in the case of thinness indicates that when balance is .

sacrificed for rigid discipline, even virtues such as diligence and self-control can become dangerous

APA. 2024. “The ‘Silent Epidemic’ of Eating Disorders.” Retrieved November 21, 2024 (https://www.apa.org/news/podcasts/speaking-ofpsychology/eating-disorder).

Galán-Puchades, María Teresa, and Màrius V. Fuentes 2022 “On Hazardous Pills for Weight Loss and Cysticercosis.” The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 107(1):216 doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.22-0196.

Jr, Harrison G. Pope, James I. Hudson, and JeanPaul Mialet 1985 “Bulimia in the Late Nineteenth Century: The Observations of Pierre Janet ” Psychological Medicine 15(4):739–43 doi: 10.1017/S0033291700004979.

Owen, Lesleigh J. 2007. “Consuming Bodies: Fatness, Sexuality, and the Protestant Ethic ”

Schwartz, Hillel 1986 Never Satisfied: A Cultural History of Diets, Fantasies, and Fat. New York : London: Free Press ; Collier Macmillan

Weber, Max 2003 “The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism.” Pp. 74–81 in Social Theory: Roots and Branches, edited by Peter Kivisto. Roxbury Publishing.

Sydney Baxter

ResearchStatement

Understanding Sociological Factors Influencing Racial Preferences in Dating Among Young AdultsintheGreaterTorontoArea

Abstract

This study examines the sociological factors influencing racial preferences in dating among young adults in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA). Using qualitative interviews with individuals aged 19-22, the research explores how media exposure, peer reinforcement, and personal experiences shape dating preferences. Social Identity Theory and intergroup dynamics suggestthatmajoritygroupsmaintainthemeans of perpetuating values associated with attraction, influencing dating choices. Social Cognitive Theory further explains how repeated exposure to media, particularly TV shows featuring main characters in romantic roles, contributes to internalized racial biases This is accompanied by peer reinforcement in school environments, which strengthens ideals of attraction. The study finds that access to different racial groups and personal experiences play a significant role in shaping racial preferences, with positive portrayals in media having a stronger impact than negative stereotypes. A grounded theory approach was used to analyze interview data, revealing that racial biases are closely tied to exposure and reinforcement. Participants who grew up in racially homogeneous settings tended to favour the dominant racial group While the study is limited by sample size, it highlights the need for larger-scale research to further investigate the formation of racial dating preferences, challenging current mainstream ideas rooted in primarilynegativebias

Introduction

As Toronto is a diverse city (Statistics Canada 2022), the dynamics of romantic relationships and race is more likely to be a prominent topic of discussion The research question, “What sociological factors influence social attitudes towards racial preferences in dating within multicultural cities, considering elements such as cultural stereotypes portrayed in media and individual experiences?” guides this investigation with a specific focus on the dynamics between macro structures of media and culture, and microstructures of relationships. The increase in

minority racial demographics within the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) over the past decades (StatisticsCanada2022)offersaninterestingshift insocialattitudestowardsinterracialcouples.

The prevalence of racial preferences in dating has become increasingly evident, with online dating statistics and social media coverage shedding light on these preferences (AdeyinkaSkold 2025). From tropes of Black male hypersexuality to the perpetuation of submissive Asian women stereotypes, the media plays a significant role in shaping societal perceptions. Stereotypes perpetuated by the media can influence how race is constructed and viewed, shaping perceptions that influence social stratification. Historically, marginalized groups suchasBlackandBrownwomenhavefacedharsh realities when navigating romantic relationships due to socially perpetuated stereotypes. In turn, these factors impact their societal position due to reinforced stereotypes that spread under the guise of “preference”

This research contributes to a sociological understanding of racial dating preferences by addressing gaps in current knowledge on the social construction of race and dating Particularly, this study seeks to understand how young people in a multicultural society perceive and propagate racial preferences in dating. By examining the potential impact on societal perceptions and relationships, it aims to provide insights into the sociological aspects of racial preferences The practical implications of this research are significant, as it addresses the sociological root of racial preferences in dating Understandingthedynamicsof datingpreferences can inform strategies to promote inclusivity and diversity in interpersonal relationships, leading to amoretolerantandopen-mindedsociety.

Dating practices have undergone significant transformations in multicultural cities where diverse populations coexist. Understanding the sociological factors influencing social attitudes towards racial preferences in dating within these urban settings is crucial for comprehending the dynamics of contemporary relationships. This literature review explores the intersection of social attitudes, race, and dating practices, considering elements such as cultural stereotypes in media and individual experiences.

Social attitudes are shaped by factors in Social Identity Theory and intergroup dynamics. As proposed by Dovidio et al (2009), individuals derive personal esteem from group membership which motivates them to associate positive distinctiveness for their group. Members of the majority group (within the context of a physical space or place) are motivated to maintain their position and may employ strategies to protect their collective identity (Dovidio et al 2009) This can result in subtle biases in societies based on race and ethnicity which manifests intergroup bias that reinforces existing disparities (Dovidio et al 2009) On the other hand, minority group members will occasionally endorse the majority group’s ideologies, out of motivation to improve their social position and group status (Dovidio et al 2009)

To summarize, the authors claim majority and minority group attitudes are influenced by the preferred group’s representations. When analyzing racial preferences, background knowledge of the processes behind majority and minority groups helps dissect how certain attitudes arise in settings of majority racial groups within dating networks. A shift within majority group preferences impacts change in social attitudes towards racial preferences in dating In multicultural settings, individuals have more freedom to make dating choices outside their own racial identity as there is an increase in distinct group types present. This dynamic will help inform how underlying forces within majority group values can impact individuals’ social attitudes.

People learn the rules of racial classification, often without obvious teaching or conscious inculcation, and race becomes “common sense”. The seemingly consistent categorization of people based on identifiable physical attributes reinforces the notion that these categories are objective groupings (Obach 1999). This is consistent with Dovidio et al ’s (2009) findings on majority group bias, where racial classification establishes unequal power dynamics. Within interracial dating contexts, power dynamics between majority-minority racial groups shape people’s dating preferences. Bloch and Solomos argue dating preferences are intertwined with employment discrimination and racial media representations (Bloch and Solomos 2010). According to their claims, individual choices including dating, reflect broader racial ideologies (Bloch and Solomos 2010). The media’s role in constructing racial stereotypes can influence broader racial ideologies, which

can impact romantic preferences (Bloch and Solomos 2010) It is important to take into consideration the societal influences and personal biases that shape these romantic inclinations The processes outlined in the literature contribute significantly to understanding how race functions socially and affects dating preferences.

Sociological perspectives on love reflect two philosophical theories, with one emphasizing specific components that differentiate it from liking or lust, and the other suggesting a subjective, private experience for individuals (Owens 2007) Love typologies, like “love styles” and Sternberg’s Triangle Theory, categorize experiences and offer insights into the different beliefs and preferences that shape romantic connections (Owens 2007) Sternberg’s Triangle Theory may be applied to understand how individuals with different racial backgrounds navigate their preferences for intimacy, passion, and commitment. Owens (2007) further claims courtship is a public and intimate process that involves stages like rapport, self-revelation, and mutual dependency Through Filter Theory, she explains the significance of shared values and the need for complementarity (Owens 2007) On the other hand, dating is seen as a casual form of interaction that includes evolving goals, rules between partners, expectations of behaviour, and Homogamy (Owens 2007) Homogamy revolves around the idea that individuals choose people similar to them to form romantic relationships, which raises questions about how racial backgrounds influence individuals’ expectations and choices in relationships. This claim would be interesting to examine during data collection. She also highlights negative traits of relationships including deception and intimate partner violence Negative dating attributes and associations with racial groups in particular could also play a role in forming racial preferences, especially if such depictions are widespread and upheld Overall, Owens piece highlights important information on the function of dating based on sociological theory

Media plays a pivotal role in shaping perceptions of love (Banaag et al. 2014). Through the use of the Internet, media has become a powerful tool that spreads information, entertainment, and interpersonal communication The authors extensively explored the link between media exposure and its effects on individuals, particularly teenagers, whose exploration of societal expectations is often guided by information from mass and social media (Banaag

et al 2014) The Cultivation Theory, developed by Gerbner and Gross, claims that prolonged exposure to media can mould individuals’ beliefs and attitudes about their social environment (Banaag et al 2014) In addition, Social Cognitive Theory emphasizes observational learning, where individuals internalize societal values presented in media (Banaag et al. 2014). These theories highlight how individuals’ beliefs, expectations, and ideals regarding relationships can be impacted by exposure to media Relating to Owens’ article on the sociology of love and dating, the spread of negative or positive associations with specific racial groups in the media can be explained, through the lens of Social Cognitive Theory and Cultivation Theory, which could impact the social attitudes of individuals towards racial preferences in dating This idea is also supported by a study on media and interracial relationship acceptance by Lienemann and Stopp (2013). This article concluded that media contact positively influenced the inclusion of out-groups within individuals, which in turn had a significant positive effect on attitudes toward interracial relationships and Black people (Lienemann and Stopp 2013). Notably, the study supported that extended contact with media representations can enhance attitudes by allowing for the inclusion of out-groups in individuals and vice-versa (Lienemann and Stopp 2013) Thus, the media serves not only as a reflection of societal norms but also as a potent force shaping individuals’ understanding and expectations of love and relationships The connection between media exposure and minority racial groups will be further explored through the personal experience collected during the interview process

Methodology

ResearchDesignandSampling

Qualitative interviews were chosen as the primary research method for an in-depth exploration of individual perceptions and experiencesforabetterunderstandingof factors influencing attitudes towards racial preferences in dating This approach facilitated the exploration of patterns in socialization, individual understanding of racial stereotypes, and the diverse opinions of racial groups and dating preferences The sampling strategy targeted young people aged 18 to 25 currently residing in the GTA who were either open to romantic relationships or currently in relationships. Convenience sampling was used given the constraints of resources, drawing participants from the researcher’s personal network Thesamplesizeincludedsix

participants, two women and four men of various racial backgrounds, including queer-identifying participants

Data collection involved the development of an interview guide consisting of three major sections: media consumption; self-identified personal preferences in dating; and personal experiences First, media consumption focused on the internalized opinions of participants toward reference groups This determined what opinions they were exposed to concerning interracial relationships and race in the media The section also asked participants to reflect on how they think their racial and gender categories are perceived in broader society, highlighting the concept of Mead’s (1934) generalized other. These questions were also made to uncover implicit influences that the participant may hold, by gathering data on observed stereotypes in the media about specific racial groups. Second, the personal preference section focuses on participants’ explicit romantic preferences. The questions were categorized based on personality, physical, racial, and relationship dynamic preferences Additional follow-up questions were designed to gauge how much the participants valued the preferences listed Overall, these questions were organized to reveal physical preferences before racial preferences, to pinpoint specific physical feature preferences without the bias of directly being asked about racial preferences. Finally, the personal experience section focused on gathering data on the participant’s social network and real-life interactions. Given that social values do not necessarily translate to behaviour, the section acted as background context to socialization and an indicator for racial preferences Questions were asked about interactions with peers, past relationships, and pressure to conform to perceived immediate norms. Participants were also asked about past experiences with attraction, specifically to provide a chronological list and racial description of their romantic interests Essentially, these questions were designed for the purpose of gauging how racial preferences were playing out in real-world settings.

After the pilot testing stage, the interview guide was refined to focus more on the implicit reinforcement of racial preference norms from peers Interviews were conducted both in-person and over the phone, with recordings and transcripts made for analysis Detailed interview notes were taken during each session. Ethical considerations were paramount, with consent forms sent to participants via email for their review and signature, ensuring informed consent and confidentiality throughout the research Undergraduate Sociology Journal, Vol. 7, No. 2, 2025

process Efforts were made to mitigate researcher bias, particularly considering the researcher’s identity as a Black female Instances of potential biases, particularly in interactions with White male participants, were acknowledged, and steps were taken to ensure neutrality and sensitivity throughout the research process

In this study, a grounded theory approach was employed to analyze the qualitative data gathered through semi-structured interviews. The analysis process began with a thorough review of written interview notes, allowing for the refinement of the interview guide to focus more on key areas such as personal experiences. Preliminary open coding was conducted by highlighting key points in the written notes and formulating initial codes. These preliminary codes, including categories like “friend groups,” “childhood crushes,” and “reinforcement in schools,” served as a foundation for creating a coding outline in NVivo. During the coding process, transcripts were systematically coded into open codes, and similar concepts were sorted into focus codes. The final focus codes included perceptions, social network demographics, preferences, racial sentiments, media consumption, relationships, social values, andreinforcement

One prominent theme was media exposure. The theme can be split into two areas, positive exposure and lack of exposure During the interviews, participants were asked about childhood TV shows and movies Participants cited Disney as a recurring channel that they watched TV shows such as Austin and Ally, Wizards of Waverly Place, Good Luck Charlie, and Victorious, among others, were some examples used The commonality between the media that participants consumed between the ages of 7-14 was the feature of White main characters. Furthermore, all participants referred to White actors as their childhood crushes. After further investigation, participants also revealed that their peers were watching similar shows with mainly White actors

These actors were portrayed in specific roles such as rock stars, princesses, or popular girls/guys. Within the structure of these shows, other characters would perpetuate the idea that attractiveness relates to these specific roles through social dialogue in the shows. For example, characters would have romantic interests or verbally praise people in these roles, showing viewers that they are associated with attractiveness. I will label these specific roles as

Roles of Attraction I define this term as statuses socially associated with individuals who possess traits that garner attraction such as; conforming to accepted standards of physical beauty, intelligence, and charisma. Roles of attraction are socially negotiated and upheld by majority groups and are therefore reinforced throughout social networks As discussed by Bloch and Solomos (2010), majority groups determine broader norms, making racialized roles of attraction dependent on racial majority-minority groups in a given environment. The environment can be physical spaces such as neighbourhoods, or can be broader with regards to media consumption habits (i e , channels watched, accounts on social media, etc.).

Based on the idea of social scripts, if a group of children is consuming content depicting middle school/high school settings that consistently place White actors in roles of attraction, there could be an internalization of this type of constructed view Similarly, the lack of other races in roles of attraction can explain why participants’ initial racial preferences were all biased towards White people, despite the varying racial identities of participants. This is consistent with Social Cognitive Theory, which argues social habits and cues can be internalized through means of observation (Banaag et al 2014). Here, observation is achieved through exposure to TV entertainment that features particular people (e g White actors) in roles of attraction. And so, children internalize these media depictions of “attractive people” into their own racial preferences. The data suggests that positive portrayals are more impactful than negative stereotypes in the formation of racial preferences. Participants were asked to list negative and positive stereotypes they observed on social media about five racial categories: White, Black, East/Southeast Asian, South Asian/Middle Eastern, and Indigenous. The recurring negative stereotypes all participants listed when asked about what they thought were commonly held racial stereotypes during the interview process included: White people as ignorant, Black people as aggressive, and East Asian/Southeast Asian people as feminized. If current literature on racial bias rooted in negative stereotypes were salient, participants would avoid racial groups associated with negative traits they do not want in partners. Auelua-Toomey et al (2024) argue that cognitive processes combined with interaction with racial social identities in interracial relationships between Asian, Black and White Americans reinforce Eurocentric hierarchy beliefs. However, when participants were asked about nonnegotiable personality preferences in a romantic relationship, there were often stark

contradictions between racial preference and blanket racial stereotypes participants consumed in broader media One example is a Black female participant, Magnolia; and a Persian female participant, Hannah Magnolia and Hannah cited “understanding” as a non-negotiable personality expectation in a partner, yet both participants had a racial preference bias towards White people. The contradiction between the commonly held negative stereotype about White people being perceived as ignorant did not impact the racial preferences of Magnolia and Hannah

Another theme was reinforcement with peers as a crucial role in reinforcing social scripts derived from media portrayals. Circling back to roles of attraction, participants reflected on attraction stratification within their middle schools and high schools During the interviews, participants were asked to list what the perceived consensus was on specific traits that were reinforced as attractive in their schools. All participants cited White people explicitly, or White dominant traits (blonde hair, blue eyes) as the ideal partner, similar to the characters in roles of attraction in the commonly watched shows of themselves and their peers. This strengthens the argument that social scripts portrayed in media can be replicated in real-life settings Additionally, participants highlighted the normalization of interracial relationships in multicultural school settings and implicit reinforcement of White as the standard in predominantly White environments. Magnolia, Hannah, and Karl connected predominantly White school settings with White-centered concepts of the ideal partner. As a Black woman, Magnolia cited White men as her racial preference. Magnolia’s high school environment was predominantly White, and she cited those in roles of attraction at her school as having similar traits to those portrayed in popular Disney channel shows (i e , charismatic, athletic, and White). These roles were upheld through the social network of her school, as she mentioned other girls would discuss their attraction for men who fit the role. Being in an environment that reinforced the idea of Whiteness as the standard could lead to the internalization of Whiteness in roles of attraction, even if individuals identify with minority racial groups.

Personal experiences were identified as influential factors in shaping racial preferences, with access to racial groups and positive or negative experiences impacting preferences significantly. Karl identifies as a White Latino

man and mentions a shift in his racial preferences. Karl explained how he was in a predominantly White city, where Whiteness was reinforced through friends, peers, and family as the ideal racial preference for a partner He further explained that White women were his preference up until he began to date a biracial Black and White Latina girl He explained how this was an “amazing experience” and how the relationship opened his preferences for Brown and Black women.

“I can’t even lie I think I was also influenced a lot about life through my music taste as well I started getting a lot into like rap and a lot into like reggae when I was like 17 and so I guess I started listening to like artists that weren’t necessarily like white and so I started getting like a bit of like you know taste and likeness in other races and in other areas too so yeah”

He cited the following relationship with a White girl as a negative experience, which he attributed to her race Karl brought up instances of ignorance and “blandness” as to why he no longer has a preference for White women In contrast, Magnolia said there were no Black men in her schools or area. She attributed the lack of Black men’s physical presence in her environment to her lack of attraction towards that particular category This would suggest that experiences with romantic interests are constrained to available racial groups in a given environment. In the context of multicultural settings, increased access to different groups offers more racial diversity in dating habits

The common conception that racial preferences are active choices that people make when assessing potential partners is the status quo explanation of why people may not date certain races. During my research, it appears that the idea that a racial preference is a swift choice between preferable dating options vs nonpreferred options is not accurate. Participants showed an understanding of differences and openness to dating when asked directly, but in practice had biases towards certain categories The question of how these biases were formed related to two categories, (1) exposure and (2) reinforcement.

The category of exposure deals with media exposure and the racial demographic(s) participants grew up with. The media participants consumed shared a common experience of watching Disney Channel in their youth Due to participants’ ages ranging from

19 to 21, the shows watched aired during the early 2000-2010’s, and the majority of shows on Disney Channel at that time had White actors. It was also mentioned that peers of participants were watching Disney Channel shows as well. This would suggest that the consumption of specifically Disney Channel was widespread and highly influential The topic of childhood crushes also revealed additional suggestions that consuming White-centered media content at a young age influenced the perception of what an attractive person is All participants cited a minimum of one White celebrity crush despite the differences in aspects of their social identities including their gender, race, sexuality, and country they grew up in. This phenomenon can be explained using Social Cognitive Theory When individuals observe media content, there is potential to internalize aspects of what is portrayed (Banaag et al., 2014). In this case, the celebrities participants cited as childhood crushes played roles that are associated with attractive people In the context of Social Cognitive Theory, White people disproportionately holding Roles of Attraction in the media that was consumed by the participants could have significantly impacted what they internalized as attractive.

Reinforcement

Disney Channel shows portrayed plots revolving around characters within similar age ranges to the participants at the time of viewing Cultivation Theory claims that prolonged exposure to media can impact individuals’ perceptions of their own social environments (Banaag et al. 2014). By picking up on the social scripts embedded in the shows that were widely consumed, Cultivation Theory can explain how these values transitioned to real-life attraction standards in the school environments of the participants This leads to the second aspect of exposure, demographics. Four of the six participants went to predominantly White high schools while the other two went to predominantly East Asian high schools Five out of the six participants had a racial bias towards the dominant race they grew up around, with one outlier. Dovido et al. (2009) explanation of majority versus minority groups and social attitudes offers the theoretical framework for how these results may have occurred. In this scenario, the majority group was responsible for reinforcing dating ideals as participants cited people within the majority group being deemed as the “standard” at their respective schools, often ending up in relationships more frequently than other groups. It is also interesting to note how the standards in predominantly White schools reflected the traits used to describe

characters in roles of attraction on Disney Channel, which include language such as “Jock” or “Popular” to describe people. Yet in schools where there was little white presence, the standard shifted to the majority group. This suggests that although media consumption played a primary role in the formulation of racial attraction bias, without the in-person day-to-day reinforcement of these ideals, individuals became biased towards the majority group in their immediate environment instead

This can be seen with three of the six participants, as they were racial minorities in their environments but developed a racial bias towards the majority group in their environment However, it appears that individuals are not completely constrained to the majority group, as the outlier Karl had similar results with the participants of Lienemann and Stopp’s study (2013) on media exposure. In this study, researchers concluded that prolonged exposure to positive reinforcement of minority groups can positively enhance individuals’ perceptions (Lienemann and Stopp 2013) Karl was the only participant who cited prolonged exposure to a minority culture (Black culture), and therefore engaged with portrayals of Black women in roles of attraction through the lyrics and videos of the music he was consuming. This was followed by a relationship with a mixed Black woman which he said was very enjoyable. This could have acted as the in-person reinforcement which combined with the positive media portrayals shifted his racial bias towards Black and Brown women instead of his previous bias towards White women.

In contrast, negative stereotypes did not appear to have a lasting impact on participants’ racial biases Bloch and Solomans (2010) claimed that racial ideologies portrayed in the media affected dating choices Based on my research, this was partially correct. While positive portrayals in the media had a significant impact on individuals, negative portrayals seemed to not have an impact. Given the taboo nature of stereotyping races, interview questions were formulated to mitigate social desirability. Participants were asked to describe negative and positive racial stereotypes they saw in the media, which was then compared to what qualities they preferred to have in a partner's personality. Positing the stereotypes as what “others” have said allowed participants to more freely discuss the topic. Essentially participants still extracted information from their schemas, shaped by personal experiences, about specific racial group stereotypes This comparison would partially reveal if there is a correlation between internalized stereotypes, personality

Undergraduate Sociology Journal, Vol. 7, No. 2, 2025

preferences, if the preferences were non–negotiable, and the racial dating/ interest history of the individual to confirm the true racial bias of the individual Due to interviews being the vehicle of data collection, there is the possibility that participants had negative sentiments toward dating particular races and did not voice this opinion, which would limit the effectiveness of this method. However, in terms of personality preferences, participants shared around 70% similarities across sexualities, gender, and race of the individuals. The contrast between the differences in racial biases and similarities in personality preferences is an area of further investigation, as any racial group can possess traits of kindness, understanding, loyalty, and respect which were consistently highlighted as the most important factors when considering a partner.

This study addresses the sociological roots of racial preferences in dating, emphasizing how social structures and cultural influences shape individualchoices.Understandingthesedynamics can inform strategies to promote inclusivity and diversity in interpersonal relationships, fostering a more tolerant and open-minded society By examining the intersection of race, attraction, and socialization, this research contributes to a broader sociological understanding of racial dating preferences, filling gaps in existing knowledge on how race and romance are socially constructedandconnected

The findings of this research provide insight into contemporary social attitudes toward dating and racial preferences, offering a lens through which to assess the broader societal impact of media portrayals and interpersonal relationships. Itexaminestheevolvingnatureof datingthrough a sociological perspective, which is crucial for understanding shifts in social attitudes toward raceandattraction.Thestudyrevealsthatmedia, particularly television shows with White main characters in Roles of Attraction play a significant role in shaping racial preferences The consistent portrayal of White individuals as desirable romantic leads, coupled with the absence of diverse racial representation in similar roles, contributes to participants initially favoring White partners, even when their own racial identities differ This process of internalization reflects the broader influence of cultural narratives in shaping individual perceptionsof desirability.

Potential limitations of the qualitative interview methodology include the possibility of participants providing inaccurate information on preferencestomaintainsocialdesirability.

Furthermore, the sample size and composition may constrain the generalizability of the findings, particularly considering the use of convenience sampling and missing racial categories in the sample. Large-scale studies on the topic of roles of attraction and the socialization process of racial preference should be conducted for higher external validity Given the limitations on sample size, further exploration into specific demographics of gender and sexuality can offer insight into how factors of larger gender roles and norms contribute to racial preferences. A suggestion would be utilizing mixed methods. Surveys can be adopted using the main categories used in the study (Media exposure, local social values in dating, and self-reported personal experience) to quantify patterns in environmental exposure to race and racial preferences while maintaining deeper personal perspectives through interviews.

Additionally, the study highlights the role of peer reinforcement in solidifying social scripts derived from media portrayals. Participants associated predominantly White school environments with White-centered ideals of attraction, reinforcing the racial preferences already shaped by media exposure. This suggests that racial preferences in dating are not simply personal choices but are socially cultivated through repeated exposure to dominant racial narratives. The research also indicates that positive portrayals are more influential than negative stereotypes in the formation of racial preferences. Representation that frames particular racial groups as desirable and aspirational plays a more defining role in shaping attraction than overtly negative depictions of other groups. Personal experiences also significantly impact racial preferences, with access to different racial groups and the nature of those interactions influencing dating choices Encounters with diverse racial communities, whether positive or negative, shape how individuals conceptualize attraction and compatibility The study challenges the notion that racial preference is an autonomous decision, suggesting instead that it is deeply embedded in social structures, cultural exposure, and reinforcement mechanisms Ultimately, this research highlights the importance of critically examining the ways in which race and desirability are constructed, offering a foundation for broader conversations on inclusion, diversity, and social change in the realm of dating and relationships

References

Auelua-Toomey, S. L., and Roberts, S. O. 2024. “Romantic racism: How Racial Preferences (and Beliefs about Racial Preferences) Reinforce Hierarchy in U.S. Interracial Relationships.” Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology 30(3):532–552. https://doi org/10 1037/cdp0000592

Adeyinka-Skold, S. (2025). Not My Type: Automating Sexual Racism in Online Dating. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 0(0). https://doi org/10 1177/23326492251321481

Banaag, M. E. K. G., K. P. Rayos, M. G. AquinoMalabanan, and E. R. Lopez. 2014. “The Influence of Media on Young People’s Attitudes towards their Love and Beliefs on Romantic and Realistic Relationships ” International Journal of Academic Research in Psychology 1(1):78–87. http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARP/v1-i1/7390.

Bloch, A , and Solomos, J 2010 “Key questions in the Sociology of Race and Ethnicity ” Race and Ethnicity in the 21st Century, pp. 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-07924-4 1.

Dovidio, J F , S L Gaertner, and T Saguy 2009 “Commonality and the Complexity of “We”: Social Attitudes and Social Change.” Personality and Social Psychology Review 13(1):3–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868308326751.

Lienemann, B. A., and H. T. Stopp. 2013. “The Association Between Media Exposure of Interracial Relationships and Attitudes Toward Interracial Relationships ” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 43(S2) https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12037.

Mead, G. H. 1934. “Play, the Game, and the Generalized Other ” Pp 152–164 in Mind, Self, and Society from the Standpoint of a Social Behaviorist, edited by C. W. Morris. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Obach, Brian K 1999 “Demonstrating the Social Construction of Race ” Teaching Sociology 27(3):252–257. https://doi.org/10.2307/1319325. Owens, E. (2007). “The Sociology of Love, Courtship, and Dating.” 21st Century Sociology. https://doi org/10 4135/9781412939645 n26

Schunk, D H 2012 “Social Cognitive Theory. In K. R. Harris, S. Graham, T. Urdan, C. B. McCormick, G. M. Sinatra, & J. Sweller (Eds.), APA educational psychology handbook, Vol. 1. Theories, constructs, and critical issues (pp. 101–123). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13273-005.

Statistics Canada. 2022. “2021 Census: Citizenship, Immigration, Ethnic Origin, Visible Minority Groups (Race), Mobility, Migration, Religion: Backgrounder.” City of Toronto. Retrieved May 2, 2025 (https://www.toronto.ca/wpcontent/uploads/2023/03/8ff2-2021-CensusBackgrounder-Immigration-EthnoracialMobility-Migration-Religion-FINAL1 1corrected pdf)

“I’d Rather Die, and Die

Jenkin Yuen

Abstract

This essay examines the issue of elder abuse within nursing homes in Hong Kong. As a multifaceted issue, both physical and emotional abuse are prevalent in these nursing homes, and are illustrated by specific case studies such as the Cambridge Nursing Home scandal in this research, illustrating the pervasive and institutionalized nature of this issue. This essay examines how Hong Kong’s urban landscape and socio-economic conditions – characterized by overcrowding, limited land, and an ageing population – act as structural factors that contribute to the issue of elder abuse in nursing homes Intersectionality and disposable ties are two relevant and useful conceptual frameworks that can help with interpreting the issue through the lens of urban sociology. The former helps us understand the causal relationships and tensions between environmental, socio-economic, and cultural factors that contribute to the issue; whereas the latter offers a way of interpreting the elderly’s resistance to the abusive conditions within nursing homes. In conjunction with the aforementioned causal link embedded with pervasive cases of mental heath issues, this paper illuminates several consequences of elder oppression within nursing homes, such as suicidal ideation

Introduction

This research paper is motivated by the hidden and unaddressed part of elderly social isolation in Hong Kong. While the intersection of alienation, loneliness, and ageing among elderly people is studied and discussed by existing works in general, this paper aims to unveil this social problem in the particular context of Hong Kong. With regard to this area or topic of study, current literature mostly covers the general ongoing problem of social isolation in Hong Kong (Chou 2018; Lee and Chou 2019; Rodrigues et al 2022; Sit et al 2022; Wong et al 2017; Yeung et al. 2020). As such, my essay attempts to fill this gap in existing literature and societal discourse surrounding the specific issue of elderly abuse in nursing homes – another indication or aspect of Hong Kong’s wider

elderly social isolation problem. Despite its severity, the issue remains conspicuously underexplored and inadequately addressed within both scholarly literature and sociopolitical spheres. The dearth of comprehensive research surrounding this specific, overlooked issue highlights the urgency for scholarly inquiry. Thus, this also constitutes the significance of my research.

By exploring this specific issue and how it reinforces the broader alienation issue of ageing individuals, this research presents itself as a work of urban sociology, as it attempts to attribute the problem to the physical and structural factors that stem from Hong Kong’s urban landscape. The essay title also presents an imaginary quote or dialogue, “I’d rather die, and die alone.” This part aims to portray the perspective of an elderly individual who experiences abuse in elderly nursing homes, as a way to draw readers’ attention to the severity of the issue, and its resulting sense of despair among these elderly people The design of this imaginary quote involves two key parts of their mindset: first, their wish to “rather die” – to commit suicide than continue living; and second, their wish and tendency to “die alone” –inspired by the work of Dying Alone by Eric Klinenberg (2001) Although the current literature does not directly explore the issue being studied, some of its insights can still be made use of as pieces of evidence in my analysis, especially since this paper relies on literature review as its major methodology. Therefore, this paper intricately connects both scholarly academic and news agency sources, the latter providing empirical findings on the susceptibility of elder abuse in Hong Kong nursing homes

Through an exploration of the structural constraints, cultural expectations, and lived experiences of elderly residents in Hong Kong’s nursing homes, this essay aims to elucidate the issue of elderly abuse within an urban landscape characterized by overcrowding, limited land, ageing population, and socio-economic pressures Building upon that, this essay offers sociological interpretations of the problem, including the tension between socioeconomic

Undergraduate Sociology Journal, Vol. 7, No. 3, 2025

status (SES) and filial piety intersection between structural factors, and the formation of disposable ties as survival mechanisms Ultimately, the analysis is for the sake of explaining the extreme suicidal mindset among elderly in Hong Kong as the final impact.

Issue Overview: The Categories of Institutional Abuse Against Elders In Hong Kong

Physical Abuse

Elder abuse in nursing homes in Hong Kong comes in two main forms: physical and emotional. Regarding physical abuse, it manifests in egregious acts that violate the physical well-being of elderly residents and lead to negative health impacts, such as sleep deprivation, frequent sickness, and hunger. As a way of illustrating the state of physical abuse in elderly nursing homes, it is marked by a series of incidents, documented in past news reports

One such incident unfolded at the Cambridge Nursing Home, where elderly residents were subjected to dehumanizing treatment, as revealed in a scandal that erupted in May 2015 (Lau 2015; Tsang 2016) Incipiently, reports revealed that early individuals were compelled to endure the humiliation of waiting naked on the rooftop before being allowed to take a shower (Lau 2015). Furthermore, elderly residents were identified as “stripped and exposed” outside the premises both before and during showering (Chan 2015). Photos and videos taken by reporters at that time captured a group of elderly residents being bathed by the nursing home’s staff altogether using hose nozzles, watering wands, sprays, and buckets of water (Chan 2015) Not only do such practices abuse affect elderly residents individually, but also perpetuate a culture of institutionalized abuse among elderly nursing homes in Hong Kong, wherein vulnerable elderly individuals are treated as objects of convenience –rather than deserving recipients of care. In response to the violations of physical abuse at the Cambridge Nursing Home, authorities took legal action by terminating the Cambridge Nursing Home’s facility license (Ngo and Lai 2015) Nevertheless, this only signals a willingness to address this as an individual case of elder abuse, not systemically; also, only if it is as extreme as this case example Further exacerbating concerns surrounding elder abuse in nursing homes, another disturbing case that came to light involved a caretaker at the same elderly nursing facility, the Cambridge Nursing Home, who physically assaulted a wheelchair-bound elderly man (Lau 2015). After being captured on video by a resident using a smartphone, the caretaker

admitted to the act of abuse (Lau 2015)

As a third case example, the pervasiveness of elder abuse in nursing homes is further highlighted by a case in 2020 involving the death of an elderly man, Wong Chi-shing (Wong 2020b) Despite being found to have died of pneumonia, an inquest revealed that Mr Wong was also found to have foreign objects, including gauze and tape, in his rectum (Wong 2020b). While nursing staff denied any wrongdoing, suspicions lingered regarding the circumstances surrounding his death, with his relatives alleging retaliation in response to a prior complaint.

These case studies and examples illustrate the severity of physical abuse in elderly nursing homes. Beyond that, the resulted loss of dignity and ongoing vulnerability to physical abuse itself extend to the emotional aspect of abuse as well

The loss of dignity that elderly residents experience embeds the emotional toll of elderly abuse. As demonstrated in the Cambridge Nursing Home scandal, many elders experience a marginalized sense of dignity from being subjected to acts of degradation and dehumanization.

Additionally, the cases of physical abuse in nursing homes highlight an ongoing vulnerability through perpetual cycles of psychological trauma among elderly residents. Through constant threats of both physical and structural harm, many residents remain susceptible to potential acts of victimization and misconduct These ontological insecurities amplify the degrees of emotional trauma, which in turn exacerbates psychological factors of mental health illness, including anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder As these risk factors for mental illness persist among Hong Kong’s aging population, this merits a deeper investigation of the various consequences of mental illness

Besides, emotional abuse may also take more subtle forms, such as the use of threats for verbal intimidation or psychological manipulation, which can be equally damaging to the individual's emotional well-being (Rivers 2024) The previous paragraph demonstrates how emotional abuse is caused by or stems from the susceptibility to physical abuse On top of that, reciprocally, emotional abuse can also inflict further physical abuse, or be imposed upon elderly residents in the form of more physical abuse. Often, to reach the goal of intimidating or manipulating residents emotionally, physical forms of violence are used by nursing home staff members to deter the elderly from certain behaviours (Lau 2015).

Therefore, emotional abuse encompasses another case of abuse in Hong Kong nursing homes While these findings suggest higher palpabilities of physical abuse, emotional abuse takes an exceptional toll on the psychological factors of mental health, leaving many elders susceptible to both distress and trauma It demonstrates a crucial recognition of the complex interplay between both physical and emotional cases of abuse that shape the marginalization of elder livelihoods

This section exposes the structural factors that shape the ongoing cases of elder abuse in

Hong Kong nursing homes. Additionally, it elaborates on the causal dependency between the structural factors and the context of Hong Kong’s urban landscape Land Scarcity and High Population Density: The Absence of Residential Options Besides Overcrowded Nursing Homes

The overcrowded urban landscape of Hong Kong is derived from its limited land availability (alias land scarcity) which poses a significant challenge to the provision of both housing units (or residential buildings) for elderly people and nursing home (or care-taking) facilities Statistically, Hong Kong’s total area is 2754.97 km2, with a land area of 1050 km2 and the fourth-highest population density around the world (7140/km2) (Hong Kong SAR Government Census and Statistics Department 2023). On the first level, land scarcity causes limited residential options for elderly people to live in, or for their adult children to place their elderly parents in, especially also due to the extremely high and increasing housing prices as a result of land scarcity Thus, this leaves adult children with no choice but to place their elderly parents in nursing homes On the second level, the accessibility and availability of nursing homes themselves are inadequate due to land scarcity. Limited land availability disallows inadequate construction and operation of sufficient elderly homes that are spatial enough to accommodate the relatively large number of elderly inhabitants as well. As a result, this leads to an unbalanced supply of and demand for nursing homes.

As residential housing demands compete with the need for institutional care facilities, resources are stretched thin, exacerbating the shortage of available options for elderly care. This is not a mere influence on the physical infrastructure of nursing homes, but also on the quality and accessibility provided to elderly residents because the former affects the latter by confining excessive numbers of residents in a limited, physical space. The cramped quarters and overcrowded conditions within most nursing homes reflect the broader struggle for space in Hong Kong’s urban environment – characterized by a high population density Residents find themselves living in close quarters, with limited privacy and personal space Not only do such conditions compromise the comfort and wellbeing of elderly individuals, but create an environment ripe for abuse and neglect as well. Moreover, the limited land availability of land for expansion hampers efforts to address the systemic issues plaguing the elder care system, perpetuating a cycle of inadequate care and institutional failure

The spatial problem is itself a problem of quality – not just an environmental problem of quantity. On a side note, due to their goal of profitmaximization more than as a community service or initiative, nursing homes take advantage of the land scarcity factor. In doing so, they try to accommodate as many elder residents as possible in the facility – as long as they seek and reach out for such services, and frames land scarcity as an ongoing problem that has adversely affected elderly people’s basic livelihood. Then, they frame themselves as a rare chance for Hong Kong elderly people to have a shelter.

Hong Kong faces a demographic transition characterized by an ageing population; in 2021, over a fifth of the population was reported as aged 65 or older (The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region 2022). According to the United Nations, this percentage is projected for an estimated increase by 40% by 2050 This is controversial, as several nursing homes frame a hospitable service by accommodating the increasing cases of elders in need, despite exceeding the maximum occupancy of residents

As another structural factor in Hong Kong, the unaffordability of alternative care options for elderly individuals increases the reliance on elderly nursing homes as the primary or most accessible care-taking service provider, which contributes further to the risk of abuse within these settings Major alternatives include, for instance, hiring a Filipino or Indonesian foreign domestic helper (FDH) from specialized agencies within the formal, institutionalized system, or the adult children taking care of their elderly parents by themselves – in the case of elderly individuals who have (an) adult child(ren). However, to be explained below, both alternatives are less affordable compared to elderly nursing homes, hence making nursing homes the more dominant care-taking service provider in this oligopoly of the elder care industry

First, the high cost of hiring FDHs places a significant financial burden on families who are already struggling with the high cost of living in Hong Kong This is especially seen among adult children who are already spending a larger part of their disposable income on housing rents of the unit they themselves live in, again, owing to land scarcity, and do not have enough money left for hiring FDHs for elderly relatives.

As a result, with less adequate services and facilities, and despite this being known by the adult children already, elderly nursing homes control price-setting in the market of elder care by setting a more “affordable” price for adult children. Here, “affordable” refers to any price that is amply lower than the total cost of hiring a FDH. Not to mention, hiring a FDH only tackles the care-taking part, the shelter/accommodation part is still not tackled, and even becomes a heavier burden because hiring a private helper requires providing shelter for both the elderly person and the helper. As such, the total cost of hiring a FDH to be borne by an adult child is not just the amount of wage received by the helper, but also including a separate housing unit that can accommodate both their parent(s) and the FDH. The minimum wage for a FDH is HK$4,630 (~US$600) per month, plus accommodation and food (or food allowance), plus return airfare to/from their home country at least once in every two-year contract (AIG Insurance Hong Kong 2021) This amounts to over HK$25,000 (~US$3200) per month, while the average monthly salary in Hong Kong is only HK$36,500 (~US$4650) (Hong Kong SAR Government Census and Statistics Department 2024). The average price of traditional elderly homes “range[s] from HK$8,000 [~US$1020] to $14,000 [~US$1780] per month, excluding extra services” (Kwok 2020) Therefore, nursing homes manipulate the market of supply and demand of/for elder care services, forcing lower- to middle-class adult children to send their elderly parents there as a superficially “affordable” option Second, the demanding work culture in Hong Kong further complicates the issue, making it difficult for adult children to provide care for their elderly parents by themselves With long working hours, frequent over-time working, and – in some cases – the pressure to maintain multiple jobs in order to earn enough money, many adult children consider taking care of their parents by themselves a very difficult task, causing an imbalance between their demands of work and caregiving responsibilities (Chan et al. 2021; Ko et al. 2007; Ng and Feldman 2008; Wong et al 2019; Zou and Leung 2019). As a result, they are forced to resort to placing their elderly parents in nursing homes despite the infamously low quality of care provided in most of them

This section analyses the structural factors of elder abuse in Hong Kong nursing homes by drawing on the interplay of these factors and the concept of disposable ties Incorporating these theoretical frameworks will expose a complex interplay between social identities and dynamics of power, in addition to its role in perpetual elder abuse cases within Hong Kong’s urban landscape.

Understanding the Causal Relationships and Tensions between Environmental, Socio-economic, and Cultural Factors

First, the interplay between socioeconomic status (SES) and filial piety represents a fundamental tension within the “elderscape” of Hong Kong, particularly in the case of elderly individuals who have adult children. Unlike in western cultures, filial piety is a traditional principle of ethical conduct in Chinese culture, as it prescribes adult children with various moral obligations to supervise the needs of their aging parents. In this context, filial piety functions as a cultural factor, whilst SES acts as a socio-economic factor by virtue of personal income The inherent cultural essence notwithstanding, filial piety is rarely indispensable in situating elderly parents in nursing homes, irrespective of being conscious of risking their vulnerability to an abusive environment. In essence, the verdict of allocating elderly parents to nursing homes is less concerned about choice than about obligation On account of experiencing socioeconomic barriers to healthcare alternatives, lower-class families may be obligated to approach nursing homes as an affordable option for senior health care; conversely, upper-class families can afford various alternatives to palliative care, including FDHs, professional maids, as well as intrafamilial caregiving practices. Correspondingly, the intersection of SES and filial piety highlights two key consequences: 1) the development of one variable constraining the other, and 2) the perpetuation of disparities across elder care based on socioeconomic barriers to a widespread accessibility of healthcare service providers

The second intersection highlights a multifaceted dynamic between unaffordable care alternatives and the demanding work culture in Hong Kong, which further perpetuates the

reliance on elderly nursing homes While the paper previously characterized Hong Kong’s demanding work culture as a structural barrier to caregiving, this inequality is also shaped by an unequal distribution of affordable health care. That is, I present a complex interplay between the following two factors: A) demanding work culture, and B) unaffordable health care alternatives. On the one hand, the causal link from A to B characterizes Hong Kong’s demanding work culture as a systematic obstacle to caregiving for the needs of elderly parents. On the other, from B to A, the structural factors of affording alternatives to health care include various practices of increasing SES such as dual employment, which thereby reifies the implications of a highly demanding work culture Thus, recognizing the dialectic or symmetrical nature in the relationship between the two variables – one cultural and the other economic – is imperative to unravelling the causal factors of elder care inequality.

Third, this issue pinpoints an intersection between land scarcity and an ageing urbanized population in Hong Kong. On account of adjusting high levels of supply and demand for elderly nursing homes, land scarcity restricts supply, whilst the ageing population increases demands, thereby widening imbalances between the supply and demand of health care services Noteworthily, as both factors shape these disparities by virtue of being commonplace within the urban context of Hong Kong, this structures a push and pull effect on both the supply of and demand for elder health care provision Additionally, both factors may not necessarily produce a similar outcome simultaneously, but the magnitude potentially owes to the co-existence of the two factors within Hong Kong’s urban landscape This demonstrates a habitually inconsistent intersection between land scarcity and an ageing urbanized population, that nevertheless characterizes the result of an insufficient access to health care beyond elder nursing home institutions.

Disposable ties is a term coined by Matthew Desmond (2012) in his work of Disposable Ties and the Urban Poor to refer to the interpersonal ties that lack authentic, emotional connection between the stakeholders. The concept originated as a way of understanding how urban

Sociology Journal, Vol. 7, No. 3, 2025

individuals rely on these ties as a survival strategy to, for instance, ensure one’s own accessibility to certain resources or necessities through mutual effort (Desmond 2012) In this subsection, I argue that the concept helps us understand how elderly residents in nursing homes use it as a survival strategy against abuse, but falls short in depicting the full picture as it understates the emotional authenticity and depth of the ties

In arguing for the effectiveness of this conceptual framework in describing the issue, the elderly residents indeed rely on each other’s help to lower their risk of being abused in the nursing homes. For instance, they help each other lie about certain things, such as behaviours that they might have engaged in but are unaccepted or not tolerated by the badtempered and unreasonable nursing home staff, or according to unreasonable, unwritten rules and standards in these nursing homes (Cheng et al. 2010; Yang et al. 2020). Often, this mutual aid of hiding or lying about certain things for each other among the residents is a survival strategy to counter physical abuse Additionally, with shared experiences of physical and emotional abuse, such as constantly being intimidated and manipulated by nursing home staff, the residents share mutual empathy by relating to each other’s feelings of despair, loss of self-dignity, etc. (Cheng et al. 2010). This provision of emotional support and companionship for each other is another survival strategy to resist the physical and, especially, emotional abuse.

However, as one would normally notice, there is a contradiction between the original definition of disposable ties and what is seen between the elderly nursing home residents – the absence and presence of deeper emotional ties respectively First, they offer emotional support to one another by relating to each other’s experiences of abuse in the nursing homes and the corresponding feelings of despair and torment, as mentioned above. Second, besides the abusive experiences, they also relate to each other’s general feeling of loneliness as an ageing individual in a fast-moving urban city. In these homes where a group of elderly is gathered, emotional resonance takes place. Therefore, based on these two levels of emotional support, the ties between elderly residents in nursing homes are not always purely disposable or formed out of absolute necessity, but characterized by deeper emotional understanding too. In this case, the conceptual framework only represents a part of the situation.

The mental health of Hong Kong’s elderly population is a growing concern, with increasing rates of depression, anxiety, and chronic loneliness observed in recent years. A survey conducted by the Sau Po Centre on Ageing found that about 10% of respondents reported experiencing severe chronic loneliness (Knott 2020). Moreover, another study found that one-third of elderly individuals surveyed exhibited at least one of depression, anxiety and chronic loneliness symptoms (CE Noticias Financieras 2022) These findings underscore the heavy mental health burden faced by the elderly population in Hong Kong while struggling to cope with feelings of despair and hopelessness

The social impact of mental health issues in Hong Kong are eminently common among seniors, particularly through the demographic consequences of suicide In 2022, more than 1,080 suicide cases were accounted in Hong Kong, with 40% of these cases involving a demographic age structure of 60 and older (CE Noticias Financieras 2022). This accounts for a suicide rate nearly twice the population average of Hong Kong. Furthermore, the societal implications of these cases remain severe, as Hong Kong’s suicide rate increased by 5% from 2018 to 2019 (Yip 2020) These statistics demonstrate the prevalence and severity of suicide cases involving seniors in urbanized contexts. The extent of suicidal ideation among victims of elder abuse will be investigated in the sequential sub-section. In 2022, Hong Kong recorded 1,080 suicides, with more than 40% of them occurring among individuals aged 60 and older (CE Noticias Financieras 2022) That means, the suicide rate among older adults in Hong Kong is nearly twice the population average. Besides, the problem of suicide among Hong Kong elderly is not just severe, but increasingly severe, as the suicide rate increased by more than 5% from the year of 2018 to 2019 (Yip 2020) These statistics underscore the severity of the issue within this urban demographic In the next sub-section, the ways in which the issue leads to the mental problems and suicide mentality will be explored

From Nursing Home Abuse to Elderly Suicidal Mindset

This subsection highlights three crucial levels of impact on the mental health of elder populations in Hong Kong from perpetual cases

Undergraduate Sociology Journal, Vol 7, No 3, 2025

of abuse. Based on the interconnection between these pathways, the cases of abuse in nursing homes amplify elderly mental health issues.