Mapping

Mapping

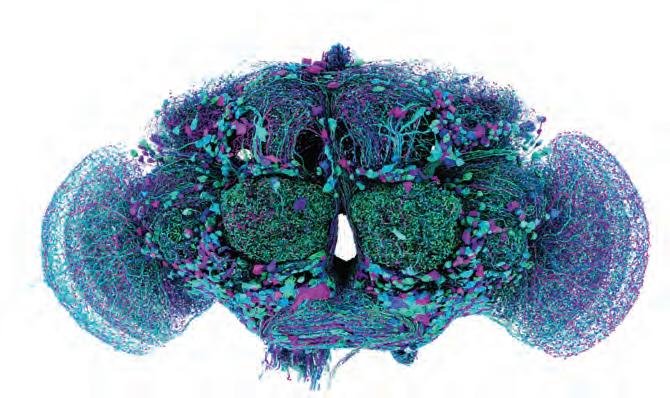

Researchers untangled every neuron in the tiny head of a fruit fly. Co-led by UVM scientist Davi Bock, this first-ever brain map provides insight into how animals—including you—think.

| BY JOSHUA BROWN

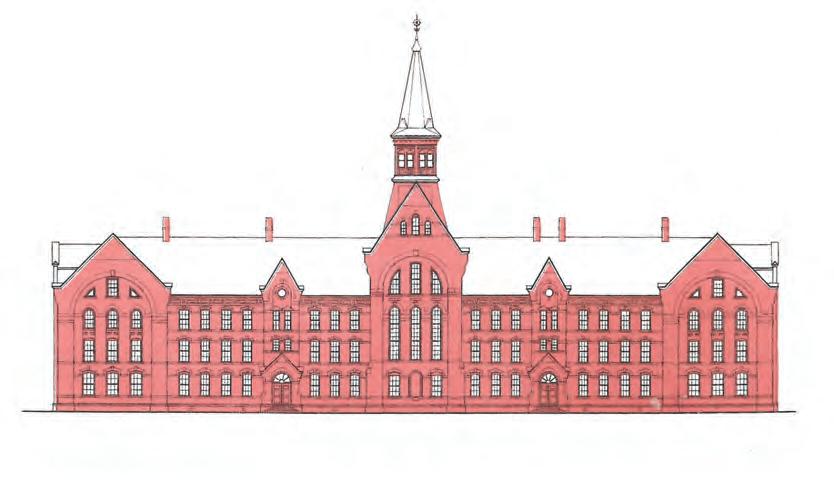

Two centuries ago this summer, General Lafayette helped dedicate the centerpiece of UVM life: Old Mill.

| BY ED NEUERT

TICK... TICK... BOOM

Researchers across UVM work to understand the spread of tick populations, and to help develop a vaccine against Lyme disease.

| BY KRISTEN MUNSON

FRONT COVER: Color-enhanced Scanning Electron Micrograph of Drosophila melanogaster, also known as the common fruit fly or vinegar fly. Live, unfixed specimen; natural state. Magnification: 210X

David Scharf / Science Source

An estimated crowd of 4,000 joined the Vermont men’s soccer team on the Church Street Marketplace on Sunday, January 26, to celebrate the Catamounts 2024 National Championship. The Catamounts processed up Church Street to the top of the block, where fans and invited guests gathered around the stage to hear from the National Champions. Director of Athletics Jeff Schulman’89, UVM Interim President Patty Prelock, Burlington Mayor Emma MulvaneyStanak, and Vermont Governor Phil Scott spoke to the crowd about the Catamount’s achievements and their lasting effect on the state of Vermont.

Mulvaney-Stanak concluded her remarks by reading a Burlington proclamation declaring January 26, 2025, “University of Vermont

Men’s Soccer Team Division I National Champions Day.”

Head Coach Rob Dow and players Nick Lockermann, Adrian Schulze Solano, Yaniv Bazini, and Zach Barrett addressed the crowd, thanking Catamount Country for their support all along the way to the championship.

“The support you have given us throughout this whole season, throughout this whole tournament especially in the Final Four, was just outstanding. It was amazing,” said Schulze Solano. “It lifted us up and it pushed us in every moment. It meant so much for the team. Playing in front of the green wall in North Carolina–we will never forget it our whole lives.”

Read more on page 22.

Use a mobile camera to scan the QR, or visit go.uvm.edu/paradevid to watch a video recap of the celebratory parade.

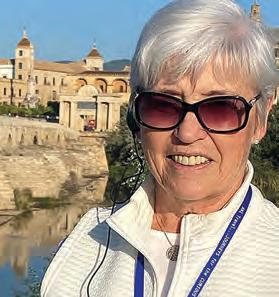

Spring, when it finally arrives in Vermont, is a time when we start to make new plans, and make room for change. It is at this time of the year that our seniors look forward to commencement and the beginning of a new journey. And in a few weeks Dr. Marlene Tromp will join UVM as its 28th President. I know our entire community looks forward to welcoming her.

President Tromp will be joining an institution that in February gained the prestigious R1 designation from the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching—the highest research classification in the Carnegie system. This is a recognition of our extremely robust research enterprise, and is a designation earned by less than 3 percent of higher education institutions in the nation. It reflects not only our commitment to academic excellence but also our role as a driver of innovation and opportunity for Vermont and beyond.

The scope of UVM research can be seen throughout this issue, including in the work of neurological scientist Davi Bock’s groundbreaking brain-mapping, and in our faculty and staff across our campus who are developing an understanding of the drivers behind the spread of tick populations, and are spurring the development of a Lyme disease vaccine to mitigate the effects of that tick migration—a clear example of our Planetary Health Initiative in action.

At the same time, we have had to adjust to an unprecedented amount of uncertainty and concern over federal actions originating from our nation’s capital. We are working closely with our faculty and staff, as well as our congressional delegation and other leaders in the state, to plan for any research or other implications, while continuing to promote and advocate for our work as a university, and to ensure our continued compliance with all federal laws. Throughout this time, we have emphasized our steadfast commitment to the values of Our Common Ground. Our longstanding commitment to these values, our dedication to the success of our entire community, our land grant mission, and our continued focus on impactful research guide us as we navigate through this evolving landscape in higher education.

Amid this uncertainty, our student-athletes continue to make us proud. The campus is still buzzing

about the incredible success of our men’s soccer team capturing the soccer program’s first-ever NCAA championship. You can read more about that in this issue, as well as the success of our field hockey and women’s basketball teams. And away from the field, our Army ROTC program, for the third time in a decade, received the General Douglas MacArthur Award for Leadership as the best program in the Northeast. We’re so proud of the accomplishments of all our students.

This season is also a time of change for me. I have accepted a new role as Senior Vice President for Academic Affairs and Provost at the University of Arizona. While this new opportunity is truly exciting to me—especially the chance to spend more time with my grandchildren in Scottsdale, Arizona—it will be bittersweet for me to leave UVM. I have dedicated the past 30 years of my life in service to this institution, and I have made innumerable connections with colleagues and students who are dear to me. It has been an honor to serve as interim president, and I will forever treasure my time here and all that we accomplished together. UVM will always have a special place in my heart. I know this great university will continue to thrive because of the incredible faculty, staff, alumni, donors, and students who are the heartbeat of our community.

—Patricia A. Prelock Interim President , University of Vermont

When Dr. Jeffrey Rubman M.D. ’71 and Carol Rubman look back on their decades of service to Burlington’s New North End, their story isn’t just about practicing medicine—it’s about ensuring care endures for generations to come.

From Jeff’s decision to open a primary care practice in an underserved neighborhood in the 1970s to their extraordinary act of donating that very practiceand later the building - to UVM, the Rubmans have built a legacy of changing lives.

Read more at go.uvm.edu/rubman

PUBLISHER University of Vermont

Patricia A. Prelock, Interim President

EDITORIAL BOARD

Alessandro Bertoni, Interim Chief Communications and Marketing Officer, chair Krista Balogh, Ed Neuert, Benjamin Yousey-Hindes

EDITOR

Ed Neuert

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Cody Silfies

CLASS NOTES EDITOR

Cheryl Carmi

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Joshua Brown, Cheryl Carmi, Kevin Coburn, Liz Crawford. Ren Dillon, Joshua Defibaugh, Hannah Fischer, Doug Gilman, Kristen Munson, Ed Neuert, Su Reid-St. John, Nate Scandore, Lisa Wartenberg Vélez, Basil Waugh, Adam White

PHOTOGRAPHY

Joshua Benes, Joshua Brown, Raj Chawla, Joshua Defibaugh, Jaime Dickinson, Ren Dillon, Andy Duback, Bruce Gibbs, Justin Gural, Leo He, Chinh Le Duc, Juliane Liebermann, Peter Miller, Ed Neuert, David Scharf, David Seaver, Cody Silfies, Tyler Sloan, Amy Sterling, Camara Stokes Hudson, Cheryl Sullivan, UVM Silver Special Collections, VT Fish and Wildlife, Alex Weiss, Sam Yang

STUDENT DESIGN SUPPORT

Jared Carnesale

ADDRESS CHANGES

UVM Foundation 411 Main Street Burlington, VT 05401 (802) 656-9662, alumni@uvm.edu

CORRESPONDENCE

Editor, UVM Magazine 16 Colchester Avenue Burlington, VT 05405 magazine@uvm.edu

CLASS NOTES alumni.uvm.edu/classnotes

UVM MAGAZINE Issue No. 96, May 2025

Publishes Spring / Fall Printed in Vermont by Lane Press

UVM MAGAZINE ONLINE uvm.edu/uvmmag

instagram.com/universityofvermont

x.com/uvmvermont

facebook.com/universityofvermont

youtube.com/universityofvermont

Thanks to a medical innovation led by UVM alum and Associate Professor of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics Sean Diehl, Ph.D.’03, thousands of babies this past winter in the U.S. and abroad were spared hospitalization for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). RSV affects children—in general, the younger the child, the worse the effects—and is particularly dangerous for infants under 6 months. The antibody pioneered by Diehl and his colleagues was approved for U.S. use by the FDA in 2023 and has proven more than 90 percent effective in preventing hospitalizations.

Read more: go.uvm.edu/goodmedicine

The Vermont Gallium Nitride (V-GaN) Tech Hub—a consortium led by UVM and including GlobalFoundries and the State of Vermont—has been awarded nearly $24 million in funding from the U.S. Economic Development Administration—the largest research award in UVM history. The Tech Hub plans to train over 500 new employees in the semiconductor workspace and engage over 6,000 K-12 students across Vermont in STEM participation in the next five years.

Read more: go.uvm.edu/leadingedge

Thanks in great part to the efforts of UVM pediatricians, Vermont has earned distinction for its commitment to maternal and infant health, becoming the only state in the nation to receive an “A” grade on the 2024 March of Dimes Report Card. The study evaluated maternal and infant health in all 50 states, using such key indicators as preterm birth rates, access to prenatal care, and the availability of resources for maternal and infant health.

Read more: go.uvm.edu/healthya

The UVM Alumni Association named Allan Strong ’83 the 2025 recipient of the George V. Kidder Outstanding Faculty Award. Strong is director of the Wildlife and Fisheries Biology Program within the Rubenstein School of Environment and Natural Resources. The Kidder Award honors one full-time University of Vermont faculty member for excellence in teaching and extraordinary contributions to the enrichment of campus life. Established in memory of Dr. George V. Kidder, UVM Class of 1922, this award has been presented annually since 1974. The late George Kidder served the university for more than 70 years, including many years as Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences.

Read more: go.uvm.edu/kidder25

Acting Provost, Senior Vice President, and Professor of Mechanical Engineering

Linda S. Schadler has been elected to the National Academy of Engineering (NAE), one of the highest professional honors accorded to an engineer, for her “contributions to the fundamental understanding, property control, and commercial application of polymer nanocomposites.”

Members are elected to the NAE by their peers in the Academy, recognizing outstanding achievement in teaching, research, and engineering practice. She follows in the footsteps of her late father, Dr. Harvey W. Schadler, a leading metallurgist at General Electric who was elected to the NAE in 1991.

Read more: go.uvm.edu/highhonors

I’m so proud of these cadets. They work tirelessly to perfect their craft as Army leaders… They will be second lieutenants soon enough, and I’m proud to say that we have some of the best.”

– Lt. Col. Travis McCracken, UVM ROTC professor of military science, commenting on UVM ROTC winning the General Douglas MacArthur Award for Leadership, given to the best ROTC program in the Northeast region. This is the third time UVM ROTC has won the award in the last 10 years.

Read more: go.uvm.edu/rotcaward

Maybe the best antidote to anxiety about the rise of Artificial Intelligence is a bit of humor? Vermonters awoke on April Fool’s Day to find a UVM “news” story hitting the university’s website and local media announcing the creation by fictitious researchers of CatGPT–the world’s first AI chatbot trained on pure Vermont wisdom. “Unlike conventional AI models that rely on vast datasets from the entire internet,” read the piece, “CatGPT was trained exclusively on Vermont-centric sources, including town meeting minutes dating back to the 1700s, weathered diner-counter wisdom, and a classified archive of debates over the proper spelling of ‘creemee’.”

Read more, and see a video of CatGPT in action: go.uvm.edu/catgpt

UVM Distinguished Professor Emeritus awarded the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

When asked for his favorite success-related proverb, Wolfgang Mieder demurs. “I do not have one—I am not hung up on success. I’m just trying to do the best I can.”

His best is clearly exceptional. In April, at a ceremony at UVM, Mieder, University Distinguished Professor of German and Folklore, Emeritus and the holder of a UVM honorary degree, was awarded the Order of Merit of his native Federal Republic of Germany.

“It is my immense privilege to bestow the Order of Merit upon Professor Wolfgang Mieder in recognition of his extraordinary contributions to education, to the study of language, and to the friendship between our nations,” said Dr. Sonja Kreibich, Consul General of Germany to the New England states, who presented the award. “Through decades of work on proverbs and figures of speech, Professor Mieder has enriched our understanding of

how language shapes thought, how wisdom is passed down through generations, and how cultures connect through shared expressions. He has given meaning to the idea that words are more than just words—they are windows into history, society, and the human spirit.”

The Order of Merit—Bundesverdienstkreuz der Bundesrepublik Deutschland in German— was established in 1951 and is the highest civilian honor awarded by the Federal Republic of Germany. It is given to recognize outstanding political, economic, social, and intellectual achievements, as well as exceptional social, charitable, and philanthropic work. For Mieder, it’s a recognition and celebration of his lifelong commitment to the study and teaching of Germany’s cultural, literary, linguistic, and folk traditions.

Mieder’s career is a testament to longevity and dedication. He taught at UVM for 50 years,

including 31 years as the chair of the former Department of German and Russian (now the Program in German, Russian, and Hebrew in the School of World Languages and Cultures), and retired in 2021. During his noteworthy career, he has written and edited over 200 books and over 500 articles in his primary areas of expertise: proverbs, fairy tales, and international folklore.

“To get this recognition from my former homeland means a lot,” said Mieder. Born in Leipzig, Germany, he has lived in the United States since he was 16 and has received dozens of other honors and awards, including the Lifetime Scholarly Achievement Award from the American Folklore Society and the European Fairy Tale Prize. Having the Order of Merit added to that list “still blows me away,” he said. “It isn’t necessarily common that a professor gets this type of award, so it was quite unexpected.”

LEADERSHIP | On March 20, the UVM Board of Trustees announced that Marlene Tromp, Ph.D., will become the university’s 28th president. She will formally assume the post later this summer.

A humanities scholar with three decades of experience in teaching, research, and higher education administration, Tromp is currently professor of English and president of Idaho’s Boise State University, a position she has held since 2019.

“The leader of UVM is also a vital leader for the community and state, and Tromp brings with her the experience and ability for great success that will benefit all three,” said Cynthia Barnhart, Board of Trustees chair and co-chair of the Presidential Search Advisory Committee. “She has demonstrated excellence as a leader and a scholar who can foster deep and meaningful connections across the university and beyond.”

“I came to Vermont with a clear feeling for UVM’s strength in research, its focus on student success, and the fulfillment of its land grant mission to Vermont and the nation,” Tromp said. “This is a university that has the power to truly lead the nation and even the world on several fronts, and I’m so excited to work with my colleagues, the students, alumni, and friends to improve individual lives and the life of the community.”

In her six years as president of Boise State University (BSU), Tromp successfully guided the institution through the challenges of the pandemic and led efforts that significantly increased student enrollments and affordability. Under her leadership, BSU achieved record graduation rates and levels of philanthropic funding, while also expanding its research funding. She also led the formation of strategic industry partnerships and programs to deepen BSU’s engagement with its surrounding community. She has won numerous awards for her teaching, scholarship, and community service, and currently serves on the NCAA Division I

Board of Directors and consults on higher education with the Federal Reserve Board of San Francisco.

A scholar with a concentration in Victorian literature and culture and its relationship to current society, Tromp has published widely in her field, including nine books and dozens of peer-reviewed papers. Prior to her tenure at BSU, she was campus provost and executive vice chancellor at the University of California at Santa Cruz; vice provost and dean of the New College of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences at Arizona State University; and chair and director of women’s studies and chair of the faculty at Denison University.

This is a university that has the power to truly lead the nation and even the world on several fronts.

The selection of Tromp follows an extensive global search process that began in September of last year. A Presidential Search Advisory Committee co-chaired by Ron Lumbra ’83 and Cynthia Barnhart and including members of UVM’s faculty, students, staff, and alumni, sought input from across the university community and examined more than 100 candidates who expressed interest in the position.

Raised in Wyoming, Tromp earned her Bachelor of Arts degree from Creighton University as a first-generation college student, a Master of Arts in English from the University of Wyoming, and a Ph.D. from the University of Florida.

Tromp will succeed Suresh Garimella, who led UVM as the institution’s 27th president from 2019 until October 2024, when he became president of the University of Arizona. Provost Patricia Prelock served as interim president of UVM from October through May 18, when she became provost of the University of Arizona.

Scan the QR or visit go.uvm.edu/tromptalks to hear Dr. Tromp talk about her thoughts on joining UVM and the opportunities ahead for higher education.

University joins the highest level of U.S. research institutions

RESEARCH | The University of Vermont has joined the ranks of the nation’s toptier research institutions by achieving an R1 Research Activity Designation, a recognition reserved for universities with the highest level of research activity as designated by the prestigious Carnegie Classification, a program of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching administered by the American Council on Education.

This accomplishment, announced February 13, marks a transformative moment for the university and is a result of decades of investment in cuttingedge research and development, faculty excellence, and academic innovation.

“Attaining R1 status will extend UVM’s ability to attract the best talent, secure groundbreaking grants, and contribute to solving global challenges,” said UVM Interim President Patricia Prelock. “This milestone reflects not only our commitment to academic excellence but also our role as a driver of innovation and

Achieving R1 status is a transformative step for any university, signifying a leap into the highest echelon of research institutions

an institution-wide effort to explore the inextricable linkage of human wellbeing and the health of the environment and find solutions for greater global health.

opportunity for Vermont and beyond. It is a testament to the extraordinary dedication of our faculty, staff, and students who have worked tirelessly to elevate our research enterprise and expand its impact.”

The Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education is a framework used to categorize U.S. colleges and universities based on their research activity and institutional characteristics. Established in 1973 by the Carnegie Commission on Higher Education, the classification has become a key benchmark for assessing the research impact and academic mission of institutions.

UVM attracted over $260 million in extramural support for the 2024 fiscal year—more than doubling the university’s annual research funding in the last five years—led by the Larner College of Medicine, which garnered over $100 million for life-saving research.

Much of UVM’s research enterprise is related to its Planetary Health Initiative,

For a flagship, land-grant university such as UVM, achieving R1 status carries special significance, as it strengthens its foundational mission to serve the public through education, research, and broad engagement with the community. R1 status allows UVM to build on its success to pursue new areas of funding and expand its capacity for cutting-edge research. R1 status will also enhance the university’s recruitment in the years to come of new undergraduate and graduate students and new faculty members.

“Achieving R1 status is a transformative step for any university, signifying a leap into the highest echelon of research institutions,” Vice President for Research Kirk Dombrowski said. “For UVM, this achievement not only demonstrates how much we want to accomplish but recognizes the innovation, discovery, and scholarship our investigators and students have achieved over the years.”

Read more on R1 designation’s significance, and the opportunities it presents, on page 24.

JOSHUA BROWN

Even as UVM’s status as a research institution has been recognized with R1 Carnegie classification, the university has, along with colleges and universities across the U.S., been intensely engaged in interpreting the current federal government actions around higher education.

In this atmosphere, university administrators have listened to concerns that have arisen from across the campus community, continued their commitment to free expression, and worked to support individuals and groups who may feel vulnerable.

A federal actions website has been created to offer information and access to resources. And to help plan for and stay up to date with the latest developments, Operations Teams for Federal Response began convening weekly in March. Comprising faculty, staff, administrators, and deans, these groups focus on four key areas: research, immigration, UVM’s Our Common Ground values, and faculty affairs. The efforts of these groups support a core team of senior leaders to help shape strategy and policy as UVM navigates the changing landscape for higher education.

| Young entrepreneurs are getting substantial support from two UVM initiatives, including the largest undergraduate prize for a business pitch competition in the nation.

UVM Innovations hosted the final presentations of the second annual Joy and Jerry Meyers Cup in March at the Alumni House’s Silver Maple Pavilion. Chip Meyers and his wife, Louise, fund this effort, representing the Meyers Family Trust, in honor of his parents, Joy and Jerry Meyers, who met as undergraduate students at UVM. Out of the three UVM undergraduate teams that presented their business ideas to a panel of judges, Campus Storage Solutions won the grand prize of $225,000 in cash.

“Winning feels amazing. We prepared so long for this and to have everything come to fruition is just incredible,” Ethan Israel ’26, Campus Storage Solutions’ founder, said. “My team and and the advisors we’ve had made this possible and made it a wonderful experience.”

Israel, who served as the company’s CEO, was inspired to start Campus Storage Solutions with Logan Vaughan ’27 after facing their own personal challenges with storing and moving belongings over the summer while away from college. Campus

Storage Solutions, team includes Israel, Vaughan, the CFO, and Ally Updegrove ’25, who serves as the company’s CMO.

Also in March, Matthew McPherson, a high school entrepreneur from Flemington, N.J., was named the winner of the 2025 Vermont Pitch Challenge, a Shark Tanklike competition for teens. McPherson was awarded the competition’s top prize—a full-tuition scholarship to UVM—for his business venture, Boxer Breeze, after presenting his innovative plan to a panel of judges at UVM. McPherson, a high school senior, will be attending UVM this fall.

Boxer Breeze is an eco-friendly underwear brand that combats textile waste by using sustainable materials like bamboo fiber and organic cotton. The business plan also implements a closed-loop recycling system, where customers can return used pairs for discounts on future purchases, promoting sustainability in the fashion industry.

“This opportunity has been one of the most life-changing things to ever happen to me,” said McPherson. “Any of the finalists could have won today, and to have this feeling of being in first place and being a winner in this amazing competition is something I’ll hold near me forever.”

Grace Glynn G’20 in the field. Inset is the elusive false mermaid weed, not seen in Vermont for over a century until last year.

AGRICULTURE | Grace Glynn G’20, the Vermont state botanist with the Department of Fish and Wildlife and a graduate of UVM’s Field Naturalist Master’s Program, received a flurry of media attention last June when she rediscovered false mermaid weed (Floerkea proserpinacoides), a plant not seen in Vermont for over a century. She was interviewed over 20 times and appeared in a lengthy story in the New York Times.

Glynn says she jumped up and down and shouted in excitement when she discovered the plant. It all started when a colleague, turtle biologist Molly Parren, sent Glynn a photo she’d taken in the field of another endangered plant.

“Something caught my eye in the corner of the photo,” says Glynn. “And it was Floerkea!”

False mermaid weed is what’s known as a spring ephemeral plant. It emerges in April, produces a small, white, radially symmetrical flower head less than a centimeter wide, and is dormant again by June. Its seeds resemble tiny seashells. The common name derives from its resemblance to marsh mermaid weed, an aquatic plant that can also grow on muddy riverbanks. For four years, Glynn had been searching for false mermaid weed during its short spring growth window in the hopes of finding it.

“I just could not believe it,” says Glynn. “I had imagined finding this species many times in my head. But this wasn’t the way that I ever thought it would happen.”

Weston “Wes” Testo G’18, center, works with colleagues José Nicolás Zapata and Deli Heal ’25. Inset is the new fern species they identified.

| For more than six years, Assistant Professor of Plant Biology Weston “Wes” Testo G’18 has worked with a research colleague, Sonia Molino, a fellow fern specialist from the Department of Biosciences at the Universidad Europea de Madrid, to study Parablechnum—the most diverse genus in the fern family Blechnaceae, with about 70 species known globally. They have published several related research articles, frequently drawing from the important collection of fern specimens at UVM’s Pringle Herbarium. With nearly 400,000 plant specimens from around the world, the Pringle Herbarium is one of the largest in the Northeast. Nearly 40,000 of Pringle’s specimens are ferns, helping make UVM a hub of global fern research. Many of the specimens in the collection represent species that remain undescribed to science.

The team, which included UVM doctoral student José Nicolás Zapata and undergraduate Deli Heal,

focused on a fern from the Cordillera del Cóndor, a mountain range along the border of Ecuador and Peru, home of the indigenous Shuar people, that is famous among tropical biologists for its many endemic species. This isolated and geologically distinct area is home to a remarkably unique flora. The diminutive fern they focused on only grows upon sandstone cliffs along small rivers in the cordillera, and had been collected on two different occasions in 2006.

In an article published this February in the journal Brittonia, the team provided the first complete description of the new species. They also had to decide what to name it, and settled on Parablechnum shuariorum, in honor of the Shuar people and their efforts to conserve the habitat of this and other rare Cordillera del Cóndor species.

“I had kind of a hard time in school when I was younger,” recalls UVM senior Charlie Meecham. “It was really challenging socially.” But in third grade, her teacher made a lasting impression. “I definitely think about her when I think about teaching,” Charlie says. “She was an adult outside of my family that really listened to me. I could tell she believed in me and the other students in the class. She is still a huge inspiration for me and my teaching aspirations.”

Story by Doug Gilman

Charlie Meecham is just one of the extraordinary individuals who make up the Class of 2025. Use a mobile camera or visit go.uvm.edu/ meet2025 to meet more.

On her journey to become an early childhood educator, Charlie navigates the challenges associated with her physical disability – a genetic connective tissue disorder known as Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome. “I’ve had to work super hard,” she explains. “It affects my whole body, my mobility, and my energy.”

Despite the challenges, she is well on the way to her goal. In the culminating experience of the program, Charlie was a full-time student-teaching intern with a classroom of first graders at Allen Brook School in Williston.

Before that, she completed practicums at Pine Forest Children’s Center and Burlington Children’s Space, and civic learning at the Greater Burlington YMCA.

“She takes the time to listen and understand what the students are saying and thinking,” says Maria McCormack, Charlie’s mentor teacher at Allen Brook. “As she takes on more curriculum-planning and lesson-building responsibilities, she always considers the students’ unique needs and preferences.”

Inquisitive young minds give Charlie an opportunity to educate the students about her disability: “They are so curious and ask the best questions. It’s a magical thing.”

When she was 6 years old, Charlie’s family moved from England to Rhode Island, and then to Washington, D.C., when she was 12. Though still a U.K. citizen, she just passed the U.S. citizenship exam. During her senior year of high school, she started working at a preschool where her mom worked. “It was during

COVID, so things were kind of crazy,” she remembers. “It was also during the Brood X cicadas emergence that occurs every 17 years. Watching the kids and the teachers explore and learn about the cicadas was incredible, because I had never seen anything like that.”

Entering college, Charlie planned to study biology. But as a first-year student she took Assistant Professor Kaitlin Northey’s Child Development class.

“And I thought, this is so cool, so I transferred into Early Childhood Education,” she says. “I have not had a moment of regret since. You can really see the learning and the wheels turning in their young minds minute-to-minute. And the family connection is so strong. Relationships with the families—that’s been so rewarding for me.”

Educator preparation programs at UVM pride themselves on “early and often” field placements beginning in the first year and continuing throughout the program. Students engage in service-learning, practicums and teaching internships in a variety of inclusive learning settings—fully supported by dedicated faculty and experienced mentor teachers.

Charlie received the UVM Presidential Scholarship for each of her four years. As a senior, she received the Joan Greening Student Teaching Award and the MP McDaniels Scholarship Award. For her junior year, she earned the APEX Scholarship and the Burack Family Scholarship.

“She is the type of student you always want to have in your class because she gets others excited about learning,” Northey says. “Having her as a teaching assistant in my Child Development course has been an absolute joy.”

Throughout her journey in early childhood education, Charlie’s sense of purpose has been clear and unwavering. “It just always feels like the right thing to do,” she says.

Vermont’s Teacher of the Year helps launch the next generation of educators

EDUCATION | “Let’s spend a couple of minutes breaking the ice a bit,” says UVM Lecturer Caitlin MacLeod-Bluver, as the low hum of pre-class conversation in the Waterman 426 classroom settles down. It’s 4:30 on a Tuesday afternoon in November. Outside the classroom windows the sunlight is fading, but inside the two dozen or so UVM education majors and nine guest students from Winooski High School are just getting started. For the Winooski students, a mixture of 9th and 11th graders, this may be their first time in a college class, but they’re already very familiar with the instructor.

To them she’s Ms. MacLeod-Bluver, their teacher at Winooski High, whose innovative skill was recognized this fall when the Vermont Agency of Education named her Vermont Teacher of the Year for 2025.

Impact on future educators is what’s on display in Waterman 426. As the class—EDSC 2160, Curriculum, Instruction, and Assessment, quiets down, MacLeodBluver and her co-instructor, Jenn Keller, review the schedule for the next hour. The UVM students have been working in groups to create project-based learning assessments for high school learners that can engage them in an active way. Through this approach, says MacLeod-Bluver, the targeted students will “not just be writing essays that get stored in a file cabinet, graded and moved on from, but an authentic piece of learning that high school students would care about.”

The UVM students found the interaction valuable. “This was honestly really fun,” wrote one UVM student in a post-class assessment. “The [WHS] students were super-engaged, and I really appreciated their honest feedback…. Having a tangible audience

I’ve always loved working with students. I have always loved working with young people... I truly just fell in love with teaching

helps us guide our work better and create something that is ultimately more student-centered.”

For MacLeod-Bluver, fostering these kinds of inventive approaches in students who will soon become the next generation of teachers is a driving force in her career. It began for her during her undergraduate years at Wesleyan University.

“I’ve always loved working with students. I have always loved working with young people. And then when I was a junior, I did a summer teaching program. And I truly just fell in love with teaching.” She later earned a master’s in education at Boston University and taught in the Boston Public Schools for eights years. Later she and her husband moved to Vermont, and she has taught in Winooski for the last six years.

MacLeod-Bluver’s role as a combination high school teacher/UVM adjunct instructor is an outgrowth of the UVM Department of Education’s broader plan to develop deeper partnerships with local Vermont schools, according to Katie Revelle, director of community collaboration for the College of Education and Social Services’ Department of Education. “I sit on the University Outreach Council, and I think this type of partnership represents the kind of work the council hopes to support,” says Revelle. The Outreach Council’s stated mission is to “expand access of traditionally marginalized and under-represented populations throughout the state of Vermont to higher education through intentional programming and outreach.”

Teaching high school all day and a UVM class in the evening is a big effort, but one that MacLeod-Bluver clearly sees as a calling. “I teach at UVM because I want better teachers everywhere,” she says. “So I was really excited to teach at UVM. It was my first time working with aspiring teachers and really helping them. And it was so rewarding…. I truly realize how sacred this job is. That’s why I’ve been doing it for so long.”

PRE-MED | Autumn Polidor’s path to medicine began with a realization: Vermont faced a shortage of family doctors, and she wanted to help. That decision led her to a major career change, on to medical school, and ultimately to a specialty in addiction treatment.

Autumn’s career path began far from the world of health care. As a studio art major at UVM, she explored her creative passions and graduated in 2003. “I wasn’t really sure what I wanted to do,” she says. “I had this very rough idea of becoming an artist, but I couldn’t figure out how to make it feasible.”

After graduation, Autumn worked in a bakery and pursued small creative business ventures. Despite these efforts, the businesses’ seasonal nature and inconsistent income led her to search for different work. Her turning point came when she read an article about Vermont’s shortage of family doctors. “I thought, ‘Oh, I could do that.’ And I started looking into pre-med programs,” she explains, ultimately deciding on UVM’s Post-Bacc Pre-Med Program.

Autumn’s story is one of thousands made possible by the Post-Bacc Program, which for 30 years has provided the education and mentorship necessary for aspiring healthcare professionals to pursue careers in medicine, dentistry, nursing, and more. With an 83 percent medical school matriculation rate, the program remains a vital pathway for those seeking to make a difference in health care.

“The Post-Bacc Program gives you support with an advisor,” Autumn recalls. “I felt like I could trust the guidance I was getting. It was a big change in terms of my identity, going from artist to scientist. But we were all making this transition and change and doing it in our own ways. It made it feel more manageable and doable.”

Surrounded by peers with diverse backgrounds, Autumn found the support and confidence to pursue medical school. “Most people [in the program] didn’t have a straight-up science background,” she says. “That was confidence-building.”

The program provided the prerequisites for medical school and a strong support system, helping Autumn navigate the next steps in her career–attending medical school at UVM and then completing a family medicine residency at Oregon Health and Science University. Autumn, who grew up in Vermont, returned to the state in 2022 and now serves patients remotely through Rogue Community Health.

“The Post-Bacc Program was a huge turning point for me,” says Autumn. “It gave me the confidence, guidance, and community I needed to take this leap into medicine. I’ll always be grateful for that support.”

Use a mobile device to scan this QR or visit go.uvm.edu/postbacc30 to read more about UVM’s PostBacc Pre-Med Program.

By Kristen Munson

Joshua Faulkner squats in a corn field, scooping out the insides of a hole. He holds a handful of dark gray soil and squeezes it like a sponge. Beside him, a row of yellowed winter rye shakes in the wind.

“It’s a little dry,” Faulkner says. “… But not bad. Everyone is crossing their fingers that we don’t have a repeat of 2023. It really didn’t start raining last year until mid-July.”

He’s referring to the statewide flooding July 10-11, 2023, that devastated feed and vegetable crops and caused about $69 million in agricultural damages. (Despite crossed fingers, flooding occurred again on the one-year anniversary.) A 2023 survey conducted by the Vermont Agency of Agriculture, Food and Markets found that nearly 34 percent of respondents said their most significant

losses were to feed crops, with the average suffering $61,000 in losses.

After the 2023 floods, water gauges along three Vermont rivers Faulkner monitors indicated phosphorus levels three times higher than the previous two summers. With leakage from agricultural fields common after heavy rains, could there be alternative ways for dairy farmers to limit nutrient runoff and increase their resilience to extreme weather events?

“Can a dairy farm sequester as much carbon as they emit in their production system? Can a dairy farm be net zero?” asks Faulkner, a research associate professor at the University of Vermont. “In order to [answer] that we have to measure a lot of things.”

Scan this QR code with a mobile camera or visit go.uvm.edu/ faulknervid to watch a video of Joshua Faulkner’s field work or

That is why Faulkner is gathering soil samples in the middle of a corn field in St. Albans one morning in June. He is part of a team of UVM researchers investigating how to make Vermont’s dairy production more sustainable. They are midway into a six-year study, called the Dairy Soil & Water Regeneration project, administered by Dairy Management Inc. and the Soil Health Institute, that involves seven universities and a U.S. Department of Agriculture research site, and spans farms from Vermont, New York, Wisconsin, Texas, Idaho, and California. The idea is to test how methods such as cover cropping, no-till planting, and different fertilizer applications affect water quality, crop yield, economics, and greenhouse gas emissions.

“A lot of the public thinks that greenhouse gas emissions in agriculture are mainly diesel fuel and electricity, and they are not,” Faulkner says. “They come from soil emissions and from manure. So, we are measuring gas emissions from these systems to see if we can determine if this new approach to growing feed and managing soil not only helps with resilience but helps with mitigation at the same time.”

Faulkner pounds a slide hammer into the soil and pulls a long tube of earth from the ground. The sample will be used to test the soil’s bulk density, water-holding capacity, and carbon concentration. Higher compaction means less space for air and water and organic matter. It means less healthy soil.

agricultural runoff, and soak up excess moisture. Practices such as reducing tillage and implementing crop rotation provide additional benefits, reducing erosion and adding nutrients back into depleted soil. But how do various fertilization and drainage techniques affect water quality? How do soil health and various management practices impact carbon emission and sequestration?

Scan this QR code with a mobile camera or visit go.uvm.edu/ greenupdairy to read an expanded version of this story.

“Low-bulk density—that is a really good thing,” Faulkner says. “It means the management practices of the farm are working.”

“There is no question that soil is the most valuable resource on the farm,” Faulkner says. “If we lose our soils, they take years, in some cases, hundreds of years, to build back. How do we conserve those soils and really maximize [their] health … so that they are sustainable in the long run, but they also maintain productivity for the farm?”

Building soil health can improve resilience from extreme weather events, as living roots in the ground hold soil in place, reduce

Can a dairy farm sequester as much carbon as they emit in their production system? Can a dairy farm be net zero? In order to [answer] that we have to measure a lot of things.”

“It takes a tremendous amount of data to help answer those questions,” Faulkner says. “So that means a lot of time in the field. A lot of sampling work. A lot of runoff water quality measurements.”

While they are still a year away from having hard numbers to share, Faulkner is interested in what the study will more broadly reveal about the sustainability of dairy farming.

“This is the first time we’ve taken a wholesystems look at dairy forage production,” he says. “The other thing is the soil’s ability to sequester carbon. And some people have taken measurements here and there, but this is the first rigorous documentation of that in our dairy systems. And it may be different in Wisconsin than it is here in Vermont and different in California or Texas. We need that local information.”

University Press of Mississippi

By Tony Magistrale and Michael Blouin

go.uvm.edu/kingnoir

Professor and former Chair of English Tony Magistrale, along with coauthor Michael Blouin, explores Stephen King’s deep ties to crime fiction, shedding new light on the iconic author’s influences and storytelling through a hard-boiled lens—complete with a never-before-published essay by King himself.

Oxford University Press

By Courtenay Harding go.uvm.edu/recoverschiz

Alumna Courtenay Harding ’76 G’81,’84 shares groundbreaking

research from decades-long NIMH studies revealing that recovery from schizophrenia is not only possible but common—challenging long-held assumptions in the field of psychiatry.

Harper/HarperCollins

By Jan Gangsei

go.uvm.edu/deadbelowdeck

Jan Gangsei ’92 brings a fresh twist to teen mystery with Dead Below Deck, a reversechronological thriller set aboard a spring break cruise. As secrets unravel from end to beginning, the novel explores themes of privilege, identity, and family, earning praise from Kirkus Reviews for its inventive structure and compelling, well-supported final reveal.

Counterpoint Press

By Maria Hummel

go.uvm.edu/goldenseal

UVM English professor Maria Hummel explores themes of friendship, betrayal, and healing in 1990s Los Angeles. Praised by the Los Angeles Times as “haunting and tragic” yet ultimately hopeful, the novel was longlisted for the Joyce Carol Oates Prize and is a finalist for the 2025 Vermont Book Award for fiction.

Penguin Random House

By Aria Aber

go.uvm.edu/goodgirl

In her acclaimed debut novel, Good Girl, UVM Assistant Professor Aria Aber follows the coming-of-age journey of

Published a book?

Launched a podcast? Working on a film, show, or digital project?

Let us know at magazine@uvm.edu

an Afghan refugee’s daughter through Berlin’s glittering, destructive nightlife. Praised by the New York Times for its poetic power, the novel is a finalist for the 2025 Women’s Prize for Fiction.

Directed by Peter Sanders go.uvm.edu/onshoulders

Filmmaker Peter Sanders ’92, known for award-winning documentaries like “The Disappeared” and “Altina,” explores 150 years of medical innovation in his latest film, “On the Shoulders of Giants: The History of NYU Langone Orthopedics.” Continuing a family legacy of documentary storytelling, Sanders’ newest work is available on YouTube and Amazon Prime.

Whales are not just big, they’re a big deal for healthy oceans. When they poop, whales move tons of nutrients from deep water to the surface. Now new research co-led by Joe Roman, a UVM biologist, reveals that whales also move tons of vital ocean nutrients thousands of miles—in their urine.

In 2010, scientists revealed that whales, feeding at depth and pooping at the surface, provide a critical resource for plankton growth and ocean productivity. Roman’s study, published in the journal Nature Communications, shows that whales also carry huge quantities of nutrients horizontally, across whole ocean basins, from rich, cold waters where they feed to warm shores near the equator where they mate and give birth. Much of this is in the form of urine—though sloughed skin, carcasses, calf feces, and placentas also contribute.

The study calculates that in oceans across the globe, great whales—including right whales, gray whales, and humpbacks—transport about 4,000 tons of nitrogen each year to low-nutrient coastal areas in the tropics and subtropics. They also bring more than 45,000 tons of biomass. And before the era of human whaling decimated populations, these long-distance inputs may have been three or more times larger.

Use a mobile camera or visit go.uvm.edu/joeroman to read more about Joe Roman’s study.

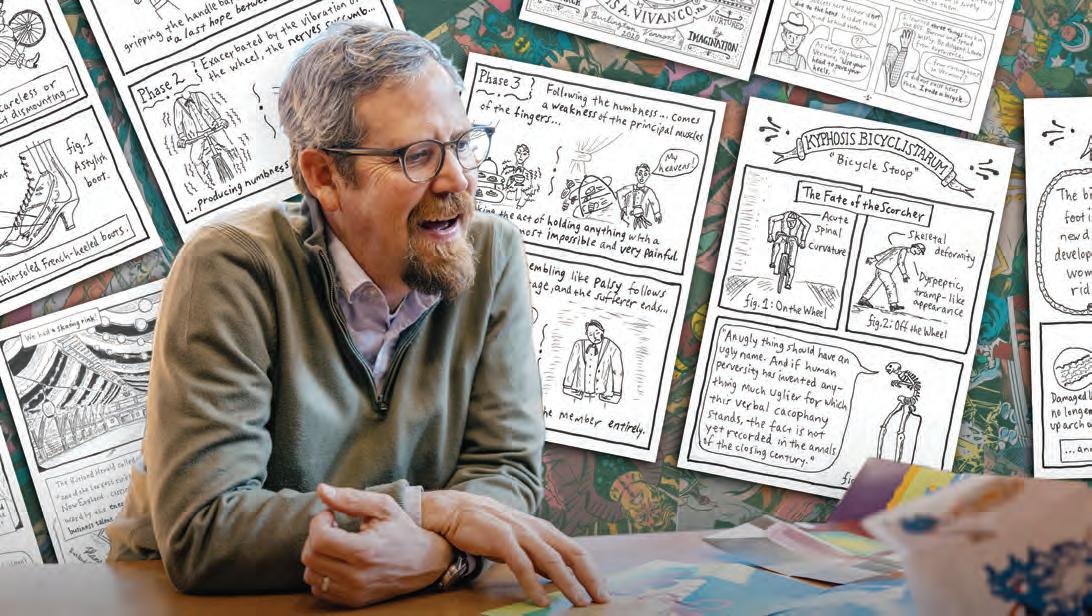

Anthropologist Luis Vivanco’s work highlights the power of comics to illuminate complex stories and reshape how research is communicated.

STORY BY JOSHUA DEFIBAUGH

Use a mobile device or visit go.uvm.edu/vivanco to read more about Vivanco’s work and view his comics at The Illustrated Wheel.

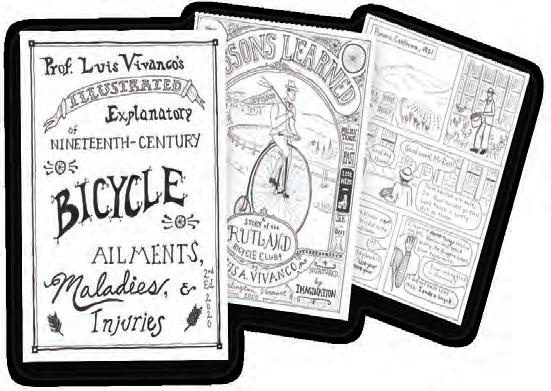

RESEARCH | What do bicycles, anthropology, and comics have in common? For UVM professor Luis Vivanco, everything. Swapping research papers for hand-drawn comics, he’s bringing history, culture, and even 19th-century bicycle ailments to life—one comic panel at a time.

On a frigid afternoon in January, students and community members in Billings Library aren’t poring over primary documents or using the space to study. Instead, they’re drawing comics. At one table, a student draws peacocks. Another student, a quick study of faces. Across the room, Luis Vivanco discusses drawing and comics — and leads this monthly meeting, called Working Wednesdays, part of his Comics-Based Research Lab at UVM.

of the Department of Anthropology in the College of Arts and Sciences — is a latecomer to the illustrated medium. But he’s come to realize that, just as the pen is mightier than the sword, so too is the comic often more resonant than the research report.

And he’s discovered other researchers across campus embracing comics too. The Larner College of Medicine’s Dana Health Sciences Library, for instance, hosts many examples of “graphic medicine,” like comics and illustrations on vaccines, how children cope with war in Ukraine, and the cost of diabetes care in New York City.

“The more conversations I have on campus here, the more I realize people are interested in comics,” Vivanco said. “For example, I hadn’t known about Jeremiah Dickerson, a psychiatry professor in the medical school who teaches this one-credit

comics course to medical students, using graphic medicine to tell illness stories in comics form.”

Knowing that colleagues across the university are interested in comics — while some faculty members are already using comics to teach and translate research — inspired Vivanco to start the Comics-Based Research Lab. To spread the word, he participated in the Office of Research’s Faculty Activity Network, which encourages faculty members to share and experience each other’s laboratories, studios, or other research spaces. Last October, faculty members from the Rubenstein School, Larner College of Medicine, College of Education and Social Services, and others showed up to learn about comics-based research and Vivanco’s approach.

Vivanco’s trajectory into comics began in 2017, when he was the director of the UVM Humanities Center. “Someone asked me if they could organize a comics conference. People were taking comics and graphic novels seriously, and I didn’t have much awareness,” Vivanco said. But during one of these conferences, the Pulp Culture Comic Arts Festival, inspiration struck. “I sat in on a panel discussion that featured history professors from around the country, and one of them recently published a graphic novel through Oxford University Press. That was his research.”

Vivanco’s work as an environmental anthropologist lately revolves around bicycles. For more than a decade, he’s studied the history of urban bicycle culture, the political debate over bikes in past centuries, and how green urbanism adopted bicycle culture and why.

“I wrote a book about the anthropology of bicycles and one small piece of that book was on the history of bicycles in Vermont in the 1800s, when there was this huge bicycle craze,” Vivanco said. After awakening his love of drawing and establishing his grounding, he started taking his lecture material and archival sources on the history of bicycles and turning it into mini-comics.

Ultimately, for Vivanco and others, comics help people see. After drawing — both doodling and seriously producing comics — for years, comics have become more than a useful ethnographic tool for him.

“When you’re in the field, drawing, you might be paying very close attention to details that the typical training in cultural anthropology might ignore,” Vivanco said. “And when you pair the traditional ethnographic report with the comic, they reinforce each other.”

VERMONT | This winter UVM added its 11th property to the Natural Areas Program with the acquisition of Joe’s Pond, a protected sanctuary in Morrisville, Vt., with a rich history. Lifelong Morristown, Vt., resident and UVM alumnus Ron Stancliff ’63 donated the property, which is held by a conservation easement through the Stowe Land Trust and has been conserved since 2005. The easement ensures that the forest, wildlife habitat, natural communities, and native flora and fauna will be protected, the water body and adjacent wetlands will be conserved, and the property will remain undeveloped for present and future generations. It contains a breathtaking 11.3-acre pond bordered by a 19-acre mixed hardwood and softwood forest filled with hiking trails. The natural pond acts as a home to numerous species of birds, snapping turtles, and fish, including bullpout, suckers, and grass pickerel.

Joe’s Pond – Morristown and the nearby Molly Bog Natural Area trace their names to early settlers, both Micmac tribe members. UVM’s Molly Bog, acquired over 50 years ago, remains a protected sanctuary, dedicated only to research and monitoring to protect its delicate plant communities. Stancliff’s generous donation allows both properties to now be integrated into the UVM Natural Areas system. Unlike Molly Bog, Joe’s Pond – Morristown is open to the public, offering opportunities for non-motorized recreation like hiking, kayaking, skiing, and snowshoeing. The pond also presents a rich environment for research and monitoring. The property is already utilized by the State of Vermont for bat monitoring, and it holds potential for studies on recreation management, forest health, wildlife communities, and more. The property shouldn’t be confused with Vermont’s other Joe’s Pond, in Danville, that is well known for its annual ice-out competition.

BY NATE SCANDORE

THE BIGGEST GOAL IN VERMONT MEN’S SOCCER HISTORY PROPELLED THE CATAMOUNTS TO THE FIRST-EVER NATIONAL TITLE BY AN AMERICA EAST TEAM.

It was a moment that left Vermonters everywhere jubilant, with hearts racing and tears spilling down joyful faces. For the first time in the history of the University of Vermont’s athletic programs, the UVM men’s soccer team did what was considered the unthinkable, being crowned the 2024 Men’s Soccer Division I National Champions. This was no ordinary victory—it was the culmination of years of grit, hard work, and a mentality that nobody—no one—saw coming. They’re not underdogs. They’re just dogs.

Many may have speculated that this team was written off from the beginning. “Not good enough. Not big enough. Won’t sustain success long enough.” Those were the doubts that swirled around the Catamounts, the noise they had to block out every time they stepped on the field. But this team, led by Head Coach Rob Dow, wasn’t here to prove people wrong. They were here to show that Vermont never backs down.

UVM’s regular season was a statement. Finishing 10-2-6, never surrendering a loss at home from Virtue Field or on any neutral fields, they were relentless—never losing their will to win. Their ability to score 22 goals in the 76th minute or later—17 of them in the 83rd minute or beyond throughout the entirety of the season—was a testament to the never-say-die mentality that defined this team. They weren’t just playing and winning games. They were making history.

defied every expectation, tearing through the toughest fields in college soccer. Vermont became the first team in America East history to make it to the NCAA National Championship game, and with every step forward, they proved the doubters wrong. They beat four different seeded opponents—#7 Hofstra, #2 Pittsburgh, #3 Denver, and #13 Marshall—each one more formidable than the last. But the Catamounts kept coming, unrelenting and unstoppable.

“THEY ALWAYS DOUBTED US. WE ALWAYS COME OUT ON TOP. THAT’S VERMONT.”

– UVM FORWARD MAXIMILIAN KISSEL

After clinching a share of the America East Regular Season Championship, the Catamounts opened the conference tournament with a seat-gripping nail biter against UMBC from Virtue Field, witnessing Yaniv Bazini score the golden goal in the 106th minute for the Catamounts, securing UVM the 2-1 victory over the Retrievers in overtime, punching Vermont its ticket to the conference championship match. Bazini registered both Catamount goals for Vermont in the semifinals of the tournament, building hefty momentum for what was still to come.

An exhilarating America East Championship game took place on a crisp November evening, when Vermont defeated Bryant 2-1 with a go-ahead goal from Maximilian Kissel in the 86th minute of action, securing the program’s second conference championship in the last four years. Head Coach Rob Dow spoke on what it meant heading into the NCAA tournament. “I’ll tell you; this championship game puts us in the echelon of ready. We’re ready for the NCAA Tournament.”

And then came the NCAA Tournament. The Catamounts

The National Championship game itself was nothing short of cinematic. Down by a goal with 9:34 on the clock, just when it seemed like all hope might slip away, the Cardiac Cats did it again. David Ismail connected with Marcell Papp for the equalizing goal, sending the championship game into overtime. Kissel, who demonstrated his clutch abilities all season long, stood tall and delivered the most iconic moment in Vermont men’s soccer history. Scoring an overtime goal 4:53 into extra time, sending the crowd and fans at home into a frenzy, Kissel sealed UVM soccer’s first-ever team National Championship. The goal wasn’t just the culmination of a match—it was the culmination of a season defined by perseverance, heart, and unity.

“First of all, super proud to be this coach for the University of Vermont men’s soccer team,” said Head Coach Rob Dow at the post-game press conference. “This team played phenomenal tonight, put in the center of a lot of pressure, had an amazing season, and I’m just really excited about going home and celebrating with all of our fans that we could hear from afar.”

(Continued on next page.)

“IT’S OUR ENTIRE COMMUNITY, THE STATE OF VERMONT THAT MAKES THIS SPECIAL.

–

But it wasn’t just Kissel. Every player stepped up when it mattered. Redshirt senior Yaniv Bazini, who led the team with 30 points (14 goals, 2 assists), scored in every NCAA Tournament game leading up to the final. His equalizer against Denver in the semifinals was a moment of pure magic, reminding everyone that the Catamounts were never out of it.

The heart of the team, though, was its defense. First-year goalkeeper Niklas Herceg was nothing short of heroic. After coming into the season injured, he didn’t just find his form—he became the backbone of Vermont’s defense. He posted six shutouts, three of them in the NCAA Tournament, including a legendary penalty-kick save to go along with a five-save performance against #3 Denver in the semifinals. His .855 save percentage was the best in the NCAA, and in a season where every save mattered, he was the rock the team leaned on.

Defenders Max Murray and Zach Barrett, both graduate students who sit atop the record books for most games played in UVM men’s soccer history over their college careers, held the line in the back, blocking attacks with the ferocity of players who knew this was their time. The team’s collective defense was a wall that never wavered. Together, they became a fortress that other teams simply couldn’t break through.

But what made this team special wasn’t just their talent—it was their belief. There were no underdogs on this team. Just dogs. When people doubted them, they showed up and they fought. The Catamounts didn’t need anyone’s validation. They knew who they were. “They always doubted us,” said Kissel. “We always come out on top. That’s Vermont.”

From start to finish, from the very first whistle of the season to the final goal in the championship match, this was a team that never gave up and never let the pressure of the moment get to them. The constant roadblocks and the doubt? That fueled their fire.

And let’s talk about their journey—their incredible, almost surreal journey. Traveling nearly 9,000 miles throughout the NCAA Tournament, playing through adversity, overcoming every challenge in their path. This team was unseeded going in, yet they made history. UVM became the first unseeded team to reach the National Championship game since Akron in 2018, and now, they’re the first America East team ever to win a National Championship.

Throughout the NCAA Tournament, this team led all other teams in goals scored, putting up 13 goals in total—a testament to their offensive dynamism. And they did it all with a mentality that was as unstoppable as the men on the field. They were more than just a team—they were a movement. They were the embodiment of what it means to be from Vermont: hardworking, tough, and resilient.

Head Coach Rob Dow summed up what makes Vermont soccer stand above the rest: “It’s our entire community, the state of Vermont that makes this special. As we’ve all identified, we’re a small state, but a state that’s built on family values within our community, working hard, having a resilient culture, and appreciating what you have,” said Dow. “It doesn’t have to be a lot but really appreciating what life is about, and that’s the people around you. I’d like to win a national championship every year, I want to repeat next year, but you know, some years it may not happen, and I know our fans are so loyal through difficult times and this is how we got here, and those are the things we see and feel within Chittenden County and the state of Vermont.”

For Vermont, this championship isn’t just a victory—it’s a legacy. It’s a story of a team that believed in themselves when not a lot did, that defied the odds and walked away as the best in the nation. They’ve set the bar for what’s possible and, in doing so, have inspired generations of athletes to come. The first-ever National Championship for Vermont men’s soccer will be remembered not just as a title, but as a symbol of everything the state and its people stand for—resilience, pride, and the unbreakable spirit of the Green Mountains.

This team didn’t just make history— they made us all believe.

It was a moment of pure triumph that no one in the University of Vermont’s field hockey program will ever forget. After years of pushing for greatness, this November the Catamounts made history by winning their first-ever America East Championship, earning a place in the NCAA Tournament for the first time in program history.

The road to the title was nothing short of dramatic. In the semifinals, Vermont took on the #1 seed UAlbany Great Danes—a powerhouse that had dominated the conference all season. It was an intense battle that tested every ounce of Vermont’s strength, but they held their ground. Goalkeeper Merle Vaandrager was a brick wall in the cage, earning two shutouts during the tournament, adding to her six shutouts on the season, leading every goalie in the America East Conference. Her six shutouts tied a program record, and her semifinal performance was crucial as UVM held UAlbany to zero goals, securing their place in the conference championship game.

“This is one gritty team. To give up only three shots on goal and secure a shutout against UAlbany in a semifinal was no

small feat,” said Head Coach Kate Pfeifer. “I’m so proud of the way they battled, executed our game plan, and got it done.”

The America East final saw Vermont go head-to-head against second-seeded New Hampshire in a battle that tested their heart and resolve. Things didn’t look good. Down 2-0 at halftime, the Catamounts found themselves staring down an uphill battle. It was only the second time in a month they had given up more than one goal, and the first half felt like it might just slip away. But this team had something different. They had grit and belief.

Vermont wasn’t going to let their season end without a fight. As the second half began, the Catamounts roared back to life.

In just 12 minutes, they scored three goals, overturning the deficit in a stunning display of determination. Meg Weyer, a player who had worked tirelessly all season, scored the first multi-goal game of her career, including the gamewinner in the 46th minute. The comeback was nothing short of spectacular, as it set the tone for future UVM field hockey teams to look up to for years to come.

“I just had full faith in the team that they could rise to the

moment, and I think that’s what they have done all tournament,” said Head Coach Kate Pfeifer following the championship win. “They have risen to the occasion and not lost belief in themselves just because it’s a top-ranked opponent or an opponent we have lost to before. We have been able to really face it and execute when it matters.”

Throughout the tournament, the Catamounts showed exactly why they were worthy of their title. They entered the championship match ranked in the nation’s top 20 in numerous categories: shutouts per game (7th), goals per game (17th), scoring margin (18th), and defensive saves (19th). But it wasn’t just their stats that spoke to their power— it was their will to win.

On offense, first-year Marie Dijkstra led the charge with 29 points (11 goals, 7 assists), finishing the season as the team’s top scorer. Junior Sophia Lefranc was instrumental, contributing eight goals and four assists, including three total goals in the first two playoff games, and let’s not forget the legacy of Sophia Drees, who finished her career as the program’s all-time leader in assists, with eight on the season and a total of 74 career points.

This victory wasn’t just about scoring goals or racking up stats—it was about something deeper. It was about believing. Vermont wasn’t just playing for a championship; they were playing for their place in history. Every player, every coach, and every fan knew that this was a moment of destiny. From being underdogs to being crowned champions, the Catamounts had proven that they belonged among the nation’s elite.

—Nate Scandore

UVM’s women’s basketball team headed back to the NCAA Tournament for the second time in the last three years after defeating top-seed UAlbany in the conference title game on March 14, capturing its eighth America East championship in program history.

The Catamounts, who won nine of their last 10 games in the regular season, faced No. 2 North Carolina State in the first round in Raleigh, N.C. on March 22. In a game broadcast live on ESPN, the Wolfpack of N.C. State bested the Catamounts, 75-55.

“We really felt like we played really well for three quarters,” said Mayer Women’s Head Coach Alisa Kresge. “We lost some momentum in the fourth, and we made some errors defensively and, of course, N.C. State and their outstanding team capitalized off of that and really made that push at the end…. I think our play today really spoke volumes about our program and where we’re at. I couldn’t be prouder of this group, just showing so much fight and poise in an incredible environment. It was outstanding and this is what it’s all about.”

What does R1 mean for—and about—UVM?

Dombrowski: UVM has always prided itself on a teacher-scholar model, and if we are going to be serious about that, then scholarship is half of that work. So R1 is a measure, fit to modern university systems, asking: what’s the mass of scholarship happening at your university? And it measures surrogates for that, like how much time are we paying people to spend on research or scholarship? And how big is our investment in the next generation of scholars, in producing Ph.D.s? Getting to R1 is partly about scale—we have a lot of research going on across campus! And achieving R1 status is a validation of our robust teacher-scholar model that’s hard to validate in other ways.

What could R1 allow UVM to accomplish that we haven’t been able to do in the past?

The big question is talent. How much talent can we attract? R1 puts us on a more equal footing with our peers in recruiting that next generation of highly talented faculty and

students. Scholars, graduating today with a Ph.D., see an R1 designation as a sign that a university is serious about research and scholarship. For many graduate students, the belief is that if you want to work at an R1, you have to graduate from an R1. There are other knock-on benefits too. Being an R1 is an advantage for opening doors to certain large foundations, like the Ford Foundation, or others that are invitationonly, that provide major funding. R1 makes us credible as an applicant in that space to say: we have the kind of infrastructure, partnership programs, and scale that would allow us to succeed with very large grants.

When you imagine UVM’s best flight path, in terms of our research endeavor, over the next, say, five years, what are you seeing?

The big outcome is that we should see more large-scale projects—like centers and major infrastructure grants—that bring more interdisciplinary science and scholarship to our campus. This will provide greater levels of support for our graduate students. We’ll

have a larger, more competitive, vibrant, scholarly space on campus. It won’t turn the grass blue or suddenly put skyscrapers on our campus. We’ll look like we look, but we should feel different over the next 10 years in in terms of opportunity and excitement. And that trickles down directly to the undergraduate experience. If you get the best faculty, with a great scholarly ecosystem, you get the best students.

Step back from the higher ed space for a minute and imagine some smart ninthgrade kid who asks, “what is the point of research? Why should I care?”

You know, “research” polls terribly among high school students. If you say to students, “Do you want to go to a research university?” they’re like, “Oh no, I don’t think so.” And that’s because they went to high school, right? In high school, we taught them that research is writing a 15-page paper that has to have 35 sources cited in some particular way. Then they get slaughtered because their thesis statement wasn’t like the one

on the worksheet. Or we taught them: go to a chemistry lab and you’re going to have to repeat this set of facts and draw this diagram in this pre-set way—about an experiment whose outcome has already been determined. Who wants to do that?

But if you say to students, “Would you like to go to a college where you sit, listening in class all day? Or to a college where you’re part of an R&D team trying to cure cancer?” Then they say, “I will do the R&D any day.” We’ve introduced them to research! If you say to them, “Would you like to work in a behavioral pharmacology lab? We’re going to be working with rats in a series of experiments, trying to figure out how cognition works. This will help us understand emotional development that we can translate into improving things from AI to early childhood education.” Students will do that in a second.

Did you as a young scholar have a moment where you realized that research was exciting for you? As a kid, I was constantly building things. In my backyard, we tried to build a hydrofoil surfboard for behind a boat; it must have been the late ’70s or early ’80s. It never worked, just for the record! I nearly broke my neck, but we wanted to figure out: can we make something that would, in theory, rise up out of the water? Now you look out on Lake Champlain, they’re all over.

What’s in UVM’s research enterprise that is compelling to a traditional chamber of commerce perspective, or a fiscally conservative state legislator who’s saying, “Okay, research is nice, but show me the money.” We’ve added a hundred million dollars a year in university research spending since I got here. We were at about $120 million; now we’re above $220 million. That’s economic impact. Research brings in high-paying jobs, highly educated people, and economic energy. Research lays the groundwork for Burlington and Vermont to be the kind of high-tech, high-impact space that every community is trying to attract. We know that our business and engineering students are snapped up by tech companies around here. And if we could make more, they would take more! OnLogic, Beta, and other fast-growing companies here are eager for our graduates. They just keep saying to

me, “How can you make more?” That’s a way that keeps those companies here, makes them viable here, and creates innovation.

We want to help build up Burlington as a “knowledge town.” Everyone knows what a country town looks like, or a university town, an industrial town, a company town, or post-industrial town. What we are trying to think of is: what is a knowledge town? When I was a kid, Cambridge, Massachusetts, was a parking lot. It was one of the most economically depressed areas in the world. But Cambridge leaned into the work that was going on at Harvard and MIT and brought that out to build a biotech industry that is unprecedented in the world. It’s created prosperity; it made Boston functional. Now the economy that’s around those universities is ten times the size of the universities themselves.

“Would you like to go to a college where you sit, listening in class all day? Or to a college where you’re part of an R&D team trying to cure cancer?”

You suggest that research and scholarship are largely synonymous. Let me push back on that a little bit. When you think about “research,” how much is that defined by a STEM vocabulary—science and engineering? And how much of “scholarship” is the domain of the humanities—history, English, art?

I’m a cultural anthropologist by training. There’s a classic called Laboratory Life, by Bruno Latour, an anthropologist. The book is an ethnography of Jonas Salk’s lab. Latour treated Salk and other scientists like the primates that we all are. He went in and he wrote down what they did. He just sat and studied the work and the workers of the lab the way you would as an anthropologist.

Latour’s conclusion is that this lab is a place that takes lab coats, paper, chemicals, ink, typewriters, mice, human help, and coffee—and turns them into sentences. Salk objected, saying, “No, we don’t make sentences here; we make knowledge, we make science.” And Latour said, “Well, no, really, you make sentences. They come out as papers and lectures.” And in a way he was right: at the end of the day, what comes out of the university? We don’t make vaccines here. We don’t make cars here. Every car in our parking lot, none of them were made at UVM, right? What we make here is understanding of the world— published in articles and books and studies. Our engineers write papers and books, and our anthropologists write papers and books, and our English professors write papers and books. That’s what we do.

I don’t think the chasm between the sciences and the humanities is real. It’s an easy target. It’s a scapegoat for different levels of different funding and market forces within the university, right? There are subjects that fall out of favor in a student market sense. And there are things that become popular, and it’s easy to give them labels and see one as some higher calling. And I just don’t buy it. More Americans buy history books than buy engineering books by far. There’s a lot of rhetoric about how these things are opposed, and there’s a lot of hurt feelings about the way that market forces are working within universities. I get that piece, but I don’t think it’s because somehow there’s something so different going on one side than on the other.

Anything else that we should know?

I have no idea what we should all know, but I’m glad I work at a place dedicated to that idea. Achieving R1 is a great moment for us. This is a celebration of the work of hundreds of people in all kinds of spaces at UVM. The recipe was simple: make it fun to go after competitive grants; build the infrastructure around folks who want to do research and scholarship; support the people who are dying for this chance; then get out of the way of the people who have been hungry for this bigger stage, these new opportunities to learn and explore. This is why they became professors.

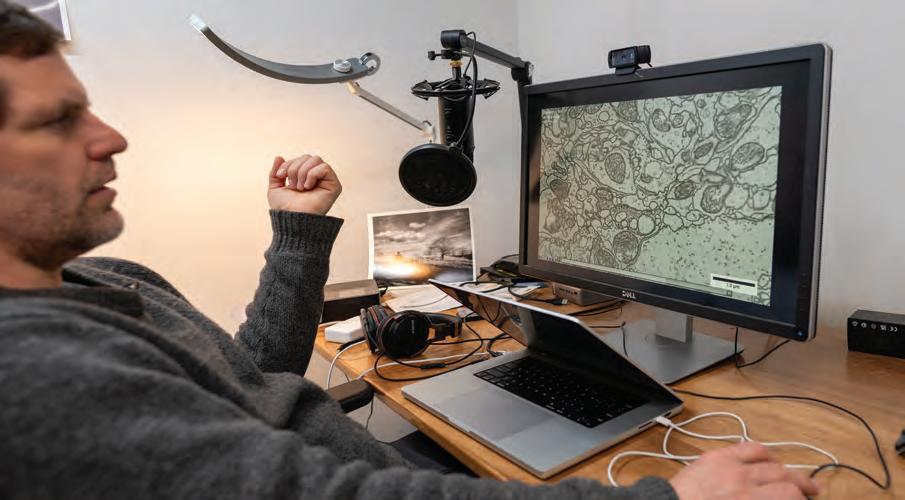

Story by Joshua Brown

There are no fruit flies in Davi Bock’s kitchen.

But head down into the basement of his 1850s farmhouse, on the end of a dirt road in Glover, Vt., and you’ll find them by the millions. Well, not really. But—in one corner, on a laptop computer linked to the wider world with high-speed, fiber-optic cable—you can surf and plunge into 21 million photos of one fruit fly’s brain.

Bock points to a spectral gray image, roughly the shape of Princess Leia’s hairdo. “This is the optic lobe,” he says, pointing to one side of the picture that sticks out like a bun. “You’re seeing hundreds of images mosaic together to encompass the whole fly brain from tip to tip.” On a large monitor, the brain appears about a foot wide. In an actual fruit fly, the brain is smaller than a poppy seed.

Color-enhanced Scanning Electron Micrograph (SEM) of Drosophila melanogaster, also known as the common fruit fly or vinegar fly. Live, unfixed specimen; natural state. Magnification: 130X.

Photo by: David Scharf / Science Source

Inside that speck, some 140,000 neurons are linked together—hundreds of feet of microscopic, living spaghetti—to form more than 50 million connections called synapses. Bock—a biologist who grew up in Jericho, Vt., and joined the faculty of UVM’s Larner College of Medicine in 2019—co-led an effort, over the last 12 years, to photograph, trace, and label every neuron and synapse in a fruit fly’s tiny head. His work, which yielded the first complete map of the neural wiring in the brain of a complex organism, made the cover of the journal Nature in October 2024—and was reported by news outlets around the world, including the BBC, which described it as a “huge leap to unlock the human mind.”