KRISHNA REDDY: Printmaker, Pioneer, Philosopher

Complete Viscosity Intaglio Prints

Umesh Gaur

Preface – Sasha Suda, Director, Philadelphia Museum of Art

Introduction and Acknowledgements

Essays

1. Krishna Reddy: Printmaker, Pioneer, Philosopher – Umesh Gaur

2. Krishna Reddy’s Variations: Sculpting Metal Plates and Printing Simultaneous Colors - Christina Taylor

3. The Print as Process: Krishna Reddy’s Transformative Experiments – Umesh Gaur

4. Postwar Printmaking in Paris: Krishna Reddy at Atelier 17 - Christina Weyl

5. Krishna Reddy: The Movement of Life - Heather Hughes

6. From Line to Form: Krishna Reddy’s Evolution into Figuration – Carol Huh

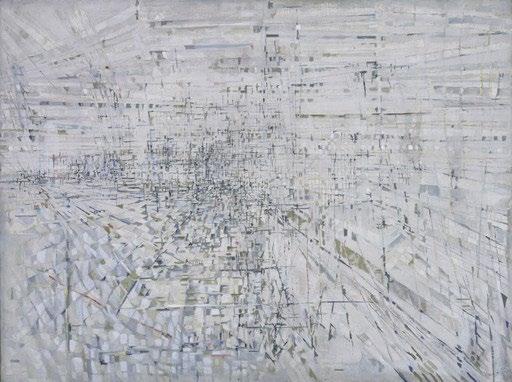

7. Imagining Space: Krishna Reddy and Mid-20th Century Abstraction - Jeffrey Wechsler

8. Passing the Torch: Krishna Reddy and Generations of Printmakers - Judith Brodsky

Complete Viscosity Intaglio Prints

Centennial Timeline, 1925-2025

Major Institutional Collections

Bibliography

Glossary

Authors

Preface

Sasha Suda Director, Philadelphia Museum of Art

Introduction and Acknowledgements

Krishna Reddy: Printmaker, Pioneer, Philosopher

Umesh Gaur

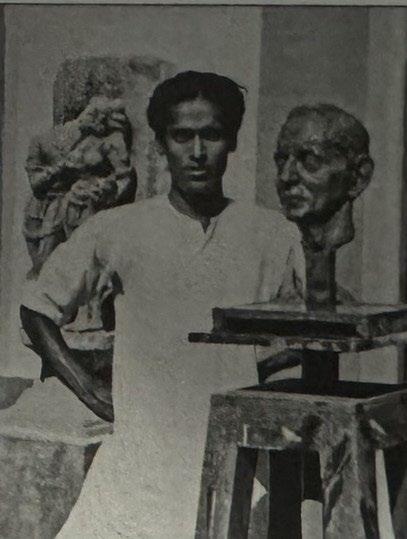

Krishna Reddy's artistic journey was shaped as much by life experience as by technical mastery. Over seven decades, spanning continents from rural India to studios in Paris and New York, and a prolific teaching career at New York University, Reddy's career was grounded in his spirituality, his relentless pursuit of knowledge, and the profound philosophical underpinnings of life.

In 1998, when Krishna Reddy was retiring from active printmaking, he wrote an essay titled "Art Expression as a Learning Process." In this essay, he reflected on his long career as a student, artist, and educator. This essay was not a traditional artist statement. It was deeply reflective of his life, which he described as a lifelong process of discovery, curiosity, wonder, and connection with both humanity and the world around him. What impressed me most was the fact that Reddy rooted his art not only as self-reflection, but as a reflection of his genuine desire to understand our place in this universe.

Reddy began the essay by stating that humans are not separated from nature but are a part of its ongoing and ever-changing dynamics. He emphasized that modern life has given us artificial compartments, such as economic systems, politics, and social hierarchy. He felt that this had isolated humanity from nature, spirituality, and individual creativity. Reddy firmly believed that every person, regardless of their background or circumstances, has tremendous potential to be creative. What matters most is not the person's talent, but their ability to wonder like a child and be aware of the world around them without preconceived notions. For him, art began by seeing the world around him. He felt that art is not a matter of style or

beautification but instead should emerge from the beautiful world in which we live. He believed the great artists were also great thinkers, not great stylists, and that their art emerged from their sense of wonderment.

Reddy went further to criticize the modern art world, where he felt that commercial interests and the artist's reputation had overshadowed artistic creativity in some cases. He believed art has to be lived, not merely created or performed, and it should grow out of the artist's commitment to truth and their dedication to inner transformation.

The Philosopher's Apprentice: Encounters That Shaped a Pioneer

Reddy's journey began in Nandanoor, a village in Andhra Pradesh, in a family grounded in rural traditions. Despite not being born into privilege, his teachers recognized his artistic sensitivity and his hunger for learning from a young age. This early display of determination and passion set the stage for his future artistic endeavors.

Reddy's artistic turning point occurred during his early education at Kala Bhavana, the art school founded by Rabindranath Tagore at Shantiniketan. This school, which embraced a radical alternative to conventional colonial education, nurtured young art students in the spirit, mind, and body, emphasizing a connection to nature in open-air classrooms. There, Reddy studied under some of India's most influential modernists, like Nandlal Bose, Ramkinkar Baij, and Binode Bihari Mukherjee, each of whom believed that art was not separated from life. These influential artists shaped Reddy's deep respect for

materials and processes and instilled in him the idea that artistic practice is also a path of personal and philosophical inquiry. It was here that Reddy encountered the notion that art must serve a higher purpose and could be a path for self-understanding and ethical living. He wholeheartedly imbibed the idea that the artist must be in harmony with nature and develop a power of internal vision.

It was around this time that Reddy developed a close relationship with Jiddu Krishnamoorthi, a profound thinker and philosopher whose teachings emphasized personal freedom and self-awareness. Krishnamoorthi's ideas struck Reddy as a challenge to look within and pursue artistic truth, not influenced by tradition or imitation. This internal freedom would eventually become central to Reddy's approach to art making. He often spoke of "entering the plate without preconceptions," a mindset that echoes Krishnamoorthi's idea of "observing without the observer".

It was Jiddu Krishnamurti who encouraged Krishna to go to London to pursue art, where he met another thinker, V. K Krishna Menon, who also greatly influenced him. Menon was a philosopher–diplomat who became India's ambassador to the United Nations. Menon challenged Reddy to think of art as a moral act and introduced him to the idea that an artist, like a philosopher, should explore ideas of human dignity, universality, and their role in society.

Reddy's encounters with thinkers like Jiddu Krishnamoorthi and Krishna Menon gave him a distinctive vision of art as a journey of inner transformation. Their influence was profound, shaping not only his artistic philosophy but also the very nature of his prints. Reddy's prints are not narrative, but contemplative. He is not just a maker of prints, but a questioner of meanings, a testament to the profound and transformative power of his encounters.

Atelier 17: The Laboratory Where a Pioneer Emerged

Founded by Stanley William Hayter in 1926, Atelier 17 was a collaborative print laboratory where experimentation and artists came together. The list of people who passed through his doors reads like a who's who of 20th-century modernism: Picasso, Miró, Giacometti, Ernst, and later Peterdi and Nevelson.

When Reddy joined Atelier 17 in 1951, Hayter had only just reestablished the center in Paris after a break of more than a decade. The situation for printmaking in postwar Paris was quite different from what Hayter left behind in 1939 when he moved the workshop to New York during World War II. It was not assured that his workshop would flourish again. Krishna Reddy's arrival and his eagerness to experiment supercharged the studio's reintegration into Paris, solidifying its position as a leader in cutting-edge technical research in printmaking.

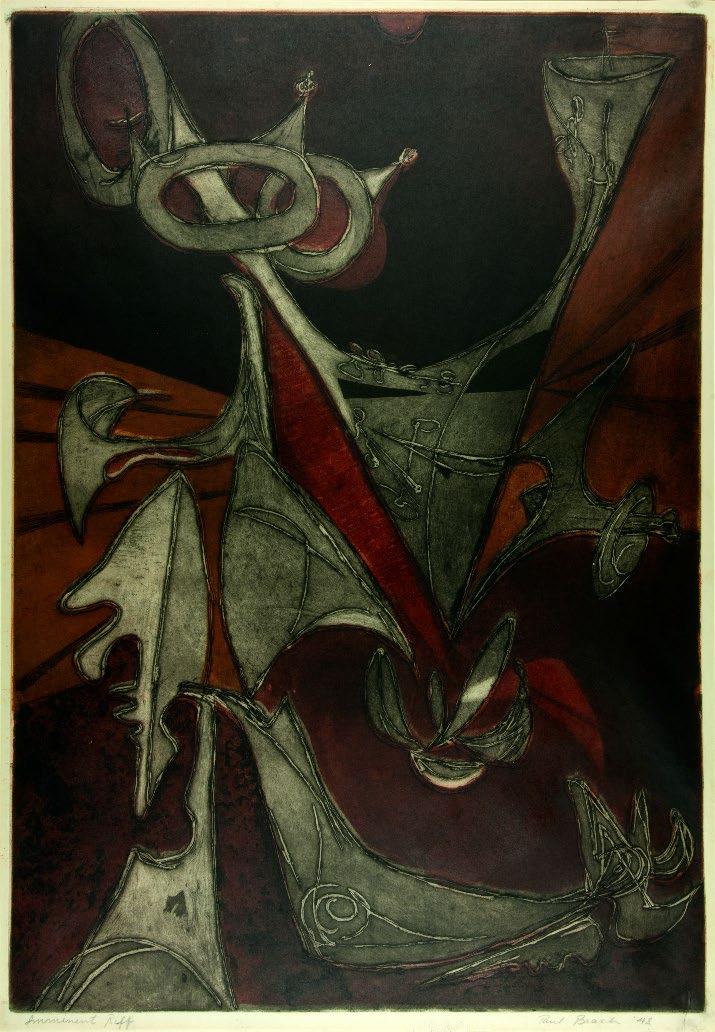

Reddy's most celebrated achievement and what makes him a pioneer was his transformation of the viscosity printing technique. Hayter had already developed the concept of viscosity printing, which involved using inks of varying thicknesses to print multiple colors from a single plate. But it was Reddy, working in close collaboration with fellow artist Kaiko Moti, who transformed this method from a technical curiosity into a true art form. Their partnership, marked by shared vision and relentless experimentation, led to the discovery that variations in ink viscosity and roller pressure could produce multiple-colored radiant images never seen before in intaglio printmaking.

Viscosity printing would become Reddy's vehicle, with which he continued to innovate and experiment for the rest of his career into the 1990s. The plate, for Reddy, was not just a template; it was a partner in a dialogue. He used to say, "The Plate has its own life, it tells you what it wants".

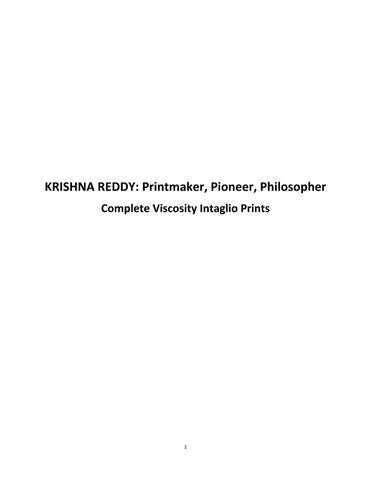

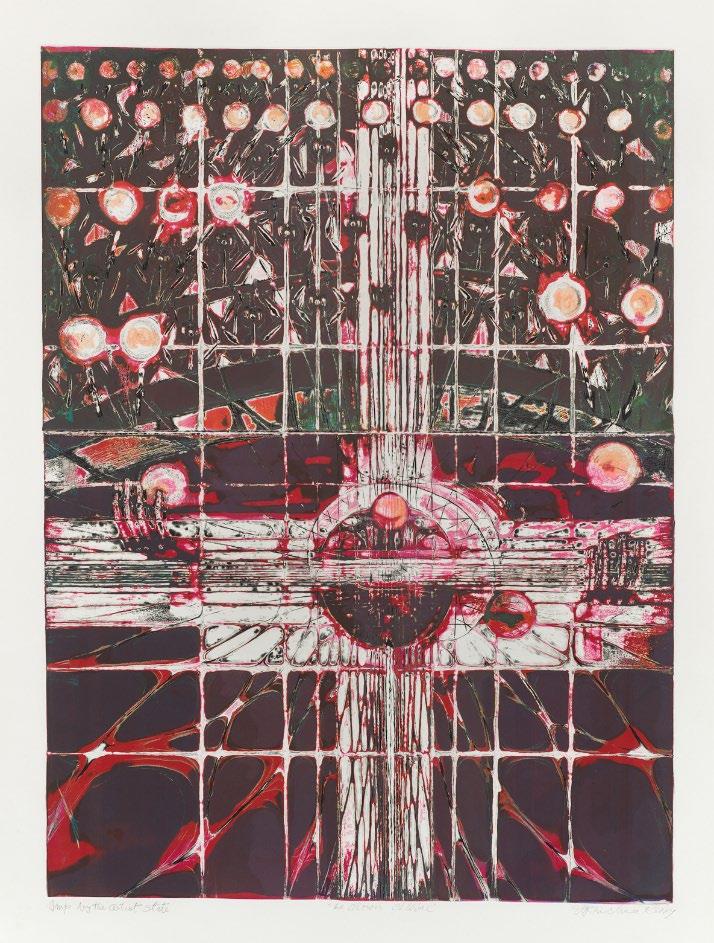

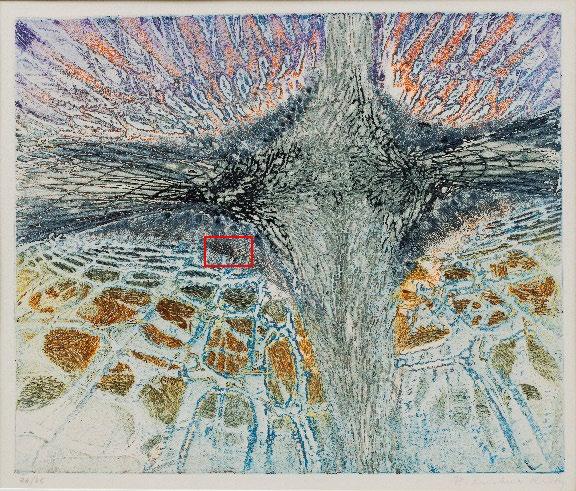

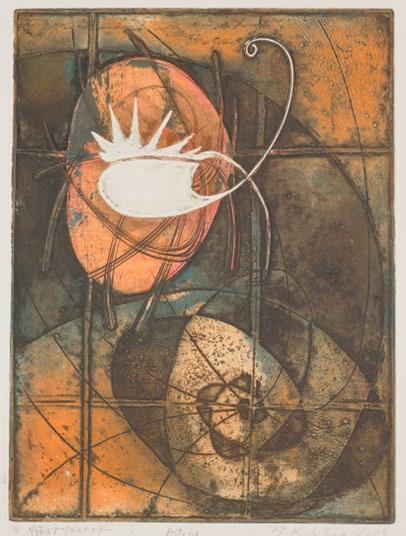

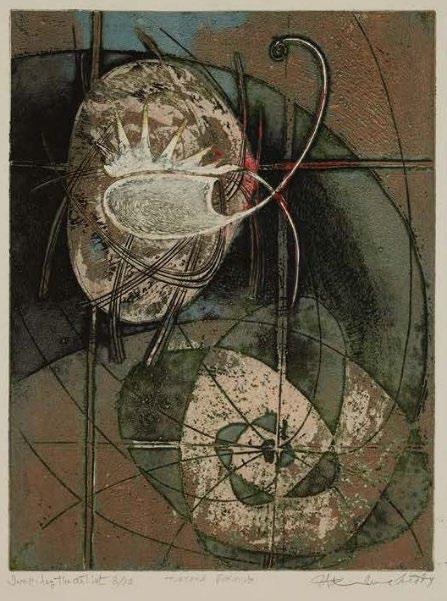

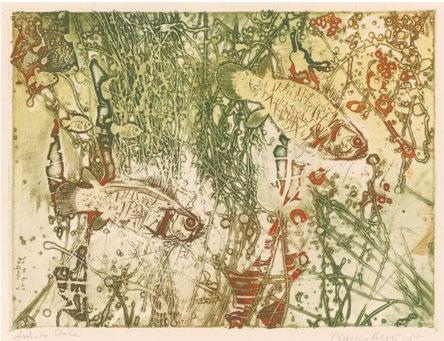

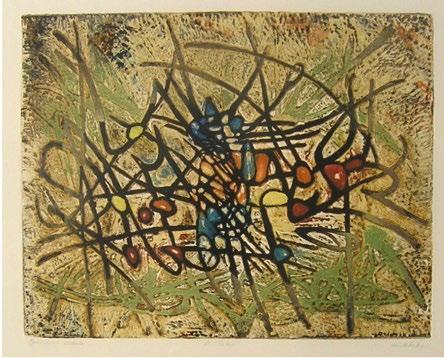

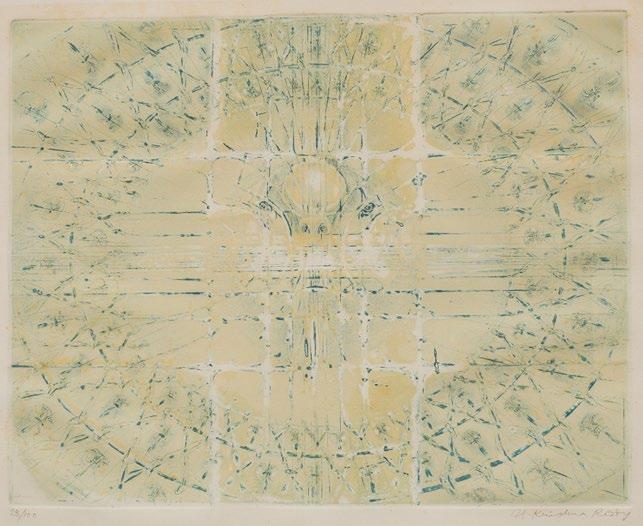

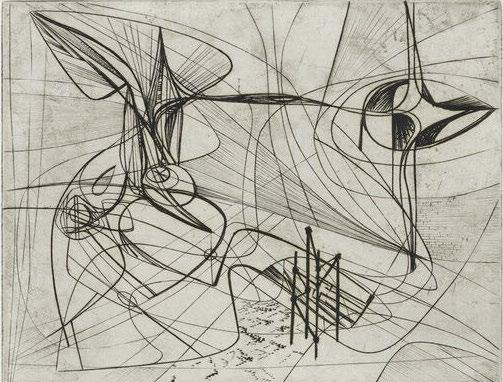

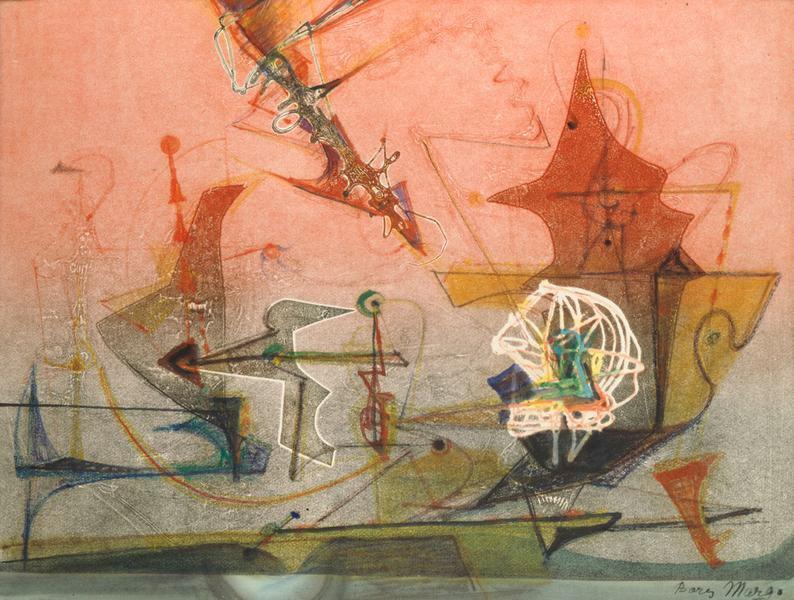

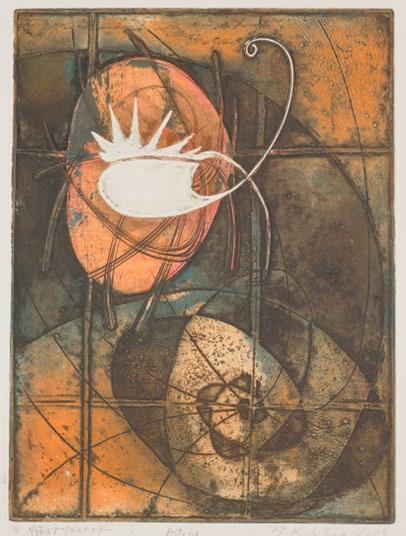

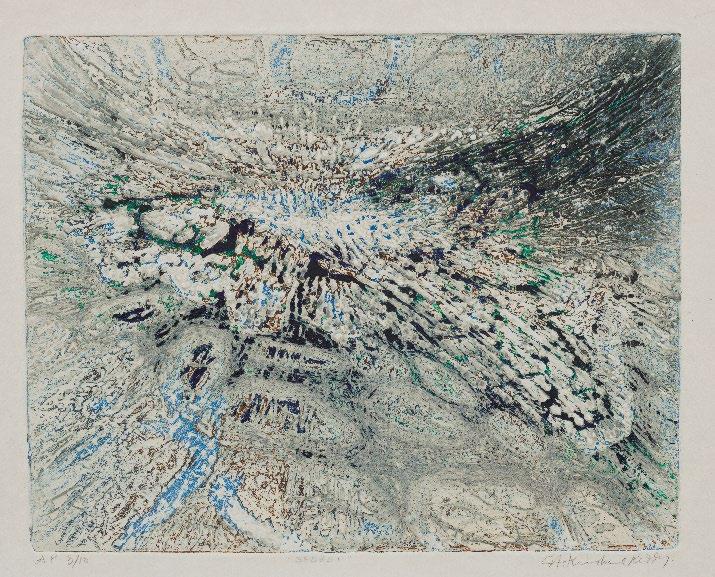

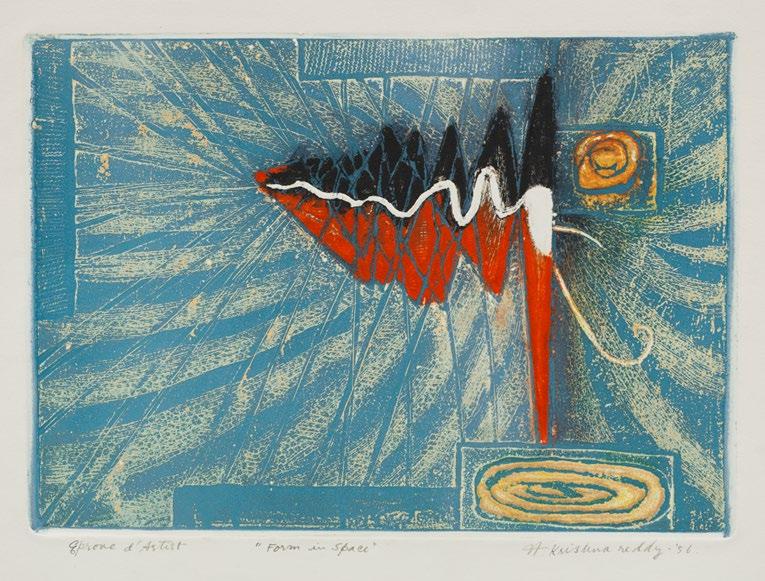

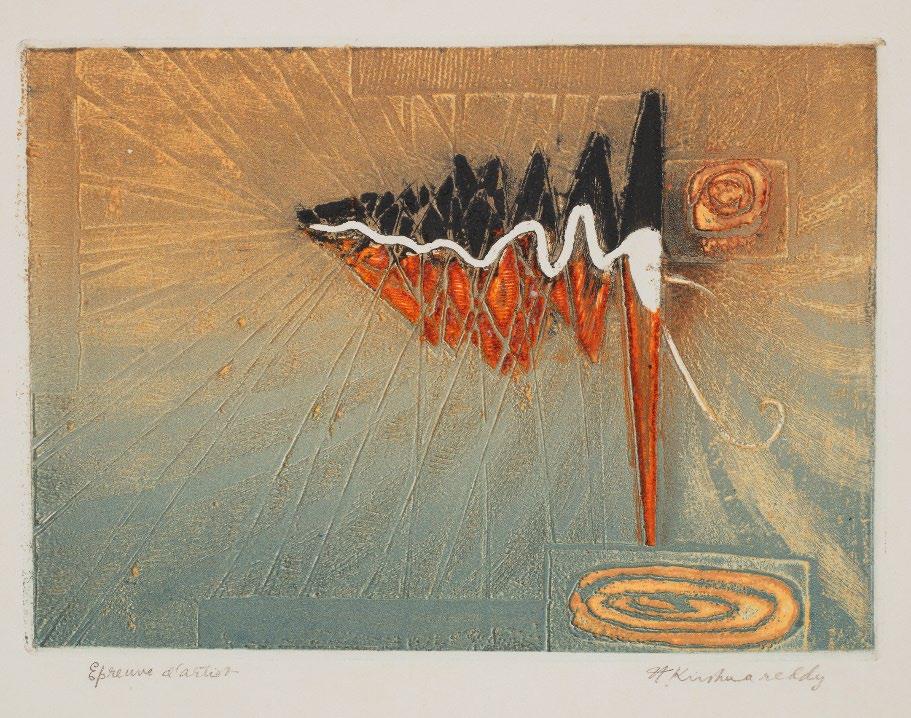

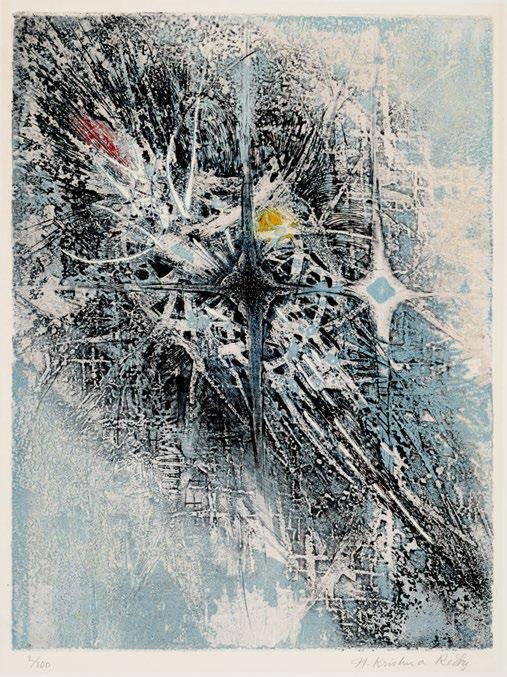

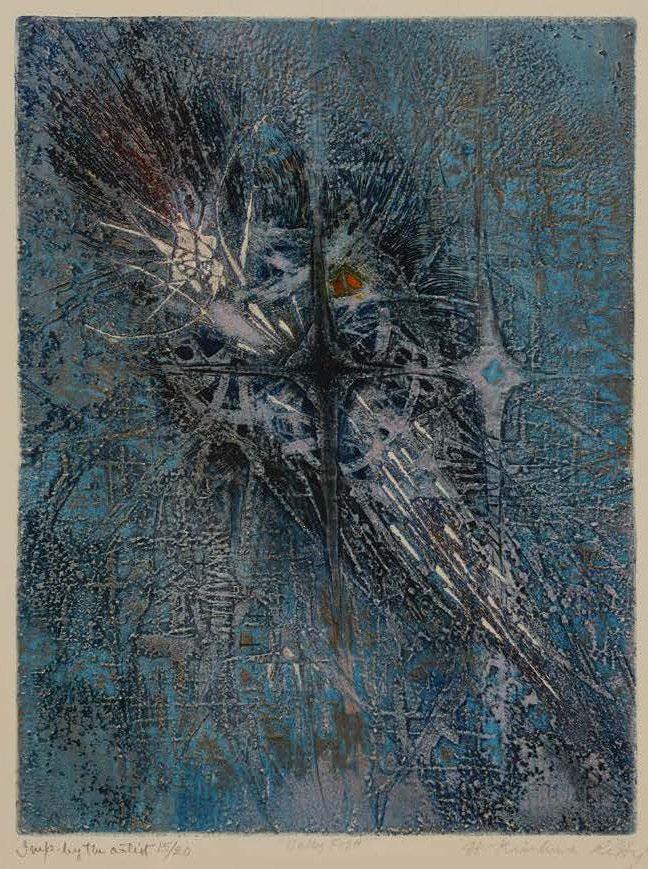

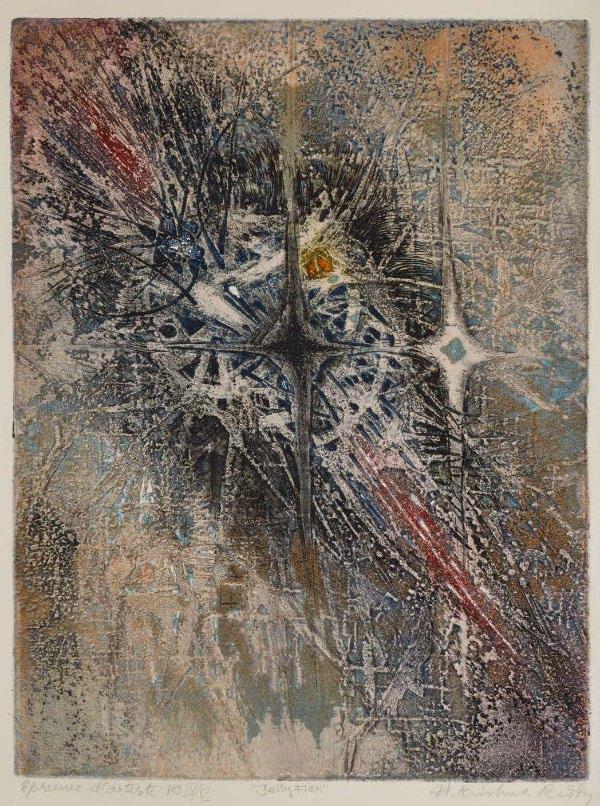

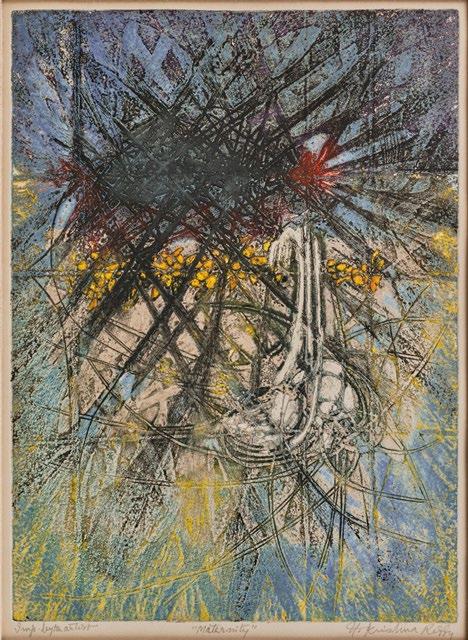

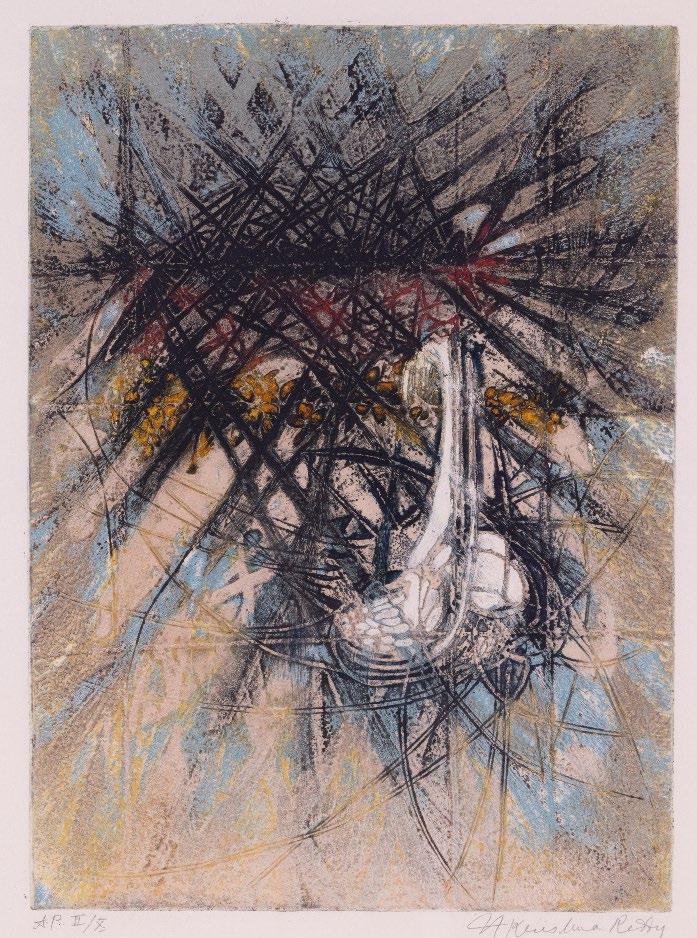

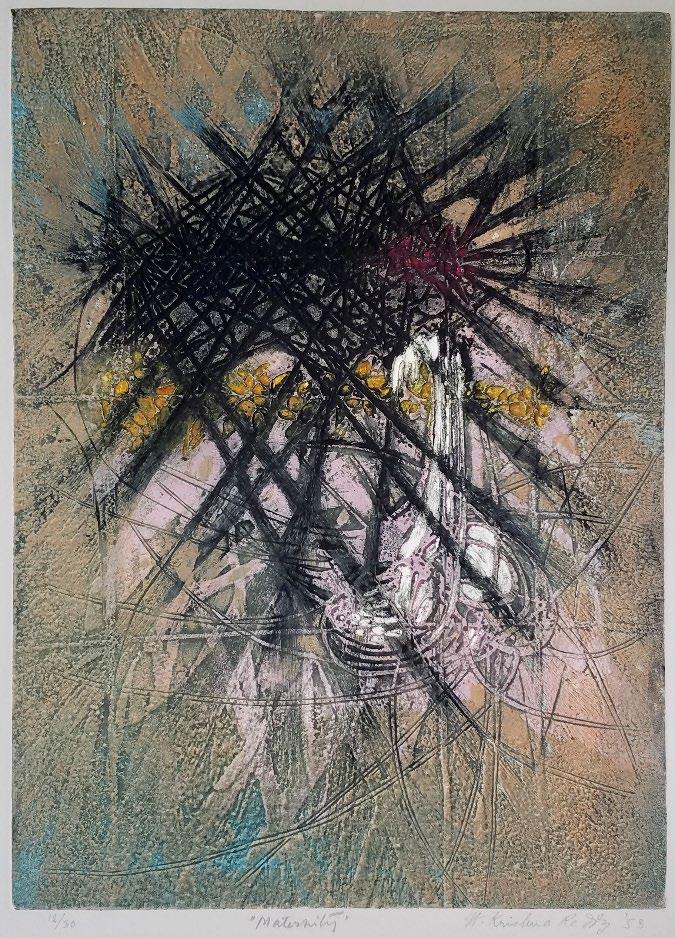

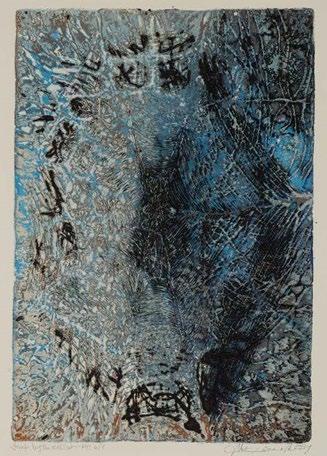

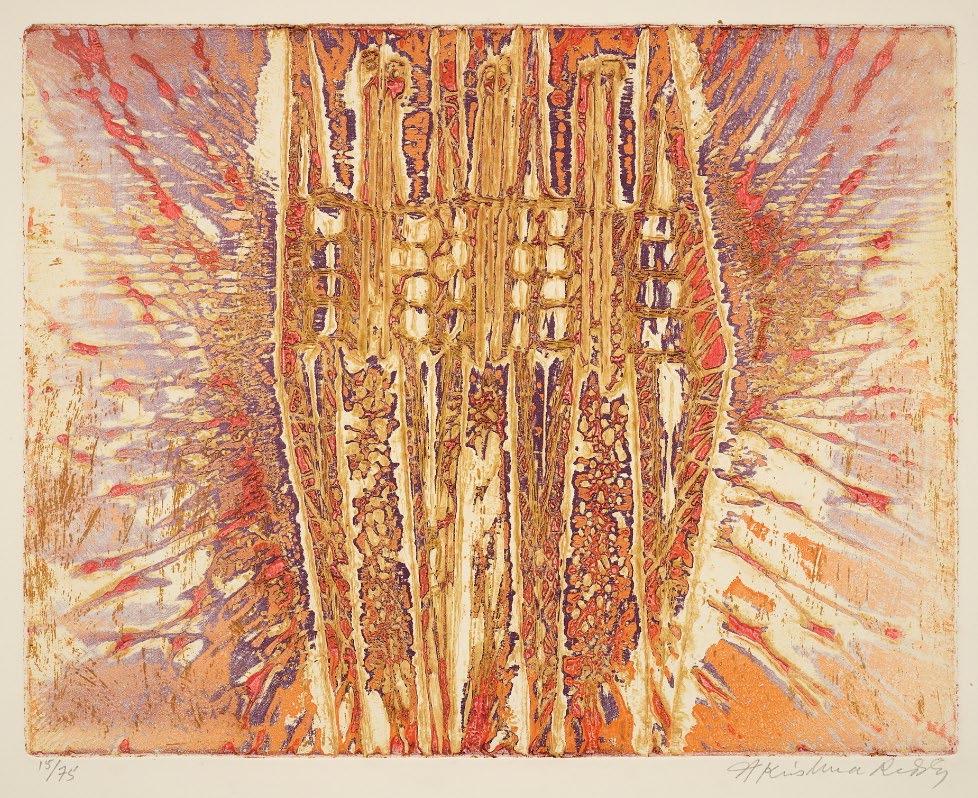

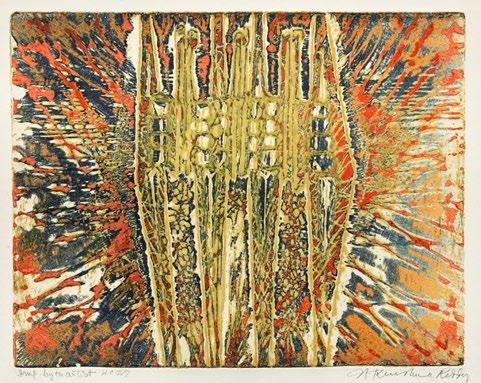

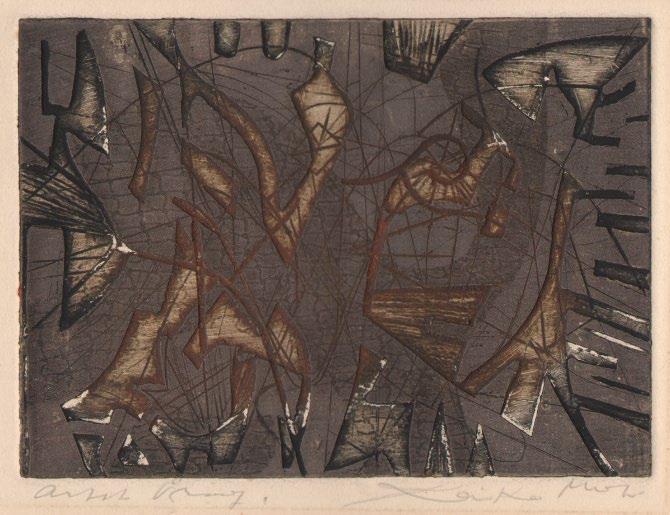

3 – Maternity, 1955-58

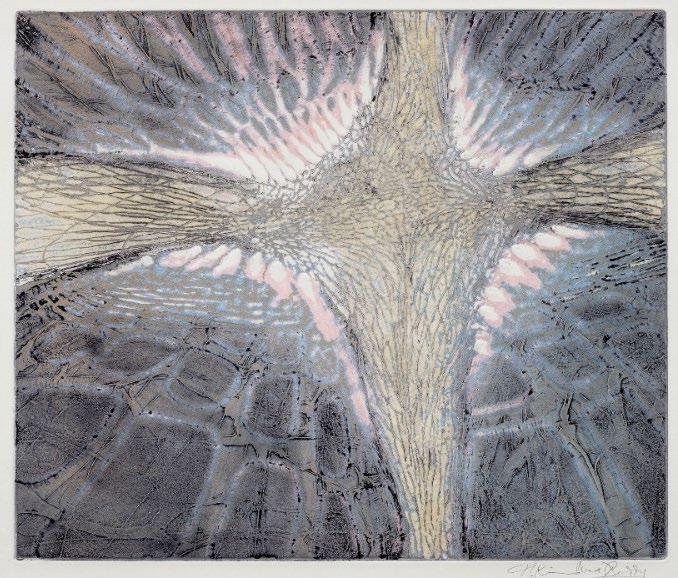

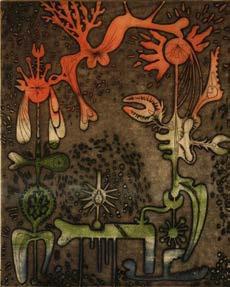

Reddy approached printmaking as an artist, scientist, and philosopher. Works like Germination II, Fish and Maternity (Fig. 1-3) are not just visual marvels; they are mediations on the interconnectedness of life. Reddy brought to printmaking the Shantiniketan-trained respect for nature, Krishnamoorthi inspired attentiveness to perception, and the scientist's delight in process and variation. His fusion of the viscosity technique with philosophy was unprecedented, and it is here that his pioneering legacy took root.

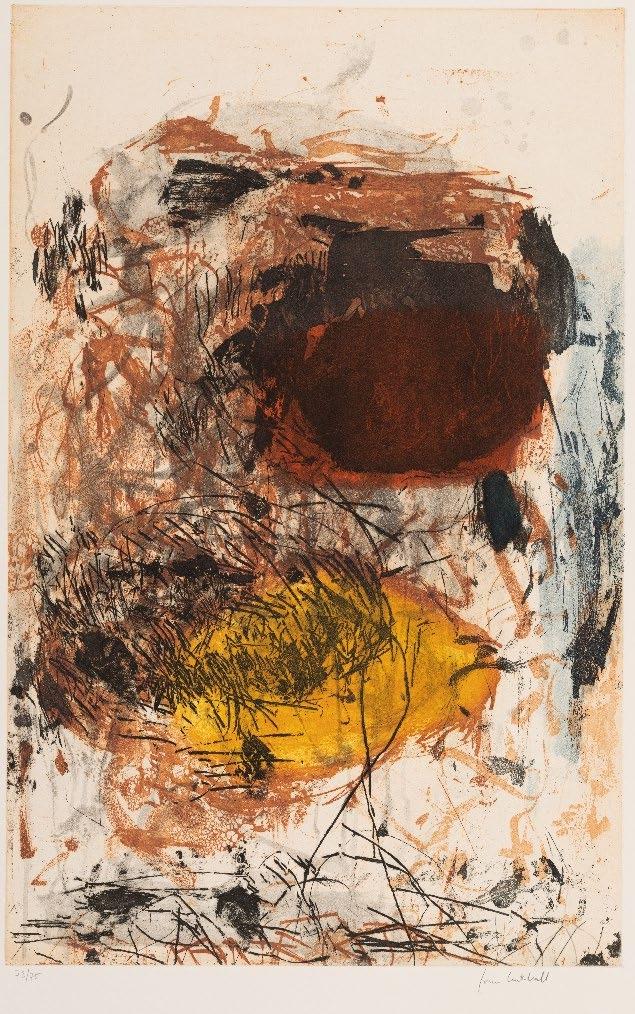

At a time when prints were seen as secondary to painting, Reddy insisted that each viscosity print was a unique work of art in its own right. The uniqueness of each of Reddy's viscosity prints blurred the lines between painting and printmaking, and in doing so, Reddy helped elevate the medium of printmaking.

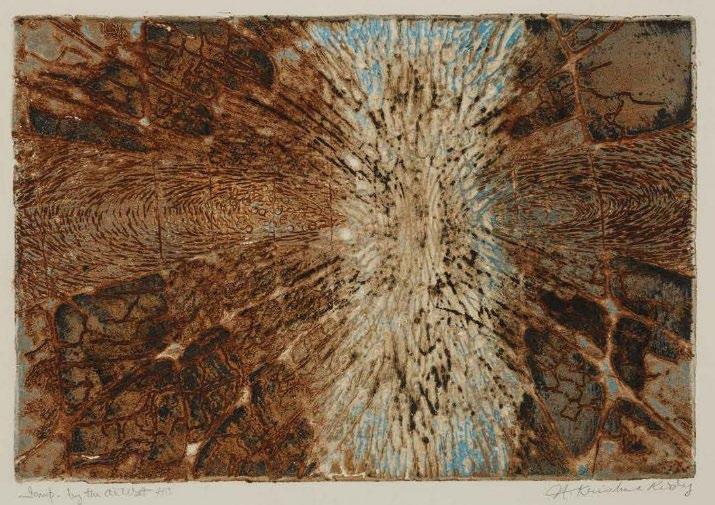

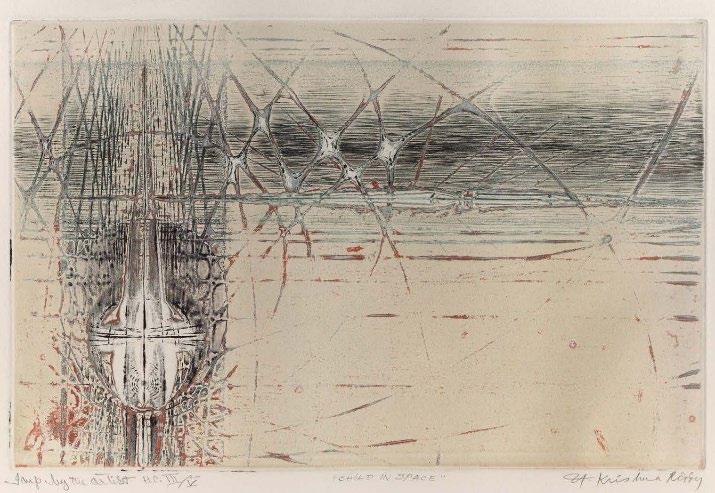

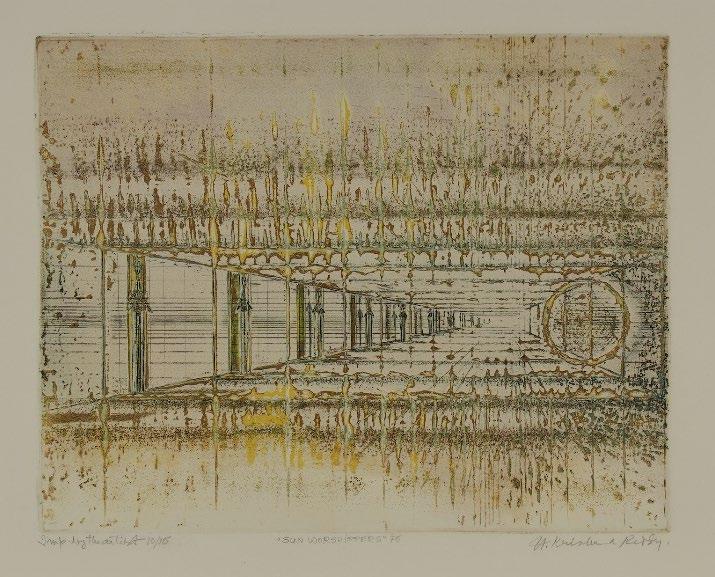

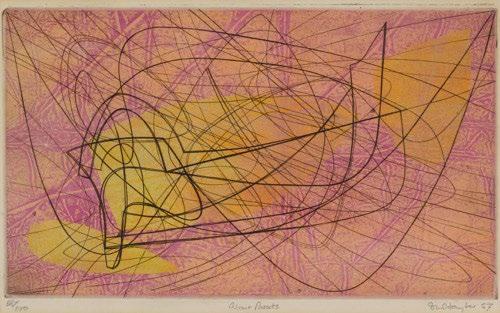

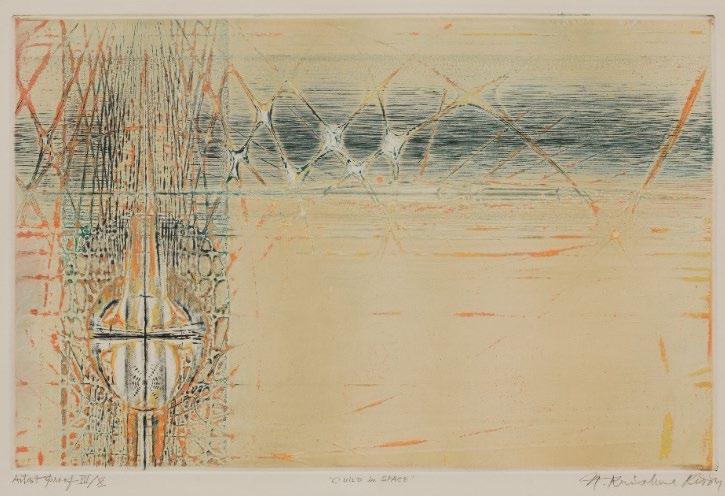

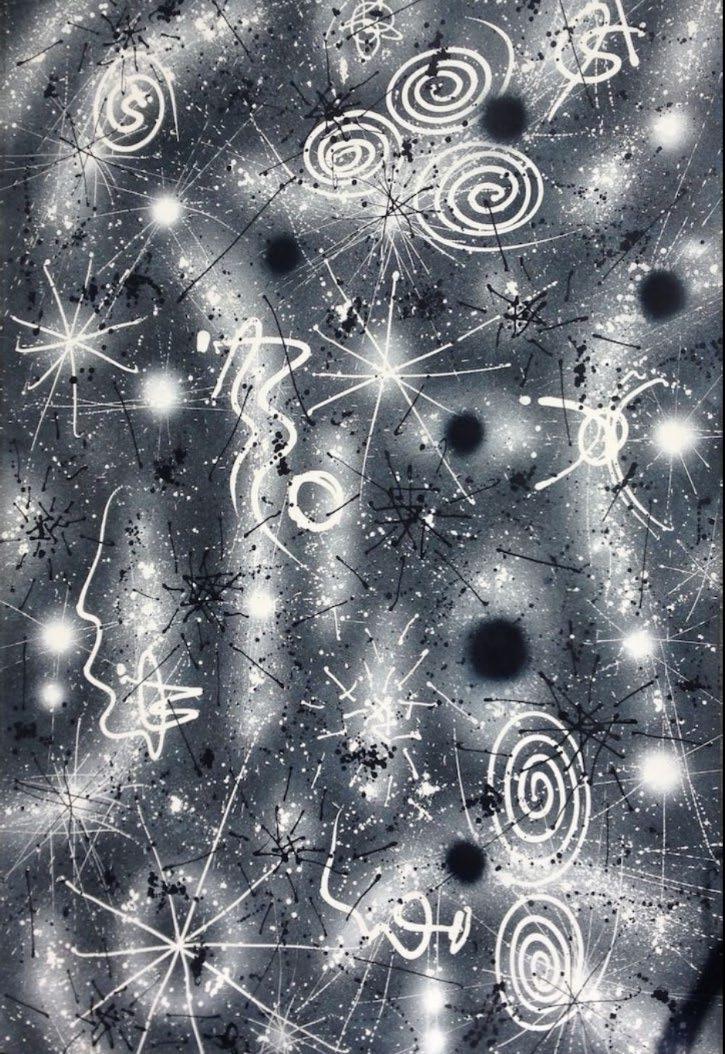

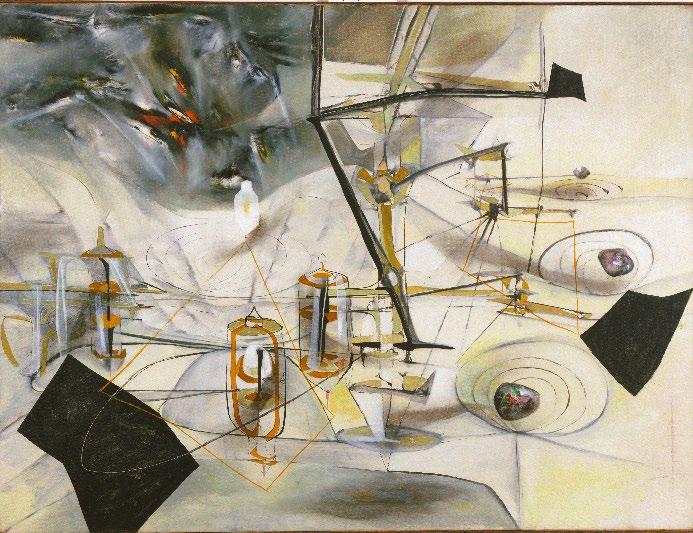

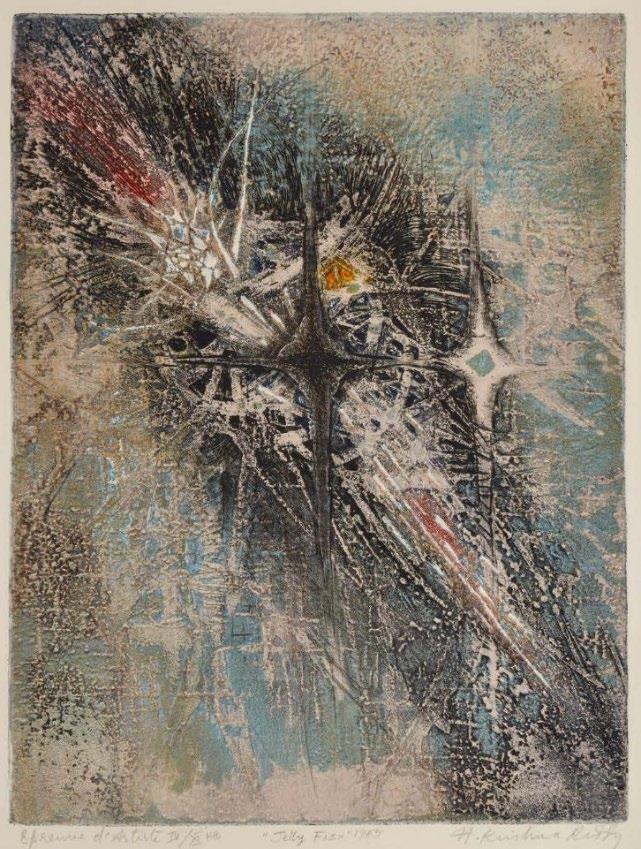

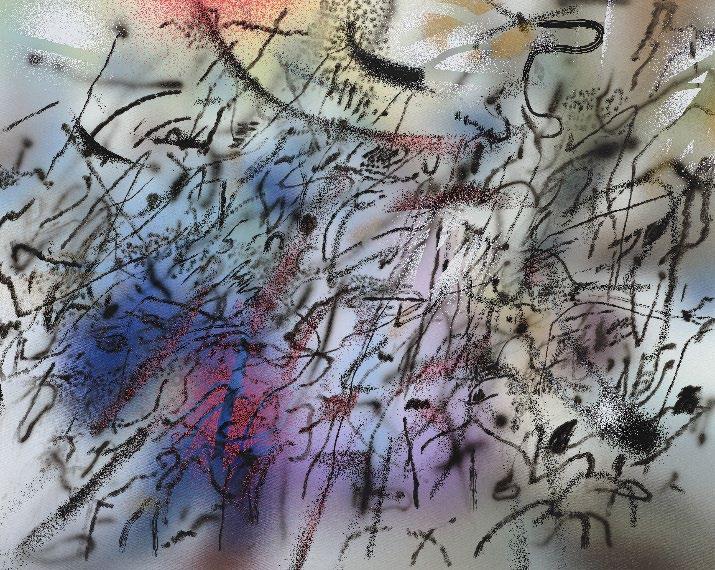

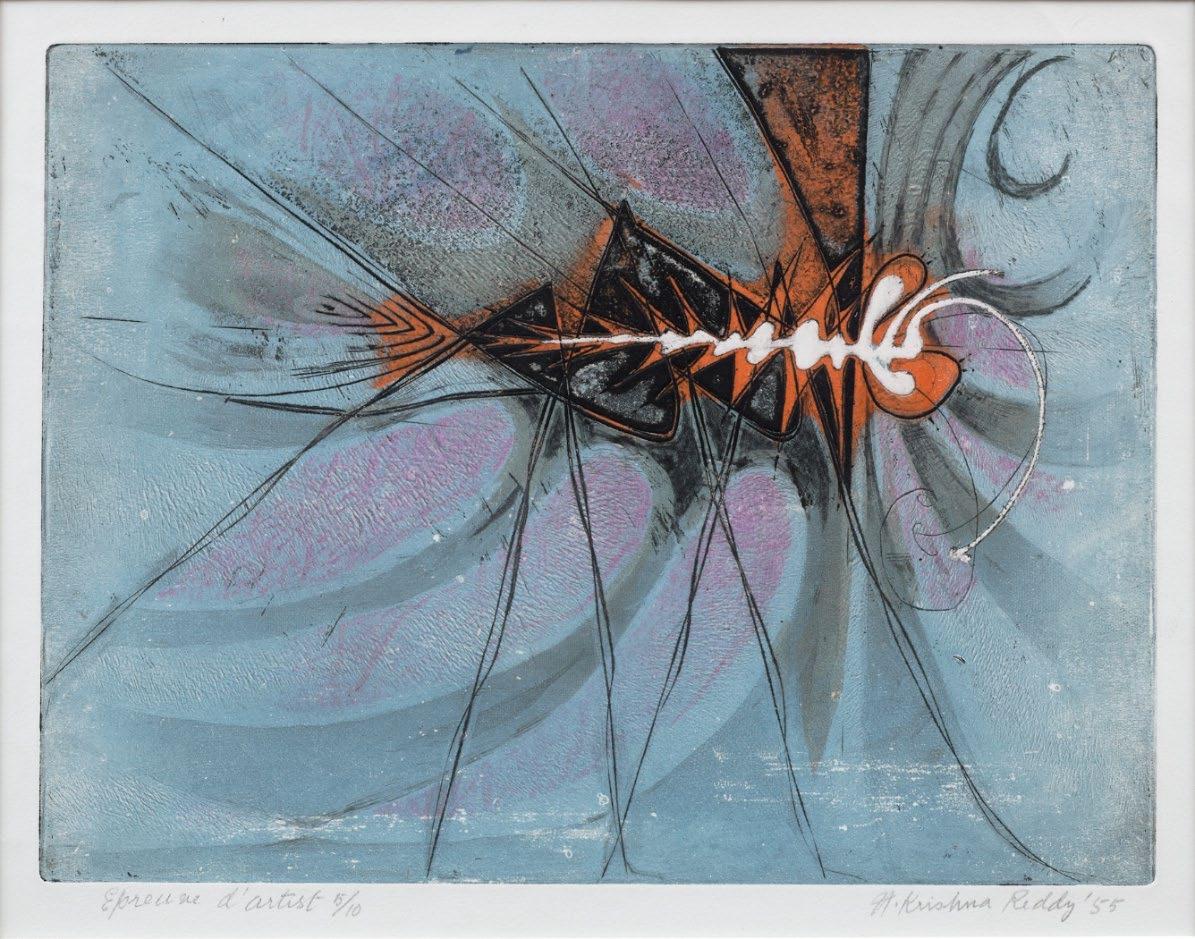

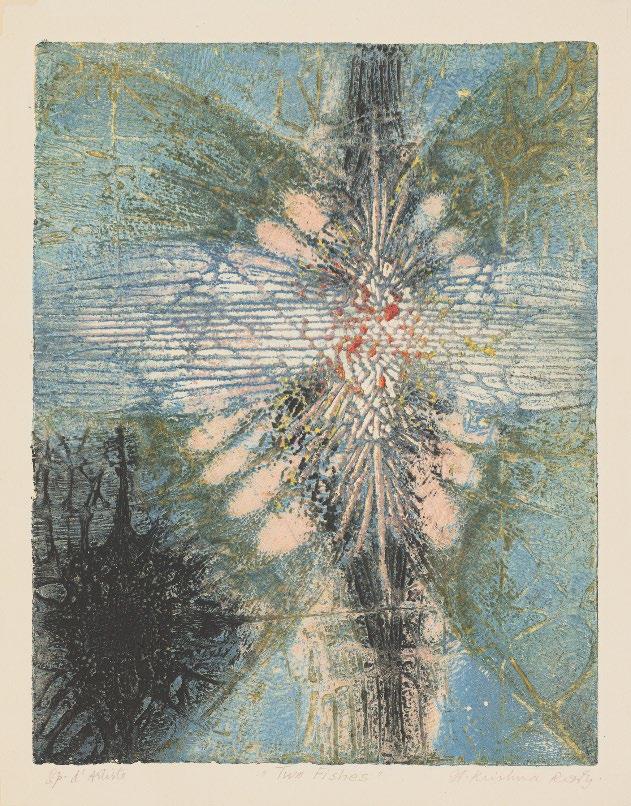

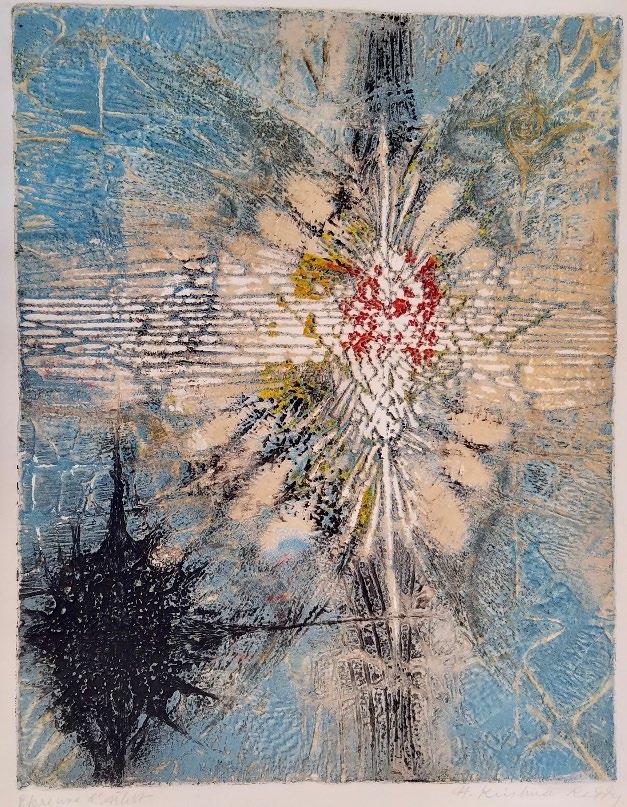

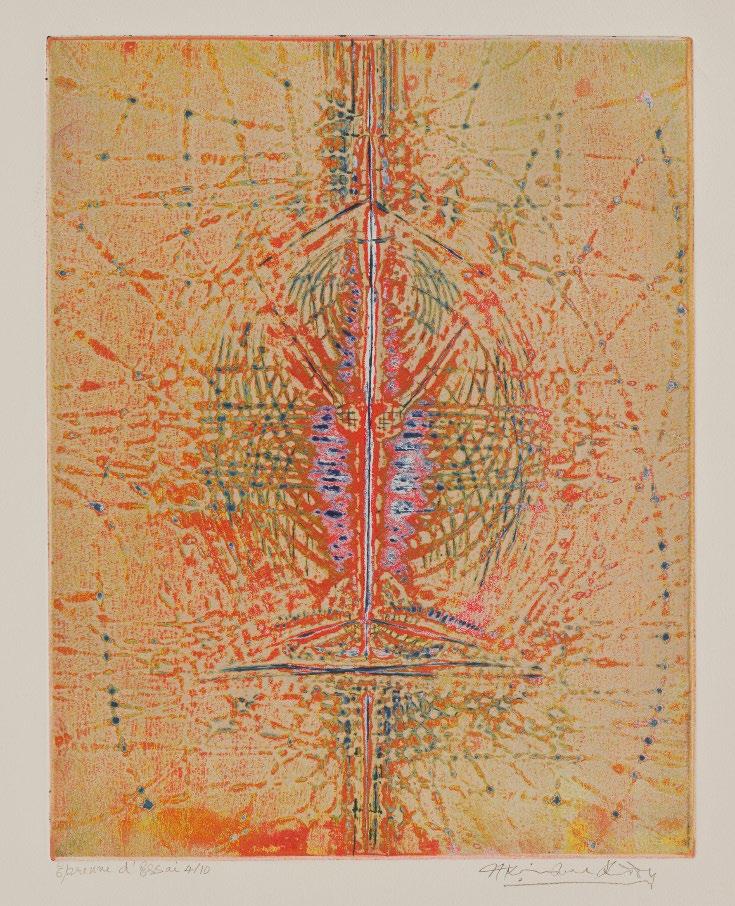

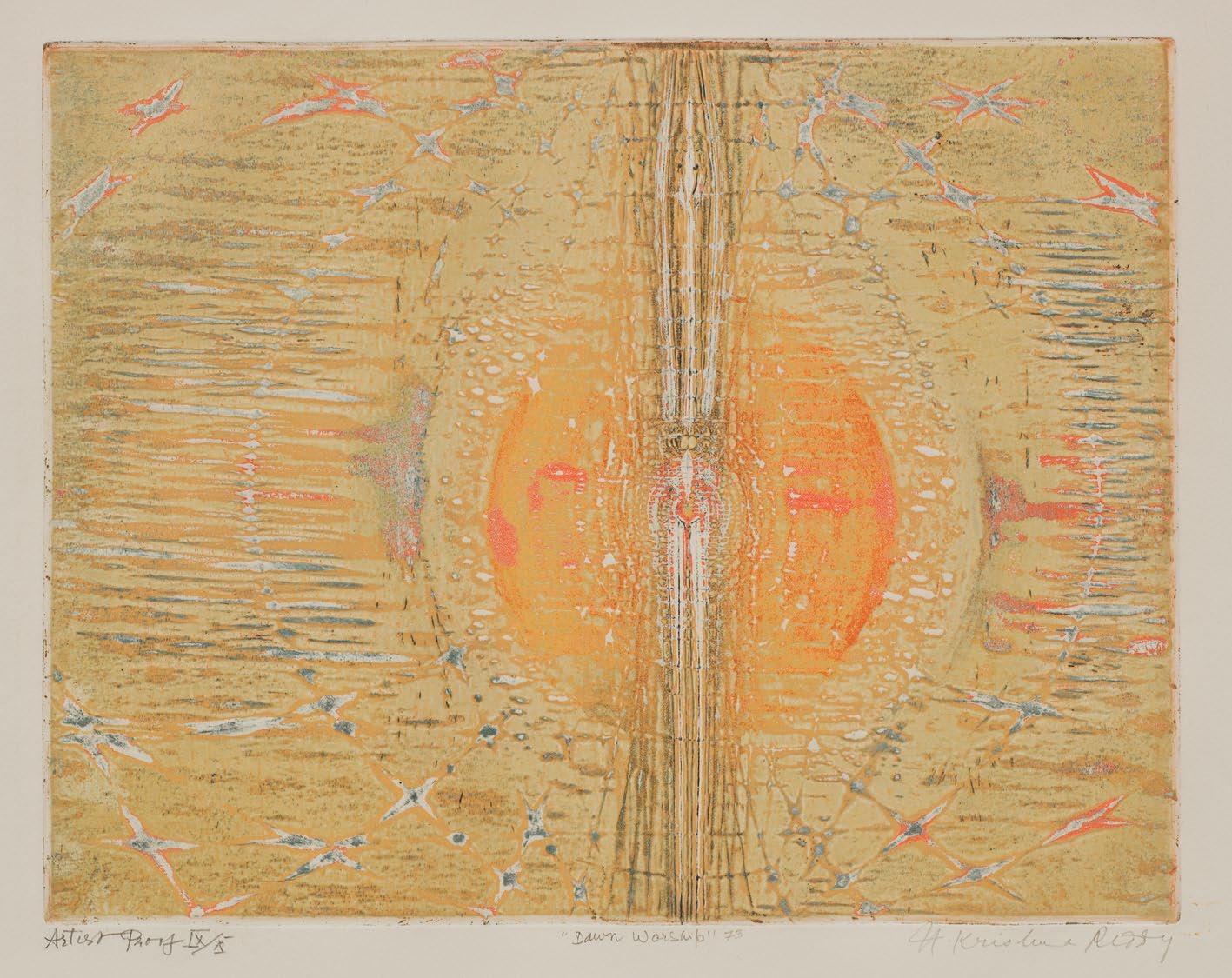

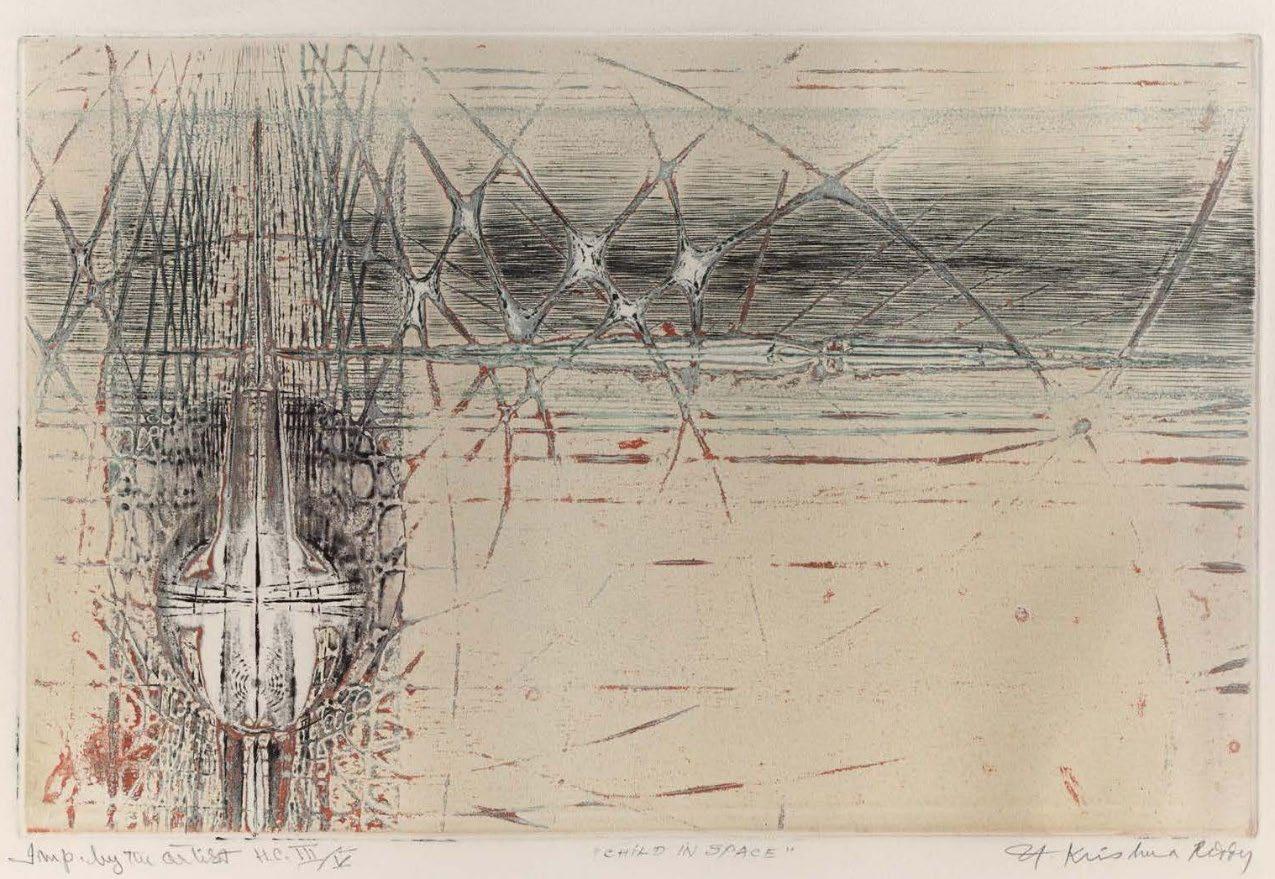

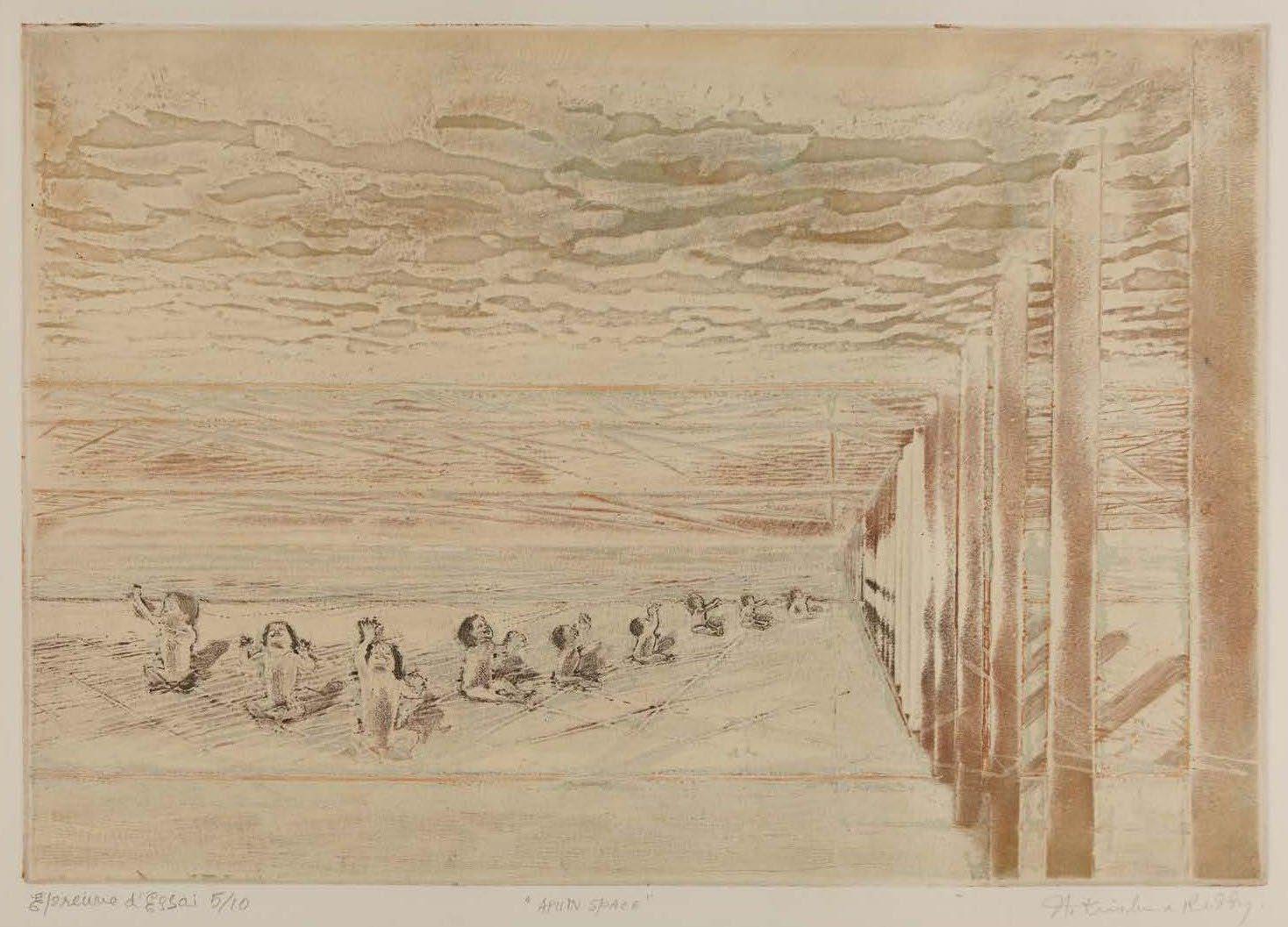

Krishna Reddy's association with Atelier 17 also placed him at the crossroads of modernist spatial invention and the organic surrealist tradition, particularly the strand rooted in automatism This technique encouraged spontaneous, subconscious mark-making. Reddy absorbed the visual language pioneered by painters like Joan Miró, André Masson, and Roberto Matta, where flowing, loosely applied inks or pigments created dreamlike, indeterminate forms suspended in uncertain environments. In works like Child in Space and Sun Worshipers (Fig. 4-5), you can feel the influence of surrealism, automatism, and the subconscious. Unlike many painters of the movement, however, Reddy translated these ephemeral forms into print, a medium typically more rigid and process-bound thus pushing the boundaries of both surrealism and intaglio printmaking. In the crucible of Atelier 17, Krishna Reddy emerged not only as a technical innovator but as a spiritual and intellectual pioneer, one who redefined what the print could be.

While Paris and Atelier 17 had offered him the space to transform viscosity intaglio into a powerful new printmaking language, New York became the arena where he deepened this work teaching, mentoring, and engaging in lifelong philosophical inquiry. In this dynamic and diverse city, Reddy's influence would radiate outward, not only through his technical innovations but through the generations of artists he inspired.

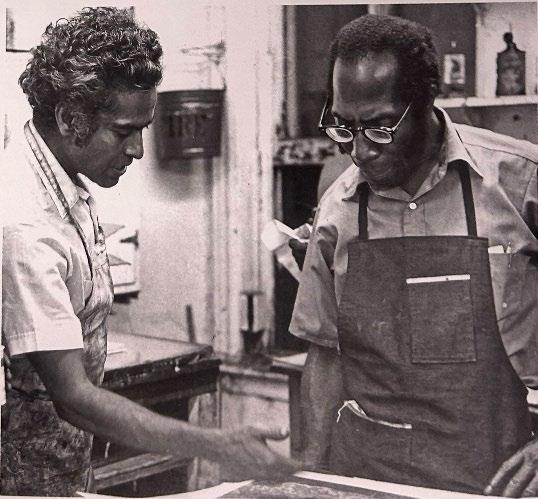

Reddy's renewed collaboration with master printmaker Robert Blackburn in 1968 in New York was another pivotal moment in his career. Their partnership, which began in postwar Paris, found fertile ground in Blackburn's Manhattan-based Printmaking Workshop. Founded in 1947, the workshop was one of the first inclusive, open-access studios in the U.S. Blackburn's ethos of collaboration and accessibility resonated deeply with Reddy, who brought his exacting technical knowledge of multiviscosity printing to the workshop. Reddy's presence introduced a new dimension of rigor, and his unique techniques provided fresh possibilities for artists looking to expand beyond traditional intaglio methods.

Through demonstrations, collaborations, and mentorship, Reddy inspired a new generation of American printmakers who learned his methods along with his belief that technique and philosophy should evolve together.

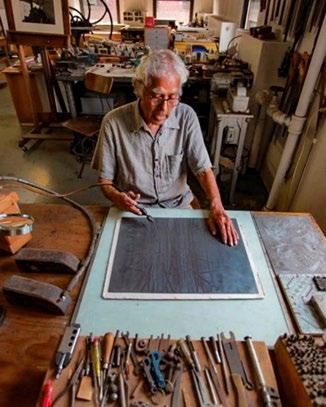

In 1976, Reddy joined the faculty of New York University's Department of Art and Art Education. He professed his method of integrating material, process, and philosophical inquiry. He often remarked, "The closer one gets to the materials, the more pliable they become to one's senses." This ethos shaped his workshops, which resembled laboratories rather than classrooms places of exploration, intuition, and dialogue.

At NYU, Reddy started the Color Print Atelier, a specialized studio dedicated to viscosity color printing. Within this environment, artists and educators from across the globe gathered to explore not only the mechanics of Reddy's technique but also its metaphysical underpinnings. Reddy would later describe this phase as one of "great revelation and learning," where teaching and discovery were indivisible.

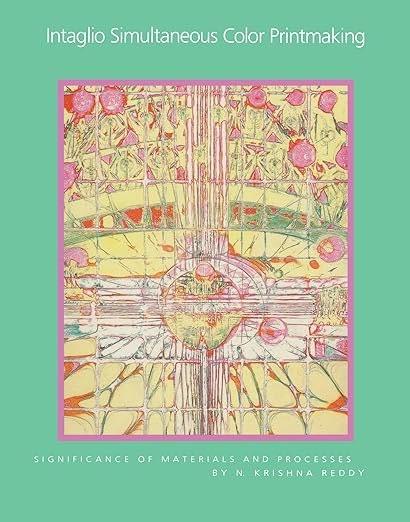

While at NYU, drawing on thirty years of studio notes, Reddy published a seminal book, New Ways of Color Printmaking: The Significance of Materials and Processes (1988). Even today, the book remains a foundational resource in the field of viscosity printing and a testament to Reddy's unique synthesis of science, art, and introspective practice.

Reddy traveled extensively across the United States in the 1970s and 1980s, conducting lectures and workshops that established him as a pioneer in the field of printmaking.

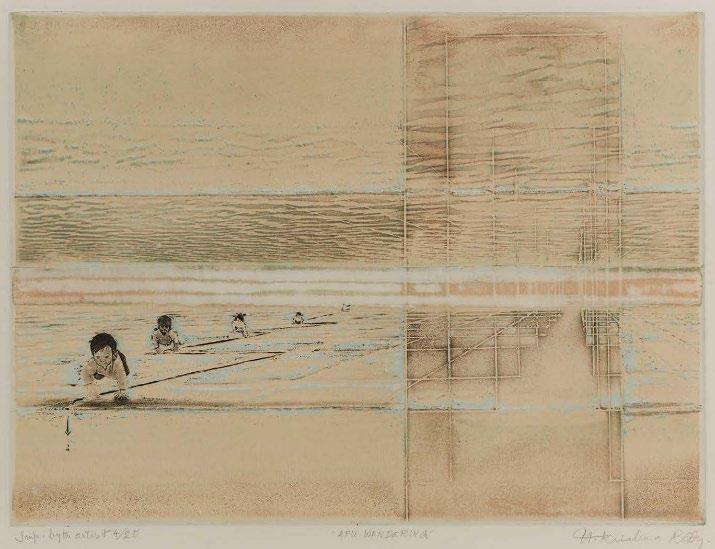

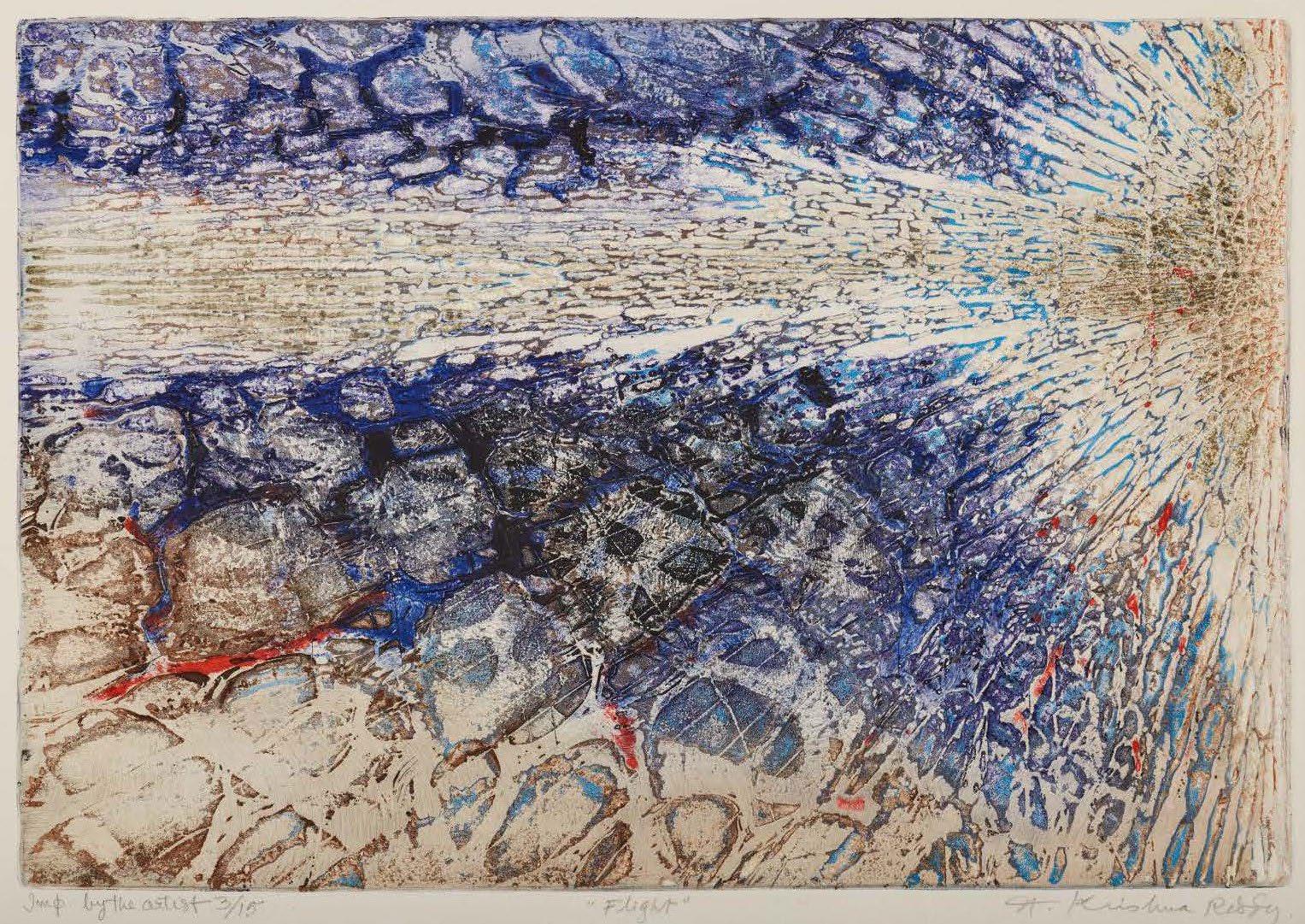

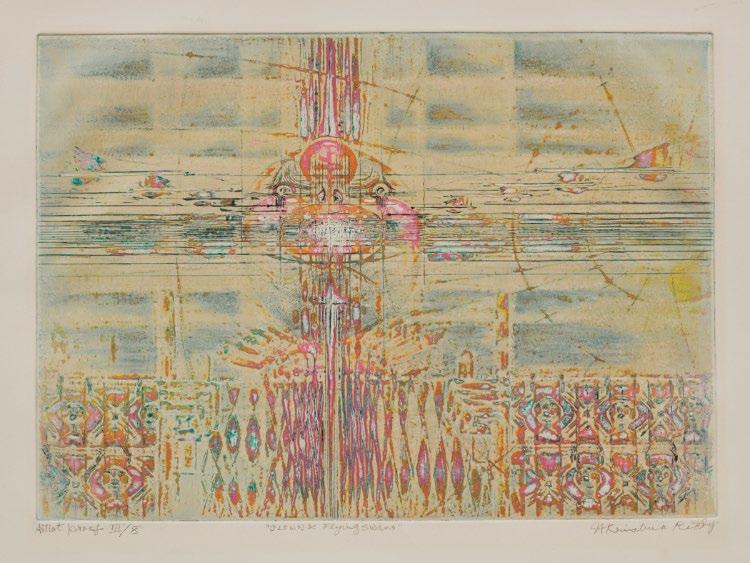

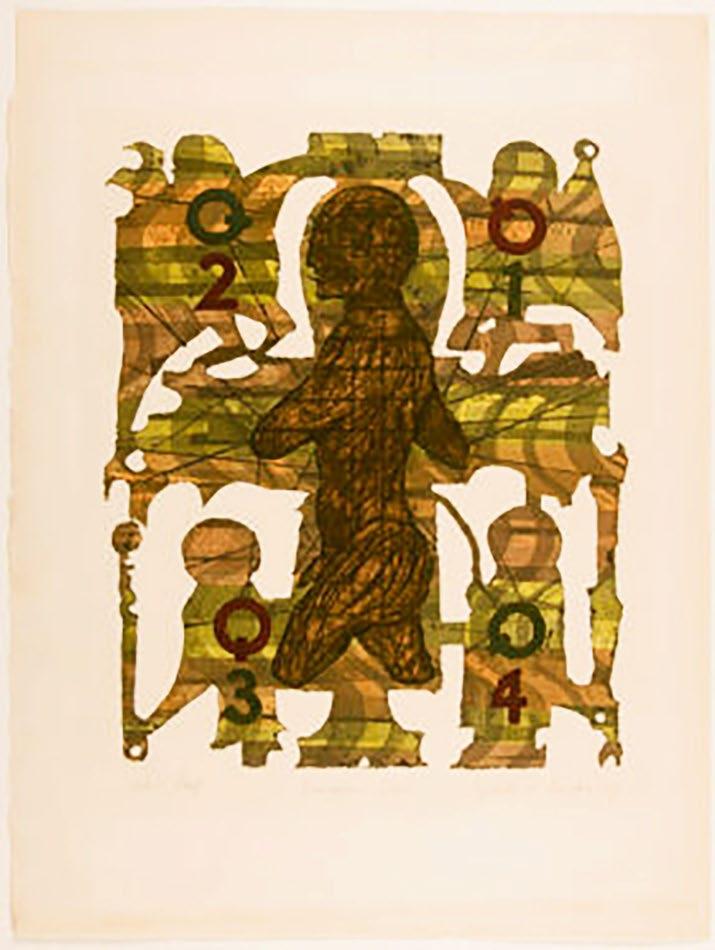

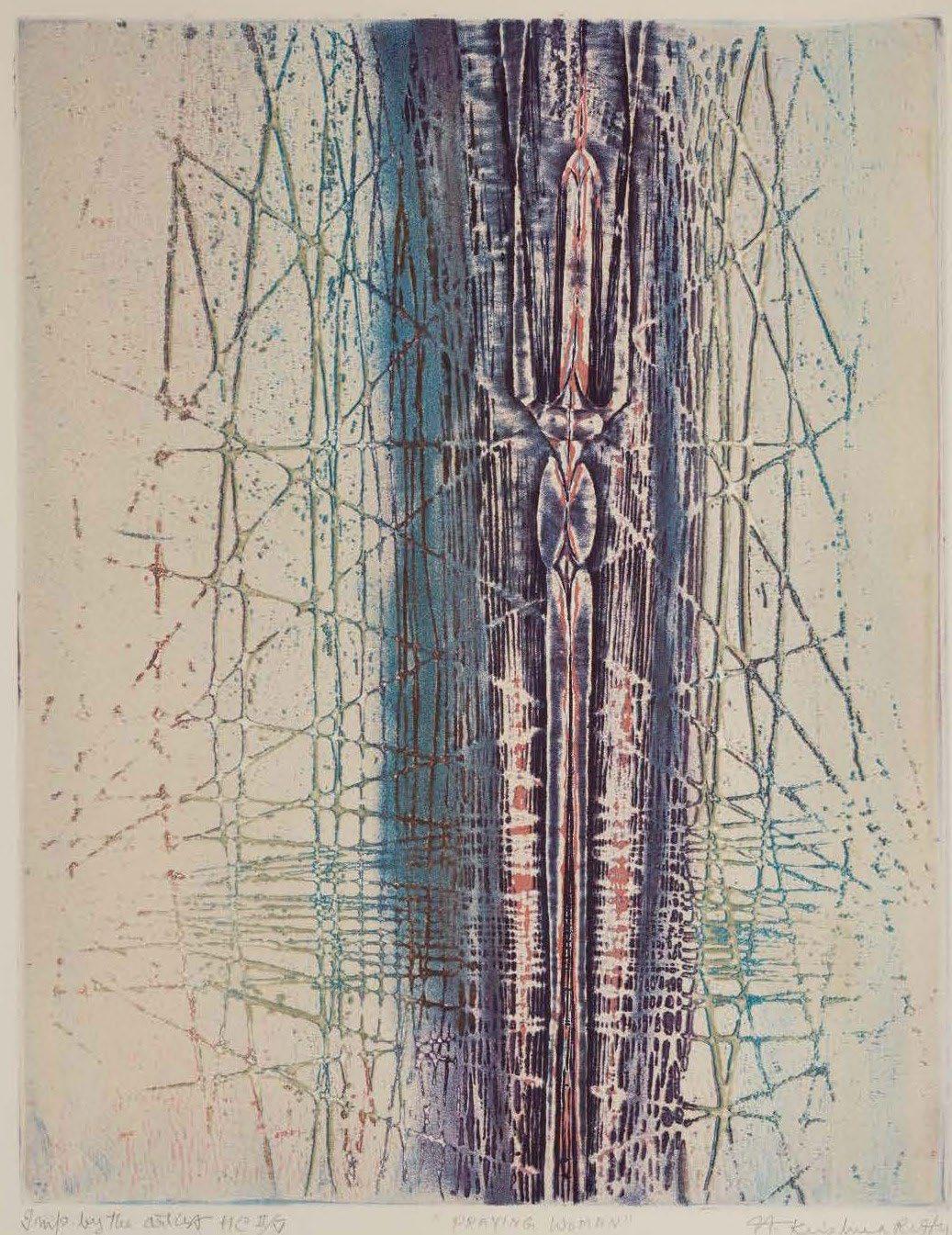

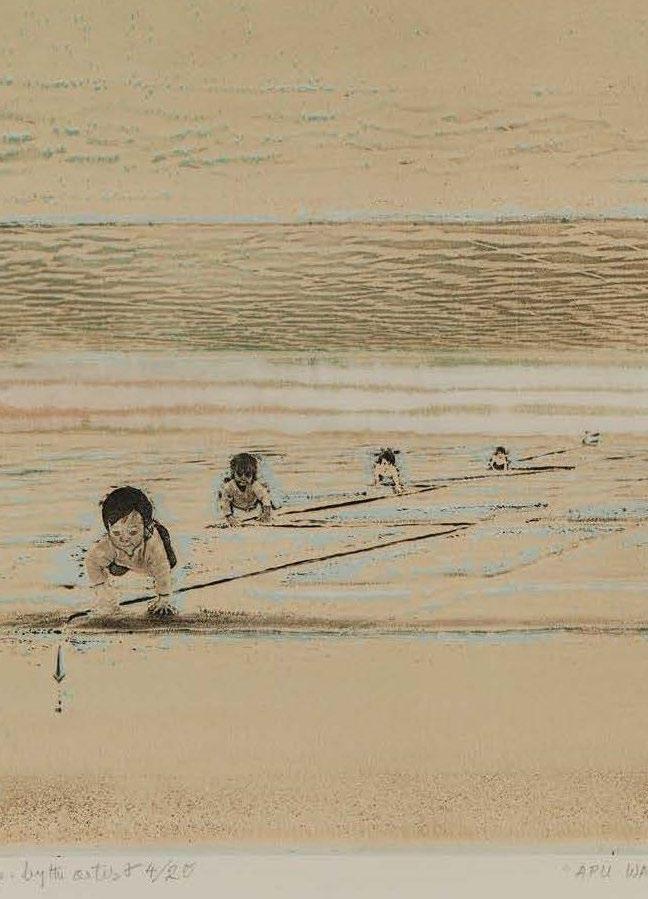

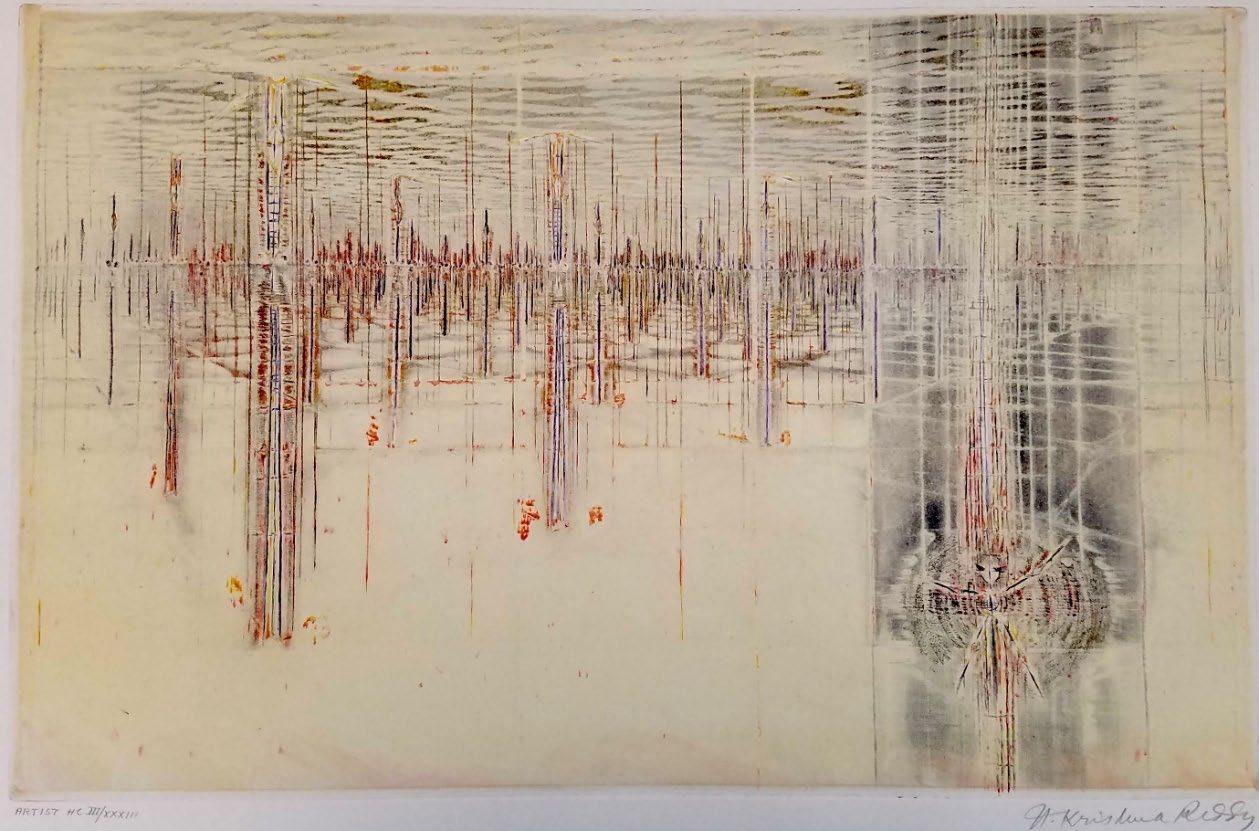

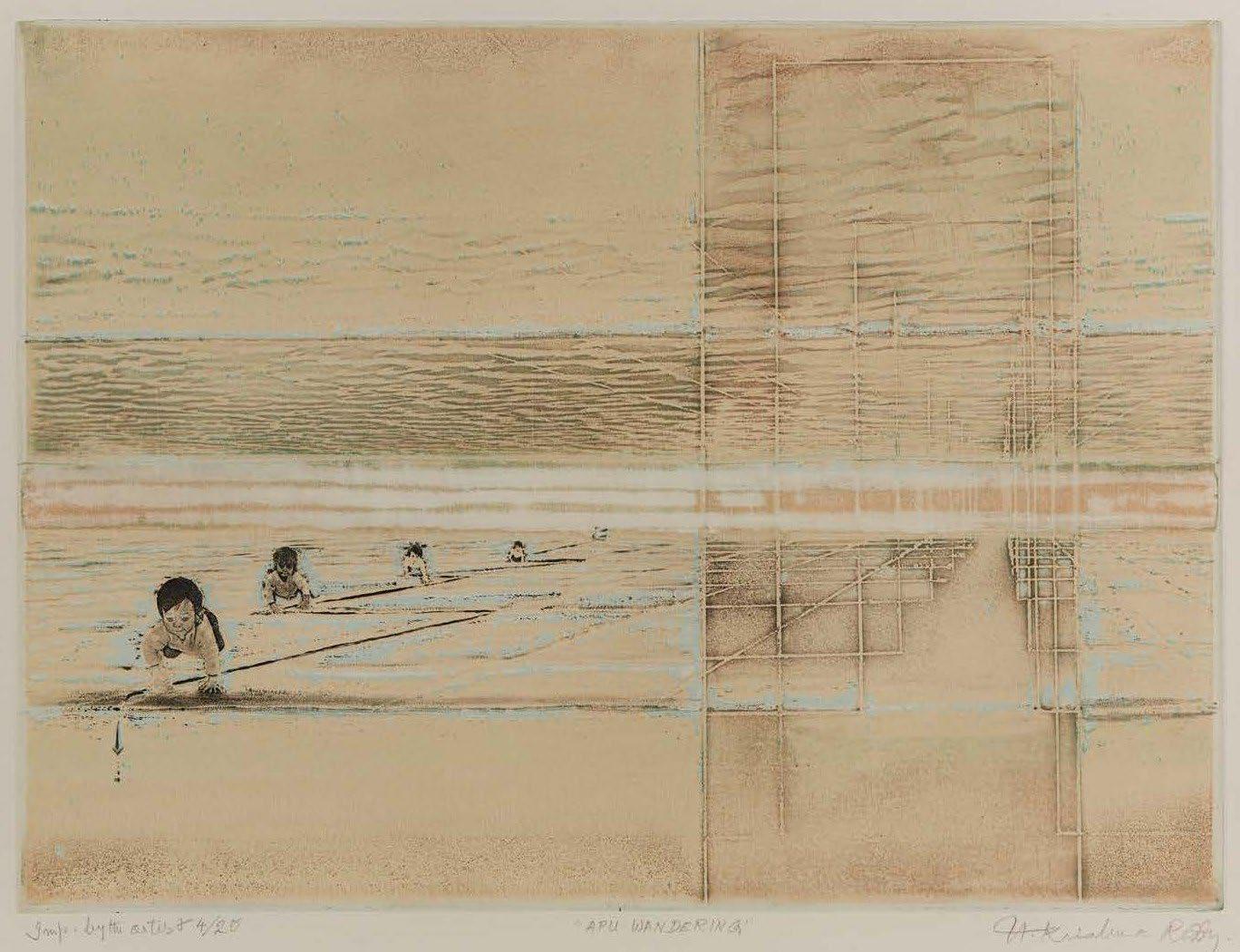

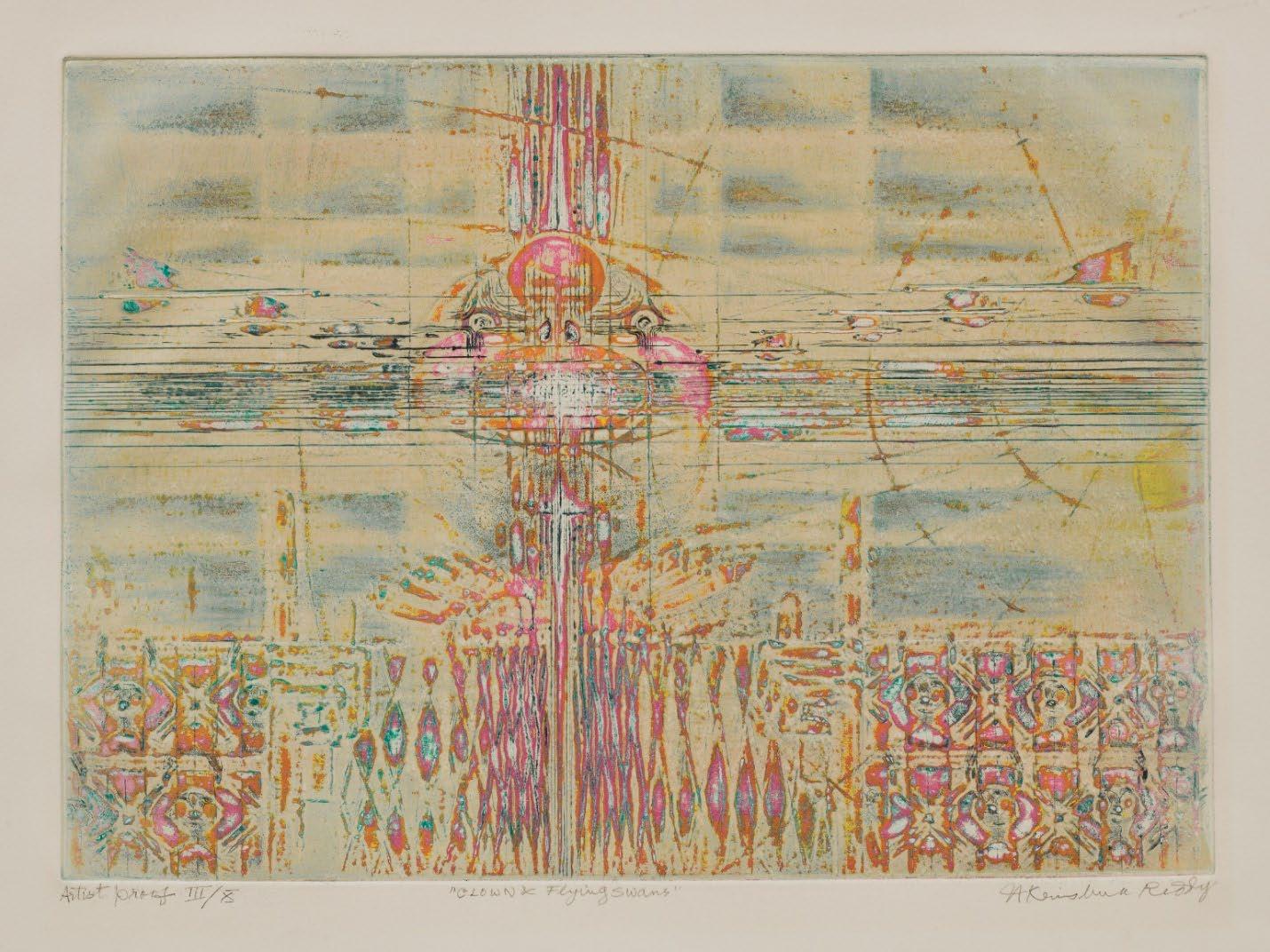

During this prolific period, Reddy's personal life also underwent profound changes. He and his wife, artist Judith Blum Reddy, adopted their daughter Arpana shortly before relocating to New York. Between 1974 and 1976, Reddy created a series of prints Apu Crawling, Apu's Space, Child in Space, Child Descending in which childhood became a metaphor for awakening consciousness, innocence, and creative potential.

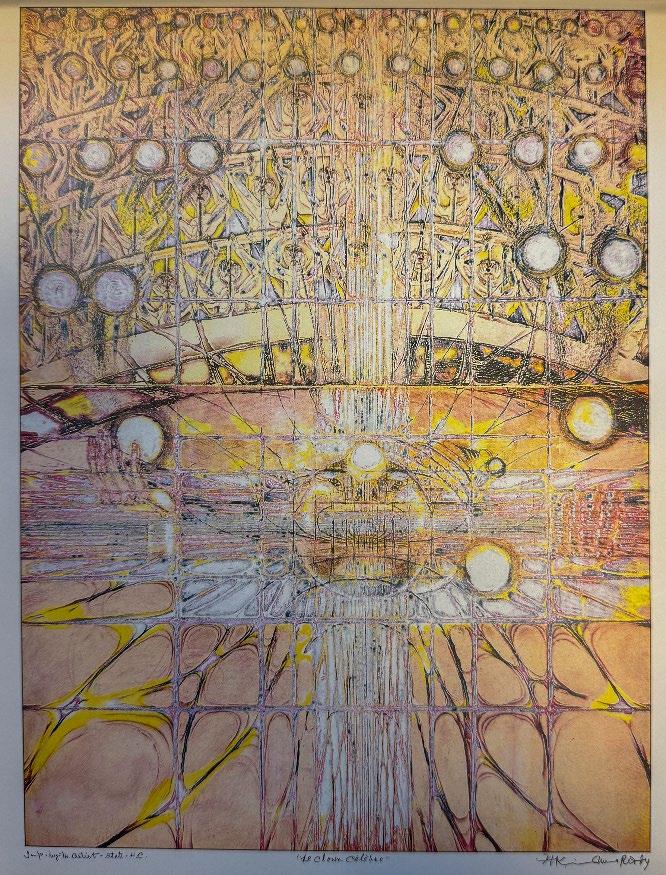

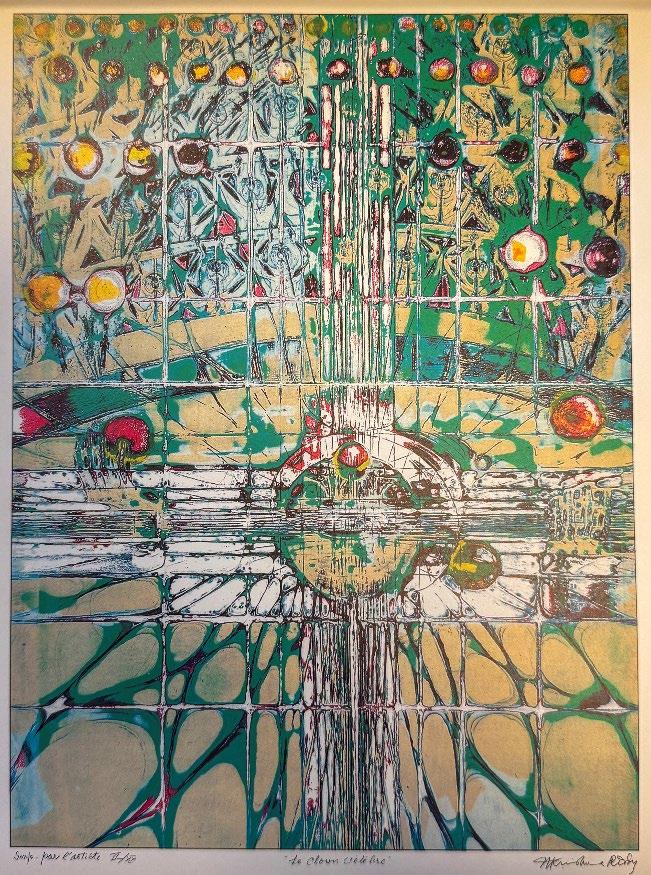

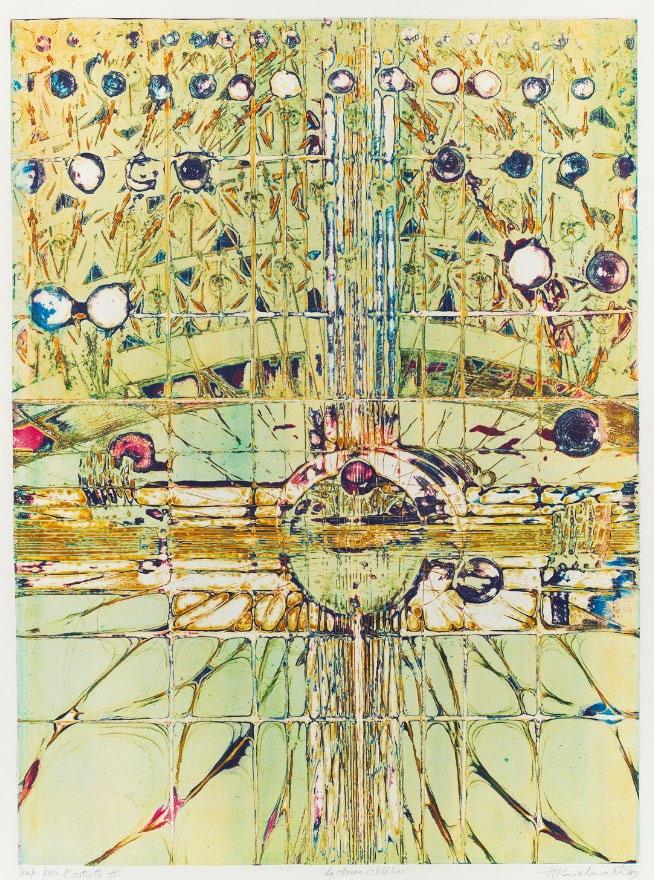

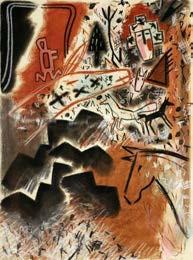

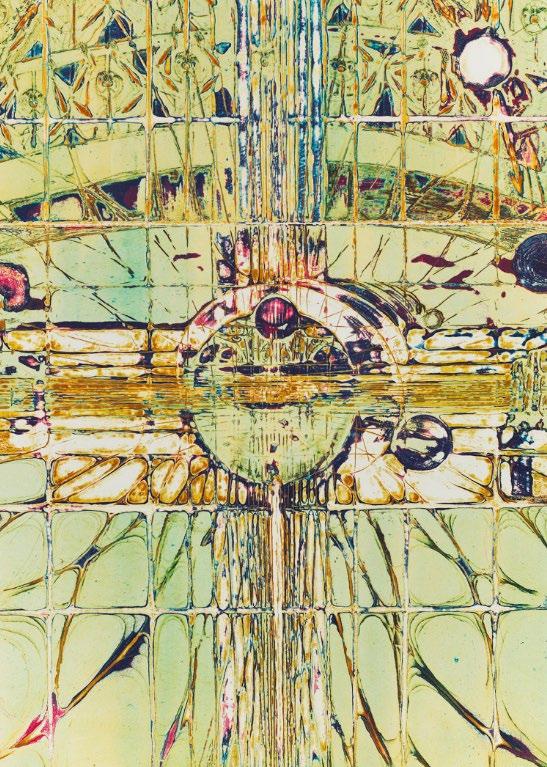

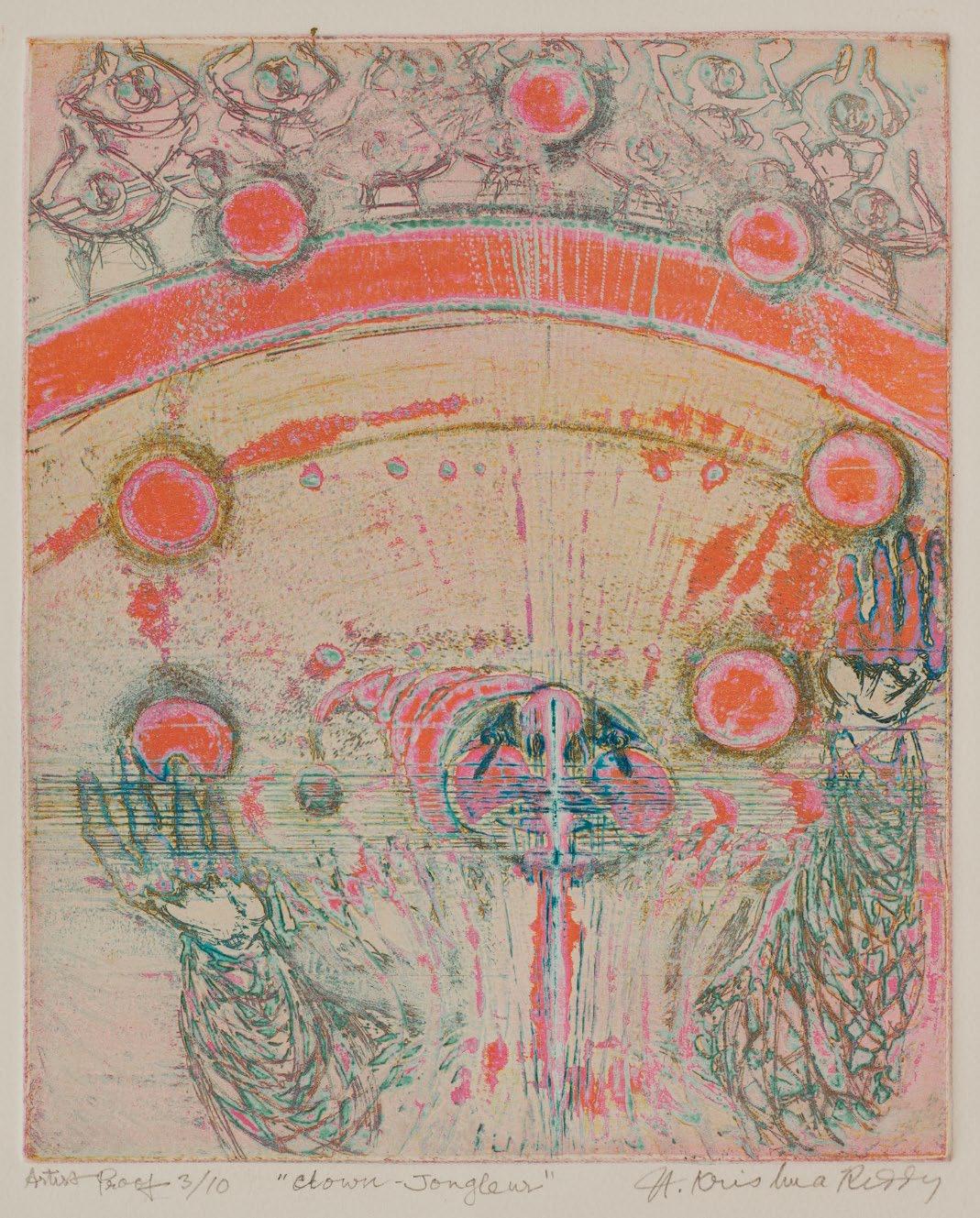

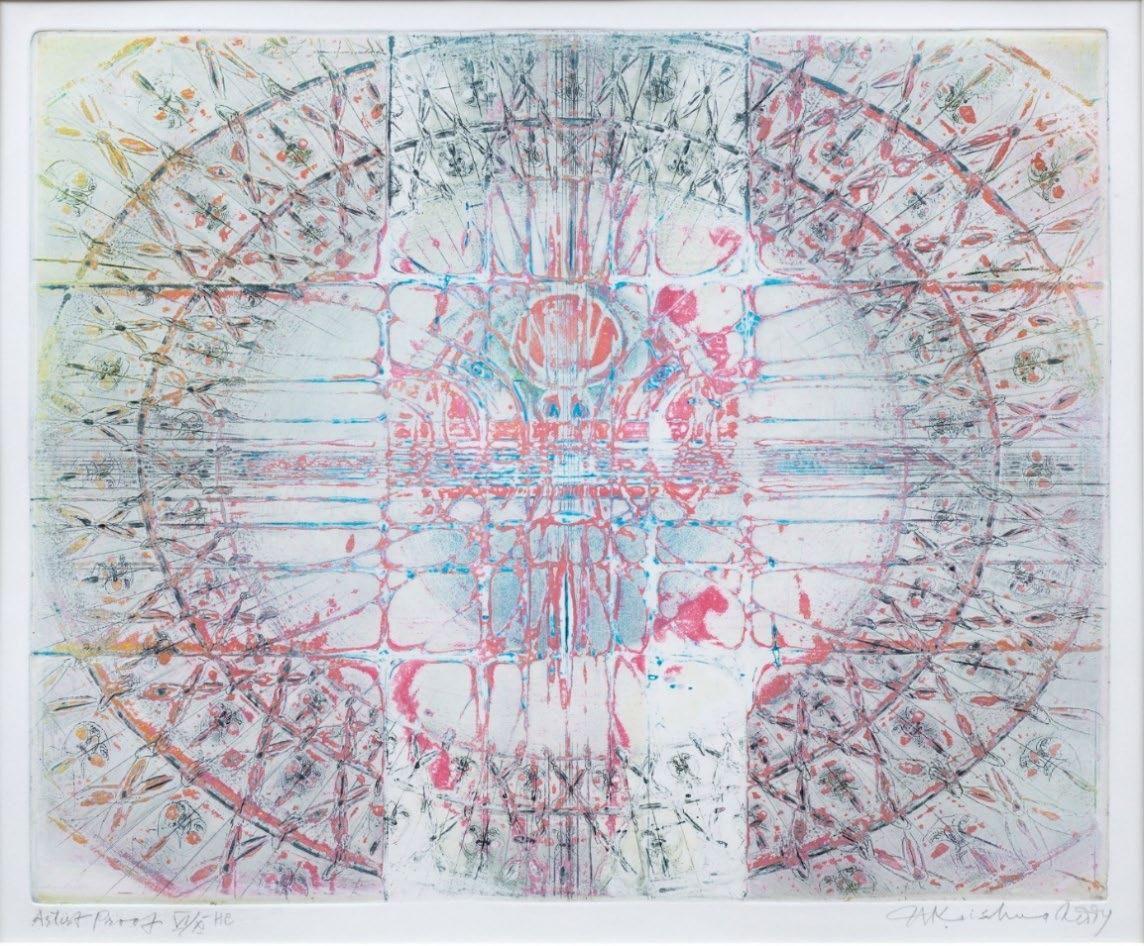

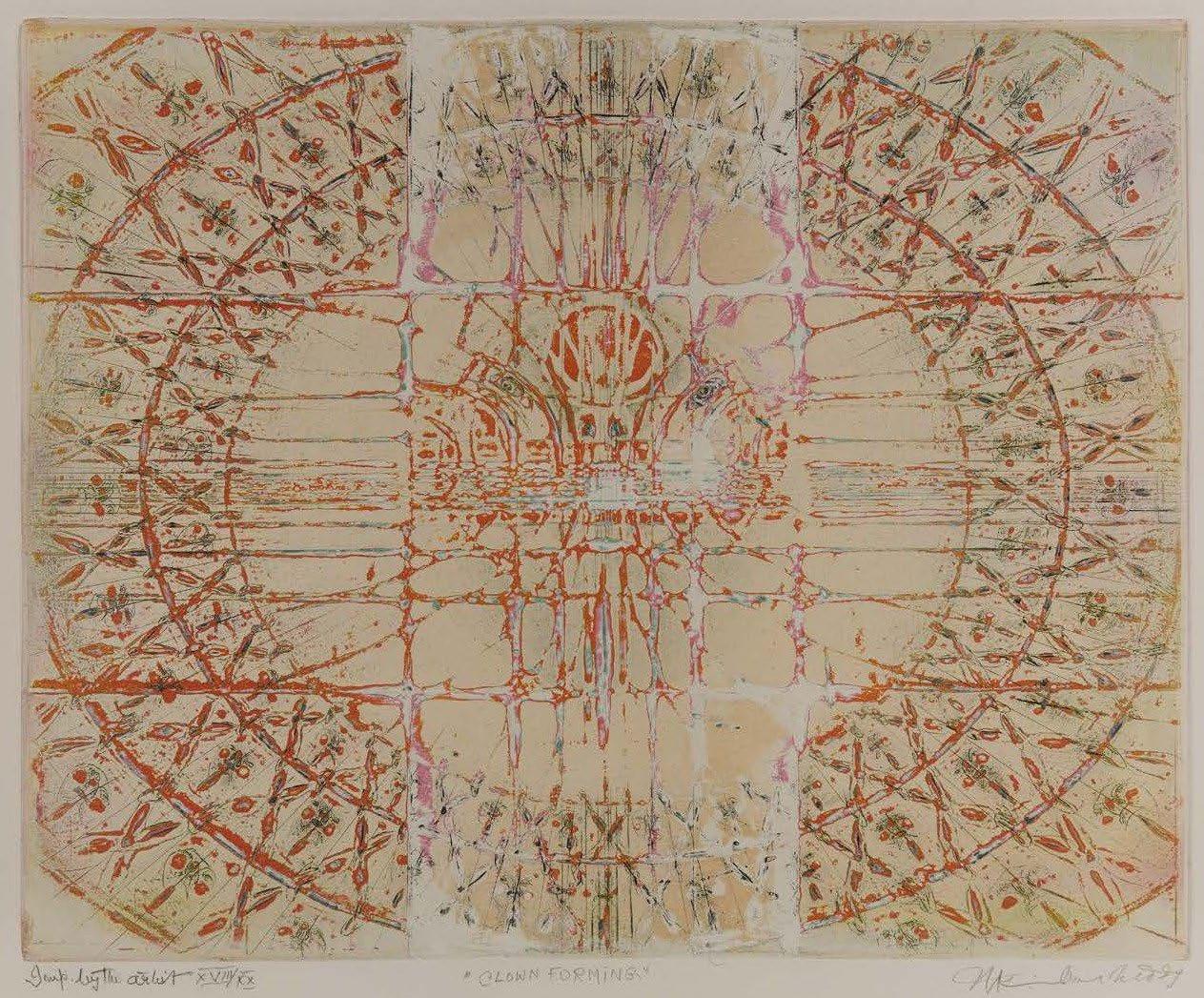

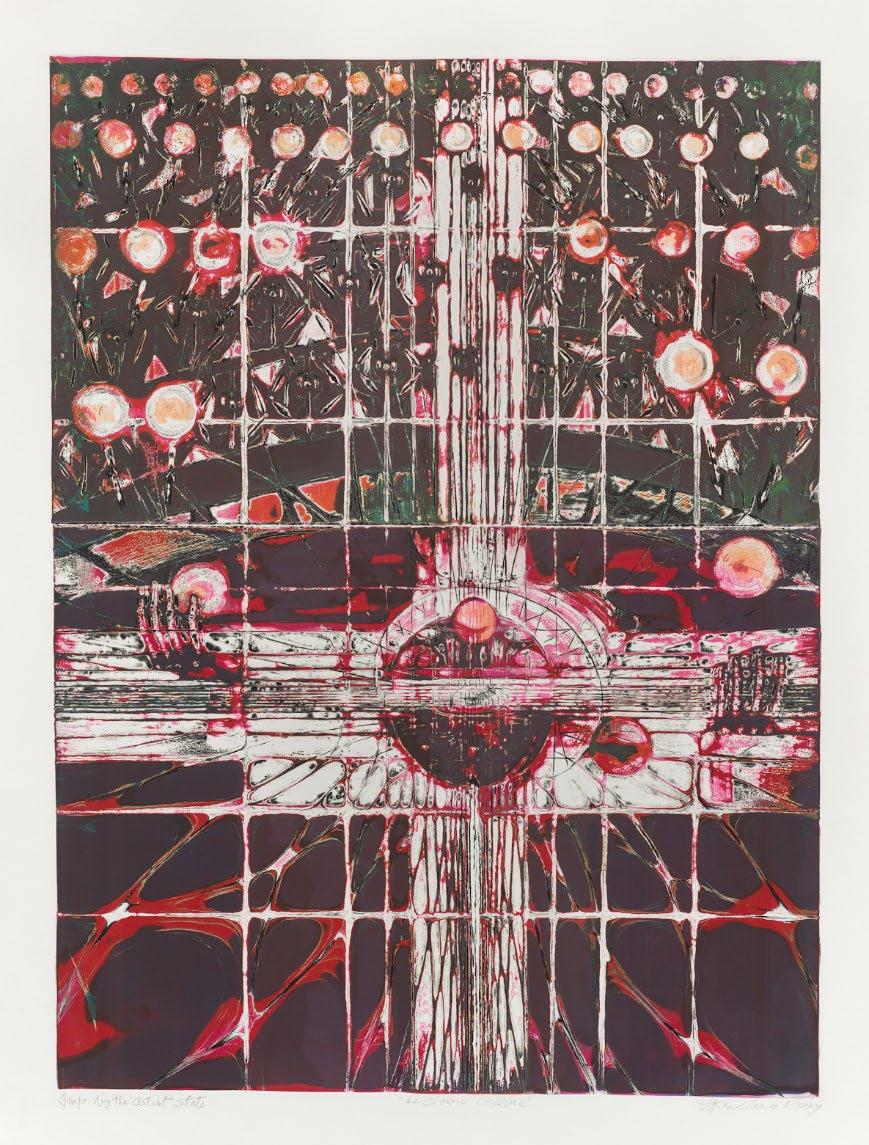

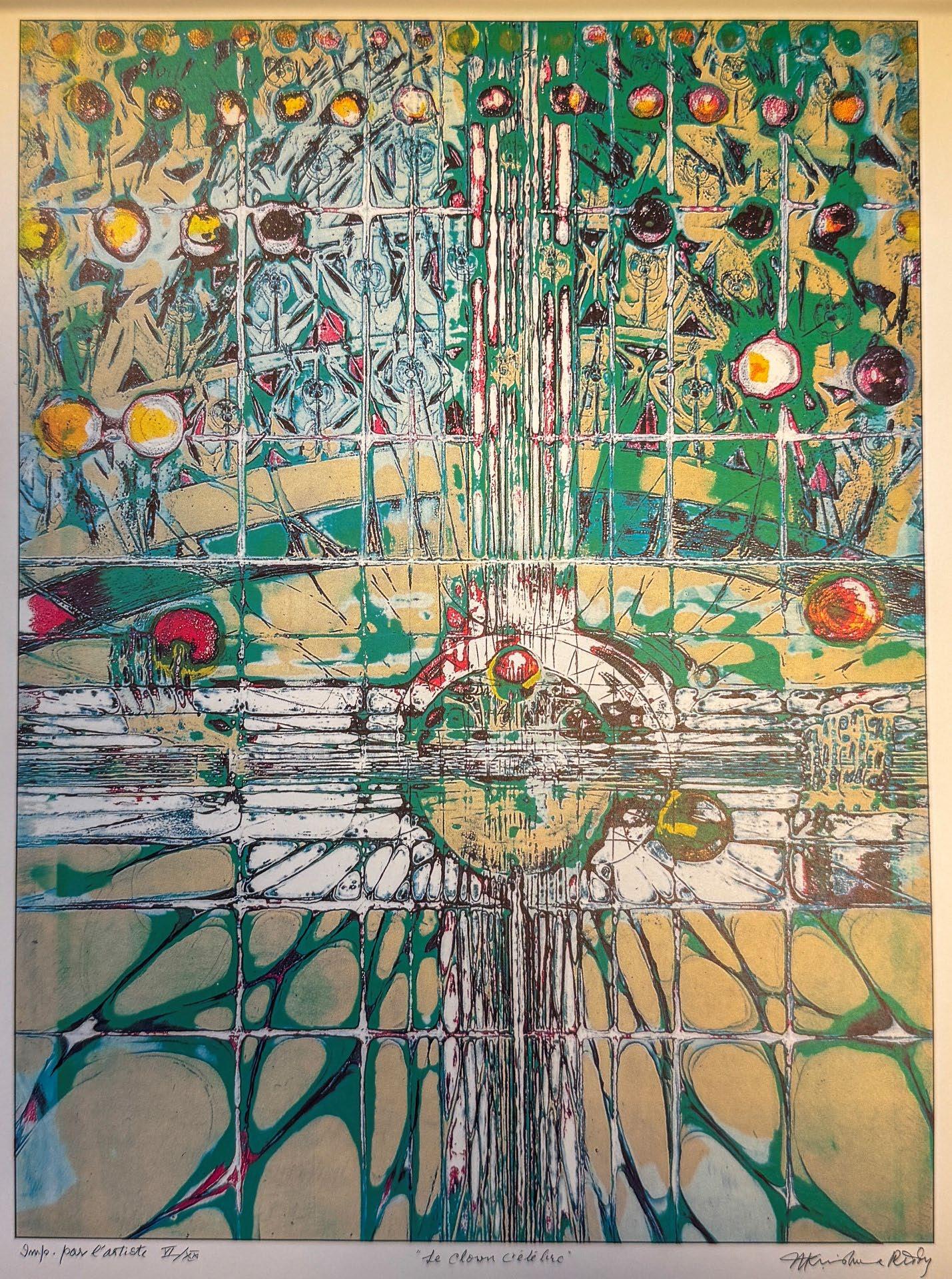

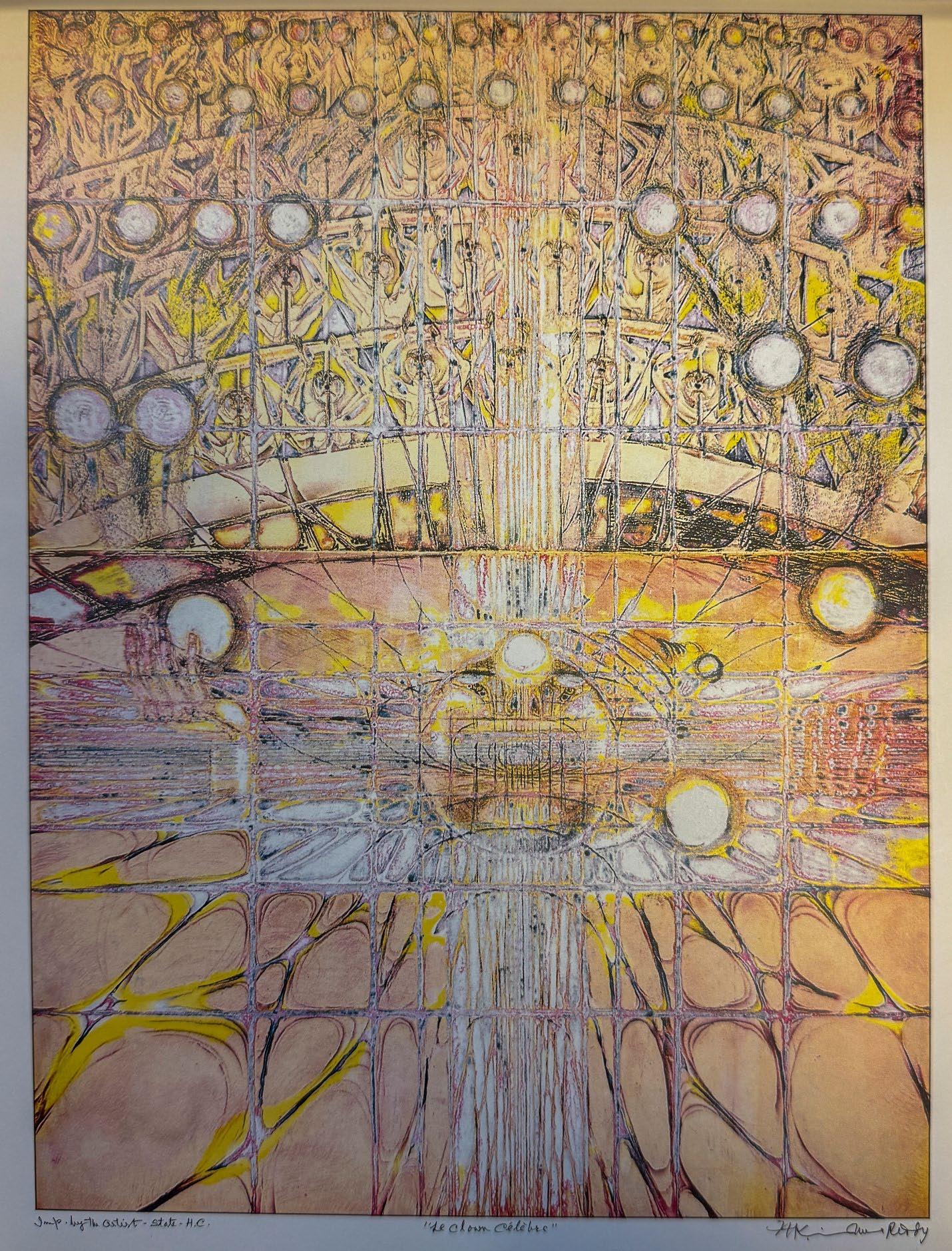

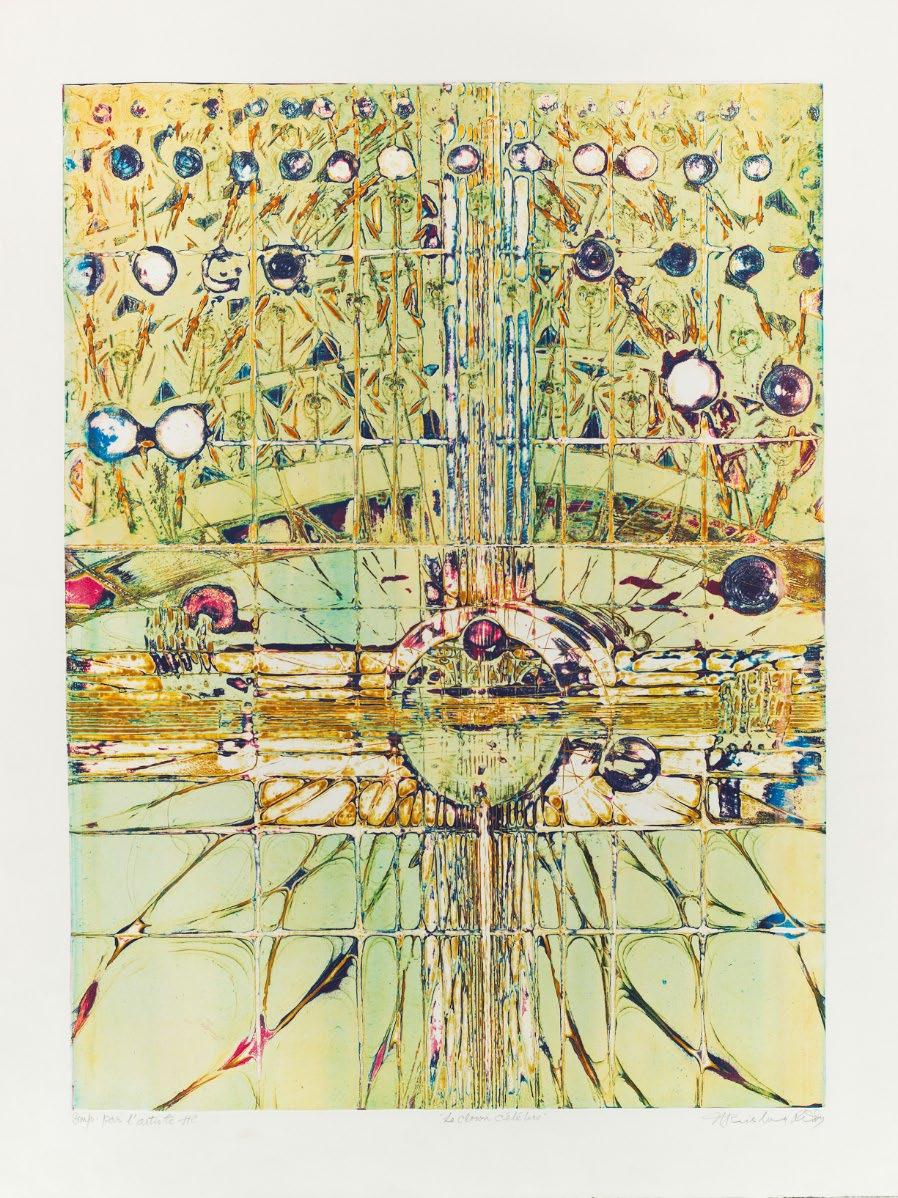

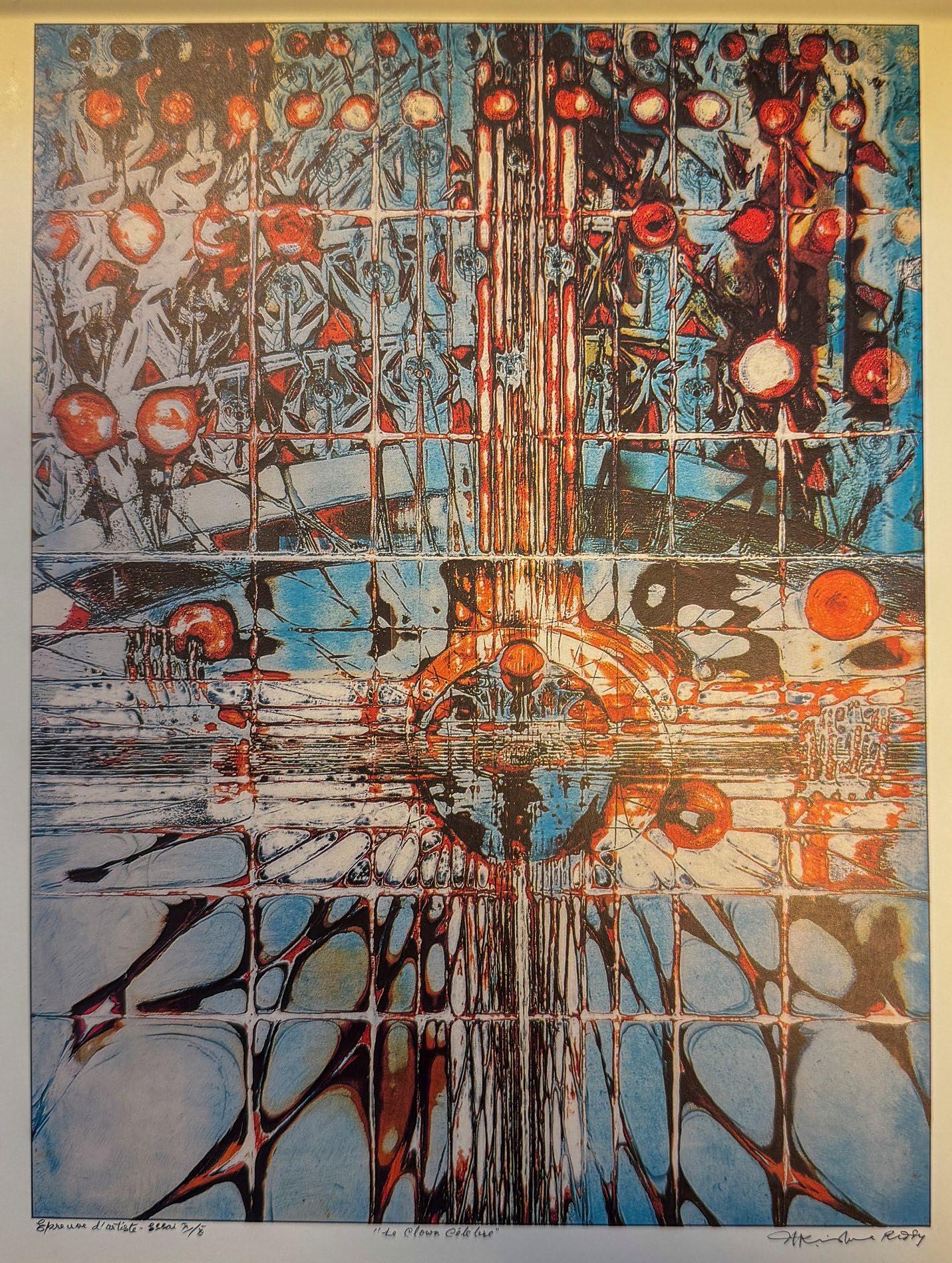

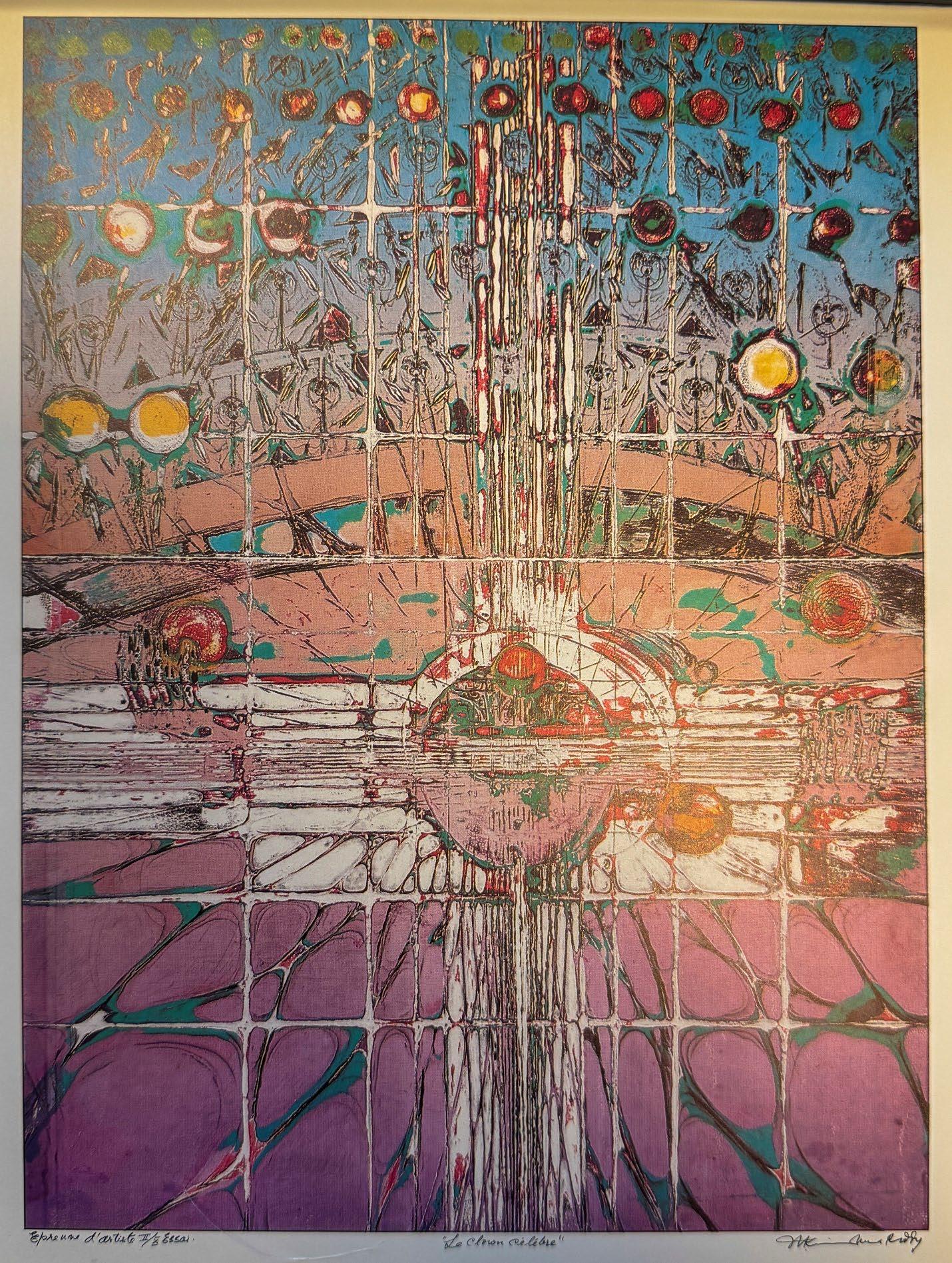

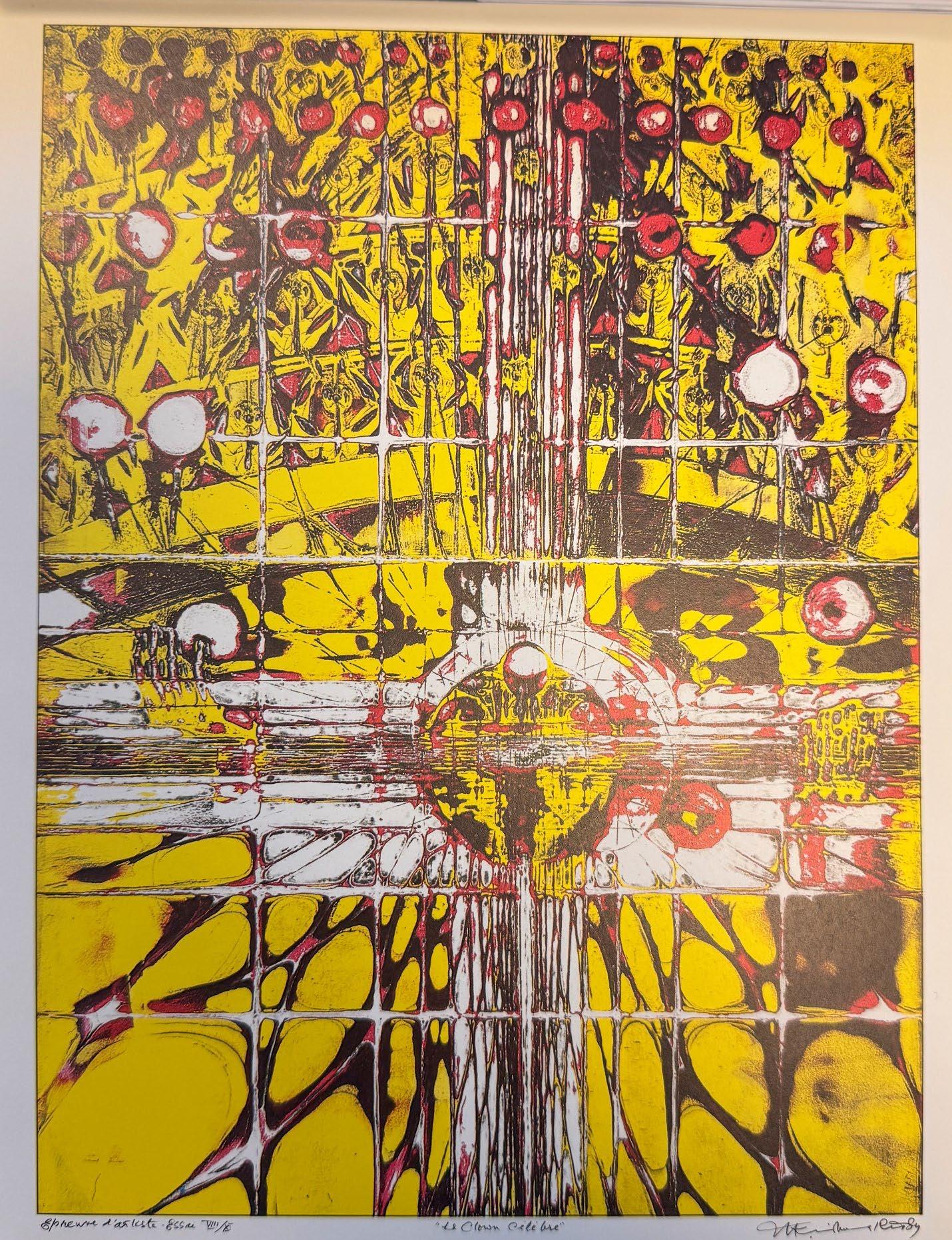

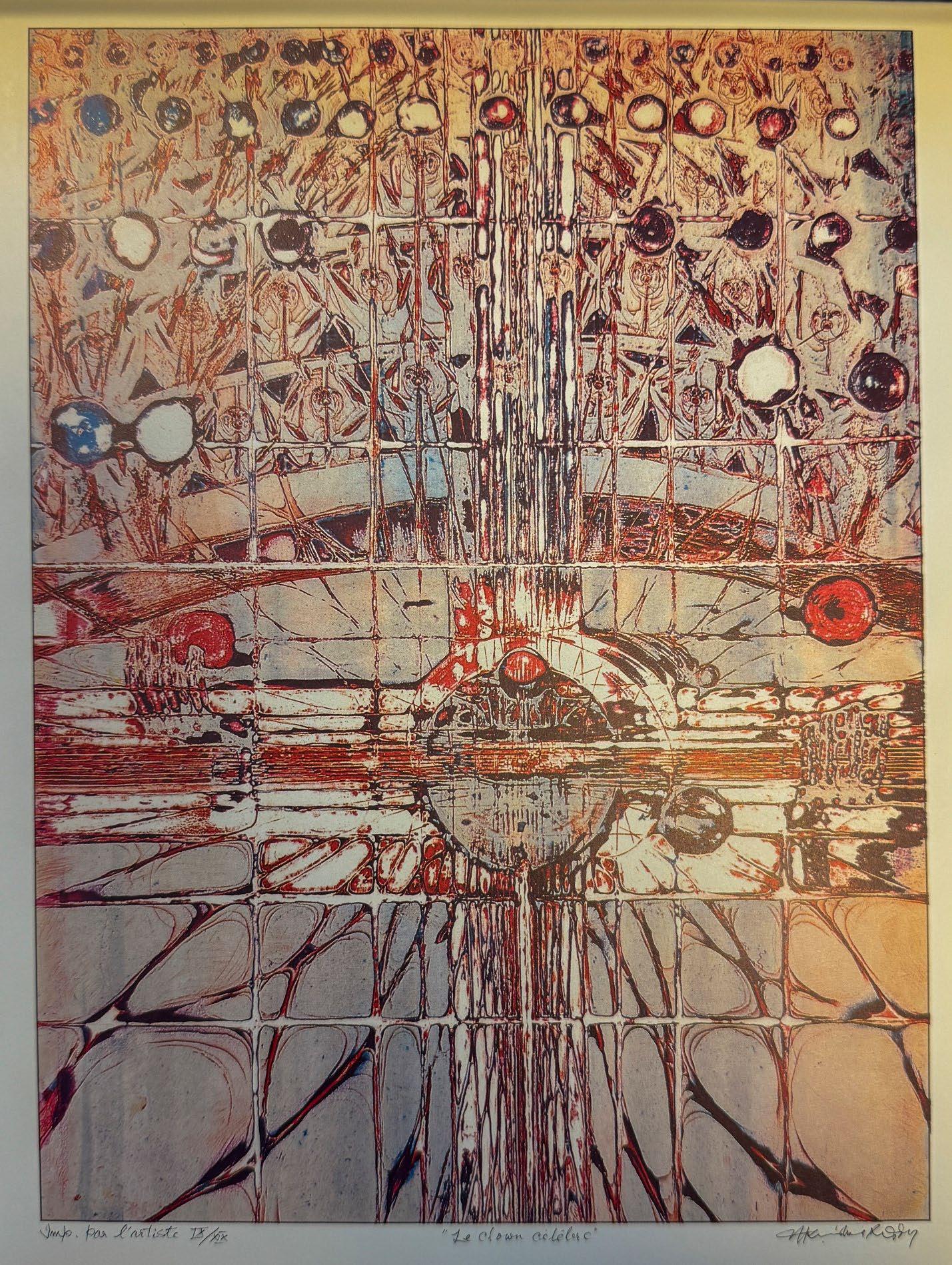

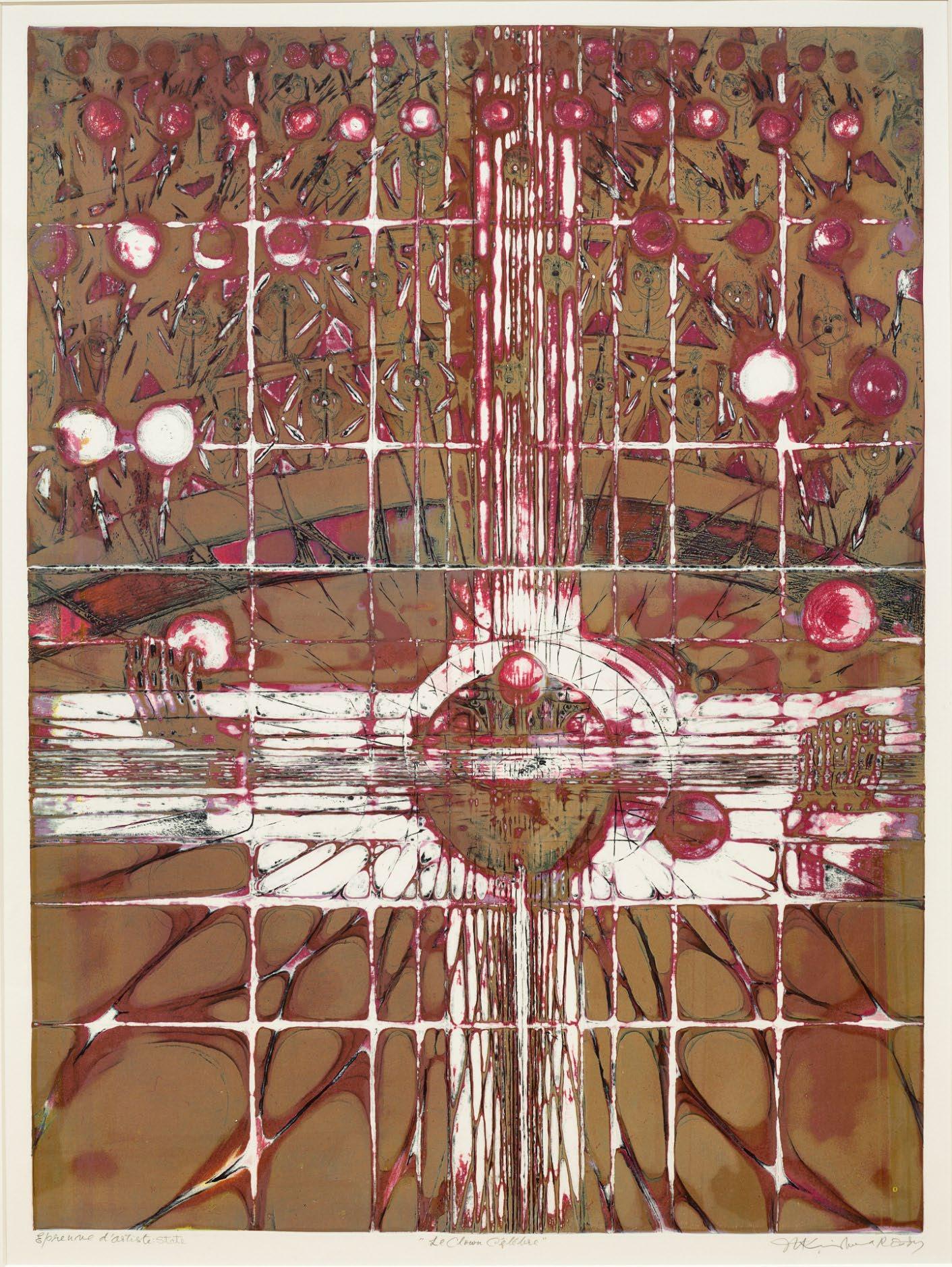

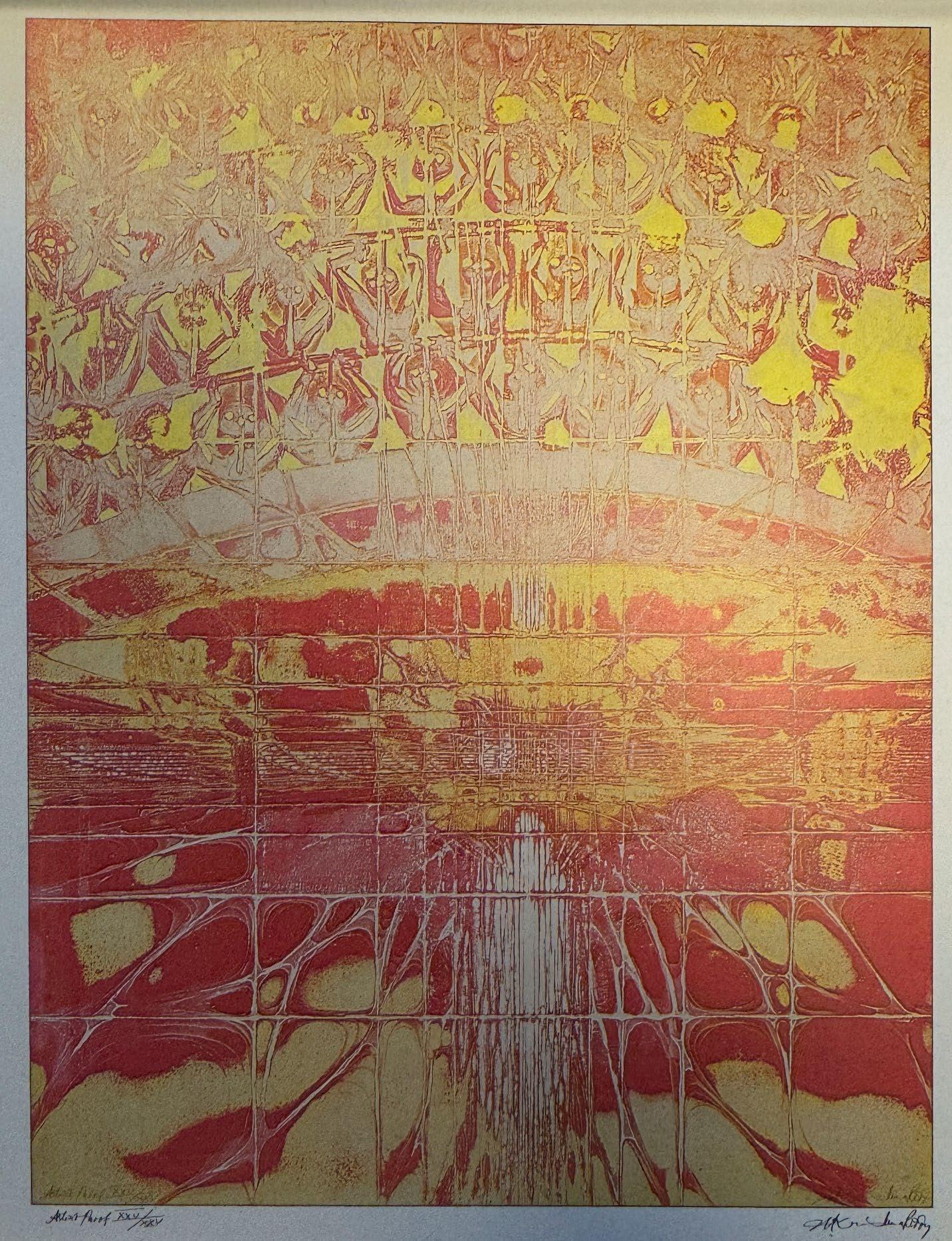

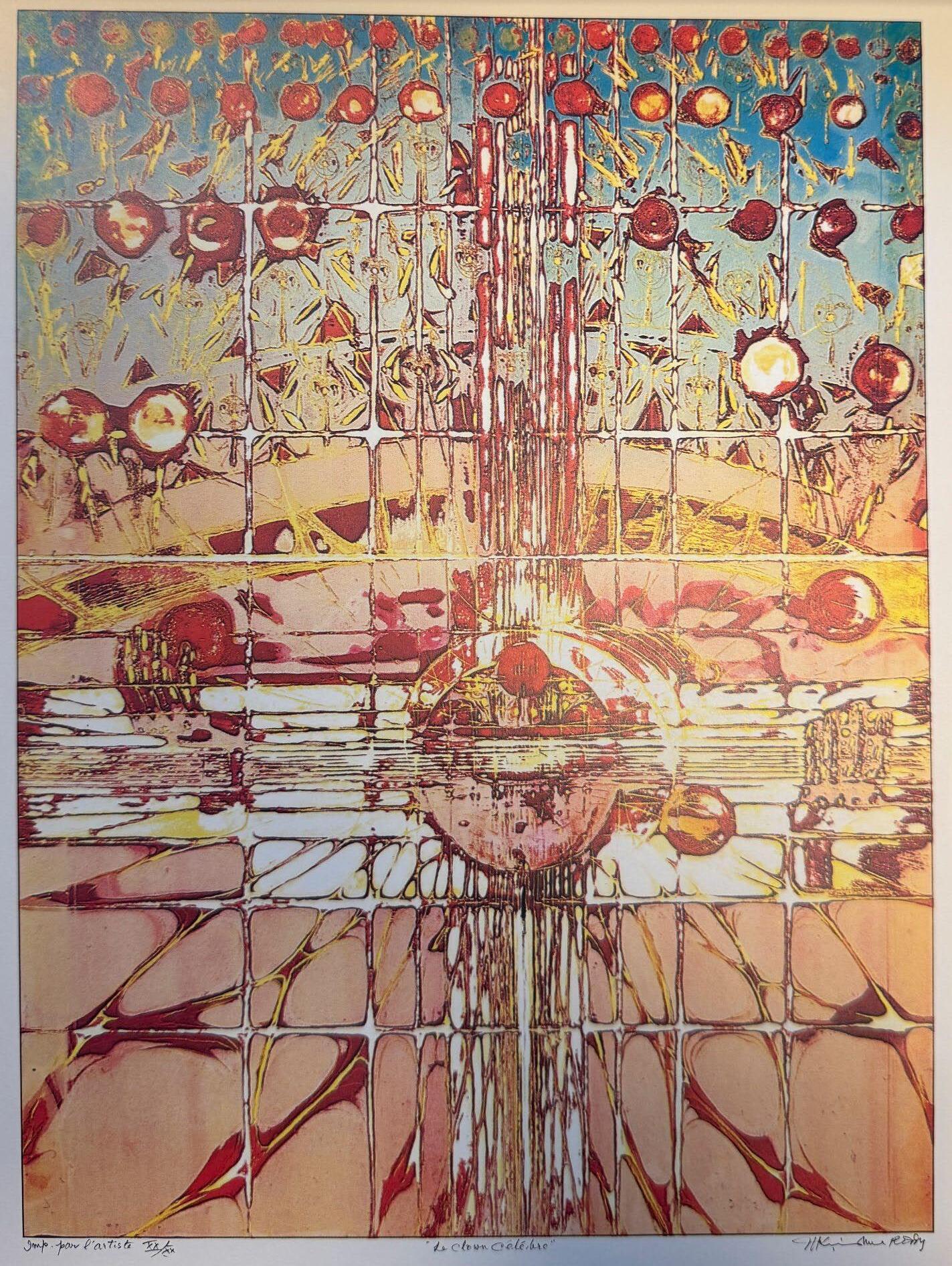

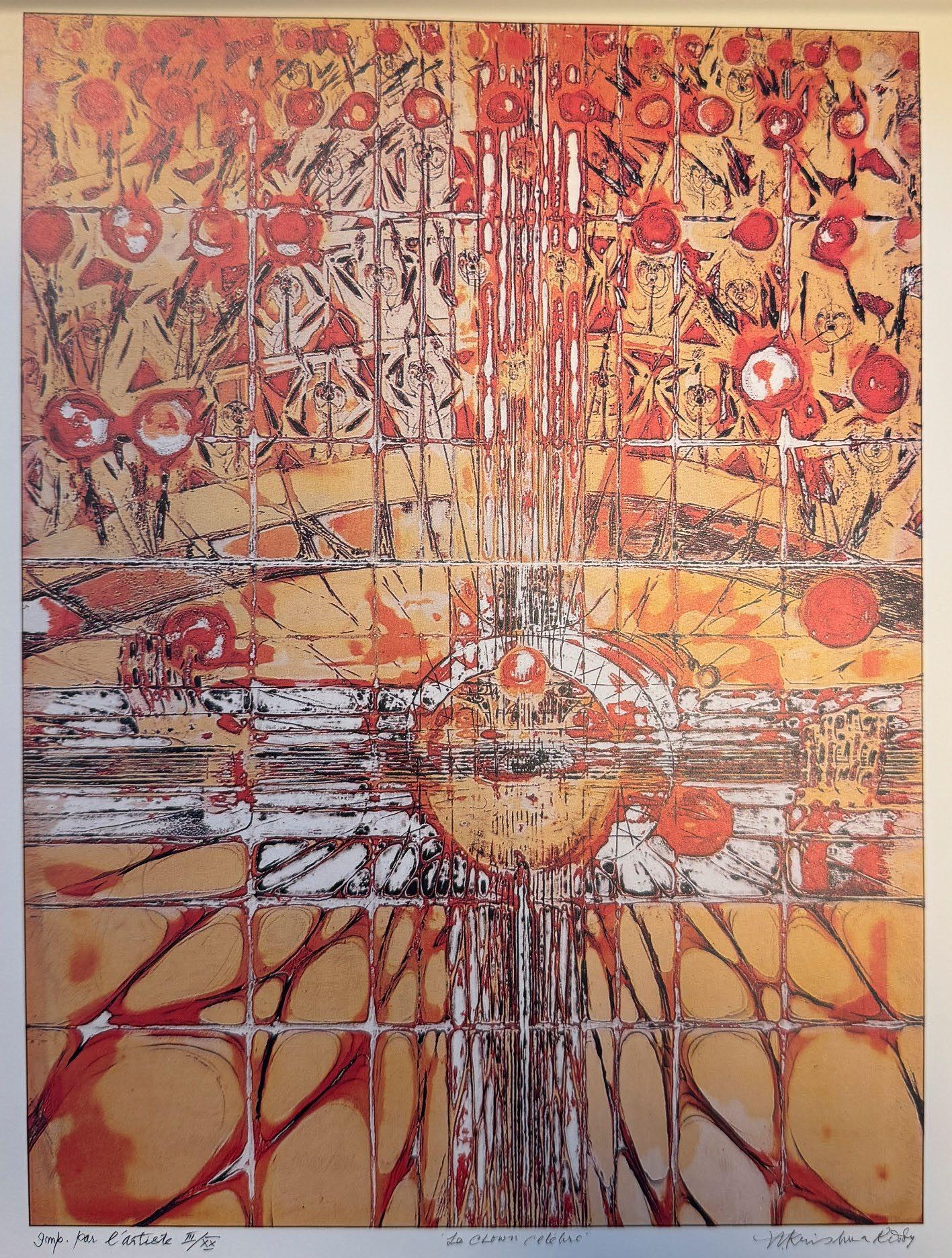

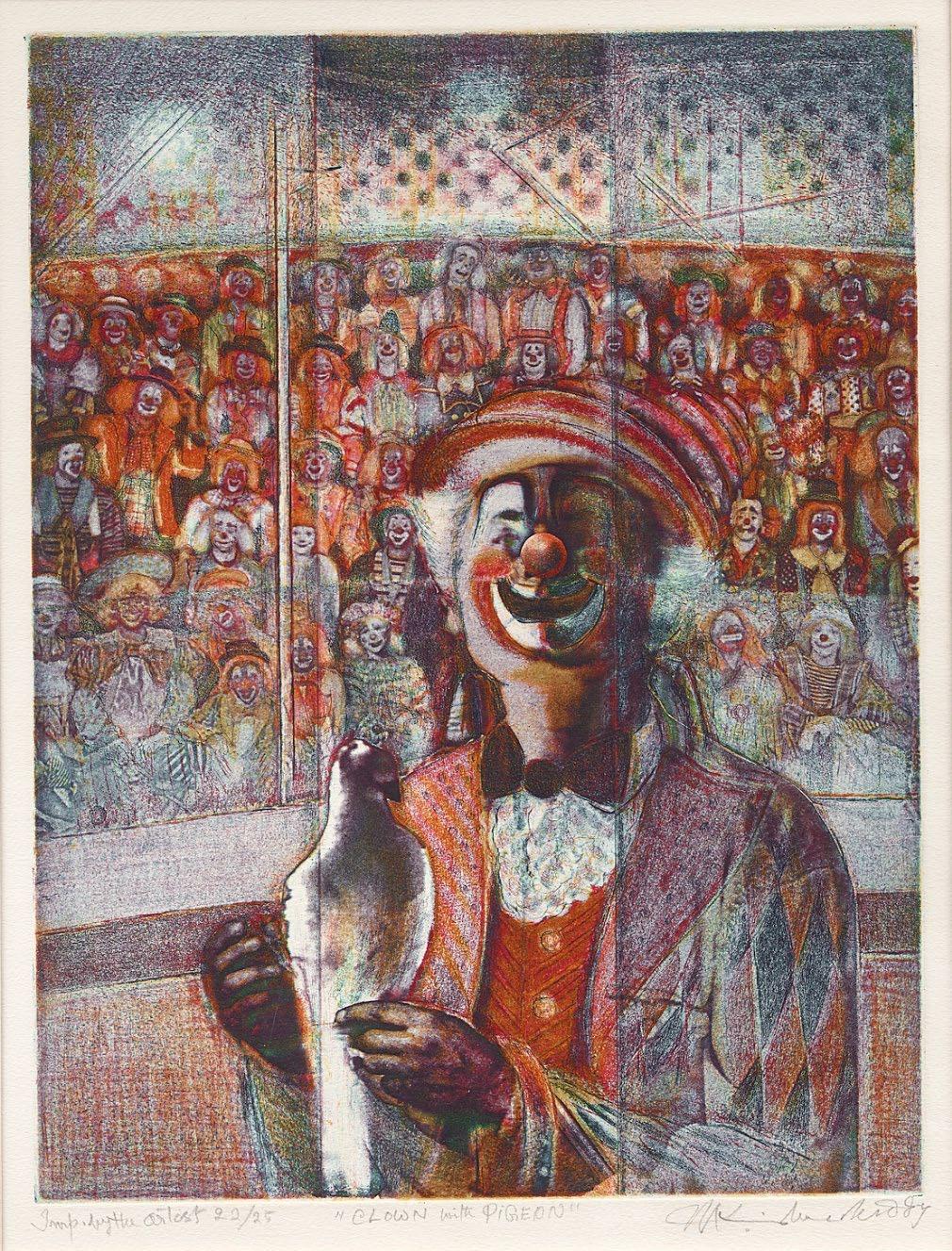

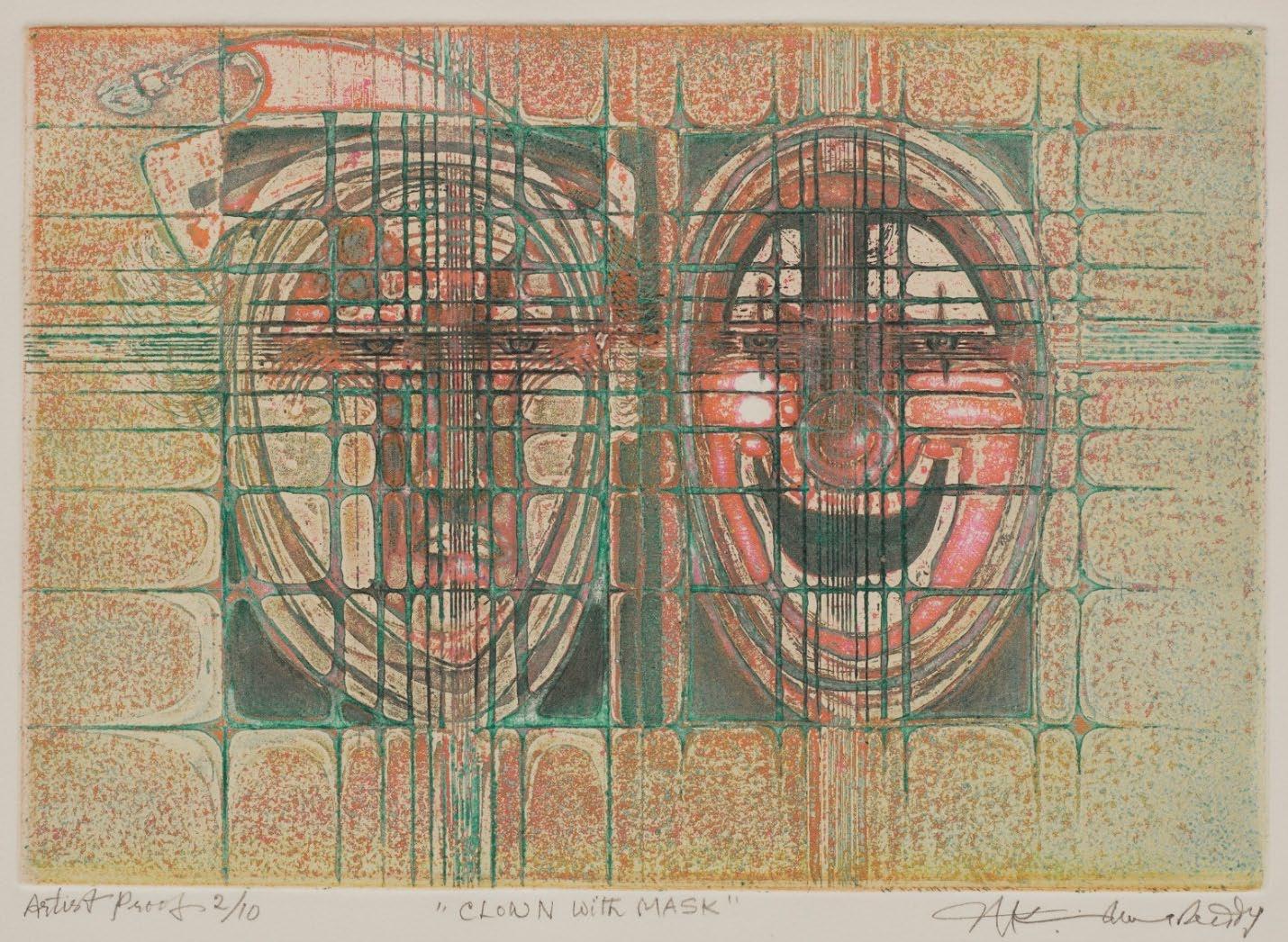

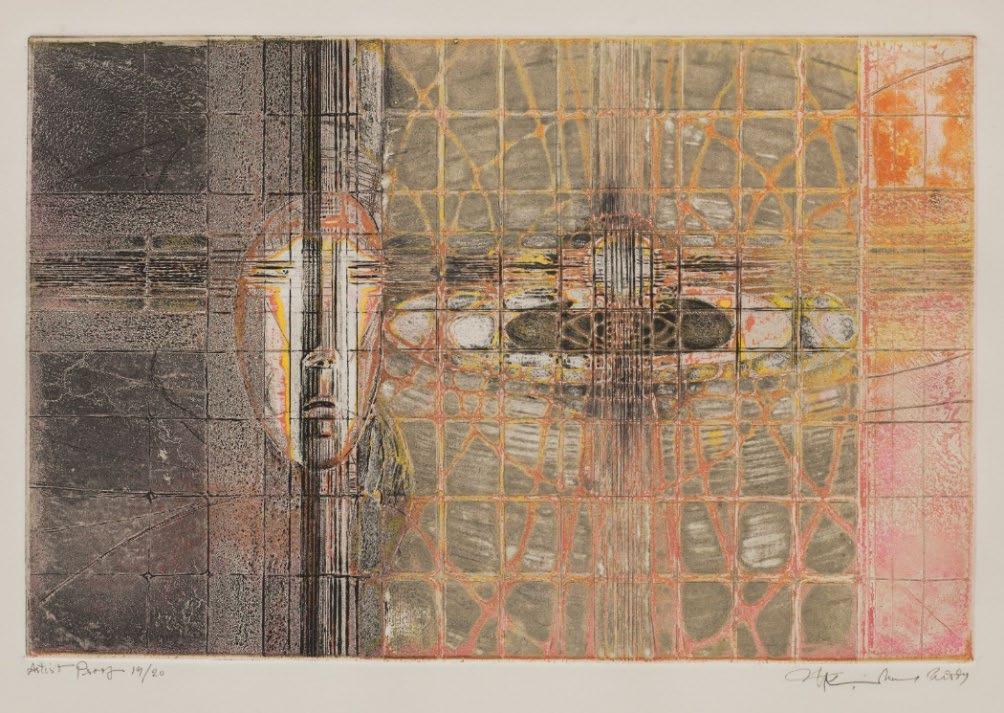

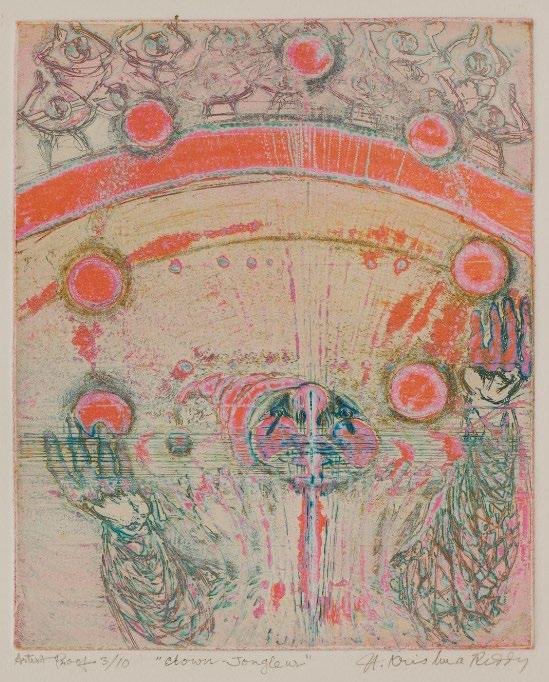

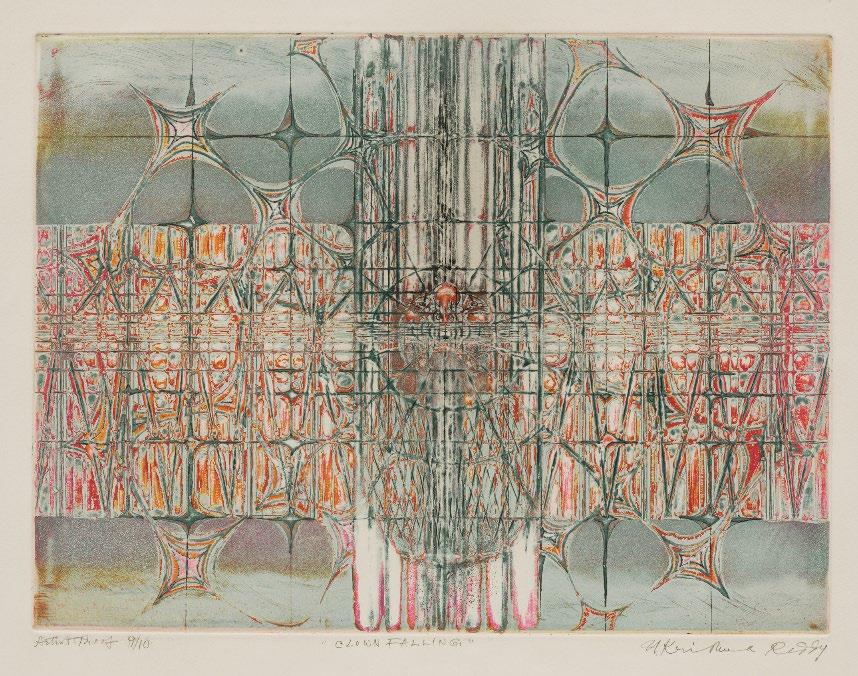

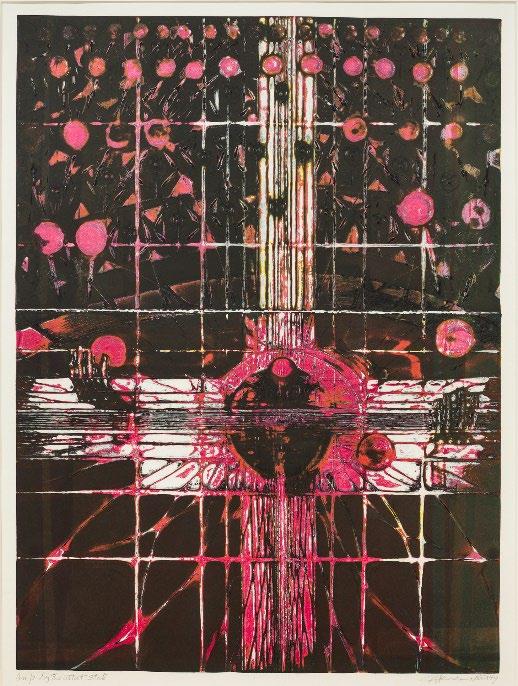

Arpana's love of the circus led Reddy to what is considered his most ambitious project: the Clown series (Fig. 7-8). The Great Clown , widely considered his magnum opus, is a masterwork philosophical, tender, and technically dazzling. It's not just a portrait of a performer. It's a meditation on vulnerability, resilience, and transcendence. The series, which Reddy worked on between 1974 and 1976, is a profound exploration of the human condition, utilizing the figure of the clown as a metaphor for life's complexities.

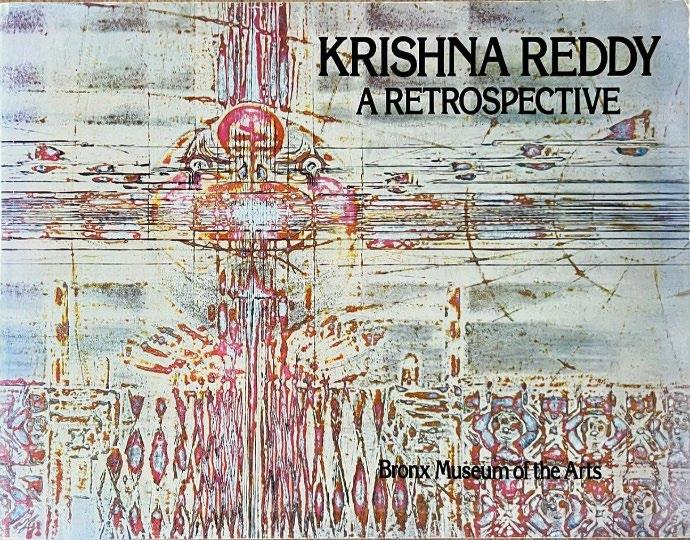

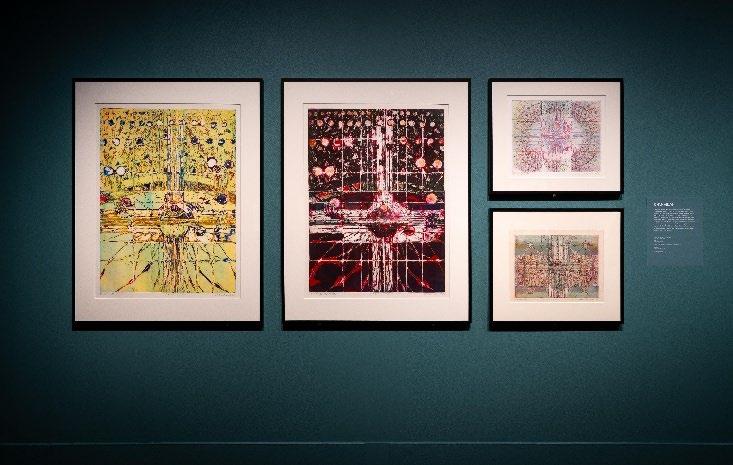

Reddy's artistic achievements but also underscored his significance in the art world. The exhibition made clear that Reddy's influence extended beyond the studio he was redefining what it meant to be a modern print artist.

The retrospective exhibition traveled to India in 1982–83, supported by the Indian Council for Cultural Relations (ICCR), and was exhibited at the Lalit Kala Akademi and other institutions. For many Indian audiences, this was the first time they encountered Reddy's revolutionary viscosity techniques, and the show positioned him firmly within the canon of post-independence Indian modernism.

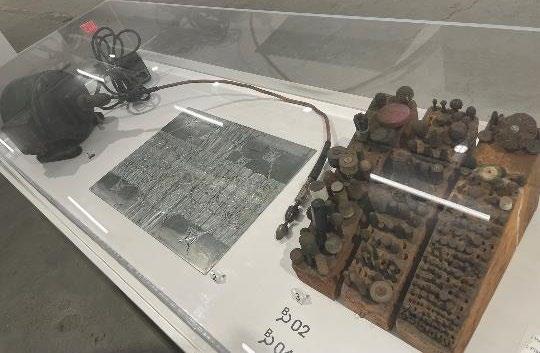

At the heart of Reddy's New York life was his SoHo loft on Wooster Street. It was part home, part studio, and part sanctuary, a place where philosophy and practice merged. Filled with the hum of the press, the smell of ink, and outfitted with specialized tools (including his famous dental drill "Pierre"), the space reflected his meticulous technical prowess as well as his profound curiosity. It was also a place where Reddy and his wife Judy welcomed visiting artists, students, and friends who often found themselves in deep philosophical conversation, surrounded by worksin-progress.

Judith Blum Reddy's presence made this environment even richer. A formidable artist in her own right, she fostered, with Krishna, a life rooted in mutual respect, dialogue, and intellectual exploration. Their home carried forward the spirit of Atelier 17 a workshop of minds as much as hands.

In 1981, Krishna Reddy: A Retrospective was organized at the Bronx Museum of the Arts, curated by Susan Fillin-Yeh. This landmark exhibition was the first major New York exhibition to fully showcase the depth of Reddy's printmaking, sculpture, and drawing. It not only celebrated

Reddy retired from NYU in 2001 but continued his involvement with the artistic world. His teachings continued through the Krishna Reddy Papers an expansive archive housed at NYU's Bobst Library, containing correspondence, experimental prints, lectures, and unpublished writings.

Krishna Reddy's New York years synthesized a lifetime of inquiry into a radiant legacy. In New

York, the printmaker became a philosopher in full and a pioneer who, through material and meaning, reshaped the language of modern art.

The Artist as a Way of Life

Krishna Reddy was not merely a technician or a teacher, nor was he simply a modernist or a mystic; he was all of these at once, and more. Reddy's life was a journey across cultures, philosophies, and

mediums, but at its core was an enduring commitment to wonder, integrity, and transformation. In every phase of his life from Santiniketan to Paris, from New York to his studio in SoHo, Reddy upheld a belief that creativity is not an act of will, but a process of listening, inquiry, and surrender. He transcended stylistic labels, technical categories, and cultural boundaries. And in doing so, he lived the very title of this book Printmaker, Pioneer, Philosopher with rare conviction and grace.

Krishna Reddy’s Variations: Sculpting Metal Plates and Printing Simultaneous Colors

Christina Taylor

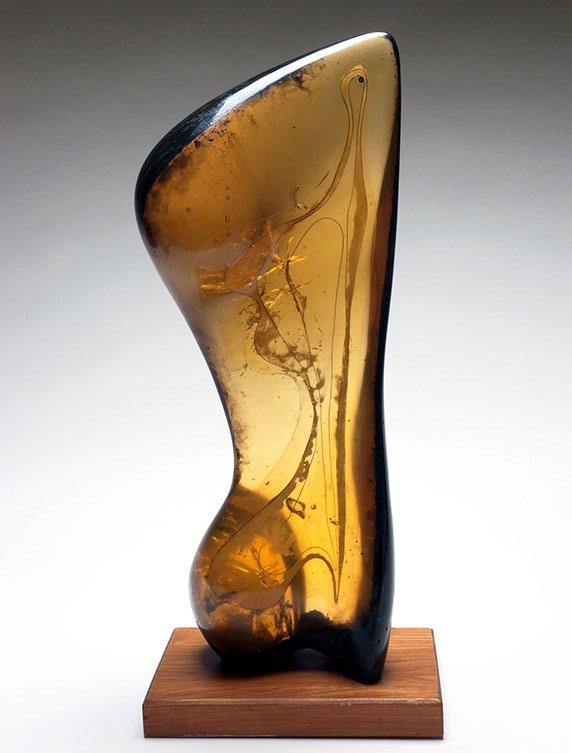

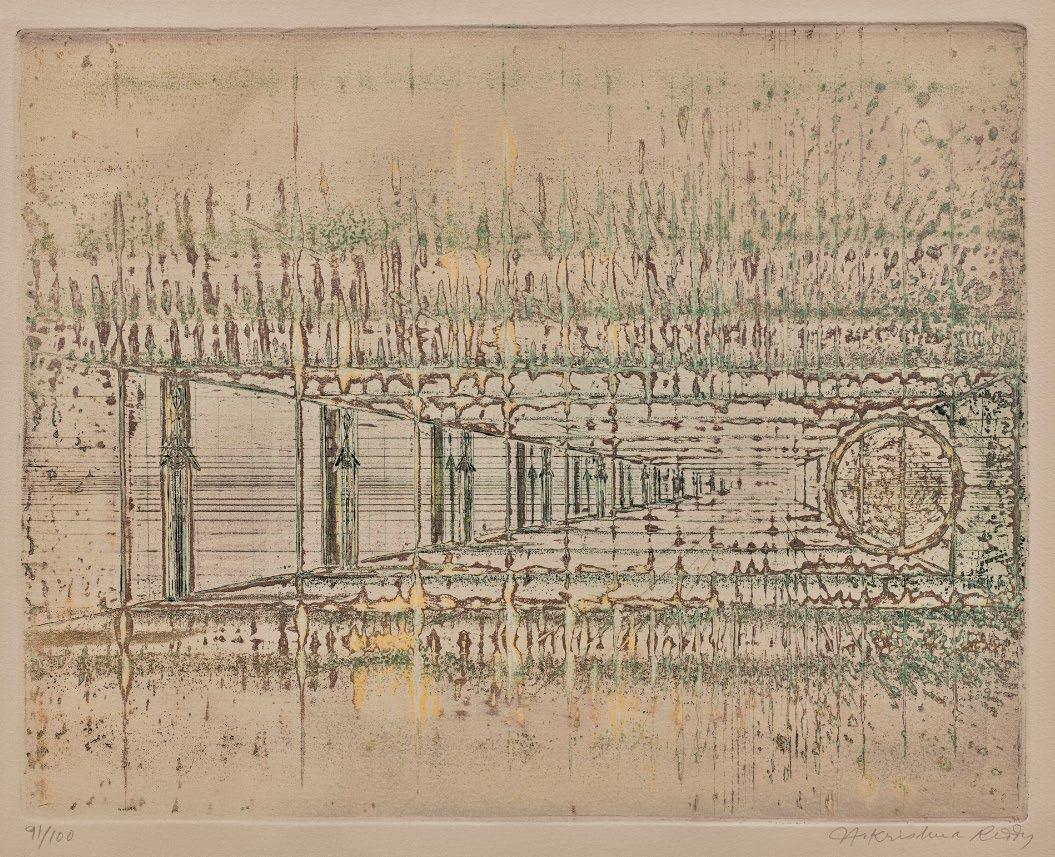

Both Reddy’s plate preparation and inking techniques play a critical role in how he achieves limitless variations amongst his impressions. Reddy rejected the concept of identically printed editions, and instead, harnessed printmaking to create radically different images from a single plate. No two prints are the same. With a background as a sculptor, Reddy did not see printmaking merely as a flat, graphic process that translated his ideas into images on paper, but rather, he saw the potential of printmaking to highlight the three-dimensionality of the materials and methods required to build his varied surfaces. Both his plates and prints exude these sculptural sensibilities. During the early 1950s, Reddy was living in Paris and visited Atelier 17, an experimental printmaking studio founded by Stanley William Hayter.

“Hayter established Atelier 17 in 1926 to develop print media as another means of expression and bring them closer to the artist. The Atelier’s primary focus was on experimentation and the discovery of new technical and expressive possibilities in printmaking, particularly intaglio.” 1

This focus on experimentation resonated with Reddy and he became an active member, and ultimately the co-director of the workshop from 1964 to 1976. Reddy held a deep interest in color and found that he was able to express color with printmaking in a way that he couldn’t in sculpture, and soon he shifted his artistic practice towards printmaking. Typically in printing, each color in the final image requires a separate plate, and only when the inked plates are printed successively in perfect registration is the full color image realized. Reddy was inspired to explore the possibility of applying all colors at once to a single plate and therefore eliminating the need for multiple plates. At Atelier 17 alongside his colleagues Kaiko Moti and Hayter, Reddy developed a method where the viscosities (or degree of oiliness) of printing inks are manipulated so that simultaneous inking and printing from one plate is possible.

“We will print this plate in a single pass through the press. The possibilities of [simultaneous color printing] are extraordinary, both in the number and in the richness, vividness and intensity of colors achieved.” 2

In addition to modifying colored inks and applying those inks to the plate’s surface in particular ways, Reddy’s method of simultaneous color printing also required the thoughtful creation of the layered metal printing plate. This essay pairs detail images and new research with Reddy’s own descriptions of his process to clearly define his platemaking and inking techniques and illustrate how each plays an important role in how he developed his life’s work.

1 Reddy, ”Intaglio Simultaneous Color Printmaking: Significance of Materials and Processes,” 31-32.

2 Reddy, ”Intaglio Simultaneous Color Printmaking: Significance of Materials and Processes,” 108.

Sculpting the metal plates

Reddy begins the process of creating a print with a metal plate. Prints, and by extension printing plates, are often considered two-dimensional because of their relative thinness compared to their height and width. But no material exists in only two dimensions and Reddy recognized that “…the plate has intrinsic sculptural qualities, that it lends itself to carving and sculpting…” 3. As Reddy developed his innovative printing techniques, he not only embraced the depth of the plate as he would any other sculptural medium, but he also relied on the three-dimensionality of his metal plates to achieve the pulsating and vibrating color effects during the printing process.

“To prepare such a plate, a certain amount of relief is necessary, whether it be caused by open-biting, by aquatint…or by breaking up the surface of the plate with a variety of tools. The principle behind any of these techniques is the same: to create a range of depths within the plate which will in turn contribute to the density of the print…” 4

Although this essay will separate Reddy’s plate manipulation techniques into three categories –chemical etching, hand tools, and machine tools – he consciously built up his images into each metal plate by combining and layering many techniques. Reddy describes how “the making of an image on a plate can occur in so many ways; each process, combined with any other, opens up rich possibilities. The combinations are innumerable.” 5 .

Chemical etching

Etching is a method of selectively removing metal from the surface of the plate with strong acids or mordants. Etchings are traditionally printed intaglio, where the design is etched and inked below the surface of the plate, however, etchings can also be printed in relief, or from the unaltered surface of the plate. During printing, Reddy was able to combine aspects of intaglio, relief, and viscosity inking because of the way he prepared and sculpted his plates before any printing began.

Open Bite (Deep Etch)

Open bite refers to etching large, “open” areas of a plate without a mechanism to break up or roughen the surface (such is common with aquatint). When a metal plate with open bite is inked and printed intaglio, the color is not as dark and saturated because there is no roughened surface for the ink to cling to. However, Reddy was utilizing open bite etching to alter the depth of the plate to facilitate viscosity inking with rollers, rather than intaglio inking. Reddy would often use a deep acid bite as the first step to establish the image; sometimes etching the plate in the acid for hours at a time to get a very deep etch 6 . After the image was established, he would take hand and machine tools to further refine and sculpt the plate.

3 Reddy, ”Intaglio Simultaneous Color Printmaking: Significance of Materials and Processes,” 35.

4 Reddy, ”Intaglio Simultaneous Color Printmaking: Significance of Materials and Processes,” 36.

5 Reddy, ”Intaglio Simultaneous Color Printmaking: Significance of Materials and Processes,” 66.

6 Johnson, 2025.

“Deep biting with acid produces stepped levels down into the plate, thus forming a succession of reliefs. The action of the acid creates hard edges, which will show up as heavy linear structures in the print. These may be kept as a bold, well-defined image, or they may be modified – by use of a scraper, emery paper and burnisher – revealing subtle, undulating structures.” 7

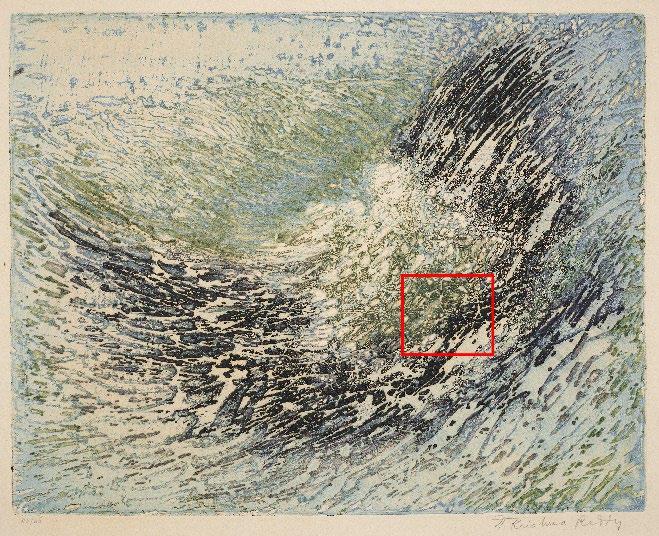

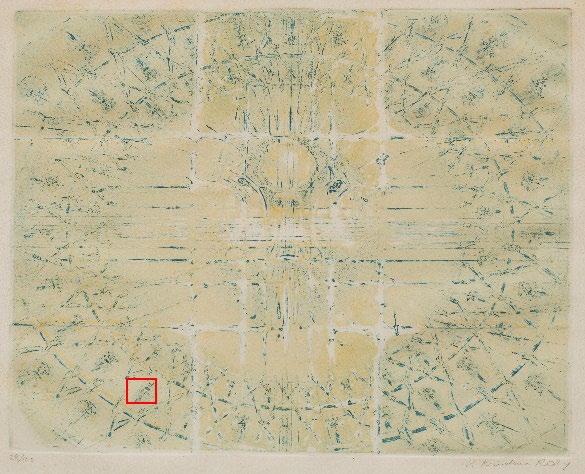

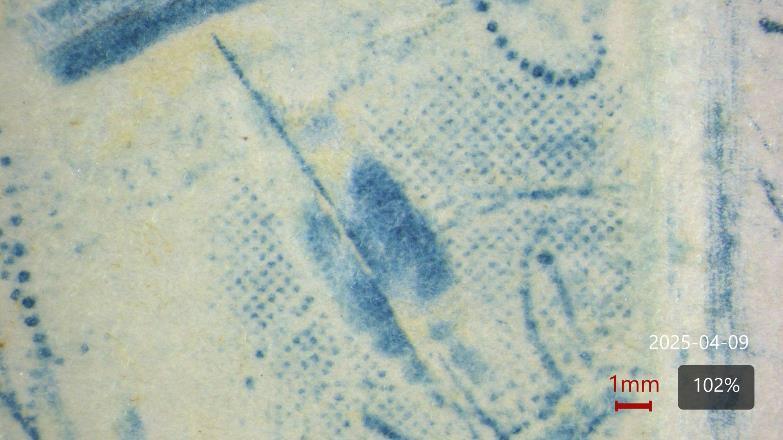

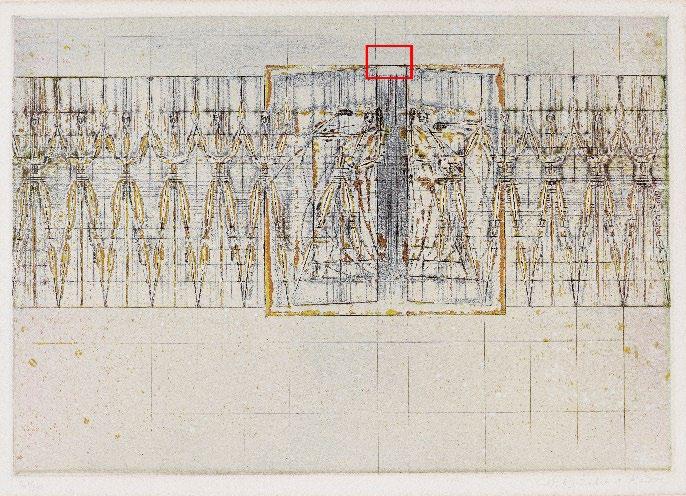

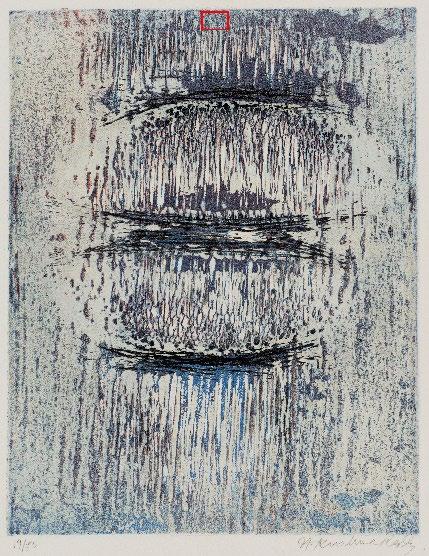

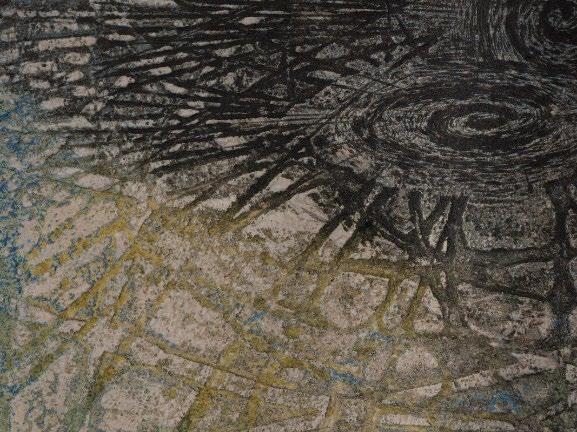

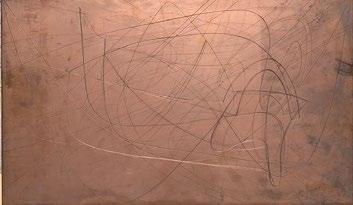

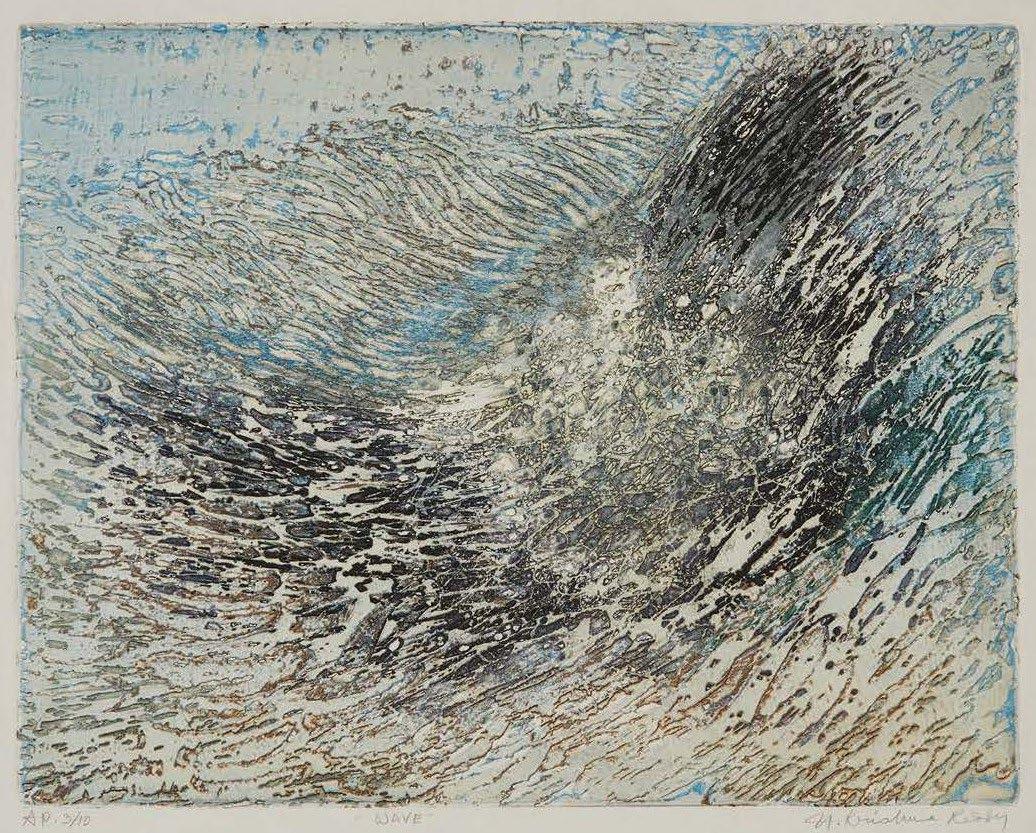

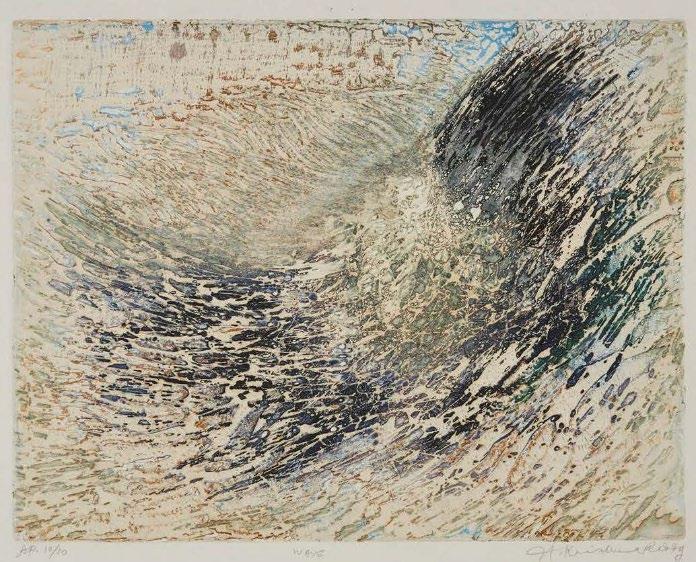

Fig. 1: Wave, overall image; location of detail marked in red Fig. 2: Wave, raking light detail; the “stringy” lines in relief compared to the bulbous dimensionality from the deep open bite etch (Photo by Jason Wierzbicki, Division of Conservation, Philadelphia Museum of Art)

“I developed a way of structuring fine relief lines on the plate, using a highly polymerized cellulosic paint and a funnel made of wax paper. The paint flowed continuously in strings without a break.” 8

Here Reddy is describing how he applied an acid-resistant paint to the plate before he submerged the plate in acid to etch it deeply via open bite. After the plate was removed from the acid, and the plate was cleaned off, where the stringy paint protected the plate from the acid the plate remained in relief in those fine lines. The surrounding bulbous shapes are deeply etched and are what give the prints their extreme dimensionality, especially visible in a side or raking light (Fig. 2).

Aquatint

Rosin ground aquatint is an early method of adding tonal variations to a print. In order to roughen the surface enough to hold ink, the clean plate is covered with rosin dust, and then the dust is melted and fused to the plate with heat. When the plate is etched, the acid “bites” and lowers the level of the plate around each grain of rosin. Once the etching is complete, the plate is cleaned of acid and rosin, and the texture has changed from smooth and polished, to rough and gritty. Depending on what the artist hopes to achieve, the rosin particles can vary from coarse to very fine.

7 Reddy, ”Intaglio Simultaneous Color Printmaking: Significance of Materials and Processes,” 36.

8 Bronx Museum of the Arts, ”Krishna Reddy, a Retrospective,” 68.

“Inspite of the length of time aquatint has been in use, it remains a beautiful new territory to explore. Aquatint is capable of tonal distinctions which no other method can produce. And it has an element of surprise.” 9

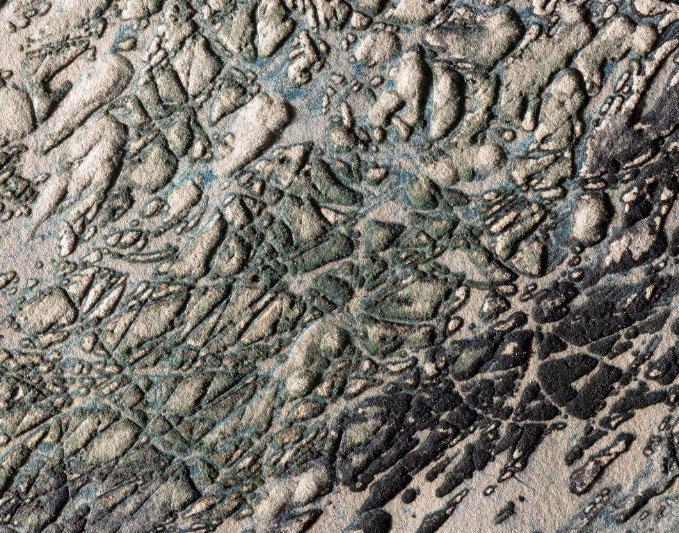

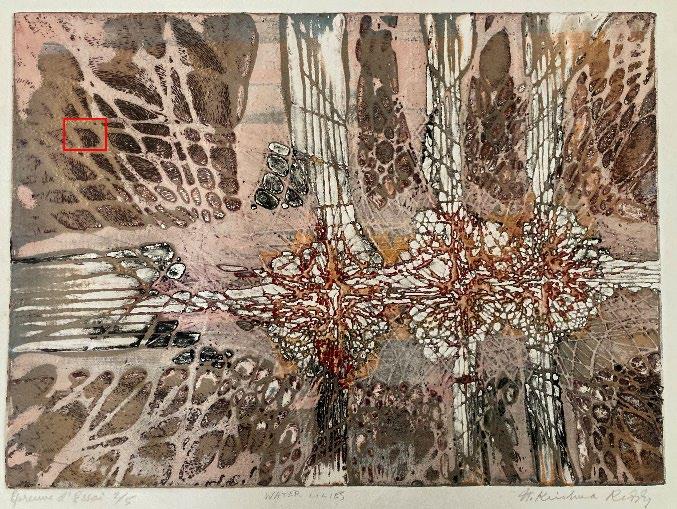

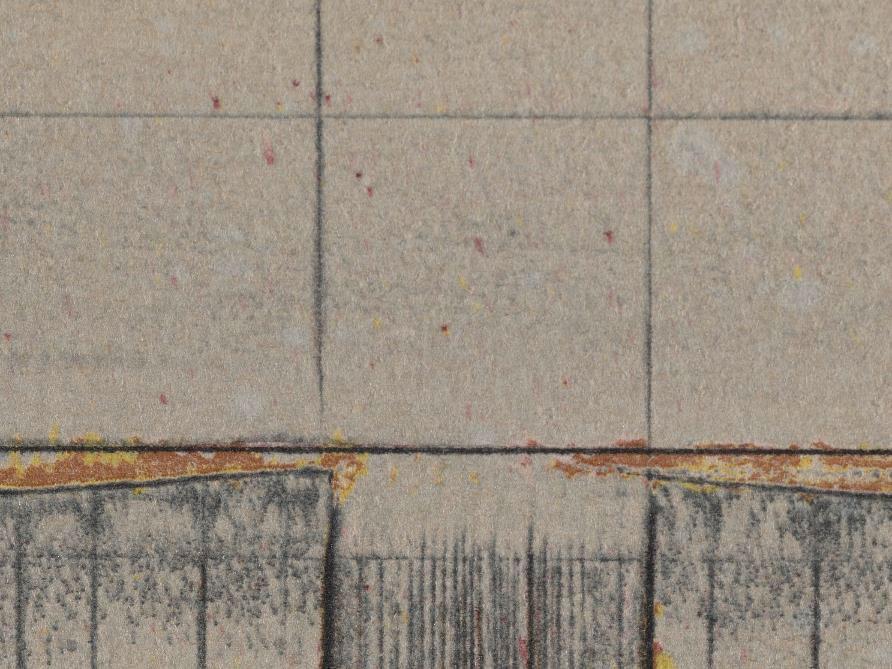

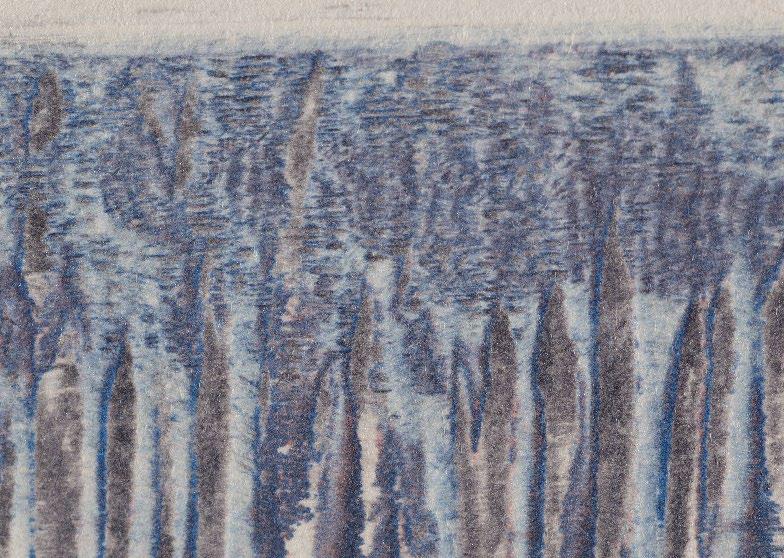

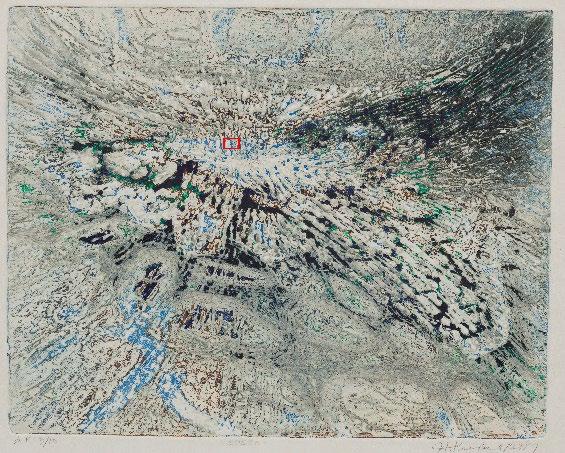

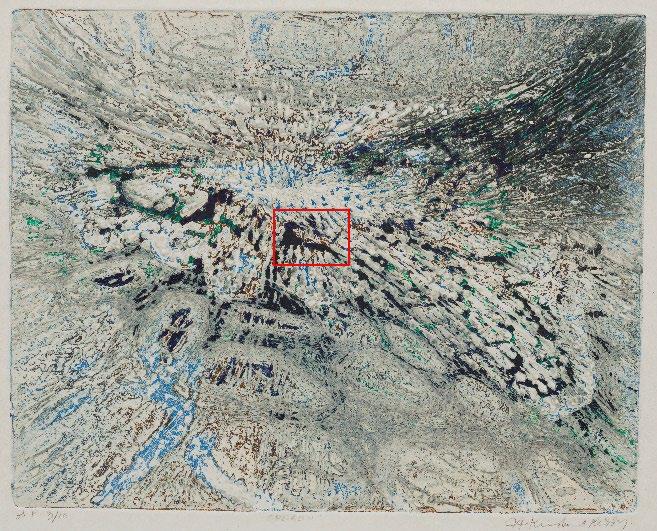

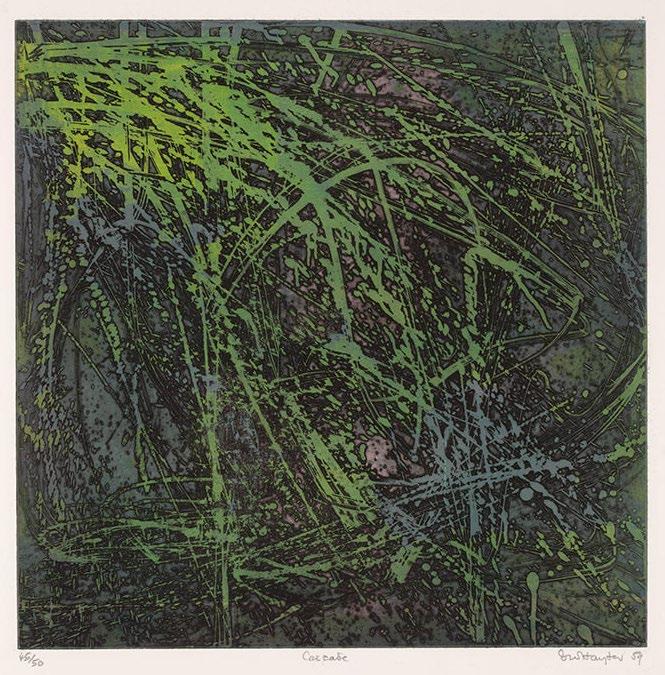

In his print Waterform (Fig. 3), he superimposed a series of aquatints creating a range of textures. Evidence of coarser rosin particles are visible as distinct white islands where the plate was protected during etching. The surrounding ink is rich and dimensional, a result of a deeply etched aquatint capable of holding a large quantity of ink (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3: Waterform, overall image; location of detail marked in red Fig. 4: Waterform, raking light detail; the aquatint texture (white islands) and thick intaglio ink layer (black and gray ink) (Photo by Jason Wierzbicki, Division of Conservation, Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Halftones

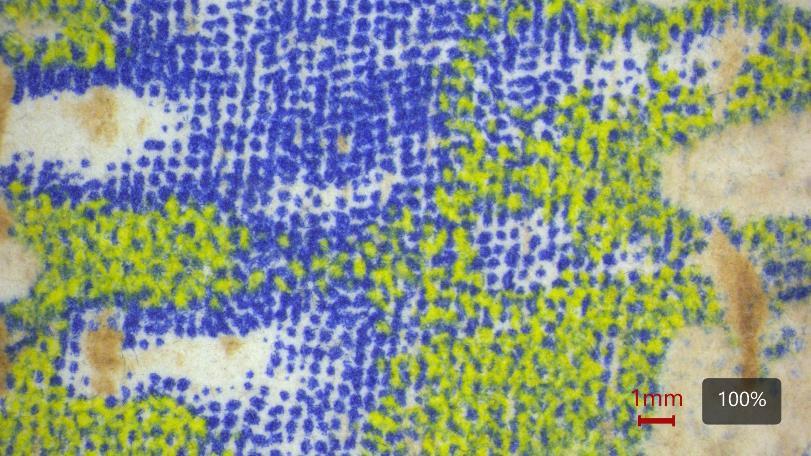

“Playing with halftones – worked by means of aquatint, photographic dot screens, or hand and machine tools – can bring extreme subtlety and richness to the print. Minute indentations in the plate create porous areas. When printed in the simultaneous color process, dots and streaks of pure color are juxtaposed side by side, producing effects similar to those sought after by the Impressionists. Seen from a distance, the print has an overall quality of richness, made up of shimmering areas of luminous color. The half-tone can be also scraped down to form shadows of the initial work, thus probing the illusory as well as the actual dimensionality of the plate.” 10

9 Reddy, ”Intaglio Simultaneous Color Printmaking: Significance of Materials and Processes,” 43.

10 Reddy, ”Intaglio Simultaneous Color Printmaking: Significance of Materials and Processes,” 36.

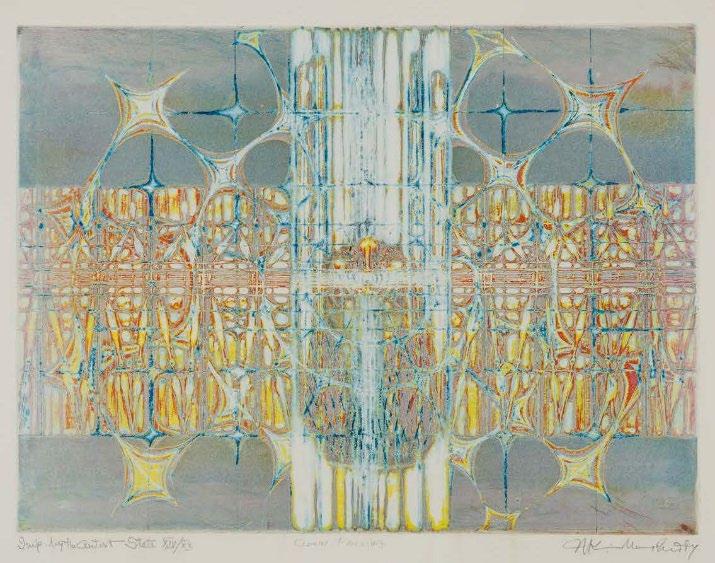

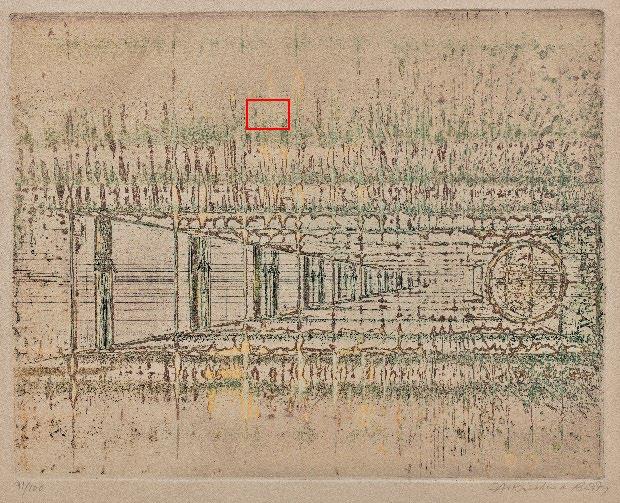

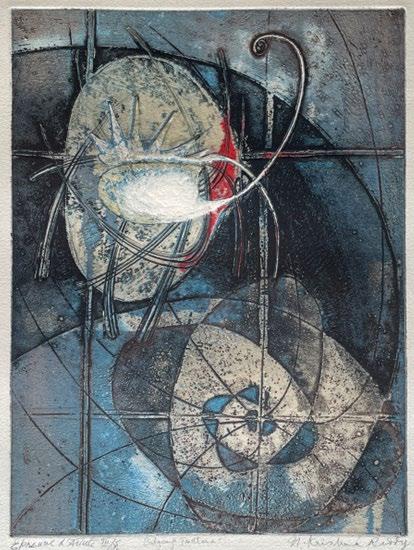

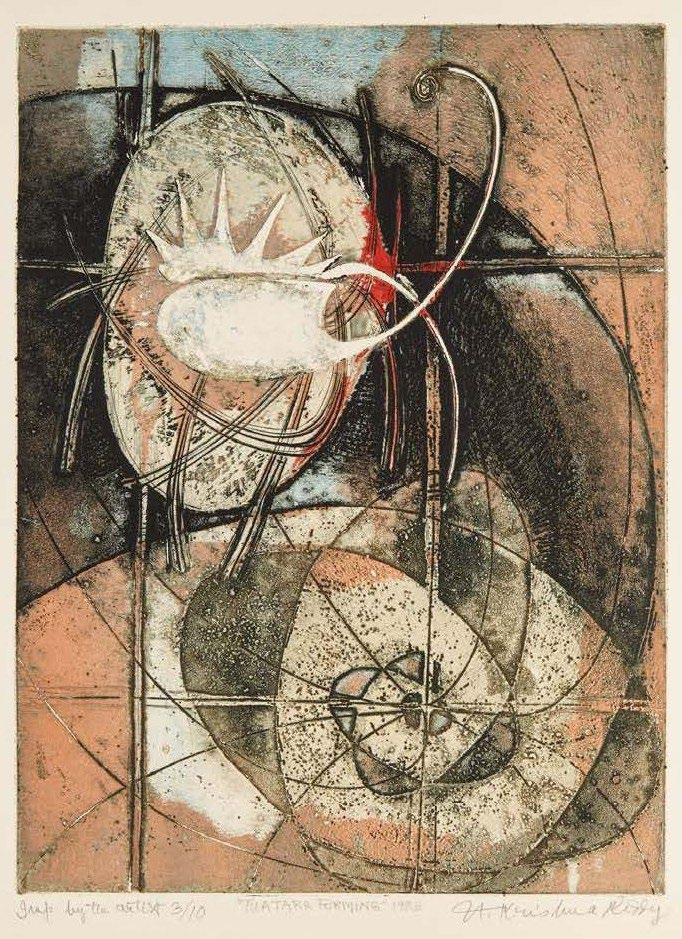

To chemically etch a halftone, the image is photographically exposed to a metal plate where the values are broken up by a dot screen (a plastic sheet filled with black dots). The dots create the illusion of continuous tone and can range in size with both random and mechanical dot patterns. The concept of a dot pattern – whether added through aquatint, machine tools, or photographic halftones – was central to Reddy’s practice. In Clown Forming (Fig. 5), he utilized a photographic halftone technique, and then further manipulated the plate by scraping and sanding down the surface to break up the mechanical dot patterns (Fig. 6). He also added variable dots using machine tools and strong linear elements with engraving.

Fig. 5: Clown Forming, overall image; location of detail marked in red

Fig. 6: Clown Forming, detail; the regular dot pattern is a characteristic of the photo-halftone screen. Reddy further manipulated the plate’s surface by both scraping portions of the halftone away and by adding additional marks with hand and machine tools.

Hand tools

Hand tools do not require electricity or another power source to operate. Reddy utilized a range of hand tools – from those specifically designed for printmaking and engraving to metal working and dental tools. Zinc and copper – both metals that Reddy used to make his prints – are hard enough to hold up during the pressure required of printing, but soft enough to manipulate by hand with steel tools.

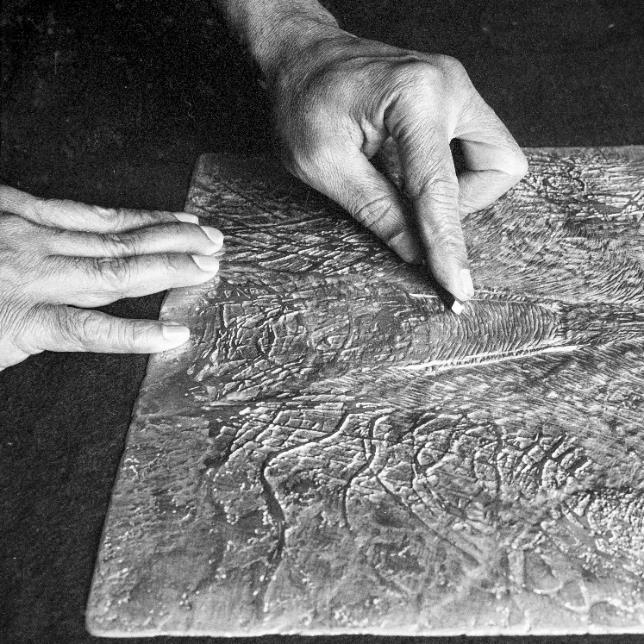

“The experience of handling tools…brings the artist in very close contact with the materials, and especially with the plate. Once a healthy awareness and sensitivity have been established, the plate is seen to be an extremely pliable substance. Developing images is now considered in terms of direct carving, engraving and gouging, with no recourse to acid. Hand tools, while they can be the most laborious method of working a metal plate, give the greatest sense of intimacy.” 11

Reddy utilized three main categories of hand tools: 1. tools to create lines, 2. tools to create repeated patterns, and 3. removal or softening tools.

11 Reddy, ”Intaglio Simultaneous Color Printmaking: Significance of Materials and Processes,” 36.

Tools to create lines

Burins and engraving tools

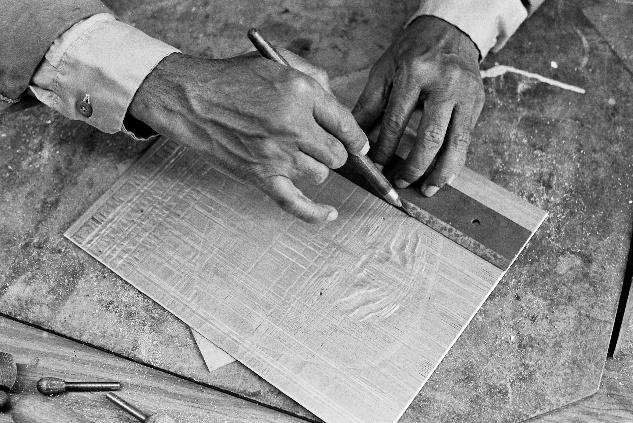

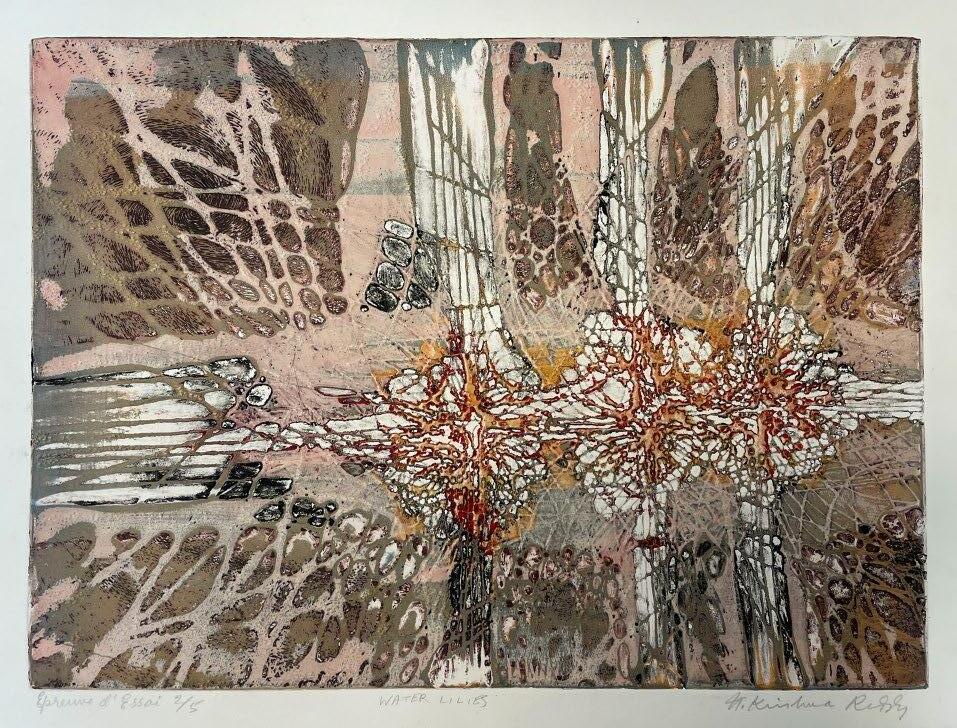

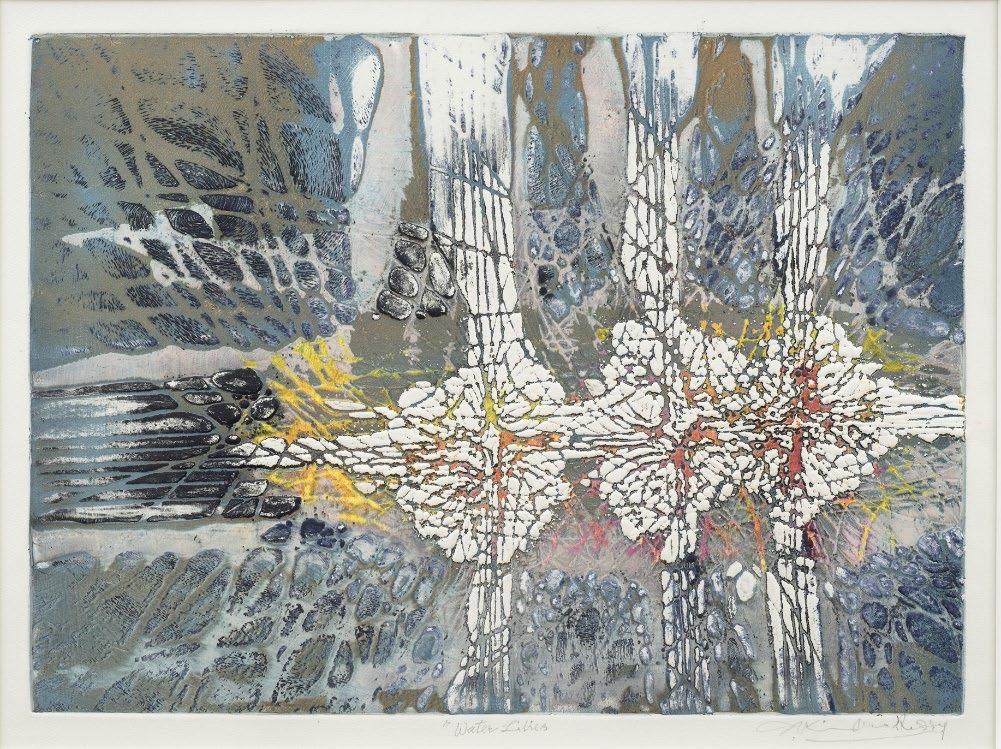

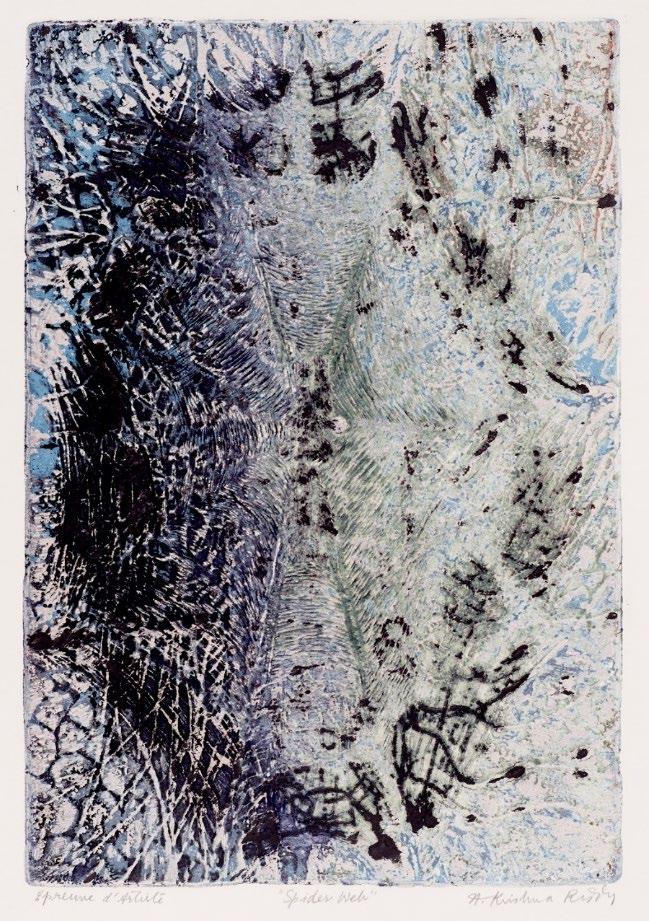

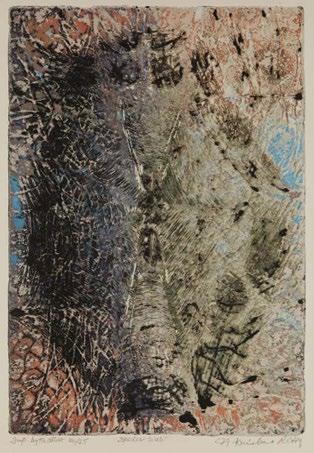

7: Krishna Reddy engraving with a burin into the metal plate for Spiderweb. Fig. 8: Water Lilies, overall; location of detail (below) marked in red

A burin is a steel cutting tool with a thin, pointed blade used to cut a design into a metal printing plate. Because of the shape of the tool, as the artist carves into the metal, the lines characteristically swell and taper depending on the depth of the cut (Fig. 9). The plate is then inked and printed intaglio. Although engraving was invented centuries prior, Reddy and other Atelier 17 artists were fascinated by the depth of line and sculptural quality achieved using burins and various engraving tools (Fig. 10).

9: Water Lilies, detail – normal light; the characteristic swelling and tapering of the engraved lines is notable where Reddy employed the burin (Photo by Jason Wierzbicki, Division of Conservation, Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Fig. 10: Water Lilies, detail – raking light; the depth of gouging that Reddy achieved with the burin is highlighted in raking light (Photo by Jason Wierzbicki, Division of Conservation, Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Drypoint Needles

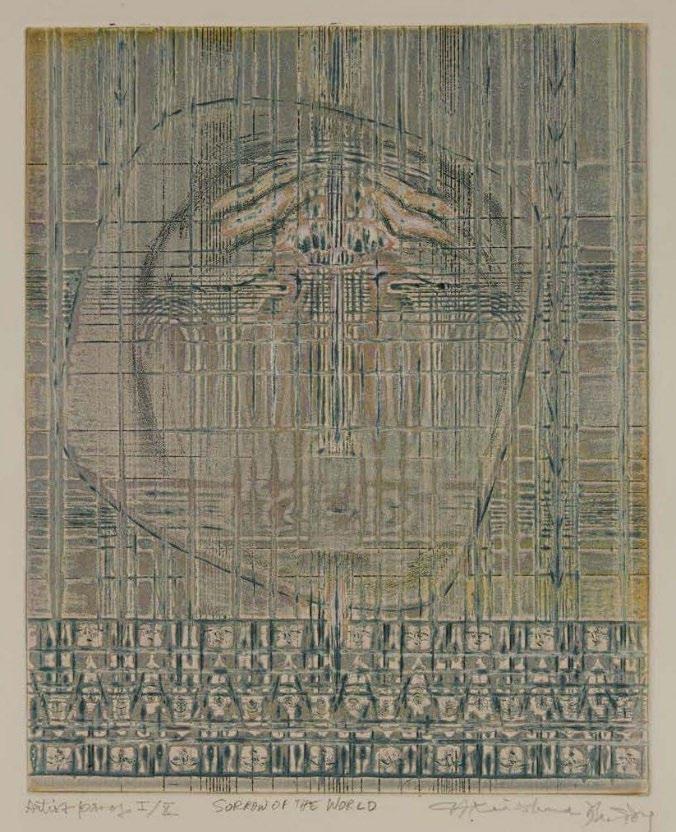

Fig. 11: Krishna Reddy laying out the composition for Sorrow of the World on the plate by directly scratching drypoint lines into the metal.

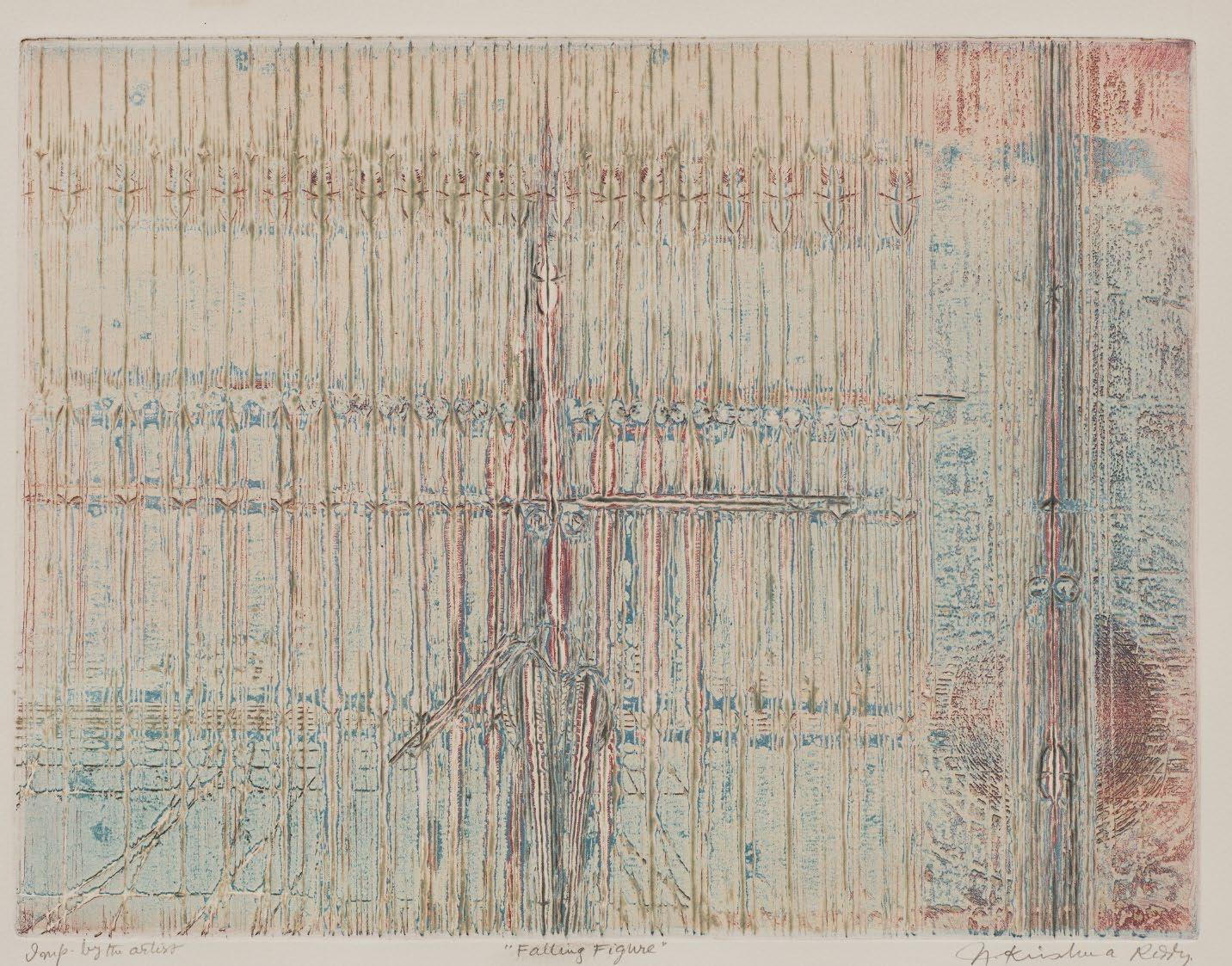

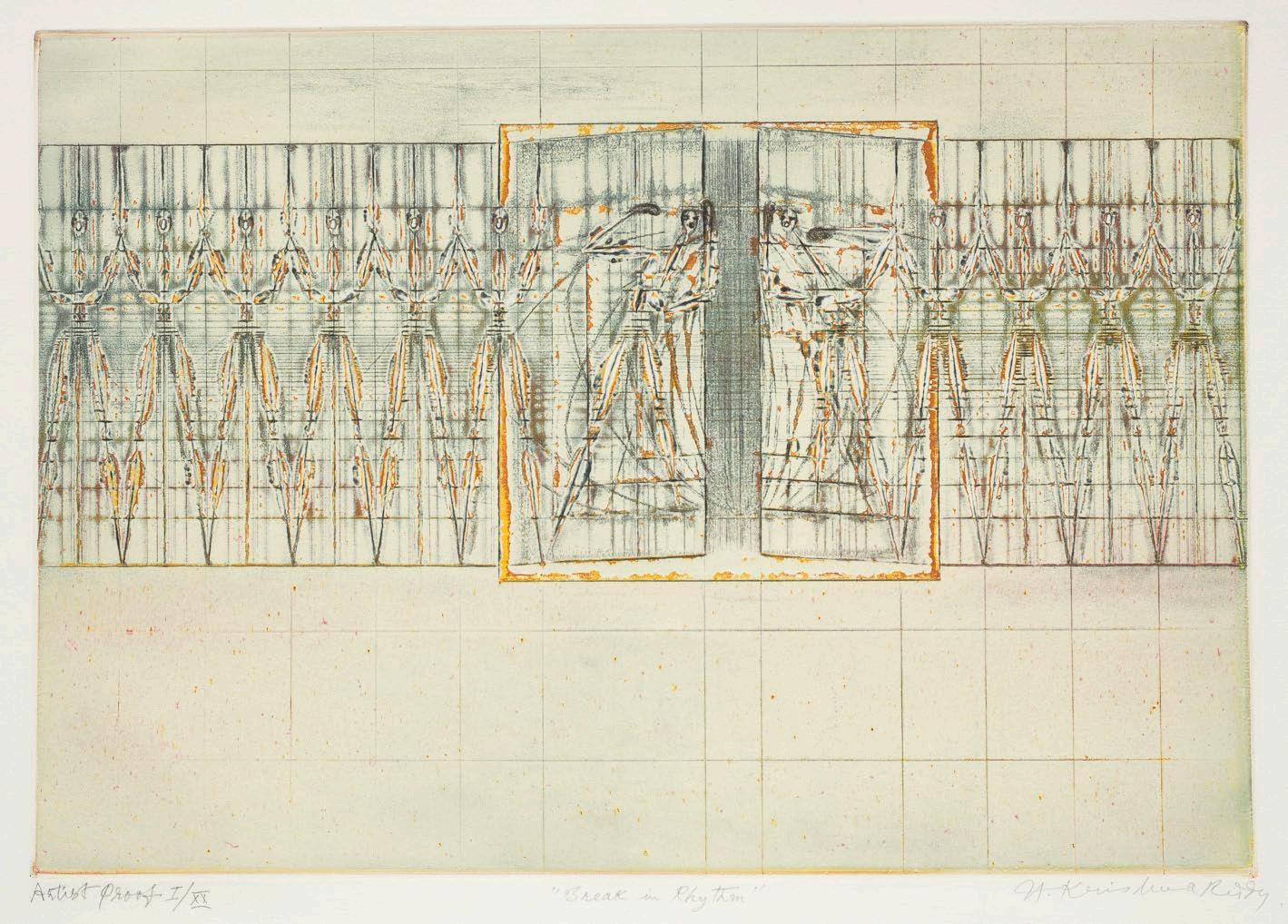

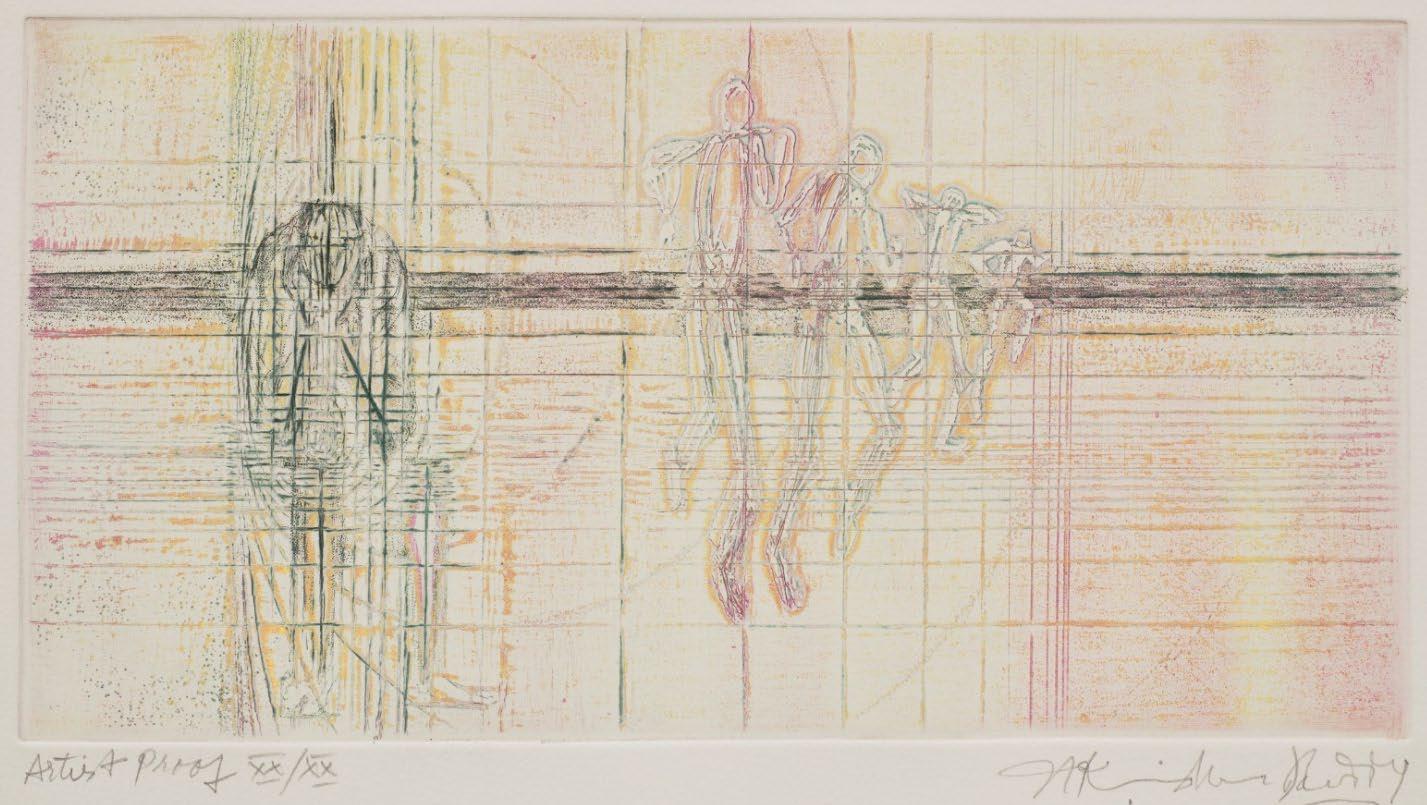

Drypoint is an intaglio printing technique where the image is drawn or scratched directly into the metal plate. Unlike engraving, the lines are much shallower and metal is not removed from the plate, it is instead displaced creating a burr where ink gathers during printing. When printed, the scratched line and adjacent metal burr create a characteristic soft and velvety line (Fig. 13). In some cases, Reddy would use a drypoint needle to map out his composition, especially when he didn’t establish the image initially with a deep etch. When employing drypoint, he often used a ruler to create structured lines and grids within which he would build up his compositions.

Fig. 12: Rhyme Broken, overall; location of detail marked in red

Fig. 13: Detail of Rhyme Broken – The characteristic fine and fuzzy drypoint lines are notable where Reddy drew directly on the plate (Photo by Jason Wierzbicki, Division of Conservation, Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Tools to create repeated patterns

Roulette

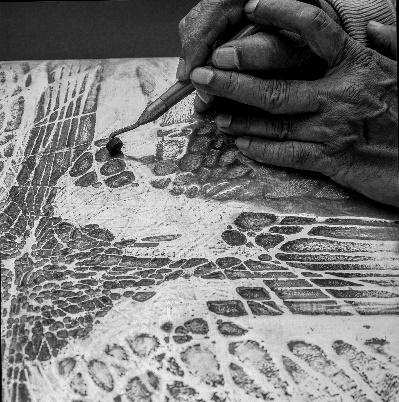

Fig. 14: Krishna Reddy using a wheeled roulette tool to add repeating texture to the plate for Water Lilies.

A roulette is a wheeled tool with fine teeth, that when rolled over the metal plate, creates indentations that will hold ink during printing. Roulettes come in a variety of styles – most commonly in dot, line or irregular patterns – and Reddy utilized these different types of roulettes to add repeating patterns (Fig. 16). Unlike etching techniques such as aquatint and halftone, the roulette was a way for the artist to add texture in a direct and immediate way.

Fig. 15: Flower, overall; location of detail marked in red Fig. 16: Flower, detail image; Reddy utilized a wheeled roulette tool with a wide line pattern, then rolled the roulette in opposite directions to create this cross-hatched effect (Photo by Jason Wierzbicki, Division of Conservation, Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Removal or softening tools

Scraper and burnisher

Fig. 17: Krishna Reddy using a burnisher to smooth areas of the metal plate for Sorrow of the World so it does not collect ink.

Scrapers and burnishers are often used in tandem. A scraper is a triangular shaped steel tool with three sharp edges, so that when dragged across the printing plate, metal is removed or scraped away. A burnisher is a rounded steel tool, polished to a high finish to polish and remove scratches from the plate’s surface. Reddy often used scrapers and burnishers to manipulate the depth of his plates, but he also used the tools to modify or make changes to his composition (Figs. 18-21).

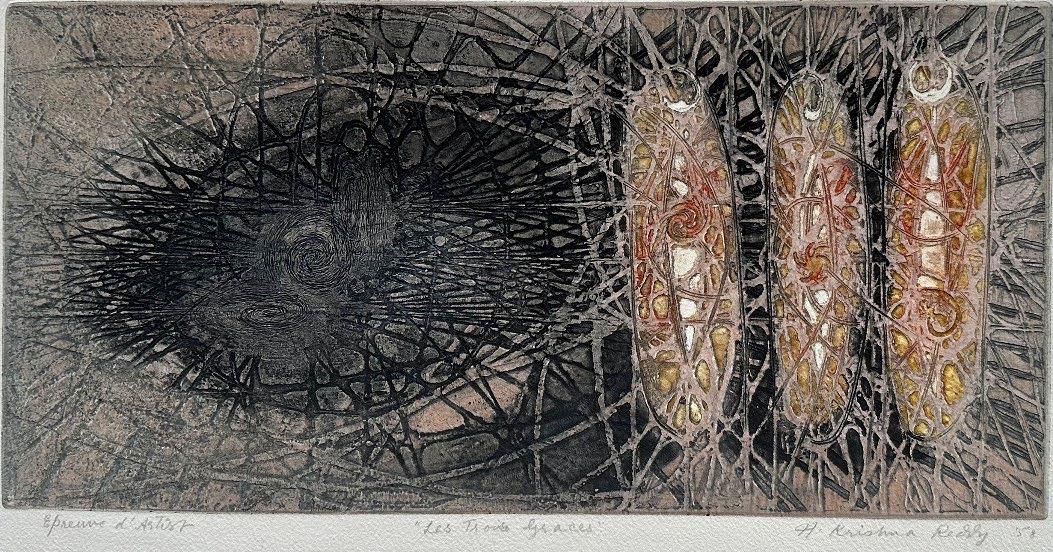

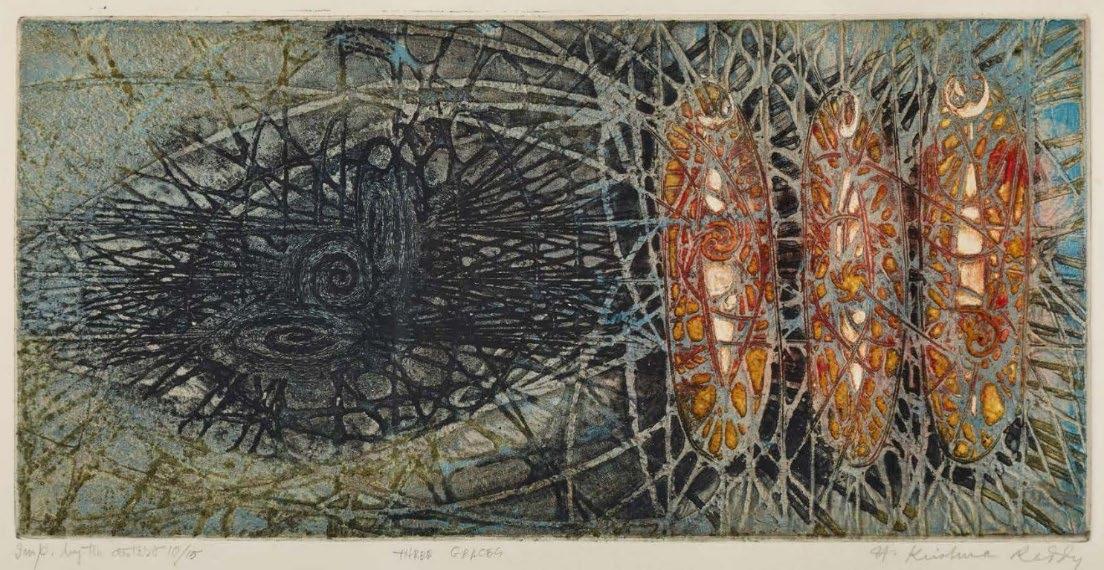

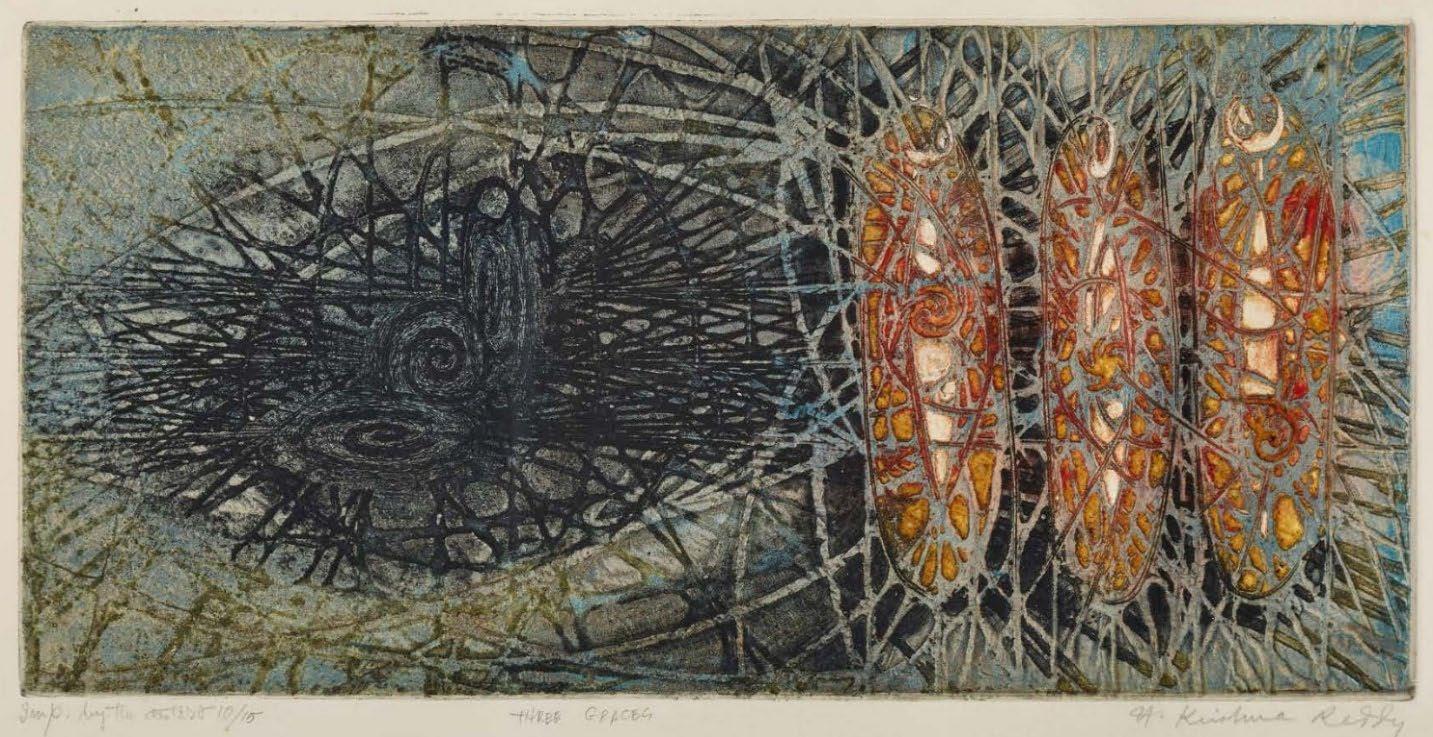

Fig. 18: Three Graces, overall; location of detail marked in red

Fig 19: Three Graces, detail; horizontal lines remain visible (before they are scraped away and no longer seen in the later state [Fig. 21]) (Photo by Jason Wierzbicki, Division of Conservation, Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Fig 20: Three Graces, overall; location of detail marked in red

Fig 21: Three Graces, detail; Reddy scraped away areas (horizontal lines seen in Fig. 19), giving him the space to add spirals to the composition with burins (Photo by Jason Wierzbicki, Division of Conservation, Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Machine tools

Reddy used a variety of electrically powered machine tools to sculpt and modify his plates. When walking into his studio, some might question whether a printmaker indeed occupied the space filled with unconventional machines and tools. It is evident that he felt comfortable manipulating the metal plates using a variety of tools, and over time came to embrace machine tools for much of his work.

Fig. 22: Krishna Reddy in his studio surrounded by unconventional printmaking tools.

“Machine tools enable the entire plate to be worked with such ease that image-building, or its removal, becomes rapid. Machine tools encourage spontaneity and can be of great value in strengthening the expression of the artist…akin to the directness of contact experienced in painting and sculpture.” 12

12 Reddy, ”Intaglio Simultaneous Color Printmaking: Significance of Materials and Processes,” 108.

A flex-shaft rotary tool is a power tool that uses a flexible shaft to transmit rotational power from a motor to a handpiece. This handpiece then holds the grinding or polishing tools, allowing Reddy to work on objects with greater precision and ease (Fig. 23). Reddy’s tools varied greatly from grinding and polishing tools, to cutting and stippling tools, and each created their own marks and effects in the printing plate.

When describing the process of making his print Blossoming, Reddy recalls “both the reliefs and the textures were worked by machine tools using several serrated steel and stone grinders. This was the first time I carved a whole plate with machine tools.” 13

suggest

The Vibro-tool® is an electric engraving tool manufactured by Burgess Vibrocrafters Inc. intended for a variety of purposes, including but not limited to engraving metal, decorating glassware, and tooling leather. Rather than rotating, the motor vibrates at high speeds “at the rate of 120 strokes per second…[adding] power to your skill.” 14 Reddy held this tool more like a pencil and created linear dot strokes and other textures in his plates (Fig. 27).

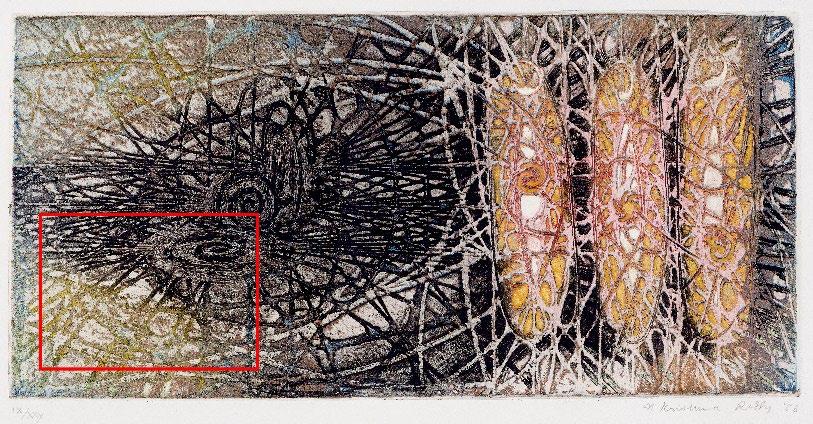

Fig. 28: Sun Worshippers, overall; location of detail marked in red Fig. 29: Detail of Sun Worshippers; dotted Vibrotool® texture printed in green ink (Photo by Jason Wierzbicki, Division of Conservation, Philadelphia Museum of Art)

14 Mittermeier, “Vibro-Tool,” 31.

Building simultaneous color for printing

Traditionally, to print in color, an artist or printer was required to separate each color from the image, create plates for each color, and print them all in perfect registration to build up to the full color image. Simultaneous color printing, by contrast, eliminates the need for color separation and allows the artist or printer to apply all the colors to a single plate before printing it one time through the press. Although artists at Atelier 17, and especially Reddy, mastered simultaneous color printing, he was not the first to apply simultaneous color techniques to his prints. Reddy utilized established simultaneous color printing techniques, such as à la poupée, with innovative ones, such as viscosity printing, to maximize the potential of simultaneous color printing.

To many, these methods are technically complex and counterintuitive, however, Reddy felt that simultaneous color printing simplified and integrated the printing process with the creation of art, rather than the printing process acting solely as a means to an end. Utilizing one plate was of utmost importance to his philosophy as an artist. “With the new methods of selectively depositing both the intaglio and surface colors on the same plate we can print all the colors in one operation. In this way we can achieve a color print of great graphic quality and with a directness never realizable before. 15”

Intaglio vs. surface color

Etchings and engravings are traditionally printed intaglio, where the design is etched or carved into the plate and the ink sits in the grooves for printing; however, etchings can also be printed in relief, or from the remaining unetched surface of the plate. Reddy blurred the line between intaglio and relief printing by combining various simultaneous color printing techniques. It is critical to understand the difference between intaglio inking and surface color inking when thinking about simultaneous color. When inking intaglio, Reddy covered the plate with ink, and then by wiping with tarlatans he drove ink into the grooves of the plate while simultaneously removing ink from the surface. This was the first step in the inking process. After inking and wiping intaglio, when inking surface colors, Reddy rolled the ink over the intaglio-inked plate in one careful pass. Reddy often modified the viscosity of the surface color inks, as well as selected various roller densities to apply multiple (up to three or four) colors onto the multilayered surface of the plate. By combining intaglio, relief, and viscosity inking he maximized the possibilities of expression in a single plate.

15 Reddy, Indian Council for Cultural Relations, “Krishna Reddy, a Retrospective,” I Introduction.

Intaglio Inking Techniques

À la poupée

À la poupée is “a color mixing process in which the intaglio plate is inked in different colors in different areas with “dollies” or “poupées” of rolled canvas or felt, and wiped one area at a time with tarlatan and by hand.” 16 À la poupée inking causes adjacent inks to blend and mix somewhat during the wiping process. In some cases, Reddy would avoid inking certain intaglio sections of the plate, which resulted in areas of the print that are embossed from the pressure of printing yet maintain the bright paper tone without any transfer of ink.

Fig. 30: Three Graces, overall; location of detail marked in red

Fig. 31: Detail of Three Graces; à la poupée inking of the black and yellow inks blend where they meet and mix on the plate during the wiping process (Photo by Jason Wierzbicki, Division of Conservation, Philadelphia Museum of Art)

16 Reddy, ”Intaglio Simultaneous Color Printmaking: Significance of Materials and Processes,” 133.

Viscosity printing

Surface Color Inking Techniques

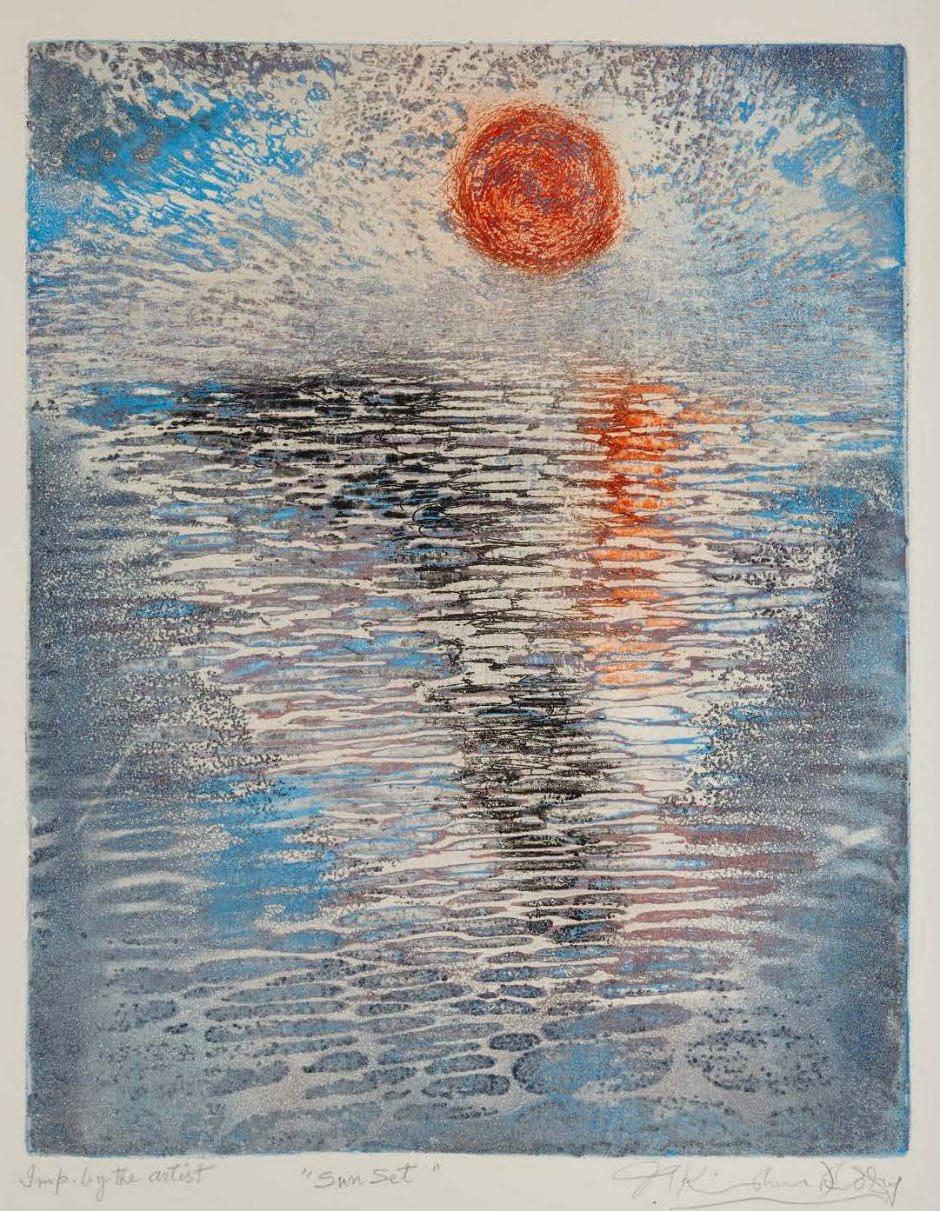

Viscosity printing is a relief or surface color technique. Surface colors are applied to the plate once all intaglio colors are already in place. Printing inks used for viscosity printing are oil-based. Viscosity refers to the degree of oiliness of the ink. Raw linseed oil is added to printing ink to alter the viscosity. Inks with less oil are considered “dry” and viscous (such as ink straight out of the can). Inks with more oil are considered “wet” and fluid (such as ink that is modified with raw linseed o il). When inks of varying viscosities are rolled over one another, they mix or repel one another in predictable ways. Superimposition and juxtaposition are the two fundamental methods of viscosity printing.

Superimposition

Superimposition of colors leads to an optical mixing effect, where the layered colors combine to make a third, separate color. When the “dry” and viscous ink is rolled onto the plate first, the second “wet” and fluid ink will be absorbed into that first ink layer and combine on the plate. The “dry” ink layer acts like a thirsty sponge and readily absorbs the “wet” ink. In this detail of Splash, where the bright orange and blue inks are superimposed, they mix to create a deeper brown.

Fig. 32: Splash, overall; location of detail marked in red

Fig. 33: Detail of Splash; superimposition – or mixing – of blue and orange inks to create brown where they overlap.

Juxtaposition

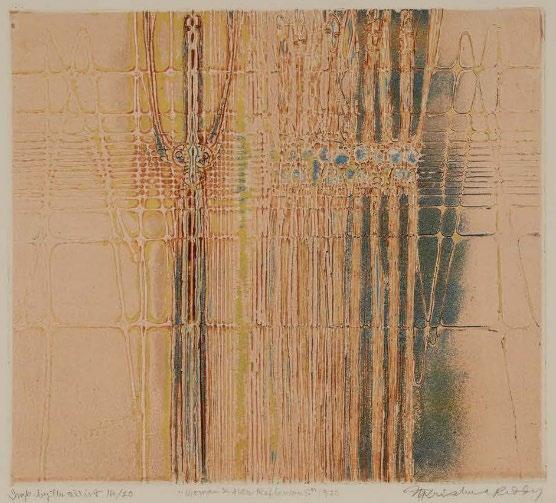

Fig. 34: Krishna Reddy illustrating the capability of inks to juxtapose one another when the viscosities are varied.

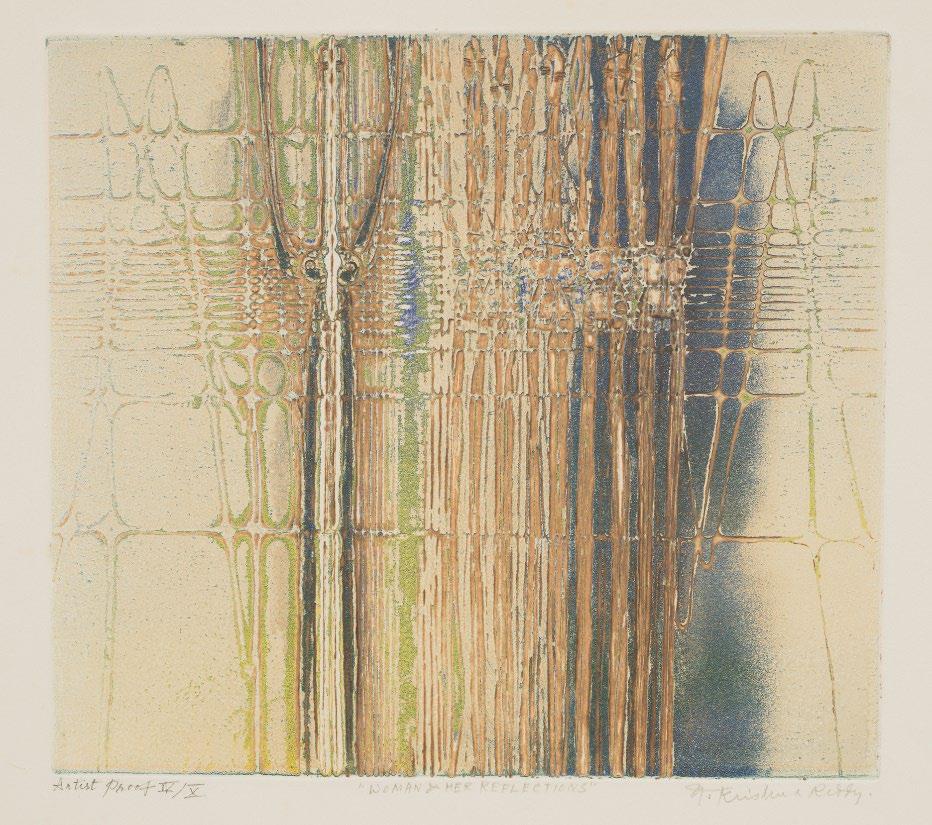

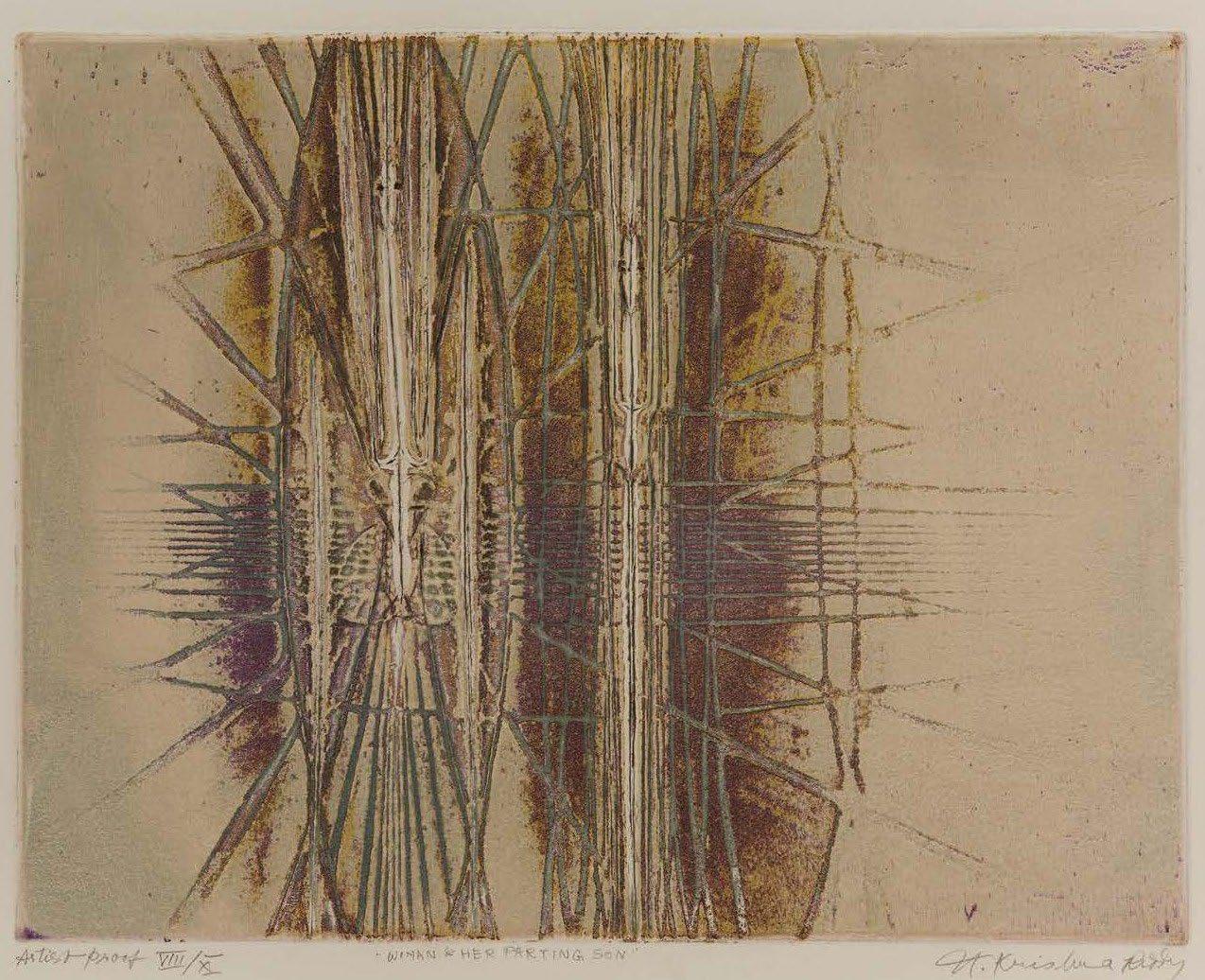

Juxtaposition of colors maintains two distinct colors, even when the colors are rolled over one another. When the viscosities of the ink are reversed, and a “wet” and fluid ink is rolled on the plate first followed by a “dry” and viscous ink, the “dry” ink layer still absorbs some of the first ink layer like a sponge, but instead of mixing on the plate, the inks mix on the roller. What is left of the plate are two colors juxtaposed side by side that do not mix. In this detail of Woman and Her Reflections (Fig. 36), the bright yellow and blue do not overlap to create green but rather sit side by side.

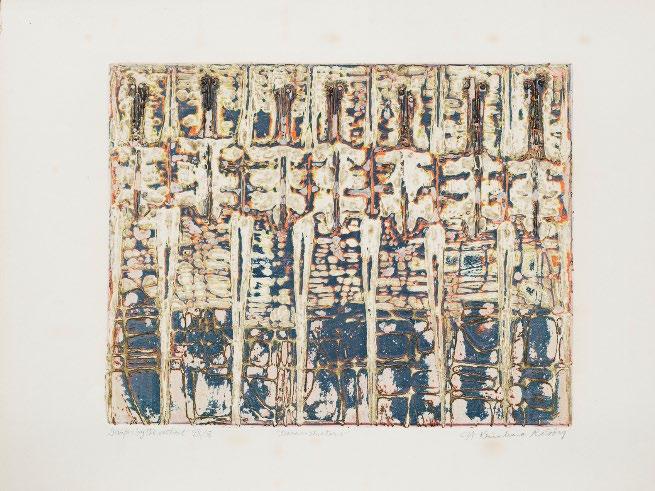

Fig. 35: Woman and Her Reflections, overall; location of detail marked in red Fig. 36: Detail of Woman and Her Reflections; juxtaposition – without mixing – of blue and yellow inks.

The viscosity of inks can be varied and manipulated to add three to four colors to a plate. In addition to the difference in oil-content, colors are applied to the plate with rollers of different densities. Softer rollers flex and reach deeper into the plate, whereas harder rollers are stiff and only contact the upper surface of the plate. By altering the combination of roller densities and ink viscosities, Reddy was able to achieve an almost limitless variety of colors effects.

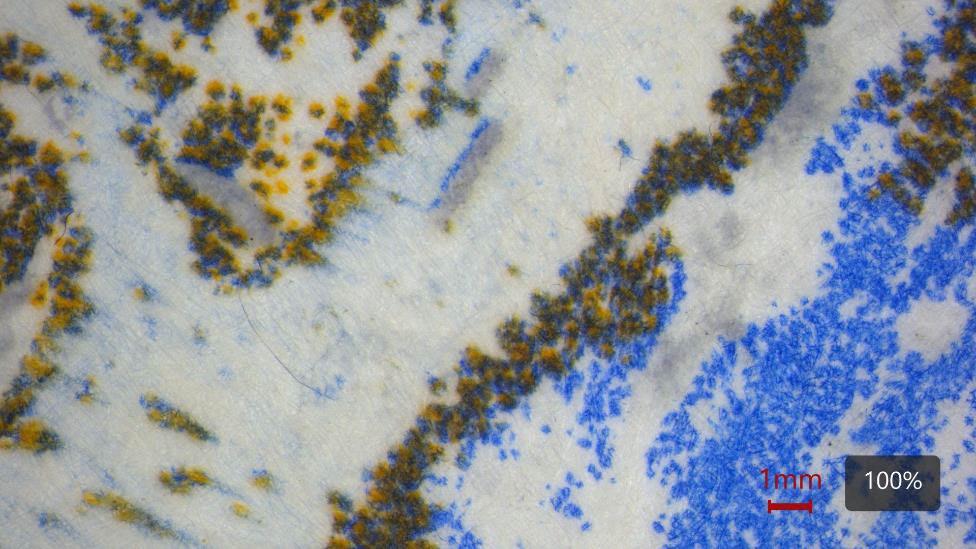

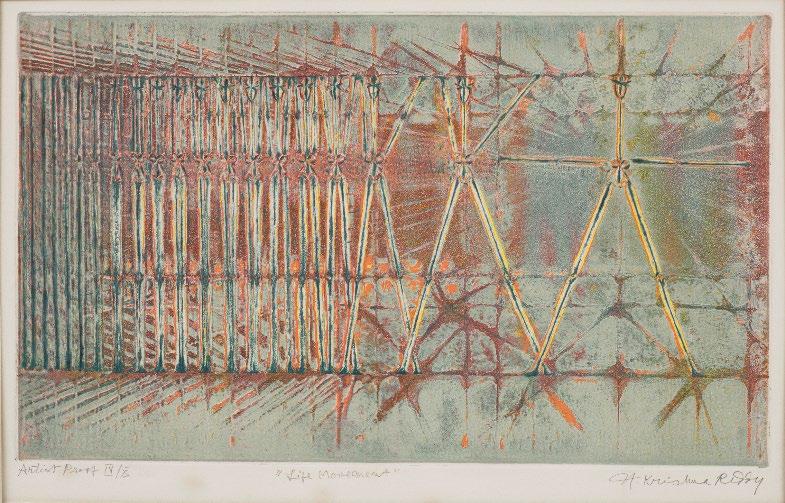

Pointillist broken color

Pointillist broken color or “pointillist manner” is an advanced viscosity printing technique that employs the theories of juxtaposition of colors on a small, dot scale. The plate is first prepared with small dots, such as an aquatint etched to varying depths, a photo halftone, or dotted texture created with machine or hand tools. The intaglio ink is applied first and sits in the lowest sections of the plate. The viscosities of the surface colors are varied and printed juxtaposed as described above. Because the dots are on such a small scale the juxtaposition of the three (or more colors) leads to what Reddy describes as “prints vibrantly shimmering with a full range of colors but that can be created as simply as an aquatint print in black and white.” 17

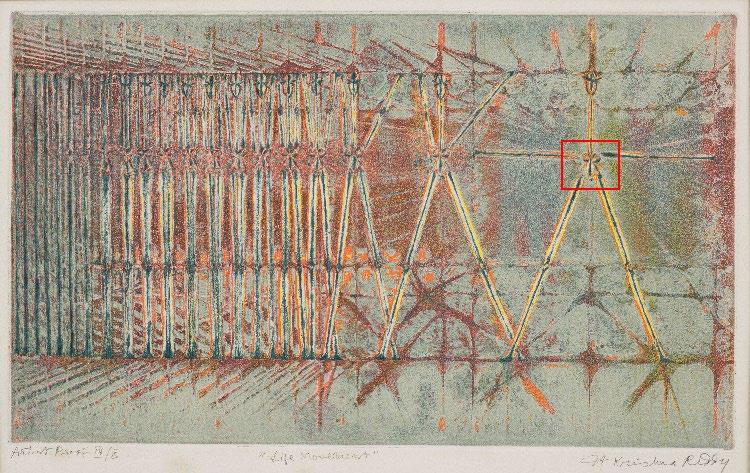

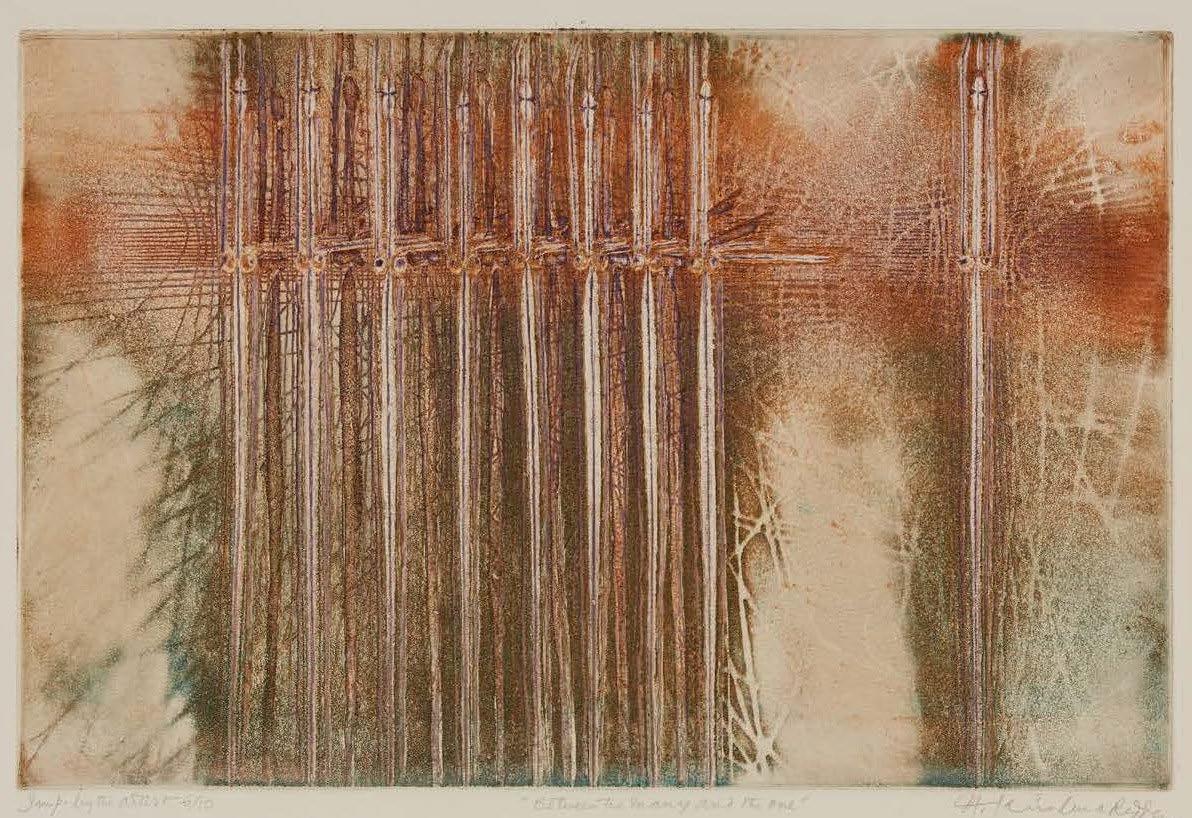

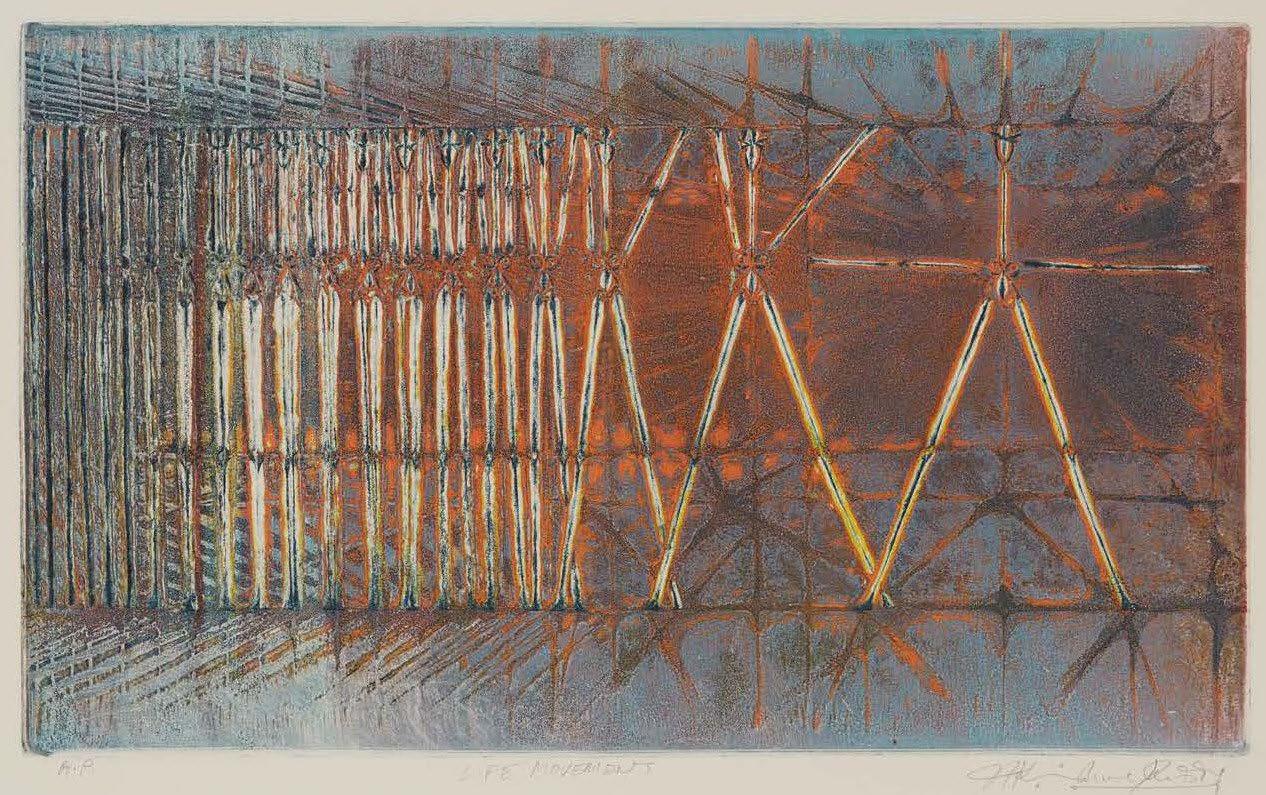

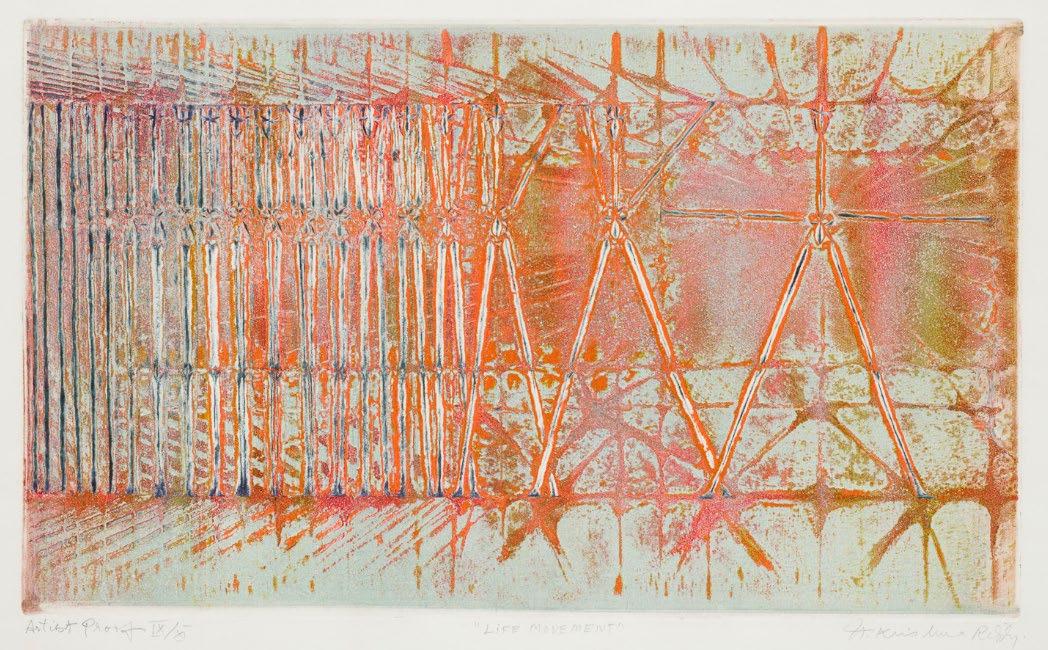

Fig. 37: Life Movement, overall; location of detail marked in red

Fig. 38: Detail of Life Movement; the pointillist broken color technique where the juxtaposition of red, yellow, and blue inks in the background achieve a pulsating gray (Photo by Jason Wierzbicki, Division of Conservation, Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Contact process

After inking intaglio and surface rolling color onto his plates, Reddy would sometimes add a final layer of ink in select areas with a direct contact process. He first rolled color ink onto a thick glass slab, then he turned the printing plate face-down onto the ink slab and selectively pressed the back of the plate with his hands and fingers. Where he applied pressure, ink would transfer from the slab to the plate. 18 On prints where he utilized the contact process, Reddy drew notations on the back of his plates, so when the plate was face down, he knew exactly where he needed to apply pressure. 19

17 Reddy, ”Intaglio Simultaneous Color Printmaking: Significance of Materials and Processes,” 115.

18 Reddy, ”Intaglio Simultaneous Color Printmaking: Significance of Materials and Processes,” 32.

19 Williams, May 2025.

Fig. 39: Splash, overall; location of detail marked in red

Fig. 40: Detail of Splash in raking light; Reddy added the dark blue/black ink via the contact process. The application of ink corresponds to where he applied pressure from the back of the plate, not from rolling ink on the surface (Photo by Jason Wierzbicki, Division of Conservation, Philadelphia Museum of Art)

“His experiments in [Atelier 17’s] method of simultaneous color printing from a single plate led to the discovery of a very personal and elaborate operation which distinguished his work at that time and to this day from all of the other artists using the simultaneous method.” 20 – Stanley William Hayter

Reddy carefully considered every aspect when making his prints. From the intimate and personal use of tools he selected when sculpting and modifying his metal plates to the discerning and intentional addition of color to even the smallest surface. Although some would consider Reddy a master of his materials, he viewed materials as a limitless means for an artist to explore.

“The process involved in working a plate and making a print from it are pathways of learning and discovery. Recognition that the image is shaped by a material process brings clarity, humility, and a sense of participation in the act of composition to the artist. The closer one gets to the materials – the more one learns of their nature, their behavior and their interaction – the more pliable they become to one’s senses. One works directly and spontaneously – like a potter feeling for his image through the clay. This journey into the deeper sources of materials should heighten our sensibilities and deepen our understanding, essential in creating a vital work of art.” 21

References

Bronx Museum of the Arts. Krishna Reddy, a Retrospective November 5, 1981 to February 28, 1982. 1981.

20 Hayter, Stanley William, Bronx Museum of the Arts, “Krishna Reddy: A Retrospective,” 10.

21 Reddy, ”Intaglio Simultaneous Color Printmaking: Significance of Materials and Processes,” 1.

Indian Council for Cultural Relations and Birla Academy of Art and Culture. Krishna Reddy, a Retrospective. 1984.

Johnson, Mark (artist and former student of Krishna Reddy) in discussion with the author, April 26, 2025.

Mittermeier, Frank. “Vibro-Tool.” Gunsmith Supplies, Imported and Domestic Tools, 1952, pg. 31. https://archive.org/details/FrankMittermeierCatalog1952/mode/2up?view=theater

Reddy, Krishna. Intaglio Simultaneous Color Printmaking: Significance of Materials and Processes Albany, State University Of New York Press, 1988.

Williams, Michael Kelly (artist and former student of Krishna Reddy) in discussion with the author, May 6, 2025.

The Print as Process: Krishna Reddy’s Transformative Experiments

Umesh Gaur

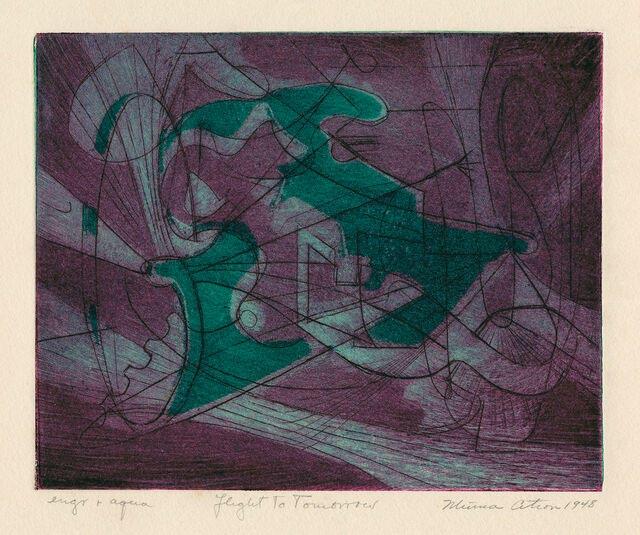

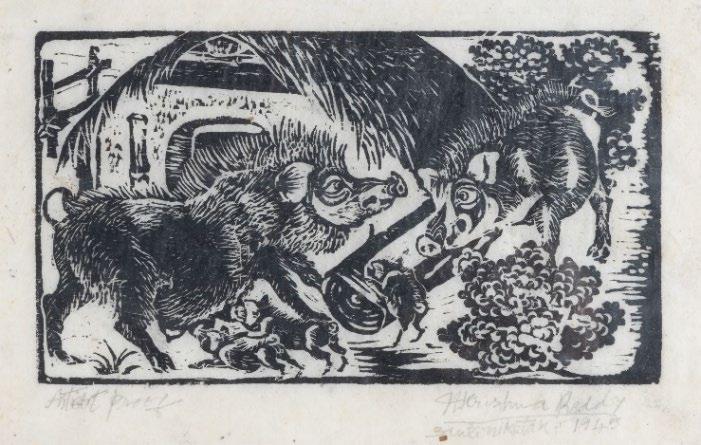

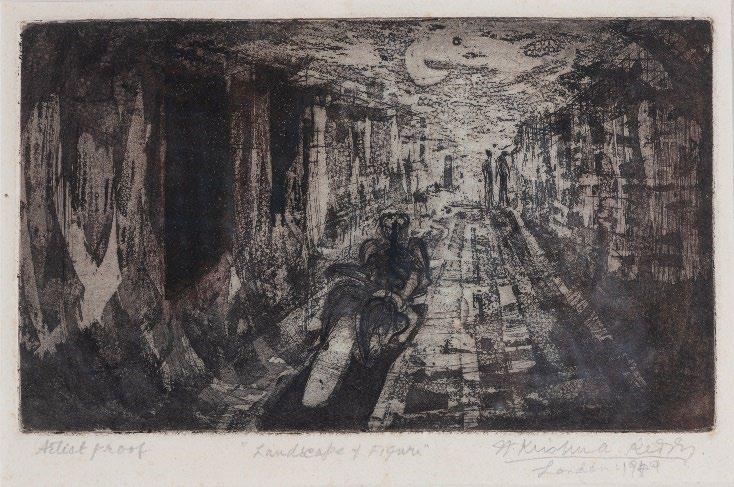

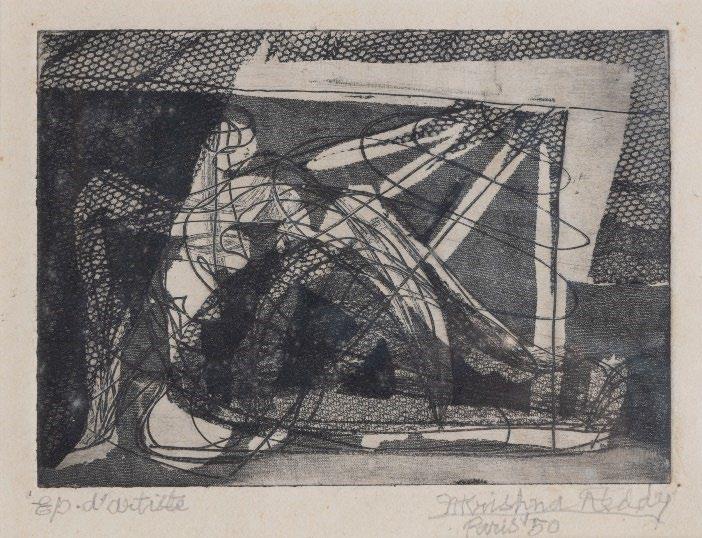

Krishna Reddy’s sustained engagement with printmaking began in the mid-1940s during his time at Santiniketan, where he experimented with a range of techniques including woodcuts, engravings, etchings, and lithographs, most of which were executed in monochrome. These early investigations laid the foundation for what would become a lifelong inquiry into both the material possibilities and the philosophical dimensions of the printmaking process.

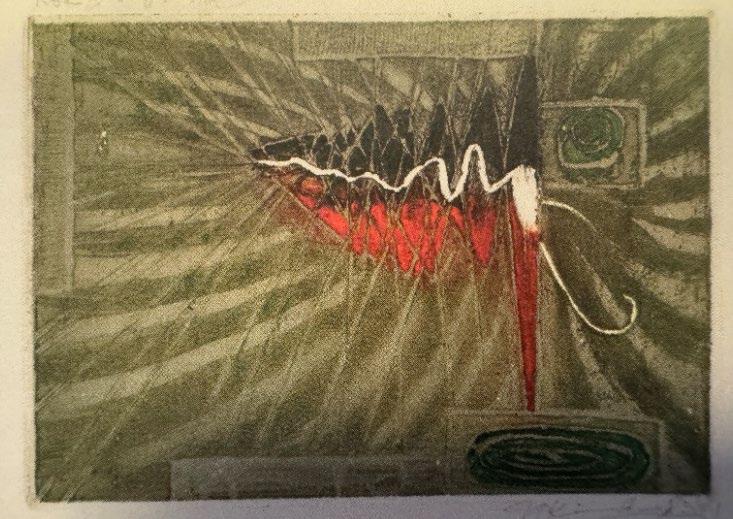

A pivotal transformation occurred in the early 1950s, when Reddy joined Atelier 17 in Paris under the mentorship of Stanley William Hayter. It was here, amidst a community of avant-garde artists, that Reddy’s fascination with color in printmaking took root. What followed was an accidental discovery. While preparing a plate for inking, Reddy observed a small amount of colorless linseed oil left on a glass surface where colored ink was going to be rolled using a brayer; the ink did not adhere to the surface where the linseed oil was. This unexpected resistance prompted a series of systematic experiments conducted alongside fellow artist Kaiko Moti and with the support of Hayter. The group began altering the ratio of ink to linseed oil to explore how differences in viscosity affected the way inks would mix or repel and also how they would spread onto each other by adjusting the thickness of the inks on the plate. 22

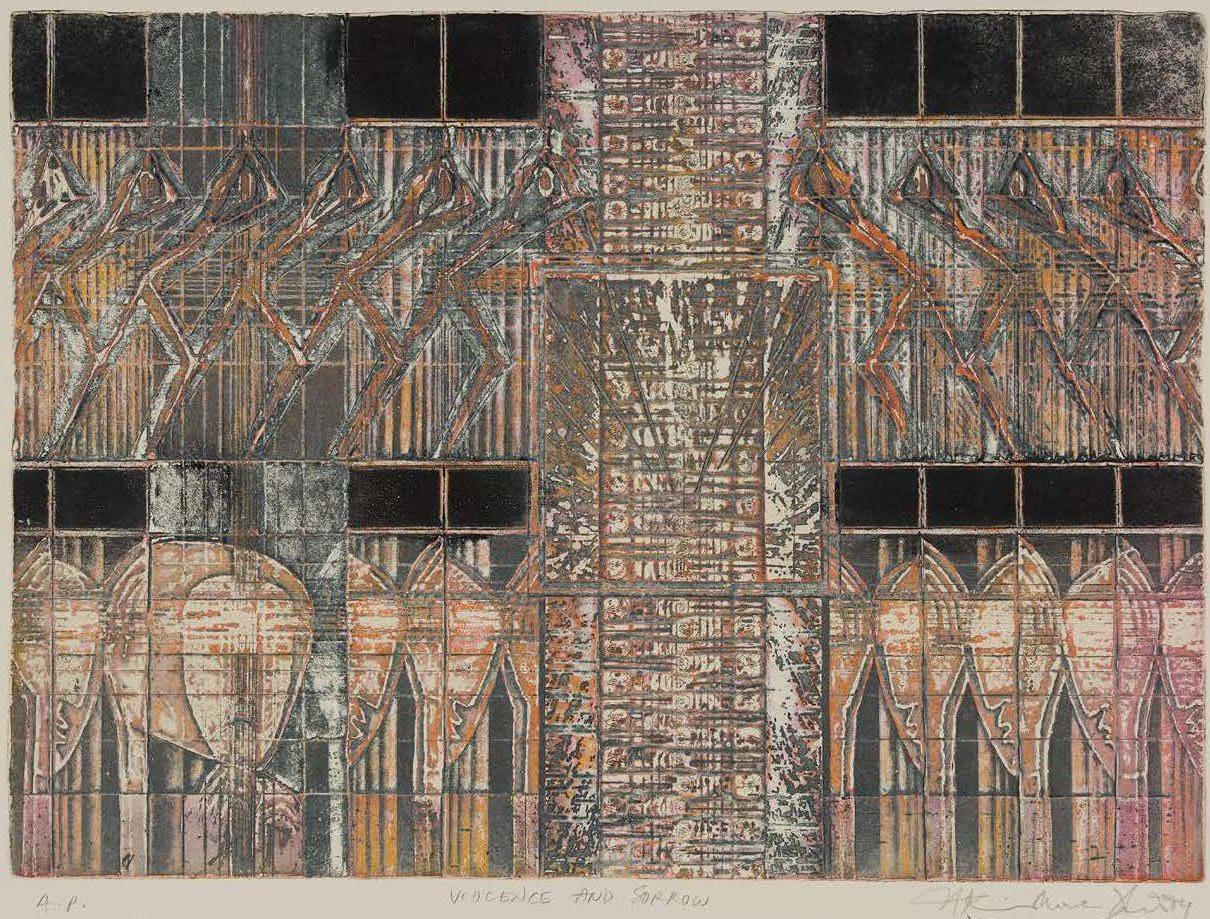

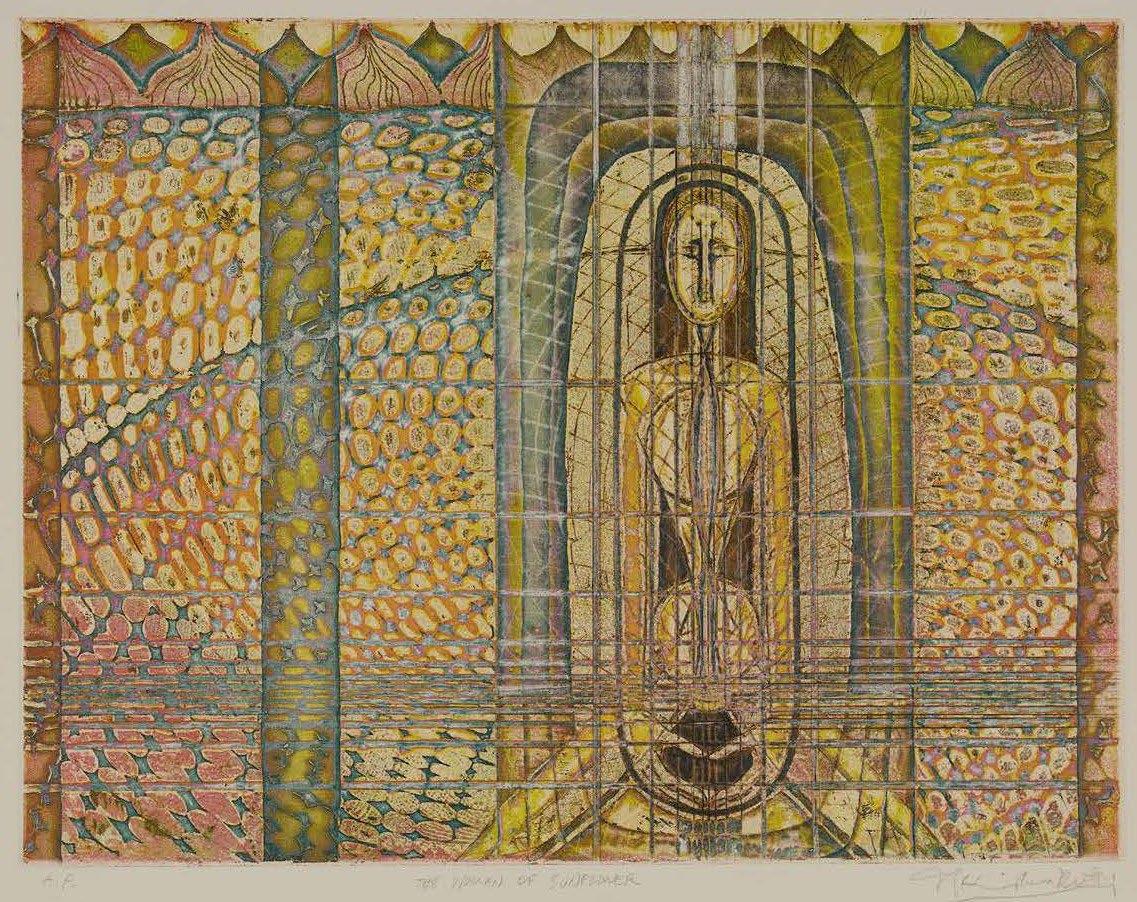

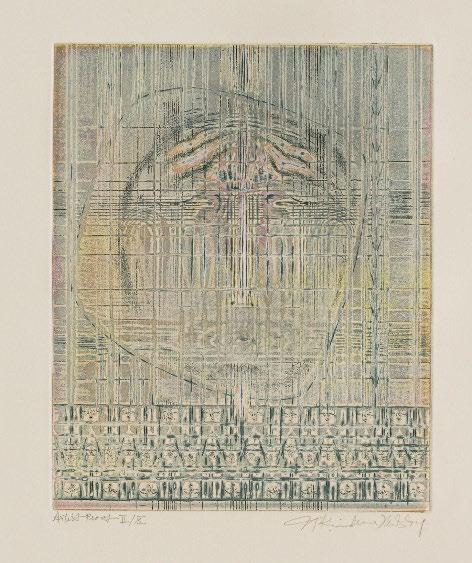

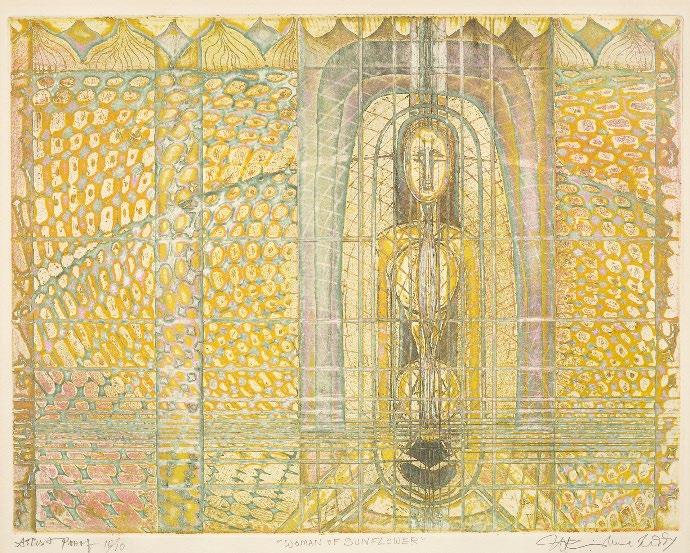

This serendipitous moment would become the foundation of viscosity intaglio printing, a revolutionary technique that allowed for multicolor printing from a single plate. Reddy, more than anyone, made this process his own, refining it over decades into a highly expressive language of form and color. From his first prints in 1952 to The Great Clown (1981), and culminating in Woman of Sunflower (1997), Reddy continuously pushed the boundaries of what viscosity intaglio printing could produce from a carved plate, treating each impression as a unique act of transformation.

Reddy’s approach to printmaking was unconventional and introspective. He viewed the plate not as a static tool for repetition but as a living surface, a space of transformation. Printmaking for him was a meditative dialogue between artist and material, one that favored process over product and evolution over finality.

Influenced by his background in sculpture, Krishna Reddy developed a deeply tactile and labor-intensive approach to printmaking. He treated his plates almost like sculptural forms etching, carving, gouging, burnishing, and polishing them over extended periods, sometimes for years. From each plate, he created multiple impressions, adjusting the ink colors, wiping methods, and viscosity to generate compositions that were emotionally and visually distinct. What sets Reddy’s process apart is that these are not simply variations or steps toward a final image; most impressions were a fully realized work, complete in its emotional resonance, formal precision, and symbolic meaning.

22 Private communication with Krishna Reddy, January-February, 2006.

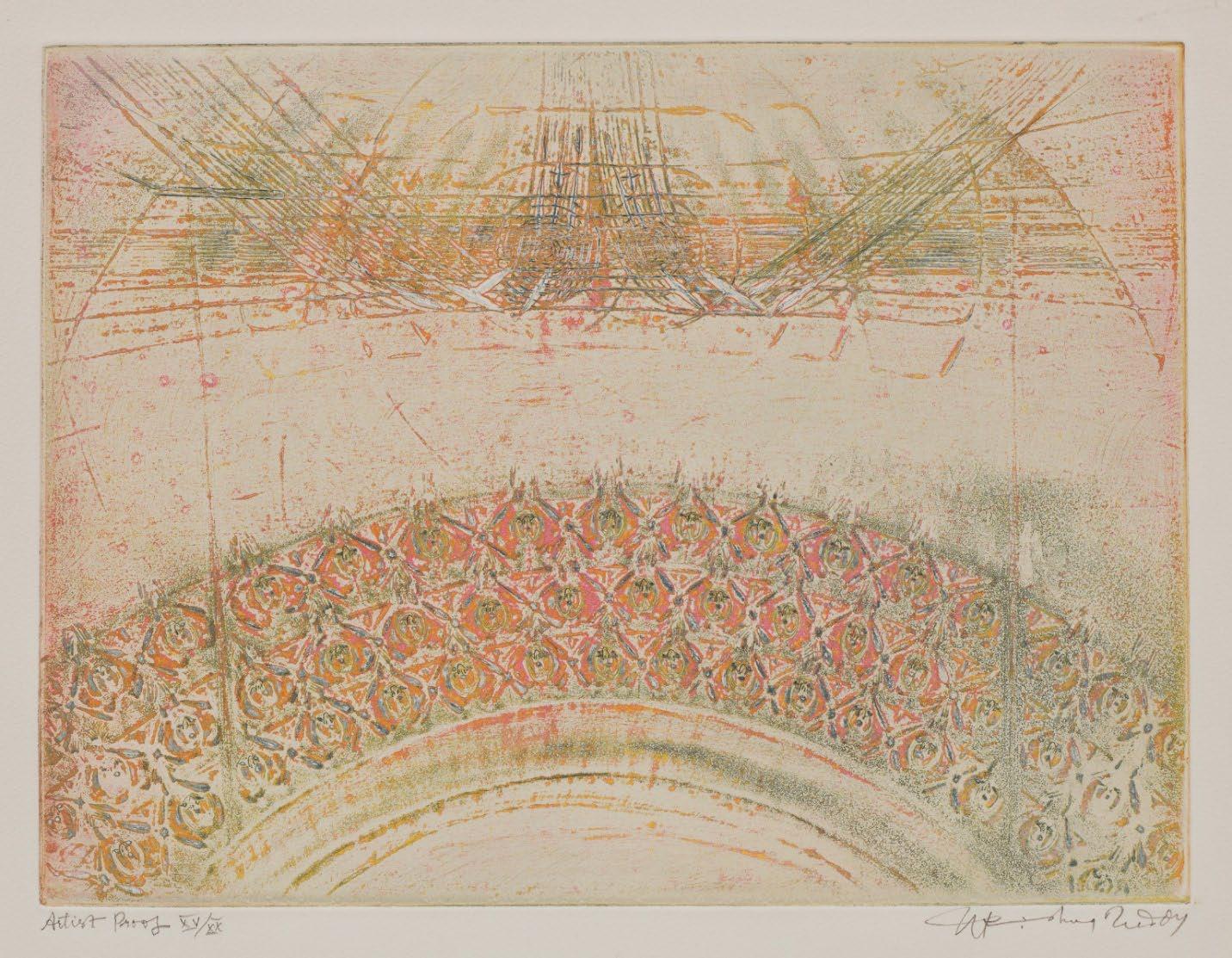

While Reddy arrived at a final version fairly quickly for some plates, the majority of the fifty-four viscosity intaglio plates he created a wide range of impressions each with its own distinct palette and surface treatment. Before selecting an impression for editioning, he typically produced many trial proofs and artist’s proofs, using each as an opportunity to explore the plate’s full expressive potential. This commitment to variation was not an eccentric detour, but a core tenet of Reddy’s artistic philosophy. While most printmakers worked toward a uniform edition, Reddy embraced the idea that each impression could reveal something new. His goal was not a final, perfected image, but the unfolding of multiple possibilities.

Over the past twenty-five years, I have had the privilege of assembling a complete collection of viscosity intaglio prints made from all fifty-four plates that Krishna Reddy created during his lifetime. In addition to acquiring representative impressions from each plate, my collecting has focused on documenting the striking variations for some of the prints that Reddy produced,

This essay examines Krishna Reddy’s experimental printmaking through five works in which he embraced this principle of variation. These case studies reveal not only what Reddy printed, but how his creative process unfolded demonstrating that, for him, the act of making was inseparable from the act of thinking.

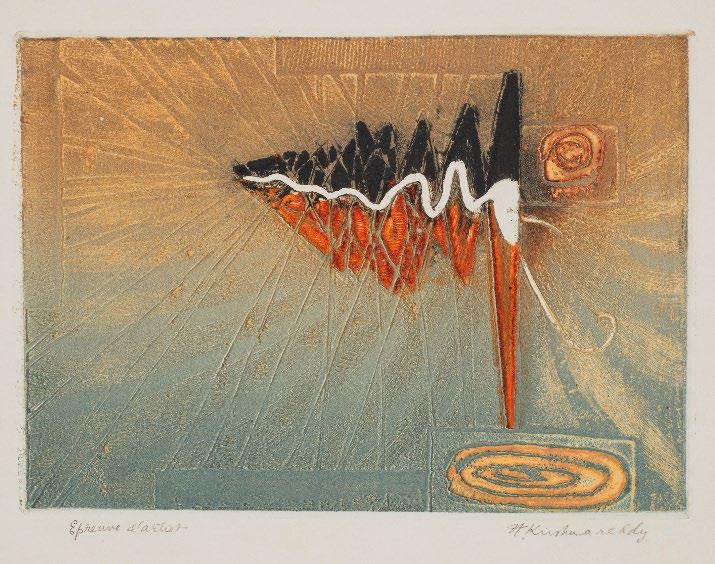

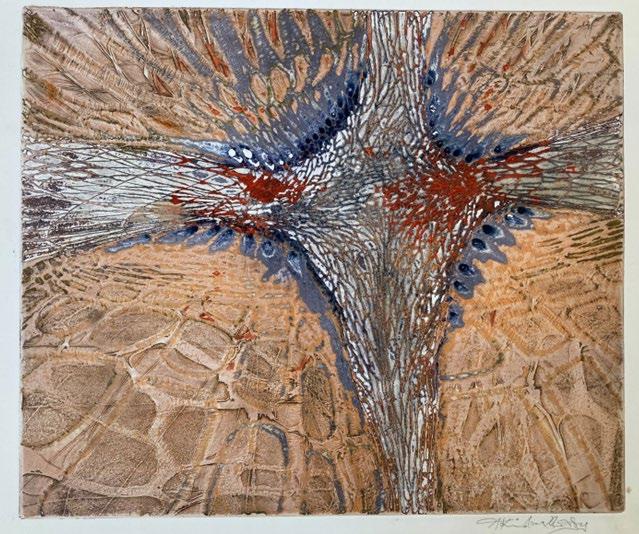

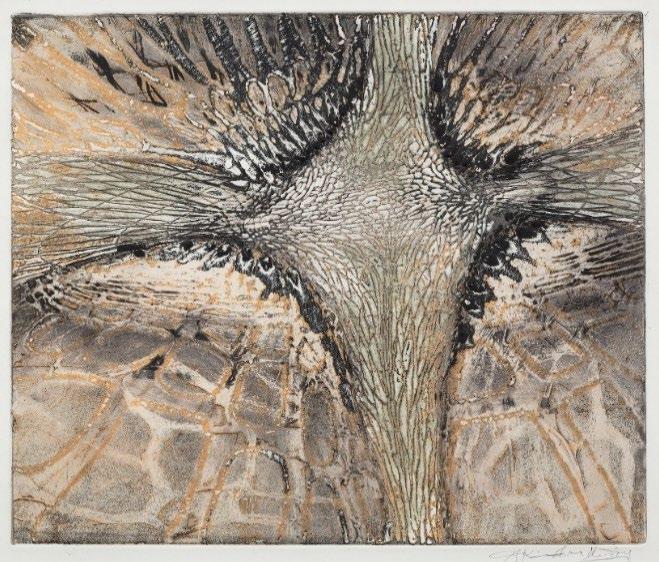

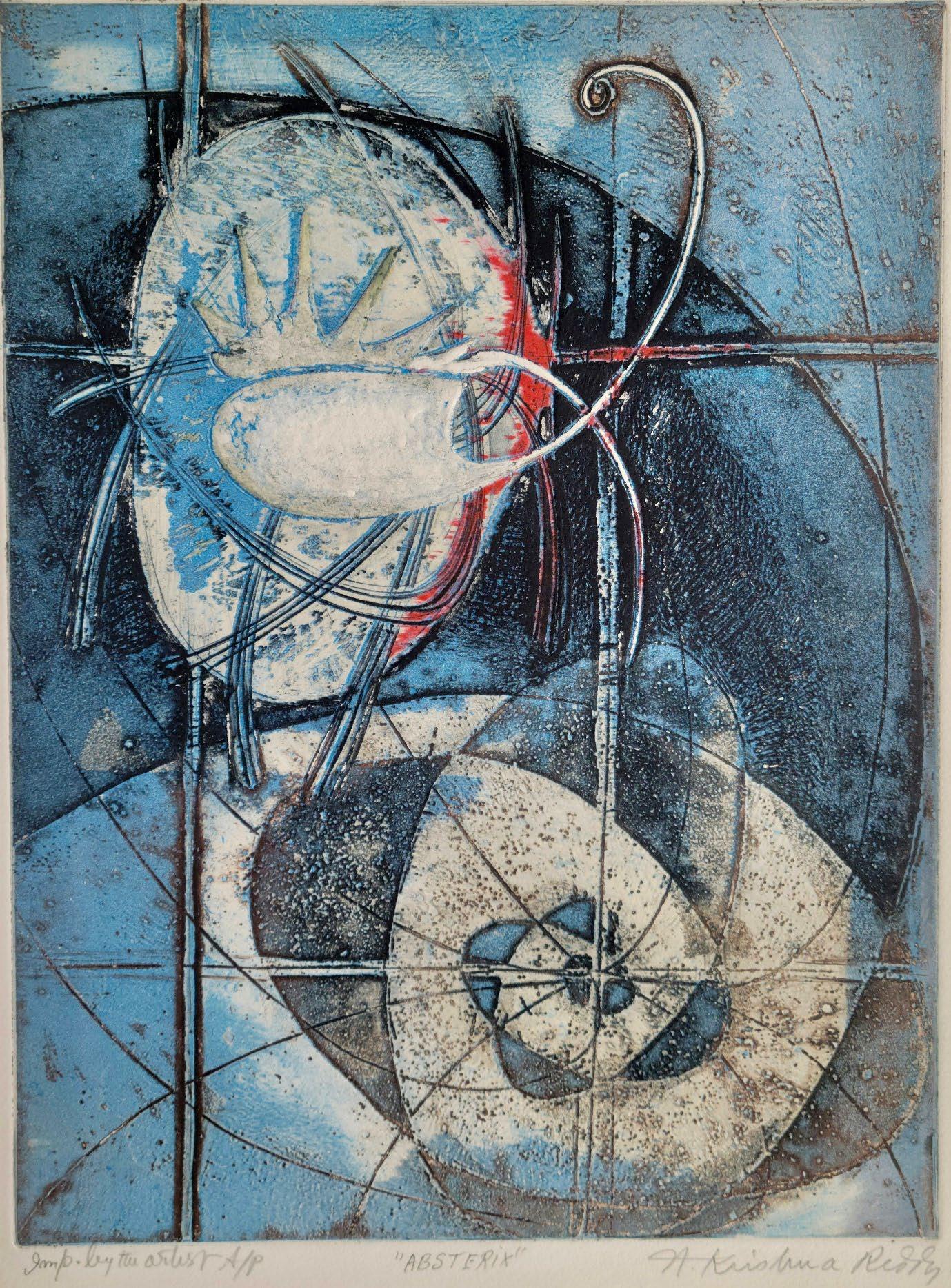

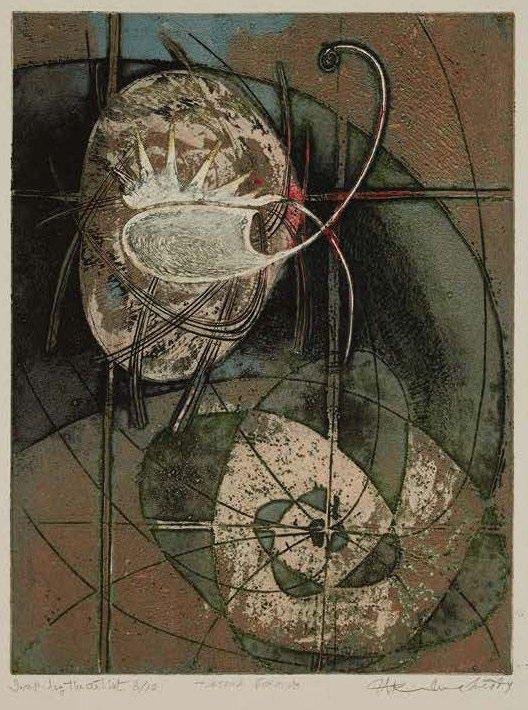

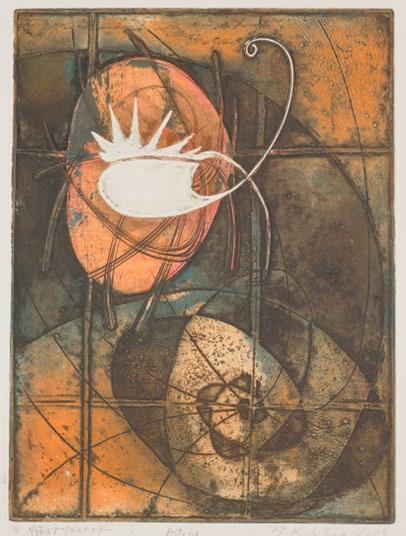

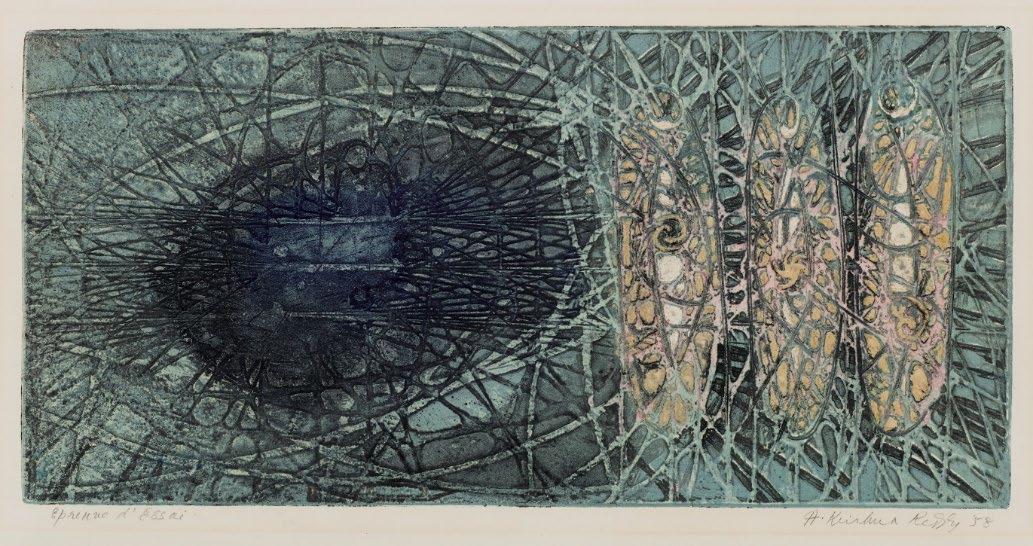

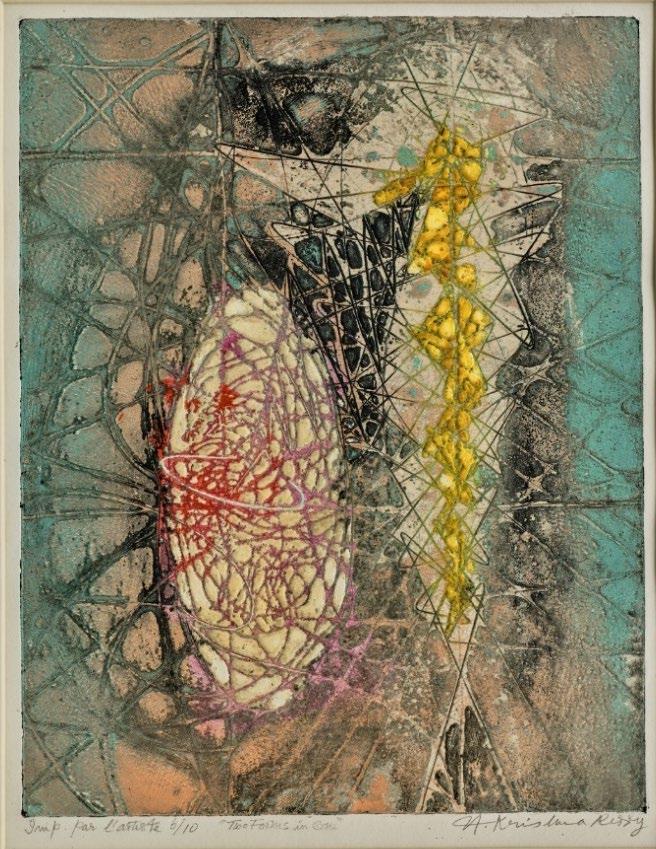

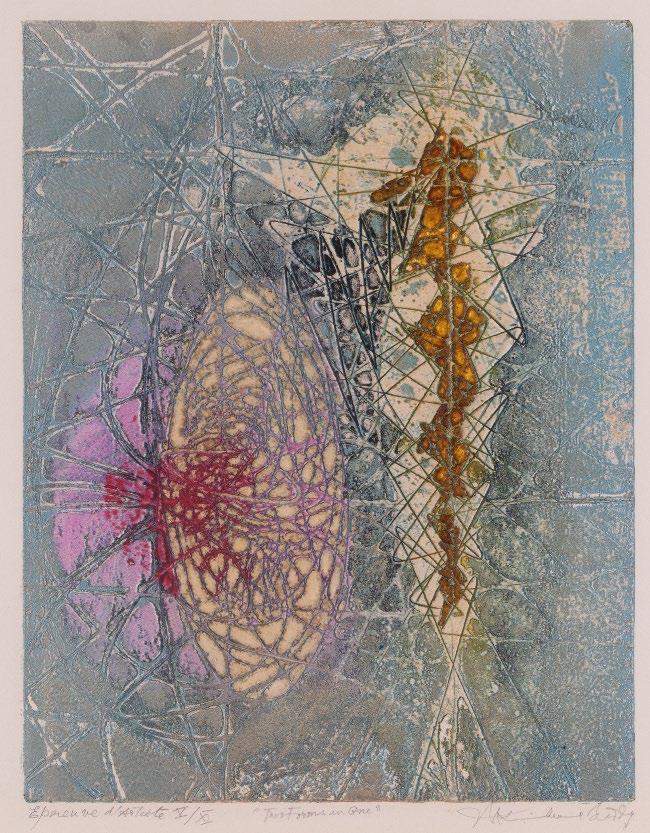

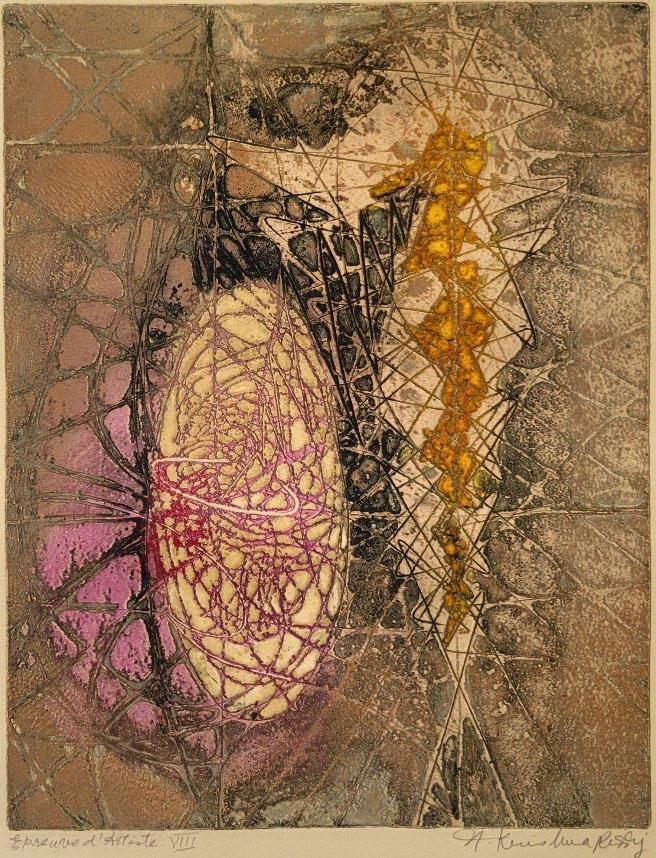

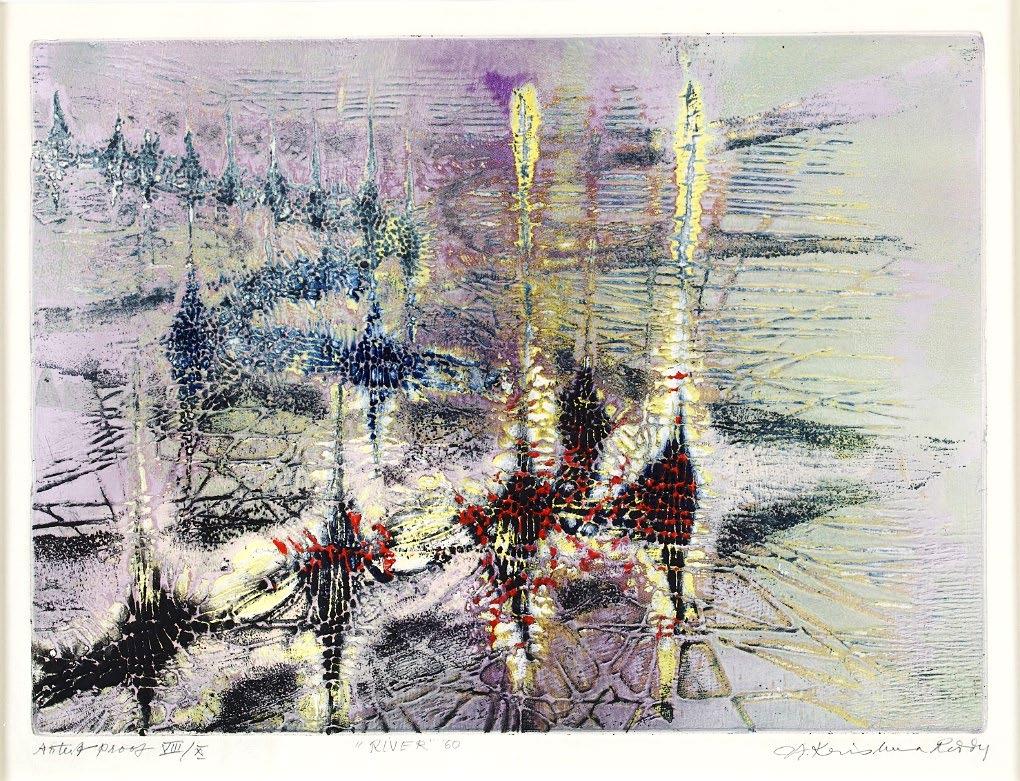

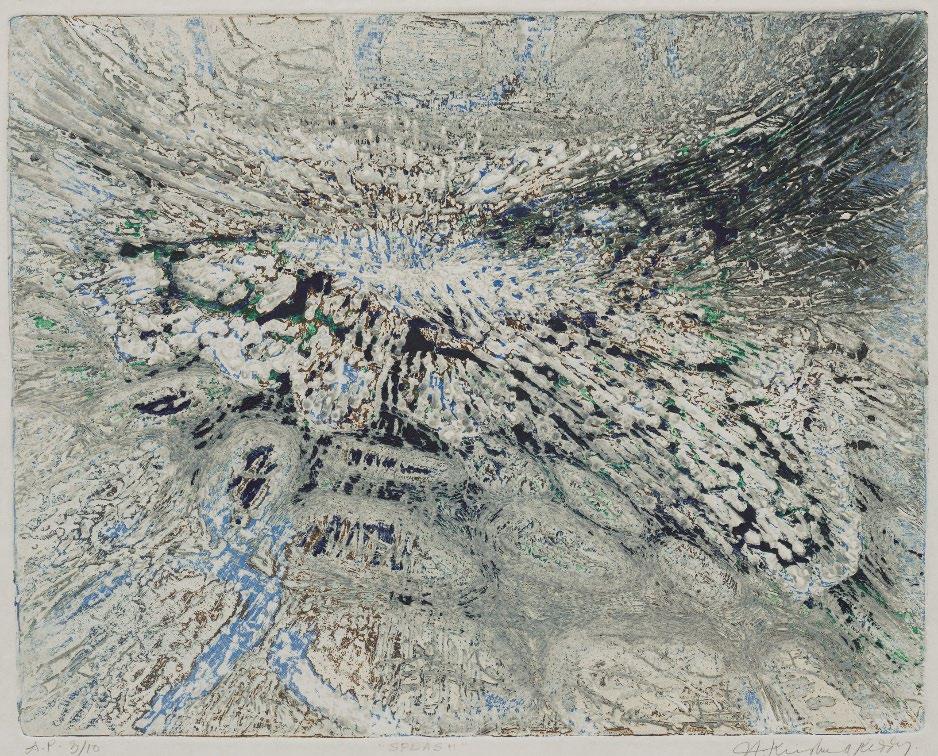

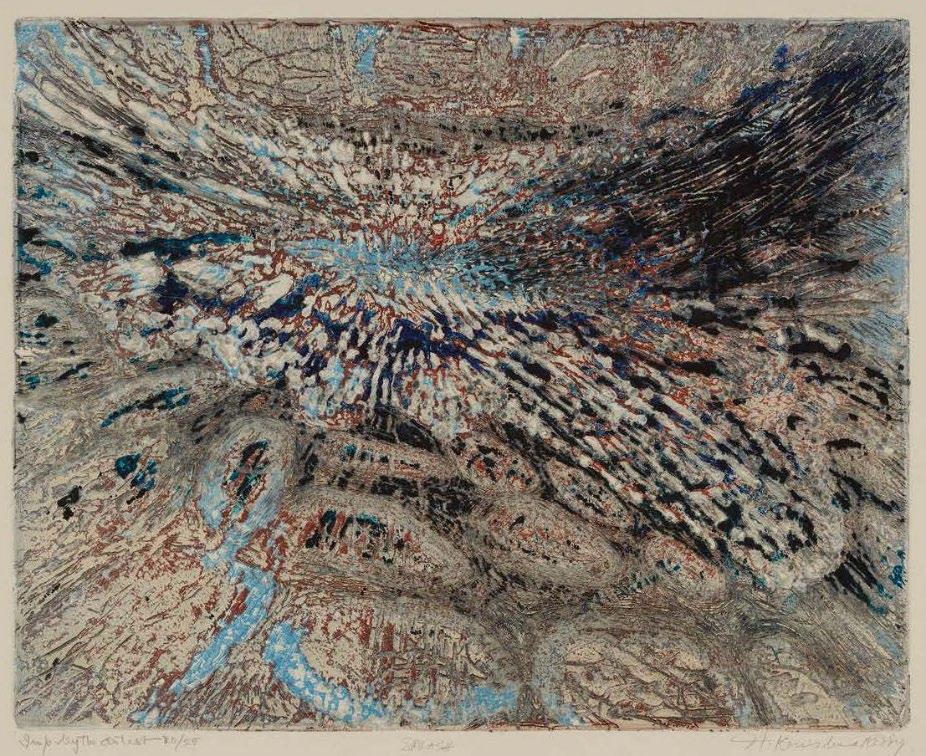

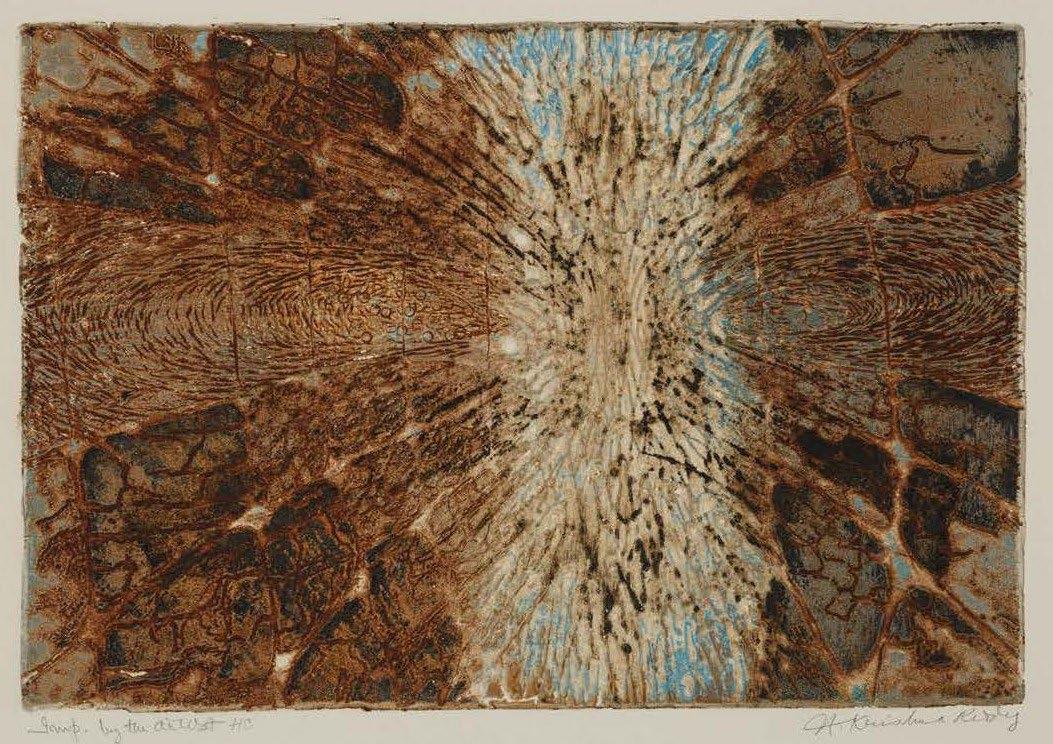

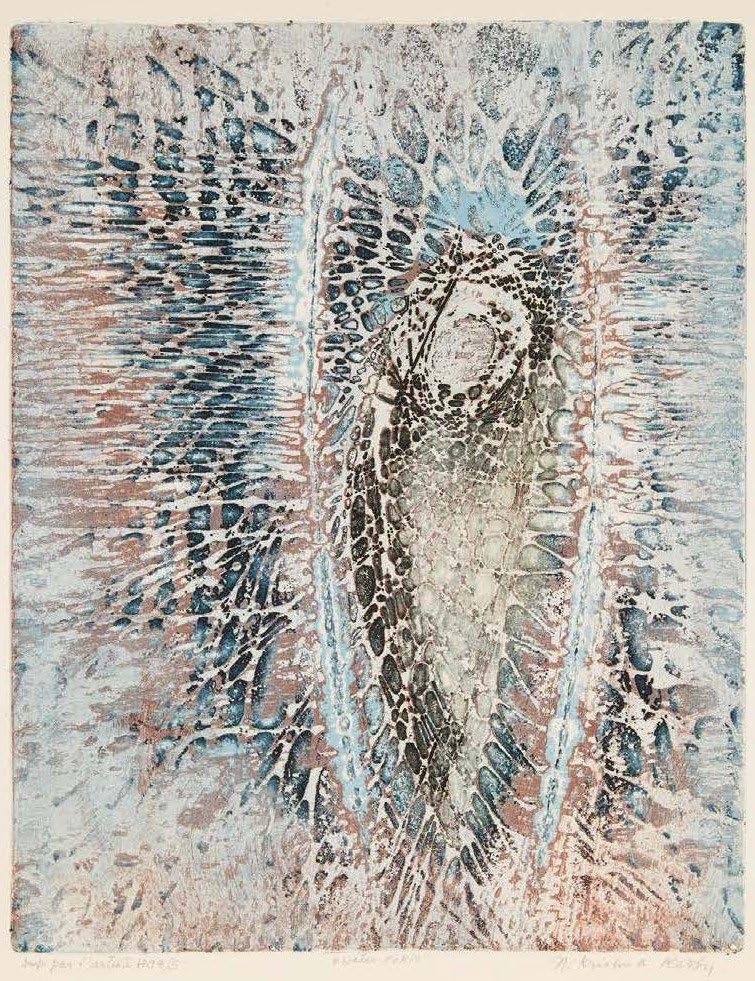

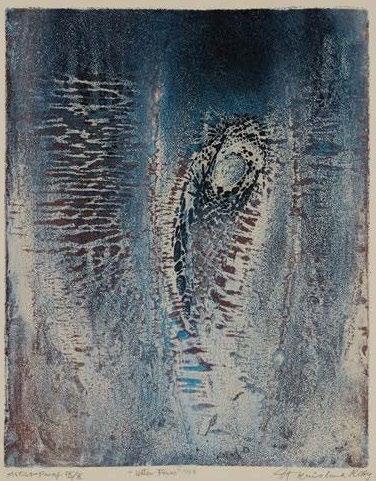

Krishna Reddy’s Tuatara (1953) is one of the earliest examples of his unique approach to printmaking. Even early in his career, Reddy saw each impression as a chance to create something new. The three versions of Tuatara in grey, orange, and brown show us how he used color, texture, and technique to give each print its own character and emotional impact.

At the center of the image in all three versions is a large, glowing white shape that looks like a seed or pod, surrounded by pointed spikes. In two of the impressions, this form is joined by a striking red mark near its edge. Together, the pod and red accent shift in appearance and feeling from one print to another.

Although the pod keeps the same general shape in all three versions, its surface and mood changes. In the Grey Impression, the pod is textured and seems full of energy. It stands out brightly against a cool, blue background. The spikes are sharp and active. A bold red accent slashes across the right side of the form. It looks like a sudden burst or a wound, adding drama and intensity.

In the Orange Impression, the feeling is very different. The white pod is smooth and flat, almost like a symbol or icon. The background is filled with warm colors rust, orange, and gold. The red accent is missing here, which makes the composition feel calm and quiet. Without the red, the pod seems still and self-contained, no longer pulsing with energy.

The Brown Impression falls somewhere in between. The pod has texture again, but not as intense as in the Grey version. It sits in a rich background of earthy greens and browns. The red mark returns, but it is smaller and softer and blends more into its surroundings. This version feels balanced less dramatic than the Grey, more alive than the Orange. The pod seems fully developed.

By changing how he inked, wiped, and colored the same plate, Reddy turned one image into three very different works of art. The white pod shifts from glowing and energetic (Grey), to quiet and iconic (Orange), to grounded and full (Brown). The red accent plays a key role, adding emotion and rhythm where it appears and changing the mood entirely when it is absent.

In Tuatara, we don’t just see one image in different colors we see a single idea unfolding in three different ways.

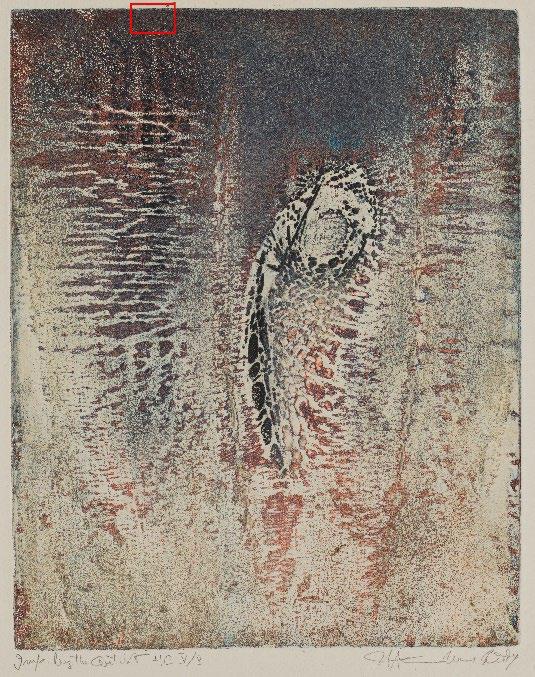

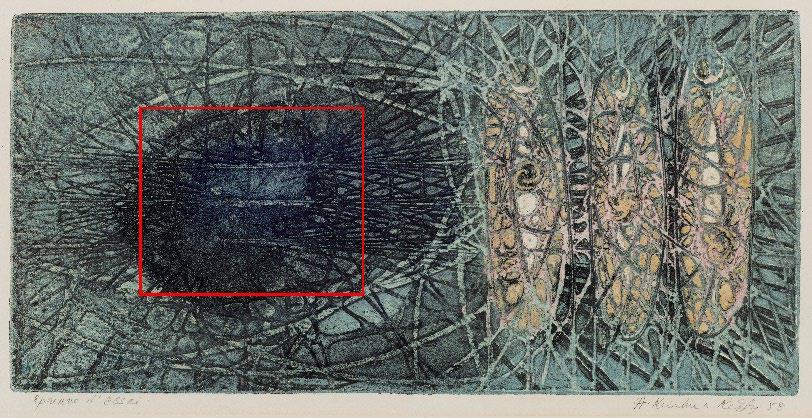

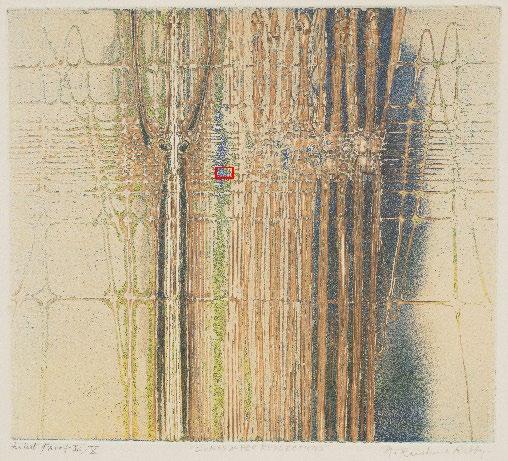

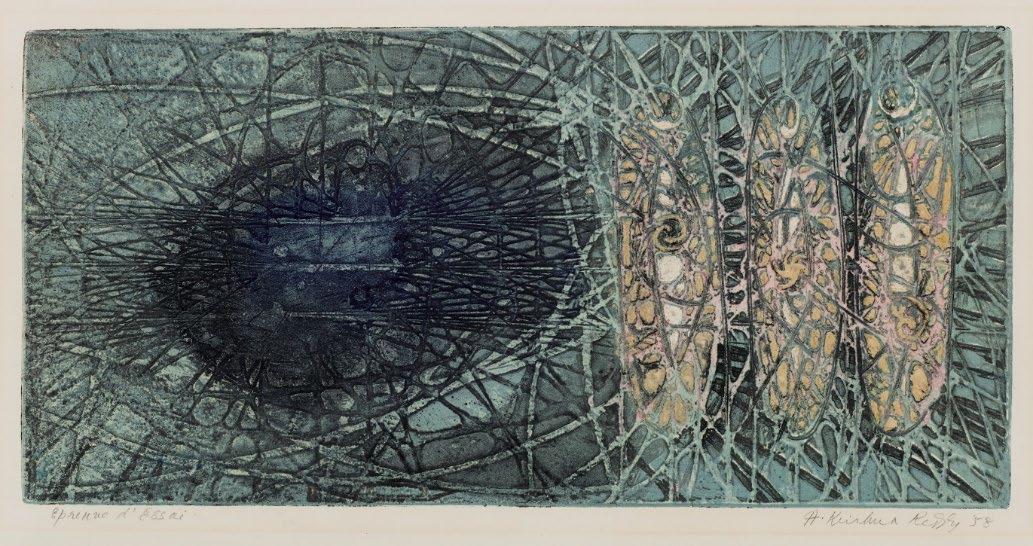

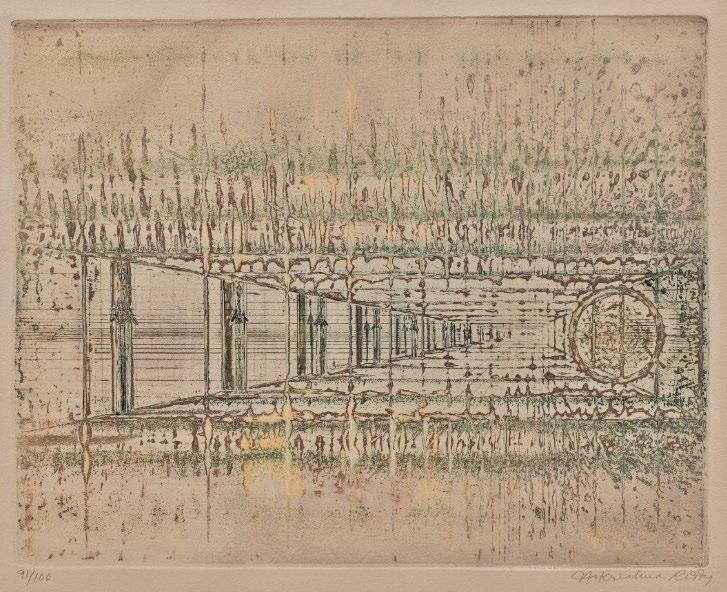

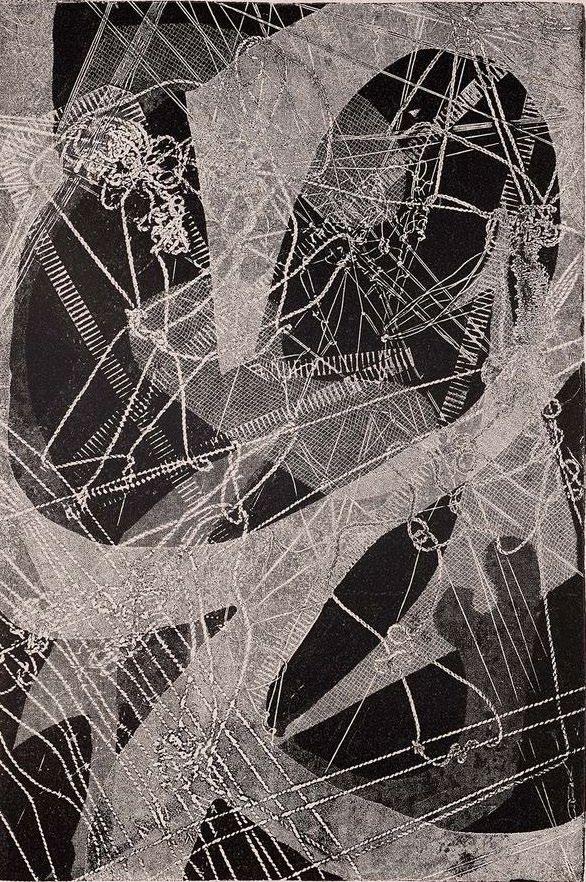

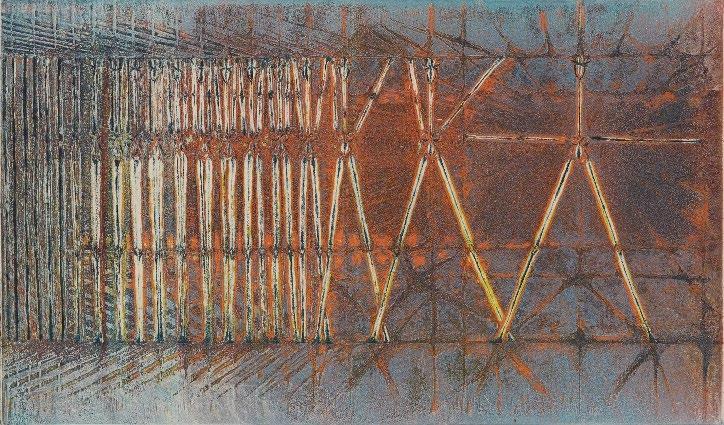

While in Tuatara Reddy created variation primarily through changes in color and wiping, his prints, Three Graces (1953) and Water Form (1961), reveal another key dimension of his experimental approach: the ability to generate strikingly different impressions by continuously modifying the plate itself.

In Three Graces, this process of transformation is especially evident. A trio of pod-like forms floats on the right, framed by a lattice of radiating lines elements that remain consistent across all impressions. The real evolution unfolds on the left side of the composition, where a cluster of spirals gradually emerges across three versions. Studying these reveals how Reddy repeatedly returned to the plate, not just to refine, but to draw out the latent energy embedded in form. 23

In the first impression, the spirals are barely discernible submerged in a dense matrix of cross-hatched lines and directional strokes. The ovoid field is chaotic, gesturing toward structure but lacking resolution. The spirals hint at form but remain embryonic and indistinct.

By the second impression, they begin to take shape. The outlines sharpen, and Reddy isolates the forms from their turbulent surroundings likely through burnishing or additional engraving on the plate. The composition gains clarity, and the spirals assert themselves as intentional, autonomous presences within the field.

In the third impression, the spirals reach full articulation. Deepened and structurally refined, they glow with tonal contrast and surface complexity. They no longer seem tentative but pulse with energy at the core of the image. The surrounding lines now appear to radiate from these spirals, converting chaos into concentration.

Viewed together, the three impressions trace a journey from latency to presence. The spirals evolve from hidden potential to fully realized form. The plate was not a fixed template, but a sculptural surface, to be revised, reimagined, and brought to life anew.

23 Christina Taylor’s essay images…..

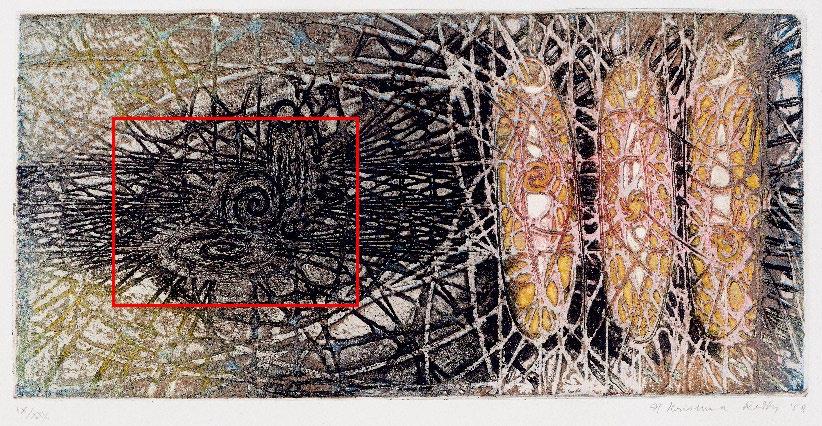

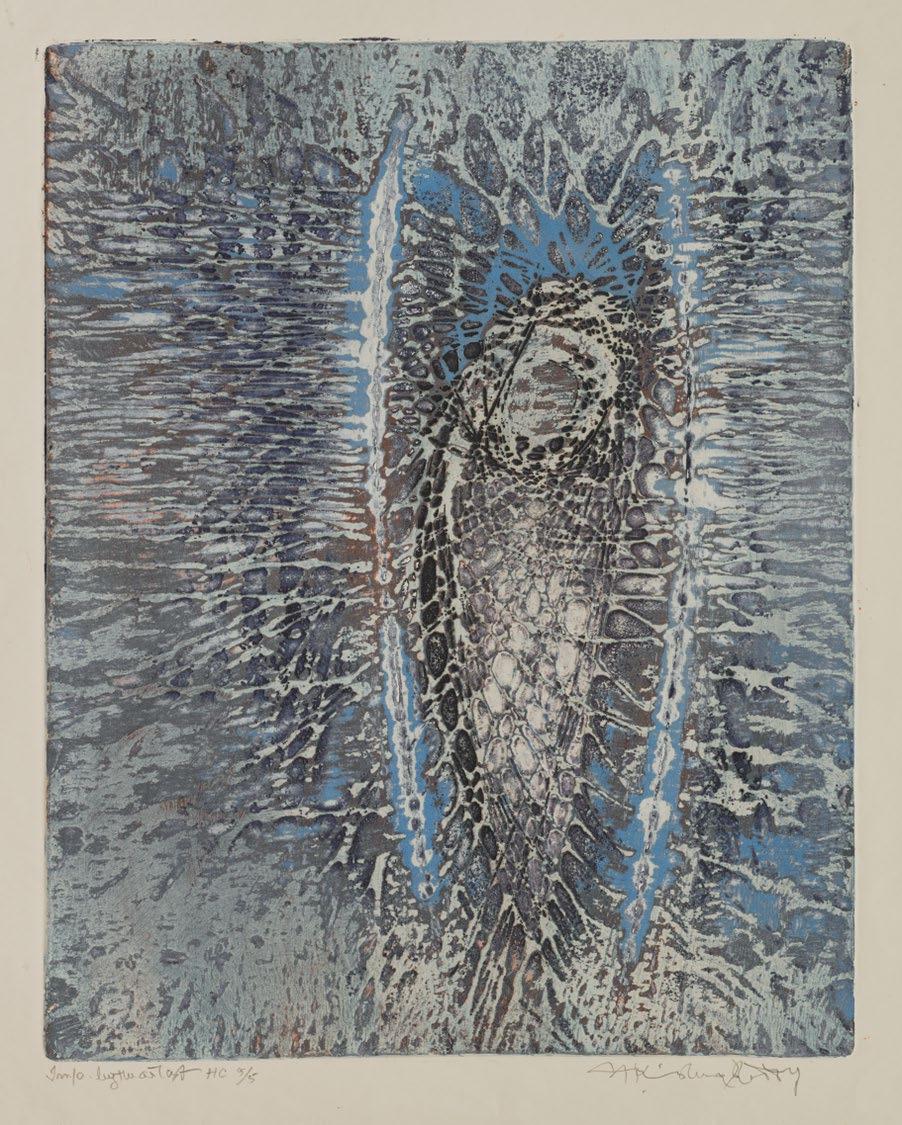

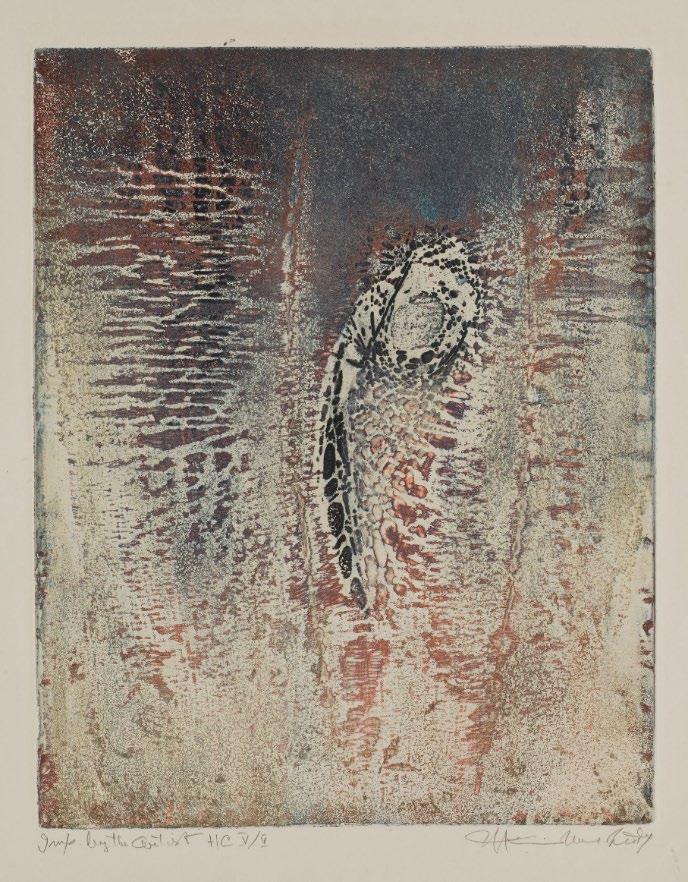

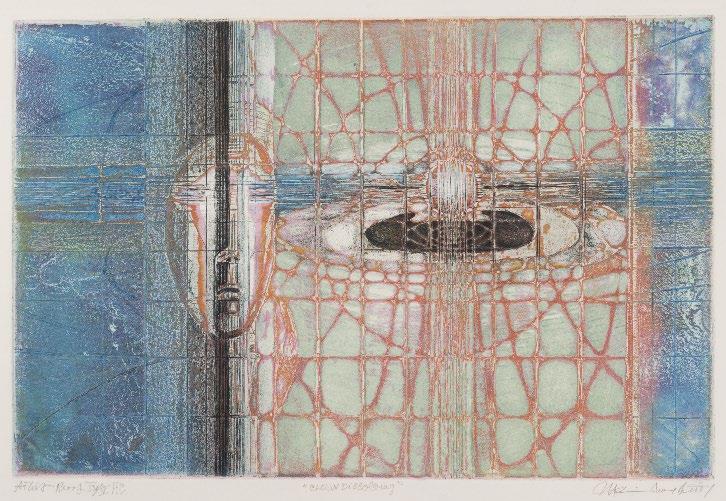

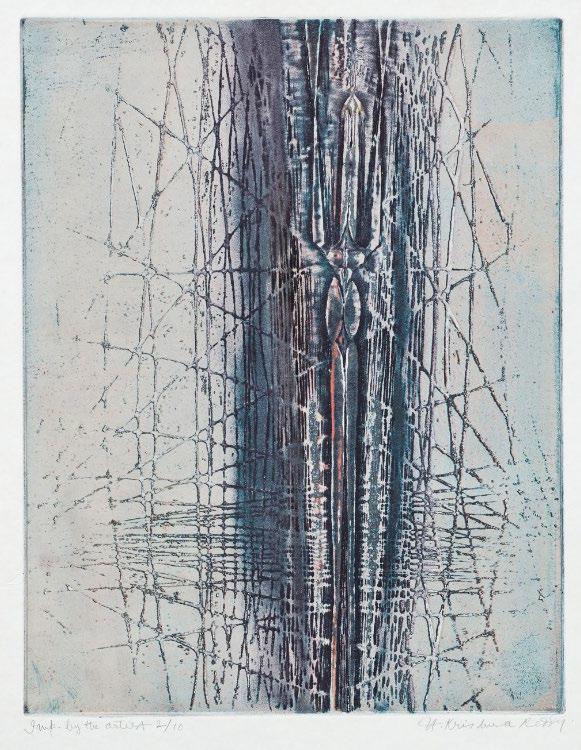

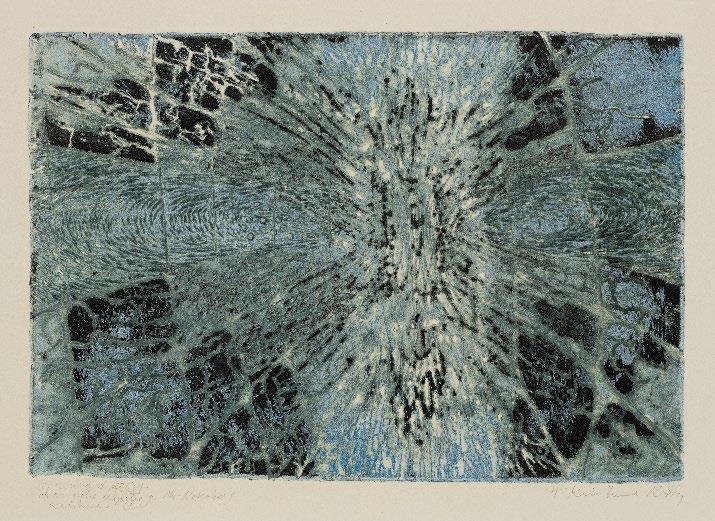

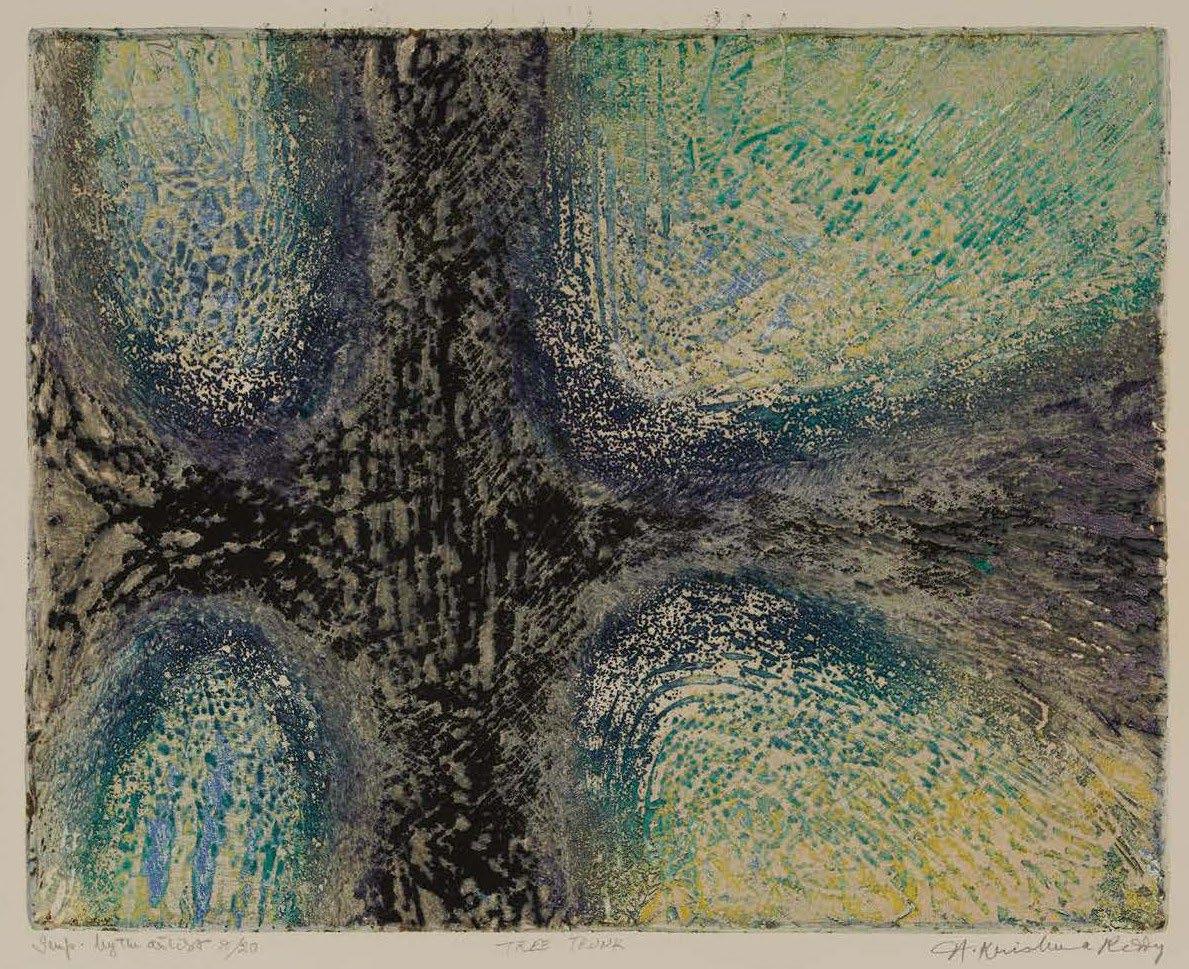

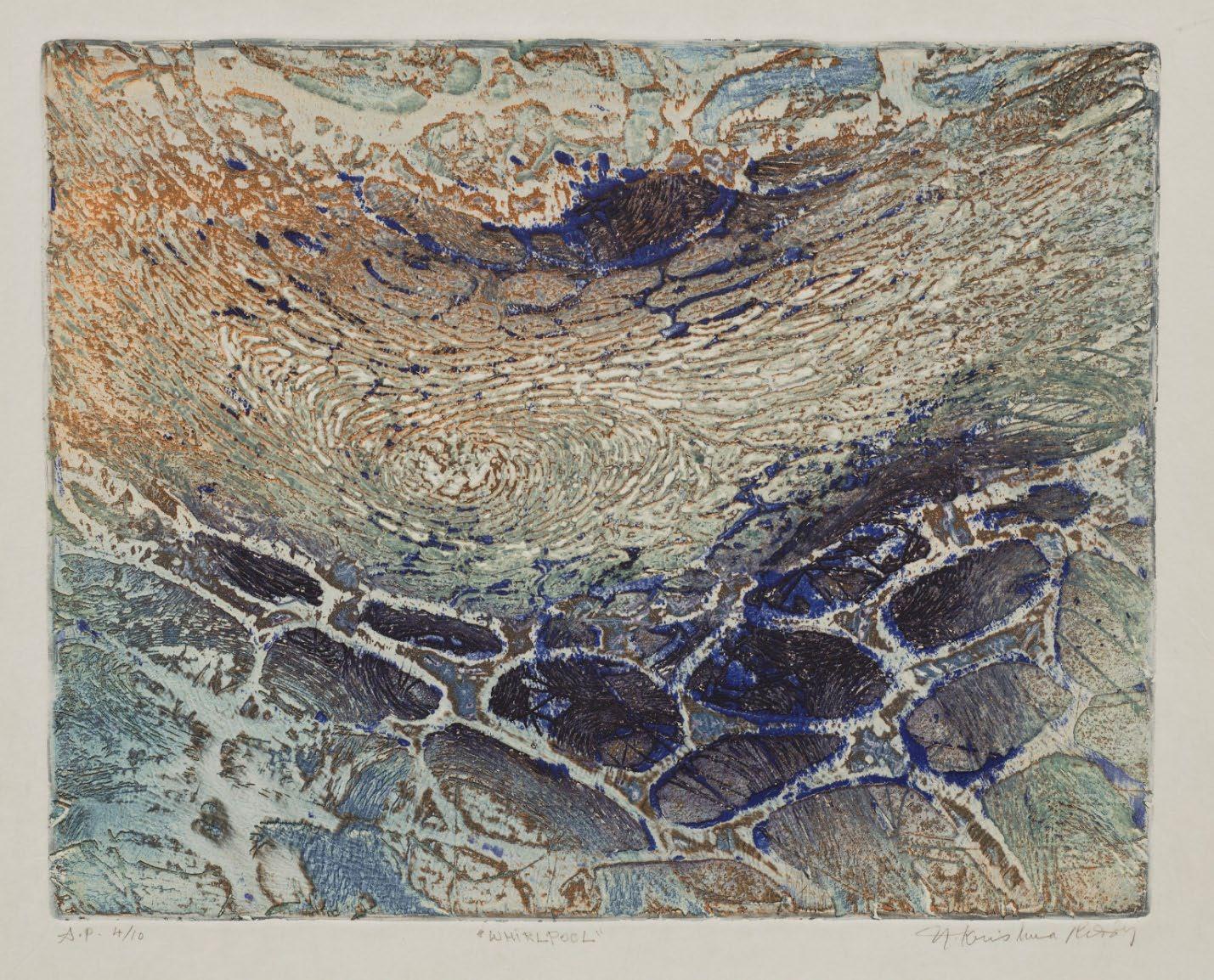

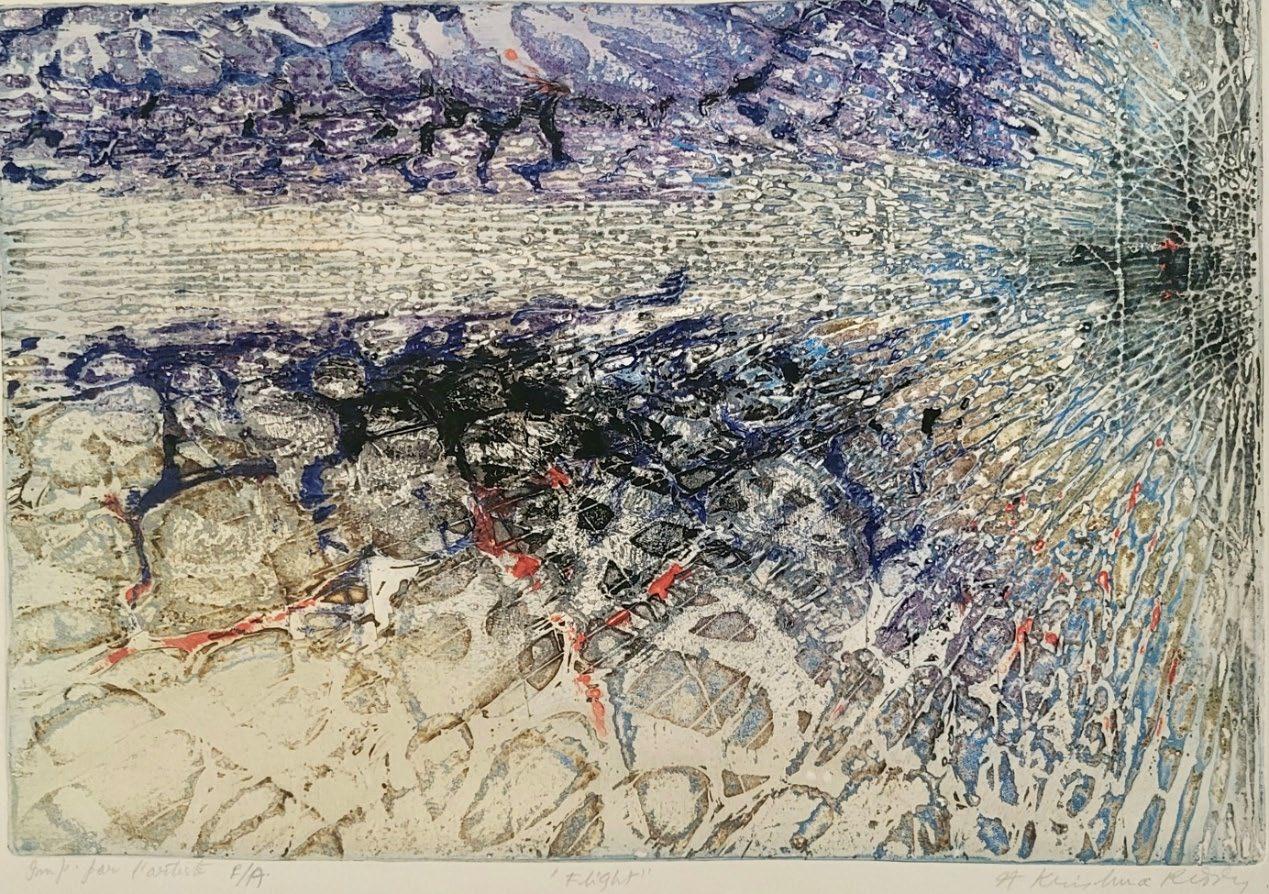

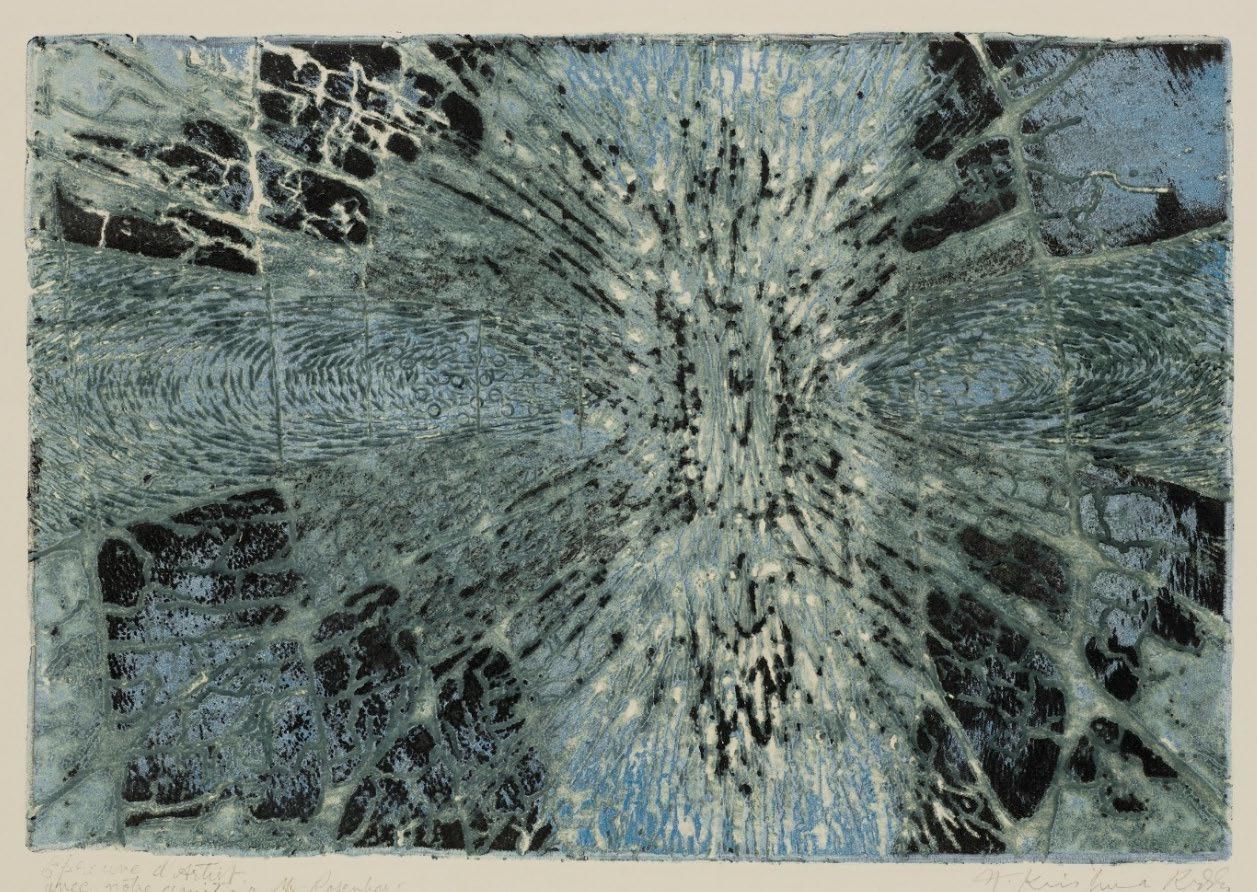

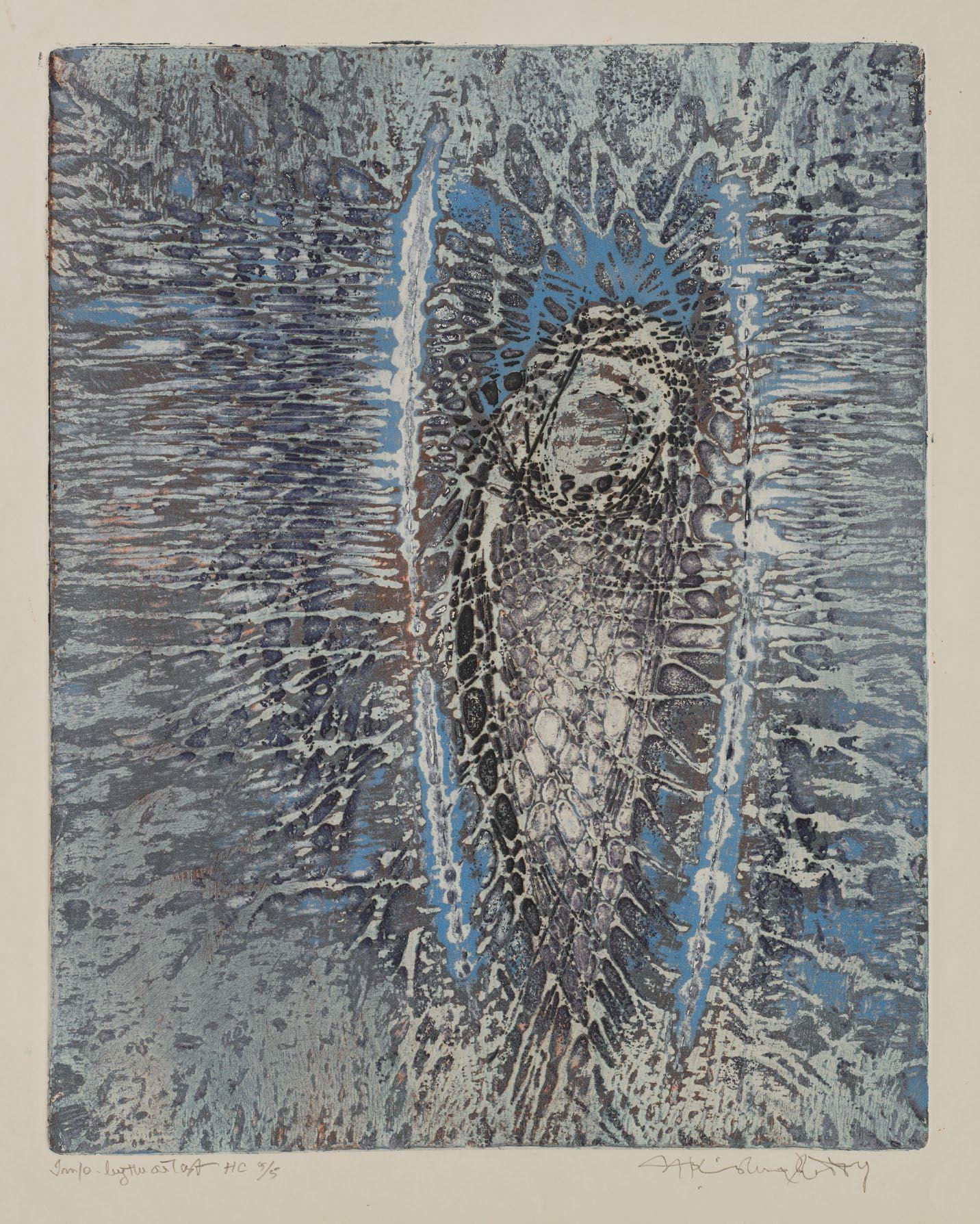

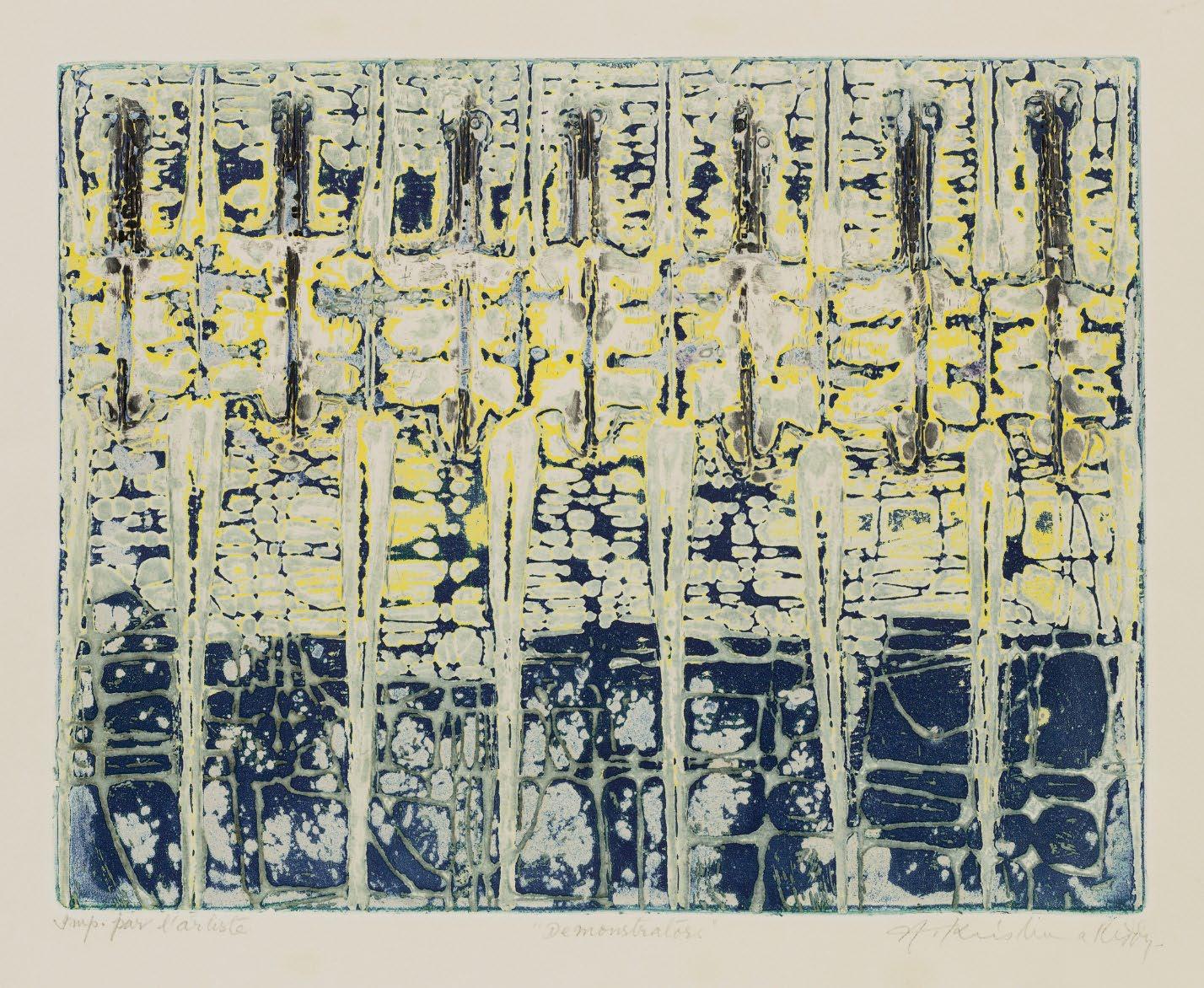

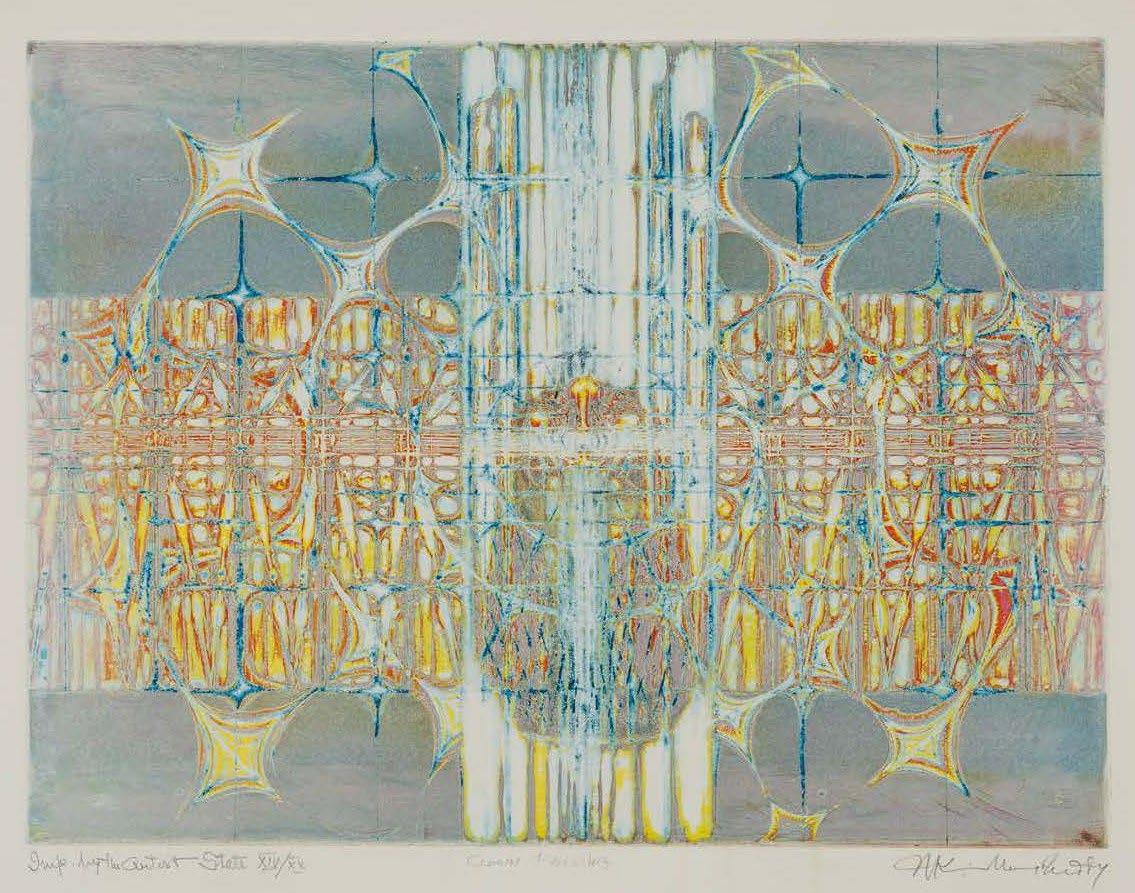

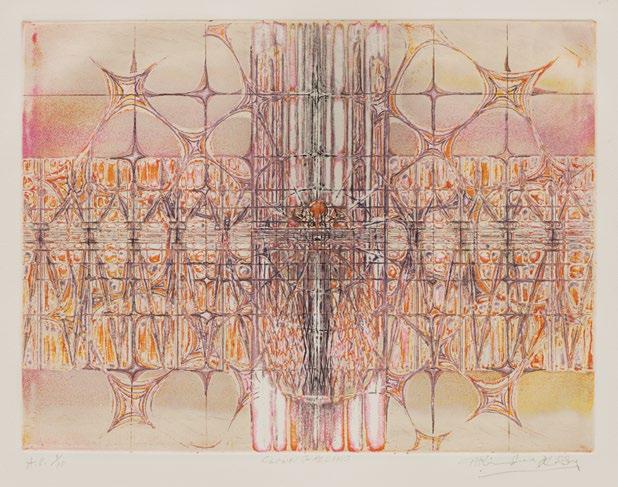

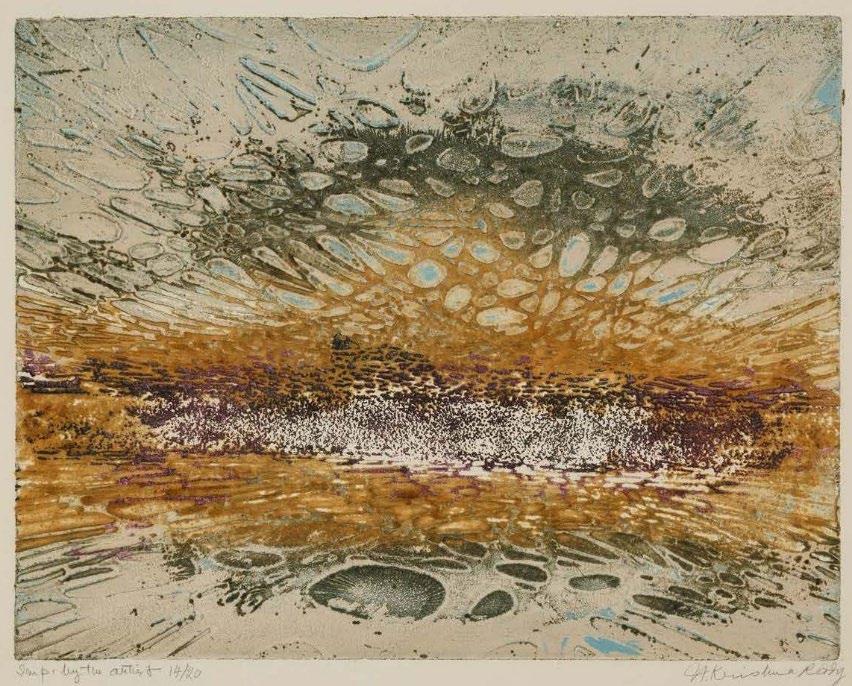

While the three impressions of Three Graces (1953) were created by Reddy progressively carving more material out of the plate, Water Form (1966) shows the opposite approach. 24 In this case, Reddy began by using machine tools to carve into the plate, building a richly textured surface with raised patterns and incised lines. He then applied a fine aquatint for subtle tonal variation and selectively polished certain areas of the plate to heighten the contrast between light and shadow. 25

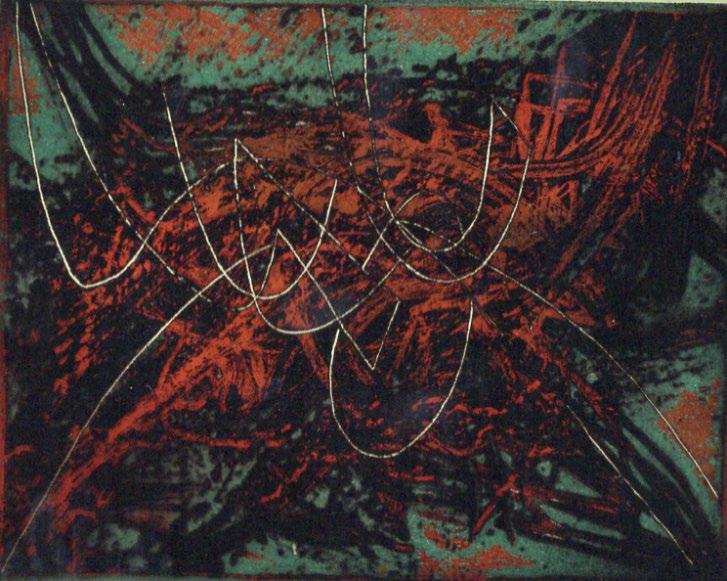

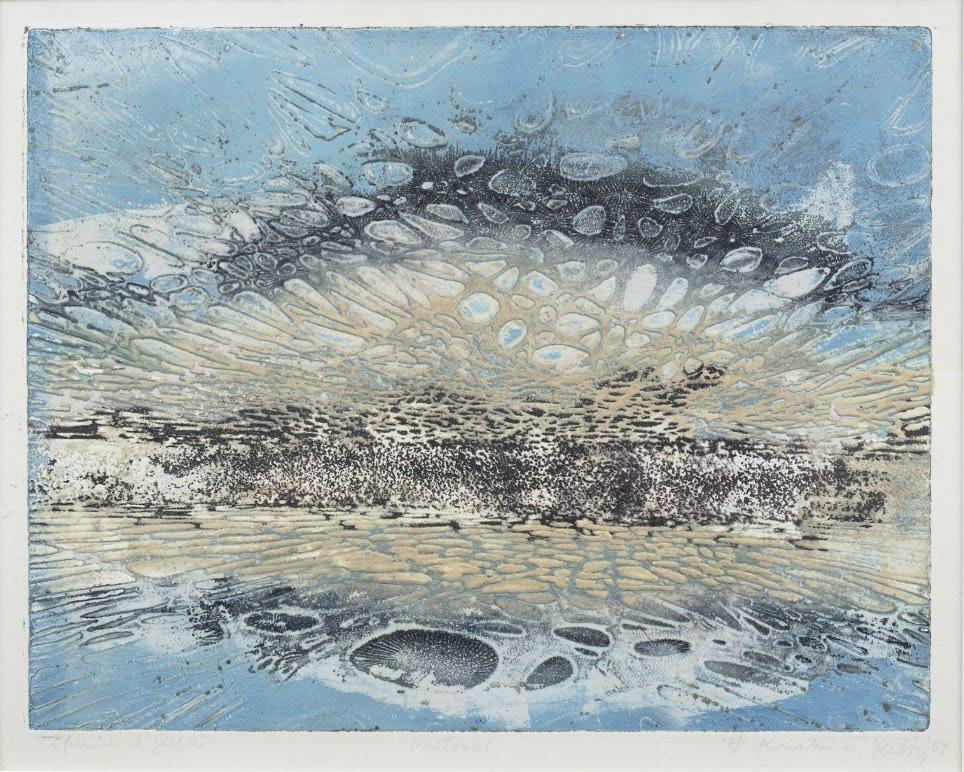

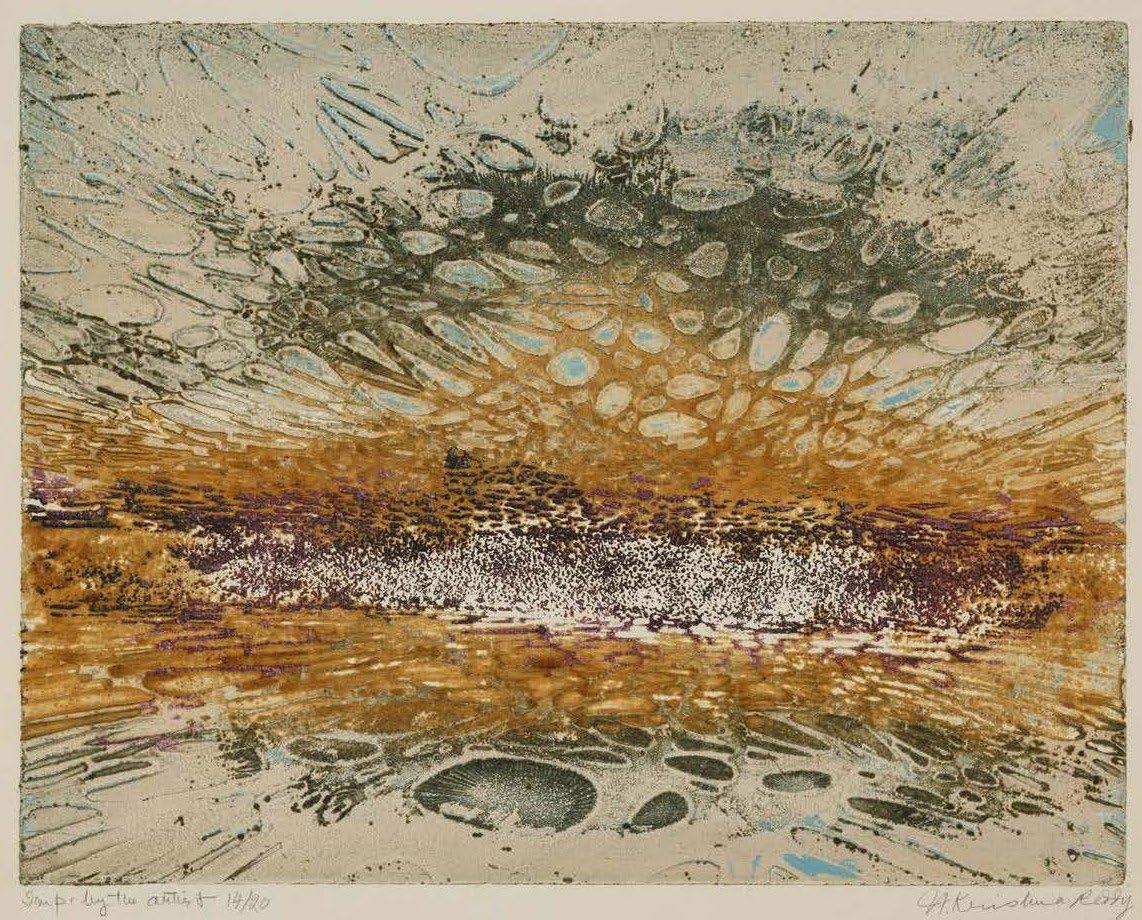

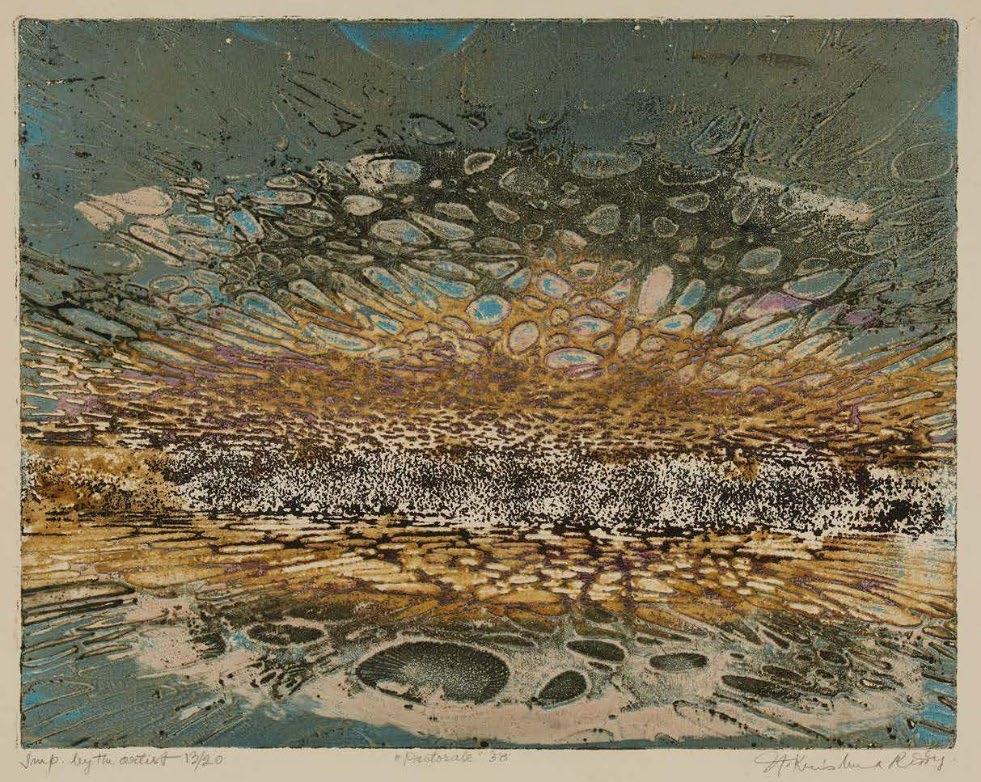

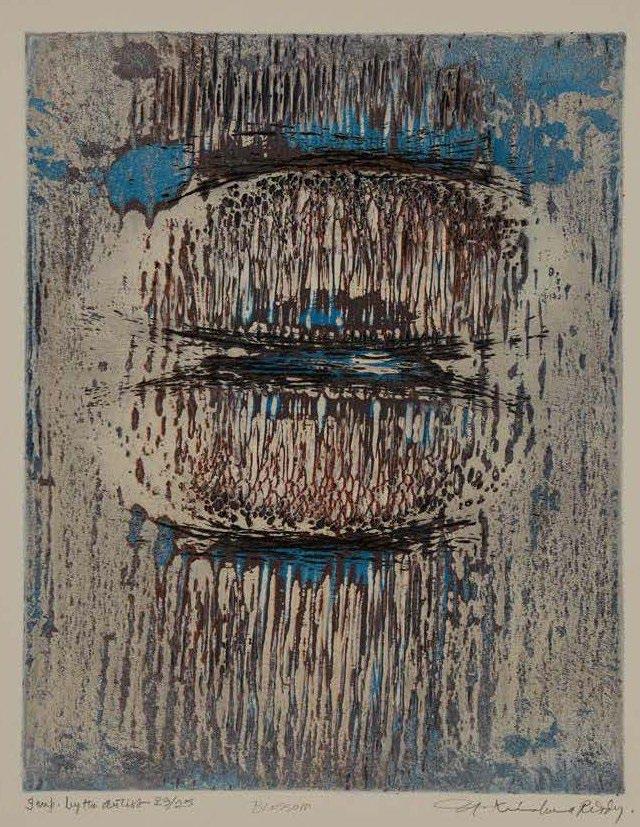

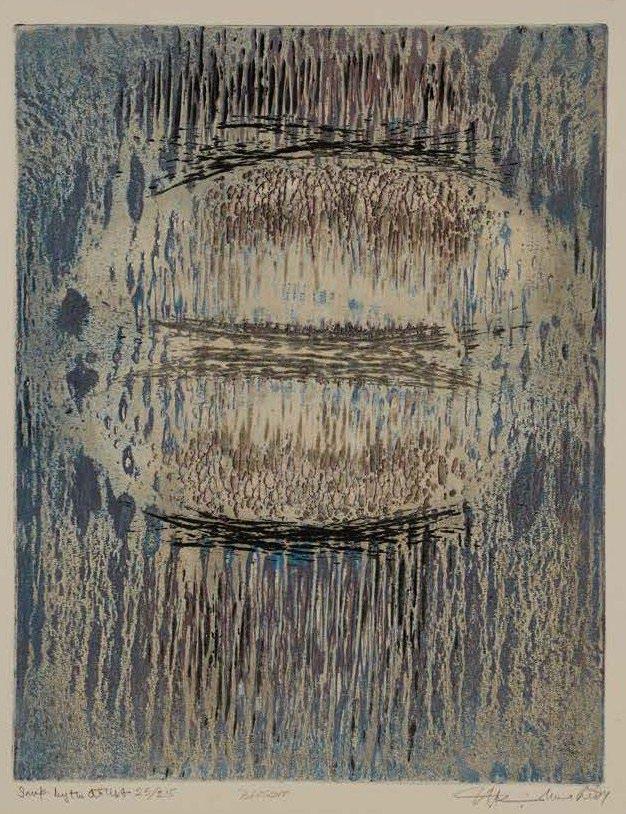

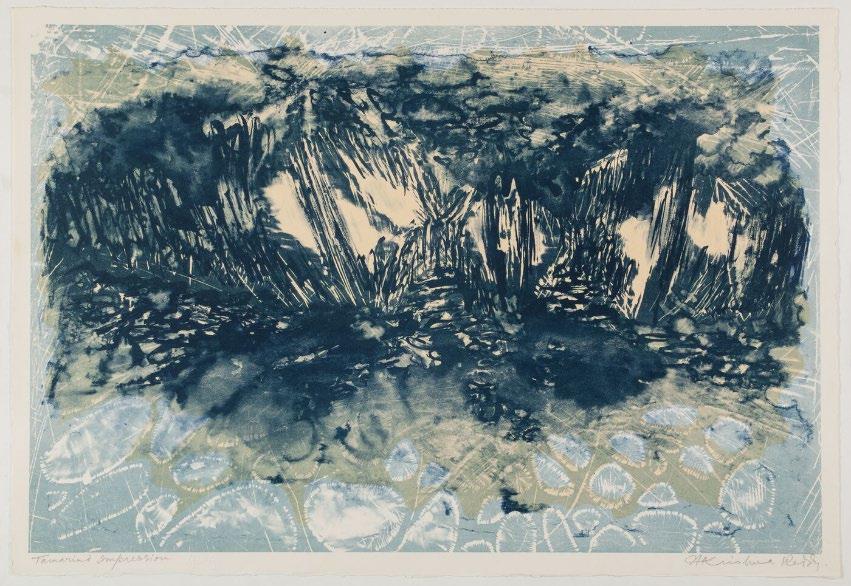

The Blue Impression presumably represents an earlier state of the plate, likely printed after the initial carving. Here, the image glows with deep blues, turquoise, and soft whites. The central form, set within the textured background, resembles a seed, pod, or shell. It feels solid and still, as if embedded in layers of sediment. The etched lines are strong and clear, emphasizing the tactile nature of the plate. The overall feeling is one of stillness, like water that has dried up and left behind quiet, mineral traces.

The Brown Impression, in contrast, shows the plate after Reddy had further polished and refined it. Reddy used earth tones rust, ochre, and cream to create a grounded, almost fossil-like atmosphere. The central form, which previously felt heavy, now seems to float in a flowing, watery environment. The hard lines from the earlier impression have softened into wave-like rhythms and the entire surface appears alive with motion.

The Blue and Brown impressions of Water Form highlight Reddy’s sculptural way of thinking and his belief that forms should emerge naturally through process. Through carving, polishing, inking, and re-

24 Private communication with Dr. Heather Hughes, Philadelphia Museum of Art, April 2025.

25 Krishna Reddy – A Retrospective, exhibition catalog, Bronx Museum of Art, 1981, p 69.

inking, Reddy unlocked the energy within a single plate, using it not to represent water directly, but to express change, growth, and transformation.

It is important to note that these impressions are not mere variants or technical steps toward a final state. Each Water Form impression is a fully resolved work, with its own emotional tone. The Blue Impression is not simply a precursor to the Brown; it holds its own integrity and vision and does not simply reflect a linear progression.

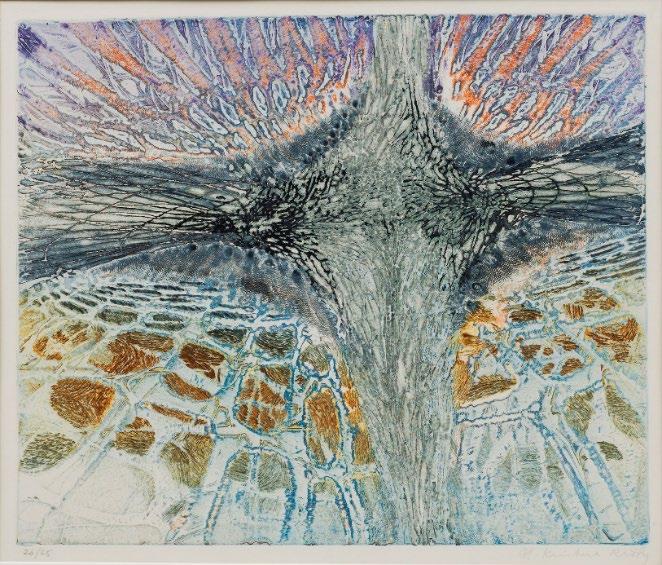

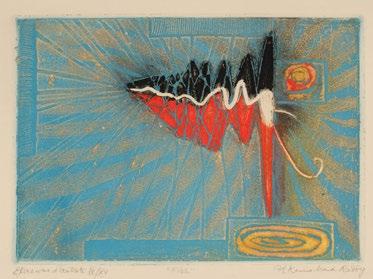

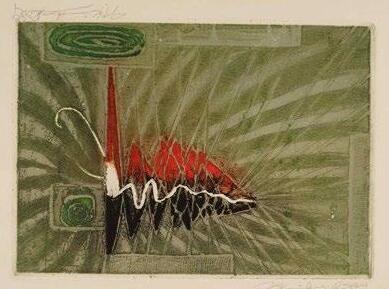

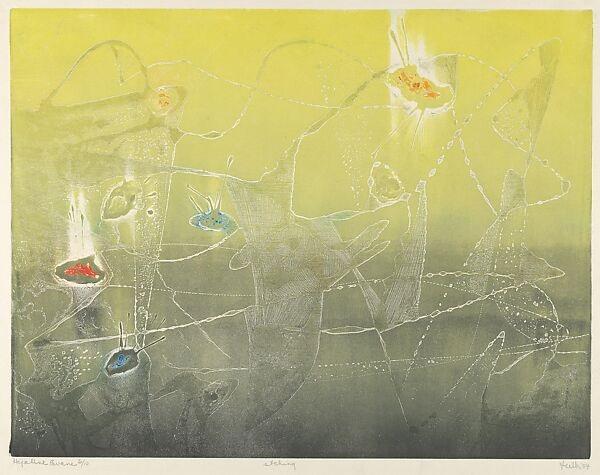

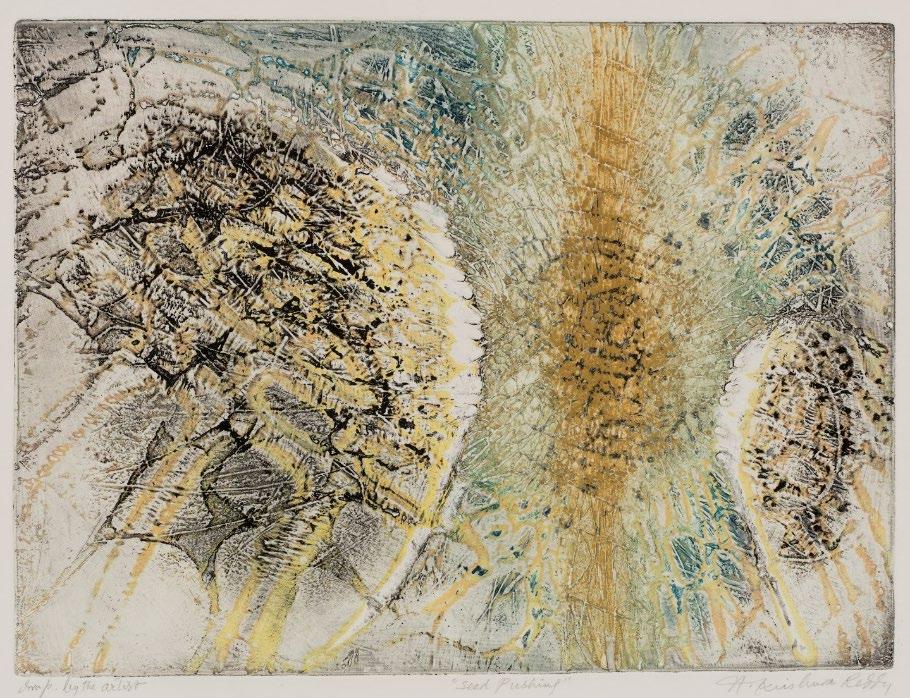

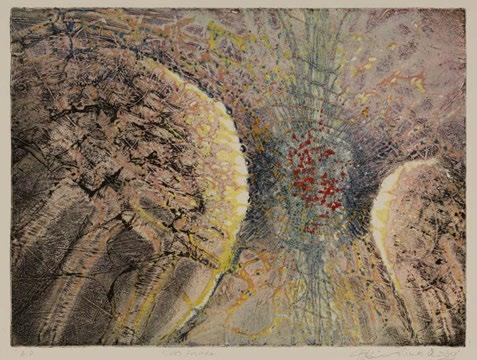

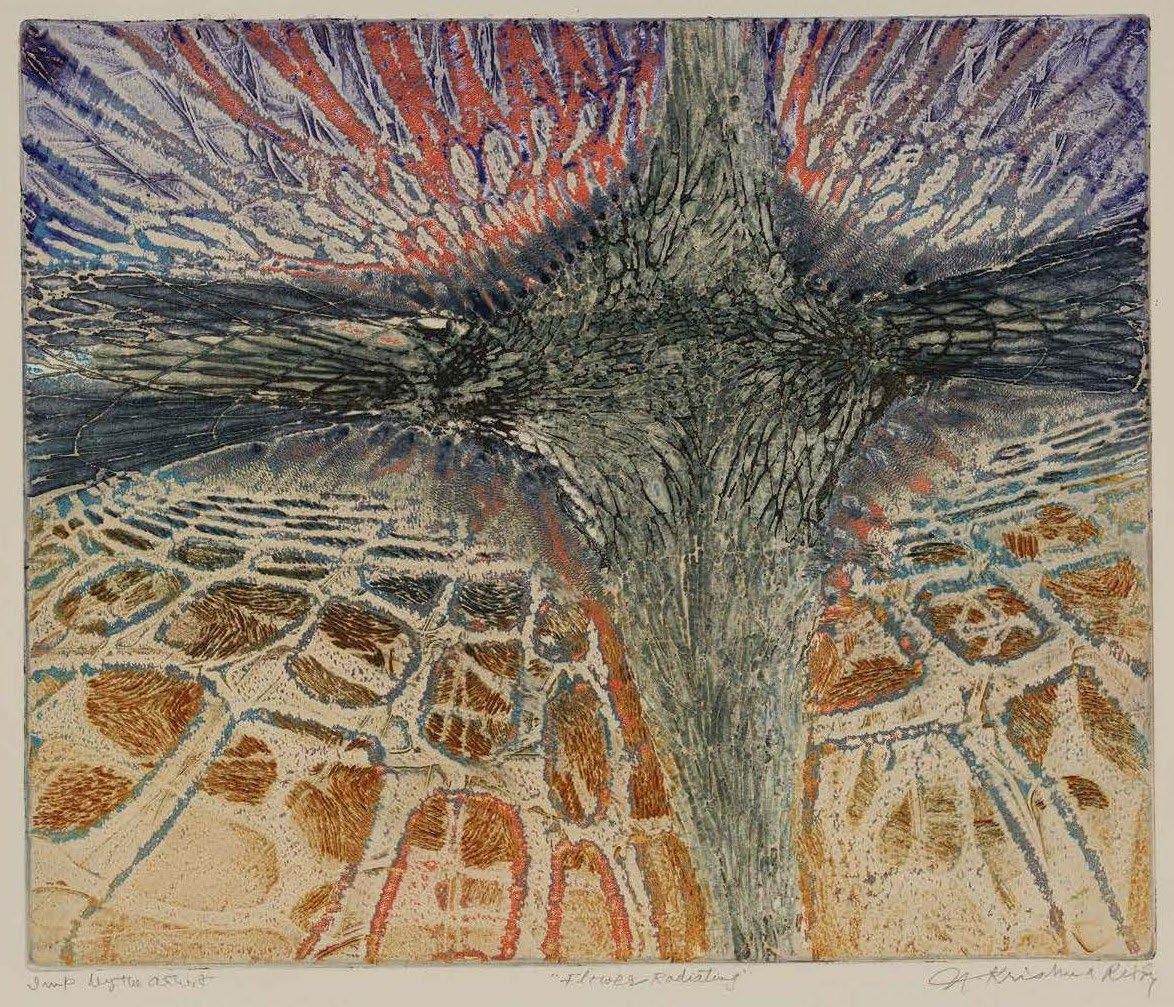

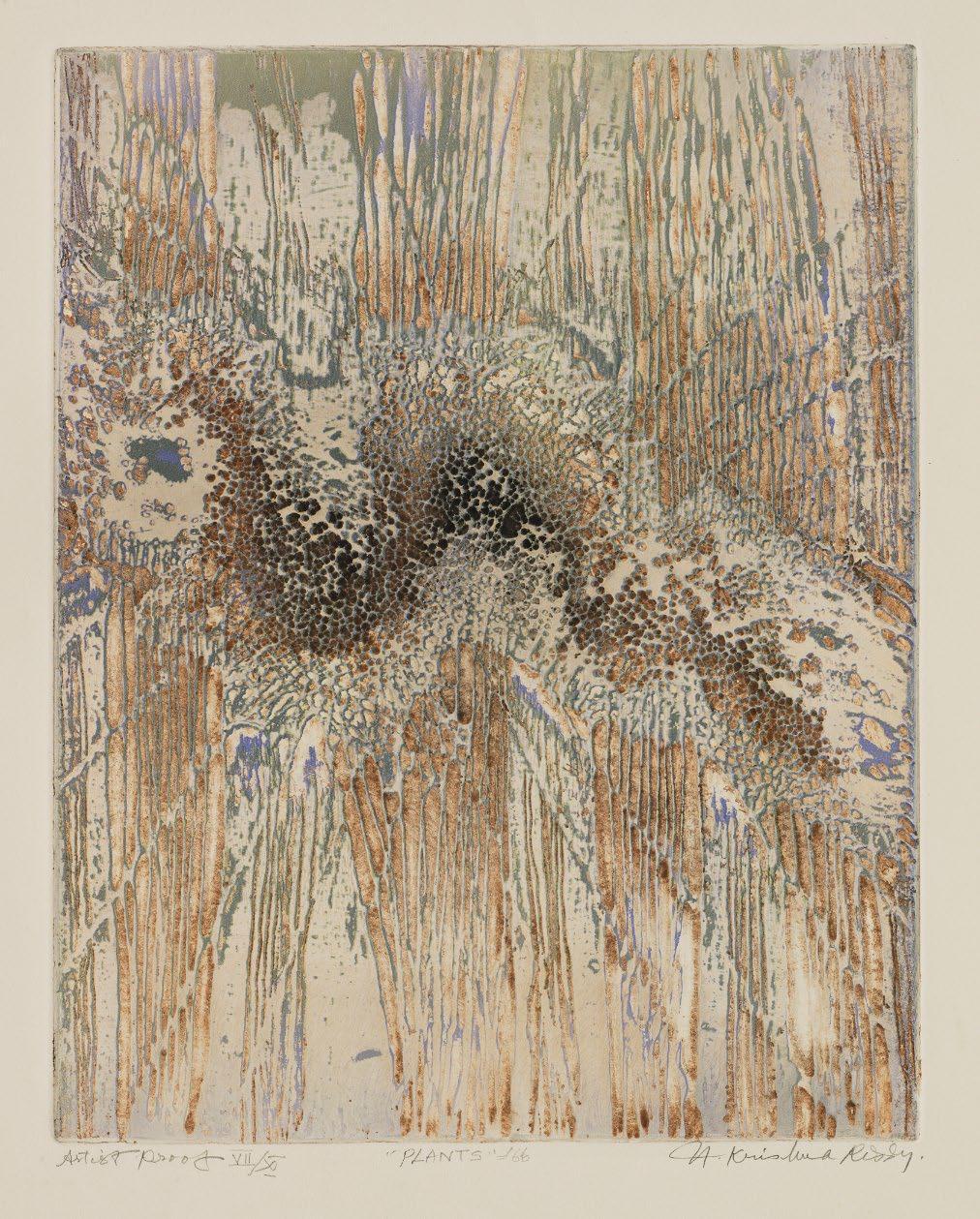

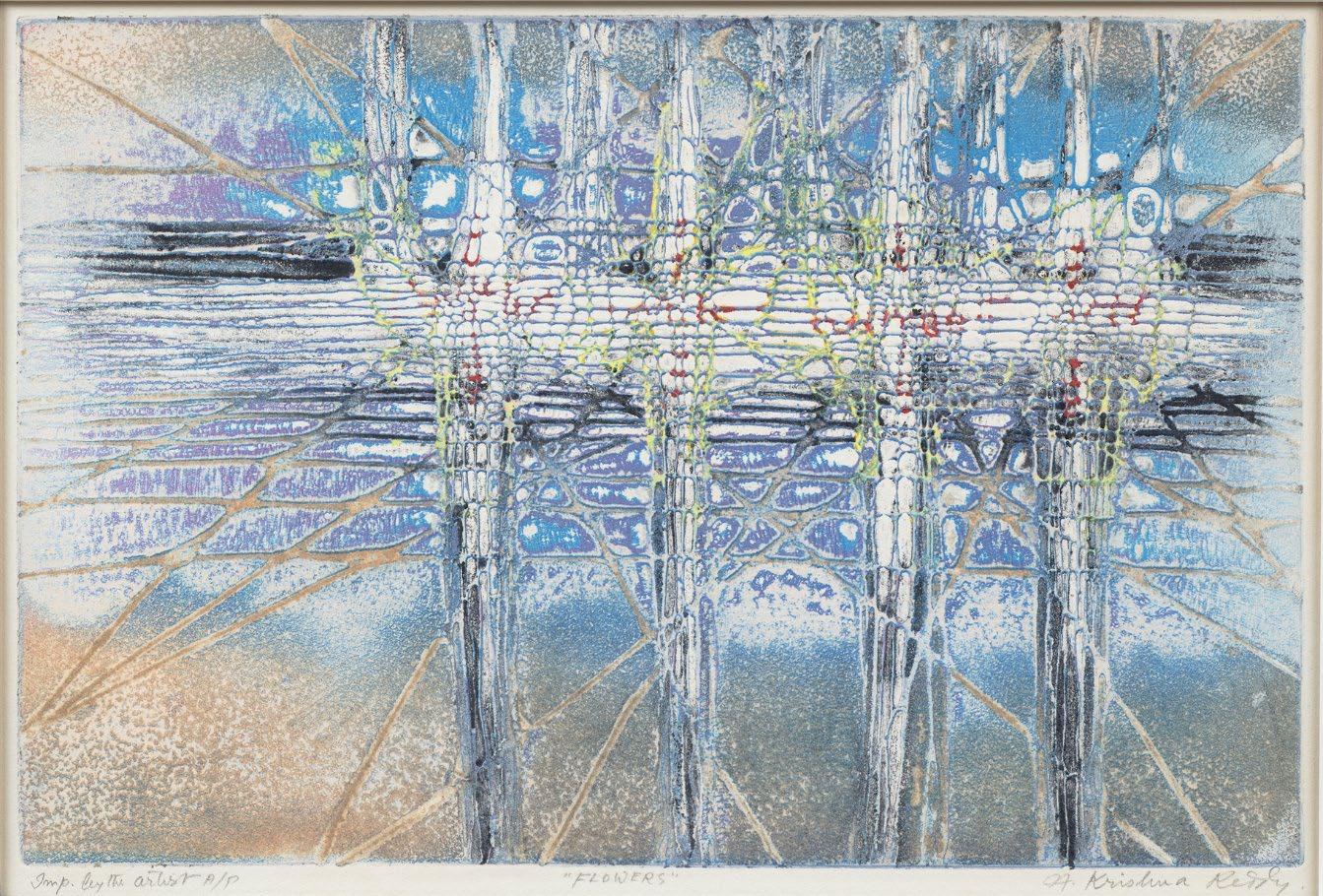

The four impressions of Flower (1961), offer another rare window into Krishna Reddy’s working process and his search for visual and conceptual clarity through variation. These prints three trial proofs and the editioned print of Flower (1961), all made from the same plate, illustrate how Reddy used color, ink viscosity, and surface texture to explore emotional meaning and spatial depth. Through them, we see his thinking unfold as he experimented, refined, and eventually arrived at the final com position.

In the trial proofs, Reddy tested earthy colors like ochre, rust, and dark gray. These early prints with muscular shapes at their center seem alive and full of tension. Red and white highlights draw the eye to areas where energies meet and diverge, while dark, richly inked backgrounds add weight and intensity. These images suggest something raw and organic at times resembling geological formations or cellular structures.

Reddy experimented deeply in each trial, adjusting how the inks were wiped and layered. Though the central form remained the same, the surface appearance changed: in one version it looks rough and fibrous, in another, soft and flowing. These proofs became visual studies, showing how process and material could shape meaning.

The editioned print, however, took the work in a new direction. Using cooler colors blues, purples, and greens Reddy created a much lighter and more open image. The dense textures and weight of the proofs gave way to a glowing, airy composition. The central form, which looked heavy in the proofs, now seemed to float and radiate light. Technically, the editioned print shows Reddy’s precise control of ink viscosity and tone. The wiping is clean and careful, and the colors are blended subtly.

Comparing the trial proofs and the editioned print shows more than just stylistic differences it reveals a transformation in concept. The proofs represent a stage of becoming, where energy and form are still taking shape. The editioned print brings that energy into balance, softening the intensity and creating a calm, harmonious image.

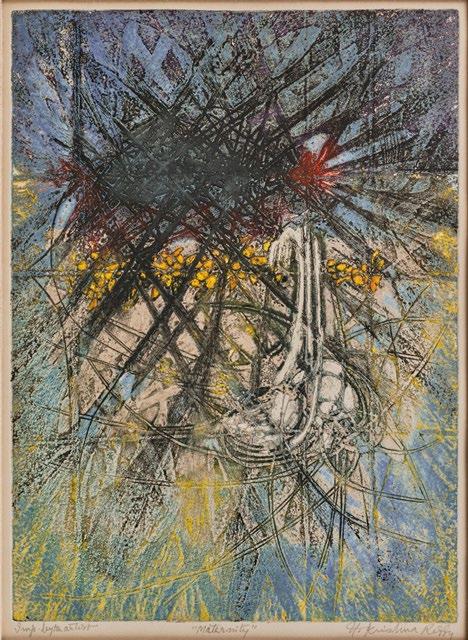

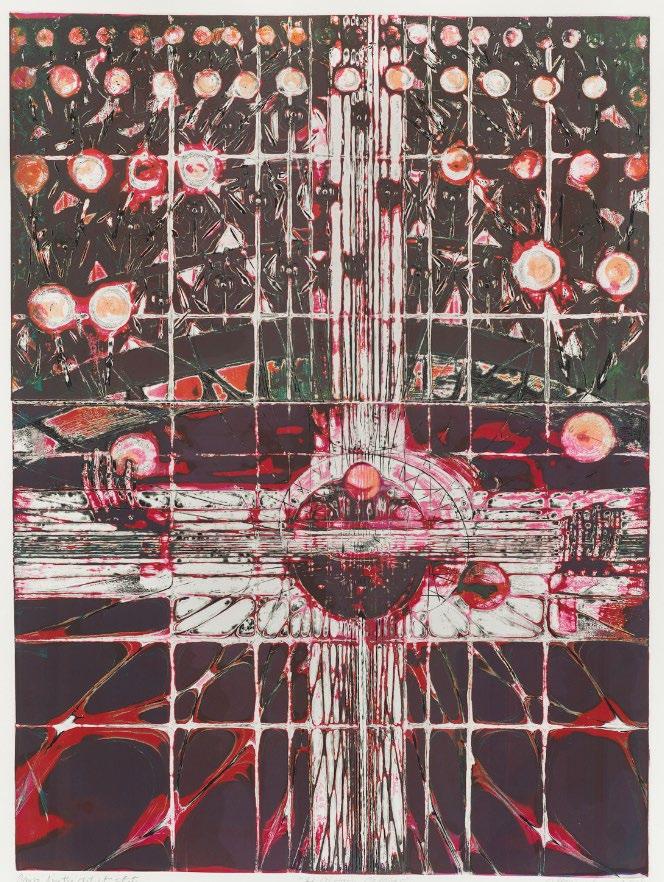

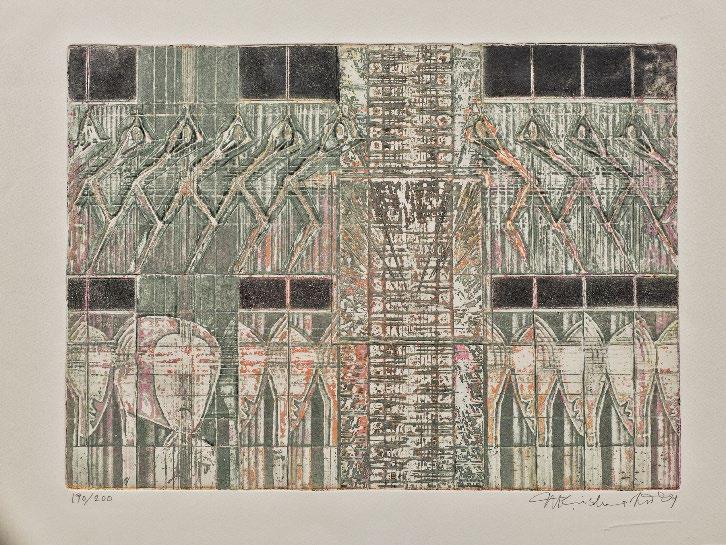

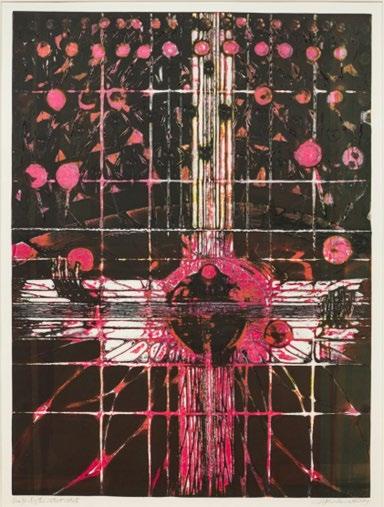

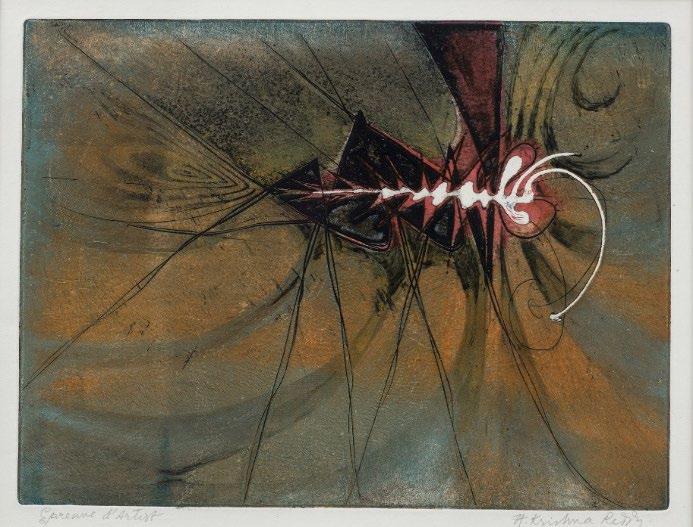

Krishna Reddy’s The Great Clown (1981), widely considered his magnum opus, offers another powerful example of his ability to evoke emotion and mood through technique. The print brings together Reddy’s conceptual depth and technical mastery, but what makes it especially compelling is his use of color and process as tools for emotional exploration and not just visual effect. Each impression, with its unique palette and surface treatment, transforms the viewer’s experience, subtly altering the image’s emotional tone and interpretive resonance.

13 -

This print was published by Galerie in Sweden, though all impressions were printed by Krishna Reddy in New York. In addition to an edition of seventy-five, Reddy created about a hundred unique impressions, each with distinct variations. A close examination of four such prints reveals how the clown figure assumes different personalities, expressing a range of moods and emotional states.

At the center of the composition is the clown, juggling multiple balls. His round, exaggerated nose becomes the visual anchor. From this point radiates a web of lines and shapes that give the print its intricate structure and energy. In the background, a large, seated audience watches. Their presence suggests the weight of public expectation and the tension between creativity and performance.

In some impressions, bright colors make the clown’s nose and the balls stand out vividly. In others, those same elements blend softly into the surrounding patterns. This shifting visibility echoes a central idea of the work: how perception changes with context.

The Black Impression feels heavy and intense. Deep reds, blacks, and whites dominate, with dense lines and dark tones creating a somber mood. The clown seems burdened by his act, isolated under the audience’s gaze, suggesting the loneliness of modern life.

The Green Impression brings a brighter atmosphere. Lively greens, yellows, and golds create a sense of renewal. The clown appears lighter and more at ease, and the image speaks of vitality and connection.

The Yellow Impression takes the image into a dreamlike space. Pastel tones and diffused light make the clown appear to dissolve into glowing air. Here, the clown becomes more than a performer, he is a symbol of transcendence and inner peace, far removed from the crowd’s judgment.

The Rainbow Impression restores playfulness and joy. Bold pinks, greens, blues, and yellows fill the image with celebration. The clown regains his sense of humor, surrounded by color and motion. Yet Reddy’s careful surface treatment ensures that this impression still carries depth and reflection.

Across these four impressions Black, Green, Yellow, and Rainbow the clown shifts from solemn to radiant, from confined to free. Each version explores a different emotional and philosophical space. Together, they reveal The Great Clown as far more than a depiction of circus life. It becomes a meditation on change, perception, and the pressures of being seen and navigating the roles of both performer and self.

The Great Clown embodies Reddy’s belief in printmaking as a living, evolving process. Each impression offers new insight, inviting viewers to see differently. Through this masterwork, Reddy celebrates the richness of perception, the endurance of the creative spirit, and the layered complexities of human experience.

Across these case studies Tuatara, Three Graces, Water Form, Flower, and The Great Clown a consistent picture emerges. Reddy treated each print not as a final product but as a step in an unfolding process. He used the plate as a site of transformation to uncover new visual, emotional, and symbolic possibilities. His method challenged the conventions of printmaking by emphasizing variation over edition, evolution and creativity over finality.

Postwar Printmaking in Paris: Krishna Reddy at Atelier 17

Christina Weyl

When Krishna Reddy joined Atelier 17 in 1951, this avant-garde printmaking studio had only just reopened in Paris after a break of more than a decade. Founded by the British artist Stanley William Hayter (1901-1988), the studio had locations in prewar Paris (1927-1939) and New York (1940-1955) before its return to Paris in 1950. The situation for printmaking in postwar Paris was quite different from what Hayter left behind in 1939 as the Nazis marched towards the French capital, and it was not assured that his workshop would flourish again in the city of its founding. Krishna Reddy’s arrival early in Atelier 17’s postwar trajectory and his eagerness to experiment supercharged the studio’s reintegration into Paris and firmly cemented its position as a leader of cutting-edge technical research.

Atelier 17 is widely recognized as a revolutionary force in the graphic arts and twentieth-century Modernism, more generally. Over its sixty-one-year history, Atelier 17 welcomed over one thousand artists from across the globe who worked collectively and collaboratively to experiment and to push the boundaries of printmaking beyond its traditional functions. 26 Their efforts centered around reviving engraving as a creative and not a reproductive medium, innovating in many metalplate intaglio techniques such as etching, aquatint, sugar lift, and developing viscosity printmaking. The last is an area that Krishna Reddy obviously advanced during his years at Atelier 17 and beyond. For Hayter, Reddy, and other members of Atelier

26 For foundational scholarship about Atelier 17, see Joann Moser, Atelier 17: A 50th Anniversary Retrospective Exhibition (Madison, WI: Elvehjem Art Center, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1977).

17, printmaking was not simply a method for reproducing drawings or making copies of the same image. Instead, they valued each step in the process for its capacity to generate insights and spark creative discovery, whether for their future work in the graphic arts or in their endeavors in painting, sculpture, and collage. Many artists of Atelier 17, in fact, did not produce complete editions, as we have come to understand them a series of identical impressions printed from the same matrix. Prints made at Atelier 17 might instead be highly variable, inked in different color waves, hand-wiped to produce idiosyncratic effects, or signed with different orientations.

Atelier 17’s roster includes a wide spectrum of artists practicing many aesthetic styles and approaches, reflecting the studio’s long history, transcontinental locations, and global membership. Despite this diversity, a few things remained constant for any artist who came to Atelier 17. First, workshop members were rigorously committed to exploring new techniques. Atelier 17 was less a school and Hayter insisted he was not a teacher and in this non-hierarchical context members were expected to share discoveries. The second constant flows from the first: with its unique balance of collective and individual work, Atelier 17 provided an extraordinary space of sociality and the exchange of ideas. Although artists might experience significant challenges in traveling from their home country to New York or Paris, joining Atelier 17’s community was for most all

Currently, The Atelier 17 Project is working to celebrate Atelier 17’s centennial in 2027 by encouraging new research and exhibitions about the workshop and its members.

members a defining experience in their lives and professional careers. Inside or outside the studio, the workshop’s polyglot membership found community and mutual support that have, in many cases, lasted a lifetime.

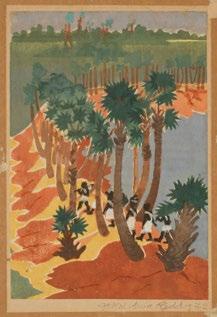

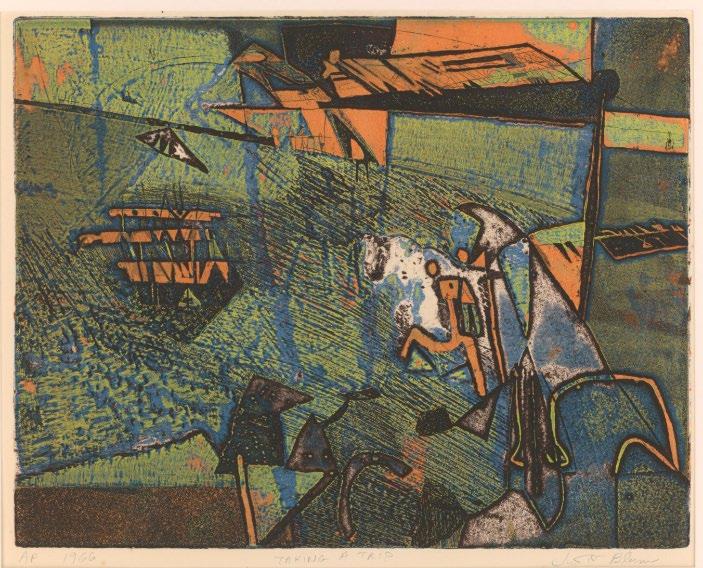

Fig. 1: Krishna Reddy, untitled relief print landscape, 1942. Multicolor woodblock, image: 8 x 5.5 in, Paper: 11.75 x 7.625 in.

Krishna Reddy did not, ostensibly, come to Paris to join Atelier 17 or to learn more about printmaking, though it is interesting to note he had made some

27 Transcription of interview with Krishna Reddy titled “Environments,” January 25, 1981. Krishna Reddy Papers; MC 244; Box 3, Folder 3; New York University Archives. Reddy says: “In India, I made prints and woodblocks. There were many presses in India. But I was not involved, and I would occasionally do printing, because I always loved graphics.” Thank you to Tyrus Clutter for providing access to his research photos of these interview transcripts.

28 Hayter and Zadkine had become acquainted with each other before the outbreak of World War II, when both

woodblocks in India (fig. 1). 27 By way of study at the Slade School of Art in London, he had the opportunity to learn from the noted British sculptor, Henry Moore. Reddy’s move to Paris facilitated additional instruction in direct carving and modeling from Ossip Zadkine, the Russian-born sculptor who taught at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière. 28 Although Atelier 17’s first location in postwar Paris at 278, rue de Vaugirard was a solid thirty-minute walk away from the Grande Chaumière and the city’s other ateliers libres in Montparnasse, Hayter’s extensive social network kept the workshop connected with Paris’s artistic community. As was typical of student life in Paris and the city’s café culture, which brought people together for socializing around meals and the evenings, Reddy once described in an interview how he began to “meet these printmakers coming from Hayter’s place.” 29 “Slowly,” he continued, “I started working with him [Hayter].”

briefly occupied studios on villa Chauvelot (now villa Santos-Dumont) in the 15th arrondissement. Before settling into his longtime studio at 100 bis, rue d’Assas, Zadkine lived at 3, villa Chauvelot. In the late 1920s, Hayter and his first wife Edith Fletcher occupied the upstairs studio at 23, villa Chauvelot. For more about the artists who lived on this street, see: https://www.lilianlau.com/2014/04/hidden -paris-villasantos-dumont/ 29 Reddy, “Environments,” 1981.

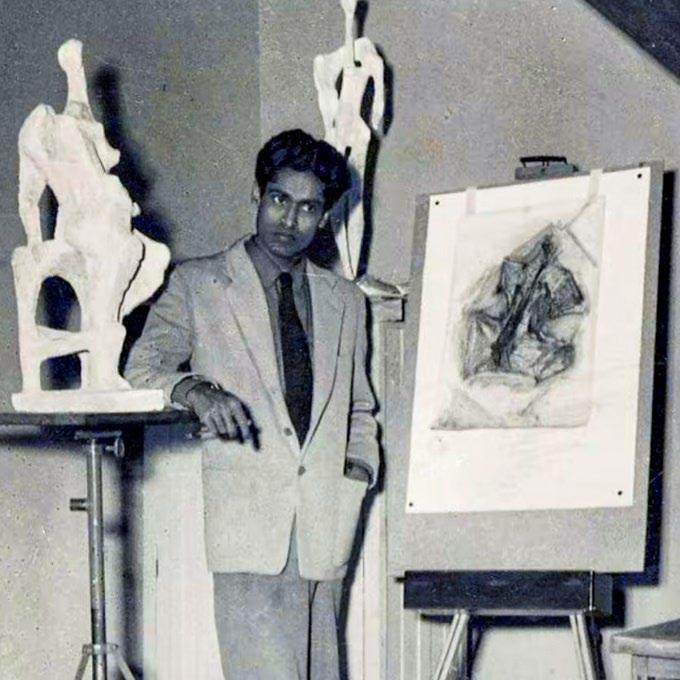

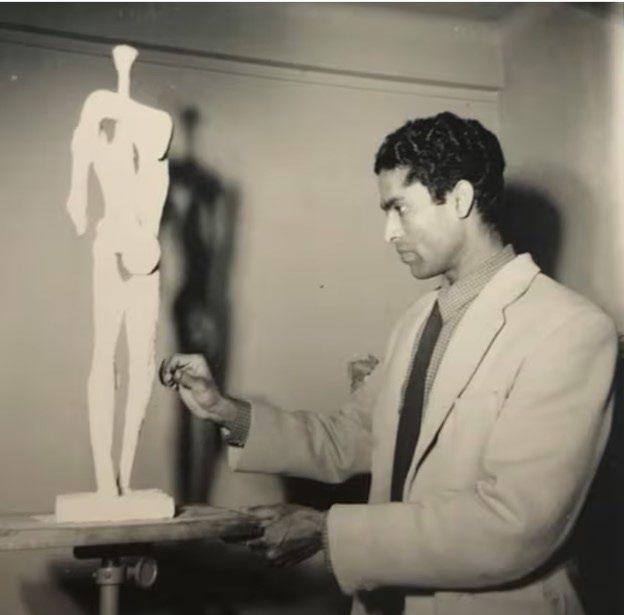

Even as Reddy began to visit Hayter’s studio, he reportedly maintained a very strong interest in sculpture, spending six days with Zadkine and one

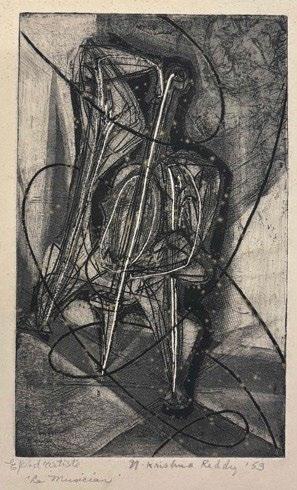

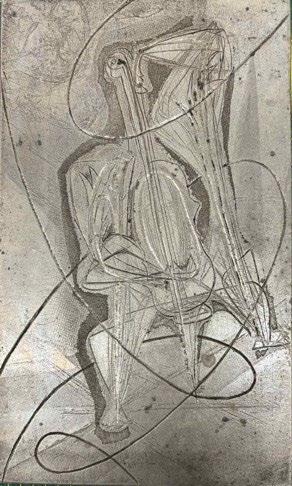

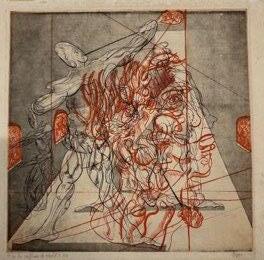

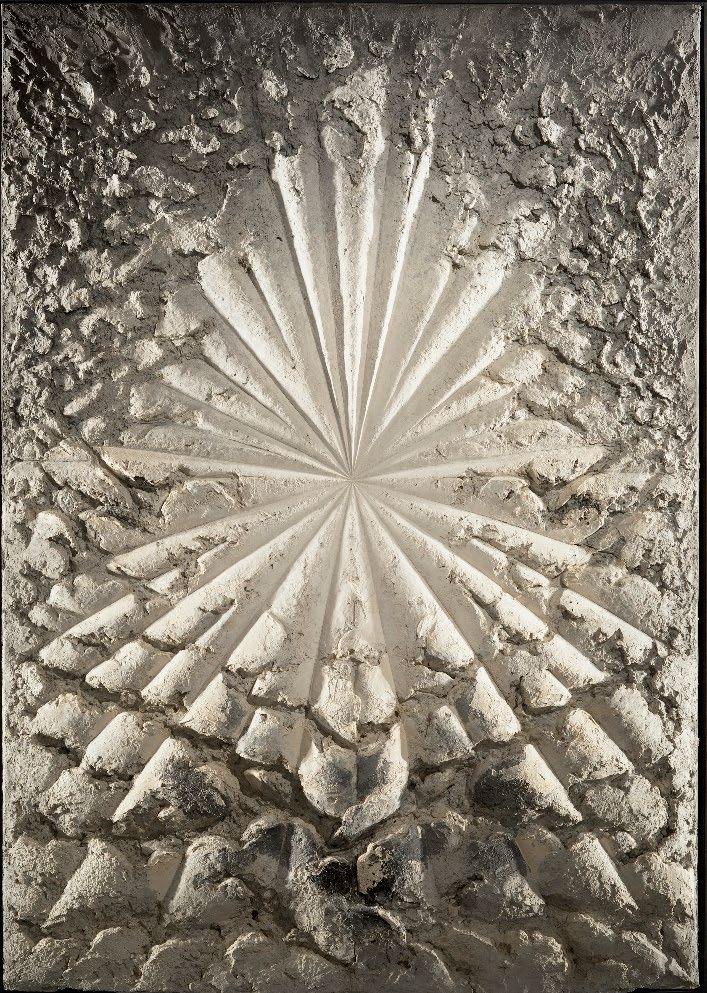

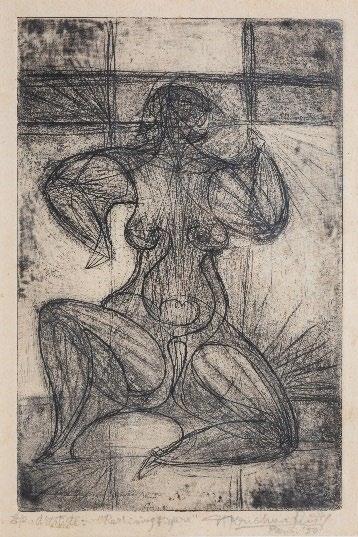

at Hayter’s studio. 30 With his feet quite literally in both doors, it is no wonder that his first etchings and engravings made at Atelier 17 during the early 1950s integrate his sculptural ideas and subject matter onto a metal plate. In these black-and-white compositions, figures are reclining, posed at tables, or playing instruments. Some bear direct relationships to finished sculptures Reddy completed around the same time, and this association is apparent in a work like The Musician (fig. 2-3) Reddy completed the terra cotta featuring a vertically oriented, standing figure who wraps their arms around a large stringed instrument. In the related print, Reddy created a more dynamic composition by tilting the musician’s body on an angle while adding several deeply engraved swirls a signature technique of Hayter and the Atelier 17 workshop (fig. 4).

It is worth pausing briefly to consider why Reddy spent his entire week working in the studios of either Hayter or Zadkine. As artists from all over the world arrived in Paris, they might only have funds to cover the rent of a small one-room apartment. Workshops like Hayter’s or Zadkine’s known within the city as ateliers libres or “open studios” offered an attractive alternative to the academic environment of the École des Beaux-Arts and were crucial to a young artist’s ability to produce art that they might exhibit or sell. Reddy claimed he had “no facilities” throughout the sixties to produce sculpture. 31 Certainly he did not have space or funds to set up his own printmaking studio, and he relied on access to Atelier 17’s presses and chemicals to produce his prints from the 1950s and 1960s. Beyond their practical advantages, the city’s ateliers libres also provided less experienced artists with the opportunity to mix freely with “the greats,” to borrow Reddy’s words. 32

30 Reddy, “Environments,” 1981.

31 Reddy, “Environments,” 1981.

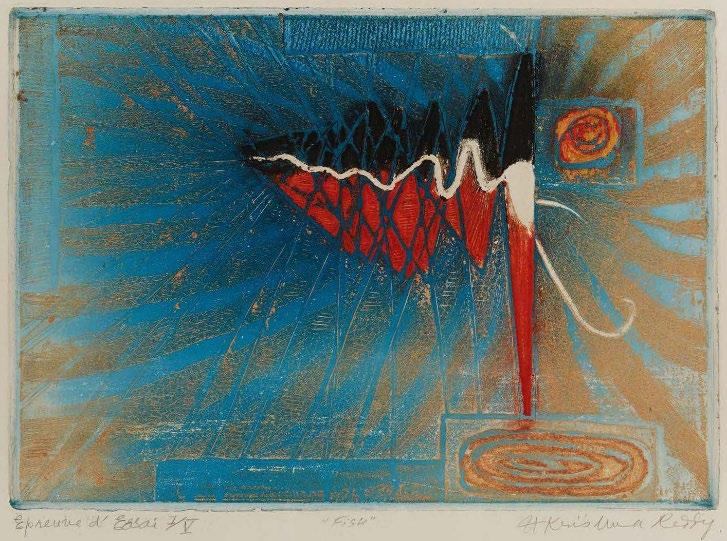

After an initial period of training and learning the ins-and-outs of engraving and etching, Reddy began to experiment with inking his plates in various color combinations, as can be seen in two variant impressions of the plate for Fish: one in blue, yellow, red, and black and the second (signed in the inverse orientation) in shades of green with red and

32 Reddy, “Environments,” 1981.

black (figs. 5-6). Historically, achieving multi-color intaglio prints was a time-intensive process, usually involving one of three approaches: first, inking à la poupée, a technique where artists would apply spot color by hand to particular areas of the same plate; second, jigsaw plate printing where pieces of a plate would be inked individually and reassembled during printing; and third, printing au repérage, where artists prepare two or more plates and run each separately and in succession through the printing press. 33

33 For more on the history of color printing, see Ad Stijnman, Engraving and Etching, 1400-2000: A History of the Development of Manual Intaglio Printmaking Processes (London; Houton, Netherlands: Archetype; Hes

and De Graaf, 2012), 347–75; Ad Stijnman and Elizabeth Savage, eds., Printing Colour, 1400-1700: History, Techniques, Functions and Receptions (Boston: Brill, 2015).

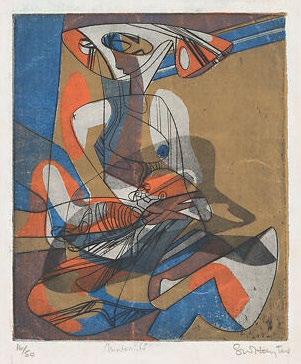

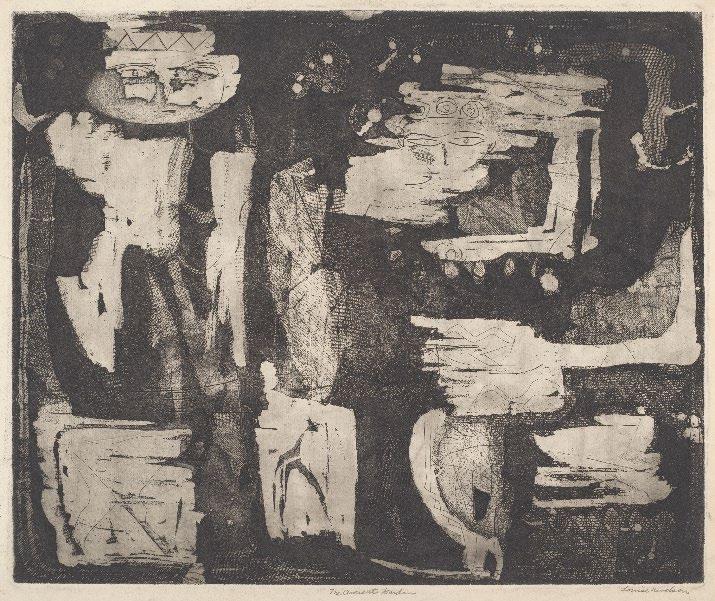

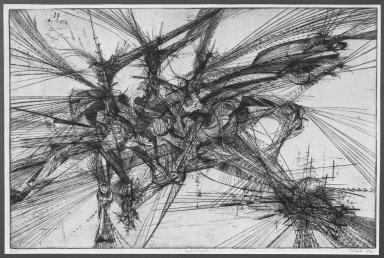

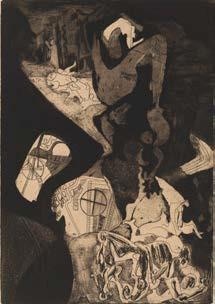

Fig 9: Stanley William Hayter, Maternity, 1940. Engraving, soft-ground etching, 9 × 7 1/2 in. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

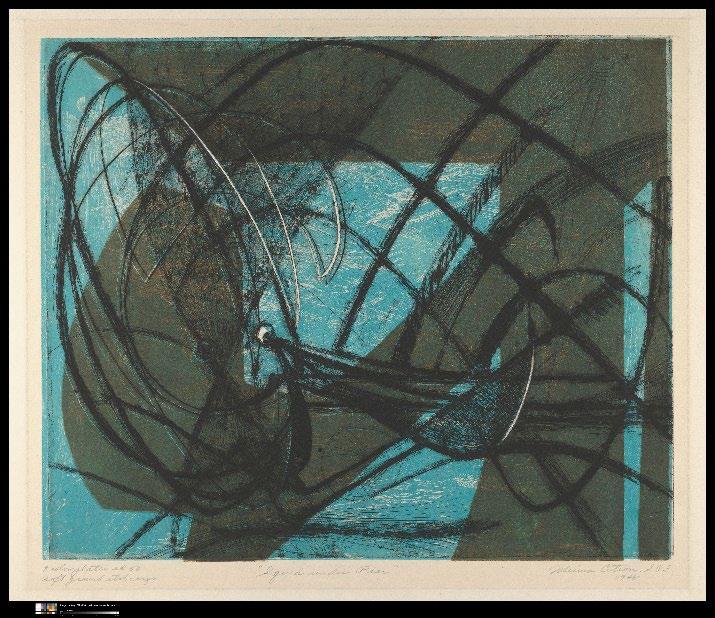

Fig. 10: Stanley William Hayter, Cinq Personnages, 1946. Engraving and soft-ground etching, Plate: 14 15/16 × 24 in. Dolan/Maxwell, Philadelphia.

As is discussed elsewhere in this volume, Reddy completed these astonishing, multi-color prints with only one pass through the press.

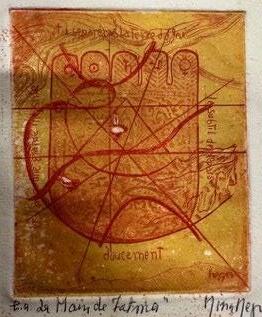

The idea of simplifying the complex problem of multi-color intaglio prints was one that had intrigued Hayter and Atelier 17’s members since the workshop’s earliest days in prewar Paris. Nina Negri, an Argentinian who was among Atelier 17’s first prewar members, experimented in La main de Fatima (1933) with inking the grooves of her plate in dark orange and inking the unetched surface of the plate in yellow (fig. 7). She also overlayed multiple plates, combining a black-and-white inking of the plate for Les souffleurs de verre with the redinked plate for Le feu to create a composite impression (fig. 8). 34 While Atelier 17 was located in New York City, workshop members collaborated to develop a new strategy for color printing whereby they employed silk screen stencils. 35 With his Maternity (1940), Hayter screened blue and orange

34 In his 1949 book, Hayter alludes the prewar effort to print in color but does not cite Negri specifically: “some experiments were made by applying surface color with a roller to an uninked plate, making one impression, then cleaning the plate and inking it, for intaglio printing, in black and reprinting on the same paper.” Stanley William Hayter, New Ways of Gravure (New York: Pantheon, 1949), 158. These two examples by Negri clearly fall within Hayter’s description of the type of experiments prewar members were conducting.

35 At this moment, artists in the United States were increasingly practicing silk screen printmaking thanks to

the efforts of various divisions within the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration and, more specifically, the Graphic Arts Division of the Federal Art Project. During the early 1940s, Hayter knew many artists active in the newly formed Silk Screen Group and penned a somewhat controversial article for Serigraph Quarterly, a publication the group later renamed the National Serigraph Society would issue through the 1950s. Stanley William Hayter, “The Silk Screen,” Serigraph Quarterly I, no. 4 (November 1946): 1.

tempera onto a damp sheet of paper, after which he printed the intaglio plate inked in black (fig. 9). 36

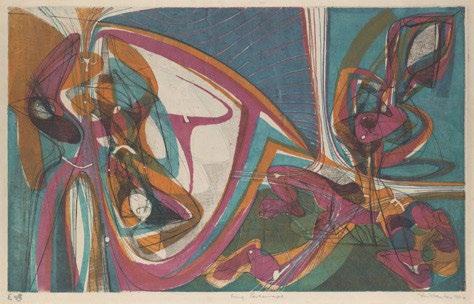

By the middle of the 1940s, Hayter and fellow workshop members most notably Fred Becker, Ezio Martinelli, James Goetz, and Karl Schrag tweaked this process and discovered how to squeegee inks of different viscosities through a silk screen stencil directly onto a copper plate. This plate now loaded with black ink applied into the intaglio lines, plus several levels of stenciled color on the surface would go through the printing press only one time. Hayter’s Cinq Personnages (1946) was their first success with this technique, which eventually would become known as simultaneous color printing (fig. 10). 37

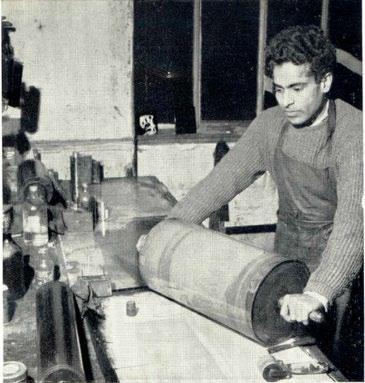

Fig. 11: Krishna Reddy printing at Atelier 17, ca.1961. Reproduced in catalogue for Reddy’s 1961 exhibition at Galleria XXII Marzo, Venice.

12: Kaiko Moti, Fishes, 1955. Engraving, open bite etching, sheet: 22 x 30 in. Dolan/Maxwell, Philadelphia.

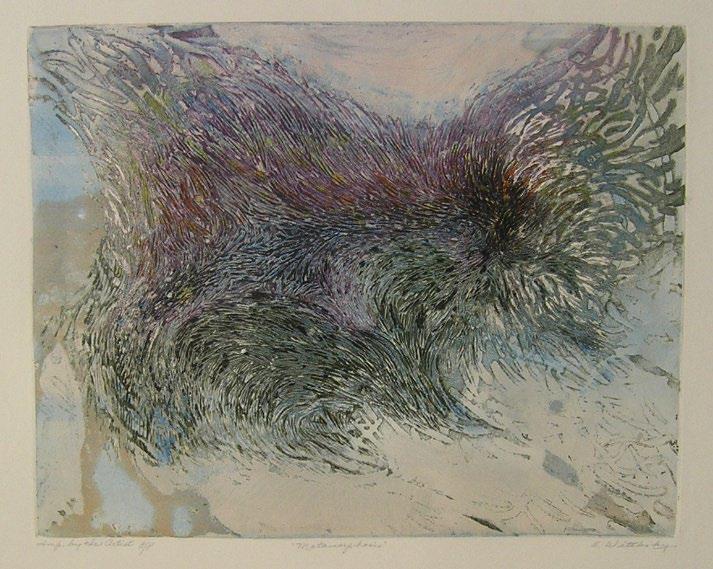

Fig. 13: Shirley Witebsky, L' Arbre, c. 1958. Color etching and aquatint, image: 14" x 17 3/4 in. Dolan/Maxwell, Philadelphia.

36 Hayter, New Ways of Gravure, 159.

37 The whole process is described in Hayter, 155–61. While Hayter did not use the term “simultaneous color

Reddy’s breakthrough with viscosity printmaking during the 1950s and 1960s flow from this lineage and the longstanding curiosity at Atelier 17 to create multi-color prints. Unquestionably, Reddy built upon the fundamental properties behind printing” in the 1949 edition of New Ways of Gravure, the term does appear in the 1981 edition.

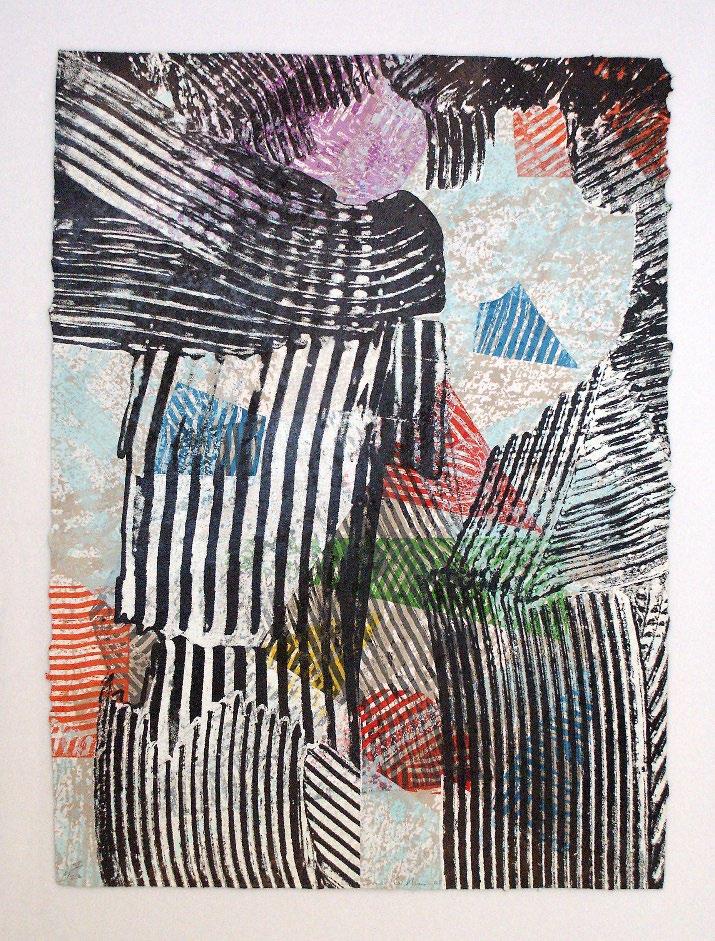

Hayter’s simultaneous color printing, namely altering the viscosity of inks. But viscosity printing, as Reddy perfected it, relied on the interplay of inks and transparent color applied with large rollers not screens of varying hardness which would deposit ink onto the topographical levels peaks and valleys of a deeply sculptural plate (fig. 11). As was typical of the workshop collective nature, Reddy developed and refined his methods alongside other members such as fellow Indian transplant Kaiko Moti and Shirley Witebsky, Reddy’s first wife who had come over to France from Minnesota (figs. 12-13). 38 Reddy separated himself from these peers, however, as he became increasingly enchanted with the magic of viscosity printmaking and carving sculptural depths into his metal plates. Over time, he became one of viscosity printmaking’s most visible practitioners, promoting it through his solo exhibitions, participation in European print annuals, and teaching the process to new arrivals at Atelier 17 and later the Color Print Studio at New York University.