Chandni Chowk: A Photographer’s Paradise

Chandni Chowk is a photographer's dream. The hustle and bustle, the colors, the smells of the streets, the bazaars, and the vibrant havelis of Chandni Chowk can be overwhelming on first encounter. Life at its chaotic best is lived on these streets, day in and day out. It is also a place that can overwhelm you and throw you into a dazzling storm of colors and sounds. Yet, within the chaos lie the kernels of beauty that the passionate, intrepid photographer can discover through patience, persistence, and resilience.

What truly distinguishes Chandni Chowk, in addition to its rich history, is the genuine warmth and openness of its people. Regardless of their busy schedules, the shopkeepers we photographed always made time to offer us chai. The artisans graciously opened up their workshops. The vendors were more than willing to be photographed, often pausing mid-task to strike a pose, as if life itself were a stage. We formed deep connections with many of these individuals, visiting them multiple times to capture their moods and emotions. They are not just subjects in our photographs; they're also in our hearts.

allowed the city and its people to be our guides, leading us into havelis, bazaars, temples, workshops, and iconic eateries. Harvey, a portrait photographer par excellence, was not just capturing appearances but the very essence of a person in a single frame. Margarita, with her captivating smile, would often walk into a stranger's home and emerge with stunning portraits, her camera reflecting the warmth of newfound friendships. As for me, I found myself immersed in the bazaars and streets, trying to capture the fleeting moments that told stories in a glance, a gesture, a burst of laughter.

As we, Harvey, Margarita, and I, wandered through the vibrant lanes of Chandni Chowk, we did so without a fixed plan. Instead, we

Photographing Chandni Chowk requires more than just technical skill. You don't control the moment; you wait for it to unfold. The place is chaos at its most beautiful. Every street presents its own possibilities, and you never know what you might capture next. Every face hides a story, and it's up to you to reveal it. Every corner bursts with life, and if you give it your time, your passion, your curiosity, everything falls into place, and you get an extraordinary image that takes your breath away. The thrill of the unexpected is what makes Chandni Chowk such a photographer's paradise.

The Iconic Markets of Chandni Chowk

Chandni Chowk is a collection of markets, each with its own personality. From the bustling lanes of Kinari Bazaar selling wedding goods, to the intense smells of spices in Khari Baoli, to the maze of shops specializing in sanitary hardware in Chawri Bazaar, to the iconic book market at Nai Sarak, these markets are the heart of Chandni Chowk's busy life.

The origins of these markets go back to Jahanara Begum, the daughter of Emperor Shah Jahan. In the seventeenth century, she commissioned the octagonal chowk in front of what is now the Town Hall. This central square became so renowned that, over time, the entire street on which it stood came to be called Chandni Chowk, a name that today often refers to much of Old Delhi itself. Traders from across the world were drawn here, bringing silk, spices, perfumes, and jewels to a marketplace that thrived under royal patronage and was frequented by the Mughal court.

Over the centuries, these markets have evolved into specialized areas of trade and expertise, where people, not just from Delhi but from various parts of the world, continue to come to shop. The same family has owned and operated some iconic shops for generations. Many are tiny, tucked within narrow winding streets. Still, within them, you encounter the skills, pride, and traditions of people who run them. Whether it is zari borders, books, perfumes, or light fixtures, many shopkeepers have been selling the same goods for decades.

What is most remarkable about Chandni Chowk's markets is the human connection between seller and buyer. Shopkeepers often know their customers by name. They never rush the buyers, and the deals are made over chai and friendly chats, as if commerce itself were an excuse for companionship.

Most of these markets are embedded in crowded, narrow lanes that are inaccessible to cars and trucks. Consequently, the goods are moved in and out of the lanes in the old-fashioned way. Thela Wallahs (men pulling wooden carts) and porters carry large bundles seamlessly through the crowds. These are the workers who make these markets function. They move everything from wedding clothes to electrical supplies. Still, they are rarely acknowledged - their labor woven invisibly into the fabric of the bazaar.

Each market, besides having a specialty, has its own rhythm, its own sounds, and its own character. Together, they create a lively, colorful world where you shop the old-fashioned way by touching, seeing, smelling, and negotiating.

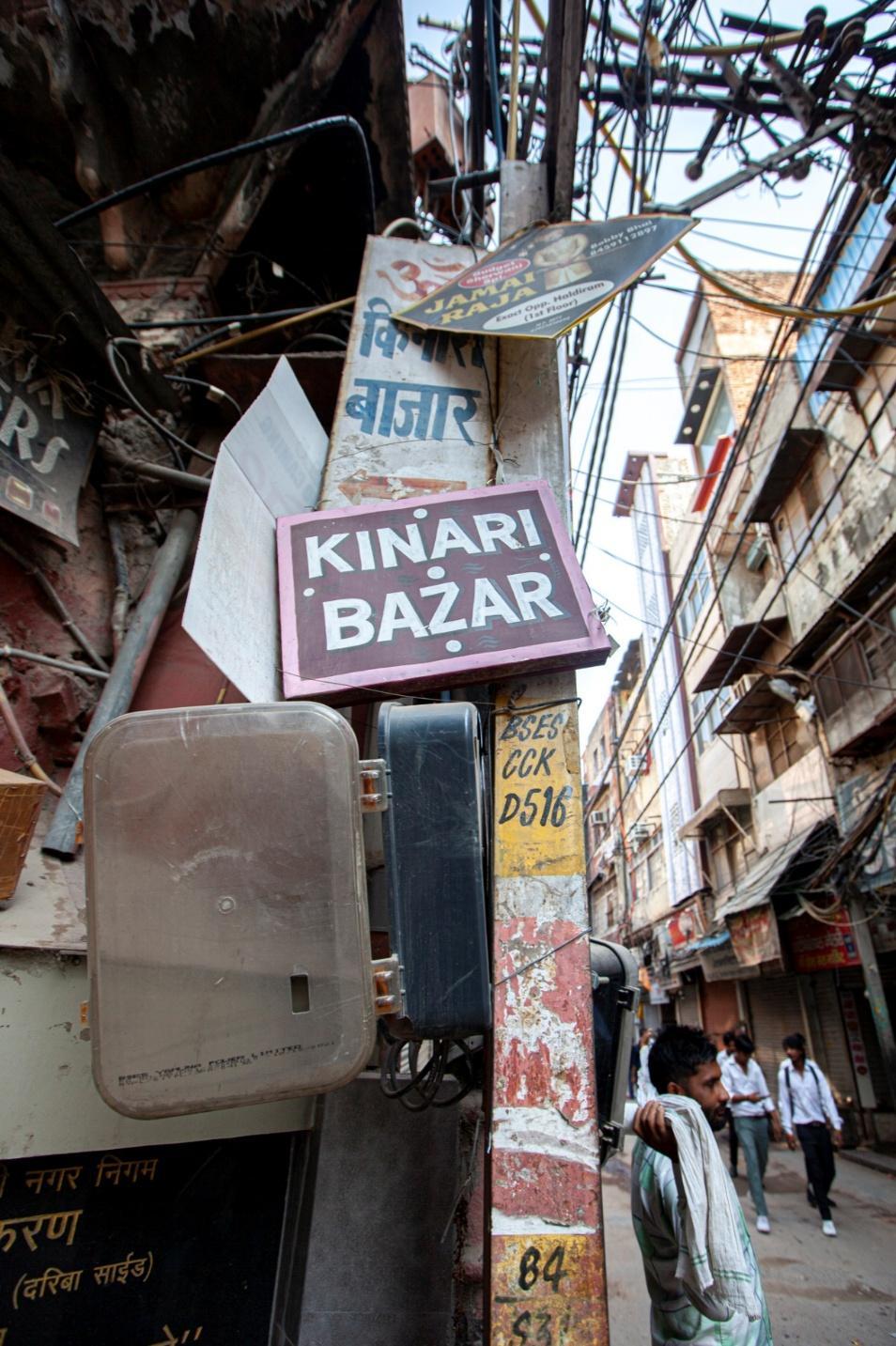

Kinari Bazaar: Where Indian Wedding Dreams Begin

Indian weddings are grand affairs, often spanning several days, and sometimes even weeks. Several traditional rituals, parties, and celebrations precede the main wedding day. All of these events require a special outfit; it is customary for wedding guests to acquire several new outfits for these occasions. This trend is also spreading across the Indian American community in the U.S. Nowadays, the parents of the bride and groom frequently travel to India to purchase wedding outfits, not just for the bride and groom, but also for members of their family and friends. For many, the first stop is Kinari Bazaar in Chandni Chowk.

Kinari Bazaar is the oldest and most famous wedding market not only in Delhi but in all of India. You can find every imaginable trim, lace, and embellishment used to decorate traditional Indian formal clothing. For generations, brides, grooms, tailors, and designers have made their way here to get zari and gota laces, sequins, beads, velvets, brocades, tassels, and more to design custom outfits for weddings. The market is filled with small shops, each glowing with its specialty. There's even a store entirely dedicated to buttons, a universe contained in a single detail.

A few years ago, I went to Kinari Bazaar with my brother and his wife, Swati, who was putting together her outfit for an upcoming wedding. As we stepped into the bazaar, it felt like entering a world that shimmered and sparkled. Swati visited many shops in search of the perfect hand-embroidered border, glittering sequins, and special buttons. Every shopkeeper was proud to show us their collection. Everything was so beautiful, gold-stitched lace, pearl buttons, presenting a limitless selection of adornments. Brides-to-be, fashion designers, tailors, and families all come here with the same goal: to find that one right embellishment that will make their outfit special.

While I took photographs, my brother and sister-in-law picked out fabrics, trims, sequins, and buttons. Each item was thoughtfully matched and chosen so that her outfit gradually came together - built from the treasures of Kinari Bazaar.

Visiting Kinari Bazaar is more than just a shopping trip. For some families, it is itself one of the wedding rituals, a prelude shimmering with anticipation.

Khari Baoli: The Heart of India's Spice Trade

I moved to the U.S.in the 1970s, when the Indian immigrant community was still small and finding Indian groceries was a real challenge. I remember driving over 100 miles to Queens, New York, to buy a few basic spices. Today, in New Jersey, where we live, there are hundreds of Indian grocery stores. You can find almost everything now. But if you're looking for the brightest red chilies, the creamiest cashews, or the freshest spices, there's one place you must go: Khari Baoli in Chandni Chowk.

Khari Baoli is Asia's largest spice and dry goods market. Everywhere you look, there are sacks and piles of spices: turmeric, cardamom, cumin, saffron, nutmeg, dried rose petals, and more. The air is thick with fragrance sharp, sweet, pungent, earthy all layered into an invisible tapestry. Kashmiri almonds, Afghan apricots, Iranian pistachios, and giant, flavorful cashews from South India flood the street. Walking through the lanes, one sees red chilies stacked high, yellow lentils in baskets, rare Ayurvedic herbs, and blocks of asafetida. Traders shout out prices, buyers bargain, and thela wallahs and porters weave through the crowds.

I am most impressed by the stores that specialize in just red chilies. They offer chilies that range from mild to ultra-spicy, each providing a unique sensory experience. Some vary in fragrance, adding another layer of intrigue to their appeal. Others even impart a different red hue to dishes dark ruby or glowing orange-red. The large mounds of these dried red chilies, sitting directly on the floor, are a sight to behold. They glow like heaps of burning embers, with their wrinkled skin catching the light to create a visual spectacle, a treat for the photographer's eyes.

One special aspect of Khari Baoli is its unusually wide main road, something rare in the Chandni Chowk area where most streets are narrow. The market, established in the 1600s during the Mughal era, expanded quickly, with carts laden with goods and caravans that came via the overland route that is now known as the Grand Trunk Road. Some say the road was widened by demolishing buildings and pushing them back, but this has never been reliably established. What is beyond doubt is that Khari Baoli grew into the great artery of the spice trade, carrying an unstoppable tide of aromas and commodities into the city.

What makes Khari Baoli truly special isn't just the people who know the trade inside and out, but the way a single sniff can tell them everything about a spice. It's the smell of fresh spices clinging to your clothes, the sense of history that lingers in the air, that makes it an unforgettable experience, as if you are walking through the very soul of India's kitchen.

Stepping into Dariba Kalan is like entering a time capsule. The street, which translates to 'Street of Incomparable Pearls,' was established in the early 1600s during the Mughal era. It served as a bustling hub for jewelers, gem traders, and goldsmiths, catering to the royal jewelry trade. The jewelers of Dariba were also the bankers of the Mughal empire and they offered their best gems to the royal family, frequently visiting their royal patrons in the Red Fort.

The market continues to thrive today in silver jewelry. While there are some larger jewelry showrooms, you see mostly small jewelry stores selling silver chains, nose rings, toe rings, anklets, and ornaments for weddings and festivals. Many small shops also specialize in imitation bridal jewelry at affordable prices. These shops are popular with brides-to-be and families preparing for weddings. You often see brides-to-be holding up earrings next to a lehenga photo, trying to find the perfect match for their big day.

Dariba was once a thriving center for Delhi's goldsmiths, who were commissioned to make ornaments for the royal families during the Mughal era. Today, their handmade traditional ornaments are considered old-fashioned, as younger Indians now prefer machine-made branded jewelry from modern showrooms. Yet, amidst this shift, you see a few old-timers still practicing their craft in Dariba Kalan, working with tiny hammers, files, and blowtorches to create custom-made ornaments.

In addition to silver traders, many shops in Dariba Kalan sell traditional ittar (perfume) and oils. These shops are filled with small glass bottles of natural perfume oils. The fragrance of rose, jasmine, sandalwood, and even a potent, spicy blend called shamama lingers in the air. I picked up a small bottle of attar as a keepsake, reminding me of my mother, who always kept a few of these little bottles on her dressing table.

Ballimaran: A Walk Through Verse and Style

Ballimaran, the neighborhood that once housed India's most cherished Urdu poet, Mirza Ghalib, is a living testament to his enduring legacy. His humble haveli, now transformed into a museum, stands as a reminder of his immortal verses.

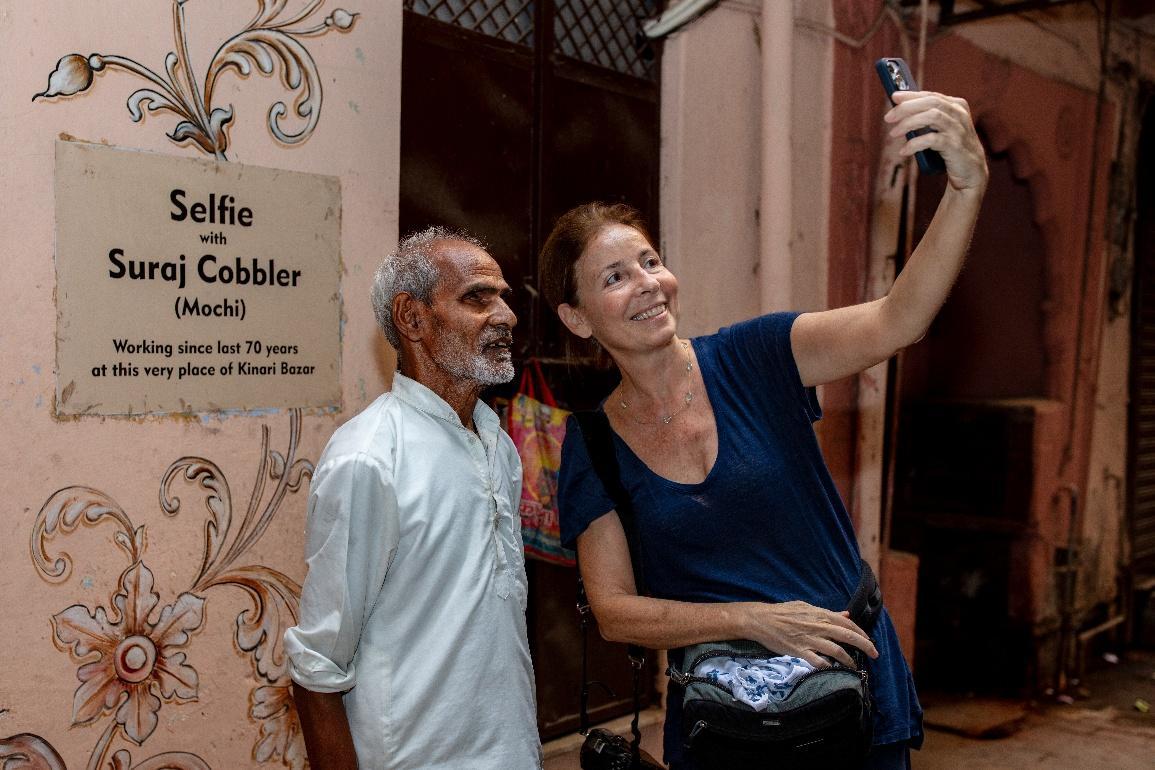

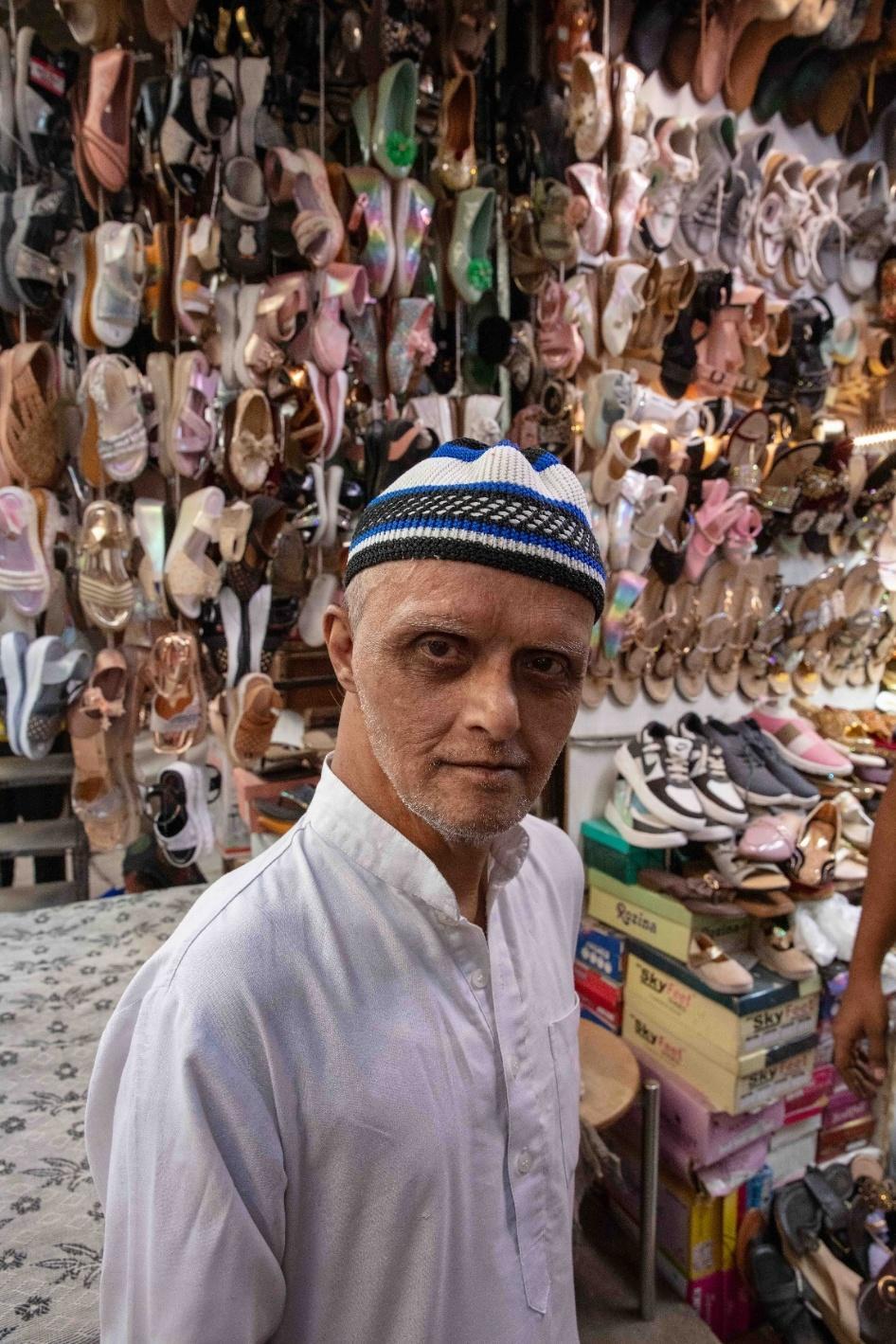

Long ago, this area was home to Muslim families who worked in small trades making shoes, stitching clothes, repairing glasses. Today, the market is still filled with small, family-run shops that sell shoes, sunglasses, and bags. Among glittering juttis, leather sandals, knock-off sneakers, you also find cheap fashion shoes stacked high in pyramids outside tiny shops. There are endless shops selling spectacles, frames, and sunglasses, displayed neatly in glass cabinets that resemble walls of mirrors.

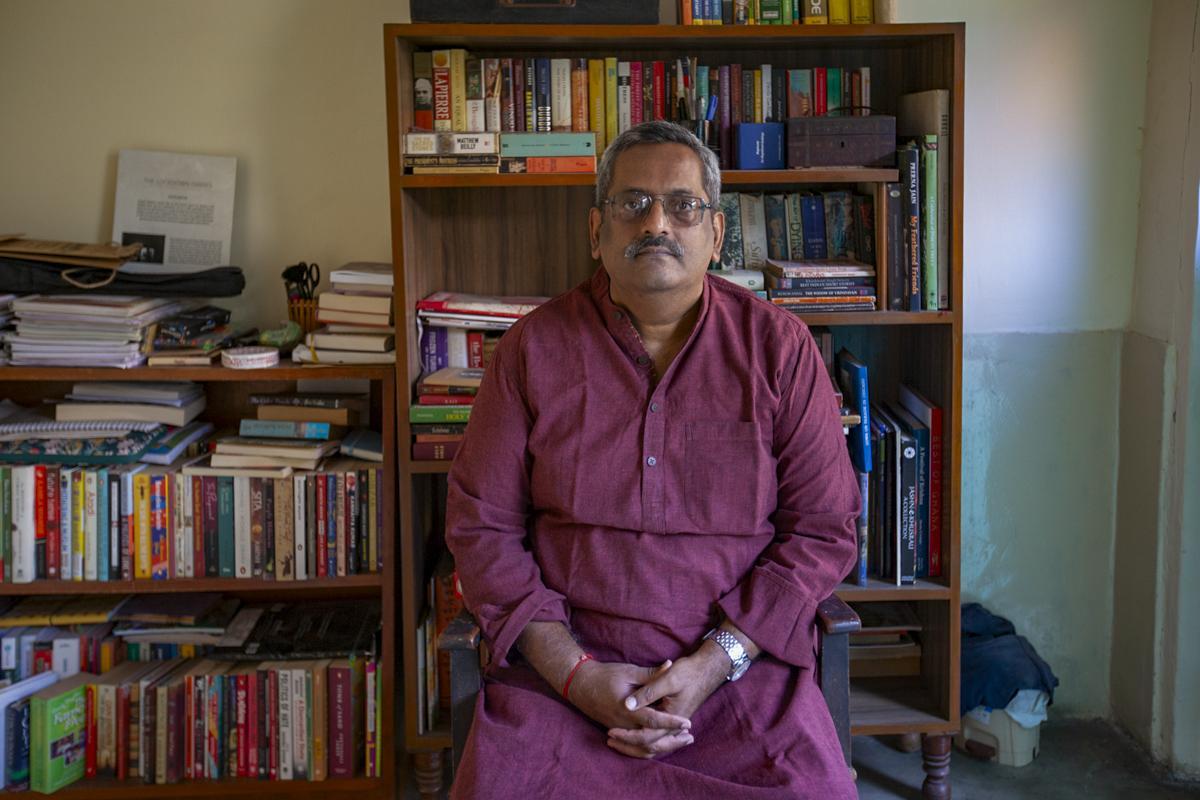

Walking through Ballimaran with my brother-in-law, Sudhanshu Mani, was a profoundly personal experience. He is a lover and self-taught scholar of Ghalib's poetry. He recently wrote a book comparing the works of Ghalib and Shakespeare and has even created and acted in a musical about Ghalib that has toured many cities. He's also known across India as the pioneer who led the development of the Vande Bharat modern trains, ushering in a new era of high-speed rail across the country. I photographed Sudhanshu in Ghalib's Haveli, dressed as Ghalib, wearing a Mughal-style hat and long coat, his expression calm and thoughtful as he quietly took in the moment.

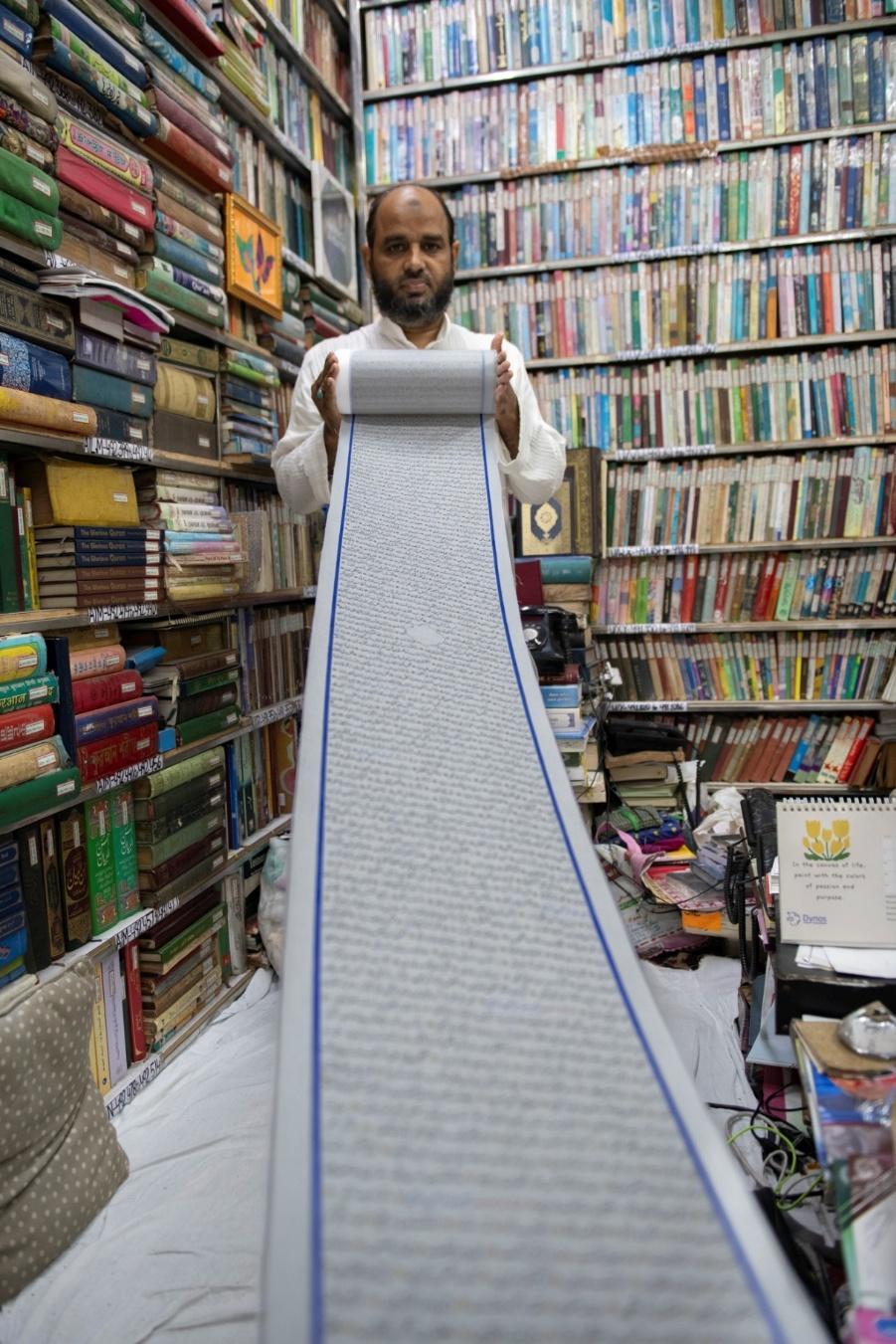

Nai Sarak: The Literary Spine of Chandni Chowk

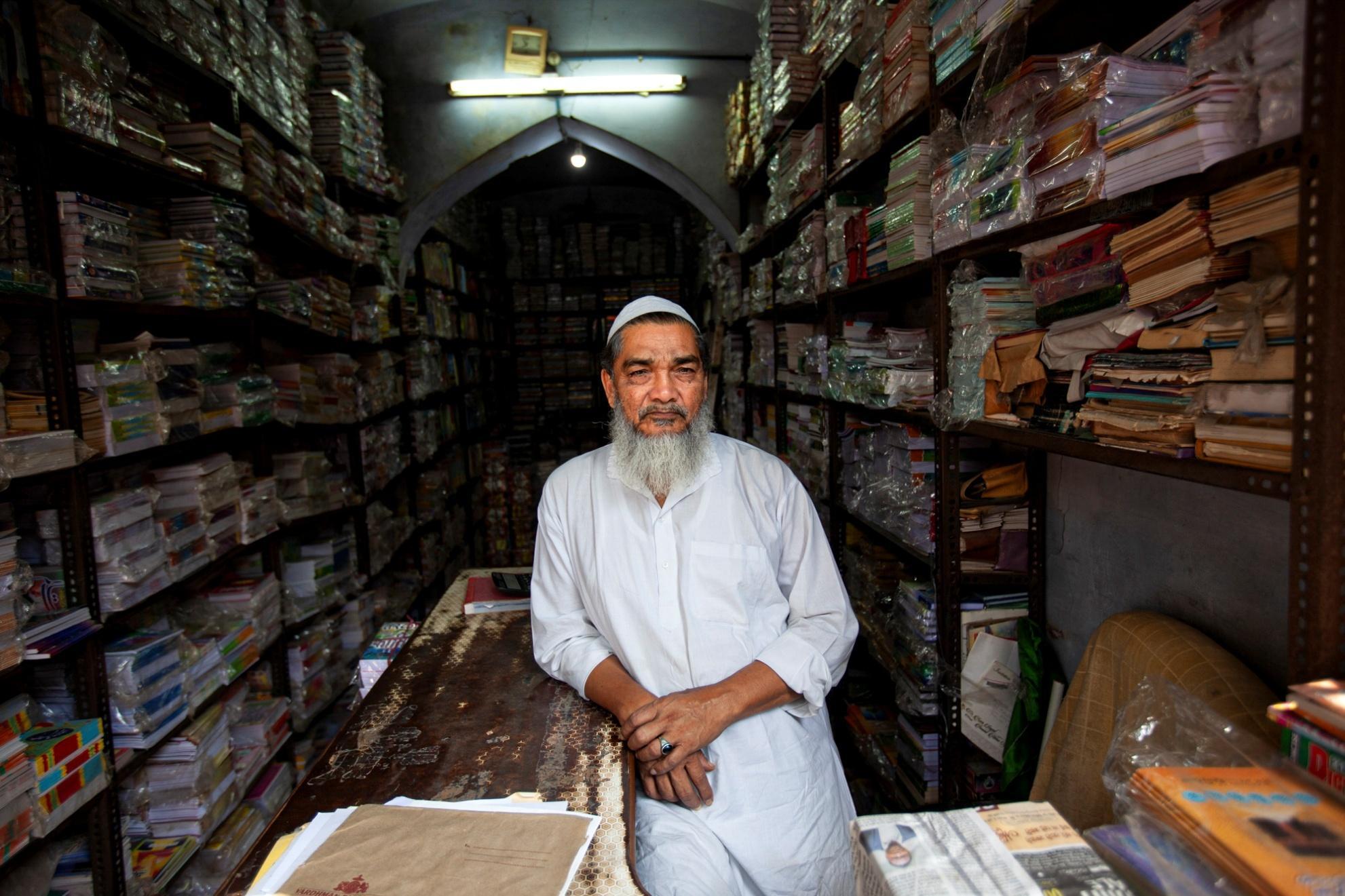

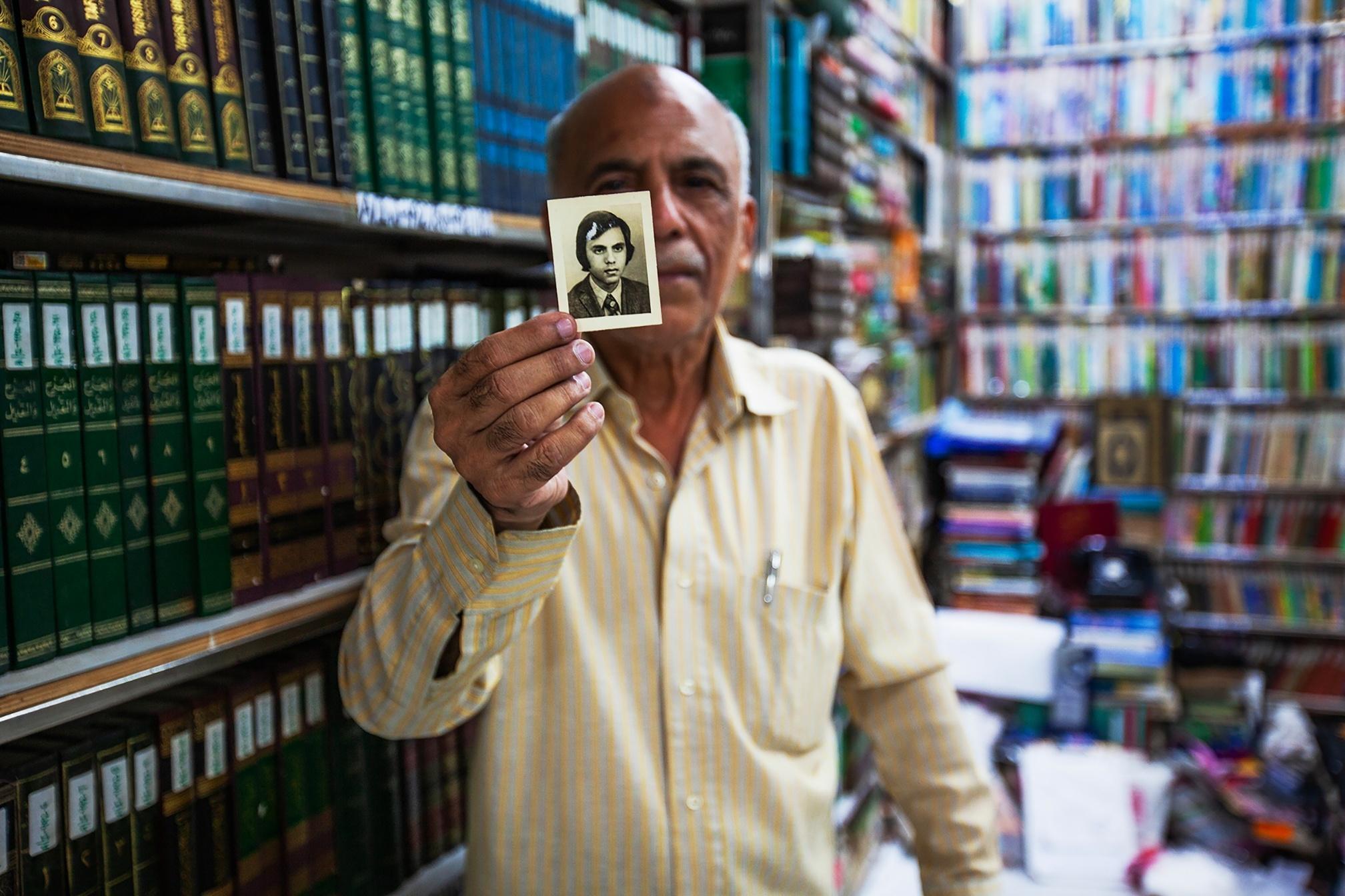

Built after the uprising of 1857, Nai Sarak has exuded a unique charm, attracting book lovers, teachers, students, and publishers, for textbooks and stationery. Its shelves are adorned with religious books, test preparation books, and even rare and old publications. These stores also offer a treasure trove of used books and calligraphy supplies. The allure doesn't end there; this is also where you can find handmade paper, fancy gold-edged bookmarks, and collectible pens.

As I strolled through Nai Sarak with my camera, a flood of childhood memories washed over me. I vividly recall the excitement of a new school year when my mother and I visited this market to buy our textbooks. The shopkeeper would bundle them together with jute string, and we would carry them home, brimming with anticipation, to explore the fresh pages and discover what we would be learning the following year.

The pace in this market is slower than in some other parts of Chandni Chowk. Students compare notes and prices, parents bargain with shopkeepers, and readers quietly search for hard-to-find titles. Shopkeepers know their books well and can quickly find what you need even from stacks that seem impossible to sort.

In an era dominated by online shopping and e-books, Nai Sarak stands as a testament to resilience. It continues to thrive, unwavering in its commitment to being the literary backbone of Chandni Chowk.

Chawri Bazar and Kucha Chelan: Echoes of Craft

In India, a wedding card is more than just an invitation mailed to its intended recipients. Families traditionally deliver the cards in person to friends and relatives along with dry fruits and sweets. The card designs vary from simple to elaborate, consisting of intricately decorated, multilayered cardboard boxes that reflect the theme of various wedding events.

A few years ago, I went to Chawri Bazar with my sister and niece, as they were looking for a wedding invitation card for my niece's upcoming wedding. We saw displays of cards ranging from a classic and straightforward printed card to elaborate boxes that resembled miniature treasure chests covered in embroidered silk fabrics. Some boxes had multiple compartments to include sweets, dry fruits, or artisanal chocolates as a token of sharing joy while adding sweetness and hospitality to the invitation. My sister chose a boxed card that wasn't just an invitation; it was an experience. It had multiple inserts, each an invitation for wedding events such as Mehendi, Sangeet, Reception, and Wedding. It was wrapped in a sheer organza sleeve tied with a satin ribbon.

Next to Chawri Bazar is a market called Kucha Chelan, which specializes in sanitary goods as well as kitchen and bathroom fixtures. Decades ago, my grandfather ran a successful plumbing business throughout India from a modest store in the area. Back then, it was a wholesale hub for brass and copper hardware, and these streets rang with the sound of copper being hammered and brass being polished. He could never have imagined that one day his lane would be filled with elaborate bathroom showrooms, including a transformed, luxurious version of his store, now featuring kitchen fixtures, run by his greatgrandson!

Chor Bazaar: Recycling India's Machines

Hidden behind Jama Masjid lies Chor Bazaar, also known as Kabadi Bazaar. It is one of India's oldest and most significant markets for used auto parts. The word "Chor" means a thief. Years ago, the market had a reputation for selling automotive parts that had been stolen; however, that is no longer true. Most stores now carry goods salvaged from old cars for recycling. While in the U.S., old cars are crushed and sent to landfills, places like Chor Bazaar give old machines a new life.

It's a place to find a rare carburetor, a side mirror from a discontinued car model, or a vintage motorbike part. Mechanics from small garages and car owners seeking affordable ways to repair their old cars come here to find used parts. There is a smell of grease and oil in the air.

For a photographer, Chor Bazaar offers a wealth of great images. The market feels chaotic at first, but there's an impressive system behind it all. Parts for cars, motorcycles, and scooters are stacked in a jumbled fashion. Still, the sellers are very knowledgeable and have their own inventory tracking system. On one of my visits, I asked a shopkeeper a made-up question: Do you have a clutch for a 2002 Toyota Corolla? Without any hesitation, he said, "Yes, sir, I have it right there, hidden behind those stacks of clutches at the back. Please come back in an hour, and I will pull it out for you, and it'll cost you ₹6,000." I wasn't looking for a part, but his confident, quick response said it all. These shopkeepers don't have any written lists of parts or computers. Still, years of working with these parts, fixing things, and dealing with automobiles of all makes and models have turned them into walking encyclopedias of the parts they carry.

Tucked away from the main road, Neel Katra is a cluster of narrow lanes and small courtyards filled with cloth shops and textile traders. It has been at the heart of Delhi's cloth trade for centuries.

The name "Neel Katra" originates from the words "neel," meaning indigo dye, and "katra," meaning a market area. During the Mughal period, this area was renowned for its trade in indigo-dyed fabrics. Although indigo is no longer the primary focus, the market is now filled with cloth in every color, texture, and pattern imaginable.

Walking through Neel Katra, you see shops stacked with rolls and rolls of cotton, silk, satin, chiffon, and velvet fabrics. Shopkeepers unroll them to show off delicate embroidery, shiny sequins, and rich prints. Their customers include retailers, fashion designers, and families shopping for weddings or special events. In today's age of online shopping, Neel Katra continues to thrive because people still want to see, touch, and feel the fabric before making a purchase.

Bhagirath Palace stands as a testament to India's rich history. This sprawling market, the largest in the country for electrical goods and lighting, is housed within the grand 19th-century haveli that once belonged to Begum Samru, wife of a a European mercenary who inherited his estate. The architectural elegance of this bygone era still shows through in the market, as arched doorways and faded frescoes peek through a maze of signboards, dangling wires, and towering stacks of electrical supplies.

To a photographer, Bhagirath Palace is a sensory storm. Endless shops filled with light fixtures, fans, switches, wires, transformers, and a wide variety of electrical parts inundate the view. Contractors, electricians, retailers, and homeowners visit here, enticed by the promise of unbeatable prices. They are confident that they can find anything they need, from decorative light fixtures to industrial circuit breakers, at prices that won't break the bank. Merchants practicing their trade at small counters also offer repairs. You often see them repairing fans or rewiring a chandelier with soldering irons, screwdrivers, and pliers.

Kucha Chaudhary: Delhi's Camera Market

Opposite Bhagirath Palace is Kucha Chaudhary. No sign marks the entrance; for those who know photography, this narrow lane in Chandni Chowk is legendary. The air is filled with the sound of shutters clicking. This is Delhi's Camera Market, considered sacred ground for photographers based in Delhi. They come here, not just to buy gear and get it repaired, but also to connect with other photographers, forming a unique and vibrant community.

As you step into the cramped and messy market, you're greeted by shopkeepers who exude a deep knowledge of camera gear and expertise in camera repair. In this bustling space, you will also find a small shop less than three feet wide, specializing in repairing electronic flashes.

I came to this market a few years ago when my old Minolta camera stopped functioning. A friend of mine said, "Go to the camera market. They will surely fix it for you." I was skeptical, but when I got there, the technician opened the camera like a surgeon, carefully examining each part, and fixed it in no time. I have been coming back since then.

All the images I've shot for this book were captured on a Canon DSLR. When I acquired this advanced camera a few years ago, I also upgraded all my lenses to the professional L-series. Working within a budget, I opted for the EF 70–200 mm f/4L IS II zoom lens instead of the faster f/2.8L IS III zoom lens, which was almost twice the cost. On one of my trips to the Camera Market, I found a used f/2.8 lens; the seller offered me a phenomenal trade for my f/4, noting that the f/2.8 was a tough sale, but my trade-in, the f/4, would fly off the shelf in no time.

Life on the Streets

The streets of Chandni Chowk, perpetually alive with sounds, colors, and a vibrant mix of people, are a testament to the enduring nature of street life. Its narrow, winding lanes not only connect homes and places of work but also become meeting grounds where peddlers sell their goods and, for some, where life itself unfolds. For centuries, people have made their living on these open streets. The street is a shop, a salon, an office, and an open stage where daily life plays out its timeless drama.

You see cobblers sitting on wooden platforms, repairing shoes. Many of them have been working in the same spot for decades, their tools neatly displayed, ready to polish and repair shoes while breathing new life into them.

You will find barbers giving haircuts or shaves on the sidewalks. You also see men walking around with ear-cleaning tools in a bag, ready to offer their services. In most cases, these barbers and ear-cleaners have learned their skills from their ancestors.

You may even find a masseuse, to whom people have been coming for years to ease their aching backs, shoulders, and legs, with their skillful hands and oil. You don’t need an appointment, and locals have trusted them for generations.

The streets of Chandni Chowk are sprinkled with chai stalls. The chai wallah has often been serving from the same place for so long that he is known to every shop around him, and within minutes, he can deliver steaming cups to nearby customers. The fragrance of cardamom and ginger drifts through the air, a comfort as familiar as the clink of glasses on his counter, creating a warm sense of belonging for the customers.

Walking through the lanes, you are enveloped in the delicious smells and flavors drifting from the food stalls. It’s not just the vendors along the roadside; there are also small shops open to the street that specialize in one or two dishes, some of which have been operating for decades, deeply rooted in history. While strolling, you might stop for a samosa, pick up some jalebis to take home, or savor freshly grilled kebabs. Each bite feels like tasting history itself, recipes unchanged for centuries.

Early in the morning, you may also find someone bathing in the open, having filled a bucket of water from a public faucet. Years ago, there were hand pumps gushing water into buckets, but now you see very few of these. In the evenings, many sleep on the same streets where they work during the day, seemingly undisturbed by the noise and chaos around them.

Balloon sellers and cotton-candy vendors weave through the crowds, bringing joy and color to the scene. Street performers, such as a young girl walking a tightrope to the beat of loud music, a skill she learned in childhood, perform with quiet charm. Her balance, fragile yet unshaken, mirrors the rhythm of Chandni Chowk itself: precarious, vibrant, enduring.

Ancestral Families of Chandni Chowk

Chandni Chowk is a neighborhood where many families have lived for generations. While some families are living in old havelis, most residents live joyfully in modest homes.

The Mathur Bahadurs were one of the oldest affluent residents of Chandni Chowk. During the Mughal and the British Raj eras, these families served as legal and financial advisors. Their grand havelis were places where neighbors gathered, legal and financial issues were settled, and guests were welcomed. In the early twentieth century, most of these families moved to secluded gardened bungalows in the newly established area near Chandni Chowk called Civil Lines. Yet, the memory of Chandni Chowk remains vivid in their collective consciousness. One of the descendants of such families is Atul Bahadur, a childhood friend of my brother, who lives in Civil Lines with his wife, Ashwini. I have known Ashwini for many years, as she is highly respected in Delhi art circles. Her knowledge and connections in Chandni Chowk turned out to be the driving force behind this book, and she became our guide when I started working on it. It is through her that I met Ashok Mathur, whom we now fondly call "Mr. Chandni Chowk."

Ashok Mathur has a Haveli near Nai Sarak; his family has lived there for several generations. A cultural enthusiast at heart, Ashok is very active in the Chandni Chowk community and frequently gives walking tours of the area, occasionally organizing ghazal and musical evenings, as well as talks in his haveli. He has walked us through Chandni Chowk's hidden corners, introducing us to many families who, like him, continue to make Chandni Chowk what it is. "Our roots are not just in the soil," he once said. "They are in memory. If we don't live them, they dry up."

In Ballimaran, we visited the home of Hakim Masroor Hasan, descendant of a prominent family of hakims who practice Unani medicine.. Today, Masroor continues the tradition of healing in the same haveli that breathes with life. Shelves lined with herbal concoctions, handwritten prescriptions, and whispered consultations continue a tradition of healing that has remained unbroken for over a century. His son Muneeb is now a lawyer in the Supreme Court, continuing the family's legacy of public service.

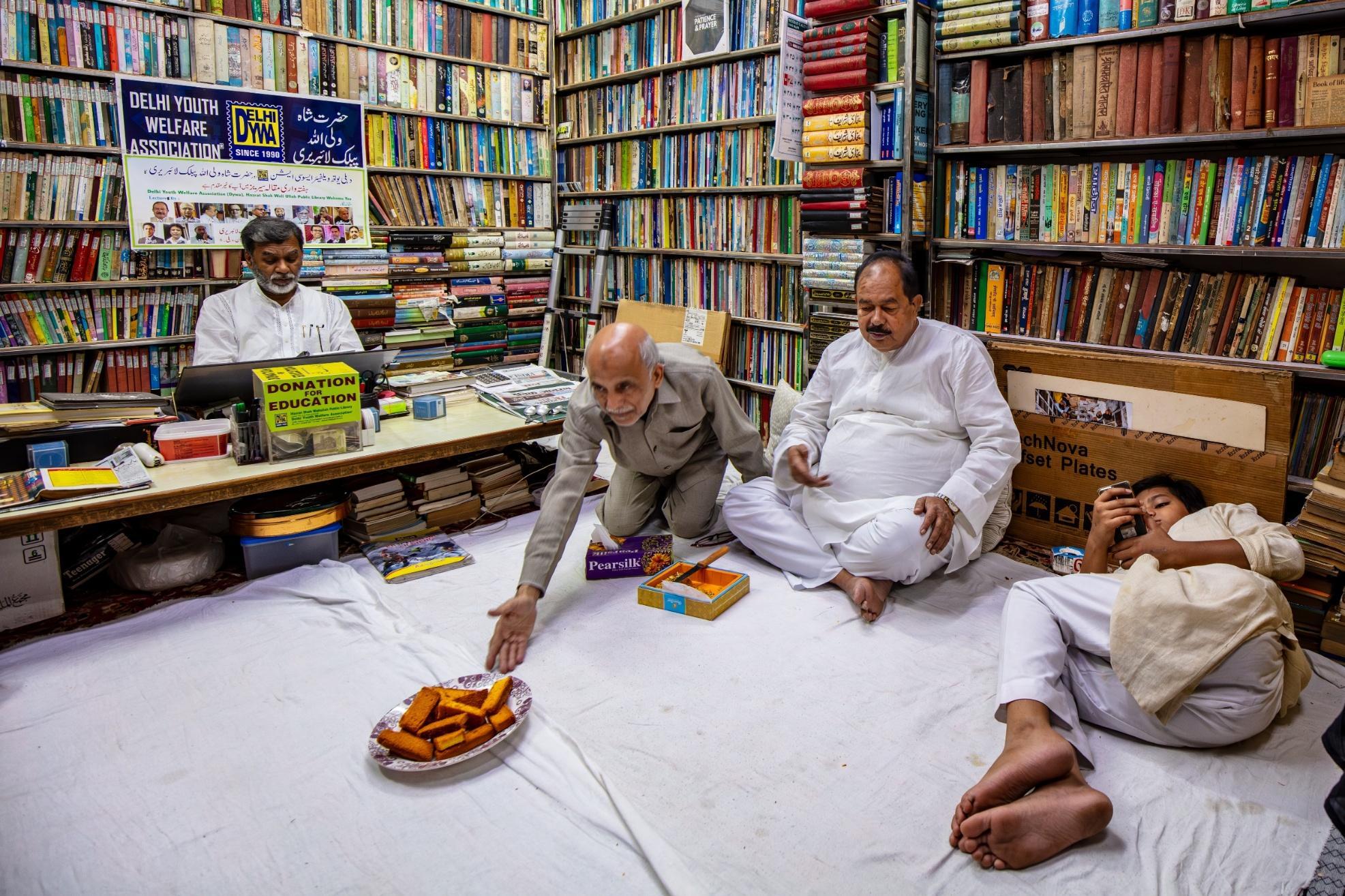

Asad Bhai's family has been printing and retailing Qurans for many generations. Although he has recently moved out of Chandni Chowk, he still maintains his haveli as a cherished place for family gatherings and worship. He invited us to a traditional lunch one day, called a dastarkhwan. We enjoyed a ceremonial spread of a conventional Muslim meal, where a tablecloth was laid out on the floor. We sat around it on the floor, sharing fragrant biryani, kebabs, and rich curries from the same central platter. Meanwhile, Asad Bhai's wife served us rotis warmed on a small angithi chulha in the center. Dastarkhwan signifies generosity, hospitality, and unity, where family and friends eat together.

On a rooftop overlooking Chandni Chowk, Gopal Sharma practices kabutar bazi a Mughal-era tradition of pigeon flying. He releases a flock of pigeons, guiding their synchronized flight with whistles.

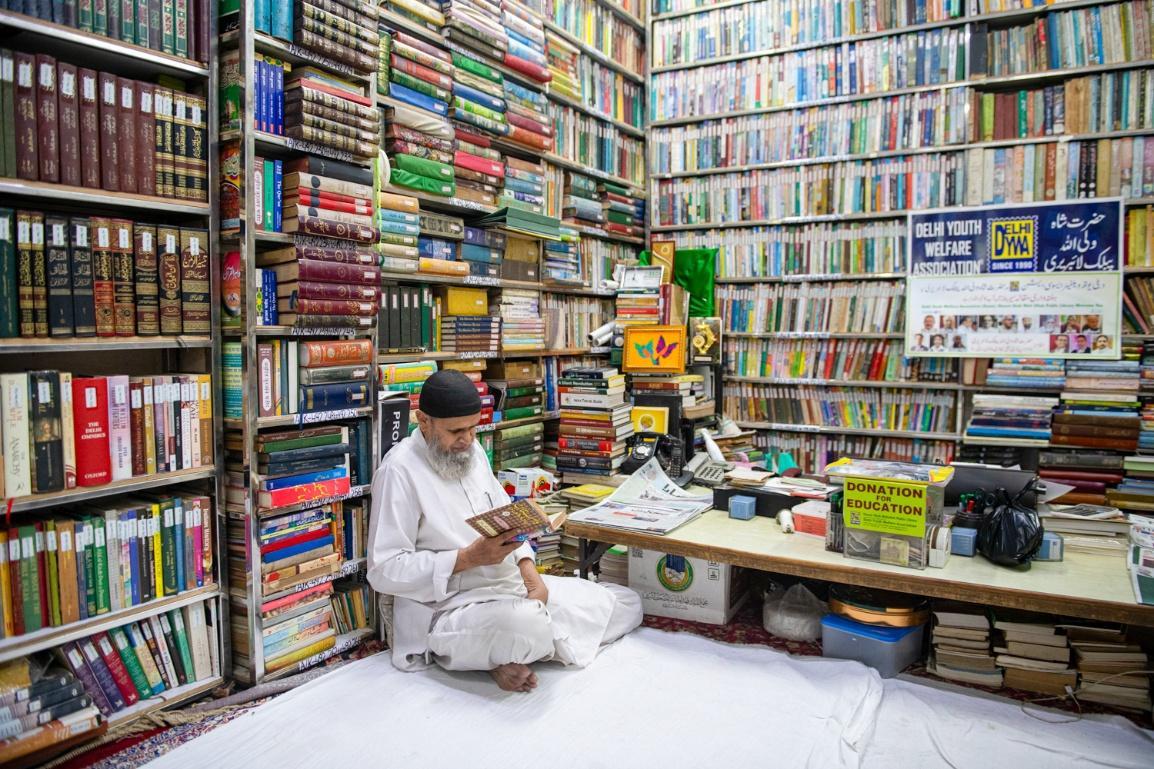

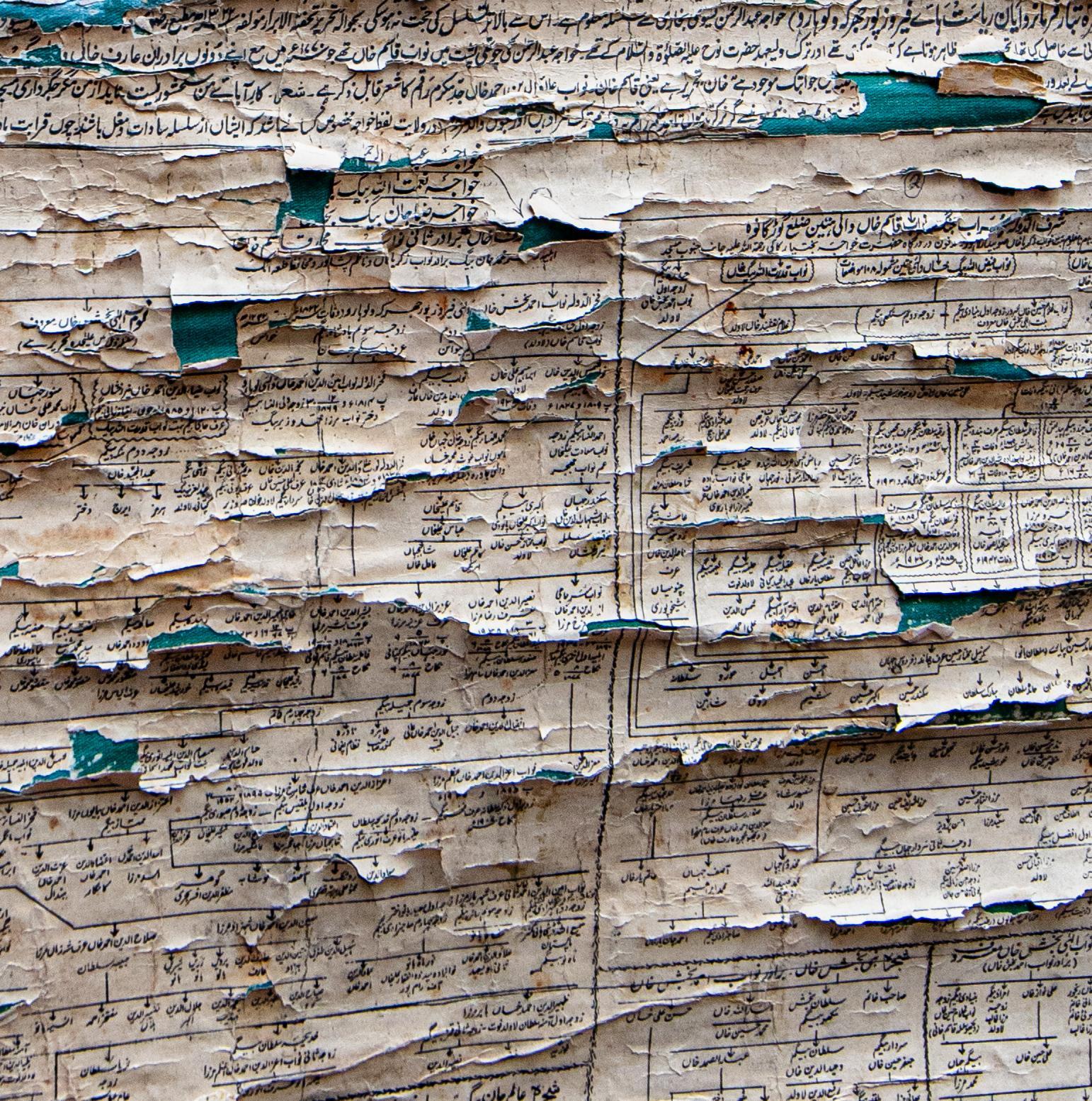

Not far from Jama Masjid, we visited the home of Mirza Naseem Changezi, an oral historian and freedom fighter born in 1910. His modest haveli, lined with shelves of Persian, Arabic, and Urdu books, functions as a baithak (sitting room) for storytelling and intellectual exchange. Mirza Changezi's encyclopedic knowledge of Delhi's vanished shrines, Mughal customs, and the days of Partition was not found in books but in his memory. Today, his son, Mirza Sikander Beg, continues to steward the family's legacy, curating the Shah Waliullah Library, which houses over 2,000 volumes from Changezi's personal collection.

Not all families live in big havelis. Tucked within lanes and courtyards are smaller, humbler homes. These homes are often rented, sometimes barely a single room, where generations of families live in quiet dignity. These are the homes of hospitality workers, shop assistants, street vendors, rickshaw drivers, and countless others whose livelihoods form the lifeblood of Chandni Chowk's economy. In many cases, they have served the same employer for generations.

While many families have moved out of Chandni Chowk to modern homes and high-rise apartments in other parts of Delhi, these families continue to live, work, and worship in Chandni Chowk. "Living here isn't always easy," Ashok once told me after a long day of photographing. "But every morning, I wake up and I hear the street come alive, vendors calling out, temple bells, azan, school kids laughing. Where else can I live with that kind of music?"

Moving the City: The Human Engines of Old Delhi

The cycle rickshaw drivers who pedal visitors through its bustling bazaars and the Thela Wallahs and porters who shoulder its commerce are the human engines of Chandni Chowk. They keep the city moving through their strength and perseverance.

Rickshaws, three-wheeled vehicles powered by a person pedaling, have been a part of Chandni Chowk as long as I can remember. They are deeply intertwined with the Chandni Chowk cultural fabric, contributing to its unique character. They are the best mode of transportation in the crowded, narrow market lanes. But more than that, they offer a unique sensory experience from the perch of the rickshaw seat, allowing you to immerse yourself in the sights, sounds, and smells of the market, from the aroma of spices to the lively chatter of vendors and shoppers.

Every winter, I take a trip to India to attend the renowned Art Fair in Delhi. In 2025, Carol Huh, the curator of Contemporary Asian Art at the Smithsonian National Museum of Asian Art, accompanied me. Naturally, anyone visiting India with me doesn't just see the art fair they get the whole Delhi experience. It always includes a visit to the Chandni Chowk area. I believe the best way to experience the vibrant markets of Chandni Chowk is to take a ride in a rickshaw.

Carol and I climbed onto a rickshaw with a red vinyl seat, which had a few patches held together with duct tape. Rafiq, a thin man wearing a faded cap and a friendly smile, was our driver.

"Kinari Bazaar?" I asked. He nodded. "Yes, sir. Sit. I take you, then you see all Old Delhi."

The narrow lanes of Kinari Bazaar are where Delhi comes to dress up rows upon rows of zardozi borders, sequins, lace trims, brocade, tassels, and wedding finery glinting under shop lights. Carol, soaking it all in, said, "It feels like a carnival," and wanted to know if Rafiq drove the rickshaw every day.

"Every day, Memsaab," he said. "Since 2002. Before that, I was in Bihar. Farming. But Delhi has more work." "Long hours?" I asked. "Morning till dark, sir. In the Delhi wedding season, it is madness

Behind us, another rickshaw rang its bell, eager to pass. As we entered Dariba Kalan, Carol noted the contrast less frantic, more ceremonial. It was a corridor lined with jewelry shops, selling silver chains, nose rings, anklets, and filigree earrings that glinted behind glass. But the stillness didn't last. We soon emerged into the very noisy Chawri Bazar, a place filled with wedding cards, paper goods, and brass fittings.

"Now I show you one more," Rafiq grinned, "Ballimaran. For glasses. Shoes. Style!"

He wasn't wrong. The mood changed again as we rolled into Ballimaran, a lively street where sunglasses hung like decorations and shoes were stacked high in roadside pyramids fake Adidas, glittering juttis, bright neon sandals. We saw a barber giving someone a shave right on the sidewalk, while his next customer waited with a cup of tea in hand. This was street fashion at its boldest loud, raw, and full of life. Rafiq brought us back to the Jama Masjid area, where our car was parked.

"How much?" I asked. He shook his head. "You tell me, sir." I handed him ₹200. It wasn't much for masterful navigation and stories. He accepted it with a graceful nod.

"Come again," he said with a grin. "Next time, I show Memsaab Fatehpuri. Or Sitaram Bazaar.”

Seeing Chandni Chowk from the seat of a cycle rickshaw isn't just a tourist experience it's a unique perspective that offers a profound understanding of this place. It's the best way to take in the crowded beauty of this place without getting swallowed by it. In a rickshaw, you move slowly, close to the ground, close to the people. And drivers like Rafiq aren't just taking you from one place to another; they're storytellers and guides, offering a perspective that's both intimate and enlightening.

There are also larger auto rickshaws on the road. They're faster, louder, and just as essential, a lifeline for locals and delivery workers. But in the tight inner lanes of Chandni Chowk, it's only the humble cycle rickshaw that can get through.

In the bustling heart of Chandni Chowk, where cars struggle to navigate and most lanes are too narrow even for scooters, the true heroes of the marketplace emerge-the Thela Wallahs. These men, who push wooden carts laden with goods through the chaos, and the porters, who balance enormous loads on their heads, are the human force that keeps Chandni Chowk running like a well-oiled machine. Their work is not just hard, it's a testament to their resilience and determination, honed over years of navigating these crowded streets.

The thela is a simple wooden cart with strong iron wheels, perfect for moving through the narrow lanes of Chandni Chowk. Thelas carry all kinds of goods: sacks of spices from Khari Baoli, bundles of fabric from Neel Katra, and reams of paper from Chawri Bazaar.

These men are very knowledgeable about every shortcut, every corner, and how to move quickly through crowds, rickshaws, and animals wandering in the narrow streets. If something needs to reach a small shop down a narrow lane, it's the Thela Wallahs who will get it there.

For a photographer, the sight of a Thela Wallah pushing a cart stacked high with parcels or a porter balancing a large bundle of goods is iconic. It represents the raw, unfiltered energy of Chandni Chowk a place where human perseverance triumphs over urban chaos.

Just as necessary are the porters men who carry heavy loads on their heads, often climbing stairs or ducking through tight alleyways. They carry everything from lentil sacks to stacks of cloth, delivering goods directly into shops with strength and balance that is truly amazing.

The Living Culinary Heritage

Delhiites unanimously agree on one thing: Chandni Chowk is a timeless food haven. The fact that many food joints have stood the test of time for over a century makes it not just a place of historical significance, but also a living testament to its culinary heritage.

Strolling through Chandni Chowk is a sensory journey that takes you back in time. Depending on the area, you'll witness samosas sizzling, kebabs grilling, and sweets simmering in syrup. The symphony of cooking and food orders blends with the already vibrant street sounds, creating a unique rhythm.

Street food vendors scattered throughout Chandni Chowk play a central role in the local food culture. They move through the narrow lanes with carts and baskets, carrying a variety of delicious snacks, from kachoris and chaat to kulfi and seasonal treats like daulat ki chaat. Each vendor has their own route or a set location and loyal customers who have been enjoying their delights for years.

Delhi’s tropical weather calls for falooda and kulfi. Since 1947, Giani’s Di Hatti has been serving its iconic rabri falooda, so thick and creamy that you need a lot of patience to relish it. Kuremal Mohan Lal Kulfi Wale takes kulfi to the next level, stuffing frozen, flavored milk into hollowed-out fruits sliced open like a surprise dessert. And then there is Hazari Lal Khurchan Wale, who has been making the most delicious khurchan, with layers of slowly thickened milk topped with sugar, cardamom, and a shimmer of silver, in the same way for more than 90 years.

While the street food of Chandni Chowk remains alive and well, the food scene is evolving. In 2024, Dawatpur, the largest food court in India, opened in the new, modern, and air-conditioned Chandni Chowk mall. But for me and many others in Delhi, the real magic of food in Chandni Chowk still lies in its streets where jalebi boils in open cauldrons and kebabs roast on charcoal grills just as they have for over a century.

The Paratha Wali Guli (Lane)

My visits to India, especially when my mother was alive, always included a cherished ritual - a stroll through Gali Paranthe Wali in Chandni Chowk. This narrow lane, steeped in history, has always been one of Delhi’s most iconic food destinations. The eateries here serve deep-fried parathas, hot and crispy, straight off the tawa, stuffed with a variety of fillings.

We always returned to the same paratha wallah in the corner, featuring nearly thirty spicy, savory, and sweet fillings. My mother must have tried them all. My favorites have always been Gobhi (cauliflower) and Mooli (radish), served with tangy chutney, pickles, and a peppery aloo sabzi.

The first shops in Gali Paranthe Wali began in the 1870s as a row of eateries catering to vegetarian Jain and Bania merchants. By the early twentieth century, more than twenty shops lined the lane, each family-run and offering its unique selection of fillings. Many shops have closed in recent years, and now fewer than ten remain, all still operated by descendants of the original families who started them.

Gali Paranthe Wali has been featured in Bollywood films, some filmed on-site, and others recreated to evoke the flavor of Old Delhi. For me, Gali Paranthe Wali will forever be tied to memories of my mother. I picture her sitting on a narrow bench, her eyes lit up with excitement. She would always say she wanted to try something new, but somehow, she always returned to her favorites.

At Natraj Dahi Bhalle Wala, the menu has stayed the same since 1940, featuring only two dishes-Dahi Bhalle and Aloo Tikki. The Dahi Bhalle, with perfectly soaked lentil fritters, smothered in creamy house-made yogurt and topped with tamarind chutney and spices, are a delight for the taste buds. The Aloo Tikki, golden and crisp, offers a burst of tang and heat.

Served on leaf bowls or paper plates, these dishes have stood the test of time, just like the shop itself. The shop is simple, featuring a street-level counter and modest seating upstairs. During my photo walks, I stop here often, not just for the food, but to watch families, students, office workers, and tourists gathered in a semicircle around this corner shop.

What makes Natraj special is its steady tradition. The recipes have remained essentially unchanged for over 80 years. There are no branches, no flashy signs, just quiet, reliable, two simple dishes.

My grandson, Archie, loves jalebis, though thanks to his health-conscious parents, he enjoys only one or two every month usually store-bought and lacking in freshness. As I buy them for Archie in the US, I am often reminded of Old Famous Jalebi Wala near Dariba Kalan. Once you’ve tasted their jalebis fresh, hot, and glistening with pure desi ghee and syrup, you realize how far most jalebis have strayed from their authenticity.

Established in 1884, this small shop consistently draws crowds, enticed by caramelized sugar and warm ghee. The jalebis are thick, crisp, and syrupy, following their secret age-old recipe.

Bollywood icon Raj Kapoor and former Prime Ministers, including Atal Bihari Vajpayee, Jawaharlal Nehru, and Rajiv Gandhi, are known to have relished the jalebis here. I dream of taking Archie there one day, watching him bite into a warm jalebi, syrup dripping down his fingers, hoping the memory will stay with him as it has with me.

The Mughal Cook’s Legacy

As a passionate foodie, I maintain a list of the twenty best meals of my life. Karim’s Hotel, behind Jama Masjid, has been on that list forever.

Founded in 1911 by Haji Karimuddin, a descendant of Mughal court cooks, the restaurant’s initial offerings were limited to aloo gosht and dal, served with roomali roti More than a century later, their menu has expanded exponentially and now essentially defines the best Mughlai cuisine available in Delhi.

Over the years, the restaurant has expanded into dining areas in multiple buildings across the street from each other. The central kitchen is on the second floor with an open window. You hear waiters yelling orders from the street level to the kitchen. At the same time, the head server sits in one corner on the street, surrounded by piping hot, ready-to-serve curries in large metal containers. The smell of charcoal and the aromas of spice fill the air. The rotis arrive hot, and slow-cooked gravies are thick, each bite steeped in tradition. The smoky mutton burra and overnight-cooked nihari are unforgettable here. Even though Karim’s now has branches in other places, nothing compares to the original.

For me, eating at Karim’s has become a quiet ritual of my trips to Chandni Chowk. It captures the heart of Delhi’s rich and lasting food traditions. Every time I go to Karim’s, it moves up a notch on my list of top twenty meals of my lifetime.

A Walk Through Matia Mahal: The Heartbeat of Chandni Chowk

To truly feel the spirit of Chandni Chowk, you have to walk through Matia Mahal. But take your time: breathe in the smells, listen to the sounds, and soak in the atmosphere.

Matia Mahal is a narrow, lively street filled with color, movement, and mouthwatering smells. It is one of the busiest and most exciting parts of Chandni Chowk. The street is filled with rickshaws, vendors, and pedestrians all trying to navigate the same tight and crowded space, yet somehow, it all flows.

Stepping into Matia Mahal from Jama Masjid, one's senses are immediately tantalized by the aroma of sizzling kebabs, fresh tandoori bread, and sweet attars (perfume oils) sold in tiny shops. The street is home to two culinary gems: the famous Karim's Hotel, known for serving dishes made with recipes from the Mughal royal kitchens, and Al-Jawahar, another favorite for Mughlai food. Both are always bustling with people savoring juicy kebabs, rich kormas, and fragrant biryanis. The variety and richness of Mughlai cuisine served here will leave you excited and hungry for more.

For a photographer, Matia Mahal is more than just a food street. It's a cultural hub of small shops selling embroidered kurtas, prayer caps, tasbihs (prayer beads), and Muslim religious books. During the holy month of Ramadan, the whole of Matia Mahal transforms into a vibrant celebration. Colorful decorations and food stalls appear on the streets, and the lively buzz of people eating, shopping, and chatting fills the air, lasting well into the night.

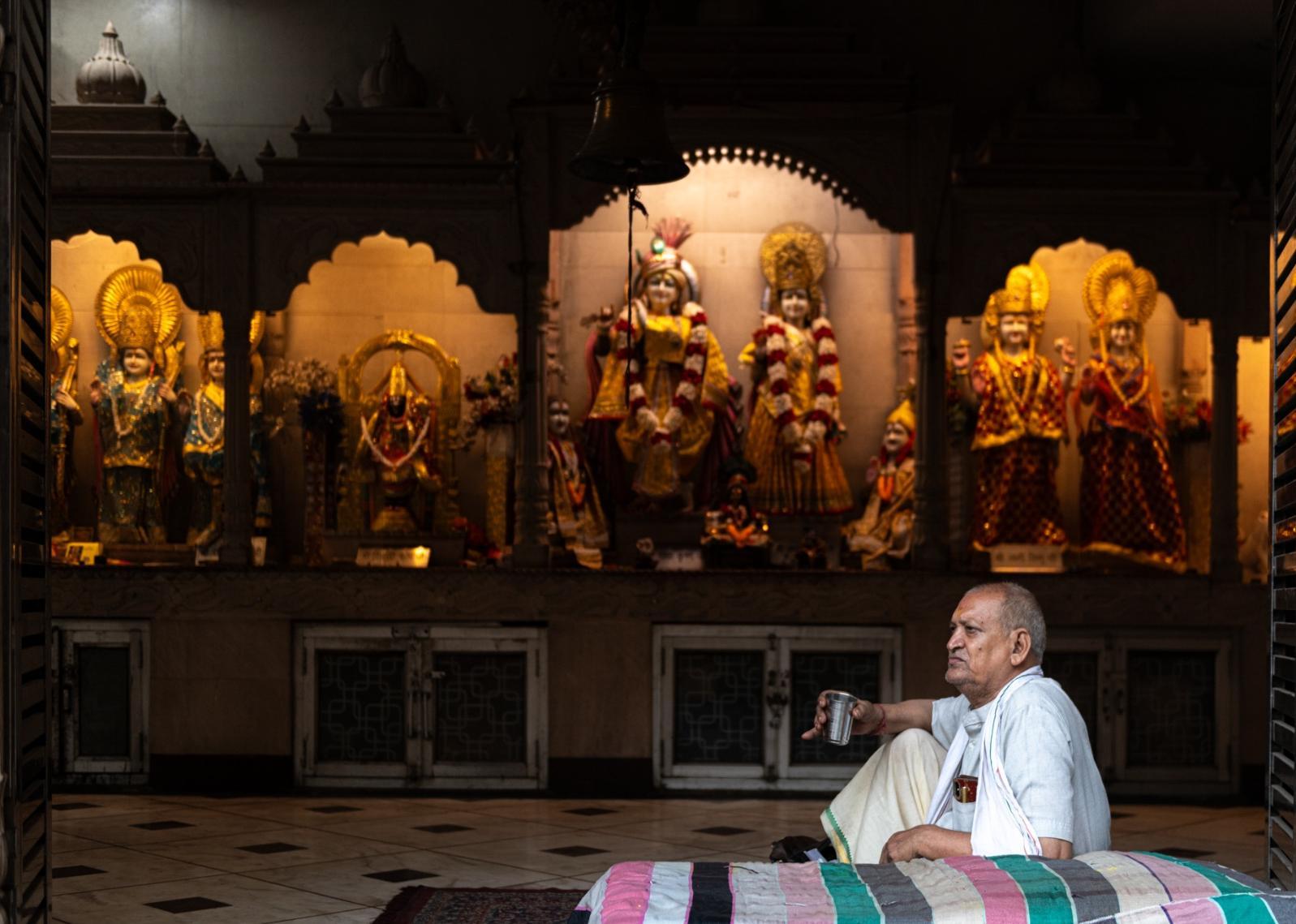

A Sacred Mosaic: Faith in the Old City

Chandni Chowk is also a place of deep spirituality. Walk a few steps in any direction, and you'll see people praying in mosques, offering flowers and lighting incense in temples and shrines, or volunteering in the kitchen of a gurudwara. Faith is visible everywhere here, woven into the rhythm of daily activities.

Constructed by the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan in the 17th century, the grandeur of Jama Masjid, one of India's largest mosques, is a testament to Mughal architecture. It has not only served as a place of worship but also as a communal space where the Muslim community gathers, rests, and contemplates. Jama Masjid, a pivotal landmark in the spiritual and social life of Old Delhi, is a beacon of the Muslim community's spiritual journey in the city.

Established in 1656, during Shah Jahan's reign, the Shri Digambar Jain Lal Mandir stands as Delhi's oldest Jain temple. The Jain community, renowned for its acumen in commerce and wealth management, has long upheld its temples, as evidenced by the opulent beauty of the Jain sacred spaces in Chandni Chowk. The newer, smaller Jain temples nestled in the narrow lanes of neighborhoods like Dariba Kalan and Kucha Mahajani, adorned with marble, glass, and intricately designed paintings, are a testament to the unwavering faith of this community.

Built in the 18th century is a Hindu temple called Gauri Shankar Mandir. Dedicated to Lord Shiva, it houses a silver-covered lingam said to be over 800 years old. Devotees stop by to pray throughout the day; shopkeepers before opening their shops, rickshaw drivers between their rides, locals living in Chandni Chowk, and visitors passing through. It stands as a reminder that devotion here is simple, steady, and shared by all.

Roadside temples are also scattered all over Chandni Chowk. These are tiny temples, and in some cases, just a shrine in an alcove occupying the interstitial spaces between shops and buildings. While going to work in the morning, shopkeepers stop for a few moments to light a lamp, place marigold flowers, or say a prayer before beginning their day.

Nearby stands the Central Baptist Church, built in 1858. Urdu inscriptions on its walls speak to Delhi's diverse past. The church also runs a school for local children of all backgrounds, offering education and care to families in the area. It remains both a place of worship and community service.

A little further down the street is the Sis Ganj Sahib Gurudwara. It was built on the site where the ninth Sikh Guru, Guru Tegh Bahadur, was executed in 1675 for defending religious freedom. Run by volunteers and supported by donations, its langar (community kitchen) serves over 10,000 free meals every day, reflecting the Sikh belief in selfless service to the community. The gurudwara continues to embody Sikh values of equality and service.

What truly sets Chandni Chowk apart is not just the multitude of places of worship it houses, but the harmonious coexistence of these diverse traditions. The call to prayer from the mosque may harmonize with the ringing of temple bells nearby. A Sikh volunteer may serve hot food while, across the street, a Hindu priest ties a sacred red thread around a worshipper's wrist. This is more than mere tolerance; it's a genuine coexistence. People of different faiths not only reside near each other here, but they also share space, time, and everyday experiences. The sacred life of this neighborhood serves as a poignant reminder that peace isn't just a distant dream; it's a living reality. This coexistence is what truly defines Chandni Chowk's sacred mosaic

A Stillness in Motion: Photographing Friday Prayers at Jama Masjid

Jama Masjid attracts visitors from around the world to marvel at its architecture and appreciate its significance. But Fridays are different. The pulse of Chandni Chowk begins to change; streets get quieter and traffic eases. By mid-morning, Muslim men in white kurtas and prayer caps start to converge on the mosque. Women and younger girls, segregate into the covered courtyards on the side of the mosque. Everyone removes their shoes and washes their hand and feet as all men secure a place on the floor in the mosque's vast central courtyard.

Then the Adan begins the call to prayer echoing across sandstone, cutting through the din of the city. It's not just a summons; it's a declaration, a moment of pause and realignment. When the imam begins to deliver the khutbah, the Friday sermon, the atmosphere becomes even deeper. This is Jumu'ah, the most important prayer of the week, a time of collective reflection and unity.

For a photographer, this is when the visual narrative shifts. The courtyard becomes a sea of worshippers; rows aligned with calligraphic precision. Jama Masjid's geometry, its arches, domes, and minarets, guide the eye, but it's the people who complete the frame. Thousands rise, bow, and prostrate in unison, like a wave of movement across the stone. You see closed eyes, calloused hands with palms open to the sky, and foreheads resting against stone.

After the prayer, the atmosphere lightens immediately. Laughter returns. Children run around. Friends embrace. Vendors reappear on the steps. The devotees put on their shoes and return to their everyday lives.

Dussehra in Chandni Chowk: A Festival of Tradition and Community

There is no place in India where Dussehra is celebrated with as much enthusiasm as in Chandni Chowk. The festival, marking the victory of good over evil, has been part of Chandni Chowk's traditions since the Mughal era, when Hindu festivals were celebrated alongside Islamic ones with royal support, making them a symbol of Delhi's shared cultural spirit. This long history gives the festival special significance in Old Delhi. Dussehra is not just a festival, it's a celebration of our shared values and the triumph of righteousness over evil.

The heart of these celebrations is the Ramlila, a theatrical presentation of the epic Ramayana that spans eleven days, brought to life through music, drama, and colorful sets. While several Ramlilas take place all over Delhi, some of the best ones are held in Chandni Chowk, the Ramlila Maidan grounds near the Red Fort being the most famous stage. While some professional actors are now starting to appear in these Ramlilas, for the most part, the actors hail from local families that have performed in Ramlilas for generations. The climax of Dussehra's eleven-day celebration is the burning of Ravana's effigy, symbolizing the victory of good over evil.

In Chandni Chowk, there is another long-standing tradition, the Ramlila Savari, a grand procession through the streets during the Dussehra festival. Actors dressed as Lord Ram, Sita, Lakshmana, Hanuman, and other characters ride on decorated chariots, reenacting scenes from the Ramayana. Local marching bands, dancers, and costumed demons join in, transforming the streets into a moving theatre; a veritable treat for photographers. This procession is one of the most anticipated events of the season.

These memories are personal to me. My uncle lived near Nai Sarak, and during our entire Dussehra holidays, we would stay with him to enjoy the Ramlila and Savari every day. We spent evenings following the processions and at dusk went to the Ramlila, all the while indulging in Chandni Chowk's famous street food jalebis, kachoris, and chai. For us, the festival was just as much about family and food as it was about the processions and performances.

The Last Keepers of Craft

As a child walking through the lanes of Ballimaran, I recall being surrounded by the sounds of hammers striking silver to create ultra-thin silver foil for decorating sweets, paan, and ceremonial offerings. The artisans, known as varak wale, hammered all day on small nuggets of silver, each placed between layers of ox-gut leather (pattas), until it flattened int a delicate, translucent sheet. These leaves were then transferred to wax paper, ready to be used for decorating sweets at a Halwai (sweet maker). Today, this art has been completely replaced with machine-made varaks. With it, the ancient rhythm of a hammer and hands has faded into silence a victim of technology. This is a craft that has completely disappeared.

Not so long ago, Chandni Chowk was a thriving hub of artisans, each practicing a trade that is now on the brink of extinction. Yet, if you delve deep into the old lanes, you’ll still find a few artisans. They endure, quietly and skillfully, keeping their crafts alive with the same passion and dedication as before. Their perseverance is truly inspiring.

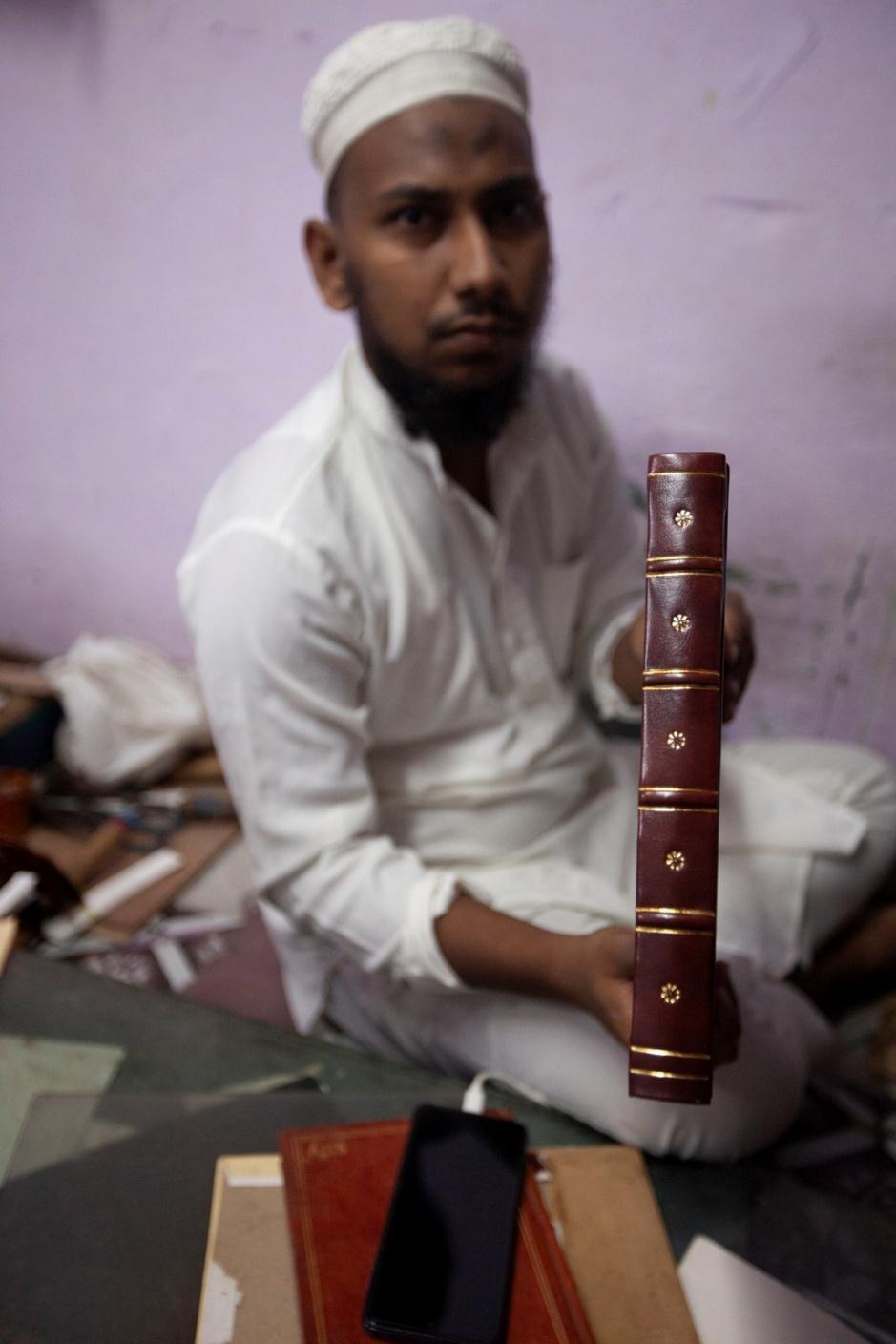

In a dimly lit workshop off Nai Sarak, we photographed a young bookbinder in a room filled with piles of worn ledgers, heirloom Qurans, and rare books in need of repair. Each book is taken apart, re-sewn by hand, its cover re-lined with cloth or leather. “Binding a book is like fixing a broken story,” he told us, his eyes gleaming with pride. This skill still survives, albeit only in a few workshops.

In the narrow back lanes of Chandni Chowk, the Kalaiwalas, traditional tinners, once practiced a humble yet essential craft: restoring brass and copper utensils with a gleaming layer of tin. Before every major family celebration, households would send their brass parats and degchis to the Kalaiwala. Today, in the age of stainless steel and non-stick cookware, this profession is on the decline, being called upon only occasionally to revive treasured heirloom utensils for weddings and festivals.

In a modest workshop tucked into a narrow lane of Chandni Chowk, we photographed a group of zardozi karigars, sitting cross-legged, quietly embroidering sheer veils with gold and silver threads. Bent over wooden frames, their fingers stitched paisleys, vines, and floral motifs onto thin, shimmering fabrics. After hours of meticulous labor, the fabrics they craft are eventually transformed into glamorous gowns to be walked down a distant runway in a fashion show.

Inside Haveli Haider Quli sits a master watchmaker, Ikhlas Ahmed Shafi, who was trained in Switzerland. Surrounded by cuckoo clocks, vintage wall clocks, and century-old timepieces, he meticulously brings back life to heirlooms and discarded watches. His unique skills make him among the last watchmakers in Delhi with this level of expertise, a true treasure in the city.

In Sui Walan and Ballimaran, a few master artisans still practice the art of Khatati engraving Quranic verses and Urdu poetry into marble. These meticulous calligraphic engravings were once commissioned for mosques, mausoleums, and shrines; however, machine engraving has since overtaken much of the demand. A handful of ustads still chisel each curve and line of Naskh script to preserve the rhythm and language in stone, which no machine can replicate, keeping this art alive.

These artisans, stitching pages, polishing brass, embroidering gold, repairing clocks, or carving stone, are the last keepers of crafts that once defined Chandni Chowk’s living heritage. Their work, now rare, is crucial for the continuity of our cultural heritage. To lose them would be to lose a vital thread of Chandni Chowk’s story. Their work is a testament to the urgency of preserving these crafts.

1

Renaissance · Rejuvenation · Resurgence · Revival

In 2015, I had the opportunity to visit India with my daughters. They were eager to take a walking tour of Chandni Chowk, a place that held many of my childhood memories. We decided to engage the services of a newly formed organization called India City Walks. To our delight, their guides were not just tour leaders, but dedicated historians and storytellers who shared our passion for Chandni Chowk. It was an experience that set the tone for how I see the neighborhood today and, in some ways, precipitated the idea of this book.

Today, guided walks in Chandni Chowk are not just a trend, but a unique experience waiting to be discovered. These tours go beyond the usual sightseeing, unveiling hidden shrines, introducing you to old artisans still practicing their traditional trades, and always include a food crawl through the old city for a tasting at the iconic eateries of Chandni Chowk. This renewed interest in walking tours reflects a growing desire among Delhiites to engage more intimately with the history of Old Delhi. Walking tours have

now become a vital way of connecting people with the city's living heritage.

Complementing this resurgence in interest in Chandni Chowk is an exciting body of recent emerging literature. A trio of powerful literary voices Swapna Liddle, Rana Safvi, and William Dalrymple has been at the forefront of this rediscovery of Chandni Chowk.

Swapna Liddle's books, Chandni Chowk: The Mughal City of Old Delhi and Shahjahanabad: Mapping a Mughal City, reveal how the area was built and choreographed to include imperial life, bazaars, inns, and clustered neighborhoods. Her writing reminds us how Chandni Chowk was designed not just as a marketplace, but as a stage where the urban life of Shahjahanabad unfolded in all its splendor and diversity."1 Her scholarship continues to shape how Chandni Chowk is understood today.

2

Rana Safvi's books, Where Stones Speak and The Forgotten Cities of Delhi, guide us through the living culture of Chandni Chowk. Her walking trails map points out Sufi shrines, hidden eateries, craftspeople, and street traditions. She writes: "To walk through Chandni Chowk is to experience a living museum, where every turn whispers a story, every aroma recalls a tradition, and every crumbling façade holds a memory."2 Her voice has given Chandni Chowk a sense of continuity between past and present.

No list of chroniclers of Chandni Chowk would be complete without William Dalrymple. Though Scottish by birth, Dalrymple has made Delhi his home. In City of Djinns, he walks us through Ballimaran, Turkman Gate, and Khari Baoli, bringing to life the unseen layers of Chandni Chowk. His later work, The Last Mughal, traces the 1857 uprising through the very lanes of Chandni Chowk where we photographed. Dalrymple observes, "Chandni Chowk is where Delhi's past and present collide where the ghosts of Mughal grandeur jostle with the relentless pulse of the modern bazaar."3 Through his work, Chandni Chowk has reached a global audience.

Yet, beyond walking tours and books, a groundswell of cultural renaissance has taken hold in Chandni Chowk over the last few years. Three remarkable individuals, Atul Khanna, Vijay Goel, and Abu Sufiyan, are at the heart of this revival.

Located in the Chunnamal compound and founded by Atul Khanna, Kathika Cultural Center is dedicated to preserving and promoting the art and culture of Chandni Chowk. Housed in two restored 19th-century Havelis facing each other, Kathika is both a museum and a performance space that hosts exhibitions, workshops, and classes to engage the public in the art form.

"What made you start this?" I once asked. He smiled and said, "Because memory needs a home. And stories need walls to echo off of. If we don't give them space, they vanish."

From musical, theatrical, and literary presentations to student workshops and heritage walks, Kathika reactivates memories by putting them back in circulation. It has become a vital meeting place for culture and memory in Old Delhi.

Whenever I return to Chandni Chowk, I stay at Haveli Dharampura, which has been restored by Vijay Goel, a senior politician and passionate preservationist. Mr. Goel acquired the rundown and crumbling haveli in 2005, restoring it over the next six years to preserve its architectural details and convert it into a 14-room heritage hotel. Goel's wife and daughter now manage the hotel, which offers more than just lodging. Its guests are treated to Chandni Chowk's rich cuisine, as well as live Kathak and musical

performances by local artists. Just a few yards away from Dharampura is Golden Haveli, a smaller, second haveli that is an equally warm and charming heritage hotel. These projects have brought new life to onceneglected historic buildings.

Abu Sufiyan is leading a digital marketing platform based on a communitybased effort called Purani Dilli Walo Ki Baatein. It started as a Facebook page and, in just a few years, has established itself as a beloved digital archive of Old Delhi's heritage. His initiative has ensured that local voices remain central to the telling of Chandni Chowk's story.

Another quiet preservation effort is underway at the Hazrat Shah Waliullah Library in Chooriwalan. Founded in 1987, during a time of curfew and unrest, it began as a shelter and has evolved into a sanctuary for learning. Named after the 18th-century scholar Shah Waliullah Dehlavi, it is a nonprofit library entirely run by volunteers and local donors. It is by no means a grand place, but a place where you will undoubtedly find older men reading Urdu papers and magazines, students preparing for exams, and children discovering folktales. It functions as a communal living room, a baithak, to meet and discuss politics, cricket, books, or prices in the bazaar. The library remains a modest yet important anchor for the community.

These local initiatives now coexist with significant municipal and private interventions. While some, like the Chandni Chowk Metro Station and the pedestrianization of the main road, are welcomed for making Chandni Chowk more accessible, others, like the construction of the high-rise Chandni Chowk mall with a three-story food court, have sparked debates about their impact on the traditional character of Chandni Chowk. The ageold markets, street vendors, and ancestral households now find themselves woven into a new urban fabric. Heritage hotels and high-rises, tradition and convenience, all share the same narrow lanes. Yet this evolution carries both promise and loss. Wider roads, better amenities, and greater safety are welcome, but they also smooth away the textures, the closeness, the human press of bodies and voices that give Old Delhi its unmistakable character.

Thanks to literary voices like Swapna Liddle, Rana Safvi, and William Dalrymple, who celebrate and research the history of Old Delhi, and to entrepreneurs like Atul Khanna, Vijay Goel, and Abu Sufiyan, who keep its culture alive, the memories and traditions of Chandni Chowk are preserved, recited, and shared.

I hope Chandni Chowk is evolving but not erasing its history. I hope it will not be replaced but only remade. And in that remaking, I hope its legacy will continue not in sepia, but in bold, living color.

3