President of the University of Maine and University of Maine at Machias Vice Chancellor for Research and Innovation for the University of Maine System

EXPLORATION AND DISCOVERY

• climatechange.umaine.edu

President of the University of Maine and University of Maine at Machias Vice Chancellor for Research and Innovation for the University of Maine System

• climatechange.umaine.edu

THE CLIMATE CHANGE INSTITUTE fosters learning and discovery through excellence in graduate academic programs, addresses local and global needs through basic and applied research, and contributes research-based knowledge to make a difference in people’s lives. It is dedicated to improving the quality of life for people in Maine and around the world, and promoting responsible stewardship of human, natural and financial resources, now and in the future.

CCI celebrates its 50th anniversary in 2022 as the world is rapidly coming to the realization that climate change is affecting health, resources, economy and frequency and magnitude of catastrophic events and geopolitics. CCI’s contributions to society are evolving rapidly in response.

“The age of climate decision is here, and our actions will define the course of civilization and the health of the planet.”

Paul Andrew Mayewski Director, Climate Change Institute by CBS 60 Minutes

by CBS 60 Minutes

INSTITUTE scientists conduct climate change research around the globe — from the deserts of Peru into the Andes, across the Arctic onto the summit of Greenland, throughout the Himalayas/Tibetan Plateau to its highest reaches on Mt. Everest, across the vast Antarctic continent and the sub-Antarctic islands of the Southern Ocean, and from Maine’s rocky shores and islands to its mountains. To us, climate change has four interactive components: physical, chemical, biological and social.

CCI’s work has led to important discoveries with far-reaching implications: abrupt climate change that revolutionized the field of climate science; the role of marine-based ice sheets for past and future sea level rise; the state of glaciers in Antarctica, Greenland, South America, Asia and New Zealand with implications for sea level rise, water resources and ocean circulation; plausible scenario planning for future climate change and impacts; documentation of the unprecedented rise in human-source pollutants over the last century and longer, and impacts on health, economy and quality of life; the impact of climate change on civilizations and ecosystems past and present; and reducing uncertainty in climate prediction.

Now two decades into the 21st century, it is increasingly apparent that climate change is a major challenge with ever-increasing impacts on local to global scales. CCI researchers have the extensive field, laboratory and interpretation expertise needed to tackle the critically important complex issues related to climate change, and impacts on humans and the ecosystem.

The realization that climate change challenges exist for all, but that excluded and disadvantaged communities bear the greatest burden, is an ever-present force. It compels CCI to search for more understanding of our role in the physical, chemical, biological and social fabric of the climate system, and to apply our emerging knowledge base more effectively in the challenging years ahead. CCI contributions strive collectively toward a cleaner, healthier, natural resource-protective environment, and toward reducing the climate change impacts on health, food security, resource depletion, the economy, and both societal and ecosystem disruption.

THE UNIFYING research theme of the Climate Change Institute, formerly the Institute for Quaternary Studies (IQS), has been the natural variability of Earth’s climate, and the mechanisms driving that variability. From its beginning, IQS research focused on the physical, biological and human dimensions of climate changes of the past. Faculty, as well as CCI graduate and undergraduate students, have carried out expeditions and conducted research in Maine and throughout the world.

Evidence collected from sedimentary deposits in oceans, lakes, bogs, glacial deposits, glacial ice and archaeological sites has revealed natural

environmental changes spanning tens of thousands of years. Collectively, this research reveals how the climate of our carbon-enriched atmosphere compares with the Earth’s natural long-term variability.

At its 50th anniversary, the work of the Climate Change Institute has come to encompass the distant past and the present, and anticipate the future of our rapidly changing world.

Fifty years ago, discerning leaders at the University of Maine realized the importance of Earth’s recent geological history — the period that includes the Quaternary ice ages to the present. After extensive research, founding director Harold W. Borns, Jr. designed and established a first-of-itskind research institute focused on this theme. As planned, the Institute for Quaternary Studies (as of 2002, the Climate Change Institute) included geologists, biologists, anthropologists, physicists, historians and others.

For more than 50 years, CCI has gathered valuable insights about the past, providing guidance for anticipating and adapting to the challenges of our future.

“For more than 50 years, the unifying research theme of the IQS/CCI has been to understand the natural variability of Earth’s climate and the mechanisms driving that variability.”

— George Jacobson, Professor Emeritus, Climate Change Institute

A half century of world-renowned researchHarold

W. Borns, Jr.† Founding Director IQS (now CCI)

THE CLIMATE CHANGE INSTITUTE (CCI) is one of the oldest climate research units in the United States and likely the first with a multi- and interdisciplinary focus. CCI is a global leader in climate change research and, in combination with its UMaine academic unit partners, offers a robust array of graduate and undergraduate research programs.

CCI integrates transformational field, laboratory and modeling activities to understand the physical, chemical, biological and socio-cultural components of the climate system of

the past and present to better predict future changes in climate, and their impacts here in Maine and across the globe. Institute investigations span the last 2 million years to the present — a time of multimillennial to centennial scale climate changes punctuated by abrupt (annual to decadal) shifts in climate.

CCI investigations inform predictions for future climate change based on an understanding of the full dynamic range of the natural climate system and the evolving dramatic influence of human activity.

The Climate Change Institute has major themes that, together, describe its breadth of contributions and linkages across the University of Maine and at state, national and international levels, and expectations for the future of CCI and climate change at the University of Maine. CCI’s research, education and outreach represent the current evolution of the Institute’s approach to the rapidly emerging understanding of climate change and the implications of change.

“CCI has a legacy of major scientific contributions to understanding the timing, causes, and mechanisms of natural and human-forced climate change, and the effects of physical and chemical climate changes on the biological, economic, social, and political conditions of humans and the ecosystem.”

— Paul Andrew Mayewski, Director, Climate Change Institute

“Maine Won’t Wait” is the state’s first integrated mitigation and adaptation climate action plan, providing an essential framework for our future informed by science.

Ivan Fernandez, University of Maine Distinguished Maine Professor in the School of Forest Resources, the Climate Change Institute, and the School of Food and Agriculture, and a member of the Maine Climate Council

WHEN MAINE Gov. Janet Mills convened the Maine Climate Council in September 2019, she announced an executive order to make Maine’s economy carbon neutral by 2045. The council’s four-year plan for climate action, released December 2020, is titled “Maine Won’t Wait.”

The Maine Climate Action Plan is a pathway for what needs to be done, say experts from the University of Maine, University of Maine at Machias, University of Maine School of Law, University of Southern Maine and University of Maine at Farmington, who helped inform and craft the plan with government officials, scientists,

business and industry leaders and citizens.

The path includes investing in renewable energy, harnessing natural climate solutions to store carbon, and building resilience in farms, forests and fisheries to survive and thrive in the 21st century.

Among the experts from the University of Maine System serving on council subcommittees/working groups:

Scientific and technical subcommittee: I. Fernandez, (co-chair), B. Beal, S. Birkel, A. Daigneault, J. Kelley, R. Kersbergen, G. Koehler, B. Lyon, J. Rubin, A. Soucy, R. Steneck, R. Wahle, A. Weiskittel.

Energy working group: J. Thaler, J. Ward.

Transportation working group: J. Rubin.

Coastal and marine working group: H. Leslie, (co-chair), K. Bell, D. Townsend, H. Train.

Natural and working lands working group: H. Carter, I. Fernandez.

Community resilience planning, public health, and emergency management working group: T. Johnson, E. Stancioff, A. Barton.

Buildings, infrastructure, and housing working group: D. Dixon, S. Shaler.

Equity subcommittee: D. Ranco, J. Rubin.

“The indicators of climate change are accelerating and so, too, must our response. We have seen time and again that science-informed policy is cost-effective for American society.”

The new graduate training program to foster systems perspectives to address the Arctic’s complex changes builds on UMaine’s strengths and expertise in polar biophysical research, crosscultural perspectives and integration of knowledge systems, Arctic law and policy, and socio-environmental systems research.

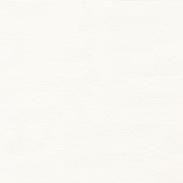

Photo by Benjamin Burpee

Photo by Benjamin Burpee

“UMaine’s Climate Change Institute has been an internationally recognized leader in polar science for more than four decades. This new training program builds off of our legacy to advance understanding of the interconnected impacts of Arctic change on people and ecosystems, both in the Arctic and in Maine.”

Jasmine Saros, Professor and Associate Director of the Climate Change Institute, School of Biology and Ecology, Environmental Sciences

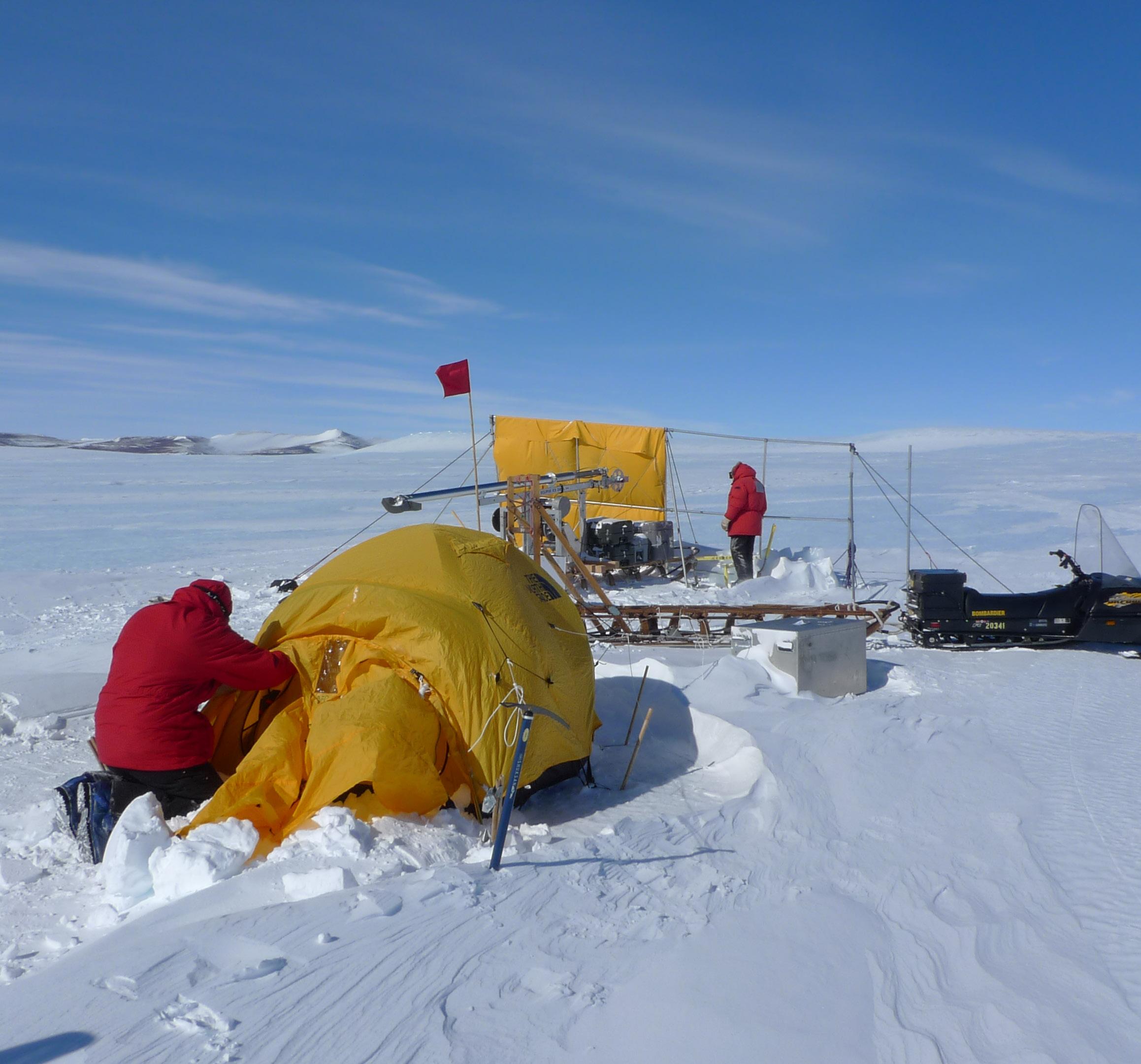

THE UNIVERSITY OF MAINE is training future Arctic scientists to help address the socio-environmental challenges resulting from the world’s most rapidly changing environment with a nearly $3 million award from the National Science Foundation.

The new UMaine initiative, Systems Approaches to Understanding and Navigating the New Arctic, is funded by the NSF Research Traineeship (NRT)

Program, which encourages the development and implementation of “bold, new, potentially transformative models” for science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) graduate education training.

The new NRT program builds on the success of CCI’s Adaptation to Abrupt Climate Change Interdisciplinary Graduate Education and Research Training program, 2012–19.

Arctic

The new Arctic initiative to train graduate students in the interdisciplinary field of Arctic systems science is led by Jasmine Saros, associate director of UMaine’s Climate Change Institute and a professor of lake ecology. Its focus is on the interconnected nature of environmental and social changes in the Arctic and Northern Hemisphere.

Over the next five years, the program is expected to train nearly 60 master’s and Ph.D. students, including 20 funded trainees in ecology, earth sciences, anthropology, economics and marine sciences. Their training will include an interdisciplinary curriculum, Arctic field experience, and research focused on changes in Maine, southwest Greenland and the Arctic–North Atlantic.

YR1 Cohort Graduate Students: Sydney Baratta, Katherine Follansbee, Amanda Gavin, Ligia Naveira, Maya Reda-Williams.

Photo by Stephanie Comer

Photo by Stephanie Comer

From top left, clockwise:

Kristin Schild

Research Assistant Professor

School of Earth and Climate Sciences, and CCI; Research focus: glaciology, characterizing iceberg geometry and quantifying iceberg melt rates

Associate Professor of Paleoecology and Plant Ecology

CCI and School of Biology and Ecology; Research focus: climate change, extinction and biotic interactions through time

Katherine Allen

Assistant Professor, School of Earth and Climate Sciences; Research focus: paleoceanography

Professor and Department Chair, Civil and Environmental Engineering, and CCI; Research focus: hydrology and water resources, climate science, environmental sustainability, environmental data analytics

Assistant Professor of Mammalogy and Mammalian Health School of Biology and Ecology; Research Focus: ecology and evolution of mammalian energetics in a changing world

George H. Denton Associate Professor of Earth Sciences, and UMaine alumnus

CCI and School of Earth and Climate Sciences; Research focus: mechanisms of late Quaternary climate change

The JIRP program is a destination for student, faculty and research teams from colleges, universities, research institutes and professional programs from around the world.

Photo by Andrew Opilia

The JIRP program is a destination for student, faculty and research teams from colleges, universities, research institutes and professional programs from around the world.

Photo by Andrew Opilia

“This site has the longest record of glacier change in North America. It’s a great location to study glacier change over time.”

Seth Campbell, Assistant Professor, Climate Change Institute, and School of Earth and Climate Sciences, and Director of Academics and Research for the Juneau Icefield Research Program

IN 2019, the University of Maine began offering a six-credit summer field course in which students learn how to study glaciers and their environments, and the field method ologies and skills needed to conduct polar research.

Juneau Icefield Research Program (JIRP), established in 1946, is the longest operating field research and training program of its kind in North America. Seth Campbell, assistant professor of glaciology, and a UMaine and JIRP alumnus, directs academics and research for JIRP.

JIRP focuses on training the next generation of scientists to help solve

major environmental issues such as climate change, and conducting cutting-edge research in glacier and mountain environments of interest and benefit to society.

For three quarters of a century, the Juneau Icefield Research Program has inspired scientists, environmentalists, science policy advocates and educators, and developed into a thriving global community science research and education resource. UMaine’s partnership advances many new opportunities for undergraduate and graduate students, educators and researchers.

JIRP is now a collaborative endeavor run primarily through the University of Maine School of Earth and Climate Sciences, one of CCI’s academic partners, with significant research support from the University of Maine Climate Change Institute and University of Alaska Southeast Department of Environmental Sciences.

UMaine scientists study the effects of climate change — from across the planet to marine fisheries and coastal communities in Maine — and contribute critical expertise that informs citizens and businesses about how to respond to the changing climate.

“Science-informed decision-making in the face of climate change about the future we want is always more cost-effective than constantly trying to catch up, or investing in the past. As the report states, business as usual is not an option.”

Ivan Fernandez, University of Maine Distinguished Maine Professor in the School of Forest Resources, the Climate Change Institute, and the School of Food and Agriculture

NEARLY EVERY climate-related parameter measured in Maine is accelerating, according to “Maine’s Climate Future — 2020 Update.”

Maine’s Climate Future — Update 2020

“Maine’s Climate Future — 2020 Update” builds on the 2009 and 2015 “Maine’s Climate Future” reports, and the 2018 “Coastal Maine Climate Futures” report. It demonstrates the progression of accelerating change in the climate in Maine and its effects, reflecting dramatic evidence for accelerating climate change around the globe with often dire consequences.

Key findings include faster rates of warming along the coast compared to interior and northern Maine, and changes in Maine winters. Average minimum temperatures in Maine are warming 60% faster than average maximums. Maine is getting three to four times more large storms, as well as more rain events of all sizes.

The report points to the growing evidence of impacts of these changes on Maine farms, fields, forests,

marine resources, and numerous cultural and economic aspects. It also discusses possible future conditions in Maine, underscoring that steps taken now to reduce greenhouse gas emissions determine which alternative future Maine experiences.

Maine’s Climate Future

The report looks at examples of evidence of effects in Maine, drawn from the scientific literature and news media accounts of Maine people and their experiences. Those examples include growing seasons more than two weeks longer, with warmer springs and even warmer falls, and a particularly warm summer season in the Gulf of Maine. And the weather overall is becoming more variable and more uncertain.

Report co-authors are Ivan Fernandez, Sean Birkel, Catherine Schmitt, Julia Simonson, Brad Lyon, Andrew Pershing, Esperanza Stancioff, George Jacobson and Paul Andrew Mayewski.

NSF Fellows: from top left, clockwise, Kit Hamley, Anna McGinn, William Kochtitzky and Frankie St. Amand; center, Elizabeth Leclerc

NSF Fellows: from top left, clockwise, Kit Hamley, Anna McGinn, William Kochtitzky and Frankie St. Amand; center, Elizabeth Leclerc

programs is the number of nationally competitive fellowships awarded to students. The National Science Foundation supports an average of 200 UMaine graduate students each year as research assistants.

FIVE UNIVERSITY OF MAINE graduate students in climate change research received National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowships.

Anna McGinn in the Climate Change Institute and the School of Policy and International Affairs; William Kochtitzky in the School of Earth and Climate Sciences, and CCI; Kit Hamley in CCI; Frankie St. Amand in the Department of Anthropology and CCI; and Elizabeth Leclerc in Interdisciplinary Studies are master’s students.

Kochtitzky conducted research on the volcanic and glacial evolution of the Nevado Coropuna Ice Cap in the southern Peruvian Andes.

Hamley investigated the origins of an extinct canid — the warrah — that was endemic to the Falkland Islands.

McGinn evaluated existing climate change adaptation projects in developing countries to understand potential co-benefits and/or negative impacts on the communities. St. Amand explored intersections between climate change and human behavior over the last 12,000 years.

Leclerc studied past relationships between humans and their environments during periods of rapid change.

PLANET EXPEDITION included scientists from Nepal, the U.S., UK and India, a team of Sherpas and porters, National Geographic organizational staff and media teams, and local logistics support — all with the goal of documenting the impact of human activity (local to global) on one of the planet’s most extreme environments.

Climate Change Institute director Paul Andrew Mayewski was expedition and science leader for this biological, geological, glaciological, meteorological and mapping expedition. Five other CCI members were involved — faculty member Aaron Putnam and

graduate students Heather Clifford, Laura Mattas, Mario Potocki and Peter Strand. Accompanied by Sherpas and a film crew, the science summit team of Mariusz Potocki, Baker Perry (Appalachian State University) and Tom Matthews (Loughborough University, UK) collected the highestever ice core (at 8,020 meters) and installed the two highest weather stations in the world (at 8,430 meters and 7,945 meters).

Members of the science team working from Everest base camp and throughout the Khumbu and adjacent valleys conducted comprehensive biodiversity surveys, sampled water/snow/ice water quality, highest elevation helicopter-based lidar scan, expanded the elevation records for high-dwelling species, documented the past history of the mountain’s glaciers and assessed the current state of glacier downwasting.

The highest altitude ice core and highest automatic altitude weather station set two of the expedition’s three Guinness World Records.

Numerous scientific papers have and will continue to emerge from this expedition, which set in motion a framework for monitoring the rapidly changing climate and environment in the Everest region.

Photos, left to right: Everest base camp (foreground) and Khumbu Icefalls (center) with climbers lighting their way as they start out in the early morning hours for high camps to acclimatize and for the ascent of Everest.

Photo by Mariusz Potocki; Mario Potocki (center) recovering highest ice core ever collected (8,020m).

Photo by Dirk Collins, National Geographic

“Relatively little information exists for mountain regions above 15,000 feet, leaving big scientific questions only partially answered.”

— Paul Andrew Mayewski, Distinguished Maine Professor and Director of the Climate Change Institute

From top to bottom: Laura Mattas collects a boulder sample that will help reconstruct the Ice age history of the Khumbu Glacier; Peter Strand and team collect a sample for cosmogenic dating at the base of the Khumbu Icefall;

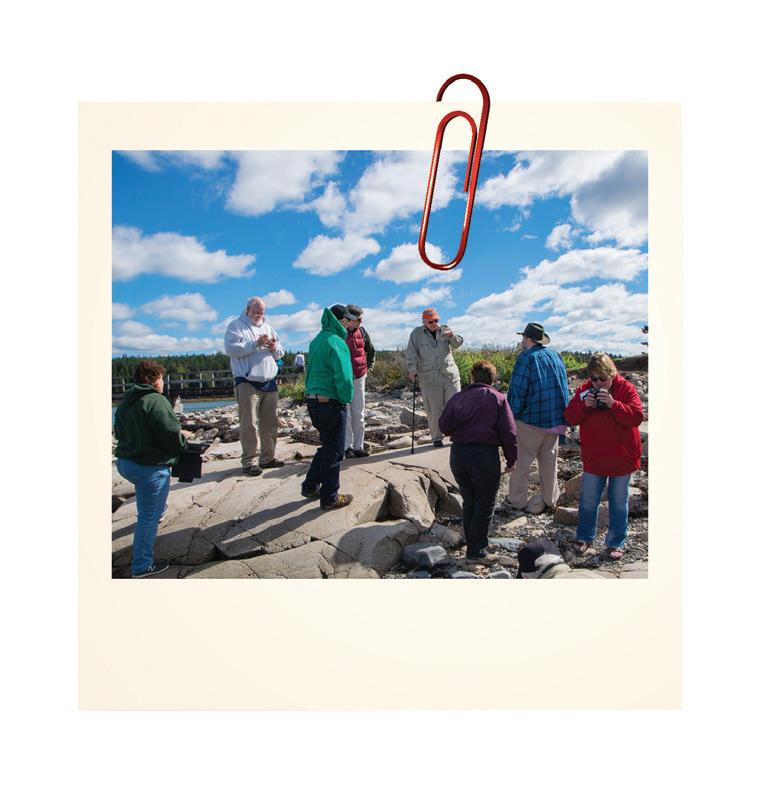

Alice Kelley, a geoarchaeologist, and Joseph Kelley, a marine geologist, use varied geological and geophysical concepts and tools to answer archaeological questions. The wife and husband team collaborated on archaeological and geological research projects worldwide.

“The faunal remains. The fish bones. The bird bones. The mammal bones. The fish ear bones. All of these tell us what was in the Gulf of Maine in the past.”

— Alice Kelley, Associate Research Professor, Climate Change InstituteMAINE’S COASTLINE is dotted with more than 2,000 archaeologically documented shell middens and virtually all of them are eroding into the ocean. Some quite rapidly, which is putting valuable records of cultural and environmental history at risk.

Alice Kelley, an associate research professor, and professor emeritus Joseph Kelley, both in the Climate Change Institute, and the School of Earth and Climate Sciences, are working with a team of archaeologists and geologists from UMaine and the Maine Historic Preservation Commision to survey these fragile archaeological sites using

ground-penetrating radar.

The goal of the Maine Sea Grant-funded project is to better understand the current state of Maine’s many shell midden sites — to document what is there and has the potential to be lost, and the rates at which erosion is happening.

The University of Maine-led research is the first concerted use of ground-penetrating radar technology on the coast to rapidly assess the state’s fragile middens, many of which, due to time and budget constraints, have not been visited by archaeologists since the 1970s.

The information will help land and cultural resource managers triage the most at-risk sites for preservation or conservation of the ancient history in the ancient sites. Or, at worst, emergency archaeological excavation.

Currently, the Maine Midden Minders, guided by Alice Kelley and Bonnie Newsom, CCI faculty associate, is working with conservation groups, tribal organizations, and individuals to monitor and document change at shell heaps along the Maine coast.

Cindy Isenhour explores ways to change linear production-consumption-disposal systems into more circular, less carbonintensive economies.

Cindy Isenhour, Associate Professor, Department of Anthropology and Climate Change Institute

Cindy Isenhour, Associate Professor, Department of Anthropology and Climate Change Institute

IN MAINE, the reuse economy takes many forms. And it has for generations. The state is home to at least 450 formal reuse businesses, according to Cindy Isenhour, a professor of anthropology and climate change at the University of Maine.

In her cultural anthropology research, Isenhour explores the state’s vibrant reuse markets and their potential to advance social, environmental and economic public policy goals.

While Maine has not yet implemented formal policies to

specifically support reuse, some evidence suggests that many communities are contributing to waste-reduction and sustainability goals through reuse. In most applications, reusing instead of producing items saves water, energy, time and labor.

Cindy Isenhour leads ResourcefulME, a five-year project funded by a $265,000 award from the National Science Foundation that explores the potential of Maine’s secondhand economies in Maine. It began with a spatial analysis of formal reuse markets nationwide by Andrew Crawley, a UMaine professor of regional economic development, and included a statewide survey of more than 600 households that found almost 90% of Maine residents participate in the reuse economy.

The project also was a springboard for UMaine’s first digital ethnography field school led by Isenhour and Kreg Ettenger, associate professor of anthropology and director of the Maine Folklife Center. To explore Maine’s reuse economy, students traveled statewide to reuse sites — from transfer stations and used book stores to cobblers and thrift shops. They learned ethnographic research techniques, including participant observation, interview protocols and questionnaire design, and tools for data management and analysis.

“The benefit of reuse is that you’re using the same product, in its same form, for longer. The act of reusing a second-hand good offsets demand for new production.”

In conjunction with Coastal Maine Climate Futures, the Climate Change Institute has developed online data tools for plotting maps and time series of temperature and precipitation data for coastal, central and northern Maine climate divisions, from 1895 to present.

should expect significant environmental changes as humans and other factors create increased instability in the climate system. The best approach in adapting to uncertainty is to consider a variety of plausible outcomes in all planning capacities.”

— Sean Birkel, Assistant Professor, Climate Change Institute and Cooperative Extension, Maine State Climatologist

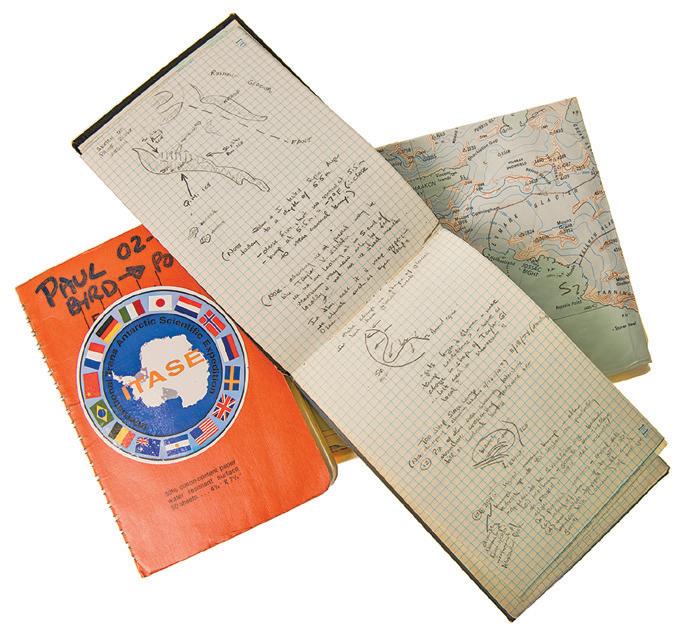

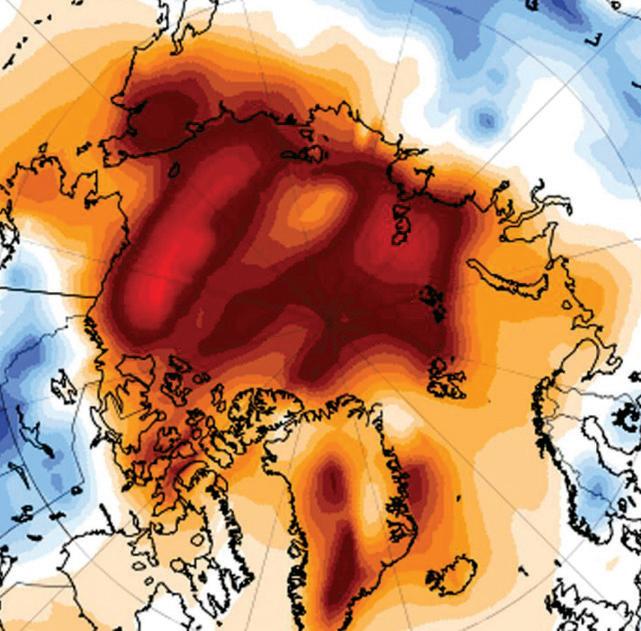

MAINERS CAN expect significant environmental change to continue in the coming decades due to increased greenhouse gas emissions and patterns of variability in the climate system, say University of Maine researchers Sean Birkel, the Maine state climatologist, and Paul Andrew Mayewski, Climate Change Institute director.

Their report — “Coastal Maine Climate Futures” — provides a base for coastal Maine planners to prepare for a variety of plausible short- and long-term climate

challenges in their communities, where fishing, forestry, tourism and agriculture are economic cogs.

Maine’s coastal climate is strongly influenced by a number of factors, including El Niño/Southern Oscillation, volcanic eruptions and warming in the Arctic associated with increasing greenhouse gas emissions.

Sean Birkel and Paul Andrew Mayewski analyzed historical climate trends, climatecommodity connections and sources of climate variability that affect Maine to put forth five plausible climate scenarios for 2020–40. The scenarios: no additional change to the current “new normal”; moderate warming; another abrupt Arctic warming and even greater Arctic sea ice collapse; cooling from increased volcanic activity; and drying from more frequent and extreme El Niño events.

Underlying the plausible scenarios presented in this report is some predictability, the authors note.

Maine should expect significant environmental changes as human and other factors create increased instability in the climate system. Birkel and Mayewski suggest that the best approach to planning, adapting to and operating successfully within uncertainty is to be prepared for a variety of changes ranging from a general warming trend to occasional annual short-term scale diversions to cooler and drier weather associated with volcanic and El Niño events, respectively.

“Maine

Maine’s largest ice storm occurred in 1998. Subsequent warming winters could increase the likelihood of such events and similar conditions like these ice-coated trees in December 2013.

WEATHER AND CLIMATE extremes — such as heat waves, cold waves, drought, heavy precipitation and damaging storms — are becoming more common as climate warming occurs in conjunction with intensification of the hydrologic cycle, and changes in atmospheric circulation.

As shown in the Fourth National Climate Assessment, heavy precipitation in the northeastern U.S. increased at a higher rate than anywhere else in the U.S. Likewise, the Maine’s Climate Future Update reports (2015 and 2020) show that 2005–2014 was the wettest 10 years on record, and that daily precipitation events of 2, 3 and 4 inches have increased in frequency. Impacts from heavy precipitation include

flooding, damage to infrastructure and crops, and erosion and environmental degradation resulting from runoff.

Maine’s climate may be getting wetter overall, but extreme drought can occur as well. For example, 2020 brought the driest May-to-September period on record, which led to crop disaster area declarations by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Other stand-out extremes: “Summer in March” 2012, with temperatures reaching into the 80s March 21–23; February 2015 — coldest since 1934; record warm winter 2016; record warm fall 2017; the damaging October 30, 2017 windstorm; record high minimum monthly temperature August 2021.

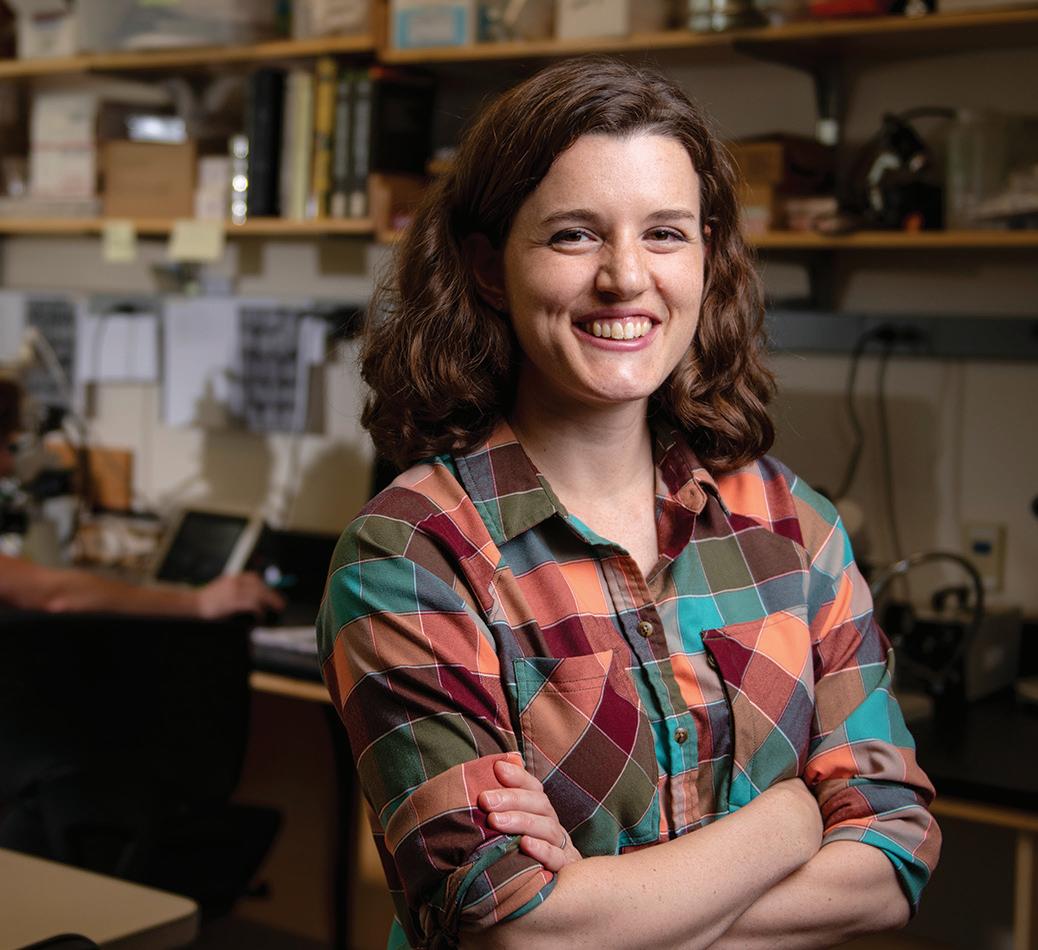

Average temperature departure from normal (°C) for the March 2012 heatwave. Data Source: Climate Forecast System Reanalysis

Second warmest since 1895 (2010 and 2012 tied for first).

January 2021

Tied with 1956 for warmest monthly minimum temperature since 1895. June 2021

Second hottest maximum monthly temperature since 1895 (1999 is first).

August 2021

Warmest minimum monthly temperature since 1895. Summer 2021

Warmest minimum June–August temperature since 1895.

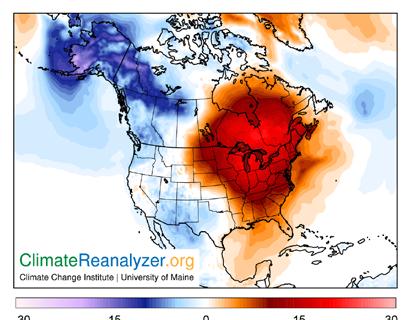

According to NOAA data for 2021, average daily sea surface temperature across the North Atlantic (0°–60°N, 0°–80°W) was record high almost continuously from the beginning of September through the end of the year.

“Most people who have lived in Maine their whole lives have anecdotes for how climate has changed since they were kids. It’s hard not to notice.”

— Sean Birkel, Assistant Professor, Climate Change Institute and Cooperative Extension, Maine State Climatologist

Sea surface temperature (SST) map generated using data from the NOAA Optimum Interpolated SST (OISST) dataset version 2.1.

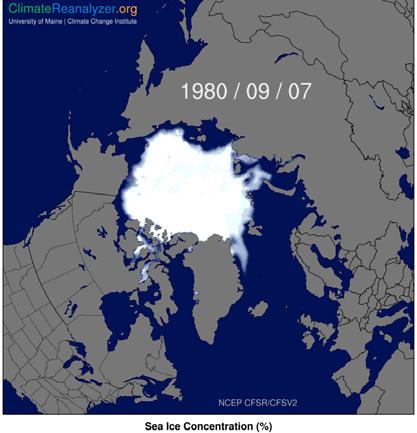

CLIMATE REANALYZER is an online platform for visualizing an array of climate and weather models and data sets.

The most visited page on Climate Reanalyzer is Today’s Weather, which provides an overview of the current patterns of temperature, precipitation and other measures across the globe.

Site visitors can use reanalysis pages to dig into climate trends and teleconnections over past decades by plotting maps, time series and correlations for different variables.

Other pages on the site can be used to view and animate daily maps and time series of global ocean surface temperature, and Arctic and Antarctic sea ice.

Climate Reanalyzer also has weather forecast maps from the leading U.S. regional and global models. These maps can be animated to yield useful visuals in the classroom.

Climate Reanalyzer continues to evolve as new data sets and other content become available.

Today’s weather with current global temperature and other measures.

Global reanalysis maps, time series and correlations.

U.S. temperature and precipitation since 1895.

Daily ocean surface temperature and sea ice.

Weather forecasts with animation. 2,000-3,000 hits daily. ClimateReanalyzer.org

“Climate Reanalyzer has visualization and analysis tools that can be used by researchers, educators and students, and the general public.”

— Sean Birkel, Assistant Professor, Climate Change Institute and Cooperative Extension, Maine State Climatologist

Paul Andrew Mayewski and his team’s discoveries have been critical in advancing climate research. One example is the paradigm shift in climate science that demonstrated that atmospheric circulation patterns can change abruptly (in less than one to five years) resulting in long-term changes in temperature, precipitation and storms. Humans have dramatically altered the chemistry of the atmosphere with significant impacts on human and ecosystem health. Ultra-high-resolution laser sampling, developed by CCI, of ice cores reveals storm-scale events going back at least hundreds of years.

Photo by Mariusz Potocki

Photo by Mariusz Potocki

“At the beginning of my career, the thought was we couldn’t do anything to Mother Earth. But we’ve done a lot and we’ve done it fast.”

— Paul Andrew Mayewski, Director of the Climate Change Institute, Distinguished Maine Professor

PAUL ANDREW MAYEWSKI was a sophomore at the State University of New York when Professor Parker Calkin showed the class a picture taken in Antarctica. Mayewski was transfixed by this place that holds 90% of the ice on Earth. Since then, he has led more than 60 expeditions to the remotest reaches of the polar regions and into Earth’s highest mountain regions. He is the first human to explore parts of Antarctica, traversed by foot, ski, snowmobile and tractor thousands of miles across Antarctica, and has led major national and international climate research expeditions to the three poles (Antarctica, Greenland, the Himalayas/Tibetan Plateau).

His exploration and scientific achievements have earned him numerous awards, including the first-ever international medal for Excellence in Antarctic Research and the Explorer’s Club Lowell Thomas Medal, plus media prominence, including the Emmy Award-winning “Years of Living Dangerously.”

Glaciochemist Mariusz “Mario” Potocki drills ice cores to obtain timelines of climate history. Including the highest ice core ever collected on the planet — 26,312 feet above sea level from Mount Everest in 2019. And during breaks on research expeditions, the Climate Change Institute research assistant takes awardwinning photographs of his surroundings.

During his initial research excursions, Potocki took pictures of landscapes and inhabitants — including seals, penguins, sea turtles, elephants and monkeys — to share with family and friends.

Now he also shares them on Instagram and his website for people worldwide to enjoy.

“I like to show the world’s beauty in my photos so people may understand that it’s worth caring for and saving for future generations,” says Potocki, a UMaine Ph.D. student.

CCI has developed a transparent framework needed for assessing impacts and addressing vulnerability in a changing climate where intended goals are mitigation, adaptation, sustainability, resilience, opportunity and entrepreneurship.

CLIMATE FUTURES is an emerging Climate Change Institute product designed for the public, industry, nongovernmental organizations, and state, U.S. and foreign governments. It includes climate understanding tools and information; a framework for assessing vulnerability, impacts, and assets affecting humans and ecosystems; and emphasizes plausible scenario climate change prediction planning.

Climate prediction models are essential elements in planning for the impacts of climate change. However,

existing climate models based on classic IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), while absolutely essential stepping blocks, do not capture the full local-to-regionalscale climate change known to exist in the past; nor do they capture the realities of nonlinearities such as abrupt climate change (ACC) in the past and currently emerging climate system, or the full health consequences of changes in the chemistry of the atmosphere, and as a consequence the full range of plausible scenarios for future climate.

The Climate Futures Framework is based largely on Sean Birkel’s Climate Reanalyzer software. It offers a transformative mechanism and a platform for assessing and quantifying climate change, vulnerability, impacts, and opportunities based on classic IPCC and past climate analog change predictions. They are presented in the form of locale-specific plausible scenarios that go beyond standard linear climate predictions.

For more information: climatechange.umaine. edu/climate-matters/ climate-futures/

“Climate change defines the 21st century in ways that we are only beginning to understand. How can we plan for the future without understanding climate change impacts on human and ecosystem health, food systems, energy production, the economy, geopolitics, and the future of storms, floods, droughts, wildfires and other extreme events?”

— Paul Andrew Mayewski, Director, Climate Change Institute

The Allan Hills blue ice area contains 2.7 million years (Ma) old ice and one of the most promising sites to recover the oldest continuous ice core paleoclimate record.

“The Allan Hills Blue ice area is well known for one of the largest collections of Antarctic meteorites and the oldest direct carbon dioxide and methane measurements from air bubbles trapped in ~2 million year (Ma) ice. We hope to recover the oldest continuous ice core paleoclimate record.”

Andrei Kurbatov, Associate Professor, Climate Change Institute and School of Earth and Climate SciencesCCI RESEARCHERS will be focusing again on the Allan Hills blue ice area in Antarctica as part of the new Center for Oldest Ice Exploration, or COLDEX. The project, led by Oregon State paleoclimatologist Ed Brook, aims to transform the current understanding of Earth’s climate system by discovering and recovering some of the oldest ice on Earth. Andrei Kurbatov, Paul Andrew Mayewski and graduate students will be part of the multidisciplinary team from Oregon State University; American Meteorological Society; Dartmouth

College; University of California, Berkeley; University of California, Irvine; University of California San Diego; University of Kansas; University of Maine; University of Texas at Austin; University of Washington; University of Minnesota Duluth; University of Minnesota Twin Cities; Princeton University; Amherst College; and Brown University.

Using CCI’s W.M. Keck Laser Ice Facility state-of-the-art laser ablation system, UMaine researchers will be unraveling continuous climate change history going back millions of years.

Since 2004, the University of Maine team has been working with many leading paleoclimate scientists to find the ice core site that will extend the currently oldest continuous 800,000 years old Antarctic ice core record.

In collaboration with University of Washington scientists, during the Austral summer of 2016, the UMaine team finally identified a location in the Allan Hills where a high-quality, million year, undisturbed ice archive might be preserved. Ice-penetrating radar data show that a kilometer below the ice surface 1 million year (Ma) old ice can be present.

THE PACIFIC OCEAN is the largest reservoir of water and heat on the planet, and changes in the tropical Pacific, such as the El Niño Southern Oscillation, can influence climate on a global scale. For example, ice cores taken from the summit of Mt. Hunter in Denali National Park show summers there are at least 1.2-2 degrees Celsius warmer than summers were during the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries.

CCI Research Assistant Professor Dominic Winski and Professor Karl Kreutz found that warming of the tropical Pacific Ocean has contributed to the unprecedented melting of Mt. Hunter’s glaciers by altering how air moves from the tropics to the poles.

They suspect melting of mountain glaciers may accelerate faster than melting of sea level glaciers as the Arctic continues to warm.

The National Science Foundation awarded the University of Maine and its collaborators $570,000 to reconstruct 1,500 years of summer climate and wildfire history in Alaska. The team will use an ice core from Denali National Park in Alaska, gathered from some of the highest and most inaccessible peaks in the country.

Studies that combine past records of summer climate and wildfire are critically needed, says CCI Assistant Professor Dominic Winski. “Right now, the climate and landscape are changing. We know that in many areas, this means more wildfires, but we do not yet fully understand the relationship between climate and wildfire as we move into the future.”

“Mountain glaciers in Alaska and around the world are shrinking rapidly. Understanding the history of climate and glacier change in these regions is critical for predicting their contribution to sea level rise.”

— Karl Kreutz, Professor, Climate Change Institute, and School of Earth and Climate Sciences

UMaine has several state-of-the-art energy-efficient buildings on campus. The Versant Power Astronomy Center is one. It is heated using ground source heat pump technology and is constructed to LEED Silver building performance standards.

insignificant each action may seem.”

— Dan Dixon, Director, UMaine Office of Sustainability; Research Assistant Professor, Climate Change InstituteTHE OFFICE OF SUSTAINABILITY is committed to working with all University of Maine constituents to reduce the environmental footprint of the campus. Through ongoing education and outreach efforts, the goal is for sustainability awareness and a genuine concern for the health of our environment to become second nature

to every member of the UMaine community. The deep-rooted dedication to sustainability began in 1865 with UMaine’s establishment as Maine’s land grant institution. Its greatest contribution to sustainability is through its dedicated interdisciplinary teaching programs that strive to inspire core sustainability values in all its graduates.

In February 2007, the University of Maine became a charter signatory of the American College & University Presidents’ Climate Commitment (ACUPCC). Now known as the Carbon Commitment, many colleges and universities have signed to date, recognizing their unique responsibility to serve as role models for their communities and to develop solutions to combat global warming.

By signing The Carbon Commitment, UMaine agreed to develop a Climate Action Plan to achieve carbon neutrality as soon as possible. Additionally, UMaine has committed to reduce its Scope-1 GHG emissions to zero by 2030, and achieve net campus carbon neutrality by 2040.

“Everything we do affects the world around us. To achieve a sustainability state of mind, we must regularly consider the effects of each action in our daily lives, no matter how mundane and

Understanding past behavior of El Niño is essential to figuring out how it will function in the future.

“Not only do archaeological studies of El Niño contribute to climatology, they also offer lessons of resilience and adaptation from past peoples with millennia of experience dealing with these events.”

— Dan Sandweiss (archaeologist), Department of Anthropology, and Kirk Maasch (climatologist), School of Earth and Climate Sciences; both professors in the Climate Change Institute

FOR THREE decades, Dan Sandweiss and Kirk Maasch have worked together to unravel the prehistory of El Niño, a recurrent climatic perturbation that affects much of the world.

Sandweiss and Maasch work on the coast of Peru, where El Niño can be disastrous. Along this desert coast, well-preserved archaeological remains offer many proxies for past climate, including shells, fish and plants that encode events through their growth patterns, geochemistry and/or biogeography.

Archaeological contexts also provide good chronological control and offer insight into the conundrum of El Niño

frequency increasing through the Holocene at the same time as coastal populations and social complexity also grew. This apparent paradox points to long-term adaptations to what might otherwise be considered as a series of unmitigated disasters.

CCI graduate student Heather Landazuri studies a 1580 AD survey of survivors of the first major El Niño event after the Spanish conquest of Peru in 1532 AD. Given that some alive during the 1578 AD event were born before the conquest, she hopes to reconstruct coping strategies based on millennial traditions, while also translating the document into English to make it more broadly available to scholars of climate and disaster.

Together with CCI graduate student Elizabeth Leclerc, Landazuri has created a digital historical atlas based on the contents of the document. In the future, they will refine the atlas through ground-truthing.

The field team surveys the Kingsbury Fish & Wildlife Area, once the location of an ordnance plant that manufactured ammunition for World War II.

Photo by Jennifer Phillippee

Photo by Jennifer Phillippee

KATHERINE GLOVER seeks to understand the impact of climate change and human activity on ecosystems, and how they can change between different stable states. A National Geographic Society Early Career grant funded her work to understand past change in the Grand Kankakee Marsh.

Once covering more than 1,000 square miles of northern Indiana, public works projects drained and dredged the “Everglades of the North” in the 19th century for farmland.

The impact of settler exploitation persists in the Kankakee Marsh today, with only about 5% of the original marsh remaining. Student-led soil sampling and analysis at Department of

Natural Resources sites showed that carbon stocks were reduced in locations with a history of dredging (Ferrara et al., 2020, Wetlands).

“It’s important work toward understanding the complexity of wetland ecosystems and their pathway toward restoration,” says Glover. “It also helps to educate others on the ecological benefits of marshes more broadly.”

Educational outreach complemented research for the Kankakee Paleo Project. Four University of Maine undergraduates designed place-based K–12 education materials on the environmental history of the Grand Kankakee Marsh. High schoolers can engage in exercises to identify landscape features caused by receding glaciers, and use Climate Reanalyzer to make climate projections for their region. Human impact is the theme for an elementary school exercise on how to structure a debate argument, and for 6th–7th grade curriculum that synthesizes historical events with biodiversity loss in a timeline activity. All modules are available with online curriculum hubs, including College, Career, and Civic Life (C3) Teachers, and the Science Education Resource Center.

“Even in complex ecosystems that have been restored, the impact of human disturbance is persistent and measurable.”

— Katherine Glover, Associate, Climate Change InstitutePhoto by Meredith Helmick

The Maine Climate Council’s four-year plan for climate action calls for increasing public education about climate change, and enhancing educational opportunities for climate science and clean energy careers.

Photo caption: Abi Bradford ’15, foreground, and Seth Campbell, assistant professor, use ground-penetrating radar to determine the depth of Ruth Glacier in Denali National Park.

Photo by Karl Kreutz

Photo by Karl Kreutz

MAINE ADOPTED the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) in 2019, and in 2021 the Maine Department of Education put out a statewide call to gather climate education resources to support learning about climate change in Maine’s classrooms. In response, colleagues at the Climate Change Institute have created a Climate Education Resources webpage with links to short videos, interactive data tools, maps, and other media that can help Maine educators engage students in science practices and crosscutting concepts as they learn about climate and global change.

Resources for students include short videos of research expeditions to

remote areas around the world, such as Mount Everest, Antarctica and Greenland. CCI researchers describe methods they use to study climate, including how and why ice cores are collected, how landscape features show changes in sea level in Maine over time, and how the consumption of goods by humans has an impact on climate.

With each resource, the CCI team identifies related Next Generation Science Standards and suggested student grade levels. All are designed to make it easier for students to explore and think scientifically about how and why climate is changing, and what the changing climate means in their lives and in Maine communities.

Ice Age Trail Map and Guide: Identifies where landscape features show evidence of Maine’s most recent glaciation (developed by Professor Hal Borns).

Interactive Environmental Change Model: Students can model how different climate scenarios could affect North American bioregions.

Earth Energy Balance Model: Students can plug in different values for CO2 and albedo to model effects on Earth’s temperature.

Climate Change: Scientific Evidence or Alternative Facts?: CCI video and classroom discussion guide for evaluating evidence.

Links to current climate work in Maine: Impacts for town planning, agriculture, natural resources and future implications.

The Climate Reanalyzer and associated activity guide

“Climate change factors richly into the Next Generation Science Standards. Yet we know that climate and weather information and data focused on Maine can be hard for teachers to find in forms that are accessible and engaging for students.”

— Molly Schauffler, Assistant Research Professor, Climate Change Institute

The warming climate affects Maine’s ecology and natural systems. Some of the most visible changes occur in winter, where milder temperatures have shortened the average period of lake ice cover, and where snowpack is less reliable than in past decades. Phenology indicators include earlier plant greenup in spring and later dormancy in fall.

“Maine

the changing climate. Data products play an important role in our climate adaptation, mitigation, and education efforts.”

— Sean Birkel, Assistant Professor, Climate Change Institute and Cooperative Extension, Maine State Climatologist

(MCO) is overseen by Sean Birkel, the NOAA-recognized Maine State Climatologist, in an effort to provide climate services to Maine stakeholders. MCO is based at the University of Maine and supported jointly by the Climate Change Institute and Cooperative Extension.

Climate services involve the production and translation of climate information to facilitate climate decision-making, policy and planning.

As part of this effort, a website has been developed (mco.umaine.edu) to provide Maine stakeholders with ready access to daily and monthly climate data, weather forecasts, NOAA seasonal

climate outlooks and other resources.

Research undertaken in association with MCO by Birkel, colleagues and graduate students includes studies of extreme precipitation, changes in the growing season, climate linkages between Maine and the Arctic, and the development of weather and climate data products for agricultural stakeholders.

Birkel is currently serving on the Scientific and Technical Subcommittee of the Maine Climate Council, where he contributed to the 2020 “Scientific Assessment of Climate Change in Maine and Its Effects in Maine.” He also contributed to the University of Maine-led report “Maine’s Climate Future — 2020 Update.”

Over the past century, temperature has risen 3°F and precipitation has increased 6 inches on average across the state. Winters are getting shorter and milder, and heavy precipitation events are occurring more frequently. Sea level along the coast has risen over 7 inches.

By monitoring the changing climate, trends, and associated impacts here in Maine, we are better able to develop adaptation and mitigation strategies for the future.

faces both challenges and opportunities inSean Birkel

The fortified hilltop site of Nadin-Gradina, one of many in the area, is centrally located in the Ravni Kotari, a lowlying region in northern Dalmatia (Croatia) traditionally valued for its agriculture and livestock.

— Gregory Zaro, Associate Professor, Department of Anthropology, and Climate Change Institute

— Gregory Zaro, Associate Professor, Department of Anthropology, and Climate Change Institute

TODAY, MORE than half of the global human population resides within cities, which have long been a significant force in landscape change. However, living in a highly populated and largely urbanized world has its challenges, where issues related to urban growth and sprawl, rural-tourban migration, resource management and conservation demand our attention. Yet, these variables are not entirely new, but rather can be traced in many world regions over the course of millennia.

Ongoing collaborative research along Croatia’s eastern Adriatic coast is working to unravel this millennial-scale process of urbanization and landscape

change from about 3,000 years ago to present. By focusing on the emergence and evolution of cityscapes in the past, the archaeological and historical records reveal not only the character of ancient landscapes, but they also provide historical context to the expansive urban settings of the contemporary world.

The Nadin-Gradina archaeological site emerged around 1000 BCE and evolved into the Roman municipium Nedinum about a millennium later. The site was abandoned sometime in the 6th century CE before its revival in the Late Middle Ages, subsequently becoming a frontier town along the Venetian/Ottoman border.

Artifacts collected during excavation indicate shifting cultural contacts throughout the eastern Mediterranean. Remains of animal bones and carbonized fragments of plants, seeds and wood point to a changing landscape characterized by mixed arrays of domesticated and wild species as the region became more intensively urbanized.

“The archaeological and historical records can be used not only to ‘uncover the past,’ but, importantly, to provide much-needed context to the anthropogenic landscapes that dominate our world.”

Brenda Hall and colleagues mapped and dated deposits from now-extinct Falkland Islands glaciers and cored lake sediments to reconstruct past climate change.

Brenda Hall and colleagues mapped and dated deposits from now-extinct Falkland Islands glaciers and cored lake sediments to reconstruct past climate change.

climate changes afford insight

future. Nature has already performed the experiments that show us how different components of the Earth system respond to climate change. We just have to learn how to read the clues.”

SciencesWHAT CAUSES the Earth to go into and out of ice ages? Traditionally, researchers have linked ice age cycles on Earth with changes in the amount of incoming solar radiation in summer at high latitudes in the Northern Hemisphere, but this mechanism cannot explain coeval Southern Hemisphere glaciation.

To understand the pattern and origin of Southern Hemisphere climate change, Brenda Hall and colleagues traveled to the remote Falkland Islands in the South Atlantic region.

“We wanted to compare the timing and pattern of glaciation with that in the Northern Hemisphere, as well as with

parts of the climate system thought to be important in controlling global temperatures, such as CO2 ,” Hall says. Hall and colleagues are finding evidence of an unusually long and dynamic Southern Hemisphere glacial period that cannot be explained readily by traditional hypotheses about ice age cycles.

Brenda Hall and her students use cosmogenic surface exposure dating to determine the timing of former ice fluctuations in the Falkland Islands. When rocks melt out of glaciers, they are exposed to incoming cosmic rays, which causes reactions within elements in the rock surfaces. These reactions cause the formation of new cosmogenic isotopes, the buildup of which allows calculation of the time since exposure.

“Past

into the

— Brenda Hall, Professor, Climate Change Institute and School of Earth and Climate

An expedition team from CCI, University of Heidelberg and University of Bern on Colle Gnifetti, Monte Rosa, Western European Alps retrieved one of the longest ice cores from the Alps. It was the first to be analyzed with CCI’s next-generation laser facility.

“We’re exploring the convergence of the world’s two major crises: man-made climate change and epidemic disease. Climate impacts the likelihood of new disease outbreaks. We study past cases to be prepared for the future.”

— Alexander More, Associate Professor, Long Island University and Climate Change InstituteHOW WILL climate change affect new outbreaks of epidemic disease?

How do pandemics and climate change impact air quality? These are some of the crucial questions that a collaboration between the Climate Change Institute and the Science of the Human Past at Harvard University have tackled in a nine-year collaboration that included professors Paul Andrew Mayewski, Andrei Kurbatov, Elena Korotkikh, Pascal Bohleber, Nicole Spaulding (CCI), and Associate Professor Alexander More (CCI-Harvard-LIU) and Professor Michael McCormick (Harvard). In 2013, supported by the Arcadia Fund, a joint team of University of

Heidelberg, University of Bern and CCI scientists retrieved an ice core from Monte Rosa, in the western European Alps. After analyzing the ice with a next-generation laser system designed, built and operated at CCI’s W.M. Keck Laser Ice Facility, the power of interdisciplinary analysis — combining ultra-high-resolution climate and historical data — began to reveal answers to the greatest challenges of our time.

Climate change affects how infectious disease spreads — changing how animals, insects, and humans move and source their food and water

— but it can also decrease air quality.

Six and a half million people die due to air pollution every year, according to the World Health Organization. Our research, first authored by CCI Ph.D. student Heather Clifford — including the longest, highest-resolution, continuous Saharan dust record — has shown that more intense Saharan dust storms will reach Europe and cross the Atlantic.

Such storms present a significant health risk, by increasing the number of fine particles (PM2.5) in the air, a direct cause of cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. Iron-rich, red Saharan dust also darkens glaciers, speeding up their melting and aids cholera bacteria reproduction.

Caribou (reindeer) are one of two species of megagrazers to survive the Pleistocene extinctions, along with muskox. Both species’ populations are strongly impacted by climate change, and their role in shaping tundra ecosystems is an ongoing area of research.

Photo by Daniel Ackerman

— Jacquelyn Gill, Associate Professor of

and Plant Ecology, Climate Change Institute, and School of Biology and Ecology

Photo by Daniel Ackerman

— Jacquelyn Gill, Associate Professor of

and Plant Ecology, Climate Change Institute, and School of Biology and Ecology

THE ARCTIC is warming three times faster than the Earth’s average, which is having a profound impact on plants, animals and the human communities that rely on these ecosystems. At the end of the last ice age, these environments were home to a diverse population of woolly mammoths and other megafauna, inhabiting a unique environment known as the Mammoth Steppe.

Today, these giant beasts no longer roam this “Serengeti of the Ice Age,” but there’s a growing interest in the role that surviving megafauna may play in maintaining a resilient tundra. To

tackle this question, Jacquelyn Gill and her team are investigating the impacts of ancient and modern grazers in promoting ecological resilience, preventing shrub encroachment and maintaining the integrity of the permafrost.

“It may be too late for woolly mammoths,” Gill says, “but the surviving members of the Mammoth Steppe may be an important conservation tool in a warming world.”

In New England, alpine plant communities are tiny islands of tundra dating back to the end of the last ice age. As the climate warmed, Arctic vegetation tracked the receding glaciers northward, leaving behind populations of plants above the treeline that have persisted for thousands of years. These iconic ecosystems draw thousands of tourists every year to these unique vistas, but we know almost nothing about their long-term resilience. Graduate student Andrea Tirrel and undergraduate Mike Cianchette sampled the vegetation on Mount Mansfield, Vermont, to learn how a century of warming has impacted these highelevation ecosystems.

“Large herbivores are some of our most threatened species today, but we’re just beginning to understand how their extinctions impact the ecosystems they live in. This is especially important in the Arctic, which has seen so many profound changes in the last 20,000 years.”

Paleoecology

Our involvement as donors to graduate programs at UMaine has become one of the most rewarding aspects of our lives. UMaine has helped us to target giving to those areas that we value most and to see funds being put to use highly efficiently and with maximum impact. We have also learned that faculty and students at UMaine participate in one of the best collaborative work environments, one that attracts and supports some remarkable people and allows them to accomplish outstanding work.

THE PURPOSE of the Dan and Betty Churchill Exploration fund is to finance student involvement in Climate Change Institute expeditions in order to further the education of talented students and to support first-class research in those instances where funds would not be available from public sources. The fund has provided seed money to cover travel costs on many expeditions that have produced significant results, which, in turn, permitted successful applications

for substantial public funding.

Dan Churchill had a career in international corporate finance, and Betty in federal service, that allowed them to live and work in Europe for 23 years. They believe that broad quality education, including international exposure, as well as first-class research in globally important areas, including climate change, are needed more now than ever.

Paul Andrew Mayewski notes that the Climate Change Institute has benefited from Dan and Betty Churchill’s presence since 2005 in so many remarkable ways. The Churchill funding has opened the way for exploration for many CCI graduate students. Dan and Betty have shared their experiences in industry and government, and their respect and love for looking forward and into new places.

The Churchills have accompanied researchers on some CCI expeditions to remote reaches of the Earth and they have helped move climate science into the policy arena. Now, they are providing even more opportunities for the Climate Change Institute to remain in the forefront of discovery and in charting pathways forward for the constantly emerging challenges posed by climate change.

“It has been an undiluted pleasure to feel that we are contributing in some way to important work at the CCI, addressing some of the most critical environmental and climate issues the world faces today. But perhaps the most rewarding aspect has been to come to know and develop friendships with young people who are committing their lives to science and service that make a difference in the world.”

— Daniel D. Churchill, Class of 1963; Betty R. Churchill, Honorary Alumna, Class of 2021

A 14,000-year paleoecological reconstruction of the Falkland Islands found that seabird establishment occurred during a period of regional cooling 5,000 years ago. Their populations, in turn, shifted the Falkland Islands ecosystems through the deposit of high concentrations of guano that helped nourish tussac, produce peat and increase incidence of fire.

This terrestrial-marine link is critical to the islands’ grasslands conservation efforts, says Dulcinea Groff, who led the research as a UMaine Ph.D. student in ecology and environmental sciences, part of a National Science Foundationfunded Interdisciplinary Graduate Education Research Traineeship in Adaptation to Abrupt Climate Change in CCI.

Groff conducted the Falkland Islands research during expeditions in 2014 and 2016 led by Jacquelyn Gill, a UMaine CCI associate professor of paleoecology and plant ecology.

Every year since 1982, professor emeritus Joseph Kelley, CCI and School of Earth and Climate Sciences, captured photos of the fastest deteriorating portion of Maine’s coast, located in Camp Ellis, for use in his work as a state marine geologist, and research and teaching at the University of Maine.

The public now has the opportunity to view decades of geologic transformation captured in thousands of images depicting dramatic changes in Maine’s coastal vistas.

Kelley partnered with the Maine Geological Survey to archive 8,000 of his landscape images, most of which depict the coast, in an online database on the state agency’s website. Users have access to photos capturing vistas at particular moments in history and time series collections featuring the shifting geology of certain places over time. The U.S. Geological Survey provided more than $30,000 in funding for the archiving project.

The coast of Maine always changes, and every photograph of it captures an iteration no one will witness again, says Kelley, whose research conducted in the last 38 years included studies of the response of developed and pristine shorelines to sea level change.

On the north coast of Peru, CCI-affiliated researchers have discovered the oldest adobe architecture in the Americas, constructed with ancient mud bricks carved from natural clay deposits created by El Niño flooding. Led by archaeologist Ana Cecilia Mauricio, now a professor of archaeology at the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, this research began when Mauricio was an Interdisciplinary Ph.D. student (awarded 2015; M.S. in Quaternary and Climate Studies awarded 2012) in geoarchaeology in the Climate Change Institute, advised by CCI faculty members Dan Sandweiss and Alice Kelley.

The discovery was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in late 2021 and highlighted in Nature. Kelley and Sandweiss are co-authors on the paper.

The pre-Hispanic bricks were carved from sedimentary layers deposited by El Niño floods, rather than being created by mixing clay, temper and water as were later adobes. The finds at Los Morteros date the invention of adobe architecture to more than 5,100 years ago, according to the international research team. In the Andes, early adobe monumental structures are associated with communal ceremonies and the rise of social complexity.

Mauricio has been conducting archaeological and geoarchaeological studies at the site of Los Morteros and its surroundings since 2012. She has demonstrated that the mound — once thought to be a natural phenomenon — is the site of monumental architecture. This work builds on prior georadar studies at the site in 2006 and 2010 by CCI researchers Dan Sandweiss, Alice Kelley, and Joseph Kelley and Daniel Belknap, both in CCI and the School of Earth and Climate Sciences.

Experts from the University of Maine, Harvard and Long Island universities, and the University of Maine School of Law have created a website with 10 talking points titled “Why Climate Change Matters to Your Security, Health & Wealth.” The site offers a one-stop shop for undecided voters and the general public to understand how climate change affects the most sensitive aspects of their everyday lives, and how efforts to reduce and reverse its effects represent the defining opportunity of our time. Paul Andrew Mayewski, Distinguished Maine Professor and director of the Climate Change Institute (CCI) at UMaine; Alexander More, associate professor of environmental health at LIU and research associate at Harvard and CCI; and Charles H. Norchi, the Benjamin Thompson Professor of Law at the University of Maine School of Law and director of the Center for Oceans and Coastal Law, framed the talking points and the research supporting them.

The history of South America’s retreating glaciers is the focus of a three-year National Science Foundation study led by Brenda Hall, University of Maine professor of glacial geology in the School of Earth and Climate Sciences and CCI.

The research will help clarify the timing of the last ice age termination in the Southern Hemisphere and the forces behind it by studying the glaciers in the Cordillera Darwin. Delving deeper into the last ice age termination, the largest natural warming event in recent geological history, could provide more context for understanding rising global temperatures and improve climate predictions.

Research team members include George Denton and Aaron Putnam, both with the School of Earth and Climate Sciences and CCI; Joellen Russell, an Earth-system modeler from the University of Arizona, and Patricio Moreno, a paleoecologist from the University of Chile.

As the climate continues to warm, scientists expect the frequency, intensity and duration of heat waves — consecutive days with extreme daily temperatures — to increase.

Bradfield Lyon found the spatial area of heat waves also is important.

By mid-century (2031–55), in a middle-of-theroad greenhouse gas emissions scenario, the average area of heat waves could increase by 50%.

And if greenhouse emissions continue unabated, the average heat wave area could increase by 80%, says the associate research professor with the CCI and School of Earth and Climate Sciences.

As the physical size of these affected regions increases, more people will be exposed to heat stress, Lyon says. Larger heat waves would also increase electrical loads and peak energy demand on the grid as more people and businesses turn on air conditioning in response.

Lyon’s study could provide a framework for utilities to stress-test their capacities to meet requirements during spatially extensive heat waves. This could inform management decisions and planning.

A discovery by University of Maine researchers challenges what was believed to be the established volcanic source of particles found in an ice core from the South Pole. The new findings also add to the global record of volcanic activity and are relevant to several research disciplines.

Detailed records of past volcanic eruptions are often required to understand volcanic activity-climate system interactions, and reconstructions of how past volcanic events have affected human history.

In many parts of the world, historical records are sporadic, short and not well documented, according to Andrei Kurbatov, associate professor in the School of Earth and Climate Sciences and CCI.

In the last decade, Kurbatov and Martin Yates, electron beam laboratory manager and instructor of Earth sciences at UMaine, in collaboration with Nelia Dunbar and Nels Iverson from the New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology, developed a method of extracting volcanic ash particles from ice core samples to measure their geochemical composition.

The methodology provides additional means to refine the history of global volcanism captured in polar ice core records, says Kurbatov. With funding from the National Science Foundation, the team will explore volcanic deposits in the South Pole ice core to further refine the global record of volcanism.

To understand industrial-age glacier recession and climate warming in New Zealand, an international research team led by the University of Maine will document the past 10,000 years of natural variations by studying the moraines of retreating glaciers and rings of temperature-sensitive trees in the Southern Hemisphere.

The data will allow scientists to compare the Holocene-era glacier and climate changes in the Southern Alps of New Zealand and the European Alps — mountain ranges on opposite sides of the planet. The goal is to understand natural climate drivers, and whether documented climatic anomalies of the Northern Hemisphere were regional or global in scope.

The three-year collaborative research project, funded by a nearly $637,000 award from the National Science Foundation, is led by Aaron Putnam, associate professor in the School of Earth and Climate Sciences and CCI.

In New Zealand’s Southern Alps, the research team will use the latest in cosmogenic nuclide technology to date glacial landforms and recently deglaciated organic remains to establish accurate timelines of glacier changes. In addition, tree rings of South Island silver pines will be used to document climatic fluctuations on annual timescales.

Archaeological research focused on the World War II German prisoner of war (POW) camp that was located on Passamaquoddy land in eastern Maine has been recognized with a 2019–20 American Fellowship from the American Association of University Women (AAUW).

The fellowship provides a $6,000 grant to support the work of UMaine assistant professor of anthropology and CCI Bonnie Newsom with Passamaquoddy Tribal Historic Preservation Officer Donald Soctomah, leading to publication of the results of their archaeological study of the former site of the POW camp — one of seven in Maine. In 2013, Newsom collaborated with Soctomah and supervised an archaeological study of the site as part of a U.S. Department of Defense munitions clean-up effort.

Newsom will use the technical report from that study as the basis for a broader manuscript focused on the history of the POW camp in Passamaquoddy homeland, including results of the site excavations. The current communitybased research expands on the social aspects of a World War II POW camp on Passamaquoddy land.

New evidence shows that Arctic ecosystems undergo rapid, strong and pervasive environmental changes in response to climate shifts, even those of moderate magnitude, according to an international research team led by the University of Maine.

Links between abrupt climate change and environmental response have long been considered delayed or dampened by internal ecosystem dynamics, or only strong in large-magnitude climate shifts. The research team, led by Jasmine Saros, CCI associate director, found evidence of a “surprisingly tight coupling” of environmental responses in an Arctic ecosystem experiencing rapid climate change.

Using more than 40 years of weather data and paleoecological reconstructions, the 20-member team quantified rapid environmental responses to recent abrupt climate change in West Greenland. It found that after 1994, mean June air temperatures were 2.2 degrees C higher and mean winter precipitation doubled to 40 millimeters. Since 2006, mean July air temperatures shifted 1.1 degree C higher.

The “nearly synchronous” environmental response to those highlatitude abrupt climate shifts included increased ice sheet discharge and dust, and advanced plant phenology.

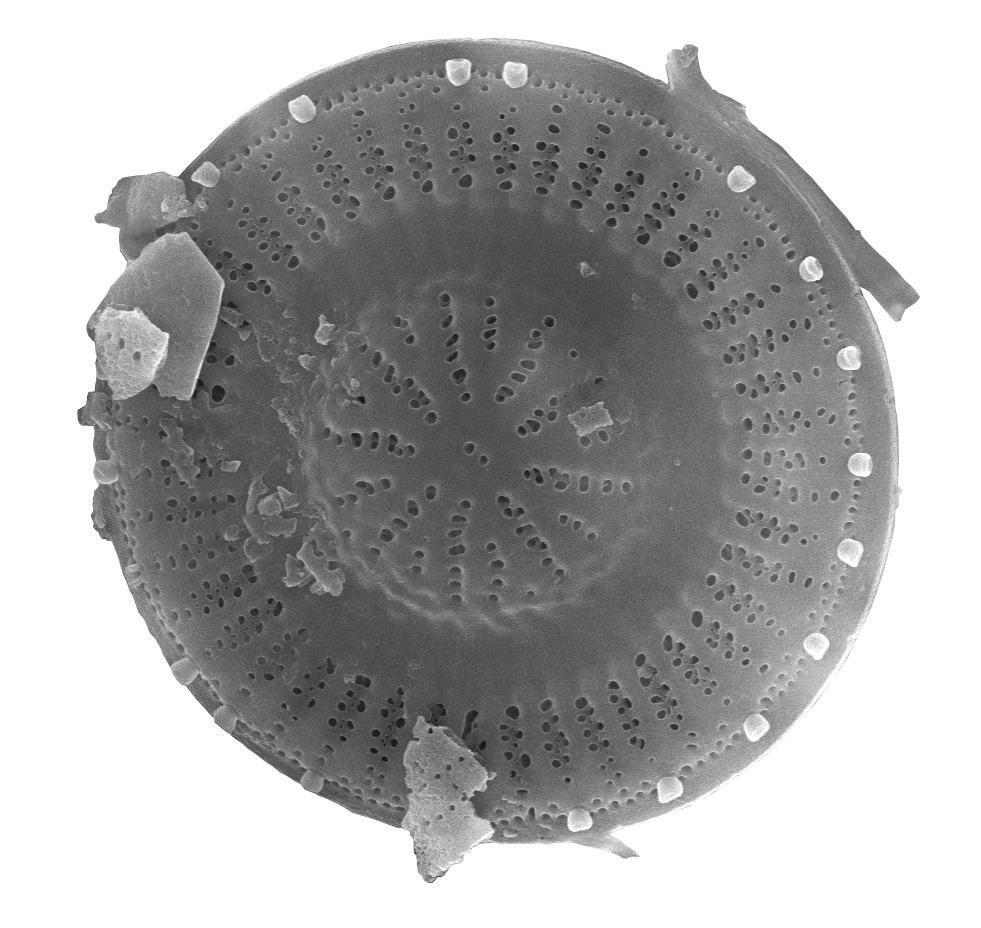

Just above the Arctic Circle, a University of Maine-led research team conducted a large-scale experiment to test the role of lakes’ thermal structure on Discostella stelligera, a species of diatom whose abundance is often used as an indicator of warminginduced changes in lakes throughout the northern hemisphere.

UMaine researchers are studying the effects of a changing climate on lakes by looking at a species of single-celled algae that leave microscopic silica fossils in lake sediments, creating a paleolimnological record of past environmental conditions that can extend thousands of years.

The team, led by Jasmine Saros, professor of paleoecology and lake ecology in the School of Biology and Ecology and CCI, shared the findings in the journal Limnology and Oceanography Letters.

Saros and her team evaluated the abundance of the species in two small Arctic lakes near Kangerlussuaq, Greenland. In many Arctic lakes during the summer, a warm, less dense layer of water, heated by the sun, forms at the surface and “floats’”on the cooler, denser water below. The point at which these two layers meet is known as the mixing depth.

Many climate- and environmental-related factors can influence a lake’s thermal structure, including atmospheric temperature, solar radiation, wind strength, changing water chemistry and turbidity. The researchers confirmed that D. stelligera thrive in lakes with shallower mixing depths.

Monitoring concentrations of dissolved organic carbon in Maine lakes before and after severe rainstorms could inform management strategies to help ensure consistent, high-quality drinking water, according to University of Maine researchers.

In their study, working with local drinking water districts, Kate Warner and Jasmine Saros, researchers in CCI and the School of Biology and Ecology, found that increasingly frequent and extreme rain events can contribute to short-term abrupt changes in the quantity and quality of lakes’ dissolved organic carbon.

The goal is to better understand the effect of severe rainstorms on freshwater ecosystems and, in particular, how dissolved organic carbon is changing in Maine lakes that are used for drinking water.

Katherine Allen, a UMaine assistant professor in the School of Earth and Climate Sciences and CCI, has received a more than $584,000 National Science Foundation CAREER Award to study Gulf of Maine temperatures from the early Holocene to the present.

In August 2021, Allen led a research team on a 10-day expedition in the Gulf of Maine to collect plankton, seawater and marine sediments. Allen analyzes the chemical composition of marine microfossils — shells — that have accumulated on the sea floor for thousands of years to understand past ocean conditions.